TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

—The transcriber of this project created the book cover image using the title page of the original book. The image is placed in the public domain.

The Disaster to the West Wind. Page 67.

ELM ISLAND STORIES.

THE

YOUNG SHIP-BUILDERS

OF

ELM ISLAND.

BY

REV. ELIJAH KELLOGG,

AUTHOR OF “LION BEN OF ELM ISLAND,” “CHARLIE BELL OF ELM ISLAND,”

“THE ARK OF ELM ISLAND,” “THE BOY FARMERS OF ELM

ISLAND,” “THE HARD SCRABBLE OF

ELM ISLAND,” ETC.

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS.

NEW YORK:

LEE, SHEPARD & DILLINGHAM, 49 GREENE STREET.

1871.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1870, by

LEE AND SHEPARD,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

ELECTROTYPED AT THE

BOSTON STEREOTYPE FOUNDRY,

19 Spring Lane.

PREFACE.

The natural progress of this series has brought us to a period in the history of our young friends, when, instead of labors in a measure voluntary, pursued at home, amid home comforts, they toil for exacting masters or the public, enter into competition with others, feel the pressure of responsibility, learn submission, and are tied down to rigid rules and severe tasks. The manner in which they meet and sustain these new and trying relations shows the stuff they are made of; that the fear of God in a young heart is a shield in the hour of temptation, the foundation of true courage, and the strongest incentive to manly effort; that he who does the best for his employer does the best for himself; that the[4] boy in whose character are the germs of sterling worth, and a true manhood, will scorn to lead a useless life, eat the bread he has not earned, and live upon the bounty of parents and friends.

ELM ISLAND STORIES.

1. LION BEN OF ELM ISLAND.

2. CHARLIE BELL, THE WAIF OF ELM ISLAND.

3. THE ARK OF ELM ISLAND.

4. THE BOY FARMERS OF ELM ISLAND.

5. THE YOUNG SHIP-BUILDERS OF ELM ISLAND.

6. THE HARD-SCRABBLE OF ELM ISLAND.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Learning a Trade | 9 |

| II. | Gunning on the Outer Reefs | 21 |

| III. | Internal Improvements | 37 |

| IV. | The West Wind | 53 |

| V. | Haps and Mishaps | 71 |

| VI. | Parson Goodhue and the Wild Gander | 89 |

| VII. | Charlie gets new Ideas while in Boston | 107 |

| VIII. | No give up to Charlie | 120 |

| IX. | Charlie learning a new Language | 133 |

| X. | Where there’s a Will there’s a Way | 146 |

| XI. | Pomp’s Pond | 152 |

| XII. | Charlie unconsciously prefigures the Future | 166 |

| XIII. | Better let sleeping Dogs alone | 186 |

| XIV. | Victory at last | 196 |

| XV. | The Surpriser surprised | 207 |

| XVI.[8] | Why Charlie didn’t want to sell the Wings of the Morning | 222 |

| XVII. | Charlie exploring the Coast | 236 |

| XVIII. | Charlie becomes a Freeholder | 256 |

| XIX. | Charlie in the Ship-yard | 272 |

| XX. | The first Trouble and the first Prayer | 289 |

THE YOUNG SHIP-BUILDERS

OF

ELM ISLAND.

CHAPTER I.

LEARNING A TRADE.

The question, What shall I do in life? is, to an industrious, ambitious boy, desirous to make the most of himself, quite a trying one.

Thoughts of that nature were busy at the heart of John Rhines; he now had leisure to indulge them, as, upon his return from Elm Island, he found that the harvesting was all secured, and the winter school not yet commenced. The whole summer had been one continued scene of hard work and pleasurable excitement. Missing his companions, being somewhat lonesome and at a loss what to do with himself, he would take his gun, wander off in the woods, and sitting down[10] on a log, turn the matter over in his mind. At one time he thought of going into the forest and cutting out a farm, as Ben had done; he had often talked the matter over with Charlie, who cherished similar ideas. Sometimes he thought of learning a trade, but could not settle upon one that suited him, for which, he conceived, he had a capacity. Again, he thought of being a sailor; but he knew that both father and mother would be utterly opposed to it. While thus debating with himself, that Providence, which we believe has much to do with human occupations, determined the whole matter in the easiest and most natural manner imaginable. John Rhines, though a noble boy to work, had never manifested any mechanical ability or inclination whatever. If he wanted anything made, he would go over to Uncle Isaac and do some farming work for him, while he made it for him.

It so happened, while he was thus at leisure, that his father sent him down to the shop of Peter Brock with a crowbar, to have it forged over. (The readers of the previous volume well know that Ben, when at home, had tools made on purpose for him, which nobody else could handle.) This was Ben’s bar. Captain Rhines had determined[11] to make two of it, and sent it to the shop with orders to cut it in two parts, draw them down, and steel-point them. John, having flung down the bar and delivered the message, was going home again, when Peter said,—

“Won’t you strike for me to draw this down? It’s a big piece of iron. My apprentice, Sam Rounds, has gone home sick; besides, when I weld the steel on, I must have somebody to take it out of the fire and hold it for me, while I weld it.”

“I had rather do it than not, Peter. I want something to do, for I feel kind of lonesome.”

Stripping off his jacket, he caught up the big sledge, and soon rendered his friend efficient aid.

“There’s not another boy in town could swing that sledge,” said Peter. “Do you ever expect to be as stout as Ben?”

“I don’t know; I should like to be.”

“Are you done on the island?”

“Yes.”

“They say you three boys did a great summer’s work.”

“We did the best we could.”

“I know that most of the people thought it wasn’t a very good calculation in your brother[12] Ben to go off and leave three boys to plan for themselves, and that there wouldn’t be much done—at any rate that’s the way I heard them talk while they were having their horses shod.”

“That was just what made us work. If a man hires me, and then goes hiding behind the fences, and smelling round, to see whether I am at work or not, I don’t think much of him; but if he trusts me, puts confidence in me, won’t I work for that man! Yes, harder than I would for myself. But what did they say when they came home from husking?”

“O, the boot was on the other leg then; there never was such crops of corn and potatoes raised in this town before on the same ground. Has your father got his harvest in?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I’ve got a lot of axes to make for the logging swamp; my apprentice has got a fever; I must have some one to strike; I tried for Joe Griffin, but he’s going into the woods, and Henry too; why can’t you help me?”

“I don’t know how.”

“All I want of you is to blow and strike; you will soon learn to strike fair; you are certainly strong enough.”

“Reckon I am. I can lift your load, and you on top of it.”

“Well, then, why can’t you help me? I’m sure I don’t know what I shall do.”

“If father is willing, I’ll help you till school begins.”

The result was, that John, in a short time, evinced, not only a great fondness, but also a remarkable capacity for the work, made flounder and eel-spears, clam-forks, and mended all his father’s broken hay-forks and other tools.

John worked with Peter till school began. The day before going to school, he went to see Charlie, as passing to and from the island in winter was so difficult they seldom met.

To the great surprise of Charlie, Ben, and Sally, who never knew John to be guilty of making anything, he presented Charlie with two iron anchors for the Sea-foam, with iron stocks and rings complete, and Ben with an eel-spear and clam-fork, very neatly made.

“What neat little things they are!” said Charlie, looking at the anchors. “Where did you get them?”

“Made them,” replied John, “at Peter’s shop.”

“Why, John,” said Ben, “you’ve broken out in a bran-new place!”

John then told him that he had been at work in the blacksmith’s shop, how well he liked it, and that, after school was out, he meant to ask his father to let him learn the trade.

“John,” said Ben, “Uncle Isaac, Joe Griffin, and myself have been talking this two years about going outside gunning. If I go, I want to go before the menhaden are all gone; for we shall want bait, in order that we may fish as well as gun. It is late now, and the first north-easter will drive the menhaden all out of the bay.”

“I heard him and Joe talking about it the other day; they said they calculated to go.”

“Well, tell them I’m ready at any time, and to come on, whenever they think it is suitable.”

John and Charlie went to the shore to sail the Sea-foam,—a boat, three feet long, rigged into a schooner,—and try the new anchors. While they were looking at her, Charlie fell into a reverie.

“Didn’t she go across quick, that time, Charlie?”

No reply.

“Charlie, didn’t she steer herself well then?”

Still no answer.

“What are you thinking about, Charlie?”

“You see what a good wind she holds, John?”

“Yes.”

“And how well she works, just like any vessel?”

“Well, then, what is the reason we couldn’t dig out a boat big enough to sail in, and model her just like that? These canoes are not much better than hog’s troughs.”

“It would take an everlasting great log to have any room inside, except right in the middle.”

“We could dig her out very thin, and make her long enough to make up for the sharp ends.”

“It would be a great idea. I should like dearly to try it.”

The boys now went to bed and talked boat till they worked themselves into a complete fever, and were fully determined to realize this novel idea; for, as is generally the case in such matters, the more they deliberated upon and took counsel about it, the more feasible it seemed; then they considered and magnified the astonishment of Fred and Captain Rhines when they should sail over in their new craft, and finally settled down into the belief that, if they realized their idea, it would not fall one whit short of the conception and construction of the Ark herself.

But the main difficulty—and it was one that seemed to threaten failure to the whole matter—was,[16] where to obtain a log, as one of sufficient size for that purpose would make a mast for a ship of the line, and was too valuable, even in those days, to cut for a plaything, as it was by no means certain that she would ever be anything more: there were indeed trees enough, with short butts, large enough for their purpose, had they wanted to make a common float, or a canoe, with round ends, like a common tray; but, as they were to sharpen up the ends vessel fashion, give her quite a sharp floor, and take so much from the outside in order to shape her, it was necessary that the tree should be long, as well as large, to be recompensed by length for the room thus taken from the inside, and leave sufficient thickness of wood to hold together.

While Charlie was debating in his own mind whether to ask his father to permit him to cut such a tree, John, with a flash of recollection that sent the words from his lips with the velocity of a shell from a mortar, exclaimed, jumping up on end in bed,—

“I have it now! there’s a log been lying all summer in our cove, that came there in the last freshet, with no mark on it, more than thirty feet long, and I know it’s more’n five feet through: it’s[17] a bouncer, I tell you; but it’s hollow at the butt, and I suppose that’s what they condemned it for; but I don’t believe the hollow runs in far. It’s mine, for I picked it up and fastened it.”

“But you are going to school. You can’t help me make it; and we should have such a good time. It is too bad!”

“Well, I can do this much towards it. I don’t care a great deal about going to school the first day; they won’t do much. I’ll help you tow it over, and haul it up; and if you don’t get it done before, when school is done, I’ll come on, help you make sugar, and finish the boat.”

“Then I won’t do any more than to dig some of it out. I won’t make the outside till you come.”

In the morning they went over to look at it, and found the hollow only extended about four feet. It was afloat and fastened with a rope, just as John had secured it in the spring. They towed it home without attracting notice, as they considered it very important to keep the matter secret till the craft was completed.

“Then,” said Charlie, “if we should spoil the log, and don’t make a boat, there will be nobody to laugh at us.”

Putting down skids, they hauled it up on to the grass ground with the oxen, and, with a cross-cut saw, made it the right length. As all above the middle of the log had to be cut away, and was of no use to them, it was evident, that if they could split it in halves, the other half would make a canoe, clapboards, or shingles.

“This is a beautiful log,” said Charlie. “It is too bad to cut half of it into chips. It is straight-grained and clear of knots; we will split it.”

“Split it!” said John; “‘twould take a week!”

“No, it won’t. We can split it with powder.”

“I never thought of that.”

They bored holes in the log at intervals of three feet, filled them part full of powder, and drove in a plug with a score cut in the side of it. Into this they poured powder, to communicate with that in the hole. They then laid a train, and touched them all at once, when the log flew apart in an instant, splitting as straight as the two halves of an acorn.

“I’ll take the half you don’t want, boys,” said Ben, who, unnoticed, had watched their proceedings; “it will make splendid clapboards.”

During the winter, on half holidays, and at every leisure moment, John Rhines was to be[19] found at the blacksmith’s shop. At length he could contain himself no longer, but went to his father and asked permission to learn the blacksmith’s trade of Peter. John anticipated a hard struggle in obtaining his father’s consent, if indeed he obtained it at all, as there was a large farm to take care of, plenty to do at home, and enough to do with. But Captain Rhines, who had always said, if a boy would only work steadily, his own inclinations should be consulted in choice of occupation, was so rejoiced to find he didn’t want to go to sea, of which he had always been apprehensive, that he yielded the point at once.

“It is a good trade, John,” said he, “and always will be; but I wouldn’t think of learning a trade of Peter.”

“Why not, father?”

“Because he’s no workman; he’s just a botcher.”

“Who shall I learn of?”

“I’ll tell you, my son; go to Portland and learn to do ship-work; there’s money in that; ship-building is going to be the great business along shore for many a year to come. You’ll make more money forging fishermen’s anchors, or doing the iron-work of a vessel, in one season, than you would mending carts, shoeing old horses and oxen,[20] making axes, pitchforks, and chains in three years. My old friend, Captain Starrett, has a brother who is a capital workman, a finished mechanic, learned his trade in the old country—and his wife is a first-rate woman; she went from this town. I’ll get you a chance there.”

Captain Rhines went to Portland in the course of the winter, and secured an opportunity for John to begin to work the first of May.

CHAPTER II.

GUNNING ON THE OUTER REEFS.

Ben thought it was now a favorable time to do something to the house, and made up his mind to speak to Uncle Isaac and Sam when they came on for their gunning excursion, in order to obtain the aid of one to do the joiner, and the other the mason work, for he and Charlie could do the outside work. While preparing the cargo of the Ark, Ben had laid by, from time to time, such handsome, clear boards and plank as he came across, which were now thoroughly seasoned, having been kept in the chamber of the house. He also had on hand shingles and clapboards.

They now began to remove the hemlock bark from the roof, and replace it with shingles. To work with tools, to make something for his father and mother, was ever a favorite employment of Charlie.

Aside from this, his great delight was to make boats; his house under the big maple was half full[22] of boats, of all sizes, from three inches to two feet long. As he sat by the fire in the evenings, he was almost always whittling out a boat. When he went to Boston, in the Perseverance, he sought the ship-yards and boat-builders’ shops. He had a boat on each corner of the barn, one on the top of the big pine, and one on the maple, besides having made any number for John, Fred, and little Bob Smullen.

He was now greatly exercised in spirit in respect to the boat he was to make from the big log. He had resolved to make a model, and then imitate it, and was racking his brain in respect to the proportions; for he was very anxious she should be a good sailer.

He had not a moment to spare while they were shingling the house, it being necessary to do it quickly, for fear of rain; but the moment the roof was completed, he hid himself in the woods, and with blocks set to work upon the model.

While thus busied, he recollected having heard Captain Rhines say, that if anybody could model a vessel like a fish, it would sail fast enough. He thought a mackerel was the fastest fish within his reach.

“There are mackerel most always round the[23] wash rocks,” said he. “I’ll model her after a mackerel.”

The next morning, just before sunrise, he was off the reef, in the “Twilight,” and succeeded in catching three mackerel and some rock-fish. Not wishing any spectators of his proceedings, he hid the biggest mackerel in some water, to keep him plump, took the others, and went in to breakfast. He next took some of the blue clay from the bed of the brook, that was entirely free from stones and grit, and would not dull a razor; and, mixing it with water and sand, till it was of the right consistence, put it into a trough. Into this paste he carefully pressed the fish; then he took up the trough, and, finding a secret place at the shore, where the sun would come with full power, he placed it on the rocks, and sifted sand an inch thick over the clay and fish, and left it to harden.

In the course of three days, he found the fish had putrefied, and the clay gradually hardened under the sand without breaking. He now swept off the sand, exposing it to the full force of the sun till it was completely dry; then he made a slow fire, and put the trough and clay into it, increasing the heat gradually till he burned the trough away, and left the clay with the exact[24] impress of the mackerel in it, as red and hard as a brick.

“There’s the shape of the mackerel, anyhow,” said Charlie, contemplating his work with great satisfaction; “but how I’m going to get a model from it is the question; however, there is time enough to think of that between this and spring.”

He deposited his model in his house under the great maple, and devoted all his time to helping his father improve the appearance of the house.

Our readers will recollect that the logs, of which the house was built, were hewed square at the corners and windows; so Ben and Charlie just built a staging, and, stretching a chalk line, hewed the whole broadside from the ridge-pole to the sill square with the corners. They accomplished this quite easily at the ends, but on the front and back it was more difficult to hew the top log under the eaves; but they worked it out with the adze.

Originally the house had but two windows on a side, and, as these were on the corners to admit of putting in others, it looked queer enough. They now cut out places for two more in a side, and intended, after having smoothed the walls, to clapboard[25] them; but their work was interrupted for the time by the arrival of Uncle Isaac, Joe Griffin, Uncle Sam, and Captain Rhines, to go on the long-talked-of gunning excursion.

“I don’t see,” said Uncle Isaac, “how you do so much work; I think it is wonderful, the amount you and this boy have done since we were here.”

“There’s one thing you don’t consider,” said Ben: “a person here is not hindered; there’s not some one running in and out all the time, and he is not stopping to look at people that go along the road; he’s not plagued with other people’s cattle, and don’t have to fence against them; he’s not out evenings visiting, but goes to bed when he has done work, and the next morning he feels keen to go to work again. It’s my opinion, if a man is contented, he will stand his work better, live longer, and be happier, on one of these islands than anywhere else.”

As they were to start at twelve o’clock at night, they went to bed at dark. Captain Rhines slept on board the vessel, as he could wake at any hour he chose. He was to call the others if the weather was good; if not, they were to wait for another chance. It was bright moonlight; a little wind, north-west, just enough to carry them along, and[26] perfectly smooth. The place to which they were bound was an outlying rock in the open ocean, more than seven miles beyond the farthest land, upon which, even in calm weather, the ground swell of the ocean broke in sheets of white foam, and with a roar like thunder; but when a strong northerly wind had been blowing for a day or two, it drove back the ground swell, and when the northerly wind in its turn died away, there would be a few hours, and sometimes a day or two, of calm, when there was not the least motion, and you might land on the rock; but it was a delicate and dangerous proceeding, requiring great watchfulness, for although there might be no wind at the spot, yet the wind blowing at sea, miles distant, might in a few moments send in the ground swell and cut off all hope of escape. As the north wind made no ground swell, the rock could be approached on the south side, even when a moderate north wind was blowing.

They were familiar with all these facts, and had accordingly chosen the last of a norther, that had been blowing two days, and was dying away.

Some hours before day they arrived at the place—a large barren rock, containing about three acres, with a little patch of grass on the highest[27] part of it, and a spring of pure water, that spouted up from the crevices in the rock; a quantity of wild pea vines and bayberry bushes were growing there, among which, in little hollows in the rock, the sea-gulls laid their eggs, without any attempt at a nest.

As they neared the rock, they sailed through whole flocks of sea-birds; some of them, asleep on the water, with their heads beneath their wings, took no notice of them; others, as they heard the slight ripple made by the vessel’s bows, flew or swam to a short distance, and then remained quiet.

Not a word was spoken save in whisper, when, at a short distance outside the rock, the sails were gently lowered, and the anchor silently dropped without a splash to the bottom. The “decoys,” that is, wooden blocks made and painted in imitation of sea-birds, and the guns, were put into the canoe, and landing in a little cove, they gently hauled the canoe upon the sea-weed, and anchored their decoys with lines and stones a little way from the rock, so as to present the appearance of a flock of sea-fowl feeding, and, lying down, awaited daybreak.

The sea-fowl lie outside during the night, but as the day breaks they begin to fly into the bay after[28] food and water, and when they see the decoys, they light down among them and are shot; they are also shot on the wing as they fly over; and in those days they were very numerous among all the rocks and islands.

It was a terribly wild and desolate place; the tide at half ebb revealed the rock in its full proportions; on the shore side it ran out into long, broken points, ragged and worn, with innumerable holes and fissures, fringed with kelp, whose dark-red leaves, matted with green, lay upon the surface of the water; while on the ocean side, the long, upright cliffs dropped plump into the sea, and were covered with a peculiar kind of sea-weed, short, because, worn by the ceaseless action of the waves, it had no time to grow: all impressed the mind with a singular feeling of loneliness and desolation.

These hardy men, born among the surf, and by no means given to sentiment, could not repress a feeling of awe, as they lay there silent, and listened to the roar of the sea, that rolled in eddies of white foam among the ragged points, being raised by the north wind, while on the other side there was not a motion.

There is something in the hoarse roar of the[29] surf, when heard in the dead hours of night on such a spot, that is more than sublime—it is cruel, relentless. As we listen to it in such a place, from which there is more than a possibility that we may not escape, we realize how impotent is the strength or skill of man against the terrific rush of waters. We call to mind how many death-cries that sullen roar has drowned, how many mighty ships that gray foam has ground to powder, and look narrowly to see if the giant that thus moans in his slumbers is not about to rouse himself for our destruction. Yet to strong natures there is an indescribable charm that clings to places and perils like these, and does not fade away with the occasion, but lives in the memory ever after. These men could have shot sea-fowl enough near home, without fatigue or peril; but that very safety would have diminished the pleasure.

It was evident that thoughts similar to those we have described were passing through Ben’s mind.

He said, in a whisper, “Uncle Isaac, do you suppose the sea ever breaks over here?”

“I suppose it does,” was the reply; “but only when a very high tide and a gale of wind come together. Old Mr. Sam Edwards came on here once in November, and his canoe broke her[30] painter and got away from him, and he had to stay ten days, when a vessel took him off; but they had a desperate time to get him; and when they got him he couldn’t speak. He piled up a great heap of rocks to stand upon, to make signals to vessels, and to keep the wind off; and when he went on the next spring they were gone.”

“But there is white clover growing here, and red-top, which shows that the salt water cannot come very often, nor stay very long when it does come.”

It was now getting towards day; they had three guns apiece, which they loaded, and placed within reach of their hands. As the day broke, the birds began to come, first scattering, then in flocks; as they came on, they continued to fire as fast as they could load, the birds falling by dozens into the water, until the birds were done flying, the sun being well up.

They now took the canoe and picked up the dead and wounded birds, many of the latter requiring a second shot, then going on board the schooner with their booty, got their breakfast, after which they ran off ten miles to sea, on to a shoal, to try for codfish; and as they had menhaden and herring for bait, they caught them in plenty.

“Halloo!” said Ben; “I’ve got a halibut; stand by, father, with the gaff.”

They caught three more in the course of the forenoon. After dinner they split and salted their fish, and cutting out the nape and fins of the halibut, threw all the rest away, as in those days they did not think it worth saving.

“Now,” said Uncle Isaac, “what do you think of having a night at the hake?”

They ran into muddy bottom near to the rock, anchored, and lay down to sleep till dark, and then began to catch hake. The hake is a fish that feeds on the muddy bottom, and bites best in the night.

Just before day they went on to the rock again, and shot more birds than before. Uncle Isaac and the others were so much engrossed with their sport, that they thought of nothing else. But Ben, who was naturally vigilant, and had noticed that there was a little air of wind to the south, and the sea had a different motion, kept his eye upon it, and shoved the canoe to the edge of the water. All at once he exclaimed, in startling tones,—

“To the boat! The sea is coming!”

They seized their guns, and sprang into the canoe.

“I’ll shove off,” said Ben.

Uncle Isaac and Captain Rhines took the oars, while Uncle Sam, on his knees, was ready to bale out what water might come in.

The great black wave could now be seen rolling up higher and higher as it came. Ben, giving the canoe a vigorous shove, which sent her some yards from the rock, leaped in, and grasped the steering paddle, keeping her directly on to meet the threatening wave. As she met it and rose upon it, she stood almost upright; and for a moment it seemed as if she would fall back and be dashed on the rock; but the powerful strokes of the resolute oarsmen, added to the momentum she had already attained, forced her up the ascent, and they were safe. Had they been twice her length nearer the rock, they had been lost, as the sea, arrested in its progress by the rock, “combed” (curled over), when nothing could have saved them.

“A miss is as good as a mile,” said the captain, as he looked back and saw the spot where they had so lately stood white with foam.

“I’ve left my best powder-horn,” said Ben.

“We’ve left a couple dozen of birds,” said Uncle Isaac; “but we’ve enough without them.”

They now dressed the fish they had caught,[33] went to sleep, and slept till noon; then, as they had a fair wind home, debated, while sitting in the little cabin, what they should do more.

“We have some bait left,” said Uncle Isaac; “we ought to do something more.”

“Hark!” cried the captain, whose ear had caught a familiar sound; “mackerel, as I am a sinner!”

Rushing on deck, they saw mackerel all around the vessel, leaping from the water, their white bellies glancing in the sun. In a moment lines were thrown over with bait, and soon numbers of them were flapping on the deck.

It was now near sundown, the wind began to blow in fitful gusts, and once in a while, amid the constant dash of waves, a great sea would come and break with a roar far above the general dash of waters. But they were too eager in the pursuit of their prize to heed the weather.

At length a few drops of rain falling on the captain’s bare arms caused him to look up and around.

He instantly exclaimed,—

“Haul in your lines; we must be out of this; we are full near enough to these breakers to have them under our lee, and night coming on.”

It was a most perilous position to the eye of a landsman, and not without risk to them. The vessel was rolling heavily at her anchor less than a quarter of a mile from the rock, and abreast of the middle and highest part of it, while its long, shoal points stretched out each way for more than a mile, white with foam; the whole ground also, for three or four miles around the rock, was full of shoal spots and sunken reefs, which made a bad, irregular sea; and the roar from so many breakers was terrible. But if there is anything that will do its duty in a heavy head-beat sea, it is an old-fashioned pinkie.

As the little craft, gathering way, came up to the wind, the sea poured in floods over her bows, while, with whole sail and her lee rail under water, she jumped through it, and gradually drew off from the dangerous reefs.

Leaving the long reefs to the leeward, they now kept away before it with a fair wind for home. Taking in all but the foresail, they went along under moderate sail, that they might split their fish as they went, and before dark.

When they reached the island, it was quite dusk. The sea was pouring in sheets of foam upon the rocks, and the white froth, drifting to[35] leeward, had filled the main channel; so that to enter it seemed, to an inexperienced eye, to be rushing into the very jaws of destruction; but, as they dashed along by the very edge of the surf that fringed the “Junk of Pork,” just when the little vessel, rising on the crest of a tremendous wave, seemed to be rushing directly on the rocks, Ben, who stood at the fore-sheet, hauled it aft, the captain put down his helm, and the vessel, luffing up, shot through the froth and around the point into the quiet harbor in front of the house. Uncle Isaac let go the anchor, and in a moment she was peacefully riding where there was not a ripple, with the roar of surf all around her, and bunches of white froth drifting lazily alongside.

It is these strong contrasts which make the charm of life along shore, and that so attach rugged spirits to the sea; and though those who live among these scenes do not talk about them as others do, who seldom witness them, yet they feel them, and they are a part of their life. Taking out the birds and guns, they put them into the canoe to take on shore. Charlie met them there, and was dumb with astonishment at the sight of so many birds.

They were wet, tired, cold, and hungry, for they[36] had been fishing day and night; but as they entered the house, all was changed. A blazing fire was roaring in the great chimney, and flinging its cheerful light on the bright pewter on the dressers and snow-white floor.

The table stood in the floor, covered with smoking victuals, and Sally, with her handsome face shining with joy, stood ready to greet her husband. Sailor was at her side, wagging his tail with frantic violence, ready to jump upon his master as soon as Sally should release him. There were also warm water, soap, and towels to wash the “gurry” from their hands, and the salt of the spray from their faces. Great was the physical and mental happiness of these tired, hungry men, as they sat down to eat, conscious that they had succeeded in their efforts, and obtained the means of comfort and support for their families.

Perhaps some of our readers may think it strange that Ben should want to go fishing when he had been engaged in that business all summer; but the fish caught in the hot weather were salted very heavily, in order to keep them, and that they might bear exportation to all parts of the world; but these were to be slack salted for their own use.

CHAPTER III.

INTERNAL IMPROVEMENTS.

Before his father and friends returned home, Ben agreed with Uncle Isaac and Sam to come and commence work on the house whenever he should send for them, and at the same time made an arrangement with his father to take some fish and lumber to Salem in the schooner, and procure for him some bricks, hearth-tiles, window-glass, door-hinges, latches, materials for making putty, and other things needed about the house.

“My nephew, Sam Atkins,” said Uncle Isaac, “who is a capital workman, is coming home to stay a good part of the winter. He works on all the nicest houses in Salem. I’ll bring him on with me.”

It may not be amiss, for the information of those who have not read the first volume of the series, to glance for a moment at the house, in respect to which all these improvements were contemplated. Ben wanted to dig a cellar, a few rods off, and[38] build a good frame house, of two stories; but Sally preferred to finish the old walls. She said it was large enough, that the timber walls would be warmer than any frame house, and she loved the first spot. “Better save the money to buy cows, or to help some young man along that wanted a vessel.”

The kitchen extended the whole length of the house, and occupied half its width. At the eastern end a door opened directly to the weather; there was no entry. In the corner beside the door was a ladder, by which access was gained to the chamber through a scuttle in the floor.

Against the wall at the other end were the dressers, and under them a small closet. There was no finish around the chimney, and on either side of it two doors, of rough boards, hung on wooden hinges, opened into the front part of the house, which was in one large room. The cellar, which only extended under the front part of the house, was reached by a trap door.

The floors were well laid, of clear stuff, and the kitchen floor was white and smooth by the use of soap, and sand, and much friction.

The first thing Ben did when his men, Uncle Isaac, Atkins, and Robert Yelf, came, was to build[39] a porch, into which was moved Charlie’s sink, and at one end of which a store-room was made, where Sally could do part of her work, while everything was in confusion.

During the time the joiners were at work upon the porch, Ben and Charlie dug a cellar under the rest of the house, hauled the rocks from the shore, and Uncle Sam built the wall, and also took up the stone hearths in the front part of the house, and laid them with tiles, and built two fireplaces. He also laid a hearth with tiles in the kitchen, leaving a large stone in one corner to wash dishes on.

“Ben,” said Uncle Sam, “I told you, when I laid your door-steps, that they were the best of granite, and would make as handsome steps as any in the town of Boston, and that whenever you built a new house, if I was not past labor, I would dress them for you. I have brought on my tools, and now am going to do it.”

“I’m very much obliged to you, Uncle Sam, but I am able and willing to pay you for it now.”

“No, you ain’t going to pay me; ’twill be something for you to remember me by.”

They now set up their joiner’s bench in the front part of the house, where they could have a[40] fire in cold days. Ben and Charlie worked with them, and the work went on apace. At Sally’s request, they began with the kitchen, removing the dressers from the western end, and finishing off a bedroom, leaving room sufficient at the end for a stairway to go down into a nice milk cellar, which Uncle Sam had parted off, and floored with brick, and the joiners put up shelves, with a glass window in the end, and another in the top of the door that led to it from the kitchen. They also replaced the dressers in the kitchen. At the eastern end they made an entry, on one side of it a dark closet to keep meats in from the flies, and on the other chamber stairs, instead of the ladder, and under these cellar stairs, replacing the old trap door.

They then finished the room, ceiling it, both the walls and overhead. It was not customary then to paint. Everything was left white, and scoured with soap and sand. Carpets were not in vogue, and floors were strewn with white sand.

Sally was jubilant, and declared it was nothing but a pleasure to do work, with so many conveniences.

“I thought I was made,” said she, “when I got a sink, and especially a crane, instead of a birch withe, to hang my pot on. Now I’ve got a sink,[41] a crane, porch, meal-room, cellar stairs, chamber stairs, milk cellar, and kitchen, all ceiled up.”

In the front room the work proceeded more slowly, as there was a good deal of panel-work, and this occupied a great deal of time.

There were then no planing mills, jig saws, circular saws, or mortising machines, but all was done by hand labor. There were no cut nails then, but all were wrought, with sharp points that split the wood, which made it necessary to bore a great deal with a gimlet.

A happy boy was Charlie Bell in these days, as Uncle Isaac and Atkins gave him all the instruction in their power; and to complete the sum of his enjoyment, after he had worked with them six weeks, Uncle Isaac set him to making the front and end doors of panel-work, under his immediate inspection. He also had an opportunity to talk about the Indians, and seemed to be a great deal more concerned to know about their modes of getting along, and manufacturing articles of necessity or ornament, without tools of iron, than about their murdering and scalping.

Uncle Isaac could not, from personal knowledge, give him much information in respect to these matters, as, at the time he was among them, they[42] were, and had been for a long period, supplied, both by the French and English, with guns, knives, hatchets, needles, and files; but he could furnish Charlie with abundant information which he had obtained from his Indian parents; for, as they have no books, but trust to their memories, they, by exercise, become very accurate, and their traditions are, in this way, handed down from father to son.

“But,” said Charlie, who had heard about Indians having cornfields, “how could they cut down trees and clear land with stone hatchets?”

“They didn’t cut them down; they bruised the bark, and girdled them, and then the trees died, and they set them on fire.”

“I should think it would have taken them forever, most, to clear a piece of land in that way.”

“So it did; but they did not clear one very often. When they got a field cleared, they planted corn on it perhaps for a hundred years.”

“I should think it would have run out.”

“They always made these fields by the salt water, and put fish in the hills. They taught the white people how to raise corn.”

“I have heard they made log canoes. How could they cut the trees down with their stone[43] hatchets? and, more than all, how could they ever dig them out?”

“I will tell you, Mr. Inquisitive. An Indian would take a bag of parched corn to eat, a gourd shell to drink from, his stone hatchet, and go into the woods, find a suitable tree,—generally a dead, dry pine, with the limbs and bark all fallen off,—and at the foot of it would build a camp to sleep under. Then he would get a parcel of wet clay, and plaster the tree all around, then build a fire at the bottom to burn it off. The wet clay would prevent its burning too high up. Then he would sit and tend the fire, wet the clay, and beat off the coals as fast as they formed, till the tree fell; then cut it off, and hollow it in the same way.”

“I should think it would have taken a lifetime.”

“It did not take as long as you might suppose; besides, time was nothing to them. They did no work except to hunt, make a canoe, or bow and arrows. The squaws did all the drudgery.”

Uncle Isaac now went home to stay a week, and see to his affairs, and Atkins with him. In this interval, Charlie began to think about his long-neglected boat. He had already the exact model of the fish, but he wished to get it in a shape to[44] work from. Mixing some more clay and sand, he filled the mould with it, into which he had pressed the fish, having first greased it thoroughly, that it might not stick. He now set it to dry, putting it in the cellar at night. When thoroughly dry, he turned it out, made an oven of stones, and baked it, so that it was in a state to be handled without crumbling. He did not wish Ben or Sally to observe his proceedings; and, as it was too cold to stay in the woods or barn, he resorted to his bedroom. Uncle Isaac, when there, slept with Charlie, and kept his chest beside their bed.

Charlie was sitting on the bed, with the model in his hand, looking at it, and contriving how to work from it; and so intently was he engaged, that Uncle Isaac, who, unknown to him, had returned, and wanted something from his chest, came upon him before he could shove it under the bed.

“What have you got there, Charlie?”

“O, Uncle Isaac, I’m so sorry to see you!”

“Sorry to see me, Charlie? Indeed, I’m sorry to hear you say so.”

“O, I didn’t mean that,” replied Charlie, excessively confused. “I—I—I—only meant that I was sorry you caught me with this in my hand.”

He then told Uncle Isaac what he was about,[45] adding, in conclusion, “You see, when I am trying to study anything out, I don’t like to have folks that know all about it looking on; it confuses and quite upsets me.”

“But if you ever make the boat, you will have to make it out of doors, in plain sight.”

“Yes, sir; but if I succeed in making a good model, I know I can imitate it on a large scale, and shan’t be afraid then to do it before folks; but if I can’t, why, then I will burn the model up, and nobody will be the wiser for it, or know that I tried and couldn’t. I’m not afraid to have any one see me handle tools.”

“You have no reason to be, my boy. Yet, after all, it was a very good thing that I surprised you before you got any farther; for, had you built a large boat after these lines, she never would have been of any use to you.”

“Why not?”

“Because this is precisely the shape of a mackerel, to a shaving.”

“Well, don’t a mackerel sail?”

“Yes, sail like blazes, under water; but I take it you want your boat to sail on top of water. All a fish has to do is to carry himself through the water; but a boat or vessel has to carry cargo, and[46] bear sail. A vessel made after that model wouldn’t stand up in the harbor with her spars in, and a boat made like it would have to be filled so full of ballast, to keep her on her legs, that she would be almost sunk; and the moment you put sail on her, in anything of a working breeze, her after-sail would jam her stern down, and she would fill over the quarter.”

Charlie looked very blank indeed at this, which seemed at one fell blow to render abortive all his patient toil, and annihilate those sanguine hopes of proud enjoyment he and John had cherished, when they should appear in their new craft among the fleet of dug-outs, then below contempt, and witness the look of mingled astonishment and envy on the faces of the other boys, especially as he began to feel a growing conviction that what Uncle Isaac had said was but too true. Still struggling against the unwelcome truth, he replied, after a long pause, “But a mackerel keeps on his bottom.”

“Yes, because he’s alive, and can balance himself by his fins and tail; but he always turns bottom up the minute he is dead.”

“I heard Captain Rhines say, one time, that if a vessel could be modelled like a fish, she would[47] sail. I thought he knew, and so I determined to try it.”

“Captain Rhines does know, but he spoke at random. He didn’t mean exactly like a fish, but somewhat like them,—sharp, and with a true taper, having no slack place to drag dead water, but with proper bearings.”

“Then this model, with proper alterations, would be the thing, after all,” said Charlie, a gleam of hope lighting up his clouded features.

“Sartain, if you should—”

“O, don’t tell me, Uncle Isaac, don’t! It’s no use for me to try to make a boat if I can’t study it out of my own head. I think I see what you mean. I thank you very much, and after I try and see what I can do, I want you to look at it, and see how I’ve made out, and tell me how and where to alter it. I hope you won’t think I am a stuck-up, ungrateful boy, because I don’t want you to tell me.”

“Not by any means, Charlie; it is just the disposition I like to see in you. I have no doubt you will think it all out, and then, my boy, it will be your own all your life.”

“Yes, sir; for, when I went to school, I minded that the boys who were always running up to the[48] master with their slates, or to the bigger boys, to be shown about their sums, were great dunces, while the smart boys dug them out themselves.”

“I never went to school, but I suppose they forgot how to do them as fast as they were told.”

“That was just the way of it.”

The next day there came a snow-storm and a severe gale; the sea roared and flung itself upon the ramparts of the harbor as though it would force a passage; but, with roaring fires in the two fireplaces, the inmates of the timber house worked in their shirt sleeves, and paid very little attention to the weather.

“It is well you got on when you did, Uncle Isaac,” said Ben; “but you will have to stay, now you are here, for there will be very little crossing to the main land for the rest of the winter.”

“But what if any of my folks are sick? I told Hannah to make a signal on the end of the pint if anything happened.”

“In case of necessity, Charlie and I could set you off in the schooner.”

While Uncle Isaac was putting up the mantel-piece in the front room, which had a great deal of old-fashioned carving about it, he set Atkins and Charlie at work upon the front stairs; thus Charlie[49] was so constantly and agreeably occupied as to have but little leisure to spend upon boats. But when this job was over, which had been most interesting and exciting, he began to give shape to the ideas that had been germinating in his brain at intervals during the day, and in his wakeful hours at night.

He wanted some plastic material that would become hard when dry, with which to make his alterations, and determined to use putty. Leaving that portion of his model which was to be under water as it was, he made it fuller from that mark, by sticking on putty, and then, with his knife and a chisel, paring off or adding to correspond with his idea of proportions. For a long time did he puzzle over it, striving in vain to satisfy himself, and several times scraped it all off to the bare brick. At length he came to a point where he felt he could accomplish no more.

The next night, at bed-time, with a palpitating heart, he brought it forward for Uncle Isaac’s inspection. After looking at it long and carefully, he said,—

“I wish Joe Griffin was here. I ain’t much of a shipwright, though I have worked some in the yard, and made a good many spars for small vessels;[50] but he is, and has worked in Portsmouth on mast ships. But I call that a beautiful model, and think it shows a first-rate head-piece. She’s very sharp, and will want a good deal of ballast; so there won’t be much room in her as far as depth is consarned; but then she’s so long ’twill make up for it. She’s a beauty, and if you can ever make another on a large scale like her, I’ll wager my life she’ll sail. I suppose you’ll kind of expect me to find some fault, else you’ll think I’m stuffing you. It strikes me, that in the run, she comes out from the first shape a thought too quick; that it would be better if the swell was a leetle more gradual, not sucked out quite so much; but then I don’t want you to alter it for anything I say; but I’m going to call Ben and Robert Yelf up to see it.”

“O, don’t, Uncle Isaac! Father knows all about vessels, and Mr. Yelf is a regular shipwright.”

“So much the better; they’ll be able to see the merits of it.”

Ben and Yelf made the same criticism as Uncle Isaac, upon which Charlie amended the fault, till they expressed themselves satisfied.

“That boy,” said Yelf, as they went down stairs, “if he lives, and gives his mind to it, will make a first-rate ship-builder.”

“Ever since he has been with me,” was the reply, “he has been, at leisure moments, making boats. I believe he has a fleet, great and small, as numerous as the whole British navy.”

Not the least industrious personage among this busy crew was Ben Rhines, Jr.

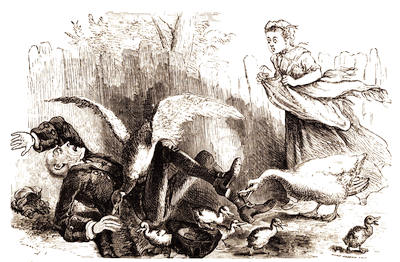

From morning to night, with a devotion worthy of a better cause, he improved every moment, doing mischief, till his mother was, at times, almost beside herself. One moment she would be startled by a terrific outcry from the buttery. Ben had tumbled down the buttery stairs; anon from the front entry he had fallen down the front stairs; then, from the cellar, he was kicking and screaming there.

This enterprising youth, bent upon acquiring knowledge, was determined to explore these new avenues of information. Twice he set the room in a blaze, by poking shavings into the fire, and singed his mischievous head to the scalp, and had a violent attack of vomiting in consequence of licking the oil from Uncle Isaac’s oil-stone. His lips were cut, and he was black and blue with bruises received in his efforts. Despite of all these mishaps, Ben enjoyed himself hugely; he had piles and piles of blocks, great long shavings, both[52] oak and pine, that came from the panels and the banisters; he would bury the cat and Sailor all up in shavings, and then clap his hands, and scream with delight, to see them dig out; he would also hide from his mother in them, and lie as still as though dead; he could pick up plenty of nails on the floor to drive into his blocks, and didn’t scruple in the least to take them from the nail-box if he got a chance. The moment Uncle Isaac’s back was turned, in went his fingers into the putty; he carried off the chalk-line, to fish down the buttery stairs, and, when caught, surrendered it only after a most desperate struggle.

“What a little varmint he is!” said Uncle Isaac. “If he don’t break his neck, he’ll be a smart one.”

“I believe you can’t kill him,” said Sally, “or he would have been dead long ago. He’s been into the water and fire, the oxen have trod on him, and a lobster shut his claws on his foot; why he ain’t dead I don’t see.”

CHAPTER IV.

THE WEST WIND.

It was now the middle of March, and the lower part of the house was finished.

“Ben,” said Uncle Isaac, “we want to go off now. Charlie can finish these chambers as well as I can.”

“I have not seasoned stuff to finish but one of them now, and hardly that. It’s too rough to go off in your canoe; stay till Saturday afternoon, and part off some bedrooms up stairs with a rough board partition, and make some rough doors, so that we can use them for sleeping-rooms, and then Charlie can finish them next winter, for he will have to go to making sugar soon. If you’ll do that I’ll set you off in the schooner.”

Uncle Isaac parted off the chambers, and they now had plenty of room. They put the best bed in one of the front rooms; the family bedroom was off the kitchen, and there were bedrooms above.

Charlie was now desirous to complete his boat, but his mother wanted the flax done out. He therefore concluded to put it off till John came on to help him make sugar.

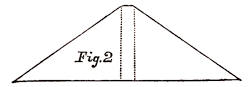

When Uncle Isaac reached home, John’s school had been out a week; but the weather was so rough he could not reach the island; and when he did arrive, Ben and Charlie were just finishing up the flax. The boys now cleared out the camp, scoured the kettles, put fresh mortar on the arch, hauled wood, and prepared for sugar-making. They resolved to tap but few trees at first, in order to have more leisure to work on their boat. The greatest mechanical skill was required to shape the outside. This pertained entirely to Charlie; but the most laborious portion of the work was the digging out such an enormous stick, and removing such a quantity of wood at a disadvantage, as, after they had chopped out about a foot of the surface, it would be difficult to get at, and the work must be done with adze and chisel, and even bored out with an auger at the ends. They decided to remove a portion of it before shaping the outside, as the log would lie steadier. Charlie accordingly marked out the sheer, then put on plumb-spots, and hewed the sides and the upper surface fair and smooth.

He then lined out the shape and breadth of beam, and made an inside line to rough-cut by, and at leisure times they chopped out the inside with the axe, one bringing sap or tending the kettle, while the other worked on the boat.

“John,” said Charlie, stopping to wipe the perspiration from his face, “I’m going to find some easier way than this to make a boat; it’s too much like work.”

“There is no other way. I’ve seen hundreds of canoes made, and this is the way they always do.”

“Don’t you remember when we were clearing land, that we would set our nigger[1] to burning off logs, and when it came night, we would find that he had burned more logs in two than we had cut with the axe?”

“Yes.”

“Uncle Isaac told me one night, that the Indians burned out canoes, and I am going to try it.”

“I thought they always made them of bark.”

“He said they sometimes, especially the Canada Indians, made them of a log, in places where they had a regular camping-ground, and didn’t want to carry them.”

“You’ll burn it all up, and we can never get another such a log.”

“You see if I do.”

Charlie got a pail of water, and made a little mop with rags on the end of a stick, then got some wet clay, and put all around the sides of the log where he didn’t want the fire to come. He then built a fire of oak chips right in the middle, and the whole length. The fire burned very freely at first, for the old log was full of pitch, and soon began to dry the clay, and burn at the edge; but Charlie put it out with his mop, and forced it to burn in the middle.

When the chips had burned out, Charlie took the adze, and removed about three inches of coal, and made a new fire.

“Not much hard work about that,” said John, who looked on with great curiosity.

They now went about their sugar, once in a while stepping to the log to remove the coal, renew the fire, or apply water to prevent its burning in the wrong direction.

When he had taken as much wood from the inside as he thought it prudent to remove before shaping the outside, he began to prepare for that all-important operation; but as he was afraid the[57] clear March sun and the north-west winds would cause her to crack, he built a brush roof over her before commencing.

Now came the most difficult portion of the work, as it must be done almost entirely by the eye, by looking at the model and then cutting; but as the faculties in any given direction strengthen by exercise, and we are unconsciously prepared by previous effort and application for that which follows, thus Charlie experienced less difficulty here than he had anticipated, and at length succeeded in making it resemble the model, in Ben’s opinion, as nearly as one thing could another. Now their efforts were directed to finish the inside; and, having used the fire as long as they thought prudent, they resorted to other tools, as they wished so to dig her out as to have the utmost room inside, and to make her as light as possible. The risk was in striking through by some inadvertent blow. Though it may seem strange to those not versed in such things, yet Charlie could give a very near guess at the thickness by pressing the points of his fingers on each side, and when he was in doubt, he bored a hole through with a gimlet, and then plugged it up. They at length left her a scant inch in thickness,[58] except on the bottom and at the stern and bow. There she was so sharp that the wood for a long distance was cut directly across the grain.

“I wish,” said Charlie, “I had shaped the outside before digging her out at all.”

“Why so?” said John.

“Because, in that case, I could have left more thickness at the bow; but I couldn’t leave it outside and follow the model.”

In order to avoid taking the keel out of the log, and to have all the depth possible, they put on a false keel of oak; as the edge was too thin to put on row-locks, they fastened cleats on the inside, and put flat thole-pins in between them and the side, which looked neat, and were strong enough for so light, easy-going a craft, that was intended for sailing rather than carrying; they also put on a cut-water, with a billet-head scroll-shaped, and with mouldings on the edges.

As it was evident she would require a good deal of ballast, to enable her to bear sail, they laid a platform forward and aft, raised but a very little from the bottom, merely enough to make a level to step or stand on; but amidships they left it higher, to give room for ballast.

Their intention was, at some future time, to put[59] in head and stern-boards, or, in other words, a little deck forward and aft, with room beneath to put lines, luncheon, and powder, when they went on fishing or sailing excursions; but they were too anxious to see her afloat to stop for that now. They therefore primed her over with lead color, to keep her from cracking, and the very moment she was dry, put her in the water.

Never were boys in a state of greater excitement than they, when, upon launching her into the water, with a hearty shove and hurrah, she went clear across the harbor, and landed on the Great Bull. They got into the Twilight, and brought her back, and found she sat as light as a cork upon the water, on an even keel, and was much stiffer than they expected to find her. She was eighteen feet long, and four feet in width, eighteen inches deep.

Having persuaded Sally to get in and sit down on the bottom,—for as yet they had no seats,—they rowed her around the harbor.

“Now we can go to Indian camp ground, or where we are a mind to,” said Charlie.

“Yes,” replied John, “we can go to Boston; and if we want to go anywhere, and the wind is ahead, we can beat: how I do want to get sail on her!”

There was still much to be done—a rudder and tiller, bowsprit, thwarts for the masts, and masts’ sprits, a boom and sails to make. They did not, however, neglect their work; but now that they had succeeded in their purpose, and the agony was over, though still very anxious to finish and get her under sail, they tapped more trees, and only worked on her in such intervals as their work afforded. In these intervals Charlie made the rudder, and tiller, and thwarts for the masts.

We are sorry to say that he now manifested something like conceit, which, being a development so strange in him, and so different from the natural modesty of his disposition, can only be accounted for by supposing that uniform success had somewhat turned his head, and produced temporary hallucination.

From the time he made his own axe handle, when he first came on the island, till now, he had always succeeded in whatever he undertook, and been praised and petted; and even his well-balanced faculties and native modesty were not entirely unaffected by such powerful influences.

Ben advised him to secure the mast thwarts with knees, as is always done in boats, to put a breast-hook in the bow, and two knees in the stern,[61] to strengthen her, as she was dug out so thin, and the wood forward and aft cut so much across the grain; but, flushed with success, Charlie thought he knew as much about boat-building as anybody, and, for the first time in his life, neglected his father’s counsel. He thought knees would look clumsy, and that he could fasten the thwarts with cleats of oak, and make them look neater; and thus he did. They were now brought to a stand for lack of material, cloth for sails, rudder-irons, and spars.

Elm Island, although it could furnish masts in abundance for ships of the line, produced none of those straight, slim, spruce poles, that are suitable for boat spars. It was very much to the credit of the boys, that, although aching to see the boat under sail, and well aware that Ben would not hesitate a moment, if requested, to let them leave their work and go after the necessary articles, they determined to postpone the completion of her till the sugar season was over. Meanwhile, they painted her, and, after the paint was dry, rowed off in the bay: they also put the Twilight’s sail in her; and, though it was not half large enough, and they were obliged to steer with an oar, they could see that she would come up to the wind, and was an[62] entirely different affair from the Twilight, promising great things.

They hugged themselves while witnessing and admiring her performance, saying to each other,—

“Won’t she go through the water when she gets her own sails, spars, and a rudder!”

It must be confessed, Charlie was not at all sorry to see the flow of sap diminished; and no sooner was the last kettle full boiled, than off they started for the main land.

Immediately on landing, Charlie bent his steps towards Uncle Isaac’s, on whose land was a second growth of spruce, amongst which were straight poles in abundance.

John, after bolting a hasty meal, hurried to Peter Brock’s shop; there, with some assistance from Peter, he made the rudder-irons, a goose-neck for the main-boom, another for the heel of the bowsprit, which was made to unship, a clasp to confine it to the stem, and the necessary staples.

When Charlie returned the next night with his spars, they procured the cloth for the sails, and went back to the island.

Ben cut and made the sails; and, in order that everything might be in keeping, pointed and[63] grafted the ends of the fore, main, and jib-sheets, and also made a very neat fisherman’s anchor; but he persisted in making the sails much smaller than suited their notions.

They had some large, flat pieces of iron that came from the wreck that drove ashore on the island the year before; these they put in the bottom for ballast, and upon them, in order to make her as stiff as possible, some heavy flint stones, worn smooth by the surf, which they had picked up on the Great Bull.

Until this moment they had been unable to decide upon a name, but now concluded to call her the “West Wind.”

They put the finishing touch to their work about three o’clock in the afternoon, and, with a moderate south-west wind, made sail, and stood out to sea, close-hauled.

All their hopes were now more than realized; loud and repeated were their expressions of delight as they saw how near she would lie to the wind, and how well she worked. The moment the helm was put down, she came rapidly up to the wind, the foresail gave one slat, and she was about; then they tried her under foresail alone, and found she went about easily, requiring no help.

“Isn’t she splendid?” asked John; “and ain’t you glad we built her?”

“Reckon I am: what will Fred say when he sees her? and won’t we three have some nice times in her?”

“It was a good thing for us, Charlie, that we had Ben to cut the sails and tell us where to put the masts.”

They avoided the main land, as they did not wish to attract notice till they were thoroughly used to handling her, and knew her trim; and, after sailing a while, hauled down the jib, kept away, and went back “wing and wing.”

“Some time,” said Charlie, “we’ll go down among the canoes on the fishing-ground, and when the fishermen are tugging away at their oars with a head wind, go spanking by them, the spray flying right in the wind’s eye.”

At length, feeling that they knew how to sail, they determined to go over to the mill and exhibit her.

Notwithstanding their efforts to keep it secret, the report of their proceedings had gone round among the young folks. Some boy saw John at work upon the rudder-irons in Peter’s shop, though he plunged his work into the forge trough the moment he saw that he was observed.

Little Bob Smullen also saw Charlie hauling down the spars with Isaac’s oxen, and when he asked Charlie what they were for, he told him, “To make little boys ask questions.”

The wind came fresh off the land, which suited their purpose, as they wished to sail along shore on a wind, and desired to display the perfections of their boat to the greatest advantage, and above all show her superiority to the canoes, which could only go before the wind, or a little quartering. The wind was not only fresh, but blew in flaws; and as they could not think, upon such an occasion, of carrying anything less than whole sail, they put in additional ballast, and took a barrel of sap sugar, which Fred was to sell for them, and five bushels of corn, to be ground at the mill.

They were to spend the night at Captain Rhines’s, intending in the morning to go down to Uncle Isaac’s point and invite him to take a sail with them. Charlie considered that the best part of the affair.

They beat over in fine style, fetching far to the windward of the mill, in order to have opportunity to keep away a little and run the shore down, intending to run by the wharf, and then tack and beat back in sight of whoever might be there.[66] When about half a mile from the shore, they were espied by little Tom Pratt, who was fishing from the wharf. He had heard the talk among the big boys, and, rushing into the mill, he bawled out, “It’s coming! it’s coming! I seed it! that thing from Elm Island.”

Out ran Fred, Henry Griffin, Sam Hadlock, and Joe Merrithew. In a few moments another company came from the store and the blacksmith’s shop, among whom were Captain Rhines, Yelf, and Flour.

John was steering, and every few moments a half bucket of salt water would strike in the side of his neck and run out at the knees of his breeches, while Charlie baled it out as fast as it came in.

“Only look, Charlie! see what a crowd there is on the wharf! I see father and Flour, and there’s old Uncle Jonathan Smullen, with his cane.”

“I see Fred and Hen Griffin,” said Charlie: “when we get a little nearer, I mean to hail ’em.”

“Slack the fore and jib sheets a little, Charlie. I’m going to keep her away and run down by the wharf.”

As they ran along seven or eight hundred yards from the wharf, Charlie, standing up to windward,[67] waved his cap to Fred, and cheered. It was instantly returned by the whole crowd.

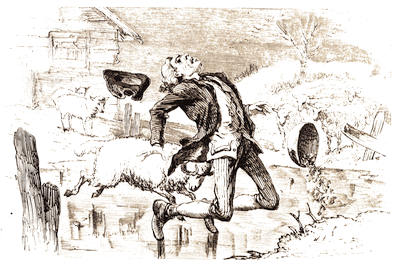

At that moment a hard flaw, striking over the high land, heeled her almost to upsetting; and as she rose again, she split in two, from stem to stern. Charlie, who was just waving his hat for a second cheer, went head foremost into the water. One half the boat, to which were attached the masts, bowsprit, and rudder, fell over to leeward; the cable, which was fastened into a thole-pin hole, running out, anchored that part, while the other half drifted off before the wind towards Elm Island.

John and Charlie clung to the half that was left, while the barrel of sugar, the corn, both their guns, powder and shot, went to the bottom.

It was but a few moments before Captain Rhines, with Flour and Fred Williams, came in a canoe, and took them off.

Every one felt sorry for the mishap, and Fred felt so bad that he cried.

It was the first boat that had ever been made or owned in the place, or even seen there, except once in a great while, when a whaleman or some large vessel came in for water, or lost their way; the inhabitants all using canoes, as did also the fishermen and coasters.

As the anchor held one half the boat, it furnished a mark to tell where the contents lay; and while Fred and Henry Griffin were towing back the other half, the rest grappled for and brought up the corn, guns, and sugar, not much of which was dissolved.

It was a bitter disappointment to Charlie and John, but they bore it manfully, and went up to Captain Rhines’s to put on dry clothes and spend the night, Fred walking along with them, striving to administer consolation.

“I wouldn’t feel so bad about it, Charlie,” said he; “we’ve got the other half; why couldn’t you fasten them together again?”

“So you could, Charlie,” said John, “and she would be as good as ever.”

“But what would she look like? No, I never want to touch her again; let her go; but I know one thing, that is, if I live long enough, I’ll build a boat that will sail as well as she did, and not split in two either.”

Uncle Isaac, hearing of the shipwreck, came in to Captain Rhines’s in the evening to see and comfort the boys.

“It’s not altogether the loss of the boat makes me feel so bad, Uncle Isaac,” said Charlie.

“I’m sure I don’t see what else you have to feel bad about.”

“It’s because father told me to fasten her together with knees, and put a hook in the eyes of her; but I thought I knew so much, I wouldn’t do it. I wanted her to look neat; and see how she looks now! I never was above taking advice before, and hope I never shall be again.”

Notwithstanding Charlie’s resolution never to touch the boat again, he changed his mind after sleeping upon it.

The two boys now reluctantly separated, as it was time for John to go to his trade. Fred and Henry set Charlie on to the island, putting the masts, sails, &c., in their canoe, and towing the two halves. Ben never said to Charlie, “I told you so,” but did all he could to cheer him up, and told him he had made a splendid boat; that he watched them till they were half way over, and that she sailed and worked as well as any Vineyard Sound boat (and they were called the fastest) he ever saw. The boys put the pieces of the boat and the spars in the sugar camp, and then Henry and Fred returned.

Charlie seemed very cheerful and happy while the boys were there; but when they were gone, he[70] put his head in his mother’s lap, and fairly broke down. Sally was silent for some time: at length she said,—

“Charlie, I think your goose wants to set. I should have set her while you was gone, but the gander is so cross, I was afraid of him.”

Charlie started up in an instant. This was a tame goose, that had mated with a wild gander they had wounded and caught, and Charlie was exceedingly anxious to raise some goslings, and instantly put the eggs under the goose.

The wild ganders have horny excrescences on the joint of their wings, resembling a rooster’s spur, with which they strike a very severe blow, and are extremely bold and savage when the geese are sitting. They seize their antagonist with their bills, then strike them with both wings, and it is no child’s play to enter into a contest with them.

CHAPTER V.

HAPS AND MISHAPS.

It is frequently the case that trials, which are very hard to bear at the time, prove, in the end, to be the source of great and permanent benefit. The sequel will show that the wreck of the West Wind, which was so galling to Charlie and John at the moment, was, in the result, to exert a favorable influence upon their whole lives.

The spring was now well advanced, and there were so many things to occupy Charlie’s attention that boat-building was altogether out of the question. Indeed, for a time, he felt very little inclination to meddle with it, and thought he never should again. There were sea-fowl to shoot, and Charlie had now become as fond of gunning as John. The currant bushes were beginning to start, the buds on the apple, pear, and cherry trees in the garden, whose development he watched as a cat would a mouse, were beginning to swell, and early peas and potatoes were to be planted. The[72] robins also returned, and began to repair their last year’s nests, bringing another pair with them,—their progeny of the previous summer.

Charlie was hoping and expecting that the swallows, who came in such numbers to look at the island and the barn the summer before, would again make their appearance; but, notwithstanding all these sources of interest and occupation, and though he felt at the time of his misfortune that it would be a long time, if ever, before he should again think of undertaking boat-building, it was not a fortnight before he found his thoughts running in the accustomed channel, and, as he tugged at the oars, pulling the Twilight against the wind, he could but think how much easier and pleasanter would have been the task of steering the West Wind over the billows; and he actually found himself, one day, in the sugar camp, looking at the pieces of the wreck, and considering how they might be put together; but several other subjects of absorbing interest now presented themselves in rapid succession, which effectually prevented his cogitations from taking any practical shape.

A baby, whose presence well nigh reconciled Charlie to the loss of the boat, made its appearance.[73] He was exceedingly fond of the little ones, and was looking forward to the time when he could have the baby out doors with him.

Mrs. Hadlock had come over to stay a while, and one day undertook to put the baby in the cradle; but little Ben stoutly resisted this infringement on his rights. He fought and screamed, declaring, as plainly as gestures and attempts at language could, that the cradle was his; that he had not done with it, and would not give it up. In this emergency, Charlie bethought himself of the willow rods (sallies), which the boys had helped him peel the spring before, and determined to make the baby a cradle, which should altogether eclipse that of Sam Atkins. The rods being thoroughly dry, he soaked them in water, when they became tough and pliant. He stained part of them with the bright colors he had procured in Boston the year before, some red, others blue and green. He then wove his cradle, putting an ornamental fringe round the rim, and also a canopy over it. The bottom was of pine, but he made the rockers of mahogany that Joe Griffin had given him. When the willow was first peeled, it was white as snow, but by lying had acquired a yellowish tinge, and was somewhat soiled in working. Charlie therefore[74] put it under an empty hogshead, and smoked it with brimstone, which removed all the yellow tinge, and the soil received from the hands, making it as white as at first. When finished, it excited the admiration of the household, none of whom, except Ben, had ever seen any willow-work before.

“Well, Charlie,” said Mrs. Hadlock, “that beats the Indians, out and out.”

“It will last a great deal longer than their work,” said he; “but I don’t think I could ever make their porcupine-work.”

Ben, Jr., appreciated the new cradle as highly as the rest, instantly clambered in, and laid claim to it, and was so outrageous, wishing to appropriate both, though he could use but one at a time, that his father gave him a sound whipping. He fled to Charlie for consolation, who, to give satisfaction all round, made him a willow chair, and dyed it all the colors of the rainbow.

Charlie now prepared to give a higher exhibition of his skill. He selected some of the best willows of small size, and made several beautiful work-baskets, of various sizes and colors. He then took some of the longest rods, of the straightest grain, and with his knife split the butt in four pieces, two or three inches in length; then took a piece of[75] hard wood (granadilla), made sharp at one end, and with four scores in it; inserting the point in the split, he put the other end against his breast, and pushed it through the whole length of the rod, thus dividing it into four equal parts. He then put the quarters on his thigh, and with his knife shaved off the heart-wood, leaving the outside sap reduced to a thin, tough shaving, like cloth. This he made up into skeins, and kept it to wind the rims and handles of his baskets. He told them that a regular workman had a piece of bone or ivory to split the rod with, and an instrument much like a spoke-shave to shave it to a ribbon, but he made a piece of wood and a knife answer his purpose.

Charlie’s West India wood was constantly coming into use, for one thing or another, and Joe Griffin could not have given him a more acceptable or useful present.

He also used his skeins of willow for winding the legs of the three chairs he made, one for his mother, one for Hannah Murch, and one for Mrs. Hadlock. The legs were made of stout willow, and wound with these bands.