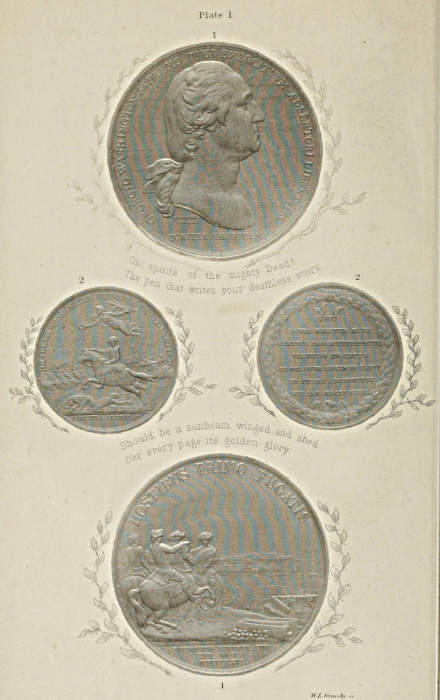

Plate 1.

1

2

W. L. Ormsby, sc.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Memoirs of the Generals, Commodores and other Commanders, who distinguished the, by Thomas Wyatt This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Memoirs of the Generals, Commodores and other Commanders, who distinguished themselves in the American army and navy during the wars of the Revolution and 1812, and who were presented with medals by Congress for their gallant services Author: Thomas Wyatt Release Date: November 3, 2015 [EBook #50377] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MEMOIRS OF THE GENERALS *** Produced by Richard Hulse and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE: A list of illustrations has been added to the table of contents.

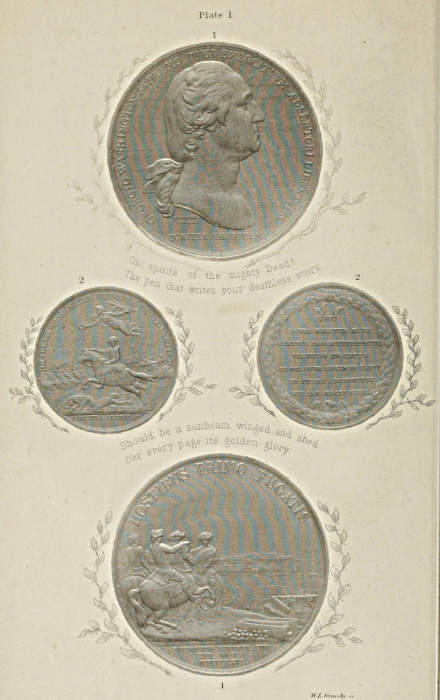

Plate 1.

1

2

W. L. Ormsby, sc.

BY THOMAS WYATT, A.M.,

AUTHOR OF THE “KINGS OF FRANCE,” ETC. ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY EIGHTY-TWO ENGRAVINGS ON STEEL

FROM THE ORIGINAL MEDALS.

PHILADELPHIA:

PUBLISHED BY CAREY AND HART

MDCCCXLVIII.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1847, by

CAREY AND HART,

In the office of the Clerk of the District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

T. K. & P. G. COLLINS, PRINTERS,

No. 1, Lodge Alley.

Americans, proud of the achievements of their countrymen, who in the field of honor have fought with superior valor for the independence or glory of their native land, will look with complacency on the decisive stamp of nationality which a work of this kind necessarily possesses; while it is [iv]equally true, that the world will find, in the circumstances of the age, or period of the gallant deeds when LIBERTY was so nobly asserted, and when the invincibility of the proud “mistress of the seas” was so successfully contested, a bright page of history on which our national pride may justly dwell.

Here, as in “Old Rome,” where the public honors are open to the virtue of every citizen, the lives of those heroes who have been distinguished by their country’s highest rewards, will develop virtuous deeds, heroic exertions and patriotic efforts, when all now commemorated shall be no more. Nor is it difficult to predict, that a like high pre-eminence of virtue and of public services will long perpetuate the glorious annals of America. It has appeared to us that there has been no publication in which the illustrious commanders of our two wars, who have been signalized by the presentation of gold medals, &c., have been singled out, and their lives illustrated in connection with graphic delineations of the beautiful and glorious emblems of their country’s gratitude. This work is now offered to the public as a text-book of men who have sealed their patriotic devotion with wounds and scars, as well as of historical incidents sacred to patriotism. Our plan admits of none of the embellishments of romance; on the contrary it confines itself to the simple facts as they really were, giving to each commander that share of bravery and virtue which his country has thought proper to signalize by the medals, &c., awarded him. The biographical scope we take admits only of the relation of the principal events of their lives, more particularly in the department in which they rose to fame, and we have endeavored to do our part with all the accuracy that conciseness will allow; leaving to others to give more finished and full-sized portraits, which, in judicious hands, may be the more entertaining and instructive, as they are more in detail.

We trust, however, though aware it may not be possible to avoid some error, or to satisfy every expectation, that from the efforts we have made, and the scrupulous impartiality we have endeavored to observe, as well as on account of the authentic materials which have been kindly furnished us, we shall be found to have been successful in our attempt to aid in the perpetuation of the fame of men so well entitled to lasting celebrity, and to the gratitude of posterity.[v]

We acknowledge our indebtedness to former historians and biographers; but, in a greater degree, we have to thank those officers now living who have so kindly supplied us with facts drawn from their own private papers, &c. We have also to return our most grateful acknowledgments to the representatives of the illustrious dead who have so cheerfully contributed to our materials.

In conclusion, it is hoped that they, and the public, will dwell with pleasure and satisfaction on these pages.

THE AUTHOR.

| PAGE | FIGURE; PLATE | |

| GEN. GEORGE WASHINGTON, | 9 | 1; 1 |

| GEN. ANTHONY WAYNE, | 17 | 4; 2 |

| MAJ. JOHN STEWART, | 40 | 3; 2 |

| LIEUT. COLONEL DE FLEURY, | 42 | 5; 2 |

| MAJ. ANDRE, CAPTURE OF, | 48 | 10; 4 |

| GEN. NATHANIEL GREENE, | 52 | 6; 3 |

| GEN. HORATIO GATES, | 59 | 8; 3 |

| GEN. DANIEL MORGAN, | 63 | 7; 3 |

| COL. EAGER HOWARD, | 70 | 9; 4 |

| COL. WILLIAM A. WASHINGTON, | 79 | 2; 1 |

| MAJ. HENRY LEE, | 84 | 11; 4 |

| GEN. WINFIELD SCOTT, | 89 | 12; 5 |

| GEN. EDMUND P. GAINES, | 101 | 14; 5 |

| GEN. JAMES MILLER, | 113 | 13; 5 |

| MAJ.-GENERAL JACOB BROWN, | 129 | 16; 6 |

| MAJ.-GENERAL RIPLEY, | 135 | 17; 6 |

| GEN. PETER B. PORTER, | 147 | 15; 6 |

| GEN. ALEXANDER MACOMB, | 151 | 18; 7 |

| GEN. ANDREW JACKSON, | 160 | 19; 7 |

| GEN. ISAAC SHELBY, | 164 | 20; 7 |

| [viii]GEN. WM. HENRY HARRISON, | 175 | 21; 8 |

| LIEUT.-COLONEL CROGHAN, | 181 | 22; 8 |

| PAUL JONES, | 186 | 23; 8 |

| CAPT. THOMAS TRUXTUN, | 193 | 24; 9 |

| COM. EDWARD PREBLE, | 202 | 25; 9 |

| CAPT. ISAAC HULL, | 206 | 26; 9 |

| CAPT. JACOB JONES, | 214 | 27; 10 |

| CAPT. STEPHEN DECATUR, | 222 | 28; 10 |

| COM. BAINBRIDGE, | 229 | 29; 10 |

| OLIVER HAZARD PERRY, | 236 | 30; 11 |

| COM. ELLIOTT, | 241 | 31; 11 |

| LIEUT. WILLIAM BURROWS, | 249 | 32; 11 |

| LIEUT. EDWARD R. McCALL, | 257 | 33; 12 |

| CAPT. JAMES LAWRENCE, | 261 | 34; 12 |

| CAPT. THOMAS MACDONOUGH, | 270 | 35; 12 |

| CAPT. ROBERT HENLEY, | 278 | 36; 13 |

| CAPT. STEPHEN CASSIN, | 281 | 37; 13 |

| COM. WARRINGTON, | 285 | 38; 13 |

| CAPT. JOHNSTON BLAKELEY, | 289 | 39; 14 |

| CAPT. CHARLES STEWART, | 297 | 40; 14 |

| CAPT. JAMES BIDDLE, | 307 | 41; 14 |

Among those patriots who have a claim to our veneration, George Washington claims a conspicuous place in the first rank. The ancestors of this extraordinary man were among the first settlers in America; they had emigrated from England, and settled in Westmoreland county, Virginia. George Washington, the subject of these memoirs, was born on the 22d February, 1732.

At the time our hero was born, all the planters throughout this county were his relations—hence his youthful years glided away in all the pleasing gayety of social friendship. In the tenth year of his age he lost an excellent father, who died in 1742, and the patrimonial estate devolved to an elder brother. This young gentleman had been an officer in the colonial troops, sent in the expedition against Carthagena. On his return, he called the family mansion Mount Vernon, in honor of the British admiral with whom he sailed. George Washington, when only fifteen years of age, ardent to serve his country, then at war with France and Spain, solicited the post of midshipman in the British navy, but the interference of a fond mother suspended, and for ever diverted him from[10] the navy. His devoted parent lived to see him acquire higher honors than he ever could have obtained as a naval officer; but elevated to the first offices, both civil and military, in the gift of his country. She, from long established habits, would often regret the side her son had taken in the controversy between her king and her country. The first proof that he gave of his propensity to arms, was in the year 1751, when the office of adjutant-general of the Virginia militia became vacant by the death of his brother, and Mount Vernon, with other estates, came into his possession. Washington, in his twentieth year, was made major of one of the militia corps of Virginia. The population made it expedient to form three divisions. When he was but just twenty-one, he was employed by the government of his native colony, in an enterprise which required the prudence of age as well as the vigor of youth. In the year 1753, the encroachments of the French upon the western boundaries of the British colonies, excited such general alarm in Virginia, that Governor Dinwiddie deputed Washington to ascertain the truth of these rumors; he also was empowered to enter into a treaty with the Indians, and remonstrate with the French upon their proceedings.

On his arrival at the back settlements, he found the colonists in a very unhappy situation, from the depredations of the Indians, who were incessantly instigated by the French to the commission of continual aggressions. He found that the French had actually established posts within the boundaries of Virginia. Washington strongly remonstrated against such acts of hostility, and in the name of his executive, warned the French to desist from those incursions. On his return, his report to the governor was published, and evinced that he had performed this honorable mission with great prudence.

It was in consequence of the French calling themselves the first European discoverers of the river Mississippi, that[11] made them claim all that immense region, whose waters run into that river. They were proceeding to erect a chain of posts from Canada to the Ohio river, thereby connecting Canada with Louisiana, and limiting the English colonies to the east of the Alleghany mountains. The French were too intent on their favorite project of extending their domain in America, to be diverted from it by the remonstrances of a colonial governor.

This induced the Assembly of Virginia to raise a regiment of three hundred men to defend their frontiers and maintain the right claimed by their king.

Of this regiment, Professor Fry, of William and Mary College, was appointed colonel, and George Washington lieutenant-colonel. Fry died soon after the regiment was embodied, and was succeeded by our hero, who paid unremitting attention to the discipline of his new corps. The latter advanced with his regiment as far as Great Meadows, where he received intelligence, by the return of his scouts whom he had sent on to reconnoiter, that the enemy had built a fort, and stationed a large garrison at Duquesne, now Pittsburgh. Having now arrived within fifty miles of the French post, Washington held a council of war with the other officers, but while they were deliberating, a detachment of the French came in sight and obliged them to retreat to a savanna called the Green Meadows. On an eminence in the savanna they began to erect a small fortification, which he named Fort Necessity.

On this redoubt they raised two field-pieces. On the following day they were joined by Captain McKay, with a company of regulars, amounting now to about four hundred men. Scarcely had they finished their entrenchments when an advanced guard of the French appeared in sight, at which the Americans sallied forth, attacked and defeated them; but[12] the main body of the enemy, amounting to fifteen hundred men, compelled them to retire to their fort.

The camp was now closely invested, and the Americans suffered severely from the grape shot of the enemy, and the Indian rifles. Washington, however, defended the works with such skill and bravery, that the besiegers were unable to force the entrenchments. After a conflict of ten hours, in which one hundred and fifty of the Americans were killed and wounded, they were obliged to capitulate. They were permitted to march out with the honors of war, to retain their arms and baggage, and to march unmolested into the inhabited parts of Virginia. The legislature of Virginia, impressed with a high sense of the bravery of our young officer, voted their thanks to him and the officers under his command, and three hundred pistoles to be distributed among the soldiers engaged in this action.

Great Britain now began to think seriously of these controversies, and accordingly dispatched two regiments of veteran soldiers from Ireland, commanded by General Braddock. These arrived early in 1755, and their commander, being informed of the talents and bravery of George Washington, invited him to serve in the campaign as his aid-de-camp.

The invitation was joyfully accepted by Washington, who joined General Braddock near Alexandria, and proceeded to Fort Cumberland; here they were detained, waiting for provisions, horses, wagons, &c., until the 12th of June. Washington had recommended the use of pack horses, instead of wagons, for conveying the baggage of the army. Braddock soon saw the propriety of it and adopted it. The state of the country, at this period, often obliged them to halt to level the road, and to build bridges over inconsiderable brooks. They consumed four days in traveling over the first nineteen miles.[13] On the 9th of July they reached the Monongahela, within a few miles of Fort Duquesne, and pressing forward, without any apprehension of danger, a dreadful conflict ensued; the army was suddenly attacked in an open road, thick set with grass.

An invisible enemy, consisting of French and Indians, commenced a heavy and well directed fire on the uncovered troops. The van fell back on the main body, and the whole was thrown into disorder. Marksmen leveled their pieces particularly at the officers and others on horseback.

In a short time, Washington was the only aid-de-camp left alive and not wounded. On him, therefore, devolved the whole duty of carrying the general’s orders. He was, of course, obliged to be constantly in motion, traversing the field of battle on horseback in all directions. He had two horses shot under him, and four bullets passed through his coat, but he escaped unhurt, though every other officer on horseback was either killed or wounded. The battle lasted three hours, in the course of which General Braddock had three horses shot under him, and finally received a wound, of which he died soon after the action was over. On the fall of Braddock, his troops gave way in all directions, and could not be rallied till they had crossed the Monongahela. The Indians, allured by plunder, did not pursue. The vanquished regulars soon fell back to Dunbar’s camp, from which, after destroying such of the stores as they could spare, retired to Philadelphia.

Washington had cautioned the gallant but unfortunate general in vain; his ardent desire of conquest made him deaf to the voice of prudence; he saw his error when too late, and bravely perished in his endeavors to save the division from destruction. Amid the carnage, the presence of mind and abilities of Washington were conspicuous; he rallied the troops, and, at the head of a corps of grenadiers, covered the[14] rear of the division, and secured their retreat over the ford of Monongahela.

Kind Providence preserved him for great and nobler services. Soon after this transaction, the regulation of rank, which had justly been considered as a grievance by the colonial officers, was changed in consequence of a spirited remonstrance of Washington; and the governor of Virginia rewarded this brave young officer with the command of all the troops of that colony. The troops under his command were gradually inured in that most difficult kind of warfare called bush-fighting, while the activity of the French and ferocity of the Indians were overcome by his superior valor.

Washington received the most flattering marks of public approbation; but his best reward was the consciousness of his own integrity.

In the course of this decisive campaign, which restored the tranquillity and security of the middle colonies, Washington had suffered many hardships which impaired his health. He was afflicted with an inveterate pulmonary complaint, and extremely debilitated, insomuch that, in the year 1759, he resigned his commission and retired to Mount Vernon. By a due attention to regimen, in the quiet bowers of Mount Vernon, he gradually recovered from his indisposition.

During the tedious period of his convalescence, the British troops had been victorious; his country had no more occasion for the exertion of his military talents. In 1761, he married the young widow of Colonel Custis, who had left her sole executrix to his extensive possessions, and guardian to his two children. The union of Washington with this accomplished lady was productive of their mutual felicity; and as he incessantly pursued agricultural improvements, his taste embellished and enriched the fertile fields around Mount Vernon. But the time was approaching when Washington was[15] to relinquish the happiness of his home to act a conspicuous part on the great theatre of the world.

For more than ten years had the colonies and their mother country been at variance from causes of usurpation and tyranny, and the awful moment was fast approaching when America was to throw off her fetters and proclaim herself free. In 1775, Washington was elected commander-in-chief of the whole American army. The American army were, at the time of this appointment, entrenched on Winter Hill, Prospect Hill and Roxbury, Massachusetts, communicating with each other by small posts, over a distance of ten miles; the head-quarters of the American army was at Cambridge, while the British were entrenched on Bunker’s Hill, defended by three floating batteries on Mystic river below.

Washington having now arrived at the army, which consisted of fourteen thousand, he was determined to bring the enemy to an alternative, either to evacuate Boston, or risk an action. General Howe, the British commander, preferred the latter, and ordered three thousand men to fall down the river to the castle, to prepare for the attack, but during their preparations, they were dispersed by a storm; which so disabled them for their intended attack, that they at last resolved to evacuate the town.

Washington, not wishing to embarrass the British troops in their proposed evacuation, detached part of his army to New York, to complete the fortifications there; and with the remainder, took peaceable possession of Boston, amid the hearty congratulations of the inhabitants, who hailed him as their deliverer.

When the Americans took possession of Boston, they found a multitude of valuable articles, which were unavoidably left by the British army, such as artillery, ammunition, many[16] woolens and linens, of which the American army stood in the most pressing need.

Washington now directed his attention to the fortifications of Boston; and every effective man in the town volunteered his services to devote two days in every week till it was completed. By a resolve of Congress of March 25th, 1776, a vote of thanks was passed to General Washington and the officers and soldiers under his command, for their wise and spirited conduct in the siege and acquisition of Boston. Also a gold medal to General Washington, of which the following is a description:—

Occasion.—Evacuation of Boston by the British troops.

Device.—The head of General Washington, in profile.

Legend.—Georgio Washington, supremo duci exercitum adsertori libertatis comitia Americana.

Reverse.—Troops advancing towards a town which is seen at a distance. Troops marching to the river. Ships in view. General Washington in front, and mounted, with his staff, whose attention he is directing to the embarking enemy.

Legend.—Hostibus primo Fugatis.

Exergue.—Bostonium recuperatum 17 Martii, 1776.

Anthony Wayne, of whose military career America has much to boast, the son of a respectable farmer in Chester county, Pennsylvania, was born on the 1st of January, 1745. His propensities and pursuits being repugnant to the labors of the field, his father resolved to give him an opportunity of pursuing such studies as his acquirements might suggest, and accordingly placed him under the tuition of a relative of erudition and acquirements, who was teacher of a country school. Our young hero was by no means an attentive student; his mind seemed, like the young Napoleon, bent on a military life, for instead of preparing his lessons for recitation during his leisure hours, he employed himself in ranging his playmates into regiments, besieging castles, throwing up redoubts, &c. &c.

He was removed from the county school into an academy of repute in Philadelphia, where he soon became an expert mathematician, sufficiently so, that on his leaving school he became a land surveyor, with a very respectable and lucrative business. At the persuasion of Dr. Franklin, he removed to Nova Scotia, as agent for a company of settlers about to repair to that province on a scheme of emigration.[18]

As an able negotiator he acquitted himself honorably, and returned to Pennsylvania, where he married the daughter of Benjamin Penrose, an eminent merchant of Philadelphia, and settled once more on a farm in his native county. The aspect of affairs between the mother country and the provinces at this time convinced our young hero that desperate means must soon be resorted to to prevent invasion from abroad and insurrection at home. Satisfied that the controversies between the two countries would only be adjusted by the sword, he determined to apply himself to military discipline and tactics, that whenever his country required it, he might devote his energies in raising and preparing for the field a regiment of volunteers. The moment arrived, and young Wayne was only six weeks in completing a regiment, of which he was unanimously chosen colonel. At the sound of taxation the undaunted spirit of liberty burst forth, and thousands of young and fearless patriots thronged around the sacred banner to enrol themselves in a cause which must eventually end in freedom. News of the opening of the revolution at Bunker’s Hill and Lexington arrived, and Washington, who had accepted the command of the army, repaired to the seat of war.

Congress, now sitting at Philadelphia, called upon the colonies for regiments to reinforce the northern army, and the one raised by the exertions of Anthony Wayne was the first called into service, and upon him was conferred the command. His orders to join General Lee at New York were quickly obeyed, whence he proceeded with his regiment to Canada, to be stationed at the entrance of Sorel river.

Shortly after his arrival there, news arrived that a detachment of six hundred British light infantry were advancing toward a post called Trois Rivières (Three Rivers). Anxious to check their advance, or strike before they could concentrate[19] their forces, three regiments, commanded by Wayne, St. Clair and Irvine, commenced their march for that purpose. Unfortunately, however, untoward circumstances compelled them to retreat with considerable loss of men, and Colonels Wayne and St. Clair severely wounded. The movements now devolved upon Wayne, who collected the scattered troops and returned to his former post at Sorel river, where he remained but a short period, being followed by a heavy British column, giving him only sufficient time to leave the fort before the enemy entered it. The retreat was made good by the able conduct of Wayne, who, with his stores and baggage, safely arrived at Ticonderoga.

At a consultation among the generals it was determined that at this post they should take their stand. After reconnoitering the fortifications, and finding them so well prepared to resist an attack, the British general re-embarked his forces and retired to Canada.

Immediately on the withdrawal of the British troops, General Gates repaired to Washington’s army, leaving Colonel Wayne in entire charge of Ticonderoga. This high compliment paid to Colonel Wayne, agreeable to the troops and approved of by Congress, caused the gallant soldier to be promoted to the rank of Brigadier-general. He remained at this post six months, when, Washington having marched his main army into Jersey, General Wayne solicited permission to join him, which he did at Bound Brook, a few miles from Brunswick, in New Jersey. Soon after the arrival of Wayne, General Howe, having received reinforcements from England, at New York, took up his line of march across Jersey, in order to intercept the American army before reaching Philadelphia. Washington conceived the plan of General Howe to be to surprise the city of Philadelphia and disperse the congressional assembly, who were then sitting there; he accordingly[20] dispatched Wayne and his troops to meet and strike them, in order to resist their passage at Chad’s Ford. This was done, and a sharp conflict ensued, which was gallantly kept up until late in the evening, when it was thought prudent to retreat; the loss sustained by the Americans was stated to be three hundred killed and four hundred taken prisoners. The statement given by the British general himself, was one hundred killed and four hundred wounded, but which was afterwards ascertained to be nearly double that number. In this battle the young patriot Lafayette first drew his sword in the cause of America’s freedom, and although severely wounded in his leg at the very onset of the battle, he continued to cheer and encourage his soldiers, (with the blood flowing from his wound, having bound his sash around it,) till the end of the conflict.

The British, taking a circuitous route, now marched with all haste towards Philadelphia, and Washington wishing to give them the meeting before reaching the city, retired to Chester, where both armies met at some distance from the Warren tavern, on the Lancaster road. General Wayne commenced the action with great spirit, but a violent storm came on which rendered it impossible for the battle to continue, and each army withdrew from the field.

Washington, in order to save Philadelphia, with the main army fell back and crossed the Schuylkill at Parker’s ferry, leaving General Wayne with about fifteen hundred men to watch the enemy, who had retreated back about three miles. After remaining at that post for four days, he was apprised of the near approach of the British army, and after giving three distinct orders to one of his colonels to lead off by another road and attack the enemy in the rear, which order was not understood, and consequently not obeyed, gave the British time to come upon them before they could make good their retreat.[21] The enemy fell upon them with the cry of “No quarters,” and one hundred and fifty of his brave men were killed and wounded in this barbarous massacre. The next battle at which this valiant soldier distinguished himself, was at Germantown. The British having taken a position in the immediate vicinity of that village, General Wayne, moving with much secrecy, attacked them in their camp at the dawn of day, but after many hours of hard fighting and a succession of untoward circumstances, was obliged to retreat. The loss of the Americans in this action, was one hundred and fifty-two killed, five hundred and twenty-one wounded, and four hundred taken prisoners; the loss of the British was eight hundred killed and wounded.

The British army remained in nearly the same position till the 26th of October, when General Howe, with a detachment of his troops, took peaceable possession of Philadelphia. Watson, in his Annals of Philadelphia, says,—“As they entered the city, Lord Cornwallis at their head led the van. They marched down Second street without any huzzaing or insolence whatever, and the citizens thronged the sidewalks with serious countenances, looking at them. The artillery were quartered in Chestnut street, between Third and Sixth streets. The State House yard was made use of as a parade ground.”

Congress had previously been removed to Lancaster, in the interior of the state, sixty miles from Philadelphia. Washington and his army were posted at White Marsh, about fourteen miles from Philadelphia, and in order to draw the commander-in-chief from his strong position, the British general, Howe, marched his soldiers to the neighborhood of the American lines, and after many demonstrations of attack, finding that Washington was not disposed to bring on another action, retreated again to the city. This gave Washington an opportunity[22] of proceeding to Valley Forge, where, in the month of December, with his almost famished and naked soldiers, they cheerfully commenced building huts with their own hands in the woods. Early in January, General Wayne repaired to Lancaster, where the government was then located, to use his exertions in raising supplies, both of provisions and clothing, for the army.

In part did he succeed, but the scarcity of provisions becoming so great, that Washington was at length compelled to detach a body of troops, under General Greene, with orders to obtain “an immediate supply of provisions by any means within his power.” This was done by seizing every animal fit for slaughter; and by this means the immediate wants of the starving troops were supplied.

In order to prevent a similar deplorable state of want, our gallant hero, who knew no danger, in the month of February, a most inclement season, left the army with a body of troops on an expedition to New Jersey, to secure cattle on the banks of the Delaware.

This, of all others, was a dangerous enterprise, for the British were wintering in detachments in many places near the Delaware. However, in our hero bravery knew no fear, and for the relief of his suffering soldiers he was determined to attack and wrest from the British, (whenever he came in contact,) provisions for his men and sustenance for his horses. After several skirmishes, which might really be termed battles, he succeeded, by his soldier-like and judicious management, in capturing from them and sending to the American camp several hundred fine cattle, some excellent horses, and a large amount of forage. About the middle of March he returned to Valley Forge, to receive the thanks of his commander-in-chief and the blessings of the army. The British remained in quiet possession of Philadelphia till the 18th of June following,[23] when they commenced their march through Jersey. On the same day Washington left Valley Forge in order to follow them, and on the 24th encamped about five miles from Princeton, while the British had encamped at Allentown. During the winter General Howe had requested to be recalled, and the command now devolved upon Sir Henry Clinton. Wayne, with four thousand men, was ordered, accompanied by Lafayette, with one thousand men, to take a position near Monmouth Courthouse, about five miles in the rear of the British camp, in order to prevent their reaching the Highlands of New York. Washington, who had determined to attack the British the moment they moved from their ground, received intelligence on the morning of the 28th of June that they were on their way. The troops were immediately under arms, and General Lee ordered to march on and attack the rear, as the enemy advanced towards the troops of Wayne and Lafayette. This was done, and the Americans, though much fatigued by their previous march, fought with such determined bravery that the British gave way. Taking advantage of the night, which saved them from a total rout, they withdrew to the heights of Middletown, leaving behind them two hundred and forty-five killed of their soldiers, and many of their officers; others they had before interred. The following is an extract of a letter of Wayne to a friend:—

“Paramus, 12th July, 1778.

“We have been in perpetual motion ever since we crossed the Delaware until yesterday, when we arrived here, where we shall be stationary for a few days, in order to recruit a little after the fatigue which we have experienced in marching through deserts, burning sands, &c. &c.

“The enemy, sore from the action of the 28th ult., seemed[24] inclined to rest also. They are now in three divisions; one on Long Island, another on Staten Island, and a third in New York.

“The victory on that day turns out to be much more considerable than at first supposed. An officer who remained on the ground two or three days after the action, says that nearly three hundred British had been buried by us on the field, and numbers discovered in the woods, exclusive of those buried by the enemy, not much short of one hundred. So that by the most moderate calculation, their killed and wounded must amount to eleven hundred, the flower of their army, and many of them of the richest blood of England.

“Tell those Philadelphia ladies who attended Howe’s assemblies and levees, that the heavenly, sweet red-coats, the accomplished gentlemen of the guards and grenadiers, have been humbled on the plains of Monmouth. These knights have resigned their laurels to rebel officers, who will lay them at the feet of those virtuous daughters of America, who cheerfully gave up ease and affluence in a city, for liberty and peace of mind in a cottage.

“Adieu, and believe me

“Yours most sincerely,

“Anthony Wayne.”

The British commander, having in the night escaped from his adversary, took a strong position on the high grounds about Middletown, where remaining, however, but a few days, he proceeded to Sandy Hook, and passed over to New York.

Washington, at this time, proceeded by slow and easy marches to the Highlands of the Hudson.

It was his intention to fortify West Point, and the Highlands of the North River; accordingly the works at Stony and Verplanck’s Points were commenced for that purpose,[25] yet only on Verplanck’s a small but strong work had been completed and garrisoned by seventy men, under Captain Armstrong, while the works on Stony Point, of much greater extent and of incomparably more importance, were unfinished. To secure these valuable positions was a matter of great magnitude both to the British as well as American commander-in-chief; hence was the determination of fortifying the Highlands, so as to comprehend within it these important positions. To arrest the progress of these fortifications, Sir Henry Clinton sailed with a fleet up the Hudson, and landed his troops in two divisions; the one under General Vaughan, destined against the works at Verplanck’s on the east side of the river—the other, which he commanded in person, against those of Stony Point, on the west side. The fortifications on Stony Point being unfinished, were abandoned without resistance, on the approach of the enemy, who instantly commenced dragging some heavy cannon and mortars to the summit of the hill, and on the next morning about sunrise opened a battery on Fort Fayette, erected on Verplanck’s, the distance across being about one thousand yards.

The cannonade during the day, from the very commanding position of Stony Point, as also from vessels and gun-boats in the river, occasioned much injury to the fort; which, being invested both by water and land, and no means of saving the garrison now remaining, Captain Armstrong, (who had command,) after a gallant resistance, was compelled to surrender himself and troops prisoners of war. Sir Henry proceeded immediately to place both forts in what he supposed a perfect state of defence, especially that of Stony Point, which he garrisoned with six hundred men, under the command of an officer distinguished for his bravery and circumspection. In consequence of Washington being now at West Point, Sir Henry declined a further movement up the Hudson, but remained[26] with his army at Phillipsburg, about midway between New York and Stony Point. Immediately on the arrival of Wayne at head quarters, Washington commenced laying plans for the recapture of Stony Point, and in a conference between the commander-in-chief and Wayne, the latter, emphatically to express his willingness to undertake the perilous enterprise, is said to have remarked:—“General, if you will only plan it, I will storm Hell!”

As no industry had been wanting in completing or repairing the works at Stony Point, which the length of possession by the British would admit of, that post was now in a very strong state of defence; its garrison consisted of the seventeenth regiment of foot, the grenadier companies of the seventy-first and some artillery; the whole under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Johnson. The garrison at Verplanck’s was under the conduct of Lieutenant Colonel Webster, and was at least equal in force to that of Stony Point. General Wayne was appointed to the difficult and arduous task of surprising and storming Stony Point, for which Washington provided him with a strong detachment of the most active infantry in the American service. These troops had a distance of about fourteen miles to travel over high mountains, through deep morasses, difficult defiles and roads exceedingly bad and narrow, so that they could only move in single files during the greatest part of their journey. About eight o’clock in the evening of the 15th of July, the van arrived within a mile and a half of their object, where they halted, and the troops were formed into two columns as fast as they came up. While they were in this position, Wayne, with most of his principal officers, went to reconnoitre the works, and to observe the situation of the garrison. It was near midnight before the two columns approached the place; that on the right, consisting of Febiger and Meigs’ regiments, was led by General[27] Wayne. The van, consisting of one hundred and fifty picked men, led by the most adventurous officers, and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Fleury, advanced to the attack, with unloaded muskets and fixed bayonets. They were preceded by an avant-guard, consisting of an officer of the most distinguished courage, accompanied by twenty of the most desperate private men, who, with other officers, were intended to remove the abatis, and whatever obstructions lay in the way of the succeeding troops. The column on the left, was led by a similar chosen van, with unloaded muskets and fixed bayonets, under the command of Major Stewart; and that was also preceded by a similar avant-guard. The general issued the most positive orders to both columns, (which they strictly adhered to,) not to fire a shot on any account, but to place their whole reliance on the bayonet. The two attacks seem to have been directed to opposite points of the works; whilst a detachment under Major Murfree engaged the attention of the garrison, by a feint in their front. They found the approaches more difficult than even their knowledge of the place had induced them to expect; the works being covered by a deep morass, which, at this time, happened to be overflowed by the tide.

The general, in his official papers, says, “that neither the deep morass, the formidable and double rows of abatis, or the strong works in front and flank could damp the ardor of his brave troops; who, in the face of a most incessant and tremendous fire of musketry, and of cannon loaded with grape-shot, forced their way at the point of the bayonet through every obstacle, until the van of each column met in the centre of the works, where they arrived at nearly the same time.” General Wayne was wounded in the head by a musket-ball, as he passed the last abatis; but was gallantly supported and assisted through the works by his two brave aids-de-camp,[28] Fishbourn and Archer, to whom he acknowledges the utmost gratitude in his public letter. Colonel Fleury, a French officer, had the honor of striking the British standard with his own hand, and placing in its room the American stars and stripes. Major Stewart and several other officers received great praise; particularly the two Lieutenants Gibbons and Knox, one of whom led the avant-guard on the right, and the other on the left. Both, however, had the good fortune to escape unhurt, although Lieutenant Gibbons lost seventeen men out of twenty in the attack.

There is nothing in the annals of war which affords more room for surprise, and seems less to be accounted for, than the prodigious disparity between the numbers slain in those different actions, which seem otherwise similar or greatly to correspond in their principal circumstances, nature and magnitude. Nothing could well be supposed, from its nature and circumstances, more bloody, in proportion to the numbers engaged, than this action; and yet the loss on both sides was exceedingly moderate.

Nothing could exceed the triumph of America and Americans generally, upon the success of this enterprize, and the vigor and spirit with which it was conducted.

It must, indeed, be acknowledged, that considered in all its parts and difficulties, it would have done honor to the most veteran soldiers. General Washington, the Congress, the General Assembly, and the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, were emulous in their acknowledgments, and in the praises which they bestowed upon General Wayne, his officers and troops. In these they particularly applaud the humanity and clemency shown to the vanquished, when, by the laws of war, and stimulated by resentment from the remembrance of former cruelty received from the British,[29] they would have been justified in putting the whole garrison to the sword.

As soon as Stony Point was taken, the artillery was directly turned against Verplanck’s, and a furious cannonade ensued which necessarily obliged the shipping at the latter place to cut their cables and fall down the river. The news of this disaster, and of Webster’s situation, who also expected an immediate attack on the land side, no sooner reached Sir Harry Clinton, than he took the most speedy measures for the relief of Verplanck’s. The whole British land and naval force was in motion. But, however great the importance or value of Stony Point and Verplanck’s, Washington was by no means disposed to hazard a general engagement on their account; more especially in a situation where the command of the river would afford such decisive advantages to his enemy in the disposition and sudden movement of their troops, whether with respect to the immediate point of action, or to the seizing of the passes, and cutting off the retreat of his army, as might probably be attended with the most fatal consequences.

In his letter to Congress, he says, that it had been previously determined in council not to attempt keeping that post, and that nothing more was originally intended than the destruction of the works and seizing the artillery and stores. This adventurous and daring feat kept the advanced posts of the British in a state of serious alarm.

By the journals of Congress for July 26, 1779, it appears that the attack on the fort at Stony Point was ordered by General Washington on the 10th of July. General Wayne issued his orders on the 15th, on the night of which day the attack was made. The prisoners taken were five hundred and forty-three; not a musket was fired by the Americans; and although the laws of war and the principle of retaliation for[30] past cruelty, would have justified the sacrifice of the garrison, yet not a man was killed who asked for quarters. Soon after this gallant action, General Wayne repaired to his family in Chester county, and thence to the seat of Government, to use his exertions in stimulating the councils of the nation in behalf of the suffering army, one-half of which was at this time nearly barefooted, and otherwise destitute of comforts. As the winter was now approaching, Washington was preparing to take up his quarters at Morristown, New Jersey, in order to restrain the British, who were then stationed at New York, from incursions into the adjacent country.

In May, 1780, Wayne was ordered to repair to the camp at Morristown, and resume his command in the Pennsylvania line. Little more than useless marches, and casual skirmishes with the enemy was accomplished during this year.

In November of the same year Wayne appears before his government supplicating supplies for his soldiers. This he accomplished, and returned in December to his winter quarters at Morristown, where he remained till the end of February, 1781. Receiving orders to join the southern army under General Greene, now in Virginia, Wayne accordingly commenced collecting his troops; but, from so many and unaccountable delays, it was May before he could concentrate them at York, Pennsylvania. Early in June the Pennsylvania troops, eleven hundred in number, formed a junction with Lafayette, whom they met in Virginia, and determined at once to march against Cornwallis, who was now retreating. Lafayette held a position about twenty miles in the rear of the British, whilst the advanced corps of Wayne kept within eight or nine miles, with the intention of commencing an attack on the rear guard, after the main body should have passed the river. Lafayette, having received intelligence that the enemy were preparing to cross the James river, he immediately[31] took a position at Chickahominy church, eight miles above Jamestown. Early the following morning, Wayne believing that the main army of the British had effected its passage, was determined to march forward and attack the rear guard; but upon arriving within sight he found he was mistaken, and that he had now to confront the whole British force with only five hundred men; the only safe mode which he could now calculate upon, was that of attacking vigorously and retreating precipitately. “For,” said he, “moments decide the fate of battles,” and accordingly the firing was commenced with great firmness at three o’clock, and continued till five in the afternoon.

In this severe but gallant action one hundred and eight of the Continental troops were killed, wounded and taken; most of the officers were severely wounded, and many of the field officers had their horses killed under them. Lafayette, in his official notice of this action, says—“From every account the enemy’s loss has been very great, and much pains taken to conceal it.”

In a letter from General Washington to Wayne, he adds:—“The Marquis Lafayette speaks in the handsomest manner of your own behavior, and that of the troops, in the action at Green Spring. I think the account which Lord Cornwallis will be obliged to render of the state of southern affairs, will not be very pleasing to ministerial eyes and ears, especially after what appears to have been their expectations by their intercepted letters of March last. I am in hopes that Virginia will be soon, if not before this time, so far relieved as to permit you to march to the succor of General Greene, who, with a handful of men, has done more than could possibly have been expected; should he be enabled to maintain his advantage in the Carolinas and Georgia, it cannot fail of having the most important political consequences in Europe.”[32] The movements of Cornwallis indicated a permanent post at Yorktown, a short distance up the York river, where he had removed the principal part of his forces, and commenced his fortifications. Washington hearing of this movement, commanded Lafayette to take early measures to intercept the retreat of Cornwallis, should he discover the intended blow, and attempt a retreat by North Carolina.

At the interposition of the Marquis Lafayette with his government, a French fleet, consisting of three thousand troops, were equipped and dispatched to the assistance of struggling America; and on the 2d September landed at Burwell’s Ferry, near this place. Lafayette, who was encamped about ten miles from General Wayne, on hearing of the arrival of the French fleet, requested an interview with him. In a letter to a friend, Wayne describes an accident that occurred to him on his way thither:—“After the landing of the French fleet, and pointing out to them the most proper position for their encampment, I received an express from the Marquis Lafayette, to meet him on business of importance that evening. I proceeded accordingly, attended by two gentlemen and a servant. When we arrived in the vicinity of the camp, about ten o’clock at night, we were challenged by a sentry, and we made the usual answer, but the poor fellow being panic-struck, mistook us for the enemy, and shot me in the centre of the left thigh; then fled and alarmed the camp. Fortunately, the ball only grazed the bone, and lodged on the opposite side to which it entered.” The main works of Cornwallis were at his strongly fortified garrison at Yorktown, on the York river. He also occupied Gloucester, on the opposite side, where he erected works to keep up the communication with the country. General Washington reached the neighborhood of this interesting scene of operation on the 14th of September, and immediately proceeded on board the Ville de Paris, (flag-ship of[33] the French admiral,) where the plan of the siege was concerted.

Subjoined is an extract of General Wayne’s diary of the siege of Yorktown and capture of Lord Cornwallis:

“On the 28th of September, 1781, General Washington put the combined army in motion, at five o’clock in the morning, in two columns, (the Americans on the right and the French on the left,) and arrived in view of the enemy’s lines at York about four o’clock in the afternoon.

“29th. Completed the investiture. The enemy abandoned their advanced chain of works this evening, leaving two redoubts perfect within cannon-shot of their principal fortifications.

“30th. The allied troops took possession of the ground vacated by the British, and added new works.

“1st October. The enemy discovering our works commenced a cannonade, continuing through the day and night with very little effect.

“2d. Two men killed by the enemy’s fire.

“3d. A drop-shot from the British killed four men from the covering party.

“4th. The redoubts were perfected; the enemy’s fire languid.

“5th. Two men killed by rocket-shot.

“6th. Six regiments, viz., one from the right of each brigade marched at six o’clock, P. M., under the command of Major General Lincoln and Brigadier Generals Clinton and Wayne, and opened the first parallel within five hundred and fifty yards of the enemy’s works and their extreme left, which was continued by the French to the extreme right.

“7th. The parallel nearly complete, without any opposition, except a little scattered fire of musketry, and a feeble[34] fire of artillery, by which a few of the French troops were wounded and one officer lost his leg.

“8th. Completed the first parallel; two of the Pennsylvanians were killed by rocket-shot.

“9th. At three o’clock P. M., the French opened a twelve gun battery on the extreme right of the enemy; and at five o’clock the same day, a battery of ten pieces was opened on their extreme left, by the Americans, with apparent effect.

“10th. At daybreak three more batteries were opened, (one of five heavy pieces by the Americans, and two containing twenty-two by the French,) opposite the centre of the British works; at five P. M., another American battery of two ten inch howitzers was also opened, which produced so severe a fire, that it in a great degree silenced that of the enemy; at seven o’clock P. M., the Caron, of forty-four guns, was set on fire by our balls and totally consumed.

“11th. Second parallel opened this night by the Pennsylvanians and Marylanders, covered by two battalions under General Wayne, on the part of the Americans.

“12th. Nothing material.

“13th. That part of the second parallel which was opened, nearly completed.

“14th. A little after dark, two detached redoubts belonging to the enemy were stormed; that on the extreme left by the light infantry, under the Marquis Lafayette, in which were taken a major, captain, and one subaltern, seventeen privates, and eight rank and file killed.

“Our army lost, in killed and wounded, forty-one. The other was carried by the French, under the Baron de Viominial, who lost, in killed and wounded, about one hundred men. Of the enemy eighteen were killed, and three officers and thirty-nine privates were made prisoners. The above attacks were supported by two battalions of the Pennsylvanians,[35] under General Wayne; whilst the second parallel was completed by the Pennsylvanians and Marylanders, under Colonel W. Stewart.

“15th. Two small batteries were opened this evening.

“16th. The enemy made a sortie, and spiked seven pieces of artillery, but were immediately repulsed, the spikes drawn, and the batteries again opened.

“17th. The enemy beat the chamade at ten o’clock A. M., Cornwallis now sent out a flag, proposing a cessation of hostilities for twenty-four hours, and that commissioners might be appointed to meet to settle the terms upon which the garrisons of York and Gloucester should surrender. General Washington would only grant a cessation for two hours; previously to the expiration of which, his lordship, by another flag, sent the following terms, viz:—The troops to be prisoners of war; the British to be sent to Great Britain, and not to act against America, France, or her allies, until exchanged; the Hessians to Germany, on the same conditions; and that all operations cease until the commissioners should determine the details. To this his excellency returned for answer:—That hostilities should cease, and no alterations in the works, or any new movement of the troops, take place, until he sent terms in writing; which he did on the 18th, at nine o’clock, A. M., allowing the enemy two hours to determine. They again requested more time; and the general granted them until one o’clock, when they acceded to the heads of the imposed terms, and nominated Colonel Dundas and Major Ross, on their part, to meet with Colonel Laurens and Viscount de Noailles on ours, to reduce them to form, which was completed by nine o’clock at night; and on the 19th, at one o’clock P. M., the capitulation was ratified and signed by the commander of each army, when the enemy received a guard of Pennsylvania and Maryland troops in one of their principal[36] works, and one of the French troops in another. At four o’clock, the same afternoon, the British army marched out of Yorktown with colors cased, between the American and French troops, drawn up for the purpose, and then grounded their arms agreeably to capitulation.”

After this successful struggle, General Wayne was commanded to repair without delay to the aid of General Greene, who was encamped near Savannah, Georgia, in which state the enemy had been long rioting without the fear of opposition from either regulars or militia. Not, however, before the 19th of January, 1782, did he reach the Savannah river, and having crossed it with a detachment of the first and fourth regiments of dragoons, with this force, aided by a small state corps and a few spirited militia, he soon routed the enemy from some of their strongest posts. Wayne receiving intelligence of a body of Creek Indians being on their march to Savannah, detached a strong party of horse under Colonel McCoy, dressed in British uniform, in order to deceive and decoy them. This deception succeeded, and the Indians were all surrounded and taken without the least resistance.

General Wayne, in a letter to a friend, dated the 24th of February, writes, “It is now upwards of five weeks since we entered this state, during which period not an officer or soldier with me has once undressed for the purpose of changing his linen; nor do the enemy lie on beds of down—they have once or twice attempted to strike our advance parties. The day before yesterday they made a forward move in considerable force, which induced me to advance to meet them; but the lads declined the interview, by embarking in boats and retreating by water to Savannah, the only post they now hold in Georgia.” This post remained in possession of the British till the month of May, when the British administration, having resolved upon abandoning all offensive operations in America,[37] it was ordered to be evacuated. Accordingly, on the 11th of July, 1782, Savannah was delivered into the possession of General Wayne, whose time was now fully occupied in replying to the numerous applications of the merchants and citizens of that place. About the end of November, General Wayne, with the light infantry of the army, and the legionary corps, reached the vicinity of Charleston, S. C., where Greene was posted near the Ashley river, a convenient position to attack the rear of the enemy when the hour of evacuation should arrive; but a proposition from the British General, to be permitted to embark without molestation if he left the town untouched, was acceded to, and on the morning of the 14th of December, General Wayne had also the honor and satisfaction of taking peaceable possession of Charleston, thus closing his last active scene in the war of the American revolution.

General Wayne continued busily engaged at the south till the following July, when he took passage for Philadelphia in very delicate health, having contracted a fever while in Georgia.

In 1784, Wayne was elected by his native county to the General Assembly, where he took deep interest in every act which agitated the Legislature. His family estates, which had so long been inoperative, now claimed his attention; which, for the space of two years, was most assiduously devoted to them. President Washington nominated Wayne to the Senate as Commander-in-chief of the United States army—which was confirmed and accepted the 13th of April, 1792. The object of this high and honorable post being bestowed on Wayne, was to bring to a close the war with the confederated tribes of Indians, which was raging on the northwestern frontier. During the four years of Indian warfare, General Wayne suffered severely from his previous[38] disease, living, however, to witness the termination of those troubles which had so long existed, but not to share in the happy results which his bravery and exalted wisdom had consummated. He died at Presque Isle, on the 15th of December, 1796. An able writer thus portrays the character of this exalted man:—

“The patriotism, spirit and military character of General Anthony Wayne are written on every leaf of his country’s history, from the dawn of the revolution to the close of his eventful life. If you ask who obeyed the first call of America for freedom? It was Wayne! he was first on the battleground and last to retire. If you ask who gallantly led his division to victory on the right wing at the battle of Germantown? Who bore the fiercest charge at the battle of Monmouth? Who, in the hour of gloom, roused the desponding spirits of the army and nation by the glorious storming and capturing of Stony Point? It was General Anthony Wayne.

“In Congress, July 26th, 1779, it was resolved unanimously, that the thanks of Congress be presented to Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, for his brave, prudent and soldierly conduct, in the spirited and well-conducted attack of Stony Point.”

A gold medal was voted to him at the same time, of which the following is a description taken from the original in the possession of his family. (See Plate II.)

Occasion.—Taking of Stony Point, on the North River, by storm.

Device.—An Indian Queen crowned, a quiver on her back, and wearing a short apron of feathers: a mantle hangs from her waist behind: the upper end of the mantle appears as if passed through the girdle of her apron, and hangs gracefully by her left side. She is presenting, with her right hand, a[39] wreath to General Wayne, who receives it. In her left hand, the Queen is holding up a mural crown towards the General. On her left and at her feet an alligator is stretched out. She stands on a bow: a shield, with the American stripes, rests against the alligator.

Legend.—Antonio Wayne Duci Exercitas comitia Americana.

Reverse.—A fort, with two turrets, on the top of a hill: the British flag flying: troops in single or Indian file, advancing in the front and rear up the hill: numbers lying at the bottom. Troops advancing in front, at a distance, on the edge of the river: another party to the right of the fort. A piece of artillery posted on the plain, so as to bear upon the fort; ammunition on the ground: six vessels in the river.

Legend.—Stony Point expugnatum.

Exergue.—15th July, 1779.

It is a singular fact that no biographical memoir can be found of this gallant officer.

By the journals of Congress for July 26, 1779, we find, that that body passed a unanimous vote of thanks to General Wayne, and the officers and soldiers, whose bravery was so conspicuous at the memorable attack on Stony Point; particularly mentioning Colonel De Fleury and Major Stewart, as having led the attacking columns, under a tremendous fire. By the same resolve of Congress, we find, that a medal, descriptive of that action, was ordered to be struck and presented to Major Stewart. (See Plate II.)

In a communication soon after the close of the war, it says, that Major Stewart was killed by a fall from his horse, near Charleston, South Carolina. Should this meet the eye of any of the representatives of the late Major Stewart, the publishers of these memoirs would feel grateful for any particulars respecting that distinguished officer, as they may be added in another edition.[41]

Occasion.—Taking the fort of Stony Point.

Device.—America, personified in an Indian queen, is presenting a palm branch to Captain Stewart: a quiver hangs at her back: her bow and an alligator at her feet: with her left hand she supports a shield inscribed with the American stripes, and resting on the ground.

Legend.—Johanni Stewart cohortis prefecto comitia Americus.

Reverse.—A fortress on an eminence: in the foreground, an officer cheering his men, who are following him over a battis with charged bayonets in pursuit of a flying enemy; troops in Indian files ascending the hill to the storm, front and rear: troops advancing from the shore: ships in sight.

Exergue.—Stony Point oppugnatum, 15th July, 1779.

Very little is known of the hero of the following memoir previous to his leaving his native country. He was educated as an engineer, and brought with him to this country testimonials of the highest order. His family were of the French noblesse; his ancestor, Hercule André de Fleury, was canon of Montpelier, and appointed by Louis XIV. preceptor to his grandson. At the age of seventy years he was made cardinal and prime minister, and by his active and sagacious measures the kingdom of France prospered greatly under his administration.

De Fleury, the subject of this brief sketch, was pursuing his profession when the news of the American revolution reached the shores of France. Endowed by nature with a spirit of independence, vigorous intellect, undaunted courage, and a spirit of enterprise, he seemed peculiarly fitted to encounter perils and hardships, which his daring, prompt and skillful maneuvers, in some of the sharpest battles of the revolution, proved most true. He read with excited anxiety, again and again, of the oppression and tyranny exercised by the mother country against the colonies.

Next came the news that at once decided our young hero[43] on embarking for America; the colonies had actually revolted, had thrown off the yoke of tyranny and usurpation, declaring themselves a free and independent people. This was a struggle, but it must be conquered. De Fleury reached the shores of America, was received by the Commander-in-chief, received a commission, and commenced his revolutionary campaign, to which he adhered with that unflinching constancy which leaves no doubt of the purity and disinterestedness of his motives. Soon after the battle of Brandywine our hero was dispatched to Fort Mifflin in the capacity of engineer, described in the following letter from General Washington to Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel Smith, in which he says:—“Enclosed is a letter to Major Fleury, whom I ordered to Fort Mifflin to serve in quality of engineer. As he is a young man of talents, and has made this branch of military service his particular study, I place confidence in him. You will, therefore, make the best arrangement for enabling him to carry such plans into execution as come within his department. His authority, at the same time that it is subordinate to yours, must be sufficient for putting into practice what his knowledge of fortification points out as necessary for defending the post; and his department, though inferior, being of a distinct and separate nature, requires that his orders should be in a great degree discretionary, and that he should be suffered to exercise his judgment. Persuaded that you will concur with him in every measure, which the good of the service may require, I remain,” &c.

For six days previous to the evacuation of Fort Mifflin, the fire from the enemy’s batteries and shipping had been incessant. Major Fleury kept a journal of events, which were daily forwarded to General Washington, from which the following are extracts.

“November 10th, at noon.—I am interrupted by the bombs[44] and balls, which fall thickly. The firing increases, but not the effect; our barracks alone suffer. Two o’clock:—the direction of the fire is changed; our palisades suffer; a dozen of them are broken down; one of our cannon is damaged; I am afraid it will not fire straight. Eleven o’clock at night:—the enemy keep up a firing every half hour. Our garrison diminishes; our soldiers are overwhelmed with fatigue.

“11th. The enemy keep up a heavy fire; they have changed the direction of their embrasures, and instead of battering our palisades in front, they take them obliquely and do great injury to our north side. At night:—the enemy fire and interrupt our works. Three vessels have passed up between us and Province Island, without any molestation from the galleys. Colonel Smith, Captain George, and myself wounded. These two gentlemen passed immediately to Red Bank.

“12th. Heavy firing; our two eighteen pounders at the northern battery dismounted. At night:—the enemy throw shells, and we are alarmed by thirty boats.

“13th. The enemy have opened a battery on the old Ferry Wharf; the walk of our rounds is destroyed, the block-houses ruined. Our garrison is exhausted with fatigue and ill-health.

“14th. The enemy have kept up a firing upon us part of the night. Day-light discovers to us a floating battery, placed a little above their grand battery and near the shore. Seven o’clock:—the enemy keep up a great fire from their floating battery and the shore; our block-houses are in a pitiful condition. At noon:—we have silenced the floating battery. A boat, which this day deserted from the fleet, will have given the enemy sufficient intimation of our weakness; they will probably attempt a lodgment on the Island, which we cannot prevent with our whole strength.

“15th—at six in the afternoon.—The fire is universal from[45] the shipping and batteries. We have lost a great many men to-day; a great many officers are killed or wounded. My fine company of artillery is almost destroyed. We shall be obliged to evacuate Fort Mifflin this night. Major Talbut is badly wounded.

“16th. We were obliged to evacuate the fort last evening. Major Thayer returned from thence a little after two this morning. Everything was got off that possibly could be. The cannon could not be removed without making too great a sacrifice of men, as the Vigilant lay within one hundred yards of the southern part of the works, and with her incessant fire, hand grenades and musketry, from the round-top, killed every man that appeared upon the platforms.”

After this devastating conflict, Fleury was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the army. He had already received from Congress the gift of a horse, as a testimonial of their sense of his merit at the battle of Brandywine, where a horse was shot under him.

“To the President of Congress—

“Head Quarters, West Point, 25th July, 1779.

“Sir:—Lieutenant-Colonel Fleury having communicated to me his intention to return to France at the present juncture, I have thought proper to give him this letter to testify to Congress the favorable opinion I entertain of his conduct. The marks of their approbation, which he received on a former occasion, have been amply justified by all his subsequent behavior. He has signalized himself in more than one instance since; and in the late assault of Stony Point, he commanded one of the attacks, was the first that entered the enemy’s works, and struck the British flag with his own hands, as reported by General Wayne. It is but justice to him to declare, that, in the different services he has been[46] of real utility, and has acquitted himself in every respect as an officer of distinguished merit, one whose talents, zeal, activity, and bravery, alike entitle him to particular notice. I doubt not Congress will be disposed to grant him every indulgence. I have the honor to be, &c. &c.

G. Washington.

West Point, 28th July, 1779.

I certify that Lieutenant-Colonel Fleury has served in the army of the United States since the beginning of the campaign in 1777, to the present period, and has uniformly acquitted himself as an officer of distinguished merit for talents, zeal, activity, prudence, and bravery; that he first obtained a captain’s commission from Congress, and entered as a volunteer in a corps of riflemen, in which, by his activity and bravery, he soon recommended himself to notice; that he next served as brigade major, with the rank of major, first in the infantry and afterwards in the cavalry, in which stations he acquired reputation in the army, and the approbation of his commanding officers, of which he has the most ample testimonies; that towards the conclusion of the campaign of 1777, he was sent to the important post of Fort Mifflin, in quality of engineer, in which he rendered essential services, and equally signalized his intelligence and his valor. That in consequence of his good conduct on this and on former occasions, he was promoted by Congress to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, and has been since employed in the following stations, namely, as a sub-inspector, as second in command in a corps of light infantry, in an expedition against Rhode Island, and lastly as commandant of a battalion of light infantry, in the army under my immediate command; that in[47] each of these capacities, as well as the former, he has justified the confidence reposed in him, and acquired more and more the character of a judicious, well-informed, indefatigable and brave officer. In the assault of Stony Point, a strong, fortified post of the enemy on the North River, he commanded one of the attacks, was the first that entered the main works, and struck the British flag with his own hands.

G. Washington.

In July, 1779, Congress passed a vote of thanks to Colonel De Fleury, with a gold medal (see Plate II.) for his bravery and courage at Stony Point. During the two years De Fleury was attached to the American army, he took a conspicuous post in all the battles fought within that period; and such was his bravery, that every commander under whom he had the honor to serve, recommended him to the especial notice of Congress.

Occasion.—Taking the fort of Stony Point.

Device.—A soldier helmeted and standing against the ruins of a fort: his right hand extended, holding a sword upright: the staff of a stand of colors reversed in his left: the colors under his feet: his right knee drawn up, as if in the act of stamping on them.

Legend.—Virtutis et audiciæ monum, et præmium D. De Fleury equiti gallo primo muros resp. Americ. d. d.

Reverse.—Two water batteries, three guns each: one battery firing at a vessel: a fort on a hill: flag flying: river in front: six vessels before the fort.

Legend.—Aggeres paludes hostes victi.

Exergue.—Stony Pt. expugn. 15th July, 1779.

John Andre, a British officer, was clerk in a mercantile house in London; being anxious for a military life, he obtained a commission as ensign in the regiment commanded by Sir Henry Clinton, then about to embark for America. His energetic and enterprising spirit soon raised him to the rank of major and aid-de-camp to Sir Henry. Benedict Arnold, the American traitor, a man guilty of every species of artifice and deception, smarting under the inflictions of a severe reprimand from his superiors, for misconduct, was resolved to be revenged by the sacrifice of his country. By artifice he obtained command of the important post of West Point. He had previously, in a letter to the British commander, signified his change of principles, and his wish to join the royal army. A correspondence now commenced between him and Sir Henry Clinton, the object of which was to concert the means of putting West Point into the hands of the British. The plot was well laid, correct plans of the fort drawn, and as they supposed, the execution certain. The arrangement was effected by Major John Andre, aid-de-camp to Sir Henry Clinton, and adjutant-general of the British army. Andre, who had effected all the arrangements with Arnold, received[49] from him a pass, authorizing him, under the feigned name of Anderson, to proceed on the public service to the White Plains, or lower, if it was required.

He had passed all the guards and posts on the road without suspicion, and was proceeding, with the delicate negotiation, to Sir Henry, who was then in New York.

Having arrived within a few miles of Tarrytown, he was accosted by three individuals who appeared loitering on the road. One of them seized the reins of his bridle, while another in silence pointed a rifle to his breast. Andre exclaimed, “Gentlemen, do not detain me; I am a British officer on urgent business; there is my pass,” at the same time drawing from his breast a paper, which he handed to one of the three, while the other two, looking with anxious scrutiny over the shoulders of their comrades, read as follows:—

Head Quarters, Robinson’s House, Sept. 22d, 1780.

Permit Mr. John Anderson to pass the guards to the White Plains, or below, if he chooses. He being on public business by my direction.

B. Arnold, M. Gen’l.

Andre made a second effort to be dismissed; when one of the men requested to know, how a British officer came in possession of a pass from an American general. A notice appeared some time since, purporting to be from a person who had remembered the circumstance, and an actual acquaintance of Paulding, Van Wart and Williams, that Paulding wore a British uniform, which accounted for the fatal mistake made by Andre, in so quickly declaring himself to be a British officer. The three militia men insisted upon Andre’s dismounting, which he did. They then led him to the side of[50] the road, and told him he must divest himself of his clothing, in order to give them an opportunity to search him. This was done with reluctance, after offering his splendid gold watch, his purse, nay thousands, to be permitted to pass; but no bribe could tempt, no persuasion could allure: they were Americans! Paulding, Van Wart and Williams had felt the hand of British wrong; they had been robbed, ill-treated, and trampled on, and would sooner suffer death than aid the enemy of Washington.

This, then, was the appalling moment. Andre knew that all must be divulged. He had but one hope, that their ignorance might prevent their being able to read the papers contained in his boot. In this he was mistaken, for Paulding first seizing the papers, read them aloud to his comrades in a bold voice. Nothing can picture the terrible treachery, which, to their uneducated minds, was planned in these papers.

Andre was speechless, and as pale as death. His fortitude seemed to forsake him; and laying his hands on Paulding’s arms, exclaimed, in tones of pity not to be described, “Take my watch, my horse, my purse, all! all I have—only let me go!” But no! the stern militia men could not be coaxed or bribed from their duty to their country. By a court martial ordered by General Washington, Andre was tried, found guilty, and agreeably to the law of nations, sentenced to suffer death.

Though he requested to die like a soldier, the ignominious sentence of being hung was executed upon him the 2d of October, 1780, at the early age of twenty-nine years.

Benedict Arnold effected his escape, remained in the British service during the war, then returned to London, where he died in 1801.

“By a vote of Congress, 3d of November, 1780, a silver medal or shield (See Plate IV.) was ordered to be struck and presented to John Paulding, David Williams, and Isaac Van[51] Wart, who intercepted Major John Andre in the character of a spy, and notwithstanding the large bribes offered them for his release, nobly disdaining to sacrifice their country for the sake of gold, secured and conveyed him to the commanding officer of the district, whereby the conspiracy of Benedict Arnold was brought to light, the insidious designs of the enemy baffled, and the United States rescued from impending danger.”

A pension of two hundred dollars, annually, during life, was bestowed on each of them.

Occasion.—Capture of Major Andre, Adjutant-General of the British army.

Device.—A shield.

Legend.—Fidelity.

Reverse.—A wreath.

Legend.—Vincit amor Patriæ.

Nathaniel Greene, the son of a preacher of the Society of Friends, was born on the 27th of May, 1742, in Warwick, Rhode Island.

Nathaniel received the first rudiments of his education among that peaceful sect; but being of a strong and robust form, he often had to intersperse his hours of study by a relaxation of labor in the field, at the mill, or at the anvil. His early years were passed at the home of his parents, and in the garb of a strict Quaker, till he was twenty years of age, when he commenced the study of law.

Not long, however, did he continue his studies, for in 1773, when the states began to organize their militia, his attention turned to the subject, and he became a member of the “Kentish Guards,” a military company composed of the most respectable young men in his county. For this he was dismissed from the Society of Friends; yet he ever after regarded the sect with great respect.