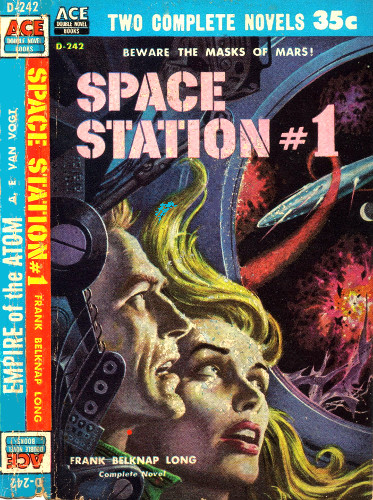

by FRANK BELKNAP LONG

ACE BOOKS

A Division of A. A. Wyn, Inc.

23 West 47th Street, New York 36, N. Y.

SPACE STATION 1

Copyright 1957, by A. A. Wyn, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Printed in U. S. A.

[Transcriber's Note: Extensive research did not uncover any evidence

that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

INTRIGUE IN EARTH'S OUTER ORBIT

Tremendous and glittering, the Space Station floated up out of the Big Dark. Lieutenant Corriston had come to see its marvels, but he soon found himself entrapped in its unsuspected terrors.

For the grim reality was that some deadly outer-space power had usurped control of the great artificial moon. A lovely woman had disappeared; passengers were being fleeced and enslaved; and, using fantastic disguises, imposters were using the Station for their own mysterious ends.

Pursued by unearthly monsters and hunted with super-scientific cunning, Corriston struggles to unmask the mystery. For upon his success depended his life, his love and the future of Earth itself.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

CORRISTON

He saw all the sights of the Space Station ... in fact, he saw too much....

HAYES

His decision would mean the beginning or the end for a world.

CLAKEY

This bodyguard needed special protection himself.

CLEMENT

Sometimes it seemed as if he were leading a double life.

HENLEY

With him for a friend one didn't need an enemy.

HELEN RAMSEY

Her father had made her a virtual prisoner.

It was a life-and-death struggle—cruel, remorseless, one-sided. Corriston was breathing heavily. He was in total darkness, dodging the blows of a killer. His adversary was as lithe as a cat, muscular and dangerous. He had a knife and he was using it, slashing at Corriston when Corriston came close, then leaping back and lashing out with a hard-knuckled fist.

Corriston could hear the swish of the man's heels as he pivoted, could judge almost with split-second timing when the next blow would come. He was bleeding from a cut on his right shoulder, and there was a tumultuous throbbing at his temples, an ache in his groin.

The fact that he had no weapon put him at a terrifying disadvantage. He had been close to death before, but never in so confined a space or in such close proximity to a man who had certainly killed once and would not hesitate to kill again.

His determination to survive was pitted against what appeared to be sheer brute strength fortified by cunning and a far-above-average agility. He began slowly to retreat, backing away until a massive steel girder stopped him. He was battling dizziness now and his heart had begun a furious pounding.

He found himself slipping sideways along the girder, running his hands over its smooth, cold surface. To his sweating palms the surface seemed as chill as the lid of a coffin, but he refused to believe that it could trap him irretrievably. The girder had to end somewhere.

The killer was coming close again, his shoes making a scraping sound in the darkness, his breathing just barely audible. Corriston edged still further along the girder. Inch by inch he moved parallel to it, fighting off his dizziness, making a desperate effort to keep from falling. The wetness on his shoulder was unnerving, the absence of pain incredible. How seriously could a man be stabbed without feeling any pain at all? He didn't know. But at least his shoulder wasn't paralyzed. He could move his arm freely, flex the muscles of his back.

How unbelievably cruel it was that a ship could move through space with the stability of a completely stationary object. How unbelievably cruel at this moment, when the slightest lurch might have saved him.

The girder was stationary and immense, and in his tormented inward vision he saw it as a strand in a gigantic steel cobweb, symbolizing the grandeur of what man could accomplish by routine compulsion alone.

In frozen helplessness Corriston tried to bring his thoughts into closer accord with reality, to view his peril in a saner light. But what was happening to him was as hard to relate to immediate reality as a line half remembered from a play. See how the blood of Caesar followed it, as if rushing out of doors to be resolved if Brutus so unkindly knocked or no....

But the killer wasn't Brutus. He was unknown and invisible and if there had been any Brutuslike nobility in him, it hardly seemed likely that he would have chosen for his first victim a wealthy girl's too talkative bodyguard and for his second Corriston himself.

The killer was within arm's reach again when the barrier that had trapped Corriston fell away abruptly. He reeled back, swayed dizzily, and experienced such wild elation that he cried out in unreasoning triumph. Swiftly he retreated backwards, not fully realizing that no real respite had been granted him. He was free only to recoil a few steps, to crouch and weave about. Almost instantly the killer was closing in again, and this time there was no escape.

Another metal girder stopped Corriston in midretreat, cutting across his shoulders like a sharp-angled priming rod, jolting and sobering him.

For an eternity now he could do nothing but wait. An eternity as brief as a dropped heartbeat and as long as the cycle of renewal and rebirth of worlds in the flaming vastness of space. Everything became impersonal suddenly: the darkness of the ships' between-deck storage compartment; the Space Station toward which the ship was traveling; the Martian deserts he had dreamed about as a boy.

The killer spoke then, for the first time. His voice rang out in the darkness, harsh with contempt and rage. It was in some respects a surprising voice, the voice of an educated man. But it was also a voice that had in it an accent that Corriston had heard before in verbal documentaries and hundreds of newsreels; in clinical case histories, microfilm recorded, in penal institutions, on governing bodies, and wherever men were in a position to destroy others—or perhaps themselves. It was the voice of an unloved, unwanted man.

The voice said: "You're done for, my friend. I don't know what the Ramsey girl told you, but you came looking for me, and it's too late now for any kind of compromise."

"I wasn't looking for a deal," Corriston said. "If it's any satisfaction to you, Miss Ramsey told me nothing. But I saw a man killed; and I couldn't find her afterwards. I think you know what happened to her. Knife me, if you can. I'll go down fighting."

"That's easy to say. Maybe you didn't come looking for me. But you know too much now to go on living. Unless you—wait a minute! You mentioned a deal. If you're lying about the Ramsey girl and will tell me where she is, I might not kill you."

"I wasn't lying," Corriston said.

"Hell ... you're really asking for it."

"I'm afraid I am."

"It won't be a pleasant way to die."

"Any way is unpleasant. But I'm not dead yet. Killing me may not be as easy as you think."

"It will be easy enough. This time you won't get past me."

Corriston knew that the conversation was about to end unless something unexpected happened. And he didn't think there was much chance of that. Had he been clasping a metal tool, he would have swung hard enough to kill with it. But he wasn't clasping anything. He was crouching low, and suddenly he leapt straight forward into the darkness.

His head collided with a bony knee and his hands went swiftly out and around invisible ankles. He tightened his grip, half expecting the knife to descend and bury itself in his back. But it didn't. The other had been taken so completely by surprise that he simply went backwards, suddenly, and with a strangled oath.

Instantly Corriston was on top of him. He shifted his grip, releasing both of the struggling man's ankles and remorselessly seizing his wrists. He raised his right knee and brought it savagely downward, again and again and again. A cry of pain echoed through the darkness. The killer, crying out in torment, tried to twist free.

For an instant the outcome remained uncertain, a see-saw contest of strength. Then Corriston had the knife and the struggle was over.

Corriston made a mistake then of relaxing a little. Instantly, the killer rolled sideways, broke Corriston's grip, and was on his feet. He did not attempt to retaliate in any way. He simply disappeared into the darkness, breathing so loudly that Corriston could tell when the distance between them had dwindled to the vanishing point.

Corriston sat very still in the darkness, holding on tightly to the knife. His triumph had been unexpected and complete. It had been close to miraculous. Strange that he should be aware of that and yet feel only a dark horror growing in his mind. Strange that he should remember so quickly again the horror of a man gasping out his life with a thorned barb protruding from his side.

It had begun a half-hour earlier in the general passenger cabin. It had begun with a wonder and a rejoicing.

Tremendous and glittering, the Space Station had come floating up out of the Big Dark like a golden bubble on an onrushing tidal wave. It had hovered for an instant in the precise center of the viewscreen, its steep, climbing trail shedding radiance in all directions. Then it had descended vertically until it almost filled the lower half of the screen, and finally was lost to view in a wilderness of space.

When it appeared for the second time, it was larger still and its shadow was a swiftly widening crescent blotting out the nearer stars.

"There it is!" someone whispered.

It had been unreasonably quiet in the general passenger cabin, and for a moment no other sound was audible. Then the whisper was caught up and amplified by a dozen awestruck voices. It became a murmur of amazement and of wonder, and as it increased in volume, the screen seemed to glow with an almost unbelievable brightness.

Everyone was aware of the brightness. But how much of it was subjective no one knew or cared. To a man in the larger darkness of space, a dead sea bottom on Mars, or a moon-landing ship wrapped in eternal darkness on a lonely peak in the Lunar Apennines may glow with a noonday splendor.

"They said a space station that size could never be built," David Corriston said, leaning abruptly forward in his chair. "They quoted reams of statistics: height above the center of the Earth in kilometers, orbital velocity, relation of mass to maneuverability. The experts had a field day. They went far out on a limb to convince anyone who would listen that a station weighing thousands of tons would never get past the blueprint stage. But the men who built it had enough pride and confidence in human skill to achieve the impossible."

The girl at Corriston's side looked startled for an instant, as though the ironclad assurance of so young a man was as much of a surprise as his unexpected nearness, and somehow even more disquieting older.

She was certainly somewhat older than he was—about three or four years. She was an exceptionally pretty girl, her fair hair fluffed out from under a blue beret, her ship's lounge jacket a youth-accentuating miracle of casual tailoring that would have looked well on a woman of any age. She had the kind of eyes Corriston liked best of all in a woman: longlashed, observant, and bright with glints of humor.

She had the kind of mouth he liked too—a mouth which suggested that she could be, by turns, capricious, level-headed, and audaciously friendly with strangers without in any way inviting familiarity. There was a certain paradoxical timidity in her gaze too. It was manifesting itself now in an obvious reluctance to be startled too abruptly by space engineering talk from a young man who had taken her companionability for granted and who was obviously given to snap judgments.

She brushed back the hair on her right temple, her brown eyes upraised to study Corriston more closely.

He hoped that she would realize upon reflection that she was behaving foolishly. He had taken a certain liberty in talking to her as he would have talked to an old acquaintance in a long-awaited meeting of minds. On the big screen a space station that couldn't be built was sweeping in toward the ship with eighty-five years of unparallelled scientific progress behind it.

First had come the Earth satellites, eight of them in their neat little orbits. They had used low-energy fuels, had kept close to the Earth, and no one had seriously expected them to do more than record weather information and relay radio signals. For fifteen years they could be seen with small telescopes and even with the unaided eye on bright, cloudless nights in both hemispheres.

First had come these small, relatively unimportant artificial moons and then, on a night in October 1972, the first space platform had been launched. Soon the sky above the Earth was swarming with radar warning platforms, a dozen men to operate them, and carrier-based jets equipped with formidable atomic warheads.

Nevertheless, how could anyone have known that in another twenty years interplanetary space flight would become a war-averting reality? How could anyone have known that by the year 2007 there would be human settlements on Mars and by the year 2022 the actual transportation to Mars of city-building materials?

Corriston was beginning to feel uncomfortable. He wished that the girl would say something instead of just continuing to stare at him. She seemed to be interested in his uniform. She appeared to be gazing at him interrogatively, as if she wanted to know more about him before promising anything.

He wondered what her unconscious purpose was. Did she see in him the quiet, determined type who was all set to accomplish something important. Or was she regretting he wasn't the hard-living, cynical type who had been everywhere and done everything?

Well, one way to find out was to be himself: a man average in every way, but with a hard core of idealism in his nature, a creative mind and enough independence and self-assurance to give a good account of himself in any struggle which brought his central beliefs under fire or placed them in long-range jeopardy.

And so Corriston suddenly found himself talking about the Station again.

"Not many people have grasped the importance of it yet," he said. "One station will service our needs, instead of fifty-seven, one tremendous central terminal and re-fueling depot for all of the ships. Do you realize what that could mean?"

Abruptly there was a startling warmth in the girl's eyes, an unmistakable look of interest and encouragement.

"Just what could it mean?" she asked.

"Any kind of steady growth across the years leads to centralization, to bigness. And that bigness becomes time-hallowed and magnified out of all proportion to its original significance. The Space Station is no exception. It started with the primitive Earth satellites and branched out into fifty-seven larger stations. Now it's tremendous, a single central station that can impose its influence in ship clearance matters with an almost unanswerable finality."

A shadow had come into the girl's eyes. "But not completely without checks and balances. The Earth Federation can challenge its supremacy at any point."

"Yes, and I'm glad that the challenge remains a factor to be reckoned with. As matters stand now the Station's prestige can't be implemented with what might well become the iron hand of an intolerable tyranny. As matters stand, the Station is actually a big step forward. People once talked of centralization as if it were some kind of indecent human bogey. It isn't at all. It's simply a fluid means to an end, a necessary commitment if a society is to achieve greatness. If the authority behind the Station respects scientific truth and human dignity—if it remains empirically minded—I shall serve it to the best of my ability. No one knows for sure whether what is good outbalances what is bad in any human institution, or any human being. A man can only give the best of himself to what he believes in."

"Sorry to interrupt," an amused voice said, "but the captain wants you to join him in a last-minute celebration: a toast, a press photograph—that sort of nonsense. A six hour trip, and he hasn't even been introduced to you. But if you don't appear at his table in ten minutes he'll throw the book at me."

Corriston looked up in surprise at the big man confronting them. He had approached so unobtrusively that for an instant Corriston was angry; but only for an instant. When he took careful stock of the fellow his resentment evaporated. There was a cordiality about him which could not have been counterfeited. It reached from the breadth of his smile to his gray eyes puckered in amusement. He was really big physically, in a wholly genial and relaxed way, and his voice was that of a man who could walk up to a bar, pay a bill and leave an everlasting impression of hearty good nature behind him.

"Well, young lady?" he asked.

"I'm not particularly keen about the idea, Jim, but if the captain has actually iced the champagne, it would be a shame to disappoint him."

Corriston was aware that his companion was getting to her feet. The interruption had been unexpected, but much to his surprise he found himself accepting it without rancor. If he lost her for a few moments he could quickly enough find her again; and somehow he felt convinced that the big man was not a torch-carrying admirer.

"I'll have to stop off in the ladies' lounge first," she said. She had opened her vanity case and was making a swift inventory of its contents. "Two shades of lipstick, but no powder! Oh, well."

She smiled at the big man and then at Corriston, gesturing slightly as she did so.

"We've just been discussing the Station," she said. "This gentleman hasn't told me his name—"

"Lieutenant David Corriston," Corriston said quickly. "My interest in the Station is tied in with my job. I've just been assigned to it in the very modest capacity of ship's inspection officer, recruit status."

The big man stared at Corriston more intently, his eyes kindling with a sudden increase of interest. "Say, I wonder if you could spare me a few minutes. When my friends ask me I'd like to be able to talk intelligently about the terrific headaches the research people must have experienced right from the start. The expenditure of fuel alone...."

"See you in the Captain's cabin, Jim," the girl said.

She moved out from her chair, her expression slightly constrained. Was it just imagination, or had the big man's immoderate expansiveness grated on her and brought a look of displeasure to her young face? Corriston couldn't be sure, and his brow remained furrowed as he watched her cross the passenger cabin and disappear into the ladies' lounge.

"I'm Jim Clakey," the big man said.

Corriston reseated himself, a troubled indecision still apparent in his stare. Then gradually he found himself relaxing. He nodded up at the big man. "Sit down, Mr. Clakey," he said. "Ask me anything you want. Security imposes some pretty rigid restrictions, but I'll let you know when you start treading on classified ground."

Clakey sat down and crossed his long legs. He was silent for a moment. Then he said: "You know who she is, of course."

Corriston shook his head. "I'm afraid I haven't the slightest idea."

"She isn't traveling under her real name only because her father is a very sensible and cautious man. You'd be cautious too, perhaps, if you were Stephen Ramsey."

Clakey's gaze had traveled to the ladies' lounge, and for an instant he seemed unaware of Corriston's incredulous stare.

"You mean I've actually been sitting here talking to Stephen Ramsey's daughter?"

"That's right," Clakey said, turning to grin amiably at Corriston. "And now you're talking to her personal bodyguard. I'm not surprised you didn't recognize her, though; very few people do. She doesn't like to have her picture taken. Her dad wouldn't object to that kind of publicity particularly, but she's even more cautious than he is."

The door of the ladies' lounge opened and two young women came out. They were laughing and talking with great animation and were quickly lost to view as other passengers changed their position in front of the viewscreen.

The door remained visible, however—a rectangle of shining whiteness only slightly encroached upon by dark blue drapes. Corriston found himself staring at it as his mind dwelt on the startling implications of Clakey's almost unbelievable statement.

"Biggest man on Mars," Clakey was saying. "Cornered uranium; froze out the original settlers. They're threatening violence, but their hands are tied. Everything was done legally. Ramsey lives in a garrisoned fortress and they can't get within twenty miles of him. He's a damned scoundrel with tremendous vision and foresight."

Corriston suddenly realized that he had made a serious psychological blunder in sizing up Clakey. The man was a blabbermouth. True, Corriston's uniform was a character recommendation which might have justified candor to a moderate extent. But Clakey was talking outrageously out of turn. He was becoming confidential about matters he had no right to discuss with anyone on such short acquaintance. Corriston suddenly realized that Clakey was slightly drunk.

"Look here," Corriston said. "You're talking like a fool. Do you know what you're saying?"

"Sure I know. Miss Ramsey is a golden girl. And I'm her bodyguard ... important trust ... sop to a man's egoism."

An astonishing thing happened then. Clakey fell silent and remained uncommunicative for five full minutes. Corriston had no desire to start him talking again. He was appalled and incredulous. He was debating the advisability of getting up with a frozen stare and a firm determination to take himself elsewhere when the crazy, loose-tongued fool leapt unexpectedly to his feet.

"She's taking too long!" he exclaimed. "It just isn't like her. She'd never keep the captain waiting."

As he spoke, another woman came out of the ladies' lounge. She was small, dark, very pretty, and she seemed a little embarrassed when she saw how intently Clakey was staring at her. Then a middle-aged woman came out, with a finely-modeled face, and a second, younger woman with haggard eyes and a sallow complexion who was in all respects the opposite of attractive.

"She's been in there for fifteen minutes," Clakey said, starting toward the lounge.

"It takes a good many women twice that long to apply makeup properly," Corriston pointed out. "I just don't see—"

"You don't know her," Clakey said, impatiently. "I may have to ask one of those women to go in after her."

"But why? You can't seriously believe she's in any danger. We both saw her go into the lounge. She made the decision on the spur of the moment and no one could have known about it in advance. No one followed her in. You were sitting right here watching the door."

But Clakey was already advancing across the cabin. He was reeling a little, and a dull flush had mounted to his cheekbones. He seemed genuinely alarmed. Corriston was about to follow him when something bright flashed through the air with a faint swishing sound.

A startled cry burst from Clakey's lips. He clutched at his side, staggered, and half-swung about, a look of incredulous horror in his eyes.

Corriston's mouth went dry. He stood very still, watching Clakey lose all control over his legs. The change in the stricken man's expression was ghastly. His cheeks had gone dead white, and now, as Corriston stared, a spasm convulsed his features, twisting them into a horrible, unnatural caricature of a human face—a rigidly contorted mask with a blanched, wide-angled mouth and bulging eyes.

A passenger saw him and screamed. His knees had given way and his huge frame seemed to be coming apart at the joints. He straightened out on the deck, jerking his head spasmodically, propelling himself backwards by his elbows. Almost as if with conscious intent, his body arched itself, sank level with the floor, then arched itself again.

It was as though all of his muscles and nerves were protesting the violence that had been done to him, and were seeking by muscular contractions alone to dislodge the stiff, thorned horror protruding from his flesh.

He went limp and the barbed shaft ceased to quiver. Corriston had a nerve-shattering glimpse of a swiftly spreading redness just above Clakey's right hipbone. The entire barb turned red, as if its feathery spines had acquired a sudden, unnatural affinity for human blood.

Corriston started forward, then changed his mind. Several passengers had moved quickly to Clakey's side and were bending above him. Someone called out: "Get a doctor!"

Corriston turned abruptly and strode toward the ladies' lounge. Brushing aside such scruples as he ordinarily would have entertained, he threw open the door and went inside.

He called out: "Miss Ramsey?" When he received no answer he searched the lounge thoroughly. There was no one there. He was thinking fast now, desperately fast. He hadn't seen her come out and neither had Clakey. He'd seen four women come out: three young women and an elderly one. None of them faintly resembled the girl he'd been talking to.

The first young woman had emerged almost immediately. He remembered how intently Clakey had been watching the door. Clakey had sat down to discuss the Station with him, and in less than two minutes the first young lady had emerged. Then neither of them had taken their eyes from the door for five or six minutes. The second young lady had apparently known someone in the crowd. She had seemed annoyed by Clakey's persistent stare and had disappeared quickly. The elderly woman had looked her age. Her walk, her carriage, the lines of her face had borne the unmistakable stamp of genteel aging, and the dignity inseparable from it. The last woman had been the drab creature.

Corriston had a poor memory for faces and he knew that he couldn't count on recognizing any of them—except perhaps the elderly woman—if he saw them again.

It was good that he could smile, even at his own inanities. It relieved tension. Almost instantly the smile vanished. His aspect became that of a man in deadly danger on the brink of a hundred foot precipice, a man completely in the dark and yet grimly determined not to go over the edge or take a single step in the wrong direction.

Where, he asked himself, do women ordinarily go when they vanish into thin air? Wasn't it pretty well established that ghosts were likely to follow the path of least resistance and fulfill obligations entered into in the flesh?

The captain's cabin! The captain would be disappointed if she failed to appear at least briefly at his table; and she had promised to do so. It was a wild, premeditated assault on the rational, but putting the irrational aspect of it aside, it was also realistic and reasonable. If by some incredible miracle she had eluded Clakey's vigilance and actually slipped from the lounge, she would almost certainly have gone straight to the captain's cabin.

Corriston left the ladies' lounge faster than he had entered it. He shut the door firmly and stood for an instant staring at the passengers who had gathered in an even tighter knot around Clakey and were making it difficult for an alarmed young ship's doctor to get to him. He was quite sure in his own mind that Clakey would not need the assistance of a doctor.

Then he turned and headed for the captain's cabin. Anyone could have gotten in. The door was ajar and there was no one guarding it. He threw the door wide and everything was just as he'd expected to find it: It was completely empty.

No guests at all to welcome Corriston to the big, empty cabin. Then he saw that there was another door opposite.

Corriston was getting scared, really scared. There was an odd, detached, whimsical feeling at the surface of his mind, but it cloaked something distinctly sinister. He had more than half-expected the captain to be absent from his cabin. But something about the silence and the emptiness chilled him to the core of his being.

With an effort he shook the feeling off. He didn't know where the inner door led to. He hesitated for an instant, realizing that the mere existence of a second door could complicate his search to the point of futility. If it led to a second cabin—well and good. But if it didn't....

He strained his ears to catch the sound of voices. There were no voices. He could have simply crossed to the door and looked beyond it. But the state of his nerves, and an odd habit he had of being precise and cautious under tension, made him explore the other possibilities first.

The door might conceivably be a trap. A trap does not have to be contrived in advance with some clearly defined purpose in mind. Circumstances can take a door or a window and turn it into a trap. A glove or a weapon left lying about can be picked up by an innocent man and snare him most damnably by seeming to point up his guilt.

What purpose did the inner door serve? Did it open on a corridor leading back to the general passenger cabin? If it did, it wouldn't be a trap; it would simply have "blind alley" stamped all over it.

Corriston suddenly realized that he was succumbing to a crazy kind of inaction. The door could lead almost anywhere, and if he had any sense at all he'd go through it fast.

Go through it he did, in six long strides. He'd been right about one thing—the blind alley part. He found himself, in not quite total darkness, in what was unquestionably an intership passageway. There was just light enough for him to make out the shadowy walls on both sides of him. Rather they were like metal bulkheads that gave off just enough reflected light for him to see by.

He wouldn't have considered ten or twelve seconds spent with a pocket flash a waste of time. But he had no pocket flash. The best he could do was stretch out both of his arms to determine just how far apart the bulkheads were. They were less than six feet apart.

Well, no sense in measuring the walls. A girl he'd talked to and liked instantly had vanished in a dark world, and he knew now that there was more than mere liking in the way he felt about her. He didn't dare ask himself how much more, not in so confined a space and with his chances of finding her again dwindling with every second that passed.

The passageway ended in a blank wall, less than forty feet from its beginning. Corriston saw the wall and was advancing toward it when he suddenly realized that the deck itself wasn't continuous. In his path, and almost directly underfoot, a companionway entrance yawned, so unexpectedly close that another short step would have sent him plunging into it. He saw the faint light reflected on its circumference and halted just in time to avoid a possibly fatal fall.

He knelt and stared down into a spiraling web of darkness. He could see a faint glimmer of light on metal and knew that he was bending above either a circular staircase or a companionway ladder. It turned out to be a staircase. Down it he went, moving cautiously, holding on to the supporting guide rail as he descended deeper and deeper into the darkness.

The darkness became almost absolute when the stairs ended. For a moment, at least, what appeared to be utter blackness engulfed him. Then gradually his vision became more effective. He could make out the faint outlines of stationary objects, of depths beyond depths, of crisscrossing lines and angles.

In utter darkness the glint of metal often seemed to draw the eyes like a magnet, to make itself known even without illumination. But there seemed to be a faint glow far off somewhere. He couldn't be sure, but light there should have been if—as he more than half-suspected—he was in one of the ship's below-deck ballast or storage compartments.

The deck beneath his feet was straight and level and cluttered with no impediments. He moved forward warily, testing every step until a wall of metal stopped him. He halted abruptly, felt along the barrier and became aware that it was studded with small bolts and was just a little corrugated. Exhibit A: one supporting metal beam, rough and slightly uneven in texture. Abruptly he reached the end of it and found himself underway again, still moving cautiously to avoid unseen pitfalls. He had not progressed more than a dozen feet when he heard the scrape of footsteps other than his own, and someone moved up close to him and blocked his way in the darkness.

For an instant the wild thought went through his mind that the someone was the captain. But he had seen and talked with the Captain and that self-contained, blunt-spoken man wasn't nearly as big physically as the path-blocker seemed to be.

The someone did not speak. But Corriston could sense the enmity flowing from him, the utter refusal to budge an inch, the determination to make his nearness a deadly threat in itself. Then the someone moved back a step. The far-off light could hardly have been an illusion, because for the barest instant Corriston could dimly make out the huge bulk of the man and the glint of the knife in his hand.

Two big men in the space of half an hour! The first had ceased to draw breath and the second was his killer. Corriston was suddenly sure of it. He knew it instinctively.

Then began the struggle which had almost robbed Corriston of his life, the cruel, one-sided, impossible-to-win struggle in total darkness.

And Corriston had won it.

Now almost in disbelief, Corriston looked down at the knife he had taken from the loser, telling himself that it was impossible that so much could have happened in so short a time and that he could still be alive at the end of it.

The wound in his shoulder was no longer painless, but it had ceased to bleed profusely, and his exploring fingers convinced him that the knife had severed no more than a superficial ligament. He strained his ears in the sudden quiet, listening for a possible return of his adversary. He did not think that the defeated man would attempt a second attack. But there was no telling what he might or might not do. Probably he'd ascended the companionway by now and was mingling with the other passengers.

The final link in Corriston's search had snapped. Even while battling for his life, he had felt close to the vanished girl. The man who had killed Clakey had been at least a link, a link that, short of Corriston's total defeat, might have been seized upon with physical violence and made to yield up its secret.

Now Corriston found himself wondering if the defeated man had been telling the truth. Had the link been non-existent from the first? Was the killer as completely in the dark as he was as to the whereabouts of Ramsey's daughter?

It was difficult to believe that the man had been lying. Despite his hatred and denials he had offered Corriston a deal: "Tell me where the girl is and I may not kill you." The deal part had been a lie, of course. He would have gone on and attempted to kill Corriston anyway. But his plea for information, that tentative, cunning feeler in the dark had seemed genuine.

What had been the man's purpose in killing Clakey? Why had Clakey been murdered in the general passenger cabin, in plain view of the other passengers? Because the killer had seen the girl go into the lounge and thought she was still there? And because he wanted free and instant access to her, with Clakey out of the way? It was the only answer that made sense.

The killer must have known that Clakey was in Ramsey's employ and had been guarding Ramsey's daughter. Why then had he been unable to take advantage of his crime in any way? Apparently neither he nor a possible confederate had succeeded in what almost certainly had been a pattern of violence directed at Ramsey through his daughter—a plan obviously worked out in advance, ready to be put into operation the instant a promising opportunity presented itself.

Into Corriston's mind flashed an ugly picture of the girl pinioned by strong arms and with a handkerchief pressed to her face. She had ceased to struggle and was being spirited quickly away. The picture became even more intolerable when he saw her held captive in a cabin difficult to locate, at the mercy of men without compassion.

But for some reason he'd never cease to be thankful for, it hadn't happened that way. Something had gone wrong with the plan, and the killer didn't even know when and why and how she had vanished. Sharing Corriston's frustration, he had been struggling simply to save himself, to keep Corriston from identifying and exposing him. The fury he'd displayed was not difficult to understand.

Corriston found himself becoming more confident again, less dominated by despair. The change in his mood surprised him but he seized upon it gratefully and started building on it. There was only one logical next move. He must find the captain quickly and enlist his help. He must take the master of the ship fully into his confidence. With every gift of persuasion at his command, he must make the captain see how the danger of Ramsey's daughter was mounting and would continue to mount with every minute that she remained unfound.

He still felt dizzy, and his head was aching a little, but he moved quickly through the darkness, his faculties heightened by an intensity of purpose which enabled him to find the companionway without colliding with obstacles or taking a wrong turn. Up the stairway he climbed, still clutching the knife, prepared for a possible second encounter with its original owner.

An attempt to regain the knife by trickery and stealth would not have surprised him. In fact, it was not at all difficult for him to picture a silent form flattened against the stair-rail, waiting for just the right moment to come hurtling toward him out of the darkness. For a moment, as he ascended, the strain became almost unendurable. Then the darkness dissolved above him, and he was advancing toward the captain's cabin through the narrow passageway which he had spanned with his arms spread wide.

He did not stop to span it this time. He emerged into the cabin and stood for an instant blinking in the sudden light. The cabin was still deserted. It was anybody's guess where the captain had gone or when he would be returning, and Corriston decided not to wait. He walked to the door, opened it and stepped out into the general passenger cabin.

No one saw him immediately. There were several passengers fairly close to him, but they were being attentive for the moment to the words and gestures of a tall, dignified looking man with observant brown eyes, a ruddy complexion, and gold braid on his shoulders. The tall man was Captain John Sanders.

"I'd be a hypocrite and a liar if I said there was no justification for alarm," Sanders was saying, in a voice loud enough to carry to where Corriston was standing. "Strict regulations prescribe that sort of thing. But it's no way for a captain to keep the respect of his passengers."

Corriston felt himself stepping forward before he even thought about it. But he halted abruptly when the captain said: "There's a murderer on the loose aboard this ship. You may as well accept that fact right now. Each of you has to be on his guard. It's only right and proper that you should keep your eyes and ears open, and stay worried. If you do, our chances of catching up with him before the ship berths should be reasonably good."

The captain paused, then went on quickly: "We'll get him eventually. You can be sure of that. He'll never get past the inspection each of you will have to undergo when we reach the Station. But if we catch him before we reach the Station, you'll be spared an investigative ordeal distinctly on the rugged side."

Corriston was suddenly aware that he was being stared at. Everyone was staring at him.

"My God!" the Captain cried out, staring the hardest of all. "Where did you get that wound? Who attacked you? And what were you doing in my cabin?"

Corriston walked up to the Captain and said in a voice that trembled a little. "May I talk to you privately, sir? What I have to say won't take long."

"Why not?" Sanders demanded. "That uniform you're wearing makes it mandatory. All right, come back into my cabin."

They went back into the cabin. The captain shut the door and turned to face Corriston with a shocked concern in his stare.

"You've had it rough, Lieutenant. I can see that."

"Plenty rough," Corriston conceded. "But it's not myself I'm worried about."

"Did you know that a man has just been murdered?"

"I know," Corriston said.

"With a poisoned barb. A Martian barb. It's a plant found only on Mars. We have him stretched out on a table in the sick bay now. But he isn't sick; he's a corpse. Tell me something, Lieutenant, did you just tangle with the man who did it?"

"I think so," Corriston said. "In fact, I'd stake my commission on it."

"I see. Well, you'd better tell me about it. Tell me everything."

Corriston told him.

The captain was silent for a long moment. Then he said, "But we've no Miss Ramsey on the passenger list. And I certainly didn't invite her to drink a toast with me in my cabin. Are you sure of your facts, Lieutenant?"

Corriston's jaw fell open. He stared at the captain in stunned disbelief. "Of course I'm sure. Why should I lie to you?"

"How should I know? It's unfair to ask me that. If Ramsey's daughter was on this ship, you can rest assured I'd have known about it. After all, Lieutenant—"

"But she was on board and you didn't know. Isn't that obvious? Look, she was traveling incognito. The trip to the Station takes only five hours. Perhaps in so short a trip—"

"No 'perhaps' about it. I'd have known."

"But she is on board, I tell you. I talked to her. I talked to Clakey. Don't make me go over the whole thing again. We've got to find her. Ramsey's enemies would stop at nothing. I'm afraid to think of what they might do to his daughter!"

"Nothing will happen to his daughter. She's on Earth right this minute in her father's house, as safe as any girl that wealthy can ever be. Lieutenant, listen to me. I've got a great deal of respect for that uniform you're wearing. Don't make me lose it. When you come to me with a story like that—"

"All right. You don't believe me. Will you check the passenger list, just to be sure?"

"I'll do more than that, Lieutenant. I'll assemble all of the passengers and check them off personally. I'll give you an opportunity to look them over while I'm doing it. Later you can ask them as many questions as you wish. There'll be a murderer among them, but that shouldn't disturb you too much. You've already met. Perhaps you can identify him for us. Ask each of the men who made a non-existent Miss Ramsey disappear and the one who turns pale will be our man."

Suddenly the captain reddened. "I'm sorry, Lieutenant, I didn't mean to be sarcastic. But a murder on my ship naturally upsets me. I'll be completely frank with you. There's a very remote possibility that Miss Ramsey actually is on board without my knowledge. She hasn't had much publicity. I believe I've only seen one photograph of her, one taken several years ago. But you've got to remember that a captain is usually the first to get wind of such things. It comes to him by a kind of grapevine. She's a golden girl—actually the goldenest golden girl on Earth."

Now Corriston was in a steel-walled cell and the captain's voice seemed only a far-off echo sympathizing with him.

And it was an echo, for the captain was gone and he would probably never see him again. It was all very simple—that part of it—all very clear. The captain had faithfully kept his word. The captain hadn't let him down. But any man can end up a prisoner when everyone disbelieves him and he has no way of proving that he is telling the truth.

It was hard to believe that a day and a night had passed, and that the Captain had kept his word and gone ahead with the roll call. It was even harder to believe that he, Corriston, was no longer on the ship, but in a sanity cell on the Space Station, and that the ship was traveling back toward Earth.

He shut his eyes, and the events of the past thirty hours unrolled before him with a nightmare clarity, and yet with all of the monstrous distortions which a nightmare must of necessity evoke.

Darkness and time and space. And closer at hand the frowns of forthright, honest men appalled by mental abnormality in a new recruit, an officer with a steel-lock determination to keep the truth securely guarded and safe from all distortion.

There had come the tap on his shoulder and a stern voice saying: "You'd better come with us, Lieutenant." He had just told the captain the whole horrible story. He had not been believed.

"Tell me about it," said the recruit in the bunk opposite Corriston. "It will help you to talk. Remember, we're not prisoners. We mustn't think of ourselves as prisoners. We can go out and exercise. We can walk around the Station for a half-hour or so. We've only got to promise we'll come back and lock ourselves in. They trust us. It could happen to anyone.

"Space-shock. Not a fancy word at all. I'm getting over it; you've a certain distance to go. Or so they say. But we're still in very much the same boat and talking always helps. Talk to me, Lieutenant, the way you did last night."

Corriston looked at the pale youth opposite him. He had close-cropped hair and friendly blue eyes, and he seemed a likeable enough lad. He was Corriston's junior by several years. But there was an aura of neuroticism about him that made Corriston uneasy. But hell, why shouldn't he get it off his chest. Talking just might help.

"It's true," Corriston said. "Every word of it."

"I believe you, Lieutenant. But quite obviously they didn't. Why not strike a compromise. Say I'm one-tenth wrong in believing you and they're nine-tenths right in not believing you. That means there may be some little quirk in what happened to you that doesn't quite fit into the normal pattern. Put that down to space-shock—a mild case of it. I'm not saying you have it, but you could have it."

The kid was grinning now, and Corriston had to like him.

"Okay," he said. "You can believe this or not. The captain lined all of the passengers up and checked them off by their cabin numbers. I didn't see her. Do you understand? She just wasn't there! I thought I recognized two of the women who had come out of the ladies' lounge, but I couldn't even be sure of that. One of the two denied ever having stepped inside the lounge, and the other was vague about it."

"I see."

"The captain really sailed into me for a moment, lost his temper completely. 'A fine officer you are, Lieutenant. It's painful to be on the same ship with the kind of officers the training schools turn out when the Station finds itself short of personnel. Is the Station planning to trust ships' clearance to hallucinated personnel?

"'All right, you talked to a girl—some girl. She didn't even tell you she was Ramsey's daughter; Clakey told you. And he's dead. Not only is he dead, he wasn't listed on the passenger list as Clakey at all. His name was Henry Ewers. I don't know what you believed, Lieutenant. I don't care what you think you saw. You tangled with someone and he stabbed you. He was real enough ... obviously the man who killed Ewers. But you let him get away, so even that isn't too much to your credit.'"

"If I had been you," the kid said, "I've had knocked him down."

"No." For the first time Corriston smiled. "To tell you the truth, the captain is a good guy. He's one of those blunt, moody, terribly human individuals you encounter occasionally, men who speak their minds on all occasions and are instantly sorry they did. You have to like them even when they seem to insult you."

"He made up for it then?"

"I'll say he did. He knew that when we landed the officials would be breathing right down my neck. He wanted to give me every chance. So he kept the officials away from me until I'd convinced myself Ramsey's daughter just couldn't be on board.

"He let me look at every piece of luggage that was taken off the ship. He had some cargo to unload and he let me inspect that too, every crate. Most of the crates were too small to conceal a drugged and unconscious girl—or any girl for that matter. The ones that weren't, he opened for me and let me look inside.

"He let me watch every passenger leave the ship. Then, when all of the passengers had left, he stationed officers in the three main passageways and I went through the ship from bow to stern. I went into every stateroom and into every intership compartment. No one could have kept just a little ahead of me or behind me, dodging back into a compartment the instant I'd vacated it. They would have been instantly spotted by one of the officers.

"The Captain wasn't to blame at all for what happened later ... when I tried to convince the commanding officers here that I was completely sane."

"I see. He must have really liked you."

"I guess he did. And I liked him."

The kid nodded. "And the murderer's still at large. That makes it rough for the sixty odd passengers they're holding in quarantine. How long do you think they'll hold them in the Big Cage?"

"As long as they can. They'll keep them under close guard and increase their vigilance every time there's a suspicious move in the cage. They'll be screened perhaps a dozen times. But most of them are influential people. Most of them have booked passage on the Mars' run liner that's due here next week. They can't hold them forever. They'd start pulling wires on Earth by short wave and there'd be a legislative uproar.

"Suppose they refuse to let them send messages?"

"They won't refuse. I'm sure of that."

The kid was thoughtful for a moment. Then he said: "Tell me more about Ramsey. Just what do you think is happening on Mars?"

"No one knows exactly what is happening," Corriston said. "But to the best of my knowledge the overall picture is pretty ugly. The original settlers have their backs to the wall with a vengeance. Now there are armed guards at their throats. Ramsey has taken over. He has resorted to legal trickery to freeze them out.

"There are perhaps fifty important uranium claims on Mars and Ramsey has consolidated all of the holdings into a single major enterprise. To say that he's cornered the market in uranium would be understating the case. He has taken possession by right of seizure, and the colonists can't get to him. They're living a hand-to-mouth existence while he lives in a heavily guarded stronghold behind three miles of electrified defenses."

The kid nodded again. "Yes, that's the picture when you unscramble it, I guess. But most of it is kept hidden from the general run of tourists."

"Naturally. Ramsey has the power to keep it under wraps."

"Do you think the colonists had anything to do with Clakey's murder and Miss Ramsey's disappearance? Or I guess I should say Henry Ewers' murder."

"Clakey, Ewers—his name doesn't matter. I'm convinced that he was Miss Ramsey's bodyguard."

"But you haven't answered my question."

"I can't answer it with any certainty. Did the colonists hire a killer and book passage for him on the ship? It's difficult to believe that the kind of men who colonized Mars would resort to murder."

"But there are a few scoundrels in every large group of men. And what if they became so desperate they felt they had to fight fire with fire?"

"Yes, I'd thought of that. It may be the answer."

A half-hour later the kid was taken away and Corriston found himself completely alone. There are few events in human life more unnerving than the totally unexpected removal of a sympathetic listener when dark thoughts have taken possession of a man.

The kid wasn't forcibly removed from the cell. He left without protesting and no rough hands were laid on him, no physical violence employed. But he was not at all eager to leave, and if the guards who came for him had eyed him less severely, his attitude might have been the opposite of complacent.

"Sorry, kid," one of them said. "Your discharge has been postponed. Somebody on the psycho-staff wants to give you another test. I guess you didn't interpret the ink blots right."

He looked at Corriston and shook his head sympathetically. "It's tough, I know. Once you're here waiting to be released can wear you down. I shouldn't be saying this, but it stands to reason it might even slow up your recovery a bit. It's easy to blame the docs, but you've got to try to understand their side of it. They have to make sure."

When the door clanged shut behind the kid, Corriston crossed to his cot, sat down, and cradled his head in his arms. The fact that he was still free to go outside and walk around the Station was no comfort at all. That kind of freedom could be worse than total confinement. He could never hope to escape from observation. The guards were under orders to watch him, and wherever he turned there'd be eyes boring into the back of his neck.

On Earth a man under surveillance could duck quickly into a side street, run and weave about, and emerge on a broad avenue in the midst of a crowd. He could walk calmly then for a block or two, and turn in at a bar. He could drown his troubles in drink.

There were bars on the Station, of course. But Corriston knew that if he tried to mingle with officers of his own rank on the upper levels, he'd quickly enough find himself drinking alone. He could picture the off-duty personnel edging quickly and resentfully away from him, as though he'd suddenly appeared in their midst with a big, yawning hole in his skull.

Suddenly utter weariness overcame Corriston. He loosened his belt, elevated his legs, and relaxed on the cot.

He was asleep almost before he could close his eyes. How long he slept he had no way of knowing. He only knew that he was awakened by a sound—the strangest sound a man could hear in space. It was as if a gnat or a mosquito had developed a sudden, avaricious liking for his blood-type and was determined to gorge itself to bursting at his expense.

The buzzing seemed to go on interminably as he hovered between sleeping and waking. On and on and on, with absolutely no letup. Then, abruptly, it ceased. There was a faint swishing sound and something solid thudded into the hardwood directly above him.

With a startled cry Corriston leapt from the cot, caught the iron edge of the bed-guard to keep from falling, and stared up in horror at the shining expanse of wall space overhead.

The cell was in almost total darkness. But from the barred window opposite, a faint glimmer of light penetrated in a diffuse arc, just enough light to enable him to make out the quivering stem of the barb.

It was a barb. This was so beyond any possibility of doubt. It had lodged in the hardwood scarcely a foot above his cot and it was still quivering.

Cold sweat broke out on Corriston's palms as he realized how close death had come, and how almost miraculous had been his escape. Had he raised himself to slap at the "mosquito" the barb could just as easily have buried itself in his skull.

Corriston hesitated for an instant, his eyes on the barred window and the faint glow beyond. Then his gaze passed to the wall switch. He decided against switching on the light immediately. He stooped low and moved quickly to the window, taking care to keep his head well below the sill.

For a moment he listened, his every nerve alert. There was no stir of movement in the darkness beyond the sill, nothing at all to indicate that someone was crouching there.

Finally, with an almost foolhardy recklessness, he raised his head and stared out between the bars. He could see right across to the wall opposite. The wall was less than eight feet away, and the space between the wall and his cell appeared to be unoccupied. This did not surprise him.

It was utterly silly to think that a man intent on willful murder would have lingered for any great length of time in so narrow a space. After having shot his bolt, his immediate concern would have been to get away as quickly as possible.

No, definitely, the man was gone, and if he had more barbs to release he would choose another time and place.

Even then Corriston did not switch on the light. He had no particular desire to examine the wood-embedded barb in a bright light. He could see it clearly enough from where he stood. It was exactly like the barb which had sealed the lips of that blabbermouth Clakey.

Corriston went back to his cot and sat down. He told himself it would be highly dangerous to leave the cell and give the killer another chance. He had saved himself by refusing to slap a non-existent mosquito. But in the shadows of the Station there would be no mosquitoes—non-existent or otherwise. The killer would simply crouch in shadows, await his chance, and take careful aim.

What he had to do was find Miss Ramsey, and prove his sanity. If he stayed in the cell, the shadows would continue to deepen about him, would become intolerable, and perhaps even drive him to the verge of actual madness.

He had to convince the killer that he couldn't be silenced easily and perhaps not at all.

Corriston stood up. He ran his hands down his body, taking pride in its muscular solidity, its remarkable integrity under strain. He still felt lithe and confident; his physical vitality was unimpaired.

He had really known all along that he would be leaving the cell. On Earth you could dodge into a narrow alley between tall buildings or lean on a stroller platform and be carried underground so fast that your pursuers would be left blank-faced. If he stayed alert he could do the same thing on the Station, even though there were no moving pavements to leap upon. Quite possibly he could even slip out unnoticed. They might not even be watching the cell door because he had behaved himself so well up to now. Psycho-cases were permitted to roam, but if they stayed in their cells precautions would naturally be relaxed in their favor.

Corriston now was about to develop a sudden, unanticipated impulse to roam. The fact that he was completely sane gave him an edge over the space-shocked recruits. There is nothing quite so terrifying to a man who doubts his own sanity than the thought that unseen eyes are keeping tabs on him. He feels guilty and acts guilty and almost invariably his caution deserts him.

Corriston was quite sure that he could carry it off, even if he felt eyes boring into his back the instant he left the cell. He'd simply bide his time and seize the first opportunity which presented itself.

Actually, it was easier than he'd imagined it could be. He simply opened the cell door, walked out; and there was no one in sight to observe him. So far, so good. The corridor outside was completely deserted, and when he reached the end of it there was still no one.

He turned left into a large, square reception room and crossed it without hurrying, his shoulders held straight. Photoelectric eyes? Yes, possibly, but he had no intention of letting the thought worry him. If he were being watched mechanically, there was nothing he could do about it and somehow he didn't think that he had crossed any photoelectric beams. Certainly no doors had swung open or closed behind him, and photoelectric alarm system without visible manifestations could be dismissed as a not too likely possibility.

When Corriston emerged in the glass-encased, wide-view observation promenade on the Station's Second Level, he was no longer alone. On all sides men and women jostled him, walking singly and in pairs, in uniform and in civilian clothes, or hurrying off in dun-gray, space-mechanic anonymity.

The promenade was crowded almost to capacity and yet the men and women seemed mere walking dots scattered at random beneath the immense structures of steel and glass which walled them in. A feeling of unreality came upon Corriston as he stared upward. He deliberately moderated his stride, as if fearful that a too rapid movement in any one direction might send him spinning out into space with a glass-shattering impetus which he would be powerless to control.

It was an illogical fear and yet he could not entirely throw it off, and he did not seriously try. It was not nearly as important as the possibility that he might be being followed. There was no one behind him who looked in the least suspicious, and no one in front of him either. But how could he be completely sure?

The answer was that he couldn't. He had to trust his instincts, and so far they had given him every assurance that he was moving in a free, independent orbit of his own, completely unobserved.

And then, quite suddenly, he ceased to move at all.

Something quite startling was taking place throughout the length and breadth of the observation promenade. The men in uniform were exchanging alarmed glances and departing in haste. The civilians were crowding closer to the panes. They were collecting in awestruck groups of blinding light crisscrossed high above their heads.

They were all looking in one direction, but a few of them had been taken so completely by surprise that they stood motionless in the middle of the promenade. Corriston was one of the motionless ones, but his eyes were quick to seek out the nearest viewpane.

At first he thought that a gigantic meteor had appeared suddenly out of the stellar dark and was rushing straight toward the Station with a velocity so great as to be almost unimaginable.

Then he realized that it wasn't a meteor. It was a spaceship. And it wasn't rushing straight toward the Station. It had either bypassed or encircled the Station and passed beyond it, for it was now heading out into space again. He could see the long, bright trail left by its rocket jets, the diffuse incandescence in its wake.

An officer with two stripes on his shoulder was standing almost at Corriston's elbow. He hadn't turned to depart, and for some reason he seemed reluctant to do so. The space-ship's erratic course seemed to absorb him to the exclusion of all else.

He started swearing under his breath. Then he saw Corriston and a strange look came into his face. He looked at Corriston steadily for a moment, then looked quickly away.

Corriston edged slowly away from him and joined the nearest group of civilians. They were all talking at once and it was hard to understand precisely what they were saying. But after a moment a few enlightening fragments of information greatly lessened his bewilderment.

"That freighter was preparing to land at the Station, but for some reason it couldn't make contact. It never even began to decelerate."

"How do you know?"

"I asked one of the officers—that gray-haired man over there. He was plenty worried. I guess that's why he talked so freely. He'd had some kind of dispute with the captain, apparently. He told me that trouble developed aboard that freighter when it was eight or ten thousand miles away. An emergency message came through, but for some reason the captain kept it pretty much to himself."

Watching the freighter's hull blaze with friction as it went into a narrow orbit about Earth, Corriston tried hard to make himself believe that the particular manner of a spaceman's departure was simply one, tragic aspect of a calculated risk, that men who lived dangerously could hardly expect to die peacefully in their beds. But it was a rationalization without substance. In an immediate and very real sense he was inside the freighter, enduring an eternity of torment, sharing the agonizing fate that was about to overtake the crew.

Nearer and nearer to Earth the freighter swept, completely encircling the planet like a runaway moon with an orbital velocity so great the eye could hardly follow it.

"It will blast out a meteor pit as wide as the Grand Canyon if it explodes on land," someone at Corriston's elbow said. "I wouldn't care to be within a hundred miles of it."

"Neither would I. It could wipe out a city, all right—any city within a radius of thirty miles. This is really something to watch!"

The freighter had encircled Earth twice and was now so close to its blue-green oceans and the dun-colored immensity of its continental land masses that it had almost disappeared from view. It had dwindled to a tiny, glowing pinpoint of radiance crossing the face of the planet, an erratically weaving firefly that had abandoned all hope of guiding itself by a light that was about to flare up with explosive violence and put an end to its life.

The freighter was invisible when the end came. It was invisible when it struck and rebounded and channeled a deep pit in a green valley on Earth. But the explosion which followed was seen by every man and woman on the Station's wide-view promenade.

There were three tremendous flares, each opening and spreading outward like the sides of a funnel, each a livid burst of incandescence spiraling outward into space.

As seen from the Station the flares were not, of course, so tragically spectacular. They resembled more successive flashes of almost instantaneous brightness, flashes such as had many times been produced by the tilting of a heliograph on the rust-red plains of Mars under conditions of maximum visibility.

It takes an experienced eye to interpret such phenomena correctly, and among the spectators on the promenade there were a few, no doubt, who were not even quite sure that the freighter had exploded.

But Corriston had no doubts at all on that score. The full extent of the tragedy would be revealed later by radio communication from Earth.

There was a long silence before anyone spoke. The group around Corriston seemed paralyzed by shock, unable to express in words how blindly hopeful they had dared to be, or how fatalistic from the first. There were a few moist eyes among the women, an awkward, almost reverent shuffling of feet.

Then the young man at Corriston's elbow cleared his throat and said in a barely audible whisper: "It didn't come down in the sea."

"I know," Corriston said. "It came down in North America, close to the Canadian border."

"In the United States?"

"Yes, I think so. We can't be sure. It's too much to hope there was no destruction of human life after an explosion of that magnitude."

Corriston suddenly realized that he was behaving like a man who had taken complete leave of his wits. He was drawing more and more attention to himself when he should have been bending all of his efforts toward making himself as inconspicuous as possible.

Fortunately the agitation of everyone on the promenade was helping to remedy his blunder. His wisest course now was simply to recede as an individual, to move silently to the perimeter of the group and just as silently vanish.

He was confident that he could accomplish it. He began elbowing his way backwards until there were a dozen men and women in front of him. He let himself be observed briefly as a grim-lipped spectator who had taken such an emotional pounding that he could endure no more. Suddenly he saw his chance and took it. There was another small group of civilians close to the group he had joined, and he ducked quickly behind them, using their turned-away backs as a shield. He edged toward a paneled door on his right, his only concern for the moment being a comparatively simple one. He must get away from the crowded promenade as swiftly as possible.

He reached the door, swung the panel wide, and stepped into the long, brightly-lighted compartment beyond without a backward glance. Almost immediately he perceived that he had committed an act of folly. The compartment was a promenade cafeteria and it was crowded with an overflow of agitated men and women discussing the tragedy in heated terms.

Keep cool now. None of these people are interested in you. Keep cool and keep on walking. There's another door and you can be through it in less than a minute, Corriston told himself.

There was a pretty waitress behind the long counter, and as he came abreast of her she smiled at him. For an instant he hesitated, eyed the stool opposite her, and fought off an incongruous but almost irresistible impulse to sit down. Quick warmth and sudden sympathy. Yes, he could do with a bit of both, Corriston thought.

It was sheer insanity, but he did sit down. He eased himself into the stool and ordered a cup of coffee.

"Something with it?" the waitress asked. "A sandwich, or—"

"No, no, I don't think so," Corriston said quickly. "Just the coffee."

The waitress seemed in no hurry to depart. "It was pretty terrible what happened. Wasn't it?"

"Did you see it?" Corriston asked.

"I saw most of it. I saw the ship go past the Station and start to explode. I saw that black wing, or whatever it was, drop off. Then someone started shouting in here and I came back. They say it crashed on Earth."

"That's right," Corriston said, telling himself that he was a damned fool for wanting to look at her hair and hear her friendly woman's voice when every passing second was adding to his danger.

"You saw it crash?"

Corriston nodded. "I just came from the promenade."

"That was a crazy thing to ask you. How excited can you get? I saw you come through that door. You looked kind of pale."

"I still feel that way," Corriston said.

The waitress then said a surprising thing: "I wonder what it is about some men. You just have to look at them once and you know they're the sort you'd like to be with when something terrible happens. You know what I mean?"

"Sure," Corriston said. "Any port in a storm."

The waitress smiled again. "I don't mean that, exactly. Please don't think I'm handing you a line. There's just something ... comfortable about you. You go all pale when something bad happens to other people. That's good; I like that. It means you can feel for other people. You're a gentle sort of guy, but I bet you can take care of yourself and anyone you care about. I just bet you can."

The waitress flushed a little, as if afraid that she had said too much. She turned and walked slowly toward the coffee percolator at the far end of the counter.

He was glad now that he had ordered the coffee. The coffee would help too. He suddenly felt that he was under observation, that hostile eyes were watching him. But it was no more than just a feeling; and coffee and sympathy might drive it away.

How blindly, stupidly foolish could a guy be? Corriston thought. If he had any sense at all he wouldn't wait for the coffee. He'd get up quickly and head for the door at the other end of the cafeteria. He'd either do that, or swing about abruptly and attempt to catch the silent watcher by surprise.

Corriston decided to wait for the coffee.

The waitress looked at him strangely when she returned. She set the coffee down before him and started to turn away, her eyes troubled. Then, suddenly, she seemed to change her mind. She leaned close to him and whispered: "You'd better leave by the promenade door. That man over there has been watching you. I know him very well. He's a Security Guard."

Corriston nodded and stared at her gratefully for a moment. He was more relieved than alarmed. It was far better to have a Security Guard watching him than a killer with a poisoned barb. He wasn't exactly happy about it, but he was confident he could elude the agent.

The waitress' eyes were suddenly warm and friendly again. "Space-shock?" she asked.

"So they claim," Corriston said. "I happen to think they're mistaken."

He started sipping the coffee. It was hot but not steaming hot. He could have tossed it off like a jigger of rye but he had some quick thinking to do.

"Tell me," he said. "Just where is that guard sitting?"

"At the other end of the counter," the waitress replied, the anxiety coming back into her eyes. "He's close to the door. You'd have to go past him. Maybe I'm wrong, but I think you want to get away from him. So you'd better go the way you came—by the promenade door."

"That's not too good an idea, I'm afraid," Corriston said. "He'd follow me and get assistance on the promenade. What's beyond the other door? Where does it lead to?"

"It opens on a corridor," the waitress said quickly. "If you can get past him you might have a better chance that way. There's nothing but a corridor with two side doors. One opens on an emergency stairway that goes down to the Master Sequence Selector compartments."

She seemed to take pride in her knowledge. Due to a space-shocked guy's difficulties, the Master Sequence Selector had become an important secret shared between them. Corriston wondered if she knew that the Selector functioned on thirty-two separate kinds of automatic controls.

If he ever got the chance, he'd come back and tell her exactly how grateful he was. Right at the moment one consideration alone dominated his thinking. If he could get past the guard he could hide out in an intricate maze of machinery. Even if they sent a dozen guards down to look for him it would take them some time to locate him. He could hide-out and gain a breathing spell.

The waitress had a very small hand. Abruptly Corriston clasped it and held it for an instant, his fingers exerting a firm, steady pressure. "Thanks," he said.

Corriston swung about without glancing toward the end of the counter. He'd pass the guard quickly enough; there was no sense in alerting the man in advance. As for recognizing him, that would be no problem at all. You couldn't mistake a Security Guard no matter what kind of clothes he wore.

Corriston took his time. He walked slowly, refusing to hurry. A man under surveillance should never hurry. He should be casual, completely at his ease, for there is no better way of keeping an observer guessing.

He kept parallel with the long counter, his shoulders swaying a little with the assurance of a man who knows exactly where he is going. Presently the entire length of the counter was behind him, and he was less than a yard from the door.

He hadn't glanced once at the counter. He didn't intend to now. One quick leap would carry him through the door and beyond it, and to hell with recognizing the guard. When it was touch and go and odd man out, you altered your plan as you went along.

He'd seen a girl disappear when everyone said it didn't happen. Confined to a psycho-ward, he had simply walked out, eluded a killer, and watched a ship explode on the green hills of Earth. He'd survived all that, so how could one lone Security Guard stop him now?

He was preparing to leap, when something got in his way—a shadow—a shadow for an instant between himself and the door, and then a dark bulk stepping right into the shoes of the shadow and filling it out.

The Security Guard was not at all the kind of person he'd expected him to be. He was not a big ape, not even a muscular-looking man. He had simply seemed big for the instant he took to fill the place of his shadow. He was a man of average height, average build. He blocked the doorway without bluster, looking very calm and relaxed. Only his eyes were cold and accusing and dangerously narrowed as he surveyed Corriston from head to foot.

"I'm afraid you'll have to go back to the ward now," he said. "You picked a bad time to take a turn about the Station. Ordinarily you'd be privileged to do so. That's part of the therapy. But you picked a very bad time."

"I'm beginning to realize that," Corriston said. "I couldn't help it, though. I had no way of knowing that freighter was out of control. I'm afraid you've made a mistake, too, though. I'm not going back to the cell."

Corriston had been watching the man's right arm. Suddenly it went back and his fist started rising, started coming up fast at an angle that could have sent it crashing against Corriston's jaw.

Corriston had no intention of letting that happen. He side-stepped quickly and delivered a smashing blow to the pit of the guard's stomach. The blow was so solid that it doubled the guard up. His knees buckled and he started to fold.

Corriston didn't take the folding for granted. A second blow caught the man squarely on the jaw and a third thudded into his rib section. For an instant he looked so dazed that Corriston felt sorry for him.

He was still half-doubled up when he sank to the floor and straightened out. He straightened out on his side first, and then rolled over on his back and stopped moving. His lips hung slackly, his eyes were wide and staring.

The look on his face gave Corriston a jolt. It was a very strange look. The fact that his features had become slack was not startling in itself, but there was something unnatural, unbelievable, about the way that muscular relaxation had overspread his entire countenance. His features were putty-gray and they seemed to have no clearly defined boundaries.

His nose, eyes, and forehead looked as if the ligaments which held them together had snapped from overstrain or had been severed by a surgeon's scalpel ... severed and allowed to go their separate ways without interference.

In fact, there was no real expression on the man's face at all—no recognizably human expression—not even the stuporous look of a man knocked suddenly unconscious.

There was agitation now in the cafeteria, a hum of angry voices, a rising murmur that was coming dangerously close. Corriston shut his mind to it. He knelt at the guard's side and swiftly unbuttoned the unconscious man's heavy service jacket. He felt around under the jacket until he was satisfied that he could move on through the doorway with a clear conscience. The guard's heart was beating firmly and steadily. There was a reassuring warmth under the jacket as well, a complete absence of clamminess.

Suddenly the guard groaned and started to roll over on his side again. Corriston didn't wait for him to complete the movement. He arose quickly and was through the door in four long strides.

He preferred not to run. He was not so much fleeing as seeking a security he was entitled to, a reasonably safe port in a storm that was threatening to take away his freedom by blanketing him in a dark cloud of unjust suspicion and utter tyranny.