Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text. List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

By Frances Elliot

———

Old Court Life in France

2 vols. 8º.

Old Court Life in Spain

2 vols. 8º.

BY

FRANCES ELLIOT

AUTHOR OF “DIARY OF AN IDLE WOMAN IN ITALY,”

“PICTURE OF OLD ROME,” ETC.

![]()

ILLUSTRATED

———

VOLUME I.

———

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

The Knickerbocker Press

Copyright, 1893, by

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London

By G. P. Putnam’s Sons

Made in the United States of America

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

TO MY NIECE

THE COUNTESS OF MINTO

THIS WORK IS

INSCRIBED

I CANNOT express the satisfaction I feel at finding myself once more addressing the great American public, which from the first has received my works with such flattering favour.

I have taken special pleasure in the production of this new edition of Old Court Life in France, which was first published in America some twenty years ago, and which is, I trust, now entering into a new lease of life.

That the same cordial welcome may follow the present edition, which was accorded to the first, is my anxious hope.

A new generation has appeared, which may, I trust, find itself interested in the stirring scenes I have delineated with so much care, that they might be strictly historical, as well as locally correct.

To write this book was, for me (with my knowledge of French history) a labour of love. It takes me back to the happiest period of my life, passed on the banks of the historic Loire: to Blois, Amboise, Chambord, and, a little further off, to the lovely plaisances of Chenonceaux and Azay le Rideau, the woods of magnificent Versailles, and Saint Cloud (now a desolation), on to the walls of the palatial Louvre, the house-tree of the great Kings and Queens of France—never can all these annals be fitly told! Never can they be exhausted!

To be the guide to these romantic events for the American public is indeed an honour. To lead where they will follow, with, I trust, something of my own enthusiasm, is worth all the careful labour the work has cost me.

With these words I take my leave of the unknown friends across the sea, who have so kindly appreciated me for many years. Although I have never visited America, this sympathy bridges space, and draws me to them with inexpressible cordiality and confidence, in which sentiment I shall ever remain, leaving my work to speak to them for me.

Frances Elliot.

June, 1893.

TO relate the “Court life” of France—from Francis I. to Louis XIV.—it is necessary to relate, also, the history of the royal favourites. They ruled both court and state, if they did not preside at the council. The caprice of these ladies was, actually, “the Pivot on which French history turned.”

Louis XIII. was an exception. Under him Cardinal Richelieu reigned. Richelieu’s “zeal” for France led him unfortunately to butcher all his political and personal opponents. He ruled France, axe in hand. It was an easy way to absolute power.

Cardinal Mazarin found France in a state of anarchy. The throne was threatened with far more serious dangers than under Richelieu. To feudal chiefs were joined royal princes. The great Condé led the Spanish troops against his countrymen. Yet no political murder stains the name of the gentle Italian. He triumphed by statescraft,—and married the Infanta to Louis XIV.

Cardinal de Retz possessed much of the genius of Richelieu. No cruelty, however, attaches to his memory. But De Retz was on the wrong side, the side of rebellion. He was false to his king and to France. Great as were his gifts, he fell before the persevering loyalty of Mazarin.[Pg ]

The personal morality of either of these statesmen ill bears investigation. Marion de l’Orme was the mistress and the spy of Richelieu; Mazarin—it is to be hoped—was privately married to the Queen Regent Anne of Austria. Cardinal de Retz had, as a contemporary remarks, “a bevy of mistresses.”

We have the authority of Charlotte de Bavière, second wife of Phillippe Duc d’Orléans, brother of Louis XIV., in her Autobiographical Fragments, “that her predecessor, Henrietta of England, was poisoned.” No legal investigation was ever made as to the cause of her sudden death. There is no proof “that Louis XIV. disbelieved she was poisoned.”

The number of the victims of the St. Bartholomew-massacre is stated by Sully to have been 70,000. (Memoirs, book I., page 37.) Sully and other authorities state “that Charles IX., at his death, manifested by his transports and his tears the sorrow he felt for what he had done.” Further, “that when dying he sent for Henry of Navarre, in whom alone he found faith and honour.” (Sully, book I., page 42.)

That Sorbin, confessor to Charles IX., should have denied this is perfectly natural. Henry of Navarre would stink in the confessor’s nostrils as a pestilent heretic. As to the credibility of Sorbin (a bigot and a controversialist), I would refer to the Mémoires de l’état de France sous Charles IX., vol. 3, page 267.

According to the Confession de Saucy, Sorbin de St. Foy “was made a Bishop for having placed Charles IX. among the Martyrs.”

Frances (Minto) Elliot.

August, 1873.

ALL my life I have been a student of French memoir-history. In this species of literature France is remarkably rich. There exist contemporary memoirs and chronicles, from a very early period down to the present time, in which are preserved not only admirable outlooks over general events, but details of language, character, dress, and manners, not to be found elsewhere. I was bold enough to fancy that somewhat yet remained to tell;—say—of the caprices and eccentricities of Louis XIII., of the homeliness of Henri Quatre, of the feminine tenderness of Gabrielle d’Estrées, of the lofty piety and unquestioning confidence of Louise de Lafayette, of the romantic vicissitudes of Mademoiselle de Montpensier; and that some pictures might be made of these old French personages for English readers in a way that should pourtray the substance and spirit of history, without affecting to maintain its form and dress.

In all I have written I have sought carefully to work into my dialogue each word and sentence recorded of the individual, every available trait or peculiarity of character to be found in contemporary memoirs, every tradition that has come down to us.

To be true to life has been my object. Keeping close to the background of history, I have endeavoured to group the figures of my foreground as they grouped themselves in actual life. I have framed them in the frames in which they really lived.

Frances Elliot.

Farley Hill Court,

Christmas, 1872.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I— | Francis I. | 1 |

| II— | Charles de Bourbon | 6 |

| III— | Brother and Sister | 12 |

| IV— | The Quality of Mercy | 20 |

| V— | All Lost Save Honour | 28 |

| VI— | Broken Faith | 33 |

| VII— | La Duchesse d’Étampes | 42 |

| VIII— | Last Days | 49 |

| IX— | Catherine de’ Medici | 55 |

| X— | A Fatal Joust | 58 |

| XI— | The Widowed Queen | 63 |

| XII— | Mary Stuart and Her Husband | 67 |

| XIII— | A Traitor | 74 |

| XIV— | The Council of State | 80 |

| XV— | Catherine’s Vengeance | 86 |

| XVI— | The Astrologer’s Chamber | 94 |

| XVII— | At Chenonceau | 101 |

| XVIII— | A Dutiful Daughter | 113 |

| XIX— | Before the Storm | 122 |

| XX— | St. Bartholomew | 129 |

| XXI— | The End of Catherine de’ Medici | 139 |

| XXII— | The Last of the Valois | 146 |

| XXIII— | Don Juan | 158 |

| XXIV— | Charmante Gabrielle | 172 |

| XXV— | Italian Art | 186 |

| XXVI— | Biron’s Treason | 198 |

| XXVII— | A Court Marriage | 207 |

| XXVIII— | The Prediction Fulfilled | 215 |

| XXIX— | Louis XIII. | 227 |

| XXX— | The Oriel Window | 235 |

| XXXI— | An Ominous Interview | 244 |

| XXXII— | Love and Treason | 254 |

| XXXIII— | The Cardinal Duped | 263 |

| XXXIV— | The Maid of Honour | 271 |

| XXXV— | At Val de Grâce | 283 |

| XXXVI— | The Queen Before the Council | 291 |

| XXXVII— | Louise de Lafayette | 302 |

| Notes | 317 |

WE are in the sixteenth century. Europe is young in artistic life. The minds of men are moved by the discussions, councils, protests, and contentions of the Reformation. The printing press is spreading knowledge into every corner of the globe.

At this period, three highly educated and unscrupulous young men divide the power of Europe. They are Henry VIII. of England, Charles V. of Austria, and Francis I. of France. Each is magnificent in taste; each is desirous of power and conquest. Each acts as a spur to the others both in peace and in war. They introduce the cultivated tastes, the refined habits, the freedom of thought of modern life, and from the period in which they flourish modern history dates.

Of these three monarchs Francis is the boldest, cleverest, and most profligate. The elegance, refinement, and luxury of his court are unrivalled; and this luxury strikes the senses from its contrast with the frugal habits of the ascetic Louis XI. and the homely Louis XII.

His reign educated Europe. If ambition led him towards Italy, it was as much to capture the arts of that classic land and to bear them back in triumph to France, as to acquire the actual territory. Francis introduced the French Renaissance, that subtle union of elaborate ornamentation with purity of design which was the renovation of art. When and how he acquired such exact appreciation of the beautiful is unexplained. That he possessed judgment and taste is proved by the monuments he left behind, and by his patronage of the greatest masters of their several arts.

The wealth of beauty and colour, the flowing lines of almost divine expression in the works of the Italian painters of the Cinque-cento, delighted the sensuous soul of Francis. Wherever he lived he gathered treasures of their art around him. Such a nature as his had no sympathy with the meritorious but precise elaboration of the contemporary Dutch school, led by the Van Eycks and Holbein. It was Leonardo da Vinci, the head of the Milanese school, who blended power and tenderness, that Francis delighted to honour. He brought Cellini, Primaticcio, and Leonardo from Italy, and never wearied of their company. He established the aged Leonardo at the Château de Clos, near his own castle of Amboise, where the painter is said to have died in the arms of his royal patron.

As an architect, Francis left his mark beyond any other sovereign of Europe. He transformed the gloomy fortress-home—embattled, turreted, and moated—into the elaborately decorated, manorial château. The bare and foot-trodden space without,

enclosed with walls of defence, was changed into green lawns and overarching bowers breaking the vista toward the royal forest, the flowing river, and the open campagne.

Francis had a mania for building. Like Louis XIV., who in the century following built among the sandhills of Versailles, Francis insisted on creating a fairy palace amid the flat and dusty plains of Sologne. Here the Renaissance was to achieve its triumph. At Chambord, near Blois, were massed every device, decoration, and eccentricity of his favourite style. So identified is this place with its creator, that even his intriguing life peeps out in the double staircase under the central tower—representing a gigantic fleur-de-lys in stone—where those who ascend are invisible to those who descend; in the doors, concealed in sliding panels behind the arras; and in many double walls and secret stairs.

Azay le Rideau, built on a beautifully wooded island on the river Indre, though less known than Chambord, was and is an exquisite specimen of the Renaissance. It owes the fascination of its graceful outlines and peculiar ornamentation to the masterhand which has graven his crowned F and Salamander on its quaint façades. The Louvre and Fontainebleau are also signed by these monograms. He, and his son Henry II., made these piles the historic monuments we now behold.

Such was Francis, the artist. As a soldier, he followed in the steps of Bayard, “Sans peur et sans reproche.” He perfected that poetic code of honour which reconciles the wildest courage with generosity towards an enemy. A knight-errant in love of danger and adventure, Francis comes to us as the perfect type of the chivalrous Frenchman; ready to do battle on any provocation either as king or gentleman, either at the head of his army, in the tournament, or in the duello. He loved all that was gay, bright, and beautiful. He delighted in the repose of peace, yet no monarch ever plunged his country into more ruinous and causeless wars. Though capable of the tenderest and purest affection, no man was ever more heartless and cruel in principle and conduct.

Francis, Duc de Valois,[1] was educated at home by his mother, Madame Louise de Savoie, Duchesse d’Angoulême, Regent of France, together with his brilliant sister, Marguerite, “the pearl of the Valois,” poetess, story-teller, artist, and politician. Each of these royal ladies was tenderly attached to the clever, handsome youth, and together formed what they chose to call “a trinity of love.” The old Castle of Amboise, in Touraine, the favourite abode of Louis XII., continued to be their home after his death. Here, too, the hand of Francis is to be traced in sculptured windows and architectural façades, in noble halls and broad galleries, and in the stately terraced gardens overlooking the Loire which flows beneath its walls. Here, under the formal lime alleys and flowering groves, or in the shadow of the still fortified bastions, the brother and sister sat or wandered side by side, on many a summer day; read and talked of poetry and troubadours, of romance and chivalry, of Arthur, Roland, and Charlemagne, of spells and witcheries, and of Merlin the enchanter whose magic failed before a woman’s glance.

Printing at that time having become general, literature of all kinds circulated in every direction, stirring men’s minds with fresh tides of knowledge. Marguerite de Valois, who was called “the tenth Muse,” dwelt upon poetry and fiction, and already meditated her Boccaccio-like stories, afterwards to be published under the title of the Heptameron. Francis gloated over such adventures as were detailed in the roundelay of the “Four Sons of Aymon,” a ballad of that day, devoured the history of Amadis de Gaul, and tried his hand in twisting many a love-rhyme, after the fashion of the “Romaunt of the Rose.”

In such an idyllic life of love, of solitude, and of thought, full of the humanising courtesies of family life, was formed the paradoxical character of Francis, who above all men possessed what the French describe as “the reverse of his qualities.” His fierce passions still slumbered, his imagination was filled with poetry, his heart beat high with the endearing love of a brother and a son. His reckless courage vented itself in the chase, among the royal forests of Amboise and of Chanteloup, that darkened the adjacent hills, or in a tustle with the boorish citizens, or travelling merchants, in the town below.

Thus he grew into manhood, his stately yet condescending manners, handsome person, and romantic courage gaining him devoted adherents. Yet when we remember that Francis served as the type for Hugo’s play of Le Roi s’amuse we pause and—shudder.

THE Court is at Amboise. Francis is only twenty, and still solicits the advice of his mother, Louise de Savoie, regent during his minority. Marguerite, now married to the Duc d’Alençon, has also considerable influence over him. Both these princesses, who are with him at Amboise, insist on the claims of their kinsman, Charles de Montpensier, Duc de Bourbon,—in right of his wife, Suzanne, only daughter and heiress of Pierre, the last duke,—to be appointed Constable of France. It is an office next in power to the sovereign, and has not been revived since the treasonable conspiracy of the Comte de St. Pol, in the reign of Louis XI.

Bourbon is only twenty-six, but he is already a hero. He has braved death again and again in the battle-field with dauntless valour. In person he is tall and handsome. In manners, he is frank, bold, and prepossessing; but when offended, his proud nature easily turns to vindictive and almost savage revenge. Invested with the double dignity of General of the royal forces and Constable of France, he comes to Amboise to salute the King and the princesses, who are both strangely interested in his career, and to take the last commands from Francis, who does not now propose accompanying his army into Italy.

There is a restless, mobile expression on Bourbon’s dark yet comely face, that tells of strong passions ill suppressed. A man capable of ardent and devoted

love, and of bitter hate; his marriage with his cousin Suzanne, lately dead, had been altogether a political alliance to bring him royal kindred, wealth, and power. Suzanne had failed to interest his heart. It is said that another passion has long engaged him. Francis may have some hint as to who the lady is, and may resent Bourbon’s presumption. At all events, the Constable is no favourite with the King. He dislikes his fanfaronnade and haughty address. He loves not either to see a subject of his own age so powerful and so magnificent; it trenches too much on his own prerogatives of success. Besides, as lads, Bourbon and Francis had quarrelled at a game of maille. The King had challenged Bourbon but had never fought him, and Bourbon resented this refusal as an affront to his honour.

The Constable, mounted on a splendid charger, with housings of black velvet, and attended by a brilliant suite, gallops into the courtyard. His fine person is set off by a rich surcoat, worn over a suit of gilded armour. He wears a red and white panache in his helmet, and his sword and dagger are thickly incrusted with diamonds.

At the top of the grand staircase are posted one hundred archers, royal pages conduct the Constable through the range of state apartments.

The King receives Bourbon in the great gallery hung with tapestry. He is seated on a chair of state, ornamented with elaborate carving, on which the arms of France are in high relief. This chair is placed on a raised floor, or dais, covered with a carpet. Beside him stands the grand master of the ceremonies, who introduces the Constable to the King. Francis, who inclines his head and raises his cap for an instant, is courteous but cold. Marguerite d’Alençon is present; like Bourbon, she is unhappily mated. The Duc d’Alençon is, physically and mentally, her inferior. When the Constable salutes the King, Marguerite stands apart. Conscious that her brother’s eyes read her thoughts, she blushes deeply and averts her face. Bourbon advances to the spot where she is seated in the recess of an oriel window. He bows low before her; Marguerite rises, and offers him her hand. Their eyes meet. There is no disguise in the passionate glance of the Constable; Marguerite, confused and embarrassed, turns away.

“Has your highness no word of kindness for your kinsman?” says the Constable, in a low voice.

“You know, cousin, your interests are ever dear to me,” replies she, in the same tone; then, curtseying deeply to the King, she takes the arm of her husband, M. d’Alençon, who was killing flies at the window, and leaves the gallery.

“Diable!” says Francis to his confidant, Claude de Guise, in an undertone; “My sister is scarcely civil to the Constable. Did you observe, she hardly answered him? All the better. It will teach Bourbon humility, and not to look too high for a mate.”

“Yet her highness pleaded eagerly with your Majesty for his advancement.”

“Yes, yes; that was to please our mother. Suzanne de Bourbon was her cousin, and the Regent promised her before her death to support her husband’s claims.”

Meanwhile, the Constable receives, with a somewhat reserved and haughty civility, the compliments of the Court. He is conscious of an antagonistic atmosphere. It is well known that the King loves him not; and whom the King loves not neither does the courtier.

A page then approaches, and invites the Constable, in the name of Queen Claude, to join her afternoon circle. Meanwhile, he is charged to conduct the Constable to an audience with the Regent-mother, who awaits him in her apartments.

The King had been cool and the Princess silent and reserved: not so the Regent Louise de Savoie, who advances to meet the Constable with unmistakable eagerness.

“I congratulate you, my cousin,” she says, holding out both her hands to him, which he receives kneeling, “on the dignity with which my son has invested you. I may add, that I was not altogether idle in the matter.”

“Your highness will, I hope, be justified in the favour you have shown me,” replies the Constable, coldly.

“Be seated, my cousin,” continues Louise. “I have desired to see you alone that I might fully explain with what grief I find myself obliged, by the express orders of my son, to dispute with a kinsman I so much esteem as yourself”—she pauses a moment, the Constable bows gravely—“the inheritance of my poor cousin, your wife, Madame Suzanne de Bourbon. Suzanne was dear to me, and you also, Constable, have a high place in my regard.”

Louise ceases. She looks significantly at the Constable, as if waiting for him to answer; but he does not reply, and again bows.

“I am placed,” continues the Regent, the colour gathering on her cheek, “in a most painful alternative. The Chancellor has insisted on the legality of my claims—claims on the inheritance of your late wife, daughter of Pierre, Duc de Bourbon, my cousin. I will not trouble you with details. My son urges the suit. My own feelings plead strongly against proceeding any further in the matter.” She hesitates and stops.

“Your highness is of course aware that the loss of this suit would be absolute ruin to me?” says Bourbon, looking hard at Louise.

“I fear it would be most disastrous to your fortunes. That they are dear to me, judge—you are by my interest made Constable of France, second only in power to my son.”

“I have already expressed my gratitude, madame.”

“But, Constable,” continues Louise de Savoie, speaking with much animation, “why have you insisted on your claims—why not have trusted to the gratitude of the King towards a brave and zealous subject? Why not have counted on myself, who have both power and will, as I have shown, to protect you?”

“The generosity of the King and your highness’s favour, which I accept with gratitude, have nothing to do with the legal rights of my late wife’s inheritance. I desire not, madame, to be beholden in such matters even to your highness or to his Majesty.”

“Well, Constable, well, as you will; you are, I know, of a proud and noble nature. But I have desired earnestly,” and the Regent rises and places herself on another chair nearer the Constable, “to

ascertain from your own lips if this suit cannot be settled à l’amiable. There are many means of accommodating a lawsuit, Duke. Madame Anne, wife of two kings of France, saved Brittany from cruel wars in a manner worthy of imitation.”

“Truly,” replies Bourbon, with a sigh; “but I know not what princess of the blood would enable me to accommodate your highness’s suit in so agreeable a manner.”

“Have you not yourself formed some opinion on the subject?” asks Louise, looking at the Constable with undisguised tenderness.

“No, madame, I have not. Since the hand of your beautiful daughter, Madame Marguerite, is engaged, I know no one.”

“But—” and she hesitates, and again turns her eyes upon him, which the Constable does not observe, as he is adjusting the hilt of his dagger—“but—you forget, Duke, that I am a widow.”

As she speaks she places her hand upon that of the Constable, and gazes into his face. Bourbon starts violently and looks up. Louise de Savoie, still holding his hand, meets his gaze with an unmistakable expression. She is forty years old, but vain and intriguing. There is a pause. Then the Constable rises and drops the hand which had rested so softly upon his own. His handsome face darkens into a look of disgust. A flush of rage sends the blood tingling to the cheeks of Louise.

“Your highness mistakes me,” says Bourbon. “The respect I owe to his Majesty, the disparity of our years, my own feelings, all render such an union impossible. Your highness does me great honour, but I do not at present intend to contract any other alliance. If his Majesty goes to law with me, why I will fight him, madame,—that is all.”

“Enough,” answers Louise, in a hoarse voice, “I understand.” The Constable makes a profound obeisance and retires.

This interview was the first act in that long and intricate drama by which the spite of a mortified woman drove the Duc de Bourbon—the greatest general of his age, under whom the arms of France never knew defeat—to become a traitor to his king and to France.

YEARS have passed; Francis, with his wife, Queen Claude, daughter of Louis XII. and Anne of Brittany, is at Chambord, in the Touraine. Claude, but for the Salic law, would have been Queen of France. In her childhood, she was affianced to Charles, son of Philip the Fair, afterwards Charles V. of Germany, the great rival of Francis. Francis had never loved her, the union had been political; yet Claude is gentle and devoted, and he says of her, “that her soul is as a rose without a thorn.” This queen—the darling of her parents—can neither bear the indifference nor the infidelity of her brilliant husband, and dies of her neglected love at the early age of twenty-five.

Marguerite d’Alençon, the Duke her husband, and the Court, are assembled for hunting in the forests of Sologne. Chambord, then but a gloomy mediæval fortress lying on low swampy lands on the banks of the river Casson, is barely large enough to accommodate the royal party. Already Francis meditates many changes; the course of the river Loire, some fifteen miles distant, is to be turned in order to bathe the walls of a sumptuous palace, not yet fully conceived in the brain of the royal architect.

It is spring; Francis is seated in the broad embrasure of an oriel window, in an oak-panelled saloon which looks towards the surrounding forest. He eagerly watches the gathering clouds that veil the sun and threaten to prevent the boar-hunt projected for that morning. Beside him, in the window, sits his sister Marguerite. She wears a black velvet riding-habit, faced with gold; her luxuriant hair is gathered into a net under a plumed hat on which a diamond aigrette glistens. At the farther end of the room Queen Claude is seated on a high-backed chair, richly carved, in the midst of her ladies. She is embroidering an altar-cloth; her face is pale and very plaintive. She is young, and though not beautiful, there is an angelic expression in her large grey eyes, a dimpling sweetness about her mouth, that indicate a nature worthy to have won the love of any man, not such a libertine as Francis. Her dress is plain and rich, of grey satin trimmed with ermine; a jewelled coif is upon her head. She bends over her work, now and then raising her wistful eyes with an anxious look towards the King. The Queen’s habits are sedentary, and the issue of the hunting party is of no personal interest to her; she always remains at home with her children and ladies. Many attendant lords, attired for hunting, are waiting his Majesty’s pleasure in the adjoining gallery.

“Marguerite,” says the King, turning to the Duchesse d’Alençon, as the sun reappears out of a bank of cloud, “the weather mends; in a quarter of an hour we shall start. Meanwhile, dear sister, sit beside me. Morbleu, how well that riding-dress becomes you! You are very handsome, and worthy to be called the Rose of the Valois. There are few royal ladies in our Court to compare to you”; and Francis glances significantly at his gentle Queen, busy over her embroidery, as if to say—“Would that she resembled you!”

Marguerite, proud of her brother’s praise, reddens with pleasure and reseats herself at his side. “By-and-by I shall knock down this sombre old fortress,” continues Francis, looking out of the window at the gloomy façade, “and transform it into a hunting château. The situation pleases me, and the surrounding forest is full of game.”

“My brother,” says Marguerite, interrupting him and speaking in an earnest voice, for her eyes have not followed the direction of the King’s, which are fixed on the prospect; she seems not to have heard his remarks, and her bright look has changed into an anxious expression; “my brother, tell me, have you decided upon the absolute ruin of Bourbon? Think how his haughty spirit must chafe under the repeated marks of your displeasure.” They are both silent. Marguerite’s eyes are riveted upon the King. Francis is embarrassed. He averts his face from the suppliant look cast upon him by his sister, and again turns to the window, as if to watch the rapidly passing clouds.

“My sister,” he says at length, “Bourbon is not a loyal subject; he is unworthy of your regard.”

“Sire, I cannot believe it. Bourbon is no traitor! But, my brother, if he were, have you not tried him sorely? Have you not driven him from you by an intolerable sense of injury? Oh, Francis, remember he is our kinsman, your most zealous servant;—did he not save your life at Marignano? Who among your generals is cool, daring, valiant, wise as Bourbon? Has he not borne our flag triumphantly through Italy? Have the French troops under him ever known defeat? Yet, my brother, you have now publicly disgraced him.” Her voice trembles with emotion; she is very pale, and her eyes fill with tears.

“By the mass, Marguerite, no living soul, save our mother, would dare to address me thus!” exclaims the King, turning towards her. He is much moved. Then, examining her countenance, he adds, “You are strangely agitated, my sister. What concern have you with the Constable? Believe me, I have made Bourbon too powerful.”

“Not now, not now, Francis, when you have, at the request of a woman—of Madame de Châteaubriand too—taken from him the government of Milan; when he is superseded in his command; when our mother is pressing on him a ruinous suit, with your sanction.”

At the name of Madame de Châteaubriand Marguerite’s whole countenance darkens with anger, the King’s face grows crimson.

“My sister, you plead Bourbon’s cause warmly—too warmly, methinks,” and Francis turns his head aside to conceal his confusion.

“Not only has your Majesty taken from him the government of Milan,” continues Marguerite, bitterly, unheeding the King’s interruption, “but he has been replaced by Lautrec, brother of Madame de Châteaubriand, an inexperienced soldier, unfitted for such an important post. Oh, my brother, you are driving Bourbon to despair. So great a general cannot hang up his victorious sword.”

“By my faith, sister, you press me hard,” replies the King, recovering the gentle tone with which he always addressed her; “I will communicate with my council; what you have said shall be duly considered. Meanwhile, if Bourbon inspires you with such interest, as it seems he does, tell him to humble his pride and submit himself to us, his sovereign and his master. If he do, he shall be greater than ever, I promise you.” As he speaks, he glances at Marguerite, whose eyes fall to the ground. “But see, my sister, the sun is shining; and there is some one already mounting in the courtyard. Give the signal for departure, Comte de Saint-Vallier,” says the King in a louder voice, turning towards two gentlemen standing at an opposite window in the gallery. The King has to repeat his command before the Comte de Saint-Vallier hears him. “Saint-Vallier, you are in deep converse with De Pompérant. Is it love or war?”

“Neither, Sire,” replies the Captain of the Royal Archers, looking embarrassed.

“M. de Pompérant, are you going with us

to-day to hunt the boar?” says the King, advancing towards them.

“Sire,” replies De Pompérant, bowing profoundly, “your Majesty does me great honour; but, with your leave, I will not accompany the hunt. Urgent business calls me from Chambord.”

“Ah, coquin, it is an assignation; confess it,” and a wicked gleam lights up the King’s eyes.

“No, Sire,” says De Pompérant. “I go to join the Constable de Bourbon, who is indisposed.”

“Ah! to join the Constable!” Francis pauses and looks at him. “I know he is your friend,” continues he, suddenly becoming very grave. “Where is he?”

“At his fortress of Chantelle, Sire.”

“At Chantelle! a fortified place, and without my permission. Truly, Monsieur de Pompérant, your friend is a daring subject. What if I will not trust you in his company, and command your attendance on our person here at Chambord?”

“Then, Sire, I should obey,” replies De Pompérant; “but let your gracious Majesty remember the Duc de Bourbon is ill; he is a broken and ruined man, deprived of your favour. Chantelle is more a château than a fortress.”

“Go, De Pompérant; I did but jest. Tell Bourbon, on the word of a king, that he has warm friends near my person; that if the Regent-mother gains her suit against him, I will restore tenfold to him in money, lands, and honour. Adieu, Monsieur de Pompérant. You are dismissed. Bon voyage.”

Now, the truth was that De Pompérant had come to Chambord upon a secret mission from Bourbon, who wished to assure himself of those gentlemen of the Court upon whom he could rely in case of rebellion. The Comte de Saint-Vallier had just, while standing at the window, pledged his word to stand by Bourbon for life or death.

The King is now mounting his horse in the courtyard, a noble bay with glittering harness. He gives the signal of departure, which is echoed through the woodland recesses by the bugles of the huntsmen. A lovely lady attired in white has joined the royal retinue in the courtyard. She rides on in front beside the King, who, the better to converse with her, has placed his hand upon her horse’s neck. This is Françoise, Comtesse de Châteaubriand, the favourite of the hour—at whose request Bourbon had been superseded in the government of Milan by her brother Lautrec.

Behind this pair rides Marguerite d’Alençon with her husband, the Comte de Guise, Montmorenci, Bonnivet, and other nobles. A large cavalcade of courtiers follows. Since her conversation with her brother, Marguerite looks thoughtful and anxious. She is so absent that she does not even hear the prattle of her husband, who is content to talk and cares not for reply. On reaching the dense thickets of the forest she suddenly reins up her horse, and, falling back a little, beckons the Comte de Saint-Vallier to her side.

“M. le Comte,” she says in a loud voice, so as to be overheard by her husband and the other gentlemen riding in advance, “tell me when is the Court to be graced by the presence of your incomparable daughter, Madame Diane, Grande Seneschale of Normandy?”

“Madame,” replies Saint-Vallier, “her husband, Monseigneur de Brèzè, is much occupied in his distant government. Diane is young, much younger than her husband. The Court, madame, is dangerously full of temptations to the young.”

“We lose a bright jewel by her absence,” says Marguerite, abstractedly. “M. le Comte,” she continues in a low voice, speaking quickly, and motioning to him with her hand to approach nearer, “I have something private to say to you. Ride close by my side. You are a friend of the Constable de Bourbon?” she asks eagerly.

“Yes, madame, I am.”

“You are, perhaps, his confidant? Speak freely to me; I feel deeply the misfortunes of the Duke. I would aid him if I could. Is there any foundation for the suspicion with which my brother regards him? You will not deceive me, Monsieur de Poitiers?”

Saint-Vallier does not answer at once. “The Constable de Bourbon will never, I trust, betray his Majesty,” replies he at last, with hesitation.

“Alas! my poor cousin! Is that all the assurance you can give me, Monsieur de Saint-Vallier? Oh! he is incapable of treason,” exclaims Marguerite with enthusiasm; “I would venture my life he is incapable of treason!”

A courier passes them at this moment, riding with hot speed. He nears the King, who is now far on in front, and who, hearing the sound of the horse’s hoofs, stops and listens. The messenger hands the King a despatch. Francis hastily breaks the seal. It is from Lautrec, the new governor of Milan. Bourbon is in open rebellion.

Bourbon in open rebellion! This intelligence necessitates the instant presence of the King at Paris.

FRANCIS is at the Louvre, surrounded by his most devoted friends and councillors, Chabannes, La Trémouille, Bonnivet, Montmorenci, Crequi, Cossé, De Guise, and the two Du Bellays. The Louvre is still the isolated stronghold, castle, palace, and prison, surrounded by moat, walls, and bastions, built by Philippe Auguste on the grassy margin of the Seine. In the centre of the inner court is a round tower, also moated, and defended by ramparts, ill-famed in feudal annals for its oubliettes and dungeons, under which the river flows. Four gates, with posterns and towers, open from the Louvre; that one opposite the Seine is the strongest. The southern gate—which is low and narrow, with statues on either hand of Charles V. and his wife, Jeanne de Bourbon—faces the Church of Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois.[2] Beyond are gardens and orchards, and a house called Fromenteau, where lions are kept for the King’s amusement.

These are the days of stately manners, intellectual culture, and increasing knowledge. Personal honour, as from man to man, is a religion, of which Bayard is the high priest; treachery to woman, a virtue inculcated by the King. The idle, vapid life of later courts is unknown under a monarch who, however addicted to pleasure, cultivates all kinds of knowledge, whose inquiring intellect seeks to master all science, to whom indolence is impossible. His very meals are chosen moments in which he converses with authors, poets, and artists, or dictates letters to Erasmus and the learned Greek Lascaris. Such industry and dignity, such grace and condescension, gather around him the great spirits of the age. He delights in their company.

It is the King’s boast that he has introduced into France the study of the Greek language, Botany, and Natural History. He buys, at enormous prices, pictures, pottery, enamels, statues, and manuscripts. As in his fervid youth at Amboise, he loves poetry and poets. Clément Marot is his chosen guest, and polishes the King’s rhymes, of which some delicate and touching stanzas (those on Agnes Sorel,[3] especially) have come down to us.

Even that witty heretic, Rabelais, found both an appreciative protector and intelligent friend in a sovereign superior to the prejudices of his age. With learning, poetry, wit, and intellect, come luxury and boundless extravagance. Brantôme speaks as with bated breath of the royal expenditure. These are the days of broad sombrero hats fringed with gold and looped up with priceless jewels and feathers; of embroidered cloaks in costly stuffs—heavy with gold or silver embroidery—hung over the shoulder; of slashed hose and richly chased rapiers; of garments of cloth-of-gold, embroidered with armorial bearings in jewels; of satin justaucorps covered with rivières of diamonds, emeralds, and oriental pearls; of torsades and collars wherein gold is but the foil to priceless gems. The ladies wear Eastern silks and golden tissues, with trimmings of rare furs; wide sleeves and Spanish fardingales, sparkling coifs and jewelled nets, with glittering veils. They ride in ponderous coaches covered with carving and gilding, or on horses whose pedigrees are as undoubted as their own, covered with velvet housings and with silken nets woven with jewels, their manes plaited with gold and precious stones. But these illustrious ladies consider gloves a royal luxury, and are weak in respect of stockings.

Foremost in every gorgeous mode is Francis. He wears rich Genoa velvets, and affects bright colours—rose and sky-blue. A Spanish hat is on his head, turned up with a white plume, fastened to an aigrette of rubies, with a golden salamander his device, signifying, “I am nourished and I die in fire” (“Je me nourris et je meurs dans le feu”).

How well we know his dissipated though distinguished features, as portrayed by Titian! His long nose, small eyes, broad cheeks, and cynical mouth. He moves with careless grace, as one who would say, “Que m’importe? I am King of France; nought comes amiss to me.”

Now he walks up and down the council-room in the Louvre which looks towards the river. His step is quick and agitated, his face wears an unusual frown. He calls Bonnivet to him and addresses him in a low voice, while the other nobles stand back.

“Am I to believe that Bourbon has not merely rebelled against me, but that the traitor has fled into Spain and made terms with Charles?”

“Your Majesty’s information is precise.”

“What was the manner of his flight?”

“The Duke, Sire, waited at his fortress of Chantelle until the arrival of Monsieur de Pompérant from your Majesty’s Court at Chambord, feigning sickness and remaining shut up within his apartments. After Monsieur de Pompérant’s arrival, a litter was ordered to await his pleasure, and De Pompérant, dressed in the clothes of the Duke and with his face concealed by a hood, was carried into the litter, which started for Moulins, travelling slowly. Meanwhile Bourbon, accompanied by a band of gentlemen, was galloping on the road to the frontier. He was last seen at Saint-Jean de Luz, in the Pyrenees.”

“By our Lady!” exclaims Francis, “such treason is a blot upon knighthood. Bourbon, a man whom we had made as great as ourselves!”

“The Duke, Sire, left a message for your Majesty.”

“A message! Where? and who bore it?”

“De Pompérant, Sire, who has already been arrested at Moulins. The Duke begged your Majesty to take back the sword which you had given him, and prayed you to send for the badge which he left hanging at the head of his bed at Chantelle.”

“Diable! does the villain dare to point his jests at his sovereign?” and Francis flushes to the roots of his hair with passion. “I wish I had him face to face in a fair field”—and he lays his hand on the hilt of his sword;—“but no,” he adds in a calmer voice, “a traitor’s blood would but soil my weapon. Let him carry his perfidy into Spain—’twill suit the Emperor; I am well rid of him. Are there many accomplices, Bonnivet?”

“About two hundred, Sire.”

“Is it possible! Do we know them?”

“The Comte de Saint-Vallier, Sire, is the principal accomplice.”

“What! Saint-Vallier, the Captain of our Archers! That strikes us nearly. This conspiracy, my lords,” says Francis, advancing to where Guise, La Trémouille, Montmorenci, and the others stand somewhat apart during his conversation with Bonnivet, “is much more serious than I imagined. I must remain in France to wait the issue of events. You, Bonnivet, must take command of the Italian campaign.”

Bonnivet kneels and kisses the hand of Francis.

“I am sorry for Jean de Poitiers,” continues Francis, turning to Guise. “Are the proofs against him certain?”

“Sire, Saint-Vallier accompanied the Constable to the frontier.”

“I am sorry,” repeats the King, and he passes his hand thoughtfully over his brow and muses.

“Jean de Poitiers, my ci-devant Captain of the Guards, is the father of a charming lady; Madame Diane, the Seneschale of Normandy, is an angel, though her husband, De Brèzè—hum—why, he is a monster. Vulcan and Venus—the old story, eh, my lords?”

There is a general laugh.

A page enters and announces a lady humbly

craving to speak with his Majesty. The King smiles, his wicked eyes glisten. “Who? what? Do I know her?”

“Sire, the lady is deeply veiled; she desires to speak with your Majesty alone.”

“But, by St. Denis—do I know her?”

“I think, Sire, it is the wife of the Grand Seneschal of Normandy—Madame Diane de Brèzè.”

There is a pause, some whispering, and a low laugh is heard. The King looks around displeased. “I am not surprised,” says he. “When I heard of the father’s danger I expected the daughter’s intercession. Let the lady enter.”

With a wave of his hand he dismisses the Court, and seats himself on a chair of state under a rich canopy embroidered in gold with the arms of France.

Diane enters. She is dressed in long black robes which sweep the floor. Her head is covered with a thick lace veil which she raises as she approaches the King. She weeps, but her tears do not mar her beauty, which is absolutely radiant. She is exquisitely fair and wonderfully fresh, with golden hair and dark eyebrows—a most winsome lady.

She throws herself at the King’s feet. She clasps her hands. Her sobs drown her voice.

“Pardon, Sire, pardon my father!” she at length falters. The King stoops forward, and raises her to the estrade on which he stands. He looks tenderly into her soft blue eyes, his hands are locked in hers.

“Your father, madame, my old and trusted servant, is guilty of treason.”

“Alas! Sire, I fear so; but he is old, too old for punishment. He has been hitherto a true subject of your Majesty.”

“He is blessed, madame, with a most surpassing daughter.” Francis pauses and looks steadfastly at her with eyes of ardent admiration. “But I fear I must confirm the sentence of my judges, madame; your father is certain to be found guilty of treason.”

“Oh! Sire, mercy, mercy! grant me my father’s life, I implore you”; and again Diane falls prostrate at the King’s feet, and looks supplicatingly into his face. Again the King raises her.

“Well, madame, you are aware that you desire the pardon of a traitor; on what ground do you ask for his life?”

“Sire, I ask it for the sake of mercy; mercy is the privilege of kings,” and her soft eyes seek those of Francis and rest upon them. “I have come so far, too, from Normandy, to invoke it—my poor father!” and she sobs again. “Your Majesty will not send me back refused, broken-hearted?” Still her eyes are fixed upon the King.

“Mercy, Madame Diane, is, doubtless, a royal prerogative. I am an anointed king,” and he lets go her hands, and draws himself up proudly, “and I may use it; but the prerogative of a woman is beauty. Beauty, Madame Diane,” adds Francis, with a glance at the lovely woman still kneeling at his feet, “is more potent than a king’s word.”

There is silence for a few moments. Diane’s eyes are now bent upon the ground, her bosom heaves. Francis contemplates her with delight.

“Will you, fair lady, deign to exercise your prerogative?”

“Truly, Sire, I know not what your Majesty would say,” replies Diane, looking down and blushing.

Something in his eyes gives her hope, for she starts violently, rises, and clasping her hands together exclaims, “How, Sire! do I read your meaning aright? can I, by my humble service to your Majesty——”

“Yes, fair lady, you can. Your presence at my Court, where your adorable beauty shall receive due homage, will be my hostage for your father’s loyalty. Madame Diane, I declare that the Comte de Saint-Vallier is PARDONED. Though he had rent the crown from off our head, your father is pardoned. And I add, madame, that it was the charm of his daughter that rendered a refusal impossible.”

Madame Diane’s face shines like April sunshine through rain-drops; a smile parts her lips, and her glistening eyes dance with joy; she is more lovely than ever.

“Thanks, thanks, Sire!” And again she would have knelt, but the King again takes her hands, and looks into her face so earnestly that she again blushes.

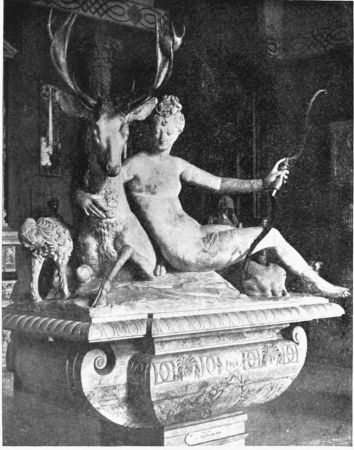

Did that look of the King fascinate her? or did the sudden joy of saving her father move her heart with love? Who can tell? It is certain, however, that from this time Diane left Normandy, and became one of the brightest ornaments of that beauty-loving Court. Diane was a woman of masculine understanding, concealed under the gentlest and most fascinating manners; but she was also mercenary, intriguing, and domineering. Of her beauty we may judge for ourselves, as many portraits of her are extant, especially one of great excellence by Leonardo da Vinci, in the long gallery at Chenonceau.

Diane was soon forsaken, but the ready-witted lady consoled herself by laying siege to the heart of the son of Francis, Prince Henry, afterwards Henry II.

Henry surrendered at discretion. Nothing can more mark the freedom of the times than this liaison. Yet both these ladies—Diane de Poitiers and her successor in the favour of the King, the Duchesse d’Étampes—were constantly in the society of two most virtuous queens Claude, and Elinor of Spain, the successive wives of Francis.

THE next scene is in Italy. The French army lies encamped on the broad plains of Lombardy, backed by snowy lines of Alpine fastnesses.

Bonnivet, in command of the French, presumptuous and inexperienced, has been hitherto defeated in every battle. Bourbon, fighting on the side of Spain, is, as before, victorious.

Francis, stung by the repeated defeat of his troops, has now joined the army, and commands in person. Milan, where the plague rages, has opened its gates to him; but Pavia, distant about twenty miles, is occupied by the Spaniards in force. Antonio de Leyva is governor. Thither the French advance in order to besiege the city.

The open country is defended by the Spanish forces under Bourbon. Francis, maddened by the presence of his cousin, rushes onward. Montmorenci and Bonnivet, flatterers both, assure him that victory is certain by means of a coup de main.

It is night; the days are short, for it is February. The winter moon lights up the rich meadow lands divided by the broad Ticino and broken by the deep ditches and sluggish streams which surround the city. Tower, campanile, dome, and turret, with here and there the grim façade of a mediæval palace, stand out in the darkness.

Yonder among the meadows are the French, darkening the surrounding plain. Francis knows that the Constable is advancing to support the garrison of Pavia, and he desires to carry the city by assault before his arrival. Ever too rash, and now excited by a passionate sense of injury, Francis, with D’Alençon, De la Trémouille, De Foix, and Bonnivet, leads the attack at the head of his cavalry. Now he is under the very walls. Despite the dim moonlight, no one can mistake him. He wears a suit of steel armour inlaid with gold; a crimson surcoat, embroidered with gilt “F’s”; a helmet encircled by a jewelled crown, out of which rises a yellow plume and golden salamander. For an instant success seems certain; the scaling-ladders thick with soldiers are already planted against the lowest walls, and the garrison retreats under cover of the bastions. A sudden panic seizes the troops beneath, who are to support the assault. In the treacherous moonlight they have fallen into confusion among the deep, slimy ditches; many are drifted away in the current of the great river. A murderous cannonade from the city walls now opens on the assailants and on the cavalry. Francis falls back. The older generals conjure him to retreat and raise the siege before the arrival of Bourbon, but, backed by Bonnivet and Montmorenci, he will not hear of it. The battle rages during the night. The morning light discovers the Spaniards commanded by Bourbon and Pescara, with the whole strength of their army, close under the walls. Again the King leads a fresh assault—a forlorn hope, rather. He fights desperately; the yellow plumes of his helmet wave hither and thither as his horse dashes wildly from side to side amidst the smoke, in the thickest of the battle. See, for an instant he falters,—he is wounded and bleeding. He recovers, however, and again clapping spurs to his horse, scatters his surrounding foes; six have already fallen by his hand. Look! his charger is pierced by a ball and falls with his rider. After a desperate struggle the King extricates himself; now on foot, he still fights furiously. Alas! it is in vain. Every moment his enemies thicken around him, pressing closer and closer. His gallant followers drop one by one under the unerring aim of the Basque marksmen. La Trémouille has fallen. De Foix lies a corpse at his feet. Bonnivet in despair expiates his evil counsel by death.[4] Every shot takes from him one of the pillars of his throne. Francis flings himself wildly on the points of the Spanish pikes. The Royal Guards fall like summer grass before the sickle; but where the King stands, still dealing desperate blows, the bodies of the slain form a rampart of protection around him. His very enemies stand back amazed at such furious courage. While he struggles for his life hand to hand with D’Avila and D’Ovietta, plumeless, soiled, and bloody, a loud cry rises from a thousand voices—“It is the King—LET HIM SURRENDER—Capture the King!” There is a dead silence; the Spanish troops fall back. A circle is formed round the now almost fainting Francis, who lies upon the blood-stained earth. De Pompérant advances. He kneels before the master whom he has betrayed, he implores him to yield to Bourbon.

At that hated name the King starts into fresh fury; he grasps his sword, he struggles to his feet. “Never,” cries he in a hoarse voice; “never will I surrender to that traitor! Rather let me die by the hand of a common marksman. Go back, Monsieur de Pompérant, and call to me the Vice-King of Naples.”

Lannoy advances, kneels, and kisses his hand. “Your Majesty is my prisoner,” he cries aloud, and a ringing shout is echoed from the Spanish troops.

Francis gives him his sword. Lannoy receives it kneeling, and replaces it by his own. The King’s helmet is then removed; a velvet cap is given to him, which he places on his head. The Spanish and Italian troopers and the deadly musketeers silently creep round him where he lies on the grass, supported by cushions, one to tear a feather from his broken plume, another to cut a morsel from his surcoat as a relic. This involuntary homage from his enemies is evidently agreeable to Francis. As his surcoat rapidly disappears under the knives of his opponents, he smiles, and graciously acknowledges the rough advances of those same soldiers who a moment before thirsted for his blood. Other generals with Pescara advance and surround him. He courteously acknowledges their respectful salutations.

“Spare my poor soldiers, spare my Frenchmen, generals,” says he.

These unselfish words bring tears into Pescara’s eyes.

“Your Majesty shall be obeyed,” replies he.

“I thank you,” replies Francis with a faltering voice.

A pony is now brought to bear him into Pavia. Francis becomes greatly agitated. As they raise him up and assist him to mount, he turns to his escort of generals—

“Marquis,” says he, turning to Pescara, “and you, my lord governor, if my calamity touches your hearts, as it would seem to do, I beseech you not to lead me into Pavia. I would not be exposed to the affront of entering as a prisoner a city I should have taken by assault. Carry me, I pray you, to some shelter without the walls.”

“Your Majesty’s wishes are our law,” replies Pescara, saluting him. “We will bear you to the monastery of Saint-Paul, without the gate towards Milan.”

To Saint-Paul the King was carried. It was from thence he wrote the historic letter to his mother, Louise de Savoie, Regent of France, in which he tells her, “all is lost save honour.”

WE are at Madrid. Francis has been lured hither by incredible treachery, under the idea that he will meet Charles V., and be at once set at liberty.

He is confined in one of the rooms of the Alcazar, then used as a state prison. A massive oaken door, clamped and barred with iron, opens from the court from whence a flight of steps leads into two small chambers which occupy one of the towers. The inner room has narrow windows, closely barred. The light is dim. There is just room for a table, two chairs, and a bed. It is a cage rather than a prison.

On a chair, near an open window, sits the King. He is emaciated and pale; his cheeks are hollow, his lips are white, his eyes are sunk in his head, his dress is neglected. His glossy hair, plentifully streaked with grey, covers the hand upon which he wearily leans his head. He gazes vacantly at the setting sun opposite—a globe of fire rapidly sinking below the low dark plain which bounds his view.

There are boundless plains in front of him, and on his left a range of tawny hills. A roadway runs beneath the tower, where the Imperial Guards are encamped. The gay fanfare of the trumpets sounding the retreat, the waving banners, the prancing horses, the brilliant accoutrements, the glancing armour of the imperial troops, mock him where he sits. Around him is Madrid. Palace, tower, and garden rise out of a sea of buildings burnt by southern sunshine. The church-bells ring out the Ave Maria. The fading light darkens into night. Still the King sits beside the open window, lost in thought. No one comes to disturb him. Now and then some broken words escape his lips:—“Save France—my poor soldiers—brave De Foix—noble Bonnivet—see, he is tossed on the Spanish pikes. Alas! would I were dead. My sister—my little lads—the Dauphin—Henry—Orléans—I shall never see you more. Oh, God! I am bound in chains of iron—France—liberty—Glory—gone—gone for ever!” His head sinks on his breast; tears stream from his eyes. He falls back fainting in his chair, and is borne to his bed.

Francis has never seen Charles, who is at his capital, Toledo. The Emperor does not even excuse his absence. This cold and cautious policy, this death in life, is agony to the ardent temperament of Francis. His health breaks down. A settled melancholy, a morbid listlessness overwhelms him. He is seized with fever; he rapidly becomes delirious. His royal gaoler, Charles, will not believe in his danger; he still refuses to see him. False himself, he believes Francis to be shamming. The Spanish ministers are distracted by their master’s obstinacy, for if the French King dies at Madrid of broken heart, all is lost, and a bloody war with France inevitable.

At the moment when the Angel of Death hovers over the Alcazar, a sound of wheels is heard below. A litter, drawn by reeking mules and covered with mud, dashes into the street. The leather curtains are drawn aside, and Marguerite d’Alençon, pale and shrunk with anxiety and fatigue, attended by two ladies, having travelled from Paris day and night, descends. Breathless with excitement, she passes quickly up the narrow stairs, through the anteroom, and enters the King’s chamber. Alas! what a sight awaits her. Francis lies insensible on his bed. The room is darkened, save where a temporary altar has been erected, opposite his bed, on which lights are burning. A Bishop officiates. The low voices of priests, chanting as they move about the altar, alone break a death-like silence. Marguerite, overcome by emotion, clasps her hands and sinks on her knees beside her brother. Her sobs and cries disturb the solemn ordinance. She is led almost fainting away. Then the Bishop approaches the King, bearing the bread of life, and, at that moment, Francis becomes suddenly conscious. He opens his eyes, and in a feeble voice prays that he may be permitted to receive it. So humbly, yet so joyfully, does he communicate that all present are deeply moved.

In spite, however, of the presence of Marguerite in Madrid, the King relapses. He again falls into a death-like trance. Then, and then only, does the Emperor yield to the reproaches of the Duchesse d’Alençon and the entreaties of his ministers. He takes horse from Toledo and rides to Madrid almost without drawing rein, until he stops at the heavy door in the Alcazar. He mounts the stairs and enters the chamber. Francis, now restored to consciousness, prompted by a too generous nature, opens his arms to embrace him.

“Your Majesty has come to see your prisoner die,” says he in a feeble voice, faintly smiling.

“No,” replies Charles, with characteristic caution and Spanish courtesy, bowing profoundly and kissing him on either cheek; “no, your Majesty will not die, you are no longer my prisoner; you are my friend and brother. I come to set you free.”

“Ah, Sire,” murmurs Francis in a voice scarcely audible, “death will accomplish that before your Majesty; but if I live—and indeed I do not believe I shall, I am so overcome by weakness—let me implore you to allow me to treat for my release in person with your Majesty; for this end I came hither to Madrid.”

At this moment the conversation is interrupted by the entrance of a page, who announces to the Emperor that the Duchesse d’Alençon has arrived and awaits his Majesty’s pleasure. Glad of an excuse to terminate a most embarrassing interview with his too confiding prisoner, Charles, who has been seated on the bed, rises hastily—

“Permit me, my brother,” says he, “to leave you, in order to descend and receive your august sister in person. In the meantime recover your health. Reckon upon my willingness to serve you. Some other time we will meet; then we can treat more in detail of these matters, when your Majesty is stronger and better able to converse.”

Charles takes an affectionate leave of Francis, descends the narrow stairs, and with much ceremony receives the Duchess.

“I rejoice, madame,” says he, “to offer you in person the homage of all Spain, and my own hearty thanks for the courage and devotion you have shown in the service of the King, my brother. He is a prisoner no longer. The conditions of release shall forthwith be prepared by my ministers.”

“Is the King fully aware what those conditions are, Sire?” Marguerite coldly asks.

Charles was silent.

“I fear our mother, Madame Louise, Regent of France,” continues the Duchesse d’Alençon, “may find it difficult to accept your conditions, even though it be to liberate the Sovereign of France, her own beloved son.”

“Madame,” replies Charles evasively, “I will not permit this occasion, when I have the happiness of first saluting you within my realm, to be occupied with state affairs. Rely on my desire to set my brother free. Meanwhile the King will, I hope, recover his strength. Pressing business now calls me back to Toledo. Adieu! most illustrious princess, to whom I offer all that Madrid contains for your service. Permit me to kiss your hands. Salute my brother, the King, from me. Once more, royal lady, adieu!”

Marguerite curtseys to the ground. The Emperor, with his head uncovered, mounts his horse, again salutes her, and attended by his retinue puts spurs to his steed and rides from the Alcazar on his return to Toledo. Marguerite fully understands the treachery of his words. Her heart swelling with indignation, she slowly ascends to the King’s chamber.

“Has the Emperor departed already?” Francis eagerly asks her.

“Yes, my brother; pressing business, he says, calls him back to Toledo,” replies Marguerite bitterly, speaking very slowly.

“What! gone so soon, before giving me an opportunity of discussing with him the terms of my freedom. Surely, my sister, this is strange,” says Francis, turning eagerly towards the Duchess, and then sinking back pale and exhausted on his pillows.

Marguerite seats herself beside him, takes his hand tenderly within both her own, and gazes at him in silence.

“But, my sister, did my brother, the Emperor, say nothing to you of his speedy return?”

“Nothing,” answers Marguerite, drily.

“Yet he assured me, with his own lips, that I was already free, and that the conditions of release would be prepared immediately.”

“Dear brother,” says the Duchess, “has your imprisonment at Madrid, and the conduct of the Emperor to you this long time past, inclined you to believe what he says?”

“I, a king myself, should be grieved to doubt a brother sovereign’s word.”

“Francis,” says Marguerite, speaking with great earnestness and fixing her eyes on him, “what you say convinces me that you are weakened by illness. Your naturally acute intellect is dulled by the confusion of recent delirium. If you were in full possession of your senses you would not speak as you do. My brother, take heed of my words—you will never be free.”

“How,” exclaims the King, starting up, “never be free? What do you mean?”

“Calm yourself, my brother. You are, I fear, too weak to hear what I have to say.”

“No, no! my sister; suspense to me is worse than death. Speak to me, Marguerite; speak to me, my sister.”

“Then, Sire, let me ask you, when you speak of release, when the Emperor tells you you are free, are you aware of the conditions he imposes on you?”

“Not accurately,” replies Francis. “Certain terms were proposed, before my illness, that I should surrender whole provinces in France, renounce my rights in the Milanese, pay an enormous ransom, leave my sons hostages at Madrid; but these were the proposals of the Spanish council. The Emperor, speaking personally to a brother sovereign, would never press anything on me unbecoming my royal condition; therefore it is that I desire to treat with himself alone.”

“Alas! my brother, you are too generous; you are deceived. Much negotiation has passed during your illness, and since my arrival. Conditions have been proposed by Spain to the Regent, that she—your mother—supported by the parliament of your country, devoted to your person, has refused. Listen to me, Francis. Charles seeks to dismember France. As long as it remains a kingdom, he intends that you shall never leave Madrid.”

“Marguerite, my sister, proceed, I entreat you!” breaks in Francis, trembling with excitement.

“Burgundy is to be ceded; you are to renounce all interest in Flanders and in the Milanese. You are to pay a ransom that will beggar the kingdom. You are to marry Elinor, Queen Dowager of Portugal, sister to Charles, and you are to leave your sons, the Dauphin and the Duc d’Orléans, hostages in Spain for the fulfilment of these demands.”

Francis turns very white, and sinks back speechless on the pillows that support him. He stretches out his arm to his sister and fondly clasps her neck. “Marguerite, if it is so, you say well,—I shall never leave Madrid. My sister, let me die ten thousand deaths rather than betray the honour of France.”

“Speak not of death, dearest brother!” exclaims Marguerite, her face suddenly flushing with excitement. “I have come to make you live. I, Marguerite d’Alençon, your sister, am come to lead you back to your army and to France; to the France that mourns for you; to the army that is now dispersed and insubordinate; to the mother who weeps for her beloved son.” Marguerite’s voice falters; she sobs aloud, and rising from her chair, she presses her brother in her arms. Francis feebly returns her embrace, tenderly kisses her, and signs to her to proceed. “Think you,” continues Marguerite more calmly, and reseating herself, but still holding the King’s hand—“think you that councils in which Bourbon has a voice——” At this name the King shudders and clenches his fist upon the bed-clothes. “Think you that a sovereign who has treacherously lured you to Madrid will have any mercy on you? No, my brother; unless you agree to unworthy conditions, imposed by a treacherous monarch who abuses his power over you, here you will languish until you die! Now mark my words, dear brother. Treaties made under duresse, by force majeure, are legally void. You will dissemble, my generous King—for the sake of France, you will dissemble. You must fight this crafty emperor with his own weapons.”

“What! my sister, be false to my word—I, a belted knight, invested by the hands of Bayard on the field

of Marignano, stoop to a lie? Marguerite, you are mad!”

“Oh, Francis, hear me!” cries Marguerite passionately, “hear me; on my knees I conjure you to live, for yourself, for us, for France.” She casts herself on the floor beside him. She wrings his hands, she kisses his feet, her tears falling thickly. “Francis, you must, you shall consent. By-and-by you will bless me for this tender violence. You are not fit to meddle in this matter. Leave to me the care of your honour; is it not my own? I come from the Regent, from the council, from all France. Believe me, brother, if you are perjured, all Europe will applaud the perjury.”

Marguerite, whose whole frame quivers with agitation, speaks no more. There is a lengthened pause. The flush of fever is on the King’s face.

“My sister,” murmurs Francis, struggling with a broken voice to express himself, “you have conquered. Into your hands I commit my honour and the future of France. Leave me a while to rest, for I am faint.”

Treaties made under duresse by force majeure are legally void. The Emperor must be decoyed into the belief that terms are accepted by Francis, which are to be broken the instant his foot touches French soil. It is with the utmost difficulty that the chivalrous monarch can be brought to lend himself to this deceit. But the prayers of his sister, the deplorable condition of his kingdom deprived of his presence for nearly five years, the terror of returning illness, and the thorough conviction that Charles is as perfidious as he is ambitious, at length prevail. Francis ostensibly accepts the Emperor’s terms, and Queen Claude being dead, he affiances himself to Charles’s sister, Elinor, Queen Dowager of Portugal.

Francis was perjured, but France was saved.

RIDING with all speed from Madrid—for he fears the Emperor’s perfidy—Francis has reached the frontier of Spain, on the banks of the river Bidassoa. His boys—the Dauphin and the Duc d’Orléans, who are to replace him at Madrid as hostages—await him there. They rush into their father’s arms and fondly cling to him, weeping bitterly at this cruel meeting for a moment after years of separation. Francis, with ready sympathy, mingles his tears with theirs. He embraces and blesses them. But, wild with the excitement of liberty and insecure while on Spanish soil, he cannot spare time for details. He hands the poor lads over to the Spanish commissioners. Too impatient to await the arrival of the ferry-boat, which is pulling across the river, he steps into the waters of the Bidassoa to meet it. On the opposite bank, among the low scrub wood, a splendid retinue awaits him. He springs into the saddle, waves his cap in the air, and with a joyous shout exclaims, “Now I am a king! Now I am free!”

The political vicissitudes of Francis’s reign are as nothing to the chaos of his private life; only as a lover he was never defeated. No humiliating Pavia arrests his successful course. At Bayonne he finds a brilliant Court; his mother the Regent, and his sister Marguerite, await his arrival. After “Les embrasseurs d’usage,” as Du Bellay quaintly expresses it, the King’s eye wanders over the parterre of young beauties assembled in their suite, “la petite bande des dames de la Cour.” Then Francis first beholds Anne de Pisselieu, afterwards Duchesse d’Étampes. No one can compare to her in the tyranny of youth, beauty, and talent. A mere girl, she already knows everything, and is moreover astute, witty, and false. In spite of the efforts of Diane de Poitiers to attract the King (she having come to Bayonne in attendance on the Regent-mother), Anne de Pisselieu prevails. The King is hers. He delights in her joyous sallies. Anne laughs at every one and everything, specially at the pretensions of Madame Diane, whom she calls “an old hag.” She declares that she herself was born on Diane’s wedding-day!

Who can resist so bewitching a creature? Not Francis certainly. So the Court divides itself into two factions in love, politics, and religion. One party, headed by the Duchesse d’Étampes—a Protestant, and mistress of the reigning monarch; a second by Madame Diane de Poitiers—a Catholic, who, after many efforts, finding the King inaccessible, devotes herself to his son, Prince Henry, a mere boy, at least twenty years younger than herself, and waits his reign. Oddly enough, it is the older woman who waits, and the younger one who rules.

The Regent-mother looks on approvingly. Morals, especially royal morals, do not exist. Madame Louise de Savoie is ambitious. She would not see the new Spanish Queen—a comely princess, as she hears from her daughter Marguerite—possess too much influence over the King. It might injure her own power. The poor Spanish Queen! No fear that her influence will injure any one! The King never loves her, and never forgives her being forced upon him as a clause in the ignominious treaty of Madrid. Besides, she is thirty-two years old and a widow; grave, dignified, and learned, but withal a lady of agreeable person, though of mature and well-developed charms. Elinor admired and loved Francis when she saw him at Madrid, and all the world thought that the days were numbered in which Madame d’Étampes would be seen at Court. “But,” says Du Bellay, either with perfect naiveté or profound irony—“it was impossible for the King to offer to the virtuous Spanish princess any other sentiments than respect and gratitude, the Duchesse d’Étampes being sole mistress of his heart!” So the royal lady fares no better than Queen Claude, “with the roses in her soul,” and only receives, like her, courtesy and indifference.

The King returns to the Spanish frontier to receive Queen Elinor and to embrace the sons, now released, to whom she has been a true mother during the time they have been hostages at Madrid.

By-and-by the Queen’s brother—that mighty and perfidious sovereign, Charles V., Emperor of Germany—passing to his estates in the Netherlands, “craves leave of his beloved brother, Francis, King of France, to traverse his kingdom on his way,” so great is his dread of the sea voyage on account of sickness.

Some days before the Emperor’s arrival Francis is at the Louvre. He has repaired and embellished it in honour of his guest, and has pulled down the central tower, or donjon, called “Philippine,” which encumbered the inner court. By-and-by he will pull down all the mediæval fortress, and, assisted by Lescot, begin the palace known as the “Old Louvre.”

Francis is seated tête-à-tête with the Duchesse d’Étampes. The room is small—a species of boudoir or closet. It is hung with rare tapestry, representing in glowing colours the Labours of Hercules. Venetian mirrors, in richly carved frames, fling back the light of a central chandelier, also of Venetian workmanship, cunningly wrought into gaudy flowers, diamonded pendants, and true lovers’ knots. It is a blaze of brightness and colour. Rich velvet hangings, heavy with gold embroidery, cover the narrow windows and hang over the low doors. The King and the Duchess sit beside a table of inlaid marble, supported on a pedestal, marvellously gilt, of Italian workmanship, on which are laid fruits, wines, and confitures, served in golden vessels worked in the Cinque-cento style, after Cellini’s patterns. Beside themselves, Triboulet,[5] the king’s fool, alone is present. As Francis holds out his cup time after time to Triboulet, who replenishes it with Malvoisie, the scene composes itself into a perfect picture, such as Victor Hugo has imagined in Le Roi s’amuse; so perfect, indeed, that Francis might have sung, “La donna è mobile,” as he now does in Verdi’s opera of Rigoletto.

“Sire,” says the Duchess, her voice dropping into a most delicious softness, “do you leave us to-morrow?”

The King bows his head and kisses her jewelled fingers.

“So you persist in going to meet your brother, the Emperor Charles, your loving brother of Spain, whom I hate because he was so cruel to you at Madrid.” The Duchess looks up and smiles. Her eyes are beautiful, but hard and cruel. She wears an ermine mantle, for it is winter; her dress is of the richest green satin, embroidered with gold. On her head is a golden net, the meshes sprinkled with diamonds, from which her dark tresses escape in long ringlets over her shoulders.

Francis turns towards her and pledges her in a cup of Malvoisie. The corners of his mouth are drawn up into a cynical smile, almost to his nostrils. He has now reached middle life, and his face at that time would have made no man’s fortune.

“Duchess,” says he, “I must tear myself from you. I go to-morrow to Touraine. Before returning to Paris, I shall attend my brother the Emperor Charles at Loches, then at Amboise on the Loire. You will soon follow me with the Queen.”

“And, surely, when you have this heartless king, this cruel gaoler in your power, you will punish him and revenge yourself? If he, like a fool, comes into Touraine, make him revoke the treaty of Madrid, or shut him up in one of Louis XI.’s oubliettes at Amboise or Loches.”

“I will persuade him, if I can, to liberate me from all the remaining conditions of the treaty,” said the King, “but I will never force him.” As he speaks Triboulet, who has been shaking the silver bells on his parti-coloured dress with suppressed laughter, pulls out some ivory tablets to add something to a list he keeps of those whom he considers greater fools than himself. He calls it “his journal.”

The King looks at the tablets and sees the name of Charles V.

“Ha! ha! by the mass!—how long has my brother of Spain figured there?” asks he.

“The day, Sire, that I heard he had put his foot on the French frontier.”

“What will you do when I let him depart freely?”

“I shall,” said Triboulet, “rub out his name and put yours in its place, Sire.”

“See, your Majesty, there is some one else who agrees with me,” said the Duchess, laughing.

“I know,” replies Francis, “that my interests would almost force me to do as you desire, madame, but my honour is dearer to me than my interests. I am now at liberty,—I had rather the treaty of Madrid should stand for ever than countenance an act unworthy of ‘un roi chevalier.’ ”