| PAGE | |

| THE SECRET ROSE: | |

| DEDICATION | 3 |

| TO THE SECRET ROSE | 5 |

| THE CRUCIFIXION OF THE OUTCAST | 7 |

| OUT OF THE ROSE | 20 |

| THE WISDOM OF THE KING | 31 |

| THE HEART OF THE SPRING | 42 |

| THE CURSE OF THE FIRES AND OF THE SHADOWS | 51 |

| THE OLD MEN OF THE TWILIGHT | 61 |

| WHERE THERE IS NOTHING, THERE IS GOD | 69 |

OF COSTELLO THE PROUD, OF OONA THE DAUGHTER OF DERMOTT AND OF THE BITTER TONGUE | 78 |

| ROSA ALCHEMICA | 103 |

| THE TABLES OF THE LAW | 141 |

| THE ADORATION OF THE MAGI | 165 |

| EARLY STORIES. | |

| JOHN SHERMAN | 183 |

| DHOYA | 283 |

As for living, our servants will do that for us.—Villiers de L’Isle Adam.

Helen, when she looked in her mirror, seeing the withered wrinkles made in her face by old age, wept, and wondered why she had twice been carried away.—Leonardo da Vinci.

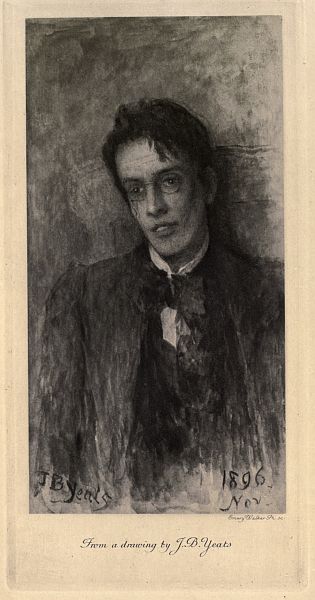

My Dear A.E.—I dedicate this book to you because, whether you think it well or ill written, you will sympathize with the sorrows and the ecstasies of its personages, perhaps even more than I do myself. Although I wrote these stories at different times and in different manners, and without any definite plan, they have but one subject, the war of spiritual with natural order; and how can I dedicate such a book to anyone but to you, the one poet of modern Ireland who has moulded a spiritual ecstasy into verse? My friends in Ireland sometimes ask me when I am going to write a really national poem or romance, and by a national poem or romance I understand them to mean a poem or romance founded upon some famous moment of Irish history, and built up out of the thoughts and feelings which move the greater number of patriotic Irishmen. I on the other hand believe that poetry and romance cannot be made by the most conscientious study of famous moments and of the thoughts and feelings of others, but only by looking into that little, infinite, faltering, eternal flame that we call ourselves. If a writer wishes to interest a certain people among whom he has grown up, or fancies he has a duty towards them, he may choose for the symbols of his art their legends, their history, their beliefs, their opinions, because he has a right to choose among things less than himself, but he cannot choose among the substances of art. So far, however, as this book is visionary it is Irish; for Ireland, which is still predominantly Celtic, has preserved with some less excellent things a gift of vision, which has died out among more hurried and more successful nations: no shining candelabra have prevented us from looking into the darkness, and when one looks into the darkness there is always something there.

A man, with thin brown hair and a pale face, half ran, half walked, along the road that wound from the south to the town of Sligo. Many called him Cumhal, the son of Cormac, and many called him the Swift, Wild Horse; and he was a gleeman, and he wore a short parti-coloured doublet, and had pointed shoes, and a bulging wallet. Also he was of the blood of the Ernaans, and his birth-place was the Field of Gold; but his eating and sleeping places were the four provinces of Eri, and his abiding place was not upon the ridge of the earth. His eyes strayed from the Abbey tower of the White Friars and the town battlements to a row of crosses which stood out against the sky upon a hill a little to the eastward of the town, and he clenched his fist, and shook it at the crosses. He knew they were not empty, for the birds were fluttering about them; and he thought how, as like as not, just such another vagabond as himself was hanged on one of them; and he muttered: ‘If it were hanging or bowstringing, or stoning or beheading,[8] it would be bad enough. But to have the birds pecking your eyes and the wolves eating your feet! I would that the red wind of the Druids had withered in his cradle the soldier of Dathi, who brought the tree of death out of barbarous lands, or that the lightning, when it smote Dathi at the foot of the mountain, had smitten him also, or that his grave had been dug by the green-haired and green-toothed merrows deep at the roots of the deep sea.’

While he spoke, he shivered from head to foot, and the sweat came out upon his face, and he knew not why, for he had looked upon many crosses. He passed over two hills and under the battlemented gate, and then round by a left-hand way to the door of the Abbey. It was studded with great nails, and when he knocked at it, he roused the lay brother who was the porter, and of him he asked a place in the guest-house. Then the lay brother took a glowing turf on a shovel, and led the way to a big and naked outhouse strewn with very dirty rushes; and lighted a rush-candle fixed between two of the stones of the wall, and set the glowing turf upon the hearth and gave him two unlighted sods and a wisp of straw, and showed him a blanket hanging from a nail, and a shelf with a loaf of bread and a jug of[9] water, and a tub in a far corner. Then the lay brother left him and went back to his place by the door. And Cumhal the son of Cormac began to blow upon the glowing turf that he might light the two sods and the wisp of straw; but the sods and the straw would not light, for they were damp. So he took off his pointed shoes, and drew the tub out of the corner with the thought of washing the dust of the highway from his feet; but the water was so dirty that he could not see the bottom. He was very hungry, for he had not eaten all that day; so he did not waste much anger upon the tub, but took up the black loaf, and bit into it, and then spat out the bite, for the bread was hard and mouldy. Still he did not give way to his anger, for he had not drunken these many hours; having a hope of heath beer or wine at his day’s end, he had left the brooks untasted, to make his supper the more delightful. Now he put the jug to his lips, but he flung it from him straightway, for the water was bitter and ill-smelling. Then he gave the jug a kick, so that it broke against the opposite wall, and he took down the blanket to wrap it about him for the night. But no sooner did he touch it than it was alive with skipping fleas. At this, beside himself with anger, he rushed to the[10] door of the guest-house, but the lay brother, being well accustomed to such outcries, had locked it on the outside; so he emptied the tub and began to beat the door with it, till the lay brother came to the door and asked what ailed him, and why he woke him out of sleep. ‘What ails me!’ shouted Cumhal, ‘are not the sods as wet as the sands of the Three Rosses? and are not the fleas in the blanket as many as the waves of the sea and as lively? and is not the bread as hard as the heart of a lay brother who has forgotten God? and is not the water in the jug as bitter and as ill-smelling as his soul? and is not the foot-water the colour that shall be upon him when he has been charred in the Undying Fires?’ The lay brother saw that the lock was fast, and went back to his niche, for he was too sleepy to talk with comfort. And Cumhal went on beating at the door, and presently he heard the lay brother’s foot once more, and cried out at him, ‘O cowardly and tyrannous race of friars, persecutors of the bard and the gleeman, haters of life and joy! O race that does not draw the sword and tell the truth! O race that melts the bones of the people with cowardice and with deceit!’

‘Gleeman,’ said the lay brother, ‘I also make[11] rhymes; I make many while I sit in my niche by the door, and I sorrow to hear the bards railing upon the friars. Brother, I would sleep, and therefore I make known to you that it is the head of the monastery, our gracious abbot, who orders all things concerning the lodging of travellers.’

‘You may sleep,’ said Cumhal, ‘I will sing a bard’s curse on the abbot.’ And he set the tub upside down under the window, and stood upon it, and began to sing in a very loud voice. The singing awoke the abbot, so that he sat up in bed and blew a silver whistle until the lay brother came to him. ‘I cannot get a wink of sleep with that noise,’ said the abbot. ‘What is happening?’

‘It is a gleeman,’ said the lay brother, ‘who complains of the sods, of the bread, of the water in the jug, of the foot-water, and of the blanket. And now he is singing a bard’s curse upon you, O brother abbot, and upon your father and your mother, and your grandfather and your grandmother, and upon all your relations.’

‘Is he cursing in rhyme?’

‘He is cursing in rhyme, and with two assonances in every line of his curse.’

The abbot pulled his night-cap off and[12] crumpled it in his hands, and the circular brown patch of hair in the middle of his bald head looked like an island in the midst of a pond, for in Connaught they had not yet abandoned the ancient tonsure for the style then coming into use. ‘If we do not somewhat,’ he said, ‘he will teach his curses to the children in the street, and the girls spinning at the doors, and to the robbers upon Ben Bulben.’

‘Shall I go, then,’ said the other, ‘and give him dry sods, a fresh loaf, clean water in a jug, clean foot-water, and a new blanket, and make him swear by the blessed Saint Benignus, and by the sun and moon, that no bond be lacking, not to tell his rhymes to the children in the street, and the girls spinning at the doors, and the robbers upon Ben Bulben?’

‘Neither our blessed Patron nor the sun and moon would avail at all,’ said the abbot; ‘for to-morrow or the next day the mood to curse would come upon him, or a pride in those rhymes would move him, and he would teach his lines to the children, and the girls, and the robbers. Or else he would tell another of his craft how he fared in the guest-house, and he in his turn would begin to curse, and my name would wither. For learn there is no[13] steadfastness of purpose upon the roads, but only under roofs, and between four walls. Therefore I bid you go and awaken Brother Kevin, Brother Dove, Brother Little Wolf, Brother Bald Patrick, Brother Bald Brandon, Brother James and Brother Peter. And they shall take the man, and bind him with ropes, and dip him in the river that he may cease to sing. And in the morning, lest this but make him curse the louder, we will crucify him.’

‘The crosses are all full,’ said the lay brother.

‘Then we must make another cross. If we do not make an end of him another will, for who can eat and sleep in peace while men like him are going about the world? Ill should we stand before blessed Saint Benignus, and sour would be his face when he comes to judge us at the Last Day, were we to spare an enemy of his when we had him under our thumb! Brother, the bards and the gleemen are an evil race, ever cursing and ever stirring up the people, and immoral and immoderate in all things, and heathen in their hearts, always longing after the Son of Lir, and Aengus, and Bridget, and the Dagda, and Dana the Mother, and all the false gods of the old days; always making poems in praise of those kings and queens of the demons, Finvaragh, whose home[14] is under Cruachmaa, and Red Aodh of Cnocna-Sidhe, and Cleena of the Wave, and Aoibhell of the Grey Rock, and him they call Donn of the Vats of the Sea; and railing against God and Christ and the blessed Saints.’ While he was speaking he crossed himself, and when he had finished he drew the nightcap over his ears, to shut out the noise, and closed his eyes, and composed himself to sleep.

The lay brother found Brother Kevin, Brother Dove, Brother Little Wolf, Brother Bald Patrick, Brother Bald Brandon, Brother James and Brother Peter sitting up in bed, and he made them get up. Then they bound Cumhal, and they dragged him to the river, and they dipped him in it at the place which was afterwards called Buckley’s Ford.

‘Gleeman,’ said the lay brother, as they led him back to the guest-house, ‘why do you ever use the wit which God has given you to make blasphemous and immoral tales and verses? For such is the way of your craft. I have, indeed, many such tales and verses well nigh by rote, and so I know that I speak true! And why do you praise with rhyme those demons, Finvaragh, Red Aodh, Cleena, Aoibhell and Donn? I, too, am a man of great wit and learning, but I ever glorify our gracious abbot,[15] and Benignus our Patron, and the princes of the province. My soul is decent and orderly, but yours is like the wind among the salley gardens. I said what I could for you, being also a man of many thoughts, but who could help such a one as you?’

‘Friend,’ answered the gleeman, ‘my soul is indeed like the wind, and it blows me to and fro, and up and down, and puts many things into my mind and out of my mind, and therefore am I called the Swift, Wild Horse.’ And he spoke no more that night, for his teeth were chattering with the cold.

The abbot and the friars came to him in the morning, and bade him get ready to be crucified, and led him out of the guest-house. And while he still stood upon the step a flock of great grass-barnacles passed high above him with clanking cries. He lifted his arms to them and said, ‘O great grass-barnacles, tarry a little, and mayhap my soul will travel with you to the waste places of the shore and to the ungovernable sea!’ At the gate a crowd of beggars gathered about them, being come there to beg from any traveller or pilgrim who might have spent the night in the guest-house. The abbot and the friars led the gleeman to a place in the woods at some distance, where many[16] straight young trees were growing, and they made him cut one down and fashion it to the right length, while the beggars stood round them in a ring, talking and gesticulating. The abbot then bade him cut off another and shorter piece of wood, and nail it upon the first. So there was his cross for him; and they put it upon his shoulder, for his crucifixion was to be on the top of the hill where the others were. A half-mile on the way he asked them to stop and see him juggle for them; for he knew, he said, all the tricks of Aengus the Subtle-hearted. The old friars were for pressing on, but the young friars would see him: so he did many wonders for them, even to the drawing of live frogs out of his ears. But after a while they turned on him, and said his tricks were dull and a shade unholy, and set the cross on his shoulders again. Another half-mile on the way, and he asked them to stop and hear him jest for them, for he knew, he said, all the jests of Conan the Bald, upon whose back a sheep’s wool grew. And the young friars, when they had heard his merry tales, again bade him take up his cross, for it ill became them to listen to such follies. Another half-mile on the way, he asked them to stop and hear him sing the story of White-breasted[17] Deirdre, and how she endured many sorrows, and how the sons of Usna died to serve her. And the young friars were mad to hear him, but when he had ended they grew angry, and beat him for waking forgotten longings in their hearts. So they set the cross upon his back, and hurried him to the hill.

When he was come to the top, they took the cross from him, and began to dig a hole to stand it in, while the beggars gathered round, and talked among themselves. ‘I ask a favour before I die,’ says Cumhal.

‘We will grant you no more delays,’ says the abbot.

‘I ask no more delays, for I have drawn the sword, and told the truth, and lived my vision, and am content.’

‘Would you, then, confess?’

‘By sun and moon, not I; I ask but to be let eat the food I carry in my wallet. I carry food in my wallet whenever I go upon a journey, but I do not taste of it unless I am well-nigh starved. I have not eaten now these two days.’

‘You may eat, then,’ says the abbot, and he turned to help the friars dig the hole.

The gleeman took a loaf and some strips of cold fried bacon out of his wallet and laid[18] them upon the ground. ‘I will give a tithe to the poor,’ says he, and he cut a tenth part from the loaf and the bacon. ‘Who among you is the poorest?’ And thereupon was a great clamour, for the beggars began the history of their sorrows and their poverty, and their yellow faces swayed like Gara Lough when the floods have filled it with water from the bogs.

He listened for a little, and, says he, ‘I am myself the poorest, for I have travelled the bare road, and by the edges of the sea; and the tattered doublet of particoloured cloth upon my back and the torn pointed shoes upon my feet have ever irked me, because of the towered city full of noble raiment which was in my heart. And I have been the more alone upon the roads and by the sea because I heard in my heart the rustling of the rose-bordered dress of her who is more subtle than Aengus, the Subtle-hearted, and more full of the beauty of laughter than Conan the Bald, and more full of the wisdom of tears than White-breasted Deirdre, and more lovely than a bursting dawn to them that are lost in the darkness. Therefore, I award the tithe to myself; but yet, because I am done with all things, I give it unto you.’[19]

So he flung the bread and the strips of bacon among the beggars, and they fought with many cries until the last scrap was eaten. But meanwhile the friars nailed the gleeman to his cross, and set it upright in the hole, and shovelled the earth in at the foot, and trampled it level and hard. So then they went away, but the beggars stared on, sitting round the cross. But when the sun was sinking, they also got up to go, for the air was getting chilly. And as soon as they had gone a little way, the wolves, who had been showing themselves on the edge of a neighbouring coppice, came nearer, and the birds wheeled closer and closer. ‘Stay, outcasts, yet a little while,’ the crucified one called in a weak voice to the beggars, ‘and keep the beasts and the birds from me.’ But the beggars were angry because he had called them outcasts, so they threw stones and mud at him, and went their way. Then the wolves gathered at the foot of the cross, and the birds flew lower and lower. And presently the birds lighted all at once upon his head and arms and shoulders, and began to peck at him, and the wolves began to eat his feet. ‘Outcasts,’ he moaned, ‘have you also turned against the outcast?’

One winter evening an old knight in rusted chain-armour rode slowly along the woody southern slope of Ben Bulben, watching the sun go down in crimson clouds over the sea. His horse was tired, as after a long journey, and he had upon his helmet the crest of no neighbouring lord or king, but a small rose made of rubies that glimmered every moment to a deeper crimson. His white hair fell in thin curls upon his shoulders, and its disorder added to the melancholy of his face, which was the face of one of those who have come but seldom into the world, and always for its trouble, the dreamers who must do what they dream, the doers who must dream what they do.

After gazing a while towards the sun, he let the reins fall upon the neck of his horse, and, stretching out both arms towards the west, he said, ‘O Divine Rose of Intellectual Flame, let[21] the gates of thy peace be opened to me at last!’ And suddenly a loud squealing began in the woods some hundreds of yards further up the mountain side. He stopped his horse to listen, and heard behind him a sound of feet and of voices. ‘They are beating them to make them go into the narrow path by the gorge,’ said someone, and in another moment a dozen peasants armed with short spears had come up with the knight, and stood a little apart from him, their blue caps in their hands.

‘Where do you go with the spears?’ he asked; and one who seemed the leader answered: ‘A troop of wood-thieves came down from the hills a while ago and carried off the pigs belonging to an old man who lives by Glen Car Lough, and we turned out to go after them. Now that we know they are four times more than we are, we follow to find the way they have taken; and will presently tell our story to De Courcey, and if he will not help us, to Fitzgerald; for De Courcey and Fitzgerald have lately made a peace, and we do not know to whom we belong.’

‘But by that time,’ said the knight, ‘the pigs will have been eaten.’

‘A dozen men cannot do more, and it was not reasonable that the whole valley should[22] turn out and risk their lives for two, or for two dozen pigs.’

‘Can you tell me,’ said the knight, ‘if the old man to whom the pigs belong is pious and true of heart?’

‘He is as true as another and more pious than any, for he says a prayer to a saint every morning before his breakfast.’

‘Then it were well to fight in his cause,’ said the knight, ‘and if you will fight against the wood-thieves I will take the main brunt of the battle, and you know well that a man in armour is worth many like these wood-thieves, clad in wool and leather.’

And the leader turned to his fellows and asked if they would take the chance; but they seemed anxious to get back to their cabins.

‘Are the wood-thieves treacherous and impious?’

‘They are treacherous in all their dealings,’ said a peasant, ‘and no man has known them to pray.’

‘Then,’ said the knight, ‘I will give five crowns for the head of every wood-thief killed by us in the fighting’; and he bid the leader show the way, and they all went on together. After a time they came to where a beaten track wound into the woods, and, taking this,[23] they doubled back upon their previous course, and began to ascend the wooded slope of the mountains. In a little while the path grew very straight and steep, and the knight was forced to dismount and leave his horse tied to a tree-stem. They knew they were on the right track: for they could see the marks of pointed shoes in the soft clay and mingled with them the cloven footprints of the pigs. Presently the path became still more abrupt, and they knew by the ending of the cloven footprints that the thieves were carrying the pigs. Now and then a long mark in the clay showed that a pig had slipped down, and been dragged along for a little way. They had journeyed thus for about twenty minutes, when a confused sound of voices told them that they were coming up with the thieves. And then the voices ceased, and they understood that they had been overheard in their turn. They pressed on rapidly and cautiously, and in about five minutes one of them caught sight of a leather jerkin half hidden by a hazel-bush. An arrow struck the knight’s chain-armour, but glanced off harmlessly, and then a flight of arrows swept by them with the buzzing sound of great bees. They ran and climbed, and climbed and ran towards the thieves, who[24] were now all visible standing up among the bushes with their still quivering bows in their hands: for they had only their spears, and they must at once come hand to hand. The knight was in the front, and smote down first one and then another of the wood-thieves. The peasants shouted, and, pressing on, drove the wood-thieves before them until they came out on the flat top of the mountain, and there they saw the two pigs quietly grubbing in the short grass, so they ran about them in a circle, and began to move back again towards the narrow path: the old knight coming now the last of all, and striking down thief after thief. The peasants had got no very serious hurts among them, for he had drawn the brunt of the battle upon himself, as could well be seen from the bloody rents in his armour; and when they came to the entrance of the narrow path he bade them drive the pigs down into the valley, while he stood there to guard the way behind them. So in a moment he was alone, and, being weak with loss of blood, might have been ended there and then by the wood-thieves he had beaten off, had fear not made them begone out of sight in a great hurry.

An hour passed, and they did not return; and now the knight could stand on guard no[25] longer, but had to lie down upon the grass. A half-hour more went by, and then a young lad, with what appeared to be a number of cock’s feathers stuck round his hat, came out of the path behind him, and began to move about among the dead thieves, cutting their heads off. Then he laid the heads in a heap before the knight, and said: ‘O great knight, I have been bid come and ask you for the crowns you promised for the heads: five crowns a head. They bid me tell you that they have prayed to God and His Mother to give you a long life, but that they are poor peasants, and that they would have the money before you die. They told me this over and over for fear I might forget it, and promised to beat me if I did.’

The knight raised himself upon his elbow, and opening a bag that hung to his belt, counted out the five crowns for each head. There were thirty heads in all.

‘O great knight,’ said the lad, ‘they have also bid me take all care of you, and light a fire, and put this ointment upon your wounds.’ And he gathered sticks and leaves together, and, flashing his flint and steel under a mass of dry leaves, had made a very good blaze. Then, drawing off the coat of mail, he began to anoint[26] the wounds: but he did it clumsily, like one who does by rote what he had been told. The knight motioned him to stop, and said: ‘You seem a good lad.’

‘I would ask something of you for myself.’

‘There are still a few crowns,’ said the knight; ‘shall I give them to you?’

‘O no,’ said the lad. ‘They would be no good to me. There is only one thing that I care about doing, and I have no need of money to do it. I go from village to village and from hill to hill, and whenever I come across a good cock I steal him and take him into the woods, and I keep him there under a basket, until I get another good cock, and then I set them to fight. The people say I am an innocent, and do not do me any harm, and never ask me to do any work but go a message now and then. It is because I am an innocent that they send me to get the crowns: anyone else would steal them; and they dare not come back themselves, for now that you are not with them they are afraid of the wood-thieves. Did you ever hear how, when the wood-thieves are christened, the wolves are made their godfathers, and their right arms are not christened at all?’

‘If you will not take these crowns, my good[27] lad, I have nothing for you, I fear, unless you would have that old coat of mail which I shall soon need no more.’

‘There was something I wanted: yes, I remember now,’ said the lad. ‘I want you to tell me why you fought like the champions and giants in the stories and for so little a thing. Are you indeed a man like us? Are you not rather an old wizard who lives among these hills, and will not a wind arise presently and crumble you into dust?’

‘I will tell you of myself,’ replied the knight, ‘for now that I am the last of the fellowship, I may tell all and witness for God. Look at the Rose of Rubies on my helmet, and see the symbol of my life and of my hope.’ And then he told the lad this story, but with always more frequent pauses; and, while he told it, the Rose shone a deep blood-colour in the firelight, and the lad stuck the cock’s feathers in the earth in front of him, and moved them about as though he made them actors in the play.

‘I live in a land far from this, and was one of the Knights of Saint John,’ said the old man; ‘but I was one of those in the Order who always longed for more arduous labours in the service of the Most High. At last there came[28] to us a knight of Palestine, to whom the truth of truths had been revealed by God Himself. He had seen a great Rose of Fire, and a Voice out of the Rose had told him how men would turn from the light of their own hearts, and bow down before outer order and outer fixity, and that then the light would cease, and none escape the curse except the foolish good man who could not, and the passionate wicked man who would not, think. Already, the Voice told him, the wayward light of the heart was shining out upon the world to keep it alive, with a less clear lustre, and that, as it paled, a strange infection was touching the stars and the hills and the grass and the trees with corruption, and that none of those who had seen clearly the truth and the ancient way could enter into the Kingdom of God, which is in the Heart of the Rose, if they stayed on willingly in the corrupted world; and so they must prove their anger against the Powers of Corruption by dying in the service of the Rose of God. While the knight of Palestine was telling us these things we seemed to see in a vision a crimson Rose spreading itself about him, so that he seemed to speak out of its heart, and the air was filled with fragrance. By this we knew that it was the very Voice of God which[29] spoke to us by the knight, and we gathered about him and bade him direct us in all things, and teach us how to obey the Voice. So he bound us with an oath, and gave us signs and words whereby we might know each other even after many years, and he appointed places of meeting, and he sent us out in troops into the world to seek good causes, and die in doing battle for them. At first we thought to die more readily by fasting to death in honour of some saint; but this he told us was evil, for we did it for the sake of death, and thus took out of the hands of God the choice of the time and manner of our death, and by so doing made His power the less. We must choose our service for its excellence, and for this alone, and leave it to God to reward us at His own time and in His own manner. And after this he compelled us to eat always two at a table to watch each other lest we fasted unduly, for some among us said that if one fasted for a love of the holiness of saints and then died, the death would be acceptable. And the years passed, and one by one my fellows died in the Holy Land, or in warring upon the evil princes of the earth, or in clearing the roads of robbers; and among them died the knight of Palestine, and at last I was alone. I fought in every[30] cause where the few contended against the many, and my hair grew white, and a terrible fear lest I had fallen under the displeasure of God came upon me. But, hearing at last how this western isle was fuller of wars and rapine than any other land, I came hither, and I have found the thing I sought, and, behold! I am filled with a great joy.’

Thereat he began to sing in Latin, and, while he sang, his voice grew fainter and fainter. Then his eyes closed, and his lips fell apart, and the lad knew he was dead. ‘He has told me a good tale,’ he said, ‘for there was fighting in it, but I did not understand much of it, and it is hard to remember so long a story.’

And, taking the knight’s sword, he began to dig a grave in the soft clay. He dug hard, and a faint light of dawn had touched his hair and he had almost done his work when a cock crowed in the valley below. ‘Ah,’ he said, ‘I must have that bird’; and he ran down the narrow path to the valley.

The High-Queen of the Island of Woods had died in childbirth, and her child was put to nurse with a woman who lived in a hut of mud and wicker, within the border of the wood. One night the woman sat rocking the cradle, and pondering over the beauty of the child, and praying that the gods might grant him wisdom equal to his beauty. There came a knock at the door, and she got up, not a little wondering, for the nearest neighbours were in the dun of the High-King a mile away; and the night was now late. ‘Who is knocking?’ she cried, and a thin voice answered, ‘Open! for I am a crone of the grey hawk, and I come from the darkness of the great wood.’ In terror she drew back the bolt, and a grey-clad woman, of a great age, and of a height more than human, came in and stood by the head of the cradle. The nurse shrank back against the wall, unable to take her eyes[32] from the woman, for she saw by the gleaming of the firelight that the feathers of the grey hawk were upon her head instead of hair. But the child slept, and the fire danced, for the one was too ignorant and the other too full of gaiety to know what a dreadful being stood there. ‘Open!’ cried another voice, ‘for I am a crone of the grey hawk, and I watch over his nest in the darkness of the great wood.’ The nurse opened the door again, though her fingers could scarce hold the bolts for trembling, and another grey woman, not less old than the other, and with like feathers instead of hair, came in and stood by the first. In a little, came a third grey woman, and after her a fourth, and then another and another and another, until the hut was full of their immense bodies. They stood a long time in perfect silence and stillness, for they were of those whom the dropping of the sand has never troubled, but at last one muttered in a low thin voice: ‘Sisters, I knew him far away by the redness of his heart under his silver skin’; and then another spoke: ‘Sisters, I knew him because his heart fluttered like a bird under a net of silver cords’; and then another took up the word: ‘Sisters, I knew him because his heart sang like a bird that is happy in a silver cage.’[33] And after that they sang together, those who were nearest rocking the cradle with long wrinkled fingers; and their voices were now tender and caressing, now like the wind blowing in the great wood, and this was their song:

When the song had died out, the crone who had first spoken, said: ‘We have nothing more to do but to mix a drop of our blood into his blood.’ And she scratched her arm with the sharp point of a spindle, which she had made the nurse bring to her, and let a drop of blood, grey as the mist, fall upon the lips of the child; and passed out into the darkness. Then the others passed out in silence one by one; and all the while the child had not opened his pink eyelids or the fire ceased to dance, for the one was too ignorant and the other too full of gaiety to know what great beings had bent over the cradle.

When the crones were gone, the nurse came to her courage again, and hurried to the dun[34] of the High-King, and cried out in the midst of the assembly hall that the Sidhe, whether for good or evil she knew not, had bent over the child that night; and the king and his poets and men of law, and his huntsmen, and his cooks, and his chief warriors went with her to the hut and gathered about the cradle, and were as noisy as magpies, and the child sat up and looked at them.

Two years passed over, and the king died fighting against the Fer Bolg; and the poets and the men of law ruled in the name of the child, but looked to see him become the master himself before long, for no one had seen so wise a child, and tales of his endless questions about the household of the gods and the making of the world went hither and thither among the wicker houses of the poor. Everything had been well but for a miracle that began to trouble all men; and all women, who, indeed, talked of it without ceasing. The feathers of the grey hawk had begun to grow in the child’s hair, and though his nurse cut them continually, in but a little while they would be more numerous than ever. This had not been a matter of great moment, for miracles were a little thing in those days, but for an ancient law of Eri that none who had any blemish of body could[35] sit upon the throne; and as a grey hawk was a wild thing of the air which had never sat at the board, or listened to the songs of the poets in the light of the fire, it was not possible to think of one in whose hair its feathers grew as other than marred and blasted; nor could the people separate from their admiration of the wisdom that grew in him a horror as at one of unhuman blood. Yet all were resolved that he should reign, for they had suffered much from foolish kings and their own disorders, and moreover they desired to watch out the spectacle of his days; and no one had any other fear but that his great wisdom might bid him obey the law, and call some other, who had but a common mind, to reign in his stead.

When the child was seven years old the poets and the men of law were called together by the chief poet, and all these matters weighed and considered. The child had already seen that those about him had hair only, and, though they had told him that they too had had feathers but had lost them because of a sin committed by their forefathers, they knew that he would learn the truth when he began to wander into the country round about. After much consideration they decreed a new law commanding every one upon pain of death to mingle artificially[36] the feathers of the grey hawk into his hair; and they sent men with nets and slings and bows into the countries round about to gather a sufficiency of feathers. They decreed also that any who told the truth to the child should be flung from a cliff into the sea.

The years passed, and the child grew from childhood into boyhood and from boyhood into manhood, and from being curious about all things he became busy with strange and subtle thoughts which came to him in dreams, and with distinctions between things long held the same and with the resemblance of things long held different. Multitudes came from other lands to see him and to ask his counsel, but there were guards set at the frontiers, who compelled all that came to wear the feathers of the grey hawk in their hair. While they listened to him his words seemed to make all darkness light and filled their hearts like music; but, alas, when they returned to their own lands his words seemed far off, and what they could remember too strange and subtle to help them to live out their hasty days. A number indeed did live differently afterwards, but their new life was less excellent than the old: some among them had long served a good cause, but when they heard him praise it and their labour,[37] they returned to their own lands to find what they had loved less lovable and their arm lighter in the battle, for he had taught them how little a hair divides the false and true; others, again, who had served no cause, but wrought in peace the welfare of their own households, when he had expounded the meaning of their purpose, found their bones softer and their will less ready for toil, for he had shown them greater purposes; and numbers of the young, when they had heard him upon all these things, remembered certain words that became like a fire in their hearts, and made all kindly joys and traffic between man and man as nothing, and went different ways, but all into vague regret.

When any asked him concerning the common things of life; disputes about the mear of a territory, or about the straying of cattle, or about the penalty of blood; he would turn to those nearest him for advice; but this was held to be from courtesy, for none knew that these matters were hidden from him by thoughts and dreams that filled his mind like the marching and counter-marching of armies. Far less could any know that his heart wandered lost amid throngs of overcoming thoughts and dreams, shuddering at its own consuming solitude.[38]

Among those who came to look at him and to listen to him was the daughter of a little king who lived a great way off; and when he saw her he loved, for she was beautiful, with a strange and pale beauty unlike the women of his land; but Dana, the great mother, had decreed her a heart that was but as the heart of others, and when she considered the mystery of the hawk feathers she was troubled with a great horror. He called her to him when the assembly was over and told her of her beauty, and praised her simply and frankly as though she were a fable of the bards; and he asked her humbly to give him her love, for he was only subtle in his dreams. Overwhelmed with his greatness, she half consented, and yet half refused, for she longed to marry some warrior who could carry her over a mountain in his arms. Day by day the king gave her gifts; cups with ears of gold and findrinny wrought by the craftsmen of distant lands; cloth from over sea, which, though woven with curious figures, seemed to her less beautiful than the bright cloth of her own country; and still she was ever between a smile and a frown; between yielding and withholding. He laid down his wisdom at her feet, and told how the heroes when they die return to the world and begin[39] their labour anew; how the kind and mirthful Men of Dea drove out the huge and gloomy and misshapen People from Under the Sea; and a multitude of things that even the Sidhe have forgotten, either because they happened so long ago or because they have not time to think of them; and still she half refused, and still he hoped, because he could not believe that a beauty so much like wisdom could hide a common heart.

There was a tall young man in the dun who had yellow hair, and was skilled in wrestling and in the training of horses; and one day when the king walked in the orchard, which was between the foss and the forest, he heard his voice among the salley bushes which hid the waters of the foss. ‘My blossom,’ it said, ‘I hate them for making you weave these dingy feathers into your beautiful hair, and all that the bird of prey upon the throne may sleep easy o’ nights’; and then the low, musical voice he loved answered: ‘My hair is not beautiful like yours; and now that I have plucked the feathers out of your hair I will put my hands through it, thus, and thus, and thus; for it casts no shadow of terror and darkness upon my heart.’ Then the king remembered many things that he had forgotten without[40] understanding them, doubtful words of his poets and his men of law, doubts that he had reasoned away, his own continual solitude; and he called to the lovers in a trembling voice. They came from among the salley bushes and threw themselves at his feet and prayed for pardon, and he stooped down and plucked the feathers out of the hair of the woman and then turned away towards the dun without a word. He strode into the hall of assembly, and having gathered his poets and his men of law about him, stood upon the daïs and spoke in a loud, clear voice: ‘Men of law, why did you make me sin against the laws of Eri? Men of verse, why did you make me sin against the secrecy of wisdom, for law was made by man for the welfare of man, but wisdom the gods have made, and no man shall live by its light, for it and the hail and the rain and the thunder follow a way that is deadly to mortal things? Men of law and men of verse, live according to your kind, and call Eocha of the Hasty Mind to reign over you, for I set out to find my kindred.’ He then came down among them, and drew out of the hair of first one and then another the feathers of the grey hawk, and, having scattered them over the rushes upon the floor, passed out, and none dared to follow[41] him, for his eyes gleamed like the eyes of the birds of prey; and no man saw him again or heard his voice. Some believed that he found his eternal abode among the demons, and some that he dwelt henceforth with the dark and dreadful goddesses, who sit all night about the pools in the forest watching the constellations rising and setting in those desolate mirrors.

A very old man, whose face was almost as fleshless as the foot of a bird, sat meditating upon the rocky shore of the flat and hazel-covered isle which fills the widest part of the Lough Gill. A russet-faced boy of seventeen years sat by his side, watching the swallows dipping for flies in the still water. The old man was dressed in threadbare blue velvet, and the boy wore a frieze coat and a blue cap, and had about his neck a rosary of blue beads. Behind the two, and half hidden by trees, was a little monastery. It had been burned down a long while before by sacrilegious men of the Queen’s party, but had been roofed anew with rushes by the boy, that the old man might find shelter in his last days. He had not set his spade, however, into the garden about it, and the lilies and the roses of the monks had spread out until their confused luxuriancy met and mingled with the narrowing circle of the fern.[43] Beyond the lilies and the roses the ferns were so deep that a child walking among them would be hidden from sight, even though he stood upon his toes; and beyond the fern rose many hazels and small oak trees.

‘Master,’ said the boy, ‘this long fasting, and the labour of beckoning after nightfall with your rod of quicken wood to the beings who dwell in the waters and among the hazels and oak-trees, is too much for your strength. Rest from all this labour for a little, for your hand seemed more heavy upon my shoulder and your feet less steady under you to-day than I have known them. Men say that you are older than the eagles, and yet you will not seek the rest that belongs to age.’ He spoke in an eager, impulsive way, as though his heart were in the words and thoughts of the moment; and the old man answered slowly and deliberately, as though his heart were in distant days and distant deeds.

‘I will tell you why I have not been able to rest,’ he said. ‘It is right that you should know, for you have served me faithfully these five years and more, and even with affection, taking away thereby a little of the doom of loneliness which always falls upon the wise. Now, too, that the end of my labour and the[44] triumph of my hopes is at hand, it is the more needful for you to have this knowledge.’

‘Master, do not think that I would question you. It is for me to keep the fire alight, and the thatch close against the rain, and strong, lest the wind blow it among the trees; and it is for me to take the heavy books from the shelves, and to lift from its corner the great painted roll with the names of the Sidhe, and to possess the while an incurious and reverent heart, for right well I know that God has made out of His abundance a separate wisdom for everything which lives, and to do these things is my wisdom.’

‘You are afraid,’ said the old man, and his eyes shone with a momentary anger.

‘Sometimes at night,’ said the boy, ‘when you are reading, with the rod of quicken wood in your hand, I look out of the door and see, now a great grey man driving swine among the hazels, and now many little people in red caps who come out of the lake driving little white cows before them. I do not fear these little people so much as the grey man; for, when they come near the house, they milk the cows, and they drink the frothing milk, and begin to dance; and I know there is good in the heart that loves dancing; but I fear them for all that.[45] And I fear the tall white-armed ladies who come out of the air, and move slowly hither and thither, crowning themselves with the roses or with the lilies, and shaking about their living hair, which moves, for so I have heard them tell each other, with the motion of their thoughts, now spreading out and now gathering close to their heads. They have mild, beautiful faces, but, Aengus, son of Forbis, I fear all these beings, I fear the people of the Sidhe, and I fear the art which draws them about us.’

‘Why,’ said the old man, ‘do you fear the ancient gods who made the spears of your father’s fathers to be stout in battle, and the little people who came at night from the depth of the lakes and sang among the crickets upon their hearths? And in our evil day they still watch over the loveliness of the earth. But I must tell you why I have fasted and laboured when others would sink into the sleep of age, for without your help once more I shall have fasted and laboured to no good end. When you have done for me this last thing, you may go and build your cottage and till your fields, and take some girl to wife, and forget the ancient gods. I have saved all the gold and silver pieces that were given to me by earls and knights and squires for keeping them from the[46] evil eye and from the love-weaving enchantments of witches, and by earls’ and knights’ and squires’ ladies for keeping the people of the Sidhe from making the udders of their cattle fall dry, and taking the butter from their churns. I have saved it all for the day when my work should be at an end, and now that the end is at hand you shall not lack for gold and silver pieces enough to make strong the roof-tree of your cottage and to keep cellar and larder full. I have sought through all my life to find the secret of life. I was not happy in my youth, for I knew that it would pass; and I was not happy in my manhood, for I knew that age was coming; and so I gave myself, in youth and manhood and age, to the search for the Great Secret. I longed for a life whose abundance would fill centuries, I scorned the life of fourscore winters. I would be—nay, I will be!—like the Ancient Gods of the land. I read in my youth, in a Hebrew manuscript I found in a Spanish monastery, that there is a moment after the Sun has entered the Ram and before he has passed the Lion, which trembles with the Song of the Immortal Powers, and that whosoever finds this moment and listens to the Song shall become like the Immortal Powers themselves; I came back to[47] Ireland and asked the fairy men, and the cow-doctors, if they knew when this moment was; but though all had heard of it, there was none could find the moment upon the hour-glass. So I gave myself to magic, and spent my life in fasting and in labour that I might bring the Gods and the Fairies to my side; and now at last one of the Fairies has told me that the moment is at hand. One, who wore a red cap and whose lips were white with the froth of the new milk, whispered it into my ear. To-morrow, a little before the close of the first hour after dawn, I shall find the moment, and then I will go away to a southern land and build myself a palace of white marble amid orange trees, and gather the brave and the beautiful about me, and enter into the eternal kingdom of my youth. But, that I may hear the whole Song, I was told by the little fellow with the froth of the new milk on his lips, that you must bring great masses of green boughs and pile them about the door and the window of my room; and you must put fresh green rushes upon the floor, and cover the table and the rushes with the roses and the lilies of the monks. You must do this to-night, and in the morning at the end of the first hour after dawn, you must come and find me.’[48]

‘Will you be quite young then?’ said the boy.

‘I will be as young then as you are, but now I am still old and tired, and you must help me to my chair and to my books.’

When the boy had left Aengus son of Forbis in his room, and had lighted the lamp which, by some contrivance of the wizard’s, gave forth a sweet odour as of strange flowers, he went into the wood and began cutting green boughs from the hazels, and great bundles of rushes from the western border of the isle, where the small rocks gave place to gently sloping sand and clay. It was nightfall before he had cut enough for his purpose, and well-nigh midnight before he had carried the last bundle to its place, and gone back for the roses and the lilies. It was one of those warm, beautiful nights when everything seems carved of precious stones. Sleuth Wood away to the south looked as though cut out of green beryl, and the waters that mirrored them shone like pale opal. The roses he was gathering were like glowing rubies, and the lilies had the dull lustre of pearl. Everything had taken upon itself the look of something imperishable, except a glow-worm, whose faint flame burnt on steadily among the shadows, moving slowly[49] hither and thither, the only thing that seemed alive, the only thing that seemed perishable as mortal hope. The boy gathered a great armful of roses and lilies, and thrusting the glow-worm among their pearl and ruby, carried them into the room, where the old man sat in a half-slumber. He laid armful after armful upon the floor and above the table, and then, gently closing the door, threw himself upon his bed of rushes, to dream of a peaceful manhood with his chosen wife at his side, and the laughter of children in his ears. At dawn he rose, and went down to the edge of the lake, taking the hour-glass with him. He put some bread and a flask of wine in the boat, that his master might not lack food at the outset of his journey, and then sat down to wait until the hour from dawn had gone by. Gradually the birds began to sing, and when the last grains of sand were falling, everything suddenly seemed to overflow with their music. It was the most beautiful and living moment of the year; one could listen to the spring’s heart beating in it. He got up and went to find his master. The green boughs filled the door, and he had to make a way through them. When he entered the room the sunlight was falling in flickering circles on floor and walls and table,[50] and everything was full of soft green shadows. But the old man sat clasping a mass of roses and lilies in his arms, and with his head sunk upon his breast. On the table, at his left hand, was a leathern wallet full of gold and silver pieces, as for a journey, and at his right hand was a long staff. The boy touched him and he did not move. He lifted the hands but they were quite cold, and they fell heavily.

‘It were better for him,’ said the lad, ‘to have told his beads and said his prayers like another, and not to have spent his days in seeking amongst the Immortal Powers what he could have found in his own deeds and days had he willed. Ah, yes, it were better to have said his prayers and kissed his beads!’ He looked at the threadbare blue velvet, and he saw it was covered with the pollen of the flowers, and while he was looking at it a thrush, who had alighted among the boughs that were piled against the window, began to sing.

One summer night, when there was peace, a score of Puritan troopers under the pious Sir Frederick Hamilton, broke through the door of the Abbey of the White Friars which stood over the Gara Lough at Sligo. As the door fell with a crash they saw a little knot of friars gathered about the altar, their white habits glimmering in the steady light of the holy candles. All the monks were kneeling except the abbot, who stood upon the altar steps with a great brazen crucifix in his hand. ‘Shoot them!’ cried Sir Frederick Hamilton, but none stirred, for all were new converts, and feared the crucifix and the holy candles. The white lights from the altar threw the shadows of the troopers up on to roof and wall. As the troopers moved about, the shadows began a fantastic dance among the corbels and the memorial tablets. For a little while all was silent, and then five troopers who were the[52] body-guard of Sir Frederick Hamilton lifted their muskets, and shot down five of the friars. The noise and the smoke drove away the mystery of the pale altar lights, and the other troopers took courage and began to strike. In a moment the friars lay about the altar steps, their white habits stained with blood. ‘Set fire to the house!’ cried Sir Frederick Hamilton, and at his word one went out, and came in again carrying a heap of dry straw, and piled it against the western wall, and, having done this, fell back, for the fear of the crucifix and of the holy candles was still in his heart. Seeing this, the five troopers who were Sir Frederick Hamilton’s body-guard darted forward, and taking each a holy candle set the straw in a blaze. The red tongues of fire rushed up and flickered from corbel to corbel and from tablet to tablet, and crept along the floor, setting in a blaze the seats and benches. The dance of the shadows passed away, and the dance of the fires began. The troopers fell back towards the door in the southern wall, and watched those yellow dancers springing hither and thither.

For a time the altar stood safe and apart in the midst of its white light; the eyes of the troopers turned upon it. The abbot whom[53] they had thought dead had risen to his feet and now stood before it with the crucifix lifted in both hands high above his head. Suddenly he cried with a loud voice, ‘Woe unto all who smite those who dwell within the Light of the Lord, for they shall wander among the ungovernable shadows, and follow the ungovernable fires!’ And having so cried he fell on his face dead, and the brazen crucifix rolled down the steps of the altar. The smoke had now grown very thick, so that it drove the troopers out into the open air. Before them were burning houses. Behind them shone the painted windows of the Abbey filled with saints and martyrs, awakened, as from a sacred trance, into an angry and animated life. The eyes of the troopers were dazzled, and for a while could see nothing but the flaming faces of saints and martyrs. Presently, however, they saw a man covered with dust who came running towards them. ‘Two messengers,’ he cried, ‘have been sent by the defeated Irish to raise against you the whole country about Manor Hamilton, and if you do not stop them you will be overpowered in the woods before you reach home again! They ride north-east between Ben Bulben and Cashel-na-Gael.’

Sir Frederick Hamilton called to him the[54] five troopers who had first fired upon the monks and said, ‘Mount quickly, and ride through the woods towards the mountain, and get before these men, and kill them.’

In a moment the troopers were gone, and before many moments they had splashed across the river at what is now called Buckley’s Ford, and plunged into the woods. They followed a beaten track that wound along the northern bank of the river. The boughs of the birch and quicken trees mingled above, and hid the cloudy moonlight, leaving the pathway in almost complete darkness. They rode at a rapid trot, now chatting together, now watching some stray weasel or rabbit scuttling away in the darkness. Gradually, as the gloom and silence of the woods oppressed them, they drew closer together, and began to talk rapidly; they were old comrades and knew each other’s lives. One was married, and told how glad his wife would be to see him return safe from this harebrained expedition against the White Friars, and to hear how fortune had made amends for rashness. The oldest of the five, whose wife was dead, spoke of a flagon of wine which awaited him upon an upper shelf; while a third, who was the youngest, had a sweetheart watching for his return, and he rode a little way before[55] the others, not talking at all. Suddenly the young man stopped, and they saw that his horse was trembling. ‘I saw something,’ he said, ‘and yet I do not know but it may have been one of the shadows. It looked like a great worm with a silver crown upon his head.’ One of the five put his hand up to his forehead as if about to cross himself, but remembering that he had changed his religion he put it down, and said: ‘I am certain it was but a shadow, for there are a great many about us, and of very strange kinds.’ Then they rode on in silence. It had been raining in the earlier part of the day, and the drops fell from the branches, wetting their hair and their shoulders. In a little they began to talk again. They had been in many battles against many a rebel together, and now told each other over again the story of their wounds, and so awakened in their hearts the strongest of all fellowships, the fellowship of the sword, and half forgot the terrible solitude of the woods.

Suddenly the first two horses neighed, and then stood still, and would go no further. Before them was a glint of water, and they knew by the rushing sound that it was a river. They dismounted, and after much tugging and coaxing brought the horses to the river-side.[56] In the midst of the water stood a tall old woman with grey hair flowing over a grey dress. She stood up to her knees in the water, and stooped from time to time as though washing. Presently they could see that she was washing something that half floated. The moon cast a flickering light upon it, and they saw that it was the dead body of a man, and, while they were looking at it, an eddy of the river turned the face towards them, and each of the five troopers recognized at the same moment his own face. While they stood dumb and motionless with horror, the woman began to speak, saying slowly and loudly: ‘Did you see my son? He has a crown of silver on his head, and there are rubies in the crown.’ Then the oldest of the troopers, he who had been most often wounded, drew his sword and cried: ‘I have fought for the truth of my God, and need not fear the shadows of Satan,’ and with that rushed into the water. In a moment he returned. The woman had vanished, and though he had thrust his sword into air and water he had found nothing.

The five troopers remounted, and set their horses at the ford, but all to no purpose. They tried again and again, and went plunging hither and thither, the horses foaming and[57] rearing. ‘Let us,’ said the old trooper, ‘ride back a little into the wood, and strike the river higher up.’ They rode in under the boughs, the ground-ivy crackling under the hoofs, and the branches striking against their steel caps. After about twenty minutes’ riding they came out again upon the river, and after another ten minutes found a place where it was possible to cross without sinking below the stirrups. The wood upon the other side was very thin, and broke the moonlight into long streams. The wind had arisen, and had begun to drive the clouds rapidly across the face of the moon, so that thin streams of light seemed to be dancing a grotesque dance among the scattered bushes and small fir-trees. The tops of the trees began also to moan, and the sound of it was like the voice of the dead in the wind; and the troopers remembered the belief that tells how the dead in purgatory are spitted upon the points of the trees and upon the points of the rocks. They turned a little to the south, in the hope that they might strike the beaten path again, but they could find no trace of it.

Meanwhile, the moaning grew louder and louder, and the dance of the white moon-fires more and more rapid. Gradually they began[58] to be aware of a sound of distant music. It was the sound of a bagpipe, and they rode towards it with great joy. It came from the bottom of a deep, cup-like hollow. In the midst of the hollow was an old man with a red cap and withered face. He sat beside a fire of sticks, and had a burning torch thrust into the earth at his feet, and played an old bagpipe furiously. His red hair dripped over his face like the iron rust upon a rock. ‘Did you see my wife?’ he cried, looking up a moment; ‘she was washing! she was washing!’ ‘I am afraid of him,’ said the young trooper, ‘I fear he is one of the Sidhe.’ ‘No,’ said the old trooper, ‘he is a man, for I can see the sun-freckles upon his face. We will compel him to be our guide’; and at that he drew his sword, and the others did the same. They stood in a ring round the piper, and pointed their swords at him, and the old trooper then told him that they must kill two rebels, who had taken the road between Ben Bulben and the great mountain spur that is called Cashel-na-Gael, and that he must get up before one of them and be their guide, for they had lost their way. The piper turned, and pointed to a neighbouring tree, and they saw an old white horse ready bitted, bridled, and saddled. He[59] slung the pipe across his back, and, taking the torch in his hand, got upon the horse, and started off before them, as hard as he could go.

The wood grew thinner and thinner, and the ground began to slope up toward the mountain. The moon had already set, and the little white flames of the stars had come out everywhere. The ground sloped more and more until at last they rode far above the woods upon the wide top of the mountain. The woods lay spread out mile after mile below, and away to the south shot up the red glare of the burning town. But before and above them were the little white flames. The guide drew rein suddenly, and pointing upwards with the hand that did not hold the torch, shrieked out, ‘Look; look at the holy candles!’ and then plunged forward at a gallop, waving the torch hither and thither. ‘Do you hear the hoofs of the messengers?’ cried the guide. ‘Quick, quick! or they will be gone out of your hands!’ and he laughed as with delight of the chase. The troopers thought they could hear far off, and as if below them, rattle of hoofs; but now the ground began to slope more and more, and the speed grew more headlong moment by moment. They tried to pull up, but in vain, for the horses seemed to[60] have gone mad. The guide had thrown the reins on to the neck of the old white horse, and was waving his arms and singing a wild Gaelic song. Suddenly they saw the thin gleam of a river, at an immense distance below, and knew that they were upon the brink of the abyss that is now called Lug-na-Gael, or in English the Stranger’s Leap. The six horses sprang forward, and five screams went up into the air, a moment later five men and horses fell with a dull crash upon the green slopes at the foot of the rocks.

At the place, close to the Dead Man’s Point, at the Rosses, where the disused pilot-house looks out to sea through two round windows like eyes, a mud cottage stood in the last century. It also was a watchhouse, for a certain old Michael Bruen, who had been a smuggler in his day, and was still the father and grandfather of smugglers, lived there, and when, after nightfall, a tall schooner crept over the bay from Roughley, it was his business to hang a horn lanthorn in the southern window, that the news might travel to Dorren’s Island, and from thence, by another horn lanthorn, to the village of the Rosses. But for this glimmering of messages, he had little communion with mankind, for he was very old, and had no thought for anything but for the making of his soul, at the foot of the Spanish crucifix of carved oak that hung by his chimney, or bent double over the rosary of stone beads brought[62] to him in a cargo of silks and laces out of France. One night he had watched hour after hour, because a gentle and favourable wind was blowing, and La Mère de Miséricorde was much overdue; and he was about to lie down upon his heap of straw, seeing that the dawn was whitening the east, and that the schooner would not dare to round Roughley and come to an anchor after daybreak; when he saw a long line of herons flying slowly from Dorren’s Island and towards the pools which lie, half choked with reeds, behind what is called the Second Rosses. He had never before seen herons flying over the sea, for they are shore-keeping birds, and partly because this had startled him out of his drowsiness, and more because the long delay of the schooner kept his cupboard empty, he took down his rusty shot-gun, of which the barrel was tied on with a piece of string, and followed them towards the pools.

When he came close enough to hear the sighing of the rushes in the outermost pool, the morning was grey over the world, so that the tall rushes, the still waters, the vague clouds, the thin mist lying among the sand-heaps, seemed carved out of an enormous pearl. In a little he came upon the herons, of whom[63] there were a great number, standing with lifted legs in the shallow water; and crouching down behind a bank of rushes, looked to the priming of his gun, and bent for a moment over his rosary to murmur: ‘Patron Patrick, let me shoot a heron; made into a pie it will support me for nearly four days, for I no longer eat as in my youth. If you keep me from missing I will say a rosary to you every night until the pie is eaten.’ Then he lay down, and, resting his gun upon a large stone, turned towards a heron which stood upon a bank of smooth grass over a little stream that flowed into the pool; for he feared to take the rheumatism by wading, as he would have to do if he shot one of those which stood in the water. But when he looked along the barrel the heron was gone, and, to his wonder and terror, a man of infinitely great age and infirmity stood in its place. He lowered the gun, and the heron stood there with bent head and motionless feathers, as though it had slept from the beginning of the world. He raised the gun, and no sooner did he look along the iron than that enemy of all enchantment brought the old man again before him, only to vanish when he lowered the gun for the second time. He laid the gun down, and crossed himself three times, and said a[64] Paternoster and an Ave Maria, and muttered half aloud: ‘Some enemy of God and of my patron is standing upon the smooth place and fishing in the blessed water,’ and then aimed very carefully and slowly. He fired, and when the smoke had gone saw an old man, huddled upon the grass and a long line of herons flying with clamour towards the sea. He went round a bend of the pool, and coming to the little stream looked down on a figure wrapped in faded clothes of black and green of an ancient pattern and spotted with blood. He shook his head at the sight of so great a wickedness. Suddenly the clothes moved and an arm was stretched upwards towards the rosary which hung about his neck, and long wasted fingers almost touched the cross. He started back, crying: ‘Wizard, I will let no wicked thing touch my blessed beads’; and the sense of a great danger just escaped made him tremble.

‘If you listen to me,’ replied a voice so faint that it was like a sigh, ‘you will know that I am not a wizard, and you will let me kiss the cross before I die.’

‘I will listen to you,’ he answered, ‘but I will not let you touch my blessed beads,’ and sitting on the grass a little way from the dying man, he reloaded his gun and laid it across his knees and composed himself to listen.[65]

‘I know not how many generations ago we, who are now herons, were the men of learning of the King Leaghaire; we neither hunted, nor went to battle, nor listened to the Druids preaching, and even love, if it came to us at all, was but a passing fire. The Druids and the poets told us, many and many a time, of a new Druid Patrick; and most among them were fierce against him, while a few thought his doctrine merely the doctrine of the gods set out in new symbols, and were for giving him welcome; but we yawned in the midst of their tale. At last they came crying that he was coming to the king’s house, and fell to their dispute, but we would listen to neither party, for we were busy with a dispute about the merits of the Great and of the Little Metre; nor were we disturbed when they passed our door with sticks of enchantment under their arms, travelling towards the forest to contend against his coming, nor when they returned after nightfall with torn robes and despairing cries; for the click of our knives writing our thoughts in Ogham filled us with peace and our dispute filled us with joy; nor even when in the morning crowds passed us to hear the strange Druid preaching the commandments of his god. The crowds passed, and one, who had laid down his knife to yawn and stretch himself, heard a voice speaking far off,[66] and knew that the Druid Patrick was preaching within the king’s house; but our hearts were deaf, and we carved and disputed and read, and laughed a thin laughter together. In a little we heard many feet coming towards the house, and presently two tall figures stood in the door, the one in white, the other in a crimson robe; like a great lily and a heavy poppy; and we knew the Druid Patrick and our King Leaghaire. We laid down the slender knives and bowed before the king, but when the black and green robes had ceased to rustle, it was not the loud rough voice of King Leaghaire that spoke to us, but a strange voice in which there was a rapture as of one speaking from behind a battlement of Druid flame: “I preached the commandments of the Maker of the world,” it said; “within the king’s house and from the centre of the earth to the windows of Heaven there was a great silence, so that the eagle floated with unmoving wings in the white air, and the fish with unmoving fins in the dim water, while the linnets and the wrens and the sparrows stilled their ever-trembling tongues in the heavy boughs, and the clouds were like white marble, and the rivers became their motionless mirrors, and the shrimps in the far-off sea-pools were still, enduring eternity in patience, although it was hard.” And as he[67] named these things, it was like a king numbering his people. “But your slender knives went click, click! upon the oaken staves, and, all else being silent, the sound shook the angels with anger. O, little roots, nipped by the winter, who do not awake although the summer pass above you with innumerable feet. O, men who have no part in love, who have no part in song, who have no part in wisdom, but dwell with the shadows of memory where the feet of angels cannot touch you as they pass over your heads, where the hair of demons cannot sweep about you as they pass under your feet, I lay upon you a curse, and change you to an example for ever and ever; you shall become grey herons and stand pondering in grey pools and flit over the world in that hour when it is most full of sighs, having forgotten the flame of the stars and not yet found the flame of the sun; and you shall preach to the other herons until they also are like you, and are an example for ever and ever; and your deaths shall come to you by chance and unforeseen, that no fire of certainty may visit your hearts.”’

The voice of the old man of learning became still, but the voteen bent over his gun with his eyes upon the ground, trying in vain to understand something of this tale; and he had so[68] bent, it may be for a long time, had not a tug at his rosary made him start out of his dream. The old man of learning had crawled along the grass, and was now trying to draw the cross down low enough for his lips to reach it.

‘You must not touch my blessed beads,’ cried the voteen, and struck the long withered fingers with the barrel of his gun. He need not have trembled, for the old man fell back upon the grass with a sigh and was still. He bent down and began to consider the black and green clothes, for his fear had begun to pass away when he came to understand that he had something the man of learning wanted and pleaded for, and now that the blessed beads were safe, his fear had nearly all gone; and surely, he thought, if that big cloak, and that little tight-fitting cloak under it, were warm and without holes, Saint Patrick would take the enchantment out of them and leave them fit for human use. But the black and green clothes fell away wherever his fingers touched them, and while this was a new wonder, a slight wind blew over the pool and crumbled the old man of learning and all his ancient gear into a little heap of dust, and then made the little heap less and less until there was nothing but the smooth green grass.

The little wicker houses at Tullagh, where the Brothers were accustomed to pray, or bend over many handicrafts, when twilight had driven them from the fields, were empty, for the hardness of the winter had brought the brotherhood together in the little wooden house under the shadow of the wooden chapel; and Abbot Malathgeneus, Brother Dove, Brother Bald Fox, Brother Peter, Brother Patrick, Brother Bittern, Brother Fair-brows, and many too young to have won names in the great battle, sat about the fire with ruddy faces, one mending lines to lay in the river for eels, one fashioning a snare for birds, one mending the broken handle of a spade, one writing in a large book, and one shaping a jewelled box to hold the book; and among the rushes at their feet lay the scholars, who would one day be Brothers, and whose school-house it was, and for the succour of whose tender years the great fire was supposed[70] to leap and flicker. One of these, a child of eight or nine years, called Olioll, lay upon his back looking up through the hole in the roof, through which the smoke went, and watching the stars appearing and disappearing in the smoke with mild eyes, like the eyes of a beast of the field. He turned presently to the Brother who wrote in the big book, and whose duty was to teach the children, and said, ‘Brother Dove, to what are the stars fastened?’ The Brother, rejoicing to see so much curiosity in the stupidest of his scholars, laid down the pen and said, ‘There are nine crystalline spheres, and on the first the Moon is fastened, on the second the planet Mercury, on the third the planet Venus, on the fourth the Sun, on the fifth the planet Mars, on the sixth the planet Jupiter, on the seventh the planet Saturn; these are the wandering stars; and on the eighth are fastened the fixed stars; but the ninth sphere is a sphere of the substance on which the breath of God moved in the beginning.’

‘What is beyond that?’ said the child.

‘There is nothing beyond that; there is God.’

And then the child’s eyes strayed to the jewelled box, where one great ruby was gleaming in the light of the fire, and he said, ‘Why[71] has Brother Peter put a great ruby on the side of the box?’

‘The ruby is a symbol of the love of God.’

‘Why is the ruby a symbol of the love of God?’

‘Because it is red, like fire, and fire burns up everything, and where there is nothing, there is God.’

The child sank into silence, but presently sat up and said, ‘There is somebody outside.’

‘No,’ replied the Brother. ‘It is only the wolves; I have heard them moving about in the snow for some time. They are growing very wild, now that the winter drives them from the mountains. They broke into a fold last night and carried off many sheep, and if we are not careful they will devour everything.’

‘No, it is the footstep of a man, for it is heavy; but I can hear the footsteps of the wolves also.’

He had no sooner done speaking than somebody rapped three times, but with no great loudness.

‘I will go and open, for he must be very cold.’

‘Do not open, for it may be a man-wolf, and he may devour us all.’

But the boy had already drawn back the heavy wooden bolt, and all the faces, most of[72] them a little pale, turned towards the slowly-opening door.

‘He has beads and a cross, he cannot be a man-wolf,’ said the child, as a man with the snow heavy on his long, ragged beard, and on the matted hair, that fell over his shoulders and nearly to his waist, and dropping from the tattered cloak that but half-covered his withered brown body, came in and looked from face to face with mild, ecstatic eyes. Standing some way from the fire, and with eyes that had rested at last upon the Abbot Malathgeneus, he cried out, ‘O blessed abbot, let me come to the fire and warm myself and dry the snow from my beard and my hair and my cloak; that I may not die of the cold of the mountains and anger the Lord with a wilful martyrdom.’

‘Come to the fire,’ said the abbot, ‘and warm yourself, and eat the food the boy Olioll will bring you. It is sad indeed that any for whom Christ has died should be as poor as you.’

The man sat over the fire, and Olioll took away his now dripping cloak and laid meat and bread and wine before him; but he would eat only of the bread, and he put away the wine, asking for water. When his beard and hair had begun to dry a little and his limbs had ceased to shiver with the cold, he spoke again.[73]

‘O blessed abbot, have pity on the poor, have pity on a beggar who has trodden the bare world this many a year, and give me some labour to do, the hardest there is, for I am the poorest of God’s poor.’