| Vol. II.—No. 103. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. | |

| Tuesday, October 18, 1881. | Copyright, 1881, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

During the war of 1812-14, between Great Britain and the United States, the weak Spanish Governor of Florida—for Florida was then Spanish territory—permitted the British to make Pensacola their base of operations against us. This was a gross outrage, as we were at peace with Spain at the time, and General Jackson, acting on his own responsibility, invaded Florida in retaliation.

Among the British at that time was an eccentric Irish officer, Colonel Edward Nichols, who enlisted and tried to make soldiers of a large number of the Seminole Indians. In 1815, after the war was over, Colonel Nichols again visited the Seminoles, who were disposed to be hostile[Pg 802] to the United States, as Colonel Nichols himself was, and made an astonishing treaty with them, in which an alliance, offensive and defensive, between Great Britain and the Seminoles was agreed upon. We had made peace with Great Britain a few months before, and yet this astonishing Irish Colonel signed a treaty binding Great Britain to fight us whenever the Seminoles in the Spanish territory of Florida should see fit to make a war! If this extraordinary performance had been all, it would not have mattered so much, because the British government refused to ratify the treaty; but it was not all. Colonel Nichols, as if determined to give us as much trouble as he could, built a strong fortress on the Appalachicola River, and gave it to his friends the Seminoles, naming it "The British Post on the Appalachicola," where the British had not the least right to have any post whatever. Situated on a high bluff, with flanks securely guarded by the river on one side and a swamp on the other, this fort, properly defended, was capable of resisting the assaults of almost any force that could approach it; and Colonel Nichols was determined that it should be properly defended, and should be a constant menace and source of danger to the United States. He armed it with one 32-pounder cannon, three 24-pounders, and eight other guns. In the matter of small-arms he was even more liberal. He supplied the fort with 2500 muskets, 500 carbines, 400 pistols, and 500 swords. In the magazines he stored 300 quarter casks of rifle powder, and 763 barrels of ordinary gunpowder.

When Colonel Nichols went away, his Seminoles soon wandered off, leaving the fort without a garrison. This gave an opportunity to a negro bandit and desperado named Garçon to seize the place, which he did, gathering about him a large band of runaway negroes, Choctaw Indians, and other lawless persons, whom he organized into a strong company of robbers. Garçon made the fort his stronghold, and began to plunder the country round about as thoroughly as any robber baron or Italian bandit ever did, sometimes venturing across the border into the United States.

All this was so annoying and so threatening to our frontier settlements in Georgia, that General Jackson demanded of the Spanish authorities that they should reduce the place, and they would have been glad enough to do so, probably, if it had been possible, because the banditti plundered Spanish as well as other settlements. But the Spanish Governor had no force at command, and could do nothing, and so the fort remained, a standing menace to the American borders.

Matters were in this position in the spring of 1816, when General Gaines was sent to fortify our frontier at the point where the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers unite to form the Appalachicola. In June of that year some stores for General Gaines's forces were sent by sea from New Orleans. The vessels carrying them were to go up the Appalachicola, and General Gaines was not sure that the little fleet would be permitted to pass the robbers' stronghold, which had come to be called the Negro Fort. Accordingly he sent Colonel Clinch with a small force down the river, to render any assistance that might be necessary. On the way Colonel Clinch was joined by a band of Seminoles, who wanted to recapture the fort on their own account, and the two bodies determined to act together.

Meantime the two schooners with supplies and the two gun-boats sent to guard them had arrived at the mouth of the river; and when the commandant tried to hold a conference with Garçon, the ship's boat, bearing a white flag, was fired upon.

Running short of water while lying off the river's mouth, the officers of the fleet sent out a boat to procure a supply. This boat was armed with a swivel and muskets, and was commanded by Midshipman Luffborough. The boat went into the mouth of the river, and seeing a negro on shore, Midshipman Luffborough landed to ask for fresh-water supplies. Garçon with some of his men lay in ambush at the spot, and while the officer talked with the negro the concealed men fired upon the boat, killing Luffborough and two of his men. One man got away by swimming, and was picked up by the fleet; two others were taken prisoners, and, as was afterward learned, Garçon coated them with tar and burned them to death.

It would not do to send more boats ashore, and so the little squadron lay together awaiting orders from Colonel Clinch. That officer, as he approached the fort, captured a negro, who wore a white man's scalp at his belt, and from him he learned of the massacre of Luffborough's party. There was no further occasion for doubt as to what was to be done. Colonel Clinch determined to reduce the fort at any cost, although the operation promised to be a very difficult one.

Placing his men in line of battle, he sent a courier to the fleet, ordering the gun-boats to come up and help in the attack. The Seminoles made many demonstrations against the works, and the negroes replied with their cannon. Garçon had raised his flags—a red one and a British Union-jack—and whenever he caught sight of the Indians or the Americans, he shelled them vigorously with his 32-pounder.

Three or four days were passed in this way, while the gun-boats were slowly making their way up the river. It was Colonel Clinch's purpose to have the gun-boats shell the fort, while he should storm it on the land side. The work promised to be bloody, and it was necessary to bring all the available force to bear at once. There were no siege-guns at hand, or anywhere within reach, and the only way to reduce the fort was for the small force of soldiers—numbering only one hundred and sixteen men—to rush upon it, receiving the fire of its heavy artillery, and climb over its parapets in the face of a murderous fire of small-arms. Garçon had with him three hundred and thirty-four men, so that besides having strong defensive works and an abundant supply of large cannon, his force outnumbered Colonel Clinch's nearly three to one. It is true that Colonel Clinch had the band of Seminoles with him, but they were entirely worthless for determined work of the kind that Colonel Clinch had to do. Even while lying in the woods at a distance, waiting for the gun-boats to come up, the Indians became utterly demoralized under the fire of Garçon's 32-pounder. There was nothing to be done, however, by way of improving the prospect, which was certainly hopeless enough. One hundred and sixteen white men had the Negro Fort to storm, notwithstanding its strength and the overwhelming force that defended it. But those one hundred and sixteen men were American soldiers, under command of a brave and resolute officer, who had made up his mind that the fort could be taken, and they were prepared to follow their leader up to the muzzle of the guns and over the ramparts, there to fight the question out in a hand-to-hand struggle with the desperadoes inside.

Finally the gun-boats arrived, and preparations were made for the attack. Sailing-Master Jairus Loomis, the commandant of the little fleet, cast his anchors under the guns of the Negro Fort at five o'clock in the morning on the 27th of July, 1816. The fort at once opened fire, and it seemed impossible for the little vessels to endure the storm of shot and shell that rained upon them from the ramparts above. They replied vigorously, however, but with no effect. Their guns were too small to make any impression upon the heavy earthen walls of the fortress.

Sailing-Master Loomis had roused his ship's cook early that morning, and had given him a strange breakfast to cook. He had ordered him to make all the fire he could in his galley, and to fill the fire with cannon-balls. Not long after the bombardment began, the cook reported that breakfast was ready; that is to say, that the cannon-balls[Pg 803] were red-hot. Loomis trained one of his guns with his own hands so that its shot should fall within the fort instead of burying itself in the ramparts, and this gun was at once loaded with a red-hot shot. The word was given, the match applied, and the glowing missile sped on its way. A few seconds later, the earth shook and quivered, a deafening roar stunned the sailors, and a vast cloud of smoke filled the air, shutting out the sun.

The hot shot had fallen into the great magazine, where there were hundreds of barrels of gunpowder, and the Negro Fort was no more. It had been literally blown to atoms in a second.

The slaughter was frightful. There were, as we know already, three hundred and thirty-four men in the fort, and two hundred and seventy of them were killed outright by the explosion. All the rest, except three men who miraculously escaped injury, were wounded, most of them so badly that they died soon afterward.

One of the three men who escaped unhurt was Garçon himself. Bad as this bandit chief was, Colonel Clinch would have spared his life, but it happened that he fell into the hands of the sailors from the gun-boat; and when they learned that Garçon had tarred and burned their comrades whom he had captured in the attack on Luffborough's boat, they turned him over to the infuriated Seminoles, who put him to death.

This is the history of a strange affair, which at one time promised to give the government of the United States no little trouble, even threatening to involve us in a war with Spain.

It was my fortune to spend the first twenty years of my life in a region where black bears were quite numerous. Our little community was often thrown into excitement by the discovery that Bruin had been engaged in some before-unheard-of mischief, and not infrequently were all the men and boys in the neighborhood mustered to surround a piece of woods, and capture a bear that was known to be there hidden away. Some of these occasions were full of excitement and danger, and maybe I shall some time tell about them; but just now I want to relate an experience with a bear that happened when I was about twelve years old.

It was a part of my business in summer-time to drive the cows to pasture every morning, and home every night. Like most boys, however, I loved play a little too well, and sometimes it would be very late before the cattle would be safely shut up for the night.

One day I had played about longer than usual after school, and when I reached home it was almost sunset. I persuaded a playmate of about my own age to accompany me, and started for the pasture. It was something more than half a mile away, and in getting to it, we followed down an old road which was now partially unused. But barefoot boys are nimble fellows, and before it was dark we were at the bars of the pasture. There stood the cows, as usual, waiting patiently for some one to come for them, and a little way out from them were the young cattle in a group. Down went the bars, and the cows started out, when all at once there was a great confusion among the young creatures. They ran in every direction, and appeared terribly frightened at something.

In a moment we saw what it was. A large black bear was coming across the pasture near them. I don't suppose he meant to trouble the cattle, but that was his nearest way to pass from the woods to a corn field which he had in view, and he happened to come along there just as we did.

It required no long council of war for us to decide to retreat as fast as possible, and taking to the road, we made the best time we could until we came to the top of a little hill. Here we mustered up courage to stop and look behind us. But there was the bear coming right up the road after us. We did not look back a second time, you may be sure, and in a very few moments we burst into my father's kitchen, and when we could get breath, exclaimed: "A b—a bear! A great big black bear chased us, and he's coming right up here!"

All that night we dreamed of bears. The cows did not come home, nor did the bear come after us, as we expected he would; but when father went down the next morning, he found the bear's tracks in the road, and following them up, he found where the old fellow had entered the corn field and taken his supper. Shortly afterward he was shot near the same place.

ersonal adornment was the earliest motive that led primitive man to cultivate other arts than those which were necessary to his existence. Just as soon as he had killed such wild animals as were dangerous, or were wanted for food, he probably set about carving some kind of design on his weapons. After a while, when he found more time, he went straight away to fashioning ornaments for his own person. If you should go to the Museum of Natural History in New York city, where the rude implements of men who lived many thousands of years ago are to be found, you will see many such early ornaments. Some of these ornaments are of the very roughest and coarsest kind, and would not be considered either pretty or becoming to-day. Early man took a small stone, and with infinite trouble bored a hole through it with a flint; then he strung it on a shred of sinew, and wore it around his neck. He was probably very selfish about this simple ornament, and it is quite likely that many years passed before he made any such beads for his wife, or allowed her to wear them.

Gradually, however, man's artistic tastes were awakened, and he first cut the sides of the soft stones, then polished them, though many thousands of years passed before he learned how to engrave on hard stones. Gem-engraving is so old, however, that it is difficult to give it a date. You will find very often in collections a hard stone, which has something engraved on it, belonging to a very ancient period; but the material was fashioned into some form or other by people who had lived many centuries before. Cameo-cutting came after gem-engraving, and those who are learned in such matters tell us that there were cameos made as early as 162 years before Christ.

Now what is a cameo? It may be a portrait, or a group of figures, or any design, cut on a hard material, where the work executed in relief, or the part which stands out, is of a different color from the ground. In order, then, to make a cameo you must have some hard substance composed of different layers. Such stones are called banded stones. There are many minerals, such as the onyx, the carnelian, or sard, where there are two layers of the same substance one on top of the other, but of different colors. The upper crust may be pure white or a pale fawn-color, and the lower layer red, or olive, or black. Then the contrast is very handsome. In order to get the materials[Pg 804] on which cameos were to be engraved, the Greeks and Romans travelled a great distance, even as far as India. It is believed that cameo-cutting was at its greatest state of perfection in the second century of the Christian era, when the Roman lapidaries, as workers in precious stones are called, carried on their work.

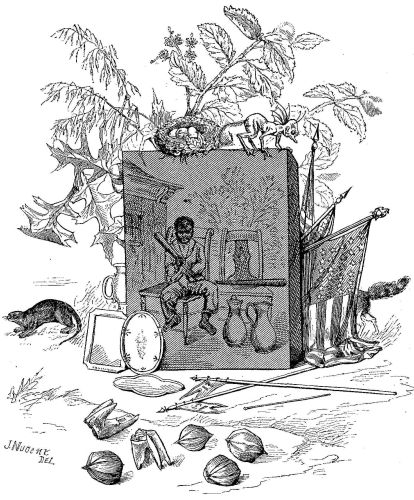

But a cameo need not be made of stone, for some of the finest that have come down to us were fashioned by the Romans by cutting layers of glass of different colors. It may seem strange to young readers to be told that although to-day we are very perfect in glass-making, there are a great many things the Romans could have taught us in this art. Now the reason why they were so skilled in glass manufacture was because they used glass as a substitute for porcelain, which was not then invented. The illustration which accompanies this article represents a very fine cameo designed by a very great English artist, whose name was John Flaxman. This cameo, which was cast, was made of white and blue porcelain, and was probably intended as a decoration for one of those beautiful urns which Wedgwood, the famous potter, manufactured in England almost a hundred years ago.

To-day a great many cameos are made, but not out of hard stones. The shell of the conch, found in Florida and the West Indies, is the material used. The white surface is cut into the figure and left. The under layer of the shell, or the ground, which is of a brownish hue when polished, gives that contrast which a cameo should have. We do not take as much trouble to make a cameo as did the ancients. They cut the stone with tiny drills, the points of which are believed to have been diamonds. The shell cameo being much softer, can be scraped or cut with small chisels. Of the old cameos there are two famous ones, one cut on an agate, the other on an onyx. Nothing in modern art is as fine, and for the one on the onyx, which is known as the Vienna gem, as much as 12,000 gold ducats was paid by the Emperor Rudolph in the sixteenth century. By the study of ancient cameos a great deal is learned, for they show us the actual pictures of the dress and costumes of people who lived more than 1800 years ago. But more than that: on some of these cameos we have the exact likenesses of great personages, who as Roman Emperors once ruled the world. In ancient times cameos were used, just as they are to-day, as ornaments, only the Greeks and Romans, men and women, wore them set in gold on their shoulders, as they held together the folds of their flowing draperies.

In the United States there are quite a number of cameo-makers, who cut good likenesses on shells; but the great art which existed in the time of Augustus has passed away.

AUTHOR OF "TOBY TYLER," ETC.

The work of preparing the dinner had occupied so much time that it was nearly the regular hour for supper before the last boy arose from the lowly table, and not one of them had any desire to fish or hunt. They sat around the fire, dodging the smoke as best they could, until the setting sun warned them that they must get their bedroom work done at once, or be obliged to do it in the dark.

This task was remarkably simple; it consisted in each boy finding his blanket, wrapping himself in it, and lying on the ground, all in a row, like herrings in a box.

Nor did they wait very long for slumber to visit their eyelids, for in ten minutes after they were ready it came to all, even to Tip, who had curled himself up snugly under Tim's arm.

Had any of the party been experienced in the sport of "camping out," they would have studied the signs in the sky for the purpose of learning what might have been expected of the weather; but as it was, they had all laid themselves down to sleep without a thought that the dark clouds which had begun to gather in the sky were evidences of a storm.

It was nearly midnight, and up to that time not one of them had awakened from the heavy sleep into which he had first fallen, when Tim became painfully aware that something was wrong. He had been dreaming that he was again on the Pride of the Wave, that Captain Pratt had thrown him overboard because he had been trying to steer, and just as he struck the water he awoke with a start.

The moment his eyes were open he understood the reason for his dream; he was lying in a large pool of water, and the blanket in which he had wrapped himself so comfortably was thoroughly saturated with it. At first he was at a loss to account for this sudden change of condition, and then the loud patter of rain on the canvas roof told the story plainly. A storm had come up, and the tent, being on the slope of a hill, was serving as a sort of reservoir for little streams of water that were rapidly increasing in size.

Tip, roused by his master's sudden movement, had started from his comfortable position, and walked directly into the water, very much to his discomfort and fear; howling loudly, he jumped among the sleepers with such force as at once to awaken and terrify them.

It required but a few words from Tim to make them understand all that had happened, for some of them were nearly as wet as he was, and all could hear the patter of the rain, which seemed to increase in violence each moment.

A lonesome prospect it was to think of remaining in[Pg 805] the tent the rest of the night, unable to sleep because of the water that poured in under the canvas, or trickled down through three or four small holes in the roof.

For several moments none of them knew what to do, but stood huddled together in sleepy surprise and sorrow, until Tim proposed that since he could hardly be more wet than he was, he should go out and dig a trench which would lead the water each side of the tent. But that plan was abandoned when it was discovered that a hatchet and a spoon were the only tools they had.

In order to get some idea of the condition of affairs, Tim lighted first one match and then another; but the light shed was so feeble that Captain Jimmy proposed building a small fire, which would both illuminate and heat the interior.

Tim acted upon this suggestion at once. With some newspapers and small bits of wood that were still dry he succeeded in kindling such a blaze as shed quite a light, but did not endanger the canvas. But he forgot all about the smoke, and this oversight he was reminded of very forcibly after a few moments.

Careful examination showed that the water only came in from the upper or higher side of the tent, but it was pouring in there in such quantities that before long the interior would be spread with a carpet of water.

"We've got to dig a ditch along this side, so's the water will run off," said Tim, after he had surveyed the uncomfortable-looking little brooks, and waited a moment in the hope that Bill or Captain Jimmy would suggest a better plan.

All saw the necessity of doing something at once, and the moment Tim gave them the idea, they went to work with knives, spoons, or any other implements they could find. It did not take much time, even with the poor tools they had, to dig a trench that would carry away any moderate amount of water, and after that was done, they gathered around the fire, for consultation.

But by that time they began to learn that smoke was even more uncomfortable to bear than water. For some time it had been rising to the top of the tent, escaping in small quantities through the flaps and holes; but only a portion of it had found vent, and the tent was so full that they were nearly suffocated.

They covered their eyes, and tried to "grin and bear it"; but such heroic effort could only be made for a short while, and they were obliged to run out into the pelting rain in order to get the pure air.

It was no fun to stand out-of-doors in a storm, and, acting on Captain Jimmy's suggestion, the party returned after a few moments to "kick the fire out."

But such a plan was of very little benefit, since the embers would smoke despite all they could do, and out they ran again, seeking such shelter as they could find under the trees, where it was not long before they came to the conclusion that camping out in a rain-storm was both a delusion and a snare.

In half an hour the tent was so nearly freed from smoke that they sought its shelter again, and when they were housed once more, they presented a very forlorn appearance.

At first they decided that they would remain awake until daylight; but as the hours rolled on, this plan was abandoned, for one after another wrapped himself in his blanket, concluding he could keep his eyes open as well lying down, and proved it by going to sleep at once.

They did not sleep very soundly, nor lie in bed very late. When they awakened, it was not necessary to look out-of-doors in order to know if it was raining, for the[Pg 806] water was falling on the thin shelter as hard and as persistently as if bent on beating it down.

SHORT RATIONS.

SHORT RATIONS.

As soon as the boys were fairly out of bed they began to ask how breakfast could be cooked, and what they were to have in the way of food, all of which questions Tim answered in a way that left no chance for discussion. He cut eleven slices of bread, spread them thickly with butter, placed over that a slice of cake, and informed the party that they would begin the day with just that sort of a breakfast. Of course there was some grumbling, but the dissatisfied ones soon realized that Tim had done his best under the circumstances, and they ate the bread and cake very contentedly.

That forenoon was not spent in a very jolly manner, and the afternoon was a repetition of the forenoon, save that at supper-time Tim gravely informed them that there was hardly enough cooked provisions for breakfast.

Unfortunately for them, the boys were not as sleepy when the second night came, and the evening spent in the dark was not a cheerful one. The rain was still coming down as steadily as ever, and they had ceased to speculate as to when it would stop. It was after they had been sitting in mournful silence for some time that Bill Thompson started what was a painful topic of conversation.

"How long will the victuals last, Tim?"

"They're 'most gone now, 'cept the pork an' 'taters, an' the eggs, that I never thought of until a minute ago."

"If it would only stop rainin', Jim could go out fishin', an' I could go out huntin', an' in a day we could get more'n the crowd of us could eat in a week. I'll tell you what I will do"—and Bill spoke very earnestly: "I'll take Tip an' go out alone in the mornin', whether it rains or not."

"Why not all go?" said Tim, pleased with the plan. "Supposin' we do get wet, what of that? We can get dry again when the sun does come out, an' it'll be better'n stayin' here scrouchin' around."

There were a number of the boys who were of Tim's way of thinking, and the hunting party was decided upon for the following day, regardless of the weather.

After breakfast next morning some of the boys who had been the most determined to join the hunting party, the night before, concluded to wait a while longer before setting out, and the consequence was that no one save Tim, Bill, and Bobby had the courage to brave the drenching which it was certain they must get.

This time Bill had a more effective weapon than the one he used at the bear-hunt. He had borrowed a fowling-piece of quite a respectable size, and had brought with him a supply of powder and shot.

Bill covered the lock of the gun with the corner of his jacket to prevent the cap from getting wet, and on they went, rapidly getting drenched both by the rain and by the water which came from the branches of the trees.

For some time Tip steadily refused to run among the bushes, but after much urging he did consent to hunt in a listless sort of way, barking once or twice at some squirrels that had come out of their holes to grumble at the weather, but scaring up no larger game.

Just at a time when the hunters were getting discouraged by their ill luck, Tip commenced barking at a furious rate, and started off through the bushes at full speed.

Bill was all excitement; he made up his mind that they were on the track of a deer at least, and he was ready to discharge his weapon at the first moving object he should see.

After running five minutes, during which time they made very little progress, owing to the density of the woods, Bobby halted suddenly, and in an excited manner pointed toward a dark object some distance ahead, which could be but dimly seen because of the foliage.

Bill was on his knee in an instant, with gun raised, and just as he was about to pull the trigger, Tim saw the object that had attracted Bobby's attention.

He cried out sharply, and started toward Bill to prevent him from firing, but was too late. Almost as he spoke, the gun was discharged, and mingled with Tim's cries could be heard the howling of a dog.

"You've shot Tip! you've shot Tip!" cried Tim, in an agony of grief, as he rushed forward, followed by Bill and Bobby, looking as terrified as though they had shot one of their companions.

When Tim reached the spot from which the cries of pain were sounding, he found that his fears were not groundless, for there on the wet leaves, bathed in his own blood, that flowed from shot-wounds on his back and hind-legs, was poor Tip. He was trying to bite the wounds that burned, and all the while uttering sharp yelps of distress.

Tim, with a whole heart full of sorrow such as he had never known before, knelt by the poor dog's side, kissing him tenderly, but powerless to do anything for his suffering pet save to wipe the blood away. His grief was too great to admit of his saying anything to the unfortunate hunter who had done him so much mischief, and poor Bill stood behind a tree crying as if his heart was breaking.

Each instant Tim expected to see Tip in his death struggle, and he tried very hard to make the dog kiss him; but the poor animal was in such pain that he had no look even for his master.

It was nearly fifteen minutes that the three were gathered around the dog expecting to see him die, and then he appeared to be in less pain.

"Perhaps he won't die after all," said Bill, hardly even daring to hope his words would prove true. "If we could only get home, Dr. Abbott would cure him." Then, as a sudden thought came to him, he turned quickly to Bobby, and said, eagerly: "Run back to the camp as quick as you can, an' tell the fellers what has happened. Have them get everything into the boat, so's we can get right away for home."

Bobby started off at full speed, and Tim, now encouraged to think that Tip might yet recover, began to look hopeful.

Bill set to work cutting down some small saplings, out of which he made a very good litter. On this Tip was placed tenderly, and with Bill at one end and Tim at the other, they started down the path toward the camp. To avoid jolting the dog, thus causing him more pain, they were obliged to walk so slowly that when they reached the beach the boys were putting into the boat the last of their camp equipage.

Each of the party wanted to examine poor Tip, but Bill would not permit it, because of the delay it would cause. He arranged a comfortable place in the bow where Tip could lie, and another where Tim could sit beside him, working all the time as if each moment was of the greatest importance in the saving of Tip's life.

At last all was ready, the word was given to push off, and the campers rowed swiftly toward home.

Peter Keens was in most respects a very good boy; but he had one fault, which, though it might not at first thought seem a very grave one, can never be indulged in without bringing many worse ones in its train, and sadly lowering the whole tone of a boy's character. He was full of curiosity—that curiosity which leads one to be always prying into the affairs of others. The boys at school of course knew his failing, and found in it reason for playing many a trick upon him, which is not to be wondered at. One day, when a number of the older boys[Pg 807] had remained after hours to consult on the formation of a club, he crept into the entry and listened at the door. They found out that he was there, and all got out of a window, and locked Peter in, keeping him prisoner until after dark, when he was let out, frightened and hungry.

The next morning he was greeted on the play-ground by shouts of "Spell it backward!" He could not guess what was meant, and was still more puzzled as they continued to call him "Double—back—action," "Reversible-engine," and other bits of school-boy wit. He begged them to tell him, and at last some one suggested, in a tone of great disgust, "Spell your name backward, booby, and then you'll see."

He did, and he saw: Keens—backward.

But he was not yet ready to cultivate straightforward spelling. That club still bothered him; he could not give up his strong desire to find out its secrets. By dint of much listening and spying he gathered that it was to meet one night in a barn belonging to the father of one of the boys, and he made up his mind to be there. He crept near the door as darkness closed in, and listened intently. They were inside surely, for he could hear something moving about; but he wanted to hear more than that, so he ventured to raise the wooden latch. It made no noise; he cautiously opened the door a trifle, and peeped in. It was dark and quiet, so he opened it wider. It gave a loud grating creak; a scurry of quick footsteps sounded on the floor, and then a white thing suddenly rose before him, tall and ghostly. In an agony of fright and horror, he turned to run, but the thing with one fearful blow struck him down, trampled heavily over him, and sped away with a loud "Ba-ha-ha-ha-a-a!"

As Peter limped home, muddy, battered, and bruised, he wondered if any of the boys knew that Farmer Whippletree's wretched old billy-goat was in the barn that night.

They did.

"How did you leave William, Peter?" he was asked at least twenty times in the course of the next day. In the grammar class a boy who was called on for a sentence wrote, "A villain is more worthy of respect than a sneak."

"Oh no, not quite that," remarked the teacher, "but—neither can be a gentleman."

On a morning in early July he received as usual the family mail from the carrier at the door, and carried it to his mother, examining it as he went. A postal card excited his curiosity; it was, he knew, from his aunt, in whose company he was to go to the mountains, and he was anxious to know what she said. But one of his friends was waiting for him to go and catch crabs and minnows for an aquarium, and as the morning hours are the best for such work, they were in a hurry. So he slipped it into his pocket to read as he went along, intending to place it where it might be found on the hall floor when he came back, that his mother might be deceived into thinking it had been accidentally dropped there.

But he forgot all about it before they had gone twenty steps. He spent the morning at the creek, and the afternoon at his friend's house, returning home in the evening. As he passed through the hall to his mother's room, the thought of it suddenly flashed on his mind. He felt in his pocket, with a sinking at his heart, but the card was gone.

Where? He could not pretend to imagine, as he thought of the roundabout ramble he had taken. He got up early the next morning, and carefully hunted over every step of the ground, but all in vain. It would have been well if he had gone at once to his mother, and confessed what he had done; but he delayed, still cherishing a hope of finding what he had lost, and the longer he waited, the more impossible it became to tell. He remembered that a boy had once said to him, "A sneak is sure to be a coward."

More than a week after this, Peter was sitting on the piazza one evening after tea, reading to his mother, when his friend of the creek expedition came in.

"Here is a card I found, addressed to you, Mrs. Keens," he said. "It must be the one you were hunting for last week, Pete."

She took it in some surprise, failing to observe the color which mounted to Peter's face as he saw it. As she read it, a troubled expression overspread her own.

"Ten days old, this card," she exclaimed. "'Wednesday, the 14th'—what does it mean, Peter?" She passed it to him, and he read as follows:

"July 3.

"My dear Ruth,—I write to give you ample notice of a change in our plans in consequence of Robert's partner desiring to take a trip late in the season, obliging us to go early. So Robert, having finished his business in Canada, is to meet us on Wednesday, the 14th, at Plattsburg. Shall stop for Peter on the evening of the 13th. Please have him ready.

"Katherine."

This was the 13th. Peter stared at his mother in dismay.

"I do not quite understand yet," she said. "Where did you get this card, Philip?"

"I found it just now in the arbor where I have my museum; it had slipped behind a box. You lost it the day we played there, didn't you, Pete?"

"How came you to have it there, Peter?"

"I—it was in my pocket, ma'am, and I dropped it, I suppose."

"Why was it in your pocket? Why didn't you bring it to me?"

"I wanted—I was just going to read it."

Phil touched his hat, and quietly took his departure. Mrs. Keens said no more, but looked again at the dates on the card.

At this moment a hack drove up, from which issued a most astonishing[Pg 808] outpouring of noisy, laughing, chattering blue-flannelled boys, followed by a mother who looked just merry enough to be commander of such a merry crew.

"Hurrah! Hurrah! Pete, we're off! All ready? We can only stay two hours."

"Such a tent—big, striped, and a flag to it; and—"

"Father's going to let us boys shoot with a gun."

"Isn't it jolly to have two weeks less to wait?"

Peter did not look at all jolly, as through his half-bewildered mind struggled a dim perception of the dire evil the loss of that card might have worked for him. When the clamor of greeting and questioning had somewhat subsided, Mrs. Keens said, slowly:

"No, Peter is not ready;" and the tone of her voice sent a heavier weight down into his heart, and a bigger lump into his throat. "Your card has only just reached me, Katherine."

"Oh dear! dear!" His aunt shook her head in distress, and five boy faces settled into blank dismay. "Why, why, surely you don't mean, Ruth—eh? Can't you hurry things up a little? Boys don't need much, you know! Or—can't he be sent after us?" Peter followed his mother to the dining-room as she went to order a hasty lunch for the travellers.

"Mother, can't I?—can't I?" he sobbed.

She put her arms around him, with streaming eyes, feeling the keenness of the disappointment for him as deeply as he ever could feel it for himself.

"Oh, my boy! my boy! my heart is sad and sore that you should be mean and sly and deceitful, and not for once only, but as a habit. No, it is your own doing, and you must abide by the consequences. I never could have brought myself to punish you so, but you have punished yourself, and I trust it may be the best thing which could have happened to you."

The story of Paul Dombey and his sister Florence is one of the sweetest and most pathetic stories Charles Dickens ever told. One can scarcely think of these children—motherless (the mother died when Paul was born), and Florence worse than fatherless, for her father had never forgiven her birth six years before that of the wished-for son, and had never given her a kind word or look, living in the great, comfortless, lonely Dombey house, and finding all their happiness in each other—without tears. For it was to the sister so cruelly neglected and despised that Paul turned from the very first. It was she who on the day of his christening won from him his first laugh. "As she hid behind her nurse, he followed her with his eyes, and when she peeped out with a merry cry to him, he sprang up and crowed lustily, laughing outright when she ran in upon him, and seeming to fondle her curls with his tiny hands while she smothered him with kisses." And as he grew out of babyhood, much as it displeased the father (who would have had his idol care for no one but himself), little Paul was never content save when his sister was by his side.

A pale, delicate, old-fashioned child he proved to be, this boy whom Mr. Dombey proudly thought would in years to come be his partner in the immense business of which he had been the only head for twenty years, but which then would be, as in old times, "Dombey & Son"; and in spite of all the care that money could procure for him, he gradually grew weaker and weaker. Mr. Dombey believed in "money," and in but little else, and would have taught his little son also to believe in its all-sufficient power, but the child was wiser than the father. "If it's a good thing," said he, "and can do anything, I wonder why it didn't save me my mamma; and it can't make me quite well and strong either." At last it was decided that he should be sent to the sea-side, in hopes that the fresh sea-air would bring the health and strength that could not be found at home. And with him, of course, went Florence.

"But the boy remaining as weak as ever, a little carriage was got for him, in which he could lie at his ease, and be wheeled to the sea-shore. Consistent in his odd tastes, the child set aside the ruddy-faced lad who was proposed as a drawer of this carriage, and selected instead his grandfather—a weazen old crab-faced man in a suit of battered oil-skin, who had got tough and stringy from long pickling in salt-water. With this notable attendant to pull him along, and Florence walking by his side, he went down to the margin of the ocean every day. 'Go away, if you please,' he would say to any child that came to bear him company. 'Thank you, but I don't want you.' Then he would turn his head and watch the child away, and say to Florence, 'We don't want any others, do we?—kiss me, Floy.' His favorite spot was a lonely one far away from most loungers; and with Florence sitting by his side at work, or reading to him, or talking to him, and the wind blowing on his face, and the water coming up among the wheels of his bed, he wanted nothing more.

"One time he fell asleep, and slept quietly for a long time. Awaking suddenly, he listened, started up, and sat listening. Florence asked him what he thought he heard. 'I want to know what it says,' he answered, looking steadily into her face. 'The sea, Floy—what is it that it keeps on saying?'

"She told him it was only the noise of the rolling waves.

"'Yes, yes,' he said. 'But I know that they are always saying something—always the same thing. What place is that over there?' He rose up, looking eagerly at the horizon.

"She told him that there was another country opposite; but he said he didn't mean that: he meant farther away—farther away."

There was a strange, weird charm for little Paul in the ever-restless ocean, and the winds that came he knew not whence and went he knew not whither.

"If you had to die," he said once, looking up into the face of his odd, shy friend Mr. Toots, "don't you think you would rather die on a moonlight night, when the sky was quite clear, and the wind blowing, as it did last night? Not blowing, at least, but sounding in the air like the sea sounds in the shells. It was a beautiful night. When I had listened to the water for a long time, I got up and looked out. There was a boat over there, in the full light of the moon—a boat with a sail like an arm, all silver. It went away into the distance, and it seemed to beckon—to beckon me to come."

Poor little Paul! It was not long before he obeyed the fancied summons, for soon after this visit to the sea-shore the gentle, loving little fellow died—died with his arms about his sister's neck; and almost his last words were, as he smiled at his mother's spirit waiting to bear him to heaven: "Mamma is like you, Floy. I know her by the face."

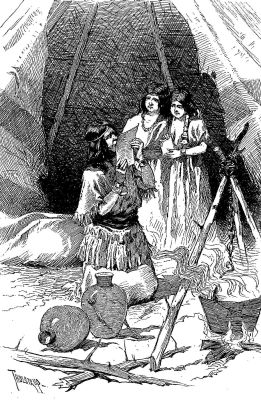

alking leaves?" said Ni-ha-be, as she turned over another page of the pamphlet in her lap, and stared at the illustrations. "Can you hear what they say?"

"With my eyes."

"Then they are better than mine. I am an Apache. You were born white."

There was a little bit of a flash in the black eyes of the Indian maiden. She had not the least idea but that it was the finest thing in all the world to be the daughter of Many Bears, and it did not please her to find a mere white girl, only Indian by adoption, able to see or hear more than she could.

Rita did not reply for a moment, and a strange sort of paleness crept across her face, until Ni-ha-be exclaimed:

"It hurts you, Rita! It is bad medicine. Throw it away."

"No, it does not hurt."

"It makes you sick?"

"No, not sick. It says too much. It will take many days to hear it all."

"Does it speak Apache?"

"No, not a word."

"Nor the tongue of the Mexican pony men?"

"No. All it says is in the tongue of the blue-coated white men of the North."

"Ugh!" Even Ni-ha-be's pretty face could express the hatred felt by her people for the only race of men they were at all afraid of.

There were many braves in her father's band who had learned to talk Mexican-Spanish. She herself could do so[Pg 811] very well, but neither she nor any of her friends or relatives could speak more than a few words of broken English, and she had never heard Rita use one.

"There are many pictures."

"Ugh! Yes. That's a mountain, like those up yonder. There are lodges, too, in the valley. But nobody ever made lodges in such a shape as that."

"Yes, or nobody could have painted a talking picture of them."

"It tells a lie, Rita. And nobody ever saw a bear like that."

"It isn't a bear, Ni-ha-be. The talking leaf says it's a lion."

"What's that? A white man's bear?"

Rita knew no more about lions than did her adopted sister, but by the time they had turned over a few more pages their curiosity was aroused to a high degree.

Even Ni-ha-be wanted to hear all that the "talking leaves" might have to say in explanation of those wonderful pictures.

It was too bad of Rita to have been "born white" and not to be able to explain the work of her own people at sight.

"What shall we do with them, Ni-ha-be?"

"Show them to father."

"Why not ask Red Wolf?"

"He would take them away and burn them. He hates the pale-faces more and more every day."

"I don't believe he hates me."

"Of course not. You're an Apache now, just as much as Mother Dolores, and she's forgotten that she was ever white."

"She isn't very white, Ni-ha-be. She's darker than almost any other woman in the tribe."

"We won't show her the talking leaves till father says we may keep them. Then she'll be afraid to touch them. She hates me."

"No, she doesn't. She likes me best, that's all."

"She'd better not hate me, Rita. I'll have her beaten if she isn't good to me. I'm an Apache."

The black-eyed daughter of the great chief had plenty of self-will and temper. There could be no doubt of that. She sprang upon her mustang with a quick, impatient bound, and Rita followed, clinging to her prizes, wondering what would be the decision of Many Bears and his councillors as to the ownership of them.

A few minutes of swift riding brought the two girls to the border of the camp.

"Rita, Red Wolf!"

"I see him. He is coming to meet us, but he does not want us to think so."

That was a correct guess. The tall, hawk-nosed young warrior, who was now riding toward them, was a perfect embodiment of Indian haughtiness, and even his sister was a mere "squaw" in his eyes. As for Rita, she was not only a squaw, but was not even a full-blooded Apache, and was to be looked down upon accordingly.

He was an Indian and a warrior, and would one day be a chief like his father. Still, he had so far laid aside his usual cold dignity as to turn to meet that sisterly pair, if only to find out why they were in such a hurry.

"What scared you?"

"We're not scared. We've found something. Pale-face sign."

"Apache warriors do not ask squaws if there are pale-faces near them. The chiefs know all. Their camp was by the spring."

"Was it?" exclaimed Ni-ha-be. "We have found some of their talking leaves. Rita must show them to father."

"Show them to me."

"No. You are an Apache. You can not hear what they say. Rita can. She is white."

"Ugh! Show leaves now."

Ni-ha-be was a squaw, but she was also something of a spoiled child, and was less afraid of her brother than he may have imagined. Besides, the well-known rule of the camp, or of any Indian camp, was in her favor. All "signs" were to be reported to the chief by the finder, and Ni-ha-be would make her report to her father like a warrior.

Rita was wise enough to say nothing, and Red Wolf was compelled to soften his tone a little. He even led the way to the spot near the spring where the squaws of Many Bears were already putting up his "lodge."

There was plenty of grass and water in that valley, and it had been decided to rest the horses there for three days before pushing on deeper into the Apache country.

The proud old chief was not lowering his dignity to any such work as lodge pitching. He would have slept on the bare ground without a blanket before he would have touched one pole with a finger. That was "work for squaws," and all that could be expected of him was that he should stand near and say "Ugh!" pleasantly when things were going to please him, and to say it in a different tone if they were not.

Ni-ha-be and Rita were favorites of the scarred and wrinkled warrior, however, and when they rode up with Red Wolf, and the latter briefly stated the facts of the case—all he knew of them—the face of Many Bears relaxed into a grim smile.

"Squaw find sign. Ugh! Good!"

"Rita says they are talking leaves. Much picture. Many words. See!"

Her father took from Ni-ha-be and then from Rita the strange objects they held out so excitedly, but to their surprise he did not seem to share in their estimate of them.

"No good. See them before. No tell anything true. Big lie."

Many Bears had been among the forts and border settlements of the white men in his day. He had talked with army officers, and missionaries, and government agents. He had seen many written papers and printed papers, and had had books given him, and there was no more to be told or taught him about nonsense of that kind. He had once imitated a pale-face friend of his, and looked steadily at a newspaper for an hour at a time, and it had not spoken a word to him.

So now he turned over the three magazines in his hard brown hand with a look of dull curiosity mixed with a good deal of contempt.

"Ugh! Young squaws keep them. No good for warriors. Bad medicine. Ugh!"

Down they went upon the grass, and Rita was free to pick up her despised treasures, and do with them as she would. As for Red Wolf, after such a decision by his terrible father, he would have deemed it beneath him to pay any further attention to the "pale-face signs" brought into camp by two young squaws.

Another lodge of poles and skins had been pitched at the same time with that of Many Bears, and not a great distance from it. In fact, this also was his own property, although it was to cover the heads of only a part of his family.

In front of the loose "flap" opening which served for the door of this lodge stood a stout, middle-aged woman, who seemed to be waiting for Ni-ha-be and Rita to approach. She had witnessed their conference with Many Bears, and she knew by the merry laugh with which they gathered up their fallen prizes that all was well between them and their father. All the more for that, it may be, her mind was exercised as to what they had brought home with them which should have needed the chief's inspection.

"Rita!"

"What, Ni-ha-be?"

"Don't tell Mother Dolores a word. See if she can hear for herself."

"The leaves won't talk to her. She's Mexican white, not white from the North."

Nobody would have said, to look at her, that the fat, surly-faced squaw of Many Bears was a white woman of any sort. Her eyes were as black and her long jetty hair was as thick and coarse and her skin was every shade as dark as were those of any Apache housekeeper among the scattered lodges of that hunting party. She was not the mother of Ni-ha-be. She had not a drop of Apache blood in her veins, although she was one of the half-dozen squaws of Many Bears. Mother Dolores was a pure Mexican, and therefore as much of an Indian, really, as any Apache or Lipan or Comanche—only a different kind of Indian, that was all.

Her greeting to her two young charges—for such they were—was somewhat gruff and brief, and there was nothing very respectful in the manner of their reply. An elderly squaw, even though the wife of a chief, is never considered as anything better than a sort of servant, to be valued according to the kind and quantity of the work she can do.

Dolores could do a great deal, and was therefore more than usually respectable, and she had quite enough force of will to preserve her authority over two such half-wild creatures as Ni-ha-be and Rita.

"You are late. Come in. Tell me what it is."

Rita was as eager now as Ni-ha-be had been with her father and Red Wolf; but even while she was talking, Dolores pulled them both into the lodge.

"Talking leaves!"

Not Many Bears himself could have treated those poor magazines with greater contempt than did the portly dame from Mexico.

To be sure, it was many a long year since she had been taken a prisoner and brought across the Mexican border, and reading had not been among the things she had learned before coming.

"Rita can tell us all they say by-and-by, Mother Dolores. She can hear what they say."

"Let her, then. Ugh!"

"RITA, THE LEAVES HAVE SPOKEN TO HER."

"RITA, THE LEAVES HAVE SPOKEN TO HER."

She turned page after page in a doubtful way, as if it were quite possible one of them might bite her; but suddenly her whole manner changed.

"Ugh!"

"Rita," exclaimed Ni-ha-be, "the leaves have spoken to her."

She had certainly kissed one of them. Then she made a quick motion with one hand across her brow and breast.

"Give it to me, Rita; you must give it to me."

Rita held out her hand for the book, and both the girls leaned forward with open mouths to learn what could have so disturbed the mind of Dolores.

It was a picture: a sort of richly carved and ornamented doorway, but with no house behind it, and in it a lady with a baby in her arms, and over it a great cross of stone.

"Yes, Dolores," said Rita, "we will give you that leaf."

It was quickly cut out, and the two girls wondered more and more to see how the fingers of Dolores trembled as they closed upon that bit of paper.

She looked at the picture again with increasing earnestness. Her lips moved silently, as if trying to utter words her mind had lost. Then her great fiery black eyes slowly closed, and the amazement of Ni-ha-be and Rita was greater than they could have expressed, for Mother Dolores sank upon her knees, hugging that picture. She had been an Apache Indian for long years, and was thoroughly "Indianized"; but upon that page had been printed a very beautiful representation of a Spanish "Way-side Shrine of the Virgin."

This year the forest fires have been more extensive and more destructive than usual, especially in Michigan, where not a drop of rain had fallen for nearly eighty days. The fire, when once started, rushed on through green trees and dry trees, through corn fields and clover fields, at the rate of twenty miles an hour. Swamps full of stagnant water were dried up in a flash. Horses galloped wildly before the flame, but were overtaken by it, and left roasting on the ground. Trees two miles distant from the flames had their leaves withered by the heat.[Pg 813] Some sailors who were out on the lake found the heat uncomfortable when they were seven miles from shore. Of course, wherever the lake was near, people tried to reach it. One farmer put all his family into his wagon, and started off. The fire was so close that the sparks burned holes in the children's dresses. Just then the tire came off one of the wheels. Usually, when this accident happens, the wagon has to stop, for the best of wheels generally fall to pieces in a few rods when they have lost their tires; but this wheel stood seven miles of jolting and bumping, up hill and down, over roots and ruts, while the frightened horses were galloping like mad creatures. Another farmer had gathered his neighbors about him to assist him in threshing his wheat. While the great machine was doing its work, the alarm was given that the woods were on fire. Hastily putting horses to the machine and to a wagon, the farmer and his friends abandoned homestead and newly gathered crop, and made an effort to save the valuable threshing-machine, even if all else must go. Before they gained the road a mare with a colt at her heels came madly galloping toward them, and becoming entangled among the horses attached to the machine, blocked their progress. The fire was almost upon them. The men cut the traces and let the horses go, but the great threshing-machine, to whose very existence fire was a necessity, had to be abandoned to the fury of the devouring element.

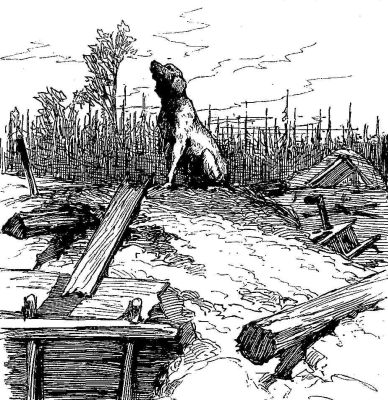

In the lake, people waded into the water up to the neck; then they were safe indeed from the flame, but almost choked by the smoke, while the sparks fell on them like snow-flakes in a heavy storm. Thousands of land-birds were suffocated as they flew before the flames, or were drowned in the lake. Bears and deer in their terror sought the company of man. A man and a bear stood together up to their necks in water all night, and the man said that the bear was as quiet as a dog. Two other bears came and stood close to a well from which a farmer was flinging water over his house. Our artist saw a very pathetic scene: the flames had swept away the homestead, and when the wave of fire had passed, no living thing remained but the faithful house-dog, which had crouched down in a ditch. It went again to its old place, and neither hunger nor solitude could persuade it to quit the ruins where its master had perished. It stood at its post, faithfully guarding the charred timbers of what a short time before had been a happy home.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Girls and boys who are looking for a useful and tasteful holiday gift for mother, aunt, or elder sister, may unite in the making of the folding camp-stool, which we illustrate below. It is made of black walnut rods, joined, with hinges and with a broad cross-bar. On the top of the cross-bar is fastened a leather handle, by which to carry the stool when folded (Fig. 2). The upright wooden rods in the back are hinged to and support the cane seat, as shown by Fig. 1. The other upper rods are pushed into the notches on the under side of the seat in unfolding the chair. A leather satchel may be added, as in the engraving, but this is not necessary. The seat is covered with a four-cornered piece of brown woollen Java canvas, embroidered in cross stitch with fawn-colored filling silk in three shades. Ravel out the threads of the canvas from the last cross stitch row to a depth of an inch and a quarter, fold down the canvas on the wrong side so as to form loops a quarter of an inch deep on the edge, and catch every ten such loops together with a strand of fawn-colored silk in three shades, for a tassel, which is tied with similar silk. Cut the tassels even, and underlay the cover with a thin cushion.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Have dolls gone out of fashion? Very few of our little girls mention them in their letters. We hope that there are dolls and play houses and lovely little tea sets, just as there used to be, and we shall be glad to have the younger ones write about them. How many of you are learning to decorate china, and which little girls have painted the prettiest cups and saucers for mamma's birthday? What are the boys doing in these bright days of autumn? Marbles, tops, balls, hoops, and such toys are always the style, we know, among the boys. Which boy has drawn the best map? Who has made the finest work-box or bracket with his scroll-saw? Write about these things.

Now that the long evenings are coming, you may tell us, if you please, about your home amusements. Hands up! Every uplifted hand is the sign that its owner knows a pleasant evening game, and Our Post-office Box will be delighted to hear how it is played, so that all the young people may play it if they wish to do so.

And now one word more to exchangers. Listen, please. Try to confine your exchanges to useful, unique, valuable, or beautiful things of which you are making collections. As we have said before, in every case exchangers should write to each other, and arrange the exchange, settle the postage, and determine the details before they trust their articles to the mail or express. Every day brings us complaints, and some of them very bitter ones, from boys and girls who accuse others of having treated them unfairly. This would be made impossible if there were always an exchange of views before the exchange of goods. Hereafter we shall publish no notices of withdrawal from our exchange list. When your supplies are exhausted it would be well for you to notify your correspondents, for the reason that several weeks must elapse before we can publish your notice of withdrawal, and all that time you, though innocent, are exposed to the suspicion of being either dishonest or careless.

Eagle Grove, Iowa.

Not seeing any letters from this place, I thought I would write and tell you about my pets. I am a little girl nine years old, and live on a farm, and have to depend on my pets for playmates, as my little brother is dead, and I have no sister. I have a little gray kitten which I call Maggie, and my dog is a shepherd, and I call him Brave. He will speak for something to eat, and shake hands with me, and when I am at school, will watch until school is out, and then come and meet me. I have a little colt named Rosa, and a little calf named Mera, and a black cow named Mink. Our hired man takes Young People this year, and I want to take it next. I read all the little letters, and I think that "Susie Kingman's Decision" was splendid, and I hope "Tim and Tip" will be as good. I thought Jimmy Brown's monkey was funny. I do wish he would tell us some more of the monkey's tricks. My ma is writing this for me, but I tell her what to say, as it is such hard work for me to write.

Ethelyn I. G.

It is in order for any little girl to employ her mother as an amanuensis, and if she dictates the letter, we consider it her own.

Paris, France.

We left Lucerne August 2, and crossed the Brünig Pass as far as Sarnen, where the horses were watered. We only stopped there fifteen minutes. The next place we slopped at was Lungern, and we reached Brienz for the night. We took a funny big row-boat, and two men to row it across to Giessbach Falls, and reached Interlachen August 3. We drove to Grindelwald, and saw two glaciers; and August 11 we came to Berne, saw the Bears' Den, the distant snow mountains, and the Cathedral clock. We heard the organ, which was the finest I ever heard, more beautiful than the organ in Lucerne. We drove one afternoon in the woods, and saw some chamois that are kept by the city. We left Berne, and came back to Lucerne. There we staid till the snow fell on all the mountains near the lake, and it was very cold.

September 1, we left Lucerne, and came to Bâle. On the journey, part of the way the train went in the water, for it had rained a long time, and the country was flooded. The peasants stood about talking and trying to save their gardens and fences. Two or three little children at one of the houses were being carried along over the water on a big horse. There was one little village saved from flooding by their cutting large drains through the principal roads.

When we reached Bâle the river Rhine was overflowing its banks, and it was rushing down and carrying great trees, parts of houses, fences, etc., along with it. There was great fear that it would carry away the old bridge, and the firemen of the city put large piles of railroad irons to weight it down, so that it should not be floated down the river, and carried away from its supports. The cellar of one of the buildings was full of stores, iron safes, etc., and they bricked up the doors to keep out the water. One street was so flooded that they made a board plank-walk above the water.

We saw the Münster, and the cloister walk, and curiosities in the tower of the Münster. In one room they had old musical instruments, and books, with the music in them written in all the old ways. In the Museum we saw Holbein's sketches. He was born in Bâle, and they are proud of his pictures. We liked a sketch of two lambs and a bat. At the Zoological Gardens we saw a fish-otter. He twirled round and round in the water, would dive and swim and turn somersaults.

September 4, we left Bâle by the night train for Troyes, France. There we got into a funny little "'bus," drove to a little hotel, and had our coffee and milk. We saw the Cathedral, and then took the train for Foutainebleau.

Harry G.

San Francisco, California.

We take Harper's Young People, and like it very much. We liked the "Two-headed Family," but wished it had been a continued story. "Tim and Tip" is a very nice story so far, but I hope it will not end so sadly as "Toby Tyler" did, by Tip's getting killed. I liked "Phil's Fairies" very much, and "Aunt Ruth's Temptation." We would like to have the violin which some one offered for exchange, but have not got enough curiosities to make four or five dollars' worth. This is our first letter to Young People. We have taken it from the first number. I have two King Charles spaniels, and they are very clever. I have a great deal of pleasure in teaching them tricks.

Helen T. F. and Joseph M. N.

Washington, D. C.

I have returned from my summer vacation, which I spent in Virginia. My baby brother was very glad to see me. I have four pets—a red bird, goat, pigeons, and a little dog. I drive my little brother out in my goat-wagon. When papa left me in the country, on his way home, the cars ran off the track, and smashed the tender, and he was six hours detained in the hot sun. I was waiting every day to hear from home, to know whether he was hurt, but no one was injured. When my brother and I were coming home, a mule got on the track, and delayed the freight train, so that we were seven hours behind time, and I did not get home in time to see the President's funeral.

W. H. T.

How thankful you must be that your dear father escaped unhurt!

Hillhurst, Washington Territory.

I am a little girl seven years old. I have taken Young People since Christmas, and like it ever so much. This is the first letter I have ever written. I have lived in New Tacoma ever since I was one year old, until about two months ago. I am now living in the country, fourteen miles from New Tacoma. I like it much better than I did in town, for there are so many pretty ferns, leaves, and mosses, and other things too. I read so many letters from little boys and girls who write to Young People, I thought I would write one. I hope you will print this. I want to surprise papa. He does not know I am writing this. I will show it to him when it is printed.

Anna S. H.

Your writing was so large and plain, dear, that we enjoyed reading your first letter.

West Winsted, Connecticut.

Have you room for another in Our Post-office Box? As I was picking grapes yesterday morning, I was surprised at finding a double one about one inch long. I must tell you of a kitten that I found last evening. I was sitting out-of-doors, and I heard a poor little kitten mew. It was nearly dead with hunger. I took it in and fed it, and now it is getting so that it feels itself quite at home. I like Young People very much, and am very eager for it to come. I only wish that it would come every day instead of every week. I hope this will be published, as I have never seen one of my letters in print.

Henry J.

Lebanon, Pennsylvania.

I am thirteen years old, and live in Lebanon. There is a small creek running near our house, and there I go to procure subjects for my microscope. I do a great deal of experimenting in philosophy. I examined a specimen of larvæ of a dragon-fly, so my teacher said. But it don't look a bit like larvæ. It was about half an inch long, and the size (in thickness) of a cambric needle. Under a microscope it presents an appearance I could not describe. I would like to send it to the President of the Natural History Society, but it must be kept in water, and so could not be easily sent.

I like Young People very much, particularly "Tim and Tip." I don't think Tip was so much of a bear-dog, after all.

Frank B.

Baraboo, Wisconsin.

Papa says Young People has been a great benefit to us children, and I for one think the world of it. I have been intending to write to the Post-office Box for a long time. I will be eleven years old next New-Year's, and I have a little sister who will soon be able to read Young People too.

We children are now busy gathering hickory-nuts and butternuts and the beautiful autumn leaves, and when these pleasures are over, our out-door fun will be about finished until coasting-time. It is delightful out-of-doors now. Papa often goes out with us. We find lovely flowers in the early spring, as soon as the snow goes away, and later we search for wild strawberries, and then in their turns come the raspberries, plums, and blackberries, so that all the year there is something sweet and bright to invite us under the blue sky. The birds sing for us on our rambles, and we often see squirrels frisking around in the trees, and sometimes we startle a rabbit, and see him run for his home. Last spring a beautiful red fox fled past us, not more than twenty feet away. Papa said the hounds were after him, and as he was near his den in the rocks, he did not mind our presence.

Yesterday we observed as the funeral day of our dead President, and it was very mournful. The two posts of the G. A. R., and all the other societies, with brass music, fifes, and drums, marched through the streets, and great crowds of people gathered in the court-house and church, as the day was rainy. I suppose it was a sad day over the whole country, but nobody could feel as sorrowful as the President's children and their mamma and grandma were feeling.

Nettie J.

We hope that poor hunted fox escaped in safety to his home, and we are of the opinion that he had nothing to fear from you. You have given us a very pleasant sketch of your life. You ought to have bright eyes and plump rosy cheeks after so much exercise in the fresh air and sunshine. Did you find the beautiful bitter-sweet, with its clustering berries, on your autumnal expeditions, and did you bring home great bunches of golden-rod and aster, as well as of autumn leaves? We always load our arms with more treasures than we know what to do with when we go to the woods or the pleasant country lanes at this season. Far back in our memory are pictures of autumn walks we used to take with our little companions on Friday afternoons, a kind teacher going with us, and helping us discover the most charming places. Only those pupils who had been perfect the whole week were allowed to join these delightful parties. We learned a good deal about botany in our walks, and our love for nature grew deep and true.

In reply to the Holly Springs branch of the Natural History Society I give below a brief synopsis of the katydid.

The katydid is an American grasshopper of a transparent green color, named from the sound of its note. The song that the katydid sings is produced by a pair of taborets, one in the overlapping portion of each wing-cover, and formed by a thin transparent membrane stretched in a strong frame. The friction of the frames of the taborets against each other, as the insect opens and shuts its wings, produces the sound. During the day it hides among the leaves of the trees and bushes, but at early twilight its notes come forth from the groves and forests, continuing till dawn of day. These insects are now comparatively rare in the Atlantic States, though the writer has heard their noise at night, indicating that they were not rare in the hills back of Nyack and Verdritge Hook, better known as Rockland Lake Point, on the Hudson River. In some parts of the West their incessant noise at night deprives people of their sleep. From good authority I can state that katydids are found only in North America. They are called "grasshopper-birds" by the Indians, who are in the habit of roasting and grinding them into a flour, from which they make cakes, considered by them as delicacies. The katydid is interesting in captivity, and if fed on fruits, will live thus for several weeks. Like other grasshoppers, after the warm season they rapidly become old, the voice ceases, and they soon perish.

I would suggest that some of our members learn all they can about the golden-rod, and send what they find out about it to the Post-office Box.

President C. H. Williamson,

293 Eckford St., Brooklyn, N. Y.

Most of you have known what it is to be awakened in the night by the tolling of fire-bells, or perhaps you have been frightened by hearing somebody rushing past the door shouting "Fire! fire!" at the top of his voice. It is always an alarming and thrilling experience, and none of us ever grow used to it. But if you have read in this number the article entitled "A Forest Fire," and have looked at the picture of the lonely dog lingering beside the ruins of his home, you are sure that no fire you have ever seen was so dreadful as that. Think of the poor birds scorched, or blown to sea and drowned, and the wild animals so terrified that for the time they grew tame! One little girl of whom we heard was determined to save her canary-bird, so she took it with her, under some carpet which her father kept wet while the family crowded close together beneath its thick folds. The poor pet was dead when they[Pg 815] at last were able to stir from their shelter. Hundreds of children who had comfortable homes like yours were deprived of them during those dreadful days of smoke and wind and flame.

We are permitted to make some quotations from a private letter written by a young lady to a friend in Brooklyn:

Port Sanilac, Michigan.

You asked some of us to write a vivid account of the fire to you, but to do so goes entirely beyond the power of my pen. It was simply awful! During those dreadful days I was too frightened to know what I was doing. I cried every time I would think that just as we had got a home it would all be swept away in a minute. I was nearly sick when the danger and excitement were over.

The heat was perfectly unbearable. It seemed as if we would suffocate unless we could get a free breath of fresh air. The air was just as if it had come from an oven, and the leaves on our trees in front of the house are as brown as if they had been put into an oven and baked, and this even after all the rain we have had since.

It was so dark here on the Monday after you left that we lit our lamps at two o'clock, and at five I went out of the door to go into the office, and I could not see my hand before my face, and so hot! It was enough to make stouter hearts than mine quail. Most of the people here had their trunks packed. We did not, because we felt, if our house went, we did not care for anything else. My eyes ache so that I can not see to write much in the evenings now, or to do any work. I send you some papers giving fuller descriptions of the calamity than I can.

Eva.

There is a great deal of suffering in this part of Michigan, and it will take a great many hands and heads to relieve it. It will be a long time before the farms can be in good order again, the homes rebuilt, the schools and churches once more erected. Cold weather is coming. We hope you will ask your parents and teachers if they can not suggest to you some way of helping the poor people there. They need tools, books, food, clothing, and in fact everything which makes life comfortable. Boys and girls can have a share in the privilege of aiding them, if they really wish it, for in a great undertaking like this we can all help if we try.

Troy, Alabama.

This is my second letter to Young People. Everybody here is so sorry about the death of the President. Our post-office and court-house are draped in mourning. All the business of the town was suspended on Friday, September 23, and there were addresses in the evening by some of the orators of the place.

Eddie M.

The sorrow at the death of our dear President has been universal. We are sure all the boys who read Our Post-office Box will grow up better and stronger men if they learn all they can about James A. Garfield, who was a noble boy before he became a great and good man.

Verona, New Jersey.

I have taken Young People for a long time, and like it very much, as I think everybody must who reads it. The stories that I prefer are "Aunt Ruth's Temptation," "Penelope," "The Violet Velvet Suit," "A Bit of Foolishness," the Jimmy Brown stories, and Aunt Marjorie's "Bits of Advice." I have spent the summer at Verona, but am soon going home to Brooklyn. I have two brothers and one sister, all younger than myself. I will be very much obliged if you will tell me what Queen Victoria's last name was both after and before her marriage?

Etta.

The family name of the royal family of England is Guelph, and the Queen, being a queen, did not take her husband's name when she was married, as other ladies do. We do not wonder that you did not know the Queen's name, as neither she nor any of her family ever use it. And we do not wonder that you feel an interest in knowing all you can about this good Queen, who has won every American heart by the sympathy she has shown us in our great trouble this summer.

South Glastenbury, Connecticut.

Most of the girls who write to you seem to love cats. I hate them. I think they are very treacherous, and incapable of caring for anything but their own comfort. I have never had one, and never mean to. My pet is a noble St. Bernard dog, named Bruno.

Augusta C.

You are in good company in your liking for dogs. Prince Bismarck has a magnificent hound, which accompanies him everywhere. Sir Walter Scott was devoted to dogs, so that he grieved very deeply if any of his favorites died. But why hate poor puss? She has her good points too, and we hope some of the girls who love her will write us a letter or two in her defense.

Kansas City, Missouri.

I have taken Harper's Young People from the first, and have all the numbers except one or two. I liked "Toby Tyler" ever so much, and think the new story is fully as good. I have a canary-bird that I am trying to tame. I let him fly around in the room for five or ten minutes every day. But as this is my first letter, I will say good-by for this time.