BELEAGUERED IN PEKING

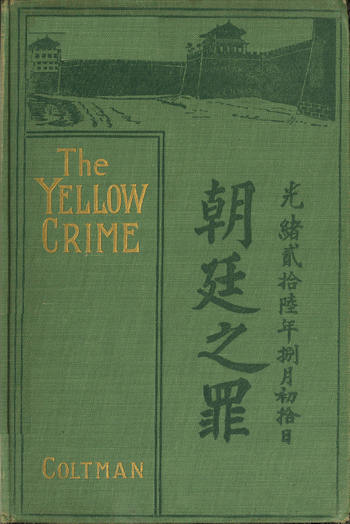

THE BOXER’S WAR AGAINST THE FOREIGNER

BY

ROBERT COLTMAN, Jr., M.D.

Professor of Surgery in Imperial University; Professor of Anatomy, the Imperial Tung Wen Kuan; Surgeon, Imperial Maritime Customs; Surgeon, Imperial Chinese Railways. Author of “The Chinese, Their Present and Future: Medical, Political, and Social.”

Illustrated with Seventy-seven Photo-Engravings

PHILADELPHIA:

F. A. DAVIS COMPANY, PUBLISHERS 1901

Copyright, 1901

By F. A. DAVIS COMPANY

Mount Pleasant Printery J. Horace McFarland Company Harrisburg · Pennsylvania

PREFACE

IN THE following pages I have endeavored to give an accurate and comprehensive account of the Siege in Peking and of the Boxer movement that led up to it.

Authentic details furnished by representatives of those legations whose work has been specially mentioned have made possible a greater detail in those cases. I regret that others who had promised me accounts of their work have failed to furnish the promised material.

The siege at Pei Tang or North Cathedral, coincident with that of the legations and civilians, is not described for the reason that we were absolutely cut off from them for over sixty days and knew nothing of their movements. Much detail that might be interesting to many I have been obliged to omit, as it would make the book too cumbersome.

I make no claim for the book as a literary effort, the object being to state the facts in the clearest manner possible. The illustrations are[iv] from actual photographs, the authenticity of which is absolutely proved, and these carefully studied, add much to the information of the volume.

To my sixteen-year-old son, the youngest soldier to shoulder a rifle during the siege, I am indebted for much of the diary and great help in copying. A considerable portion of the book was written with bullets whistling about us as we sat in the students’ library building of the English legation.

There are several men whose work entitles them to decorations from all the countries represented in the siege, and their names will be indelibly written in our memories even if the powers and ministers concerned overlook them. I refer to F. A. Gamewell, August Chamot, Colonel Shiba, and Herbert G. Squiers.

ROBERT COLTMAN, Jr., M.D.

Peking, China, September 10, 1900.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Riot at Marco Polo Bridge—Men Wounded by Captain Norregaard—Dr. Coltman Accompanies Governor Hu as Special Commissioner to Investigate—Anti-Foreign Feeling Expressed by Generals of Tung Fu’s Army—A Bargain with Prince Tuan | 1 |

| II. | Yu Hsien Appointed Governor of Shantung, Removed by British Demands, Only to be Rewarded—Yuanshih Kai Succeeds Him—Causes of Hatred of Converts by People and Boxers—The Boxers and Their Tenets—The Empress Consults Astrologers | 31 |

| III. | Cables to America Describing Growth of Boxer Movement from January to June, 1900 | 46 |

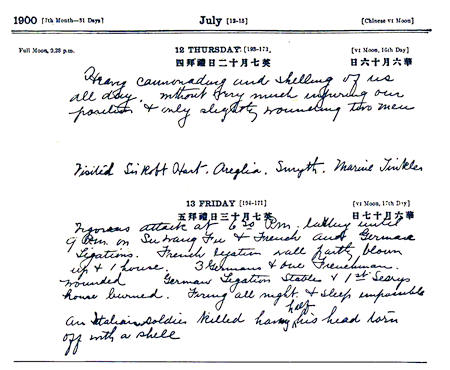

| IV. | Diary of the Author from June 1 to June 20 | 62 |

| V. | Diaries of the Author and His Son from June 20 to End of Siege | 78 |

| VI. | Reflections, Incidents, and Memoranda Written During Siege | 143 |

| VII. | Work During Siege Done by Russians—Work by Americans | 167 |

| VIII. | Work Done by Staff of Imperial Maritime, Customs, and British Legation Staff | 190 |

| IX. | Work Done by Austro—Hungarians—Mr. and Mrs. Chamot | 209 |

| X. | Edicts Issued by the Empress During Siege, with a Few Comments Thereon | 221 |

| XI. | Now What? | 245 |

Beleaguered in Peking

CHAPTER I

RIOT AT MARCO POLO BRIDGE—MEN WOUNDED BY CAPTAIN NORREGAARD—DR. COLTMAN ACCOMPANIES GOVERNOR HU AS SPECIAL COMMISSIONER TO INVESTIGATE—ANTI-FOREIGN FEELING EXPRESSED BY GENERALS OF TUNG FU’S ARMY—A BARGAIN WITH PRINCE TUAN.

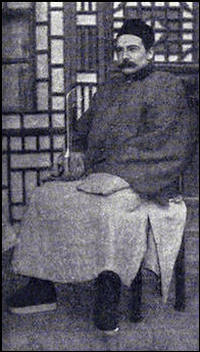

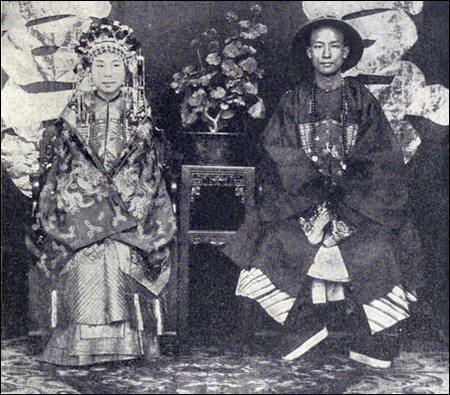

The author in Chinese dress

IN THE autumn of 1898, in the month of October, very shortly after the famous coup d’état of the Empress Dowager of China, an event occurred which may have been the influence that shaped after-events, or it may be that this occurrence was but the premature explosion of a mine being prepared by the Empress and her evil advisers, intended to shake the civilized world at a later date. I refer to the riot at Lukouch’iao, known to the English-speaking world as Marco Polo bridge, from its having been accurately described by that early traveler.[2] This place had curiously enough been chosen as the northern terminus of the Hangkow-Peking railway, although ten miles west of Peking, and the road consequently is generally known as the Lu Han railway.

The political history of the struggle between the Russian, French and British diplomats in Peking, with reference to obtaining the concession for, and the financing of, this road, is very interesting, and would fill a book of its own; but there is no reason why it should enter into this narrative more than to state that finally the Belgians, acting for Russia and France, obtained the concession to build and finance this greatest trunk line of China.

To connect this line with the existing Peking-Tientsin railway, a short track was laid from Fengtai, the second station south of Peking, to Lukouch’iao, and a fine iron bridge built over the Hum Ho or Muddy river, a few hundred yards west of the original stone Marco Polo bridge. This short connecting line is but three miles in length, and is the property of the Peking-Tientsin railway.

With this prelude, allow me to proceed with the event with which I was somewhat closely identified, and am able to speak of with knowledge and accuracy.[3]

MARBLE BRIDGE LEADING TO “FORBIDDEN CITY”

A beautiful bridge, which would be a credit to any city. Marco Polo, the great traveler, nearly a thousand years ago described a similar bridge, thus showing how old is Chinese civilization compared with our own.

On October 23 I was called to Fengtai to amputate the leg of a poor coolie, who had been run over by the express train from Tientsin; and after the operation partook of tiffin at the residence of A. G. Cox, resident engineer of the Peking section of the Peking-Tientsin railway. His other guests were Major Radcliffe, of the Indian army service, on what is known as[4] language-leave in China, and C. W. Campbell, official interpreter of the British legation.

During the meal the newly completed iron bridge was spoken of by Mr. Cox, and we were all invited to accompany him after tiffin on a trolley to inspect the bridge. This I was unable to do, as a professional engagement in Peking in the afternoon at four o’clock prevented.

The next morning I received the following telegram, which should have been delivered the night before; but owing to the closing of the city gates no attempt was made to deliver it:

“Coltman, Peking:—Come to Fengtai at once. Cox and Norregaard both seriously wounded in riot at Lukouch’iao.

“Knowles.”

I immediately rode in my cart to Machiapu, the Peking terminus of the Peking-Tientsin railway, and wired down to Fengtai for an engine to come and take me down.

In an hour’s time I reached Fengtai, and went at once to the residence of Mr. Cox, to find both himself and Captain Norregaard, the resident engineer and builder of the bridge at Lukouch’iao, with bandages about their heads, and a general appearance of having been roughly used. Their story of the riot was told me while I removed the dressings, applied by my assistant, a native medical student of the railway hospital at Fengtai, the day before.

Mr. Cox stated that he and his two guests had gone shortly after tiffin on a trolley to Captain Norregaard’s residence, near the bridge, and having added Norregaard to their party, proceeded on foot to the bridge. Near the eastern entrance stood a party of Kansu soldiers, numbering fifty or more, who, upon the approach of the foreigners, saluted them with offensive epithets, in which the well-known “yang kuei tzu” or “foreign devil” was frequently repeated.

Mr. Campbell, who spoke Chinese fluently, remonstrated with the men, and endeavored to have them stand aside and allow the party to cross the bridge; but they obstinately barred the entrance, and warned the foreigners back.

At this juncture a military official of low rank appeared on the track, and Campbell appealed to him to quiet the men, and to allow them to inspect the bridge. This officer replied that the men were not of his company and he had no power over them; but Campbell, knowing well the Chinese nature, at once told him that they should consider him responsible for any trouble, whether he was their particular officer or not.

Upon this the officer ordered the men to open a passage for the foreigners, which they promptly did, and the party of four crossed the bridge. The officer, after they had entered the bridge, left the men and disappeared. They remained a quarter[6] of an hour on the farther side of the bridge and then returned.

As they again neared the eastern side, they saw the same gang of ruffians awaiting them, with stones in their hands, and, upon their arriving within range, were saluted with a volley of stones, many of which took effect. They valiantly charged upon the men, and Cox, being rather severely hit, and spying out the man who had struck him, chased him right into the crowd and knocked him down with a terrific blow. As Cox stands six feet four, and is a remarkably muscular man, this fellow’s punishment was severe.

The mob, however, turned upon Cox, who was separated from his companions some thirty odd feet, and, surrounding him, bore him by sheer weight and number to the ground, not, however, before he had placed several of them hors du combat.

At this moment Captain Norregaard received a severe stone cut just above his eyes, which severed a small artery and covered his face with blood. Not knowing how dangerously he was wounded, and believing Mr. Cox to be in danger of his life, Norregaard drew his revolver and fired two shots into the mob. The effect was instantaneous. The brutal cowards dropped Cox at once, and ran away like sheep toward their encampment, half a mile distant.

After tying a handkerchief around his head, and assisting Cox to get up, the party hastily ran to the residence of Norregaard and brought Mrs. Norregaard and her eight-year-old son to the trolley, upon which the whole party returned to Fengtai.

Cox then sent a command out by wire for all the engineers working on the Lu Han railway to give up their posts and retire with him to Tientsin to await the settlement of the riot by the Chinese officials, as well as to obtain some guaranty of future good conduct on the part of the government troops, who were yet to arrive from the southwest.

After dressing the wounds of these two gentlemen they took the train for Tientsin, and the writer returned to Peking.

The next day, or two days after the riot, I received a message from Hu Chih-fen, the governor of Peking, requesting me to call upon him at Imbeck’s hotel at once. I found the old gentleman with twenty retainers awaiting me. He stated that he had been appointed a special commissioner by the Empress Dowager to proceed to Lukouch’iao and investigate the circumstances connected with the riot two days previously, as well as to inquire minutely into the condition of two wounded soldiers reported by their officers to have been wantonly shot and dangerously hurt[8] by Captain Norregaard. He desired me to accompany him into the camp, and examine the wounds as an expert, so that he could make a proper report to the Empress.

I confess I did not much care to go alone into the camp of the famous Kansu, haters of foreign, but I was under many obligations to Governor Hu, and wanted to oblige him. Besides, there was a spice of adventure about the undertaking that was pleasant to a correspondent. I preferred to go armed, however, as, although knowing a revolver would be of no use in a hostile camp for offensive warfare, yet if Governor Hu remained with me, I reasoned, I could by placing a revolver to his head and holding him hostage prevent any harm to myself—believing as I did that the Empress’ special commissioner’s person would be sacred in the eyes of her generals. The sequel proved how false this belief was, and that before many hours.

So I requested permission to return home for a moment to obtain a small instrument I might need, as well as to inform my wife of my leaving the city, that she might not be anxious if I did not return until after dark.

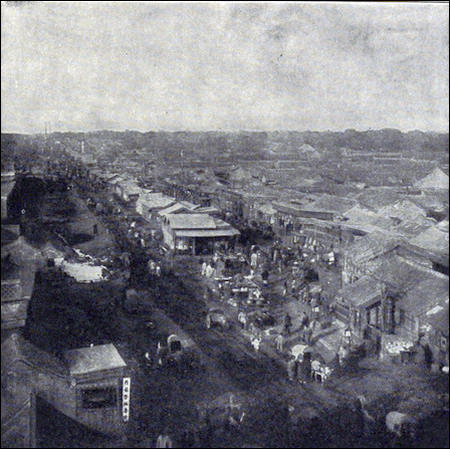

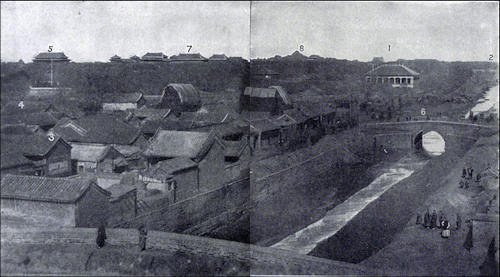

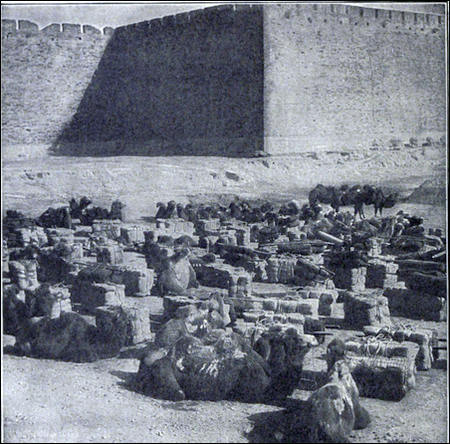

MAIN STREET OF PEKING FROM THE CITY WALL

This shows the main street of Peking—its “Market Street,” as Philadelphians might say, or its “Strand,” from the English point of view. Although a main street it is scarcely better than a country road, and busy trading seems to be going on in the foreground in the open air. Here and there a sign indicates that business is conducted within, and that unavoidable feature of a Chinese city, the open pool of stagnant water, is in evidence.

Governor Hu replied that I could get whatever instrument I needed at the railway hospital at Fengtai, and that he would send one of his retainers with a message to my wife. I insisted, however, that a return home was imperative, and that I would rejoin him in half an hour. Whereupon he decided to order tiffin in the meantime, and told me to hurry back, take tiffin with him[10] at the hotel, and we would then proceed to Machiapu, where a special train would be waiting for us.

I hastened home, obtained my Smith & Wesson six-shooter, and, after a good tiffin with Governor Hu, rode in a springless cart to Machiapu, entrained, and was speedily at the station at Lukouch’iao.

Upon our alighting from the cars we were met by a sub-official from the camps, and were accompanied by him, and about twenty Kansu soldiers, to the entrance to the railroad bridge, the site of the riot two days before.

Here Hu ordered the bridge watchmen to be brought before him, and he interrogated them as to the occurrences described by Cox and Norregaard. The two watchmen’s stories were the exact counterpart of the two foreigners’; they agreed in every particular, and placed the whole blame on the Kansu soldiers.

I was surprised at the fearless testimony of these two poor watchmen, one of whom was afterward murdered by the soldiers for testifying against them.

Hu now walked to an inn in the village of Lukou, and told the sub-official to order the general and colonels of all the regiments quartered near-by to appear before him at once, as he would hold an investigation by order of the[11] Empress. He and I drank tea until they arrived.

The first, a General Chang, appeared in about fifteen minutes. We knew some one of importance was coming by the hubbub in the courtyard, the murmur of voices, and the sound of horses’ moving feet. Then a soldier appeared in the doorway, and announced:

“General Chang, of the Kansu cavalry, has arrived.”

“Ch’ing,” replied Hu, and immediately there stood before us as ferocious looking a ruffian as the world could well produce. A tall, weather-beaten man, fifty years of age or more, with rather heavy (for a Chinaman) yet black mustaches, and a more than ordinarily prominent nose; dressed in a dark blue gown, satin high-top boots, official hat with premier button and peacock feather, held at right angles from the rear of his button by an expensive piece of jade. His eyes were deep-set and small, and the whole expression of his face was ferocious and cruel.

He only slightly inclined his head to Hu, took no notice of me, and, ignoring Chinese ceremony, proceeded at once to the highest seat in the little room, and seated himself in the intensely stiff attitude of the god of war one usually sees in a Chinese temple. Hu seemed completely taken aback at this insolence,[12] and allowed the ruffian to remain in the seat of honor throughout the interview.

Before Hu had become acquainted, by his polite questions, with the age, rank, and province of his haughty guest, four other military officers of the rank of colonel and lieutenant-colonel had arrived, namely, Chao, Ma, Wang, and Hung.

Finding their general in the head seat, and noting his imperious bearing, they took their cue from him and maintained throughout the interview the most lofty manner, and treated Hu more like a subordinate than a civil officer of the premier rank and a special high commissioner of Her Majesty the Empress Dowager.

After a few mouthfuls of tea, Hu informed them in most polite and bland terms that as he was Director-General of imperial railways, as well as Governor of the metropolitan prefecture of Shuntienfu, Her August Majesty, the Empress Dowager, etc., etc., etc., had appointed him to visit the general and officers of the Kansu regiments in camp at this place, to inquire into the circumstances of the late riot.

He stated also that he came gladly because he felt that, by careful inquiry into the circumstances, it could doubtless be proved that the soldiers had acted in a rowdy manner without the knowledge and consent of their officers, and[13] that by a well-worded report the latter would escape all blame, and the matter could be settled to the satisfaction of all, especially as no lives had been lost, or imperial property destroyed.

General Chang haughtily replied that it was entirely unnecessary for Hu to come out at all; that Prince Ching had sent a messenger to him in the morning, and the Empress was doubtless aware, through this messenger, of the exact circumstances of the case already, and consequently Hu might as well return and save himself any further trouble.

His impudent manner indicated that, having given his own side of the case to a trusty henchman of Prince Ching’s, and obtained that influential prince’s partial testimony in his favor, he did not care one way or the other for anything Hu might report later.

But Hu, although very quiet and apparently humble, was firm and determined, and upon the conclusion of Chang’s defiant speech, replied:

“It is very well that Her Majesty should have as early a report as possible, and I am glad you have informed her of the events; but as I have been appointed to inquire officially, I should not return without having done my duty, and I hope that none of the officers present will refuse any testimony I require, and compel me to report a lack of respect for Her Majesty’s commands.”

Chang bit his lips and pulled his mustaches fiercely at this, but said nothing. But Colonel Chao took up the cudgels in a most unexpected manner. Excitedly rising, he commenced a most venomous speech against the introduction of railways into China. He denounced them as the instrumentality of the foreigner to subjugate the country, declaring they had taken away the employment of thousands of carters, boatmen, and wheelbarrow coolies; that they had raised the price of rice and other cereals; that they employed foreigners at high wages, who carried all the money out of the country at the same time that they abused and maltreated the natives under their control, and wound up his rather long discourse by declaring that the abolishing of railways and driving into the sea of every foreigner was the duty of every loyal soldier or subject of the empire.

Hu mildly endeavored to interrupt him several times by telling him that the railways were all Chinese property, and the foreign employees were their Empress’ own employees; but Chao drowned Hu’s every utterance so that the old man, after several attempts, was, perforce, obliged to keep quiet until the irate colonel had exhausted himself and sat down blowing like a porpoise.

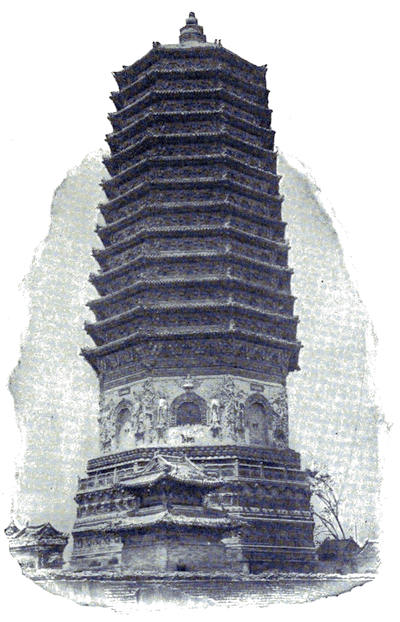

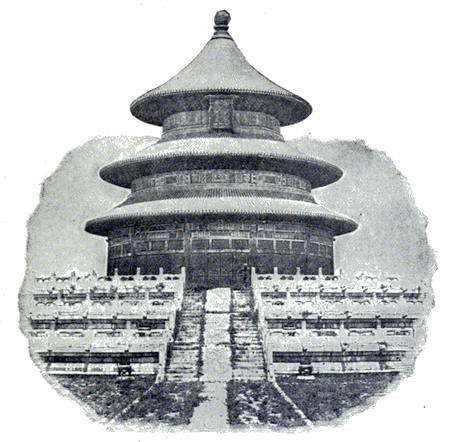

PAGODA NEAR PEKING

In and around Peking are to be seen many specimens of noble architecture; among which is this beautiful Pagoda, built hundreds of years ago. Such buildings are not erected now, and in some instances they are found standing almost solitary and alone, miles from any great city.

I knew Hu was very unwilling that I should hear all of this speech, which he realized I would perfectly understand, and I felt sure he regretted having brought along a surgeon versed in Chinese.

To me it was a revelation. I had heard that the Mohammedan troops from Kansu, under the famous general Tung Fu Hsiang, were ordered to Peking immediately after the coup d’état to support the Empress in her anti-foreign policy. I had heard that they were fanatical, ignorant, and intensely hostile to foreigners. But that they would dare to insult the Empress, in the person of a special commissioner appointed by imperial edict, and reveal the purpose of their general in such open language, and that before a foreigner, I would scarcely have believed short of the testimony of my own ears.

Hu realized that it was useless to attempt to argue with or conciliate these men, and at once set about the object of his visit, as yet unachieved, namely, to find out the condition of the wounded soldiers.

So, upon Colonel Chao’s finishing his diatribe, he politely turned to General Chang, without further noticing the enraged colonel, and said:

“I have been told two of your men have been wounded by one of the foreign engineers, and as I have a very skilful surgeon in my employ, who attends to all the people who are injured on the railway, I have brought him along to examine[17] your men, and if you will permit him I am sure he can heal them.”

He then introduced me as Man Tai Fu, my Chinese title. They sullenly acknowledged my presence, for the first time, by a slight nod in my direction, and General Chang asked Hu if he had an interpreter who could converse with me.

“Oh, he doesn’t need an interpreter,” replied Hu; “he has lived in China fifteen years, has sons and daughters born here, and speaks our language like a native.”

Upon this, my nearest neighbor, Lieutenant-Colonel Wang, relaxed a little, and observed that he had never talked with a foreigner, and would be glad to make my acquaintance. I replied that it was a mutual pleasure, and asked his age, province, and personal name, which pleased him greatly.

As it was rapidly growing darker, however, and we had not yet seen the wounded men, Hu cut short our budding conversation by requesting General Chang to show them to me.

He curtly declared, “They are in camp half a mile away, and he can go and see them if he wants to.”

“Will you go?” inquired Hu.

“Yes, if you will go with me,” I replied, not caring to venture alone into the hostile camp,[18] especially after what I had seen of the temper of their leaders; but I added, “I think it would be much better to have them brought here.”

“Yes, yes, that is better,” said Hu; but General Chang interrupted him by saying:

“Impossible! they are too ill to be moved, and on this cold day would surely take cold and die.”

“Have them well wrapped up and brought quickly,” said Hu, without paying attention to the interruption, “for it is getting late, and although I have ordered the city gates not to close until our return to Peking, I am anxious to avoid keeping them open any later than necessary.”

General Chang then strode across the room to the door opening into the court, where upwards of three hundred of his men were standing packed like sardines, listening to everything we had been saying, as Chinese custom is, and shouted out:

“Bring the two wounded men in here.”

Now all of the men had seen Governor Hu snubbed, had heard Colonel Chao revile him and his railroads, and had heard their general say the men would die if brought out in the cold; so, supposing they were to act in a similar way, they, upon receiving this order, held a confab, and a very noisy confab, too, among themselves for a few moments before replying.

As I watched Governor Hu’s face grow pale as the commotion increased, I felt that we were in real danger right in the midst of the officers, and that my previous view that I could insure my own safety by threatening Hu’s life would avail nothing, as they hated him as much if not more than myself. I could plainly see that I must change my man, and make the general my target if the necessity arose.

Then a voice shouted out from the soldiers almost the exact words of the general.

“They cannot be brought here; the exposure would kill them.”

Chang looked at Hu to see what effect this had upon him, but Hu was no coward, and calmly replied:

“They must be brought if it kills them; by Her Majesty’s commission, I demand it.”

The general was bluffing; he sullenly gave in.

“Bring those men at once, dead or alive, you scoundrels,” he shouted stentoriously, “and in a hurry, too!”

“Aye, aye,” responded a hundred throats, and a number of men left the courtyard at once.

The camp must have been some distance away, for it was over half an hour and nearly candle-lighting time before the two men, each carried on a litter on the shoulders of six men, were brought in.

The first man was covered up in blankets, and pretended to be unconscious; but he proved to have no fever, had a slow pulse, and absolutely no wound but a scratch at the lower end of his right shoulder-blade, which might have been made by a finger-nail, or possibly by a pistol-ball grazing the skin.

The hypocrite Chang bent over me as I was examining, and asked in a voice of pretended sympathy:

“Is he badly hurt? Can he recover? And how long will he be ill?” to which I replied:

“Not badly hurt; he will recover; and I will guarantee he is all right day after to-morrow if you will send him at once to my railroad hospital at Fengtai.”

I said this, thinking that the British minister in Peking, Sir Claude MacDonald, might be glad to get hold of these men for proper punishment, and that if they were in the hospital at Fengtai they could easily be obtained; otherwise I would have ordered this man to be dismissed at once as shamming.

The second man also pretended to be much worse off than he really was, but he did in fact have a small bullet-wound in his shoulder, from which I extracted with forceps a fragment of blue cotton cloth, and then sent him also to the hospital, predicting his recovery within ten days.

General Chang thanked me for my interest, and promised to reward me for my services when the men recovered; then, nodding coolly to Governor Hu, he and his staff marched out of the inn and left us, and allowed a subordinate to escort us to the special train that brought us down, which was as great a lack of courtesy and positive insult as he could give to the Empress Dowager’s high commissioner.

Our return journey was without incident. The city gates were open awaiting us, and were closed immediately upon our entrance. Governor Hu immediately memorialized the throne, stating the result of his inquiries, reported the impudence of Colonel Chao, and made the request that he be turned over to the Board of Punishments for a penalty.

The Empress acknowledged the memorial, and she decided to deprive Colonel Chao of one step in rank, degrading him to a major. This appeared in an edict at once; at the same time she commended Hu for his promptness and general ability.

But, alas for Governor Hu! General Tung Fu Hsiang, the man who was to prove the curse of China, was unacquainted with all these circumstances, and had yet to be heard from. This man had obtained his reputation first as a brigand, and afterward as a leader of Her Majesty’s army[22] in putting down a rather formidable rebellion of the Mohammedans in his own province of Kansu. Bold, cruel, and unscrupulous, he had murdered his own provincials, who were but poorly armed and without military discipline, in a most ruthless manner, and had not only suppressed the uprising, but nearly exterminated the rebels.

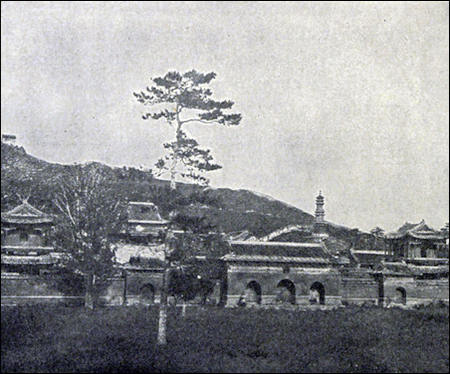

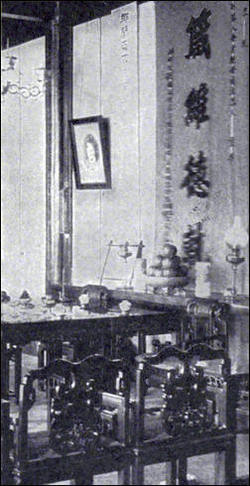

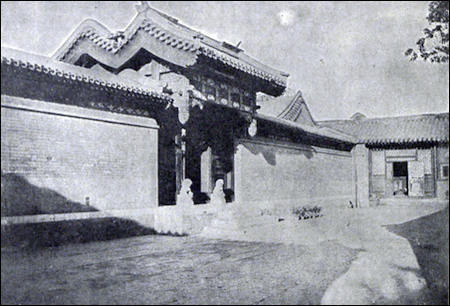

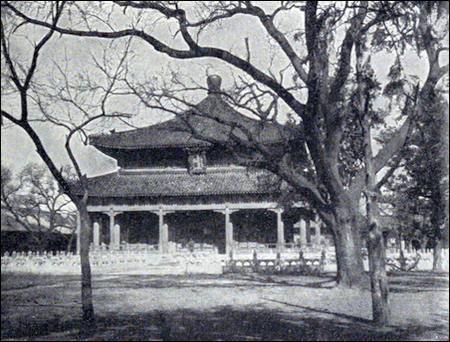

A temple in the Summer Palace grounds

His fame spread far and wide as a wonderful general, so that when the Empress again assumed power by forcibly seizing the throne from the[23] weak but good-intentioned Kuang Hsu, she decided at once to bring this man Tung and his Kansu ruffians to Peking to assist her in maintaining her authority against all comers. It was en route to Peking that his advance corps, under General Chang, had the trouble at Lukouch’iao.

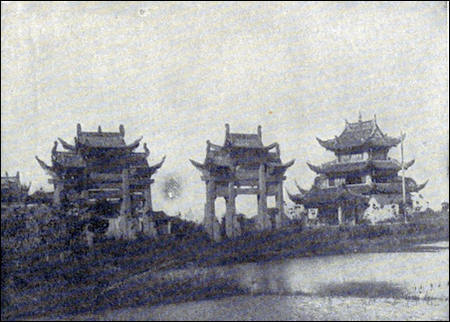

MEMORIAL ARCHES

It is doubtful if we should have been able to learn so much of the “Forbidden City” and of the beautiful and remarkable things to be seen in the Palace grounds had it not been for this Siege. These are most beautiful from a Chinese point of view, the architecture dating back for many ages. These arches are built of immense blocks of stone, beautifully fitted and arranged.

As soon as Tung Fu Hsiang learned of Colonel Chao’s degradation, he was wild with rage,[24] taking the view at once that the insult was not only upon Chao but also upon himself.

Knowing the Empress was in a precarious condition without troops she could depend upon, this courageous adventurer, at his first audience upon his arrival in Peking, promptly told Her Majesty that unless Chao were restored to his rank immediately, and Governor Hu were removed from his offices as Governor of Peking and Director-General of Railways, as well as prevented from taking his seat in the tsung-li-yamen, or foreign office, to which he had just been appointed, he, Tung, would disband his army and return to Kansu at once.

The Empress remonstrated with him in vain, alleging that Hu had only done his duty, and that with his knowledge of foreigners he would be a valuable official in the tsung-li-yamen. But Tung remained obdurate, and the Empress reluctantly yielded and dismissed Hu to private life, where he has ever since remained.

As Governor Hu was alone responsible, by his firm friendship for the English, for obtaining for the Hong Kong and Shanghai banking corporation, an English company, the loan for extending the Peking-Tientsin railway, and had signed the contract which gave the real control of the railway to the English stockholders, his dismissal from office should have been prevented by diplomatic[25] action. As it was, only a mild remonstrance by the diplomatic representative of Great Britain was made, and the tsung-li-yamen passed it, as usual, unheeded. Governor Hu remarked to me a few days after his dismissal, very bitterly, “If I had been the friend to Russia I have been to England I should not now be in disgrace.”

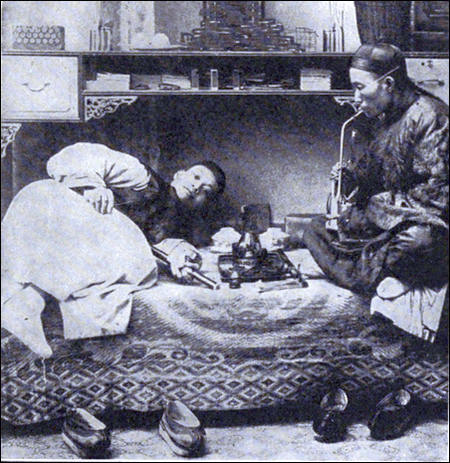

He was replaced in the office of Governor of Peking by Ho Yun Nai, and in the office of Director-General of Railways by Hsu Ching Ch’eng, ex-minister to Germany and Russia. The first of these officials was a well-known hater of foreigners, who was suggested by General Tung. The latter was a corrupt opium-eater, already in the pay of Russia, as Chinese president of the Manchurian railway, and was suggested by a high palace eunuch, himself in the pay of Russia.

Tung’s influence in Peking now became all-powerful; his soldiers swaggered about the streets in their fancy red and black uniforms, growing daily more menacing to the foreigners they passed, until finally several incipient riots occurred which resulted in one foreigner having several ribs broken and others being assaulted, so that a few of the foreign ministers united and requested that his army corps be removed some distance from the capital. The Empress agreed reluctantly to this, but only sent them a little over a hundred li away.

Tung, early after his arrival, made the acquaintance of Prince Tuan, a stupid, ignorant Manchu, who soon became his complete tool. The question of a successor to the sickly Emperor, Kuang Hsu, had been discussed for several years, as he had as yet no issue, and seemed likely at any time to die childless. The sons of Tuan, of Duke Lan, and of Prince Lien were all considered eligible, and from amongst them must be chosen the future Emperor of China.

Tung saw that Tuan would become his tool much more completely than either of the others, and proposed an alliance between Tuan’s son and a daughter of his own, agreeing to support the younger Tuan’s candidacy for the throne, with his whole army, if necessary, to accomplish the purpose. Tuan agreed to this, but stated the succession must be made without its being known that he was under obligations to favor Tung’s daughter, but that when an apparently open competition for selection of an empress was made, and the various eligible damsels appeared at the court, Tung’s daughter should arrive from Kansu in time and be the favored recipient.

On this understanding everything became smooth sailing, and the consummation of their plans, as far as Tuan’s interest was concerned, occurred, when in solemn conclave of all the[27] princes of the blood and great ministers of state, on January 24, 1900, Pu Chun, son of Prince Tuan, was solemnly named as successor to the previous emperor, Tung Chih; and poor sickly little Kuang Hsu was succeeded without a successor to himself, but a successor to his uncle being appointed, which, by imperial edict, makes him an interloper.

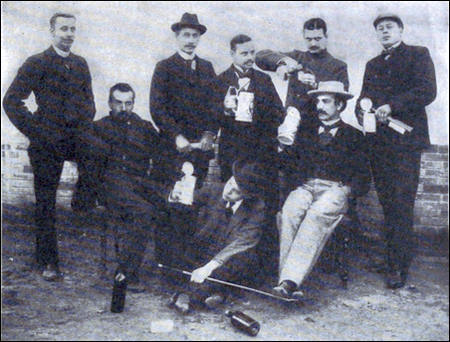

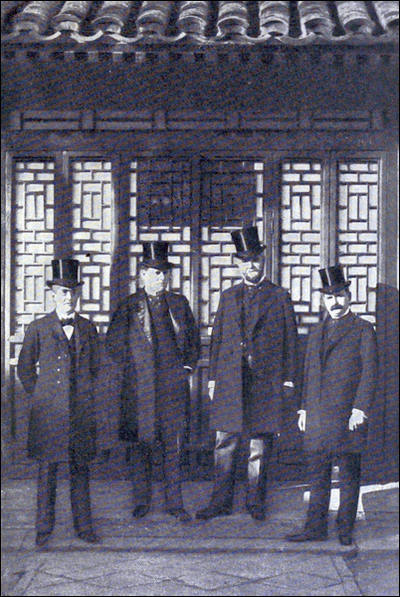

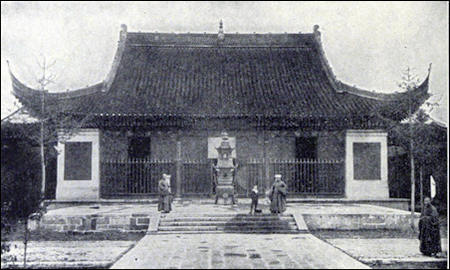

CHINESE STATESMEN

A group of Chinese officials of the highest class; in Peking, previous to the Siege.

This was a nice piece of vengeance the Empress Dowager worked out, partly to avenge herself on her nephew for his unsuccessful attempt to shelve her and run his government himself. Tung’s intensely anti-foreign sentiments soon made him many friends at court, among the oldest and most conservative Manchus, as well as some of the Chinese. But it was among the former that his influence was greatest.

Many of these men, stupid in the extreme, and too cowardly themselves ever to have originated any of the designs that have since been worked out, joyfully fell in with the plans inspired by his ambition for his own success, but always put forward as for the salvation of his country.

Hsu Ting, Kang Yi, Ch’i Shin, Ch’ung Ch’i, Ch’ung Li, Na T’ung, and Li Ping Heng became his warmest friends and admirers, and formed a cabal which soon controlled the entire administration of government. By Tung’s direction all important offices, as they became vacant, or could be readily made so, were to be filled by the Manchu friends of the cabal or, if Chinese, as rarely occurred, then a Chinese who was of their own set and their own creature. This gave them a powerful patronage under their disposal in the lucrative taotaiships and[29] other posts formerly more or less evenly divided between Manchu and Chinese, but now almost entirely limited to Manchus.

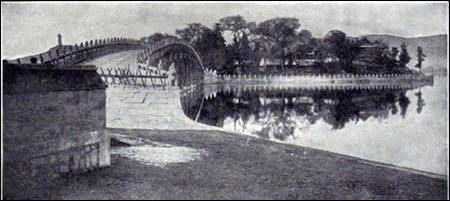

BRIDGE AT WAN SHOA SHAN, NEAR PEKING

That the Chinese appreciate the picturesque, both in situation and in architecture, is shown in this picture.

Kang Yi was sent on a mission southward through all the provinces to extort money to raise more armies, as well as to feel the pulse of the people in regard to, and encourage them in, their anti-foreign tendencies. Li Ping Heng was sent to examine and report on all the defenses of the Yangtze valley, as well as to denounce any official of progressive tendencies. Yu Hsien was to succeed the latter as Governor of Shantung, and to sow in that province the seeds of disorder and riot that yielded such a bitter crop when they ripened; just as only a poorly-organized, semi-patriotic, but fully[30] looting society could do—an organization that was to be called the I Ho Ch’uan or Boxer organization.

This programme has been fully carried out, and what the result has been will be described in part only (as we in the north only know part) in the following chapters.

CHAPTER II

YU HSIEN APPOINTED GOVERNOR OF SHANTUNG, REMOVED BY BRITISH DEMANDS, ONLY TO BE REWARDED—YUAN-SHIH KAI SUCCEEDS HIM—CAUSES OF HATRED OF CONVERTS BY PEOPLE AND BOXERS—THE BOXERS AND THEIR TENETS—THE EMPRESS CONSULTS ASTROLOGERS

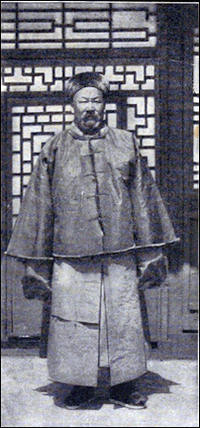

HSU CHING CHENG

Ex-minister to Germany, member of Tsung-li-yamen. Beheaded Aug. 9, for favoring peace.

WITH the appointment of the Manchu Yu Hsien as Governor of Shantung province, to be the successor to the anti-foreign Li Ping Heng, whose removal the Germans had succeeded in effecting, commenced the governmental recognition of the Boxers’ society as an agent to expel missionaries, merchants, and diplomats alike. This man, whose hatred of foreigners exceeded that of his predecessor, was no sooner in office than he caused the literati all over the province to revive among the masses the “Great Sword” and “Boxer” organizations, which had been a bit shaken by the removal of their encourager, Li Ping Heng.

The foreign residents of Shantung, who had hoped the new government would be an improvement over the old, soon found they were worse off than before. The native Christians were persecuted most bitterly by their heathen neighbors, and their complaints at the yamens treated with disdain.

Yu Hsien did his work thoroughly and rapidly, knowing the foreign power which had compelled the removal of Li Ping Heng would also cause his removal. But as he was only placed in Shantung for the deliberate purpose of making trouble, his removal would mean for him a better post as the reward of his success.

This came when the “Boxers” of Chianfu prefecture attacked and murdered a young missionary of the Church of England named Brookes, who was traveling from Chianfu city to his station of P’ingyin.

The British government demanded his removal from office, and the Chinese government acquiesced; but their treatment of him upon his arrival in Peking alone would have sufficed for an intelligent observer to make clear the policy of the Empress without any other confirmatory evidence, abundance of which, however, was not lacking.

Instead of being reprimanded, we find him granted immediate audience with the Empress,[33] and the next day’s Court Gazette informed an astonished world that the Empress had written with her own brush the character “Fu,” happiness, and conferred it upon him publicly. Then followed his appointment as Governor of Shansi, a rich mineral province in which the “Peking Syndicate,” an Anglo-Italian company promoted by Lord Rothschild, held valuable concessions. In this province, too, were the long-worked missionary establishments of the American Board (Congregationalist) and the China Inland Missions.

The Chinese all understood this as an appreciative approval from the Empress, and so, too, did all the older foreign residents; but the diplomatic corps, beyond a feeble remonstrance from the British and United States ministers, did nothing. So, to-day Yu Hsien is pursuing in Shansi the same policy he did in Shantung, the results of which must turn out similarly.

The Empress appointed as successor to Yu Hsien the man who had turned traitor to the unfortunate young Emperor, Kuang Hsu, Yuanshih Kai. This man is well known to foreigners. He was formerly Chinese resident at Seoul, and it was largely due to him that the China-Japan war occurred. After the war he was made commanding-general of a force of foreign-drilled troops stationed at Hsiao Chan, south of Tientsin.

Yuan is one of the shrewdest and most unscrupulous men of China, and the Empress, in rewarding him by this appointment for his service to her in making known the Emperor’s purpose to send her into captivity, gave power to a man who would desert her, when it suited him, as quickly as he had the weak, but well-meaning, Emperor.

Yuan, upon his arrival in Shantung, found himself in a difficult position. If he encouraged the Boxers he would make enemies of the foreigners. If he was severe with the Boxers he would be removed by the Empress, influenced as she was by General Tung Fu Hsiang and his cabal.

Being a man of great wealth and having a perfect knowledge of the situation, he steered a course that would obviate his striking on either rock. He subscribed to the Boxer organizations where they obeyed him, and punished them where they were refractory, and soon had Shantung, which was in a ferment when he took charge, fairly well in hand.

He gave it to be understood that they would, in time, be able to exterminate foreigners; but they must patiently drill and practice gymnastics until such time as he considered that they had reached perfection, and must not on any account injure a foreigner too early, as it would bring[35] down trouble before the government was prepared to meet it. At the same time he allowed them to pillage and murder the native Christians freely, well knowing this would please the Court, and would not be actively taken up by the foreign powers as an infringement of treaty-rights, which it certainly was.

Evidently his idea was, too, that Tung Fu Hsiang’s plan to drive out and exterminate all foreigners was an entirely impossible one, and that if he could keep his province from committing any overt act that would lead to a foreign war, for a year’s time, the Chihli authorities, all the Manchus, and Tung Fu Hsiang himself would have brought on the war and ruined themselves, while he, Yuan, would then have a chance to cut loose from the conservatives, and come to the front in the new regime, which must come, as a reformer. That he will do this I fearlessly prophesy.

The Boxer organization was not started by Tung Fu Hsiang, but was, by his advice, given imperial sanction and infused with new life and activity. A similar organization, known in olden times in China under the same name, was a volunteer militia for national defense. The recent revival has not only been for defense, but to exterminate the Christian religion and the people who brought it.

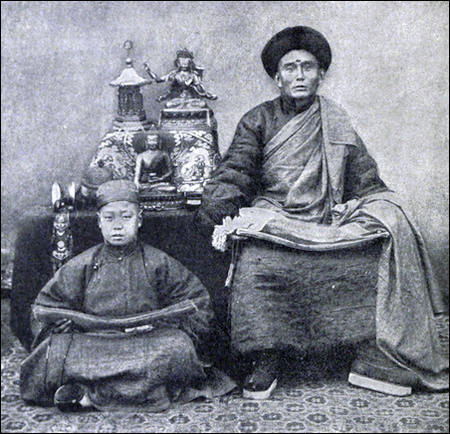

A MONGOLIAN LLAMA

Great learning is possessed, according to the Chinese standard, by these priests. The young student or candidate on the left is receiving instruction.

That the Chinese people have much to complain of from the aggressive attitude of many native Christians, and particularly the Roman Catholic Christians, no sane man will deny. For years it has been the practice of the priests and of many of the Protestant missionaries to assist their converts in lawsuits against the heathens,[37] and to exert an unjust influence in their behalf. To “get even” with an enemy it is only necessary for a convert to tell his priest or pastor that he has been persecuted in some way for his religious belief, to induce the missionary to take up the cudgel in his defense. I have heard heathen Chinese often assert that these men (converts) appear good enough to their priests, who see very little of their ordinary behavior, but behind the father’s back they are overbearing and malicious to all their neighbors, who hate them because they fear them.

After years of residence in China, I have come to the conclusion that it has been a mistake of the Powers to insert in their treaties provisions making the preaching of Christianity a treaty-right, in spite of Chinese objection. Nearly all of the riots in China have come from attempts to force the Chinese officials to stamp deeds conveying property to missionaries for residences or chapels. The animosity incurred in forcing a missionary establishment upon an interior city, town, or village is not obliterated in a lifetime. It may be barely tolerated in time of peace, only to be demolished when the country is disturbed. This applies to the China that has been—barbarian, uncivilized China.

Should the reformers come into power, and religious toleration be granted as the result of[38] civilization, then there would be no reason why the missionaries should not work in the more remote parts of the empire; but China, as it has been and is, would be much more peaceful for all concerned if the proselyting work was carried on only in the treaty ports. I don’t expect any of the missionary body to agree to this statement, but doubtless many of their supporters, thinking people, who will take the trouble to reason it out, will believe it, supported as it is by the testimony of all the residents of China acquainted with the problem. There are many reasons for the Chinaman’s hatred of the foreigners, but his religion is the chief one.

In the late riots the railways have been attacked and destroyed, but that came only after a half-year’s successful campaign against the converts had led them to want to root out the people who brought both the religion and the railways. While I am a Christian myself, and would gladly see China a Christian nation, I cannot help seeing that the policy which has been pursued in forcing Christianity upon the Chinese, in the aggressive manner we have, practically at the point of the sword, has not been a success, and has given to such men as Tung Fu Hsiang a powerful argument with which to persuade his ignorant followers to exterminate alike the foreigner and his converts.

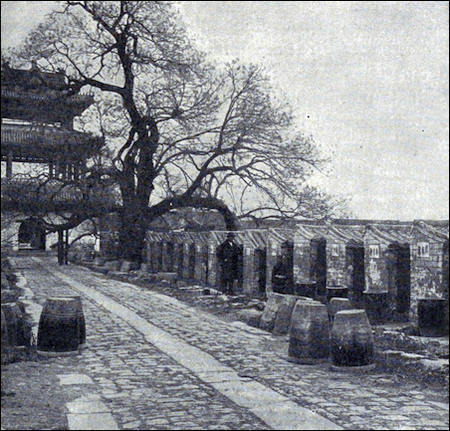

INDIVIDUAL EXAMINATION ROOMS FOR CIVIL SERVICE DEGREES

A remarkable feature of Chinese social and political customs is the method of selection for public office. The candidates for examination are installed in the little rooms or houses shown in this picture; a supply of water is placed in the large jars at the entrance, and the candidate is expected, regardless of the pangs of hunger, to remain constantly in this little room until he shall have passed this examination, which sometimes lasts two or three days.

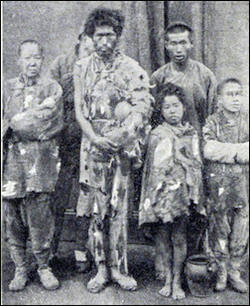

The Boxers are principally of two sorts: the ignorant villager and the city loafer or vagabond. The first easily becomes a fanatical enthusiast; the latter has joined simply to obtain loot. When[40] it became an assured fact that the Empress sanctioned the movement the ranks were rapidly filled, because rewards and preferment were held out as inducements to serve, and the majority of China’s population, being poverty-stricken in the extreme, would join any movement that promised an increased income. The Boxer headquarters was the palace of Prince Tuan in Peking. From this place emissaries were sent with instructions, first into Shantung and afterward throughout Chihli, to coöperate with the already-existing secret societies, as well as to organize new companies. Every city, town, and village was visited, the head men consulted, and the young men and boys enrolled.

Their gymnastic exercises, from which they derive their name, were taught them, and they were promised that when they had attained perfection they would be given service under the Empress with good pay and rapid promotion. They were told that if they would go regularly through the ceremonies prescribed every day, in from three to six months they would acquire indomitable courage, and would be invulnerable to bullets and sword-cuts, and that the youngest child would be a match for a grown man of the uninitiated. That thousands believed this nonsense there is no doubt; and thousands of little boys from ten years of age upward[41] eagerly enrolled. The exercise consisted of bowing low to the ground, striking the forehead into the earth three times each toward the east, then south, then throwing themselves upon their backs and lying motionless for several minutes, after which they would throw themselves from side to side a number of times, and, finally rising, go through a number of posturings, as though warding off blows and making passes at an enemy. As a uniform they were given a red turban, a red sash to cross the chest, and red “tae tzio,” or wide tape, to tie in the trousers at the ankle.

The time set for their uprising was fixed for the Chinese eighth moon, seventeenth day, being two days after the annual “harvest festival,” or pa yueh chieh. The premature explosion of the movement was not anticipated by those who originated it, but it is largely due to its going off at half-cock, so to speak, that enabled the Powers to combat it so readily after they were aware of its existence as a real government agency.

Doubtless the government intended before that time to give arms and ammunition to all grown men; but, in the first place, they were to arm themselves with swords and spears only. They were told, among other things, that at the time of their uprising myriads of regiments of angelic[42] soldiers would descend from the skies to assist them in their righteous war against foreigners.

The Empress herself believed this story as well as the possibility of their being invulnerable to foreign bullets. She is exceedingly superstitious, and in the early part of May consulted the Chinese planchette to read her destiny. Two blind men, holding the instrument under a silk screen, wrote in the prepared sand underneath the following message from the spiritual world:

“Ta Chieh Lin T’ou

Hung Hsieh Hung Liu

Pai Ku Ch’ung Ch’ung

Chin Tsai Chin Ch’in

Tan Kan

T’ieh Ma Tung Hsi Tscu

Shui Shih Shui Fei

Ts’ai pai shiu.”

The interpretation of this would read in English:

“The millennium is at hand;

Blood will flow like a deluge;

Bleaching bones everywhere

Will this autumn time be seen.

Moreover, the iron horse

Will move from east to west;

Who’s right and who’s wrong

Will then be clearly established.”

The millennium is used by the Chinese as a critical period in a cycle of years. The iron[43] horse is supposed to mean war. The Empress understood this to mean that in the war which she intended to commence it would be clearly shown by her success that she was right.

A GROUP OF PROMINENT CHINESE OFFICIALS

These men are connected with the Tsung-li-yamen.

The Boxers, however, completely spoiled all her plans by their eagerness to obtain loot. Being promised the spoil of the foreigners after the contemplated uprising in the eighth moon,[44] they regarded the property of the Christians and their teachers as already mortgaged to them; and, fearful lest the government troops would acquire some of it, they commenced the campaign themselves before the appointed time. How the government at first made feeble efforts to restrain them, and afterward completely gave in and joined with them is now a matter of history.

The monumental idiocy of the idea that China could successfully defy the whole civilized world was only possible to such brains as those possessed by the densely ignorant Manchus who surrounded the Empress as her cabinet. Several of the tsung-li-yamen ministers, like Prince Ch’ing and Liao Shou Heng, weakly tried to reason them out of it, and were promptly given back seats.

Of the others remaining in the tsung-li-yamen after their retirement, none dared say anything against the movement for fear they also would be shelved. But as they were not strong enough to please the Empress in her final dealings with the foreigners, she, a few days before the commencement of the siege, appointed Prince Tuan as head of the yamen, in place of Prince Ch’ing, and at the same time appointed two fire-eating foreign-haters, Chi Shui and Na T’ung, to seats in that obstructive body. These men, with Tung[45] Fu Hsiang and the cabinet, must be held responsible for the murders of Baron von Ketteler, F. Huberty James, David Oliphant, H. Warren, Ed Wagner, and the other civilians and guards killed during the siege, as well as for many missionaries in the province that have doubtless perished, but of whose fate we, being besieged, had no certain knowledge.

That the Powers, in the settlement of their crimes, will treat them as murderers, as they are, we can scarcely doubt, and we hope none of them in any way implicated will be allowed to escape capital punishment.

CHAPTER III

CABLES TO AMERICA DESCRIBING GROWTH OF BOXER MOVEMENT FROM JANUARY TO JUNE, 1900

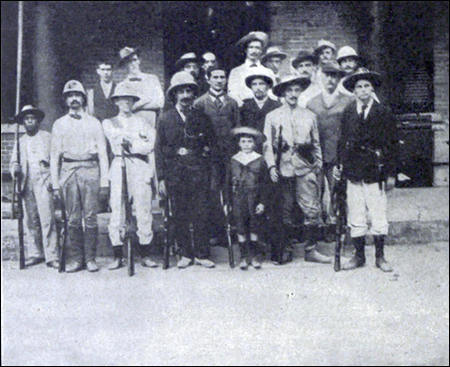

CHUNG LI

Manchu Boxer Chief

THE murder of the Church of England missionary, Brookes, in Chinanfu prefecture, Shantung province, by the Boxers, was the beginning of the explosion. On January 4, 1900, I cabled home the occurrence of the murder. On January 5 I cabled that the Americans in Taianfu, two days’ journey by cart south of the scene of the murder, were in danger, and that the United States minister had requested that they be protected; also that the Empress Dowager had expressed to Sir Claude MacDonald, through the tsung-li-yamen, her horror at the deed, and from thenceforth, under the respective dates given below, I sent cables recording the Boxer progress.

January 13. Christians in Shantung are being constantly pillaged by marauding parties of Boxers.[47] The Taianfu district is especially dangerous, as the prefect will not allow them to be interfered with. Dr. Smith, of Pang Chuang, in northern Shantung, has also written and telegraphed the United States legation that matters in his district are in the same condition. Christians murdered, chapels burned and looted, and no redress obtainable from the officials.

January 15. An imperial edict was issued yesterday which really commends the Boxers, and is sure to cause trouble. Upon Baron von Ketteler representing this to the tsung-li-yamen he was given no satisfactory answer to account for it.

January 24. Boxer movement is rapidly spreading, and the situation fills many with alarm. Prince Tuan’s son has been chosen as the successor to the Emperor, which is an unfavorable omen.

January 25. An edict has been promulgated apparently from the Emperor, but really from the Empress Dowager, stating that, because of his childless condition and infirm health, he has decided for the good of the state to appoint Pu Chun, son of Prince Tuan, as his successor.

February 5. Although the Boxer movement continues to increase in the northern provinces, Peking remains quiet.

February 10. The anti-foreign crusade is proceeding apace. Jung Lu, Hsu Tung and Kang Yi have assumed great power, and are constantly[48] with the Empress. The Boer successes in the Transvaal are being used to show the masses that a very little country can defy a big government if only the hearts of the people are in the struggle. British prestige here declining rapidly as a consequence. A Boxer mob has attacked the Germans building the railway in Shantung, and driven the foreigners away from their work. As Baron von Ketteler insists upon their going on with the work, the tsung-li-yamen finds it difficult to please both the throne and the foreigners.

February 12. A letter received from a Presbyterian missionary in Chinanfu states that over seventy families of Christians have been mobbed and looted in his district, and that they can obtain no redress from the local officials, and that the Boxers, knowing this, are rapidly increasing and growing bolder.

February 15. Imperial edict orders the suspension of any native papers showing reform tendency, and the editors to be imprisoned.

February 19. The annual audience with the foreign ministers took place with most scant ceremony and in a shabby apartment. This was done with the direct purpose of insulting them, but none remonstrated.

February 23. A French priest from Tientsin informs me that all that district is pervaded by the Boxers, who openly avow they are drilling to[49] come to Peking and drive out and exterminate all foreigners.

February 25. Several thousand armed Boxers have possession of the German railway building at Kaomi in Shantung, and state their purpose is to drive out the foreigner.

February 28. Yuan Shih Kai, Governor of Shantung, has sent a private messenger, an ex-drillmaster in his army corps, to Baron von Ketteler, the German minister, to say he will disperse the Boxers at Kaomi and restore quiet.

March 14. The man who obtained for the British syndicate the concession known as the Peking syndicate’s Shansi concessions to mine and build railways, was arrested for assisting foreigners to obtain concessions in China. Upon Sir Claude MacDonald’s demanding his release, the Empress promptly sentenced him to imprisonment for life. This will deter others from helping foreigners in any capacity.

March 15. United States Minister Conger, having protested against the Empress using Yu Hsien, ex-governor of Shantung, in any province where American interests are great, is greatly displeased to learn to-day that, so far from heeding, the Empress has actually appointed him Governor of Shansi, in which are not only a number of American missionary stations, but the interests of the Peking syndicate.

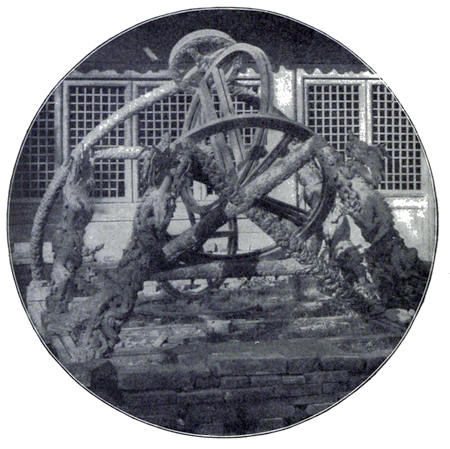

ANCIENT ASTRONOMICAL INSTRUMENTS

These peculiar instruments, which are of great astronomical merit, were made during the reign of Kublai Khan, A. D. 1264. An especial interest attaches to this illustration, on account of the attempt of the Germans to remove these instruments to Berlin, and the protest made against it by General Chaffee, of the U. S. Army. The engraving shows the instruments just as they were used for hundreds of years, before they were taken apart for removal to Europe.

April 24. Boxers aggregating nearly 10,000 have collected in one place near Paotingfu, and are very disorderly. The outlook is very threatening, not only there but at Tungchow, thirteen[51] miles south of Peking, and at Tsunhua, to the east of Peking. At all these places there are large American missionary stations.

May 17. Boxer movement has now assumed definite shape and alarming proportions. They have destroyed several Catholic villages east of Paotingfu, and are moving on the property of the American Board’s mission at Choochow at Kung Tsun. They have also looted the London mission’s premises, and killed several Christians. Boxers are now daily to be seen practicing in Peking and the suburbs. Situation is growing serious here.

May 18. I have been warned by one of the princes that I should take my family from Peking, as he states his own elder brother is a Boxer, and that foreigners are no longer safe in Peking. Have fully informed the United States minister of the situation, but he believes the official promises that all is well.

May 21. Foreign ministers have held a meeting and discussed question of bringing legation guards to Peking. The French minister favored this, but Conger opposed, stating he believed the government resolutely means to suppress the Boxers. No action was taken, it being decided to await further developments.

May 24. The tsung-li-yamen has not yet replied to the joint note sent them by the foreign ministers four days ago, requesting that the Boxers[52] be dealt with summarily. Unless an immediate and vigorous foreign pressure is applied, a general uprising is sure.

May 25. General Yang was killed at Ting-hsing, Hsien, near Paotingfu, either by his own soldiers or the Boxers. The soldiers then joined the Boxers.

May 26. The tsung-li-yamen has sent a vague and temporizing reply to the foreign ministers’ demand requiring the suppression of the Boxers. They are now regularly enrolled at the residences of several of the princes in this city.

May 28, a.m. The foreign ministers held another meeting to-day, but still deferred any action looking toward defense, as the tsung-li-yamen promises that it will shortly issue a strong edict that will suppress the Boxers. Pichon distrusts the Chinese promises and again advocates strong legation guards.

May 28, 4.10 p.m. Boxers have burned the bridge and destroyed the track at Liuliho, forty-five miles west of Peking, on the Lu Han railway, and are advancing toward Marco Polo bridge, twelve miles from here. The foreigners employed on the railway have all fled. The Tientsin train is overdue, and our communication with the coast threatened. The legations are just beginning to wake up to the fact that the Boxer movement is a perilous one.

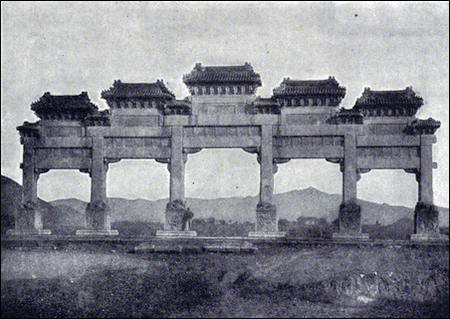

FAMOUS ARCH OF THE MING TOMBS

A celebrated traveler has said that it was worth encircling the earth to see this beautiful piece of architecture. Were it in the middle of Paris or New York, it would arouse great admiration and wonder; but, situated as it is in the midst of a wild and barren landscape, with huge mountains for a background, and representing as it does, the burial place of a mighty dynasty that for ages ruled a stupendous nation, it fills the beholder not only with wonder and admiration, but with awe.

May 29. At last it has come to our very door. Not only Liuliho and Changhsintien, on the Lu Han railroad, have been destroyed, but the junction at Fengtai, only six miles from here, has been attacked, looted, and burned, and all the foreign employes have fled to Tientsin. The foreign ministers now want guards badly, but, as it is not yet known whether the railroad is torn up[54] at Fengtai, there is no certainty of getting them quickly. The fate of a large party of French and Belgian women and children, known to reside at Changhsintien, is not known. Legation street is crowded with villainous-looking ruffians congregating to loot if opportunity offers. Until troops arrive the situation is precarious.

May 30. The tsung-li-yamen has requested the foreign ministers not to bring troops, assuring them they are not necessary; but the situation here has at last impressed them, and they have disregarded the yamen and ordered up guards at once. The populace are quite excited, and only need a slight cause to break out.

May 30, p.m. Viceroy of Chihli has forbidden guards taking train at Tientsin. Fifteen warships are reported at Taku.

May 31. Viceroy of Chihli has been ordered by the yamen to allow guards to take train for Peking, but requested ministers to bring only small guards, as last year. Troops have arrived.

June 1. Populace seems cowed and sullen. Riots in the city may now be prevented, but the problem of dealing with the movement is one requiring active diplomatic effort.

June 2. Station buildings south of Paotingfu on the Lu Han railway have been burned, and railroad destroyed. Party of thirty Belgians, including women and children, attempted to escape[55] to Tientsin, and were attacked by Boxers. Several known to be killed; fate of remainder unknown. Said to be surrounded when their native interpreter left to obtain help. Native Christians of the American Board’s mission at Choochow, and the American Presbyterian mission at Kuan-hsien, are pouring steadily into Peking, to escape murder at the hands of the Boxers. All their houses have been looted and burned.

June 2, 8 p.m. Serious dissension among Chinese ministers, Prince Ching favoring moderation and suppression of the Boxers. He is said to be secretly supported in this by Jung Lu and the tsung-li-yamen. Prince Tuan, supported by Hsu Tung, Kang Yi, and other intensely anti-foreign ministers, is favoring the Boxer movement. A crisis is imminent.

June 3. Church of England missionaries Robinson and Norman killed at Yungching by Boxers, and their chapels looted and burned. Boxers now have entire control of country from Tientsin to Paotingfu, and thence northeastward to Peking; native troops make no effort to suppress them. All religious and missionary work in North China is ended unless treaty powers compel observance of treaty provisions, and demand indemnities for each and every infringement.

June 4. Native converts from the west of Peking report that many thousand Boxers are[56] assembling at Choochow preparing to attack the foreigners and converts in Peking. The missionaries are convinced of the truth of this, and have informed their legations, who will not believe it. Dr. Taylor, of the American Presbyterian mission at Paotingfu, telegraphed to the American minister: “We are safe at present, but prospects threatening.”

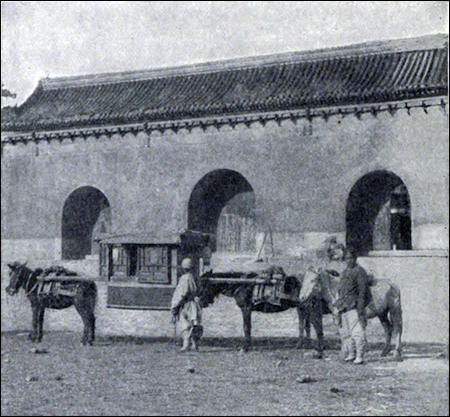

CHINESE LITTER

A typical method of Chinese conveyance. The litter is supported by poles to the backs of two animals, one in front, the other behind; in it the traveler can make himself comfortable. Beyond are the massive tombs of the Ming Dynasty, the famous arches of which are shown elsewhere.

June 4 (afternoon). Morning train arrived from Tientsin four hours late, owing to burning[57] of bridge and destruction of station building at Huangtsun by Boxers. Noon train now overdue, and, as the telegraph wires have been cut, is unheard from. Unless foreign troops are immediately placed to guard the railway we shall be cut off from help by way of the sea.

June 5. The American missionaries in Paotingfu have been attacked, and have wired for help. The tsung-li-yamen, when appealed to by United States minister, said it would telegraph the local officials to do so. But unless a relief party rescues them speedily their fate is certain death.

June 5, p.m. American Methodist mission at Tsunhua, with twelve children and four women, are beset and have wired for help. Trains from Tientsin have ceased to arrive; we are sending a courier overland with mails.

June 6. United States consul at Tientsin has wired the minister here that the Tientsin native city is in great excitement, and the situation is very serious; he advised that no women or children attempt to enter Tientsin from Peking, as they could not get through. Fate of Paotingfu missionaries unknown, as we can get no telegrams through.

June 6, p.m. United States consul wires from Tientsin that the situation there is growing steadily worse; an attack is imminent. Here in Peking[58] we are all collecting in the legations, but have insufficient arms and ammunition. Nevertheless we will make a determined stand.

June 7. I have overwhelming evidence that government officials are the real causes of the Boxer movement, acting under the direction of the Empress. Therefore the tsung-li-yamen and cabinet are supporting this movement, which is intended to exterminate all foreigners and Christian converts. The senile cabinet has persuaded the Empress this is possible, and they are quite willing to face the inevitable foreign war that their policy entails. The imbecility of this idea does not in any way interfere with the facts. The foreign powers should all prepare for war at once, or entrust the work to those powers nearest and best fitted to successfully undertake it. The sooner this is done the less will be the loss of life and property. The tsung-li-yamen yesterday promised Sir Claude MacDonald, through the secretary of Prince Ching, that if the foreign ministers would not press for a personal audience with the Empress, as they intended doing, Prince Ching would guarantee the restoration of the interrupted railway in two days, and a general amelioration of the condition of affairs. Another useless edict was put out to-day mildly enjoining officials to distinguish between good and bad Boxers, and punish only the bad.

June 7, p.m. Twenty converts have been murdered at Huangtsun, thirteen miles south. Missionaries at Tungchow have decided to abandon their valuable compound, and have telegraphed the United States minister to send them a guard of marines to escort the women and children to Peking. This compound contains a valuable college, and will inevitably be burned.

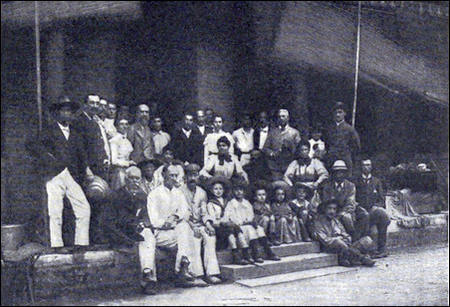

| Hsü Yung I Beheaded Aug. 9, 1900. |

Wang Wen Shao. |

Chao Shu Chiao Boxer Chief. |

Conger U. S. Minister. |

Yü Keng Minister to Paris. |

A group in front of the American Legation

June 8. Tungchow missionaries have arrived safely in Peking. Two other stations on the Tientsin railway, Lofa and Langfang, have been[60] burned, as well as the college compound at Tungchow. Tsung-li-yamen has refused to allow a reinforcement of the legation guards now in Peking. Although thirty warships of all nationalities are at Taku, Peking is completely isolated. Why America, after Secretary Hay’s much vaunted open-door policy, should allow her representative to be denied sufficient guard for the safety of himself and his countrymen is something one cannot comprehend, unless the representative has not kept his government well informed.

June 8, p.m. Most alarming situation. Missionaries from all compounds in this city compelled to abandon their homes and seek refuge in the Methodist mission, which is nearer the legations, being a half mile east of the United States legation. They have a few shotguns and very little ammunition, and are surrounded by their terrified converts, who have fled with them. Prince Ching’s promise of restored railway has proved false. The foreign ministers now realize they have been fooled again, and have lost two days’ valuable time. We call upon our government to make haste and rescue our wives and families quickly or it will be too late.

June 9. Emperor and Empress return to-day to the city from the summer palace. Another futile edict has been put out to further delude the foreign ministers. It is known that Prince[61] Ching has expostulated with the cabinet, but to no purpose.

June 9, p.m. United States Minister Conger has sent in all twenty marines to assist the Methodist mission compound in their defense. Still no word from Paotingfu missionaries.

June 10. Five hundred marines and sailors left Tientsin to relieve us. They can get as far as Anting, twenty miles south of here, by train, and will then have to march the remainder of the distance. If prompt they should arrive to-morrow. Methodist mission is fortifying the place with strong brick walls and barbed wire.

After this telegram I was notified that the wires south were cut, and sent only one message more, on July 12, by way of Kiachta, relating the murder of the Japanese secretary and urging prompt government action looking to our rescue.

The history of the growth of the Boxer movement seems to me to have been clearly shown by these telegrams, so that any one of ordinary understanding could have been, by June 1, if in possession of this series of dispatches, fully acquainted with the situation.

The United States minister, the British minister, and the French minister were each acquainted with all the above major facts and much more minor detail.

CHAPTER IV

DIARY OF THE AUTHOR FROM JUNE 1 TO JUNE 20

CHAO SHU CHIAO

Boxer Member of Cabinet

THE following transcription of my diary gives the principal events in the situation up to the date of the close siege, going back a little in point of time from the last chapter.

June 1. After three days of exciting mental strain, we can at last breathe easier. Rumors continue to fill the air of plots within the palace, riots against the Catholic cathedral, railway being torn up between here and Tientsin, etc. But the solid fact remains that a few foreign guards have arrived at six legations, and a machine gun will now have something to say in one’s behalf if the excited populace’s thirst for foreign blood becomes too pressing.

With the exception of M. Pichon, the French minister, all the other ministers are greatly to blame for their tardy recognition of the impending trouble, and they have very nearly had the[63] odium of a preventible foreign massacre to answer for.

Sir Claude MacDonald, for whom the entire English community outside his legation feel, and have openly expressed, the greatest contempt, would not believe that there was any danger coming, and vigorously opposed Pichon’s advice that the troops be sent for ten days ago.

Mr. Conger seconded Sir Claude, partly because the United States legation quarters are so limited that the second secretary and his wife are obliged to live in two rooms over the main office building, and partly because he believed the government willing and capable of putting down the disorder. Both were suddenly converted when Fengtai, only six miles away, was burned, and the Boxers were reported marching unopposed upon Peking. Then the most exciting telegraphing for warships to come to Taku, and guards and machine guns to come to Peking, became the order of the day.

Had the Boxers been at all organized they could have torn up the track for a mile or two at Fengtai, and effectually cut off the troops from arriving in time to prevent any city riots. Fortunately, they seem to have been carried away by the desire to loot, and after they had carried off all the furniture and belongings of the eight foreign residences at Fengtai, and robbed the[64] Empress’ private car of all movable property, they were content to set fire to the stations and machine shops, and then clear out home to the adjoining villages.

June 4. None of the Boxers have been punished, and they have grown bolder, burning the next station below Fengtai, known as Huangtsun, thirteen miles from Peking, killing two Church of England missionaries named Robinson and Norman at Yungching, and defeating a force of Cossacks sent out from Tientsin to search for the surviving Belgians escaping from the Lu Han railway. In spite of this, and with seventeen men-of-war at Tangku, the foreign ministers, besides bringing up each a guard of fifty or seventy-five men to protect his own legation, are doing nothing—that we can see at any rate—to pacify the country. Why they don’t land a large force, come to Peking, and seize the old reprobates that they all know are the real bosses of the Boxer movement in Peking, and hold them responsible for any further movement, nobody knows.

Every minister can tell you that Hsu Tung, Kang Yi, Chung Li, Chung Chi, and Chao Shu Chiao, with Prince Tuan, are the real causes of all the present disorder. Although they all know this, they still pretend to believe the assurances of the government to the contrary....

June 13. Events have been too exciting to allow of one sitting down quietly to write. The missionaries from Tungchow, thirteen miles south of Peking, have fled into this city, and all their college plant, private residences, and property have been destroyed by soldiers sent from the taotai’s yamen to protect them. All the Peking missionaries have gathered together in the Methodist mission compound, where, with such arms as they could collect—a few shotguns, rifles, and revolvers—and with a guard of twenty marines, sent by Mr. Conger, United States minister, they have fortified themselves with barbed wire and brick fences, and are “holding the fort.”

For days we have heard no word from our Presbyterian missionaries at Paotingfu. The last word, now some days since, which came through the tsung-li-yamen and is therefore untrustworthy, was that they were safe at present. Wires south have been cut since the burning of the college buildings at Tungchow, and I have been unable to write home the developments daily occurring.

On the 10th of June, just before the wires were cut, we had a message from United States Consul Ragsdale, saying eight hundred odd troops were coming to our assistance, but to-day is the fourth day since its receipt, and we only know of their reaching Lofa, a burned station on the railway to Tientsin, on Monday night. We have[66] been expecting them every hour since, but no definite word of their arrival at any other place has reached us. Why they don’t send natives in advance we can’t imagine.

June 18. Eleven days we have been besieged in Legation street. Our little guard of four hundred and fifty marines and sailors of all nationalities have kept unceasing watch night and day, and are nearly exhausted. Eleven days ago we were told that an army was marching to our relief, and although they had only eight miles to come we have not yet seen them, nor do we know their whereabouts.

We have nightly repelled attacks of Boxers and soldiers of the government, and have killed in sorties over two hundred of them; but we have millions about us, and unless relieved must soon succumb. Our messengers to the outside world have been captured and killed, and our desperate situation, while it may be guessed, cannot be truly known.

With fifty men-of-war now at Taku we have to remain within our barricaded streets and witness the destruction of all the mission premises and private foreign residences on the outside.

The American Board mission’s large property, the two large Catholic cathedrals known as the South cathedral and the East cathedral, the two compounds of the American Presbyterian mission,[67] the Society for Propagation of the Gospel mission, the International Institute, and the London mission have all furnished magnificent conflagrations, which we have beheld without being able in any way to prevent.

At each place the furious Boxers, aided by their soldier sympathizers, have murdered, with shocking mutilation, all the gatekeepers as well as any women and children in the neighborhood suspected of being Christians or foreign sympathizers.

At the South cathedral the massacre was shocking; so much so that when some of the poor mutilated children came fleeing across the city, bringing the news of what was going on, a relief party was organized from our little force, consisting of twelve Russians, twelve American marines, and two civilians, W. N. Pethick and M. Duysberg, armed with shotguns, who, risking conflict with the Manchu troops, marched two miles from our barricades and, coming on the Boxers suddenly in the midst of the ruins, fired a number of volleys into them, killing over sixty, upon which the rest fled. They then collected the women and children hidden in the surrounding alleys, and marched them back to us, where they are for the present safe.

I have just finished dressing the wounded head of a little girl ten years of age, who, in[68] spite of a sword cut four inches long in the back of her head and two fractures of the outer table of the skull, walked all the way back here, leading a little sister of eight and a brother of four. As she patiently endured the stitching of the wound, she described to me the murder of her father and mother and the looting of her home. One old man of sixty carried his mother of eighty upon his back and brought her into temporary safety; but how long before we are all murdered we cannot say.

Our anxiety has been something frightful, and at this moment, many days since we were told that troops were coming to our relief, we are apparently no nearer rescue than at first. We can’t comprehend it. Night before last, after being driven away by our hot rifle fire, the Boxers turned on the defenseless shopkeepers in the southern city, and burned many acres of the best business places and native banks.

They also burned the great city gate, known as the Chien Men, an imposing structure of many stories high, which must have illuminated the surrounding country for miles. Surely our troops must have seen the glare, if they were within forty miles of us. We begin to fear they have met with an overwhelming force of Chinese soldiers, and have been driven back to Tientsin.

The tsung-li-yamen, or foreign office, is utterly[69] powerless, and yet it continues to send us messages stating it is going to protect us, and it has the Empress issue daily edicts, which, while apparently condemning the Boxers, really encourage them.

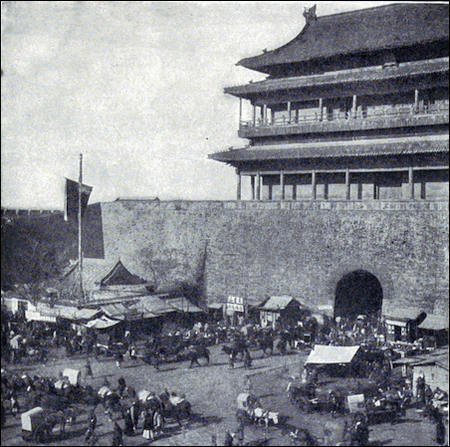

MAIN GATE TO PEKING, DESTROYED BY BOXERS SEPT. 16, 1900

This is one of Peking’s main and most imposing gates. Notice the massive building above the wall; note the solidity of the wall itself; an idea of its great height can be formed by noticing how small a proportion is occupied by the arch and yet how small a proportion of the arch is actually required for the passing vehicles.