It does not lie within the plan of this volume to

review at any length the history of Turkey, or to sketch the lives of

the Sultans who have reigned during the century; it will answer,

however, to make our work intelligible and clear, if the life of the

reigning Sultan of Turkey, Abdul Hamid II. is presented briefly.

He is the second son of Abdul Medjid, who was Sultan

from 1839 to 1861. He was born September 5th, 1842; and his mother

having died when he was quite young, he was adopted by his

father’s second wife, herself childless, who was very wealthy and

made him her heir. His early life was quiet and uneventful; his boyhood

was a continual scene of merry idleness. His education consisting

mostly in amusements and tricks devised for his entertainment by the

court slaves: and in an unusually early and complete initiation into

the depravities of harem life. Indeed up to manhood all the learning he

had acquired, amounted to but little more than the ability to read in

the Arabic and Turkish tongues. His mother had died of consumption and

his constitution was delicate. He had inherited a taste for drink, but

his doctor who was a Greek, assured him it would be his destruction.

“Then I will never touch wine or liquor again,” said Abdul

Hamid, and he kept his word.

The turning point in his life came, when in 1867 his

[214]Uncle Abdul Aziz, then Sultan, took his own son

and his two nephews, Murad and Hamid, to the Paris Exposition, England

and Germany. He saw with a quick and appreciative eye. He acquired a

taste for political geography, and for European dress, customs and

interests. What he then learned was to modify very considerably the

subsequent course of his life. From April, 1876, both he and his

brother Murad were kept under strict surveillance and not allowed to

take any part in the political movements going on in

Constantinople.

Abdul Aziz, the reigning Sultan, was determined to defy

the Turkish law of succession and proclaim his son in June, as heir

presumptive to the throne, thus displacing Murad and Hamid, who both

were before him in rights of succession. At this crisis, Midhat Pasha,

the leading and most progressive statesman and strong adherent of

Murad, planned a revolution and Abdul Aziz, was deposed and Murad was

proclaimed Sultan, May 31st, and so recognized by the Western powers:

but he was never girded with the sword of Othman in the Mosque of

Eyout, a ceremony equivalent to a Western Coronation.

His ill-health, increased by excessive use of liquor and

the mistaken treatment of his physician, rendered him mentally

incapable of ruling: though a celebrated Dr. Liedersdorf, sent for from

Vienna, is said to have stated, “If I had Sultan Murad under my

own care in Vienna, I would have him all right in six weeks.”

In consequence of this mental indisposition, Murad V.

was deposed August 30th, and Abdul Hamid II. was proclaimed on August

31st, and girded with the [215]sword of Othman a few days later.

He was then living in a small palace in the Valley of Sweet Waters,

which he inherited from his father. He was very fond of agriculture,

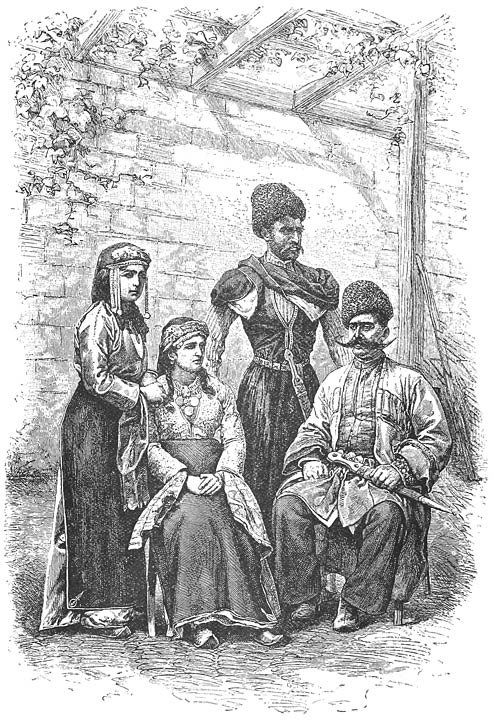

and amused himself by cultivating a model farm. To his mother, who is

said to have been an Armenian from Georgia, in Russia, he owed a

quality very rare in the family of the Sultans, the spirit of economy.

He never allowed his expenses to exceed his income before he came to

the throne. In this charming retreat he resided quietly with his wife

and two children, all eating at the same table, and showing in his

dress and surroundings his preference for European modes of life. The

only concession he made to Orientalism in personal dress, was in

wearing the “fez,” which he disliked, but continued to wear

as the necessary token of his nationality.

Six weeks after he was proclaimed Sultan, it was

announced that a scheme of reform for the whole Ottoman Empire, was in

course of preparation. It was published in January, and while it was a

much less sweeping reform than Midhat wished, it provided for a Senate

and a House of Representatives, which last was to take control of the

finances, the system of taxation was to be revised and better laws were

to be enacted for the provinces.

Election to the lower house was to be by universal

suffrage; for the upper house electors were restricted to two classes:

the noble and the educated.

Abdul Hamid cordially disapproved of this check on the

absolute power enjoyed by predecessors.

He was willing to do justice and to temper it with

mercy, but to be placed in the position of a servant to his people was

odious to himself. [216]

At a council held, when only his other ministers were

present, the Sultan asked, what should be done with Midhat Pasha. Two

of those present said: “Let him die.” But Abdul Hamid was

not bloodthirsty, hence he only banished him to Arabia where two years

later he was poisoned.

The Sultan was restive under the constitution and the

Pashas, against whose cruelty and extortion the most of the reforms

were aimed, sided with their sovereign. In 1875, Midhat Pasha had

outlined the situation thus to the English Ambassador:

“The Sultan’s Empire is being rapidly

brought to destruction; corruption has reached a pitch that it has

never before attained. The service of the state is starved, while

untold millions are being poured into the palaces and the provinces are

being ruined by the uncontrolled exactions of the Governors who

purchase their appointments at the palace: and nothing can save the

country but a complete change of system.”

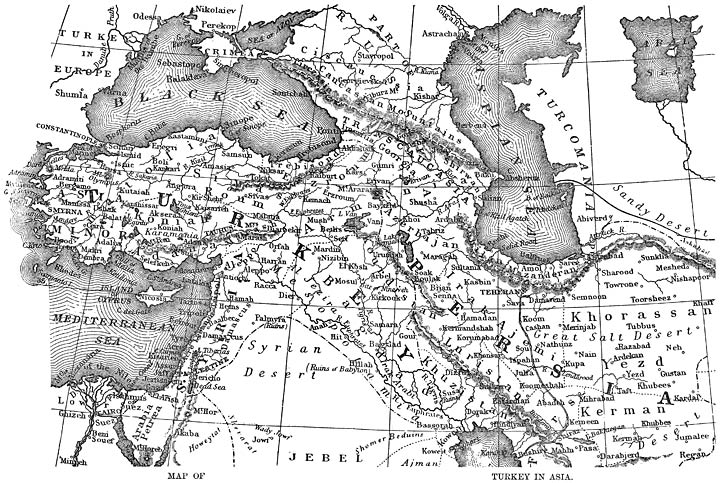

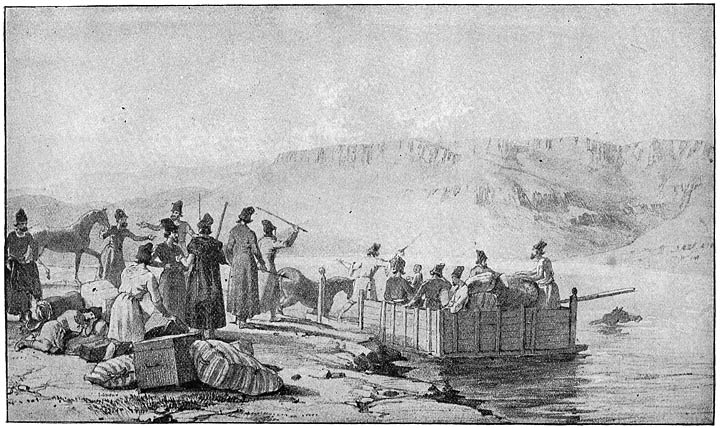

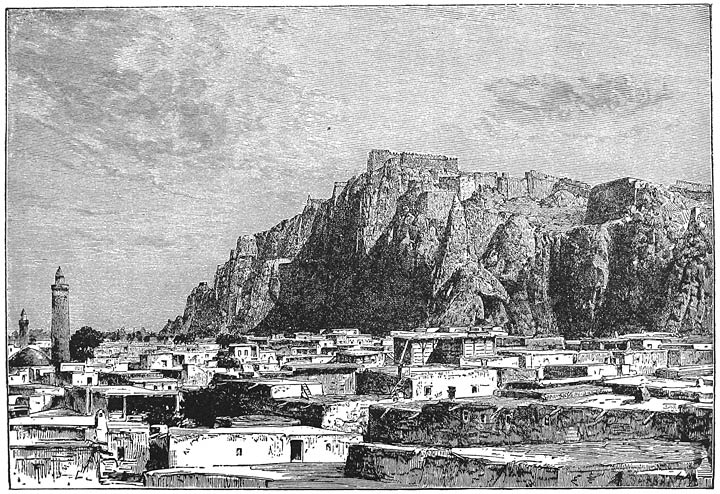

And the very worst governed portion of all his Empire

was Armenia. We are officially told that its government for the last

thirty years has been horrible.

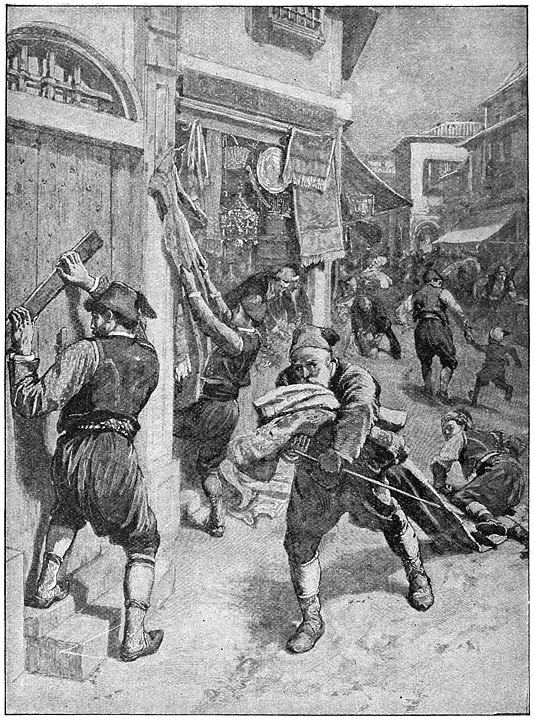

In an Armenian village recently plundered by bandits,

the famous Hungarian Professor, Arminius Vambery, an intimate friend of

the Sultan, once asked, “Why do you not get help from the

Governor of Erzeroum?” “Because,” answered the

villagers, “he is at the head of the robbers. God alone and his

representative on earth—the Russian Czar, can help us.”

This brigandage, is one of the greatest curses of the Turkish Empire,

exercising a rule of terror and oppression, and now legalized,

apparently, by the transformation of [219]the Kurdish

horsemen—robbers—into the Hamidieh—the Sultan’s

own Cavalry.

Such being the spirit of the Pashas who had grown rich

by plunder and official theft, of course they were opposed to the

Constitution, and by the will of the Sultan it was abrogated after two

sessions had been held. This was soon followed by the dismissal of the

Ministers who had formed the triumvirate, and the Sultan resumed his

despotic and absolute sway. Assured that England would not suffer the

dismemberment of his Empire we have seen him refusing to guarantee the

enforcement of promised reforms and provoking the war with Russia; but

as we have already told this story, we will give some pictures of the

Sultan as drawn by his admirers; leaving the horrors of the Armenian

massacres to bear witness as to the honesty of his professed devotion

to the welfare of his Christian subjects and his promises to observe

the terms of said treaty in the amelioration of the condition of all

who were suffering under the murderous oppression of Kurds and

Circassians.

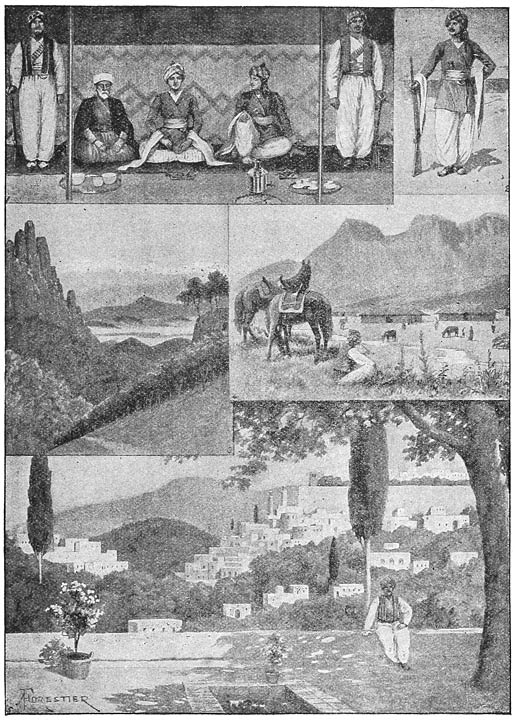

Professor Vambery, a most remarkable linguist who writes

and speaks all the languages of Europe like a native, spent some time

in Turkey a few years ago and was received into closest conference by

the Sultan.—Here are extracts from what he has written of

him:

“I must own that the education of Abdul Hamid,

like that of all Oriental princes was defective, very defective indeed;

but an iron will, good judgment and rare acuteness have made good this

short-coming; and he not only knows the multifarious relations and

intricacies of his own much tried Empire but is thoroughly conversant

with European politics: and I am [220]not going far from fact when

I state that it has been solely the moderation and self-restraint of

Sultan Abdul Hamid which has saved us hitherto from a general European

conflagration. As to his personal character, I have found the present

ruler of the Ottoman Empire of great politeness, amiability and extreme

gentleness. When sitting opposite to him during my private interviews,

I could not avoid being struck by his extremely modest attitude, by his

quiet manners and by the bashful look of his eyes. * * At his table,

though wine is served to European guests, it is not offered to the

Sultan or any other Mohammedan.

“His views on religion, politics and education

have a decidedly modern tone, and yet he is a firm believer in the

tenets of his religion, and likes to assemble around him the foremost

Mollahs and pious Sheiks on whom he profusely bestows imperial favors;

but he does not forget from time to time to send presents to the Greek

and the Armenian patriarchates, and nothing is more ludicrous than to

hear this prince accused by a certain class of politicians in Europe of

being a fanatic and an enemy to Christians,—a prince who by

appointing a Christian for his chief medical attendant and a Christian

for his chief minister of finance, did not hesitate to intrust most

important duties to non-Mohammedans. * * *”

[Doubtless he wanted the best men he could find as his

physician and minister of finance, and these men were found among the

Christians. Let the last year tell whether he be the friend or the

enemy of the Christians.]

“In reference to the charge of ruthless despotism

laid upon Sultan Abdul Hamid in connection with his [221]abrogation of the charter granted during the

first months of his reign, I will quote his own words. He said to me

one day:—‘In Europe the soil was prepared centuries ago for

liberal institutions, and now I am asked to transplant a sapling to the

foreign, stony and rugged ground of Asiatic life. Let me clear away the

thistles, and stones, let me till the soil, and provide for irrigation

because rain is very scarce in Asia and then we may transport the new

plant; and believe me that nobody will be more delighted at its

thriving than myself.’”

Thus far the professor. And now, it is to be wondered if

he calls the extermination of the Armenians the clearing away of the

thistles and does he propose to irrigate the soil of Armenia with the

blood of its noblest race. Is he not rather slitting the veins of Asia

Minor and pouring out its heart’s best blood?

That the Sultan was a warm personal friend of Gen. Lew

Wallace does not make him any the less a despot; neither because Hon.

S. S. Cox, who succeeded Gen. Wallace was an admirer of the Sultan as

the following quotation will show; does that make him the less a

fanatic and the most remorseless shedder of blood that Europe has seen

since the days of Tamerlane.

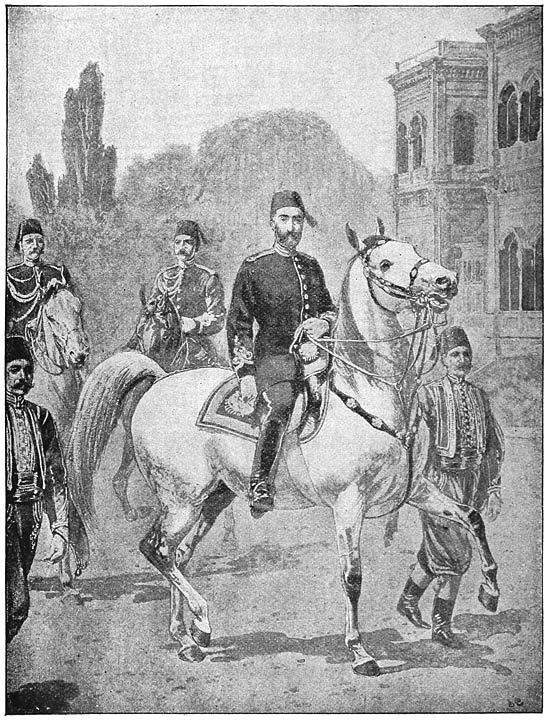

“The Sultan is of middle size and of Turkish type.

He wears a full black beard, is of a dark complexion and has very

expressive eyes. His forehead is large, indicative of intellectual

power. He is very gracious in manner though at times seemingly a little

embarrassed. * * *

“As Caliph he is the divine representative of

Mohammed. His family line runs back with unbroken links to the

thirteenth century. He is one of the most industrious, [222]painstaking, honest, conscientious and vigilant

rulers of the world. He is amiable and just withal. His every word

betokens a good heart and a sagacious head. [What a comment the horrors

of the many months just past furnishes to this flattering estimate a

Mohammedian conscience!]

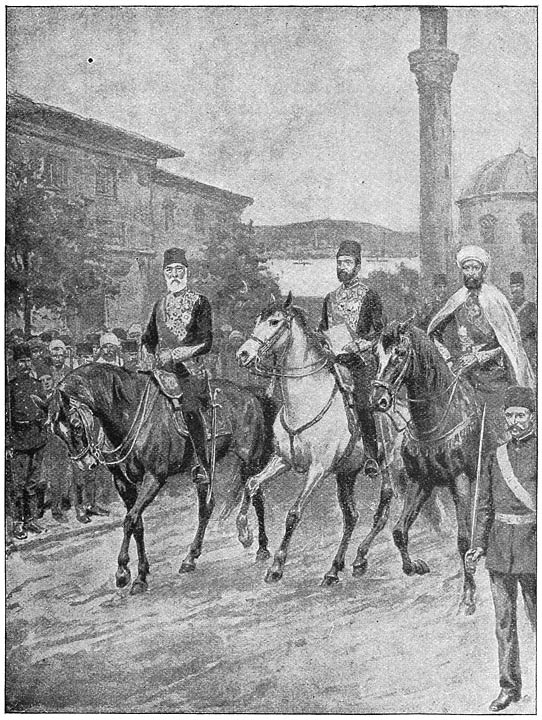

“He is an early riser. After he leaves his

seraglio and has partaken of a slight repast his secretaries wait on

him with portfolios. He peruses all the official correspondence and

current reports. He gives up his time till noon to work of this

character. Then his breakfast is served. After that he walks in his

park and gardens, looks in at his aviaries, perhaps stirs up his

menagerie, makes an inspection of his two hundred horses in their fine

stables, indulges his little daughters in a row upon the fairy lake

which he has had constructed, and it may be attends a performance at

the little theatre provided for his children in the palace. At 5 P. M.

having accomplished most of his official work, he mounts his favorite

white horse, Ferhan, a war-scarred veteran for a ride in the park. The

park of the palace Yildiz where he lives comprises some thousand acres.

It is surrounded by high walls and protected by the

soldiery.”

But all this does not tell us what the man at heart is

any more than if some flatterer of Nero should expatiate on the

esthetic taste of Nero and his love of the fine arts and his skill as a

violinist when he sat at night in his marble palace and enjoyed the

blazing magnificence of Rome. It is as foreign to the present situation

as if some one should praise the skill of Nero’s horsemanship as

he drove his mettled steeds with firm reins along the course lighted by

the blazing torches [223]of the tar-besmeared Christians, whom he

accused of having set the city on fire.

The persistence with which the Sultan has followed out

his purpose of exterminating the Armenians, in the face of a horrified

and indignant Christendom, marks his audacity and contempt of

Christians as sublime in height, as infernal in spirit, and bottomless

in its cruelty.

Gibbon in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire can

scarcely find polite words enough to express his contempt for the forms

of early Christianity and praised the Turks as possessing the rarest of

qualities when he said: “The Turks are distinguished for their

patience, discipline, sobriety, bravery, honesty and modesty,”

and Hon. Sunset Cox echoed the same when he wrote, “It is because

of these solid characteristics, and in spite of the harem, in spite of

autocratic power, in spite of the Janissary and the seraglio that this

race and rule remain potent in the Orient. His heart (the heart of the

present Sultan) is touched by suffering, and his views lean strongly to

that toleration of the various races and religions of his realm, which

other and more boastful nations would do well to imitate.”

The facts given in the chapters on The Reign of Terror

will be sufficient commentary on such praise.

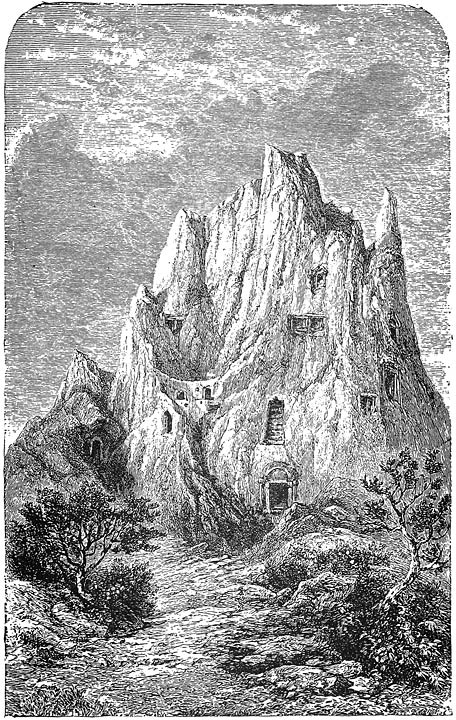

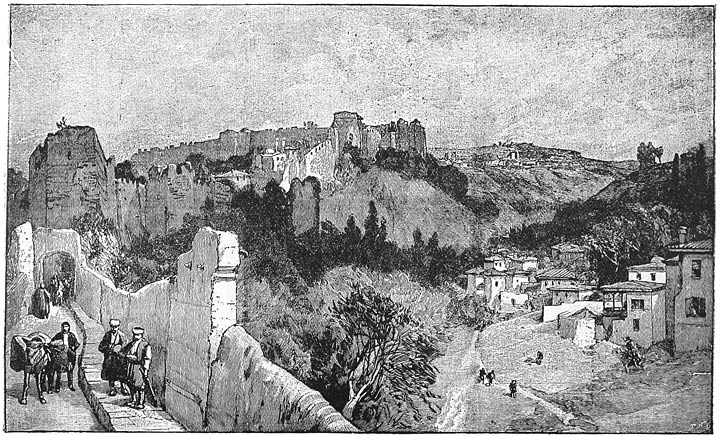

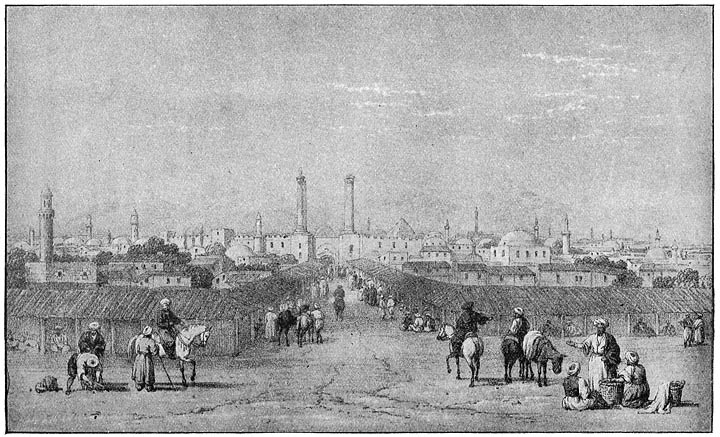

Probably no building in all Europe has so many

associations with tragical events as that of the palace of the Sultan

of Turkey—the autocrat whose rule is absolute over more than

thirty million subjects. From this palace go forth the edicts which

involve the death of thousands and which control the governments of

distant provinces. Fifty years ago the Sultans governed a huge

territory in Europe, but one province after another [224]has

been freed from their yoke, until Turkey in Europe has dwindled in size

to less than half its former area. But the Asiatic possession of the

Sultan have not diminished, and the events in Armenia which have

recently horrified the whole world, show what that possession means.

Nor are these massacres a new or unparalleled feature of Turkish rule.

Similar horrors have been perpetrated before under the cognizance of

the Sultans and the only reason why the indignation now aroused on the

subject is deeper and more intense, is that it is now impossible to

conceal them, and in the days of the telegraph and cheap newspapers

they are set in the light of publicity. The Turk is no worse now than

he has always been, and is only trying to govern at the end of the

nineteenth century as he governed in the sixteenth. As an eminent

writer has said: “The Turk is still the aboriginal savage

encamped on the ruins of a civilization which he destroyed.”

In some respects Abdul Hamid is better than his

predecessors, and until the reports of the Armenian horrors were

published, he was believed to be a great deal better; but they have

proved that he has the same nature, and is at heart as fierce and

relentless as they. The character of the man is of so much greater

moment to his subjects than in other lands, because of the utter

absence of even the semblance of constitutional government. The

government of Turkey is a despotism pure and simple. It is tempered

only by the dread of assassination or deposition, and even those

calamities may come rather from a wise and merciful policy than from

massacre. The Pashas who surround the Sultan, the successors of those

who deposed his uncle and his brother, applaud the atrocities,

[225]and are willing instruments in the perpetration

of them. The danger to the Sultan’s person is far more likely to

come through weakness and lack of vigor in persecution than from

indignation at wholesale slaughter. The Sultan fully appreciates this

fact, and lives in constant dread of treachery.

An interesting story of the present Sultan is related by

Mr. W. T. Stead, in an article in his Review of Reviews, which

in some measure explains the singular mixture in his character of

fanaticism, such as that which produced the Armenian massacres, with

the marked ability and intelligence he displays in the conduct of

national affairs. It appears that when he was a mere youth, he was

conspicuous even in Constantinople, which is notorious for its

immorality, for the gross excesses of his private life. There was then

little probability of his ever ascending the throne, and as he was

condemned by his position to a life of idleness, he plunged into all

the wickedness of the capital, and lived a life of debauchery. Suddenly

he changed his course. He quitted his evil ways and became a devout

follower of Mohammed, was attentive at the Mosque and gave all his

thoughts to his religion. From that time until now his religious

enthusiasm has been the most prominent feature of his character. But

with the change came a fierce intolerance, a desire that others should

follow his example and determination, evinced since his accession, that

in his own dominions no enemy of the Prophet, nor any who did not avow

themselves his followers, should have peace or rest until they accepted

the faith. This spirit accounts for the crusade against the Armenians

whom he hates because they are Christians. [226]

The real cause for all the trouble in the Turkish Empire

will be found to lie within the spirit and purpose of the Sultan

himself. His conduct towards the Powers will serve to most abundantly

confirm this view.

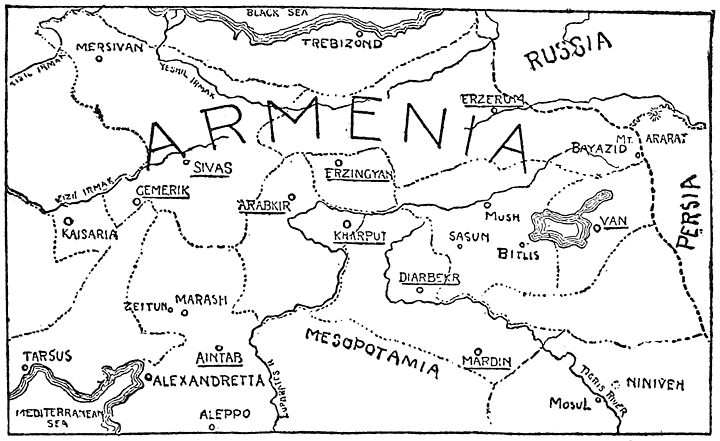

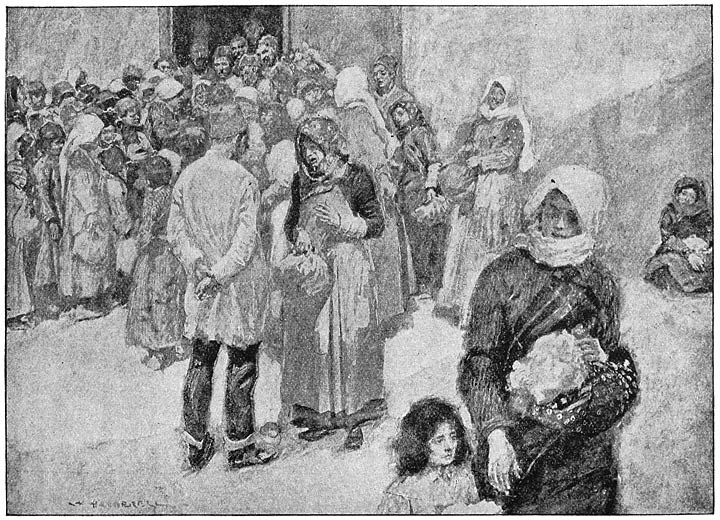

The condition of Armenia under Turkish rule has for many

years been a scandal to Christendom. After the horrors of the Blood

bath of Sassoun had been made known to the world a commission of the

Powers were sent to investigate and report on the massacres which had

been perpetrated.

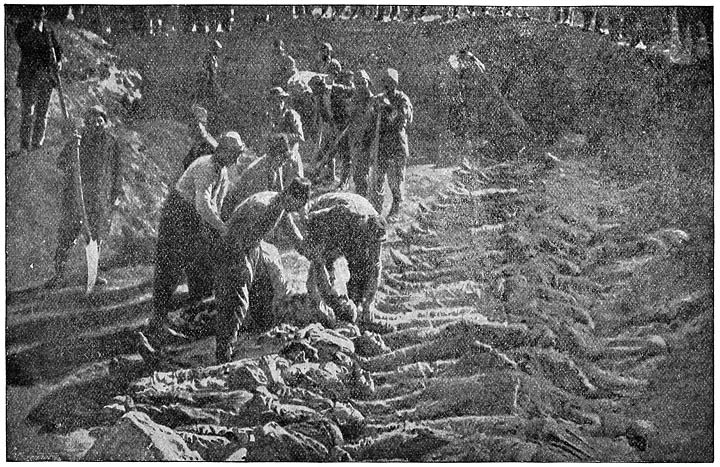

The investigation of the latest atrocities showed that

the Armenians had been wantonly tortured and murdered, and that

indescribable atrocities had been perpetrated. Men, women, and children

were proved to have been hacked to pieces, and no respect had been

shown to age or sex. Whole villages had been depopulated, and the fact

of any community being Christian seemed to have been sufficient to

provoke the murderous hostility of the authorities. Where the Turks did

not commit the outrages themselves, they remained inactive while the

Kurds committed them, and their inactivity amounted to connivance,

because the Armenians are not allowed to arm themselves for their own

protection. There was legitimate grounds for foreign powers urging

reforms upon the Sultan, as in 1878, when the Berlin Congress was

inclined to strip him of his Armenian provinces, he promised that

Armenia should be governed better than it had been, and England became

sponsor for the performance of his promises. Under those conditions the

Sultan was allowed to retain the provinces, and his failure to effect

the reforms was therefore a distinct breach of faith. The [227]Ambassadors of England, France and Russia

accordingly presented to the Sultan on May 11th a demand for twelve

specific changes in the government of Armenia. The scheme outlined

included the appointment of a High Commissioner, with whom should be

associated a commission to sit at Constantinople, for the purpose of

carrying out all reforms. The full details of the plan were not made

public, but among the suggestions made were these: The appointment of

governors and vice-governors in six Armenian vilayets—Van,

Erzeroum, Sivas, Bitlis, Harpoot, and Trebizond; that either the

governor or the vice-governor of each vilayet should be a Christian;

that the collection of taxes be on a better basis; with various other

reforms in the judicial and administrative departments: especially that

torture should be abolished; the gendarmérie to be recruited

from Christians as well as Mohammedans, and the practical disarmament

of the Kurds. Note the names of these vilayets as they are the centers

of the horrible massacres that followed the Porte’s true answer

to all its own promises of reform.

To this project of reforms the following memorandum was

attached:—

“The appended scheme, containing the general

statement of the modifications which it would be necessary to introduce

in regard to the administration, financial and judicial organization of

the vilayets mentioned, it has appeared useful to indicate in a

separate memorandum certain measures exceeding the scope of an

administrative regulation, but which form the very basis of this

regulation and the adoption of which by the Porte is a matter of

primary importance.” [228]

These different points are:

1. The eventual reduction of the number of vilayets.

2. The guarantee for the selection of the valis.

3. Amnesty for Armenians sentenced or in prison on

political charges.

4. The return of the Armenian emigrants or exiles.

5. The final settlement of pending legal proceedings for

common law crimes and offences.

6. The inspection of prisons and an inquiry into the

condition of the prisoners.

7. The appointment of a high commission of surveillance

for the application of reforms in the provinces.

8. The creation of a permanent committee of control at

Constantinople.

9. Reparation for the loss suffered by the Armenians who

were victims of the events at Sassoun, Talori, etc.

10. The regularization of matters connected with

religious conversion.

11. The maintenance and strict application of the rights

and privileges conceded to the Armenians.

12. The position of the Armenians in the other vilayets

of Asiatic Turkey.

After much delay the Porte replied that it could not

accept the proposals made. Of course not. Why should the Sultan do

anything to favor the Armenians or even to prevent the recurrence of

these terrible outrages unless compelled to do so by something more

than advice! Yet the Sultan would be anxious to know what the three

Powers would do about it. He was not kept long in suspense, so far as

England was concerned. Orders were issued for the English fleet to

proceed to Constantinople, and France and Russia were informed of the

fact. The news reached the Sultan [229]and appears to have convinced

him that it was not safe to trifle any longer with the demands of the

powers. He accordingly telegraphed that he would accede to the

principle of reform outlined for him.

The Sultan, learning also that the British Cabinet had

met to consider Turkey’s reply to the plan of reform for Armenia,

submitted by Great Britain, France and Russia, telegraphed to Rustem

Pasha, the Turkish Ambassador in London, instructing him to ask the

Earl of Kimberly, the British Foreign Minister, to postpone a decision

in the matter.

The Earl of Kimberly acceded to the request. In the

meanwhile the Porte handed to the British, French and Russian

Ambassadors a fresh and satisfactory reply, acceding to the principle

of control by the Powers, but asking that the period be limited to

three years.

While these promises were being so freely made, letters

from Armenia, in July, represented Turkish cruelty as unabated; the

position of affairs never so grave and critical; and the Armenians to

have reached the ultimate limit of despair. Yet in August the world was

informed that Turkey had decided to accept in their entirety the

Armenian reforms demanded by the Powers, and that the acceptance of

these reforms was primarily due to the pressure brought to bear on the

government by Sir Philip Currie, the British Ambassador, who

communicated to the government a confidential note from Lord Salisbury

to the effect that the Porte must accept the proposals of the powers

unconditionally, or England would use sharper means than those adopted

by Lord Rosebery to settle affairs in Armenia. [230]

The summer passed in fruitless and endless negotiations.

Later in September a press telegram from London voiced the situation as

follows:—

“European diplomacy seems already weary of the

question, which Turkish diplomacy has handled with an evident ability,

based upon temporization and inertia, as well as upon its knowledge of

the jealousy existing between the three Powers which proclaim so loudly

that they want nothing else but the happiness of the Armenians.

“The question has not progressed one iota, despite

all the negotiations, memoranda, appointments of commissions, and even

the (awful!) rumor, one month ago, of the assembling of the British

fleet in Besika Bay, at the entrance of the Dardanelles. England,

France and Russia, however, had the way clear before them, if they had

been really in accord and seriously willing to accomplish the

humanitarian mission they pretended to assume. Article sixty-one of the

Berlin Treaty gave the Powers the right to see that the same rights

granted to Bulgaria should be granted also to Armenia. This article has

remained a dead letter in regard to the latter country since 1878. When

the Sassoun atrocities were recently committed, the Powers merely sent

to the Porte a memorandum, requesting it to cease its persecution of

Armenians. During two or three months the European Ministers at Pera

awaited the decision of the Sultan. Whenever they sent their dragomans

to the Foreign Minister, Said Pasha caused his secretary to answer in

the Spanish manner, ‘hasta la

mañana’ (to-morrow a reply will be given). Finally

the three Powers thought of using the rights conferred upon them by

Article sixty-one, and required Abdul Hamid to consent [231]that

a European Commission of Control should be sent to Armenia, in order to

see that reforms be practically applied there. The Sultan will fight

stubbornly before accepting them, which would amount to the abandonment

of a portion of his sovereignty, and it remains to be seen how much the

Powers, jealous of their respective influence at the Porte, are in

earnest and how anxious they are promptly to enforce the acceptation of

their Control Commission.”

The Turks continued to play a waiting game in Armenian

affairs. Remembering the treaty of Berlin, they were shrewd enough to

play off one Power against another so as to retain absolute control

over their internal affairs, though they had forfeited all right to

rule by their outrageous and brutal massacres. The Congress of Berlin

was at the time a costly thing to the Eastern Christians but was

destined to prove almost their utter ruin.

The Turks did not find it hard to pick flaws in the plan

of administrative reform when they did not intend to have any reform.

The whole scheme was without any security against the renewal of the

Sassoun massacres. Everybody who was interested in Armenia protested

against the plan, but it was the best that mere diplomacy could do.

Thus the summer passed filled with plenty of promises,

but without any fulfilment, until suddenly the signal was given and the

horrors of Sassoun were reënacted throughout all the provinces of

Armenia.

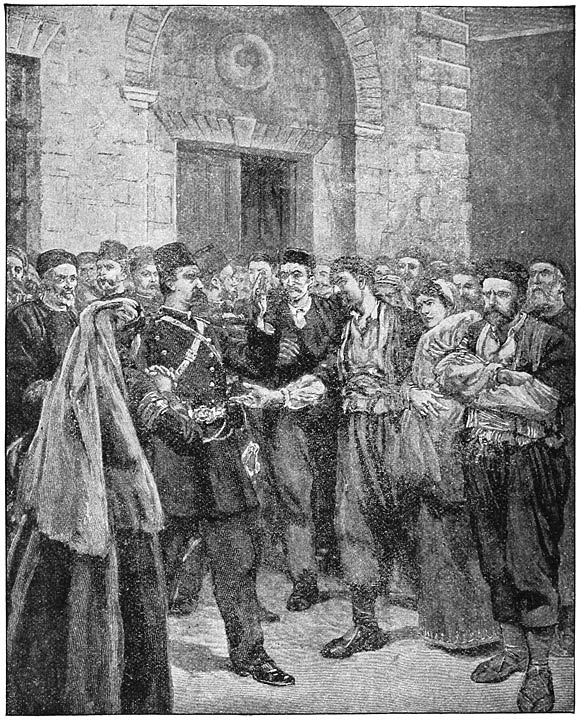

At a mass meeting of Armenians held in New York, free

expression was given to the feeling of horror with which the news of

the Turks’ outrages was received there. There seemed to be no

doubt in the minds of these [232]people as to the truth of the

reports from Asia Minor, and many were of the opinion that still more

terrible news would be received. Mr. Dionian presided, and in calling

the meeting to order, said that Armenia and Turkey could never be

friends, and that Armenia must either be liberated or annihilated.

Dr. P. Ayvard also spoke, and then Dr. S. Aparcian

offered resolutions, which were unanimously adopted, saying in

part:—

Resolved, That we most respectfully and

appealingly call upon all the great Powers of Europe, and of our

adopted and well loved country of America, to the deplorable condition

of Armenia, and trust that the moral interests of Europe will demand

taking immediate steps to put an end to this rule of anarchy and

lawlessness prevailing there, and that the United States of America

will give their moral support.

Knowing the Turk as they did, the Armenians in this

country were prepared for the confirmation of these reports. In due

time it came.

A prominent Turk laughed when he saw the report, and

said it was a mere fabrication, and that if there was any slaughter it

was not committed by the Turks. As to the Turks being opposed to the

Armenians because of their being Christians, he said: “People who

have lived in the Orient know that to be absurd. We have Christians and

Jews among us, and as long as they obey the laws of the land they are

treated the same as the members of our faith. Of course,” he

added, “when people become revolutionists and conspire against

our Government, then we take measures to punish them. The Armenians are

revolutionists, and their revolutionary societies exist in every city

in this country, while the head-centre is at Naples.”

[233]

The Turk laughed and blamed the Armenian revolutionists.

The Porte denied the outrages at first then charged the trouble to the

Armenians, until the terrible situation at Trebizond and Erzeroum could

no longer be kept from the knowledge of Christendom. The prisons in

Trebizond were filled with wounded and helpless Armenians: the

Mohammedans were well armed and the governor entirely in sympathy with,

even if not the instigator of the outrages.

Meanwhile the European manager of the United Press at

Constantinople gave the first detailed account of the appalling

massacres to which Armenian Christians had been subjected since the

Sultan Abdul Hamid gave perfidious assent to the reforms demanded by

the European Powers. The harrowing and shameful facts were told on the

authority of American Christian men, who witnessed them, and their

narrative had the unqualified endorsement of Mr. Terrell, the United

States Minister to Turkey. In view of such conclusive testimony to the

duplicity and faithlessness of an incorrigible ruler, it seems

incredible that Christian peoples will let their rescuing hands be

stayed any longer by sordid jealousy and greed, or that they will any

longer consent to bear a share of the responsibility for such crimes

against humanity. The blood of the slaughtered thousands of their

fellow Christians in Armenia cries against them from the ground.

By this trustworthy evidence the conclusion was

justified that within the six provinces mainly concerned in the

proposed reforms, no fewer than fifteen thousand Armenians were

assassinated, while the number of those rendered homeless and robbed of

all their possessions, did not fall short of two hundred thousand.

[234]The places and dates exposed the aim of the

hellish atrocities committed, and drove home the guilt to their authors

and accomplices. On October 20, the Sultan authorized Kiamil Pasha, his

Grand Vizier, to accept the reforms proposed for the Armenian provinces

by the European Powers, and to promise that they should be forthwith

carried out. On the next day, October 21, when there had been ample

time for the reception of orders telegraphed from Constantinople, the

Kurds and Turks throughout Armenia, openly incited and assisted by the

regular troops, entered on a scheme of wholesale murder and

devastation. The purpose of this preconcerted iniquity, as disclosed by

its disgraceful antecedents and its horrible results, was to vent upon

the helpless Armenians the venom and the spite engendered by enforced

submission to the will of the Christian Powers. It was to enforce at

one vindictive stroke the programme of extermination devised in 1890,

but prosecuted hitherto with some show of secrecy and caution. It was

to make of Armenia a solitude, and then with satanic mockery, to offer

exact fulfilment of the pledge of peace and of reform.

All the circumstances showed that with this flagitious

rupture of the Sultan’s plighted word, the person directly and

primarily chargeable was the Sultan himself. He sanctioned the plot of

extermination, if he did not personally concoct it in 1890, the

relentless though disavowed execution of which at last provoked the

interposition of Christian Powers. No sooner had Kiamil Pasha been

reluctantly permitted to agree to the reforms exacted for Armenia, than

he was summarily dismissed by Abdul Hamid from the Grand Vizierate,

lest he should [237]execute the agreement in good faith. The new

Ministers selected by the Sultan were drawn mainly from the scum of

Constantinople, and their first act was to protest that time must be

given to the Porte for the proper enforcement of the reform project.

Time was needed to render reforms superfluous through the sweeping

destruction of its intended beneficiaries. It was needed to perpetrate

the design of annihilation on a scale of vast proportions. The Sultan

well wished to hide his privity to such a devilish transaction, but he

dared not disavow his agents, lest they should divulge his

instructions. Accordingly, when high Turkish officials, unmistakably

implicated in the Armenian enormities, were subjected to the nominal

penalty of a recall at the imperative instance of England’s

representative, they were decorated and promoted by Abdul Hamid, whose

secret aims and wishes were thus betrayed.

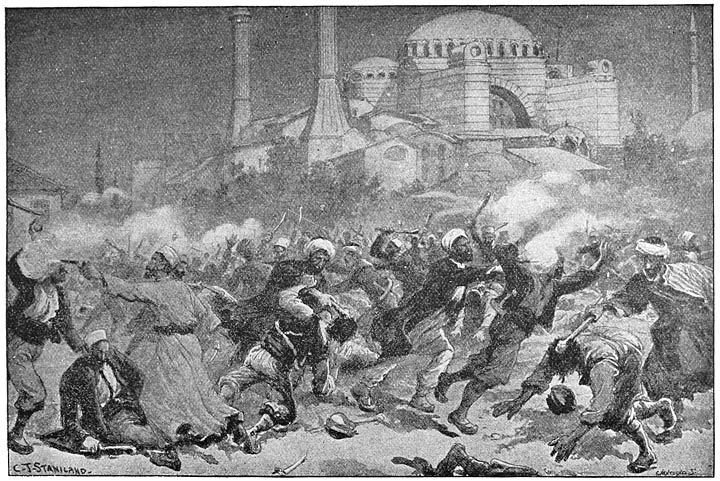

On November 10, the Kurds made an attack on Harpoot, but

were easily repulsed. On November 11, a party of the soldiers and

leading Turks met the Kurds in conference, during the progress of which

a bugle was sounded, at which signal the soldiers withdrew. The Kurds

thereupon advanced with yells. There was no effort on the part of the

soldiers and Armenians to resist, and the Turks joined in the killing

and plundering. The Armenian school was burned, and then began an

attack upon the Christian quarter, the buildings in which were also set

on fire. The Christians were without weapons of any sort, and trusted

entirely to the Government to protect them. The Armenians remained in

the girls’ seminary until that building was set on fire, and then

they appealed to the Governor for protection. They obtained a guard of

soldiers, all but [238]two of whom afterward deserted. These two

remained and carried out the orders issued to them, to fight the fires

which had been kindled.

The burning continued for three days. The Armenians were

stripped of everything but their clothing. All the Christian villages

around were burned by the Kurds. The outrages continued unchecked until

the Government at Constantinople ordered the troops to take action.

Fourteen Kurds were then shot, when the murders and pillaging ceased

instantly. The districts of Diarbekir, Malatia, Arabkir, Kyin and Palu

were made desolate. Thirty-five villages were destroyed, and thousands

of the inhabitants embraced Islamism in consequence of the pressure

brought to bear upon them.

The Turkish troops which were on their way to Zeitoun to

suppress the trouble there, were concentrated at Marash, where they

awaited the return of the delegation sent to Zeitoun to negotiate with

the Armenians in control there for their surrender.

The Government said they were projecting more extensive

relief work, and would welcome foreign aid through a joint

commission.

Despite this promise of greater relief, the Government

was bent on continuing the work of extermination—all promises to

the contrary notwithstanding.

The tidal wave of horror and indignation swept over

Europe, and found expression in most intense and emphatic speech; it

was even felt in the Cabinets of Diplomacy and in Constantinople. There

seemed to be more iron in their blood and energy in their action and

purpose in their speech.

The general situation was not changed, but it was

[239]apparent that a change was about to take place.

The representatives of the Powers, some of whom were awaiting

instructions from their Governments in regard to the matter of sending

additional guardboats into the Bosphorus, seemed to be unanimous in

their insistence on the issue of permits for the admission of such

boats by the Sultan, and the Ambassadors held a meeting to consider the

situation as presented by the Sultan’s refusal to permit the

passage of the additional boats through the straits, and to decide on a

concerted plan of action.

For several days the wires were hot with the assertion

that all the Powers were united and determined to carry their demands

to a successful termination. The Sultan was unofficially informed that

if he continued to maintain his stubborn attitude, a forced entry of

the Dardanelles would possibly be made.

As previously, and with equal pertinence, at this hour

of crisis the continental press devoted much space to the affairs of

the Orient, and the Sultan was the recipient of much newspaper advice.

One writer in particular urged him to remain master of the situation,

and to show himself promptly disposed to fulfil his engagements. In

that case the crisis would remain an internal one; but if it should

assume an international aspect it would be peacefully adjusted on the

basis of the maintenance of the integrity of Turkey which would be

asserted by France and Russia, the two Pacific Powers. It was also

telegraphed from Constantinople that the Czar, in reply to a personal

appeal from the Sultan, consented to waive the Russian demand for a

second guardship in the Bosphorus. At the same time she was prepared to

[240]resent any aggressive action that England might

undertake alone.

The Sultan knew very well that there would be no

concerted action of the Powers—that England and Russia would

never agree as to any joint action, and yet to give color of necessity

to his refusal, it was given out that the Powers had decided to depose

him, using for this purpose the forces aboard the second guardship which

they demanded should be permitted to enter the Bosphorus. This was to

stir up the populace against the Powers. Then to furnish another excuse

the report was circulated that the Sultan was in daily fear of sharing

the fate of Ishmail Pasha at the hands of the Softas and the Young

Turkish party.

The Sultan’s letter to Lord Salisbury was often

quoted as a confirmation of the report that the Sultan was panic

stricken. It will be recalled that Lord Salisbury in his speech at the

Lord Mayor’s banquet on November 9th, declared that, if the

Sultan will not heartily resolve to do justice to them, the most

ingenious constitution that can be framed will not avail to protect the

Armenians; that through the Sultan alone can any real permanent

blessings be conferred on his subjects. “What if the

Sultan,” exclaimed the British Prime Minister—

“What if the Sultan is not persuaded? I am bound

to say that the news reaching us from Constantinople does not give much

cheerfulness in that respect. You will readily understand that I can

only speak briefly on such a matter. It would be dangerous to express

the opinions that are on my lips lest they injure the cause of peace

and good order.”

These words seemed to be freighted with some

[241]ominous significance, and they would have been,

if there had been any purpose to make them mean anything.

In a remarkable letter to Lord Salisbury which he read

publicly at a conference in London, the Sultan used a most beseeching

tone to show that the possible dissolution of his Empire was lying

heavy on his mind. It sounded like a most abject plea for mercy, a cry

for the postponement of the fate which the Powers seemed to be

preparing for the terrified monarch. In this note the Sultan said:

“I repeat, I will execute the reforms. I will take

the paper containing them, place it before me and see that it is put in

force. This is my earnest determination and I give my word of honor, I

wish Lord Salisbury to know this and I beg and desire his Lordship,

having confidence in these declarations, to make another speech by

virtue of the friendly feeling and disposition he has for me and my

country. I shall await the result of this message with the greatest

anxiety.”

It will be noted that the Sultan’s communication

contained no denial that there are wrongs to be remedied in the

administration of his government in Armenia and elsewhere. There is no

plea that the terms of solemn treaty obligations have been observed.

The letter is a tacit confession that the interposition of the Powers

as far as it had gone was justifiable and that the reports of the

atrocities in Asia Minor, which were at first strenuously denied by the

Turkish Government, were true.

It was only a shrewd plea of helplessness to persuade

the Powers not to enforce their demands and nothing more. In his

rejoinder to the Sultan’s letter, Lord [242]Salisbury substantially admits the hopelessness

of reform under the Sultan’s government as now constituted and

administered.

A few days after this correspondence the fear of the

Sultan seemed to have vanished, and he was brave enough to refuse

permission to the Powers to send extra guardboats into the

Bosphorus.

At this time it looked as if Sir Philip Currie, the

British Ambassador, would act alone, and that he really meant to force

the passage of the Dardanelles.

But the Sultan knew he would not dare to do it, and he

knew also that the Powers were not agreed to use force. England proved

herself impotent before the crafty diplomacy of the timid

Sultan.

It is folly at this day to pretend to believe that the

Sultan ever intended of his “spontaneous good-will” to

protect the Armenians even as human beings from the cruelty of Kurd or

Turkish officials.

The horrors of December and January give the lie direct

to every promise made at Constantinople. The Sultan had outwitted

England, if indeed England ever were in earnest, and by circulating a

rumor of a Turco-Russian alliance, most effectually checked all danger

of intervention by force—the only argument to which the Turk will

ever yield—and proceeded to commit yet greater crimes if that

were possible.

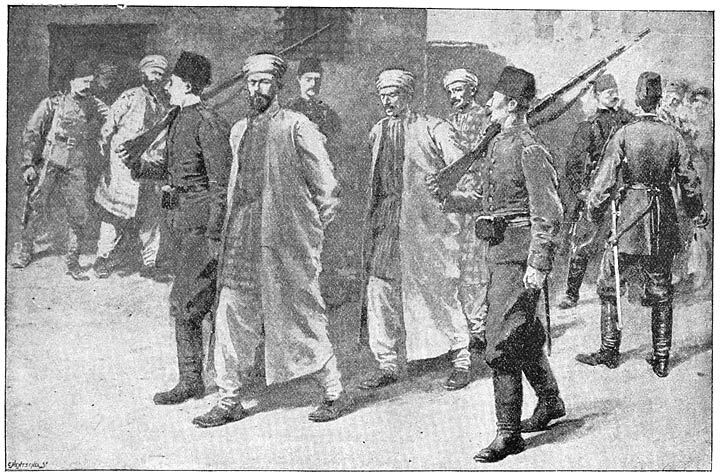

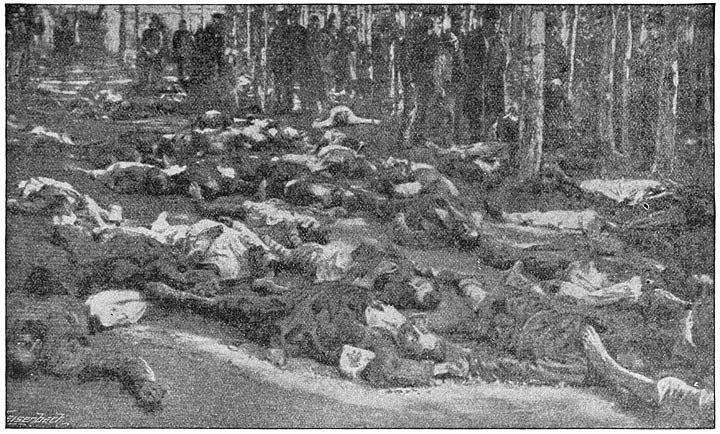

Under the very eyes of the Russian, English, and French

delegates at Moush, the witnesses who had the courage to speak the

truth to the representatives of the Powers were thrown into prison, and

not a hand was raised to protect them: and within a stone’s throw

of the foreign consuls and the missionaries, loyal Armenians were being

hung up by the heels, the hair of their heads [243]and

beards plucked out one by one, their bodies branded with red-hot irons,

and defiled in beastly ways, and their wives and daughters dishonored

before their very eyes. And all that philanthropic England has to offer

its protégés, for whose protection she holds Cyprus as a

pledge, is eloquent sympathy.

She received Cyprus by secret convention, and now holds

it as the price of innocent blood. The rewards of iniquity are in her

hand. It was worse than folly; it was the refinement of cruelty to send

a commission to investigate the outrages in Armenia, thereby irritating

the Turk to the height of possible fury as his deeds were proclaimed to

the world and then leave him free to wreak his compressed wrath upon

the Christians for whose protection no hand would be uplifted. The

Powers saw Armenia in misery, bleeding, dying, and passed by on the

other side, saying, we are bound by the terms of the Berlin Treaty not

to interfere with Turkey in the administration of her domestic affairs;

we are sorry for you; we wish the Sultan would listen to our advice and

not be quite so severe in his chastisement, but really you must have

given him some cause for his anger.

Yes, such provocation as the lamb gave to the wolf that

charged it with soiling the water, though it was drinking much farther

down the stream.

The humiliation of England as one of the Great Powers

was complete when in the House of Commons March 16th, in reply to

questions that were put to him Mr. Curzon Under Secretary of Foreign

Affairs was obliged to say that reports received by the Government

confirmed the statements that a great number of forced conversions from

Christianity to Islamism were still [244]being made in Asia

Minor. Under the circumstances of cruelty and systematic debauchery of

defenceless Christian women through the devastated districts of

Anatolia, he said, the British Consuls in Asia Minor had been

instructed to report such cases, and representations in regard to them

were constantly being made to the Government in Constantinople.

Representations were constantly being made! What did the

Porte care for representations? How England was compelled to quaff the

contempt even of the Turk who laughs or sneers as his mood may be over

these representations of English Consuls and missionaries. The Sublime

Porte—which means the Sultan—cabled the Turkish Legation at

Washington to deny most emphatically the statements that appeared in

the American religious press regarding forcible conversions to

Islam.

The Sublime Porte affirmed that “the stories

related therein are mere inventions of revolutionists, and their

friends intended to attract the sympathy of credulous people. There is

no forcible conversion to Islamism in Turkey and no animosity against

Protestantism.” This is sublime impudence. The statements thus

contradicted, represented conditions certified to by official reports,

by careful investigations made by correspondents of newspapers in

England and the United States, and by hundreds of private letters from

persons in the region where the massacres occurred. Moreover, this

declaration of the Sultan is contradicted by centuries of Mohammedan

history, by the ruins of ancient churches throughout all Asia Minor and

Mesopotamia, and by daily prayer concerning the Christians:—

“Oh Allah make their children orphans, * * give

[245]them and their families * * their women, their

children, * * their possessions and their race, their wealth and their

lands as booty to the Moslems, O Lord of all creatures.”

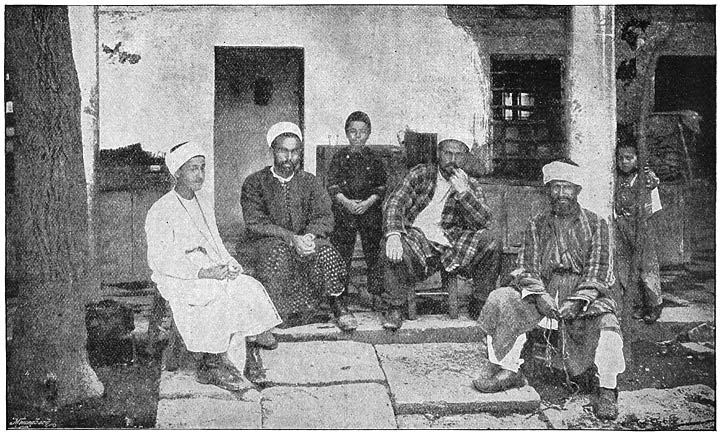

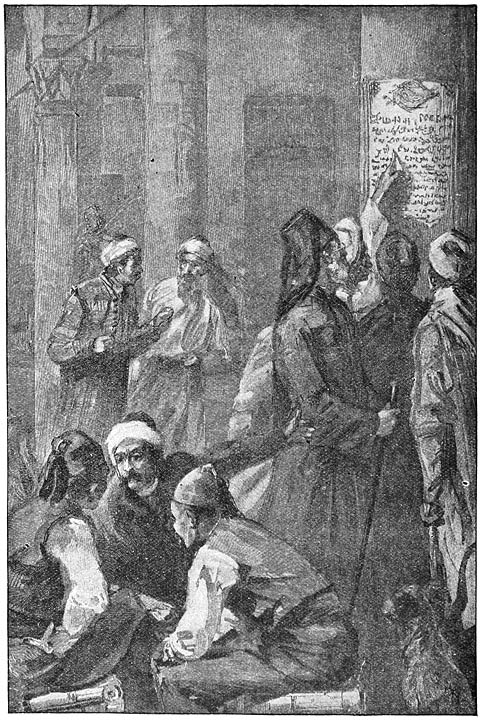

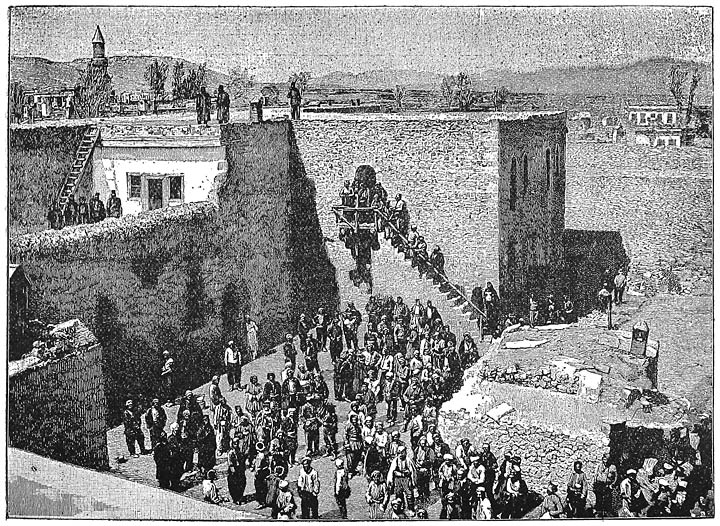

The Softas are, properly speaking, the pupils who are

engaged in the study of Mussulman theology and law in the medresses, or

schools attached to the mosques, the range of their studies, however,

being practically limited to learning to read the Koran. The Softas

take their name from a corruption of the past-participle

soukhte—burned—applied to them because they are supposed to

be consumed by the love of study of sacred things, and devoted to a

life of meditation. The Softas follow their studies in the school

building, sleeping and eating at the imaretts, where free lodgings and food

are provided for them out of the legacies of the pious. If their

families can afford to do so, they furnish them with clothing and

bedding; if not, these are given to them from the same charitable fund.

The number of Softas is very large, for one reason because of their

exemption from military service. After long-continued study of Arabic,

and the Koran and its commentaries, the Softa, after an examination

which, though nominally arduous, is almost invariably passed

successfully, takes the title of Khodja.

The Khodja—khavadje, reader or singer—a

scholar who has taken his diploma in the medresse, teaches for several

years, in fact till he has conducted a class of Softas through the same

course he had himself taken, when, on application to the Ministry of

Worship, at whose head is the Sheikh-ul-Islam, and, after a severe

examination, he receives the title of Ulema. The Mussulman does not

arrive at this dignity until he has [246]reached the age of

thirty or thirty-five. It confers numerous privileges, for those

doctors escape military service, unless in the event of the djihad, or

sacred war, and from their ranks are filled the Judgeships, the

curacies (so to speak) of the mosques, the professorships in the

medresses, the trusteeships connected with the administration of the

trust funds for pious and charitable purposes, etc., etc.

The Imaums—who are the real priests and have

charge of the public religious service—are selected from among

the Ulema. The title of Imaum comes from the Arabic, and is the

equivalent of leader or outpost. There is as a rule one Imaum to each

mosque of minor importance—messdjid—while two, or, at most,

three, one of whom is designated the chief authority, are appointed to

the principal mosques—djamis. Even the Ulema—the word is

plural and signifies wise men—are subject to military duty when a

holy war is proclaimed.

The term Softa includes all the grades above mentioned,

from the Imaum, or priest, to the Softa proper, or mere students of the

Koran. They are usually distinguishable in Turkey by wearing a white

turban around their fez, or skull cap. Sultan Abdul Medjid some years

ago endeavored to induce his subjects to wear a European dress, and

succeeded so far that almost without exception every one except the

very lowest in the public service adopted it. But the Softas to a man

retain the old-fashioned baggy, slouchy dress which Abdul Medjid wished

to get rid of.

Who can believe that through fear of the uprising of a

few thousand Softas, the Sultan planned a fanatical uprising of the

Kurds in distant Armenia. How could [247]that benefit the

Softas save as it were permitted them to beat, kill and plunder the

Armenians in Stamboul?

If the fear of the Softas prompted it, still what a

heartless wretch to doom seventy-five thousand to death and hundreds of

thousands to starvation and outrage when to admit the fleets of Europe

would have protected him from any possible insurrection in

Constantinople.

The Turkish Government itself was directly and actively

responsible for the outrages in Asia Minor; it not merely permitted,

but actually ordered them. But there was in Constantinople itself a

most serious conspiracy against the dynasty, which threatened to turn

out the Sultan and revolutionize the whole form of government. As a

sort of counter-irritant, which haply might cure this, the Government

might have indeed resorted to any extravagance or conduct elsewhere.

More than one monarch has begun a foreign war to quell disaffection at

home. Why should not the Porte think a general harrying of the

Armenians a ready way of allaying incipient disloyalty among the

Faithful?

This conspiracy was made by what was known as the Young

Turkey party. It included most of the Softas, and students in all

colleges, and many lawyers, doctors, officers of the army and navy, and

even civil servants of the Porte. Back of these were multitudes of the

general populace. There were many who denied Abdul Hamid’s legal

right to be Sultan while his elder brother was living. There were

others, numbered by millions, who held that the Caliph must be an Arab

and that the Sultan was therefore not to be recognized as the true

Commander of the Faithful. Moreover, many, indeed all the leaders of

Young Turkey, demanded [248]the carrying out of the Hatt of

1877, establishing a Constitution and Parliament, and denounced the

suppression of that promised system as a gross breach of faith and

wrong to the people of the Empire. It may not be generally remembered;

men’s memories are so short; but it is a fact that a

constitutional government was once officially proclaimed in Turkey. The

plan was conceived by Midhat Pasha, then Grand Vizier, and formally

approved by the Sultan. A Constitution was promulgated. A Parliament,

consisting of a Senate and an elective Assembly, was created, and its

first session was opened by Abdul Hamid in person on March 19, 1877.

Later in the same year its second session was opened, and the Sultan

publicly declared that the Constitution should thenceforth be the

supreme law of the land, in practice as well as in theory. But before

the end of the year one designing politician managed to get Parliament

involved in a corrupt job, and then, to avoid investigation, persuaded

the Sultan to issue a decree abrogating the Constitution and abolishing

Parliament! It was a coup d’état, and it was

successful; thanks largely to the indifference of the Powers, and

especially of England.

The Young Turkey leaders demanded the restoration of the

Constitution. In order to accomplish that they proposed to get rid, in

some way, of the Sultan who first decreed and then abrogated that

instrument. There were threats of assassination, and something like a

reign of terror prevailed at Yildiz Kiosk. The Sultan took as many

precautions against treachery as ever did the Russian Czar. The man who

brought about the abolition of the Parliament by his rascality was a

cabinet minister. He, too, was threatened with [249]death. The strictest repression was practiced.

The merest hint was enough to cause a man’s arrest and summary

execution. But in spite of all, the revolutionary movement grew.

Mysterious placards appeared on the walls, calling for fulfilment of

the Hatt of 1877. The name of Midhat Pasha, who suffered martyrdom for

having given Turkey a Constitution, was spoken now and then, in

whispers only, but in tones of grateful reverence. A whisper of

“The Constitution,” too, went round. Army and navy were

becoming secretly leavened with the idea. The Sultan and his Ministers

did not know whom to trust.

And now that we have seen what a fiasco this brilliantly

projected great naval demonstration proved itself to be; and how

cleverly the Sultan played his pawns against Castles and Kings and

Queens, and checkmated all the Powers of Europe, we will leave him in

his hell of infamy bathed in the blood of nearly a hundred thousand

slain, with the voices of agonized and outraged mothers and daughters

raining maledictions upon his accursed head, while we try to be patient

until the rod of the Almighty shall smite the wicked, till the day of

reckoning and of vengeance shall come in the day of the Lord at hand.

We leave the Sultan in his palace to the companionship, perhaps the

guidance, of Khalil Rifaat Pasha, the new Grand Vizier, the voice of

history and the righteous judgments of God, but as for Islam, as a

system of government over Christian populations, we can but pray daily

for its speedy, utter and final overthrow. [250]