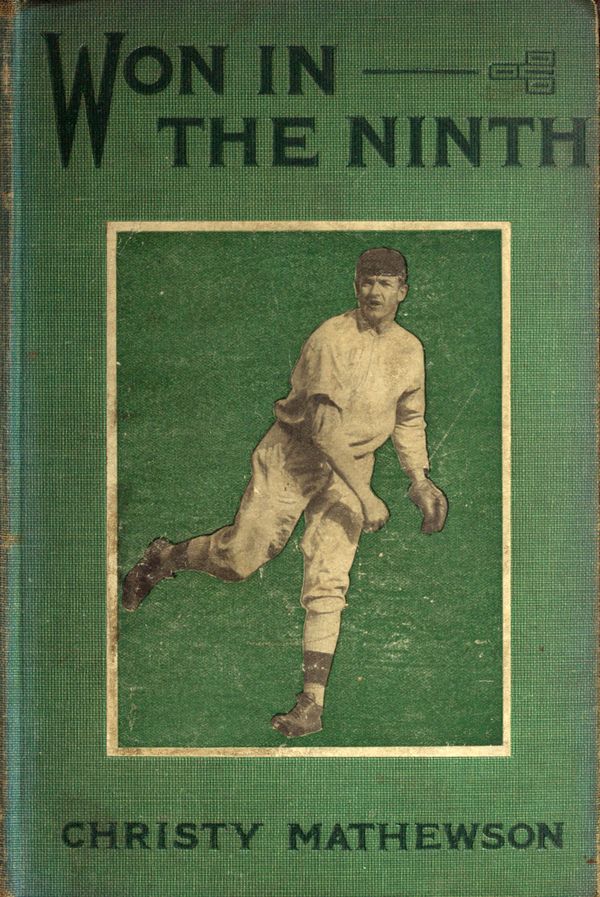

BY

THE FAMOUS PITCHER OF THE NEW YORK GIANTS

THE FIRST OF A SERIES

OF STORIES FOR BOYS ON

SPORTS TO BE KNOWN AS

THE WELL-KNOWN WRITER ON SPORTS

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

NEW YORK

1910

Copyright, 1910, by

R. J. BODMER COMPANY

THE NEW YORK BOOK COMPANY, SALES AGENTS

NEW YORK, N. Y.

To the memory of Henry Chadwick, “The Father of Baseball,” whose life was centered in the sport, and who, by his rugged honesty and his relentless opposition to everything that savored of dishonesty and commercialism in connection with the game, is entitled to the credit, more than any other, of the high standing and unsullied reputation which the sport enjoys to-day, and to the boys who love the great American game I dedicate this book.

C. M.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | THE WINTER TERM | 1 |

| II. | THE LOWELL SPIRIT | 9 |

| III. | GETTING ACQUAINTED | 14 |

| IV. | THE JERRY HARRIMAN SCHOLARSHIP PRIZES | 23 |

| V. | THE FIRST LINE-UP | 32 |

| VI. | PICKING THE VARSITY | 46 |

| VII. | HAL AND CROSSLEY | 56 |

| VIII. | BAD NEWS FROM HOME AND FLIGHT | 63 |

| IX. | THE DIAMOND MEDAL | 79 |

| X. | UNDER SUSPICION | 84 |

| XI. | THE STUDENT DETECTIVES | 98 |

| XII. | HAL IS DISCOVERED | 104 |

| XIII. | HANS TAKES A TRIP | 117 |

| XIV. | PREPARATIONS AT THE RIVAL COLLEGE | 133 |

| XV. | THE “LOWELL REPORTER” | 142 |

| XVI. | THE ALUMNI GAME | 158 |

| XVII. | THE MAKING OF A FAN | 169 |

| XVIII. | THE TRIP TO JEFFERSON | 185 |

| XIX. | BEFORE THE BATTLE | 193 |

| XX. | THE FIRST GAME | 204 |

| XXI. | RETURNING HOME | 220 |

| XXII. | DISTINGUISHED FANS | 226 |

| XXIII. | THE SECOND STRUGGLE | 231 |

| XXIV. | HANS’ SECOND TRIP TO NEW YORK | 245 |

| XXV. | THE FINAL GAME | 252 |

| XXVI. | HAL-HONUSED | 271 |

| XXVII. | AWARDING THE PRIZES | 288 |

| XXVIII. | SATO WRITES HOME | 293 |

WON IN THE NINTH

“Eyah! Eyah! Hughie, RAH-RAH.” A wiry red-haired boy about twenty-three years old swung lightly from the train with a big valise in his hand into a crowd of college boys in caps and heavy ulsters. They gathered round him at once, and while one crowd took charge of his valise, he was lifted on to the shoulders of a half dozen fellows and carried through the streets to his rooms in Elihu Dormitory. In a twinkling his rooms and the halls outside were blocked with the lads of Lowell who had come to welcome the most popular boy in school, Hughie Jenkins.

It was the day of the opening of the winter term of the University. Hughie Jenkins had been the successful manager for three years of the College Baseball team and on the Thanksgiving Day previous, Hughie as Captain of the Football Eleven, with the help of the other members of the team, had won the College Championship for the first time in five years.

The boys of Lowell University had never been[2] very successful in football against their old rivals at Jefferson, and the fellows were so chock-full of enthusiasm over it that they had not yet had enough opportunity to satisfy it. As each of the members of the team had arrived he had been welcomed in much the same way, but the great welcome was, of course, given to “good old Hughie” as they called him, and now that he was with them again it was possible, taking the boys’ view of it, for the work of the University to go on.

As Captain Larke had said, “Hughie is entitled to all the credit we can give him. He has been a wonder at baseball because he has always kept the boys fighting[3] hard to win, no matter what the score was, and we have won many a game just because we wanted to do our best for him, and the way he made us get out and win in the last few minutes of the big football game kind of shows that he knows how to put them over.”

“That’s right,” said Kirkpatrick, who was right end on the team, “if good old Hughie hadn’t put some of the fight back in us when that old score was 0 to 0 in the last five minutes of play, and then himself kicked that field goal from Jefferson’s twenty-five-yard line, we wouldn’t have won.”

“Well,” said Hughie, “this is fine all right, boys. We did win, didn’t we! and it’s very kind of you to try to give me all the credit, but if it hadn’t been for the other ten fellows on the team, I guess I couldn’t have done very much, and anyway it took eleven pretty good men to beat that team from Jefferson.”

Then, turning to Johnny Everson he said, “Gee, I wish the snow would melt. I’d like to find out what kind of new fellows we have who can play baseball.”

And that was just like Hughie. Here it was winter, with snow on the ground, and a month or two of cold weather still in sight. He had hardly got rested from the football campaign, and now he was wishing it was time to get out the bats, balls, and masks!

“It gets me,” said Delvin to Gibbie over in one corner, “how that old boy hustles and is thinking about all kinds of things all the time, but I guess that’s the way to win out.”

“In time of peace prepare for war,” said Hughie. “Now I am wondering right now whom we are going to get to take the place of old boy Penny on first (Fred Penny had been the sensation of the college world at the first bag), and who will take Johnny King’s place as catcher and will he be able to work that delayed throw trick with Johnny Everson and the shortstop? And by the way, who is going to take Joe Brinker’s place at short, besides the couple of other places that are vacant?

“Boys,” continued Hughie, “this is going to be my last year at school here. You fellows have helped me win the championship before. It’s all right about the football business, but this last year with you, we’ve simply got to have another winning nine. Let’s give a good old cheer for the football boys, and then let’s give another for the grand old game of ball, and then you go and tell all the fellows who can play ball that I want to see them in the cage next week, and tell all of them that think they can play ball to come, too. Sometimes some of these chaps who think they can’t do it turn out the best of all.”

And that evening when the boys got talking by themselves they forgot all about football, and the fellows who had been to school last year had to tell all over again about the wonderful stunts that Lowell boys had pulled off in the past, just as if most of them hadn’t heard them all before.

“Say, Johnny,” said Fred Larke, a Junior from Kansas and Captain of the Baseball Nine, to Johnny[5] Everson, “I was trying to tell Robb here (Robb was from Georgia) how Johnny King and you and Joe Brinker figured out that delayed-throw-to-second trick that won that game from Princeville last year.”

“Well,” said Johnny, “it didn’t really win the game, you know, because we were ahead then, but it kept the other fellows from winning. You see, some one said to us in the visitors’ dressing room of Bailey Oval that Walker of the Princeville team was a slow thinker. ‘I have a new trick for fellows that can’t think quick,’ said King, the catcher, and he explained it to us so we would be on the job if the chance came. Sure enough it did.

“In the last half of the ninth inning of the game with Princeville College, the Lowell boys were one run to the good. Princeville College was at bat, of course.

“Walker, the first man up, had gotten to first on a hit and reached second on a sacrifice and he was the lad they said didn’t think quick. This was just the thing we figured might happen. King had said, ‘If that fellow gets on second, I can pull off this new trick, which I call the delayed throw. Let Joe cover the bag and Johnny stall.’ On the first ball pitched, this Walker took a big lead off second, and Brinker covered the bag, King motioned quick as if to throw, and I stood still. Walker first started back toward second, but when he saw that King didn’t throw he slowed down. Brinker, walking back to his place at short, said to Walker, ‘We’d have got you that time, old boy, if King had thrown[6] the ball.’ For just one fatal moment Walker turned around to answer Brinker’s remark and in that instant King threw the ball to me as I hustled for the bag. Of course, I caught it and jabbed it against the runner and before he knew how it was done, he was out.

“Of course you couldn’t work that on a real live player, but we won the game on that play because the next batter drove out a long single on which Walker could have scored. Looking at it one way, it was won in the dressing room because that’s where we fixed up the scheme.”

“It pays to keep thinking about the game all the time, doesn’t it?” commented Larke.

That brought up the other story of another game with Biltmore University a couple of years before which Lowell lost, and Everson had to tell that, too.

“I wasn’t there,” said Everson, “because it was two years ago, which was before my time, and there was a whole lot of luck about it, too, but it was this way. There were three on bases and Merry, our mighty slugger, at bat with two out. Score was 3 to 0 against us and it was our last half of the ninth, too; Merry hit the first ball pitched for a homer over the right field fence, and four runs would have scored, only for little Willie Keefer, right fielder for Biltmore, who was playing well out toward the fence.

“The grounds were down by the railroad and right field was down hill and rough. Inside, the fence sloped at an angle of 65 degrees, being straight on[7] the outside and covered with signs. Willie started with the crack of the bat, leaped upon the slope of the fence and started to run along it, going higher and higher and just as the ball was going over his head, straight as a bullet, he put up his right hand, and caught the ball fairly; then Willie went over the fence with the ball in his mitt, rolling over in the dirt.

“Willie climbed back over the fence, and the runs didn’t count because while the umpire couldn’t see it plainly, our fellows in the right bleachers could see Willie all the time and they were, of course, square enough to say that the ball was fairly caught, even if it did lose the game for us.”

And so they talked and talked until long after time to be in bed, and told all the stories about the great Lowell clubs of the past, the great pitchers, the catchers and the fielders; and the fellows called it the first meeting of the Hot Stove League of Lowell University 19—. This talking League lasted through part of February, by which time the freshies who had done wonders on the high-school teams at home, and who had come to Lowell with high hopes of making the team, had a pretty good idea of the kind of enthusiasm and loyalty and, most important, the hard work they would have to show to get on the team at Lowell.

The night of Hughie Jenkins’ return a boyish-looking chap, who had come all the way from California to Lowell University, only five months before, wrote a long letter to his folks back home, and[8] among other things he said the boys had begun to talk baseball, and he was going to try to be on the team and also that he was going to try for the position of pitcher. Further, that he was going to try for one of the Jerry Harriman Prizes. His name was Case.

Lowell University wasn’t one of those little colleges about which books for boys are often written, nor was it just a big college. It was the greatest University in the East. It had thousands of students and hundreds of teachers. It was a rich college with dozens of buildings. A great many hundreds of the boys who had been graduated from it, poor boys and rich boys and medium-fortuned boys, now held high positions in the big world outside.

Two of the boys who had attended school there years before and who had played on its athletic teams had become Presidents of the United States, and every year while these men were in the White House they came to attend the big football and baseball games, and acted just like boys again, while the games were going on at least. Other boys had been made members of the Cabinet and a great many had become Senators and Representatives in Congress while still others had become famous ministers, doctors and merchants.

The students were made up of sons of rich families and poor alike. Boys from the farms and from the city. Of those who were lucky in having rich[10] fathers, there were quite a number at school every year. Some of them had finely furnished rooms, servants, automobiles and other things which a rich man’s son generally has, and it must be said that a great many, in fact, most of these boys developed into men of fine character and ability, and made their marks in the world.

A few thought they were better than those who didn’t have so much spending money, but they didn’t get very far or do so much in the world, either in school or after they got out.

The spirit of Lowell was democratic, and with the exception of these foolish fellows, the sons of the rich associated with the poor fellows, particularly where the honor and fame of the school were at stake.

The poor fellows associated with the rich boys whenever they got a chance. They lived in cheaper rooms and worked a little harder, because the bright boys soon figured out that they would have to hustle to keep up with the rich fellows.

Some of them worked during the vacations and earned enough money to keep them at school during the winter just as they do at other colleges, and some of them looked after furnaces around town, or waited on tables at the boarding houses and did other things to assure their schooling. Fully as many of the poor fellows who had been graduated had become rich and famous in life, and one of the two who had become President of the United States was a poor farmer’s boy.

The Faculty of the University wanted the students[11] to mix with each other and didn’t want any difference to be shown between rich boys and poor, so they encouraged all athletic games, and this brought about exactly what they wanted. There is nothing like athletics to put boys on a common ground, and a fellow was always welcome to show what he could do.

They had a fine athletic association. The equipment was the best that money could buy. The best coaches in the world were secured to train the boys in the different sports, and everything was done in a business-like way. This made it possible to select the teams on merit alone.

Any fellow who thought he could do something in the line of college sports had only to report for a trial at the proper time, and at the place called for in the notice, and he was given a chance to show what he could do. The merit system picked him out and in that way the best possible team was secured. If he had done one thing better than some other fellow, he got the job, and he could keep it until some other fellow who could do it better turned up and pushed him out of the position.

If a fellow thought he could pitch he was given a chance to show what he could do before the coach who was engaged especially to try out the pitchers. If the coaches thought he “had it in him,” they would bring it out. Very often, some young fellow showed up who proved to be a wonder, and he got on the Varsity the first year.

This spirit attracted from all over the country boys who wanted to enter college. It made college[12] life very attractive and more students came every year, and somehow Lowell University got more and more in the habit of having winning teams in most college sports. Likewise, it was usually Lowell boys who carried off the lion’s share of the Jerry Harriman Scholarships in baseball.

In baseball, Lowell had most always been the champion. Her basketball and hockey teams were only beaten when outlucked; her crew was beaten but twice in twenty years. Only in football did she seem to fall behind. Year after year she would get a team together that would win its way through the games with the other schools in the East, hardly ever scored against, only to fall before her old time rival college in the West in the final game of the year. This happened in spite of the fact that all of the cunning and ability of her coaches, captains and managers were used to get a team together that could beat Jefferson College.

But this past fall they had finally turned the trick against Jefferson and won for the first time in five years. Half-back last year and Captain and Half-back this year, good old Hughie Jenkins who had won the baseball Championship three times, had done it, and now he was back after the Christmas vacation, and when he had time to think about something besides his studies he would be thinking about baseball and the gaps in last year’s winner that would have to be filled because the old standbys like Fred Penny, Johnny King, Joe Brinker and others had been graduated.

“Well,” said Hughie one evening about the middle of January, to his roommate and chum, Johnny Everson, “I have about five weeks before the 15th of February to dream that the new fellows who think they can play ball are going to be as good as the old boys and I am going to have another winner this year, if—well, we just have to win the Championship this year, that’s all.”

Little did he know that among those who had seen him on the day he got back after the holidays, were almost a half dozen boys who had been in school only five months who would make the Varsity this year, and whose names would be written very near the top of the Roll of Honor in Lowell’s Hall of Fame, and that another fellow, one who was destined to be greater than all the rest, had not yet arrived.

Harold Case mounted the stairs of his boarding house to the little hall room that he had called home for the last five months. It had been his first time away from home and he was lonesome and maybe just a little homesick, for he had come all the way from California to attend school at Lowell. Though he was a poor boy, he had never had to look out for himself before.

Perhaps his room—there was only one small one—helped to make him lonesome. It was comfortably furnished and the meals which Mrs. Malcolm served her student boarder were good, but this was Harold’s first white winter. He had lived all of his eighteen years in the balmy climate of the Golden State, and he missed the warm sun and the bright green of the orange leaves and the yellow fruit which he had been used to back home, and he hadn’t become accustomed to wearing overcoat and rubbers yet as they did every day here in the East.

He had just come in from class. His feet were wet and he was cold and the register which was supposed to heat his room was cold; for the weather was beginning to get mild for Eastern folks, and they[15] had let the furnace fire get low. But it was still too cold and chilly for this boy from the far West, and he was wishing he were back among the fruit groves near his home.

He was lonesome, too, because he missed the chums back home. He had not been fortunate in making friends during his few months at college. Boys are apt to make friends through the games they play together and Harold was not familiar with the boys’ sports that are indulged in during the cold New England winters.

He had never had a pair of skates on in his life and didn’t know what it was to skim over the smooth ice with a pair of sharp steel blades fastened to his[16] shoes. He had never enjoyed the sensation of coasting or hitching on to bob-sleds, nor had he ever seen snow before coming to Lowell.

Think of living eighteen years, and going to school two-thirds that long, and never being mixed up in a snowball fight!

So you see the fact that it was winter and only winter sports were indulged in put Harold out of it for the time being, and because he wasn’t used to the climate, and didn’t know what fun winter sports would provide, he rather felt that he didn’t care for them, and the other fellows paid little attention to him, and he had not made any friends.

This was hard luck of course, and if the other boys had thought about it at all, they would no doubt have encouraged him to join them, but they were not particularly interested at the moment in anyone who didn’t like the things they liked.

As a matter of fact, Harold, as they called him back home, was a really good fellow. He was very boyish looking for his eighteen years. He was a well built fellow, but modest and somewhat backward about pushing himself forward. His hair was brown and his features were good although no one would call him handsome. His eyes were light blue and clear, his mouth was firm, and if the other fellows only knew it, he was as quick as a flash in any game he was familiar with, and he was as graceful as a deer in motion. He could run almost as fast as a deer, too.

His parents were not in easy circumstances and it[17] was harder than Harold knew for Mr. Case to spare the money which he did to send him to Lowell. Harold would perhaps have been just as well pleased to attend a college in California (just now when he thought of the cold Eastern winter he wished to goodness that he had), but his father had been a Lowell man, having been graduated with the class of 18—, and while it was a little hard on him financially to do so, he had always wanted Harold to be a Lowell man, and he was willing to work a little more out there in California to do what he wanted for his son. He felt sure Harold would make his mark in the world and he also had an idea that his boy would add something to the fame of Lowell one way or the other.

At the same time the understanding was that after he got out of school and began to earn money, Harold was to pay back this college money, and so while there was enough to be fairly comfortable for his first year, the young fellow always kept in mind the fact that he was in a way living on borrowed money, and that the less he spent the smaller the amount would be to be paid back.

For this reason, he had secured a room in a somewhat cheaper and quieter part of town, some distance away from the campus, instead of taking up his quarters in one of the Students’ Halls, and this fact also, and because he was in a house with no other students, served to keep him from making friends as easily as he might. If he had been living where there were a lot of other fellows he would not have[18] been so lonesome, and the boys at Lowell would have known sooner what a grand fellow he was.

Harold looked at his watch to see how long it would be to dinner time, for he had a good appetite even if he was cold, and just then the dinner gong sounded. He went down to the dining room where he found Mrs. Malcolm and her young son, a lad of twelve, already seated at table. The dinner was good, and Harold noticed a more cheerful air in Mrs. Malcolm’s conversation. This was rather a surprise as there had been a noticeable lack of laughter in the house lately, at least so he had been thinking.

Mrs. Malcolm was a widow and had come to the college town, thinking she could add something to the small income left her by her husband by establishing herself in the boarding-house business. She had three other rooms to rent, but up to this time Harold had been the only boarder she was lucky enough to get, and lately she had been a little bit discouraged. With a larger house than she needed for herself and son and only one boarder, the increased expense was more than Harold was paying her, so she was losing money on her idea.

This evening, however, she was more cheerful, and she soon gave the reason. She had secured two other students as boarders that day. One was to come that evening, and had taken the room next to Harold’s on the same floor, and the other had taken the little room over his on the third floor, but this fellow only rented the room with the privilege of taking his meals where he pleased.

“The young man who is coming to-night is a freshman like yourself,” said Mrs. Malcolm. “His home is in Texas; I think you will like him and it will be real nice for you to have some one else in the house. His name is Hagner.”

When dinner was over Harold went up to his room to do some studying.

“I feel as though I could be chums with a Mexican greaser to-night,” thought Harold, “and I certainly will be glad to meet him.”

Shortly afterward the door bell rang and Harold heard an expressman bringing a trunk up the stairs, followed by the footsteps of a young man and also a lighter step, no doubt that of Mrs. Malcolm. After a few moments there was a knock at his door, and when he opened it Mrs. Malcolm asked him if she might introduce him to the new boarder, Mr. Hagner.

Harold found a big, raw-boned, awkward-looking German, a young fellow about six feet tall, weighing fully 175 pounds. He was heavy set, bow-legged, and had massive shoulders and long arms, but when he moved around there was a wonderful ease and grace apparent in his movements, which was a surprise.

Mrs. Malcolm soon went out and left the two together in Hagner’s room. Harold started to leave, too, saying that he would come in after Hagner had unpacked.

“Don’t need to go for that reason,” said Hagner, as he opened his trunk, ready to unpack.

“All right, if you don’t mind,” said Harold. “I’m kind of lonesome to-night, anyhow.”

“What’s the matter?” asked the other, “anything gone wrong?”

“No,” said Harold, “but you see I’m from California and I don’t like this blamed snow and cold. I’d rather be back where it’s warm every day like I’m used to.”

“How long have you been here?” asked Hagner. “This must be your first year, too?”

“It is. I’ve been here five months and it’s been mighty cold for three months of that time. When did you come?”

“I just got in yesterday,” said Hagner, starting to unpack. “Never saw snow before in my life. I am from Texas myself and we don’t have it down there either. It’s wet, ain’t it? Don’t like it much myself. Guess I’ll have to stand it, though. Don’t expect to see Texas again for a couple of years, anyhow.”

Harold began to feel more cheerful. Here was a fellow to whom he could tell about college. Compared with Hagner, Harold was an old timer, and he began to feel good. Hagner kept on taking things out of his trunk. He was having a hard time, getting something out that seemed to be laid in crosswise between the clothes. Harold looked, and just then out it came, and there stood Hagner with an old baseball bat in his hand. He reached in with his left and pulled out an old fielder’s mitt, which had a big hole right through the middle.

Harold’s eyes bulged. “Do you play ball?” he asked.

“A little,” said the other; “used to play around the back lots down home. Had to play hookey from Sunday school to get a chance. Had to work week days after school. You play?”

“Some,” said Harold.

“What position?”

“Pitcher,” said Harold, falling into the other’s way of talking. “What’s your place?”

“Short,” said Hagner.

“Going to try for the team?” asked Harold.

“Will if they want me. You?”

“I’m going to make them want me. The best pitcher they had last year is gone and they need some one.”

“Better try for something else. Everybody thinks he can pitch. Only a few know how.”

“Well, I’m a Southpaw pitcher, and I was pretty good on the High School team out home. Southpaws are scarce.”

“Left handed, eh! You look quick, too. Think you might make a first baseman.”

“I’d rather pitch,” said Harold.

“All right, sir,” said Hagner. “You can pitch if you want to and if they want you, but if they give me a chance any place, I think I can stop them all right, and if I miss one occasionally, I think I can hold the job with my bat. What’s your first name? Mine’s John, but you can call me Hagner.”

“My first name is Harold, but you had better call me by my last name, too.”

And so they talked baseball until long after midnight, and their enthusiasm for the great American game made them friends at once, and Harold went to bed feeling that the world was bright and warm and that spring would be coming pretty soon, and he made up his mind right there not to get homesick any more, but to dig more into his studies so that his marks wouldn’t interfere with the amount of time he wanted to give to baseball when practice started.

When Lowell University won the college baseball Championship in 1876 the victory was to a large extent due to the wonderful all-round work of Jerry Harriman. As a pitcher he had never up to that time had an equal, and he could play almost any other position on the team well. In those days a club would have only one pitcher and he was expected to pitch almost every game of the season, which often meant pitching every day in the week but Sunday. When not pitching he played an outfield position.

This is a whole lot different than the way the game is conducted in the colleges to-day. In these days a nine will sometimes have half a dozen pitchers and they don’t do anything but pitch and then only in their regular turns. Besides being a great pitcher Jerry was also a great batter. This was also unusual because very seldom do you find a good pitcher who can bat, but Jerry could both pitch and bat and he made a great name for himself as a college athlete.

After he had been graduated he went into business in a city in the Middle West, and became very wealthy.

As a young lad he had been weak physically and his heart was said to be affected. In fact, he was not expected to live to grow up. When he was thirteen years old the doctors said he couldn’t live a year. There came to his home town, however, about this time, a young man who opened a school of Physical Culture. He had a wonderfully well developed body, was a great enthusiast on athletics, and he made a great effort to get the young boys around town who were weak physically to come to him.

He made his living by forming gymnasium classes among the business men of the town and by his work with them got many a staid old business man, who was constantly confined to his office, into the habit of taking exercise regularly, and he made many a man who had become fat and sick through lack of exercise strong again physically.

But he had a particular interest in the boys and he was especially fond of getting up classes for poor young fellows who were, as said before, undeveloped and weak. He taught these youngsters for nothing what he knew about the fine results of taking exercise regularly, and many a poor fellow who would have died young, he developed into a strong and healthy young man who lived long and became prominent in business and politics.

Among the young fellows who came to the attention of this Professor Mitchell was young Harriman, who by this time, however, was so weak that he couldn’t join any of the classes. In fact, Jerry couldn’t walk across the room without holding on to a[25] chair or something, and even the Professor had some doubts as to his ability to do anything for him.

However, the case interested him and he came every day to the house for some weeks and had Jerry do such exercises as he could. At first there was no improvement that could be noticed, but after a couple of months of the most careful and lightest exercise possible, a very decided improvement began to be noticed. Very soon, by carefully doing exactly as the Professor told him, Jerry began to get stronger, until by the end of the first year all trace of his heart trouble had disappeared and the Professor told him that if he would only make it his business to take his exercises every day he would some day be as strong as any boy.

It is not the idea of this chapter to go into all the details of how Harriman became a strong young man. It is only fair to say, however, that to him his regular and systematic exercise became as important as his meals or washing his face, night and morning. When he saw how exercise was improving him physically he became almost a crank on the subject.

At any rate, he made a resolution that some day he would be just as well developed physically as any athlete in the world, and he kept this idea foremost in his thoughts, because he could see that if he had a perfect physical development, his mental capacity would increase in proportion. In the end he became a wonderfully well developed lad and was a living example of what exercise will do for a boy, or man either, for that matter.

During this time he went to school, and soon was able to join the games of the other boys. In the High School and in the Preparatory College he went in for athletics, and by the time he entered Lowell, even he laughed when anybody recalled the fact that seven or eight years before the doctors had given him up to an early death from heart trouble.

It has been necessary to give this much of the details of this part of his life in order to show what it meant to Harriman to become the greatest pitcher who had ever been in the box for any college in the country, and also to give the boys who read this good reason for his great interest in college athletics, after he had gone into business and become wealthy, as shown by the scholarship prizes which he gave each year to the best athletes in the various colleges of the country.

A Jerry Harriman Scholarship meant free tuition and Five Hundred Dollars per year for living expenses at any college in the country selected by the winner, for the complete college course. Mr. Harriman was liberal in the number of scholarship prizes offered. Several young fellows, generally poor boys, were presented each year with a complete college education. There was a scholarship for the best all-round football player, for basketball, for hockey and each of the track and field events.

The scholarships were awarded by the Intercollegiate Athletic Association, and were given without restriction to the one chosen by the Association, except that a nominee’s college had to submit to Mr.[27] Harriman a record of the prize winner’s standing in his studies. In this particular a good average standing was required. It was the argument of Mr. Harriman that the pursuit of athletics in college need not interfere with a fellow’s studies and that if you give a boy a well developed body his brain will get the benefit of it, and with an average record as a student, any boy might be expected to make his way in the world.

Now baseball was the game which Jerry Harriman liked above all others. He liked best to see it played and to play it himself, and so when he came to make up his list of scholarship prizes he gave the baseball fellows the best of it. He was then and still is a real “fan.” He loved to see new stars developed on the diamond.

He thought it was the best and squarest game in the world and he wanted his boys, as he called all college boys, to love and play the game. Therefore he had always offered four scholarships in baseball, one for the leading pitcher, one for the leading infielder, one for the leading outfielder and batter, and one for the best all-round infielder and batsman.

Naturally, having been the baseball champions for so long, the Lowell nine generally got most of these scholarship prizes and it was very pleasing to Mr. Harriman to see his old college secure so many of them.

The talk around the University wherever the students gathered often came around to these scholarship prizes, especially as the time for baseball approached.

Fellows like Jenkins, Larke, Everson and other of the older fellows, some of whom had won them in years past, would bring up the subject when they noticed any of the young freshmen around, just to get them to thinking about it, and a good many youngsters had developed an ambition to try for a scholarship and some of them to win one, just from hearing these older fellows talk. And generally these talks would turn from a discussion of the records of winners of the prizes to the most thrilling performances of the individual stars.

The day of the first meeting in the cage called by Hughie, to give him a chance to look over the candidates for the team, was the first time that Case and Hagner had been present at one of these talks.

Hughie had given a general talk about the game and had talked with each of the candidates, asking various questions, such as “what position do you play?” “Can you bat? Can you pitch?” etc. After they had all thrown the ball around for an hour, just playing catch so that Hughie could notice the way the different fellows threw and swung, they sat around gossiping with each other, nobody wanting to go home, when one of the older fellows would say something about the Scholarship Prizes.

Generally there was some one present who didn’t know the details and this offered a chance to tell all about the prizes.

In this case it was Hagner, who had been at school only a few weeks, and all he knew about the prizes was what Case had been able to tell him. After[29] Everson had finished explaining the prizes fully the talk, as usual, drifted on to the wonderful records of the prize winners of the past. Not that sensational catches or such other stunts as unassisted triple plays would in themselves secure one of the prizes, for they would not.

Only the official scorer’s records showing the standing of the candidates were considered, but it was generally the fellow who had the best record for any given position who got the chance to pull off the thrilling plays, because only the good players can do the wonderful things.

When the talk turned to fielders who had been famous on some of the old Lowell teams, it wasn’t long before they were telling stories about great catches made by some of the fielders on championship teams of years gone by.

On such occasions Fred Larke never forgot to tell about that great catch made by Jimmy Ryan. How he in one game jumped clear over the fence in right field which separated the bleachers from the playing field, and caught a fly ball while falling into the crowd.

Johnny Everson then had to tell his story of Hughie Jenkins’ greatest catch, when he was playing short in one of the Biltmore College games. There was an enormous crowd out. The stands wouldn’t hold them all, so they were let out on the field and there were so many that they crowded close to the base lines. In the ninth inning the score was tied, one out, and Bill Everett of Biltmore College on[30] third. The batter hit a high foul ball into the crowd back of third base. Some of them were seated but most of them were standing. Jenkins hustled across from his position at short, hurled himself through the air without paying any attention to the crowd, caught the ball fair and square and then fell in among the spectators. That made two out, but Hughie was after the third one. Bill Everett touched third after the catch and started for home. Hughie couldn’t see but he guessed that Everett had started. He climbed up out of the crowd, stepped on the people he had knocked down, and threw to the plate without looking. The ball went straight into the catcher’s mitt and Everett was out easily. In the next inning Lowell won the game.

Then, of course, Miner Black had to tell his remarkable catch story about Jimmie Siegel in a twenty inning game with Eastern Pennsylvania. How in the eighteenth inning with a runner on first base, the mightiest hitter of the Pennsylvania nine drove a hard hit ball to left center. Just at that moment, however, Siegel had put his hand in his hip pocket to get out his handkerchief, as the day was hot and the game was a hard one.

Jimmie, of course, started after the ball, and made an effort to pull his hand out of his pocket while running. It wouldn’t come out. He jerked and jerked and still it stuck. Meantime the ball had to be caught on the run and Jimmie had to make a try for it some way. He leaped in the air, twisted, stuck up his left hand and caught it with his back to the diamond. Jimmie threw the ball into the diamond with his left hand. Strange to say his right hand then came out of his pocket easily. He wiped the perspiration off his face, grinned, and the crowd went wild for they realized why he had gone after it with one hand.

After such talks the “freshies,” who had made some pretty fine catches on the back lots at home, always made a resolution to do something equally startling when they got on the Varsity, and the candidates at Lowell this year were a good deal like all the other freshmen candidates who had gone before them in this respect. This really was a good thing for the boys, although, of course, many of them never realized their ambitions for such fame.

“Well, what do you think of your freshman phenoms?”

It was Johnny Everson who was speaking. Johnny besides being the regular second baseman of the Varsity was the chum of Hughie Jenkins, the manager of the team and his chief adviser with Captain Larke. Johnny knew the game from top to bottom and across the middle. They called him “a little bunch of brains and nerves,” and he deserved the compliment.

He was small in size, but large in brains and many a game had been won for the college by his quick work at trying moments, to say nothing of the fact that he was largely responsible for the discovery and development of many of the plays which had come to be known as “inside baseball.” He had an aggressive chin which seemed to be always pointing forward, and his eye was as quick and accurate as a sharpshooter’s.

“We seem to have a good many gaps to fill and I guess we will find mostly yaps to fill them with,” he went on; “anyway that’s the way I feel to-night after looking over the unpromising material that we put through the stunts at the cage to-day.”

“I don’t feel discouraged. You can never tell, of course, on one trial, but watching some of those youngsters this afternoon made me think that with a little training some of them will make good,” said Hughie.

“Let’s go over the list and mark the fixtures we can count on, and then we can tell what we have to do to get a real nine together,” said Everson.

“All right. At second we have you,” said Hughie, “and I guess we won’t need to worry about the Keystone bag, and at third we have Delvin, who I think, will develop this year into a great star at the near station. Captain Larke will handle left field all right as usual, Miner Black will come back stronger than ever this year in the box, and George Gibbs will, I think, do the catching all right. That’s just about half a team, isn’t it?”

“Now, at the first sack we need somebody to take Penny’s place, and I must confess that I did not notice any likely candidate, unless it was Dill.”

“We are going to have a hard time, I think, to find some one at short in place of our good friend Joe Brinker.”

“Did you notice the bowlegged and awkward-looking German named Hagner in the cage to-day?” broke in Everson. “If he wasn’t so big and awkward looking, he might be able to bat and we could play him in the outer gardens, but I hardly think he would ever make a shortstop.”

“I hardly think so either,” said Jenkins, “but I had a talk with him and he said he could play short.[34] I have also had a report from Texas, where he came from, that he is a perfect terror at bat. I can hardly hope though that he will be able to fill Brinker’s place. I think if we could figure out some scheme to remodel his anatomy we might be able to make something out of him. Still he may be a diamond in the rough. I don’t think you can tell anything about any of them until you see them work in the open air for a week or two.”

“What do you think about right field?” asked Johnny.

“If I am not mistaken,” answered Hughie, “we have the real prize package in that young chap from Georgia, Robb (a regular cracker name, isn’t it)? Did you notice him at all? Did you ever see more speed? I am knocking on wood when I talk about him, because I don’t want to fool myself, but if I was a scout for a professional team, and saw this fellow Robb playing ball on some back lot, I think I’d buy him without instructions from headquarters.”

“Lots of them look like stars the first few days of spring,” said Johnny. “I noticed Robb particularly, too. I was thinking that while he is a clean-cut looking fellow, I’d hate to get into a fight with him, because he looks like a chap who has no fear of anything.”

“Besides Robb there were half a dozen others who looked like they might be made into fielders,” said Hughie. “There was Talkington, McKee, Raymur, Oakley, Lunley, and Flack. If any of them know how to swing a bat, I think we will be[35] able to teach them what they need to know about catching flies.”

“As usual most of the candidates want to pitch and if Miner is all right this year we won’t need any one to help him, except, perhaps, a left-hander. Did you notice anything promising along this line? I was so busy looking over the fielders and possible first basemen that I didn’t pay much attention to the pitchers. I rather liked the delivery of Crossley the short time he was throwing. He looked promising for a rich man’s son.”

“Besides that will be easier when old man Young gets here and we get them out for coaching. You can also pick them out in batting practice. Just tell them to throw straight swift balls over the plate and you can pick out the poor ones anyhow, because a pitcher who can’t put a straight ball over nine times out of ten, isn’t worth developing. Then by the time Young gets a chance at them for a week we’ll know which are no good at all, and what ones it will pay him to coach.”

“I had a talk,” said Johnny, “with that California lad, Case. He is a quiet chap and unassuming. He says he is a southpaw pitcher too, and he may be what we are looking for.”

A few days after this talk in Hughie’s room the snow began to melt and within a week Lowell field, which had for months been covered with snow and ice, suddenly took on a greenish look, the ground became dry and firm and everyone began to feel the spring in the air. One day, not long after, there[36] appeared upon the bulletin board the following notice:

University Baseball. Outdoor practice. On the field at 1 P. M. February 25th. Candidates must bring their own suits.

Hugh Jenkins, Manager.

There was joy in the hearts of the hundred, for there were about that number who hoped to be picked for the Varsity. Out of the hundred, at least ninety were certain to be disappointed as far as the Varsity was concerned, for there were only about ten places to fill, counting the substitutes.

Of course, there was a chance that a fellow would get on the second squad which might help him to the Varsity next year, and then there was always the freshman team which was formed last and which generally was an all pitcher team, so to speak, because every man on it had nursed secret hopes of making the Varsity his first year, as a pitcher.

Harold Case was out early. He had come to the field with Hagner and was now sitting on the steps of the clubhouse waiting for Hagner, who had become his good friend. It was a strange friendship that had sprung up between these two—the tall big-boned and awkward German lad, almost a man in looks, and this young and exceedingly graceful Western lad, and both were profiting by it.

While he was sitting there, what was left of last year’s champions trotted out on the field. Gibbs, second catcher last year, and Larke, old cronies;[37] Black and Delvin; and last of all, of course, the inseparables, Everson and Jenkins. The rest of the candidates straggled out on to the field in twos and threes, to the number of fully a hundred, and presently Hagner came out with his old bat and glove in hand and Harold got up and they walked over to the diamond together.

“Better not let yourself out any to-day,” said Hagner, as they approached the others who had already paired off and were tossing balls back and forth to each other.

Before Harold had time to answer, however, Jenkins had said the same thing practically.

“Getting ready for a baseball season isn’t quite like developing a football team,” said Hughie. “In football you have to get the team in shape for one or two big games, each of them requiring a terrific outburst of energy, without thinking about the morrow, but in the case of a baseball nine you have to develop your bodies to withstand the strain of a long series of games, mostly in warm weather, and you must start slowly and get into condition gradually, so do not try to do it all to-day.

“Another thing, in football we train the team to withstand hard knocks, a sort of bull-dog development, while a baseball team must have the nice strength of a greyhound so as to enable it to keep going at top speed for a long time, and so I want you to go easy.”

So he had them stand in circles, making five or six groups, and pass around medicine balls, an[38] exercise to strengthen the trunk muscles. Then they paired off again, and tossed the baseball to each other two by two—gently—just like boys playing catch.

All at once Hughie called out, “Come on, boys, around the field,” and starting off in front he trotted all the way round the field along the fence. By the time they got started on the second round a lot of the fellows were puffing and blowing hard and found it difficult to keep up, but Hughie knew how important it was for a ball player to have wind and he knew this kind of a stunt practiced a couple of times a day would fix them up in good shape by the time the games started.

Then he called them all up to the plate for batting practice, and asked if there was any fellow around who could pitch. He knew, of course, that Miner Black was there, but Miner knew enough not to say anything. What Hughie wanted was to find out what kind of control these new fellows who thought they could pitch had with a slow straight ball. Hughie and Coach Young, who had arrived, stood back of the plate with Everson and Larke watching.

Out of the dozen youngsters who said they would try he picked out Hackett and told him to go into the box.

“Now go ahead,” said Hughie. “Don’t use any curves and don’t try to burn them over; just give us some slow straight balls and try to get them across the plate.”

What he really was trying to do besides give the[39] men batting practice was to get a line on the new pitching material, and this was the best way to get it.

Then he had the batters take turns at the plate, and each fellow was expected to stay there until he had made a hit, Hughie standing by showing each, especially the new ones, how to stand up to the ball and meet it fairly. Hackett, the first pitcher, didn’t seem to be able to get them anywhere near the plate, and so Hughie told the next one, Crossley, to go in and give it a trial. He was a little better, but they had finally to call on Miner to put a few over.

As usual, Miner was long on control. Johnny Everson stepped to the plate. Miner served one up and bing! The ball went scurrying out to right field. Each fellow took his turn at bat. Boys like Delvin, Larke and Gibbs—standing up like veterans and cracking the hits out in fine shape, giving a little more running practice to some of the youngsters who had been sent out to the field to chase the balls.

Finally it came Hagner’s turn. He stepped up to the plate and stood there rather slouchily and loosely, far away from the mark as if he were afraid of the ball.

“Better step up a little closer,” said Hughie, “he won’t hit you.”

“All right,” said Hagner, “I want to learn all about it.”

Miner served up one to him straight as an arrow. Hagner swung hard at it and missed. He felt a bit surprised himself. The next one he fouled off the[40] bat near his hands. Just as Miner sent up the third ball Hagner stepped back from the plate, swung the bat easily, met it squarely and crack went the ball in a white streak clean over the center field fence!

Miner looked at him surprised and said, “You can’t do that again.”

The next time Hagner came up, Miner decided to use some curves and make him earn his hit. He sent up what looked like a fast straight ball about waist high. Hagner swung on it and missed. The ball had a terrific out curve and, of course, Hagner understood they were only to be straight. He eyed Miner closely and when he started to pitch Hagner stooped over to watch the ball like a hawk. On came[41] the ball, starting wide of the plate and Hagner first decided it was a ball and then as the inshoot started in toward the plate, quick as a wink Hagner swung his bat and over the fence she went again.

The fellows went wild. Hughie and Everson standing back of the batting cage looked at each other. “What do you know about that?” asked Everson.

“I don’t know anything,” said Hughie. “For a big awkward fellow, he seems to be about the quickest thing I ever saw. Why! he didn’t even look ready to hit at that ball until it started to shoot in toward the plate, and I was sure he was going to let it go by. If he can bat like that regularly, we’ll play him some place if he fumbles every ball that is batted to him.”

Pretty soon Hughie asked, “Haven’t we got another left-hander here?”

“There ought to be,” said Everson, looking around. “Here, Case, get out there and show what you can do. This is your chance.”

“Thanks,” said Case in his polite way. “I’ll try if you want me to.” He walked into the box and picked up the ball where Miner had dropped it. He had not really tried to pitch since last summer and was a little nervous. The first ball went a little bit wide. The second one nearly hit the batter. The line of waiting batters grinned.

“Southpaws are either very good or very bad,” said Captain Larke to Delvin. After he had thrown a dozen balls or so, however, Case’s arm got in[42] working order and only an occasional ball went wide of the plate.

“He seems to be pretty good on the straight ones,” said Jenkins. “If he can do as well when we let them begin to try the curves, I think we can put him on as a substitute.”

“What do you think of the bunch in general?” asked Everson.

“Well,” said Hughie, “I think I can see a team out of this crowd all right, though I am not quite sure of Dill at first base. This fellow Robb seems to be a fine batter and so does Talkington. Coach Young says there was one of the young pitchers that looked good, too—young Radams. If this Hagner knows as much about any position as he seems to about batting, I think I’ll let him choose his position. Think of trying to tell him how to stand up to the plate. He’s just a natural ball player. Don’t believe he knows himself how he hits them. Black told me, after he came out of the box, that he did his best to fool Hagner every time after that first time up, and you know how he succeeded. We’ll know more when we get them out on the diamond in the various positions.”

By this time the sun was sinking and it was too dark for further practice. Hagner and Case walked over to the clubhouse together.

“You sure made a hit with the crowd to-day, Hagner,” said Case.

“I made five hits with my bat,” said Hagner, “two of them over the fence.”

“Guess you will make the team all right,” remarked Case. “I heard Jenkins say, any fellow who can bat like that can take his pick of positions and play any one he likes.”

“Good. I’ll play shortstop if they give a choice.”

“Wish I had made as big a hit as you,” said Case.

“You did, because I heard Everson and Jenkins talking it over, too; and they said you had excellent control, and if you did well with the curves they could carry you with the team. If I were you, however, I’d learn to play some position, and make your way as a utility player. You see, left-handed pitchers are all right, but with a regular pitcher like this Miner Black here, you wouldn’t often get a chance to pitch more than an inning or two, anyhow.”

“I don’t know,” said Case, “how good this Miner Black is, but I think I can beat him to the regular pitching job.”

“All right,” said Hagner, “but if you don’t have any more luck at ousting him than most of the fellows have had hitting him, you’ll be out of a regular job on the team for a long time. I’d practice playing the first bag. Still think you’d make a first baseman.”

“I don’t think so,” said Case, as they entered the dressing room to change their clothes, “besides either Dill or Ross seems sure to land the job.”

The second week of out-door practice the regular work of the boys was increased. At batting practice every fellow was expected to run clear around the bases after he made his hit. The coaches and managers[44] got a line on the base-running ability of the boys in this way. Hagner, Robb, Case and Talkington all showed up well in this direction.

Toward the end of the week the fellows were lined up on the diamond at their regular positions, the coaches trying out the various candidates for the fielding jobs. Hughie batted grounders to the infield, to each of them in turn.

After each play the ball was thrown from base to base in all of the different combinations necessary to all the imaginary situations, from short to first it went, from first to third, from third home, and from there to second, a white streak, the speed of the players increasing daily as the men got surer of their positions.

Others were batting flies to the outfield and the coaches were moving about watching the work of each man as he was tried in the different positions. Each of the fielders was given a variety of work, at bunting and the fielding of bunts, catching high infield flies, picking up sizzling grounders, etc. This work enabled Hughie to pick out his first line-up for the first and second squads.

By the middle of March the two squads were playing practice games among themselves.

The first squad generally lined up as follows:

| 1st Base | Dill |

| 2nd Base | Everson |

| 3rd Base | Delvin |

| Short | Hagner |

| Right Fielder | Robb |

| [45]Center Fielder | Talkington |

| Left Fielder | Larke |

| Catcher | Gibbs |

| Pitcher | Black |

The second squad was composed of a miscellaneous crew generally lined up as follows:

| 1st Base | Ross |

| 2nd Base | Gane |

| 3rd Base | Conley |

| Short | Wallach |

| Right Fielder | Raymur |

| Center Fielder | Oakley |

| Left Fielder | McKee |

| Catcher | McLuin |

| Pitcher | Radams |

Harold Case was a sort of substitute pitcher for both squads. He would relieve Black for a while for the first squad and Radams for the other squad, so that both teams got plenty of practice in batting a left-hand pitcher. There was no way for him to find out in advance what Jenkins thought of him, but he had high hopes of making the team, and he felt absolutely confident that if he ever got a chance in one of the full regular games, he would be able to make good. Crossley also was given a good deal of work during these practice games, as he gave promise of doing well and it began to look as though the choice for left-hand pitchers would be between these two.

On the 21st day of March as Harold with the other members of the squads was in the dressing room after practice, the head coach came into the room with a slip of paper in his hand which he posted on the Bulletin Board. There was a rush to read the notice as soon as the coach had departed, and several faces, as they turned away, wore a look of disappointment, while others seemed proud and happy.

Hagner and Case finally finished dressing and turned to the board to read the bulletin before going out. This is what they read:

Varsity Training Table—The training table will start in the morning at Prettyman’s and the following men for the first squad will report there for breakfast—Everson, Delvin, Larke, Gibbs, Black, Hagner, Robb, Talkington, Dill, Case, Radams, Ross and Huyler. About the first of next month the list may be increased or changed. Breakfast at eight o’clock sharp. Members are required to be on time.

Hugh Jenkins, Manager.

“Guess I’ll get a chance to pitch after all,” said[47] Harold. It was a great day for him and he was highly elated. The 19— Varsity had begun to take definite shape, and being named on it meant recognition by the great student body as possessing something worth while in the line of ability. The news spread rapidly through the University and wherever the boys who had been named went they were treated with honor and respect.

Breakfast the first morning at the training table was a good deal of a get-together, get-acquainted affair. I do not know what it is that makes the choice of nicknames or how it is that it comes easier to know some fellows by either their first or last names, others by an abbreviation of one or the other, and still others by adoption of something entirely different, but when boys get to a certain stage of acquaintance with each other there comes a spontaneous desire to bestow a nickname and these names generally fit in a remarkable way. Harold Case went to breakfast known as Case and came out to be forever known to Lowell men as Hal.

John Hagner started to drink his coffee that morning as Hagner and when he had folded his napkin he was known as both Hans and Honus, why nobody ever could tell, and the names stuck to him for life.

Charles Radams came away with the nickname Babe and as Babe he went down into the Lowell Book of Heroes.

Everson had always been Everson before. He was Everson when he sat down to the table that morning, and he was still Everson when he left the room,[48] though why this little brainy Crab should have gotten off without a nickname is far beyond me.

You would think that Larke, who was always jolly, either whistling or singing when not eating or asleep, would have been named The Lark years before, but no, they called him just Cap., yet they had always called Gibbs, Gibbie.

If there were a regular rule for nicknames they would undoubtedly have called Black, White, but they always referred to him as Miner. Delvin they generally called Arthur.

There was something stiff about Dill which was a good deal like the way he played first base in the few games he lasted on the Varsity that year, and the dispenser of nicknames overlooked him entirely at that first breakfast. In fact, he never did acquire one, for he was dropped from the team before anyone could really find a good name to fit him. Pickle would have been a good name for him, and also his fate so far as the team was concerned.

Talkington was a quiet young chap, who said very little either at the table or on the field, so that “Talkie” or “Mr. Speaker,” or anything like that wouldn’t seem natural at all, so they called him “Tris” and let it go at that.

Robb might really have been given a fitting name at the end of the season. If they had waited until then they would undoubtedly have called him Robb because he had developed into the greatest base stealer the game ever knew, but somebody had passed him the oatmeal that morning, after he had[49] demanded it vigorously, with a “Here you are, Tyrant,” and Ty he is to-day—a very short name for so long a fellow.

A week later they played the first real game of the season, the first real test of the line-up as it had been worked out by Jenkins. The game, which was with Colfax, a small neighboring college, was not an important one. Never had they been able to beat Lowell and rarely in all the games that had taken place between the two teams had Lowell been even scored upon. As it was, it was hardly even a test game for the Varsity. Hal sat on the players’ bench with his chin on his hands, and watched the Colfax boys getting licked.

There wasn’t anything very exciting about sitting on the bench and there was nothing very encouraging about the playing of even the Lowell boys. With the exception of a hair-raising one-handed stop by Hagner of a fast grounder over second, and a wonderfully accurate throw to first without getting into position, and the fine work of Gibbie behind the bat in stopping Babe Radams’ wild drops and curves which the Colfax boys struck at blindly, the game was dull and uninteresting.

If the Colfax team had not had the usual attack of stage fright that struck it whenever it played Lowell, it probably would have won. Dill on first dropped three throws in succession made by Everson to catch runners at first, and if it had not been for the accurate throwing of Gibbie to Delvin and Everson who nipped all base runners as they tried to reach[50] second and third, there is no knowing but that the Colfax team might have scored, to say nothing of the possibility of winning. Hagner had fumbled an easy grounder, only to make a jumping catch of a high liner from the bat of the next man, which he promptly threw to first completing a double as Dill did not miss that one.

Ty in right field had misjudged the only chance he had but had recovered the ball in time to catch his man at third with a quick throw and Delvin at the bag to receive it.

By the end of the seventh inning the score stood 8 to 0 in favor of Lowell in spite of the poor playing. The Varsity had batted well, nearly every one had made hits, Everson had 1; Honus, 2; Delvin,[51] 1; Ty, 2; Tris, 2; Cap., 1; Gibbie, 1; Dill, 1; and even Babe Radams had dropped a Texas Leaguer over second. Hal had sat on the bench all the time with Ross and Miner and some of the second squad.

At the beginning of the eighth, Jenkins turned to Ross and said: “You cover the first bag,” and then to Hal, “Go on in the box for a little real practice, Hal.” “That’s all right, Babe,” noticing a look of disappointment on Radams’ face. “You are doing fine, but you can’t have all the practice.”

“Remember, Hal,” he called from the bench, “let them hit it, but we can’t have any scoring against us.”

“All right,” said Hal, as he picked up the ball.

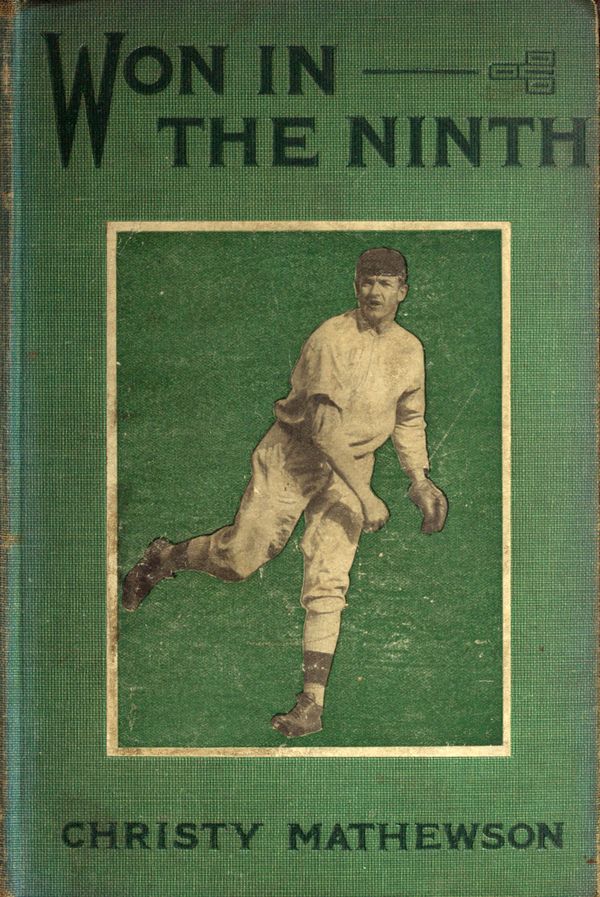

The first man up hit the first ball pitched for a base. The second batter laid down a neat bunt along the first base line. Ross, the first baseman, came in for it, and Hal hustled over to cover the bag. Meantime the batter who was fast man, was tearing down the base line like mad. Ross made a good pick-up and turned to throw.

By that time the batter was only a few feet from the bag where Hal was to receive the throw. Ross had to throw quick and in doing so threw the ball at Hal’s feet. Hal reached down, made a neat pick-up, and the umpire waved the runner out.

There was now one out with a man on second. The third batter hit a hard one at Everson, who retired the runner at first, the man on second reaching third. The next batter hit a slow bounder between the box and first. Hal started after the ball, grabbed[52] it on the bounce with one hand and without stopping raced to first base, which he reached just ahead of the runner, making the third out.

As he walked to the bench Jenkins came up to meet him and patting him on the back, said: “Good boy, Hal,” which was fine, Hal thought.

It was his turn at bat, and he walked to the plate with high hopes of making at least a two bagger. The first ball looked like a straight one so Hal took a good swing at it and missed. “That’s all right,” called Hughie from the coaching lines, “there will be two more better ones coming over directly.” The next was a ball. The third was a slow one, and as Hal noticed the left-fielder playing pretty far out he thought he would just tap it for a nice little short fly back of third. He thought of this as the ball was coming toward him from the pitcher’s hands. He whirled his bat with a short, quick swing and—thud—he heard the ball strike the catcher’s mitt.

“Well,” he heard Hughie calling him, “you only need one to hit it, and you got one left.” The next two balls he fouled off. The next two the umpire called balls and it was two strikes and three balls. Hal set himself for the last one. It was now or never. Here was probably his only chance to-day to make a hit and he might not get into another game for weeks and show what he could do with his bat. Slowly the pitcher started to wind up. Hal watched every move. Here it came waist high and straight. Now watch it. He swung at it hard. He heard[53] first—a tick, then a thud. He had made a foul tip and the ball had struck in the catcher’s mitt.

“That’s all right,” he heard Hughie saying, “we don’t expect pitchers to hit ’em anyhow.” But Hal was disappointed and sore as he walked to the bench. The next two men were retired on infield hits, and as Hal walked to the box to pitch the first half of the ninth inning he was nervous and mad at himself.

The result was he served up four bad balls in succession and there was a man on first. The next up hit the first ball right at Ross who was hugging the base and he booted it. Hal was over on first bag in a jump but Ross got the ball to him too late to earn an assist and there were two men on and nobody out. The crowd began to yell, “Take him out.” “Where’s Miner?” but Jenkins paid no attention. Many a pitcher had given a base on balls, and Hal was not responsible for the second man.

He got ready to pitch as he faced the batter; he somehow felt the man was going to bunt. As he delivered the ball he started toward the plate on the run, following the ball in. The batter bunted. Hal was almost on top of him. He reached out, caught the ball off the bat before it had reached the ground, thus making a caught fly out of what would have been a perfect bunt, whirled around and fired the ball to Everson at second, who nearly missed it because the play was almost too quick for him, thus completing a remarkable double play.

The crowd cheered. He heard them saying: “Oh! You! Hal! Good boy! You needn’t take him[54] out!” and he felt so good he went back into the box and struck out the next batter and the game was over. Then there was the usual rush to get the sweaters, and the fans and players hustling to get off the field as fast as they could together—the fans to get home to dinner and the players to the shower baths and rub-downs.

Hal hustled along with the rest. On the way he caught up with and passed Jenkins and Everson, together as usual. They did not see him, but he heard Jenkins say: “He looks more like a fielder than a pitcher,” and he thought they meant him. Later, as he walked along to his boarding house with Hans, they talked about the game, and the part each of them had taken in it, and Hans said, “I think you[55] would make a good first baseman,” but Hal, who thought he had come out of his pitching test pretty well said, “But you see they don’t need a first baseman (they all have their bad days like Dill and Ross to-day), and they may need a good pitcher any time.”

There were quite a number of disappointed candidates the day the Varsity list was posted. The disappointment was felt most by the boys who had an idea that they were the real thing as pitchers. A pitcher can rarely do anything but pitch, and a large percentage of boys who think they have the pitching ability do not make good when put to the real test. And so when they picked out the candidates for the Varsity that year, a great number of fellows who had high hopes missed even the second squad and finally landed on the freshman team.

Among the fellows who had hopes of making the team was Edward Crossley. He had reported as a pitcher and had been given a good many try-outs in the batting practice, and at first Hughie was attracted by his work and had one or two talks with him about his experience. Hughie’s first impression was that Crossley could be developed into a substitute or extra pitcher as he was strong and could throw a swift ball. He also seemed to be able to serve up curves fairly well. But Hughie had to change his mind about Crossley. He was too erratic.

The trouble with Crossley was that he was a spoiled son of a very rich man. He had the most[57] luxurious rooms of any of the fellows at Lowell. He had a servant and an automobile. He had lots of money to spend and he didn’t hesitate to “blow it” as the boys say. He was a good fellow with the boys whom he chose to make his friends and he liked and was liked by those with whom he came in contact as long as no one tried to do things different from the way he wanted them done.

Crossley had been brought up to think that every thing he wanted he could have. The fault was largely with his parents. They gave him everything he asked for and denied him nothing. Once in a while his parents would try to curb his desire for one thing or another, and then Crossley would pout and his parents gave in.

This gave Crossley a very wrong idea of the world in general. But he was to find that there were other people in the world besides himself and that they had ideas of their own and that many of them were just as selfish in their ideas as he was. When he met this kind of a fellow he got furiously angry.

When he came to Lowell he naturally thought that the son of so wealthy a man as his father would receive special attention by the college people and students. When he found out that merit alone counted in Lowell affairs, he was furious. When he saw some fellow who could do some one thing better than he could and who, therefore, received the attention which his accomplishment warranted, he became very jealous.

When he wanted anything that came to him as a[58] desire, he would stop at nothing in his efforts to get it, by hook or crook.

The result of it all was that after he had been at college for a few months he had not done anything worth while for himself, and outside of a small number of fellows who were brought up like himself he had not made many friends who would do him any good.

One of the things he asked his father for in the early spring was a new automobile. His father would just as soon have sent it as not, but he had been reading something about other boys doing wonderful things in football at college, and he was disappointed that his son wasn’t in it. So he had what to him was a brilliant idea, and he wrote his son that he would present him with a new $15,000 imported car the day he was named for the Varsity. This looked easy to Crossley.

At home, Crossley, the rich man’s son, had bought the suits for the High School nine. His father had fixed up a fine ball park for the boys to play in and he had done all this because his son had asked him to and because he had insisted upon it.

Of course, Crossley had a right, under the circumstances, to say which position on the team he would play, and he had promptly selected the job as pitcher. At first he was no good at all, but he hired a professional player to teach him and at the end of the year he had developed into a pretty good pitcher. In fact, he might easily have become a first-class flinger if his habits had been steady. Crossley had come to[59] Lowell from White College, a little school in the West, and he had been the pitcher for the team there.

When Hughie first began to take notice of Crossley he couldn’t understand how a fellow could do so well one day and so poorly another. It puzzled him a good deal. He finally wrote to a friend who was coach at White College and from him he found out what the trouble was. Crossley had been a good pitcher for White. As good as they ever had, but he would not observe the training rules and he would smoke cigarettes and take an occasional drink. This made him erratic and unreliable at times.

Furthermore, he had a terribly jealous disposition and bad temper and couldn’t stand it to have anybody but himself praised when he was around. Hughie’s friend doubted very much if Crossley would be of any real service at Lowell, especially if he continued his habits there as at White.

Hughie read this with a good deal of interest but Crossley had shown up pretty well in practice and Jenkins was inclined to think that the boy might have gotten over his childishness since, being at Lowell. So Hughie decided to reserve his judgment.

When the first Varsity list was made up a few days later, Hughie and the coaches had finally to decide between Crossley and Hal as left-hand pitchers. They both showed up about the same in the box and the decision was finally made in Hal’s favor. So his name went on the list and Crossley was sent to the second squad.

Now Crossley had wanted this automobile very[60] much and he was disappointed. He felt that Case had beat him out of the position. He became furiously jealous and made a resolution that he would “get” Hal in one way or another. What the way was he himself did not know, but he had a cunning mind and he decided to lay some deep plans to undermine Hal, and then he would get the job and the auto.

A day or two after the Colfax game, the two squads were lined up for general practice. The practice was principally devoted to batting and base running. One squad would take the field lined up in the regular positions, and the other at bat. Each batter remained at the plate until he got a hit. Then he ran to first of course. From there he was expected to steal his way round the bases.

Of course it is hard to steal a base when the other side knows what you are going to do, but stealing bases is a very important part of the game. Everson was on the lines helping Hughie instructing on base stealing. And squad No. 2 was at bat. Hal had been asked to see what he could do at the second bag. A few minutes afterward Crossley came up for his turn at bat, and made a hit and went to first. Then Hughie, who was on the coaching line back of first, told him to steal on the next ball pitched. Crossley was a good runner and Hal was not used to the position. He had stuck to the bag the way first basemen do, to receive the throw from the catcher. The catcher threw quickly to Hal who had the ball in his hand waiting for Crossley when the[61] latter was still fifteen feet from the base. The natural thing for Crossley to have done was to slide. Instead he came the rest of the way standing up, and when he was five feet from the bag he gave a jump for the bag, and landed with both feet, spikes and all, on Hal’s right foot, cutting him badly, and knocking him down. They both rolled over in the dirt, and Hal had to be picked up and carried from the field.

Hughie and Everson had hold of Crossley and were calling him various kinds of names for such bone-headed conduct—for once in their lives both of these boys had been fooled—they thought what they had seen was Crossley’s idea of stealing a base and were wondering where he got such an idea.

Hal himself as he was carried from the field by Hans, thought it was his own fault standing on second base as he did with the ball in his hands, instead of running up the line out of the path of the runner and touching him out before he got to the bag.