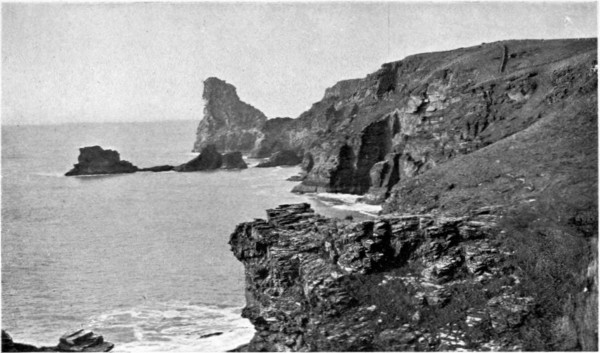

Photo: R. Webber, Boscastle]

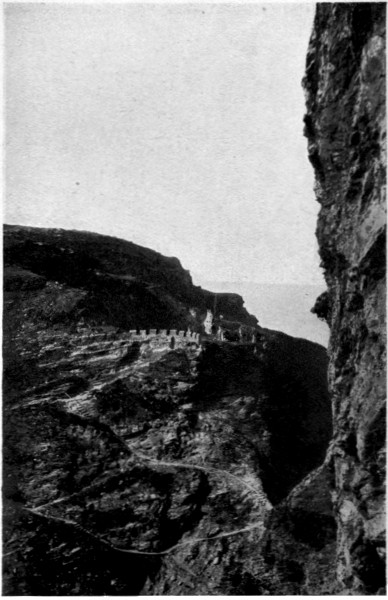

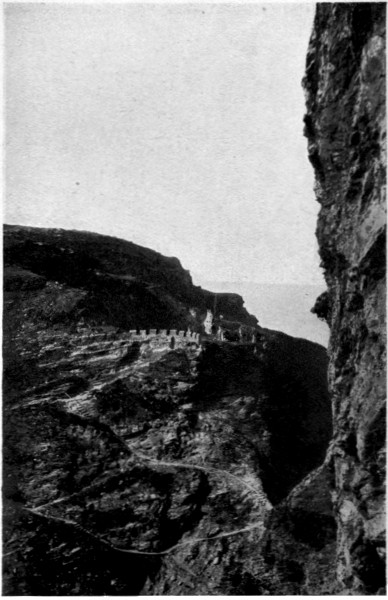

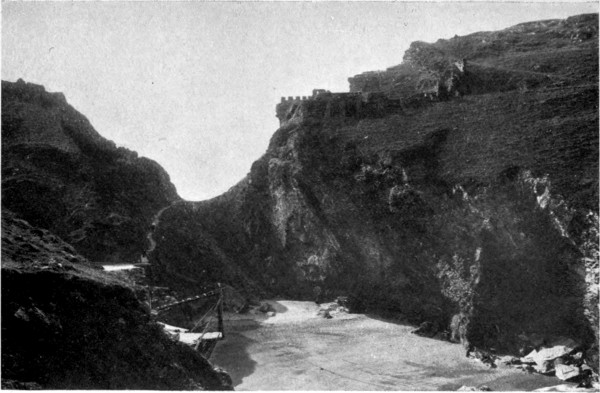

KING ARTHUR’S CASTLE AND EXECUTION ROCK, TINTAGEL

[Frontispiece

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover has been created by the transcriber using the actual cover from the book and the title page. This new cover is placed in the public domain.

Please see the detailed transcriber’s note at the end of this book.

Photo: R. Webber, Boscastle]

KING ARTHUR’S CASTLE AND EXECUTION ROCK, TINTAGEL

[Frontispiece

THE LOST LAND

OF KING ARTHUR

BY

J. CUMING WALTERS

“On the one hand we have the man Arthur, ... on the other is a greater Arthur, a more colossal figure, of which we have, so to speak, but a torso, rescued from the wreck of the Celtic Pantheon.”—Professor Rhys.

“There is truth enough to make him famous besides that which is fabulous.”—Bacon.

WITH SIXTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

CHAPMAN AND HALL, Ltd.

1909

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

BREAD STREET HILL, E.C., AND

BUNGAY, SUFFOLK

Within a small area in the West Country may be found the principal places mentioned in the written chronicles of King Arthur—places with strange long histories and of natural charm. In these pages an impressionist view is given of the region once called Cameliard and Lyonnesse. We have ventured into by-ways seldom entered, and we trust to have gathered a few details which may not be wholly without interest in their place. Facts are meagre about King Arthur, and romance has so overlaid reality that his realm seems now to be veritably a part of fairy-land. In this respect the journey is profitless, save that, by taking Malory as a guide, we are led to a few delightful and half-forgotten localities out of the ordinary route, from which romance has not been wholly dislodged and where tradition survives and is strong.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | OF THE KING AND HIS CHRONICLERS | 1 |

| II. | OF LYONNESSE AND CAMELIARD | 32 |

| III. | OF ARTHUR THE KING AND MERLIN THE ENCHANTER | 61 |

| IV. | OF TINTAGEL | 86 |

| V. | OF CAERLEON-UPON-USK | 113 |

| VI. | OF THE ROUND TABLE AND KING ARTHUR’S BATTLES | 130 |

| VII. | OF CAMELOT AND ALMESBURY | 159 |

| VIII. | OF ST. KNIGHTON’S KIEVE AND THE HOLY GRAIL | 183 |

| IX. | OF CAMELFORD AND THE LAST BATTLE | 194 |

| X. | OF GLASTONBURY AND THE PASSING OF ARTHUR | 216 |

THE LOST LAND OF KING ARTHUR

“What an enormous camera-obscura magnifier is Tradition! How a thing grows in the human Memory, in the human Imagination, when love, worship, and all that lies in the human Heart, are there to encourage it!”—Carlyle.

No pretence can be made that a complete or exhaustive history of King Arthur is given in this and the following chapters. Only parts of his story and parts of the story of his most illustrious knights are woven into this mosaic of fact and fiction. Sometimes only a few threads of the romance are to be discovered; at other times many are gathered into the fabric.

I have taken those portions only of the Arthurian fable, built upon a small substratum of historic fact, which suited the immediate purpose in view;[2] the rest, a huge mass, which it would have been unprofitable to introduce, has perforce been omitted. The primary object has been simply to call attention to the reputed relics of the great hero, to mark some of the floating traditions of his power, and to speak of a few of the localities which bear his name or are associated with his deeds; and I have striven to add a little to the living interest in the mouldering monuments, to brush away a little of the dust of ages from existing evidences, to lift a little the veil of mystery which darkens, disguises, or shrouds the lineaments of the king. As we find him in history, and as he is represented in romance, he is so noble a figure that we should dread to lose him or the conjuring influence of his name. The proud and triumphing Roman reeled for a time under the shock of Arthur’s hosts. The Saxon felt his almost invincible power. Christendom hailed his noble order and rejoiced in his imperial sway. Now, where he ruled and made his kingdom, are submerged cities, fallen towers, the wash of waters, the “trackless realm of Lyonnesse.” The sea has swept over his territory, and the deep shadows of centuries have fallen upon his deeds. His fame has been made imperishable by mighty pens, and many a mountain fastness holds his[3] name and gives it forth to the world; many a towering rock preserves his story; many a frowning height perpetuates his deeds; many a wild torrent proclaims his name. So by a hundred contrivances does the memory of King Arthur endure, and he looms, a giant, behind the mist of ages. Six hundred localities in the British Isles alone, it has been computed, cherish traditions of King Arthur, and his praise is sung by a multitude of voices, and in every region where Celtic influence has been felt. Such an influence as this cannot proceed wholly from the dry bones of fiction, or from the golden toys of romance. Legends gather about a great name, just as ivy covers the ruined column of old time; but the underlying base is there. Those who contend that King Arthur never lived are open to the charge of allowing the leaves of fable to hide from their eyes the ruined but giant pillar beneath.

In the early unwritten history of this island the invading Brythonic race mastered the inhabitants, the Goidels or Gauls, who had amalgamated with the Neolithic race, and gave the country the name of Britannia. To them is attributed the building of Stonehenge and the round barrows in which the dead were interred. The Cambrians, the[4] Welsh, and the people of Brittany are their linguistic descendants. So hardy, stalwart, and venturesome were the Brythons that they gradually spread themselves over the greater part of the country and penetrated far to the north. They offered determined defiance to the Romans three centuries before the Christian era, and successively resisted Norsemen and Saxons until five centuries of the Christian era had passed. Driven first to the west, they took up their abode in the wilds of Wales, and in Cornwall and Devon, and only succumbed at last to the exterminating campaign of the Saxons, who first cut off the Britons of the north and the south, and then defeated the two divisions of the race, first at Chester and then at Bath. The crucial battle between Briton and Saxon was under the leadership of the last of the British chiefs, the Arthur of history and romance, and Cerdic the victorious leader of the “Pagans.” Cerdic, sailing across the channel in his chiules, or long ships, had landed at the Isle of Wight, fought King Natanleod of Hampshire, with whom he maintained a five years’ campaign, and, triumphant at last, and reinforced by the followers of his son and his nephews, had established the West Seaxe, or Wessex Kingdom.

But, if defeated by the British at Mount Badon,[5] the Saxons were not long in reversing the issue, and Cerdic’s son Cymric, and his nephews Stuffa and Whitgar, lived to see their rivals well-nigh exterminated. At Wodensbury in Wiltshire the remnants of the British race joined with the Angles in driving the hated Saxon from the sovereignty of Wessex, but this, too, was without permanent result; for Cerdic’s next of descent, Cadwalla, restored the supremacy of his house and race.

Cerdic is said to have died in 534, a date of some importance as helping us to fix the true Arthurian era. The history of many of his contemporaries is almost as vague as Arthur’s own, but Cerdic stands out as a man of no uncertain history, and he serves the purpose of allowing us to test the probabilities of Arthur’s reputed career. That Cerdic’s record should be more definite, though extremely brief, is due to the fact that he was a conqueror; that Arthur’s record should be less definite, though extremely long, is due to the fact that he was vanquished, and that his story became mixed with the fables of a generation which did not know him. In the one case we have concrete facts duly preserved; in the other we have merely a name which fires the imagination, and a few events which in the course of time are magnified by romance. Allegory is but truth’s[6] shadow, and the very songs we deem idle, even the loosely-strung nursery rhymes, may have inner significance, as Carlyle has told us; men never believed in songs that were meaningless, and “never risked their soul’s life on allegories.” Real history and precious lore are bound up in these shrunken shrouds of withered myths, and it is safe to assume that the name that is enshrined in a folk-song is the name of a transcendent hero, a truly great man deemed more than human, merged into the preternatural, the ideal, or the divine. And, like the student at the Wayside Inn of Sudbury Town, we can—

Here it is that—

But how the romance of King Arthur originated, how it came to be written, how it was developed and elaborated, how from a simple history it came to be invested with special significance[7] and to be impregnated with spiritual meanings—to explain this, it is necessary in some measure to trace the course of early English literature and to mark the advance of the English race. The story leads us back to dim times and small beginnings. It recalls the semi-barbarism of the first centuries, the fierce conflicts of contending tribes, the domination of Rome, the last supreme encounters between Briton and Saxon, and the making of that race which we believe inherits the hardy and heroic qualities of both. No doubt the substratum of fact is overlaid with superstitions, and fantasy has reared her airy edifices upon the frailest of history’s foundations. The narrow track leading backward to the times of Arthur is often undefined and irretraceable, and the traveller finds that unstable bridges have been cast across the gulfs which have broken up the way. Very seldom, therefore, can a strong foothold be obtained, and one is often disposed to abandon the pursuit of truth as hopeless. The tendency has ever been to strain facts to uncertain conclusions in order to fit the exigencies of romance.

As discoverable error ever leads to general doubt, there are not lacking those who deny that King Arthur ever existed. He is declared to be[8] a myth, a type, a symbol, an allegorical figure. Even Caxton, in printing Malory’s history, was obliged to confute the sceptics by the mention of what he deemed unassailable facts. It was “most execrable infidelity,” said he, to doubt the existence of Joshua, David, Judas Maccabæus, or Alexander; all the world knew there was a Julius Cæsar and a Hector; “and,” he demanded to know with just indignation, “shall the Jewes and the heathen be honoured in the memory and magnificent prowesse of their worthies? Shall the French and German nations glorifie their triumphs with their Godfrey and Charles [Charlemagne], and shall we of this island be so possesst with incredulities, diffidence, stupiditie, and ingratitude, to deny, make doubt, or expresse in speech and history, the immortal name and fame of our victorious Arthur? All the honour we can doe him is to honour ourselves in remembrance of him.”

Having thus made it a point of national pride and honour with us to accept and believe in King Arthur, Caxton proceeded to advance the proofs of his existence, which were that his life was written in “many noble volumes,” while his “sepulture” might be seen at Glastyngburye [Glastonbury], that the print of his seal was preserved[9] in Westminster Abbey, and that “in the castel of Dover ye may see Gawayn’s skulle and Cradok’s mantel; at Wynchester, the rounde table; in other places, Lancelotte’s sworde, and many other thynges.” These irrefutable facts admitted, to his thinking, of but one conclusion. “All these thynges consydered, there can no man reasonably gaynsaye but there was a King of thys lande named Arthur.” The quaint prologue to Malory’s romance abundantly testifies that serious arguments must have been already advanced against Arthur’s existence in order to call for so spirited a rebuke and so complete an answer. But, as a matter of fact, the truth of the histories referring to his exploits had been challenged from the first, and in spite of the immense popularity they enjoyed and the influence they possessed, they seem never to have been implicitly and unanimously accepted as veracious records.

Three Welsh poets are supposed to have been the first to celebrate the deeds of Arthur—the full-throated Taliesin, Aneurin, and Llywarch Hên. The two latter bards commemorated the heroes who fell at the battle of Cattraeth, in the year 603. Aneurin’s poem, “Gododin,” about a thousand lines in length, is preserved in a manuscript[10] of the thirteenth century. The writer, who was present at the battle he describes, is supposed by some to have been Gildas, the first historian; others say he was the son of Gildas.[1] The poem is of a most obscure character, and doubt has actually arisen as to the particular battle to which it refers, a theory having been advanced that it celebrated a disaster which befell the Britons at Stonehenge in 472. But Cattraeth is supposed to have been Degstan, or Dawstane, in Liddlesdale, at which the Saxons were defeated; and when such divergencies as these are possible in regard to locality, persons, and dates, the value of Aneurin’s poem as history may easily be estimated. The principal fact which Aneurin tells us is that of “three warriors and threescore and three hundred, wearing the golden torques,” only four escaped “from the conflict of gashing weapons,” one being himself. Another of those[11] who escaped from Cattraeth was Kynon, known as “the dauntless,” whose love for the daughter of Urien supplied the bards with a theme. Urien himself fell in this great battle, and it was the poet Llywarch Hên (buried, it is said, in the Church of Llanever, near Bala Lake) who wrote his elegy. Llywarch Hên passed his younger days at King Arthur’s Court as a free guest and a counselling warrior. His career is well summarised by George Borrow in Wild Wales, Chapter LXXIII.

Of the third and most important prophet and bard, Taliesin, Prince of Song, we are told that he was the son of Saint Henwg; that he had a miraculous birth; that he spake in wonderful verse at his nativity and sang riddling tales; that he was invited by King Arthur to his Court at Caerleon; and that, having presided over the Round Table as a “golden-tongued knight,” he became chief of the Bards of the West. A cairn near Aberystwyth marks the site of his grave. The story of the bard of the radiant brow, of his wonderful delivery from pirates, and of his poems, which excelled those of all others, has always been a popular one, but the sifting of truth from fiction is no easy task. His allusions to Arthur probably have no superior value to the[12] references of Aneurin and Llywarch Hên, and we are forced therefore to dismiss them from account. Sir Walter Scott, in the introduction to one of his poetic romances, justly reminded his readers that the Bards, or Scalds, were the first historians of all nations, and that their intention was to relate events they had witnessed or traditions that had reached them. “But,” he added, “as the poetical historian improves in the art of conveying information, the authenticity of his narrative invariably declines. He is tempted to dilate and dwell upon events that are interesting to his imagination, and, conscious how indifferent his audience is to the naked truth of his poem, his history gradually becomes a romance.” Such were the early historians, as well as bards, upon whose records the English chroniclers relied.

These chroniclers were Gildas and Nennius, of whom no very certain biographical facts can be discovered, though the latter is said to have been a monk at Bangor. Gildas is the reputed author of a treatise, De Excidio Britanniæ, blindly copied by Bede, which supplied a history of Britain from the time of the Incarnation to the year 560 A.D. But darkness enshrouds the historian, of whose country, parentage, and period much is surmised and little is discoverable. The[13] erudite author of Culture in Early Scotland, Dr. Mackinnon, believes that the writer of the gloomy and pessimistic work on the destruction of Britain was a Romanised Briton, who migrated to Brittany to escape the pitiless severity of the Saxons, and there founded the monastery of Ruys. It has even been claimed that Gildas was a native of Clydesdale, and if this were so another link would exist to connect Arthur himself with Scotland, for the historian was so closely identified with the race and the cause championed by that king that his surname was taken from Arthur’s famous battle of Badon, which, again, is said by some to have been fought in the Lowlands.[2] Gildas was the wisest of the Britons according to Alcuin, and Dr. Mackinnon thinks that his chronicle should be accepted as authentic, in spite of its occasional errors and its undoubted bias. The stern character of the writer is evinced by his denunciations not only of Saxon excesses, but of the clerical vices of his age. In short, Gildas was a religious devotee, an austere and uncompromising critic of the demoralising customs of the time; a species of prophet, also, who saw in corruption and degeneration the signs of coming [14]destruction for the race to which he belonged. Roman influence had undermined the morals of the people and enervated public and social life. The story Gildas tells is one of unrelieved gloom, but it stands out in contrast to other narratives by its rugged simplicity and its freedom from the more romantic elements. Murder, sacrilege, and immorality were bringing about wholesale desolation, and the patriotic Gildas saw no future before his country but absolute ruin and racial extinction. His allusions to Arthur are scanty, incidental, and none too complimentary, and they have assumed importance only as bases for the construction of bold theories by subsequent writers.

In Somerset, near the ancient British settlement of Brean, is a rocky islet known as Steep Holm, 400 feet high and about a mile and a half in circumference. In this desolate place it is said that Gildas Badonicus took refuge during the time of conflict between Britons and Saxons, and that here he composed the greater part of De Excidio Britanniæ. Leland records that the hermit “preached every Sunday in a church by the seashore, which stands in the country of Pebidiane, in the time of King Trifunus; an innumerable multitude hearing him. He always wished to be a faithful subject to King Arthur. His brothers,[15] however, rebelled against that king, unwilling to endure a master. Hueil (Howel), the eldest, was a perpetual warrior and most famous soldier, who obeyed no king, not even Arthur himself.” Steep Holm was invaded by pirates, and Gildas was compelled to seek another asylum. He chose Glastonbury, and there he died. His attitude was pessimistic in the extreme. “The poor remnant of our nation,” he said, “being strengthened that they might not be brought to utter destruction, took arms under Ambrosius, a modest man, who, of all the Roman nation, was then alone in the confusion of this troubled period by chance left alive. His parents, who, for their merit, were adorned with the purple, had been slain in the same broils, and now his progeny, in these our days, although shamefully degenerated from the worthiness of their ancestors, provoked to battle their conquerors, and, by the goodness of God, obtained the victory.” In this dismal strain did he write of triumphs, and the power with which he described defeat may therefore easily be guessed.

The answer that has been given to the question, oft repeated: Why is history so silent on King Arthur? is a strange one. It is said that Gildas, on hearing that Arthur had slain his brother[16] Howel, was so deeply offended that he determined that the hero should not be celebrated by him. In revenge, he cast into the sea “many excellent books which he had written concerning the acts of Arthur, and in the praise of his nation, by reason of which thing you can find nothing of so great a prince expressed in authentic writings.” Gildas himself supplies another explanation, for he bewailed the loss of national records “which have been consumed in the fires of the enemy, or have accompanied my exiled countrymen into distant lands.” His own sources of information were those which he found in Armorica and other portions of the Continent.

Nennius is supposed to have compiled another comprehensive history comparable with that of Gildas—Historia Britonum—the period embraced being from the days of Brute the Trojan to the year 680 A.D. But so much doubt prevails as to his work, that the history, despite the later date, has been ascribed to Gildas himself. Both may have been forgeries of the tenth or eleventh century. For five or six centuries the story of Arthur was “folk-lore,” and was preserved in snatches of song, a few fragments of which still exist. Such a legend, as Longfellow says, can only—

Songs in praise of heroes, real or mythical, always exist among rude peoples—the sagas which nations unwillingly let die. They are the repository of national history, the inspiration of an aspiring and progressive race, the embodiment of its hopes, the treasury of its traditions. Mythology, “the dark shadow which language throws on thought,” is the first outcome of mental activity and percipience—the struggle for human expression of all that is marvellous and memorable. All the early history of races is mixed and engloomed with dim allegories. Intense reverence for divinities, or the awe of them, leads to the making of fables and the reciting of marvels, in which the gods speak and act as men, or men speak and act as gods. The thoughts of primitive peoples are concentrated upon the hero, the commanding figure who typifies their desires, and about whose name cluster legends of victory. Not infrequently, divine qualities are attributed to that hero who thus looms majestically upon the[18] horizon of history, and ultimately becomes a religion. “The gods of fable are the shining moments of great men,” Emerson said, and whether the Arthurs and Odins of mythology were men worshipped as deities, or deities divested of divinity and transformed into historic heroes, the after-ages must always have some difficulty in deciding. What we know is that the interval between language and literature is crowded with shadowy mythological lore, and little of the light flashed back from to-day can illumine the haunted, mystic, twilight time of phantom and superstition.

Yet Geoffrey, Archdeacon of Monmouth, and afterwards Bishop of St. Asaph (1100-1154), in giving shape and substance to the Arthurian legends and traditions, had no better material to work with than that supplied by the British folk-songs, the tainted records of Gildas and Nennius, and the so-called Armoric collections of Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford, who flourished in the eleventh century, and connected the Arthur of Brittany with the Arthur of Siluria. Geoffrey’s famous Chronicon sive Historia Britonum, dedicated to Robert, Earl of Gloucester, and given to the world in the Latin tongue in the year 1115, was professedly a translation of the Brut y Brenhined,[19] a “history of the Kings of Britain, found in Brittany,” best described in Wordsworth’s phrase: “A British record long concealed in old Armorica, whose secret springs no Gothic conqueror e’er drank.”

In reality his imagination had been fired by the bardic celebrations of Arthur’s triumphs, the songs still sung vauntingly by an unconquered race. The old monkish chronicler manifested a marvellous ingenuity in imparting circumstantiality of the most convincing character to his narrative. He connected place-names of great repute with eponymous heroes; he linked the truths of the Roman occupation with the half-truths or fables of the British resistance; he wove some of the most striking Scriptural facts into the fabric of the romance; he so leavened falsehood with reality that the imposture was hard to detect, especially in an uncritical age, and the effect was most impressive upon the minds of an unreasoning generation. His inventions did not extend to incidents; these he took from the chronicles to hand, and he can only be charged with a free amplification of the records, and a readjustment of the events which had been described. Notwithstanding all the craft and devices of the chronicler, however, his history was almost immediately challenged,[20] William of Newburgh, a Yorkshire monk, declaring that Geoffrey had “lied saucily and shamelessly,” with many other hard terms. He charged the supposed chronicler with making use of, and wholly depending upon, the old Breton tales, and with adding to these contestable compilations “increase of his own.” Nor was William of Newburgh alone in his protests and denunciation. Giraldus Cambriensis, by a parable, implied that Geoffrey’s work was a deceit. There was a man at Caerleon, he said, who could always tell a liar because he saw the devil and his imps leaping upon the man’s tongue. The Gospel of St. John was given him; he placed it in his bosom; and the evil spirits vanished. Then the History of the Britons, by “Geoffrey Arthur” (“Arthur” was a by-name of Geoffrey’s), was handed to him, and the imps immediately reappeared in greater numbers, and remained a longer time than usual on his body and on his book. Cœdit quæstio. But all this did not prevent Geoffrey’s masterpiece in nine books from attaining a remarkable popularity both in its original form and when translated, as it rapidly was, into the Anglo-Saxon and the Norman-French languages, where it could be fully understanded of the people. It covered the history of the Britons from the time[21] of Brut, great-grandson of Æneas of Troy, to Cadwallader’s death in 688.

The first translators were Geoffrey Gaisnar or Gaimar, in 1154 (the original history had been published only seven years previously), who turned the story into Norman-French verse, and Wace, a native of Jersey, who obtained the favour of the Norman kings, and was the author of two long romances in Norman-French—the famed Brut, or Geste des Bretons, and the almost equally famous Roman de Rou. The former work was a free metrical rendering, published in Henry II.’s reign, of Geoffrey’s Chronicle, with some new matter. Wace, according to Hallam the historian, was a prolific versifier who has a “claim to indulgence, and even to esteem, as having far excelled his contemporaries without any superior advantages of knowledge.” It was in emulation of him that several Norman writers composed metrical histories.

Then came Layamon, a Midland priest living at a noble church at Emly, or Arley, who at the close of the twelfth century produced the first long poem written in the English language. He did not go to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s work direct, but wrote an amplified imitation of Wace’s version of the Chronicle. Layamon’s paraphrase[22] contained just over double the number of lines in Wace’s poem, the additions consisting chiefly of interpolated dramatic speeches. There were already Cymric, Armoric, Saxon, and Norman ingredients in the medley of history and romance, and to these Layamon added a slight Teutonic element, for the chansons of the Trouvères had carried the fame of Arthur into Germany, and already new legends with new meanings were germinating from the loosely-scattered seed. With Artus for the central figure and with courtly chivalry for the theme, these variations and expansions of the story of the British chief exercised as powerful and enduring an influence upon the people of France and Germany as they had done, and continued to do, upon the people of Britain. The good priest seems to have had no other object in writing in good plain Saxon the story of King Arthur than to make widely known among his countrymen the noble deeds in which he evidently had an abounding faith. In fact, his purpose was purely patriotic. The only guile he employed was in supplying the names of many persons and places, in addition to the speeches, all of which circumstances served to magnify the literary imposture. Walter Map, or Mapes, a man of the Welsh Marches, with a reputation for[23] exceeding frankness and honour, followed Layamon and introduced other and more striking details of permanent value. Map was the friend of Becket, and is believed to have been for some time the king’s chaplain. For the love of the king his work was done. His Latin satirical poems display his chief characteristics, and it is as a wit rather than a writer that he was famous at the Court. Yet it was this man who is held to have conceived the character of the pure and stainless knight Sir Galahad, assigning to him what is in some respects the chief, or at all events the worthiest, position in the Arthurian list of knights. If Sir Galahad, stainless, chivalrous, alone capable of achieving the Quest of the Grail, were the creation of Walter Map, to him we owe that spiritual and religious element which refines and enriches King Arthur’s history. Map wrote the story of the Grail, a Christianised rendering of Celtic myth, and to him probably we owe the moving and impressive Mort, with those notable outbursts which rank among the treasures of our literature. He, however, had the originals to work upon. The Welsh had taken their legends to Brittany, the troubadours were singing them, and the German and the French chroniclers were at work. And though there is no doubt that Map[24] contributed in a considerable degree to the romances, it must be faithfully recorded that questions have arisen whether he was really capable of doing all that has been attributed to him, and whether, if he had the capacity, he would also have had the inclination. “Spotless spirituality,” such as he is supposed to have infused into the story, is scarcely consistent with the character of the man whose Anacreontics are often lacking in refinement.[3]

So far, it will be easily conceded, very little has been advanced in the way of proof of the existence of the British prince and hero, of the Cymric “Dux Bellorum,” of the Chief of the Siluri or Dumnonii, the name given to the remnant of the British races driven westward by the Saxons. We can understand Milton questioning who Arthur was, and doubting “whether any such reigned in Britain.” “It had been doubted heretofore, and may be again with good reason,” he wrote, notwithstanding the fascination possessed by—

Geoffrey’s “monument of stupendous delusion” had not deceived him, and Sir Thomas Malory’s laborious compilation, while winning unstinted admiration for its beauty, richness, and delectation, would be as unconvincing historically as were Caxton’s quaintly-argued evidences. All the tributaries which now combined to make the full broad current of Arthurian literature were infected at their sources, numerous and widely separated as those sources were. If Malory depended, as we have the authority of the best scholars for believing, upon the several ancient romances of Merlin, the inventions and adaptations of Walter Map, the mysterious compilations of pseudonymous “Helie de Bouri” and “Luces de Gast,” with other manuscripts—some of which are untraced—of like character, it was obvious that he was only presenting us with an aggregation of the impostures, inventions, fables, and falsities of the centuries preceding. That Malory had a conscientious belief in the romance is extremely probable, though in the absence of all information concerning him—for he is a name, a great name, and little more—we can only infer this from the scrupulous manner in which he has performed his task and from the commendatory form in which it was issued in the year 1485.

Judged purely as literature, and with every allowance made for want of uniformity in level as well as for the tediousness of numberless digressions, Malory’s romance only admits of one opinion; and to him and to Caxton (who, despite the humility of his prologues and epilogues, and his professions of “simpleness and ignorance,” was a scholar and a master of middle-class English) the race is under a perpetual debt.[4] The compiler does not seem to be open to the charge levelled against him by Sir Walter Scott, that he “exhausted at hazard, and without much art or combination, from the various French prose folios”; on the contrary it is easy to conceive that he exercised that “painful industry” with which he is credited by the writer of the Preface to the edition of 1634. In addition to this, he stamped his own individuality upon the work, and manifested a singular purity of taste by removing the grosser elements which stained many of the earlier versions, and by preserving all that was best as literature and in keeping with the finest and truest spirit of romance. We know from the scholarly investigations of Dr. Sommer and Sir[27] Edmund Strachey how judicious Malory was in translating from his “French books,” or in making abstracts, or in amending and enlarging. With true insight he chose the material that was of good report and of genuine worth; the dross he cast aside. Malory may have belonged to a Yorkshire family, judging from the fact that Leland recorded that a Malory possessed a lordship in that county, but there is no slight authority for believing that he was a Welshman and a priest—“a servant of Jesu both day and night,” as he himself said. That he was a good and earnest Christian his own work proves beyond all question, for he imparted all the religious ardour to the romance that he could, and accentuated that element when it had already been introduced.

The romance of Arthur was enriched, to use Gibbon’s words, with the various though incoherent ornaments which were familiar to the experience, the learning, or the fancy of the twelfth century. Every nation enhanced and adorned the popular romance, until “at length the light of science and reason was re-kindled, the talisman was broken, the visionary fabric melted into air, and by a natural though unjust reverse of public opinion the severity of the present age became[28] inclined to question the existence of Arthur.” That Arthur’s name should stream like a cloud, man-shaped, from mountain-peak is the fault of the mediæval writers who, in taking the British king for their hero, could represent no age but their own, and had no consciousness of anachronism. It came natural to them in speaking of the sixth-century knights to endow them with the attributes of the thirteenth and fourteenth century, and to describe Arthur’s Britain much as they would have described the Britain of a Henry or an Edward. The Arthur of Geoffrey, of Walter Map, and of Malory is as impossible as the Arthur of Wagner, Lytton, Swinburne, and Tennyson. Most of the writers on chivalry have either viewed and treated the Knights of the Round Table as contemporary heroes, or have altogether idealised them. We are forced to the conclusion that Geoffrey and all the other mediæval chroniclers had no real conception of the character of the age of which they wrote; if they discovered real names and real persons they transported them to an imaginary world and invested them with fabulous attributes. They made reality itself unreal, transformed heroes into myths, and buried history beneath romance; they had no power to recognise truth even when it appeared to them.

King Arthur was a traditional and historic chieftain of rude times, the man of an epoch, a hero to be sung and remembered. His life must have been a tumult; his seventy odd battles were the events of his era. Whether he represents a nascent civilisation, or whether, following the Romans, he simply maintained a barbaric splendour in the cities they had made or by means of some enlightened laws they had instituted, is a matter of dispute. But he is the “gray king,” the elemental hero, not the advanced type. It is a remarkable fact that English scholars have until quite recently done so little to popularise Arthurian literature. Malory’s version remained almost inaccessible until Southey issued his edition, and the best work of all was undertaken for us in latter years by Dr. Sommer, a German. Considering the hold on the imagination which the romance possessed, little was done to elucidate the obscurities and to solve the mysteries concerning not only the authors but the heroes themselves and the land to which they belonged. Much has been conjectured, but we feel that we are dealing more with phantoms and fancies than with realities and facts. Yet what an inspiration King Arthur has been! His name has lingered, his memory has been treasured in national ballads. Poets have in[30] all ages hovered round the subject, and some have alighted upon it, only perhaps to leave it again as beyond their scope.

Milton, Spenser, Dryden, Warton, Collins, Scott and Gray, together with derided and half-forgotten Blackmore; Lytton, with his ambitious epic, doomed to unmerited neglect; Rossetti, James Russell Lowell, and lastly, Arnold, Morris, Swinburne, and Tennyson—these have lifted the romance into the highest and purest realm of poetry, and have impregnated the story with new meanings and illuminated it with rich interpretation.

All have felt the influence of Arthur’s history, “its dim enchantments, its fury of helpless battle, its almost feminine tenderness of friendship, its fainting passion, its religious ardours, all at length vanishing in defeat and being found no more.” We have seen how the Arthurian history, real or fabulous, arose from early traditions and grew as each chronicler handled it and combined with it the traditions and the fictions of other races. It lost nothing by its transfusion into new tongues, but was enriched by the imaginations of the adapters and combined with the stories already[31] current in other lands. The hero that Celtic boastfulness had created became the representative hero of at least three peoples in these early times, and the songs of the Trouvères speedily spread his fame over Western Europe. We find Arthur represented as the master of a vast kingdom, and his power extending to Rome itself; and we find him claimed as the natural hero of nearly every race which heard his praise and was kindled to valour by the example of his exploits. Each country seemed bent upon supplying at least one representative of the Table Round, and eagerly competed for the pre-eminence and perfection of the knight of its choice. The kingdom allotted to him was without limit, and as the elder Disraeli would put it, “fancy bent her iris of many-softened hues over a delightful land of fiction.”

Lost though King Arthur’s realm is, the land of the ancient British chieftain must have been real, and it is most possible that we tread the dust which covers it in journeying from Caerleon to Glastonbury, from Glastonbury to Camelford, from Camelford to Tintagel. To these places is our pilgrimage directed.

“I betook me among those lofty fables and romances which recount in solemn cantos the deeds of knighthood founded by our victorious kings, and from hence had in renown over all Christendom.... Even these books proved to me so many incitements to the love and steadfast observation of virtue.”—Milton.

Drayton.

No matter how far the chroniclers of old departed from fact in the details of their narratives, they grouped the incidents around a central figure, a magnificent ancient hero; and, more than that, they specified the actual locality in which that hero had won his renown. But just as they magnified the hero out of all proportion, so they extended the area of his realm beyond all[33] possibility: hence the difficulties that meet us in the search for truth.

Of the Celts, Ralph Waldo Emerson has perhaps left us, in brief, the best record. He sums up the greatness and the importance of the race by saying that of their beginning there is no memory, and that their end is likely to be still more remote in the future; that they had endurance and productiveness and culture and a sublime creed; that they had a hidden and precarious genius; and that they “made the best popular literature of the Middle Ages in the songs of Merlin and the tender and delicious anthology of Arthur.” This race was not likely to take a narrow view of its possessions, or to assign a small territory to its greatest monarch. Its claim may be preposterous, but that comes of the consciousness of superior strength and of daring imagination. Britain was not large enough for the Celts; they required not a country but a continent. And when their songs were sung, their stories told, and their great Arthur’s name celebrated throughout the west, they boldly affirmed that the west was his, and that he had subdued and ruled the whole civilised world. Arthur’s England became in their eyes the perfect realm, the ideal place; and the survival of[34] this idea may be discovered in the works of the poets, old and new.

was Llywarch Hên’s allusion to the slaughter of bards, evincing his belief in their sacred character. Song was to the Cymry at once education, a vent for national feeling, and a memorial of great events. The bard ranked beside the artisan as one of the pillars of social life. He had only one theme, his country’s hope, misfortune, and destiny; and, as M. Thierry has aptly said, the nation, poetical in its turn, extended the bounds of fiction by ascribing fantastic meaning to the words. “The wishes of the bards were received as promises, their expectations as prophecies; even their silence was made expressive. If they sang not of Arthur’s death, it was a proof that Arthur yet lived; if the harper undesignedly sounded some melancholy air, the minds of his hearers spontaneously linked with the vague melody the name of a spot, rendered mournfully famous by the loss of a battle with the foreign conqueror. This life of hopes and recollections gave charms, in the eyes of the latter Cambrians, to their country of rocks and[35] morasses.” How much we really owe, then, to historic fact and how much to bardic song the accounting of Camelot and Avalon, Tintagel and Almesbury, as the famous and redoubtable spots of Arthurian accomplishments and occupation, would be difficult to decide. Literary genius from the first centres in the minstrel, who is both composer and singer, who stimulates to action and records events, who is himself “doer” and “seer.”

But for this rich and sustained Celtic influence our literature would be poor indeed, would be less romantic, less poetic, and lacking in the vitality of human passions, human hopes and aspirations, human suffering and despair. For the dominant note in Celtic literature—and this particularly applies to the Arthurian legend which, despite its boasts, is a story of failure—is an indefinable melancholy, an exquisite regret; the poetry may be, as Matthew Arnold said, drenched in the dew of natural magic, and the romances may be threaded with radiant lights, but there always remains the underlying sombreness of texture or the overhanging cloud-darkening of the scene. Joyous music concludes in a minor key or is broken by a sudden note of pathos. The Celtic bards sang of war, but though the[36] heroes always went forth bravely to battle it has been recorded that they “always fell.” Victories are less frequently celebrated than defeats are mourned. The glory of the Celt was vast and transcendent, but from minstrel-times it was a fading glory. Work as the history-weavers might with the golden shuttles of romance their tears mingled with the gleaming strands, and the tissue as it left the loom was a medley of broken lights and shadows. Nevertheless, the pictures they have left us of chivalrous times remain unsurpassed for the grandeur of their conception: they remain the model and despair of all ages.

The description of Arthurian England, the “Logris” of the chroniclers, comports with the suggestions of romance, but ill accords with the facts.[5] Even if we grant the Round Table and[37] the Quest of the Grail, the fact remains that the times were barbarous and that the Britons of the sixth century had only reached the outer borders of civilisation. The exploits of the knights themselves are indicative of a prevailing state of lawlessness verging perilously upon absolute savagery. Appalling rites were practised in the castle strongholds, and the life neither of man nor woman was deemed precious. The romancers themselves do not disguise that the purpose and the methods of the knights were little superior to the purpose and methods of those whom they warred against; and the common practice of the knights to “reward themselves” in their own ways for victories achieved disposes at once of the contention that their motives were unselfish, or that their chivalry was pure and disinterested. The England of King Arthur was therefore by[38] no means like to be the ideal land of peace, beauty, and content which poets have imagined. Neither can we concede the whole claim to Arthur’s undisputed possession of the entire kingdom. The freedom with which the chroniclers spoke of the king’s unmolested journey north, south, east, and west, only proves that they made an unwarrantable use of names. Among the places loosely mentioned or referred to at random in the romance, or perchance confused in the writers’ minds with places within a small area, we must count all those beyond the Severn and Trent, unless we adopt the alternative theory and accept the north as Arthur’s realm. To these we add all the large proportion of places, more or less fantastically named, which seem to have had no existence out of the chroniclers’ brain. Where shall we look for Carbonek, for the land of Petersaint, for Joyous Isle, for Waste Lands, for Lonazep, for Goothe, for Case, for the Castles of Grail, La Beale Regard, Pluero, Jagent, and Magouns? to say nothing of a host of others. And are we to be deluded by the familiarity with which Jerusalem, Tuscany, Egypt, Turkey, and Hungary are spoken of, into believing that these distant places were really visited by Arthur and his knights? Even if we were to concede all the[39] localities mentioned in Malory’s work we should be confronted by a new difficulty in the Mabinogion, where quite a fresh series of towns and countries is mentioned in addition to many of the old ones. But while in the Mabinogion the west of Europe is almost exclusively dealt with, the English, French, and German historians would be content with nothing less than the best part of the hemisphere. No petty view, however, must be taken of the Arthur-land of romance. If Caerleon was his capital, we must believe that he was not unknown north of the Humber, and that he had a castle in old Carlisle. Calydon and Brittany, Ireland and Wales, acknowledged his power and felt his sway. The Roman himself met Arthur face to face; knights carried his fame to Constantinople—so the early historians asseverate, and so they doubtless sincerely believed.

But the more cautious student will confine his attention to a group of but half-a-dozen places in South Wales, Devonshire, and Cornwall, and will doubt the truth of tradition even when it mingles with the nomenclature of the romance. Of Lyonnesse whelmed beneath the waves we have no knowledge; it is a lost and perhaps half fabulous region. Cameliard, whose boundaries are fairly well known, is strewed with doubtful relics,[40] and preserves a multitude of strange stories. These are all that remain to us when we have traversed King Arthur’s land. Lyonnesse is reported to have been a region of extreme fertility, uniting the Scilly Isles with Western Cornwall. The hardy Silures were the inhabitants of this tract, and were remarkable for their industry and piety. No fewer than one hundred and forty churches testified to the latter quality, and the rocks called Seven Stones mark the site of their largest city. Tradition is untrustworthy as to any great cataclysm, but the Saxon chronicle declared that Lyonnesse was destroyed by a “high tide” on November 11, 1099. The assumption is that where the sea now sweeps with tremendous force, between Land’s End and the Scillies, once lay a fair region, another Atlantis, which formed no unimportant part of King Arthur’s realm. The etymology of the name Scilly is more or less doubtful. The word has been identified with Silura, or Siluria, the land of the Silures—that is, South Wales. Malory’s Surluse, or Surluce, reminiscent of the French Sorlingues, if it be not Scilly must remain unidentified. The first mention of it is in the history of La Cote Male Taile, where it is said that Sir Lancelot and the damsel Maledisant (afterwards known as Bienpensant)[41] “rode forth a great while until they came to the border of the county of Surluse, and there they found a fair village with a strong bridge like a fortress.” A later reference shows that it was in and about Cornwall that the knights were at this time staying and seeking adventures with the king; and the “riding forth a great while to the border of the country of Surluse” would fit in with the idea that Cornwall and Scilly were not then divided by the sea, but formed part of the kingdom of Lyonnesse. Sir Tristram, who is essentially a Lyonnesse knight, was sought in the country of Surluse when he had vanished during the period of King Mark’s treachery; and there seems no doubt that, though an accessible part of the kingdom, it was a considerable distance away, and perhaps somewhat out of the beaten track. Sir Galahalt, “the haut prince,” was its ruler, and he was resorted to by the knights; but we are distinctly told that “the which country was within the lands of King Arthur,” and for that reason Sir Galahalt could not even arrange a joust without obtaining his sovereign’s consent. Again, Sir Galahalt was known as Sir Galahalt “of the Long Isles,” which admits of a fair deduction, and seems not without its significance in this argument.

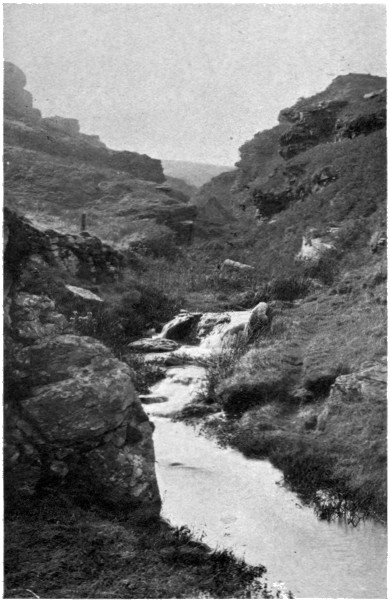

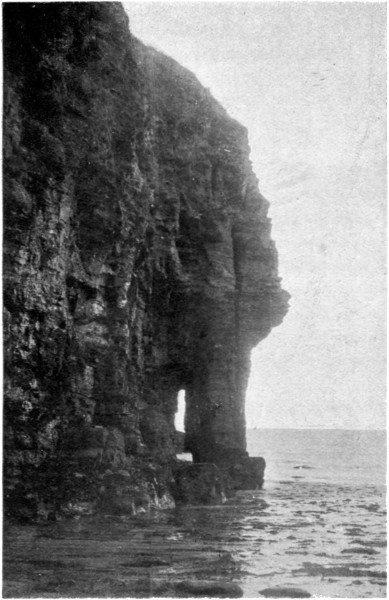

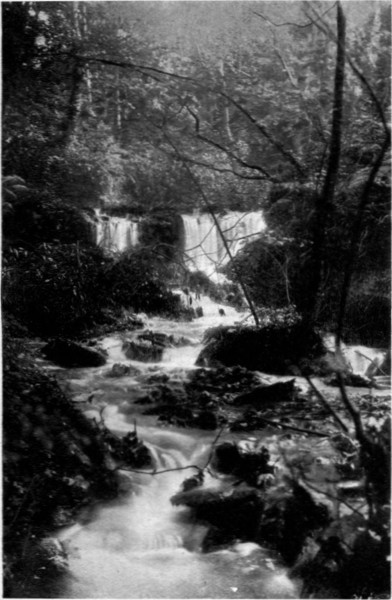

Photo: R. Webber, Boscastle]

THE ROCKY VALLEY, TINTAGEL

[To face p. 40

The “guarded Mount,” dedicated to St. Michael, overlooks the long Atlantic waves, the waste of waters, and “towards Namancos and Bayona’s hold,” and this Ultima Thule is thronged with traditions of Arthur and his lost territory. Grim, cavernous Pengwaed, or Land’s End, with its granite rocks; the Lizard, and Penzance, the last town in England, are all stored with these old memories; and the waves flooding the bays tell of that younger time over which hangs perpetual shadow. This is the Lyonnesse of Tennyson’s imagining, the

where long hillocks dip down to the sea-line, where the coast spreads out into shifting treacherous sand, and where amid the dreary plains the Silures fought their battles for life and freedom.[6] At Vellan, Arthur slaughtered so many Danes that the mill next day was worked with blood. Land’s End still shows its “Field of Slaughter,” and by the coast Arthur and Mordred met during [43]the last conflict. Lyonnesse may have included Armorica also, still rich with its incomparable traditions and its unsurpassed folk-songs. For once the people of Brittany, Cornwall, and Wales, speaking practically the same tongue, lavished all their poetic wealth upon the Arthurian cycle of legendary history, claimed the knights in common, and each still claims to possess the more famous shrines. Merlin’s forest thus becomes a part of Lyonnesse; Joyous Gard (as we shall presently see) can still be found in Brittany, instead of Northumberland; and Avalon, instead of being a pilgrim’s resort in Somerset, is an island off the Breton coast, seen dimly from the wild moorland country, strewn with dolmens, and reaching down to a shore of silvery sands. Between the orange-coloured rocks “the sea rushes up in deep blue and brilliant green waves of indescribable transparency. On a bright summer day the whole scene is one of unspeakable radiance. Delightful little walks wind round the western headland, where more groups of rock appear, as weird and fantastic as the first.”[7] And across the stretch of azure sea lies the dim islet which Breton legend affirms is King Arthur’s resting-place. When we consider the French sources of[44] the history compiled by Geoffrey, Wace, and Map, the reasonableness of believing that Avalon was at first located in Brittany becomes at once apparent, and the wonder is that in this and many other cases the transference of the scenes to England should have been so complete or that English equivalents should have been so readily accepted.

The more obscure names of places would doubtless be identified if the search were more assiduous in Brittany than in Britain, and if the original Breton nomenclature were used as a basis. Tristram, Iseult, and Lancelot at least are French, and the prevailing tone of the romances in which they figure is French; we must look to Brittany for some part of the scenery.[8] At various times it has been stated that Sir Lancelot’s Joyous Gard was none other than Alnwick, or else Bamborough Castle, in Northumberland, a structure which dates from the year 554, and[45] may have been the site of an earlier stronghold.[9] But why Sir Lancelot, a Breton Knight of Arthur’s Court, whose exploits are confined to Lyonnesse, the southern portion of King Arthur’s territory, should have had his castle located in the north cannot be determined, unless we so far revise our opinions as to credit (as some have done) the existence of a Scotch knight of that name. Instead of looking to Northumberland for Sir Lancelot’s stronghold, and endeavouring to identify Bamborough as his residence, why not turn straightway to France, his native land, and accept such facts as are there to be found? The chronicle of Malory itself says that Joyous Gard was “over sea.” Beyond the forest of Landerneau may still be seen the traditional site of a Chateau de la Joyeuse-Garde, with an ancient gateway and a Gothic vault of the twelfth century remaining. Here at least we find the name; the Breton regards the spot as that which Lancelot, the Breton knight, claimed as his own; and the[46] scene is in that Armorica from which the original traditions sprang, or, at least, where they took earliest root.[10] In addition to Joyous Gard, Brittany boasts of its Tristan Island in the Bay of Douarnenez, named after the “Tristan des Léonais” who was the rival of King Mark. King Mark, too (“Marc’h,” in the original, signifying horse, and so named because of his pointed ears), has his own locality, for according to Breton legend he was not ruler of Cornwall but of Plomarc’h, which place lies a little to the east of Douarnenez and contains the ruins of his “palace.” But Renan justly inquired, if Armorica saw the birth of the Arthurian cycle, how was it that we failed to find there any traces of the nativity?

Cameliard is a tract in some respects not so hard to define or locate as Lyonnesse. The town of Brecknock, three miles from which is Arthur’s Hill, seems to have marked one of its borders, and its capital was a now undiscoverable city, Carohaise. Ritson believes that Arthur’s kingdom could not have been considerable, and he is disposed to grant him the lordship only over Devon and Cornwall, with perhaps some territory[47] in South Wales, the land called Gore or Gower. Be that as it may, his name, by a series of links, extends from Cornwall to Northumberland, from the Scillies to London, and from London to Carlisle. The British tribe, the Silures, to which Arthur belonged, occupied the region now divided into the counties of Hereford, Monmouth and Glamorgan. Brecknock and Radnor may have been added, and it is certain that Arthur had supreme dominion over Cornwall and part of Somerset and Devon. Any “kings” of these places, such as Erbin, father of Geraint, must have been tributary to him. Tacitus has left us an account of the valour, the determination, and the warrior qualities of the Silures, who had Iberian blood in their veins. It was after the Roman and Saxon invasions that they removed their seat of Government from London to Siluria, Arthur having his court at Caerleon. The Britons were a Christian race, for that religion had been introduced among the Latinised Brythonic tribes before the end of the second century. This race prevailed over the Goidels and Ivernians in the territory, and on the recall of the Roman legions one of the Brythons succeeded the Dux Britanniarum and thus became the head of the Cymry (or Cambroges, “fellow-countrymen”). Saxon[48] Cerdic and his son Cymric for twenty years found it impossible to break through the forest districts west of the Avon, which formed the outwork of the British forces; and we may almost take it for granted that at one time the whole of the west country was in Arthur’s power, a line from Liddlesdale in the north to the southern extremity of Lyonnesse, taking in Cumberland, Wales (and perhaps Staffordshire and Shropshire), Devon and Cornwall, roughly marking the boundary. But his reported excursions north of the Trent and to the east counties would also lead to the inference that for some time the tribe overran the major part of the country. Hence we can account for the large number of scattered memorials of the monarch found in all parts of the land, though superstition may have attached his name to many places where he was absolutely unknown. Arthur’s Seats, or Quoits, abound. They are to be found both in North and South Wales, and the name seems to have been given to any rock or commanding situation which in the popular fancy was fit to bear it. In Anglesey, in the wooded grounds of Llwyliarth a seat of the Lloyd family, a rocking stone, the famous Maen Chwf, is called Arthur’s Quoit. Cefn Bryn ridge in Glamorganshire, an imposing elevation, is crowned with a[49] cromlech, together with numerous cairns and tumuli. The cromlech, known as Arthur’s Stone, is a mass of millstone grit fourteen feet long and seven feet two inches deep, and rests upon a number of upright supporters each five feet high. In the Welsh Triads this cromlech, which is near the turnpike road from Reynoldstone to Swansea, is alluded to as “the big stone of Sketty,” and it ranks as one of the wonders of Wales. Another such stone is to be found in Moccas parish, Herefordshire, the cromlech in this case being eighteen feet long, nine feet broad, and twelve feet thick, and supported originally by eleven upright pillars. The colossal king was to have colossal monuments. Brecknockshire has several imposing memorials of Arthur. Five miles south of Brecon rise the twin peaks of the mountain range, and they are designated Arthur’s Chair. A massive British cromlech adjoining the park of Mocras Court is called Arthur’s Table. On the edge of Gossmoor there is a large stone upon which are impressed marks resembling four horse-shoes. Tradition asserts that these marks were made by the horse King Arthur rode when he resided at Castle Denis and hunted on the moors. Between Mold and Denbigh is Moel Arthur, an ancient British fort, defended by two ditches of great[50] depth. At Rhuthyn (Ruthin) in the vicinity King Arthur is said to have beheaded his enemy Huail (Howel), to whom Gildas refers. The record might be extended indefinitely, though no valid argument can be based upon any of the facts. The indiscriminate use of Arthur’s name often shows an extravagance of imagination and a reckless disregard of what is appropriate. Between Mold and Ruthin, for instance, is Maen Arthur, a stone which popular fancy has adjudged to bear the exact impression of the hoof of the king’s steed. There is something like substantial reason for believing that the British hero was connected with Monmouth, Cardiff, and even with Dover, and either the Arthur of the Silures or another British chief seems to have reached Carlisle—that is, if the chronicles did not confuse Cardoile with Carduel. The Cumbrian Arthur figures in two ancient ballads, “The Marriage of Gawaine,” and “The Boy and the Mantle,” while Scott’s poem of Arthur and his Court at Carlisle is, of course, too well known to need more than a reference. In the time of Baeda Carlisle was known as Lugubalia, which name by corruption became Luel. The British prefix Caer, a stone fort, made the name Caer-Luel, and as such it was long known. It gradually degenerated into Carliol,[51] and finally became Carlisle. That the ancient city should have become confused with Caerleon is natural and explicable. Yet Arthur’s connection with a portion of the north is strongly insisted on. Where Wigan now stands he fought a famous battle. Pendragon Castle in Westmoreland claims him as its founder; and passing by easy stages we find ourselves confronted with a Northumbrian Arthur. From this point the transition to Scotland itself is extremely easy, the lowland part of that country being claimed as the veritable Cameliard.

According to no mean authority, we must leave England entirely and search in the North alone for the sites, not only of King Arthur’s battles, but for all the places connected with his exploits and his residence. Badon is then found in Linlithgowshire at Bowden Hill, and the great battle of Arderydd is located at Arthuret in Liddlesdale. The Scotch Merlin and the Scotch Lancelot are the king’s companions, and a Scotch Gildas is the historian. The resting place of Avalon is then found in the caverns of the Eildon Hills, and the voice to rouse him from his charmed sleep will echo through them and “peal proud Arthur’s march from fairyland.” As a curious fact it may be mentioned that nearly all the heroes of the[52] “Four Ancient Books of Wales” are traced to Scotland, and admittedly in the Arthurian legend the British king was connected with as northern a place as the Orkneys by the marriage of his sister to the king of those islands. Of King Arthur, the Scotch ballad rudely tells that when he ruled that land he “ruled it like a swine.” The story of the king was the diversion of James V., who may have known that Drummelziar on the Tweed could boast of a Holy Thorn like Glastonbury, that there was an Arthur’s Oven on the Carron near Falkirk, and that Guinevere’s sepulchre was at Meigle in Strathmore. Edinburgh, or Agnet, is positively represented as the site where the Castle of Maidens stood, and the lion-shaped Arthur’s Hill is supposed to confirm the tradition that here the king abode and made his name.[11] His tomb is pointed out in Perthshire, and all the machinery of the romances is claimed as of Scotch origin and invention. The names of localities are traced, and by transporting Arthur boldly to the Lowlands we account more easily for his rapid incursions into Northumberland and of the country north of the Trent, if we cannot[53] for his equally rapid journeys to Dover and Almesbury and Winchester.

Are not the interchangeability of names and the duplication of persons and places susceptible of a very simple explanation? Caerleon, or Carduel, was confused with Carlisle, each in itself a fitting and likely place for Arthurian exploits; the historians were grievously misled as to Winchester and the part it occupied in the romances; and we know now that various contradictions simply arose from the confusion in the minds of the chroniclers, who never seemed to have been quite certain whether Caledonia and Calydon were not one and the same, whether Camelot was inland or by the sea, whether Joyous Gard was a few days’ or a few months’ journey from Cornwall, whether Camelot was in England or in Wales, whether Arthur’s “owne castell” at Tintagel could be reached by “riding all night” from London, or whether Lyonnesse was Cornwall or Brittany. A hundred topographical complexities meet us wherever we look, and the sole conclusion of the matter is that Geoffrey and his successors inextricably mixed Scotch, Welsh, and Armoric details both in regard to the stories and the localities. The historians made no effort to be consistent[54] in their allusions, to reconcile contradictory statements, or to account for abrupt changes of scene from the South-West to the North. While they endeavoured to concentrate Arthur’s kingdom in South Wales and Cornwall they made occasional sweeps to Berwick and Edinburgh, and annihilated the distance between Dover and Carlisle. To add to the confusion there were names, especially in the Lowlands of Scotland and in the West of England, of the same derivation, and, as Mr. Glennie has demonstrated, it is as easy to discover a Caledonian Caerleon, Avalon, or Camelot as it is to discover any of them in the district once called Cameliard. The unravelling of the skein, which became more and more entangled as new hands developed the romances, is now almost an impossibility. Arthur’s own name was changed, and it has been affirmed that he is still confused with Arthurius of Gwent, and with others of like name who were distinct persons. The conclusion of the whole matter must be that names in the romances are a source of error and confusion; that different significances were attached to them by the chroniclers themselves, and that if the truth be ever established totally new meanings may be expected.

Let me here give one instance of possible confusion[55] of names, and broach a somewhat bold theory. The name Camelford, the scene of the last battle, is by some said to be derived from the Anglo-Saxon gafol, meaning “tribute,” the spot so called marking the ford where of old time tribute was paid. The name Guildford is also declared to have a similar signification, and, in fact, to be but a variation of Camelford. If this be so, a curious point arises. Guildford is mentioned towards the close of the Arthurian history. Sir Lancelot and the king having parted company, it is recorded that Arthur “departed towards Winchester with his fellowship. And so by the way the king lodged in a towne called Astolat, which is now in English called Gilford.” Upon this Mr. Aldis Wright observes: “Guildford in Surrey is no doubt the place alluded to; but I am not aware that the name of Astolat or Astolot (Caxton) is given to it in any authentic history.” It may be argued that King Arthur would be more likely to pass through Guildford, Surrey, than through Camelford, Cornwall. But his starting point is not certain, and it must be specially noted that the Winchester to which he was making his way was not Winchester in Hampshire but “Camelot, that is, Winchester” (Book XVIII., c. 9). The unauthorised and even absurd interpolation that[56] Camelot was Winchester at once changes the whole argument. Disregarding this misleading explanation we find that Arthur was on his way to Camelot from one of his Courts, and if Camelot was in Somersetshire it is most likely that Camelford would be one of the intermediate stages. But the importance of the whole contention is this: Astolat, as frequently mentioned in connection with the “faire maide” Elaine and Sir Lancelot’s worthiest love episode, is undiscoverable. The name is unknown outside romance; and though we are assured that it is “now in English called Gilford,” no authority can be found for the assertion. Besides, Guildford in Surrey was rather beyond the borders of the British Kingdom, even granting occasional excursions to Middlesex and Kent. But if Guildford were synonymous with Camelford, as the derivation permits us to believe, then Astolat was none other than Camelford, and at once there are light and order where formerly prevailed obscurity and confusion. Another point worth mention is that, although tradition marks Camelford as the actual scene of important events in the Arthurian history, and although from its situation, its proximity to Tintagel, and its steep hill suitable to be crowned by a baron’s castle such as Sir Bernard of Astolat[57] possessed, we may safely surmise that it was well known to the ever-journeying knights, yet the actual name of Camelford is never mentioned in the chronicles. As it was of Anglo-Saxon origin, this omission would easily be accounted for in the earliest records, while if Astolat was the traditional name it is at once clear how it could equally be applied to Camelford and to Guildford. We must of course remember that where the chroniclers themselves sought to elucidate they too often confused; the finger-posts they set up have started many upon weary and fruitless journeys, and the guidance offered with such confidence turns out most commonly to be the most random of guesses. If, however, we may place the slightest credence in the “Astolat, which is now in English called Gilford,” as much can be said for “Gilford” being “Gafolford” or Camelford, as for its being “Gyldeford” or Guildford. The stretch of low-lying level fields on either side of the Camel, the sharp-peaked hills in the distance, the dark meres among the hills, and the angry sea lashing against the rocks visible a mile or two away, all accord with the typical scenery of King Arthur’s realm, and make us not unwilling to believe that famous Astolat was here to be found.

When all is told, when all the searching is[58] ended, it is found that some half-dozen places only stand out pre-eminent from the host of localities in the West in each of which only a single seed seems to have germinated; and these half-dozen places, like the last citadels of the hero, resist every effort and assault of the invader to dislodge the traditions of Arthur. I have not attempted to write a history of these places, but only to say something of their aspect to-day and of the chief events and ancient traditions linked with their names. Now and again I mention facts of later date for the purpose of showing that these famous spots have continued to be the centres of activity and connected with great characters; but in the main I confine myself to the legends of Arthur and to the episodes of chivalry. To have attempted more would have entailed not only a far more comprehensive work, but the treatment of the subject in a more scientific spirit than is here displayed. The object has been to deal rather with the romantic side than with the technical, for which the deep scholarship of a Rhys or a Müller alone can be the qualification. It is necessary to premise also that of the most conspicuous Arthurian localities nothing but the bare tradition can be recorded.[59] That tradition lives and is cherished, but its origin is undiscoverable. The sap lingers in the branches, but the roots are detached and lost. The legend is spread everywhere, but there are no verities. The visitor to the Arthurian scenes finds nothing but eponymous names and superstitions—indeed, the evidence present leads him to other conclusions than those he seeks. He looks for a British encampment, and he finds a post-Roman; he looks for a relic of Arthur, and he finds one of Antoninus. What is persistently ascribed to the British hero, or associated with his times, is either intangible or is irreconcilable with existing facts. Castles he is said to have inhabited were built centuries after his death, and there can only remain the free speculation that they mark the site of a former structure of which no trace remains and of which no record was made. Spots which are called King Arthur’s grave, or his seat, or his hunting-ground, or his camp, neither he nor his band, it often happens, could ever have been near. We look for persons, and we find a crowd of phantoms; we eagerly watch for demonstrations, and we find myth and fable; we hope to see the clear page of history, and we find a page that is undecipherable or blotted with shadows. Records[60] are effaced, song and story delude, the track to truth is almost closed. Everything crumbles into dust at the touch, like Guinevere’s golden hair, and nothing is now left but the pure romance. And some of us may be content and almost glad to have it so.

The Birth of Merlin, Act III. sc. iv.

The fact that the name Art(h)us does not occur in the Gildas manuscript has led to the inference that the king was unknown to that chronicler; and the assumption that he is alluded to as Ursus (the Bear) tends to confirm the theory of those who would affirm that he is no more than a solar myth. It must be understood that the Arthur of romance, as we now know him, was a character ever increasing in importance and prominence as the history was re-written and elaborated; at first[62] a minor actor in the drama, he at length became the leading figure and the centre around which all the other characters were grouped. The Arthur of the historian Nennius is the original personage to whom all the famed attributes have been accorded by subsequent writers. With so much doubt and confusion, involving the identity of the person himself, it is inevitable that even more doubt and confusion should exist when we come to detailed events. Even the name of Arthur’s father is variously given, a circumstance which caused Milton to question the veracity of the whole history; and the date of his birth, of his death, the age at which he died and other smaller points, lead to nothing but endless contradiction. The number of his battles is variously given as twelve and seventy-six; he is said to have wedded not one but three Guineveres (Gwenhwyvar); his age at death varies from just over thirty years to over ninety; and the date of the last battle is 537, 542, or 630.[12] King Arthur’s actual name[63] may have been Arthur Mab-Uther; his genealogical line has been traced back to Helianis, nephew of Joseph; the year 501 is now usually accepted as the date of his birth; and St. David, son of a prince of Cardiganshire, is mentioned not only as his contemporary but as a near relative.[64] If the Sagas were compared with the Arthurian romances numerous points of resemblance could be shown. Olaf is the Arthur of the story, Gudrun the Guinevere, and Odin is the Merlin, while the city of Drontheim serves as Caerleon. The story recounting how Arthur magically obtained his sword Excalibur finds an exact parallel in the story of Sigmund, Volsung’s son; and even the emblem of the dragon is not lacking,[13] for in the story of the Volsung we learn that Sigurd’s shield bore the image of that monster, “and with even such-like image was adorned helm, and saddle, and coat-armour.” But again it must be remembered that Arthur’s kingdom is reported to have extended to Iceland itself; in fact, the bounds of his kingdom were only set by the chroniclers where their own definite geographical knowledge ended.

“We cannot bring within any limits of history,” Sir Edward Strachey has properly said, “the events which here succeed each other, when the Lords and Commons of England, after the death of King Uther at St. Albans, assembled at the greatest church of London, guided by the[65] joint policy of the magician Merlin and the Christian bishop of Canterbury, and elected Arthur to the throne; when Arthur made Caerleon, or Camelot, or both, his headquarters in a war against Cornwall, Wales, and the North, in which he was victorious by the help of the King of France; when he met the demand for tribute by the Roman Emperor Lucius with a counterclaim to the empire for himself as the real representative of Constantine, held a parliament at York to make the necessary arrangements, crossed the sea from Sandwich to Barflete in Flanders, met the united forces of the Romans and Saracens in Burgundy, slew the emperor in a great battle, together with his allies, the Sowdan of Syria, the King of Egypt, and the King of Ethiopia, sent their bodies to the Senate and Podesta of Rome as the only tribute he would pay, and then followed over the mountains through Lombardy and Tuscany to Rome, where he was crowned emperor by the Pope, ‘sojourned there a time, established all the lands from Rome into France, and gave lands and realms unto his servants and knights,’ and so returned home to England, where he seems thenceforth to have devoted himself wholly to his duties as the head of Christian knighthood.”

This is the very monstrosity of fable, the grossness of which carries with it its own condemnation. These facts, however, are not insisted upon by Malory, though such claims for Arthur were made by the credulous and less scrupulous writers. Romance has entirely remodelled his character, and has filled in all the gaps in his life-story in that triumphant manner in which Celtic genius manifests its power. The legendary Arthur is made to realise the sublime prophecies of Merlin, and as those prophecies waxed more bold and arrogant in the course of ages the proportions of the hero were magnified to suit them. Merlin had cherished the hope of the coming of a victorious chief under whom the Celts should be united, but the slaughter at Arderydd when the rival tribes fought each other, almost destroyed all such aspirations. Nevertheless the prophet foretold the continuance of discord among the British tribes, until the chief of heroes formed a federation on returning to the world, and his prediction concluded with the haunting words: “Like the dawn he will arise from his mysterious retreat.” Mr. Stuart Glennie calls Merlin a barbarian compound of madman and poet, prophet and bard, but denies that he was a mythic personage or a poetic creation. He was, like Arthur[67] himself, an actual pre-mediæval personage, and, as in the case of Arthur, we have no means of determining his origin, his nationality, or the locale of his wanderings. But if, as Wilson observes in one of his “Border Tales,” tradition is “the fragment which history has left or lost in its progress, and which poetry following in its wake has gathered up as treasures, breathed upon them its influence and embalmed them in the memories of men unto all generations,” we shall extract a residuum of truth from the fanciful fables of which Merlin is the subject.

Myrdin Emrys, the Welsh Merlin, is claimed as a native of Bassalleg, an obscure town in the district which lies between the river Usk and Rhymney. The chief authority for this is Nennius; but according to others the birthplace was Carmarthen, at the spot marked by Merlin’s tree, regarding which the prophecy runs that when the tree tumbles down Carmarthen will be overwhelmed with woe. What we know of Merlin in Malory’s chronicle is that he was King Arthur’s chief adviser, an enchanter who could bring about miraculous events, and to whom was delivered the royal babe upon a ninth wave of the ocean; a prophet who foretold his sovereign’s death, his own fate, and the infidelity of Guinevere; a[68] warrior, the founder of the Round Table, and the wise man who “knew all things.” Wales and Scotland alike claim as their own this most striking of the characters in the Arthurian story. Brittany also holds to the belief that Merlin was the most famous and potent of her sons, and that his influence is still exercised over that region. Matthew Arnold, gazing at the ruins of Carnac, saw from the heights he clambered the lone coast of Brittany, stretching bright and wide, weird and still, in the sunset; and recalling the old tradition, he described how—