Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed. Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text. List of Illustrations (In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol (etext transcriber's note) |

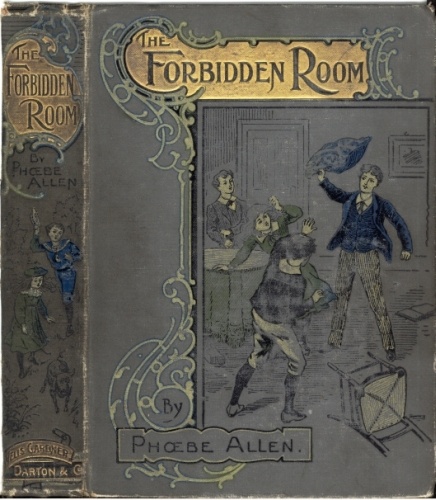

THE FORBIDDEN ROOM.

OR

“MINE ANSWER WAS MY DEED.”

BY

PHŒBE ALLEN.

AUTHOR OF “PLAYING AT BOTANY,” ETC., ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY J. JELLICOE.

LONDON:

WELLS GARDNER, DARTON & CO.

3 PATERNOSTER BUILDINGS.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | “BOYS AND GIRLS, AND ALL SORTS” | 1 |

| II. | “WHO’S WHO” | 7 |

| III. | NOTES AND QUERIES | 12 |

| IV. | “IN THE ROSY SUMMER WEATHER” | 16 |

| V. | BOAR HUNTING | 21 |

| VI. | “IN THE CUCKOO COPSE” | 28 |

| VII. | COMING TO BLOWS | 33 |

| VIII. | OGRES | 37 |

| IX. | “QUITE ’STRORDINARY FUN” | 42 |

| X. | “YOU’VE NEVER BEEN QUARRELLING” | 51 |

| XI. | “TARRY THE BAKING” | 55 |

| XII. | “LIVE PURE, SPEAK TRUTH, RIGHT WRONG” | 63 |

| XIII. | “NO, NO, IT IS NOT JUST” | 71 |

| XIV. | “A PUNITIVE EXPEDITION” | 78 |

| XV. | “FIRST CATCH YOUR BIRD” | 82 |

| XVI. | “A COWARD’S TRICK” | 89 |

| XVII. | EXECUTING A SENTENCE | 96 |

| XVIII. | “WE’RE AWFULLY SORRY NOW” | 105 |

| XIX. | “THEY HAVE NOT GONE YET” | 115 |

| XX. | THE KING OF MUFFS | 119 |

| XXI. | “A VERY SAD LITTLE BOY” | 129 |

| XXII. | “NOW THESE BE SECRET THINGS” | 134 |

| XXIII. | “TOUCH YOU!” | 142 |

| XXIV. | “HURRAH! HURRAH!” | 149 |

| XXV. | A TRAGICAL AFTERNOON | 155 |

| XXVI. | “WHATEVER WILL THE MASTER SAY?” | 162 |

| XXVII. | WHAT THE MASTER DID SAY | 171 |

| XXVIII. | “A PRETTY PICTURE” | 179 |

| XXIX. | “WHERE’S GASTON” | 187 |

| XXX. | “THE BESTEST BEST” | 193 |

NEVER within the memory of middle-aged Libbie, the dairymaid, had there been such a bustle of preparation within the walls of Gaybrook Farm, as on a certain June day, not many summers back.

From early dawn—which means somewhere between three and four o’clock—old Mrs. Busson, the farmer’s wife, had been awake and astir.

From the lumber-room in the attics, to the parlour, with its high-arched fire-place, filled in to-day with boughs of green and big bowls of June roses, and from the cheese-room, under the roof, to the brew-house in the yard below, every nook and corner in the roomy old farm had been visited, on some pretence or another, by the time that noon and the dinner-hour arrived simultaneously.

“And yet,” declared Polly, the rosy-cheeked “odd-girl,” “though the Missus hasn’t been off her feet for all these hours, she’s as fresh as a sky-lark.”

“Ay, as brisk as a bee amongst clover,” chimed in old Simon, the shepherd. Leaning against the wall of an outhouse, his dim eyes followed Mrs. Busson’s quick movements as she flitted from dairy to larder, finally disappearing into the garden, as nimbly as though she were seventeen instead of seventy.

“And what’s it all about?” asked Simon, slowly; “I forgets again.”

Polly sighed. Already three times that morning she had given the explanation to the old man, and the importance of being his informant was wearing off.

“What’s it all about?” repeated Simon.

“Don’t you mind, Simon; I told you that the Missus’ ladies, them she was nurse two years ago, are coming down with their children to stay some while at the farm. There! if they were all live princes and princesses the mistress couldn’t fuss more about them. My word! Simon; the cakes, and the pies, and the jams, and the junkets are something to see.”

“Is it boys or gals that is coming?” asked Simon, with a note of alarm in his voice. “Be they young, or the middlin’ mischieevious age?”

“Oh! that I can’t tell yer; they be all sorts, I think.”

“Mussey me! boys an’ girls an’ all sorts,” cried the old shepherd; and, as if to make preparation at once against the approaching foe, he whistled to his equally ancient dog, who was making an exhaustive examination of a bare veal knucklebone, and tottered towards the meadows.

But Simon’s heart was not the only one which, amongst all the pleasant stir of preparation at the farm, was filled with alarm at the thought of the impending visitors.

One Gaston Delzant, a small, black-haired, black-eyed French boy, aged seven, was literally trembling within his patent leather shoes at the prospect of the coming guests.

He had not been long in England, and though the healthy life at Gaybrook, and Mrs. Busson’s fostering care had worked wonders in strengthening the feeble little creature, Gaston still looked, as the burly farmer declared, “just a poor little snip of a frog-fed Frenchy.”

“Don’t talk that sort of unfeeling way, Busson, before the child,” his wife had admonished him, “for, don’t you make any mistake, though he’s slow to speak, he understands sharp enough all that he hears.”

Indeed, so far as poor Gaston’s peace of mind was concerned, this was only too true.

He understood so perfectly all that the maids said, as they interchanged their fears that the young gentlemen from school would teaze him out of his senses, that on the day of their arrival, Gaston was wildly planning some means of escape from the farm.

But perhaps the general fragrance of cakes and pies which filled the house and imparted a flavour of festivity to the atmosphere exercised a reassuring influence on Gaston, for after all he abandoned his intention of taking refuge in a remote barn, the paradise of owls and bats, and remained instead to face the enemy.

And here it was approaching in very earnest.

The clock was still striking four, and Mrs. Busson was giving her last look to the tea-table, when the sound of wheels became audible, and presently, through a cloud of dust from the high road, emerged the two Noah’s-ark like vehicles, popularly known as the “station conveyances.”

“Boys and gals, and all sorts, I should say it war,” muttered Simon, looking from behind a quick hedge, whilst with one delighted cry of “Bless their dear hearts, there they are to be sure,” the mistress of Gaybrook Farm flung wide her doors and flew to greet her guests.

Every part of her trim little person, from her lavender topknot to the toes of her neat pattens, was so quivering with rapturous glee that as she sped down her flower-bordered pathway, she seemed the very embodiment of smiling welcome.

Yet, although Mrs. Busson’s appearance was hailed by a round of vociferous cheering from the new arrivals, her bright face clouded suddenly as she glanced from one carriage-load to the other.

“Why!” she gasped; “wherever is Miss Agatha—Mrs. Durand, I should say?”

“Left behind, left behind,” came in a chorus of voices. “We’ve all got to take care of ourselves, Mrs. Busson, and we’re all going to be the most awfully good lot that ever were.”

By this time the two flies had been drawn up behind each other, and such was the general bustle and tumult of the alighting that when the last of the “awfully good lot” had actually descended from the carriage, Mrs. Busson found herself holding her head with both hands, in order to make sure that it was still in its place.

As for Gaston, he had made a clean bolt of it, and now from behind the case of a tall Dutch clock, which stood at the foot of the stairs, peeped furtively at the invading host.

THE contents of the first fly did not seem so alarming, at least not as to numbers, for it only contained three occupants, human occupants that is.

On the front seat was a rather demure-looking girl of fourteen, whose general air of youthful anxiety suggested that she was more or less in charge of the party. Beside her was a dark-haired boy about a year younger.

“ ‘Fat, flabby and fractious,’ that’s what you ought to be labelled,” one of his boy cousins had declared at starting, and, though it was an ungracious remark, and not likely to improve Andrew Durand’s temper, yet even in the excitement of arrival, he still did not look, well—quite the reverse of his cousin’s description.

Not only had he taken the lion’s share of the front seat of the fly, but he had almost monopolised the back one too; first, with his feet, which he had comfortably disposed in a line with his indolent overgrown person, and secondly, with his innumerable possessions.

Amongst these was a canary in a cage, a guinea-pig in a box, a huge butterfly net—its extra long handle making it an undesirable addition to luggage—sundry tin cases, with unpleasantly sharp corners, a geological hammer and various tools of a kindred nature, a violin, along with divers other items, which contributed to form the pile of non-squeezable luggage, beside which poor little Marion, the third passenger, had to accommodate herself as best she might.

“Nonsense, she has heaps of room for her size,” Andrew had ruled at starting from the station, when the others had remonstrated with him; “How much more can an infant like that want?”

Marion, commonly known as Marygold, perched herself very contentedly on the edge of the seat, and, always ready to make the best of a situation, announced cheerily:

“I ’spect I’ll manage somehow, for all my hair can sit on the air,” and certainly the cloud of golden hair that surrounded the sweet-tempered little face did seem the most important part of her very small person.

Fly No. 2 was more closely packed. It contained Jack and Phil Kenyon, schoolboy brothers of eleven and ten; their cousin, Diana Durand, who was ten years old yesterday; Tryphoena Kenyon, always called Phoena, who was just a year younger than Di; and last of all, six-year old Hubert, the youngest of the Kenyons.

He was so small that, when the cheering began he jumped up on the seat, for he felt that otherwise he might be overlooked, and he flung his hat so frantically into the air that the latter fell into the road and he himself toppled into Di’s arms.

“Here, hurry up, Miss Annie,” cried Phil, coming to the door of the first fly; “don’t you see that your old go-cart’s stopping the way? I say, can’t you give a hand to Faith and help her with all that pile of rubbish? You don’t mean to tell me that she’s been nursing that bowl of gold-fish all the way from the station?”

“Oh! it’s all right,” began Faith; but Phil went on:

“What a muff you are, Andrew, to want all these blessed playthings, and here’s poor little Marygold squeezed to a jelly.” Then, calling Jack to his aid, Phil began to grapple with Andrew’s manifold possessions in good earnest, to Mrs. Busson’s great satisfaction. Their cousin, meanwhile, stood by giving directions which no one heeded, and grumbling at the way in which his property was handled. Even Hubert was more helpful, whilst Marygold, in the exuberance of joy at being relieved from her cramped position, was so eager to render assistance that in her zeal she tipped nearly all the water and the inmates too out of the gold-fish bowl.

“I think, Mrs. Busson,” said Faith, her soft voice sounding like a dove’s note amongst the chattering of many starlings, “if you will show me Andrew’s room I’ll put away some of his things, and get him to rights first of all.”

“Oh! yes,” jeered Jack, “take the precious baby to his nursery, and let him have all his toys. Shall we come and help you, Fay?”

But Faith gave him an imploring look, such as might soften the heart even of a schoolboy on teazing bent, and, following Mrs. Busson, she disappeared into the house.

The others were content to remain in the old-fashioned roomy porch. Here they made friends with Dragon, the watch-dog, and Thief, a very talkative magpie, who, in his big wicker cage, embowered in purple flowering clematis, made a perfect picture.

“And now, please,” said Mrs. Busson, reappearing presently, “I’ll have to be told who’s who, not but what I can see that you two”—looking at Jack and Phil—“belong to each other, and that you’re Miss Julia’s boys—Mrs. Kenyon, as I ought to say.”

“Right you are,” cried Phil, whilst Diana of the ready tongue added:

“And Phoena and Hubert are Aunt Julia’s children too.”

“Ah! to be sure, I can see you have your mamma’s eyes,” said Mrs. Busson, taking Phoena’s pale face between her hands and looking into the child’s grey thoughtful eyes. “And so your papa and mamma are still in India, are they? And you go to school, do you, as well as your brothers?”

“Oh! no,” said Di; “only Jack and Phil go to school. They’d be there now if scarlet fever hadn’t broken out.”

“Yes, it was awfully slicey for us,” chimed in the brothers, “for, as we didn’t catch the fever, we got off that and the lessons too.”

“Yes,” said Hubert, “it was jolly fine fun for them.”

Whether their natural protectors considered the arrangement “jolly fine fun” too, our readers may perhaps gather from the letter which that week’s Indian mail carried to Mrs. Kenyon, touching the matter:

“My dear Julia, how true it is that troubles never come singly. The outbreak of fever at your boys’ school was tiresome enough, as it forced us to begin the holidays for the children at home sooner than was intended, and upset all our arrangements for the summer; however, we resigned ourselves very happily to the inevitable, and I had made arrangements with dear old Pattie for receiving us all at the farm, and we were actually starting thither this morning, when a wire from Edinburgh arrived at breakfast, summoning me to my mother-in-law. She is very ill, and old Mr. Durand begs me to come at once, so I am obliged to let the children go down to Gaybrook without me.

“There was, moreover, such indignation when I proposed sending Sarah in charge of the party—your boys resenting the idea of having a nurse tacked on to them so bitterly—that, after consultation with Faith, who is as trustworthy as if she were thirty instead of thirteen, I decided to let the young people take care of themselves; besides, I knew, what my young rebels did not, that Pattie has already secured a very efficient nursery-maid in disguise, namely, her niece, Ruth Argue, who used to be nurse at the Rectory, and who is to be at the farm as long as our party is there. And so, about an hour ago, they set off, a merry troop on the whole, though poor Fay looked rather oppressed by the sense of her responsibility, whilst Andrew, I regret to add, looked decidedly peevish. If Fay were not there I should feel rather anxious about him. No doubt your schoolboys will do him good with their wholesome chaff, but unfortunately his aunt, with whom he has been at the seaside, has so spoilt him and allowed him to think so much of his health, that I’m afraid he is not likely to prove an acceptable companion. I hope he will soon be strong enough to go to school, for then he will lose his priggishness, but there is no question that he is very clever, and takes real interest in subjects that most boys don’t care about. I sometimes think if only the others would try and learn a little from him about natural history, for instance, instead of always jeering him when he mentions it, it would be better for all parties. Altogether, if I could only have kept Andrew with me, I should feel happier about this expedition. Still, they all started, rich in good intentions of showing consideration both to Mrs. Busson and each other, so we can only hope that they will fulfil one tenth of them.

“Always your affectionate sister,

“Agatha Durand.

“P.S.—I forgot to mention that the children will find a playfellow at the farm, the grandson of old Madame Delzant, who, you remember, used to live at Gaybrook. Both his parents, neither of whom lived in England, are dead, and when old Madame died, some months ago, not long after the child had arrived in England, Pattie took possession of him, and is keeping him till it suits an uncle in Paris to come and fetch him. I am wondering whether the presence of this small stranger will conduce or otherwise to the harmony of the party.”

WHETHER the new-comers would contribute to the harmony of his life, was troubling Gaston’s mind, when he emerged from his hiding-place behind the clock, and made a cautious survey of the intruders.

“They don’t look very cruel,” he thought, peeping through the crack of the parlour door and eyeing them anxiously as they sat round the tea-table, “still I’m glad that I shall have my tea by myself.”

It certainly was a very happy party that was gathered at Mrs. Busson’s well-spread board, at which the hostess was presiding, helped by the very efficient “nursery-maid-in-disguise.”

Mrs. Busson was quite in her element, flitting round the table, and encouraging her guests to try one dish after the other. But it was hard work to satisfy their curiosity on a hundred points, as well as their healthy appetites.

Such a shower of miscellaneous questions assailed her patient ears:

“Has the grass been cut yet?”

“Dear! yes, the mowing machines have been at work all this day in the long meadow, and there will be plenty of new-mown grass to make hay of to-morrow.”

“And who’s asking about butterflies? Oh! yes, there’s plenty of them.”

“Ah! but are there any Hipparchia Janira out yet?” asked Andrew.

“Never heard of that kind of creature,” was the reply, whilst Phil interrupted with, “Oh! he only means an old cabbage-butterfly.”

“That’s all you know,” began Andrew, indignantly, “but I’ll tell—”

“There, there,” broke in Mrs. Busson’s soothing tones, “if you did say the name wrong, it’s no wonder, but there’s abundance of butterflies of all sorts to be had here, that I do know, so I wouldn’t worry my poor little head about the name of any particular one,” she added, in blissful unconsciousness of Andrew’s disgust at her misplaced consideration and of the other boys’ keen delight thereat.

Meanwhile, Diana, who liked to have a finger in every pie, was eagerly enquiring as to the day for cheese-making.

“Oh! that’ll be the day after to-morrow, and the next day there’ll be a grand jam-boiling. The girls are gathering the gooseberries already.”

“And what is it you want to know, my dear?”—this to Marygold.

“Will the bees be swarming soon?” enquired that small person.

“Well, that I can’t say for certain; we’ve had a fairish number already, but maybe there’ll be a swarm yet, and then you shall make bee-music, that you shall, to your heart’s content.”

“And—and—” asked Hubert, who between his struggles with a huge bit of cake and attempts to make himself heard was as scarlet as a field poppy, “is there a nice little pond, where I can catch fish with nice pinky wriggling worms?”

“Yes, bless his dear little soul, there’s a pond to be sure, and perhaps just a fish or two in it,” replied Mrs. Busson, proceeding to empty half a pot of blackberry jam on to Hubert’s plate. “Well, and what is it you are going to ask?” she added to Phoena, who had hardly eaten any of the good cheer as yet; but though she was so silent, her small white face, with its starry eyes, had been full of thought.

“I want to know, please, are there any glow-worms about here?” she asked.

“Bound to be some soon, if there are none yet,” was the reply, “I’ve seen many a one down on the bank in the water-meadow of a summer’s evening, when the twilight’s wearing through.”

“Oh!” burst from Phoena, her face all aglow, but Andrew cut her short.

“What do you know about glow-worms?” he asked, in a tone of unmitigated contempt, “what’s the Latin name for them?”

“She doesn’t know, and she doesn’t want to know,” cried Jack, “so you can keep your mouldy old Latin for yourself.”

“Or talk it to Dragon,” put in Di, whose tongue had unfortunately a rather sharp point, “for it’s only dog-latin, so Phil says.”

Without condescending to note this last insult, Andrew resumed his attack on Phoena.

“You had better leave glow-worms—in fact, all insects—alone,” he remarked, “until you’ve learnt something about them. When I’ve time, I can teach you a lot about them; in the meanwhile, you may carry my insect boxes for me when I go on my entomological expeditions.”

“There, if you young gentlemen want to hunt insecks,” broke in Mrs. Busson, who felt that the atmosphere was becoming rather storm-laden, “I do wish you’d hunt the garden slugs, they’re just ruinating all our green-stuff.”

“Oh! we’ll ruinate them,” cried the schoolboys, but Andrew added, “They are, of course, most destructive garden pests. Now I wonder if any of you know how many teeth a garden slug has.”

“Never had the pleasure of accompanying one to a dentist’s,” said Di. Whereupon there was a general laugh.

“There’s nothing to laugh at in your ignorance,” cried Andrew, “a garden slug—”

“Look here,” cried Jack, “if you talk of that disgusting brute again, I’ll—” but remembering his manners, he stopped short.

“Well,” persisted Andrew, “it has no less than twenty-eight thousand teeth.”

“What a lot of toof-ache it must have,” said Marygold, feelingly.

“But, Andrew,” questioned Phoena, seriously, “which garden slug is that? Is it the grey—”

“It’s the garden slug, I tell you,” said Andrew, impatiently, evidently not appreciating Phoena’s thirst for further knowledge.

“Yes, but there are several kinds,” said Phoena, growing eager now.

“There’s the—”

“Oh, Phoena, do look at your cup,” cried Faith, from the other end of the table, “you’ll upset your tea in another minute.”

But the warning came too late.

Carefulness at meals, or indeed at any other time, was unfortunately not dreamy Phoena’s strong point, and before Faith had finished speaking, the whole contents of her hitherto untasted cup had overflowed its borders and was trickling in a whitey brown streamlet down the table.

“There, there, my dear, never mind,” exclaimed kindly Mrs. Busson, “it’s the first cup of tea you’ve ever spilt in my house, and I do hope it won’t be the last, by a long way.”

And as Ruth set to work to repair the damage, Andrew profited by the diversion to ask for some lettuce for his guinea-pig, and thus change the slug subject. He felt he had gone far enough in that department.

THERE was something in its irregular rambling style of architecture that gave to Gaybrook Farm, as Di expressed it, a particularly “holiday-house” look.

Nobody quite knew how old it was, but the various additions to the original building, which had been evidently made at different intervals, suggested the handiwork of several generations, and seeing that, as Mrs. Busson was fond of saying, “Busson’s great grandfather had been born there, and that Busson himself was no chicken, the farm must have been standing, well over a hundred years at any rate.”

But though so strangely irregular, it was a very substantial pile of buildings.

The red, pan-tiled roof of the main portion seemed, as it were, to run up-hill, and from under this the first floor projected, supported by heavy black beams.

It was in this part of the house, in low ceilinged rooms, with little old casement windows, and long window panes, that Mrs. Busson had arranged to bestow her visitors.

For this end of the house, “the up-hill part,” as Hubert called it, comprised all the living rooms of the family. There was the large house place below, with the roomy parlours on either side, the best bedrooms above, and the attics another storey higher.

Beneath the lower roof of the building, which was thatched and much weather-worn, were all the various farmhouse offices.

Foremost amongst these was the kitchen. Oh! such a kitchen it was. Flanked by the store-room and larders, and a dairy a little further on, which opened out into a spacious back yard, and with the baking and brewing-houses, and the wood and the wash sheds, it formed a regular little quadrangle.

Over the kitchen was a long, low room, filled with linen-presses, and fragrant with lavender and dried rose-leaves, for Mrs. Busson held fast to old traditions in these matters of household economy; whilst almost adjoining was a huge apple-room, and overhead the vast cheese-loft.

Between the linen room and the apple store was another chamber door (if that door had never been there, this story would never have been written). To judge, however, from the cobwebs which hung like a thick grey mist about its cracks and hinges, that door must have been long, very long unopened.

“Now mind, you girls,” Mrs. Busson had cautioned her hand-maidens, before the children’s arrival, “whatever happens, you never let the little gentlemen and ladies go trying to get in there.”

Unanimously, the girls promised obedience.

But that same evening, directly after tea, their mistress reiterated her commands.

“Whatever you do, don’t drop a hint to Master Andrew of what’s in that room,” she said, “for I’ll be bound he’d be up to some mischief, and so, I suspect, would Miss Phoena too, if they only guessed.”

“Very good, ma’am,” said the trusty Nell (she was cheese-room maid), “chances are, if we manage well, they’ll never so much as notice the door. Young things are mostly for getting out of doors.”

And at starting, it seemed as if Nell was likely to prove a true prophet.

All through the next morning, in spite of the oppressive midsummer heat, the children were flitting about in all directions.

“Like so many sunbeams at play,” Mrs. Busson declared.

Early dawn had found Jack and Phil out in the hay-field, tossing the new hay with more energy than skill, and it had needed all Fay’s gentle persuasions to induce Hubert to attend to the most necessary details of his hurried toilette, before rushing out to join his brothers. As for Di, whose swiftness of foot, combined with her ruddy locks, had long ago earned her the title of “Scarlet Runner,” she too was up with the sun, or very nearly, and had found her way to the little stream which ran through the Crow-bell meadow, and was wading in its shallow waters in search of water-cress.

Little Marygold, her whole person, saving her head, concealed in a holland overall, was standing knee-deep in a tangle of sweet-briar, honeysuckles, climbing roses, and a score of sweet, old-fashioned blossoms which grew together to the left of the flower-garden, in a patch of rank disorder, under cover of which the “posy-border” melted into the orchard beyond, without making a too rude transition.

Marygold was supremely happy, searching the foxglove bells and the dew-brimmed cups of the lilies, in the fond hope of discovering some of those belated fairies, who, she firmly believed, took their night’s rest in these flowery shelters.

“There must be some somewhere,” she cried, in her clear, piping voice.

“Oh, Phoena, do come and help me to look for them.”

But though Phoena was not forthcoming, she was not far off.

For though she had left the house, intent on reaching a certain sainfoin field, whose brilliant blossoms gleamed bewitchingly in the early sunlight, her wanderings had been arrested after the first few yards. The sight of a wounded snail, crawling slowly, slowly even for a snail, along the ash-strewn path, which led from the back yard to the kitchen garden, had checked Phoena’s progress, who, wherever anything was sick or sorry, was a veritable sister of pity. Moreover, having lately heard about the snail’s marvellous faculty for mending its damaged shell, Phoena thought this was a favourable opportunity for seeing how this feat was performed. So, with the help of sticks and stones, she forthwith made it a hospital beneath the shade of a laurel bush. Converting her handkerchief into an awning above the sticks, Phoena conveyed her interesting patient into these specially prepared quarters, exhorting him to set to work at once on the repairing of his shell. She would gladly have foregone her breakfast for the pleasure of watching him, but she feared by so doing to draw public attention to her “anxious case.”

Accordingly, she reluctantly obeyed the summons of the loud breakfast bell, with the result, alas! that on her return, she discovered that the thankless snail, after the way of some vagrants, had decamped!

Out of the whole party, Andrew was the only “slug-a-bed,” and even he managed to be ready to go out by nine o’clock, having secured Faith’s attendance on himself as bearer of his butterfly net and sundry other things necessary to the success of his expedition.

“I say,” cried Phil, catching sight of the net, “can’t you leave those poor beggars in peace for to-day at least?”

“Yes,” chimed in Jack, “and I call it awful hard lines on Fay; I bet she doesn’t want to go swinking after you all this hot morning. As it is, she’s had to feed your old gold-fish already, and clean your precious canary. Why don’t you strike, Fay, and tell Miss Annie to look after his own toys?”

“Because Fay always wants peace at any price,” put in the Scarlet Runner, more promptly than pacifically. “But I wouldn’t do—”

“Never mind, Di,” broke in Faith, knowing well how swiftly such gathering clouds might develop into storms, “we’re only going out for a little time, because I must come home and write to mother.”

“Oh! you good Faith,” came in a chorus of heartfelt applause.

The heroism involved in writing a letter to-day roused general admiration. But steady-going Faith generally put duty before pleasure; sometimes, it must be owned, to her companions’ regret, notably to Di’s. For the latter had been known to declare that she wished the man who had invented such worrying words as “duty and obedience” had been stung to death by hornets. But then, as Di’s long-suffering nurse had remarked more than once during that young person’s earlier career, “Miss Diana was a handful.”

THAT first morning at Gaybrook passed like a flash of lightning. There was so much to be seen and explored. From the poultry-yard, where its scores of feather inmates held a world of delight, to the water-meadows, which formed the limit of the farm boundaries, and were so designated because they were intersected by the little river Gay.

Here an old punt proved very attractive to the elder boys, when they tired of the hay-field. To the copse, adjoining the water-meadows, Di retired, partly to practise a little climbing in private—an exercise, which to her regret, she could not well pursue in the London Square garden—and also animated by the hope of surprising some big nest—a pheasant’s perhaps.

Phoena was lost to sight amongst tall rows of peas and French beans in the garden. “Probably preaching sermons to the bees,” Phil declared. Hubert and Marygold agreed to join forces. They started by conscientiously trying to secure a “personal interview” with everything in feathers in the farmyard, Hubert doing his utmost to work the scarlet-wattled turkey-cock into an ungovernable rage. That pleasure exhausted, this young pair next betook themselves to a vast apple-orchard.

This new ground promised scope for endless adventure; it suggested such a wide field for enterprise.

In many places the high rank grass was over Hubert’s head, once Marygold’s brilliant locks entirely disappeared, so that, as she reminded Hubert, it must be like those jungle places in Injia, of which his father had told them so many stories.

“You don’t think,” said Hubert, a little apprehensively, “that there are any wild beasts hidden about under the grass to spring out and eat us, you know?”

Marygold didn’t feel quite sure.

“Suppose we go and ask Mrs. Busson,” she suggested, standing still.

But Hubert dissented.

“No, don’t let’s,” he said, “because p’raps she’d be afraid for us then, and say we had better not come in, and that would be a pity.”

Marygold thought that on the whole Hubert’s advice was sound.

“Besides,” she added, with some vagueness of speech, “I expect we’d have time to run if any came. Lions roar ever so loud, and tigers’ eyes gleam ever so far off. Besides, you know in the book at home with a man riding a camel on the cover, it says there are no more wild beasts in England.”

Reinforced by these reflections, the small adventurers plunged boldly into the grassy sea, hand-in-hand for the first few steps, but very soon Marygold broke away with a cry of delight from Hubert. Her sharp eyes had discovered a glorious find, the first of many to follow.

It was a currant bush that she had espied, half-buried under the rank growth of grass, the clusters of fruit showing redly amongst the coarse green blades that went near to hiding it altogether.

The children’s glee knew no bounds.

“I b’lieve,” cried Marygold, her voice piercingly shrill with excitement, “that we’ve found ’Laddin’s garden with the trees bearing the wonderful fruit that was jewels, you know.”

For now, in addition to currant-bushes, red, white, and black, Hubert had lighted on some raspberry canes with ripening fruit too.

“Don’t you know,” went on Marygold, “that in the fairy-book it says, that the white, red, and yellow fruit were really pearls and rubies and topaz and—”

“I expect,” broke in Hubert, whose utterance was somewhat impeded by the handfuls of fruit, which he had been diligently cramming into his mouth, “I expect that it’s really a sort of buried-alive garden, for it is quite real fruit, Marygold, and raver sour.”

“I’ll tell you,” was the reply, “it must belong to the fairies, and Mrs. Busson can’t know anything about it.”

“ ’Spose we keep it all a secret,” said Hubert.

“Oh! but you always say that,” said Marygold, reproachfully, “and then you never do. No, let’s say that we’ve found a garden but we can’t say where.”

“Yes,” cried Hubert, “and let’s get a cabbage leaf and put some of the fruit in it, just to show them that it’s all true.”

The idea was a charming one, but it was not carried out. For on their way to the kitchen garden, Hubert pulled Marygold back.

“Look! look!” he gasped, pointing to the end of the big orchard, “there are some wild beasts.”

Following the direction of his frantically waving arm, Marygold descried the black backs of some dozen little pigs, bobbing up and down in the high grass and looking like a shoal of porpoises leaping in the sea.

“They’re only pigs, little pigs,” said Marygold; but fired by a spirit of adventure, Hubert dashed off in pursuit, declaring that “of course, they were big, wild boars.”

But he was treading unknown ground, and although he was not “infirm and old,” like the minstrel in his poetry-book, he was young and not very steady on his feet, and presently the stump of one of those “buried-alive trees” proved fatal to his further progress. With a sudden yell he tottered and fell downwards amongst the grass.

Marygold, who had followed on his heels, was quickly helping Hubert to rise, questioning him anxiously as to the extent of his injuries, when from the depths of a dry ditch, which skirted two sides of the orchard, an odd little figure suddenly appeared and slowly advanced to the scene of Hubert’s disaster.

There was a droll mixture of curiosity and anxiety on Gaston’s small sallow face as he approached this detachment of the dreaded invaders.

Libbie had given him his breakfast in the dairy that morning, when she found that he was too nervous to face the new-comers; and since then Gaston had betaken himself to the shelter of the big ditch in this remote orchard, making sure that there, at any rate, he would be left to his own company and that of the little pigs.

For the latter he entertained quite a warm affection.

But Hubert’s cry of distress had lured him out of his retreat, and having satisfied himself that he was bigger than either Marygold or her cousin, his fears for his own safety abated.

“Ah! where have you harm?” he asked, scanning Hubert carefully, who was still gasping heavily from the shock of his sudden downfall.

“Are you the little French boy?” asked Marygold, by way of answer.

“I am Anatole Jules Gaston Delzant,” was the reply, “And I am more big than you,” he added, as he drew himself up to his full height beside Hubert.

The latter, who was entirely diverted from his injuries by the sight of Gaston, was quite ready to make friends, all the more so when he learned that though the French boy was

nearly two years older than himself, he was not inclined to treat him as a baby.

And so in a wonderfully short time the three children became firm allies, and when the dinner-bell rang and Ruth came in search of her charges, she found them in hot pursuit of the black pigs; Gaston having greatly increased Hubert’s keenness for this sport by his accounts of the boar-hunts in France.

“What a pity that dinner has come so soon,” said the children.

THAT mid-day meal was a very merry one. Everybody had so much to tell, and each had had such delightful experiences in his or her own particular line.

True, Di had not found a pheasant’s nest, but she had practised her climbing to her satisfaction, if not to the benefit of her garments, which showed sundry tattered traces of the results of her morning’s occupation. The boys, according to their own account, had tried their hands at everything in turn—haymaking, boating, fishing; whilst Marygold and Hubert were so voluble and persistent in detailing their marvellous adventures, that even Andrew was forced to allow them a hearing, although he had tried hard to hold forth about some marvels in natural history with which he had meant to impress his companions.

“Shut up about your old crawlers and creepers,” said Phil, “let’s hear what the infants have to say.”

Jack actually dropped his spoon, laden as it was with cherry-tart, to call again for details of the boar-hunt.

“By-the-way, where is that little French beggar?” asked Andrew, with infinite condescension. For Gaston was not at table.

Though encouraged by his playfellows and urged by Ruth, he had come as far as the threshold of the parlour, one peep through the doorway at the big boys waiting to take their places at the table, had put all Gaston’s courage to flight, and with a murmured “Ah! but I cannot, I cannot,” the poor little waif had returned to his shelter in the orchard ditch.

“I expect he’s stopped behind to have some spree with the pigs,” said Phil, turning to begin a whispered conversation with Jack.

Poor Mrs. Busson—to say nothing of poor Mrs. Busson’s black porkers—would have trembled to hear how those two boys were plotting to organize a jolly good boar-hunt all for themselves. As for Gaston, he would certainly have sought a yet deeper ditch and a more remote orchard if he had heard the tone in which Andrew announced after dinner, that he meant to take an early opportunity of “sampling that French frog.”

Happily, however, for all parties, the effects of that singularly hot day, coupled perhaps with the very hearty dinner, made themselves felt even by the adventure-thirsty infants; so that all, from Andrew downwards, readily fell in with Faith’s suggestion that they should adjourn to the shade of the Cuckoo-copse on the other side of the water-meadow.

“Mrs. Busson has had two splendid swings put up there,” she announced, “on two of the biggest oaks, and there’s a lovely stretch of moss and bracken under the trees, where we can all sit and lounge about as we like.”

And so, greatly to Mrs. Busson’s and Ruth’s relief, the whole party, refreshed, but likewise subdued, by their plentiful repast, presently decamped together to the Cuckoo-copse.

Phil and Jack, however, carefully assured Libbie that she might depend on them to drive up the cows from the long meadow in time for milking.

“No need to call Jerry, the cowman, from the hay,” they declared.

“There, I do hope,” cried Libbie, seeing the children troop off, “that they won’t have broken any bones before milking-time comes.”

“Hold your tongue,” said Mrs. Busson, “I’d a deal sooner break all my own. Just you go down in a minute, Ruth, and take a birds’-eye view of the little dears, to make sure they are going on all right.”

Ruth did go, and brought back a very satisfactory report.

“They’ve all settled down as quiet as lambs,” she declared, “Miss Fay’s needle-working, Miss Di seems writing a letter, Miss Phoena’s got a book, and all the young gentlemen look like going to sleep.”

“Bless their dear hearts, they must be just a picture for good behaviour,” said Mrs. Busson fervently; and so they were, at any rate at the moment when Ruth saw them.

“Beware of the bluest sky,” says the old adage, and the picture of good behaviour in the Cuckoo-copse was alas! not painted in durable colours. Di was the first to break the sleepy silence which had reigned at most for ten minutes.

“I say, boys,” she began, “isn’t this just the sort of copse to make exploring expeditions in?” and, heedless of Fay’s imploring look, signifying that she would do well to let “sleeping boys” lie, Diana proceeded to demonstrate how twenty travellers at least might set out in as many different directions, without interfering with each other’s field of enterprise.

“Oh! yes, oh! yes,” cried the younger children, “let’s start exploring.”

“P’raps we’ll find some more buried gardens,” suggested Hubert.

“Or earfmen, little earfmen,” shrieked Marygold.

Even Phoena dropped her book, fired by a sudden desire to hunt an ant’s nest.

“Oh, blow the ants,” said Jack, “I want to find a jolly old fox burrow, and dig out the cubs.”

“Plaguey hot work in this weather,” remarked Phil, with a yawn, “a hornet’s nest, that we could blow up this evening, would be better.”

“Oh! but I’d like to find an earfman,” piped Marygold again, “one that could hide under Fay’s thimble.”

“Shut up that rot,” said Andrew, crossly, “and I say, Di, keep out of that nettle-bed, will you? None of you are to disturb those nettles, do you hear, all of you, I’m the eldest, and I mean what I say.”

“Do you?” retorted Di, “and please, your majesty, why can’t I begin my explorations by jumping into the very middle of that nettle-bed if I see fit as I most probably shall.”

“Because, probably, amongst those nettles there’ll be some Hipparchia.”

“Now, chain up with that jargon,” broke in Jack, “we’re not going to stand a butterfly-butcher bossing it over us.”

“You horrid boy,” cried Faith, “that sounds so ugly.”

“There, Mrs. Faith, you show your ignorance of the best verse of the period,” was the retort, “for I was quoting from a very fine piece of modern poetry, eh, Di?’

“Here’s the original, I declare,” said Phil, stretching out his hand from where he was sprawling on the grass, and snatching up the paper on which Di had been busily scribbling before she had arisen, on exploration bent. “Capital,” went on Phil, glancing at the paper, “you’ve improved on it since the morning. Now, pay attention, Miss Annie, here is something worth listening to.”

“Oh, never mind about reading it now,” said Faith, whose previous acquaintance with Di’s verses was not encouraging as to the results of their declamation, “don’t read them now, Phil.”

Phil turned a deaf ear. Scrambling up the nearest tree, he perched himself astride one of the branches best adapted for his purpose, and then proceeded to declaim:

“And now, gentlemen and ladies, you’ll kindly join in the chorus,” said Phil, “I’ll lead it.”

And the chorus was taken up with such goodwill, and so much noise, that every owl within a radius of at least a mile must have been startled from his afternoon’s nap, whilst old widow Pugsley, who was a proverb for deafness, paused in her hay-tossing to remark that “Mussa Busson had a rare lot of merry youngsters down yonder in the Cuckoo-copse.”

UNFORTUNATELY, they were not all having a song together down in that shady copse.

Faith had, indeed, been coerced into joining the chorus; with Jack shouting it into one ear, and Di shrieking into the other, it would have been vain to resist, but Andrew was as dumb as a fish.

If he had had a grain of sense he would have scored off his tormentors by joining lustily in the song against himself, but instead of that, he swelled with silent rage, whilst he reflected on the best way of avenging this insult.

His first step in that direction was to round on Hubert, and fling him head foremost into a thicket of brambles. Hubert’s hearty “Let him be caught,” etc., turned abruptly into a dolorous howl, which served as the signal for opening hostilities.

Down from his branch clambered Phil, and by the time Faith had rescued battered Hubert from his thorny surroundings, Andrew was struggling in the strong clutches of his cousins.

“Leave Andrew alone, do boys,” besought Fay and Phoena in one breath. By this time, the offender was stretched full length on the ground, but Di, whose sense of justice was always greater than that of mercy, declared that Andrew ought not to be let off.

Even little Marygold, strong in her unfailing loyalty to Hubert, piped out shrilly that “he ought to be made to say that he was dreffully sorry, before he was released.”

“Of course, he must offer a humble apology,” said Phil, digging each of his knees into Andrew’s sides, and shaking his arms violently to and fro above his prostrate head, whilst Jack was adjusting what he called “hobbles” upon his victim’s feet. “It was beastly mean of you,” went on Phil, “to attack one of the infants, and if you won’t apologise as you should, we’ll help you to.”

“Yes,” chimed in Jack, “you can take your choice entirely. You can either stay where you are, and you must be jolly comfortable, I am sure,”—here Jack seated himself on Andrew’s fettered feet,—“till we are all tired of sitting on you, by turns, or you may now and at once accept our terms and regain your liberty. Make your choice.”

“He must have the terms read over to him,” said Di. “Phil, dictate them!”

“Don’t please hurt him really,” put in the forgiving Hubert, “because the scratches have done hurting now.”

“Recommendations to mercy are not in order now,” ruled Jack, with a gesture of command. “Shut up, will you!”—this to Andrew, who was wriggling with all his might beneath the weight of his captors, “Di, come here!”

After exchanging a few whispers with Jack, Di returned to her former position under the oak, and, taking up her pen and paper, proceeded to note the articles of the treaty. They were soon ready.

“These terms,” said Jack, taking the paper from Di, “are far too lenient, but let me state at once, that no interruption on the part of the public will be allowed to interfere with the course of justice.” Then, clearing his throat, he began, “Prisoner on the ground, the chief end and aim in administering justice being the restoration of peace to the public, we do here invite you to return to your former position in our midst, as a free and law-abiding citizen, on the following conditions. That you shall, in the first place, repeat after me, in such words as I shall dictate, a full apology to Hubert, for the dastardly assault upon his person, whereby you sought to do him grievous bodily harm; and, in the second place, that you shall, in a clear voice, and with due emphasis, rehearse after Diana the said Diana’s spirited verses, setting forth your evil deeds, the audience assisting you at the close of each separate verse with a repetition of the chorus. Prisoner on the ground, give tongue, do you accept our terms, yea or nay?”

“Get off, will you,” cried Andrew, who was perilously near tears. “Faith, they’re suffocating me.”

“Oh! Jack,” interposed Faith, “do leave him alone, you will hurt—”

“My dear Faith, his well-being is in no one’s hands but his own,” said Jack, emphasizing this statement with a rapid rise and fall of his person on the unfortunate Andrew’s chest, “what’s simpler? he has only to accept our terms, and then he rises a free man.”

“Fa-a-ith, I’m suf-fo-cating,” gasped the culprit.

“Oh! please, please,” besought Marygold, with clasped hands, and terror in her face, “do let him go now.”

“You say,” began Jack, “that—”

“I’ll say I’m sorry,” gasped Andrew, “on condit—”

“No, no conditions,” broke in Jack, “you must—”

“Look here, boys, it really isn’t fair,” said Faith, “you’re two to one, and you know that Andrew isn’t half as strong as either of you.”

“Yes,” added Phoena, “and if you go on bullying him much more, it’s acting rather as he did to Hubert.”

“Well, there’s something in that,” admitted Jack, “after all, Phil, it’s only poor Annie, and it’s just a girl’s trick to knock over one of the infants to show her strength.”

“Yes, just the sort of thing a little girl would do,” echoed Phil, “here, get up, Miss Annie, we’ll forgive you. Lend me a hand, Jack, we must help a lady to rise properly.”

Therewith Jack seized one luckless arm, whilst Phil held fast the other, so between them the “lady” was certainly assisted to rise, with good will, if not exactly with courtesy!

“And now we’ll conclude this entertainment,” said Jack, “with a new kind of rock-it” and with a significant wink at Phil, they set to work to shake Andrew backwards and forwards between them, till every tooth in his head must have trembled in its socket.

And all the time they sang loudly in his ears, to a tune of their own, the offending chorus of Di’s song.

Though Andrew was a year older, and much taller than Jack, and “twice as fat as both he and Phil put together,” as his cousins always assured him, the treatment received at their hands so far cowed him, that once released, he slunk away without a word.

But, coward as he was, he could not resist the temptation of pinching Marygold’s arm viciously as he passed behind her.

“Oh! oh! he did pinch me hard,” she cried, with a very pink face and quivering lips. She would have spilt her blood to avenge any injury inflicted upon Hubert, but she struck no blow to avenge her own. “You are a werry mean boy,” she said, “but p’raps you can’t help it, for I heard Ruth say that you seemed a poor house-lamb sort of young gentleman.”

Possibly this withering remark hit Andrew harder than her small fists could have done.

Phil and Jack greeted this statement with a roar of approving laughter, which Andrew, happily, did not see fit to resent.

Clearly his recent chastisement had made him, temporarily, a wiser, as well as a sadder boy.

FOR the next quarter of an hour, perhaps, certainly no longer, comparative calm reigned amongst the little party.

But the spirit of discord having once broken bounds in their midst, the happy peace of that glorious summer afternoon, which might have worn away so merrily, was gone, and sad to say, wrangling soon began again. First of all, Di, bent on being idle herself, took to teasing Phoena. The latter was trying to read, but Di confiscated her book. Then she ridiculed Fay, who was making a knock-about frock for Marygold’s big doll to wear in the hayfields. Meanwhile Phil and Jack decided to give Hubert a lesson in tree-climbing, and though they began their instructions with the best intentions, they soon started teazing him when he showed himself somewhat unamenable to their orders.

“Look here,” said Phil, indicating a very inaccessible limb of a birch tree, “you’re a regular little molly, but you’ll have to climb up to that branch and ride-a-cock-horse on it before we’ve done with you.”

“But I’ll tumble down, I know I will,” said Hubert, with an amount of caution which his six years made very excusable.

“Well, and if you do tumble down, and if you do break your precious little neck—”

“But I’ll be deaded then,” shrieked Hubert.

“Well, and what are the odds?” asked Jack, with a coolness that curdled Marygold’s blood, “much better that you should die like a man—”

“But I ain’t a man yet and I don’t want to die like one,” yelled Hubert, who was being prodded up the tree now by both his brothers.

“You’re wicked, bad boys,” cried Marygold, “I’ll deliver you, Hubert, I will deliver you.”

Therewith she flew upon Phil and hanging all her weight upon his arm, strove to disable him from tormenting Hubert any further.

“I do wish a big ogre would come now and gobble you up,” she gasped.

Then as the boys still persisted that Hubert must reach the perilous point first indicated, Marygold grew quite desperate.

“Please, please don’t break his pore little neck,” she pleaded. There was such real horror in her voice, she looked so pitiful with her brilliant blue eyes brimming over with tears, that the sight of her face helped Hubert quite as effectually as any ogre might have done. For it did gain Hubert’s welcome “deliverance.”

And Marygold gained something further still. For when she suggested that as it had got cooler now, they might all have a really nice game before tea time, Jack and Phil actually consented to “give the infants a turn,” and graciously permitted them to choose the game they would play.

“Oh! ogres, ogres!” they cried, “for this wood will be just beautiful.”

“There’ll be such heaps of room, you know,” added Marygold, “for the little innocents to play at gaffering strawberries and picking up sticks.”

“And such splendid bushes,” went on Hubert, “for the wicked ogre and his blood-thirsty wife to hide in.”

“Come on,” shouted Phil, “you must all come and play.”

“ ‘I’ll be the ogre’s wife,” volunteered Di, “and Andrew always likes to be the ogre because he’s only got to sit still and receive the live prey as it’s brought in.”

“All right,” said Phil, the master of the ceremonies, “Fay’ll be the infants’ mother, Phoena must be the ogre’s cook, and Jack his caterer, and I’ll be the old man of the wood who’ll side with the infants.”

“At that rate,” objected Jack, “there’ll only be the two kids to bag; there ought to be a better show of game than that.”

“Where’s that French froggy?” asked Andrew, suddenly, “we may as well make him come and play.”

“Yes,” assented Jack, “infants, where’s his Froggy-ship to be found?”

“I think he’s in the orchard,” said Hubert, whilst Marygold added, “But you won’t call him froggy, will you? for he’s a good little boy and very frightened.”

“Oh! is he?” cried Andrew, “then we’ll have some fun with him.”

“Oh! Fay, you won’t let them tease him,” pleaded Marygold, who felt in honour bound, if she betrayed Gaston’s whereabouts, to provide for his safety, “you promise me you won’t.”

“No, no, we won’t bully him,” cried several voices.

Comforted by these assurances, the infants set off to fetch Gaston. They found him sitting disconsolately amongst the long grass. Tired of boar-hunting all by himself, he was playing with an ugly, unsavoury looking toad.

So the children’s invitation to join their game in the wood was acceptable, though his face betrayed some alarm when Gaston understood that he was to play with all the big boys and girls too.

“But we’re all going to be ever, ever so kind to you,” said Hubert.

Thus re-assured, he consented to come. Indeed the prospect of a real good romp soon raised his spirits and voice too, to such a pitch of volubility, that Phil declared that he could hear Monsieur Frog chattering “like a vanful of monkeys” before either he or the infants came in sight.

“Here he is, here’s Gaston,” announced the latter, with a note of pride in their voice, bred of a certain sense of proprietorship in the small foreigner.

“Bonjour, Monsieur Grenouille,” began Andrew.

But Gaston did not heed him. His good manners might have put his new acquaintance to shame.

Pulling off his cap, he fan straight to Faith, attracted by her gentle face, and standing bare-headed before her, executed the most perfect bow.

(“With his feet in the first position,” Di sneered, “and his hands hanging straight at his sides.”)

“Good day, Mees,” Gaston stammered.

But when Faith threw her arms round him and kissed his small pale face, he swiftly abandoned all formality and nestled up to her side, as if he had found a long-lost and sorely-missed shelter.

“I told you he was a good little boy,” said Marygold.

“A precious Molly, though,” remarked Andrew.

“Molly yourself,” retorted Jack, “come on now and let’s begin sport.”

“And you,” said Phil, turning to Marygold, “tell Gaston the rules of the game.”

These were of a delightfully simple nature.

“Fay’s our mother,” began Marygold, “and Hubert and you and I are her little children and we pretend that we’ve come into the wood to gaffer strawberries and pick up sticks. And we pretend that we don’t know there’s a wicked ogre’s den behind the bushes. He’s always wanting children to eat you know, so he sends out a bad man, that’s Jack—to catch us. When we see him coming, Phil, (that’s the old man of the wood who tries to protect us) comes to fight him off and we have to run away as fast as ever we can.”

“And we yell as loud as we can,” added Hubert, shrieking this item of information at the tip of his voice.

“There, now do you see, the wicked ogre has gone away to hide,” said Marygold, “with his wife, that’s Di, and his cook, that’s Phoena. So we’d better go to Fay. She’s dreadfully sorry when we get caught, but very often she gets caught herself.”

Then from the leafy depths of an old oak, Phil gave the signal for the game to begin.

“My little dears,” he cried, “come out to play.”

“That means, come out to be eaten,” said Hubert.

Therewith Gaston, who by this time was not so sure that this new form of amusement was likely to prove so very charming, was dragged off to play his part in the ogre game.

“It really is quite strordinary fun,” Hubert assured him.

CERTAINLY if ear-piercing shrieks constituted “strordinary fun” Hubert’s statement was fully justified.

From the very onset the game was wildly exciting, even to the bigger boys. Even Phil, as he jeered the ogre from the tall oak, forgot to call it a baby game, and as Jack executed his “flying squirrel trick,” which meant taking flying leaps from branch to branch, in order to view the land, he began to think that, after all, this sport with the infants was rather fine.

Faith, meanwhile, played her part as an anxious parent perfectly. Hither and thither she fluttered between the different points of danger, with out-stretched arms and skirts, like a good old hen protecting her precious bantlings.

In and out of the hazel bushes and the briar tangles—ay, even into nettle-beds—the infants dashed, caring nothing for pricks and stings and scratches, so long as they could evade the long arm of Jack, the ogre’s caterer, and escape the fierce eyes of the ogre and his wife. These latter would now and again show themselves, glaring ferociously through the bushes, and clamouring loudly for fresh food to be brought to their larder.

After a time, Faith allowed herself to be taken prisoner, and for a moment quite a solemn awe fell upon her companions whilst they watched the proceeding which followed in the ogre’s camp.

First, the captive was securely bound to the slim stem of a birch, then the ogre called on his wife and cook to come and judge if she were fit for immediate dressing.

With rounded eyes and parted lips the three little ones waited almost breathlessly, whilst Di, supported by Phoena,

who carried a long iris leaf to represent a knife, advanced to make the inspection.

Di thrust her fingers into Faith’s cheeks, examined her tongue to see if it would “pay for salting,” pinched her arms, and finally agreed with the cook that she must be cooped up and fattened.

“She shall be fed up on snail soup and luscious slimy slugs,” said the ogre—Andrew was always good at acting,—whilst Di added:

“Tadpole tea is even more nourishing than Bovril, and I’ve seen many skeletons grow stout on caterpillars in oil.”

“See that she has them then,” said the ogre, in a voice that sounded like thunder, “but for our immediate food, my dear wife, we must catch some smaller fry.”

“Yes,” replied the ‘dear wife,’ “one of those little dears yonder, if nicely stuffed and roasted, would make a tasty morsel for supper. Suppose we order that little girl with the cloud of golden hair, which, by the way, would make quite a pretty table garnish.”

Diana’s tone was so business-like that Marygold almost shook in her shoes.

“Or that tender youth crouching beside that ash,” said the ogre, pointing to Gaston, “he’d make a toothsome savoury. Ah!” catching sight of Hubert, who peeped out from the edge of a nettle-bed, “there’s a pair of those small boys, I see. Jack, my caterer, catch them at once, and have them served for supper as grilled green goslings.”

“Certainly, sir,” said Jack, “they’ll make delicious mouthfuls for your greedy-ship and lady. Now, if you will withdraw, and pretend to sleep, I will proceed to secure these desirable young dishfuls.”

Thus pressed, the ogre household retired into semi-privacy, and immediately afterwards the air was rent with the sound of loud snoring.

“They’re only pretending to sleep,” Marygold explained to Gaston, dragging him behind some hazel bushes, whence he could see the sham sleepers. “They think that we haven’t heard them making their wicked plans, you know. But, oh! look at Phil.”

Armed with a long thistle, Phil was advancing stealthily upon the ogre, who was leaning against the trunk of a tree, snoring lustily, with fast-closed eyes. In another minute Phil would have tickled the ogre’s nose with the spikey weapon he carried.

But Gaston, untrained in the tactics of ogre warfare, instead of observing the breathless silence maintained by the others, gave vent to a loud giggle. This instantly roused the ogre to a knowledge of his danger, and caused Phil to be ignominiously routed.

In the general confusion which ensued Marygold was captured and bound to a tree, with the delightful prospect of being turned into a white soup before sunset.

“You little duffer,” cried Phil, savagely, turning upon the trembling Gaston, “you spoilt all the sport with that idiotic giggle of yours. Now you shall be punished for that by being delivered up to the ogre in exchange for Faith.”

“Yes, master Froggy,” put in Jack, seeing that Gaston really looked alarmed, “you’ll have to pay for that giggle with your blood, so come on.”

Planting his heels firmly together, Gaston resisted resolutely.

It might be all play, still, the big English boy’s voice sounded very angry, and his face looked very fierce.

“Come on,” said Phil, giving Gaston a desperate tug.

“Oh! but, but, I pray you, have pity,” began the boy.

But his entreaty for pity came too late. Negotiations with the ogre, initiated by Jack, were already begun.

And now Phil was addressing the ogre himself.

“Look here, you old wretch,” he was saying, “respect our flag of truce,”—here he waved his handkerchief—“and we’ll parley with you.” And as the ogre graciously signified his consent, Phil went on:

“Here’s a handsome offer, a jolly little roasting pig, a real Paris nouverty, all ready for dressing, which we’ll give in exchange for the victim that you caught first.”

“And if you don’t say ‘Yes,’ ” put in Hubert, who was well versed in the customs of the game, “we’ll sell him cheap at the nearest cannibal market, so you’d better make up your mind quick.”

Very pompously the ogre advanced.

“Let the article for exchange be exposed,” he said, “and on the faith of an ogre no unfair advantage shall be taken.”

By this time poor Gaston was on the brink of tears. The sudden change in the complexion of affairs from all the previous screaming, shouting, and running, to the dignified air of solemnity which now invested the proceedings, filled him with alarm. Consequently, when, at a sign from Phil, Hubert advanced, and, seizing Gaston by one arm, helped to drag “the article” forward for closer inspection, all notion of it being only a game disappeared from Gaston’s mind, and he really thought that he was facing certain death.

He was rather a baby for his age, but then he had never had elder brothers, and this was his first experience of big English boys and of ogres.

“He—he won’t really eat me,” he faltered.

“Eat you! of course he will. Skin, bones, and grizzle,” said Phil, thoroughly enjoying Gaston’s dismay; “someone always has to be eaten up at the end of the game to make it real.”

“But—but the last time that you did play, who was eated up then?” enquired Gaston, with not unnatural curiosity still holding back.

“Oh, an awfully jolly little chap,” said Phil, cheerfully, “very like you. I don’t think he would have minded it much if they hadn’t eaten so much mustard with him.”

“They won’t have of mustard to eat with me,” cried Gaston, “for Mrs. Busson was this morning not able to find any.”

“Pepper’ll do as well, or better,” said Phil, coolly, “hurry up, we’re not going to wait any longer. Don’t you hear the ogre sharpening his front teeth on the backbone of the giant that he ate for breakfast this morning? Come on, I say.”

“But no, no, I won’t come, I won’t,” yelled Gaston, trying to throw himself on the ground. “I won’t be eated, I won’t be eated!”

Vainly he looked round for succour. His last friend, Marygold, was herself a captive, and of course, Jack, the caterer, was not on his side.

“Be good enough to come on, gentlemen,” said the ogre, “having begun proceedings, you’re bound to go on with them. Shall my official, Jack, come to your assistance?”

Thereupon Jack came forward, and now, to his exceeding terror, Gaston found himself lifted bodily between the two bigger boys and carried forcibly into the clutches of the ogre.

The latter began to examine him at once. By this time, Gaston was a quaking jelly.

“Hm,” pronounced the ogre, “he’ll do fairly well, provided he’s eaten at once. Cook, come here and take my orders.”

Then, as Gaston fought and struggled with all his might, the ogre remarked, “Now, no struggling, if you please. Don’t you know that over-exertion on your part will spoil your flavour, and make you horribly tough? Jack, my caterer, I fear we shall have to chastise this small object before cooking him, as an example to others, you know.”

“Yes, indeed,” said Jack, “a nice chance of dinner we should have, if all the legs of mutton took to kicking us, and all the calves’ heads began to butt at us.”

“Well, make up your mind, Mr. Ogre,” said Phil, “are you prepared to take over this little porker, or not?”

“I am,” was the reply, “and as he persists in showing fight, we’ll see what a little beating will do for him. It answers admirably in the case of beefsteaks, you know. Take charge of him, Jack.”

“All right,” said that official; then, with a wink at Phil, “just hold him down a minute, while I tie his pettitoes together. Mr. Ogre, kindly assist us.”

“Don’t be afraid,” whispered Hubert in Gaston’s ear, as he lay on the ground, “they won’t really hurt you, Phil won’t let them.”

But playing at bullying is a dangerous game with the best intentioned of schoolboys, and Andrew was the prince of bullies when he was secure from any risk to his own precious person. With such a tiny victim as poor Gaston, he felt perfectly safe. But he had reckoned without his host, or at any rate, without his host’s teeth.

For as soon as he came within biting range of Gaston, the latter, who, as we said, had long ago forgotten that he was supposed to be playing, caught Andrew’s hand between his teeth, and hung on to his fingers for dear life.

Andrew danced and yelled with pain.

“You nasty, abominable little wretch,” he shrieked, “won’t I pay you out for this.”

“What are you about, boys?” cried Faith, who, tied up with her back to this exciting scene, was terrified at these alarming sounds. “Di, do go and see what they are doing.”

But Di was busy now giving chase to Hubert, whom she had been stealthily trying to capture, so she had no ears for Fay.

As to Phoena, no one heeded her gentle remonstrances.

“It’s only fun, Gaston,” she assured him.

“Of course it is, we’re only rotting you,” said Phil.

“Oh, are we,” cried Andrew, savagely, breaking off a stout hazel switch as he spoke, “we’ll see about that; ogre or no ogre, I’ll teach him to bite me again. Hold him down, Jack, and I’ll give him the jolliest licking he’s ever yet had.”

And before anyone could stop him, Andrew had delivered a cruel cut on Gaston’s small prostrate person.

A piercing yell from the victim rang and echoed again through the wood.

“You shall have plenty more,” said Andrew, lifting the switch to strike afresh, but the elder boys fell upon him.

“Shut up, will you,” they cried, “it’s beastly mean to hit such a little chap. Trying to kick him now, are you? You’d better.” And without more ado the cousins, aided by Hubert, who had returned, panting, but free, brought Andrew to the ground for the second time that afternoon.

“Now we’ll see if a little beating won’t make him tender,” said Jack, wrenching the stick from Andrew.

So it fell out that the rod which he had prepared for another’s back, fell upon Andrew’s own in no very gentle strokes.

“There, I’ll be bound that’s the best licking you’ve ever had in your life,” cried Jack, with genuine satisfaction. “Shouldn’t be surprised if it made a man of you, old chap,” he added, breaking the stick in two pieces and flinging the fragments high up into a tree.

Too mortified to howl, and too cowardly to retaliate, Andrew skulked off in sullen silence.

Gaston was nowhere to be seen. Once freed from his tormentors’ clutches he had flown out of sight and sound of the copse.

“He went so fast, I believe he flew,” said Hubert, who, if the truth must be told, had been so absorbed in watching Andrew’s chastisement, that he had had no attention to spare for anything else.

“DEAR, dear Miss Faith, whatever has been happening?” enquired Ruth, anxiously. She had come to meet the little party as they returned in answer to the tea-bell’s summons.

Once within sight of shelter, Gaston had lifted up his voice in piteous weeping. Shaking and sobbing, he displayed the marks of ill-treatment that he had received at the hands of his so-called play-fellows that afternoon.

The sight of Andrew’s swollen nose and bleeding fingers, and the disturbed air pervading the whole company put the finishing stroke to Ruth’s alarm.

“You’ve never been quarrelling, I do hope,” she added, as fervently as if the bare possibility were not to be contemplated for a single instant by any sane person.

“Oh! haven’t we!” responded Jack, cheerfully; “and it’s done us all a jolly lot of good.”

“And made us awfully hungry,” added Phil.

And, to judge from the promptness with which they fell upon the good things provided for them, that afternoon’s misdoings had certainly not blunted the mis-doers’ appetites.

The girls, however, did not follow suit. Marygold was tired, and really very sad for Gaston, who was nowhere to be seen. Even Di was unusually subdued, whilst Fay and Phoena were thoroughly ashamed of the results of the first afternoon of taking care of themselves. Indeed, the latter’s sorrowful face, and yet more, her untasted tea, attracted Phil’s attention from his own plate.

“Hullo, Phoena,” he laughed, “whose funeral are you arranging for now? Why, your face is as long as all King Cole’s fiddlers put together.”

Phoena started. She had been very far away in thought-land just then.

“I was thinking,” she began.

“A good thing then,” said Di, “that you didn’t upset your tea this time.”

But Phoena went on: “I was thinking what a pity it seems that this time yesterday we all had such a lot of good intentions, and this afternoon we all managed to forget them so quickly.”

“Yes, indeed,” said Faith, with a sigh.

“A pity we couldn’t bottle them,” said Di, flippantly, “and label them to be used when wanted.”

“Or pickle them,” sneered Andrew.

“No, but do listen,” besought Phoena. Somehow when her eager face was all aglow with enthusiasm and her large eyes shining like lamps no one could resist listening to Phoena. “I’ve been thinking how in the old days, when they must have been just as fond of fighting as you boys are now, they had a very good plan for helping people not to forget their good intentions.”

“Really,” jeered Andrew, “pray how did they manage that, Mrs. Solomon?”

“Did they advertise them like Sunlight Soap?” broke in Di.

“Well, yes; they did something like that,” said Phoena; “that is, they made their good intentions so public that for very shame sake they had to fulfil them.”

“Oh! now I see what you mean,” said Di, who had plenty of wits when she chose to use them; “you’re thinking of those old creatures who were called—oh! what was their name? Cru—cru—something?”

“Cruets!” yelled Hubert, whose last spelling lesson had ended with that word.

“Crusaders, you little donkey,” said Andrew, with withering scorn.

“Yes,” said Phoena; “of course the Crusaders were amongst the people I meant, for you see when they once decided to deliver the Holy City, they did wear a red cross on their arm as an outward badge of their intentions; but I wasn’t thinking of them so much as of Arthur’s knights of the Round Table; that glorious company, you know, the flower of men.”

“I see,” said Di; “of course, by accepting knighthood they did advertise their good intentions.”

“Yes, but before they could be knights they had to bind themselves by vows to keep those good intentions,” said Phoena; “and those vows bound them fast like chains, from which they never could be set free without shame and dishonour until they had fulfilled them.”

“Then pray are we all to wear chains?” enquired Andrew.

“Chain up yourself,” said Phil, “and let Phoena speak, will you? Go on, Phoena.”

“Well, if you don’t mind listening,” she continued, “this is what I thought. Though we haven’t got a King Arthur, and——”

“But we’ve got Mrs. Busson’s round table in the window,” put in the irrepressible Di.

“And though we can’t get the Archbishop of Canterbury to come and bless our sieges—yes, don’t laugh, that is the proper name for our seats—and though we can’t have our names put in letters of gold over each of our places, yet I don’t see why we shouldn’t have a sort of Round Table here, and agree to promise to do as far as we can all that Arthur made his knights promise to do.”

“But where are the heathen to come from whom we ought to smash up?” asked Phil.

“I expect we might find something like them still,” remarked Fay.

“You see this is what my book says,” said Phoena, producing a volume from under the table, where she had evidently been studying it out of sight on her knees: “ ‘The knight was to take an oath to fulfil the duties of his profession, namely: to speak the truth, to maintain the right, to protect women, the poor and the distressed, to practise chivalry, to pursue infidels, to despise all temptations to ease and gluttony, and to uphold their honour in every perilous adventure.’ ”

“H’m!” remarked Jack, “rather a large order, but as Andrew always likes to be cock-of-the-walk let’s make him the first knight, and see how he manages to keep his vows.”

“I’ve no objection to being the Grand Master of the Order,” said Andrew, who was secretly rather pleased at being noticed again after his recent disgrace, “but before taking vows and that sort of thing there is a deal to be considered. In the first place,” he continued, in the tone of superiority that he loved to assume, “what kind of armour, I wonder, would be suitable.”

“Oh! the right kind for you would be plate armour,” said Di, quickly, glancing at the amount of jam and cream with which Andrew had heaped his plate, “nothing else would suit you.”

“Happy hit, Di,” laughed Phil. “If you go on at this rate, Miss Annie, we shall have to label you the ‘hold-all’ when we take our luggage home again.”

“You dare!” began Andrew; but happily Ruth, who was perhaps doing duty as constable in plain clothes this evening, happened to appear at that moment to enquire if she could clear the table—all the others had finished their tea—whereupon Andrew, being far more anxious to clear his plate than his character, devoted all his attention to the former pursuit.

And so, when Mrs. Busson and Ruth finished dismantling the table, they were able to record with fervent thankfulness that at any rate the tea had been partaken of in peace and quietness.

IT was rather wonderful how eagerly all the children took to Phoena’s idea of founding a Knighthood of the Order of Good Intentions.

The fact was that in one form or another it possessed distinct attractions for each member of that rather mixed company.

Notably to the schoolboys, to whom the prospect of being bound by a vow to pitch into all evil-doers was highly acceptable.

“Those young beggars who are always riling the farmer by making short cuts across his meadows will come under that head,” said Phil, “we’ll teach them the way they should go and no mistake.”

“That we will,” echoed Jack.

“Yes, but remember that you ought to meet your foes in fair fight,” remarked Faith. “Knights weren’t supposed to bully, you know.”

They were all indoors now, for the sultry heat of that oppressive summer day had ended in a tremendous thunder-storm, which had driven everyone, even the most ardent haymaker, under shelter. True, Phil and Jack were disappointed of their row on the river, and so was Andrew of his expedition into the lanes, where he had intended to besmear the tree trunks with the beer and treacle mixture he had been preparing, nevertheless all the boys resigned themselves very happily to their enforced imprisonment, so keen were they on discussing the details of Phoena’s scheme.

“Of course,” said Andrew, “as I’ve consented to be your Head it will be for me to draw up the laws by which our Order is to be governed.”

There was instantly a roar of dissentient voices, above which Phoena at length made herself heard.

“Perhaps if your name were Arthur instead of Andrew,” she said slowly, “it might seem a pity not to make you the King, but as it is, wouldn’t it be better for us all to agree that our King is absent—”

“Fighting the Paynims,” broke in Di.

“Exactly,” said Phoena, “and we should all be left on oath to defend the honour of the Round Table.”

“Yes, and couldn’t we make it this way?” suggested Fay; “that the King was to bestow golden spurs on the knight who could show the noblest record on his return?”