BULLETIN NO. 216

Federal Security Agency U.S. OFFICE OF EDUCATION

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

| Vocational Division | Business Education |

|---|---|

| Bulletin No. 216 | Series No. 14 |

Prepared by

ROSCOE R. RAU, Executive Vice President and Secretary

National Retail Furniture Association

and

WALTER F. SHAW, Regional Agent, Business Education Service

U. S. Office of Education

| FEDERAL SECURITY AGENCY | Paul V. McNutt, Administrator |

|---|---|

| U. S. OFFICE OF EDUCATION | John W. Studebaker, Commissioner |

| UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE | WASHINGTON: 1941 |

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C.

Price 75 cents

| Page | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| FOREWORD | v | ||

| Unit | I. | THE SALESMAN AS A BUSINESS BUILDER | |

| Specialized selling of home furnishings as a career | 3 | ||

| Increasing sales and earnings | 5 | ||

| Fundamentals for good selling | 8 | ||

| The daily check-up—A perpetual inventory | 10 | ||

| Unit | II. | TECHNIQUE OF SALESMANSHIP | |

| Sale objectives | 17 | ||

| Starting the simple sale | 17 | ||

| The all-important interview | 20 | ||

| Three general considerations for closing sales | 23 | ||

| Meeting the customer | 24 | ||

| Unit | III. | SALESMANSHIP APPLIED | |

| How to demonstrate values | 29 | ||

| Contrast in buying methods of women and men | 35 | ||

| Enriching your vocabulary | 40 | ||

| Hidden factors that increase sales | 42 | ||

| Unit | IV. | STYLE AS A SELLING FACTOR | |

| Significance of style | 49 | ||

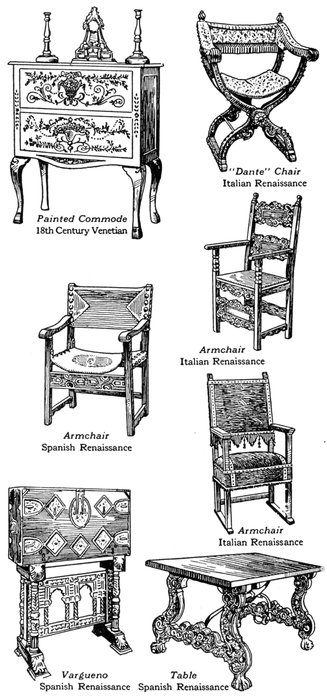

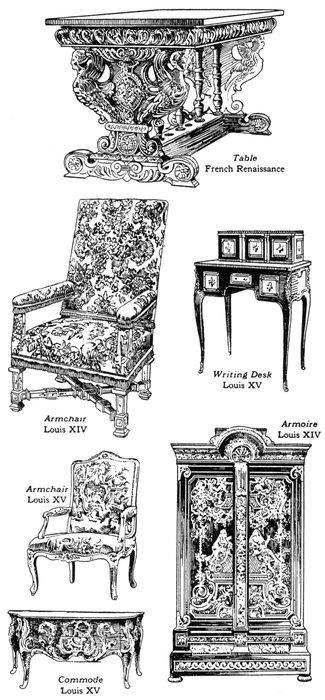

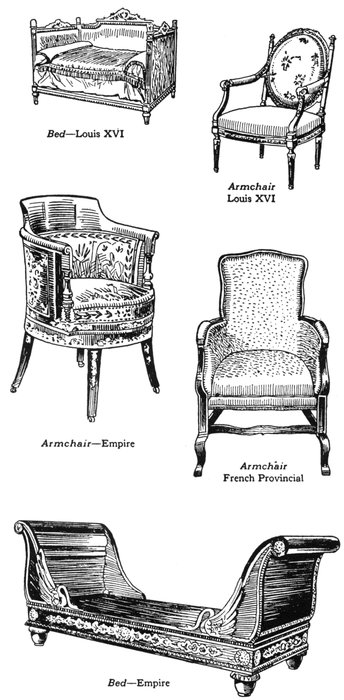

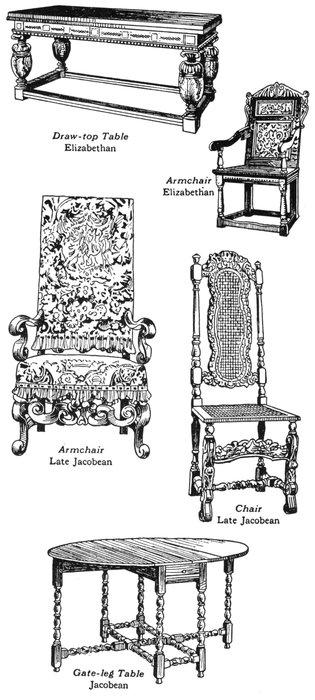

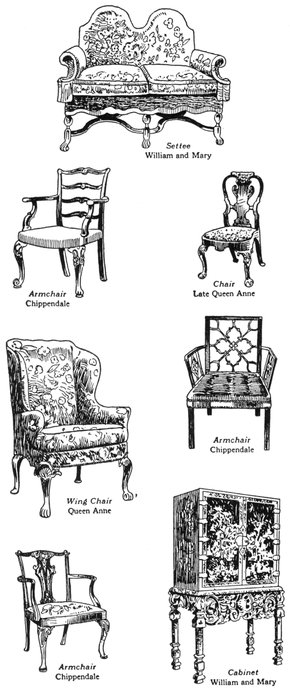

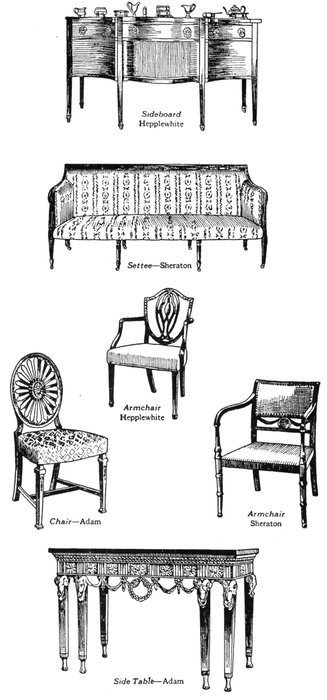

| Period styles from Renaissance to Early Colonial | 50 | ||

| American styles | 70 | ||

| Using style appeal in selling | 74 | ||

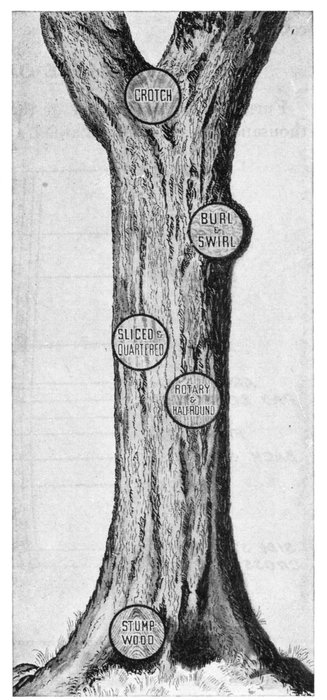

| Unit | V. | FURNITURE WOODS—THEIR ORIGIN AND USE | |

| Value and price in relation to home furnishings | 83 | ||

| Principal furniture woods | 85 | ||

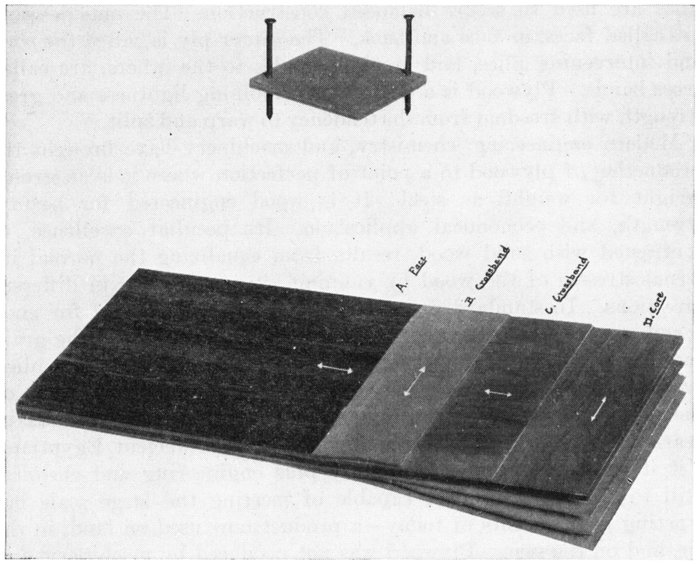

| Making the most of wood structure and its appeal to the eye | 86 | ||

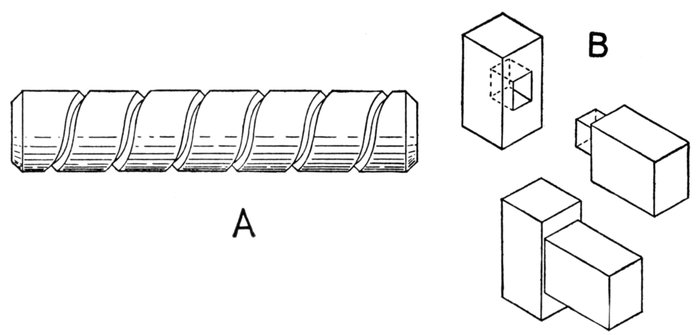

| Importance of craftsmanship | 92 | ||

| Unit | VI. | SELLING SLEEP EQUIPMENT | |

| Selling equipment to meet customer's needs | 107 | ||

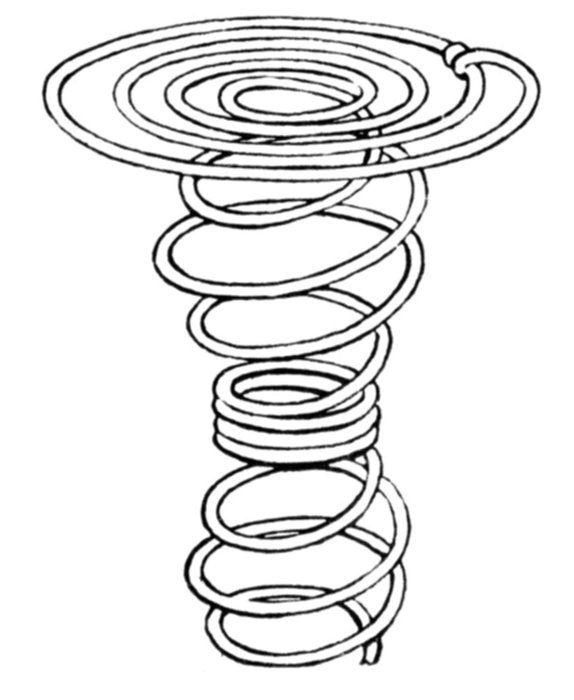

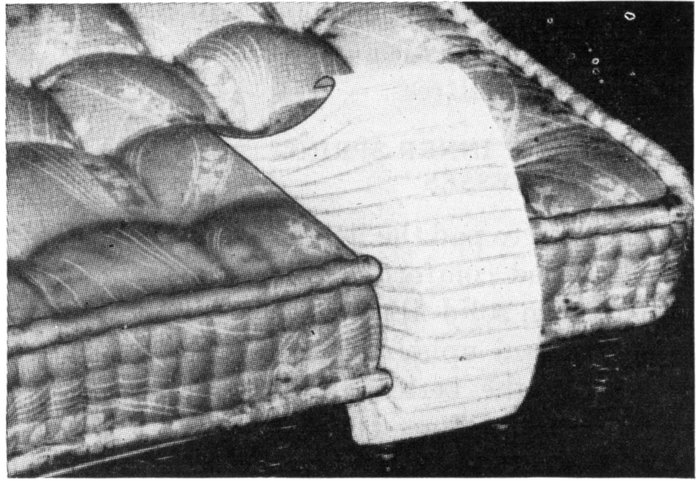

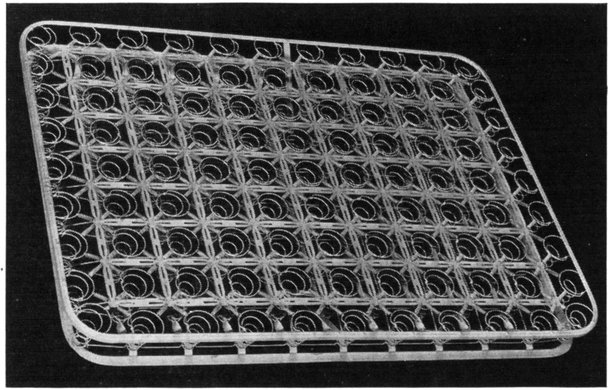

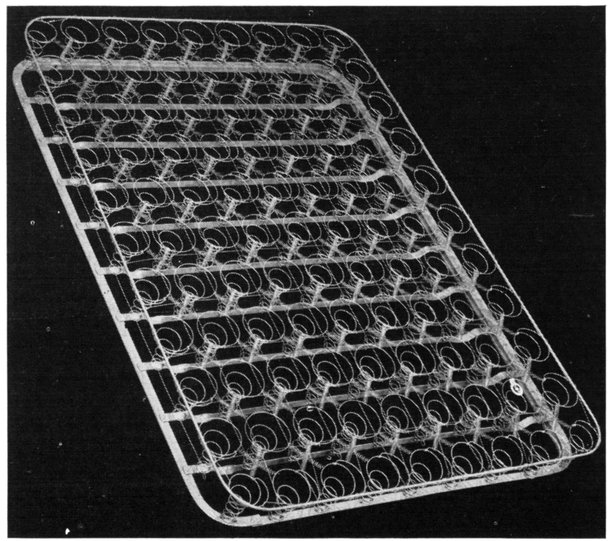

| Mattresses and springs | 112 | ||

| Pillows | 123 | ||

| Studio couches and sofa beds | 126 | ||

| Unit | VII. | AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ART OF INTERIOR DECORATION | |

| Interior decoration as a selling method | 131 | ||

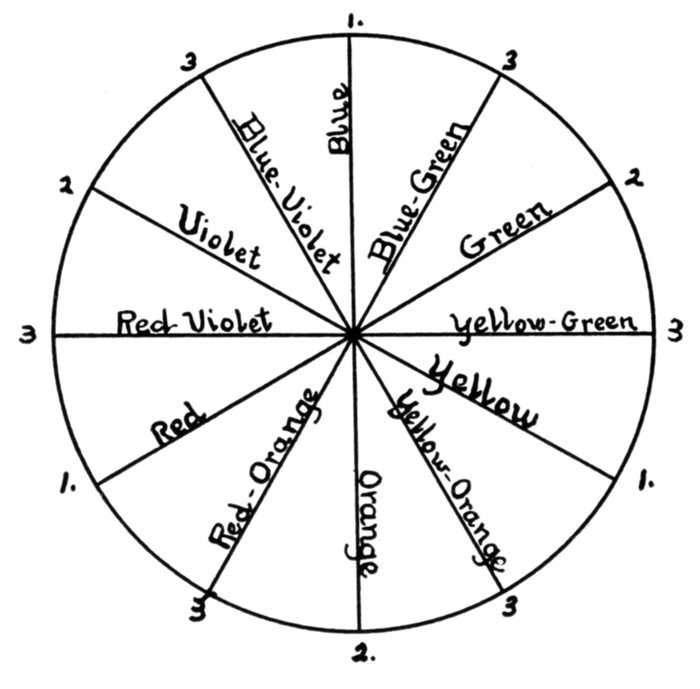

| Emotional values of light, color, line, and proportion | 133 | ||

| Color management in decoration | 139 | ||

| Principles of furniture arrangement | 141[Pg iv] | ||

| Unit | VIII. | FLOOR COVERINGS AND FABRICS | |

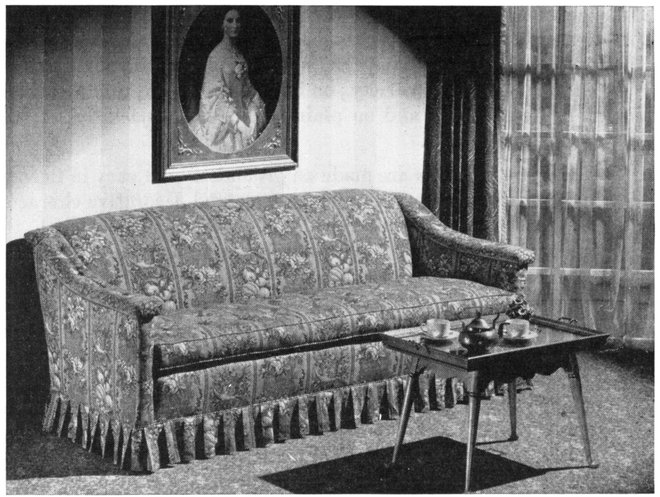

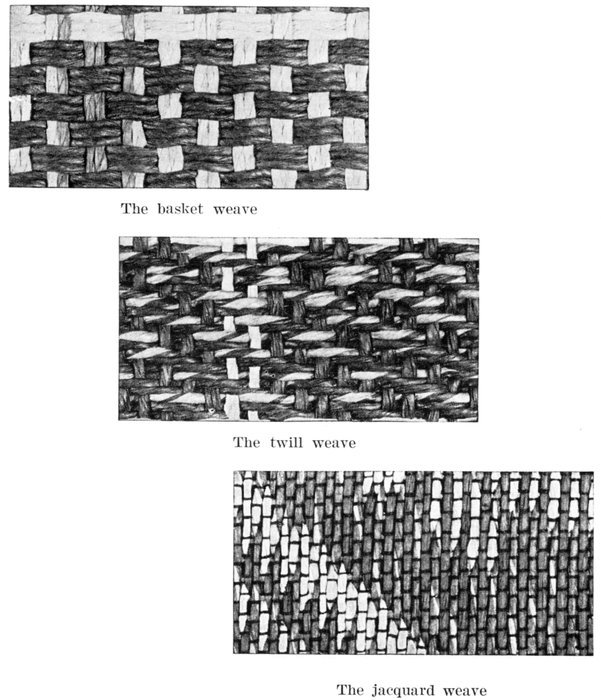

| Drapery and upholstery fibers and fabrics | 153 | ||

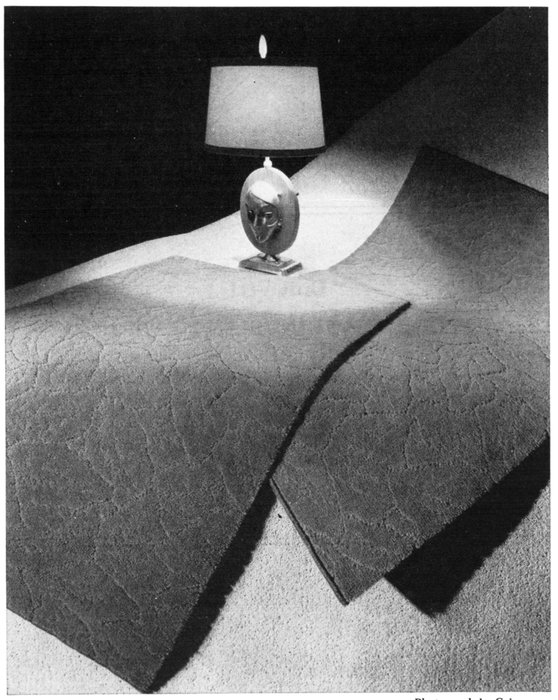

| Floor coverings | 159 | ||

| Selling coverings for other floors | 171 | ||

| Use of ensembles in selling | 172 | ||

| Unit | IX. | FURNISHING THE LIVING ROOM, HALL, AND DINING ROOM | |

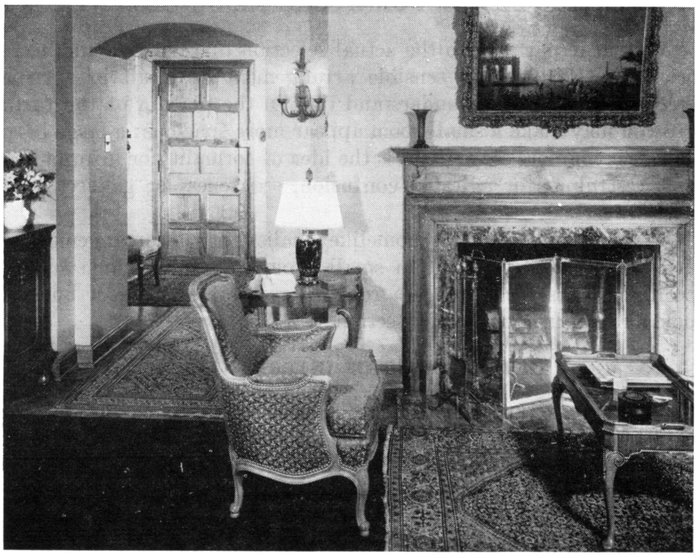

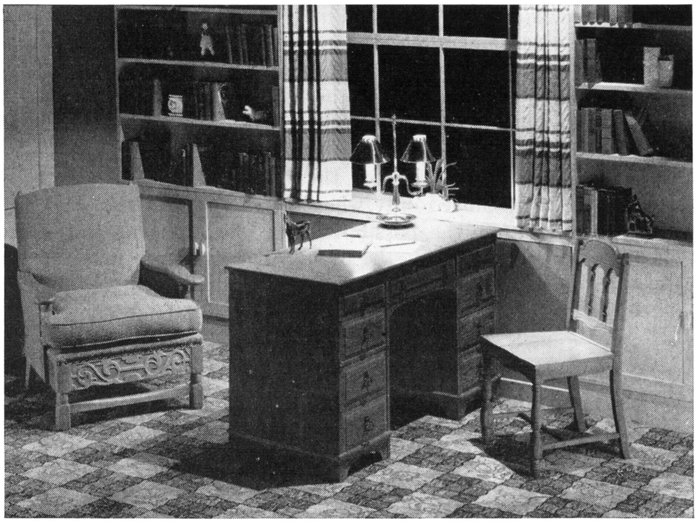

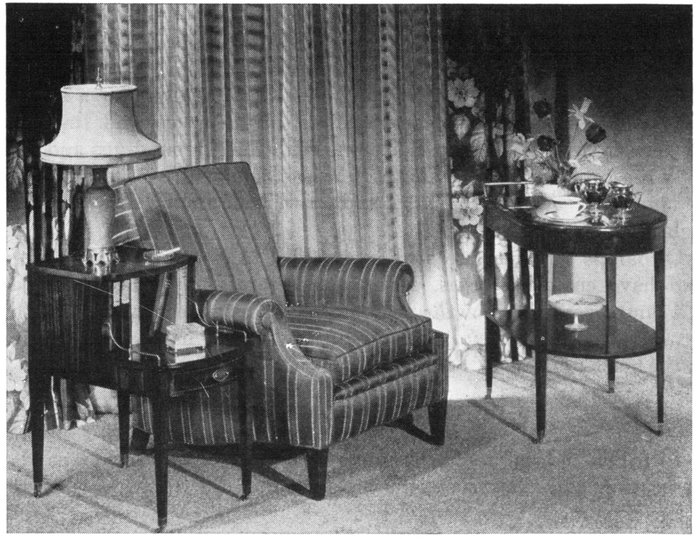

| Furnishing the living room | 179 | ||

| Distinctive hall furniture | 186 | ||

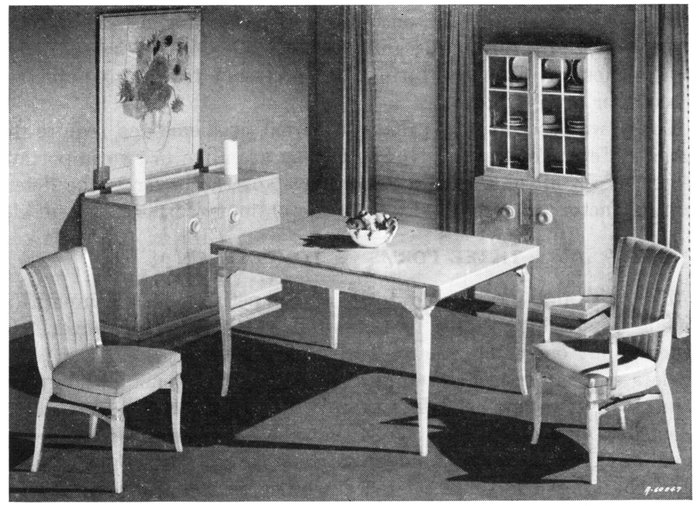

| Securing hospitable dining room atmosphere | 190 | ||

| Ensemble selling | 196 | ||

| Unit | X. | FURNISHING THE BEDROOM, SUNROOM, KITCHEN, AND BREAKFAST ROOM | |

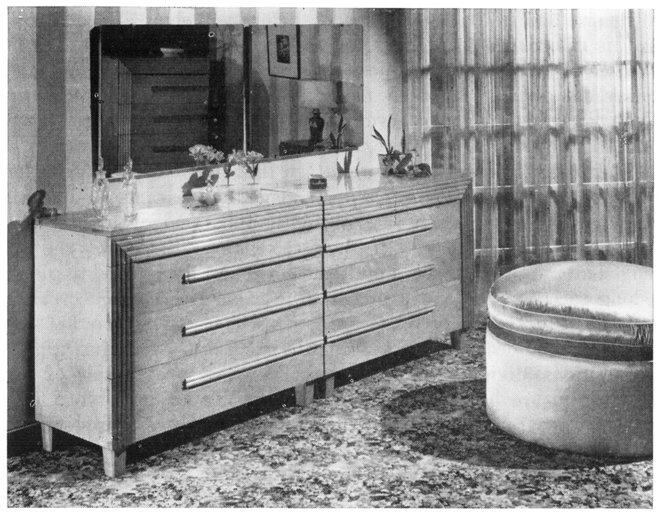

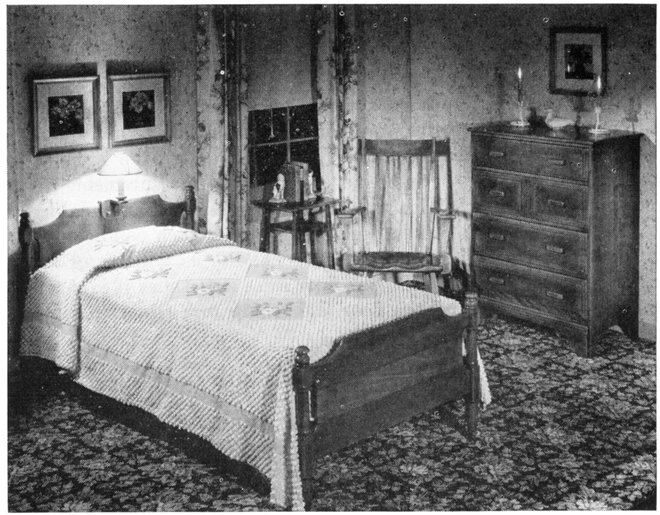

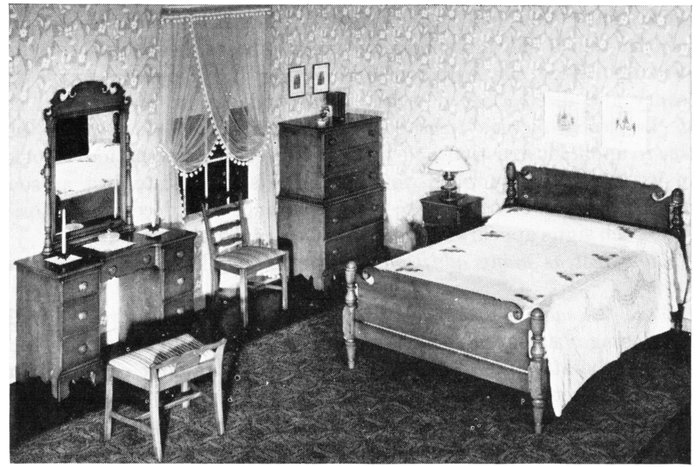

| Furnishing the bedroom | 205 | ||

| Furnishing the sunroom | 214 | ||

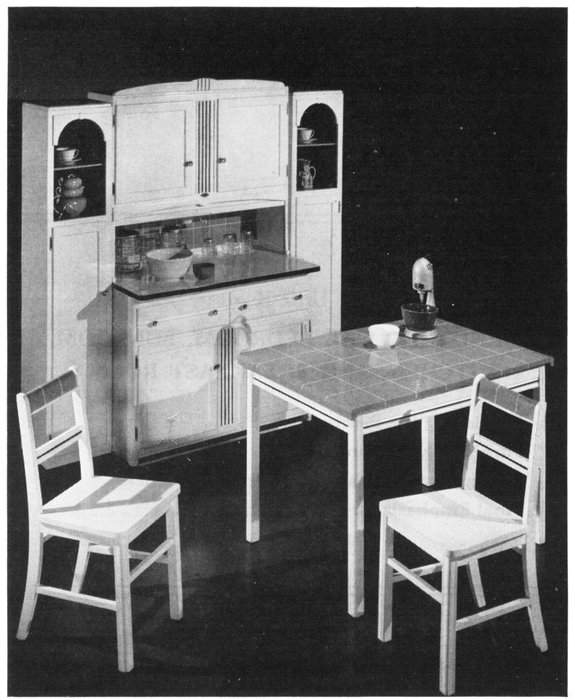

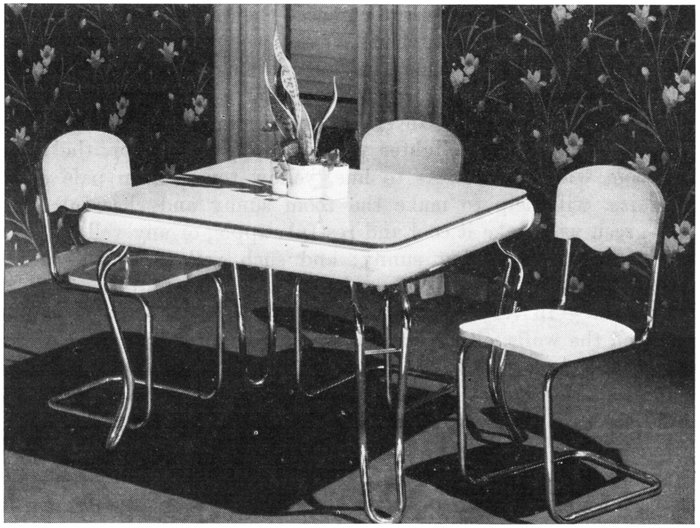

| Equipping the breakfast room and kitchen | 217 | ||

| Final emphasis for alert salespersons | 221 | ||

| Unit | XI. | ACCESSORIES THAT MEAN "PLUS" SALES | |

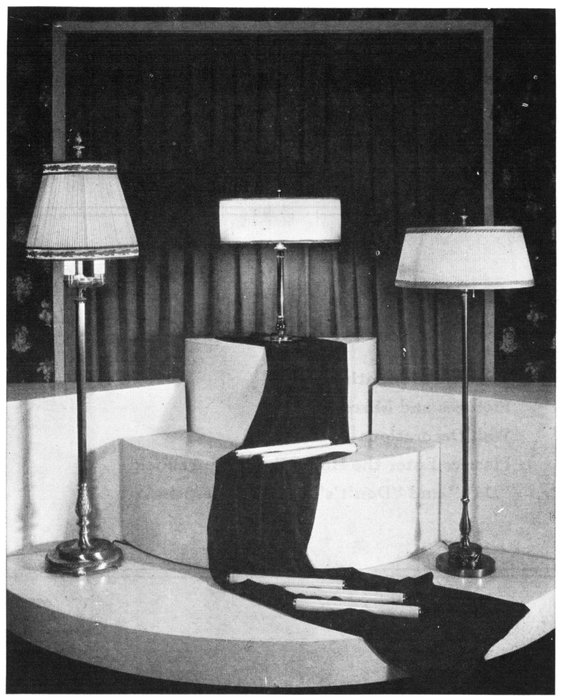

| Lamps and lighting | 227 | ||

| Pictures and mirrors | 232 | ||

| Wall decorations | 235 | ||

| Plastics enter the home furnishings field | 237 | ||

| "Do's" and "Don't's" for the salesperson | 241 | ||

| APPENDIXES | |||

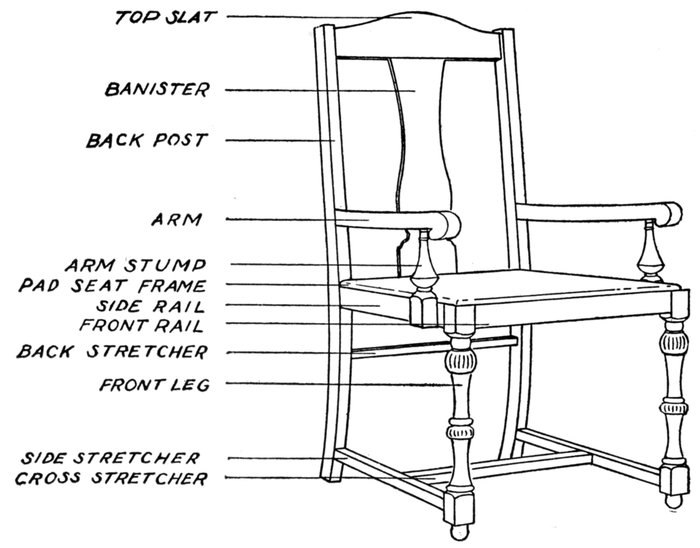

| A. | Glossary of terms | 247 | |

| B. | General reading list | 250 | |

| C. | A suggested teaching outline for a group leader | 252 | |

| D. | The leading furniture woods | 255 | |

| E. | Common rug terms | 263 | |

| F. | An advertising check list | 265 | |

| G. | Fivefold selling plan for floor coverings | 266 | |

| H. | Color and style in modern advertising copy | 267 | |

| I. | Check list for planning a store-wide promotion | 269 | |

| J. | Ready reference index | 271 | |

This bulletin has been prepared for use by those who seek self-improvement as members of a group engaged in the study of home furnishings and how to sell them agreeably, intelligently, and competitively.

More than $2,500,000,000 is expended annually in this country for home furnishings. Under present conditions the layman cannot become an expert on the multitude of things he has to buy, and he must purchase many articles more or less blindly. Since much structural detail is hidden from view, the integrity of the dealer is more than merely an advantage—it is a necessity. There are hundreds of interesting and vital facts concerning home furnishings which consumers may learn from retail dealers and members of their sales organizations and which, if they become generally known, will result in greater discrimination and economy in buying and will be reflected in more charming, suitable, and comfortable furnishings in the home.

This bulletin presents at once opportunity and challenge to those who sell home furnishings:

Opportunity to those who see furniture as a symbol of achievement and distinction. These hear the call to bring beauty out of drab surroundings, and to shape the visible garments of life, and even life itself, making it finer, richer, and a thing of greater worth.

Challenge to those who in selling home furnishings must be conscious of the wide extension of education in the home furnishing art, the rapid improvement in the general taste and specific knowledge of the customer, the tendency to shop in the large centers, the increasing number of small decorators, and the trend to furnished rooms and apartments.

For the convenience of users of this bulletin, the subject matter has been arranged in the form of units, each of which is intended to be made the basis for a minimum of 2 hours discussion and study. With each unit is a set of stimulating questions and a brief reading list. A more detailed reading list will be found in the appendix. This bulletin, hence, may serve as a short unit course for those who can spare time for no more than 8 or 10 group meetings. Certain groups may prefer not to follow the units in the order suggested and to concentrate for a longer time on such important topics as period furniture, interior decoration, the furniture woods, or various room arrangements. For these, selected material may be used for[Pg vi] short unit courses in specialized fields. For instance, the last five units, taken together, may serve many salesmen of home furnishings as a basic course in the art of interior decoration.

Attention also is called to the grouping of subject matter to accommodate those who may wish to use this bulletin for reference purposes and in sales meetings called by the management. The individual salesman who uses this material in such a manner will be aided in building up a body of related and organized knowledge which may have application any day in his work with his customers.

At times the text makes generous use of the personal pronoun. This has been done deliberately with the thought that there should be present in every meeting of a group a feeling of comradeship and personal loyalty to a common cause. Hence, at times the text employs the pronouns "we," "our," "you," and "yours," to replace the more formal terms, "the salesperson," the "retailer," or "the representative of the store."

Especial acknowledgment is due Rosalie Flank, style authority and a former director of advertising and public relations for the American Furniture Mart, for many contributions to, and much valuable criticism of, the last five units, which deal with problems of interior decoration. Most of unit XI, which discusses "Accessories and Facts That Mean 'Plus' Sales," and section D of unit III, "Hidden Factors That Increase Sales," were prepared by her. To Frier McCollister, representing the National Association of Bedding Manufacturers, credit is due for much of the material in unit VI, "Selling Sleep Equipment." The authors also have consulted freely Clark B. Kelsey's "Furniture—Its Selection and Use," National Committee on Wood Utilization, United States Department of Commerce, and "The Road to Higher Earnings" issued by the National Retail Furniture Association.

The authors gratefully acknowledge contributions and assistance in editorial reading and criticism from Marie White, agent, Home Economics Education, U. S. Office of Education, Washington, and William J. Cheyney, vice president, National Retail Furniture Association, eastern office, New York, N. Y. Others who assisted in the preparation of special material for this training program are:

Helen Arms, stylist, John M. Smyth Furniture Co., Chicago, Ill.

Smith Cady, director, Home Furnishings Industry Committee, Chicago, Ill.

Charles E. Close, secretary, The Veneer Association, Chicago, Ill.[Pg vii]

Burdett Green, secretary, American Walnut Manufacturers Association, Chicago, Ill.

Chester K. Hayes, executive director, Household Science Institute, Chicago, Ill.

Phillips A. Hayward, Chief, Forest Products Division, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, Washington, D. C.

Leo J. Heer, managing editor, National Furniture Review, Chicago, Ill.

J. P. Kramer, advertising department, Bigelow-Sanford Carpet Co., New York, N. Y.

George N. Lamb, secretary, Mahogany Association, Inc., Chicago, Ill.

Kenneth Lawyer, State supervisor for distributive education, Springfield, Ill.

Robert B. Palmer, advertising manager, Duff & Repp, Kansas City, Mo.

A. M. Sullivan, director for vocational education, Board of Education, Chicago, Ill.

Jay Van Den Berg, Van Den Berg Bros., Grand Rapids, Mich.

Illustrations, charts, and tabulations have been reproduced with permission of the American Furniture Mart; The Merchandise Mart; American Walnut Manufacturers Association, Chicago, Ill.; The Floor Covering Advertising Club, New York, N. Y.; Grignon, furniture photographer for the American Furniture Mart; Henri, Hurst, & McDonald, Inc., advertising, Chicago, Ill.; Home Furnishings News Bureau, Chicago, Ill.; Institute of Carpet Manufacturers of America, New York, N. Y.; Delmar Kroehler, president, Kroehler Manufacturing Co., Naperville, Ill.; Mahogany Association, Inc., Chicago, Ill.; National Association of Bedding Manufacturers, Chicago, Ill.; National Committee on Wood Utilization, U. S. Department of Commerce, Washington; National Furniture Review, Chicago, Ill.; National Retail Furniture Association, Chicago, Ill.; The Seng Co., Chicago, Ill.; U. S. Department of Commerce, Forest Products Division, Washington, D. C.; and The Veneer Association, Chicago, Ill.

Special acknowledgment is made to the following publishers for permission to quote from one or more of their publications:

The American Home, editorial department, New York, N. Y.

Dodd, Mead & Co., Inc., New York, N. Y.

Frederick J. Drake & Co., Inc., Chicago, Ill.

House Beautiful, New York, N. Y.

J. B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

The New York School of Interior Decoration, New York, N. Y.

The Seng Co., Chicago, Ill.

This Bulletin has been prepared at the direction, and under the supervision of B. Frank Kyker, Chief of the Business Education Service, U. S. Office of Education, Federal Security Agency.

J. C. Wright,

Assistant U. S. Commissioner for Vocational Education.

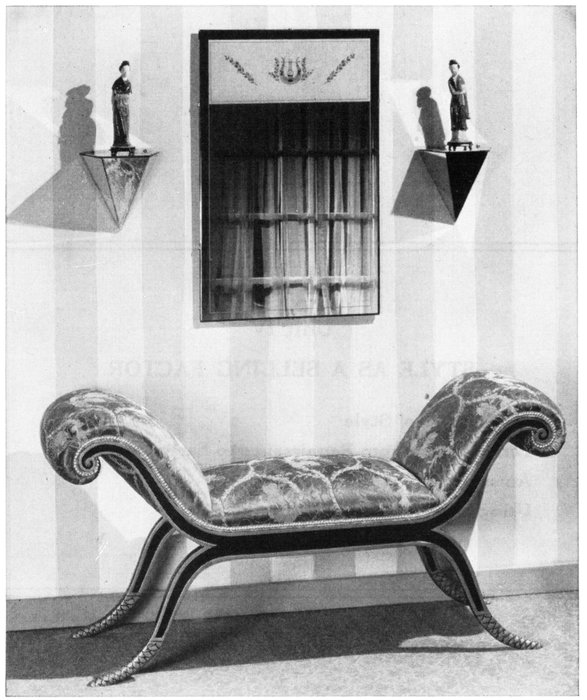

Figure 1.—Contemporary French grouping is expressed in this attractive chair with natural finished wood frame, tufted back, and rust figured beige damask upholstery. The combined lamp stand and plant table is a modern favorite.

SELLING HOME FURNISHINGS

Unit I.—THE SALESMAN AS A BUSINESS BUILDER

Selling home furnishings at retail is one of the most pleasant and fascinating of occupations. It is clean work, physically agreeable, mentally stimulating, and free from deadening routine. Moreover, it is a growing field with limitless possibilities. True, there always will be malcontents who proclaim that the people of America are losing interest in their homes, that restless excitement is their god. Facts indicate, however, that our people are turning their thoughts and aspirations, in increasing measure, to the enduring satisfactions of the home.

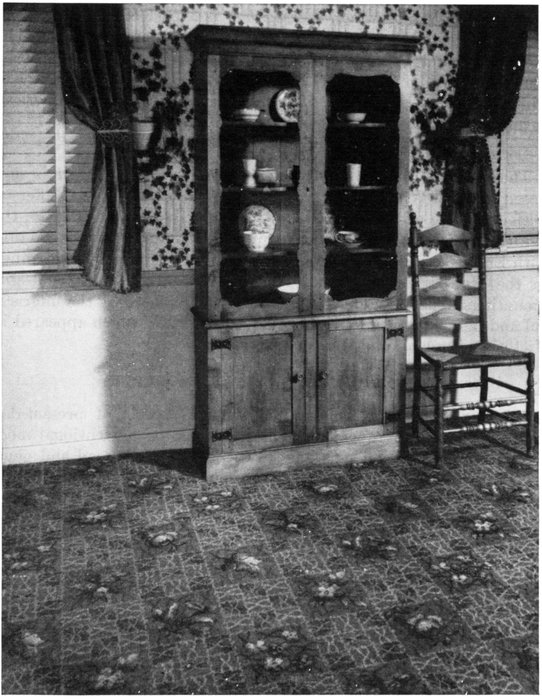

All available data on buying habits indicate that selling methods should be revised to meet the buyer's interest as it shifts from what furniture is to what furniture will do. This is a logical development. For many years American women have been influenced by the cleverest advertising in the world to desire and to buy finished products on the basis of performance and with little or no concern as to how they are made. To these women, rugs, chairs, tables, and lamps are parts whose interest depends chiefly on how they are combined with other parts to form harmonious wholes. According to a number of comprehensive surveys, three out of every five women who are interested in furniture are concerned chiefly with its effect in making their homes more attractive. If this is true, those who sell home furnishings must have a sound knowledge not only of their merchandise but also of the art of arranging and combining that merchandise to insure comfort and beauty in completely furnished rooms.

This specialized selling of home furnishings as a career, therefore, means mastery of the art of interior decoration. If interior decoration be defined as the sum of the processes by which a home is made beautiful to look at and comfortable to live in, then all who sell home furnishings must understand style, design, materials, and construction. Every furniture salesman who consistently maintains a[Pg 4] high sales volume as a result of his own skill will be found to employ the methods of the interior decorator whether he adopts the professional title or not.

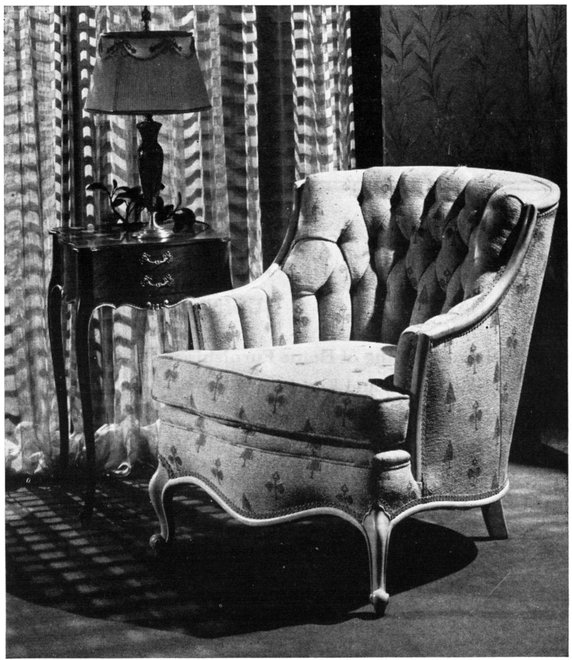

Figure 2.—A suggestive progress-program for those who sell home furnishings which may be modified in terms of situations. Promotion steps are shown on five training levels of increasing difficulty and responsibility.

The fighter who carries a punch in one hand only will lose a good many bouts. The carpenter uses a ripsaw for one operation and a crosscut for another. The salesman is in precisely the same situation. He always can make some sales merely by showing furniture and quoting prices. He always can make more sales by a skillful presentation[Pg 5] of style, design, materials, and construction. But in order to build a personal following and to sell to the highest possible percentage of his customers the largest possible amount of merchandise, he must become a competent adviser in the creative processes of home furnishings.

Figure 2 is a diagram of an educational program which, starting with preparatory training in the early years of the secondary school, continues through a period of cooperative part-time training which combines education in the school and on the job, until full-time employment assures continued opportunity to study progressively on three training levels of increasing difficulty and responsibility. Mastery in ability to sell home furnishings implies adequate understanding of materials and selling techniques acquired at each of these training levels.

There are three ways by which one can increase his sales and earnings:

1. Increase the daily average number of customers waited on.

2. Increase the average percentage of customers sold.

3. Increase the average volume of each sale.

In order to increase your daily average of people waited on, you must (a) arrange to secure customers for the otherwise idle hours of the day; and (b) develop the ability to speed up the selling process, which will enable you to sell to more people during the active hours.

(a) To secure customers for the otherwise idle hours of the day, begin with the "lookers" and your "call trade." The woman who has been planning what is to her an important purchase frequently will want to consult her husband or a friend in whose judgment she has confidence. If you have been successful in creating real interest in your merchandise, it will not be difficult to make an evening appointment, obviously as a means of saving the time of the husband or the friend.

When you suggest an early or late appointment you may readily promise exceptional service. You will be assured of the individual attention of your group under conditions removed from the confusion of regular store traffic. If the appointment is during the early morning hours or during evening hours, it will be easy to group the pieces as they are to be used and thus show them as they might actually look in the home.

Then, too, you always will have some sales under way or coming up with old customers, and in many cases you can, by acting in advance, arrange appointments which will occupy otherwise empty time, thus leaving the more active periods of the business day open for routine selling. Time which cannot be spent with customers should be devoted to developmental work.

(b) Among many ways to speed up the selling process are the following:

1. Get down to business, and stay there. Much time is wasted both before the sale is made and afterward in purely extraneous talk, not calculated in any way to advance the sale or build confidence. Within the limits imposed by courtesy, confine the conversation to the business in hand. And don't yield to the easy temptation to talk about yourself.

2. So far as is possible, eliminate the element of guesswork in showing merchandise. Find out enough about your customer's room and what is in it, and about her tastes and plans, to enable you to avoid confusion and resistance, and to cut down the amount of time spent in showing goods there is no chance to sell.

3. Be sure that your appearance, manner, and language are such as to inspire quick confidence. This will make it unnecessary to spend too much time in demonstrating the fitness and value of your merchandise. Alertness, faultless courtesy, and unfeigned interest in the customer's comfort and convenience are vital.

4. Know your stock, including the small occasional pieces whose location is often shifted, so thoroughly that you can go directly to any piece you want to show. In a sale involving several articles, particularly if they must be shown on different floors, plan and route the selling process to eliminate unnecessary movement, and if the display is made during regular store hours, try to close the sale somewhere above the first floor, with its noise, confusion, and beckoning suggestion of the open door.

Much of our study will be directed toward discussing methods for increasing the percentage of sales made to customers waited on. Everything is important, and every improvement in equipment will help. Doubtless what is most needed is more knowledge, which we can acquire; more patience, which we can force ourselves by a sheer[Pg 7] effort of the will to summon and employ; and more energy, which we can and will develop in the degree that we recognize and desire its rewards.

The first requirement of one who would increase the size of individual sales is that he shall trade up consistently. Obviously, this does not mean that the salesmen should disregard prudence and common sense and try to sell a $100 article to the buyer who can afford to spend only $50 or $75, nor does it mean use of high-pressure selling methods. It does mean that he should develop the ability to estimate the buyer's tastes, means, and real needs, and to present elements of value in his merchandise other than price.

Ten years ago a woman who made a shopping tour through 12 department and furniture stores reported that 8 out of 10 salesmen quoted the price of every article immediately, with strong emphasis upon its low price. A number of salesmen mentioned the wood and finish of the article, quoted the price with the usual comments, and stopped—their entire stock of ideas apparently exhausted by this effort. This same kind of selling is still too prevalent. Today's emphasis upon service for specific needs rather than upon low price to build sales volume has given us an ever-increasing number of salespersons who understand that it is foolish to start a sale from the bottom, foolish to assume that no one desires or can afford to buy good things, and not only foolish but dishonest to discuss furniture of poor quality and low price in terms which fairly could be applied only to better quality and higher price.

A second and extremely important way to increase the size of your average sale is by the skillful suggestion of related merchandise.

A great many persons buy home furnishings only when they need them as a physical utility. Quite naturally, they get along with the minimum number of pieces and buy for the lowest prices consistent with their ideas of desirable quality.

To be prepared for this type of emergency or "suggestion selling" each salesman should work out for himself, with the help of other salesmen, and by wide reading of trade journals, magazines, newspaper articles, and books in his field, a list of articles in the home-furnishings field which naturally belong together. These lists of "naturals" should be memorized for ready recall at any moment.

"Specials," modern accessories, new designs in small occasional pieces, when advertised to the public, lend themselves to a [Pg 8]suggestion-selling program used in connection with a carefully selected call list. In suggestion selling, emphasis should be upon the quality of charm or fitness to be added to a particular room, with the furnishings of which the salesman already is familiar.

Those who buy furniture for satisfactions other than utility naturally buy—insofar as their means will permit—whatever pieces they believe to be necessary in order to insure those satisfactions. It is clear that salesmen in order to sell to this type of customer must be able to arouse the interest of these utility and price buyers in other satisfactions.

To do this, they must be able to sell something more than furniture. They must sell on the basis of the enticement of comfort and cushioned ease, the lure of beauty, the appeal of smartness and style. They must sell distinction, the acclaim of friends and guests, the pride and pleasure of the children, and the joy of living in an attractive home.

Does this tend to provoke a skeptical smile from those who have been selling furniture for years? Well, let those smile whose earnings have been wholly satisfactory. As for the others, let them remember that in diminished volume is told the story of those who consistently have attempted to sell furniture as nothing more than furniture and who have stolidly ignored the power of imagination and sentiment in quickening interest and deepening desire.

Sales experts are agreed that it is impossible to formulate a selling plan that will apply to all salespersons. There are no magic words to be spoken in the presence of potential buyers that will cause them to call loudly for an order blank and reach for a fountain pen. There are certain fundamentals which will help a man to become a better salesman.

Webster defines tact as "a nice discernment of delicate skill in saying and doing what is expedient or suitable in given circumstances." Tact is one of the most valuable assets in salesmanship and must be exercised at all times. Many sales of home furnishings have been lost in discussions with a prospect who was inclined to be belligerent. Under no circumstances enter into an argument. You have heard the well-known axiom, "Win an argument and lose a sale." The fact that you have sound sales arguments to use in presenting your sales story does not mean that you must argue[Pg 9] with the prospect to prove your point. Explain tactfully your side of the story and, if your statement is questioned, try to prove it. But rather than enter into an argument about it, pass on to another point, and, if necessary, refer later to the point in question from a different angle.

Some salesmen are so anxious to tell all they know about their product that unquestionably they develop a habit of interrupting a prospect every time he speaks. This reflects adversely on the salesman; often it prevents the prospect from telling of the features particularly liked or the real objection to the proposition. When your prospective customer starts to speak, listen, and above all, when answering a question, don't exaggerate. Many a sad failure in selling has resulted from an exaggeration of facts to the point where the prospect will not believe anything the salesman has said.

Sincerity breeds conviction and if you are convinced of the statement you make, your attitude will go a long way in making your prospective customer believe your story. Know your product and its advantages; be sincere and enthusiastic when you are presenting them. Be natural. It will pay.

All have known salesmen who have talked themselves out of sales. This is a fault common to many. Some types evidently believe that if they talk fast enough, do not permit the prospect to bring up objections or say anything, and put the pen in the prospect's fingers and get him to sign on the dotted line, a good sale has been made. The day for this kind of selling is gone. Today's buyer wants information and she wants a chance to think about that information after she gets it. Make your statement about your product and let your customer think about it. Be careful not to bury one important sales feature by showering several more on top of it before the customer has had time to decide on the merits of the first. Give your customer an opportunity to ask questions and express her opinion. Often, if allowed to talk, the prospect will sell herself.

An objection or reason for not buying may be real or it may be merely an excuse. In any event, the salesman must be able to answer it effectively in order to close the sale. If the customer[Pg 10] raises an objection, be sure you understand it. Don't jump at conclusions as to what the objection is going to be. After you understand it clearly, repeat it. Sometimes when an objection is repeated the customer immediately can see for herself that it is not a valid objection.

Salesmen interested in fundamentals will do well to remember four points of value in selling:

1. Talk to your customer as though she knows about the product but explain everything as though she knew nothing about it.

2. Treat your customer with unfailing courtesy.

3. Assume that she is able financially to buy anything on the floor even if her general appearance leaves room for some doubt. When basic facts are established, suggest justifiable time-payment plans as an arrangement she might prefer—but do this tactfully since many women are sensitive about money and credit ratings.

4. Make your sales story complete. Tell it simply, directly, earnestly, and honestly.

Elementary fundamentals should be brought up time and again. You may know you are beyond the stage where you need to be told to keep the ears clean, the hair combed, the shoes polished, and suits pressed, but there are some angles on this matter of keeping a perpetual personal inventory which may be reviewed profitably many times. Consider the advantages of a daily check-up.

Some women are inclined to trust to first impressions of appearance and manner. A salesman may find it difficult and sometimes impossible to win their confidence if there is anything in his appearance, manner, language, or actions to detract attention or arouse prejudice. If these important personal matters are neglected, it means reduced income through the loss of some sales and an unnecessary loss of time in many others.

One of the best ways to guard against these losses is to work out a sort of perpetual inventory of your own good and bad points, and to keep this inventory up to date, making a systematic check-up.

Certain principles as to proper dress for men in home-furnishing stores of dignity have been established. One metropolitan store insists that salesmen wear dark suits; black shoes always; white collars either attached or detached, not necessarily starched; neckties, dark preferably, and in harmony with the suit. This store never permits[Pg 11] removal of coat or vest even in summer. Many stores, however, permit vests off in summer and supply uniform coats to all salesmen—dark palm beach or similar material. Arbitrary rules without reason are worse than none. The store mentioned above feels that the factors listed as important simply conform to the laws of good taste in reflecting the store to its clientele. No store can afford to tolerate slovenly attire, shoddy language, or indifferent effort.

If, in good faith, interested salesmen will run through the following list of questions before they go to work each morning for 2 or 3 months, they will find the results in increased sales unexpectedly profitable.

Have I had the food, sleep, and exercise necessary to enable me to meet all customers, even on the longest and busiest day, with energy and enthusiasm?

Do I feel and look fit, alert, competent, and prosperous?

Is there anything to attract unpleasant attention to my hair, fingernails, teeth, tie, or shoes?

Do I meet all customers without reference to age, sex, or dress, as if I were genuinely glad to see them and sincerely interested in serving them intelligently and well?

Am I businesslike without being brusque? dignified without being stiff? unvaryingly polite but never oily or servile?

Do I treat all customers with real courtesy, and none with cheap or offensive familiarity?

Do I ever permit myself to look or act bored, tired, indifferent, or sullen?

Is my voice pleasant?

Do I talk enough, or too much?

Do I talk carefully and well, without grammatical blunders or slang, and with an adequate command of words, or do I stumble, use poorly chosen words, and repeat myself until my customers are bored or repelled?

Do I slouch, or get into awkward and ungraceful postures, or sit on the arms of chairs or sofas?

Do I play with a pencil, watch chain, or sales book, or jingle keys or money in my pocket?

Do I ever show merchandise carelessly, as if it were of no value or importance?

Do I ever get into an argument with a customer when there is the slightest possibility of giving offense?

Whatever your present earning power may be, wide experience warrants the belief that you can raise it appreciably by improving your present rating in these factors which together give outward expression to your personality as your customers see it.

1. Do you think a salesman can be sincere and use "high pressure" methods at the same time?

2. Do you feel you are doing a customer a favor or imposing on her in urging her to come to a decision, particularly when grading-up?

3. A customer says: "I like this suite, but the price is a little more then I'd counted on paying." What is the best way of handling this customer to close a sale?

4. A customer says: "I've just about decided on this one, but I'd like my husband to see it." What is the right way to handle this situation? Should an attempt be made to close the sale then and there? What has been your experience?

5. A customer is sold on a modern suite, and has her mother with her. Her mother is not sold on modern furniture. How would you handle this situation?

6. A customer wants an Early American bedroom, is apparently satisfied with the suite, which happens to be birch, and asks: "Is it solid maple?" How do you answer?

7. If the president of the First National Bank and his wife came in at 5:30 to look at a dining-room suite, how would you handle the first 5 minutes of the conversation?

8. Select a bedroom suite from the floor selling for $99 and one selling at $179, and demonstrate the points of superiority in the more costly set?

Bolling, Cunliffe L. Retail Salesmanship. Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd., London, 1930.

Kenagy, H. G. and Yoakum, C. S. The Selection and Training of Salesmen. McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York, N. Y. 1925.

Kelsey, Clark. Furniture: Its Selection and Use. National Committee on Wood Utilization, United States Department of Commerce. Superintendent of Documents, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C.

National Retail Dry Goods Association, 101 West Thirty-first Street, New York, N. Y. 1935. Furniture Sales Manual.

Pelz, V. H. Selling At Retail. McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York, N. Y. 1926.

Reyburn, Samuel W. Selling Home Furnishings Successfully. Prentice-Hall, Inc., New York, N. Y.

Simmons, Harry. How To Get The Order. Harper & Bros., New York, N. Y. 1937.

Stewart, Ross and Gerald, John. Home Decoration. Garden City Publishing Co., Inc., Garden City, N. Y. 1938.

Whitehead, Harold. How To Run a Store. The Thomas Y. Crowell Co., New York, N. Y. 1921.

----. The Business of Selling. American Book Co., New York, N. Y. 1923.

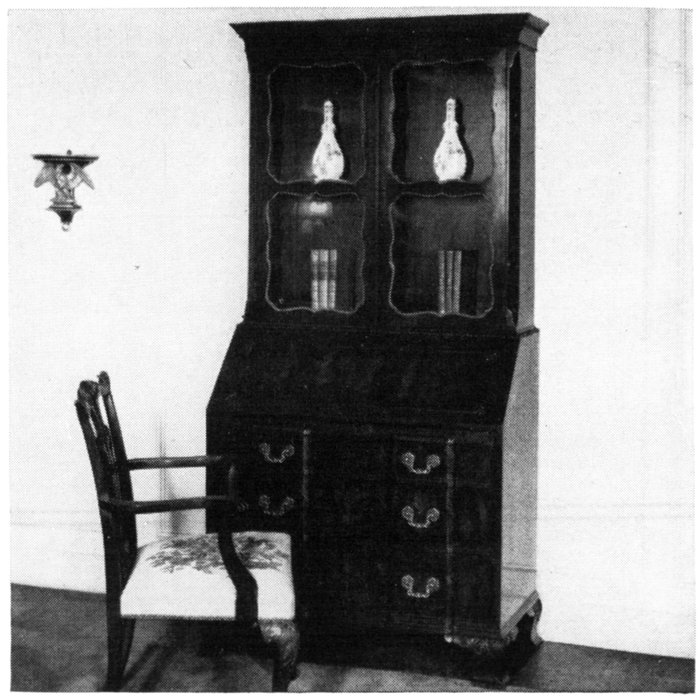

Figure 3A.—A block front Chippendale secretary. The pulls are all pierced chased brass. The broken pediment is ornamented by the unusual addition of a hand-carved leaf carving. The ribband back chair has the cabriole ball and claw and leaf carving on the knees and is upholstered in a hand-blocked tapestry.

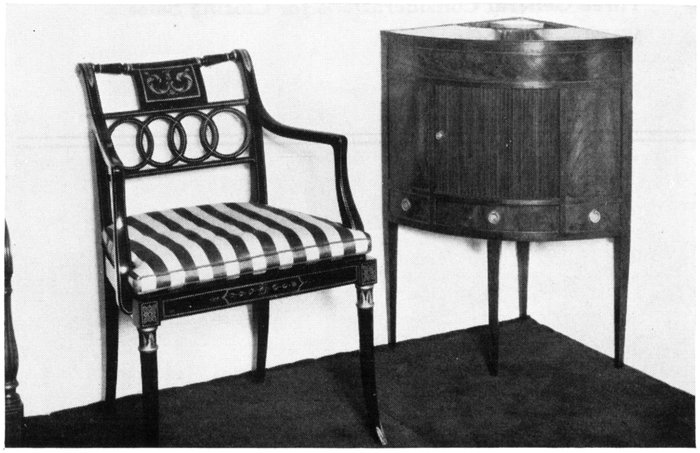

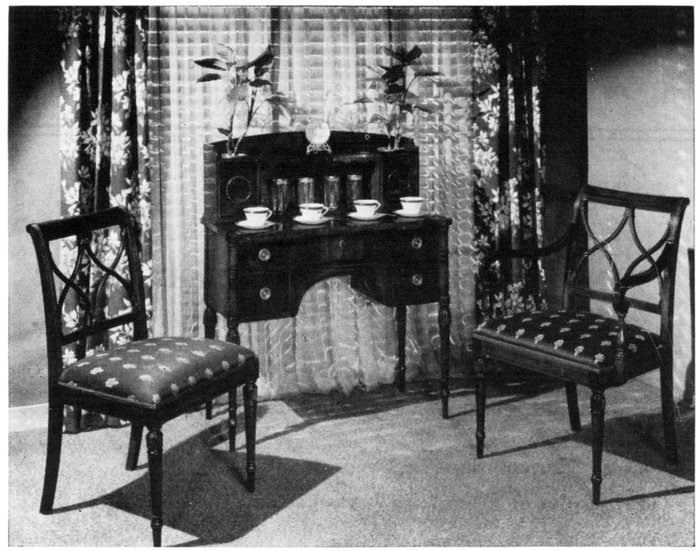

Figure 3B.—This copy of a Sheraton corner stand has tambour sliding front drawers and a copper-lined plant container at the back. The chair at the side is a Sheraton decorated armchair, in black with gold decoration. The upholstery is green and ivory striped satin.

Unit II.—TECHNIQUE OF SALESMANSHIP

When you start toward the display floor with a customer who has asked for a particular article, you have—or should have—five objectives:

1. To close a sale, if possible, for an article of the best quality warranted by the customer's needs and means.

2. To sell any additional merchandise in which you can arouse an interest.

3. To make the sale in such a way that the merchandise will stay sold, and the customer will become a loyal business friend.

4. To secure and record any information as to the customer's home and tastes that may lead to possible future sales.

5. To do these things without wasting time so that you may get another customer and repeat the process.

In order to attain these objectives you must gain the confidence of the buyer, and here your success will depend upon what happens in the first 5 minutes. It is during these crucial minutes that the customer forms the impressions which so often lead her either to bestow her confidence or withhold it.

The experienced salesman is accustomed to form a quick judgment of the customer and to base his opening procedure on that judgment. The technique presented here is designed particularly to help this salesman make large sales or handle small sales which may be expected to produce future business.

Let us assume that your customer has not asked for an advertised chair, and that there is nothing in her appearance or manner to enable you to make a close guess as to her tastes and means. All you know is that she is interested in an easy chair. Since she has not told you exactly what kind of chair she wants, it is safe to assume that she doesn't know. On the other hand, you may be certain she wants a chair to serve some particular purpose of her own. The chances are that she has only a vague idea as to the particular[Pg 18] type of chair which will best serve this purpose; you as yet have no idea whatever. Accordingly, you must choose one of three methods for starting the sale.

The first is to lead her through your stock in the hope that she will see a chair that pleases her and buy it. This sometimes will happen, and there are some customers—though few—who can be sold in no other way. However, this method wastes so much time, and results in such a heavy percentage of lost sales, that it should be your last resort. It is open to three serious objections:

First, it will not help you win the customer's confidence. By relinquishing all control of the interview, you forfeit her respect for you as a competent adviser in the processes of home furnishing, and become merely an order taker. If she happens to like your merchandise, you are fortunate; but you can do nothing to influence her toward liking it.

Second, no one can look at a great many different things, however interesting and beautiful, without becoming confused and losing the power of discriminating judgment. The woman who is shown furniture by this undirected method is likely to become tired and certain to become confused, and may be expected to decide to "think it over," "look around," or "bring her husband."

Moreover, you cannot show many chairs, even by this method, without making some comments about them. If you are like many salespersons you will fall into the habit of describing half the pieces shown either as the most beautiful, the smartest, the most comfortable, the latest, or the best bargain. If this happens, any normally intelligent person will suspect that you are either insincere or incompetent.

Third, if a sale results, it is likely to be at an unnecessarily low-price level unless the question of credit limit is involved; and in any event there will be no sale of additional merchandise, no information of future value, no loyal business friendship.

You may decide to make a persistent and, if necessary, a high-pressure effort to "sell" her something. This method, like the first, will work with a limited number of buyers. However, it results in much wasted time by reason of the high percentage of returns for credit or exchange, and in ill-feeling and impaired confidence which over a period of years make it difficult for the salesman to build up a personal following among the buyers of his community.

As a matter of cold fact, this method of selling home furnishings has caused the retailers an immense loss in public confidence, as well as in money. Because of wrong selling methods, multitudes of women now stay out of certain stores except on those rare occasions when they are forced by actual needs to enter. Although these women want to buy, they are afraid of being sold.

More accurately, they are afraid of being sold the wrong thing. Most of the women who ask to see a chair or rug or other home-furnishings merchandise really want something much more important to themselves, although they do not tell us about it. They want beauty, comfort, distinction, or social prestige. In other words, they want to buy furniture as a means of making their homes more attractive; but their past experience, or the experience of their friends, often leads them to believe that the salesman will not really help them. To overcome their hesitancy, they must be made to feel at the beginning of the interview that no one is trying to sell them, or even to let them buy, but rather that the desire of the salesman is to help them buy.

The third possible course of action is based upon a study of the customer's needs. The salesman will seek to discover the customer's purpose in looking at easy chairs and then to show her the particular pieces in stock which are best adapted to serve that purpose. He will need information about the size, style, and coloring of the chair required, and the amount that the buyer is able or willing to pay for it. Do not, at the outset, ask for this information.

In selling home furnishings avoid questions which will force the buyer to make definite commitments in advance as to her tastes or the amount of money she is prepared to spend. In the first place, it is probable that if she had fixed ideas on these subjects she would have told you exactly what she wanted at once. If you force her by direct questions to make a statement, she may feel impelled to abide by it later; you thereby have placed yourself and your stock under an unnecessary handicap.

In the second place you run the risk of annoying her, since few women welcome a direct question at the beginning of a sales interview as to how much they are prepared to spend. Finally, such questions may be so clumsy and amateurish in technique as to under-mine a customer's confidence in your ability. Your questions at the outset should be directed toward determining her needs. If such questions are skillfully put, she will welcome them as evidence that you are trying to help her buy economically and intelligently.

Upon leaving the elevator take your customer directly to an easy chair which you know to be good-looking and comfortable, conservative both in design and coloring, and neither your cheapest nor your most costly quality. By choosing a conservative rather than an extreme style you run no risk of impairing her confidence in your taste and judgment, and by picking a piece in the middle price range you run no risk of offending her if she is in the market for a costly chair, or of alarming her if she is a buyer for a cheap chair. Moreover, you are in the safe position of being able to shift ground in either direction without loss of prestige. Don't ask her how she likes this chair, and don't make any flattering comments on it. Merely say, in effect: "I don't know how close this particular chair comes to what you have in mind; but at least it is attractive and comfortable. If you care to sit down in it for a moment, and to tell me a little about your requirements, or about your room, perhaps I can save you the time and trouble of looking at a great number of unsuitable pieces. Is the chair for your living room?" If the answer is "Yes," proceed: "Then it will of course have to fit in with your other things in that room."

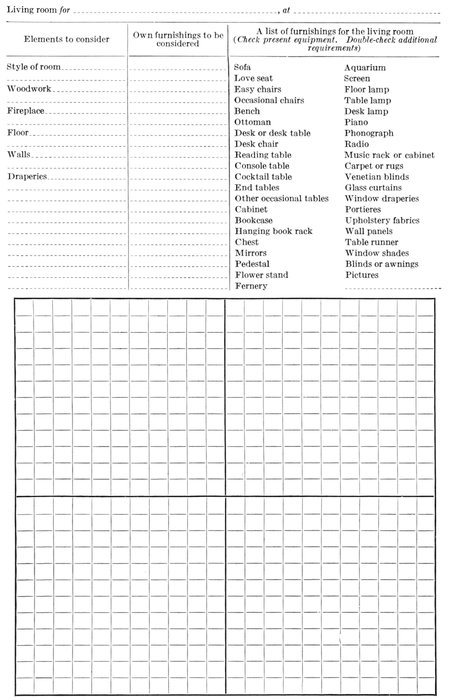

At this point you may wish to draw up a small table and lay the living-room floor plan[1] on it with the first page so placed that the customer can easily see it. Then draw up a chair for yourself. It is important to move with a poise and assurance which will cause the buyer to know you are following the usual procedure. By the time you are seated she will likely have read enough of the first page to be interested and awaiting your next move.

In many simple sales it will be unnecessary to ask many questions, or to enter the answers on the plan. Since you cannot know this at the start of the interview, however, it is usually wise to show the plan, even if you make no actual use of it. The effect of this procedure catches interest, places the transaction on a more professional basis, and helps create confidence in yourself and your store as skillful and competent advisers in the selection of furniture.

Figure 4.—Room arrangement plan

Note to salesperson.—If you do not have a floor plan and have not seen the room in question, take blank paper and pencil. Block in window and door openings and location of "other" furniture. Then proceed as suggested, recommending nothing that will not enhance the attractiveness of the room for its particular use. Always date your sketch; place upon it the name of your customer, and file for later reference.

If you decide to use the plan, spread it on the table, and say, in effect: "This device helps us to serve our patrons who are interested in buying furniture that will add to the comfort and beauty of their homes. In your own case, for example, we have scores of chairs that are good looking and that are good values. Yet, if you were to look at all of them you would undoubtedly find that some are too large or too small and that the great majority will not harmonize perfectly in design, style, or coloring with the other things in your own particular room. By using this device you can give me a clear picture of your room as you want it to look. Then I can show you only such pieces as promise to meet your requirements, and you in turn may select the one chair that seems most suitable. Do you have a guest chair in mind, or one for the special use of a member of the family? If for a member of the family, the sex, size, and individual preference must be taken into account; if for guests, the general decorative character of the room only.

"The new chair will be seen against the background of the walls and the floor coverings, and as a part of the group to which it belongs. Hence, we must be sure it will harmonize with these other elements. Your rug, for example, is——?" Enter important information which is given on the floor plan under the heading "Floor covering." Information needed includes the type of rug (which may give you an idea of the buyer's price level); coloring; and type of design (which will indicate to you the characteristic features of the new chair necessary to insure harmony). Then proceed in the same way with the walls, woodwork, draperies, and principal upholstery fabrics.

If by this time your customer shows signs of impatience, you may wish to say in effect that you can show her several chairs that will fill the requirements admirably. Then go to work.

If, on the other hand, the buyer clearly is interested, ask for the size of her room and for the description and location of her other furniture, and block in the information on the floor plan, using the method shown in the typical floor plan, page 21. Here the best procedure is to start from the point of intersection of the 2 heavy lines, or axes, and count in 4 directions, using the scale of ¼-inch square for each foot. For example, if the room is 16 × 24 feet, count 12 squares from the center in both directions to locate the end walls, and 8 squares in both directions to locate the side walls. When this information is recorded you will get an idea as to the correct size and proper location for the new chair. Be sure to locate windows and doors accurately and indicate the exposure of the room with reference to the compass points.

These preliminaries when completed will give a clear picture of the room, a fair idea of your customer's price range, and a good start toward her confidence. Thank her and introduce yourself simply by[Pg 23] saying, "I am Mr. Smith. If you are pleased by what I have shown you today, I shall hope to see you again as other living-room needs arise. May I fill in your name and address, so that this plan may be filed for use when you are next in the store?"

You must be guided by your best judgment. If you have reason to think the customer has confidence in you, show first the particular chair that you honestly believe is best for her purpose, introducing it with a brief, pointed, and purely impersonal comment on its beauty, style, and peculiar fitness for her own purpose. Don't use superlatives. She may not like this piece well enough to buy it immediately, in which case you will be seriously handicapped in trying to interest her in another one. If, on the contrary, you do not feel assured of her complete confidence, probably it will be wiser to show your second or third best piece first, holding the best in reserve.

As soon as you detect signs of real interest in a chair, build up a little group based on the principles of harmony which are stated and illustrated in unit VII, page 142. In some cases a small table will be enough; but usually it will be better to use a larger table, a lamp, and often a small rug and a length or two of drapery fabrics, if you stock them. The purpose of this procedure is to help the customer see your chair as an integral part of her own room and to emphasize its desirability as a means of making that room more attractive. If she already has the pieces necessary to form a complete group when the chair is added, select pieces as nearly like her own as possible. If not, select pieces that harmonize perfectly with the chair. Don't tell her that she ought to have these pieces. Merely show them without comment, and defer any attempt to sell anything more than an easy chair until after the chair has been sold.

Some salesmen make the serious and costly mistake of assuming that every customer will be exacting and hard to sell, and that a large percentage of them enter the store with no real intention of buying. The really able salesman knows that this is not true. Under present conditions the woman who enters a furniture store or department may be presumed to have an active interest in furniture. When you have found her real needs and offered her something that satisfies them, there in an excellent chance that she will be ready to buy. If so, take the order at once. Don't make the tactical blunder of[Pg 24] showing additional merchandise, or of completing all the steps necessary to close a difficult sale. Many salesmen talk themselves out of a sale by suggesting unnecessary alternatives. In other words, prepare carefully and intelligently for the order, expect it, and take it at the first opportunity.

At the start of a sale it is safe to assume that the buyer is thinking in terms of her own interests. Don't tell her that a given chair is in the latest or most popular style until you know that she is interested in the latest rather than the best style for her particular room. Don't tell her that it is your best-selling number; or that Mrs. Jones just bought a piece like it; or that you think, or the buyer thinks, or the head of the house thinks it "wonderful."

As a general, but by no means invariable, rule, don't quote a price—unless you are asked for it—until you see definite signs of interest in the piece under consideration; and even then not until you have prepared for it by a brief but convincing statement as to quality or desirability. However, when you are asked the price of an article, give it immediately and without apology or comment.

All first impressions and most sales start at the front door of your store or department. For any lack of promptness and courtesy at this point there will be a penalty.

Anyone who enters the store should be met immediately. If it happens to be a customer, whether man or woman, a long delay for any reason will be resented, and even a moment's pause to finish a conversation may be regarded as an affront. It is impossible to overestimate the importance of this matter, both to yourself and to your house. In a competitive market few persons will buy from the man who treats them discourteously, nor will they return to the store where they have met with discourtesy if another store with better methods is accessible. Moreover, one offended customer can do more damage through word-of-mouth advertising than a thousand lines of newspaper space can repair.

The visitor should be greeted with a smile, a bow, and the words "Good morning" or "Good afternoon." Test both your smile and your bow before a mirror and improve them if any improvement is[Pg 25] possible. A genuine infectious smile is literally a priceless asset. After this greeting usually you will be told what is wanted. If not, after a slight pause, ask: "May I show you something?" or "What may I show you?" Don't ask: "Can I help you?" "Are you interested in furniture?" "What can I do for you?" or "Anything, today?"

For the purpose of illustration, suppose the customer is a woman who asks to see a sofa bed. Don't ask her how much she wants to pay, or even what sort of sofa bed she wants. If the stock is on another floor it will be enough to say: "We will take the elevator, please," and indicate the direction. Do not precede her. Walk abreast, and, if the aisle is crowded, drop behind. If she is carrying a parcel of burdensome size ask her if you may have it.

Although many successful salesmen begin at once to draw out information as to the customer's requirements, it is better practice to defer such questions until you are in the presence of your merchandise and beyond the possibility of noise and confusion. Whether it is wise to try a few impersonal remarks, or to keep still, from the front door to the sales floor, will depend upon your judgment of the individual customer.

1. This unit discussed three methods of starting the sale. How would you proceed to sell furnishings for the new clubhouse at the community center?

2. What would you do to correct a wrong attitude toward use of certain types of furniture in a living room?

3. A woman tells you that she cannot afford costly furnishings. What steps would you take to show her that good taste is not necessarily expensive?

4. Of what advantage is the study of advertising to the young man who expects to become a furniture salesman?

5. What use should be made of dealers' aids furnished by the manufacturer of products you are to sell?

6. Give five sources of information regarding prospects which a retail furniture salesman may use.

7. What should a good furniture salesman know about the history of his firm?

8. Why is the excessive use of superlatives an indication of ignorance of the article being sold?

9. (a) Of what value is a knowledge of competing goods? (b) How should such knowledge be used?

(Most libraries will have other excellent books discussing retail salesmanship and these should be consulted freely.)

Rolling, Cunliffe L. Retail Salesmanship. Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd., London and Pitman Publishing Co., New York, N. Y. 1930.

de Schweinitz, Dorothea. Occupations in Retail Stores. International Text Book Co., Scranton, Pa. 1937. (Study sponsored by National Vocational Guidance Association and the U. S. Employment Service).

Jackson, Alice and Bettina. The Study of Interior Decoration. Doubleday Doran & Co., Inc., Garden City, N. Y.

Pelz, V. H., Selling At Retail. McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York, N. Y. 1926.

Richert, G. Henry. Retailing Principles and Practices. Gregg Publishing Co., New York, N. Y. 1938.

Simmons, Harry. How to Get the Order. Harper & Bros., New York, N. Y. 1937.

Whitehead, Harold. The Business of Selling. American Book Co., New York, N. Y. 1923.

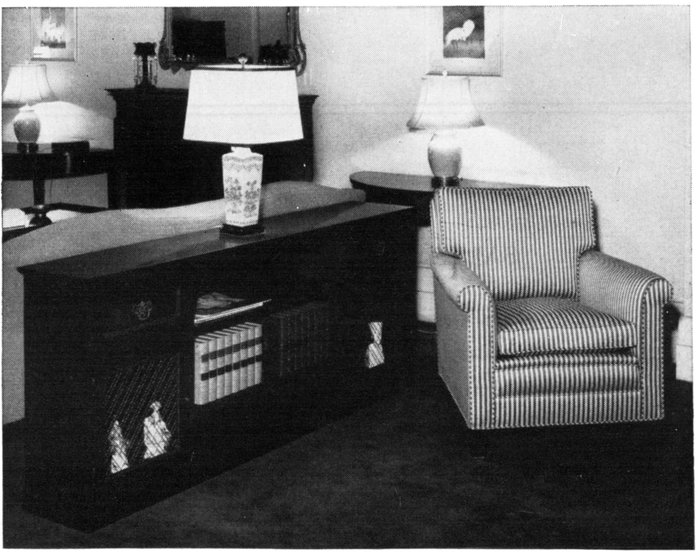

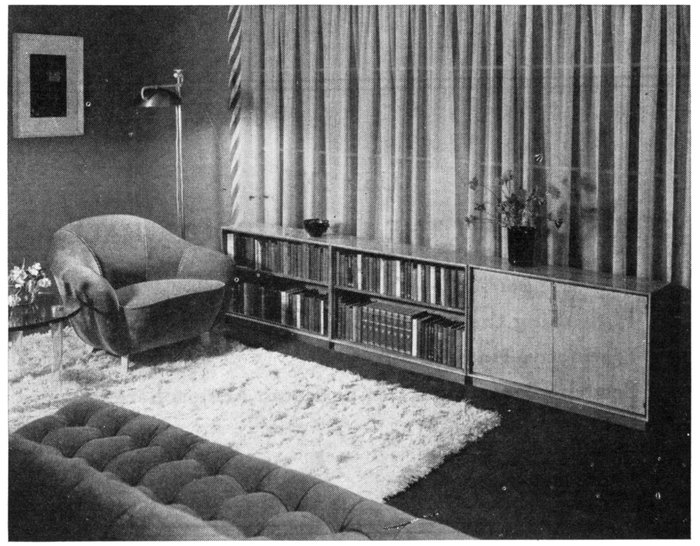

Figure 5.—Useful because it can be placed behind a divan or against a wall is this low eighteenth century cabinet for books, radio, magazines, or bric-a-brac. Beside the cabinet is an eighteenth century lounge chair, upholstered in rose and white striped satin.

Unit III.—SALESMANSHIP APPLIED

Old or young, rich or poor, we are much alike. What interests us is what touches ourselves. When we make our choices we do not always accept or reject things because of their intrinsic worth but because they appeal strongly to the group of instincts, emotions, and habits which just then is motivating the inner life and influencing decisions.

The salesman who is clever enough to present his merchandise in the ways that appeal most directly and powerfully to these inner controls enjoys a great advantage over one who lacks this ability.

It goes without saying that this ability presupposes thorough knowledge of the merchandise. This is fundamental.

A given rug which enters our stock from the receiving room may have 30 points of possible interest to buyers, but not all these points will appeal to all buyers. Carefulness and system will enable us to pick and emphasize the strongest points for each buyer provided we know the entire 30. But if we know 20 only, or 15, or 10, no amount of skill can save us from losing some sales.

Under present conditions it is extremely difficult to acquire full and accurate knowledge of the merchandise we are called upon to sell, but we can get this information now if we want it badly enough; we must get it if we seriously desire to increase our earning power.

All possible information is important, because any part of it may be necessary, in a given situation, in order to make a sale. We must get this information wherever we can find it. In the case of a newly arrived easy chair, for example, it may come from three sources:

1. From personal inspection.—A cursory inspection will tell us that the chair is a medium-size piece, slenderly and gracefully proportioned; with open padded arms; loose cushion seat; a back of pronounced rake; cabriole front legs with carved claw feet; covered in a small-figure reseda green damask; and priced at $85. We should be[Pg 30] able to identify its style, and the tag may indicate the name of the manufacturer.[2]

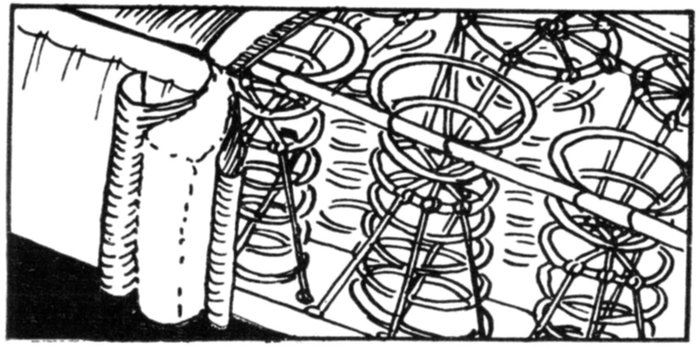

A more careful inspection will tell us that the exposed wood is solid mahogany, finely finished; the front legs skillfully carved; all legs with a degree of curvature that eliminates danger of breaking under strain; frame corner-blocked; seat springs set on webbing, or steel frame, with a dustproof bottom of cambric; loose cushion of spring construction; and the covering a close-woven, wear-resisting fabric with silk warp and cotton waft.

2. From the buyer or manager.—

a. Name of manufacturer, in order that we may be governed in making statements about this chair by our general knowledge of his line, as to quality of materials, skill of workmen, and inspection standards, and also in order to use the name in cases where we believe that it will have prestige value.

b. Details of concealed construction, including frame; method of springing; build-up of seat, back, and arms; stuffers used; strength of fiber and color in the covering.

c. Information as to whether the piece can be duplicated, and if so, at what price and in what time; also as to whether it can be supplied in other colors, or in other materials, and if so, location of samples, method of figuring price, and time required for delivery.

d. Historic source of the design, and any interesting information as to its fashion value, gained by the buyer at the markets.

3. From books and magazines.—

a. The historical background of the style to which the chair belongs, and the most effective methods of developing its style appeal.

b. Types of rooms and color schemes with which it can be used harmoniously.

Equally comprehensive information is necessary for all other items in your stock. Without it the percentage of purchasers that we can be sure of reaching with a key appeal will be reduced, and our earning power correspondingly limited.

Assuming that we have acquired adequate knowledge of the materials and construction of our merchandise, how are we going to use it effectively. We suggest a few general principles as guides to sound practice:

Both materials and construction normally are factors to be employed in closing a sale, but not in opening it.—If you went into a store and asked to see a pair of shoes and the salesman, seizing the first model at hand, assured you that it was made of tanned box calf, with waterproof soles, cork filling, and tacked insoles, by a process involving more than 150 separate operations, all of which made it a wonderful value at $8.50, would you tell him to wrap up a pair? Hardly.

Neither materials nor construction would interest you until you were comfortably fitted with a shoe that satisfied your ideas of style and color, and at a price within your buying limit.

When a customer asks for an advertised article and seems pleased with its appearance, the demonstration of its value can start at once. In any other situation it must wait until you find something with which she is pleased.

There are those who appear to believe that selling is a game in which the object is to beat down the customer's opposition and make her buy. In dealing with customers of any type above the most unenlightened, this idea always has proved a boomerang.

In talking materials and construction, preserve a sense of relative values.—When we say about a $35 chair everything that properly could be said about one priced at $65, our customer either believes or disbelieves us. If she disbelieves, the sale is lost. If she believes, our chance to get more than $35 of her money is lost. Even if we leave out of account the basically important matter of business honesty, it is unwise to overstate the values of any article. In a well-managed furniture store every article possesses points of merit sufficient to sell it on the basis of what can be fairly claimed for it. To claim more, whether intentionally or through ignorance of the facts, is to deceive our customers, and—inevitably—to cut down our sales volume.

Demonstrate the value of all merchandise under serious consideration whether you believe it to be necessary or not.—Many sales of advertised articles or merchandise chosen on the basis of its decorative appeal can be closed without discussion of materials or construction. As a safety-first measure, these factors should be mentioned somewhat carefully after the order has been booked. Sometimes a customer will buy an article in complete good faith, and yet within the next half[Pg 32] hour will start shopping in other stores to see whether or not she has bought wisely. Even more important is the fact that in every case the new purchase, when delivered, is subject to inspection and criticism not only by members of the family but also by neighbors and friends. Some of this criticism is bound to be adverse, and unless we have taken the precaution to build up an unshakable confidence in the excellence and value of our merchandise there may be a telephone order to come and get it, or at least a loss of goodwill and future patronage.

These precautionary build-ups can of course be brief. For example, if you have sold a bedroom suite on the basis of appearance only, it will be enough to say in substance: "You have bought this suite because of its beauty and style, which will continue to delight you always. But before you leave I want you to realize that these fine qualities rest on a foundation of sturdy construction. This dresser, for example, is * * *."

Contacting the "I'll-buy-later" prospect.—There is always the chance that the sale can be closed. A woman's statement that she is not yet ready to buy is in many cases merely a "defense mechanism"—a psychological device to serve as an excuse to leave if she senses that high-pressure selling effort is being applied. It is possible that if we answer, in effect, "Please don't think of yourself as a customer, but rather as a valued guest of the store. This is not a busy hour for me, and while you are here I hope you will let me show you some more of the new things, which are particularly interesting this season," we may be able to develop the confidence and desire necessary to effect a sale.

If we fail to do this, we can at least see to it that the customer leaves with a clear impression of the value of the pieces she has been considering. If this impression is sufficiently clear and deep she may come back. Otherwise, in all likelihood, she will not.

The shopper in a hurry.—Many of us habitually make little or no effort with the customer who enters with the warning "I am in a great hurry," or "I have just a moment to look around today, and will come back later when I have more time." This is a mistake. Such statements may or may not be entirely true. In many cases they are another form of defense mechanism—a way out, prepared in advance. In other cases, they are merely a form of exhibitionism—a native desire to appear important. Such customers, properly handled, often can be held indefinitely, with the average chance to make a sale.

Price important in judging value.—Those who sell are rightfully apt to think of value as the total sum of a number of costs. While this method of evaluation is not fundamental economically, never[Pg 33]theless our opinions often crystallize when we view the cost records. Our customer, however, is dually interested in what it costs to make and distribute what we sell her and in what our product means to her through its uses in her home. The merchant's, and hence the salesman's obligation, is to satisfy her that the price she pays is in strict conformity with the actual reasonable costs of making and delivering the goods. Simultaneously, however, we must teach her how our product will fit into her home, the satisfaction it will give her, the use it will stand through the years, in order that she may correctly weigh her satisfaction against her cost and reach a final conclusion as to her purchase.

This does not mean, of course, that the price should be stated first, but simply that it must be stated at the time it becomes important in the mind of the buyer. Assuming a skillfully conducted preliminary talk, this will normally be after an article has been tentatively accepted on the basis of appearance, and fitness, but before the beginning of a serious effort to close the sale.

Avoid resistance, and answer unspoken objections.—Use of the "How do you like this?" type of question sets up unnecessary hazards of resistance and should be avoided. The same is true of positive assertions not susceptible of immediate proof, and also of statements which tend to suggest inner doubts.

If you say of a certain sheen-type rug, "This rug, in pattern and coloring reproducing one of the celebrated Isphans of seventeenth century Persia, is woven of a special brand of imported oriental wools, by methods which give to its deep, close pile almost unlimited durability, plus this rich, velvet-like softness and luster," you add to its value without setting up a possible source of resistance to unspoken objections. But if you say, "The construction of this rug makes it the best value on the market," you cannot prove your statement, which may serve to remind the buyer that other stores are offering special values, or that her friend is enthusiastic about a rug bought recently at Blank's.

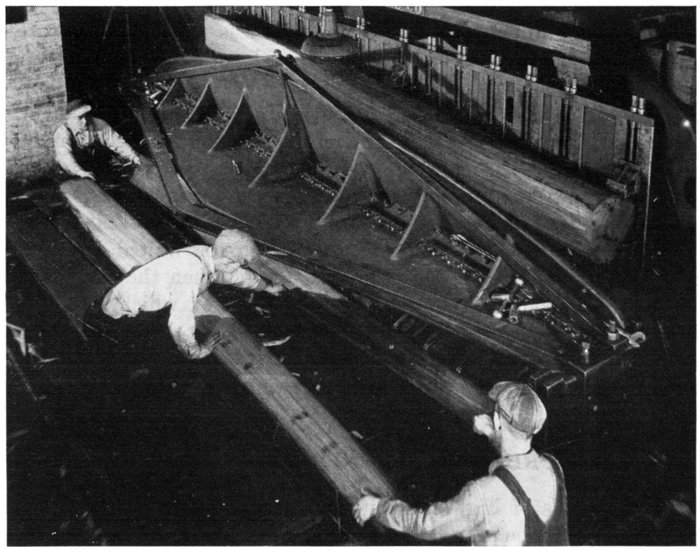

Unproved assertions destroy confidence.—Suppose you are trying to sell a table with mahogany-veneer top and red gum legs. To call it a mahogany table will lose the sale immediately, if the customer knows woods. To say that it has a mahogany-veneer top and mahogany finish gum legs may suggest to the buyer that a veneer is a poor substitute for solid wood, and that gum cannot be desirable if it must be finished to look like something else. To ignore the whole matter of materials and construction and to try to sell the table on its beauty and fitness alone may cause the customer to wonder just what you are trying to conceal, which will mean loss of confidence in yourself and your merchandise.

The wise course is to tell the entire truth about the piece in a perfectly matter-of-fact way designed to avoid any invidious comparisons of woods or processes. For example: "This table whose design and coloring you so much admire is as sturdy as it is good looking. Following the practice of some old eighteenth century cabinetmakers, the maker of this piece has combined several woods. Those used in the top are built into the modern five-ply construction, which brings out the full beauty of grain of the mahogany upper ply, ensures freedom from any danger of warping or splitting, and provides the strength of steel. For the legs he has used the beautiful straight-grained red gum of the South."

It is a costly folly to try to sell one material or process by condemning another. We show a table, for example, and speak of "solid American walnut" as if no other wood or construction were worthy of consideration; and 5 minutes later, finding that we have misjudged her price level, we stammer and stumble over an attempt to convince her that plywood is an acceptable substitute.

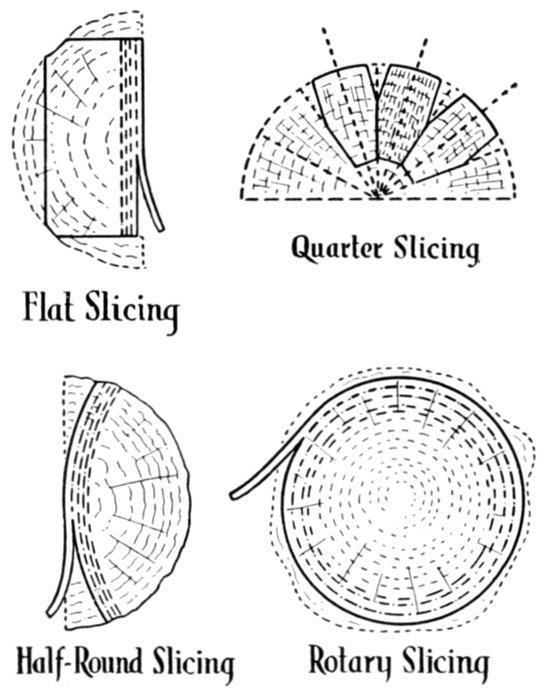

These are the dangerous devices of mental laziness. When a customer asks us if mahogany is better than birch, or Axminster carpets better than velvets, or solid construction better than veneer, a positive answer is misleading. We certainly should know that mahogany, like birch, varies in excellence according to the individual board; that some Axminsters are better than some velvets, and vice versa; and that the construction is best which best meets the particular requirements of design and purpose, in furniture precisely as in shoes or ships.

The fact is that everything used in making home furnishings of worthy quality has stood the test of time, and therefore is interesting and desirable in its own right. If we cannot make it seem so to customers, we have not learned enough about it.

In selling materials and construction, repetition is needed.—We must be governed by the results of our preliminary talk in picking out for emphasis the particular points which promise to be of interest to each customer. Having made these points, we sometimes need to repeat them, in varying language and in different parts of our sales talk. Moreover, we must never forget that many things which are as familiar to us as the multiplication table are strange to our customers, and therefore difficult to remember.

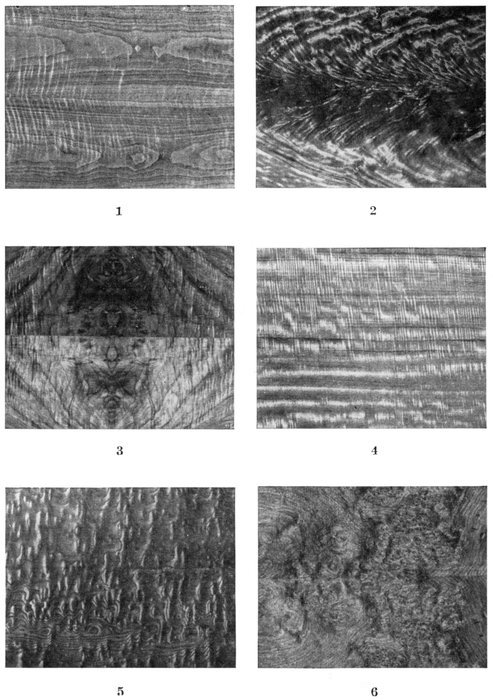

We know, for example, that concealed differences in construction may make one easy chair worth twice as much as another of identical appearance; that in sliced walnut veneers, figured woods may cost 5 or 10 times as much as plain; but most buyers do not know such things. Accordingly, if we merely state such facts, but fail to groove[Pg 35] a memory channel by one or more repetitions, there is an excellent chance that even the customer who wants and can afford good things will look elsewhere, completely forget what we have told her, and buy a cheaper article in the honest belief that she is getting something equally good. What too often happens is that in building up the value of our merchandise we fail to fix the facts in the customer's mind.

Treat merchandise carefully, and show it under the most favorable conditions.—It is self evident that valuable merchandise must be so handled as to imply that it is of distinguished excellence.

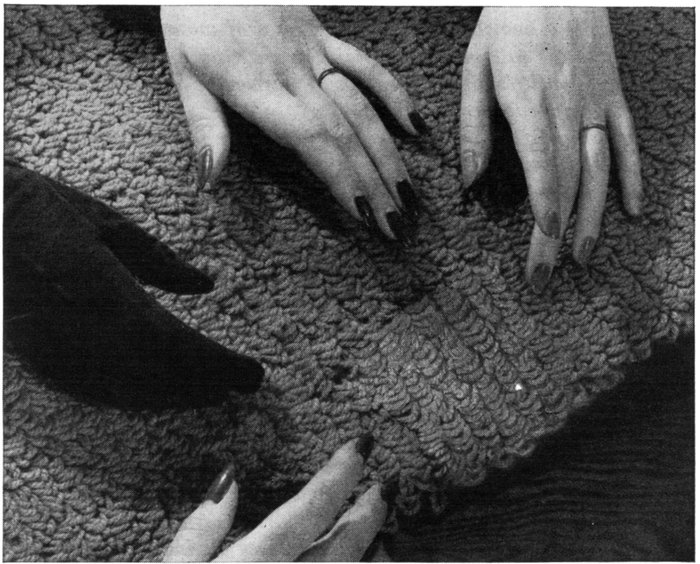

Respect in handling inspires respect.—A woman will not buy an article unless and until she has identified it with herself—conceived of it as belonging to herself, and in her own home. Suppose that we are showing her a length of drapery fabric. If we crush it, or handle it as if it were calico or cheesecloth, or chance to step on it before she makes this unconscious identification with herself, she will think less of it; if after, she will think less of us. Either reaction will be harmful.

In departments using rug racks, often it is necessary to remove a rug and show it on the floor before the sale can be closed. If we do this in a way that permits the piece to fall in a wrinkled heap on the floor we will not damage the rug, but we will hurt the buyer's opinion of it. A shrewd salesman will ask his customer to walk on the rug; but he will not walk on it himself.

The same care applies to showing furniture. It is folly to jerk a drawer violently, or pound a table or dresser top, or thump the seat of an easy chair, or sit on the arm of a sofa. Such actions reveal an awkwardness and lack of poise which one does not associate with good homes and their furnishings. Then, too, your customer, if she is seriously considering a purchase, thinks of you subconsciously as pounding her table or sitting on the arm of her sofa.

Similar care should be given to the language with which you characterize or describe your merchandise. Many an automobile salesman has lost a live prospect because he insisted on calling a beautiful car a "job." "This stuff," or even "these goods," may lose the sale of a fine damask. Wrong inflection in phrases like "It is veneered," "This is a cretonne," often is fatal.

In this bulletin the buyer of home furnishings is referred to as "she." This is done partly for simplicity, and partly because most buyers are women.

As a matter of fact, men do play an extremely important part in the purchase of home furnishings, and they are likely to be the determining factor in large sales. This is so much the case that clever salesmen and decorators frequently try to get the man involved even in the earlier stages of a large sale, while many highly successful oriental-rug men make no serious effort on a sale of any importance until the man is actively interested.

Accurate percentages impossible.—Such data as we have indicate that, in the purchase by average-income families of the kinds of merchandise carried by furniture stores, 5 percent or less of the buying is done by men alone, 50 percent or more by women alone, and the remaining 40 percent by men and women together.

The percentages, which are of approximate accuracy only, vary widely with different classifications of merchandise. Women probably buy from 75 to 85 percent of all curtains, draperies, mattresses, and pillows; men alone buy considerably more than 5 percent of lamps, refrigerators, and small electric appliances; and men and women together buy from 60 to 70 percent of room-size rugs and the more important items of furniture.

These figures indicate that women have some part in considerably more than 50 percent of all sales in our business. There is reason to believe that they initiate fully 85 percent of all sales. This means, among other things—

1. That we must expect and be set for competition and delayed sales in the majority of cases, because three women out of every four shop in more than one store before buying furniture.

2. That we must conduct every interview with a woman shopper in a way calculated to influence her to return in case an immediate sale cannot be made. This will demand—

a. Prompt and skillful service, with every effort to save her time; because women of the intelligent classes in recent years have come to attach great value to their shopping time and to resent any waste of it as a result of inefficient salesmanship or store service.

b. Careful attention to those elements of salesmanship discussed under "The daily check-up," unit I, p. 10, because women are strongly influenced by first impressions, and in a competitive market rarely return to the salesperson who made an unpleasant first impression.

c. Belief that "high-pressure" selling is a mark of inadequacy both in the salesman and the firm he represents. The customer of today is rightfully resentful of it, although it is true that some seem to react positively to it. Intelligent selling is marked by efficiency in fitting merchandise to a customer's desire and need, coupled with an understanding of her capacity to purchase without financial strain, and readiness to offer the best value commensurate with these limitations.

d. Convincing demonstration of the value of merchandise under consideration, even in cases where we are morally certain that there will be no immediate sale; because in the absence of such demonstration there will assuredly be no later sale. This is a point at which many consistently fail, with an enormous total loss in sales as an inevitable result.

3. That salesmen and merchants alike discard any smug conviction that "our old customers will always come back to us when new purchases are under consideration," and must turn to the development of an efficient follow-up system. The repeat purchases of old customers are not as a rule sufficient to assure the continued success of any retail business. Surveys in 1940 show that 60 percent of the home furnishings customers of the country shift to another store for their "next" purchase. This does not mean that they never return to the original establishment. It does show the need for salesmen and merchants to keep in touch with those whose confidence they have once developed. Properly handled, the customer likes the friendly follow-up and unquestionably it affects her shopping habits.

While generalizations on human motives and thought patterns always are dangerous, a few observations are set down here for consideration.

As buyers of home furnishings, women are in general more conservative in matters of price than men. Women's traditional role has been that of the conserver, rather than of the earner. Her attitude in the furniture store is due partly to this fact, partly to the fact that under present conditions she feels that a larger measure of personal and social satisfaction is to be gained by expenditure in[Pg 38] fields other than home furnishings. Her capacity as family purchasing agent compels her to keep constantly in mind a wide range of immediate and future needs, and to plan the division of her dollar on that basis.

Women are more interested in details than men; more inclined to postpone decisions; more indirect in their thinking; more responsive to appeals based upon instinctive and emotional reactions; less attentive; and less responsive to complete-explanation sales talk.

Women respond more strongly than men to appeals based upon time saving, efficiency, durability, quality, and the guaranty of performance, and far less strongly than men to appeals based upon family affection or sympathy. Appeals to elegance or modernity make a stronger appeal to men than to women.

Women respond more quickly to appeals made to their dislikes than to their likes, but with men the case is reversed. This fact, coupled with woman's habit of indirect thinking and her reluctance to go on record, makes questionable the use of the "yes-channel" method of selling which is often successful in dealing with men. The theory is that by asking questions to which the logical answer will be "yes" in the earlier stages of the sale, you groove the way for a final "yes." It is good theory, but fails with women buyers.

For the same reason the habit of repeating the question "How do you like this piece?" or "Isn't this beautiful, desirable, etc.?" is dangerous. Women do not like to be cross-questioned, or forced to declare themselves. Their inner response to a "don't you like" question is likely to be destructively negative, no matter what they may choose to say out loud.

Women respond more directly and strongly to the appeal of color than do men, and less strongly to the appeal of line and form. They often have strong prejudices against certain colors, certain types in texture, pattern, and proportion. These the salesman must uncover skillfully and avoid in showing merchandise.

The buying psychology of a woman naturally is influenced by her age, social position, experience, and income. On the upper levels of intelligence and income women buy much as men do. They are interested in "reason why" talk; their thinking is direct and their decision prompt. On the low levels we find women who, however shrewd in buying foodstuffs or clothing, have had little experience in the purchase of furniture and floor coverings. Lacking both taste and knowledge, these women often are childishly credulous. They buy on the basis of easy terms and what is to them eye-appeal, and have little or no concern with what would constitute value in the upper levels.