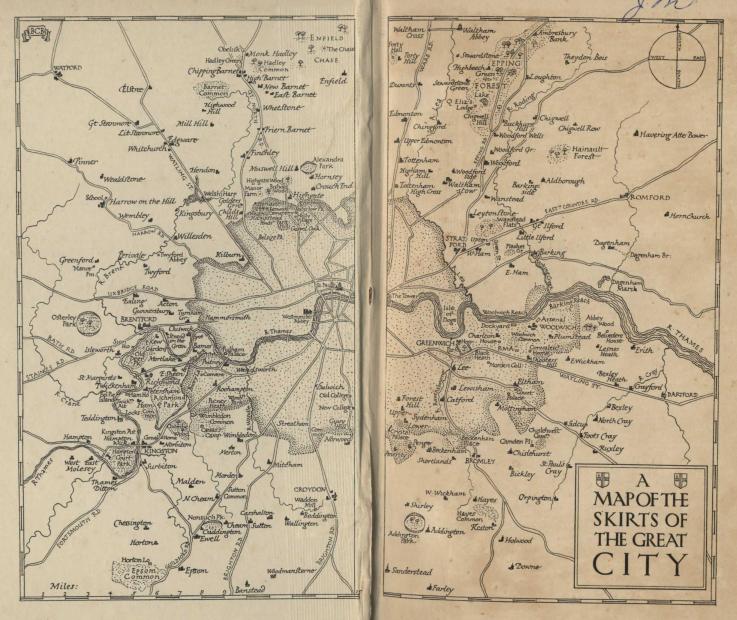

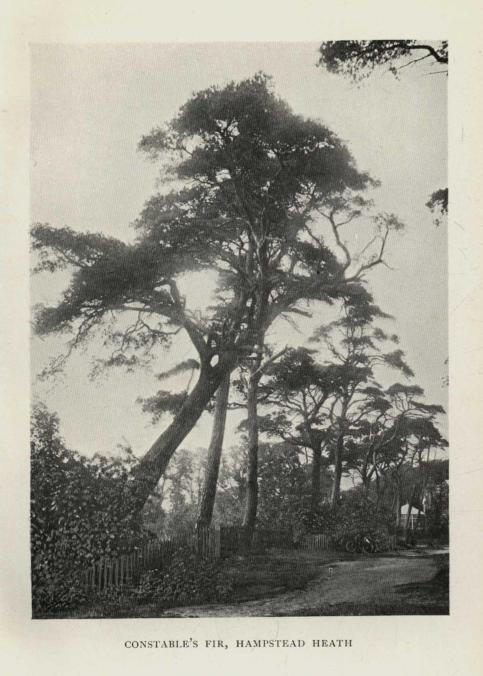

A map of The Skirts of the Great City

A map of The Skirts of the Great City

BY

MRS. ARTHUR G. BELL

WITH SIXTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR BY

ARTHUR G. BELL

AND SEVENTEEN OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

First Published in 1907

CONTENTS

CHAP.

I. HAMPSTEAD AND ITS ASSOCIATIONS

II. HIGHGATE, HORNSEY, HENDON, AND HARROW

III. SOME INTERESTING VILLAGES NORTH OF LONDON, WITH WALTHAM ABBEY AND EPPING FOREST

IV. HAINAULT FOREST, WOOLWICH, AND OTHER EASTERN SUBURBS OF LONDON

V. GREENWICH AND OTHER SOUTH-EASTERN SUBURBS OF LONDON

VI. OUTLYING LONDON IN NORTH-EAST SURREY

VII. CROYDON, CARSHALTON, EPSOM, AND OTHER SUBURBS IN NORTH-WEST SURREY

VIII. WANDSWORTH, PUTNEY, BARNES, AND OTHER SOUTHERN SUBURBS

IX. WIMBLEDON, MERTON, MITCHAM, AND THEIR MEMORIES

X. RIVERSIDE SURVEY FROM MORTLAKE TO RICHMOND

XI. RICHMOND TOWN AND PARK, WITH PETERSHAM, HAM HOUSE, AND KINGSTON

XII. RIVERSIDE MIDDLESEX FROM FULHAM TO HAMPTON COURT

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

IN COLOUR

HAMPTON COURT PALACE . . . . . . Frontispiece

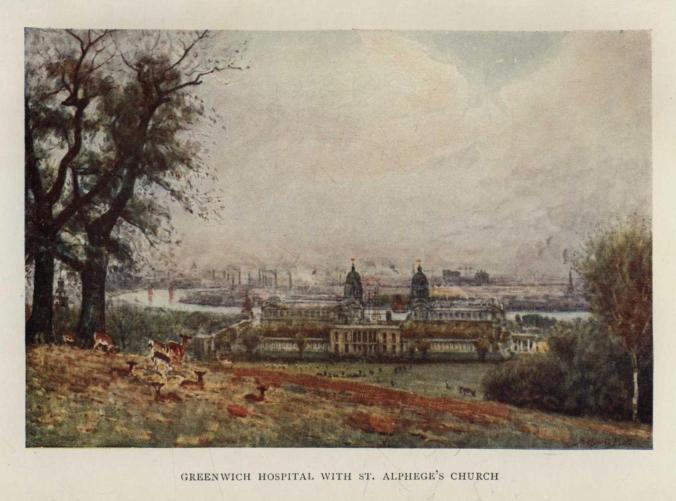

GREENWICH HOSPITAL, WITH ST. ALPHEGE'S CHURCH

RICHMOND FROM TWICKENHAM FERRY

RICHMOND PARK, WITH THE WHITE LODGE

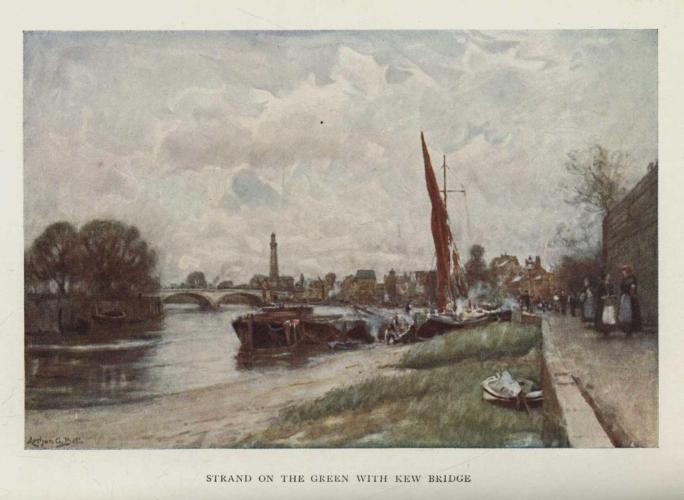

STRAND ON THE GREEN, WITH KEW BRIDGE

IN MONOTONE

MAP. FROM A DRAWING BY B. C. BOULTER . . . . . . Front Cover

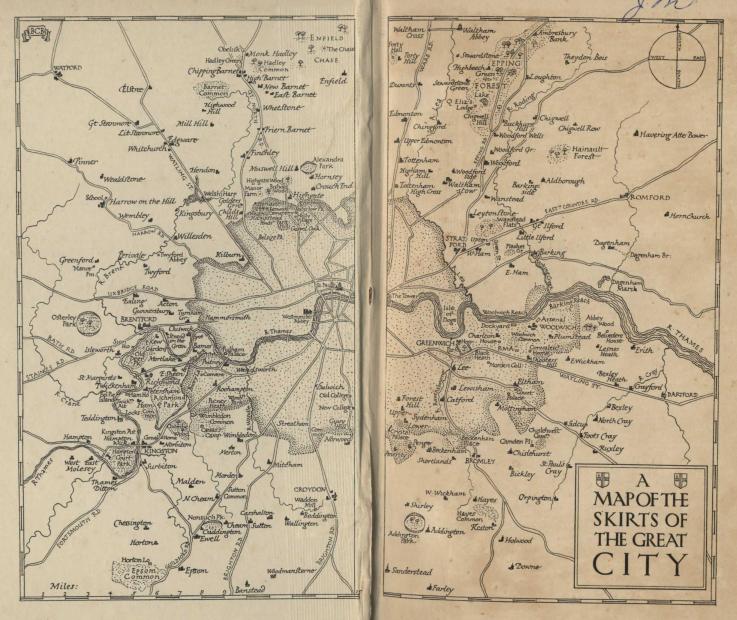

THE SPANIARDS, HAMPSTEAD HEATH

from a photograph by Messrs. Valentine, Dundee.

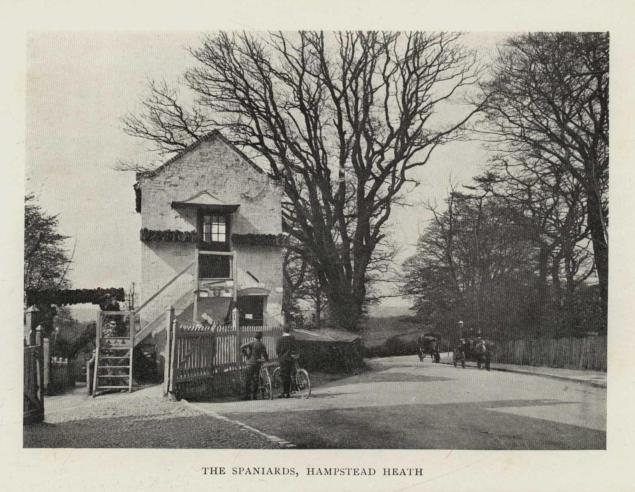

CONSTABLE'S FIRS

From a photograph by Messrs. Frith, Reigate.

HARROW-ON-THE-HILL

From a photograph by Messrs. Gale and Polden.

BYRON'S TOMB, HARROW

From a photograph by Messrs. Valentine, Dundee.

WALTHAM CROSS

From a photograph by Messrs. Frith, Reigate.

THE THAMES AT WOOLWICH

From a photograph by Messrs. Valentine, Dundee.

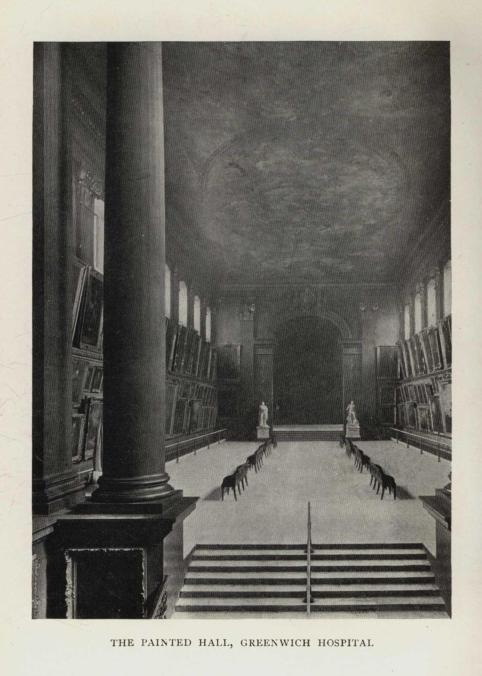

THE PAINTED HALL, GREENWICH HOSPITAL

From a photograph by the London Stereoscopic Company.

RUINS OF ELTHAM PALACE

From a photograph by Messrs. Frith, Reigate.

DULWICH COLLEGE

From a photograph by Mr. Bartlett, Dulwich.

THE CRYSTAL PALACE

From a photograph by the London Stereoscopic Company.

THE OLD PALACE, CROYDON

From a photograph by Messrs. Roffey and Clark, Croydon.

THE WANDLE, NEAR CARSHALTON

From a photograph by Messrs. Valentine, Dundee.

CARSHALTON POND

From a photograph by Messrs. Valentine, Dundee.

THE COCK INN, SUTTON

From a photograph by Messrs. Frith, Reigate.

THAMES DITTON

From a photograph by Messrs. Valentine, Dundee.

BUSHEY PARK

From a photograph by Messrs. Frith, Reigate.

THE SKIRTS OF THE

GREAT CITY

In his remarkable work Les Récits de l'Infini, the famous French astronomer, Camille Flammarion, hit upon a somewhat original device to bring vividly before his readers the fact that the heavenly bodies are seen by the dwellers upon earth, not as they are now, but as they were when the light revealing them left them countless ages ago. Having endowed an imaginary observer with immortality, he takes him from star to star, showing him all the kingdoms of the world at the various stages of their development, and finally makes him a witness of the Creation by the aid of the light that first shone upon the waters of chaos. Unfortunately, the student of history cannot hope to share the supernatural facilities of vision of Flammarion's hero, but for all that he can lay to heart some of the lessons of the astronomer's story by bringing to bear upon his task the sympathetic imagination which alone can enable him to reconstruct the past, and by remembering that that past should be judged not by the light of modern progress, but by such illumination as was available {2} when it was still the present. No matter what the subject of study, the accumulation of facts is of little worth without the power of realising their interdependence, and this is very specially the case with the complex theme of London, in which an infinite variety of conflicting elements are welded into an unwieldy and by no means homogeneous whole, for in spite of the obliteration of landmarks and the levelling influences of modern times, each of its component parts has a psychological atmosphere of its own. Illusive, intangible, often almost indefinable, that atmosphere affects everything that is seen in it, and is a factor that must be reckoned with, if a trustworthy picture of the past or present is to be called up. The truth of this is very forcibly illustrated in the outlying suburbs of London, with which the present volume deals, for though these suburbs now appear to the cursory observer to bear the relation of branches to a parent stem, many indications prove that they were all not so very long ago independent communities, which were gradually absorbed by their aggressive neighbour, whose appetite grew with what it fed upon, and is still unsatisfied. This is very notably the case with Hampstead, which less than a century ago was still a mere village, the history of which can be traced back for more than a thousand years, and which, through all its vicissitudes, may justly be said to have been true to itself, for its inhabitants have from first to last resisted with more or less success every attempt to merge its individuality in that of the metropolis.

The name of Hampstead, originally spelt Hamstede, signifies homestead, and the first settlement on the site of the present suburb is supposed to have been a farm, situated in the district now known as Frognal, round about which a hamlet grew up that was until after the Reformation included in the parish of Hendon. The earliest historical reference to Hamstede occurs in a charter bearing date 978, in which Edward the Peaceable granted the manor to his minister Mangoda, and many theories have been hazarded to explain the difficulty arising from the fact that the king died in 975, the most plausible of which is that the copyist was guilty of a clerical error. In any case, a later charter, issued by Ethelred II. in 986, gave the same manor to the monks of Westminster, a gift confirmed by Edward the Confessor, and retained until the dissolution of the monasteries in the sixteenth century.

A touch of romance is given to the laconic description in Doomsday Book of the Hamstede Manor, by the mention of Ranulph Pevrel as holding one hide of land under the abbot, for that villein married the Conqueror's former mistress, the beautiful Ingelrica, and the fact that the lovers were in fairly prosperous circumstances is proved by Ranulph having owned nearly six times as much land as any other dweller on the estate. Incidentally, too, the effect of the Conquest on the value of property is reflected in the sudden decrease in that of the manor of Hamstede, which was worth one hundred shillings under Edward the Confessor, and only fifty under his successor.

Unfortunately, next to nothing is known of the history of the little settlement on the hill in Norman and mediæval times, but at the Reformation the manor was included in the newly formed see of Westminster, whose first bishop, Thomas Thirlby, appears to have lost no time in dissipating the episcopal revenues, for much of his property, including that at Hampstead, soon reverted to the Crown. The manor was given in 1550 by Edward VI. to Sir Thomas Wrothe, and after changing hands many times in the succeeding centuries, it became the property about 1780 of Sir Spencer Wilson, to whose great-nephew, Sir Spencer Maryon Wilson, it now (1907) belongs.

The history of the neighbouring manor of Belsize greatly resembles that of Hampstead, for it was given in the thirteenth century to the monks of Westminster by means of a grant from Sir Roger Brabazon, chief justice of the King's Bench. It remained the property of the abbey until the time of Henry VIII., when it was transferred to the Dean and Chapter of Westminster, who leased it to a member of the Wade or Waad family, whose descendants held it until 1649. Since then it has been sold many times, and the manor has been occupied by many celebrities, including Lord Wotton and his half-brother the second Earl of Chesterfield, but in 1720 it was converted into a place of amusement, and gradually sank into what was known as a 'Folly House,' the resort of gamblers and rakes. Closed in 1745, possibly on account of its evil reputation, it was restored a few years later to the dignity of a {5} private residence, and between 1798 and 1807 it was the home of the famous but ill-fated Spencer Perceval, who became Chancellor of the Exchequer at the latter date, and Prime Minister two years later. Some sixty years ago, the ancient mansion with the grounds in which it stood were sold for building, with the inevitable result that the rural character of what had long been one of the most charming spots near London, was quickly destroyed. Belsize and Hampstead are now for all practical purposes one, though two hundred and forty acres of the former still belong to the Dean and Chapter of Westminster, whilst the bounds of the latter as accepted by the Commission of 1885 remain precisely what they were in Anglo-Saxon times before the cataclysm of the Conquest that removed so many landmarks.

It is difficult, indeed almost impossible, to determine when Hampstead first became a separate parish, but there is no doubt that it was still a part of Hendon in the early years of the sixteenth century, for it can be proved that the rector of the mother church was then paying a separate chaplain, whose duty it was to hold services in the chapel of the Blessed Virgin that is supposed to have occupied the site of the present Church of St. John. It is, however, equally certain that before the end of the reign of Elizabeth, Hampstead had its own church-wardens, for in 1598 they were summoned to attend the Bishop of London's visitation.

At whatever date Hampstead seceded from Hendon, the chapelry of Kilburn seems to have {6} been from the first included in the new parish, and the history of this chapelry is so typical of ecclesiastical evolution that it deserves relation here. The story goes that the first settler in the wilds of Kilburn was a hermit named Godwin, who some time in the reign of Edward I. built himself a cell on the banks of the little stream, the name of which, signifying the cold brook, is very variously spelt—the usual form being Keybourne, which rose on the west of the Heath, flowed though the district now known as Bayswater, fed the Serpentine, and finally made its way to the Thames, but has long since been degraded into a covered-in sewer. Shut in by a dense forest, of which Caen Wood is a relic, the lovely spot was an ideal retreat for meditation and prayer, but the recluse soon tired of its seclusion. He returned to the world, gave his little property to the all-absorbing Abbey of Westminster, by whose abbot it was a little later bestowed upon three highly born ladies named Christina, Emma, and Gunilda, who, fired with enthusiasm by the example of the saintly Queen Matilda, whose maids of honour they had been, had resolved to devote the rest of their lives to the service of God. Leaving behind them all their wealth, they took up their abode in the remote hut, but they were not left entirely to their own devices, for small as was the community it was raised to the dignity of a sisterhood of the Benedictine order, and a chaplain was soon sent to hold services and superintend the daily routine of the sisters' life. This chaplain was none other than the ex-hermit Godwin, and it is impossible to help {7} wondering whether there may not perhaps have been some secret attachment between him and one of the fair maidens. His readiness to return to a place he had intended to leave for ever is certainly suggestive, but his conduct appears to have been in every way exemplary, and he remained at his post till his death. Meanwhile the three original occupants of the nunnery had been joined by several other ladies, a new chaplain was appointed, the little oratory with which Christina, Emma, and Gunilda had been content was enlarged into a chapel, and a considerable grant of land was bestowed upon the community, which continued to grow until what had been but an insignificant settlement had become an important priory, owning much property in the neighbourhood and elsewhere. Strange to say, however, this prosperity was presently succeeded by a time of great distress, for in 1337 Edward III. granted a special exemption from taxation to the nuns because of their inability to pay their debts. It would, indeed, seem that the sisters had not after all been able to manage their own temporal affairs successfully, but had been too generous to the many pilgrims who claimed their hospitality as a right, but very little is really known of the later history of the priory, except that when under the name of the Nonnerie of Kilnbourne it was surrendered to the commissioners of Henry VIII. its annual value was assessed at £74, 7s. 11d. The nuns whose lives had been given up to aiding the poor and distressed were now compelled to beg their daily bread, the rapacious king exchanged their lands for certain {8} estates owned by the Knights Hospitallers of Jerusalem. Later, the site of the ancient priory was granted to the Earl of Warwick, and after changing hands many times it became the property of the Upton family, one of whom built the spacious church of St. Mary close to the spot where Godwin's little oratory once stood. Near to it is the headquarters of the hard-working sisters of St. Peter's, who carry on under the modern conditions of densely populated Kilburn the traditions of their gentle predecessors, the memory of whose old home is preserved in the names of the Abbey and Priory Roads. Not far away, too, rises the stately spire of the noble Church of St. Augustine, one of Pearson's finest Gothic designs, so that the whole neighbourhood would seem, in spite of all the changes that have taken place, to be still haunted by the spirits of those who withdrew to it so many centuries ago to worship God in solitude.

Although actual historical data relating to the bygone days of Hampstead are few, it is possible, with the aid of a little imagination, to call up various pictures of different stages in its long life-story which, even if not strictly accurate in detail, may serve to give a fairly true impression. When, for instance, Ranulph Pevrel brought his bride to the homestead of which he was the chief villein, the whole of the present Heath and the surrounding districts were wild uncultivated lands, with here and there a little clearing representing the sites of the future villages of Highgate, Hendon, Hornsey, Willesden, and Kilburn; whilst deep in the recesses {9} of the woods were many bubbling springs, the fountain-heads of the Holbourne, the name of which is preserved in that of Holborn, also called the river of Wells, because of the many rills that fed it, but generally known as the Fleet, which gave its name to Fleet Road in Haverstock Hill, and Fleet Ditch and Fleet Street in London; the Brent, which joins the Thames at Brentford; the Tybourne, or double brook, so called because its two arms encircle the Isle of Thorney; and the Westbourne, of which the rivulet beside which Godwin built his cell was one of the many tributaries.

On the banks of these picturesque streams groups of pilgrims no doubt often halted to rest on their way from London viâ the Roman Watling Street, to worship at the tomb of England's first martyr at St. Albans, or at the nearer forest shrines dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, of which there is known to have been one at Willesden, one at Muswell Hill, where the Alexandra Palace now stands, and one at Gospel Oak, which is supposed to owe its quaint name, of comparatively recent origin, to the fact that portions of the Gospel used to be read beneath a spreading oak at the ceremony of beating the bounds of the parish, discontinued since 1896.

It is also certain that the Highgate and Hampstead forests were a favourite hunting-ground of the civic authorities and wealthy citizens of London, but this, of course, would check rather than promote the opening out of the woodlands, and for more than a century and a half after the Conquest there was little or no building on the northern heights. {10} Gradually, however, as the population of the city increased, attention was drawn to the many advantages enjoyed by Hampstead, of which its plentiful water-supply was the chief. There were many water-mills on the upper courses of the streams, whose 'clack,' according to a Norman writer of the twelfth century, was delightful to the ear, and almost from time immemorial the Heath has been looked upon as a paradise by the washerwomen of the neighbourhood, who long enjoyed certain privileges, including that of washing the linen of the royal family. What is now called Holly Hill used to be called Cloth Hill, because it was the public drying-ground, and even now it is sometimes used for that purpose.

It seems certain that the chalybeate wells of Hampstead were known to the Romans, but they were practically forgotten until the sixteenth century, when they were rediscovered, but little notice was taken of them until the close of the seventeenth century, when the value of their medicinal properties was recognised and the foundations were laid for the conversion of Hampstead into a fashionable health resort. It will be interesting to take a farewell look at the old-world hamlet on the eve of its transformation, which can be done with the aid of a Field Book in a manuscript volume now in the Hampstead Free Library, describing a survey made in 1680, showing that waste lands stretched on either side of the main road to London, and that there were but half a dozen houses in what are now High and Heath Streets, of which one was the King {11} of Bohemia Tavern, the site of which is occupied by one bearing the same name, that keeps green the memory, dear to the people of Protestant England, of the Elector Palatine Frederick V., who was elected king of Bohemia in 1619. There was also an inn where Jack Straw's Castle now stands, and one known as Mother Haugh's not far away. The gibbet on which a murderer was hung in chains in 1693 rose up on the west of the North End Road, and on the very summit of Mount Vernon was the mill that gave its name to Windmill Hill. Such were some of the features of Hampstead when in in 1698 the Countess of Gainsborough, on behalf of her infant son the earl, then lord of the manor, gave to the poor of the parish the six acres of land that are now known as the Well's Charity Estate, the administration of which was entrusted to fourteen trustees, who appear to have been aware from the first of the exceptional value of the chalybeate wells on the property. They were of course careful to safeguard to the people to whom they were responsible the right to drink the waters on the spot, and to carry them away for use at home at certain hours of the day, but subject to various restrictions. They leased the well to a succession of tenants, who exploited it with more or less success. The temporary booths and shelters that at first sufficed for the visitors to the well were soon supplemented by substantial buildings, and a brisk trade was done at the Flask Tavern in Flask Walk, where the waters were bottled, that was only pulled down a few years ago, {12} and has been replaced by a new inn bearing the same name.

Advertisements in the London press, notably one in the Postman for 20th April 1700, reflect the efforts made by the lessees of the well to attract custom, and prove that the waters were sold in various parts of the city at the rate of 3d. per flask, and that the messengers who fetched it from the well were expected to return the flasks daily. The public buildings which gathered about the famous chalybeate springs included a long room in which balls and other entertainments were given, a pump-room where the waters were dispensed, a public-house for the supply of less innocuous drinks, a place of worship known as Sion Chapel, which as time went on became a kind of Gretna Green, for any one could be married in it for five shillings; raffling and other shops, stables, and coach-houses. Gardens, with an extensive bowling-green, were laid out, and in fine weather open-air concerts were given; in a word, no pains were spared to attract the beau monde.

A new era now began for Hampstead, for it became the fashion for London doctors to recommend the drinking of the waters on the spot. Novelists, including Fanny Burney and Samuel Richardson, laid the scenes of some of their most exciting episodes at the spa, and on every side stately mansions, standing in their own grounds, rose up for the wealthy patrons who elected to have private residences at Hampstead. What is still known as Well Walk, and was then a beautiful grove, was the favourite promenade of the patients {13} who came to take the waters, and some of the later buildings of the spa are still standing, including the long room, that is now a private residence, after going through many vicissitudes, it having at one time served as a chapel, and at another as a barrack.

The fame of the Hampstead spa seems to have been fully maintained throughout the whole of the eighteenth century, and many are the descriptions in the contemporary press of the gay and, alas, often rowdy scenes that took place in it; but at the beginning of the nineteenth century, though the entertainments were still attended by middle-class crowds, who replaced the aristocratic gatherings of days gone by, faith in the efficacy of the waters died out, and all that now recalls their fame is a commemorative drinking-fountain in Well Walk. To atone for this, however, a reputation of a nobler kind than that of a mere pleasure or health resort was growing up for Hampstead, for by this time it had become the favourite home of many men and women of genius, culture, and refinement, who were able to appreciate its intrinsic charm, and by their association with it have conferred upon it a lasting glory. In some cases the actual houses, in others only the sites of the houses occupied by them can be identified, and their favourite open-air resorts have been again and again described. In what is now the High Street, in a stately mansion, part of which alone remains, the site of the remainder being occupied by the Soldiers' Daughters' Home, lived the high-minded politician Sir Henry Vane, and from it he was taken in 1662 to be beheaded on Tower Hill, in spite of the fact {14} that he had opposed the execution of Charles I. and had been pardoned by Charles II. Later, the same house was occupied by Bishop Butler, and in the garden is still preserved the ancient mulberry-tree beneath which he and his ill-fated predecessor loved to sit. A little lower down the hill still stands Rosslyn House, much changed, it is true, since it was the home of the famous lawyer Alexander Wedderburn, who became Lord Chancellor in 1793, for the beautiful grove of Spanish chestnuts that once surrounded it is replaced by the houses of Lyndhurst Road.

The poet Gay was a constant frequenter of the spa at Hampstead, and often visited his friend, the brilliant essayist Sir Richard Steele, in his charming retreat on the site of the present Steele's Studios, opposite to which was the ancient hostelry, the Load of Hay. Gay may possibly often have met Addison and Pope, perhaps even have gone with them to meetings of the famous Kit Cat Club at the Upper Flask Tavern, now a private residence known as Heath House, to which Richardson's heroine, Clarissa Harlowe, is said to have fled from her dissipated suitor Lovelace, and in which lived for many years and died, the learned annotator of Shakespeare, George Steevens, who bought the tavern in 1771.

THE SPANIARDS, HAMPSTEAD HEATH

To the Bull and Bush Inn, still standing in the Hendon Road, the great painter Hogarth often repaired, and in its garden is a fine tree planted by him, whilst later Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds used frequently to visit it. The actor {15} Colley Cibber, the more famous David Garrick, and the poet Dr. Akenside, were fond of strolling on the Heath, and to lodgings near the church came Dr. Johnson, who when there sometimes received a call from Fanny Burney, who was often at the spa, as is proved by her vivid description of it in Evelina. At North End House, now known as Wildwoods, not far from the Bull and Bush Inn, lived the elder Pitt, Lord Chatham, during his temporary insanity, shut up in a little room, with an oriel window looking out towards Finchley, and the opening in the wall still remains through which his food and letters were handed to him. Caen Wood, or Kenwood House, was the country seat of the great advocate, Lord Mansfield, whose London house was burned by the Gordon rioters in 1780, and a short distance from it is the famous hostelry of the 'Spaniards,' described by Dickens in Barnaby Rudge and alluded to in the Pickwick Papers, that is said to have derived its name from its having been at one time occupied by the Spanish ambassador to the court of James I. To the 'Spaniards' the followers of Lord George Gordon marched after their mad proceedings in the City, and it was thanks to the courage and promptitude of its landlord, Giles Thomas, that it and Caen House were saved from destruction.

No less famous than the 'Spaniards' is the ancient inn known as 'Jack Straw's Castle,' now transformed into a modern hotel, the name of which has never been satisfactorily explained, for it is really impossible to connect it with the devoted follower of Wat Tyler, with whom it was long supposed to have been {16} associated. To it the beau monde used to repair after the races that were held on the Heath, before Epsom and Ascot rivalled it in public favour. Dickens and his friends were fond of going to supper at Jack Straw's Castle in summer evenings, and of late years it has been a favourite meeting-place of authors and artists, Lord Leighton, amongst many others, having been a frequent guest.

Within easy reach of the 'Spaniards' and Jack Straw's Castle, in a house still named after him, dwelt the great lawyer Lord Erskine, who defended Lord George Gordon at the latter's trial for high treason, securing his acquittal; and the broad holly hedge dividing the garden from the Heath, as well as the wood of laurel and bay trees, on what is known as Evergreen Hill, are said to have been planted by his own hands. At Heath House, on the highest point of the Heath, lived Samuel Hoare, the enlightened lover of literature and defender of the oppressed, who was the first to advocate the cause of the negro in England, and amongst his many distinguished guests were the poets Samuel Rogers, Wordsworth, Crabbe, Campbell, and Coleridge, the noted writer John James Park, the first historian of Hampstead, whose work, on its Topography and Natural History, published in 1814, is still the chief authority on the subject up to that date; the philanthropist William Wilberforce, and the not less devoted Sir Samuel Buxton, who succeeded him in 1824 as leader of the anti-slavery party.

Bolton House, on Windmill Hill, was long the home of the cultivated sisters Joanna and Agnes {17} Baillie, with whom Sir David Wilkie sometimes stayed, and Mrs. Barbauld, whose husband was minister of the Presbyterian chapel on Rosslyn Hill, lived first in a house near to them, and later in one in Church Row. Mrs. Siddons, after her retirement from the stage, occupied for several years the house known as Capo di Monte, overlooking the beautiful Judges' Walk, beneath the elms of which assizes are said to have been held in 1663, when the Great Plague of London was raging. The poet-painter William Blake sometimes stayed at a farm at North End, the same later frequented by John Linnell; and the Vale of Health, in which stood the picturesque cottage owned by Leigh Hunt, will be for ever associated with the memory of that eloquent writer and of the greater John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Lord Byron, all of whom are known to have visited him there. Keats was with him for some days in 1816, and in 1817 took rooms in what is now No. 1 Well Walk, where he wrote the greater part of Endymion. Later he went to board with his friend Charles Armitage Brown in a house at the bottom of John Street, known as Lawn Bank, and marked by a tablet, next door to which lived Charles Wentworth Dilke, later editor of the Athenæum, by whom the poet was introduced to Fanny Brawne, with whom he fell in love at first sight. Hyperion, the Eve of St. Agnes, and five of the six celebrated sonnets were written at Lawn Bank, and Keats was looking forward to his marriage with his beloved Fanny when the illness which was to prove fatal began. She and her mother nursed him with the {18} utmost devotion, but nothing could save him, and he was already doomed when he left them to go to Rome in 1821. His memory is still held in great honour in Hampstead, but it was reserved to an American lady, Miss Anne Whitney, who presented his bust to the Parish Church in 1895, to give practical proof of a desire to do him honour in the district he loved so well.

The Arctic explorer, Sir Edward Parry, is said to have had his headquarters at Hampstead; Prince Talleyrand lived in Pond Street during his exile from France; and Edward Irving, founder of the Irvingite sect, is said to have had a house there for a short time. The historian Sir Thomas Palgrave resided on the Green from 1834 to 1861; the poet William Allingham died in Lyndhurst Road in 1889; the novelist Diana Muloch, and the less celebrated Elizabeth Meteyard, were often in the neighbourhood. The mother of Lord Tennyson shared Rosemount, in Flask Walk, with her daughter, and was often visited there by her illustrious son. Sir Rowland Hill, the famous Postmaster-General, resided for thirty years and died at Bertram House, near St. Stephen's Church, and Hampstead was long the home of the novelist Sir Walter Besant and the well-known bibliophile Dr. Garnett.

What may perhaps be called the art era of Hampstead, when it became associated with the names of the most distinguished painters of England, was inaugurated at the end of the eighteenth century by the arrival there of George Romney, who took a house on the hill long supposed to have been that {19} now known as the Mount, in Heath Street, though the recent discovery of a deed of tenancy seems to prove it to have been Prospect House on Cloth Hill, now the Constitutional Club. However that may be, the artist soon found his new quarters too small, and built on to them a large studio for the painting of historic pictures, which Flaxman, who visited him in it, called a fantastic structure, and in which, later, when it had become the Holly Bush Assembly Rooms, Constable gave lectures on landscape painting to the members of the Literary and Scientific Society of Hampstead. Romney did little or no work in Hampstead, for his health was already undermined when he embarked on his new enterprise, and his sojourn left no permanent impress on the neighbourhood, when he fled to Kendal to die in the arms of his long-neglected wife.

Far otherwise was it with Constable, who has done more than any one man to interpret for future generations what Hampstead was in the first half of the nineteenth century, for the Heath and the grand views from its summit inspired some of his finest landscapes, and many of his most charming drawings give details of its scenery. Even before his marriage in 1816 Constable used constantly to go up to Hampstead from his London lodgings to paint, and in 1821 he took a small cottage, No. 2 Lower Terrace, still very much what it was then, for his wife and their three little children. There they lived until 1826, when they removed to the present No. 25 Downshire Hill, but in 1827 Constable gave up his London studio, and settled down permanently {20} with his family in Well Walk, at which house is uncertain, some saying it was No. 40, others No. 46. There his wife, to whom he was devotedly attached, died, and her loss made him cling to Hampstead more closely than ever. She was buried in the churchyard of St. John, where later her husband was laid to rest beside her.

CONSTABLE'S FIRS, HAMPSTEAD HEATH

Though the fame of no one of them is quite equal to that of Constable, many other resident artists have aided in maintaining the æsthetic traditions of Hampstead. Some of the best works of William Collins were produced in a house on the Green, and his friend Edward Irving often visited him there. Sir Thomas Beechey retired to Hampstead after his long career of activity; Edward Duncan, Edward Dighton, and Thomas Davis, all resided for some time and died there. Paul Falconer Poole was looked upon as a Hampstead artist par excellence, for he worked in the neighbourhood for some twenty-five years. William Clarkson Stanfield was devoted to the old town, and lived in what is now the Public Library, in Prince Arthur Road, from 1847 to 1865, when he removed to Belsize Park Gardens, then St. Margaret's Road, dying in his new home in 1869. Alfred Stevens, who lived for some time in Hampstead, and died there in 1875, executed the beautiful monument to the Duke of Wellington for St. Paul's, in the temporary church of St. Stephen's, which he rented for the purpose. The sculptor John Foley passed away at the Priory, Upper Terrace, in 1874, and in 1888 Frank Holl died in the house he had built for himself in Fitz-John's Avenue. The last {21} twenty years of the long life of Miss Margaret Gillies, one of the first Englishwomen to adopt art as a profession, were spent at No. 25 Church Row, and Mrs. Mary Harrison, one of the first members of what is now the Old Water-Colour Society, resided for sixteen years and died at Chestnut Lodge. Even more intimately associated with Hampstead than any of these was George du Maurier, for he turned its scenery and the familiar incidents of its Heath to account in many of his clever drawings for Punch. 'It was,' says his friend Canon Ainger, writing in the Hampstead Annual for 1897, 'by the Whitestone Pond that the endless round of galloping donkeys suggested to him the famous caricature of the "Ponds Asinorum," and it was near a familiar row of cottages at North End that he saw the little creature of eight years old who told her drunken father "to 'it mother again if he dared."'

Du Maurier brought home his bride in 1862 to a house in Church Row, and it was there, and in New Grove House on the Upper Heath, to which he removed later, that his best work was done. He lived at Hampstead through the exciting time of the boom in his famous novel Trilby, which is said to have hastened his end, and on his death in 1896 he was buried in the churchyard of St. John.

The Parish Church of Hampstead replaces, as already stated, a much earlier chapel that was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin. It was completed in 1745, and successfully enlarged in 1747 under the auspices of the beloved Canon Ainger, who was {22} vicar from 1876 to 1895. It is a typical example of the style of the period of its foundation, and the ivy-clad tower that rises from the eastern end composes well with its surroundings, the eighteenth-century houses of Church Row forming a kind of avenue leading up to the main entrance.

The next oldest church in Hampstead is the Roman Catholic chapel of St. Mary in Holly Place, built in 1816, whose first minister was the French Abbé Morel, who was banished from France during the Revolution, and was visited in his retreat by many famous exiles, including the Duchesse d'Angoulême. He became so attached to his English home that he refused to return to his native land when he was recalled, and he died at Hampstead in 1852, leaving behind him a great reputation for sanctity. The year of his death was completed the Protestant church of Christ Church—the lofty spire of which is a notable landmark—associated with the memory of the Rev. Dr. Bickersteth, who, after ministering in it for thirty years, became Bishop of Exeter; and later were erected the churches of St. Saviour and St. Stephen's, that have been supplemented by many other places of worship of different denominations, so that the parish presents indeed a remarkable contrast to the time when the little sanctuary on the hill met the needs of the whole district.

To a certain Mrs. Lessingham belongs the unenviable distinction of having been the first to alienate public land on the Heath by enclosing, in 1775, the grounds of what is still known as Heath {23} House. Her right to do so was contested, but at the trial which ensued she came off victorious, and an example was set which has been all too often followed. The jury actually decided that the land in dispute was of no value, and the vital question at issue, of the power of the lord of the manor to grant permissions for enclosure, was left undecided. Not until 1870 were any really efficient steps taken to preserve for the people the use of the beautiful Heath, but at that date the nucleus of the present extensive estate was secured in perpetuity. Two hundred acres of land were then bought by the Metropolitan Board of Works, and to them were later added the 265 acres of Parliament Hill, the name of which is said by some to commemorate the fact that the conspirators of the Gunpowder Plot watched from it for the blowing up of the Houses of Parliament, whilst others associate it with Cromwell's having placed cannon on it to defend the capital. In 1898 the property of the nation on the northern heights was still further augmented, through the combined efforts of many public societies and private individuals, by the acquisition of the celebrated and beautifully laid out Golder's Hill estate, with the house that once belonged to David Garrick, and was used as a convalescent home for soldiers after the South African war.

Hampstead Heath, with its dependencies, is now universally acknowledged to be one of the most beautiful of the many beautiful open spaces near London, and is the resort on Sundays and Bank {24} holidays of thousands of pleasure-seekers. The views from it, especially from Parliament Hill, are magnificent, embracing London with the dome of St. Paul's, the Tower, and the Houses of Parliament, the Surrey Hills, Harrow, Highgate, Hendon, and Barnet, differing but little, if at all, from what they were when Leigh Hunt and John Keats enjoyed them, and Constable painted his famous landscapes.

Highgate

Perched on a hill that is twenty-five feet higher than the loftiest point of Hampstead Heath, Highgate originally commanded as fine a prospect as it, but unfortunately many of the best points of view are now built over, though from the terrace behind the church, and parts of the cemetery, some idea can still be obtained of the beautiful scene that was the delight of Hogarth and of Morland, of Coleridge and Wordsworth, and many other artists and poets who, at one time or another, resided on the hill.

The name of Highgate is generally supposed to be derived from the Tollgate that used to stand at the entrance to the Bishop of London's park, a two-storied house of red brick, built over an archway that was pulled down in 1769, and to which there are many references in the ancient records of Middlesex. Norden, for instance, in the Speculum Britanniæ bearing date 1593, says: 'Highgate, a hill, over which is a passage, and at the top of the same hill is a gate through which all manner of passengers have their waie; the place taketh the name of this highgate on the hill.... When the {26} waie was turned over the saide hill to leade through the parke of the Bishop of London, there was in regard thereof a toll raised upon such as passed that waie by carriage.'

The Gate House Inn, though considerably modified, still remains to preserve the memory of the building at which the tolls were levied, and in it the quaint ceremony of swearing on the horns was practised until quite late in the nineteenth century. On the subject of this ceremony there has been of late years much learned controversy, but the most plausible explanation of its origin appears to be that the horns—after which, by the way, so many London inns are named—on which the oath was sworn, were merely the symbol of the gatekeeper's right to exact toll from the drovers of the sheep or cattle who passed beneath the archway. The conversion of the custom into an apparently unmeaning farce was probably the result of a harmless frolic indulged in by some gay young travellers that, to use a slang expression, 'took on' with the public, and was gradually expanded into the complex burlesque purporting to give the initiated, by virtue of the oath on the horns, the freedom of Highgate. The ceremony has often been described, and is referred to in the much quoted lines of Byron, who, with a party of friends, once took the oath:—

'Many to the steep hill of Highgate hie,

Ask ye Boeotian shades the reason why:

'Tis to the worship of the solemn horn,

Grasp'd in the holy hand of mystery,

In whose dread name both men and maids are sworn,

And consecrate the oath with draught and dance till morn.'

Until about 1850 it was customary at the inn to stop every stage-coach that passed, and from its passengers select five to whom to administer the oath. These five were led into the principal room, the horns, mounted on a long pole, were produced, and in the presence of a number of witnesses the neophytes were compelled to listen uncovered to the following absurd speech from the landlord:—

'Take notice what I now say ... you must acknowledge me to be your adopted father. I must acknowledge you to be my adopted son. If you will not call me father, you forfeit a bottle of wine. If I do not call you son, I forfeit the same. And now, my good son, if you are travelling through this village of Highgate and you have no money in your pocket, go, call for a bottle of wine at any house you may think proper to enter, and book it to your father's score. If you have any friends with you, you may treat them as well, but if you have any money of your own you must pay for it yourself, for you must not say you have no money when you have.... You must not eat brown bread when you can get white, unless you like brown the best.... You must not kiss the maid while you can kiss the mistress, unless you like the maid best, but sooner than lose a good chance you may kiss them both. And now, my good son, I wish you a safe journey through Highgate and this life. I charge you, my good son, that if you know any in this company who have not taken this oath, you must cause them to take it or make each of them forfeit a bottle of wine.... So now, my son, God bless you; kiss the {28} horns or a pretty girl if you see one here, whichever you like best, and so be free of Highgate.'

The horns or the girl duly kissed as the case might be, and the oath administered, other absurd speeches were made, the farce often ending in somewhat rowdy merriment. Long after the custom was discontinued, too, the crier of Highgate kept a wig and gown in readiness to be donned by any one desirous of obtaining the freedom of Highgate, and the expression 'he has taken the oath' came as time went on to signify he knows how to look after his own interests. In the Gate-House Inn a huge pair of mounted horns is still preserved, and a few years ago a party of enthusiastic local antiquarians amused themselves by going through the ancient farce according to the best authenticated traditions, but whether any of the newly made freemen availed themselves of the privilege of kissing mistress or maid is not recorded.

One of the earliest historical references to Highgate is in the grant made by Edward III. in 1363 to a certain William Phelippe, 'as a reward for his care of the highway between Highgate and Smithfelde, of the privelege of taking customs of all persons using the road for merchandize,' and it has been suggested that this Phelippe may have been one and the same with the 'nameless hermit' who preceded the holy man William Litchfield, to whom in 1386 the Bishop of London gave, to quote his own words, 'the office of the custody of our chapel of Highgate beside our Park of Hareng, and of the house to the same chapel annexed.' This chapel and hermitage were successively occupied by several recluses, the {29} last of whom is supposed to have been a certain William Foote, on whom they were conferred in 1531. The dwelling-house was given in 1577, by Queen Elizabeth, to a favourite protégé of hers named John Farnehame, whose lease was later transferred to the founder of the 'Publique and Free Grammar School of Highgate,' Sir Roger Cholmeley, Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench under Edward VI., who fell into disgrace with Queen Mary, and after suffering imprisonment for some years, lived in great retirement at Hornsey. Sir Roger obtained a licence to build a school, and Bishop Grindal gave him the old Hermitage Chapel, with two acres of land, under certain conditions, one being that the people of Highgate as well as the pupils should have the use of the chapel. It was to serve, in fact, as a kind of chapel of ease to Hornsey, an incidental proof that there were already at the time of the agreement a number of inhabitants in the hamlet of the Highgate. Sir Roger Cholmeley died before the projected work was begun, but his wishes were carefully carried out by his trustees, and the first stone of the institution, which was to have such a long career of usefulness, was laid in 1576.

It does not appear quite clear whether the old Hermitage Chapel was pulled down to give place to a new one, or enlarged to meet the needs of the increased congregation, but in any case the school chapel was the only place of worship in Highgate until 1834, when the parish was separated from Hornsey, and the fine Gothic church of St Michael, the lofty spire of which is a landmark for many miles {30} round, was erected. Five years later the cemetery, that is still the most beautiful suburb of the dead near London, was consecrated, and since then many famous men and women have been buried in it, including the philosopher and chemist Michael Faraday; the eloquent writer Henry Crabb Robinson; the lawyers Judge Payne and Lord Lyndhurst; the artists John James Chalon, Sir William Ross, and John George Pinwell; the poet-painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti; the theologian Frederick Maurice; the novelists George Eliot and Mrs. Henry Ward; the pugilist Tom Sayers; and the no less celebrated cricketer John Lillywhite.

For many years the land round the old school chapel had served as a cemetery, and in it was buried in 1534 the poet Samuel Coleridge, who had lived for many years in Highgate, and when a year later the old school chapel was replaced by the present one, a beautiful Gothic building designed by Cockerell, it was wisely decided to erect the latter over the tomb, that is now enclosed in a crypt approached by a flight of steps from the western side of the building. The new schoolhouse, classrooms, etc., completed in 1869, that replace those that had been in use for some four centuries, and in which many men of note were educated, including Nicolas Rowe the dramatist, harmonise well with the chapel, and the institution bids fair long to maintain in the future the reputation it won in the past.

Highgate no doubt owed its early prosperity and rapid growth during the last hundred and fifty years to its situation at the junction of the two main roads {31} from London that meet in the High Street, not far from the old village green, in the midst of which there used to be a pond, now filled in and planted with trees, round about which the village lads and lasses were wont to dance, and the elder residents to gather to gossip of a summer evening. Before the Bishop of London consented in 1386 to allow a road to be made through his park, Highgate could only be reached by a narrow lane, by way of Crouch End, Muswell Hill, and Friern Barnet, but the new thoroughfare very quickly became the chief highway to the north, and is associated with many noteworthy events and royal progresses. It remained, indeed, without a rival until the beginning of the nineteenth century, when an Act of Parliament was passed sanctioning a licensed company to make a way from the foot of Highgate Hill to join the main road, a principal feature of which was the piercing of a tunnel seven hundred and sixty-five feet long by twenty-four wide and nineteen high, which, alas, was but poorly engineered, for it fell in with a great crash before it was opened to traffic. The tunnel was then replaced by the present fine archway, spanning the road, that was completed in 1813, and for the use of which a toll was levied until 1876, when it was finally remitted.

Unfortunately the once beautiful village of Highgate has of late years been transformed into a somewhat prosaic suburb, but a few relics remain to bear witness to more picturesque days gone by. At the foot of the ascent, a little above the Archway Tavern, opposite the Dick Whittington public-house, {32} is a railed-in stone supposed to occupy the exact site of the one on which the penniless boy, the future Sir Richard Whittington, rested, weary and worn from his long tramp on foot, and heard the bells ring out: 'Turn again, Whittington, thrice Lord Mayor of London Town.'

Within sight of this stone are the Whittington Almshouses, that represent those of the ancient foundation of Sir Richard in Paternoster Row, and were built in 1822 by the Mercers Company, as trustees of the Lord Mayor's will made in 1421, bequeathing the funds for erecting and endowing a college of priests and choristers, and building homes for thirteen poor men. With their picturesque chapel and general air of comfort, it must be owned that they contrast favourably with the ancient almshouses not far off in Southwood Lane, that were founded in 1658 by Sir John Wollaston, and added to seventy years later by Edward Pauncefoot.

Within the grounds of Waterlow Park, part of which was given to the public by Sir Sydney Waterlow, is the famous Lauderdale House, built about 1650, that was long the residence of the infamous Viceroy of Scotland under Charles II., the Duke of Lauderdale, who was probably often visited in it by his venial tool, Archbishop Sharp. To Lauderdale House the dissipated king brought the merry-hearted Nell Gwynn, and it was here that she is said to have forced her royal lover to acknowledge himself to be the father of her boy, the future Duke of St. Albans, by threatening to drop the child out of the window if he refused to do so.

Quite close to Lauderdale House, in a cottage that was pulled down in 1869, lived the poet-patriot Andrew Marvell, who was the friend of Milton and the bitter enemy of his fair neighbour Nell Gwynn, who tried in vain to soften his animosity. Opposite to Marvell's cottage, in Cromwell House, now a branch of the Ormond Street Children's Hospital, resided General Ireton and his wife Bridget, the daughter of the Protector; and a little higher up, in what is now called the Bank, was Arundel House, the seat of the Earls of Arundel, supposed to have been at one time the residence of Sir Thomas Cornwallis, and to have been visited by Queen Elizabeth in 1589 and James I. in 1604. It is, however, more famous as having been the death-place of Francis Bacon, who expired in it in 1626, his end having been hastened, it is popularly believed, through an experiment he tried on his way from London with a view to finding out whether flesh could be preserved in snow.

The courageous William Prynne, who was so cruelly maltreated on 30th June 1637, and his fellow-sufferers for conscience' sake, Dr. Bastwick and the Rev. Henry Burton, were often at Highgate; to the house of Sir Thomas Abney, Dr. Watts came more than once; and the famous Jacobite prelate, Bishop Atterbury, was the frequent guest of his brother Dr. Atterbury, when the latter was minister of Highgate chapel. In a house on the Green lived and died Dr. Henry Sacheverel, the leader of the Tory party in the struggle of 1709, and the intimate friend of Addison. Sir Richard Baker, author of the Chronicles of England, who died in the Fleet Prison in great {34} poverty in 1645, wrote much of his valuable work in a house on the Hill. The famous Calvinistic Methodist, Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, who chose the eloquent preacher Whitefield as one of her favourite chaplains, resided for some time in Highgate; and Church House on the Green was long the home of Sir John Hawkins, the author of the Standard History of Music, who used to drive to London every day in a coach and four.

Hogarth, whilst he was apprentice to a silversmith, was fond of going to the still standing but much altered Flask Inn, outside which the Whitsun morris-dancers used to foot it merrily for the 'honour of Holloway,' as described in the popular comedy Jack Dunn's Entertainment, first published in 1601. The great painter is said to have delighted in making sketches of the frequenters of the bar at the Flask Inn, especially of the tipsy brawlers, whose distorted grimaces he hit off to the life. At another well-known hostelry, the Bull Inn, on the Great North Road, looking down upon Finchley, George Morland, an artist of a very different type to Hogarth, was a familiar figure, for he found plenty of congenial subjects near by, and was on friendly terms with the drivers of all the stage-coaches that halted at the tavern. He used, it is said, to settle his score with mine host with sketches which, if they could now be traced, would be worth as many hundreds of pounds as shillings they then represented.

Occupying a commanding position on the west of the Green was the stately mansion Dorchester {35} House, the seat of Henry, Marquis of Dorchester, from whom it was purchased in the reign of Charles II. by the eccentric philanthropist William Blake, who turned it into a school that ceased to exist in 1688. The mansion, after various vicissitudes, was pulled down; and in one of the houses, now No. 3 The Grove, that were built on its site, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge lived as the paying-guest of a surgeon named Gilman for nineteen years. There he was often visited by Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats, Leigh Hunt, Charles Lamb, Henry Crabb Robinson, Edward Irving, Mr. and Mrs. Cowden Clarke—the latter of whom has eloquently described her stay with the poet in her charming book, My Long Life—and Thomas Carlyle, who dwelt enthusiastically on the glorious view from the windows of the house, that is still, by the way, much what it was in Coleridge's time.

The parish church of Highgate, in which there is a tablet with a long inscription to the memory of Coleridge, and part of the cemetery occupy the site of the mansion-house built in 1694 by Sir William Ashurst, then Lord Mayor of London, and the villas of the present Fitzroy Park replace a fine old house erected in 1780 by Lord Southampton, and named after him. In one of the new houses on this beautiful estate lived the well-known sanitary reformer Dr. Southwood Smith, and near to the Park is Dufferin Lodge, the seat of Lord Dufferin, that was the maiden home of the eloquent writer, the Honourable Mrs. Norton, grand-daughter of Richard Brinsley Sheridan.

In a little house known as the Hermitage, on West Hill, where a modern terrace now stands, and opposite to which there used to be an ash-tree popularly supposed to have been planted by Nelson when he was a boy, dwelt the notorious gambler Sir Wallis Porter, who was often joined there by the Prince Regent; and it was in it that the forger Henry Fauntleroy is said to have long lain hidden from the officers of the law in search of him. In Millfield Lane, and in the charming little Ivy Cottage, now enlarged and known as Brookfield House, the famous comedian, Charles Mathews, dwelt for many years. Millfield Cottage, next door to it, was for a time a favourite retreat of John Ruskin, and in the same lane, as related by Leigh Hunt in his Lord Byron and his Contemporaries, John Keats presented his brother poet with a volume of his poems, the first of many generous gifts.

West Hill, Highgate, is associated with several interesting memories. It was on it that Queen Victoria, in the year after her accession, was saved from what might have been a very serious accident by the landlord of the neighbouring Fox and Crown Inn, who arrested the frightened horses of the royal carriage, at the risk of his own life, as they were dashing down the steep descent. In West Hill Lodge the poets William and Mary Howitt lived and worked for several years, and not far from their old home is Holly Lodge, once the residence of the Duchess of St. Albans, and long the home of the generous and hospitable Baroness Burdett-Coutts, a worthy successor of her aristocratic predecessor, who {37} built in Swain's Lane hard by a group of model cottages known as Holly Village.

In the picturesque cottage opposite to the chief entrance to the grounds of Holly Lodge the philanthropist Judge Payne died in 1870; David Williams, founder of the Royal Literary Fund, and Dr. Rochemond Barbauld, husband of the authoress, were at different times ministers of the Presbyterian chapel in Southwood Lane; and on the site of the once notorious Black Dog Tavern, on the hill going down to Holloway, are the chapel and home of the Passionist Fathers, from which, instead of the ribald songs of drunken revellers, perpetual prayers now go up for the restoration of England to the mother church of Rome.

Hornsey

Little now remains of the beautiful forests which were for many centuries one of the most distinctive characteristics of the northern heights of London, though there are still some unenclosed portions of the vast estate that belonged to the Bishop of London, such as Highgate and Caen Woods, where it is possible to forget for a time the near neighbourhood of the ever-growing towns of Hampstead and Highgate. Equally rapid has been the transformation of the two mother parishes of Hendon and of Hornsey, that from isolated picturesque villages have grown into suburbs of the great metropolis. The latter especially retains scarcely anything to recall the days when it was a favourite summer retreat of the Bishop of London, who had a palace in the park of Haringay, as it was called, until the time of Elizabeth, on Lodge Hill, on the outskirts of {38} what later became the property of Lord Mansfield. The little forest hamlet of Haringay, in which the bishop's retainers used to live, was probably situated in the heart of the wood, now replaced by Finsbury Park, and its one inn, pulled down so recently as 1866, became in course of time first a noted tea-house, and later a place of resort of the aristocracy, who used to practise pigeon-shooting in its garden.

With Hornsey Park are associated many interesting historic memories. It was, for instance, in it that the discontented nobles used to meet to concert measures against the hated favourite of Richard II., Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford. In its palace the Duchess of Gloucester and her confederates, the astrologer Richard Bolingbroke and the Rev. Canon Southwell, concocted the plot against the life of Henry VI., and it was there that the last-named was accused of invoking at the celebration of mass the blessing of God on the evil enterprise, an incident turned to account by Shakespeare in his play of Henry VI. Through Hornsey and Highgate rode Richard III. when still Duke of Gloucester, after the sudden death of Edward IV., accompanied by the doomed boy-king Edward V., and it was in the outskirts of the park that the royal procession was met by the mayor and corporation of London. Almost on the same spot Henry VII. was later welcomed by the loyal citizens of his capital on his way back from a successful expedition against Scotland, and there is a tradition that after the execution at Smithfield, in 1305, of the Scottish patriot Sir William Wallace, his dismembered remains were {39} allowed to rest for a night, on their way north, in the bishop's chapel.

The ivy-clad tower, bearing the arms of Bishops Savage and Warham, who occupied the see of London, the former from 1497 to 1500, the latter from 1500 to 1504, is all that now remains of the ancient church of Hornsey that was founded at the end of the fifteenth century. The new building that was skilfully added on to the tower was begun in 1832, and is said to have been constructed of the materials of the bishop's palace. It contains little of interest except a kneeling effigy of a certain Francis Masters, a boy of about sixteen, and the monument to the Rev. Dr. Atterbury, removed from Highgate Chapel on its demolition, but in the churchyard is the tomb of the poet Samuel Rogers, who died in London in 1855.

Hendon

Hendon, which for many centuries has enjoyed the singular privilege, first granted in 1066, of immunity from all tolls, has retained far more of its ancient rural character than either Highgate or Hornsey, for in spite of the many modern villas that have of late years sprung up within its boundaries, it is still a village in touch with the open country. Its church, though not architecturally beautiful, is finely situated on a lofty hill, and its picturesque, well laid out churchyard, in which rest Nathaniel Hone the painter and Abraham Raimbach the engraver, commands a charming and extensive view, taking in Harrow, Edgware, Stanmore, Elstree, and Mill Hill, with the distant heights of Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire.

The ancient manor of Hendon belonged at the time of the Conquest to the abbots of Westminster, but changed hands many times between the twelfth and eighteenth centuries. The old manor-house (replaced first by an Elizabethan mansion and later by the present Hendon Place, built about 1850) was sometimes occupied by the ecclesiastical owners, and in it, as the guest of the reigning abbot of Westminster, Cardinal Wolsey rested in Holy Week 1530 on his way from Richmond to York after his fall. In 1757 the manor-house was sold by the Earl of Powis, to whose family it had long belonged, to the actor David Garrick, since whose death it has changed hands more than once.

The various rivulets that unite to form the Brent take their rise in Hendon parish, and within its bounds is the beautiful open space, three hundred and fifty acres in extent, known as the Wyldes, a name that probably means the lonely or the unenclosed, that was for more than four centuries the property of Eton College, to which it was given in 1449 by the founder, Henry VI. Part of this fine estate has recently been bought for the public and added to Hampstead Heath, and the remainder, if the necessary funds can be collected, is to be acquired for the formation of a garden suburb, which, if it is ever laid out according to the present plans, will be an ideal addition to the attractions of the northern heights of London. The ancient home farm of the Wyldes is still standing on the edge of Hampstead Heath, but it remains a private residence, and is not included in the scheme of purchase. {41} Its fine barns and outhouses have been thrown into one house, the red-tiled roofs and weather-boarded walls of which present very much the same appearance that they did several centuries ago, and the quaint old homestead, long known as Collin's Farm, but now renamed the Wyldes, has long been a favourite haunt of artists and authors. In it the painter John Linnell and his family resided for a long time, receiving amongst their many guests Constable, Morland, and Blake; and when they removed to London in 1827 their rooms were occupied successively by Samuel Lever, Charles Dickens, and Birket Foster. Ford Madox Brown, Edward Carpenter, the Russian author Stepniak, and Olive Schreiner were often at the Wyldes; and the whole neighbourhood of Hendon was dear to Mrs. Alfred Scott Gatty, the authoress of Parables from Nature, who spent much of her girlhood at the vicarage.

Within an easy walk of Hendon, on the right bank of the Brent, is the still picturesque village of Kingsbury, supposed to occupy the site of one of Cæsar's camps, and to have got its name from its having been the property of King Edward the Confessor, who gave it to the Abbey of Westminster. The quaint little church of St. Andrew, said to be built of Roman bricks and to retain traces of Saxon work, all now hidden in a coating of rough cast, is set on a hill amidst venerable elm-trees dominating the village, which contains many typical old-fashioned cottages, and on the east is the beautiful Kingsbury Lake, or Welsh Harp, an artificial reservoir some three hundred and fifty acres in extent, formed on {42} the eastern course of the Brent as a source of supply for the Regent's Park Locks, a most successful piece of engineering work, presenting the appearance of a natural sheet of water, that is a favourite haunt of a great variety of water-fowl, and is well stocked with fish. Unfortunately, the opening of the Welsh Harp racecourse and station, both named after an ancient inn hard by, has done much to destroy the peaceful seclusion of the beautiful district of Kingsbury, but country lanes still lead from it in many directions, in one of which, running eastward towards Edgware Road, is the farmhouse called High or Hyde House, in which Oliver Goldsmith lived for some time, calling his temporary home the Shoemakers' Paradise, because of a tradition that it was built by a votary of St. Crispin, the patron saint of workers in leather. There many choice spirits visited the poet, and Boswell relates that he once called at the Shoemakers' Paradise, and Goldsmith being out at the time, he nevertheless, 'having a curiosity to see his apartments, went in and found curious scraps of descriptions of animals scrawled upon the walls with a black lead pencil,' evidently notes for the History of Animated Nature.

Two miles north of Hendon, with which it is connected by a beautiful lane leading through fields, is the village of Mill Hill, the church of which, a somewhat commonplace structure, was founded in 1829 by the philanthropist William Wilberforce. Opposite to it is the Congregationalist College, that occupies the site of the beautiful Botanic Garden laid out by the well-known botanist Peter Collinson, the {43} friend and fellow-worker of Linnæus, who was often with him at Mill Hill; and not far off is St. Joseph's College of the Sacred Heart, with a fine chapel and campanile, the latter surmounted by a statue of the patron saint, that is a landmark for many miles round.

Harrow

From the loftier Highwood Hill, close to Mill Hill, a noble view is obtained of the beautiful Harrow Weald, that stretches away in a north-westerly direction to Harrow-on-the-Hill, and is dotted with picturesque villages and hamlets, some of which are still unspoiled by the invasion of the builder. The Hill, crowned by the parish church and famous school of Harrow, rises up abruptly from an undulating plain, and forms a conspicuous feature of the whole neighbourhood, for it is visible from many widely separated points of the northern, southern, and south-western suburbs of London. The name of Harrow, that is a modern adaptation of the Herges of Doomsday Book, is differently interpreted by scholars, some being of opinion that it signifies the church, others the military camp on the hill. In any case, the manor was held soon after the Conquest by Archbishop Lanfranc, and remained in the possession of his successors until 1543, when Archbishop Cranmer exchanged it with Henry VIII. for other property. Three years later it was given to Sir Edward, afterwards Lord, North, and after changing hands several times, it passed to the Rushout family, to whose present representative it now belongs.

The exact site of the ancient manor-house of {44} Harrow is not known, for its ecclesiastical owners early removed to a mansion at Haggeston, now Headstone, near Pinner, supposed to have been close to the present manor farm. However that may be, it seems certain that in 1170, soon after his return home from France, the great Archbishop Thomas à Becket spent several days at Harrow-on-the-Hill, for the story goes that he was on that occasion so grievously insulted by the rector of the parish, the Rev. Nizel de Sackville, that he revenged himself by excommunicating him from the altar of Canterbury Cathedral on the following Christmas Day, just four days before his own assassination in the same building. The parish church of Harrow was built by Archbishop Lanfranc, who died just before its consecration, a ceremony that was performed by his successor, the greatly venerated St. Anselm, who, it is related, was interrupted during the service by two canons sent by the Bishop of London to contest his right to officiate on the occasion. The sacred oil, it is said, was carried off by the emissaries, so that the service could not proceed, and the point at issue was later submitted to St. Wulstan, Bishop of Worcester, the sole remaining Saxon prelate of England, who decided in favour of St. Anselm, since which time the special rights at Harrow of the Archbishop of Canterbury have never again been called in question.

All that now remains of the building associated with Archbishop Lanfranc and St. Anselm is the lower portion of the tower, the western gateway, which has well-preserved Norman pillars, and a finely {45} sculptured lintel. The massive stone font is, however, probably the very one in which baptisms took place in the eleventh century. The main body of the present church—that was recently well restored and enlarged under the direction of Sir Gilbert Scott—dates from the fifteenth century. Its most noteworthy features are the lead-encased wooden spire, the stone porch with the priest's chamber above it, and the open timber roof with figures of angels playing on musical instruments on the corbels. In the church are several interesting fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth century brasses, and in the churchyard is a much defaced ancient tombstone known as Byron's Tomb, on which the poet, who was educated at Harrow, was fond of resting, and to which he referred in an often-quoted letter to his publisher, Mr. John Murray, dated May 26, 1822, and also in the well-known lines—

'Again I behold where for hours I have ponder'd,

As reclining, at eve, on yon tombstone I lay;

Or round the steep brow of the churchyard I wander'd,

To catch the last gleam of the sun's setting ray.'

The view from Byron's Tomb, now enclosed within railings, from the terrace outside the churchyard, the school buildings, and other points of vantage on the Hill, is not perhaps quite so inspiring as that from Hampstead Heath immortalised by Constable, but there is a quiet charm about it, and it is very extensive, embracing parts of Surrey, Buckinghamshire, and Berkshire, with Windsor Castle, the Crystal Palace, and Leith Hill Tower as its most conspicuous features.

The chief interest of Harrow is, of course, the famous school, that ranks second only to Eton amongst the great centres of education in England, and is intimately associated with the memory of many distinguished men, including amongst the headmasters Dr. Vaughan, who ruled from 1844 to 1859, and his successor Dr. Butler, who held office until 1885; while amongst the students were the intrepid traveller James Bruce, the Oriental Sir William Jones, the accomplished scholar Dr. Samuel Parr, Admiral Lord Rodney, the witty writer Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the novelist Theodore Hook, the statesmen Sir Robert Peel, Lord Ripon, Lord Aberdeen, Lord Palmerston, and Sir Spencer Perceval, Cardinal Manning, Archbishop Trench, the philanthropist Lord Shaftesbury, and, most celebrated of them all, the poet Lord Byron.

Founded in 1571 by John Lyon, a yeoman of the hamlet of Preston, to whom there is a fine brass in Harrow Church, the school had in it from the first the elements of growth, and its interests were watched over with untiring care for twenty years by its generous originator. No detail was too trivial for his consideration, and the statutes laid down by him were eminently practicable yet sufficiently elastic to allow of future development, though their simple-hearted author certainly never dreamt of what that development was to be. The salaries of the masters, the books to be used, were all specified; and it is a noteworthy fact that very special stress was laid on the exercise of shooting, all parents being bound to give their boys 'bowstrings, shafts, {47} and braces,' that they might practise archery, which at that time represented what rifle-shooting does now. To arouse the ambition of the students, a prize of a silver arrow was given every year to the best marksman out of six or twelve carefully selected competitors, and it was not until 1771 that the ancient custom was discontinued by the then headmaster, Dr. Heath, on account, he said, of the rowdy crowds who used to flock from London to witness the contests, and the serious interruption it caused in the routine of the school work. The butts at which the students, in picturesque costumes of white and green, used to shoot, and the little hill on which they stood, are gone, their place being taken by modern houses; but the silver arrow made for the competition of 1772 is preserved in the school library, a silent witness to John Lyon's recognition of the fact, on which Lord Roberts and other enlightened patriots are now laying such stress, that every boy should learn how to aid in the defence of his native country.

The first endowment of Harrow School was made in 1575, when Lyon bequeathed to the governors certain lands at Harrow and Preston; but it was not until 1615, twenty years after his death, that his instructions were carried out for the building of a 'large and convenient schoolhouse, three stories high, with a chimney in it, and meet and convenient roomes for the schoolmaster and usher to dwell in, and a cellar under the said roomes to lay in wood and coales ... divided into three several roomes, one for ye master, the second for ye usher, and the {48} third for ye schollers.' Until 1650 this house met all the requirements of the institution, the students boarding, as they do now, in outlying houses; and the big class-room, known for many generations as the Fourth Form Room, with the three small apartments above it and the attic called the Cockloft, still remain much what they were four hundred years ago, and are venerated by all Harrovians as the most ancient portion of their beloved school. The rest of the present buildings are all modern; a new wing with a speech-room, class-rooms, and a library, were added in 1819, and in 1877 it was in its turn supplemented by yet another speech-room. The chapel now in use replaces two earlier ones, and was built in 1857, after the designs of Sir Gilbert Scott. The Vaughan library, commemorating the headmaster after whom it is named, was opened in 1863; and the beautiful Museum buildings, that are perhaps the most satisfactory from an æsthetic point of view of the recent erections, were completed in 1886.

Of the many beautiful villages north of London that have of late years been transformed into suburbs of the ever-growing metropolis, few retain any of their original character, or can, strictly speaking, be called picturesque. Tottenham, in spite of its fine situation, with the river Lea forming its eastern and the New River its western boundaries, is to all intents and purposes a town, the restored High Cross, about which there has been so much learned controversy, the ancient parish church, and two or three old houses near the green, alone bearing witness to the good old times when the quaint poem of The Tournament of Tottenham was written. It is much the same with Edmonton, where, in the still standing Bay Cottage, Charles Lamb lived for some time and died, and in the churchyard of which he and his sister are buried, and where John Keats served his apprenticeship to a surgeon and wrote his earliest poems. It bears but a faint resemblance to the village into which John Gilpin of immortal fame dashed on his famous ride after {50} his vain attempt to pull up at the Bell Inn, on the left-hand side of the road from London. The once charming little hamlet of Whetstone, too, a short distance further north, where, according to local tradition, the soldiers halted to sharpen their swords on the way to Barnet Field, is rapidly losing its rural appearance. On the other hand, the scattered settlement of Friern Barnet—beyond the completely modernised Finchley—with its picturesque church that retains a fine Norman doorway, is still quite a country place; whilst Edgware, the two Stanmores, Elstree, High Barnet, East Barnet, and Enfield, though they too are already marked for destruction, are as yet full of the aroma of the past. Edgware, situated on the ancient Watling Street, prides itself on owning the forge in which Handel, having taken refuge from a storm, was inspired by the rhythmic beats of the hammer on the anvil with the famous melody of the 'Harmonious Blacksmith'; and it also owns several quaint old inns, one of which, the Chandos Arms, preserving the memory of the great mansion—known as The Canons, because it occupied the site of a monastery—that was built for the Duke of Chandos whilst he held the lucrative post of paymaster to the forces, but was pulled down after his death by his successor. Fortunately, however, the richly decorated private chapel of The Canons, in which Handel was organist from 1718 to 1721, and containing the organ on which he played, is still preserved as part of the parish church of Little Stanmore, or Whitchurch, a pretty village about half a mile from Edgware, and in its graveyard Handel and the {51} blacksmith whose name is so closely associated with his are buried not far from each other.

Great Stanmore, near to which are the eighteenth-century mansion known as Bentley Priory, replacing a suppressed monastery, and the beautiful Stanmore Park, the seat of Lord Wolverton, is beautifully situated on a hill commanding very extensive views, and has two churches, one now disused, containing some interesting seventeenth and eighteenth century effigies, the other a somewhat uninteresting modern building. The chief charm of the old-fashioned village of Elstree, originally called Eaglestree, because it was much frequented by eagles, is the fine artificial reservoir haunted by water-fowl, which is nearly as extensive as that of Kingsbury, and it also owns a beautiful old Elizabethan mansion.

High Barnet