Victoria Falls, Zambesi

Victoria Falls, Zambesi

| PAGE | ||

| The Grand Cañon of Arizona | William Haskell Simpson | 3 |

| In Rainbow-Land | Amy Sutherland | 16 |

| Traveling in India | Mabel Albert Spicer | 25 |

| Where the Sunsets of All | ||

| the Yesterdays are Found | Olin D. Wheeler | 38 |

| Firecrackers | Erick Pomeroy | 51 |

| Curious Clocks | Charles A. Brassler | 64 |

| Motoring through the | ||

| Golden Age—Part I | Albert Bigelow Paine | 74 |

| Motoring through the | ||

| Golden Age—Part II | Albert Bigelow Paine | 97 |

| Letter-Boxes in Foreign Lands | A. R. Roy | 119 |

| Lost Rheims | Louise Eugénie Prickett | 124 |

| Where Dorothy Vernon Dwelt | Minna B. Noyes | 135 |

| Glimpses of Foreign Fire-Brigades | Charles T. Hill | 142 |

| Dutch Cheeses | H. M. Smith | 162 |

| A Geography City "Come Alive" | Lindamira Harbeson | 167 |

| The Giant and the Genie | George Frederic Stratton | 180 |

| Out in the Big-Game Country | Clarence H. Rowe | 195 |

| Victoria Falls, Zambesi | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

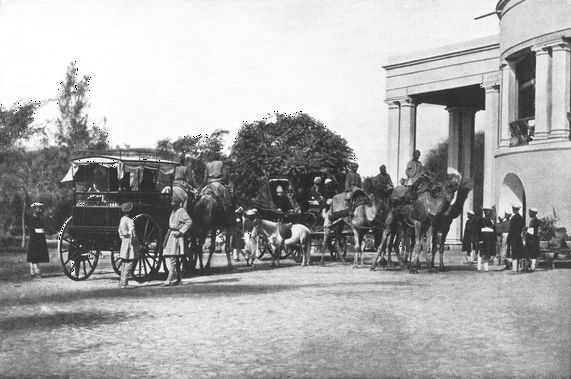

| Camel Carriages of the Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab | 32 |

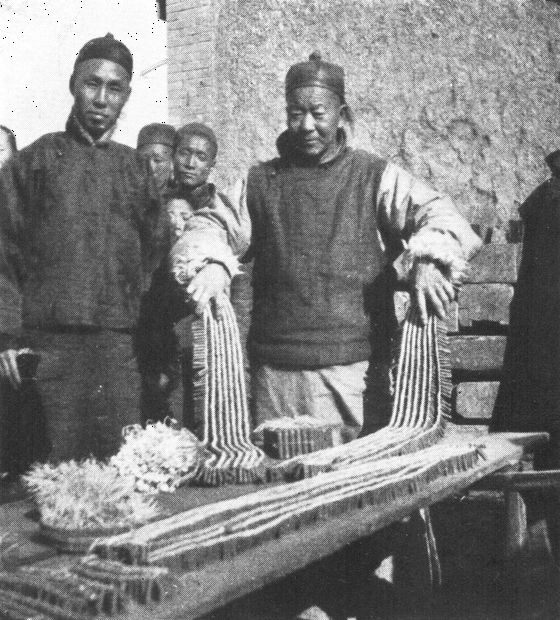

| Strings of Firecrackers | 60 |

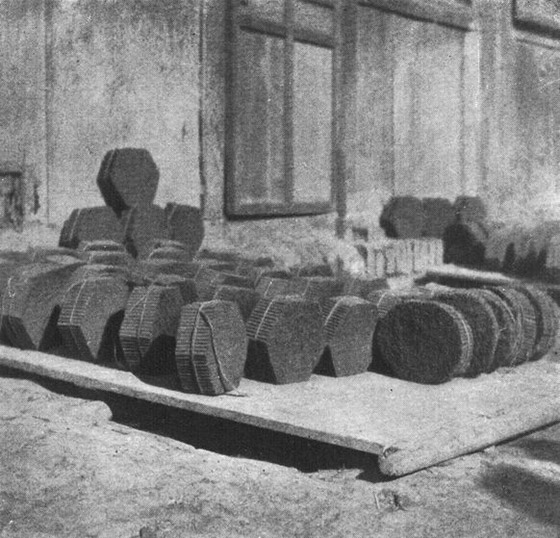

| Hexagonal Bundles of Firecrackers Drying in the Sun | 60 |

| View of Constantinople from the Galata Side | 170 |

Many of those who seek and love earth's greatest scenery have declared that they found it at the Grand Cañon of Arizona. Travelers flock to it from the ends of the earth, though the majority of the visitors, numbering every year about a hundred thousand, are Americans.

The Grand Cañon of the Colorado River, in northern Arizona, is indeed a world wonder, and there is no other chasm in the world worthy to be compared with it. It is more than two hundred miles long, including Marble Cañon, is from ten to thirteen miles wide in the granite gorge section, and is more than a mile deep. It was created ages and ages ago by the erosive action of water, wind, and frost, and it is still being deepened and widened imperceptibly year by year.

The Colorado River, which drains a region of 4 three hundred thousand square miles and is two thousand miles long from the rise of its principal source, is formed in southern Utah by the junction of the Grand and the Green Rivers, and, flowing through Utah and Arizona to tide-water at the Gulf of California, it dashes in headlong torrent through this titanic gorge—this dream of color, tinted like a rainbow or a sunset.

The cañon is reached by a railroad running to the rim, and may be visited any day in the year. It is unlike most other scenery, because when standing on its rim you look down instead of up. Imagine a gigantic trough, filled with bare mountains on each side and sloping to a narrow channel, which in turn is carved deeply and steeply out of solid granite. You come upon it unawares from the level, timbered, plateau country. The experience is an absolutely unique one. Only when you go down one of the trails to the bottom and look up is the view more nearly like other grand mountain vistas. The first glimpse always is from the upper edge, and, having no previous standard of measurement, you find it difficult to adjust yourself to this strange condition. The distant rim swims in a bluish haze. The nearer red rocks forming the inner 5 cañon buttes—crowned with massive table-lands that look like temples, minarets, and battlements—reflect the sunlight in myriad hues. It seems a vast illusion rather than reality. No wonder that the first look often awes the spectator into silence and tears!

But, before you have been here long, you will wish to know how it all happened. You will ask how the cañon was made.

That question was asked by a little girl of Captain John Hance, one of the pioneer guides. Hance contests with a few other early comers the distinction of being the biggest "romancer" in Arizona. He told her that he dug it all himself.

"Why, Captain Hance!" she said, in astonishment, "what did you do with all the dirt?"

He quickly replied, "I built the San Francisco Peaks off there with it!"

Just between ourselves, no one absolutely can tell just how the miracle occurred, for no human being was there at the time. But the geologist has put together, bit by bit, thousands of facts, dug from the rocks which here lie exposed like a mammoth layer-cake and his explanation is so convincing that it must stand as at least the probable truth.

6 Here may be seen rocks of the four geological periods which are among the very oldest of our earth. The rocks of later periods were here once, too, making a layer more than two miles high resting on what is to-day the top, but in some remote age they were shaved off by some great natural force, perhaps a glacier.

The eating away of the rocks which formed the cañon itself is modern. Scientists say it was done, as it were, last Monday or Tuesday, for it was when the top two thirds had been "shaved off," as we have said, that the Colorado River began to cut the Grand Cañon through the rocks that formed the lower third.

While the cracking of the crust, caused by internal fires, may have helped the process of cañon-making, the result of erosion is seen everywhere. Every passing shower, every desert wind, every snowfall, changes the contour of the region imperceptibly but surely. The cañon is Nature's open book in which we may read how the earth was built.

With the coming of the railroad, when this century was yet a baby, tourists began to flock in, hotels were built, highways constructed, trails 7 bettered, and other improvements made. To-day the traveler finds here every comfort.

Although first glimpsed by white men in 1540, when the Spanish conquistadors appeared,—one expedition journeying from the Hopi pueblos in Tusayan across the Painted Desert,—the big cañon remained unvisited, except for Indians and trappers, until 1858, when Lieutenant Ives, of the army engineer corps, made a brief exploration of the lower reaches of the Colorado, coming out at Cataract Creek. It was not thoroughly explored until the year 1869, when Major John W. Powell made his memorable voyage from the entrance to the mouth of the great gorge, passing down the Green and Colorado Rivers. Though he lost two boats and four men, he pushed on to the end. It is fitting that the United States Government has erected to his memory a massive monument of native rock with bronze tablets on one of the points near El Tovar Hotel.

Powell's outfit consisted of nine men and four rowboats. The distance traveled exceeded one thousand miles, from what is now Greenriver, Utah, through the series of cañons to the mouth of the Rio Virgin. In the spring of 1871 he 8 again started with three boats and descended the river to the Crossing of the Fathers. The following summer Lee's Ferry was his point of departure and he went as far as the mouth of Kanab Wash.

Beginning with the Russell and Monett party, in 1907, several others have essayed to duplicate Powell's achievement, and successfully, too, though without adding to our scientific knowledge of the cañon. The trips are exceedingly dangerous, for the rapids conceal rocks that would wreck any boat, and the currents are treacherous. It is safer, by far, to sit at home and read Powell's story.

The average traveler spends too short a time at the cañon. He arrives in the morning and leaves in the evening. Those wise ones, who go about things in more leisurely fashion, stay from three days to a week.

There are certain things that everybody does. Simply by looking through the big telescope at the "lookout," an intimate view may be had of the far-off north rim and of the river gorge five miles below in an air line. It is easier than actually going to those places, though both are accessible. The north rim, or Kaibab Plateau, is about a 9 quarter of a mile higher than the south rim, where you are standing, and is thickly forested with giant pines. Clear streams are found here, and wild game in abundance. Mountain-lions hide in the rocks, and bobcats haunt the trees. It is the home of the bear, too; you may see two "sassy" young sample specimens outside the house where the Indians stay, opposite El Tovar Hotel. The way across the cañon to the north side is not an easy one, as the Colorado must be crossed in a steel cage suspended from a cable, which stretches dizzily from bank to bank. Then follows the stiff climb up Bright Angel Creek, along a trail seldom used.

The Hopi House, where the Indians give their dances every evening for free entertainment of guests, is another attraction. It is occupied by representatives of the Snake Dance Hopis, whose home is many miles northeast across the Painted Desert. You won't see the Snake Dance, of course, but you will witness ceremonies just as interesting, participated in by men, women and children of the Hopi and Navajo tribes. The little tots, especially, are very "cute." They execute difficult steps in perfect time and with the utmost solemnity, while the drummer beats the 10 tom-tom, and the singer chants his weird songs.

Here you may see Navajo silversmiths at work, fashioning curious ornaments from Mexican coins and turquoise, also deft weavers of blankets and baskets.

The Havasupai Reservation, in Cataract Cañon, is about sixty miles away, and Indians from that hidden place of the blue waterfalls are frequent visitors around the railway station.

All of these Indians understand the language of Uncle Sam. Many of them are Carlisle or Riverside graduates, and one young Hopi is writing a history of his tribe in university English.

Have you ever ridden a mule? If not, you will learn how at the cañon, for only on muleback can travelers easily make the trip down and up the trail. Walking is all right going down, but the climb coming back will tire out the strongest hiker: hence the mule, or burro, long as to ears, long as to memory, and "sad as to his songs."

Of the visitors, fat and lean, tall and short, old and young, to each is assigned a mule of the right size and disposition, together with a khaki riding-suit, which fits more or less, all surmounted by hats that are useful rather than ornamental. It is a motley crowd that starts off in the morning, 11 in charge of careful guides, from the roof of the world—a motley crowd, but gay and suspiciously cheerful. It is likewise a motley crowd that slowly climbs up out of the earth toward evening—but subdued and inclined still to cling to the patient mule.

"What did you see?" asked curious friends.

Quite likely they saw more mule than cañon, being concerned with the immediate views along the trail rather than the thrilling vistas unfolding at each turn. Nine out of ten of them could tell you their mule's name, yet would hesitate to say much about Zoroaster or Angel's Gate. They could identify the steep descent of the Devil's Corkscrew, for they were a part of it; the mystery of the deep gulf, stretching overhead and all around, probably did not reach them. That is the penalty one pays for being too much occupied with things close at hand.

Yet only by crawling down into the awe-full depths can the cañon be fully comprehended afterward from the upper rim.

All trail parties take lunch on the river's bank. The Colorado is about two hundred feet wide here, and lashed into foam by the rapids. Its roar is like that of a thousand express-trains. 12 The place seems uncanny. At night, under the stars, you appear to be in another world.

No water is to be found on the south rim for one hundred miles east and west of El Tovar, except what falls in the passing summer showers, and that is quickly soaked up by the dry soil. All the water used for the small army of horses and mules maintained by the transportation department, likewise for the big hotel and annex and other facilities, is hauled by rail in tank-cars from a point one hundred and twenty-five miles distant. The vast volume of water in the Colorado River, only seven miles away, is not available. No way has yet been found to pump economically the precious fluid from a river that to-day is thirty feet deep, and to-morrow is seventy feet deep, flowing below you at the depth of over a mile.

Another curious fact is this: the drainage on the south side is away from the cañon, not into it. The ground at the edge of the abyss is higher than it is a few miles back.

During the winter of 1917 there was an unusual fall of snow, which covered the sides and bottom of the cañon down to the river. Nothing like it had been seen for a quarter of a century. 13 Generally, what little snow falls is confined to the rim and the upper slopes. At times the immense gulf was completely filled with clouds, and then the cañon looked like an inland lake. As a rule, this part of Arizona is a land of sunshine; the high altitude means cool summers; the southerly latitude means pleasant winters.

Naturally, a place like the Grand Cañon has attracted many great artists and other distinguished visitors. Moving-picture companies have staged thrilling photo-plays in these picturesque surroundings. Photographers by the score have trained their finest batteries of lenses on rim, trail, and river, some of them getting remarkable results in natural colors.

Unmoved by this galaxy of talent, however, the Grand Cañon refuses wholly to give up its secrets. Always there will be something new for the seeker and interpreter of to-morrow.

The Grand Cañon is a forest reserve and a national monument. A bill has been introduced in Congress to make it a national park. Meanwhile, the United States Forest Service and the railway company are doing all they can to increase the facilities for visitors. A forest ranger is located near by. His force looks out for fires, 14 and polices the Tusayan Forest district. Covering such a large area with only a few men, a system has been worked out for locating fires quickly. Fifteen minutes saved, often means victory snatched from defeat. Water is not available, for this is a waterless region except during the short rainy season, so recourse must be had to other devices, such as back-firing and smothering with dirt.

Official government names for prominent objects in the region have been substituted for most of the old-time local names. For example, your attention is invited to Yavapai Point, so called after a tribe of Indians, instead of O'Neill's Point. These American Indian words are musical and belong to the country, and the names of Spanish explorers and Aztec rulers also seem suited to the place. Thus the great cañon has been saved the fate of bearing the hackneyed or prosaic names that have been given to many places of wonderful natural beauty throughout our country. Think of a "Lover's Leap" down an abyss of several thousand feet! That atrocity, happily, has been spared us in this favored region.

This great furrow on the brow of Arizona 15 never can be made common by the hand of man. It is too big for ordinary desecration. Always it will be the ideal Place of Silence. Let us continue to hope that the incline railway will not be established here, suitable though it may be elsewhere, nor the merry-go-round. The useful automobile is barred on the highway along the edge of the chasm, though it is permitted in other sections.

It has been my good fortune to meet at the cañon many noted artists, writers, lecturers, "movie" celebrities, singers, and preachers. The impression made upon each one of them by this titanic chasm is almost always the same. At first, outward indifference—on guard not to be overwhelmed, for they have seen much, the wide world over. Then a restrained enthusiasm, but with emotions well in check. After longer acquaintance, more enthusiasm and less restraint. At the end, full surrender to the magic spell.

Until only a few years ago, the Greatest Wonder of the World lay hidden away in one of the most savage parts of Africa. The natives of that region, terrified by its mysterious columns of vapor and its subterranean thunder, did not venture within many miles of it. The white men who had looked upon it could be counted on the fingers of one hand.

And yet, more than fifty years have passed since the explorer Livingstone, journeying eastward along the Zambesi, first beheld that rainbow mist rise above the forest. Of its cause he could learn nothing from the savages; and so, except for his own conjectures, he came quite unprepared upon his splendid discovery. He approached it by the river, which above the Falls is a mile wide, and below them runs for fifty miles at the bottom of a gorge between four and five hundred feet deep, whose twin walls of black, precipitous rock show for all that distance scarcely 17 a ledge or slope where the smallest plant may cling. So, after a peep downward at the Falls, from the island on their brink which now bears his name, he left his new-found marvel less than half seen, and departed whence he came.

And the loneliness of those vast solitudes brooded once more over forest and river, to be broken only at rare intervals by some wandering hunter, or perhaps by a party of men adventuring through endless toil and danger to behold a wonder whose fame, even then, spread as far as that tiny portion of South Africa where white men dwelt and civilization held sway. So things remained until the day of Cecil Rhodes, under whose auspices went forth the voortrekkers, or pioneers, to colonize the vast land now called Rhodesia, in the heart of which the Victoria Falls lie. Many of these voortrekkers, and their wives and children, died at the hands of the savage Amatabele tribe of natives; but the survivors in the end were victorious, and the country became their own.

Cecil Rhodes died, and was laid in his lonely grave among the Matopo Hills, on a rocky summit which looks far out over the land he loved. But his wishes were remembered, the greatest 18 and the least of them; and still, year by year, the Central African Railway grows, every year a little, northward through the forests. And now it has reached the Zambesi, and over that hitherto unconquerable gorge has been thrown one of the most wonderful railway bridges ever built; and close by has sprung up a great hotel, so that the Victoria Falls and their surroundings are attainable at last by all the world.

For many days the approaching traveler has been flying through a mighty tropical forest, in which a path has been cut for the railway line, but which is otherwise so undisturbed, so vast and silent and lonely, that it is hard to believe white men can ever make a home in it. Here the lion prowls at his own sweet will, and legions of antelopes, great and small, graze on the sweet veldt. And here elephants wander in troops of fifty or more, and in the swamps the hippopotamus plows his way through the papyrus reed and the ten-foot Rhodesian grass. The little iron shanties of the railway men are the only signs of civilized life. The natives of the country are few and far between; their kraals, with the conical huts peculiar to this race of Africans, look down from the rare, slight eminences.

19 There is no change in the scenery, little to give warning of the wonder that one approaches. Only, above the noise of the train, a far-off murmur of sound grows upon the ear; and a little while later, floating upward from out the forest, there comes in sight a long line of snowy vapor, which, as the low sun touches it, glows with soft, many-colored lights. This mist-cloud is caused by the sudden narrowing of the great Zambesi River in the Chasm, not two hundred yards wide, which receives the Falls at the end of their leap. The cloud rises at times as much as five hundred feet into the air, and there condenses into rain, which falls in eternal showers glorious in this thirsty land, and makes in the country close about the Falls one perpetual spring.

This tract of land is known as the Rain Forest, and in its tropical magnificence, its soft and delicate beauty, can surely be surpassed by nothing on earth. All about the path laboriously cut through its jungles, rise the trunks of splendid trees, which seem to tower into the very sky; their stems, and the earth about them, are hidden in masses of giant ferns, whose long sprays sway and quiver continually under the weight of the falling drops. Strange plants of many kinds 20 grow here; orchids droop from the trees, and palms raise their graceful heads from out the tangle. Through it all drift the rainbow vapors, and from between the trees the sun strikes in long, slanting rays, and lights up the wet vegetation, the rising mist, the falling raindrops, with an effect so tenderly and unutterably lovely that it often brings tears to the eyes.

In places the forest is more open, and here the giant Rhodesian grass grows, twelve feet high, its flower-heads heavy with wet; and palms, free from the jungle and able to grow as they will, rise thirty feet into the air, their every fringed leaf hung with gems.

At any time a few steps will take the traveler from out this Forest of Rainbows, to where he may stand on the very verge of the terrific Chasm. Here he is directly opposite the Falls, which come rushing over the further tip in a mass of foam as white as snow, to fall with a roar more than four hundred feet into the dreadful abyss. By leaning over, it is possible at times to see the river at the bottom, a boiling, turbulent torrent racing furiously to the right along its rock-bound bed; but more often all is hidden in the mist, which is hurled upward so densely that in places the 21 Chasm seems choked with it, and it rushes past the observer with an audible sound and a suggestion of irresistible force, awe-inspiring to a degree. Opposite the Main Falls, a spot known to the natives as Shongwe, the Caldron, it is so heavy as to blot out sky, forest, and even the Falls themselves, and we are in a strange twilight, half smothered in vapors and wholly deafened with the thunderous roar of the Falls so close at hand.

Everywhere are double rainbows of surpassing brightness, sometimes arches, sometimes complete, glowing circles. They are so close, one may watch their melting colors as in a soapbubble; and they move and change continually with the sun or the movements of the spectator. They gleam softly in the cloud, brilliantly against the stern black cliffs; and tiny rainbows by hundreds dance in the falling sheets of water and among the palms and ferns of the forest.

A strange circumstance cannot fail to strike the observer, and awe him, as perhaps nothing else could, with a sense of the vast depth of the fissure into which he fearfully gazes. The spray and rain bring into being hundreds of streams, which flash over the edge of the cliff opposite the 22 Falls in an eternal effort to rejoin their parent river. But they never reach the bottom. Long before they are half-way down, they vanish, dissipated once more into spray, and borne upward in the form of lighted mist.

Of the radiant beauty of the whole scene, one writer, a traveler of renown, says:

"I believe that on that day I was gazing at the most perfectly beautiful spectacle of all this beautiful world.

"As the sun's rays fell on that kaleidoscopic, ever-moving, changing scene, made up of rock, water, mist, and shivering foliage, the coloring of it all was gorgeous, yet of sweetly tender tints under that luminous, pearly atmosphere formed by the spray-mist. Below, where one caught glimpses of the rushing water, it was turned brown and golden, blue and rich dark green. The cliff, sparkling with dripping water, was of shining black and glowing bronze. The foliage of the Rain Forest was of the green of an eternal spring, and a myriad jewels of twinkling light were made by the water-drops on the trembling leaves. A glorious rainbow spanned the Chasm, and other rainbows flitted in the haze. As for the tender, pale beauty of the Cataract and of the 23 luminous, pearly mist, no words could convey it to the imagination."

Another writer says: "The beauty of the pearl-tinted atmosphere, and the glory of the dazzling rainbows, are the first and the last impressions that the Victoria Falls give to the mind."

The eastern extremity of the cliff opposite the Falls is known as Danger Point; and here the Chasm turns abruptly at right angles, and becomes the famous Gorge which for fifty miles zigzags across country, with the Zambesi like a silver cord at the bottom of it. Just at the turning-point, a mass of rock has fallen from the cliff and lies below in the river—a mass which, it is interesting to note, Livingstone describes as just ready to fall, and which in his drawing of the scene is represented as almost parted from the rest. Along the Gorge a strong, cold wind blows always, and bears the mist as far as the railway bridge and the exquisite palm groves near it.

Above the Falls, the scene is scarcely less fair. Here lies the broad Zambesi, placid and calm under its sunny skies, with its fifty islands, palm-crowned, wonderful, kept ever green and spring-like by the soft spray-showers. On the banks 24 grows the burly baobab, whose trunk is as large as a house; lovely forest fringes either shore, and gay-plumaged birds flit among the flowering trees and feast on the plentiful wild fruits. From here the mists of Victoria take the form of five towering pillars, bending with the wind, white below, but dark farther up, where they condense into rain. Livingstone says of the river at this point: "No one can imagine the beauty of the view from anything witnessed elsewhere. It had never been seen before by European eyes; but scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight."

The monstrous footprints of the hippopotami are thick along the banks, and crocodiles lie sunning themselves in the open spaces. Tiny gray monkeys, with wise black faces, swing from the miles of creeper which festoon the trees. Green parrots shriek, and strange great reptiles crash a path through the tangle. The savage natives punt or paddle their dugouts on the placid bosom of the river. So recent is the white man's advent that the whole is scarcely changed from the day when David Livingstone first looked upon it and realized, with beating heart, the Wonder he had found.

Here in the Western world, where everything is hustle and bustle, where express-trains, automobiles, telephones, telegraphs, pneumatic tubes, and, most recently, aëroplanes save us hours of time, it is difficult to realize that on the other side of the world things are moving along at the same slow pace at which they did centuries ago. Also, here in America, where everybody is saying, "I have no time, I have no time, I have no time!" it seems strange to think that there are countries where time has no value whatsoever, where people believe they have to live thousands and thousands of lives before they reach their heaven, and, consequently, have no regard for time.

Imagine spending the whole night in the train to go one or two hundred miles! Imagine, also, everybody's surprise if some traveler should attempt to take with him into an American sleeping-car 26 a roll of bedding, a box of ice, sawdust, and bottles of soda-water, a huge lunch-basket, spirit-lamps, umbrella-cases, hat-boxes, suitcases and bags without number, a talkative parrot, and a folding chair or two! He would be thought quite mad, of course, and would not be allowed to enter the car. Yet this is how people travel in the trains of India. Sometimes, to be sure, the chairs and noisy parrot are left at home, but quite as often golf-sticks and a folding cot are substituted. Native travelers often carry their cooking-utensils and stoves with them. No one is in a hurry, and the train often waits quite long enough at stations for them to install their stoves on the platform, and cook a good dish of rice.

Most trains have first-, second-, and third-class carriages. Europeans and Americans usually travel first-class, for the best in India is bad enough when compared with the luxuries of travel in Western countries. Most of the carriages are about half as long as those in America, and divided into two compartments without a corridor, each having a lavatory at one end. Running along each side of the compartment, just under the windows, is a long, leather-covered bench, which serves as a seat during the day, and 27 a berth at night. It is equally uncomfortable in both capacities. Above this, folded up against the side of the car, is a leather-covered shelf that lets down to form the upper berth.

My first experience in Indian trains was at night. My turbaned servant arranged my bedding on a bench in a compartment reserved for ladies, switched on an electric fan, salaamed, and went off to find his place in a servants' compartment adjoining. Most trains have special compartments for servants. It is impossible to travel comfortably in India without native servants.

While I was in the dressing-room, preparing for the night, I heard a noise outside, and, looking out, saw an old man with a lantern, down on his knees looking under the berths. He said that he was looking for me, that he was afraid I had missed the train.

Finally, after a great ringing of bells, tooting of whistles, waving of lanterns, and chattering of natives, we pulled out into the darkness and heat. The electric fan burred, mosquitos hummed and bit, the train rocked wildly from side to side.

I was just dozing off, when lights were flashed in my eyes. More bells, whistles, and chattering 28 natives! The door burst open, and an Englishman ordered his man to put his luggage in the compartment. I called out that it was reserved for ladies, and he disappeared with a "Sorry!"

Out into the darkness again, only to be aroused at the next station by the guard, who shouted, "Tickets, please!" The night was one prolonged nightmare of heat, noise, jolting, and mosquitos. By five, I was beginning to sleep, when I was startled by a cry of "Chota Hazree!" I sat up in alarm, wondering what those dreadful-sounding words could mean, when the shutters by my head were suddenly lowered, and a tray of toast and tea thrust in at me. I accepted it, and gave up all idea of sleep. The dreadful-sounding words, I found, meant "little breakfast."

Sometimes we had our meals from a tiffin basket which we carried with us, sometimes from a restaurant car, or again at the station café while the train waited, and sometimes, when all of these failed us, not at all. During the winter, traveling was more comfortable. It was so cold that we needed heavy rugs over us. Some of the express-trains go from twenty to thirty miles an hour.

Each time that the train stops, there is great 29 confusion. The natives arrive at the station hours ahead of time. Here they squat patiently until the train arrives, when they quite lose their heads. In an attempt to find places in the crowded carriages, they run excitedly up and down the platform, clinging to one another, clutching at their clumsy luggage, and screaming at their servants and the trainmen. Equally agitated groups pour out of the cars and scurry off to find bullock carts or ekkas to drive them to the town, which is usually some distance from the station. Boys and women with sweets, fruit, drinking-water, toys, cheap jewelry, and various articles of native production cry their wares at the car windows. Others sell newspapers, which are apt to be weeks old, if the purchaser does not insist upon seeing the date. The platform presents a riot of strange costumes, bright colors, quick-moving figures with jingling bangles and ankles, unholy odors, and clamorous sounds.

At the stations, we were met in different parts of India by the greatest imaginable variety of conveyances—carriages with footmen and drivers in state livery, sent by the native princes, hotel and public carriages after models never dreamed of in America, bullock carts, elephants, camels, 30 rickshaws, and, in Calcutta and Bombay, taxi-automobiles.

When your driver starts off down the street at a reckless gait, clanging a bell in the floor of the carriage with his foot, and a boy on a step at the back calls out "Tahvay!" as you bowl along, you wonder if you have not taken, by mistake, a police wagon or an ambulance. But it is all right; you hear the same shouting and clanging of bells from all the other carriages along the route. This noise is necessary to make the idlers who stroll along the streets hand in hand get out of the way of the carriages.

There are so many horses in India that one wonders why any one should ever walk, and, in fact, very few do. They are of all grades, differing as much as does the shabbiest beggar from the most gorgeous raja. The conveyances to which they are harnessed range from the rickety public ekkas to the royal gold and silver coaches used on state occasions. One sees these wretched-looking public carriages that can be hired for a few cents filled with lazy natives and pulled along by a poor little pony that looks as if it were half-starved. Contrasting with these poor over-worked creatures are the thoroughbreds which 31 literally die in the stables of the princes for lack of exercise.

When we were visiting in the native states, the chiefs sometimes offered us saddle-horses. The first time I rode one of these, I started off gaily, nothing fearing. From a gentle canter my mount suddenly broke into a dead run. Supposing that horses in all countries understood the same language, I said "Whoa," first mildly, persuasively, then loudly, imploringly; but without the slightest effect. On he sped faster and faster, until he overtook another horse, apparently a friend of his, for he slowed down to a walk beside it. I learned afterward that a sound similar to that used in America to make a horse go is used in India to make him stop. So the poor dear did not understand in the least my frantic cries of "Whoa!"

The only other swift-moving animal that it was my misfortune to encounter in India was a camel. This was in the north, in the desert of Rajputana. We were going to visit some tombs about five miles from the city. The others went in carriages, but I preferred to try the "fleet-footed camel." The creature knelt docilely enough to let me climb into the saddle back of the driver; 32 then he unfolded his many-jointed legs and rose, throwing me forward and backward in a most uncomfortable manner.

He walked haughtily about the grounds of the guest-house a few minutes, turning up his nose at everybody, then suddenly let his hind legs collapse, almost throwing me off. The driver succeeded in making him understand that there was no use making a fuss, that he would have to take us. Off across the desert he started, at a gait so rough that I know of nothing with which to compare it. At first, I tried to hold to the saddle, but it was too slippery, so there was nothing to do but to throw my arms about the driver, and hang on to him with all my might. I returned in a carriage!

At Mysore and several other places, we saw camel-carriages. They make a queer sight, these ungainly, loose-jointed animals shambling along in the harness. In Bikanir, we watched the camel corps drill. The natives in this part of India are very finely built men, and they look most imposing in their gaily colored uniforms and turbans as they sit erect on the arrogant camels who snub even their masters.

Camel carriages of the Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab

There are so many slow, lazy ways of traveling 33 in India that it is difficult to say which is the slowest.

Perhaps the bullocks, when they walk, are the slowest of all. They do, however, sometimes trot, and that at a rather brisk pace. They are beautiful animals, and very different from those in America. Their skin is wonderfully soft and silky. Between their shoulders is a large gristly hump. From their chin down between their fore legs hangs a loose, flabby fold of skin.

Of these, the most beautiful are the huge white bulls sacred to the Hindu god Shiva. These lead a life of leisure and luxury. They roam about the streets unmolested, eating from the fruit- and vegetable-stalls at will. Some are housed in the temples of the god.

Those who are not so lucky as to be held sacred have a rather hard time of it. They do most of the heavy hauling, and often suffer very cruel treatment from their drivers. In fact, no other animal is so much the victim of the cruelty and ignorance of the natives as these poor bullocks.

We drove in all sorts of curious-looking conveyances behind these somewhat refractory creatures. Once we drove out into a desolate region to visit some deserted temples, seated on the floor 34 of a bullock cart with an arched cover of plaited bamboo over us. The men along the road walked faster than our bullocks, which went so slowly that, had it not been for the jolting of the cart, we should scarcely have known that we were moving.

In the southernmost part of the peninsula, along the Malabar coast, where there are no trains, we traveled in cabin-boats rowed by natives. It took them all night to row from Quilan to Travandrum, about fifty miles along the backwater. They sang from the moment they began to row, timing the stroke of the oar to the rhythm of their song. In the morning, they appeared as smiling and fresh as they had the evening before when we started.

In Madras, we rode in rickshaws like those of China and Japan. In many parts of India, men take the place of animals, both in carrying people and in transporting cargo. Several times we were carried up mountains in dholies by coolies. These dholies consist of a seat swung between two poles by ropes. They are carried by two or four men, who trot off up the hill with the poles resting on their shoulders, while the passenger dangles between them. They used to come down the mountains so fast that we were quite terrified. 35 The seat would twist and sway, hit against trees, graze along the side of rocks, while our porters would dance along, talking and laughing, without paying the slightest attention to us. Then there are various kinds of push-carts used in different parts of the country.

Of course, the really Indian way of traveling is on elephants. Very few, however, except princes and foreign travelers, ever ride on these lordly animals. In the "zoos" in Calcutta and Bombay there are elephants for the children to ride. The riders climb steps to a platform the height of the elephant's back, then jump into the howdah, where they are tied fast to make sure of their not falling. The old huthi, as the elephant is called there, sways off, waving his trunk, flopping his ears, and blinking his eyes. He makes a tour of the gardens, then returns to the platform to get other children.

At Jaipur, Gwalior, and a number of other towns where there is a fort on a hill, elephants can be hired for the ascension. The huge creatures knelt down while we clambered into the howdah with the aid of ladders. When they rose, it seemed like an earthquake to us on their backs. They climbed the hill so slowly that the 36 others of the party who walked arrived ahead of us. Our huthi would smell about carefully with his trunk before taking each step, then he would put a huge foot forward cautiously, and throw his great weight upon it slowly, as if afraid that the earth would give way under him. It took him so long to accommodate his four feet to each step, that I was thankful he had not as many as a centiped.

To appreciate an elephant in all his glory, one should see him in the splendor of princely procession. Designs in bright colors are painted on his forehead and trunk, trappings of silver ornament his tusks, head, and ankles, a rich cloth of gold and silver embroidery hangs over his colossal sides, and on his back is perched a rare howdah, often of gold and silver, with silk hangings. Aloft in the howdah rides the prince, resplendent with gold, silk, and jewels. In front, on the elephant's neck, sits the mahout, urging him on with strange-sounding grunts, and prods from a short pointed spear.

The elephants are reserved for state occasions. Most of the princes now have automobiles, which they look upon much as a child does its latest toy. The mass of the people depend upon the bullocks 37 and horses to cart them about. There are now, also, in most parts of the empire, telephones and telegraphs; but they are such ancient systems and so unreliable that they are not to be compared with ours. India is through and through a lazy country, where nobody is in a hurry.

In Montana, Idaho, and northern Wyoming lies the region where center the headwaters of the Missouri, Yellowstone, Green, and Snake rivers—the last named a branch of the Columbia. In the early years of the last century it was virtually the center of all human activity in the Rocky Mountain region, being a prolific, but dangerous, trapping-ground for the fur trade of those days.

Here the cloud-piercing peaks of the American Rockies reach their greatest altitude, and the scenery is of the wildest and most impressive character. The Grand Teton, 13,747 feet elevation, overlooking the magnificent Jackson Lake basin, has been climbed but twice by white men.

Since the Yellowstone Park was established, in 1872, the wonders of this region have been more or less familiar. But prior to 1870 they were 39 believed to exist largely in the fertile imagination of the trapper.

The Park region, as we will call it, lay between the old-time northern and southern routes of frontier-day travel across the continent. It is true there were Indian trails leading across and through it, but the Indians, superstitious by nature, seem to have avoided the localities of the geysers and hot springs, and their north and south bound trails lay to the east or west of these areas that now fascinate and interest us.

In 1807, along one of these outside trails—one that just skirted the eastern side of the geyser zone, which here lies along a well-defined north-and-south axis—came the first white man who visited the region. He saw the two beautiful lakes, Jackson and Yellowstone, the dazzling Grand Cañon and its two falls, probably some of the hot springs, and possibly some of the inferior geysers. His trail is shown—marked "Colter's Route in 1807"—on the map of the great explorers Lewis and Clark in 1814. But it was after their return to civilization that they learned of this "hot springs brimstone" locality.

John Colter was a prince of adventurers. His life as a border hero, explorer, and trapper rivals 40 that of any character of fiction; his discovery of the Yellowstone, while on a mission to an Indian tribe, was purely accidental, but it brought him lasting fame. He, himself, probably never realized its importance.

Two or three other old-time and adventurous mountaineers, particularly James, or "Jim," Bridger, afterward visited this locality, but people in general utterly refused seriously to consider, let alone believe, what these men told them regarding it.

Bridger was a man of remarkable ability as a guide and mountaineer, although unable to read, or even to write his own name. He was the discoverer of Great Salt Lake, and as a guide and natural-born scout had no superior, if, indeed, an equal, among frontiersmen. In this capacity he served numerous government and other expeditions and explored and traversed a large part of what was then the Far West. He could tell many a good story about his hairbreadth escapes, and lived to a ripe old age.

To attempt a word-picture of this region and its weird and unusual features is almost useless, and yet every one who visits it endeavors to do so. No words can be found adequately to describe 41 the hot springs, that are numbered by the thousands, and the marvelous hues of their waters and their basins, rimmed and ornamented by fluted and beaded parapets of indescribable delicacy and beauty. Nor can the geysers, leaping suddenly from their deep, nether-world reservoirs, be pictured by words in such a way as to convey to the mind a real image of their strange and fascinating reality.

The first printed description of one of them was by another trapper, Warren A. Ferris, of the old American Fur Company. He visited a geyser area in 1834, but his account of it was not published until July, 1842.

Numerous waterfalls are found here, from cascades a few feet in height to cataracts having twice the leap of Niagara; lakes lie deeply embosomed among the high peaks or the heavy forests, and one of them, twenty miles in length and a mile and a half above the ocean, is now being navigated—think of it!—by motor-boats; thousands of miles of crystal trout-streams, kept supplied with trout by the government hatcheries, radiate in every direction; a natural glass cliff, an Indian quarry for arrow-heads in the ancient days, towers above a lake formed at its base by 42 the wise and cunning beavers. There is, too, a low mountain of pure sulphur, with beautiful boiling sulphur-pools splashing at its foot; and, in contrast to these, there is a gruesome volcano of mud belching from a dark, malodorous cavern, while almost beside this is a beautiful, clear pool of hot water formed by a stream flowing from beneath a green Gothic arch.

The wonderful cañons, exhibiting such different phases of nature's sublime handiwork, awe the beholder. One shows the marvelous way in which lava, cooling, arranges itself in massive, black, symmetric slabs and columns; these enclose a beautiful fall that adds a touch of lightness and beauty. The Grand Cañon is the most startling and extraordinary example of color harmony and nature sculpture to be found in the universe. A Japanese, in the poetic imagery of his race, has said that these brilliant cañon walls have caught and emblazoned upon their mural precipices the sunsets of all the yesterdays—a beautiful conception. One stands awed to silence in the presence of "Nature's immensities" seen here and is almost overwhelmed by the profound splendors and majestic glories of this cañon.

In another respect this park land stands in a 43 category by itself. By federal enactment all of the Yellowstone Park proper and some additional territory bordering it has been made a vast national game-preserve, something not originally planned.

As settlement has increased and the valleys have become occupied by farmers and ranchmen, the game has been forced into the higher valleys and parks of the mountains, or into their remote recesses. Here, within the park boundaries, deer, elk, antelope, bears, mountain-sheep, moose, bison, and the smaller game, birds (between 150 and 200 species), and fur-bearing animals, have a refuge where no hunter or trapper penetrates and danger rarely intrudes. In the Jackson Lake country, hunting is allowed for a limited period.

There are thousands of these various animals that know they are absolutely immune from harm by man when within the bounds of this park. Most of them have never seen a dog nor heard the sound of a rifle. Under these conditions their natural timidity is greatly lessened, and many of them, even bears, become surprisingly tame.

From the supply which Yellowstone Park affords, state and city parks and various game-preserves 44 are being stocked. Experienced men round up the yearling elk into corrals near the railway sidings, and there load them into freight-cars, with plenty of alfalfa hay, and then they are forwarded to their destination. Many carloads are shipped each winter.

The writer recently visited the park in winter to see the game animals. Heavy snows covering their pastures drive them down from their high ranges to the lower hills, cañons, and draws about Gardiner and Mammoth Hot Springs, and here the Government, during times of storm and stress, feeds them alfalfa hay and thus saves them from starvation. Elk by hundreds, or even thousands, dot the hillsides,—there are from 30,000 to 40,000 of them by actual count,—while antelope in goodly numbers range on the open and lower hill-slopes. In Gardiner Cañon beside the road the beautiful mule-deer and the white-tailed deer, touchingly innocent and trustful, and the mountain-sheep—the big-horn fellows—stand or lie, eating alfalfa, and enjoying the protecting care of a beneficent, animal-loving government. They become almost as domesticated as barn-yard animals. Indeed, at Mammoth Hot Springs, the 45 deer actually haunt the kitchen doors and rear themselves on their hind legs against the porch railings, or even climb the steps and peer into the doors and windows, mutely begging for food, which they often take from one's hand. At night they lie on the snow under the large trees, or, in some cases, even sleep in the large cavalry-barns, which have been vacant since the soldiers were removed from the park in the fall of 1916.

Over at the bison range and corral on Lamar River, in the northeastern corner of the park, one sees an interesting sight. Here the mountain scenery of the park reaches its finest development. In summer or winter the ride to the corral from Mammoth Hot Springs is a treat. In summer the bison herd of about three hundred—there is a so-called wild herd of about a hundred some miles farther south—ranges in a beautiful valley and on the adjoining hills and mountain-slopes near the Petrified Forest and Death Gulch. It is under the care of a keeper who lives here with his family, in a comfortable home provided by the Government. The bison are rounded up at intervals during the summer so that their condition and whereabouts shall be always known. The 46 herd originally consisted of only twenty-one animals, purchased by the Government in 1902 at a cost of $15,000.

In January, 1917, I made a trip by sleigh, drawn by a pair of sturdy horses, to the bison corral. On the hills at intervals along the entire route large bands of elk were to be seen. The snow was more than two feet deep, and it required two days, mostly at a walk, to travel the thirty-five miles between Gardiner and the corral. The thermometer registered from ten to fifteen degrees below zero, and for the week following the mercury ranged, in the morning, from thirty-two to fifty degrees below.

In winter the bison are kept in a large pasture-corral a square mile in extent, lying along Rose Creek and Lamar River, and here they remain very contentedly. Long before daylight each morning the herd congregates about the corral gate, waiting for feeding-time. Soon after daylight a sleigh is driven into the inclosure, loaded with alfalfa hay and drawn by a pair of horses that have become so accustomed to the buffalo as to pay no attention to them, even though the latter crowd close about them. The hay is pitch-forked to the ground as the sleigh is slowly driven 47 along, and the animals line themselves out, following it until all are supplied. In an hour or two, after they have eaten their fill, they "mosey" over to the steaming creek that has its sources in some hot springs in the hills, drink slowly and long, and then sedately walk back along deep trails in the snow, the mother bison followed by their calves, to the feeding-ground, where most of them then lie down and sleep for a good part of the day. Mock fights or hunting jousts are indulged in by some of the younger animals and afford variety and amusement, to the participants at least. In the dim light of a winter morning the animals resemble a herd of young elephants.

Reference has been made to the fact that this particular locality is especially interesting from a geographical standpoint. Including the Jackson Lake country it is in this respect one of the most important and interesting regions on the continent. It lies on both sides of the great Continental Divide, which twists and turns in all directions in its course northward and southward.

Outside of the limits of Yellowstone Park itself, the mountain structure found here is, perhaps, not greatly different from that of other parts of the Rockies. The Teton range lies south 48 of the park, and is one of the most prominent and commanding in the entire Rocky Mountain chain. The park region itself seems to be a vent for the pent-up heat of the earth. It is not improbable that these boiling springs and geysers may serve as escape-valves, and be the means of preventing very serious volcanic disturbances, such as occurred here in past ages.

As a watershed the region is equally remarkable. It has been noted that here four of the largest rivers of our country have their sources, interlacing with one another. It is, indeed, a network of thousands of mountain streams forming, ultimately, four great rivers, each flowing to a different point of the compass. The headwaters of the Snake River, joining with the Columbia, find their way into the North Pacific Ocean. The waters of the Green, after a journey through the great cañons of the Southwest, flow into the Pacific through the Gulf of California. To the east flows the Yellowstone, which merges its waters with those of the Missouri, and, after a journey of three thousand miles, flows into the Atlantic through the Gulf of Mexico.

This unique region is no longer difficult of access. Railways reach it from three sides, the 49 north, west, and east, and the Government has spent between one million and two million dollars in establishing excellent roads to enable travelers to view the beauties of the Yellowstone. Here is to be found the finest automobile trip of its length in the country, supplemented by telephone-lines and large and costly hotels. The construction of these buildings must be carried on in winter, and the nails used have to be heated in order to handle them.

With the year 1917 will disappear the last remnant of the old stage-coaching days, a mode of travel which for years was the only method of land travel in the West, and which until now has been the method of transportation in the park. Beginning with this season, automobiles will displace the horses and coaches and numerous other changes in the way of increased comfort, convenience, and pleasure have been planned. The old six-day now becomes one of five days, with several advantageous changes in route and in the time to be spent at different points.

The policy of our Government in establishing these national parks has since been followed by other nations, and it has been praised by such thoughtful observers as, for example, Lord Bryce, 50 ex-ambassador to this country from England. That it has accomplished the object of its originators and is a blessing to mankind is now beyond question.

This is the thirteenth day of the fifth moon of the thirty-third year of Kwang-su, very early in the morning—that is, "very early" for me, because I ordered my "boy" last evening to call me at eight o'clock this morning and not a minute before. Here, in the rambling old temple where we live, we have learned to go to bed with the sun on the fourteenth and on the last day of each Chinese moon, because we know that the wailing pipes of the early morning celebrations before the gods on the first and fifteenth of the moon will be certain to wake us at a truly heathenish hour. But when an extra, unannounced, unexpected festival day is ushered in with cymbals, pipes, and firecrackers, then we just have to lose our morning sleep and try not to lose our tempers. This morning is one of those dawns of misery. Even as I write the temple bells, the 52 drums, and those peculiar jig-time horns are setting up a discordant hubbub in the courtyards, while at intervals a big cracker sends me springing into the air with a start that fearfully tries my nerves. At first this morning I endeavored to sleep, but I soon gave that up to don my kimono and sally forth to find out the cause of this gratuitous Fourth of July. Out on the terrace in front of the inner gates of the temple, to which the rays of the rising sun had not yet bent down, there was gathered a small group of men and boys watching such a display of firecrackers as would have attracted a whole City Hall Park full of people at home. Yet their interest was apparently much like their numbers—very small. They just gazed at the exploding end of the red string of noise without any comments and without any more evident interest than they took in seeing that the small boys picked up all of the unexploded crackers that were blown out of the danger circle by their more powerful brothers. My appearance in a kimono and straw sandals seemed to furnish them with more excitement than the rope of crackers which hung from the firecrackers pole hard by. Such a din! Can you imagine a string of firecrackers, large and small 53 woven together, of over one hundred thousand?

But I am getting ahead of my story. By way of introduction I meant only to tell you that I have for some time been planning to write a letter to your good editor in the hope that he might be willing to pass on to you of the fast-disappearing American "firecracker age" my story of how this country, the native land of the "whip-guns," manufactures and uses these crackers which we think of as belonging only to our Fourth of July.

The desire and determination to write this letter had their birth one day in a city of North China when I was walking along the street where many of the firecracker-makers live—since dubbed "Firecracker Row" on my private chart of the city—and when I suddenly realized how much I should have liked as a boy, when I was "shooting off crackers," to see these places and to know their ways of manufacture. It is difficult not to be interrupted nor to interrupt these lines. Now there are two little pigtailed heads stretched up just over my window-sill, peeping in and asking if I do not wish to buy the tiger-lilies they have gathered on the hillside. So first I will try to tell you how the crackers are made and then how they are used out here, in the hope that you may 54 find as much interest in reading the story as I have found in gathering the information and pictures for it.

Several times I went into the city to visit Firecracker Row, and on one occasion took a series of photographs to show more clearly than words will do the important steps in the process of manufacture. The first step consists in cutting the rough brown paper into pieces long enough to make a hollow tube of several layers in thickness, and wide enough to give the tube a length just twice that of the finished cracker. From the top of his pile the workman takes a pack of these slips, lays them out with one end arranged just like steps, and then slides down the stairs, as it were, with a brush of paste, so as to make the outer ends of the slips stick fast when rolled against the tube. Then he bends the other—the dry—end around an iron nail, and places the nail under a board, which rolls it along the slip until all the paper has curled around it. Once the cracker skeleton is thus formed, he gives it an extra roll or two down the bench for good measure, slides it off the nail into a basket, and has another started before you realize what he is about. Then one of the small apprentices in the 55 shop arranges the skeletons together in a six-sided bundle, like those on the drying board in Cut II, in each of which he puts just five hundred and seven. Why that particular number, I could not find out.

Once dry, the skeletons receive their covering garment of red paper, which makes them so truly "little redskins"—this from the hands of one of the workers without the aid of any machine whatever. He just rolls one of the narrow slips around the tube with his fingers and hurries the growing agitator into another basket to await the time for stuffing in the material that will make him such a lively fellow. Once more, however, they all have to be packed up into the six-sided bundles, this time with two stout strings tied around them a third of the way from the top and bottom, leaving the middle free. The worker takes his big knife and chops right down through the whole bundle to make the clean ends for the tops of the shorter tubes.

These shorter tubes next have a thin paper covering pasted over both tops and bottoms before the bottoms are closed by tapping them with a nail that is just a little larger than the hole in the tube, so that it crowds down some of the paper 56 from the sides. With the bundles right side up, the workman then makes holes in the paper cover over the top, scatters on this the powder dust, and distributes it fairly evenly among the five hundred and seven hungry ones by means of a light brush. When the dust has been tamped a little, the powder finds its way to the middle of the tube in the same manner, the fuse is inserted by another workman, the top layer of dust added, and the whole supply of bottled fun packed in by another tamping with a nail and mallet. Completed and still crowded together in the bundles, the little redskins, with the fuses sticking out of their caps, seem to wear a festive, promising look that clearly says: "You give us a light, and we'll do the rest. And what a high old time it will be!"

When asked how many of these bundles one man could make in a day, the good-natured master of the shop said that one man is counted on to make twenty bundles up to the point where the powder is put in, when the crackers are passed along to others to finish and weave into strings. What a "string" means here in this land, where the diminutive "packs" we used to buy for a nickel would be scored, may be gathered from a glance at those which the maker is holding up in Cut I 57 and at those on the drying-boards in the view shown in Cut II.

Once the crackers have been fully prepared for stringing, either they are put together in such strings as you see in the pictures or they have bigger fellows—four or five times the size of the little ones—plaited in at regular intervals. Then they are wrapped neatly with red or white paper in long packages bearing on the face a red slip with the shop's name printed on it in gilt characters. Some of these packets would have seemed monstrous—needlessly extravagant—in those days when I used to make one or two nickel packs last the better part of a Fourth of July morning by firing them one by one in a hole in the tie-post or under a tin can. To give these longer strings sufficient strength to hang from a pole, as is the usual way of firing them, the workmen weave in with the fuses a light piece of hemp twine. But even this is not an adequate protection against a break in those monster strings that come out on special occasions. The one that started this letter to you was fifteen feet long when I arrived on the scene to investigate the disturbance and had already lost one-half its numbers (I have seen strings from thirty to fifty feet 58 long). To keep such a string from breaking, the Chinese fasten it at intervals to a rope which runs through the pulley at the top of the pole, and then draw the line up until the bottom clears the ground. As the explosions tear away the lowest crackers, the rope is let down and, at the same time, held out away from the bottom of the pole to make a graceful curve of the last few feet of the string. When such long strings have eaten themselves up, you can imagine the amount of fragments around the base of the pole. There are literally basketfuls of them to be first wetted down to guard against fire and then swept up or allowed to blow away when the winds so will.

Thus far you have heard only of little and big crackers. However, there are many distinguishing names among the Chinese for the several varieties and sizes, which I am going to give you before passing on to the story of the special uses of crackers in the Chinese life. First come the ordinary pien p'ao, or "whip-guns," the small ones which derive their name from the similarity which their explosion bears to the snapping of a whip. Sometimes they are called simply "whips," in the same way that the Chinese speak of many things by shortened or changed names. To make 59 these names seem more real to you I have had my Chinese teacher write out for me on separate slips the characters which represent them. More diminutive than the ordinary crackers are the "small whips," about an inch long, that are made especially for the small children to use without danger. For one American cent you could buy about one hundred of these. Then above the whip-guns the next class is the "bursting bamboos," which are said to have taken their name from the fact that in early times bamboo was used as the tubes for these crackers. If such were the case, a line of them must have "made the splinters fly." Even still more powerful are the "hemp thunderers," or, to take a little liberty with the translation, the "hemp sons of thunder," whose name also indicates their construction and their magnitude. Bearing a close similarity in power to our cannon crackers, these have been known at times to break the second-story paper windows in a small compound. They play an important part in the worshiping, or propitiating of the gods in our courtyard, inasmuch as it is considered good form to set them off at intervals while the whip-guns—which my teacher assures me "do not require any watching"—are keeping up their 60 unbroken stream of praise and prayer. They may be considered as good lusty "Amens" throughout the service.

Slightly different in form are the "double noises," which are nothing more or less than our "boosters" that go off first on the ground and again up in the air. To intersperse these throughout the explosions of the whips during any special demonstration is also considered good form. Then allied to these we find another booster, which when it explodes on the ground drives ten others up into the air to become the "flying in heaven ten sounds" with the Chinese. These are only "for play," and that chiefly in the homes from the thirteenth to the seventeenth days of the first moon of the year. With the "lamp flower exploders," that is, our flower-pot, the list of the most common forms of crackers and fire-works becomes exhausted, although the Chinese have several other less usual species, together with many alternative names for both these and the ones I have mentioned.

Strings of firecrackers

Hexagonal bundles of firecrackers

drying in the sun

The time when the Chinese receive most crackers is at the New Year season, when, among the well-to-do families of Tientsin and Peking, it is customary to give a boy the equivalent of our fifty 61 cents for his purchases. In Peking the shops issue special red notes, like our old "shinplasters" in value, for this one use at the New Year. In giving the cracker money to the boys, the parents often make smaller presents to the girls, who are wont to buy paper flowers with their pennies, in proof of which the Chinese have a proverb which runs, "Girls like flowers; boys like crackers."

But this juvenile use of the whip-guns consumes only an infinitesimal part of the whole supply of the year. At many festivals and on many occasions the head of the house, the manager of the shop, or the officers of the gild require great quantities of these propitious harbingers. Greatest of all occasions is the passing of the year, when the people keep up the successor to the ancient custom of setting off the "bamboo guns" in order to drive away the evil spirits of the past twelvemonth and to usher in all that is good for the coming one. All night long the crackers have been popping in the town below, and an early gathering in the temple is held to add the final touch before the new day shall break.

When morning came, I wandered leisurely to my office through the business section of the town to watch the fun at the big shops. Never shall 62 I forget the picture of that street with its dozen or more great red strings of crackers hanging in front of the bigger hongs and seemingly waiting for some word to start the fusillade. Fortunately this came and the storm broke as I waited. For sheer noise, vivacity, and demonstrative liveliness I never have seen the equal of those snarling, bursting lines that poured out their wrath with incessant fervor upon the evil spirits below and shot up their welcome to the good ones above. Then, although this display on New Year's Day seemed grand enough to last a long time, there came more explosions as the shops took down their doors and began their routine business on the fifth or sixth of the moon. Furthermore, custom demands in certain parts that throughout the first ten days of the year there shall be occasional snappings of the whips, to be followed on the fifteenth, at the Feast of Lanterns, by a still greater demonstration.

When a new shop is opened, it is customary for all the front boards to be left up until just before the opening ceremony takes place; then one or two boards are taken down, the manager and his assistants come out to light a string of crackers, and, as the whips are snapping, the remaining 63 boards come down to the sound of this propitious music of the land. Very often there are several strings hung from poles or tripods, and one is lighted after the other in such a way as to maintain a long, unbroken stream of noise.

In most parts of the empire it is also customary for an official, when he receives the seals of office from his predecessor, to have a string of crackers let off at the proper moment. And I must confess to having yielded myself to the pressure of my Chinese assistants in having purchased a few for use at the time we opened our new office at this place. Likewise, when a military official is leaving a post, he is usually accorded a send-off with crackers which have been subscribed for by his men.

And thus, from what has gone before, you may catch some idea of the persistency with which the little redskins have poked their noses into almost all the important celebrations of the Chinese life.

Many of the German cities of the Middle Ages enjoyed great prosperity, which they liked to exhibit in the form of splendid churches and other public buildings; and each one tried to excel the others. When, therefore, in the year 1352, Strassburg was the first to erect a great cathedral clock, which not only showed the hour to hundreds of observers, but whose strokes proclaimed it far and near, there was a rivalry among the rich cities as to which should set up within its walls the most beautiful specimen of this kind.

The citizens of Nuremberg, who were renowned all over the European world for their skill, were particularly jealous of Strassburg's precedence over them.

In 1356, when the Imperial Council, or Reichstag, held in Nuremberg, issued the Golden Bull, an edict or so-called "imperial constitution" which promised to be of greatest importance to the welfare 65 of the kingdom, a locksmith, whose name is unfortunately not recorded, took this as his idea for the decoration of a clock which was set up in the Frauenkirche in the year 1361. The emperor, Charles IV, was represented, seated upon a throne; at the stroke of twelve, the seven Electors, large moving figures, passed and bowed before him to the sound of trumpets.

This work of art made a great sensation.

Other European cities, naturally, desired to have similar sights, and large public clocks were therefore erected in Breslau in 1368, in Rouen in 1389, in Metz in 1391, in Speyer in 1395, in Augsburg in 1398, in Lübeck in 1405, in Magdeburg in 1425, in Padua in 1430, in Dantzic in 1470, in Prague in 1490, in Venice in 1495, and in Lyons in 1598.

Not all, of course, were as artistic as that of Nuremberg; but no town now contented itself with a simple clockwork to tell the hours. Some had a stroke for the hours, and some had chimes; the one showed single characteristic moving figures, while others were provided with great astronomical works, showing the day of the week, month, and year, the phases of the moon, the course of the planets, and the signs of the zodiac.

66 On the town clock of Compiègne, which was built in 1405, three figures of soldiers, or "jaquemarts," so-called (in England they are called "Jacks"), struck the hour upon three bells under their feet; and they are doing it still. The great clock of Dijon has a man and a woman sitting upon an iron framework which supports the bell upon which they strike the hours. In 1714 the figure of a child was added, to strike the quarters. The most popular of the mechanical figures was the cock, flapping his wings and crowing.

The clock on the Aschersleben Rathaus shows, besides the phases of the moon, two pugnacious goats, which butt each other at each stroke of the hour; also the wretched Tantalus, who at each stroke opens his mouth and tries to seize a golden apple which floats down; but in the same moment it is carried away again. On the Rathaus clock in Jena is also a representation of Tantalus, opening his mouth as in Aschersleben; but here the apple is not present, and the convulsive efforts of the figure to open the jaws wide become ludicrous.

One of the first clocks with which important astronomical works were connected is that of the Marienkirche in Lübeck, now restored. Below, at the height of a man's head, is the plate which 67 shows the day of the week, month, etc.; these calculations are so reliable that the extra day of leap-year is pushed in automatically every four years. The plate is more than three meters in diameter. Above it is the dial, almost as large. The numbers from 1 to 12 are repeated, so that the hour-hand goes around the dial only once in twenty-four hours. In the wide space between the axis which carries the hand and the band where the hours are marked, the fixed stars and the course of the planets are represented. The heavens are here shown as they appear to an observer in Lübeck. In the old works the movement of the planets was given incorrectly, for they all were shown as completing a revolution around the sun in 360 days. Of course this is absurd. Mercury, for example, revolves once around the sun in eighty-eight days, while Saturn requires twenty-nine years and 166 days for one revolution. When this astronomical clock was repaired, some years ago, a very complicated system of wheels had to be devised to reproduce accurately the great difference in the movement of the planets. The work consumed two years. There are a great number of moving figures on the Lübeck clock, but they are not of the most 68 conspicuous interest. In spite of this, however, they excite more wonder among the crowds of tourists who are always present when the clock strikes twelve than the really remarkable and admirable astronomical and calendar works.

The Strassburg clock has, more than all others, an actually world-wide fame; and no traveler who visits the beautiful old city fails to see the curious and interesting spectacle which it offers daily at noontime. To quote from one such visitor: "Long before the clock strikes twelve, a crowd has assembled in the high-arched portico of the stately cathedral, to be sure of not missing the right moment. Men and women of both high and low degree, strangers and townspeople alike, await in suspense the arrival of the twelfth hour. The moment approaches, and there is breathless silence. An angel lifts a scepter and strikes four times upon a bell; another turns over an hour-glass which he holds in the hand. A story higher, an old man is seen to issue from a space decorated in Gothic style; he strikes four times with his crutch upon a bell, and disappears at the other side, while the figure of Death lets the bone in its hand fall slowly and solemnly, twelve times, upon the hour-bell. In still another story of the 69 clock, the Saviour sits enthroned, bearing in the left hand a banner of victory, the right hand raised in benediction. As soon as the last stroke of the hour has died away, the apostles appear from an opening at the right hand of the Master. One by one they turn and bow before Him, departing at the other side. Christ lifts His hand in blessing to each apostle in turn, and when the last has disappeared, He blesses the assembled multitude. A cock on a side tower flaps his wings and crows three times. A murmur passes through the crowd, and it disperses, filled with wonder and admiration at the spectacle it has witnessed."

In 1574, the Strassburg astronomical clock replaced the older one. It was mainly the work of Dasypodius, a famous mathematician, and it ran until 1789. Later, the celebrated clock-maker, Johann Baptist Schwilgué (born December 18, 1772), determined to repair it. After endless negotiations with the church authorities, he obtained the contract, and on October 2, 1842, the clock, as made over, was solemnly reconsecrated.

In very recent days, the clock of the City Hall in Olmütz, also renovated, has become a rival to that of the Strassburg Cathedral. In the year 70 1560, it was described by a traveler as a true marvel, together with the Strassburg clock and that of the Marienkirche in Dantzic. But as the years passed, it was most inconceivably neglected, and everything movable and portable about it was carried off. Now, after repairs which have been almost the same as constructing it anew, it works almost faultlessly. In the lower part of the clock is the calendar, with the day of the year, month, and week, and the phases of the moon, together with the astronomical plate; a story higher, a large number of figures move around a group of angels, and here is also a good portrait of the Empress Maria Theresa. Still higher is an arrangement of symbolical figures and decorations, which worthily crowns the whole. A youth and a man, above at the left, announce the hours and quarters by blows of a hammer. The other figures go through their motions at noonday. Scarcely have the blows of the man's hammer ceased to sound, when a shepherd boy, in another wing of the clock, begins to play a tune; he has six different pieces, which can be alternated. As soon as he has finished, the chimes, sixteen bells, begin, and the figures of St. George, of Rudolph of Hapsburg, with a priest, and of Adam and Eve, 71 appear in the left center. When they have disappeared, the chimes ring their second melody, and the figures of the right center appear,—the three Kings of the East, before the enthroned Virgin, and the Holy Family on the Flight into Egypt. When the bells ring for the third time, all the figures show themselves once more.

Clocks operated by electricity are, of course, the product of recent times.

England's largest electric clock was, as our illustration shows, recently christened in a novel manner. The makers, Messrs. Gent & Co., of Leicester, entertained about seventy persons at luncheon on this occasion, using one of the four mammoth dials as a dining-table, a "time table," as the guests facetiously styled it.