Millbank Penitentiary

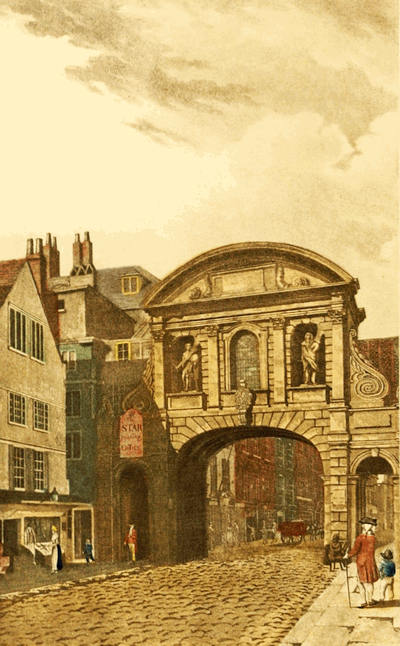

Temple Bar

A famous gateway which stood before the Temple in London built by the noted architect, Christopher Wren, in 1670. According to ancient custom when the sovereign wishes to visit the City of London, he asks permission of the lord mayor to pass through this gateway into the city.

EDITION NATIONALE

Limited to one thousand registered and numbered sets.

NUMBER 307

INTRODUCTION

Millbank Prison stood for nearly a century upon the banks of the Thames between Westminster and Vauxhall, a well-known gloomy pile by the river side, with its dull exterior, black portals, and curious towers. This once famous prison no longer attracts the wide attention of former days but the very name contains in itself almost an epitome of British penal legislation. With it one intimately associates such men as John Howard and Jeremy Bentham; an architect of eminence superintended its erection; while statesmen and high dignitaries, dukes, bishops, and members of Parliament were to be found upon its committee of management, exercising a control that was far from nominal or perfunctory, not disdaining a close consideration of the minutest details, and coming into intimate personal communion with the criminal inmates, whom, by praise or admonition, they sought to reward or reprove. Its origin and the causes that brought it into being; its object, and the success or failure of those who ruled it; its annals, and the curious incidents with which they are filled,—these are topics of much interest to the general reader.

At this distant time it is indeed interesting to observe how thoroughly John Howard understood the subject to which he had devoted his life. In his prepared plan for the erection of the prison he anticipates exactly the method we are pursuing to-day, after more than a century of experience. “The Penitentiary Houses,” he says, “I would have built in a great measure by the convicts. I will suppose that a power is obtained from Parliament to employ such of them as are now at work on the Thames, or some of those who are in the county gaols, under sentence of transportation, as may be thought most expedient. In the first place, let the surrounding wall, intended for full security against escapes, be completed, and proper lodges for the gatekeepers. Let temporary buildings of the nature of barracks be erected in some part of this enclosure which will be wanted the least, till the whole is finished. Let one or two hundred men, with their proper keepers, and under the direction of the builder, be employed in levelling the ground, digging out the foundation, serving the masons, sawing the timber and stone; and as I have found several convicts who were carpenters, masons, and smiths, these may be employed in their own branches of trade, since such work is as necessary and proper as any other in which they can be engaged. Let the people thus employed chiefly consist of those whose term is nearly expired, or who are committed for a short term; and as the ground is suitably prepared for the builders,[7] the garden made, the wells dug, and the building finished, let those who are to be dismissed go off gradually, as it would be very improper to send them back to the hulks or gaols again.”

Suggestions such as these may have seemed impossible to those to whom they were propounded; but that the plan of action was simple and feasible, is now most satisfactorily proved. Elam Lynds, the celebrated governor of Sing-Sing prison, in the State of New York, acted precisely in this manner, encamping out in the open with his hundreds of prisoners, and compelling them in this way to build their own prison-house, cell by cell, as bees would build a hive. De Tocqueville, commenting on this seemingly strange episode of prison history, observes that “the manner in which Mr. Elam Lynds built Sing-Sing would no doubt raise incredulity, were not the fact quite recent, and publicly known in the United States. To understand it we have only to realize what resources the new prison discipline of America placed at the disposal of an energetic man.”

Plans for the new penitentiary buildings were actually prepared, and operations about to commence, when the Government suddenly decided to suspend further proceedings. The principle of transportation had never been entirely abandoned. Western Africa had indeed been selected for a penal settlement, and a few convicts sent there in spite of the deadly character of the climate. But the[8] statesmen of the day had fully recognized that they had no right to increase the punishment of imprisonment by making it also capital; and the Government, despairing of finding a suitable place of exile, was about to commit itself entirely to the plan of home penitentiaries, when the discoveries of Captain Cook in the South Seas drew attention to the vast territories of Australasia. Embarking hotly on the new project, the Government could not well afford to continue steadfast to the principle of penitentiaries, and the latter might have fallen to the ground altogether, but for the interposition of Jeremy Bentham. This remarkable man published, in 1791, his “Panopticon, or the Inspection House,” a valuable work on prison discipline, and followed it, in 1792, by a formal proposal to erect a prison on the plan he advocated.

The outlines on which this model prison was to be constructed were also indicated in a memorandum by Mr. Bentham: “A circular building, an iron cage, glazed, a glass lantern as large as Ranelagh, with the cells on the outer circumference,”—such was his main idea. Within, in the very centre, an inspection station was so fixed that every cell and every part of a cell could be at all times closely observed; but, by means of blinds and other contrivances, the inspectors were concealed, unless they saw fit to show themselves, from the view of the prisoners; by which the feeling of a sort of invisible omnipresence was to pervade the whole place.[9] There was to be solitude or limited seclusion ad libitum; but, unless for punishment, limited seclusion in assorted companies was to be preferred. As we have seen, Bentham proposed to throw the place open as a kind of public lounge, and to protect the prisoners from ill-treatment they were to be enabled to hold conversations with the visitors by means of tubes reaching from each cell to the general centre.

Bentham’s project had much to recommend it and it was warmly embraced by Mr. Pitt and Lord Dundas, the Home Secretary. But secret influences were hostile to it. It is believed that King George III opposed it from personal dislike of Bentham who was an advanced radical. Year after year, although taken up by Parliament, the measure hung fire. At last in 1810 active steps were taken to re-open the question, thanks to the vigour with which Sir Samuel Romilly called public attention to the want of penitentiaries. Nothing now would please the House of Commons but immediate action; and this eagerness to begin is in strange contrast with the previous long years of delay.

Negotiations were not re-opened with Bentham, except in so far as he was entitled to remuneration for his trouble and original outlay. Eventually his claims were referred, by Act of Parliament, to arbitration, and so settled. The same Act empowered certain supervisors to be appointed, hereafter to become possessed of the lands in Tothill Fields, which Bentham had originally bought on behalf of[10] the Government. These lands were duly transferred to Lord Farnborough, George Holford, Esq., M. P., and the Rev. Mr. Becher, and under their supervision the Millbank Penitentiary as it now stands was commenced and finished.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Introduction | 5 | |

| I. | The Building of the Penitentiary | 15 |

| II. | Early Management | 33 |

| III. | The Great Epidemic | 48 |

| IV. | The Penitentiary Reoccupied | 73 |

| V. | Serious Disturbances | 107 |

| VI. | A New Regime | 132 |

| VII. | Ingenious Escapes | 166 |

| VIII. | The Women’s Wards | 198 |

| IX. | The Millbank Calendar | 236 |

| X. | The Penitentiary Impugned | 275 |

| XI. | Last Days of Millbank | 293 |

List of Illustrations

| Temple Bar, London | Frontispiece | |

| Bow Street Office, London | Page | 40 |

| Millbank Penitentiary, Westminster | ” | 108 |

| Prisoners at Dartmoor Marching to Their Work | ” | 194 |

MILLBANK

PENITENTIARY

CHAPTER I

THE BUILDING OF THE PENITENTIARY

Choice of Site—Ancient Millbank—Plan of new Building—Penitentiary described—Committee appointed to Superintend—Opening of Prison in 1816—First Governor and other officers—Supreme Authority—First Arrangements.

The lands which Jeremy Bentham bought from Lord Salisbury were a portion of the wide area known then as Tothill Fields; speaking more exactly, they lay on either side of the present Vauxhall-bridge Road. This road, constructed after the purchase, intersected the property, dividing it into two lots of thirty-eight and fifteen acres respectively. It was on a slice of the larger piece that the prison was ultimately built, on ground lying close by the river. This neighbourhood, now known as a part of Pimlico, was then a low marshy locality, with a soil that was treacherous and insecure, especially at the end towards Millbank Row. People were alive twenty years ago who had shot snipe in the bogs and quagmires round about this spot. A large distillery, owned by a Mr. Hodge, stood near[16] the proposed site of the prison; but otherwise these parts were but sparsely covered with houses. Bentham, speaking of the site he purchased, declared that it might be considered “in no neighbourhood at all.” No house of any account, superior to a tradesman’s or a public-house, stood within a quarter of a mile of the intended prison, and there were in this locality one other prison and any number of almshouses, established at various dates. Of these the most important were Hill’s, Butler’s, Wicher’s, and Palmer’s—all left by charitable souls of these names; and Stow says, that Lady Dacre also, wife of Gregory Lord Dacre of the South, left £100 a year to support almshouses which were built in these fields “more towards Cabbage Lane.” Here, also, stands the Green Coats Hospital, erected by Charles I, but endowed by Charles II for twenty-five boys and six girls, with a schoolmaster to teach them. Adjoining this hospital is a bridewell described by Stow as “a place for the correction of such loose and idle livers as are taken up within the liberty of Westminster, and thither sent by the Justices of the Peace, for correction—which is whipping, and beating of Hemp (a punishment very well suited for idlers), and are thence discharged by order of the Justices as they in their wisdom find occasion.” Again, Stow remarks: “In Tothill Fields, which is a large spacious place, there are certain pest-houses; now made use of by twelve poor men and their wives, so long as it shall please[17] God to keep us from the Plague. These Pest-houses are built near the Meads, and remote from people.” Hospitals, bridewells, alms and pest-houses—the chief occupants of these lonely fields, formed no unfitting society for the new neighbour that was soon to be established amongst them.

As the prison, when completed, took its name from the mill bank, that margined the Thames close at hand, I must pause to refer to this embankment. I can find no record giving the date of the construction of this bank, which was no doubt intended to check the overflow of the river, and possibly, also, to act as one side of the mill-race, which served the Abbot of Westminster’s mill. This mill, which is in fact the real sponsor of the locality, is marked on the plan of Westminster from Norden’s survey, taken in Queen Elizabeth’s reign, in 1573. It stands on the bank of the Thames, almost opposite the present corner of Abingdon and Great College Streets; but it is not quite clear whether it was turned by water from the river, brought along Millbank, or by the stream that came from Tothill Street, which, taking the corner of the present Rochester Row, flowed along the line of the present Great College Street, and under Millbridge to the Queen’s slaughter-house. “The Millbank,” says Stow, “is a very long place, which beginneth by Lindsey House, or rather by the Palace Yard, and runneth up to Peterborough House, which is the farthest house. The part from against College[18] Street unto the Horse Ferry hath a good row of buildings on the east side, next to the Thames, which is mostly taken up with large wood-mongers’ yards, and Brew-houses; and here is a water house which serveth this side of the town; the North Side is but ordinary, except one or two houses by the end of College Street; and that part beyond the Horse Ferry hath a very good row of houses, much inhabited by the gentry, by reason of the pleasant situation and prospect of the Thames. The Earl of Peterborough’s house hath a large courtyard before it and a fine garden behind it, but its situation is but bleak in the winter, and not over healthful, as being so near the low meadows on the South and West Parts.” But it was on one edge of these low, well-wooded meadows that Millbank Penitentiary was to be built.

The first act was to decide upon the plan for the new prison buildings. It was thrown open to competition by public advertisement and a reward was offered for the three best tenders. Mr. Hardwicke was eventually appointed architect and he estimated that £259,725 would be required for the work with a further sum of £42,690 for the foundations. Accommodation was to be provided at this price for six hundred prisoners, male and female, in equal proportions; and the whole building was intended solely for the confinement of offenders in the counties of London and Middlesex. By subsequent decisions, arrived at after the work was first undertaken,[19] the size of Millbank grew to greater proportions, till it was ultimately made capable of containing, as one great national penitentiary, all the transportable convicts who were not sent abroad or confined in the hulks. Of course its cost increased pari passu with its size. By the time the prison was finally completed, the total expenditure had risen as high as £458,000. And over and above this enormous sum, the outlay of many additional thousands was needed within a few years, for the repairs or restoration of unsatisfactory work.

The Penitentiary, as it was commonly called, looked on London maps like a six-pointed star-fort, as if built against catapults and old-fashioned engines of war. The central point was the chapel, a circular building which, with the space around it, covered rather more than half an acre of ground. A narrow building, three stories high, and forming a hexagon, surrounded the chapel, with which it was connected at three points by covered passages. This chapel and its annular belt, the hexagon, form the keystone of the whole system. It was the centre of the circle, from which the several bastions of the star-fort radiated. Each of these salients was in shape a pentagon, and there were six of them, one opposite each side of the hexagon. They were built three stories high, on four sides of the pentagon, having a small tower at each external angle; while on the fifth side a wall about nine feet high ran parallel to the adjacent hexagon. In these[20] pentagons were the prisoners’ cells, while the inner space in each, in area about two-thirds of an acre, contained the airing yards, grouped round a tall, central watch-tower. The ends of the pentagons joined the hexagon at certain points called junctions. The whole space covered by these buildings has been estimated at about seven acres; and something more than that amount was included between them and the boundary wall, which took the shape of an octagon, and beyond it was a moat.

Such is a general outline of the plan of the prison. Any more elaborate description might prove as confusing as was the labyrinth within to those who entered without such clues to guide them as were afforded by familiarity and long practice. There was one old warder who served for years at Millbank, and rose through all the grades to a position of trust, who was yet unable, to the last, to find his way about the premises. He carried with him always a piece of chalk, with which he blazed his path, as does the backwoodsman the forest trees. Angles at every twenty yards, winding staircases, dark passages, innumerable doors and gates,—all these bewildered the stranger, and contrasted strongly with the extreme simplicity of modern prison architecture. Indeed Millbank, with its intricacy and massiveness of structure, was suggestive of an order that has passed. It was one of the last specimens of an age to which Newgate belonged; a period when the safe custody of criminals[21] could be compassed, people thought, only by granite blocks and ponderous bolts and bars. Such notions were really a legacy of mediævalism, bequeathed by the ruthless chieftains, who imprisoned offenders within their own castle walls. Many such keeps and castles long existed as prisons; having in the lapse of time ceased to be great residences, and they served until recently cleared as gaols or houses of correction for their immediate neighbourhood.

On the 9th February, 1816, the supervisors reported that the Penitentiary was now partly ready for the reception of offenders, and begged that a committee might be appointed to take charge of the prison, under the provisions of an act by which the king in Council was thus empowered to appoint “any fit and discreet persons, not being less than ten or more than twenty, as and for a Committee to Superintend the Penitentiary House for the term of one year, then next ensuing, and until a fresh nomination or appointment shall take place.” Accordingly, at the court at Brighton, on the 21st of February of the same year, his Royal Highness the prince regent in Council nominated the Right Hon. Charles Abbot, Speaker of the House of Commons, and nineteen others to serve on this committee, and it met for the first time at the prison on the 12th of March following. The Right Hon. Charles Long, George Holford, Esq., and the Rev. J. J. Becher, were among the members of the new committee, but they continued their[22] functions as supervisors distinct from the other body, until the final completion of the whole building in 1821.

The first instalment of prisoners did not arrive till the 27th of July following. In the interval, however, there was plenty of work to be done. The preparation of rules and regulations, the appointment of a governor, chaplain, matron, and other officials, were among the first of them; and the committee took up each subject with characteristic vigour. It was necessary also to decide upon some scale of salaries and emoluments; to arrange with the Treasury as to the receipts, custody, and payments of the public moneys; and to ascertain the sorts of manufactures best suited to the establishment, and the best method of obtaining work for the convicts, without having to purchase the materials.

On the 10th of March Mr. John Shearman was appointed governor. This gentleman was strongly recommended by Lord Sidmouth, who stated in a letter to the Speaker that, having been induced to make particular inquiries respecting his qualifications and his character, he had found them well adapted to the office in question. Mr. Shearman’s own account of himself was, that he was a native of Yorkshire, but chiefly resident in London; that he was aged forty-four, was married, had eight children, and that he had been brought up to the profession of a solicitor, but for the last four years[23] had been second clerk in the Hatton Garden police office. Before actually entering upon his duties, the committee sent Mr. Shearman on a tour of inspection through the provinces, to visit various gaols, and report on their condition and management.

He eventually resigned his appointment, however, because he thought the pay insufficient, and because the committee found fault with his frequent absences from the prison. He seems to have endeavoured to carry on a portion of his old business as solicitor concurrently with his governorship. His journals show him to have been an anxious and a painstaking man, but neither by constitution nor training was he exactly fitted for the position he was called upon to fill as head of the Penitentiary.

At the same time, on the recommendation of the Bishop of London, the Rev. Samuel Bennett was appointed chaplain. Touching this appointment the bishop wrote, “I have found a clergyman of very high character for great activity and beneficence, and said to be untainted with fanaticism.... His answer is not yet arrived; but I think he will not refuse, as he finds the income of his curacy inadequate to the maintenance of a family, and is precluded from residence on a small property by want of a house and the unhealthiness of the situation.”

Mr. Pratt was made house-surgeon, and a Mr. Webbe, son of a medical man, and bred himself to that profession, was appointed master manufacturer;[24] being of a mechanical turn of mind, he had made several articles of workmanship, and he produced to the committee specimens of his shoe-making, and paper screens.

There was more difficulty in finding a matron. “The committee,” writes Mr. Morton Pitt, “was fully impressed with the importance of the charge, and with the difficulty of finding a fit person to fill this most essential office.” Many persons were of opinion that it would be impracticable to procure any person of credit or character to undertake the duties of a situation so arduous and so unpleasant, and the fact that no one had applied for it was strong proof of the prevalence of such opinions. Mr. Pitt goes on: “The situation is a new one. I never knew but two instances of a matron in a prison, and those were the wives of turnkeys or porters. In the present case it is necessary that a person should be selected of respectability as to situation in life. How difficult must it be to find a female educated as and having the feelings of a gentlewoman, who would undertake a duty so revolting to every feeling she has hitherto possessed, and even so alarming to a person of that sex.”

Mr. Pitt, however, had his eye on a person who appeared to him in every way suitable. He writes: “Mrs. Chambers appears to me to possess the requisites we want; and I can speak of her from a continued knowledge of her for almost thirty years,[25] since she was about fifteen. Her father was in the law, and clerk of the peace for the county of Dorset from 1750 to 1790. He died insolvent, and she was compelled to support herself by her own industry, for her husband behaved very ill to her, abandoned her, and then died. She has learned how to obey, and since that, having kept a numerous school, how to command. She is a woman forty-three years of age, of a strong sense of religion and the most strict integrity. She has much firmness of character with a compassionate heart, and I am firmly persuaded will most conscientiously perform every duty she undertakes to the utmost of her power and ability.” Accordingly Mrs. Chambers was duly appointed.

The same care was exhibited in all the selections for the minor posts of steward, turnkeys male and female, messengers, nurses, porters, and patrols; and most precise rules and regulations were drawn up for the government of everybody and everything connected with the establishment. All these had, in the first instance, to be submitted for the approval of the Judges of the Court of King’s Bench, and subsequently reported to the king in Council and both Houses of Parliament.

The supreme authority in the Penitentiary was vested in the superintending committee, who were required to make all contracts, examine accounts, pay bills, and make regular inspection of prison and prisoners. A special meeting of the committee was[26] to be convened in the second week of each session of Parliament, in order to prepare the annual report. Under them the governor attended to the details of administration. He was to have the same powers as are incident to a sheriff or gaoler,—to see every prisoner on his or her admittance; to handcuff or otherwise punish the turbulent; to attend chapel; and finally, to have no employment other than such as belonged to the duties of his office. The chaplain was to be in priest’s orders, and approved by the bishop of the diocese, and to have no other profession, avocation, or duty whatsoever. Besides his regular Sunday and week-day services, he was to endeavour by all means in his power to obtain an intimate knowledge of the particular disposition and character of every prisoner, male and female; direct them to be assembled for the purposes of religious instruction in such manner as might be most conducive to their reformation. He was expected also to allot a considerable portion of his time, after the hours of labour, to visiting, admonishing and instructing the prisoners, and to keep a “Character-Book,” containing a “full and distinct account from time to time of all particulars relating to the character, disposition, and progressive improvement of every prisoner.” Intolerance was not encouraged, for even then the visitation of ministers other than those of the Established Church was permitted on special application by the prisoners. Such ministers were only[27] required to give in their names and descriptions, and were admitted at such hours and in such manner as the governor deemed reasonable, confining their ministrations to the persons requiring their attendance. No remuneration was, however, to be granted to these additional clergymen. The duties prescribed for the house-surgeon were of the ordinary character, but in cases of difficulty he was to confer with the consulting physician and other non-resident medical men. The master manufacturer was to act as the governor’s deputy if called upon, and was charged more especially with the control and manufacture of all materials and stores. It was his duty to make the necessary appraisement of the value of work done, and to enter the weekly percentage. The total profit was thus divided: three-fourths to the establishment, or 15s. in the pound; one twenty-fourth to the master manufacturer, the taskmaster of the pentagon, and the turnkey of the ward; leaving the balance of one-eighth, or 2s. 6d. in the pound to be credited to the prisoner.

For the rest of the officers the rules were what might be expected. The steward took charge of the victualling, clothing, etc., and superintended the cooking, baking, and all branches of the domestic economy of the establishment; the taskmasters overlooked the turnkeys, and were responsible for all matters connected with the labour and earnings of the prisoners; and the turnkeys, male and female, each having charge of a certain number of[28] prisoners, were to observe their conduct, extraordinary diligence, or good behaviour. The turnkey was expected to enforce his orders with firmness, but was expected to act with the utmost humanity to all prisoners under his care. On the other hand, he was not to be familiar with any of the prisoners, or converse with them unnecessarily, but was to treat them as persons under his authority and control, and not as his companions or associates. The prisoners themselves were to be treated in accordance with the aims and principles of the establishment. On first arrival they were carefully examined by the doctor, cleansed, deprived of all money, and their old clothes burned or sold. Next, entering the first or probation class, they remained therein during half of the period of their imprisonment. Their time in prison was thus parcelled out: at the hour of daybreak, according to the time of the year, they rose; cell doors opened, they were taken to wash, for which purpose soap and round towels were provided; after that to the working cells until 9 a.m., then their breakfast—one pint of hot gruel; at half-past nine to work again till half-past twelve; then dinner—for four days of the week six ounces of coarse beef, the other three a quantity of thick soup, and always daily a pound of bread made of the whole meal. For dinner and exercise an hour was allowed, after which they again set to work, stopping in summer at six, and in winter at sunset. They were then again locked[29] up in their cells, having first, when the evenings were light, an hour’s exercise, and last of all supper—another pint of gruel, hot.

The turnkeys were to be assisted by wardsmen and wardswomen, selected from the more decent and orderly prisoners. These attended chiefly to the cleanliness of the prison, and were granted a special pecuniary allowance. “Second class” prisoners were appointed also, to act as trade instructors. Any prisoner might work extra hours on obtaining special permission. The general demeanour of the whole body of inmates was regulated by the following rule: “No prisoner shall disobey the orders of the governor or any other officer, or shall treat any of the officers or servants of the prison with disrespect; or shall be idle or negligent in his work, or shall wilfully mismanage the same; or absent himself without leave from divine service, or behave irreverently thereat; or shall be guilty of cursing or swearing, or of any indecent expression or conduct, or of any assault, quarrel, or abusive words; or shall game with, defraud, or claim garnish, or any other gratuity from a fellow-prisoner; or shall cause any disturbance or annoyance by making a loud noise, or otherwise; or shall endeavour to converse or hold intercourse with prisoners of another division; or shall disfigure the walls by writing on them, or otherwise; or shall deface, secrete, or destroy, or pull down the printed abstracts of rules; or shall wilfully injure[30] any bedding or other article provided for the use of prisoners.” Offences such as the foregoing were to be met by punishment, at the discretion of the governor, either by being confined in a dark cell, or by being fed on bread and water only, or by both such punishments; more serious crimes being referred to the committee, who had power to inflict one month’s bread and water diet and in a dark cell. Any extraordinary diligence or merit, on the other hand, was to be brought to the notice of the Secretary of State, in order that the prisoner might be recommended as an object for the royal mercy. When finally discharged, the prisoners were to receive decent clothing, and a sum of money at the discretion of the committee, in addition to their accumulated percentage, or tools, provided such money or such tools did not exceed a value of three pounds. Moreover, if any discharged prisoner, at the end of twelve months, could prove on the testimony of a substantial housekeeper, or other respectable person, that he was earning an honest livelihood he was to be entitled to a further gratuity not exceeding three pounds.

The early discipline of the prisoners in Millbank, as designed by the committee, was based on the principle of constant inspection and regular employment. Solitary imprisonment was not insisted upon, close confinement in a punishment cell being reserved for misconduct. All prisoners on arrival were located at the lodge, and kept apart, without[31] work, for the first five days; the object in view being, to awaken them to reflection, and a true sense of their situation. During this time the governor visited each prisoner in the cell for the purpose of becoming acquainted with his character, and explaining to him the spirit in which the establishment had been erected. No pains were spared in this respect. The governor’s character-books, which I have examined, are full of the most minute, I might add trivial, details. After the usual preliminaries of bathing, hair-cutting, and so forth, the prisoners passed on to one of the pentagons and entered the first class.

The only difference between first and second class was, that the former worked alone, each in his own cell; the latter in company, in the work rooms. The question of finding suitable employment soon engaged the attention of the committee. At first the males tried tailoring, the females needlework. Great efforts were made to introduce various trades. Many species of industry were attempted, skilled prisoners teaching the unskilled. Thus, at first, one man who could make glass beads worked at his own trade, and had a class under him; another, a tinman, turned out tin-ware, in which he was assisted by his brother, a “free man” and a more experienced workman; and several cells were filled with prisoners who manufactured rugs under the guidance of a skilful prison artisan. But Mr. Holford, one of the committee, in a paper laid before his colleagues,[32] in 1822, was forced to confess that all these undertakings had failed. The glass-bead blower misconducted himself; the free tinman abused the confidence of the committee, probably by trafficking, and the rug-maker was soon pardoned and set at large. By 1822 almost all manufactures, including flax breaking, had been abandoned, and the prisoners’ operations were confined to shoe-making, tailoring, and weaving. Mr. Holford, in the same pamphlet, objects to the first of these trades, complaining that shoemakers’ knives were weapons too dangerous to be trusted in the hands of prisoners. Tailoring was hard to accomplish, from the scarcity of good cutters, and weaving alone remained as a suitable prison employment. In fact, thus early in the century, the committee were brought face to face with a difficulty that even now, after years of experience, is pressing still for solution.

CHAPTER II

EARLY MANAGEMENT

System proposed and Discipline to be enforced—Conduct of Prisoners; riotous in Chapel—Outbreak of Females—Revolt against Dietary—Millbank overgoverned—Constant interference of Committee—Life inside irregular and irksome.

The system to be pursued at the Penitentiary has now been described at some length. Beyond doubt—and of this there is abundant proof in the prison records—the committee sought strenuously to give effect to the principles on which the establishment was founded. Nevertheless their proceedings were more or less tentative, for as yet little was known of so-called “systems” of prison discipline, and those who had taken Millbank under their charge were compelled to feel their way slowly and with caution, as men still in the dark. The Penitentiary was essentially an experiment—a sort of crucible into which the criminal elements were thrown, in the hope that they might be changed or resolved by treatment into other superior forms. The members of the committee were always in earnest, and they spared themselves no pains. If they had a fault, it was in over-tenderness towards the felons committed to their charge.[34] Millbank was a huge plaything; a toy for a parcel of philanthropic gentlemen, to keep them busy during their spare hours. It was easy to see that they loved to run in and out of the place, and to show it off to their friends; thus we find the visitor, Sir Archibald Macdonald, bringing a party of ladies to visit the pentagon, when “the prisoners read and went through their religious exercises,” which edifying spectacle gave great satisfaction to the persons present. Again, at Christmas time the prisoners were regaled with roast beef and plum pudding, after which they returned thanks to the Rev. Archdeacon Potts, the visitor (who was present, with a select circle of ladies and gentlemen), “appearing very grateful, and singing ‘God save the King.’” With such sentiments uppermost in the minds of the superintending committee, it is not strange that the gaoler and other officials should be equally kind and considerate. No punishment of a serious nature was ever inflicted without a report to the visitor, or his presence on the spot. All of the female prisoners, when they were first received, were found to be liable to fits, and the tendency gave Mr. Shearman great concern, till it was found that by threatening to shave and blister the heads of all persons so afflicted immediate cure followed. Two Jewesses, having religious scruples, refused to eat the meat supplied, whereupon the husband of one of them was permitted to bring in for their use “coarse meat and fish, according to[35] the custom of the Jews;” and later we find the same man came regularly to read the Jewish prayers, as he stated, “out of the Hebrew book.” Many of the women refused positively to have their hair cut short; and for a time were humoured. In February, 1817, all the female prisoners were assembled, and went through a public examination, before the Bishops of London and Salisbury, to show their progress in religious instruction, and acquitted themselves greatly to the satisfaction of all present.

Judith Lacy, having been accused of stealing tea from a matron’s canister, which had been put down, imprudently, too near the prisoner, was so hurt at the charge, that it threw her into fits. She soon recovered, and it was quite evident she had stolen the tea. Any complaint of the food was listened to with immediate attention. Thus the gruel did not give satisfaction and was repeatedly examined.

“A large number of the female prisoners still refuse to eat their barley soup,” says the governor in his journal on the 23rd April, 1817, “several female prisoners demanding an increase of half a pound of bread,” being refractory. Next day some of them refused to begin work, saying they were half-starved.

Mary Turner was the first prisoner released. She was supposed to be cured of the criminal taint. Having equipped her in her liberty clothing, “she was taken into the several airing grounds in which were her late fellow-prisoners. The visitor (Sir[36] Archibald Macdonald) represented to them in a most impressive manner the benefits that would result to themselves by good behaviour. The whole were most sensibly affected, and the event,” he says, “will have a very powerful effect on the conduct of many and prove an incentive to observe good and orderly demeanour.”

Next day all of the female prisoners appeared at their cell windows, and shouted vociferously as Mary Turner went off. This is but one specimen of the free and easy system of management. Of the same character was a petition presented by a number of the female prisoners, to restore to favour two other convicts who had been punished by the committee. Indeed, the whole place appears to have been like a big school, and a degree of license was allowed to the prisoners consorting little with their character of convicted criminals.

This mistaken leniency could end but in one way. Early in the spring the whole of the inmates broke out in open mutiny. Their alleged grievance was the issue of an inferior kind of bread. Change of dietary scales in prisons is always attended with some risk of disturbance, even when discipline is most rigorously maintained. In those early days of mild government riot was, of course, inevitable. The committee having thought fit to alter the character of the flour supplied, soon afterwards, at breakfast-time, all the prisoners, male and female, refused to receive their bread. The women complained[37] of its coarseness; and all alike, in spite of the exhortations of the visitor, Mr. Holford, left it outside their cell doors. Next day, Sunday, the bread was at first taken, then thrown out into the passages. The governor determined to have Divine Service as usual, but to provide against what might happen, deposited within his pew “three brace of pistols loaded with ball.” To make matters worse, the Chancellor of the Exchequer arrived with a party of friends to attend the service. The governor (Mr. Shearman’s successor) immediately pointed out that he was apprehensive that in consequence of the newly adopted bread the prisoners’ conduct would not be as orderly as it had ordinarily been. At first the male prisoners were satisfied by raising and letting fall the flaps of the kneeling benches with a loud report, and throwing loaves about in the body of the chapel, while the women in an audible tone cried out, “Give us our daily bread.” Soon after the commencement of the communion service, the women seated in the gallery became more loudly clamorous, calling out most vociferously, “Better bread, better bread!” The men below, in the body of the church, now rose and stood upon the benches; but again seated themselves on a gesture from the governor, who then addressed them, begging them to keep quiet. Among the women, the confusion and tumult was continued, and was increased by the screams of alarm from the more peaceable. Many fainted, and others[38] in great terror entreated to be taken away. These were suffered to go out in small bodies, in charge of the officers, and so continuously removed, until all of the women had been withdrawn. About six of them, as they came to the place where they could see the men, made a halt and most boisterously assailed them, calling them cowards, and such other opprobrious names. After the women had gone the service proceeded without further interruption, after which the Chancellor of the Exchequer (who was present throughout) addressed the men, giving them a most appropriate admonition, but praising their orderly demeanour, which he promised to report to the Secretary of State. Afternoon service was performed without the female congregation, and was uninterrupted except by a few hisses from the boys.

Next morning the governor informed the whole of the prisoners, one by one, that the new brown bread would have to be continued until the meeting of the committee; whereupon many resisted when their cell doors were being shut, and others hammered loudly on the woodwork with their three-legged stools; and this was accompanied by the most hideous shouts and yells. In one of the divisions, four prisoners, who were in the same cell, were especially refractory, “entirely demolishing the inner door, every article of furniture, the two windows and their iron frames; and, having knocked off large fragments from the stone of the[39] doorway, threw the pieces at, and smashed to atoms the passage windows opposite.” One of them, by name Greenslade, assaulted the governor, on entering the cell, with part of the door frame; but he parried the blow, drove the prisoner’s head against the wall, and was also compelled, in self-defence, to knock down one Michael Sheen. Such havoc and destruction was accomplished by the prisoners, that the governor repaired to the Home Secretary’s office for assistance. Directed by him to Bow Street, he brought back a number of runners, and posted them in various parts of the building, during which a huge stone was hurled at his head by a prisoner named Jarman, but without evil consequences. A fresh din broke out on the ringing of the bell on the following morning, and neither governor nor chaplain could permanently allay the tumult; the governor determined thereupon to handcuff all the turbulent males immediately. The effect was instantaneous. Although there were still mumblings and grumblings, it was evident that the storm would soon be over. In the course of the day all the refractory were placed in irons, and all was quiet in the male pentagon. Yet many still muttered, and all was still far from quiet. There was little doubt at the time that a general rising of the men was contemplated, and the governor felt it necessary to use redoubled efforts to make all secure, calling in further assistance from Bow Street. The night passed, however, without any outbreak, and next[40] morning all the prisoners were pretty quiet and orderly. Later in the day the committee met and sentenced the ringleaders to various punishments, chiefly reduction in class, and by this time the whole were humble and submissive. Finally five, who had been conspicuous for good conduct, were pardoned.

It is satisfactory to find that the committee firmly resisted all efforts to make them withdraw the objectionable bread, and acted on the whole with spirit and determination. How far the governor was to blame cannot clearly be made out, but the confidence of the committee was evidently shaken, and a month or two later he was called upon to resign. He refused; whereupon the committee informed him that they gave him “full credit for his capacity and talents in his former line of life, but did not deem he had the talent, temper, or turn of mind, necessary for the beneficial execution of the office of governor of the institution.” There was not the slightest imputation against his moral character, the committee assured him; but they could not retain him. He would not resign, and they were consequently compelled to remove him from office.

Bow Street Office, London

The principal police court of the City of London, established on Bow Street in 1749.

There can be no doubt but that Millbank in these early days was over much governed. The committee took everything into their own hands, and allowed but little latitude to their responsible officers. Governor Shearman complained the visitors (members of the committee) who, he says, “went to the Penitentiary, and gave orders and directions for things to be done by inferior officers, which I thought ought to come through me.... Prisoners were occasionally removed from one ward to another, and I knew nothing of it—no communication was made to me; and if the inferior officers had a request to make, they got too much into the habit of reserving it to speak to the visitors; so that I conceived I was almost a nonentity in the situation.” The prisoners, even, were in the habit of saying they would wait till the visitor came, and would ask him for what they wanted, ignoring the governor altogether. Indeed it appears from the official journals that the visitors were constantly at the prison. A Mr. Holford admits that “for a considerable time he did everything but sleep there.” But their excuse was that they were not fortunate in their choice of some of their first officers; and knew therefore they must watch vigilantly over their conduct, to keep those who fulfilled expectations, and to part with those who appeared unfit for their situations. Besides which it was necessary to see from time to time how the rules first framed worked in practice, and what customs that grew up should be prohibited, and what sanctioned, by the committee, and adopted into the rules.

It must be confessed that the committee do not appear to have been well served by all their subordinates. The governors were changed frequently;[42] the first “expected to find his place better in point of emolument, and did not calculate upon the degree of activity to be expected in the person at the head of such an establishment; the second was not thought by the committee to have those habits of mind—particularly those habits of conciliation—which are required in a person at the head of such an establishment;” the third was seized with an affection of the brain, and was never afterwards capable of exercising sufficient activity. The first master manufacturer, who as will be remembered was appointed because he was of a mechanical turn of mind, was removed because he was a very young man, and his conduct was not thought steady enough for the post he occupied. The first steward was charged with embezzlement, but was actually dismissed for borrowing money from some of the tradesmen of the establishment. The first matron was also sent away within the first twelve months, but she appears to have been rather hardly used, although her removal also proves the existence of grave irregularities in the establishment. The case against Mrs. Chambers was that she employed certain of the female prisoners for her own private advantage. Her daughter was about to be married; and to assist in making up bed furniture a portion of thread belonging to the establishment was used by the prisoners, who gave also their time. The thread was worth a couple of shillings, and was replaced by Mrs. Chambers. A second charge[43] against the matron was for stealing a Penitentiary Bible. Her excuse was that a number had been distributed among the officers,—presents, as she thought, from the committee,—and she had passed hers on to her daughter. But for these offences, when substantiated, she was dismissed from her employment.

Entries made in the Visitors’ Journal, however, are fair evidence that matters were allowed by the officials to manage themselves in rather a happy-go-lucky fashion. One day new prisoners were expected from Newgate; but nothing was ready for them. “Not a table or a stool in any working cell; and one of those cells where the prisoners were to be placed, in which the workmen had some time since kept coals, was in the dirty state in which it had been left by them. Not a single bed had been aired.” The steward did not know these prisoners were expected, and had ordered no rations for them. But he stated he had enough, all but about two pounds. Upon which the visitor remarks, “If sixteen male prisoners can be supplied without notice, within two pounds, the quantity of meat sent in cannot be very accurate.” Again, the visitor finds the doors from the prison into the hexagon where the superior officers lived “not double-locked as they ought to be, and two prisoners together in the kitchen without a turnkey.” The daily allowance of food issued to the prisoners was not the right weight. He says: “There are in the bathing-room[44] at the lodge several bundles of clothes belonging to male prisoners who have come in between the 1st and 21st of this month; they are exactly in the state in which they were when the subject was mentioned to the committee last week; some of them are thrown into a dirty part of the room—whether intended to be burned I do not know; the porter thinks they are not. I do not believe any of the female prisoners’ things have been yet sold. I understand from the governor he has not yet made any entry in the character-book concerning the behaviour of any male prisoner since he came into the prison, or relative to any occurrence connected with such prisoner.”

All this will fairly account for any extra fussiness on the part of the committee. Doubtful of the zeal and energy of those to whom they confided the details of management, they were continually stepping in to make up for any shortcomings by their own activity. But the direct consequence of this interference was to shake the authority of the ostensible heads. Moreover, to make the more sure that nothing should be neglected, and no irregularity overlooked, the committee encouraged, or at least their most prominent member did, all sorts of talebearing, and a system of espionage that must have been destructive of all good feeling among the inmates of the prison. Mr. Pitt, when examined by the Select Committee, said, “Mr. Holford has mentioned[45] to me: ‘I hear so and so; such and such an abuse appears to be going forward; but I shall get some further information.’ I always turned a deaf ear to these observations, thinking it an erroneous system, and that it was not likely to contribute to the good of the establishment.” He thought that if the committee members were so ready to lend a willing ear to such communications, it operated as an encouragement to talebearing; the consequences of which certainly appeared to have been disputes, cabals, or intrigues. Mr. Shearman remarks at some length on the same subject: “I certainly did think there was a very painful system going on in the prison against officers, ... by what I might term ‘spyism.’ I have no doubt it all arose from the purest motives, thinking it was the best way to conduct the establishment, setting up one person to look after another.” The master manufacturer and the steward in this way took the opportunity of vilifying the governor; and there is no doubt the matron, Mrs. Chambers, fell a victim to this practice. She was the victim of insinuation, and the evil reports of busybodies who personally disliked her.

It is easy to imagine the condition of Millbank then. A small colony apart from the great world; living more than as neighbours, as one family almost—but not happily—under the same roof. The officials, nearly all of them of mature age,[46] having grown-up children, young ladies and young gentlemen, always about the place, and that place from its peculiar conditions, like a ship at sea, shut off from the public, and concentrated on what was going on within its walls. Gossip, of course, prevalent—even malicious; constant observation of one another, jealousies, quarrels, inevitable when authority was divided between three people, the governor, chaplain, and matron, and it was not clearly made out which was the most worthy; subordinates ever on the look-out to make capital of the differences of their betters, and alive to the fact that they were certain of a hearing when they chose to carry any slanderous tale, or make any underhand complaint. For there, outside the prison, was the active and all-powerful committee, ever ready to listen, and anxious to get information. One of the witnesses before the committee of 1823 stated, “From the earliest period certainly the active members of the Superintending Committee gave great encouragement to receive any information from the subordinate officers, I believe with the view of putting the prison in its best possible state; that encouragement was caught with avidity by a great many, simply for the purpose of cultivating the good opinion of those gentlemen conducting it; and I am induced to think that in many instances their zeal overstepped perhaps the strict line of truth; for I must say that during the whole period I was there, there was a continual complaint, one[47] officer against another, and a system that was quite unpleasant in an establishment of that nature.”

Of a truth the life inside the Penitentiary must have been rather irksome to more people than those confined there against their will.

CHAPTER III

THE GREAT EPIDEMIC

Failure threatens the great experiment—General sickness of the Prisoners—Virulent disorder attacks them—The result of too high feeding and ill-chosen dietary—Disease succumbs to treatment—Majority transferred to hospital ships at Woolwich—Very imperfect discipline maintained—Conduct of prisoners often outrageous—Sent by Act of Parliament to the Hulks as ordinary Convicts.

The internal organization of Millbank, which has been detailed in the last chapter, is described at some length in a Blue Book, bearing date July, 1823. But though Millbank was then, so to speak, on its trial, and its value, in return for the enormous cost of its erection, closely questioned, it is probable that its management would not have demanded a Parliamentary inquiry but for one serious mishap which brought matters to a crisis. Of a sudden the whole of the inmates of the prison began to pine and fall away. A virulent disorder broke out, and threatened the lives of all in the place. Alarm and misgiving in such a case soon spread; and all at once the public began to fear that Millbank was altogether a huge mistake. Here was a building upon which half a million had been spent, and now, when barely completed, it[49] proved uninhabitable! Money cast wholesale into a deadly swamp, and all the fine talk of reformation and punishment to give way to coroners’ inquests and deaths by a strange disease. No wonder there was a cry for investigation. Then, as on many subsequent occasions, it became evident Millbank was fulfilling one of the conditions laid down as of primary importance in the choice of site. Howard had said that the Penitentiary House must be built near the metropolis, so as to insure constant supervision and inspection. Millbank is ten minutes’ walk from Westminster, and from the first has been the subject of continual inquiry and legislation. The tons of Blue Books and dozens of Acts of Parliament which it has called into existence will be sufficient proof of this. It was, however, a public undertaking, carried out in the full blaze of daylight, and hence it attracted more than ordinary attention. What might have passed unnoticed in a far-off shire, was in London magnified to proportions almost absurd. This must explain state interference, which now-a-days may seem quite unnecessary, and will account for giving a national importance to matters oftentimes in themselves really trivial.

But this first sickness in the Penitentiary was sufficiently serious to arrest attention, and call for description in detail.

In the autumn of 1822, the physicians appointed to report on the subject state that the general health[50] of the prisoners in Millbank began visibly to decline. They became pale and languid, thin and feeble; those employed in tasks calling for bodily exertion could not execute the same amount of work as before, those at the mill ground less corn, those at the pump brought up less water, the laundry-women often fainted at their work, and the regular routine of the place was only accomplished by constantly changing the hands engaged. Throughout the winter this was the general condition of the prisoners. The breaking down of health was shown by such symptoms as lassitude, dejection of spirits, paleness of countenance, rejection of food, and occasional faintings. Yet, with all this depression of general health, there were no manifest signs of specific disease; the numbers in hospital were not in excess of previous winters, and their maladies were such as were commonly incident to cold weather. But in January, 1823, scurvy—unmistakable sea scurvy—made its appearance, and was then recognized as such, and in its true form, for the first time by the medical superintendent, though the prisoners themselves declared it was visible among them as early as the previous November. Being anxious to prevent alarm, either in the Penitentiary itself or in the neighbourhood, the medical officer rather suppressed the fact of the existence of the disease; and this, with a certain tendency to make light of it, led to the omission of many precautions. But there it was, plainly evident;[51] first, by the usual sponginess of the gums, then by “ecchymosed” blotches on the legs, which were observed in March to be pretty general among the prisoners.

Upon this point, the physicians called in remarked that the scurvy spots were at their first appearance peculiarly apt to escape discovery, unless the attention be particularly directed towards them, and that they often existed for a long time entirely unnoticed by the patient himself. And now with the scurvy came dysentery, and diarrhœa, of the peculiar kind that is usually associated with the scorbutic disease. In all cases, the same constitutional derangement was observable, the outward marks of which were a sallow countenance and impaired digestion, diminished muscular strength, a feeble circulation, various degrees of nervous affections, such as tremors, cramps, or spasms, and various degrees of mental despondency.

With regard to the extent of the disease, it was found that quite half of the total number were affected, the women more extensively than the men; and both the males and females of the second class, or those who had been longest in confinement, were more frequently attacked than the newest arrivals. Some few were, however, entirely exempt; more especially the prisoners employed in the kitchen, while among the officers and their families, amounting in all to one hundred and six individuals, there was not a single instance of attack recorded.

Such then was the condition of the prisoners in the Penitentiary in the spring of 1823. To what was this sudden outbreak of a virulent disorder to be traced? There were those who laid the whole blame on the locality, and who would admit of no other explanation. But this argument was in the first instance opposed by the doctors investigating. Had the situation of the prison been at fault, they said, it was only reasonable to suppose that the disease would have shown itself in earlier years of the prison’s existence; whereas, as far as they could ascertain, till 1822-3 it was altogether unknown. Moreover, had this been the real cause, all inmates would alike have suffered; how then explain the universal immunity of the officers in charge? Again, if it were the miasmata arising upon a marshy neighbourhood that militated against the healthiness of the prison, there should be prevalent other diseases which marsh miasmata confessedly engender. Besides which, the scurvy and diarrhœa thus produced are associated with intermittent fevers, in this case not noticeable; and they would have occurred during the hot instead of the winter season. Lastly, if it were imagined that the dampness of the situation had contributed to the disease, a ready answer was, that on examination every part of the prison was found to be singularly dry, not the smallest stain of moisture being apparent in any cell or passage, floor, ceiling, or wall.

But indeed it was not necessary to search far[53] afield for the causes of the outbreak; they lay close at hand. Undoubtedly a sudden and somewhat ill-judged reduction in diet was entirely to blame. For a long time the luxury of the Penitentiary had been a standing joke. The prison was commonly called Mr. Holford’s fattening house. He was told that much money might be saved the public by parting with half his officers, for there need be no fear of escapes; all that was needed was a proper guard to prevent too great a rush of people in. An honourable member published a pamphlet in which he styled the dietary at Millbank “an insult to honest industry, and a violation of common sense.” And evidence was not wanting from the prison itself of the partial truth of these allegations. The medical superintendent frequently reported that the prisoners, especially the females, suffered from plethora, and from diseases consequent upon a fulness of habit. Great quantities of food were carried out of the prison in the wash-tubs; potatoes, for instance, were taken to the pigs, which Mr. Holford admitted he would have been ashamed to have seen thus carried out of his own house. It came to such a pass at last that the committee was plainly told by members of the House of Commons, that if the dietary were not changed, the next annual vote for the establishment would probably be opposed. In the face of all this clamour the committee could not hold out; but in their anxiety to provide a remedy, they went from one extreme to[54] the other. Abandoning the scale that was too plentiful, they substituted one that was altogether too meagre. In the new dietary solid animal food was quite excluded, and only soup was given. This soup was made of ox heads, in the proportion of one to every hundred prisoners; it was to be thickened with vegetables or peas, and the daily allowance was to be a quart, half at midday, and half in the evening. The bread ration was a pound and a half, and for breakfast there was also a pint of gruel. It was open to the committee to substitute potatoes for bread if they saw fit, but they do not seem to have done this. The meat upon an ox head averages about eight pounds, so that the allowance per prisoner was about an ounce and a quarter. No wonder then that they soon fell away in health.

The mere reduction in the amount of food, however, would not have been sufficient in itself to cause the epidemic of scurvy. Scurvy will occur even with a copious dietary. Sailors who eat plenty of biscuit and beef are attacked, and others who are certainly not starved. The real predisposing cause is the absence of certain necessary elements in the diet, not the lowness of the diet itself. It is the want of vegetable acids in food that brings about the mischief. The authorities called in were not exactly right, therefore, in attributing the scurvy solely to the reduced diet. The siege of Gibraltar was quoted as an instance where semi-starvation superinduced the disease. Again, the scurvy prevalent[55] in the low districts round Westminster was traced to a similar deficiency and the severe winter, also to the want of vegetable diet. This last was the real explanation; of this, according to our medical knowledge, there is not now the faintest doubt. Long enforced abstinence from fresh meat and fresh vegetables is certain sooner or later to produce scurvy. At the same time it must be admitted that the epidemic of which I am writing was aggravated by the cold weather. It had its origin in the cold season, and its progress kept pace with it, continued through the spring, actually increasing with summer.

During the months of May and June the disorder was progressive, but the early part of July saw a diminution in the numbers afflicted. At this time the prison population amounted to about eight hundred.

There was a total of thirty deaths. In spite of this slight improvement for the better, it is easy to understand that the medical men in charge were still much troubled with fears for the future. Granting even that the disease had succumbed to treatment, there was the danger, with all the prisoners in a low state of health, of relapse, or even of an epidemic in a new shape. Hence it was felt that an immediate change of air and place would be the best security against further disease. But several hundred convicts could not be sent to the seaside like ordinary convalescents; besides which[56] they were committed to Millbank by Act of Parliament, and only by Act of Parliament could they be removed. This difficulty was easily met. An Act of Parliament more or less made no matter to Millbank—many pages in the statute book were covered already with legislation for the Penitentiary. A new act was immediately passed, authorizing the committee to transfer the prisoners from Millbank to situations more favourable for the recovery of their health. In accordance with its provisions one part of the female prisoners were at once sent into the Royal Ophthalmic Hospital in Regent’s Park, at that time standing empty; their number during July and August was increased to one hundred and twenty, by which time a hulk, the Ethalion, had been prepared at Woolwich for male convicts, and thither went two hundred, towards the end of August. Those selected for removal were the prisoners who had suffered most from the disease. This was an experiment; and according to its results the fate of those who remained at Millbank was to be determined. “The benefit of the change of air and situation,” says Dr. Latham, “was immediately apparent.” Within a fortnight there was less complaint of illness, and most of the patients already showed symptoms of returning health. Meanwhile, among the prisoners left at Millbank there was little change, though at times all were threatened with a return of the old disorder, less virulent in its character, however, and[57] missing half its former frightful forms. By September, a comparison between those at Regent’s Park or the hulk and those still in Millbank was so much in favour of the former that the point at issue seemed finally settled. Beyond doubt the change of air had been extremely beneficial; nevertheless, of the two changes, it was evident that the move to the hulks at Woolwich had the better of the change to Regent’s Park. On board the Ethalion the prisoners had suffered fewer relapses and had gained a greater degree of health than those at Regent’s Park. On the whole, therefore, it was considered advisable to complete the process of emptying Millbank. The men and women alike were all drafted into different hulks off Woolwich. These changes were carried out early in December, 1823, and by that time the Millbank Penitentiary was entirely emptied, and it remained vacant till the summer of the next year.

The inner life of the Penitentiary went on much as usual in the early days of the epidemic. There are at first only the ordinary entries in the governor’s Journal. Prisoners came and went; this one was pardoned, that received from Newgate or some county gaol. Repeated reports of misconduct are recorded. The prisoners seemed fretful and mischievous. Now and then they actually complained of the want of food. One prisoner was taken to task for telling his father, in the visiting cell, that six prisoners out of every seven would die[58] for want of rations. But at length the blow fell. On the 14th February, 1823, Ann Smith died in the infirmary at half-past nine. On the 17th, Mary Ann Davidson; on the 19th, Mary Esp; on the 23rd, William Cardwell; on the 24th, Humphrey Adams; on the 28th, Margaret Patterson. And now, by order of the visitor, the prisoners were allowed more walking exercise. Then follow the first steps taken by Drs. Roget and Latham. The governor records, on the 3rd March, that the doctors recommend each prisoner should have daily four ounces of meat and three oranges; that their bread should be divided into three parts, an orange taken at each meal. Accordingly the steward was sent to Thames Street to lay in a week’s consumption of oranges.

An entry soon afterwards gives the first distinct reference to the epidemic. “The medical gentlemen having begged for the bodies of such prisoners as might die of the disorder now prevalent in the prison, in order to make post-mortem examinations, the same was sanctioned if the friends of the prisoner did not wish to interfere.” Deaths were now very frequent, and hardly a week passed without a visit from the coroner or his deputy.

On the 25th of March the governor, Mr. Couch, who had been ailing for some time past, resigned his charge into the hands of Captain Benjamin Chapman. Soon afterwards there were further additions to the dietary—on the 26th of April two[59] more ounces of meat and twelve ounces of boiled potatoes; and the day after, it was ordered that each prisoner should drink toast-and-water,—three half-pints daily. Lime, in large tubs, was to be provided in all the pentagons for the purpose of disinfection.

About this period there was a great increase of insubordination among the prisoners. It is easy to understand that discipline must be relaxed when all were more or less ailing and unable to bear punishment. The sick wards were especially noisy and turbulent. One man, for instance, was charged with shouting loudly and using atrocious language; all of which, of course, he denied, declaring he had only said, “God bless the king, my tongue is very much swelled.” Upon this the turnkey in charge observed that it was a pity it was not swelled more, and Smith (the prisoner) pursued the argument by hitting his officer on the head with a pint pot. Later on they broke out almost into mutiny. The governor writes as follows: “At a quarter to eight o’clock Taskmaster Swift informed me that the whole of the prisoners in the infirmary ward of his pentagon were in the most disorderly and riotous state, in consequence of the wooden doors of the cells having been ordered by the surgeon to be shut during the night; that the prisoners peremptorily refused to permit the turnkeys to shut their doors, and made use of the most opprobrious terms, threatening destruction to whoever might attempt to shut[60] their doors. Their shouts and yells were so loud as to be heard at a considerable distance. I immediately summoned the patrols, and several of the turnkeys, and making them take their cutlasses, I repaired to the sick ward. I found the wooden doors all open, and the prisoners, for the most part, at their iron gates, which were shut. The first prisoner I came to was John Hall. I asked him the reason he refused to shut his door when ordered. He answered in a very insolent tone and manner, ‘Why should I do so?’ I then said, ‘Shut your door instantly,’ but he would not comply. I took him away and confined him in a dark cell. In conveying him to the cell he made use of most abusive and threatening language, but did not make any personal resistance.” Five others who were pointed out as prominent in the mutiny were also punished on bread and water in a dark cell, by the surgeon’s permission.

Nor were matters much more satisfactory in the female infirmary wards. “Mrs. Briant, having reported yesterday, during my absence at Woolwich, that Mary Willson had ‘wilfully cut her shoes,’ and, having stated the same verbally this morning, I went with her into the infirmary, where the prisoner was, and having produced the shoes to her (the upper-leather of one of them being palpably cut from the sole), and asked her why she cut them, she said she had not cut them, that they had come undone whilst walking in the garden. This[61] being an evident falsehood, I told her I feared she was doing something worse than cutting her shoes by telling an untruth. She answered in a very saucy manner, they were not her shoes, and that she had not cut them. She became at length very insolent, when I told her she deserved to be punished. She replied she did not care whether she was or not. I then directed the surgeon to be sent for; when not only the prisoner, but several others in the infirmary, became very clamorous, and evinced a great degree of insubordination. I went out with the intention of getting a couple of patrols, when I heard the crash of broken glass and loud screams. I returned as soon as possible with the patrols into the infirmary. The women generally attempted to oppose my entrance, and a group had got Willson amongst them, and said she should not be confined. I desired the patrols to lay hold of her, and take her to the dark cell (I had met with Dr. Hugh when going for the patrols, who under the circumstances sanctioned the removal of the prisoner). In doing so, Betts and Stone were assaulted with the utmost violence; I myself was violently laid hold of, and my wrist and finger painfully twisted. I had Willson, however, taken to the dark cell, when, having summoned several of the turnkeys and officers of the prison, I with considerable difficulty succeeded in taking six more of them who appeared to be most forward in this disgraceful riot. Several of the large panes in the passage windows were broken;[62] and the women seized everything they could lay their hands on, and flung them at the officers, who, in self-defence, were at length compelled to strike in return. I immediately reported the circumstance to Sir George Farrant, the visitor, who came to the prison soon after. I accompanied him, with Dr. Bennett (the chaplain) and Mr. Pratt (the surgeon), through the female pentagon and infirmary, when a strong spirit of insubordination was obvious. Sir George addressed them, and so did Dr. Bennett, and pointed out the serious injury they were doing themselves, and that such conduct would not pass unpunished. We afterwards visited the dark refractory cells, where the worst were confined; two of whom, on account of previous good-conduct and favourable circumstances, were liberated. For myself, I never beheld such a scene of outrage, nor did I observe a single individual who was not culpably active.”

As a general rule, the prisoners in the Penitentiary were in these days so little looked after, and had so much leisure time, that they soon found the proverbial mischief for idle hands. Having some suspicions, the governor searched several, and found up the sleeves of five of them, knives, playing cards (made from an old copy-book), two articles to hold ink, a baby’s straw hat, some papers (written upon), and an original song of questionable tendency. The hearts and diamonds in the cards had been covered with red chalk, the clubs and spades[63] with blacking. “Having received information that there were more cards about, he caused strict search to be made, and found in John Brown’s Bible, one card and the materials for making more, also a small knife made of bone. In another prisoner’s cell was found another knife and some paste, ingeniously contrived from old bread-crumbs.” But even these amusements did not keep the prisoners from continually quarrelling and fighting with one another. Any one who had made himself obnoxious was severely handled. A body of prisoners fell upon one Tompkins, and half killed him because he had reported the irreverent conduct of several of them while at divine service. The place was like a bear-garden; insubordination, riots, foul language, and continual wranglings among themselves—it could hardly be said that the prisoners were making that rapid progress towards improvement which was among the principal objects of the Penitentiary.