The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Chautauquan, Vol. III, May 1883, by The Chautauquan Literary and Scientific Circle This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Chautauquan, Vol. III, May 1883 Author: The Chautauquan Literary and Scientific Circle Editor: Theodore L. Flood Release Date: June 15, 2015 [EBook #49217] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHAUTAUQUAN, VOL. III, MAY 1883 *** Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland, Music transcribed by June Troyer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A MONTHLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE PROMOTION OF TRUE CULTURE. ORGAN OF

THE CHAUTAUQUA LITERARY AND SCIENTIFIC CIRCLE.

Vol. III. MAY, 1883. No. 8.

President, Lewis Miller, Akron, Ohio.

Superintendent of Instruction, J. H. Vincent, D. D., Plainfield, N. J.

General Secretary, Albert M. Martin, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Office Secretary, Miss Kate F. Kimball, Plainfield, N. J.

Counselors, Lyman Abbott, D. D.; J. M. Gibson, D. D.; Bishop H. W. Warren, D. D.; W. C. Wilkinson, D. D.

| REQUIRED READING | |

| History of Russia. | |

| Chapter X.—Alexander Nevski—Mikhail of Tver | 427 |

| A Glance at the History and Literature of Scandinavia. | |

| VII.—Esaias Tegnér: Johann Ludvig Runeberg | 429 |

| Pictures from English History. | |

| VIII.—The Last Great Invader of France | 432 |

| Physiology | 434 |

| To the Nightingale | 436 |

| SUNDAY READINGS. | |

| [May 6th.] | |

| Filthy Lucre | 436 |

| [May 13th.] | |

| A Christian Described | 437 |

| [May 20th.] | |

| The Unity of the Divine Being | 439 |

| [May 27th.] | |

| Readings from Thomas À Kempis.—Of Bearing With the Defects of Others | 440 |

| The Romance of Astronomy—Astrology | 441 |

| Amusements—Tennis | 441 |

| Celia Singing | 442 |

| German-American House-Keeping | 442 |

| Changes in Fashions | 446 |

| The History and Philosophy of Education | |

| VI.—Greece and Its Relation to the East | 446 |

| Daffodils at Sea | 448 |

| The Worth of Fresh Air | 449 |

| Street Manners | 452 |

| Satisfied | 452 |

| Tales from Shakspere | |

| As You Like It | 453 |

| Memorial Bell | 457 |

| C. L. S. C. Work | 457 |

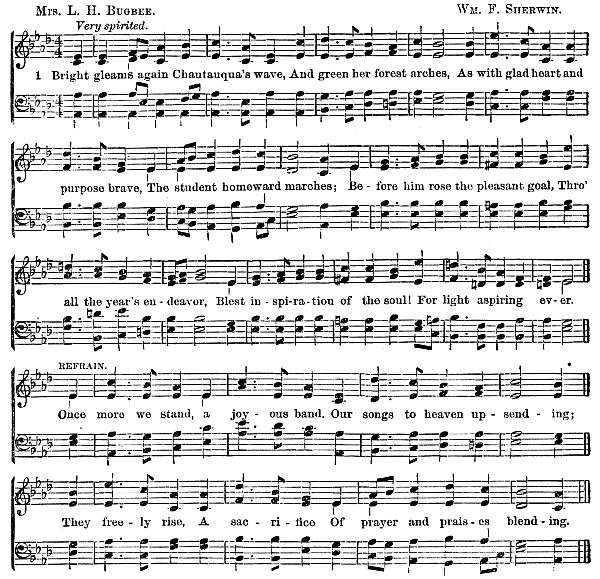

| C. L. S. C. Song | 458 |

| Discrepancies in Astronomy | 458 |

| Longfellow’s Birthday | 459 |

| Local Circles | 459 |

| Outline of C. L. S. C. Studies—May | 463 |

| Questions and Answers | |

| Fifty Questions and Answers on “Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie.” | 463 |

| C. L. S. C. Round-Table | 464 |

| Edwin and Charles Landseer | 466 |

| The Sonnet | 466 |

| A Tour Round the World | 466 |

| Applications of Photography | 471 |

| Daniel Webster versus Stephen Girard | 472 |

| May | 473 |

| Talk from Headquarters | |

| Concerning Chautauqua—1883 | 474 |

| The Chautauqua School of Languages | 475 |

| Editor’s Outlook | |

| The C. L. S. C. on the Pacific Coast | 476 |

| Trial by Jury | 476 |

| Stevens’s Madame De Staël | 477 |

| The Educational Problem | 478 |

| Editor’s Note-Book | 479 |

| Editor’s Table | 481 |

| C. L. S. C. Notes on Required Readings For May | |

| History of Russia | 482 |

| History and Literature of Scandinavia | 482 |

| Pictures from English History | 484 |

| Physiology | 484 |

| Sunday Readings | 484 |

| Evangeline | 485 |

| Pronouncing Vocabulary | 486 |

| Books Received | 486 |

By Mrs. MARY S. ROBINSON.

We have seen that Mstislaf the Brave defied the tyranny of Andreï Bogoliubski, in his attempt to intimidate Novgorod the Great.[A] When Vsevolod, surnamed Big Nest, by reason of his large family, would force the city to his will, Mstislaf again came to its rescue; and when Iaroslaf of the Big Nest family, continuing the feud, betook himself to Torjok near the Volga, where he obstructed the passage of the merchants and brought famine upon the great city, Mstislaf the Bold, of Smolensk, son of the Brave, left his powerful capital, one of the strongest of Russia’s fortified cities, and went to the help of the distressed people. “Torjok shall not hold herself higher than the Lord Novgorod,” he swore in princely fashion, “I will deliver his lands, or leave my bones for his people to bury.” Thus he became champion and prince of the Republic. Between Iaroslaf and his brothers Iuri of Vladimir, and Konstantin of Rostof ensued one of the family wrangles common to the times, that was settled on the field of Lipetsk (1216), where Konstantin allied with Mstislaf won his cause, and Iaroslaf was compelled to renounce both his claims and his captives. When the bold Mstislaf had put the affairs of the principality in order, he took formal leave of the vetché, assembled in the court of Iaroslaf, and resisting their entreaties to abide with them, went as we have seen to the aid of Daniel of Galitsch.[B] But according to his wish he was buried beside his father, the Brave, who, when at the height of his greatness was borne down with disease, commanded that he should be carried to Saint Sophia in Novgorod, received there the eucharist amid the congregated citizens, crossed his once mighty arms upon his breast, and closed his eyes forever upon the scenes that had witnessed his achievements. In the cathedral lie the two warriors in mute company, with the consort of Iaroslaf the Great, his son Vladimir, who laid its foundations, the archbishop Nikita, whose prayers extinguished a conflagration, and a goodly company of other illustrious dead.

In course of time the Iaroslaf who had renounced his claim to the Republic after the defeat at Lipetsk, was elected its prince, he being also Prince of Suzdal; but he was compelled to make good his claim before the Grand Khan in Asia, and perished in the desert journey. Of his two sons, Andreï succeeded him at Vladimir (Suzdal), and Alexander at Novgorod.

The incoming of the Tatars had left the Russian realm a prey to its northern neighbors,—the Finnish tribes, the Livonians and Swedes. In his early years Alexander proved his capacity for leadership by a battle won against these united forces near one of the affluents of the Neva—an exploit that gained him his surname Nevski, and that has been commemorated in the historical ballads of his people. An Ingrian, a newly Christianized chief in the Russian service, on the eve of the engagement, beheld Boris and Gleb, the martyred sons Saint Vladimir, the Castor and Pollux of Russian tradition, standing in a phantom boat, rowed by phantom oarsmen, toward the camp of their countrymen—going to the help of their kinsman Alexander. “Row, my men!” said one of the brothers, “row, for the rescue of the Russian land!” In the hour of conflict, one of the captains pursued Burger, the Swedish general, through the water to his ship, but swam back successfully and mixed again in the fray, when he reached the firm land. The exploits of another knight are sung who brought in three Swedish galleys. Gabriel, Skuilaf of Novgorod, tore away Burger’s tent and hewed down its ashen post, amid the cheers of his men; and Alexander with a stroke of his lance “imprinted his seal on Burger’s face.” Rough work was this, in rude times; but thus was the national strength asserted, and the national honor protected.

Novgorod, like all the republics of medieval times, recognized the principle of caste distinctions, and hence was subject to the dissensions consequent upon an enlarged freedom in conflict with these class divisions. Its tendency was toward oligarchy. As monarchies adjacent to it increased in size and strength, it was constrained to form protective alliances now with the one, now with the other; but to the latest period of its independence it cautiously guarded its civic rights and laws against the encroachments of princely power. Some differences between the citizens and Alexander led him to withdraw from the city; but the incursions of the Sword-Bearers with their train of northern tribes, made his presence again necessary at the head of the army. He conducted a campaign characterized by extreme bitterness on both sides, and ending in a conflict on Lake Peïpus, the Battle of the Ice, in 1242, when a multitude of the Tchudi were exterminated and the Livonian Knights were seriously crippled. The Grand Master expected to see his[428] redoubtable foeman before the walls of Riga; but Alexander contented himself with reprisals, and a recovery of the lands wrested from the Republic.

Through a score or more of years, partly by reason of its remote northern location, and its relations with the western powers, Novgorod had evaded the imposition of the Tatar yoke, put upon the rest of the realm. But the time came when the khan at Saraï determined to bring under his sway the region of the lakes; and Alexander, with his brother Andreï, was summoned to the Horde for confirmation of their duties as vassal princes. Batui, the khan, received the hero of the Neva with consideration, and added to his domains large tracts of Southern Russia, including the Principality of Kief; but with these largesses was imposed the humiliating task of raising tribute for the Mongol court. When the posadnik announced this hard command to the vetché of Novgorod, the people, paying no heed to his cautious and qualified phrasing, uttered a terrible cry, and tore him limb from limb. A rebellion, headed by Alexander’s son, Vasili, gathered force, till the rumor spread that the Asiatics were moving toward the city. Yielding for a time to the necessity imposed upon them, the people again rallied, this time around Saint Sophia, and declared they would meet their fate, be it what it might, rather than submit to the unendurable subjugation. Alexander sent them word that he must leave them to themselves, and go elsewhere. The Mongol emissaries were at the gates: the people in the acquiescence of despair admitted them to their streets. During the days that the baskaks, census-takers and tax-gatherers, went from house to house—and the days were many, for the city covered an area hardly less than that of London in this century—its industries were suspended, its stirring, joyous life extinguished in silence and gloom. The priceless possession of the state, its freedom and independence, was lost: and though the great lords and wealthy burghers might still boast of their wealth, the simple citizens had lost what they had believed to be an enduring heritage, and what they had cherished as an enduring hope.

Yet a restricted freedom still remained: nor till three centuries later was this sacrificed to the power of the Muscovite and the unity of the Russias. Even then the history of the republic belonged to the Empire. The right of representation, of government by laws, and by the free consent of the governed, were matters of history not to be forgotten. The most rigid of Russian despots could not utterly ignore them, and they have produced an element of unrest that, however painful in its immediate results, is yet inevitable and healthful and hopeful. They have been one of the influences at work, bringing to tens and hundreds of thousands of lips the watch-word uttered since the reign of Nicholas, on the rivers, on the mountain boundaries, in the mines, the residence of the noble, the factory, and the hut of the peasant—Svobodnaya Rossia: Free Russia.

Everywhere the collection of the tribute was attended with revolts. One in Suzdal, sure to bring terrible reprisals upon the people, compelled Alexander to a second journey to the Horde, where he had also to excuse himself for failure to send his military contingent. The chronicles aver that the men were defending their western frontiers at this time. The khan detained his noble vassal for a year. On his return journey the prince, whose bravery had endured so sore a conflict with his sagacity and prudence, and whose health had weakened, died at a town several days’ journey from Vladimir. When the tidings were brought to Novgorod, the Metropolitan Kyrill, who was celebrating a religious service, announced to the congregation: “Learn, my dear children, that the sun of Russia is set.” “We are lost,” they answered, and sobs were heard from all parts of the church.

Long will this Alexander, “helper of men,” be revered by his countrymen. Religion and patriotism with them are one; hence it is not strange that he is enrolled among the saints of the Church. As protector of the modern capital, his name is given to its stateliest promenade. The monastery dedicated to his memory is one of the three Lauras, or seats of the Metropolitans, filled with treasures and shrines of the illustrious dead. Thither repair the sovereigns before the undertaking of momentous enterprises, even as the Nevski bowed before the Divine Justice in Saint Sophia, ere he went forth upon his expeditions and journeys. His timely submission saved the realm from further exhaustion, while his military successes preserved it from sinking under the hardest subjection that has ever been imposed upon a European people.

Daniel, a son of this renowned prince, received as part of his appanage the devastated town of Moscow, which up to this time had been an obscure place, unnoticed by the annalists, beyond the mention of its origin. They record that in 1043 the Grand Prince Iuri Dolgoruki,[C] while on a journey, tarried at the domain of a boyar who for some reason he caused to be put to death; that having his attention directed to certain heights washed by the river Moskova, he brought settlers thither, who built a village on the spot at present covered by the Kreml. A little church, Our Savior of the Pines, is still preserved, a relic of these early days. Daniel and his sons increased their domains by the annexation of several cities; and during the life of Iuri, the second son, was initiated a feud with the house of Tver, that endured through eighty years ere it was closed by the merging of the principality into that of Moscow. The contests of the two kinsmen at the court of the Horde, illustrate the subserviency of the princes to their conquerors. With many of them no deceptions or malice were too base for the forwarding of their purposes. Iuri, by his representations, contrived to obtain the arrest of the Prince of Tver. While the khan was enjoying the chase in the region of the Caucasus, Mikhail was pilloried in the market-place of a town of Daghestan, an object of wondering comment to the populace. Both there and when held a prisoner in his tent, he bore his sufferings with fortitude, consoling himself with prayer and with the Psalms of David. As his hands were bound, an attendant held the open book before him. His nobles would have contrived his escape, but he remonstrated: “Escape and leave you to the anger of my foe? Leave my principality to go down without its ruler and father? If I can not save it, I can, at least, suffer with it.” Later, when speaking with his young son, Konstantine, of their far-off home, tears filled his eyes, and his soul was troubled. He repeated the words of the Fifty-fifth Psalm: “Fearfulness and trembling are come upon me, and horror hath overwhelmed me.” An attendant priest endeavored to console him with the words: “Cast thy burden upon the Lord and he shall sustain thee. He suffers not the righteous to be moved.” The prince responded: “O, that I had wings like a dove; then would I flee away and be at rest.” Iuri had procured a death-warrant for his cousin, and attended by hired ruffians approached the tent, from which the boyars and attendants had been ordered away. “I know his purpose,” said Mikhail, as they took his hand in parting. When the murder was done, Kavgadi, a Tatar, beholding the torn and naked body, exclaimed against the indignity, and ordered it to be covered with a mantle. Long did the Tverians bewail their martyred prince. His body, incorruptible, it was averred, was recovered and laid to rest in their cathedral, where the pictured record of his fate is still vivid on its walls. He, too, is a saint, exalted by suffering, as Alexander was exalted by heroism. Some years later,[429] when his son, Dmitri of the Terrible Eyes, met at Saraï the murderer of his father, “his sword leaped from its scabbard,” and laid him low. He rendered not unwillingly his own life in its prime as atonement for this act of filial vengeance. Then, as now, a quick, and, as they say, an uncontrollable impulse moved many a Russ to similar, sometimes to inexplicable acts.

A third Prince of Tver escaped from the plots of his grasping Muscovite neighbor, Ivan Kalita, or Alms-bag, (1328) so called from that article that hung ever at his girdle. Yet as he acquired great wealth by his prudent management, which increased the commerce and industries of his realm, he had not repute for self-denying charity. He established markets and fairs along the Volga, that added to his revenues with many hundred pounds of silver: probably in the poltiras, or half-pounds, current from the time of Saint Vladimir to the fifteenth century. About the year 1389 coins of silver and copper were substituted for the marten skins that had been used as a medium of barter. A hundred and fifty years later were introduced the rouble and copek,[D] the coins most in use of the modern currency. Ivan also enriched the Kreml with several stately churches, among them the Cathedral of the Assumption—Uspenski Sobor—where for above three hundred years the tsars have crowned themselves,—the most sacred of all the Russian churches in the estimation of the people. From one of its interior corners rises the shrine of the Metropolitan, Saint Peter, who is said to have prophesied to his sovereign: “If thou wilt comfort my hoary years, wilt build here a temple worthy of thy estate, and our religion; this thy city shall be chief of all the cities of Russia. Through many centuries shall thy race reign here in strength and glory. Their hands shall prevail against their enemies, and the saints shall dwell in their borders.”

Kalita is regarded as the first of the Muscovite princes.

[To be continued.]

By L.A. SHERMAN, Ph.D.

Now that we have finished our Carolinian romance, shall we hear something of the author? He is certainly a brilliant poet, for his story which we have been reading is no deep-planned and long worked-over effort, but was written in the few days after a severe sickness when the author could not yet leave his couch. He wrote it to occupy his mind, and beguile the time. How is he esteemed in Sweden? Will it be thought incredible when I say no old hero, not even Charles XII., is reverenced there more deeply, no name is cherished so fondly,—that no man so nearly seems worthy to be called the father of his country, as this same poet-bishop, Esaias Tegnér?

All this is hard to explain, so many-sided was the life he led. We need to realize that he was more active as a bishop and party-leader than a poet. Then to appreciate him in the last capacity we must go among the Swedes themselves. We shall find in him the bond of unity of a whole nation, in that he has sung best the ancient glory of the race, and discovered to the world the heroic integrity of the Northern character. We shall note that it is he whose words are most, next to the Bible, on the lips of every Swede. If we go into a peasant’s cottage, far from railways and culture, we shall be sure to find some one who has not only heard of the great poet, but can even repeat for us whole cantos from his “Frithiof’s Saga,”—perhaps all of “Axel” itself. And nobody even sets about learning these poems by heart: they cling to the memory in spite of the reader.

But we must begin our history. Who were Tegnér’s parents? What was their rank in life? C. W. Böttiger, Tegnér’s son-in-law, who wrote a short life of the poet, shall answer for us:—

“A few years ago north of the church in Tegnaby, there was seen a gray cottage fallen into ruins, with moss-grown walls and two little windows of which one, according to the ancient custom of the province, was in the roof. The people regarded it with a kind of reverence; and if one asked the reason, the hat was raised with the answer: ‘The Bishop’s grandfather once lived there.’ His name was Lucas Esai´asson, his wife’s Ingeborg Mänsdotter. According to testimony handed down traditionally in the parish, this Lucas Esaiasson was a poor but exceedingly industrious and pious man. A peasant during a greater part of the time when Charles XII. was king, he continued yet twenty years after the ‘shot,’ a Carolinian at the plow. This and his Bible were his dearest treasures, and all he had to leave to fourteen children, for whom he procured bread with the plow after he had given them names from the Scriptures. There was one called Paul, another John, a third Enoch, and so on. A whole temple-progeny was growing up under his lowly roof: the Old and New Testaments were embracing each other in his cottage. The youngest son, born on the day of King Charles’s death, was named Esaias. The older brothers inherited their father’s plow, and became peasants; Esaias inherited his father’s Bible and became a minister.”

We wish we could continue to quote Mr. Böttiger, but his story proceeds too slowly. This Esaias was the father of our poet. Showing unusual aptitude for books, he was taken from the farm where he had gone out to service, and placed in the school of Wexiö. Coming from the by or village of Tegn, and having but one name, he was entered in the school register, kept after the manner of the time in Latin, as Esaias Tegnérus. The latter, the Latin suffix us being omitted, became afterward the family name.

In due time this Esaias Tegnér passed to the university, and after graduation was ordained as we have seen, a minister. He is remembered as a talented preacher, and merry man of society. He married a pastor’s daughter whose mother was celebrated for wit, force of character, and poetic gifts. Like qualities reappear in a marked degree in our poet, who was the fifth son of this marriage. He was born in Kykerud [Chikerood], November 13, 1782, and took his father’s name.

Ten years later the minister’s family was broken up by the death of the father. Two daughters and four sons were thus left in a measure to the charity of the world. The young Esaias was soon taken into the counting-room of one Jacob Branting, a crown-bailiff of the province and friend of the deceased pastor. Here he learned to keep accounts and developed rapidly into a valuable clerk. All the leisure he could command was given steadily to books. He read everything he could find, particularly the old Norse sagas, and amused himself by turning some of the driest themes of history and biography into poetical form. The crisis in his life came early. He had been in Branting’s office four years, and so won the respect and love of his employer as to be thought of already as the future son-in-law and successor to the office of bailiff. But Branting had observed the lad’s genius for books, and was beginning to think him fitted for something higher. One night, as they were riding together, Esaias astonished him by rehearsing with some minuteness the principles of astronomy, which he had gathered from his reading. Branting’s decision was at once made. “You shall study,” said he. “As for the means,[430] God will supply the sacrifice, and I will not forget you.”

Young Esaias commenced at once to study Latin, Greek, and French. So remarkable was his memory that he was able, after glancing a few times over a list of fifty or sixty words, to repeat them with their meanings. To his other tasks he added later, the study of English, which he learned by the aid of a translation of Ossian. A change soon follows. Lars Gustaf, his oldest brother, not yet graduated from the university, had been asked to serve as tutor in the family of a rich manufacturer and owner of mines in Rämen. Lars consented on condition that he might bring with him Esaias; for during his temporary absence from the university he had undertaken to guide his brother’s work. The rich proprietor into whose house they were to enter was Christopher Myhrman, a name prominent in the history of Swedish manufactures. He had himself built up the foundries and mills of Rämen, turning the wilderness into a large and flourishing town. Amid his multifold business cares he always found time to read his favorite Latin authors, and enjoy the society of his family, whose circle at that time comprised eight vigorous sons and two blooming daughters.

“To this place, and to this circle it was,” says Mr. Böttiger, “that Lars Gustaf and Esaias Tegnér betook themselves one beautiful summer afternoon in July, 1797. They had traveled in a carriage over the road on which the owner of the mills had been obliged, twenty years before, to bring his wife home upon a pack-saddle; but they left the coach behind them and now came on foot at their leisure through the forest. Suddenly there burst upon their gaze the loveliest prospect. On a point of land, extending out into the water thickly set with islands, and encircled with birch and fir, lay like a beautiful promise the pleasant garden sloping in terraces to the sea, girded with the setting sun and covered with shady trees. ‘Who knows what dwells under their branches,’ perhaps the poet-stripling was already asking, with quickened pulses. We know what dwelt beneath them. It was his good fortune he was coming here to meet; it was amidst this smiling and magnificent nature that his talents were destined to develop, his powers to be confirmed, his wit to grow; it was over the threshold of this patriarchic tabernacle that his knowledge was to be brought to ripeness, and his heart find a companion for life.

“What here in the first room attracted his attention was the big book-cases. He found them richly supplied not only with Swedish, English, and French works, but also Greek and Roman authors of every sort. With greedy eyes he fixed himself especially by the side of a folio, on whose leathern back he read: Homerus. It was Castalio’s edition, printed in Basel in 1561. Here was an acquaintance to make. He made it immediately, and in a manner of which his own account is worthy of being told:—

“‘So without any grammatical foundation, I resolved to attempt the task immediately. At the outset it naturally proceeded slowly and tediously. The many dialectic forms of which I had no idea at all, laid me under great difficulties, which would probably have discouraged any less energetic will. The Greek grammar I had used was adapted to prose writers: of the poetic dialects nothing was said. I was therefore compelled just here to devise a system for myself, and further, to make notes from that time, which now show that among many mistakes I sometimes was right. To give way before any sort of difficulty was not at all my disposition; and the farther I went, the easier my understanding of the poet became. With the prose writers Xenophon and Lucian, I also made at this time a flying acquaintance; but they interested me little, and my principal work continued to be with Homer, and also Horace in Latin, whom I had not known before. French literature was richly represented in this library; Rousseau’s, Voltaire’s, and Racine’s works were complete, and were not neglected either. Of Shakspere there was only Hamlet, which strangely enough interested me very little. In German literature there was not a single poet. That language I was compelled to learn from the usual instruction books, and thus conceived a repugnance to it which lasted for a long time.’”

Thus in his first sojourn of seven months in Rämen, the future poet read the Iliad through three times, the Odyssey twice, and from the same book-shelves Horace, Virgil, and Ovid’s Metamórphoses. He was almost insane in his application to study; yet his constitutional vigor, strange to say, remained unimpaired. In 1799 he entered the university of Lund, whither his father and two brothers had preceded him. We will not linger for details of his industry there. It will not surprise us to learn that on the “promotion” (graduation) of his class in 1803, Esaias Tegnér was given the primus, or first place.

Immediately after the ceremony of graduation, Tegnér hastened to greet his friends and especially Jacob Branting and Christopher Myhrman, whose liberality had in part sustained him at the university. “At Rämen he was met with open arms by the older members of the family, and with secret trembling by a beating heart of sixteen years, where his image stood concealed behind the memories of childhood. His summer became an idyl,—the first happiness of love. . . . The traveler who approaches Rämen finds in the pine woods beside the way a narrow stone, bearing the letters E. T., and A. M. By this, one August evening, two hearts swore to each other eternal fidelity.”

The university of Lund hastened to appropriate to itself its brilliant alumnus, as private instructor in Æsthetics. Three years later occurred his marriage with Anna Myhrman. For several years his lyre was silent. He believed success for him lay in the line of scholarship, and only for solace or merriment he tuned its chords. In 1808 appears the first truly national and characteristic poem of this skald, “To the Defenders of Sweden.” “This warlike dithyramb sounded like an alarm-bell through every national breast. Tones at once so defiant and so beautiful had not been heard before. These double services as instructor and poet attracted the attention of the throne. It was manifested by a commission investing Tegnér with the name, rank and honor of professor.”

It was during this period that Tegnér’s literary reputation neared its radiant meridian. Poems of various sort came forth with strange rapidity,—as yet, however, none of much extent. There were at this time two schools of poetry in Sweden,—the mystical, or “phosphoristic,” and the Gothic. The former inclined toward foreign, especially German, models, the latter maintained the sufficiency of national models and subjects. Tegnér, though an ardent disciple of the Gothic school, disdained discussion, and maintained that the best argument was example. Such example he was himself destined soon to furnish. In 1820 appeared his “sacredly sweet Whitsun Idyl,” “The Children of the Lord’s Supper,” which has been so well rendered into English by Mr. Longfellow. Though clear and simple as the brooks and sunshine this poem lacks the stir and vigor which it was so easy for Tegnér to impart. In the next year this lack was supplied in the poem of “Axel,” and almost at the same time by the publication of his “Frithiof’s Saga,”—“the apples,” says Geijer [Yeiyer], “through which the gods yet show their power to make immortal.” This is an old Norse legend which Tegnér has rewritten and modernized, and at the same time charged full with the fervor of his mighty soul. “It would be superfluous to recount here the applause with which this master poem of Northern poetic genius was vociferously greeted by all the educated world; how Goethe from his throne of poetical eminence bowed his laurel-crowned gray locks in homage to it; how[431] all the languages of Europe, even the Russian, Polish and modern Greek, hastened to appropriate to themselves greater or less portions of the same; how in the poet’s own country it soon became a living joy upon the lips of the people, a treasure in the day-laborer’s cot as in the prince’s halls. Its author’s name has gone abroad together with that of Linnæus, and wherever one goes one hears it mentioned with respect and admiration.”

Of this “Frithiof’s Saga” our space forbids us to speak at greater length. Mr. Longfellow has given an excellent analysis of the poem (North American Review for July, 1837), and it has been rendered into English, entirely or in part, no less than nineteen times. We have but to record that this example of the clear treatment of a Gothic or Northern subject was the necessary and final argument against the school of Phosphorists. From the day when the “Frithiof” appeared, we hear of no other model or standard of poetic excellence in Sweden.

With the publication of these longer poems Tegnér’s career as a poet virtually terminates. He never estimated his gifts at their real value, and gave to the practice of his art only leisure moments. To the end of his life the success of his “Frithiof” was a standing surprise to him. His chief fondness was for Greek,—the department in which twelve years before he had been made a university professor. But his life henceforth was to be little with his beloved Greek authors, little with his muse. Not long after graduation he had been ordained and placed for a time in charge of two parishes in the neighborhood of Lund. Now, in January, 1824, came the intelligence that he had been elected to the vacant bishopric of Wexiö. The spirit which breathed from his “Nattvardsbarnen” (Children of the Lord’s Supper) had won the hearts of the clergy, and this was their tribute of love and confidence. He accepted with reluctance, removing to the scene of his future labors in May of the same year. He threw himself into his new duties with all energy. The various interests of his diocese, particularly the schools, received his unremitting care. In the fourteen years that follow he became the acknowledged head of the Swedish Church. In the National Diet he was also an active member. But now we approach the end of this remarkable career. There was a trace of insanity in the family, and Tegnér had long feared he might become a victim. In his poetic facility he saw only a mental intensity emanating from that source; and he was doubtless right. Overwork had also aggravated the danger. Ere long he grew full of great and impossible schemes. He wrote to Mr. Longfellow that he was about to issue a new edition of his writings in a hundred volumes! Finally, in 1838, he was sent to the insane hospital at Schleswig. After a short stay he seemed to mend, and returned to his labors, as all thought, restored. But his vital energy was slowly waning. In 1845 he was obliged to seek release from public duty, and in the year following was stricken with paralysis. It was not the first attack of this kind that had come upon him, but it was the last. “His head now possessed its old-time soundness; his voice had recovered its usual clearness. Only the evening before his death he was attacked by a slight delirium, which was betrayed by his speaking often of Goethe as his countryman. Resigned and peaceful he neared his end. Water and light were still his refreshments. When the autumn sun one day shone brightly into his sick chamber, he broke forth with the words, ‘I lift up my hands to God’s house and mountain,’ which he often afterward repeated. They were his last Sun-song. To his absent children he sent his farewell greeting; to his oldest son a ring with Luther’s picture, which he had worn on his hand for thirty years. Shortly before midnight on the second of November, 1846,—the most beautiful aurora borealis lighted up the sky—the spirit of the skald gently broke its fetters. Scarcely a sigh betrayed the separation to his kneeling wife, who read upon his face, lit up at once by the moon and death, ‘blessed peace and heavenly rapture.’”

Tegnér’s successor in Swedish belles-lettres was Rúneberg, of whom we shall now give a brief sketch. Tegnér belongs to the romantic era of European literature, and, as we know, it would be hard to find a more purely romantic poet. Runeberg was destined to found in Sweden the modern or realistic school. He was the son of a “merchant-captain,” and born in 1804 in Finland. He was sent to college, became professor of Latin, and finally of Greek. He caught in some way the spirit of the coming change, unlearned the old methods in which he had begun to write, and in 1832 published his “Elk Hunters.” This was the beginning of nature-writing in Sweden. It was followed by the delicate idyl of “Hanna,” the brilliant “Christmas Eve,” and finally “Nadeschda” and “King Fjalar.” These bear favorable comparison with anything in modern literature. In his shorter pieces, and notably the “Ensign Stal’s Stories,” Runeberg has earned perhaps greater fame. His death occurred in 1877. The school he founded is continued by the living pens of Wirsén, Carl Snoilsky, and Viktor Rydberg.

We will translate, to close our sketch, a random morsel of Runeberg, not as an example of his genius and skill, but rather of his simplicity and love of nature. The meter is already familiar to us in “Hiawatha,” and was borrowed by both Runeberg and Longfellow from the national epic of Finland, the “Kalevála.”

[To be continued.]

By C. E. BISHOP.

You remember Franklin’s story of the speckled axe; how he turned the grindstone to polish it up nice, and, tiring of the revolutions, concluded he “liked a speckled axe best.” There was a king of England who had a very speckled character and the people of England (who turned the grindstone for him) long liked their king’s speckled character best of all the kings that they had known.

When Prince of Wales he “cut up” so that he got the name of “Madcap Harry,” some of the most amusing of his pranks being highway robbery and burglary, for all which he was admired in his day and immortalized, along with Jack Falstaff, by Shakspere. One of the light spots on this character is his obedience to the commitment by Chief Justice Gascoigne; and although it belongs to the realm of tradition, it is so pleasant to believe and is so quaintly told by Lord Campbell that we’ll e’en accept it: One of the Prince’s gang of cut purses had been captured and imprisoned by Gascoigne, and the Prince came into court and demanded his release, which was denied. The Prince, says the chronicle, “being set all in a fury, all chafed and in a terrible maner, came up to the place of jugement, men thinking that he would have slain the juge, or have done to him some damage; but the juge sitting still without moving, declaring the majestie of the king’s place of jugement, and with an assured and bolde countenance, had to the Prince these words following: ‘Sir, remember yourself. I kepe here the place of the kinge, your soveraine lorde and father, to whom ye owe double obedience: wherefore eftsoones in his name I charge you desiste of your wilfulness and unlawfull enterprise, and from hensforth give good example to those whiche hereafter shall be your propre subjectes. And nowe, for your contempte and disobedience, go you to the prison of the Kinge’s Benche, whereunto I committe you, and remain ye there prisoner untill the pleasure of the kinge, your father, be further knowen.’”

The prince’s better nature, and a sense of his family’s precarious situation before the law perhaps, induced him to accept the sentence and go to jail. On hearing this the king is recorded as saying: “O merciful God, how much am I bound to your infinite goodness, especially for that you have given me a juge who feareth not to minister justice, and also a sonne, who can suffre semblably and obeye justice.”

In keeping with this wonderful “spasm of good behavior” is the sudden change that came over the Madcap as soon as he became King Henry V. He became as remarkable for his austere piety as he had been for his wickedness. Unfortunately, his piety took the shape of burning Lollards (the shouting Methodists of that day), and he signed the warrant under which the brave and innocent Sir John Oldcastle, his old friend and boon companion, was hung up in chains over a slow fire.

There could be but two outlets in those days for such a degree of piety as Henry had achieved: as whatever he undertook must be bloody and cruel, the choice lay between a crusade or an invasion of France. As the latter promised the most booty and least risk he seemed to have a call in that direction. The attempt seemed about equal to an able bodied man attacking a paralytic patient in bed. The king of France was insane: his heir was worthless and lazy; the queen regent was an unfaithful wife and an unnatural mother, who took sides with the faction that was trying to dethrone the king and destroy his and her son. The kingdom was torn to pieces by civil strife between the Orleanists and the Burgundians, each vying with the other in cruelty, treachery, violence and plundering the government and outraging the people. There was an awful state of affairs—just the chance for a valiant English king.

Henry put up a demand for the French crown, under the pseudo claim of Edward III., whose house his father had deposed. A usurper claiming a neighbor’s crown by virtue of the usurped title of an overturned and disinherited dynasty; as if one stealing a crown got all the reversions of that crown by right. Henry would have made a good claim agent in our day! And the English people, with the remembrance of Cressy and Poictiers, of the Black Prince, and the captive King of France, and all the booty and cheap glory that made England so rich and vain sixty years before, fell in with Henry’s amiable designs on France. It was perfectly clear to the whole nation, from the chief justice down to the clodhopper, that Henry’s claim to the crown of France was a clear and indefeasible one; that the war would be for a high and holy right—and could not fail to pay.

And this was the main object of Henry after all: to divert the kingdom’s attention from his own usurped title by a foreign war; to fortify usurpation at home by attempted usurpation abroad. His father had enjoined upon him this policy, in Shakspere’s words—

So in July, 1415, Henry and 30,000 more patriots, sailed across the channel on 1,500 ships and landed unopposed at the mouth of the Seine. It took them six weeks and cost half the army to reduce the Castle of Harfleur, surrounded by a swamp, and then his generals advised him to abandon the campaign. But he dare not go back to his insecure throne with failure written on his very first attempt at glory; the expedition had cost too much money and he must have something to show for it. So boldly enough he struck for the heart of France.

This whole campaign was a close copy after the invasion by Edward III. in 1346. There was the same unopposed march to the walls of Paris, almost over the same ground; the retreat before a tardy French host; the lucky crossing of the river Somme, over the identical Blanchetacque Ford, and the bringing to bay of the English by many times their own number of French, were all faithfully repeated; while the battle of Agincourt took place only a short distance from the field of Cressy, and in its main features was a repetition of that engagement. But in one respect, honorable to him, Henry did not copy after Edward and the Black Prince. He forbade all plundering and destruction; a soldier who stole the pix from a church at Corby was instantly executed.

The description of the scenes before the battle, when,

the contrary despondency of the English, the lofty, heroic tone of Henry with his men, when he declared gaily he was glad there were no more of them to share the honor of whipping ten to one of the French; and his proclamation that any man who had no stomach for this fight might depart; we “could not die in that man’s company that fears his fellowship to die with us.” But his humble prostration in the solitude of his own tent when he prayed piteously,—[433]

All this makes up one of Shakspere’s most moving scenes. The action and the result of this battle are as inexplicable as those of Cressy and Poictiers. We know that now, as then, the sturdy English archers did their fearful execution on the massed French. France had learned nothing in seventy years of defeats and adversity; she had no infantry, entrusted no peasantry with arms: still depended on gentlemen alone to defend France—and again the gentlemen failed her. Sixty thousand were packed in a narrow passage between two dense forests. On this mass the bowmen fired their shafts until these were exhausted. Then throwing away their bows, swinging their axes and long knives, and planting firmly in the earth in front of them their steel-pointed pikes, they waited the charge of the French chivalry. The mud was girth-deep. The horses stumbled under their heavily-armored riders. Such as reached the English line struck the horrid pikes and were hewn down by the stalwart axmen. They break and retreat, carrying dismay and confusion to the main body. The pikes are pulled up, and the line advanced. A charge of English knights is hurled upon the broken mass of French, and their return is covered by the axmen, who advance and form another line of pikes to meet the countercharge of French. So it goes on, until the French host is a mob, and the English are everywhere among them, hewing, stabbing, and thrusting. “So great grew the mass of the slain,” said an eye-witness, “and of those who were overthrown among them, that our people ascended the very heaps, which had increased higher than a man, and butchered their adversaries below with swords and other weapons.” It all lasted three hours before the French could be called defeated, for they were so numerous and were packed so closely that even retreat was long impossible. Before the battle had been decided, every Englishman had four or five prisoners on his hands, whom he was holding for ransoms. This was the grand chance to recoup all their losses and sufferings and grievous denial of plunder. This was a predicament for a victorious army, and if a small force of the French had made a rally they might then have reversed their defeat on the scattered English. Henry tried to avert such a catastrophe by sounding the order for every man to put all his prisoners to death: but cupidity saved many, nevertheless.

The flower of the chivalry of France perished on this field, greatly to the relief and benefit of France. Seven of the princes of the blood royal, the heads of one hundred and twenty of the noble families of France, and eight thousand gentlemen were counted among the 30,000 slain. The feudal nobility never recovered from the blow,—but France did, all the sooner for lack of them.

The victorious army made its way to Calais, and Henry returned to England, “covered with glory and loaded with debt.” But there was unlimited exultation when Henry came marching home, into London, under fifteen grand triumphal arches, insomuch that an eye-witness says, “A greater assembly or a nobler spectacle was not recollected to have been ever before in London.”

Campaign after campaign into France followed; she being plunged deeper and deeper into civil war, anarchy, and mob-rule. Rouen fell in 1419, and the two kings arranged a peace and a marriage between Henry and the princess Catherine. (The courtship in Shakspere is racy.) In 1420 the two kings, side by side, made a triumphant entry into Paris, and Henry was acknowledged as successor to the French crown after Charles VI. should die. Another great demonstration was seen in London when the French Catherine was crowned Queen of England (1421). Ah! there was a fearful Nemesis awaiting this newly-married pair in the insanity of their son, inherited from Catherine’s father. And England was to pay dearly for her French glory in the miseries of the reign of Henry VI. and the dreadful Wars of the Roses. Indeed, she was already paying dearly in the load of taxation and the loss of life those wars had entailed, insomuch that even now there was a scarcity of “worthy and sufficient persons” to manage government affairs in the boroughs and parishes.

The English army in France met with a sudden reverse, the commandant, the Duke of Clarence, being slain. More troops had to be raised and taken to France, and in the effort to keep his grasp on the prostrate kingdom, Henry himself was prostrated in the grasp of an enemy he could not resist. So, on the 31st of August, 1422, in the midst of his campaign, Henry died.

The priests came to his bedside and recited the penitential psalm: when they came to “Thou shalt build up the walls of Jerusalem,” the dying man said: “Ah, if I had finished this war I would have gone to Palestine to restore the Holy City.” He was the last of the crusade dreamers, and the last of the great invaders of France among English kings. In a few years all that he had won, and all that the greatest English generals and the prowess of her archers could avail were scattered by a mere girl creating and leading to victory new French armies.

And this bauble of war was all there was of Henry Fifth’s reign, the pride of the House of Lancaster. So we can hardly join in the lamentation of the Duke of Bedford:

The historian, White, pretty well sums up this “speckled character:”

“His personal ambition had been hurtful to his people. In the first glare of his achievements, some parts of his character were obscured which calm reflection has pointed out for the reprobation of succeeding times. He was harsh and cruel beyond even the limits of the harsh and cruel code under which he professed to act. He bought over the church by giving up innovators to its vengeance; he compelled his prisoner, James I. of Scotland, to accompany him in his last expedition to France to avenge a great defeat his arms sustained at Beaugé at the hands of the Scotch auxiliaries, and availed himself of this royal sanction to execute as traitors all the Scottish prisoners who fell into his hands. His massacre of the French captives has already been related, and we shall see how injuriously the temporary glory of so atrocious a career acted on the moral feelings of his people when it blunted their perception of those great and manifest crimes and inspired the nobles with a spirit of war and conquest which cost innumerable lives and retarded the progress of the country in wealth and freedom for many years.”

[To be continued.]

It is hard in this world to win virtue, freedom, and happiness, but still harder to diffuse them. The wise man gets everything from himself, the fool from others. The freeman must release the slave—the philosopher think for the fool—the happy man labor for the unhappy.—Jean Paul F. Richter.

Our last article gave us a complete description of the human organization. In the present number we will inquire how we move this complex system of bones, nerves, flesh, and tissues.

We will take a particular motion and see if we can understand that. For instance, you bend your arm. You know that when your arm is lying on the table you can bend the forearm on the upper arm (or part above the elbow) until your fingers touch your shoulder. How is this done?

Look at the arm in a skeleton; you will see that the upper part is composed of one large bone, called the humerus, the fore part of two bones, the radius and ulna. If you look carefully you will see that the end of the humerus, at the elbow, is curiously rounded, and the end of the ulna, at the elbow, is scooped out in such a way that one fits loosely into the other. If you try to move them about, one on the other, you will find that you can easily double the ulna very closely on the humerus, without their ends coming apart; and as you move the ulna you will notice that its end and the end of the humerus slide over each other. But they will slide only one way—up and down. If you try to slide them from side to side they get locked. At the elbows, then, we have two bones fitting into each other, so that they will move in a certain direction; their ends are smoothed with cartilage, kept moist with a fluid and held in place by ligaments, and this is all called a joint.

In order that this arm may be bent some force must be used. The radius and ulna (the two move together) must be pushed or pulled toward the humerus, or the humerus toward the radius and ulna. How is this done in your arm? Imagine that a piece of string were fastened to either the radius or ulna, near the top: let the string be carried through a little groove, which there is at the upper end of the humerus, and fastened to the shoulder-blade. Let the string be just long enough to allow the arm to be straightened out, so that when the arm is straight the string will be just about tight. Now draw your string up into a loop and you will bend the fore-arm on the humerus. If this string could be so made that every time you willed it so, it would shorten itself, it would pull the ulna up and would bend the arm; every time it slackened the arm would fall back into a straight position.

In the living body there is not a string, but a band of tissues placed very much as our string is placed, and which has the power of shortening itself when required. Every time it shortens the arm is bent, every time it lengthens again the arm falls back into its straight position. This body, which can thus lengthen and shorten itself, is called a muscle. If you put your hand on the front of your upper arm, half way between your shoulder and elbow, and then bend your arm, you will feel something rising up under your hand: this is the muscle shortening or, as we shall now call it, contracting.

But what makes the muscle contract? You willed to move your arm, and moved it by making the muscle contract; but how did your will accomplish this? If you should examine, you would find running through the muscle soft white threads, or cords, which you have already learned to recognize as nerves. These nerves seem to grow into and be lost in the muscle. If you trace them in the other direction you would find that they soon join with other similar nerves, and the several cords joining together form stouter nerve-cords. These again join others, and so we should proceed until we came to quite stout white nerve-trunks, as they are called, which pass between the vertebræ of the neck into the vertebral column, where they mix in the mass of the spinal cord. What have these nerves to do with the bending of the arm? Simply this: If you should cut through the delicate nerves entering the muscle, what would happen? You would find that you had lost all power of bending your arm. However much you willed it, the muscle would not contract. What does this show? It proves that when you will to move, something passes along the nerves to the muscle, which something causes the muscle to contract. The nerve, then, is a bridge between your will and the muscle—so that when the bridge is broken the will can not get to the muscle.

If, anywhere between the muscle and the spinal cord, you cut the nerve, you destroy communication between the will and the muscle. If you injure the spinal cord in your neck you might live, but you would be paralyzed; you might will to bend your arm, but could not.

In short, the whole process is this: by the exercise of your will a something is started in your brain. That something passes from the brain to the spinal cord, leaves the spinal cord and travels along certain nerves, picking its way along the bundles of nervous threads which run from the upper part of the spinal cord, until it reaches the muscle. The muscle immediately contracts and grows thick. The tendon pulls at the radius, the radius with the ulna moves on the fulcrum of the humerus at the elbow-joint, and the arm is bent.

Why does the muscle contract when that something reaches it? We must be content to say that it is the property of the muscle. But it does not always possess this property. Suppose you were to tie a cord very tightly around the top of the arm close to the shoulder. If you tied it tight enough the arm would become pale, and would very soon begin to grow cold. It would get numb, and would seem to be heavy and clumsy. Your feeling in it would be blunted, and soon altogether lost. You would find great difficulty in bending it, and soon it would lose all power. If you untied the cord, little by little the cold and clumsiness would pass away, the power and warmth would come back, and you would be able to bend it as you did before. What did the cord do to the arm? The chief thing was to press on the blood-vessels, and so stop the blood from moving in them. We have seen that all parts of the body are supplied with blood-vessels, veins and arteries. In the arm there is a very large artery, branches from which go into all parts of the muscle. If, instead of tying the cord about the arm, these branches alone were tied, the arm, as a whole, would not grow cold or limp, but if you tried to bend it, you would find it impossible. All this teaches that the power which a muscle has of contracting may be lost and regained as the blood is stopped in its circulation, or allowed to circulate freely.

Our next question is, What is there in the blood that thus gives to the muscle the power of contracting, or that keeps the muscle alive? The answer is easy. What is the name given to this power of a muscle to contract? We call it strength. Straighten out your arm upon the table and put a heavy weight in your hand; then bend your arm. Find the heaviest weight that you can raise in this way, and try it some morning after your breakfast, when you are in good condition. Go without dinner, and in the evening when tired and hungry, try to raise the same weight in the same way. You will not be able to do so. Your muscle is weaker than it was in the morning, and you say that the want of food makes you weak; and that is so, because the food becomes blood. The things which we eat are changed into other things which form part of the blood, and this blood going to the muscle gives it strength. What is true of the relations of the blood to the muscles is true of all other parts of the body. The brain and nerves and spinal cord have a more pressing need of pure blood. The faintness which we[435] feel from want of food is quite as much weakness of the brain and of the nerves as of the muscles, perhaps even more so.

The whole history of our daily life is, briefly told, this: The food we eat becomes blood; the blood is carried all over the body, round and round, in the torrent of the circulation; as it sweeps past them or through them, the brain, nerves, muscles and skin pick out new food for their work, and give back the things they have used or no longer want; as they all have different work, some pick up what others have thrown away. There are also scavengers and cleansers to take up things which are wanted no longer, and to throw them out of the body.

Thus the blood is kept pure as well as fresh. Thus it is through the blood brought to them, that each part does its work.

But what is blood? It is a fluid. It runs about like water, but while water is transparent, blood is opaque. Under a microscope you will see a number of little round bodies—the blood-discs, or blood-corpuscles. All the redness there is in blood belongs to these. These red corpuscles are not hard, solid things, but delicate and soft, yet made to bear all the squeezing they get as they drive around the body. Besides these red corpuscles, are other little bodies, just a little larger than the red, not colored at all, and quite round. These are all that one can see in blood, but it has a strange property which we will study. Whenever blood is shed from a living body, within a short time it becomes solid. This change is called coagulation. If a dish be filled with blood, and you were to take a bunch of twigs and keep slowly stirring, you would naturally think it would soon begin to coagulate; but it does not, and if you keep on stirring you find that this never takes place. Take out your bundle of twigs, and you will find it coated all over with a thick, fleshy mass of soft substance. If you rinse this with water you will soon have left nothing but a quantity of soft, stringy material matted among the twigs. This stringy material is, in reality, made up of fine, delicate, elastic threads, and is called fibrin; by stirring you have taken it out. If the blood had been left in the dish for a few hours, or a day, you would find a firm mould of coagulated blood floating in a colorless liquid. This jelly would continue shrinking, and the fluid would remain; this fluid is called serum, and it is the blood out of which the corpuscles have been strained by the coagulation. All these various things, fibrin, serum, corpuscles, etc., make up the blood. This blood must move, and how does it move? You have had the different organs which assist in its circulation described, but let us illustrate.

All over the body there are, though you can not see them, networks of capillaries. All the arteries end in capillaries, and in them begin all veins. Supposing a little blood-corpuscle be squeezed in the narrow pathway of a capillary in the muscle of the arm. Let it start in motion backward. Going along the narrow capillary it would hardly have room to move. It will pass on the right and left other capillary channels, as small as the one in which it moves; advancing, it will soon find the passage widening and the walls growing thicker. This continues until the corpuscle is almost lost in the great artery of the arm; thence it will pass but few openings, and these will be large, until it passes into the aorta, or great artery, and then into the heart. Suppose the corpuscle retrace its journey and go ahead instead of backward. It will go through passages similar to the other, and it would learn these passages to be veins. At last the corpuscle would float into the vena cava, thence to the right auricle, from there to the right ventricle, by the pulmonary artery to the lungs; there it, with its attendant white corpuscles, serum and other substances, would be purified, then sent by pulmonary vein to the left auricle and ventricle, and then pumped over the body again. Some one may ask, What is the force that drives or pumps the blood? Suppose you had a long, thin muscle fastened at one end to something firm, and a weight attached to it. Every time the muscle contracted it would pull on the weight and draw it up. But instead of hanging a weight to the muscle, wrap it around a bladder of water. If the muscle contract now, evidently the water will be squeezed through any opening in the bladder. This is just what takes place in the heart. Each cavity there, each auricle and ventricle is, so to speak, a thin bag with a number of muscles wrapped about it. In an ordinary muscle of the body the fibers are placed regularly side by side, but in the heart, the bundles are interlaced in a very wonderful fashion, so that it is difficult to make out the grain. They are so arranged that the muscular fibers may squeeze all parts of each bag at the same time. But here is the most wonderful fact of all. These muscles of the auricles and ventricles are always at work contracting and relaxing of their own accord as long as the heart is alive. The muscle of your arm contracts only at your will. But the heart is never quiet. Awake or asleep, whatever you are doing or not doing, it keeps steadily on.

Each time the heart contracts what happens? Let us begin with the right ventricle full of blood. It contracts; the pressure comes on all sides, and were it not for the flaps that close and shut the way, some of the blood would be forced back into the right auricle. As it is, there is but one way,—through the pulmonary artery. This is already full of blood, but, because of its wonderful elasticity, it stretches so that it holds the extra fluid. The valve at its mouth closes, and the blood is safely shut in, but the artery so stretched contracts and forces the blood along into the veins and capillaries of the lungs, in turn stretching them so that they must force ahead the blood which they already contain. This blood is forced into the pulmonary vein, thence to the left auricle; the auricle forces it into the ventricle, and the latter pumps it into the aorta; the aorta overflows as the pulmonary artery did, and the blood goes through every capillary of the body into the great venæ cavæ, which forces it into the right auricle; thence to the ventricle where we started. In this passage every fragment of the body has been bathed in blood. This stream rushing through the capillaries contains the material from which bone, muscle, and brain are made, and carries away all the waste material which must be thrown off.

The actual work of making bone or muscle is performed outside of the blood in the tissues. You say, the capillaries are closed, and how can the blood get to the tissues? It will be necessary here to speak of a certain property of membranes in order that you understand how the tissues are built up by the blood apparently closed within the veins. If a solution of sugar or salt be placed in a bladder with the neck tied tightly, and this placed in a basin of pure water, you will find that the water in the basin will soon taste of sugar or salt and after a time will taste as strong as the water in the bladder. If you substitute solid particles, or things that will not dissolve, you will find no change. This property which membranes, such as a bladder, have, is called osmosis. It is by osmosis chiefly that the raw, nourishing material in the blood gets into the flesh lying about the capillaries. It is by osmosis chiefly that food gets out of the stomach into the blood. It is by this property that the worn-out materials are drained away from the blood, and so cast out of the body. By osmosis the blood nourishes and purifies the flesh. By osmosis the blood is itself nourished and kept pure.

We must now understand how we live on this food we eat. Food passing into the alimentary canal is there digested. The nourishing food-stuffs are dissolved out of the innutritious and pass into the blood. The blood thus kept supplied with combustible materials, draws oxygen from[436] the lungs, and thus carries to every part of the body stuff to burn and oxygen to burn it with. Everywhere this oxidation is going on, changing the arterial blood to venous.

From most places where there is oxidation, the venous blood comes away hotter than the arterial, and all the hot venous blood mingling, keeps the whole body warm. Much heat is given up, however, to whatever is touching the skin, and much is used in turning liquid perspiration into vapor. Thus, as long as we are in health, we never get hotter than a certain degree.

Everywhere this oxidation is going on. Little by little, every part of the body is continually burning away and continually being made anew by the blood. Though it is the same blood, it makes very different things: in the nerves it makes nerve; in the muscle, muscle. It gives different qualities to different parts: out of one gland it makes saliva, another gastric juice; out of it the bone gets strength and the muscle power to contract. But the far greater part of the power of the blood is spent in heat, or goes to keep us warm.

One thing more we have to note before we answer the question, why we move. We have seen that we move by reason of our muscles contracting, and that, in a general way, a muscle contracts because a something started in our brain by our will, passes through the spinal cord, through certain nerves, until it reaches the muscle, and this something we may call a nervous impulse. But what starts this?

All the nerves do not end in the muscles, but many in the skin. These nerves can not be used to carry nervous impulses from the brain to the skin. By no effort of yours can you make the skin contract. For what purpose then are these nerves? If you prick your finger, you feel the touch, or say that you have sensation in your finger. If you were to cut the nerve leading to the finger you would lose this power of feeling. These nerves, then, ending in the fingers have a different use from those ending in the muscles. The latter carry an impulse from the brain to the muscles, and are called motor nerves. The former carry impulses from the skin to the brain, and are called sensory nerves, or those which bring about sensations. Motor nerves are of but one kind, but there are several kinds of sensory nerves, each kind having a special work to do. The several works which these nerves do are called the senses. By means of these sensory nerves we receive impressions from the external world, sensations of heat, cold, roughness, good and bad odors, taste, sound, and the color and form of things. Thus impressions of the external world are made upon the brain, and it is these impressions that stimulate the brain to action. The brain worked on by them, through ways that we know not of, governs the muscles, sends commands by the motor nerves, and rules the body as a conscious, intelligent will.

By DRUMMOND OF HAWTHORNDEN.

SELECTED BY THE REV. J.H. VINCENT, D.D.

By Rev. WILLIAM ARNOT.

These “ways,” as described by Solomon in the preceding verses, are certainly some of the very worst. We have here literally the picture of a robber’s den. The persons described are of the baser sort: the crimes enumerated are gross and rank: they would be outrageously disreputable in any society, of any age. Yet when these apples of Sodom are traced to their sustaining root, it turns out to be greed of gain. The love of money can bear all these.

This scripture is not out of date in our day, or out of place in our community. The word of God is not left behind obsolete by the progress of events. “All flesh is as grass, and all the glory of man as the flower of grass. The grass withereth, and the flower thereof falleth away; but the word of the Lord endureth for ever” (1 Peter, i: 24, 25). The Scripture traces sin to its fountain, and deposits the sentence of condemnation there,—a sentence that follows actual evil through all its diverging paths. A spring of poisonous water may in one part of its course run over a rough, rocky bed, and in another glide silent and smooth through a verdant meadow; but, alike when chafed into foam by obstructing rocks, and when reflecting the flowers from its glassy breast, it is the same lethal stream. So from greed of gain—from covetousness which is idolatry, the issue is evil, whether it run riot in murder and rapine in Solomon’s days, or crawl sleek and slimy through cunning tricks of trade in our own. God seeth not as man seeth. He judges by the character of the life stream that flows from the fountain of thought, and not by the form of the channel which accident may have hollowed out to receive it.

When this greed of gain is generated, like a thirst in the soul, it imperiously demands satisfaction: and it takes satisfaction wherever it can be most readily found. In some countries of the world still it retains the old-fashioned form of iniquity which Solomon has described: it turns free-booter, and leagues with a band of kindred spirits, for the prosecution of the business on a larger scale. In our country, though the same passion domineer in a man’s heart, it will not adopt the same method, because it has cunning enough to know that by this method it could not succeed. Dishonesty is diluted, and colored, and moulded into shapes of respectability, to suit the taste of the times. We are not hazarding an estimate whether there be as much of dishonesty under all our privileges as prevailed in a darker day: we affirm only that wherever dishonesty is, its nature remains the same, although its form may be more refined. He who will judge both mean men and merchant princes requires truth in the inward parts. There is no respect of persons with him. Fashions do not change about the throne of the Eternal. With him a thousand years are as one day. The ancient and modern evil-doers are reckoned brethren in iniquity, despite the difference in the costume of their crimes. Two men are alike greedy of gain. One of them being expert in accounts, defrauds his creditors, and thereafter drives his carriage; the other, being robust of limb, robs a traveler on the highway, and then holds midnight revel on the spoil. Found fellow-sinners, they will be left fellow-sufferers. Refined dishonesty is as displeasing to God, as hurtful to society, and as unfit for heaven, as the coarsest crime.

This greed, when full grown, is coarse and cruel. It is not[437] restrained by any delicate sense of what is right or seemly. It has no bowels. It marches right to its mark, treading on everything that lies in the way. If necessary, in order to clutch the coveted gain, “it takes away the life of the owners thereof.” Covetousness is idolatry. The idol delights in blood. He demands and gets a hecatomb of human sacrifices.

Among the laborers employed in a certain district to construct a railway, was one thick-necked, bushy, sensual, ignorant, brutalized man, who lodged in the cottage of a lone old woman. This woman was in the habit of laying up her weekly earnings in a certain chest, of which she carefully kept the key. The lodger observed where the money lay. After the works were completed and the workmen dispersed, this man was seen in the gray dawn of a Sabbath morning stealthily approaching the cottage. That day, for a wonder among the neighbors, the dame did not appear at church. They went to her house, and learned the cause. Her dead body lay on the cottage floor: the treasure-chest was robbed of its few pounds and odd shillings, and the murderer had fled. Afterward they caught and hanged him.

Shocking crime!—to murder a helpless woman in her own house in order to reach and rifle her little hoard, laid up against the winter and the rent! The criminal is of a low, gross, bestial nature. Be it so. He was a pest to society, and society flung the troubler off the earth. But what of those who are far above him in education and social position, and as far beyond him in the measure of their guilt? How many human lives is the greed of gain even now taking away in the various processes of slavery? Men who hold a high place, and bear a good name in the world, have in this form taken away the life of thousands for filthy lucre’s sake. Murder on a large scale has been and is done upon the African tribes by civilized men for money.

The opium traffic, forced upon China by the military power of Britain, and maintained by her merchants in India, is murder done for money on a mighty scale. Opium spreads immorality, imbecility, and death through the teeming ranks of the Chinese populations. The quantity of opium cultivated on their own soil is comparatively small. The government prohibited the introduction of the deadly drug until England compelled them to legalize the traffic. British merchants brought it to their shores in ship-loads notwithstanding, and the thunder of British cannon opened a way for its entrance through the feeble ranks that lined the shore. Every law of political economy, and every sentiment of Christian charity, cries aloud against nurturing on our soil, and letting loose among our neighbors, that grim angel of death. The greed of gain alone suggests, commands, compels it. How can we expect the Chinese to accept the Bible from us while we bring opium to them in return? British Christians might bear to China that life for which the Chinese seem to be thirsting, were it not that British merchants are bearing to China that death which the best of her people loathe.

A bloated, filthy, half-naked laborer, hanging on at the harbor, has gotten a shilling for a stray job. As soon as he has wiped his brow, and fingered the coin, he walks into a shop and asks for whisky. The shopkeeper knows the man—knows that his mind and body are damaged by strong drink—knows that his family are starved by the father’s drunkenness. The shopkeeper eyes the squalid wretch. The shilling tinkles on the counter. With one hand the dealer supplies the glass, and with the other mechanically rakes the shilling into the till among the rest. It is the price of blood. Life is taken there for money. The gain is filthy. Feeling its stain eating like rust into his conscience, the man who takes it reasons eagerly with himself thus: “He was determined to have it; and if I won’t, another will.” So he settles the case that occurred in the market-place on earth, but he has not done with it yet. How will that argument sound as an answer to the question, “Where is thy brother?” when it comes in thunder from the judgment-seat of God?

Oh that men’s eyes were opened to know this sin beneath all its coverings, and loathe it in all its disguises! Other people may do the same, and we may never have thought seriously of the matter; but these reasons, and a thousand others, will not cover sin. All men should think of the character and consequences of their actions. God will weigh our deeds; we should ourselves weigh them beforehand in his balances. It is not what that man has said, or this man has done; but what Christ is, and his members should be. The question for every man through life is, not what is the practice of earth, but what is preparation for heaven. There would not be much difficulty in judging what gain is right and what is wrong if we would take Christ into our counsels. If people look unto Jesus when they think of being saved, and look hard away from him when they are planning how to make money, they will miss their mark for both worlds. When a man gives his heart to gain, he is an idolater. Money has become his god. He would rather that the Omniscient should not be the witness of his worship. While he is sacrificing in this idol’s temple, he would prefer that Christ should reside high in heaven, out of sight and out of mind. He would like Christ to be in heaven, ready to open its gates to him, when death at last drives him off the earth; but he will not open for Christ now that other dwelling-place which he loves—a humble and contrite heart. “Christ in you, the hope of glory;” there is the cure of covetousness! That blessed Indweller, when he enters, will drive out—with a scourge, if need be—such buyers and sellers as defiled his temple. His still small voice within would flow forth, and print itself on all your traffic,—“Love one another, as I have loved you.”

On this point the Christian Church is very low. The living child has lain so close to the world’s bosom that she has overlaid it in the night, and stifled its troublesome cry. After all our familiarity with the Catechism, we need yet to learn “what is the chief end of man,” and what should be compelled to stand aside as a secondary thing. We need from all who fear the Lord, a long, loud testimony against the practice of heartlessly subordinating human bodies and souls to the accumulation of material wealth.

By the REV. W. JAY.