UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Fred A. Seaton, Secretary

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Conrad L. Wirth, Director

HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER TWENTY-FOUR

This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents.

by G. D. Pope, Jr.

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 24

Washington, D. C., 1956

The National Park System, of which Ocmulgee National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people.

In presenting this reconstruction, based in a large measure upon interpretations which took their origins from the work conducted at Ocmulgee, the National Park Service would like to acknowledge the debt of archeology to three gentlemen of Macon, Ga. Charles C. Harrold, Walter A. Harris, and Linton M. Solomon were aware of the importance of the large mound and village site close to their community and deeply interested in its thorough study and ultimate preservation. It was through their devoted efforts that the large-scale excavations were undertaken, and the site of this important work preserved as Ocmulgee National Monument.

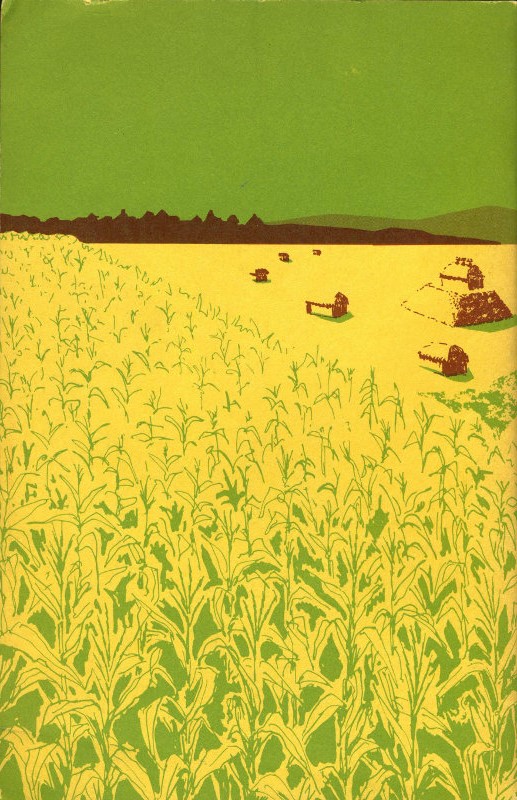

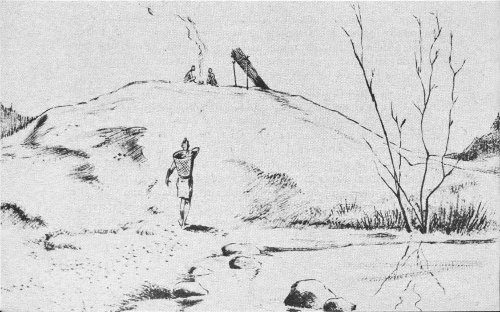

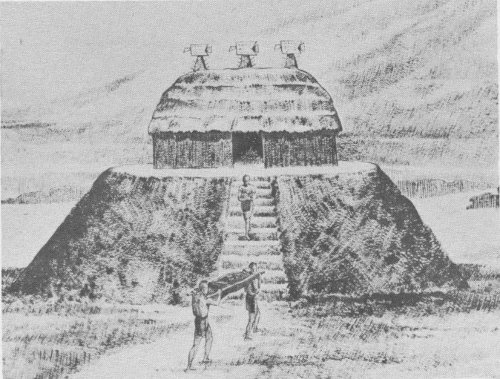

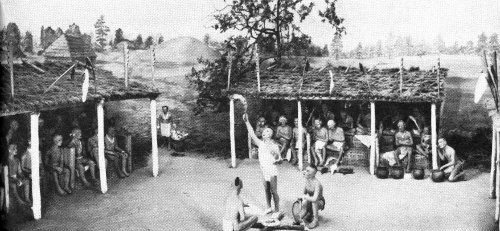

Ancient Life at Ocmulgee. Artist’s conception of temple mound village of about A. D. 1000, seen from the riverside.

From the middle of the 18th century until 1934 the Indian mounds near the present city of Macon, Ga., had been a subject for speculation to all who saw them. A ranger journeying with Oglethorpe, founder of the Georgia Colony, mentions “three Mounts raised by the Indians over three of their Great Kings who were killed in the Wars.” A more discerning traveler in the same century could learn that contemporary Indians and generations of their ancestors knew nothing of the origin of these mounds, where ghostly singing was said to mark the early morning hours. As late as 1930, however, even specialists could only add that the large pyramidal mound showed connections with the cultures of the Mississippi Valley and that a second mound had served as a burial mound.

In 1933, it was possible, with labor furnished by the Civil Works Administration, to begin a systematic exploration of the Ocmulgee mounds and adjoining sites. This work continued until 1941, most of it being performed by the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps. In 1933, also, the citizens of Macon purchased the land and gave it to the Nation. Ocmulgee National Monument was authorized by Congress in June 1934 and established by Presidential proclamation in December 1936.

Eight years’ work, involving the removal of untold tons of earth and the recovery of hundreds of thousands of artifacts, has established the archeological significance of Ocmulgee. It has demonstrated the existence here in one small area of material remains from almost every major period of Indian prehistory in the Southeast. Being one of the first large Indian sites in the South to be scientifically excavated, Ocmulgee provided many of the important details in our expanding knowledge of that story.

It is the middle-Georgia chapter of this story we shall tell here. In it we can follow the Indian almost from the time of his earliest recognition on this continent to that of his final defeat and later dispossession 2 by the white man. The period covered may be close to 10,000 years; and while the evidence is often scanty, we can detect in it the unmistakable signs of steady cultural progress. During that time the Indian passed from the simple life of the nomadic hunter to the complex culture of tribes which, enjoying the products of an advanced agriculture, could devote their surplus energy to the development of religious or political systems. In the final pages we can study the effects of the increasing impact of European civilization on the alien culture of a self-sufficient people.

Every school boy knows that at the time of its discovery North America was the Red Man’s continent. He knows that white people, equipped with the weapons and knowledge of an advanced civilization, took this land by persuasion or by force. For most of us our knowledge of the American Indian begins and ends with the brief interval in time where these two races were involved in a bitter struggle.

Our knowledge is limited because until recently no one really knew the answers to such questions as “Where did the Indian come from?” Many thought that he had been preceded by another race of superior intelligence, the “Mound Builders”; and in general our information about him had rested on a great deal of ingenious speculation with very little actual knowledge to back it up. The people most actively interested in the problem are the archeologists. They have been studying it intensively for about 75 years; and, while their work was at first mostly descriptive, the last 25 years have seen tremendous strides in both the techniques of their research and the soundness of their interpretations. Now we know a good deal about the Indian and have traced his career on this continent back to a time when our own past becomes almost equally dim and shadowy. But this information is still mostly to be found in big books, or in special studies that are hard to obtain; so it may be helpful to outline briefly here what we know today of the origins and early career of this particular branch of the human race.

In the Old World, human history has been traced to its beginnings through fossil remains suggesting a stage of development earlier than man. In the Western Hemisphere, however, no such remains have been found, which indicates that the American Indian must have immigrated here from another continent. In searching for his closest relatives, therefore, scientists are now agreed that certain physical peculiarities show the modern as well as the prehistoric Indian to be most closely linked to the peoples of eastern Asia.

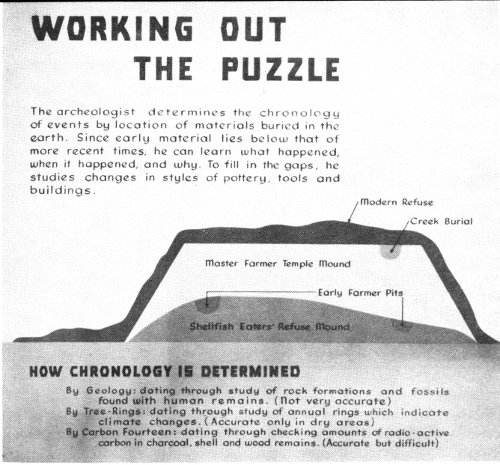

Museum exhibit panel. Arrangement of cultural features idealized.

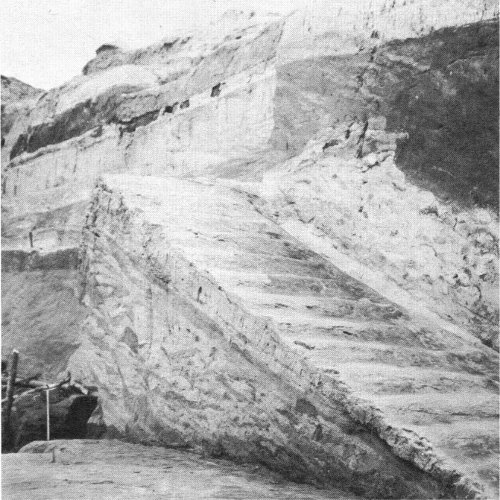

The archeologist determines the chronology of events by location of materials buried in the earth. Since early material lies below that of more recent times he can learn what happened, when it happened, and why. To fill in the gaps he studies changes in styles of pottery, tools and buildings.

HOW CHRONOLOGY IS DETERMINED

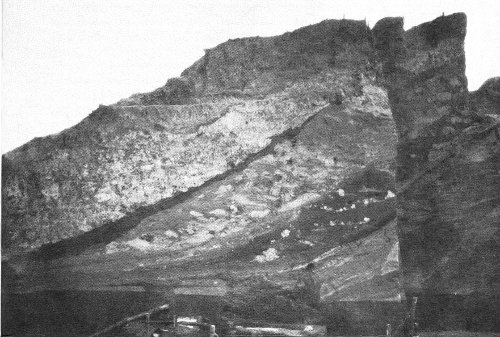

Cross section, east slope of Funeral Mound, Ocmulgee National Monument. Arrangement of construction elements confused by erosion and wash from top and side of successive mound stages.

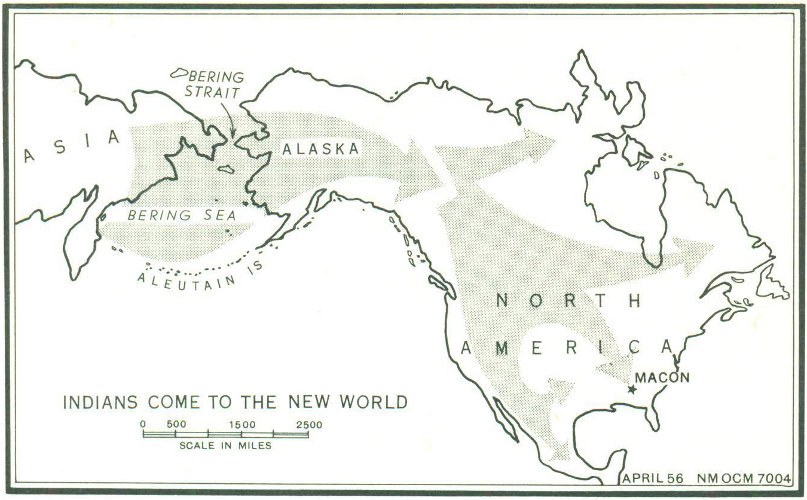

INDIANS COME TO THE NEW WORLD

Most living American Indians share with the east Asians a group of features which are considered to be distinctive of the great Mongoloid division of mankind. These include: straight dark hair, dark eyes, light yellow-brown to red-brown skin, sparse beard and body hair, prominent cheekbones, moderately protruding jaws, rather subdued chin, and large face. Since the question of race determination, however, is one of extreme complexity, it should also be pointed out that while the majority of modern Indians as well as prehistoric skeletal remains in America share enough of these features in common to be regarded as predominantly Mongoloid, they as well as the east Asians themselves, possess other physical traits like stature and head form which vary widely from group to group. Some of these other traits may be explained by the influence of different environments acting over long periods of time, but others point to an admixture of non-Mongoloid features in some of the earliest migrants to these areas. It is just the meaning of this mixture of apparently diverse elements which makes the problem of ultimate origins so difficult; and we shall have to be content for now with the general relationship which seems to have been established. If the earliest wanderers to the Americas were primarily a blend of other racial elements, their influence on the physical type of later American Indians has been largely submerged by the Mongoloid features of the vast majority of later arrivals.

Asia, too, is the closest great land mass to this continent, and from it there are more practicable means of access than from any other area. Even today the Bering Strait could be crossed by rafts, for islands at the middle cut the open water journey into two 25-mile stretches. Eskimos make the trip in their skin boats, or in winter by dog sled over 5 the frozen surface of the strait. In the past, the journey must have been even simpler. During the several worldwide glaciations of the Pleistocene Epoch, a geological period which began more than 600,000 and ended about 10,000 years ago, great masses of ice spread across the surface of the continents in the higher latitudes. Since the growth of these ice sheets was nourished by falling snow, the seas, which supplied the necessary moisture, were reduced in volume as the ice expanded. The maximum drop in sea level has been calculated as between 200 and 400 feet, but the floor of Bering Strait is so shallow that a drop of as little as 120 feet would have been sufficient to create a dry land bridge between the continents. Further lowering must have increased the area and elevation of this passage, but the main effect of this was simply to extend the length of the interval during which the bridge remained open. This may have continued well into the period of milder climate after the time of maximum ice advance.

Another peculiar condition in this region at this time was the presence of considerable areas untouched by glacial ice. These included the foothills and coastal plain along Alaska’s northern coast as well as the great central Yukon Valley. This surprising situation was probably due to the small amount of moisture left in the winds which had passed over the high and cold mountain chains bordering the southern coast and the second great mass of the Brooks Range to the north. Furthermore, the broad Mackenzie Valley, leading south along the eastern slopes of the Rockies, was the area latest to be covered by glacial ice and first to open up with the return of warmer conditions. It may even be that the ice failed to cover this region during the last one or more of the minor advances which together make up the latest, or Wisconsin, glacial period.

Taken all together, therefore, the conditions described provided man with a chilly but relatively dry and passable route from the Asiatic mainland to Alaska and thence to the warmer interior sections of North America. For a considerable period this route must have been flanked with glacial ice lying only a few miles away on one side or both through a total distance of some 2,000 miles. It is one of man’s distinctive qualities, however, that he is able to adapt himself to extremes; and it is probable that the game he lived on was itself acclimated to living close to the edges of the ice sheets. We are less certain about the conditions under which this journey was begun at its Asiatic end; but it seems likely that there, too, ice would have formed in the high mountain masses, but that the valleys and lowland would have remained open as they did farther east.

We are confident in our knowledge of where man came from to the New World and how he was able to make the trip. We are on less certain ground, however, when we try to determine when he arrived. Estimates have varied widely, changing with every increase in our 6 knowledge. From the first enthusiastic attempts to fit the Indian into the Old Stone Age chronology which was just then unfolding for the Old World, the cold reasoning of skeptical scientists brought down the maximum age of human occupation of this hemisphere to something like 3,000 years. Beginning in 1925, however, a series of finds has provided unquestionable evidence that men using very distinctive weapons were living on this continent, largely by hunting the mammoth and a great bison, both now extinct, during the period when the ice was receding for the last time. The typical channeled or fluted spear point of this people has even been found lately along the northern Alaska coast. So, while we still cannot say that this characteristic artifact was brought from Asia rather than being developed here in America, it is at least an interesting coincidence that man hunted large and now extinct game in Alaska in areas where conditions were at times particularly well suited to his immigration.

Other evidence shows that the users of this telltale point were not the first to live in the region of the western plains; at least some of their numbers had been preceded by men whose stone work was almost as unusual and equally easy to identify. Recently developed methods of dating by the use of radioactive carbon-14 show that the span of time when the channeled point users, Folsom man, roamed the Plains included one date of about 8000 B. C. For his predecessors, we feel justified in pushing this date a good 2,000 or 3,000 years further back; and there are even hints taken quite seriously by leading archeologists that man was here many thousands of years before that. We know that the great climatic swings marking the principal stages of the Pleistocene Epoch were actually composed of repeated lesser pulsations. Like a mighty pump, the changing climate worked upon all life within thousands of miles of the shifting ice fronts, driving it southward with icy winds and then sucking it back toward the north as cold and damp were replaced by heat and drought. Man followed the game; and this, rather than any planned migration, probably accounts for the wide spread of his earliest remains.

American Indians, then, are most closely related to the present inhabitants of eastern Asia, where they, too, had their origin. They came to this country as its first human inhabitants some 12,000 to 15,000 years ago at the very least. They did not come all at once, or even in one limited period of time, but probably in a fairly continuous succession of small hunting bands following the game. Their earliest migrations hither were doubtless the indirect result of great fluctuations in climate which marked the coming and going of the ice during the glacial age; and it was the peculiar conditions existing about the present region of Bering Strait that encouraged them to explore the now accessible region to the east. Once they had reached the New World, their hunting travels probably carried them back and forth in 7 both directions so that a knowledge of the seemingly limitless territory beyond became fairly general.

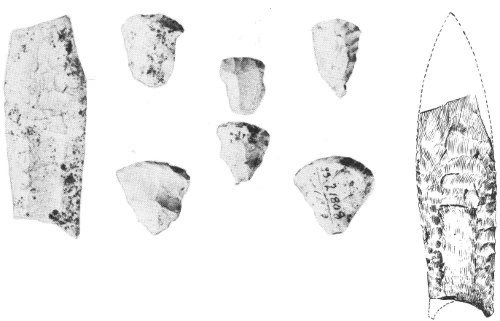

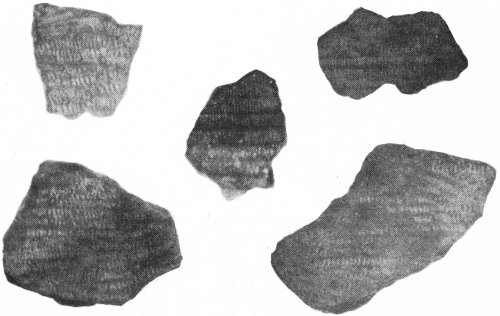

Broken Clovis point and sharp-cornered scrapers from Ocmulgee excavations. Point length 3¹¹/₁₆ inches. Artist’s reconstruction of point at left.

The disappearance of the land bridge must have been very gradual by human standards. Successive generations would have found the journey increasingly difficult, but this would only have led to the adoption of other measures such as waiting for winter ice or the use of rafts or boats to cross the widening stretches of open water. Once arrived, they began to spread out over the country, moving on as the game became scarce to where it was more abundant, looking for new and unpeopled areas whenever they began to catch sight too often of members of other bands hunting the same territory. Not many years would be needed to cover the vast expanse of the two continents. With movements of only 20 or 30 miles each year, it might have happened in as little as a dozen generations; but we can say for sure that man had reached southern Patagonia by about 6000 B. C., possibly far earlier. By then, we may assume, the new homeland had been explored with some thoroughness; and portions of it had already been inhabited for thousands of years. It was by no means filled up; but many of its potentialities were known, and American Indians were well started on their own peculiar course of development.

The roving existence led by these Wandering Hunters brought them into the region which is now Georgia at a relatively early date. We do not know by what route they came here, for it is easier to seek out the geographic limitations which restricted the first migrants to the New World to a single point of entry than it is to trace the wanderings of their descendants over some 8,000,000 square miles of North America. Nevertheless, we are beginning to get a few hints.

Mammoth Hunters, from Museum exhibit panel.

Fluted point sites have been found in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia; and single fluted points have been found in a number of places in Georgia, though possibly more often north than south of Macon. One fluted specimen, however, was actually excavated from the Macon Plateau, a designation adopted for the hilltop terrain of the Ocmulgee excavations. The recovery here of other tools of the same greatly decomposed flint strengthens the likelihood of a true “paleo-Indian” occupation at Ocmulgee. The inclusion among them of many thumbnail scrapers of a type recently shown to be distinctive of eastern fluted point sites is especially significant.

The fluted point, missing the forward one-third of its length, was a fine specimen of the so-called Clovis type of these artifacts, and so typical of thousands of such implements which have been picked up at random in the eastern United States as well as in the West. The Clovis point is like its Folsom cousin in several ways, particularly in having a long channel flake removed from one or both of its faces, possibly as a means of reducing its total thickness, and in the grinding of the edge along the lower sides and across the base to avoid cutting the lashings which bound it to the shaft. Like the smaller Folsom point, too, it is named for a site in the western High Plains, where its 9 position underlying Folsom on some sites and its association with mammoth bones give us definite clues to its age west of the Mississippi.

Unlike Folsom, however, the Clovis fluted point is not limited to the region on the east flank of the Rockies. Instead, it has been found from Alaska to Costa Rica and from Vermont to Florida. Its use, too, seems to have been less specialized. Folsom man was a bison hunter; and the abundant grasses of the Plains probably account for the rather definite limits of his range. The big Clovis points, on the other hand, were certainly used on mammoth; but we do not know that this over-sized quarry was their only target. Possibly the mammoth was more adaptable than the bison and could seek out other areas as the changing climate made its accustomed haunts unlivable; or it may have been the Clovis hunters who were the more flexible and could shift more readily to other kinds of game when the mammoth disappeared from the scene.

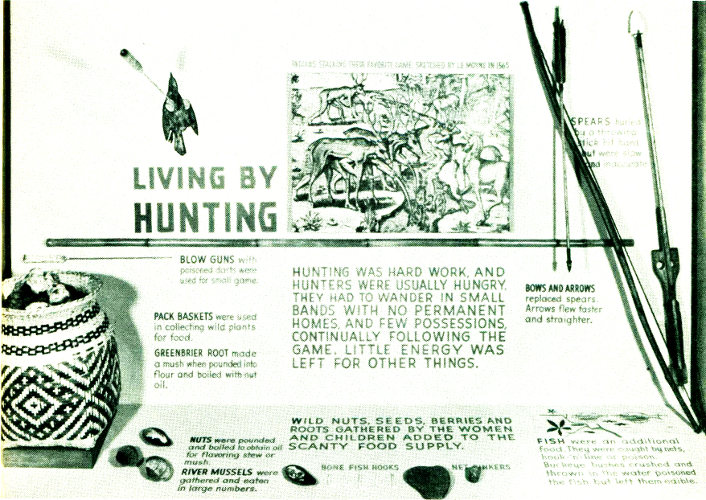

Hunting was hard work. Museum exhibit case.

The wide geographic range of the point is matched by the variety of shapes which are included in the type, though all have a family resemblance built around the distinctive channel formed on one or both faces. Until it is found in a context permitting direct dating, however, the real problem in the East hinges on the significance of this family resemblance. The question is whether this resemblance is a result of chance, or whether it indicates contact with the makers of the fluted points in the West whose age is now reasonably well established.

Hunter with atlatl (throwing stick).

Perhaps the only thing we can say definitely about these early nomadic hunters would be that their unusual fluted type of projectile point occurs in the eastern United States and has been found in clearly defined contexts which suggest a greater age than that known for any other recognized types in these areas. This distinctive weapon is thought to be a variety of the western Clovis fluted point, which has been found in the West beneath Folsom, and therefore antedating 8000 B. C.

Their simple living was obtained with the aid of a few tools and weapons of stone and wood. Being constantly on the move, they could erect no very permanent dwellings; and a rough lean-to shelter was doubtless their only protection from the elements. Hunting was the major activity of the men; for, with fish from the streams, the game which they killed made up the chief element of their diet. The women were not idle, however; for in addition to preparing the food and caring for the children, they spent many hours in gathering the nuts, roots, and berries which made such a necessary and welcome supplement to their daily fare. It is doubtful that the bow and arrow, which to us are almost inseparable from our picture of the Indian, had yet been invented; but the thrusting spear and the thrown javelin were very effective at close range. At greater distances the hunter could bring down his game with the dart propelled by a throwing stick. This increased the effective length of his arm and imparted the resulting greater thrust to the butt of the shaft.

Also missing in their equipment were the pottery cooking vessels of the later Indians, which so simplified the preparation of foods by boiling and thus added variety to the menu. Stone boiling, of course, could be accomplished by means of heated rocks dropped into some suitable container, such as a pit in the ground lined with a skin; but the method was tedious and probably less used for that reason.

Organization for such a life was simple. Since they must move with the game on which they depended, group size had to be limited; for large bodies of people could not move easily from place to place. Moreover, the population was not large, and there was plenty of room to spread out. For all these reasons the hunting band was probably made up of a few related families, numbering on the average perhaps 50 people who habitually camped together. Leadership in such a small group would not be a matter of too great importance; and the chief might be chosen for skill in hunting or for an outstanding personality. Possibly he inherited the office, but in any case his authority is not likely to have been very great. The band doubtless accepted his choice of campsite, his direction in the hunt, or arbitration in disputes; but in doing so it was more likely to be out of respect for his ability than in recognition of his official position.

Even at this simple stage of culture, though, there were doubtless well defined rules of conduct. All primitive peoples today share certain universals of social life. From these we may confidently infer that every man was part of a clearly defined kin group, that the structure and relationships of this group determined into what similar group he might marry, and which were forbidden to him as sources for choosing a mate. We can also be reasonably certain that while antisocial acts like murder, adultery, and theft might not be punished by the community at large, strong measures to hold them in check 12 were generally approved even though they might have to be initiated privately. In short, the rudiments of social living were already thousands of years old. The lives of these early Georgians were different from our own in countless material ways; but even at this early date their primary problems were the same as ours. They must have food, shelter, and protection for individual survival; and the continued existence of the group required the education of its younger members in the skills and habits and community organization of their elders. The means to these ends were crude, and by our standards extremely simple; but they were not developed without considerable ingenuity; and hard work made up for many technical shortcomings.

Our knowledge starts to increase as we come to the period beginning about 5,000 years ago. Here a few of the details of Indian life in the Southeast emerge rather clearly. Curiously enough it was the food habits of these Shellfish Eaters which first led to their identification; and even today our scanty information on them still tends to center around this feature of their lives. From the nature of the evidence we will soon present, it is easy to infer that the principal food of many of the groups of this period was shellfish. This may not seem especially remarkable; but we know that, in shifting to a principal reliance on the lowly mussel, clam, or oyster, they accomplished, in effect, a local revolution in man’s pattern of living. They had discovered that an almost inexhaustible supply of these prolific creatures was to be had for the taking in places along the rivers and the ocean shore where conditions favored their growth. Perhaps the taste for this form of diet was difficult to acquire, but once achieved it freed them for generations from the hard necessity of moving their camp every time the game grew scarce. At last they could settle in one place; and the numerous sites they occupied tell us not only that life was easier but that the abundant food supply contributed also to a marked increase in the population.

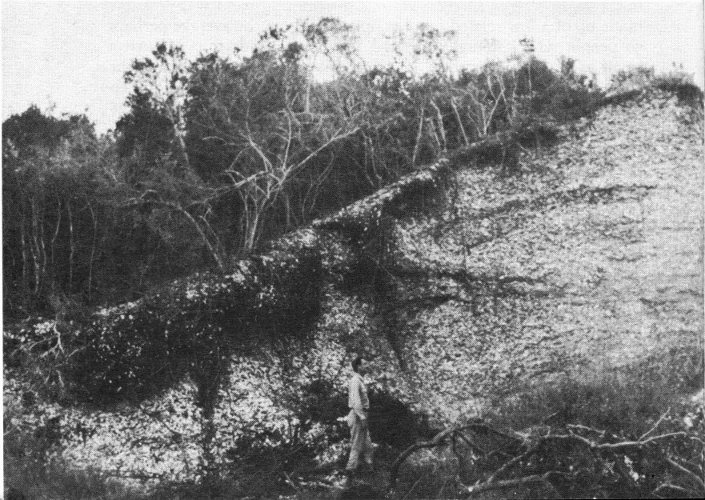

Shellfish Eater campsites were gradually raised on mounds of their own shell refuse, sometimes even larger than this. Courtesy Florida Board of Parks and Historic Memorials.

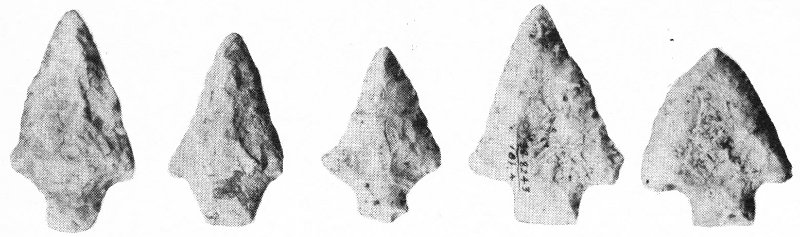

Dart points of the shellheap dwellers were heavy, but workmanship varied from crude to very careful. Length, 2¼ to 2⅞ inches.

Our chief reminder of the presence of these early shell gatherers lies in the piles of shells which mark the scene of their activities. Of course the bones of deer, bear, rabbit, turkey, and other wildlife mixed with the shells show us that to vary their diet they did a good bit of hunting and fishing as well. The river and coastal shorelines are dotted with such refuse heaps, often of monumental size, from Florida to Louisiana and northward inland to the Ohio River and along the coast as far as Maine. It may be doubted that these were all produced by related peoples, or that they even represent the same time period; for it is certain that many of them were still growing in fairly recent years. Still, the fact remains that in the southern area as far north as Kentucky and Tennessee the sites represent the oldest camps yet to be uncovered following the earlier paleo-Indian period; and that besides the evidence of a remarkably uniform economy, they disclose a great similarity in the tools, weapons, and ornaments of their inhabitants.

Projectile points (a term we use because “arrowhead” implies use of the bow and arrow) make up by far the most numerous type of artifact recovered; and these tend to be long and heavy, although proportions 14 may be either narrow or broad. The size of these points indicates that instead of the bow and arrow the dart was used with the “atlatl,” the Aztec name we have adopted for the throwing stick or spear thrower. This is confirmed by the presence of many antler hooks for the end of the throwing stick. Shaped much like the hook of a giant crochet needle, these engaged the notched butt of the dart shaft. Additional evidence is found in the special stone, antler, or shell weights which were attached to the shaft to add momentum to the throw.

Mullers and pot boilers were important kitchen tools.

Tools included grooved stone axes, chipped drills, and large chipped knife or scraper blades. Mullers, or flared-end “bell” pestles, were used to reduce wild plant foods to edible form; but the mortars or trays with which they were used are thought to have been made mostly of wood. Vessels of soapstone or sandstone were added to the skinlined pit or basket, and the flat pieces of steatite with a large hole bored in them may have been used with these containers for stone boiling. Fish were caught with bone fishhooks and with nets weighted with grooved or notched stones. Bone was also used for awls, which were probably employed in making baskets and for simple stitching operations as in the making of leather moccasins or 15 leggings, as well as for projectile points and flaking tools. Bone heads served as ornaments, as did bone pins which were often decorated, though the plainer ones may have been used merely to secure clothing. Shell was worked into beads of many varieties, and into gorgets or pendants in addition to the atlatl weights mentioned.

Shell mound people of the Archaic period are the first whose axes we can surely identify. The hafting groove encircled the ax completely or, in the three-quarter-groove form, was omitted from the bottom edge. Length, 22 inches.

Life on the shell mounds, or in the camps along streams and rivers where this source of food was of minor importance, was hardly different in most of its material aspects from that of the wandering hunters who had gone before. Permanent dwellings were still apparently unknown; and the rough shelters which were built were doubtless much the same crude lean-to of poles and brush or tree bark as formerly. Areas which appear to have been floored with clay and the remains of many hearths indicate that the shell mounds themselves were the actual habitation sites. This is confirmed by the presence of the numerous articles of daily living mixed in with the shells. The dead, too, were buried directly in the mound, most commonly in small round pits which required that the corpse be tightly flexed. Dogs were also buried in this manner occasionally, and we can guess either that they were loved by their masters or that they held some special religious significance. The fact that a very few shell mounds were intentionally formed into a large ring, as much as 300 feet in diameter, provides a definite hint of religious ceremonialism. From the few objects of daily use or adornment placed with the dead, we can assume they believed in an after life.

The life of these Indians continued unchanged in any of its major features until perhaps 2000 or 1500 B. C. About that time, according to radiocarbon dating, the knowledge of pottery making seems to have reached them in some manner which has not yet been determined. Perhaps they even discovered it for themselves; but it seems more probable that the idea reached them from some fairly distant tribe, and that by local experiment they developed their own techniques from a hazy understanding of the principles involved. At any rate, the upper levels of the older shell mounds begin to yield “sherds” (fragments) of a coarse undecorated pottery which contains innumerable 16 tiny holes running through the paste in all directions. These are the channels which remain after some vegetable material like grass or moss fibers was burned out when the vessel was fired. Any substance mixed with the clay to make it easier to handle and keep it from cracking during the drying out and final firing of the pot is known as “temper,” and the process itself is called “tempering.” Later potters learned that a temper of sand, crushed shell, or, better still, crushed rock or crumbled bits of old pottery made stronger and better pottery; and therefore “fiber-tempered” wares usually represent the oldest type of pottery we find in any region where they occur. While this pottery was undecorated at first, its makers in the Georgia area later developed a type of decoration composed most often of lines of indentations, or punctates, made with the point of a stick or a bone tool.

Except for caves, a rough windbreak to give protection from bad weather was probably the only shelter known to the earliest Indians.

This new item in the household inventory was probably one of the most significant advances which ever took place in the life of the American Indian, and second in importance only to the later introduction of agriculture. With it, the awkward and tedious routine of stone boiling came to an end, and soups and stews enlarged the menu and became at once the easiest prepared and one of the most appetizing of the foods used. Pottery, too, marks a big change in the work of the archeologist when it appears in the cultures which he is studying. Types of projectile points and other stone artifacts have a way of continuing in use for long periods without change. Clay vessels, however, seem to have been constantly changing in form or decoration or construction, possibly because the potter’s clay is so plastic and 17 responsive to any fancy it is desired to express, and there are many different ways of producing similar results. For this reason, it forms a sensitive indicator of the passage of time and is one of our best clues to relationships between sites and the cultures of their inhabitants.

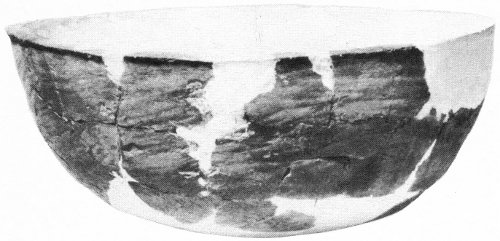

Fiber-tempered pottery might be only a crude beginning of the potter’s art, but even these vessels were large and strong enough to be highly useful. Width, 15 inches.

No sizable shell mounds of these Archaic peoples, as they are known to the archeologist, have been found in the central-Georgia area. Numerous sites occur here, however, which contain no pottery but are littered with scraps of worked flint and where large numbers of the heavy Archaic projectile points are plowed up annually. At other sites, including those on the Macon Plateau, these points are found with a considerable quantity of the distinctive fiber-tempered pottery. It appears, therefore, that the Shellfish Eaters proper were a limited portion of the population of that era and that others with just about the same material equipment followed the old hunting and gathering life in temporary camps. The shell heaps themselves were occupied for rather brief periods by single groups of people. Possibly the large shell mounds represent an annual camping spot for numerous groups who used them successively and at other times of the year lived chiefly on game or along the smaller rivers where shellfish were available but not in such vast quantities. This would account for the smaller accumulations of shells in some areas; and it could be that recent changes in the courses of such rivers as the Ocmulgee and the Oconee, brought about by industrial activity and flood control measures, have resulted in the obliteration of small heaps of this sort.

In any case, it appears that the Macon Plateau had again demonstrated its advantages as a habitation site, and that a people with a material culture similar to that of the Shellfish Eaters dwelt here at intervals during the period 2000 B. C. to 100 B. C. Their residence was not continuous for very long at any one time, however, since their lives depended on hunting. Instead they probably moved about over a fairly large area, returning every so often to the familiar banks of the Ocmulgee to set up their village again and to hunt the surrounding region until the game once more became scarce.

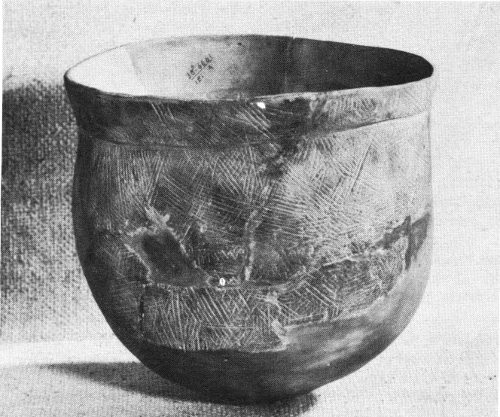

Simple stumping, as in this Mossy Oak jar, often appears like crude scratching. Height, 10 inches.

The woven basketry fabric which produced these impressions is among the earliest recorded in eastern North America.

The next period which can be clearly identified on the Macon Plateau is the one whose inhabitants we have called Early Farmers. It lasted for roughly 1,000 years and naturally witnessed considerable change; yet the evidence for this change in middle Georgia is tantalizingly slender. There are more and larger sites, and the increase of population reflected in these might be thought to signify an increased food supply such as the beginnings of planting and tending a few crops could produce. Direct evidence for the introduction of such hoe cultivation, however, is lacking; and we can only say that a number of different lines of reasoning lead us to believe that some plants—possibly pumpkins, beans, sunflowers, and tobacco—probably were being cultivated before the period ended. Through the provision of increased leisure and stability, an assured food supply may well have been one of the factors permitting an enrichment of Indian life at this time. Since this cannot yet be demonstrated, however, we must turn to what we do know. Perhaps the reader will not be too surprised to learn that we shall again be talking about pottery, since we have already mentioned it as one of the archeologist’s most unfailing sources of information.

Like most archeological field work the excavations at Ocmulgee did not result in an independent body of information which could be added unchanged to the total fund of our archeological knowledge. We know in detail what was found; but we must turn to work in nearby and more distant areas for assistance in its correct interpretation. In the present case, four main types of pottery occurred more or less intermixed at almost the deepest levels excavated on the plateau. The first of these was the fiber-tempered ware described in the previous section. The other three are tempered with sand or with “grit” (finely crushed stone) in varying amounts. Like the fiber-tempered pottery these three types are important time markers in the Southeast. It would be tedious to go in detail through all the steps involved in placing them in their proper position in the time scale; but some idea of the nature of the problem might help us to gain an understanding of its complexities. It could help us, too, to realize what a jigsaw puzzle an archeological reconstruction is likely to be.

First let us see what we know about the earliest appearance of pottery in eastern North America. It has long been thought, and radiocarbon 20 tests have recently demonstrated, that the earliest pottery known in this section has come chiefly from the area drained by the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers from New York State to Illinois and south as far as north Georgia. This pottery has such close parallels at a like early period in northeastern Asia that many students believe it may have been brought here by direct migration, though naturally over a period of generations. Its chief characteristic is the roughening of its surfaces with the marks of twisted cords and somewhat later with those made by a plaited basketry fabric. Here, some believe, must have been the models which stimulated the shellheap dwellers to their first experiments in making pottery.

Restored eagle effigy of white quartz boulders near Eatonton, Ga. Length, 102 feet; width, 120 feet.

The two sand-tempered wares in the early Macon Plateau collections referred to above are Mossy Oak Simple Stamped and Dunlap Fabric Marked. The name of the first of these combines that of the site with which it was first principally identified with an indication of its general type, i. e., exhibiting the straight grooves left by the paddle used in finishing the pot. The paddle itself may have been carved with simple straight grooves, or it may have been wrapped with a thong or smooth bit of plant fiber such as honeysuckle vine. Dunlap, on the other hand, is the name of a family which had long owned a large 21 part of the Ocmulgee area, while the type designation refers to the use of a piece of woven basketry used in finishing the vessel.

In order to place these two types of pottery we must examine their occurrence on the Georgia coast and in north Georgia. Such a study reveals that the simple stamping follows directly after fiber tempering on the coast; and that in north Georgia, where the latter is absent, it lies immediately above a fabric-marked pottery very similar to Dunlap. It would seem likely, then, that this latter type of pottery might have worked its way south by the end of the period in which fiber temper was in vogue. Both types exhibit a kind of finish which, like the early cordmarking farther north, resulted from techniques that had probably been found most effective in working the wet clay. Some sort of implement was needed for thinning and compacting the vessel walls, and experiment has shown that a paddle with roughened surface is more efficient for this purpose than a smooth one. No doubt this is caused by the more tenacious adherence of the wet clay to the latter. In any event, different ways were found of roughening a flattened stick or paddle, whether by wrapping various materials about it or carving it with deep grooves; and some groups may well have rolled up a piece from an old broken basket or bit of matting and found it equally useful. Then, if a smooth surface were desired, the marks of any of these implements could be erased easily by smoothing with a wet hand.

Reconstructed pottery stamps. Designs taken from sherds excavated at the Swift Creek site. Total length of paddle, 9 inches.

Fragments of Swift Creek stamp designs. Scale about two-fifths.

The time we have been describing belongs to the general period of eastern United States archeology known as Early Woodland. The Adena culture, which apparently spread from centers in the Ohio Valley, belongs to this period and is well known for its elaborate burial mounds and other distinctive features which are regarded as typical markers over a wide area. While no burial mounds are known from middle Georgia at this time, the fabric-marked and simple-stamped pottery does belong to a general class of wares occurring also in Adena sites. It seems also to relate Ocmulgee to a pair of eagle effigy mounds of stone near Eatonton, Ga.; and bird symbolism is likewise a distinctive Adena feature, though one more fully developed in the following Middle Woodland stage. So it appears that a few traits have been found to connect this period quite definitely with some of the broader currents affecting other areas in the same time span.

The fourth pottery type found mixed in the lower levels at Ocmulgee was Swift Creek Complicated Stamped. Actually this was either grit- or sand-tempered; but its outstanding characteristic was the complex patterns with which the paddles were carved. The type is named for the Swift Creek site only a few miles down the river which was occupied almost exclusively by the people of this culture. This ware covers a longer time span than the other two types, and its distinctive influence was exhibited in some sections even into historic times. In its early stages, it probably served as the source for a tradition of complicated stamping which covered most of the Southeast and even spread to some extent beyond its limits. We don’t know just when it began. In northwest Florida and on the Georgia coast it seems to fall in the Middle Woodland period. Since the type site, though, is close to its 23 apparent center of development, its occurrence on the plateau mixed with Mossy Oak and Dunlap may well represent its true position and thus place its origins in Early Woodland.

Swift Creek villagers preferred these roughly chipped axes to ones of ground stone. Many are too light for real chopping and may have been weapons, kitchen tools, or even digging implements. Length, 22 inches.

During its long history, a number of changes may be seen in the form and decoration of Swift Creek pottery. The commonest vessel shape consists of a deep jar with slightly flaring rim and nearly conical base. Many of the earlier pieces had four small bumps at the point of the base, as a sort of reminder of the feet which were common, also, on earlier pottery in nearby areas; these disappeared in the later examples. The lip of the jar, too, was only crudely finished in the earliest forms, being left rough and irregular or sometimes haphazardly notched or scalloped with pressure from the potter’s finger. In time the edge tended to be pushed out a little; and this gradually developed into a smooth outward fold of the lip and finally a collar of smooth clay about an inch in width about the rim. This extreme “folded rim,” however, occurs after the Master Farmer period shortly to be described.

As for decoration, no description can adequately convey the wealth and variety of complex and often highly attractive designs with which Swift Creek pottery is stamped. The fragments illustrated give some idea of the general effect obtained, but only a painstaking reconstruction of the entire stamp can do them adequate justice. Intricate and beautifully proportioned combinations of curved and straight lines are numerous. Despite the cruder efforts which are naturally common, one is constantly surprised at the artistry exhibited in even the less expertly conceived decorative motifs.

As we should expect, this form of expression underwent such changes as might occur in the development of any form of art. The earliest paddles were carved with many narrow, shallow grooves in a pattern of two or more chief design elements. Smaller elements were used to connect these, fill in blank spaces, and generally round out the paddle. In time, however, the designs grow bolder and were more deeply cut as the motifs became better organized and as unnecessary filler elements could be eliminated. These, of course, are not the 24 sort of differences to enable one to judge a particular sherd as early or late; but in very general terms, they describe the distinctions which become apparent when large numbers of sherds from different time periods are examined. It should also be pointed out that this remarkable pottery style covered such a wide area that any simplified description can only suggest a few general features which appear widely applicable, while recognizing that particular areas had their own varying histories of the type.

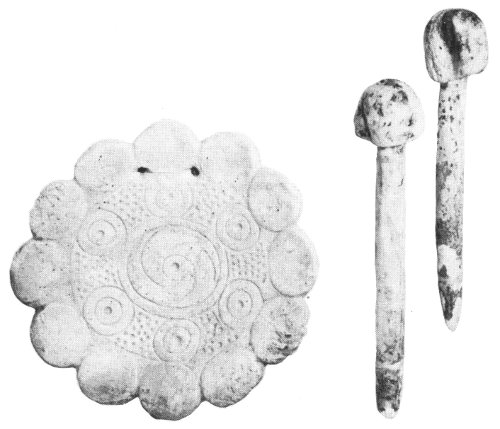

Straight tubes of steatite or soapstone are the earliest known form of pipe. They probably belonged only to shamans or medicine men. These come from north Georgia. Lengths, 2 inches and 11 inches.

Nothing has been said about other distinctive features of this period of development in Georgia. Projectile points vary from heavy, shapeless forms with stems to smaller triangular ones without. Flat stones with two holes through them were once presumed to have been used as gorgets, i. e., hung upon the chest as a sort of decoration, but they may well have been atlatl weights or served some other purpose. “Boatstones” and the prismatic form of atlatl weight are also said to occur, but there is some disagreement on this and even on the continued exclusive use of the atlatl in this period at all. In some areas the large numbers of smaller points may suggest that the bow and arrow were beginning to be used. The characteristic ax of the period was roughly chipped in a double-bitted form. Steatite or soapstone was still fashioned into crude bowls and the perforated net sinkers or pot boilers we have noted previously, as well as into short tubular pipes which are found in the region of central Georgia.

Just as Mossy Oak and Dunlap in Georgia appear to reflect more noteworthy developments farther north, so Swift Creek has its more spectacular parallels, too. These relate to Hopewell, the outstanding culture of the Middle Woodland period. The Hopewell burial mounds and other massive and complex earthen structures were accompanied 25 by an overall artistic achievement in pottery, chipped and polished stone, bone, sheet mica, and copper which is probably without equal among North American Indians. These materials were traded far and wide so that Hopewellian influence is strongly indicated in the neighboring states of Florida, Alabama, and Tennessee. Even Georgia shows some evidence of Hopewell connections, although in middle Georgia this is confined to the complicated stamped pottery. Types evidently related to Swift Creek occur frequently in classic Hopewell sites. In north Georgia, however, elaborately carved stone pipes are said to denote this relationship, and it is even more clearly indicated by a number of burial mounds. One of them, built of stones, contained a burial displaying such typical Hopewell features as a covering of mica plates and a breast plate and celt of copper.

During the Early Farmer period, then, we feel that the Indians in middle Georgia must have become more settled. Fragile pottery is not easily carried in any quantity by wandering bands of hunters. On the other hand, the technique of gathering wild foods is not likely to have become suddenly so efficient that this alone could account for the large increase in population which must be reflected in the more numerous sites. Knowledge of planting and plant care, too, is likely to have spread piecemeal rather than as a single unit. Hence, as we have already stated, this seems the most likely period for the Indians to have begun learning to raise some of the many plants which not too long afterwards became so important in their existence.

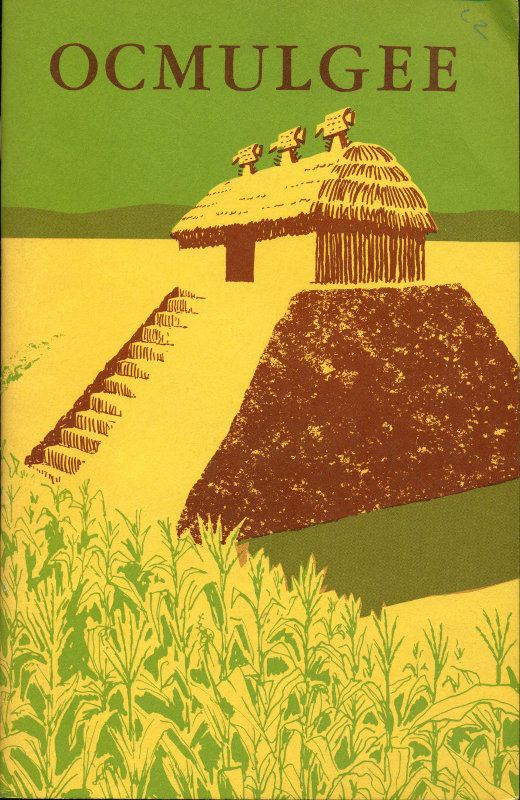

This temple mound is a lasting memorial to the energy of the Master Farmers, the fourth group to occupy Ocmulgee.

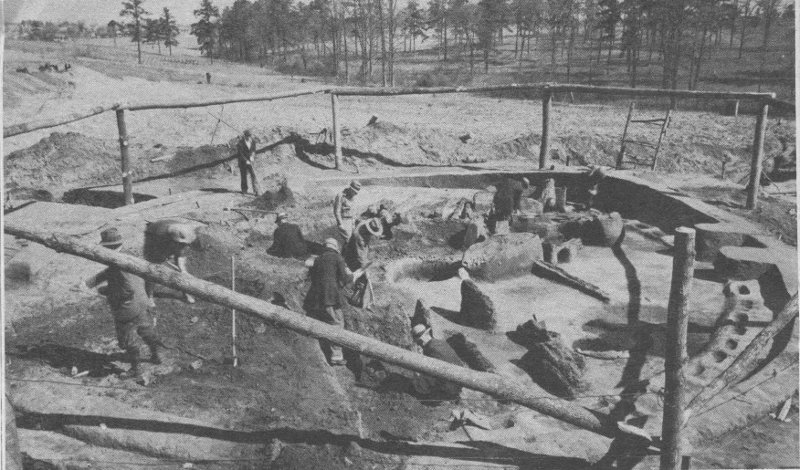

Early stage in excavation of the ceremonial earthlodge at Ocmulgee.

In central Georgia, though, we see instead a different side of their lives. We follow the experiments made by the Indian women of the several tribes in trying to improve the pottery which had now become such an important utensil in their homes. Stronger vessels would break less easily; so paste was improved from time to time, if this end was not outweighed by other considerations. The attractiveness of the finished piece, however, was soon a matter of universal concern, at least to the potters themselves; and as their skill increased and their ideas and standards became more clearly defined, we can follow a process which never ceases to astonish us by its workings in our own society. The whims of fashion surprise and puzzle us today as they are expressed in our women’s clothing, our automobiles, our houses, and our furnishings. Evidently, however, if we may judge by the variations in his wife’s pottery, they were hardly less a problem to the Indian of 2,000 years ago.

We now come to the period in Ocmulgee history which is the most plentifully supplied with facts resulting from the excavations. The Master Farmers, which is the name chosen for these people in the Museum exhibits, were newcomers to Ocmulgee. It may be that their arrival was strongly resisted by the Early Farmers who had claimed 29 title to these lands for the past thousand years. About A. D. 900, they moved into this area, probably from a northwesterly direction, and started to build villages with some very novel features.

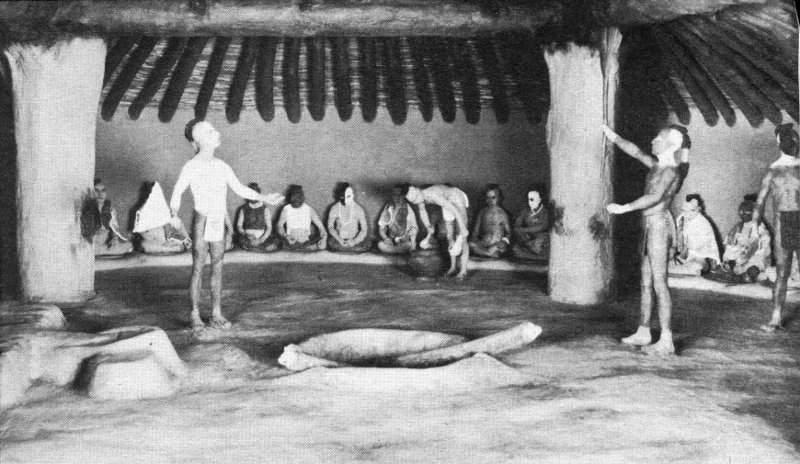

Council meeting in Master Farmer winter temple. Museum diorama.

We do not know where this migration had its start; students of the subject believe that it may have begun in the Mississippi Valley near the mouth of the Missouri River. We do know, however, that some of their closest relatives settled in northeastern Tennessee; and perhaps, as the ancestral group journeyed up the Tennessee River it split apart at the point of that river’s abrupt northward bend in northern Alabama. Then a succeeding generation, which took central Georgia for its home, settled in two places near the Ocmulgee River. The smaller village was about 5 miles below the present city of Macon on a limestone remnant known as Brown’s Mount; the larger, with which we are here concerned, was the “Ocmulgee Old Fields” of the early settlers, across the river from the modern city and adjoining its eastern limit.

The most important feature distinguishing these people from their predecessors, however, was not their town but their very way of life. They were farmers; besides tobacco, pumpkins, and beans, they cultivated the New World staff of life, corn. This way of life enabled them to settle in one place long enough and in sufficient numbers to create a large village, and to develop the religious and ceremonial complex which was expressed in its numerous distinctive structures. They built it on the rolling high ground above the river, where their square, thatched houses were scattered among the many buildings connected with their form of worship. These latter consisted of rectangular wooden structures which we call temples, and a circular chamber with a wooden framework covered with clay which was a form of earthlodge. From our knowledge of the later Indian pattern in this area, we believe that these represented the summer and winter temples, respectively, of the tribe. Here the grown men took part in religious ceremonies and held their tribal councils; and here the chief could render decisions in individual disputes, or in matters of importance to the tribe as a whole.

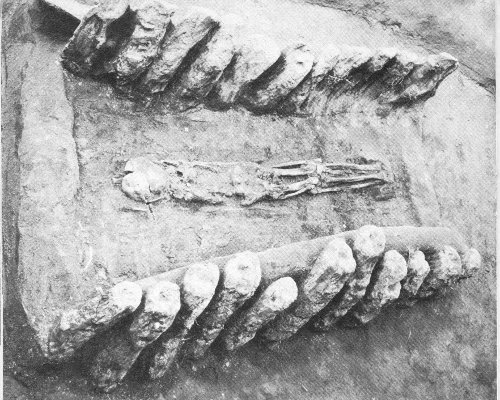

A log tomb and its central location may indicate the principal burial in the first stage of the Funeral Mound. The face-down position could result from the reassembled bones being wrapped in a skin or mat for burial.

Masses of shell beads must have been valued possessions of many of the earlier temple mound dignitaries.

Perhaps the single outstanding archeological feature to be disclosed by the excavations at Ocmulgee is the preserved floor and lower portions of one of these winter temples. The remains consist of a low section of clay wall outlining a circular area some 42 feet in diameter. At the foot of the wall, a low clay bench about 6 inches high encircles the room and is divided into 47 seats, separated by a low ramp of clay. Each seat has a shallow basin formed in its forward edge, and three such basins mark seats on the rear portion of a clay platform which interrupts the circuit of the bench opposite the long entrance passage.

This platform, on the west side of the lodge and extending from the wall almost to the sunken central fire pit, is the most remarkable feature of all. Slightly higher than the bench, it forms an eagle effigy strongly reminiscent of a number of such effigies embossed on copper plates which are a part of the paraphernalia of the Southern Cult religion, to be described in a later section. Surface modeling of the tapering body section may once have been present, but is now so much obliterated that only a sort of scalloped effect across the shoulders can be made out. Nevertheless this feature is present on at least two of the plates mentioned, one from the Etowah site in north Georgia and the other from central Illinois. Moreover both of these figures, which represent the spotted eagle, are distinguished by the same, almost square, shape of the body and wings with only a slight taper from their base toward the shoulder. Finally, the head of the platform eagle is almost entirely filled with a clear representation of the “forked eye,” which is presented also, though in smaller scale, on the two figures in question, and is a distinctive symbol of the Southern Cult. The entire ceremonial chamber has been reconstructed on the basis of burned portions of the original which were uncovered by excavation. It forms one of the principal exhibits of the monument, and represents a unique archeological treasure.

Other structures uncovered included a small circular hut framed with poles and containing a large fireplace, out of all proportion to the size of the building. This was evidently a sweathouse where steam was produced by throwing water on heated stones; but it is not known whether this common form of purification was related to their religion 32 or merely a sanitary feature of the village life. At the west edge of the village the tribal chiefs and religious leaders were buried in great log tombs where from one to seven bodies, possibly those of wives and retainers, were deposited with masses of shell beads and other ornaments befitting their rank. Over the whole was raised a low flat-topped mound with 14 clay steps leading to the summit.

Fourteen clay steps, buried under later mound construction, led up the west slope of the earliest funeral mound to its summit.

Beside their large and thriving religious center, we can reconstruct many aspects of their daily lives in which the Master Farmers were different from their predecessors. This difference is noted in their tools, weapons, and household utensils. These have survived because they were made of such durable material as stone and pottery. The many smaller projectile points now making their appearance suggest that the bow and arrow were in general use at this time. Greater range 33 and accuracy have been advanced as possible reasons for adopting this weapon in place of the spear thrower and dart, which preceded the bow in most parts of the world. Perhaps equally important was an increase in tribal unrest and strife which made a larger quantity of relatively small and light missiles more effective in the brief skirmishes of Indian warfare than two or three of the bulkier darts. With regard to their other equipment, surprisingly few bone tools have been preserved; but this may be due to their greater use of cane, which was very effective for knives, awls, and other implements but did not last as well as bone. Evidence has also been found to show that they manufactured and used basketry and a simple twined weave type of cloth fabric.

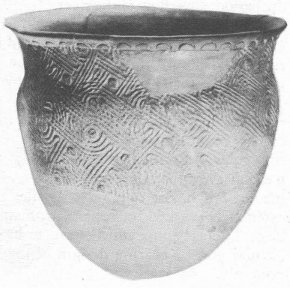

Pottery for everyday use was plain but well made and came in a large variety of pleasing shapes. Diameter of jar on right, 14 inches.

The pottery obtained in excavation has already been studied in considerable detail because of the recognized importance of this time marker to the archeologist. It is here that we find one of the most noticeable differences between these people from the Mississippi Valley and the native Georgia tribes whose pottery had developed along very different lines for some thousand years or more. Now, in place of the many forms of surface roughening which marked the history of the latter, plain surfaces become the rule. Jar forms have rounded bottoms, are often as broad as they are tall, or broader, and show a tendency toward constricted openings. One common form has a straight sloping shoulder which turns in from the rounded body contour of the pot rather suddenly. Its slope may continue without 34 change to the rim, but more often it will turn upward again to form a slight lip or even a short neck. These contrast with the deep jars of the preceding period in which the mouth, regardless of neck or rim treatment, tends almost to equal the largest diameter, and in which the base is conoidal, i. e., rounded to at least the suggestion of a point.

The clay figures which often adorned the rims of open bowls represented all manner of creatures both real and imaginary. About one-third actual size.

Of course the Master Farmers made other types of pottery, too. Some were open bowls, and others had an incurving rim which gracefully repeated the curve of the lower portion just below the belly. There were also deep, straight-sided jars with extremely thick walls, and big shallow bowls several feet in diameter which have been called salt pans from the belief that the type was sometimes used in the making of that substance. Actually they were probably the large family food bowl in common use also in later times. Impressions of a twined cloth fabric on the outer surfaces of the latter, some cord marking, and crude scoring or other treatment of the sides of the former were exceptions to the general rule of smooth surfaces during this period.

In place of surface decoration, however, we find another form of elaboration which is somewhat less common but equally distinctive. This is the attempt to depict some form, either natural or supernatural, in the body of the vessel or attached to it in some way as an independent figure. Small heads suggesting a fox or an owl or some night creature with big staring eyes grow out of the rim of a bowl and peer into it. The small handles which are fairly common on the straight-shouldered 35 jars often have two little earlike knobs at the top; and knobs and bosses with more or less modeling of the body of the pot are frequently used to represent gourds or squashes or some other vegetable which is not easy to identify. One curious style of jar has a neck which is closed at the top, something like a gourd, but has an opening about an inch in diameter below this on the side. Modeling at the top suggests ears, a style of hair arrangement, or some other human or animal feature that gives rise to the name, “blank-faced effigy bottle.”

Effigy bottles were usually a finer grade of pottery and generally accompanied burials. The hole in the human figure is in the back of the head; the face is painted white, the body red, and the hair the natural brown of clay. Diameter of bottle, 5⁵/₁₆ inches.

In time, other changes began to mark the village of the Master Farmers. The temples, built originally at ground level, were rebuilt occasionally; and with the leveling of the old building to make way for the new the surrounding ground surface was raised at first into a small platform. Gradually this platform was increased in height and size until the mound at the south side of the village was some 300 feet broad at the base and almost 50 feet high. The other temple mounds grew in a similar fashion but were either started later or were 36 less important and so never achieved as great a size. The earthlodges, too, were sometimes rebuilt and often on the same site; but no attempt was made to increase their elevation. The funeral mound, however, followed the pattern of the others; and in each new layer of the seven there were fresh burials of the village leaders, and on top of each a new wooden structure which may have been connected with the preparation of the dead for their final rites. In the later stages, too, the flat summit area was surrounded by an enclosure of wooden posts.

The structure atop the funeral mound may have been for preparing corpses for burial. From Museum exhibit.

At the northwest corner of the village lay a cultivated field which surrounded the site of one of the earlier temples. This was no ordinary field since most of these must have lain in the bottom land below the village. From its position, then, could we infer some sacred purpose, possibly to create an offering to the spirits, or by the power in its seed absorbed from the surroundings to increase the yield of the villagers’ crops? In any case, the mounds for succeeding structures were gradually raised above it; and by this act the rows were buried and thus preserved as conclusive proof of the advanced state of culture which the Master Farmers had achieved.

The construction of all these mounds and earthlodges required a large amount of material as well as innumerable man-hours of labor. Two series of great linked pits, averaging about 7 feet deep and 18 by 37 40 feet in area, seem to indicate that the earth was obtained immediately outside the main village limits, for they have been traced around considerable portions of its north and south borders. They do not enclose the entire area occupied by the temple mounds, though, because at least three of these mounds lie outside their confines today; others were destroyed in the construction of Fort Hawkins and the adjacent portions of East Macon a little farther to the north. It is not unlikely that the irregular ditches formed by these pits served also as a protection against raids on the village; for otherwise, why would their course have outlined the village area so closely?

All the evidence, then, points to the existence here at Ocmulgee of a town of Indians who lived in a state of culture as advanced in some respects as any to be found north of Mexico. We see a prosperous community devoted chiefly to the yearly round of activities designed to cement its relationship with the powerful unseen forces on which its well-being depended. Not too much work was required with the abundant rainfall on this fertile soil to raise the principal food supply for an entire family. The men, like all later Indians, hunted to supply the meat for their diet; but they had plenty of free time to devote to the construction and repair of the town’s several temple buildings. Here they gathered at stated intervals to go through the time-honored ritual first taught to their fathers by the very spirits themselves, those spirits which gave man the fish and the game and finally the wonderful gift of the corn plant. All of these gifts and many more must be accepted with reverence and treated according to the rules established for their proper use; otherwise the spirits would be offended, the game would disappear, and the fields would wither and die.

This series of cultivated rows buried beneath the fill of later mound construction confirms our belief that the temple mound builders lived mainly by farming.

Of all the annual round of ceremonies the most important was that in honor of the deity whose gift of corn had the miraculous power to renew itself every year. The summer temple, then, was the scene of the year’s biggest festival when the new crop was ripe. All the fires of the village were put out; and after the men had fasted and purified 38 themselves with the sacred drink, the new fire was lit and offered with the first of the new corn to the Master of Breath. With this act the sins of the past year were forgiven, and the town entered upon a new year with rejoicing. But ever so often the temple needed to be rebuilt, perhaps at the death of the chief priest, who may at the same time have been the chief of the town as well. This called for a mound to be built or the old one to be enlarged and raised higher as a mark of extra devotion; and every man must have given his allotment of working days to complete the project, even if several years were required before it was finished. For the new mound was proof to the divine forces of how much their gifts had been appreciated, and a plea that their favor might continue and the town prosper. Also it was proof to all the surrounding tribes of the wealth and strength of the village which was able to erect and maintain these large structures and at the same time to live in plenty and defend itself from its enemies.

General view of excavations northeast of ceremonial earthlodge, showing portion of trench surrounding the village.

Much of this reconstruction depends heavily on our knowledge of the later tribes of the Southeast and on broader analogies as well. Archeological proof does not exist for much that we have inferred. Yet we know that what we find here could not have been built by villagers living at the level of bare subsistence. Economic surplus was essential, and we know the Indians had the corn with which to create it. Strong leadership was needed to carry such large projects to completion; and with it there must have been a social and religious class system to organize the economic and priestly functions of such a community. The temple priests and their assistants and 39 retainers would have formed a rather numerous class with high status in a society so clearly impressed with the importance of the physical expression of its religious ideas. Wealth and power may likewise have rested with a specialized warrior class which controlled the governing function of the group, or it may be that these were combined with the religious duties of the priestly class. Whatever the system employed, several hundred unusually important individuals given special burial in the Funeral Mound attest to the distinctions which existed. Class differences of this sort are the most common basis for a high degree of social and political control; and Ocmulgee is a good example of the real attainments of some American Indians along these lines.

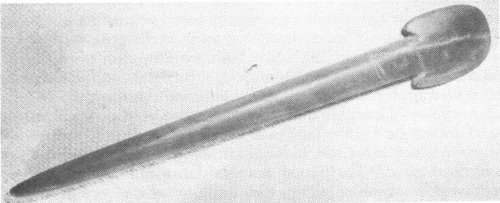

Ungrooved ax, or celt, of the temple mound builders.

In spite of the relatively large amount of information we have about them, however, we know surprisingly little of the ultimate fate of the Master Farmers. We do know that these first bearers of an alien culture from the Mississippi Valley did not persist very long in the area in terms of its previous history. Within 200 years the busy village was deserted, only to be visited by an occasional traveling band descended from the Early Farmers who had lived on in nearby sections. We do not know even whether the last occupants left here in a body to settle elsewhere, whether they gradually died off, whether they were absorbed into the surrounding population, or whether they were finally exterminated by neighbors who had themselves developed large settled communities capable of effective military action. Other ideas came to Georgia from the Mississippi Valley, but Ocmulgee lay silent and was passed by. Only in the last chapter of Indian history in this State was the site again reoccupied for a brief time. Here at the end, to be described in our final chapter, we find the Creek Indians once more living among the haunts of their ancestors.

Model of portion of Lamar village, showing ball post in plaza at foot of smaller mound.

After the mound village at Ocmulgee was abandoned we lose the thread of Indian history in this area for about 250 years. When we pick it up again in the Reconquest period, it is at a new village some 3 miles down the river. Much had happened in the meantime, though; and we are able to piece together a good bit of the story.

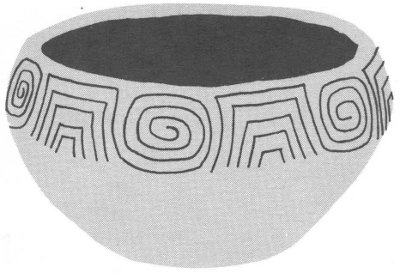

In the first place, it is clear that the Master Farmers had been only a small group which had settled in this one small section of Georgia; and that the Early Farmers did not leave Georgia when they gave up their settlements along the Ocmulgee. We cannot say for certain either that they even quit the valley entirely. Their distinctive pottery seems to have continued the course of development already outlined, but during the interval a variety of new influences came in from other regions to produce a number of striking changes. Noteworthy among these were the “carinated” bowl form and incised and pinched or punctate decoration around the shoulder or rim. In its extreme form the first of these may be described as a shallow bowl with flaring sides which abruptly turn inward to form a distinct shoulder and inward-sloping rim. The angle thus produced may be as sharp as 90°, and the shoulder itself may vary from abrupt to more or less gently rounded. It is this flattened rim which normally bears the broad, deep incised-line decoration in the form of scrolls alternating with nested flat-topped pyramids or with inverted chevrons, all worked into a continuous pattern similar to the Greek fret. Below the shoulder, the body of the bowl still carries the old complicated stamping, but gradually the pattern becomes less distinct and the paddle is applied several times to the same spot. It is even impossible sometimes to make out any design whatever in the overall roughening.

Another new element is to be found in a series of notches, bosses, or circular impressions which are applied just below the lip on jars or bowls with only complicated stamping, or at the point of the shoulder on “bold incised” vessels. The lip of most vessel shapes, except the carinated bowl, is thickened by folding or with an added strip of clay, and it is the lower edge of this band which is often pinched or otherwise worked to produce a notched or beaded effect. On the carinated bowls there is commonly a line of circular impressions made with the end of 41 a piece of cane or other hollow tube situated on the point or bend of the shoulder to separate the area of incised decoration from the body stamping below. Circles of this sort are sometimes used in place of the beading around the rim.

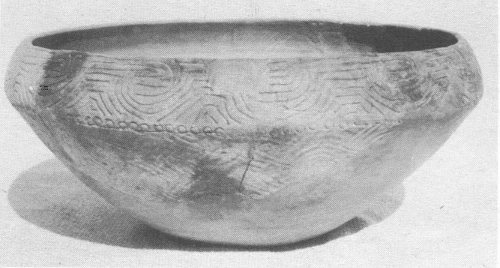

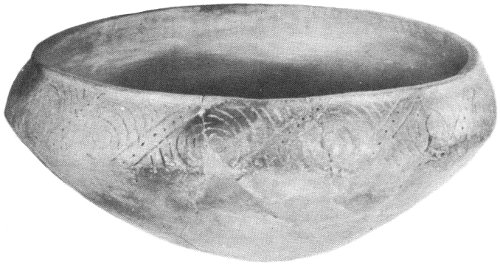

Pottery bowl showing carinated shoulder, bold incising, complicated stamping, and reed punctates typical of Lamar Bold Incised. Diameter, 16 inches.

Lamar Complicated Stamped jar. Clearly defined stamping more common in early Lamar period. Height, 9¼ inches.

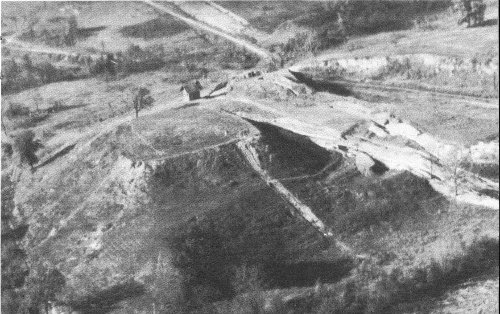

Whether the incised decoration and the carinated bowl form came from the Florida or the Mississippi Valley area has not yet been settled. Temple mounds, however, are a definite Mississippian trait; and the Lamar village below Macon, which has given its name to the archeological period we are discussing, is typical in possessing two mounds with an adjacent open court. The larger mound is rectangular, while 42 the smaller is circular; but the latter is most unusual in its spiral ramp which leads counterclockwise to the top in four complete traverses about the mound. Mounds showing this feature have been reported by early travelers, but this is the only one known to exist today.

Lamar mound with spiral ramp, after initial clearing.

The village occupied a low natural ridge of higher ground in the swamp close to the river. This position may have been chosen for its inconspicuous and defensible nature, or to be close to good farmland; but we do know that it was surrounded by a palisade of upright logs some 3,500 feet in length to protect it from enemy attacks. Within the enclosed area, the rectangular houses were grouped about the mounds and the nearby court. Their construction consisted of a framework of light posts interlaced with cane which was plastered with clay and roofed with sod or some sort of grass thatch. Some of them were raised on low dirt platforms, evidently as a protection from the periodic overflow of the river.

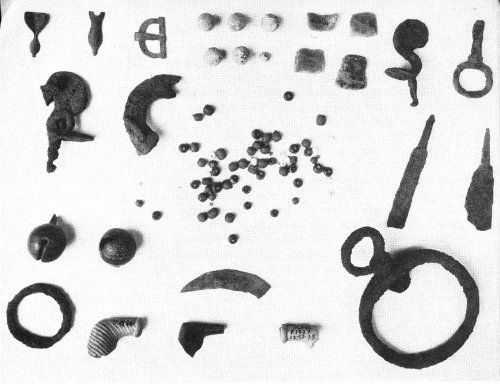

The life of these late prehistoric farmers was otherwise much the same as that of their predecessors who had lived on the bluffs up the river. To be sure, the region was now more thickly settled, and other villages like theirs could be reached by a short journey in almost any direction. Farming was doubtless the principal activity; and burned corncobs and beans have been found, indicating two of the important crops. Hunting, likewise, continued as a major pursuit; and the small, triangular projectile points tell us that the bow was now the favorite weapon even though large, stemmed dart or spear points were still made. Small, flat celts of triangular outline were used. Shell was extensively worked for ornament, mainly in the form of large beads, large, knobbed pins which seem to have dangled from the ears, and circular gorgets bearing designs of the Southern Cult, to be discussed presently.

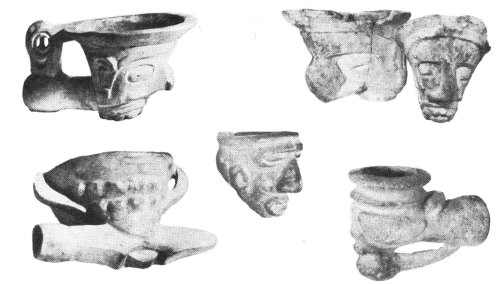

Pipes in both plain and fancy styles were numerous.

Gorgets were made of the outer shell, and large beads and these knobbed “ear bobs” from the inner whorl of the marine whelk, or conch. “Ear bobs” about 5 inches long.

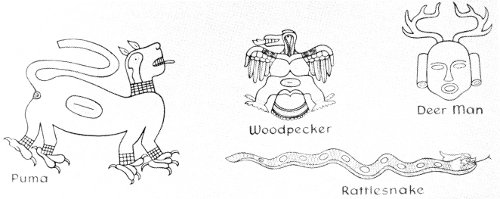

Some of the important beings of the Southern Cult as depicted on shell or copper: Puma, Woodpecker, Deer Man, Rattlesnake.

Finally, smoking appears to have become so habitual that it may have been released from the religious implications which everywhere seem to accompany the use of tobacco in aboriginal America. Pipes in an astonishing variety of skillfully executed shapes, principally of clay but also in stone, have been found scattered throughout the village refuse. Human heads with great goggle eyes, bird and animal heads, boats (?), and a stylized representation of a hafted celt are common.

DeSoto probably encountered some distant towns of these people when he explored Georgia in 1540, and they were undoubtedly the ancestors of various historic Creek Indian tribes of this State. We have suggested that their culture was a mixture of very old elements in the region, such as complicated stamping, with newer ideas coming in with the Master Farmers or even later, such as temple mounds and incised decoration. We know from work in other areas that the Early Farmer bearers of the Swift Creek tradition had continued their existence uninterrupted save only in the immediate vicinity of Macon. Therefore, despite the admixture of many outside influences, we see in the reappearance here of one of their major cultural elements, the old paddled pottery surfaces, proof that the basic culture and presumably the people themselves were still the same. In effect, an actual reoccupation of the area seems indicated; and it is this fact that the museum exhibits recognize in the name “Reconquest” given to the period we are discussing.

The culture represented at the Lamar site just described, which is the type site for this archeological period, covered a very wide geographical range and lasted in some locales into the historic period. Typical Lamar pottery is found on numerous sites in regions as widely separated as Florida, Alabama, the Carolinas, and even parts of Tennessee. We know that it was made by the historic Cherokee, which accounts for the persistence of complicated stamping into historic times mentioned earlier, and possibly also by some Siouan-speaking 45 tribes in the Carolinas, as well as by the early Creeks. While not all elements of the culture were uniformly shared in all of these areas, there can be little doubt that the material aspects of the lives of these different groups were surprisingly much alike. This may appear the more remarkable when one considers the difference in language and even the active hostility of such historic tribes as the Creek and the Cherokee. Nevertheless, one has only to consider the diversity of modern European nations sharing a single culture which we know as “Western Civilization” to realize that language, nationality, and culture are not mutually interrelated on any one-to-one basis.

Mention has been made of the Southern Cult. Briefly, this is the name given to the religious idea behind a group of frequently recurring symbols, and the paraphernalia on which they are depicted, which have been found all the way from Oklahoma and the Great Lakes to Florida and the gulf coast. These unusual articles occur in association with the platform mounds, and at some sites appear to be limited to the graves of an important class of personages who had the unique privilege of burial within the sacred structures atop the mounds.

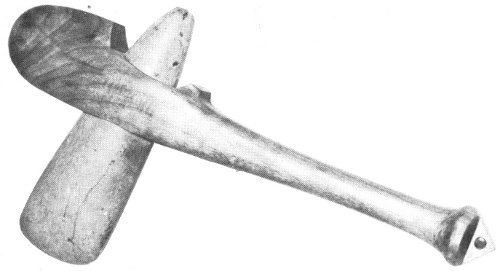

The objects themselves appear to be symbols of office or religious vessels or regalia of diverse sorts. They include engraved circular gorgets of shell, engraved copper plaques, hafted ceremonial axes made of copper or from a single piece of stone, as well as stone axheads either so finely made or of such soft material that they could not have been put to practical use. A ceremonial atlatl looks to us more like a mace or sceptre; both this form and that of the hafted ax are reproduced in beautifully chipped flint, and these are found in association with long blades and reproductions of other elements of the cult in the same material. Vessels include conch shell cups and pottery bottles of various forms.