MR. AVERAGE MAN’S IMPRESSION OF THE MEANING OF CERTAIN RUSSIAN WORDS

Transcriber’s Note:

Minor errors in punctuation and formatting have been silently corrected. Please see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered during its preparation.

MR. AVERAGE MAN’S IMPRESSION OF THE MEANING OF CERTAIN RUSSIAN WORDS

Acknowledgment is hereby made to the “Christian Science Monitor,” “Universal Service” (Hearst), and “Asia Magazine” for courtesies extended, in using some of the material that appeared in those publications.

| CHAPTER | PAGE |

| Preface | 9 |

| I. Entering Red Land | 13 |

| II. With the Red Soldiers | 21 |

| III. On to Moscow | 41 |

| IV. Moscow | 51 |

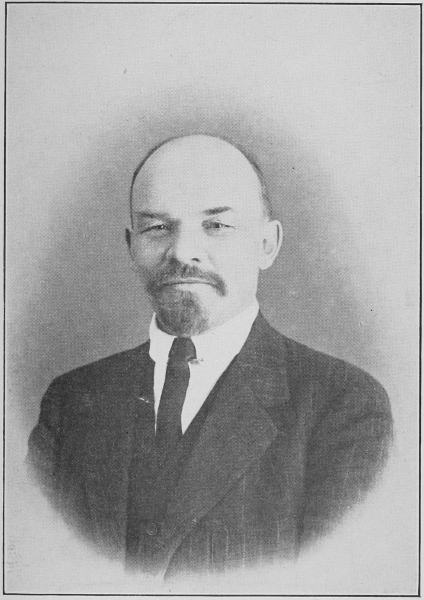

| V. Interview With Lenin | 64 |

| VI. Who Is Lenin? | 72 |

| VII. Petrograd | 87 |

| VIII. Bolshevik Leaders—Brief Sketches | 102 |

| IX. Women and Children | 112 |

| X. Government Industry and Agriculture | 120 |

| XI. Propaganda | 138 |

| XII. Coming Out of Soviet Russia | 144 |

| Appendix | 157 |

| I. Code of Labor Laws | 159 |

| II. Resolutions Adopted at the Conference of the Second All-Russian Congress of Trades Unions | 191 |

| III. Financial Policy and Results of the Activities of the People’s Commissariat of Finance | 241 |

| IV. Reports: (a) Metal Industry; (b) Development of Rural Industries; (c) Nationalization of Agriculture | 255 |

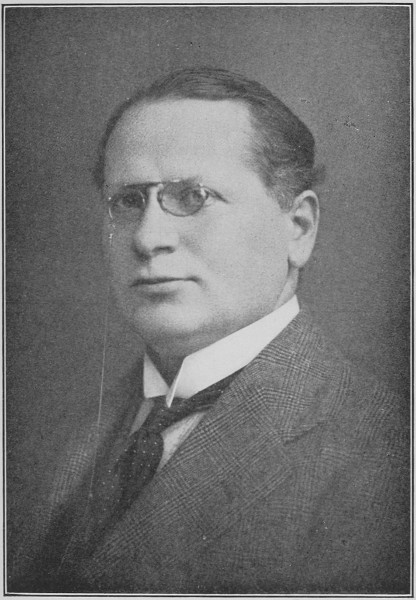

| Mr. Average Man’s Impression of the Meaning of Certain Russian Words | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Red Army’s Infantry Division | 22 |

| Trotzky, Commissar of War and Marine | 30 |

| Lenin and Mrs. Lenin, Moscow, 1919 | 38 |

| Lenin in the courtyard of the Kremlin, Moscow, Summer of 1919 | 46 |

| Lenin at his desk in the Kremlin, 1919 | 50 |

| Lenin in Switzerland, March, 1919 | 62 |

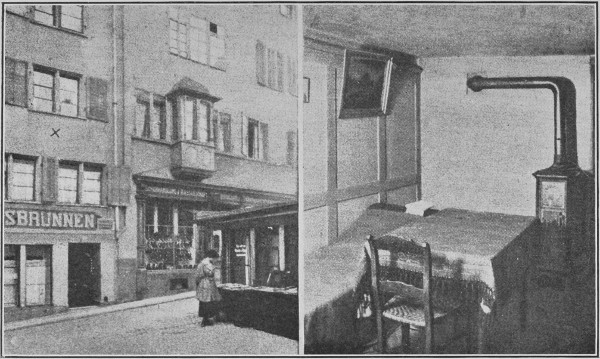

| Exterior and Interior of Lenin’s Home in Zurich | 70 |

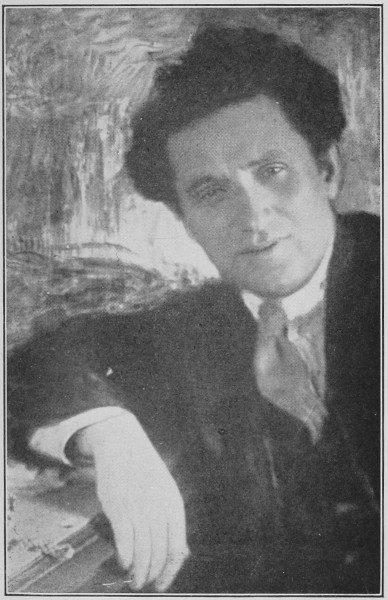

| Gorky and Zinovieff | 78 |

| Zinovieff, President of the Petrograd Soviet | 86 |

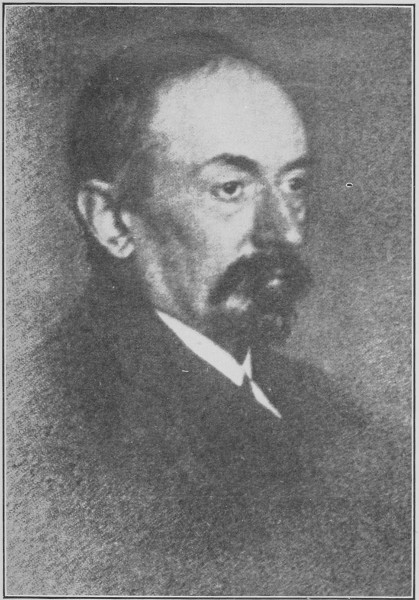

| Chicherin, Commissar of Foreign Affairs | 94 |

| Litvinoff, Assistant Commissar of Foreign Affairs | 102 |

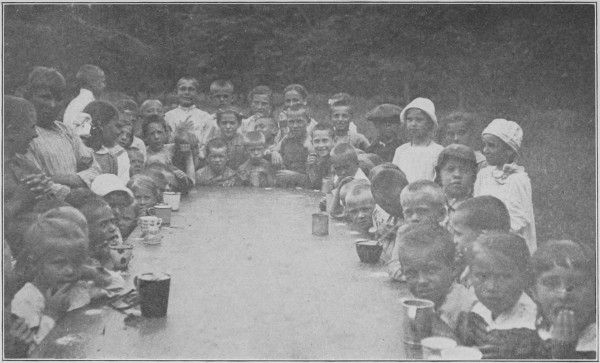

| Children of the Soviet School at Dietskoe Selo | 110 |

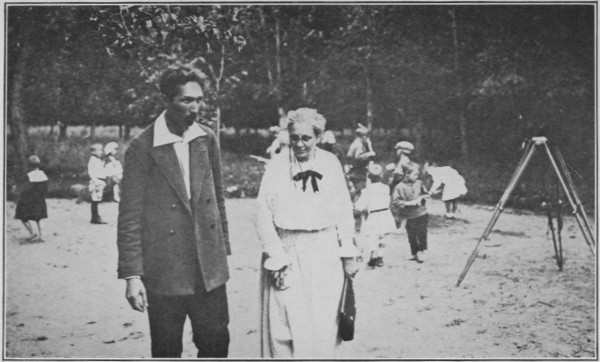

| Mrs. Lenin visiting a Soviet School | 118 |

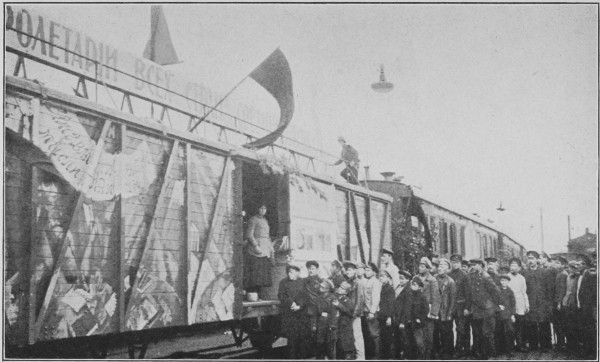

| Soviet Propaganda Train | 126 |

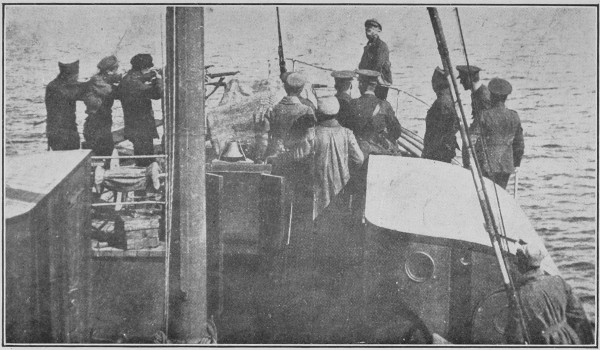

| “Red Terror” | 142 |

Of the five weeks I spent in Soviet Russia ten days were spent in Moscow and eight in Petrograd. The remainder of the time I traveled along the Western Front, from the Esthonian border to Moghilev, with leisurely stops at Pskov, Vitebsk, Polotzk, Smolensk, and numerous small towns. I tried to see as much as possible of this vast and unknown land in the short time at my disposal, and I tried especially to check up from first-hand observation some of the many things I had heard on the outside. I also tried to test the truth of what was told me in Russia itself,—to find visible evidence of the fairness of the claims made. Some popular fancies were quickly dispelled. Disproof of others came sometimes in vividly concrete fashion.

Soviet Russia is not unanimously Bolshevist, any more than the United States has ever been unanimously Democratic or Republican, or Prohibitionist. The speculators are not Bolshevist, nor are the irreconcilable bourgeoisie, nor the Monarchists, nor the Cadets nor the Menshevists, nor the Social Revolutionists and Anarchists. Nevertheless Russia stands overwhelmingly in support of the Soviet Government, just as the United States stands overwhelmingly in support of Congress and the Constitution. There are many who are opposed to Soviet rule in its present form, and this opposition is not confined to the old bourgeoisie and the anarchists. It prevails to a certain extent—variously estimated—among the peasants. But it is an opposition which ceases at the military frontier of the nation. I found many critics of Soviet rule within Soviet Russia, but they insisted that whatever changes are to be made in the government must be made without foreign interference. At present their first interest is the defence of Russian soil and the Russian state against foreign assault and foreign interference.

The peasant opposition is mainly due to the deficiencies in transportation and the shortage of manufactured articles. They blame this on the government, much as other peoples lay their troubles to “the government.” The peasants are reluctant to give up their grain for paper money which is of no value to them unless it will buy shoes and cloth and salt and tools,—and of these necessities there are not enough to go round. While the blockade continued the government was striving vigorously to overcome the shortage of manufactured articles brought about by the blockade, knowing that this alone would satisfy the peasants. They claimed to have made encouraging progress, especially in the production of agricultural machinery, of which they were trying to have the largest possible supply ready by spring.

Whatever the state of mind of the peasants, they are certainly better off materially than the city workers. In all the villages I visited I found the peasants faring much better than were the Commissars in Moscow. They had plentiful supplies of good rye bread on their tables, with butter and eggs and milk,—almost unknown luxuries in the cities. Their cattle looked well fed and well cared for. It was harvest time and the farmers were gathering in their crops. They told me that the season had been exceptionally bountiful.

I learned after my return to America that there had been a great deal of agitation among the upholders of the old Russian order in this country last summer and early fall over the pogroms which were said to have been carried on by the Bolsheviki. I found nothing but cooperation and sympathy and understanding between the Russians and the Jews. There was no discrimination whatsoever, as far as I could see. Jews and Russians share alike in the councils of the Soviet Government and in the factories and workshops.

In fact I found nothing but the utmost kindness and good will towards the whole world, all through Russia. "If they will only let us alone they have nothing to fear from us,—not even propaganda,"—was said to me over and over again. There were no threats made against the interventionists. The Soviet forces merely went ahead and demonstrated their strength and ability to defend themselves, and left the record of their achievements to speak for itself.

“You will never return alive. They will slaughter you. They will rob you of everything. They will take your clothes from your very back.”

With stubborn conviction the dapper young Lettish gentleman spoke to me as he attempted to change my mind about going into Soviet Russia. He was attached to the Foreign Information Bureau of Latvia. He had been in Riga all through the Bolshevist régime, from November, 1918, to May, 1919, when the German army of occupation in the Baltic provinces drove them out. There was nothing he could not tell me about that régime. He was especially eager to impart his experiences to foreign journalists.

“Was it really so terrible, then?” I asked him.

“Nothing could have been worse,” he repeated. "Many persons were killed by the Bolshevists—I saw them myself—but not so many as when the Germans began their slaughter. There was the Bolshevist program of nationalization. They nationalized the land. They nationalized the factories. They nationalized the banks and the large office buildings, and even the residences.

“Aristocratic women were taken from their comfortable homes and forced to wait on Bolshevist Commissars in the Soviet dining-rooms. One of our leading citizens, a man who through hard work had accumulated a great fortune, was put to work cleaning streets. His fine house with thirty or forty beautiful rooms, where he lived quite alone with his wife and servants, was taken away from him, and he was moved into a house in another part of the city on a mean street where he had never been before. His home was taken over by the ‘state’ and seven families of the so-called proletariat were lodged in it. One of our generals was compelled to sell newspapers on the streets. Our leading artists were forced to paint lamp posts—and the color was red. They made the university students cut ice.”

“And the women—did they nationalize them?” I interrupted.

“Well, no, they didn’t do that here in Riga,” he said, “but that was because they were not here long enough to put it into effect. They were so busy confiscating property in the six months they held sway that they had little time for anything else. No, they didn’t nationalize the women in Riga, but you will find they have done so in Moscow.

“But you must not go to Moscow,” he added. “You will surely never return alive—but if you do, please come and tell me what you have seen.” And mournfully he wished me a safe journey.

I returned to the Foreign Office the next day determined to get permission at once to pass through the Lettish front into Soviet Russia. It was a hot August day. Officers and attachés sat around panting, obviously bored that any one should come at this time to annoy them. Yet despite the heat, they were willing enough to argue with me when they learned that I wished to go into Soviet Russia. Like the young man I talked to before, they tried hard to dissuade me. They were full of forebodings.

“You will be robbed of the clothes on your back the minute you fall into the hands of the Bolshevists,” they insisted.

“You must be crazy,” said one particularly friendly officer, whose blonde hair stood straight up from his head so that he looked perpetually frightened.

“But I am an American correspondent,” I repeated over and over again, not knowing what else to say.

“So that is it,” said the officer, seeming to understand all at once. And shortly after that the Foreign Office at Riga decided to recommend the General Staff that I be permitted to pass the lines. But still they urged me not to go.

“You will come back naked if you come back alive,” they shouted to me in parting.

I left Riga on a troop train at six o’clock in the evening of September 1, 1919, bound for Red Russia. By noon the following day we had reached a small town, where I disembarked with the soldiers. The front was fifteen versts away. There the Reds had established themselves, I was told, in old German trenches near the town of Levenhoff, 107 versts from Riga.

I carried a heavy suitcase, an overcoat and an umbrella, and the thought of trudging in the wake of the less heavily caparisoned soldiers was discouraging. I accosted a smart young officer with blonde mustaches. He listened to me with interest.

“I am an American correspondent,” I said, “accredited to your headquarters.”

He glanced at my papers and shrugged his shoulders with such an air of indifference that I thought he was not going to help me at all. But he told me to follow him, and a short distance up the road we came upon a peasant driving a crude hay-rick drawn by a single gaunt horse.

After a brief parley, none of which I understood, the peasant got down from his high seat, hoisted my suitcase into the vehicle, and I followed it. I sat flat on the floor with my feet braced against the sides of the springless cart, and we started jolting and bumping down the rough road which ran parallel with the tracks. The peasant sat on a board laid across the front of the rick.

We had gone only a short way when the booming of guns came from both sides of us. My driver, however, seemed unconscious of it. We went on for another five versts. The guns grew louder and I saw shrapnel shells burst uncomfortably near. They came thicker and faster.

I remembered the peace of Riga some twenty-four hours before this. I wanted to tell the driver to turn around and go back, and then I remembered that we did not speak the same language, and certainly, judging from his impassive back, we were not thinking the same thoughts. There was an instant when I stopped thinking altogether, and when I knew that I could not have opened my mouth had I tried to speak. A shell burst some forty feet away and a piece of shrapnel about the size of a grape-fruit landed on the floor of the hay-rick between my outspread legs, broke two slats on the floor of the wagon and dropped harmlessly to the ground. Then at last the driver turned around, his face white as chalk. His panic, instead of communicating itself to me, had the very opposite effect and I suddenly lost all sense of danger. With a boldness, which surprises me whenever I think of it, I shouted to him:

“For Christ’s sake, go on!”

The driver obeyed reluctantly but soon turned around again.

“Go on!” I cried.

A few minutes later we approached a clump of trees under which stood a Lettish gun, surrounded by four or five officers. My driver stopped to talk to them, evidently inquiring whether it was safe to go on. One of the officers nodded, the others laughed, and one said in good English, “Everything is all right.”

At four o’clock we reached the headquarters at the front. I presented my pass to the commanding officer, a stocky young fellow with humorous wrinkles around his eyes.

“You are an American,” he said, observing me keenly.

“From New York,” I said. “I am going to Moscow on important business for my paper.” I told him more, giving most impressive details. I convinced him.

“Well,” he said finally, “you will have to wait until morning. Both of us are using heavy artillery now.”

I insisted. I wanted to go at once.

“Well, go then,” he said with his first show of impatience. He called a lieutenant, gave him brief instructions and washed his hands of me.

Right across the neutral zone you could see the Bolshevist trenches, running at right angles to the railroad with barbed wire on each side so that a motor train couldn’t rush through. “You can’t go into the front line trenches,” the commanding officer told me. “Nobody is allowed in there except military men, but you can go through the opening in the barbed wire and start across.” That was the best I could do, so the lieutenant took me around those barbed wires and down into a ditch at the edge of the railroad and pointed to me to climb the bank. Well, I climbed up somehow, it was about twenty-five feet; and started down that track with my big suitcase and a heavy overcoat on, holding up my umbrella with a white handkerchief tied to it.

It was a very hot day and I had to walk two miles across the neutral zone—two miles right straight down the tracks. You could see the Bolshevist trenches in the distance. Pretty soon the firing started. I couldn’t feel anything dropping near me, so I decided those Lettish soldiers were popping their heads out of the trenches to see this fool go across and the Bolshevists were taking pot shots at them.

The Lettish officer had told me: “If they start to fire on you, roll off down the bank and crawl back to our positions.” But I would have had to roll twenty-five feet and probably crawl a mile. So I kept on. A scattering rifle fire spat out from the Red trenches and the shells screamed steadily overhead. My suitcase dragged heavily and I was uncomfortably warm, but I made good progress. I had covered about half the distance when a rifle bullet whipped by my ear. I plunged along the track with redoubled speed.

As I came within fifty yards of the barbed wire which the Russians had strung across the tracks, Red soldiers shouted up at me from their trenches and motioned for me to come down into the adjoining field where there was a gap in the wire. A few moments later I was in the first-line trench of the Red army.

I was hot and exhausted and still resentful of that shot. I spoke first: “Why did you shoot at me?” They did not understand, but one of them evidently knew I was speaking English. He called down the trench to another soldier who ran up. He was a tall young Slav, and showed white teeth in a broad smile as he greeted me in good English.

“Hello, America,” he said.

“Why did you shoot at me?” I repeated indignantly.

“Oh,” he made a deprecatory gesture.

“One of the comrades made a mistake,” he said. “He shot at you without orders. But you also made a mistake.”

“What was that?” I asked.

“You carried a white flag,” he said, grinning. “It should have been red.”

I asked to be taken to the commanding officer and two soldiers were detailed to escort me. One of the “comrades” laid down his rifle and picking up my suitcase led the way down the trenches; the other shouldered his rifle and followed close behind me. I kept my eye on the suitcase and trudged along.

They were both very friendly, and with a great show of their English began talking to me at once.

“Do you know,” said one of them, “that the dock workers are on strike in New York?” And while I was still wondering to myself how Russia, shut off from all the rest of the world, could have heard this piece of news, the other “comrade” burst out:

“Who is going to win the pennant in the National League?”

“Where do you learn these things?” I asked.

“From the bulletins,” he replied briefly. I learned later that the wireless at Moscow works twenty-four hours a day, and that it grabs from the air practically all the news that is wirelessed from America to European countries. Each morning in Moscow bulletins carrying this information are printed and distributed in the industries, in the peasant villages and among soldiers.

For three versts we walked along the railroad track, and at last reached the headquarters at Levenhoff. I was taken to the commanding officer, who spoke English fairly well.

“What do you want here?” he asked looking me over keenly.

I had expected that question and had my answer ready. I knew I would have to give an explanation, but what I did not know was that I would have to give that explanation over and over again all the way from Levenhoff to Moscow.

“I came to look you over,” I said. “In the world outside there are many conflicting stories about Soviet Russia and I want to see for myself what is going on here. I am not a spy. I should like to be allowed to go to Petrograd and Moscow and to travel through the country and then return to America and tell what I have seen.”

RED ARMY’S INFANTRY DIVISION

Parading on the Famous Hodinskoe Polie in Moscow.

The Red officer took a long look at me and turned to a telephone. I knew just enough Russian at that time to get the drift of his conversation. He called up the Brigade headquarters and reported that an “Amerikanski” journalist had come across the lines and wanted to proceed into the country. There was much conversation while I stood waiting nervously. Presently he hung up the receiver and turning to me said, “You will have to report to the Brigade Command at Praele.”

“And is there a train?” I asked when I learned that I had twenty-two more versts to go to Praele. There was not; I must drive there in a droshky. It would be ready for me in a few minutes. And the officer gave some orders. Presently the droshky arrived and a great powerful Red Guard with a rifle slung over his shoulder motioned to me to get in. He climbed in after me and we drove off.

It was early evening by now. Vast stretches of country swept away from us on either side of the road. I tried to talk to my burly guard, but his English was as meager as my Russian. Our conversation resolved itself into wild gestures and signs. The night was clear, brightly moonlit, and about nine o’clock it grew very cold. The chill crept into every crevice of my clothing and penetrated to my very bones, and I lost all interest in the country around us.

For hours we seemed to drive through the chill and dampness. I was fairly frozen when I realized that the guard suddenly took off his coat and silently offered it to me. I refused to take it, of course, thanking him—“Spasiba, Tovarishch!” I said. He chuckled at my Russian and repeated Tovarishch, the Russian word for comrade.

We reached Praele at midnight. My guard took a receipt for me from the commanding officer as though I were a bundle of clothes or a package of groceries, and returned to Levenhoff....

“What do you want here?”

I delivered my speech of explanation. The next question was welcome. “Would you like something to eat before you sleep?” I was very hungry. The officer called a soldier who went out and returned with some black bread and tea, with apple sauce. When I had finished eating, my guard took me to a large barrack room where about thirty soldiers were sleeping in their uniforms on wooden bunks built in around the walls. Several of them woke when we came in and looked me over with interest. They passed cigarettes and apples. We smoked and munched for awhile together, and presently every one settled down to sleep.

I awoke about nine the next morning. The soldiers were all up and gone. A guard came in and led me to a building across the street where three officers and two privates were breakfasting together. A pleasant-faced Russian woman presided over the stove. A place was made for me at the table and I was served with a very unsavory coffee-colored liquid, one egg, a small piece of butter, and plenty of black bread. While we ate a young Russian boy about thirteen years old played the violin,—the Internationale, the Marseillaise, and some charming folk-songs.

We returned to the barracks after breakfast and a little later the Commissar attached to brigade headquarters came in to see me. He could not speak English, so we carried on our conversation through the Commandant. First of all he asked what I wanted in Soviet Russia. I went through my patter and they left me. For half an hour I sat wondering what would happen next. Then the Commandant returned.

“We believe you are telling the truth,” he said. “We are glad to have people come in from the outside to learn what we are doing and what we hope to do under Soviet rule. But some whom we have allowed to come in have gone out and told outrageous lies about our country and our people; others have come across our lines and have gone away and revealed our military positions to the enemy. We are defending ourselves and must be careful. You must pass on to the Division Command at Rejistza, thence to Army Headquarters, and finally to the High Command for investigation. After that you will be allowed to remain in Soviet Russia—or you will be deported.”

That evening I was taken under guard across country to a small railway station where we caught a train which brought us to Rejistza at four o’clock in the morning. A bed was found for me in the station master’s house. At eight o’clock my guard woke me and dragged me off to the Commissar and the military Commandant at Division Headquarters, turned me over to them and took a receipt for me delivered in good order.

After breakfast of black bread and tea came the question, “What do you want here?” I was told that I would have to wait till the following day for a decision on my case. Meanwhile I could walk about and see the town. The Commandant filled out a slip of paper which he told me I was to show to any one who offered to interfere with my stroll.

I found Rejistza a fair-sized town. The people were going about their business in normal fashion. They appeared to be in good health and they were all well clothed. Many of the shops were closed for lack of wares; others were open, though none seemed to have much stock. There was, however, an abundance of fruit in the stalls, and some vegetables. The streets were dirty. Carpenters were at work on some of the houses, many of which were badly out of repair.

I began looking for some one who could speak English, and soon discovered a young Russian boy who was eager to talk about his town.

“But why are your streets so dirty?” I asked him.

“Oh, Rejistza always was a dirty town, but we are cleaning it up now as fast as possible,” he added with civic pride that was obviously newly acquired.

The streets were full of sturdy, well-clad soldiers moving through to the Dvinsk front where the Reds were bringing up reinforcements to stop the Polish offensive. Bands were playing and the soldiers marched by in good order, with heads erect, singing the Internationale.

I walked down towards the river Dvina. The sun was shining, the air crisply cold. A crowd of children came bounding out of a school-house and scampered towards a large park to enjoy their recess hour. They ran about playing games much as children in this country do. One group quickly marked out a space on the sidewalk with chalk and began skipping and hopping in and put among the chalked squares. Others played tag and still others played hiding games. They were all busy. The teachers had come out into the park with the children, and for an hour children and teachers alike played and talked together in the sunlight. Here or there sat a teacher on a park bench surrounded by a crowd of alert children who hung upon every word as she related Russian fairy tales.

And when the hour was over every one trooped back into the school-room with as much ardor as when they came out into the park. I wandered over to the river, but soon returned to the school-house. I wanted to find out what a Russian school-room was like.

I slipped in through the door and took a seat near by. No one took notice of me. The teacher continued her talking and the children listened with as much interest as they had outside when she was telling them of the wonderful deeds of the heroes of folk-lore. For an hour I sat and listened and then walked away still unnoticed. I returned through the town to the Commissar’s house quite unmolested.

That day I dined with the Commissar and four or five of his staff. I had looked forward to the meal all day, and was grateful when at last we sat down to table. Cabbage soup and a small piece of fish were served to each of us. The others talked a great deal; I waited for more food, but none came, and I went to bed that night with a great gnawing inside of me.

I was awakened at four o’clock in the morning by a new guard who led me off to a train. The decision had been made, as the Commandant had promised it would be. The train was bound for Velikie Luki. The new guard and I had breakfast on board—black bread and two apples.

It was four in the afternoon when we reached our destination. A droshky carried us five versts to the headquarters of the 15th Army, where I was again delivered into the hands of a Commissar.

Wearily I repeated my lines, thinking much more about the possibility of getting a meal from this Commissar than I did about getting a pass into Moscow. I must have looked as hungry and tired as I felt, for the Commissar instead of granting the pass took me to his home, which was only a short way down the street.

His house seemed to me to be the most comfortable place I had ever seen. I was introduced to his wife, who came to meet us at the door. Two children soon appeared and then the Commissar’s mother, and at once we began talking like old friends. I was taken to a cheerful room where I dusted and washed myself, and when I returned to the others the evening meal was set forth on the table. It seemed almost bountiful to me after the meager portions of cabbage soup and black bread I had been eating for the past few days. Actually it was only cabbage soup again, one fish ball for each, some kasha, black bread and tea. I ate ravenously, and I am afraid I gave my host and hostess the impression that I was a glutton.

I went to bed early that night feeling well fed for the first time in days. In the morning I set forth early for headquarters with the Commissar and there was turned over to a guard, who took me out to show me Velikie Luki.

The town was crowded with soldiers strolling idly along the streets, soldiers marching briskly to the railroad station, soldiers falling in and out of barracks, soldiers everywhere,—and singing, always singing, with bands and without, ceaselessly singing their beloved Internationale. The troops were moving out to the Dvinsk and Denikin fronts. The thoroughfares were crowded with civilians watching the regiments pass by—men, women, and children, shouting, waving caps and handkerchiefs, and joining in the chorus of the soldiers’ song.

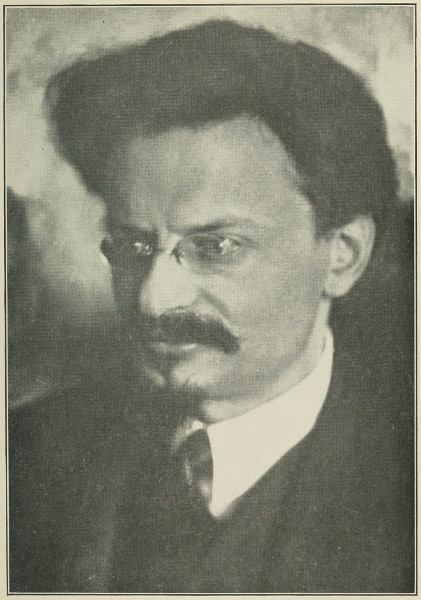

TROTZKY

Commissar of War and Marine

I followed the marching lines to the railway station. Trains were pulling out and empty cars moving in as fast as they could be loaded. And how they were loaded! Passenger cars, box cars, flat cars, jammed with shouting, laughing soldiers, waving good-bye, joking and singing. Every inch of space carried a soldier. Platforms, steps, roofs, and even the engines were covered with scrambling, good-natured Reds. A train already filled drew in and emptied a load of men back from the front for a rest. The wounded were carried off carefully. From the end of the train a detachment of about two hundred disarmed soldiers marched up the platform under guard. These were the first prisoners I had encountered, and I was anxious to see what would be done with them. They marched away from the station and I asked my guard if we might follow them. He made no objection. The townspeople paid no attention to the prisoners. Evidently they were an accustomed sight.

They went about a mile down a long side street, parallel to the railroad, and then turned abruptly across lots and entered a large barrack. A sentry was posted outside, but after a little explanation my guard obtained permission for us to go in. The prisoners were seated on the floor, with their backs to the wall. Two soldiers brought in steaming samovars through a side door and others carried in great loaves of bread. Tea was made and handed around to the prisoners and the bread was cut in large chunks and given to them. The captives ate hungrily, their guards chatting and laughing with them. While they were still eating, two more Red soldiers entered, with bundles of printed pamphlets, which they distributed among the prisoners, who ate, drank, and read.

If there was a German soldier there, he received German literature; if a Lithuanian, he received Lithuanian literature; if he happened to be French—well, they had it in all languages. All the while they were holding the prisoners they fed them three times a day, sometimes bread and tea and sometimes cabbage soup, and they kept them reading all the time; when they were not reading some of the Commissars were in there talking with them, telling them about the world, and what the war was about and why they were sent there. They had the organization of it perfected to such an extent that prisoners were not there five minutes before they were eating, and they were not eating five minutes before they were reading.

Bolshevist warfare does not end with the taking of prisoners. The propaganda follows. The Soviet leaders think more of it than they do of bullets. They say it is more effective. Three times on the western front I witnessed this same scene where prisoners were brought in.

In Russia they like very much to take prisoners. The only objection is that they haven’t got much food and they don’t like to starve them. They told me that they would like to take a million prisoners a day, if they had plenty of food and paper. After all, the biggest war they were carrying on in Russia was a war of education. All along the battle-front you could see streamers telling the other side what the thing was about—you could read them a hundred yards away. At night they put two posts in the ground and fastened the streamer between them. In the morning, when the sun rose, there it was.

During the two days I spent in Velikie Luki, and later at many other places along the front, I sought every opportunity to study the Red army. I am not an expert and cannot report upon the technical details of military equipment. There seemed no lack of small arms or cannon. In general the soldiers were warmly clad and strongly shod. Certainly they were in good spirits. The relations between officers and men were interesting. There was no lack of discipline. Off duty all ranks mingled as comrades, men and officers joking, laughing, singing, or talking seriously together. Under orders the men obeyed promptly. I found it the same at the front, in the barracks, and at headquarters with the Commissars and highest officers. When there was no serious work to be done they associated without distinction.

Wherever I met the Red soldiers I was struck with this combination of comradeship and discipline. On more than one occasion I have gone into a commandant’s office along the front, at some high command, and found him playing cards or checkers with his men. Privates and under-officers would crowd in unceremoniously and engage in voluble chatter without the slightest indication of superiority or deference to rank. Then, suddenly, perhaps a ring on the telephone, and the commander would receive a report of some development along the front. A brisk order would bring the room to attentive silence; cards and checkerboards and fiddles would be shoved aside. The men would file out to their posts. They seemed to have an instant appreciation of the distinction between comradeship in the barracks and discipline on duty.

The ordinary Red soldier gets 400 rubles a month, with rations and clothes. Soviet officials told me that there were 2,000,000 thoroughly trained and equipped men in the fighting forces, with another million in reserve and under training. About 50,000 young officers, they said, chosen from the most capable peasants and workers, had already graduated from the officers’ training schools under the Soviet Government. Thousands of others had been developed from the ranks.

It is easy for the casual observer to misjudge that subtle and all-important element known as “morale.” I think that I am perhaps more than ordinarily skeptical of manifestations of patriotic fervor, knowing something of the means by which every general staff keeps up the fighting spirit of the ranks. But I retain from my contact with the Red soldiers a sense of peculiar zeal and dogged grit. Certainly they do not want to fight. They want to go home and settle down in peace. But this frankly confessed distaste for slaughter seems only to emphasize their determination to see the struggle through to the end. For all their war weariness they did not act like men driven unwillingly into battle. I tried to imagine myself enduring what many of them have endured for over five years, betrayed by their first leaders, overwhelmingly defeated by their first enemy, and still struggling on against new assaults from those they had been taught to believe were their friends and allies.

I tried to imagine what vast process of propaganda could have stimulated this unyielding endurance. Propaganda there undoubtedly was. Just as the Allied armies had their attendant organizations of welfare workers and entertainers to keep up the morale, so the Red Army was accompanied by a carefully organized system of revolutionary propaganda. I suppose the American soldier would not have fought so well had he not been constantly reminded that he was fighting to make the world safe for Democracy. The Red soldier is persuaded that he fights to keep Russia safe for the Revolution. This ideal is deeply personal. He feels it is his revolution; he feels that he accomplished it regardless of his leaders, certainly in spite of some of them; and now it is his to defend against attacks from without and within. In judging this thing I find myself turning away from generalizations and disregarding what I was told by those enthusiasts who have the Red Army in their keeping. I come back again and again to the men themselves. Before I left Russia I had seen a great many soldiers. I had lived with them, traveled with them, slept in their barracks, eaten in their mess. To the American of course, the conditions under which the European masses manage to maintain existence, even in normal times, is always a matter of surprise and wonder. The Soviet Government does everything possible for the Red Army. It is their constant thought and care. But the utmost that can be provided, even of bare subsistence, seems painfully inadequate to the westerner.

The preferential treatment of the soldiers, of which I had heard so much before I saw it and shared it, consists principally in maintaining an uninterrupted supply of black bread and tea. It may be propaganda, it may be a peculiar quality in the spiritual and physical composition of the Russian peasant. Whatever it is, I do not believe that any other European army would endure so long on a ration of black bread and tea. An occasional apple or cigarette were luxuries, all too quickly consumed and forgotten. The black bread and tea, constant and unvaried, will ever remain for me the symbol both of the efficiency of the Soviet Commissary and of the zeal of the Red soldier. Black bread and tea and song. Their love for song is amazing,—all songs, but principally the Internationale. They march off to the front singing, they limp back from battle singing, they sing on the trains, and in the barracks, and at mess; they sing while they are playing checkers and they sing while they are sweeping stables. They wake up at night and sing. I have heard them do it.

I was told that about seventy-five percent of the Czar’s officers were in the Soviet Army. This was no sign that they were converted to communism. Their spirit remained essentially patriotic. They supported the Soviet Government, not because it was a Socialist government, but because it was the government. They fought to defend Russia.

It was Trotzky who insisted on allowing these old officers to come into the army. Many of the Communists thought they would betray the soldiers on the front and turn them over to the enemy. But Trotzky said it was a question of permitting the experienced officers to train the men and teach them military tactics or the Red Army would be destroyed. Trotzky had his way. At every army post, whether it was a company, a brigade, a regiment or a division, wherever there was an old army officer there was a trusted Commissar who worked in the office, and every move the old army officer made was known to the Commissar.

The following manifesto, drawn up and signed by 137 officers of the old régime, appealing to their former messmates to quit the counter-revolution and stop making war upon the Soviet Government, which the people had established and would defend against all attacks, was sent through the Denikin lines:

"Officers—Comrades:

"We address this letter to you with the intention of avoiding useless and aimless shedding of blood. We know quite well that the army of General Denikin will be crushed, as was that of Kolchak and of many others who have tried to put at their mercy a working people of many millions of men. We know equally well that truth and justice are on the side of the Red Army, and that you only remain in the ranks of the White Army through ignorance regarding the Soviet Republic and the Red Army, or because you fear for your fate in case of the latter’s victory. We think it our duty above all to write you the truth about the position made for us in the Red Army. First we guarantee to you that no officers of the White Army passing over into our camp are shot. That is the order of the Supreme Revolutionary Council of War.

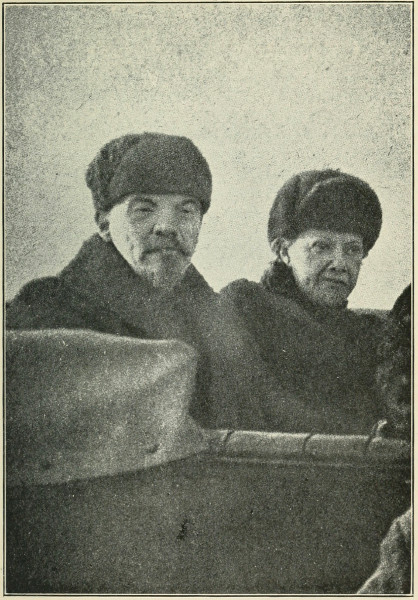

LENIN AND MRS. LENIN, MOSCOW, 1919

"If you come with the simple desire to lessen the sufferings of the working population, to lessen the shedding of blood, nobody will touch you. As to officers who express the desire to serve loyally in the Red Army they are received with respect and extreme courtesy. We have not to submit to any kind of outrage or humiliation. Everywhere our needs are attentively supplied. Full respect for the work of specialists of every kind is the fundamental motive of the policy of the present government and of its authorized representatives in the Red Army. Quite unlike the practice in the old army, you are not asked, ‘Who are your parents?’ but only one thing—‘Are you loyal?’ A loyal officer who is educated and who works advances rapidly on the ladder of military administration, is received everywhere with respect, attention, and kindness. Among the troops an exemplary discipline has been introduced.

“From the material point of view we could not be better treated. As for the Commissars, in the vast majority of cases we work hand in hand with them, and in case of disagreement the most highly authorized representatives of the power of the Soviets take rapidly decisive measures for getting rid of the differences. In a word, the longer we serve in the Red Army, the more we are convinced that service is not a burden to us. Many of us began to serve with a little sinking of the heart, solely to earn a living, but the longer our service has lasted the more we are convinced of the possibility of loyal and conscientious service in this army. That is why, officer comrades, we allow ourselves to call you such although we know that the word ‘comrade’ is considered insulting among you, because among us it indicates relations of simple cordiality and mutual respect. Without proposing that you should make any decision, we beg you to examine the question, and in your future conduct to take account of our evidence. We wish to say one thing more,—we congratulate ourselves that in fulfilling obligations loyally we are not the servants of any foreign government. We are glad to serve neither German imperialism, nor the imperialism which is Anglo-Franco-American. We do what our conscience dictates to us in the interest of millions and millions of workers, to which number the vast majority of the company of the officers belong.”

Before leaving Velikie Luki I wandered with my guard down a street of the town and came upon a Soviet bookstore. Inside were thousands of books and pamphlets, in what seemed to me all the languages of the world. The store was full of men and women buying these books and pamphlets. I learned that this store and many others like it had been opened almost two years before, and that knowledge of history and social conditions throughout the world was thus being brought to millions of Russians formerly held in darkness.

Later in the afternoon of that day the Commissar informed me that I was free to go on to Smolensk and that if I passed muster there I could go anywhere I desired in Russia. I was given another guard, a big fellow who had spent ten years in England and returned to Russia when the Czar was overthrown. He so much resembled the Irish labor leader, Jim Larkin, that I called him “Larkin” throughout the course of our journey together.

He had an exclamation which he used frequently when I was too pertinacious to suit him.

“God love a duck, what do you want now?” he would roar with a despairing gesture, and the tone of his voice also was despairing. It may be that he was justified in his complaint, for there was much that I wanted to know and to see.

On the last day of our journey towards Moscow he turned to me and said, “I haven’t prayed for ten years or more,—not since I was down and out in Glasgow, Scotland, and wandered into a Salvation Army headquarters. Then I did go down on my knees and pray for help, but I decided since that praying wasn’t my job. But God love a duck, when I get you safely into Moscow I’m going down on my knees again and thank God that this job is over and ask Him to save me from any more Americans of your kind.”

But there was, after all, some excuse for my troubling him so often and so much. “Larkin” slept on every possible—and impossible—occasion, and the sound of his snores, with which I can think of nothing worthy of comparison, kept me awake, so that in self-defence I used to rouse him every time we reached a station to ask questions about where we were and why we had stopped there and what the people were doing and why they were doing it. When I had him sufficiently awake to begin to smoke I could snatch a bit of sleep for myself, for he invariably sat up until he had smoked eight or ten cigarettes, after which his snoring began again and my rest ended.

“Larkin’s” real name was August Grafman, which sounded Teutonic. He was a Russian Jew, however, and a good fellow. I hope to see him again sometime, and I commend him to any other Americans who want to see for themselves what is going on in Russia at the present time. He spoke English readily and perfectly, and from him I obtained much information I might otherwise have missed. There was the time when we waited for a train at a small station in the course of our journey towards Smolensk. All at once a commotion arose on the other side of the station. Hurrying around, we saw a man running, pursued by three or four Red soldiers. Two officers coming toward the station drew their sabres and held them before the man, who stopped and his pursuers captured him. They brought him back to the station and I observed that he was a Jew. I wondered if his crime was that of his race, remembering stories of pogroms. The Jew was brought into the station and seated on a bench. Immediately the soldiers surrounded him, and one of them stood up in front of him and made a long speech. At its conclusion he sat down, and another rose and made an address. Finally a third vociferously questioned the man. At last the Jew arose, the soldiers made way for him, and he left the station. “Larkin” who had been too much interested in the proceedings to talk to me, now satisfied my curiosity.

The Jew had been caught in the act of picking the pockets of a soldier. Furthermore it was his third offence. The first man who spoke had tried to impress the Jew with the enormity of the crime of robbing a man who was on his way to defend his country. He had said, “Don’t you realize that a man going out to fight carries nothing with him except what he actually needs, whether it be money or anything else, and that it is worse to rob a soldier on this account than an ordinary civilian, with a home, and all his treasures about him?” The second man had talked of the defence of the country; the soldiers were going to fight so that when the fighting ended there would be enough for every one and no need for stealing. The third had tried to obtain a promise that the man would not again steal from soldiers. He had been successful, and, “now the Jew is free,” said Larkin.

“But it was his third offense,” I said. “I should think they would punish him severely.”

“Larkin” gave me a pitying glance. “You don’t understand the Russians,” he said simply. “They are kind and in their own new born freedom they want every one to be free.”

At last our train arrived and we got on. To Smolensk and then to Moscow, I thought. But it was not so simple as that. Our train was going to Moghilev direct, so we had to get off again at Polotsk at nine in the evening, where we found that we were half an hour too late to catch the train for Smolensk. “Larkin” hunted around for a sleeping place for us when we learned that we would have to stay overnight in the town, and finally won the favor of the Commissar, who took us to what he called the “Trainmen’s Hotel,” a large building near the station. In the room into which we were ushered there were about twenty beds, the linen on which was far from clean. Two of the beds in one corner of the room were assigned to us and we lay down fully dressed. After what seemed a few minutes I was awakened by a vigorous kick, and found a huge Russian standing over me, brandishing his arms and speaking harshly and menacingly at me. I hurriedly shook “Larkin” out of his profound slumber, and at the end of a brief but spirited discussion between the two in Russian, he informed me that the man had been working all night in the railroad shop and had come in to sleep. He resented finding his bed occupied. I suspected “Larkin” of enjoying the joke on me, as I clambered out and shivered in the cold, but his enjoyment was brief, for he was almost immediately ordered out by another man who entered and claimed his bed.

The two of us wandered out forlornly into the cold foggy morning and went back to the station. The Commissar there made us comfortable in his office until daylight, when we went down the track to a water tank and had a “hobo wash” after which we ate our breakfast—one egg each, black bread and tea, in the Soviet restaurant in the station.

We had been told that we could not get a train to Smolensk before four o’clock in the afternoon, but at eleven the Commissar told us that a trainload of soldiers going to the Denikin front would be passing through at two in the afternoon and that it might be possible to arrange for our transportation on this train, if we wished it. We did wish it and at two o’clock we were in a box car full of soldiers en route to Smolensk, which we would reach at ten that night.

The soldiers sang all evening—Russian soldiers always sing, no matter how crowded, how hungry, or how weary—but one by one they dropped off to sleep, huddled up in all sorts of positions. The train jolted along, slowly, it seemed to me, and it was too dark to see anything through the window. My guard went to sleep, and I remember thinking we must be near Smolensk and that I would have to stay awake since he seemed to find his responsibilities resting lightly. The stopping of the train roused me, and thinking that we had arrived at Smolensk I shook “Larkin” who looked at his watch and exclaimed, “Why it’s midnight. We must have passed Smolensk.”

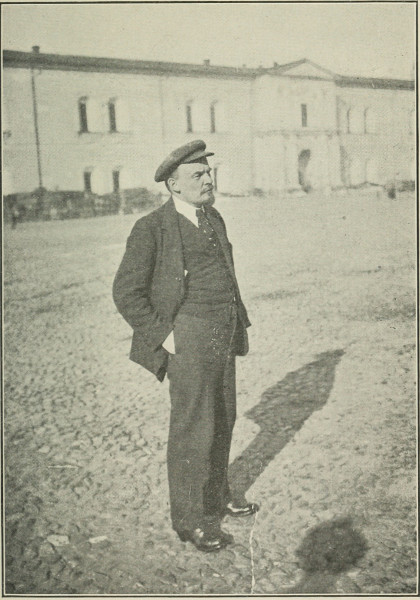

LENIN IN THE COURTYARD OF THE KREMLIN, MOSCOW, SUMMER OF 1919

Surely enough, we had gone through Smolensk and were seventy five versts on the other side of it, bound for the Denikin front. I had no objections to going there eventually but I preferred to have permission first, so we hastily bundled out of the train and went into the station. “Larkin” approached the door of the Commissar’s office and tried to brush past the Red Guard who sat there, and who objected to such an unceremonious entrance. After an interminable discussion—perhaps five minutes,—I said, “He wants to see your credentials. Why don’t you show them to him? Do you want us both to be arrested?”

But the Red guard had lost patience by this time. A snap of his fingers brought a policeman who arrested “Larkin” and before I had finished the “I told you so,” I could not restrain, I found the heavy hand of the law on my own shoulder. The two of us were marched down the street and locked in a little dark room in what was apparently the town jail.

In the two hours of solitude that followed I shared all my dismal forebodings with that unfortunate guard. We would be taken for spies and as spies we would certainly be shot. I couldn’t be sorry that this penalty would be inflicted upon anyone so stupid and obstinate and generally asinine as he, but I at least wanted to get back to America and tell people how stupid a big Russian could be. There were probably some adjectives also, I am not sure that he listened. In any event I could not see the signs of contrition that might at least have lightened my apprehensions.

At the end of two hours two Red soldiers opened the door of our cell and escorted us to the police station where we were taken at once before the judge, a simple, but very determined looking peasant, who examined first the Red Guard who had caused our arrest, the policeman who had arrested us, and two soldiers who had witnessed the affair.

“Larkin” in the meantime very reluctantly interpreted whatever comments and explanations I had to make. He became more and more stubborn and taciturn. The Red Guard told his story, which was verified by the policeman. The two soldiers further attested to the truth of the tale and stated that we had been entirely at fault. Then the judge asked my guard for an explanation, and with the air of one playing a forgotten ace which would take trick and game, “Larkin” produced our credentials and laid them triumphantly on the judge’s desk.

When he had read them the judge rose and made a statement which I demanded my guard should translate.

“Oh he is just saying,” said “Larkin,” “to please tell the American that we are sorry this thing happened. We are only working people and we must be careful to guard our country. The Red Guard at the door was simply obeying orders and doing his duty, and we want the American to understand that no deliberate offence was intended. There are so many people making war on us, both inside and outside, and we have to be careful.”

When “Larkin” had translated my reply, which was to the effect that we acknowledged our fault, and had only congratulations for the men who understood their duty and had the courage to perform it, and that I regretted having been the cause of so much trouble, the judge himself led us to a first-class train coach in the yards, unlocked it, and told us to enter and spend the rest of the night there.

“At eight o’clock in the morning this coach will be picked up by the train to Smolensk. Now, go to sleep, you won’t have to be on the watch this time,” he said with a suggestion of a smile.

Weary as I was I still remembered a few more things to say to “Larkin” who was by this time somewhat subdued. It was not until I had threatened to report him to the Moscow Government, and had again told him that it was a brutal thing to take advantage of men who were doing their duty under the most difficult circumstances conceivable, that my mind was lightened sufficiently so that I could go to sleep.

Of one thing I had been convinced—the general efficiency of organization which I had encountered again and again in Soviet Russia. The people were universally kind, but with strangers they took no chances. Well, I concluded, they could not have been blamed if they had kept us in jail for a long while, until they had checked up my entire record in Russia, at least. And I was grateful that my prison record amounted to two hours only, thanks to the expedition with which they administer trial to suspects in Red Russia.

Shut up in our coach we sped on to Smolensk the next day. Another twenty-four hours in Smolensk, where I was given permission to proceed to Moscow and again I boarded a train. I had been relayed from one army post to another; from the company to the regiment, from the regiment to the brigade, from the brigade to the division, from the division to the army command, and from the army command to the high command. And after eight days I was almost within reach of Moscow. On the morrow I would be off for Moscow itself.

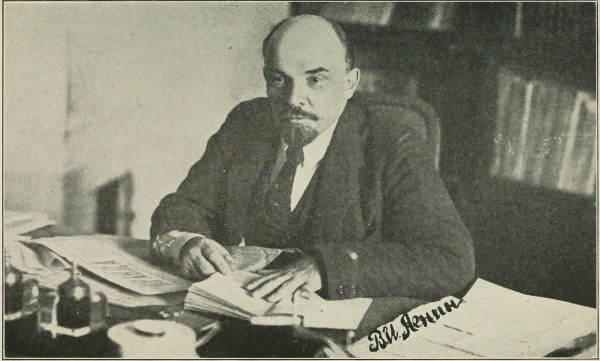

LENIN AT HIS DESK IN KREMLIN, 1919

I reached Moscow on Sunday afternoon and was taken at once by “Larkin” to the Foreign Office at the Metropole hotel. As we drove through the picturesque town of many churches we passed great numbers of people enjoying the sunshine. The parks and squares were full of romping children.

In the Foreign Office I was greeted by Litvinoff, who gave me credentials which granted me freedom of action—freedom to go where I pleased and without a guard as long as I remained in Soviet Russia; and Communist life began for me.

The Metropole hotel, like all others in Soviet Russia, had been taken over by the Government. The rooms not occupied by the Foreign Office were used as living rooms by Government employees. The National hotel is used entirely for Soviet workers, and the beautiful residence in which Mirbach, the German ambassador, was assassinated is now the headquarters of the Third International.

No one was allowed to have more than one meal a day. This consisted of cabbage soup, a small piece of fish and black bread, and was served at Soviet restaurants at any time between one o’clock in the afternoon and seven at night. There were a few old cafés still in existence, run by private speculators, where it was possible to purchase a piece of meat at times, but the prices were exorbitant. In the Soviet restaurants ten rubles was charged for the meal, while in the cafés the same kind of meal would have cost from 100 to 150 rubles.

The Soviet restaurants had been established everywhere, in villages and small towns as well as in cities. In the villages and railway stations they were usually in the station building itself or near it. In the cities they were scattered everywhere, so as to be easily accessible to the workers. Some of them were run on the cafeteria plan; in others women carried the food to the tables for the other workers. One entered, showed his credentials to prove that he was a worker and was given a meal check, for which he paid a fixed sum. Needless to say, there was no tipping. I had not the courage to experiment by offering a tip to these dignified, self-respecting women. I think they would have laughed at my “stupid foreign ways” had I done so.

The old café life of Moscow was a thing of the past. If you wished anything to eat at night you had to purchase bread and tea earlier in the day and make tea in your room. This was very simple because the kitchens in hotels were used exclusively for heating water. At breakfast time and all through the evening a stream of people went to the kitchen with pails and pitchers for hot water which they carried to their rooms themselves where they made their tea and munched black bread. There were no maids or bell boys to do these errands for you, and the only service you got in a hotel was that of a maid who cleaned your room each morning.

The working people would buy a pound or two of black bread in the evening on their way home. They had their samovars on which they made tea, and if they felt so inclined ate in the evening. For breakfast they again had tea and black bread like every one else. As a result of this diet hundreds of thousands of people were suffering from malnutrition. The bulk of the people in the city were hungry all the time.

I found the tramway service,—reduced fifty percent because of the lack of fuel,—miserably inadequate for the needs of the population which had greatly increased since Moscow became the capital. The citizens in their necessity have developed the most extraordinary propensities in step-clinging. They swarm on the platforms and stand on one another’s feet with the greatest good nature, and then, when there isn’t room to wedge in another boot, the late-comers cling to the bodies of those who have been lucky enough to get a foothold, and still others cling to these, until the overhanging mass reaches half-way to the curb. I tried it once myself—and walked thereafter. There were not many automobiles to be seen. The Government had requisitioned all cars. The motors were run by coal oil and alcohol, and the Government had very little of these.

During my second day in Moscow I met some English prisoners walking quite freely in the streets. I went up to a group of three and told them I was an American, and asked how they were getting on. They said they wanted to go home because the food was scarce, but aside from the lack of food they had nothing to complain of.

“Of course food is scarce,” said one, “but we get just as much as anyone else. Nobody gets much. You see us walking about the streets. No one is following us. We are free to go where we please. They send us to the theatre three nights a week. We go to the opera and the ballet. That’s what they do with all prisoners.”

Another broke in enthusiastically to say that if there were only food enough he would be glad to stay in Russia. Several of their pals, they told me, were working in Soviet offices.

They belonged to a detachment of ninety English who had been captured six months before, on the Archangel front. Before they went into action, they said, their commanding officer told each one to carry a hand grenade in his pocket, and if taken prisoner to blow off his head.

“The Bolsheviki,” he told us, "would torture us—first they would cut off a finger, then an ear, then the tip of the nose, and they would keep stripping us and torturing us until we died twenty-one days later.

“Well, before we knew it the Bolsheviki had us surrounded. There was nothing to do but surrender—and none of us used his bomb. The Bolsheviks marched us back about ten miles to a barrack, where we were told to sit down. Pretty soon they brought in a samovar and gave us tea and bread, and when we were about half through eating they brought in bundles of pamphlets. The pamphlets were all printed in English, mind you, and they told us why we had been sent to Russia.”

I recognized in his description the thing I had seen myself on the Western Front a few days before. I asked him if that was the usual way of treating prisoners.

“Yes,” he said, “that’s the way they do it. They don’t kill you. They just feed you with tea and bread, and this—what they call on the outside ‘propaganda’ and they say to you, ‘you read this stuff for a week,’ and you do, and you believe it—you can’t help it.”

It was bitterly cold in Moscow, though the Bolshevists made light of the September weather and laughed at my complaints. “Stay the winter with us,” they said, “and you will learn what cold is.” The city was practically without heat. The chill and damp entered my bones and pursued me through the streets and into my bed at night. One can stand prolonged exposure and cold if there is only the sustaining thought of a glowing fire somewhere, and a warm bed. But in Moscow there was no respite from the relentless chill. One was cold all day and all night. The aching pinch of it tore at the nerves. I marvelled at the endurance of the undernourished clerks and officials in the great damp Government office buildings, where it was often colder than in the dry sunshine outside.

All the large department stores and the clothing and shoe shops had been taken over by the Government. Here and there, however, were small private shops, selling goods without regard to Government prices.

The Soviet stores were arranged much like our large department stores. One could go in and buy various commodities, shoes in one department, clothing in another, and so on. Soviet employees had the right at all times to purchase in these stores at Soviet prices. They carried credentials showing they were giving useful service to the Government. Without credentials one could buy nothing—not even food—except from the privately-owned shops.

To these the peasant speculators would bring home-made bread in sacks and sell it to the shop speculators, who in turn demanded as much as eighty rubles a pound. This was the only way of getting bread without credentials because the Government had taken control of the bakeries. In a Soviet store a pound of bread could be bought for ten rubles.

All unnecessary labor in Soviet stores had been eliminated. Young girls and women acted as clerks; very few men were employed in any capacity. The manager, who usually was to be found on the first floor, was a man, and he directed customers to the departments which sold the things they wished to purchase. The elevators were running not only in the stores, but in the office buildings.

White collars and white shirts could be bought in some stores, but they were rationed so that it would have been impossible to buy three or four shirts at one time. The windows in the stores were filled with articles, but there was no attempt to display goods, and there was no advertising.

A shine, a shave and a hair-cut were obtainable at the Soviet barber shops. They were not rationed; one could buy as many of these as desired.

Theatres and operas were open and largely attended in Moscow, and the actors and actresses, as well as the singers, did not seem to mind the cold.

The streets were but dimly lighted, because of the fuel shortage, but I saw and heard of no crimes being committed. I wandered about the city through many of its darkest streets, at all hours of the night, and was never molested. Now and then a policeman demanded my permit, which, when I had shown it, was accepted without question. The city was well policed, the streets fairly clean, and the government was doing everything possible to prevent disease. Orders were issued that all water must be boiled, but as all Russians drink tea this order was not unusual or difficult to carry out.

The telephone and telegraph systems seemed to me unusually good. Connections by telephone between Moscow and Petrograd were obtained in two minutes. Local service was prompt and efficient, and connections with wrong numbers were of rare occurrence.

Many newspapers were being published, the size of all being limited on account of the shortage of paper. In addition to the Government newspapers and the Bolshevist party papers there were papers of opposing parties, notably publications controlled by the Menshevists and the Social Revolutionists.

All of them were free from the advertising of business firms, since the Government had nationalized all trade. Of course there was no “funny page” or “Women’s Section.”

As soon as news came from the front great bulletins were distributed through the city and posted on the walls of buildings where every one could read them. These bulletins contained the news of both defeat and victory. If prisoners had been taken or a retreat had been necessary, the populace was informed of it frankly. There was no attempt to keep up the “morale” of the civilian population by assuring it that all went well and that victory was certain. Any one in Soviet Russia who accepted the responsibilities of the new order did so knowing that it meant hardship and defeat—for a time.

In Moscow many statues have been erected since the revolution. Skobileff Square,—now called Soviet Square,—has a statue of Liberty which takes the place of the old statue of Skobileff. I saw sculptors at work all over the city, putting in medallions and bas-reliefs, on public buildings. In Red Square, along the Kremlin wall, are the graves of many who fell in the revolution. Sverdlov, formerly president of the executive committee, and a close friend of Lenin, is buried here. I was told that his death had been a great loss to the Soviet Government.

Moscow, like all the other Russian cities I saw, had schools everywhere, art schools, musical conservatories, technical schools, in addition to the regular schools for children.

On “Speculator’s Street” in Moscow all kinds of private trading went on without interference. I found this street thronged with shoppers and with members of the old bourgeoisie selling their belongings along the curb; men and women unmistakably of the former privileged classes offering, dress suits, opera cloaks, evening gowns, shoes, hats, and jewelry to any one who would pay them the rubles that they, in turn, must give to the exorbitant speculators for the very necessities of life.

These irreconcilables of the old regime, unwilling to cooperate with the new government and refusing to engage in useful work which would entitle them to purchase their supplies at the Soviet shops, at Soviet prices, were compelled to resort to the speculators and under pressure of the constantly decreasing ruble and the wildly soaring prices, were driven to sacrifice their valuables in order to avoid starvation. Any one who desired and who had the money could buy from the speculators; but one pays dearly for pride in Soviet Russia. The speculators charged seventy-five rubles a pound for black bread that could be bought in the Government shops for ten rubles. The right to buy at the Soviet shops and to eat in the Soviet restaurants was to be had by the mere demonstration of a sincere desire to do useful work of hand or brain. Nevertheless these defenders of the old order still held out—fewer of them every day, to be sure—and the speculators throve accordingly.

It seemed at first glance a strange anomaly. I could see through the windows of the speculator’s shops canned goods and luxuries, and even necessities, for which the majority of the population were suffering. I asked why the Government did not put its principles into practice by requisitioning all these stocks and ending the speculation. There were many things in their program, the Bolshevists said, which could not be carried out at once because the energy of the Government was consumed in the mobilization of all available resources for national defence. There were thousands of speculators all over Russia, and it would take a small army to eliminate them entirely. Half measures would only drive them underground where they would be a constant source of irritation and anti-Government propaganda. It was better to let them operate in the open, they said, where they could be kept under observation and restrained within certain limits.

Meanwhile the speculators were eliminating themselves and dragging with them the recalcitrant bourgeoisie on whom they preyed. Hoarded wealth and old finery do not last forever. As the ruble falls and the speculator’s prices rise their victims are compelled to sacrifice more and more of their dwindling resources. The Government prices are a standing temptation to reconciliation. Only the obdurate bourgeoisie and the speculators suffer from the depreciation of the ruble. Every two months wages are adjusted to meet depreciation, by a Government commission which acts in conjunction with the Central Federation of All Russian Professional Alliances, representing skilled and unskilled labor. This serves to stabilize the purchasing power of the workers earnings, although in the past unavoidable and absolute dearth of necessities has tended to work against this stabilization.

In the meantime the falling ruble and the avaricious speculator between them drive thousands of the stubborn into the category of useful laborers. Every day brings numbers who have, either through a change of heart, or by economic necessity, been driven to ask for work which will entitle them to their bread and food cards. Thus the Communists, too busy with the military defence of their country to attend to the last measures of expropriation, make use of the irresistible economic forces of the old order and allow the capitalists to expropriate themselves.

LENIN IN SWITZERLAND, MARCH, 1916

I found no Red terror. There was serious restriction of personal liberty and stern enforcement of law and order, as might be expected in a nation threatened with foreign invasion, civil war, counter revolution, and an actual blockade. While I was in Moscow sixty men and seven women were shot for complicity in a counter revolutionary plot. They had arms stored in secret places and had been found guilty of circularizing the soldiers on the Denikin front, telling them that Petrograd and Moscow had both fallen. They made no concealment of their purpose to overthrow the Government and went bravely to their execution. Several days later two bombs were exploded under a building in which a meeting of the Executive Committee of the Communist party was being held. Eleven of the Communists were killed and more than twenty wounded. The cadet counter revolutionists, it was charged, committed this outrage as reprisal for the execution of their comrades. But no terror or persecution followed. Instead great mass meetings were held everywhere to protest against all terrorist acts. Intrigue and propaganda were met with counter propaganda and popular enthusiasm for the Soviet Government.

Before leaving Moscow for Petrograd I applied at the Foreign Office for permission to go to the Kremlin and interview Lenin. I was told that permission would be granted, and an appointment was made for me to meet Lenin at his office at three o’clock on the following day.

A quarter of an hour ahead of the hour set for my appointment with Lenin, I hastened to the Kremlin enclosure, the well-guarded seat of the executive government. Two Russian soldiers inspected my pass and led me across a bridge to obtain another pass from a civilian to enter the Kremlin itself and to return to the outside. I had heard that Lenin was guarded by Chinese soldiers, but I looked in vain for a Chinese among the guards that surrounded the Kremlin. In fact I saw but two Chinese soldiers during my entire stay in Soviet Russia.

I mounted the hill and went toward the building where Lenin lives and has his office. At the outer door two more soldiers met me, inspected my passes, and directed me up a long staircase, at the top of which stood two more soldiers. They directed me down a long corridor to another soldier who sat before a door. This one inspected my passes and finally admitted me to a large room in which many clerks, both men and women, were busy over desks and typewriters. In the next room I found Lenin’s secretary who informed me that “Comrade Lenin will be at liberty in a few minutes.” It was then five minutes before three. A clerk gave me a copy of the London Times, dated September 2, 1919, and told me to sit down. While I read an editorial the secretary addressed me and asked me to go into the next room. As I turned to the door it opened, and Lenin stood waiting with a smile on his face.

It was twelve minutes past three, and Lenin’s first words were, “I am glad to meet you, and I apologize for keeping you waiting.”

Lenin is a man of middle height, close to fifty years of age. He is well proportioned, and very active, physically, in spite of the fact that he carries in his body two bullets fired at him in August, 1918. His head is large, massive in outline, and is set close to his shoulders. His forehead is broad and high, his mouth large, the eyes wide apart and there appears in them at times a very infectious twinkle. His hair, pointed beard, and mustache, have a brown tinge. His face has wrinkles,—said by some to be wrinkles of humor,—but I am inclined to believe them the result of deep study, and of the suffering he endured through long years of exile and persecution. I would not minimize the contribution that his sense of humor has made to these lines and wrinkles, for no man who lacked a sense of humor could have overcome the obstacles he has met.

During our conversation his eyes never left mine. This direct regard was not that of a man who wished to be on guard; it bespoke a frank interest, which seemed to me to say, “We shall be able to tell many things of interest to each other. I believe you to be a friend. In any event we shall have an interesting talk.”

He moved his chair close to his desk and turned so that his knees were close to mine. Almost at once he began asking me about the labor movement in America, and from that he went on to discuss the labor situation in other countries. He was thoroughly informed even as to the most recent developments everywhere. I soon found myself asking him questions.

I told him that the press of various countries had been saying that Soviet Russia was a dictatorship of a small minority. He replied, "Let those who believe that silly tale come here and mingle with the rank and file and learn the truth.

"The vast majority of industrial workers and at least one-half of the articulate peasantry are for Soviet rule, and are prepared to defend it with their lives.

“You say you have been along the Western Front,” he continued. “You admit that you have been allowed to mingle with the soldiers of Soviet Russia, that you have been unhampered in making your investigation. You have had a very good opportunity to understand the temper of the rank and file. You have seen thousands of men living from day to day on black bread and tea. You have probably seen more suffering in Soviet Russia than you had ever thought possible, and all this because of the unjust war being made upon us, including the economic blockade, in all of which your own country is playing a large part. Now I ask you what is your opinion about this being a dictatorship of the minority?”

I could only answer that from what I had seen and experienced I could not believe that these people, who had found their strength and overthrown a despotic Czar, would ever submit to such privations and sufferings except in defence of a government in which, however imperfect, they had ultimate faith, and which they were prepared to defend against all odds.

“What have you to say at this time about peace and foreign concessions?” I asked.

He answered, “I am often asked whether those American opponents of the war against Russia—as in the first place bourgeois—are right who expect from us, after peace is concluded, not only resumption of trade relations but also the possibility of securing concessions in Russia. I repeat once more that they are right. A durable peace would be such a relief to the toiling masses of Russia that these masses would undoubtedly agree to certain concessions being granted. The granting of concessions under reasonable terms is also desirable to us, as one of the means of attracting into Russia the technical help of the countries which are more advanced in this respect, during the co-existence side by side of Socialist and capitalist states.”

In reply to my next question about Soviet power he replied:

"As for the Soviet power, it has become familiar to the minds and hearts of the laboring masses of the whole world which clearly grasped its meaning. Everywhere the laboring masses, in spite of the influence of the old leaders with their chauvinism and opportunism which permeates them through and through, became aware of the rottenness of the bourgeois parliaments and of the necessity of the Soviet power, the power of the toiling masses, the dictatorship of the proletariat, for the sake of the emancipation of humanity from the yoke of capital. And the Soviet power will win in the whole world, however furiously, however frantically the bourgeoisie of all countries may rage and storm.

“The bourgeoisie inundates Russia with blood, waging war upon us and inciting against us the counter revolutionaries, those who wish the yoke of capital to be restored. The bourgeoisie inflict upon the working masses of Russia unprecedented sufferings, through the blockade, and through their help given to the counter revolutionaries, but we have already defeated Kolchak and we are carrying on the war against Denikin with the firm assurance of our coming victory.”