TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Blank space in some sample documents in the text is denoted by ____.

Footnotes are all within a specific Table, including the Table of Contents. They are positioned at the bottom of that Table, as in the original text, and are denoted by [*] or [**].

Page numbering of the original text has been retained. It is in the form a-b, where a is a Chapter number or Appendix letter, and b is the sequential number within that section. For example B-3 is the third page in Appendix B.

Obvious punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

The cover image was created by the transcriber

and is placed in the public domain.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

FM 4-02.7 (FM 8-10-7)

TACTICS, TECHNIQUES, AND PROCEDURES

OCTOBER 2002

HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY

DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

[Pg i] [*]FM 4-02.7 (FM 8-10-7)

FIELD MANUAL

HEADQUARTERS

NO. 4-02.7 (8-10-7)

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY

Washington, DC, 1 October 2002

HEALTH SERVICE SUPPORT IN A NUCLEAR, BIOLOGICAL,

AND CHEMICAL ENVIRONMENT

TACTICS, TECHNIQUES AND PROCEDURES

| Page | |||

| Preface | viii | ||

| CHAPTER | 1. | NUCLEAR, BIOLOGICAL, AND CHEMICAL WARFARE ASPECT OF THE MEDICAL THREAT | 1-1 |

| 1-1. | General | 1-1 | |

| 1-2. | Medical Threat | 1-1 | |

| 1-3. | Nuclear, Biological, Chemical, and Radiological Dispersal Device Threats—The Health Service Perspective | 1-2 | |

| CHAPTER | 2. | COMMAND AND CONTROL | 2-1 |

| 2-1. | General | 2-1 | |

| 2-2. | Health Service Support Command and Control Planning Considerations | 2-1 | |

| 2-3. | Health Service Support Command and Control Appraisal of the Support Mission | 2-2 | |

| 2-4. | Health Service Support Units | 2-2 | |

| 2-5. | Movement/Management of Contaminated Facilities | 2-3 | |

| 2-6. | Leadership on the Contaminated Battlefield | 2-5 | |

| 2-7. | Homeland Security | 2-6 | |

| CHAPTER | 3. | LEVELS I AND II HEALTH SERVICE SUPPORT | 3-1 |

| 3-1. | General | 3-1 | |

| 3-2. | Level I Health Service Support | 3-2 | |

| 3-3. | Level II Health Service Support | 3-2 | |

| 3-4. | Forward Surgical Team | 3-3 | |

| 3-5. | Actions Before a Nuclear, Biological, or Chemical Attack | 3-3 | |

| 3-6. | Actions During a Nuclear, Biological, or Chemical Attack | 3-4 | |

| 3-7. | Actions After a Nuclear, Biological, or Chemical Attack | 3-4 | |

| 3-8. | Logistical Considerations | 3-5 | |

| [ii] 3-9. | Personnel Considerations | 3-5 | |

| 3-10. | Disposition and Employment of Treatment Elements | 3-6 | |

| 3-11. | Civilian Casualties | 3-6 | |

| 3-12. | Nuclear Environment | 3-7 | |

| 3-13. | Medical Triage | 3-8 | |

| 3-14. | Biological Environment | 3-8 | |

| 3-15. | Chemical Environment | 3-9 | |

| 3-16. | Operations in Extreme Environments | 3-10 | |

| 3-17. | Medical Evacuation in a Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Environment | 3-10 | |

| CHAPTER | 4. | LEVELS III AND IV HOSPITALIZATION | 4-1 |

| 4-1. | General | 4-1 | |

| 4-2. | Protection | 4-3 | |

| 4-3. | Decontamination | 4-8 | |

| 4-4. | Emergency Services | 4-10 | |

| 4-5. | General Medical Services | 4-11 | |

| 4-6. | Surgical Services | 4-11 | |

| 4-7. | Nursing Services | 4-12 | |

| 4-8. | Conventional Operations | 4-13 | |

| CHAPTER | 5. | OTHER HEALTH SERVICE SUPPORT | 5-1 |

| Section | I. | Preventive Medicine Services | 5-1 |

| 5-1. | General | 5-1 | |

| 5-2. | Disease Incidence Following the Use of Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Weapons | 5-1 | |

| 5-3. | Preventive Medicine Section | 5-3 | |

| 5-4. | Preventive Medicine Detachment | 5-3 | |

| Section | II. | Veterinary Services | 5-4 |

| 5-5. | General | 5-4 | |

| 5-6. | Food Protection | 5-4 | |

| 5-7. | Food Decontamination | 5-4 | |

| 5-8. | Animal Care | 5-5 | |

| Section | III. | Laboratory Services | 5-5 |

| 5-9. | General | 5-5 | |

| 5-10. | Level II | 5-5 | |

| 5-11. | Level III | 5-5 | |

| 5-12. | Level IV | 5-6 | |

| 5-13. | Level V (Continental United States) | 5-6 | |

| 5-14. | Field Samples | 5-6 | |

| Section | IV. | Dental Services | 5-7 |

| 5-15. | General | 5-7 | |

| 5-16. | Mission in a Nuclear, Biological, or Chemical Environment | 5-7 | |

| [iii] 5-17. | Dental Treatment Operations | 5-7 | |

| 5-18. | Patient Treatment Considerations | 5-7 | |

| 5-19. | Patient Protection | 5-8 | |

| Section | V. | Combat Operational Stress Control | 5-9 |

| 5-20. | General | 5-9 | |

| 5-21. | Leadership Actions | 5-9 | |

| 5-22. | Individual Responsibilities | 5-10 | |

| 5-23. | Mental Health Personnel Responsibilities | 5-11 | |

| Section | VI. | Health Service Logistics | 5-11 |

| 5-24. | General | 5-11 | |

| 5-25. | Protecting Supplies In Storage | 5-12 | |

| 5-26. | Protecting Supplies During Shipment | 5-12 | |

| 5-27. | Organizational Maintenance | 5-12 | |

| Section | VII. | Homeland Security Response | 5-13 |

| 5-28. | Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and High-Yield Explosive Response | 5-13 | |

| 5-29. | Capabilities of Response Elements | 5-14 | |

| APPENDIX | A. | MEDICAL EFFECTS OF NUCLEAR, BIOLOGICAL, AND CHEMICAL WEAPONS AND TOXIC INDUSTRIAL MATERIAL | A-1 |

| A-1. | General | A-1 | |

| A-2. | Physical Effects of Nuclear Weapons | A-1 | |

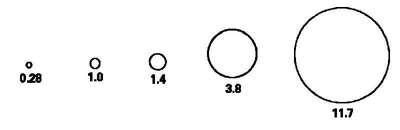

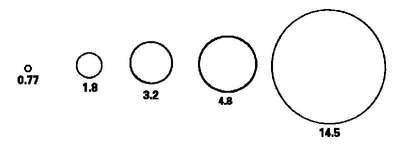

| A-3. | Physiological Effects of Nuclear Weapons | A-4 | |

| A-4. | Biological Effects of Thermal Radiation | A-7 | |

| A-5. | Physiological Effects of Ionizing Radiation | A-8 | |

| A-6. | Handling and Managing Radiologically Contaminated Patients | A-10 | |

| A-7. | Radiological Patients in Stability Operations and Support Operations | A-13 | |

| A-8. | Effects of Biological Weapons | A-14 | |

| A-9. | Behavior of Biological Weapons | A-15 | |

| A-10. | Management of Biological Warfare Patients | A-16 | |

| A-11. | Effects of Chemical Weapons | A-17 | |

| A-12. | Behavior of Chemical Weapons | A-17 | |

| A-13. | Characteristics of Chemical Agents | A-19 | |

| A-14. | Management of Chemical Agent Patients | A-23 | |

| A-15. | Management of Toxic Industrial Material Patients | A-23 | |

| APPENDIX | B. | SAMPLE/SPECIMEN COLLECTION AND MANAGEMENT | B-1 |

| Section | I. | Introduction | B-1 |

| B-1. | General | B-1 | |

| B-2. | Sample/Specimen Background Information | B-2 | |

| B-3. | Sample/Specimen Collection and Preservation | B-3 | |

| B-4. | Chain of Custody | B-8 | |

| [iv] Section | II. | Sampling Techniques and Procedures | B-9 |

| B-5. | General | B-9 | |

| B-6. | Expended Material | B-11 | |

| B-7. | Environmental Samples | B-11 | |

| B-8. | Collection of Air and Vapors | B-12 | |

| B-9. | Collection of Water Samples | B-13 | |

| B-10. | Collection of Soil Samples | B-15 | |

| B-11. | Collection of Contaminated Vegetation | B-16 | |

| B-12. | Medical Specimens | B-16 | |

| B-13. | Collection of Medical Specimens | B-17 | |

| B-14. | Post Mortem Specimens | B-19 | |

| B-15. | Reporting, Packaging, and Shipment | B-20 | |

| B-16. | Handling and Packaging Materials | B-21 | |

| B-17. | Collection Reporting | B-23 | |

| B-18. | Sample/Specimen Background Documents | B-27 | |

| APPENDIX | C. | GUIDELINES FOR OPERATIONAL PLANNING FOR HEALTH SERVICE SUPPORT IN A NUCLEAR, BIOLOGICAL, AND CHEMICAL ENVIRONMENT | C-1 |

| C-1. | General | C-1 | |

| C-2. | Predeployment | C-1 | |

| C-3. | Mobilization | C-2 | |

| C-4. | Establish a Medical Treatment Facility | C-3 | |

| C-5. | Operate a Medical Treatment Facility Receiving Contaminated Patients. | C-4 | |

| C-6. | Preventive Medicine Services | C-5 | |

| C-7. | Veterinary Services | C-6 | |

| C-8. | Dental Services | C-6 | |

| C-9. | Combat Operational Stress Control | C-6 | |

| C-10. | Medical Laboratory Services | C-6 | |

| C-11. | Health Service Logistics | C-7 | |

| C-12. | Homeland Security | C-8 | |

| APPENDIX | D. | MEDICAL PLANNING GUIDE FOR THE ESTIMATION OF NUCLEAR, BIOLOGICAL, AND CHEMICAL BATTLE CASUALTIES | D-1 |

| Section | I. | Introduction | D-1 |

| D-1. | General | D-1 | |

| D-2. | Medical Planners' Tool | D-1 | |

| Section | II. | Medical Planning Guide for the Estimation of Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Battle Casualties (Nuclear)—AMedP-8(A), Volume I | D-1 |

| D-3. | General | D-1 | |

| D-4. | Medical Planning Considerations | D-2 | |

| [v] D-5. | Triage | D-3 | |

| D-6. | Evacuation | D-3 | |

| D-7. | In-Unit Care | D-3 | |

| D-8. | Hospital Bed Requirements | D-4 | |

| D-9. | Medical Logistics | D-4 | |

| D-10. | Medical Force Planning | D-4 | |

| Section | III. | Medical Planning Guide for the Estimation of Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Battle Casualties (Biological)—AMedP-8(A), Volume II | D-4 |

| D-11. | General | D-4 | |

| D-12. | Medical Planning Considerations | D-6 | |

| D-13. | Triage | D-6 | |

| D-14. | Evacuation | D-6 | |

| D-15. | In-Unit Care | D-7 | |

| D-16. | Patient Bed Requirements | D-7 | |

| D-17. | Medical Logistics | D-7 | |

| D-18. | Medical Force Planning | D-8 | |

| Section | IV. | Medical Planning Guide for the Estimation of Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Battle Casualties (Chemical)—AMedP-8(A), Volume III | D-8 |

| D-19. | General | D-8 | |

| D-20. | Medical Planning Considerations | D-10 | |

| D-21. | Triage | D-11 | |

| D-22. | Evacuation | D-11 | |

| D-23. | In-Unit Care | D-11 | |

| D-24. | Patient Bed Requirements | D-12 | |

| D-25. | Medical Logistics | D-12 | |

| D-26. | Medical Force Planning | D-12 | |

| APPENDIX | E. | EXAMPLE X-__, ANNEX__, TO HSS PLAN/OPERATION ORDER__, MEDICAL NBC STAFF OFFICER PLANNING FOR HSS IN AN NBC ENVIRONMENT | E-1 |

| APPENDIX | F. | EMPLOYMENT OF CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL COLLECTIVE PROTECTION SHELTER SYSTEMS BY MEDICAL UNITS | F-1 |

| Section | I. | Introduction | F-1 |

| F-1. | General | F-1 | |

| F-2. | Types of Collective Protection Shelter Systems | F-1 | |

| Section | II. | Employment of the Chemically and Biologically Protected Shelter System | F-2 |

| F-3. | Establish a Battalion Aid Station in a Chemically Biologically Protected Shelter | F-2 | |

| [vi] F-4. | Division Clearing Station in a Chemically Biologically Protected Shelter | F-4 | |

| F-5. | Forward Surgical Team in a Chemically Biologically Protected Shelter | F-6 | |

| Section | III. | Employment of the Chemically Protected Deployable Medical Systems and Simplified Collective Protection Systems | F-8 |

| F-6. | Collective Protection in a Deployable Medical System-Equipped Hospital | F-8 | |

| F-7. | Chemically/Biologically Protecting the International Organization for Standardization Shelter | F-11 | |

| F-8. | Chemically/Biologically Protecting the Vestibules | F-12 | |

| F-9. | Chemically/Biologically Protecting Air Handler Equipment | F-12 | |

| F-10. | Establish Collective Protection Shelter Using the M20 Simplified Collective Protection System | F-12 | |

| F-11. | Casualty Decontamination | F-12 | |

| Section | IV. | Operations, Entry, and Exit Guidelines | F-13 |

| F-12. | Operations | F-13 | |

| F-13. | Decontamination of Entrance Area | F-13 | |

| F-14. | Procedures Prior to Entry | F-14 | |

| F-15. | Entry/Exit for the Collective Protection Shelter System | F-14 | |

| F-16. | Resupply of Protected Areas | F-17 | |

| APPENDIX | G. | PATIENT DECONTAMINATION | G-1 |

| Section | I. | Introduction | G-1 |

| G-1. | General | G-1 | |

| G-2. | Immediate Decontamination | G-2 | |

| G-3. | Patient Decontamination and Thorough Decontamination Collocation | G-2 | |

| G-4. | Patient Decontamination at the Battalion Aid Station (Level I) | G-5 | |

| G-5. | Patient Decontamination at the Medical Company Clearing Station (Level II) | G-5 | |

| G-6. | Patient Decontamination at a Hospital (Level III and IV) | G-5 | |

| G-7. | Prepare Hypochlorite Solutions for Patient Decontamination | G-5 | |

| G-8. | Classification of Patients | G-6 | |

| G-9. | Patient Treatment | G-6 | |

| Section | II. | Patient Decontamination Procedures | G-7 |

| G-10. | Decontaminate a Litter Chemical Agent Patient | G-7 | |

| G-11. | Decontaminate an Ambulatory Chemical Agent Patient | G-14 | |

| G-12. | Biological Patient Decontamination Procedures | G-18 | |

| G-13. | Decontaminate a Litter Biological Agent Patient | G-18 | |

| G-14. | Decontaminate an Ambulatory Biological Agent Patient | G-19 | |

| G-15. | Decontaminate Nuclear-Contaminated Patients | G-20 | |

| G-16. | Decontaminate a Litter Nuclear-Contaminated Patient | G-21 | |

| G-17. | Decontaminate an Ambulatory Nuclear-Contaminated Patient | G-21 | |

| [vii] APPENDIX | H. | FIELD EXPEDIENT PROTECTIVE SYSTEMS AGAINST NUCLEAR, BIOLOGICAL, AND CHEMICAL ATTACK | H-1 |

| H-1. | General | H-1 | |

| H-2. | Protection Against Radiation | H-1 | |

| H-3. | Expedient Shelters for Protection Against Radiation | H-2 | |

| H-4. | Expedient Shelters Against Biological and Chemical Agents | H-5 | |

| APPENDIX | I. | DETECTION AND TREATMENT OF NUCLEAR, BIOLOGICAL, AND CHEMICAL CONTAMINATION IN WATER | I-1 |

| I-1. | General | I-1 | |

| I-2. | Detection of Contamination in Water | I-1 | |

| I-3. | Procedures on Discovery of Contamination in Water | I-1 | |

| I-4. | Treatment of Contaminated Water | I-2 | |

| APPENDIX | J. | FOOD CONTAMINATION AND DECONTAMINATION | J-1 |

| J-1. | General | J-1 | |

| J-2. | Protection of Food From Contamination | J-2 | |

| J-3. | Nuclear | J-3 | |

| J-4. | Biological | J-4 | |

| J-5. | Chemical | J-5 | |

| GLOSSARY | Glossary-1 | ||

| REFERENCES | References-1 | ||

| INDEX | Index-1 | ||

DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

[*] This publication supersedes FM 8-10-7, 22 April 1993. Change 1, 26 November 1996

The purpose of this field manual (FM) is to provide doctrine and tactics, techniques, and procedures for health service support (HSS) units and personnel operating in a nuclear, biological, and chemical (NBC), radiological dispersal device (RDD), and toxic industrial material (TIM) environment. The manual provides information for use by commanders, planners, leaders, and individuals in providing HSS under these adverse conditions.

The use of trade or brand names in this publication is for illustrative purposes only. Their use does not constitute endorsement by the Department of Defense (DOD).

The proponent of this publication is the United States (US) Army Medical Department Center and School (AMEDDC&S). Send comments and recommendations directly to Commander, US Army Medical Department Center and School, ATTN: MCCS-FCD, 1400 East Grayson Street, Fort Sam Houston, Texas 78234-5052.

The use of the term "level of care" in this publication is synonymous with "echelon of care" and "role of care." The term "echelon of care" is the old North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) term. The term "role of care" is the new NATO and American, British, Canadian, and Australian (ABCA) term.

The use of the term TIM in this publication is inclusive of RDD.

The use of the term "Health Service Support" in this publication is synonymous with Combat Health Support as used in other publications. Health Service Support is the term used in Joint Publications to describe medical support to Joint Forces.

Radiological and chemical detection devices discussed in this publication are currently being replaced through modernization or new device developments. The users should adapt the application of doctrine as described to fit the new devices when issued/authorized.

Unless this publication states otherwise, masculine nouns and pronouns do not refer exclusively to men.

This publication implements NATO Standardization Agreements (STANAGs) 2475, Medical Planning Guide for the Estimation of NBC Battle Casualties (Nuclear)—Allied Medical Publication (AMedP) 8(A), Volume I; 2476, Medical Planning Guide of NBC Battle Casualties (Biological)—AMedP-8(A), Volume II; 2477, Planning Guide for the Estimation of NBC Battle Casualties (Chemical)—AMedP-8 (A), Volume III. It is also in consonance with the following NATO STANAGs and ABCA Quadripartite Standardization Agreements (QSTAGs):

| TITLE | STANAG | QSTAG |

| Warning Signs for the Marking of Contaminated or Dangerous Land Areas, Complete Equipments, Supplies and Stores | 2002 | 501 |

| Emergency Alarms of Hazard or Attack (NBC and Air Attack Only) | 2047 | 183 |

| [ix]Interoperable Chemical Agent Detector Kits | 608 | |

| Emergency War Surgery | 2068 | |

| Commander's Guide on Nuclear Radiation Exposure of Groups | 2083 | 898 |

| Reporting Nuclear Detonations, Biological and Chemical Attacks, and Predicting and Warning of Associated Hazards and Hazard Areas—ATP-45(B) | 2103 | 187 |

| Friendly Nuclear Strike Warning | 2104 | 189 |

| Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Reconnaissance | 2112 | |

| NATO Handbook on the Medical Aspects of NBC Defensive Operations—AMedP-6(B) | 2500 | |

| Concept of Operations of Medical Support in Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Environments—AMedP-7(A) | 2873 | |

| Medical Aspects of NBC Defensive Operations | 1330 | |

| Principles of Medical Policy in the Management of a Mass Casualty Situation | 2879 | |

| Medical Aspects of Mass Casualty Situations | 816 | |

| Guidelines for Air and Ground Personnel Using Fixed and Transportable Collective Protection Facilities on Land | 2941 | 2000 |

| Training of Medical Personnel for NBC Operations | 2954 |

a. After World War II, the Soviet Union represented the principal threat to the national security interests of the US. During this period, the military capability of the Soviet Armed Forces grew enormously. Starting in the later years of the 1980s, the international security environment has undergone rapid, fundamental, and revolutionary changes. With the collapse of Soviet communism, the Soviet Union disintegrated as a viable economic and political system. The Warsaw Pact dissolved as a political and military entity. The central Soviet government was replaced by the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), dominated by the Russian Republic. The cohesion of Soviet strategic military capability has been fractured by—

The ultimate outcome of these events in terms of US national security interests is unclear. The military capabilities of CIS like Russia, Ukraine, Kazakstan, and Belarus remain formidable. The capabilities include strategic nuclear and impressive conventional, biological, and chemical warfighting capabilities.

b. From a global perspective, the economic power and influence of developing and newly industrialized nations continue to grow. Centers of power (global or regional) cannot be measured solely in military terms. Nation states pursuing their own political, ideological, and economic interests may become engaged in direct or indirect competition and conflict with the US. More nations have acquired significant numbers of modern, lethal, combat weapon systems; developed very capable armed forces; and become more assertive in international affairs. In the absence of a single, credible, coercive threat, old rivalries and long repressed territorial ambitions will resurface, causing increased tensions in many regions. Political, economic, and social instability and religious, cultural, and economic competition will continue to erode the influence of the US over the rest of the world. This erosion will also reduce the US influence of traditional regional powers over their neighbors. This environment will encourage the continued development, or acquisition, of modern armed forces and equipment by less influential nations; thus raising the potential for the use of NBC/RDD weapons during internal conflict and armed confrontations in developing regions of the world.

c. A third dimension to the threat is terrorist, rogue groups, and belligerents employing a number of chemical and biological agents and the possible use of TIM to injure or kill US personnel. The actions may be isolated or may be imposed by groups of individuals. Most will have the financial backing of nations, large organizations, or groups that have the desire to cause harm and create public distrust in our government.

Medical threat is the composite of all ongoing or potential enemy actions and environmental conditions that [1-2] will reduce combat effectiveness through wounding, injuring, causing disease, and/or degrading performance. Soldiers are the targets of these threats. Weapons or environmental conditions that will generate wounded, injured, and sick soldiers, beyond the capability of the HSS system to provide timely medical care from available resources, are considered major medical threats. Weapons or environmental conditions that produce qualitatively different wound or disease processes are also major medical threats. Added to the combat operational and disease and nonbattle injury (DNBI) medical threats are adversary use of the following types of weapons, agents, and devices:

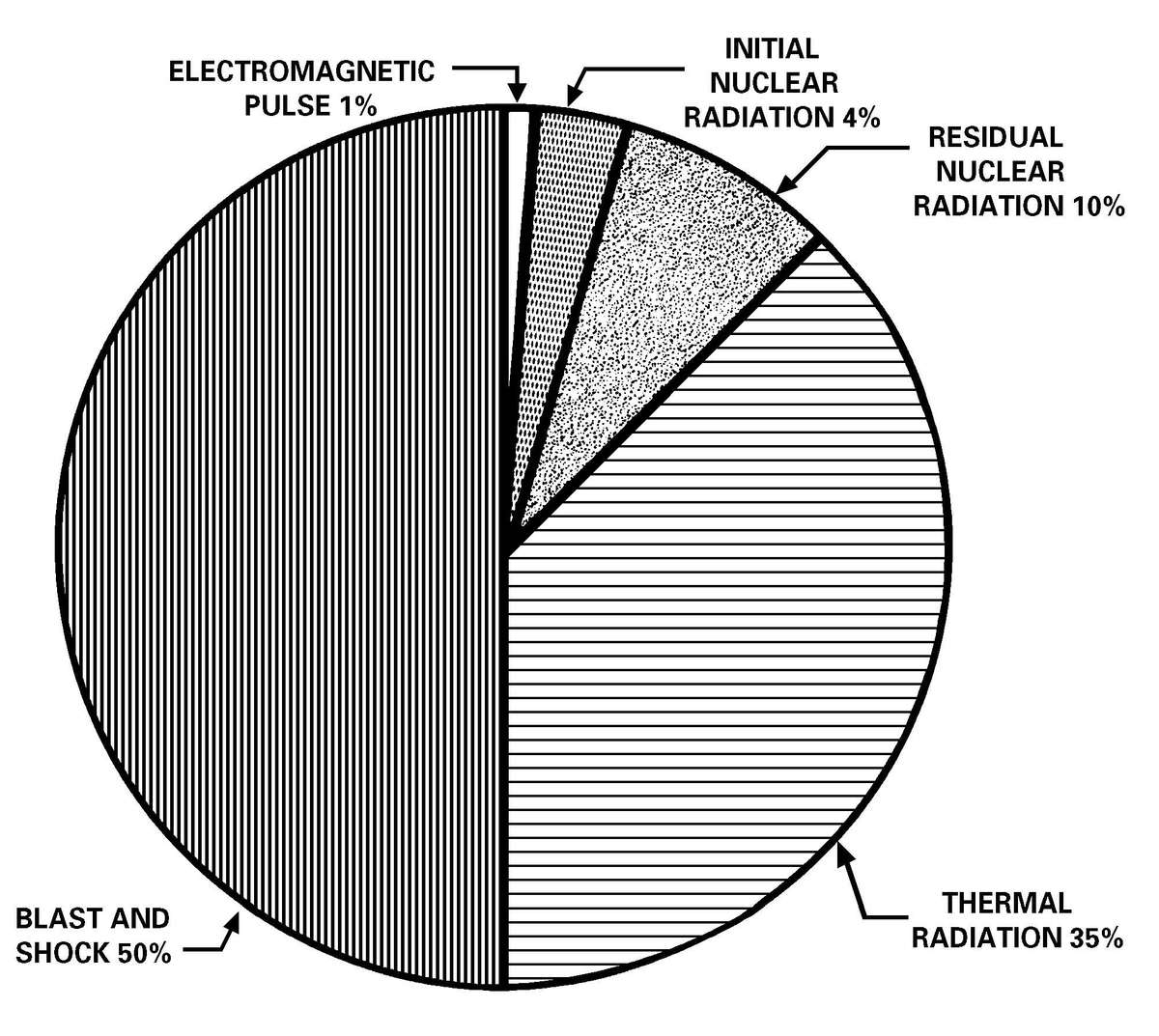

a. Nuclear Weapons and Radiological Dispersal Device Threats. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, the number of countries with known nuclear capable military forces has almost doubled. Available information suggests that a number of countries in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa have or may have nuclear weapons capability within the next decade. Table 1-1 lists those countries known to have, suspected of possessing, or seeking, nuclear weapons. Planners can expect, as a minimum, 10 to 20 percent casualties within a division-sized force that has experienced a nuclear strike. In addition to the casualties, a nuclear weapon detonation can generate an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) that will cause catastrophic failures of electronic equipment components. Radiological dispersal devices, comprised of an explosive device with radioactive material, can be detonated without the need for the components of a nuclear weapon. The RDD can disperse radioactive material over an area of the battlefield causing effects from nuisance levels of radioactive material to life-threatening levels without the thermal and, in most cases, the blast effects of a nuclear detonation. For nuclear weapons effects see Appendix A.

[1-3] Table 1-1. Countries Possessing or Suspected of Possessing Nuclear Weapons

| KNOWN TO POSSESS | SUSPECT OR SEEKING |

|---|---|

| UNITED STATES OF AMERICA | IRAQ |

| RUSSIA | NORTH KOREA |

| UKRAINE | IRAN |

| BELARUS | LIBYA |

| KAZAKSTAN | ALGERIA |

| PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA | SOUTH AFRICA |

| FRANCE | ISRAEL |

| UNITED KINGDOM | |

| PAKISTAN | |

| INDIA |

b. Biological Warfare.

(1) Biological warfare (BW) is defined by the US intelligence community as the intentional use of disease-causing organisms (pathogens), toxins, or other agents of biological origin (ABO) to incapacitate, injure, or kill humans and animals; to destroy crops; to weaken resistance to attack; and to reduce the will to fight. Historically, BW has primarily involved the use of pathogens in assassinations or as sabotage agents in food and water supplies to spread contagious disease among target populations.

(2) For purposes of medical threat risk assessment, we are interested only in those BW agents that incapacitate, injure, or kill humans or animals.

(3) Known or suspect BW agents and ABOs can generally be categorized as naturally occurring, unmodified infectious agents (pathogens); toxins, venoms, and their biologically active fractions; modified infectious agents; and bioregulators. See Table 1-2 for examples of known or suspected BW threat agents. Also, Table 1-3 presents possible developmental and future BW agents.

Table 1-2. Examples of Known or Suspect Biological Warfare Agents

| PATHOGENS | TOXINS |

|---|---|

| BACILLUS ANTHRACIS (ANTHRAX) | BOTULINUM TOXIN |

| FRANCISELLA TULARENIUS (TULAREMIA) | MYCOTOXINS |

| YERSINIA PESTIS (PLAGUE) | ENTEROTOXIN |

| BRUCELLA SPECIES (BRUCELLOSIS) | RICIN |

| VIBRIO CHOLERAE (CHOLERA) | |

| VARIOLA (SMALLPOX) | |

| VIRAL HEMORRHAGIC FEVERS |

[1-4] Table 1-3. The Future of Biological Warfare Agents

| CURRENT THREAT | FUTURE |

|---|---|

| PATHOGENS | MODIFIED PATHOGENS |

| LIMITED NUMBER OF TOXINS | EXPANDED RANGE OF TOXINS (ORGANO-TOXINS) |

| AGENTS OF BIOLOGICAL ORIGIN | PROTEIN FRACTIONS |

| AGENTS OF BIOLOGICAL ORIGIN |

(4) Many governments recognize the industrial and economic potential of advanced biotechnology and bioengineering. The same knowledge, skills, and methodologies can be applied to the production of second and third generation BW agents. Naturally occurring infectious organisms can be made more virulent and antibiotic resistant and manipulated to render protective vaccines ineffective. These developments complicate the ability to detect and identify BW agents and to operate in areas contaminated by the BW agents. For biological agent characteristics and effects see Appendix A. The first indication that a BW agent release/attack has occurred may be patients presenting at a medical treatment facility with symptoms not fitting the mold for endemic diseases in the area of operations (AO). See Appendix B for sampling requirements, sampling procedures, packaging and shipping, and chain of custody requirements.

c. Chemical Warfare.

(1) Since World War I, most western political and military leaders have publicly held chemical warfare (CW) in disrepute. However, evidence accumulated over the last 50 years does not support the position that public condemnation equates to limiting development or use of offensive CW agents. The reported use of chemical agents and biological toxins in Southeast Asia by Vietnamese forces; the confirmed use of CW agents by Egypt against Yemen; and later by Iraq against Iranian forces; and the probable use of CW agents by the Soviets in Afghanistan indicate a heightened interest in CW as a force multiplier. Also, an offensive CW capability is developed as a deterrent to the military advantage of a potential adversary. For a list of common chemical agents, their characteristics, behavior, and effects see Appendix A. Table 1-4 lists those countries known or suspected of having offensive chemical weapons.

(2) The Russian Republic has the most extensive CW capability in Europe. Chemical strikes can be delivered with almost any type of conventional fire support weapon system (from mortars to long-range tactical missiles). Agents known to be available in the Russian inventory include nerve agents (O-ethyl methyl phosphonothiolate [VX], thickened VX, Sarin [GB], and thickened Soman [GD]); vesicants (thickened Lewisite[L] and mustard-Lewisite mixture[HL]); and choking agent (phosgene). Although not considered CW agents, riot control agents are also in the Russian inventory.

(3) The US is in the process of destroying its stockpiles of CW weapons. Many weapons have already been destroyed and the storage facilities have been rendered safe of all CW agent residues.

[1-5] Table 1-4. Nations Known or Suspected of Possessing Chemical Weapons

| KNOWN TO POSSESS | SUSPECTED OF POSSESSING |

|---|---|

| UNITED STATES OF AMERICA | PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA |

| RUSSIA | NORTH KOREA |

| FRANCE | EGYPT |

| LIBYA | ISRAEL |

| IRAQ[*] | ETHIOPIA |

| IRAN | TAIWAN |

| SYRIA | BURMA |

| [*] FOLLOWING THE PERSIAN GULF WAR (1990-91), THE UNITED NATIONS (UN) BEGAN DESTROYING CW MUNITIONS DISCOVERED DURING INSPECTION VISITS TO IRAQ BY UN ARMS CONTROL INSPECTORS. INCLUDED AMONG THE CW MUNITIONS DISCOVERED WERE SOME 2,000 AERIAL BOMBS AND 6,200 ARTILLERY SHELLS FILLED WITH MUSTARD AND SEVERAL THOUSAND 122 MILLIMETERS (mm) ROCKET WARHEADS FILLED WITH NERVE AGENT (GB). IRAQ ALSO DECLARED SURFACE TO AIR MISSILE (SCUD) WARHEADS FILLED WITH NERVE AGENT (GB AND GF). TABLE 1-5 PROVIDES A LIST OF KNOWN CW AGENTS. | |

Table 1-5. Chemical Warfare Agents

| NERVE | VESICANT | INCAPACITATING | CHOKING | BLOOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TABUN (GA) | SULFUR MUSTARD (HD) | CNS DEPRESSANT (BZ) | PHOSGENE (CG) | HYDROGEN CYANIDE (AC) |

| GB | HL | CHLORINE (CL) | DIPHOSGENE (DP) | CYANOGEN CHLORIDE (CK) |

| GD | L | CHLOROPICRIN (PS) | ||

| GF | PHOSGENE OXIME (CX) | D-LYSERGIC ACID DIETHYLAMIDE (LSD) | ||

| VX |

d. Toxic Industrial Materials.

Toxic industrial materials can present a medical threat for deployed forces. Toxic industrial materials are comprised of toxic industrial biologicals (TIB), toxic industrial chemicals (TIC), and toxic industrial radiological (TIR) materials. These materials are found throughout the world and are used on a daily basis for commercial and private purposes. Large storage facilities, transportation tankers (over the road and railcars), as well as smaller containers of material, pose a danger to the health of personnel. Accidental spills or releases and terrorist actions can all lead to release of these materials into the environment causing potential casualty producing effects. Medical treatment facilities and nuclear power plants use radioactive materials that can pose a health hazard if accidentally released or used by hostile forces, terrorists, or others to contaminate an area. Biological materials used in medical research and pharmaceutical manufacturing may be used by hostile forces, terrorists, or others to produce casualties. Many TICs produce the same effects on personnel as CW agents. As a matter of fact, many TICs are of the same chemical structure as CW agents. However, there is quite a difference in their potency; in most TICs the potency is much lower. [1-6] For example, chlorine used to treat water supplies has also been used as a CW agent; organophosphate pesticides can cause the same effects as some nerve agents. Hostile forces, terrorists, or others may use RDDs to produce casualties as well. For detailed information on toxic industrial materials see FM 8-500.

The US forces may be attacked by or exposed to NBC, TIM, lasers, advanced electronics, high explosives, fuel-air, thermobaric, and conventional weapons; or a combination of these weapons/materiel. Mass casualty situations will be the rule and not the exception. Mass casualty situations can occur anyplace on the battlefield. Combined NBC and conventional weapons injuries may predominate. Command and control (C2) will be essential to prevent casualties and to provide effective HSS. However, C2 (to include HSS C2) elements may be primary targets. Effective HSS in an NBC environment can be accomplished, but only if necessary preparations to survive and to be mission capable are taken. Increased HSS C2 actions are needed to maintain HSS proximity to the supported force; to clear the battlefield; to move and resupply the HSS units, while managing multiple simultaneous mass casualty incidents; and to rapidly evacuate patients. Health service support C2 units must push HSS augmentation to mass casualty sites, clear the site, evacuate the patients to Medical Treatment Facilities (MTFs) that can provide essential care or out of the AO; decontaminate and extract medical forces from NBC contaminated areas and redistribute or redeploy the HSS forces. Within medical units, C2 will be challenged by the use of protective clothing and equipment, the need to move (either to the patients or out of the contaminated area), and obtaining additional support. Health service support advisers and staff officers must provide guidance to commanders on continued duty for personnel who have been exposed to NBC weapons/agents and TIM effects. Leaders must greatly increase coordinating, preplanning, using tactical standing operating procedures (TSOPs), and establishing multiple C2 mechanisms. See Appendix C for guidelines on operational planning for health service support in an NBC or TIM environment. See Appendix D for medical planning guide on NBC casualties. See Appendix E for a sample format of a "medical NBC staff officer appendix to annex Q."

a. Battle situational understanding is of great importance on the NBC battlefield. The number of casualties from each NBC attack will overwhelm any single medical unit or MTF causing the medical commander/leader to take action. To the extent possible, the commander/leader should be prepared for the requirement instead of reacting to it. To ensure responsive C2 the HSS plan must consider:

b. Clearing the battlefield will require preplanning and close coordination at all levels. Early resuscitation, stabilization, and prompt medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) are mandatory for survival of the sick and wounded.

c. For conventional operations C2 see FM 8-10. Field Manual 8-55 provides HSS planning for conventional operations.

d. Provisions for emergency medical care of civilians, consistent with the military situation. All non-DOD civilian care must be approved by the AO Commander in Chief/senior official and coordinated with the civil affairs unit and/or country team. For eligibility of care determinations guidance, see FM 8-10.

e. For additional information on planning operations in an NBC environment see FMs 8-10, 4-02.10, 4-02.4, 4-02.6, 4-02.283, 8-9, 8-10-6, 8-10-26, 8-284, and 8-285. Higher headquarters must distribute timely plans and directives to subordinate units to ensure that the subordinate unit's HSS plan supports their plan.

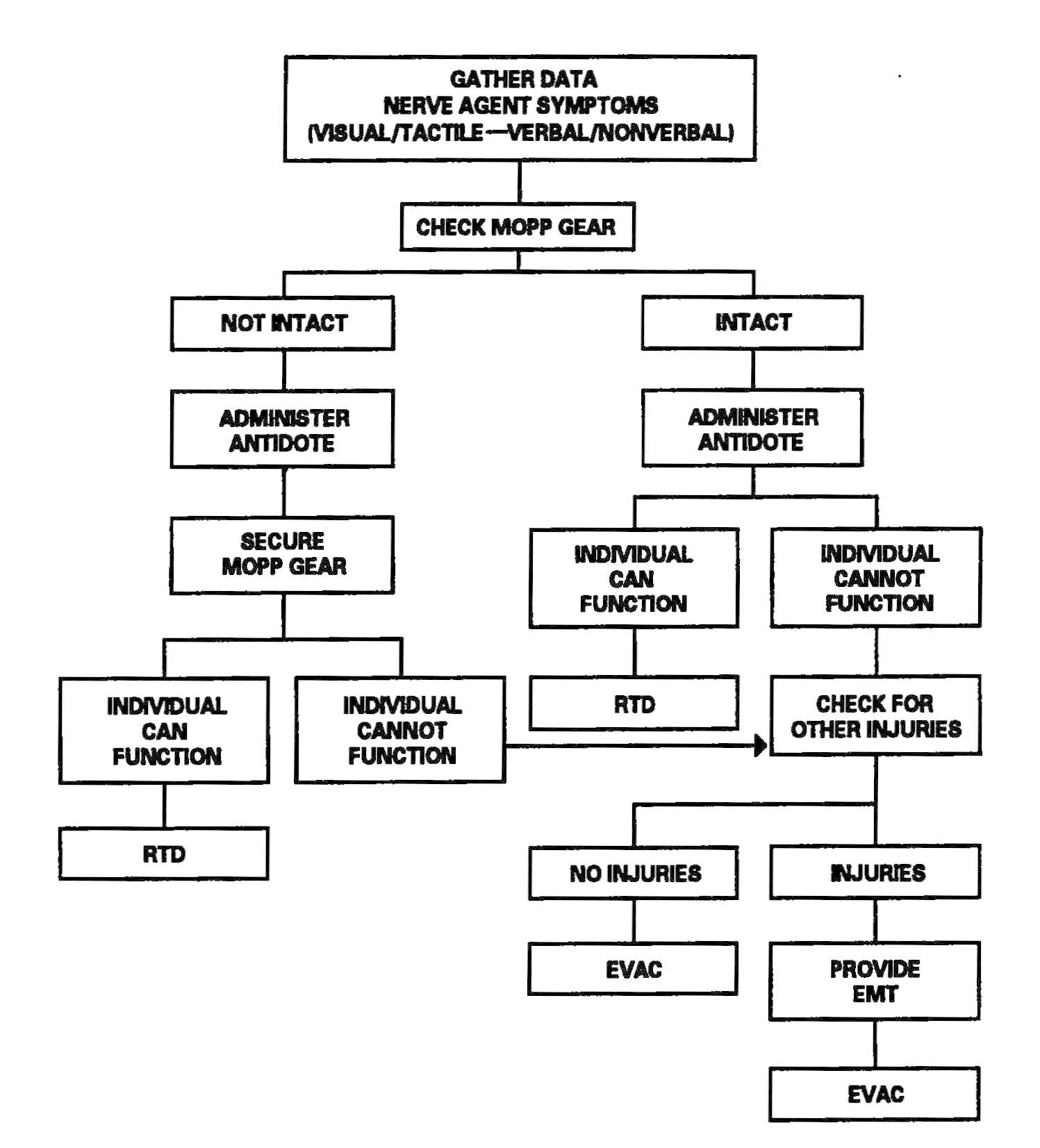

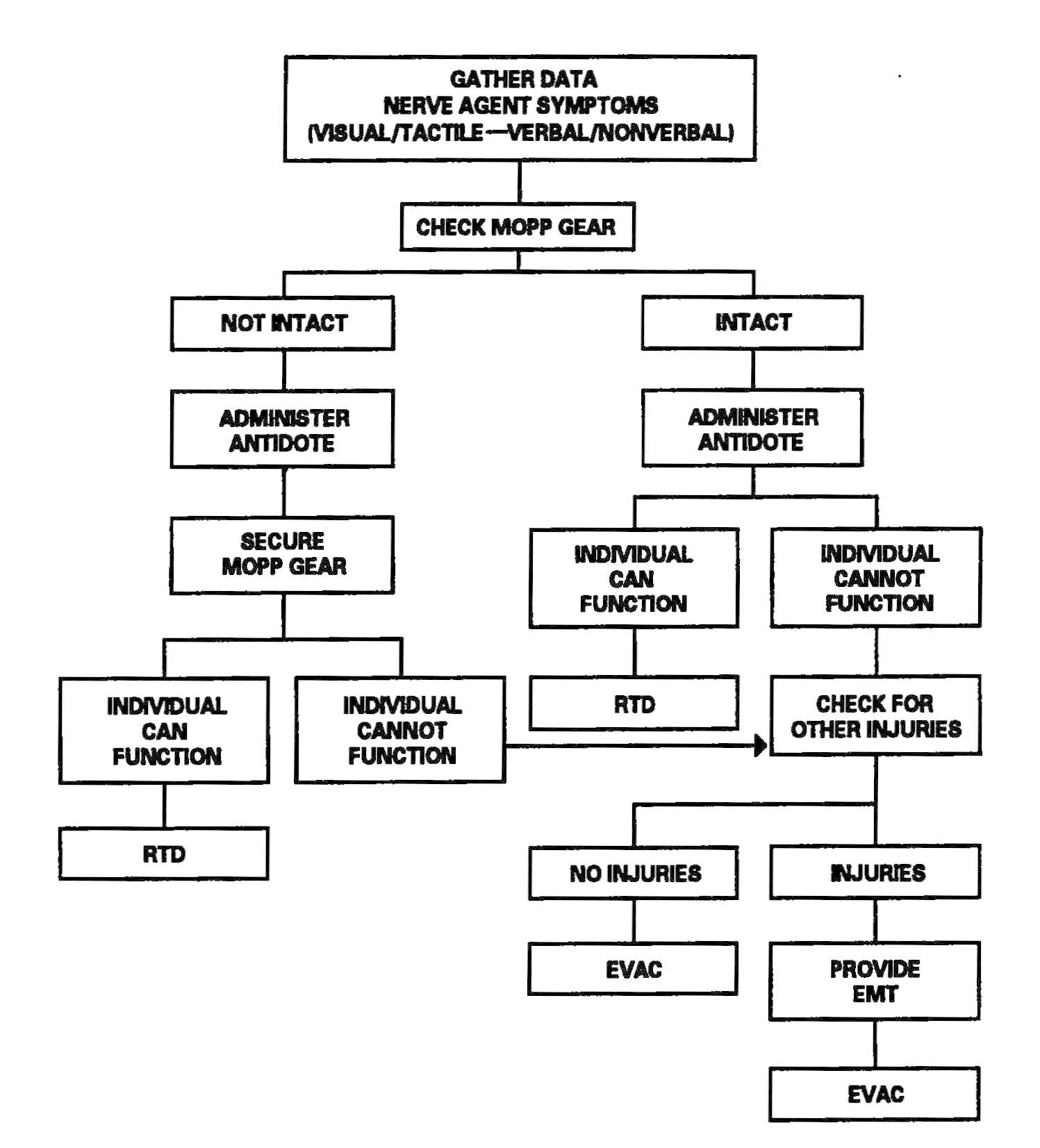

The HSS personnel make an appraisal of the supported mission to determine the expected patient load. Once the appraisal has been accomplished, HSS personnel prepare for the HSS mission by assigning personnel responsibilities. Using triage and EMT decision matrices for managing patients in a contaminated environment improves treatment proficiency. See Figure 2-1 for a sample decision matrix. Training HSS personnel in the use of simple decision matrices should enhance their effectiveness and contribute to a more efficient battlefield HSS process. Prior training for designated nonmedical personnel in patient decontamination procedures will enhance their effectiveness in the overall patient care mission. See Appendix D for planning factors on the estimation of NBC casualties.

Health service support units must plan, train, and routinely practice mass casualty management. The NBC attack or TIM event will likely be in conjunction with enemy conventional operations. But, the TIM event may be caused by terrorist or belligerent action. There will likely be increased conventional casualties in addition to the NBC/TIM related casualties. The supply and transportation units will be using the MSR in [2-3]support of the combat commander's requirements; thus, impacting on patient MEDEVAC and HSS unit resupply. Communications will be disrupted. Therefore, HSS C2 must plan and prepare for conducting operations with limited or no communications with other HSS organizations.

Figure 2-1. Sample triage and emergency medical treatment decision matrix.

Operations in a contaminated area require the HSS commander/leader to operate with contaminated or potentially contaminated assets. The following provides guidance in determining how to operate with contaminated facilities:

[2-4] a. Fulfill Health Service Support Principles. In making his decision to move or continue to operate with contaminated facilities, the commander/leader must apply the principles of conformity, proximity, flexibility, mobility, continuity, and control. The unit's operation must conform to the tactical commander's operation plan (OPLAN). Health service support must be provided to the tactical unit as far forward as possible; this ensures prompt, timely care. Additionally, the HSS commander/leader must be flexible; his support must be tailored to meet the supported commander's OPLAN requirements. Therefore, HSS assets must be as mobile as the unit they support. Finally, the HSS commander/leader must control his assets. Dispersion on the integrated battlefield may enhance unit survivability; but the HSS commander/leader may not be able to maintain control of his assets, they may become compromised.

b. Decision to Move. The HSS commander/leader (when deciding to move his unit to an uncontaminated area or in support of the tactical commander's plan) must base his decision to move on several factors.

(1) Protection available. What type of protection is available in the new area? Will he need to establish the units' collective protection shelter (CPS) systems, or are indigenous shelters available (for example, buildings, tunnels, caves)? Does the unit have sufficient individual protective equipment for unit personnel?

(2) Persistency. If his unit has been in a contaminated area, is the contamination persistent or nonpersistent? Is the area he will move to contaminated or clean? Persistency determines the MOPP level; the degree of threat; and performance decrement caused by the protective measures used. The level of contamination will determine whether employment of CPS is viable. The MTF may be able to continue to operate at the location by employing CPS. Personnel and patient decontamination must be accomplished before processing into the CPS.

(3) Patients. Before moving the entire facility, the HSS commander/leader must consider the number and types of patients at the MTF; his ability to redirect en route patients to the new MTF location; and his ability to evacuate the patients currently on hand. All patients should be stabilized before movement; but, MEDEVAC must be continued.

(4) Alternate facilities. Alternate facilities may be used (if the facility can be configured to ensure continuity of care or provide a protected area for patients) until the relocating activity is up and operating. This is a viable consideration when CPS is not available or the current location is contaminated with a persistent agent. Patient decontamination cannot be performed in an area heavily contaminated with a persistent agent.

(5) Medical evacuation. Consideration must always be given to the patient. Routes of MEDEVAC must be disseminated to supported and supporting units. The ability to evacuate patients during the move must continue. All MEDEVAC considerations must be addressed before any move.

(6) Mobility. An MTF that is not 100 percent mobile requires movement support. Thus, the commander/leader must coordinate movement support requirements with higher headquarters.

[2-5] (7) Mission. The primary consideration is the support mission of the MTF. The tactical commander requires continuous HSS for his personnel; when a move jeopardizes the quality of care, the move may be delayed.

(8) Sustainability. Hand-in-hand with the mission is sustainability (the ability of the unit to continue its support mission). If the current location of the MTF hinders the unit's ability to sustain its support mission, then the MTFs support to the unit is in question. Similarly, if moving the MTF will result in a disruption of support, then the move may not be viable.

(9) Decontamination. When a nonpersistent agent hazard exists and a CPS is not available, patients may be directed to another MTF until the hazard is gone; or the MTF can move to a contamination free area. Certain facilities may be decontaminated, patient protection procedures applied, and the operation continued. However, an MTF contaminated with a persistent agent requires time-consuming and resource-intensive decontamination operations; it may include replacement of contaminated shelters.

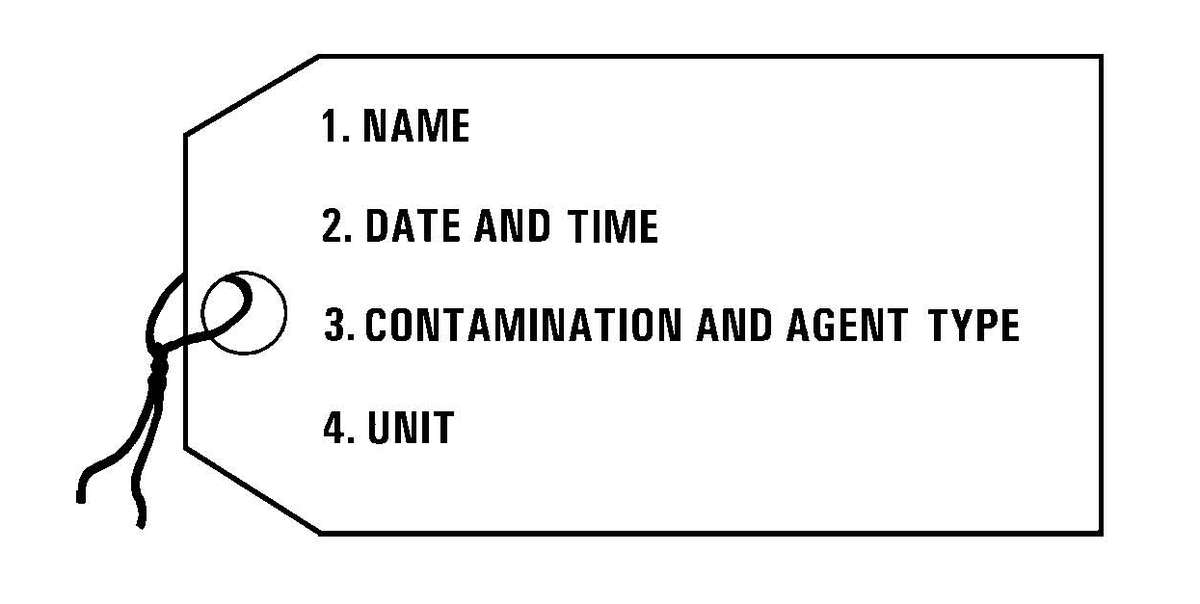

c. Management of Contaminated and "Clean" Facilities. Facilities contaminated with a persistent agent may be too resource intensive to decontaminate. Operating with a combination of contaminated assets and "clean" assets may be necessary. Mark contaminated assets with standard warning tags. Use these assets in contaminated environments and along contaminated routes. Keep clean assets in operation in clean areas. Of primary importance is proper marking and the avoidance of cross contamination.

d. Medical Supplies and Equipment for Patient Treatment. Are sufficient medical supplies and equipment available to perform the anticipated mission? Does the unit have special medical equipment sets available (chemical agent patient decontamination and chemical agent patient treatment medical equipment sets)?

a. Operating on a contaminated battlefield will stress leadership. Heat stress from being in higher levels of MOPP for long periods of time may lead to dehydration. The commander/leader must ensure that his personnel rest, drink, and eat sufficiently to allow them to continue with the mission. In the midst of activity, rest, hydration, and nutrition are often overlooked; however, a good leader will ensure that his personnel needs are met. See FM 21-10 for work/rest cycles and water drinking requirements. Individuals may suffer hyperventilation because of the enclosed feelings. Personnel remaining in MOPP Level 4 around the clock may suffer from increased sleep loss. Use of CPS can reduce this problem by allowing the personnel to rest out of their MOPP gear. Leaders must share leadership responsibilities and delegate responsibilities as much as possible so that each one gets sufficient rest to maintain unit effectiveness. Further, leaders should concentrate on supervision or unit mission, rather than on generation of new procedures during and after an attack. The NBC battlefield will, therefore, require more proactive and dedicated leaders who can balance the needs of their personnel and the mission. Further, leaders will be challenged by an additional logistics burden of providing nontraditional respiratory protection for personnel against TIMs. For detailed information on combat operational stress control (COSC) see FM 8-51 and FM 22-51.

DANGER

The standard NBC protective mask will not protect personnel from most TICs.

b. Leadership must plan for and establish procedures to maintain personnel performance during NBC operations. Personnel performance while wearing MOPP is degrading. At MOPP Level 3 or 4, all but the most basic patient care procedures may have to be suspended because—

Commanders and leaders must plan for and be prepared to support homeland security efforts; especially, for response to chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosive (CBRNE) events. Depending upon the location of the event, the response may be to a military installation in support of the weapons of mass destruction—installation support team (WMD-IST) or to an event site off a military installation. Response to a CBRNE event off a military installation will normally require a request for Department of Defense support to the event from the first responders to the event (usually from the incident commander or lead federal agency [Federal Bureau of Investigation or Federal Emergency Management Agency]). See Appendix C for planning considerations.

a. The use of NBC weapons is a condition of battle and HSS personnel must prepare to operate in these environments. Added is the dimension of TIM releases/incidents in the operational area. The importance of preventive medicine (PVNTMED) measures and first aid (self-aid, buddy aid, and combat lifesaver [CLS] support) are even more critical. Heat and stress injuries related to MOPP wear are issues for the HSS leadership as well as the force he is supporting. The stress load on personnel is increased by the concerns of being exposed to TIM releases. Considering that staffing of HSS units is based upon the minimum required to provide support on a conventional battlefield, they will be challenged to provide the same level of HSS in these environments.

b. The HSS leadership must quantify the HSS capability to their commanders. The medical staff must review OPLANS and make recommendations to reduce the number of patients. Medical NBC training programs must stress the essential imperative of immediate decontamination, the need to monitor your buddy for NBC and heat or combat/operational stress injury effects, and the proper use of NBC defense prophylaxis, pretreatments, insect repellents, barrier creams, and immunizations.

c. Maintaining close proximity to the supported force has been a major tenet of HSS doctrine and a critical factor in reducing the mortality rate. Maintaining this proximity and finding a place clean enough to provide necessary care requires intense coordination with the supported force. Alternate casualty collection points, decontamination sites, medical treatment sites, and MEDEVAC routes must be established, coordinated and communicated to the lowest level practical. Communication will be much more difficult, but must be maintained. Timely reports through the HSS technical channels will allow an optimal HSS response. Replacements for HSS front line losses must be rapidly filled after NBC weapons are employed.

d. Contamination (NBC and TIMs) can significantly hinder HSS operations. To maximize the unit's survivability and HSS capabilities and to avoid such contamination, leaders must use—

e. On the NBC battlefield, as on the conventional battlefield, HSS is focused on keeping soldiers in the battle. Effective and efficient PVNTMED measures, triage, emergency medical treatment (EMT), decontamination, advanced trauma management (ATM), and contamination control in the AO saves lives, assures judicious MEDEVAC, and maximizes the return to duty (RTD) rate.

a. Level I (unit-level) HSS may consist of a combat medic section, a MEDEVAC section, and a treatment squad. The treatment squad operates the Level I MTF (battalion aid station [BAS]). Level I HSS is supported by first aid in the form of self-aid/buddy aid and the CLS. See FM 4-02.4 for detailed information on conventional Level I HSS.

b. When operating under an NBC threat or when NBC attack is imminent, the BAS must prepare for continuation of its mission. Should an attack occur or a downwind hazard exist, the BAS must seek out a contamination free area to establish a clean treatment area, or must establish collective protection to continue the mission. Some BASs have Chemically Biologically Protected Shelter (CBPS) Systems. When available, these systems serve as the primary shelter for the BAS; they are operated in the full chemical/biological (CB) mode when attack is imminent or has occurred. See Appendix F for information on establishing a BAS in a CBPS system. When operating in the CB mode only patients requiring life- or limb-saving procedures are allowed entry at the BAS. Patients that have minor injuries that can be managed in the contaminated EMT area of the patient decontamination site will receive treatment in this area. After treatment, these patients will have the integrity of their MOPP restored by taping the damaged area and returned to duty. Patients with injuries that require further treatment, but who can survive evacuation to the Level II MTF will have their MOPP spot decontaminated, their injuries managed, the integrity of their MOPP restored, and be directed to an evacuation point to await transport to the Level II MTF (example, an individual with a splinted broken arm). When patients or personnel are contaminated or are potentially contaminated, they must be decontaminated before admission into the clean treatment area (see FM 3-5 for personnel decontamination procedures and Appendix G for patient decontamination procedures).

a. In the brigade, Level II HSS consists of—

b. In the division, HSS is the same as for the brigade, except patients may be evacuated from the BSA DCS, but not evacuated from the BAS.

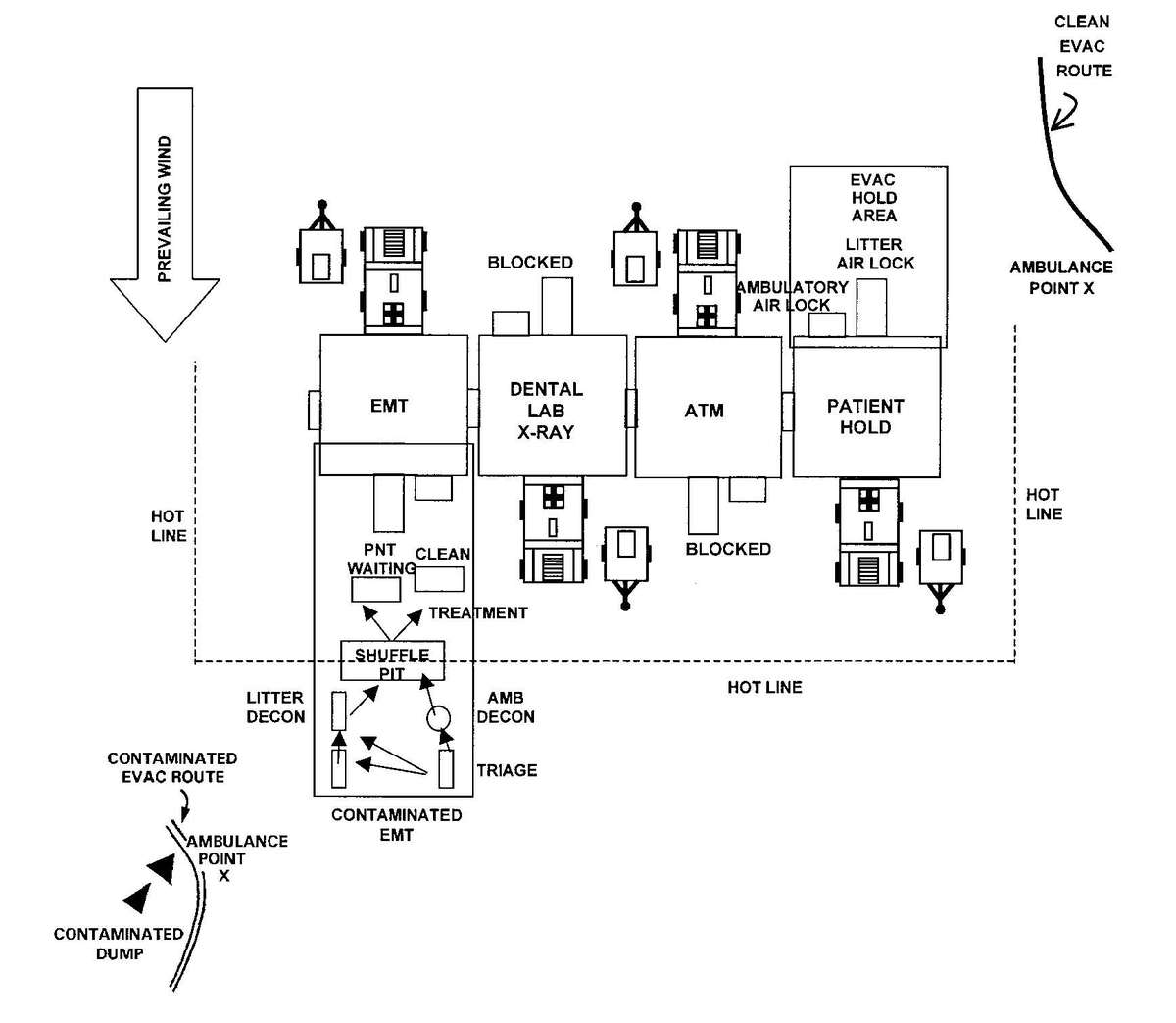

c. When operating under an NBC threat or when NBC attack is imminent, the DCS must prepare for continuation of its mission. Should an attack occur or a downwind hazard exist the DCS must seek out a contamination free area, or must establish collective protection to continue the mission. The DCS in some medical companies have four CBPS Systems; they are complexed to provide space for DCS operations. These systems are operated in the CB mode when attack is imminent or has occurred. See Appendix F for information on establishing a DCS in CBPS Systems. When operating in the CB mode only patients requiring life- or limb-saving procedures are allowed entry. Patients with minor injuries that can be managed in the contaminated EMT area of the patient decontamination site will receive treatment in this area. After treatment, these patients will have the integrity of their MOPP restored by taping the damaged area and returned to duty. Patients with injuries that require further treatment, but who can survive evacuation to the Level III MTF will have their MOPP spot decontaminated, their injuries managed, and be directed to an evacuation point to await transport to the Level III MTF (example, an individual with a splinted broken arm). When personnel and patients are contaminated or are potentially contaminated, they must be decontaminated before admission into the clean treatment area (see FM 3-5 for personnel decontamination procedures and Appendix G for patient decontamination procedures).

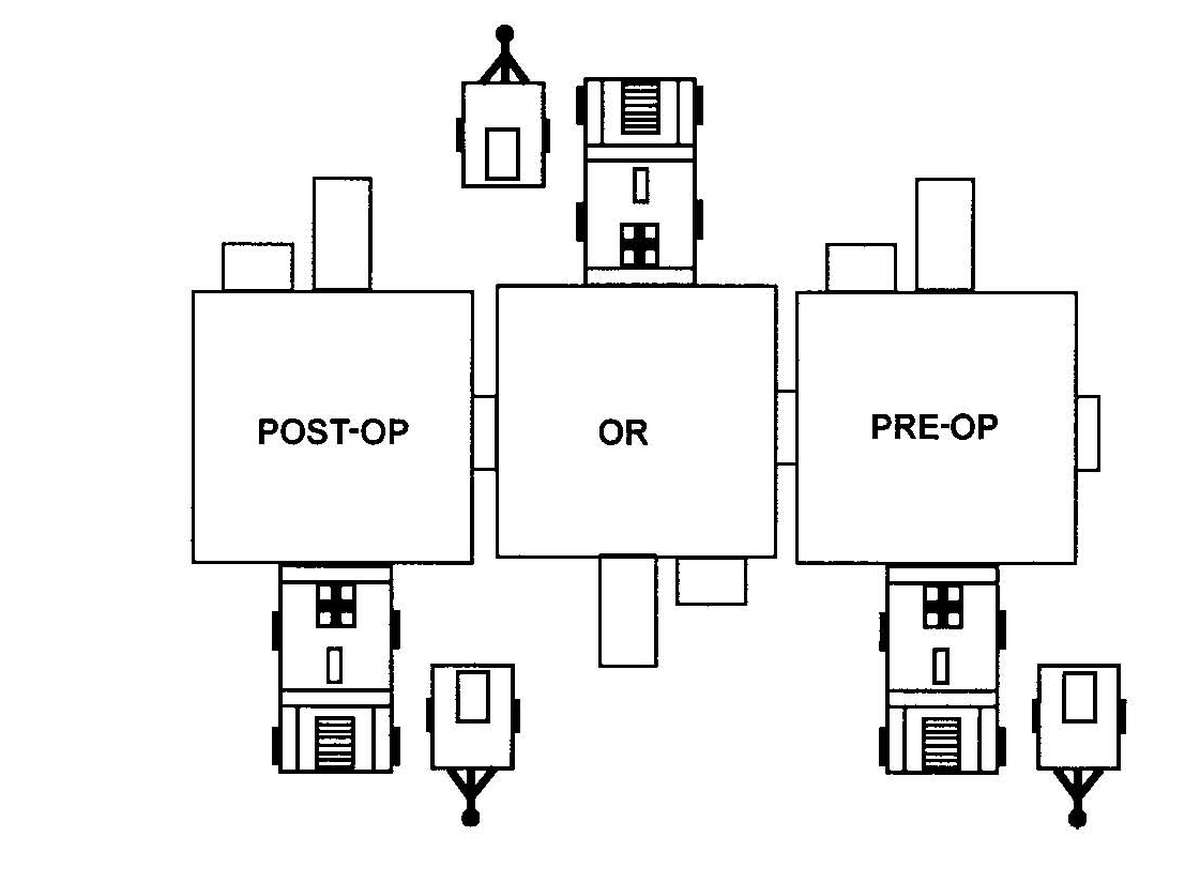

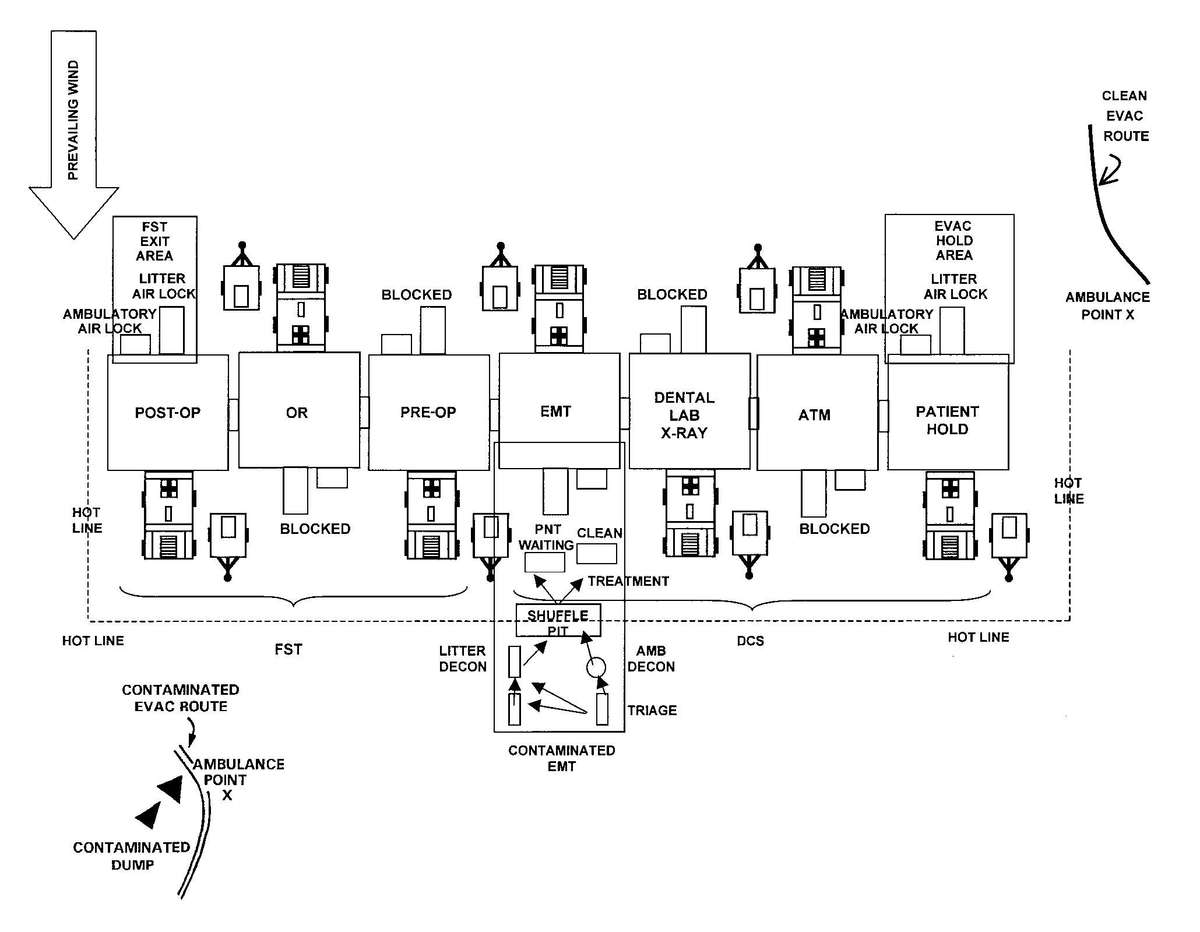

Forward surgical teams (FST) are either organic to divisional and nondivisional medical units or are forward deployed in support of divisional or nondivisional medical companies to provide a surgical capability. Field Manual 8-10-25 describes FST operations. However, when forward deployed and NBC contamination is imminent the FST must employ collective protection in order to continue their support mission. When operating in a contaminated area the FST CBPS Systems must be complexed with the DCS CBPS. The FST cannot operate in an NBC environment without the support of the DCS. They do not have the capability to decontaminate patients. All patients are decontaminated in the DCS patient decontamination area. They are then processed into the EMT section of the DCS; where they are triaged and routed to the FST for surgery, if required. See Appendix F for FST employment of collective protection procedures.

a. Given the disruption of transportation, communications, and operations during and following an NBC attack, it should be clear that preparation is the key to survival and effectively providing HSS. Preparing a simple and complete TSOP and HSS plan that really integrates NBC is the first step. Critical training for medical personnel before an NBC attack is how to—

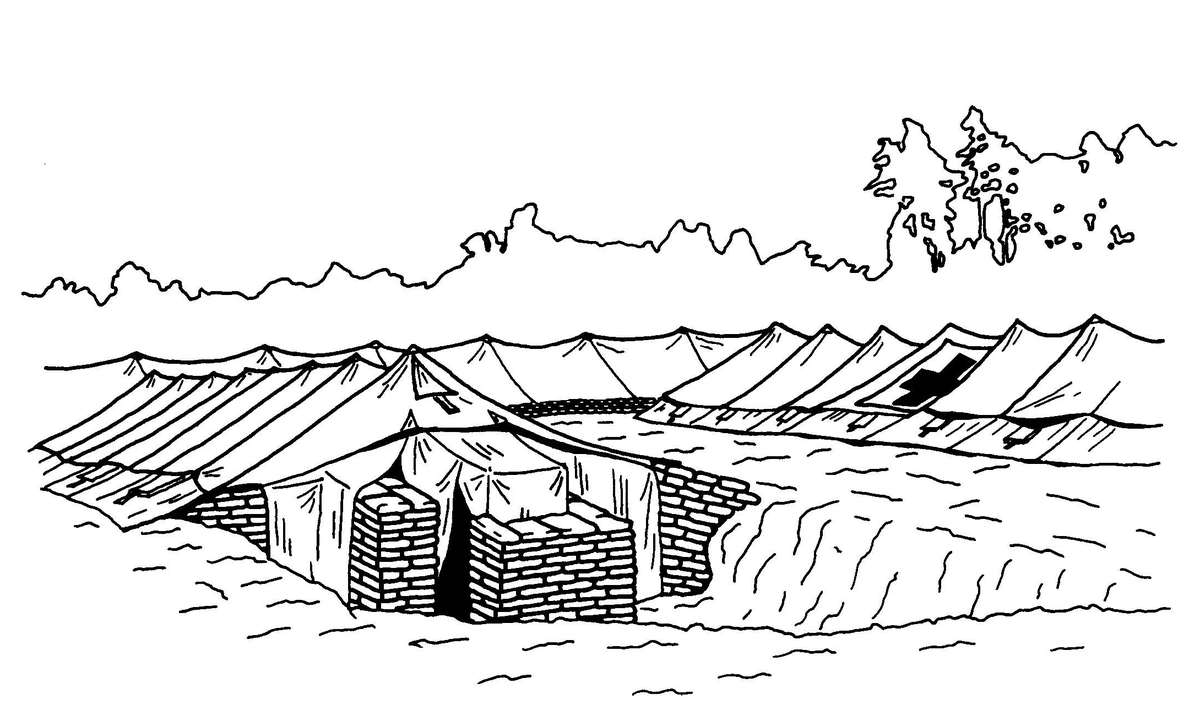

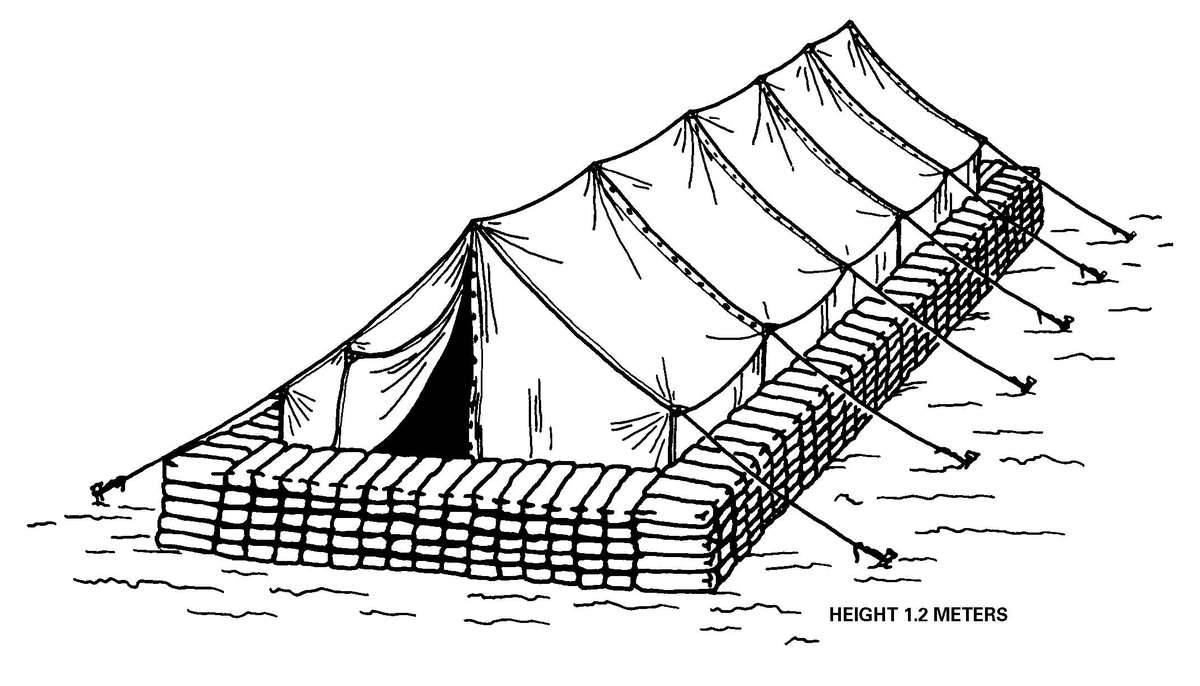

b. Even minimal site preparation (nuclear hardening or CB protecting) may improve survival, greatly reduce contamination, and maintain the ability to continue to provide HSS. See the discussion below for more information on each environment. As with other military personnel, HSS personnel must keep their immunizations current; use available prophylaxis against suspect CB agents; use pretreatments for suspect chemical agents; use insect repellents, and have antidotes and essential medical supplies readily available for known or suspected NBC effects. The best defense for HSS personnel is to protect themselves, their patients, medical supplies, and equipment by applying contamination avoidance procedures. They must ensure that stored medical supplies and equipment are in protected areas or in their storage containers with covers in place. One method of having supplies and equipment protected is to keep them in their shipping containers until actually needed. When time permits and warnings are received that an NBC attack is imminent, or that a downwind hazard exists, HSS personnel should employ their CPS (see Appendix F) or seek protected areas (buildings, tents, or other ABOVE ground shelters for biological or chemical attack; culverts, ravines, basements, or other shielded areas for nuclear) for themselves and their patients.

c. Other tasks include:

While it is possible that the NBC attack will be discrete short events, the more likely scenario is the enemy will use NBC throughout the conflict. The warning and reporting system will provide as much notice as is possible. Using the information provided, HSS personnel will continue their mission by using the best available protected areas. If warned of a nuclear attack, they take up positions within the best available shelter; movement out of these positions will be directed by leadership when it is safe to do so.

All personnel must survey their equipment to determine the extent of damage and their capabilities to continue the mission. Initially, patients from nuclear detonations will be suffering thermal burns or blast injuries. Also, expect patients and HSS personnel to be disoriented. Nuclear blast and thermal injuries will immediately manifest, most radiation-induced injuries will not be observed for several hours to days. Chemical agent patients will manifest their injuries immediately upon exposure to the agent, except for blister agents. [3-5] Biological agent patients may not show any signs of illness for hours to days after exposure, except for trichothecene (T2) mycotoxins. All patients arriving at Levels I and II MTFs must be checked for NBC contamination. Patients are decontaminated before treatment (see Appendix G) to reduce the hazard to HSS personnel, unless life- or limb-threatening conditions exist. Patients requiring treatment before decontamination are treated in the EMT area of the patient decontamination station. Examples of patient conditions that may require treatment at the contaminated treatment station of the patient decontamination area—

a. Health service logistics (HSL) personnel must train and prepare to operate in all battlefield situations. Operating in an NBC environment requires the issue of chemical patient treatment medical equipment set and chemical patient decontamination medical equipment set. Expect disruption of MSR and communications systems and plan accordingly. See FM 4-02.1 and FM 8-10-9 for details on HSL operations.

b. The medical platoon (Level I) is authorized two chemical agent patient treatment medical equipment sets and one chemical agent patient decontamination medical equipment set. Each chemical agent patient treatment medical equipment set has enough supplies to treat 30 patients. Each chemical agent patient decontamination medical equipment set has enough consumable supplies to decontaminate 60 patients.

NOTE

The chlorine granules in the chemical agent patient decontamination set are used to prepare the hypochlorite solutions for use to decontaminate patients.

c. The brigade, divisional, and nondivisional medical companies are authorized five chemical agent patient treatment medical equipment sets and three chemical agent patient decontamination medical equipment sets. These medical equipment sets are for use at the DCS patient decontamination station.

During NBC actions, HSS personnel requirements increase; thus, HSS reinforcement or replacements are necessary. Plans for HSS in a NBC battlefield must include efforts to conserve available HSS personnel and ensure their best use. HSS personnel will be fully active in providing EMT or ATM care; they will provide more definitive treatment as time and resources permit. However, to provide care they must be [3-6] able to work in a shirt-sleeved environment, not in MOPP Levels 3 or 4. Nonmedical personnel conduct search and rescue operations for the injured or wounded; they provide immediate first aid and decontamination. See FM 3-5, for detailed information on personnel and equipment decontamination operations. See FMs 4-02.283, 8-284, and 8-285 for detailed information on treatment of NBC patients.

a. Select sites for the BAS and DCS that are located away from likely enemy target areas. Cover and concealment is extremely important; they increase protection for operating the MTF.

b. Operating a CBPS System in the CB mode at the BAS requires at least eight medical personnel. The senior NCO performs patient triage and limited EMT and minor injury care in the patient decontamination area. One trauma specialist supervises patient decontamination and manages patients during the decontamination process. Two trauma specialists work on the clean side of the hot line and manage the patients until they are placed in the clean treatment area or are sent into the CBPS for treatment. They also manage the patients that are awaiting MEDEVAC to the DCS. The physician, physician assistant, and two trauma specialists provide ATM in the clean treatment area or inside the CBPS. See Appendix F for CPS entry/exit procedures.

c. When the BAS or DCS are receiving NBC contaminated patients, they require at least eight nonmedical personnel from supported units to perform patient decontamination procedures. These facilities are only staffed to provide patient care under conventional operational conditions. Without the augmentation support, they can either provide patient decontamination or patient care, but not both.

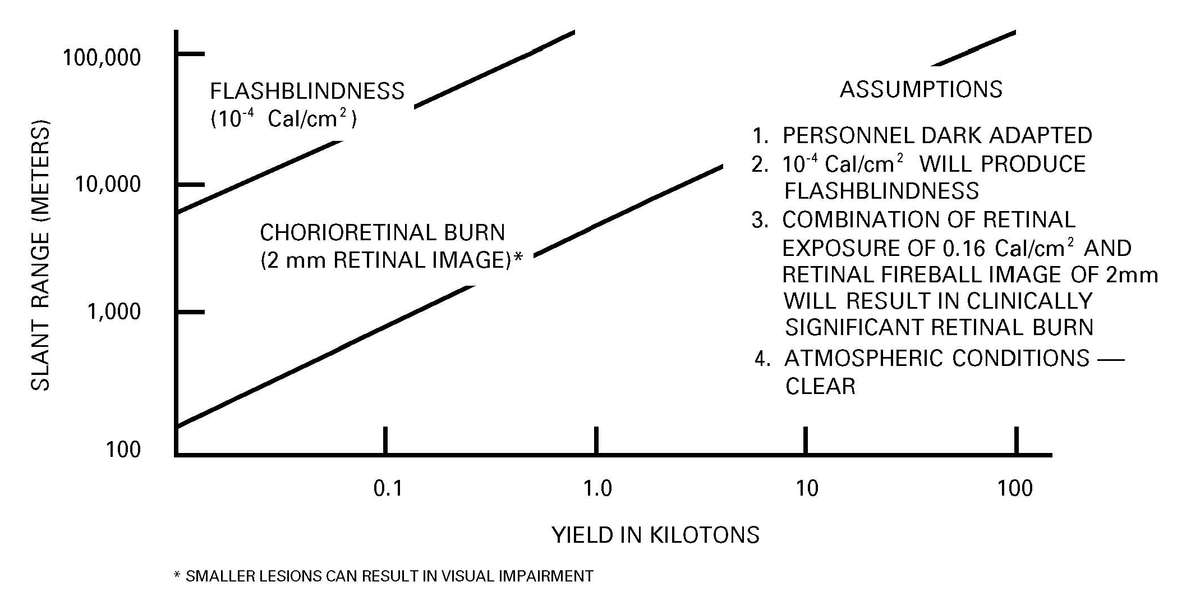

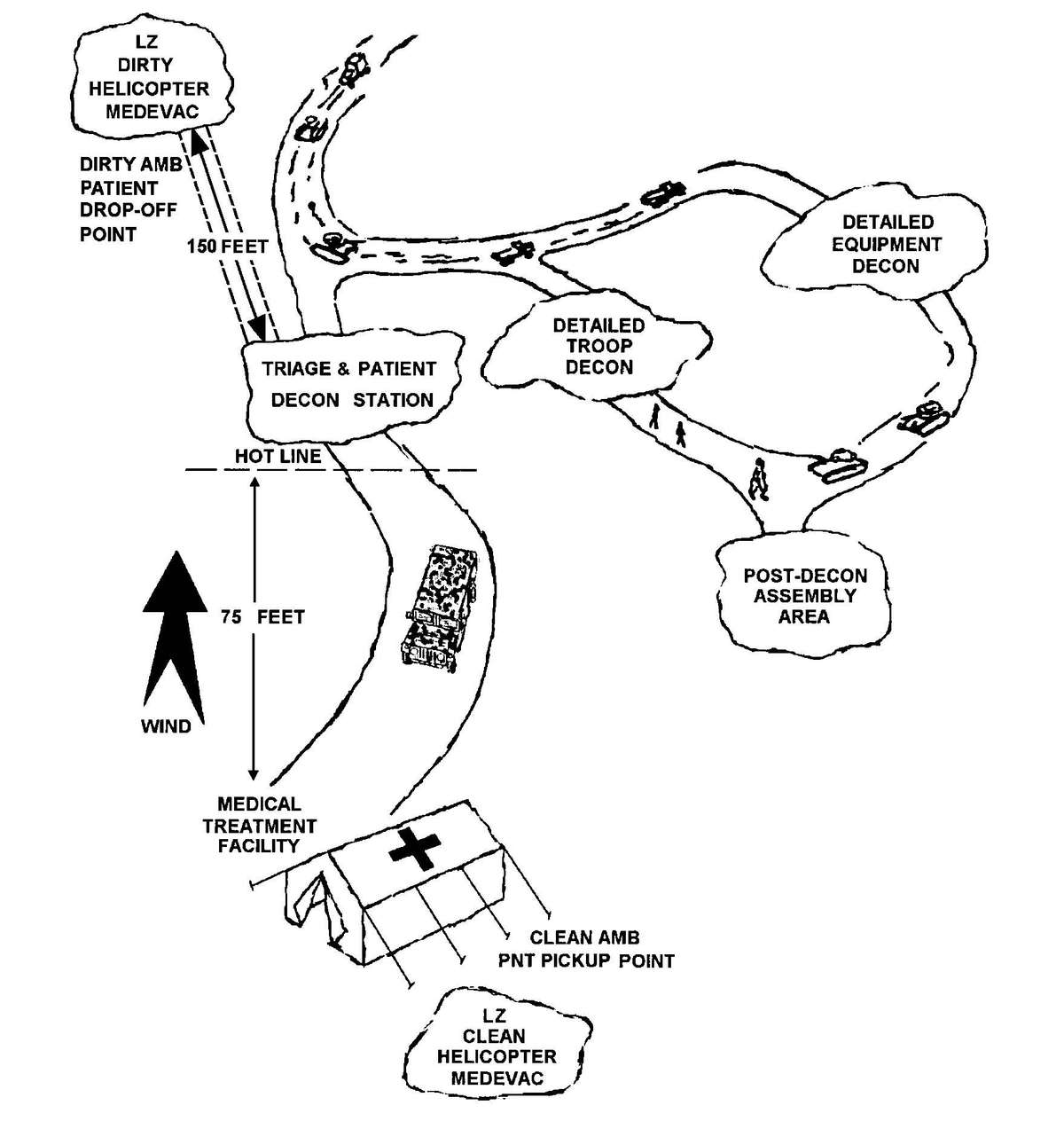

d. A patient decontamination station is established to handle contaminated patients (see Appendix G). The station is separated from the clean treatment area by a "hot line" and is located downwind of the clean treatment area or CPS. Personnel on both sides of the "hot line" assume a MOPP level commensurate with the threat agent employed (normally MOPP Level 4). The patient decontamination station should be established in a contamination-free area of the battlefield. However, it may be necessary to establish a patient decontamination station that is collocated with an MTF that is employing a CBPS, in a chemical vapor hazard area in order to decontaminate patients and clear the battlefield before moving the MTF to a clean area. When CPS systems are not available, the clean treatment area is located upwind 30 to 50 meters of the contaminated work area. When personnel in the clean working area are away from the hot line, they may reduce their MOPP level. Chemical monitoring equipment must be used on the clean side of the hot line to detect vapor hazards due to slight shifts in wind currents; if vapors invade the clean work area, HSS personnel must re-mask to prevent low-level CW agent exposure and minimize clinical effects (such as miosis).

Civilian casualties may become a problem in populated or built-up areas, as they are unlikely to have protective equipment and training. The BAS and DCS may be required to provide assistance when civilian medical resources cannot handle the workload. However, aid to civilians will not be undertaken without command approval, or at the expense of health services provided to US personnel.

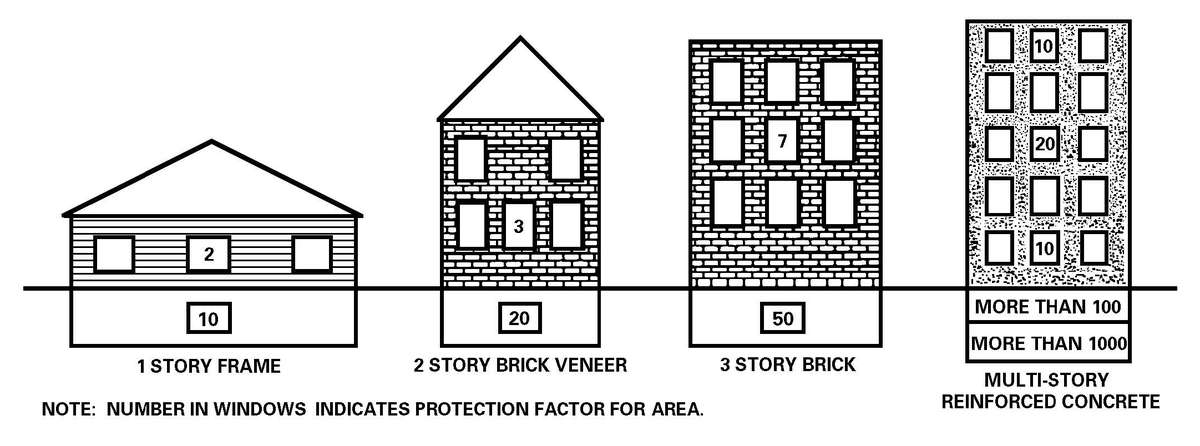

a. The HSS mission must continue in a nuclear environment; protected shelters are essential to continue the support role. Well-constructed shelters with overhead cover and expedient shelters (reinforced concrete structures, basements, railroad tunnels, or trenches) provide good protection from nuclear attacks (see Appendix H). Armored vehicles provide some protection against both the blast and radiation effects of nuclear weapons. Patients generated in a nuclear attack will likely suffer multiple injuries (combination of blast, thermal, and radiation injuries) that will complicate medical care. Nuclear radiation patients fall into three categories:

b. Medical units operating in a radiation fallout environment will face three problems:

c. Decontamination of most radiological contaminated patients and equipment can be accomplished with soap and water. Soap and water will not neutralize radioactive material. However, it will remove the material from the skin, hair or material surface. See Appendix G for specific patient decontamination procedures. The waste can become a concentrated point of radiation and must be managed and monitored.

d. Commanders and leaders must consider the radiation exposure levels for themselves, their staffs, and patients when operating in or determining if the unit will enter a radiologically contaminated [3-8] area. The commander and leader must establish an operational exposure guide for their unit and personnel. The operational exposure guide (OEG) is established for either battlefield exposures as shown in Table 3-1 or for exposures in stability operations and support operations as shown in Table 3-2. The tables present radiation exposure status (RES) categories; however, they can be used to establish OEGs based on the same exposure criteria.

Table 3-1. Radiation Exposure Status Categories for Tactical Operations

| RES-O | THE UNIT HAS HAD NO RADIATION EXPOSURE. |

| RES-1 | THE UNIT HAS BEEN EXPOSED TO GREATER THAN 0 cGy BUT LESS THAN OR EQUAL TO 75 cGy. |

| RES-2 | THE UNIT HAS BEEN EXPOSED TO GREATER THAN 75 cGy BUT LESS THAN OR EQUAL TO 125 cGy. |

| RES-3 | THE UNIT HAS BEEN EXPOSED TO GREATER THAN 125 cGy. |

Table 3-2. Radiation Exposure Status Categories During Stability Operations and Support Operations

| RES-O | <0.05 cGy | ||

| RES-1A | 0.05 TO 0.5 cGy | ||

| RES-1B | 0.5 TO 5 cGy | ||

| RES-1C | 5 TO 10 cGy | ||

| RES-1D | 10 TO 25 cGy | ||

| RES-1E | 25 TO 75 cGy |

Medical triage is the classification of patients according to the type and seriousness of illness or injury; this achieves the most orderly, timely, and efficient use of HSS resources. However, the triage process and classification of nuclear patients differs from conventional injuries. See FM 4-02.283 for nuclear patient triage and treatment procedures.

a. A biological attack (such as the enemy use of bomblets, rockets, spray or aerosol dispersal, release of arthropod vectors, and terrorist or insurgent contamination of food and water) may be difficult to recognize. Frequently, it does not have an immediate effect on exposed personnel. All HSS personnel must monitor for BW indicators such as—

b. Passive defensive measures (such as immunizations, good personal hygiene, physical conditioning, using arthropod repellents, wearing protective mask, and practicing good sanitation) will mitigate the effects of many biological agent intrusions.

c. The HSS commanders and leaders must enforce contamination control to prevent illness or injury to HSS personnel and to preserve the facility. Incoming vehicles, personnel, and patients must be surveyed for contamination. Ventilation systems in MTFs (without CPS) must be turned off if BW exposure is imminent.

d. Decontamination of most BW contaminated patients and equipment can be accomplished with soap and water. Soap and water will not kill all biological agents; however, it will remove the agent from the skin or equipment surface. See Appendix G for specific patient decontamination procedures.

e. Treatment of BW agent patients may require observing and evaluating the individual to determine necessary medications, isolation, or management. See FM 8-284 for specific treatment procedures for BW agent patients.

f. Medical surveillance is essential. Most BW agent patients initially present common symptoms such as low-grade fever, chills, headache, malaise, and coughs. More patients than normal may be the first indication of biological attack. Daily medical treatment summaries, especially DNBI, need to be prepared and analyzed. Trends of increased numbers of patients presenting with unusual or the same symptoms are valuable indicators of enemy employment of BW agents. Daily analysis of medical summaries can provide early warnings of BW agent use, thus enabling commanders to initiate preventive measures earlier and reduce the total numbers of troops lost due to the illness. See FM 4-02.17 for information of medical surveillance procedures. See FM 8-284 for preventive, protective, and treatment procedures.

a. Consider that all patients generated in a CW agent environment are contaminated. The vapor hazards associated with contaminated patients may require HSS personnel to remain at MOPP Level 4 for long periods. The MTF must be set up in clean areas or employ CPS. If there is liquid agent contamination, or a continued vapor hazard, the MTF should be moved and be decontaminated, mission permitting.

b. Initial triage, EMT, and decontamination are accomplished on the "dirty" side of the hot line. Life-sustaining care is rendered, as required, without regard to contamination. Normally, the senior health care sergeant performs initial triage and EMT at the BAS. Secondary triage, ATM, and patient disposition are accomplished on the clean side of the hot line. When treatment must be provided in a contaminated environment outside the CPS, the level of care may be greatly reduced because medical personnel and patients are in MOPP Level 3 or 4. However, lifesaving procedures must be accomplished. See FM 8-285 for specific treatment of CW agent patients.

c. Decontamination of most chemically contaminated patients and equipment requires the use of materials that will remove and neutralize the agent. See FM 3-5 for equipment decontamination procedures and Appendix G for specific patient decontamination procedures.

Enemy employment of NBC weapons or TIMs in the extremes of climate or terrain warrants additional consideration. Included are the peculiarities of urban terrain, mountains, snow and extreme cold, jungle, and desert operations in an NBC environment with the resultant NBC-related effects upon medical treatment and MEDEVAC. For a more detailed discussion on NBC aspects of urban terrain, mountain, snow and extreme cold, jungle, and desert operations, see FMs 3-06.11, 31-71, 90-3, 90-5, and 90-10.

a. In mountain operations, passes and gorges may tend to channel the nuclear blast and the movement of chemical and biological agents. Ridges and steep slopes may offer some shielding from thermal radiation effects. Close terrain may limit concentrations of troops and fewer targets may exist; therefore, a lower patient load may be anticipated. However, the terrain will complicate patient evacuation and may require patients to be decontaminated, treated, and held for longer periods than would be required for other operational areas.

b. The effects of extreme cold weather combined with NBC-produced injuries have not been extensively studied. However, with traumatic injuries, cold hastens the progress of shock, providing a less favorable prognosis. Thermal effects will tend to be reinforced by reflection of thermal radiation from snow and ice-covered areas. Care must be exercised when moving chemically contaminated patients into a warm shelter. A CW agent on the patient's clothing may not be apparent. As the clothing warms to room temperature, the CW agent will vaporize (off-gas), contaminating the shelter and exposing occupants to potentially hazardous levels of the agent. A three-tent system is suggested for processing patients in extreme cold operations. The first tent (unheated) is used to strip off potentially contaminated clothing. The second (heated) is used to perform decontamination, perform EMT and detect off gassing. The third (heated) is used to provide the follow on care and patient holding.

c. In rain forests and other jungle environments, the overhead canopy will, to some extent, shield personnel from thermal radiation. However, the canopy may ignite and create forest fires and result in burn injuries. By reducing sunlight, the canopy may increase the persistency effect of CW agents near ground level. The canopy also provides a favorable environment for BW agent dispersion and survival.

d. In desert operations, troops may be widely dispersed, presenting less profitable targets. However, the lack of cover and concealment exposes troops to increased hazards. Smooth sand is a good reflector of nuclear thermal and blast effects; generating increased numbers of injuries. High temperatures will increase the discomfort and debilitating effects on personnel wearing MOPP, especially heat injuries.

a. An NBC environment forces the unit leadership to consider to what extent he will commit MEDEVAC assets to the contaminated area. If the battalion or task force is operating in a contaminated [3-11] area, most or all of the organic medical platoon MEDEVAC assets will operate there. However, efforts should be made to keep some ambulances free of contamination. For conventional MEDEVAC operations see FM 8-10-6 and FM 8-10-26.

b. We have three basic modes of evacuating patients (personnel [litter bearers], ground vehicles, and aircraft). Using litter bearers to carry the patients involves a great deal of stress. Cumbersome MOPP gear, added to climate, increased workload, and the fatigue of battle, will greatly reduce personnel effectiveness. If personnel must enter a radiologically contaminated area, an OEG must be established (see Table 3-1). Radiation exposure records are maintained by the NBC NCO and made available to the commander, staff, and medical leader. The exposure is entered into the individual's medical record. Based on the OEG, the commander and leaders will decide which MEDEVAC assets will be sent into the contaminated area. Again, every effort is made to limit the number of MEDEVAC assets that are contaminated. Medical evacuation considerations should include the following:

(1) A number of ambulances will become contaminated in the course of battle. Optimize the use of resources; use those already contaminated (medical or nonmedical) before employing uncontaminated resources.

(2) Once a vehicle or aircraft has entered a contaminated area, it is highly unlikely that it can be spared long enough to undergo thorough decontamination. However, operational decontamination should be performed to the greatest extent possible. This will depend upon the contaminant, the tempo of the battle, and the resources available to the MEDEVAC unit. Normally, contaminated vehicles (air and ground) will be confined to dirty environments. See FM 3-5 for details on decontamination procedures.

(3) Use ground ambulances instead of air ambulances in contaminated areas; they are more plentiful, are easier to decontaminate, and are easier to replace. However, this does not preclude the use of aircraft. If an air ambulance is deployed into a contaminated area, use it for repeated MEDEVAC missions rather than sending other clean aircraft into the area.

(4) The relative positions of the contaminated area, forward line of own troops (FLOT), and threat air defense systems will determine where helicopters may be used in the MEDEVAC process. One or more helicopters may be restricted to contaminated areas; use ground vehicles to cross the line separating clean and contaminated areas. The ground ambulance proceeds to an MTF with a patient decontamination station (PDS); the patient is decontaminated and treated. If further MEDEVAC is required, a clean ground or air ambulance is used. The routes used by ground vehicles to cross between contaminated and clean areas are considered dirty routes and should not be crossed by clean vehicles, if mission permits. Consider the effects of wind and time upon the contaminants; some agents will remain for extended periods of time.

(5) Keep the helicopter rotor wash in mind when evacuating patients, especially in a contaminated environment. The intense rotor wash will disturb the contaminants and further aggravate the condition. The aircraft must be allowed to land and reduce to flat pitch before patients are brought near. This will reduce the effects of the rotor wash. Additionally, a helicopter must not land too close to a decontamination station (especially upwind) because any trace of contaminants in the rotor wash will compromise the decontamination procedure.

c. Immediate decontamination of rotor wing aircraft and ground vehicles is accomplished to minimize crew exposure. Units include decontamination procedures in their standing operating procedures (SOP). A sample aircraft decontamination station that may be tailored to a unit's needs is provided in FM 3-5.

d. Evacuation of patients must continue, even in an NBC environment. The HSS leader must recognize the constraints NBC places on operations; then plan and train to overcome these deficiencies.

e. To minimize the spread of contamination inside the MEDEVAC aircraft, plastic sheeting should be placed under the litter to catch any contaminant that drips off the patient or litter. The plastic sheeting can be removed with the patient, removing any contamination with it. When plastic sheeting is not available, placing a blanket under the litter will reduce the amount of agent that makes contact with the inside of the aircraft.

NOTE

The key to mission success is detailed preplanning. A HSS plan must be prepared for each support mission. Ensure that the HSS plan is in concert with the tactical plan. Use the plan as a starting point and improve on it while providing HSS.

f. Medical evacuation by United States Air Force (USAF) aircraft will be severely limited until runway repairs and decontamination has occurred. Aerial flights from contaminated areas into uncontaminated airspace and destinations may be impossible for extended periods of time; some nations will not allow patients from contaminated areas to travel through or over their country. Therefore, patient holding on-site (or in theater) for an extended period of time must be anticipated.

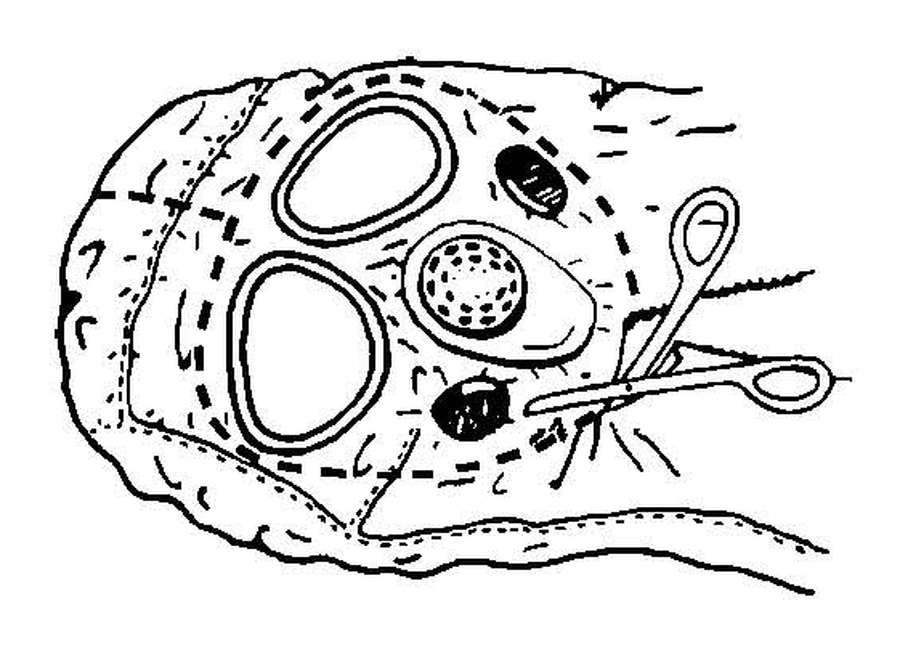

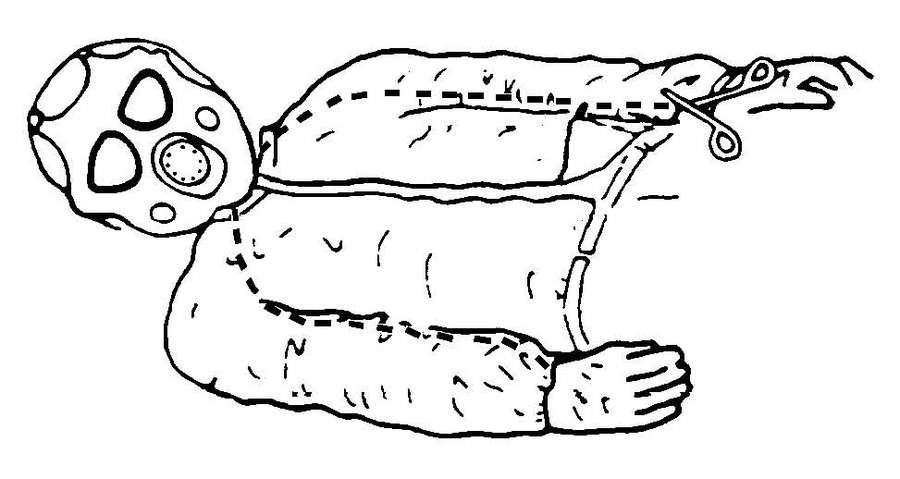

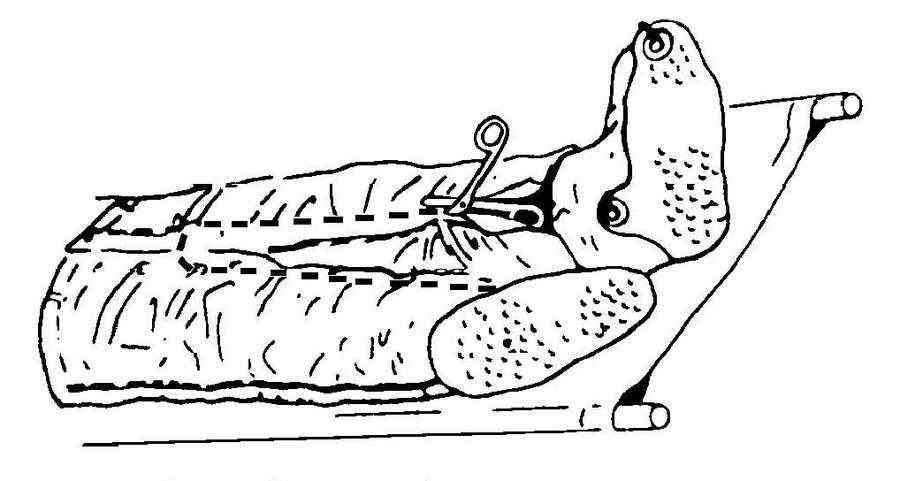

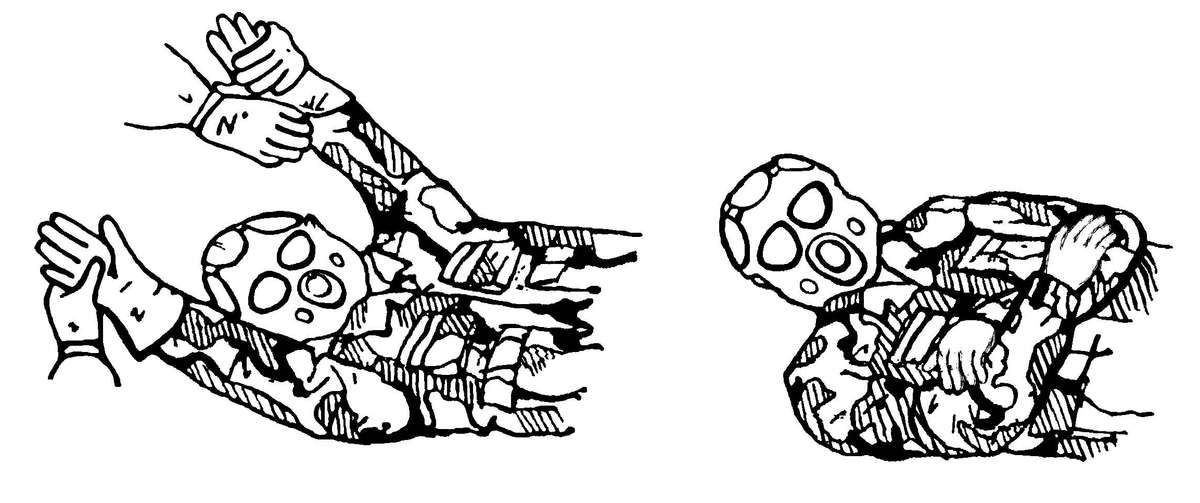

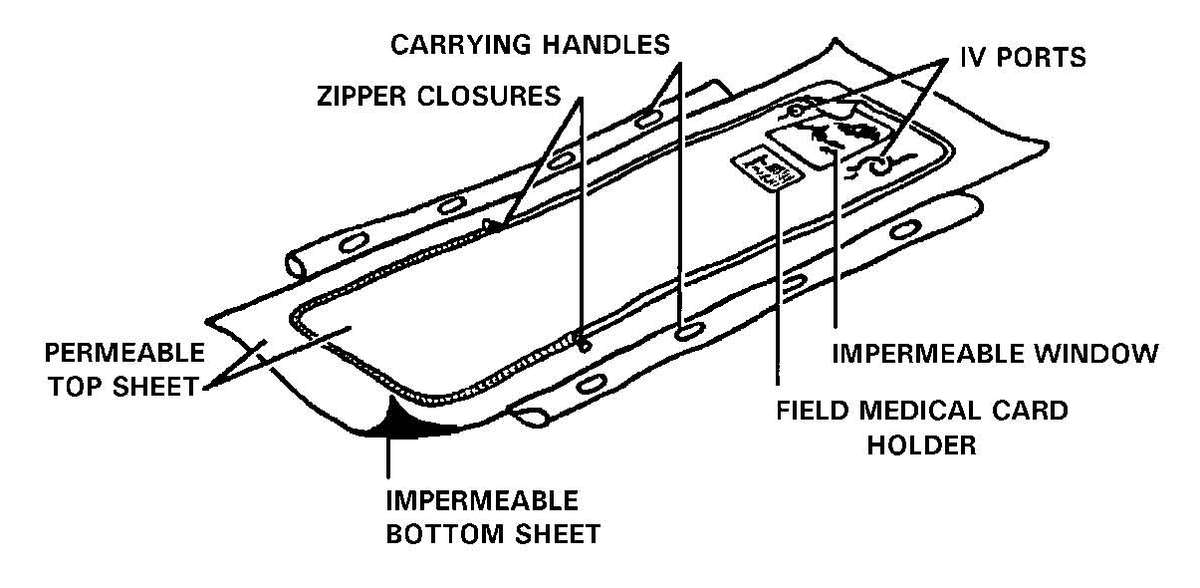

g. Patient protection during evacuation must be maintained. Patients that have been decontaminated at the PDS at an MTF will have had their MOPP ensemble removed. The forward deployed MTFs will not have replacement MOPP ensembles for the patients. These patients must be placed in a patient protective wrap (PPW) before they are removed from the clean treatment area for evacuation (see the PPW instruction sheet/PPW label for use of the PPW). The PPW provides the same level of protection as the MOPP ensemble. The patient does not have to wear a protective mask when inside the PPW. The patient is placed inside the PPW that is on a litter. The PPW may also have a battery-operated blower that can provide a reduction of the body heat load and reduce the carbon dioxide level within the PPW. The PPW will provide protection for the patient for up to 6 hours and is a one-time use item. The blower is reusable, remove it and the attachment devices from the used PPW and return it to the patient movement items inventory. See FM 4-02.1 for a discussion on patient movement items.

WARNING

DO NOT place contaminated patients in the PPW. It is for use with uncontaminated/decontaminated patients only.

a. Many factors must be considered when planning for Levels III and IV hospital support on the integrated battlefield. The hospital staff must be able to defend against threats by individuals or small groups (two or three) of infiltrators and survive NBC strikes or TIM incidents while continuing their mission. This threat may include the introduction of NBC or TIM in the hospital area, the water or food supplies; and the destruction of equipment and/or supplies. On the larger scale of surviving NBC strikes and continuing to support the mission, operating in a contaminated environment will present many problems for hospital personnel. The use of NBC weapons or TIM release can compromise both the quality and quantity of health care delivered by medical personnel due to the contamination at the MTF; constrain mobility and evacuation; and contaminate the logistical supply base. While providing hospital support, consider the following assumptions:

(1) Their location, close to other support assets, makes them vulnerable to NBC strikes and release/dispersion of TIMs.

NOTE

When using existing civilian hospitals, the materials for an RDD may be at these hospitals. Exploding the material in place is very practical for a small team of terrorists.

(2) Large numbers of casualties are produced in a short period of time. Many of these casualties may have injuries that are unfamiliar to hospital personnel. These injuries may include—

(3) In addition to the wounding effects of NBC weapons on troops, their use will have other effects upon the patient care delivery system.

(4) Mission-oriented protective posture reduces the efficiency of all personnel.

[4-3] (5) Without CPS systems, hospitals may operate for a limited time in a nonpersistent agent environment, but are incapable of operating in a persistent agent environment.

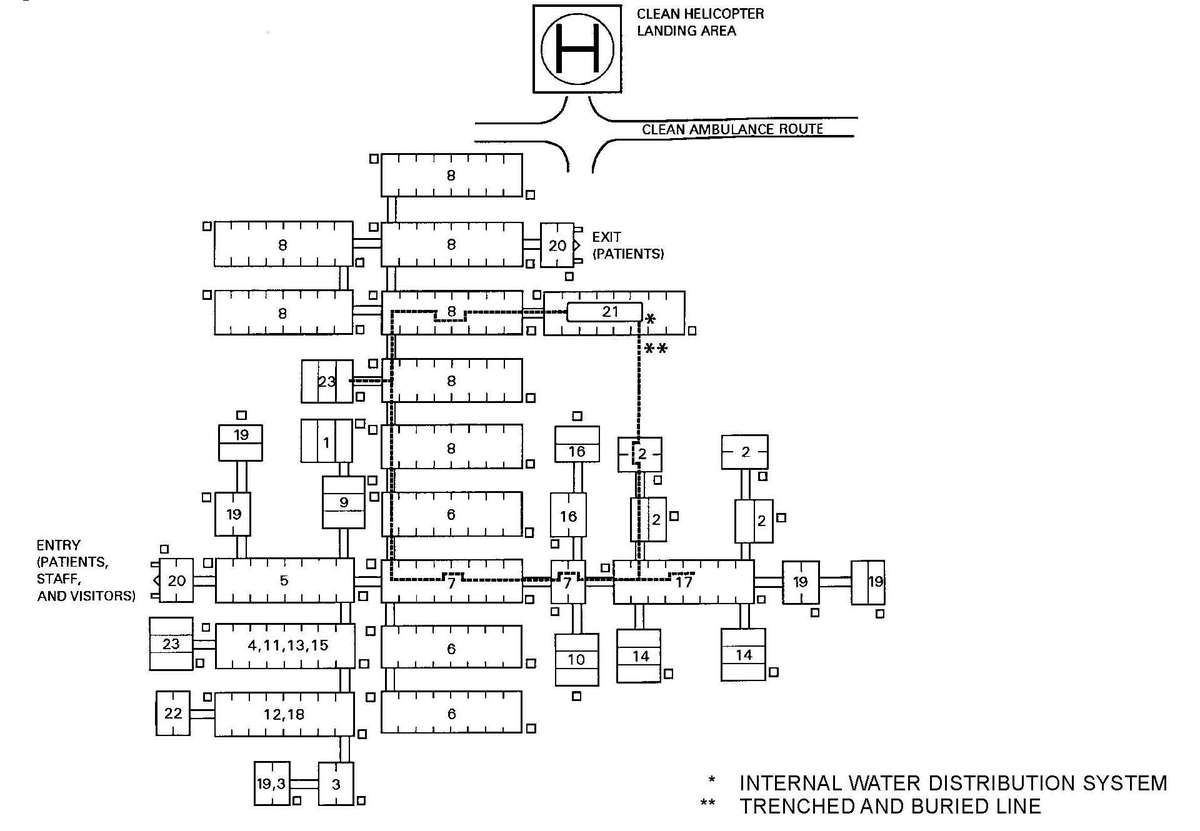

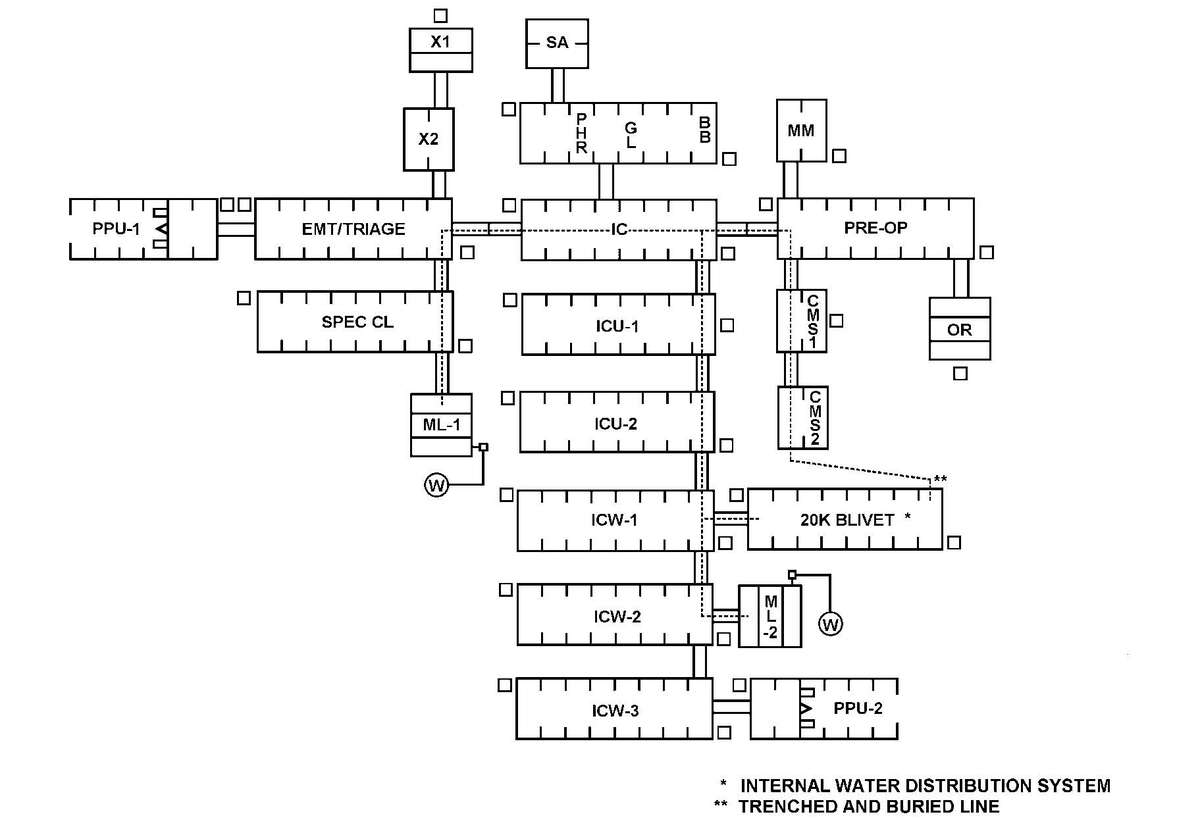

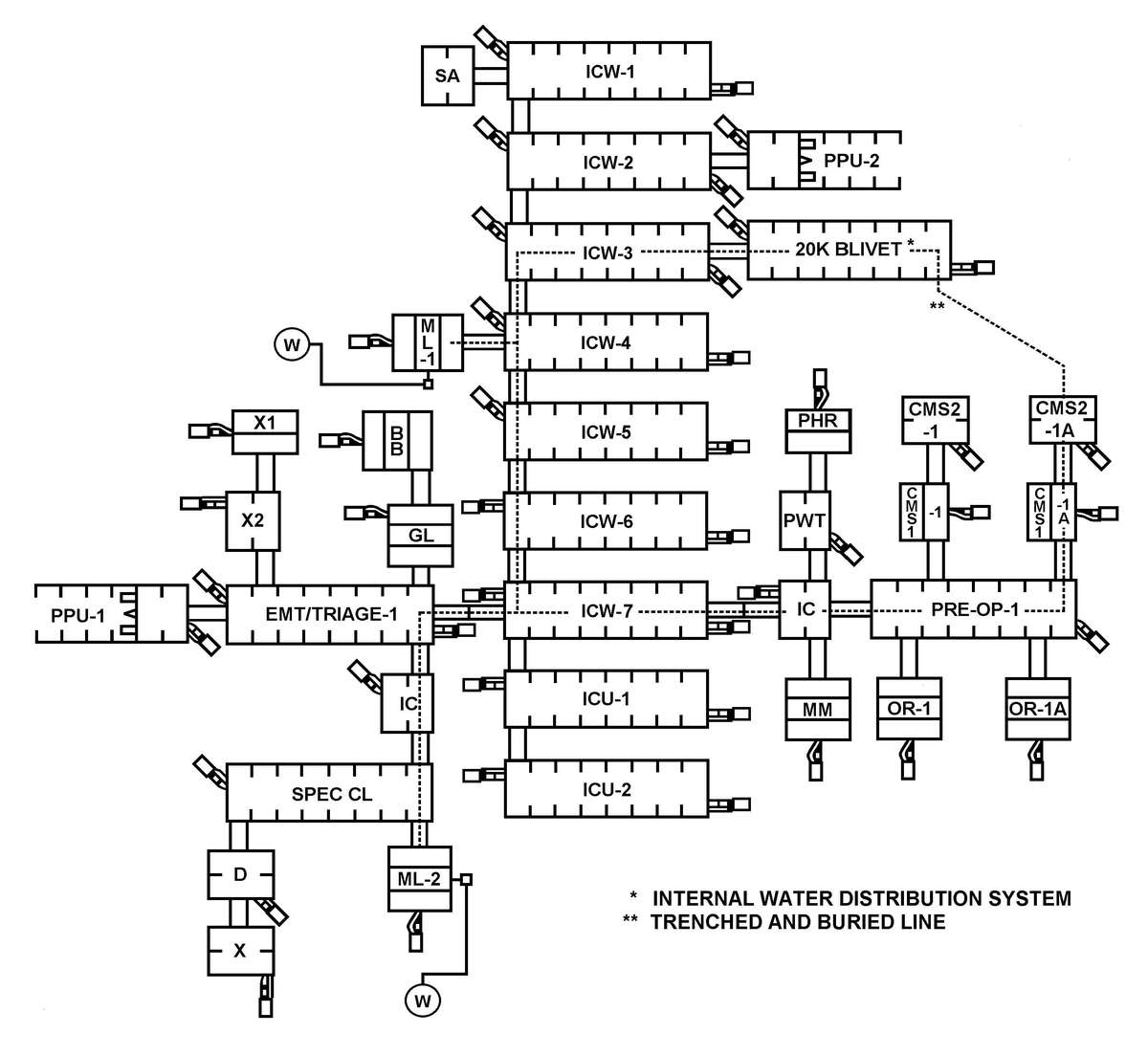

b. There are currently two force modernization initiative hospital systems in the force structure. The Medical Force 2000 (MF2K) system consists of the CSH, the field hospital (FH), and the general hospital (GH). The Medical Reengineering Initiative (MRI) consists of only one hospital system—the CSH. The MF2K CSH is a corps asset, whereas, the FH and GH are the echelon above corps hospital systems. The MRI CSH will be located in the corps and at echelons above corps. The MRI CSH will replace the FH and GH at echelons above corps. See FM 4-02.10, FM 8-10-14, and FM 8-10-15 for detailed information on these hospital systems.

a. Protection of hospital assets requires intensive use of intelligence information and careful planning. The limited mobility of hospitals makes their site selection vital to minimize collateral damage from attacks on other units.

b. Many defensive measures will either impede or preclude performance of the hospital mission. Successful hospital defense against an NBC threat is dependent upon accurate, timely receipt of information via the nuclear, biological, and chemical warning and reporting system (NBCWRS). This information will allow the hospital to operate longer without the limitations and problems associated with the use of the CPS and personnel assuming MOPP Levels 3 and 4. The detailed information (provided in the NBC 5 and 6 reports respectively) on the areas affected and the types of agents used allows the hospital staff to—

(1) Protective procedures.