Photo by International News Service

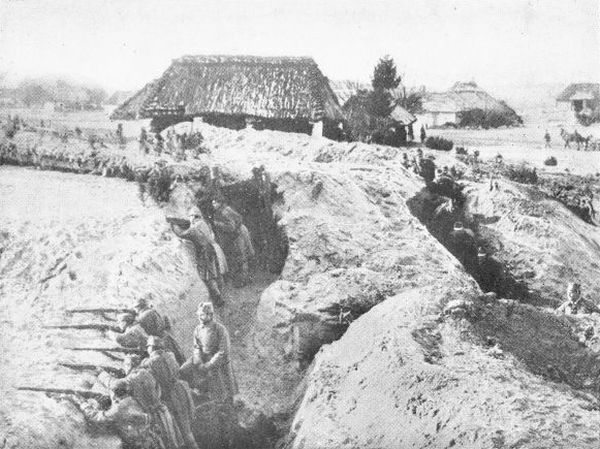

BELGIAN SOLDIERS BEHIND THE ENTRENCHMENT ON THE ROAD TO MALINES

Photo by International News Service

BELGIAN SOLDIERS BEHIND THE ENTRENCHMENT ON THE ROAD TO MALINES

Compiled by

F. B. OGILVIE

Copyright 1915 by J. S. Ogilvie Publishing Company

New York

J. S. OGILVIE PUBLISHING COMPANY

57 Rose Street

Our thanks are due and are hereby tendered to Dr. Mary Merrit Crawford of Brooklyn, N. Y., for her letters regarding the Paris hospital patients, to the New York Times for the article, "Three Months in the Trenches," by Bert Hall, and for other letters; and to the New York Sun and various other publications for the numerous items of intense human interest which help to make this collection an accurate record of conditions at the front in the colossal European War.

THE PUBLISHERS

Letters received from soldiers in the field describe many features of the various campaigns of the war, the descriptions coming from representatives of widely differing classes of society. Unlike the rigid censorship imposed on the allied troopers by their official censors; the letters of Germans in the field show that wide liberty of expression is allowed, with only the names of places, troop divisions, and commanders, and occasionally dates, deleted.

At the front are many men of prominence in many walks of life. Some of the greatest present-day poets and novelists are in the field, and that, too, serving in humble capacities, taking their risks side by side with the men in the ranks or as non-commissioned officers and sharing the daily routine of the common soldier's life. Undemocratic as officialdom is in times of peace, and harsh as its discipline has been pictured in time of war, letters from notables at the front show a surprising spirit of democracy in the relations of high and low on the battlefield, in the trenches, and on the march.

The letters from the front include missives penned or scribbled by nobles and members of the royal families, high military officials, authors, Socialists, tradesmen, skilled workmen, and writers who, in peace times, have been more expert with the farmhand's scythe or manure fork, or with the street cleaner's broom than with the pen[4] that is supposedly mightier, and certainly to them more unwieldy, than the sword.

Nevertheless, even among the privates, it is extremely rare that a letter shows illiteracy to any marked degree. In the letters written by high and low alike, there is to be noted a certain theatrical consciousness of the stage on which they are now engaged in battle before the world.

AMERICAN WHO SERVED WITH THE FRENCH FOREIGN LEGION, NOW AN AIRMAN, GIVES VIVID ACCOUNT OF "DITCH" LIFE.

Bert Hall, who wrote the article printed herewith, is an American, and has had experience both as a racing automobile driver and an airman. At the beginning of the war he joined the French Foreign Legion, but was afterward transferred to the French Aviation Corps.

By Bert Hall.

There was no hands-across-the-sea Lafayette stuff about us Americans who joined the Foreign Legion in Paris when the war broke out. We just wanted to get right close and see some of the fun, and we didn't mind taking a few risks, as most of us had led a pretty rough sort of life as long as we could remember.

For my part, auto racing—including one peach of a smash-up in a famous race—followed by three years of flying, had taken the edge off my capacity for thrills, but I thought I'd get a new line of excitement with the legion in a big war, and I reckon most of the other boys had much the same idea.

We got a little excitement, though not much, but[6] as for fun—well, if I had to go through it again I'd sooner attend my own funeral. As a sporting proposition, this war game is overrated. Altogether, I spent nearly three months in the trenches near Craonne, and, believe me, I was mighty glad when they transferred me (with Thaw and Bach, two other Americans who've done some flying) to the Aviation Corps, for all they wouldn't take us when we volunteered at the start because we weren't Frenchmen, and have only done so now because they've lost such a lot of their own men, which isn't a very encouraging reason.

But anyway if the Germans do wing us, it's a decent, quick finish, and I for one prefer it to slow starvation or being frozen stiff in a stinking, muddy trench. Why, I tell you, when I got wounded and had to leave, most of the boys were so sick of life in the trenches that they used to walk about outside in the daytime almost hoping the Germans would hit them—anything to break the monotony of the ceaseless rain and cold and hunger and dirt!

It wasn't so bad when we first got there, about the beginning of October, as the weather was warmer (though it had already begun to rain and has never stopped since), but we were almost suffocated by the stench from the thousands of corpses lying between the lines—the German trenches were about four hundred yards away—where it wasn't safe for either side to go out and bury them. They were French mostly, result of the first big offensive after the Marne victory, and, believe me, that word just expresses it—they were the offensivest proposition in all my experience.

Well, as I was saying, we reached the firing line on October 4, after marching up from Toulouse,[7] where they'd moved us from Rouen to finish our training. We went down there in a cattle truck at the end of August in a hurry, as they expected the Germans any minute; the journey took sixty hours instead of ten, and was frightfully hot. That was our first experience of what service in the Foreign Legion really meant—just the sordidest, uncomfortablest road to glory ever trodden by American adventurers.

After we'd been at Toulouse about a month, they incorporated about two hundred of us recruits—thirty Americans and the rest mostly Britishers, all of whom had seen some sort of service before—in the Second Regiment Etranger which had just come over from Africa on its way to the front. They put us all together in one company, which was something to be thankful for, as I'd hate to leave a cur dog among some of the old-timers—you never saw such a lot of scoundrels. I'll bet a hundred dollars they have specimens of every sort of criminal in Europe, and, what's more, lots of them spoke German, though they claimed to have left seventeen hundred of the real Dutchies behind in Africa. Can you beat it? Going out to fight for France against the Kaiser among a lot of guys that looked and talked like a turn verein at St. Louis!

Why, one day Thaw and I captured a Dutchie in a wood where we were hunting squirrel—as a necessary addition to our diet—and, believe me, when we brought him into camp he must have thought he was at home, for they all began jabbering German to him as friendly as possible, and every one was quite sad when he went off in a train with a lot of other prisoners bound for some fortress in the West of France.

But that was only a detail, and now I'm telling[8] you about our arrival in the trenches. The last hundred miles we did in five days, which is some of a hurry; but none of the Americans fell out, though we were all mighty tired at the end of the last day's march. Worse still, that country had all been fought over, and there were no inhabitants left to give us food and drinks as we had had before at every resting place, which helped us greatly. Along the roadside lots of trees had been smashed by shell fire, and there were hundreds of graves with rough crosses or little flags to mark them, and every now and then we passed a broken auto or a dead horse lying in the gutter.

At the end of the fifth day we got our first sample of war—quite suddenly, without any warning, as we didn't know we were near the firing line. We had just entered a devastated village when there came a shrill whistling noise like when white hot iron is plunged into cold water, then a terrific bang as a shell burst about thirty yards in front of our columns, making a hole in the road about five feet deep and ten in diameter, and sending a hail of shrapnel in all directions. One big splinter hit a man in the second rank and took his head off—I think he was a Norwegian; anyway, that was our first casualty. No one else was injured.

Our boys took their baptism of fire pretty coolly, though most of us jumped at the bang and ducked involuntarily to dodge the shrapnel, which, by the way, isn't very dangerous at more than thirty yards, though it does a lot of harm at shorter range. Personally, I wasn't as scared as I expected, and most of the others said the same. At first, one is too interested to be frightened, and by the time the novelty has worn off one has gotten[9] fairly used to it all—at least that seemed to be our general opinion.

There were no more shells after that one, and we continued our march till nightfall, when we camped in an abandoned village. Next morning there were 100 big auto trucks ready to take us to a point about forty miles along the lines, and we clambered aboard them and set off at a good speed—all but twenty unlucky lads, who were left to pad the hoof as a guard for our mules and baggage. My pal, William Thaw, was among the number; he marched for thirteen hours practically without a stop, and when he reached our camp he lay right down in the mud by the roadside and went straight off to sleep, though it was raining like sixty and he was drenched to the skin. But he was all right again in the morning, though it was a man's job to wake him up.

Next day we set off before dawn, having received orders to take our place in the trenches about eight miles away. It soon got light, and after marching about half an hour we were unlucky enough to be seen by a German aeroplane which signaled us to their batteries. The first shell burst near, the second nearer, the third right among us, killing nearly a dozen old-timers; and we were forced to break ranks and take cover until nightfall, as they'd got the range and it would have been suicide to try and go on. Pretty good shooting that at five or six miles' distance!

The French talk a lot about their artillery, but, believe me, the Dutchies are mighty fine gunners, especially with their cannon—even the very biggest.

Why, one day when my company was having its usual weekly rest from the trenches, there were a couple of hundred of us bunking in a big barn fully eight miles behind our lines. About three in the afternoon along came a German aeroplane, and half an hour later they dropped a couple of shells between the barn and a church some thirty yards farther back, just by way of showing what they could do. We thought that was all, and settled down comfortably for the night; but not a bit of it! At ten o'clock sharp a shell dropped plump onto the barn itself and killed five or six and wounded a dozen more, none of them Americans. We got out on the jump, though of course it was raining; and we were wise, for in the next half hour they hit the barn eleven times without a single miss, and at ten-thirty there weren't any big enough bits of it left to make matches of. The barn was perhaps thirty yards long by fifteen wide, but remember they were firing at a range of ten miles or so and in pitch darkness. Of course, they had got their guns trained right in the afternoon and just waited till night to give us a pleasant surprise. I did hear those were Austrian mortars, not German; anyway, they were good enough for us, I can tell you.

But to go back to my story: We broke ranks and fled to cover, and remained in hiding all that day near a ruined farm with shells falling all about, though they didn't do much damage. But our old-timers didn't like it one little bit. They had not been used to that kind of thing in Africa, and then the Germans and Austrians didn't at all fancy the idea of being fired upon by their own people. In our company all of the Sergeants and[11] most of the other non-coms were Austrian—not that they turned out later to be any the worse fighters for that. There was one Sergeant named Wiedmann who fought like a lion; he was the bravest man in the regiment. Poor chap, I've just heard he was killed the other day by a hand grenade, and I'm sorry. He was a real white man if ever I knew one. Our Lieutenant was a German named Bloch, and only the Captain was a Frenchman. But all this mixture of races led to some rather curious results, as the following story will show:

Among the recruits who joined us at Paris there were two young fellows from Corsica—the Corsican brothers, we called them, as they always stuck together—who said they belonged to the Corsican militia, but preferred to volunteer, as they wanted to see some fighting right away. Besides French, they spoke English fluently, and used to jabber away together in some local patois, but they were both very smart soldiers and were soon promoted Corporals and got along fine. Every one liked them, and they stood very well with the officers as well. After we had been in the trenches about ten days these two chaps disappeared one wet night and left behind a note for the Colonel, which I was lucky enough to see. It ran something like this:

Most Honored Sir:

Though we have spent a most agreeable time in your regiment—of which we have a good opinion, although the discipline is sometimes rather more lax than we are accustomed to—we feel that the moment has come for us to join our friends, which we were unable to do at the mobilization, when we[12] naturally preferred the Foreign Legion to a concentration camp.

We will give a good account of you to our friends and hope to have the pleasure of meeting you again before long.

Otto X——

Ober-Lieutenant, Potsdam Guards.

Hermann Y——

Lieutenant, Potsdam Guards.

Wouldn't that fease you? The Colonel nearly blew up.

Well, at nightfall we resumed our march by separate companies. Our Captain didn't know the country, so of course we got lost. It was raining heavily, and the mud was frequently knee deep. Add to that incessant tumbles into numberless shell holes full of water, and you will realize that we were a pretty sad procession that finally at three A. M. scrambled into the stinking ditch where we were to spend the greater part of the next three months.

For three or four days we had nothing to do but dodge the shrapnel and try and keep warm, as the enemy maintained a constant artillery fire—with a regular interval for luncheon—starting about six A. M. and stopping toward five P. M.; and they got the range. I tell you, one lies pretty flat when there's any shrapnel about. Some of the English boys were killed the second day, but we Americans have been fine and lucky—only one killed the whole time, though we have had some very narrow shaves. For instance, Thaw had his bayonet knocked off his rifle by a "sniper" while on sentry-go, and another boy named Merlac had his pipe taken clean out of his mouth by a shrapnel ball in the trenches. It didn't hurt him at all, but[13] I never saw any one look so surprised in my life. Shortly afterward Jimmy Bach (who is now in the Aviation Corps with Thaw and me) had his head cut by a rifle bullet which just grazed it without doing more than make a deepish scratch. I myself had a close squeak the very day of our arrival in the trenches. A piece of shell weighing three or four pounds smashed to bits the pack on my back—including my best pipe, which I couldn't replace until I got back to Paris—without so much as bruising me, though it scared me something dreadful.

Our company had an eight days' "shift" in the trenches, followed by three days' rest at a camp four miles in the rear.

During the week's duty it was impossible to wash or take off one's clothes, and we quickly got into a horrible condition of filth. To begin with, there was a cake of mud from head to foot about half an inch thick; but what was worse was the vermin which infested our clothes almost immediately and were practically impossible to get rid of. They nearly broke the heart of Lieutenant Bloch. He had a wonderful crop of bright red whiskers, of which he was as proud as a kitten with its first mouse, because he thought they gave him a really warlike appearance, and he was always combing them and squinting at them in a little pocket mirror. Well, one day the lice got into these whiskers and fairly gave him hades. He bore it for a week, scratching away at his chin until he was tearing out chunks of hair by the roots; but at last he could stand no more, and had to have the whole lot shaved off. He was the saddest thing you ever saw after that, with a little[14] chinless face like a pink rabbit, and was so ashamed he hardly dared show himself in daylight.

But mud and vermin were only minor worries, really; our proper serious troubles were cold and hunger. It's pretty cool in the middle of France toward the end of November, and for some reason—I guess because they were such a lot of infernal thieves at our depot—we never got any of the clothes and warm wraps sent up from Paris for us. It was just throwing money away to try it. My wife mailed me three or four lots of woolen sweaters and underclothes, but I never received a single thing, and the rest of the boys had much the same experience.

That was bad, but the hunger was something fierce. The Foreign Legion is not particularly well fed at any time—coffee and dry bread for breakfast, soup with lumps of meat in it for luncheon, with rice to follow, and the same plus coffee for dinner, and not too much of anything, either. But in our case all the grub had to be brought in buckets from the relief post, four miles away, by squads leaving the trenches at three A. M., ten A. M., and five P. M., and a tough job it was, what with the darkness and the mud and the shell holes and the German cannonade, to say nothing of occasional snipers taking pot shots at you with rifles. I got one bullet once right between my legs, which drilled a hole in the next bucket in line and wasted all our coffee.

As you can imagine, quite a lot of the stuff used to get spilt on the way, and then the boys carrying it used to scrape it up off the ground and put it back again, so that nearly everything one[15] ate was full of gravel and, of course, absolutely cold. More than once when the cannonade was especially violent we got nothing to eat all day but a couple of little old sardines; and, believe me, it takes a mighty strong stomach to stand that sort of treatment for any length of time. As far as we Americans were concerned, who were mostly accustomed to man-sized meals, the net result was literally slow starvation.

The second night in the trenches we had an alarm of a night attack. I crept out to a "funk-hole" some thirty yards ahead of our trench with a couple of friends. It was nearly ten o'clock and there was a thin drizzle. We stared out into the darkness, breathing hard in our excitement. The usual fireworks display of searchlights and rockets over the German trenches was missing—an invariable sign of a contemplated attack, we had been told. Suddenly I glimpsed a line of dim figures advancing slowly through the darkness. "Hold your fire, boys," I gasped. "Let them get good and close before you loose off." They came nearer, stealthily, silently. We raised our rifles. Suddenly my friend on the right rolled over, shaking with noiseless laughter. For a moment we thought he was mad. Then we, too, realized the truth. The approaching column, instead of eager, bloodthirsty Germans, was a dozen harmless domestic cows, strays, doubtless, from a deserted farm. There were considerable casualties among the attacking force, and for a week at least the American section of the Foreign Legion had an ample diet.

The next night the three of us were out there again, but there was still no attack, though we had[16] rather a nasty experience all the same. We were crawling back to our trench about midnight when suddenly we found ourselves under a heavy fire. One bullet went through Thaw's kepi, but we soon saw that instead of coming from the Germans, the fire was directed from a section of our own trenches who thought there was an attack. We yelled, but they went on shooting. I was so mad that I shot back at them, but luckily there was no damage done anywhere.

Two nights later there really did come an attack in considerable force. A lot of us crawled out into a hollow in front of our trench and, starting at about forty yards' distance, we let them have it hot and heavy. We had our bayonets fixed, but they didn't get near enough to charge. I think we kept up America's reputation for marksmanship; anyway, they melted away after about half an hour, and in the morning there were several hundred dead bodies in front of the trench—they had taken the wounded back with them. The bodies were still there when I left, nearly three months later. I crawled out a night or two afterward and had a look at them, and was lucky enough to get an iron cross as a souvenir off a young officer. He was lying flat on his back with a hole between the eyes, and he had the horriblest grin human face ever wore; his lips were drawn right back off the teeth so that he seemed to be snarling like a wild beast ready to bite.

We took no prisoners at all; in fact, none of them got near enough, and our Colonel didn't think it worth while risking a counter-charge. To tell the truth, we hardly took any prisoners any time, except here and there an occasional straggler.[17] I've heard stories about the Dutchies surrendering easily, but you can take it from me that's all bunk. I used to think that one Irishman could lick seventeen Dutchmen; but, believe me, when they get that old uniform on they are a very different proposition. On one occasion a company of the Legion surrounded a Lieutenant and eleven men. They called on them to surrender, but not a bit of it. They held out all day and fought to the last gasp. At last only the Lieutenant and one soldier were left alive, both wounded. Again they refused to give in, and they had to kill the Lieutenant before the last survivor finally threw down his rifle and let them carry him off. I heard he died on the way to the station, and I'm mighty sorry; he was a white man, if he was a German.

One remarkable thing about the prisoners we did get was their exceedingly thorough knowledge of everything going on, not only of the war in general, but of all that was taking place back of our trenches. Their spy system is something marvelous. Why, they knew the exact date our reinforcements were coming on one occasion nearly a week beforehand, when the majority of our fellows hadn't even an idea there were any expected!

In some cases they got information from French villagers whom they had bought before they retreated. I saw one such case myself. We were bivouacked in a ruined village, and a lot of us were sleeping in and around a cottage that hadn't been damaged. We were downstairs, while the owner of the cottage and his wife and kid had the upstairs room. One of our boys happened to go outside in the night and, by jingo! he saw the fellow coolly signaling with a lamp behind his curtain. He went along and told the Captain, who[18] was at the schoolhouse, and they came back with a couple of under officers and arrested them red-handed. He tried to hide under the bed, and howled for mercy when they pulled him out. His wife never turned a hair—the Sergeant told me she looked as if she was glad he'd been caught. They shot him there and then in his own yard, and his wife was around in the morning just as if nothing had happened.

After that we always used to be very suspicious of any house or village that wasn't devastated when everything round had been chewed up; there was nearly always a spy concealed somewhere not far off. To give you a case in point: There was a fine big château near Craonelle, where our trenches were, that hadn't been bombarded, though they had stripped most of the furniture and stuff out of it. Well, one fine day the General commanding our section thought it would be a convenient place to hold a big pow-wow. He and his staff had only been seated at the table about ten minutes when a whacking great 310-millimeter shell burst right on top of the darned place, followed by a perfect hail of others. The General and his staff ran for their lives; luckily none of them were badly hurt, though they got the deuce of a scare.

After the bombardment some of us went along to look at what was left of the château, and—will you believe me?—we found a little old Dutch sous-off half choked in the cellar, but still hanging on to the business end of a telephone. I call that the pluckiest thing I've seen at the war, and I can tell you we were mighty sorry to have to shoot[19] him. He never turned a hair, either, and we didn't even suggest bandaging his eyes. He knew what was coming to him from the start; that he was as good as a dead man from the moment he got into the cellar. He told us he had been there a week, just waiting for some confiding bunch of French officers to come along and hold a meeting.

It's funny how some men meet death, anyway. We had one nigger prize fighter along with us named Bob Scanlon. He was the blackest coon you ever saw, until one day there came a great big "marmite" that burst almost on top of him and buried him in the mud. We dug him out, and he wasn't even scratched, but ever afterward he has been a kind of mulatto color, he was so darned scared by the narrowness of his escape.

Another boy, an Englishman, got out of the trench one day to stretch his legs, as he said he was tired of sitting still. Some one called to him to come down and not be a fool, as the Germans were keeping up a constant rifle fire, and after a minute or two he jumped back into the trench. "They didn't get you, did they?" called out some one. "Oh, no!" he answered, sitting down. Then all of a sudden he just keeled over slowly sideways without a sound, and, believe me, when they went to pick him up he was as dead as David—plugged clean through the heart. He never even felt the shock of it. If they do ever get me, that's the way I hope to die.

Bert Hall.

LATTER'S UN-FRENCH WAYS AMUSINGLY DEPICTED BY PARISIAN JOURNALIST FOR HIS READERS.

The thousands of English soldiers now on French soil are, to Frenchmen, strange, exotic creatures, the study of which is full of delightful surprises. Recently a French journalist traveled to the trenches, interviewed several specimens of the genus Tommy Atkins, and published the results in a Paris newspaper.

One Tommy was "of the species crane," with thin legs and arms like telegraph wires, by no means as taciturn as the Frenchman had believed Englishmen to be. He told the Frenchman some tall yarns.

"In one fight our battalion lost five hundred men," he vouchsafed. "One bullet, which just scratched my nose, killed my pal beside me."

Another Tommy dwelt on the awful fact that he had been "twenty-two days on water without any tea in it." He, too, had been in the thick of the fray and had killed several of the enemy with his own hand, which, recounts the Frenchman, filled him with "a gentle joy."

"Are the inhabitants of this part of France hospitable?" the journalist inquired of another Englishman.

"Awfully nice!" replied the soldier. These words the correspondent, after giving them in English, to show how strange they look, translates: "Terriblement aimable"—a combination which must appear perfectly incomprehensible to Frenchmen, who do not see how a thing can be "awful" and "nice" at the same time.

At a village in Northern France the newspaper man found some English soldiers instructing a lot of village boys in the rudiments of football.

"When the French team scored a point," he writes, "I said to one of the Englishmen: 'But aren't you ashamed to let them beat you at your own game?' To which the Briton replied: 'Ah, but we want to encourage the people of France to take up sports!'"

Football was being played wherever there were Englishmen. Often the games were between teams of English and French soldiers. Where a ball was not to be had, the players were quite content to kick about a bundle of clothes.

When not thus engaged, the English soldier finds time to enter the lists of Cupid. The French writer tells of one Tommy whom he saw "promenading proudly before the awe-struck glances of the villagers with three girls on his arm!"

"The English? Oh, they're good fellows!" remarked a villager in whose house a number of the allies of France were quartered. "They're in bed snoring every night at eight. They get together in my kitchen while I make their tea and sing sentimental songs. They're all musical." The journalist adds, in corroboration of this statement, that he himself heard Tommies "singing discordantly to the accompaniment of the cannon."

Also he found that Tommy had a sense of humor. On one occasion, he learned, a German officer came charging at the head of his men into an English trench. Leaping over the edge of it, he fell headlong into a sea of black mud, from which he picked himself up, black and dripping, and exclaimed:

"What a confounded nuisance this old war is, isn't it?"

Whereupon a Tommy, about to run his bayonet through the intruder, burst into roars of laughter, and made him a prisoner instead.

"And the Tommies are philosophers, too," writes the Frenchman. "I heard one of them say solemnly to a comrade: 'If you have any money, spend it all to-day. You may be dead to-morrow!'"

"Jean Berger, 'simple soldat' of the Second Regiment of Infantry, should, after the war, be Jean Berger, V. C. He is a Frenchman—yes; but listen to this story:

"He, a boy of about eighteen years of age, lies in hospital here, wounded badly, but not dangerously, in the side and also in the hand.

"Jean belongs to an old Alsatian family. After the war against Prussia, his grandfather refused to submit to the rule of the conquerors, and left the province to settle in Normandy. He passed his hatred of the Prussians on to his son, and the son instilled it in the four grandchildren.

"When war broke out, two of the sons were already in the army, one as an officer, and the father, calling to him the two boys who were not yet of age to be called upon by the military authorities, said to them: 'Go and enlist! And be sure to join regiments which will operate on the Alsatian frontier.'

"Jean joined the Second Regiment of Infantry, which was soon under orders for Upper Alsace. Before it arrived at the scene of operations, however, fresh instructions were received, and the Second went to operate with the English on the[23] left. He went through the terrible ordeal of the battle of the Marne, and, with his regiment, now sadly diminished in numbers, but with its dash and spirit as of old, he formed one of the stupendous line drawn up to face the Germans in their tremendously strong positions on the Aisne.

"It was during one of the almost innumerable fights which, battles in themselves, are making up that Homeric struggle of the nations on the River Aisne that the Colonel leading the gallant Second was shot down. Machine guns were raking the quickly thrown-up trenches; showers of rifle bullets were falling everywhere around. With that heroism which takes account of nothing save the object in view, Jean rushed out of his shelter to carry his Colonel to safety.

"Through a rain of leaden death he passed scatheless, reached his Colonel, and carried him to safety.

"As he was performing his glorious act, he passed an officer of the Grenadier Guards wounded severely in the leg who called out for water.

"'All right!' cried Jean. 'I'll be back in a minute or two.'

"He put the Colonel in the shelter of a trench where the Red Cross men were at work, procured some wine from one of the doctors, and set forth again to face the bullet showers. And again he went out untouched.

"Reaching the English officer, Jean held up the flask to the wounded man's lips, but, before he could drink, a bullet struck the young Frenchman in the hand, carrying away three fingers, and the[24] flask fell to the ground. Quickly, as though the flask had merely slipped out of one hand by accident, Jean picked it up with the other; and, supported by the young Frenchman, the English officer drank.

"While he was doing so, a bullet drilled Jean through the side. Yet, in spite of the intense pain, he managed to take off his knapsack, and, searching in it, discovered some food, which he gave to his English comrade.

"'But what about you, yourself?' asked the officer.

"'Oh,' replied Jean brightly, 'it's not long since I had a good meal!'

"As the Guardsman was eating, he and Jean discovered that near them was a wounded German soldier, who, recovering from the delirium of wounds, was crying out for food and drink. The Englishman, taking the flask, which had still some wine in it, and also the remainder of the food from the Frenchman's knapsack, managed, though suffering great pain, to roll himself along till he reached the spot where the German soldier lay. There, however, he found he was, by himself, too weak to give the poor fellow anything.

"So he shouted to Jean to come to his assistance, and, though movement could only be at the cost of great pain, the young Frenchman managed, too, to reach the place, and together, Englishman and Frenchman, succored the dying German. One held him up while the other poured wine between his parched lips.

"Then human nature could stand no more, and all three fell, utterly exhausted, in a heap together. All through the long night, a night continuously[25] broken by the roar of cannon, death watched over that strange sleeping place of the three comrades of three great warring nations.

"In the morning, shells bursting near them aroused the English officer and the French soldier. Their German neighbor was dead, and for a long time they could only wonder how the day of battle was going. When the forenoon was well advanced, they saw Germans advancing.

"Jean, who can speak German, called out: 'We are thirsty; please give us something to drink.' He was heard by some officer of Uhlans, who rode up, and, dismounting and covering them with his revolver, asked what was the matter.

"'We are thirsty,' replied Jean.

"The German looked at the little group. He saw his countryman lying dead with an empty flask beside him, and guessed what was the scene of comradeship and bravery which the spot had witnessed. He gave instructions to an orderly, and wine was brought and given to the two wounded men. Surely that is a scene and a deed which will wipe out many a bitter thought and memory of war!

"Just then the cannonade burst forth again with tremendous fury, and the German force which had come up had to retire. Shells were soon bursting all around, and fragments struck the English officer. He became delirious with pain, and the young Frenchman—stiff, feverish, and weak himself—saw that it was necessary to do something to bring the officer to a place where he would be safe and would receive attention.

"Jean tried to lift the Englishman, but found that he had not sufficient strength left to take his comrade on his shoulder. So, half lifting him, and dragging and rolling him at times, the gallant[26] little piou-piou brought the wounded English officer nearer and nearer to safety and help. The journey was two miles long! * * * But at last it was over."

"The two men came upon some trenches occupied by the allied forces; they were recognized and taken in charge by an officer of the English Red Cross. They had both just enough strength left to shake hands and say good-by.

"'If I live through this,' said the officer of the Guards, 'I shall do my best to get you the British Victoria Cross. I've your number and that of your regiment. God bless you, mon camarade!' And the Guardsman lost consciousness.

"Jean Berger lies in hospital here in Angers; he is expected to recover.

"That is the story; and that is why I believe that England will think that Jean Berger, 'simple soldat' of the Second Regiment of Infantry, should become Jean Berger, V. C.

"For the two nations have become one by blood shed and bravery displayed, and, in addition, a little incident which I can relate will show that there is a precedent for a union of honors as there is evidence of a complete union of hearts.

"In the British Expeditionary Force there is an English soldier, a member of a cyclist corps, who is proud to wear upon his breast the 'médaille militaire' of the French Army.

"The story of the stirring incident has been told to me by Henri Roger, a young soldier of the Fifth Infantry who saw it from the trenches and who is now lying wounded in hospital here.

"During one of the engagements last week on the River Aisne, the Fifth was holding an intrenched[27] position and was faced in the distance by a strong force of the enemy. To the right and left of the opposing forces were large clumps of trees, in one of which a force of English troops had taken up a position, a fact regarding which the Germans were unaware. In the other wood, it was soon discovered, lay a considerable body of German infantry with several machine gun sections.

"A road ran beside the wood in which the enemy lay hidden, and along it a force of French infantry was seen to be advancing. How were they to be saved from the ambush into which they were marching? That was the problem, and it was a difficult one.

"Every time the French troops in the trenches endeavored to signal to their oncoming comrades hidden German sharpshooters picked off the signalers. Soon the position seemed to be almost desperate; every moment the intrenched French soldiers expected to hear the hideous swish of the Maxims mowing down their unsuspecting comrades.

"Suddenly, however, something happened which attracted the attention of the French and German trenches. From the wood where the English lay hidden a cyclist dashed—the English, too, had seen the danger, and a cyclist had been ordered to carry a message of warning to the advancing French column, several hundreds strong.

"The cyclist bent low in his saddle and darted forward; he had not gone a hundred yards before he fell, killed by a well-aimed German bullet. A minute later another cyclist appeared, only, in a second or two, to share his comrade's fate.

"Then a third—the thing had to be done! The bullets whizzed round him, but on he went over the fire-swept zone. The Frenchmen held their breath as they watched the gallant cyclist speeding toward the French column; puffs of smoke from the wood where the Germans were showed that the sharpshooters were redoubling their efforts. But the cyclist held on and soon passed beyond some high ground where he was sheltered from the Germans, but could still be seen by the intrenched French.

"The Frenchmen could not resist a loud 'Hurrah!' when they saw the daring cyclist dismount on reaching the officer in command of the troops which he had dared death to save.

"The officer heard the message and took in the position at a glance. He gave an order or two instantly, and turned to the Englishman.

"Then there was a fine but simple battle picture which should live.

"The deed which had saved hundreds of lives was one of those which bring glory as of old back to the horror of modern warfare. Courage, and courage alone, had triumphed, unsupported by any of the murderous machinery of the armies of to-day.

"That was what the French officer recognized. He saluted the gallant fellow standing by the cycle. Then, with a simple movement, took the 'médaille militaire'—the Victoria Cross of France—from his own tunic and pinned it on the coat of the Englishman.

"'I am glad,' young Roger told me when he had finished relating the story, 'to have lived to see that deed. It was glorious!'"

TRAGEDY AND HUMOR MIXED.

Dr. Mary Merritt Crawford, who in 1907 became widely known as Brooklyn's first woman ambulance surgeon, and who has established for herself since that time an enviable reputation in the medical profession, served in the American Ambulance Hospital at Neuilly-Sur-Seine under Dr. du Bouchet and Dr. Joseph Blake. Her letters recounting her experiences among the wounded describe in the most graphic manner the terrible nature of the wounds inflicted in modern warfare.

She writes:

"We have been getting so many men with frozen feet from the trenches. They have had much snow near Ypres, they say, and the cold is terrible. Last night one poor Frenchman, who had been in the trenches for several weeks before he was wounded, was told he would be sent away to-morrow. His regiment is still up north and he would be sent there. He went almost mad with despair and tried to kill himself. This is the only case I've come directly in contact with, although I've heard of others. I wonder there aren't more. Most of the little 'piou-pious' take it with wonderful stoicism. It is fate, and they accept it, but no one wants to go back to trench fighting. I[30] don't blame them for anything they do. Human flesh and blood cannot stand it beyond a certain point."

"Two days ago we had a poor wretch admitted, who had, by actual count, 150 shrapnel wounds on him. You never saw anything so ghastly as he was. The shell had burst so close that all his hair was singed, and he was literally peppered with pieces of shell. He died to-night and I couldn't help but be glad a little, for his suffering would have been so awful and long-drawn out had he lived.

"To-day I'm dismissing one of my little zou-zous (Zouaves). He gave me one of his buttons as a souvenir, and when I gave him 2 francs he wouldn't take it until I told him to keep it as a souvenir, not as money. Then he did finally consent. He had to go out in the same dirty uniform, all blood-stained and with the bullet hole in his coat. The French Government is making the gray-blue clothes as fast as possible. I've seen a number when walking in Paris. They are the same cut as before, not as trim and compact as our service clothes, but the men inside are splendid, and as patients, ideal."

"I must write you just one story that came to me at the ambulance just before Christmas, even[31] though it is a little late. We had a French soldier brought in frightfully wounded. He came from the region around St. Mihiel. One leg had to be amputated, and, besides that, he had half a dozen other wounds. His dog came with him—hunting dog of some kind. This dog had saved his master's life. They were in the trenches together, when a shell burst in such a way as to collapse the whole trench. Every one in it was killed or buried in the collapse, and this dog dug and dug until he got his master's face free, so that he could breathe, and then he sat by him until some reinforcements came and dug them all out. Every one was dead but this man. We have both the dog and the man with us. The dog has a little house all to himself in the court, and he has blankets and lots of petting, and every day he is allowed to be with his master for a little while."

"I am very tired to-night. For some time now I've had charge of the dental cases, in addition to my regular work. Just now I have nine of them. They are the men who have fractures of the upper or lower jaws besides other wounds. The American dentists here are doing wonderful work—some of the most brilliant that is done in any department. Such deformities you never saw. The whole front of one man's face is gone, and how we are going to build him a new one I don't see, but as soon as he is ready we'll begin grafting and plastic work generally. One of these men is a black boy, the saddest figure in the whole hospital to me. His identification tag was lost in transit. He doesn't read or write or speak a word of French and none of our Senegalesi, Moroccans, Algerians, or Tunisians can talk to him. He is[32] utterly alone and lost. In the course of time the Government will place him, but it will be a long process. His wound is ghastly. The bullet hit his front teeth, but as his lips must have been drawn back in a snarl or laugh at the time, no wound appears there. The whole of his left upper and lower teeth were blown out, upper and lower jaw fractured and literally his whole left cheek blown away. You can put your fingers right into his mouth from just in front of his ear and see the inner side of his lips. It is awful taking care of him, but he is as patient as some poor dog who knows you are trying to help him.

"Next week I am going to have all my jaw cases photographed together. Their deformities are frightful, but they are cheery. One man whose whole front face is almost gone is now radiant. You see he couldn't smoke because he couldn't suck in the air, having no upper teeth or lip. Well, the dentists built him a kind of 'false front' of soft rubber, and now he is 'très gentil,' as he says, and can smoke nicely. My poor black boy is much better. Dr. Blake did a marvelous operation on his face and closed in most of the gap. Suddenly to-day we discovered he was talking French. Before he wouldn't say a word—couldn't, poor fellow!—and seemed not to understand. He says his name is Hramess ben something or other. Also he says that he fought for three days with that ghastly, blown-to-pieces face, and didn't give up until he got the bullet in his back. Did I tell you we got the bullet out, and he has it as a souvenir? He nearly died of mortification because we had thought he was a Senegalesi—he is so dark. He says he is an Algerian, and has told us his regiment.

Photo by International News Service

REMARKABLE GENERAL VIEW OF THE AUSTRIAN TRENCHES NEAR JASIONNA, SHOWING THE COVERED SHELTERS AS WELL AS OPEN DITCHES AND THE WINDING LANES OF CIRCULATION

"I must finish this letter with an attempted account of our wonderful fête de Noël, which was held here this afternoon [this letter was written on Christmas Eve], and which will terminate at midnight with a mass in the chapel. A famous opera singer is to sing Gounod's 'Ave Maria,' and I'm going to prop open my weary eyes and attend it.

"We decorated the wards and halls with holly and mistletoe, which grows in great abundance and richness here in France. We had the tree all lighted by electric bulbs downstairs, with a beautiful Santa Claus giving out gifts. All walking cases filed in and received small gifts. Many came in chairs, too. Meantime a trained chorus was walking through the halls from floor to floor, singing Christmas carols, and finally Santa Claus carried his gifts to all the bed patients. In the meanwhile the chapel was filled with soldiers and nurses, and many patriotic songs were sung. The singing made me so homesick that the tears came and I had to go back to my sick men. I bought each man a package of cigarettes and a box of matches, and I gave an enlargement of the group photo I sent you to each man in it. Also I lent them my big silk American flag to help decorate.

"Ahmed, the big Turco, who came to me with seven shrapnel wounds, but is now almost well, and who I told you is the proud husband of two wives and the father of six sons—he does not count the daughters—got hold of the flag somehow, and now it hangs proudly over his bed. By the way, he heard this morning that one of his wives, Fatima, has presented him with a son, so now he has seven. Such joy! While I was down[34] at noon buying the tobacco and a few little things for K—— I saw a little doll, chocolate in color, dressed as a baby. I bought it and put it on Ahmed's pillow when he wasn't looking. The instant he spied it he let off a yell: 'Mon fils de Tunis!' and hugged that poupée and carried on most delightfully.

"I also bought a wooden crane, whose head, neck, and feet move, for Moosa, the black Senegalesi. I told you about him a long time ago, but not by name. He is the one who said a prayer over his wound and tried to bite every one who came near him. He has become quite tame under the influence of Dr. Chauneau, who is the most charming old Frenchman imaginable. Moosa got toys exactly like a child and was just as delighted. He laughs just like a typical Southern darky does, and is altogether funny. They keep him in a red jacket and cap, and the color effect is splendid. It reminds me of chocolate and strawberry ice cream.

"That Turco, Ahmed, whom I've spoken of several times, and who is absolutely devoted to me, keeps the ward in a perfect gale. Last night the men had a regular circus there, and it was all fomented by that old rascal. I've told you how he insists on calling me 'maman' and is jealous as a spoiled child if I show any extra attention to any of the other patients in the ward. Well, last night old Ahmed was very much excited when I came in after supper. He has learned some English, which he now mixes with his French and Arabic. When I asked him what was the trouble he said: 'Spik, maman?' meaning might he talk. I graciously gave him permission, whereupon he burst into burning speech.

"He said they were all French, both Arabs and Frenchmen, and the English were their allies, weren't they? Yes. They were all wounded? Yes. All in the same cause? Yes. Some had more than one wound; he had seven? Yes. Then why weren't they all fed alike? Why should Risbourg sit in bed, never walking, never going to the table to eat—in fact, never doing any of the things they all had to do—and yet have extra feeding? You see, Risbourg is the case I told you of that nearly died of hemorrhage from a small arm wound. He had to be transfused and he is on extra feeding to make up his blood. He does eat enormously, and I love to see him do it.

"Well, I noticed that Risbourg was the only one who wasn't laughing, so I called Ahmed to attention and told him the story of the hemorrhage, whereupon he gave me a huge wink to show that it was all a joke. Risbourg didn't regard it as such, so I went over and told him that I understood, and that I wanted him to eat as much as he wanted, and that it was all right. He is really very devoted to me, and said: 'You, doctor, you understand, but all the time Ahmed tells the nurse to tell you that I eat too much.'

"By this time they were all crowding around him trying to make up, and he added: 'I know why they say such things! It is because I am of the infantry of France, and they are zouaves and tirailleurs (artillerymen) of Africa. I am alone among them.'

"Well, this was getting serious, so I made a speech and told them they were all Frenchmen and brothers, and we all 'vived la France!' Then Old Incorrigible had to pipe up again: 'Mais, maman, Risbourg said I didn't smell good. And[36] he spat when I said I was a Frenchman. And also he said he was a German.'

"I said: 'Risbourg, did you tell him you were a German?' Risbourg smiled broadly (he has one tooth gone just like Dave Warfield) and said: 'Yes, doctor, but because the Irish boy told me to. Je fais une plaisance.' So then I pointed out to him that he had had his little joke, and Ahmed had had his, when he said that he ate too much. Great applause from the Arabs, who quickly got the ethical point. So we all made up and shook hands."

The following letter, written by Prince Joachim of Prussia, the youngest son of the German Emperor, was addressed to a wounded comrade in arms by the Prince, himself at that time recovering from a wound suffered in battle. Prince Joachim, who is 24 years old, is a Lieutenant in the First Prussian Infantry Guards. In a tone of easy-going comradeship, not usually associated with the stern and imperious Hohenzollerns, the young Prince wrote to his friend and fellow-guardsman, Sergt. Karl Kummer, who had been sent, badly wounded, to the home of his sister at Teplitz:

My dear Kummer: How sincerely I rejoiced to receive your very solicitous letter! I was sure of Kummer for that; that no one could hold him back when the time came to do some thrashing! God grant that you may speedily recover, so that you can enter Potsdam, crowned with glory, admired, and envied. Who is nursing you?

The old proud First Guard Regiment has proved that it was ready to conquer and to die. Kummer, if I can in any way help you, I shall[37] gladly do so, by providing anything that will make you comfortable. You know how happy I have always been for your devotion to the service, and how we two always were for action (Schwung). I, too, am proud to have been wounded for our beloved Fatherland, and I regret only that I am not permitted to be with the regiment. Well, may God take care of you! Your devoted

Joachim of Prussia.

Interesting, too, is a letter written on Sept. 5 by Ernest II., Duke of Saxe-Altenburg, who, besides being a Lieutenant of the Prussian Guard and Chief of the Eighth Infantry Regiment of Thuringia, is Duke of Saxe-Altenburg (since 1908), of Juliers, Cleves and Berg, Engern, and Westphalia; Landgrave in Thuringia, Margrave of Misnia, Count of Henneberg, Marche, Ravensberg, and Seigneur of Ravenstein and Tonna. In 1898 the Duke married Princess Adelaide of Schaumburg-Lippe, thus uniting two great German houses. His own house was started in 1655 by Ernst, Duke of Saxe-Hildburghausen. His letter follows:

We have lived through a great deal and done a great deal, marching, marching, continually, without rest or respite. On Aug. 10 we reached Willdorf, near Jülich, by train, and from the 12th of August we marched without a single day of rest except Aug. 16, which we spent in a Belgian village near Liége, until to-day, when we reached ——. These have been army marches such as history has never known.

The weather was fine, except that a broiling heat blazed down upon us. The regiment can point back to several days' marches of fifty kilometers[38] ——. Everywhere our arrival created great amazement, in Louvain as well as in Brussels, into which the entire —— marched at one time. At first we were taken for Englishmen in almost every village, and we still are, because the inhabitants cannot realize that we have arrived so early. The Belgians, moreover, in the last few days almost invariably set fire to their own villages.

On Aug. 24 we first entered battle; I led a combined brigade consisting of ——. The regiment fought splendidly, and in spite of the gigantic strain put upon it, it is still in the best of spirits and full of the joy of battle. On that day I was for a long time in the sharpest rifle and artillery fire. Since that time there have been almost daily skirmishes and continual long marches; the enemy stalks ahead of us in seven-league boots.

On Aug. 26 we put behind us a march of exactly twenty-three hours, from 6:30 o'clock in the morning until 5:30 the next morning. With all that, I was supposed to lead my regiment across a bridge to take a position guarding a new bridge in course of construction; but the bridge, as we discovered in the nick of time, was mined; twenty minutes later it flew into the air.

After resting for three hours in a field of stubble, and after we had all eaten in common with the men in a field kitchen—as we usually do—we continued marching till dark.

The spirit among our men is excellent. To-night I am to have a real bed—the fourth, I believe, since the war began. To-day I undressed for the first time in eight days.

The battle of Lyck, the victory of which has[39] heretofore been attributed solely to Field Marshal von Hindenburg, would appear to have been won by his subordinate, Gen. Curt E. von Morgen, according to the following letter, written by Gen. von Morgen to his friend Dr. Eschenburg, Mayor of Lübeck, the city where, in peace times, Gen. von Morgen was stationed as commander of the Eighty-first Infantry Brigade. Gen. von Morgen is 56 years old. He has been in the army since 1878, when he was appointed Lieutenant in the Sixty-third Infantry Brigade. He served in the German campaign in the Kamerun in 1894 and suppressed the rebellion there in 1896 and 1897. In the latter year he served also in the Thessaly campaign, attached to the headquarters of Edhem Pasha, and in 1898 he accompanied the German Emperor on the latter's journey to Palestine. The General wrote:

Suwalki, Sept. 13.

Yesterday, after a short fight, I captured Suwalki, and I am now seated in the Government Palace. This morning I marched into the city with my division, and was greeted at the city limits by a priest and the Mayor, who offered me bread and salt. (The Russian officials had fled.) It was a glorious moment for me. I have appointed a General Staff officer as Governor of the Government of Suwalki.

To-morrow we continue to march against the enemy. The army of Rennenkampf is completely destroyed. Thirty thousand men captured. Rennenkampf and the Commander in Chief, Nicholas Nicholaiewitch, fled from Insterburg in civilian garb.

The plan of the Russians was to get us into a pot, but it was frustrated. The Twelfth Russian Army Corps, which was advancing from the south[40] to flank our army, was beaten by me on Sept. 7, at Bialla, and on Sept. 9 at Lyck and was forced back over the border.

You know that I always yearned for martial achievements. I had never expected them to be as great and glorious as these, however. I owe them in the first place to the vigorous offensive and bravery of my troops. I was probably foolhardy on Sept. 9, when I attacked a force thrice my superior in numbers, and in a fortified position; but even if I had been beaten I should have carried out the task assigned to me, for this Russian corps could no longer take part in the decisive battle. And so, in the evening, I sent in my last battalion and attacked by storm the village of Bobern, lying on the left wing. This, my last effort, must so have impressed the Russians that they began the retirement that very night. On the morning of the 10th of September the last trenches were taken.

My opponents were picked troops of the Russian Army—Finnish sharpshooters.

Health conditions with me are tolerable.

(In a later note, Gen. von Morgen added that Gen. von Hindenburg, his Commander in Chief, sent word that he would never forget the valorous deeds that had made possible these victories, and that even before the battle of Lyck the Iron Cross of the Second Class had been accorded to Gen. von Morgen. When he entered Lyck, Gen. von Morgen said, the inhabitants kissed his hands.)

A letter containing a personal touch was sent from the front in the early part of the war by Rudolf Herzog, one of Germany's greatest living poets and novelists. The letter, as originally published,[41] was in rhymed verse. The poet, who visited this country about a year ago and was fêted by Germans in all the chief cities he visited, is the author of numerous novels and romances, dating from 1893 to the present. Herzog lives in a fine old castle overlooking the Rhine, mentioned in his letter, which is as follows:

It had been a wild week. The storm-wind swept with its broom of rain. It lashed us and splashed us, thrashed noses and ears, whistled through our clothing, penetrated the pores of our skin. And in the deluge—sights that made us shudder—gaunt skeleton churches, cracked walls, smoking ruins piled hillock high; cities and villages—judged, annihilated.

Of twenty bridges, there remained but beams rolled up by the waters—and yawning gaps.

Not a thought remained for the distant homeland and dear ones far away; the only thought, by day and by night: On to the enemy, come what may! No mind intent on any other goal. No time to lose! No time to lose! Haste! Haste!

And forward and backward and criss-cross through the gray Ardennes the Chief Lieutenant and I, racing day after day.

Captain of the Guard! You? From the Staff Headquarters?

He shouts my name as he approaches:

"Congratulations! Congratulations!"

And he waves a paper above a hundred heads.

"Telegram from home! Make way, there, you rascals! At the home of our poet—I've just learned it—a little war girl has arrived!"

I hold the paper in my outstretched hand. Has the sun broken suddenly into the enemy's land? Light and life on all the ruins? * * *

Springtime scatters the shuddering Autumn dreariness.

My little girl! I have a little girl in my home! * * *

You bring back my smile to me in a heavy time. * * *

I gaze up at the sky and am silent. And far and near the busy, noisy swarm of workers is silent. Every one looks up, seeking some point in the far sky. Officers and men, for a single heart-throb, listen as to a distant song from the lips of children and from a mother's lips, stand there and smile around me in blissful pensiveness, as if there were no longer an enemy. Every one seems to feel the sun, the sun of olden happiness.

And yet it had merely chanced that on the German Rhine, in an old castle lost amid trees, a dear little German girl was born.

The following is written from the front by Corp. T. Trainor:

We have had German cavalry thrown at us six times in the last four hours, and each time it has been a different body, so that they must have plenty to spare. There is no eight hours for work, eight hours for sleep, and eight hours for play with us, whatever the Germans may do.

The strain is beginning to tell on them more than on us, and you can see by the weary faces and trembling hands that they are beginning to break down.

One prisoner taken by the French near Courtrai sobbed for an hour as though his heart were broken, his nerves were so much shaken by what he had been through. The French are fighting[43] hard all round us with a grit and go that will carry them through.

Have you ever seen a little man fighting a great, big, hulking giant who keeps on forcing the little chap about the place until the giant tires himself out, and then the little one, who has kept his wind, knocks him over? That's how the fighting here strikes me.

We are dancing about round the big German Army, but our turn will come. Our commanders know their business, and we shall come out on top all right.

Sergt. Major McDermott does not write under ideal literary conditions, but his style is none the worse for the inspiration furnished by the shrieking shell.

I am writing to you with the enemy's shells bursting and screaming overhead; but God knows when it will be posted, if at all.

We are waiting for something to turn up to be shot at, but up to now, though their artillery has been making a fiendish row all along our front, we haven't seen as much as a mosquito's eyelash to shoot at. That's why I am able to write, and some of us are able to take a bit of rest while the others keep "dick."

There is a fine German airship hanging around like a great blue bottle up in the sky, and now and then our gunners are trying to bring it down, but they haven't done it yet.

It's the quantity, not the quality of the German shells that is having effect on us, and it's not so much the actual damage to life as the nerve-racking row that counts for so much.

Townsmen who are used to the noise and roar of streets can stand it better than the countrymen, and I think you will find that by far the fittest men[44] are those of regiments mainly recruited in the big cities.

A London lad near me says it's no worse than the roar of motor 'buses and other traffic in the city on a busy day.

The Gaelic spirit has not deserted Sergt. T. Cahill under fire. He writes:

The Red Cross girleens with their purty faces and their sweet ways are as good men as most of us, and better than some of us. They are not supposed to venture into the firing line at all, but they get there all the same, and devil a one of us durst turn them away.

Mike Clancy is that droll with his larking and bamboozling the Germans that he makes us nearly split our sides laughing at him and his ways.

Yesterday he got a stick and put a cap on it so that it peeped up above the trench just like a man, and then the Germans kept shooting away at it until they must have used up tons of ammunition.

But Mike Clancy was not the only practical joker in the trenches, as the following from a wounded soldier shows:

Our men have just had their papers from home, and have noted, among other things, that "Business as Usual" is the motto of patriotic shopkeepers.

In last week's hard fighting the Wiltshires, holding an exposed position, ran out of ammunition, and had to suspend firing until a party brought fresh supplies across the open under a heavy fire.

Then the wag of the regiment, a Cockney, produced a biscuit tin with "Business as Usual"[45] crudely printed on it, and set it up before the trenches as a hint to the Germans that the fight could now be resumed on more equal terms.

Finally the tin had to be taken in because it was proving such a good target for the German riflemen, but the joker was struck twice in rescuing it.

A wounded private of the Buffs relates how an infantryman got temporarily separated from his regiment at Mons, and lay concealed in a trench while the Germans prowled around.

Just when he thought they had left him for good ten troopers left their horses at a distance and came forward on foot to the trench.

The hidden infantryman waited until they were half way up the slope, and then sprang out of his hiding place with a cry of "Now, lads, give them hell!" Without waiting to see the "lads" the Germans took to their heels.

Why Highland kilts are not the ideal uniform for modern warfare is concisely summed up by Private Barry:

Most of the Highlanders are hit in the legs. * * * It is because of tartan trews and hose, which are more visible at a distance than any other part of their dress. Bare calves also show up in sunlight.

Private McGlade, writing to his aged mother in County Monaghan, bears witness to the oft-made assertion that the German soldiers object to a bayonet charge:

I am out of it with a whole skin, though we were all beat up, as you might expect after four days of the hardest soldiering you ever dreamed of. We had our share of the fighting, and I am glad[46] to say we accounted for our share of the German trash, who are a poor lot when it comes to a good, square ruction in the open.

We tried hard to get at them many times, but they never would wait for us when they saw the bright bits of steel at the business end of our rifles.

Some of our finest lads are now sleeping their last sleep in Belgium, but, mother dear, you can take your son's word for it that for every son of Ireland who will never come back there are at least three Germans who will never be heard of again.

Before leaving Belgium we arranged with a priest to have masses said for the souls of our dead chums, and we scraped together what odd money we had, but his Reverence wouldn't hear of it, taking our money for prayers for the relief of the brave lads who had died so far from the old land to rid Belgian soil of the unmannerly German scrubs.

Some of the Germans don't understand why Irishmen should fight so hard for England, but that just shows how little they know about us.

Seven British soldiers who after the fighting round Mons last week became detached from their regiments and got safely through the German lines arrived in Folkestone to-day from Boulogne. They belonged to the Irish Rifles, Royal Scots, Somerset Light Infantry, Middlesex and Enniskillen Fusiliers, and presented a bedraggled appearance, wearing old garments given them by the French to aid their disguise.

One of the seven, a Londoner, described the fight his regiment had with the Germans at a village near Maubeuge.

The British forces were greatly outnumbered[47] by the Germans, but held their ground for twenty-four hours, inflicting very heavy loss on the enemy, although suffering severely itself.

He declared that the Germans held women up in front of them when attacking. "It was worse than savage warfare."

Paddy, an Irishman, stated that the soldiers got little or no food during the fighting. "When we got our bacon cooking the Germans attacked us."

A Scotsman of the party said he saw a hospital flying the Red Cross near Mons destroyed by shrapnel. "When we were ordered to retire," he continued, "we did so very reluctantly. But we did not swear. Things are so serious there, it makes you feel religious."

Equally interesting are some of the letters from men with the fleet. Tom Thorne, writing to his mother in Sussex, says:

Before we started fighting we were all very nervous, but after we joined in we were all happy and most of us laughing till it was finished. Then we all sobbed and cried.

Even if I never come back, don't think I've died a painful death. Everything yesterday was as quick as lightning.

We were in action on Friday morning off Heligoland. I had a piece of shell as big as the palm of my hand go through my trousers, and as my trouser legs were blowing in the breeze I think I was very lucky.

A gunroom officer in a battle cruiser writes:

The particular ship we were engaged with was in a pitiful plight when we had finished with her—her[48] funnels shot away, masts tottering, great gaps of daylight in her sides, smoke and flame belching from her everywhere. She speedily heeled over and sank like a stone, stern first. So far as is known, none of her crew was saved. She was game to the last, let it be said, her flag flying till she sank, her guns barking till they could bark no more.

Although we ourselves suffered no loss, we had some very narrow escapes. Three torpedoes were observed to pass us, one within a few feet. Four-inch shells, too, fell short or were ahead of us. The sea was alive with the enemy's submarines, which, however, did us no damage. They should not be underrated, these Germans. That cruiser did not think, apparently, of surrender.

What naval warfare seems like to the "black squad" imprisoned in the engineroom is described by an engineer of the Laurel, who went through the "scrap" off Heligoland. Writing to his wife he says:

It was a terribly anxious time for us, I can tell you, as we stayed down there keeping the engines going at their top speed in order to cut off the Germans from their fleet. We could hear the awful din around and the scampering of the tars on deck as they rushed about from point to point, and we knew what was to the fore when we caught odd glimpses of the stretcher bearers with their ghastly burdens.

We heard the shells crashing against the sides of the ship or shrieking overhead as they passed harmlessly into the water, and we knew that at any moment one might strike us in a vital part and send us below for good.

It is ten times harder on the men whose duty is in the engineroom than for those on deck taking[49] part in the fighting, for they, at least, have the excitement of the fight, and if the ship is struck they have more than a sporting chance of escape. We have none.

The most dramatic letters come from the French. On one of the fields of battle, when the Red Cross soldiers were collecting the wounded after a heavy engagement, there was found a half sheet of notepaper, on which was written a message for a woman, of which this is the translation:

Sweetheart: Fate in this present war has treated us more cruelly than many others. If I have not lived to create for you the happiness of which both our hearts dreamed, remember that my sole wish is now that you should be happy. Forget me. Create for yourself some happy home that may restore to you some of the greater pleasures of life. For myself, I shall have died happy in the thought of your love. My last thought has been for you and for those I leave at home. Accept this, the last kiss, from him who loved you.

Writing from a fortress on the frontier, a French officer says the Colonel in command was asked to send a hundred men to stiffen some reservist artillery in the middle of France, far away from the war area. He called for volunteers. "Some of you who have got wives and children, or old mothers, fall out," he said. Not a man stirred. "Come, come," the Colonel went on. "No one will dream of saying you funked. Nothing of that kind. Fall out!" Again the ranks were unbroken. The Colonel blew his nose violently. He tried to speak severely, but his voice failed him. He fried to frown, but somehow it[50] turned into a smile. "Very well," he said, "you must draw lots." And that was what they did.

Twenty-two grandsons and great-grandsons of Queen Victoria are under arms in the war, and all but five of them are fighting with the Germans.

The Cunard liners Saxonia and Ivernia were converted into prison ships by the British. The German prisoners were delighted with the transfer to the roomy cabins, where they could keep warm and dry in contrast to the unfavorable conditions under which they lived in the camps at the Newbury Race Course.

Reindeer meat and lamb, imported from Iceland, found their way into the markets of Berlin since the war began. The reindeer meat is a novelty and the supply is plentiful. The supply of game in the markets of Berlin ran short long before, since hunting had almost ceased. Poultry in the markets was still in great quantities, although eggs were not so plentiful, as the supply usually comes from Galicia, which was then overrun by the Russians.

A sale of small Belgian flags in Paris and throughout France brought about $40,000 for the benefit of the Belgian refugees. The sale was prolonged in the outlying provinces. There was every manifestation of enthusiasm.

Once gay Ostend is desolated. The city lives in an atmosphere of fear. The spectre of famine is[51] continually before the inhabitants, who subsist on wounded, emaciated horses purchased at $4 a head from the Germans. They are the only meat the people can buy. There are no vegetables, and scarcely any coffee and no tea. Many convicts from prisons in Germany, distinguished by their shorn heads, are employed in grave digging work about the city.

The hygiene committee of the French Chamber of Deputies has won over the veto of General Joffre that a number of committeemen be allowed to inspect the hospitals at the front with a view to certain reforms. General Joffre opposed the proposal. The Minister of War, however, agreed that twelve of the committee should go on the inspection trip.

That the battle of Crouy was one of the bloodiest engagements of the war is demonstrated by the stories told by wounded soldiers reaching Paris to-day. An officer gives this thrilling account of the affray:

"After our successful advantage the Germans counter attacked with fearful violence. How strongly they were reinforced is shown by the fact that they were 40,000 against less than 10,000 French. They first drove us from Vregny to Crouy, then, because further reinforcements were still reaching them, we were compelled to quit Crouy, Bucy, Moncel, Sainte Marguerite and Missy.

"These attacks certainly hit us hard, but our losses are not comparable with those of the Germans, for we killed an inconceivable number of them. A battery covering our retreat alone annihilated two battalions of Germans who advanced,[52] as usual, in a mass. We could not resist, so we left a small rearguard force with the mission to hold on to the last man so that the bulk of our 10,000 men could recross the Aisne.

"This force took cover behind an old wall and belched fire on the advancing Germans until its ammunition was exhausted. The Germans managed to reach the other side of the wall, and even grasped the barrels of our rifles thrust through gaps. 'Surrender!' they cried. 'We won't harm you.' But we continued mowing them down with six mitrailleuses. The carnage was frightful, and that moment a shell splinter struck me.

"A shell fire directed on our positions in the Valley de Chivres was fearful. Those of our troops who escaped said it was a continuous rain of Jack Johnsons, which are impossible to dodge.

"Next day the Germans tried to pursue us across the Aisne, but our artillery repulsed two determined attacks, decimating several regiments, which were forced to retreat to Moncel."

It is a curious thing that shell explosions always make hens lay. Just whether it's shock or not no one is able to say as yet, but as soon as the soldiers see a stray chicken after a fusillade they make a dash for it in hopes of finding an egg. Some of the soldiers are suggesting running a poultry farm on the explosion system.

Petrograd reports that the German officers in command of the Turks induced the temperate Osmanlis to drink cognac before going into battle. Russian soldiers assert that many Turks fell from dizziness before reaching the Russian bayonets. So unused are many of the Turks to alcohol that[53] small quantities of the cognac completely befuddled them.

Kaiser Wilhelm has presented the Turkish Government with a series of motion picture films of the Germans in battle along the Western front. These pictures will be reproduced in Constantinople in public and are hoped to be a stimulant to enthusiasm in the Turkish capital.

Switzerland's neutrality has thus far cost her $22,000,000. This includes the expenses of mobilization along the frontiers and other purely military expenditures. It is an enormous sacrifice for the Swiss people, but the spirit in which it is being borne is the most striking proof of the determination of the country to remain neutral.

Efforts are being made by the Washington Humane Society to have laws enacted prohibiting the exportation of horses and mules to the war. The life of a horse or mule at the front in Europe varies between three days and three weeks. The life of the beast depends upon the service to which it is put.

Eight Belgian heroes prevented the Germans from piercing a weak spot in the Allies' line near Dixmude. A patrol of eight Belgians with a machine gun saw a column of Germans advancing. The patrol took shelter in a deserted farm house. Not until the German column was one hundred yards away did the Belgians open fire. Then the machine gun shot a spray of death into the column, whose front rank just seemed to melt to the[54] ground. The Germans pressed on bravely, their officers urging them with hoarse cries. But discipline had to bow to death, and the first rush was stayed. Behind their rough shelter the Belgians fired steadily, though outnumbered twenty to one. For two hours the unequal fight continued, and still the Belgians continued to pick off individual Germans or melted down any threatening rush with a shower of flame and death from the machine guns. When relief finally came three of the Belgians were dead and the other five desperately wounded.