The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Shogun's Daughter, by Robert Ames Bennet This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Shogun's Daughter Author: Robert Ames Bennet Illustrator: W. D. Goldbeck Release Date: March 31, 2015 [EBook #48615] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SHOGUN'S DAUGHTER *** Produced by Shaun Pinder, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

A Volunteer with Pike: The True Narrative of One Dr. John Robinson and his Love for the Fair Señorita Vallois. Illustrated in color by Charlotte Weber-Ditzler.

Crown 8vo $1.50

Into the Primitive. Illustrated in color by Allen T. True.

Third edition. Crown 8vo $150

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

CHICAGO

THE SHOGUN’S

DAUGHTER

BY

ROBERT AMES BENNET

Author of “For the White Christ,”

“Into the Primitive,” etc.

WITH 5 PICTURES IN COLOR

BY W. D. GOLDBECK

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1910

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1910

Published October 1, 1910

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London, England

THE·PLIMPTON·PRESS

[W·D·O]

NORWOOD·MASS·U·S·A

To

MY WIFE

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Eastern Seas | 1 |

| II | In Kagoshima Bay | 9 |

| III | The Gentleman with Two Swords | 22 |

| IV | Yoritomo’s Betrothed | 38 |

| V | The Coasts of Nippon | 44 |

| VI | A Wild Night | 55 |

| VII | On the Tokaido | 71 |

| VIII | The Geisha | 86 |

| IX | Nippon’s Greetings | 102 |

| X | The Princess Azai | 117 |

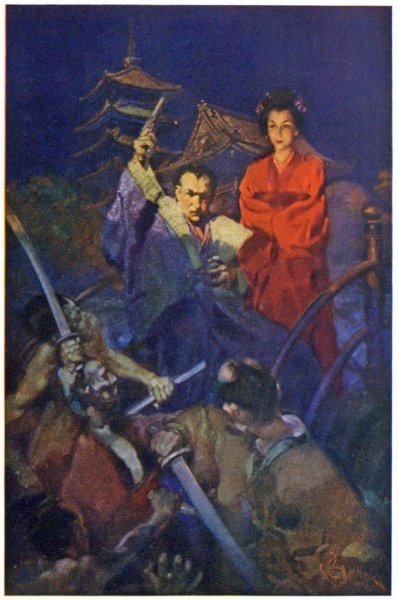

| XI | Rout of the Ronins | 129 |

| XII | Escort to the Princess | 143 |

| XIII | The Prince of Owari | 154 |

| XIV | Before the Shogun | 168 |

| XV | Requital | 182 |

| XVI | Mito Strikes | 194 |

| XVII | In the Pit of Torment | 204 |

| XVIII | The Shadow of Death | 220 |

| XIX | The Garden of Azai | 235 |

| XX | Love Laughs at Locksmiths | 250 |

| XXI | Jarring Counsellors | 262 |

| XXII | Tea with the Tycoon | 280 |

| XXIII | Lessons and Love | 296 |

| XXIV | Ensnared | 310 |

| XXV | Hara-Kiri | 320 |

| XXVI | Hovering Hawks | 330 |

| XXVII | Son by Adoption | 344 |

| XXVIII | High Treason | 352 |

| XXIX | Intrigue | 366 |

| XXX | My Wedding Eve | 373 |

| XXXI | In the Power of Mito | 387 |

| XXXII | Led Out to Execution | 398 |

| XXXIII | Bared Blades | 407 |

| XXXIV | Conclusion | 418 |

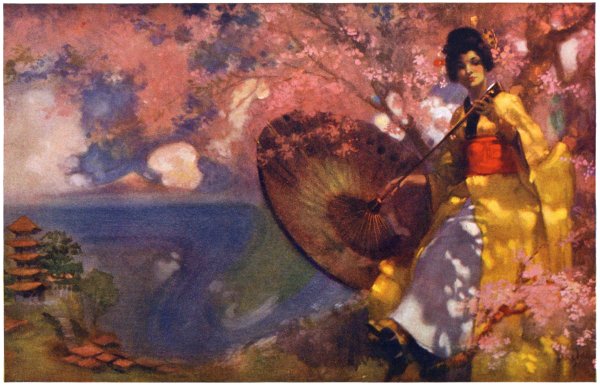

| The Princess Azai | Frontispiece |

| Page | |

| She dropped her blue robe from her graceful shoulders | 98 |

| A row of little pearls gleamed between her smiling red lips | 126 |

| “Is this loyal service?” she asked | 246 |

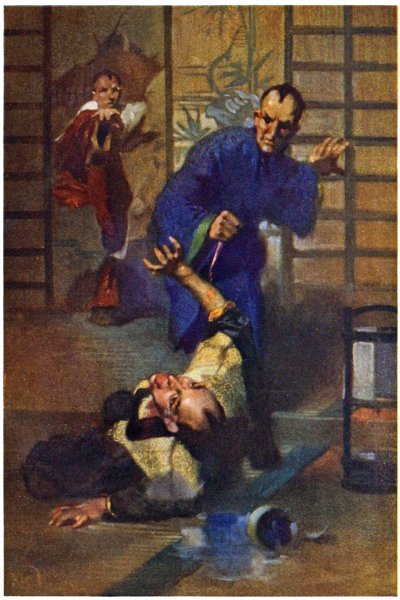

| Gengo struck with deadly aim | 360 |

My first cruise as a midshipman in the navy of the United States began a short month too late for me to share in the honors of the Mexican War. In other words, I came in at the foot of the service, with all the grades above me fresh-stocked with comparatively young and vigorous officers. As a consequence, the rate of promotion was so slow that the Summer of 1851 found me, at the age of twenty-four, still a middie, with my lieutenancy ever receding, like a will-o’-the-wisp, into the future.

Had I chosen a naval career through necessity, I might have continued to endure. But to the equal though younger heir of one of the largest plantations in South Carolina, the pay of even a post captain would have been of small concern. It is, therefore, hardly necessary to add that I had been lured into the service by the hope of winning fame and glory.

2 That my choice should have fallen upon the navy rather than the army may have been due to the impulse of heredity. According to family traditions and records, one of my ancestors was the famous English seaman Will Adams, who served Queen Elizabeth in the glorious fight against the Spanish Armada and afterwards piloted a Dutch ship through the dangerous Straits of Magellan and across the vast unchartered expanse of the Pacific to the mysterious island empire, then known as Cipango or Zipangu.

History itself verifies that wonderful voyage and the still more wonderful fact of my ancestor’s life among the Japanese as one of the nobles and chief counsellors of the great Emperor Iyeyasu. So highly was the advice of the bold Englishman esteemed by the Emperor that he was never permitted to return home. For many years he dwelt honorably among that most peculiar of Oriental peoples, aiding freely the few English and Dutch who ventured into the remote Eastern seas. He had aided even the fanatical Portuguese and Spaniards, who, upon his arrival, had sought to have him and his handful of sick and starving shipmates executed as pirates. So it was he lived and died a Japanese noble, and was buried with all honor.

With the blood of such a man in my veins, it is not strange that I turned to the sea. Yet it is3 no less strange that three years in the service should bring me to an utter weariness of the dull naval routine. Notable as were the achievements of our navy throughout the world in respect to exploration and other peaceful triumphs, it has ever surprised me that in the absence of war and promotion I should have lingered so long in my inferior position.

In war the humiliation of servitude to seniority may be thrust from thought by the hope of winning superior rank through merit. Deprived of this opportunity, I could not but chafe under my galling subjection to the commands of men never more than my equals in social rank and far too often my inferiors.

The climax came after a year on the China Station, to which I had obtained an assignment in the hope of renewed action against the arrogant Celestials. Disappointed in this, and depressed by a severe spell of fever contracted at Honkong, I resigned the service at Shanghai, and took passage for New York, by way of San Francisco and the Horn, on the American clipper Sea Flight.

We cleared for the Sandwich Islands August the twenty-first, 1851. The second noon found us safe across the treacherous bars of the Yangtse-Kiang and headed out across the Eastern Sea, the southwest monsoon bowling us along at a round twelve knots.

4 The double lassitude of my convalescence and the season had rendered me too indifferent to inquire about my fellow-passengers. We were well under way before I learned that, aside from the officers and crew, I was the only person aboard ship. In view of the voyage of from five to six months’ duration which lay before me, this discovery roused me to the point of observing the characters of the skipper and his mates. Much to my chagrin, I found that all were Yankees of the most pronounced nasal type.

As a late naval officer no less than as a Southern gentleman, I could not humble myself to social intercourse with the bucko mates. Fortunately Captain Downing was somewhat less unbearable, and had the good taste to share my interest in the mysterious islands of Japan, as well as my detestation of China. Even as the low, dreary coast of Kiangsu faded from view in our wake, we attained to a cordial exchange of congratulations over the fact that we were at last quit of the filth and fantasies of the Celestial Empire.

As we wheeled about from the last glance astern, Downing pointed over the side with a jerk of his thumb. “Look at that dirty flood, Mr. Adams. Just like a China river to try to turn the whole sea China yellow! Conceited as John Chinaman himself!”

“Give the devil his due,” I drawled. “Biggest5 nation on earth, and close upon the biggest river.”

“Aye, and thank Providence, every last one of their three hundred million pigtails lie abaft my taffrail, and every drop of that foul flood soon to lose itself in clean blue water!” He stared ahead, combing his fingers through his bushy whiskers, his shrewd eyes twinkling with satisfaction. “Aye! blue water—the whole breadth of the Pacific before us, and Asia astern.”

“Not all Asia,” I corrected. “We have yet to clear the Loo Choos.”

“The Loo Choos,” he repeated. “Queer people, I guess. They are said to be a kind of Chinamen.”

“It’s hard to tell,” I replied. “They may be Chinese. Yet some say the islands are subject to Japan.”

“To Japan? Then they’ve got good reason to be queer!” He paced across the deck and back, his jaw set and eyes keen with sudden resolve. “By ginger, I’ll do it this passage, sir, danged if I won’t! I’ve been wanting to see something of the Japanese islands ever since I came out to the China seas as a cabin-boy, and that’s fifty years gone.”

“You’d run out of your course for a glimpse of the Japanese coast?” I exclaimed, no less incredulous than delighted.

“More than a glimpse, Mr. Adams. Van6 Diemen Strait is a shorter course than the Loo Choo passage, and with this weather—”

“Midst of the typhoon season,” I cut in with purposeful superciliousness of tone.

The captain of a clipper is as sensitive to any aspersions on his seamanship as the grayest master of navigation in the navy. Downing bit snappily. “Typhoon be damned! I navigated a whaler through uncharted seas twenty odd years, and never lost my ship. I’ll take the Sea Flight through Van Diemen Strait, blow or calm, sir.”

“No doubt,” I murmured with ambiguous suavity.

He scowled, puzzled at my smile. “You naval officers! Commanded my first ship before you were born—before I had need of a razor. What’s more, I’m third owner in this clipper, and I’ve discretion over my course. The skipper who carries the first cargo out of a Japanese port is going to get the cream, and I’ve an idee the Japs are loosening up a bit. I’m going to put into Kagoshima Bay, where the old Morrison tried to land the castaway Japs in ’thirty-seven.”

“She was fired upon most savagely by the soldiers of the Prince of Satsuma,” I replied. “Why not try Nagasaki?”

“Nagasaki?—Deshima!” he rumbled. “I’m7 no Dutchman or yellow Chinee, to be treated like a dog. What’s more, it’s too far up the west coast. No! I’ll chance Kagoshima. That Satsuma king or mandarin, whatever he is, may have changed his mind since the Morrison, or there may be a new one now, with more liberal idees.”

“Since you’re resolved upon it, skipper, I must confess I have reasons of my own to be pleased with your plan,” I said, and at his interested glance, I told him somewhat in detail of my daring ancestor Will Adams, the first Englishman ever to reach the Land of the Rising Sun and the only European ever made a Japanese noble.

“H’m. Married a Japanese wife, and left children by her,” commented Downing, and he grinned broadly. “I must ask leave for you to land and look up your heathen kin.”

“You forget yourself, sir,” I caught him up. “Be kind enough hereafter to refrain from impertinence when speaking of persons related to me.”

He stared in astonishment. “Well, I’ll be durned! Two hundred years and more since your forefather died, you said—”

“None the less,” I insisted sharply, “my cousins are my cousins, sir. If there are any of my ancestor’s Japanese descendants now living, they are related to me, however remote may be the8 degree. Therefore they are entitled to be spoken of with respect.”

“Well, I’ll swan!” he muttered. “No offence, Mr. Adams.”

I bowed my acceptance of his uncouth apology, but maintained my dignity. “As I have said, sir, my ancestor was ennobled by the great Emperor Iyeyasu. Heathen or not, rest assured that his Japanese descendants, if any survive, are at the least gentlefolk.”

“No doubt, no doubt,” he grunted. “You’ll soon have a chance to inquire. I’m going to take my ship up Kagoshima Bay, fog, shine, or blow.”

He turned on his heel, and ordered the helmsman to put the ship’s head due east. I went below in a glow of pleasant anticipation. There was no mistaking the look in Downing’s face. Nothing could now shake his stubborn resolve. I was to see the mysterious Cipango of Marco Polo and Mendez Pinto, the Iappan of my ancestor,—the land that for almost two and a half centuries had shut itself in from all communication with the wide world other than through the severely restricted trade with the Dutch and Chinese at Nagasaki.

Dawn of the third day found us ten miles off the north shore of the small volcanic island that stands second in the entrance to Van Diemen Strait. The lurid glare reflected from its crater into the ascending clouds of smoke had served as a beacon during the last hours of darkness. Daylight confirmed the calculations of our position by the sight of the beautiful smoking cone of Horner’s Peak, lying twenty-five or thirty miles to the northeast on the southern extremity of Satsuma, and the rugged peninsula of Osumi, ending in the sharp point of Cape Satanomi, a like distance to the eastward.

The moment our landfall was clear in the growing light, the Sea Flight came around and headed straight between the two peninsulas. A run of three hours before the monsoon, over the bluest of white-capped seas, brought us well up into the entrance of Kagoshima Bay, with Horner’s Peak a few miles off on the port beam, and the bold, verdant hills of Osumi to starboard. Close along each shore the sea broke on half-10submerged rocks, but the broad channel showed no signs of reefs or shoals, and Downing stood boldly in, without shortening sail.

Having none of the responsibility of navigating the ship, I was able to loll upon the rail and enjoy to the utmost the magnificent scenery of the bay. On either shore the mountainous coast trended off to the northward, an emerald setting to the sapphire bay, with the lofty broken peak of a smoking volcano towering precipitously at the head of the thirty-mile stretch of land-girded waters. Far inland still loftier peaks cast dim outlines through the summery haze.

Every valley and sheltered mountain-side along the bay showed heavy growths of pines and other trees, among which were scattered groups of straw-thatched, high-peaked cottages. Many of the slopes were under cultivation and terraced far up towards the crests, while every cove was fringed with the straggling hovels of a fishing village.

In every direction the bay was dotted with the square white sails of fishing smacks and small junks,—vessels that differed from Chinese craft in the absence of bamboo ribs to the sails and still more in the presence of the yawning port which gaped in their sterns. I concluded that this extraordinary build was due to the Japanese policy of keeping the population at home, for11 certainly none but a madman could have dreamed of undertaking any other than a coastwise cruise in one of these unseaworthy vessels. Another peculiarity was that not one of the craft showed a trace of paint.

The majestic apparition of the Sea Flight in their secluded haven seemed to fill the Japanese sailors with wildest panic. One and all, their craft scattered before her like flocks of startled waterfowl, for the most part running inshore for shelter at the nearest villages or behind the verdant islets that rose here and there above the rippling blue waters. A few stood up the bay, probably to spread the alarm, but the clipper easily overhauled and passed the swiftest.

By noon, though the wind had fallen to a light breeze, we had sailed some thirty miles up the bay and were within three miles of the volcano, which stood out, apparently on an island, with a deep inlet running in on either side. On the Satsuma shore, across the mouth of the western inlet, our glasses had long since brought to view the gray expanse of Kagoshima, rising to a walled hill crowned with large buildings, whose quaint, curved roofs and many-storied pagoda towers recalled China.

All along the bay shores, great bells were booming the alarm, and crowds of people rushed about the villages in wild disorder, while the junks and smacks12 continued to fly before us as if we were pirates. Smiling grimly at the commotion raised by his daring venture, Downing shortened sail and stood into the opening of the western inlet until we could make out clearly with the naked eye the general features of the city and its citadel.

So far the lead had given us from forty to eighty fathoms. When we found thirty fathoms with good holding ground, Downing decided that caution was the better part of curiosity, and gave orders to let go anchor. Hardly had we swung about to our cable when a large half-decked clipper-built boat bore down upon us from the city with the boldness of a hawk swooping upon a swan. The little craft was driven by the long sculls of a number of naked brown oarsmen in the stern. Amidships and forward swarmed twenty or thirty soldiers, clad in fantastic armor of brass and lacquered leather, and bearing antique muskets and matchlocks.

In the stern of the guard-boat fluttered a small flag with the design of a circled white cross, while from the staff on the prow a great tassel of silky filaments trailed down almost to the surface of the water. Beneath the tassel stood two men with robes of gray silk and mushroom-shaped hats tied to their chins with bows of ribbon. I should have taken them for priests had not each carried13 a brace of swords thrust horizontally through his sash-like belt.

At a sign from the older of these officers, the boat drove in alongside the starboard quarter. As Downing and I stepped to the rail and gazed down upon them, the younger officer flung aboard a bamboo stick that had been cleft at one end to hold a piece of folded paper. Downing spun about to pick up the message. But I, calling to mind the reputed courtesy of the Japanese, was seized with a whim to test their reputation in this respect, and bowed profoundly to the officers, addressing them with Oriental gravity: “Gentlemen, permit me to request you to come aboard and favor me with your company at dinner.”

Together the two swordsmen returned my bow, slipping their hands down their thighs to their knees and bending until their backs were horizontal. After a marked pause they straightened, their olive faces aglow with polite smiles, and the younger man astonished me by replying in distinct though oddly accented English: “Honorable sir, thangs, no. To-morrow, yes. You wait to-morrow?”

Before I could answer, his companion muttered what seemed to be a grave remonstrance. He was replying in tones as liquid and musical as Italian when Downing swung back beside me.

14 “Look here, Mr. Adams,” he grumbled, thrusting out a sheet of crinkly yellow paper. “Just like their heathen impudence!”

I hastened to read the message, which was written, in the Chinese manner, with an ink-brush instead of a quill, but the words were in English, as legible and brief as they were to the point:

“You bring our people shipwrecked? Yes? Take them Nagasaki. You come trade? Yes? Go. Cannon fire.”

Downing scowled upon the bizarre soldiers and their commanders with contemptuous disapproval, and pointing to the message, bawled roughly: “Ahoy, there, you yellow heathen, this ain’t any way to treat a peaceful merchantman. Must take us for pirates.”

The younger officer looked up, with his polite smile, and asked in a placid tone: “You come why?”

“Trade, of course. What else d’ you reckon?”

“Trade? You go Nagasaki. Thangs.”

“Nagasaki!” growled Downing. “Take me for a Dutchman? You put back, fast as you can paddle, and tell your mandarin, or whatever he calls himself, that here’s an American clipper lying in his harbor, ready to buy or barter for tea, chinaware, or silks.”

“Thangs. You go Nagasaki—you go Nagasaki,”15 reiterated the officer, smiling more politely than ever, and signing us down the bay with a graceful wave of his small fan. “No get things aboard. You go Nagasaki. Ships no can load.”

“That’s easy cured,” replied Downing. “Tell your mandarin I’ll get under way first thing to-morrow and run in close as our draught will let us. If we can’t come ’longside his bund, we can lighter cargo in sampans.”

The officers exchanged quick glances, and the younger one repeated his affable order with unshaken placidity: “You go Nagasaki. Thangs.”

Without waiting for further words, both bowed, and the older one signed to the scullers with his fan. The men thrust off and brought their graceful craft about with admirable dexterity. Again their officers bent low in response to my parting bow, and the long sculls sent the boat skimming cityward, across the sparkling water, at racing speed.

Downing nodded after them and permitted his hard mouth to relax in a half grin. “That’s the way to talk to heathen, Mr. Adams. No begging favors; just straight-for’a’d offer to trade. You’ll see to-morrow, sir.”

At this moment the impatient steward announced dinner, and we hastened below with appetites sharpened by pleasant anticipations. The more we discussed the courteous speech16 and manners of our visitors the more we became convinced that they had meant nothing by their notice to leave, but would soon return with a cordial assent to our proposals.

To our surprise, the afternoon wore away without a second visit either from the guard-boat or any other craft. Junk after junk and scores of fishing smacks sailed past us cityward, but all alike held off beyond hail. Still more noteworthy was the fact that no vessel came out of the inlet or across from the city.

At last, shortly before sunset, we sighted four guard-boats, armed with swivels, bearing down upon us from the nearest point of the city. Our first thought was that we were to be attacked as wantonly as had been the Morrison and other ships that had sought to open communication with the Japanese. But at half a cable’s length they veered to starboard and began to circle around the Sea Flight in line ahead, forming a cordon. It was not difficult to divine that their purpose was to prevent us from making any attempt at landing.

That they intended to maintain their patrol throughout the night became evident to me when, after lingering over two bottles of my choice Madeira with the skipper, I withdrew from the supper-table to my stateroom. The cabin air being close and sweltering and my blood somewhat17 heated from the wine, I turned down my reading lamp and leaned out one of my stern windows. Refreshed by the cool puffs of the night breeze that came eddying around the ship’s quarters as she rocked gently on a slight swell, I soon began to heed my surroundings with all the alertness of a sailor in a hostile port.

The night was moonless and partly overcast, but the pitch darkness served only to make clearer the beacon fires which blazed along the coast so far as my circle of vision extended. No beacons had been fired immediately about Kagoshima, but the city was aglow with a soft illumination of sufficient radiance to bring out the black outlines of the guard-boats whenever they passed between me and the shore in their slow circling of the ship. The booming of the bells, however, had ceased, and the only sounds that broke the hot, damp stillness of the night were the lapping of ripples alongside and the low creaking of the ship’s rigging.

An hour passed and I still lolled half out of my window, puffing a Manila cheroot, when I heard a slight splash directly below me. It was a sound such as might be made by a leaping fish, but in Eastern waters life often depends on instant vigilance against treachery. I drew back on the second to grasp a revolver and extinguish the lamp. Within half a minute I was back again18 at my window, peering warily down into the blackness under the ship’s stern. There seemed to be a blot on the phosphorescent water.

“Whoever you are,” I said in a low tone, “sheer off until daylight, or I will fire.”

The response was an unmistakable sigh of relief, followed by an eager whisper: “Tojin sama—honorable foreigner, only one man come.”

Almost at the first word I knew that my visitor was the younger officer of the guard-boat.

“You come alone?” I demanded. “What for?”

“Make still, honorable foreigner!” he cautioned. “Ometsuke hear.”

“Ometsuke?”

“Watchers—spies.”

“You’ve slipped through the guard-boats on a secret visit!” I whispered, curiosity fast overcoming my caution. “Why do you come?”

“To go in ship, honorable sir,—England, ’Merica, five continents go—no stop. In boat to pay, gold is.”

For a moment astonishment held me mute. Who had ever before heard of a Japanese voluntarily leaving his own shores? Many as had been picked up by whalers and clippers in the neighboring seas, I knew of no instance where the rescued men had not been either wrecked or blown too far out to sea to be able to navigate their miserable junks into a home port. The19 thought flashed upon me that the man might be a criminal. Only the strongest of motives could have impelled him to seek to break the inflexible law of his country against foreign travel. But the memory of his smiling, high-bred face was against the supposition of guilt.

He broke in upon my hesitancy with an irresistible appeal: “Tojin sama, you no take me? One year I wait to board a black ship and go the five continents.”

“Stand by,” I answered. “I’ll drop you a line. But bear in mind, no treachery, or I’ll blow you to kingdom come!”

“Honorable sir!” he murmured, in a tone of such surprise and reproach as to sweep away my last doubt.

Having no line handy, I whipped the bedclothes from my berth and knotted the silken coverlet to one of the stout linen sheets. The latter I made fast to a handle of my sea-chest, and lowered the coverlet through the cabin window, exposing outboard as little as possible of the white sheet.

“Stand by,” I whispered downward. “Here’s your line.”

In a moment I felt a gentle tugging at the end of the line, followed by a soft murmur: “Honorable sir, pleased to haul.”

Though puzzled, I hauled in on the line, to which something of light weight had been made20 fast. The mystery was soon solved. The end of the line brought into my grasp two longish objects. A touch told me they were sheathed swords. My visitor had proved his faith by first sending up his weapons.

I cleared the line and dropped it down again, with a cordial word of invitation: “Come aboard! Can you climb?”

“I climb, tojin sama,” he whispered back.

There was a short pause, and then the line taughtened. He came up with seamanlike quickness and agility. His form appeared dimly below me as he swung up, hand over hand. I reached out and helped him draw himself in through the window. Pushing him aside, I sought to jerk in my line. It taughtened with a heavy tug.

“What’s this?” I exclaimed. “You made fast to your boat. It should have been cast adrift.”

“Boat loose is,” he replied, with unfailing suavity.

“The line is fast,” I retorted.

I felt his hands on the sheet, and he leaned past me out of the window.

“Your dunnage, of course!” I muttered, and, regretful of my impatience, I fell to hauling with him.

One good heave cleared our load from the boat, which was left free to drift up the harbor with wind and tide. The thought that it might be21 sighted and overhauled by the guard-boat patrol quickened my pull at the line. A few more heaves brought up to the window a cylindrical bundle or bale, which the Japanese grasped and drew inboard before I could lend a hand.

My visitor was aboard, dunnage and all, and, so far as I could tell, he had not been detected either by the men of the guard-boats or the watch above us on the poop.

For a full half-minute I leaned out, listening intently. No alarm broke the peaceful stillness of the night. I closed the window and drew the curtains. Having carefully covered the panes, I struck a lucifer match and crossed over to light my large swinging lamp. Three more steps brought me to the stateroom door, which I locked and bolted. Turning about as the lamp flamed up to full brightness, I saw my guest standing well to one side of the window, his narrow oblique eyes glancing about the room with intense yet well-bred curiosity.

His dress was far different from what it had been aboard the guard-boat. In place of the baggy trousers and flowing robes of silk, his body was now scantily covered with a smock-like garment of coarse blue cotton, and his legs were wound about with black leggings of still coarser stuff. On his feet were straw sandals, secured only with a leather thong that passed between the great and second toes. His bare head gave me my23 first chance to view at close quarters the curious fashion in which, after the manner of his country, his hair was shaved off from brow to nape, and the side locks twisted together and laid forward on the crown in a small gun hammer cue.

All this I took in at a glance as I turned back towards him. Meeting my gaze, he beamed upon me with a grateful smile and bowed far over, sliding his hands down his thighs to his knees in the peculiar manner I had observed when he was aboard the guard-boat.

Not to be outdone in politeness, I bowed in response. “Welcome aboard the Sea Flight, sir. Pray be seated.”

At the word, he dropped to what seemed to be a most uncomfortable posture on his knees and heels.

“Not that,” I protested, and I pointed to a cushioned locker. “Have a seat.”

He shook his head smilingly, and replied in an odd Dutch dialect, as inverted as his English but far more fluent, that he was quite comfortable.

“Very well,” I said in the same language. “Let us become acquainted. I am Worth Adams of South Carolina, lately resigned from the navy of the United States.”

“’Merica?” he questioned.

I bowed, and catching up from under the window his curved long sword and straight short sword,24 or dirk, I presented them to him by the sheaths. He waved them aside, bowing and smiling in evident gratification at my offer. I insisted. He clasped his hands before him, palm to palm, in a gesture of polite protest. I drew back and hung the weapons on the wall rack that held my service sword. He flung himself across, beside his bale of dunnage, and plucked at the lashings.

As I turned to him he unrolled the oiled paper in which the bundles were wrapped. The contents opened out in a veritable curio shop of Oriental articles. There were three or four pairs of straw sandals, two pairs of lacquered clogs, a folding fan, a bundle of cream-colored, crinkly paper, a tiny silver-bowled pipe, two or three small red-lacquered cases, a black mushroom hat of lacquered paper, and a number of robes, toed socks and other garments, all of silk and some exquisitely embroidered in gold thread and colors.

From the midst of one of the silken heaps he uncovered a sword whose silk-corded hilt and shark-skin scabbard were alike decorated with gold dragons. Straightening on his knees, he held the weapon out to me, his face beaming with grateful friendship. “Wo—Wort—Woroto Sama, honorable gift take.”

“Gift!” I exclaimed. “I cannot accept so splendid a gift from you.”

“Exkoos!” he murmured in an apologetic tone,25 and holding the sword with the edge towards himself and the hilt to his left, he slowly drew it out until two or three inches of the mirror-like blade showed between the twisted dragon of the guard and the lip of the scabbard. Pointing first to the shark-tooth mark running down the length of the blade and then to a Chinese letter near the guard, he explained persuasively, “Good, Masamune him make.”

“The more reason why I should refuse such a gift,” I insisted.

He rose to his feet and bowed with utmost dignity. “You him take. Low down Yoritomo me, honorable son high honorable Owari dono, same Shogun brother.”

“What! Your father a brother of the Shogun—of your Emperor?”

He stood a moment pondering. “Shogun cousin,” he replied.

“You mean, your father and the Shogun are cousins?”

He nodded, and again held out the sword. “You him take.”

“With pleasure!” I responded, and I accepted the gift as freely as it was offered. A cousin of the Emperor of Japan should be well able to afford even such extravagant gifts as this beautiful weapon.

“My thanks!” I cried, and I half turned to26 bare the sword in the full light of the lamp. Though of a shape entirely novel to me, the thick narrow blade balanced perfectly in my grasp. Being neither tall nor robust, I found it rather heavy, and the length of the hilt convinced me that it was intended to be used as a two-handed sword by the slightly built Japanese. I presented it, hilt foremost, to Yoritomo. “Pray show me, sir, how you hold it.”

He stared at me in a bewildered manner. I repeated my request, and thrust the hilt into his hand. After a moment’s hesitancy, which I mistook for confusion, he reached for the scabbard as well, sheathed the sword, and thrust it into his narrow cotton sash. When he turned to kneel beside his dunnage, I flushed with anger at what I took to be a deliberate refusal of my request.

He rose with a wooden chopstick in his hand. Politely waving me to one side, he stepped out into the clear centre of the stateroom and bent to set the chopstick upright on the floor. Even had the ship been motionless, I doubt if he could have made the little six-inch piece of wood stand on end for more than a fraction of a second. Yet, having placed it in position, he suddenly freed it and sprang back to strike a two-handed blow with the sword, direct from the sheath, with amazing swiftness. The chopstick, caught by the razor-edged blade before it could topple27 over, was clipped in two across the middle. In a twinkling the blade was back in its sheath.

“Mon Dieu!” I gasped. “That is swordsmanship!”

I held out my hand to him impulsively. He bowed and placed the sword on my palm. The splendid fellow did not know the meaning of a handshake. Much to his astonishment I caught his hand and gave it a cordial grip. I addressed him in my best Dutch, inverting it as best I could to resemble his own dialect: “My dear sir! You wish to see the world? You shall travel as my guest.”

He caught up one of his lacquer cases and opened it to my view. Within it lay a few dozen oval gold coins, hardly more than enough to have paid his passage to New York. There could be no doubt that he had vastly underestimated the purchasing value of his coins in foreign lands. He explained in his quaint Dutch: “The punishment for exchanging money with foreigners is death. So also it is death to leave Dai Nippon. I can die but once.”

“They will never kill a cousin of their Emperor!”

He smiled. “Death will be welcome if I can first bring to my country a better knowledge of the tojin peoples and their ways.”

Even an Adams of South Carolina might well be proud to act as cicerone to an Oriental prince.28 Yet I believe I was actuated more by the subtle sympathy and instinctive understanding that was already drawing me to him, despite the barriers of alien blood and thought and language which lay between us.

“Put up your gold,” I said. “You will have no need for it. I am wealthy and free from all ties. You shall travel with me and see the world as my guest.”

He caught my meaning with the intuition of a thorough gentleman, and his black eyes flashed me a glance of perfect comprehension. He laid down the box of coins and took up one of the silken garments, with an apologetic gesture at the coarse dress he was wearing. I shook my head.

“No,” I said. “There’s been no outcry from the guard-boats, so I’m sure I can stow you away until we are clear of your country. But it will be best to disguise you, to guard against any chance glimpse. What’s more, the sooner you don Occidental clothes the better, if you wish to avoid annoyance from the rudeness of our shipmates. You’re perhaps an inch the shorter; otherwise we are about of a build, and I’ve a well-stocked wardrobe.”

While speaking I proceeded to haul out three or four suits from my lockers, and signed him to take his pick. The gesture was more intelligible to him than my words. He bowed, smiled, and29 chose the least foppish of the suits. I laid out my lightest slippers, a tasselled smoking-cap, linen, et cetera, and drew his attention to the conveniences of a well-furnished washstand.

He took up and smelled the small cake of perfumed soap and was about to try his flashing teeth upon it, when I showed him its use by washing my hands. At this his smile brightened into delight, and, casting loose his girdle, he dropped his short robe from him as one would fling off a cloak. The leggings and sandals followed the robe, and he stood before me nude yet unabashed, his lithe figure like a statue of gold bronze.

Fortunately I was too well acquainted with the peculiar variations of etiquette and manners exhibited by the different peoples of the East and West to betray my astonishment at this exposure. I poured him the bath for which he seemed so eager, and politely excused myself with the explanation that I must provide him with refreshments.

As I had my own private larder in the second stateroom, I had no need to call upon the steward for a luncheon, having on hand various sweets, potted meats, English biscuits, and Chinese conserves, in addition to my wines. When I returned with a well-stocked tray, I found my guest struggling to don his linen over his coat. His relief was unmistakable when I signed him to lay aside everything and slip on a loose lounging-robe.

30 Following my example, he seated himself at the little folding table. When served, he waited, seemingly reluctant to eat alone. Accordingly I served myself, and fell to without delay. At my first mouthful he also caught up knife and fork and began to eat with undisguised heartiness yet with a nicety and correctness of manners that astonished me. When I expressed my surprise that our table etiquette should be so similar, he explained with charming candor that he was but copying my actions.

I could not repress my admiration. “Here’s to our friendship!” I said, raising my glass to him. “May it soon ripen to the mellowness of this wine.”

I doubt if he sensed the meaning of the words, but he raised his glass, and his face glowed with responsive pleasure as together we drank the toast. The act of good-fellowship seemed to bring him still nearer to me, and as I gazed across into his glowing face I could almost forget our differences of race. In my robe and smoking-cap his color and the obliqueness of his eyes appeared less pronounced, and I realized that in all other respects his features differed little from my own. True, my eyes were dark blue and his jet black, and though my nose was rather low between the eyes, his was still flatter. But below their bridges our noses rose in the same softly aristocratic31 curve. The outlines of our faces were of a like oval contour, there was a close similarity about our mouths and chins, and even our eyebrows curved with an identical high and even arch.

“My friend,” I said, “do not answer unless you feel free to explain,—but I wonder that you, a relative of the Emperor, should be compelled to start your travels in this secret manner.”

“Shogun, not Emperor,” he corrected. “Law over Shogun, too. I travel naibun—incognito. Shimadzu Satsuma-no-kami my friend. I teach Raugaku—the Dutch learning,—war ways, history, engineering. No man know real me at Kagoshima. Daimio of Satsuma gone Yedo. I steal aboard. No man know. Shogunate no punish daimio, my friend.”

“They would punish even the Prince of Satsuma if they found you had escaped from his province?”

My guest nodded. “Very old law.”

“Yet you would leave the country at the risk of death?”

His smile deepened into a look of solemn joy. I give his broken Dutch a fair translation.

“My soul is in the eyes of Woroto Sama. There is trust between us. I speak without concealment. The tojin peoples of the west have dealt harshly with the Chinese. The black ships have destroyed many forts and bombarded great cities. I fear the black ships may come to devastate Dai Nippon;32 yet my people know even less of your people than did the Chinese. The Dutch of Deshima warn us to heed the demands of the tojin to open our ports. The officials in control of the Shogunate shut their ears.”

My lip curled. “The English are a nation of shopkeepers, and our Yankees are no less keen for bargains. They will never rest until they have found a market for their wares in every country on earth. If they cannot get into your ports peacefully, sooner or later they will break in by force.”

“Such, then, is the truth,” he murmured. “Namu Amida Butsu! I ask only that I may live to bring back to Dai Nippon a clear report of the power and ways of the tojin peoples.”

“Nothing could please them more,” I replied. “Count on me to help you fulfil your noble mission!”

He thanked me with almost effusive gratitude, yet with a nobility of look that dignified the Oriental obsequiousness of his words and manner. To cut short his thanks, I went out for a second bottle of wine. He had drunk his share of the first with gusto. Returning briskly, I caught sight of my guest’s face for the first time without its pleasant smile. It was drawn and haggard with fatigue. Putting aside the wine, I asked him if he did not wish to turn in. He signed that he33 would lie down upon the floor. But I explained the use of a bed, which seemed an absolute novelty to him, and bundled him into my berth before he could protest. He fell asleep almost as his head sank upon the pillow.

I stowed his dunnage in a locker, and hastened to extinguish the lamp and open the window, for the room was suffocatingly hot. As I leaned out of the window I caught a glimpse of one of the guard-boats sculling leisurely across the belt of light between the Sea Flight and Kagoshima. Yoritomo’s boat had evidently drifted away through their cordon undetected. Five minutes later I was outstretched on a locker, as fast asleep as my guest.

I awoke with what I took to be a crash of thunder dinning in my ears. But the bright glare of sunshine that poured in through the stern windows told of a clear sky. No less unmistakable was the loud shouting of commands on the deck above me and the sharp heeling of the ship to port. The Sea Flight was already under way and her crew piling on more sail as swiftly as Downing and his bucko mates could drive them with volleying oaths and orders.

As I sprang to my feet the explanation of the situation quickly came in the barking roar of an old-style twelve-pounder carronade. This was my supposed thunder. During the night the34 Satsuma men had either brought up a gun-boat or placed a battery on the nearest point of land, and now they had at last opened fire on the tojin ship that refused to leave after due warning.

I stared out the nearest window, and sighted our guard-boats of the night, sculling along in our wake, not a biscuit’s throw distant. Their gunners stood by the little swivels, slow-match in hand, and the soldiers held their antique muskets trained upon us. But the firing was all from the shore. A puff of smoke showed me where the carronade was concealed behind a long stretch of canvas upon a point near the lower end of Kagoshima. The ball plunged into the water half a cable’s length short of us.

Before the gunners could reload, the Sea Flight drew off on the starboard tack with swiftly gathering headway, and drew out of range. The crews of the guard-boats were for a time able to keep their swift clipper-built craft close astern, but the ship, once under full sail, soon began to outdistance her pursuers.

The purpose of the Japanese became clear to me when I saw them lay down their arms without giving over the pursuit. They had no desire to harm us, but were inflexibly determined to drive us out of their port. And follow us they did, though long before we had tacked down into the mouth of the great bay they were visible35 only through a glass, as little black dots bobbing among the whitecaps.

Yoritomo had roused from his profound sleep as we came about for the first time to tack off the Osumi shore. When I had returned his smiling salute, he listened to my account of our flight with quiet satisfaction, and explained that, since we had not left peaceably, the Satsuma men were compelled to resort to these forceful measures. Otherwise their lord, though in Yedo, would be punished for permitting our ship to remain in his harbor.

While my guest then took a morning bath, I closed the door between my staterooms, and ordered the steward to serve me a hearty breakfast in the vacant room. When he had gone, I locked the door and called in Yoritomo, whom I had assisted to dress in his Occidental garments. Thus attired, and with my smoking-cap over his cue, he might easily have passed for an Italian or Spanish gentleman had it not been for the slant of his eyes.

After we had breakfasted, we found seats beside one of the sternports, and spent the morning viewing the receding scenery of the bay and conversing in our inverted Dutch. Eager as I was to make inquiries about my friend and his country, he showed still greater curiosity regarding myself and the wide world from which his people had36 been cut off for so long a period. The result was that by midday I had told him a vast deal, and gathered in turn a mere handful of vaguely stated facts.

Meantime the Sea Flight, having tacked clear of the mouth of the bay, raced down to Cape Satanomi with the full sweep of the monsoon abeam. No less to my gratification than my surprise, Yoritomo proved to be a good sailor, and watched our swift flight along the coast with wondering delight. The heavy rolling of the ship in the trough of the sea affected him no more than myself.

Before long we cleared the outjutting point of Cape Satanomi and, veering to port until upon an easy bowline, drove due east into the vast expanse of the Pacific. I pointed to the craggy tip of the cape where the breakers foamed high on the dark rocks, and rose, with a wave of my hand. “Farewell to Dai Nippon! Come—Downing will be tumbling below for dinner, now that we are clear of land—come and meet the hairy tojin.”

Yoritomo bowed and, with a last glance at the fast-receding cape, followed me out into the passage. We found Downing already at his pork and beans. But he paused, with knife in air, to stare at my companion, gaping as widely as did the steward.

37 “Good-day, skipper,” I said. “Allow me to introduce to you my Japanese cousin Lord Yoritomo.”

“Cousin?—lord?” he spluttered. “Danged if he’s not the first danged stowaway I ever—”

“You mistake,” I corrected, “I invited the gentleman aboard as my guest for the passage. He will share my staterooms, and you are to look to me for his passage money.”

“Well, that’s a different matter, Mr. Adams,” grunted Downing. “If you’re fool enough to—”

“Mason,” I called sharply to the steward, “lay a plate for His Lordship.”

As this is not an account of the travels incognito of my friend Yoritomo, I do not propose to give even a résumé of our trip to America and our European experiences. Nor shall I give the particulars of the family dissension that estranged me from home and, to a degree, from my country.

Enough to say that, despite our incongruous and mutually incomprehensible mental worlds, the Autumn of 1852 found me bound to my Japanese protégé and friend by indissoluble ties of sympathy and love. Strange and inverted as seemed many of his ideas to our western ways of thinking, he had proved himself worthy of the warmest friendship and esteem.

Considering this, together with my longing for adventure, and my freedom from all the ties of family, acquaintance, and habit that bind a man to his country, it will not be thought extraordinary that I at last determined to accompany my friend on his return to Japan. My decision was made at the time when he was spurred to redoubled effort in his studies of the Occident by39 the news that the proposed American expedition to his country was at last approaching a consummation under the vigorous superintendence of Commodore Perry.

It was then my friend told me, with his ever-ready smile, that, should the law be rigidly enforced against him upon his return, he would be bound to a cross and transfixed with spears. Yet under the menace of so atrocious a martyrdom, he labored night and day to complete his studies, that he might return to his people and guide them from disaster upon the coming of the hairy tojin—the Western barbarians.

Few could have resisted the inspiration of so lofty a spirit, the contagion of such utter devotion and self-sacrifice. When my friend was willing to give all for his country, should not I be willing to do a little for the constellation whose brightest star was my own sovereign State, the great Commonwealth of South Carolina?

After all, though President Fillmore and Commodore Perry were Yankees, the flag was the flag of the South no less than of the North, and I had served under it. The purpose of the expedition was peaceful. There flashed upon me a plan by which I might further the success of the expedition and at the same time aid my friend in his purpose.

“Tomo!” I cried, “you insist that you must sail before the American expedition,—that you40 must risk all to reach Yedo and advise your government to welcome the fleet of my countrymen. Very well! I will no longer seek to dissuade you. I will go with you and help you persuade Dai Nippon to enter into friendly relations with America.”

He stared at me, startled and distressed. “Impossible, Worth! They might regard you as a spy. You would be risking death!”

“In all the world I have one friend, and only one,” I rejoined. “The thought of parting from him has been for months a constant source of anxiety and pain. It is pleasant to be rid of such distress. I am going with you to Yedo.”

His eyes widened almost to Occidental roundness, the pupils purpling with the intensity of his emotion. “My thanks, brother! But it is impossible—impossible!”

“At the worst they can only send me packing in a bamboo cage, to be shipped out of Nagasaki by the Dutch.”

“That is the usual course with wrecked sailors, but should you go with me, they might torture and execute you as a spy.”

“Not with Perry’s fleet in Eastern waters,” I replied. “I give your government credit for at least a modicum of statesmanship. Yet even supposing they lack all wisdom, I choose to take the risk. There is no room for argument. You41 are going, so am I. Why, sir, it’s an adventure such as I have been longing for all my life! You cannot turn me from it.”

“If not I, others can and will. The ometsukes are everywhere. You could not so much as effect a landing.”

“And you?” I demanded.

“I am Japanese. There is a chance for me to slip through. But you—”

“Disguised in Japanese dress! Can I not talk good Japanese? Have I not accustomed myself to your costume? A little more practice with the chopsticks and clogs—”

“Your eyes! In all Japan there is to be found no one with round eyes of violet blue.”

“I can learn to squint; and have you not told me of the deep-brimmed hats worn by your freelances, the ronins? You have said that many high-born Japanese have faces no darker than my own, and that brown hair is not unknown.”

“You will risk your life to come with me!” he protested.

I laughed lightly. “You have so little to say of your Japanese ladies, Tomo. Perhaps I wish to see what they are like.”

“That is a jest. I have told you that our women of noble families are seldom to be seen by strangers.”

“There are those others,” I suggested.

42 He gazed at me in mild reproach. “Do not jest, Woroto. I have seen that you have nothing to do with the joro of the Occident. You are not one to dally with those of the Orient.”

“But the geishas—the artists—they must be charming.”

“It is their art to charm.”

“Tomo,” I said, sobering myself, “I know it is a rudeness to ask, but, pardon me, are you married?”

“No.”

“Is there no maiden of noble family—?”

“None,” he answered. “There was once a geisha—But we men of samurai blood are supposed to despise such weakness. Since then I have devoted my life to that which you so generously have helped me to attain.”

“You have no desire ever to marry?” I persisted.

“We hold it a duty to ancestors and families for every young man and maiden to marry,” he replied. “It is not as we wish, but as our parents choose. More than ten years ago His Highness the Shogun arranged with my father that I should marry his daughter Azai.”

“You refused! But of course you were still a boy.”

“You mistake. The arrangement was for the future. The maiden was then only six years of age.”

43 “Six? and ten years ago? Then she is now sixteen,—a princess of sixteen! Tomo, you’re as cold-blooded as a fish! A princess of sixteen, and you never before so much as hinted at your good fortune! Of course she is beautiful?”

He gazed at me in patient bewilderment over the inexplicable romantic emotionalism of the tojin.

“She is said to be beautiful,” he replied, calmly indifferent. “I cannot say. I have never seen her. You know that Japanese ladies do not mingle with men in your shocking tojin fashion.”

At once I set about perfecting myself in certain practices which so far had afforded me little more than idle amusement. The knack of holding on a Japanese clog or the lighter sandal by gripping the thong that passes between the great toe and its mate is not acquired at the first trial or at many to follow. Still more difficult is the ability to sit for hours, crouched on knees and heels, in the Japanese fashion. I practised both feats with a patient endurance born of intense desire. Yoritomo had suffered as great inconvenience while learning to wear Occidental dress and to sit on chairs.

There were many other accomplishments, hardly less irksome, in which I had to drill myself, that I might be prepared to play the rôle of a Japanese gentleman. For recreation between times, I devoted my odd hours to cutlass fencing with an expert maître d’armes and to pistol practice. For this last I purchased a brace of Lefaucheux revolvers, which, though a trifle inferior to the Colt in accuracy, possessed the45 advantage of the inventor’s water-proof metallic cartridges. The convenience and superiority of this cartridge over the old style of loading with loose charges of powder and ball only need be mentioned to be realized.

Yoritomo was so desirous of witnessing the outcome of President Bonaparte’s manipulation of politics that we lingered in Paris until the coup d’état which marked the fall of the French Republic and the ascension of Bonaparte to the imperial throne as Napoleon III. Confirmed by this event in his opinion of the instability, violence, and chicanery of Occidental statesmanship, my friend announced his readiness to leave Europe.

The American packets had already brought word of the sailing of Commodore Perry from Newport News on November the twenty-fourth. As his route to China lay around the Cape of Good Hope, there had been no need to hurry away on our shorter passage by the Peninsular and Oriental route across the Isthmus of Suez and down the Red Sea.

We sailed on January the third, 1853, and, confident of our advantage of route, stopped twice on our way, that Yoritomo might study the administration of the British East India Company in Ceylon and India and the Dutch rule in Java. As a result, we did not reach Shanghai until the end of April.

46 It is in point to mention that during the voyage I gave my friend frequent lessons in Western swordsmanship and in turn received as many from him in Japanese fence, using heavy, two-handed foils of bamboo. Though the Japanese art is without thrusts, I was taught by many a bruise that it possesses clever and powerful cuts.

At Shanghai, we found already assembled three ships of the American squadron, including the huge steam frigate Susquehanna. The Commodore was expected to arrive soon from Hong-kong in the Mississippi.

My plan had been to charter a small vessel, and run across to the Japanese coast, where we hoped to be able to smuggle ourselves ashore, and make our way to Yedo in the disguise of priests. Owing, however, to the alarm of the foreign settlement over the victories of the Taiping rebels in the vicinity of Shanghai, there were few vessels in port and none open to charter.

We were already aware that, under the strict orders of the Navy Department, we could not join the American expedition without subjecting ourselves to the fetters of naval discipline. As a last resort and in the hope of gaining the assent of the Commodore to land us in disguise, we might have considered even this humiliating course. But the very object of Yoritomo’s return to his native shores was to reach Yedo and present his47 case to the Shogun’s government before the arrival of the foreigners.

Fearful of delay, we hired a Chinese escort and rode south across country to Cha-pu, on the Bay of Hang-Chow, the port from which the ten annual Chinese junks sail to Nagasaki. Though our escort did not always manage to prevent their bigoted countrymen from making the journey disagreeable for the “foreign devils,” we reached our destination without loss of life or limb.

The vile treatment of the Celestials was quickly forgotten in the graciousness of our welcome by the little colony of Japanese exiles whom we found located at Cha-pu. Careful as was Yoritomo to conceal his identity from his countrymen, they at once divined that he was a man of noble rank, and invariably knelt and bowed their foreheads to the dust whenever they came into his presence.

The Cha-pu merchants were greatly impressed by such deference on the part of the proud little men of Nippon, yet neither this nor my gold enabled us to obtain passage on one of their clumsy junks. The five vessels of the summer shipment to Nagasaki were not due to sail before August, and the jabbering heathen refused point-blank to risk the extinction of their Japanese trade either by advancing the date of sailing or by chartering a separate junk. Their unvarying48 reply was that no one could land anywhere in Japan without being detected by the spies.

One merchant alone betrayed a slight hesitancy over refusing us outright, and he, after dallying with my ultimate offer for a fortnight, at last positively declined the risk. I next proposed to buy a junk and man it with fishermen from the Japanese colony. But Yoritomo soon found that not one of the exiles dared return to Dai Nippon, great as was their longing.

Mid-May had now come and gone. Hopeless of obtaining aid from the Chinese, we rode back overland to Shanghai, agreed that it would be better to sail with Perry than after him. To our dismay, we discovered that the American squadron had sailed for the Loo Choo Islands two days before our arrival.

In this darkest hour of our enterprise we chanced upon our golden opportunity. Shortly after our departure for Cha-pu a New Bedford whaler, the Nancy Briggs, had put into Shanghai to replace a sprung foremast. She was now about to sail for the Straits of Sangar, bound for the whaling grounds east of the Kurile Islands. I met her skipper upon the bund, and within the hour had closed a bargain with him to land us on the Japanese coast within twenty miles of the Bay of Yedo. For this I was to pay him a49 thousand dollars in gold, and pilot his ship through Van Diemen Strait.

By nightfall Yoritomo and I were aboard the Nancy Briggs with our dunnage and had settled ourselves in the little stateroom vacated by the first mate. We awoke at sunrise to find the ship under way down the Whang-po to the Yang-tse-Kiang. Another sunrise found the whaler in blue water, running before the monsoon out across the Eastern Sea.

Though far from a clipper, the Nancy Briggs was no tub. We sighted Kuro, the westernmost island of Van Diemen Strait, and its blazing volcanic neighbor Iwogoshima, on June the second, eight days over a year and nine months since the Sea Flight bore me up the superb Bay of Kagoshima. The interval had been crowded with events in our physical and mental worlds scarcely less momentous to myself than to my friend.

But it was no time for me to indulge in retrospection. I had engaged to navigate the Nancy Briggs through the narrow waters of an uncharted strait. The rainy season was well under way, with all the concomitants of heavy squalls and dense fogs. As already mentioned, a lucky glimpse of Kuro, soon confirmed as a landfall by the red glare of Iwogoshima, enabled me to set our course to pass through the strait.

We ran in under reefed topsails, feeling our50 way blindly by compass and log in true whaler fashion. The Yankees took the risk as a matter of course, but I, between the difficulty of calculating the effects of the capricious squalls on our headway and my ignorance of the set of the powerful currents around this southern extremity of Japan, found my responsibilities as pilot no light burden. I was correspondingly relieved when a rift opened in the smothering masses of vapor which shrouded all view of sea and land, and I saw looming up abeam the well-remembered point of bold Cape Satanomi.

Once clear of the strait, out in the open waters of the Pacific, we packed on all sail to outdrive the heavy following sea, and entered upon the run of over five hundred miles along the southeast coasts of Kiushiu, Shikoku, and Hondo, the main island. Though the weather continued wet and foggy, we were favored by a half gale from the south and by the drift of the Japan Current, which here flows little less swiftly than does our Gulf Stream off Hatteras.

Regardless of the whales which we frequently sighted, our skipper, true to his agreement, held on under full sail, night and day, until we made a landfall of Cape Idzu, the southernmost point of the great promontory which lies southwest of Yedo Bay. We could not have desired conditions more favorable to enable us to approach the coast51 unobserved. Night was coming on and the gale freshening, but there was no fog. Our skipper shortened sail, and stood boldly in between the east coast of Idzu and the chain of islands trending southward from the mouth of the outer Bay of Yedo.

Had the gale fallen at sundown, I might have persuaded the skipper to hold on across and land us on the west coast of Awa, off the mouth of the inner bay. Unfortunately the wind moderated so little and the sky became so overcast that he ran in under the lee of the great hulking volcano laid down on the charts as Vries Island, but by Yoritomo called Oshima.

We were here in the mouth of the outer bay, and the skipper stated that he was prepared to fulfil his contract by landing us on the island. When I protested against being thus marooned, he declared that he would put us ashore on Vries Island or nowhere. At this I demanded that he run up the outer bay and set us adrift in his gig. He declared that to do so would be sheer murder, since no boat could outride the billows in the open bay. However, an offer of half of Yoritomo’s Japanese gold coins altered his opinion, and the appearance of the rising moon, which began to glimmer at intervals through the scurrying clouds, enabled us to persuade him that he could run up to within the southern point of52 Awa and beat out again without endangering his ship.

The moment he ordered the ship brought about, Yoritomo and I hastened to prepare ourselves for the landing by shifting into our Yamabushi, or mountain-priest robes, which with other articles of costume we had obtained from the Japanese at Cha-pu. We had been dressing each other’s hair in the Japanese fashion and shaving clean ever since the passage of Van Diemen Strait. Our dunnage was already lashed together in two compact bundles, wrapped about with many thicknesses of waterproof oiled paper.

To the outside of the bundles, I now tied my revolvers and Yoritomo his sword and dirk, all alike wrapped in oil paper, together with two pairs of straw sandals and black leggings and our deep-brimmed basket hats of coarse-wove rattan. The night was far too wild for us to risk being flung into the breakers with any unnecessary weight about us. That we might not be hampered by our loose dress, we bound up our long sleeves to our shoulders and tucked the skirts of the robes through the back of our girdles.

When we went up on the deck with our dunnage, a gleam of moonlight showed us the dim, smoking mass of Vries Island already a full two leagues astern, while ahead, across eighteen miles or more of racing foam-crested billows, loomed the mountainous53 coast of Awa. We made our way along the pitching deck to where the skipper stood with a group of sailors beside the gig. They were lashing down a number of empty water breakers in the bow and stern and under the thwarts, and there was an oil cask made fast to the bow with a five-fathom line.

“Ready, hey?” shouted the skipper, when I made our presence known by touching his arm. “Well, it’s on your own head, sir. I’m doing my best for you, as I’m a God-fearing Christian. But it’ll take a sight of special providence to bear you safe into haven once you cut adrift.”

I pointed to the oil cask. “A drag?”

“Aye. Keep you from broaching. Best kind of drag. She’s three-quarters full of oil, and the head riddled with gimlet holes. The oil will spread and keep the waves from breaking over you.”

“I’ve heard of that whaler’s trick,” I replied, gripping his broad hand. “And the gig is unsinkable with those breakers aboard. We’re bound to win through. I’ll lash our dunnage in the sternsheets myself.”

The moon went behind a cloud, but one of the sailors raised the lantern that he was holding beneath the bulwark and set it within the gig. Our bundles were soon secured, and we had only to lean upon the bulwark and gaze over the starboard54 bow towards the dim coast of Awa. Though under shortened sail, the old Nancy ran before the gale at so famous a rate that within two hours the outpeeping moon showed us the furious surf along the rocky coast, two miles on our starboard beam.

As agreed, the skipper now put the ship’s head to the northwest and stood on across the mouth of the inner bay until we sighted the surf on the western coast. Our time had come.

The gig already hung outboard. At the word from the skipper, Yoritomo sprang into the sternsheets and I into the bow, ready to cast off. Six men stood by to lower away and one to cut loose our cask drag, which had been swung outboard in a handy sling.

“Ready, skipper!” I called.

“Aye, aye—Good luck to you, sir!” he cried, and wheeling about, he began bawling his orders to bring the ship about on the port tack.

I had chosen a moment when the moon was edging out through a cloud rift, so that the deft-handed Yankees had ample light for their work. Within half a minute the ship, already running close aslant the waves, came around into the trough of the sea. Over she heeled, until she was all but lying on her beam ends. A little more and she must have turned turtle. The sea boiled up alongside until the water poured over the bulwark. Yet our men stood coolly to their posts.

“Let go the falls!” I shouted, above the howl of the gale.

The gig splashed into the seething water. In an instant I had cast loose the bow block.

56 “Clear!” cried Yoritomo from the stern.

“Cut!” I yelled.

The oil cask plunged from its severed sling as the gig swung swiftly down the receding wave to the leeward of the Nancy. I caught one glimpse of the gallant old whaler staggering up and swinging her stem around into the gale. A faint cheer came ringing down the wind. Then we were out from under her lee, in the full sweep of the gale.

Though I had always prided myself upon my skill in handling small craft, I must confess that the narrow gig would have swamped or turned turtle within the first minute had it not been for our drag and the breaker floats. Before we had swung around to the drag, a comber broke over us and filled our little cockleshell to the gunwales. As she came out of the smother, still afloat but heavy as a log, we fell to with our bailers like madmen. We now knew she could not sink, but without freeboard she would not ride head on to the cask, and the first wave that caught us broadside might roll us over.

Fortunately the oil oozing from the cask was already filming over the surface around us, so that high as we were flung up by the racing billows and low as we sagged into their troughs, no more crests broke upon us. The moment the boat rode easier, I sprang upon a thwart and gazed57 about for a parting glance of the Nancy Briggs. But the moon was already covered by a wisp of the scurrying stormrack. When its silvery rays again shone upon the wild sea, I fancied that I caught a glimpse of the whaler standing out towards the open ocean on the starboard tack.

The deep booming of surf on a rocky shore brought my gaze about, and as we topped the next wave I saw that we were abeam the high cliffs of Cape Sagami, at the western point of the entrance to the inner bay. I swung aft into the sternsheets, where Yoritomo crouched ankle-deep in the wash, still frantically bailing.

“Belay!” I shouted.

He dropped his bailer, and looked over the side at the surf-whitened shore in blank astonishment.

“So swift!” he cried, “so swift!”

“Wind, wave, and tide,” I rejoined. “I’ve known a boat to make less speed under sail. Only trouble, with our present bearings, we’ll pile up on that outjutting point of the east coast.”

“Before that, Uraga,” he replied.

“According to chart, we’ll drift clear of the west coast, and there’ll be no guard-boats out of harbor to-night.”

“But the moonlight; they may sight us,” he insisted.

“A mile offshore, among these waves! Even if they had night-glasses, they could not tell the58 gig from a sampan, nor ourselves from storm-driven fishermen. You say the bay swarms with fishers.”

“Then there is now only the danger of delay from being cast up on the east shore.”

“A delay apt to prove permanent if we drift upon a lee shore in the surf that’s running to-night,” I added.

“I know you fear death as little as I do,” he said. “We are brothers in spirit. But that my message should be delayed or lost—the gods forbid!”

“We’re not yet on the rocks, Tomo. We’ve deep water and to spare for a while,” I cried, springing up to take our bearings as the moon was again gliding behind the clouds.

We were now well past Cape Sagami and opposite a bight whose southern shore, lying under the lee of its hill-crowned cliffs, was free of all surf. Leading down through the face of the cliffs from the terraced hillsides above were many wooded ravines, at the foot of which villages nestled upon bits of level ground near the water’s edge. Here was a haven that might possibly be gained by casting the drag adrift and rowing in aslant the wind. But it was below Uraga, Yedo’s port of entry for the native craft, and Yoritomo had impressed upon me the great need to win our way past that nest of government59 inspectors and spies. The attempt to run under a lee would be no more desperate an undertaking beyond Uraga than here.

I crouched down again beside my friend, and waited anxiously for the next glimpse of the moon. But the weather had suddenly thickened. Gusts of rain began to dash upon us out of the blackening sky. The rifts closed up until there was not even a star visible, and the rain increased until it poured down aslant the gale in torrents. The roar of the pelting deluge drowned the boom of the surf and beat down the wave crests. We had not even the phosphorescent foam of the combers to break the inky darkness about us.

The rain was too warm to chill us, but the down-whirling drops struck upon our bare limbs with the sting of sleet. We crouched together in the sternsheets, peering westward into the thick of the aqueous murk in search for the lights of Uraga. One glimpse would have given us fair warning to prepare for my desperate scheme to work under the lee of the point some two miles beyond.

Death was inevitable should we drive past that point, across the bend of the bay, to the outjutting cape on the east shore. Nor was it enough for us to clear the cape. Even should we escape destruction there, and even should we drift on up into the northeast corner of the bay, across from Yedo, we would no less certainly perish60 in the surf. On the other hand, could I but win the shelter of the point above Uraga, out of the full sweep of the in-rolling seas, I might be able to sheer over to the west shore and gain the shelter of one of the capes shown on the chart drawn for me by Yoritomo.

Failing to sight the lights of Uraga, I was in a pretty pickle. To cut adrift from our drag was quite sufficiently hazardous without the certainty that if we put in too soon we should go to wreck on the Uraga cape, and if we held on too late, be cast up on the outjutting point of the east coast. We were utterly lost in the dense night of whirling wind and rain and swift-heaving waves. Without means to measure the passage of time, I could not even reckon our position by estimating our rate of drift.

“No use watching, Tomo,” I at last shouted. “We could not see even a lighthouse so thick a night, and we’ve drifted past by now. Hand me your dirk.”

“Aye,” he replied, and I felt him turn about to where his dunnage was lashed down. In a few minutes he turned back and thrust the hilt of his short sword into my hand. He asked no questions, but waited calmly for me to direct him.

With a few touches of the razor-edged blade I cut loose the oars, which had been lashed under61 the gunwales. As I pressed the dirk hilt back into his hand, I gave him his orders: “Go forward and cut the line when I say; then aft, and stand by to bail.”

Without a word he crept away towards the bows through the down-whirling deluge and blackness. I followed to a seat on the forward thwart, and waited while three of the great billows flung us high and dropped us into the trough behind them. As we sagged down the slope of the third, I dipped my oar-blades and shouted, “Cut!”

The fourth wave shouldered us skyward. As we topped the crest the feel of the wind on my back told me that the gig’s head was falling off to port. A quick stroke brought her back square into the wind. We shot down the watery slope, but before we could climb to another crest Yoritomo had crept past me to his post in the pointed stern.

With utmost caution I headed the boat a few points to westward, and began to pull aslant the waves, with the wind on our port bow. It was a ticklish moment, for I did not know how the gig would handle. Without the drag of our abandoned cask, she might well be expected to fall off into the trough of the sea.

The struggle was now on in desperate earnest. But as I bent to my oars with all my skill and strength, I realized by the way the gig responded to my efforts that we had at least a fighting62 chance. Yet it was no easy matter to hold the bows quarteringly to wind and waves as we shot up and down the dizzy slopes, and Yoritomo was kept busy bailing out the water that all too frequently poured in over the rocking gunwales.

At last, through the howling of the gale and the slashing roar of the rain on the waters, I heard a deeper note, the welcome boom of the surf on the west shore. Whether we were as yet abreast the cape above Uraga I could not tell, but I held on as before, regardless of whatever reefs or shoals might lie off this rocky coast. Soon the surf roar, which had sounded abreast of us, seemed to fall away. I gave a shout, and bent to my oars with redoubled energy. We were drifting past the point, out into the turn of the bay beyond.

After a quarter-hour or so, to my vast relief the force of the wind lessened and the waves ran lower. We were edging around the cape, under the high lee of the westerly trending shore. Another quarter-hour, and we were in comparatively quiet water.

“Tomo,” I called, “shall we attempt a landing? We can make it with ease under the shelter of the hills.”

“So near across the point from Uraga?” he answered. “Could we not coast up the west shore? Every mile we float nearer to Yedo is two miles of walking saved.”

63 “But what if we should fetch up on a lee shore? You’ve marked more than one promontory on the west coast.”

“Hold farther out, then,” he said. “By morning we might drift all the way up the bay and across the Shinagawa Shoals, into the mouth of the Sumida River.”

“Clear to Yedo?” I cried. “Yet your chart makes it less than thirty miles, and it’s only a question of holding the boat a few points aslant the wind. We’ve seen how lightly the gig rides. There’s only the danger of those promontories, and I’ve the wind to steer by. We’ll do it, Tomo!”

“Commodore Perry may already be at Nagasaki,” he added, by way of final argument for haste.

“Give me your robe,” I said.

He slipped off the loose garment without demur, and crept forward to press it into my hand. We were now in water in which the boat could be safely allowed to drift without guidance. I flung the oars inboard and lashed the robe to one of them so as to make a small triangular sail. While I worked I gave Yoritomo his instructions. Soon the sail was ready. I handed it over to my friend, and with the second oar for rudder made my way aft to the sharp stern. A few strokes brought us around with the wind on our port quarter.64 Immediately Yoritomo stepped his oar mast through the socket in the forward thwart, and set sail.

Though so small, the little cotton triangle drew well, as I could tell by the ease with which the gig responded to her helm. Another proof was the quickness with which we ran out from under our sheltering highland into the full sweep of the gale and the high waves of the open bay. Scudding aslant the wind as nearly north as I could reckon our bearings from the drive of the rain torrents, we hurled along through the black night, utterly lost to all sense of time and distance.