The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Blood Covenant, by H. Clay Trumbull

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

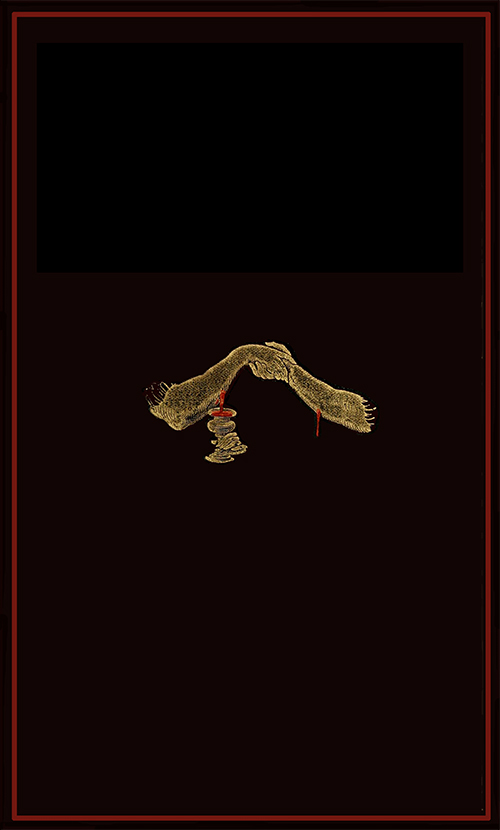

Title: The Blood Covenant

A Primitive Rite and its Bearings on Scripture

Author: H. Clay Trumbull

Release Date: February 11, 2015 [EBook #48236]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BLOOD COVENANT ***

Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

A PRIMITIVE RITE

AND ITS BEARINGS ON SCRIPTURE

BY

H. CLAY TRUMBULL D.D.

Author of “Kadesh Barnea.”

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1885

COPYRIGHT, 1885

BY H. CLAY TRUMBULL

GRANT & FAIRES

PHILADELPHIA

It was while engaged in the preparation of a book—still unfinished—on the Sway of Friendship in the World’s Forces, that I came upon facts concerning the primitive rite of covenanting by the inter-transfusion of blood, which induced me to turn aside from my other studies, in order to pursue investigations in this direction.

Having an engagement to deliver a series of lectures before the Summer School of Hebrew, under Professor W. R. Harper, of Chicago, at the buildings of the Episcopal Divinity School, in Philadelphia, I decided to make this rite and its linkings the theme of that series; and I delivered three lectures, accordingly, June 16-18, 1885.

The interest manifested in the subject by those who heard the Lectures, as well as the importance of the theme itself, has seemed sufficient to warrant its presentation to a larger public. In this publishing, the form of the original Lectures has, for convenience sake, been adhered to; although some considerable additions to the text, in the way of illustrative facts, [iv] have been made, since the delivery of the Lectures; while other similar material is given in an Appendix.

From the very freshness of the subject itself, there was added difficulty in gathering the material for its illustration and exposition. So far as I could learn, no one had gone over the ground before me, in this particular line of research; hence the various items essential to a fair statement of the case must be searched for through many diverse volumes of travel and of history and of archæological compilation, with only here and there an incidental disclosure in return. Yet, each new discovery opened the way for other discoveries beyond; and even after the Lectures, in their present form, were already in type, I gained many fresh facts, which I wish had been earlier available to me. Indeed, I may say that no portion of the volume is of more importance than the Appendix; where are added facts and reasonings bearing directly on well-nigh every main point of the original Lectures.

There is cause for just surprise that the chief facts of this entire subject have been so generally overlooked, in all the theological discussions, and in all the physio-sociological researches, of the earlier and the later times. Yet this only furnishes another illustration of the inevitably cramping influence of a pre-conceived fixed theory,—to which all the ascertained facts must be conformed,—in any attempt at thorough [v] and impartial scientific investigation. It would seem to be because of such cramping, that no one of the modern students of myth and folk-lore, of primitive ideas and customs, and of man’s origin and history, has brought into their true prominence, if indeed he has even noticed them in passing, the universally dominating primitive convictions: that the blood is the life; that the heart, as the blood-fountain, is the very soul of every personality; that blood-transfer is soul-transfer; that blood-sharing, human, or divine-human, secures an inter-union of natures; and that a union of the human nature with the divine is the highest ultimate attainment reached out after by the most primitive, as well as by the most enlightened, mind of humanity.

Certainly, the collation of facts comprised in this volume grew out of no pre-conceived theory on the part of its author. Whatever theory shows itself in their present arrangement, is simply that which the facts themselves have seemed to enforce and establish, in their consecutive disclosure.

I should have been glad to take much more time for the study of this theme, and for the re-arranging of its material, before its presentation to the public; but, with the pressure of other work upon me, the choice was between hurrying it out in its present shape, and postponing it indefinitely. All things considered, I chose the former alternative.

In the prosecution of my investigations, I acknowledge kindly aid from Professor Dr. Georg Ebers, Principal Sir William Muir, Dr. Yung Wing, Dean E. T. Bartlett, Professors Doctors John P. Peters and J. G. Lansing, the Rev. Dr. M. H. Bixby, Drs. D. G. Brinton and Charles W. Dulles, the Rev. Messrs. R. M. Luther and Chester Holcombe, and Mr. E. A. Barber; in addition to constant and valuable assistance from Mr. John T. Napier, to whom I am particularly indebted for the philological comparisons in the Oriental field, including the Egyptian, the Arabic, and the Hebrew.

At the best, my work in this volume is only tentative and suggestive. Its chief value is likely to be in its stimulating of others to fuller and more satisfactory research in the field here brought to notice. Sufficient, however, is certainly shown, to indicate that the realm of true Biblical theology is as yet by no means thoroughly explored.

H. CLAY TRUMBULL.

Philadelphia, August 14, 1885.

| PAGE | |

| Preface | iii |

LECTURE I.

THE PRIMITIVE RITE ITSELF.

(1.) Sources of Bible Study, 3. (2.) An Ancient Semitic Rite, 4. (3.) The Primitive Rite in Africa, 12. (4.) Traces of the Rite in Europe, 39. (5.) World-wide Sweep of the Rite, 43. (6.) Light from the Classics, 58. (7.) The Bond of the Covenant, 65. (8.) The Rite and its Token in Egypt, 77. (9.) Other Gleams of the Rite, 85.

LECTURE II.

SUGGESTIONS AND PERVERSIONS OF THE RITE.

(1.) Sacredness of Blood and of the Heart, 99. (2.) Vivifying Power of Blood, 110. (3.) A New Nature through New Blood, 126. (4.) Life from any Blood, and by a Touch, 134. (5.) Inspiration through Blood, 139. (6.) Inter-Communion through Blood, 147. (7.) Symbolic Substitutes for Blood, 191. (8.) Blood Covenant Involvings, 202.

LECTURE III.

INDICATIONS OF THE RITE IN THE BIBLE.

(1.) Limitations of Inquiry, 209. (2.) Primitive Teachings of Blood, 210. (3.) The Blood Covenant in Circumcision, 215. (4.) The Blood Covenant Tested, 224. (5.) The Blood Covenant and its Tokens in the Passover, 230. (6.) The Blood Covenant at Sinai, 238. (7.) The Blood Covenant in the Mosaic Ritual, 240. (8.) The Primitive Rite Illustrated, 263. (9.) The Blood Covenant in the Gospels, 271. (10.) The Blood Covenant Applied, 286.

APPENDIX.

Importance of this rite strangely undervalued, 297. Life in the blood, in the heart, in the liver, 299. Transmigration of souls, 310. The Blood-Rite in Burmah, 313. Blood-stained tree of the covenant, 316. Blood-Drinking, 320. Covenant-Cutting, 322. Blood-Bathing, 324. Blood-Ransoming, 324. The Covenant-Reminder, 326. Hints of Blood Union, 332.

INDEXES.

LECTURE I.

THE PRIMITIVE RITE ITSELF.

Those who are most familiar with the Bible, and who have already given most time to its study, have largest desire and largest expectation of more knowledge through its farther study. And, more and more, Bible study has come to include very much that is outside of the Bible.

For a long time, the outside study of the Bible was directed chiefly to the languages in which the Bible was written, and to the archæology and the manners and customs of what are commonly known as the Lands of the Bible. Nor are these well-worked fields, by any means, yet exhausted. More still remains to be gleaned from them, each and all, than has been gathered thence by all searchers in their varied lore. But, latterly, it has been realized, that, while the Bible is an Oriental book, written primarily for Orientals, and therefore to be understood only through an [4] understanding of Oriental modes of thought and speech, it is also a record of God’s revelation to the whole human race; hence, its inspired pages are to receive illumination from all disclosures of the primitive characteristics and customs of that race, everywhere. Not alone those who insist on the belief that there was a gradual development of the race from a barbarous beginning, but those also who believe that man started on a higher plane, and in his degradation retained perverted vestiges of God’s original revelation to him, are finding profit in the study of primitive myths, and of aboriginal religious rites and ceremonies, all the world over. Here, also, what has been already gained, is but an earnest of what will yet be compassed in the realm of truest biblical research.

One of these primitive rites, which is deserving of more attention than it has yet received, as throwing light on many important phases of Bible teaching, is the rite of blood-covenanting: a form of mutual covenanting, by which two persons enter into the closest, the most enduring, and the most sacred of compacts, as friends and brothers, or as more than brothers, through the inter-commingling of their blood, by means of its mutual tasting, or of its inter-transfusion. [5] This rite is still observed in the unchanging East; and there are historic traces of it, from time immemorial, in every quarter of the globe; yet it has been strangely overlooked by biblical critics and biblical commentators generally, in these later centuries.

In bringing this rite of the covenant of blood into new prominence, it may be well for me to tell of it as it was described to me by an intelligent native Syrian, who saw it consummated in a village at the base of the mountains of Lebanon; and then to add evidences of its wide-spread existence in the East and elsewhere, in earlier and in later times.

It was two young men, who were to enter into this covenant. They had known each other, and had been intimate, for years; but now they were to become brother-friends, in the covenant of blood. Their relatives and neighbors were called together, in the open place before the village fountain, to witness the sealing compact. The young men publicly announced their purpose, and their reasons for it. Their declarations were written down, in duplicate,—one paper for each friend,—and signed by themselves and by several witnesses. One of the friends took a sharp lancet, and opened a vein in the other’s arm. Into the opening thus made, he inserted a quill, through which he sucked the living blood. The lancet-blade was carefully [6] wiped on one of the duplicate covenant-papers, and then it was taken by the other friend, who made a like incision in its first user’s arm, and drank his blood through the quill, wiping the blade on the duplicate covenant-record. The two friends declared together: “We are brothers in a covenant made before God: who deceiveth the other, him will God deceive.” Each blood-marked covenant-record, was then folded carefully, to be sewed up in a small leathern case, or amulet, about an inch square; to be worn thenceforward by one of the covenant-brothers, suspended about the neck, or bound upon the arm, in token of the indissoluble relation.

The compact thus made, is called, M’âhadat ed-Dam (معاهدة الدم), the “Covenant of Blood.” The two persons thus conjoined, are, Akhwat el-M’âhadah (اخوة المعاهدة), “Brothers of the Covenant.” The rite itself is recognized, in Syria, as one of the very old customs of the land, as ’âdah qadeemeh (عادة قديمة) “a primitive rite.” There are many forms of covenanting in Syria, but this is the extremest and most sacred of them all. As it is the inter-commingling of very lives, nothing can transcend it. It forms a tie, or a union, which cannot be dissolved. In marriage, divorce is a possibility: not so in the covenant of blood. Although now comparatively rare, in view of its responsibilities and of its indissolubleness, this [7] covenant is sometimes entered into by confidential partners in business, or by fellow-travelers; again, by robbers on the road—who would themselves rest fearlessly on its obligations, and who could be rested on within its limits, however untrustworthy they or their fellows might be to any other compact. Yet, again, it is the chosen compact of loving friends; of those who are drawn to it only by mutual love and trust.

This covenant is commonly between two persons of the same religion—Muhammadans, Druzes, or Nazarenes; yet it has been known between two persons of different religions;[1] and in such a case it would be held as a closer tie than that of birth[2] or sect. He who has entered into this compact with another, counts himself the possessor of a double life; for his friend, whose blood he has shared, is ready to lay down his life with him, or for him.[3] Hence the leathern case, or Bayt hejâb (بيت حجاب) “House of the amulet,”[4] [8] containing the record of the covenant (’uhdah, عهدة), is counted a proud badge of honor, by one who possesses it; and he has an added sense of security, because he will not be alone when he falleth.[5]

I have received personal testimony from native Syrians, concerning the observance of this rite in Damascus, in Aleppo, in Hâsbayya, in Abayh, along the road between Tyre and Sidon, and among the Koords resident in Salehayyah. All the Syrians who have been my informants, are at one concerning the traditional extreme antiquity of this rite, and its exceptional force and sacredness.

In view of the Oriental method of evidencing the closest possible affection and confidence, by the sucking of the loved one’s blood, there would seem to be more than a coincidence in the fact, that the Arabic words for friendship, for affection, for blood, and for leech, or blood-sucker, are but variations from a common root.[6] ’Alaqa (علق) means “to love,” “to adhere,” “to feed.” ’Alaq (علق), in the singular, means “love,” “friendship,” “attachment,” “blood.” As the plural of ’alaqa (علقة), ’alaq means “leeches,” or “blood-suckers.” The truest friend clings like a leech, and draws blood in order to the sharing thereby of his friend’s life and nature.

A native Syrian, who had traveled extensively in [9] the East, and who was familiar with the covenant of blood in its more common form, as already described, told me of a practice somewhat akin to it, whereby a bandit-chieftain would pledge his men to implicit and unqualified, life-surrendering fidelity to himself; or, whereby a conspirator against the government would bind, in advance, to his plans, his fellow conspirators,—by a ceremony known as Sharb el-’ahd (شرب العهد) “Drinking the covenant.” The methods of such covenanting are various; but they are all of the nature of tests of obedience and of endurance. They sometimes include licking a heated iron with the tongue, or gashing the tongue, or swallowing pounded glass or other dangerous potions; but, in all cases, the idea seems to be, that the life of the one covenanting is, by this covenant, devoted—surrendered as it were—to the one with whom he covenants; and the rite is uniformly accompanied with a solemn and an imprecatory appeal to God, as witnessing and guarding the compact.

Dr. J. G. Wetzstein, a German scholar, diplomat, and traveler, who has given much study to the peoples east of the Jordan, makes reference to the binding force and the profound obligation of the covenants of brotherhood, in that portion of the East; although he gives no description of the methods of the covenant-rite. Speaking of two Bed´ween—Habbâs and [10] Hosayn—who had been “brothered” (verbrüdert), he explains by saying: “We must by this [term] understand the Covenant of Brotherhood[7] (Chuwwat el-Ahĕd [خوة العهد]), which is in use to-day not only among the Hadari [the Villagers], but also among the Bed´ween; and is indeed of pre-Muhammadan origin. The brother [in such a covenant] must guard the [other] brother from treachery, and [must] succor him in peril. So far as may be necessary, the one must provide for the wants of the other; and the survivor has weighty obligations in behalf of the family of the one deceased.” Then, as showing how completely the idea of a common life in the lives of two friends thus covenanted—if, indeed, they have become sharers of the same blood—sways the Oriental mind, Wetzstein adds: “The marriage of a man and woman between whom this covenant exists, is held to be incest.”[8]

There are, indeed, various evidences that the tie of blood-covenanting is reckoned, in the East, even a closer tie than that of natural descent; that a “friend” by this tie is nearer and is dearer, “sticketh closer,” than a “brother” by birth. We, in the West, are accustomed to say, that “blood is thicker than water”; but the Arabs have the idea that blood is thicker than milk, [11] than a mother’s milk. With them, any two children nourished at the same breast are called “milk-brothers,”[9] or “sucking brothers”;[10] and the tie between such is very strong. A boy and a girl in this relation cannot marry, even though by birth they had no family relationship. Among even the more bigoted of the Druzes, a Druze girl who is a “sucking sister” of a Nazarene boy is allowed a sister’s privileges with him. He can see her uncovered face, even to the time of her marriage. But, the Arabs hold that brothers in the covenant of blood are closer than brothers at a common breast; that those who have tasted each other’s blood are in a surer covenant than those who have tasted the same milk together; that “blood-lickers,”[11] as the blood-brothers are sometimes called, are more truly one, than “milk-brothers,” or “sucking brothers”; that, indeed, blood is thicker than milk, as well as thicker than water.

This distinction it is which seems to be referred to in a citation from the Arabic poet El-A’asha, by the Arabic lexicographer Qamus, which has been a puzzle to Lane, and Freytag, and others.[12] Lane’s translation [12] of the passage is: “Two foster-brothers by the sucking of the breast of one mother, swore together by dark blood, into which they dipped their hands, that they should not ever become separated.” In other words, two milk-brothers became blood-brothers, by interlocking their hands under their own blood, in the covenant of blood-friendship. They had been closely inter-linked before; now they were as one; for blood is thicker than milk. The oneness of nature which comes of sharing the same blood, by its inter-transfusion, is rightly deemed, by the Arabs, completer than the oneness of nature which comes of sharing the same milk; or even than that which comes through having blood from a common source, by natural descent.

Travelers in the heart of Africa, also, report the covenant of “blood-brotherhood,” or of “strong-friendship,” as in vogue among various African tribes; although, naturally retaining less of primitive sacredness there than among Semites. The rite is, in some cases, observed after the manner of the Syrians, by the contracting parties tasting each other’s blood; while, in other cases, it is performed by the inter-transfusion of blood between the two.

The first mention which I find of it, in the writings of modern travelers in Africa, is by the lamented hero-missionary, [13] Dr. Livingstone. He calls the rite Kasendi. It was in the region of Lake Dilolo, at the watershed between the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic, in July, 1854, that he made blood-friendship, vicariously, with Queen Manenko, of the Balonda tribes.[13] She was represented, in this ceremony, by her husband, the ebony “Prince Consort”; while Livingstone’s representative was one of his Makololo attendants. Woman’s right to rule—when she has the right—seems to be as clearly recognized in Central Africa, to-day, as it was in Ethiopia in the days of Candace, or in Sheba in the days of Balkees.

Describing the ceremony, Livingstone says:[14] “It is accomplished thus: The hands of the parties are joined (in this case Pitsane and Sambanza were the parties engaged). Small incisions are made on the clasped hands, on the pits of the stomach of each, and on the right cheeks and foreheads. A small quantity of blood is taken off from these points, in both parties, by means of a stalk of grass. The blood from one person is put into a pot of beer, and that of the second into another; each then drinks the other’s blood, and they are supposed to become perpetual friends, or relations. During the drinking of the beer, some of the party continue beating [14] the ground with short clubs, and utter sentences by way of ratifying the treaty. The men belonging to each [principal’s party], then finish the beer. The principals in the performance of ‘Kasendi’ are henceforth considered blood-relations, and are bound to disclose to each other any impending evil. If Sekeletu [chief of Pitsane’s tribe—the Makololo—] should resolve to attack the Balonda [Sambanza’s—or, more properly, Manenko’s—people], Pitsane would be under obligation to give Sambanza warning to escape; and so, on the other side. [The ceremony concluded in this case] they now presented each other with the most valuable presents they had to bestow. Sambanza walked off with Pitsane’s suit of green baize faced with red, which had been made in Loanda; and Pitsane, besides abundant supplies of food, obtained two shells [of as great value, in regions far from the sea, ‘as the Lord Mayor’s badge is in London,’] similar to that [one, which] I had received from Shinte [the uncle of Manenko].”[15]

Of the binding force of this covenant, Livingstone says farther: “On one occasion I became blood-relation to a young woman by accident. She had a large cartilaginous tumor between the bones of the forearm, which as it gradually enlarged, so distended the muscles as to render her unable to work. She applied [15] to me to excise it. I requested her to bring her husband, if he were willing to have the operation performed; and while removing the tumor, one of the small arteries squirted some blood into my eye. She remarked, when I was wiping the blood out of it, ‘You were a friend before; now you are a blood-relation; and when you pass this way always send me word, that I may cook food for you.’”[16]

Of the influence of these inter-tribal blood-friendships, in Central Africa, Dr. Livingstone speaks most favorably. Their primitive character is made the more probable, in view of the fact that he first found them existing in a region where, in his opinion, the dress and household utensils of the people are identical with those which are represented on the monuments of ancient Egypt.[17] Although it is within our own generation that this mode of covenanting in the region referred to, has been made familiar to us, the rite itself is of old, elsewhere if not, indeed, there; as other travelers following in the track of Livingstone have noted and reported.

Commander Cameron, who, while in charge of the Livingstone Search Expedition, was the first European traveler to cross the whole breadth of the African continent in its central latitudes, gives several illustrations [16] of the observance of this rite. In June, 1874, at the westward of Lake Tanganyika, Syde, a guide of Cameron, entered into this covenant of blood with Pakwanya, a local chief.

“After a certain amount of palaver,” says Cameron, “Syde and Pakwanya exchanged presents, much to the advantage of the former [for in the East, the person of higher rank is supposed to give the more costly gifts in any such exchange]; more especially [in this case] as he [Syde] borrowed the beads of me and afterward forgot to repay me. Pakwanya then performed a tune on his harmonium, or whatever the instrument [which he had] might be called, and the business of fraternizing was proceeded with. Pakwanya’s head man acted as his sponsor, and one of my askari assumed the like office for Syde.

“The first operation consisted of making an incision on each of their right wrists, just sufficient to draw blood; a little of which was scraped off and smeared on the other’s cut; after which gunpowder was rubbed in [thereby securing a permanent token on the arm]. The concluding part of the ceremony was performed by Pakwanya’s sponsor holding a sword resting on his shoulder, while he who acted [as sponsor] for Syde went through the motions of sharpening a knife upon it. Both sponsors meanwhile made a speech, calling down imprecations on Pakwanya and all his [17] relations, past, present, and future, and prayed that their graves might be defiled by pigs if he broke the brotherhood in word, thought, or deed. The same form having been gone through with, [with] respect to Syde, the sponsors changing duties, the brother-making was complete.”[18]

Concerning the origin of this rite, in this region, Cameron says: “This custom of ‘making brothers,’ I believe to be really of Semitic origin, and to have been introduced into Africa by the heathen Arabs before the days of Mohammed; and this idea is strengthened by the fact that when the first traders from Zanzibar crossed the Tanganyika, the ceremony was unknown [so far as those traders knew] to the westward of that lake.”[19] Cameron was, of course, unaware of the world-wide prevalence of this rite; but his suggestion that its particular form just here had a Semitic origin, receives support in a peculiar difference noted between the Asiatic and the African ceremonies.

It will be remembered, that, among the Syrians, the blood of the covenant is taken into the mouth, and the record of the covenant is bound upon the arm. The Africans, not fully appreciating the force of a written record, are in the habit of reversing this order, according to Cameron’s account. Describing the rite [18] as observed between his men and the natives, on the Luama River, he says: “The brotherhood business having been completed [by putting the blood from one party on to the arm of the other], some pen and ink marks were made on a piece of paper, which, together with a charge of powder, was put into a kettleful of water. All hands then drank of the decoction, the natives being told that it was a very great medicine.”[20] That was “drinking the covenant”[21] with a vengeance; nor is it difficult to see how this idea originated.

The gallant and adventurous Henry M. Stanley also reports this rite of “blood-brotherhood,” or of “strong friendship,” in the story of his romantic experiences in the wilds of Africa. On numerous occasions the observance of this rite was a means of protection and relief to Stanley. One of its more notable illustrations was in his compact with “Mirambo, the warrior chief of Western Unyamwezi;”[22] whose leadership in warfare Stanley compares to that of both Frederick the Great[23] and Napoleon.[24]

It was during his first journey in pursuit of Livingstone, in 1871, that Stanley first encountered the forces of Mirambo, and was worsted in the conflict.[25] Writing [19] of him, after his second expedition, Stanley describes Mirambo, as “the ‘Mars of Africa,’ who since 1871 has made his name feared by both native and foreigner from Usui to Urori, and from Uvinza to Ugogo, a country embracing 90,000 square miles; who, from the village chieftainship over Uyoweh, has made for himself a name as well known as that of Mtesa throughout the eastern half of Equatorial Africa; a household word from Nyangwé to Zanzibar, and the theme of many a song of the bards of Unyamwezi, Ukimbu, Ukonongo, Uzinja, and Uvinza.”[26] For a time, during his second exploring expedition, Stanley was inclined to avoid Mirambo, but becoming “impressed with his ubiquitous powers,”[27] he decided to meet him, and if possible make “strong friendship” with him. They came together, first, at Serombo, April 22, 1876. Mirambo “quite captivated” Stanley. “He was a thorough African gentleman in appearance.... A handsome, regular-featured, mild-voiced, soft-spoken man, with what one might call a ‘meek’ demeanor; very generous and open-handed;” his eyes having “the steady, calm gaze of a master.”[28]

The African hero and the heroic American agreed to “make strong friendship” with each other. Stanley thus describes the ceremony: “Manwa Sera [Stanley’s [20] ‘chief captain’] was requested to seal our friendship by performing the ceremony of blood-brotherhood between Mirambo and myself. Having caused us to sit fronting each other on a straw-carpet, he made an incision in each of our right legs, from which he extracted blood, and inter-changing it, he exclaimed aloud: ‘If either of you break this brotherhood now established between you, may the lion devour him, the serpent poison him, bitterness be in his food, his friends desert him, his gun burst in his hands and wound him, and everything that is bad do wrong to him until death.’”[29] The same blood now flowed in the veins of both Stanley and Mirambo. They were friends and brothers in a sacred covenant; life for life. At the conclusion of the covenant, they exchanged gifts; as the customary ratification, or accompaniment, of the compact. They even vied with each other in proofs of their unselfish fidelity, in this new covenant of friendship.[30]

Again and again, before and after this incident, Stanley entered into the covenant of blood-brotherhood with representative Africans; in some instances by the opening of his own veins; at other times by allowing one of his personal escort to bleed for him. In January, 1875, a “great magic doctor of Vinyata” came to Stanley’s tent to pay a friendly visit, “bringing with him a fine, fat ox as a peace offering.” After [21] an exchange of gifts, says Stanley, “he entreated me to go through the process of blood-brotherhood, which I underwent with all the ceremonious gravity of a pagan.”[31]

Three months later, in April, 1875, when Stanley found himself and his party in the treacherous toils of Shekka, the King of Bumbireh, he made several vain attempts to “induce Shekka, with gifts, to go through the process of blood-brotherhood.” Stanley’s second captain, Safeni, was the adroit, but unsuccessful, agent in the negotiations. “Go frankly and smilingly, Safeni, up to Shekka, on the top of that hill,” said Stanley, “and offer him these three fundo of beads, and ask him to exchange blood with you.” But the wily king was not to be dissuaded from his warlike purposes in that way. “Safeni returned. Shekka had refused the pledge of peace.”[32] His desire was to take blood, if at all, without any exchange.

After still another three months, in July, 1875, Stanley, at Refuge Island, reports better success in securing peace and friendship through blood-giving and blood-receiving. “Through the influence of young Lukanjah—the cousin of the King of Ukerewé”—he says, “the natives of the mainland had been induced to exchange their churlish disposition for one of cordial welcome; and the process of blood-brotherhood had [22] been formally gone through [with], between Manwa Sera, on my part, and Kijaju, King of Komeh, and the King of Itawagumba, on the other part.”[33]

It was at “Kampunzu, in the district of Uvinza, where dwell the true aborigines of the forest country,”—a people whom Stanley afterwards found to be cannibals—that this rite was once more observed between the explorers and the natives. “Blood-brotherhood being considered as a pledge of good-will and peace,” says Stanley, “Frank Pocock [a young Englishman who was an attendant of Stanley] and the chief [of Kampunzu] went through the ordeal; and we interchanged presents”—as is the custom in the observance of this rite.[34]

At the island of Mpika, on the Livingstone River, in December, 1876, there was another bright episode in Stanley’s course of travel, through this mode of sealing friendship. Disease had been making sad havoc in Stanley’s party. He had been compelled to fight his way along through a region of cannibals. While he was halting for a breakfast on the river bank over against Mpika, an attack on him was preparing by the excited inhabitants of the island. Just then his scouts captured a native trading party of men and women who were returning to Mpika, from inland; and to them his interpreters made clear his pacific [23] intentions. “By means of these people,” he says, “we succeeded in checking the warlike demonstrations of the islanders, and in finally persuading them to make blood-brotherhood; after which we invited canoes to come and receive [these hostages] their friends. As they hesitated to do so, we embarked them in our own boat, and conveyed them across to the island. The news then spread quickly along the whole length of the island that we were friends, and as we resumed our journey, crowds from the shore cried out to us, ‘Mwendé Ki-vuké-vuké’ (‘Go in peace!’)”[35]

Once more it was at the conclusion of a bloody conflict, in the district of Vinya-Njara, just below Mpika Island, that peace was sealed by blood. When practical victory was on Stanley’s side, at the cost of four of his men killed, and thirteen more of them wounded, then he sought this means of amity. “With the aid of our interpreters,” he says, “we communicated our terms, viz., that we would occupy Vinya-Njara, and retain all the canoes unless they made peace. We also informed them that we had one prisoner, who would be surrendered to them if they availed themselves of our offer of peace: that we had suffered heavily, and they had also suffered; that war was an evil which wise men avoided; that if they came with two canoes with their chiefs, two canoes [24] with our chiefs should meet them in mid-stream, and make blood-brotherhood; and that on that condition some of their canoes should be restored, and we would purchase the rest.” The natives took time for the considering of this proposition, and then accepted it. “On the 22nd of December, the ceremony of blood-brotherhood having been formally concluded, in mid-river, between Safeni and the chief of Vinya-Njara,” continues Stanley, “our captive, and fifteen canoes, were returned, and twenty-three canoes were retained by us for a satisfactory equivalent; and thus our desperate struggle terminated.”[36]

On the Livingstone, just below the Equator, in February, 1877, Stanley’s party was facing starvation, having been for some time “unable to purchase food, or indeed [to] approach a settlement for any amicable purpose.” The explorers came to look at “each other as fated victims of protracted famine, or [of] the rage of savages, like those of Mangala.” “We continued our journey,” goes on the record, “though grievously hungry, past Bwena and Inguba, doing our utmost to induce the staring fishermen to communicate with us; without any success. They became at once officiously busy with guns, and dangerously active. We arrived at Ikengo, and as we were almost despairing, we proceeded to a small island opposite this settlement, and [25] prepared to encamp. Soon a canoe with seven men came dashing across, and we prepared our moneys for exhibition. They unhesitatingly advanced, and ran their canoe alongside of us. We were rapturously joyful, and returned them a most cordial welcome, as the act was a most auspicious sign of confidence. We were liberal, and the natives fearlessly accepted our presents; and from this giving of gifts we proceeded to seal this incipient friendship with our blood, with all due ceremony.”[37] And by this transfusion of blood, the starving were re-vivified, and the despairing were given hope.

Twice, again, within a few weeks after this experience, there was a call on Stanley of blood for blood, in friendship’s compact. The people of Chumbiri welcomed the travelers. “They readily subscribed to all the requirements of friendship, blood-brotherhood, and an exchange of a few small gifts.”[38] Itsi, the king of Ntamo, with several of his elders and a showy escort, came out to meet Stanley; and there was a friendly greeting on both sides. “They then broached the subject of blood-brotherhood. We were willing,” says Stanley, “but they wished to defer the ceremony until they had first shown their friendly feelings to us.” Thereupon gifts were exchanged, and the king indicated his preference for a “big goat” of Stanley’s, [26] as his benefaction—which, after some parleying, was transferred to him. Then came the covenant-rite. “The treaty with Itsi,” says Stanley, “was exceedingly ceremonious, and involved the exchange of charms. Itsi transferred to me for my protection through life, a small gourdful of a curious powder, which had rather a saline taste; and I delivered over to him, as the white man’s charm against all evil, a half-ounce vial of magnesia; further, a small scratch in Frank’s arm, and another in Itsi’s arm, supplied blood sufficient to unite us in one, and [by an] indivisible bond of fraternity.”[39]

Four years after this experience of blood-covenanting, by proxy, with young Itsi, Stanley found himself again at Ntamo, or across the river from it; this time in the interest of the International Association of the Congo. Being short of food, he had sent out a party of foragers, and was waiting their return with interest. “During the absence of the food-hunters,” he says, “we heard the drums of Ntamo, and [we] followed with interested eyes the departure of two large canoes from the landing-place, their ascent to the place opposite, and their final crossing over towards us. Then we knew that Ngalyema of Ntamo had condescended to come and visit us. As soon as he arrived I recognized him as the Itsi with whom, in 1877, I [27] had made blood-brotherhood [by proxy]. During the four years that had elapsed, he had become a great man.... He was now about thirty-four years old, of well-built form, proud in his bearing, covetous and grasping in disposition, and, like all other lawless barbarians, prone to be cruel and sanguinary whenever he might safely vent his evil humor. Superstition had found in him an apt and docile pupil, and fetishism held him as one of its most abject slaves. This was the man in whose hands the destinies of the Association Internationale du Congo were held, and upon whose graciousness depended our only hope of being able to effect a peaceful lodgment on the Upper Congo.” A pagan African was an African pagan, even while the blood-brother of a European Christian. Yet, the tie of blood-covenanting was the strongest tie known in Central Africa. Frank Pocock, whose covenant-blood flowed in Itsi’s veins, was dead;[40] yet for his sake his master, Stanley, was welcomed by Itsi as a brother; and in true Eastern fashion he was invited to prove anew his continuing faith by a fresh series of love-showing gifts. “My brother being the supreme lord of Ntamo, as well as the deepest-voiced and most arrogant rogue among the whole tribe,” says Stanley, “first demanded the two asses [which Stanley had with him], then a large [28] mirror, which was succeeded by a splendid gold-embroidered coat, jewelry, glass clasps, long brass chains, a figured table-cloth, fifteen other pieces of fine cloth, and a japanned tin box with a ‘Chubb’ lock. Finally, gratified by such liberality, Ngalyema surrendered to me his sceptre, which consisted of a long staff, banded profusely with brass, and decorated with coils of brass wire, which was to be carried by me and shown to all men that I was the brother of Ngalyema [or, Itsi] of Ntamo!”[41] Some time after this, when trouble arose between Stanley and Ngalyema, the former suggested that perhaps it would be better to cancel their brotherhood. “‘No, no, no,’ cried Ngalyema, anxiously; ‘our brotherhood cannot be broken; our blood is now one.’” Yet at this time Stanley’s brotherhood with Ngalyema was only by the blood of his deceased retainer, Frank Pocock.

More commonly, the rite of blood-friendship among the African tribes seems to be by the inter-transfusion of blood; but the ancient Syrian method is by no means unknown on that continent. Stanley tells of one crisis of hunger, among the cannibals of Rubunga, when the hostility of the natives on the river bank was averted by a shrewd display of proffered trinkets from the boats of the expedition. “We raised our anchor,” he says, “and with two strokes of the oars [29] had run our boat ashore; and, snatching a string or two of cowries [or shell-money], I sprang on land, followed by the coxswain Uledi, and in a second I had seized the skinny hand of the old chief, and was pressing it hard for joy. Warm-hearted Uledi, who the moment before was breathing furious hate of all savages, and of the procrastinating old chief in particular, embraced him with a filial warmth. Young Saywa, and Murabo, and Shumari, prompt as tinder upon all occasions, grasped the lesser chiefs’ hands, and devoted themselves with smiles and jovial frank bearing to conquer the last remnants of savage sullenness, and succeeded so well that, in an incredible short time, the blood-brotherhood ceremony between the suddenly formed friends was solemnly entered into, and the irrevocable pact of peace and good will had been accomplished.”[42]

Apparently unaware of the method of the ancient Semitic rite, here found in a degraded form, Stanley seems surprised at the mutual tasting of blood between the contracting friends, in this instance. He says: “Blood-brotherhood was a beastly cannibalistic ceremony with these people, yet much sought after,—whether for the satisfaction of their thirst for blood, or that it involved an interchange of gifts, of which they must needs reap the most benefit. After an incision [30] was made in each arm, both brothers bent their heads, and the aborigine was observed to suck with the greatest fervor; whether for love of blood or excess of friendship, it would be difficult to say.”[43]

During his latest visit to Africa, in the Congo region, Stanley had many another occasion to enter into the covenant of blood with native chiefs, or to rest on that covenant as before consummated. His every description of the rite itself has its value, as illustrating the varying forms and the essential unity of the ceremony of blood-covenanting, the world over.

A reference has already been made[44] to Stanley’s meeting, on this expedition, with Ngalyema, who, under the name of Itsi, had entered into blood-brotherhood with Frank Pocock, four years before. That brotherhood by proxy had several severe strains, in the progress of negotiations between Stanley and Ngalyema; and after some eight months of these varying experiences, it was urgently pressed on Stanley by the chiefs of Kintamo (which is another name for Ntamo), that he should personally covenant by blood with Ngalyema, and so put an end to all danger of conflict between them. To this Stanley assented, and the record of the transaction is given accordingly, under date of April 9, 1882: “Brotherhood with Ngalyema was performed. We crossed arms; an incision [31] was made in each arm; some salt was placed on the wound, and then a mutual rubbing took place, while the great fetish man of Kintamo pronounced an inconceivable number of curses on my head if ever I proved false. Susi [Livingstone’s head man, now with Stanley], not to be outdone by him, solicited the gods to visit unheard-of atrocious vengeances on Ngalyema if he dared to make the slightest breach in the sacred brotherhood which made him and Bula Matari[45] one and indivisible for ever.”[46]

In June, 1883, Stanley visited, by invitation, Mangombo, the chief of Irebu, on the Upper Congo, and became his blood-brother. Describing his landing at this “Venice of the Congo,” he says: “Mangombo, with a curious long staff, a fathom and a half in length, having a small spade of brass at one end, much resembling a baker’s cake-spade, stood in front. He was a man probably sixty years old, but active and by no means aged-looking, and he waited to greet me.... Generally the first day of acquaintance with the Congo river tribes is devoted to chatting, sounding one another’s principles, and getting at one another’s ideas. The chief entertains his guest with gifts of food, goats, beer, fish, &c.; then, on the next day, [32] commences business and reciprocal exchange of gifts. So it was at Irebu. Mangombo gave four hairy thin-tailed sheep, ten glorious bunches of bananas, two great pots of beer, and the usual accompaniments of small stores. The next day we made blood-brotherhood. The fetish-man pricked each of our right arms, pressed the blood out; then, with a pinch of scrapings from my gun stock, a little salt, a few dusty scrapings from a long pod, dropped over the wounded arms, ... the black and white arms were mutually rubbed together [for the inter-transfusion of the flowing blood]. The fetish-man took the long pod in his hand, and slightly touched our necks, our heads, our arms, and our legs, muttering rapidly his litany of incantations. What was left of the medicine Mangombo and I carefully folded in a banana leaf [Was this the ‘house of the amulet?’[47]], and we bore it reverently between us to a banana grove close by, and buried the dust out of sight. Mangombo, now my brother, by solemn interchange of blood,—consecrated to my service, as I was devoted in the sacred fetish bond to his service,—revealed his trouble, and implored my aid.”[48]

Yet again, Stanley “made friendship” with the Bakuti, at Wangata, “after the customary forms of blood-brotherhood”;[49] similarly with two chiefs, Iuka [33] and Mungawa, at Lukolela;[50] with Miyongo of Usindi;[51] and with the chiefs of Bolombo;[52] of Yambinga,[53] of Mokulu,[54] of Irungu,[55] of Upoto,[56] of Uranga;[57] and so all along his course of travel. One of the fullest and most picturesque of his descriptions of this rite, is in connection with its observance with a son of the great chief of the Bangala, at Iboko; and the main details of that description are worthy of reproduction here.

The Bangala, or “the Ashantees of the Livingstone River,” as Stanley characterizes them, are a strong and a superior people, and they fought fiercely against Stanley, when he was passing their country in 1877.[58] “The senior chief, Mata Bwyki (lord of many guns), was [now, in October, 1883,] an old grey-haired man,” says Stanley, “of Herculean stature and breadth of shoulder, with a large square face, and an altogether massive head, out of which his solitary eye seemed to glare with penetrative power. I should judge him to be six feet, two inches, in height. He had a strong, sonorous voice, which, when lifted to speak to his tribe, was heard clearly several hundred yards off. He was now probably between seventy-five and eighty [34] years old.... He was not the tallest man, nor the best looking, nor the sweetest-dispositioned man, I had met in all Africa; but if the completeness and perfection of the human figure, combining size with strength, and proportion of body, limbs, and head, with an expression of power in the face, be considered, he must have been at one time the grandest type of physical manhood to be found in Equatorial Africa. As he stood before us on this day, we thought of him as an ancient Milo, an aged Hercules, an old Samson—a really grand looking old man. At his side were seven tall sons, by different mothers, and although they were stalwart men and boys, the whitened crown of Mata Bwyki’s head rose by a couple of inches above the highest head.”

Nearly two thousand persons assembled, at Iboko, to witness the “palaver” that must precede a decision to enter into “strong friendship.” At the place of meeting, “mats of split rattan were spread in a large semicircle around a row of curved and box stools, for the principal chiefs. In the centre of the line, opposite this, was left a space for myself and people,” continues Stanley. “We had first to undergo the process of steady and silent examination from nearly two thousand pairs of eyes. Then, after Yumbila, the guide, had detailed in his own manner, who we were, and what was our mission up the great river; how we had built towns [35] at many places, and made blood-brotherhood with the chiefs of great districts, such as Irebu, Ukuti, Usindi, Ngombé, Lukolela, Bolobo, Mswata, and Kintamo, he urged upon them the pleasure it would be to me to make a like compact, sealed with blood, with the great chiefs of populous Iboko. He pictured the benefits likely to accrue to Iboko, and Mata Bwyki in particular, if a bond of brotherhood was made between two chiefs like Mata Bwyki and Tandelay, [Stanley,] or as he was known, Bula Matari.”

There was no prompt response to Stanley’s request for strong friendship with the Bangala. There were prejudices to be removed, and old memories to be overborne; and Yumbila’s eloquence and tact were put to their severest test, in the endeavor to bring about a state of feeling that would make the covenant of blood a possibility here. But the triumph was won. “A forked palm branch was brought,” says Stanley. “Kokoro, the heir [of Mata Bwyki], came forward, seized it, and kneeled before me; as, drawing out his short falchion, he cried, ‘Hold the other branch, Bula Matari!’ I obeyed him, and lifting his hand he cleaved the branch in two. ‘Thus,’ he said, ‘I declare my wish to be your brother.’

“Then a fetish-man came forward with his lancets, long pod, pinch of salt, and fresh green banana leaf. He held the staff of Kokoro’s sword-bladed spear, [36] while one of my rifles was brought from the steamer. The shaft of the spear and the stock of the rifle were then scraped on the leaf, a pinch of salt was dropped on the wood, and finally a little dust from the long pod was scraped on the curious mixture. Then, our arms were crossed,—the white arm over the brown arm,—and an incision was made in each; and over the blood was dropped a few grains of the dusty compound; and the white arm was rubbed over the brown arm [in the intermingling of blood].”

“Now Mata Bwyki lifted his mighty form, and with his long giant’s staff drove back the compressed crowd, clearing a wide circle, and then roaring out in his most magnificent style, leonine in its lung-force, kingly in its effect: ‘People of Iboko! You by the river side, and you of inland. Men of the Bangala, listen to the words of Mata Bwyki. You see Tandelay before you. His other name is Bula Matari. He is the man with the many canoes, and has brought back strange smoke-boats. He has come to see Mata Bwyki. He has asked Mata Bwyki to be his friend. Mata Bwyki has taken him by the hand, and has become his blood-brother. Tandelay belongs to Iboko now. He has become this day one of the Bangala. O, Iboko! listen to the voice of Mata Bwyki.’ (I thought they must have been incurably deaf, not to have heard that voice). ‘Bula Matari and Mata Bwyki [37] are one to-day. We have joined hands. Hurt not Bula Matari’s people; steal not from them; offend them not. Bring food and sell to him at a fair price, gently, kindly, and in peace; for he is my brother. Hear you, ye people of Iboko—you by the river side, and you of the interior?’

“‘We hear, Mata Bwyki!’ shouted the multitude.”[59] And the ceremony was ended.

A little later than this, Stanley, or Tandelay, or Bula Matari, as the natives called him, was at Bumba, and there again he exchanged blood in friendship. “Myombi, the chief,” he says, “was easily persuaded by Yumbila to make blood-brotherhood with me; and for the fiftieth time my poor arm was scarified, and my blood shed for the cause of civilization. Probably one thousand people of both sexes looked on the scene, wonderingly and strangely. A young branch of a palm was cut, twisted, and a knot tied at each end; the knots were dipped in wood ashes, and then seized and held by each of us, while the medicine-man practised his blood-letting art, and lanced us both, until Myombi winced with pain; after which the knotted branch was severed; and, in some incomprehensible manner, I had become united forever to my fiftieth brother; to whom I was under the obligation of defending [him] against all foes until death.”[60]

The blood of a fair proportion of all the first families[38] of Equatorial Africa now courses in Stanley’s veins; and if ever there was an American citizen who could appropriate to himself preeminently the national motto, “E pluribus unum,” Stanley is the man.

The root-idea of this rite of blood-friendship seems to include the belief, that the blood is the life of a living being; not merely that the blood is essential to life, but that, in a peculiar sense, it is life; that it actually vivifies by its presence; and that by its passing from one organism to another it carries and imparts life. The inter-commingling of the blood of two organisms is, therefore, according to this view, equivalent to the inter-commingling of the lives, of the personalities, of the natures, thus brought together; so that there is, thereby and thenceforward, one life in the two bodies, a common life between the two friends: a thought which Aristotle recognizes in his citation of the ancient “proverb”: “One soul [in two bodies],”[61] a proverb which has not lost its currency in any of the centuries.

That the blood can retain its vivifying power whether passing into another by way of the lips or by way of the veins, is, on the face of it, no less plausible, than that [39] the administering of stimulants, tonics, nutriments, nervines, or anæsthetics, hypodermically, may be equally potent, in certain cases, with the more common and normal method of seeking assimilation by the process of digestion. That the blood of the living has a peculiar vivifying force, in its transference from one organism to another, is one of the clearly proven re-disclosures of modern medical science; and this transference of blood has been made to advantage by way of the veins, of the stomach, of the intestines, of the tissue, and even of the lungs—through dry-spraying.[62]

Different methods of observing this primitive rite of blood-covenanting are indicated in the legendary lore of the Norseland peoples; and these methods, in all their variety, give added proof of the ever underlying idea of an inter-commingling of lives through an inter-commingling of blood. Odin was the beneficent god of light and knowledge, the promoter of heroism, and the protector of sacred covenants, in the mythology of the North. Lôké, or Lok, on the other hand, was the discordant and corrupting divinity; [40] symbolizing, in his personality, “sin, shrewdness, deceitfulness, treachery, malice,” and other phases of evil.[64] In the poetic myths of the Norseland, it is claimed that at the beginning Odin and Lôké were in close union instead of being at variance;[65] just as the Egyptian cosmogony made Osiris and Set in original accord, although in subsequent hostility;[66] and as the Zoroastrians claimed that Ormuzd and Ahriman were at one, before they were in conflict.[67] Odin and Lôké are, indeed, said to have been, at one time, in the close and sacred union of blood-friendship; having covenanted in that union by mingling their blood in a bowl, and drinking therefrom together.

The Elder Edda,[68] or the earliest collection of Scandinavian songs, makes reference to this confraternity of Odin and Lôké. At a banquet of the gods, Lôké, who had not been invited, found an entrance, and there reproached his fellow divinities for their hostility to him. Recalling the indissoluble tie of blood-friendship, he said:

In citing this illustration of the ancient rite, a modern historian of chivalry has said: “Among barbarous people [the barbarians of Europe] the fraternity of arms [the sacred brotherhood of heroes] was established by the horrid custom of the new brothers drinking each other’s blood; but if this practice was barbarous, nothing was farther from barbarism than the sentiment which inspired it.”[70]

Another of the methods by which the rite of blood-friendship was observed in the Norseland, was by causing the blood of the two covenanting persons to inter-flow from their pierced hands, while they lay together underneath a lifted sod. The idea involved seems to have been, the burial of the two individuals, in their separate personal lives, and the intermingling of those lives—by the intermingling of their blood—while in their temporary grave; in order to their [42] rising again with a common life[71]—one life, one soul, in two bodies. Thus it is told, in one of the Icelandic Sagas, of Thorstein, the heroic son of Viking, proffering “foster-brotherhood,” or blood-friendship, to the valiant Angantyr, Jarl of the Orkneys. “Then this was resolved upon, and secured by firm pledges on both sides. They opened a vein in the hollow of their hands, crept beneath the sod, and there [with clasped hands inter-blood-flowing] they solemnly swore that each of them should avenge the other if any one of them should be slain by weapons.” This was, in fact, a three-fold covenant of blood; for King Bele, who had just been in combat with Angantyr, was already in blood-friendship with Thorstein.[72]

The rite of blood-friendship, in one form and another finds frequent mention in the Norseland Sagas. Thus, in the Saga of Fridthjof the Bold, the son of Thorstein:

A vestige of this primitive rite, coming down to us through European channels, is found, as are so many other traces of primitive rites, in the inherited folk-lore of English-speaking children on both sides of the Atlantic. An American clergyman’s wife said recently, on this point: “I remember, that while I was a school-girl, it was the custom, when one of our companions pricked her finger, so that the blood came, for one or another of us to say ‘Oh, let me suck the blood; then we shall be friends.’” And that is but an illustration of the outreaching after this indissoluble bond, on the part of thirty generations of children of Norseland and Anglo-Saxon stock, since the days of Fridthjof and Bjorn; as that same yearning had been felt by those of a hundred generations before that time.

Concerning traces of the rite of blood-covenanting in China, where there are to be found fewest resemblances to the primitive customs of the Asiatic Semites, Dr. Yung Wing, the eminent Chinese educationalist and diplomat, gives me the following illustration: “In the year 1674, when Kănhi was Emperor, of the present dynasty, we find that the Buddhist priests of Shanlin Monastery in Fuhkin Province had rebelled against the authorities on account of persecution. In their encounters with the troops, they fought against great [44] odds, and were finally defeated and scattered in different provinces, where they organized centres of the Triad Society, which claims an antiquity dated as far back as the Freemasons of the West. Five of these priests fled to the province of Hakwong, and there, Chin Kinnan, a member of the Hanlin College, who was degraded from office by his enemies, joined them; and it is said that they drank blood, and took the oath of brotherhood, to stand by each other in life or death.”

Along the southwestern border of the Chinese Empire, in Burmah, this rite of blood-friendship is still practiced; as may be seen from illustrations of it, which are given in the Appendix of this work.

In his History of Madagascar, the Rev. William Ellis, tells of this rite as he observed it in that island, and as he learned of it from Borneo. He says:

“Another popular engagement in use among the Malagasy is that of forming brotherhoods, which though not peculiar to them, is one of the most remarkable usages of the country.... Its object is to cement two individuals in the bonds of most sacred friendship.... More than two may thus associate, if they please; but the practice is usually limited to that number, and rarely embraces more than three or four individuals. It is called fatridá, i. e., ‘dead blood,’ either because the oath is taken over the blood of a [45] fowl killed for the occasion, or because a small portion of blood is drawn from each individual, when thus pledging friendship, and drunk by those to whom friendship is pledged, with execrations of vengeance on each other in case of violating the sacred oath. To obtain the blood, a slight incision is made in the skin covering the centre of the bosom, significantly called ambavafo, ‘the mouth of the heart.’ Allusion is made to this, in the formula of this tragi-comical ceremony.

“When two or more persons have agreed on forming this bond of fraternity, a suitable place and hour are determined upon, and some gunpowder and a ball are brought, together with a small quantity of ginger, a spear, and two particular kinds of grass. A fowl also is procured; its head is nearly cut off; and it is left in this state to continue bleeding during the ceremony.[74]

“The parties then pronounce a long form of imprecation, and [a] mutual vow, to this effect:—‘Should either of us prove disloyal to the sovereign, or unfaithful to each other,[75] then perish the day, and perish [46] the night.[76] Awful is that, solemn is that, which we are now both about to perform! O the mouth of the heart!—this is to be cut, and we shall drink each other’s blood. O this ball! O this powder! O this ginger! O this fowl weltering in its blood!—it shall be killed, it shall be put to excruciating agonies,—it shall be killed by us, it shall be speared at this corner of the hearth (Alakaforo or Adimizam, S. W.) And whoever would seek to kill or injure us, to injure our wives, or our children, to waste our money or our property; or if either of us should seek to do what would not be approved of by the king or by the people; should one of us deceive the other by making that which is unjust appear just; should one accuse the other falsely; should either of us with our wives and children be lost and reduced to slavery, (forbid that such should be our lot!)—then, that good may arise out of evil, we follow this custom of the people; and we do it for the purpose of assisting one another with our families, if lost in slavery, by whatever property either of us may possess; for our wives are as one to us, and each other’s children as his own,[77] and our riches as common property. O the mouth of the heart! O the ball! O the powder! O the ginger! O this miserable fowl weltering in its blood!—thy liver do we [47] eat, thy liver do we eat. And should either of us retract from the terms of this oath, let him instantly become a fool, let him instantly become blind, let this covenant prove a curse to him: let him not be a human being: let there be no heir to inherit after him, but let him be reduced, and float with the water never to see its source; let him never obtain; what is out of doors, may it never enter; and what is within may it never go out; the little obtained, may he be deprived of it;[78] and let him never obtain justice from the sovereign nor from the people! But if we keep and observe this covenant, let these things bear witness.[79] O mouth of the heart! (repeating as before),—may this cause us to live long and happy with our wives and our children; may we be approved by the sovereign, and beloved by the people; may we get money, may we obtain property, cattle, &c.; may we marry wives, (vady kely); may we have good robes, and wear a good piece of cloth on our bodies;[80] since, amidst our toils and labor, these are the things we seek after.[81] And this we do that we may with all fidelity assist each other to the last.’

“The incision is then made, as already mentioned; a small quantity of blood [is] extracted and drank by the covenanting parties respectively, [they] saying as they take it, ‘These are our last words, We will be like rice and water;[82] in town they do not separate, and in the fields they do not forsake one another; we will be as the right and left hand of the body; if one be injured, the other necessarily sympathizes and suffers with it.’”[83]

Speaking of the terms and the influence of this covenant, in Madagascar, Mr. Ellis says, that while absolute community of all worldly possessions is not a literal fact on the part of these blood-friends, “the engagement involves a sort of moral obligation for one to assist the other in every extremity.” “However devoid of meaning,” he adds, “some part of the ceremony of forming [this] brotherhood may appear, and whatever indications of barbarity of feeling may appear in others, it is less exceptionable than many [of the rites] that prevail among the people.... So far as those who have resided in the country have observed its effects, they appear almost invariably to have been safe [49] to the community, and beneficial to the individuals by whom the compact was formed.”

Yet again, this covenant of blood-friendship is found in different parts of Borneo. In the days of Mr. Ellis, the Rev. W. Medhurst, a missionary of the London Missionary Society, in Java, described it, in reporting a visit made to the Dayaks of Borneo, by one of his assistants together with a missionary of the Rhenish Missionary Society.[84]

Telling of the kindly greeting given to these visitors at a place called Golong, he says that the natives wished “to establish a fraternal agreement with the missionaries, on condition that the latter should teach them the ways of God. The travelers replied, that if the Dayaks became the disciples of Christ, they would be constituted the brethren of Christ without any formal compact. The Dayaks, however, insisted that the travelers should enter into a compact [with them], according to the custom of the country, by means of blood. The missionaries were startled at this, thinking that the Dayaks meant to murder them, and committed themselves to their Heavenly Father, praying that, whether living or dying, they might lie at the feet of their Saviour. It appears, however, that it is the custom of the Dayaks, when they enter into a covenant, to draw a little blood from the arms of the [50] covenanting parties, and, having mixed it with water, each to drink, in this way, the blood of the other.

“Mr. Barenstein [one of the missionaries] having consented [for both] to the ceremony, they all took off their coats, and two officers came forward with small knives, to take a little blood out of the arm of each of them [the two missionaries and two Dayak chiefs]. This being mixed together in four glasses of water, they drank, severally, each from the glass of the other; after which they joined hands and kissed. The people then came forward, and made obeisance to the missionaries, as the friends of the Dayak King, crying out with loud voices, ‘Let us be friends and brethren forever; and may God help the Dayaks to obtain the knowledge of God from the missionaries!’ The two chiefs then said, ‘Brethren, be not afraid to dwell with us; for we will do you no harm; and if others wish to hurt you, we will defend you with our life’s blood, and die ourselves ere you be slain. God be witness, and this whole assembly be witness, that this is true.’ Whereupon the whole company shouted, Balaak! or ‘Good,’ ‘Be it so.’”

Yet another method of observing this rite, is reported from among the Kayans of Borneo; quite a different people from the Dayaks. Its description is from the narrative of Mr. Spenser St. John, as follows: “Siñgauding [a Kayan chief] sent on board to request [51] me to become his brother, by going through the sacred custom of imbibing each other’s blood. I say imbibing, because it is either mixed with water and drunk, or else is placed within a native cigar, and drawn in with the smoke. I agreed to do so, and the following day was fixed for the ceremony. It is called Berbiang by the Kayans; Bersabibah, by the Borneans [the Dayaks]. I landed with our party of Malays, and after a preliminary talk, to allow the population to assemble, the affair commenced.... Stripping my left arm, Kum Lia took a small piece of wood, shaped like a knife-blade, and, slightly piercing the skin, brought blood to the surface; this he carefully scraped off. Then one of my Malays drew blood in the same way from Siñgauding; and, a small cigarette being produced, the blood on the wooden blade was spread on the tobacco. A chief then arose, and, walking to an open place, looked forth upon the river, and invoked their god and all the spirits of good and evil to be witness of this tie of brotherhood. The cigarette [blood-stained] was then lighted, and each of us took several puffs [receiving each other’s blood by inhalation], and the ceremony was over.”[85] This is a new method of smoking the “pipe of peace”—or, the cigarette of inter-union! Borneo, indeed, furnishes many illustrations of primitive customs, both social and religious.

One of the latest and most venturesome explorers of North Borneo was the gallant and lamented Frank Hatton, a son of the widely known international journalist, Joseph Hatton. In a sketch of his son’s life-work, the father says[86]: “His was the first white foot in many of the hitherto unknown villages of Borneo; in him many of the wild tribes saw the first white man.... Speaking the language of the natives, and possessing that special faculty of kindly firmness so necessary to the efficient control of uncivilized peoples, he journeyed through the strange land not only unmolested, but frequently carrying away tokens of native affection. Several powerful chiefs made him their ‘blood-brother’; and here and there the tribes prayed to him as if he were a god.” It would seem from the description of Mr. Hatton, that, in some instances, in Borneo, the blood-covenanting is by the substitute blood of a fowl held by the two parties to the covenant, while its head is cut off by a third person; without any drinking of each other’s blood by those who enter into the covenant. Yet however this may be, the other method still prevails there.

Another recent traveler in the Malay Archipelago, who, also, is a trained and careful observer, tells of this rite, as he found it in Timor, and other islands of that region, among a people who represent the Malays, [53] the Papuan, and the Polynesian races. His description is: “The ceremony of blood-brotherhood, ... or the swearing of eternal friendship, is of an interesting nature, and is celebrated often by fearful orgies [excesses of the communion idea], especially when friendship is being made between families, or tribes, or kingdoms. The ceremony is the same in substance whether between two individuals, or [between] large companies. The contracting parties slash their arms, and collect the blood into a bamboo, into which kanipa (coarse gin) or laru (palm wine) is poured. Having provided themselves with a small fig-tree (halik) they adjourn to some retired spot, taking with them the sword and spear from the Luli chamber [the sacred room] of their own houses if between private individuals, or from the Uma-Luli of their suku [the sacred building of their village] if between large companies. Planting there the fig-tree, flanked by the sacred sword and spear, they hang on it a bamboo-receptacle, into which—after pledging each other in a portion of the mixed blood and gin—the remainder [of that mixture] is poured. Then each swears, ‘If I be false, and be not a true friend, may my blood issue from my mouth, ears, nose, as it does from this bamboo!’—the bottom of the receptacle being pricked at the same moment, to allow the blood and gin to escape. The [blood-stained] tree remains and grows as a witness of their contract.”

Of the close and binding nature of this blood-compact, among the Timorese, the observer goes on to say: “It is one of their most sacred oaths, and [is] almost never, I am told, violated; at least between individuals.” As to its limitless force and scope, he adds: “One brother [one of these brother-friends in the covenant of blood] coming to another brother’s house, is in every respect regarded as free [to do as he pleases], and [is] as much at home as its owner. Nothing is withheld from him; even his friend’s wife is not denied him, and a child born of such a union would be recognized by the husband as his; [for are not—as they reason—these brother-friends of one blood—of one and the same life?]”[87]

The covenant of blood-friendship has been noted also among the native races of both North and South America. A writer of three centuries ago, told of it as among the aborigines of Yucatan. “When the Indians of Pontonchan,” he said, “receive new friends [covenant in a new friendship] ... as a proof of [their] friendship, they [mutually, each], in the sight of the friend, draw some blood ... from the tongue, hand, or arm, or from some other part [of the body].”[88] [55] And this ceremony is said to have formed “a compact for life.”[89]

In Brazil, the Indians were said to have a rite of brotherhood so close and sacred that, as in the case of the Bed´ween beyond the Jordan,[90] its covenanting parties were counted as of one blood; so that marriage between those thus linked would be deemed incestuous. “There was a word in their language to express a friend who was loved like a brother; it is written Atourrassap [‘erroneously, beyond a doubt,’ adds Southey, ‘because their speech is without the r’]. They who called each other by this name, had all things in common; the tie was held to be as sacred as that of consanguinity, and one could not marry the daughter or sister of the other.”[91]

A similar tie of adopted brotherhood, or of close and sacred friendship, is recognized among the North American Indians. Writing of the Dakotas, or the Sioux, Dr. Riggs, the veteran missionary and scholar, says: “Where one Dakota takes another as his koda, i. e., god, or friend, [Think of that, for sacredness of union—‘god, or friend’!] they become brothers in each other’s families, and are, as such, of course unable to intermarry.”[92] And Burton, the famous traveler, who [56] made this same tribe a study, says of the Dakotas: “They are fond of adoption, and of making brotherhoods like the Africans [Burton is familiar with the customs of African tribes]; and so strong is the tie that marriage with the sister of an adopted brother is within the prohibited degree.”[93]

Among the people of the Society Islands, and perhaps also among those of other South Sea Islands, the term tayo is applied to an attached personal friend, in a peculiar relation of intimacy. The formal ceremony of brotherhood, whereby one becomes the tayo of another, in these islands, I have not found described; but the closeness and sacredness of the relation, as it is held by many of the natives, would seem to indicate the inter-mingling of blood in the covenanting, now or in former times. The early missionaries to those islands, speaking of the prevalent unchastity there, make this exception: “If a person is a tayo of the husband, he must indulge in no liberties with the sisters or the daughters, because they are considered as his own sisters or daughters; and incest is held in abhorrence by them; nor will any temptations engage them to violate this bond of purity. The wife, however, is excepted, and considered as common property for the tayo.[94] Lieutenant Corner [a still earlier voyager] also added, that a tayoship formed [57] between different sexes put the most solemn barrier against all personal liberties.”[95] Here is evidenced that same view of the absolute oneness of nature through a oneness of blood, which shows itself among the Semites of Syria,[96] among the Malays of Timor,[97] and among the Indians of America.[98]

And so this close and sacred covenant relation, this rite of blood-friendship, this inter-oneness of life by an inter-oneness of blood, shows itself in the primitive East, and in the wild and pre-historic West; in the frozen North, as in the torrid South. Its traces are everywhere. It is of old, and it is of to-day; as universal and as full of meaning as life itself.

It will be observed that we have already noted proofs of the independent existence of this rite of blood-brotherhood, or blood-friendship, among the three great primitive divisions of the race—the Semitic, the Hamitic, and the Japhetic; and this in Asia, Africa, Europe, America, and the Islands of the Sea; again, among the five modern and more popular divisions of the human family: Caucasian, Mongolian, Ethiopian, Malay, and American. This fact in itself would seem to point to a common origin of its various manifestations, in the early Oriental home of the now scattered peoples of the world. Many references to [58] this rite, in the pages of classic literature, seem to have the same indicative bearing, as to its nature and primitive source.

Lucian, the bright Greek thinker, who was born and trained in the East, writing in the middle of the second century of our era, is explicit as to the nature and method of this covenant as then practised in the East. In his “Toxaris or Friendship,”[99] Mnesippus the Greek, and Toxaris the Scythian, are discussing friendship. Toxaris declares: “It can easily be shown that Scythian friends are much more faithful than Greek friends; and that friendship is esteemed more highly among us than among you.” Then Toxaris goes on to say[100]: “But first I wish to tell you in what manner we [in Scythia] make friends; not in our drinking bouts as you do, nor simply because a man is of the same age [as ourselves], or because he is our neighbor. But, on the contrary, when we see a good man, and one capable of great deeds, to him we all hasten, and (as you do in the case of marrying, so we think it right to do in the case of our friends) we court him, and we [who would be friends] do all things together, so that we may not offend against friendship, or seem [59] worthy to be rejected. And whenever one decides to be a friend, we [who would join in the covenant] make the greatest of all oaths, to live with one another, and to die, if need be, the one for the other. And this is the manner of it: Thereupon, cutting our fingers, all simultaneously, we let the blood drop into a vessel, and having dipped the points of our swords into it, both [of us] holding them together,[101] we drink it. There is nothing which can loose us from one another after that.”