ILLUSTRATED BY FORTY-FIVE ENGRAVINGS.

THE SECOND EDITION.

VOLUME II.

[11]

CHAP. VI.

THE RELIGIOUS AND POLITICAL PASSIONS OF THE COMMUNITY

ILLUSTRATED BY ANECDOTES OF POPULAR TUMULTS.

The first violent effervescence of party after the year 1700 originated

from the intemperance of certain Sectaries, who omitted no opportunity

of attacking the Established Church; one of the members of which,

Sacheverell, equally intemperate, contrived to raise the Demon of

Discord throughout the Nation by Sermons calculated to make all good

Churchmen detest him. In these half religious, half political contests,

the populace uniformly arrange themselves on the side of Liberty—that

Liberty which prompts them to assume the reins of Justice, and to

dispense it according to the best of their shallow judgments; but their

whips are firebrands, and indiscriminate destruction is substituted for

the terrors of the [12]Law; their Culprits are seized at the instigation

of some infamous leader, and punishment is inflicted before passion

subsides. While Sacheverell's trial was depending in 1709-10, the

many-headed monster of this monstrous Metropolis thought proper to

pronounce sentence on the harmless wainscot, pews, and other woodwork

of Mr. Burgess's Meeting, near Lincoln's-inn-fields, whither they

were conveyed and burnt. When this wicked exploit was accomplished,

and they had contrived to kill a young man in their undistinguishing

fury, they proceeded to Fetter and Leather lanes, and several other

places in which Meetings were situated; and would probably have

committed incredible mischief, had not the Queen's guards dispersed

them, and seized several of the ringleaders; one of whom was tried

and condemned, but afterwards reprieved. Some of those infatuated men

stopped coaches in the streets, to demand money of the passengers, to

drink Sacheverell's health; which occasioned an official communication

from the Queen to the Lord Mayor. Her Majesty declared her knowledge

of the riots, bonfires, illuminations, the assaults and stoppage of

coaches to demand money, in opposition to her Proclamation, and in

contempt of the proceedings of the High Court of Parliament; and that

she was credibly informed that great part of those lawless proceedings

were committed through the culpable inactivity of [13]the Magistracy;

at which she expressed great displeasure; and concluded by charging

the Mayor and City Officers, at their peril, to apprehend all persons

exciting tumults and hawking seditious papers through the streets

for sale. To the above letter the Corporation addressed an humble

answer, observing that the insolent attacks on the Constitution and

Her Majesty's Prerogative, by the publication of books and pamphlets

intended to infuse Republican tenets in the minds of her subjects, had

roused them to a consideration of their fatal tendency; they therefore

declared their detestation of such doctrines, their determination to

support the Protestant succession, and, in obedience to her commands,

to suppress all riotous assemblies, and to oppose with undaunted vigour

all attempts to disturb the peace of her reign, or the serenity of her

Royal mind, at home and abroad.

The Queen addressed a similar complaint to the Magistrates of

Middlesex; and received assurances of support from them, those of

Westminster, and the Lieutenancy of London.

After these professions of prevention, riots occurred on the 14th of

October, 1710, with the watch-word of "Sacheverell and High Church;"

and the mob beat off the Constables with brands from the numerous

bonfires they had lighted.

The month of November teemed with the seeds of riot; but the vigilance

of Government was [14]then excited, and secret means employed to discover

those preparatives by which the mob were to be set in motion. Some of

the emissaries employed on this occasion gave information that a house

near Drury-lane contained certain effigies, intended to represent the

Pope, the Pretender, and the Devil; this trio were accompanied by

four Cardinals, four Jesuits, and four Monks, who were to have been

exhibited in due state on the evening of November 17, the anniversary

of Queen Elizabeth's accession, and then burnt, in testimony of the

abhorrence entertained against the Head of the Roman Catholic faith,

his engine for establishing it again in England, and his Majesty of

the Infernal regions, together with the inferior instruments of the

dissemination of his doctrines. Thus informed, Government preferred

opposing such public support of their cause, and wisely intimated

by their conduct that they were willing to rest it on the conscience

of each individual of the community, rather than terrify wavering

Protestants into their measures: in consequence, they issued orders

to seize the figures; which being promptly obeyed, the Messengers and

guards conveyed them in safety to the Earl of Dartmouth's office, by

whose means the sentence of the mob was probably more privately

performed, and the evening passed away without any particular

occurrence. This event was eagerly seized upon by the partizans of

the day; those of [15]Government discovering in it the stamina of a

thousand horrors intended to involve the Roman Catholicks and the

Established Church in one grand ruin; those of the Antimonarchical side

deeming the intended procession a mere common occurrence, occasionally

resorted to by the populace with the best motives. By us , who have

known the infernal proceedings accompanying the cry of "No Popery,"

riots of any kind must be dreaded; and we cannot but approve the

vigilance of the then Government in terminating the existence of an

expiring habit, whose vigorous movements were marked in the following

disgusting "Account of the burning the Pope at Temple-bar in London,

the 17th of November 1679;" an account that compels us to hail with

ten-fold reverence the auspicious Revolution of 1688, that defined

the boundaries of the Sovereign's and the People's right. At the

present period, praised be Heaven! a Jury of twelve men would make

the instigators of such a procession tremble: and every Protestant

in the City would fly from it with indignation; and yet with all our

modern mildness the faith in question gains no proselytes:—a memorable

memento of the liberality of the age[15:A]!

[16]

"Upon the 17th of November the bells began to ring about three o'clock

in the morning in the City of London; and several honourable and

worthy gentlemen belonging to the Temple as well as the City,

(remembering the burning both of London and the Temple, which was

apparently executed by Popish villainy[16:A]) were pleased to be at the

charge of an extraordinary triumph, in commemoration of that blessed

Protestant Queen, which was as follows: In the evening of the said day,

all things being prepared, the solemn procession began from Moorgate,

and so to Bishopsgate-street, and down Hounsditch to Aldgate, through

Leadenhall-street, Cornhill, by the Royal Exchange, through Cheapside,

to Temple-bar, in order following.

[17]1st. Marched six whifflers, in pioneers' caps and red

waistcoats.

2. A bellman, ringing his bell, and with a dolesome voice

crying all the way "Remember Justice Godfrey."

3. A dead body , representing Justice Godfrey in the habit

he usually wore, and the cravat wherewith he was murdered

about his neck, with spots of blood on his wrists, breast,

and shirt, and white gloves on his hands, his face pale and

wan, riding upon a white horse, and one of his murderers

behind him to keep him from falling, in the same manner as he

was carried to Primrose-hill.

4. A Priest came next, in a surplice and a cope embroidered

with dead men's sculls and bones and skeletons , who

gave out pardons very plentifully to all that would murder

Protestants, and proclaiming it meritorious.

5. A Priest alone, with a large silver cross.

6. Four Carmelite Friars, in white and black habits.

7. Four Grey Friars, in their proper habits.

8. Six Jesuits, carrying bloody daggers .

9. Four wind-musick, called the waits, playing all the way.

10. Four Bishops, in purple, with lawn sleeves, and golden

crosses on their breasts, and crosiers in their hands.

11. Four other Bishops, in their pontificalibus, [18]with

surplices and rich-embroidered copes, and golden mitres on

their heads.

12. Six Cardinals, in scarlet robes and caps.

13. Then followed the Pope's chief Physician, with Jesuits

powder in one hand and an urinal in the other.

14. Two Priests in surplices, with two golden crosses.

"Lastly, the Pope, in a glorious pageant or chair of state, covered

with scarlet; the chair being richly embroidered and bedecked with

golden balls and crosses. At his feet was a cushion of state; and two

boys sat on each side the Pope in surplices, with white silk banners

painted with red crosses and bloody consecrated daggers for murdering

Protestant kings and princes, with an incense-pot before them censing

his Holiness. The Pope was arrayed in a rich scarlet gown lined through

with ermines and adorned with gold and silver lace, with a triple-crown

on his head, and a glorious collar of gold and precious stones about

his neck, and St. Peter's keys, a great quantity of beads, Agnus

Dei's, and other Catholic trumpery about him. At his back stood the

Devil , his Holiness's privy-counsel, hugging and whispering him all

the way, and often instructing him aloud to destroy his Majesty, to

contrive a pretended Presbyterian plot, and to fire the City again;

to which purpose he held an infernal torch in his hand. The whole

procession was attended with [19]150 torches and flambeaus by order;

but there were so many came in volunteers as made the number to be

several thousands. Never were the balconies, windows, and houses more

filled, nor the streets more thronged, with multitudes of people,

all expressing their abhorrence of Popery with continual shouts and

acclamations ; so that in the whole progress of their procession by a

modest computation it is judged there could be no less than 200,000

spectators.

"Thus with a slow and solemn state in some hours they arrived at

Temple-bar, where all the houses seemed to be converted into heaps of

men, women, and children, who were diverted with variety of excellent

fire-works. It is known that Temple-bar since its rebuilding is adorned

with four stately statues of Stone, two on each side the Gate; those

towards the City representing Queen Elizabeth and King James, and the

other two towards the Strand King Charles I. and King Charles II.: now,

in regard of the day, the statue of Queen Elizabeth was adorned with a

crown of gilded laurel on her head, and in her hand, a golden shield

with this motto inscribed thereon, "The Protestant Religion, Magna

Charta." Several lighted torches were placed before her, and the Pope

brought up near the gate.

"Having entertained the thronging spectators for some time with

ingenious fire-works, a very great bonfire was prepared at the Inner

Temple-gate; [20]and his Holiness, after some compliments and reluctances,

was decently tumbled into the flames; the Devil who till then

accompanied him left him in the lurch, and, laughing, gave him up

to his deserved fate. This last act of his Holiness's tragedy was

attended with a prodigious shout of the joyful spectators. The same

evening there were bonfires in most streets of London, and universal

acclamations, crying, "Let Popery perish, and Papists with their plots

and counter-plots be for ever confounded. Amen. "

Protestant Postboy, Nov. 20, 1711.

The brutal ferocity of the scenes just described appeared in a more

matured state in the acts of an inconsiderable part of the populace

in 1712: indeed, had their numbers or their courage equalled the

fiend-like qualities of their souls, the consequences must have been

dreadful to the publick. Fortunately, however, there were but fifty

Mohawks , and their cowardice made them an easy prey to justice;

but not before they had committed the most unheard-of excesses, of

which the wounds they inflicted with their swords on the peaceable

passenger of the streets at night were the least. They treated women

in a manner too brutal for a man of the least spirit to repeat, and

their exploits were marked in every other respect with the violation

of decency: Modesty and Innocence became their victims, Impudence and

Lasciviousness they patronized and protected. [21]The Queen issued a

Proclamation on this hateful occasion pregnant with just resentment,

and offered a reward of 100l. for the apprehension of any of the

offenders. The Gazette of March 18, 1711, mentions that Sir William

Thomas, Bart. had been apprehended (who was accompanied by two men then

unknown) for assaulting a gentleman in St. James's Park between nine

and ten at night on the 15th, and calls on the injured person to appear

in evidence before the Secretary of State: but whether the charge

applies to the above outrages is not discoverable from the notice.

April 19 following the Gazette mentions seven men and seven women who

had been assaulted.

At the Quarterly Sessions of that period the Justices had received

orders to put the law in force against Vice and Immorality; and in

consequence of a petition from the inhabitants of Covent-garden,

complaining of the indecency and riots of the loose women and their

male followers in the vicinity of the Theatre, they issued warrants for

their apprehension. The execution of those were violently opposed; and

the Justices were compelled to state to the Privy Council and the Lord

Lieutenant of Middlesex, that the Constables were dreadfully maimed,

and one mortally wounded by Ruffians aided by 40 Soldiers of the

guards, who entered into a combination to protect the women.

In May, Lord Inchinbroke, Sir Mark Cole, [22]and some others, were found

guilty on the charge of being principals in some or other of the above

vile proceedings. After having complimented Government on the propriety

of preventing the populace from publicly burning effigies, it would be

injustice to the latter not to acknowledge they might have pleaded high

authority for doing it. On the 5th of November 1712, the Queen's guards

made a bonfire before the gates of St. James's Palace; into which the

Pretender's effigy was thrown and shot at. Such is Human Nature! The

Lord Mayor appears, however, to have done his duty, by requesting his

fellow citizens to keep at home on the night of the anniversary of

Elizabeth's accession.

One of the oddest occurrences I have yet met with under this head was

a political contest between the Whig and Tory Footmen, who served the

Members of the House of Commons. These worthy patriots had inviolably

observed a custom, for many years previous to 1715, of imitating their

masters in the choice of a Speaker, modestly conceiving themselves a

deliberative body. Now, as the parties happened at this period to be

nearly balanced, much animosity naturally ensued; and, not possessing

the forbearance of their superiors, they had recourse to active

hostilities, and severely beat each other, till the rising of the House

compelled them to desist; but, on the following Monday, the battle was

renewed, and the [23]Tories having gained the day by dint of blows, they

carried their Speaker three times round Westminster-hall, and then,

in pursuance of antient usage, they adjourned to a good dinner at an

adjacent alehouse, and to expend their crown each in toasting their

success.

The accession of George I. was celebrated, in the month of July of

the same year, in the customary manner by the peaceable part of the

community; but the more violent assembled, to the amount of several

hundreds, at the Roebuck Tavern, Cheapside, where they burnt the

effigies of the Pretender habited in mourning before the door,

accompanied by a peal from Bow bells; and the populace were plentifully

supplied with liquor. The same persons, joined by many young men and

apprentices, busily employed themselves between the above date and

October 22, the anniversary of the King's coronation, in preparing the

effigies of the old Triumvirate for the same fate; but the Jacobin

interest, then in full effervescence, contrived to drop printed bills,

and to insinuate that those loyal persons meant to burn the effigies

of the late Queen and Dr. Sacheverell. To repel such ideas, the Loyal

Society deputed their Stewards to the Lord Mayor with a relation of

their real intention, who forbid a procession, but permitted them

to consume the effigies where they pleased. Thus privileged, they

adorned their hats with cockades of white [24]and orange, and sallied

forth with effigies of the Pope, the Pretender, the Earl of Man, the

Duke of Ormond, and Lord Bolingbroke, accompanied by link-bearers,

and precipitated them into a fire near Bow-church. Hence they went to

Lincoln's-Inn-fields, and assisted at the hateful orgies of the same

description ordered by the foolish Duke of Newcastle, whose power

ought to have been exerted in a far different way, as the sequel will

shew. The Jacobites, full of rage and disappointment, trod on their

kibes, but were afraid to commit open violence. These processions

and burnings were repeated again on King William's anniversary, and

on the 5th of November; and, had the subject been less serious, the

exhibition of the warming-pan and sucking bottle might have excited

a smile. Some slight opposition occurred on these evenings; but the

Loyal Society of the Roebuck routed the Jacobites on all sides. The

day of the inauguration of Queen Elizabeth, November 17, shews the

folly and wickedness of suffering the populace to exercise their

brutal celebrations uncontrouled. The Loyal Society met at their usual

rendezvous in Cheapside, whence they sent a deputation to examine a

house near Aldersgate, where certain effigies were placed under the

guard of a man with a hanger, said to be those of Cromwell, Ireton,

Bradshaw, and Dr. Burnet, which the Jacobites intended to burn that

evening. However, upon viewing the harmless [25]figures, they were found

to be the representatives of George I. King William, Marlborough,

Newcastle, and Dr. Burnet. The Deputies immediately seized them, and

proceeded without opposition and no little triumph to the Roebuck. At

8 o'clock in the evening shouts of High Church and Ormond, &c. &c.

announced the approach of the Pretender's friends, who poured into

Cheapside from the neighbouring streets, proclaiming their intention

of tearing the house to pieces. The attack commenced with stones and

bricks, which soon demolished the windows; they then prepared for the

assault; but the Loyal Society, thinking to terrify them, fired with

powder only. The Jacobites, perceiving they had sustained no injury,

renewed the attack, when a second volley, accompanied by ball, laid two

of them dead on the pavement, and wounded several others. Then the

Mayor made his appearance with the posse comitatus, and the Jacobites

fled. Thus the Tragedy proceeded scene after scene; and in which way

were either party benefited by the catastrophe? Rioters acting with a

majority are like the officious bear who flattened his friend's nose in

order to kill a fly that teased him; those on the side of a minority

can expect nothing but disgrace and hanging: a well-ordered government

should therefore suppress the turbulence of both. Another attempt was

subsequently made upon the Roebuck, but the Trained [26]Bands prevented

the accomplishment of its demolition. The Coroner's Jury returned a

verdict of justifiable homicide on the two bodies.

During the rebellious year 1716 there were many violations of public

decorum, which, if not really dangerous to lives and property, were

alarming and extremely offensive to the quiet Citizens. One of those

was the exploding a train of powder and nauseous combustibles within

Shower's Dissenting Meeting in the Old Jewry in the midst of an

evening service. The sudden flash, the smoke, and suffocation, put the

audience into a most violent ferment; and the attempts on all sides to

escape occasioned the only injury done by this stupid contrivance of a

mischievous partisan, who probably congratulated himself on observing

broken pews, bruised bodies, scattered shoes, wigs, scarves, and

watches; a chaos begun and ended in smoke.

The anniversary celebrations which were usually accompanied by

conviviality and pleasure seem in this turbulent year to have been

authorised days for riot, fighting, and disorder, or stated times for

the display of brutal courage. Were the circumstances more congenial

to humanity, many instances might be given. The very focus of those

mischiefs were the various mug -houses, as they were politely termed,

or in other words Club-taverns. That of Salisbury-court was regularly

assaulted in July, and the leader, a [27]Bridewell apprentice, was shot

by the Master of the House, for which he was tried and acquitted;

but five of the rioters were executed. The members of the Roebuck

mug-house carried their loyalty into the street on the first of August,

where they had an enormous bonfire, and a table near it, when they

drank their glasses of wine, and pronounced healths, accompanied by

the brazen lungs of the trumpet. Several of those gentlemen having

heard that the Jacobites held religious meetings in various parts

of the town, where they prayed for their lawful King without naming

him, determined to distribute some of their numbers in each, and when

the proper time arrived they exclaimed King George and their Royal

Highnesses, &c.: to which others added Amen. This expedient served

to confound if not to convince; but neither lenity nor punishment

operated with the fiery Jacobites, who dared to bury two of the above

rioters with grand funeral honours in September, and would have made a

procession of young persons in pairs habited as mourners to pass every

mug-house in the City, had not the officers of the Police interfered

and apprehended several.

The gentry of the Roebuck attracted public notice on the King's return

from one of his excursions to Hanover, by a fresh exhibition of

obnoxious effigies, which they had prepared some time before, and shown

for two-pence each [28]person. Those were dragged about till the thousand

links that attended them were almost consumed, the persons who rode as

Highland prisoners jaded, and the Man in armour who represented the

King's champion sufficiently cooled (for it was January, good reader),

when they halted at Charing-cross, and committed the inanimate part

of the procession to the flames. As this folly was protected by three

files of soldiers, the Jacobites remained perdu.

The months of May and June 1717 were war-like periods in Westminster,

and marked by furious battles between the butchers of St. James's

market and the footmen and valets of the same courtly City. After

several actions the footmen solicited and obtained the assistance

of the Bridewell-boys; to balance this accession of strength, the

fraternities of Westminster, Clare, and Bloomsbury-markets were

summoned, and joined the St. James's.

The Roebuck Society seem to have been exhausted by their exertions in

the latter end of 1717, and determined to decline active hostility

against the Jacobites; but I find them subsequently roused, and the

assailants in a pitched battle and siege of Newgate-market. One of

them describes the Society in the following lines—a paraphrase from

Martial, lib. xiii. Ep. c.

"As Deer upon the rocks where Dogs can't go

Look down, and vex the noisy pack below,

[29]So stands our Roebuck far above the spite

Of ill-look'd curs that growl but cannot bite;

And if they yelp against our Sun at noon,

'Tis but like puppies barking at the Moon."

The Nonjurors, unwilling to resign their pretensions and the Pretender,

continued their secret meetings. Government, however, appears to have

used summary measures with them. Mr. Hawes's meeting opposite St.

James's was stormed in October 1717 by two Justices, two of the King's

messengers, and a guard of soldiers, when an hundred persons were found

within, to whom the Justices tendered the oaths; five accepted them,

but the rest refused, and were dismissed after being compelled to

declare their names and residences: the preacher escaped. Dr. Welton,

the ejected or Nonjuring rector of St. Mary's Whitechapel, held the

same kind of assemblies at his house in Goodman's-fields, which was

visited in the same manner; but the Doctor thinking proper to resist,

the door was broken open, and about 200 persons were discovered, all

of whom except 40 refused the oaths. The Doctor not only rejected

the oath, but acknowledged he did not pray for the Royal family. His

escapes for a long time after furnished matter for paragraphs in the

newspapers.

The year 1718 closed with a faint revival of the turbulence of party.

In this instance the Bridewell-boys acted with hardened effrontery and

[30]violence against the Loyalists. This period produced the long-required

interference of the Civil Power to prevent the Roebuck processions;

but this happy event was succeeded by the unjustifiable conduct of

the Spital-fields weavers, who were injured by the too common use of

foreign calicoes. These indiscreet persons, instead of applying for

redress to the Legislature, proceeded to terrify the wearers into a

compliance with their wishes, by throwing pernicious liquids on the

gowns of females, and tearing them from their backs in the most brutal

manner. The Police were compelled to interfere; but to little purpose,

till they were fired upon, and several killed and wounded, and others

committed to prison, whence some were conveyed corpses through the

raging of a Gaol fever, and others to the Pillory; but it was a long

time before the effervescence was allayed, and a paper war exhausted.

London was remarkably quiet from the above period till November 1724;

but that year produced a thief that seemed calculated to perform

successfully every scheme of desperation. He enjoyed a limited sway,

and during the time he was at large the publick were in constant

apprehension. Sheppard finished his career at Tyburn in the midst of

an incredible number of spectators; and their conduct occasions this

notice of him. The Sheriff's-officers, aware of the person they had to

contend with, thought it prudent to [31]secure his hands on the morning

of execution. This innovation produced the most violent resistance on

Sheppard's part; and the operation was performed by force. They then

proceeded to search him, and had reason to applaud their vigilance,

for he had contrived to conceal a penknife in some part of his dress.

The ceremony of his departure from our world passed without disorder;

but, the instant the time expired for the suspension of the body, an

undertaker, who had followed by his friends' desire with a hearse and

attendants, would have conveyed it to St. Sepulchre's church-yard for

interment; but the mob, conceiving that Surgeons had employed this

unfortunate man, proceeded to demolish the vehicle, and attack the

sable dependants, who escaped with difficulty. They then seized the

body, and in the brutal manner common to those wretches beat it from

each to the other till it was covered with bruises and dirt, and till

they reached Long-acre, where they deposited the miserable remains at

a public-house called the Barley-mow. After it had rested there a few

hours the populace entered into an enquiry why they had contributed

their assistance in bringing Sheppard to Long-acre; when they

discovered they were duped by a bailiff, who was actually employed by

the Surgeons; and that they had taken the corpse from a person really

intending to bury it. The elucidation of their error [32]exasperated them

almost to phrensy, and a riot immediately commenced, which threatened

the most serious consequences. The inhabitants applied to the Police,

and several Magistrates attending, they were immediately convinced the

civil power was insufficient to resist the torrent of malice ready to

burst forth in acts of violence. They therefore sent to the Prince

of Wales and the Savoy, requesting detachments of the guards; who

arriving, the ringleaders were secured, the body was given to a person,

a friend of Sheppard, and the mob dispersed to attend it to the grave

at St. Martin's in the Fields, where it was deposited in an elm coffin,

at ten o'clock the same night, under a guard of Soldiers, and with the

ceremonies of the church.

The Weekly Journal of November 21, 1724, gives a brief abstract of

Sheppard's life, published at the time, which may amuse the reader.

"An Abridgement of the Life, Robberies, Escapes, and Death,

of John Sheppard, who was executed at Tyburn on Monday the

16th instant, 1724.

"The celebrated Jack Sheppard, whose eminence in his

profession rendered him the object of every body's curiosity,

having made his exit on Monday last at Tyburn, in a manner

suitable to his extraordinary merits, we hope a short summary

of his most remarkable performances, before [33]and since his

repeated escapes out of Newgate, together with his behaviour

at the place of execution, will not be a disagreeable

entertainment to our readers.

"He was born in 1701, and put apprentice by the charitable

interposition of Mr. Kneebone, whom he afterwards robbed, to

one Mr. Owen Wood, a Carpenter, in Drury-lane. Before his

time was out he took to keep company with one Elizabeth Lyon,

who proved his ruin: of her he gave this character. That

'there is not a more wicked, deceitful, lascivious wretch

living in England.' The first robbery he ever committed was

of two silver spoons at the Rummer-tavern, Charing-cross.

He owned several other robberies, particularly that of Mr.

Pargiter in Hampstead, for which the two Brightwells were

tried and acquitted; in relation to which he often said

jocosely, 'Little I was that large lusty man that plucked

him from the ditch,' as Pargiter had deposed at Brightwell's

trial. He was long comrade with Blueskin, lately executed,

who, according to the account Sheppard gave of him, was 'a

worthless companion, a sorry thief, and that nothing but his

attempt on Jonathan Wild could have made him taken notice

of:' afterwards he broke out of St. Giles's round-house,

throwing a whole load of bricks, &c. on the people in the

street who stood looking at him, and made his escape. After

this he broke out of New Prison; then out of [34]the condemned

hold in Newgate; but his last escape from Newgate having made

the greatest noise, we shall insert the following particulars.

"Thursday, October the 15th, just before three in the

afternoon, he went to work, taking off first his handcuffs;

next with main strength he twisted a small iron link of the

chain between his legs asunder; and the broken pieces proved

extremely useful to him in his design; the fetlocks he drew

up to the calves of his legs, taking off before that his

stockings, and with his garters made them firm to his body,

to prevent their shackling: he then proceeded to make a hole

in the chimney of the Castle about three feet wide, and six

feet high from the floor, and with the help of the broken

links aforesaid, wrenched an iron bar out of the chimney,

of about two foot and half in length, and an inch square; a

most notable implement. He immediately entered the Red room,

which is directly over the Castle, and went to work upon the

nut of the lock, and with little difficulty got it off, and

made the door fly before him; in this room he found a large

nail, which proved of great use in his farther progress.

The door of the entry between the Red room and the Chapel

proved an hard task, it being a laborious piece of work; for

here he was forced to break away the wall, and dislodge the

bolt which was fastened on the other side: this occasioned

much noise, and he was very fearful of being [35]heard by the

master-side debtors. Being got to the Chapel, he climbed over

the iron spikes, with ease broke one of them off, and opened

the door on the inside: the door going out of the Chapel to

the leads, he stripped the nut from off the lock, and then

got into the entry between the Chapel and the leads, and

came to another strong door, which being fastened by a very

strong lock, he had like to have stopped, and it being full

dark, his spirits began to fail him, as greatly doubting of

success; but cheering up, he wrought on with great diligence,

and in less than half an hour, with the main help of the nail

from the Red room, and the spike from the Chapel, wrenched

the Box off, and so was master of the door. A little farther

in his passage another stout door stood in his way; and this

was a difficulty with a witness; being guarded with more

bolts, bars, and locks, than any he had hitherto met with:

the chimes at St. Sepulchre's were then going the eighth

hour: he went first upon the box and the nut, but found it

labour in vain; he then proceeded to attack the fillet of

the door; this succeeded beyond expectation, for the box of

the lock coming off with it from the main post, he found his

work was near finished. He was got to a door opening in the

lower leads, which being only bolted on the inside, he opened

it with ease, and then clambered from the top of it to the

higher leads, and went over the wall. He saw the streets

were lighted, the shops being still [36]open, and therefore

began to consider what was necessary to be further done. He

found he must go back for the blanket which had been his

covering a-nights in the Castle, which he accordingly did,

and endeavoured to fasten his stockings and that together, to

lessen his descent, but wanted necessaries, and was therefore

forced to make use of the blanket alone: he fixed the same

with the Chapel spike into the wall of Newgate, and dropped

from it on the Turner's leads, a house adjoining the prison;

it was then about nine of the clock, and the shops not yet

shut in. It fortunately happened, that the garret door on

the leads was open. He stole softly down about two pair of

stairs, and then heard company talking in a room, the door

being open. His irons gave a small clink, which made a woman

cry, 'Lord! what noise is that?' A man replied, 'Perhaps

the dog or cat;' and so it went off. He returned up to the

garret, and laid himself down, being terribly fatigued; and

continued there for about two hours, and then crept down

once more to the room where the company were, and heard a

gentleman take his leave, who being lighted down stairs,

the maid, when she returned, shut the chamber door: he then

resolved at all hazards to follow, and slip down stairs; he

was instantly in the entry, and out at the street-door, and

once more contrary to his own expectation, and that of all

mankind, a free man.

"He passed directly by St. Sepulchre's [37]watch-house, bidding

them good-morrow, it being after twelve, and down Snow-hill,

up Holborn, leaving St. Andrew's watch on his left, and then

again passed the watch-house at Holborn-bars, and made down

Gray's-Inn-lane into the fields, and at two in the morning

came to Tottenham-court, where getting into an old house in

the fields, he laid himself down to rest, and slept well for

three hours. His legs were swelled and bruised intolerably,

which gave him great uneasiness; and having his fetters

still on, he dreaded the approach of the day. He began to

examine his pockets, and found himself master of between

forty and fifty shillings. It raining all Friday, he kept

snug in his retreat till the evening, when after dark he

ventured into Tottenham, and got to a little blind chandler's

shop, and there furnished himself with cheese, bread, small

beer, and other necessaries, hiding his irons with a great

coat. He asked the woman for an hammer, but there was none

to be had; so he went very quietly back to his dormitory,

and rested pretty well that night, and continued there all

Saturday. At night he went again to the chandler's shop, and

got provisions, and slept till about six the next day, which

being Sunday, he began to batter the basils of the fetters in

order to beat them into a large oval, and then to slip his

heels through. In the afternoon the master of the shed, or

house, came in, and seeing his irons, asked him, 'For God's

sake, [38]who are you?' He told him, 'an unfortunate young man,

who had been sent to Bridewell about a bastard-child, and

not being able to give security to the Parish, had made his

escape.' The man replied, 'If that was the case it was a

small fault indeed, for he had been guilty of the same things

himself formerly,' and withal said, 'However, he did not like

his looks, and cared not how soon he was gone.'

"After he was gone, observing a poor-looking man like a

Joiner, he made up to him, and repeated the same story,

assuring him that twenty shillings should be at his service,

if he could furnish him with a Smith's hammer, and a

puncheon. The man proved a shoe-maker by trade, but willing

to obtain the reward, immediately borrowed the tools of

a blacksmith his neighbour, and likewise gave him great

assistance, so that before five that evening he had entirely

got rid of his fetters, which he gave to the fellow, besides

his twenty shillings.

"That night he went to a cellar at Charing-cross, and

refreshed very comfortably, where near a dozen people were

all discoursing about Sheppard, and nothing else was talked

on whilst he staid amongst them. He had tied an handkerchief

about his head, tore his woollen cap, coat, and stockings

in many places, and looked exactly like what he designed to

represent, a beggar-fellow; and now concluding that Blueskin

[39]would have certainly been decreed for death, he did fully

resolve and purpose to have gone and cut down the gallows the

night before his execution.

"On Tuesday he hired a garret for his lodging at a poor

house in Newport-market, and sent for a sober young woman,

who for a long time past had been the real mistress of his

affections, who came to him, and rendered all the assistance

she was capable of affording. He made her the messenger to

his mother, who lodged in Clare-street. She likewise visited

him in a day or two after, begging on her bended knees of

him to make the best of his way out of the kingdom, which

he faithfully promised; but could not find in his heart to

perform.

"He was oftentimes in Spital-fields, Drury-lane,

Lewkenor's-lane, Parker's-lane, St. Thomas's-street, &c.

those having been the chief scenes of his rambles and

pleasures.

"At last he came to a resolution of breaking the house of the

two Mr. Rawlins's, brothers and pawnbrokers in Drury-lane,

which he accordingly put in execution, and succeeded; they

both hearing him rifling their goods as they lay in bed

together in the next room. And though there were none others

to assist him, he pretended there was, by loudly giving out

directions for shooting the first person through the head

that presumed to stir, which effectually quieted them, while

he [40]carried off his booty, with part whereof, on the fatal

Saturday following, being the 31st of October, he made an

extraordinary appearance; and from a carpenter and butcher

was now transformed into a gentleman; he went into the

City, and was very merry at a public-house not far from the

place of his old confinement. At four that same afternoon,

he passed under Newgate in a Hackney-coach, the windows

drawn up, and in the evening he sent for his mother to the

Sheers alehouse, in Maypole-alley, near Clare-market, and

with her drank three quarterns of brandy; and after leaving

her drank in one place or other about that neighbourhood

all the evening, till the evil hour of twelve, having been

seen and known by many of his acquaintance; all of them

cautioning him, and wondering at his presumption to appear

in that manner. At length his senses were quite overcome

with the quantities and variety of liquors he had all the

day been drinking, which paved the way for his fate; and

when apprehended, he was altogether incapable of resisting,

scarce knowing what they were doing with him, and had but two

second-hand pistols scarce worth carrying about him.

"From his last re-apprehension to his death some persons

were appointed to be with him constantly day and night; vast

numbers of people came to see him, to the great profit both

of himself and those about him; several persons of [41]quality

came, all of whom he begged to intercede with his Majesty

for mercy, but his repeated returning to his vomit left no

room for it; so that, being brought down to the King's-bench

bar, Westminster, by an habeas corpus, and it appearing

by evidence that he was the same person, who, being under a

former sentence of death, had twice made his escape, a rule

of court was made for his execution, which was on Monday

last. The morning he suffered he told a gentleman, that 'he

had then a satisfaction at heart, as if he was going to enjoy

an estate of 200l. a year.'"

A tumult of a different description in some particulars, but

originating from an execution, happened in May 1725, when the infamous

Jonathan Wild expiated his numerous offences at Tyburn. The mob in

the former case were willing to have rescued Sheppard, because he

was a man utterly unfit to be at large ; but they would have torn

Wild to pieces, because he was the means of ridding the publick of

many villains, though one of the blackest die himself. Jonathan Wild

was born at Wolverhampton in 1684, and commenced his active life as

a buckle-maker, whence he migrated to London, where he became in a

short period thief-taker general. In this office his body received a

greater variety of wounds than the hardiest soldier ever exhibited;

[42]his scull actually suffered two fractures; and his throat was scarred

by the erring knife of a wretch hanged by his means, the companion of

Sheppard. That the reader may fully comprehend this man's crimes, I

shall insert an abstract of his indictment.

"That he hath for many years past been a confederate with great numbers

of highwaymen, pick-pockets, house-breakers, &c.

"That he hath formed a kind of corporation of thieves, of which he

is the director; and that his pretended services in detecting and

prosecuting offenders consisted only in bringing those to the gallows

who concealed their booty, or refused to share it with him.

"That he hath divided the town and country into districts, and

appointed distinct gangs for each, who regularly accounted with him

for their robberies. He had also a particular set to steal at churches

in time of Divine service; and also other moving detachments to attend

at Court on birth-days, balls, &c. and upon both Houses of Parliament,

Circuits, and Country Fairs.

"That the persons employed by him were for the most part felons

convict, who have returned from transportation before their due time

was expired; of whom he made choice for his agents, because they could

not be legal evidence against him, and because he had it in his power

to take [43]from them what part of the stolen goods he pleased, and

otherwise abuse or even hang them at his will and pleasure.

"That he hath from time to time supplied such convicted felons with

money and clothes, and lodged them in his own house the better to

conceal them, particularly some against whom there are now informations

for diminishing and counterfeiting broad pieces and guineas.

"That he hath not only been a receiver of stolen goods, as well as of

writings of all kinds, for near fifteen years last past, but frequently

been a confederate, and robbed along with the above-mentioned convicted

felons.

"That, in order to carry on these vile practices, and gain some credit

with the ignorant multitude, he usually carried about him a short

silver staff as a badge of authority from the government, which he used

to produce when he himself was concerned in robbing.

"That he had under his care and direction several warehouses for

receiving and concealing stolen goods, and also a ship for carrying off

jewels, watches, and other valuable goods to Holland, where he has a

superannuated thief for his factor.

"That he kept in pay several artists to make alterations, and transform

watches, seals, snuff-boxes, rings, and other valuable things, that

they might not be known; several of which he used [44]to present to such

as he thought might be of service to him.

"That he seldom helped the owners to lost notes and papers, unless he

found them able to specify and describe them exactly, and then often

insisted on more than half the value.

"That he frequently sold human blood, by procuring false evidence to

swear persons into facts of which they were not guilty; sometimes to

prevent them from being evidences against himself, at other times for

the sake of the great reward given by the government."

This consummate criminal, after dealing so widely and to an enormous

amount, fell a sacrifice to a paltry theft of a little lace stolen

from a window on Holborn-hill, when Wild's usual foresight so far

deserted him as to enable the person he employed while he waited on

the Bridge to turn evidence against him. His execution attracted

the greatest concourse of spectators ever known to have assembled

on a similar occasion; and an incredible number of thieves of every

description attended, to wreak their vengeance on their general enemy.

They shouted incessantly with frantic yells of joy, and threw stones at

the miserable man as he rode, till his head streamed with blood; but,

when he fell from the cart, the air was literally rent by reiterated

cries of triumph. Wild had endeavoured to commit suicide; but the

dose of laudanum [45]intended for the purpose, proving too great, his

stomach rejected it in time to save his life. It, however, rendered him

nearly insensible, and consequently prevented the anguish he must have

experienced in his last moments from the conduct of his enemies and the

brutality of the populace.

Several prosecutions were instituted in 1725, in order to prevent a

shamefully indecent practice of the populace, which was the storming of

hearses and tearing from them the various heraldic ornaments used at

funerals.

A dissolute young man named Gibson, a Mercer, and one of the Society

of friends, occasioned very serious riots in the summer of 1727 by

persisting to preach in defiance of the elders of Gracechurch street

meeting, and indeed of the whole posse of the Police, who were more

than once compelled to convey him by force to St. George's fields,

where he was permitted to hold forth unmolested. Gibson had a mob

constantly surrounding him, which committed many extravagances.

He afterwards rented the London Assurance Coffee-house in Birchin-lane,

before which he erected a sign representing a person extended on his

back with the head bloody and a hat and wig near him. Several persons

supposed to have committed the assault were shewn hiding under bushes.

In another part of the design, the wounded person waded through a

marsh [46]supported by crutches, and a friend assisted him towards a

house on a hill. The other side represented him lying on his face,

and again washing blood and tears from his features; a rising moon in

each painting lighted the scene, under which was inscribed "Gibson

from Gracechurch-street."—The aim of Gibson in this allegory was to

introduce himself to the publick in a pitiable situation, to shew the

Quakers in a disgraceful light as assassins, and to compliment the

friend by whom he was placed in his new house.

The populace had not indulged in their favourite excesses for several

years; but, an opportunity occurring in September 1729, they seized it

with avidity. The King had been to Hanover, and, returning in safety,

a party from Whitechapel chose to express their loyalty by breaking

many hundreds of windows on each side of the way between that place

and Charing-cross, under a pretence that the inhabitants should have

illuminated them. The damage done by these desperadoes is said to have

amounted to more than 1000l.; and it is remarkable that the King

rode through the same street within an hour after the havock had been

committed; no doubt, infinitely vexed that he was the innocent cause of

so much injury to his peaceable subjects.

The public mind was greatly agitated in 1733 by the introduction of

an Excise bill into the House of Commons, which experienced great

[47]opposition, and was deferred till June in that year. The populace,

highly elated, made effigies of the Minister, burnt them in various

places, and demonstrated their joy by breaking numbers of windows.

This excess was repeated on the anniversary of the above event with

increased violence, when, in addition to breaking the Lord Mayor's

windows, they broke his officers' heads; but several of the ringleaders

were apprehended, and sent to different prisons.

On the 30th of March, 1734, a disgraceful tumult occurred in

Suffolk-street, Charing-cross, occasioned by several young men whose

situation in life ought to have produced far different conduct. They

met at a house in the above street under the denomination of the

Calves-head club, prepared a fire before the door, and after several

indecent orgies appeared at the first-floor windows with wine and a

calf's head dressed in a napkin cap, which they threw into the flames

with loud huzzas. As the populace assembled round the fire were

entertained with plenty of beer, they shouted at many of the toasts

drank by the Club ; but, some being proposed that interfered with

the Majesty of the People, they were considered as the signal for

attack, which immediately commenced with so much impetuosity as to

render it necessary for the founders of the feast to fly for their

lives. The mob broke all the windows of the house, forcibly entered it,

and demolished [48]every article in their way, to the amount of several

hundred pounds. The royal guards put an end to the tumult. I have a

print, published immediately after the transaction, which faithfully

represents the wickedness and folly of it.

"The Hyp Doctor" observed on this occasion: "It is an honour to the

Dissenters, that we do not hear of one of their body who belonged

to this ingenious and refined cabal. It must not be overlooked,

that if the report be right, the Calves-heads were bought in St.

James's-market; the double entendre was intended to have wit

prepense ; but methinks the emblem was wrong-headed ; for how can a

Calf , which is a tame gentle creature , and incapable of sin ,

represent a supposed Tyrant, or a bad Monarch? Some of the parties

concerned were, as the chronicles of Suffolk-street record it, sons of

nobles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, besides Commoners;

but the transaction was carried on , like Io in the farce , by a

Bull rather than a Calf (by which it might appear to be more

Irish than English), if you examine the criticism of the Shew .

It was a sequel to Punch at the masquerade, putting his Opera bills

into the hands of some too great for a familiar mention; but neither

the Haymarket Punch, nor the Suffolk-street Puppet-shew took : one

was acted but once, the other was not acted thoroughly the first time:

the people were the criticks , the connoisseurs, [49]and corrected the

play. We are now assured it had no plot ; the head had no brains ,

like Æsop's masks: this may be true, but no credit to a tragi-comedy:

it only proved they were no Poets , and but indifferent actors .

Was there none who bore a Calf's-head couped , as the Heralds speak,

in his coat of Arms? The device of the escutcheon might be more

significant than that of the Club . Such a proceeding might have

been proper in a slaughter-house ; but, perhaps, they were replenished

with the wisdom of the Egyptians, who worshiped Osiris in the form of

a Calf : was it an Essex or a Middlesex Calf?—Baa be the motto

of this speculation. The Gens Vitellia, the Vitellian family at

Rome, were denominated from the like. This adds light from the Roman

history."

The next disturbance of the public peace proceeded from the dregs

of the people, who were exasperated beyond measure at the laudable

attempts of their superiors to suppress the excessive use of Gin ;

and their resentment became so very turbulent in September 1736, that

they even presumed to exclaim in the streets, "No Gin no King :"

in consequence, double guards were posted at Kensington, St. James's,

Somerset-house, and the Rolls. Besides these precautions, 500 of

the Grenadier-guards, and the Westminster troop of Horse-militia,

were distributed as patroles, and in Hyde and St. James's Parks,

Covent-garden, &c.

[50]

Many satirical and pleasant attacks upon that pernicious liquor

appeared in the diurnal publications; two of which are worth preserving:

"To the dear and regretted memory of the best and most potent of cheap

liquors, Geneva; the solace of the hen-pecked husband, the kind

companion of the neglected wife, the infuser of courage in the tame

and standing army, the source of the thief's resolution, the support

of pawnbrokers, tally-men, receivers of stolen goods, and a long et

cetera of other honest fraternities, alike useful and glorious to

the Commonwealth. A Victor , fuller of fire than Bajazet, and who

destroyed more men than Tamerlane in his numerous conquests. The bane

of chastity, the foe of honesty, the friend of infidelity, the very

spirit of sedition , through the inhuman malice of —— and ——, by

the edge of an Act of Parliament, cut off in her prime September 19,

1736, anno regni Georgii secundi decimo. Her constant votary Nicholas

No-shoes , in testimony of a friendship subsisting after death, erects

this monument.

"Attend, my Sons, and you, my friends, draw near,

And on my last remain bestow a tear;

Your dear, dear Punch, must yield his nect'rous breath,

And ere to-morrow noon submit to death.

No hopes of pardon, no reprieve is nigh,

My death is sign'd: and must I, must I die?

It is resolv'd.—Then rouse your noble souls,

And crown this night with cheerful flowing bowls;

[51]Let none but you, my friends, support my pall,

And bilk those fops who triumph in my fall

[51:A]."

Numberless evasions of the Act were practised; and even Apothecaries

were tempted to retail Gin under the specious name of a medicine or

cordial.

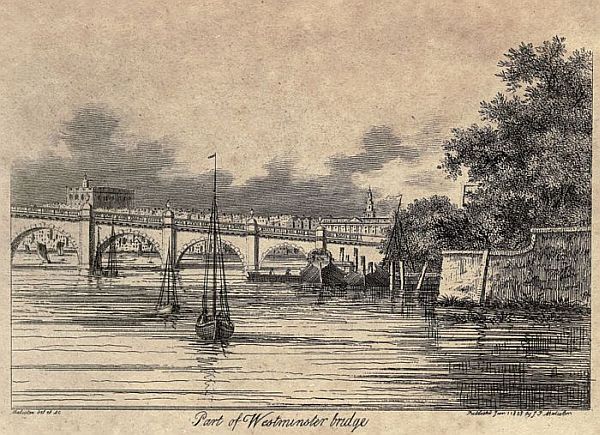

The month of July 1736 afforded a singular popular explosion ,

contrived in the following strange manner. A brown paper parcel,

which had been placed unobserved near the side-bar of the Court of

King's-bench, Westminster-hall, blew up during the solemn proceedings

of the Courts of Justice assembled, and scattered a number of printed

bills, giving notice, that on the last day of Term five Acts of

Parliament would be publicly burnt in the hall, between the hours of

twelve and one, at the Royal Exchange, and at St. Margaret's hill,

which were the Gin Act, the Smuggling Act, the Mortmain Act, the

Westminster Bridge Act, and the Act for borrowing 600,000l. on the

Sinking fund.

One of the bills was immediately carried to the Grand Jury then

sitting, who found it an infamous libel, and recommended the offering

of a reward to discover the author.

The labourers and weavers of Spitalfields were infected with a

contagious mania at the same period, which led them to suppose that

numbers of Irishmen had recently arrived in London, for the purpose of

working at under-prices and starving [52]them. Influenced by a species

of despair they assembled in crowds, and proceeded to Brick-lane,

Whitechapel, where they immediately attacked a house supposed to

contain Irishmen, and completely destroyed it, bearing away the

furniture in triumph; but they lost one man, and had several wounded,

by a musket discharged amongst them from the house. The neighbouring

Magistrates, alarmed at this outrage, immediately attended at the scene

of action, and read the Riot Act, but without effect, although the

Tower Hamlet association and a party of the Tower guard were summoned

to their assistance; nor did they desist till a company of Regulars

dispersed them by force.

Several severe combats occurred between the English and Irish in other

parts of the town, in which much mischief was done to each party.

The cause appears to have originated chiefly through the parsimony

of the person who contracted to erect the new church of St. Leonard

Shoreditch, in employing no other than Irish labourers at five or six

shillings a week, when the British demanded twelve shillings. These two

affairs occurring nearly together led government to suspect the authors

of the paper-plot, and the rioters, or at least their leaders, to have

been connected in seditious if not treasonable designs.

An estimate was made in July 1738 of the numbers convicted under the

Act for preventing the excessive use of spirituous liquors. Claims were

entered at the Excise-office by 4000 persons [53]for the 5l. allowed

to the informer from the penalty of 100l., 4896 such convictions

having taken place. 3000 persons paid 10l. each to avoid being sent

to Bridewell; and it was computed that 12,000 informations had been

laid within the bills of mortality only. It is therefore not to be

wondered at that the newspapers frequently mentioned the quiet and

decency observed in the streets subsequent to these convictions; but

in effecting them several informers were killed, and others dreadfully

hurt, by the mob.

It sometimes happens that articles of information are so vaguely

mentioned in the public papers, that, though they might be understood

by their contemporaries, we are at a loss to comprehend them. An

instance of this kind occurred in August 1757, when a number of riotous

persons assembled before the Craven-arms, Southampton-street, with

an intention to level it with the earth, and destroy the goods; but

for what reason the papers are silent. The officers of the Police

attended, but were beat off with stones; and it was two o'clock in the

morning before two serjeants and twenty-four soldiers of the guards

could disperse them; at which hour fourteen were apprehended, several

wounded, and two were afterwards committed to prison. The following

letter was sent on this occasion to Mr. Justice Fielding:

[54]Christ-church, Surrey, Aug. 13, 1757.

"Sir,

"We beg leave to acquaint you, that the house known by the sign of the

Craven-arms, in Southampton-street, belongs to a charity in our parish;

and we therefore beg the favour of you to use what methods shall seem

right to prevent the populace doing any farther damage to it: and as

to any extraordinary expence which may happen on this account, the

trustees will readily pay. A Committee of the Trustees of the Charity

will be immediately called, and they will do themselves the pleasure of

waiting on you. We are, Sir, &c.

Jackson, Rector,

Bartho. Payne, Churchwarden.

Henry Bunn, Secretary to the Trust[54:A]."

[55]

Nothing particular occurred for upwards of a year after the above

outrage; but in October 1758, the brutality of the mob was excited by

the interment of Mr. Wilson, an undertaker and pawnbroker, who had kept

the Punch-bowl near Moorgate. The cause of their resentment proves that

a British mob generally acts upon a noble principle; as the deceased

was reported to have left a legacy of 200l. to be paid in groats to

those persons who were then imprisoned at his suit, though he died

rich. This malice from the grave justly exasperated all who knew of it;

and their anger was properly inflamed by observing that a detachment

of the Artillery company, to which Wilson had belonged, intended to

pay him military honours on the way to Islington, where he was to be

buried. Every mark of abhorrence and contempt consequently ensued

from an astonishing number of persons, who severely hurt each other

by collision; and it was with the utmost difficulty that the priest

performed his office.

I am sorry to add that at the same time some miscreants in the middle

rank of life, inflamed by dissipation, were in the practice of

pretending to fight every evening on Ludgate-hill, for the diabolical

pleasure of dealing blows indiscriminately on peaceable passengers;

and, to use their own [56]words, "in order to see the claret run." These

wretches who thus wantonly attacked the publick, broke the leg of a

Constable, and bruised several watchmen, before they could secure two

of them, who were committed till the Constable recovered.

Five years passed without producing a single offence committed by

numbers acting under temporary impulse; at length an affray happened

between certain Irish chairmen and sailors, who were all inflamed by

liquor, drank in honour of the election held in Covent-garden March

1763. After they had abused each other with the usual language of

vulgar irritation, a challenge was offered by a chairman to fight

the best sailor present: this ended in the defeat of the Irishman,

who was instantly reinforced by his brethren, when a general attack

with pokers, tongs, fenders, &c. &c. commenced on the sailors; those,

supported by a party of unarmed soldiers, drove their antagonists from

the field, and immediately proceeded to demolish every chair they could

find. These outrages continued till evening, and by that time a general

muster of chairmen had taken place, who, exasperated to madness, beat

down men, women, and children, in their progress to the scene of

action, where a dreadful conflict was prevented by a party of Soldiers

from the Savoy, whose exertions accomplished the capture of some of the

ringleaders, but not before a Soldier and a Sailor, and three other

persons, had been [57]dangerously wounded, and the King's-head ale-house

almost demolished.

The hardy seamen, defenders of our island, are excellent subjects when

on-board their respective ships, but they are very apt to be turbulent

on shore; another instance of which succeeded the Covent-garden riot

almost immediately, though the cause was different. The conduct of the

Sailor is generally exceedingly thoughtless: low drinking-houses and

women are their favourite sources of amusement; and the keepers of

the former, united with the latter, never fail to make them repent,

as far as their insensible minds are susceptible. The Police of the

Tower Hamlets, aware of this, frequently sent peace-officers to houses

of ill-fame, in order to apprehend the most obnoxious inmates; and in

pursuit of this laudable custom several women and a few sailors were

sent to the Round-house in March 1763. On the following morning they

were taken before the Magistrates then assembled at the Black-horse

near the Victualling-office for examination; there numbers of Sailors

collected, and demanded the release of their comrades, which the

Justices complied with; but, still dissatisfied, they insisted on the

enlargement of the women. This presumptuous request was, however,

positively refused, and the Magistrates, dreading the consequences,

sent three different times for detachments of Soldiers to support their

authority, and as an equipoise for the increasing numbers of the

[58]Sailors, who assembled from all sides to the amount, it is said, of

more than a thousand: the Riot Act was read no less than three times

to no purpose, during which time the Sailors had obtained flags from

the shipping, and having marshalled themselves in a line of battle,

they bore down on the Soldiers drawn up to receive them. At the

instant the commanding officer of the latter was about to pronounce

the dreadful word Fire! a naval officer made his appearance in front

of the Sailors, and intreated the order might be reserved till he

had endeavoured to convince his brethren of the impropriety of their

conduct. He then addressed himself to the Sailors, and said they would

forfeit the favour of the King, who had promised to take off their

R's; to which he added other arguments, and at length prevailed upon

two-thirds of them to follow him to Tower-hill, where he dismissed them.

A Serjeant and twelve Soldiers were sent about four o'clock on the same

afternoon to Clerkenwell Bridewell, as an escort to eight of the women

who had occasioned the riot. Those were pursued by a party of Sailors,

and overtaken at Chiswell-street. The instant release of the prisoners

was demanded and refused, when one of the Soldiers fired, and wounded

a Sailor and a Baker; but, as the assailants became more violent after

this precipitation, the Serjeant wisely determined to resign his

charge, rather than cause farther bloodshed.

[59]

The Weavers resident in Spital-fields were the next disturbers of the

public peace. Those useful members of Society had long disputed with

their employers respecting their wages; and at length a compromise

took place, when printed papers of the various prices of their work

were distributed, in order to prevent future disputes. Some avaricious

master-weavers, however, thought proper to reduce the weaving of

certain articles one half-penny per yard; and hence the riots, which

commenced with the destruction of the looms belonging to one of the

most active opponents of the journeymen, whose effigies they afterwards

placed in a cart, hanged, and burnt. This conduct, though highly

improper, was innocence compared with that now to be related, which

originated in the strange folly and wickedness of Seamen almost at the

same time. The narrative was compiled from the minutes of the Coroner's

Inquest.

"On Thursday last an inquisition was taken in Holywell-street,

Shoreditch, upon the bodies of Ralph Meadows and John Whitrow, two

of the persons killed in the late riot before a public house, known

by the sign of the Marquis of Granby's-head, in Holywell-street. The

inquisition lasted six hours. It appeared in the evidence, that on

Monday last, about one o'clock, a great mob assembled before and in

the dwelling-house of Thomas Kelly the publican, committing outrages;

that on application to two Magistrates, [60]they wrote to the Lieutenant

of the third regiment of foot-guards, then on duty, with an Ensign

and 100 men under his command, in Spital-fields, on account of a late

riot there, acquainting him, that there was a great mob assembled in

Holywell-street, Shoreditch, who had broke open a house in a violent

and outrageous manner, to the terror of his Majesty's quiet subjects,

and in breach of the peace; and desiring him to attend with a proper

force to disperse the mob and stop their proceedings.

"The Lieutenant assembled as many of his men as the short notice would

permit, before the passage door leading to the said public house, where

he found a great crowd of people; and on going into the house with

the Justices' order in his hand, he found some very desperate fellows

in it, some in sailors' habits, who were cursing and swearing that

they would not leave the house, but do what they pleased; one of them

behaving in a very affronting manner to the Lieutenant, some of the

soldiers led him out. About three o'clock, the Lieutenant prevailed on

them to depart, and they went away quietly, leaving only a crowd of

people standing before the passage door, who had gathered there out

of curiosity. The Lieutenant then withdrew himself, leaving only a

Serjeant, Corporal, and twelve private soldiers, which he did at the

solicitation of the publican, who was afraid of a second attack. The

Lieutenant then went to dinner, and informed the Serjeant he [61]would

return in an hour. For about half an hour all was quiet; and then a

gentleman came up to the Serjeant, and bade him take care of himself,

as there was a body of sailors coming up the street, d—ing their eyes,

declaring, 'they would clear the soldiers, and pull the house down.'

The Serjeant seeing them advance, looked round to the soldiers, and

said, 'There they come;' and ordered his men to stand to their arms,

and he would meet the rioters, but bade them fix their bayonets. He

approached about twelve yards towards the rioters, and pulled off his

hat, and said, 'Gentlemen, I hope you do not come with any intent to

make a disturbance.' They d—ned their eyes, and informed him, that

'they had got one man, and would have the landlord of the house.' The

Serjeant, telling them 'that he was placed there by an order from the

civil power to take care of the house and preserve the peace,' returned

to his command. The sailors then advanced, and some of them mounted the

sign-post, and to prevent their getting up, some of the soldiers gently

struck them with their pieces; but the Serjeant, finding them resolute

to take down the sign, ordered the soldiers to let them, and informed

the soldiers, that he was then in hopes to disperse them without

mischief. As soon as the sign was down, they gave a huzza, and some

of them called out, 'Now for the landlord,' and in a riotous manner

advanced with their sticks towards the passage which the soldiers

were guarding. [62]The Serjeant informed them he could not admit them

into the house upon any account: upon which they began to beat with

their sticks, and press on the soldiers; and the serjeant ordered the

soldiers to charge (which is fixing their musquets breast high) but it

had no effect: they then assaulted the soldiers with pieces of brick,

tile, and great quantities of mud, and forced two bayonets from the

musquets, one of which was broke, and the other was taken up by one of

the sailors, with which he made a full push at the Serjeant, but he

happily warded it off with his halbert; and the sailors got between

him and his men, and attacked them with such violence that they were

forced into the passage which leads to the public-house, and thereupon

a battle ensued, and the Serjeant used all his endeavours to come to

his men, but he was prevented by the sailors, and received several

blows. The men being thus pressed into the passage, were obliged to

fire, and two pieces were discharged, which, from the faint report, and

no mischief being done, and the sailors not giving way, the witnesses

all declared, that they believed the pieces were loaded with gunpowder

only. The sailors continuing to press violently upon the soldiers, and

endeavouring to force the passage, the soldiers fired again, and two

men, amongst the rioters, were seen to drop.

"The sailors now became very desperate, and most violently assaulted

the soldiers with their sticks; and the soldiers were, through

inevitable [63]necessity, in defence of their lives, and for the public

peace, obliged to fire, and the firing continued till they cleared the

passage and street before it, which was very soon done: upon which the

Serjeant took the opportunity of running to his men, and cried out,

'For God's sake fire no more.' He then drew all his men out of the

passage, and formed a square in the street, and ordered them to ease

their arms, and on looking about him he saw three men lying dead in the

street, two of which appeared to be sailors. Several of the soldiers'

fingers were bloody from the blows they received from the rioters. In

the riot two sailors jumped into a window belonging to a butcher's

house, near the public-house, and one of them taking a chopper out of

the shop, endeavoured to rush by the Corporal into the passage to the

public-house, but was seized by the Corporal to prevent his going in,

by which means the Corporal's hand was cut by the chopper to such a

degree, that he was obliged to be sent to an hospital.

"The witnesses swore, that they verily believed the soldiers were

obliged to fire in defence of their lives, as well as for the

preservation of the public peace; and the Jury were well satisfied with

the evidence before them.

"The Coroner, in summing up the evidence, distinguished between murder,

manslaughter, and justifiable or excusable homicides, both voluntary

[64]and involuntary; and chance-medley, or homicide by misadventure; under

one of which classes, he informed the Jury, the present case must fall.

He observed, that the soldiers did not come to that place wantonly to

do an injury, but were called in, as the Lieutenant understood, and

so called it (when he produced his authority) in his evidence, 'by an

order from the civil power,' to suppress the rioters, and preserve

the King's peace; and whether the civil power had taken the proper

steps before applying to the military, or whether the notice sent to

the Lieutenant was a legal warrant or order, or not, were not matters

of their enquiry; for that, supposing a Justice of Peace should issue

an illegal warrant, and an officer should be killed in the execution

of it, in that case the party killing would be deemed a murderer; for

the officer was obliged to execute his office: he is not supposed to

be a judge of law; he is only a minister of Justice, and the party

had a legal remedy, if he had been improperly arrested. The Coroner

said, that the conduct of the military power upon that occasion was

the immediate subject of their enquiry; that, if the Jury gave credit

to the witnesses, the major part of whom were disinterested persons,

the soldiers did not fire till they were pressed to it, by inevitable

necessity, in defence of their own lives, and for the preservation

of the public peace; and in killing any of the rioters, had done

no more [65]than 'Justifiable Homicides' of inevitable necessity, for