229

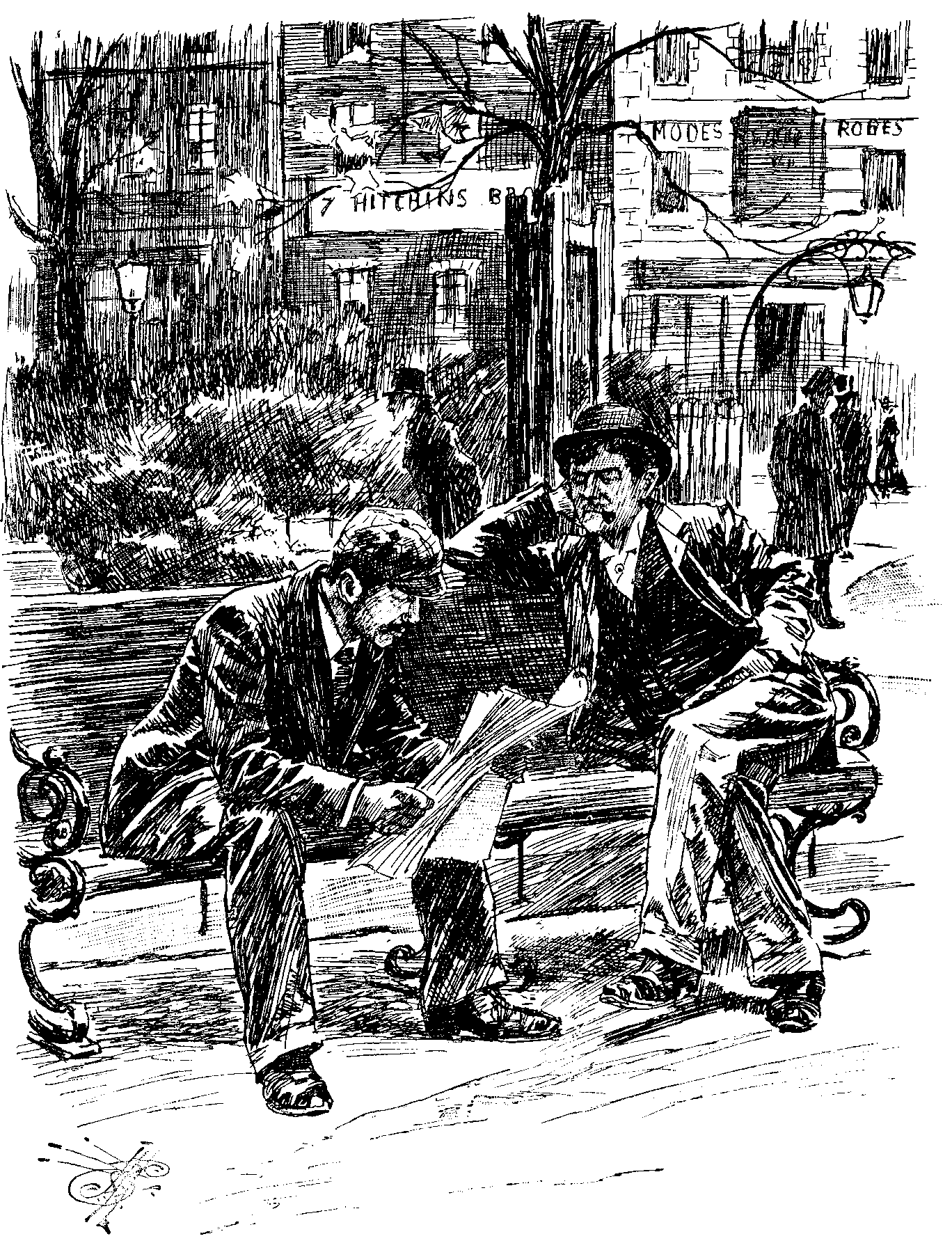

A FITTING OPPORTUNITY.

Comfortable Citizen (to Irish Beggar, who has asked for an old Coat).

"But what use would my Things be to you? You're such a Scare-crow, and I'm so stout!"

Irish Beggar. "Ah, yer Honour, but it's yourself that has plenty of Spare Clothes!"

(By Q. H. Gladstonius Flaccus, Junior.)

Clearly not the Leader of the Flock.—Of course, the reverend gentleman cannot be considered as a shepherd as long as his name is Head-lam.

Dearest Gladys,—You have made immense progress since you first came out. Still, you will be all the better for an occasional hint from your more sophisticated friend. Your brief engagement to the serious young stamp-collector was—whatever may be said against it—at least, an experience, and I don't at all disapprove of Cissy, and Baby Beaumont, and the other clever boys, but—why call Captain Mashington "Jack"? That wonderful tennis-player, Mrs. Lorne Hopper has merely, tacitly, lent him to you, she will soon be in London again, and then, shooting and theatricals over, "Jack" will also go back to the city of mist and fog. You will be obliged to return him, whether "with thanks" or not. He is definitely charming, but charmingly indefinite, and, in fact, he is playing with you as you and Oriel played with each other, as Miss Toogood is now playing with Oriel, and as someone (let us hope) will, some day, play with Miss Toogood. Of course, as long as you both know it's a game and "play the rules" it's all right.

I enjoyed your letter telling me how "splendidly" the theatricals went off, and that "everyone said it was a great success." My dear child, you are delightful—quite refreshing; and have kept, in all its early bloom, your astonishing talent for believing that people mean, literally, what they say. How on earth can you, or any of the other performers, know whether it was a success or not? Of course everyone said it was. Quite so; who would be rude enough to say it was a failure? The more atrocious the performance, the more praise it would get. Guests invariably flatter amateurs to their faces; and, on the other hand, however admirable it may have been, they never fail to abuse it to everyone else. I don't know whether it's jealousy, or simply irritation at being obliged to sit still (generally in the dark), and look on while others are showing off and enjoying themselves; but I do know that they criticise severely, without exception, all amateur entertainments. As I am your most intimate friend, of course people think it safe to disparage you to me, and I have had various accounts. All the men agreed that it was "awful rot," and the women that it was quite absurd, very dull, and as long as the Cromwell Road; that our dear Cissy was quite too ridiculously conceited as a manager, attempting effects, suitable only for Drury Lane, on a tiny drawing-room stage; for instance, those dreadful stone steps, on which you were to "trip down," and over which you tripped up. You see, my informant caught you tripping!

Cissy, poor incompetent darling, made, it seems, touching attempts to be "topical," and "up to date," by allusions of the tritest and lamest description to the Empire, the Czar, and dynamite, and by wearing a huge green carnation. The whole thing completely missed fire, I am told; and was the usual tedious exhibition of complacent young vanity. You're too sensible to be offended, dear, especially as I can no more form a judgment from their description than from yours—knowing you all to be prejudiced. However, I quite believe you looked sweet in your pretty costume, and I wish I had been there to see the fun.

Last night, at dinner, I met your old admirer, Mr. Goldbeiter. He told me he wanted to be married, and asked me "to look out for a nice wife for him." I am afraid the sort of man who says that lives to be an old bachelor. I could have looked after him better, but that on my other side was a person in whom I take great interest; that is to say, someone I have only just met. The Lyon Taymers would like him. He is a writer, perfectly "new"; and at present the cause of great disputes as to who discovered him. He is beautiful, of course young, and will be very agreeable when he has settled on his pose; at present, he's a little undecided about it.

Not having read a line of his, or even knowing he was an author, I began with my usual formula, "I am so interested in your work, Mr. de Trouvaille" (he's French by descent). He was a little doubtful of me at first, but I think we shall become friends. He said nothing about having met me in a previous existence, did not ask if I believed in instantaneous sympathy, and omitted to inquire which was not my day at home. So, you see, he is not quite like everyone else. Before the end of dinner, he had spoken, very respectfully, but not unfavourably, of my eyes, and he is going to send me his book, Enchantment. He belongs to the new literary school they call "Sensitivists." I wonder what it means! Good-bye, dear.

Ever your loving

"Nullis Medicabilis Herbis," &c.—A youthful author suffering

from a violent attack of the critics.

230

231

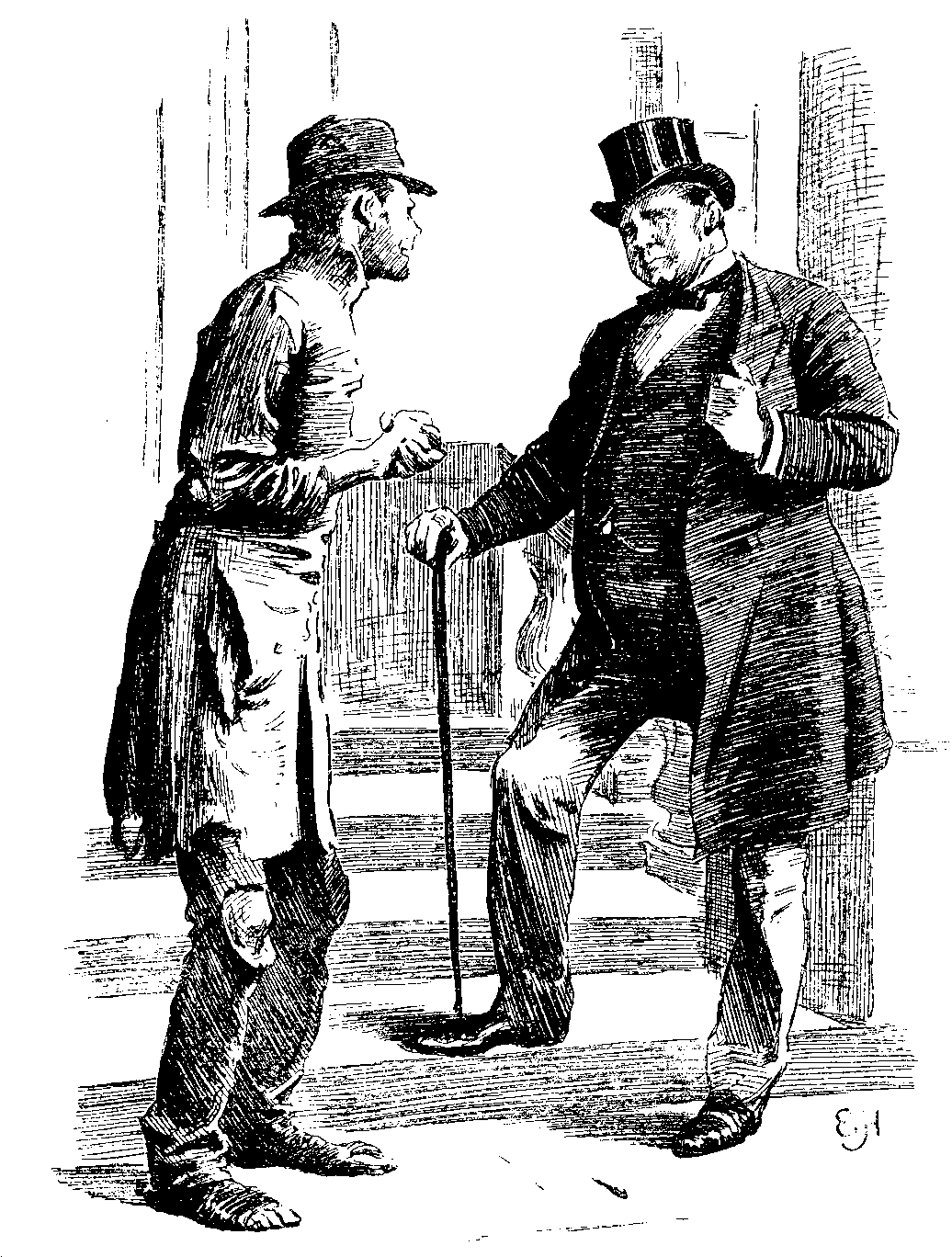

Scene—The interior of a classic Country Villa. Present—An aged, illustrious, but retired, Statesman and Leader, engaged now in thrumming a lyre. To him enter his youthful successor, with certain scrolls.

Senex (eagerly). My dear Primula! So glad you have come! The very man I wished to see. Be seated.

Juvenis (depositing scrolls). A thousand thanks. Delighted to see you looking so well, my dear Gladstonius.

Senex (cheerily). Never better, thank the gods!—and the ocularius!

[Twangles nimbly.

Juvenis. Ah! Cincinnatus, in retirement, pleased himself with the plough; your recreation was wont to be the axe or the banjo; now I perceive it is the—harp!

Senex (sharply). Not at all, Primula, not at all. This is not a harp!

[Plays and sings.

Juvenis (astounded). Charming, I'm sure!

Senex (beaming). Think so? I fear you flatter.

Juvenis. Not at all. You may say, with your new favourite—

Senex (modestly). Very pretty! But I fear the ever-youthful Muses may disdain an Old Man's belated wooing.

Juvenis (slily). Even a Grand Old Man's?

Senex (shuddering). Nay, no more of that, an' you love me. By the way, I wanted to consult you on a little musical matter.

Juvenis (dubiously). Ah! Concerning yon Hibernian Harp, I presume?

Senex (impatiently). Dear me, no! The Hibernian Harp be—jangled. As, indeed, it is, and unstrung into the bargain.

Juvenis (relieved). Why, have you then, like the other Minstrel Boy, "torn its chords asunder"?

Senex. Well, no, not that exactly. I fear its native thrummers will spare others that trouble. But—ahem!—it is the Horatian Lyre that interests me at present.

Juvenis. I see:—

Senex (musingly). Hum! I have not yet tried the Tibia—the shrill pipe—but I may.

Juvenis. Doubtless; and you are quite equal to it.

Senex (drily). Thanks! But I've no wish, my dear Primula, "to play the rôle of elderly Narcissus." At present my part is only that of Echo—to the Venusian's vibrant voice.

[Muses.

Juvenis (taking advantage of the opportunity). Well, my dear Gladstonius, there are one or two little matters upon which I want to take your opinion. For example, Cæcilius——

Senex (quickly). "Cæcilius, who provoked the populace to such a degree, that Cicero could hardly restrain them from doing him violence." Do you want me to play the part of Cicero?

Juvenis (taken aback). Well—ahem!—hardly that, perhaps. But——

Senex (interrupting him). My dear Primula, as I have already said in response to an appeal from a friend of the modern Orbilius (not like Horace's pedagogue, "Plagosus," though), "After a contentious life of fifty-two years, I am naturally anxious to spend the remainder of my days in freedom from controversy."

Juvenis. Oh! Quite so—of course. But ahem!—the people are a little pressing——

Senex. Eh? To hurtful measures? What says Augustus's "pleasant mannikin" again, à propos?

[Thrums.

Juvenis. Doubtless. One such as yourself, "retired from business," like your beloved Horace on his Sabine farm.

But of me it cannot—yet—be said—

Senex. Hah! Sir John Beaumont's version. Not so bad, but might be improved, I think. By the way, why should not you and I do the "Satires"—together?

Juvenis. Charmed, I am sure. Just now, however, I fear I'm a little too busy.

Senex. Pooh! Only occupies one's odd moments, and is as easy as shaving, or shaping a new Constitution. For example, I'll give you an impromptu version—call it adaptation if you like—of the first "Ad Mæcenatem":

Juvenis. Oh! thanks, so much! Only——

Senex. It won't take ten minutes. Listen!

[Tunes up and sings.

Ad Roseberiam.

There! What think you of that—for an impromptu?

Juvenis (rousing himself). Oh, excellent—most excellent! How do you do it? And now, my dear Gladstonius, with your kind permission, we will go——

Senex (promptly). To dinner! Exactly, my dear Primula.

Come along, my boy!!!

[Skips away, followed slowly by his guest.

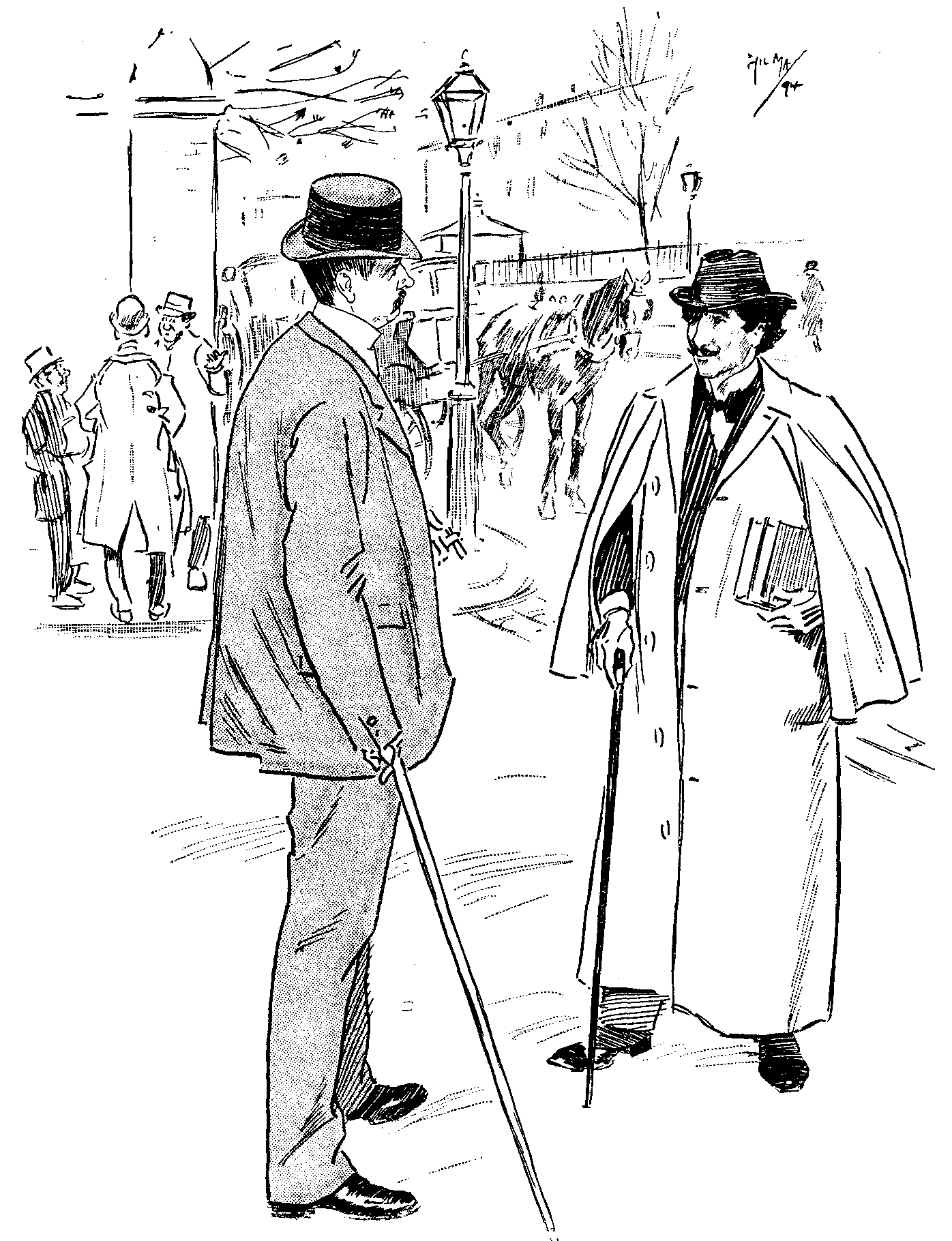

A POLITICAL CONFERENCE.

"Gladstonius parvam rem Horatianam compositionis suoe ad Roseberium recitans."

A GOOD GUESS.

First 'Arry (who has been reading City Article). "I say, what's 'Brighton A's' mean?"

Second 'Arry (of a Sporting turn). "'Brighton 'Arriers,' I s'pose."

WONDERFUL WHAT AN ADJECTIVE WILL DO.

Brown (newly married—to Jones, whom he entertained a few evenings previously). "Well, what did you think of us, old Boy, eh?"

Jones. "Oh, pretty Flat. Er—awfully pretty Flat!"

Mr. Punch, Sir,—Magistrates are beginning, not a moment too soon, to protest against the ridiculous pockets in ladies' dresses, which afford such a temptation to the felonious classes! I should like to draw attention to an invention of my own which, I think, quite meets the difficulty. It is called the "Patent Unpickable Electrical Safety Pneumatic Combination Purse-Pocket," and it does not matter in the least in what part of the dress this pocket is placed. No sooner is the thief's hand in contact with the purse than a powerful voltaic circuit is at once formed, and by the principle of capillary attraction, coupled with that of molecular magnetisation, the hand is firmly imprisoned. Scientific readers will readily understand how this happens. In his efforts to release his hand the thief touches a button, when an electrical search light of five thousand candle-power is at once thrown around, a policeman's rattle of a peculiarly intense tone is set going, several land torpedoes discharge simultaneously from all sides of the dress, while the voice of a deceased judge issuing from a concealed phonograph pronounces a sentence of seven years' penal servitude on the now conscience-stricken depredator.

Yours,

Born 1818. Died November 3, 1894.

["The unique characteristic of Mr. Walter's life was his relation to The Times."—Obituary Notice in the Times Newspaper.]

233

A deputy-assistant of the Baron has been perusing with great contentment The Catch of the County, by Mrs. Edward Kennard, a lady who is already responsible for The Hunting Girl; Wedded to Sport, and a number of other romances dear to the heart of those who follow the hounds. The deputy-assistant reports that he was delighted with the newest of the authoress's novels, and found the three volumes rather too short than too long. Now that London is in the midst of November and its fogs, those who dwell near the frosted-silvery Thames can take a real pleasure in stories of the country. To sum up, The Catch of the County must (to adopt the slang of the moment) have "caught on." A fact that must be as satisfactory to Mrs. Kennard as to her readers. And when both supply and demand are pleased, Messrs. F. V. White & Co., the publishers, must also (like Cox and Box) be "satisfied."

A Baronitess writes: "Gaily-bound Christmas books have been facing me for some time, and, with an insinuating look, seem to say, 'Turn over a new leaf.' We do; many new leaves."

Blackie and Son could be called first favourites in the boys' field of literature. They make a good start with Wulf the Saxon and In the Heart of the Rockies, both by G. A. Henty. They are both capital specimens of the Hentyprising hero.

In Press-Gang Days. By Edward Pickering. A story, not a newspaper romance, though it is a new edition of the type of the wicked uncle, who makes use of "the liberty of the Press" to have his nephew bound—as if he were a book worth preserving—and taken off to sea. This proceeding made an impression on our good brave youth, who, after fighting with Nelson, learnt that "an Englishman should do his duty," escapes a French prison, and returns to "give what for" to his uncle.

Most interesting and practical is The Whist Table, edited by Portland, especially to those whose only idea of the game is after the style of the man in Happy Thoughts who knows that the scoring had something to do with a candlestick and half-a-crown. In this book they will find a helping hand which gives the "c'rect" card to play. Both these books, published by John Hogg, are pig-culiarly good.

"A powerful finish," quoth the Baron, leaning upon the chair-arm, and, like the soldier in the old ballad, wiping away a tear which he had most unwillingly shed over the last chapter of Children of Circumstance, "a very powerful finish. There is some comedy, too, in the story (which, I regret to say, is spun out into three volumes)—rather Meredithian perhaps, but still forming some relief to the sicknesses, illnesses and deaths—there are certainly three victims of Iota's steel and one doubtful—of which the narrative has more than its fair share." Of the comedy portion, the courtship of Jim and Rica is excellent. But where other novels err in superfluity of description and lack of dialogue, the fault of this one is just the other way, and the dialogues may be, not "skipped," but bounded over. Nothing of the earlier portion, nor the powerful final chapter of this story can be missed: as for the intermediate stage, when the intelligent and experienced novel-reader has once grasped the characters, he can drop in on them now and then, in a friendly way, and see how they are getting on.

The Baron congratulates Messrs. Macmillan on a charming little book called Coridon's Songs, which are not all songs sung by that youthful Angler-Saxon whose parent was Izaak Walton, but also songs by Gay, Fielding, and Anonymi. To these worthy Master Austin Dobson hath written a mighty learned and withal entertaining preface, the gems of the book being the illustrations, done by Hugh Thomson in his best style, "wherewith," quotes the incorrigible Baron, "I am Hughgely pleased." 'Tis an excellent Christmas present, as, "if I may be permitted to say so," quoth the Baron, sotto voce, "to those whom Providence hath blest with friends and relatives expecting gifts in the coming 'festive season,' is also a certain single volume entitled Under the Rose, an illustrated work, not altogether unknown, as a serial, in Mr. Punch's pages, and highly recommended by

Rus in Urbe.—Fancy there being a "Rural Dean of St. George's, Hanover Square"! His name was mentioned one day last week in the Times' "Ecclesiastical Intelligence." It is the Rev. J. Storrs. Not "Army and Navy Storrs," nor "General Storrs," but "Ecclesiastical Storrs."

Happy Application.—Our Squire has a shooting party every Saturday to stay till Monday, and longer if they can. He calls it "The Saturday and Monday Pops."

(To Mr. Punch.)

Dear Mister,—To you, who are a so great lover of the theatre, english and french, I send my impressions of the first of the new drama of Mister Sardou. It is to you of to spread them in the country of the immortal Shikspir. Allow that I render my homages to this name so illustrious, me who have essayed since so long time to speak and to write the language of that great author. And see there, in fine I can to do it!

It wants me some words for to praise the put in scene of this new drama at the theatre of Mistress Sarah Bernhardt. Gismonda! It is magnificent! It is superb! It is a dream! Ah! if your Shikspir could see this luxury of decorations, this all together so glorious! Him who had but a curtain and an etiquette! And Molière? And Racine? Could they make to fabricate of such edifices, of such trees, of such furniture? They had not these—how say you in english—"proprieties," which belong to the proprietor? Yes, I think that I have heard the phrase, "offend against the proprieties." We never offend against them in the theatres of Paris; they are always as it should be. But here, at the Renaissance, Mistress Bernhardt has done still more. Each scenery is a picture of the most admirables, a veritable blow of the eye.

I go to give you of them a short description. The first picture is the Acropolis, under the domination of the Florentines at the end of the fourteenth century. What perfume of poetry antique! What costumes! That has the air of an account of Boccaccio, of a picture of Botticelli. One sees there the figures of Angelico, the colours of Veronese. It is an Alma-Teddama of the middle age. And when Mistress Bernhardt and her following, all resplendent of costume, are assembled upon the scene, one can see realised a group from the Decameron. And the second picture, and the third, and the fourth? Can I say more of them? They are superb. In the fourth there is a cypress high of six yards, there, alone, at the middle of the scene. One says he is natural. That may be. In any case he is marvellous. But the fifth picture, it is sublime! One cannot more! It is the last word of the modern theatre! It wants me the words, it wants me the place for to speak of it. Shikspir alone would have could to render justice to this picture so ravishing.

As to the action of the piece, you will desire to know something. Frankly I tell you I observed it not. In the middle of this luxury of decorations there wander here and there some persons, dressed at the mode the most beautiful, who speak in effect not too shortly. There are veritable discourses—how say you "conférences"?—on florentine history, of the most interestings, but a little long. The brave Frenchmans pronounce the Italian names in good patriots. They imitate not the accent of our perfidious neighbours of the Triple Alliance. Ah no! They say them as in french. And what names! Acciajuoli! It is like a sneeze. And Mistress Bernhardt is gentle, caressing, passionate, contemptuous, and terrible turn to turn; she murmurs softly, and at the fine she screams. And Mister Guitry is severe and menacing; he speaks at low voice, and at the fine he shouts. But after all what is that that is that that? One thinks not to it. The decorations, the costumes! See there that which one regards, that which one applauds, that which one shall forget never!

Be willing to agree the assurance of my high consideration.

Misther Punch, Sorr,—Frinchmen are that consaited they think no one can invint anything but thimselves. It's as well known as the story of Mulligan's leather breeches that the first Earl of Mayo inwinted Mayernase sauce (ah! bother the spellin' now), and called it after himself and his eldest son, Lord Naas; faix, there ye have it, Mayonaas; and isn't it called Paddy Bourke's butther to this day all over County Kildare; and many a bite of could salmon have I ate wid that same; and don't believe, Sorr, thim that tell you it's onwholesome, for, if you'll get the laste sup of the crathur wid it, it's just as harmless as new milk from the cow; and shure it's meself that ought to know, bein' cook to a lady that has the best blood of ould Ireland in her body; and her husband—God help him, poor man!—is an Englishman; but we can't be all perfect, and whin I make thim sauces to his taste he just sends me out a glass of wine, wid his compliments, and wid mine to your honour,

I remane your honour's obadient Servant,

***This Correspondence must now cease. This is the second time we've said this.—Ed.

234

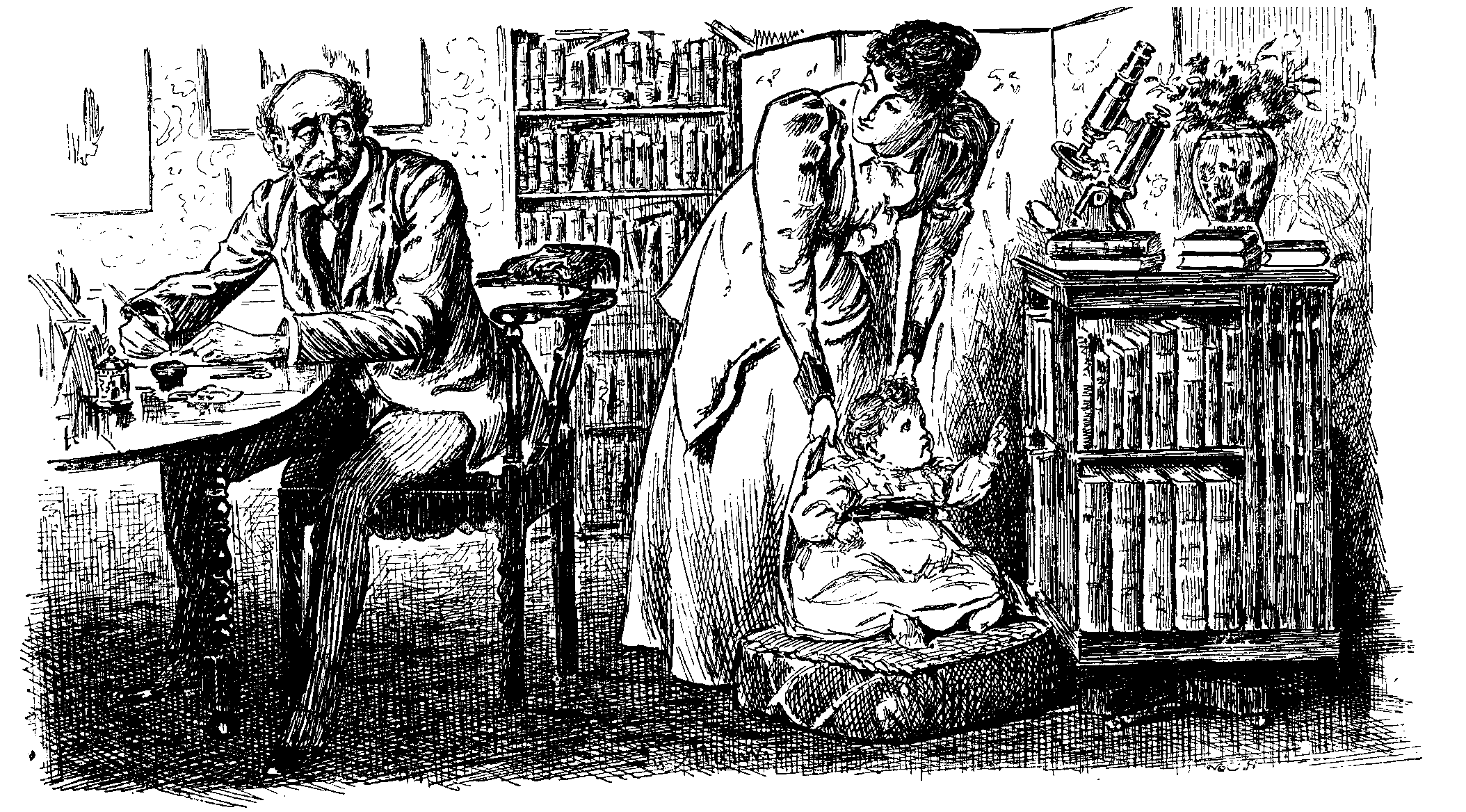

L'ART D'ÊTRE GRAND-PÈRE.

Daughter and Mamma. "Papa, dear, Baby wants to play with your new Microscope. May he have it?"

Grandpapa (deep in differential and integral calculus). "My new Microscope? Oh, yes, of course, dear! But he must mind and be very careful with it!"

Air—"The Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò."

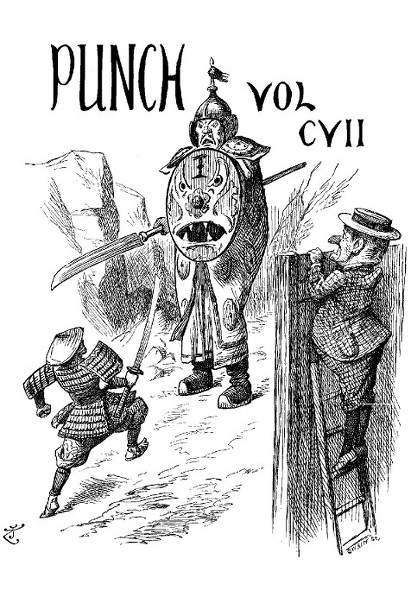

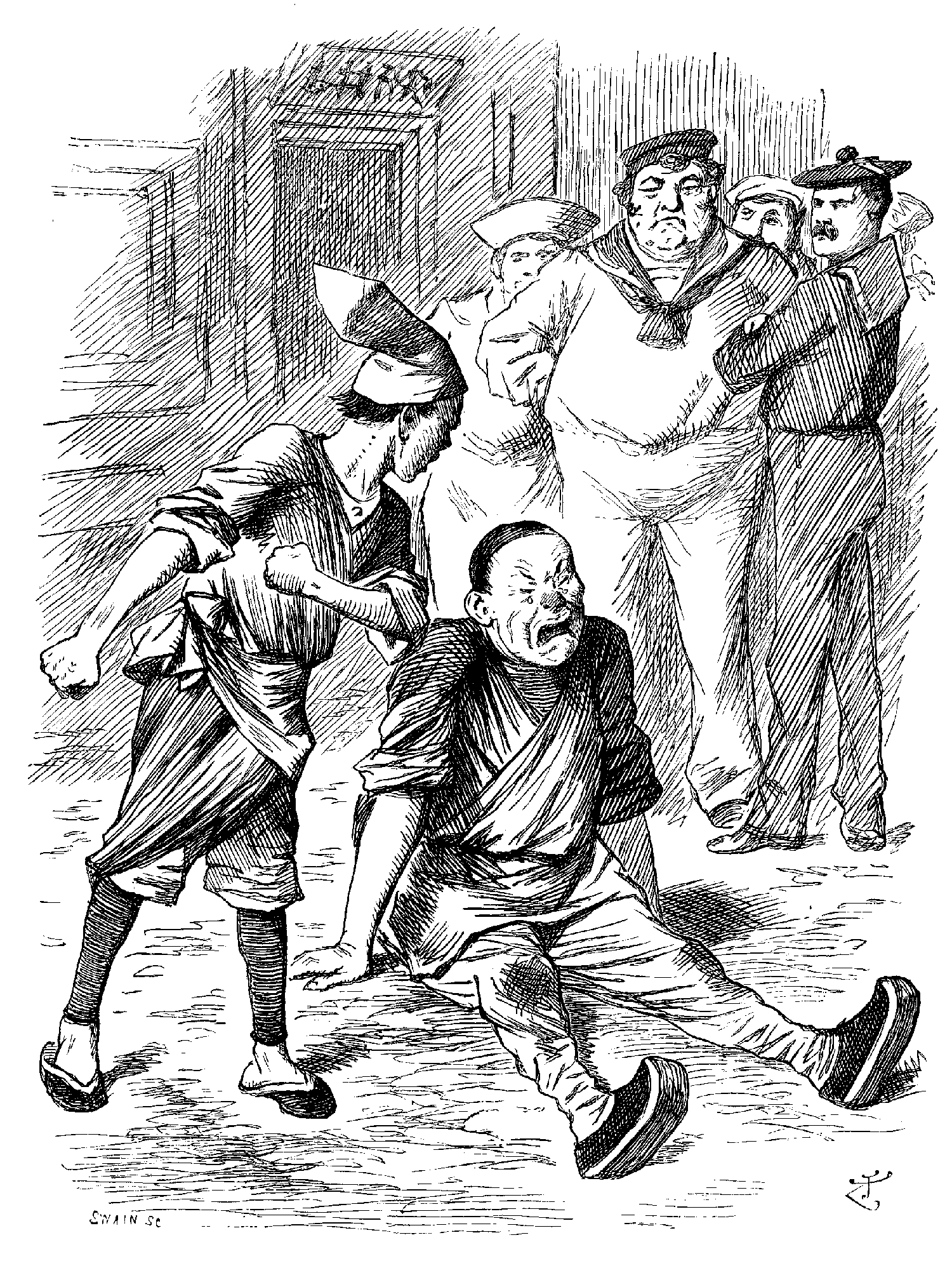

A TOUCHING APPEAL.

Johnny Chinaman. "BOO-HOO! HE HURTEE ME WELLY MUCH! NO PEACEY MAN COME STOPPY HIM!"

(By a Courteous Conductor.)

Securing a "P. S."

I have supposed that you have been appointed Secretary to the Public Squander Department. You will have much to do, so the less you have to read, the better. Under these circumstances, I merely supply you at this moment with the following

Examination Paper for Would-be Private Secretaries.

1. Give your autobiography, either as (1) a good story against yourself, (2) a minute in four lines, or (3) a long yarn suitable for filling up the time when things have to be kept going for three-quarters of an hour to accommodate your chief.

2. Describe your duties to your chief (1) when he is in town but wants to be thought away in the country, and (2) when you have to assist him as "Vice-chair" at a dinner party.

3. Given that you have for neighbours at a political banquet a race-horse owner, a supporter of the temperance cause, a theatrical proprietor, and a rural dean. Write an anecdote that will interest all of them, and cause the conversation between them to be general.

4. Take the following facts. Owing to a blunder, a ship has been sent to a wrong port, carrying a wrong cargo to a wrong receiver, who has sent it away, and thus prevented it being used for its right purpose. This trifling error of judgment has caused a war that could easily have been prevented. Explain all this away in such a manner that the statement when delivered by your chief shall be received with "general cheering" in the House of Commons.

5. Write a short essay showing your points and testing your capabilities. 235

236

237

BOUGHT AND SOLD.

Dealer. "What? this 'ere little 'oss bin Shot over? Lor' bless y', heeps o' times!"

II.—Preliminary Canters.

I said, when I last took up my pen as a veracious chronicler of the recent history of Mudford (for this is the name of our village; not elegant, perhaps, but none the less true to life), that my meeting deserved a chapter to itself. It does. It deserves, in point of fact, many chapters, though I only purpose to give it one. But it must be the third chapter, and not the second. For before this meeting was held, many things happened, and as I look back I often wonder how it was that I was enabled to endure all the trials and tribulations which Fortune had in store for me, and that I am spared to write this unpretending account of all that happened. I say this, because I have been reading of late historical romances, and I find from them that a little moralising is never out of place in the course of a story.

The first thing I did was to issue a bill, stating that the meeting would be held. It was headed, "Mudford," and announced that I—described as Timothy Winkins, Esq., J.P. (for I boast that proud distinction through an error of the Lord Chancellor of the period, who mistook me for a member of his party, which I was not)—that I would explain the provisions and working of the Parish Councils Act, that "questions would be invited at the close," and that "all persons were cordially invited to attend." I sent a copy of this to every one in the village, and then fondly imagined that I should hear no more about the matter till the fateful night approached. In that I was mistaken, however.

Next morning, as I was sitting in my study—curiously enough getting ready some notes for what was to be my epoch-making speech—I saw coming up the drive two ladies, whom I recognised as Mrs. Letham Havitt and Mrs. Arble March, both ladies, I remembered, who had made themselves prominent in politics in the village, Mrs. Havitt as a leading light of the Women's Liberal Federation, and Mrs. March as a Lady Crusader (is that right?) of the Primrose League. A moment later, and those ladies were ushered into my room.

"We've come," said Mrs. Havitt, cutting the cackle, and coming at once to the 'osses, "we've come to see you about that meeting."

"Oh, indeed!" I murmured. "Yes, the meeting."

"We notice," said Mrs. Arble March, taking up the running, "that you only say 'persons' may attend the meeting. Now we're very much afraid that women won't understand that they may come."

"But surely," I protested, feebly, "a woman is a person."

"Well, we think" (this as a duet) "that you ought to say that 'all persons, men or women, married or single, are invited to attend.'"

I was a good deal staggered, and thought of asking whether they wouldn't like the name of the village altered, or my name printed without the J.P., but I refrained. I promised to print new bills, and I did it. I thought it would be a poor beginning to a peaceful revolution to have an angry woman in every household.

Those were my first visitors. After that I had about two calls a day. One day the Vicar dropped in to afternoon tea, to congratulate me on my public spirit. I confess I felt rather pleased. I had evidently done the right, the high-minded, the patriotic thing. My mind became filled with visions of myself as Chairman of the Parish Council, the head man of a contented village. Just before he left, however, the Vicar suggested that I should advise the electors to elect into the chair someone who had had previous training of what its duties and responsibilities were, and I suddenly remembered that the Vicar was the present Chairman of the Vestry. Then somehow I guessed why I had been favoured with a visit. The curious thing was, that my next caller (who arrived half an hour afterwards) came to say that the most satisfactory thing in the whole Act was, that the clergyman could not take the chair. Then my memory once more told me what manner of man I was talking to—he was a prominent local preacher. I was being nobbled.

And so it went on. My answer to all who came was, that they could come and ask me questions at the meeting. Is was a convenient plan enough—at the time. Yet my suggestions—like chickens and curses—came home to roost—at the meeting. And that, as I have said, is the third chapter.

238

["The billiard-season has set in in real earnest."—Daily Paper.]

A UTILITARIAN.

The Vicar. "And how do you like the new Chimes, Mrs. Weaver? You must be glad to hear those beautiful Hymn-tunes at night! They must remind you of——"

Mrs. Weaver. "Yes; that be so, Sir. I've took my Medicine quite regular ever since they was begun!"

Curious.—A lady who had read the two recent controversies anent the Lords and the Empire got slightly muddled. "Well, I've never seen anything wrong," she said, "in Promenade Peers."

Florence! O glorious city of Lorenzo the Magnificent, cradle of the Renaissance, birthplace of Dante, home of Boccaccio, where countless painters and sculptors produced those deathless works which still fascinate an admiring world, at last I approach thee! I arrive at the station, I scramble for a facchino, I drive to my hotel. It is night. To-morrow all thy medieval loveliness will burst upon my enraptured eyes.

In the morning up early and out. Immediately fall against a statue of a fat man in a frock coat and trousers. Can this be Michael Angelo's David? No, no! It is Manin by Nono. Turn hastily aside and discover a quay. Below is a waste of mud, through which meander a few inches of thick brown water. The Arno! Heavens, what associations! Raise my eyes and perceive on the opposite bank a gasometer. Stand horror-stricken in the roadway, and am nearly run over by a frantic bicyclist. Save myself by a great effort and cling for support to a gaslamp until I can recover from the shock. Resolve then to seek out the medieval loveliness. Start along the quay. Ha, there is a statue! Doubtless by Michael Angelo. Hardly; the face seems familiar. Of course, it is Garibaldi! Turn and fly up a narrow street. Here at last is something old, here at last are the buildings on which Dante may have looked, in which Fra Angelico may have painted, here at last——. Why, what's this? It's an omnibus. It fills the street. Wedge myself in a doorway, and when it has passed within three inches of my toes, hurry down a side street, a still narrower one. Here, perhaps, Benvenuto Cellini devised some glorious metal work. Ha, there is a silversmith's even to this day! Look! what are those things in the window, above the inscription "English Spoken"? They are teapots from Birmingham! Resolve to avoid small streets, and hurry on to large open piazza. Now for some architecture by Giotto, some sculpture by Donatello! Yes, there is an equestrian statue. Doubtless one of the Medici. At last! No, it's not. It's Victor Emanuel. At least, the inscription says so, though the likeness, not being a speaking one, gives no information. Turn sadly aside and contemplate some melancholy modern copies of the regular architecture of rectangular Turin.

Begin to feel depressed. Have not yet found the romantic medievalism. Somewhat revived by déjeuner, resolve to seek it in the suburbs. Of course, Fiesole. A pilgrimage to the home of Fra Angelico. Sublime! Will go on foot, avoiding the high road. Climb by narrow ways, past garden walls. Behind them may be the gardens where Boccaccio's stories were told; down these narrow roads Fra Angelico may have passed. How exquisite to meditate far from the tourist crowd! Filled with enthusiasm, and gazing at the beautiful blue sky, arrive at the top, and stumble headlong over some obstacle in the road. It is the rail of a tramway! Stagger feebly to the Piazza just as the electric tramcar bumps and rumbles up the hill. From it descends a crowd, carrying, not lilies, as in Angelico's pictures, but Bædekers. And I hear no tale from the Decameron, but a mingled confusion of strange tongues. "Ja, ja, ja; what a squash; nous étions un peu serrés mais enfin; ach wunderschön; un soldo signore; ja, ja, ja; wal, I guess this is Feaysolay, che rumore nel tram; I say, let's buy one of these straw fans for Aunt Mary; they're awfully cheap, only half a franc, and look worth half-a-crown; ah voilà le café; wollen sie ein Glas Bier trinken; ja, ja, ja!" Resolve to abandon search for medieval loveliness, and go down sadly in the tramcar.

But one art remains. In the country where Verdi still writes I can at least enjoy music. So after dinner seek the Trianon. It sounds like a music-hall; but then here, even in a music-hall, there must be music. As I enter, a familiar sound bursts upon my ear. The singer is Italian, the words are French, but the tune is English. She is singing "The Man that Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo."

"Ah!" sighed Mrs. R. sadly, when her advice had not been taken by her daughter, "I'm a mere siphon in the family!" 239

(A Story in Scenes.)

PART XX.—"DIFFERENT PERSONS HAVE DIFFERENT OPINIONS."

Scene XXX.—Lady Maisie's Room at Wyvern.

Time—Saturday night, about 11.30.

Lady Maisie (to Phillipson, who is brushing her hair). You are sure Mamma isn't expecting me? (Irresolutely.) Perhaps I had better just run in and say good night.

Phillipson. I wouldn't recommend it, really, my lady; her ladyship seems a little upset in her nerves this evening.

Lady Maisie (to herself). Il-y-à de quoi! (Aloud, relieved.) It might only disturb her, certainly.... I hope they are making you comfortable here, Phillipson?

Phill. Very much so indeed, thank you, my lady. The tone of the Room downstairs is most superior.

Lady Maisie. That's satisfactory. And I hear you have met an old admirer of yours here—Mr. Spurrell, I mean.

Phill. We did happen to encounter each other in one of the galleries, my lady, just for a minute; though I shouldn't have expected him to allude to it!

Lady Maisie. Indeed! And why not?

Phill. Mr. James Spurrell appears to have elevated himself to a very different sphere from what he occupied when I used to know him, my lady; though how and why he comes to be where he is, I don't rightly understand myself at present.

Lady Maisie (to herself). And no wonder! I feel horribly guilty! (Aloud.) You mustn't blame poor Mr. Spurrell, Phillipson; he couldn't help it!

Phill. (with studied indifference). I'm not blaming him, my lady. If he prefers the society of his superiors to mine, he's very welcome to do so; there's others only too willing to take his place!

Lady Maisie. Surely none who would be as fond of you or make so good a husband, Phillipson!

Phill. That's as maybe, my lady. There was one young man that travelled down in the same compartment, and sat next me at supper in the room. I could see he took a great fancy to me from the first, and his attentions were really quite pointed. I am sure I couldn't bring myself to repeat his remarks, they were so flattering!

Lady Maisie. Don't you think you will be rather a foolish girl if you allow a few idle compliments from a stranger to outweigh such an attachment as Mr. Spurrell seems to have for you?

Phill. If he's found new friends, my lady, I consider myself free to act similarly.

Lady Maisie. Then you don't know? He told us quite frankly this evening that he had only just discovered you were here, and would much prefer to be where you were. He went down to the Housekeeper's Room on purpose.

Phill. (moved). It's the first I've heard of it, my lady. It must have been after I came up. If I'd only known he'd behave like that!

Lady Maisie (instructively). You see how loyal he is to you. And now, I suppose, he will find he has been supplanted by this new acquaintance—some smooth-tongued, good-for-nothing valet, I daresay?

Phill. (injured). Oh, my lady, indeed he wasn't a man! But there was nothing serious between us—at least, on my side—though he certainly did go on in a very sentimental way himself. However, he's left the Court by now, that's one comfort! (To herself.) I wish now I'd said nothing about him to Jem. If he was to get asking questions downstairs——He always was given to jealousy—reason or none!

[A tap is heard at the door.

Lady Rhoda (outside). Maisie, may I come in? if you've done your hair, and sent away your maid. (She enters.) Ah, I see you haven't.

Lady Maisie. Don't run away, Rhoda; my maid has just done. You can go now, Phillipson.

Lady Rhoda (to herself, as she sits down). Phillipson! So that's the young woman that funny vet man prefers to Us! H'm, can't say I feel flattered!

Phill. (to herself, as she leaves the room). This must be the Lady Rhoda, who was making up to my Jem! He wouldn't have anything to say to her, though; and, now I see her, I am not surprised at it!

[She goes; a pause.

Lady Rhoda (crossing her feet on the fender). Well, we can't complain of havin' had a dull evenin', can we?

Lady Maisie (taking a hand-screen from the mantelshelf). Not altogether. Has—anything fresh happened since I left?

Lady Rhoda. Nothing particular. Archie apologised to this New Man in the Billiard Room. For the Booby Trap. We all told him he'd got to. And Mr. Carrion Bear, or Blundershell, or whatever he calls himself—you know—was so awf'lly gracious and condescendin' that I really thought poor dear old Archie would have wound up his apology by punchin' his head for him. Strikes me, Maisie, that mop-headed Minstrel Boy is a decided change for the worse. Doesn't it you?

Lady Maisie (toying with the screen). How do you mean, Rhoda?

Lady Rhoda. I meantersay I call Mr. Spurrell——Well, he's real, anyway—he's a man, don't you know. As for the other, so feeble of him missin' his train like he did, and turnin' up too late for everything! Now, wasn't it?

Lady Maisie. Poets are dreamy and unpractical and unpunctual—it's their nature.

Lady Rhoda. Then they should stay at home. Just see what a hopeless muddle he's got us all into! I declare I feel as if anybody might turn into somebody else on the smallest provocation after this. I know poor Vivien Spelwane will be worryin' her pillows like rats most of the night, and I rather fancy it will be a close time for poets with your dear mother, Maisie, for some time to come. All this silly little man's fault! 240

Lady Maisie. No, Rhoda. Not his—ours. Mine and Mamma's. We ought to have felt from the first that there must be some mistake, that poor Mr. Spurrell couldn't possibly be a poet! I don't know, though; people generally are unlike what you'd expect from their books. I believe they do it on purpose! Not that that applies to Mr. Blair; he is one's idea of what a poet should be. If he hadn't arrived when he did, I don't think I could ever have borne to read another line of poetry as long as I lived!

Lady Rhoda. I say! Do you call him as good-lookin' as all that?

Lady Maisie. I was not thinking about his looks, Rhoda—it's his conduct that's so splendid.

Lady Rhoda. His conduct? Don't see anything splendid in missin' a train. I could do it myself if I tried?

Lady Maisie. Well, I wish I could think there were many men capable of acting so nobly and generously as he did.

Lady Rhoda. As how?

Lady Maisie. You really don't see! Well, then, you shall. He arrives late, and finds that somebody else is here already in his character. He makes no fuss; manages to get a private interview with the person who is passing as himself; when, of course, he soon discovers that poor Mr. Spurrell is as much deceived as anybody else. What is he to do? Humiliate the unfortunate man by letting him know the truth? Mortify my Uncle and Aunt by a public explanation before a whole dinner-party? That is what a stupid or a selfish man might have done, almost without thinking. But not Mr. Blair. He has too much tact, too much imagination, too much chivalry for that. He saw at once that his only course was to spare his host and hostess, and—and all of us a scene, by slipping away quietly and unostentatiously, as he had come.

Lady Rhoda (yawning). If he saw all that, why didn't he do it?

Lady Maisie (indignantly). Why? How provoking you can be, Rhoda! Why? Because that stupid Tredwell wouldn't let him! Because Archie delayed him by some idiotic practical joke! Because Mr. Spurrell went and blurted it all out!... Oh, don't try to run down a really fine act like that; because you can't—you simply can't!

Lady Rhoda (after a low whistle). No idea it had gone so far as that—already! Now I begin to see why Gerry Thicknesse has been lookin' as if he'd sat on his best hat, and why he told your Aunt he might have to be off to-morrow; which is all stuff, because I happen to know his leave ain't up for two or three days yet. But he sees this Troubadour has put his poor old nose out of joint for him.

Lady Maisie (flushing). Now, Rhoda, I won't have you talking as if—as if—— You ought to know, if Gerald Thicknesse doesn't, that it's nothing at all of that sort! It's just—— Oh, I can't tell you how some of his poems moved me, what new ideas, wider views they seemed to teach; and then how dreadfully it hurt to think it was only Mr. Spurrell after all!... But now—oh, the relief of finding they're not spoilt; that I can still admire, still look up to the man who wrote them! Not to have to feel that he is quite commonplace—not even a gentleman—in the ordinary sense!

Lady Rhoda (rising). Ah well, I prefer a hero who looks as if he had his hair cut, occasionally—but then, I'm not romantic. He may be the paragon you say; but if I was you, my dear, I wouldn't expect too much of that young man—allow a margin for shrinkage, don't you know. And now I think I'll turn into my little crib, for I'm dead tired. Good night; don't sit up late readin' poetry; it's my opinion you've read quite enough as it is!

[She goes.

Lady Maisie (alone, as she gazes dreamily into the fire). She doesn't in the least understand! She actually suspects me of—— As if I could possibly—or as if Mamma would ever—even if he—— Oh, how silly I am!... I don't care! I am glad I haven't had to give up my ideal. I should like to know him better. What harm is there in that? And if Gerald chooses to go to-morrow, he must—that's all. He isn't nearly so nice as he used to be; and he has even less imagination than ever! I don't think I could care for anybody so absolutely matter-of-fact. And yet, only an hour ago I almost——But that was before!

By Ben Trovato.—Mr. Arthur Roberts is always interested in current events, with a view to new verses for his topical songs. A friend came up to him one day last week with the latest Globe in his hand, just as the Eminent One was ordering dinner for a party of four. "They're sure to take Port Arthur!" cried the friend, excitedly. "I never touch it myself," said Mr. Roberts, "but I'll order a bottle."

With a Difference.—It is common enough, alas! for a man of high aspirations to be "sorely disappointed," but it is quite a new thing to be "sorely appointed," which is the case with Professor W. R. Sorley, who has recently been placed in the Moral Philosopher's Chair at the University of Aberdeen.

The New Broom.—The Republican Party in the United States declare—apparently with some show of likelihood—that they will "sweep the country." All honest citizens and anti-Tammany patriots must heartily hope that they will sweep it clean.

Most of the libretto of W. S. Gilbert's latest whimsical opera, entitled His Excellency, is evident proof of his excellency in this particular line and on these particular lines. Among principals, Mr. Barrington has perhaps a trifle the best of it; while the part given to our Gee-Gee, alias George Grossmith, is not so striking as his costume, both he and Mr. John Le Hay, whose make-up is wonderfully good, being somewhat put in the shade by the gaiety of the two charming young ladies Miss Jessie Bond and Miss Ellaline Terriss, who act with a real appreciation of the fun of the situation in which their dramatic-operatic lot is cast. But, after all said and sung, it is the brilliancy of the Hussars, under the command of Corporal, afterwards Colonel, Playfair, that carries the piece, and takes the audience by storm. The music by Dr. Carr would not of itself carr-y the piece were "the book" less fancifully funny than it is, and did it not contain some capital lines which are quickly taken by an appreciative audience. There is plenty of "go" in the Carr-acteristic music for the dance of Hussars; but the most catching "number" is a song of which the first bars irresistibly call to mind the song with a French refrain sung by Miss Nesville in A Gaiety Girl. Was Dr. Osmond Carr the composer of that air? or as "that air" sounds vulgar, let us substitute "that tune." If so the resemblance is accounted for, and if he wasn't, then it is only an accidental resemblance of a few bars that at once strikes the retentive ear of the amateur. Scenery and costumes are all excellent in His Excellency.

In the New York Critic a suggestion is made that it would be a graceful thing for Editors of Magazines to bring out occasionally a "Consolation Number," containing only rejected contributions. But why not give the Editor's reasons for rejecting them as well? This would be such a "consolation" to the public, if not to the authors! A specimen number might be made up somewhat as follows:—

1. "A Dream of Fair Wages."—A Rondel by Tennyson Keir Hardie Morris Snooks.

[Rejected as a mixture of bad politics with worse poetry.]

2. "Children of Easy Circumstances."—By Ω. Φ.!

[An up-to-date story, with several risky situations in it; the risk, however, has been reduced to a minimum by the gifted Authoress having contracted to indemnify the Publisher and Editor against any legal consequences that may ensue. Printed "without prejudice," and should be read in a similar spirit.]

3. "On the Magnetisation of Mollusca." By Leyden Jarre, F.S.L.

[Rejected because, although an extremely able and interesting paper in itself, it is found by experience that this sort of high-science essay requires high people to write it if it is to have a chance of being read. Nobody under the rank of a Duke should dabble in magazine science. What's the use of calling it a Peery-odical otherwise, eh?]

4.

[Rejected because this kind of "symposium" on topical subjects can be got much better, as the above writers have chiefly got it, from the daily papers. Without some magazine padding of the sort, however, "none is genuine," and the above is not much more hopeless drivel than is usually inserted.]

On the List.—Without going back to the still undiscovered horrors in the East End, we have sufficient material in the two diamond robberies Holborn district and a bomb in Mayfair to warrant us in asking where is that much-wanted Sherlock Holmes?

The L.C.C. and the Church.—"The church was condemned as dangerous by the London County Council." Is not such a paragraph as the above calculated to frighten all the good people who are so anxious on the subject of religious education? Why, certainly. Fortunately the church in question is only "All Saints Church, Mile End," which had to be repaired and restored, and which was re-opened by "Londin" (which signature, with "B" for "Bishop" before it, would become "Blondin") last Thursday. "All's well that ends well," as says the Eminently Divine Villiams.

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation are as in the original.