The Project Gutenberg EBook of Cornish Saints and Sinners, by J. Henry Harris This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Cornish Saints and Sinners Author: J. Henry Harris Illustrator: L. Raven-Hill Release Date: August 26, 2014 [EBook #46690] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CORNISH SAINTS AND SINNERS *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Les Galloway and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Cornish Saints and Sinners

By the Same Author

THE FISHERS

Crown 8vo.

BY

J. HENRY HARRIS

WITH NUMEROUS DRAWINGS BY

L. RAVEN-HILL

LONDON: JOHN LANE, THE BODLEY HEAD

NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY. MCMXV

NEW EDITION

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, LONDON AND BECCLES, ENGLAND

CORNISH SAINTS AND SINNERS

We were three.

Guy Moore, who had scraped through his "final," and eaten his call dinner, and talked sometimes of full-bottomed wigs and woolsacks.

George Milner, surnamed the "Bookworm."

Myself.

It was an old arrangement between Guy and myself to go somewhere as soon as the Long Vacation commenced, and the Bookworm, a relation of Guy's, was included on account of his[Pg 2] health. The doctor told him that if he did not take a timely rest now he'd never read all the books in the British Museum library, which he had set himself to do before going to Paris to read there, and then some other place, and so on. Bookworms are like that. Our mutual friend was an earnest young man, and had the reader's look about the eyes; and when he went to bed he read unknown books in his sleep. The doctor said, "Get him away—plenty of air, plenty of walking, no books."

We met in Guy's chambers, and talked Cornwall; but the trouble was with the Bookworm, who wanted to take a truck-load of books with him.

We decided on going to Penzance, and then rambling just where we would. A visit to the land of a lost language attracted the Bookworm, who at once added a few score books to be read on the spot.

Guy was appointed guardian of the common purse, and empowered to make all arrangements.

The books were left behind.

A splendid day in August we had for our run westward. The Bookworm had a corner, and by-and-by the spirit of wonder crept over him as he looked at the blue skies and the green[Pg 3] grass. There was a world outside of books, after all.

"Here's the briny! Out with your head, man, and suck it all in; it's the wine of life," shouted Guy.

Up went all the blinds, and down went all the windows, and every one who could gazed upon the blue sea shoaling into green with white-flaked edging on the frizzling sands. It is the custom to pay this homage to the sea for being good enough to be just where it is, between Starcross and Teignmouth. Right and left, the Bookworm saw heads thrust out and faces in ecstasy, as though the whole human freight of the flying train was in rapt adoration. White handkerchiefs waved, and the pure voices of children trilled spontaneous anthems whenever the vexatious tunnels permitted them to gaze upon old England's symbol of power and freedom. It was a new experience to the Bookworm, and it surprised him that anything not printed and stitched and bound should stir so much emotion. It was Nature's book in red sandstone and blue sea illuminated by the sun, on which his tired eyes rested for a few moments; he felt refreshed by the mere vision, his pulses throbbing with new sensations. And when the vision passed in the broad valley of the Teign, he asked simply—

"Is there more of this?"

"Plenty," said Guy, promptly.

According to Guy's account, we were to have just whatever we liked, when we liked, and where we liked. Seascape and moorscape, hill and vale, sailing and fishing, riding and driving, and golfing, and all that sort of thing. And then there were certain mysterious regions where we were to find tracks of the fairies, and come across odds and ends of things, and people too. We were not to have any guide-books; he insisted on that. What was the good of guide-books to fellows on their rambles? Who cared how many yards he was from anywhere, or how many miles it was from one place to another? All that was worth remembering could be picked up on the spot, and then there wouldn't be any danger of everything running into one blurred outline of travel, just as happened to a fellow after tramping for weeks through picture-galleries and curio-shops, and all that sort of thing. Guy said he knew a fellow who did the whole county most thoroughly guide-book in hand. He started from Bude, and did the north coast; and then he turned around and did the south coast. He scored his guide-book like a chart of navigation, and his marginal notes played leap-frog all over the show. When he got to Plymouth he lost the precious book, and if it wasn't for railway labels and hotel bills, he wouldn't have known where he'd been.

A commercial man, having totted up his[Pg 5] accounts, seemed greatly interested in Guy's remarks, and glided into the conversation. He told us he hadn't had a holiday for thirty years, and never expected another in this life. He became quite confidential, and gave us his views about happiness in the world to come. He never intended going "on the road" again for a living in the next world, he said, if there were any telephones about. He didn't like telephones when the boss was always at the other end.

We ran through the apple country, and the commercial man said these orchards were simply nothing to be compared with those a few miles away, where the real Devon cider was made. He told some funny stories about cider and its makers—the way in which sweet cider was discovered, and the hand that Old Nick had in the matter.

"It's a short story," said he, good-naturedly. "Old John Bowden had the finest orchard land in South Devon, and it appears that in the olden times the land was the property of Tavistock Abbey, and the good Fathers used to come over every season to make cider and have a frolic. Sometimes the good old cider, being no respecter of persons, got into the good Fathers' heads. Now, you must know that the best of cider is a trifle sharp to the palate—the natives call it 'rough'—and the Fathers were in[Pg 6] the habit of toning some rare good stuff, reserved for high days and holidays, in empty wine-casks. One season, the wine-casks falling short, the Abbot of Tavistock drew up a sort of prize competition, like the magazines do now, offering something tasty to the inventor of a process for making 'rough' cider sweet without the use of wine, which, I suppose, worked out expensive, and, moreover, encouraged more drinking than was allowed under the tippling act. I must now tell you that, for a very long time, things hadn't gone on smoothly between the monks of Tavistock Abbey and Old Nick, who was constantly prowling about the premises, picking up little bits of information, and making the good Fathers uncomfortable. Well, he chanced upon this prize competition notice on an old door covered over with cast horse-shoes and vermin nailed up for 'good luck' and to keep his satanic majesty off the premises. However, there he was, and read the notice.

"A very obliging little old man turned up at the orchards one season, and offered his services, and was taken in to do odd jobs about the pound-house, and as he wasn't particular about his bed, he was allowed to curl himself up in one of the big empty cider-casks. In truth, after the work was over for the day, the good Fathers had other fish to fry, and thought no more about him; but the strange workman was[Pg 7] most busy when he was supposed to be sound asleep.

"Of all the Fathers of the Abbey, Brother John was the keenest on winning the prize for turning 'rough' cider into sweet, and he spent hours in the pound-house alone, spoiling good stuff, without getting one foot forrarder. 'Dang my old buttons!' said he, after another failure.

"It wasn't so much the language as the temper of Brother John which attracted the notice of the little old man who slept in the cask, and he whispered something which made the good brother turn pale and tremble in his shoes. He was not above temptation, it is true, but he was a brave man for all that, and dissimulated so well that the stranger was so off his guard as to sleep in his cask and leave one of his cloven feet sticking out of the bung-hole. Brother John bided his time and covered the bung-hole, and then arranged for such a flow of cider into the cask upon the sleeping stranger as to settle his hash, unless it was the very old Nick himself. Old Nick it was, and when he awoke to the situation he was so hot with passion that the cider bubbled in the cask, and he disappeared, leaving the strongest of strong smell of brimstone behind. Brother John kept the secret to himself, not knowing what might come of it; but when he tasted the cider his eyes sparkled, for it was[Pg 8] as sweet as honey, and when sweet cider was wanted at the Abbey, he used to pour it 'rough' upon the fumes of burning sulphur, and, lo and behold! it became sweet. It was Old Nick who gave away the secret to Brother John, who was smart enough to learn it. A Devon man calls sweet cider 'matched,' on account of its connection with old Brimstone."

"Did Brother John patent the process?" asked Guy.

"No, he didn't, though Old Nick tempted him; but Brother John was too wide awake to have his fingers burnt by patent lawyers and their agents."

"Is that story in print?" asked the Bookworm, preparing to make a note for future reference.

"I should say not. It's just one of those trifles you pick up on the road. Plenty about when Old Nick is concerned. They say his majesty didn't cross the Tamar in olden days; or, if he did, then he hopped back again in double-quick time. That may be, but he's a season ticket-holder now, and has good lodgings, and I ought to know, for I do business all through the country," said the man of samples, stepping out of the carriage.

"A trifle rough on us lawyers," said Guy. "Poor beggar has suffered, I suppose."

Across the bridge, and we are in the land[Pg 9] of pasties and cream—the land of a lost language, of legend and romance, where the old seems new and the new seems old, and the breath of life everywhere.

Penzance.

The proper thing to do when you awake at Penzance is to run down to the sea and bathe. We were told all about it in the smoking-room. It is a sort of ceremony with something belonging to it. When once you've bathed in the sea you're free of the country, like the Israelites, after swimming the Jordan. Everybody asks his neighbour, "Have you bathed?" If you have, it's all right.

We missed the Bookworm soon after breakfast, but Guy said we would soon find him if we drew the libraries. Guy supposed that reading was like dram-drinking to a fellow who had got[Pg 11] himself into the Bookworm's condition, and it would be just as well to let him have a dose occasionally. We decided to "do" Penzance on our own account.

There's nothing much to "do." All the streets run down to the sea, and then run up again. It is a capital arrangement and saves one asking questions. It is humiliating for a Londoner to be seen asking his way about, and takes the fine bloom off his swagger not to be able to find his way to the next street, in a town all the inhabitants of which could be put into one corner of the Crystal Palace. Guy said he'd rather walk miles than ask such a silly question.

Penzance had a reputation long before any modern rivals were heard of, and was the Madeira of England before the Riviera made its début as a professional beauty in the sunny south. Professional beauties want "touching up" sometimes, and Penzance has been doing a little in that way lately, though without destroying the charm which draws admirers, and keeps them. It is one of those towns in which you seem to be always walking in the shadow of a long yesterday. Go into the market, and buy a rib of beef, and you are brought face to face with an ancient cross whose age no man can surely tell. You buy a fish, still panting, from the creel of a wrinkled specimen of human antiquity which takes snuff, and bargains in unfamiliar words.[Pg 12] Shops with modern frontages are filled with dark serpentine, which carries you back to geologic time; and at the photographers, the last professional beauty on the stage is surrounded by monuments in stone, weathered and hoary before the Druids used them for mystic rites. And the names are strange. A sound of bitter wailing is in Marazion, and Market Jew brings to mind the lost ten tribes. You learn in time that Market Jew has nothing to do with Jewry, nor Marazion with lamentation; but all this comes gradually, and there is ever the sensation of having an old and vanished past always with you. You may step from Alverton Street, Pall Mall and Piccadilly rolled into one, with its motor-cars and bikes, knickers and chiffons, into Market Jew, reminding you of antiquity and gabardines, or vice versâ, just as you happen to be taking your walks abroad.

Penzance has one "lion"—Sir Humphry Davy. Sir Humphry and his little lamp is a story with immortal youth, like that of Washington and his little hatchet. Sir Humphry meets you at unexpected places and times—there was something ŕ la Sir Humphry on the breakfast menu. We heard about him soon after our arrival, from an American tourist of independent views. He said that Sir Humphry would not be a boss man now because he didn't know a good thing when he had it, and gave away his[Pg 13] invention in a spirit of benevolence, which was destructive of all sound commercial principles. Then he figured out how many millions, in dollars, Sir Humphry might have made, if only he had patented his little lamp and run the show himself.

Sir Humphry is a sort of patron saint, and some people feel all the better for looking at his statue in marble outside the Market House. He was born here, but his bones rest in peace at Geneva. They may be brought over at the centenary of his death, and canonized by the miners, whose saint he is, and God reward him for placing science at the service of humanity.

We found ourselves in the Morrab Gardens; the Public Library is there, and Guy said we might surprise the Bookworm if he came out to breathe. We didn't see him, but we saw the gardens—a little paradise with exotic blooms, and fountains playing, and the air laden with perfume. We sat down, but didn't feel like talking—a delicious, do-nothing sort of feeling was over us. We didn't know then what it was, but found that it was the climate—the restful, seductive climate.

A couple of fishwomen with empty baskets passed us, and they talked loud enough, but it might have been Arabic for all we knew. The letters of the alphabet seemed to be waltzing with the s's and z'z to the old women's accompaniment,[Pg 14] and words reached us from a distance like the hum of bees. We were inclined to sleep, so moved on; but the feeling while it lasted was delicious. It may be only coincidence, but the Bookworm discovered that Morrab is a Semitic word, and means "the place of the setting sun." The Morrab Gardens face the west; and to sit in a library in a miniature garden of Eden with an Arabic name is, in his opinion, the height of human enjoyment. The natives think a lot of the garden.

Serpentine and saints are common—the former is profitable; but there was an over-production of the latter a long time ago, and the market is still inactive. Some parishes had more than one saint, and some saints had more than one alias, to the great confusion of all saint lovers. The memory of saints, however, will last as long as the Mount stands. The Mount, dedicated to St. Michael, makes one curious about the early history of the good people who came here long ago, when the sea was salt enough to float millstones. The cheapest way of coming across in those days from the "distressful country," was to sit on a millstone and wait for a fair breeze. The saints were quite ready to grind any other man's corn as soon as they landed, and the millstones were convenient for that purpose. The rights of aliens to eat up natives were articles of belief and practice.

Penzance appeared on the saints' charts as the "Holy Headland," which was a mark to steer by; but St. Michael, it appears, drifted out of his course, and landed at the Mount, where the giant lived, and thereby hangs a tale.

Saint Michael and the Conger.

There are more St. Michaels than one, but the hero of this story landed at the Mount in a fog. The Mount was then the marine residence of an ancient giant, well known as keeping a sharp look-out for saints through a telescope, which he stole from an unfortunate Phœnician ship laden with tin and oysters. The giant had an evil reputation, but did nothing by halves. He was asleep when St. Michael landed; and when he slept, he snored, and when he snored, the Mount shook.

The poor saint was in a terrible funk, wandering about for days, reading the notices which the giant posted up warning saints not to land, unless they wished to be cooked in oil, after the manner of sardines. There was nothing to be picked up just then but seaweed, and the dry bones which the giant threw away—and there wasn't enough on the bones to support a saint after he had done with them. St. Michael had got rid of the very last drop of the best LL. whisky, and sat on the empty keg, and dreamed of his own peat fire at Ballyknock, and the little shebeen where a[Pg 16] drop was to be had for the asking. It was fear of the fierce giant above which alone kept him from singing the poem which he had composed about "Home, sweet home."

The saint was very sad, and had almost given up hope, when something in the sea attracted his attention, and he saw a great conger rise, tail first, and stretch itself, until the tail topped the rock. Its head remained in the sea. The giant was snoring, and the Mount shook. St. Michael was the gold medallist of his college, and could put two and two together with the help of his fingers. "A sign," said he, girding on his sword, and putting on his best pair of spurs. The conger was to be for him a Jacob's ladder.

So he dug his spurs well into the fish's side, and climbed and climbed until he reached the top, and, with one mighty stroke, cut off the giant's head. There wasn't much personal estate—only the telescope—and the saint took that, but forgot to send a "return" to Somerset House, and pay death duties. The conger wagged his tail, by way of saying he was tired and wanted to be off, so the saint slipped down quite easily—so easily that he found the earth hard when he touched bottom. Those who have eyes to see may see the mark to this day.

Then the conger disappeared in the sea, but returned again, this time head first, and licked the saint's hand, who blessed it. Now the[Pg 17] conger is very fine and large, and abundant in its season, and the white scars down its sides are the marks of the saint's spurs, which tell the story of the climb. There are some who say it was a bean-stalk which grew in the night for the saint to climb, and those who believe it, may.

The giant's blood flowed over the cliff, and a church sprung up, which St. Michael dedicated to himself, and then went away, for the Mount was not inhabited in those days.[A]

This was the beginning of the war between the saints and giants, which continued for centuries, and might have lasted until now, only the saints came out on top.

Saint Michael crops up in various places, and, for convenience, I may add here what is known of him. He became the patron saint of the county after meeting with the arch-enemy at Helston. There was no time to advise the newspapers, and get special correspondents on the spot, but it was reported that the battle was tough and long. The enemy carried a red-hot boulder under his arm, and hurled it at the saint; but he was out of practice, and the ball went wide. Then the saint got in with his trusty blackthorn, and basted the enemy so well that he couldn't fly away fast enough for comfort.

N.B.—The boulder was picked up when cool, and is still on view at the Angel Hotel.

Saint Michael, having now done enough for mere reputation, grew ambitious, and turned author, and that finished him. He wrote "The Story of my Life," but the publishers returned the manuscript with compliments; and when he found he had to pay double postage on the unstamped parcels, his great heart broke.

The Bookworm got back in time for dinner. He had been to all the libraries, and made friends of all the curators, and was going to have a good time.

We met the American gentleman in the smoking-room, and he gave us more opinions. He said this part of the world was a durned sight too slow for the twentieth century. It was, say, two hundred years behind the age. He expected that an American citizen would come across one day, and just show the people what to do, and how to do it. This Cornwall was a big show for the man who knew how to handle it. He took a special interest in the matter, because of the Gulf Stream, and he wasn't sure whether or no this part of the old country came within the Monroe doctrine. If it's England where the British flag waves, then isn't it America where American water runs? And if the Gulf Stream wasn't America, what was? He told us frankly that he, John B. Bellamy, Kansas City, Mo., U.S.A., had ideas.

Dolly Pentreath, the fishwife of Mousehole, had a reputation as wide, but different, as Sir Humphry's. Her portrait is sold in Penzance, wherein Dolly is only a name now. She belonged to the adjoining parish of Paul, and so there is no statue to her in the Market-place, where she sold fish, and talked the old Cornish with the real twenty-two carat stamp upon it. The Bookworm said Dolly's fame had done a good deal towards advertising the land of a lost[Pg 20] language. He showed us the portrait of a determined-looking, passionate old party in short skirts, and a creel on her back. We had seen already several ancient dames carrying fish quite as capable of taking care of themselves, which indicated that if the language is lost, the race survives. It's a nice walk along the shore to Mousehole. We might have lingered at Newlyn, only the Bookworm wanted to get upon classic ground, where old Dolly used to smoke her pipe, and drink her flagon of beer with the best, and talk Cornish—the real old lingo, hot, sweet, and strong, so that those who heard her once never forgot it. Dolly lived to one hundred and two, and then departed, carrying with her, in her queer old brain, the completest vocabulary of the Cornish language upon earth. This is the legend, to which is to be added that she had the reputation of being a "witch." There exists an ancient corner in the village where Dolly would be at home again if she could come back; and the Bookworm walked up and down, and in and out, touching the stones and rubbing shoulders against the pillars, as though he expected to feel an electric shock, or receive the straight tip from the old lady that he'd touched the spot, like Homocea. He may have passed over it, but he was happy. If he could only have found an old clay pipe that Dolly had smoked!

An old man sitting on a post watched us out[Pg 21] of a corner of his eye. He knew what we were up to, and that there was a trifle at the end of it. Guy tackled him.

"Dolly Pentreath? Oh yes; she died poor, and was buried in the parish churchyard of Paul. People came in shoals to see her monument and read the inscription."

"Had anybody got anything belonging to her?"

Not that he knew by. "She might have had a Bible or a hymn-book, but she wasn't given that way much. So many people wanted 'relics,' and if there ever were any, they would have been sold long ago."

All this was straight enough, and his blue eye looked as clear as the well of truth. We stood around him as an oracle, and he began his story.

"Dolly Pentreath was a fine woman, with a voice that you could hear to Newlyn. She had the heart of a lion, and it was told of her that when a press-gang landed in search of men for the navy, Dolly took up a hatchet and fought them back to their boats, and so cursed them in old Cornish that that crew never ventured to come again.[B] And she was artful as well as brave, and saved a man, 'wanted' by the law[Pg 22] for the purpose of hanging, by hiding him in her chimney. Dolly lived in an old house overlooking the quay, the walls of which were thick, and in the chimney was a cavity in which a man could stand upright, and it was a convenient hiding-place for many things. 'Back along' Mousehole was one family, and the ties of blood spoke eloquently; so, when a man rushed into Dolly's cottage, saying the officers were after him, and would hang him to the yardarm of the ship out in the bay, from which he had taken French leave the week before, he did not appeal in vain.

"There was no time to lose, and Dolly rose to the occasion. Up the chimney she popped the man; then, taking an armful of dried furze, she made a fire in the wide open grate, and filled the crock with water. Into the middle of the kitchen she pulled a 'keeve,' which she used for washing, and when the naval officer and his men burst into the kitchen, Dolly was sitting on a stool, with her legs bare, and her feet dangling over the 'keeve.' This was the situation.

"'A man, indeed!' quoth Dolly; 'and me washing my feet!' She was only waiting for the water to 'het,' and they might all wash their own, if they liked. Search? Of 'coose' they might, and be sugared. (This was old Cornish, of course.) Would they like to look into the crock, and see if a man was boiling there?

"Search they did, and found no man; but Dolly found her tongue, and let them have it; and then she found her thick shoes and let them fly; and then she made for the chopper, and that cleared the house. Dolly made the most noise when she heard the poor man cough in his hiding-place. The aromatic smoke from the burning furze tickled his throat, and though life depended on silence, he could not keep it. Then Dolly gave tongue, and old Cornish—the genuine article—rattled amongst the rafters, like notes from brazen trumpets blown by tempests. She threw wide her door, and, with bare legs and feet, proclaimed to all the world the mission of the young lieutenant and his men, who now saw anger in all eyes, and made good their retreat whilst in whole skins. Then Dolly liberated the man in the chimney. In the dark night a fishing lugger stole out of Mousehole with the deserter on board, and made for Guernsey, which, in those days, was a sort of dumping-ground for all who were unable to pay their debts at home, or were 'wanted' for the hangman."

The old man, with true blue eyes, turned a quid in his mouth, and said, with the simplicity of a child, "And that man was my mother's father."

Guy was preparing to cross-examine the man of truth, but we would not have it. It was his[Pg 24] own witness. He had found him sitting on an iron stump, and was bound to treat him as a witness of truth. Why shouldn't his own mother's father have been a deserter from the king's ship, and been saved by Dolly Pentreath? Guy agreed; but, said he, it was suspicious that that man should have been sitting on that very stump, at the very right moment, and have the right story on the tip of his tongue for the right people to listen to. There was too much "coincidence." We let it go at that.

The Bookworm had the old man with the truthful blue eyes all to himself for a time, and discovered the very room in the Keigwin Arms in which Dolly was wont to take her pint and her pipe at her ease, and the window out of which she would thrust her hard old face and shout to the fishers when they came to the landing-place. The old lady was keen on her bargains, and when she had bought her "cate," she trudged into Penzance with "creel" on back, and spoiled the Egyptians, according to the rules of art. The costume of the fishwife is the same now as then—the short skirt, the turned-up sleeves, the pad for resting the creel. Newhaven fishwives, but with less colour.

The Bookworm tried some old Cornish, which he had picked up the previous day, upon the old man with the truthful blue eyes, but he shook his head mournfully. "Karenza whelas karenza,"[Pg 25] repeated the Bookworm; but the old man looked blank, and did not blush at not knowing the family language. The finest chords of his heart were untouched; but he brightened up when the Bookworm sought his hand furtively, and left something there. Guy said he was perpetuating testimony.

The old fellow offered to go with us to Paul, and show us Dolly's monument, but Guy said the place was consecrated ground, and something tragic might happen if he refreshed his memory too largely on the spot. The truthful-looking eyes were unabashed.

"I don't care," said the Bookworm, as we walked along the road—"I don't care; we have received from the old fellow the impressions which he received from those who saw Dolly Pentreath in life—her passionate self-will and pluck, her artfulness, her readiness of tongue, and quickness in making a situation. What could be more dramatic in a cottage with only a fireplace, a wash-tray, and a stool in it for accessories? I don't care how much is invention—the living impression is that Dolly would have done this under the circumstances, and so the true woman has been presented to us."

"I wish you joy of her, only I'm glad she doesn't cook my dinner," said Guy. "Let us reckon up her virtues—she snuffed, she smoked, she took her pint, and she cussed upon small[Pg 26] provocation; these are the four cardinal virtues in your heroine. I wonder how often she was before her betters for assault and battery, and using profane language in an unknown tongue?"

We saluted the monolith in the churchyard in memory of Dolly Pentreath, but no one can say for certain that it covers the ashes of that ancient volcano in petticoats. Guy said he could not thrill unless he was sure the old lady was there, and the Bookworm ought to do all the thrilling for the party.

We were glad to have seen the monument, and the Bookworm said it was a sign of the bonne entente which is to be. "The Republic of Letters is superior to public prejudices and racial antipathies," he added, with a magnificent wave of the hand.

We saluted, the monument, including the shades of Dolly and Prince Lucian, if they happened to be around, and departed with the conviction that we had behaved very nicely towards the lost language and the "Republic of Letters."

The American citizen was not very interested in our doings. He thought that one language was good enough for the whole earth, and that was English, improved by the United States. There were languages still spoken in America which, he guessed, wouldn't be missed if they died out, as well as the people who spoke them. He wasn't gone on lost languages, or lost trades, or lost anything, but was a living man, and wanted people about[Pg 28] him to show life. He had been told to take back some "relics" of the late King Arthur, because there was money in them, and he was going to Tintagel to look round—a button, or shoe-lace, or lock of hair picked up on the spot would fetch something considerable. There was a market for "relics" on the other side. We told him we weren't keen on "relics" for commercial purposes, and were going the other way first, so he would have it all his own way as far as we were concerned.

We reached the Land's End at the lowest of low water, and touched the very last bit of rock visible, so as to be able to say we'd touched the very last stone of dry England. We left it there for future generations to touch.

Cornwall is a tract of land with one-third in pickle, and what can't be walked over can be sailed over. When you sail far enough you reach the Scilly Isles, which is a sort of knuckle-end to the peninsula which once was land. There isn't very much to be found out in books about the land under the sea. Of course it is there, or water wouldn't be on top.

The Cornwall under the sea is the land of romance, where, some say, King Arthur was born. There is no getting away from this land under the sea, for the old fairies rise from it still, and spread enchantment. We were told that every little boy and girl born in the peninsula is[Pg 29] breathed over by the fairies, and in after-life, wherever they may be, they turn their faces in sleep towards the west, and dream. From under the sea there rises, morn and eve, the sound of bells, telling their own tale with infinite charm. The stranger who comes into the county must hear these sounds and thrill, and see in sunshine and shadow, on hill and in coombe, on moor and fen, the fluttering of impalpable wings; for if he hears and sees them not, he will depart the stranger he came, though he live a lifetime in the land. In Cornwall everything is alive—the mine, the moor, the sea, the deep pools, the brooks, the groves, the sands, the caves; everything has its moan and harmony and inspiration. And the land under the sea, which is called Lyonesse by the poets, was a fairy zone, and some say it sank in the night, and some say other things harder to believe.

Cornwall under the sea has been there a long time. Some people, who like to be accurate above all things, say it disappeared in the year 1089, and contained 140 parish churches, and God wot how many chapels, and baptistries, and holy wells, and places. The only survivor was a Trevelyan, of Basil, near Launceston, who was on the back of a swimming horse. As it is not improbable that the inhabitants of Lyonesse traded with somebody elsewhere and owed them money, it is wonderful that the bad debts should[Pg 30] have been wiped out without a murmur, and that no entry has been found in any court, or in the accounts and deeds of abbeys and priories of any interest in the 140 parish churches, and chapels, and holy wells, and baptistries. The Trevelyans seem to have been a larkish family, for when one of them was arrested for debt, he fetched a beehive and presented it to the bailiffs, who ran away from honey and honeycomb as fast as they could. The chimes which rise from the 140 parish churches under the sea are very beautiful to those who hear them. The square-set man who tacked himself on to us smiled when we asked him to say honestly if he had heard them. He had heard people say that they had. Some people are wonderfully quick at hearing.

The fact remains that from Land's End to Scilly is blue water, and from Scilly to Sandy Hook is blue water also. There are some other facts of almost equal interest, if one cares about them; but the first and foremost fact is, that every one standing for the first time upon the bluff, perpendicular cliffs at the Land's End, turns his face seawards, and says, "There's nothing between me and America." Many people also think that the waves breaking on the dark rocks travel all the way from Sandy Hook without stopping for the privilege of dying on English soil. Wherever they come from they're welcome, and so also are the winds laden with Atlantic[Pg 31] brine, which certainly have touched no land since they left the other side. No American tourist ever comes as far west as Penzance without rushing to the Land's End to get a lung-full of home air, as pure and unadulterated as it can be got in this old country.

Guy was particularly interested in the Gulf Stream, which we found was another matter of unfailing interest to everybody, and at all times and seasons. Some things may be explained every hour of the day without being explained away, like the sun's light, or a rainbow, or a new baby's eyes. Guy wanted to have the Gulf Stream pointed out to him, just as though it were painted red on the chart, or sent up clouds of steam. There wasn't much fun in looking for the Gulf Stream, only, being on the spot, one was obliged to do it. We had heard such a lot about it at the hotel, and the square-set man told us that people always made a dash for the Gulf Stream when they came here. His story of the old lady bringing eggs with her to cook in the Stream kept us in good temper when we found for ourselves that the water was just the same as any other sea-water, as far as we could tell, and that we should not have suspected the Gulf Stream of being near if we hadn't been told. Guy said it was a fine thing to know it was somewhere about, even if we couldn't see it, because it was a sort of link between the old world[Pg 32] and the new, and made it easy to understand why Mr. Choate was made a Bencher. Guy promised to think the matter out, and put it in another way if we couldn't quite understand the reference.

The square-set man said he was sure there was a Gulf Stream, because foreign seaweed was picked up sometimes; and if it wasn't for the Stream, early potatoes and broccoli wouldn't be early, and the flowers at Scilly would be just the same as at other places. It's a long way for a stream to come, and the square-set man told us that at one time it must have been stronger than now, for it carried away the mainland between us and Scilly; but when Guy cross-examined him on what he called a question of fact, he broke down, and finished off by saying that that was what "people said." Guy was willing that there should be a Gulf Stream, but he bristled when told that the peninsula was snapped off like a carrot, and carried away by a stream from the Gulf of Mexico. His English pride was hurt, and he declared that he'd rather do without early potatoes and broccoli and flowers from Scilly for the rest of his life than that foreign water should ever be said to have carried away English acres, and so many of them. The invasion of England by the Gulf Stream indeed! Then where were the Navy League, and the Coast Defence Committee, and Mr. Balfour's great speech in the House of Commons?

There was one spot that we must see and stand upon, and the square-set man was sure of himself this time. We must go and stand upon the rock where Wesley stood before composing the hymn, "Lo, on a narrow neck of land." People come from all quarters of the universe for this privilege, and some people actually go away and compose hymns and send copies to the square-set man. He did not say what he did with them, but he did not talk respectfully of an absent lady who mailed him a poem from New York and forgot the postage stamps.

It was Guy's idea to stay where we were. He put it very nicely to the Bookworm about "communing with Nature, the great unwritten book, and all that sort of thing, you know." Guy was afraid that he would make a bee-line for the library if we returned to Penzance, and that we should have to dig him out again. "We'll keep him in the open, and let the square-set man stuff him with pre-historic monuments—something solid, you know, after the Gulf Stream." Guy's mind was constantly running on the Gulf Stream. He didn't care a fig for the stream, he said, in the course of the evening, and it was welcome to travel where it would; but when it came to taking away English soil, he wouldn't hear it; no, not if all the scientists in the universe were against him.

Most people carry away something—pebbles,[Pg 34] or blooms, or bits of seaweed, or something of that sort—and there's plenty left; and all seem to carry away "impressions." The guide-books don't help the impressionists much, for everything appears different to every other person, as though the local fairies had a hand in it.

The square-set man called upon us in the evening, and told us stories of people whom he had conducted around the cliffs, and from monument to monument. The cliffs, we found, were "grand," "sublime," or "terrible;" and the rest was summed up in "charming," "queer," "fantastic," "unaccountable," "odd," "sweet," and the like. Specialists, of course, had their own pet phrases; but our friend was particularly struck with the fancy of the gentleman who saw in the cliffs only admirable situations for solving the great mystery. The higher the point, the more he seemed delighted. "Now, this is what I call a grand place for committing suicide," he finished off by saying, and "tipped" so liberally that Mr. Square-set is on the look-out for his return. An emotion once so deeply stirred will surely need be stirred again, he hinted.

When we asked Square-set to sit down and chat a bit, he said he'd be very pleased to "tich-pipe;" and when I passed him my pouch, he said he hadn't smoked since he was a young man.

"What you want to touch-a-pipe for if you[Pg 35] don't smoke, I can't imagine," said Guy; and then we found that "tich-pipe" had nothing to do with the weed, but simply meant an interval of rest.

The Bookworm made a note.

No one ever comes here without inquiring for "wreckers"—Cornish wreckers are in demand. Guy put artful questions artfully, but could get no admissions beyond that—that he had "heard tell" that in ancient days things were done which no honest, God-fearing man should do. He was always being asked about wreckers and their doings, and a real, live sample on show would be a fortune to any man. What was called "wrecking" now was simply picking up and carrying away little odds and ends which the sea threw up high and dry upon the beaches. And why not? Who had a better title to them?

Guy said he supposed it was all right; and he remembered there was authority for saying that the king is rex because all wrecks belong to him. If so, then wreckers are rexers in their own right,[Pg 37] and can do no wrong. Mr. Square-set was not impressed, but he assured us that the double-dyed villain of Cornish romances innumerable was extinct now, and Mr. Carnegie's millions could not purchase a specimen for the British Museum. It was a disappointment not to find a "wrecker"—the bold, bad man who tied lanterns to cows' tails, and sent up false lights to lure passing ships to destruction. We wanted to shake hands with one and stand him drinks, and make notes of his bushy eyebrows and the colour of his eyes, and then turn him inside out to discover what his secret thoughts were when hatching diabolical plans. Our faith in Cornish romances received a great shock just then, and Guy's cherished ambition to write "The Chronicles of Joseph Penruddock, Wrecker," suffered frost-bite. The world will never know more.

Of deeds of derring-do for the saving of life our square-set friend was full. This was another picture—a picture of black night and tempest, and noble souls wrestling with death and destruction, with scarce one faint chance in their favour. He told us of a man who hung over the precipitous cliff which we had stood on that morning, shuddering as we looked down in the full light of day, and the sea calm as the surface of a mirror; he told us of a man who descended that cliff by a rope when a storm was raging, and the sea "boiling" beneath him, and how he brought back in[Pg 38] his arms a burden, battered, but still living, and how, in mid-air, the strands of the rope were chafed, so that those above trembled as they hauled. And as he spoke an inward glow spread over the man's face and revealed him. Guy seized the man's hands in both his own and wrung them, saying, "Great Scott! and you are the man who did this thing!" He told us afterwards that he couldn't help himself, and wasn't the least ashamed of being a bit "soft" just then. To think that this hero was the man we picked up scratching himself against a cromlech and looking for a job!

We couldn't get away from the sea now, and Mr. Square-set told us how differently sailors in misfortune were treated now than formerly—how they were fed and clothed and sent from one end of the country to the other, wherever they wished to go—in fact, by rail. In his young days it was not so, and a shipwrecked mariner was compelled to tramp wherever he chose to go, either to his own home or to the next port, in the hope of getting a berth. But a tramp in fine weather, sleeping in the fields and outhouses at night, and begging at decent houses by day, was very much enjoyed by the men, who became heroes when they returned home. He told us the story of

Two Ancient Mariners

who hailed from Cornwall, and once found themselves stranded in the port of London, with little but what they stood upright in. They were young men and merry-hearted, and stood by each other in fair weather or foul, as shipmates should. They hailed from the same fishing village, and wished to be home during the "feast" week, which was near at hand. Failing to find a coasting vessel bound west, they started to walk, and part of their arrangement was to take it in turns to call at gentlemen's houses and ask for assistance. They preferred not to go to the same house together, but to leave one on the look-out, in case of "squalls." They got on well enough for some days, sleeping where they could, and telling yarns of peril and disaster, most likely, in their opinion, to melt the hearts of hearers. And the story went like this—

"They came to a great gentleman's house, and it was Tommy Hingston's turn to go in, and Bill Baron's to watch outside. Tommy went up, as bold as brass, and asked for the gentleman, who was at home, and received him very kindly; and when he found he had come from London, he asked him for the latest news.

"'There's fine news, sure 'nuff,' says Tom.

"'Then let me have it, my man.'

"'Haven't 'ee heard it, yer honour? Haven't[Pg 40] 'ee heard that London was as black as night at noon-day?'

"'Most remarkable,' said the gentleman; 'and can you tell me what caused the darkness?'

"'Sartin sure I can. A monstrous great bird flew over the town, and shut out the sun with his wings.'

"'That is astonishing. And did you hear anything else?'

"'Ess; they've a-turned Smithfield Market into a kitchen, and all the people are to be fed upon whitepot.'

"'You really mean it?'

"'I tasted it, yer honour,' replied Tom.

"'And was there anything else worthy of notice?'

"Tom scratched his head. 'There was something else,' he added, in a sort of hardly-worth-talking-about style. 'The River Thames catched on fire.'

"'Ah,' said the gentleman, rising and ringing the bell; 'and I have "catched" a rank imposter, and, being a magistrate, will commit you forthwith to prison as a rogue and a vagabond.'

"Billy Baron was keeping watch outside, and as his mate did not return, he grew uneasy. By-and-by he marched up and 'faced the brass knocker,' and was brought before the gentleman, who was now writing out a committal order, and[Pg 41] Tom he saw standing, bolt upright, by the side of a man who had charge of him.

"Billy was a soft-hearted man, and burst into tears. Then the gentleman told Billy, in very straight terms, what he thought of his mate—a lying imposter, whom he was sending to prison.

"'Never!' said Billy, firmly. 'I'll lay my life on him.'

"'Very well; then, tell me, did you see a great bird fly over London, so large as to hide the light of the sun with its wings?'

"'No, sir,' replied Billy. 'I didn't see the bird, but I seed four horses dragging an egg, which people said a great bird had laid.'

"'You are a truthful man,' said the gentleman.

"'I hope so,' said Billy, with one eye on his mate.

"'I hope so, too. Then, tell me, did you eat some whitepot at Smithfield Market?'

"'No, I didn't, yer honour, but I seed a store full of gurt horn spoons.'

"'He told me something else, and I'm sure you'll answer truthfully. He told me he saw the River Thames on fire.'

"'However cud 'ee have said that, Tom?' blurted out Billy, reproachfully. 'He never seed the river on fire, but what we did see was waggon and waggon-loads of fish carted away with burnt fins and tails.'

"'And they would have been taken from the burning river?'

"'I do not doubt it; but, mind, I dedn't zee it,' said Billy, with the air of a martyr to the truth.

"The gentleman, no longer able to contain himself, sent Tom and Billy down to the kitchen, and gave them the best 'blaw out' they had on the journey. And, when they left, he told them, by way of compliment, that they were 'real Cornish diamonds, and the best pair of liars' he had ever known.

"And they were hard to beat," said Mr. Square-set.

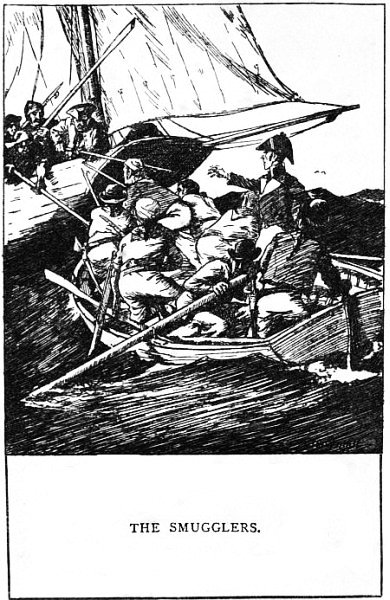

Our square-set friend owned up to smuggling as one of the virtues of his countrymen. The real thing is getting scarce now. One evening he brought an old acquaintance with him, introducing him crisply as "Uncle Bill." We saw a good deal of Uncle Bill afterwards, who was ninety next birthday, and ready and willing to "fight, wrassel, or run" with any man of his age in this country or the next. We did not doubt him, for his blue eye was clear, he moved easily, and his pink finger-tips and filbert-shaped nails[Pg 44] showed breed. Uncle Bill looked as though he intended to carry out his bat for a century or more. He was, he said, as sound as a bell, except that he was a bit "tiched on the wind" when walking against a hill. Never took "doctor's traade," as he contemptuously called physic, and his cure for all ills was a pipe of 'bacca to smoke and a pen'ard of gin mixed with a pen'ard of porter. He said he had done a little smuggling, in the old-fashioned way, in a small lugger, running for dear life across the Channel in a gale of wind when the King's cutters were all snug in harbour, and then landing the tubs of spirits and parcels of lace and other things under the very noses of the preventive men. "They dedn't prevent we," said Uncle Bill, his face all a-glow with the pleasures of memory. He told us that he settled down to fishing when his "calling," and that of his father before him, was interfered with; but the dash and peril and the fame of successful smuggling suited him, and warmed up the cockles of his heart now only to think about. He spoke of himself as an injured man because he received no compensation for disturbance.

Guy worked at the subject, and came to the conclusion that Cornwall was as intended by Nature for smuggling as the inhabitants were for carrying it on. Every little bay and creek and cavern, villages and farmhouses, even the[Pg 45] tombs in the parish churches, could tell tales. And the women, they were hand in glove with their husbands and sweethearts, fathers and brothers; and all that made life worth living then was made dependent on a successful "run" from a little French port with goods honestly bought and paid for, but—the sorrow and shame of it!—made contraband the moment they touched English soil.

"Bad laws made smugglers," said the Bookworm, provokingly, to Guy, who always fires up with professional wrath when he hears of anything bad in connection with the law.

"Bad fiddlesticks! People smuggled because they liked it—just as you liked it when you smuggled those nice little Tauchnitz editions last year, and without thinking of the poor devil of an author in England that you were robbing," replied Guy.

"That never occurred to me," said the Bookworm, meekly.

"Of course not. You are only a petty smuggler, but a smuggler all the same. And do you mean to tell me that 'bad laws,' forsooth, made you smuggle the books? Not a bit of it. You liked the game, and you know it."

There is a grandeur about the old smuggler which increases with age. He put his little all upon a venture—nothing of the limited liability principle about him. The lugger which left a[Pg 46] Cornish fishing cove was, as a rule, family property, owned by father and sons, or by two or three brothers. The family capital was put into one purse, carried away, and converted into honest brandy, wines, and other articles of commerce. Then the struggle commenced between the individual who pitted his own cunning and frail boat against the King's cruisers and all the resources of a mighty State. He was surrounded by "spies" from the moment his cargo was on board until he was ready to slip from his moorings. He could trust no man. And then his voyage across the Channel was a race for life—in fog, in tempest, when only a madman would run the risk, the old smuggler would "up sail and off;" and if a King's officer liked to follow, then all he'd see would be the drippings from the smuggler's keel. The god of storms was the smuggler's divinity, and he loved his little craft, which was, for the time, a thing of life fleeing from pursuit, from imprisonment, and even death when cannon-balls flew about. How the old smuggler prayed for storm and night, for any peril which would enable him to show courage and mastery over the elemental forces which should drive his pursuers to destruction!

And how he would fight when brought to bay! When becalmed, the King's cutter would send a boat alongside to board the lugger, every man armed with pistol and cutlass, and wearing[Pg 47] the uniform of authority. Then the smuggler would fight for property and life, cast off the grappling-irons, and cut down the man who ventured to set foot upon his little craft. And all the while the old man at the helm looked fixedly at the heavens and across the water to see if, perchance, a "breath of wind" was stirring—only a breath might be his salvation when he was too far inshore for the King's cutter to venture, and his men fighting off the cutters crew like heroes. Then a puff, and the sail draws; then more wind, and, inch by inch, the lugger sails away from cutter and cutter's crew, only, perhaps, to fall in with another enemy which has to be out-sailed, or out-manœuvred, or fought off, as best serves the purpose. No surrender when boat and cargo is the bread of the family.

Then the old smuggler reaches home, and every shadow may spell ruin; and all that is done is done in fear, and he has to be cunning always, and ready to fight to the death. The old smuggler belonged to the heroic age, and in all genuine stories he bulks colossal against a midnight sky black with tempest. The race has not disappeared; the conditions have changed, that is all. Uncle Bill told us that he could find a crew to-morrow if there was but a fair prospect of making five hundred pounds on the venture. And "I'd be one," said he.

If Nature intended a county for smuggling, it is Cornwall, which seems somehow to have been caught when cooling between two seas and pressed inward and upward, so that it is full of little bights and bays and caverns, which might have been vents for the gases to escape when the sea pressure at the sides became unbearable, and the earth groaned like the belle of the season in tight corsets. The caverns are given up to bats and otters and slimy things now, but in the "good old days!" The women, by all accounts, took kindly to smuggling, and stood shoulder to shoulder with their men when there was a fight with the preventive men, and ran off with the "tubs" of spirit and whatever they could carry, whilst the men held the King's officers in check. A young man who was content with a "living wage" on sea or on land wasn't thought much of by the black-haired, black-eyed damsels of the coast, who were up to snuff in the free-trade principles of their day and generation. The children were taught to look upon the sea as their own, and to regard smuggling as an honourable calling, and thousands of infant tongues prayed at night for God's blessing on smuggling ventures. And the Church was with the people, and blessed them, and shared their profits when there was no danger of being found out. "Nothing venture, nothing have" was the good old motto bound upon the smugglers' arms and[Pg 49] hearts like phylacteries, and was to them as prayer.

Uncle Bill had a pen'ard of gin in his beer to clear his pipes one evening, and told us some yarns which he had heard from his father, who was called Enoch, who died in his bed at the age of ninety-six, and would have lived longer, only he "catched a cauld dru washing his feet in fresh water."

Uncle Bill was a young man, but not too young to go courting when his father made his last run across the Channel for a cargo of spirits. It came about in this way. Enoch and his family possessed five hundred one-pound notes issued by a bank which had failed, and so were practically worthless. This was a serious matter, and Enoch proposed, at the family council, to run across to Brittany and exchange the worthless notes for tubs of good brandy. Everything was done in secrecy and in hot haste to prevent suspicion, and to get the cargo of contraband on board before news of the bank's failure reached the French merchants. Had they been members of the Japanese Intelligence Department they could not have kept the secret better. They had a splendid run, landed the cargo all serene, and cleared cent. per cent.

"I have often blessed God that there were no telegraphs in those days," said Uncle Bill, fervently.

"What became of the notes?" asked Guy.

"I don't know," replied Uncle Bill, with a lively wink. "All I know is we had the brandy."

"Is this genuine, or only make-up?" asked Guy.

"As true as the Gospel," replied Uncle Bill.

He told us many other stories, but we thought this best worth preserving, as it showed native cunning, promptness, and audacity.

"And I have lived to hear a man bless God that there were no such things as electric telegraphs," said the Bookworm, realizing that he was now in an England of a century ago.

Uncle Bill was a good old sort, and once when he came to see us he pulled a medicine-bottle from the folds of his knitted frock, and, taking out the cork, invited us to taste. It was pure cognac, and its flavour was what the old man called "rich." The spirit had not been coloured, and had a history, which the old man told with relish. News was one day brought to the coastguard station by a boatman that a cask was stranded on an adjacent beach, and the coastguard officer, who loved his joke and good company, summoned numerous good men and true (Uncle Bill being one) to go to the beach, and there hold an inquest upon the said cask and its contents.

"My men," said the coastguard officer, "I summon you in the name of the Queen (God[Pg 51] bless her) to come with me to Treganna beach, and to taste the contents of a cask which we shall find there. I think it's a brandy cask," he added, "and you are to act as Queen's tasters. Now, my men, if you declare that the contents of the cask are wines or spirits, then the same will be seized on behalf of the Crown, and the Excise will claim it; and if you further declare that the contents taste of salt water, then the cask will be staved in, and the contents run out upon the beach. You are the jurors, and meet me here in half an hour. If any of 'ee have a tin can it might be handy" said he, with a wink.

When the jurors met again, they all had something in their hands in the shape of tin cans or pitchers; and there were men upon this jury who had not tasted spirits at their own expense for many years, and they carried the largest pitchers.

The coastguard officer produced a gimlet, and broached the cask, and every man tasted.

"The smell of it was enough for me," said Uncle Bill; "but I tasted, like the rest. It went down 'ansum, sure nuff. And some of us tasted again, to make sure for sartin."

Says the coastguard officer, "What is it, my men?"

"Cognac."

"So say you all?"

"One and all, for sure."

"Then I seize the cask, in the Queen's name."

He took out a bit of chalk, and marked the broad arrow upon it; but our jugs were empty. The best of the game was to come.

"Now, my men, tell me, as good men and true, whether the brandy has been touched with salt water."

So we all tasted again, and said it was sickly, and brackish, and made such faces that you might think we were poisoned.

"And so say you all?"

"Ess, one and all."

"And your verdict is that the cask of brandy, seized in the Queen's name, is brackish?"

"That is our verdict."

"Then I order the cask to be stove in and its contents run upon the beach."

And when the head was stove in, he turned his back upon us, and every can and jug and pitcher was filled, and, if we'd only known, we'd have had more pails and buckets and pitchers.

"I've got a drop still left, and 'tis precious," said Uncle Bill.

This medicine-bottle was his gift to us, and we now knew the flavour of cognac cast upon the shore, which had never paid the Queen's penny.

"I don't wonder that smuggling was popular," said Guy.

Smuggling made the sort of sailor that Nelson loved, a man who could fight and forgive when[Pg 53] worsted, like the old smuggler of Talland, who had it recorded on his tombstone that he prayed God to pardon those wicked preventive men who shed his innocent blood.

It was in the Lizard district that smuggling reached its zenith. The Bookworm put a copy of the "Autobiography of a Smuggler" into his pocket when he tramped over to Prussia Cove, a place which Nature and a little art intended for an emporium for smugglers. Blind harbours, blind caves, hidden galleries, mysterious inlets and exits form a delicate network of safety and concealment. Only a century ago, the man who lived here was the king of Cornish smugglers and privateers, and defended himself with his own cannon.[C] Now the fine caves are fern-arched, and the water drips, drips, drips upon nothing precious. The smugglers borrowed these caves from the piskies who have re-entered into possession, for here are the piskie sands and piskie caves.

"Here, in cool grot, the piskies dwell," hummed Guy.

The caves seemed none the worse for having been smugglers' storehouses; but the gingerbeer[Pg 54] and sandwich man left his trail, as usual. What he couldn't reach or cut down, he left alone, but broken glass he left behind.

Guy ran across a gentleman anxious to tell us things. He was a "pensioner." The man with a pension is a common object by the seashore. After a time, you get to know him as a superior sort of being reduced from his high estate, and only making the two ends meet by the grace of God. "Get a pension, and don't worry" is very good advice when the pension is big enough; but generally the pension-man is a trifle seedy—his pension won't spread all over him, but leaves him minus gloves, with patched shoes, and short everywhere. This honest old gentleman was Guy's find, and he was so eager to tell all he knew, and more on top of it, that Guy was glad, at last, to get rid of him with some excuse covered deftly with a small consideration.

There is a good deal of history in Cornwall. Some may be read in stones, and some in books. The stone reading is very interesting to those who like it, and affords a good scope for imagination. Without imagination, stone reading is a trifle dull. Stones are everywhere at the Land's End and Lizard—some are stationary, and some "rock," and all are weather-worn. The Bookworm had a trick of running his hands over the surfaces of pre-historic monuments, like a blind man reading. It was just a fancy of his that he was shaking hands with antiquity. Our Mr. Square-set put his pencil mark in our Murray[Pg 56] against what is called the "show-stones," and he couldn't tell us much more than we could find out for ourselves. We thought it best to let ancient stone history alone until we had a dull Sunday, or a wet day; and look out for what was nearer our own times.

We found that the Cornishman's motto is "One and All," and that "One" comes first, so he says, "I and the King;" and, when he speaks geographically, it is Cornwall first, then England, and then the rest. Formerly, everything outside of England was Cornwall, but he is not so sure now. However, he always takes a bit of the old county with him when he travels, so that the piskies may find him. A Cornishman abroad is given to "wishtness," and so he gets up clubs in London and other places, and talks of pasties and cream, blue skies and sapphire seas, and sings "Trelawney," and dances the "Flurry" dance, and One and All's it generally.

The Cornish had their own kings and queens—and as the kings were liberal to themselves in the matter of queens, they were not always happy. The Bookworm helped us a good deal at times, and told us that the ancient kings were not much given to diplomatic correspondence, nor to the keeping of "memorials of the reign," so that modern historians had a pretty free hand. The kings, however, must have been numerous at one time, as there was a king at Gweek and[Pg 57] another at Marazion—as thick as tenants on a gentleman's estate. Cornish history had, however, been worked up by poets, and the characters of the old kings drawn by Tennyson and Kingsley were not too amiable. There was Tennyson's Cornish king, who had an uncomfortable way of sneaking round on tiptoe and striking a man in the back. The poet had not made allowance for the fact that King Modred lived in days before private inquiry offices were invented, and so was obliged to do his own dirty work, instead of employing a professional spy at per hour and expenses. For real knowledge of Cornish kings, Kingsley whips creation. Listen!

"Fat was the feasting, and loud was the harping, in the halls of Alef, King of Gweek." There was going to be a wedding, so that may pass. Then we come to details worthy of the poet historian: "Savory was the smell of fried pilchard and hake; more savory still that of roast porpoise; most savory of all that of fifty huge squab pies, built up of layers of apples, bacon, onions, and mutton, and at the bottom of each a squab, or young cormorant, which diffused both through the pie and through the ambient air, a delicate odour of mingled guano and polecat." There was a little toddy, of course, to wash it down, and a few songs with harp accompaniment, and the bride, being properly elated with the perfume of "guano and polecat," was very civil,[Pg 58] and, being a princess in her own right, and queen of Marazion, gave the vocalist a ring to remember her by. The next morning the newly-wedded pair start off on their honeymoon, and this is what happens. The King of Marazion grips his bride's arm until she screams, and says, "And you shall pass your bridal night in my dog-kennel, after my dog-whip has taught you not to give rings again to wandering harpers."

Tennyson and Kingsley have been read pretty generally by men and women of the Anglo-Saxon race, and some people may even think that the Cornish kings were like these portraits, and fed upon "guano and polecat" flavoured pies, and whipped their brides to sleep in dog-kennels in their bridal garments. Poets have always been privileged.

There were Cornish "kings," of course, just as there were Cornish "saints" and a Cornish language, and all three played their little parts, and went off the stage, without even the lights being turned down for them. With regard to the kings, this seemed to have happened: when the local rates and taxes were getting too high, and trouble was brewing about the Education Act, the kings saw that they must go under, and gave way to a Duke. Edward the Black Prince, having won his spurs in the Crusades, the kings asked him to take over what they could no[Pg 59] longer keep, or didn't want, and so, "like a Cornishman's gift, what he does not want for himself" became a proverb. The proverb may be relied on as authentic. The Prince of Wales has been the Duke of Cornwall ever since, so the Cornish people have had a very close connection with royalty from pre-historic times, as the Bookworm discovered; then through Kingsley's "guano and polecat" period, and then from Edward the Black Prince down to the present, which we can verify for ourselves every year, when the Duchy accounts are published, and the ancient tribute passes into the noble Duke's banking account. History loses much of its charm for poets and romantic souls when it enters the prosaic region of banker's ledger and cheque book, but this sort of prose has advantages.

The Cornish had a long way to walk when they wanted just to talk matters over with their sovereign. They went in their thousands to London on several occasions when things were not to their liking, and the late Queen was the first sovereign of the realm to come into the county and "God bless" the people on their own doorsteps. Charles I. came into the county under very peculiar circumstances, and, though he was qualifying for martyrdom, he found time to write a very handsome letter of thanks "to the Inhabitants of the county of Cornwall" for giving the Cromwelliams more than they bargained[Pg 60] for, or wanted even, on several occasions. This letter is still to be found painted on boards in parish churches, and as conspicuously placed as the Lord's Prayer or the Ten Commandments. The practice of reading the letter in churches and chapels has long been discontinued, but the testimony to unselfish devotion and gallant defence of a sovereign whose star was setting in blood remains.

Good Queen Bess rather liked Cornishmen, or said she did, which answered the same purpose. She said that "Cornish gentlemen were all born courtiers, with a becoming confidence," two qualities which naturally attracted her as woman and lady. Climate probably has something to do with native politeness, and that is why the Eastern races are so civil to one another.

The people are like Japs for politeness to one another on a deal. When a man is drawing the long bow and coming it too strong, the other fellow will say, "I wonder if it is so," with the slightest possible accent of suspicion in his tone. We were present when two men were trying to make a deal in horseflesh, "halter for halter," as the saying is. The owner of a weedy-looking chestnut wished to swop with the owner of a useful black cob, and his rhetoric was florid. Sometimes he drew on his imagination in praise of the chestnut, and the owner of the black cob would say, "I wonder now," just by way of note of[Pg 61] admiration. Then the chestnut's owner, growing bolder and more vigorous in his style, garnished his language with many fancy words, and wound up by asking, "Doan't 'ee believe me?" And the other man replied, as politely as a Chesterfield, "I'll believe 'ee to oblige 'ee." The Foreign Office couldn't beat it.

The Bookworm discovered that Cornwall had somehow linked itself with great names in history, or, rather, that some great names had linked themselves with Cornwall, using her as a gallant for a season, and then passing out of her life. Camelford had three successful wooers in Lord Lansdowne, Lord Brougham, and "Ossian" Macpherson; Lostwithiel was wooed and won by Joseph Addison; then Horace Walpole, jilted at Callington, made up to East Looe, still attractive, when the great Lord Palmerston came along with a buttonhole in his coat and the blarney. Then John Hampden found a first love in Grampound, and Sir Francis Drake a soft place in the bosom of Bossiney, a mere village close to the angry roar of Tintagel's sea. But all these seats were mere lights o' love, and some were swept away on account of their dissoluteness before the great Reform Bill, and then the rest went, and none were remembered on account of their gallant political lovers. Guy said it didn't make a bit of difference what the constituency was, or where, so long as the man was right. He saw a great[Pg 62] many advantages in the old pocket borough; and if he ever went into Parliament (which he might) as a stepping-stone to the Woolsack (like the veteran Lord Chancellor, who found comfortable quarters at Launceston), he'd like to have the fewest number of constituents, and those all of one mind. But the Bookworm would not have it that way, and stuck to his guns that it was the constituency which really had a seat in Parliament, and constituency and member were one and indivisible; and when not, there was failure somewhere in first principles. The Bookworm always takes these things so seriously, Guy says.

Most of the saints came into Cornwall, dropping little bits of fame and reputation as they travelled from parish to parish, and from holy well to holy well. Old Fuller says they were born under a travelling planet, "neither bred where born, nor beneficed where bred, nor buried where beneficed," but wandering ever. Cornwall is known as the "Land of Saints," and county teams are usually "Saints." "The Saints v.[Pg 64] Week-enders. Six goals to three. Five to one on Saints." It sounds a bit curious, but you get used to it.

The true story of the saints is a little mixed; the giants and the piskies come in, and wherever the saints went there was sure to be trouble. We picked up a few stories, not all in one place, but here and there. Those already published we weeded out, together with some which appeared doubtful. Some needed a little patching up in places, and the Bookworm said the most imperfect were the most genuine. The following were thought worthy of survival.

King Tewdrig and the Saints.

Irish saints swarmed as thick as flies in summer in the reign of Tewdrig the King, who built his castle on the sands at Hayle, wherein it now is, only the X-rays are not strong enough to make it visible. This Tewdrig was a good old sort, and was called Theodore by the saints as long as he had anything to give. But the saints letting it be known in the distressful land that they had struck oil, their friends and relatives swarmed across the Channel in such crowds that the King was in danger of being eaten out of house and home. He summoned the Keeper of the Victuals, and asked for a report. He had it; and it was short and sad—as sad in its way as[Pg 65] an army stores inquiry. Every living thing in air and field and wood had been devoured. All the salted meats in the keeves had disappeared, "and if you don't stop this immigration of Irish saints," said the unhappy official, "we shall be eaten up alive." The good King became serious. Whilst they were talking, a messenger came with the news that a great batch of saints had come ashore. The King and his Keeper of the Victuals—when there were any to keep—looked at each other solemnly. "Put the castle in mourning," said the King. When the new arrivals danced up to the gate, with teeth well set for action and stomachs empty, the Keeper of the Victuals spoke sadly. "The good King died," he said, "the moment he heard that more saints had arrived. Those who came first ate all his substance and emptied his keeves, and there was nothing left of him now but bones. The last words of the good King were, 'Give them my bones.'" The Keeper of the Victuals turned, as though to fetch the good King's bones for the saints to feast on; but they one and all departed and spread the story. The King played the game and ordered his own funeral; and when the time came, he got up and looked through a peep-hole to see the procession. "The saints," said he, "have spared my bones, but they will surely come and see the last of me." But he was mistaken. The story that all the keeves were[Pg 66] empty spread, and there wasn't a "saint" left in the land on the morrow. Then the King showed himself to his own people, and a law was passed, intituled "An Act against Alien Saints' Immigration." The country recovered its ancient prosperity, and the Keeper of the Victuals filled the keeves with salted meats, and there were wild birds in the air, and beasts in the field, and the King once more feasted in his own hall.

St. Ia came across the Channel on a cabbage leaf, and the wind and tide carried her gaily to King Tewdrig's shore, but when the Customs asked her what she had to declare, she only held up the cabbage leaf. As she was a princess in her own right, and good-looking for an emigrant, the Customs officers were sad, but showed her a printed paper, rule xli, which stated that "foreigners without luggage, or visible means of subsistence, must not be allowed to land." The saint pointed to the cabbage leaf, and argued that it was "luggage" and "visible means of subsistence," and would have made good her point but for the King's Chancellor, who said that the cabbage leaf, being "pickled," was a manufactured article, and liable to duty under the new fiscal regulations. St. Ia always left her purse at home when she travelled, so she was unable to pay the duty. Once more she committed herself to the mercies of the sea on her cabbage leaf, and was carried to St. Ives, where she landed, and was[Pg 67] made much of. She stayed there for a time, planted her leaf, and was blessed with a wonderful crop of pickled cabbages, the like of which had never before been seen or heard of. But she revenged herself upon King Tewdrig by writing to all the papers, and the saints, who deserted the King when they had almost eaten him up, made a fine how-de-doo, and an "Irish grievance," and the bad name which they gave the King stuck to him. The saints wrote the books in those days, and those who came after repeated what they wrote, until the people believed, and called it "history."

Guy said it was very unconstitutional to lay the fault upon the King, who, it was well known, could do no wrong. It was the duty of the Prime Minister to bear all faults, and it was noticeable that many prime ministers were round-shouldered, so that they might carry faults lightly.

The Battle of St. Breage.

The saints and piskies had a battle-royal at St. Breage. A three-line whip was sent over to Ireland, and as soon as it was known that there was a little fighting to do, and a cracked skull almost certain, for the glory of God, the saints sent up a shout, straightened their blackthorns, and came across the water in whole battalions. The cause was popular. St. Patrick had driven[Pg 68] the snakes into the sea, and why not the saints drive the piskies out of Cornwall? Hooroo! Paddy's blood was up, and he was spoiling for a bit of fun. The saints had the best of it, but so much blood was spilt on both sides that the sand was turned into stone. There is no other such stone in the district, and St. Breage had a block carved into a cross, and set up as a memorial, which may be seen to this day, only it has a hole in it which was made by the Giant Golons, who wore it on his watchchain until the date of his conversion.

"When anything has to be accounted for in this land, put it down to the saints, or the piskies, or Old Artful, and you're sure to be right. Nothing ever took place in the ordinary course of things. A month of Cornwall would be enough to drive a modern scientist stark, staring mad," said Guy.