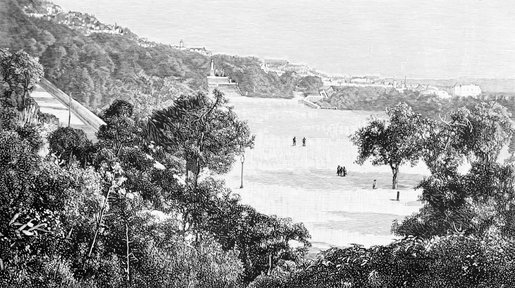

THE ALAMEDA PARADE.

BY

Henry M. Field

ILLUSTRATED

LONDON: CHAPMAN AND HALL, Limited.

1889.

[All rights reserved.]

TROW'S

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY,

NEW YORK.

To My Friend and Neighbor

IN THE BERKSHIRE HILLS,

JOSEPH H. CHOATE,

WHO FINDS IT A RELIEF NOW AND THEN

TO TURN FROM THE HARD LABORS OF THE LAW

TO THE ROMANCE OF TRAVEL:

I SEND AS A CHRISTMAS PRESENT

A STORY OF FORTRESS AND SIEGE

THAT MAY BEGUILE A VACANT HOUR

AS HE SITS BEFORE HIS WINTER EVENING FIRE.

The common tour in Spain does not include Gibraltar. Indeed it is not a part of Spain, for, though connected with the Spanish Peninsula, it belongs to England; and to one who likes to preserve a unity in his memories of a country and people, this modern fortress, with its English garrison, is not "in color" with the old picturesque kingdom of the Goths and Moors. Nor is it on the great lines of travel. It is not touched by any railroad, and by steamers only at intervals of days, so that it has come to be known as a place which it is at once difficult to get to and to get away from. Hence easy-going travellers, who are content to take circular tickets and follow fixed routes, give Gibraltar the go-by, though by so doing they miss a place that is unique in the world—unique in position, in picturesqueness, and in history. That mighty Rock, "standing out of the water and in the water," (as on the day when the old world perished;) is one of the Pillars of Hercules, that once marked the very end of the world; and around its base ancient and modern history flow together, as the waters of the Atlantic mingle with those of the Mediterranean. Like Constantinople, it is throned on two seas and two continents. As Europe at its southeastern corner stands face to face with Asia; at its southwestern it is face to face with Africa: and these were the two points of the Moslem invasion. But here the natural course of history was reversed, as that invasion began in the West. Hundreds of years before the Turk crossed the Bosphorus, the Moor crossed the Straits of Gibraltar. His coming was the signal of an endless war of races and religions, whose lurid flames lighted up the dark background of the stormy coast. The Rock, which was the "storm-centre" of all those clouds of war, is surely worth the attention of the passing traveller. That it has been so long neglected, is the sufficient reason for an attempt to make it better known.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Entering the Straits, | 1 |

| II. | Climbing the Rock, | 12 |

| III. | The Fortifications, | 18 |

| IV. | Round the Town, | 29 |

| V. | Parade on the Alameda, and Presentation of Colors to the South Staffordshire Regiment, | 35 |

| VI. | The Society of Gibraltar, | 48 |

| VII. | A Chapter of History—The Great Siege, | 63 |

| VIII. | Holding a Fortress in a Foreign Country, | 110 |

| IX. | Farewell to Gibraltar—Leaving for Africa, | 128 |

| The Alameda Parade, | Frontispiece. |

| FACING PAGE | |

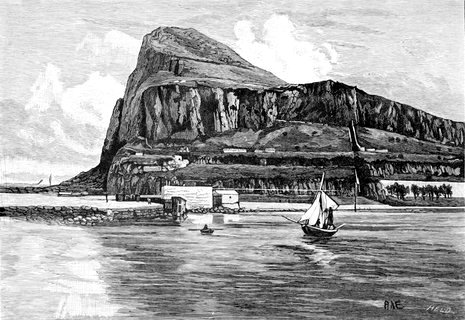

| The Lion Couchant, | 4 |

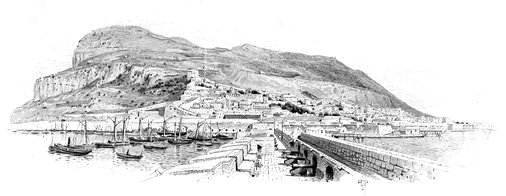

| General View of the Rock, | 12 |

| The Signal Station, | 14 |

| The New Mole and Rosia Bay, | 19 |

| The Saluting Battery, | 27 |

| Walk in the Alameda Gardens, | 62 |

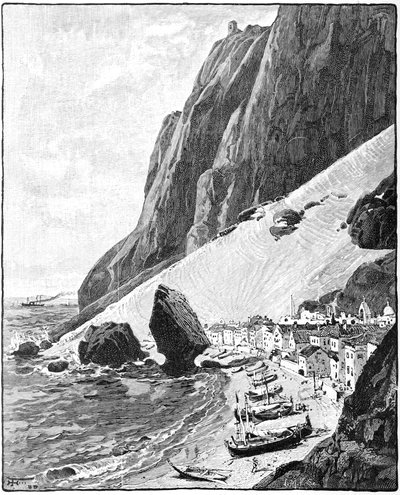

| Catalan Bay, on the East Side of Gibraltar, | 65 |

| Plan of Gibraltar, | 71 |

| "Old Eliott," the Defender of Gibraltar, | 108 |

| Windmill Hill and O'Hara's Tower, | 132 |

| Europa Point, | 143 |

I heard the last gun of the Old Year fired from the top of the Rock, and the first gun of the New. It was the very last day of 1886 that we entered the Straits of Gibraltar. The sea was smooth, the sky was clear, and the atmosphere so warm and bright that it seemed as if winter had changed places with summer, and that in December we were breathing the air of June.

On a day like this, when the sea is calm and still, groups of travellers sit about on the deck, watching the shores on either hand. How near they come to each other, only nine miles dividing the most southern point of Europe from the most northern point of Africa! Perhaps they once came together, forming a mountain chain which separated the sea from the ocean. But since the barrier was burst, the waters have rushed through with resistless power. Looking over the side of the ship, we observe that the current is setting eastward, which would not excite surprise were it not that it never turns back. The Mediterranean is a tideless sea: it does not ebb and flow, but pours its mighty volume ceaselessly in the same direction. This, the geographers tell us, is a provision of nature to supply the waste caused by the greater evaporation at the eastern end of the Great Sea. But this satisfies us only in part, since while this current flows on the surface, there is another, though perhaps a feebler, current flowing in the opposite direction. Down hundreds or fathoms deep, a hidden Gulf Stream is pouring back into the bosom of the ocean. This system of the ocean currents is one of the mysteries which we do not fully understand. It seems as if there were a spirit moving not only upon the waters, but in the waters; as if the great deep were a living organism, of which the ebb and flow were like the circulation of the blood in the human frame. Or shall we say that this upper current represents the Stream of Life, which might seem to be over-full were it not that far down in the depths the excess of Life is relieved by the black waters of Death that are flowing darkly beneath?

Turning from the sea to the shore, on our left is Tarifa, the most southern point of Spain and of Europe—a point far more picturesque than the low, wooded spit of land that forms the most southern point of Asia, which the "globe-trotter" rounds as he comes into the harbor of Singapore, for here the headland that juts into the sea is crowned by a Moorish castle, on the ramparts of which, in the good old times of the Barbary pirates, sentinels kept watch of ships that should attempt to pass the Straits from either direction: for incomers and outgoers alike had to lower their flags, and pay tribute to those who counted themselves the rightful lords of this whole watery realm. I wonder that the Free-Traders do not ring the changes on the fact that the very word tariff is derived from this ancient stronghold, at which the mariners of the Middle Ages paid "duties" to the robbers of the sea. If both sides of the Straits of Gibraltar were to-day, as they once were, under the control of the same Moslem power, we might have two castles—one in Europe and one in Africa—like the "Castles of Europe and Asia," that still guard the Dardanelles, at which all ships of commerce are required to stop and report before they can pass; while ships-of-war carrying too many guns, cannot pass at all without special permission from Constantinople.

But the days of the sea-robbers are ended, and the Mediterranean is free to all the commerce of the world. The Castle of Tarifa is still kept up, and makes a picturesque object on the Spanish coast, but no corsair watches the approach of the distant sail, and no gun checks her speed; every ship—English, French, or Spanish—passes unmolested on her way between these peaceful shores. Instead of the mutual hatred which once existed between the two sides of the Straits, they are in friendly intercourse, and to-day, under these smiling skies, Spain looks love to Barbary, and Barbary to Spain.

While thus turning our eyes landward and seaward, we have been rounding into a bay, and coming in sight of a mighty rock that looms up grandly before us. Although it was but the middle of the afternoon, the winter sun hung low, and striking across the bay outlined against the sky the figure of a lion couchant—a true British lion, not unlike those in Trafalgar Square in London, only that the bronze is changed to stone, and the figure carved out of a mountain! But the lion is there, with his kingly head turned toward Spain, as if in defiance of his former master, every feature bearing the character of leonine majesty and power. That is Gibraltar!

It is a common saying that "some men achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them." The same may be said of places; but here is one to which both descriptions may be applied—that has had greatness thrust upon it by nature, and has achieved it in history. There is not a more picturesque spot in Europe. The Rock is fourteen hundred feet high—more than three times as high as Edinburgh Castle, and not, like that, firm-set upon the solid ground, but rising out of the seas—and girdled with the strongest fortifications in the world. Such greatness has nature thrust upon Gibraltar. And few places have seen more history, as few have been fought over more times than this in the long wars of the Spaniard and the Moor; for here the Moor first set foot in Europe, and gave name to the place (Gibraltar being merely Gebel-el-Tarik, the mountain of Tarik, the Moorish invader), and here departed from it, after a conflict of nearly eight hundred years.

THE LION COUCHANT.

The steamer anchors in the bay, half a mile from shore, and a boat takes us off to the quay, where after being duly registered by the police, we are permitted to pass under the massive arches, and through the heavy gates of the double line of fortifications, and enter Waterport Street, the one and almost only street of Gibraltar, where we find quarters in that most comfortable refuge of the traveller, the Royal Hotel, which, for the period of our stay, is to be our home.

When I stepped on shore I was among strangers: even the friend who had been my companion through Spain had remained in Cadiz, since in coming under the English flag I had no longer need of a Spanish interpreter, and I felt a little lonely; for inside these walls there was not a human being, man or woman, whom I had ever seen before. Yet one who has been knocked about the world as I have been, soon makes himself at home, and in an hour I had found, if not a familiar face, at least a familiar name, which gave me a right to claim acquaintance. Readers whose memories run back thirty years to the laying of the first Atlantic Cable in 1858, may recall the fact that the messages from Newfoundland were signed by an operator who bore the singular name of De Sauty, and when the pulse of the old sea-cord grew faint and fluttering, as if it were muttering incoherent phrases before it drew its last breath, we were accustomed to receive daily messages signed "All right: De Sauty!" which kept up our courage for a time, until we found that "All right" was "All wrong." The circumstance afforded much amusement at the time, and Dr. Holmes wrote one of his wittiest poems about it, in which the refrain of every verse was "All right: De Sauty!" Well, the message was true, at least in one sense, for De Sauty was all right, if the cable was not. The cable died, but the stout-hearted operator lived, and is at this moment the manager of the Eastern Telegraph Company in Gibraltar. This is one of those great English companies, which have their centre in London, and whose "lines have" literally "gone out through all the earth." Its "home field" is the Mediterranean, from which it reaches out long arms down the Red Sea to India and Australia, and indeed to all the Eastern world. Its General Manager is Sir James Anderson, who commanded the Great Eastern when she laid the cable successfully in 1866. I had crossed the ocean with him in '67, and now, wishing to do me a good turn, he had insisted on my taking a letter to all their offices on both sides of the Mediterranean, to transmit my messages free! This was a pretty big license; his letter was almost like one of Paul's epistles "to the twelve tribes scattered abroad, greeting." It contained a sort of general direction to make myself at home in all creation!

With such an introduction I felt at home in the telegraph office in Gibraltar, and especially when I could take by the hand our old friend De Sauty. He has a hearty grip, which speaks for the true Englishman that he is. If any of my countrymen had supposed that he died with the cable, I am happy to say that he not only "still lives," but is very much alive. He at once sent off to London a message to my friends in America—a good-bye for the old year, which brought me the next morning a greeting for the new.

From the telegraph office I took my way to that of the American Consul, who gave me a welcome such as I could find in no other house in Gibraltar, since his is the only American family! When I asked after my countrymen (who, as they are going up and down in the earth, and show themselves everywhere, I took for granted must be here), he answered that there was "not one!" He is not only the official representative of our country, but he and his children the only Americans. This being so, it is a happy circumstance that the Great Republic is so well represented; for a better man than Horatio J. Sprague could not be found in the two hemispheres. He is the oldest Consul in the service, having been forty years at this post, where his father, who was appointed by General Jackson, was Consul before him. He received his appointment from President Polk. Through all these years he has maintained the honor of the American name, and to-day there is not within the walls of Gibraltar a man—soldier or civilian—who is more respected than this solitary representative of our country.

Some may think there is not much need of a Consul where there are no Americans, and yet nearly five hundred ships sailed from this port last year for America: pity that he should have to confess that very few bore the American flag! Thus the post is a responsible one, and at times involves duties the most delicate and difficult, as in the late war, when the Sumter was lying here, with three or four American ships off the harbor (for they were not permitted to remain in port but twenty-four hours) to prevent her escape. At that time the Consul was constantly on the watch, only to see the privateer get off at last by the transparent device of taking out her guns, and being sold to an English owner, who immediately hoisted the English flag, and put to sea in broad daylight in the face of our ships, and made her way to Liverpool, where she was fitted out as a blockade-runner!

Those were trying days for expatriated Americans. However, it was all made up when Peace came, and Peace with Victory—with the Union restored and the country saved. Since then it has been the privilege of the Consul at Gibraltar to welcome many who took part in the great struggle, among them Generals Grant and Sherman and Admiral Farragut. Of course a soldier is always interested in a fortress, for it is in the line of his profession; and the greatest fortification in the world could but be regarded with a curious eye by old soldiers like those who had led our armies for four years; who had conducted great campaigns, with long marches and battles and sieges—battles among the bloodiest of modern times, and one siege (that of Richmond) which lasted as long as the famous siege of Gibraltar.

But perhaps no one felt a keener interest in what he saw here than the old sea-dog, who had bombarded the forts at the mouth of the Mississippi six days and nights; had broken the heavy iron boom stretched across the river; and run his ships past the forts under a tremendous fire; only to find still before him a fleet greater than his own, of twenty armed steamers, four ironclad rams, and a multitude of fire-rafts, all of which he attacked and destroyed, and captured New Orleans, an achievement in naval warfare as great as any ever wrought by Nelson. To Farragut Gibraltar was nothing more than a big ship, whose decks were ramparts. Pretty long decks they were, to be sure, but only furnishing so many more port-holes, and carrying so many more guns, and enabling its commander to fire a more tremendous broadside.

Talking over these things fired my patriotic breast till I began to feel as if I were in "mine ain countrie," and among my American kinsmen. And as I walked from the Consul's back to the Royal Hotel, I did not feel quite so lonely in Gibraltar as I felt an hour before.

As the afternoon wore away, the Spaniards who had come in from the country to market, to buy or sell, began to disappear, and soon went hurrying out, while the belated townsmen came hurrying in. At half-past five the evening gun from the top of the Rock boomed over land and sea, and with a few minutes' grace for the last straggler, the gates of the double line of fortifications were closed for the night, and there was no more going out or coming in till morning. It gave me a little uncomfortable feeling to be thus imprisoned in a fortress, with no possibility of escape. The bustling streets soon subsided into quietness. At half-past nine another gun was the signal for the soldiers to return to their barracks; and soon the town was as tranquil as a New England village. As I stepped out upon the balcony, the stillness seemed almost unnatural. I heard no cry of "All's well" from the sentinel pacing the ramparts, as from sailors on the deck, nor the "Ave Maria santissima" of the Spanish watchman. Not even the howling of a dog broke the stillness of the night. The moon, but in her second quarter, did not shut out the light of stars, which were shining brightly on Rock and Bay. Even the heavy black guns looked peaceful in the soft and tender light. It was the last night of the year—and therefore a holy night, as it was to be marked by a Holy Nativity—the birth of a New Year, a "holy child," as it would come from the hands of God unstained by sin. A little before midnight I fell asleep, from which I started up at the sound of the morning gun. The Old Year was dead! He had been a long time dying, but there is always a shock when the end comes. And yet in that same midnight a new star appeared in the East, bringing fresh hope to the poor old world. Life and death are not divided. The very instant that the old year died, the new year was born; and soon the dawn came "blushing o'er the world," as if such a thing as death were unknown. The bugles sounded the morning call, as they had sounded for the night's repose. Scarcely had we caught the last echoes, that, growing fainter and fainter, seemed to be wailing for the dying year, before a piercing blast announced his successor. The King is dead! Long live the King!

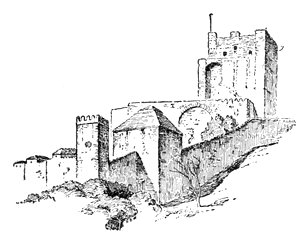

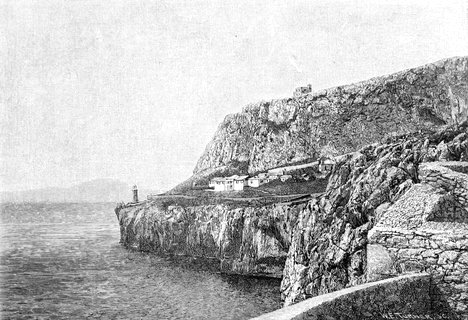

Moorish Castle.

It was a bright New-Year's morning, that first day of 1887, and how could we begin the year better than by climbing to the top of the Rock to get the outlook over land and sea? The ascent is not difficult, for though the Rock is steep as well as high, a zigzag path winds up its side, which to a good pedestrian is only a bracing walk, while a lady can mount a little donkey and be carried to the very top. If you have to go slowly, so much the better, for you will be glad to linger by the way. As you mount higher and higher, the view spreads out wider and wider. Below, the bay is placid as an inland lake, on which ships of war are riding at anchor, "resting on their shadows," while vessels that have brought supplies for the garrison are unlading at the New Mole. Nor is the side of the Rock itself wanting in beauty. Gibraltar is not a barren cliff; its very crags are mantled with vegetation, and wild flowers spring up almost as in Palestine. Those who have made a study of its flora tell us that it has no less than five hundred species of flowering plants and ferns, of which but one-tenth have been brought from abroad; all the rest are native. The sunshine of Africa rests in the clefts of the rocks; in every sheltered spot the vine and fig-tree flourish, and the almond-tree and the myrtle; you inhale the fragrance of the locust and the orange blossoms; while the clematis hangs out its white tassels, and the red geranium lights up the cold gray stone with rich masses of color.

GENERAL VIEW OF THE ROCK.

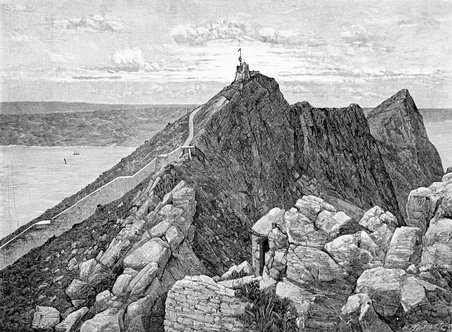

Thus loitering by the way, you come at last to the top of the Rock, where a scene bursts upon you hardly to be found elsewhere in the world, since you are literally pinnacled in air, with a horizon that takes in two seas and two continents. You are standing on the very top of one of the Pillars of Hercules, the ancient Calpe, and in full view of the other, on the African coast, where, above the present town of Ceuta, whose white walls glisten in the sun, rises the ancient Abyla, the Mount of God. These are the two Pillars which to the ancient navigators set bounds to the habitable world.

On this point is the Signal Station, from which a constant watch is kept for ships entering the Straits. There was a tradition that it had been an ancient watch-tower of the Carthaginians, from which (as from Monte Pellegrino, that overlooks the harbor of Palermo) they had watched the Roman ships. But later historians think it played no great part in history or in war until the Rock served as a stepping-stone to the Moors in their invasion and conquest of Spain. When the Spaniards retook it, they gave this peak the name of "El Hacho," The Torch, because here beacon-fires were lighted to give warning in time of danger. A little house furnishes a shelter for the officer on duty, who from its flat roof, with his field-glass, sweeps the whole horizon, north and south, from the Sierra Nevada in Spain, to the long chain of the Atlas Mountains in Africa. Looking down, the Mediterranean is at your feet. There go the ships, with boats from either shore which dip their long lateen-sails as sea-gulls dip their wings, and sometimes fly over the waves as a bird flies through the air, even while large ships labor against the wind. As the current from the Atlantic flows steadily into the Mediterranean, if perchance the wind should blow from the same quarter, it is not an easy matter to get out of the Straits. Ships that have made the whole course of the Mediterranean are baffled here in the throat of the sea. Before the days of steam, mariners were subject to delays of weeks, an experience which was more picturesque than pleasant. Thirty years ago a friend of mine made a voyage from Boston to Smyrna in the Henry Hill, a ship which often took out missionaries to the East, and now had on board a mixed cargo of missionaries and rum! Whether it was a punishment for the latter, on her return she had head winds all the way; but in spite of them was able to make a slow progress by tacking from shore to shore, for which, however, she had less room as she came into the Straits, through which, as through a funnel, both wind and current set at times with such force as in this case detained the Bostonian five weeks! "The captain," says my informant, "was a pretty good-natured man, but as he was a joint-owner of the ship, this long detention was very trying. But to me"—it is a lady who writes—"it was quite the reverse. I found it delightful to tack over to the side of Gibraltar every morning, and drift back every evening to the shores of Africa, with the little excitement from the risk of being boarded by pirates in the night! I never tired of the brilliant sunsets, the gorgeous clouds, with the snow-capped mountains of Granada for a background. But for the captain (even with missionaries on board, who were returning to America) the head winds were too much for his temper, and after vainly striving day after day to get through the Straits, he would take off his cap, scratch his head, and shake his fists at the clouds!

THE SIGNAL STATION.

"After tacking for three weeks off Gibraltar, wearing out our cordage and exhausting our larder, we put into the bay and anchored. Here we were surrounded by vessels from all parts of the world, and were so near the town that we could almost exchange greetings with those on shore. One Sunday the Spaniards had a bull-fight just across the Neutral Ground; but I preferred a quiet New England Sabbath on shipboard.

"After lying at anchor in the bay for two weeks I went on shore one day to lunch with an American lady. Returning to the ship in the evening, I betook myself to my berth. At midnight I heard unusual sounds, clanking of chains, and sailors singing 'Heave ho!' From my port-hole I could see an unusual stir, and dressing in haste went on deck. Sure enough the wind had changed, and all the vessels in the bay were alive with excitement. The captain was radiant. I could see his beaming face, for it was clear and beautiful as moonlight could make it. He invited me to stay on deck, sent for a cup of coffee, and made himself very agreeable. We were soon under way. I was in a kind of ecstasy with the novelty and the beauty of it all. The full moon, the grand scenery, the Pillars of Hercules, solemn in the moonlight, and the added charm of six hundred vessels, from large to small craft, all in full sail, made a rare picture. I sat on deck till morning, and certainly never saw a more beautiful sight than that fleet spreading its wings like a flock of mighty sea-birds, and moving off together from the Mediterranean into the Atlantic."

Such picturesque scenes are not so likely to be witnessed now; for since the introduction of steam the plain and prosaic, but very useful, "tug" tows off the wind-bound bark through the dreaded Straits into the open sea, where she can spread her wings and fly across the wide expanse of the ocean.

To-day, as we look down from the signal station, we see no gathered ships below waiting for a favoring breeze; the wind scarcely ripples the sea, and the boats glide gently whither they will, while here and there a great steamer from England, bound for Naples, or Malta, or India, appears on the horizon, marking its course by the long line of smoke trailing behind it.

To this wonderful combination of land and sea nothing can be added except by the changing light which falls upon it. For the fullest effect you must wait till sunset, when the evening gun has been fired, to signal the departing day, and its heavy boom is dying away in the distance,

"Swinging low with sullen roar."

Then the sky is aflame where the sun has gone down in the Atlantic; and as the last light from the west streams through the Straits, they shine as if they were the very gates of gold that open into a fairer world than ours.

If Gibraltar were merely a rock in the ocean, like the Peak of Teneriffe, its solitary grandeur would excite a feeling of awe, and voyagers up and down the Mediterranean would turn to this Pillar of Hercules as the great feature of the Spanish coast, a "Pillar" poised between sea and sky, with its head in the clouds and its base deep in the mighty waters. But Gibraltar is at the same time the strongest fortress in the world, and the interest of every visitor is to see its defences, in which the natural strength of the position has been multiplied by all the resources of modern warfare.

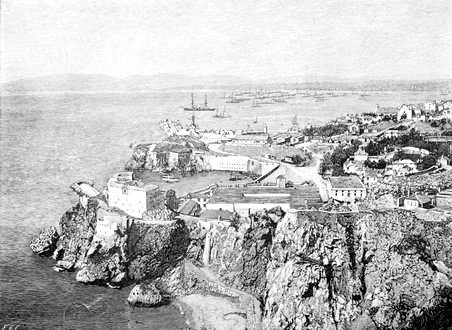

A glance at the map will show what is to be defended. The Rock is nearly three miles long, with a breadth of half to three quarters of a mile, so that the whole circuit is about seven miles. But not all this requires to be defended, for on the eastern side the cliff is so tremendous that there is no possibility of scaling it. It is fearful to stand on the brow and look down to where the waves are dashing more than a thousand feet below. The only approach must be by land from the north, or from the sea on the western side. As the latter lies along the bay, and is at the lowest level, it is the most exposed to attack. Here lies the town, which could easily be approached by an enemy if it were not for its artificial defences. These consist mainly of what is called the Line-Wall, a tremendous mass of masonry two miles long, relieved here and there by projecting bastions, with guns turned right and left, so as to sweep the face of the wall, if an enemy were to attempt to carry it by storm. Indeed the line defended is more than two miles long, if we follow it in its ins and outs; where the New Mole reaches out its long arm into the bay, with a line of guns on either side; followed by a re-entering curve round Rosia Bay, the little basin whose waters are so deep and still, that it is a quiet haven for unlading ships, but where an enemy would find himself in the centre of a circle of fire under which nothing could live; and if we include the batteries still farther southward, that are carried beyond Europa Point, until the last gun is planted under the eastern cliff, which is itself a defence of nature that needs no help from man.

THE NEW MOLE AND ROSIA BAY.

Within the Line-Wall, immediately fronting the bay, are the casemates and barracks for the artillery regiments that are to serve the guns. The casemates are designed to be absolutely bomb-proof, the walls being of such thickness as to resist the impact of shot weighing hundreds of pounds, while the enormous arches overhead are made to withstand the weight and the explosion of the heaviest shells. Such at least was the design of the military engineers who constructed them: though, with the new inventions in war, the monster guns and the new explosives, it is hard to put any limit to man's power of destruction. This Line-Wall is armed with guns of the largest calibre, some of which are mounted on the parapet above, but the greater part are in the casemates below, and therefore nearer the level of the sea, so that they can be fired but a few feet above the water, and thus strike ships in the most vital part.

The latest pets of Gibraltar are a pair of twins—two guns, each of which weighs a hundred tons! These are guarded with great care from the too close inspection of strangers. No description can give a clear impression of their enormous size. In the early history of artillery, the Turks cast some of the largest pieces in the world. Those who have visited the East, may remember the huge cannon-balls of stone, that may still be seen lying under the walls of the Round Towers on the Bosphorus. But those were pebbles compared with shot that can only be lifted to the mouth of the guns by machinery. The bore of these monsters would delight the soul of the Grand Turk, for, (as a man could easily crawl into one of them,) if the barbarous punishment of the old days were still reserved for great offenders, a Pasha who had displeased the Sultan might easily be put in along with the cartridge, and be rammed down and fired off!

The guns had recently been tried, and found to be perfect, though the explosion was not so terrible as had at first been feared. There had been some apprehension that a weapon which was to be so destructive to enemies, might not be an innocent toy to those who fired it; that it might split the ear-drums of the gunners themselves. Some years ago I was at Syra, in the Greek Archipelago, when the English ironclad Devastation was lying in port, which had four thirty-five-ton guns, (the monsters of that day,) and one of her officers said that they "never fired them except at sea, for that the discharge in the harbor would break every window in the town." But here the effect seems not to have been so great. One who was present at the firing of one of the hundred-ton guns, told me that all who stood round expected to be deafened by the concussion. Yet when it came, they turned and looked at each other with a mixture of surprise and disappointment. The sound was not in proportion to the size. Indeed our Consul tells me that some of the sixty-eight pounders are as ear-splitting as the hundred-ton guns. But an English gentleman whom I met at Naples gave me a different report of his experience. He had just come from Malta, where they have a hundred-ton gun mounted on the ramparts. One day, while at dinner in the hotel, they heard a crash, at which all started from their seats, and rushed to the windows to throw them open, lest a second discharge should leave not a pane of glass unbroken. But this came only as they left the harbor. When about three miles at sea, they saw the flash, which was followed by a boom such as they never heard before. It was the most awful thunder rolling over the deep in billows, like waves of the sea, filling the whole horizon with the vast, tremendous sound. It was as "the voice of God upon the waters."

But, of course, with the hundred-ton guns, as with any other, the main question is, not how much noise they make, but what is their power of destruction. Here the experiment was entirely satisfactory. It proved that a hundred-ton gun would throw a ball weighing 2,000 pounds over eight miles![1] With such a range it would reach every part of the bay, and a brace of them, with the hundreds of heavy guns along the Line-Wall, might be relied upon to clear the bay of a hostile fleet, so that Gibraltar could hardly be approached by sea.

But these are not the whole of its defences; they are only the beginning. There are batteries in the rear of the town, as well as in front, that can be fired over the tops of the houses, so that, if an enemy were to effect a landing he would have to fight his way at every step. As you climb the Rock, it fairly bristles with guns. You cannot turn to the right or the left without seeing these open-mouthed monsters, and looking into their murderous throats. Everywhere it is nothing but guns, guns, guns! There are guns over your head and under your feet—

and what is still more, cannon pointed directly at you, till you almost feel as if they were aimed with a purpose, and as if they might suddenly open their mouths, and belch you forth, as the whale did Jonah, though not upon the land, but into the midst of the sea!

But my story is not ended. It is a good rule in description to keep the best to the last. The unique feature of Gibraltar—that in which it surpasses all the other fortresses of Europe, or of the world—is the Rock Galleries, to which I will now lead the way. These were begun more than a hundred years ago, during the Great Siege, which lasted nearly four years, when the inhabitants had no rest day nor night. For, though the French and Spanish besiegers had not rifled guns, nor any of the improved artillery of modern times, yet even with their smooth-bore cannon and mortars they managed to reach every part of the Rock. Bombs and shells were always flying over the town, now bursting in the air, and now falling with terrible destruction. So high did these missiles reach, that even the Rock Gun, on the very pinnacle of Gibraltar, was twice dismounted. Thus pursued to the very eagle's nest of their citadel, and finding no rest above ground, the besieged felt that their only shelter must be in the bowels of the earth, and gangs of convicts were set to work to blast out these long galleries, which we are now to visit.

As it is a two miles' walk through them, we may save our steps by riding as far as the entrance. It is an easy drive up to the Moorish Castle, built by the African invader who crossed the Straits in 711, and finding the south of Spain an easy conquest, resolved to establish himself in the country, and a few years later built this castle on a shoulder of the hill, where it has stood, frowning over land and sea for nearly twelve centuries.

Here we present an order from the Military Secretary, and the officer in charge details a gunner to conduct us through the galleries. The gate is opened, and we plunge in at once, beginning on the lower level. The excavation is just like that of a railway tunnel, except that no arches are required, as it is for the whole distance hewn through the solid rock, which is self-supporting.

But it is not a gloomy cavern that we are to explore, through which we can make our way only by the light of torches, for at every dozen yards there is a large port-hole, by which light is admitted from without, at all of which heavy guns are mounted on carriages, by which they can be swung round to any quarter.

After we have passed through one tier, perhaps a mile in length, we mount to a second, which rises above the other like the upper deck of an enormous line-of-battle ship. Enormous indeed it must be, if we can imagine a double-decker a mile long!

Following the galleries to the very end, we find them enlarged to an open space, called the Hall of St. George, in which Nelson was once fêted by the officers of the garrison. It must have been a proud moment when the defenders of the Great Fortress paid homage to the Conqueror of the sea. As they drank to the health of the hero of the Battle of the Nile, they could hardly have dreamed that a greater victory was yet to come; and still less, that it would be a victory followed by mourning, when all the flags in Gibraltar would be hung at half-mast, as the flagship of Nelson anchored in the bay, with only his body on board, one week after the battle of Trafalgar.

As we tramped past these endless rows of cannon, it occurred to me that their simultaneous discharge must be very trying to the nerves of the artilleryman (if he has any nerves), as the concussion against the walls of rock is much greater than if they were fired in the open air, and I asked my guide if he did not dread it? He confessed that he did; but added, like the plucky soldier that he was: "We've got to stand up to it!"

These galleries are all on the northern side of the Rock, which, as it is very precipitous, hardly needs such a defence. But it is the side which looks toward Spain, and is intended to command any advance against the fortress from the land. Keeping in mind the general shape of the Rock as that of a lion, this is the Lion's head, and as I looked up at it afterward from the Neutral Ground, I could but imagine these open port-holes, with the savage-looking guns peering out of them, to be the lion's teeth, and thought what terror would be thrown into a camp of besiegers if the monster should once open those ponderous jaws and shake the hills with his tremendous roar.

It is not often that this roar is heard; but there is one day in the year when it culminates, when the British Lion roars the loudest. It is the Queen's birthday, when the Rock Gun, mounted on the highest point of the Rock, 1,400 feet in air, gives the signal; which is immediately caught up by the galleries below, one after the other; and the batteries along the sea answer to those from the mountain side, until the mighty reverberations not only sweep round the bay, but across the Mediterranean, and far along the African shores. Nothing like this is seen or heard in any other part of the world. The only parallel to it is in the magnificent phenomena of nature, as in a storm in the Alps, when

This is magnificent: and yet I trust my military friends will not despise my sober tastes if I confess that this "roar," if kept up for any length of time, would greatly disturb the meditations of a quiet traveller like myself. Indeed it would be a serious objection to living in Gibraltar that I should be compelled to endure the cannonading, which, at certain times of the year, makes the rocks echo with a deafening sound. I hate noise, and especially the noise of sharp explosions. I have always been of Falstaff's opinion, that

"But for those vile guns I would be a soldier."

But here the "vile guns" are everywhere, and though they may be quiet for a time, it is only to break out afterward and make themselves heard in a way that cannot but be understood.

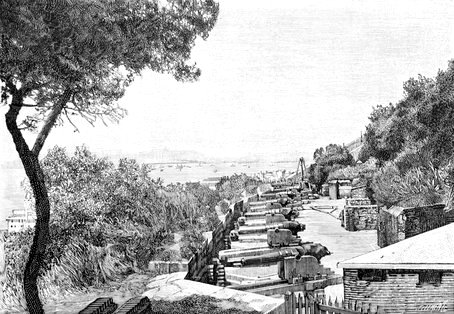

THE SALUTING BATTERY.

As I have happened on an interval of rest, I have been surprised at the quietness of Gibraltar. In all the time of my stay I have not heard a single gun, except at sunrise and sunset, and at half-past nine o'clock for the soldiers to return to their barracks. There has not been even a salute, for, although there is on the Alameda a saluting battery, composed of Russian guns taken in the Crimean War, yet it is less often used than might be supposed, for the ships of war that come here are for the most part English (the French and Spaniards would hardly find the associations agreeable), and these are not saluted since they are at home, as much as if they were entering Portsmouth.

For these reasons I have found Gibraltar so quiet that I was beginning to think it a dull old Spanish town, fit for a retreat, if not for monks, at least for travellers and scholars, when the Colonial Secretary dispelled the illusion by saying, "Yes, it is very quiet just now; but wait a few weeks and you will have enough of it." As the spring comes on, the artillerymen begin their practice. The guns in the galleries are not used, but all the batteries along the sea, and at different points on the side of the Rock, some of which are mounted with the heaviest modern artillery, are let loose upon the town.

But this is not done without due notice. The order is published in the Chronicle, a little sheet which appears every morning, and lest it might not reach the eyes of all, messengers are sent to every house to give due warning, so that nervous people can get out of the way; but the inhabitants generally, being used to it, take no other precaution than to open their windows, which might otherwise be broken by the violence of the concussion. Lord Gifford, soldier as he is, said, "It is awful," pointing to the ceiling over his head, which had been cracked in many places so as to be in danger of falling, by the tremendous jar. He told me how one house had been so knocked to pieces that a piece of timber had fallen, nearly killing an officer. This is an enlivening experience, of which I should be sorry to deprive those who like it. But as some of us prefer to live in "the still air of delightful studies," I must say that I enjoy these explosions best at a distance, as even in an Alpine storm I would not have the lightning flashing in my very eyes, but rather lighting up the whole blackened sky, and the mighty thunder rolling afar off in the mountains.

Accustomed as we are to think of Gibraltar as a Fortress, we may forget that it is anything else. But it is an old Spanish town, quaint and picturesque as Spanish towns are apt to be, with twenty thousand inhabitants, in which the Spanish element, though subject to another and more powerful element, gives a distinct flavor to the place. Indeed, the mingling of the Spanish with the English, or the appearance of the two side by side, without mingling, furnishes a lively contrast, which is one of the most piquant features of this very miscellaneous and picturesque population.

Of course, in a garrison town the military element is first and foremost. As there are always five or six thousand troops in Gibraltar, it is perhaps the largest garrison in the British dominions, unless the troops in and around London be reckoned as a garrison. But that is rather an army, of which only a small part is in London itself, where a few picked regiments are kept as Household Troops, not only to insure the personal safety of the sovereign, but to keep up the state and dignity of the court; while other regiments are distributed in barracks within easy call in case of need, not for defence against foreign enemies so much as to preserve internal order; to put down riot and insurrection; and thus guard what is not only the capital of Great Britain, but the commercial centre of the world.

Very different from this is a garrison town, where a large body of troops is shut up within the walls of a fortress. Here the military element is so absorbing and controlling, that it dominates the whole life of the place. Everything goes by military rule; even the hours of the day are announced by "gun-fire;" the morning gun gives the exact minute at which the soldiers are to turn out of their beds, and the last evening gun the minute at which they are to "turn in," signals which, though for the soldiers only, the working population of the town find it convenient to adopt; and which outsiders must regard, since at these hours the gates are opened and shut; so that a large part of the non-military part of the population have to "keep step," almost as much as if they were marching in the ranks, since their rising up and their lying down, their goings out and their comings in, are all regulated by the fire of the gun or the blast of the bugle.

The presence of so large a body of troops in Gibraltar gives a constant animation to its streets, which are alive with red-coats and blue-coats, the latter being the uniform of the artillery. This is a great entertainment to an American, to whom such sights in his own country are rare and strange. A few years ago we had enough of them when we had a million of men in arms, and the land was filled with the sound of war. But since the blessed days of peace have come we seldom see a soldier, so that the parades in foreign capitals have all the charm of novelty. In fondness for these I am as much "a boy" as the youngest of my countrymen. Almost every hour a company passes up the street, and never do I hear the "tramp, tramp," keeping time to the fife and drum, that I do not rush to the balcony to see the sight, and hear the sounds which stir even my peaceful breast.

There is nothing that stirs me quite so much as the bugle. Twice a day it startles us with its piercing blast, as it follows instantly the gun-fire at sunrise and sunset. But this does not thrill me as when I hear it blown on some far-off height, and dying away in a valley below, or answered back from a yet more distant point, like a mountain echo. One morning I was taking a walk to Europa Point, and as the path leads upward I came upon several squads of buglers (I counted a dozen men in one of them) practising their "calls." They were stationed at different points on the side of the Rock, so that when one company had given the signal, it was repeated by another from a distance, bugle answering to bugle, precisely like the echoes in the Alps, to which every traveller stops to listen. So here I stopped to listen till the last note had died away in the murmuring sea; and then, as I went on over the hill, kept repeating, as if it were a spell to call them back again:

As the English are masters of Gibraltar, I am glad to see that they bring their English ideas and English customs with them. Nothing shows the thoroughly English character of the place more than the perfect quiet of the day of rest. Religious worship seems to be a part of the military discipline. On Sunday morning I heard the familiar sound of music, followed by the soldiers' tramp, and stepping to the balcony again, found a regiment on the march, not to parade but to church. Gibraltar has the honor of being the seat of an English bishop, because of which its modest church bears the stately name of a Cathedral; and here may be seen on a Sunday morning nearly all the officials of the place, from the Governor down; with the officers of the garrison: and probably the soldiers generally follow the example of their officers in attending the service of the Church of England. But they are not compelled to this against their own preferences. The Irish can go to mass, and the Scotch to their simpler worship. In all the churches there is a large display of uniforms, nor could the preachers address more orderly or more attentive listeners. The pastor of the Scotch church tells me that he is made happy when a Scotch regiment is ordered to Gibraltar, for then he is sure of a large array of stalwart Cameronians, among whom are always some who have the "gift of prayer," and know how to sing the "Psaumes of Dawvid." These brave Scots go through with their religious exercises almost with the stride of grenadiers, for they are in dead earnest in whatever they undertake, whether it be praying or fighting; and these are the men on whom a great commander would rely to lead a forlorn hope into the deadly breach; or, as an English writer has said, "to march first and foremost if a city is to be taken by storm!"

Besides the garrison, and the English or Spanish residents of Gibraltar, the town has a floating population as motley in race and color as can be found in any city on the Mediterranean. Indeed it is one of the most cosmopolitan places in the world. It is a great resort of political refugees, who seek protection under the English flag. As it is so close to Spain, it is the first refuge of Spanish conspirators, who, failing in their attempts at revolution, flee across the lines. Misery makes strange bedfellows. It must be strange indeed for those to meet here who in their own land have conspired with, or it may be against, each other.

Apart from these, there is a singular mixture of characters and countries, of races and religions. Here Spaniards and Moors, who fought for Gibraltar a thousand years ago, are at peace and good friends, at least so far as to be willing to cheat each other as readily as if they were of the same religion. Here are long-bearded Jews in their gabardines; and Turks with their baggy trousers, taking up more space than is allowed to Christian legs; with a mongrel race from the Eastern part of the Mediterranean, known as Levantines; and another like unto them, the Maltese; and a choice variety of natives of Gibraltar, called "Rock scorpions," with Africans blacker than Moors, who have perhaps crossed the desert, and hail from Timbuctoo. All these make a Babel of races and languages, as they jostle each other in these narrow and crowded streets, and bargain with each other, and, I am afraid, sometimes swear at each other, in all the languages of the East.

Here is a field for the young American artists, who after making their sketches in Florence and Rome and Naples, sometimes come to Spain, but seldom take the trouble to come as far as the Pillars of Hercules. As an old traveller, let me assure them that an artist in search of the picturesque, or of what is curious in the study of strange peoples, may find in Gibraltar, with its neighbor Tangier, (but three hours' sail across the Straits) subjects for his pencil as rich in feature, in color, and in costume, as he can find in the bazaars of Cairo or Constantinople.

The garrison of Gibraltar, in time of peace, numbers five or six thousand men, made up chiefly of regiments brought home from foreign service, that are stationed here for a few months, or it may be a year or two, not merely to perform garrison duty, but as a place of rest to recover strength for fresh campaigns, from which they can be ordered to any part of the Mediterranean or to India. While here they are kept under constant drill, yet not in such bodies as to make a grand military display, for there is no parade ground large enough for the purpose. Gibraltar has no Champ de Mars on which all the regiments can be brought into the field, and go through with the evolutions of an army. If the whole garrison is to be put under arms, it must be marched out of the gates to the North Front, adjoining the Neutral Ground, that it may have room for its military manœuvres. When our countryman General Crawford, who commanded the Pennsylvania Reserves at the Battle of Gettysburg, was here a few years since, the Governor, Sir Fenwick Williams, gave him a review of four thousand men. But that was a mark of respect to a distinguished military visitor, and presented a sight rarely witnessed by the ordinary traveller. It was therefore a piece of good fortune to have an opportunity to see, though on a smaller scale, the splendid bearing of the trained soldiers of the British Army. One morning our Consul (always thoughtful of what might contribute to my pleasure) sent me word that there was to be a parade of one of the regiments of the garrison for the purpose of receiving new colors from the hands of the Governor. Hastening to the Alameda, (which is the only open space within the walls at once large enough and level enough even for a single regiment,) I found it already in position, the long scarlet lines forming three sides of a hollow square. Joining a group of spectators on the side that was open, we waited the arrival of the Governor, an interval well employed in some inquiries as to the corps that was to receive the honors of the day.

"What did you tell me was the name of this Regiment?" "The South Staffordshire!" But that is merely the name of a county in England, which conveys no meaning to an American. And yet the name caught my ear as one that I had heard before. "Was not this one of the Regiments that served lately in the Soudan?" It was indeed the same, and I at once knew more of it than I had supposed. As I had been twice in Egypt, I was greatly interested in the expedition up the Nile for the relief of Khartoum and the rescue of General Gordon, and had followed its progress in the English papers, where, along with the Black Watch and other famous troops, I had seen frequent mention of the South Staffordshire Regiment. As the expedition was for months the leading feature of the London illustrated papers, they were filled with pictures of the troops, engaged in every kind of service, sometimes looking more like sailors than soldiers, from which, however, they were ready, at the first alarm, to fall into ranks and march to battle. Many of the comrades who sailed from England with them left their bones on the banks of the Nile.

With this recent history in mind, I could not look in the faces of the brave men who had made all these marches, and endured these fatigues, and fought these battles, without my heart beating fast. It beat faster still when I learned that the campaign in Egypt was only the last of a long series of campaigns, reaching over not only many years, but almost two centuries! The history of this regiment is worth the telling, if it were only to show of what stuff the British Army is made, and how the traditions of a particular corps, passing down from sire to son, remain its perpetual glory and inspiration.

The South Staffordshire Regiment is one of the oldest in the English Army, having been organized in the reign of Queen Anne, when the great Marlborough led her troops to foreign wars. But it does not appear to have fought under Marlborough, having been early transferred to the Western Hemisphere. After four years' service at home it was sent to the West Indies, where it remained nearly sixty years, its losses by death being made good by fresh recruits from England, so that its organization was kept intact. Returning home in 1765, it was stationed in Ireland till the cloud began to darken over the American Colonies, when it was one of the first corps despatched across the Atlantic. As an American, I could not but feel the respect due to a brave enemy on learning that this very regiment that I saw before me had fought at Bunker Hill! From Boston it was ordered to New York, where it remained till the close of the war. No doubt it often paraded on the Battery, as to-day it parades on the Alameda. After the war it was stationed several years in Nova Scotia.

From that time it has had a full century of glory, serving now in the West Indies, and now at the Cape of Good Hope, and then coming back across the Atlantic to the River Plate in South America, where it distinguished itself at the storming and capture of Monte Video, and afterward fought at Buenos Ayres. But the "storm centre" in the opening nineteenth century was to be, not in America, North or South, nor in Africa, but in Europe, in the wars of Napoleon. This regiment was with Sir John Moore when he fell at Corunna, and afterward followed the Iron Duke through Spain, fighting in the great battle of Salamanca, and later with Sir Thomas Graham at Vittoria, and in the siege and storming of San Sebastian. It was part of the army that crossed the Bidassoa, and made the campaign of 1813-14 in the South of France. After the fall of Napoleon it returned home, but on his return from Elba was immediately ordered back to the Continent, and arrived at Ostend, too late to take part in the Battle of Waterloo, but joined the army and marched with it to Paris.

When the great disturber of the peace of the Continent was sent to St. Helena, Europe had a long rest from war; but there was trouble in other parts of the world, and in 1819 the regiment was again at the Cape of Good Hope, fighting the Kaffirs; from which it went to India, and thence to Burmah, where it served in the war of 1824-26. This is the war which has been made familiar to American readers in the Life of the Missionary Judson, who was thrown into prison at Ava, (as the King made no distinction between Englishmen and Americans), confined in a dungeon, and chained to the vilest malefactors, in constant danger of death, till the advance of the British army up the Irrawaddi threw the tyrant into a panic of terror, when he sent for his prisoner to go to the British camp and make terms with the conquerors. England made peace, but the regiment was half destroyed, having lost in Burmah eleven officers and five hundred men.

The ten years of peace that followed were spent in Bengal. When at last the regiment was called home, it was stationed for a few years in the Ionian Islands, in Jamaica, Honduras, and Nova Scotia. Then came the Russian War, when it was sent to Turkey, and fought at the Alma and Inkerman, and through the long siege of Sebastopol. Only a single year of peace followed, and it was again ordered to India, where the outbreak of the mutiny threatened the loss of the Indian Empire, and by forced marches reached Cawnpore in time to defeat the Sepoy army; from which it marched to Lucknow, where it was part of the fiery host that stormed the Kaiser-Bagh, where it suffered fearful loss, but the siege was raised and Lucknow delivered; after which, in a campaign in Oude, it helped to stamp out the mutiny.

Its last campaign was in Egypt, where it went up the Nile as a part of the River Column, hauling its boats over the cataracts, and was the first regiment that reached Korti. From this point it kept along the course of the river toward Berber (while another column, mounted on camels, made the march across the desert), and with the Black Watch bore the brunt of the fighting in the battle of Kirbekan, in which the commander of the column and the colonel of the regiment both fell.[2]

Such is the story of a hundred and fifty years. Of the hundred and eighty-four years that the Regiment has been in existence, it has spent a hundred and thirty-four—all but fifty—in foreign service, in which it has fought in thirty-eight battles, and has left the bones of its dead in every quarter of the globe. Was there ever a Roman legion that could show a longer record of war and of glory?

And now this British legion, with a history antedating the possession of Gibraltar itself, (for it was organized in 1702, two years before the Rock was captured from Spain,) had been brought back to this historic ground, bringing with it its old battle-flags, that had floated on so many fields, which, worn by time and torn by shot and shell, it was now to surrender, to be taken back to England and hung in the oldest church in Staffordshire as the proud memorials of its glory, while it was to receive new colors, to be borne in future wars. The rents in its ranks had been filled by new recruits, so that it stood full a thousand strong, its burnished arms glistening as if those who bore them had never been in the heat of battle. In the hollow square in which it was drawn up were its mounted officers, waiting the arrival of the Governor, who presently rode upon the ground, with Major-General Walker, the Commander of the Infantry Brigade, at his side; followed by other officers, who took position in the rear, according to their rank. The band struck up "God save the Queen," and the troops, wheeling into column, began the "march past," moving with such firm and even tread that it seemed as if the regiment had but one body and one soul. After a series of evolutions it was again formed in a square, for a ceremony that was half military and half religious, for in such pageants the Church of England always lends its presence to the scene. I had read of military mass in the Russian army, when the troops drawn up in battle array, fall upon their knees, while the Czar, prostrating himself, prays apparently with the utmost devotion for the blessing of Almighty God upon the Russian arms! Something of the same effect was produced here, when the Bishop of Gibraltar in his robes came forward with his assistant clergy. At once the band ceased; the troops stood silent and reverent. The silence was first broken by the singing of a Hymn, whose rugged verse had a strange effect, as given by the Regimental Choir. I leave to my readers to imagine the power of these martial lines sung by those stentorian voices:

When this song of battle died away, the voice of the Bishop was heard in a prayer prepared for the occasion. Some may criticise it as implying that the God of Battles must always be on the side of England. But such is the character of all prayers offered in time of war. Making this allowance, it seems as if the feeling of the hour could not be more devoutly expressed than in the following:

Almighty and most merciful Father, without whom nothing is strong, nothing is holy, we come before Thee with a deep sense of Thine exceeding Majesty and our own unworthiness, praying Thee to shed upon us the light of Thy countenance, and to hallow and sanctify the work in which we are this day engaged.

We beseech Thee to forward with Thy blessing, the presentation to this Regiment of the Colors which are henceforth to be carried in its ranks; and with all lowliness and humility of spirit, we presume to consecrate the same in Thy great name, to the cause of peace and happiness, truth and justice, religion and piety. We humbly pray that the time may come when the sound of War shall cease to be heard in the world; but forasmuch as to our mortal vision that blessed consummation seems still far distant, we beseech Thee so to order the course of events that these colors shall be unfurled in the face of an enemy only for a righteous cause. And in that dark hour may stain and disgrace fall upon them never; but being borne aloft as emblems of loyalty and truth, may the brave who gather round them go forward conquering for the right, and maintaining, as becomes them, the honor of the British Crown, the purity of our most holy faith, the majesty of our laws, and the influence of our free and happy constitution. Finally, we pray that Thy servants here present, not forgetful of Thine exceeding mercies vouchsafed to their regiment in times gone by, and that all the forces of our Sovereign Lady the Queen, wherever stationed and however employed, may labor through Thy grace to maintain a conscience void of offence towards Thee and towards man, always remembering that of soldier and of civilian the same account shall be taken, and that he is best prepared to do his duty, and to meet death, let it come in what form it may, who in the integrity of a pure heart is able to look to Thee as a God reconciled to him through the blood of the Atonement. Grant this, O Lord, for Thine only Son Jesus Christ's sake! Amen.

Then followed the usual prayer for the Queen:

O Lord, our Heavenly Father, high and mighty, King of kings, Lord of lords, the only Ruler of princes, who dost from Thy throne behold all the dwellers upon earth, most heartily we beseech Thee with Thy favor to behold our most gracious Sovereign Lady Queen Victoria, and so replenish her with the grace of Thy Holy Spirit that she may always incline to Thy will and walk in Thy way; endue her plenteously with heavenly gifts; grant her in health and wealth long to live; strengthen her that she may vanquish and overcome all her enemies; and finally, after this life, she may attain everlasting joy and felicity, through Jesus Christ our Lord! Amen.

The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the fellowship of the Holy Ghost, be with us all evermore! Amen.

The service ended, the Governor, dismounting from his horse, took the place of the Bishop in a service which had a sacred as well as patriotic character. Two officers, the youngest of the Regiment, advancing, surrendered the old flags, which had been carried for so many years and through so many wars, and then each bending on one knee, received from his hands the new colors which were to have a like glorious history. As they rose from their knees, the Governor remounted his horse, and from the saddle delivered an address as full of patriotic sentiment, of loyalty to the Queen and country, and as spirit-stirring to the brave men before him, as if they were to be summoned to immediate battle. With that he turned and galloped off the ground, while the Regiment unfurling its new standards, with drums beating and band playing, marched proudly away.

As it wound up the height, the long scarlet line had a most picturesque effect. It has been objected to these brilliant uniforms that they make the soldiers too conspicuous a mark for the sharpshooters of the enemy. But, however it may be in war, nothing can be finer on parade. Our modern architects and decorators, who attach so much importance to color, and insist that everything, from cottage to castle, should be "picked out in red," would have been in ecstasies at the colors which that day gleamed among the rocks and trees of Gibraltar.

Indeed, if you should happen to be sauntering on the Alameda just at evening, as the sunset-gun is fired, and should look upward to see the smoke curling away, you might see above it a gathering of black clouds—the sure sign of the coming of the terrible East wind known as the "Levanter"; and if at the same moment the afterglow of the dying day should touch a group of soldiers standing on the mountain's crest (where colors could be clearly distinguished even if figures were confused), it might seem as if that last gleam under the shadow of the clouds were itself the red cross of England soaring against a dark and stormy sky.

This was the brilliant side of war: pity that there should be another side! But the next day, walking near the barracks, I met a company with reversed arms bearing the body of a comrade to the grave. There was no funeral pomp, no waving plumes nor roll of muffled drums: for it was only a common soldier, who might have fallen on any field, and be buried where he fell, with not a stone to mark his resting-place. But for all that, he may have been a true hero; for it is such as he, the unknown brave, who have fought all the battles and gained all the victories of the world.

Turning from this scene, I thought how hard was the fate of the English soldier: to be an exile from the land of his birth, "a man without a country"; who may be ordered to any part of the world (for such is the stern necessity, if men are to defend "an Empire on which the sun never sets"); serving in many lands, yet with a home in none; to sleep at last in a nameless grave! Such has been the fate of many of that gallant regiment which I saw marching so proudly yesterday. Their next campaign may be in Central Asia, fighting the Russians in Afghanistan, amid the snows of the Himalayas. If so, I fear it may be said of them with sad, prophetic truth, as they go into battle:

The best thing that I find in any place is the men that are in it. Strong walls and high towers are grand, but after a while they oppress me by their very massiveness, unless animated by a living presence. Even the great guns, those huge monsters that frown over the ramparts, would lose their majesty and terror, if there were not brave men behind them. And so, after I had surveyed Gibraltar from every point of land and sea; after I had been round about it, and marked well its towers and its bulwarks; to complete the enjoyment I had but one wish—to sit down in some quiet nook and talk it all over.

There is no man in the world whom I respect more than an old soldier. He is the embodiment of courage and of all manly qualities, and he has given his life to his country. And if he bears in his person the scars of honorable wounds, I look up to him with a feeling of veneration. Of such characters no place has more than Gibraltar, which perhaps may be considered the centre of the military life of England. True, the movements of the Army are directed by orders from the Horse Guards in London. But here the military feature is the predominant, if not the exclusive, one; while in London a few thousand troops would be lost in a city of five millions of inhabitants. Here the outward and visible sign is ever before you: regiments whose names are historical, are always coming and going; and if you are interested in the history of modern wars, (as who can fail to be, since it is a part of the history of our times?) you may not only read about them in the Garrison Library, but see the very men that have fought in them. Here is a column coming up the street! I look at its colors, and read the name of a regiment already familiar through the English papers; that has shown the national pluck and endurance in penetrating an African forest or an Indian jungle, or in climbing the Khyber Pass in the Himalayas to settle accounts with the Emir of Cabul. There must be strange meetings of old comrades here, as well as new companionships formed between those who have fought under the same royal standard, though in different parts of the world. A regiment recalled from Halifax is quartered near another just returned from Natal or the Cape of Good Hope; while troops from Hong Kong, or that have been up the Irrawaddi to take part in the late war in Upper Burmah, can exchange experiences with their brother soldiers from the other side of the globe. Almost all the regiments collected here have figured in distant campaigns, and the officers that ride at their head are the very ones that led them to victory. To a heart that is not so dead but that it can still be stirred by deeds of daring, there is nothing more thrilling than to sit under the guns of the greatest fortress in the world, and listen to the story as it comes from the lips of those who were actors in the scenes.

But it would be a mistake to suppose that the society of Gibraltar is confined to men. The home instincts are strong in English breasts; and wherever they go they carry their household gods with them. In my wanderings about the world, it has been my fortune to visit portions of the British Empire ten thousand miles away from the mother country; yet in every community there was an English stamp, a family likeness to the old island home. Hence it is that in the most remote colony there are the elements of a good society. Whatever country the English may enter, even if it be in the Antipodes, as soon as they have taken root and become established they send back to England for their wives and daughters, that they may renew the happy life that they have lived before, so that the traveller who penetrates the interior of Australia, of New Zealand, or Van Dieman's Land, is surprised to find, even "in the bush," the refinement of an English home.

This instinct is not lost, even when they are in camps or barracks. If you visit a "cantonment" in Upper India, you will find the officers with their families about them. The brave-hearted English women "follow the drum" to the ends of the earth; and I have sometimes thought that their husbands and brothers owed part of their indomitable resolution to the inspiration of their wives and sisters.

It is this feature of garrison life, this union of "fair women and brave men," which gives such a charm to the society of Gibraltar—a union which is more complete here than in most garrison towns, because the troops stay longer, and there is more opportunity for that home-life which strangers would hardly believe to exist. Most travellers see nothing of it. Indeed it is probable that they hardly think of Gibraltar as having any home-life, since its population is always on the come and go; living here only as in a camp, and to-morrow

This is partly true. Soldiers of course are subject to orders, and the necessities of war may cause them to be embarked at an hour's notice. But in time of peace they may remain longer undisturbed. Regiments which have done hard service in India are sometimes left here to recruit even for years, which gives their officers opportunity to bring their families, whose presence makes Gibraltar seem like a part of England itself, as if it were no farther away than the Isle of Wight. This it is which makes life here quite other than being imprisoned in a fortress. I may perhaps give some glimpses of these interiors (without publicity to what is private and sacred), which I depict simply that I may do justice to a place to which I came as a stranger, and from which I depart as a friend.

Just before I left America, I was present at a breakfast given to M. de Lesseps on his visit to America to attend the inauguration of Bartholdi's Statue of Liberty. As I sat opposite the "grand Français," I turned the conversation to Spain, to which I was going, and where I knew that he had spent many years. He took up the subject with all his natural fire, and spoke of the country and the people in a way to add to my enthusiasm. Next to him sat Chief Justice Daly, who kindled at the mention of Spain, and almost "raved" (if a learned Judge ever "raves") about Spanish cathedrals. He had continued his journey to the Pillars of Hercules, and said that "in all his travels he had never spent a month with more pleasure than in Gibraltar." He had come with letters to the Governor, Lord Napier of Magdala, which at once opened all doors to him. Wishing to smooth my path in the same way, the English Minister at Madrid, who had shown me so much courtesy there, gave me a letter to the Colonial Secretary, Lord Gilford, who received me with the greatest kindness, and took me in at once to the Governor, who was equally cordial in his welcome.

The position of Governor of Gibraltar is one of such distinction as to be greatly coveted by officers in the English army. It is always bestowed on one of high rank, and generally on some old soldier who has distinguished himself in the field. Among the late Governors was Sir Fenwick Williams, who, with only a garrison of Turks, under the command of four or five English officers, defended Kars, the capital of Armenia, in 1855, repelling an assault by the Russians when they endeavored to take it by storm, and yielding at last only to famine; and Lord Napier of Magdala, who, born in Ceylon, spent the earlier part of his military life in India, where he fought in the Great Mutiny, and distinguished himself at Lucknow. Ten years later he led an English army (though composed largely of Indian troops, with the Oriental accompaniment of guns and baggage-trains carried on the backs of camels and elephants) into Abyssinia, and took the capital in an assault in which King John was slain, and the missionaries and others, whom he had long held as prisoners and captives, were rescued. He was afterward commander-in-chief of the forces in India, and, when he retired from that, no position was thought more worthy of his rank and services than that of Governor of Gibraltar, a fit termination to his long and honored career.

The present Governor is a worthy successor to this line of distinguished men. Sir Arthur Hardinge is the son of Lord Hardinge, who commanded the army in India a generation ago. Brought up as it were in a camp, he was bred as a soldier, and when little more than a boy accompanied his father to the wars, serving as aide-de-camp through the Sutlej campaign in 1845-46, and was in the thick of the fight in some hard-fought battles, in one of which, at Ferozeshah, he had a horse shot under him. When the Crimean War broke out he was ordered to the field, and served in the campaign of 1854-55, being at the Alma and at Inkerman, and remaining to the close of the siege of Sebastopol. Here he had rapid promotion, besides receiving numerous decorations from the Turkish Government, and being made Knight of the Legion of Honor. Returning to England, he seems to have been a favorite at court and at the Horse Guards, being made Knight Commander of the Bath, honorary Colonel of the King's Royal Rifle Corps, and Extra Equerry to the Queen, his honors culminating in his present high position of Governor and Commander-in-chief of Gibraltar.

The politeness of the Governor did not end with his first welcome: it was followed by an invitation to his New Year's Reception. It was but a few weeks since he had taken office; and, wishing to do a courtesy to the citizens of Gibraltar as well as to the officers of the garrison, both were included in the invitation. The Government House was the one place where all—soldiers and civilians—could meet on common ground, and form the acquaintance, and cultivate the friendly feeling, so important to the happiness of a community shut up within the limits of a fortress. Although I was a stranger, the Consul desired me to attend, as it would give me the opportunity to see in a familiar way the leading men of Gibraltar, civil and military, and further, as, owing to the recent death of his son, he could not be present nor any of his family, so that I should be the only representative of our country.

It was indeed a notable occasion. The Government House is an old Convent, which still retains its ancient and venerable look, though the flag floating over it, and the sentry marching up and down before the door, tell that it is now the seat of English power. To-night it took on its most festive appearance, entrance and stairway being hung with flags, embowered in palms, and wreathed with vines and ferns and flowers; and when the officers appeared in their uniforms, and the military band filled the place with stirring music, it was a brilliant scene.

The gathering was in a large hall, part of which was turned to a purpose which to some must have seemed strangely incongruous with the sacred associations of the place: for in the old Spanish days this was a Convent of the Franciscan Friars, who, if they ever revisit the place of their former habitation, must have been shocked to find their chapel turned into a place for music and dancing, and to hear the "sound of revelry by night," where they were wont to say midnight mass, and to offer prayers for the quick and dead!

While this was going on in one part of the hall, at the other end the Governor sat on a dais, quietly enjoying the meeting of old friends and the making of new ones. It was my good fortune to be one of the group, which gave me the best possible opportunity to see the society of Gibraltar: for here it was all gathered under one roof. Of course it was chiefly military. There was a brilliant array of officers—generals, colonels, and majors; while in still larger number were captains and lieutenants, in their gay uniforms, who, if they did not exactly realize my idea of

"Whiskered Pandours and fierce Hussars,"