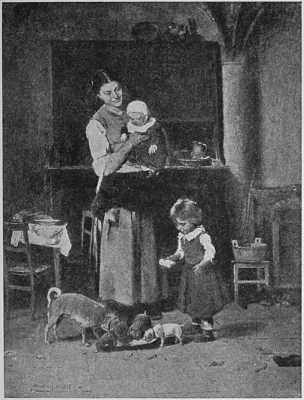

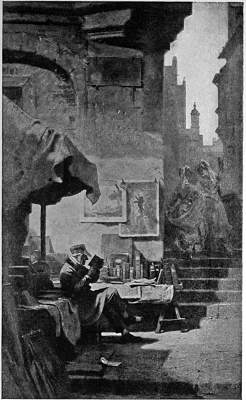

From the Painting by Jacob Alberts

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The German Classics of the Nineteenth and

Twentieth Centuries, Volume 11, by Friedrich Spielhagen and Theodor Storm and Wilhelm Raabe and Marion D. Learned and Ewald Eiserhardt

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The German Classics of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Volume 11

Masterpieces of German Literature Translated Into English

Author: Friedrich Spielhagen

Theodor Storm

Wilhelm Raabe

Marion D. Learned

Ewald Eiserhardt

Release Date: May 27, 2014 [EBook #45788]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GERMAN CLASSICS OF 19/20 CENT, VOL 11 ***

Produced by Richard Tonsing, Stan Goodman, Rachael Schultz

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

VOLUME XI

FRIEDRICH SPIELHAGEN

THEODOR STORM

WILHELM RAABE

THE GERMAN PUBLICATION SOCIETY

NEW YORK

Copyright 1914

by

The German Publication Society

VOLUME XI

Special Writers

Marion D. Learned, Ph.D., Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures, University of Pennsylvania:

The Life of Friedrich Spielhagen.

Ewald Eiserhardt, Ph.D., Assistant Professor in German, University of Rochester, N.Y.:

The Life of Theodor Storm; Wilhelm Raabe.

Translators

Marion D. Learned, Ph.D., Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures, University of Pennsylvania:

Storm Flood.

Muriel Almon:

The Rider of the White Horse; The Hunger Pastor.

Charles Wharton Stork, Ph.D., Instructor in English, University of Pennsylvania:

Consolation.

Margarete Münsterberg:

To a deceased; The City; The Heath.

| PAGE | |

FRIEDRICH SPIELHAGEN |

|

| The Life of Friedrich Spielhagen. By Marion D. Learned | 1 |

| Storm Flood. Translated by Marion D. Learned | 14 |

THEODOR STORM |

|

| The Life of Theodor Storm. By Ewald Eiserhardt | 214 |

| The Rider of the White Horse. Translated by Muriel Almon | 225 |

| To a Deceased. Translated by Margarete Münsterberg | 343 |

| The City. Translated by Margarete Münsterberg | 343 |

| The Heath. Translated by Margarete Münsterberg | 344 |

| Consolation. Translated by Charles Wharton Stork | 345 |

WILHELM RAABE |

|

| Wilhelm Raabe. By Ewald Eiserhardt | 346 |

| The Hunger Pastor. Translated by Muriel Almon | 353 |

| PAGE | |

| On the North Sea Coast. By Jacob Alberts | Frontispiece |

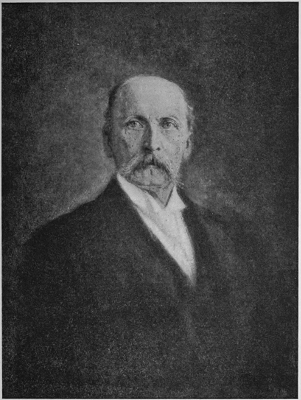

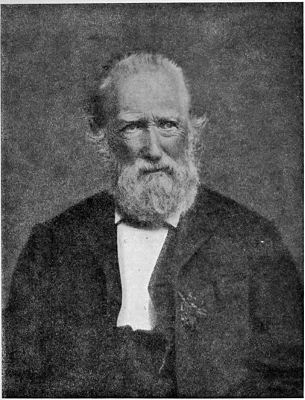

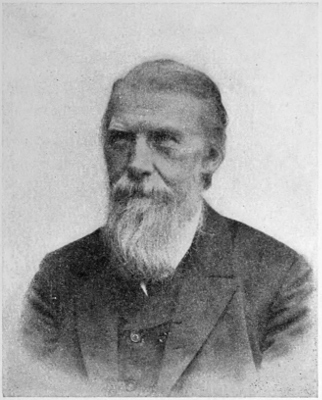

| Friedrich Spielhagen. By A. Weiss | 12 |

| The Last Day of a Condemned Man. By Michael von Munkacsy | 22 |

| Arrested Vagabonds. By Michael von Munkacsy | 62 |

| The Loan Office. By Michael von Munkacsy | 92 |

| Two Families. By Michael von Munkacsy | 112 |

| The Little Thief. By Michael von Munkacsy | 142 |

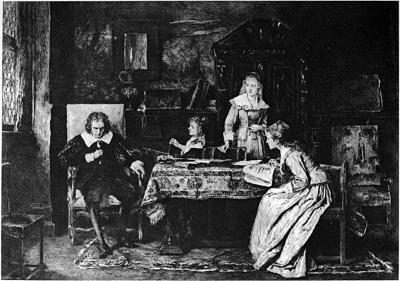

| Milton and His Daughters. By Michael von Munkacsy | 172 |

| Christ Before Pilate. By Michael von Munkacsy | 192 |

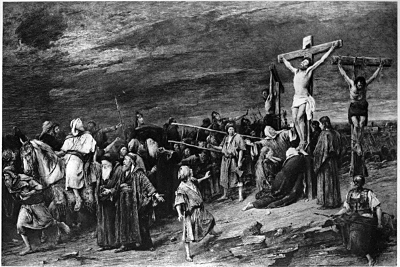

| Golgatha. By Michael von Munkacsy | 212 |

| Theodor Storm | 220 |

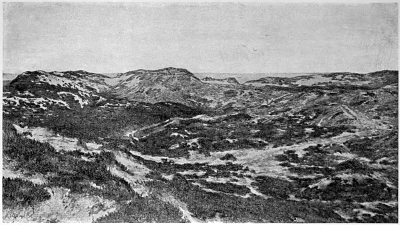

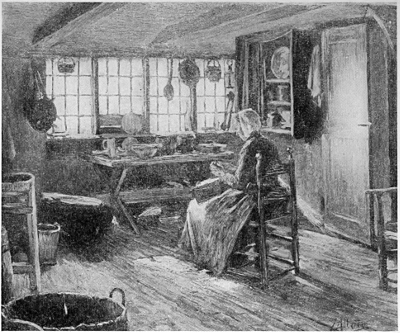

| Dunes on the North Sea. By Jacob Alberts | 236 |

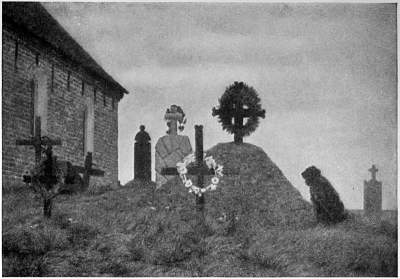

| Churchyard on a North Sea Island. By Jacob Alberts | 252 |

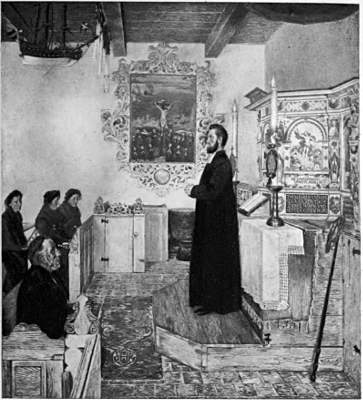

| Communion Service on a North Sea Island. By Jacob Alberts | 268 |

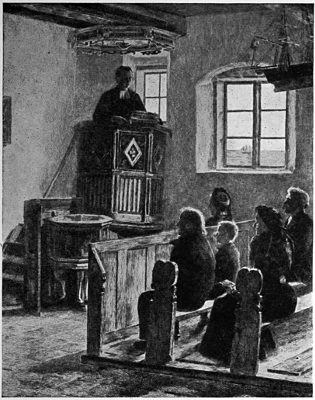

| A North Sea Islander's Congregation. By Jacob Alberts | 284 |

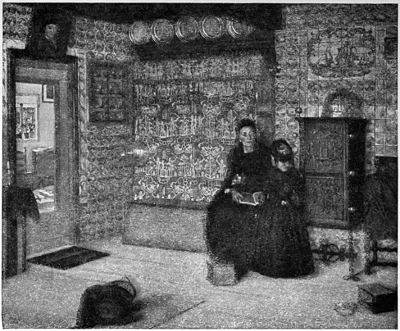

| Living-Room in a Frisian Farmhouse. By Jacob Alberts | 300 |

| A Quiet Corner. By Jacob Alberts | 316 |

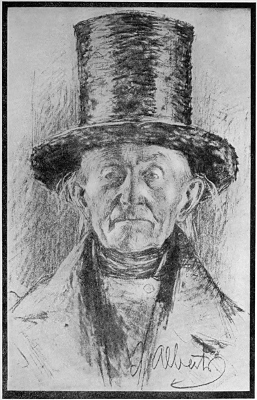

| A Gentleman of the Old School. By Jacob Alberts | 332 |

| Wilhelm Raabe | 352 |

| The Commander of the Fortress. By Karl Spitzweg | 382 |

| The Letter Carrier. By Karl Spitzweg | 412 |

| The Nightly Round. By Karl Spitzweg | 442 |

| The Stork's Visit. By Karl Spitzweg | 472 |

| The Lover of Cacti. By Karl Spitzweg | 502 |

| The Antiquarian. By Karl Spitzweg | 532 |

The illustrations in this volume, devoted to the writings of Spielhagen, Storm, and Raabe, are from paintings by Michael von Munkacsy, Jacob Alberts, and Karl Spitzweg. Munkacsy may be called an artistic counterpart to Spielhagen, inasmuch as he shared with him the conscious striving for effect, the predilection for striking social contrasts, and the desire to make propaganda for liberalism. Spitzweg was allied to Raabe in his truly Romantic inwardness, his joyful acceptance of all phases of life, his glorification of the humble and the lowly, and his inexhaustible humor. Alberts is probably the most talented living painter of that part of Germany which forms the background of Storm's finest novels: the Frisian coast of the North Sea.

Kuno Francke.

By Marion D. Learned, Ph.D.

Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures, University of Pennsylvania.

The struggle for liberal institutions, which found expression in the Wars of Liberation, the July Revolution of 1830, and the March Revolution of 1848—with visions of a German Republic, with bitter protest against the Reaction, with a new hope of a regenerated social State and a renovated German Empire—marks only the stormy stages of the liberalizing movement which is still going on in the German nation. Since 1848, radical revolt has taken on forms very different from the dreams which fired the spirits of the Forty-eighters. The sword has yielded to the pen, the scene of combat has shifted from the arsenal and the battlefield to the printed book and the Council Chamber; while the necessity of an active policy of military defense has saved the German people from the throes of bloody internal strife.

In the transition from the armed revolutionary outbreak of 1848 to the evolutionary processes of the present day, the novel of purpose and of living issues (Tendenz-und Zeitroman) has played an important part in teaching the German people to think for themselves and to seek the highest good of the individual and of the classes in the general weal of the nation as a whole. In the front rank, if not the foremost, of the novelists of living issues in this period of social and economic reform was Friedrich Spielhagen, whose novels were almost without exception novels of purpose.

Friedrich Spielhagen was born in Magdeburg in the Prussian province of Saxony, February 24, 1829. He was the son of a civil engineer, and descended from a family of foresters in Tuchheim. His seriousness and precocity won[Pg 2] him the nickname of "little old man," and also admission to the gymnasium a year before the average age of six. In 1835, when he was six years old, his father was transferred to the position of Inspector of Waterworks in Stralsund. It was here by the sea and among the dunes that the young poet spent his most plastic years, and became, like Fritz Reuter, his contemporary and literary colleague of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, the poet of the Flat Land, which he made so familiar to the German public of the '60s and '70s. Spielhagen has given his own account of the first years of his life in his autobiography entitled Discoverer and Inventor which is evidently modeled after Goethe's Poetry and Fact. Here we learn with what delight the boy accompanied his father on his tours of inspection about the harbor city, with what difficulties he contended in school, which he says was to him neither "stepmother" nor "alma mater," what deep impressions his vacation visits at the country homes of his school friends left upon his sensitive mind. Although his family never became fully naturalized in the social life of Stralsund, but remained to the end "newcomers," Spielhagen says of himself that, in his love for Pomeranian nature, he felt himself to be "the peer of the native born of Pomerania, which has come to be, in the truest sense of the word, my home land."

The sea with its endless variety of moods and scenes opened to him the secrets of his favorite poet Homer. He says: "I count it among the greatest privileges of my life that I could dream myself into my favorite poet, while the Greek original was still a book of seven seals." Following the steps of his great German model, Goethe, he tested his talents for the stage both at home, where he was playwright, manager, stage director, prompter and actor, all in one, and later on the real stage at Magdeburg only to find that he was not called to wear the buskin.

In his school days he began to read the authors of German fiction and poetry: Tieck, Arnim, Brentano, Stifter, Zschokke, Steffens, Goethe's Hermann and Dorothea and[Pg 3] Faust (First Part), Lessing, Uhland, Heine's Book of Songs, Freiligrath, Herwegh. He also browsed about in other literatures: Byron's Don Juan he read first when he was seven years of age; of Walter Scott he says: "In speaking this precious name I mention perhaps not the most distinguished, but nevertheless the greatest and most sympathetic, stimulator of my mind at that time. * * * In comparison with this splendid Walter Scott, the other English and American novelists, Cooper, Ainsworth, Marryat, and whatever their names whose novels came into my hands at that time are stars of the second and third magnitude." He regards Bulwer alone as the peer of the Scottish Bard.

The English influence of the time was reflected also in the life about him, especially in the sport-life, with its horse-racing, pigeon-shooting, card-playing (Tarok, L'Hombre, Whist or Boston) and kindred pastimes. He knew "that Blacklock was sired by Brownlock from Semiramis, and Miss Jane was bred of the Bride of Abydos by Robin Hood"—an interesting sidelight on the Byronic influence of the time. This sport-life so zealously cultivated by the gentry, and his visits to the manor houses of his school friends during the vacations, afforded him glimpses into the customs and traditions of the agrarian gentry of Pomerania, and the manorial economy and reckless life of the nobles with their castles, dependents, laborers, overseers, apprentices, volunteers and the like—the first impressions of his Problematic Characters.

In 1847 Spielhagen left Stralsund to study jurisprudence at the University of Berlin, a journey of thirty German miles in twenty-four hours. What a revelation the great capital presented to the youthful provincial, who had never seen a railroad nor a gas jet before he began the journey! Arriving before the opening of the semester he had time to take an excursion into Thuringia, which later became so dear to him and is reflected in his From Darkness to Light (second part of Problematic Characters), Always to the Fore, Rose of the Court, Hans and Grete, The Village[Pg 4] Coquette, The Amusement Commissioner, and The Fair Americans. Returning to Berlin he heard, among others, Heidemann on Natural Law and Trendelenburg on Logic. The signs of revolution were already visible in the university circles, but had not as yet awakened the interests of Spielhagen, who declared that revolution was a matter of weather, and that he himself was a republican in the sense that the others were not.

The next semester Spielhagen went to the University of Bonn, wavering between Law and Medicine. The landscape of the lower Rhineland was not congenial to him. He longed for his Pomeranian shore with its dunes and invigorating sea life. In Bonn he met leaders of the revolutionary party—Carl Schurz, "le bel homme," and Ludwig Meyer. The portrait he sketches of Carl Schurz is an outline of that which the liberator of Kinkel rounded out for himself in his long years of sturdy citizenship in America. Spielhagen warned Schurz at that time that his schemes were quixotic.

During the following vacation, on a foot-tour through Thuringia, Spielhagen witnessed the effects of the revolution and the ensuing reaction. He arrived at Frankfurt-on-the-Main just after the close of the Great Parliament. He was deeply impressed with the violence done to Auerswald and Lichnowski, and witnessed the trial of Lassalle for the theft of the jewel-casket of the Baroness von Meyendorf. His attention was thus fixed upon the personality of the great socialist reformer who was later to play such an important rôle in his novels, and of whom he said: "Lassalle set in motion the message which not only continues today, but is only beginning to manifest its depth and power, and the end of which no mind of the wise can foresee."

In Bonn Spielhagen finally went over to classical philology, and devoted much time also to modern literature. His beloved Homer, the Latin poets, Goethe's lyrics, Goetz, Iphigenia, Tasso, Wilhelm Meister, The Elective Affinities, Immermann's Münchhausen, Vilmar, Gervinus, Loebel,[Pg 5] Simrock's Nibelungen, Goldsmith's Vicar of Wakefield, Dickens and Shakespeare all claimed his attention. The most interesting incident of his stay at Bonn was his audience with the later Crown Prince Frederick, who had come with his tutor, Professor Curtius, to take up his studies at the university—an audience which was repeated at the Court of Coburg in 1867, when Spielhagen came face to face with his literary antipathy, Gustav Freytag.

After three years of vacillation in his university studies, he finally made peace with his father, and decided to take his degree in philology. To this end he entered the University of Greifswald and began the more serious study of esthetics, starting with Humboldt's Esthetic Experiments, and developing his own theory of objectivity in the novel. Meanwhile he read the English novelists Dickens, Thackeray, Fielding, Smollett, Sterne, and the Germans Lichtenberg, Rabener, Jean Paul, Thümmel, and Vischer's Esthetics. His essay On Humor and other critical works owe much to these studies. After giving his interpretation of an ode of Horace in the seminary, he worked at his dissertation, and found in Tennyson the theme for his first finished work, Klara Vere.

Having left the university, Spielhagen entered the army for his year of service. Here he gained valuable experience and information, which stood him in good stead in his novels. During this year he found time to delve again into Spinoza, whom he had studied in Berlin. The doctrines of this philosopher now had a new meaning for him and offered him a philosophic mooring which he had so much needed in deciding upon his career. Commenting on his reading he says: "I wished to win from philosophy the right to be what I was, the right to give free rein to the power which I felt to be dominant in my mind. I wished to procure a charter for 'the ruling passion' of my soul." This charter he found in Spinoza's words: "Every one exists by the supreme right of Nature, and consequently, according to the supreme right of Nature, every one does[Pg 6] what the necessity of his nature imposes, and accordingly by this supreme right of nature every one judges what is good and what is bad, and acts in his own way for his own welfare." This principle of "suum esse conservare" becomes the guiding thought in Spielhagen's life at this time. With this philosophic turn of mind came a reaction against Byron's immoral characters such as Don Juan.

He was now confronted with the problem of reconciling in his own life Freiligrath's words, "wage-earner and poet." His pedagogical faculties had been developed by the informal lectures which he had given to the circle of his sister's girl friends. After the manœuvres were over he took a position as private tutor in the family of a former Swedish officer of the "type of gentleman," as he says. In this rural Pomeranian retreat the instincts of the poet were rapidly awakened. Enraptured with the beauty of the country he adopted Friedrich Schlegel's practice of writing down his thoughts and shifting moods in the form of fragments. As the family broke up for the holidays, he strapped on his knapsack for a cross-country tour homeward, making a détour to visit an old friend at Rügen. It was here that he fell in love with Hedda, the heroine of the story On the Dunes. He felt love now for the first time in its real power, which was lacking in Klara Vere. But this new, strange passion left him only the more a poet. In one of his fragments he wrote: "The poet worships every beautiful woman as the devout Catholic does every image of the Holy Virgin, but the image is not the Queen of Heaven."

The vacation had made him discontented with his position. All the rural charm seemed changed to commonplace. He now felt a bond of sympathy with Rousseau, Victor Hugo, and George Sand, sought literary uplift in Homer, Æschylus, Shakespeare, Scott, Byron, and extended his reading to Gargantua, Tom Jones, Lamartine, Madame Bovary, and Vanity Fair, but declares he would willingly exchange Consuelo for Copperfield. It was at this[Pg 7] time when Spielhagen was in unsteady mood as to his future, that he saw for the last time his old Greifswald friend, Albert Timm, who in the last three years had sadly changed from the promising student to the cynic: "'Yes,' he cried (from the platform of the moving train) 'I am going to America, not of my own wish, but because others wish it. They may be right; in any case, I have run my course in Europe. Perhaps I shall succeed better over there, or perhaps not; it's all the same. * * * Somewhere in the forest primeval! To the left around the corner! Don't forget: to the left around the ——' and the train sped out of sight." These parting words of his shipwrecked friend reminded Spielhagen only too keenly of his own unsettled career.

At length Spielhagen decided to go to Leipzig to prepare for a professorship of literature in the university. After a tour in Thuringia, during which he saw in Ilmenau a gipsy troop which furnished him with the character of Cziska in the Problematic Characters, he again took up his study of literature and esthetics. His encounter with Kant's philosophy and Schiller's esthetic theories led him back to Goethe and Spinoza. In the midst of these philosophical problems, he received one day a letter from Robert Hall Westley, an English friend in Leipzig, "a gentleman bred and born," telling him of a vacancy in English at the "Modernes Gesamt-Gymnasium" at that place. Spielhagen accepted the position in 1854, and in good American fashion followed the method of docendo discimus. Thus he finds himself again a producer.

The first fruit of his critical studies during the early Leipzig period was the completed essay On Humor, which was now accepted and published by Gutzkow in Unterhaltungen am häuslichen Herd. This, his first printed work, gave him new courage. His studies in English led him again to the English and American poets. The offer of a Leipzig firm to publish a collection of translations of American poetry added new zest to his reading in American[Pg 8] literature. The chief source of his translations was Griswold's Poets and Poetry of America. A specimen from Emerson's Representative Men will illustrate his skill in translating:

Sphinx.

These translations appeared under the title Amerikanische Gedichte. In addition to selections from Bryant, Longfellow, Poe, Bayard Taylor, and others, he translated also George William Curtis' Nile Notes of an Howadji, which was published with the title Nil-Skizzen.

His admiration for American literature was very great, as his own words will show: "But upon this wide, entirely original, field of poetry what abundance, what variety of production! Palmettos grow by the side of gnarly oaks, and the most charming and modest flora of the prairie among the garden flowers of magic beauty and intoxicating perfume." The American poems were followed by translations of Michelet's L'Amour and other French and English works.

Spielhagen connected himself with Gutzkow's Europa and devoted himself for a time to criticism. Among the essays of this period are Objectivity in the Novel, Dickens, Thackeray, etc. At the suggestion of Kolatschek, an Austrian Forty-eighter, who had returned from America and founded the periodical Stimmung der Zeit in Vienna, Spielhagen wrote a severe criticism of Freytag's historical drama The Fabians. This attack upon Freytag was occasioned by the severe criticism of Gutzkow's Magician of Rome, published in the Grenzboten, edited by Julian[Pg 9] Schmidt and Gustav Freytag. It was Spielhagen's demand for fair play as well as his admiration for Gutzkow that drew him into the conflict.

The old home in Pomerania had been broken up by the death of his father and the marriage of his sister, and the events of his early life could now be viewed as history. Out of these events and his later experience grew his first great novel, Problematic Characters (1860, Second Part 1861). This novel deals with the conditions in Pomerania in particular, and in Germany in general, before 1848. The title is drawn from Goethe's Aphorisms in Prose: "There are problematic characters which are not adapted to any position in life and are not satisfied with any condition in life. Out of this arises that titanic conflict which consumes life without compensation." The hero, Dr. Oswald Stein, is the poet himself in his rôle as family tutor and implacable foe of the institutions of the nobility, "a belated Young German" and an incipient socialist. He falls in love with Melitta von Berkow in her Hermitage, with the impulsive Emilie von Breesen at the ball, and with Helene von Grenwitz, his pupil. Because of the latter he fights a duel with her suitor, Felix, and then goes off with Dr. Braun to begin anew at Grünwald. In the second part of this novel this unfinished story is carried to its tragic and logical conclusion, when Oswald dies a heroic death at the barricades. Although most of the chief characters drawn in the novel are types, they are modeled after prototypes in real life. Oswald, the revolutionist with a suggestion of the Byronic, echoes the poet in his early career. Dr. Braun (Franz), the man of will, is modeled on the poet's young friend Bernhard, and Oldenburg, the titanic Faust nature, is taken from his friend Adalbert of the Gymnasium days at Stralsund. Albert Timm was his boon companion at Greifswald, and Professor Berger is a composite of Professor Barthold, the historian, and Professor M——, who later became insane.

In the years 1860-62 Spielhagen was editor of the literary supplement of the Zeitung für Norddeutschland, doing valuable service as a literary journalist. In this position he had opportunity to prepare himself for the wider activities as editor of the Deutsche Wochenschrift and later (1878-84) of Westermann's Monatshefte. After 1862 he was identified with the surging life of Berlin.

In The Hohensteins (1863) the story of a declining noble family, recalling the historical novel of Scott and Hauff's Lichtenstein, the socialistic program of Lassalle begins to appear. Lassalle's doctrines find their spokesman in the hero, Bernhard Münzer, the fantastic but despotic agitator and cosmopolitan socialist; while the idealist, Baltasar, voices the reform program of the poet himself in the words: "Educate yourselves, Germans, to love and freedom."

In the next novel, In Rank and File (1866), the program of Lassalle is reflected in Leo Gutmann, a character of the Auerbach type. The mouthpiece of the poet is really Walter Gutmann, who sums up the moral of the story in these sentences: "The heroic age is past. The battle-cry is no longer: 'one for all,' but 'all for all.' The individual is only a soldier in rank and file. As individual he is nothing; as member of the whole he is irresistible." Father Gutmann, the forester, is evidently an echo of the poet's family traditions, while Dr. Paulus is an exponent of the philosophy of Spinoza. Leo's career and fall illustrate the futility of the principle of "state aid" in the reform program. Even the seven years of residence in America were not sufficient to rescue him from his visionary schemes.

In Hammer and Anvil (1869) the same theme is treated in a different form. The poet teaches here that the conflict between master and servant, ruler and subject, must be reinterpreted and recognized as a necessary condition of society. "The situation is not hammer or anvil, as the revolutionists would have it, but hammer and anvil; for every creature, every man, is both together, at every moment." Thus the "solidarity of interests" is the aim to be[Pg 11] kept in view, and is shown by Georg Hartwig, who having learned his lesson in the penitentiary now appears as the owner of a factory and gives his workmen an interest in the profits.

The most powerful of Spielhagen's novels is Storm Flood (1877), in which the inundation caused by the fearful storm on the coast of the Baltic Sea in 1874 is made a coincident parallel of the calamity brought about by the reckless speculation of the industrial promoters of the early seventies. As the catastrophe on the Baltic is the consequence of ignoring the warnings of physical phenomena in nature, so the financial crash and family distress which overwhelm the Werbens and Schmidts are the result of the violation of similar natural laws in the social and industrial world. The novelist has here reached the highest development of his art. The course of the narrative gathers in its wake all the elements of catastrophe, to let them break with the fury of the tempest over the lives of the characters, but allows the innocent children of Nature to come forth as the happy survivors of this wreck and ruin. The characters of Reinhold and Else, who find their bliss in true love, are his best creations. The poet has here proved himself a worthy disciple of Shakespeare and Walter Scott.

After this blast of the tempest, the poet turned to the more placid scenes of his native heath in the novel entitled Flat Land (1879), in which he describes the conditions of Pomerania between 1830-1840. The wealth of description and incident, the variety of motive and situation, make this story one of the most characteristic of Pomeranian scenery and life.

In the novel What Is to Come of It? (1887), liberalism, social democracy, nihilism, held in check by the grip of the Iron Chancellor, contend for the mastery. And what shall the result? The poet answers: "There is a bit of the Social Democrat in every one," but the result will be "a and lofty one and a new, glorious phase of an [Pg 12]ever-striving humanity." Here are brought into play typical characters, the Bismarckian Squire, the reckless capitalist, the particularist with his feigned liberalism.

Spielhagen's pessimism finds vent in A New Pharaoh (1889), which is a protest against the Bismarck régime. The ideals of the Forty-eighter are represented by Baron von Alden, who comes back from America to visit his old home only to find a new Pharaoh, who knows nothing of the Joseph of 1848. Finding the Germans a race of toadies and slaves, in which the noble-minded go under while the base triumph, he turns his back upon the new empire for good and all. "Nothing is accomplished by the sword which another sword cannot in turn destroy. The permanent and imperishable can be accomplished only by the silent force of reason."

In addition to his more pretentious novels, Spielhagen wrote a large number of shorter novels and short stories. To these belong Klara Vere and On the Dunes, already mentioned, At the Twelfth Hour (1863), Rose of the Court (1864), The Fair Americans (1865), Hans and Grete, and The Village Coquette (1869), German Pioneers (1871), What the Swallow Sang (1873), Ultimo (1874), The Skeleton in the Closet (1878), Quisisana (1880), Angela (1881), Uhlenhans (1883), At the Spa (1885), Noblesse Oblige (1888). The most important of Spielhagen's latest novels are The Sunday Child (1893), Self Justice (1896), Sacrifices (1899), Born Free (1900).

The place of Spielhagen in German literature is variously estimated. Heinrich and Julius Hart in Kritische Waffengänge (1884) contest his claim to a place among artists of the first rank and condemn his use of the novel for purposes of reform; while Gustav Karpeles in his Friedrich Spielhagen (1889) assigns him a place among the best novelists of his time. This latter position is more nearly correct. The modern disposition to cry art for art's sake, and to denounce all art which has a didactic purpose, is the offspring of ignorance of the real nature of art. In a general [Pg 13]way all art has a didactic purpose of varying degrees of directness. It is just this didactic purpose which has entitled the novel to its place among the literary forms, and it is this purpose which made Spielhagen's novels such a potent power in the social revolution of the later nineteenth century.

The charge has been made against Spielhagen that his characters are mechanical types used as vehicles of the author's doctrines or of the tendencies of the time. This charge is not sustained by the facts, even in the case of his first somewhat crude novel, the Problematic Characters, of which he says later: "There was not a squire in Rügen nor a townsman in Stralsund or Greifswald who did not feel himself personally offended." And the pronounced and clearly defined characters of Storm Flood, in their sharp contrasts and fierce conflicts with social tradition and natural impulse, present a vivid picture of the surging life of the New Empire.

Spielhagen possessed an intimate knowledge of literary technique. Few if any of his contemporaries had given more careful attention to the principles of esthetics and of literary workmanship, as may be seen from his critical essays and particularly the treatises, Contributions to the Theory and Technique of the Novel, and New Contributions to the Theory and Technique of the Epic and Drama.

It was but poetic justice that the novelist of the stormy days of the Revolution should be permitted to spend the declining years of his long life in the sunshine of the new Berlin, in whose making he had participated and whose life he had chronicled. He died February 24, 1911, having passed his fourscore years.

TRANSLATED AND CONDENSED BY MARION D. LEARNED, PH.D.

Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures, University of Pennsylvania.

The weather had grown more inclement as evening came on. On the forward deck groups of laborers on their way to the new railroad at Sundin were huddled more closely together between the high tiers of casks, chests, and boxes; from the rear deck the passengers, with few exceptions, had disappeared. Two elderly gentlemen, who had chatted much together during the journey, stood on the starboard looking and pointing toward the island around the south end of which the ship had to pass. The flat coast of the island, rising in a wide circuit to the promontory, became more distinct with each second.

"So that is Warnow?"

"Your pardon, Mr. President—Ahlbeck, a fishing village; to be sure, on Warnow ground. Warnow itself lies further inland; the church tower is just visible above the outlines of the dunes."

The President let fall the eye-glasses through which he had tried in vain to see the point of the church tower. "What sharp eyes you have, General, and how quickly you get your bearings!"

"It is true I have been there only once," replied the General; "but since then I have had only too much time to study this bit of coast on the map."

The President smiled. "Yes, yes, it is classic soil," said he; "there has been much contention over it—much and to no purpose."

"I am convinced that it was fortunate that the contention [Pg 15]was fruitless—at least had only a negative result," said the General.

"I am not sure that the strife will not be renewed again," replied the President; "Count Golm and his associates have been making the greatest efforts of late."

"Since they have so signally proved that the road would be unprofitable?"

"Just as you have shown the futility of a naval station here!"

"Pardon, Mr. President, I had not the deciding voice; or, more correctly, I had declined it. The only place at all adapted for the harbor would have been there in the southern corner of the bay, under cover of Wissow Point, that is on Warnow domain. To be sure, I have only the guardianship of the property of my sister——"

"I know, I know," interrupted the President; "old Prussian honesty, which amounts to scrupulousness. Count Golm and his associates are less scrupulous."

"So much the worse for them," replied the General.

The gentlemen then turned and joined a young girl who was seated in a sheltered spot in front of the cabin, passing the time as well as she could by reading or drawing in a small album.

"You would like to remain on deck, of course, Else?" asked the General.

"Do the gentlemen wish to go to the cabin?" queried the young girl in reply, looking up from her book. "I think it is terrible below; but, of course, it is certainly too rough for you, Mr. President!"

"It is, indeed, unusually rough," replied the President, rolling up the collar of his overcoat and casting a glance at the heavens; "I believe we shall have rain before sundown. You should really come with us, Miss Else! Do you not think so, General?"

"Else is weatherproof," replied the General with a smile; "but you might put a shawl or something of the kind about you. May I fetch you something?"

"Thank you, Papa! I have everything here that is necessary," replied Else, pointing to her roll of blankets and wraps; "I shall protect myself if it is necessary. Au revoir!"

She bowed gracefully to the President, cast a pleasant glance at her father, and took up her book again, while the gentlemen went around the corner to a small passage between the cabin and the railing.

She read a few minutes and then looked up and watched the cloud of smoke which was rising from the funnel in thick, dark gray puffs, and rolling over the ship just as before. The man at the helm also stood as he had been standing, letting the wheel run now to the right, now to the left, and then holding it steady in his rough hands. And, sure enough, there too was the gentleman again, who with untiring endurance strode up and down the deck from helm to bowsprit and back from bowsprit to helm, with a steadiness of gait which Else had repeatedly tried to imitate during the day—to be sure with only doubtful success.

"Otherwise," thought Else, "he hasn't much that especially distinguishes him;" and Else said to herself that she would scarcely have noticed the man in a larger company, certainly would not have observed him, perhaps not so much as seen him, and that if she had looked at him today countless times and actually studied him, this could only be because there had not been much to see, observe, or study.

Her sketch-book, which she was just glancing through, showed it. That was intended to be a bit of the harbor of Stettin. "It requires much imagination to make it out," thought Else. "Here is a sketch that came out better: the low meadows, the cows, the light-buoy—beyond, the smooth water with a few sails, again a strip of meadow—finally, in the distance, the sea. The man at the helm is not bad; he held still enough. But 'The Indefatigable' is awfully out of drawing—a downright caricature! That comes from the constant motion! At last! Again! Only[Pg 17] five minutes, Mr. So-and-so! That may really be good—the position is splendid!"

The position was indeed simple enough. The gentleman was leaning against a seat with his hands in his pockets, and was looking directly westward into the sea; his face was in a bright light, although the sun had gone behind a cloud, and in addition he stood in sharp profile, which Else always especially liked. "Really a pretty profile," thought Else; "although the prettiest part, the large blue kindly eyes, did not come out well. But, as compensation, the dark full beard promises to be so much the better; I am always successful with beards. The hands in the pockets are very fortunate; the left leg is entirely concealed by the right—not especially picturesque, but extremely convenient for the artist. Now the seat—a bit of the railing—and 'The Indefatigable' is finished!"

She held the book at some distance, so as to view the sketch as a picture; she was highly pleased. "That shows that I can accomplish something when I work with interest," she said to herself; and then she wrote below the picture: "The Indefatigable One. With Devotion. August 26th, '72. E. von W...."

While the young lady was so eagerly trying to sketch the features and figure of the young man, her image had likewise impressed itself on his mind. It was all the same whether he shut his eyes or kept them open; she appeared to him with the same clearness, grace, and charm—now at the moment of departure from Stettin, when her father presented her to the President, and she bowed so gracefully; then, while she was breakfasting with the two gentlemen, and laughing so gaily, and lifting the glass to her lips; again, as she stood on the bridge with the captain, and the wind pressed her garments close to her figure and blew her veil like a pennant behind her; as she spoke with the steerage woman sitting on a coil of rope on the forward deck, quieting her youngest child wrapped in a shawl, then bending down, raising the shawl for a moment, and looking[Pg 18] at the hidden treasure with a smile; as she, a minute later, went past him, inquiring with a stern glance of her brown eyes whether he had not at last presumed to observe her; or as she now sat next to the cabin and read, and drew, and read again, and then looked up at the cloud of smoke or at the sailors at the rudder! It was very astonishing how her image had stamped itself so firmly in this short time—but then he had seen nothing above him but the sky and nothing below him but the water, for a year! Thus it may be easily understood how the first beautiful, charming girl whom he beheld after so long a privation should make such a deep and thrilling impression upon him.

"And besides," said the young man to himself, "in three hours we shall be in Sundin, and then—farewell, farewell, never to meet again! But what are they thinking about? You don't intend, certainly," raising his voice, "to go over the Ostersand with this depth of water?" With the last words he had turned to the man at the helm.

"You see, Captain, the matter is this way," replied the man, shifting his quid of tobacco from one cheek to the other; "I was wondering, too, how we should hold our helm! But the Captain thinks——"

The young man did not wait for him to finish. He had taken the same journey repeatedly in former years; only a few days before he had passed the place for which they were steering, and had been alarmed to find only twelve feet of water where formerly there had been a depth of fifteen feet. Today, after the brisk west wind had driven so much water seaward, there could not be ten feet here, and the steamer drew eight feet! And under these circumstances no diminution of speed, no sounding, not a single one of the required precautions! Was the Captain crazy?

The young man ran past Else with such swiftness, and his eyes had such a peculiar expression as they glanced at her, that she involuntarily rose and looked after him. The next moment he was on the bridge with the old, fat[Pg 19] Captain, speaking to him long and earnestly, at last, as it appeared, impatiently, and repeatedly pointing all the while toward a particular spot in the direction in which the ship was moving.

A strange sense of anxiety, not felt before on the whole journey, took possession of Else. It could not be a trifling circumstance which threw this quiet, unruffled man into such a state of excitement! And now, what she had supposed several times was clear to her—that he was a seaman, and, without doubt, an able one, who was certainly right, even though the old, fat Captain phlegmatically shrugged his shoulders and pointed likewise in the same direction, and looked through his glass, and again shrugged his shoulders, while the other rushed down the steps from the bridge to the deck, and came straight up to her as if he were about to speak to her.

Yet he did not do so at first, for he hurried past her, although his glance met hers; then, as he had undoubtedly read the silent question in her eyes and upon her lips, he hesitated for a moment and—sure enough, he turned back and was now close behind her!

"Pardon me!"

Her heart beat as if it would burst; she turned around.

"Pardon me," he repeated; "I suppose it is not right to alarm you, perhaps without cause. But it is not impossible, I consider it even quite probable, that we shall run aground within five minutes; I mean strike bottom——"

"For Heaven's sake!" exclaimed Else.

"I do not think it will be serious," continued the young man. "If the Captain—there! We now have only half steam—half speed, you know. But he should reverse the engines, and it is now probably too late for that."

"Can't he be compelled to do it?"

"On board his ship the captain is supreme," replied the young man, smiling in spite of his indignation. "I myself am a seaman, and would just as little brook interference in such a case." He lifted his cap and bowed, took a step[Pg 20] and stopped again. A bright sparkle shone in his blue eyes, and his clear, firm voice quivered a bit as he went on, "It is not a question of real danger. The coast lies before us and the sea is comparatively quiet; I only wished that the moment should not surprise you. Pardon my presumption!"

He had bowed again and was quickly withdrawing as if he wished to avoid further questions. "There is no danger," muttered Else; "too bad! I wanted so much to have him rescue me. But father must know it. We ought to prepare the President, too, of course—he is more in need of warning than I am."

She turned toward the cabin; but the retarded movement of the ship, slowing up still more in the last half minute, had already attracted the attention of the passengers, who stood in a group. Her father and the President were already coming up the stairs.

"What's the matter?" cried the General.

"We can't possibly be in Prora already?" questioned the President.

At that instant all were struck as by an electric shock, as a peculiar, hollow, grinding sound grated harshly on their ears. The keel had scraped over the sand-bank without grounding. A shrill signal, a breathless stillness for a few seconds, then a mighty quake through the whole frame of the ship, and the powerful action of the screw working with reversed engine!

The precaution which a few minutes before would have prevented the accident was now too late. The ship was obliged to go back over the same sand-bank which it had just passed with such difficulty. A heavier swell, in receding, had driven the stern a few inches deeper. The screw was working continuously, and the ship listed a little but did not move.

"What in the devil does that mean?" cried the General.

"There is no real danger," said Else with a flash.

"For Heaven's sake, my dear young lady!" interjected the President, who had grown very pale.

"The shore is clearly in sight, and the sea is comparatively quiet," replied Else.

"Oh, what do you know about it!" exclaimed the General; "the sea is not to be trifled with!"

"I am not trifling at all, Papa," said Else.

Bustling, running, shouting, which was suddenly heard from all quarters, the strangely uncanny listing of the ship—all proved conclusively that the prediction of "The Indefatigable" had come true, and that the steamer was aground.

All efforts to float the ship had proved unavailing, but it was fortunate that, in the perilous task required of it, the screw had not broken; moreover, the listing of the hull had not increased. "If the night was not stormy they would lie there quietly till the next morning, when, in case they should not get afloat by that time (and they might get afloat any minute), a passing craft could take off the passengers and carry them to the next port." So spoke the Captain, who was not to be disconcerted by the misfortune which his own stubbornness had caused. He declared that it was clearly noted upon the maps by which he and every other captain had to sail that there were fifteen feet of water at this place; the gentlemen of the government should wake up and see that better charts or at least suitable buoys were provided. And if other captains had avoided the bank and preferred to sail around it for some years, he had meanwhile steered over the same place a hundred times—indeed only day before yesterday. But he had no objections to having the long-boat launched and the passengers set ashore, whence God knows how they were to continue their journey.

"The man is drunk or crazy," said the President, when the Captain had turned his broad back and gone back to his post. "It is a sin and shame that such a man is allowed to command a ship, even if it is only a tug; I shall start a[Pg 22] rigid investigation, and he shall be punished in an exemplary manner."

The President, through all his long, thin body, shook with wrath, anxiety, and cold; the General shrugged his shoulders. "That's all very good, my dear Mr. President," said he, "but it comes a little too late to help us out of our unhappy plight. I refrain on principle from interfering with things I do not understand; but I wish we had somebody on board who could give advice. One must not ask the sailors—that would be undermining the discipline! What is it, Else?" Else had given him a meaning look, and he stepped toward her and repeated the question.

"Inquire of that gentleman!" said Else.

"Of what gentleman?"

"The one yonder. He's a seaman; he can certainly give you the best advice."

The General fixed his sharp eye upon the person designated. "Ah, that one?" asked he. "Really looks so."

"Doesn't he?" replied Else. "He had already told me that we were going to run aground."

"He's not one of the officers of the ship, of course?"

"O no! That is—I believe—but just speak to him!"

The General went up to "The Indefatigable." "Beg your pardon, Sir! I hear you are a seaman?"

"At your service."

"Captain?"

"Captain of a merchantman—Reinhold Schmidt."

"My name is General von Werben. You would oblige me, Captain, if you would give me a technical explanation of our situation—privately, of course, and in confidence. I should not like to ask you to say anything against a comrade, or to do anything that would shake his authority, which we may possibly yet need to make use of. Is the Captain responsible, in your opinion, for our accident?"

"Yes, and no, General. No, for the sea charts, by which we are directed to steer, record this place as navigable. The charts were correct, too, until a few years ago; since [Pg 23]that time heavy sand deposits have been made here, and, besides, the water has fallen continually in consequence of the west wind which has prevailed for some weeks. The more prudent, therefore, avoid this place. I myself should have avoided it."

"Very well! And now what do you think of the situation? Are we in danger, or likely to be?"

"I think not. The ship lies almost upright, and on clear, smooth sand. It may lie thus for a very long time, if nothing intervenes."

"The Captain is right in keeping us on board, then?"

"Yes, I think so—the more so as the wind, for the first time in three days, appears about to shift to the east, and, if it does, we shall probably be afloat again in a few hours. Meanwhile——"

"Meanwhile?"

"To err is human, General. If the wind—we now have south-southeast—it is not probable, but yet possible—should again shift to the west and become stronger, perhaps very strong, a serious situation might, of course, confront us."

"Then we should take advantage of the Captain's permission to leave the ship?"

"As the passage is easy and entirely safe, I can at least say nothing against it. But, in that case, it ought to be done while it is still sufficiently light—best of all, at once."

"And you? You would remain, as a matter of course?"

"As a matter of course, General."

"I thank you."

The General touched his cap with a slight nod of his head; Reinhold lifted his with a quick movement, returning the nod with a stiff bow.

"Well?" queried Else, as her father came up to her again.

"The man must have been a soldier," replied the General.

"Why so?" asked the President.

"Because I could wish that I might always have such clear, accurate reports from my officers. The situation, then, is this——"

He repeated what he had just heard from Reinhold, and closed by saying that he would recommend to the Captain that the passengers who wished to do so should be disembarked at once. "I, for my part, do not think of submitting to this inconvenience, which it would seem, moreover, is unnecessary; except that Else——"

"I, Papa!" exclaimed Else; "I don't think of it for a moment!"

The President was greatly embarrassed. He had, to be sure, only this morning renewed a very slight former personal acquaintance with General von Werben, after the departure from Stettin; but now that he had chatted with him the entire day and played the knight to the young lady on countless occasions, he could not help explaining, with a twitch of the lips which was intended to be a smile, that he wished now to share with his companions the discomforts of the journey as he had, up to this time, the comforts; the Prussian ministry would be able to console itself, if worse comes to worst, for the loss of a President who, as the father of six young hopefuls, has, besides, a succession of his own, and accordingly neither has nor makes claims to the sympathy of his own generation.

Notwithstanding his resignation, the heart of the worthy official was much troubled. Secretly he cursed his own boundless folly in coming home a day earlier, in having intrusted himself to a tug instead of waiting for a coast steamer, due the next morning, and in inviting the "stupid confidence" of the General and the coquettish manœuvrings of the young lady; and when the long-boat was really launched a few minutes later, and in what seemed to him an incredibly short time was filled with passengers from the foredeck, fortunately not many in number, together with a few ladies and gentlemen from the first cabin, and was now being propelled by the strokes of the heavy oars,[Pg 25] and soon afterwards with hoisted sails was hastily moving toward the shore, he heaved a deep sigh and determined at any price—even that of the scornful smile on the lips of the young lady—to leave the ship, too, before nightfall.

And night came on only too quickly for the anxious man. The evening glow on the western horizon was fading every minute, while from the east—from the open sea—it was growing darker and darker. How long would it be till the land, which appeared through the evening mist only as an indistinct streak to the near-sighted man, would vanish from his sight entirely? And yet it was certain that the waves were rising higher every minute, and here and there white caps were appearing and breaking with increasing force upon the unfortunate ship—something that had not happened during the entire day! Then were heard the horrible creaking of the rigging, the uncanny whistling of the tackle, the nerve-racking boiling and hissing of the steam, which was escaping almost incessantly from the overheated boiler. Finally the boiler burst, and the torn limbs of a man, who had been just buttoning up his overcoat, were hurled in every direction through the air. The President grew so excited at this catastrophe that he unbuttoned his overcoat, but buttoned it up again because the wind was blowing with icy coldness. "It is insufferable!" he muttered.

Else had noticed for some time how uncomfortable it was for the President to stay upon the ship—a course which he had evidently decided upon, against his will, out of consideration for his traveling-companions. Her love of mischief had found satisfaction in this embarrassing situation, which he tried to conceal; but now her good nature gained the upper hand, for he was after all an elderly, apparently feeble gentleman, and a civilian. One could, of course, not expect of him the unflinching courage or the sturdiness of her father, who had not even once buttoned his cloak, and was now taking his accustomed evening walk to and fro upon the deck. But her father had[Pg 26] decided to remain; it would be entirely hopeless now to induce him to leave the boat. "He must find a solution to the problem," she said to herself.

Reinhold had vanished after his last conversation with her father, and was not now on the rear deck; so she went forward, and there he sat on a great box, looking through a pocket telescope toward the land—so absorbed that she had come right up to him before he noticed her. He sprang hastily to his feet, and turned to her.

"How far are they?" asked Else.

"They are about to land," replied he. "Would you like to look?"

He handed her the instrument. The glass, when she touched it, still had a trace of the warmth of the hand from which it came, which would have been, under other circumstances, by no means an unpleasant sensation to her, but this time she scarcely noticed it, thinking of it only for an instant, while she was trying to bring into the focus of the glass the point which he indicated. She did not succeed; she saw nothing but an indistinct, shimmering gray. "I prefer to use my eyes!" she exclaimed, putting down the instrument. "I see the boat quite distinctly there, close to the land—in the white streak! What is it?"

"The surf."

"Where is the sail?"

"They let it down so as not to strike too hard. But, really, you have the eye of a seaman!" Else smiled at the compliment, and Reinhold smiled. Their glances met for a minute.

"I have a request to make of you," said Else, without dropping her eyes.

"I was just about to make one of you," he replied, looking straight into her brown eyes, which beamed upon him; "I was about to ask you to allow yourself to be put ashore also. We shall be afloat in another hour, but the night is growing stormy, and as soon as we have passed Wissow Hook"—he pointed to the promontory—"we shall have to[Pg 27] cast anchor. That is at best not a very pleasant situation, at the worst a very unpleasant one. I should like to save you from both."

"I thank you," said Else; "and now my request is no longer necessary"—and she told Reinhold why she had come.

"That's a happy coincidence!" he said, "but there is not a moment to lose. I am going to speak to your father at once. We must be off without delay."

"We?"

"I shall, with your permission, take you ashore myself."

"I thank you," said Else again with a deep breath. She had held out her hand; he took the little tender hand in his, and again their glances met.

"One can trust that hand," thought Else; "and those eyes, too!" And she said aloud, "But you must not think that I should have been afraid to remain here! It's really for the sake of the poor President."

She had withdrawn her hand and was hastening away to meet her father, who, wondering why she had remained away so long, had come to look for her.

When he was about to follow her, Reinhold saw lying at his feet a little blue-gray glove. She must have just slipped it off as she was adjusting the telescope. He stooped down quickly, picked it up, and put it in his pocket.

"She will not get that again," he said to himself.

Reinhold was right; there had been no time to lose. While the little boat which he steered cut through the foaming waves, the sky became more and more overcast with dark clouds which threatened soon to extinguish even the last trace of the evening glow in the west. In addition, the strong wind had suddenly shifted from the south to the north, and because of this (to insure a more speedy return of the boat to the ship) they were unable to land at the place where the long-boat, which was already coming back, had discharged its passengers—viz., near the little fishing village, Ahlbeck, at the head of the bay, immediately[Pg 28] below Wissow Hook. They had to steer more directly to the north, against the wind, where there was scarcely room upon the narrow beach of bare dunes for a single hut, much less for a fishing village; and Reinhold could consider himself fortunate when, with a bold manœuvre, he brought the little boat so near the shore that the disembarkment of the company and the few pieces of baggage which they had taken from the ship could be accomplished without great difficulty.

"I fear we have jumped out of the frying-pan into the fire," said the President gloomily.

"It is a consolation to me that we were not the cause of it," replied the General, not without a certain sharpness in the tone of his strong voice.

"No, no, certainly not!" acknowledged the President, "Mea maxima culpa! My fault alone, my dear young lady. But, admit it—the situation is hopeless, absolutely hopeless!"

"I don't know," replied Else; "it is all delightful to me."

"Well, I congratulate you heartily," said the President; "for my part I should rather have an open fire, a chicken wing, and half a bottle of St. Julien; but if it is a consolation to have companions in misery, then, it ought to be doubly so to know that what appears as very real misery to the pensive wisdom of one is a romantic adventure to the youthful imagination of another."

The President, while intending to banter, had hit upon the right word. To Else the whole affair appeared a "romantic adventure," in which she felt a genuine hearty delight. When Reinhold brought her the first intimation of the impending danger, she was, indeed, startled; but she had not felt fear for a moment—not even when the abusive men, crying women, and screaming children hurried from the ship, which seemed doomed to sink, into the long-boat which rocked up and down upon the gray waves, while night came over the open sea, dark and foreboding. The[Pg 29] tall seaman, with the clear blue eyes, had said that there was no danger; he must know; why should she be afraid? And even if the situation should become dangerous he was the man to do the right thing at the right moment and to meet danger! This sense of security had not abandoned her when into the surf they steered the skiff, rocked like a nut-shell in the foaming waves. The President, deathly pale, cried out again and again, "For God's sake!" and a cloud of concern appeared even on the earnest face of her father. She had just cast a glance at the man at the helm, and his blue eyes had gleamed as brightly as before, even more brightly in the smile with which he answered her questioning glance. And then when the boat had touched the shore, and the sailors were carrying the President, her father, and the three servants to land, and she herself stood in the bow, ready to take a bold leap, she felt herself suddenly surrounded by a pair of strong arms, and was thus half carried, half swung, to the shore without wetting her foot—she herself knew not how.

And there she stood now, a few steps distant from the men, who were consulting, wrapped in her raincoat, in the full consciousness of a rapture such as she never felt before. Was it not then really fine! Before her the gray, surging, thundering, endless sea, above which dark threatening night was gathering; right and left in an unbroken line the white foaming breakers! She herself with the glorious moist wind blowing about her, rattling in her ears, wrapping her garments around her, and driving flecks of spray into her face! Behind her the bald spectral dunes, upon which the long dune grass, just visible against the faintly brighter western sky, beckoned and nodded—whither? On into the happy splendid adventure which was not yet at an end, could not be at an end, must not be at an end—for that would be a wretched shame!

The gentlemen approached her. "We have decided, Else," said the General, "to make an expedition over the dunes into the country. The fishing village at which the[Pg 30] long-boat landed is nearly a quarter of a mile distant, and the road in the deep sand would probably be too difficult for our honored President. Besides, we should scarcely find shelter there."

"If only we don't get lost in the dunes," sighed the President.

"The Captain's knowledge of the locality will be guarantee for that," said the General.

"I can scarcely speak of a knowledge of the place, General," replied Reinhold. "Only once, and that six years ago, have I cast a glance from the top of these dunes into the country; but I remember clearly that I saw a small tenant-farm, or something of the kind, in that direction. I can promise to find the house. How it will be about quarters I cannot say in advance."

"In any case we cannot spend the night here," exclaimed the General. "So, en avant! Do you wish my arm, Else?"

"Thank you, Papa, I can get up."

And Else leaped upon the dune, following Reinhold, who, hurrying on ahead, had already reached the top, while the General and the President followed more slowly, and the two servants with the effects closed the procession.

"Well!" exclaimed Else with delight as, a little out of breath, she came up to Reinhold. "Are we also at the end of our tether, like the President?"

"Make fun of me if you like, young lady," replied Reinhold; "I don't feel at all jolly over the responsibility which I have undertaken. Yonder"—and he pointed over the lower dunes into the country, in which evening and mist made everything indistinct—"it must be there."

"'Must be,' if you were right! But 'must' you be right?"

As if answering the mocking question of the girl, a light suddenly shot up exactly in the direction in which Reinhold's arm had pointed. A strange shudder shot through Else.

"Pardon me!" she said.

Reinhold did not know what this exclamation meant. At that moment the others reached the top of the rather steep dune.

"Per aspera ad astra," puffed the President.

"I take my hat off to you, Captain," said the General.

"It was great luck," replied Reinhold modestly.

"And we must have luck," exclaimed Else, who had quickly overcome that strange emotion and had now returned to her bubbling good humor.

The little company strode on through the dunes; Reinhold going on ahead again, while Else remained with the other gentlemen.

"It is strange enough," said the General, "that the mishap had to strike us just at this point of the coast. It really seems as if we were being punished for our opposition. Even if my opinion that a naval station can be of no use here is not shaken, yet, now that we have almost suffered shipwreck here ourselves, a harbor appears to me——"

"A consummation devoutly to be wished!" exclaimed the President. "Heaven knows! And when I think of the severe cold which I shall take from this night's promenade in the abominably wet sand, and that, instead of this, I might now be sitting in a comfortable coupé and tonight be sleeping in my bed, then I repent every word I have spoken against the railroad, about which I have put myself at odds with all our magnates—and not the least with Count Golm, whose friendship would just now be very opportune for us."

"How so?" asked the General.

"Golm Castle lies, according to my calculation, at the most a mile from here; the hunting lodge on Golmberg——"

"I remember it," interrupted the General; "the second highest promontory on the shore to the north—to our right. We can be scarcely half a mile away."

"Now, see," said the President; "that would be so convenient,[Pg 32] and the Count is probably there. Frankly, I have secretly counted on his hospitality in case, as I only too much fear, a hospitable shelter is not to be found in the tenant-house, and you do not give up your disinclination to knock at the door in Warnow, which would, indeed, be the simplest and most convenient thing to do."

The President, who had spoken panting, and with many intermissions, had stopped; the General replied with a sullen voice, "You know that I am entirely at outs with my sister."

"But you said the Baroness was in Italy?"

"Yet she must be coming back at this time, has perhaps already returned; and, if she were not, I would not go to Warnow, even if it were but ten paces from here. Let us hurry to get under shelter, Mr. President, or we shall be thoroughly drenched in addition to all we have already passed through."

In fact, scattered drops had been falling for some time from the low-moving clouds, and hastening their steps, they had just entered the farmyard and were groping their way between barns and stables over a very uneven courtyard to the house in whose window they had seen the light, when the rain, which had long been threatening, poured down in full force.

[Pölitz receives his guests with apologies for the accommodations and his wife's absence from the room. His manner is just a bit forced; Else, noticing it, goes out to look for Mrs. Pölitz, and brings the report that the children are sick. The President suggests that they go on to Golmberg. Pölitz will not hear of it, but Else has made arrangements—makeshifts though they are—for the trip, and insists upon leaving, even in the face of the storm. A messenger is to be sent ahead to announce them—Reinhold included, upon Else's insistence. Else goes into the kitchen, where Mrs. Pölitz pours out her soul to her—the hardheartedness of the Count, who has never married, and her[Pg 33] vain labors to keep their little home in Swantow. It sets her thinking, first about the Count, then about Reinhold—was he married or not? Wouldn't any girl be proud of him—even herself! But then there would be disinheritance! Yet she keeps on thinking of him. How would "Mrs. Schmidt" sound! She laughs, and then grows serious; tears come into her eyes; she puts her hand into her pocket and feels the compass which Reinhold had given her. It is faithful. "If I ever love, I too shall be faithful," she says to herself.

Reinhold, going out to look for the boat, wonders why he left it to accompany the others to Pölitz's house; but fortunately he finds it safe. Now his duty to the General and Else is fulfilled; he will never see her again, probably. Yet he hastens back—and meets them just on the point of leaving for Golmberg.

The President has been waiting for the storm to blow over, he says. Else is fidgety, yet without knowing why; she wonders what has become of Reinhold. The President sounds Pölitz on the subject of the railway—the nearest doctor living so far away that they cannot afford to have him come. But Pölitz says that they do not want a railway—a decent wagon road would be enough, and they could have that if only the Count would help a little. A naval station? So far as they are concerned, a simple break-water would do, he tells the President. The latter, while Pölitz is out looking for the messenger, discusses with the General the condition of the Count's tenants, in the midst of which the Count himself arrives with his own carriages to take them over to Golmberg.

A chorus of greetings follows. The Count had met the General in Versailles on the day the German Emperor was proclaimed, the General had not forgotten. The company now lacks only Reinhold, and the Count, thinking that he must have lost his way, is about to send a searching[Pg 34] party, when Else tells him that she has already done so. The Count smiles. She hates him for it, and outside, a moment later, rebukes herself for not controlling her temper. Reinhold meets her there. She commands him to accompany them. As they are leaving Else makes a remark about the doctor, which is overheard, as she intended, by the Count, who promises to send for the doctor himself.

They proceed to Golmberg. Conversation in the servants' carriage is lively, turning on the relative merits of their respective masters—how liberal the Count is; how strict, yet not so bad, the General; while a bottle of brandy passes around. In the first carriage, where Else, the President, and the General are riding, the conversation is of the Count's family and of old families in general, then of the project before them—the railroad and the naval station. The President drops that subject, finding the General not kindly disposed to it. He and Else are both thinking of her indirect request to the Count to send for the doctor. Then Else's thoughts turn again to Reinhold—his long absence—what he would think of her command to accompany them. The Count and Reinhold in the second carriage speak hardly a dozen words. Reinhold's thoughts are of Else—how hopelessly far above him she is—how he would like to run away. They arrive at Golmberg.]

The President had dropped the remark in his note that the absence of a hostess in the castle would be somewhat embarrassing for the young lady in their company, but as it was not so easily to be remedied he would apologize for him in advance. The Count had dispatched a messenger forthwith to his neighbor, von Strummin, with the urgent request that he should come with his wife and daughter to Golmberg, prepared to spend the night there. The Strummins were glad to render this neighborly service, and Madame and Miss von Strummin had already received Else in the hall, and conducted her to the room set apart for her, adjoining their own rooms.

The President rubbed his thin white hands contentedly before the fire in his own comfortable room, and murmured, as John put the baggage in order, "Delightful; very delightful! I think this will fully reconcile the young lady to her misfortune and restore her grouchy father to a sociable frame of mind."

Else was fully reconciled. To be released from the close, jolting prison of a landau and introduced into a brightly lighted castle in the midst of the forest, where servants stood with torches at the portal; to be most heartily welcomed in the ancient hall, with its strangely ornamented columns, by two ladies who approached from among the arms and armor with which the walls and columns were hung and surrounded, and conducted into the snuggest of all the apartments; to enjoy a flickering open fire, brightly burning wax tapers before a tall mirror in a rich rococo frame, velvet carpets of a marvelous design which was repeated in every possible variation upon the heavy hangings before the deeply recessed windows, on the portières of the high gilded doors, and the curtains of the antique bed—all this was so fitting, so charming, so exactly as it should be in an adventure! Else shook the hand of the matronly Madame von Strummin, thanked her for her kindness, and kissed the pretty little Marie, with the mischievous brown eyes, and asked permission to call her "Meta," or "Mieting," just as her mother did, who had just left the room. Mieting returned the embrace with the greatest fervor and declared that nothing more delightful in the world could have come to her than the invitation for this evening. She, with her Mamma, felt so bored at Strummin!—it was horribly monotonous in the country!—and in the midst of it this letter from the Count! She was fond of coming to Golmberg, anyhow—the forest was so beautiful, and the view from the platform of the tower, from the summit of Golmberg beyond the forest over the sea—that was really charming; to be sure, the opportunity but seldom! Her mother was a little indolent, and[Pg 36] the gentlemen thought of their hunting, their horses, and generally only of themselves. Thus she had not been a little surprised, too, at the haste of the Count today in procuring company for the strange young lady, just as if he had already known beforehand how fair and lovely the strange young lady was, and how great the pleasure of being with her, and of chattering so much nonsense; if she might say "thou" to her, then they could chatter twice as pleasantly.

The permission gladly given and sealed with a kiss threw the frolicsome girl into the greatest ecstasy. "You must never go away again!" she exclaimed; "or, if you do, only to return in the autumn! He will not marry me, in any case; I have nothing, and he has nothing in spite of his entail, and Papa says that we shall all be bankrupt here if we don't get the railroad and the harbor. And your Papa and the President have the whole matter in hand, Papa said as we drove over; and if you marry him, your Papa will give the concession, as a matter of course—I believe that's what it's called, isn't it? And you are really already interested in it as it is; for the harbor, Papa says, can be laid out only on the estates which belong to your aunt, and you and your brother—you inherit it from your aunt—are already coheirs? It is a strange will, Papa says, and he would like to know how the matter really is. Don't you know? Please do tell me! I promise not to tell anyone."

"I really don't know," replied Else. "I only know that we are very poor, and that you may go on and marry your Count for all me."

"I should be glad to do so," said the little lady seriously, "but I'm not pretty enough for him, with my insignificant figure and my pug nose. I shall marry a rich burgher some day, who is impressed by our nobility—for the Strummins are as old as the island, you know—a Mr. Schulze, or Müller, or Schmidt. What's the name of the captain who came with you?"

"Schmidt, Reinhold Schmidt."

"No, you're joking!"

"Indeed, I'm not; but he's not a captain."

"Not a Captain! What then?"

"A sea captain."

"Of the Marine?"

"A simple sea captain."

"Oh, dear me!"

That came out so comically, and Mieting clapped her hands with such a naïve surprise, that Else had to laugh, and the more so as she could thus best conceal the blush of embarrassment which flushed her face.

"Then he will not even take supper with us!" exclaimed Mieting.

"Why not?" asked Else, who had suddenly become very serious again.

"A simple captain!" repeated Mieting; "too bad! He's such a handsome man! I had picked him out for myself! But a simple sea captain!"

Madame von Strummin entered the room to escort the ladies to supper. Mieting rushed toward her mother to tell her her great discovery. "Everything is already arranged," replied her mother. "The Count asked your father and the President whether they wished the captain to join the company. Both of the gentlemen were in favor of it, and so he too will appear at supper. And then, too, he seems so far to be a very respectable man," concluded Madame von Strummin.

"I'm really curious," said Mieting.

Else did not say anything; but when at the entrance of the corridor she met her father, who had just come from his room, she whispered to him, "Thank you!"

"One must keep a cheerful face in a losing game," replied the General in the same tone.

Else was a bit surprised; she had not believed that he would so seriously regard the question of etiquette, which he had just decided as she wished. She did not reflect that[Pg 38] her father could not understand her remark without special explanation, and did not know that he had given to it an entirely different meaning. He had been annoyed and had allowed his displeasure to be noticed, even at the reception in the hall. He supposed that Else had observed this, and was now glad that he had meanwhile resolved to submit quietly and coolly to the inevitable, and in this frame of mind he had met her with a smile. It was only the Count's question that reminded him again of the young sea captain. He had attached no significance either to the question or to his answer, that he did not know why the Count should not invite the captain to supper.

Happily for Reinhold, he had not had even a suspicion of the possibility that his appearance or non-appearance at supper could be seriously debated by the company.

"In for a penny, in for a pound," he said to himself, arranging his suit as well as he could with the aid of the things which he had brought along in his bag from the ship for emergencies. "And now to the dickens with the sulks! If I have run aground in my stupidity, I shall get afloat again. To hang my head or to lose it would not be correcting the mistake, but only making it worse—and it is already bad enough. But now where are my shoes?"

In the last moment on board he had exchanged the shoes which he had been wearing for a pair of high waterproof boots. They had done him excellent service in the water and rain, in the wet sand of the shore, and on the way to the tenant-farm—but now! Where were the shoes? Certainly not in the traveling bag, into which he thought he had thrown them, but in which they refused to be found, although he finally, in his despair, turned the whole contents out and spread them about him. And this article of clothing here, which he had already taken up a dozen times and dropped again—the shirt bosoms were wanting! It was not the blue overcoat! It was the black evening coat, the most precious article of his wardrobe, which he was accustomed to wear only to dinners at the ship-owners',[Pg 39] the consul's, and other formal occasions! Reinhold sprang for the bell—the rotten cord broke in his hand. He jerked the door open and peered into the hall—no servant was to be seen; he called first softly and then more loudly—no servant answered. And yet—what was to be done! The coarse woolen jacket which he had worn under his raincoat, and had, notwithstanding, got wet in places had been taken away by the servant to dry. "In a quarter of an hour," the man had said, "the Count will ask you to supper." Twenty minutes had already passed; he had heard distinctly that the President, who was quartered a few doors from his room, had passed through the hall to go downstairs; he would have to remain here in the most ridiculous imprisonment, or appear downstairs before the company in the most bizarre costume—water-boots and black dress suit—before the eyes of the President, whose long, lean figure, from the top of his small shapely head to his patent-leather tips, which he had worn even on board ship, was the image of the most painful precision—before the rigorous General, in his closely buttoned undress uniform—before the Count, who had already betrayed an inclination to doubt his social eligibility—before the ladies!—before her—before her mischievous brown eyes! "Very well," he concluded, "if I have been fool enough to follow the glances of these eyes then this shall be my punishment, I will now do penance—in a black dress coat and water-boots."