This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: In Byways of Scottish History

Author: Louis A. Barbé

Release Date: May 26, 2014 [eBook #45766]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IN BYWAYS OF SCOTTISH HISTORY***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/inbywaysofscotti00barbrich |

——————

——————

——————

By

LOUIS A. BARBÉ B.A.

Officier d'Académie

Author of "The Tragedy of Gowrie House" "Viscount Dundee"

"Kirkcaldy of Grange" etc.

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW BOMBAY

1912

————

When the author of the following papers came to Scotland, many years ago, he knew nothing of the country that was to become his home, and was hardly less ignorant of its history. To acquire some acquaintance with both he followed the same plan: he began with the highways, as indicated, in the one case, by the advertisements of the railway and steamboat companies, and, in the other, by the works of Tytler and Hill Burton. Before long, however, he learned that the knowledge thus obtained might be pleasantly supplemented by independent excursions off the beaten track. Topographically the result was the discovery of charming bits of scenery, of which he still recalls the picturesque beauty with delight. Historically, too, he found his way into interesting nooks and corners which his early guides had either ignored entirely or contented themselves with referring to in the briefest words. The outcome of some of his explorations—if it be not presumptuous to apply such a term to them—is set forth in the present volume. In venturing to publish it, he is not without a hope that the interest which he has felt in his rambles through some of the byways of Scottish history may, to some extent, be shared by others. If he should be disappointed in this, he will have to admit that he has done less than justice to subjects that had it in them to be made pleasant and attractive.

Those subjects are varied, but, as regards most of them, not wholly unconnected. Dealing, as they mainly do, with the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, they have, at least, a certain chronological unity, and may, in [Pg vi] some slight degree, help to supplement the general knowledge of one of the most picturesque periods in the history of Scotland.

What has so far been said does not, it must be allowed, apply very directly to one of the papers contained in the present collection. It cannot be claimed for the "Longtail" myth, of which the story is here given, that it is essentially Scottish. It may, however, be urged in support of its right to appear here, that it was French at a time when, as regards antipathy against England, the agreement between France and Scotland was a very close one. And, if further justification be needed, it may be found in the fact that some of the Scottish chroniclers are amongst those who supply the most valuable information concerning both the prevalence and the alleged origin of the quaint medieval belief that Englishmen had tails inflicted on them in punishment of the impiety of some of their pagan forefathers.

In connection with this paper the author has the pleasant duty of expressing his thanks to Dr. George Neilson, to whom he is indebted for several illustrative passages; and also to Mr. Barwick, of the British Museum, without whose ready help a number of others would have remained inaccessible.

Some of the papers have appeared, mostly in a condensed form, in the Glasgow Herald and the Evening Times, and thankful acknowledgment is made of the permission readily granted to make further use of them.

Responsibility is admitted, at the same time that indulgence is craved, for the translations of old French poetry and medieval Latin verse which occur in some of the sketches.

In the case of the latter, more particularly, it has not always proved an easy task to supply English versions of the monkish doggerel. It is hoped, however, that if the letter has been freely dealt with, the spirit has been preserved.

————

| Page | |

| Mary, Queen of Scots | 1 |

| The Four Marys | 25 |

| Mary Fleming | 35 |

| Mary Livingston | 49 |

| Mary Beton | 61 |

| Mary Seton | 69 |

| The Song of Mary Stuart | 79 |

| Maister Randolphe's Fantasie | 91 |

| The First "Stuart" Tragedy and its Author | 129 |

| Loretto | 141 |

| The Isle of May | 153 |

| Edinburgh and Her Patron Saint | 191 |

| The Rock of Dumbarton | 199 |

| James VI as Statesman and Poet | 209 |

| The Invasion of Ailsa Craig | 225 |

| The Story of a Ballad—"Kinmont Willie" | 237 |

| A Raid on the Wee Cumbrae | 247 |

| Riotous Glasgow | 253 |

| The Old Scottish Army | 267 |

| The Story of the "Long-tail" Myth | 291 |

| Index | 361 |

More than three hundred years have elapsed since Mary Stuart was sent to the scaffold by Elizabeth, and met death with that noble fortitude which awed her enemies and which has half redeemed her fame in the eyes even of those who regard the tragedy of Fotheringay as an act no less of justice than of expediency. But even at the present time interest in her memory has not died away; nor can the question of her innocence or of her guilt be yet said to have been definitely settled by all that has been written about her in the interval. It hardly seems probable that it ever will be, for it is still a question of politics with some and of religion with many. And even in the rare instances where judgment is not blinded by the prejudice or the partiality of party or of creed, it is affected by an influence, nobler and more excusable [Pg 2] indeed, but not less powerful nor less misleading—by unreasoning sentiment, by the sympathy which the romance of the unfortunate Queen's chequered career, her legendary beauty, her long captivity, and her heroic death awaken.

In the controversy which has now raged for three centuries, and in the course of which every incident of Mary's life has repeatedly been submitted to the closest scrutiny, anxiety to get at facts, to add to the weight of evidence, to discover fresh witnesses, to unearth new documents bearing on the points at issue, has led to a disregard of her personality more complete, perhaps, than in the case of any of her contemporaries, and contrasting strangely with the abundance of intimate details which go to make up our knowledge of her great rival. To most of us Elizabeth is as distinctly, almost tangibly, present as though she had reigned in our day. She moves through the pages of history surrounded by a train of courtiers scarcely less familiar to us than those of our own generation. The Queen of Scots, on the contrary, seems to be but little more than an historical abstraction. It is scarcely too much to say that many for whom it would be an easy task to follow her, step by step, from Linlithgow to Fotheringay, to recall all the events of which she was the central figure, to discuss all the problems which her name suggests, would be at a loss to furnish such details as could bring before us the features of the woman whose beauty doubtless finds frequent mention in their discourses, or bring together such particulars as would [Pg 3] justify all that they are ready to admit, and perhaps even to assert, concerning her talents and her accomplishments. It may, therefore, be neither inopportune nor uninteresting if, forgetting for a while the history of the Queen, we give our attention to the individuality of the woman; if, turning to the "treasures of antiquity laid up in old historic rolls", we endeavour, not to clear up the mystery of Darnley's murder, nor to explain the fatal marriage with Bothwell; not to pronounce on the authenticity of the sonnets, nor to solve the enigma of the famous letters; but to present a picture of the first lady of the land as she appeared to the crowds that had hurried to Leith to welcome her return, or that lined the Canongate as she rode to the Parliament House; to show her at her sports with her attendant Marys at Stirling or at St. Andrews; to listen to the conversation with which she entertained the courtiers of Amboise and of Holyrood, and to glance at the pages of the volumes over which she mused in the retirement of her library or the solitude of her prison.

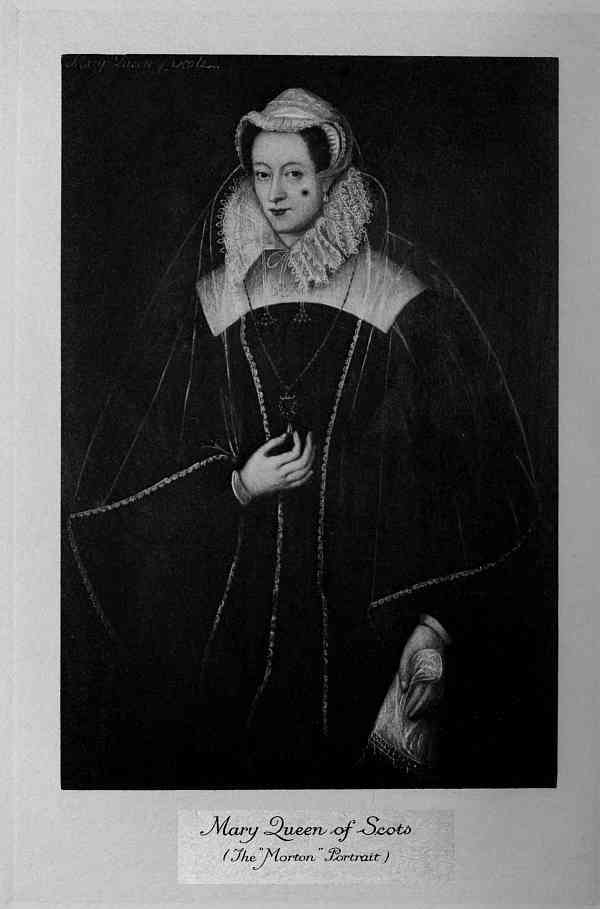

The historians of Mary Stuart all agree in telling us that she was the most beautiful woman of her age; and it must be admitted that this is fully borne out by all that can be gathered from contemporary writers. It is not only such poetic enthusiasts as Michel de l'Hôpital, Du Bellay, and Ronsard, or such courtly flatterers as Brantôme and Castelnau, who pronounce her beauty to have been matchless—far exceeding "all that is, shall be, or has ever been", but the serious and dignified chroniclers [Pg 4] whom Jebb has brought together in his valuable folios—Strada, Blackwood, and even de Thou—also grow eloquent in praise of her charms. But perhaps the most convincing testimony that can be adduced is contained in a poem,[1] composed by an Englishman who was confessedly hostile to Mary, and whose satire was so keenly felt by her that she made it the subject of a formal complaint to Elizabeth. The words attributed to her—for the passage in which they occur is in the form of a confession on her part—are scarcely less forcible than those of her avowed partisans and admirers:

It is most remarkable, however, that no extant portrait justifies the praises so lavishly bestowed on Mary. As to this, the courtesy of the late Mr. Wylie Guild, of Glasgow, afforded us an opportunity of forming an opinion based on the evidence of his remarkable collection of portraits of the Queen of [Pg 5] Scots—a collection which comprised, besides reproductions of most of the paintings claiming to be authentic, a series of over four hundred engravings, many of them by Clouet, and dating from the period of Mary's stay in France. We were compelled to agree with the possessor of that unique iconography that none of them showed the dazzling charms which poets and chroniclers have celebrated. And the portraits which various exhibitions have since then enabled us to examine, have only confirmed that earlier judgment. To reconcile this very striking contradiction seems difficult. Possibly the truth may be that the fascination of Mary's face consisted less in the regularity of outline or the striking beauty of any one feature than in the expression by which it was animated.[2] Her complexion, though likened by [Pg 6] Ronsard to alabaster and ivory,[3] does not seem to have possessed the clearness and brilliancy which the comparison implies; for Sir James Melville, though anxious to vindicate his Queen's claim to be considered "very lovely" and "the fairest lady in her country", acknowledged that she was less "white" than Elizabeth.[4] The brightness of her eyes, which Ronsard likened to stars, and Chastelard to beacons,[5] has not been questioned; but their colour is a point about which there is less unanimity, opinions varying between hazel and dark grey. As regards her hair the discrepancy of contemporary authorities is even greater. Brantôme and Ronsard describe a wealth of golden hair, and this is to a certain extent confirmed by Sir James Melville, who, when called upon by Elizabeth to pronounce whether his Queen's hair was fairer than her own, [Pg 7] answered that "the fairnes of them baith was not their worst faltes".[6] To this, however, must be opposed the testimony of Nicholas White, who, writing to Cecil in 1563, described the Queen as black-haired. The explanation of this may possibly lie in Mary's compliance with the fashion, introduced about this time, of wearing wigs. Indeed, Knollys informed White that she wore "hair of sundry colours",[7] and, in a letter to Cecil, praised the skill with which Mary Seton—"the finest busker of hair to be seen in any country"—"did set such a curled hair upon the Queen, that was said to be a perewyke, that showed very delicately".[8]

According to one account, the Queen of Scots wore black, according to another, auburn ringlets on the morning of her execution. Both, however, agree in this, that when the false covering fell she "appeared as grey as if she had been sixty and ten years old".

Mary's hand was white, but not small, the long, tapering fingers mentioned by Ronsard[9] being, indeed, a characteristic of some of her portraits. She was of tall stature, taller than Elizabeth, which made the Queen of England pronounce her cousin to be too tall, she herself being, according to her own standard, "neither too high nor too low".[10] Her voice was irresistibly soft and sweet. Not only [Pg 8] does Brantôme extol it as "trés douce et trés bonne",[11] and Ronsard poetically celebrate it as capable of moving rocks and woods,[12] but Knox, although ungraciously and unwillingly, also testifies to its charm. He informs us that, at one of her Parliaments, the Queen made a "paynted orisoun", and that, on this occasion, "thair mycht have been hard among hir flatteraris, 'Vox Dianæ!' The voice of a goddess (for it could not be Dei) and not of a woman! God save the sweet face! Was thair ever oratour spack so properlie and so sweitlie!"[13]

When, to this description, we have added that Mary Stuart was of a full figure[14] and became actually stout in later life; that she is described in the report of her execution and represented in several portraits as having a double chin, we shall have given a picture of her which, though wanting in some details, is as complete as it is possible to sketch at this length of time.

Mary Stuart is not infrequently mentioned as one of the precocious children of history. But the legend of her scholarly acquirements originates with Brantôme, an authority not always above suspicion when the glorification of princes is his theme, and it is not unnecessary to look more closely into the matter before we accept his glowing panegyric of the youthful prodigy. He informs us that Mary was "very learned in Latin",[15] and that, when only [Pg 9] thirteen or fourteen years of age, she publicly delivered at the Louvre, in the presence of King Henry II, Catherine de' Medici, his Queen, and the whole French Court, a Latin discourse which she had composed in justification of her own course of studies, and in support of the view that it is befitting in women to devote themselves to letters and to the liberal arts. This speech is also referred to by Antoine Fouquelin in the dedication of a textbook of Rhetoric which he composed for the young Princess.[16] He records the admiration with which Mary had been listened to by the noble company, and the high hopes which the elegant oration had awakened. That she herself set some value on this production may be assumed from the fact that she was at the pains of translating it into French; and the mention of it in the inventory of books delivered by the Earl of Morton to James VI in 1578, where it appears as "ane Oratioun to the King of Franche of the Quenis awin hand write", would seem to imply that she looked back with pride upon her youthful triumph. This interesting manuscript has now disappeared; nevertheless, it is not impossible to obtain from another source a fairly accurate idea of the speech which called forth such high praise from the French courtiers. It happens that the National Library in Paris possesses the Latin themes written by Mary Stuart in 1554, the year before the oratorical performance at the Louvre. Amongst the exercises contained in the [Pg 10] morocco-bound volume, fifteen refer to the same subject as the speech, and, it is fair to suppose, were intended as a preparation for the princely pupil's "speech-day".[17] Disappointing as it may be to ardent admirers of the Queen of Scots, it must be admitted that her themes do not bear out the praises bestowed on her Latinity, but contain such solecisms as would probably have been fraught with unpleasant consequences to a less noble and less fair scholar. Neither need the substance of Mary's apology for learned women excite our enthusiasm. To string together, with a few commonplace remarks, lists of names evidently supplied by her tutor and taken by him from Politian's Epistles, was no very remarkable achievement on the part of a child who, if she began her classical studies as early as her fellow pupil and sister-in-law Elizabeth did, had already devoted fully five years to Latin at the date of her famous speech.

But, though the Queen's early proficiency may have been overrated, there can be no doubt that, in later life, she possessed considerable familiarity with the language of Virgil and of Cicero. We know from contemporary letters that, after her return to Scotland, she continued her studies under Buchanan[18] and that, faithful to the habit which she had acquired in France, of devoting two hours a day to her books,[19] she regularly read "somewhat of Livy" with him "after her dinner".

[Pg 11] The catalogue of the books[20] contained in the royal library affords further information as to the nature and extent of her acquaintance with Latin literature. In it we find mention, amongst others of lesser note, of Horace, Virgil and Cicero, of Æmilius Probus and Columella, of Vegetius and Boethius. Neither did she neglect the Latinity of the Middle Ages. In prose it is represented by such forgotten names as those of Bertram of Corvey, of Ludolph of Saxony, of Joannes de Sacrobosco, and of Nicolaus de Clamangiis, the authors of ponderous treatises on science and on theology; the latter subject being one which her interest in the great ecclesiastical revolution of the age rendered particularly attractive to her. Amongst contemporary Latin poets her favourites seem to have been Petrus Bargæus, Louis Leroy, Sir Thomas Craig of Riccarton, and George Buchanan, whose dedication to her of his translation of the Psalms has not unjustly been pronounced to stand "unsurpassed by all the verses that have been lavished upon her during three hundred years by poets of almost every nation and language of Europe".[21]

Whether the Queen of Scots was acquainted with Greek cannot be determined with certainty. Neither Brantôme nor Con nor Blackwood has given information on this head. If, on the one hand, her numerous Latin and French translations of Greek authors do not point to a great familiarity with it, [Pg 12] on the other, the knowledge that she used such versions for the purpose of linguistic study, and the presence on her shelves of Homer and Herodotus, of Sophocles and Euripides, of Socrates and Plato, of Demosthenes and Lucian in the original tongue, justify the supposition that, even though she may not have rivalled the fair pupils of Ascham and of Aylmer, the productions of Athenian genius were not sealed books to her.

Amongst modern languages Spanish was that with which Mary had the slightest acquaintance, and so far as may be judged from the works which she possessed, her reading in it was limited to a book of chronicles and a collection of ballads.[22] As might be expected from her early surroundings, she was more familiar with Italian. She could both speak and write it. Indeed, among the verses attributed to her there is an Italian sonnet addressed to Elizabeth. It is scarcely credible that she had not read Dante; nevertheless, it is worthy of notice that his "Divine Comedy" does not appear in the catalogue of her library[23] where, however, Petrarch, Boccaccio, and Ariosto figure by the side of the less-known Bembo.

Though born in Scotland, Mary Stuart never possessed great fluency in the language of the country over which she was called to rule. Her knowledge of it was acquired chiefly, if not wholly, after her return from France. Her father, from [Pg 13] whom she might have learnt it in childhood, she never knew. For her mother the northern Doric remained through life a foreign tongue. The attendants with whom she was surrounded in her earliest infancy were either French or had been educated in France. It is therefore questionable whether she could express herself in what was nominally her native tongue, even when she sailed from Dumbarton on her journey to the court of the Valois. That she forgot whatever she may then have known of it is beyond doubt. Seven years after she had left France she was still making efforts to learn English, using translations—amongst others an English version of the Psalms—for the purpose, but not meeting with signal success. Conversing with Nicholas White, in 1569, she began with excuses for "her ill English, declaring herself more willing than apt to learn the language".[24] It was on the 1st of September of the preceding year that she wrote what she herself describes as her first letter in English. This circumstance may warrant its reproduction, though as an historical document merely, it possesses no importance. It is addressed to Sir Francis Knollys: "Mester Knollis, y heuu har sum neus from Scotland; y send zou the double off them y vreit to the quin my gud sister, and pres zou to du the lyk, conforme to that y spak zesternicht vnto zou, and sut hesti ansur y refer all to zour discretion, and wil lipne beter in zour gud delin for mi, nor y kan persuad zou, nemli in this langasg; excus my iuel [Pg 14] vreitin for y neuuer vsed it afor, and am hestet.... Excus my iuel vreitin thes furst tym."[25]

The testimony of Mary's library,[26] to which we have already appealed, and which is the more valuable and the more trustworthy that the books which it contained were undoubtedly collected by herself and for her own use, bears out what has been so often stated with regard to her love of French literature. In history it shows her to have been acquainted not only with the foremost chroniclers; not only with Froissart, in whose picturesque narrative her native Scotland is mentioned with such grateful remembrance of the hospitality shown him; not only with Monstrelet, from whose ungenerous treatment of the heroic Joan of Arc she may have learnt, even before her own experience taught her the hard lesson, how the animosity of party can blunt all better feeling; but also with the lesser writers, with those whose works never reached celebrity even in their own day and whose names have long ceased to interest posterity, with Aubert and Bouchet, Sauvage and Paradin.

It may be regarded as a proof of her good taste that she set but little store on the dreary romances of the time, written either in imitation or in continuation of "Amadis de Gaul", whilst to Rabelais,[27] on the contrary, she accorded the place of honour which he deserved.

[Pg 15] As regards the poets of France, all that Brantôme has told us of her partiality for them finds its justification in the almost complete collection of their works which she brought to Scotland with her. Amongst all others, however, Du Bellay, Maison-Fleur, and Ronsard were her special favourites. For the last, in particular, her enthusiasm was unbounded. It was to the verses in which he embodies the love of a whole nation that she turned for solace when the fresh sorrow of her departure from France was her heaviest burthen; it was over his pages that her tears flowed in the bitterness which knew no comfort as she sat a lonely captive in the castles of Elizabeth. As a token of her admiration she sent him from her prison a costly service of plate with the flattering inscription: "A Ronsard, l'Apollon des Français".[28]

It has been asserted by Brantôme, and repeated ever since on his authority, that Mary Stuart herself excelled in French verse. The elegiac stanzas quoted by him have been admired in all good faith by succeeding generations "for the tender pathos of the sentiments and the original beauty of the metaphors". It is painful to throw discredit on the time-honoured tradition, but the late discovery of a manuscript once in Brantôme's possession has proved, beyond the possibility of a doubt, that the "Elegy on the Death of Francis II" was not composed by his wife. This was at once established by Dr. Galy of Périgueux, the possessor of the manuscript. [Pg 16] Having since then been favoured by him with a copy of other poems contained in it and acknowledged by Brantôme as his own productions, and having compared them carefully with the "pathetic sentiments" and "original metaphors", as well as with the expressions and even the rhymes of the Elegy, we have no hesitation in going a step further, and pronouncing that the latter is from the pen of the unscrupulous Lord Abbot himself.[29] Apart from this, there still remain a few poems attributed to Mary, and authenticated, not indeed by her signature, but by what is almost as authoritative, her anagrams: "Sa vertu m'atire", or "Va, tu meriteras".[30] However interesting these poetical effusions may be as relics, their literary merit is of no high order, and they are assuredly not such as to deserve for the author a place amongst the poets of her century.

Before closing our remarks on Mary Stuart's scholarship and literary acquirements we would dwell for a moment on the subject of her handwriting, for that too has been made the subject of admiring comment by some of her biographers. Con has recorded that "she formed her letters elegantly and, what is rare in a woman, wrote swiftly".[31] [Pg 17] Some reason for his admiration may be found in the fact that Mary had adopted what Shakespeare styles "the sweet Roman hand", which at that time was only beginning to take the place of the old Gothic, and, in Scotland particularly, had all the charm of a fashionable novelty. The specimen now before us shows a bold, rather masculine hand, of such size that five short words—"mon linge entre mes fammes"—fill a line six inches long. The letters are seldom joined together, and the words are scattered over the page with untutored irregularity and disregard for straight lines. On the whole we cannot but allow the force of Pepys' exclamation on being shown some of the Queen's letters: "Lord! How poorly methinks they wrote in those days, and on what plain uncut paper!"[32]

Our sketch of Mary Stuart would not be complete if we limited ourselves to the more serious side of her character merely. If she did not deserve the reputation for utter thoughtlessness and frivolity which some of her puritanical contemporaries have given her, she was undoubtedly fond of amusements. The memoirs and correspondence of the time often show her seeking recreation in popular sports and pastimes; indeed, Randolph describes life at the Scottish Court for the first two years after her return from France as one continual round of "feasts, banquetting, masking, and running at the ring, and such like".[33] It was to Mary, as Knox testifies, that [Pg 18] the introduction into Scotland of those primitive dramatic performances known as Masques or Triumphs was due. They soon became so popular that they formed the chief entertainment at every festival. The Queen herself and her attendants, particularly the four Marys, often took part in them, either acting in mere dumb show or reciting the verses which the elegant pen of Buchanan supplied, and singing the songs which Rizzio composed, and of which the melodies may very possibly be those which, wedded to more modern verse, are still popular amongst the Scottish peasantry. Not only were these masques performed in the large halls of the feudal castles, but in the open air also, near the little lake at the foot of Arthur's Seat. It may cause some astonishment at the present day to find not only the maids of honour, but even the Queen herself, assuming the dress of the other sex in these masquerades. Yet the Diurnal of Occurrents[34] records, without expressing either indignation or even astonishment at the fact, that "the Queen's Grace and all her Maries and ladies were all clad in men's apparel" at the "Maskery or mumschance" given one Sunday evening in honour of the French Ambassador.

Like her cousin of England, Mary was fond of dancing, and, as her Latin biography informs us, showed to great advantage in it.[35] From a passage quaintly noted as "full of diversion" in Sir James Melville's Memoirs, we learn that the knight being [Pg 19] pressed by Queen Elizabeth to declare whether she or his own sovereign danced best, answered her with courtly ambiguity that "the Queen dancit not so hich and so disposedly as she did".[36] In reply to the same royal enquirer he also stated that Mary "sometimes recreated herself in playing upon the lute and virginals", and that she played "reasonably for a queen", not so well, however, as Elizabeth herself.[37] We gather from Con[38] and Brantôme that her voice was well trained, and that she sang well.

The indoor amusements in favour at Holyrood were chess, which James VI condemned as "over wise and philosophic a folly",[39] tables, a game probably resembling backgammon, and cards. That these last were not played for "love" merely, is shown by an entry in the Lord Treasurer's accounts of "fyftie pundis" for Her Majesty "to play at the cartis".[40] Puppets or marionettes were also in great vogue. A set of thirty-eight, together with a complete outfit of "vardingaills", "gownis", "kirtillis", "sairkis slevis", and "hois", is mentioned in an inventory of the time, where we see these "pippenis"—an old Scottish corruption of the French "poupine"—dressed in such costly stuffs as damask brocaded with gold, cloth of silver, and white silk.[41]

[Pg 20] Quieter employment for the leisure hours of the Queen and her ladies was supplied by various kinds of fancy-work, amongst which knitting and tapestry are particularly mentioned. To the latter she devoted much of her time, both at Lochleven, where she requested to be allowed "an imbroiderer, to draw forth such work as she would be occupied about",[42] and in England. Whilst she was at Tutbury, Nicholas White once asked her how she passed her time within doors when the weather cut off all exercises abroad. She replied "that all that day she wrought with her needle, and that the diversity of the colours made the work seem less tedious, and continued so long at it till very pain made her to give over.... Upon this occasion she entered into a pretty disputable comparison between carving, painting, and working with the needle, affirming painting, in her own opinion, for the most commendable quality."[43]

At his interview with Elizabeth, Sir James Melville was asked what kind of exercises his Queen used. He answered, that when he received his dispatch, the Queen was lately come from the Highland hunting. Her undaunted behaviour on this occasion is recorded by an eyewitness, Dr. William Barclay of Gartley, who tells us that she herself gave the signal for letting the hounds loose upon a wolf, and that in one day's hunting three hundred and sixty deer, five wolves, and some wild goats were slain.[44]

[Pg 21] In common with her father, who took great pains to introduce "ratches" or greyhounds and bloodhounds into Scotland, and with her great-grandson, Charles II, who gave his name to a breed of spaniels, Mary Stuart shared a great fondness for dogs. In her happier days she always possessed several, which she entrusted to the keeping of one Anthone Guedio and a boy. These canine pets were provided with a daily ration of two loaves, and wore blue velvet collars as a distinguishing badge.[45] During her captivity, her dogs were amongst her most faithful companions. Writing from Sheffield to Beton, Archbishop of Glasgow, she said: "If my uncle, the Cardinal of Guise, has gone to Lyons, I am sure he will send me a couple of pretty little dogs, and you will buy me as many more; for, except reading and working, my only pleasure is in all the little animals that I can get. They must be sent in baskets well-packed, so as to keep them warm."[46] The fidelity of one of these dumb friends adds to the pathos of the last scene of her sad history. "One of the executioners," says a contemporary report, "pulling off her clothes, espied her little dog which was crept under her clothes, which would not be gotten forth but by force, and afterwards would not depart from the dead body, but came and lay betwixt her head and shoulders, a thing diligently noted."[47]

[Pg 22] In recording one of his interviews with Queen Mary, Knox gives us information concerning another of the sports with which she beguiled her time, for he tells us that it was at the hawking near Kinross that she appointed him to meet her.[48] Archery, too, seems to have been a favourite amusement. She had butts both at Holyrood and St. Andrews. Writing to Cecil in 1562, and again in 1567, Randolph informs him that the Queen and the Master of Lindsay shot against Mary Livingston and the Earl of Murray; and that, in another match, the Queen and Bothwell won a dinner at Tranent from the Earl of Huntley and Lord Seton.[49] Neither did she neglect the "royal game", for one of the charges brought against her and embodied in the articles given in by the Earl of Murray to Queen Elizabeth's commissioners at Westminster, stated that a few days after Darnley's murder "she past to Seytoun, exercing hir one day richt oppinlie at the feildis with the pallmall and goif".

To sketch Mary's character further would be trenching on debatable ground and overstepping the limits which we have imposed upon ourselves. There is one trait, however, which may be recorded on the authority even of her enemies—her personal courage. Randolph represents her as riding at the head of her troops "with a steel bonnet on her head, and a pistol at her saddle-bow; regretting that she was not a man to know what life it was to lie all night in the fields, or to walk upon the causeway with a jack and a knapscull, a Glasgow buckler, [Pg 23] and a broadsword". The author of the poem preserved in the Record Office, to which we have already made reference, allows that "no enemy could appal her, no travail daunt her intent", that she "dreaded no danger of death", that "no stormy blasts could make her retire", and he likens her to Tomiris:

But never, surely, was her fortitude shown more clearly to the world than when, three hundred years ago, "she laid herself upon the block most quietly, trying her chin over it, stretching out her hands, and crying out: 'In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum'".

Reference is seldom made to the Queen's Marys, the four Maids of Honour whose romantic attachment to their royal mistress and namesake, the ill-fated Queen of Scots, has thrown such a halo of popularity and sympathy about their memory, without calling forth the well-known lines:

To those who are acquainted with the whole of the ballad, which records the sad fate of the guilty Mary Hamilton, it must have occurred that there is a striking incongruity between the traditional loyalty of the Queen's Marys and the alleged execution of one of their number, on the denunciation of the offended Queen herself, for the murder of an illegitimate child, the reputed offspring of a criminal intrigue with Darnley. Yet a closer investigation of the facts assumed in the ballad leads to a discovery more unexpected than even this. It establishes, beyond the possibility of a doubt, that, of the four family-names given in the stanza as those of [Pg 26] the four Marys, two only are authentic. Mary Carmichael and Mary Hamilton herself are mere poetical myths. Not only does no mention of them occur in any of the lists still extant of the Queen's personal attendants, but there also exist documents of all kinds, from serious historical narrative and authoritative charter to gossiping correspondence and polished epigram, to prove that the colleagues of Mary Beton and Mary Seton were Mary Fleming and Mary Livingston. How the apocryphal names have found their way into the ballad, or how the ballad itself has come to be connected with the Maids of Honour, cannot be determined. There is, however, in Knox's History of the Reformation, a passage which has been looked upon as furnishing a possible foundation of truth to the whole fiction. It is that in which he records the commission and the punishment of a crime similar to that for which Mary Hamilton is represented as about to die on the gallows. "In the very time of the General Assembly there comes to public knowledge a haynous murther, committed in the Court; yea, not far from the queen's lap: for a French woman, that served in the queen's chamber, had played the whore with the queen's own apothecary. The woman conceived and bare a child, whom with common consent, the father and mother murthered; yet were the cries of a new-borne childe hearde, searche was made, the childe and the mother were both apprehended, and so was the man and the woman condemned to be hanged in the publicke [Pg 27] street of Edinburgh. The punishment was suitable, because the crime was haynous."[50] Between this historical fact—for the authenticity of which we have also the testimony of Randolph[51] —and the ballad, which substitutes Darnley and one of the Maids of Honour for the queen's apothecary and a nameless waiting-woman, the connection is not very close. Indeed, there is but one point on which both accounts are in agreement, though that, it is true, is an important one. The unnatural mother whose crime, with its condign punishment, is mentioned by the historian, was, he says, a French woman. The Mary Hamilton of the ballad, in spite of a name which certainly does not point to a foreign origin, is also made to come from over the seas:

[Pg 28] It does not, however, come within the scope of the present paper to examine more closely into the ballad of Mary Hamilton. It suffices to have made it clear that, whatever be their origin, the well-known verses have no historical worth or significance, and no real claim to the title of "The Queen's Marie" prefixed to them in the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.[52] Except for the purpose of correcting the erroneous, but general belief, which has been propagated by the singular and altogether unwarranted mention of the "Four Marys", and the introduction of the names of two of them in the oft-quoted stanza, there would, in reality, be no necessity for any allusion to the popular poem in a sketch of the career of the fair Maids of Honour, whose touching fidelity through good and evil fortune has won for them a greater share of interest than is enjoyed by any of the subordinate characters in the great historical drama of which their royal mistress is the central figure.

The first historical and authoritative mention of the four Marys is from the pen of one who was personally and intimately acquainted with them—John Leslie, Bishop of Ross. It occurs in his description of the departure of the infant Mary Stuart from the small harbour at the foot of the beetling, castle-crowned rock of Dumbarton, on that memorable voyage which so nearly resembled a flight. "All things being reddy for the jornay," writes the chronicler, in his quaint northern idiom, "the Quene being as than betuix fyve and sax yearis of aige, wes delivered [Pg 29] to the quene dowarier hir moder, and wes embarqued in the Kingis awin gallay, and with her the Lord Erskyn and Lord Levingstoun quha had bene hir keparis, and the Lady Fleming her fadir sister, with sindre gentilwemen and nobill mennis sonnes and dochteres, almoist of hir awin age; of the quhilkes thair wes four in speciall, of whom everie one of thame buir the samin name of Marie, being of four syndre honorable houses, to wyt, Fleming, Levingstoun, Seton and Betoun of Creich; quho remainit all foure with the Quene in France, during her residens thair, and returned agane in Scotland with her Majestie in the yeir of our Lord ImVclxi yeris."[53] Of the education and early training of the four Marys, as companions and playmates of the youthful queen, we have no special record. The deficiency is one which our knowledge of the wild doings of the gayest court of the age makes it easy to supply. For the Scottish maidens, as for their mistress, intercourse with the frivolous company that gathered about Catherine de' Medici was but indifferent preparation for the serious business of life. Looking back on "those French years", doubtless they too, like her, "only seemed to see—

[Pg 30] Brantôme, to whom we are indebted for so much personal description of Mary Stuart, and so many intimate details concerning her character, tastes, and acquirements, is less communicative with respect to her four fair attendants. He merely mentions them amongst the court beauties as "Mesdamoiselles de Flammin, de Ceton, Beton, Leviston, escoissaises".[54] He makes no allusion to them in the pathetic description of the young queen's departure from her "sweet France" on the fateful 24th of August, a date which subsequent events were destined to mark with a fearful stain of blood, in the family to which she was allied. Yet, doubtless they, too, were gazing with tearful eyes at the receding shore, blessing the calm which retarded their course, trembling with vague fears as their voyage began amidst the cries of drowning men, and half wishing that the English ships of the jealous Elizabeth might prevent them from reaching their dreary destination. That they were with their royal namesake, we know. Leslie, who, with Brantôme and the unfortunate Chastelard, accompanied the idol of France to her unsympathetic northern home, again makes special note of "the four maidis of honour quha passit with hir Hienes in France, of her awin aige, bering the name everie ane of Marie, as is befoir mencioned".

During the first years of Mary Stuart's stay in her capital, the four maids of honour played conspicuous parts in all the amusements and festivities of the court, and were amongst those who incurred [Pg 31] the censure of the austere Reformers for introducing into Holyrood the "balling, and dancing, and banquetting"[55] of Amboise and Fontainbleau. Were our information about the masques acted at the Scottish Court less scanty, we should, doubtless, often find the names of the four Marys amongst the performers. Who more fit than they to figure in the first masque represented at Holyrood, in October, 1561, at the Queen's farewell banquet to her uncle, the Grand Prior of the Knights of St. John, and to take their places amongst the Muses who marched in procession before the throne, reciting Buchanan's flattering verses in praise of the lettered court of the Queen of Scots?

Had Marioreybanks given us the names of those who took part in the festivities which he describes as having taken place on the occasion of Lord Fleming's marriage, can we doubt that the Marys would have been found actively engaged in the open-air performance "in the Parke of Holyroudhous, under Arthur's Seatt, at the end of the loche"?[56] Indeed, it is not matter of mere conjecture, but of authentic historical record, that on more than one occasion Buchanan did actually introduce the Queen's namesakes amongst the dramatis personæ of the masques [Pg 32] which, as virtual laureate of the Scottish Court, he was called upon to supply. The Diurnal of Occurrents mentions that "upoun the ellevint day of the said moneth (February) the King and Quene in lyik manner bankettit the samin (French) Ambassatour; and at evin our Soveranis maid the maskrie and mumschance, in the quhilk the Queenis Grace and all hir Maries and ladies were all cled in men's apperell; and everie ane of thame presentit ane quhingar, bravelie and maist artificiallie made and embroiderit with gold, to the said Ambassatour and his gentilmen, everie ane of thame according to his estate".[57] That this, moreover, was not the first appearance of the fair performers we also know, for it was they who bore the chief parts in the third masque acted during the festivities which attended the Queen's marriage with Darnley; and it was one of them, perhaps Mary Beton, the scholar of the court, who recited the verses which Buchanan had introduced in allusion to their royal mistress's recovery from some illness otherwise unrecorded in history:

That the four Nymphs mentioned in this, the only fragment of the masque which has been preserved, [Pg 33] were the four Marys, is explained by Buchanan's commentator, Ruddiman: "Nymphas his vocat quatuor Mariæ Scotæ corporis ministras, quæ etiam omnes Mariæ nominabantur". It is more than probable, too, that the Marys were not merely spectators of the masque which formed a part of the first day's amusements, and of which they themselves were the subject-matter. It may still be read under the title of "Pompa Deorum in Nuptiis Mariæ", in Buchanan's Latin poems. Diana opens the masque, which is but a short mythological dialogue, with a complaint to the ruler of Olympus that one of her five Marys—the Queen herself is here included—has been taken from her by the envious arts of Venus and of Juno:

In the dialogue which follows, and in which five goddesses and five gods take part, Apollo chimes in with a prophecy which was only partially accomplished:

[Pg 34] In his summing up, which, as may be imagined, is not very favourable to the complainant, the Olympian judge also introduces a prettily turned compliment to the Marys:

The whole pageant closes with an epilogue spoken by the herald Talthybius, who also foretells further defections from Diana's maidens:

As was but natural, the Queen's favourite attendants possessed considerable influence with their royal lady, and the sequel will show, in the case of each of them, how eagerly their good offices were sought after by courtiers and ambassadors anxious for the success of their several suits and missions. In a letter which Randolph wrote to Cecil on the 24th of October, 1564, and which, as applying to the Marys collectively, may be quoted here, we are shown the haughty Lennox himself condescending to make pretty presents to the maids with a view to ingratiating himself with the mistress. "He presented also each of the Marys with such pretty things as he thought fittest for them, such good means he hath to win their hearts, and to make his way to further effect."[58]

It is scarcely the result of mere chance that, in the chronicles which make mention of the four Marys, Mary Fleming's name usually takes precedence of those of her three colleagues. She seems to have been tacitly recognized as "prima inter pares". This was, doubtless, less in consequence of her belonging to one of the first houses in Scotland, for the Livingstons, the Betons, and the Setons might well claim equality with the Flemings, than of her being closely related to Mary Stuart herself, though the relationship, it is true, was only on the side of the distaff, and though there was, moreover, a bar sinister on the royal quarterings which it added to the escutcheon of the Flemings. Mary Fleming—Marie Flemyng, as she signed herself, or Flamy, as she was called in the Queen's broken English—was the fourth daughter of Malcolm, third Lord Fleming. Her mother, Janet Stuart, was a natural daughter of King James IV. Mary Fleming and her royal mistress were consequently first cousins. This may sufficiently account for the greater intimacy which existed between them. Thus, after Chastelard's outrage, it was Mary Fleming whom the Queen, dreading the loneliness which had rendered the wild attempt possible, called in to sleep with her, for protection.

[Pg 36] Amongst the various festivities and celebrations which were revived in Holyrood by Mary and the suite which she had brought with her from the gay court of France, that of Twelfth Night seems to have been in high favour, as, indeed, it still is in some provinces of France at the present day. In the "gâteau des Rois", or Twelfth Night Cake, it was customary to hide a bean, and when the cake was cut up and distributed, the person to whom chance—or not infrequently design—brought the piece containing the bean, was recognized sole monarch of the revels until the stroke of midnight. On the 6th of January, 1563, Mary Fleming was elected queen by favour of the bean. Her mistress, entering into the spirit of the festivities, with her characteristic considerateness for even the amusement of those about her, abdicated her state in favour of the mimic monarch of the night. A letter written by Randolph to Lord Dudley, and bearing the date of the 15th of January, gives an interesting and vivid picture of the fair maid of honour decked out in her royal mistress's jewels: "You should have seen here upon Tuesday the great solemnity and royall estate of the Queen of the Beene. Fortune was so favourable to faire Flemyng, that, if shee could have seen to have judged of her vertue and beauty, as blindly she went to work and chose her at adventure, shee would sooner have made her Queen for ever, then for one night only, to exalt her so [Pg 37] high and the nixt to leave her in the state she found her.... That day yt was to be seen, by her princely pomp, how fite a match she would be, wer she to contend ether with Venus in beauty, Minerva in witt, or Juno in worldly wealth, haveing the two former by nature, and of the third so much as is contained in this realme at her command and free disposition. The treasure of Solomon, I trowe, was not to be compared unto that which hanged upon her back.... The Queen of the Beene was in a gowne of cloath of silver; her head, her neck, her shoulders, the rest of her whole body, so besett with stones, that more in our whole jewell house wer not to be found. The Queen herself was apparelled in collours whyt and black, no other jewell or gold about her bot the ring that I brought her from the Queen's Majestie hanging at her breast, with a lace of whyt and black about her neck." In another part of the same letter the writer becomes even more enthusiastic: "Happy was it unto this realm," he says, "that her reign endured no longer. Two such nights in one state, in so good accord, I believe was never seen, as to behold two worthy queens possess, without envy, one kingdom, both upon a day. I leave the rest to your lordship to be judged of. My pen staggereth, my hand faileth, further to write.... The cheer was great. I never found myself so happy, nor so well treated, until that it came to the point that the old queen herself, to show her mighty power, contrary unto the assurance granted me by the younger queen, drew me [Pg 38] into the dance, which part of the play I could with good will have spared to your lordship, as much fitter for the purpose."[59]

The queen of this Twelfth-Tide pageant was also celebrated by the court poet Buchanan. Amongst his epigrams there is one bearing the title: "Ad Mariam Flaminiam sorte Reginam":

The "Faire Flemyng" found an admirer amongst the English gentlemen whom political business had brought to the Scotch Court. This was Sir Henry Sidney, of whom Naunton reports that he was a statesman "of great parts". As Sir Henry was born in 1519, and consequently over twenty years older than the youthful maid of honour, his choice cannot be considered to have been a very judicious one, nor can the ill-success of his suit appear greatly astonishing. And yet, as the sequel was to show, [Pg 39] Mary Fleming had no insuperable objection to an advantageous match on the score of disparity of age. In the year following that in which she figured as Queen of the Bean at Holyrood, the gossiping correspondence of the time expatiates irreverently enough on Secretary Maitland's wooing of the maid of honour. He was about forty at the time, and it was not very long since his first wife, Janet Monteith, had died. Mary Fleming was about two-and-twenty. There was, consequently, some show of reason for the remark made by Kirkcaldy of Grange, in communicating to Randolph the new matrimonial project in which Maitland was embarked: "The Secretary's wife is dead, and he is a suitor to Mary Fleming, who is as meet for him as I am to be a page".[61] Cecil appears to have been taken into the Laird of Lethington's confidence, and doubtless found amusement in the enamoured statesman's extravagance. "The common affairs do never so much trouble me but that at least I have one merry hour of the four-and-twenty.... Those that be in love are ever set upon a merry pin; yet I take this to be a most singular remedy for all diseases in all persons."[62] Two of the keenest politicians of their age laying aside their diplomatic gravity and forgetting the jealousies and the rivalry of their respective courts to discuss the charms of the Queen's youthful maid of honour: it is a charming historical vignette not without interest and humour even at this length of [Pg 40] time. We may judge to what extent the Secretary was "set on a merry pin", from Randolph's description of the courtship. In a letter dated 31 March, 1565, and addressed to Sir Henry Sidney, Mary Fleming's old admirer, he writes: "She neither remembereth you, nor scarcely acknowledgeth that you are her man. Your lordship, therefore, need not to pride you of any such mistress in this court; she hath found another whom she doth love better. Lethington now serveth her alone, and is like, for her sake, to run beside himself. Both night and day he attendeth, he watcheth, he wooeth—his folly never more apparent than in loving her, where he may be assured that, how much soever he make of her, she will always love another better. This much I have written for the worthy praise of your noble mistress, who, now being neither much worth in beauty, nor greatly to be praised in virtue, is content, in place of lords and earls, to accept to her service a poor pen clerk."[63] We have not to reconcile the ill-natured and slanderous remarks of Randolph's letter with the glowing panegyric penned by him some two years previously. That he intended to comfort the rejected suitor, and to tone down the disappointment and the jealousy which he might feel at the success of a rival not greatly younger than himself, would be too charitable a supposition. It is not improbable that he may have had more personal reasons for his spite, and that when, in the same letter, he describes "Fleming that once was so fair", [Pg 41] wishing "with many a sigh that Randolph had served her", he is giving a distorted and unscrupulous version of an episode not unlike that between Mary Fleming and Sir Henry himself. To give even the not very high-minded Randolph his due, however, it is but fair to add that his later letters, whilst fully bearing out what he had previously stated with regard to Maitland's lovemaking, throw no doubt on Mary's sincerity: "Lethington hath now leave and time to court his mistress, Mary Fleming";[64] and, again, "My old friend, Lethington, hath leisure to make love; and, in the end, I believe, as wise as he is, will show himself a very fool, or stark, staring mad".[65] This "leisure to make love" is attributed to Rizzio, then in high favour with the Queen. This was about the end of 1565. Early in 1566, however, the unfortunate Italian was murdered under circumstances too familiar to need repetition, and for his share in the unwarrantable transaction, Secretary Maitland was banished from the royal presence. The lovers were, in consequence, parted for some six months, from March to September. It was about this time that Queen Mary, dreading the hour of her approaching travail, and haunted by a presentiment that it would prove fatal to her, caused inventories of her private effects to be drawn up, and made legacies to her personal friends and attendants. The four Marys were not forgotten. They were each to receive a diamond; "Aux [Pg 42] quatre Maries, quatre autres petis diamants de diverse façon",[66] besides a portion of the Queen's needlework and linen: "tous mes ouurasges, manches et collets aux quatre Maries".[67] In addition to this, there was set down for "Flamy", two pieces of gold lace with ornaments of white and red enamel, a dress, a necklace, and a chain to be used as a girdle. We may infer that red and white were the maid of honour's favourite colours, for "blancq et rouge" appear in some form or another in all the items of the intended legacy.[68]

As we have said, the Secretary's disgrace was not of long duration. About September he was reinstated in the Queen's favour, and in December received from her a dress of cloth of gold trimmed with silver lace: "Une vasquyne de toille d'or plaine auecq le corps de mesme fait a bourletz borde dung passement dargent".[69]

[Pg 43] On the 6th of January, 1567, William Maitland of Lethington and Mary Fleming were married at Stirling, where the Queen was keeping her court, and where she spent the last Twelfth-Tide she was to see outside the walls of a prison. The Secretary's wife, as Mary was frequently styled after her marriage, did not cease to be in attendance upon her royal cousin, and we get occasional glimpses of her in the troubled times which were to follow. Thus, on the eventful morning on which Bothwell's trial began, Mary Fleming stood with the Queen at the window from which the latter, after having imprudently refused an audience to the Provost-Marshal of Berwick, Elizabeth's messenger, still more imprudently watched the bold Earl's departure and, it was reported, smiled and nodded encouragement. Again, in the enquiry which followed the Queen's escape from Lochleven, it appeared that her cousin had been privy to the plot for her release, and had found the means of conveying to the royal captive the assurance that her friends were working for her deliverance: "The Queen", so ran the evidence of one of the attendants examined after the flight, "said scho gat ane ring and three wordis in Italianis in it. I iudget it cam fra the Secretar, because of the language. Scho said, 'Na, ... it was ane woman. All the place saw hir weyr it. Cursall show me the Secretaris wiff send it, and the vreting of it was ane fable of Isop betuix the Mouss and the Lioune, hou the Mouss for ane plesour done to hir be the Lioune, efter that, the Lioune being bound with ane corde, the Mouss schuyr the corde and let the Lioune louss.'"[70]

During her long captivity in England, the unfortunate Queen was not unmindful of the love and devotion of her faithful attendant. Long [Pg 44] years after she had been separated from her, whilst in prison at Sheffield, she gives expression to her longing for the presence of Mary Fleming, and in a letter written "du manoir de Sheffield", on the 1st of May, 1581, to Monsieur de Mauvissiére, the French ambassador, she begs him to renew her request to Elizabeth that the Lady of Lethington should be allowed to tend her in "the valetudinary state into which she has fallen, of late years, owing to the bad treatment to which she has been subjected".[71]

But the Secretary's wife had had her own trials and her own sorrows. On the 9th of June, 1573, her husband died at Leith, "not without suspicion of poison", according to Killigrew. Whether he died by his own hand, or by the act of his enemies, is a question which we are not called upon to discuss. The evidence of contemporaries is conflicting, "some supponyng he tak a drink and died as the auld Romans wer wont to do", as Sir James Melville reports;[72] others, and amongst these Queen Mary herself, that he had been foully dealt with. Writing to Elizabeth, she openly gives expression to this belief: "the principal (of the rebel lords) were besieged by your forces in the Castle of Edinburgh, and one of the first among them poisoned".

Maitland was to have been tried "for art and part of the treason, conspiracy, consultation, and treating of the King's murder". According to the law of [Pg 45] Scotland, a traitor's guilt was not cancelled by death. The corpse might be arraigned and submitted to all the indignities which the barbarous code of the age recognized as the punishment of treason. It was intended to inflict the fullest penalty upon Maitland's corpse, and it remained unburied "till the vermin came from his corpse, creeping out under the door of the room in which he was lying".[73] In her distress the widow applied to Burleigh, in a touching letter which is still preserved. It bears the date of the 21st of June, 1573.

My very good Lord,—After my humble commendations, it may please your Lordship that the causes of the sorrowful widow, and orphants, by Almighty God recommended to the superior powers, together with the firm confidence my late husband, the Laird of Ledington, put in your Lordship's only help is the occasion, that I his desolat wife (though unknown to your Lordship), takes the boldness by these few lines, to humblie request your Lordship, that as my said husband being alive expected no small benefit at your hands, so now I may find such comfort, that the Queen's Majestie, your Sovereign, may by your travell and means be moved to write to my Lord Regent of Scotland, that the body of my husband, which when alive has not been spared in her hieness' service, may now, after his death, receive no shame, or ignominy, and that his heritage taken from him during his lifetime, now belonging to me and his children, that have not offended, by a disposition made a long time ago, may be restored, which is aggreeable both to equity and the laws of this realme; and also your Lordship will not forget my husband's brother, the Lord of Coldingham, ane innocent gentleman, who was never engaged in these quarrels, but for his love [Pg 46] to his brother, accompanied him, and is now a prisoner with the rest, that by your good means, and procurement, he may be restored to his own, by doing whereof, beside the blessing of God, your lordship will also win the goodwill of many noblemen and gentlemen.[74]

Burleigh lost no time in laying the widow's petition before Elizabeth, and on the 19th of July a letter written at Croydon was dispatched to the Regent Morton: "For the bodie of Liddington, who died before he was convict in judgment, and before any answer by him made to the crymes objected to him, it is not our maner in this contrey to show crueltey upon the dead bodies so unconvicted, but to suffer them streight to be buried, and put in the earth. And so suerly we think it mete to be done in this case, for (as we take it) it was God's pleasure he should be taken away from the execucion of judgment, so we think consequently that it was His divine pleasure that the bodie now dead should not be lacerated, nor pullid in pieces, but be buried like to one who died in his bed, and by sicknes, as he did."[75]

Such a petitioner as the Queen of England was not to be denied, and Maitland's body was allowed the rites of burial. The other penalties which he had incurred by his treason—real or supposed—were not remitted. An Act of Parliament was passed "for rendering the children, both lawful and natural, of Sir William Maitland of Lethington, the younger, and of several others, who had been convicted of the [Pg 47] murder of the King's father, incapable of enjoying, or claiming, any heritages, lands, or possessions in Scotland".

The widow herself was also subjected to petty annoyances at the instigation of Morton. She was called upon to restore the jewels which her royal mistress had given her as a free gift, and in particular, "one chayn of rubeis with twelf markes of dyamontis and rubeis, and ane mark with twa rubeis".[76] Even her own relatives seemed to have turned against her in her distress. In a letter written in French to her sister-in-law, Isabel, wife of James Heriot of Trabroun, she refers to some accusation brought against her by her husband's brother, Coldingham—the same for whom she had interceded in her letter to Burleigh—and begs to be informed as to the nature of the charge made to the Regent, "car ace que jantans il me charge de quelque chose, je ne say que cest".[77] The letter bears no date, but seems to have been penned when the writer's misery was at its sorest, for it concludes with an earnest prayer that patience may be given her to bear the weight of her misfortunes.

Better days, however, were yet in store for the much-tried Mary Fleming, for in February, 1584, the "relict of umquhill William Maitland, younger of Lethington, Secretare to our Soverane Lord", [Pg 48] succeeded in obtaining a reversion of her husband's forfeiture. In May of the same year,[78] the Parliament allowed "Marie Flemyng and hir bairns to have bruik and inioy the same and like fauour, grace and priuilege and conditioun as is contenit in the pacificatioun maid and accordit at Perthe, the xxiii day of Februar, the yeir of God Im Vc lxxxij yeiris".

With this document one of the four Marys disappears from the scene. Of her later life we have no record. That it was thoroughly happy we can scarcely assume, for we know that her only son James died in poverty and exile.

Mary Livingston, or, as she signed herself, Marie Leuiston, was the daughter of Alexander, fifth Lord Livingston. She was a cousin of Mary Fleming's, and, like her, related, though more distantly, to the sovereign. When she sailed from Scotland in 1548, as one of the playmates of the infant Mary Stuart, she was accompanied by both her father and her mother. Within a few years, however, she was left to the sole care of the latter, Lord Livingston having died in France in 1553. Of her life at the French Court we have no record. Her first appearance in the pages of contemporary chroniclers is on the 22nd of April, 1562, the year after her return to Scotland. On that date, the young Queen, who delighted in the sport of archery, shot off a match in her private gardens at St. Andrews. Her own partner was the Master of Lindsay.[79] Their opponents were the Earl of Moray, then only Earl of Mar, and Mary Livingston, whose skill is reported to have been—when courtesy allowed it—quite equal to that of her royal mistress.

The next item of information is to be found in the matter-of-fact columns of an account book, in [Pg 50] which we find it entered that the Queen gave Mary Livingston some grey damask for a gown, in September, 1563,[80] and some black velvet for the same purpose in the following February.[81] Shortly after this, however, there occurred an event of greater importance, which supplied the letter-writers of the day with material for their correspondence. On the 5th of March, 1564, Mary Livingston was married to James Sempill, of Beltreis. It was the first marriage amongst the Marys, and consequently attracted considerable attention for months before the celebration. As early as January, Paul de Foix, the French Ambassador, makes allusion to the approaching event: "Elle a commencé à marier ses quatre Maries", he writes to Catharine de' Medici, "et dict qu'elle veult estre de la bande".[82] In a letter, dated the 9th of the same month, Randolph, faithful to his habit of communicating all the gossip of the Court in his reports to England, informs Bedford of the intended marriage: "I learned yesterday that there is a conspiracy here framed against you. The matter is this: the Lord Sempill's son, being an Englishman born, shall be married between this and Shrovetide to the Lord Livingston's sister. The Queen, willing him well, both maketh the marriage and indoweth the parties with land. To do them honour she will have them marry in the Court. The thing intended against your lordship is this, that Sempill himself shall come to Berwicke within these fourteen days, and desire [Pg 51] you to be at the bridal."[83] Writing to Leicester, he repeats his information: "It will not be above 6 or 7 days before the Queen (returning from her progress into Fifeshire) will be in this town. Immediately after that ensueth the great marriage of this happy Englishman that shall marry lovely Livingston."[84] Finally, on the 4th of March, he again writes: "Divers of the noblemen have come to this great marriage, which to-morrow shall be celebrated".[85] Randolph's epistolary garrulity has, in this instance, served one good purpose, of which he probably little dreamt when he filled his correspondence with the small talk of the Court circle. It enables us to refute a calumnious assertion made by John Knox with reference to the marriage of the Queen's maid of honour. "It was weill knawin that schame haistit mariage betwix John Sempill, callit the Danser, and Marie Levingstoune, surnameit the Lustie."[86] Randolph's first letter, showing, as it does, that preparations for the wedding were in progress as early as the beginning of January, summarily dismisses the charge of "haste" in its celebration, whilst, for those who are familiar with the style of the English envoy's correspondence, his very silence will appear the strongest proof that Mary's fair fame was tarnished by no breath of scandal. The birth of her first child in 1566, a fact to which the family records of the house of Sempill bear witness, establishes more irrefutably than any argument the utter falsity of Knox's unscrupulous assertion.

John Sempill, whose grace in dancing had acquired for him the surname which seems to have lain so heavily on Knox's conscience, and whose good fortune in finding favour with lovely Mary Livingston called forth Randolph's congratulations, was the eldest son of the third lord, by his second wife Elizabeth Carlyle of Torthorwold. At Court, as may have been gathered from Randolph's letters, he was known as the "Englishman", owing to the fact of his having been born in Newcastle. Although of good family himself, and in high favour at Court, being but a younger son he does not seem to have been considered on all hands as a fitting match for Mary Livingston. This the Queen, of whose making the marriage was, herself confesses in a letter to the Archbishop of Glasgow, reminding him that, "in a country where these formalities were looked to", exception had been taken to the marriage both of Mary and Magdalene Livingston on the score that they had taken as husbands "the younger sons of their peers—les puînés de leurs semblables".[87] Mary Stuart seems to have been above such prejudices, and showed how heartily she approved of the alliance between the two families by her liberality to the bride. Shortly before the marriage she gave her a band covered with pearls, a basquina of grey satin, a mantle of black taffety made in the Spanish fashion [Pg 53] with silver buttons, and also a gown of black taffety. It was she, too, who furnished the bridal dress, which cost £30, as entered in the accounts under date of the 10th of March:—

Item: Ane pund xiii unce of silver to ane gown of Marie Levingstoune's to her mariage, the unce xxv s. Summa xxx li.

The "Inuentair of the Quenis movables quhilkis ar in the handes of Seruais de Condy vallett of chalmer to hir Grace", records, further, that there was "deliueret in Merche 1564, to Johnne Semples wiff, ane bed of scarlett veluot bordit with broderie of black veluot, furnisit with ruif heidpece, thre pandis, twa vnderpandis, thre curtenis of taffetie of the same cullour without freingis. The bed is furnisit with freingis of the same cullour." To make her gift complete, the Queen, as another household document, her wardrobe book, testifies, added the following items:—

Item: Be the said precept to Marie Levingstoun xxxi elnis

ii quarters of quhite fustiane to be ane marterass,

the eln viii s. Summa xii li xii s.

Item: xvi elnis of cammes to be palzeass, the eln vi s. Summa iiij li xvj s.

Item: For nappes and fedders; v li.

Item: Ane elne of lane; xxx s.

Item: ij unce of silk; xx s.

The wedding for which such elaborate preparation had been made, and for which the Queen herself named the day, took place, in the presence of [Pg 54] the whole Court and all the foreign ambassadors, on Shrove Tuesday, which, as has already been mentioned, was on the 5th of March. In the evening the wedding guests were entertained at a masque, which was supplied by the Queen, but of which we know nothing further than may be gathered from the following entry:—

Item: To the painter for the mask on Fastionis evin to Marie Levingstoun's marriage; xij li.[88]

The marriage contract, which was signed at Edinburgh on the Sunday preceding the wedding, bears the names of the Queen, of John Lord Erskine, Patrick Lord Ruthven, and of Secretary Maitland of Lethington. The bride's dowry consisted of £500 a year in land, the gift of the Queen, to which Lord Livingston added 100 merks a year in land, or 1000 merks in money. As a jointure she received the Barony of Beltreis near Castle Semple, in Renfrewshire, the lands of Auchimanes and Calderhaugh, with the rights of fisheries in the Calder, taxed to the Crown at £18, 16s. 8d. a year.[89]

A few days after the marriage, on the 9th of March, a grant from the Queen to Mary Livingston and John Sempill passed the great seal. In this official document she styles the bride "her familiar servatrice", and the bridegroom "her daily and familiar serviter, during all the youthheid and minority of the said serviters". In recognition of their services both to herself and the Queen Regent, [Pg 55] she infeofs them in her town and lands of Auchtermuchty, part of her royal demesne in Fifeshire, the lands and lordships of Stewarton in Ayr, and the isle of Little Cumbrae in the Firth of Clyde.

After her marriage "Madamoiselle de Semple" was appointed lady of the bedchamber, an office for which she received £200 a year. Her husband also seems to have retained some office which required his personal attendance on the Queen, for we know that both husband and wife were in waiting at Holyrood on the memorable evening of David Rizzio's murder. The shock which this tragic event produced on Mary was very great, and filled her with the darkest forebodings. She more than once expressed her fear that she would not survive her approaching confinement. About the end of May or the beginning of June, shortly before the solemn ceremony of "taking her chamber", she caused an inventory of her personal effects to be drawn up by Mary Livingston and Margaret Carwod, the bedchamber woman in charge of her cabinet, and with her own hand wrote, on the margin opposite to each of the several articles, the name of the person for whom it was intended, in the event of her death and of that of her infant. Mary Livingston's name appears by the side of the following objects in the original document, which was discovered among some unassorted law papers in the Register House, in August, 1854:—

Only on one occasion after this do we find mention of Mary Livingston in connection with her royal mistress. It is on the day following the Queen's surrender at Carberry, when she was brought back a prisoner to Edinburgh. The scene is described by Du Croc, the French Ambassador. "On the evening of the next day," he writes in the official report forwarded to his court, "at eight o'clock, the Queen was brought back to the castle of Holyrood, escorted by three hundred arquebusiers, the Earl of Morton on the one side, and the Earl of Athole on the other; she was on foot, though two hacks [Pg 57] were led in front of her; she was accompanied at the time by Mademoiselle de Sempel and Seton, with others of her chamber, and was dressed in a night-gown of various colours."[90]

After the Queen's removal from Edinburgh the Sempills also left it to reside sometimes at Beltreis, and sometimes at Auchtermuchty, but chiefly in Paisley, where they built a house which was still to be seen but a few years ago, near what is now the Cross. Their retirement from the capital did not, however, secure for them the quietness which they expected to enjoy. They had stood too high in favour with the captive Queen to be overlooked by her enemies. The Regent Lennox, remembering that Mary Livingston had been entrusted with the care of the royal jewels and wardrobe, accused her of having some of the Queen's effects in her possession. Notwithstanding her denial, her husband was arrested and cast into prison, and she herself brought before the Lords of the Privy Council. Their cross-questioning and brow-beating failed to elicit any information from her, and it was only when Lennox threatened to "put her to the horn", and to inflict the torture of the "boot" on her husband, that she confessed to the possession of "three lang-tailit gowns garnished with fur of martrix and fur of sables". She protested, however, that, as was indeed highly probable, these had been given to her, and were but cast-off garments, of little value or use to anyone. In spite of this, she was[Pg 58] not allowed to depart until she had given surety "that she would compear in the council-chamber on the morrow and surrender the gear".

Lennox's death, which occurred shortly after this, did not put an end to the persecution to which the Sempills were subjected. Morton was as little friendly to them as his predecessor had been. He soon gave proof of this by calling upon John Sempill to leave his family and to proceed to England, as one of the hostages demanded as security for the return of the army and implements of war, sent, under Sir William Drury, to lay siege to Edinburgh Castle.