This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Bird Guide: Land Birds East of the Rockies

From Parrots to Bluebirds

Author: Chester A. (Chester Albert) Reed

Release Date: May 11, 2014 [eBook #45630]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BIRD GUIDE: LAND BIRDS EAST OF THE ROCKIES***

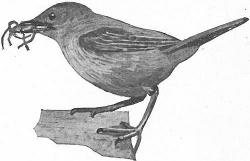

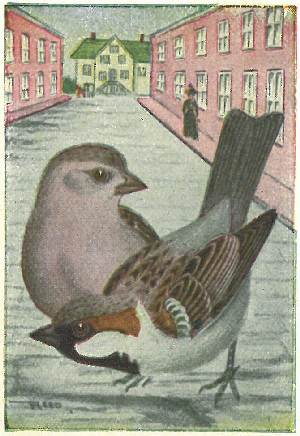

PREPARING BREAKFAST

(Two adult Chipping Sparrows breaking worm into pieces to feed young.)

BY

CHESTER A. REED

Author of

North American Birds’ Eggs, and, with Frank M. Chapman, of Color Key to North American Birds. Curator in Ornithology, Worcester Natural History Society.

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1919

Copyrighted, 1906, 1909 by CHAS. K. REED.

[Preface] [Introduction] [BIRD LIST] [Color Key] [Classification] [Index]

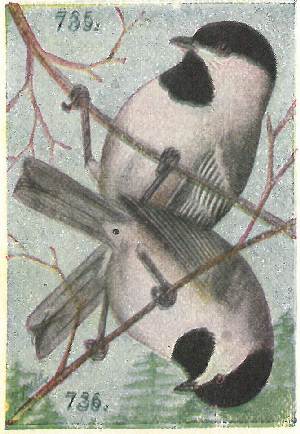

The native birds are one of our nation’s most valuable assets. Destroy them, and in a comparatively few years the insects will have multiplied to such an extent that trees will be denuded of their foliage, plants will cease to thrive and crops cannot be raised. This is not fancy but plain facts. Look at the little Chickadee on the side of this page. She was photographed while entering a bird box, with about twenty-five plant lice to feed her seven young; about two hundred times a day, either she or her mate, made trips with similar loads to feed the growing youngsters.

It has been found, by observation and dissection, that a Cuckoo consumes daily from 50 to 400 caterpillars or their equivalent, while a Chickadee will eat from 200 to 500 insects or up to 4,000 insect or worm eggs. 100 insects a day is a conservative estimate of the quantity consumed by each individual insectivorous bird. By carefully estimating the birds in several areas, I find that, in Massachusetts, there are not less than five insect-eating birds per acre. Thus this state with its 8,000 square miles has a useful bird population of not less than 25,600,000, which, for each day’s fare, requires the enormous total of 2,560,000,000 insects. That such figures can be expressed in terms better [6] understood, it has been computed that about 120,000 average insects fill a bushel measure. This means that the daily consumption, of chiefly obnoxious insects, in Massachusetts is 21,000 bushels. This estimate is good for about five months in the year, May to September, inclusive; during the remainder of the year, the insects, eggs and larvæ destroyed by our Winter, late Fall and early Spring migrants will be equivalent to nearly half this quantity.

It is the duty, and should be the pleasure, of every citizen to do all in his or her power to protect these valuable creatures, and to encourage them to remain about our homes. The author believes that the best means of protection is the disseminating of knowledge concerning them, and the creating of an interest in their habits and modes of life. With that object in view, this little book is prepared. May it serve its purpose and help those already interested in the subject, and may it be the medium for starting many others on the road to knowledge of our wild, feathered friends.

CHESTER A. REED.

Worcester, Mass.,

October 1 1905.

It is an undisputed fact that a great many of our birds are becoming more scarce each year, while a few are, even now, on the verge of extinction. The decrease in numbers of a few species may be attributed chiefly to the elements, such as a long-continued period of cold weather or ice storms in the winter, and rainy weather during the nesting season; however, in one way or another, and often unwittingly, man is chiefly responsible for the diminution in numbers. If I were to name the forces that work against the increase of bird life, in order of their importance, I should give them as: Man; the elements; accidents; cats; other animals; birds of prey; and snakes. I do not take into consideration the death of birds from natural causes, such as old age and disease, for these should be counterbalanced by the natural increase.

There are parts that each one of us can play in lessening the unnatural dangers that lurk along a bird’s path in life. Individually, our efforts may amount to but little, perhaps the saving of the lives of two or three, or more, birds during the year, but collectively, our efforts will soon be felt in the bird-world.

How Can We Protect the Birds?—Nearly all states have fairly good game laws, which, if they could be enforced, would properly protect our birds from man, but they cannot be; if our boys and girls are educated to realize the economic value of the birds, and are encouraged to study their habits, the desire to shoot them or to rob them of their eggs will be very materially lessened. It is a common practice for some farmers to burn their land over in the Spring, usually about nesting time. Three years ago, and as far back of that as I can remember, a small ravine or valley was teeming with bird life; it was the most favored spot that I know of, for the variety and numbers of [8] its bird tenants. Last year, toward the end of May, this place was deliberately burned over by the owner. Twenty-seven nests that I know of, some with young, others with eggs, and still others in the process of construction, were destroyed, besides hundreds of others that I had never seen. This year the same thing was done earlier in the season, and not a bird nested here, and, late in Summer, only a few clumps of ferns have found courage to appear above the blackened ground. Farmers also cut off a great many patches of underbrush that might just as well have been left, thus, for lack of suitable places for their homes, driving away some of their most valuable assistants. The cutting off of woods and forests is an important factor in the decrease of bird life, as well as upon the climate of the country.

Our winter birds have their hardships when snow covers the weed tops, and a coating of ice covers the trees, so that they can neither get seeds nor grubs. During the nesting season, we often have long-continued rains which sometimes cause an enormous loss of life to insect-eating birds and their young. In 1903, after a few weeks’ steady rain and damp weather, not a Purple Martin could be found in Worcester County, nor, as far as I know, in New England; they were wholly unable to get food for either themselves or their young, and the majority of them left this region. The Martin houses, when cleaned out, were found to contain young, eggs, and some adults that had starved rather than desert their family. The Martins did not return in 1904 or 1905.

Birds are subject to a great many accidents, chiefly by flying into objects at night. Telephone and telegraph wires maim or kill thousands, while lighthouses and steeples often cause the ground to be strewn with bodies during migrations. Other accidents are caused by storms, fatigue while crossing large bodies of water, nests falling from trees because of an insecure support, and [9] ground nests being trod upon by man, horses, and cattle.

In the vicinity of cities, towns, villages, or farms, one of the most fertile sources of danger to bird life is from cats. Even the most gentle household pet, if allowed its liberty out of doors, will get its full quota of birds during the year, while homeless cats, and many that are not, will average several hundred birds apiece during the season. After years of careful observation, Mr. E. H. Forbush, Mass., state ornithologist, has estimated that the average number of birds killed, per cat population, is about fifty. If a dog kills sheep or deer, he is shot and the owner has to pay damages; if a man is caught killing a bird, he pays a fine; but cats are allowed to roam about without restriction, leaving death and destruction in their wake. All homeless cats should be summarily dealt with, and all pets should be housed, at least from May until August, when the young birds are able to fly.

Of wild animals, Red Squirrels are far the most destructive to young birds and eggs; Chipmunks and Grays are also destructive but not nearly as active or impudent as the Reds. Skunks, Foxes, and Weasels are smaller factors in the decrease of bird life.

Birds of prey have but little to do with the question of bird protection for, with a few exceptions, they rarely feed upon other birds, and nearly all of them are of considerable economic value themselves. Jays, Crows, and Grackles, by devouring the eggs and young of our smaller birds, are a far greater menace than are the birds of prey, but even these have their work and should be left in the place that Nature intended for them; they should, however, be taught to keep away from the neighborhood of houses.

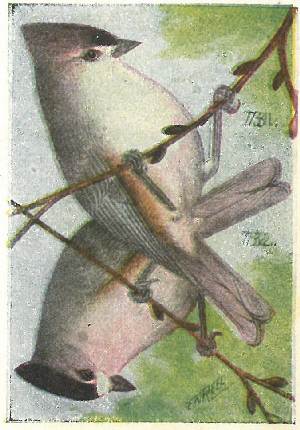

How Can We Attract Birds About Our Homes?—Many birds prefer to live in the vicinity of houses, and they soon learn where they are welcome. Keep your premises as free as possible from cats, dogs, and especially English Sparrows, and other birds will come. Robins, Orioles, [10] Kingbirds, Waxwings and a few others will nest in orchard trees, while in dead limbs or bird boxes will be found Bluebirds, Wrens, Swallows, Woodpeckers, Chickadees, etc.

A house for Purple Martins may contain many apartments; it should be erected in an open space, on a ten or twelve foot pole. Boxes for other birds should have but one compartment, and should be about six by six by eight inches, with a hole at least one and one-half inches in diameter in one side; these can be fastened in trees or on the sides or cornices of barns or sheds. It is needless to say that English Sparrows should not be allowed to use these boxes. By tying suet to limbs of trees in winter, and providing a small board upon which grain, crumbs, etc., may be sprinkled, large numbers of winter birds may be fed; of these, probably only the Chickadees will remain to nest, if they can find a suitable place.

How to Study Birds.—This refers, not to the scientific, but to the popular study of our birds, chiefly in the field. We can learn many very interesting things by watching our birds, especially during the nesting season, and the habits and peculiarities of many are still but imperfectly known. One thing to be impressed upon the student at the start is the need of very careful observation before deciding upon the identity of a bird with which you are not perfectly familiar. A bird’s colors appear to differ greatly when viewed in different lights, while in looking up in the tree tops, it is often impossible to see any color at all without the aid of a good field glass. By the way, we would advise every one to own a good pair of these, for, besides being almost indispensable for bird study, they are equally valuable for use at the seashore, in the mountains, or at the theatre. We have examined more than a hundred makes of field glasses to select the one best adapted to bird study, and at a moderate price. We found one that was far superior to any other at the same price, and was equal to most of those costing three times as much. It gives a very [11] clear image, magnifies about four diameters, and has a very large field of view. It comes in a silk-lined leather case, with cord for suspending from the shoulder, and is of a convenient size for carrying in the pocket. We have made arrangements so that we can sell these at a reasonable price (money refunded if they are not satisfactory after three days’ trial).

We should also advise every one to keep a notebook, apart from the Bird Guide. At the end of the season you can write neatly with ink on the top of the pages of the Guide, the dates of the earliest arrivals and latest departures of the birds that you have recorded. If you see a bird that you do not recognize, make the following notes, as completely as possible: Length (approximately); any bright colors or patches; shape of bill, whether most like that of a finch, warbler, etc.; has it a medium or superciliary line, eye ring, wing bars, or white in the tail; what are its notes or song; does it keep on or near the ground, or high up; are its actions quick or slow; upon what does it appear to be feeding; is it alone or with other birds, and what kind; where was it seen, in dry woods, swamp, pasture, etc.; date that it was seen. With this data you can identify any bird, but usually you will need only to glance over the pictures in the Bird Guide to find the name of the bird you have seen.

I should advise any one by all means to make a complete local list of all the birds that are found in their neighborhood, but of far greater value than the simple recording of the different species seen on each walk, will be the making a special study of one or more birds, even though they be common ones. While, of course, noting any peculiarities of any bird that you may see, select some particular one or ones and find out all you can about it. The following most necessary points are cited to aid the student in making observations: Date of arrival and whether in large flocks, pairs, or singly; where found most abundantly; upon what do they feed at the different [12] seasons; what are their songs and calls at different seasons; when and where do they make their nests; of what are they made and by which bird or both; how long does it take, and when is the first and last egg laid; how long does it take them to hatch, and do both birds or only one incubate them; upon what are the young fed at different ages; how long do they remain in the nest, and do they return after once leaving; how long before they are able to feed themselves, and do they remain with [13] their parents until they migrate. These and other notes that will suggest themselves will furnish interesting and valuable instruction during your leisure time.

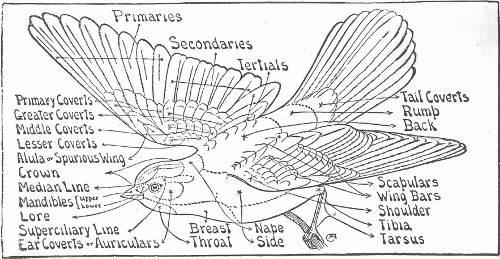

TOPOGRAPHY OF A BIRD

The numbers and names used in this book are those adopted by the American Ornithologists’ [14] Union, and are known both in this country and abroad. The lengths given are averages; our small birds often vary considerably and may be found either slightly larger or smaller than those quoted.

On some of the pages a number of sub-species are mentioned. Sub-species often cause confusion, because they are usually very similar to the original; they can best be identified by the locality in which they are found.

Of course the writing of birds’ songs is an impossibility, but wherever I have thought it might prove of assistance, I have given a crude imitation of what it sounds like to me. The nests and eggs are described, as they often lead to the identity of a bird. We would suggest that you neatly, and with ink, make a cross against the name of each bird that you see in your locality, and also that you write at the top of the page the date of the arrival and departure of each bird as you note it; these dates vary so much in different localities that we have not attempted to give them.

As many will not wish to soil their books, we would suggest that they have a leather-covered copy for the library and a cloth one for pocket use.

LAND BIRDS EAST OF THE ROCKIES

Adults have the fore part of the head orange, while young birds have the head entirely green, with only a trifle orange on the forehead.

With the exception of the Thick-Billed Parrot, which is very rarely found in southern Arizona, these are the only members of the Parrot family in the United States. They were once abundant throughout the southern states, but are now nearly extinct. They are found in heavily timbered regions, usually along the banks of streams, where they feed upon seeds and berries.

Note.—A sharp, rolling “kr-r-r-r-r.” (Chapman.)

Nest.—Supposed to be in hollow trees, where they lay from three to five white eggs (1.31 × 1.06).

Range.—Formerly the southern states, but now confined to the interior of Florida and, possibly, Indian Territory.

Anis are fairly abundant in southern Texas along the Rio Grande. Like all the members of the family of Cuckoos, their nesting habits are very irregular; ofttimes a number of them will unite and form one large nest in a bush, in which all deposit their eggs. The eggs are bluish-green, covered with a white chalky deposit (1.25 × .95).

In the southwestern portions of our country, from Texas and Kansas west to the Pacific, these curious birds are commonly found. They are locally known as “Ground Cuckoos,” “Snake-killers,” “Chaparral Cocks.” They are very fond of lizards and small snakes, which form a large part of their fare. They are very fleet runners, but fly only indifferently well. Their four to ten white eggs are laid on frail nests of twigs, in bushes.

These buff-breasted Cuckoos are natives of Cuba and Central America, being found in southern Florida only during the summer. The habits of all the American Cuckoos are practically identical and their notes or songs can only be distinguished from one another by long familiarity.

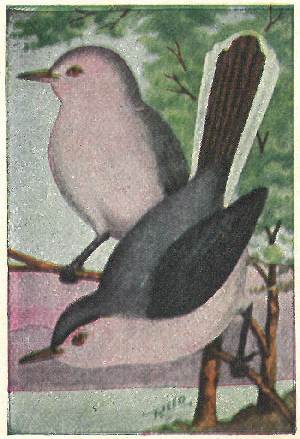

This species is the most abundant in the southern part of its range, while the Black-bill is the most common in the North. Notice that the lower mandible is yellowish, that the wings are largely rufous, and that the outer tail feathers are black, with broad white tips, these points readily distinguishing this species from the next. The eggs of this species are large and paler colored than the next (1.20 × .90). They breed from the Gulf to southern Canada and winter in Central America.

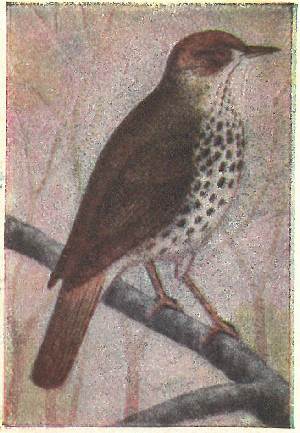

Cuckoos are of quiet and retiring habits, but on account of their mournful notes are often regarded with awe by the superstitious. They are one of our most valuable birds, for they consume quantities of the fuzzy Tent Caterpillars, that are so destructive.

Their short, rounded wings and long, broad tails give them a silent, gliding flight that often enables them to escape unnoticed.

Note.—A low guttural croak, “cow,” “cow,” etc., repeated a great many times and sometimes varied with “cow-uh,” also repeated many times.

Nest.—Flat, shabby platforms of twigs placed at low elevations in thickets or on the lower branches of trees. The four greenish-blue eggs are 1.15 × .85.

Range.—United States and southern Canada, east of the Rockies. Arrives in May and leaves in September for northern South America.

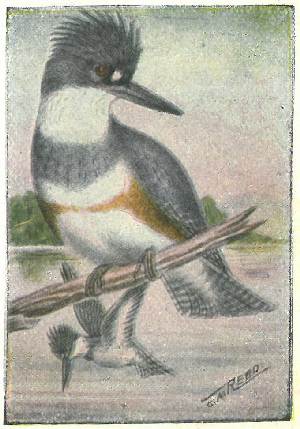

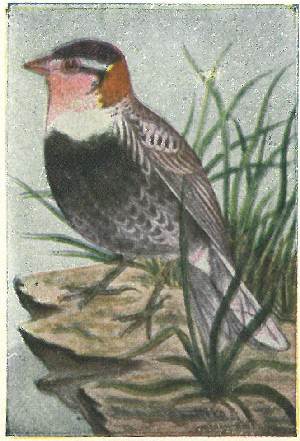

The male has the breast band and sides blue-gray, like the back, while the female has chestnut-colored sides and breast band in addition to a gray band.

Kingfishers may be found about ponds, lakes, rivers, the seaside or small creeks; anywhere that small fish may be obtained. Their food is entirely of fish that they catch by diving for, from their perches on dead branches, or by hovering over the water until the fish are in proper positions and then plunging after them.

Note.—A very loud, harsh rattle, easily heard half a mile away on a clear, quiet day.

Nest.—At the end of a two or three foot tunnel in a sand bank. The tunnel terminates in an enlarged chamber where the five to eight glossy white eggs (1.35 × 1.05) are laid upon the sand.

Range.—Whole of North America north to the Arctic regions. Winters from southern United States southward.

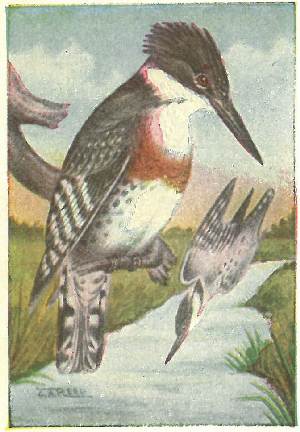

The adult male of this species has a rufous breast band, while the female has only a greenish one.

The Texan Green Kingfisher is the smallest member of the family found within our borders. You will notice that all Kingfishers have the two outer toes on each foot joined together for about two thirds of their length. This has been brought about through their habit of excavating in sand banks for nesting sites. It is quite probable that at some future distant period the three forward toes may be connected for their whole length, so as to give them a still more perfect shovel.

Note.—A rattling cry, more shrill than that of the Belted Kingfisher.

Nest.—The four to six glossy white eggs are laid on the sand at the end of a horizontal burrow in a bank, the end being enlarged into a chamber sufficiently large to allow the parent bird to turn about.

Range.—Southwestern border of the United States, from southern Texas to Arizona.

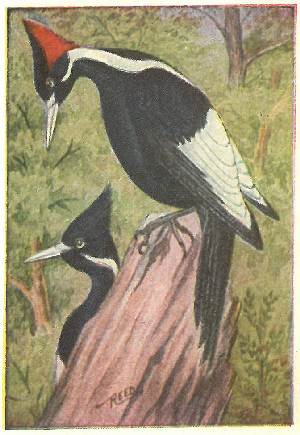

Male with a scarlet crest, female with a black one.

These are the largest and most rare of the Woodpeckers found within our borders. Their decline in numbers is due, to a certain extent, to the killing of them because of their size and beauty, but chiefly on account of cutting off of a great deal of the heavy timber where they nest. They are very powerful birds and often scale the bark off the greater portion of a tree in search for insects and grubs, while they will bore into the heart of a living tree to make their home.

Note.—A shrill two-syllabled shriek or whistle.

Nest.—In holes of large trees in impenetrable swamps. On the chips at the bottom of the cavity, they lay from three to six glossy, pure white eggs (1.45 × 1.00).

Range.—Formerly the South Atlantic States and west to Texas and Indian Territory, but now confined to a few isolated portions of Florida and, possibly, Indian Territory.

In summer these Woodpeckers are found in heavy woods, where they breed, but in Winter they are often seen on trees about houses, even in the larger cities, hunting in all the crevices of the bark in the hope of locating the larva of some insect. They usually are more shy than the Downy, from which they can readily be distinguished by their much larger size.

Note.—A sharp whistled “peenk.”

Nest.—In holes in trees in deep woods; three to six glossy white eggs (59. × .70).

Range.—Eastern U. S. from Canada to North Carolina.

Sub-Species.—393a. Northern Hairy Woodpecker (leucomelas), British America and Alaska; larger, 393b. Southern Hairy Woodpecker (audubonii), South Atlantic and Gulf States; smaller. The difference between these birds is small and chiefly in size, although the southern bird often has fewer white marks on the wing coverts. Other sub-species are found west of the Rockies.

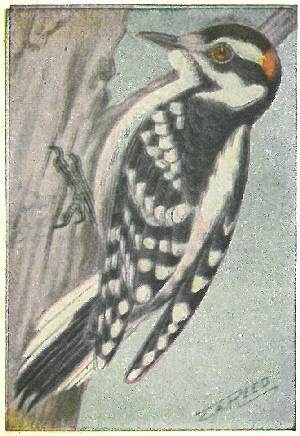

The male has a red nuchal patch while the female has none. Downies are one of the commonest of our Woodpeckers and are usually tame, allowing a very close approach before flying. They remain in orchards and open woods throughout the summer, and in winter often come to the windows in places where they are fed, as many people are in the habit of doing now. Their food, as does that of nearly all the Woodpeckers, consists entirely of insects, grubs and larvæ.

Note.—A sharp “peenk” or a rapid series of the same note, usually not as loud as that of the Hairy Woodpecker.

Nest.—In holes in trees in orchards or woods; the four to six white eggs being laid on the bare wood; size .75 × .60.

Range.—South Atlantic and Gulf States.

Sub-Species.—Northern Downy Woodpecker (medianus) North America east of the Rockies and north of the Carolinas. This variety is slightly larger than the southern, others are found west of the Rockies.

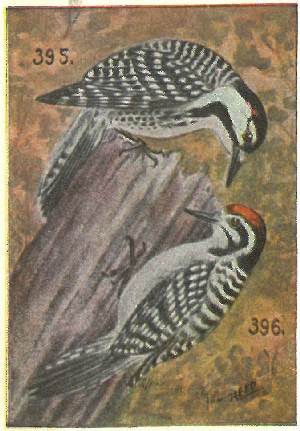

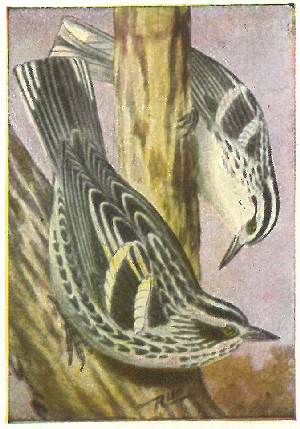

Male with a small patch of scarlet on both sides of the head; female without. The actions and habits are very similar to those of the Downy. The birds can readily be identified at a distance by the cross-barring of white on the back. Their notes are harsher than those of the Downy and have more of the nasal quality, like those of the nuthatches.

Range.—Southeastern United States, west to Texas and north to Virginia.

On account of its numerous cross-bars, this species is often known as the Ladder-backed Woodpecker. They are quite similar to the Nuttall Woodpecker that is found on the Pacific Coast, but differ in having the underparts brownish-white instead of white, and the outer tail feathers heavily barred. They are found from Texas to southeastern California and north to Colorado.

Back glossy black, without any white. Only three toes, two in front and one behind. This is the most common of the two species found within the United States. They breed from the northern edge of the Union north to the limit of trees.

Back barred with white; outer tail feathers barred with black; yellow crown patch on male mixed with white. Except on some of the higher mountain ranges these birds appear in the United States only during winter. They are very hardy and commence nesting before snow leaves.

Note.—A shrill, loud, nasal shriek, sometimes repeated.

Nest.—In holes of trees as is usual with Woodpeckers. The white eggs measure .95 × .70.

Male with a scarlet crown and throat; female with a scarlet crown and white throat; young with the head and neck mottled gray and white, with a few scarlet feathers.

This species has gained some ill-repute because of its supposed habit of boring through the bark of trees in order to get at the sap, and thus killing the trees. However, I very much doubt if they do any appreciable damage in this manner. I have watched a great many of them in the spring and fall and have clearly seen that they were feeding upon insects in the same way as the Downy.

Note.—A loud whining “whee,” and other harsh calls similar to the scream of a Blue Jay.

Nest.—In holes in trees, at heights from the ground varying from eight to fifty feet. Late in May they lay from four to seven white eggs (.85 × .60).

Range.—U. S. east of the Rockies, breeding from Virginia and Missouri to Hudson Bay, and wintering in southern U. S.

Male with a scarlet crown and crest, and a red moustache or mark extending back from the bill; female with scarlet crest but a blackish forehead and no moustache.

Next to the Ivory-bills, these are the largest of our Woodpeckers. Like that species it is very destructive to trees in its search for food. While engaged in this pursuit, they often drill large holes several inches into sound wood to reach the object of their search. Like all the Woodpeckers, they delight in playing tattoos on dry, resonant limbs with their bills.

Note.—A whistled “cuk,” “cuk,” “cuk,” slowly repeated many times, also a “wick-up” repeated several times.

Nest.—In large cavities in trees, in which they lay four to six white eggs (1.30 × 1.00).

Range.—Southern United States. The Northern Pileated Woodpecker (abietocola) is locally found in temperate N. A.

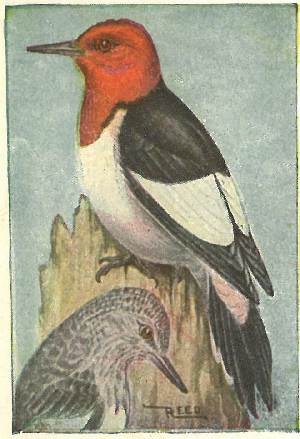

Adults with entire head and breast red; young with a gray head and back, streaked with darker.

This very handsome species is common and very well known in the Middle and Central States. They are the ruffians of the family, very noisy and quarrelsome. One of their worst traits is the devouring of the eggs and young of other birds. To partially offset this, they also eat insects and grubs and a great deal of fruit.

Note.—A loud, whining “charr,” “charr,” besides numerous other calls and imitations.

Nest.—Holes in trees in woods, orchards, or along roadsides and also in fence posts or telegraph poles. In May and June they lay four to six glossy white eggs (1.00 × .75).

Range.—United States east of the Rockies, breeding from the Gulf to New York and Minnesota. Winters in southern United States.

Male with whole top of head and back of neck red; female with forehead and hind head red but crown gray. Both sexes have the centre of the belly reddish, and have red eyes.

Like the Red-heads, these birds are noisy, but they have few of the bad qualities of the others. Besides the regular Woodpecker fare, they get a great many ants and beetles from the ground and fruit and acorns from the trees. They are also said to be fond of orange juice. In most of their range they are regarded as rather shy and retiring birds.

Note.—A sharp, resonant “cha,” “cha,” “cha,” repeated.

Nest.—In holes bored usually in live trees and at any height from the ground. Their five or six eggs are glossy white (1.00 × .75).

Range.—United States east of the Plains, breeding from Florida and Texas to southern Pennsylvania and Minnesota. Winters along the Gulf coast; occasionally strays to Massachusetts.

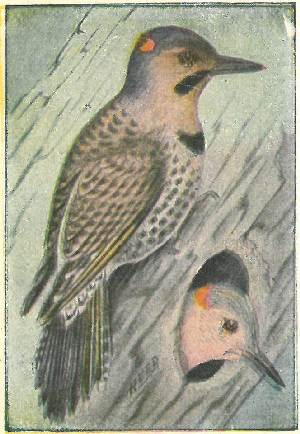

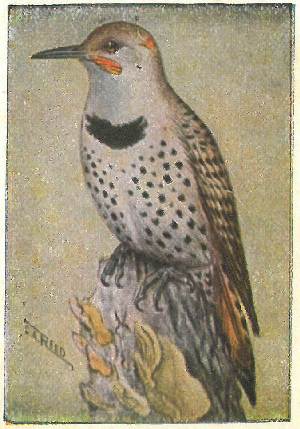

Male with a black moustache mark; female without, although young females in the first plumage show some black.

These birds are very often known as “Golden-winged Woodpeckers,” “High-holes” and about a hundred other names in different localities. Flickers are found commonly in woods, orchards, or trees by the roadside; on pleasant days their rapidly uttered, rolling whistle may be heard at all hours of the day.

Note.—A rapidly repeated whistle, “cuk,” “cuk,” “cuk”; an emphatic “quit-u,” “quit-u,” and several others of a similar nature.

Nest.—A cavity in a tree, at any distance from the ground. The white eggs usually vary in number from five to ten, but they have been known to lay as many as seventy-one, where an egg was taken from the nest each day.

Range.—South Atlantic States. The Northern Flicker (luteus) is found in North America east of the Rocky Mountains.

Crown brown and throat gray, these colors being just reversed from those of the common Flicker.

The male is distinguished by a red moustache mark, which the female lacks. The typical male Red-shafted Flicker lacks the red crescent on the back of the head, but it is often present on individuals, as there are numerous hybrids between this species and the preceding. Flickers are more terrestrial in their habits than are any others of the family; their food consists largely of ants which they get from the ground.

Note.—Same as those of the last; both species often utter a purring whistle when they are startled from the ground.

Nest.—The nesting habits are identical with those of the last and the eggs cannot be distinguished.

Range.—From the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific.

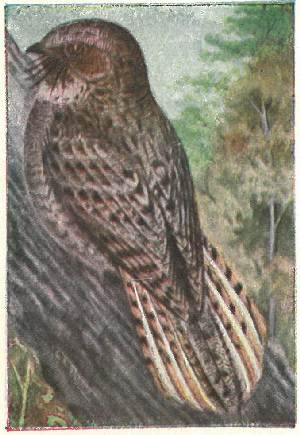

Male with the end half of the outer tail feathers white, and the edge of the outer vanes rusty; female with no white ends to the feathers. Birds of this family have small bills, but extremely large mouths adapted to catching night-flying moths and other insects. They remain sleeping during the day, either perched lengthwise on a limb or concealed beside a stump or rock on the ground, their colors harmonizing with the surroundings in either case. They fly, of their own accord, only at dusk or in the early morning. This species, which is much the largest of our Goatsuckers, is known to, at times, devour small birds, as such have been found in their stomachs.

Note.—A loudly whistled and repeated “chuck-will’s-widow.”

Nest.—None, the two eggs being laid on the ground or dead leaves in underbrush. Eggs white, blotched with gray and lavender (1.40 × 1.00).

Range.—South Atlantic and Gulf States, breeding north to Virginia and Missouri, west to Texas.

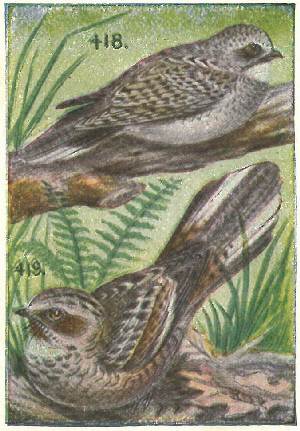

Male with broad white tips to outer tail feathers; female with narrow buffy tips. These birds are often confounded with the Nighthawk, but are very easily distinguished by the long bristles from the base of bill, the black chin, the chestnut and black barred wing feathers and the rounded tail. Whip-poor-wills are more nocturnal than Nighthawks and on moonlight nights continue the whistled repetition of their name throughout the night. They capture and devour a great many of the large-bodied moths that are found in the woods, but are never seen flying over cities like Nighthawks.

Note.—An emphatically whistled repetition of “whip-poor-will,” “whip-poor-will.”

Nest.—In June they lay two grayish or creamy white eggs (1.15 × .85), mottled with pale brown, gray and lilac. These are deposited on the ground in woods.

Range.—East of the Plains, breeding from the Gulf to Manitoba and New Brunswick. Winters south of the United States.

The female of this beautiful little Night-jar differs from the male only in having narrow buffy tips to the outer tail feathers instead of broad white ones. Like all the members of this family these birds are dusk fliers, remaining at rest on the ground in daylight. Their frosted gray plumage harmonizes so perfectly with their surroundings that it is almost impossible to see them. Their eggs are nearly immaculate, but usually show traces of the lavender blotches that mark others of the family. Their call is a mournful “poor-will-ee.” They are found from the Plains to the Pacific, but are not common east of the Rockies.

As usual with birds of this family, sexual difference in the plumage occurs chiefly on the tips of the outer tail feathers. These birds are common in the Lower Rio Grande Valley in Texas. Their eggs differ from any of the preceding in having a salmon-colored ground.

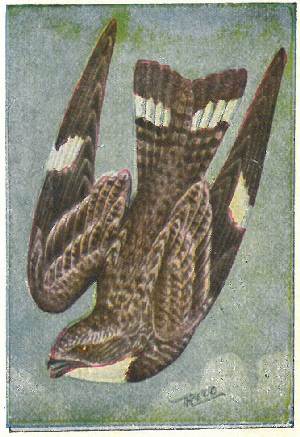

Male with white throat and white band across tail; female with rusty throat and no white on tail. Notice that the Nighthawk has a forked tail and white band across the wings, thus being readily distinguished at a distance from the Whip-poor-will.

Note.—A loud nasal “peent.”

Nest.—None, the two mottled gray and white eggs being laid on bare rocks in pastures, on the ground or underbrush, or on gravel roofs in cities; size 1.20 × .85.

Range.—United States east of the Plains, breeding from Florida to Labrador; winters south of United States. Three sub-species occur: 420a. Western Nighthawk (henryi), west of the Plains; 420b. Florida Nighthawk (chapmani); 420c. Sennett Nighthawk (sennetti), a pale race found on the Plains north to Saskatchewan.

This species is found in southern Texas and New Mexico. It differs from the last in having the primaries spotted with rusty, like those of the whip-poor-will.

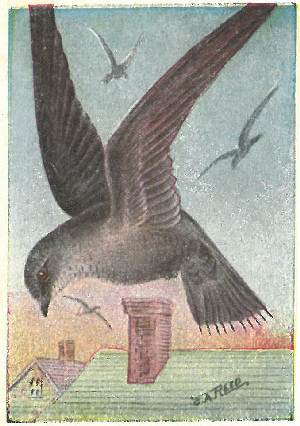

Unused chimneys of old dwellings make favorite roosting and nesting places for these smoke-colored birds. They originally dwelt in hollow trees until the advent of man furnished more convenient places, although we would scarcely consider the soot-lined brick surface as good as a clean hollow tree. Spines on the end of each tail feather enable them to hang to their upright walls, and to slowly hitch their way to the outer world. Throughout the day numbers of them are scouring the air for their fare of insects, but as night approaches, they return to the chimney.

Note.—A continuous and not unmusical twittering uttered while on the wing and also within the depths of the chimney.

Nest.—Made of small twigs or sticks glued to the sides of a chimney and each other by the bird’s saliva. The three to five white eggs are long and narrow (.75 × .50).

Range.—N. A. east to the Plains, breeding from Florida to Labrador; winters south of U. S.

This beautiful swift is one of the most graceful of winged creatures. Its flight is extremely rapid and its evolutions remarkable. They nest in communities, thousands of them often congregating about the tops of inaccessible cliffs, in the crevices of which they make their homes. No bird has a more appropriate generic name than this species—“aeronautes,” meaning sailor of the air; he is a sailor of the air and a complete master of the art.

Note.—Loud, shrill twittering, uttered chiefly while on the wing.

Nest.—Placed at the end of burrows in earthy cliffs or as far back as possible between crevices in rocks; usually in inaccessible places and as high as possible from the ground. It is a saucer-shaped structure made of vegetable materials cemented together with saliva, and lined with feathers. The four white eggs measure .87 × .52.

Range.—From the eastern foothills of the Rockies to the Pacific; north to Montana and northern California.

This little gem is the only one of the family found within the territory included in this book. Owners of flower gardens have the best opportunities to study these winged jewels, on their many trips to and fro for honey, or the insects that are also attracted thereby. With whirring wings, they remain suspended before a blossom, then—buzz—and they are examining the next, with bill lost within the sweet depths. Their temper is all out of proportion to their size, for they will dash at an intruder about their moss-covered home as though they would pierce him like a bullet. Their angry twitters and squeaks are amusing and surprising, as are their excitable actions.

Nest.—A most beautiful creation of plant fibres and cobwebs adorned with lichens and resembling a little tuft of moss upon the bough on which it is placed. In June two tiny white eggs are laid (.50 × .35).

Range.—N. A. east of the Rockies, breeding from the Gulf north to Labrador and Hudson Bay; winters south of U. S.

This pretty creature is the most graceful in appearance of the Flycatcher family, if not of the whole order of perching birds. In the southwest it is frequently known as the “Texan Bird of Paradise.” Its habits are very much like those of the Kingbird; as it gracefully swings through the air in pursuit of insects, it frequently opens and shuts its scissor-like tail. They are usually found in open country or on the borders of woodland. They rarely alight on the ground, for their long tails make them walk very awkwardly, but when they are a-wing they are the embodiment of grace.

Note.—A shrill “tzip,” “tzip,” similar to notes of Kingbirds.

Nest.—Quite large; built of all kinds of trash, such as twigs, grasses, paper, rags, string, etc.; placed in any kind of a tree or bush and at any height. The four or five creamy white eggs are spotted with brown (.90 × .67).

Range.—Breeds from Texas north to Kansas; winters south of U. S.

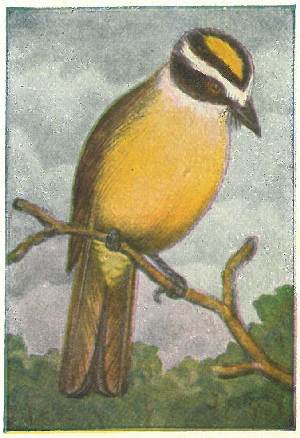

Adults with a concealed orange crown patch; young with none. From the time of their arrival in May until they leave us in August, Kingbirds are much in evidence in farmyards and orchards. They are one of the most noisy birds, always quarreling about something, and usually coming off victorious in whatever they may undertake. Crows are objects of hatred to them, and they always drive them from the neighborhood, vigorously dashing upon and picking them from above and often following them for a great distance. They have their favorite perches from which they watch for insects, usually a dead branch, a fence post, or a tall stalk in the field.

Note.—A series of shrill, harsh sounds like “thsee,” “thsee.”

Nest.—Of sticks, rootlets, grass, string, etc., placed in orchard trees or open woods at any height. Four or five creamy white eggs, specked and spotted with reddish brown (.95 × .70).

Range.—Breeds from the Gulf to southern Canada.

Differs from the common Kingbird in being larger and gray above; has black ear coverts, and no white tip to tail.

Like the last species, these are very noisy and pugnacious, and rule their domains with the hand of a tyrant. After they have mated they quarrel very little among themselves, and often several may use the same lookout twig from which to dash after passing flies or moths.

Note.—A rapidly repeated, shrill shriek: “pe-che-ri,” “pe-che-ri.”

Nest.—Rather more shabbily built but of the same materials as those used by our common Kingbird. Placed in all kinds of trees, but more often in mangroves, where they are commonly found. Three to five pinkish-white eggs, profusely blotched with brown (1.00 × .72).

Range.—West Indies and Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. Winters in the West Indies and Central America.

These tyrant flycatchers are abundant west of the Mississippi, where they are often, and perhaps more aptly, known as the Western Kingbirds. If possible, they are even more noisy and pugnacious than the eastern species. They have a great variety of notes, all rather unpleasant to the ear. Their food, like that of the other Kingbirds, consists of moths, butterflies, ants, grasshoppers, crickets, etc., etc., most of which they catch on the wing.

Note.—A shrill, metallic squeak; a low twittering and a harsh, discordant scream, all impossible to print.

Nest.—Quite large and clumsily made of paper, rags, twigs, rootlets, and grasses, placed in all sorts of locations, frequently in eave troughs or above windows. The eggs are creamy white, spotted with brown (.95 × .65).

Range.—Western United States, breeding from Texas to Manitoba and west to the Pacific; winters south of U. S.

This imposing flycatcher is the largest of the family that is found in North America. As usual with members of the family it is of a quarrelsome disposition, but hardly so much so as either the common or Arkansas Kingbirds. Their large, heavy bodies render them considerably less active than the smaller members of the family. On account of the size of the head and bill, they are often known as Bull-headed Flycatchers.

Note.—Very varied, but similar in character to those of the eastern Kingbird.

Nest.—It is said to build its nest at low elevations in trees or in thorny bushes—a large structure of twigs and rubbish with an entrance on the side. The three to five eggs have a cream-colored ground and are prominently specked about the large end with brown (1.15 × .82).

Range.—A Mexican species that is fairly common in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas.

These large flycatchers are very noisy in the mating season, but their notes are rather more musical than those of the Kingbirds. They appear to be of a quarrelsome disposition, for rarely will more than one pair be found in a single piece of woods. They also frequently chase smaller birds, but never attack larger ones, as do the Kingbirds. They have a queer habit of placing a piece of snakeskin in the hole in which their nest is located, for what purpose, unless to scare away intruders, is not known, but it seems to be a universal practice.

Note.—A clear whistle, “wit-whit,” “wit-whit,” repeated several times. This is the most common call; they have many others less musical.

Nest.—Of straw, etc., in holes of dead limbs. Eggs four to six in number; buffy white, streaked and blotched with brown.

Range.—Eastern N. A. from the Plains to the Atlantic, breeding north to southern Canada.

A Phœbe is always associated, in my mind, with old bridges and bubbling brooks. Nearly every bridge which is at all adapted for the purpose has its Phœbe home beneath it, to which the same pair of birds will return year after year, sometimes building a new nest, sometimes repairing the old. They seem to be of a nervous temperament, for, as they sit upon their usual lookout perch, their tails are continually twitching as though in anticipation of the insects that are sure to pass sooner or later.

Note.—A jerky, emphatic “phœ-be,” with the accent on the second syllable, and still further accented by a vigorous flirt of the tail.

Nest.—Of mud, grasses, and moss, plastered to the sides of beams or logs under bridges, culverts, or barns. In May or June four or five white eggs are laid (.75 × .55).

Range.—N. A. east of the Rockies, north to southern Canada; winters in southern U. S. and southward.

These birds can scarcely be called common any where, but single pairs of them may be found, in their breeding range, in suitable pieces of woodland. I have always found them in dead pine swamps, where the trees were covered with hanging moss, making it very difficult to locate their small nests. Their peculiar, loud, clear whistle can be heard for a long distance and serves as a guide-board to their location.

Note.—A loud, clear whistle, “whip-wheeu,” the first syllable short and sharp, the last long and drawn out into a plaintive ending.

Nest.—A small structure for the size of the bird, made of twigs and mosses firmly anchored to horizontal limbs or forks. Three to five eggs are laid; a rich creamy ground, spotted about the large end with brown and lavender (.85 × .65).

Range.—N. A., breeding from the latitude of Massachusetts, and farther south in mountainous regions, north to Labrador and Alaska.

In life, the Pewee can best be distinguished from the larger Phœbe, with which it is often confounded, by its sad, plaintive “pe-ah-wee,” “pee-wee” which is strikingly different from the brusque call of the Phœbe. Pewees are also found more in high, dry woods where they build their little moss-covered homes on horizontal boughs at quite a height from the ground. Like the other flycatchers they always perch on dead twigs, where their view is as little obstructed as possible.

Note.—A clear, plaintive whistle, “pe-ah-whee,” “pee-wee.”

Nest.—One of the most exquisite of bird creations, composed of plant fibres quilted together and ornamented with rock lichens; situated at varying heights on horizontal limbs, preferably oak or chestnut, and sometimes in apple trees in orchards. Eggs creamy white, specked with brown (.80 × .55).

Range.—U. S. from the Plains to the Atlantic and north to Manitoba and New Brunswick; winters in Central America.

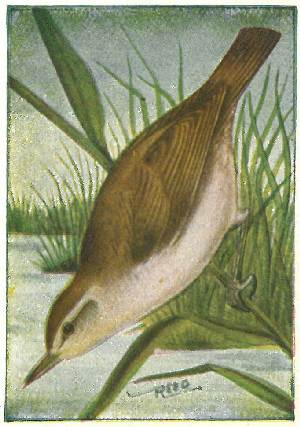

These strange little Flycatchers are found in swamps such as those usually frequented by Olive-sided Flycatchers and Parula Warblers. They are one of the few of the family to nest on the ground or very close to it. Their homes are made in the moss-covered mounds or stumps found in these swamps.

Range.—N. A. east of the Plains north to Labrador, breeding from northern U. S. northward.

This bird is very similar to the last, but the lower mandible is light, and the throat and belly white. Their favorite resorts are shady woods not far from water. Here they nest in the outer branches of bushes or trees at heights of from four to twenty feet from the ground. The nests are shallow and composed of twigs and moss. Eggs creamy with brown spots.

Range.—U. S. east of Plains, breeding from the Gulf to New England and Manitoba; winters in the Tropics.

This species is very similar to, but larger, than the well-known Least Flycatcher or Chebec. They are found in swampy pastures or around the edges of ponds or lakes, where they nest in low bushes.

Range.—U. S. east of the Mississippi, breeding from New York to New Brunswick.

Smaller than the last and with the tail slightly forked. Common everywhere in orchards, swamps, or along roadsides. They are very often known by the name of “Chebec,” because their notes resemble that word. Their nests are placed in upright forks of any kind of trees or bushes; they are made of plant fibres and grasses closely felted together. The eggs range from three to five in number and are creamy white, without markings; size .65 × .50.

Range.—N. A. east of the Rockies, breeding from middle U. S. north to New Brunswick and Manitoba.

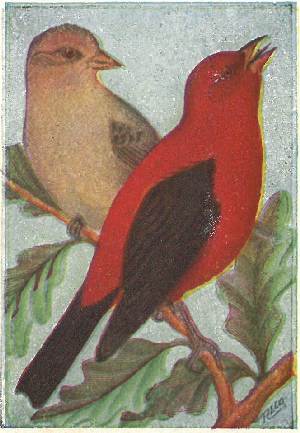

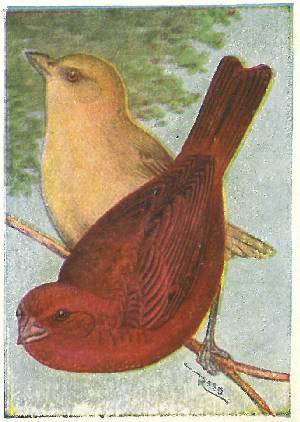

Female with only a slight tinge of pink, where the male is brilliant vermilion.

This is the most gorgeously plumed species of the American Flycatchers. It has all the active traits of the family and, to those who are only accustomed to the demure gray plumage of most eastern species, the first sight of this one as he dashes after an insect is a sight never to be forgotten.

Note.—During the mating season the male often gives a twittering song while poised in the air, accompanying it by loud snapping of the mandibles.

Nest.—Saddled on limbs of trees at low elevations from the ground; composed of small twigs and vegetable fibres closely felted together and often adorned on the outside with lichens similar to the nests of the Wood Pewee. The four eggs are of a creamy-buff color with bold spots of brown and lilac, in a wreath around the large end (.73 × .54).

Range.—Mexican border of the United States, from Texas to Arizona.

This variety, which is larger than its sub-species, is only found in the U. S. in winter, but several of the sub-species are residents in our limits. During the mating season they have a sweet song that is uttered on the wing, like that of the Bobolink.

Note.—Alarm note and call a whistled “tseet,” “tseet”; song a low, sweet, and continued warble.

Nest.—A hollow in the ground lined with grass; placed in fields and usually partially concealed by an overhanging sod or stone. The three to five eggs have a grayish ground color and are profusely specked and blotched with gray and brownish. (.85 × .60).

Range.—Breeds in Labrador and about Hudson Bay; south in winter to South Carolina and Illinois.

Sub-Species.—474b. Prairie Horned Lark (praticola). A paler form usually with the line over the eye white, found in the Mississippi Valley. 474c. Desert Horned Lark (leucolæma). Paler and less distinctly streaked above than the Prairie; found west of the Mississippi and north to Alberta.

This handsome member of the Crow family is sure to attract the attention of all who may see him. He is very pert in all his actions, both in trees and on the ground, and is always ready for mischief. In a high wind their long tail often makes traveling a laborious operation for them, and at such times they usually remain quite quiet. They are very impudent and always on the lookout for something to steal; they are also very noisy and forever scolding and chattering among themselves.

Note.—A loud, harsh “cack,” “cack,” and an endless variety of whistles and imitations.

Nest.—A large, globular heap of sticks placed in bushes or trees from four to fifty feet from the ground. The entrance to the nest is on one side and the interior is made of grass and mud. The four to six eggs are white, thickly specked with yellowish brown (1.25 × .90).

Range.—Western North America, east to the Plains and north to Alaska; resident.

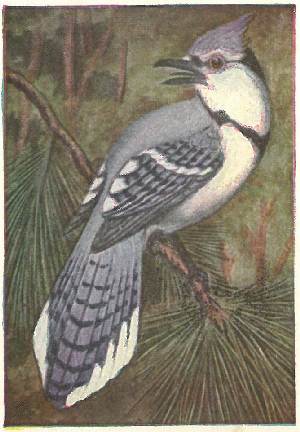

These are one of the best known and most beautiful birds that we have, but, unfortunately, they have a very bad reputation. They often rob other birds of their eggs and young as well as food and nesting material. They are very active birds and are always engaged in gathering food, usually acorns or other nuts, and hiding them away for future use.

Note.—A two-syllabled whistle or a harsh, discordant scream. Besides these two common notes they make an endless variety of sounds mimicking other birds.

Nest.—Of twigs and sticks in bushes or low trees, preferably young pines. The four eggs are pale greenish blue specked with brown (1.10 × .80).

Range.—N. A. east of the Rockies from the Gulf to Labrador, resident in the U. S. The Florida Blue Jay (florincola) is smaller and has less white on wings and tail.

This Jay is locally distributed chiefly in the southern parts of Florida, being found principally in scrub oaks. Like the Blue Jay, their food consists of animal matter and some seeds, berries, and acorns. Their habits are very similar to those of the northern bird and their calls resemble those of our bird, too. They are rather slow in flight and pass a great deal of their time upon the ground.

Note.—A “jay,” “jay,” similar to that of the Blue Jay, and a great variety of other calls.

Nest.—In the latter part of March and in April they build their flat nests of twigs, usually in bushes or scrub oaks, and lay three or four greenish-blue eggs, with brown spots; size 1.05 × .80.

Range.—Middle and southern portions of Florida chiefly along the coasts.

These Jays are very beautiful, and we are sorry to have to admit that, like all the other members of the family, they are merciless in their treatment of smaller birds. During the summer their diet consists of raw eggs with young birds “on the side,” or vice versa; later they live upon nuts, berries, insects; in fact, anything that is edible.

Note.—Practically unlimited, being imitations of those of most of the birds in the vicinity.

Nest.—Not easily found, as it is usually concealed in dense thickets. The nests are like those of other Jays, loosely made of twigs and lined with black rootlets. The four eggs that are laid in May have a grayish ground color and are thickly spotted with several shades of brown and lilac. They measure 1.05 × .80.

Range.—Fairly common in the Lower Rio Grande Valley in southern Texas.

These birds are well known to hunters, trappers, and campers in the northern woods. They are great friends, especially of the lumbermen, as some of the pranks that they play serve to enliven an otherwise tedious day. They seem to be devoid of fear and enter camp and carry off everything, edible or not, that they can get hold of. They are called by guides and lumbermen by various names, such as Whiskey Jack, Moose Bird, etc.

Note.—A harsh “ca-ca-ca,” and various other sounds.

Nest.—Usually in coniferous trees at low elevations; made of twigs, moss, and feathers. The three or four eggs are gray, specked and spotted with darker (1.15 × .80). They nest early, usually before the snow begins to leave the ground and often when the mercury is below zero.

Range.—Eastern North America from northern United States northward. 484c. Labrador Jay (nigricapillus), which is found in Labrador, has the black on the hind head deeper and extending forward around the eye.

The habits of all the ravens and crows are identical and are too well known to need mention. They are all very destructive to young birds and eggs. The Raven can be known by its large size, its very large bill, and lanceolate feathers on the throat. They are found in the mountains from Georgia and on the coast from Maine northward.

This species has the bases of the feathers on the back of the neck white. Found in southwestern United States.

The common Crow of North America, replaced in Florida by the very similar Florida Crow (pascuus).

This small species is found on the Atlantic Coast north to Massachusetts.

Clarke Crows are found abundantly in all coniferous forest on the higher mountains in their range. They are very peculiar birds, having some of the traits of Woodpeckers, but more of those of the Jays.

They are very active, very noisy, and very inquisitive, sharing with the Rocky Mountain Jay the names of “Camp Robber,” “Moose Bird,” etc. They are great travellers and may, one season, be absent where they were abundant the preceding one.

Notes.—Various calls and imitations like those of all others of the Jay family.

Nest.—Of sticks, at high elevations on horizontal boughs of coniferous trees. The four eggs have a pale greenish-gray ground, thickly sprinkled with darker (1.25 × .92).

Range.—Mountains of western North America, casually east to Kansas.

Plumage metallic green and purple, heavily spotted above and below with buffy or white.

These European birds were introduced into New York a number of years ago, and are now common there and spreading to other localities in Connecticut and about New York City. They live about the streets and in the parks, building their nests in crevices of buildings and especially in the framework of the elevated railroads of the city, and less often in trees. They lay from four to six pale-blue, unspotted eggs (1.15 × .85). How they will affect other bird life, in case they eventually become common throughout the country, is a matter of conjecture, but from what I have seen of them they are quarrelsome and are masters of the English Sparrow, and may continue their domineering tactics to the extent of driving more of our song birds from the cities.

Bobolinks are to be found in rich grass meadows, from whence their sweet, wild music is often borne to us by the breeze. While his mate is feeding in the grass or attending to their domestic affairs, Mr. Bobolink is usually to be found perched on the tip of a tree, weed stalk, or even on a tall blade of grass, if no other spot of vantage is available, singing while he stands guard to see that no enemies approach. He is a good watchman and it is a difficult matter to flush his mate from the nest, for she leaves at his first warning.

Song.—A wild, sweet, rippling repetition of his name with many additional trills and notes. Alarm note a harsh “chah” like that of the Blackbird.

Nest.—Of grasses in a hollow on the ground, in meadows. They lay four to six eggs with a white ground color, heavily spotted, clouded and blotched with brown (.85 × .62).

Range.—N. A. east of the Rockies, breeding from New Jersey and Kansas north to Manitoba and New Brunswick; winters in South America.

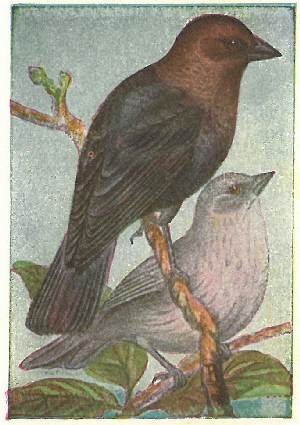

Male glossy greenish black, with a brown head; female and young, dull gray.

Groups of these birds are often seen walking sedately about among the cows in the pasture, hence their name. They are the only birds that we have that neither make a nest of their own nor care for their young. The female slyly deposits her egg in the nest of a smaller bird when the owner is absent, leaving further care of it to its new owner. Warblers, Sparrows and Vireos seem to be most imposed upon in this manner.

Notes.—A low “chack,” and by the male a liquid, wiry squeak accompanied by a spreading of the wings and tail.

Range.—U. S., chiefly east of the Rockies, breeding from the Gulf to Manitoba and New Brunswick; winters in southern U. S. A sub-species, the Dwarf Cowbird (obscurus), is found in southwestern United States; it is slightly smaller.

Male black, with head and breast bright yellow; female more brownish and with head paler and mixed with brown.

These handsome birds are common locally on the prairies, frequenting sloughs and extensive marshes and borders of lakes. They are very sociable birds and breed in large colonies, sometimes composed of thousands of birds.

Notes.—A harsh “chack,” and what is intended for a song, consisting of numerous, queer-sounding squeaks, they being produced during seemingly painful contortions of the singer.

Nest.—Of rushes woven around upright canes over water, in ponds and sloughs. The nest is placed at from four inches to two feet from the water and is quite deep inside. The four to six eggs are grayish, profusely specked with pale brown (1.00 × .70).

Range.—U. S., chiefly west of the Mississippi, north to British Columbia and Hudson Bay; winters on southwestern border of the U. S.

Male black, with scarlet and buff shoulders; female brownish black above and streaked below. Nearly all our ponds or wet meadows have their pair or colony of Blackbirds.

Note.—A harsh “cack”; a pleasing liquid song, “conk-err-ee,” given with much bowing and spreading of the wings and tail.

Nest.—Usually at low elevations in bushes, in swamps or around the edges of ponds or frequently on the ground or on hummocks in wet pastures. The nest is made of woven grasses and rushes, and is usually partially suspended from the rim when placed in bushes. The three to five eggs are bluish white, scrawled, chiefly around the large end, with blackish (1.00 × .70).

Range.—East of the Rockies, breeding north to Manitoba and New Brunswick; winters in southern U. S.

Sub-Species.—498b. Bahaman Redwing (bryanti). 498c. Florida Redwing (floridanus).

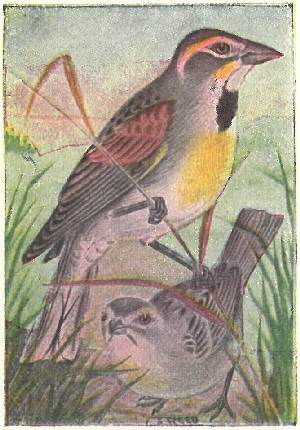

Meadowlarks are familiar friends of the hillside and meadow; their clear fife-like whistle is often heard, while they are perched on a fence-post or tree-top, as well as their sputtering alarm note when they fly up before us as we cross the field.

Song.—A clear, flute-like “tseeu-tseeer,” and a rapid sputtering alarm note.

Nest.—Of grasses, on the ground in fields, usually partially arched over. Three to five white eggs specked with brown (1.10 × .80).

Range.—N. A. east of the Plains and north to southern Canada; winters from Massachusetts and Illinois southward.

Sub-Species.—501.1. Western Meadowlark (neglecta). This race has the yellow on the throat extended on the sides; its song is much more brilliant and varied than the eastern bird. It is found from the Plains to the Pacific. 501c. Florida Meadowlark (argutula) is smaller and darker than the common.

Within the United States, these large Orioles are found only in southern Texas. They are not uncommon there and are resident. Their notes are loud, mellow whistles like those of the other Orioles. Their nests are semi-pensile and usually placed in mesquite trees not more than ten or fifteen feet from the ground.

These beautiful birds are found in southwestern United States, from California to western Texas.

They are said to sing more freely than other members of the family, but the song, while loud and clear, is of short duration. Their nests, which are semi-pensile, are often placed in giant yucca trees, or in vines that are suspended from cacti. The three or four eggs are pale blue, scrawled and spotted with black and lavender (.95 × .65).

This very brilliantly plumaged Oriole is, perhaps, the most abundant of the family in southern Texas. It is not as shy a bird as the two preceding species and is more often found in the neighborhood of houses.

With the exception of a few kinds of fruits, their food consists almost entirely of insects; all the Orioles are regarded as among our most beneficial birds.

Notes.—A harsher and more grating whistle than that of most of the Orioles.

Nest.—Usually in bunches of hanging moss, being made by hollowing out and matting the moss together and lining it with finer wiry moss. Others are placed in yucca trees, such nests being made of the fiber of the tree. Eggs dull white, scrawled about the large end with black and lavender (.85 × .60).

Range.—Found only in southern Texas. A sub-species (nelsoni) is found in New Mexico, Arizona and southern California.

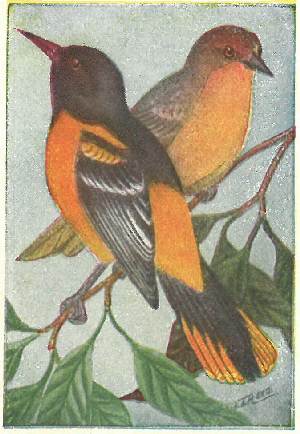

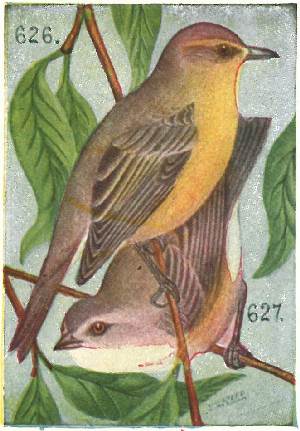

Male chestnut and black; female dull yellowish and gray; young male, second year, like female, but with black face and throat. These Orioles are usually found in open country and, as their name suggests, have a preference for orchards. They are also found abundantly in shrubbery along streams and roadsides. They feed chiefly upon worms, caterpillars, beetles, grasshoppers, etc., and are one of the most beneficial birds that we have.

Song.—A rich, loud and rapid warble, cheery and pleasing but impossible to describe; a chattering note of alarm.

Nest.—A beautiful basket of grasses woven into a deeply cupped ball and situated in forks of trees or bushes; often they are made of green grasses. Four to six white eggs, specked, scrawled and spotted with black and brown (.80 × .55).

Range.—U. S. east of the Plains, breeding from the Gulf to Massachusetts and Michigan; winters in Central America.

Male orange and black; female dull yellowish and gray.

They are sociable birds and seem to like the company of mankind, for their nests are, from choice, built as near as possible to houses, often being where they can be reached from windows. As they use a great deal of string in the construction of their nests, children often get amusement by placing bright-colored pieces of yarn where the birds will get them, and watch them weave them into their homes.

Song.—A clear, querulous, varied whistle or warble; call, a plaintive whistle.

Nest.—A pensile structure, often hanging eight or ten inches below the supporting rim, and swaying to and fro with every breeze. They lay five or six white eggs, curiously scrawled with blackish brown (.90 × .60).

Range.—N. A. east of the Rockies and breeding north to New Brunswick and Manitoba. Winters in Central America.

Male glossy black, female grayish; both sexes in winter with most of the head and breast feathers tipped with rusty. In the United States we know these birds chiefly as emigrants; but a few of them remain to breed in the Northern parts. Their songs are rather squeaky efforts, but still not unmusical. These birds are found east of the Rockies.

Male with a glossy purplish head and greenish black body; female grayish brown. This is the Western representative of the preceding; it is most abundant west of the Rockies, but is also found on the Plains. Its distribution is not so northerly and it nests commonly in its United States range. Their eggs are whitish, very profusely spotted and blotched with various shades of brown (1. × .75).

Male with purple head and greenish back; female brownish gray. All the Grackles are very similar in appearance, the colors varying with different individuals of the same species. Their habits are alike, too, and I consider them one of the most destructive of our birds.

Note.—A harsh “tchack,” and a squeaky song.

Nest.—Of sticks and twigs, usually in pines in the North and bushes in the South. Four eggs, pale bluish gray with black scrawls (1.10 × .80).

Range.—Eastern U. S., breeding north to Mass.

Sub-Species.—511a. Florida Grackle (aglæus), slightly smaller. 511b. Bronzed Grackle (æneus), with a purple head and usually a brassy back. Eastern U. S., breeding north to Labrador and Manitoba.

Similar in color to the last but much larger, and having the same habits. Eggs also larger (1.25 × .95). Southeastern U. S. The Great-tailed Grackle (macrourus), found in Texas, is still larger.

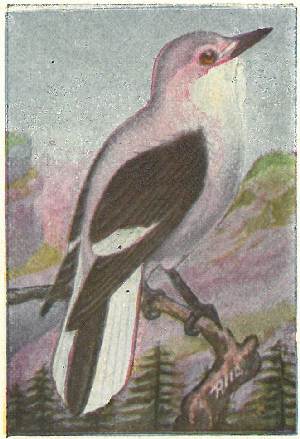

Female paler and with white on upper tail coverts. As would be judged from the large bills that these birds have, their food consists almost entirely of seeds, with occasionally a few berries and perhaps insects. In certain localities they are not uncommon, but, except in winter, they are rare anywhere in the U. S., and east of the Mississippi they can only be regarded as accidental even in winter. They have been taken several times in Massachusetts. In winter they usually travel about in small bands, visiting localities where the food supply is the most abundant.

Song.—A clear, Robin-like whistle; call, a short whistle.

Nest.—A flat structure of twigs and rootlets placed at low elevations in trees or bushes. Four eggs, greenish white, spotted with brown (.90 × .65).

Range.—Breeds in mountains of western British America and northwestern U. S. South and east in winter to the Mississippi and rarely farther.

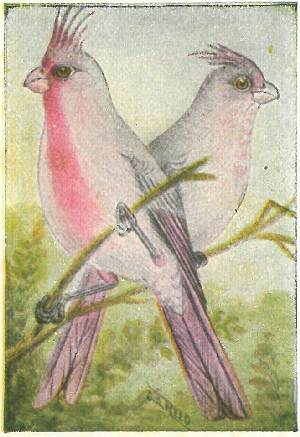

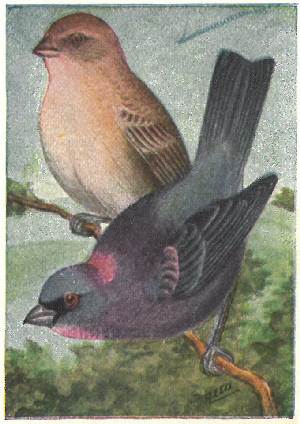

Male rosy red; female gray and yellowish.

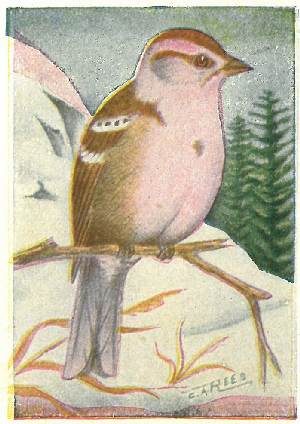

These pretty birds visit us every winter, coming from Canada and northern New England, where they are found in summer. They are very fearless birds and might almost be regarded as stupid; when they are feeding you can easily approach within a few feet of them, and they have often been caught in butterfly nets. They may, at times, be found in any kind of trees or woods, but they show a preference for small growth pines, where they feed upon the seeds and upon seeds of weeds that project above the snow.

Song.—A low sweet warble; call, a clear, repeated whistle.

Nest.—In coniferous trees, of twigs, rootlets and strips of bark; eggs three to four in number, greenish blue spotted with brown and lilac (1.00 × .70).

Range.—Breeds in eastern British America and northern New England; winters south to New York and Ohio. Several sub-species are found west of the Rockies.

Male dull rosy red; female streaked brownish gray.

These beautiful songsters are common in the northern tier of states and in Canada. In spring the males are usually seen on, or heard from, tree tops in orchards or parks, giving forth their glad carols. They are especially musical in spring when the snow is just leaving the ground and the air is bracing. After family cares come upon them, they are quite silent, the male only occasionally indulging in a burst of song.

Song.—A loud, long-continued and very sweet warble; call, a querulous whistle.

Nest.—Of strips of bark, twigs, rootlets and grasses, placed at any height in evergreens or orchard trees. The eggs resemble, somewhat, large specimens of those of the Chipping Sparrow. They are three or four in number and are greenish blue with strong blackish specks (.85 × .65).

Range.—N. A. east of the Rockies, breeding from Pennsylvania and Illinois northward; winters throughout the United States.

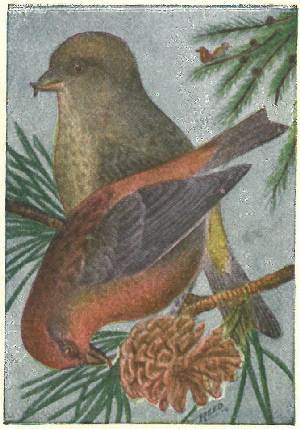

These curious creatures appear in flocks on the outskirts of our cities every winter, where they will be found almost exclusively in coniferous trees. They cling to the cones, upon which they are feeding, in every conceivable attitude, and a shower of seeds and broken cones rattling through the branches below shows that they are busily working. They are very eccentric birds and the whole flock often takes flight, without apparent cause, only to circle about again to the same trees. The flute-like whistle that they utter when in flight sounds quite pleasing when coming from all the individuals in the flock.

Song.—A low twittering; call, a short, flute-like whistle.

Nest.—In coniferous trees, of spruce twigs, shreds of bark and some moss or grass. The three or four eggs are greenish white spotted with brown (.75 × .55).

Range.—Breeds from northern New England northward and westward, and south in mountains to Georgia; winters in the northern half of the U. S.

Male, rosy; female, with yellowish.

This species seems to be of a more roving disposition, and even more eccentric than the last. They are not nearly as common and are usually seen in smaller flocks; occasionally one or two individuals of this species will be found with a flock of the American Crossbills, but they usually keep by themselves. While they may be seen in a certain locality one season, they may be absent for several seasons after, for some reason or other. They feed upon the seeds of pine cones, prying the cones open with their peculiar bills.

Notes.—Do not differ appreciably from those of the last.

Nest.—The nesting habits of this species are like those of the last, but the eggs differ in being slightly larger and in having the markings of a more blotchy character (.80 × .55).

Range.—Breeds from the northern parts of the northern tier of states northward. Winters in the northern half of the U. S.

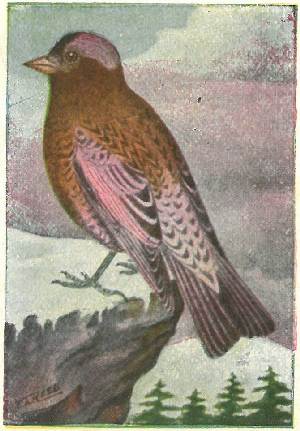

Female similar to, but duller colored than, the male.

All the members of this genus are western and northern, this one only being found east of the Rockies and then only in winter, when it occasionally is found east of the Mississippi. They wander about in rocky mountainous regions, feeding upon seeds and berries. They are very restless and stop in a place but a short time before flying swiftly away, in a compact flock, to another feeding ground.

Note.—An alarm note of a short, quick whistle.

Nest.—Built on the ground, usually beside a rock or in a crevice; composed of weeds and grass, lined with finer grass. They lay three or four unmarked white eggs in June.

Range.—Western U. S., breeding in the higher mountain ranges; in winter sometimes wandering east to the Mississippi.

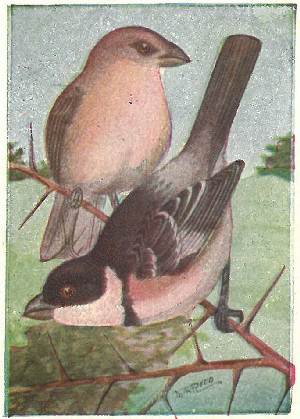

Male with a rosy breast; female without.

In winter these northern birds may be found in flocks gathering seeds from weeds by the roadside and stone walls. Their actions greatly resemble those of our Goldfinch, but their flight is more rapid.

Song.—Strong, sweet and canary-like.

Nest.—At low elevations in bushes or trees; eggs three to five, pale greenish blue with brown specks.

Range.—Breeds in the extreme north; winters south to northern U. S.

Sub-Species.—528a. Holboell Redpoll (holboelli), slightly larger. 528b. Greater Redpoll (rostrata), larger and darker.

A larger and much whiter species found in Greenland and migrating to Labrador in winter. 527b. Hoary Redpoll (exilipes), smaller and darker, but still lighter than the Redpoll; winters south to Massachusetts.

These beautiful little creatures are often known as Thistle-birds and Wild Canaries, the former name because they are often seen on thistles, from the down of which their nests are largely made, and the latter name because of the sweet canary-like song. Their flight is a peculiar series of undulations accompanied by an intermittent twitter. They are very sociable and breed usually in communities as well as travel in flocks in the winter. Their food is chiefly of seeds and they often come to gardens in fall and winter to partake of sunflower seeds, these flowers often being raised for the sole purpose of furnishing food for the finches in the winter.

Song.—Sweet, prolonged and canary-like; call, a musical “tcheer,” and a twittering in flight.

Nest.—Of thistledown, plant fibres and grasses, in forks of bushes, most often willows or alders near water. Four or five unmarked, pale bluish eggs.

Range.—N. A. east of the Rockies; breeds from Virginia and Missouri north to Labrador; winters in U. S.

Cap, wings and tail black; sides of head and back greenish. Female much duller and with no black in the crown. These little Goldfinches are very abundant throughout the West. Their flight is undulatory like that of the preceding, and all their habits are very similar. They spend the winter in bands, roving about the country, feeding on weed seeds; in summer they repair, either in small bands or by single pairs, to the edges of swamps or woodland near water, where they construct their compact homes in the forks of bushes. Their eggs are pale blue like those of the American Goldfinch, but of course are much smaller (.62 × .45). They are laid in May or June, or even earlier in the western portions of their range.

Song.—Sweet and musical, almost like that of the last species.

Range.—Western United States from the Plains to the Pacific, being abundant west of the Rocky Mountains.

These are also northern birds, being found in the U. S., with the exception of the extreme northern parts, only in winter and early spring. Their habits are just like those of the Goldfinches, for which species they are often mistaken, as the latter are dull-colored in winter. Their song and call-notes are like those of the Goldfinch, but have a slight nasal twang that will identify them at a distance, after becoming accustomed to it. They are often seen hanging head downward from the ends of branches as they feed upon the seeds or buds and when thus engaged they are very tame.

Song.—Quite similar to that of the Goldfinch.

Nest.—In coniferous trees at any elevation from the ground. They are made of rootlets and grasses, lined with pine needles and hair; the three to five eggs are greenish white, specked with reddish brown (.65 × .45).

Range.—North America, breeding northward from the northern boundary of the U. S. and farther south in mountain ranges; winters throughout the U. S.

Adults in summer black and white; in winter, washed with brownish.

When winter storms sweep across our land, these birds blow in like true snowflakes, settling down upon hillsides and feeding upon seeds from the weed stalks that are sure to be found above the snow somewhere. They are usually found in large flocks, and are very restless, starting up, as one bird, at the slightest noise, or continually wheeling about from one hill to another, of their own accord.

Song.—A low twittering while feeding and a short whistle when in flight.

Nest.—Of grass and moss lined with feathers and sunk in the sphagnum moss with which much of Arctic America is covered. Three to five eggs, pale greenish white, specked with brown. Size .90 × .65.

Range.—Breeds from Labrador and Hudson Bay northward; winters in northern United States.

Male in summer with black crown and throat and chestnut nape; female similar but duller; winter plumage, with feathers of head and neck tipped with grayish so as to conceal the bright markings.

As indicated by its name, this is a Northern species, which spends the cold months in northern U. S., traveling in flocks and resting and feeding on side hills, often with Snowflakes, or on lower ground with Horned Larks.

Song.—A sweet trill or warble, frequently given while in flight; call, a sharp chip.

Nest.—Of mosses, grasses and feathers placed on the ground in tussocks or on grassy hummocks. In June and July they lay from four to six eggs having a grayish ground color, which is nearly obscured by the numerous blotches of brown and lavender (.80 × .60).

Range.—Breeds from Labrador northward and winters south to South Carolina and Texas. A sub-species is found in the West.

Male in summer with the underparts buffy and sides of head marked with black; female, and male in winter, much duller with all bright markings covered with a brownish-gray wash.

Like the last species, these are Arctic birds found in winter, on the plains and prairies of middle U. S. They are rarely found within our limits when in their beautiful spring plumage. They are most always found in company with the following species feeding upon seeds, buds and small berries.

Song.—A sweet warble rarely heard in the United States; a clear “cheer-up” constantly uttered while on the wing.

Nest.—Of grasses, weeds and moss, lined with feathers; located on the ground in similar locations to those of the last species. The four or five eggs are similar to those of the last but lighter (.80 × .60).

Range.—Breeds about Hudson Bay and northward; winters in middle United States.

Male in summer with a black breast and crown, and chestnut nape; female, and male in winter, much duller and with all bright markings covered with grayish.

Unlike the preceding Longspurs, these are constant residents in the greater part of the Western Plains, in some localities being classed as one of the most abundant birds. They have a short, sweet song that, in springtime, is frequently given as the bird mounts into the air after the fashion of the Horned Larks. They commonly feed about ploughed fields, along the edges of which they build their nests.

Song.—A short, sweet trill; alarm note a sharp chip, and call note a more musical chirp.

Nest.—Of fine grasses, placed on the ground in open prairies or along the edges of cultivated fields, often being concealed beside a tussock; their four or five eggs are clay color marked with reddish brown and lavender (.75 × .55).

Range.—Breeds in the Great Plains from Kansas and Colorado north to Manitoba; winters south to Mexico.

Male with a black crown and patch on breast, and chestnut shoulders; female, and male in winter, dull colored with all bright markings obscured by brownish gray.

These are also common birds on the plains of middle U. S., but perhaps not so much so as the last species, with which species they are often found breeding. These finches show their close relationship to the famous Skylark of Europe by frequently indulging in the same practice of soaring aloft and descending on set wings, rapturously uttering their sweet song.

Song.—A shrill, twittering warble; call, a musical chirp.

Nest.—A neat cup of grasses in a hollow in the ground on prairies or in fields. Their four to six eggs are dull whitish clouded with brownish, the marking not being as distinct as in those of the last species (.75 × .55).

Range.—Breeds on the Great Plains from Kansas north to Saskatchewan; winters south to Mexico.

These street urchins were introduced into our country from Europe about 1850, and have since multiplied and spread out so that they now are found in all parts of our land from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Heretofore they have confined themselves chiefly in the immediate vicinity of the larger cities and towns, but it is now noted with alarm that they are apparently spreading out into the surrounding country. They are very hardy creatures, able to stand our most rigorous winters. They are fighters and bullies from the time they leave the egg, and few of our native birds will attempt to live in the neighborhood with them.

Notes.—A harsh, discordant sound, which they commence early in the morning and continue until night.