| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through the Google Books Library Project. See http://www.google.com/books?id=zcgsAAAAMAAJ |

THE

OLD MAIDS' CLUB

BY

I. ZANGWILL

AUTHOR OF

"THE BACHELOR'S CLUB," "THE BIG BOW MYSTERY," ETC.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS

BY

F. H. TOWNSEND

NEW YORK

TAIT, SONS & COMPANY

Union Square

Copyright, 1892,

by

UNITED STATES BOOK COMPANY,

[All rights reserved.]

The Reader My Book.

My Book The Reader.

chapter. Page.

THE OLD MAIDS' CLUB.

THE ALGEBRA OF LOVE, PLUS OTHER THINGS.

The Old Maids' Club was founded by Lillie Dulcimer in her sweet seventeenth year. She had always been precocious and could analyze her own sensations before she could spell. In fact she divided her time between making sensations and analyzing them. She never spoke Early English—the dialect which so enraged Dr. Johnson—but, like John Stuart Mill, she wrote a classical style from childhood. She kept a diary, not necessarily as a guarantee of good faith, but for publication only. It was labelled "Lillie Day by Day," and was posted up from her fifth year. Judging by the analogy of the rest, one might construct the entry for the first day of her life. If she had been able to record her thoughts, her diary would probably have begun thus:—

"Sunday, September 3rd: My birthday. Wept at the sight of the world in which I was to be so miserable. The [pg 10] atmosphere was so stuffy—not at all pleasing to the æsthetic faculties. Expected a more refined reception. A lady, to whom I had never been introduced, fondled me and addressed me as 'Petsie-tootsie-wootsie.' It appears that she is my mother, but this hardly justifies her in degrading the language of Milton and Shakespeare. Later on a man came in and kissed her. I could not help thinking that they might respect my presence; and, if they must carry on, continue to do so out of my sight as before. I understood later that I must call the stranger 'Poppy,' and that I was not to resent his familiarities, as he was very much attached to my mother by Act of Parliament. Both the man and the woman seem to arrogate to themselves a certain authority over me. How strange that two persons you have never seen before in your life should claim such rights of interference! There must be something rotten in the constitution of Society. It shall be one of my life-tasks to discover what it is. I made a light lunch off milk, but do not care for the beverage. The day passed slowly. I was dreadfully bored by the conversation in the bedroom—it was so petty. I was glad when night came. O, the intolerable ennui of an English Sunday! I divine already that I am destined to go through life perpetually craving for I know not what, and that I shan't be happy till I get it."

Lillie was a born heroine, being young and beautiful from her birth. In her fourth year she conceived a Platonic affection for the boy who brought the telegrams. His manners had such repose. This was followed by a hopeless passion for a French cavalry officer with spurs. Every one feared she would grow up to be a suicide or a poetess; for her earliest nursery rhyme was an impromptu distich discovered by the nursery-maid, running:

[pg 11] And her twelfth year was almost entirely devoted to literary composition of a hopeless character, so far as publishers were concerned. It was only the success of "Woman as a Waste Force," in her fourteenth year, that induced them to compete for her early manuscripts and to give the world the celebrated compilations, "Ibsen for Infants," "Browning for Babies," "Carlyle for the Cradle," "Newman for the Nursery," "Leopardi for the Little Ones," and "The Schoolgirl's Schopenhauer," which, together with "Tracts for the Tots," make up the main productions of her First Period. After the loss of the French cavalry officer she remained blasée till she was more than seven, when her second grand passion took her. It was a very grand passion indeed this time—and it lasted a full week. These things did not matter while Lillie had not yet arrived at years of indiscretion; but when she got into her teens, her father began to look about for a husband for her. He was a millionaire and had always kept her supplied with every luxury. But Lillie did not care for her father's selections, and sent them all away with fleas in their ears instead of kind words. And her father was as unhappy as his selections. In her sixteenth year her mother, who had been ailing for sixteen years, breathed her last, and Lillie more freely. She had grown quite to like Mrs. Dulcimer, and it prevented her having her own way. The situation was now very simple. Mr. Dulcimer managed his immense affairs and Lillie managed Mr. Dulcimer.

He made one last effort to get her to manage another man. He discovered a young nobleman who seemed fond of her society and who was in the habit of meeting her accidentally at the Academy. The gunpowder being thus presumably laid, he set to work to strike the match. But the explosion was not such as he expected. Lillie told him that no man was further from her thoughts as a possible husband.

[pg 12] "But, Lillie," pleaded the millionaire, "not one of the objections you have impressed upon me applies to Lord Silverdale. He is young, rich, handsome——"

"Yes, yes, yes," answered Lillie, "I know."

"He is rich and cannot be after your money."

"True."

"He has a title, which you consider an advantage."

"I do."

"He is a man of taste and culture."

"He is."

"Well, what is it you don't like? Doesn't he ride or dance well?"

"He dances like an angel and rides like the devil."

"Well, what in the name of angels or devils is your objection then?"

"Father," said Lillie very solemnly, "he is all you claim, but——." The little delicate cheek flushed modestly. She could not say it.

"But——" said the millionaire impatiently.

Lillie hid her face in her hands.

"But——" said the millionaire brutally.

"But I love him!"

"You what?" roared the millionaire.

"Yes, father, do not be angry with me. I love him dearly. Oh, do not spurn me from you, but I love him with my whole heart and soul, and I shall never marry any other man but him." The poor little girl burst into a paroxysm of weeping.

"Then you will marry him?" gasped the millionaire.

"No, father," she sobbed solemnly, "that is an illegitimate deduction from my proposition. He is the one man on this earth I could never bring myself to marry."

"You are mad!"

"No, father. I am only mathematical. I will never marry a man who does not love me. And don't you [pg 13] see that, as I love him, the odds are that he doesn't love me?"

"But he tells me he does!"

"What is his bare assertion—weighed against the doctrine of probability! How many girls do you suppose Silverdale has met in his varied career?"

"A thousand, I dare say."

"Ah, that's only reckoning English Society (and theatres). And then he has seen Society (and theatres) in Paris, Berlin, Rome, Boston, a hundred places! If we put the figure at three thousand it will be moderate. Here am I, a single girl——"

"Who oughtn't to remain so," growled the millionaire.

"One single girl. How wildly improbable that out of three thousand girls, Silverdale should just fall in love with me. It is 2999 to 1 against. Then there is the probability that he is not in love at all—which makes the odds 5999 to 1. The problem is exactly analogous to one which you will find in any Algebra. Out of a sack containing three thousand coins, what are the odds that a man will draw the one marked coin?"

"The comparison of yourself to a marked coin is correct enough," said the millionaire, thinking of the files of fortune-hunters to whom he had given the sack. "Otherwise you are talking nonsense."

"Then Pascal, Laplace, Lagrange, De Moivre talked nonsense," said Lillie hotly; "but I have not finished. We must also leave open the possibility that the man will not be tempted to draw out any coin whatsoever. The odds against the marked coin being drawn out are thus 5999 to 1. The odds against Silverdale returning my affection are 6000 to 1. As Butler rightly points out, probability is the only guide to conduct, which is, we know from Matthew Arnold, three-fourths of life. Am I to risk [pg 14] ruining three-fourths of my life, in defiance of the unerring dogmas of the Doctrine of Chances? No, father, do not exact this sacrifice from me. Ask me anything you please, and I will grant it—oh! so gladly—but do not, oh, do not ask me to marry the man I love!"

The millionaire stroked her hair, and soothed her in piteous silence. He had made his pile in pig-iron, and had not science enough to grapple with the situation.

"Do you mean to say," he said at last, "that because you love a man, he can't love you?"

"He can. But in all human probability he won't. Suppose you put on a fur waistcoat and went out into the street, determined to invite to dinner the first man in a straw hat, and supposing he replied that you had just forestalled him, as he had gone out with a similar intention to look for the first man in a fur waistcoat.—What would you say?"

The millionaire hesitated. "Well, I shouldn't like to insult the man," he said slowly.

"You see!" cried Lillie triumphantly.

"Well, then, dear," said he, after much pondering, "the only thing for it is to marry a man you don't love."

"Father!" said Lillie in terrible tones.

The millionaire hung his head shamefacedly at the outrage his suggestion had put upon his daughter.

"Forgive me, Lillie," he said; "I shall never interfere again in your matrimonial concerns."

So Lillie wiped her eyes and founded the Old Maids' Club.

She said it was one of her matrimonial concerns, and so her father could not break his word, though an entire suite of rooms in his own Kensington mansion was set aside for the rooms of the Club. Not that he desired to interfere. Having read "The Bachelors' Club," he thought it was the surest way of getting her married.

[pg 15] The object of the Club was defined by the foundress as "the depolarization of the term 'Old Maid'; in other words, the dissipation of all those disagreeable associations which have gradually and most unjustly clustered about it; the restoration of the homely Saxon phrase to its pristine purity, and the elevation of the enviable class denoted by it to their due pedestal of privilege and homage."

The conditions of membership, drawn up by Lillie, were:

1. Every candidate must be under twenty-five. 2. Every candidate must be beautiful and wealthy, and undertake to continue so. 3. Every candidate must have refused at least one advantageous offer of marriage.

The rationale of these rules was obvious. Disappointed, soured failures were not wanted. There was no virtue in being an "Old Maid" when you had passed twenty-five. Such creatures are merely old maids—Old Maids (with capitals) were required to be in the flower of youth and the flush of beauty. Their anti-matrimonial motives must be above suspicion. They must despise and reject the married state, though they would be welcomed therein with open arms.

Only thus would people's minds be disabused of the old-fashioned notions about old maids.

The Old Maids were expected to obey an elaborate array of by-laws, and respect a series of recommendations.

According to the by-laws they were required:

1. To regard all men as brothers. 2. Not to keep cats, lap-dogs, parrots, pages, or other domestic pets. 3. Not to have less than one birthday per year. 4. To abjure medicine, art classes, and Catholicism. 5. Never to speak to a Curate. 6. Not to have any ideals or to take part in Woman's Rights Movements, Charity Concerts, or other Platform Demonstrations. 7. Not to wear caps, curls, or similar articles of attire. 8. Not to kiss females.

In addition to these there were the

General Recommendations:

Never refuse the last slice of bread, etc., lest you be accused of dreading celibacy. Never accept bits of wedding cake, lest you be suspected of putting them under your pillow. Do not express disapproval by a sniff. In travelling, choose smoking carriages; pack your umbrellas and parasols inside your trunk. Never distribute tracts. Always fondle children and show marked hostility to the household cat. Avoid eccentricities. Do not patronize Dorothy Restaurants or the establishments of the Aerated Bread Company. Never drink cocoa-nibs. In dress it is better to avoid Mittens, Crossovers, Fleecy Shawls, Elastic-side Boots, White Stockings, Black Silk Bodies, with Pendent Gold Chains, and Antique White Lace Collars. One-button White Kid Gloves are also inadvisable for afternoon concerts; nor should any glove be worn with fingers too long to pick up change at booking-offices. Parcels should not be wrapped in whitey-brown paper and not more than three should be carried at once. Watch Pockets should not be hung over the bed, sheets and mattresses should be left to the servants to air, and rooms should be kept in an untidy condition.

Refrain from manufacturing jam, household remedies, gossip or gooseberry wine. Never nurse a cold or a relative. It is advisable not to have a married sister, as she might decease and the temptation to marry her husband is such as no mere human being ought to be exposed to. For cognate reasons eschew friendship with cripples and hunchbacks (especially when they have mastered the violin in twelve lessons), men of no moral character, drunkards who wish to reform themselves, very ugly men, and husbands with wives in lunatic asylums. Cultivate rather the acquaintance of handsome young men (who have been duly vaccinated), for this species is too conceited to be dangerous.

[pg 17] On the same principle were the rules for admitting visitors:

1. No unmarried lady admitted. 2. No married gentlemen admitted.

If they admitted single ladies there would be no privilege in being a member, while if they did not admit single gentlemen, they might be taunted with being afraid that they were not fireproof. When Lillie had worked this out to her satisfaction she was greatly chagrined to find the two rules were the same as for "The Bachelors' Club." To show their club had no connection with the brother institution, she devised a series of counterblasts to their misogynic maxims. These were woven on all the antimacassars; the deadliest were:

The husband is the only creature entirely selfish. He is a low organism, consisting mainly of a digestive apparatus and a rude mouth. The lover holds the cloak; the husband drops it. Wedding dresses are webs. Women like clinging robes; men like clinging women. The lover will always help the beloved to be helpless. A man likes his wife to be just clever enough to comprehend his cleverness and just stupid enough to admire it. Women who catch husbands rarely recover. Marriage is a lottery; every wife does not become a widow. Wrinkles are woman's marriage lines; but when she gets them her husband will no longer be bound.

The woman who believes her husband loves her, is capable of believing that she loves him. A good man's love is the most intolerable of boredoms. A man often marries a woman because they have the same tastes and prefer himself to the rest of creation. If a woman could know what her lover really thought of her she would know what to think of him. Possession is nine points of the marriage law. It is impossible for a man to marry a clever woman. Marriages are made in heaven, but old maids go there.

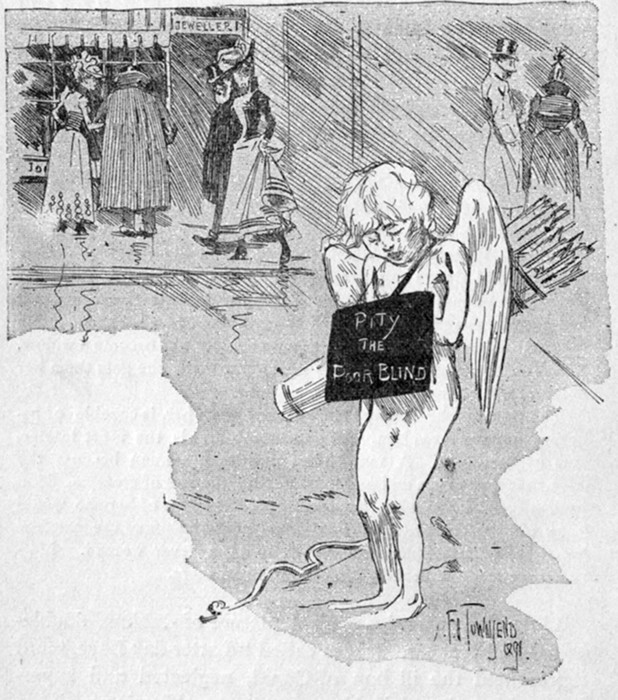

Lillie also painted a cynical picture of dubious double-edged incisiveness. It was called "Latter-day Love," and represented the ill hap of Cupid, neglected and superfluous, his quiver full, his arrows rusty, shivering with the [pg 18] cold, amid contented couples passing him by with never an eye for the lugubrious legend, "Pity the Poor Blind."

The picture put the finishing touch to the rooms of the Club. When Lillie Dulcimer had hung it up, she looked round upon the antimacassars and felt a proud and happy girl.

The Old Maids' Club was now complete. Nothing was wanting except members.

Latter-Day Love.

THE HONORARY TRIER.

Lord Silverdale was the first visitor to the Old Maids' Club. He found the fair President throned alone among the epigrammatic antimacassars. Lillie received him with dignity and informed him that he stood on holy ground. The young man was shocked to hear of the change in her condition. He, himself, had lately spent his time in plucking up courage to ask her to change it—and now he had been forestalled.

"But you must come in and see us often," said Lillie. "It occurs to me that the by-laws admit you."

"How many will you be?" murmured Silverdale, heartbroken.

"I don't know yet. I am waiting for the thing to get about. I have been in communication with the first candidate, and expect her any moment. She is a celebrated actress."

"And who elects her?"

"I, of course!" said Lillie, with an imperial flash in her passionate brown eyes. She was a brunette, and her face sometimes looked like a handsome thunder-cloud. "I am the President and the Committee and the Oldest Old Maid. Isn't one of the rules that candidates shall not believe in Women's Rights? None of the members will have any voice whatever."

[pg 20] "Well, if your actress is a comic opera star, she won't have any voice whatever."

"Lord Silverdale," said Lillie sharply, "I hate puns. They spoiled the Bachelors' Club."

His lordship, who was the greatest punster of the peers, and the peer of the greatest punsters, muttered savagely that he would like to spoil the Old Maids' Club. Lillie punned herself sometimes, but he dared not tell her of it.

"And what will be the subscription?" he said aloud.

"There will be none. I supply the premises."

"Ah, that will never do! Half the pleasure of belonging to a club is the feeling that you have not paid your subscription. And how about grub?"

"Grub! We are not men. We do not fulfil missions by eating."

"Unjust creature! Men sometimes fulfil missions by being eaten."

"Well, papa will supply buns, lemonade and ices. Turple the magnificent, will always be within call to hand round the things."

"May I send you in a hundred-weight of chocolate creams?"

"Certainly. Why should weddings have a monopoly of presents? This is not the only way in which you can be of service to me, if you will."

"Only discover it for me, my dear Miss Dulcimer. Where there's a way there's a will."

"Well, I should like you to act as Trier."

"Eh! I beg your pardon?"

"Don't apologize; to try the candidates who wish to be Old Maids."

"Try them! No, no! I'm afraid I should be prejudiced against bringing them in innocent."

"Don't be silly. You know what I mean. I could not tell so well as you whether they possessed the true apostolic [pg 21] spirit. You are a man—your instinct would be truer than mine. Whenever a new candidate applies, I want you to come up and see her."

"Really, Miss Dulcimer, I—I can't tell by looking at her!"

"No, but you can by her looking at you."

"You exaggerate my insight."

"Not at all. It is most important that something of the kind should be done. By the rules, all the Old Maids must be young and beautiful. And it requires a high degree of will and intelligence——"

"To be both!"

"For such to give themselves body and soul to the cause. Every Old Maid is double-faced till she has been proved single-hearted."

"And must I talk to them?"

"In plain English——"

"It's the only language I speak plainly."

"Wait till I finish, boy! In plain English, you must flirt with them."

"Flirt?" said Silverdale, aghast. "What! With young and beautiful girls?"

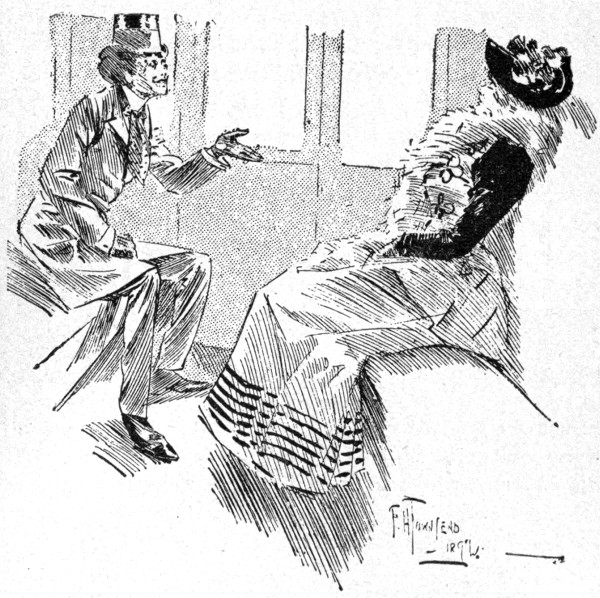

"I know it is hard, Lord Silverdale, but you will do it for my sake!" They were sitting on an ottoman, and the lovely face which looked pleadingly up into his was very near. The young man got up and walked up and down.

"Hang it!" he murmured disconsolately. "Can't you try them on Turple the magnificent. Or why not get a music-master or a professor of painting?"

"Music-masters touch the wrong chord, and professors of painting are mostly old masters. You are young and polished and can flirt with tact and taste."

"Thank you," said the poor young peer, making a wry face. "And therefore I'm to be a flirtation machine."

[pg 22] "An electric battery if you like. I don't desire to mince my words. There's no gain in not calling a spade a spade."

"And less in people calling a battery a rake."

"Is that a joke? I thought you clubmen enjoyed being called rakes."

"That is all most of us do enjoy. Take it from me that the last thing a rake does is to sow wild oats."

"I know enough of agriculture not to be indebted to you for the information. But I certainly thought you were a rake," said the little girl, looking up at him with limpid brown eyes.

"You flatter me," he said with a mock bow; "you are young enough to know better."

"But you have seen Society (and theatres) in a dozen capitals!"

"I have been behind the scenes of both," he answered simply. "That is the thing to keep a man steady."

"I thought it turned a man's head," she said musingly.

"It does. Only one begins manhood with his head screwed the wrong way on. Homœopathy is the sole curative principle in morals. Excuse this sudden discharge of copy-book mottoes. I sometimes go off that way, but you mustn't take me for a Maxim gun. I am not such a bore, I hope."

Lillie flew off at a feminine tangent.

"All of which only proves the wisdom of my choice in selecting you."

"What! To pepper them with pellets of platitude?" he said, dropping despairingly into an arm-chair.

"No. With eyeshot. Take care!"

"What's the matter?"

"You're sitting on an epigram."

"Take care! You're sitting on an epigram."

The young man started up as if stung, and removed the antimacassar, without, however, seeing the point.

[pg 23] "I hope you don't mind my inquiring whether you have any morals," said Lillie.

"I have as many as Æsop. The strictest investigation courted. References given and exchanged," said the peer lightly.

"Do be serious. You know I have an insatiable curiosity to know everything about everything—to feel all sensations, think all thoughts. That is the note of my being." The brown eyes had an eager, wistful look.

"Oh, yes—a note of interrogation."

"O that I were a man! What do men think?"

[pg 24] "What do you think? Men are human beings first and masculine afterwards. And I think everybody is like a suburban Assembly Hall—to-day a temperance lecture, to-morrow a dance, next day an oratorio, then a farcical comedy, and on Sunday a religious service. But about this appointment?"

"Well, let us settle it one way or another," Lillie said. "Here is my proposal——"

"I have an alternative proposal," he said desperately.

"I cannot listen to any other. Will you, or will you not, become Honorary Trier of the Old Maids' Club?"

"I'll try," he said at last.

"Yes or no?"

"Shall you be present at the trials?"

"Certainly, but I shall cultivate myopia."

"It's a short-sighted policy, Miss Dulcimer. Still, sustained by your presence, I feel I could flirt with the most beautiful and charming girl in the world. I could do it, even unsustained by the presence of the other girl."

"Oh, no! You must not flirt with me. I am the only Old Maid with whom flirtation is absolutely taboo."

"Then I consent," said Silverdale with apparent irrelevance. And seating himself on the piano stool, after carefully removing an epigram from the top of the instrument, he picked out "The Last Rose of Summer" with a facile forefinger.

"Don't!" said Lillie. "Stick to your lute."

Thus admonished, the nobleman took down Lillie's banjo, which was hanging on the wall, and struck a few passionate chords.

"Do you know," he said, "I always look on the banjo as the American among musical instruments. It is the guitar with a twang. Wasn't it invented in the States? Anyhow it is the most appropriate instrument to which to sing you my Fin de Siècle Love Song."

[pg 25] "For Heaven's sake, don't use that poor overworked phrase!"

"Why not? It has only a few years to live. List to my sonnet."

So saying, he strummed the strings and sang in an aristocratic baritone:

AD CHLOEN.—A Valedictory.

Lillie laughed. "My actress's name is something like Chloe. It is Clorinda—Clorinda Bell. She tells me she is very celebrated."

"Oh, yes, I've heard of her," he said.

"There is a sneer in your tones. Have you heard anything to her disadvantage?"

"Only that she is virtuous and in Society."

"The very woman for an Old Maid! She is beautiful, too."

"Is she? I thought she was one of those actresses who reserve their beauty for the stage."

"Oh, no. She always wears it. Here is her photograph. Isn't that a lovely face?"

[pg 26] "It is a lovely photograph. Does she hope to achieve recognition by it, I wonder?"

"Sceptic!"

"I doubt all charms but yours."

"Well, you shall see her."

"All right, but mention her name clearly when you introduce me. Women are such changing creatures—to-day pretty, to-morrow plain, yesterday ugly. I have to be reintroduced to most of my female acquaintances three times a week. May I wait to see Clorinda?"

"No, not to-day. She has to undergo the Preliminary Exam. Perhaps she may not even matriculate. Where you come in is at the graduation stage."

"I see. To pass them as Bachelors—I mean Old Maids. I say, how will you get them to wear stuff gowns?"

The bell rang loudly. "That may be she. Good-bye, Lord Silverdale. Remember you are Honorary Trier of the Old Maids' Club, and don't forget those chocolate creams."

THE MAN IN THE IRONED MASK.

The episode that turned Clorinda Bell's thoughts in the direction of Old Maidenhood was not wanting in strangeness. She was an actress of whom everybody spoke well, excepting actresses. This was because she was so respectable. Respectability is all very well for persons who possess no other ability; but bohemians rightly feel that genius should be above that sort of thing. Clorinda never went anywhere without her mother. This lady—a portly taciturn dame, whose hair had felt the snows of sixty winters—was as much a part of her as a thorn is of a rose. She accompanied her always—except when she was singing—and loomed like some more substantial shadow before or behind her at balls and receptions, at concerts and operas, private views and church bazaars. Her mother was always with her behind the scenes. She helped her to make up and to unmake. She became the St. Peter of the dressing-room in her absence. At the Green Room Club they will tell you how a royal personage asking permission to come and congratulate her, received the answer: "I shall be most honored—in the presence of my mother."

There were those who wished Clorinda had been born an orphan.

But the graver sort held Miss Bell up as a typical harbinger of the new era, when actresses would keep mothers instead of dog-carts. There was no intrinsic reason, they [pg 28] said, why actresses should not be received at Court, and visit the homes of the poor. Clorinda was very charming. She was tall and fair as a lily, with dashes of color stolen from the rose and the daffodil, for her eyes had a sparkle and her cheeks a flush and her hair was usually golden. Not the least of her physical charms was the fact that she had numerous admirers. But it was understood that she kept them at a distance and that they worshipped there. The Society journals, to which Clorinda was indebted for considerable information about herself, often stated that she intended to enter a convent, as her higher nature found scant satisfaction in stage triumphs, and she had refused to exchange her hand either for a coronet or a pile of dollars. They frequently stated the opposite, but a Society journal cannot always be contradicting a contemporary. It must sometimes contradict itself, as a proof of impartiality. Clorinda let all these rumors surge about her unheeded, and her managers had to pay for the advertisement. The money came back to them, though, for Clorinda was a sure draw. She brought the odor of sanctity over the footlights, and people have almost as much curiosity to see a saint as a sinner—especially when the saint is beautiful.

Gentlemen in particular paid frequent pilgrimages to the shrine of the saint, and adored her from the ten-and-sixpenny pews. There was at this period a noteworthy figure in London dress circles and stalls, an inveterate first-nighter, whose identity was the subject of considerable speculation. He was a mystery in a swallow-tail coat. No one had ever seen him out of it. He seemed to go through life armed with a white breastplate, starched shot-proof and dazzling as a grenadier's cuirass. What wonder that a wit (who had become a dramatic critic through drink) called him. "The Man in the Ironed Mask." Between the acts he wore a cloak, a crush-hat and a [pg 29] cigarette. Nobody ever spoke to him nor did he ever reply. He could not be dumb, because he had been heard to murmur "Brava, bravissima," in a soft but incorrect foreign manner. He was very handsome, with a high, white forehead of the Goth order of architecture, and dark, Moorish eyes. Nobody even knew his name, for he went to the play quite anonymously. The pit took him for a critic, and the critics for a minor poet. He had appeared on the scene (or before it) only twelve months ago, but already he was a distinguished man. Even the actors and actresses had come to hear of him, and not a few had peeped at him between their speeches. He was certainly a sight for the "gods."

Latterly he had taken to frequenting the Lymarket, where Miss Clorinda Bell was "starring" for a season of legitimate drama. It was the only kind the scrupulous actress would play in. Whenever there was no first night on anywhere else, he went to see Clorinda. Only a few rivals and the company knew of his constancy to the entertainment. Clorinda was, it will be remembered, one of the company.

It was the entr'acte and the orchestra was playing a gavotte, to which the eighteenth-century figures on the drop scene were dancing. The Man in the Ironed Mask strolled in the lobby among the critics, overhearing the views they were not going to express in print. Clorinda Bell's mother was brushing her child's magnificent hair into a more tragical attitude in view of the fifth act. The little room was sacred to the "star," the desire of so many moths. Neither maid nor dresser entered it, for Mrs. Bell was as devoted to her daughter as her daughter to her, and tended her as zealously as if she were a stranger.

"Yes, but why doesn't he speak?" said Clorinda.

"You haven't given him a chance, darling," said her mother.

[pg 30] "Nonsense—there is the language of flowers. All my lovers commence by talking that."

"You get so many bouquets, dear. It may be—as you say his appearance is so distinguished—that he dislikes so commonplace a method."

"Well, if he doesn't want to throw his love at my feet, he might have tried to send it me in a billet-doux."

"That is also commonplace. Besides, he may know that all your letters are delivered to me, and opened by me. The fact has often enough appeared in print."

"Ah, yes, but genius will find out a way. You remember Lieutenant Campbell, who was so hit the moment he saw me as Perdita that he went across the road to the telegraph-office and wired, 'Meet me at supper, top floor, Piccadilly Restaurant, 11.15,' so that the doorkeeper sent the message direct to the prompter, who gave it me as I came off with Florizel and Camilla. That is the sort of man I admire!"

"But you soon tired of him, darling."

"Oh, mother! How can you say so? I loved him the whole run of the piece."

"Yes, dear, but it was only Shakespeare."

"Would you have love a Burlesque? 'A Winter's Tale' is long enough for any flirtation. Let me see, was it Campbell or Belfort who shot himself? I for——oh! oh! that hairpin is irritating me, mother."

"There! There! Is that easier?"

"Thanks! There's only the Man in the Ironed Mask irritating me now. His dumb admiration provokes me."

"But you provoke his dumb admiration. And are you sure it is admiration?"

"People don't go to see Shakespeare seventeen times. I wonder who he is—an Italian count most likely. Ah, how his teeth flash beneath his moustache!"

[pg 31] "You make me feel quite curious about him. Do you think I could peep at him from the wing?"

"No, mother, you shall not be put to the inconvenience. It would give you a crick in your neck. If you desire to see him, I will send for him."

"Very well, dear," said the older woman submissively, for she was accustomed to the gratification of her daughter's whims.

So when the Man in the Ironed Mask resumed his seat, a programme girl slipped a note into his hand. He read it, his face impassive as his Ironed Mask. When the play was over, he sauntered round to the squalid court in which the stage door was located and stalked nonchalantly up the stairs. The doorkeeper was too impressed by his air not to take him for granted. He seemed to go on instinctively till he arrived at a door placarded, "Miss Clorinda Bell—Private."

He knocked, and the silvery accents he had been listening to all the evening bade him come in. The beautiful Clorinda, clad in diaphanous white and radiating perfumes, received him with an intoxicating smile.

"It is so kind of you to come and see me," she said.

He made a stately inclination. "The obligation is mine," he said. "I am greatly interested in the drama. This is the seventeenth time I have been to see you."

"I meant here," she said piqued, though the smile stayed on.

"Oh, but I understood——" His eyes wandered interrogatively about the room.

"Yes, I know my mother is out," she replied. "She is on the stage picking up the bouquets. I believe she sent you a note. I do not know why she wants to see you, but she will be back soon. If you do not mind being left alone with me——"

[pg 32] "Pray do not apologize, Miss Bell," he said considerately.

"It is so good of you to say so. Won't you sit down?"

The Man in the Ironed Mask sat down beside the dazzling Clorinda and stared expectantly at the door. There was a tense silence. His cloak hung negligently upon his shoulders. He held his crush hat calmly in his hand.

Clorinda was highly chagrined. She felt as if she could slap his face and kiss the place to make it well.

"Did you like the play?" she said, at last.

He elevated his dark eyebrows. "Is it not obvious?"

"Not entirely. You might come to see the players."

"Quite so, quite so."

He leaned his handsome head on his arm and looked pensively at the floor. It was some moments before he broke the silence again. But it was only by rising to his feet. He walked towards the door.

"I am sorry I cannot stay any longer," he said.

"Oh, no! You mustn't go without seeing my mother. She will be terribly disappointed."

"Not less so than myself at missing her. Good-night, Miss Bell." He made his prim, courtly bow.

"Oh, but you must see her! Come again to-morrow night, anyhow," exclaimed Clorinda desperately. And when his footsteps had died away down the stairs, she could not repress several tears of vexation. Then she looked hurriedly into a little mirror and marvelled silently.

"Is he gone already?" said her mother, entering after knocking cautiously at the door.

"Yes, he is insane."

"Madly in love with you?"

"Madly out of love with me."

He came again the next night, stolid and courteous. To Clorinda's infinite regret her mother had been taken [pg 33] ill and had gone home early in the carriage. It was raining hard. Clorinda would be reduced to a hansom. "They call it the London gondola," she said, "but it is least comfortable when there's most water. You have to be framed in like a cucumber in a hothouse."

"Indeed! Personally I never travel in hansoms. And from what you tell me I should not like to make the experiment to-night. Good-bye, Miss Bell; present my regrets to your mother."

"Deuce take the donkey! He might at least offer me a seat in his carriage," thought Clorinda. Aloud she said: "Under the circumstances may I venture to ask you to see my mother at the house? Here is our private address. Won't you come to tea to-morrow?"

He took the card, bowed silently and withdrew.

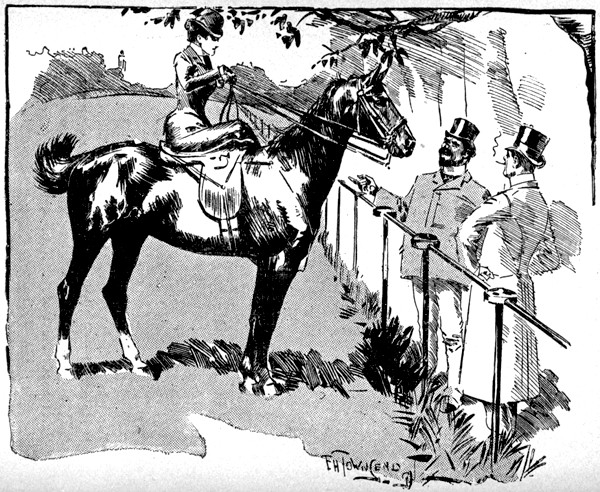

In such wise the courtship proceeded for some weeks, the invalid being confined to her room at teatime and occupied in picking up bouquets by night. He always came to tea in his cloak, and wore his Ironed Mask, and was extremely solicitous about Clorinda's mother. It became evident that so long as he had the ghost of an excuse for talking of the absent, he would never talk of Clorinda herself. At last she was reduced to intimating that she would be found at the matinée of a new piece next day (to be given at the theatre by a débutante) and that there would be plenty of room in her box. Clorinda was determined to eliminate her mother, who was now become an impediment instead of a pretext.

But when the afternoon came, she looked for him in vain. She chatted lightly with the acting-manager, who was lounging in the vestibule, but her eye was scanning the horizon feverishly.

"Is this woman going to be a success?" she asked.

"Oh, yes," said the acting-manager promptly.

"How do you know?"

[pg 34] "I just saw the flowers drive up."

"I just saw the flowers drive up."

Clorinda laughed. "What's the piece like?"

"I only saw one rehearsal. It seemed great twaddle. But the low com. has got a good catchword, so there's some chance of its going into the evening bills."

"Oh, by the way, have you seen anything of that—that—the man in the Ironed Mask, I think they call him?"

[pg 35] "Do you mean here—this afternoon?"

"Yes."

"No. Do you expect him?"

"Oh, no; but I was wondering if he would turn up. I hear he is so fond of this theatre."

"Bless your soul, he'd never be seen at a matinée."

"Why not?" asked Clorinda, her heart fluttering violently.

"Because he'd have to be in morning dress," said the actor-manager, laughing heartily.

To Clorinda his innocent merriment seemed the laughter of a mocking fiend. She turned away sick at heart. There was nothing for it but to propose outright at teatime. Clorinda did so, and was accepted without further difficulty.

"And now, dearest," she said, after she had been allowed to press the first kiss of troth upon his coy lips, "I should like to know who I am going to be?"

"Clorinda Bell, of course," he said. "That is the advantage actresses have. They need not take their husband's name in vain."

"Yes, but what am I to call you, dearest?"

"Dearest?" he echoed enigmatically. "Let me be dearest—for a little while."

She forbore to press him further. For the moment it was enough to have won him. The sweetness of that soothed her wounded vanity at his indifference to the prize coveted by men and convents. Enough that she was to be mated to a great man, whose speech and silence alike bore the stamp of individuality.

"Dearest be it," she answered, looking fondly into his Moorish eyes. "Dearest! Dearest!"

"Thank you, Clorinda. And now may I see your mother? I have never learnt what she has to say to me."

"What does it matter now, dearest?"

[pg 36] "More than ever," he said gravely, "now she is to be my mother-in-law."

Clorinda bit her lip at the dignified rebuke, and rang for his mother-in-law elect, who came from the sick room in her bonnet.

"Mother," she said, as the good dame sailed through the door, "let me introduce you to my future husband."

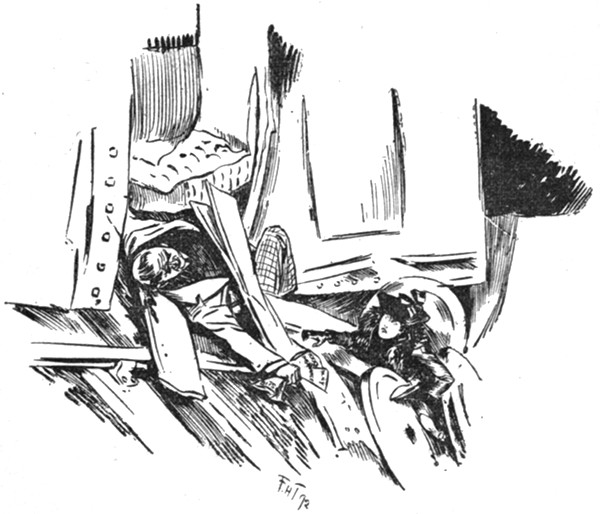

A Family Reunion.

The old lady's face lit up with surprise and excitement. She stood still for an instant, taking in the relationship so suddenly sprung upon her. Then she darted with open arms towards the Man in the Ironed Mask and strained his Mask to her bosom.

"My son! my son!" she cried, kissing him passionately. He blushed like a stormy sunset and tried to disengage himself.

"Do not crumple him, mother," said Clorinda pettishly. "Your zeal is overdone."

[pg 37] "But he is my long-lost Absalom! Think of the rapture of having him restored to me thus. O what a happy family we shall be! Bless you, Clorinda. Bless you, my children. When is the wedding to be?"

The Man in the Ironed Mask had regained his composure.

"Mother," he said sternly, "I am glad to see you looking so well. I always knew you would fall on your feet if I dropped you. I have no right to ask it—but as you seem to expect me to marry your daughter, a little information as to the circumstances under which you have supplied me with a sister would be not unwelcome.

"Stupid boy! Don't you understand that Miss Bell was good enough to engage me as mother and travelling companion when you left me to starve? Or rather, the impresario who brought her over from America engaged me, and Clorinda has been, oh, so good to me! My little drapery business failed three months after you left me to get a stranger to serve. I had no resource but—to go on the stage."

The old woman was babbling on, but the cold steel of Clorinda's gaze silenced her.

The outraged actress turned haughtily to the Man in the Ironed Mask.

"So this is your mother?" she said with infinite scorn.

"So this is not your mother!" he said with infinite indignation.

"Were you ever really simple enough to suspect me of having a mother?" she retorted contemptuously. "I had her on the hire system. Don't you know that a combination of maid and mother is the newest thing in actresses' wardrobes? It is safer then having a maid, and more comfortable than having a mother."

"But I have been a mother to you, Clorinda," the old dame pleaded.

[pg 38] "Oh, yes, you have always been a good, obedient woman. I am not finding fault with you, and I have no wish to part with you. I do find fault and I shall certainly part with your son."

"Nonsense," said the Man in the Ironed Mask. "The situation is essentially unchanged. She is still the mother of one of us, she can still become the mother-in-law of the other. Besides, Clorinda, that is the only way of keeping the secret in the family."

"You threaten?"

"Certainly. You are a humbug. So am I. United we stand. Separated, you fall."

"You fall, too."

"Not from such a height. I am still on the first rungs."

"Nor likely to get any higher."

"Indeed? Your experience of me should have taught you different. High as you are, I can raise you yet higher if you will only lift me up to you."

"How do you climb?" she said, his old ascendency reasserting itself.

"By standing still. Profound meditation on the philosophy of modern society has convinced me that the only way left for acquiring notoriety is to do nothing. Every other way has been exploited and is suspected. It is only a year since the discovery flashed upon me, it is only a year that I have been putting it in practice. And yet, mark the result! Already I am a known man. I had the entrée to no society; for half-a-guinea a night (frequently paid in paper money) I have mingled with the most exclusive. When there was no premiere anywhere, I went to see you—not from any admiration of you, but because the Lymarket is the haunt of the best society, and in addition, the virtue of Shakespeare and of yourself attracts there a highly respectable class of bishops whom I have not the opportunity of meeting elsewhere. By [pg 39] doing nothing I fascinated you—somebody was sure to be fascinated by it at last, as the dove flutters into the jaws of the lethargic serpent—by continuing to do nothing I completed my conquest. Had I met your advances, you would have repelled mine. My theories have been completely demonstrated, and but for the accident of our having a common mother——"

"Speak for yourself," said Clorinda haughtily.

"It is for myself that I am speaking. When we are one, I shall continue this policy of masterly inactivity of which I claim the invention, though it has long been known in the germ. Everybody knows for instance that not to trouble to answer letters is the surest way of acquiring the reputation of a busy man, that not to accept invitations is an infallible way of getting more, that not to care a jot about the feelings of the rest of the household, is an unfailing means of enforcing universal deference. But the glory still remains to him who first grasped this great law in its generalized form, however familiar one or two isolated cases of it may be to the world. 'Do nothing' is the last word of social science, as 'Nil admirari' was its first. Just as silence is less self-contradictory than speech, so is inaction a safer foundation of fame than action. Inaction is perfect. The moment you do anything you are in the region of incompleteness, of definiteness. Your work may be outdone—or undone. Your inventions may be improved upon, your victories annulled, your popular books ridiculed, your theories superseded, your paintings decried, the seamy side of your explanations shown up. Successful doing creates not only enemies but the material for their malice to work upon. Only by not having done anything to deserve success can you be sure of surviving the reaction which success always brings. To be is higher than to do. To be is calm, large, elemental; to do is trivial, artificial, fussy. To be has been the moth of [pg 40] the English aristocracy, it is the secret of their persistence. Qui s'excuse s'accuse. He who strives to justify his existence imperils it. To be is inexpugnable, to do is dangerous. The same principle rules in all departments of social life. What is a successful reception? A gathering at which everybody is. Nobody does anything. Nobody enjoys anything. There everybody is—if only for five minutes each, and whatever the crush and discomfort. You are there—and there you are, don't you know? What is a social lion? A man who is everywhere. What is social ambition? A desire to be in better people's drawing-rooms. What is it for which people barter health, happiness, even honor? To be on certain pieces of flooring inaccessible to the mass. What is the glory of doing compared with the glory of being? Let others elect to do, I elect to be."

"So long as you do not choose to be my husband——"

"It is husband or brother," he said, threateningly.

"Of course. I become your sister by rejecting you, do I not?"

"Don't trifle. You understand what I mean. I will let the world know that your mother is mine."

They stood looking at each other in silent defiance. At last Clorinda spoke:

"A compromise! let the world know that my mother is yours."

"I see. Pose as your brother!"

"Yes. That will help you up a good many rungs. I shall not deny I am your sister. My mother will certainly not deny that you are her son."

"Done! So long as my theories are not disproved. Conjugate the verb 'to be,' and you shall be successful. Let me see. How does it run? I am—your brother, thou art—my sister, she is—my mother,—we are—her children, you are—my womankind, they are—all spoofed."

[pg 41] So the man in the Ironed Mask turned out to be the brother of the great and good actress, Clorinda Bell. And several people had known it all along, for what but fraternal interest had taken him so often to the Lymarket? And when his identity leaked out, Society ran after him, and he gave the interviewers interesting details of his sister's early years. And everyone spoke of his mother, and of his solicitous attendance upon her. And in due course the tale of his virtues reached a romantic young heiress who wooed and won him. And so he continued being, till he was—no more. By his own request they buried him in an Ironed Mask, and put upon his tomb the profound inscription

"Here Lies the Man Who Was."

And this was why Clorinda, disgusted with men and lovers, and unable to marry her brother, caught at the notion of the Old Maids' Club and called upon Lillie.

It was almost as good a cover as a mother, and it was well to have something ready in case she lost her, as you cannot obtain a second mother even on the hire system. But Lord Silverdale's report consisted of one word, "Dangerous!"—and he rejoiced at the whim which enabled him thus to protect the impulsive little girl he loved.

Clorinda divined from Lillie's embarrassment next day that she was to be blackballed.

"I am afraid," she hastened to say, "that on second thoughts I must withdraw my candidature, as I could not make a practice of coming here without my mother."

Lillie referred to the rules. "Married women are admitted," she said simply. "I presume, therefore, your mother——"

[pg 42] "It's just like your presumption," interrupted Clorinda, and flouncing angrily out of the Club, she invited a journalist to tea.

Next day the Moon said she was going to join the Old Maids' Club.

THE CLUB GETS ADVERTISED.

"I see you have disregarded my ruling, Miss Dulcimer!" said Lord Silverdale, pointing to the paragraph in the Moon. "What is the use of my trying the candidates if you're going to admit the plucked?"

"I am surprised at you, Lord Silverdale. I thought you had more wisdom than to base a reproach on a Moon paragraph. You might have known it was not true."

"That is not my experience, Miss Dulcimer. I do not think a statement is necessarily false because it appears in the newspapers. There is hardly a paper in which I have not, at some time or other, come across a true piece of news. Even the Moon is not all made of green cheese."

"But you surely do not think I would accept Clorinda Bell after your warning. Not but that I am astonished. She assured me she was ice."

"Precisely. And so I marked her 'Dangerous.' Are there any more candidates to-day?"

"Heaps and heaps! From all parts of the kingdom letters have come from ladies anxious to become Old Maids. There is even one application from Paris. Ought I to entertain that?"

"Certainly. Candidates may hail from anywhere—excepting naturally the United States.

[pg 44] "But what, I wonder, has caused this tide of applications?"

"The Moon, of course. The fiction that Clorinda Bell intended to take the secular veil has attracted all these imitators. She has given the Club a good advertisement in endeavoring merely to give herself one."

"You suspect her, then, of being herself responsible for the statement that she was going to join the Club?"

"No. I am sure of it. Who but herself knew that she was not?"

"I can hardly imagine that she would employ such base arts."

"Higher arts are out of employment nowadays."

"Is there any way of finding out?"

"I am afraid not. She has no bosom friends. Stay—there is her mother!"

"Mothers do not tell their daughters' secrets. They do not know them."

"Well, there's her brother. I was introduced to him the other day at Mrs. Leo Hunter's. But he seems such a reticent chap. Only opens his mouth twice an hour, and then merely to show his teeth. Oh, I know! I'll get at the Moon man. My aunt, the philanthropist, who is quite a journalist (sends so many paragraphs round about herself, you know), will tell me who invents that sort of news, and I'll interview the beggar."

"Yes, won't it be fun to run her to earth?" said Lillie gleefully.

Silverdale took advantage of her good-humor.

"I hope the discovery of the baseness of your sex will turn you again to mine." There was a pleading tenderness in his eyes.

"What! to your baseness? I thought you were so good."

"I am no good without you," he said boldly.

[pg 45] "Oh, that is too rich! Suppose I had never been born?"

"I should have wished I hadn't."

"But you wouldn't have known I hadn't."

"You're getting too metaphysical for my limited understanding."

"Nonsense, you understand metaphysics as well as I do."

"Do not disparage yourself. You know I cannot endure metaphysics."

"Why not?"

"Because they are mostly made in Germany. And all Germans write as if their aim was to be misunderstood. Listen to my simple English lay."

"Another love-song to Chloe?"

"No, a really great poem, suggested by the number of papers and poems I have already seen this Moon paragraph in."

He took down the banjo, thrummed it, and sang:

THE GRAND PARAGRAPHIC TOUR.

"That is what will happen with Clorinda Bell's membership of our club," continued the poet. "She will remain a member long after it has ceased to exist. Once a thing has appeared in print, you cannot destroy it. A published lie is immortal. Age cannot wither it, nor custom stale its infinite variety. It thrives by contradiction. Give me a cup of tea and I will go and interview the Moon-man at once."

The millionaire, hearing tea was on the tray, came in to join them, and Silverdale soon went off to his aunt, Lady Goody-Goody Twoshoes, and got the address of the man in the Moon.

"Lillie, what's this I see in the Moon about Clorinda Bell joining your Club?" asked the millionaire.

"An invention, father."

The millionaire looked disappointed.

"Will all your Old Maids be young?"

"Yes, papa. It is best to catch them young."

"I shall be dining at the Club sometimes," he announced irrelevantly.

"Oh, no, papa. You are not admissible during the sittings."

"Why? You let Lord Silverdale in."

"Yes, but he is not married."

"Oh!" and the millionaire went away with brighter brow.

The Millionaire.

[pg 48] The rest of the afternoon Lillie was busy conducting the Preliminary Examination of a surpassingly beautiful girl who answered to the name of "Princess," and would give no other name for the present, not even to Turple the magnificent.

"You got my letter, I suppose?" asked the Princess.

"Oh, yes," said the President. "I should have written to you."

"I thought it best to come and see you about it at once, as I have suddenly determined to go to Brighton, and I don't know when I may be back. I had not heard of your Club till the other day, when I saw in the Moon that Clorinda Bell was going to join it, and anything she joins must of course be strictly proper, so I haven't troubled to ask the Honorable Miss Primpole's advice—she lives with me, you know. An only orphan cannot be too careful!"

"You need not fear," said Lillie. "Miss Bell is not to be a member. We have refused her."

"Oh, indeed! Well, perhaps it is as well not to bring the scent of the footlights over the Club. It is hard upon [pg 49] Miss Bell, but if you were to admit her, I suppose other actresses would want to come in. There are so many of them that prefer to remain single."

"Are you sure you do?"

"Positive. My experience of lovers has been so harassing and peculiar that I shall never marry, and as my best friends cannot call me a wall-flower, I venture to think you will find me a valuable ally in your noble campaign against the degrading superstition that Old Maids are women who have not found husbands, just as widows are women who have lost them."

"I sincerely hope so," said Lillie enthusiastically. "You express my views very neatly. May I ask what are the peculiar experiences you speak of?"

"Certainly. Some months ago I amused myself by recording the strange episodes of my first loves, and in anticipation of your request I have brought the manuscript."

"Oh, please read it!" said Lillie excitedly.

"Of course I have not given the real names."

"No, I quite understand. Won't you have a chocolate cream before you commence?"

"Thank you. They look lovely. How awfully sweet!"

"Too sweet for you?" inquired Lillie anxiously.

"No, no. I mean they are just nice."

The Princess untied the pretty pink ribbon that enfolded the dainty, scented manuscript, and pausing only to munch an occasional chocolate cream, she read on till the shades of evening fell over the Old Maids' Club and the soft glow of the candles illuminated its dainty complexion.

"THE PRINCESS OF PORTMAN SQUARE."

I am an only child. I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth, and although there was no royal crest on it, yet no princess could be more comfortable in the purple than I was in the ordinary trappings of babyhood. From the cradle upwards I was surrounded with love and luxury. My pet name "Princess" fitted me like a glove. I was the autocrat of the nursery and my power scarce diminished when I rose to the drawing-room. My parents were very obedient and did not even conceal from me that I was beautiful. In short they did their best to spoil me, though I cannot admit that they succeeded. I lost them both before I was sixteen. My poor mother died first and my poor father followed within a week; whether from grief or from a cold caught through standing bareheaded in the churchyard, or from employing the same doctor, I cannot precisely determine.

After the usual period of sorrow, I began to pick up a bit and to go out under the care of my duenna, a faded flower of the aristocracy whose declining years my guardian had soothed by quartering her on me. She was a gentle old spinster, the seventh daughter of a penniless peer, and although she has seen hard times and has almost been reduced to marriage, yet she has scant respect for my ten thousand a year. She has never lost the sense of condescension in living with me, and would be horrified to hear she is in receipt of a salary. It is to this sense of [pg 51] superiority on her part that I owe a good deal of the liberty I enjoy under her régime. She does not expect in me that rigid obedience to venerable forms and conventions which she. prescribes for herself; she regards it as a privilege of the higher gentlewoman to be bound hand and foot by fashionable etiquette, and so long as my liberty does not degenerate into license I am welcome to as much as I please of it. She has continued to call me "Princess," finding doubtless some faint reverberation of pleasure in the magnificent syllables. I should add that her name is the Honorable Miss Primpole and that she is not afraid of the butler.

Our town-house was situated in Portman Square and my parents tenanted it during the season. There is nothing very poetic about the Square, perhaps, not even in the summer, when the garden is in bloom, yet it was here that I first learnt to love. This dull parallelogram was the birthplace of a passion as spiritual and intangible as ever thrilled maiden's heart. I fell in love with a Voice.

It was a rich, baritone Voice, with a compass of two and a half octaves, rising from full bass organ-notes to sweet, flute-like tenor tones. It was a glorious Voice, now resonant with martial ecstasy, now faint with mystic rapture. Its vibrations were charged with inexpressible emotion, and it sang of love and death and high heroic themes. I heard it first a few months after my father's funeral. It was night. I had been indoors all day, torpid and miserable, but roused myself at last and took a few turns in the square. The air was warm and scented, a cloudless moon flooded the roadway with mellow light and sketched in the silhouettes of the trees in the background. I had reached the opposite side of the square for the second time when the Voice broke out. My heart stood still and I with it.

On the soft summer air the Voice rose and fell; it was [pg 52] accompanied on the piano, but it seemed in subtler harmony with the moonlight and the perfumed repose of the night. It came through an open window behind which the singer sat in the gloaming. With the first tremors of that Voice my soul forgot its weariness in a strange sweet trance that trembled on pain. The song seemed to draw out all the hidden longing of my maiden soul, as secret writing is made legible by fire. When the Voice ceased, a great blackness fell upon all things, the air grew bleak. I waited and waited but the Square remained silent. The footsteps of stray pedestrians, the occasional roll of a carriage alone fell on my anxious ear. I returned to my house, shivering as with cold. I had never loved before. I had read and reflected a great deal about love, and was absolutely ignorant of the subject. I did not know that I loved now—for that discover only came later when I found myself wandering nightly to the other side of the parallelogram, listening for the Voice. Rarely, very rarely, was my pilgrimage rewarded, but twice or thrice a week the Square became an enchanted garden, full of roses whose petals were music. Round that baritone Voice I had built up an ideal man—tall and straight-limbed and stalwart, fair-haired and blue-eyed and noble-featured, like the hero of a Northern Saga. His soul was vast as the sea, shaken with the storms of passion, dimpled with smiles of tenderness. His spirit was at once mighty and delicate, throbbing with elemental forces yet keen and swift to comprehend all subtleties of thought and feeling. I could not understand myself, yet I felt that he would understand me. He had the heart of a lion and of a little child; he was as merciful as he was strong, as pure as he was wise. To be with him were happiness, to feel his kiss ecstasy, to be gathered to his breast, delirium, But alas! he never knew that I was waiting under his window.

[pg 53] I made several abortive attempts to discover who he was or to see him. According to the Directory the house was occupied by Lady Westerton. I concluded that he was her elder son. That he might be her husband—or some other lady's—never even occurred to me. I do not know why I should have attached the Voice to a bachelor, any more than I can explain why he should be the eldest son, rather than the youngest. But romance has a logic of its own. From the topmost window of my house I could see Lady Westerton's house across the trees, but I never saw him leave or enter it. Once, a week went by without my hearing him sing. I did not know whether to think of him as a sick bird or as one flown to warmer climes. I tried to construct his life from his periods of song, I watched the lights in his window, my whole life circled round him. It was only when I grew pale and feverish and was forced by the doctors and my guardian to go yachting that my fancies gradually detached themselves from my blue-eyed hero. The sea-salt freshened my thoughts, I became a healthy-minded girl again, carolling joyously in my cabin and taking pleasure in listening to my own voice. I threw my novels overboard (metaphorically, that is) and set the Hon. Miss Primpole chatting instead, when the seascape palled upon me. She had a great fund of strictly respectable memories. Most people's recollections are of no use to anybody but the owner, but hers afforded entertainment for both of us. By the time I was back in London the Voice was no longer part even of my dreams, though it seemed to belong to them. But for accident it might have remained forever "a voice and nothing more." The accident happened at a musical-afternoon in Kensington. I was introduced to a tall, fair, handsome blue-eyed guardsman, Captain Athelstan by name. His conversation was charming and I took a lot of it, while Miss Primpole was busy flirting [pg 54] with a seductive Spaniard. You could not tell Miss Primpole was flirting except by looking at the man. In the course of the afternoon the hostess asked the captain to sing. As he went to the piano my heart began to flutter with a strange foreboding. He had no music with him, but plunged at once into the promontory chords. My agitation increased tenfold. He was playing the prelude to one of the Voice's songs—a strange, haunting song with a Schubert atmosphere, a song which I had looked for in vain among the classics. At once he was transfigured to my eyes, all my sleeping romantic fancies woke to delicious life, and in the instant in which I waited, with bated breath, for the outbreak of the Voice at the well-known turn of the melody, it was borne in upon me that this was the only man I had ever loved or would ever love. My Saga hero! my Berserker, my Norse giant!

Miss Primpole was flirting with a seductive Spaniard.

When the Voice started it was not my Voice. It was a thin, throaty tenor. Compared with the Voice of Portman Square, it was as a tinkling rivulet to a rushing full-volumed river. I sank back on the lounge, hiding my emotions behind my fan.

When the song was finished, he made his way through the "Bravas" to my side.

"Sweetly pretty!" I murmured.

"The song or the singing?" he asked with a smile.

"The song," I answered frankly. "Is it yours?"

"No, but the singing is!"

His good-humor was so delightful that I forgave his not having my Voice.

"What is its name?"

"It is anonymous—like the composer."

"Who is he?"

"I must not tell."

"Can you give me a copy of the song?"

He became embarrassed.

[pg 56] "I would with pleasure, if it were mine. But the fact is—I—I—had no right to sing it at all, and the composer would be awfully vexed if he knew."

"Original composer?"

"He is, indeed. He cannot bear to think of his songs being sung in public."

"Dear me! What a terrible mystery you are making of it," I laughed.

"O r-really there is no abracadabra about it. You misunderstand me. But I deserve it all for breaking faith and exploiting his lovely song so as to drown my beastly singing."

"You need not reproach yourself," I said. "I have heard it before."

He started perceptibly. "Impossible," he gasped.

"Thank you," I said freezingly.

"But how?"

"A little bird sang it me."

"It is you who are making the mystery now."

"Tit for tat. But I will discover yours."

"Not unless you are a witch!"

"A what?"

"A witch."

"I am," I said enigmatically. "So you see it's of no use hiding anything from me. Come, tell me all, or I will belabor you with my broomstick."

"If you know, why should I tell you?"

"I want to see if you can tell the truth."

"No, I can't." We both laughed. "See what a cruel dilemma you place me in!" he said beseechingly.

"Tell me, at least, why he won't publish his songs. Is he too modest, too timid?"

"Neither. He loves art for art's sake—that is all."

"I don't understand."

"He writes to please himself. To create music is his [pg 57] highest pleasure. He can't see what it has got to do with anybody else."

"But surely he wants the world to enjoy his work?"

"Why? That would be art for the world's sake, art for fame's sake, art for money's sake!"

"What an extraordinary view!"

"Why so? The true artist—the man to whom creation is rapture—surely he is his own world. Unless he is in need of money, why should he concern himself with the outside universe? My friend cannot understand why Schopenhauer should have troubled himself to chisel epigrams or Leopardi lyrics to tell people that life was not worth living. Had either been a true artist, he would have gone on living his own worthless life, unruffled by the applause of the mob. My friend can understand a poet translating into inspired song the sacred secrets of his soul, but he cannot understand his scattering them broad-cast through the country, still less taking a royalty on them. He says it is selling your soul in the market-place, and almost as degrading as going on the stage."

"And do you agree with him?"

"Not entirely, otherwise I should never have yielded to the temptation to sing his song to-night. Fortunately he will never hear of it. He never goes into society, and I am his only friend."

"Dear me!" I said sarcastically. "Is he as careful to conceal his body as his soul?"

His face grew grave. "He has an affliction," he said in low tones.

"Oh, forgive me!" I said remorsefully. Tears came into my eyes as the vision of the Norse giant gave away to that of an English hunchback. My adoring worship was transformed to an adoring matronly tenderness. Divinely-gifted sufferer, if I cannot lean on thy strength, thou shalt lean on mine! So ran my thought till the mist [pg 58] cleared from my eyes and I saw again the glorious Saga-hero at my side, and grew strangely confused and distraught.

"There is nothing to forgive," answered Captain Athelstan. "You did not know him."

"You forget I am a witch. But I do not know him—it is true. I do not even know his name. Yet within a week I undertake to become a friend of his."

He shook his head. "You do not know him."

"I admitted that," I answered pertly. "Give me a week, and he shall not only know me, he shall abjure those sublime principles of his at my request."

The spirit of mischief moved me to throw down the challenge. Or was it some deeper impulse?

He smiled sceptically.

"Of course if you know somebody who will introduce you," he began.

"Nobody shall introduce me," I interrupted.

"Well, he'll never speak to you first."

"You mean it would be unmaidenly for me to speak to him first. Well, I will bind myself to do nothing of which Mrs. Grundy would disapprove. And yet the result shall be as I say."

"Then I shall admit you are indeed a witch."

"You don't believe in my power, that is. Well, what will you wager?"

"If you achieve your impossibility, you will deserve anything."

"Will you back your incredulity with a pair of gloves?"

"With a hundred."

"Thank you. I am not a Briareus. Let us say one pair then."

"So be it."

"But no countermining. Promise me not to communicate with your mysterious friend in the interval."

"But how shall I know the result?"

I pondered. "I will write—no, that would be hardly proper. Meet me in the Royal Academy, Room Six, at the 'Portrait of a Gentleman,' about noon to-morrow week."

"A week is a long time!" he sighed.

I arched my eyebrows. "A week a long time for such a task!" I exclaimed.

Next day I called at the house of the Voice. A gorgeous creature in plush opened the door.

"I want to see—to see—gracious! I've forgotten his name," I said in patent chagrin. I clucked my tongue, puckered my lips, tapped the step with my parasol, then smiled pitifully at the creature in plush. He turned out to be only human, for a responsive sympathetic smile flickered across his pompous face. "You know—the singer," I said, as if with a sudden inspiration.

"Oh. Lord Arthur!" he said.

"Yes, of course," I cried, with a little trill of laughter. "How stupid of me! Please tell him I want to see him on an important matter."

"He—he's very busy, I'm afraid, miss."

"Oh, but he'll see me," I said confidently.

"Yes, miss; who shall I say, miss?"

"The Princess."

He made a startled obeisance, and ushered me into a little room on the right of the hall. In a few moments he returned and said—"His lordship will be down in a second, your highness."

Sixty minutes seemed to go to that second, so racked was I with curiosity. At last I heard a step outside and a hand on the door, and at that moment a horrible thought flashed into my mind. What certainty was there my singer was a hunchback? Suppose his affliction were something more loathly. What if he had a monstrous [pg 60] wen! For the instant after his entry I was afraid to look up. When I did, I saw a short, dark-haired young man, with proper limbs and refined features. But his face wore a blank expression, and I wondered why I had not divined before that my musician was blind!

He bowed and advanced towards me. He came straight in my direction so that I saw he could see. The blank expression gave place to one of inquiry.

"I have ventured to call upon your lordship in reference to a Charity Concert," I said sweetly; "I am one of your neighbors, living just across the square, and as the good work is to be done in this district, I dared to hope that I could persuade you to take part in it."

I happened to catch sight of my face in the glass of a chiffonier as I spoke, and it was as pure and candid and beautiful as the face of one of Guido's angels. When I ceased, I looked up at Lord Arthur's. It was spasmodically agitated, the mouth was working wildly. A nervous dread seized me.

After what seemed an endless interval, he uttered an explosive "Put!" following it up by "f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f-or two g-g-g-g-g-g-g-g——"

"It is very kind of you," I interrupted mercifully. "But I did not propose to ask you for a subscription. I wanted to enlist your services as a performer. But I fear I have made a mistake. I understood you sang." Inwardly I was furious with the stupid creature in plush for having misled me into such an unpleasant situation.

"I d-d-d-o s-s-s-s-s——" he answered.

As he stood there hissing, the truth flashed upon me at last. I had heard that the most dreadful stammerers enunciate as easily as anybody else when they sing, because the measured swing of the time keeps them steady. My heart sank as I thought of the Voice so mutilated! Poor young peer! Was this to be the end of all my beautiful visions?

[pg 61] As cheerfully as I could I cut short his sibilations. "Oh, that's all right, then," I said. "Then I may put you down for a couple of items."

He shook his head, and held up his hands deprecatingly.

"Anything but that!" he stammered; "Make me a patron, a committee-man, anything! I do not sing in public."

While he was saying this I thought long and deeply. The affliction was after all less terrible than I had a right to expect, and I knew from the advertisement columns that it was easily curable. Demosthenes, I remembered, had stoned it to death. I felt my love reviving, as I looked into his troubled face, instinct with the double aristocracy of rank and genius. At the worst the singing Voice was unaffected by the disability, and as for the conversational, well there was consolation in the prospect of having the last word while one's husband was still having the first. En attendant, I could have wished him to sing his replies instead of speaking them, for not only should I thus enjoy his Voice but the interchange of ideas would proceed less tardily. However that would have made him into an operatic personage, and I did not want him to look so ridiculous as all that.

It would be tedious to recount our interview at the length it extended to. Suffice it to say that I gained my point. Without letting out that I knew of his theories of art for art's sake, I yet artfully pleaded that whatever one's views, charity alters cases, inverts everything, justifies anything. "For instance," I said with charming naïveté, "I would not have dared to call on you but in its sacred name." He agreed to sing two songs—nay, two of his own songs. I was to write to him particulars of time and place. He saw me to the door. I held out my hand and he took it, and we looked at each other, smiling brightly.

[pg 62] "B-but I d-d-d-don't know your n-n-name," he said suddenly. "P-p-p-rincess what?"

He spoke more fluently, now he had regained his composure.

"Princess," I answered, my eyes gleaming merrily. "That is all. The Honorable Miss Primpole will give me a character, if you require one." He laughed—his laugh was like the Voice—and followed me with his eyes as I glided away.

I had won my gloves—and in a day. I thought remorsefully of the poor Saga hero destined to wait a week in suspense as to the result. But it was too late to remedy this, and the organization of the Charity Concert needed all my thoughts. I was in for it now, and I resolved to carry it through. But it was not so easy as I had lightly assumed. Getting the artists, of course, was nothing—there are always so many professionals out of work or anxious to be brought out, and so many amateurs in search of amusement. I could have filled the Albert Hall with entertainers. Nor did I anticipate any difficulty in disposing of the tickets. If you are at all popular in society you can get a good deal of unpopularity by forcing them on your friends. No, the real difficulty about this Charity Concert was the discovery of an object in aid of which to give it. In my innocence I had imagined that the world was simply bustling with unexploited opportunities for well-doing. Alas! I soon found that philanthropy was an over-crowded profession. There was not a single nook or corner of the universe but had been ransacked by these restless free-lances; not a gap, not a cranny but had been filled up. In vain I explored the map, in the hopes of lighting on some undiscovered hunting-ground in far Cathay or where the khamsin sweeps the Afric deserts. I found that the wants of the most benighted savages were carefully attended to, and that, even when they had none, they were thoughtfully [pg 63] supplied with them. Anxiously I scanned the newspapers in search of a calamity, the sufferers by which I might relieve, but only one happened during that week, and that was snatched from between my very fingers by a lady who had just been through the Divorce Court. In my despair I bethought myself of the preacher I sat under. He was a very handsome man, and published his sermons by request.

I went to him and I said: "How is the church?"

"It is all right, thank you," he said.

"Doesn't it want anything done to it?"

"No, it is in perfect repair. My congregation is so very good."

I groaned aloud. "But isn't there any improvement that you would like?"

"The last of the gargoyles was put up last week. Mediæval architecture is always so picturesque. I have had the entire structure made mediæval, you know."

"But isn't the outside in need of renovation?"

"What! When I have just had it made mediæval!"

"But the interior—there must be something defective somewhere!"

"Not to my knowledge."

"But think! think!" I cried desperately. "The aisles—transept—nave—lectern—pews—chancel—pulpit—apse—porch—altar-cloths—organ—spires—is there nothing in need of anything?"

He shook his head.

"Wouldn't you like a colored window to somebody?"

"All the windows are taken up. My congregation is so very good."

"A memorial brass then?"

He mused.

"There is only one of my flock who has done anything memorable lately."