This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Portraits of Curious Characters in London, &c. &c.

With Descriptive and Entertaining Ancedotes.

Author: Anonymous

Release Date: April 4, 2014 [eBook #45314]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PORTRAITS OF CURIOUS CHARACTERS IN LONDON, &C. &C.***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/portraitsofcurio00londiala |

WITH

DESCRIPTIVE AND ENTERTAINING ANECDOTES.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY AND FOR W. DARTON, JUN.

58, HOLBORN-HILL.

1814

Mr. Bentley resided at the corner of the avenue leading to the house formerly the Old Crown Tavern, Leadenhall-street, not far from the East-India House.

The house and character of this eccentric individual are so well described in a poem published in the European Magazine, for January 1801, that we shall transcribe it:

Many are the reports concerning his civility, and polite manner of attending to the ladies whenever they have honoured him with their commands; and several curious persons have come to town from various parts of the country, on purpose to see so remarkable a figure.

Before the powder-tax was introduced, Nathaniel frequently paid a shilling for dressing that head, which of late years he scarcely seemed to think worthy of a comb! He mends his own clothes and washes his own linen, which he proudly acknowledges. His answer to a gentleman who wished to convert him to cleanliness, was, "It is of no use, Sir; if I wash my hands to-day, they will be dirty again to-morrow." On being asked whether he kept a dog or cat to destroy rats, mice, &c. he replied, "No, Sir, they only make more dirt, and spoil more goods than any service they are of; but as to rats and mice, how can they live in my house, when I take care to leave them nothing to eat?" If asked why he does not take down his shutters which have been so long up, or why he does not put his goods in proper order, his answer is, "he has been long thinking of it, but he has not time."

With all Nathaniel Bentley's eccentricities, it must be acknowledged, he is both intelligent and polite: like a diamond begrimed with dirt, which, though it may easily conceal its lustre in such a state, can easily recover its original polish—not a diamond indeed of the first water—not a rough diamond—but an unwashed diamond.

In his beauish days, his favourite suit was blue and silver, with his hair dressed in the extremity of fashion; but now—strange fancy—his hair frequently stands up like the quills of the porcupine, and generally attended in his late shop without a coat, while his waistcoat, breeches, shirt, face, and hands, corresponded with the dirt of his warehouse.

Those who are in the practice of walking the principal streets of this metropolis, leading from Bond-street to Cornhill, must have been attracted by the daily appearance of Ann Siggs, a tall woman, walking apparently easy with crutches, and mostly dressed in white, sometimes wearing a jacket or spencer of green baize; yet always remarkably clean in her dress and appearance.

It does not appear, however, that this female ranks very high among the remarkables, having but very few eccentricities, and nothing very singular, except her dress and method of walking. The great burthen of warm clothing which she always wears, is not from affectation, or a disposition to promote popular gaze, but from the necessity of guarding against the least cold, which she says always increases a rheumatic complaint with which she is afflicted.

When we consider the great number of beggars who daily perambulate London, and the violence they commit against decency, cleanliness, and delicate feelings, one naturally feels surprised they are so often the receivers of the generosity and bounty of the passing crowds; but independent of the commendable garb which adorns the interesting figure of Ann Siggs, we have repeatedly noticed another rare quality so very uncommon among the mendicant tribe, and that is, a silent and modest appeal to the considerate passenger, which almost involuntarily calls forth inquiry.

She is about fifty-six years of age, and is said to have a brother still living, an opulent tradesman on the Surrey side of the water; she also had a sister living at Isleworth, who died some time since.

This mendicant receives from the parish of St. Michael, Cornhill, a weekly allowance, which, with the benevolence of some well-disposed persons, probably adds considerably to her comforts,

"But cannot minister to the mind diseas'd."

It appears she has lived in Eden-court, Swallow-street, upwards of fifteen years, the lonely occupant of a small back room, leaving it at 9 o'clock every morning to resume her daily walks.

Her father lived many years at Dorking, in Surrey, maintaining the character of an industrious, quiet, and honest man, by the trade of a tailor, and who having brought up a large family of eight children, died, leaving the present Ann Siggs destitute of parental protection at the age of eighteen; and after many revolutions of bright and gloomy circumstances that have attended her during her humble perambulations, which the weakest minds are by no means calculated to endure, these have in some measure wrought upon her intellects. She is however perfectly innocent.

The appellation of extraordinary may, indeed, well apply to this ingenious and whimsical man. All the remarkable eccentricities which have yet been the characteristic of any man, however celebrated, may all hide their diminished heads before Martin Van Butchell. He is the morning star of the eccentric world; a man of uncommon merit and science, therefore the more wonderful from his curious singularities, his manners, and his appearance. Many persons make use of means to excite that attention which their merit did not deserve, and for the obtaining of credit which they never possessed. It appears, as an exception to these rules, that the singularities of Martin Van Butchell have tended more to obscure, than to exalt or display the sterling abilities which even the tongue of envy has never denied him.

The father of Martin Van Butchell was very well known in the reign of George II.; being tapestry-maker to his majesty, with a salary of £50 per annum attached to the office.

The education of the son was equal to the father's circumstances; who lived in a large house, with extensive gardens, known by the name of the "Crown House," in the parish of Lambeth, where several of the gentry occasionally lodged for the beauty of the situation and air; the son, who had many opportunities of improvement, by and through the distinguished persons who paid their visits at his father's house, was early taken notice of, and very soon possessed a knowledge of the French language, and arrived at many accomplishments. He maintained a good character, with a prepossessing address; recommendations which induced Sir Thomas Robinson to solicit his acceptance to travel with his son, as a suitable companion, in a tour through Europe. This offer, it appears, was not accepted; but in a short time after, he joined the family of the Viscountess Talbot; where, as groom of the chambers, he remained many years: a situation so lucrative as to enable him to leave and pursue with vigour his endeared studies of mechanics, medicine, and anatomy.

The study of the human teeth accidentally took up his attention through the breaking of one of his own, and he engaged himself as pupil to the famous Dr. J. Hunter. The profession of dentist was the occasion of first introducing him to the notice of the public; and so successful was he in this art, that for a complete set of teeth he has received the enormous price of eighty guineas! We have heard of a lady who was dissatisfied with teeth for which she had paid him ten guineas; upon which he voluntarily returned the money: scarcely had she slept upon the contemplation of this disappointment, before she returned, soliciting the set of teeth, which he had made her, as a favour, with an immediate tender of the money which she originally paid, and received them back again.

After many years successfully figuring as a dentist, Martin Van Butchell became no less eminent as a maker of trusses for ruptured persons. A physician of eminence in Holland having heard of his skill in this practice, made a voyage for the purpose of consulting him, and was so successfully treated, that, in return for the benefit received, he taught Martin Van Butchell the secret of curing fistulas; which he has practised ever since in an astonishing and unrivalled manner.

The eccentricities of Martin now began to excite public notice; upon his first wife's death, who, for the great affection he bore towards her, he was at first determined never should be buried; after embalming the body, he kept her in her wedding clothes a considerable time, in the parlour of his own house, which occasioned the visits of a great number of the nobility and gentry. It has been reported, that the resolution of his keeping his wife unburied, was occasioned by a clause in the marriage settlement, disposing of certain property, while she remained above ground: we cannot decide how far this may be true, but she has been since buried. He has a propensity to every thing in direct opposition to other persons: he makes it a rule to dine by himself, and for his wife and children also to dine by themselves; and it is his common custom to call his children by whistling, and by no other way.

Next to his dress and the mode of wearing his beard, one of the first singularities which distinguished him, was walking about London streets, with a large Otaheitan tooth or bone in his hand, fastened in a string to his wrist, intended to deter the boys from insulting him, as they very improperly were used to do, before his person and character were so well known.

Upon the front of his house, in Mount-street, he had painted the following puzzle:

BY

HIS MAJESTY's

| Thus, said sneaking Jack, I'll be first; if I get my money, |

ROYAL | speaking like himself, I don't care who suffers. |

LETTERS PATENT,

MARTIN

VAN BUTCHELL'

NEW INVENTED

With caustic care——and old Phim

SPRING BANDS

AND FASTNINGS

Sometimes in Six Days, and always ten—

the fistulæ in Ano.

FOR

THE APPAREL

AND FURNITURE

July Sixth

OF

Licensed to deal in Perfumery, i.e.

HUMAN BEINGS

Hydrophobia cured in thirty days,

AND

BRUTE CREATURES

made of Milk and Honey,

which remained some years. In order a little to comprehend it: some years ago, he had a famous dun horse, but on some dispute with the stable-keeper, the horse was detained for the keep, and at last sold, by the ranger of Hyde-Park, at Tattersal's, where it fetched a very high price. This affair was the cause of a law-suit, and the reason why Martin Van Butchell interlined the curious notice in small gold letters, nearly at the top, as follows:—"Thus said sneaking Jack, speaking like himself, I'll be first; if I get my money, I don't care who suffers."

After losing his favourite dun horse, a purchase was soon made of a small white poney, which he never suffers to be trimmed in any manner whatever; the shoes for it are always fluted to prevent slipping, and he will not suffer the creature to wear any other. His saddle is no less curious. He humorously paints the poney, sometimes all purple, often with purple spots, and with streaks and circles upon his face and hinder parts. He rides on this equipage very frequently, especially on Sundays, in the Park and about the streets.

The curious appearance of him and his horse have a very striking effect, and always attracts the attention of the public. His beard has not been shaved or cut for fifteen years; his hat shallow and narrow brimmed, and now almost white with age, though originally black: his coat a kind of russet brown, which has been worn a number of years, with an old pair of boots in colour like his hat and about as old. His bridle is also exceedingly curious; to the head of it is fixed a blind, which, in case of taking fright or starting, can be dropped over the horse's eyes, and be drawn up again at pleasure.

Many have been the insults and rude attacks of the ignorant and vulgar mob, at different times, upon this extraordinary man; and instances have occurred of these personal attacks terminating seriously to the audacious offender. One man, we remember, had the extreme audacity to take this venerable character by the beard; in return, he received a blow from the injured gentleman, with an umbrella, that had nearly broken a rib.

We shall now endeavour to exhibit his remarkable turn for singularity, by his writings, as published at different times in the public prints, and affording entertainment for the curious:

"Corresponding—Lads—Remember Judas:——And the year 80! Last Monday Morning, at 7 o'clock, Doctor Merryman, of Queen-street, May-fair, presented Elizabeth, the wife of Martin Van Butchell, with her Fifth fine Boy, at his House in Mount Street, Grosvenor Square, and—they—are—all—well—. Post Master General for Ten Thousand Pounds (—we mean Gentlemen's—Not a Penny less—) I will soon construct—such Mail-Coach—Perch—Bolts as shall never break!

To many I refer—for my character: Each will have grace—to write his case; soon as he is well—an history tell; for the public good;—to save human blood, as—all—true—folk—shou'd. Sharkish people may—keep themselves away,——Those that use me ill—I never can heal, being forbidden—to cast pearls to pigs; lest—they—turn—and—tear. Wisdom makes dainty: patients come to me, with heavy guineas,—between ten and one; but—I—go—to—none."

Mender of Mankind; in a manly way.

In another advertisement, he says:

"That your Majesty's Petitioner is a British Christian Man, aged fifty-nine—with a comely beard—full eight inches long. That your Majesty's Petitioner was born in the County of Middlesex—brought up in the County of Surrey—and has never been out of the Kingdom of England. That your Majesty's Petitioner (—about ten years ago—) had often the high honour (—before your Majesty's Nobles—) of conversing with your Majesty (—face to face—) when we were hunting of the stag—on Windsor Forest."

"British Christian Lads (—Behold—now is the day—of Salvation. Get understanding, as the highest gain.—) Cease looking boyish;—become quite manly!—(Girls are fond of hair: it is natural.—) Let your beards grow long: that ye may be strong:—in mind—and body: as were great grand dads:—Centuries ago; when John did not owe—a single penny: more than—he—could—pay."

Many more equally whimsical advertisements might be selected, and many additional anecdotes might be told of him; but what we have here recorded concerning this complete original may be depended upon. Not one word of which is contrary to truth.

It seems that this extraordinary character was born blind, about the year 1768. Having been deprived of his father, whilst very young, he was taken care of by his father-in-law, a brass-founder; and, early in life, habituated to attend very constantly the public worship of the church of England; but it appears, the visits he then made to places of worship were more from the authority of his father-in-law, than from any relish he had for the benefit of assembling amongst religious people; on the contrary, he was averse to the practice of going to church, and therefore it is not to be wondered at, that he should be found at length professing openly, by words and actions, similar dislike even to religion itself. But his continuance in these sentiments was suddenly changed, in accidentally meeting with the Countess of Huntingdon's Hymns, and the preaching of a gentleman at Spa Fields Chapel, so that he became more and more enraptured with the sublime doctrines of the Gospel; and has ever since constantly attended upon the dissenting meetings. And though blind, he does not walk in darkness, like too many professing Christians, "who have eyes, but see not."

Those who have the use of their sight, and have been constantly resident in London, are not better acquainted with the town than poor Statham. With astonishing precision, he finds his way, from street to street, and from house to house, supplying his customers with the various periodical publications that he carries; and this only by the means of an extraordinary retentive memory. His constant companion being a stick, whereby he feels his way. Such is his care and recollection, that he has never been known to lose himself.

Whilst living with his father-in-law, he paid great attention to the brass foundery business and still remembers the process of that art. On the death of his father-in-law, poor Statham became possessed of a very small freehold estate: the produce of which is, however, so trifling, that were it not for the occasional assistance of benevolent persons, and his little magazine walk, the wants of nature could not be supplied. He uses every exertion within his power to increase his weekly pittance; but the cruelty exercised upon him by inconsiderate people has, at different times, given him severe pain and bitter disappointment: the inhumanity we allude to, is that of sending him orders for magazines to be taken to places, several miles distant, which when purchased and conveyed to the fictitious place, he has been told, "No such books have been ordered, nor is there any one of that name lives here." Now if the persons so treating a poor defenceless man, only reflected a moment, at least they would forbear the shameful exercise of such wanton cruelty.

As we have hinted at the strength of his memory, we will now produce some facts to substantiate the truth. He can repeat all the Church of England service, and a great part of the Old and New Testament; some particular portions of Scripture which he considers remarkably striking he delivers with peculiar emphasis; besides the recollection of Lady Huntingdon's Hymns. Every sermon he hears he will go over, when returned home, with astonishing precision.

Equal to his retentive memory is his ingenuity, possessing an extensive knowledge of metals, copper, tin, brass, pewter, &c. &c. He can likewise tell if pinchbeck is or not a good mixture of copper and brass of equal proportion!

And no less remarkable is his retention of hearing: we remember upon a time, a person only having been once in his company, and after an absence of some months the same gentleman paid him a second visit; poor Statham immediately looked to the spot from whence the voice proceeded, and having repeatedly turned his head, without any further information, instantly addressed the gentleman he recollected.

It appears he is extremely fond of music, and what is called spiritual singing. His mode of living is always regular and frugal; strong liquors, so much used by the poor of this country, are by him religiously abstained from. These circumstances cause him to receive the advantages of a regular good state of health, and that cheerfulness of mind and patience in suffering so very conspicuous in his character.

Since the above account was written, this unfortunate individual was found, by the road side, near Bagnigge Wells, frozen to death, on Christmas morning, December 25th, 1808, having lost his way in that memorably severe storm of frost and snow, of Christmas eve of that year.

We have now to take notice of a female who never fails to attract particular notice; she is mostly attended by a crowd: with the assistance of a musical instrument, called a guitar, she adds her own voice, which, combined with the instrument, has a very pleasing effect.

A decent modesty is conspicuous in this person, more so than in any other we have ever witnessed following so humble a calling. She is wife to a soldier in the foot-guards, and lost her sight by suckling twin children, who are sometimes with her, conducted by a girl, who seems engaged to assist the family both at home and out of doors. Cleanliness, at all times the nurse of health, is by nine-tenths of the poor of this land banished existence, as if it were matter of misery to be distinguished by a clean skin and with clean clothes; now this rarity, we speak of, is amply possessed by Anne Longman, and though not quite so conspicuous in this particular as Ann Siggs, yet she lays strong claim to pity and charitable sympathy. It cannot be supposed that her husband, possessing only the salary arising from the situation of a private in the foot-guards, can support, without additional assistance, himself, his wife quite blind, and a family of four children, without encountering some severe trials and difficulties; so that, upon the whole, it is a matter of satisfaction and pleasure to find, that, incumbered as she is, some addition is made to their support through the innocent means of amusing the surrounding spectators by her melody.

These pedestrians form a singular sight; twins in birth, and partners in misfortunes in life; they came into the world blind; and blind are compelled to wade their way through a world of difficulties and troubles.

Though nothing very remarkable can be recorded of them, yet there is something in their looks and manners that at least renders them conspicuous characters.

They are continually moving from village to village, from town to town, and from city to city, never omitting to call upon London, whether outward or homeward bound. It is observable, however, they never play but one tune, which may account for their not stopping any length of time in one place. For upwards of twenty years they have always been seen together.

John and Robert Green are visitors at most country fairs, particularly at the annual Statute Fair, held at Chipping Norton, which they never fail to attend; and at this place, it appears, they were born.

When in London, they are always noticed with a guide; and as soon as the old harmony is finished, one takes hold of the skirt of the other's coat, and in that manner proceed until they again strike up the regular tune. We are inclined to think the charity bestowed upon them is not given as a retaining fee, but rather to get rid of a dissonance and a discord which, from continual repetition, becomes exceedingly disagreeable; though in this manner they pick up a decent subsistence.

Thomas Sugden seems determined to distinguish himself from the rest of his brethren, by carrying two pigeons upon his shoulders, and one upon his head; healthy and fine birds continue so but a little time with him. He is the dirtiest among the dirty; and his feathered companions soon suffer from this disgusting propensity; one week reduces their fine plumage and health to a level with the squalid and miserable appearance of their master, whose pockets very often contain the poor prisoners, to be ready to bring them forth at the first convenient stand he thinks it most to his advantage to occupy; and from this mode of conveyance are they indebted for broken feathers, dirt, &c.

Sugden, a native of Yorkshire, lost his sight in a dreadful storm, on board the Gregson merchantman, Capt. Henley, commander: the particulars he sometimes relates, and attributes his misfortunes to an early neglect of parental admonition, when nothing but sea could serve his turn. He addresses his younger auditors upon this subject, and remonstrates with them on the advantage of obedience to their parents.

Elevated as the bell-ringing tribe are above this humble creature, the correct manner of his ringing, with hand-bells, various peals and song tunes, would puzzle the judgments of a very large portion of regular-bred belfry idlers.

Numbers of persons have attended upon his performance, particularly when his self-constructed belfry was in existence, near Broad Wall, Lambeth, containing a peal of eight bells, from which he obtained a tolerable livelihood; here he was soon disturbed, and obliged to quit, to make way for some building improvement. He has ever since exercised his art in most public places, on eight, ten, and sometimes twelve bells, for upwards of twenty-four years. He frequently accompanies the song tunes with his voice, adding considerably to the effect, though he has neither a finished nor powerful style of execution. While he performs upon the hand-bells (which he does sitting), he wears a hairy cap, to which he fixes two bells; two he holds in each hand; one on each side, guided by a string connected with the arm; one on each knee; and one on each foot. It appears, he originally came from the city of Norwich, and was employed as a weaver in that place some years, but, having (from a cold) received an injury to his sight, resigned his trade for the profession which necessity now compels him to follow.

It seems the important study of ass-braying, wild-boar grunting, and the cry of hungry pigs, has engaged for some years the attention of this original. In addition to these harmonious and delightful sounds, another description of melody he successfully performs, which is on the trumpet, French horn, drum, &c.

An Italian took a fancy to his wonderful ingenuity, and had him imported into England. As an inducement to obtain George's consent to leave the city of Lisbon, in Portugal, the place of his nativity, he was most flatteringly assured of making his fortune.

Romondo took shipping for England, safely arrived in London early in the year 1800; and soon after commenced operations in a caravan drawn by horses, nearly resembling those used by the famous Pidcock, for the travelling of his wild beasts up and down the country. In this manner Romondo began making a tour of England, from fair to fair, under the style and title of "The Little Man of the Mountain." He now became alternately pig, boar, and ass, for the Italian's profit, with an allowance of 2s. 6d. per day, for himself. It is natural to suppose such a speculation could not be attended with success; the event actually turned out so; and after some time it was given up, and our poor mountain hero left by this cunning Italian, to shift for himself.

He, however, soon after commenced operations upon his own account, and continues to this day to exercise his surprising talents!

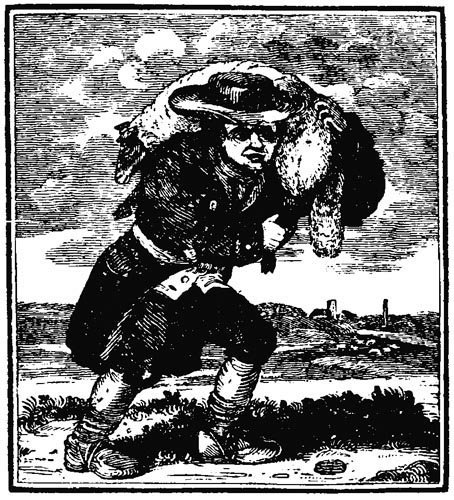

He is about forty-three years of age, wears a cocked hat, drooping a prodigious length over his shoulders, completely in the fashion of a dustman or coalheaver, and with a coat actually sweeping the ground. In height he is about three feet six inches; his legs and thighs appear like a pair of callipers; he is said to be, in temper, very good natured; and is very fond of the ladies, often kissing their elbows, which come exactly parallel with his lips, as he walks the streets of London; and in exchange, many a box on the ear has been received, with apparent good nature. At particular times, he is seen in his full dress, with a round fashionable hat, white cotton stockings, and red slippers.

From the unintelligible crying jargon this man utters, while supplicating charity, one would be induced to suppose him ignorant of the English language; but he possesses, at least, as perfect a knowledge of it as most persons in his humble sphere.

The use of his own native language is of great advantage to him, in exciting the pity and fixing the attention of the passenger; and is, besides, a great inducement to many to extend their charity to this apparently distressed stranger. Indeed he exercises every art, and leaves no method untried, to work upon the various dispositions of those he supplicates. Very often he will preach to the spectators gathered round him, presuming frequently to make mention of the name of Jesus; and, sometimes, he will amuse another sort of auditors with a song; and when begging, he always appears bent double, as if with excessive pain and fatigue. But here again is another deception and trick of a very shallow manufacture: for in the same day we have seen him, when outward-bound, in the morning, so bent double as with a fixed affliction; but on his return home in the evening, after the business of the day is closed, this black Toby reverses his position, lays aside all his restraints, walks upright, and with as firm a step as the nature of his loss will allow, begins talking English, and ceases preaching. To all appearance, a daily and universal miracle appears to be wrought; for scarcely are he and his jovial companions assembled together in one place and with one accord; or rather scarcely has liquor appeared upon the table, than the blind can see—the dumb speak—the deaf hear—and the lame walk! Here, indeed, as Pope has said, one might

"See the blind beggar dance, the cripple sing:"

Or, as he has neatly said upon a more solemn occasion,

To descend from the imitations of these poetic strains, we add, that to such assemblies1 as those just described, Toby is a visiting member, and is frequently called upon from the chair to amuse the company; and as a beggar's life is avowedly made up of extremes, from these midnight revels, he adjourns to a miserable two-penny lodging, where, with the regular return of the morning, as a carpenter putteth on his apron, or as a trowel is taken into the hand of a bricklayer; even so Black Toby, laying aside all the freaks of the evening, again sallies forth in quest of those objects of credulity, that will ever be found in a population so extensive as that of this metropolis.

Toby was employed on board a merchantman, bound from Bermuda to Memel, and in the voyage, from the severity of the weather and change of climate, lost the whole of his toes in the passage. From Memel, he found his way to England, on board the Lord Nelson privateer, and ever since has supported himself by the improper charity he receives from begging.

Sir John Dinely is descended from a very illustrious family, which continued to flourish in great repute in Worcestershire, till the late century, when they expired in the person of Sir Edward Dinely, Knight.

The present heroic Sir John Dinely has, however, made his name conspicuous by stepping into a new road of fancy, by his poetic effusions, by his curious advertisements for a wife, and by the singularity of his dress and appearance.

Sir John now lives at Windsor, in one of the habitations appropriated to reduced gentlemen of his description. His fortune he estimates at three hundred thousand pounds, if he could recover it!

In dress, Sir John is no changeling; for nearly twenty years past he has been the faithful resemblance of the engraving accompanying this account. He is uncommonly loquacious, his conversation is overcharged with egotism, and such a mixture of repartee and evasion, as to excite doubts, in the minds of superficial observers, as to the reality of his character and abilities. With respect to his exterior, it is really laughable to observe him, when he is known to be going to some public place to exhibit his person; he is then decked out with a full-bottomed wig, a velvet embroidered waistcoat, satin breeches and silk stockings. On such occasions as these, not a little inflated with family pride, he seems to imagine himself as great as any lordling: but on the day following, he may be seen slowly pacing from the chandler's shop with a penny loaf in one pocket, a morsel of butter, a quartern of sugar, and a three-farthing candle in the other.

He is still receiving epistles in answer to his advertisements, and several whimsical interviews and ludicrous adventures have occurred in consequence. He has, more than once, paid his addresses to one of his own sex, dressed as a fine lady: at other times, when he has expected to see his fair enamorata at a window, he has been rudely saluted with the contents of very different compliments. One would suppose these accidents would operate as a cooler, and allay in some degree the warmth of his passion. But our heroic veteran still triumphs over every obstacle, and the hey-day of his blood still beats high; as may be seen by the following advertisement for a wife, in the Reading Mercury, May 24, 1802:

"Miss in her Teens—let not this sacred offer escape your eye. I now call all qualified ladies, marriageable, to chocolate at my house every day at your own hour.—With tears in my eyes, I must tell you, that sound reason commands me to give you but one month's notice before I part with my chance of an infant baronet for ever: for you may readily hear that three widows and old maids, all aged above fifty, near my door, are now pulling caps for me. Pray, my young charmers, give me a fair hearing; do not let your avaricious guardians unjustly fright you with a false account of a forfeiture, but let the great Sewel and Rivet's opinions convince you to the contrary; and that I am now in legal possession of these estates; and with the spirit of an heroine command my three thousand pounds, and rank above half the ladies in our imperial kingdom. By your ladyship's directing a favourable line to me, Sir John Dinely, Baronet, at my house in Windsor Castle, your attorney will satisfy you, that, if I live but a month, eleven thousand pounds a year will be your ladyship's for ever."

Sir John does not forget to attend twice or thrice a year at Vauxhall and the theatres, according to appointments in the most fashionable daily papers. He parades the most conspicuous parts of Vauxhall, and is also seen in the front row of the pit in the theatres; whenever it is known he is to be there, the house is sure, especially by the females, to be well attended. Of late, Sir John has added a piece of stay-tape to his wig, which passes under his chin; from this circumstance, some persons might infer that he is rather chop-fallen; an inference by no means fair, if we still consider the gay complexion of his advertisements and addresses to the ladies.

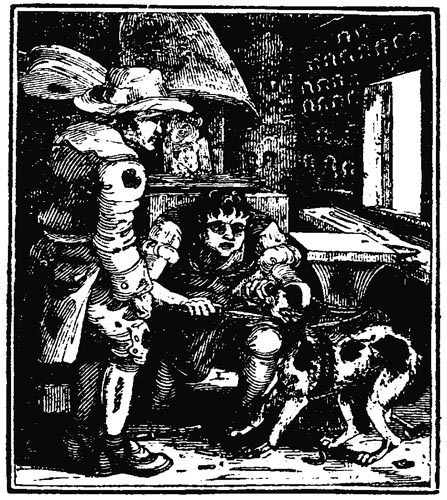

Our engraving represents two singular characters, whose eccentric humour is well worthy of the attention of the curious. Messrs. Aaron and John Trim are grocers, living at No. 449, Strand, nearly opposite to Villier's-street; at this shop curiosity would not be disappointed of the expected gratification, from the personal appearance of the two gentlemen behind the counter, if there was nothing else to strike the attention. One of the gentlemen is so short, as frequently to be under the necessity of mounting the steps to serve his customers. And the shop itself displays no common spectacle: a dozen pair of scales are strewed from one end of the counter to the other, mingled with large lumps of sugar and various other articles; the floor is so completely piled with goods, one upon the other, and in all parts so covered that there is passage sufficient but for one person at a time to be served: and we believe there is no shop in the neighbourhood so much frequented, although there are a great many in the same business within two hundred yards of A. and J. Trim. Their shop is remarkable for selling what is termed "a good article." These gentleman exercise the greatest attention to their customers, and such good humour and urbanity of manners, as to be characterised the "Polite Grocers." They were born in the same house in which they now live, and have remained there ever since; and where their father, a man well esteemed, died some years back, leaving the business to his sons, with considerable property.

The church of England never had more regular attenders upon its ministry and forms of worship than in the persons of Messrs. Aaron and John Trim, whose attendance at the public worship, at St. Martin's, in the Strand, is as regular with them as the neglect and desertion is common by the generality of its members.

The whole of the business of the Polite Grocers is conducted by themselves, with now and then the assistance of a young woman, who appears principally to have the management of the Two-penny-post; and from the extent of their trade, the smallness of their expenses, and their frugality, it is generally supposed they must be rich; but though extremely talkative upon any other subject, yet on every point relating to themselves, and their private concerns, they very properly maintain the most impenetrable closeness and reserve.

Abounding as this age does with so many temptations and examples of extravagance and waste, it requires no small portion of resolution to maintain a due observance of economy, to be kept from following the public current in its wasteful fashions and extravagant expenses. Now, that the Polite Grocers maintain this economy, cannot be doubted; and which, in the present situation of things, must be considered no small virtue. Economy without penuriousness, liberality without prodigality!

Ann Johnson is a poor industrious widow, cleanly, sober, and decent, inoffensive and honest, and quite blind. The engraved portrait of this interesting figure may be depended upon for its faithful representation of the much-to-be-pitied original. She was born at Eaton, in Cheshire, on St. Andrew's day, old style, in the year 1743, was apprenticed to a ribband weaver at the early age of ten years, and was twenty-four years old when she lost her sight, occasioned by a spotted fever.

Sitting exposed to the inclemency of hot and cold, of wet and dry weather, for upwards of six and twenty years, in the open streets of London, might naturally undermine a constitution the most vigorous and healthy. It certainly has considerably affected Ann Johnson, whose regular appearance, even in the bitterest days of winter, has been as uniform as the finest in summer, on Holborn-hill, upon the steps at the corner of Marmaduke and Thomas Langdale's house, the distillers. Here she exhibits the expert manner in which she makes laces, attracting the notice of the considerate passenger: she is rendered additionally interesting, by the cheerfulness of her conversation and the serenity of her countenance, using words, in effect, similar to the following beautiful lines:

She resides at No. 5, Church-lane, Bloomsbury, and has been an inhabitant of London upwards of thirty-eight years. We particularly recommend her to the considerate attention of every little girl or young woman, and, when they are in want of any laces, to think of Ann Johnson.—Such great industry deserves encouragement.

Such as have seen this man in London (and there are very few that have not) will be instantly struck with the accuracy of the engraving.

He has literally rocked himself about London for upwards of nineteen years, with the help of a wooden seat, assisted by a short pair of crutches; and the facility with which he moves is the more singular, when we consider he is very corpulent; he appears to possess remarkably good health, and is about fifty-six years of age. In his life we have no great deal to notice, as wonderful or remarkable. His figure alone is what renders him a striking character; not striking for the height or bulk of his person, but for the mutilated singularity and diminutive size so conspicuously attracting when upon his move in the busiest parts of London streets; in places that require considerable care, even for persons well mounted upon legs, and possessing a good knowledge in the art of walking, to get along without accidents; but even here poor Samuel works his way, whilst buried, as it were, with the press of the crowd, in a manner very expeditious, and tolerably free from accidents, except being tumbled over now and then by people walking too much in haste.

This singular woman was born in the year 1744, at Leipsic, in Germany, and died at her lodgings in Upper Charles-street, Hatton-Garden, London, July 15, 1802. She was the only daughter of an architect, of the name of Grahn, who erected several edifices in the city of Berlin, particularly the church of St. Peter. She wrote an excellent hand, and had learned the mathematics, the French, Italian, and English languages, and possessed a complete knowledge of her native tongue. Upon her arrival in England, she commenced teacher of the German language, under the name of Dr. John de Verdion. In her exterior, she was extremely grotesque, wearing a bag wig, a large cocked hat, three or four folio books under one arm, and an umbrella under the other, her pockets completely filled with small volumes, and a stick in her right hand.

She had a good knowledge of English books; many persons entertained her for her advice, relative to purchasing them. She obtained a comfortable subsistence from teaching and translating foreign languages, and by selling books chiefly in foreign literature. She taught the Duke of Portland the German language, and was always welcomed to his house; the Prussian Ambassador to our court received from her a knowledge of the English language; and several distinguished noblemen she frequently visited to instruct them in the French tongue; she also taught Edward Gibbon, the celebrated Roman historian, the German language, previous to his visiting that country. This extraordinary female has never been known to have appeared in any other but the male dress since her arrival in England, where she remained upwards of thirty years; and upon occasions she would attend at court, decked in very superb attire; and was well remembered about the streets of London; and particularly frequent in attending book auctions, and would buy to a large amount, sometimes a coach load, &c. Here her singular figure generally made her the jest of the company.

Her general purchase at these sales was odd volumes; which she used to carry to other booksellers, and endeavour to sell, or exchange for other books. She was also a considerable collector of medals and foreign coins of gold and silver; but none of these were found after her decease. She frequented the Furnival's Inn coffee house, in Holborn, dining there almost every day; she would have the first of every thing in season, and was as strenuous for a large quantity, as she was dainty in the quality of what she chose for her table. At times, it is well known, she could dispense with three pounds of solid meat; and, we are sorry to say, she was much inclined to extravagant drinking.

The disorder of a cancer in her breast, occasioned by falling down stairs, she was, after much affliction, at length compelled to make known to a German physician, who prescribed for her; when the disorder turned to a dropsy, defied all cure, and finished the career of so remarkable a lady.

The astonishing weight of this man is fifty stone and upwards, being more than seven hundred pounds; the surprising circumference of his body is three yards four inches; his leg, one yard and an inch; and his height, five feet eleven inches; and, though of this amazing size, entirely free from any corporeal defect.

This very remarkable personage received his birth in Leicester; at which place he was apprenticed to an engraver. Until he arrived at the age of twenty years, he was not of more than usual size, but after that period he began to increase in bulk, and has been gradually increasing, until within a few months of the present time. He was much accustomed to exercise in the early years of his life, and excelled in walking, riding and shooting; and more particularly devoted himself to field exercises, as he found himself inclined to corpulency; but, to the great astonishment of his acquaintance, it proved not only unavailing, but really seemed to produce a directly opposite effect. Mr. Lambert is in full possession of perfect health; and whether sitting, lying, standing, or walking, is quite at his ease, and requires no more attendance than any common-sized person. He enjoys his night's repose, though he does not indulge himself in bed longer than the refreshment of sleep continues.

The following anecdote is related of him:—"Some time since, a man with a dancing bear going through the town of Leicester, one of Mr. Lambert's dogs taking a dislike to his shaggy appearance, made a violent attack upon the defenceless animal. Bruin's master did not fail to take the part of his companion, and, in his turn, began to belabour the dog. Lambert, being a witness of the fray, hastened with all possible expedition from the seat or settle (on which he made a practice of sitting at his own door) to rescue his dog. At this moment the bear, turning round suddenly, threw down his unwieldy antagonist, who, from terror and his own weight, was absolutely unable to rise again, and with difficulty got rid of his formidable opponent."

He is particularly abstemious with regard to diet, and for nearly twelve years has not taken any liquor, either with or after his meals, but water alone. His manners are very pleasing; he is well-informed, affable, and polite; and having a manly countenance and prepossessing address, he is exceedingly admired by those who have had the pleasure of conversing with him. His strength (it is worthy of observation) bears a near proportion to his wonderful appearance. About eight years ago, he carried more than four hundred weight and a half, as a trial of his ability, though quite unaccustomed to labour. His parents were not beyond the moderate size; and his sisters, who are still living, are by no means unusually tall or large. A suit of clothes costs him twenty pounds, so great a quantity of materials are requisite for their completion.

It is reported, that among those who have recently seen him was a gentleman weighing twenty stone: he seemed to suffer much from his great size and weight. Mr. Lambert, on his departure, observed, that he would not (even were it possible) change situations with him for ten thousand pounds. He bears a most excellent character at his native town, which place he left, to the regret of many, on Saturday, April 4, 1806, for his first visit to London.

We have to announce the death of this celebrated man, which took place in this town at half past 8 o'clock on Wednesday morning last.

Mr. Lambert had travelled from Huntingdon hither in the early part of the week, intending to receive the visits of the curious who might attend the ensuing races. On Tuesday evening he sent a message to the office of this paper, requesting that, as "the mountain could not wait upon Mahomet, Mahomet would go to the mountain." Or, in other words, that the printer would call upon him to receive an order for executing some handbills, announcing Mr. Lambert's arrival, and his desire to see company.

The orders he gave upon that occasion were delivered without any presentiment that they were to be his last, and with his usual cheerfulness. He was in bed—one of large dimensions—("Ossa upon Olympus, and Pelion upon Ossa")—fatigued with his journey; but anxious that the bills might be quickly printed, in order to his seeing company next morning.

Before nine o'clock on that morning, however, he was a corpse! Nature had endured all the trespass she could admit: the poor man's corpulency had constantly increased, until, at the time we have mentioned, the clogged machinery of life stood still, and the prodigy of Mammon was numbered with the dead.

He was in his 40th year; and upon being weighed, within a few days, by the famous Caledon's balance, was found to be 52 stone 11 pounds in weight (14lb. to the stone), which is 10 stone 11lb. more than the great Mr. Bright, of Essex, ever weighed.—He had apartments at Mr. Berridge's, the Waggon and Horses, in St. Martin's, on the ground floor—for he had been long incapable of walking up stairs.

His coffin, in which there has been great difficulty of placing him, is 6 feet 4 inches long, 4 feet 4 inches wide, and 2 feet 4 inches deep; the immense substance of his legs makes it necessarily almost a square case. The celebrated sarcophagus of Alexander, viewed with so much admiration at the British Museum, would not nearly contain this immense sheer hulk.

The coffin, which consists of 112 superficial feet of elm, is built upon 2 axletrees and 4 cog wheels; and upon these the remains of the poor man will be rolled into his grave; which we understand is to be in the new burial-ground at the back of St. Martin's church.—A regular descent will be made by cutting away the earth slopingly for some distance—the window and wall of the room in which he lies must be taken down to allow his exit.—He is to be buried at 8 o'clock this morning.

N.B. There is a very good coloured portrait of Daniel Lambert, published by W. Darton, Holborn; with particulars concerning him. Price One Shilling.

Meggot was the family name of Mr. Elwes; and his name being John, the conjunction of Jack Meggot induced strangers to imagine sometimes that his friends were addressing him by an assumed appellation. The father of Mr. Elwes was an eminent brewer; and his dwelling-house and offices were situated in Southwark; which borough was formerly represented in parliament by his grandfather, Sir George Meggot. During his life he purchased the estate now in possession of the family of the Calverts, at Marcham, in Berkshire. The father died when the late Mr. Elwes was only four years old; so that little of the singular character of Mr. Elwes is to be attributed to him: but from the mother it may be traced with ease; she was left nearly one hundred thousand pounds by her husband, and yet starved herself to death. The only children from the above marriage, were Mr. Elwes, and a daughter, who married the father of the late Colonel Timms; and from thence came the entail of some part of the present estate.

Mr. Elwes, at an early period of life, was sent to Westminster School, where he remained ten or twelve years. He certainly, during that time, had not misapplied his talents; for he was a good classical scholar to the last; and it is a circumstance very remarkable, yet well authenticated, that he never read afterwards. Never, at any period of his future life, was he seen with a book; nor had he in all his different houses left behind him two pounds worth of literary furniture. His knowledge in accounts was little; and, in some measure may account for his total ignorance as to his own concerns. The contemporaries of Mr. Elwes, at Westminster, were Mr. Worsley, late Master of the Board of Works, and the late Lord Mansfield; who, at that time, borrowed all that young Elwes would lend. His lordship, however, afterwards changed his disposition.

Mr. Elwes from Westminster-School removed to Geneva, where he shortly after entered upon pursuits more congenial to his temper than study. The riding-master of the academy had then three of the best horsemen in Europe for his pupils: Mr. Worsley, Mr. Elwes, and Sir Sidney Meadows. Elwes of the three was accounted the most desperate: the young horses were put into his hands always; and he was, in fact, the rough-rider of the other two. He was introduced, during this period, to Voltaire, whom, in point of appearance, he somewhat resembled; but though he has often mentioned this circumstance, neither the genius, the fortune, nor the character, of Voltaire, ever seemed to strike him as worthy of envy.

Returning to England, after an absence of two or three years, he was to be introduced to his uncle, the late Sir Harvey Elwes, who was then living at Stoke, in Suffolk, the most perfect picture of human penury perhaps that ever existed. In him the attempts of saving money was so extraordinary, that Mr. Elwes never quite reached them, even at the most covetous period of his life. To this Sir Harvey Elwes he was to be the heir, and of course it was policy to please him. On this account it was necessary, even in old Mr. Elwes, to masquerade a little; and as he was at that time in the world, and its affairs, he dressed like other people. This would not have done for Sir Harvey. The nephew, therefore, used to stop at a little inn at Chelmsford, and begin to dress in character. A pair of small iron buckles, worsted stockings darned, a worn out old coat, and a tattered waistcoat, were put on; and forwards he rode to visit his uncle; who used to contemplate him with a kind of miserable satisfaction, and seemed pleased to find his heir bidding fair to rival him in the unaccountable pursuit of avarice. There they would sit—saving souls!—with a single stick upon the fire, and with one glass of wine, occasionally, betwixt them, inveighing against the extravagance of the times; and when evening shut in, they would immediately retire to rest—as going to bed saved candle-light.

To the whole of his uncle's property Mr. Elwes succeeded; and it was imagined that his own was not at the time very inferior. He got, too, an additional seat; but he got it as it had been most religiously delivered down for ages past: the furniture was most sacredly antique: not a room was painted, nor a window repaired: the beds above stairs were all in canopy and state, where the worms and moths held undisturbed possession; and the roof of the house was inimitable for the climate of Italy.

Mr. Elwes had now advanced beyond the fortieth year of his age; and for fifteen years previous to this period it was that he was known in all the fashionable circles of London. He had always a turn for play; and it was only late in life, and from paying always, and not always being paid, that he conceived disgust at the inclination.

The acquaintances which he had formed at Westminster-school, and at Geneva, together with his own large fortune, all conspired to introduce him into whatever society he liked best.

Mr. Elwes, on the death of his uncle, came to reside at Stoke, in Suffolk. Bad as was the mansion-house he found here, he left one still worse behind him at Marcham, of which the late Colonel Timms, his nephew, used to mention the following proof. A few days after he went thither, a great quantity of rain falling in the night, he had not been long in bed before he found himself wet through; and putting his hand out of the clothes, found the rain was dropping from the ceiling upon the bed. He got up and moved the bed; but he had not lain long, before he found the same inconveniency continued. He got up again, and again the rain came down. At length after pushing the bed quite round the room, he retired into a corner where the ceiling was better secured, and there he slept till morning. When he met his uncle at breakfast, he told him what had happened. "Ay! ay!" said the old man, seriously; "I don't mind it myself; but to those that do, that's a nice corner in the rain."

Mr. Elwes, on coming into Suffolk, first began to keep fox-hounds; and his stable of hunters, at that time, was said to be the best in the kingdom. Of the breed of his horses he was certain, because he bred them himself; and they were not broke in till they were six years old.

The keeping of fox-hounds was the only instance in the whole life of Mr. Elwes of his ever sacrificing money to pleasure. But even here every thing was done in the most frugal manner. His huntsman had by no means an idle life of it. This famous lacquey might have fixed an epoch in the history of servants; for, in a morning, getting up at four o'clock, he milked the cows. He then prepared breakfast for his master, or any friends he might have with him. Then slipping on a green coat, he hurried into the stable, saddled the horses, got the hounds out of the kennel, and away they went into the field. After the fatigues of hunting, he refreshed himself by rubbing down two or three horses as quickly as possible; then running into the house, would lay the cloth and wait at dinner. Then hurrying again into the stable to feed the horses; diversified with an interlude of the cows again to milk, the dogs to feed, and eight horses to litter down for the night. What may appear extraordinary, this man lived in his place for some years; though his master used often to call him "an idle dog!" and say, "the rascal wanted to be paid for doing nothing."

An inn upon the road, and an apothecary's bill, were equal objects of aversion to Mr. Elwes. The words "give" and "pay" were not found in his vocabulary; and therefore, when he once received a very dangerous kick from one of his horses, who fell in going over a leap, nothing could persuade him to have any assistance. He rode the chase through, with his leg cut to the bone; and it was only some days afterwards, when it was feared an amputation would be necessary, that he consented to go up to London, and, dismal day! part with some money for advice.

The whole fox-hunting establishment of Mr. Elwes, huntsman, dogs, and horses, did not cost him three hundred pounds a year!

While he kept hounds, and which consumed a period of nearly fourteen years, Mr. Elwes almost totally resided at Stoke, in Suffolk. He sometimes made excursions to Newmarket; but never engaged on the turf. A kindness, however which he performed there, should not pass into oblivion.

Lord Abingdon, who was slightly known to Mr. Elwes in Berkshire, had made a match for seven thousand pounds, which, it was supposed, he would be obliged to forfeit, from an inability to produce the sum, though the odds were greatly in his favour. Unasked, unsolicited, Mr. Elwes made him an offer of the money, which he accepted, and won his engagement.

On the day when this match was to be run, a clergyman had agreed to accompany Mr. Elwes to see the fate of it. They were to go, as was his custom, on horseback, and were to set out at seven in the morning. Imagining they were to breakfast at Newmarket, the gentleman took no refreshment, and away they went. They reached Newmarket about eleven, and Mr. Elwes began to busy himself in inquiries and conversation till twelve, when the match was decided in favour of Lord Abingdon. He then thought they should move off to the town, to take some breakfast; but old Elwes still continued riding about till three; and then four arrived. At which time the gentleman grew so impatient, that he mentioned something of the keen air of Newmarket Heath, and the comforts of a good dinner. "Very true," said old Elwes; "very true. So here, do as I do;"—offering him at the same time, from his great-coat pocket, a piece of an old crushed pancake, "which," he said, "he had brought from his house at Marcham two months before—but that it was as good as new."

The sequel of the story was, that they did not reach home till nine in the evening, when the gentleman was so tired, that he gave up all refreshment but rest; and old Mr. Elwes, having hazarded seven thousand pounds in the morning, went happily to bed with the reflection—that he had saved three shillings.

He had brought with him his two sons out of Berkshire; and certainly, if he liked any thing, it was these boys. But no money would he lavish on their education; for he declared that "putting things into people's heads, was taking money out of their pockets."

From this mean, and almost ludicrous, desire of saving, no circumstance of tenderness or affection, no sentiment of sorrow or compassion, could turn him aside. The more diminutive the object seemed, his attention grew the greater: and it appeared as if Providence had formed him in a mould that was miraculous, purposely to exemplify that trite saying, Penny wise, and pound foolish.

From the parsimonious manner in which Mr. Elwes now lived, (for he was fast following the footsteps of Sir Harvey,) and from the two large fortunes of which he was in possession, riches rolled in upon him like a torrent. But as he knew almost nothing of accounts, and never reduced his affairs to writing, he was obliged, in the disposal of his money, to trust much to memory; to the suggestions of other people still more; hence every person who had a want or a scheme, with an apparent high interest—adventurer or honest, it signified not—all was prey to him; and he swam about like the enormous pike, which, ever voracious and unsatisfied, catches at every thing, till it is itself caught! hence are to be reckoned visions of distant property in America; phantoms of annuities on lives that could never pay; and bureaus filled with bonds of promising peers and members long dismembered of all property. Mr. Elwes lost in this manner full one hundred and fifty thousand pounds!

But what was got from him, was only obtained from his want of knowledge—by knowledge that was superior; and knaves and sharpers might have lived upon him, while poverty and honesty would have starved.

When this inordinate passion for saving did not interfere, there are upon record some kind offices, and very active services, undertaken by Mr. Elwes. He would go far and long to serve those who applied to him: and give—however strange the word from him—give himself great trouble to be of use. These instances are gratifying to select—it is plucking the sweet-briar and the rose from the weeds that overspread the garden.

Mr. Elwes, at this period, was passing—among his horses and hounds, some rural occupations, and his country neighbours—the happiest hours of his life—where he forgot, for a time, at least, that strange anxiety and continued irritation about his money, which might be called the insanity of saving! But as his wealth was accumulating, many were kind enough to make applications to employ it for him. Some very obligingly would trouble him with nothing more than their simple bond: others offered him a scheme of great advantage, with "a small risk and a certain profit," which as certainly turned out to the reverse; and others proposed "tracts of land in America, and plans that were sure of success." But amidst these kind offers, the fruits of which Mr. Elwes long felt, and had to lament, some pecuniary accommodations, at a moderate interest, were not bestowed amiss, and enabled the borrowers to pursue industry into fortune, and form a settlement for life.

Mr. Elwes, from Mr. Meggot, his father, had inherited some property in London in houses; particularly about the Haymarket, not far from which old Mr. Elwes drew his first breath; being born in St. James's parish. To this property he began now to add, by engagements with one of the Adam's about building, which he increased from year to year to a very large extent. Great part of Marybone soon called him her founder. Portman Place, and Portman Square, the riding-houses and stables of the second troop of life-guards, and buildings too numerous to name, all rose out of his pocket; and had not the fatal American war kindly put a stop to his rage of raising houses, much of the property he then possessed would have been laid out in bricks and mortar.

The extent of his property in this way soon grew so great, that he became, from judicious calculation, his own insurer: and he stood to all his losses by conflagrations. He soon therefore became a philosopher upon fire: and, on a public-house belonging to him being consumed, he said, with great composure, "well, well, there is no great harm done. The tenant never paid me, and I should not have got quit of him so quickly in any other way."

It was the custom of Mr. Elwes, whenever he went to London, to occupy any of his premises which might happen to be then vacant. He travelled in this manner from street to street; and whenever any body chose to take the house where he was, he was instantly ready to move into any other. He was frequently an itinerant for a night's lodging; and though master of above a hundred houses, he never wished to rest his head long in any he chose to call his own. A couple of beds, a couple of chairs, a table, and an old woman, comprised all his furniture; and he moved them in about a minute's warning. Of all these moveables, the old woman was the only one which gave him trouble; for she was afflicted with a lameness, that made it difficult to get her about quite so fast as he chose. And then the colds she took were amazing; for sometimes she was in a small house in the Haymarket; at another in a great house in Portland Place: sometimes in a little room, and a coal fire; at other times with a few chips, which the carpenters had left, in rooms of most splendid, but frigid dimensions, and with a little oiled paper in the windows for glass.

Mr. Elwes had come to town in his usual way, and taken up his abode in one of his houses that was empty. Colonel Timms, who wished much to see him, by some accident, was informed his uncle was in London; but then how to find him was the difficulty. He inquired at all the usual places where it was probable he might be heard of. He went to Mr. Hoare's, his banker; to the Mount Coffee-house; but no tidings were to be heard of him. Not many days afterwards, however, he learnt, from a person whom he met accidentally, that they had seen Mr. Elwes going into an uninhabited house in Great Marlborough Street. This was some clue to Colonel Timms, and away he went thither. As the best mode of information, he got hold of a chairman; but no intelligence could he gain of a gentleman called Mr. Elwes. Colonel Timms then described his person—but no gentleman had been seen. A pot-boy, however, recollected, that he had seen a poor old man opening the door of the stable, and locking it after him, and from every description, it agreed with the person of old Mr. Elwes. Of course, Colonel Timms, went to the house. He knocked very loudly at the door; but no one answered. Some of the neighbours said they had seen such a man; but no answer could be obtained from the house. The Colonel, on this, resolved to have the stable-door opened; which being done, they entered the house together. In the lower parts of it all was shut and silent; but, on ascending the stair-case, they heard the moans of a person seemingly in distress. They went to the chamber, and there, upon an old pallet-bed, lay stretched out, seemingly in the agonies of death the figure of old Mr. Elwes. For some time he seemed insensible that any body was near him; but on some cordials being administered by a neighbouring apothecary, who was sent for, he recovered enough to say, "That he had, he believed, been ill for two or three days, and that there was an old woman in the house; but for some reason or other she had not been near him. That she had been ill herself; but that she had got well, he supposed, and was gone away."

They afterwards found the old woman—the companion of all his movements, and the partner of all his journeys—stretched out lifeless on a rug upon the floor, in one of the garrets. She had been dead, to all appearance, about two days.

Thus died the servant; and thus would have died, but for a providential discovery of him by Colonel Timms, old Mr. Elwes, her master! His mother, Mrs. Meggot, who possessed one hundred thousand pounds, starved herself to death; and her son, who certainly was then worth half a million, nearly died in his own house for absolute want.

Mr. Elwes, however, was not a hard landlord, and his tenants lived easily under him: but if they wanted any repairs, they were always at liberty to do them for themselves; for what may be styled the comforts of a house were unknown to him. What he allowed not himself it could scarcely be expected he would give to others.

He had resided about thirteen years in Suffolk, when the contest for Berkshire presented itself on the dissolution of parliament; and when, to preserve the peace of that county, he was nominated by Lord Craven. To this Mr. Elwes consented; but on the special agreement, that he was to be brought in for nothing. All he did was dining at the ordinary at Abingdon; and he got into parliament for the moderate sum of eighteen-pence!

Mr. Elwes was at this time nearly sixty years old, but was in possession of all his activity. Preparatory to his appearance on the boards of St. Stephen's Chapel, he used to attend constantly, during the races and other public meetings, all the great towns where his voters resided; and at the different assemblies he would dance with agility amongst the youngest to the last.

Mr. Elwes was chosen for Berkshire in three successive parliaments: and he sat as a member of the House of Commons above twelve years. It is to his honour, that, in every part of his conduct, and in every vote he gave, he proved himself to be an independent country gentleman.

The honour of parliament made no alteration in the dress of Mr. Elwes: on the contrary, it seemed, at this time, to have attained additional meanness, and nearly to have reached that happy climax of poverty, which has, more than once, drawn on him the compassion of those who passed him in the street. For the Speaker's dinners, he had indeed one suit; with which the Speaker, in the course of the session, became very familiar. The minister, likewise, was well acquainted with it: and at any dinner of opposition, still was his apparel the same. The wits of the minority used to say, "that they had full as much reason as the minister to be satisfied with Mr. Elwes—as he had the same habit with every body!" At this period of his life, Mr. Elwes wore a wig. Much about that time, when his parliamentary life ceased, that wig was worn out: so then (being older and wiser as to expense) he wore his own hair; which, like his expenses, was very small.

He retired voluntarily from a parliamentary life, and even took no leave of his constituents by an advertisement. But, though Mr. Elwes was now no longer a member of the House of Commons, yet, not with the venal herd of expectant placemen and pensioners, whose eyes too often view the House of Commons as another Royal Exchange, did Mr. Elwes retire into private life. No; he had fairly and honourably, attentively and long, done his duty there, and he had so done it without "fee or reward." In all his parliamentary life, he never asked or received a single favour; and he never gave a vote, but he could solemnly have laid his hand upon his breast, and said, "So help me God! I believe I am doing what is for the best!"

Thus, duly honoured, shall the memory of a good man go to his grave: for, while it may be the painful duty of the biographer to present to the public the pitiable follies which may deform a character, but which must be given to render perfect the resemblance on those beauties which arise from the bad parts of the picture, who shall say, it is not a duty to expiate?

The model which Mr. Elwes left to future members may, perhaps, be looked on rather as a work to wonder at than to follow, even under the most virtuous of administrations. Mr. Elwes came into Parliament without expense, and he performed his duty as a member would have done in the pure days of our constitution. What he had not bought, he never attempted to sell; and he went forward in that straight and direct path, which can alone satisfy a reflecting and good mind. In one word, Mr. Elwes, as a public man, voted and acted in the House of Commons, as a man would do who felt there were people to live after him, who wished to deliver unmortgaged to his children the public estate of government; and who felt, that if he suffered himself to become a pensioner on it, he thus far embarrassed his posterity, and injured their inheritance.

When his son was in the Guards, he was frequently in the habit of dining at the officers' table there. The politeness of his manner rendered him generally agreeable, and in time he became acquainted with every officer in the corps. Amongst the rest, was a gentleman of the name of Tempest, whose good humour was almost proverbial. A vacancy happening in a majority, it fell to this gentleman to purchase; but as money is not always to be got upon landed property immediately, it was imagined that some officer would have been obliged to purchase over his head. Old Mr. Elwes hearing of the circumstance, sent him the money the next morning, without asking any security. He had seen Captain Tempest, and liked his manners; and he never once afterwards talked to him about the payment of it. But on the death of Captain Tempest, which happened shortly after, the money was replaced.

This was an act of liberality in Mr. Elwes which ought to atone for many of his failings. But behold the inequalities which so strongly mark this human being! Mr. Spurling, of Dynes-Hall, a very active and intelligent magistrate for the county of Essex, was once requested by Mr. Elwes to accompany him to Newmarket. It was a day in one of the spring meetings which was remarkably filled with races; and they were out from six in the morning till eight o'clock in the evening before they again set out for home. Mr. Elwes, in the usual way, would eat nothing; but Mr. Spurling was somewhat wiser, and went down to Newmarket. When they began their journey home, the evening was grown very dark and cold, and Mr. Spurling rode on somewhat quicker; but on going through the turnpike by the Devil's Ditch, he heard Mr. Elwes calling to him with great eagerness. On returning before he had paid, Mr. Elwes said, "Here! here! follow me—this is the best road!" In an instant he saw Mr. Elwes, as well as the night would permit, climbing his horse up the precipice of the ditch. "Sir," said Mr. Spurling, "I can never get up there." "No danger at all!" replied old Elwes: "but if your horse be not safe, lead him!" At length, with great difficulty, and with one of the horses falling, they mounted the ditch, and then, with not less toil got down on the other side. When they were safely landed on the plain, Mr. Spurling thanked heaven for their escape. "Ay," said old Elwes, "you mean from the turnpike: very right; never pay a turnpike if you can avoid it!" In proceeding on their journey, they came to a very narrow road: on which Mr. Elwes, notwithstanding the cold, went as slow as possible. On Mr. Spurling wishing to quicken their pace, old Elwes observed, that he was letting his horse feed on some hay that was hanging to the sides of the hedge. "Besides," added he, "it is nice hay, and you have it for nothing!"

Thus, while endangering his neck to save the payment of a turnpike, and starving his horse for a halfpenny-worth of hay, was he risking the sum of twenty-five thousand pounds on some iron works across the Atlantic Ocean, and of which he knew nothing, either as to produce, prospect or situation.

In the advance of the season, his morning employment was to pick up any stray chips, bones, or other things, to carry to the fire, in his pocket; and he was one day surprised by a neighbouring gentleman in the act of pulling down, with some difficulty, a crow's nest, for this purpose. On the gentleman wondering why he gave himself this trouble.

"Oh, Sir," replied he, "it is really a shame that these creatures should do so. Do but see what waste they make!"

To save, as he thought, the expense of going to a butcher, he would have a whole sheep killed, and so eat mutton to the—end of the chapter. When he occasionally had his river drawn, though sometimes horse-loads of small fish were taken, not one would he suffer to be thrown in again, for he observed, "He should never see them more!" Game in the last state of putrefaction, and meat that walked about his plate, would he continue to eat, rather than have new things killed before the old provision was exhausted.

When any friends, who might occasionally be with him, were absent, he would carefully put out his own fire, and walk to the house of a neighbour; and thus make one fire serve both. His shoes he never would suffer to be cleaned, lest they should be worn out the sooner. But still, with all this self-denial—that penury of life to which the inhabitant of an alms-house is not doomed—still did he think he was profuse; and frequently said, "he must be a little more careful of his property." When he went to bed, he would put five or ten guineas into a bureau, and then, full of his money, after he had retired to rest, sometimes in the middle of the night, he would come down to see if it was safe. The irritation of his mind was unceasing. He thought every body extravagant; and when a person was talking to him one day of the great wealth of old Mr. Jennings, (who is supposed to be worth a million,) and that they had seen him that day in a new carriage, "Ay, ay," said old Elwes; "he will soon see the end of his money!"

Mr. Elwes now denied himself every thing, except the common necessaries of life; and, indeed, it might have admitted a doubt, whether or not, if his manors, his fish-ponds, and grounds in his own hands, had not furnished a subsistence, where he had not any thing actually to buy, he would not, rather than have bought any thing, have starved. He one day, during this period, dined upon the remaining part of a moor-hen, which had been brought out of the river by a rat! and, at another, ate an undigested part of a pike, which a larger one had swallowed, but had not finished, and which was taken in this state in a net! At the time this last circumstance happened, he discovered a strange kind of satisfaction; for he said to Capt. Topham, who happened to be present, "Ay! this is killing two birds with one stone!" Mr. Elwes, at this time, was perhaps worth nearly 800,000l. and at this period he had not made his will, of course was not saving from any sentiment of affection for any person.

As he had now vested the enormous savings of his property in the funds, he felt no diminution of it.

Mr. Elwes passed the spring of 1786 alone, at his solitary house at Stoke; and, had it not been for some little daily scheme of avarice, would have passed it without one consolatory moment. His temper began to give way apace; his thoughts unceasingly ran upon money! money! money!—and he saw no one but whom he imagined was deceiving and defrauding him.

As, in the day, he would not allow himself any fire, he went to bed as soon as day closed, to save candle; and had begun to deny himself even the pleasure of sleeping in sheets. In short, he had now nearly brought to a climax the moral of his whole life—the perfect vanity of wealth!

On removing from Stoke, he went to his farmhouse at Thaydon Hall; a scene of more ruin and desolation, if possible, than either of his houses in Suffolk or Berkshire. It stood alone, on the borders of Epping Forest; and an old man and woman, his tenants, were the only persons with whom he could hold any converse. Here he fell ill; and, as he would have no assistance, and had not even a servant, he lay, unattended, and almost forgotten, for nearly a fortnight—indulging, even in death, that avarice which malady could not subdue. It was at this period he began to think of making his will; feeling, perhaps, that his sons would not be entitled, by law, to any part of his property, should he die intestate: and, on coming to London, he made his last will and testament.

Mr. Elwes, shortly after executing his will, gave, by letter of attorney, the power of managing, receiving, and paying all his monies, into the hands of Mr. Ingraham, his lawyer, and his youngest son, John Elwes, Esq. who had been his chief agents for some time.