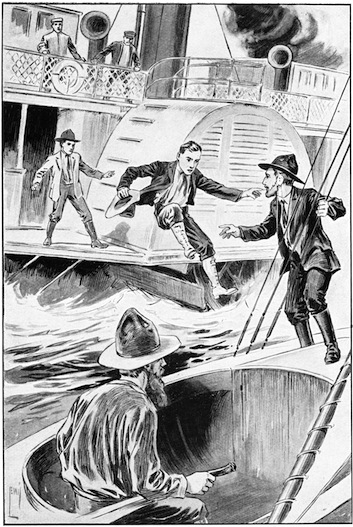

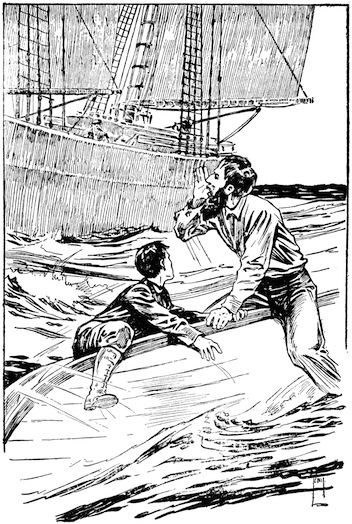

“HERE GOES!” JACK LEAPED FORWARD AND OUTWARD. HE LANDED RIGHT ON THE SLOOP’S DECK.—Page 43.

Turning over his morning mail, which Jared Fogg had just brought into the little Maine valley, Mr. Chisholm Dacre, the Bungalow Boys’ uncle, came across a letter that caused him to pucker up his lips and emit an astonished whistle through his crisp, gray beard. A perplexed look showed on his sun-burned face. Turning back to the first page, he began to read the closely written epistle over once more.

Evidently there was something in it that caused Mr. Dacre considerable astonishment. His reading of the missive was not quite completed, however, when the sudden sound of fresh, young voices caused him to glance upward.

Skimming across the deep little lake stretched in front of the bungalow came a green canoe. It contained two occupants, a pair of bright-faced lads, blue-eyed and wavy-haired. Their likeness left no doubt that they were brothers. In khaki trousers and canoeing caps, with the sleeves of their gray flannel shirts rolled up above the elbow exposing the tan of healthy muscular flesh, they were as likely a looking couple of lads as you would have run across in a muster-roll of the vigorous, clean-limbed youth of America. Regular out-of-door chaps, they. You couldn’t have helped taking an immediate liking to Tom Dacre and his young brother Jack if you had stood beside Mr. Dacre that bright morning in early summer and watched the lightly fashioned craft skimming across the water, its flashing paddles wielded by the aforesaid lusty young arms.

“Well, who would think to look at those two lads that they had but recently undergone such an experience as being marooned in the Tropics?” murmured Mr. Dacre to himself, as he watched his two nephews draw nearer.

There was a fond and proud light in his eyes as they dwelt on his sturdy young relatives. In his mind he ran over once more the stirring incidents in which they had all three participated in the Bahamas, and which were fully related in a previous volume of this series—“The Bungalow Boys Marooned in the Tropics.”

Our old readers will be able to recall, too, the bungalow, and the lake, and the country surrounding them. These environments formed the scene of the first volume of this series—“The Bungalow Boys.”

How different the little Maine lake looked now to its appearance the last time we saw it. Then it was swollen, angry, and discolored by the tumultuous waters of a cloudburst. At the water gate leading to the old lumber flume stood Tom Dacre and Sam Hartley, horror on their faces, while out on the lake, clinging to a capsized canoe, were two figures—those of a man and a boy. Suddenly the man raises his hand, and the next instant a cowardly blow has left him the sole occupant of the drifting canoe. Swept on by the current, the lad, his features distorted by fear, is being sucked into the angry waters of the flume, when a figure leaps into the water to the rescue, and——

But we are wandering from the present aspect of things. All that happened a good while ago, when the Bungalow Boys were having their troubles with the “Trubblers,” as old Jasper used to call them. At that time the little valley, not far from the north branch of the Penobscot River, was, as we know, tenanted by a desperate gang of rascals bent on ousting the lads from their strange legacy.

Everything is very different in the valley now. The old lumber camp up the creek—in the waters of which Jumbo, the big trout, used to lurk—has been painted and carpentered, and carpeted and furnished, till you wouldn’t know it for the same place. Mrs. Sambo Bijur, a worthy widow, is conducting a boarding house there to the huge disgust of the boys. Somehow, exciting—perilously so—as the old days often were, they have several times caught themselves wishing they were back again.

“It’s getting awfully tame,” were Tom’s words only the day before, when he had finished fishing the youngest of the Soopendyke family—of New York—out of the lake in which the said youngest member of the Soopendykes had been bent on drowning himself, or so it seemed. His distracted mother had rushed up and down on the shore the while.

“Like an old biddy that has discovered one of her chickens to be a duck,” chuckled Jack, in relating the story.

“And she kissed me,” chimed in Tom, with intense disgust, “and said I was a real nice boy, and if I’d come up to the boarding house some day she’d let me have a saucer of ice cream.”

Mr. Dacre had laughed heartily at this narration.

“Too old for ice cream since we defeated the wiles of Messrs. Walstein, Dampier and Co.—eh, Tom?” he exclaimed, leaning back in his big chair on the bungalow porch and laughing till the tears ran down his weather-beaten cheeks.

“It—it isn’t that, sir,” Jack had put in, “but a fellow—well, he objects to being slobbered over.”

“Better than being shot at, though, isn’t it, lads?” inquired Mr. Dacre, his gray eyes holding a merry twinkle.

“Um—well,” rejoined Tom, with a judicial air, “you know, Uncle, we’ve seen so much more exciting times in this old valley that it seems strange and unnatural to be overrun with Widow Bijur’s boarders. If it isn’t one of the little Soopendykes that’s in trouble, it’s Professor Dalhousie Dingle, with that inquiring child of his. I never saw such a child. Always asking questions. The other day the professor caught a bug and proceeded to stick a pin through it as he always does.

“‘Pa,’ asked Young Dingle, ‘does that hurt the bug?’

“‘I suppose so, my son,’ answered the professor.

“‘Then the bug doesn’t like it?’

“‘I guess not.’

“‘Will the bug die?’

“‘Undoubtedly, my boy.’

“‘Why do you kill bugs, papa?’

“‘For the purposes of science, my boy,’ answered the professor.

“‘Pa?’

“‘Yes, Douglas.’

“‘What is science?’

“‘It’s—it’s—ah, well, the art of explaining things, my boy.’

“‘Does it tell everything?’

“‘Yes, my boy.’

“‘Then what killed the Dead Sea, Pa?’”

Up to this point Mr. Dacre had listened gravely enough, but here he had to burst into a roar of laughter. When his merriment had subsided, he wished to know how the professor had dealt with such a “stumper.”

“What did he say to that, Tom?”

“Well,” laughed Tom, “I guess it was too much for him, for I heard him call Mrs. Bijur and ask her to give the lad a cookie. He said the boy’s brain was so large it was eating up his mind.”

This conversation is related so that the reader may form some idea of how the valley has changed from the last time we participated in the Bungalow Boys’ adventures therein. Mrs. Bijur had other boarders, but Mrs. Soopendyke, with her numerous progeny, and Professor Dingle and his inquiring son, were the most striking types. But while we have been relating something of the Bungalow Boys’ neighbors, they have run their canoe up to the wharf, made fast the painter, and, with paddles over their shoulders—for fear of predatory Soopendykes—made their way up to the porch.

“Out early to-day, Tom,” was Mr. Dacre’s greeting.

“Yes, we thought we’d see if we couldn’t succeed in getting a bass or two before the sun got too hot,” rejoined Tom.

“And you did?”

For answer Tom held up a string of silvery beauties.

“Not bad for two hours’ work,” laughed Jack, leaning his rod against the porch.

“No, indeed, and more especially as Jasper has just informed me that we are almost out of meat. I was thinking of taking a stroll up to Mrs. Bijur’s after a while, to see if I could borrow some. Do you boys want to go?”

Tom threw up his hands and burst into a laugh in which Jack joined.

“Might as well,” they chuckled. “At all events, there’s always something amusing going on up there. By the way, the bugologist” (Tom’s name for the dignified Professor Dingle) “is off on a new tack now.”

“Is that so?” inquired Mr. Dacre interestedly, “and what is that, pray?”

“Why he’s got some wonderful notion about a new explosive. He’s been experimenting with it for some days now.”

“A new explosive!” echoed Mr. Dacre, in an amazed tone; “well, what does he expect to do with that?”

“Sell it to the government, I guess,” chuckled Tom. “I’ll bet, though, it won’t be as effective as that electric juice we turned into the handrail of the dear old Omoo off Don Lopez’s island.”

“I think it would have to be pretty powerful to equal the effects of that, indeed,” laughed Mr. Dacre, rising and thrusting the letter which had interested him so much into a side pocket of his loose linen jacket. He reached for his hat.

“Well, let’s be starting before it gets really warm. By the way, boys, as we go along I’ve something to talk to you about. But first I want to ask you a question. I want you to answer it honestly. Aren’t you getting a bit tired of your bungalow?”

Tom and Jack exchanged glances. As we know, the bungalow and the estate surrounding it, was their “legacy” from their uncle, and not for worlds would they have admitted that they were getting a little tired of the pleasant monotony of their lives there. But being ingenuous lads they had not been able to conceal it—as has been hinted, in fact.

Tom and Jack exchanged glances. As we know, the bungalow and the estate surrounding it, was their “legacy” from their uncle, and not for worlds would they have admitted that they were getting a little tired of the pleasant monotony of their lives there. But being ingenuous lads they had not been able to conceal it—as has been hinted, in fact.

“Come,” said Mr. Dacre, a quizzical smile playing about the corners of his firm, yet kind, mouth. “Speak out; haven’t you exchanged views about the monotony of perfect plain sailing, or something of that sort?”

“Why, uncle, you must be a wizard!” exclaimed Tom. “Have you overheard us?”

Then both lads burst into a laugh, seeing how they had betrayed themselves.

“There, there,” chuckled Mr. Dacre, “you’d never do for diplomats—too honest,” he murmured, half to himself; “but, as Jasper would say—being as how you have given yourselves away, I have something to propose to you.”

“Hurray!” shouted Jack, capering about, “a trip? I’ll bet the hole out of a doughnut it’s a trip!”

“And you would win that bet,” cried Mr. Dacre, drawing out the letter from his pocket. “In the mail to-day there came a letter from a man from whom I have not heard for some time—a good many years, in fact.”

A cloud passed over Mr. Dacre’s face. They could see that for a moment he was back in the old painful past. But it passed as rapidly as a shadow on the surface of the rippling lake.

“My friend has a ranch in Washington State,” he went on, while the boys, with parted lips and sparkling eyes, fairly drank in his words. “It appears that he read in the papers about our adventures in the tropics. This letter is the result. He informs me that if I am anxious to make an investment with a part of the treasure of the lost galleon, that no better opportunity offers than the timber and fruit country of Washington. He says that he imagines that I must be anxious for rest anyhow, and, to make a long story short, he extends to me and to my two celebrated nephews”—the boys blushed—“a hearty invitation to visit him, renew old friendship, and take a look at the country. What do you say, boys—shall we go?”

Tom drew a long breath.

“Say, ever since I read that book on the Great Northwest of our country I’ve longed to get out there. Jack and I have talked it over many a time.”

Here Jack nodded vigorously.

“Will we go, uncle? Well,” Tom paused as he cast about for a fitting phrase, “well,” he burst out, “if we don’t, your Bungalow Boys will be Grumble-oh! boys.”

“Then I will write him this afternoon that we will come,” said Mr. Dacre soberly, though it was easy to see that he was almost as pleased as the lads at their decision. As for the boys, they joined in a wild half-war-dance, half-waltz that didn’t end till Jack was almost waltzed into the lake—not that in his frame of mind he would have cared.

At this stage of the proceedings an inky-black countenance, crowned with a tightly curling crop of grayish wool, projected from a rear door of the bungalow. It was Jasper—former servant of Dr. Parsons, but now attached to the Bungalow Boys’ uncle.

“Fo’ de lan’s sake!” he cried, throwing up his hands in consternation. “Dem boys done be actin’ up lak dey was two crazy pertatur bugs. Misto Dacon” (Dacre was beyond Jasper), “Mr. Dacon, sah, does I git dat meat o’ does we dine on flap jacks an’ bacum?”

“You get the meat,” laughed Mr. Dacre, regarding with intense amusement the tragic mien of his colored servitor. “Come, boys, give Jasper your fish—just to ease his mind—and insure the safety of Mrs. Bijur’s chickens—and then let’s hurry on our errand. There’s a lot to do before we start for The Great Northwest.”

“The great northwest!” echoed Tom, picking up the now despised string of bass. “If there are any two finer words in the geographies, I’ve never heard them.”

All the way to Mrs. Bijur’s—along the well-remembered trail, with its alder clumps fringing the crystal-clear Sawmill Creek and the big pool where of yore lurked Jumbo, and into which Tom had taken a header on one memorable occasion—there was naturally only one topic of conversation, the coming trip, of course. By the time they reached the former lumber camp, and the place which had more recently been the headquarters of the Trulliber gang, the boys had crossed and recrossed the continent at least half a dozen times, and the geography and animal and vegetable history of the State of Washington been thoroughly discussed. The trim buildings, now painted white, with red roofs and green shutters and doors, presented a violent contrast to the ramshackle collection of structures in which the Trullibers had squatted.

The barn in which Tom lay a prisoner, while in the next room he had heard Dan Dark and the others plotting, was now painted a vivid red, and a neat tin roof glittered above its contents of spicy-smelling hay and well-fed, sleek cows and horses. Josiah Bijur had left his widow a snug little fortune and, with true Maine thrift, she had spent it to the best advantage. Already she had more applications for boarders than her place would hold. If she could have persuaded the boys she would have liked to rent their bungalow for the overflow. But the fancy rent she offered had no allurement for them. Their share of the treasure of the galleon had made them two very independent lads.

Hamish Boggs, Mrs. Bijur’s hired man, was clambering off a load of hay as the party from the bungalow came in sight. He had just hauled it in from the mountain meadow, not far, by the way, from the foot of the cliff where Tom took that memorable slide after his imprisonment in the cave, which came near proving his grave.

Going to the rear of the wagon, which was halted on the steep grade in front of the house, he placed two big stones under each of the rear wheels.

“Don’t want the wagon to go rolling down the hill, eh, Hamish?” said Mr. Dacre, as they came up.

“No, sir,” responded Hamish emphatically; “there’s a deep pool in the creek at the bottom of this grade and if ther old wagin ever started a-runnin’ daown it—wall, by chowder, she’d take er bath whether she needed one er not.”

So saying, he proceeded to unhitch the horses and lead them toward the barn.

“Why don’t you drag the load in under the mow?” asked Tom, not quite seeing the object of leaving the load stalled in front of the house.

“Wall, yer see,” drawled Hamish, “thet mow’s got quite a sight of grass inter it naow. By chowder, ef I tried ter put this load in on top, it might raise the roof ofen it, so I’m gon’ ter shift it back a bit.”

At this juncture Mrs. Bijur appeared—a thin, sharp-featured woman in a blue calico dress, with a sunbonnet to match.

“Wall, land o’ goodness, ef it ain’t Mister Dacre,” she cried. “Wall, dear suz, what brings you here? Hamish, yer better ’tend to thet sick caow afore you put in yer hay. Do it right arter you’ve got them horses put up.”

“And leave ther hay out thar, mum?” asked Hamish.

“Yes, of course. Nobody ain’t goin’ ter steal it, be they? Go on with yer. Mr. Dacre, come in. Hev a glass of buttermilk. Dear suz! if I ain’t run off my mortal leags, an’—oh, you air a sniffin’, too, be yer?”

She broke off her torrent of talk as she noticed Mr. Dacre sniffing with a critical nose. The atmosphere was, in fact, impregnated with a very queer odor.

“Guess some senile egg must have gone off and died round here,” said Tom, with a snicker to Jack.

“It’s that perfusser,” explained Mrs. Bijur. “I tole him that he’d hev ter stop experimentin’ ef it was goin’ ter smell us out o’ house an’ home this er way. Awful, ain’t it?”

“Well, it is rather strong,” admitted Mr. Dacre, as they took seats in the stuffy parlor, with its wax fruit under their glass covers, the imitation lace tidies on the backs of the stiff chairs, and the noisy, eight-day clock ticking away like a trip-hammer.

“What ever is the professor doing?” he inquired.

“’Sperimentin’,” sniffed Mrs. Bijur, smoothing out her apron.

“Must be experimenting with cold-storage eggs,” put in Tom.

“No,” rejoined Mrs. Bijur gravely, “it’s some sort of a ’splosive. I tell you, Mister Dacre, I’m terrible skeered. Reely I be. S’pose thet stuff ’ud go off? We’d all be blown up in our beds.”

“Unless you happened to be awake, ma’am,” answered Mr. Dacre.

“Ah, but he don’t ’speriment only at night,” was the rejoinder. “He’s off all day huntin’ bugs and nasty crawly things. It’s only at night he works at it, an’ I tell yer, I’ve got my hands full with them Soopendyke children. They’re allers a-tryin’ to git inter the perfusser’s laboratory—he calls it. If they ever did, dear knows what ’ud happen. The perfusser says that ef any one who didn’t understand that stuff was to meddle with it, it might blow up.”

“Good gracious!” exclaimed Mr. Dacre, with mock anxiety. “I hope the young Soopendykes are all safely accounted for.”

“I dunno. There’s no telling whar them young varmints will git ter,” was the reply. “They’re every place all ter oncet, and no place long tergither. Tother day I cotched one tryin’ ter git inter the laboratory. Crawlin’ over ther roof, he was, and goin’ ter drop inter ther window by a water pipe. Seems ter me thet they are just achin’ ter blow themselves up, and——Good land! Look at ’em now!”

The widow rushed to the window and shook her fist at four young Soopendykes who were disporting themselves in the hay wagon, leaping about among the fragrant stuff, and pitching it at one another, to the great detriment of Hamish’s neat load.

“Where is Mrs. Soopendyke?” inquired Mr. Dacre, as the widow finished shooing—or imagined she had done so—the invading youngsters from their play.

“Lyin’ down with a headache,” was the rejoinder. “Poor woman, them young ’uns be a handful, an’ no mistake.”

As Mrs. Bijur seemed inclined to enlarge on her troubles, Mr. Dacre lost no time, as soon as he could do so, in explaining his errand.

“Meat!” exclaimed Mrs. Bijur. “Good land, go daown cellar and help yourself. The boys can give me some of those nice fresh fish in trade some time. No, you won’t pay me, Mr. Dacre. Dear suz, ain’t we neighbors, and—— Land o’ Gosh-en!”

The last words came from the good lady in a perfect shriek. And well they might, for her speech had been interrupted by a heavy sound that shook the house to its foundations.

Bo-o-o-o-m!

“Good heavens!” cried Mr. Dacre, rushing out of the door, followed by the boys. “An explosion!”

“That thar dratted explosive soup of the perfusser’s has gone off at last!” shrieked the widow, following them in most undignified haste. As they emerged from the house, a shrill cry rang out:

“Ma-ma! Oh, ma-ma!”

“Just as I thought, it’s one of them Soopendykes!” cried Mrs. Bijur. “Good land! Look at that!”

She indicated the extension of the house, a low one-storied structure, jutting out from the rear. It was in this that the professor had set up his “laboratory,” as Mrs. Bijur called it. Her exclamation was justified.

A large hole, some three feet six inches in diameter, gaped in the once orderly tin roof. Through the aperture thus disclosed, yellow smoke was pouring in a malodorous cloud, while, on a refuse pile not far away, the eldest Soopendyke, Van Peyster, aged twelve, was picking himself up with an injured expression. His Fauntleroy suit, with clean lace cuffs and collar—fresh that morning—was in blackened shreds. His long yellow curls were singed to a dismal resemblance to their former ideal of mother’s beauty. Master Van Peyster Soopendyke was indeed a melancholy object, but he seemed unhurt, as he advanced toward them with howls of:

“I didn’t mean ter! I didn’t mean ter!”

“You young catamount!” shrilled the widow. “What in the name of time hev yer bin a-doin’ of?”

“Boo-hoo! I jes’ was foolin’ with that stuff of the professor’s an’ it went off!” howled the Soopendyke youngster, while the boys likewise exploded into shouts of laughter. In the meantime, Mr. Dacre had burst in the locked door and discovered that, beyond wrecking the laboratory, the explosion had not done much harm. He had just finished his examination when Mrs. Soopendyke, her hair falling in disorder and her ample form hastily dressed, came rushing out.

“My boy! My boy!” she cried, in agonized tones. “Van Peyster, my darling, where are you hurt; are you——”

The good lady had proceeded as far as this when her eyes fell on the smoke-blackened, ragged object, which had been blown through the roof by the force of the explosion. Luckily, his having landed on the rubbish pile had saved his limbs. But Master Soopendyke, as has been said, was an alarming object for a fond parent’s eye to light upon.

“Oh, Van Peyster!” screamed his mother. “Great heavens——”

“Aw, keep still, maw. I ain’t hurt,” announced the dutiful son.

“Oh, thank heaven for that! Come to my arms, my darling! My joy! Come——”

Mrs. Soopendyke was proceeding to hurl herself upon her offspring, who was about to elude her, when from the front of the house came an appalling shriek.

“It’s Courtney!” screamed out the unhappy lady. “Oh, merciful heavens! What is happening now?”

Louder and louder came the shrieks and cries, and the party, all of them considerably alarmed, rushed around to the front of the house to perceive what this new uproar might mean. They beheld a sight that made Mrs. Soopendyke begin to cry out in real earnest.

One of her family had, in a playful mood, removed the stones which held Hamish’s hay wagon stationary on the steep grade. As a natural result, it began to slide backward down the hill. But what had thrilled the good lady with horror, and the others with not a little alarm, was the sight of three other young Soopendykes, including the baby, on the top of the load. It was from them and from Master Courtney Soopendyke, who perceived too late the mischief he had done by removing the stones, that the ear-piercing yells proceeded.

“Oh, save them! Oh, save my bee-yoot-i-ful children!” screamed Mrs. Soopendyke, wringing her hands, as the ponderous wagon, with its screaming load of children, began to glide off more and more rapidly.

“Great Scott!” shouted Mr. Dacre. “That deep hole in the creek is at the bottom of the hill!”

“Oh! Oh! Oh!” shrilled Mrs. Soopendyke, and fainted just in time to fall into the arms of Hamish, who came running round from the barn.

“Help! Fire! Murder! Send for the fire department!” screamed Mrs. Bijur, with some confusion of ideas.

In the midst of this pandemonium Tom and Jack and their uncle alone kept cool heads. Before the wagon had proceeded very far, the two Bungalow Boys were off after it, covering the ground in big leaps. But fast as they went, the wagon rumbled down the grade—which grew steeper as it neared the creek—just a little faster seemingly—than they did. Its tongue stuck straight out in front like the bowsprit of a vessel. It was for this point that both lads were aiming. Tom had a plan in his mind to avert the catastrophe that seemed almost inevitable.

Mustering every ounce of strength in his body, he made a spurt and succeeded in grasping the projecting tongue. In a second Jack was at his side.

“Swing her!” gasped out Tom. “It’s their only chance.”

But to swing over the tongue of a moving wagon when it is moving away from you is a pretty hard task. For a few seconds it looked as if, instead of succeeding in carrying out Tom’s suddenly-thought-of plan, both Bungalow Boys were going to be carried off by the wagon.

But a bit of rough ground gave them a foothold, and, exerting every ounce of power, the lads both shoved on the springy pole for all they were worth. Slowly it swung over, and the wagon altered its course.

“Steer her for that clump of bushes. They’ll stop her!” puffed out Tom.

“All right,” panted Jack, but as he gasped out the words there came an ominous sound:

Crack!

“Wow! The pole’s cracking!” yelled Jack.

The next instant the tough wood, which, strong as it seemed, was sun-dried and old, snapped off short in their hands under the unusual strain.

A cry of alarm broke out from the watchers at the top of the hill as this occurred. It looked as if nothing could now save the wagon from a dive into the creek.

But even as the shout resounded and the boys gave exclamations of disgust at their failure, the wagon drove into the mass of brush at almost the exact point for which they had been aiming. At just that instant a big rock had caught and diverted one of the hind wheels, and this, combined with the swing in the right direction already given the vehicle, saved the day.

With a resounding crashing and crackling, and redoubled yells from the terrified young Soopendykes on the top of the load, the wagon, as it plunged into the brush, hesitated, wavered, and—came to a standstill. But as the wheels ceased to revolve, Hamish’s carefully piled load gave a quiver, and, carrying the terrified youngsters with it, slid in a mighty pile off the wagon-bed.

Fortunately, the children were on top of the load, and they extricated themselves without difficulty. Hardly had they emerged, however, before a violent convulsion was observed in the toppled off heap, and presently a hand was seen to emerge and wave helplessly and imploringly.

“Who on earth can that be?” gasped the boys, glancing round to make sure all the group was there. Yes, they were all present and accounted for,—Mrs. Soopendyke, sobbing hysterically in the midst of her reunited family, the lads’ uncle, Mrs. Bijur, Hamish, and several other boarders who had been aroused by the explosion, and had set off on a run down the hill as the wagon plunged into the brush.

Before they could hasten forward to the rescue of whoever was struggling in the hay, a bony face, the nose crowned with a pair of immense horn spectacles, emerged. Presently it was joined by a youthful, pug-nosed countenance.

“Professor Dalhousie Dingle?” cried everybody, in astonishment. “And that dratted boy, Douglas Dingle!” echoed Mrs. Bijur.

“Yes, madam,” said the professor solemnly, emerging with what dignity he could, and then, taking his boy by the hand and helping him forth, “It is Professor Dingle. May I ask if this was intentional?”

“Why, dear land, perfusser, you know——”

“I only know, madam, that while my lad Douglas here and myself were searching for specimens in the thicket we suddenly found ourselves overwhelmed with an avalanche of dried grass—or, as it is commonly called—hay. Bah! I am almost suffocated!”

The professor carefully extricated a “fox tail” from his ear and then performed the same kind office for his son and heir.

“Pa-pa,” piped up the lad, “may I ask a question?”

“Yes, my lad,” beamed the professor amiably stepping down from the pile of hay, which Hamish was regarding ruefully.

“Well,” spoke up Douglas, “if we had not gotten out from under that hay, would we have been suffocated?”

“Undoubtedly, my boy—undoubtedly,” was the rejoinder. “Gross carelessness, too.”

He scowled at the assembled group.

“Would it have hurt, pa-pa?”

“Surely, my boy. Suffocation, so science tells us, is a most painful form of death.”

“Worse than measles, pa-pa?”

“Yes, my child, and——”

“Perfusser,” interrupted Mrs. Bijur, with firmness, “I want to know what you intend to do about my roof?”

It was the professor’s turn to look astonished.

“What roof, madam?” he asked, still brushing hay-seed from his long-tailed black coat.

“Ther roof of my extension whar you hed thet thar lab-or-at-ory—whar you was making them messes that was liable to blow up.”

“Well, madam?”

“Wall, sir—they done it!”

“They done—did what, madam?”

“Blowed up!” responded Mrs. Bijur, with deadly calm.

“Good heavens, madam—impossible!”

“Not with them Soopendykes around!” was the confident response. “It’s my belief they’d a turned the Garden of Eden inter a pantominium. They——”

But the professor rushed off dragging Douglas by the hand, his long coat tails flapping in the air as he sped up the road as fast as his lanky legs would carry him.

“The greatest invention of the age has gone up in smoke!” he yelled, as he flew along.

Laughing heartily over the comical outcome of events that might have proved tragic, Mr. Dacre and the boys rendered what aid they could in replacing the hay load, and then started back for the bungalow. The last they saw of the professor he was crawling about on his hands and knees, scooping up fragments of the explosive with a tin teaspoon in one hand, and waving Mrs. Bijur indignantly to one side with the other. They little imagined, as they shook with amusement at the ludicrous picture, under what circumstances they were to meet the professor again, and what a singular part his explosive was destined to play in the not very far distant future.

“Guess this will be your getting-off place.”

One of the deck hands of the smoke-grimed, shabbily painted old side-wheeler, plying between Victoria, B. C., and Seattle, paused opposite Mr. Dacre and the Bungalow Boys. They stood on the lee side of the upper deck regarding the expanse of tumbling water between them and the rocky, mountainous coast beyond. The sky was blue and clean-swept. A crisp wind, salt with the breath of the Pacific, swept along Puget Sound from the open sea.

The surging waters of the Sound reflected, but, with a deeper hue, the blue of the sky. The mountainous hills beyond were blue, too,—a purplish-blue, with the dark, inky shadows of big pines and spruces. Here and there great patches of gray rock, gaunt and bare as a wolf’s back, cropped out. Behind all the snow-clad Olympians towered whitely.

Off to port of where the steamer was now crawling slowly along—a pall of black, soft coal smoke flung behind her—was a long point, rocky and pine-clad like the mountains behind it. On the end of it was a white, melancholy day-beacon. It looked like a skeleton against its dark background.

“There’s Dead Man’s Point,” added the friendly deck hand.

“And Jefferson Station is in beyond it?” asked Mr. Dacre.

“That’s right. Must look lonesome to you Easterners.”

“It certainly does,” agreed Mr. Dacre. “Boys,” he went on, looking anxiously landward, “I don’t see a sign of a shore boat yet.”

At this point of the conversation the captain pulled his whistle cord, and the ugly, old side-wheeler’s siren emitted a sonorous blast.

Poking his head out of the pilot house window, he shouted down at Mr. Dacre and the boys:

“I’m a goin’ ter lay off here for ten minutes. If no shore boat shows up by that time, on we go to Seattle.”

“Very well,” responded Mr. Dacre, hiding his vexation as best he could. “We must—but,” he broke off abruptly, as from round the point there suddenly danced a small sloop. “I guess that’s the boat now, captain!” he hailed up.

“Hope so, anyhow,” ejaculated Tom, while the captain merely gave a grunt. He was annoyed at having to slow up his steamer. As the engine room bell jingled, the clumsy old side wheels beat the water less rapidly. Presently the old tub lay rolling in the trough of the sea almost motionless. On came the boat under a press of canvas. She heeled over smartly. In her stern was an upright figure; the lower part of his face was covered with a big, brown beard. As he saw the party, he waved a blue-shirted arm.

“That’s Colton Chillingworth!” exclaimed Mr. Dacre. “I haven’t seen him for ten years, but I’d know that big outline of a man any place.”

The deck hands were now all ready with the travelers’ steamer trunks. The boys had their suit cases, gun bags, and fishing rods in their hands.

“How on earth are we ever going to board that boat?” wondered Jack, rather apprehensively, as the tiny craft came dancing along like a light-footed terpsichorean going through the mazes of a quadrille.

“Jump!” was Mr. Dacre’s response. “These steamers don’t make landings. I’m glad Chillingworth was in time, or we might have been carried on to Seattle.”

And now the boat was cleverly run in alongside. She came up under the lee of the heavily rolling steamer, her sails flapping with a loud report as the wind died out of them.

“Hul-lo, Dacre!” came up a hearty hail from the big figure in the stern. “Hullo there, boys! Ready to come aboard?”

“Aye, aye, Colton!” hailed back Mr. Dacre. “We’ll be with you in a minute.”

“If we don’t tumble overboard first,” muttered Jack to himself.

“Better take the lower deck, sir,” suggested one of the deck hands.

Accordingly, our party traversed the faded splendors of the little steamer’s saloon and emerged presently by her paddle box. Between the side of the vessel and the big curved box was a triangular platform.

“Stand out on this, sir, and you and the boys jump from it,” suggested the deck hand.

“A whole lot easier to say than to do,” was Tom’s mental comment. He said nothing aloud, however.

In the meantime their baggage had been lowered by a sling. A second person, who had just emerged from the cabin of the little boat, was active in stowing it in the cockpit. This personage was a Chinaman. He wore no queue, however, but still clung to the loose blue blouse and trousers of his country.

“Allee lightee. You come jumpee now,” he hailed up, when the baggage was stowed.

“Here goes, boys,” cried Mr. Dacre, with a laugh. He made a clean spring and landed on the edge of the deck of the plunging sloop. The Chinaman caught him on one side, while the lad’s uncle braced himself on the other by grabbing a stay. Another instant and the boys could see him and Mr. Chillingworth warmly shaking hands.

“Go ahead, Jack,” urged Tom. But for once Jack did not seem anxious to take the lead. He hesitated and looked about him. But he only saw the grinning faces of the deck hands.

“Come on!” shouted his uncle, extending his arms. “It’s easy. We’ll catch you.”

“Hum! If I had my diving suit here, I’d feel better,” muttered the lad. “But—here goes!”

Like a boy making a final determined plunge into a cold tub on a winter morning, Jack leaped forward and outward. He landed right on the sloop’s deck, falling in a sprawling heap. But the active Chinaman had him by the arms and he was on his feet in a jiffy. Tom followed an instant later.

Hardly had his foot touched the deck before the steamer gave a farewell blast and forged onward, leaving them alone in the tossing, tumbling wilderness of wind-driven waters. Somehow the waves looked a lot bigger from the cockpit of the sloop than they had from the deck of the steamer.

They watched the big craft as with a dip and a splash of its wet plates, it gained speed again, several passengers gazing from its upper decks at the adventurous party in the little sloop. Introductions were speedily gone through by Mr. Dacre. The boys made up their minds that they were going to like Colton Chillingworth very much. He was a big-framed six-footer, tanned with wind and sun, and under his flannel shirt they could see the great muscles play as he moved about.

“This is Song Fu, my factotum,” said Mr. Chillingworth, nodding toward the Chinaman, whose yellow face expanded into a broad grin as his master turned toward him.

“How do you do, Song Fu?” poetically asked Tom, not knowing just what else to say.

“Me welly nicely, t’ank you,” was the glib response.

By this time Mr. Chillingworth had set the helm and put the little sloop about. She fairly flew through the water, throwing back clouds of spray over the top of her tiny cabin. It was exhilarating, though, and the boys enjoyed every minute of it.

But as they sped along, it soon became apparent that the wind was freshening. The sea, too, was getting up. Great green waves towered about the boat as if they would overwhelm her. The combers raced along astern, and every minute it seemed as if one of them must come climbing over, but none did.

“Got to take another reef,” said Mr. Chillingworth presently. “Can either of you boys handle a boat?”

“Well, what a question,” exclaimed Mr. Dacre. “If you had seen them managing the Omoo in that gale off Hatteras, you’d have thought they could handle a boat, and well, too.”

“That being the case, Tom here can take the tiller, while I help Fu take in sail.”

Mr. Chillingworth resigned the tiller to Tom, who promptly brought the sloop up into the wind, allowing her sails to shiver. This permitted Mr. Chillingworth and the Chinaman to get at the reef points and tie them down. This done, the owner of the boat came back to the cockpit and she was put on her course once more.

“You handled her like a veteran,” said Mr. Chillingworth to Tom, who looked pleased at such praise coming from a man whom he had already made up his mind was a very capable citizen.

The rancher went on to explain something of his circumstances. He and his wife had come out there some years before. They were doing their best to wrest a living from the rough country. But it was a struggle. Mr. Chillingworth admitted that, although he had big hopes of the country ultimately becoming a new Eldorado.

“Just at present, though, it’s a little rough,” he admitted.

“Oh, we don’t mind roughing it,” responded Tom. “We’re used to that.”

“So I should imagine from the newspaper accounts I read of your prowess,” said Mr. Chillingworth dryly.

“Oh, they wrote a lot of stuff that didn’t happen at all,” put in Jack.

“Not to mention the pictures,” laughed Mr. Dacre.

“Well,” said Mr. Chillingworth, “if there were some enterprising reporter out here now, he would find plenty to write about.”

“How’s that?” inquired Mr. Dacre.

“Why, you may have heard of Chinese smugglers—that is to say, men who run Chinamen into the country without the formality of their obtaining papers?”

Mr. Dacre nodded.

“Something of the sort,” he said.

“Well, they have been pretty active here recently. Some of the ranchers have had trouble with them.”

“But surely they have notified the authorities?” exclaimed Tom.

“That’s just it,” said Mr. Chillingworth. “They are all afraid of the rascals. Scared of having their buildings burned down, or their horses hamstrung, or something unpleasant like that.”

“Well, if you are the same old Colton Chillingworth,” smiled Mr. Dacre, “I’m sure you do not belong in that category.”

A look came over Colton Chillingworth’s face that the boys had not noticed on that rugged countenance before. Under his brown beard, his lips set firmly, and his eyes narrowed. Colton Chillingworth, with that expression on his features, looked like a bad man to have trouble with. But to Mr. Dacre’s astonishment, and the no less surprise of the boys, his reply was somewhat hesitant.

“Well, you see, Dacre,” he said uncertainly, “a married man has others than himself to look out for. By the way, my wife doesn’t know anything about the troubles. Please don’t mention them to her, will you?”

“Certainly not,” was the rejoinder. “But——”

A sudden cry from the Chinaman cut his words short. The Mongolian raised a hand, and with a long, yellow finger pointed off to the west. The boys, following with their eyes the direction in which he pointed, at first could descry nothing, but presently, as the sloop rose on the top of a wave, they could make out, in the blue distance, the sudden flash of a white sail on the Sound.

“It’s the schooner, Fu?” asked Mr. Chillingworth eagerly.

The Celestial nodded. No change of expression had come over his mask-like features, but the boys vaguely felt that behind the impenetrable face lay a troubled mind.

Mr. Dacre looked his questions.

“What is there about the schooner particularly interesting?” he asked, at length.

“Oh, nothing much,” said Mr. Chillingworth, with what seemed rather a forced laugh. “Except that she is Bully Banjo’s craft.”

“Bully Banjo?” echoed Mr. Dacre, in a puzzled tone.

“Yes. Or Simon Lake’s, to give the rascal his real name. Lake is the man who is at the present time the real ruler of the ranchers in this district,” said Mr. Chillingworth bitterly. “Dacre,” he went on, “I’m afraid that I have invited you into a troubled region. I’ll give you my word, though, that when I wrote to you things were quiet enough.”

“My dear fellow,” was the rejoinder, “don’t apologize. I myself relish a little excitement, and here are two boys who live on it.”

“If that is the case,” replied the other, with a wan smile, “they are on the verge of plenty—or I’m very much mistaken.”

Soon after the sloop beat up into the shelter of the point, the wind having by this time increased, to what appeared to the boys, to be a mild hurricane. The sky, too, was overcast, and big black clouds were rolling in, shrouding the dark trees and heights ashore in gloom, and turning the snow-covered peaks beyond to a dull gray. It began to feel chilly, too.

“We’ll have to run up here and take the trail to the ranch,” said Mr. Chillingworth, after a while.

“I thought it was quite close in here,” rejoined Mr. Dacre.

“Oh, no. It’s a biggish beat along the coast,” replied his friend, “but it’s blowing too hard now to risk beating up the shore. We’ll run in under shelter of the point there, and then we can cut across through the woods and reach the place by trail.”

“But not to-night,” observed Mr. Dacre, pulling out his watch. “It’s after four now.”

“We’ll start out to-morrow morning if the wind hasn’t gone down,” said Mr. Chillingworth. “Fu can bring the sloop round when the wind moderates.”

It was not long after this that, as they ran quite close to the shore, where the rocks sloped steeply down, that Mr. Chillingworth ordered the Chinaman to take in sail. Aided by the boys, this was soon accomplished. To the accompaniment of rattling blocks, the sails were lowered, and presently the anchor splashed overboard. The sloop then lay motionless, about thirty or forty feet off shore.

Supper was cooked and eaten in the tiny cabin, which boasted a stove. As the air had grown quite chilly, too, and the boys were wet with spray, they were all glad to warm and dry themselves in the heat. After the meal the men drew out their pipes, while Fu produced a queer-looking arrangement for smoking. Its bowl was not much bigger than a thimble and made of stone. The stem was a long, slender bit of bamboo.

“Opium?” whispered Tom to Mr. Chillingworth, as the Mongolian stepped out of the cabin to give a look to the anchor.

The rancher laughed.

“No, indeed. I would have no such stuff around me. I broke Fu of smoking opium long ago. But he still clings to his old pipe.”

The after-supper talk was mainly about ranching and prospects in Washington. Mr. Dacre appeared to be much interested in the timber aspects of the country.

“There are millions of feet of good timber around here,” said Mr. Chillingworth. “It can be bought cheap, too, right now. You see, there is no railroad here yet, and no means of getting the timber out. It wouldn’t pay to cut it. But in a few years——”

He spread his hands. Evidently he deemed the prospects to be very good. Mr. Dacre nodded thoughtfully. Then the two men produced old envelopes and stubs of pencils and fell to figuring. This didn’t interest the boys much.

“Let’s slip outside and see what’s doing,” suggested Tom to Jack, after a while.

The younger lad agreed willingly. In a few minutes they were on deck. Overhead the wind roared and shouted, but on deck, sheltered as it was by the wooded, rocky point, things were comparatively quiet. Ashore they could hear the wind humming and booming in the trees like the notes of a mighty pipe organ. Even where they stood the balsam-scented breath of the forest was borne to them. They inhaled it delightedly.

“Not unlike Maine,” decided Tom.

All at once, as they stood there enjoying the fresh air after the stuffy cabin, Jack gripped Tom’s arm tightly.

“Hark!” he whispered.

Above the hurly-burly of the wind and the clamor of the waters as they dashed against the shore, they could hear a voice upraised in what was, apparently, a tone of command. Then came a loud sound of metal rattling. The sound was unmistakable to any one who had any knowledge of seafaring.

“Some vessel’s dropped her anchor not far from us,” decided Tom.

“Right,” assented Jack, “and strain your eyes a bit and you’ll see that she’s a schooner.”

Peering into the darkness it was possible to make out, after a good deal of difficulty, the black outlines of two masts. They were barely perceptible, though, and if the boys had not heard the rattle of the anchor chain and thus known in which direction to look, they would not have made them out at all.

“Jack!” exclaimed Tom, as a sudden thought shot into his head, “that must be Bully Banjo’s schooner.”

“You think so?”

“Well, what other vessel would put in here? It’s true that we had to seek shelter, but a wind that would sink us wouldn’t bother a large vessel. This is a lonely place, and just the sort of harbor Simon Lake would seek.”

“But we are in here; surely he wouldn’t risk the chance of actual discovery?”

“But he doesn’t know we’re here. The sloop is painted black. It is unlikely that he sighted us beating in for shore this afternoon. We’d better tell the others.”

“That’s right,” agreed Jack, starting for the cabin door. But Tom laid a hand on his shoulder.

“Don’t open it,” he said. “They’d see the light.”

“Then how are we to tell them of what we have seen?”

“Tap on the cabin roof and then speak down the ventilator.”

“Good idea. We’ll do it.”

“Mr. Chillingworth,” whispered Tom, after his signal had been answered, and he had hastily warned the occupants of the cabin not to open the door, “there’s a big schooner come to anchor not far away. We thought you ought to know about it.”

The boys could hear an amazed exclamation come up the ventilator. The next instant the light was extinguished, and presently the cabin door was swiftly opened. Mr. Dacre, his friend, and Fu were soon standing by the boys on the deck, hearing their story. It was perfectly safe to talk in natural tones as the wind was blowing on shore, and it was doubtful if even had they shouted they could have been heard on the schooner.

On board the larger vessel, however, the case was different. The group on the yawl could now hear voices coming down the wind. Lights, too, began to bob about on the schooner’s decks. Evidently something was going forward.

“Our best plan is to listen and see what we can find out,” advised Mr. Chillingworth, after they had discussed the strange arrival of the schooner.

“Looks as if they had come in here for some definite purpose,” said Mr. Dacre.

“That’s right,” was the rejoinder, “and I can guess just what that purpose is. Lake’s schooner has not been round here for some time till the other day. I believe that she has just arrived from the island in the Pacific, where they say he picks up his Chinamen. They may be going to land a bunch to-night.”

“You think so?” asked Jack, his pulses beginning to beat.

“I don’t see what else they would have sought out this lonely spot for,” was the rejoinder. “Listen!”

A squeaking sound “cheep-cheep” came over the water from the schooner.

“They are getting ready to lower a boat,” cried Mr. Chillingworth. “I was right.”

“And they are going to turn a lot of Chinamen loose ashore?” gasped Tom.

“Well, they won’t turn them loose exactly,” rejoined Mr. Chillingworth, and if it had not been dark Tom would have noticed that he smiled. “Their method, so rumor has it, is to borrow some rancher’s team and wagon and drive the yellow men through the woods to a mining district to the north. Things are run pretty laxly there, and nobody asks questions so long as they get Chinese labor cheap.”

“But doesn’t every Chinaman who comes into the country have to have a certificate bearing his picture?” asked Tom. “Seems to me I’ve read that.”

“Perfectly true,” replied Mr. Chillingworth, “but it’s easy enough for men of Lake’s stripe to fake such certificates. After the men have worked at the mines a while, they leave there and mingle with their countrymen in the Chinatowns of any large Eastern or Western city. If any one asks questions, all they have to do is to show their certificates. As for the pictures, I guess one does for all. Every Chinaman looks pretty much alike.”

“That’s a fact,” agreed Mr. Dacre, “but all this must take a lot of money to engineer. Who provides the funds?”

“Ah, that’s a mystery. I’ve heard that a big syndicate is in it. It must pay tremendously. You see, the Chinamen will pay all the way from two hundred to a thousand dollars to be landed safely in the country. Lake, if he manages things right, can bring in as many as two hundred at a time. You see for yourself what that means—sixty thousand dollars at one fell swoop.”

“Phew!” whistled Mr. Dacre, “no wonder desperate men will take desperate chances for such rewards. But you mentioned an island from which Lake brings the men. Where is it?”

“That’s pure speculation,” rejoined Mr. Chillingworth. “The only reason for presuming that there is an island on which the Chinamen live till they can be run into the country is this: It is not probable that a schooner like Lake’s can run over to China. Her trips, in fact, rarely occupy more than a month or so. But as for the location of the island, I am as much in the dark as you are.”

“Hark!” cried Tom suddenly. “Isn’t that the sound of oars?”

“It is,” agreed Mr. Dacre, after listening a minute. “They’ve got a lantern in the boat, too. See, it is coming this way.”

Sure enough, they could now perceive a light coming over the water, evidently borne in the boat the splash of whose oars they had heard. On through the darkness came the moving light. Presently it stopped not far from the sloop. The occupants of the latter could see now that three men were in the little craft. One, a tall man with a sailor cap on his head, another, a short, thickset fellow, and the third man was undoubtedly a Chinaman. It was too dark to make out features, but the lantern light shone sufficiently on the occupants of the small boat for their general outlines to be apparent.

The Oriental member of the party wore loose flowing garb. On his head was a skull-cap surmounted by a button.

But after their first surprise our friends on the sloop turned their attention from the craft and its occupants to the freight with which the little boat was loaded. So far as they could make out, these were big canvas sacks about five feet or more in length. There seemed to be more than one of them. The boat rode very low in the water, apparently; whatever the freight was, it was fairly heavy.

As the oarsmen ceased their motions and the boat came to a stop, the men in her arose and the two white men laid hold of one of the bundles at either end. They lifted it, and before the party on the sloop had any idea of what they were going to do, they had swung their burden two or three times and then cast it out into the water. It sank with a sullen splash. As it did so, the Chinaman raised his hands above his head and seemed to be uttering some prayer, or invoking some deity.

But a sudden noise in their midst caused the party on the sloop to turn sharply.

For some inexplicable reason the mask-faced Fu was groveling on the deck. His lips were murmuring oriental words in a rapid sing-song. In his voice, and, above all, in his attitude, there was every indication of abject terror.

Mr. Chillingworth stepped over to him and shook him not too roughly by the shoulder.

“Fu, Fu, what’s the trouble?” he exclaimed.

“Oh, Missa Chillingworth, me welly much flaid,” stammered the Mongolian, still evidently in the bonds of fear.

“But why, Fu—why? Is it because of what they are doing in that boat?”

“Yes, Missa Chillingworth. Dey be deadee men in dose sacks. Dey dlop them in the sea for gib dem belial.”

“They are burying them you mean?”

“Yes, missa. De Chinaman he allee same plest. He say players for dem. Plenty bad for Chinaman to see.”

“And for any one else, too, I should think,” commented Mr. Chillingworth. “It is evident enough now what those fellows are up to. Some Chinamen have died during the voyage and they are burying them in this cove. Packed together as they are, it’s surprising more of them are not killed.”

A slight shudder passed through the boys as they heard. There was something uncanny, something awe-inspiring about this night burial in the lonely cove by the light of the lantern.

Presently the last of the grewsome freight of the small boat was consigned to the waves, and she was pulled back to the schooner.

“We must set a good watch to-night,” said Mr. Chillingworth. “It is important to know if those fellows land anybody.”

The others agreed. Accordingly, it fell to Tom and Jack to watch the first part of the night, while the remaining hours were carefully watched through by Mr. Dacre and Mr. Chillingworth. Fu was too badly scared by the sight of the burial of his countrymen to be of much use. It appeared, according to his belief, that if a Chinaman gazed on another’s burial without announcing himself, he would be haunted forever by the ghosts of the buried ones.

The watch was kept faithfully, and carefully, but nothing occurred apparently to mar the silence of the dark hours. Yet, when the first streaks of gray began to show above the pine-clad shoulders of the coast hills, the dim dawn showed them that no schooner was there.

During breakfast the mysterious vanishing of the schooner was discussed, with what eager interest may be imagined. They could not understand why the noise of her incoming anchor chain had not been observed. Nor yet, why the creak of the blocks and the rattle of the rigging as her sails were hoisted, had not been heard. It was Tom who solved the first part of the puzzle.

Coming on deck after breakfast, the lad found the sun sparkling down on the dancing waters, and flashing brightly on the white-capped wave tops. Looking in the direction in which he was sure the schooner had lain the night before, he perceived a dark object bobbing about on the water. It looked like a barrel. And so, on investigation, it proved to be. When the sloop was sculled alongside by her big sixteen-foot oars, they found that an anchor chain had been made fast to the keg. The schooner had silently slipped her moorings in the night. The fact that the keg was fast to her anchor chain would make it an easy matter, however, for her to pick it up again at her leisure.

“Does that mean that they saw us, do you think?” asked Mr. Dacre.

Mr. Chillingworth shook his head.

“If they had seen us,” he said rather grimly, “I hardly think we should have all been here this morning. At any rate, that is the reputation that Bully Banjo has. He has an unpleasant way of disposing of any one he thinks may have spied on him.”

“I don’t see how in the twentieth century such a rascal can be permitted at large,” said Mr. Dacre angrily. “He ought to be captured and his just deserts dealt out to him.”

“Well,” said Mr. Chillingworth, “the trouble is just this. Most of the ranchers hereabouts are poorish men. The country has not been fully cleared, and their ranches, so far, yield them small profits. This Bully Banjo pays well for the teams he borrows. Generally, when the horses are returned, there’s a twenty-dollar note with them.”

“But the man is engaged in an illegal business,” said Tom.

Again Mr. Chillingworth smiled.

“It’s mighty hard to get the average man to see that smuggling anything, from cigars to Chinamen, is illegal,” he said. “On the contrary, most men appear to have an idea it’s smart to beat Uncle Sam. But,” his voice changed and took on a stern note, “I, for one, am not going to stand for this rascal’s domineering any longer. Some weeks ago I wrote to Washington and informed the Secret Service bureau there exactly what was going on. They promised to investigate, but since then I’ve heard nothing more. You can readily see that it would be folly for me to make a stand alone against this man. Why, he’s capable of swooping down on my ranch and burning it to the ground.”

“That’s true,” mused Mr. Dacre thoughtfully. “I quite see where this Bully Banjo’s power comes in. But——”

He broke off short. Some instinct made him turn at the moment and he saw that Fu, the Chinaman, had been eagerly drinking in every word that had been said. As he met Mr. Dacre’s eyes, the Mongolian muttered something and dived into the cabin, ostensibly very busy washing dishes.

“You needn’t worry about Fu,” laughed Mr. Chillingworth. “He’s faithful as the day is long.”

“I don’t know,” said Mr. Dacre seriously. “Somehow I never like to trust a Chinaman. They remind me of cats in their mysterious way of moving about you. If that fellow wanted to, he could cause you a lot of trouble now.”

“Ah, but he won’t,” laughed Mr. Chillingworth, “and, in any event, what could he do?”

“Why,” said Mr. Dacre slowly, “he could inform Bully Banjo, for instance, that you have written to Washington and that the Secret Service may start an investigation.”

“Jove! That’s so!” exclaimed the rancher. “But,” he laughed lightly, “there’s no fear of that. Fu is as honest as the day is long. Besides, he is in my debt. I, and some friends of mine, rescued him from a gang of white roughs, who had falsely accused him of a theft, and who were going to string him up.”

“Just the same,” said Mr. Dacre, “I have found it is a good rule to trust a Chinaman just as far as you can see him, and in most cases not so far as that. But, to return to Bully Banjo’s reason for buoying his anchor, it evidently means that he intends to come back here.”

“Yes, and something else,” said Mr. Chillingworth.

“What is that?”

“Why, that he just slipped in here to bury the dead in calm water. That office performed, he has evidently made off to some other point of the coast to land his Chinamen.”

This was admitted to be a plausible explanation.

While it was calm enough in the shelter of the point the loud roaring in the pine tops, and the distant whitecaps showed that outside it was still rough. Too rough for the sloop to attempt the passage, Mr. Chillingworth declared. That being the case, it was decided to leave the sloop in the charge of Fu, and to set out overland for the ranch. When it grew calmer Fu would sail the sloop around to the waters off the ranch.

In accordance with this decision, the sloop was sculled by Fu close in under a ledge of rocks where there was deep water. The boys made the jump ashore with ease. It was then Mr. Dacre’s turn. Although it has been said that it was calm in the cove, there was still enough sea running to make the sloop quite lively, so jumping from her called for some agility. Mr. Dacre essayed the leap just as a particularly big wave came sliding under the little vessel. The consequent lurch upset his calculations and instead of landing cleanly on the rock he lost his balance, and would have fallen back into the water had not Tom seized him. In another instant Jack, too, had his uncle’s arm.

In a minute they had him up on the rock, but instead of standing upright, Mr. Dacre, his face drawn with pain, and dotted with beads of sweat, sank to the ground. It was apparent that he was suffering intense pain.

“Good gracious, Dacre, are you hurt?” asked Mr. Chillingworth, while the alarmed boys also poured out questions.

“It’s—it’s nothing,” said Mr. Dacre, with a brave attempt at a careless smile. “An old fracture of my leg. I think——”

His head fell back and his lips went white. Had Tom not caught him he would have fallen prone. Mr. Chillingworth was on the rocks in a bound as the lad’s uncle lost his senses under the keen pain.

“Here, I’m a surgeon in a rough way,” he said. “One has to be everything out in this rough country. Let me have a look at that leg.”

With a slash of his penknife, he had Mr. Dacre’s trouser leg ripped open in an instant. He ran an experienced hand over the limb. “Hum,” he said, his face growing serious, “an old fracture—broken again by that fall. Fu, get me the medicine chest out of the cabin.”

The Chinaman, his face as stolid as ever, obeyed. Mr. Chillingworth took from the mahogany box some bandages, and by the time he had done this Mr. Dacre’s eyes were opened again.

“What’s the verdict, Mr. Chillingworth?” he asked pluckily.

“Well, old man,” was the rejoinder, “I don’t know yet if it’s a fracture or just a sprain. I hope it’s the latter, and then we’ll have you on your feet in a few days. The first thing to be done is to get you back on board the sloop. I’ll stay with you while these young men and Fu push on to the ranch and get some remedies of which I will give them a list.”

Mr. Dacre made a wry face.

“Is it as bad as that? I can’t move?” he asked.

“Well, just you try it,” said Mr. Chillingworth,—but one effort was enough for the injured man.

“Well, Chillingworth, you’ve got a lame duck on your hands,” he said.

“Nonsense, we’ll soon have you all right again. Here, boys, you get hold of your uncle’s head. Fu, place a mattress and some blankets on deck there. I’ll get hold of his feet. Don’t move till I say so.”

It was not an easy task to get Mr. Dacre back on board the sloop, but it was accomplished at last without accident. He was then placed on the mattress on deck and lay there stiller than the boys had ever seen his active form.

Mr. Chillingworth dived into the cabin. When he reappeared it was with a penciled list, which he handed to Tom.

“There,” he said, “now that’s done. Just hand that to my wife and she’ll give you the necessary things. By the way, don’t breathe a word to her about Bully Banjo.”

The boys promised not to mention the occurrences of the night. Soon after, Fu was ready. He carried a small flour sack, with what provisions could be spared over his shoulders. It was arranged that they were to get horses at the ranch and ride back to the sloop, using all the speed they could. After bidding good-by to their injured uncle, and Mr. Chillingworth, the little party set out along the trail. Fu’s blue bloused and loose trousered form slipped noiselessly along in front. Behind him toiled the boys. It did not seem more than a few seconds after they had left the sloop that they were plunged into a thick forest. On every side—like the columns of a vast cathedral—shot up the reddish, smooth trunks of the great pines. Far above their dark tops could be caught occasional glimpses of the blue sky. The brush and vegetation were dense almost as in the tropics. There is a great deal of rain in Washington, and the luxuriant growth is the result. Creepers, flowering shrubs, and big ferns were everywhere, walling in the trail with an impenetrable maze of foliage.

Above them they could hear the wind blowing through the dark pines, roaring a deep, musical bass. But down on the trail it was stiflingly hot. The heavy, sweet odor of the pines, rank and resinous was everywhere. They plodded along in silence, always with that blue, silent figure gliding along just ahead. It was curious that as Tom kept his eyes riveted on the noiseless figure that Mr. Dacre’s words should have recurred to him with startling force:

“Trust a Chinaman only as far as you can see him, and in most cases not so far as that.”

For an hour or more they kept steadily on. The Chinaman in the lead had nothing to say except to turn his head with an occasional caution to avoid some obstacle in the path. As for the boys, after the first mile, they, too, relapsed into silence. It was rough going, and, although they had been through some pretty hard ground at times, this trail through the Washington forest was more rugged than anything they had hitherto encountered.

“How far did Mr. Chillingworth say it was to the ranch?” asked Jack, after a while.

“About fifteen miles this way,” rejoined Tom. “You see, this trail goes fairly parallel with the coast, but it doesn’t follow all its in and outs. In that way we cut off a good deal of distance.”

“Say that Chinaman is a talkative young party, isn’t he?” laughed Jack, after another interval of silence.

“I guess his sort don’t do much talking as a rule,” rejoined Tom, “but it seems to me that his moodiness dates from the time he saw that funeral last night out there in the cove. According to my way of thinking, he has something on his conscience.”

“Well, if he honestly believes that the ghosts of all those fellows he saw buried are going to haunt him, no wonder he has something on his mind,” chuckled Jack. “I’m going to try to get something out of him, anyhow.”

Suddenly he hailed the Chinaman.

“Hey Fu, what make trail so crooked?”

“Injun makee him longee time ago,” responded the Mongolian. “Him come lock he no movee, him go lound. Allee same Chinee,” he added, “too muchee tlouble getee him out of way. Heap more easty walk lound him.”

“There’s something in that, too, when you come to think of it,” mused Tom. “Anyway, it goes to show the difference between Indians and Chinese and white men.”

“I guess that’s the reason neither the Chinese nor the Indians have ever ‘arrived,’” commented Jack. “It takes a lot longer to go round than to keep bang on a straight course.”

“That’s right,” assented the other lad. “I really believe you are becoming a philosopher, Jack.”

“Like Professor Dingle,” was the laughing answer.

Once more the conversation languished and they plodded steadily on. But it was warmer now—almost unbearably so, down in the windless floor of the forest. From the pine needles a thick pollen-like dust rose that filled mouth and nostrils with an irritating dust. The boys’ mouths grew parched and dry. They would have given a good deal for a drink of clear, sparkling water.

“Say, Fu,” hailed Jack presently, “we find some water pretty soon?”

“Pletty soon,” grunted the Chinaman, who, despite his fragile frame, seemed tireless and entirely devoid of hunger or thirst. However, shortly after noon, when they had reached a spot where a great rock impended above the trail, while below their feet the chasm sloped down to unknown depths, the blue-bloused figure stopped short in its tireless walk and waited for the boys to come up.

“Pletty good spling here,” he said, diving off into the brush with the canteen. “Me catchum watel.”

“All right, catch all you want of it,” cried Jack, flinging himself exhaustedly on a bed of fern at the side of the rough path. The Chinaman was soon back with the water. He lit a fire and skillfully made tea. With a tin cup each of the refreshing stuff, the boys soon felt better. From the bag they lunched on salt beef, crackers and cheese, and dried apricots. As might be expected, by mid-afternoon their thirst was once more raging.

“How far is it to the ranch?” inquired Tom, for the dozenth time, as they pluckily plodded along. Not for worlds would they have let that silent, fatigueless Chinaman have perceived that they were almost worn out.

“Plitty soon we cross canyon. Ranchee him not far then,” was the response.

“Nothing for it but to stick,” muttered Tom grittily. “But, oh, what wouldn’t I give for a drink of water. I’m as dry—as dry—as those dried apricots.”

“Pooh!” retorted Jack. “They were fairly dripping with moisture compared to the way I feel.”

All at once, a few rods farther, a distant rumbling sound down in the canyon, and off to the right, was borne to their ears. Both lads listened a minute and then gave a joyous whoop.

It was water,—a considerable river, apparently. Anyhow, it was real water, no doubt of that. As they listened, they could hear it gurgling and splashing as it dashed along.

“Hi there, Fu!” hailed Jack, adopting the Chinaman’s own lingo. “We go catchum water way down in canyon.”

But for some reason or other the Chinaman did not seem anxious for the lads to do this. He shook his pig-tailed head.

“You waitee,” he advised. “By um bye find plentee welly nicee watel.”

“Well, this water right here is plentee nicee for me,” rejoined Jack. “So here goes.”

Followed by Tom, he plunged off the trail down the steep declivity, clinging to brush and small saplings as he went. Grumbling to himself in a low tone, the Chinaman followed. It was clear that he thought the proceedings foolish in the extreme.

The descent was longer as well as steeper than they had imagined it would be, but every minute the roaring voice of the concealed river or stream grew louder.

All at once, they emerged from a clump of brush, not unlike our eastern alders—almost upon the bank of a fine river. It was a lot bigger than they had expected, and was rushing along with the turbulent velocity characteristic of mountain water. Here and there were black, deep eddies dotted with circling flecks of white, yeasty foam. But the main stream dashed between its steep, rocky banks like a racehorse, flinging spray and spindrift high in the air when it encountered a check. The water was greenish—almost a glassy tint. The boys learned later that this was because it was snow water and came from the high Olympians.

Flinging themselves flat by the side of one of the eddies, they drank greedily.

“Reminds me of what that kid said when he showed his mother a fine spring he had discovered, and the good lady wished to know how to drink out of it,” chuckled Jack, as they paused for breath.

“What was that?” inquired Tom, wiping his wet mouth with the back of a sun-burned hand.

“‘Why, maw,’ said the kid, ‘you just lie on your tummy and drink uphill.’”

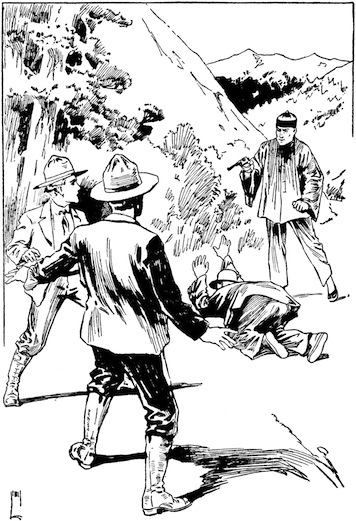

“That does pretty nearly describe it for a fact,” agreed Tom. As he spoke, both boys straightened up from their recumbent position. Hardly had they done so and were scrambling to their feet when there came a sudden, sharp crackling of the brush higher up the stream. Before they had time to recover from their surprise, or to even hazard a guess at what the noise might mean, the brush parted and a figure stepped forth.

Both boys uttered a cry of amazement as their eyes fell on the newcomer. He was a Chinaman—tall, grave, and with a face like a parchment mask.

As Fu saw him, he fell on his face and began muttering incoherent noises like those he had given vent to when he cast himself on the deck of the sloop the night before.

The newcomer was the first to speak. He did so in a deep, sonorous voice very unlike the squeaky, jerky mode of utterance of Fu.

“White boys come with me,” he said, in a tone that indicated that he did not expect to be disobeyed.

“Well, of all the nerve,” breathed the astonished Jack to himself. But before he could speak a word aloud, Tom spoke up:

“We are on our way to a ranch,” he said, “and must reach there by sundown. We’ll have to hurry on.”

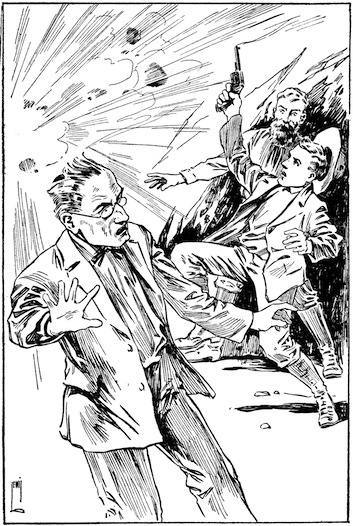

No change of expression crossed that yellow mask, but the tall Chinaman’s hand slipped into his blouse sleeve, which was loose and flowing. It was done so rapidly that before the boys had fairly noticed the movement a revolver was pointing at them; the sunlight that struck down through the dark-topped pines glinted ominously on its blued barrel.

The Chinaman, in the same level, monotonous voice, repeated his command:

“White boys come with me.”

“Why, confound it all——” burst out Tom, but somehow the sight of that tall, motionless figure, with the expressionless face staring unblinkingly at them, and the revolver pointed menacingly in their direction, made him break off short.

“Oh, all right, then,” he said. “I guess we’ll have to. You’ve got the drop on us. But if there were any authorities near, you’d hear of this.”

Before the boys had fairly noticed the movement a revolver was pointing at them.

The ghost of a smile flitted across the tall Chinaman’s hitherto fixed visage. But he made no comment. Instead, he turned to the recumbent Fu, and spoke sharply to him in Chinese. As he was addressed, Fu rose with alacrity and bowed low three times. He seemed to be terrified out of his wits, and fairly whimpered as the stern gaze of his majestic countryman fell upon him.

“White boys walk in front,” ordered the tall Chinaman, motioning toward the clump of brush from which he had so suddenly materialized.

They now saw that there was a narrow trail leading through it. And so, down this narrow path the odd procession started—the two lads in front, and behind the oddly assorted pair of Mongolians.

It would be wrong to say the boys were frightened. To be frightened, a certain amount of previous apprehension is necessary. This thing had happened so suddenly and was so utterly inexplicable that they were fairly stunned. Their sensations, as they walked among the thick-growing bushes, were not unlike those of persons in a dream. Somehow, at every turn of the path, they expected to wake up.

And wake up they did presently. The wakening came as, after traversing the narrow trail for a half mile, they suddenly emerged on a camp under a clump of big pines. At one side of the open space in which three tents were pitched, the stream boiled and roared. On the other, the precipice shot up. But the camp was screened from view from above by the brush which grew out of cracks in the cliff-face. Beyond the river another wooded precipice arose. This was a frowning rampart of bare, scarred rock. All this uneasily impressed the boys. They could perceive that they were in a sort of natural man-trap.

This sense of uneasiness increased as, their first rapid glance over, they observed details. In front of one of the tents was seated a tall, lanky figure, dressed in rough mackinack trousers, calf skin boots, a blue shirt open to expose a sinewy throat, and, to crown all, a battered sombrero. This man was seated on an old soap box and strumming on a banjo as they entered the glade.

At the sound of footsteps he looked up and showed a dark, high-cheek-boned face with a thin, hawk-like nose, and a pair of piercing, steely-gray eyes. The man was clean shaven and his lips were thin, close-pressed, and cruel. This countenance was framed in a mass of lank, black hair, so long that it hung down to the shoulders of his faded shirt.

The figure, its occupation, and the previous incidents of the adventure all combined to form an intuition which suddenly flashed with convincing force into Tom’s mind:

This place was the hidden camp of the Chinese runners, and the figure on the soap box was Bully Banjo—the feared and admired Simon Lake himself.

“Right smart work, by Chowder!” he exclaimed, setting aside his banjo and rising on his long, thin limbs as the boys and Fu were marched into his presence. His voice was as thin, sharp, and penetrating as his eyes, and was unmistakably that of a downeaster. In fact, Simon Lake was a native of Nantucket. From whaling he had drifted to sealing. From sealing to seal poaching in the Aleutian, and from that it was but a step to his present employment. A shudder that they could not suppress ran through the boys as they realized that they were in the presence of this notorious sea wolf.

But Simon Lake’s voice, setting aside its rasping natural inflection, was mild enough as he addressed them.

“Wa-al, boys, yer see thet I’ve got a smart long arm.”

“I’d like to know by what right you’ve had us brought here in this fashion,” broke out Tom indignantly. “We’re not interfering with you. Why, then, can’t you leave us alone?”

“Jes’ cos I want er bit uv infermation frum yer,” rejoined Simon easily. He leaned down and picked up a bit of wood. Then, drawing a knife, he shaped it to a toothpick and thrust it in his mouth. During the pause the boys noticed that several rough-looking men had sauntered up from various positions about the camp. Among them was one short, stocky man, who might have been the thickset man of the boat the night before. This individual’s hat was shoved back—for it was warm and stuffy in this place—exposing a ruddy stubble of hair. A bristly mustache as coarse as wire sprouted from his upper lip. This man was Zeb Hunt, Bully Banjo’s mate when afloat and chief lieutenant ashore. In some ways he was a bigger ruffian than his superior.

“Ez I sed,” resumed Simon Lake, when he had shaped the pick to his satisfaction, “I want er bit uv infermation from yer. It ain’t often thet Simon Lake wants ter know suthin’ thet he kain’t find out right smart fer hisself. But this yar time it’s diff’ent. I’m a kalkerlatin’ on you byes helpin’ me out.”

A sudden gleam came into those cold, steely eyes. A flash of warning not to trifle with him, it seemed. But it died out as suddenly as it had come, and in his monotonous Yankee drawl, Simon went on:

“Ther hull in an’ outs uv it is—how fur hez Chillingwuth gone?”

“I don’t know what you mean,” exclaimed Tom, who had decided to act as spokesman, and silenced the impetuous Jack by a look.

“Oh, yes, yer do, boy. Daon’t try ter gilflicker me. I’m ez smart ez a steel trap, boy, and ez quick as sixty-’leven, so da-ont rile me up. I’m askin’ yer ag’in—how fur hez Chillingworth gone?”

“He’s anchored down in the cove,” said Tom, willfully misunderstanding him.

Again that angry gleam shone in Bully Banjo’s eyes. His thin lips tightened till they were a mere slit across his gaunt visage.