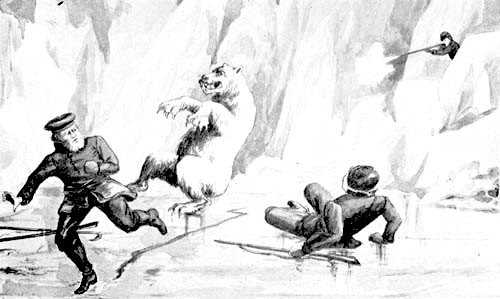

"NO USE, LADS! THE BOAT HAS BEEN SWEPT AWAY"

(See page 37)

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Among the Esquimaux, by Edward S. Ellis

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Among the Esquimaux

or Adventures under the Arctic Circle

Author: Edward S. Ellis

Release Date: March 23, 2014 [EBook #45192]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMONG THE ESQUIMAUX ***

Produced by Greg Bergquist and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

"NO USE, LADS! THE BOAT HAS BEEN SWEPT AWAY"

(See page 37)

BY

EDWARD S. ELLIS, A.M.

AUTHOR OF "The Campers Out," Etc., Etc.

PHILADELPHIA

THE PENN PUBLISHING COMPANY

1894

Copyright 1894 by The Penn Publishing Company

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I | Two Passengers on the "Nautilus" | 7 |

| II | A Colossal Somersault | 16 |

| III | An Alarming Situation | 27 |

| IV | Adrift | 38 |

| V | An Icy Couch | 46 |

| VI | Missing | 55 |

| VII | A Point of Light | 64 |

| VIII | Hope Deferred | 73 |

| IX | A Startling Occurrence | 82 |

| X | An Ugly Customer | 91 |

| XI | Lively Times | 99 |

| XII | Fred's Experience | 108 |

| XIII | The Fog | 117 |

| XIV | A Collision | 126 |

| XV | The Sound of a Voice | 135 |

| XVI | Land Ho! | 144 |

| XVII | Docak and His Home | 153 |

| XVIII | A New Expedition | 162 |

| XIX | A Wonderful Exhibition | 171 |

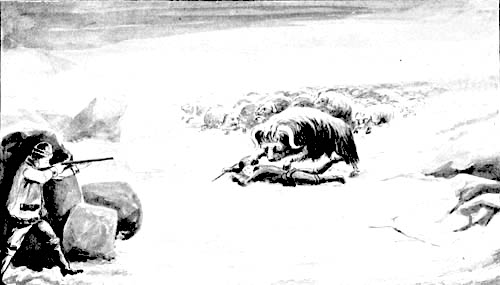

| XX | The Herd of Musk Oxen | 180 |

| XXI | Close Quarters | 189 |

| XXII | Fred's Turn | 198 |

| XXIII | In the Cavern | 207 |

| XXIV | Unwelcome Callers | 216 |

| XXV | The Coming Shadow | 225 |

| XXVI | Walled In | 234 |

| XXVII | "Come On!" | 243 |

| XXVIII | A Hopeless Task | 251 |

| XXIX | Ten Miles | 260 |

| XXX | The Last Pause | 269 |

| XXXI | Another Sound | 278 |

| XXXII | The Wild Men of Greenland | 287 |

| XXXIII | Conclusion | 301 |

AMONG THE ESQUIMAUX

The good ship "Nautilus" had completed the greater part of her voyage from London to her far-off destination, deep in the recesses of British America. This was York Factory, one of the chief posts of the Hudson Bay Company.

Among the numerous streams flowing into Hudson Bay, from the frozen regions of the north, is the Nelson River. Near the mouth of this and of the Hayes River was erected, many years ago, Fort York, or York Factory. The post is not a factory in the ordinary meaning of the word, being simply the headquarters of the factors or dealers in furs for that vast monopoly whose agents have scoured the dismal regions to the north of the Saskatchewan, in the land of Assiniboine, along the mighty Yukon and beyond the Arctic Circle, in quest of the fur-bearing animals, that are found only in their perfection in the coldest portions of the globe.

The buildings which form the fort are not attractive, but they are comfortable. They are not specially strong, for, though the structure has stood for a long time in a country which the aborigines make their home, and, though it is far removed from any human assistance, its wooden walls have never been pierced by a hostile bullet, and it is safe to say they never will be. Somehow or other, our brethren across the northern border have learned the art of getting along with the Indians without fighting them.

The voyageurs and trappers, returning from their journeys in canoes or on snow-shoes to the very heart of frozen America, first catch sight of the flag floating from the staff of York Factory, and they know that a warm welcome awaits them, because the peltries gathered amid the recesses of the frigid mountains and in the heart of the land of desolation are sure to find ready purchasers at the post, for the precious furs are eagerly sought for in the marts of the Old and of the New World.

It is a lonely life for the inhabitants of the fort, for it is only once a year that the ship of the company, after breasting the fierce storms and powerful currents of the Atlantic, sails up the great mouth of Baffin Bay, glides through Hudson Strait, and thence steals across the icy expanse of Hudson Bay to the little fort near the mouth of the Nelson.

You can understand how welcome the ship is, for it brings the only letters, papers, and news from home that can be received until another twelvemonth shall roll around. Such, as I have said, is the rule, though now and then what may be termed an extra ship makes that long, tempestuous voyage. Being unexpected, its coming is all the more joyful, for it is like the added week's holiday to the boy who has just made ready for the hard work and study of the school-room.

You know there has been considerable said and written about a railway to Hudson Bay, with the view of connection thence by ship to Europe. Impracticable as is the scheme, because of the ice which locks up navigation for months every year, it has had strong and ingenious advocates, and considerable money has been spent in the way of investigation. The plan has been abandoned, for the reasons I have named, and there is no likelihood that it will ever be attempted.

The "Nautilus" had what may be called a roving commission. It is easy to understand that so long as the ships of the Hudson Bay Company have specific duties to perform, and that the single vessel is simply ordered to take supplies to York Factory and bring back her cargo of peltries, little else can be expected from her. So the staunch "Nautilus" was fitted out, placed under the charge of the veteran navigator, Captain McAlpine, who had commanded more than one Arctic whaler, and sent on her westward voyage.

The ultimate destination of the "Nautilus" was York Factory, though she was to touch at several points, after calling at St. John, Newfoundland, one of which was the southern coast of Greenland, where are located the most famous cryolite mines in the world, belonging, like Greenland itself, to the Danish Government.

There is little to be told the reader about the "Nautilus" itself or the crew composing it, but it so happened that she had on board three parties, in whose experience and adventures I am sure you will come to feel an interest. These three were Jack Cosgrove, a bluff, hearty sailor, about forty years of age; Rob Carrol, seventeen, and Fred Warburton, one year younger.

Rob was a lusty, vigorous young man, honest, courageous, often to rashness, the picture of athletic strength and activity, and one whom you could not help liking at the first glance. His father was a director in the honorable Hudson Bay Company, possessed considerable wealth, and Rob was the eldest of three sons.

Fred Warburton, while displaying many of the mental characteristics of his friend, was quite different physically. He was of much slighter build, not nearly so strong, was more quiet, inclined to study, but as warmly devoted to the splendid Rob as the latter was to him.

Fred was an orphan, without brother or sister, and in such straitened circumstances that it had become necessary for him to find some means of earning his daily bread. The warm-hearted Rob stated the case to his father, and said that if he didn't make a good opening for his chum he himself would die of a broken heart right on the spot.

"Not so bad as that, Rob," replied the genial gentleman, who was proud of his big, manly son; "I have heard so much from you of young Mr. Warburton that I have kept an eye on him for a year past."

"I may have told you a good deal about him," continued Rob, earnestly, "but not half as much as he deserves."

"He must be a paragon, indeed, but, from what I can learn, my son, he has applied himself so hard to his studies while at school that he ought to have a vacation before settling down to real hard work; what do you think about it, Robert?"

"A good idea, provided I take it with him," added the son, slyly.

"I see you are growing quite pale and are losing your appetite," continued the parent, with a grave face, which caused the youth to laugh outright at the pleasant irony.

"Yes," said the big boy, with the same gravity; "I suffer a great loss of appetite three or four times every day; in fact, I feel as though I couldn't eat another mouthful."

"I have observed that phenomenon, my son, but it never seems to attack you until the table has been well cleared of everything on it. Ah, my boy!" he added, tenderly, laying his hand on his head; "I am thankful that you are blessed with such fine health. Be assured there is nothing in this world that can take its place. With a conscience void of offense toward God and man, and a body that knows no ache nor pain, you can laugh at the so-called miseries of life; they will roll from you like water from a duck's back."

"But, father, have you thought of any way of giving Fred a vacation before he goes to work? You know he is as poor as he can be, and can't afford to do nothing and pay his expenses."

"The plan I have in mind," replied the father, leaning back in his chair and twirling his eyeglasses, "is this: next week the 'Nautilus,' one of the company's ships, will leave London for York Factory, which is a station deep in the heart of British America. She will touch at St. John, Greenland, and several other points on her way, and may stop several weeks or months at York Factory, according to circumstances. If it will suit your young friend to go with her, I will have him registered as one of our clerks, which will entitle him to a salary from the day the 'Nautilus' leaves the dock. The sea voyage will do him good, and when he returns, at the end of a year or less, he can settle down to hard work in our office in London. Of course, if Fred goes, you will have to stay at home."

Rob turned in dismay to his parent, but he observed a twitching at the corners of his mouth, and a sparkle of the fine blue eyes, which showed he was only teasing him.

"Ah, father, I understand you!" exclaimed the big boy, springing forward, throwing an arm about his neck and kissing him. "You wouldn't think of separating us."

"I suppose not. There! get along with you, and tell your friend to make ready to sail next week, his business being to look after you while away from home."

And that is how Rob Carrol and Fred Warburton came to be fellow-passengers on the ship "Nautilus" on the voyage to the far North.

The voyage of the "Nautilus" was uneventful until she was far to the northward in Baffin Bay. It was long after leaving St. John that our friends saw their first iceberg. They should have seen them before, as Captain McAlpine explained, for, as you well know, those mountains of ice often cross the path of the Atlantic steamers, and more than once have endangered our great ocean greyhounds. No doubt numbers of them were drifting southward, gradually dissolving as they neared the equator, but it so happened that the "Nautilus" steered clear of them until many degrees to the north.

The captain, who was scanning the icy ocean with his glass, apprised the boys that the longed-for curiosity was in sight at last. As he spoke, he pointed with his hand to the north-west, but though they followed the direction with their eyes, they were disappointed.

"I see nothing," said Rob, "that looks like an iceberg."

"And how is it with you, Mr. Warburton?" asked the skipper, lowering his instrument, and turning toward the younger of the boys, who had approached, and now stood at his side.

"We can make out a small white cloud in the horizon, that's all," said Fred.

"It's the cloud I'm referring to, boys; now take a squint at that same thing through the glass."

Fred leveled the instrument and had hardly taken a glance, when he cried:

"Oh! it's an iceberg sure enough! Isn't it beautiful?"

While he was studying it, the captain added: "Turn the glass a little to the left."

"There's another!" added the delighted youth.

"I guess we've struck a school of 'em," remarked Rob, who was using his eyes as best he could; "I thought we'd bring up the average before reaching Greenland."

"It's a sight worth seeing," commented Fred, handing the glass to his friend, whose pleasure was fully as great as his own.

The instrument was passed back and forth, and, in the course of a half-hour, the vast masses of ice could be plainly discerned with the unaided eye.

"That proves they are coming toward us, or we are going toward them," said Rob.

"Both," replied Captain McAlpine; "we shall pass within a mile of the larger one."

"Suppose we run into it?"

The old sea-dog smiled grimly, as he replied:

"I tried it once, when whaling with the 'Mary Jane.' I don't mean to say I did it on purpose, but there was no moon that night, and when the iceberg, half as big as a whole town, loomed up in the darkness, we hadn't time to get out of its path. Well, I guess I've said enough," he remarked, abruptly.

"Why, you've broken off in the most interesting part of the story," said the deeply interested Fred.

"Well, that was the last of the 'Mary Jane.' The mate, Jack Cosgrove, and myself were all that escaped out of a crew of eleven. We managed to climb upon a small shelf of ice, just above the water, where we would have perished with cold had not an Esquimau fisherman, named Docak, seen us. We were nearer the mainland than we dared hope, and he came out in his kayak and took us off. He helped us to make our way to Ivignut, where the cryolite mines are, and thence we got back to England by way of Denmark. No," added Captain McAlpine, "a prudent navigator won't try to butt an iceberg out of his path; it don't pay."

"It must be dangerous in these waters, especially at night."

"There is danger everywhere and at all times in this life," was the truthful remark of the commander; "and you know that the most constant watchfulness on the part of the great steamers cannot always avert disaster, but I have little fear of anything from icebergs."

You need to be told little about those mountains of ice which sometimes form a procession, vast, towering, and awful, that stream down from the far North and sail in all their sublime grandeur steadily southward until they "go out of commission" forever in the tepid waters of the tropic regions.

It is a strange spectacle to see one of them moving resistlessly against the current, which is sometimes dashed from the corrugated front, as is seen at the bow of a steamboat, but the reason is simple. Nearly seven-eighths of an iceberg is under water, extending so far down that most of the bulk is often within the embrace of the counter current below. This, of course, carries it against the weaker flow, and causes many people to wonder how it can be thus.

While the little group stood forward talking of icebergs, they were gradually drawing near the couple that had first caught their attention. By this time a third had risen to sight, more to the westward, but it was much smaller than the other two, though more unique and beautiful. It looked for all the world like a grand cathedral, whose tapering spire towered fully two hundred feet in air. It was easy to imagine that some gigantic structure had been submerged by a flood, while the steeple still reared its head above the surrounding waters as though defying them to do their worst.

The other two bergs were much more enormous and of irregular contour. The imaginative spectator could fancy all kinds of resemblances, but the "cold fact" remained that they were simply mountains of ice, with no more symmetry of outline than a mass of rock blasted from a quarry.

"I have read," said Fred, "that in the iceberg factories of the north, as they are called, they are sometimes two or three years in forming, before they break loose and sweep off into the ocean."

"That is true," added Captain McAlpine; "an iceberg is simply a chunk off a frozen river, and a pretty good-sized one, it must be admitted. Where the cold is so intense, a river becomes frozen from the surface to the ground. Snow falls, there may be a little rain during the moderate season, then snow comes again, and all the time the water beneath is freezing more and more solid. Gravity and the pressure of the inconceivable weight beyond keeps forcing the bulk of ice and snow nearer the ocean, until it projects into the clear sea. By and by it breaks loose, and off it goes."

"But why does it take so long?"

"It is like the glaciers of the Alps. Being solid as a rock while the pressure is gradual as well as resistless, it may move only a few feet in a month or a year; but all the same the end must come."

The captain had grown fond of the boys, and the fact that the father of one of them was a director of the company which employed him naturally led him to seek to please them so far as he could do so consistent with his duty. He caused the course of the "Nautilus" to be shifted, so that they approached within a third of a mile of the nearest iceberg, which then was due east.

Sail had been slackened and the progress of the mass was so slow as to be almost imperceptible. This gave full time for its appalling grandeur to grow upon the senses of the youths, who stood minute after minute admiring the overwhelming spectacle, speechless and awed as is one who first pauses at the base of Niagara.

Naturally the officers and crew of the "Nautilus" gave the sight some attention, but it could not impress them as it did those who looked upon it for the first time.

The second iceberg was more to the northward, and the ship was heading directly toward it. It was probably two-thirds the size of the first, and, instead of possessing its rugged regularity of outline, had a curious, one-sided look.

"It seems to me," remarked Rob, who had been studying it for some moments, "that the centre of gravity in that fellow must be rather ticklish."

"It may be more stable than the big one," said Fred, "for you don't know what shape they have under water; a good deal must depend on that."

Jack Cosgrove, the sailor, who had joined the little party at the invitation of the captain, ventured to say:

"Sometimes them craft get top-heavy and take a flop; I shouldn't be s'prised if that one done the same."

"It must be a curious sight; I've often wondered how Jumbo, the great elephant, would have looked turning a somersault. An iceberg performing a handspring would be something of the same order, but a hundred thousand times more extensive. I would give a good deal if one of those bergs should take it into his head to fling a handspring, but I don't suppose—"

"Look!" broke in Fred, in sudden excitement.

To the unbounded amazement of captain, crew, and all the spectators, the very thing spoken of by Rob Carrol took place. The vast bulk of towering ice was seen to plunge downward with a motion, slow at first, but rapidly increasing until it dived beneath the waves like some enormous mass of matter cast off by a planet in its flight through space. As it disappeared, two-fold as much bulk came to view, there was a swirl of water, which was flung high in fountains, and the waves formed by the commotion, as they swept across the intervening space, caused the "Nautilus" to rock like a cradle.

The splash could have been heard miles away, and the iceberg seemed to shiver and shake itself, as though it were some flurried monster of the deep, before it could regain its full equilibrium. Then, as the spectators looked, behold! where was one of those mountains of ice they saw what seemed to be another, for its shape, contour, projections, and depressions were so different that no resemblance could be traced.

"She's all right now," remarked Jack Cosgrove, whose emotions were less stirred than those of any one else; "she's good for two or three thousand miles' voyage, onless she should happen to run aground in shoal water."

"What then would take place, Jack?" asked Fred.

"Wal, there would be the mischief to pay gener'ly. Things would go ripping, tearing, and smashing, and the way that berg would behave would be shameful. If anybody was within reach he'd get hurt."

Rob stepped up to the sailor as if a sudden thought had come to him. Laying his hand on his arm, he said, in an undertone:

"I wonder if the captain won't let us visit that iceberg?"

The boldness of the proposition fairly took away the breath of the honest sailor. He stared at Rob as though doubting whether he had heard aright. He looked at the smiling youth from head to foot, and stared a full minute before he spoke.

"By the horned spoon, you're crazy, younker!"

"What is there so crazy about such an idea?" asked Fred, as eager to go on the excursion as his friend.

Jack removed his tarpaulin and scratched his head in perplexity. He voided a mouthful of tobacco spittle over the taffrail, heaved a prodigious sigh, and then muttered, as if to himself:

"It's crazy clean through, from top to bottom, sideways, cat-a-cornered, and every way; but if the captain says 'yes' I'll take you."

Rob stepped to where the skipper stood, some paces away, and said:

"Captain McAlpine, being as this is the first time Fred and I ever had a good look at an iceberg, we would be much obliged if you will allow Jack to row us out to it. We want to get a better view of it than we can from the deck of the ship. Jack is willing, and we will be much obliged for your permission."

Fred was listening breathlessly for the reply, which, like Rob, he expected would be a curt refusal. Great, therefore, was the surprise of the two when the good-natured commander said:

"The request doesn't strike me as very sensible, but, if your hearts are set on it, I don't see any objection. Yes, Jack has my permission to take you to that mass of ice, provided you don't stay too long."

"He's crazy, too!" was the whispered exclamation of the sailor, who, nevertheless, was pleased to gratify his young friends.

The preparations were quickly made. Fred had heard that polar bears are occasionally found on the icebergs which float southward from the Arctic regions, and he insisted that they ought to take their rifles and ammunition along. Rob laughed, but fortunately he followed his advice, and thus it happened that the couple were as well supplied in that respect as if starting out on a week's hunt in the interior of the country.

When Jack was urged to do the same he resolutely shook his head, and then turned about and accepted a weapon from the captain, who seemed in the mood for humoring every whim of the youths that afternoon.

"Take it along, Jack," he said; "there may be some tigers, leopards, boa-constrictors, and hyenas prowling about on the ice. They may be on skates, and there is nothing like being prepared for whatever comes. Good luck to you!"

Rob placed himself in the bow of the small boat, and Fred in the stern, while the sailor, sitting down near the middle, grasped the oars and rowed with that long, steady stroke which showed his mastery of the art. There was little wind stirring, and the waves were so slight that they were easily ridden. The sea was of a deep green color, and when the spray occasionally dashed over the lads it was as cold as ice itself. By this time the iceberg had drifted somewhat to the southward, but its progress was so slow as to suggest that the two currents which swept against it were nearly of the same strength. Had it been earlier in the day it would probably have remained visible to the "Nautilus" until sunset.

Meanwhile, a fourth mass rose to sight in the rim of the eastern horizon, so that there seemed some truth in Rob's suggestion that they had run into a school of them. They felt no interest, however, in any except the particular specimen before them.

How it grew upon them as they neared it! It seemed to spread right and left, and to tower upward toward the sky, until even the reckless Rob was hushed into awed silence and sat staring aloft, with feelings beyond expression. It was much the same with Fred, who, sitting at the stern, almost held his breath, while the overwhelming grandeur hushed the words trembling on his lip.

The mass of ice was hundreds of feet in width and length, while the highest portion must have been, at the least, three hundred feet above the surface of the sea. What, therefore, was the bulk below. Its colossal proportions were beyond imagination.

The part within their field of vision was too irregular and shapeless to admit of clear description. If the reader can picture a mass of rock and débris blown from the side of a mountain, multiplied a million times, he may form some idea of it.

The highest portion was on the opposite side. About half-way from the sea, facing the little party, was a plateau broad enough to allow a company of soldiers to camp upon it. To the left of this the ice showed considerable snow in its composition, while, in other places, it was as clear as crystal itself. In still other portions it was dark or almost steel blue, probably due to some peculiar refraction of light. There were no rippling streams of water along and over its side, for the weather was too cold for the thawing which would be plentiful when it struck a warmer latitude.

But there were caverns, projections, some sharp, but most of them blunt and misshapen, steps, long stretches of vertical wall as smooth as glass, up which the most agile climber could never make his way.

Courageous as Rob Carrol unquestionably was, a feeling akin to terror took possession of him when they were quite near the iceberg. He turned to suggest to Jack that they had come far enough, when he observed that the sailor had turned the bow of the boat to the right, though he was still rowing moderately.

He was the only one that was not impressed by the majesty of the scene. Squinting one eye up the side of the towering mass, he remarked:

"There's enough ice there to make a chap's etarnal fortune, if he could only hitch on and tow it into London or New York harbor; but being as we've sot out to take a view of it, why we'll sarcumnavigate the thing, as me cousin remarked when he run around the barn to dodge the dog that was nipping at his heels."

The voice of the sailor served to break the spell that had held the tongues of the boys mute until then, and they spoke more cheerily, but unconsciously modulated their voices, as a person will do when walking through some great gallery of paintings or the aisles of a vast cathedral.

They were so interested, however, in themselves and their novel experience that neither looked toward the "Nautilus," which was rapidly passing from sight, as they were rowed around the iceberg. Had they done so, they would have seen Captain McAlpine making eager signals to them to return, and, perhaps, had they listened, they might have heard his stentorian voice, though the moderate wind, blowing at right angles, was quite unfavorable for hearing.

Unfortunately not one of the three saw or heard the movement or words of the skipper, and the little boat glided around the eastern end of the mountainous mass and began slowly creeping along the further side.

"Hello!" called out Rob, "there's a good place to land, Jack; let's go ashore."

"Go ashore!" repeated the sailor, with a scornful laugh; "what kind of a going ashore do you call that?"

While there was nothing especially desirable in placing foot upon an iceberg, yet, boy-like, the two friends felt that it would be worth something to be able to say on their return home that they had actually stood upon one of them.

Inasmuch as the whole thing was a fool's errand in the eyes of Jack Cosgrove, he thought it was well to neglect nothing, so he shied the boat toward the gently sloping shelf, which came down to the water, and, with a couple of powerful sweeps of the oars, sent the bow far up the glassy surface, the stoppage being so gradual as to cause hardly a perceptible shock.

"Out with you, younkers, for the day will soon be gone," he called, waiting for the two to climb out before following them.

They lost no time in obeying, and he drew the boat so far up that he felt there was no fear of its being washed away during their absence. All took their guns, and, leaving it to the sailor to act as guide, they began picking their way up the incline, which continued for fully a dozen yards from the edge of the water.

"This is easy enough," remarked Rob; "if we only had our skates, we might—confound it!"

His feet shot up in the air, and down he came with a bump that shook off his hat, and would have sent him sliding to the boat had he not done some lively skirmishing to save himself. Fred laughed, as every boy does under similar circumstances, and he took particular heed to his own footsteps.

Jack had no purpose of venturing farther than to the top of the gentle incline, since there was no cause to do so; but, on reaching the point, he observed that it was easy to climb along a rougher portion to the right, and he led the way, the boys being more than willing to follow him.

They continued in this manner until they had gone a considerable distance, and, for the first time, the guide stopped and looked around. As he did so, he uttered an exclamation of amazement:

"Where have been my eyes?" he called out, as if unable to comprehend his oversight.

"What's the matter?" asked the boys, startled at his emotion, for which they saw no cause.

"There's one of the biggest storms ever heard of in these latitudes, bearing right down on us; it'll soon be night, and we shall be catched afore we reach the ship, lads! there isn't a minute to lose; it's all my fault."

He led the way at a reckless pace, the youths following as best they could, stumbling at times, but heeding it not as they scrambled to their feet and hurried after their friend, more frightened, if possible, than he.

He could out-travel them, and was at the bottom of the incline first. Before he reached it, he stopped short and uttered a despairing cry:

"No use, lads! the boat has been swept away!"

Such was the fact.

Jack Cosgrove, of the "Nautilus," was not often agitated by anything in which he became involved. Few of his perilous calling had gone through more thrilling experiences than he, and in them all he had acquired a reputation for coolness that could not be surpassed.

But one of the few occasions that stirred him to the heart was when hurrying to disembark from the iceberg, in the desperate hope of reaching the ship before the bursting of the gale and the closing of night, he found that the little boat had been swept from its fastenings, and the only means of escape was cut off.

There was more in the incident than occurred to Rob Carrol and Fred Warburton, who hastened after him. He had been in those latitudes before, and the reader will recall the story Captain McAlpine told to the boys of the time Jack was one of three who escaped from the collision of the whaling ship with an iceberg in the gloom of a dark night.

Had it been earlier in the day, and had no storm been impending, he could have afforded to laugh at this mishap, for at the most, it would have resulted in a temporary inconvenience only. The skipper would have discovered their plight sooner or later, and sent another boat to bring them off, but the present case was a hundred-fold more serious in every aspect.

In the first place, the fierce disturbance of the elements would compel Captain McAlpine to give all attention to the care of his ship. That was of more importance than the little party on the iceberg, who must be left to themselves for the time, since any effort to reach them would endanger the vessel, the loss of which meant the loss of everything, including the little company that found itself in sudden and dire peril.

What might take place during the storm and darkness his imagination shuddered to picture. Had the boat been found where he left it a short time before, desperate rowing would have carried them to the "Nautilus" in time to escape the full force of the storm. That was impossible now, and as to the future who could say?

The rowboat, as will be remembered, was simply drawn a short distance up the icy incline, where it ought to have remained until the return of the party. Such would have been the fact under ordinary circumstances, for the mighty bulk of the iceberg prevented it feeling the shock of any disturbance that could take place in its majestic sweep through the Arctic Ocean, except from its base striking the bottom of the sea, or a readjustment of its equilibrium, as they had observed in the case of the smaller berg. It might crush the "Great Eastern" if it lay in its path, but that would have been like a wagon passing over an egg-shell.

In leaving the boat as related, the stern lay in the water. Even then it would have been secure, but for the agitation caused by the coming gale. That began swaying the rear of the craft, whose support was so smooth that it speedily worked down the incline and floating into the open water instantly worked off beyond reach.

The boys knowing so little what all this meant and what was before them, were disposed to make light of their misfortune.

"By the great horned spoon, but that is bad!" exclaimed Jack, pointing out on the water, where the boat was seen bobbing on the rising waves, fully a hundred yards away, with the distance rapidly increasing.

It seems as if in the few minutes intervening, night had fully descended. The wind had risen to a gale, and, even at that short distance the little craft was fast growing indistinct in the gathering gloom.

"It isn't very pleasant," replied Rob, "but it might be worse."

"I should like to know how it could be worse," said the sailor, turning reprovingly toward him; "I wonder if I can do it."

The last words were uttered to himself, and he hastily laid down his gun on the ice by his side. Then he began taking off his outer coat.

"What do you mean to do?" asked the amazed Fred.

"I believe I can swim out to the boat and bring it back," was the reply, as he continued preparations.

"You musn't think of such a thing," protested Rob; "the water is cold enough to freeze you to death. If you can't reach it, you will have to come back to us, with your clothing frozen stiff, and nothing will save you from perishing."

"I'll chance that," said Jack, who, however, continued his preparations more deliberately, and with his eye still on the receding boat.

He was about to take the icy plunge, in the last effort to save himself and friends, when he stopped, and, straightening up, watched the craft for a few seconds.

"No," said he, "it can't be done; the thing is drifting faster than I can swim."

Such was the evident fact. While the vast mass of ice, as has been explained elsewhere, was under the impulse of a mighty under-current, the small craft was swept away by the surface current which flowed in the opposite direction.

Even while the party looked, the boat faded from sight in the gloom.

"I can't see it," said Rob, who, like the others, was peering intently into the darkness.

"Nor I either," added Fred.

"And what's more, you'll never see it again," commented Jack, who began slowly donning his outer garments; "younkers, I've been in a good many bad scraps in my life, and more than once would have sworn I was booked for Davy Jones' locker, but this is a little the worst of 'em all."

His young friends looked wonderingly at him, unable to understand the cause of such extreme depression on the part of one whom they knew to be among the bravest of men, and in a situation that did not strike them as specially threatening.

"Don't you think this iceberg will hold together until morning?" asked Rob.

"It'll hold together for months," was the answer, "and like enough will travel hundreds of miles through the Gulf Stream before it goes to nothing."

"Then we are sure of a ship to keep us from drowning."

"I aint meaning that," said Jack, who was rapidly recovering his equanimity, though it was plain he was strongly affected by the woful turn the adventure had taken.

"And," added Fred, "Captain McAlpine knows where we are; he will remain in the neighborhood until morning—"

"How do you know he will?" broke in Jack, impatiently.

"What's to hinder him?" asked Fred, in turn, startled by the abrupt question; "he knows how to sail the 'Nautilus,' and has taken it through many gales worse than this."

"How do you know he has?"

"Gracious, Jack, I don't know anything about it; I am only saying what appears to me to be the truth."

"I don't want to hurt your feelings, lads, but I can't help saying you don't know what you're talking about. A couple of young land lubbers like you don't see things as they show themselves to one who was born and has lived all his life on the ocean, as you may say. I don't mean to scare you more than I oughter, but you can just make up your minds, my hearties, that you never was in such a fix as this, and if you live to be a hundred years old you'll never be in another half as bad."

These were alarming words, but, inasmuch as Jack did not accompany them with any explanation, neither Rob nor Fred were as much impressed as they would have been had he explained the grounds for his extreme fear. What they saw was an enforced stay on the iceberg until the following day. Although in a high latitude, the night was not unusually long, and, though it was certain to be as uncomfortable as can well be imagined, they had no doubt they would survive it and live to laugh at their mishap.

By this time the sailor felt that he had forgotten himself in the agitation caused by the loss of the boat. Although he might see the dark future with clearer vision than his young friends, it was his duty to keep their sight veiled as long as he could. Time enough to face the terrors and their direful consequences when the possibility of avoiding them no longer existed.

It will be recalled that when the little party stepped out from the small boat upon the iceberg they did so on the side farthest from the "Nautilus," so that all view of the ship was shut off, and neither Captain McAlpine nor any of his crew could observe the action of Jack and the boys.

The skipper had warrant for supposing that such an experienced sailor as the one in charge of the lads would be quick to notice the threatening change in the weather, and would make all haste to return. Inasmuch as he had failed to do so, the party must be left to themselves for the time, while the commander gave his full attention to the care of the ship—a responsibility that required his utmost skill, with no slight chance of his failure.

The storm or squall, or whatever it might be termed, was one of those sudden changes, sometimes seen in the high latitudes, whose coming is so sudden that there is but the briefest warning ere it bursts in all its fury.

By the time our friends reached the spot where they expected to find their boat it was almost as dark as night. This darkness deepened so rapidly, after losing sight of the craft, that they were unable to see more than fifty feet in any direction. Fortunately, before leaving the "Nautilus," they had donned their heaviest clothing, so that they were quite well protected under the circumstances. Had they neglected this precaution they must have perished of the extreme cold that followed.

Accompanying the oppressive gloom was a marked falling of the temperature, and a fierceness of blast which, so long as they were exposed to it, cut them to the bone. The gale, instead of blowing in their faces, swept along the side of the iceberg. They had but to withdraw, therefore, only a short distance when they were able to take shelter behind some of the numerous projections, and save themselves from its full force.

All at once the air was full of millions of particles of snow, which eddied and whirled in such fantastic fashion that when they crouched down they were so blinded that they could not see each other's forms, although near enough to clasp hands.

This lasted but a few minutes, when it ceased as suddenly as it began. The air was clear, but the gloom was profound. They could see nothing of the raging ocean, nor of a tall spire-like mass of ice, which towered a hundred feet above their heads, within a few yards of them, and which had attracted their admiration on their first visit.

It was blowing great guns. The sound of the waves, as they broke against the solid abutment of ice, and were dashed into spray and spume, was like that of the breakers in a hurricane. Inconceivable as was the bulk of the berg, they plainly felt it yield to the resistless power of the ocean. It acquired a slow sea-saw motion, more alarming than the most violent disturbance they had ever known on the "Nautilus" in a storm. The movement was slight, but too distinct to be mistaken.

For some time the three huddled together, under the protection of the friendly projection, and no one spoke a word. They had laid down their guns, for there was no need of keeping them in their hands. The metal was so intensely cold that it could be noted through the protection of their thick mittens, and they needed every atom of vitality in their shivering bodies. They pressed closer together and found comfort in the mutual warmth thus secured.

The sky was blackness itself. There was no glimpse of moon or friendly star. They were adrift on an iceberg in darkness and gloom in the midst of a trackless ocean. Whither they were going, when the terrifying voyage should end, what was to be the issue, only One knew. They could but pray and trust and hope and await the end.

It is a curious feature of this curious human nature of ours that the most hopeless depression of spirits is frequently followed by a rebound, as the highest spirits are quickly succeeded by the deepest dejection. Our make-up is such that nature reacts, and neither state can continue long without change, unless the conditions are exceptional. Were it otherwise, many a strong mind would break down under its weight of trouble.

The three had remained crouching together silent and motionless for some minutes, no one venturing to express a hope or opinion, when Rob Carrol suddenly spoke, in the cheeriest tones.

"I'll tell you what we'll do, fellows."

"What's that?" asked Fred, quick to seize the relief of hearing each other's voices.

"Let's start a fire."

"A good idee," assented Jack Cosgrove, falling into the odd mood that had taken possession of his companions; "you gather the fuel and I'll kindle it. It happens I haven't such a thing as a match about me, but I'll find a way to start it."

"Rob and I have plenty, but, if we hadn't, we could rub some pieces of ice together till the friction started a flame."

"The Esquimaux have another plan," added Rob. "They will trim a piece of ice in the form of a convex lens and concentrate the sun's rays on the object they want to set on fire. Why not try that?"

"I am afraid there isn't enough sunlight to amount to anything," replied Fred, craning his head forward and peering through the gloom, as if searching for the orb of day.

"That isn't the only way of getting up steam," remarked Jack, who, just like his honest self, was striving to dispose of his body so as to give each of the boys the greatest possible amount of warmth; "I know a better one."

"Let's hear it."

"Race back and forth along the side of the berg till we start the blood circulating; nothing like that."

"Suppose we should slip, Jack?"

"Then you'd flop into the sea; it's a good thing to take a bath when your blood is heated too much."

"If there was only a footpath where we could do that, it would be a good plan," observed Rob, "but, as it is, we shall have to huddle together till morning, when I hope Captain McAlpine will send a boat after us."

The boys noticed that Jack made no reply to this. They expected an encouraging response, but he remained silent, as though he was considering difficulties, dangers, complications, and perils of which they could form no idea.

Meanwhile the gale raged with resistless fury. There was no more fall of snow, but the wind was like a hurricane. The most vivid idea of its awful power was gained when the friends, far removed from the water's edge, and at no small elevation above it, felt drops of spray flung in their faces.

The thunder of the surges, shattered into mist and foam against the adamantine side of the iceberg, was so overpowering that, had not the heads of the three been close, they would not have heard each other's voices. The see-sawing of the colossal mass was more perceptible than ever, and caused them to think, with unspeakable dread, of the possibility of the berg breaking apart, or overturning like the other, in the effort to preserve its equilibrium.

The gale whistled around and among the projections of the ice with a weird, uncanny sound, alike and yet different from that heard when it moans through the network of ropes and rigging of a great ship. The question was whether such a vast volume of wind, impinging against the thousands of square feet of ice, would not affect the course and speed of the mass. If the hurricane drove in the same direction as the controlling current, it ought to be of much help. If opposed, it might check it; if quartering, it might make a radical change in its course.

All these speculations were in vain, however, and, as has been said, there was nothing to be done, but to wait and trust in the only One who could help them, and who had been so merciful in the past that their faith in His goodness and protecting care could not be shaken.

"My lads," said Jack, when the silence which followed their brief conversation had lasted some minutes, "there's only one thing to do, and that's to make ourselves as comfortable as we can where we are."

"Isn't that what we are doing?" asked Rob.

"Of course it is, but I didn't know but what you was trying to conjure up some other plan. If so, give it up, say your prayers, and go to bed."

It is at such times that a person realizes his helplessness and utter dependence on the great Father of all. Too much are we prone to forget such dependence, when all goes well, and too often the prayer for help and guidance is put off until too late.

It was a commendable trait in all three of the parties whose experience I have set out to tell that they never forgot their duty in this all-important matter. Rob and Fred were full of animal life and spirits, and the elder especially was inclined, from this very excess of health and strength, to overstep at times the bounds of propriety, but both remembered the lessons learned in infancy at the mother's knee, and never failed to commend themselves to their heavenly parent, not only on waking in the glad morning, but on closing their eyes at night.

Jack Cosgrove had one of those impressionable natures, tinged with innocent superstition, which is often seen in those of his calling. His faith possessed the simplicity of a child, and, though many of his doings might not square with those of a Christian, yet at heart he devoutly believed in the all-protecting care of his Maker, and was never ashamed, no matter what his surroundings, to call upon Him for help and guidance.

And so, as the three pressed closer together, adjusting themselves as best they could to pass the long, dismal hours ere the sun would shine upon them again, they were silent, and all, at the same time, communed with God, as fervently and trustfully as ever a dying Christian did when stretched upon his bed of mortal illness.

Had they possessed a blanket among them they could have spread it upon the ice, lain down upon it, and, wrapping it as best they could, passed the night with a fair degree of comfort. That, however, was out of the question. They, therefore, seated themselves under the lee, as may be said of the mass of ice, which protected them against the gale, their bodies pressed as closely together as well could be, and in this sitting posture prepared to go to sleep, if it should so prove that the blessing could be won.

One can become accustomed to almost anything. An abrupt change from the comfortable cabin of the "Nautilus" to the bleak situation on the iceberg would have filled them with a dread hardly less trying than death itself; but they had already been in the situation long enough to grow used to it. The ponderous swaying of the frozen structure, the thunderous dash and roar of the waves against its base, the screaming of the gale and the darkness of the arctic night; all these were sounds and sensations which in a certain sense grew familiar to them and did not disturb them as the hours passed.

It cannot be said that an icy seat or rest forms the most comfortable support for the body, whose warmth is likely to melt the frozen surface, but the thick clothing of the party did much to avert unpleasant consequences. Had Jack or Rob or Fred been alone, the penetrating cold most likely would have overcome him, but as has been shown, the mutual warmth rendered their situation less trying than would be supposed.

When an hour had passed, with only an occasional word spoken, Jack addressed each of the boys in turn by name. There was no response, and he spoke in a louder tone with the same result.

"They're asleep," he said to himself, "and I'm glad of it, though the sleep that sometimes comes to a chap in these parts at such times is the kind that doesn't know any waking in this world. I've no doubt, howsumever, that they're all right."

With a vague uneasiness, natural under the circumstances, he passed his hands over their faces and pinched their arms, as if to assure himself there was no mistake.

The boys were so muffled up in their thick coats and sealskin caps that were drawn about their ears, behind which the collars of their coats were raised, that only the ends of their noses and a slight portion of their cheeks could be felt. He removed his heavy mitten from one hand, and, reaching under the protecting covering about the cheeks and neck, found a healthy glow which told him all was well, and, for the time at least, he need feel no further anxiety, so far as they were concerned.

"Which being the case," he added, drawing on his mitten again, and making sure their coverings were adjusted, "I'll take a little trip myself into the land of nod."

But this trip was easier thought of than made. His rugged body, with its powerful vitality, would have soon succumbed to drowsiness, could his mind have been free of its distressing fear for the two young friends under his charge. But, though he had said little, he knew far more than he dare tell them. He had shown his alarm on discovering the loss of the boat, but though some impatient expressions escaped him, he did not explain what was in his mind.

His belief was that before morning should come the "Nautilus" would be driven so far from her course that she would be nowhere in sight, and, towering as was the iceberg in its height and proportions, it would be invisible from the deck of the ship, or, if visible, could not be identified among the others drifting through the icy ocean. Well aware, too, he was of the terrific strength of the gale sweeping across the deep, he trembled for the safety of the "Nautilus" and those on board, hardly less than he did for himself and friends. The hurricane was resistless in its power, and would drive the ship whither it chose like a cockle-shell. Icebergs were moving hither and thither through the darkness, less affected by the wind and waves than the vessel, and a collision was among the possibilities, if not the probabilities.

Inasmuch as the "Nautilus" was likely to go down under the fury of the elements, or, if she rode through it, was certain to be too far removed to be of help to the three, the question to consider was what hope of escape remained to the latter.

Although vessels penetrate Baffin Bay and far into the Arctic Ocean, they are so few in number that days and weeks may pass without any two of them gaining sight of each other. A shipwrecked sailor afloat in the South Sea, on a spar, was as likely to be picked up by some trading ship as were Jack and his companions, by any of the whalers or ships in that high latitude.

And then, supposing they did catch sight of some stray vessel, who of the captain and crew would be looking for living persons on board an iceberg? Why would they give the latter any more attention than the scores of the mountainous masses afloat in their path and which it was their first care to avoid?

If a ship should pass so near to them that they could make their signals seen there would be hope; but the chances of anything of that kind were too remote to be regarded.

Such being the outlook, where was there ground for hope? They were beyond sight of the Greenland coast, and were doubtless drifting farther away every hour. Nothing in the nature of succor was to be hoped for from land, and the brave-hearted Jack was obliged to say to himself that, so far as human eye could see, there was none from any source. Cold, starvation, and death seemed among the certainties near at hand.

And having reached this disheartening belief, he closed his eyes and joined his young friends in the land of dreams.

Having sunk into slumber, the sailor was likely to remain so until morning, unless some unexpected circumstance should break in upon his rest, and it did.

It was Rob Carrol, who, probably because of his cramped position, first regained consciousness. As his senses gradually came back to him, and the thunder of the surges and the shrieking of the gale broke in upon his brain, he stretched his benumbed limbs and yawned in an effort to make his situation more comfortable.

It struck him that there had been a change in their relative positions while asleep. Not wishing to awake his companions, he carefully shifted his limbs and body, so as not to disturb them. While doing so, he extended his hand to touch them.

He groped along one figure, which he knew at once was Jack, but he felt no other. With a vague fear he straightened up, leaned over, and hastily extended his arms about him, as far as he could reach. The next moment he roughly shook the shoulder of the sailor, and called out in a husky voice:

"Jack! Jack! wake up! Fred is gone!"

Jack Cosgrove was awake on the instant. Not until he had groped around in the darkness and repeated the name of Fred several times in a loud voice would he believe he was not with them.

"Well, by the great horned spoon!" he exclaimed, "that beats everything. How that chap got away, and why he done it, and where he's gone to gets me."

"I wonder if he took his gun," added Rob, stooping over and examining the depression in the ice, where the three laid their weapons before composing themselves for sleep; "yes," he added directly after, "he took his rifle with him."

As may be supposed, the two were in a frenzied state of mind, and for several minutes were at a loss what to do, if, indeed, they could do anything. They knew not where to look for their missing friend, nor could they decide as to what had become of him.

One fearful thought was in the minds of both, but neither gave expression to it; each recoiled with a shudder from doing so. It was that he had wandered off in his sleep and fallen into the sea.

Despite their distress and dismay, they noticed several significant facts. The wind that blew like a hurricane when they closed their eyes, had subsided. When they stood up, so that their heads arose above the projections that had protected them, the breeze was so gentle that it was hard to tell from which direction it came. It would be truth to say there was no wind at all.

Further, there was a marked rise in the temperature. In fact, the weather was milder than any experienced after leaving St. John, and was remarked by Rob.

"You don't often see anything of the kind," replied the sailor; "though I call something of the kind to mind on that voyage in these parts in the 'Mary Jane,' which was smashed by the iceberg."

But their thoughts instantly reverted to the missing boy. Rob had shouted to him again and again in his loudest tones, had whistled until the echo rang in his own ears, and had listened in vain for the response.

The tumultuous waves did not subside as rapidly as they arose. They broke against the walls of the iceberg with decreasing power, but with a boom and crash that it would seem threatened to shatter the vast structure into fragments. There were occasional lulls in the overpowering turmoil, which were used both by Rob and Jack in calling to the missing one, but with no result.

"It's no use," remarked the sailor, after they had tired themselves pretty well out; "wherever he is, he can't hear us."

"I wonder if he will ever be able to hear us," said Rob, in a choking voice, peering around in the gloom, his eyes and ears strained to the highest tension.

"I wish I knew," replied Jack, who, though he was as much distressed as his companion, was too thoughtful to add to the grief by any words of his own. "I hope the lad is asleep somewhere in these parts, but I don't know nothing more about him than you."

"And I know nothing at all."

"Can you find out what time it is?"

That was easily done. Stooping down so as to protect the flame from any chance eddy of wind, Rob ignited a match on his clothing and looked at his watch.

"We slept longer than I imagined, Jack; day-break isn't more than three or four hours off."

"That's good, but them hours will seem the longest that you ever passed, my hearty."

There could be no doubt on that point, as affected both.

"Why, Jack," called out Rob, "the stars are shining."

"Hadn't you observed that before? Yes; there's lots of the twinklers out, and the storm is gone for good."

Every portion of the sky except the northern showed the glittering orbs, and, for the moment, Rob forgot his grief in the surprise over the marked change in the weather.

"This mildness will bring another change afore long," remarked Jack.

"What's that?"

"Fogs. We'll catch it inside of twenty-four hours, and some of them articles in this part of the world will beat them in London town; thick enough for you to lean against without falling."

As the minutes passed, with the couple speculating as to what could have happened to Fred Warburton, their uneasiness became so great that they could not remain idle. They must do something or they would lose command of themselves.

Rob was on the point of proposing a move, with little hope of its amounting to anything, when the sailor caught his arm.

"Do you see that?"

The darkness had so lifted that the friends could distinguish each other's forms quite plainly, and the lad saw that Jack had extended his arm, and was pointing out to sea. The fellow was startled, as he had good cause to be.

Apparently not far off was something resembling a star, low down in the horizon and gliding over the surface of the deep. Now and then it disappeared, but only for a moment. At such times it was evidently shut from sight by the crests of the intervening waves.

It was moving steadily from the right to the left, the friends, of course, being unable to decide what points of the compass these were. Its motion in rising and sinking, vanishing and then coming to view again, advancing steadily all the while, left no doubt as to its nature.

"It's the 'Nautilus'!" exclaimed Rob; "Captain McAlpine is looking for us."

"That's not the 'Nautilus'," said Jack; "for she doesn't show her lights in that fashion. Howsumever, it's a craft of some kind, and if we can only make 'em know we're here they'll lay by and take us off in the morning."

As the only means of reaching the ears of the strangers the two began shouting lustily, varying the cries as fancy suggested. In addition, Jack fired his gun several times.

While thus busied they kept their gaze upon the star-like point of light on which their hopes were fixed.

It maintained the same dancing motion, all the while pushing forward, for several minutes after the emission of the signals.

"She has stopped!" was the joyful exclamation of Rob, who postponed a shout that was trembling on his lips; "they have heard us and will soon be here."

Jack was less hopeful, but thought his friend might be right. The motion of the star from left to right had almost ceased, as if the boat was coming to a halt. Still the sailor knew that the same effect on their vision would be produced if the vessel headed either away from or toward the iceberg; it was one of these changes of direction that he feared had taken place.

Up and down the light bobbed out of sight for a second, then gleaming brightly as if the obscuring clouds had been brushed aside from the face of the star, which shone through the intervening gloom like a beacon to the wanderer.

"Yes, they are coming to us," added Rob, forgetting his lost friend in his excitement; "they will soon be here. I wonder they don't hail us."

"Don't be too sartin, lad," was the answer of the sailor; "if the boat was going straight from us it would seem for a time as though she was coming this way; I b'lieve she has changed her course without a thought of us."

They were cruel words, but, sad to say, they proved true. The time was not long in coming when all doubt was removed. The star dwindled to a smaller point than ever, seemed longer lost to view, until finally it was seen no more.

"Do you suppose they heard us?" asked Rob, when it was no longer possible to hope for relief from that source.

"Of course not; if they had they would have behaved like a Christian, and stood by and done what they could."

"Ships are not numerous in this latitude, and it may be a long time before we see another."

"The chances p'int that way, and yet you know there's a good many settlements along the Greenland coast. It isn't exactly the place I'd choose for a winter residence—especially back in the country—but there are plenty who like it."

"In what way can that affect us?"

"There are ships passing back and forth between Denmark and Greenland, and a number v'yage to the United States, and I'm hoping we may be run across by some of them—Hark!"

A hoarse, tremulous sound came across the ocean. There was no mistaking its character; it was from the whistle of a steamer, the one whose light led them to hope for a time that their rescue was at hand. It sounded three times, and evidently the blasts were intended as a signal, though, of course, they bore no reference to the two persons listening so intently on the iceberg.

"That was the last thing I expected to hear in this latitude," remarked Rob, turning to his companion.

"I don't know why," replied Jack; "they have such craft plying along the Greenland coast. What's more, I've heard that same whistle before and know the boat; it's the 'Fox'."

"Not the 'Fox' I have read about as having to do with the Franklin expedition?" said the youth, in astonishment.

"The identical craft."

"You amaze me."

Those of my readers who are familiar with the history of Arctic exploration will recall this familiar name. It was the steam tug in which sailed the party that succeeded in finding traces of the ill-fated Franklin expedition of near a half century ago. It afterward came into the possession of the company that owns the cryolite mine at Ivigtut, and is now used to carry laborers and supplies from Copenhagen to that place. While at Ivigtut, it is occasionally employed to tow the Greenland ships in and out of the fiord.

Ah, if its crew had only heard the shouts and signals of the couple on the iceberg, how blessed it would have been! But its lights had vanished long ago, and, if its whistle sounded again, it was so far away that it could not reach the listening ears.

The restlessness of the friends, to which I have referred, now led them to attempt a search, if it may so be called, for the missing Fred. This of necessity was vague and blind, and was accompanied with but a grain of hope. Neither had yet referred to the awful dread that was in their thoughts, but weakly trusted they might find the poor fellow somewhere near asleep or senseless from a fall.

Morning was still several hours distant, but the clearing of the air enabled them to pick their way with safety, so long as they took heed to their footsteps.

"I will go down toward the spot where the boat gave us the slip," said Jack, "and I don't know what you can do, unless you go with me."

"There's no need of that; of course I can't make my way far, while the night lasts, but I remember that we penetrated some way beyond this place before camping for the night; I'll try it."

"Keep a sharp lookout, my hearty, or there'll be another lad lost, and then what will become of Jack Cosgrove?"

"Have no fear of me," replied Rob, setting out on the self-imposed expedition.

He paused a few steps away and turned to watch the sailor, who was carefully descending the incline, at the base of which they had landed.

"I hope he won't find Fred, or rather that he won't find any signs of his having gone that way," said Rob to himself with a shudder.

As the figure of the man slowly receded, it grew more indistinct until it faded from sight in the gloom. Still the youth looked and listened for the words which he dreaded to hear above everything else in the world.

Jack Cosgrove received a good scare while engaged on his perilous task. He was half-way down the incline, making his way with the caution of a timid skater, when, like a flash, his feet flew from under him, and, falling upon his back, he slid rapidly toward the waves at the base of the berg.

But the brave fellow did not lose his coolness or presence of mind. His left hand grasped his rifle, and, throwing out his right, he seized a projection of ice, checking himself within a few feet of the water and near enough for the spray from the fierce waves to be flung over him.

"This isn't the time for a bath," he muttered, carefully climbing to his feet and retreating a few paces; "it would have been a pretty hard swim out there with my heavy clothing, though I think I could manage it."

After all, what could he hope to accomplish by this hunt for Fred Warburton? If he had wandered in that direction and fallen into the sea, he had left no traces that could be discovered in the gloom of the night. He could not have gone thither and stayed there that was certain.

The sailor having withdrawn beyond the reach of the waves, sat down in as disconsolate a mood as can be imagined. A suspicion that Rob might follow caused him to turn his head and look over his shoulder.

"I don't see anything of him, and I guess he'll stay up there; I hope so, for Jack Cosgrove isn't in the mood to see or talk with any one 'cepting that lad which he won't never see nor talk to agin."

Convincing himself that he was safe against a visit from the elder youth, the sailor bowed his head, and, for several minutes, wept like one with an uncontrollable grief.

When his sorrow had partially subsided, he spent a brief while with his head still bowed in communion with his Maker.

"I don't know but what the lad is luckier than me or Rob," he added, reviewing the situation in his mind; "for we've got to foller him sooner or later. It isn't likely that any ship will come as nigh to this thing as the 'Fox' did awhile ago, and I can't see one chance in ten thousand of our being took off. We haven't a mouthful of food, and there's no way of our getting any. After a time we will have to lay down and starve or freeze to death, or both. Poor Fred has been saved all that—"

He checked his musings, for at that moment a peculiar sound broke upon his ear. It resembled that caused by the exhaust of a steamer at low pressure. One less experienced than he would have been deceived into the belief that such was its source, but Jack did not hold any such false hope for a minute even. He understood it too well.

It was made by a whale "blowing." One of those monster animals was disporting himself in the vicinity of the iceberg, and the sailor had heard the same sound too often to mistake it.

Shifting his position so as to bring him nearer the sea, he stooped and peered out in the gloom, in the direction whence came the noise. There was enough starlight for him to trace the outline of the mountainous waves, as they arose against the sky, though they were dimly defined and might have misled another.

While gazing thus, a huge mass took vague form. It was the head of a gigantic leviathan of the deep, which for a moment was projected against the sky and then sank out of sight with the same noise that had attracted Jack's notice in the first place.

The blowing was heard at intervals, for several minutes, until the distance shut it from further notice.

"I wonder if Rob noticed it," the sailor asked himself; "for if he did, he will make the mistake of believing the 'Fox' has come to take us off, and we're done with this old berg."

But nothing was heard from the youth, and the sailor remained seated on the shelf of ice, a prey to his gloomy reflections. He had made up his mind to stay where he was until the coming of day, when the question of what was to be done would be speedily settled.

Meanwhile, he wanted no company but his own thoughts. He had kept up with the elder youth, and carefully withheld his fears and beliefs from him. He felt that he could do so no longer. The farce had been played out, and the truth must be spoken.

It was impossible to note the passage of time. Jack carried no watch, but each of the boys owned an excellent timepiece. He probably fell into a doze, for, when he roused himself once more, he saw that the night was nearly over.

"I wonder what Rob is doing," he said, rising to his feet, stretching his arms, and looking in the direction where he expected to see his friend; "I hope nothing hain't happened to him."

This affliction was spared the sailor, for while he was peering through the increasing light, he caught sight of the figure of Rob making his way toward him.

"Hello, Jack, have you found anything?"

"No; have you?"

"I think I have; come and see."

As may be supposed, Jack Cosgrove was all excitement on the instant. He had not expected any such reply, and he was eager to learn the cause. As he started forward, he instinctively glanced down in quest of evidence that Fred had passed there. There was none so far as he could see, and, if there had been, it is not likely he would have been able to identify it, since all the party had been over the same spot, and some of them more than once.

"What is it?" he asked, as he reached his friend.

"It may mean nothing, but a little distance beyond where we camped the ice is broken and scratched as though some one has been that way."

"So there has, we were there yesterday afternoon."

"I haven't forgotten that, but these marks are at a place where we haven't been, that is unless it was Fred."

"How did you manage to find them in the dark?"

"I didn't; I groped over the ice as far as I could, and then sat down and waited for day. I must have slept awhile, but when it was growing light I happened to look around, and there, within a few feet of me, on my right hand, I noticed the ice scratched and broken, as though some one had found it hard work to get along. I was about to start right after him, when I thought it best to tarry for you. It is now so much lighter that we shall learn something worth knowing."

Even in their excitement they paused a few minutes to gaze out upon the ocean, as it was rapidly illumined by the rising sun. Before long their vision extended for miles, but the looked-for sight was not there. On every hand, as far as the eye could penetrate, was nothing but the heaving expanse of icy water.

Whether they were within a comparatively short distance of Greenland or not, they were not nigh enough to catch the first glimpse of the coast.

Several miles to the eastward towered an iceberg, apparently as large as the one upon which they were drifting. Its pinnacles, domes, arches, plateaus, spires, and varied forms sparkled and scintillated in the growing sunlight, displaying at times all the colors of the spectrum, and making a picture beautiful beyond description.

To the northward and well down in the horizon, was another berg, smaller than the first, and too far off to attract interest. A still smaller one was visible midway between the two, and a peculiar appearance of the sea in the same direction, Jack said, was caused by a great ice field.

Not a ship was to be seen anywhere. Their view to the southward was excluded by the bulk of the iceberg, on which they were floating.

"There's nothing there for us," remarked Rob with a sigh.

"You're right; lead the way and let's see what you found."

It took them but a few minutes to reach the place the lad had in mind, and they had no sooner done so than the sailor was certain an important discovery had been made.

Where there was so much irregularity of shape as on an iceberg, a clear description is impossible; but, doing the best we can, it may be said that the spot was a hundred feet back from where the three huddled together with an expectation of spending the night until morning. It was only a little higher, and was attained by carefully picking one's way over the jagged ice, which afforded secure footing, now that day had come.

Adjoining the place, from which the party diverged to the left, was a lift or shelf on the right, and distant only two or three paces. It was no more than waist high, and, therefore, was readily reached by any one who chose to clamber upon it.

It is no easy matter to trace one over the ice, but the signs of which Rob had spoken were too plain to be mistaken. There were scratches, such as would have been made by a pair of shoes, a piece of the edge was broken off, and marks beyond were visible similar to those which it would be supposed any one would make in clambering over the flinty surface.

Jack stood a minute or two studying these signs as eagerly as an American Indian might scrutinize the faint trail of an enemy through the forest.

"By the great horned spoon!" he finally exclaimed; "but that does look encouraging; I shouldn't wonder if the chap did make his way along there in the night, but why he done it only he can tell. Howsumever, where has he gone?"

That was the question which Rob Carrol had asked himself more than once, and was unable to answer. The ice, for a distance of another hundred feet, looked as if it might be scaled, but, just beyond that, towered a perpendicular wall, like the side of a glass mountain. There could be no progress any farther in that direction, nor, so far as could be judged, could any one advance by turning to the right or left.

There must be numerous depressions and cavities, sufficient to hide a dozen men, and it was in one of these the couple believed they would find the dead or senseless body of their friend.

"Jack," said Rob, "take my gun."

"What for?"

"I'll push on ahead as fast as I can; I can't wait, and the weapon will only hinder me."

"I've an idee of doing something of the kind myself, so we'll leave 'em here. I don't think they'll wash away like the boat," he added, as he carefully placed them on the shelf, up which they proceeded to climb.

But Rob was in advance and maintained his place, gaining all the time upon his slower companion, who allowed him to draw away from him without protest.

"There's no need of a chap tiring himself to death," concluded Jack, as he fell back to a more moderate pace; "he's younger nor me, and it won't hurt him to get a bump or so."

Rob was climbing with considerable skill. In his eagerness he slipped several times, but managed to maintain his footing and to advance with a steadiness which caused considerable admiration on the part of his more sluggish companion.

He used his eyes for all they were worth, and the signs that had roused his hope at first were still seen at intervals, and cheered him with the growing belief that he was on the right track.

"But why don't we hear something of him?" he abruptly asked himself, stopping short with shuddering dread in his heart; "he could not have remained asleep all this time, and, if he has been hurt so as to make him senseless, more than likely he is dead."

The youth was now nearing the ice wall, to which we have referred, and beyond which it looked impossible to go. The furtive glances into the depressions on his right and left showed nothing of his loved friend, and the evidences of his progress were still in front. The solution of the singular mystery must be at hand.

Unconsciously Rob slowed his footsteps, and looked and listened with greater care than before.

"What can it mean? Where can he have gone? I see no way by which he could have pushed farther, and yet he is not in sight—"

He paused, for he discovered his error. The path, if such it may be termed, which he had been following, turned so sharply to the right that it could not be seen until one was upon it. How far it penetrated in that direction remained to be learned.

Rob turned about and looked at Jack, who was several rods to the rear, making his way upward with as much deliberation as though he felt no personal interest in the business.

"I'm going a little farther, Jack, but I think we're close upon him now. Hurry after me!"

"Ay, ay," called the sailor, in return; "when you run afoul of the lad give him my love and tell him I'm coming."

This remark proved that he shared the hope of Rob, who was now acting the part of pioneer, and it did not a little to encourage the boy to push on with the utmost vigor at his command.