BILLY WHISTERS' TRAVELS

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Billy Whiskers' Travels

Author: F. G. Wheeler

Release Date: October 02, 2013 [EBook #43872]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BILLY WHISKERS' TRAVELS ***

Produced by Al Haines.

BILLY WHISKERS'

TRAVELS

BY

F. G. WHEELER

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

CARLL B. WILLIAMS

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

CHICAGO — AKRON, OHIO — NEW YORK

MADE IN U. S. A.

Copyright 1907

by

The Saalfield Publishing Co.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

ILLUSTRATIONS

A Boat was lowered to rescue Billy. (missing from source book)

Billy saw him coming, and splashed around to the far side of the fountain.

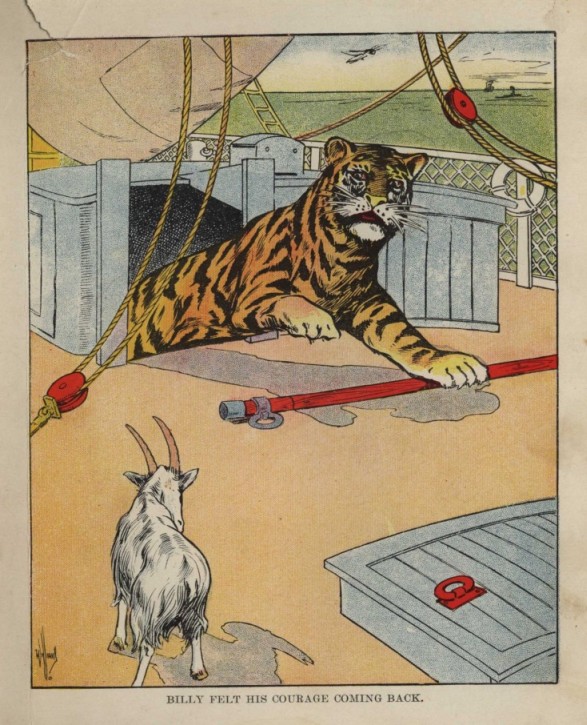

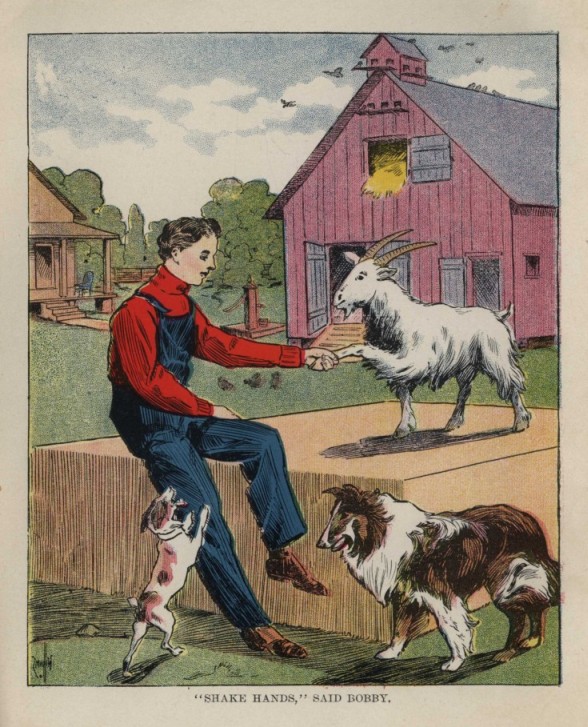

Billy felt his courage coming back.

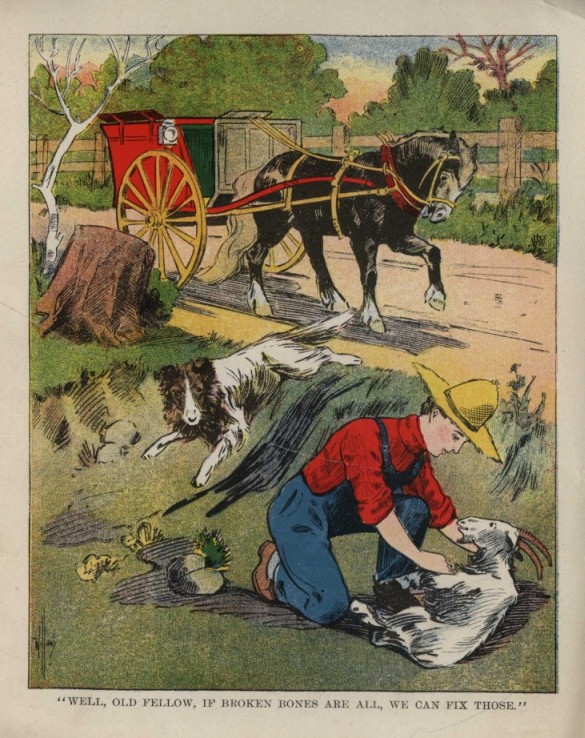

"Well, old fellow, if broken bones are all, we can fix those."

CHAPTER I

BILLY RUNS AWAY FROM HOME

he other kids of the big flock on the pretty Swiss farm

thought that they were having a very nice time, but

Billy did not like it very well. He could run faster,

jump higher and butt harder than any of the other kids

of his age, and he wanted more room. Nearly every day he stopped

for a while beside the high fence and looked out through it at the

green slopes that ran up to the mountains. The leaves looked so

much fresher and more tender there, and the sun so much brighter;

besides, there were rocky places—he could see them—which would

make such fine playgrounds and jumping places. His wise old

mother shook her head when he told her about these things.

he other kids of the big flock on the pretty Swiss farm

thought that they were having a very nice time, but

Billy did not like it very well. He could run faster,

jump higher and butt harder than any of the other kids

of his age, and he wanted more room. Nearly every day he stopped

for a while beside the high fence and looked out through it at the

green slopes that ran up to the mountains. The leaves looked so

much fresher and more tender there, and the sun so much brighter;

besides, there were rocky places—he could see them—which would

make such fine playgrounds and jumping places. His wise old

mother shook her head when he told her about these things.

"You are too little yet, Billy," she always said. "You are not yet strong enough to be out in the world alone, even if you could get away from here."

"Just wait till I get big," Billy would say, shaking his head, and then he would scamper away to slyly nip the whiskers of some sober old goat, or to romp or play fight with one of the other youngsters.

He was the most mischievous kid in the flock, and because of that his mother named him Billy Mischief. Farmer Klausen, who owned him, was nearly as proud of him as Billy's own mother could be.

"That's the smartest and strongest young goat I've got," he used to brag to his neighbor, fat Hans Zug, but for all that he kept a sharp eye on Billy and would not allow him to break away from the flock and escape, as he sometimes tried to do when they were being driven across the road from one pasture to another.

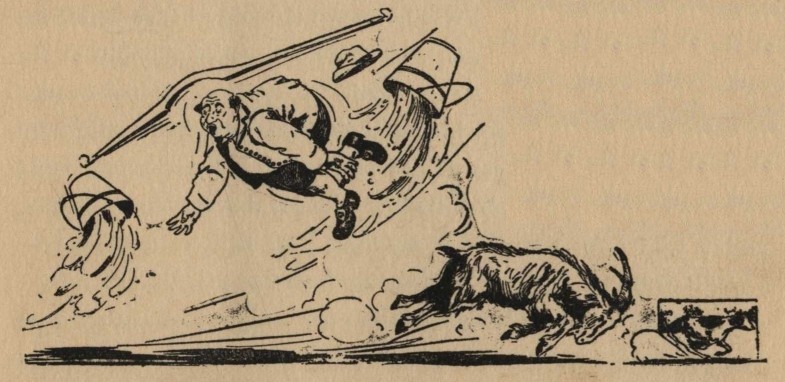

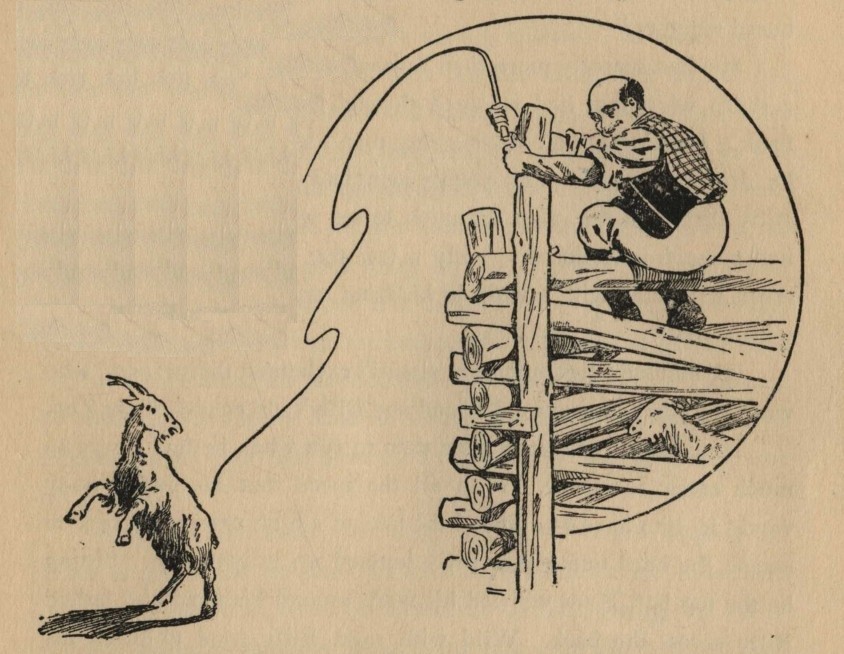

One day, when Billy was almost a full-grown goat, his chance came at last. Farmer Klausen was standing in the middle of the road to see that none got away, while his boys were driving the flock over to the lower meadows. Billy, who came up with the others, looking as innocent as a goat can look, suddenly wheeled, and with a hard jump landed his broad head and horns square in the stomach of his master. Farmer Klausen gave a yell, threw up both his hands and went heels over head into the dust, while Billy, scampering over him, ran as hard as he could for the hills.

Coming down the road toward him was fat Hans Zug with a yoke across his shoulders from which hung two great pails of goat's milk which he was taking down to the chocolate factory in the valley. Slow-witted Hans, when he saw neighbor Klausen's goat getting away, never thought of setting down his pails, but spread out his arms and stood square in the middle of the road, waving his hands and shouting: "Shoo! Shoo!" It was a big mistake to think that he could scare this scamp goat by saying "Shoo!" or by keeping his fat body in the road, for Billy came straight on with his head down, and just as Hans thought that maybe he had better step to one side, Billy gave a mighty leap and doubled Hans up just like he had Farmer Klausen.

"A thousand lightnings yet again!" yelled Hans as he went over. The two pails came down with a thud and a swish, and goat's milk ran all over the road and down the gulleys at the side. Hans Zug's dog, which had been sniffing at the roadside to see if he could find the trail of a rabbit, now jumped out and came at Billy. With one jerk of his strong little neck the runaway goat picked the dog up on his horns and tossed him clear over his head, where he landed plump on top of fat Hans and knocked the breath out of him for a second time, just as Hans was getting up. Then Billy, feeling fine from this nice bit of exercise, kicked up his heels and galloped on.

Just as he reached the woods he turned around and looked back. Farmer Klausen was on his feet again but had no time to chase Billy, for he was cracking his long whip and running from one side of the road to the other to keep the rest of the goats from breaking away. Billy could hear his loud voice from where he stood. Hans had also rolled to his feet and was holding his pudgy hands across his stomach, where he had been hit, while he looked dumbly at the rich, yellow milk which was in puddles everywhere. Thick-headed Hans was just making up his mind that the milk had really been spilled when another goat dashed by him, as fast as its feet could patter. As it drew nearer Billy saw with joy that it was his mother, and he waited for her. When she came close Billy called to her:

"Hurry up! We are never going back any more."

He kicked up his heels again in pure delight and was about to plunge into the woods when his mother called on him to wait, and he did so, though he did not like to do it, for the last of the flock was now safely in the other pasture, the gate was being closed on them and Billy knew that in a moment more Farmer Klausen and his boys and neighbor Hans would be coming after them.

When Billy's mother came up even with him she was panting so hard that she could not speak, but she did not stop. She kept right on running, and he followed, curious to see what she meant to do. As soon as they were out of sight of the men, she turned from the road into the woods, and by-and-by reached a little hollow which was all overgrown with bushes. Into this she raced, and Billy, now seeing what she was up to, scampered lightly along behind, thinking it to be great fun. The hollow grew deeper and wider and shadier as they went on, and at last she turned and scrambled up the dim, pebbly bank, where she plunged into a dry little cave. Here she lay down upon the ground to get her breath, while Billy climbed in beside her and listened. Soon he could hear the heavy pat, pat, of the feet of Farmer Klausen and his boys on the road, which was now high above them.

"They'll never find us here," he said.

"Don't 'baah' so loud or they will hear us," panted his mother. "My! I'm getting too fat to run any more, but if you were bound to go out in the world, I was bound to come with you. You're not old enough even yet to be trusted alone. But you are right about one thing; unless they catch us, we're never going back."

Suddenly they both became very still. The noise of the footsteps had died away, but there was a slow rustling of the leaves in the hollow. Something was coming toward them!

Nearer and nearer to where Billy and his mother lay hidden came the noise, and soon they saw a dim, dark-gray shape among the underbrush turn straight up toward them. It was a large wild boar, one of the fiercest animals that rove the forests of Europe. It had a great, shaggy head and cruel-looking curved tusks nearly a foot long. The two goats were in one of his hiding-places, and they knew that he would not stop to say "Beg your pardon" when he came up; whatever he had to say would be said with those sharp tusks. The space was too narrow for them to run out past him. Billy's mother was scared, but not Billy.

"The only thing for us to do is to fight," said he, and, jumping to his feet, he stood at the mouth of the little cave and gave a loud "baah!" which was to warn the boar that it had better go about its business.

The boar stopped and looked up at Billy with little wicked eyes, then he gave a loud snort, and, lowering his head, started to run straight up the hill toward them. Billy waited until the boar was close upon him, then he gave a sudden jump and landed square upon the fierce animal's back. The beast squealed and whirled around to rip Billy with his tusks, but before he could do so Billy himself had whirled and had hooked the big animal in the side. There was another squeal and Billy jumped out of the way. The animal turned and dashed after him, but in turning, his side was for an instant toward the mouth of the cave. It was just that instant for which Billy's mother was watching, and with all her might she jumped, butting him in the side with such force that he went rolling over and over, squealing and grunting, into the hollow. Billy was for jumping down after him but his mother knew better than that. She knew that it would be only an accident if they could whip this wicked animal, as the boar was so much the stronger, and that it was better to run than fight.

"Come quickly!" she cried, springing up the hill.

Billy stood for a moment, hardly knowing whether to follow her or not, but just then the boar scrambled to his feet and started after them, snorting and with fire-red eyes.

"Billy! Billy!" screamed his mother. "Do as I tell you!"

Even then, Billy, who never had known what it was to be afraid, wanted to stay and fight it out, but the sight of his mother scampering up the hill decided him. He was more afraid that he might lose her than he was that he could not whip the boar, so he took after her. The boar was also a good runner, but he was not nearly so nimble a climber as the goats and they soon out-distanced him, gaining the road, where they ran on as fast as they could go.

The road soon came to a narrow place where the trees stopped and the rocks rose straight up on either side. They were half way through this narrow stretch when Billy's mother stopped.

"Goodness!" she exclaimed. "I forgot about Farmer Klausen and his boys. They will be coming back past this way pretty soon, and if they meet us in here there will be trouble. We can't turn back on account of the boar and they will surely catch us."

"Well, then," said Billy, once more showing his bravery, "if we can't go back on account of the boar, we might just as well go on ahead and meet whatever comes, as to stand here wasting time. Maybe if we hurry we can get out before they get to us."

"I'm proud of you, Billy," said his mother.

They started to run on again, but had no more than done so when, sure enough, they saw a man coming toward them. It was fat Hans Zug, and the minute they saw who it was Billy laughed.

"Just watch me roll him over," he said, and started, as hard as he could go, toward the big round farmer.

When Hans saw Billy coming toward him this time he did not wave his arms and cry, "Shoo!" In place of that he put his hands on his stomach and turned around to run away from this little, white cannon-ball of a goat. It was comical to see the fat fellow waddling along, holding his hands in front of him, but he was making such slow progress that Billy felt sorry for him and thought that he ought to help him a little. It only took a few jumps to catch up with Hans and then—biff!—he struck him from behind so hard that Hans almost bounced when he hit the ground.

"A thousand lightnings, yet again!" yelled poor Hans.

He was just grunting his way to his hands and feet again when Billy's mother came along behind and—whack!—she gave him another tumble. This time he did not stop to look in either direction, but rolled over to the side of the road and, getting to his feet, tried to claw his way up the steep rocks, feeling almost sure that a whole regiment of goats of all colors and sizes was after him.

"Ten thousand, a hundred thousand lightnings!" wailed Hans. Billy, nearly laughing himself sick, waited for his mother, and when she came up they both pranced on. They had nearly reached the end of the narrow pass when they saw coming toward them Farmer Klausen and his two boys. The boys were running on ahead, quite a little distance in front of their father, and Billy said quickly:

"You take Chris and I will take Jacob!"

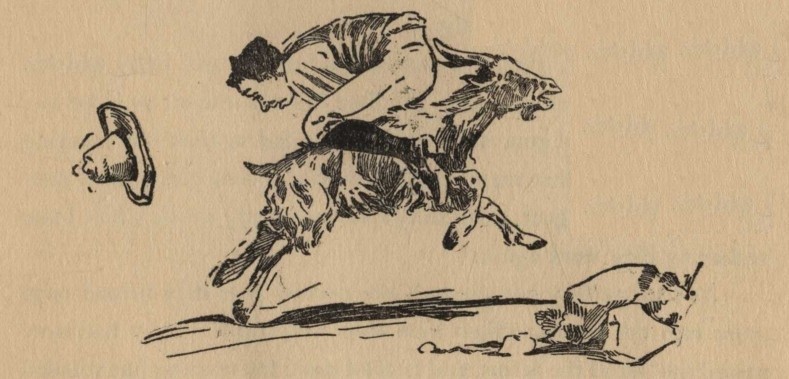

So when they came up to the boys they just dived between their legs. Billy upset Jacob easily enough, but Chris was lighter, and when the fatter goat tried to escape between his legs he simply fell over on top of her. Without stopping to think what he was doing, he grabbed his arms about her middle and hung tight, while she raced on for dear life. By this time they were up to the farmer. Billy easily dodged him, but it was not so easy for his mother. With Chris hanging on her back, Farmer Klausen was able to grab her by the horns and hold her tight.

"Billy, Billy! Help!" squealed his mother, and Billy whirled around to come back at once. He flew through the air as if he had been shot out of a gun, and when he landed against the stooping Farmer Klausen, that surprised man turned a somersault clear over Chris and the old goat, then Billy's mother easily shook Chris loose and away they went again.

As soon as they got through the narrow pass they turned once more into the woods, which here sloped upward. They had now passed the last of the farms, and beyond them lay nothing but wooded hills and the mountains. Up and up they scrambled until at last, near nightfall, they came to a little, grass-grown tableland, watered by a tiny stream that tumbled down from the mountains, and here, after taking a long drink, they rested. After a while they made a good meal from the tender young grass that grew at the side of the stream, and lay down again. Soon they were fast asleep, side by side.

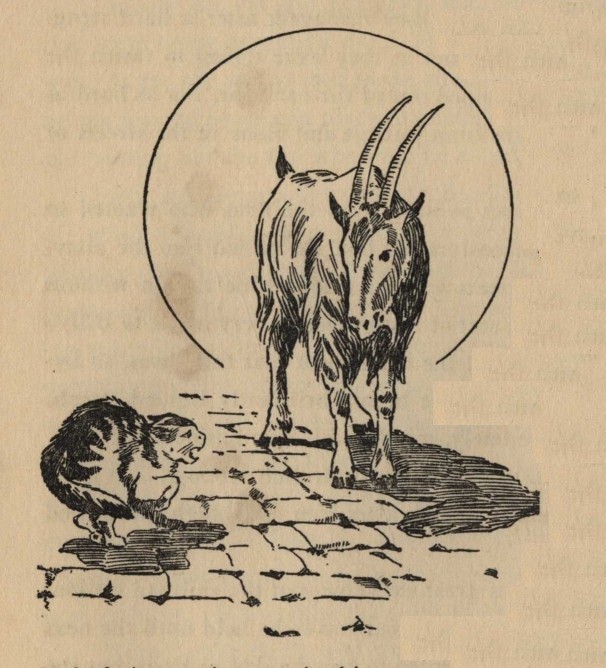

It was nearly midnight and the moon was shining brightly overhead, when they were both awakened by a terrific scream, and at the same moment a soft, heavy body landed upon Billy's back! Sharp claws struck his hide and sharp teeth sank into the back of his neck!

CHAPTER II

HE LOSES HIS MOTHER

t was a mountain lynx that had sprung upon Billy from

the rocks above. This lynx often came down to the

highest of the goat farms, and had many times annoyed

fat Hans Zug and Farmer Klausen by stealing nice, fat

young kids for his supper. This time, however, he had met his

match, for Billy's mother no sooner saw the animal light upon her

offspring than she scrambled to her feet, and, with a short, quick

jump, plunged her sharp horns into his side. The lynx screamed,

and loosing his grip on Billy, turned to fight with the mother goat.

The moment his weight was lifted, Billy, quick as a flash, ripped

at the underside of the beast with his sharp horns. That made the

animal snarl and loosen his hold upon Billy's mother, and between

them they soon, in this way, gave the lynx more than he had bargained

for, so that presently he fled howling up the steep rocks with

the two goats chasing him as far as they thought it safe. Then they

came back to their grassy spot, and bathed their hurt places in the

cool, running water.

t was a mountain lynx that had sprung upon Billy from

the rocks above. This lynx often came down to the

highest of the goat farms, and had many times annoyed

fat Hans Zug and Farmer Klausen by stealing nice, fat

young kids for his supper. This time, however, he had met his

match, for Billy's mother no sooner saw the animal light upon her

offspring than she scrambled to her feet, and, with a short, quick

jump, plunged her sharp horns into his side. The lynx screamed,

and loosing his grip on Billy, turned to fight with the mother goat.

The moment his weight was lifted, Billy, quick as a flash, ripped

at the underside of the beast with his sharp horns. That made the

animal snarl and loosen his hold upon Billy's mother, and between

them they soon, in this way, gave the lynx more than he had bargained

for, so that presently he fled howling up the steep rocks with

the two goats chasing him as far as they thought it safe. Then they

came back to their grassy spot, and bathed their hurt places in the

cool, running water.

"Now, Billy, you see what the world is like," said his mother. "Don't you wish that we were safely back in Farmer Klausen's pasture?"

Billy dipped his scratched hind leg in the water and held it there while he shook his head.

"No," he said, "this is better. Only I'm glad that I didn't get a chance to run away until I was so big and strong."

His mother sighed, but looked at him proudly.

"You are a brave young goat," she said, "and it would be a shame to keep you shut up in a pen."

In the morning they were a little stiff from their hurts, but Billy was still eager to travel and see the world, so they went on into the mountains. About noon they followed a little ravine down to a plateau where there was a whole herd of chamois. These graceful animals are about the size of a goat, but they are not so heavily built and are much swifter. At first the chamois did not want to let the goats join them, but old Fleetfoot, the leader of the herd, said that they might stay if they were not quarrelsome, but that they would have to look out for themselves if hunters came that way.

This little plateau was a beautiful place, all carpeted with grass and backed up by towering rocks. At one end was a cliff looking out over a valley, at the further end of which was a little village. Billy, in his eagerness to see the world, ran at once to the edge of the cliff.

"You reckless Billy!" cried his mother, running after him. "Don't go so close to that cliff or you will surely fall over and break your neck!"

"I'm not afraid," boasted Billy, and actually stood on his hind legs at the very edge.

Just then a few loose stones came rolling down the ravine, and like a flash the entire herd of chamois were gone, leaping across a broad chasm to a little ledge upon the other side, where there was a second path that led among the rocks.

"Oh, what shall we do?" cried Billy's mother. "Here come two hunters with guns, and we can't jump where they did. Why, it's twelve feet across there!" She was frightened half to death but not for herself, for she threw herself squarely between Billy and the hunters.

The hunters were ignorant fellows, and as soon as they caught sight of the two goats they thought that these also were chamois, and one of them, lifting his gun, shot at them, grazing the head of the mother goat. She toppled over against Billy, and that knocked him over the cliff. If it had not been for a small tree which grew out of the cliff about half way down, Billy would have been dashed to death, but the tree broke his fall and so he only lay in the valley stunned, while the hunters picked up his mother and in great glee carried her away, thinking they had shot a chamois.

When they got back to their guide he told them their mistake, and saw, too, that the goat was only stunned; so they gave it to him and he sold it next day to a man who was buying some extra goats for Hans Zug, to stock a goat farm in America.

In the meantime poor Billy lay almost dead at the base of the cliff, where a man found him about an hour later.

"You poor goat!" said the man, looking up at the cliff. "Did you fall down from that dizzy height?" and he put his hand on Billy's sleek coat. "At least you are not dead," he went on, feeling Billy's heart beat. "I'll get you some water."

He took off his little round hat and ran back to where a tiny waterfall came splashing and tumbling down the cliff, and, filling his hat full of water, brought it and emptied it on the goat's head. The cool shower revived Billy so that he raised his head a little, and by the time the man got back with the second hatful of water he was able to drink a little. This revived him still more, and presently he scrambled weakly to his feet. He stumbled and swayed and nearly fell down, but by spreading his feet out he managed to stand up, and by-and-by he took a few tottering steps. With each step he grew stronger, and after another good drink he was able to follow this kind man across the valley to the little village.

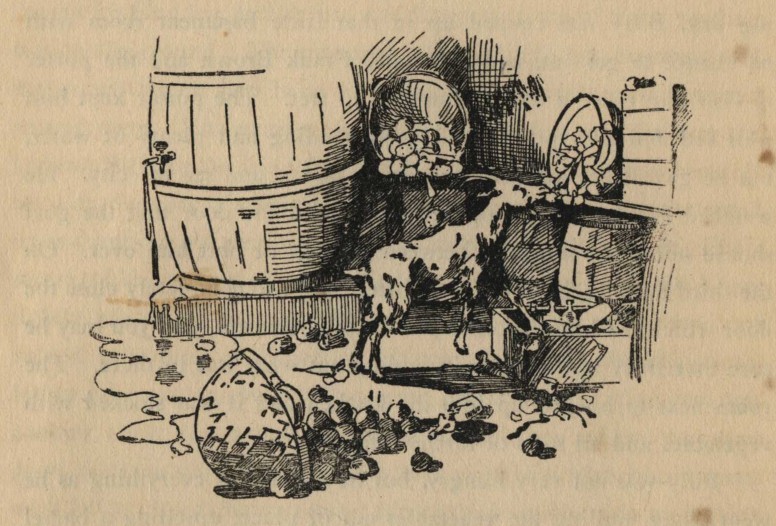

Billy was glad enough to lie down and take a nap as soon as he got to the man's house, and he did not wake up until late at night. After his good sleep he felt as strong as ever and thought he would get something to eat, then see if he could not find his mother. He found that he was tied to a fence not far from a little whitewashed building, under which ran a stream of water, but it did not take long for him to jerk himself loose. Going toward the little white building, he smelled something that reminded him of milk. He tried to get in at the door. It was fastened with a wooden button but Billy did not care for that. He went back a little piece to get a run, and bumped head first into the door, which flew open at once.

"Milk!" said Billy, sniffing around in delight. "Nice sweet milk! I'm sure that kind man would want me to have some."

There was a little board walk down the center of this spring-house, and on each side of this were a number of crocks setting in the water, each one of them covered with a plate and containing milk. A stone was laid on top of each plate to weight the crock down in the water, and in trying to nose off one of these plates Billy reached over too far and fell. He landed right among the crocks, which, of course, bumped into each other, breaking and overturning and spilling the milk, and making a great clatter. At the noise, two dogs came running down and dashed into the spring-house, where, seeing something floundering around in the water, they promptly dived in after it and Billy found himself very busy. The noise the dogs made aroused the man and his wife, and they, too, came down; the noise they made aroused the neighbors on both sides, who came running over to see what was the matter; a young man, who was coming home late from calling on a girl, passed by that way and saw the people from both sides running to this house and thought there must be a fire, so he ran to the town hall, where the rope of the fire bell hung outside, and began ringing it as loud as he could, which aroused everybody in the village. Hearing the commotion many got out of bed and came out on the streets to learn where the fire was.

All this time Billy, the cause of the hubbub, was battling with the dogs among the milk crocks in the spring-house, and using his horns right and left as hard as he could, until finally he was able to jump out between them and on to the board walk. Out of the door he dashed, upsetting the man and his wife, butting into the neighbors and, all dripping with white milk, ran like the ghost of a goat through the village street, making women and girls scream, scattering people right and left and being chased by yelping dogs and halloing men and boys.

Billy easily outran his pursuers, but he never stopped until he was far out in the country, where he crept under a stone bridge to rest from his long run. As soon as he had got his breath, he broke into a near-by field and made a splendid supper from some nice young lettuce heads, then he trotted contentedly back under his bridge and went to sleep. In the morning, bright and early, he went back into the market garden and made a fine breakfast from beet and carrot tops, all sparkling with cool dew. He enjoyed this garden very much and would like to have stayed there until all the nice vegetables were eaten up, but he remembered how Mr. Klausen had whipped him for breaking into his turnip patch one time, and made up his mind that it would not be safe to linger in this part of the country much longer, so he jumped the fence and started again on his travels.

A little dog was trotting down the road, and as soon as he saw Billy he began to bark. To ordinary persons the barking would have sounded merely like a lot of bow-wows, but in the animal language it said:

"Where did you come from, you big white tramp? You go right on away from here or I'll call the police."

Billy wasn't going to take that sort of talk from any dog, big or little, so he gave one "baah!" lowered his head, and started for that dog. The dog suddenly found out that he had very important business back home, and he started up the road as hard as he could go, with Billy close after him. There never was a dog that ran so hard and so earnestly as that one, and all the breath that he could spare from running he used in howling, to let the folks at home know that he was coming. All at once he was very anxious indeed to get home in time for breakfast, and Billy was just as anxious to toss him over a fence before he got there. Up one hill and down another went the two, lickaty-split, first a little white streak bent low in the dust, and then a bigger white streak coming along close behind in a whirling cloud. Pretty soon they came in sight of a big square farmhouse with a wide-spreading roof, and then the little dog, his tongue hanging away out, gave an extra wild howl and ran faster than ever. When they got to the house the dog turned in at the open gate with Billy right at his heels. He tore up the path and around to the kitchen door, up the steps and into the kitchen, pell-mell, where he dived under the table at which the Oberbipp family was having breakfast.

Billy did not know where he was going and did not very much care. All he knew was that he was chasing that dog and meant to catch him, so without looking, he followed, too, up the steps and under the table. Such shrieking and howling never was heard. Herr Oberbipp jumped up so quickly that he upset his chair, and in trying to catch the chair he upset himself, turning a back somersault on the floor and landing in a tub of soapsuds in which the clothes were soaking to be washed. Frau Oberbipp grabbed a loaf of bread in one hand and a sausage in the other, and never left off screaming until she was out of breath. Greta Oberbipp sprang up on her chair and shook her skirts as hard as she could, while she helped her mamma scream. Baby Oberbipp jumped up on the table at first, but the snarls and howls and "baahs" from underneath excited his curiosity so much that he soon jumped down to the floor and looked under the table. Then he began to dance on one foot and yell.

"Hang on, you Flohbeis!" he cried, for the dog, now full of courage because he was under his own table, had grabbed Billy by the nose. Shake his head as hard as he might, Billy could not loosen Flohbeis, or Fleabite, as his name would be called in English, so he reared straight up, and the table began to dance across the room toward the father of the family, while Frau Oberbipp and Greta screamed louder than ever. Herr Oberbipp was just getting out of the tub when the table got over to him, and he made a grab at it when Billy gave an extra strong jump. The table overturned, and all the breakfast things, with a mighty crash of dishes, slid on Herr Oberbipp and knocked him back in the suds again. By this time Billy had unfastened the grip of Fleabite from his nose and had butted that yelping dog into the bottom of the tall clock case; then Billy started for the door, but Herr Oberbipp was already yelling to Caspar not to let him out.

"Grab him, Caspar! Hold him!" yelled the man. "He is a nice young goat. He spoils our breakfast and we make a dinner of him."

When Billy heard that, he was more anxious than ever to get out, but Caspar had slammed the door shut, and Billy, seeing it closed, tried to butt it down. The door was too strong and Billy grew desperate. Caspar ran after him and Billy suddenly turned, running under Caspar's legs and toppling him over; then he made for the window, meaning to go through it, sash and all. But Caspar had already jumped up, and, as the goat went through a pane of glass, Caspar grabbed him by the hind legs and held him, while Billy, fairly caught and pinched in between the window bars, could only struggle with his fore feet.

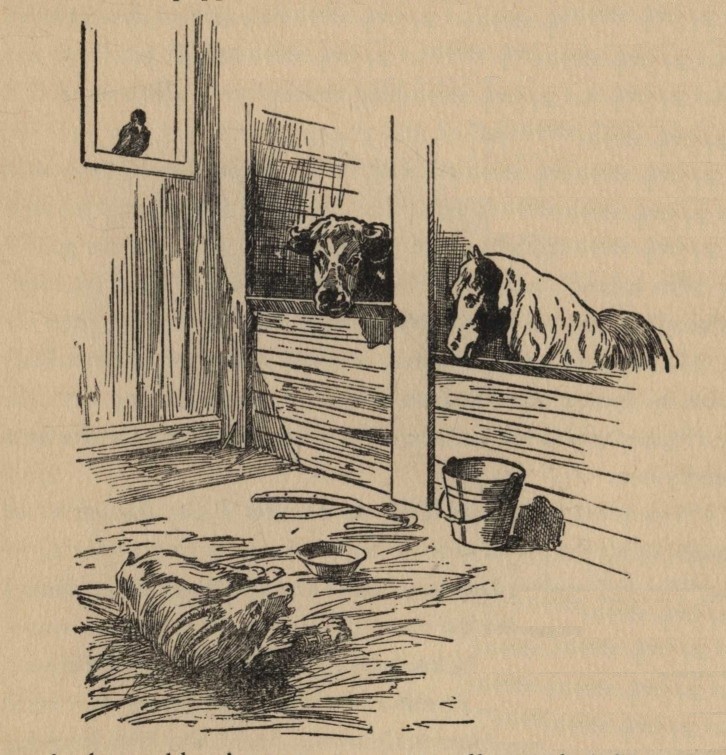

Herr Oberbipp in the meantime got himself out of the tub of water, took the butter out of his hair and the mush out of his shirt front, untangled himself from the table-cloth, wiped the coffee from his face and ran outside, where he grabbed Billy by the horns and pulled him on through the window. Herr Oberbipp was a big, strong man, and, holding Billy by the horns, he carried him at arm's length down to the barn, letting him kick and struggle all he wanted to, and there he tied the goat in a stall with a good stout wire, after which he went back to the house and washed himself. Frau Oberbipp and Greta were still screaming.

The glass had given Billy two or three little cuts, but they did not amount to much and he had already licked them clean when Caspar came out with some water and a plate of cold potatoes which Billy was very glad to get. While the goat was eating, Caspar examined the cut places, and, running into the house, brought out something which he put on the cuts. It smarted at first, and Billy tried to butt Caspar for putting it on, but by-and-by he could feel that the smarts were being soothed and that the cuts were healing by reason of the stuff that the boy had put on, so he began to see that Caspar was not such a bad sort after all. He had something to worry about, however, when, after breakfast, the farmer came out and looked the goat over.

"Roast kid is a very fine dish," said the farmer. "I don't know to whom this goat belongs, but whosever it is he owes us a meal, so we're going to roast him."

CHAPTER III

BILLY SEES HIS MOTHER AGAIN

obody, not even a goat, likes to think of being roasted

for dinner, and so, the minute he heard that, Billy gave

an extra hard tug at the wire, but it only cut his neck

and choked him and would not break. So he gave it

up and "baahed" pitifully while he looked to Caspar for help.

obody, not even a goat, likes to think of being roasted

for dinner, and so, the minute he heard that, Billy gave

an extra hard tug at the wire, but it only cut his neck

and choked him and would not break. So he gave it

up and "baahed" pitifully while he looked to Caspar for help.

"Indeed you will not roast this goat," said sturdy Caspar. "He's my goat; he chased my dog and I'm going to keep him."

Caspar looked up at his father and his father looked down at Caspar. Billy looked up at both of them. Little Caspar and big Caspar stood exactly alike, both of them with their fists doubled on their hips and both of them with square jaws and firm lips, and it was big Caspar, who, proud to see his boy looking so much like himself, finally gave in. He laughed and said:

"All right, he's your goat, but you have got to take the whippings for all the damage he does."

"Very well," said Caspar, "I'll do it," and his father walked away.

Billy was so pleased with this that he made up his mind to be very nice to the boy, and when Caspar stooped down to take the empty plate away, Billy ran his nose affectionately into young Oberbipp's hand. Right after breakfast Caspar took off the wire from Billy's neck, holding a switch in his hand to whip the goat over the nose in case he tried to butt or run away. But Billy did neither of these things. He followed his new master out in the yard, and there he was backed up between the shafts of a little wagon that had been made for Fleabite. The dog capered and barked and made a run or two at Billy, but the goat only shook his horns at him and Fleabite ran under the barn. The dog was jealous. He did not like the wagon, but, rather than have the goat hitched up to it, he wanted to haul it himself.

"It's no use, Fleabite," said Caspar, "you might as well make friends with him. Anyhow, you're not big enough to haul this wagon, and you always lay down in the harness. You can come along behind, though. I'm going to drive in to Kasedorf and show my goat to cousin Fritz."

At first Billy was afraid that Kasedorf might be the village where he had torn up the spring-house, and he had very good reasons for not wanting to go back there, but when they clattered out of the gate Caspar turned his head in the other direction, and he was very glad of this. He was so pleased with his new master that he went along at a splendid gait, pulling Caspar nicely up one hill after another. Fleabite ran along, sometimes behind, sometimes ahead, and sometimes slipping up at the side and snapping at Billy's nose; but Billy had only to shake his horns in the dog's direction and Fleabite would run about a mile before he would take it into his foolish head to try that trick again.

Pretty soon they went whizzing down a little hill and into a far prettier village than the first one. Just as they turned into the main street, along came a flock of goats driven by two men and half a dozen boys, and who should Billy see in that flock but his own mother! Of course he called loudly to her. She heard him, and though she was in the center of the flock, quickly made her way to the edge, where she kissed him. She had no time to tell him where she was going, nor he to tell her all that had happened to him since he had fallen from the cliff, but it was a joy for each of them to know that the other was still alive and in good health.

Before they could speak further, a sharp whip cracked over them and the lash landed on Billy's nose. He jumped back with the pain and again the whip cracked. This time Billy's mother got the sting of it. Billy looked around, and there, handling the whip, was fat Hans Zug! Billy, mad as a hornet, whirled and was going to make for Hans, when Caspar, who had jumped out of the cart, hit him a sharp crack across the nose with his fist, and it pained Billy so much that the tears came to his eyes and he could not see. Before he could make another start for Hans or run after his mother, Hans had passed by, and Caspar's uncle Heinrich, who had come up in the meantime, had Billy by the horns and was holding him. Billy struggled as hard as he could to get away. He wanted to butt Hans Zug for whipping his mother and himself, and he wanted to go with his mother if he could, so he was a very sulky goat.

Even when Caspar took him to his uncle's house and gave him some nice, tender vegetables and potato parings to eat, he was very sulky as he stood there munching his dinner, so that when Fleabite came up and stole some of his potato parings he butted that poor dog plump into a barbed wire fence. You must not suppose that Fleabite liked potato parings. He would not eat them at home, but he was such a jealous dog that he wanted to eat up Billy's dinner, no matter what it was. After dinner Caspar rubbed Billy's sleek coat until it was all clean and glossy, then he let Fritz have a ride in the cart. Fritz drove proudly up into the main street, and there, standing at the corner, talking to another man, was Hans Zug!

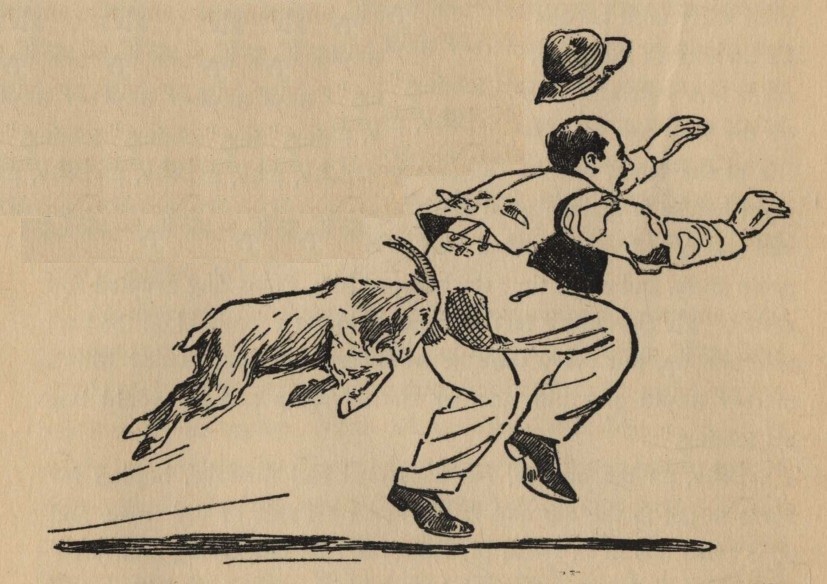

"Yes," Hans was saying in English to the other man, "I go me also by America next week. I got such a brother there what is making more as a tousand dollars a year mit such a goat farm, and I take me my goats over. I got a contract mit another Switzer what owns the land. Yess!"

Billy did not wait for any more, but raised up on his hind feet. Fritz tried his best to hold him back, but he might as well have tried to hold the wind, and Billy, feeling the tug at his reins, gave a jump that toppled Fritz over backwards out of the cart. He gave one more jump and landed with all his might and main against poor, round Hans, and as his enemy went down Billy jumped on him and ran up one side of him and down the other side. Poor Hans got up and clasped both pudgy hands on his stomach.

"A thousand lightnings yet again!" he exclaimed as he looked sorrowfully at his print in the dust. Hans had been butted that time for Billy's mother; now Billy whirled and came back to give Hans one for himself, but this time Hans was too quick for him and dodged behind a tree, letting Billy butt the tree so hard that it stunned him, and before the fiery tempered goat could make up his mind what had happened to him, Caspar came running up and grabbed him by the horns. Billy could have jerked away from Caspar, but he felt that the boy was now the best friend he had, and he did not want to hurt him, so he let Caspar pat him on his sleek sides and climb into the cart behind him.

"You'll have to walk, Fritz," said Caspar loftily. "It takes a good strong boy to manage this goat."

Billy laughed at this, but when Caspar "clicked" for him to "get up," he trotted right along without making any fuss about it.

At the next corner a carriage turned into the main street, and in it, on the seat back of the driver, were a man and a boy, the latter being of about Caspar's age.

"Oh, papa, do look at that beautiful goat!" exclaimed the boy. "Please buy him for me, won't you?"

Mr. Brown shook his head.

"I don't mind you having a goat, Frank," he said, "but I can get you just as good a one when we get back to America. There is no use in carrying a goat clear across the ocean with us when there are so many at home."

"All right," said the boy, obediently, and the carriage drove on.

Poor Billy! His heart sank. He had just heard from Hans that his mother was going to America, and he did hope that this fine looking man would buy him and take him there, too, so that he would have more chance to find his mother; but now his chance was gone. Was it though? He was not a goat to give up easily, and he made up his mind to try once more.

Billy stopped dead still to think it over. He simply could not bear to let this man get away without another trial, so suddenly he whirled, nearly upsetting the cart, and ran after the strangers. He soon caught up with them, and then, slowing down, he trotted along at the side of the carriage, showing off his beauty as much as he could.

"Oh, papa, there is that beautiful goat again," said the boy. "How I do wish I could have him! Of course you can buy me one in America, as you have promised to do, but they say that there are no goats in the world so fine as the Swiss goats, and I am sure that I never saw any so pretty as this one."

The man smiled indulgently at his son and stopped the carriage.

"How much will you take for your goat, my boy?" he asked.

"I don't want to sell him," replied Caspar. "He's my goat and I like him."

Just then Billy tossed his fine head and pranced, daintily lifting his feet.

"See how graceful he is!" exclaimed the boy. "Do buy him, papa!"

"I'll give you ten dollars for him," said the gentleman, pulling out his pocketbook.

Caspar caught his breath. He knew the value of an American dollar, and ten dollars was equal to more than forty German marks. It was a great lot of money, too much for a poor boy to refuse. Caspar drew a long sigh and began to slowly unhitch his goat. The driver of the carriage threw him a strap, and with this he tied Billy to the rear axle of the carriage.

Fleabite, as soon as Billy was safely tied, began to caper with joy and to snap at Billy's heels, but Caspar, when the man had paid him his money, grabbed Fleabite and hitched him to the cart. Then he ran up and patted Billy affectionately on the flanks, and the carriage drove away, with Billy following gladly behind in the dust.

Down the village street the carriage rolled until it came to a quaint little Swiss inn, where it turned through a wide gateway that led into a brick-paved courtyard. Here Billy was unfastened from the carriage by a servant and led back of the inn, where he was tied by the strap to a post, while Mr. Brown and his son Frank went to their mid-day meal. Billy didn't like to be tied; he was not used to it, so he began to chew his strap in two. It was very tough leather but Billy's teeth were very sharp and strong, and he had it about half gnawed through when a little, lean waiter came from the kitchen across the courtyard, carrying, high up over his head, a great big tray piled with dishes of food. The waiter saw Billy gnawing his strap in two and thought that he ought to keep him from it.

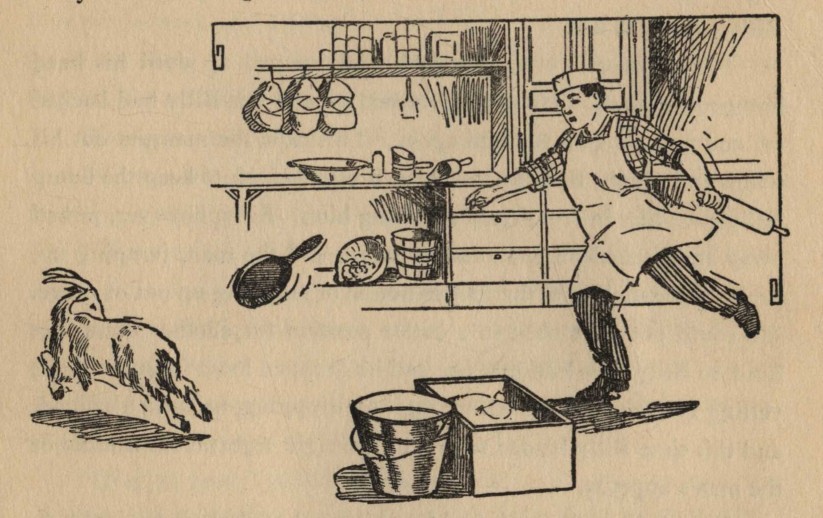

"Stop that, you hammer-headed goat!" he cried and gave Billy a kick.

Billy was not going to stand anything like that, so he gave a mighty jump and the strap parted where he had been gnawing upon it. As soon as the lean waiter saw this he started to run, but, with the heavy tray he was carrying, he could not run very fast and he looked most comical with his apron flopping out behind him and his legs going almost straight up and down in his effort to run and to balance the tray at the same time.

When Billy pulled the strap in two, the jerk of it sent him head over heels and by the time he had scrambled to his feet again the waiter was half way to the back door of the inn. The fat cook, who was looking out of the door of the summer kitchen, saw Billy start for the waiter and he started after the goat, but he got there too late, for the goat caught up with the lean waiter in about three leaps and with a loud "baah!" sent him sprawling. The big tray of dishes came down with a crash and a clatter, and meats, vegetables, gravies and relishes, together with broken dishes, were scattered all over the fellow who had kicked Billy, all over the clean scrubbed bricks, spattered up against the walls and into the long rows of geraniums that grew in a wooden trough at the end of the house.

Billy turned and was about to trot back when he saw the fat cook coming just behind him, so he ran right on across the little waiter, through the mess and to the back door. Crossing the winter kitchen he found a big, rosy-cheeked girl standing in his way and made a dive at her. With a scream she jumped and Billy's horns caught in her bright, red-checked apron, which jerked loose. With this streaming along his back, he dashed on into a long hall, and there at the far door whom did he see, just starting into the dining-room, but his old enemy, fat Hans Zug, who had that morning whipped Billy's mother and himself. Billy stood up on his hind feet for a second and shook his head at Hans, and then he started for him. Hans saw him coming.

"Thunder weather!" he cried, and ran on through the door.

He tried to shut the door behind him but he was not in time, for Billy butted against it and threw it open right out of Hans Zug's hand. The long room into which Hans had hurried was the dining-room, and here were seated, around a long table, a number of ladies and gentlemen, among them Mr. and Mrs. Brown and their son Frank, waiting for the dinner that now lay scattered around the courtyard. Everybody looked up, startled, when Hans came bursting through the door closely followed by an angry goat with a red-checked apron streaming from his horns. A great many of the men jumped up and scraped their chairs back, adding to the confusion, and a great many of the ladies screamed. Hans, not knowing what to do, started to run around and around the table with Billy close behind him and the fat cook close after Billy. Billy would easily have caught Hans except that every once in a while Hans would upset a chair in the goat's road and Billy would have to jump over the chair. Sometimes the fat cook would almost catch Billy and finally did succeed in catching the apron. When it came loose in his hand he did not know what to do with it. He started to throw it down, he started to stuff it in his pocket, he started to mop his perspiring face with it, and at last he threw it around his neck and tied the strings in front to get rid of it, then once more he chased after Billy, with the red apron flopping out behind him.

At last he grabbed Billy by the tail just as he was going to jump over the chair, and held on tightly, but Billy's jump had been too strong for him and the fat cook stumbled head over heels. Jumping up the angry cook ran until he again caught the goat, and this time he fell on top of Billy and then both rolled over and over on the floor.

"Ugh!" grunted the fat cook. "Beast animal!"

Billy jumped up in such a hurry that he simply danced on the fat cook's stomach. While Billy was doing this, Hans had stopped for a minute to mop his face and to look wildly around for some way to escape. Around and around, around and around the two raced, poor Hans puffing and blowing and his face getting redder and redder every minute with the chase.

Some men had been calsomining the wooden ceiling of the dining-room, but they had quit during meal time. At one end of the room stood two step-ladders with some long boards resting across them, and on these were a number of buckets of green calsomine. Hans had tried to get out through the doorway, but there were too many people crowded into it and he knew that if he got into that crowd Billy would surely catch him, but now he saw the step-ladders, and running to one of them started to climb up. Billy, however, was through with the cook and had taken after Hans again.

Hans, being so fat, was very slow in climbing a step-ladder, and he had only puffed his way up one step when Billy tried to help him up a little farther with his head and horns after a big running jump. Smash! went the step-ladders. Crash! went the long boards. The buckets of green calsomine flew everywhere. One of them tumbled down right over Hans' head like a hat that was a couple of sizes too large for him, and the green paint ran all over his face, down his neck and over his clothes. Another bucket of it landed in the middle of the dining-room table, splashing and splattering all over the clean cloth and over everybody who sat around it.

Billy, having done more damage than a dozen ordinary goats could hope to do in a lifetime, now made for the door, and the people there scattered very quickly to let him through. Billy himself had received his share of the green calsomine and he was a queer looking sight as he darted out and went flying up the street, with an enemy after him in the shape of the fat cook, who had grabbed down a shot-gun from where it hung over the mantlepiece in the dining-room and had started out after him.

The cook was mad clear through and he was going to kill that goat. Frank, however, was close after the cook, and being able to run much the faster, soon caught up with him.

"Wait!" he panted, tugging at the tail of the cook's white jacket. "Wait! That's my goat!" he cried. "Don't you kill my goat!"

"Away with you, nuisance!" cried the cook, jerking loose from Frank and at the same time pushing him.

Frank fell over backwards, although it did not hurt him, and while he was getting to his feet the cook took careful aim at the flying goat and pulled the trigger.

CHAPTER IV

THE BURGOMASTER IS BUMPED

illy Mischief was lucky. In his excitement the fat

cook had forgotten that the shotgun had not been loaded

for five years. The cook was so angry that he nearly

burst a blood vessel. Grabbing the gun by the barrel,

he jammed it, as he thought, butt end on the ground. Instead of

that, however, he struck his broad foot a mighty thump.

illy Mischief was lucky. In his excitement the fat

cook had forgotten that the shotgun had not been loaded

for five years. The cook was so angry that he nearly

burst a blood vessel. Grabbing the gun by the barrel,

he jammed it, as he thought, butt end on the ground. Instead of

that, however, he struck his broad foot a mighty thump.

"Thunder and hailstones!" he screamed, and jerking his foot up he began to hop along on the other leg, making the most ridiculous faces while he did it. In spite of the pain that the gun must have caused the cook, Frank could not help but laugh, and he forgot all his anger at the push the man had given him.

"What's the matter?" asked Frank when he could catch his breath. "Does it hurt?"

The cook did not understand English but he felt that Frank was poking fun at him, and stopped his dance long enough to shake his fist at Frank. He wanted to say something very sharp and cutting to the boy, but he could not think of anything strong enough, so, after drawing his breath hard two or three times and screwing up his mouth with pain, he turned the gun muzzle end down, and, using it for a crutch, swung along back to the inn, muttering and mumbling all the way.

Frank laughed so hard that he had to sit down at the edge of the sidewalk a moment to hold his sides, but all at once he thought of his goat. There it was, going up the street, and although little more than a green and white speck now, Frank bravely took after it. He probably never would have caught it except that Billy, also being tired and feeling himself free from pursuit, stopped before a big house set well back from the street, on a wide, fine lawn.

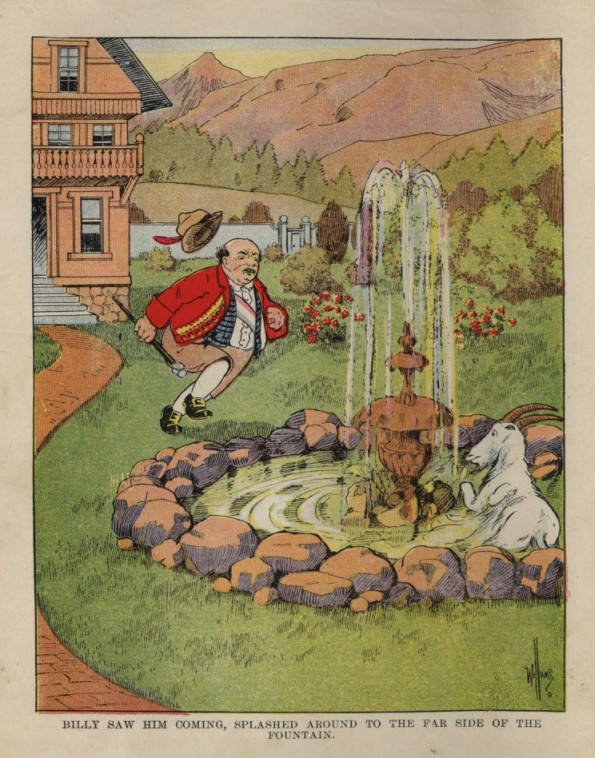

Now the house in front of which he had stopped was the residence of the burgomaster, or mayor of the village, a very pompous fellow who thought a great deal of his own importance, and in the center of his lawn he had a fountain of which he was very proud. The water in the base of the fountain was clear as crystal and it looked very cool and inviting to Billy after his dusty run, and, besides, the paint on his back felt sticky. Without wasting any time about it, Billy trotted up across the nice lawn and jumped into the fountain for a bath, just as the burgomaster came out of his front door with his stout cane in his hand.

"Pig of a goat!" cried the burgomaster, hurrying down the walk and across the lawn. "Out with him! Police!" and he drew a little silver whistle from his pocket, whistling loudly upon it; then, shaking his cane in the air, he ran up to the edge of the fountain, the waters of which were turned a bright green by this time. Billy saw him coming, but, instead of jumping out of the fountain and running away, he merely splashed around to the far side of the basin. The burgomaster ran to that side of the fountain but Billy simply splashed around out of his reach. Then the burgomaster, up on the stone coping of the fountain, began to run around and around after Billy, the goat keeping just out of his reach and the burgomaster trying to strike him with the cane. At last, after an especially hard blow, the burgomaster went plunging headlong into the green water of the basin, where he floundered about like a cow in a bath tub.

Billy jumped on him and used him as a stepping stone out of the basin, running back to the street just as Frank and a stupid looking policeman came running up from different directions. At first the policeman was going to arrest the goat, but Frank pointed to where the burgomaster was still flopping around in the fountain and the policeman ran to help the burgomaster, who was now dyed a beautiful green, face and hands and clothes, while Frank took Billy by one horn and raced back down the street with him. This was what Billy liked. He was a young goat, and, like other young animals, was playful, and he thought that Frank's racing with him was good fun, so he went along willingly enough, and when Frank let go of his horn, he galloped along beside his young master very contentedly.

Frank ran back to the hotel with his goat as fast as he could go, but when they drew near he saw a large crowd out in front and their carriage waiting for them, with the horses hitched and the driver sitting up in front. Mrs. Brown was in the carriage and Frank's father was in front of the crowd handing out money, first to one and then to the other. When Frank and his goat came up his father looked at the goat very sternly.

"See all the trouble that animal has made us!" he said. "I have had to pay out in damages nearly every cent of cash I have with me, and as there is no bank in this little village, my letter of credit is worth nothing here. We must hurry on to Bern as fast as we can, and I want you to leave that goat behind you. We can't bother with him any more. Come on and get in."

"But, father," explained Frank, "the goat did not know what he was doing."

"It does not matter," replied Mr. Brown. "There's no telling what kind of mischief he will get into next."

"But, father," again urged Frank, "if you've had to pay out all that money for him you might as well have the goat. There is no use of losing the goat and money, too."

"Get in the carriage," said Mr. Brown, sharply.

"But, father—" again Frank began to argue. This time, however, Mr. Brown cut him short, and, picking him up, put him into the carriage with a not very gentle hand. Then, climbing in himself, he ordered the driver to start.

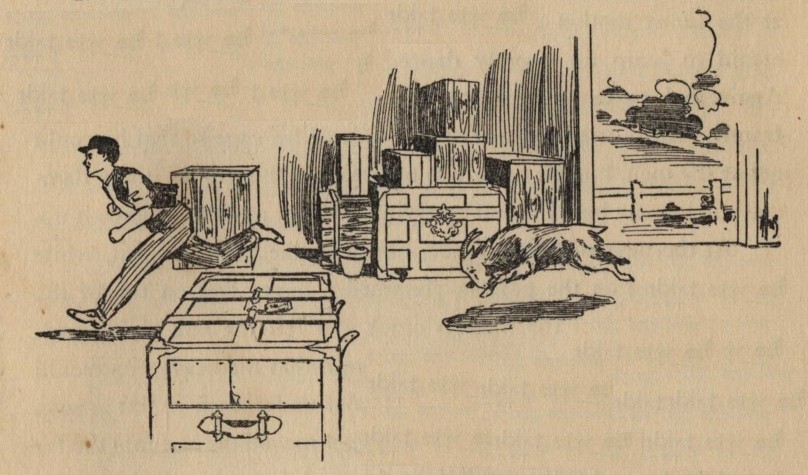

Billy had taken his place back where he had been tied the other time, and he was surprised to find the carriage moving on without him. The cook, seeing that the goat was to be left behind, started forward to give the animal a kick, but Billy was too quick for him. Wheeling, he suddenly ran between the cook's legs and doubled him over. Just behind the cook stood Hans Zug, and as Billy wriggled out sideways from beneath the cook's feet, the cook tumbled back against Hans and both of them went to the ground. Billy stood and shook his head for a moment as if to double them up again before they got to their feet, but the sight of the retreating carriage made him change his mind and he ran after it with Hans and the fat cook chasing him.

The carriage was not going very rapidly, and Billy, after he had caught up with it, merely trotted along back of the rear axle, so that when the carriage passed the burgomaster's house, Hans and the cook were not very far behind. They were bound to catch that goat and punish him for what he had done, although it is very likely that before they got through they would have sold him and kept the money. The burgomaster was still out in front, fretting and fuming, but the stupid policeman was gone. He had been sent down to the hotel to arrest the foreign boy and his goat, and he was too stupid to notice them, even with Hans and the cook paddling along behind. He had nothing in his mind but the hotel to which he had been sent. The burgomaster, however, recognized the green-tinted goat as soon as he saw him.

"There he goes!" cried the burgomaster. "Brute beast of a goat! Halt, I say!" Blowing his little whistle, he, too, so filled with anger that it made him puff up like a toad, started out after the carriage; and there they ran, the three clumsy-looking fat men, one after the other, puffing and panting and blowing, just out of reach of the goat.

Mr. and Mrs. Brown and Frank were too intent on getting up the steep street and out of the town to notice what was going on behind them, but just now they came to the top of the hill and began to go down the gentle slope on the other side. The driver whipped up his horses, the goat also increased his pace, and away they went. The cook, seeing that the goat was about to escape, made a lunge, thinking that he could grab it by the tail or the hind legs, but as he did so his feet caught on a stone and over he went. Hans Zug, being right behind him, tumbled over him, and the fat burgomaster tumbled over both of them. The burgomaster was so angry that he felt he surely must throw somebody into jail, so, as soon as he could get his breath, he grabbed Hans Zug by the collar with one hand and the cook with the other.

"I arrest you in the name of Canton Bern for obstructing a high officer!" he exclaimed, and the stupid policeman running up just then, he turned poor Hans and the cook over to him and sent them to jail.

All the hot, dusty afternoon Billy followed Mr. Brown's carriage, now up hill and now down hill, without ever showing himself to them. Whenever he thought of straying off into the pleasant grassy valleys and striking out into the world for himself again, he remembered that the Browns were going to America and that if he went with them he might see his mother again. He did not know, of course, that America was such a large place, so, while now and then he stopped at the roadside to nibble a mouthful of grass or stopped when they crossed a stream to get a drink of water, he never lost sight of them, but when he found himself getting too far behind, scampered on and overtook them.

It was not until nightfall that the carriage rolled into the city of Bern. Billy had never seen so large a city before and the rumbling of many wagons and carriages, the passing of the many people on the streets and the hundreds of lights confused and surprised him. He was not half so surprised at this, however, as Mr. and Mrs. Brown and Frank were to find Billy behind their carriage when they stopped in front of a large, handsome hotel. Frank was the first one to discover him.

"Oh, see, papa!" he cried. "My Billy followed us all the way from the village; so now I do get to keep him, don't I?"

Mr. Brown smiled and gave up.

"I'm afraid he's an expensive goat, Frank," was all he said, and then he gave Billy in charge of one of the porters who had crowded around the carriage.

"Wash the paint from this goat and lock him up some place for the night where he can't do any damage," he directed the porter.

Billy was glad enough to have the dry green paint scrubbed off his back and he willingly went with the porter to a clean little basement room, where he got a good scrubbing. Then the porter went into another room and brought him out some nice carrots with green tops still on them, and, leaving a basin of water for him to drink, went out and closed the door carefully after him. Billy liked the carrots, but he did not like to be shut up in a dark room, so he soon went all around the walls trying to find a way out. There was no way except the two doors and a high, dim window. He tried to butt the doors down but they were of solid, heavy oak, and he could not do it. In a few minutes, however the porter came back for his keys, and the moment he opened the door Billy seized his chance. Gathering his legs under him for a big jump, he rushed between the man's legs and dashed up the stairs, out through the narrow courtyard and on the street. The porter, as soon as he could get to his feet, rushed out after him, but Billy was nowhere in sight and the poor porter did not know what to do. He did not dare to go back and tell Mr. Brown that the goat had gotten loose, because he would be charged with carelessness.

In the meantime Billy had galloped up the street and turned first one corner and then another, until he came to a street much wider and brighter and busier than any of the others. By this time first one boy and then another and then another had followed him, until now there was a big crowd of them running after him and shouting at the top of their lungs.

A large dog that a lady was leading along the sidewalk by a strap broke away from his mistress as soon as he saw Billy and ran out to bark at him. Billy lowered his head and shook it at the dog. The dog began to circle round him closer and closer, barking loudly all the while. A man driving a big dray stopped to watch them; the boys crowded round in a big ring; men came from the sidewalks and joined the crowd; a carriage had to stop just behind the dray, then another; a wagon coming from the other direction could not get through; and presently the street was filled from sidewalk to sidewalk, the whole length of the block, with a big crowd of people and a jam of vehicles of all kinds. Policemen tried to push their way through the crowd and tried to get the blockade loosened and moving on, but their time was wasted.

In the meantime Billy was turning around and around where he stood, always facing the dog which now began to dart in with a snap of his teeth and dart away again, trying to get a hold on Billy. The goat was too quick, however, and dodged every time the dog made a snap. He was waiting for his chance and at last it came. The dog, in jumping away from one of his snaps, turned his body for a moment sideways to the goat and in that moment Billy gathered himself up and made a spring, hitting the dog square in the side and sending him over against the crowd. Billy followed like a little white streak of lightning and, before the dog could get on his feet, had butted him again.

Such a howling and yelling as there was among that side of the crowd; Billy and the dog were now among them and they could not scatter much for there were too many people packed solidly behind them. The dog yelped as Billy butted him and began to run around and around the circle with Billy right after him. After they had made two or three circles, Billy overtook the dog and, giving him one more good one, jumped between the legs of the crowd and wriggled his way through among carriages and wagons, under horses and between wheels, until at last he was free from the crowd.

Nobody at the outer edge noticed him getting away because they did not know what the excitement was and they were all pressing forward to see. Just as he left, somebody who could not understand what else could make such excitement cried, "Fire!"

The cry was taken up, and that made still more confusion. People began pouring into that block from every direction. More wagons and carriages came. Some one had turned in a fire alarm, and presently here came the fire engines from three or four directions at once, clanging and clattering their way to this crowded block. The city of Bern had never known so much excitement.

CHAPTER V

THE WOODEN GOAT

illy trotted contentedly on, liking all the noise and

hubbub very much but not knowing that he was the

cause of it all. Blocks away he could hear their shouting,

but he did not care to go back there, for all of that.

He was finding a great many things to interest him in the shop

windows, which were all brilliantly lighted. Before one of these low

windows he suddenly stopped. There, just inside the show window,

was a big, brown goat. Billy did not know it, but this was a wooden

goat, poised on its hind feet and ready to make a spring to butt

somebody. The Swiss woodcarvers are the finest in the world, and they

carve animals so naturally that one would think they were alive.

If even human beings can be fooled, there was very good excuse for

Billy's believing this to be a real, live goat, particularly as it had

very natural looking glass eyes; besides, its head was separate and

was cunningly arranged to shake a little bit from side to side.

illy trotted contentedly on, liking all the noise and

hubbub very much but not knowing that he was the

cause of it all. Blocks away he could hear their shouting,

but he did not care to go back there, for all of that.

He was finding a great many things to interest him in the shop

windows, which were all brilliantly lighted. Before one of these low

windows he suddenly stopped. There, just inside the show window,

was a big, brown goat. Billy did not know it, but this was a wooden

goat, poised on its hind feet and ready to make a spring to butt

somebody. The Swiss woodcarvers are the finest in the world, and they

carve animals so naturally that one would think they were alive.

If even human beings can be fooled, there was very good excuse for

Billy's believing this to be a real, live goat, particularly as it had

very natural looking glass eyes; besides, its head was separate and

was cunningly arranged to shake a little bit from side to side.

Now it is a deadly insult for one Billy goat to stand on his hind legs and wag his head at another one. Billy Mischief for one was not going to take such insults as that, even though the goat that gave it to him was much larger and older than himself, so he backed off into the middle of the street and gave a great run and jump. Crash! went the fine plate-glass window! The sharp edges of the glass cut Billy somewhat and stopped him so that he landed just inside the window glass. The other goat was right in front of him, still insultingly wagging its flowing beard at him so Billy gave one more spring from where he stood and knocked that goat sixteen ways for Sunday. It was the hardest headed goat that Billy had ever fought, and its sharp nose hurt his head considerably, almost stunning him, in fact, so that he stood blinking his eyes until the people in the store had come running up and surrounded the show window.

Billy was still dazed when the manager of the store, a nervous little man with a bald head, hit him a sharp crack across the nose with a board. The pain brought the tears to Billy's eyes and still further dazed him. The manager hit him another crack but this time on the horns, and that woke Billy up. He looked back at the broken window through which he had just come but the crowd had quickly gathered there. There were less people inside, so suddenly gathering his legs under him, he gave a spring and went clear over the manager, kicking him with his sharp hind hoofs upon the bald head as he went over. The place was a delicatessen store and Billy landed in a big tub of pickles. He did not care much for pickles anyhow, so he quickly scrambled out of them, knocked over three tall glass jars that stood on a low bench, and turned over big cakes of fine cheese. The manager was right after him with the board and hit him two or three thumps with it.

Billy was just about to turn around and go for the little bald-headed man when he noticed at the far end of the store a round, plump man with his back turned to him. There seemed something familiar about his figure and the cut of his short little coat, and it flashed across Billy at once that here was his old enemy Hans Zug.

Paying no attention to the manager and his little board, he dashed headlong down the store for the plump man. Just as Billy had almost reached him, the man turned around. It was not Hans Zug after all, but Billy was going too fast to stop now. Anyhow, ever since he had known Hans he had taken a dislike to all fat men, so he dashed straight ahead. The man darted behind the counter and ran up the aisle, Billy close after him.

There never was a fat man in the world who ran so fast as this one. Everybody had cleared out of the aisle behind the counter to make room for them. Nobody wanted to get in the way of that heavy man and the hard headed goat. The man stepped upon a pail of fish, overturning it, jumped upon the counter and was over in the center aisle, Billy right after him. Everybody in the store was packed in the center aisle, together with a lot who had come in from the outside when the excitement began, and they all made way for the fat man and for Billy. Women were screaming and men were shouting and laughing. The manager was still right after Billy with his little board and thumping him every now and then on the back, but Billy scarcely knew it, so interested was he in giving the fat man one for Hans Zug.

The man headed straight up the middle aisle for the door, but, looking over his shoulder, he found that Billy would overtake him before he got there, so he sprang over another counter, upsetting a pair of scales and some tall, open jars of fine olives. Billy was still right after him but this time the man fooled him by jumping back over the counter. Billy followed up that aisle to the end where he turned into the crowd, just as the fat man went out on the street. Here he upset two ladies and a policeman who was just coming in, and then took after the man who looked like Hans. He was flying down the street as fast as he could go. After Billy came the manager of the store and two of his clerks, and all of the boys that had congregated on the sidewalk.

Pell-mell they went, a howling, yelling mob, with the fat man and Billy in the lead. The man by this time was puffing like a steam engine and the sweat was pouring from his face in streams. His collar was wilted like a dish rag. He had lost his hat and one of his cuffs, and he could hardly get his breath.

Policemen, by this time, were coming running from every direction and one of them, who turned off a side street just then, thinking the fat man must be a thief, got right in his road and opened up his arms. The fat man, who had scarcely any strength left, fell right against the policeman who was also a very heavy fellow, and just at that time Billy overtook them and gave the man he was chasing all that was coming to Hans Zug. Down in a pile together went the fat man and the policeman. The policeman had not seen the goat and for a moment imagined that the fat man had jumped upon him and was trying to overpower him, so he pulled out his club and, though he was underneath, began, in a way that was comical, to try to pound the fat man.

They lay there, a struggling, wriggling mass, the policeman with his short arms trying to reach around the big round man on top of him in order to hit him some place. Billy Mischief had stopped and backed up to give his fallen enemy another bump, and was just in the air after his spring when the manager of the store caught his hind leg, and he also was dragged on top of the struggling two on the ground. The manager held to Billy's leg, however, and the crowd which had been following them closely now crowded around them. The manager scrambled to his feet, still holding the kicking Billy by the hind leg, and it would, probably have been all up with the goat if a big, strong man had not at that moment come up and putting his great arms around Billy, jerked him loose. Billy squirmed and struggled, but it was no use. The big man held him tightly and began to run. The store manager got to his feet and started after them, followed by his two clerks, but the big strong fellow who was carrying Billy darted down an alley, then through another alley, and before the pursuers could see where they had gone, the man darted through the back gate of a high board fence with Billy, closed the gate after him, ran along the side of a great building which was blazing with lights, ran down some cellar steps, opened the door, went in, closed it after him, turned on a light and set Billy down.

"There, you fool goat!" exclaimed the man. "I'll wash the blood off of you and nobody will know that you have been out."

The big man was the porter and he had brought Billy back to the little basement room under the hotel. So ended Billy's first night in a big city.

All that night, all the next day and night, and all the following day, Billy was cooped up in that little basement room with no chance to get out, and with only Frank Brown and the porter to visit him twice a day. How he did fret. The porter kept him well fed and saw that he had good bedding and plenty of water, but he gave Billy no more chances to escape and see the city. He watched carefully as he opened and closed the door that the goat should not again scramble between his legs or butt him over. On the third evening, however, the porter forgot to completely close the door which led into the other part of the basement, and you may be sure that Billy lost no time in finding out what was in there. The room next to his led up into the kitchen and it was stocked with vegetables and all sorts of kitchen stores.

Billy was not very hungry, but he nibbled at everything as he went along, pulling the vegetables out of place, upsetting a barrel half filled with flour in his attempt to see what was in it and working the faucet out of a barrel of syrup in his efforts to get at the sweet stuff which clung to it. Licking up all of the syrup that he cared for, Billy went on to investigate another barrel which lay on its side not far away, and knocked the faucet out of it. This, however, proved to be wine and he did not like the taste of it at all, so he trotted on out of the store-room into the laundry, leaving the two barrels to run to waste.

Everybody in the laundry had gone up into the servants' hall for their suppers, and the coast was clear for Billy. They had just finished ironing, and dainty white clothes lay everywhere. From a big pile of them that lay on a table, a lace skirt hung down, and Billy took a nibble at it just to find out what it was. The starch in it tasted pretty good, so he chewed at the lace, pulling and tugging to get it within easier reach, until at last he pulled the whole pile off the table on the dirty floor.

Hearing some steps then, he scampered out through the storeroom and into another large room where stood a big, brass-trimmed machine which he did not at all understand. It was a dynamo, which was run by a big engine in the adjoining engine-room, and it furnished the electric lights for the hotel. Two big wires ran from it, heavily coated with shellac and rubber and tightly-wound tape to keep them from touching metal things and losing their electricity. These crossed the basement room to the further wall, where they distributed the electric current to many smaller cables.

Billy sniffed at the two big cables at a point where they were very near together. They had a peculiar odor and Billy tasted them. He scarcely knew whether he liked the taste or not, but he kept on nibbling to find out, nipping and tearing with his sharp teeth until he had got down to the big copper wire on both cables; then he decided that he did not care very much for that kind of food and walked away. It was not yet dark enough for the dynamo to be started, or Billy might have had a shock that would have killed him.

Hunting further, he found over in a dark corner a nice bed which belonged to the engineer, and it looked so inviting that Billy curled up there for a sleep. When he awoke it was nearly midnight and there was a blaze of light in the basement. There was a strange whir of machinery and he could hear anxious voices. Billy, of course, did not know that he had been the cause of it but this is what had happened:

When the electric current passes through a wire, the wire becomes slightly heated and stretches a little bit. In stretching, the two cables where he had chewed them bare, came near enough together to touch each other once in a while, and that made the lights all over the big building wink, that is, almost go out for a second, and the engineer was very much worried about it.

What interested Billy more, however, was a small, wire-screened room that stood near to him. Presently a big cage, brightly lighted, came down in it with a man and a boy. It stopped when it got down into the basement, when the man and the boy stepped out, going down into the engineer's room. They were the proprietor of the hotel and his elevator boy. Billy, as curious as any boy could have been, walked into the little cage to see what it was like. The sides of it were padded with leather, there were mirrors in it that made it a place of light, and there was a seat at the back end of it. At the front side near the door a big cable passed up through it, and to this the boy who ran it had left hanging a leather pad with which he gripped the cable. Billy could barely reach it with his teeth and he pulled sharply on it. It would not come away so he hung his weight on it, and immediately the cage began to go up. Billy was in an elevator and he was taking a ride all by himself. It never stopped until it reached the top floor where a safety catch caught it. Luckily the door on the top floor had not been carefully closed, and Billy was able to slide it open with his horns and walk out into a narrow hall which had a thick velvet carpet upon it and from which opened many doors and other halls.

Billy trotted along this hallway, liking the soft feel of the carpet underneath his feet. As he did so, all the lights about the building went out and everything was dark. The cables in the cellar had at last settled down so that they lay square across each other where Billy had chewed the covering off, thus making all the electric current which ran out of the machine on the one side come right back into it on the other, with the result of burning out the dynamo so that there could be no more lights from it that night. This did not worry Billy any. Light came in from the street at the far end of the hall where some white lace curtains fluttered in the breeze. It worried a great many people who were still awake in their rooms, however, and of course they opened their doors to see about it.

By this time Billy had reached the curtains and took a nibble at one of them, and, found that it was finished with the same starch, the taste of which he had liked so much in the laundry. He wanted it down where he could get a good bunch of it in his mouth, so he pulled hard, raising up on his hind feet and throwing his weight upon it. The curtain gave way at the top but it was not so convenient as he had expected, for the long, wide curtain came right down over his back. He tried to get out from under it and his horns ran through the open work. He tried to turn round and his hind feet ran through other open work places. He tried to back out of it and his forefeet got tangled in some more of it. The more he tried to get loose from his starched meal, the more tangled up he got, and at last, growing angry, he began to jump as high in the air as he could.

In the half darkness, he was a great white figure with a long trailing white robe behind him, and the first woman he met in the hall screamed like a steam calliope. Of course her screams brought others out into the hall and everybody, even the men, began to run when they saw this jumping white ghost coming toward them, every once in a while letting out a loud "baah!" Many ladies were so frightened that when they came to their doors, instead of running into their rooms, they started down the hall ahead of Billy, shrieking and screaming at the top of their voices.

The noise only confused Billy the more. The more confused he grew, the harder he jumped and struggled to get out of the curtain, until at the very end of the hall, he came to a stairway and went down it head over heels to the next floor.