WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Portsmouth Road, and its Tributaries: To-day and in Days of Old.

The Dover Road: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike.

The Bath Road: History, Fashion, and Frivolity on an Old Highway.

The Exeter Road: The Story of the West of England Highway.

The Great North Road: The Old Mail Road to Scotland. Two Vols.

The Norwich Road: An East Anglian Highway.

The Holyhead Road: The Mail-Coach Road to Dublin. Two Vols.

The Cambridge, Ely, and King’s Lynn Road: The Great Fenland Highway.

The Newmarket, Bury, Thetford, and Cromer Road: Sport and History on an East Anglian Turnpike.

The Oxford, Gloucester, and Milford Haven Road: The Ready Way to South Wales. Two Vols.

The Brighton Road: Speed, Sport, and History on the Classic Highway.

The Hastings Road and the “Happy Springs of Tunbridge.”

Cycle Rides Round London.

A Practical Handbook of Drawing for Modern Methods of Reproduction.

Stage-Coach and Mail in Days of Yore. Two Vols. The Ingoldsby Country: Literary Landmarks of “The Ingoldsby Legends.”

The Hardy Country: Literary Landmarks of the Wessex Novels.

The Dorset Coast.

The South Devon Coast. [In the Press.

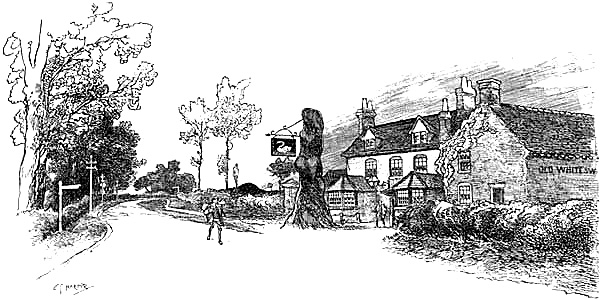

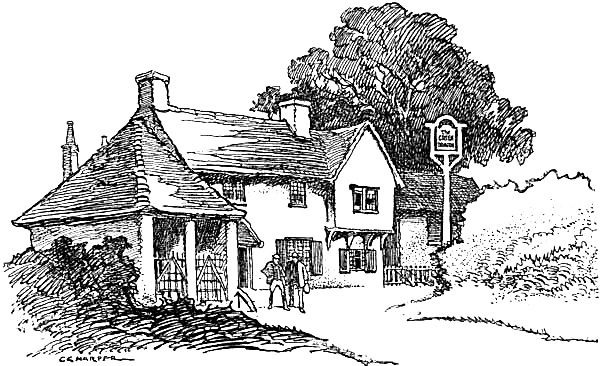

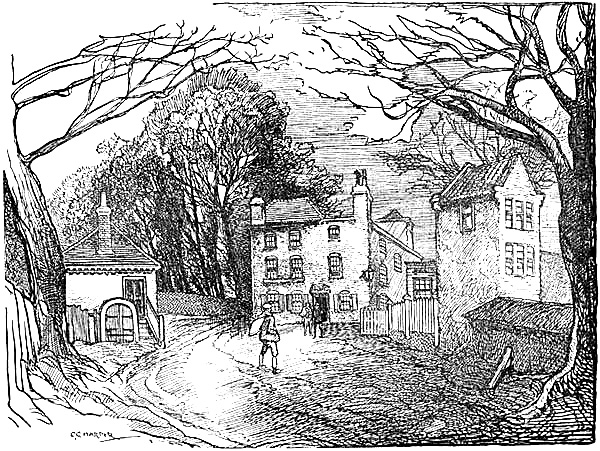

THE ROADSIDE INN.

THE OLD INNS

OF OLD ENGLAND

A PICTURESQUE ACCOUNT OF THE

ANCIENT AND STORIED HOSTELRIES

OF OUR OWN COUNTRY

VOL. I

By CHARLES G. HARPER

Illustrated chiefly by the Author, and from Prints

and Photographs

London:

CHAPMAN & HALL, Limited

1906

All rights reserved

PRINTED AND BOUND BY

HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY.

It is somewhat singular that no book has hitherto been published dealing either largely or exclusively with Old Inns and their story. I suppose that is because there are so many difficulties in the way of one who would write an account of them. The chief of these is that of arrangement and classification; the next is that of selection; the last that of coming to a conclusion. I would ask those who read these pages, and have perhaps some favourite inn they do not find mentioned or illustrated here, to remember that the merely picturesque inns that have no story, or anything beyond their own picturesqueness to render them remarkable, are—let us be thankful for it!—still with us in great numbers, and that to have illustrated or mentioned even a tithe of them would have been impossible. I can think of no literary and artistic work more delightful than[Pg vi] the quest of queer old rustic inns, but two stout volumes will probably be found to contain as much on the subject as most people wish to know—and it is always open to anyone who does not find his own especial favourite here to condemn the author for his ignorance, or, worse, for his perverted taste.

As for methods, those are of the simplest. You start by knowing, ten years beforehand, what you intend to produce; and incidentally, in the course of a busy literary life, collect, note, sketch, and make extracts from Heaven only knows how many musty literary dustbins and sloughs of despond. Then, having reached the psychological moment when you must come to grips with the work, you sort that accumulation, and, mapping out England into tours, with inns strung like beads upon your itinerary, bring the book, after some five thousand miles of travel, at last into being.

It should be added that very many inns are incidentally illustrated or referred to in the series of books on great roads by the present writer; but as those works dealing with Roads, another treating of the History of Coaching, and the present volumes are all part of one comprehensive plan dealing with the History of Travel in general, the allusions to inns in the various road-books have but rarely been repeated; while it will be found that if, in order[Pg vii] to secure a representative number of inns, it has been, in some cases, found unavoidable to retrace old footsteps, new illustrations and new matter have, as a rule, been brought to bear.

The Old Inns of London have not been touched upon very largely, for most of them are, unhappily, gone. Only the few existing ones have been treated, and then merely in association with others in the country. To write an account of the Old Inns of London would now be to discourse, in the manner of an antiquary, on things that have ceased to be.

CHARLES G. HARPER.

Petersham,

Surrey.

September, 1906.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Introductory | 1 |

| II. | The Ancient History of Inns | 13 |

| III. | General History of Inns | 28 |

| IV. | The Eighteenth Century | 42 |

| V. | Latter Days | 57 |

| VI. | Pilgrims’ Inns and Monastic Hostels | 76 |

| VII. | Pilgrims’ Inns and Monastic Hostels (continued) | 117 |

| VIII. | Historic Inns | 144 |

| IX. | Inns of Old Romance | 188 |

| X. | Pickwickian Inns | 210 |

| XI. | Dickensian Inns | 265 |

| XII. | Highwaymen’s Inns | 303 |

| LIST of ILLUSTRATIONS |

|

| SEPARATE PLATES | |

| The Roadside Inn | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| The Last of the Old Galleried Inns of London: The “George,” Southwark. (Photo by T. W. Tyrrell) | 32 |

| The Kitchen of a Country Inn, 1797: showing the Turnspit Dog. (From the engraving after Rowlandson) | 48 |

| Westgate, Canterbury, and the “Falstaff” Inn | 86 |

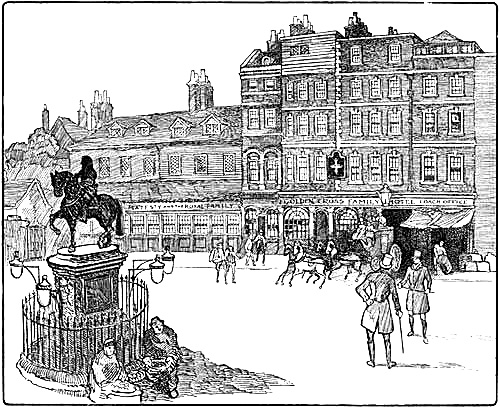

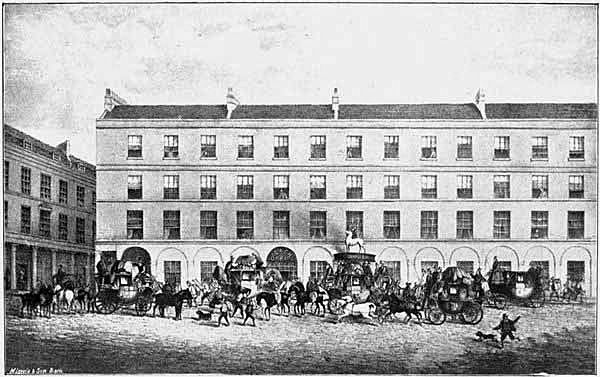

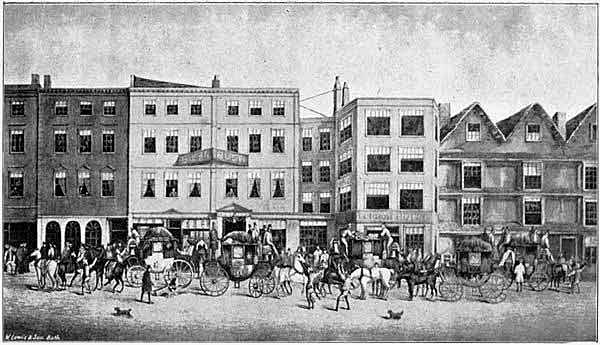

| Charing Cross, about 1829, showing the “Golden Cross” Inn. (From the engraving after T. Hosmer Shepherd) | 218 |

| The “Golden Cross,” Successor of the Pickwickian Inn, as Rebuilt 1828 | 220 |

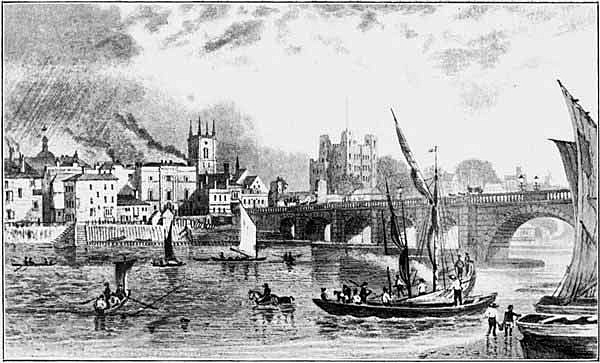

| Rochester in Pickwickian Days, showing the Old Bridge and “Wright’s” | 224 |

| The “Belle Sauvage.” (From a drawing by T. Hosmer Shepherd) | 228 |

| The Dickens Room, “Leather Bottle,” Cobham | 230 |

| The “Bull Inn,” Whitechapel. (From the water-colour drawing by P. Palfrey) | 246 |

| [Pg xii]The “White Hart,” Bath | 252 |

| The “Bush,” Bristol | 256 |

| The “Coach and Horses,” Isleworth | 276 |

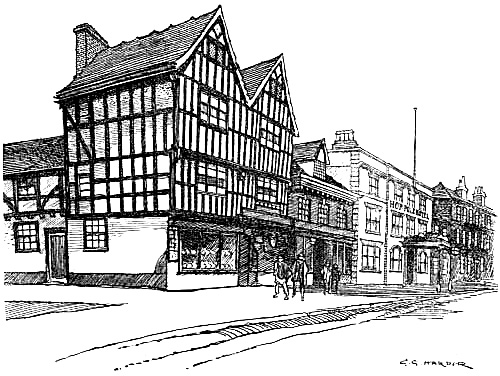

| The “Lion,” Shrewsbury, showing the Annexe adjoining, where Dickens stayed | 298 |

| The “Green Man,” Hatton | 318 |

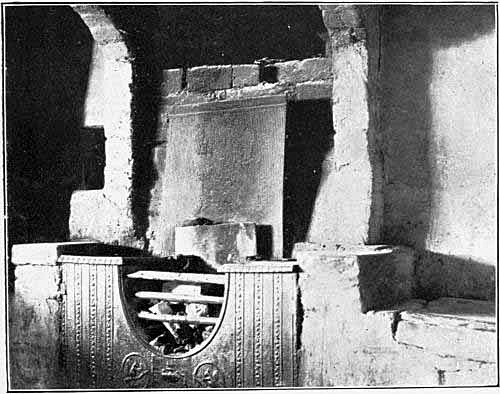

| The Highwayman’s Hiding-hole | 318 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT | |

| Vignette, The Old-time Innkeeper | Title-page |

| PAGE | |

| Preface | v |

| List of Illustrations | xi |

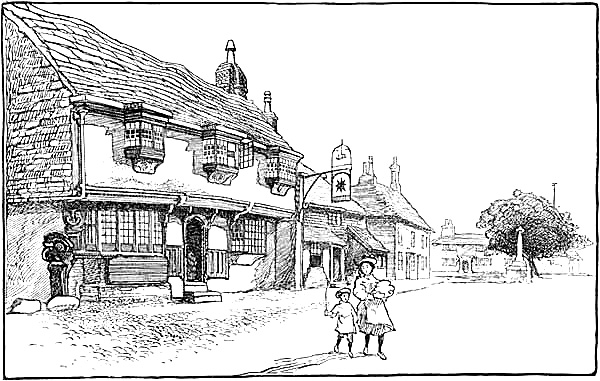

| The Old Inns of Old England, The “Black Bear,” Sandbach | 1 |

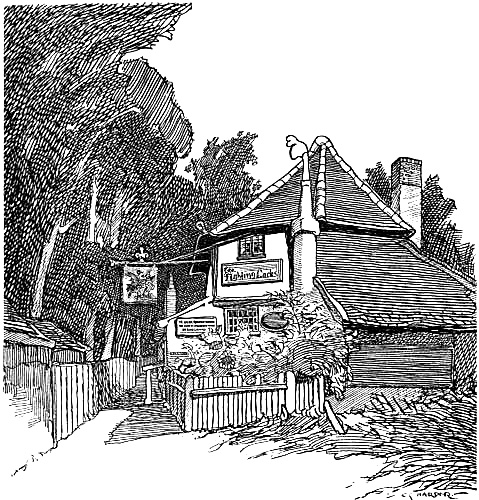

| The Oldest Inhabited House in England: The “Fighting Cocks,” St. Albans | 5 |

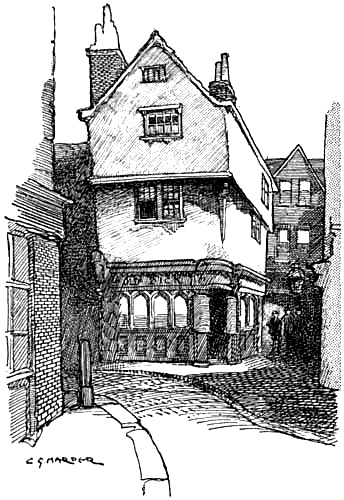

| The “Dick Whittington,” Cloth Fair | 6 |

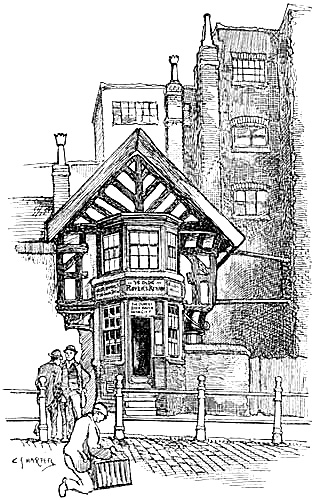

| “Ye Olde Rover’s Return,” Manchester | 7 |

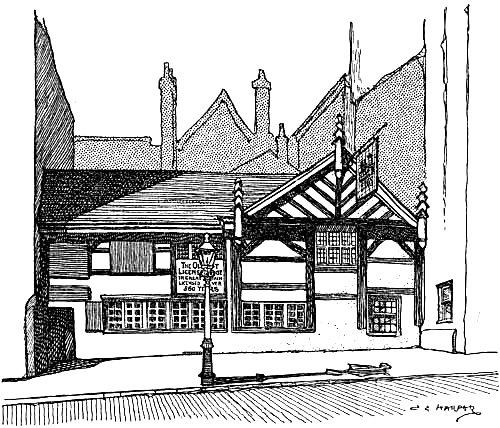

| The Oldest Licensed House in Great Britain: The “Seven Stars,” Manchester | 11 |

| An Ale-stake. (From the Louterell Psalter) | 15 |

| Elynor Rummyng | 21 |

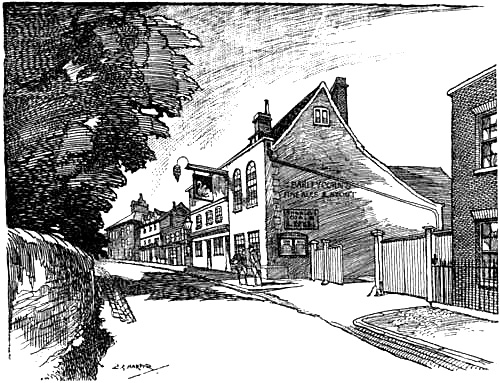

| The “Running Horse,” Leatherhead | 25 |

| Facsimile of an Account rendered to John Palmer in 1787 | 54 |

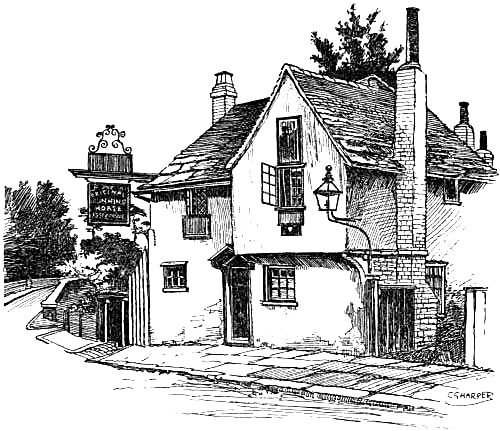

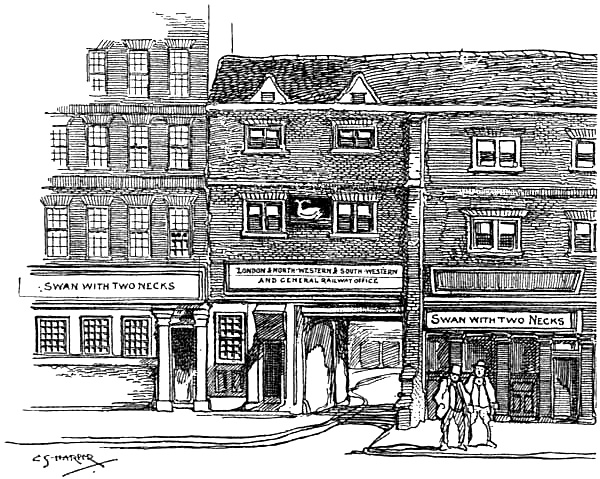

| The Last Days of the “Swan with Two Necks” | 55 |

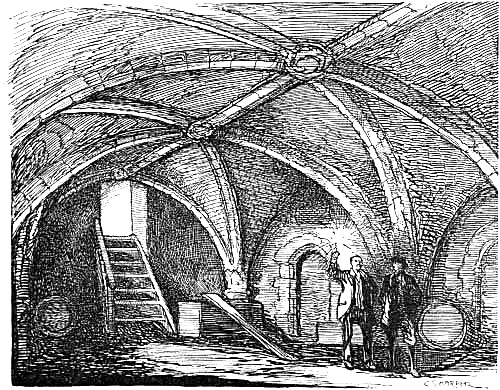

| Crypt at the “George,” Rochester | 83 |

| Sign of the “Falstaff,” Canterbury | 88 |

| House formerly a Pilgrims’ Hostel, Compton | 91 |

| The “Star,” Alfriston | 93 |

| Carving at the “Star,” Alfriston | 95 |

| [Pg xiii]The “Green Dragon,” Wymondham | 96 |

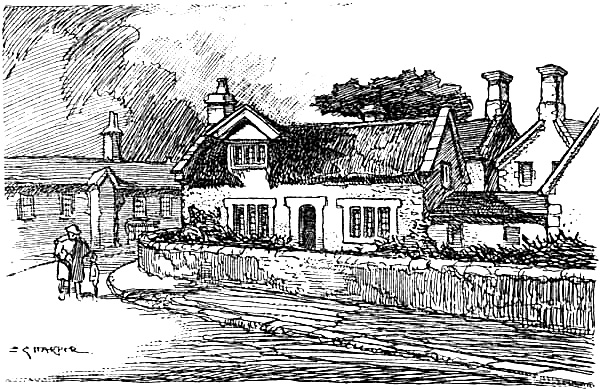

| The Pilgrims’ Hostel, Battle | 97 |

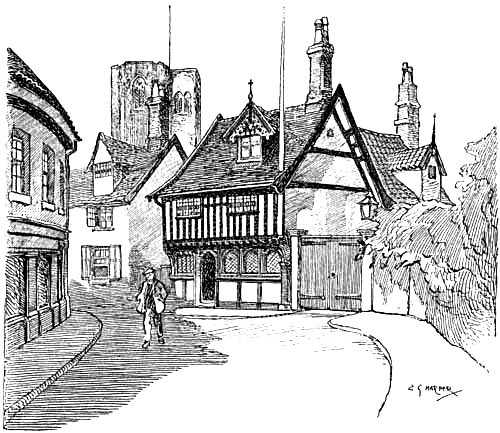

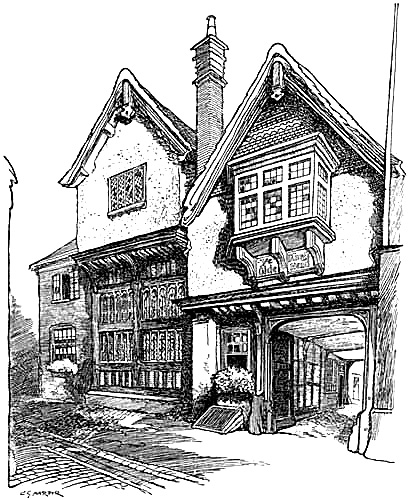

| The “New Inn,” Gloucester | 99 |

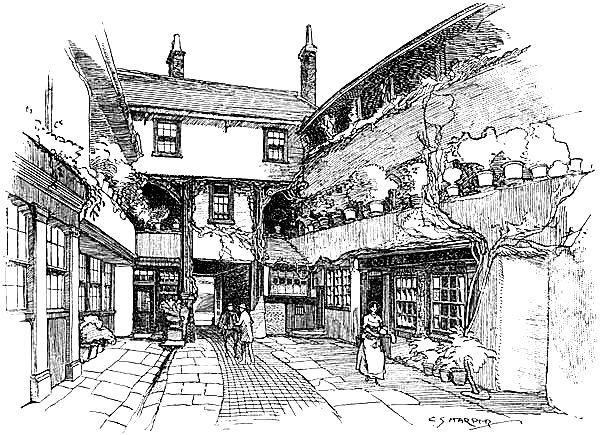

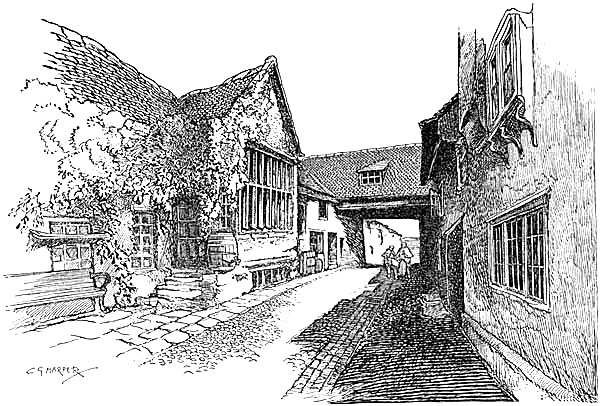

| Courtyard, “New Inn,” Gloucester | 103 |

| The “George,” Glastonbury | 109 |

| High Street, Glastonbury, in the Eighteenth Century (From the etching by Rowlandson) | 115 |

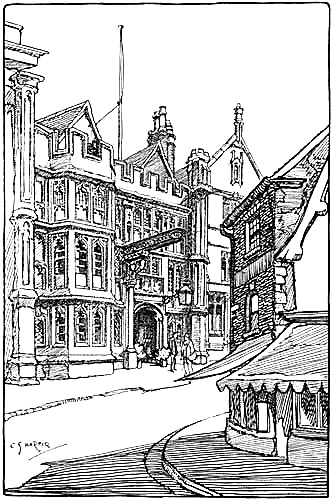

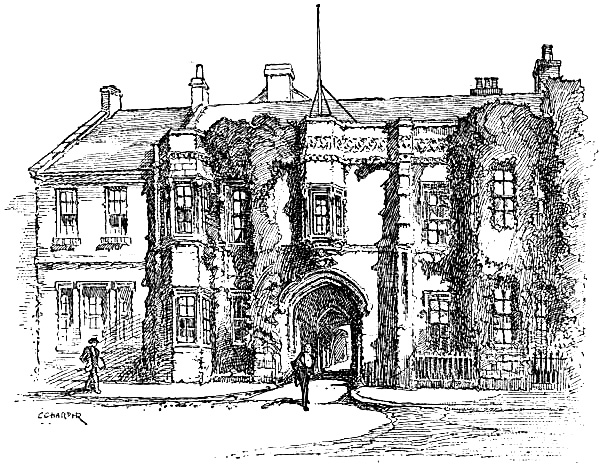

| The “George,” St. Albans | 119 |

| The “Angel,” Grantham | 121 |

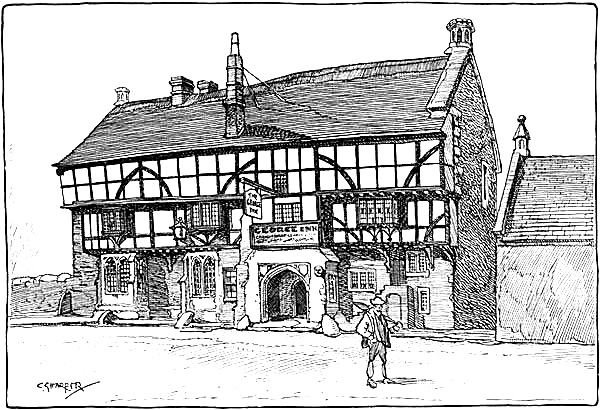

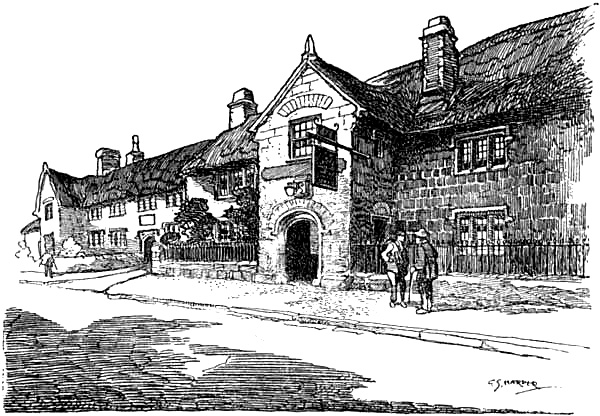

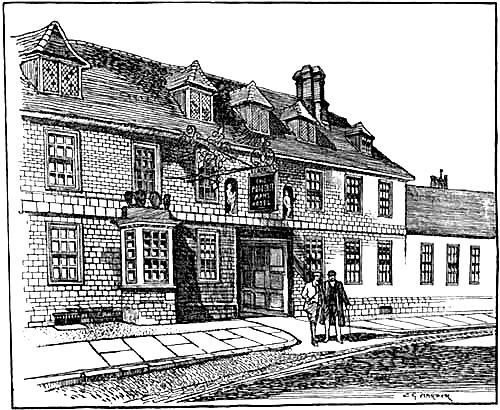

| The “George,” Norton St. Philip | 125 |

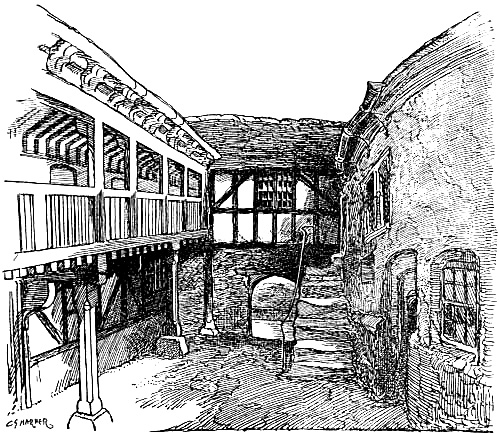

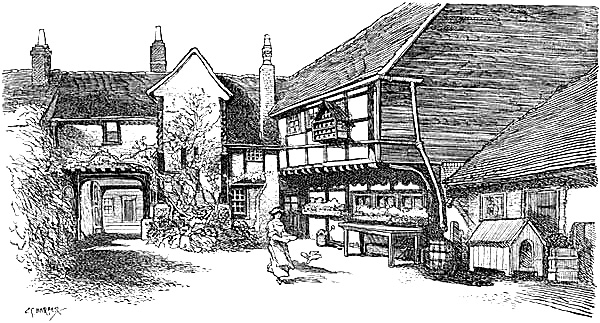

| Yard of the “George,” Norton St. Philip | 131 |

| Yard of the “George,” Winchcombe | 135 |

| The “Lord Crewe Arms,” Blanchland | 139 |

| The “Old King’s Head,” Aylesbury | 141 |

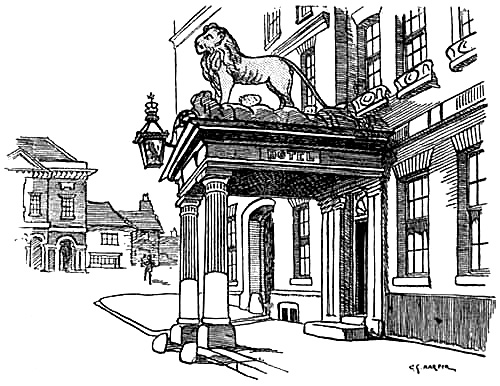

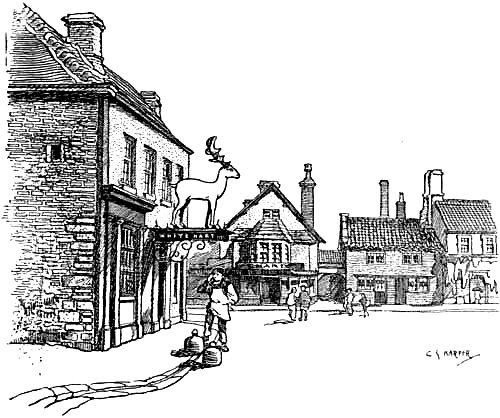

| The “Reindeer,” Banbury | 145 |

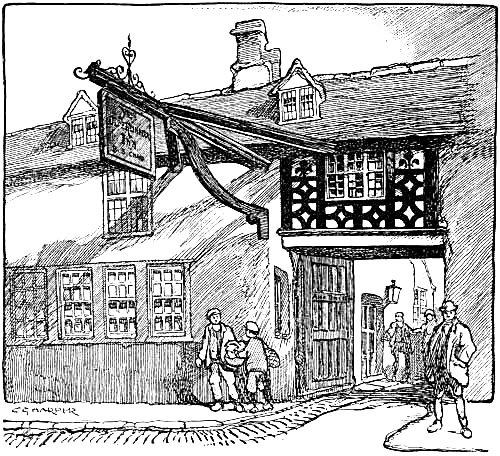

| Yard of the “Reindeer,” Banbury | 149 |

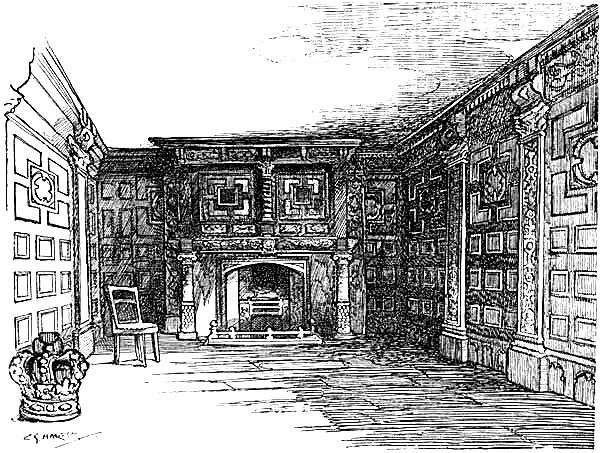

| The Globe Room, “Reindeer” Inn, Banbury | 153 |

| The “Music House,” Norwich | 157 |

| The “Dolphin,” Potter Heigham | 159 |

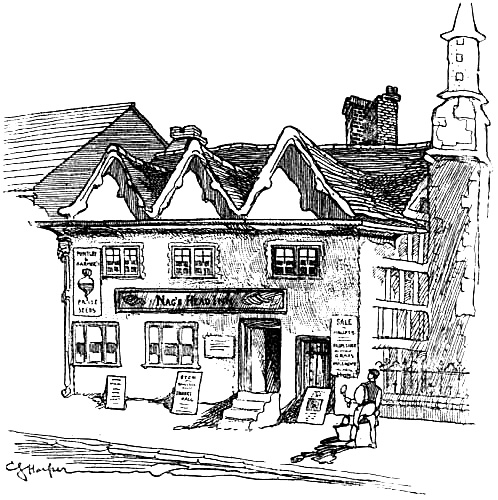

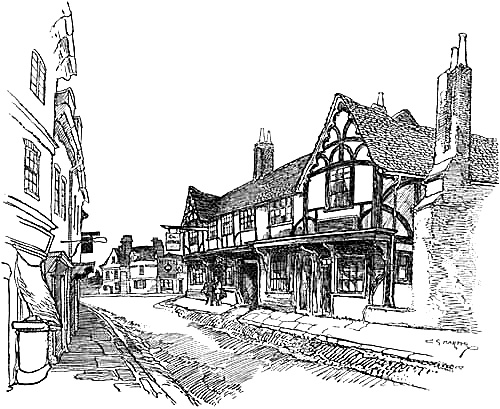

| The “Nag’s Head,” Thame | 161 |

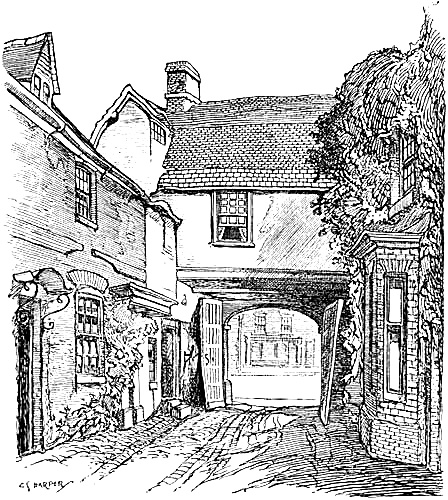

| Yard of the “Greyhound,” Thame | 163 |

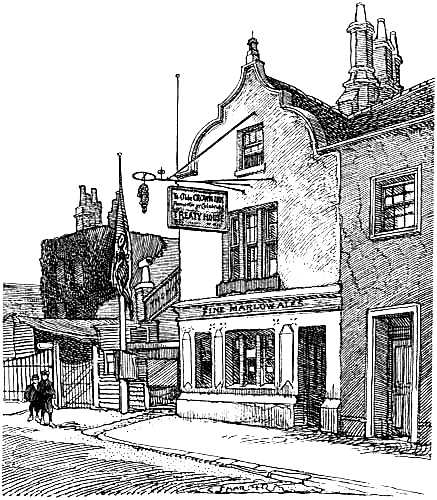

| The “Crown and Treaty,” Uxbridge | 165 |

| The “Treaty Room,” “Crown and Treaty,” Uxbridge | 167 |

| The “Three Crowns,” Chagford | 169 |

| The “Red Lion,” Hillingdon | 170 |

| Yard of the “Saracen’s Head,” Southwell | 173 |

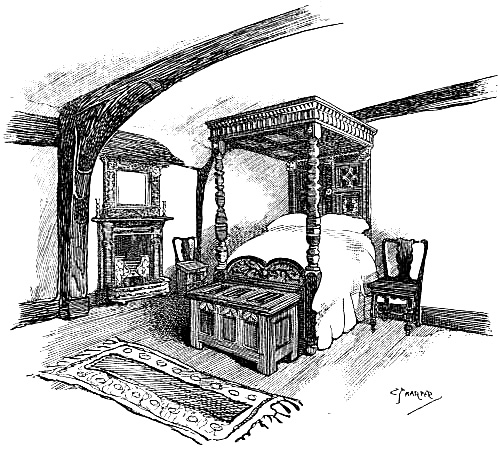

| King Charles’ Bedroom, “Saracen’s Head,” Southwell | 177 |

| The “Cock and Pymat” | 181 |

| Porch of the “Red Lion,” High Wycombe | 184 |

| The “White Hart,” Somerton | 186 |

| The “Ostrich,” Colnbrook | 191 |

| Yard of the “Ostrich,” Colnbrook | 199 |

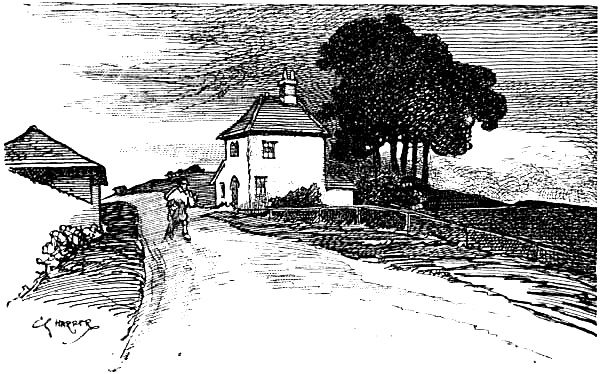

| [Pg xiv]“Piff’s Elm” | 203 |

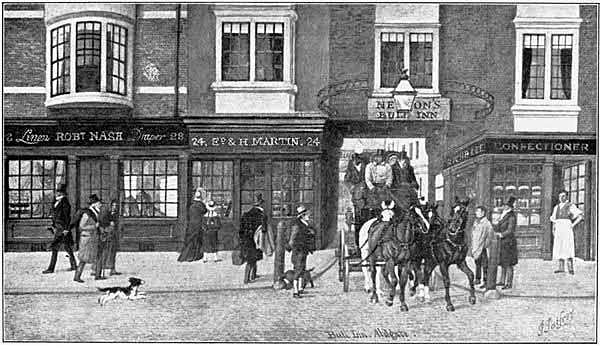

| The “Golden Cross,” in Pickwickian Days | 215 |

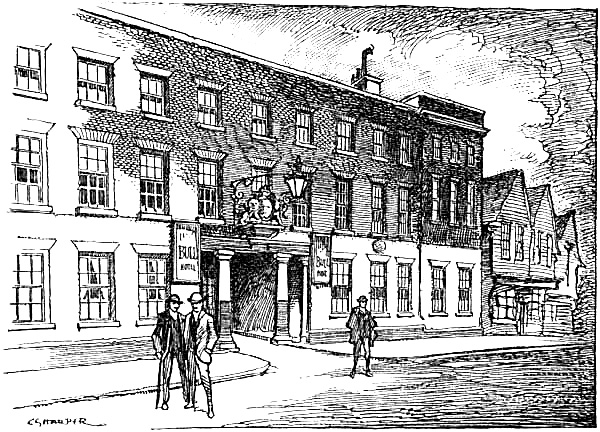

| The “Bull,” Rochester | 223 |

| The “Swan,” Town Malling: Identified with the “Blue Lion,” Muggleton | 226 |

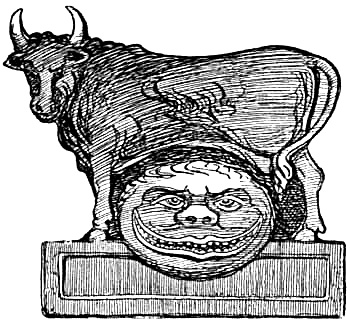

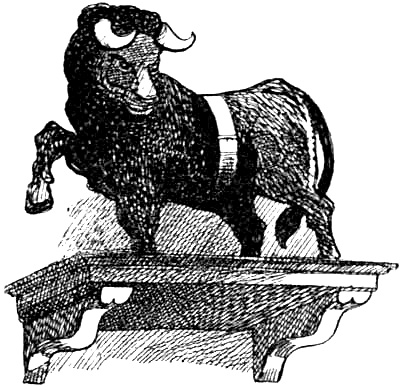

| Sign of the “Bull and Mouth” | 227 |

| The “Leather Bottle,” Cobham | 229 |

| The “Waggon and Horses,” Beckhampton | 233 |

| “Shepherd’s Shore” | 235 |

| “Beckhampton Inn” | 239 |

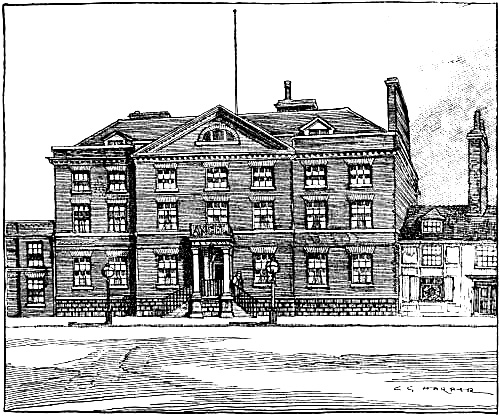

| The “Angel,” Bury St. Edmunds | 241 |

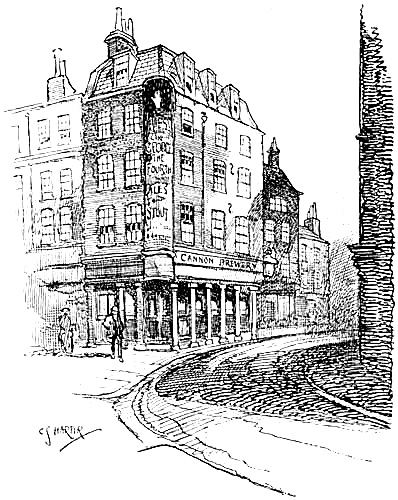

| The “George the Fourth Tavern,” Clare Market | 243 |

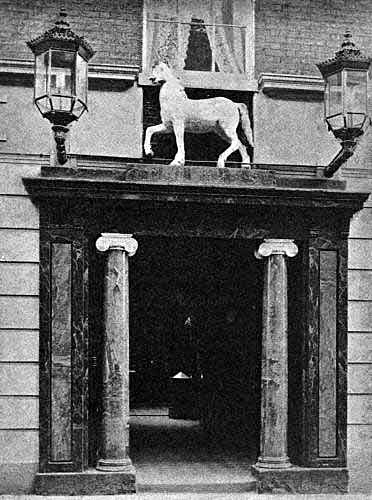

| Doorway of the “Great White Horse,” Ipswich | 247 |

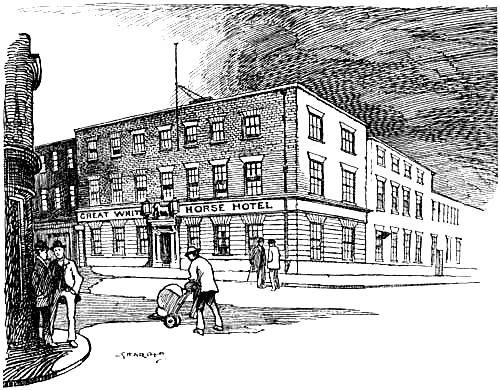

| The “Great White Horse,” Ipswich | 250 |

| Sign of the “White Hart,” Bath | 255 |

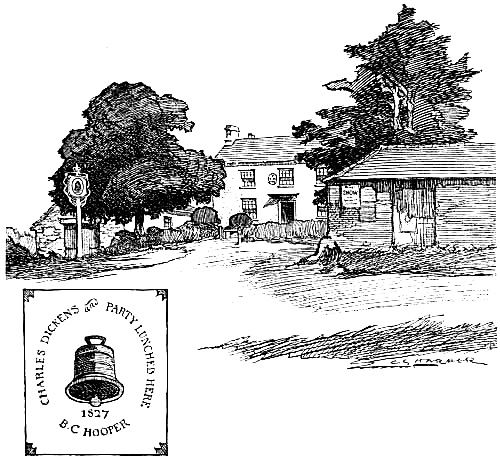

| “The Bell,” Berkeley Heath | 257 |

| The “Hop-pole,” Tewkesbury | 259 |

| The “Pomfret Arms,” Towcester: formerly the “Saracen’s Head” | 260 |

| The Yard of the “Pomfret Arms” | 261 |

| “Osborne’s Hotel, Adelphi” | 263 |

| The “White Horse,” Eaton Socon | 267 |

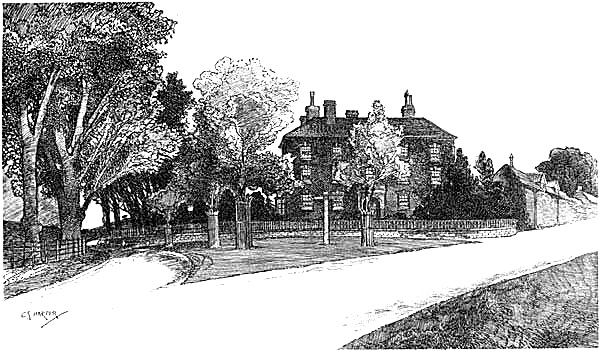

| The “George,” Greta Bridge | 269 |

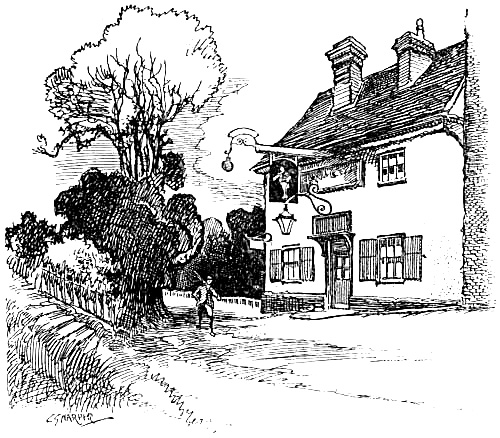

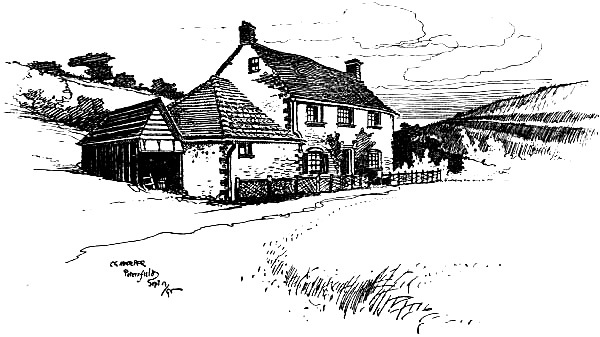

| The “Coach and Horses,” near Petersfield | 271 |

| “Bottom” Inn | 273 |

| The “King’s Head,” Chigwell, the “Maypole” of Barnaby Rudge | 279 |

| The “Green Dragon,” Alderbury | 283 |

| The “George,” Amesbury | 285 |

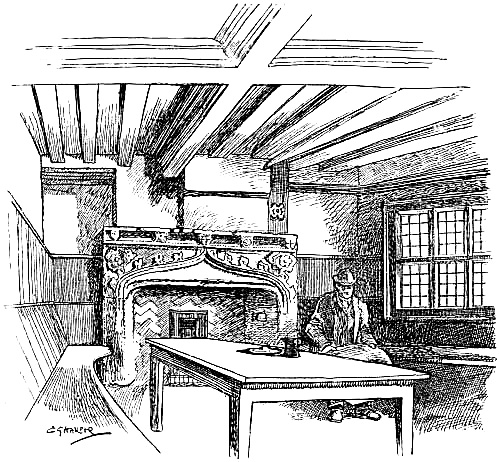

| Interior of the “Green Dragon,” Alderbury | 287 |

| Sign of the “Black Bull,” Holborn | 289 |

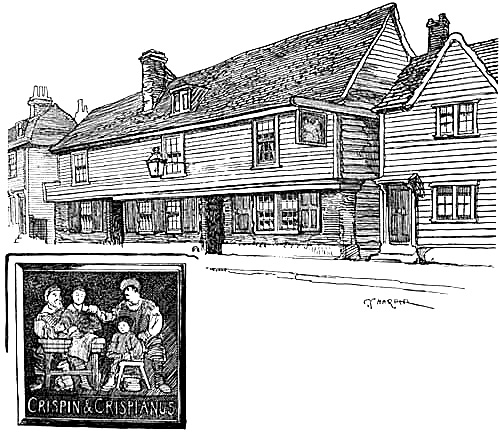

| The “Crispin and Crispianus,” Strood | 293 |

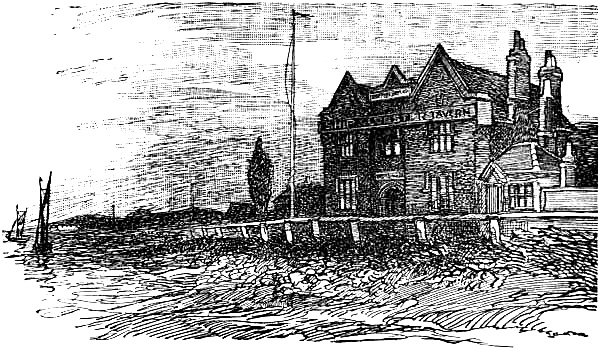

| [Pg xv]The “Ship and Lobster” | 297 |

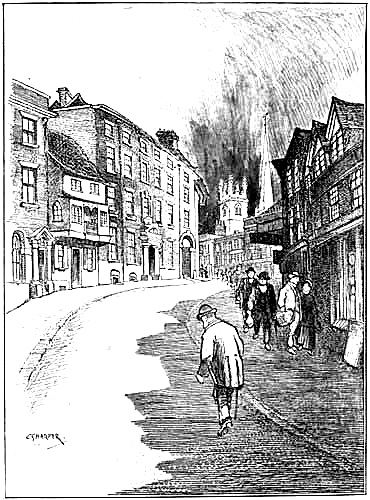

| “Jack Straw’s Castle” | 301 |

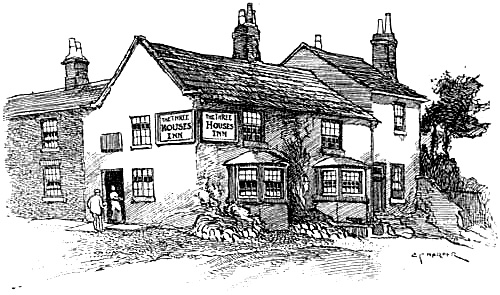

| The “Three Houses Inn,” Sandal | 308 |

| The “Crown” Inn, Hempstead | 309 |

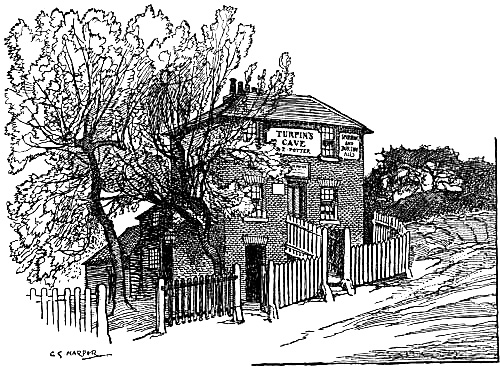

| “Turpin’s Cave,” near Chingford | 311 |

| The “Green Dragon,” Welton | 312 |

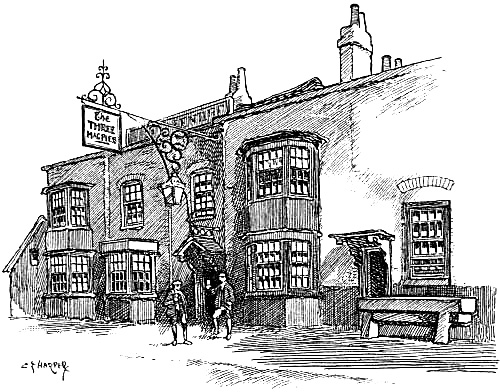

| The “Three Magpies,” Sipson Green | 313 |

| The “Old Magpies” | 315 |

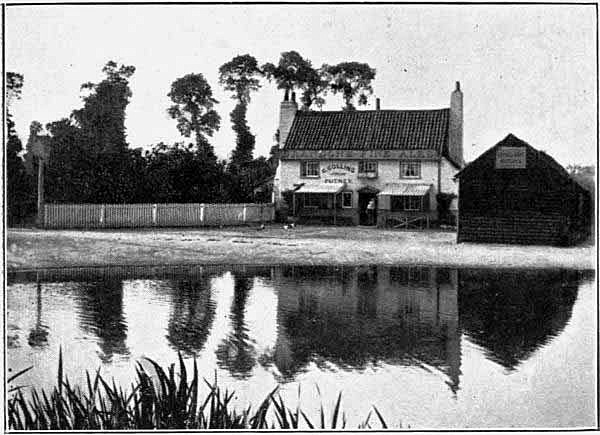

| The “Green Man,” Putney | 321 |

| The “Spaniards,” Hampstead Heath | 323 |

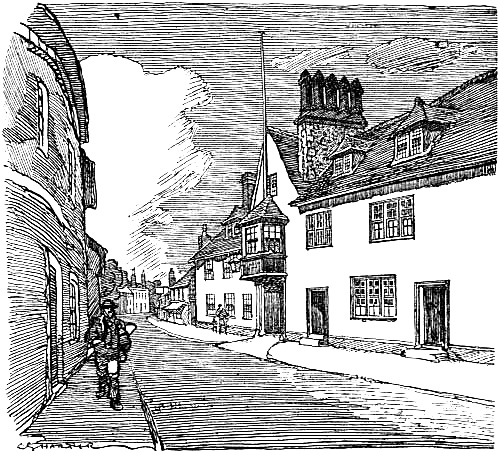

INTRODUCTORY

The Old Inns of Old England!—how alluring and how inexhaustible a theme! When you set out to reckon up the number of those old inns that demand a mention, how vast a subject it is! For although the Vandal—identified here with the brewer and the ground-landlord—has been busy in London and the great centres of population, destroying many of those famous old hostelries our grandfathers knew and appreciated, and building in their stead “hotels” of the most grandiose and palatial kind, there are happily still remaining to us a large number of the genuine old cosy haunts where the traveller, stained with the marks of travel, may enter and take his[Pg 2] ease without being ashamed of his travel-stains or put out of countenance by the modish visitors of this complicated age, who dress usually as if going to a ball, and whose patronage has rung the death-knell of many an inn once quaint and curious, but now merely “replete with every modern convenience.”

I thank Heaven—and it is no small matter, for surely one may be thankful for a good inn—that there yet remain many old inns in this Old England of ours, and that it is not yet quite (although nearly) a misdemeanour for the wayfarer to drink a tankard of ale and eat a modest lunch of bread and cheese in a stone-flagged, sanded rustic parlour; or even, having come at the close of day to his halting-place, to indulge in the mild dissipation and local gossip in the bar of an old-time hostelry.

This is one of the last surviving joys of travel in these strange times when you journey from great towns for sake of change and find at every resort that the town has come down before you, in the shape of an hotel more or less palatial, wherein you are expected to dine largely off polished marble surroundings and Turkey carpets, and where every trace of local colour is effaced. A barrier is raised there between yourself and the place. You are in it, but not of it or among it; but something alien, like the German or Swiss waiters themselves, the manager, and the very directors and shareholders of the big concern.

At the old-fashioned inn, on the other hand,[Pg 3] the whole establishment is eloquent of the place, and while you certainly get less show and glitter, you do, at any rate, find real comfort, and early realise that you have found that change for which you have come.

But, as far as mere name goes, most inns are “hotels” nowadays. It is as though innkeepers were labouring under the illusion that “inn” connotes something inferior, and “hotel” a superior order of things. Even along the roads, in rustic situations, the mere word “inn”—an ancient and entirely honourable title—is become little used or understood, and, generally speaking, if you ask a rustic for the next “inn” he stares vacantly before his mind grasps the fact that you mean what he calls a “pub,” or, in some districts oftener still, a “house.” Just a “house.” Some employment for the speculative mind is offered by the fact that in rural England an inn is “a house” and the workhouse “the House.” Both bulk largely in the bucolic scheme of existence, and, as a temperance lecturer might point out, constant attendance at the one leads inevitably to the other. At all events, both are great institutions, and prominent among the landmarks of Old England.

Which is the oldest, and which the most picturesque, inn this England of ours can show? That is a double-barrelled question whose first part no man can answer, and the reply to whose second half depends so entirely upon individual likings and preferences that one naturally hesitates[Pg 4] before being drawn into the contention that would surely arise on any particular one being singled out for that supreme honour. Equally with the morning newspapers—and the evening—each claiming the “largest circulation,” and, like the several Banbury Cake shops, each the “original,” there are several “oldest licensed” inns, and very many arrogating the reputation of the “most picturesque.”

The “Fighting Cocks” inn at St. Albans, down by the river Ver, below the Abbey, claims to be—not the oldest inn—but the oldest inhabited house, in the kingdom: a pretension that does not appear to be based on anything more than sheer impudence; unless, indeed, we take the claim to be a joke, to which an inscription,

The Old Round House,

Rebuilt after the Flood,

formerly gave the clue. But that has disappeared. The Flood, in this case, seeing that the building lies low, by the river Ver, does not necessarily mean the Deluge.

This curious little octagonal building is, however, of a very great age, for it was once, as “St. Germain’s Gate,” the water-gate of the monastery. The more ancient embattled upper part disappeared six hundred years ago, and the present brick-and-timber storey takes its place.

THE OLDEST INHABITED HOUSE IN ENGLAND: THE “FIGHTING COCKS,” ST. ALBANS.

The City of London’s oldest licensed inn is, by its own claiming, the “Dick Whittington,” in Cloth Fair, Smithfield, but it only claims to have[Pg 5] been licensed in the fifteenth century, when it might reasonably—without much fear of contradiction—have made it a century earlier. This is an unusual modesty, fully deserving mention. It is only an “inn” by courtesy, for, however interesting and picturesque the grimy, tottering old lath-and-plaster house may be to the stranger, imagination does not picture any one staying either in the house or in Cloth Fair itself while other houses and other neighbourhoods remain to choose from; and, indeed, the “Dick Whittington”[Pg 6] does not pretend to be anything else than a public-house. The quaint little figure at the angle, in the gloom of the overhanging upper storey, is one of the queer, unconventional imaginings of our remote forefathers, and will repay examination.

THE “DICK WHITTINGTON,” CLOTH FAIR.

Our next claimant in the way of antiquity is the “Seven Stars” inn at Manchester, a place little dreamt of, in such a connection, by most people; for, although Manchester is an ancient city, it is so modernised in general appearance that it is a place wherein the connoisseur of old-world inns would scarce think of looking for examples. Yet it contains three remarkably picturesque old taverns, and the neighbouring town of Salford, nearly as much a part of Manchester as Southwark is of London, possesses another. To take the merely picturesque, unstoried houses first:[Pg 7] these are the “Bull’s Head,” Greengate, Salford; the “Wellington” inn, in the Market-place, Manchester; the tottering, crazy-looking tavern called “Ye Olde Rover’s Return,” on Shude Hill, claiming to be the “oldest beer-house in the city,[Pg 8]” and additionally said once to have been an old farmhouse “where the Cow was kept that supplied Milk to The Men who built the ‘Seven Stars,’” and lastly—but most important—the famous “Seven Stars” itself, in Withy Grove, proudly bearing on its front the statement that it has been licensed over 560 years, and is the oldest licensed house in Great Britain.

“YE OLDE ROVER’S RETURN,” MANCHESTER.

The “Seven Stars” is of the same peculiar old-world construction as the other houses just enumerated, and is just a humble survival of the ancient rural method of building in this district: with a stout framing of oaken timbers and a filling of rag-stone, brick, and plaster. Doubtless all Manchester, of the period to which these survivals belong, was of like architecture. It was a method of construction in essence identical with the building of modern steel-framed houses and offices in England and in America: modern construction being only on a larger scale. In either period, the framework of wood or of metal is set up first and then clothed with its architectural features, whether of stone, brick, or plaster.

The “Seven Stars,” however, is no skyscraper. So far from soaring, it is of only two floors, and, placed as it is—sandwiched as it is, one might say—between grim, towering blocks of warehouses, looks peculiarly insignificant.

We may suppose the existing house to have been built somewhere about 1500, although there is nothing in its rude walls and rough axe-hewn timbers to fix the period to a century more or less.[Pg 9] At any rate, it is not the original “Seven Stars” on this spot, known to have been first licensed in 1356, three years after inns and alehouses were inquired into and regulated, under Edward the Third; by virtue of which record, duly attested by the archives of the County Palatine of Lancaster, the present building claims to be the “oldest Licensed House in Great Britain.”

There is a great deal of very fine, unreliable “history” about the “Seven Stars,” and some others, but it is quite true that the inn is older than Manchester Cathedral, for that—originally the Collegiate Church—was not founded until 1422; and topers with consciences remaining to them may lay the flattering unction to their souls that, if they pour libations here, in the Temple of Bacchus, rather than praying in the Cathedral, they do, at any rate (if there be any virtue in that), frequent a place of greater antiquity.

And antiquity is cultivated with care and considerable success at the “Seven Stars,” as a business asset. The house issues a set of seven picture-postcards, showing its various “historic” nooks and corners, and the leaded window-casements have even been artfully painted, in an effort to make the small panes look smaller than they really are; while the unwary visitor in the low-ceilinged rooms falls over and trips up against all manner of unexpected steps up and steps down.

It is, of course, not to be supposed that a house with so long a past should be without its legends, and in the cellars the credulous and[Pg 10] uncritical stranger is shown an archway that, he is told, led to old Ordsall Hall and the Collegiate Church! What thirsty and secret souls they must have been in that old establishment! But the secret passage is blocked up now. Here we may profitably meditate awhile on those “secret passages” that have no secrets and afford no passage; and may at the same time stop to admire the open conduct of that clergyman who, despising such underhand and underground things, was accustomed in 1571, according to the records of the Court Leet, to step publicly across the way in his surplice, in sermon-time, for a refreshing drink.

“What stories this old Inn could recount if it had the power of language!” exclaims the leaflet sold at the “Seven Stars” itself. The reflection is sufficiently trite and obvious. What stories could not any building tell, if it were so gifted? But fortunately, although walls metaphorically have ears, they have not—even in literary imagery—got tongues, and so cannot blab. And well too, for if they could and did, what a cloud of witness there would be, to be sure. Not an one of us would get a hearing, and not a soul be safe.

But what stories, in more than one sense, Harrison Ainsworth told! He told a tale of Guy Fawkes, in which that hero of the mask, the dark-lantern and the powder-barrel escaped, and made his way to the “Seven Stars,” to be concealed in a room now called “Ye Guy Fawkes Chamber.” Ye gods!

THE OLDEST LICENSED HOUSE IN GREAT BRITAIN: THE “SEVEN STARS,” MANCHESTER.

We know perfectly well that he did not escape, and so was not concealed in a house to which he could not come, but—well, there! Such fantastic tales, adopted by the house, naturally bring suspicion upon all else; and the story of the horse-shoe upon one of its wooden posts is therefore, rightly or wrongly, suspect. This is a legend that tells how, in 1805, when we were at war with Napoleon, the Press Gang was billeted at the “Seven Stars,” and seized a farmer’s servant who was leading a horse with a cast shoe along Withy Grove. The Press Gang could not legally press a farm-servant, but that probably mattered little, and he was led away; but, before he went, he nailed the cast horse-shoe to a post, exclaiming, “Let this stay till I come from the wars to claim[Pg 12] it!” He never returned, and the horse-shoe remains in its place to this day.

The room adjoining the Bar parlour is called nowadays the “Vestry.” It was, according to legends, the meeting-place of the Watch, in the old days before the era of police; and there they not only met, but stayed, the captain ever and again rising, with the words, “Now we will have another glass, and then go our rounds”; upon which, emptying their glasses, they all would walk round the tables and then re-seat themselves.

A great deal of old Jacobean and other furniture has been collected, to fill the rooms of the “Seven Stars,” and in the “Vestry” is the “cupboard that has never been opened” within the memory of living man. It is evidently not suspected of holding untold gold. Relics from the New Bailey Prison, demolished in 1872, are housed here, including the doors of the condemned cell, and sundry leg-irons; and genuine Carolean and Cromwellian tables are shown. The poet who wrote of some marvellously omniscient personage—

And still the wonder grew

That one small head could carry all he knew,

would have rejoiced to know the “Seven Stars,” and might have been moved to write a similar couplet, on how much so small a house could be made to hold.

THE ANCIENT HISTORY OF INNS

Inns, hotels, public-houses of all kinds, have a very ancient lineage, but we need not in this place go very deeply into their family history, or stodge ourselves with fossilised facts at the outset. So far as we are concerned, inns begin with the Roman Conquest of Britain, for it is absurd to suppose that the Britons, whom Julius Cæsar conquered, drank beer or required hotel accommodation.

The colonising Romans themselves, of course, were used to inns, and when they covered Britain with a system of roads, hostelries and mere drinking-places of every kind sprang up beside them, for the accommodation and refreshment alike of soldiers and civilians. There is no reason to suppose that the Roman legionary was a less thirsty soul than the modern soldier, and therefore houses that resembled our beer-shops and rustic inns must have been sheer necessaries. There was then the bibulium, where the bibulous boozed to their hearts’ content; and there were the diversoria and caupones, the inns or hotels, together with the posting-houses along the roads, known as mansiones or stabulia.

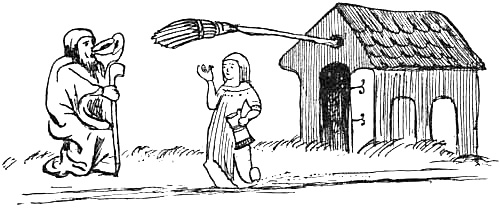

[Pg 14]The bibulium, that is to say, the ale-house or tavern, displayed its sign for all men to see: the ivy-garland, or wreath of vine-leaves, in honour of Bacchus, wreathed around a hoop at the end of a projecting pole. This bold advertisment of good drink to be had within long outlasted Roman times, and indeed still survives in differing forms, in the signs of existing inns. It became the “ale-stake” of Anglo-Saxon and middle English times.

The traveller recognised the ale-stake at a great distance, by reason of its long pole—the “stake” whence those old beer-houses derived their name—projecting from the house-front, with its mass of furze, or garland of flowers, or ivy-wreath, dangling at the end. But the ale-houses that sold good drink little needed such signs, a circumstance that early led to the old proverb, “Good wine needs no bush.”

On the other hand, we may well suppose the places that sold only inferior swipes required poles very long and bushes very prominent, and in London, where competition was great, all ale-stakes early began to vie with one another which should in this manner first attract the attention of thirsty folk. This at length grew to be such a nuisance, and even a danger, that in 1375 a law was passed that all taverners in the City of London owning ale-stakes projecting or extending over the king’s highway “more than seven feet in length at the utmost,” should be fined forty pence and be compelled to remove the offending sign.

We find the “ale-stake” in Chaucer, whose[Pg 15] “Pardoner” could not be induced to commence his tale until he had quenched his thirst at one:

But first quod he, her at this ale-stake

I will bothe drynke and byten on a cake.

We have, fortunately, in the British Museum, an illustration of such a house, done in the fourteenth century, and therefore contemporary with Chaucer himself. It is rough but vivid, and if the pilgrim we see drinking out of a saucer-like cup be gigantic, and the landlady, waiting with the jug, a thought too big for her inn, we are at any rate clearly made to see the life of that long ago. In this instance the actual stake is finished off like a besom, rather than with a bush.

AN ALE-STAKE.

From the Louterell Psalter.

The connection, however, between the Roman garland to Bacchus and the mediæval “bush” is obvious. The pagan God of Wine was forgotten, but the advertisment of ale “sold on the premises” was continued in much the same form; for in many cases the “bush” was a wreath, renewed at intervals, and twined around a permanent hoop.[Pg 16] With the creation, in later centuries, of distinctive signs, we find the hoop itself curiously surviving as a framework for some device; and thus, even as early as the reign of Edward the Third, mention is found of a “George-in-the-hoop,” probably a picture or carved representation of St. George, the cognisance of England, engaged in slaying the dragon. There were inns in the time of Henry the Sixth by the name of the “Cock-in-the-Hoop”; and doubtless the representation of haughty cockerels in that situation led by degrees to persons of self-sufficient manner being called “Cock-a-hoop,” an old-fashioned phrase that lingered on until some few years since.

In some cases, when the garland was no longer renewed, and no distinctive sign filled the hoop, the “Hoop” itself became the sign of the house: a sign still frequently to be met with, notably at Cambridge, where a house of that name, in coaching days a celebrated hostelry, still survives.

The kind of company found in the ale-stakes—that is to say, the beer-houses and taverns—of the fourteenth century is vividly portrayed by Langland, in his Vision of Piers Plowman. In that long Middle English poem, the work of a moralist and seer who was at the same time, beneath his tonsure and in spite of his orders, something of a man of the world, we find the virtuous ploughman reviewing the condition of society in that era, and (when you have once become used to the ancient spelling) doing so in a manner that is not only[Pg 17] readable to moderns, but even entertaining; while, of course, as evidence of social conditions close upon six hundred years ago, the poem is invaluable.

We learn how Beton the brewster met the glutton on his way to church, and bidding him “good-morrow,” asked him whither he went.

“To holy church,” quoth he, “for to hear mass. I will be shriven, and sin no more.”

“I have good ale, gossip,” says the ale-wife, “will you assay it?” And so glutton, instead of going to church, takes himself to the ale-house, and many after him. A miscellaneous company that was. There, with Cicely the woman-shoemaker, were all manner of humble, and some disreputable, persons, among whom we are surprised to find a hermit. What should a hermit be doing in an ale-house? But, according to Langland’s own showing elsewhere, the country was infested with hermits who, refusing restriction to their damp and lonely hermitages, frequented the alehouses, and only went home, generally intoxicated, to their mouldy pallets after they had drunk and eaten their fill and roasted themselves before the fire.

Here, then:

Cesse the souteresse[1] sat on the bench,

Watte the warner[2] and hys wyf bothe

Thomme the tynkere, and tweye of hus knaues,

[Pg 18]Hicke the hakeneyman, and Houwe the neldere,[3]

Claryce of Cockeslane, the clerk of the churche,

An haywarde and an heremyte, the hangeman of Tyborne,

Dauwe the dykere,[4] with a dozen harlotes,

Of portours and of pyke-porses, and pylede[5] toth-drawers.

A ribibour,[6] a ratonere,[7] a rakyer of chepe,

A roper, a redynkyng,[8] and Rose the dissheres,

Godfrey of garlekehythe, and gryfin the walshe,[9]

An vpholderes an hepe.

All day long they sat there, boozing, chaffering, and quarrelling:

There was laughing and louring, and “let go the cuppe,”

And seten so till euensonge and son gen vmwhile,

Tyl glotoun had y-globbed a galoun and a Iille.

By that time he could neither walk nor stand. He took his staff and began to go like a gleeman’s bitch, sometimes sideways and sometimes backwards. When he had come to the door, he stumbled and fell. Clement the cobbler caught him by the middle and set him on his knees, and then, “with all the woe of the world” his wife and his wench came to carry him home to bed. There he slept all Saturday and Sunday, and when at last he woke, he woke with a thirst—how modern that is, at any rate! The first words he uttered were, “Where is the bowl?”

A hundred and fifty years later than Piers Plowman we get another picture of an English ale-house, by no less celebrated a poet. This famous house, the “Running Horse,” still stands at Leatherhead, in Surrey, beside the long, many-arched bridge that there crosses the river Mole at[Pg 19] one of its most picturesque reaches. It was kept in the time of Henry the Seventh by that very objectionable landlady, Elynor Rummyng, whose peculiarities are the subject of a laureate’s verse. Elynor Rummyng, and John Skelton, the poet-laureate who hymned her person, her beer, and her customers, both flourished in the beginning of the sixteenth century. Skelton, whose genius was wholly satiric, no doubt, in his Tunning (that is to say, the brewing) of Elynor Rummyng, emphasised all her bad points, for it is hardly credible that even the rustics of the Middle Ages would have rushed so enthusiastically for her ale if it had been brewed in the way he describes.

His long, rambling jingles, done in grievous spelling, picture her as a very ugly and filthy old person, with a face sufficiently grotesque to unnerve a strong man:

For her viságe

It would aswage

A manne’s couráge.

Her lothely lere

Is nothyng clere,

But vgly of chere,

Droupy and drowsy,

Scuruy and lowsy;

Her face all bowsy,

Comely crynkled,

Woundersly wrynkled,

Lyke a rost pygges eare

Brystled wyth here.

Her lewde lyppes twayne,

They slauer, men sayne,

Lyke a ropy rayne:

[Pg 20]A glummy glayre:

She is vgly fayre:

Her nose somdele hoked,

And camously croked,

Neuer stoppynge,

But euer droppynge:

Her skin lose and slacke,

Grayned like a sacke;

Wyth a croked backe.

Her eyen jowndy

Are full vnsoundy,

For they are blered;

And she grey-hered:

Jawed like a jetty,

A man would haue pytty

To se how she is gumbed

Fyngered and thumbed

Gently joynted,

Gresed and annoynted

Vp to the knockels;

The bones of her huckels

Lyke as they were with buckles

Together made fast;

Her youth is farre past.

Foted lyke a plane,

Legged lyke a crane;

And yet she wyll iet

Lyke a silly fet.

·····

Her huke of Lincoln grene,

It had been hers I wene,

More than fourty yere;

And so it doth apere.

For the grene bare thredes

Loke lyke sere wedes,

Wyddered lyke hay,

The woll worne away:

And yet I dare saye

She thinketh herselfe gaye.

·····

[Pg 21]She dryueth downe the dewe

With a payre of heles

As brode as two wheles;

She hobles as a gose

Wyth her blanket trose

Ouer the falowe:

Her shone smered wyth talowe,

Gresed vpon dyrt

That bandeth her skyrt.

ELYNOR RUMMYNG.

And this comely dame

I vnderstande her name

Is Elynor Rummynge,

At home in her wonnynge:

And as men say,

She dwelt in Sothray,

In a certain stede

Bysyde Lederhede,

She is a tonnysh gyb,

The Deuyll and she be syb,

But to make vp my tale,

She breweth nappy ale,

And maketh port-sale

To travelers and tynkers,

To sweters and swynkers,

[Pg 22]And all good ale-drynkers,

That wyll nothynge spare,

But drynke tyll they stare

And brynge themselves bare,

Wyth, now away the mare

And let vs sley care

As wyse as a hare.

Come who so wyll

To Elynor on the hyll

Wyth Fyll the cup, fyll

And syt there by styll.

Erly and late

Thyther cometh Kate

Cysly, and Sare

Wyth theyr legges bare

And also theyr fete.

·····

Some haue no mony

For theyr ale to pay,

That is a shrewd aray;

Elynor swered, Nay,

Ye shall not beare away

My ale for nought,

By hym that me bought!

Wyth, Hey, dogge, hey,

Haue these hogges away[10]

Wyth, Get me a staffe,

The swyne eate my draffe!

Stryke the hogges wyth a clubbe,

They haue dranke up my swyllyn tubbe.

The unlovely Elynor scraped up all manner of filth into her mash-tub, mixed it together with her[Pg 23] “mangy fists,” and sold the result as ale. It is proverbial that “there is no accounting for tastes,” and it would appear as though the district had a peculiar liking for this kind of brew. They would have it somehow, even if they had to bring their food and furniture for it:

Insteede of quoyne and mony,

Some bryng her a coney,

And some a pot wyth honey;

Some a salt, some a spoone,

Some theyr hose, some theyr shoone;

Some run a good trot

Wyth skyllet or pot:

Some fyll a bag-full

Of good Lemster wool;

An huswyfe of trust

When she is athyrst

Such a web can spyn

Her thryft is full thyn.

Some go strayght thyther

Be it slaty or slydder,

They hold the hyghway;

They care not what men say,

Be they as be may

Some loth to be espyd,

Start in at the backesyde,

Over hedge and pale,

And all for good ale.

Some brought walnuts,

Some apples, some pears,

And some theyr clyppying shears.

Some brought this and that,

Some brought I wot ne’re what,

Some brought theyr husband’s hat.

and so forth, for hundreds of lines more.

The old inn—still nothing more than an ale-house—is in part as old as the poem, but has been[Pg 24] so patched and repaired in all the intervening centuries that nothing of any note is to be seen within. A very old pictorial sign, framed and glazed, and fixed against the wall of the gable, represents the ill-favoured landlady, and is inscribed: “Elynor Rummyn dwelled here, 1520.”

Accounts we have of the fourteenth-century inns show that the exclusive, solitary Englishman was not then allowed to exist. Guests slept in dormitories, very much as the inmates of common lodging-houses generally do now, and, according to the evidence of old prints, knew nothing of nightshirts, and lay in bed naked. They purchased their food in something the same way as a modern “dosser” in a Rowton House, but their manners and customs were peculiarly offensive. The floors were strewed with rushes; and as guests generally threw their leavings there, and the rushes themselves were not frequently removed, those old interiors must have been at times exceptionally noisome.

Inn-keepers charged such high prices for this accommodation, and for the provisions they sold, that the matter grew scandalous, and at last, in the reign of Edward the Third, in 1349, and again in 1353, statutes were passed ordering hostelries to be content with moderate gain. The “great and outrageous dearth of victuals kept up in all the realm by innkeepers and other retailers of victuals, to the great detriment of the people travelling across the realm” was such that no less a penalty would serve than that any “hosteler[Pg 25] or herberger” should pay “double of what he received to the party damnified.” Mayors and bailiffs, and justices learned in the law, were to “enquire in all places, of all and singular, of the deeds and outrages of hostelers and their kind,” but it does not appear that matters were greatly improved.

THE “RUNNING HORSE,” LEATHERHEAD.

It will be observed that two classes of innkeepers are specified in those ordinances. The “hosteler” was the ordinary innkeeper; the “herberger” was generally a more or less important and well-to-do merchant who added to his income by “harbouring”—that is to say, by boarding and lodging—strangers, the “paying guests” of that age. We may dimly perceive something of the[Pg 26] trials and hardships of old-time travel in that expression “harbouring.” The traveller then came to his rest as a ship comes into harbour from stormy seas. The better-class travellers, coming into a town, preferred the herberger’s more select table to the common publicity of the ordinary hostelry, and the herbergers themselves were very keen to obtain such guests, some even going to the length of maintaining touts to watch the arrival of strangers, and bid for custom. This was done both openly and in an underhand fashion, the more rapacious among the herbergers employing specious rogues who, entering into conversation with likely travellers at the entrance of a town, would pretend to be fellow-countrymen and so, on the understanding of a common sympathy, recommending them to what they represented to be the best lodgings. Travellers taking such recommendations generally found themselves in exceptionally extortionate hands. These practices early led to “herbergers” being regulated by law, on much the same basis as the hostelers.

Not many records of travelling across England in the fourteenth century have survived. Indeed the only detailed one we have, and that is merely a return of expenses, surviving in Latin manuscript at Merton College, Oxford, concerns itself with nothing but the cost of food and lodging at the inns and the disbursements on the road, made by the Warden and two fellows who, with four servants—the whole party on horseback—in September,[Pg 27] 1331, travelled to Durham and back on business connected with the college property. The outward journey took them twelve days. They crossed the Humber at the cost of 8d., to the ferry: beds for the entire party of seven generally came to 2d. a night, beer the same, wine 1¼d., meat 5½d., candles ¼d., fuel 2d., bread 4d., and fodder for the horses 10d.

GENERAL HISTORY OF INNS

The mediæval hostelries, generally planned in the manner of the old galleried inns that finally went out of fashion with the end of the coaching age, consisting of a building enclosing a courtyard, and entered only by a low and narrow archway, which in its turn was closed at nightfall by strong, bolt-studded doors, are often said to owe their form to the oriental “caravanserai,” a type of building familiar to Englishmen taking part in the Crusades.

But it is surely not necessary to go so far afield for an origin. The “caravanserai” was originally a type of Persian inn where caravans put up for the night: and as security against robbers was the first need of such a country and such times, a courtyard capable of being closed when necessary against unwelcome visitors was clearly indicated as essential. Persia, however, and oriental lands in general, were not the only countries where in those dark centuries robbers, numerous and bold, or even such undesirables as rebels against the existing order of things, were to be reckoned with, and England had no immunity from such dangers. In such a state of affairs, and in times when[Pg 29] private citizens were careful always to bolt and bar themselves in; when great lords dwelt behind moats, drawbridges, and battlemented walls; and when even ecclesiastic and collegiate institutions were designed with the idea that they might ultimately have to be defended, it is quite reasonable to suppose that innkeepers were capable of evolving a plan for themselves by which they and their guests, and the goods of their guests, might reckon on a degree of security.

This was the type of hostelry that, apart from the mere tavern, or alehouse, remained for so many centuries typical of the English good-class inns. It was at once, in a sense—to compare old times with new—the hotel and railway-station of an age that knew neither railways nor the class of house we style “hotel.” It was the fine flower of the hostelling business, and to it came and went the carriers’ waggons, the early travellers riding horseback, and, in the course of time, as the age of wonderful inventions began to dawn, the stage and mail-coaches. Travellers of the most gentle birth, equally with those rich merchants and clothiers who were the greatest travellers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, inned at such establishments. It was at one such that Archbishop Leighton ended. He had said, years before, that “if he must choose a place to die in, it should be an inn, it looking like a pilgrim’s going home, to whom this world was an inn, and who was weary of the noise and confusion of it.” He died, that good and[Pg 30] gentle man, at the “Bell” in Warwick Lane, in 1684.

London, once rich in hostelries of this type, has now but one. In fine, it is not in the metropolis that the amateur of old inns of any kind would nowadays seek with great success; although, well within the memory of most people, it was exceptionally well furnished with them. It was neither good taste nor good business that, in 1897, demolished the “Old Bell,” Holborn, a pretty old-world galleried inn that maintained until the very last an excellent trade in all branches of licensed-victualling; and would have continued so to do had it not been that the greed for higher ground-rent ordained the ending of it, in favour of the giant (and very vulgar) building now occupying the spot where it stood. That may have been a remunerative transaction for the ground-landlord; but, looking at these commercial-minded clearances in a broader way, they are nothing less than disastrous. If, to fill some private purses over-full, you thus callously rebuild historic cities, their history becomes merely a matter for the printed page, and themselves to the eye nothing but a congeries of crowded streets where the motor-omnibuses scream and clash and stink, and citizens hustle to get a living. History, without visible ancient buildings to assure the sceptical modern traveller that it is not wholly lies, will never by itself draw visitors.

Holborn, where the “Old Bell” stood, was, until quite recent years, a pleasant threshold to[Pg 31] the City. There stood Furnival’s Inn, that quiet quadrangle of chambers, with the staid and respectable Wood’s Hotel. Next door was Ridler’s Hotel, with pleasant bay-window looking upon the street, and across the way, in Fetter Lane, remained the “White Horse” coaching inn; very much down on its luck in its last years, but interesting to prowling strangers enamoured of the antique and out-of-date.

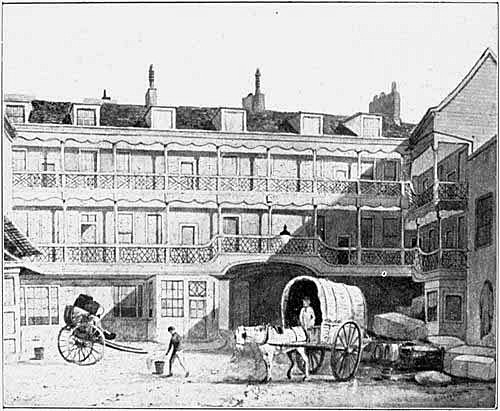

The vanished interest of other corners in London might be enlarged upon, but it is too melancholy a picture. Let us to the Borough High Street, and, resolutely refusing to think for the moment of the many queer old galleried inns that not so long since remained there, come to that sole survivor, the “George.”

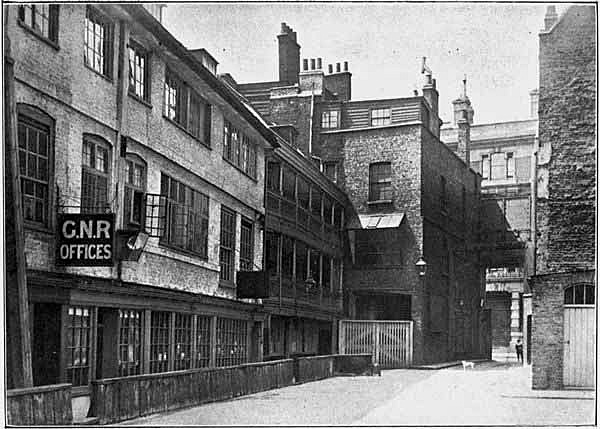

You would never by mere chance find the “George,” for it has no frontage to the street, and lies along one side of a yard not at first sight very prepossessing, and, in fact, used in these days for the unsentimental purposes of a railway goods-receiving depot. This, however, is the old yard once entirely in use for the business of the inn.

The “George,” as it now stands, is the successor of a pre-Reformation inn that, formerly the “St. George,” became secularised in the time of Henry the Eighth, when saints, even patron saints, were under a cloud. It is an exceedingly long range of buildings, dating from the seventeenth century, and in two distinct and different styles: a timbered, wooden-balustraded gallery in two storeys, and a white-washed brick continuation.[Pg 32] The long ground-floor range of windows to the kitchen, the bar, and the coffee-room, is, as seen in the illustration, protected from any accidents in the manœuvring of the railway waggons by a continuous bulkhead of sleepers driven into the ground. It is pleasing to be able to bear witness to the thriving trade that continues to be done in this sole ancient survivor of the old Southwark galleried inns, and to note that, however harshly fate, as personified by rapacious landlords, has dealt with its kind, the old-world savour of the inn is thoroughly appreciated by those not generally thought sentimental persons, the commercial men who dine and lunch, and the commercial travellers who sleep, here.

But, however pleasing the old survivals in brick and stone, in timber and plaster, may be to the present generation, we seem, by the evidence left us in the literature and printed matter of an earlier age, to have travelled far from gross to comparatively ideal manners.

THE LAST OF THE OLD GALLERIED INNS OF LONDON: THE “GEORGE,” SOUTHWARK.

Photo by T. W. Tyrrell.

The manners common to all classes in old times would scarce commend themselves to modern folk. We get a curious glimpse of them in one of a number of Manuals of Foreign Conversation for the use of travellers, published towards the close of the sixteenth century in Flanders, then a country of great trading importance, sending forth commercial travellers and others to many foreign lands. One of these handy books, styled, rather formidably, Colloquia et dictionariolum septem linguarum, including, as its title indicates, [Pg 33]conversation in seven languages, was so highly successful that seven editions of it, dating from 1589, are known. The traveller in England, coming to his inn, is found talking on the subject of trade and civil wars, and at length desires to retire to rest. The conversation itself is sufficiently strange, and is made additionally startling by the capital W’s that appear in unconventional places. “Sir,” says the traveller, “by your leave, I am sum What euell at ease.” To which the innkeeper replies: “Sir, if you be ill at ease, go and take your rest, your chambre is readie. Jone, make a good fier in his chambre, and let him lacke nothing.”

Then we have a dialogue with “Jone,” the chambermaid, in this wise:

Traveller: My shee frinde, is my bed made? is it good?

“Yea, Sir, it is a good feder bed, the scheetes be very cleane.”

Traveller: I shake as a leafe upon the tree. Warme my kerchif and bynde my head well. Soft, you binde it to harde, bryng my pilloW and cover mee Well: pull off my hosen and Warme my bed: draWe the curtines and pinthen With a pin.

Where is the camber pot?

Where is the priuie?

Chambermaid: FolloW mee, and I Will sheW you the Way: go up streight, you shall finde them at the right hand. If you see them not you shall smell them Well enough. Sir, doth it please you to haue no other thing? are you Wel?

[Pg 34]Traveller: Yea, my shee frinde, put out the candell, and come nearer to mee.

Chambermaid: I Wil put it out When I am out of the chamber. What is your pleasure, are you not Well enough yet?

Traveller: My head lyeth to loWe, lift up a little the bolster, I can not lie so loWe.—My shee friende, kisse me once, and I shall sleape the better.

Chambermaid: Sleape, sleape, you are not sicke, seeing that you speake of kissyng. I had rather die then to kisse a man in his bed, or in any other place. Take your rest in God’s name, God geeue you good night and goode rest.

Traveller: I thank you, fayre mayden.

In the morning we have “Communication at the oprysing,” the traveller calling to the boy to “Drie my shirt, that I may rise.” Then, “Where is the horse-keeper? go tell him that hee my horse leade to the river.”

Departing, our traveller does not forget the chambermaid, and asks, “Where is ye maiden? hold my shee freend, ther is for your paines. Knave, bring hither my horse, have you dressed him Well?” “Yea, sir,” says the knave, “he did Wante nothing.”

Anciently people of note and position, with large acquaintance among their own class, expected, when they travelled, to be received at the country houses along their route, if they should so desire, and still, at the close of the seventeenth century, and at the beginning of the eighteenth, the custom[Pg 35] was not unknown. Even should the master be away from home, the hospitality of his house was not usually withheld. From these old and discontinued customs we may, perhaps, derive that one by no means obsolete, but rather still on the increase, of guests “tipping” the servants of country houses.

This possibility of a traveller making use of another man’s house as his inn was fast dying out in England in the time of Charles the Second. Probably it had never been so abused in this country as in Scotland, where innkeepers petitioned Parliament, complaining, in the extraordinary language at that time obtaining in Scotland, “that the liegis travelland in the realme quhen they cum to burrowis and throuchfairís, herbreis thame not in hostillaries, but with their acquaintance and friendis.”

An enactment was accordingly passed in 1425, forbidding, under a penalty of forty shillings, all travellers resorting to burgh towns to lodge with friends or acquaintances, or in any place but the “hostillaries,” unless, indeed, they were persons of consequence, with a great retinue, in which case they personally might accept the hospitality of friends, provided that their “horse and meinze” were sent to the inns.

When the custom of seeking the shelter, as a matter of course, of the country mansion fell into disuse, so, conversely, did that of naming inns after the local Lord of the Manor come into fashion. Then, in a manner emblematic of the traveller’s[Pg 36] change from the hospitality of the mansion to that of the inn, mine host adopted the heraldic coat from the great man’s portal, and called his house the “—— Arms.” It has been left to modern times, times in which heraldry has long ceased to be an exact science, to perpetrate such absurdities as the “Bricklayers’ Arms,” the “Drovers’ Arms,” and the like, appropriated to a class of person unknown officially to the College of Heralds.

According to Fynes Morison, who wrote in 1617, we held then, in this country, a pre-eminence in the trade and art of innkeeping: “The world,” he said, “affords not such inns as England hath, for as soon as a passenger comes the servants run to him: one takes his horse, and walks him till he be cold, then rubs him and gives him meat, but let the master look to this point. Another gives the traveller his private chamber and kindles his fire, the third pulls off his boots and makes them clean; then the host or hostess visits him—if he will eat with the host—or at a common table it will be 4d. and 6d. If a gentleman has his own chamber, his ways are consulted, and he has music, too, if he likes.”

In short, Morison wrote of English inns just anterior to the time of Samuel Pepys, who travelled much in his day, and tells us freely, in his appreciative way, of the excellent appointments, the music, the good fare and the comfortable beds he, in general, found.

But this era in which Morison wrote was a trying time for all innkeepers and taverners. The[Pg 37] story of it is so remarkable that it repays a lengthy treatment.

In our own age it is customary to many otherwise just and fair-minded people to look upon the innkeeper as a son of a Belial, a sinner who should be kept in outer darkness and made to sit in sackcloth and ashes, in penance for other people’s excesses. On the one side he has the cormorants of the Inland Revenue plucking out his vitals, and generally, if it be a “tied” house, on the other a Brewery Company, selling him the worst liquors at the best prices, and threatening to turn him out if he does not maintain a trade of so many barrels a month. Always, from the earliest times, he has been the mark for satire and invective, has been licensed, sweated, regulated, and generally put on the chain; but he probably had never so bad a time as that he experienced in the last years of James the First. Already innkeepers were licensed at Quarter Sessions, but in 1616 it occurred to one Giles Mompesson, the time-serving Member of Parliament for the rotten borough of Great Bedwin, in Wiltshire, that much plunder could be extracted from them and used to replenish the Royal Exchequer, then at a low ebb, if he could obtain the grant of a monopoly of licensing inns, over-riding the old-established functions in that direction of the magistrates.

Giles Mompesson was no altruist, or at the best a perverted one, who put his own interpretation upon that good old maxim, “Who works for others works for himself.” He foresaw that while[Pg 38] such a State monopoly, under his own control, might bring a bountiful return to the State, it must enrich himself and those associated with him. He imparted the brilliant idea to that dissolute royal favourite, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, who succeeded in obtaining him a patent for a special commission to grant licenses to keepers of inns and ale-houses. The patent was issued, not without great opposition, and the licensing fees were left to the discretion of Mompesson and his two fellow-commissioners, with the only proviso that four-fifths of the returns were to go to the Exchequer. Shortly afterwards Mompesson himself was knighted by the King, in order, as Bacon wrote, “that he may better fight with the Bulls and the Bears and the Saracen’s Heads, and such fearful creatures.” Much virtue and power, of the magisterial sort, in a knighthood; likely, we consider, King and commissioners, and all concerned in the issuing of this patent, to impress and overawe poor Bung, and therefore we, James the First, most sacred Majesty by the grace of God, do, on Newmarket Heath, say, “Rise, Sir Giles!”

The three commissioners wielded full authority. There was no appeal from that triumvirate, who at their will refused or granted licenses, and charged for them what they pleased, hungering after that one-fifth. They largely increased the number of inns, woefully oppressed honest men, wrung heavy fines from all for merely technical and inadvertent infractions of the licensing laws,[Pg 39] and granted new licenses at exorbitant rates to infamous houses that had but recently been deprived of them. During more than four years these iniquities continued, side by side with the working of other monopolies, granted from time to time, but at last the gathering storm of indignation burst, in the House of Commons, in February, 1621. That was a Parliament already working with the leaven of a Puritanism which was presently to leaven the whole lump of English governance in a drastic manner then little dreamt of; and it was keen to scent and to abolish abuses.

Thus we see the House, very stern and vindictive, inquiring into the conduct and working of the by now notorious Commission. In the result Mompesson and his associates were found to have prosecuted 3,320 innkeepers for technical infractions of obsolete statutes, and to have been guilty of many misdemeanours. Mompesson appealed to the mercy of the House, but was placed under arrest by the Sergeant-at-Arms while that assembly deliberated how it should act. Mompesson himself clearly expected to be severely dealt with, for at the earliest moment evaded his arrest and was off, across the Channel, where he learnt—no doubt with cynical amusement—that he had been “banished.”

The judgment of the two Houses of Parliament was that he should be expelled the House, and be degraded from his knighthood and conducted on horseback along the Strand with his face to the[Pg 40] horse’s tail. Further, he was to be fined £10,000, and for ever held an infamous person.

Meanwhile, if Parliament failed to lay the chief offender by the heels, it did at least succeed in putting hand upon, and detaining, one of his equally infamous associates, himself a knight, and accordingly susceptible of some dramatic degradation, beyond anything to be possibly wreaked upon any common fellow. Sir Francis Mitchell, attorney-at-law, was consigned to the Tower, and then brought forth from it to have his spurs hacked off and thrown away, his sword broken over his head, and himself publicly called no longer knight, but “knave.” Then to the Fleet Prison, with certainty on the morrow of a public procession to Westminster, himself the central object, mounted, with face to tail, on the back of the sorriest horse to be found, and the target for all the missiles of the crowd: a prospect and programme duly realised and carried out.

Mompesson we may easily conceive hearing of, and picturing, all these things, in his retreat over sea, and congratulating himself on his prompt flight. But he was, after all, treated with the most extraordinary generosity. The same year, the fine of £10,000 was assigned by the House to his father-in-law (which we suspect was an oblique way of remitting it) and in 1623 he is found petitioning to be allowed to return to England. He was allowed to return for a period of three months, on condition that it was to be solely on his private affairs, but he was no sooner back than[Pg 41] he impudently began to put his old licensing patent in force again. On August 10th he was granted an extension of three months, but overstayed it, and was at last, February 8th, 1624, ordered to quit the country within five days. It remains uncertain whether he complied with this, or not, but he soon returned; not, however, to again trouble public affairs, for he returned to Wiltshire and died there, obscurely, about 1651. He lives in literature, in Massinger’s play, A New Way to pay Old Debts, as “Sir Giles Overreach.”

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

The inns of old time, serving as they did the varied functions of clubs and assembly-rooms and places of general resort, in addition to that of hotel, were often, at times when controversies ran high, very turbulent places.

The manners and customs prevailing in the beginning of the eighteenth century may be imagined from an affray which befell at the “Raven,” Shrewsbury, in 1716, when two officers of the Dragoons insisted in the public room of the inn, upon a Mr. Andrew Swift and a Mr. Robert Wood, apothecary, drinking “King George, and Damnation to the Jacobites.” The civilians refused, whereupon those military men drew their swords, but—swords notwithstanding—they were very handsomely thrashed, and one was placed upon the fire, and not only had his breeches burnt through in a conspicuous place, but had his person toasted. The officers then, we learn, “went off, leaving their hatts, wigs and swords (which were broke) behind them.”

One did not, it will be gathered from the above, easily in those times lead the Quiet Life; but that was a heated occasion, and we were then[Pg 43] really upon the threshold of that fine era when inns, taverns, and coffee-houses were the resort, not merely of travellers or of thirsty souls, but of wits and the great figures of eighteenth-century literature, who were convivial as well as literary. It was a great, and, as it seems to the present century, a curious, time; when men of the calibre of Addison, of Goldsmith and of Johnson, acknowledged masters in classic and modern literature, smoked and drank to excess in the public parlours of inns. But those were the clubs of that age, and that was an age in which, although the producers of literature were miserably rewarded, their company and conversation were sought and listened to with respect.

When Dr. Johnson declared that a seat in a tavern chair was the height of human felicity, his saying carried a special significance, lost upon the present age. He was thinking, not only of a comfortable sanded parlour, a roaring fire, and plenty of good cheer and good company, but also of the circle of humbly appreciative auditors who gathered round an accepted wit, hung upon his words, offered themselves as butts for his ironic or satiric humour, and—stood treat. The great wits of the eighteenth century expected subservience in their admirers, and only began to coruscate, to utter words of wisdom or inspired nonsense, or to scatter sparkling quips and jests, when well primed with liquor—at the expense of others. The felicity of Johnson found in a tavern chair was derived, therefore, chiefly from the[Pg 44] homage of his attendant humble Boswells, and from the fact that they paid the reckoning; and was, perhaps, to some modern ideas, a rather shameful idea of happiness.

Johnson, who did not love the country, and thought one green field very like another green field, when he spoke of a tavern chair was of course thinking of London taverns. He would have found no sufficient audience in its wayside fellow, which indeed was apt, in his time and for long after, to be somewhat rough and ready, and, when you had travelled a little far afield, became a very primitive and indeed barbarous place.

At Llannon, in 1797, those sketching and note-taking friends, Rowlandson and Wigstead, touring North and South Wales in search of the picturesque, found it, not unmixed with dirt and discomfort, at the inns. Indeed, it was only at one town in Wales—the town of Neath—that Wigstead found himself able to declare, “with strict propriety,” that the house was comfortable. Comfort and decency fled the inn at Llannon, abashed. This, according to Wigstead, was the way of it: “The cook on our arrival was in the suds, and, with unwiped hands, reached down a fragment of mutton for our repast: a piece of ham was lost, but after long search was found amongst the worsted stockings and sheets on the board.”

Then “a little child was sprawling in a dripping-pan which seemed recently taken from the fire: the fat in this was destined to fry our eggs in.[Pg 45] Hunger itself even was blunted,” and the travellers left those delicacies almost untouched. Not even the bread was without its surprises. “I devoted my attention to a brown loaf,” says Wigstead, “but on cutting into it was surprised to find a ball of carroty-coloured wool; and to what animal it had belonged I was at a loss to determine. Our table-cloth had served the family for at least a month, and our sitting-room was everywhere decorated with the elegant relics of a last night’s smoking society, as yet unremoved.”

All this was pretty bad, but perhaps even the baby in the dripping-pan, the month-old table-cloth, and the hank of wool in the loaf were to be preferred to what they had experienced at Festiniog. They had not at first purposed to make a halt at that place, having planned to stay the night at Tan-y-Bwlch, where the inn commanded a view over a lovely wooded vale. The perils and the inconveniences of the vile road by which they had come faded into insignificance when they drew near, and they began to reckon upon the comforts of a good supper and good beds at Tan-y-Bwlch. They even disputed whether the supper should be chickens or chops, but all such vain arguments and contentions faded away when they drew near and a stony-faced landlord declared he had no room for them.

We can easily sympathise here with those travellers in search of the picturesque, for we have all met with the like strokes of Fate. No doubt the beauties of the view suddenly obscured[Pg 46] themselves, as will happen when you can get nothing to eat or drink; and probably they thought of Dr. Johnson, who a few years earlier had held the most beautiful landscape capable of being improved by a good inn in the foreground. But a good inn where they cannot or will not receive you, is, in such a situation, sorrow’s crown of sorrow, an aggravation and a mockery.

It was a tragical position, and down the sounding alleys of time vibrates strange chords of reminiscence in the breasts of even modern tourists of any experience. We too, have suffered; and many an one may say, with much tragical meaning, “et ego in Arcadia vixit.”

Alas! for the frustrated purpose of Messrs. Rowlandson and Wigstead, Tan-y-Bwlch could not, or would not, receive them, and they had no choice but to journey three more long Welsh miles to Festiniog in the rain. It sometimes rains in Wales, and when it does, it rarely knows when to leave off.

Arrived there, they almost passed the inn, in the gathering darkness, mistaking it for a barn or an outhouse; and when they made to enter, they were confronted by an extraordinary landlady with the appearance of one of the three witches in Macbeth.

“Could they have beds?”

Reluctantly she said they could, telling them (what we know to be true enough) that she[Pg 47] supposed they only came there because there was no accommodation at Tan-y-Bwlch.

The travellers made no reply to that damning accusation, and hid their incriminating blushes in the congenial gloom of the fast-falling night. It was a situation in which, if you come to consider it, no wise man would give “back answers.” You have a landlady who, for the proverbial two pins, or even less, would cast you forth; and when so thrust into the inhospitable night, you have seventeen mountainous miles to go, in a drenching rain, before any other kind of asylum is reached.

Wigstead remarks that they “were not a little satisfied at being under any kind of roof,” and the words seem woefully inadequate to the occasion.

There were no chops that night for supper, nor chickens; and they fed, with what grace they could summon up, on a “small leg of starved mutton and a duck,” which, by the scent of them, had been cooked a fortnight. For sauce they had hunger only.

“Our bedrooms,” says Wigstead, “were most miserable indeed: the rain poured in at every tile in the ceiling,” and the sheets were literally wringing wet; so that, in Wigstead’s elegant phrasing, they “thought it most prudent to sacrifice to Somnus in our own garments, between blankets”: which may perhaps be translated, into everyday English, to mean that they slept in their own clothes.

They saw strange sights on that wild tour, and,[Pg 48] in the course of their hazardous travels through the then scarcely civilised interior of the Principality, came to the “pleasant village” of Newcastle Emlyn, Carmarthenshire, where they found a “decent inn” in whose kitchen they remarked a dog acting as turnspit. That the dogs so employed did not particularly relish the work is evident in Wigstead’s remark: “Great care must be taken that this animal does not observe the cook approach the larder. If he does, he immediately hides himself for the remainder of the day,” acting, in fact, like a professional “unemployed” when offered a job!

A familiar sight in the kitchen of any considerable inn of the long ago was the turnspit dog, who, like the caged mouse or squirrel with his recreation-wheel, revolved a kind of treadwheel which, in this instance, was connected with apparatus for turning the joints roasting at the fire, and formed not so much recreation as extremely hard work. The dogs commonly used for this purpose were of the long-bodied, short-legged, Dachshund type.

Machinery, in the form of bottle-jacks revolved by clockwork, came to the relief of those hard-working dogs so long ago that all knowledge of turnspits, except such as may be gleaned from books of reference, is now lost, and illustrations of them performing their duties are exceedingly rare. Rowlandson’s spirited drawing is, on that account, doubly welcome.

THE KITCHEN OF A COUNTRY INN, 1797: SHOWING THE TURNSPIT DOG.

From the engraving after Rowlandson.

Turnspits were made the subject of a very [Pg 49]illuminating notice, a generation or so back, by a former writer on country life: “How well do I recollect,” he says, “in the days of my youth watching the operations of a turnspit at the house of a worthy old Welsh clergyman in Worcestershire, who taught me to read! He was a good man, wore a bushy wig, black worsted stockings, and large plated buckles in his shoes. As he had several boarders as well as day-scholars, his two turnspits had plenty to do. They were long-bodied, crook-legged and ugly dogs, with a suspicious, unhappy look about them, as if they were weary of the task they had to do, and expected every moment to be seized upon, to perform it. Cooks in those days, as they are said to be at present, were very cross; and if the poor animal, wearied with having a larger joint than usual to turn, stopped for a moment, the voice of the cook might be heard, rating him in no very gentle terms. When we consider that a large, solid piece of beef would take at least three hours before it was properly roasted, we may form some idea of the task a dog had to perform in turning a wheel during that time. A pointer has pleasure in finding game, the terrier worries rats with eagerness and delight, and the bull-dog even attacks bulls with the greatest energy, while the poor turnspit performs his task with compulsion, like a culprit on a tread-wheel, subject to scolding or beating if he stops a moment to rest his weary limbs, and is then kicked about the kitchen when the task is over.”

[Pg 50]The work being so hard, how ever did the dogs allow themselves to be put to it? The training was, after all, extremely simple. You first, as Mrs. Glasse might say, caught your dog. That, it will be agreed, was indispensable. Then you put him, ignorant and uneducated, into the wheel, and in company with him a live coal, which burnt his legs if he stood still. He accordingly tried to race away from it, and the quicker he spun the wheel round in his efforts the faster followed the coal: so that, by dint of much painful experience, he eventually learned the (comparatively) happy medium between standing still and going too fast. “These dogs,” it was somewhat unnecessarily added, “were by no means fond of their profession.” Of course they were not! Does the convict love his crank or treadmill, or the galley-slave his oar and bench?

The turnspit was once so well-known an institution that he found an allusion in poetry, and an orator was likened, in uncomplimentary fashion, to one:

His arguments in silly circles run,

Still round and round, and end where they begun.

So the poor turnspit, as the wheel runs round,

The more he gains, the more he loses ground.

These unfortunate dogs acquired a preternatural intelligence. A humorous, but probably not true, story is told, illustrating this. It was at Bath, and some of them had accompanied their mistresses to church, where the lesson chanced[Pg 51] to be the tenth chapter of Ezekiel, in which there is an amazing deal about self-propelled chariots, and wheels. When the dogs first heard the word “wheel” they started up in alarm; on its occurring a second time they howled dolefully, and at the third instance they all rushed from the church.

Strangely modern appear the grievances raised against innkeepers in the old times. The bills they presented were early pronounced exorbitant, and so, in spite of measures intended for the relief of travellers, they remained. Indeed, throughout the centuries, until the present day, the curious in these matters will find, not unexpectedly, that innkeepers charged according to what they considered their guests would grumble at—and pay.

The eighteenth-century locus classicus in this sort is the account rendered to the Duc de Nivernais, the French Ambassador to England, who in 1762, coming to negotiate a treaty of peace, halted the night, on his way from Dover to London, at the “Red Lion,” Canterbury.

For the night’s lodging for twelve persons, with a frugal supper in which oysters, fowls, boiled mutton, poached eggs and fried whiting figure, the landlord presented an account of over £44. Our soldiers fought the Frenchman; mine host did his humble, non-combatant part, and fleeced him.

This truly magnificent bill has been preserved, not, let us hope, for the emulation of other[Pg 52] hotel-keepers, but by way of a “terrible example.” Here it is:

| £ | s. | d. | ||||

| Tea, coffee, and chocolate | 1 | 4 | 0 | |||

| Supper for self and servants | 15 | 10 | 0 | |||

| Bread and beer | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Fruit | 2 | 15 | 0 | |||

| Wine and punch | 10 | 8 | 8 | |||

| Wax candles and charcoal | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Broken glass and china | 2 | 10 | 0 | |||

| Lodging | 1 | 7 | 0 | |||

| Tea, coffee, and chocolate | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Chaise and horses for the next stage | 2 | 16 | 0 | |||

| 44 | 10 | 8 |

The Duke paid the account without a murmur, only remarking that innkeepers at this rate should soon grow rich; but news of this extraordinary charge was soon spread all over England. It was printed in the newspapers, amid other marvels, disasters and atrocities, and mine host of the “Red Lion,” like Byron in a later age, woke up one morning to find himself famous.

The country gentlemen, scandalised at his rapacity, boycotted his inn, and his brother innkeepers of Canterbury disowned him. The unfortunate man wrote to the St. James’s Chronicle, endeavouring to justify himself, and complaining bitterly of the harm that had been wrought his business by the continual billeting of soldiers upon him. But it was in vain he protested; his trade fell off, and he was ruined in six months.

Sometimes, too, there was a difference of opinion as to whether a bill had or had not[Pg 53] actually been paid, as we see by the following indignant letter:

Normanton near Stamford.

2d Septr 1755.

Madam,

My Lord Morton Received a Letter from you of the 5th Augt inclosing a Bill drawn by you on his Lp for £6 1 11, and to make up this sum pr your Account annexed to the above-mentioned Letter, you charge twelve shillings for his Servant’s eating, for which he is ready to Swear he paid you in full; then you charge for the Horses Hay for 35 Nights notwithstanding you was ordered to send the horse out to grass, and by the by when the horse came to London he was so poor as if he had been quite neglected which seems probable as he mended soon after he came here; at any rate you have used my Lord ill in the whole affair, and if you or your Servants have committed any accidental mistake either in the Lads Board or the horses hay pray see to rectify it soon, because things of that sort not cleard up and satisfied are very hurtfull to People in your publick way especially with those to whom you have already been obliged, and who at any rate will not be imposed upon. I am—

Madam—

Your humble sert

John Milne.

To Mrs Beaver

at the Black Bull

Newcastle upon Tine,

free Morton.

[Pg 54]Then there was Dover, notorious for high prices. “Thy cliffs, dear Dover! harbour and hotel,” sang Byron, who bitterly remembered the “long, long bills, whence nothing is deducted.” The “Ship,” the hotel probably indicted by the poet, has long since disappeared, but that gigantic caravanserai, the “Lord Warden Hotel,” could at one time, in its monumental charges, have afforded him material for another stanza. Magnificent as were the charges made by overreaching hosts elsewhere, they all paled their ineffectual sums-total before the sublime heights of the account rendered to Louis Napoleon when Prince-President of France. He merely remarked that it was truly princely, and paid.

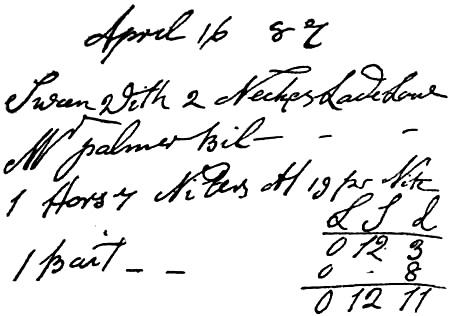

FACSIMILE OF AN ACCOUNT RENDERED TO JOHN PALMER IN 1787.

If, on the other hand, that famous coaching hostelry, the “Swan with Two Necks,” in Lad Lane, in the City of London, charged guests for[Pg 55] their accommodation as moderately as the accompanying bill for stabling a horse, the establishment should have been popular. This bill, printed here in facsimile from the original, was presented, April 16th, 1787, to John Palmer, the famous Post Office reformer, and shows that only one shilling and ninepence a night was charged. Yet he was at that time a famous man. Three years before he had established the first mail-coach, and was everywhere well known, and doubtless, in general, fair prey to renderers of bills.

THE LAST DAYS OF THE “SWAN WITH TWO NECKS.”