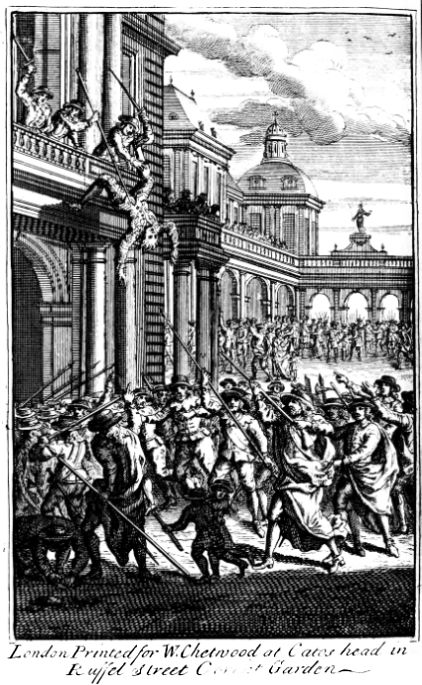

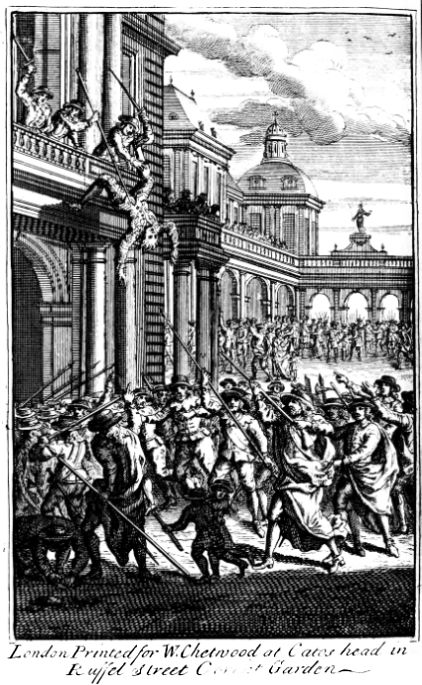

London Printed for W. Chetwood at Cato's head in

London Printed for W. Chetwood at Cato's head inRussel Street Covent Garden

London Printed for W. Chetwood at Cato's head in

London Printed for W. Chetwood at Cato's head inTHE

REVOLUTIONS

OF

PORTUGAL.

Written in French by the

Abbot DE VERTOT,

Of the Royal Academy of

INSCRIPTIONS.

Done into English from the last French Edition.

LONDON,

Printed for William Chetwood, at Cato's-Head,

in Russel-Street, Covent-Garden. M.DCC.XXI.

To His Grace

PHILIP

Duke of Wharton.

May it please your Grace;

am not ignorant of the Censure I lay my-self open to, in offering so incorrect a Work to a Person of Your Grace's [Pg vi] Judgment; and could not have had Assurance to do it, if I was unacquainted with Your Grace's Goodness. As this is not the first time of this Excellent Author's appearing in English, my Undertaking must expose me to abundance of Cavil and Criticism; and I see my-self reduced to the Necessity of applying to a Patron who is able to protect me.

Our modern Dedications are meer Daub and Flattery; but 'tis for those who deserve [Pg vii] no better: Your Grace cannot be flatter'd; every body that knows the Duke of Wharton, will say there is no praising him, as there is no loving him more than he deserves. But like other Great Minds, Your Grace may be blind to your own Merit, and imagine I am complimenting, or doing something worse, whilst I am only giving your just Character; for which reason, however fond I am of so noble a Theme, I shall decline attempting it. [Pg viii] Only this I must beg leave to say, Your Grace can't be enough admir'd for the Universal Learning which you are Master of, for your Judgment in discerning, your Indulgence in excusing, for the great Stedfastness of your Soul, for your Contempt of Power and Grandeur, your Love for your Country, your Passion for Liberty, and (which is the best Characteristick) your Desire of doing Good to Mankind. I can hardly leave so agreeable a Subject, but [Pg ix] I cannot say more than all the World knows already.

Your Grace's illustrious Father has left a Name behind Him as glorious as any Person of the Age: it is unnecessary to enter into the Particulars of his Character; to mention his Name, is the greatest Panegyrick: Immediately to succeed that Great Man, must have been extremely to the Disadvantage of any other Person, but it is far from being so to Your Grace; it makes [Pg x] your Virtues but the more conspicuous, and convinces us the Nation is not without one Man worthy of being his Successor.

I have nothing more to trouble Your Grace with, than only to wish you the Honours you so well deserve, and to beg you would excuse my presuming to honour my-self with the Title of,

May it please your Grace, Your Grace's most Obedient, Humble Servant,

Gabriel Roussillon.

mongst the Historians of the present Age, none has more justly deserv'd, neither has any acquir'd a greater Reputation than the Abbot de Vertot; not only by this Piece, but also by the Revolutions of Sweden and of Rome, which he has since publish'd.

This small History he has extracted from the[A] Writings of several French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian Authors, as well as from the Testimony of [Pg xii] many Persons, who were in Lisbon at the time of the Revolution. And I believe that it will be no difficult matter to persuade the Reader, that this little Volume is written with much more Politeness and Fidelity than any which has been publish'd on this Subject.

And indeed there could be no Man fitter to undertake the Work than Monsieur de Vertot; not only as he was Master of an excellent Style, and had all the Opportunities imaginable of informing himself of the Truth, but also as he could have no Interest in speaking partially of either the one or the other Party; and therefore might say much more justly than Salust, de Conjuratione, Quam verissime potero, paucis absolvam; eoque magis, quod mihi a Spe, Metu, Partibus Reipublicæ Animus liber est.

Would I undertake to prove the Impartiality of my Author, I could easily do it from several little Circumstances of his History. Does he not tell us, that the Inquisition is oftner a Terror to honest Men than to Rogues? Does he not paint the Archbishop of Braga in all the Colours of a Traitor? And I am fully persuaded, that if a Churchman will own and discover the Frailties, or rather the Enormities of those of his own Cloth, he will tell them in any thing else, and is worthy of being believed.

There are several Passages in the following Sheets, which really deserve our Attention; we shall see a Nation involv'd in Woe and Ruin, and all their Miseries proceeding from the Bigotry and Superstition of their Monarch, whose Zeal hurries him to inevitable Destruction, and whose Piety [Pg xiv] makes him sacrifice the Lives of 13000 Christians, without so much as having the Satisfaction of converting one obstinate Infidel.

Such was the Fate of the rash Don Sebastian, who seem'd born to be the Blessing of his People, and Terror of his Foes; who would have made a just, a wise, a truly pious Monarch, had not his Education been entrusted to a Jesuit. Nor is he the only unfortunate Prince, who, govern'd by intriguing and insinuating Churchmen, have prov'd the Ruin of their Kingdom, and in the end lost both their Crown and Life.

We shall see a People, who, no longer able to bear a heavy Yoke, resolve to shake it off, and venture their Lives and their Fortunes for their Liberty: A Conspiracy prevail, (if an Intent to revolt from an Usurping Tyrant may be call'd a Conspiracy) in which so many [Pg xv] Persons, whose Age, Quality and Interest were very different, are engag'd; and by the Courage and Publick Spirit of a few, a happy and glorious Revolution brought about.

But scarce is the new King settled upon his Throne, and endeavouring to confirm his Authority abroad, when a horrid Conspiracy is forming against him at home; we shall see a Prelate at the head of the Traitors, who, tho a bigotted Churchman, makes no scruple of borrowing the Assistance of the most profess'd Enemies of the Church to deliver her out of Danger, and to assassinate his Lawful King: but the whole Plot is happily discover'd, and those who were engaged in it meet with the just Reward of Treason and Rebellion, the Block and Gallows. Nor is it the first time that our own Nation has seen an Archbishop doing King and Country all the harm he could.

After the Death of her Husband, we see a Queen of an extraordinary [Pg xvi] Genius, and uncommon Courage, taking the Regency upon her; and tho at first oppress'd with a Load of Misfortunes, rises against them all, and in the end triumphs over her Enemies.

Under the next Reign we see the Kingdom almost invaded by the antient Usurper, and sav'd only by the Skill of a Wife and Brave General, who had much ado to keep the Foes out, whilst the People were divided at home, and loudly complain'd of the Riots and Debaucheries of their Monarch, and the Tyrannick Conduct of his Minister. But we find how impossible a thing it is, that so violent a Government should last long; his Brother, a Prince whose Virtues were as famous, as the other's Vices were odious, to preserve the Crown in their Family, is forced to depose him, and take the Government upon himself: Ita Imperium semper ad optumum quemq; ab minus bono transfertur.

ortugal is part of that vast Tract of Land, known by the Name of Iberia or Spain, most of whose Provinces are call'd Kingdoms. It is bounded on the West by the Ocean, on the East by Castile. Its Length is about a hundred and ten Leagues, and its Breadth in the very broadest part does not exceed fifty. The Soil is fruitful, the Air wholesome; and tho under such a Climate we might expect excessive Heats, yet here we always find them allay'd [Pg 2] with cooling Breezes or refreshing Rains. Its Crown is Hereditary, the King's Power Despotick, nor is the grand Inquisition the most useless means of preserving this absolute Authority. The Portuguese are by Nature proud and haughty, very zealous, but rather superstitious than religious; the most natural Events will amongst them pass for Miracles, and they are firmly persuaded that Heaven is always contriving something or other for their Good.

Who the first Inhabitants of this Country were, is not known, their own Historians indeed tell us that they are sprung from Tubal; for my part, I believe them descended from the Romans and Carthaginians, who long contended for those Provinces, and who were both at sundry times in actual possession of them. About the beginning of the fifth Century, the Swedes, the Vandals, and all those other barbarous Nations, generally known by the Name of Goths, over-run the Empire; and, amongst other Places, made themselves Masters of the Provinces of Spain. Portugal was then made a Kingdom, and was sometimes govern'd by its own Prince, at other times it was reckon'd part of the Dominions of the King of Castile.

712.About the beginning of the eighth Century, during the Reign of Roderick, the last King of the Goths, the Moors, or rather the Arabians, Valid Almanzor being their Caliph, enter'd Spain. They were received and assisted by Julian, an Italian Nobleman, who made the Conquest of those Places easy, which might otherwise have proved difficult, [Pg 3] not out of any Affection to the Arabians, but from a Desire of revenging himself on Roderick, who had debauched his Daughter.

717.The Arabians soon made themselves Masters of all the Country between the Streights of Gibraltar and the Pyrenees, excepting the Mountains of Asturia; where the Christians, commanded by Prince Pelagus, fled, who founded the Kingdom Oviedo or Leon.

Portugal, with the rest of Spain, became subject to the Infidels. In each respective Province, Governours were appointed, who after the Death of Almanzor revolted from his Successor, made themselves independent of any other Power, and took the Title of Sovereign Princes.

They were driven out of Portugal about the beginning of the twelfth Century, by Henry Count of Burgundy, Son to Robert King of France. This Prince, full of the same Zeal which excited so many others to engage in a holy War, went into Spain on purpose to attack the Infidels; and such Courage, such Conduct did he show, that Alphonso VI. King of Castile and Leon, made him General of his Army: and afterwards, that he might for ever engage so brave a Soldier, he married him to one of his Daughters, named Teresia, and gave him all those Places from which he had driven the Moors. The Count, by new Conquests, extended his Dominions, and founded the Kingdom of Portugal, but never gave himself the Royal Title.

1139.Alphonso, his Son, did not only inherit his Father's Dominions, but his Virtues also; and not content with what the Count his Father had [Pg 4] left him, he vigorously carried on the War, and encreas'd his Territories. Having obtained a signal Victory over the Arabians, his Soldiers unanimously proclaimed him King; which Title his Successors have ever since borne.

And now this Family had sway'd the Scepter of Portugal for almost the space of five hundred Years, when Don Sebastian came to the Crown; he was the posthumous Son of Don John, who died some time before his Father, Don John III. Son of the renowned King Emanuel.

1557.Don Sebastian was not above three Years of Age when the old King died; his Grandmother Catherine, of the House of Austria, Daughter to Philip I. King of Castile, and Sister to the Emperor Charles V. was made Regent of Portugal during his Minority. Don Alexis de Menezes, a Nobleman noted for his singular Piety, was appointed Governour to the young King, and Don Lewis de Camara, a Jesuit, was named for his Tutor.

From such Teachers as these, what might not be expected? They filled his Mind with Sentiments of Honour, and his Soul with Devotion. But, (which may at first appear strange or impossible) these Notions were too often, and too strongly inculcated in him.

Menezes was always telling the young Prince what Victories his Predecessors had obtain'd over the Moors in the Indies, and in almost every part of Africa. On the other hand, the Jesuit was perpetually teaching him, that the Crown of Kings was the immediate [Pg 5] Gift of God, and that therefore the chiefest Duty of a Prince was to propagate the Holy Gospel, and to have the Word of the Lord preached to those Nations, who had never heard of the Name of Christ.

These different Ideas of Honour and Religion made a deep impression on the Heart of Don Sebastian, who was naturally pious. Scarce therefore had he taken the Government of Portugal upon himself, but he thought of transporting an Army into Africa; and to that end he often conferr'd with his Officers, but oftener with his Missionaries and other Ecclesiasticks.

A Civil War breaking out about this time in Morocco, seem'd very much to favour his Design. The Occasion was this: Muley Mahomet had caus'd himself to be proclaim'd King of Morocco after the Death of Abdalla, his Father; Muley Moluc, Abdalla's Brother, opposed him, objecting that he had ascended the Throne contrary to the Law of the Cherifs, by which it is ordained, That the Crown shall devolve to the King's Brethren, if he has any, and his Sons be excluded the Succession. This occasion'd a bloody War between the Uncle and the Nephew; but Muley Moluc, who was as brave a Soldier as he was a wise Commander, defeated Mahomet's Army in three pitch'd Battles, and drove him out of Africa.

The exil'd Prince fled for Refuge to the Court of Portugal, and finding Access to Don Sebastian, told him, that notwithstanding his Misfortunes, there were still a considerable Number of his Subjects, who were loyal in [Pg 6] their Hearts, and wanted only an Opportunity of declaring themselves in his favour. That besides this, he was very well assured that Moluc was afflicted with a lingring Disease, which prey'd upon his Vitals; that Hamet, Moluc's Brother, was not belov'd by the People; that therefore if Don Sebastian would but send him with a small Army into Africa, so many of his Subjects would come over to him, that he did not in the least question but that he should soon re-establish himself in his Father's Dominions: which, if he did recover by these means, the Kingdom should become tributary to the Crown of Portugal; nay, that he would much rather have Don Sebastian himself fill the Throne of Morocco, than see it in possession of the present Usurper.

Don Sebastian, who was ever entertaining himself with the Ideas of future Conquests, thought this Opportunity of planting the Christian Religion in Morocco was not to be neglected; and therefore promis'd the Moorish King not only his Assistance, but rashly engaged himself in the Expedition, giving out that he intended to command the Army in Person. The wisest of his Counsellors in vain endeavour'd to dissuade him from the dangerous Design. His Zeal, his Courage, an inconsiderate Rashness, the common Fault of Youth, as well as some Flatterers, the Bane of Royalty, and Destruction of Princes, all prompted him to continue fixed in his Resolution, and persuaded him that he needed only appear in Africa to overcome, and that his Conquests would be both easy and [Pg 7] glorious. To this end he embarked with an Army of Thirteen Thousand Men, with which he was to drive a powerful Prince out of his own Dominions.

Moluc had timely notice given him of the Portuguese Expedition, and of their landing in Africa; he had put himself at the head of Forty Thousand Horsemen, all disciplin'd Soldiers, and who were not so much to be dreaded for their Number and Courage, as they were for the Conduct of their General. His Infantry he did not at all value himself upon, not having above Ten Thousand Regular Men; there was indeed a vast Number of the Militia, and others of the People who came pouring down to his Assistance, but these he justly look'd upon as Men who were rather come to plunder than to fight, and who would at any time side with the Conqueror.

Several Skirmishes were fought, but Moluc's Officers had private Orders still to fly before the Foe, hoping thereby to make the Portuguese leave the Shore, where they had intrench'd themselves. This Stratagem had its desir'd Effect; for Don Sebastian observing that the Moors still fled before him, order'd his Army to leave their Intrenchments, and marched against the Foe as to a certain Victory. Moluc made his Army retire, as if he did not dare to fight a decisive Battle; nay, sent Messengers to Don Sebastian, who pretended they were order'd to treat of Peace. The King of Portugal immediately concluded, that his Adversary was doubtful of the Success of the War, and that 'twould be an easier matter to overcome Moluc's Army, than [Pg 8] to join them; he therefore indefatigably pursued them. But the Moor had no sooner drawn him far enough from the Shore, and made it impossible for him to retire to his Fleet, but he halted, faced the Portuguese, and put his Army in Battalia; the Horse making a half Circle, with intent, as soon as they engaged, to surround the Enemy on every side. Moluc made Hamet, his Brother and Successor, Commander in chief of the Cavalry; but as he doubted his Courage, he came up to him a little before the Engagement, told him that he must either conquer or die, and that should he prove Coward enough to turn his back upon the Foe, he would strangle him with his own hand.

The reason why Moluc did not command the Army himself, was, that he was sensible of the Increase of his lingring Disease, and found that in all probability this Day would be his last, and therefore resolved to make it the most glorious of his Life. He put his Army, as I said before, in Battalia himself, and gave all the necessary Orders with as much Presence of Mind, as if he had enjoy'd the greatest Health. He went farther than this; for foreseeing what a sudden Damp the News of his Death might cast upon the Courage of his Soldiers, he order'd the Officers that were about him, that if during the Heat of the Battle he should die, they should carefully conceal it, and that even after his Death, his Aides de Camp should come up to his Litter, as if to receive fresh Orders. After this he was carried from Rank to Rank, where he exhorted his Soldiers to fight bravely for the [Pg 9] Defence of their Religion and their Country.

But now the Combat began, and the great Artillery being discharg'd, the Armies join'd. The Portuguese Infantry soon routed the Moorish Foot-Soldiers, who, as was before mention'd, were raw and undisciplin'd; the Duke d'Aviedo engaged with a Parry of Horse so happily, that they gave ground, and retir'd to the very Center of the Army, where the King was. Enraged at so unexpected a Sight, notwithstanding what his Officers could say or do, he threw himself out of his Litter; Sword in hand he clear'd himself a Passage, rallied his flying Soldiers, and led them back himself to the Engagement. But this Action quite exhausting his remaining Strength and Spirits, he fainted; his Officers put him into his Litter, where he just recover'd Strength enough to put his Finger upon his Mouth once more, to enjoin Secrecy, then died before they could convey him back to his Tent. His Commands were obey'd, and the News of his Death conceal'd.

Aug. 4.

1578.Hitherto the Christians seem'd to have the Advantage, but the Moorish Horse advancing at last, hemm'd in Sebastian's whole Army, and attack'd them on every side. The Cavalry was drove back upon their Infantry, whom they trampled under foot, and spread every where amongst their own Soldiers, Disorder, Fear, and Confusion. The Infidels seiz'd upon this Advantage, and Sword in hand fell upon the conquer'd Troops; a dreadful Slaughter ensu'd, some on their knees begg'd for quarter, others thought to [Pg 10] save themselves by flight, but being surrounded by their Foes, met their Fate in another place. The rash Don Sebastian himself was slain, but whether he fell amidst the Horror and Confusion of the Battle, not being known by the Moors, or whether he was resolv'd not to survive the Loss of so many of his Subjects, whom he had led on to a Field of Slaughter, is doubtful. Muley Mahomet got off, but passing the River Mucazen, was drown'd. Thus perish'd, in one fatal Day, three Heroick Princes.

The Cardinal, Don Henry, great Uncle to Don Sebastian, succeeded him; he was Brother to John III. the late King's Grandfather, and Son to Emanuel. During his Reign, his pretended Heirs made all the Interest they could in the Court of Portugal, being well assur'd that the present King, who was weak and sickly, and sixty-seven Years old, could not be long-liv'd; nor could he marry, and leave Children behind him, for he was a Cardinal, and in Priest's Orders. The Succession was claim'd by Philip II. King of Spain; Catherine of Portugal, espous'd to Don James, Duke of Braganza; by the Duke of Savoy; the Duke of Parma; and by Antonio, Grand Prior of Crete: They all publish'd their respective Manifesto's, in which every one declar'd their Pretensions to the Crown.

Philip was Son to the Infanta Isabella, eldest Daughter of King Emanuel. The Dutchess of Braganza was Granddaughter to the same King Emanuel, by Edward his second Son. The Duke of Savoy's Mother was the Princess Beatrix, a younger Sister of the Empress [Pg 11] Isabella. The Duke of Parma was Son to Mary of Portugal, the second Daughter of Prince Edward, and Sister to the Dutchess of Braganza. Don Lewis, Duke of Beja, was second Son to King Emanuel by Violenta, the finest Lady of that Age, whom he had debauch'd, but whom the Grand Prior pretended to have been privately married to that Prince. Catherine de Medicis, amongst the rest, made her Claim, as being descended from Alphonso III. King of Portugal, and Maud Countess of Bolonia. The Pope too put in his Claim; he would have it, that after the Reign of the Cardinal, Portugal must be look'd upon as a fat Living in his Gift, and to which, like many a modern Patron, he would willingly have presented himself.

But notwithstanding all their Pretensions, it plainly appear'd that the Succession belong'd either to Philip King of Spain, or to the Dutchess of Braganza, a Lady of an extraordinary Merit, and belov'd by the whole Nation. The Duke, her Spouse, was descended, tho not in a direct Line, from the Royal Blood, and she herself was sprung from Prince Edward; whereas the King of Spain was Son to Edward's Sister: besides, by the Fundamental Laws of the Kingdom, all Strangers were excluded the Succession. This Philip own'd, since thereby the Pretensions of Savoy and Parma vanish'd; but he would by no means acknowledge himself a Stranger in Portugal, which he said had often been part of the Dominions of the King of Castile. Each had their several Parties at Court, and the Cardinal King was daily [Pg 12] press'd to decide the Difference, but always evaded it; he could not bear to hear of his Successors, and would willingly have liv'd to have bury'd all his pretended Heirs: however, his Reign lasted but 17 Months, and by his Death Portugal became the unhappy Theatre of Civil Wars.

1580.By his last Will he had order'd, that a Juncto, or Assembly of the States, should be call'd, to settle the Succession; but King Philip not caring to wait for their Decision, sent a powerful Army into Portugal, commanded by the Duke of Alba, which ended the Dispute, and put Philip in possession of that Kingdom.

1581.We cannot find that the Duke of Braganza us'd any Endeavours to assert his Right by force of Arms. The Grand Prior indeed did all he could to oppose the Castilians; the Mob had proclaim'd him King, and he took the Title upon him, as if it had been given by the States of Portugal: and his Friends rais'd some Forces for him, but they were soon cut in pieces by the Duke of Alba, than whom Spain could not have chosen a better General. As much as the Portuguese hate the Castilians, yet could they not keep them out, being disunited among themselves, and having no General, nor any Regular Troops on foot. Most of the Towns, for fear of being plunder'd, capitulated, and made each their several Treaty; so that in a short time Philip was acknowledg'd their lawful Sovereign by the whole Nation, as being next Heir Male to his great Uncle, the late King: of such wondrous use is open Force to support a bad Cause!

After him reign'd his Son and Grandson, Philip III. and IV. who us'd the Portuguese not like Subjects, but like a conquer'd People; and the Kingdom of Portugal saw itself dwindle into a Province of Spain, and so weaken'd, that there was no hope left of recovering their Liberty: Their Noblemen durst not appear in an Equipage suitable to their Birth, for fear of making the Spanish Ministers jealous of their Greatness or Riches; the Gentry were confin'd to their Country-Seats, and the People oppress'd with Taxes.

The Duke of Olivarez, who was then first Minister to Philip IV. King of Spain, was firmly persuaded, that all means were to be us'd to exhaust this new Conquest; he was sensible of the natural Antipathy of the Portuguese and Castilians, and thought that the former could never calmly behold their chief Posts fill'd with Strangers, or at best with Portuguese of a Plebeian Extraction, who had nothing else to recommend 'em but their Zeal for the Service of Spain. He thought therefore, that the surest way of establishing King Philip's Power, was to remove the Nobility of Portugal from all Places of Trust, and so to impoverish the People, that they should never be capable of attempting to shake off the Spanish Yoke. Besides this, he employ'd the Portuguese Youth in foreign Wars, resolving to drain the Kingdom of all those who were capable of bearing Arms.

As politick as this Conduct of Olivarez might appear, yet did he miss his aim; for carrying his Cruelty to too high a pitch, at a time when the Court of Spain was in distress, [Pg 14] and seeming rather to plunder an Enemy's Country, than levying Taxes from the Portuguese, who daily saw their Miseries encrease, and be the consequence of their Attempt what it would, they could never fare worse; unanimously resolv'd to free themselves from the intolerable Tyranny of Spain.

1640.Margaret of Savoy, Dutchess of Mantua, was then in Portugal, where she had the Title of Vice-Queen, but was very far from having the Power. Miguel Vasconcellos, a Portuguese by Birth, but attach'd to the Spanish Interest, had the Name of Secretary of State, but was indeed an absolute and independent Minister, and dispatch'd, without the knowledge of the Vice-Queen, all the secret Business; his Orders he receiv'd directly from d'Olivarez, whose Creature he was, and who found him absolutely necessary for extorting vast Sums of Money from the Portuguese. He was so deeply learn'd in the Art of Intriguing, that he could perpetually make the Nobility jealous of one another, then would he foment their Divisions, and encrease their Animosities, whereby the Spanish Government became every day more absolute; for the Duke was assur'd, that whilst the Grandees were engag'd in private Quarrels, they would never think of the Common Cause.

The Duke of Braganza was the only Man in all Portugal, of whom the Spaniards were now jealous. His Humour was agreeable, and the chief thing he consulted was his Ease. He was a Man rather of sound Sense, than quick Wit. He could easily make himself[Pg 15] Master of any Business to which he apply'd his Mind, but then he never car'd much for the Trouble on't. Don Theodosius, Duke of Braganza, his Father, was of a fiery and passionate Temper, and had taken care to infuse in his Son's Mind an Hereditary Aversion to the Spaniards, who had usurp'd a Crown, that of Right belonged to him; to swell his Mind with the Ambition of repossessing himself of a Throne, which his Ancestors had been unjustly depriv'd of; and to fill his Soul with all the Courage that would be necessary for the carrying on of so great a Design.

Nor was this Prince's Care wholly lost; Don John had imbib'd as much of the Sentiments of his Father as were consistent with so mild and easy a Temper. He abhorr'd the Spaniards, yet was not at all uneasy at his Incapacity of revenging himself. He entertain'd Hopes of ascending the Throne of Portugal, yet did he not shew the least Impatience, as Duke Theodosius, his Father, had done, but contented himself with a distant Prospect of a Crown; nor would for an Uncertainty venture the Quiet of his Life, and a Fortune which was already greater than what was well consistent with the Condition of a Subject. Had he been precisely what Duke Theodosius wish'd him, he had never been fit for the great Design; for d'Olivarez had him observ'd so strictly, that had his easy and pleasant manner of Living proceeded from any other Cause but a natural Inclination, it had certainly been discover'd, and the Discovery had prov'd fatal both to his[Pg 16] Life and Fortune: at least the Court of Spain would never have suffer'd him to live in so splendid a manner in the very Heart of his Country.

Had he been the most refin'd Politician, he could never have liv'd in a manner less capable of giving Suspicion. His Birth, his Riches, his Title to the Crown, were not criminal in themselves, but became so by the Law of Policy. This he was very sensible of, and therefore chose this way of Living, prompted to it as well by Nature as by Reason. It would have been a Crime to be formidable, he must therefore take care not to appear so: At Villa-Viciosa, the Seat of the Dukes of Braganza, nothing was thought of but Hunting-Matches, and other Rural Diversions; the Brightness of his Parts could not in the least make the Spaniards apprehend any bold Undertaking, but the Solidity of his Understanding made the Portuguese promise themselves the Enjoyment of a mild and easy King, provided they would undertake to raise him to the Throne. But an Accident soon after happen'd, which very much alarm'd Olivarez.

Some new Taxes being laid upon the People of Evora, which they were not able to pay, reduc'd 'em to Despair; upon which they rose in a tumultuous manner, loudly exclaiming against the Spanish Tyranny, and declaring themselves in favour of the House of Braganza. Then, but too late, the Court of Spain began to be sensible of their Error, in leaving so rich and powerful a Prince in the Heart of a Kingdom so lately subdued, [Pg 17] and to whose Crown he had such Legal Pretensions.

This made the Council of Spain immediately determine, that it was necessary to secure the Duke of Braganza, or at best not to let him make any longer stay in Portugal. To this end they nam'd him Governour of Milan, which Government he refus'd, alledging the Weakness of his Constitution for an Excuse: besides, he said he was wholly unacquainted with the Affairs of Italy, and by consequence not capable of acquitting himself in so weighty a Post.

1640.The Duke d'Olivarez, seem'd to approve of the Excuse, and therefore began to think of some new Expedient to draw him to Court. The King's marching at the head of his Army to the Frontiers of Arragon, to suppress the rebelling Catalonians, was a very good Pretence; he wrote to the Duke of Braganza, "to come at the head of the Portuguese Nobility to serve the King in an Expedition, which could not but be glorious, since his Majesty commanded it in Person." The Duke, who had no great relish for any Favour confer'd by the Court of Spain, excus'd himself, upon pretence that "his Birth would oblige him to be at a much greater Expence than what he was at present able to support."

This second Refusal alarm'd d'Olivarez. Notwithstanding Don John's easy Temper, he began to be afraid that the Evorians had made an impression upon his Thoughts, by reminding him of his Right to the Throne.[Pg 18] It was dangerous to leave him any longer in his Country, and equally dangerous to hurry him out of it by force; so great a Love had the Portuguese ever bore to the House of Braganza, so great a Respect did they bear to this Duke in particular. He must therefore treacherously be drawn into Spain, nor could any properer means be thought of, for compassing this end, than by shewing him all the seeming Tokens of an unfeigned Friendship.

France and Spain were at that time engag'd in War, and the French Fleet had been seen off the Coasts of Portugal. This gave the Spanish Minister a fair opportunity of accomplishing his Ends; for it was necessary to have an Army on foot, under the Command of some brave General, to hinder the French from making a Descent, or landing any where in Portugal. The Commission was sent to the Duke of Braganza, with an absolute Authority over all the Towns and Garisons, as well as a Power over the Maritime Forces; in short, so unlimited was the Command given him, that the Minister seem'd blindly to have deliver'd all Portugal into his power: but this was only the better to colour his Design. Don Lopez Ozorio, the Spanish Admiral, had private Orders sent him, that as soon as Don John should visit any of the Ports, he should put in, as if drove by stress of Weather; then artfully invite the General aboard, immediately hoist sail, and with all possible expedition bring him into Spain. But propitious Fortune seem'd to have taken him into her Protection; a violent Storm arose, which dispers'd the Spanish Fleet, part of[Pg 19] which suffer'd shipwreck, and the rest were so shatter'd, that they could not make Portugal.

This ill Success did not in the least discourage Olivarez, or make him drop his Project; he attributed the Escape of the Duke of Braganza to meer Chance: he wrote him a Letter, full of Expressions of Friendship, and as if he had with him shar'd the Government of the whole Kingdom, wherein he deplor'd the Loss of the Fleet, and told him, that the King now expected that he would carefully review all the Ports and their respective Fortifications, seeing that the Fleet, which was to defend the Coasts of Portugal from the Insults of the French, had miserably perish'd. And that his Villany might not be suspected, he return'd him Forty Thousand Ducats to defray his Expences, and to raise more Troops, in case there should be a necessity of them. At the same time he sent private Orders to all the Governours of Forts and Citadels, (the greatest part whereof were Spaniards) that if they should find a favourable occasion of securing the Duke of Braganza, they should do it, and forthwith convey him into Spain.

This entire Confidence which was repos'd in him, alarm'd the Duke; he plainly saw that there was Treachery intended, and therefore thought it just to return the Treachery. He wrote an Answer to Olivarez, wherein he told him, that with Joy he accepted the Honour which the King had confer'd upon him, in naming him his General, and promis'd so to discharge the important [Pg 20] Trust, as to deserve the Continuation of his Majesty's Favour.

But now the Duke began to have a nearer Prospect of the Throne; nor did he neglect this opportunity of putting some of his Friends into Places of Trust, that they might be the more able to serve him upon occasion; he also employ'd part of the Spanish Money in making new Creatures, and confirming those in his Interest whom he had already made. And as he partly mistrusted the Spaniards Design, he never visited any Fort, but he was surrounded by such a Number of Friends, that it was impossible for the Governours to execute their Orders.

Mean while the Court of Spain loudly murmur'd at the Trust which was repos'd in Don John, they were ignorant of the Prime Minister's Aim, and therefore some did not stick to tell the King, that his near Alliance to the House of Braganza made him overlook his Master's Interest; seeing that it was the highest Imprudence to put so absolute an Authority into the hands of one who had such Pretensions to the Crown, and to entrust the Army to the Command of one, who in all probability might make the Soldiers turn their Arms against their lawful Sovereign. But the more they complain'd, the better was the King pleas'd, being persuaded that the Plot was artfully laid, since no one could unravel the dark Design. Thus Braganza not only had the liberty, but was oblig'd to visit all Portugal, and by that means laid the Foundation of his future Fortune. The Eyes of the Many were every where drawn [Pg 21] by his magnificent Equipage, all that came to him, he mildly, and with unequal'd Goodness heard; the Soldiers were not suffer'd to commit the least Disorders, and he laid hold of all Opportunities of praising the Conduct of the Officers, and by frequent Recompences bestow'd upon them, won their Hearts. The Nobility were charm'd with his free Deportment, he receiv'd every one of them in the most obliging manner, and paid each the Respect due to his Quality. In short, such was his Carriage, that the People began to think there could be no greater Happiness for them upon Earth, than the Restoration of the Prince to the Throne of his Ancestors.

Mean while his Party omitted nothing that they thought might contribute to the establishing of his Reputation. Amongst others, Pinto Ribeiro, Comptroller of his Household, particularly distinguish'd himself, and was the first who form'd an exact Scheme for the Advancement of his Master. There was no Man more experienc'd in Business, who at the same time was so careful, diligent, and watchful: he was firm to the Interest of the Duke, not doubting but that if he could raise him to the Throne, he should raise himself to some considerable Post. His Master had often privately assur'd him, that he would willingly lay hold of any fair Opportunity for his Restoration, yet would not rashly declare himself, as a Man who had nothing to lose; that notwithstanding he might endeavour to gain the Minds of the People, and to make new Creatures, yet he must do it[Pg 22] with that Caution, that it might appear his own Work, and done without the Consent and Knowledge of the Duke.

Pinto had spar'd no pains in discovering who were, and the Number of the Disaffected, which he daily endeavoured to encrease; he rail'd against the present Government sometimes with Heat, at other times with Caution, always accommodating himself to the Humour of the Company which he was in: tho indeed so great was the Hatred which the Portuguese bore the Spaniards, that there was no need of Reserve in complaining of them. He would often remind the Nobility what honourable Employments their Forefathers had borne, when Portugal was govern'd by its own Kings. Then would he mention the Summons which had so much exasperated the Nobility, and by which they were commanded to attend the King in Catalonia. Pinto us'd to complain of this Hardship as of a kind of Banishment, from which they would scarce find it possible to return; that the Pride of the Spaniards, who would command them, was insufferable, and the Expence they should be at intolerable; that this was only a plausible Pretence to drain Portugal of its bravest Men, that in all their Expeditions they might be assur'd of being expos'd where the greatest Danger was, but that they must never hope to share the least part of the Glory.

When he was amongst the Merchants and other Citizens, he would bewail the Misery of his Country, which was ruin'd by the Injustice of the Spaniard, who had transfer'd[Pg 23] the Trade, which Portugal carried on with the Indies, to Cadiz. Then would he remind them of the Felicity which the Dutch and Catalonians enjoy'd, who had shaken off the Spanish Yoke. As for the Clergy, he did not in the least question but that he should engage 'em in his Interest, and exasperate 'em most irreconcileably against the Castilians; he told them, that the Immunities and Privileges of the Church were violated, their Orders contemn'd and neglected, and that all the best Preferments and fattest Livings were possess'd by foreign Incumbents.

When he was with those, of whose Disaffection he was already convinc'd, he would take care to turn his Discourse to his Master, and talk of his manner of Living. He would often complain, that that Prince shew'd too little Affection for the Good of his Country, and Concern for his own Interest; and that at a time when it was in his power to assert his Title to the Crown, he should seem so regardless of his own Right, and lead so idle a Life. Finding that these Insinuations made an impression upon the People, he went still farther: To those who were publick-spirited, he represented what a glorious thing it would be for them to lay the Foundations of a Revolution, and to deserve the Name of Deliverers of their Country. Those who had been injur'd and ill-treated by the Spaniards, he would excite to the Desire of Revenge; and the Ambitious he flatter'd with a Prospect of the Grandeurs and Preferments they might expect from the new King, would they once raise him to the[Pg 24] Throne. In short, he manag'd every thing with so much Art, that being privately assur'd of the unshaken Affection of many to his Master, he procur'd a Meeting of a considerable Number of the Nobility, with the Archbishop of Lisbon at the head of them.

This Prelate was of the House of Acugna, one of the best Families of all Portugal; he was a Man of Learning, and an excellent Politician, belov'd by the People, but hated by the Spaniards, and whom he had also just cause to hate, since they had made Don Sebastian Maltos de Norognia, Archbishop of Braga, President of the Chamber of Opaco, whom they had all along prefer'd to him, and to whom they had given a great share in the Administration of Affairs.

Another of the most considerable Members of this Assembly, was Don Miguel d'Almeida, a venerable old Man, and who deserv'd, and had the Esteem of every body; he was very publick-spirited, and was not so much griev'd at his own private Misfortunes, as at those of his Country, whose Inhabitants were become the Slaves of an usurping Tyrant. In these Sentiments he had been educated, and to these with undaunted Courage and Resolution he still adher'd; nor could the Entreaties of his Relations, nor the repeated Advices of his Friends, ever make him go to Court, or cringe to the Spanish Ministers. This Carriage of his had made them jealous of him. This therefore was the Man whom Pinto first cast his eyes upon, being well assur'd that he might safely entrust him with the Secret; besides which, no one could be [Pg 25] more useful in carrying on their Design, his Interest with the Nobility being so great, that he could easily bring over a considerable Number of them to his Party.

There were, besides these two, at this first Meeting, Don Antonio d'Almada, an intimate Friend of the Archbishop's, with Don Lewis, his Son; Don Lewis d'Acugna, Nephew to that Prelate, and who had married Don Antonio d'Almada's Daughter; Mello Lord Ranger, Don George his Brother; Pedro Mendoza; Don Rodrigo de Saa, Lord-Chamberlain: with several other Officers of the Houshold, whose Places were nothing now but empty Titles, since Portugal had lost her own natural Kings.

Conostagio.The Archbishop, who was naturally a good Rhetorician, broke the Ice in this Assembly; he made an eloquent Speech, in which he set forth the many Grievances Portugal had labour'd under since it had been subject to the Domination of Spain. He reminded them of the Number of Nobility which Philip II. had butchered to secure his Conquest; nor had he been more favourable to the Church, witness the famous Brief of Absolution, which he had obtain'd from the Pope for the Murder of Two Thousand Priests, or others of Religious Orders, whom he had barbarously put to death, on no other account but to secure his Usurpation: And since that unhappy time the Spaniards had not chang'd their inhuman Policy; how many had fallen for no other Crime but their unshaken Love to their Country! That none of those who were there present, could call their Lives [Pg 26] or their Estates their own: That the Nobility were slighted and remov'd from all Places of Trust, Profit, or Power: That the Church was fill'd with a scandalous Clergy, since Vasconcellos had dispos'd of all the Livings, and to which he had prefer'd his own Creatures only: That the People were oppress'd with excessive Taxes, whilst the Earth remain'd untill'd for want of hands, their Labourers being all sent away by force, for Soldiers to Catalonia: That this last Summons for the Nobility to attend the King, was only a specious Pretence to force them out of their own Country, lest their Presence might prove an Obstacle to some cruel Design, which was doubtless on foot: That the mildest Fate they could hope for, was a tedious, if not a perpetual Banishment; and that whilst they were ill-treated by the Castilians abroad, Strangers should enjoy their Estates, and new Colonies take possession of their Habitations. He concluded by assuring them, that so great were the Miseries of his Country, that he would rather chuse to die ten thousand Deaths, than be obliged to see the Encrease of them; nor would he now entertain one thought of Life, did he not hope that so many Persons of Quality were not met together in vain.

This Discourse had its desir'd effect, by reminding every one of the many Evils which they had suffer'd. Each seem'd earnest to give some instance of Vasconcellos's Cruelty. The Estates of some had been unjustly confiscated, whilst others had Hereditary Places and Governments taken from them;[Pg 27] some had been long confin'd in Prisons thro the Jealousy of the Spanish Ministers, and many bewail'd a Father, a Brother, or a Friend, either detain'd at Madrid, or sent into Catalonia as Hostages of the Fidelity of their unhappy Countrymen. In short, there was not one of those who were engag'd in this Publick Cause, but what had some private Quarrel to revenge: but nothing provoked them more than the Catalonian Expedition; they plainly saw, that it was not so much the want of their assistance, as the desire of ruining them, which made the Spanish Minister oblige them to that tedious and expensive Voyage. These Considerations, join'd to their own private Animosities, made 'em unanimously resolve to venture Life and Fortune, rather than any longer to bear the heavy Yoke: but the Form of Government which they ought to chuse, caus'd a Division amongst them. Part of the Assembly were for making themselves a Republick, as Holland had lately done; others were for a Monarchy, but could not agree upon the choice of a King: some propos'd the Duke of Braganza, some the Marquis de Villareal, and others the Duke d'Aviedo, (all three Princes of the Royal Blood of Portugal,) according as their different Inclinations or Interests byass'd them. But the Archbishop, who was wholly devoted to the House of Braganza, assuming the Authority of his Character, set forth with great strength of Reason, That the Choice of a Government was not in their power; that the Oath of Allegiance which they had taken to the King[Pg 28] of Spain, could not in conscience be broken, unless it was with a design to restore their rightful Sovereign to the Throne of his Fathers, which every one knew to be the Duke of Braganza; that they must therefore resolve to proclaim him King, or for ever to continue under the Tyranny of the Spanish Usurper. After this, he made 'em consider the Power and Riches of this Prince, as well as the great number of his Vassals, on whom depended almost a third part of the Kingdom. He shew'd 'em it was impossible for 'em to drive the Spaniards out of Portugal, unless he was at their head: that the only way to engage him, would be by making him an Offer of the Crown, which they would be under a Necessity of doing, altho he was not the first Prince of the Royal Blood. Then began he to reckon all those excellent Qualities with which he was endow'd, as his Wisdom, his Prudence; but above all, his affable Behaviour, and inimitable Goodness. In short, his Words prevail'd so well upon every one, that they unanimously declared him their King, and promis'd that they would spare no Pains, no Endeavours to engage him to enter into their Measures: after which, having agreed upon the time and place of a second Meeting, to concert the ways and means of bringing this happy Revolution about, the Assembly broke up.

Pinto observing how well the Minds of the People were dispos'd in favour of his Master, wrote privately to him, to acquaint him with the Success of the first Meeting, and advis'd him to come, as if by chance, to Lisbon, that[Pg 29] by his Presence he might encourage the Conspirators, and at the same time get some Opportunity of conferring with them. This Man spent his whole time in negotiating this grand Affair, yet did it so artfully, that no one could suspect his having any farther Interest in it, than his Concern for the Publick Welfare. He seemingly doubted whether his Master would ever enter into their Measures, objecting his natural Aversion to any Undertaking which was hazardous and requir'd Application: then would he start some Difficulties, which were of no other use but to destroy all Suspicion of his having any Understanding with his Master, and were so far from being weighty enough to discourage them, that they rather serv'd to excite their Ardour.

Upon the Advice given by Pinto, the Duke left Villa-viciosa, and came to Almada, a Castle near Lisbon, on pretence of visiting it as he had done the other Fortifications of that Kingdom. His Equipage was so magnificent, and he had with him such a number of the Nobility and Gentry, as well as of Officers, that he looked more like a King going to take possession of a Kingdom, than like the Governour of a Province, who was viewing the Places and Forts under his Jurisdiction: he was so near Lisbon, that he was under an obligation of going to pay his Devoirs to the Vice-Queen. As soon as he enter'd the Palace-yard, he found the Avenues crowded with infinite numbers of People, who press'd forward to see him pass along; and all the Nobility came to wait upon him, and to[Pg 30] accompany him to the Vice-Queen's. It was a general Holiday throughout the City, and so great was the Joy of the People, that there seem'd only a Herald wanting to proclaim him King, or Resolution enough in himself to put the Crown upon his Head.

But the Duke was too prudent to trust to the uncertain Sallies of an inconstant People. He knew what a vast difference there was between their vain Shouts, and that Steddiness which is necessary to support so great an Enterprize. Therefore after having paid his respects to the Vice-Queen, and taken leave of her, he return'd to Almada, without so much as going to Braganza-House, or passing thro the City, lest he should encrease the Jealousy of the Spaniards, who already seem'd very uneasy at the Affection which the People had so unanimously express'd for the Duke.

Pinto took care to make his Friends observe the unnecessary Caution which his Master us'd, and that therefore they ought not to neglect this Opportunity, which his Stay at Almada afforded them, to wait upon that Prince, and to persuade, nay, as tho it were to force him to accept the Crown. The Conspirators thought the Counsel good, and deputed him to the Duke to obtain an Audience. He granted them one, but upon condition there should come three of the Conspirators only, not thinking it safe to explain himself before a greater Number.

Miguel d'Almeida, Antonio d'Almada, and Pedro Mendoza, were the three Persons pitched upon; who coming by night to the Prince's,[Pg 31] and being introduc'd into his Chamber, d'Almada, who was their Spokesman, represented in few words the present unhappy State of Portugal, whose Natives, of what Quality or Condition soever, had suffer'd so much from the unjust and cruel Castilians: That the Duke himself was as much, if not more expos'd than any other to their Treachery; that he was too discerning not to perceive that d'Olivarez's Aim was his Ruin, and that there was no other Place of Refuge but the Throne; for the restoring him to which, he had Orders to offer him the Services of a considerable Number of People of the first Quality, who would willingly expose their Lives, and sacrifice their Fortunes for his sake, and to revenge themselves upon the oppressing Spaniards.

He afterwards told them, that the Times of Charles V. and Philip II. were no more, when Spain held the Ballance of Europe in her hand, and gave the neighbouring Nations Laws: That this Monarchy, which had been once so formidable, could scarce now preserve its antient Territories; that the French and Dutch not only wag'd War against them, but often overcame 'em; that Catalonia itself employ'd the greatest part of their Forces; that they scarce had an Army on foot, the Treasury was exhausted, and that the Kingdom was governed by a weak Prince, who was himself sway'd by a Minister, abhor'd by the whole Nation.

He then observ'd what foreign Protection and Alliances they might depend on, and be assur'd of; most of the Princes of Europe[Pg 32] were profess'd Enemies to the House of Austria; the Encouragement Holland and Catalonia had met with, sufficiently shew'd what might be expected from that able[B] Statesman, whose mighty Genius seem'd wholly bent upon the Destruction of the Spanish King; that the Sea was now open, and he might have free Communication with whom he pleas'd; that there were scarce any Spanish Garisons left in Portugal, they having been drawn out to serve in Catalonia; that there could never be a more favourable Opportunity of asserting his Right and Title to the Crown, of securing his Life, his Fortune, and his Liberty, which were at stake, and of delivering his Country from Slavery and Oppression.

We may easily imagine, that there was nothing in this Speech which could displease the Duke of Braganza; however, unwilling to let them see his Heart, he answer'd the Deputies in such a manner, as could neither lessen, or encrease their Hopes. He told them, that he was but too sensible of the Miseries to which Portugal was reduc'd by the Castilians, nor could he think himself secure from their Treachery; that he very much commended the Zeal which they shew'd for the Welfare of their Country, and was in an especial manner oblig'd to them for the Affection which they bore him in particular; that notwithstanding what they had represented, he fear'd that matters were not ripe for so dangerous an Enterprize, whose Consequence, should they not bring it to a happy Period, would prove so fatal to them all.

Having return'd this Answer, (for a more positive one he would not return) he caress'd the Deputies, and thank'd them in so obliging a manner, that they left him, well satisfy'd that their Message was gratefully receiv'd; but at the same time persuaded, that the Prince would be no farther concerned in their Design, than giving his content to the Execution of it, as soon as their Plot should be ripe.

After their Departure, the Duke confer'd with Pinto about the new Measures which they must take, and then return'd to Villa-viciosa; but not with that inward Satisfaction of Mind which he had hitherto enjoy'd, but with a Restlessness of Thought, the too common Companion of Princes.

As soon as he arriv'd, he communicated those Proportions, which had been made him, to the Dutchess his Wife. She was of a Castilian Family, Sister to the Duke of Medina Sidonia, a Grandee of Spain, and Governor of Andalusia. During her Childhood, her Mind was great and heroick, and as she grew up, became passionately fond of Honour and Glory. The Duke, her Father, who perceived this natural Inclination of hers, took care to cultivate it betimes, and gave the Care of her Education to Persons who would swell her Breast with[C] Ambition, and[Pg 34] represent it as the chiefest Virtue of Princes. She apply'd herself betimes to the Study of the different Tempers and Inclinations of Mankind, and would by the Looks of a Person judge of his Heart; so that the most dissembling Courtier could scarce hide his Thoughts from her discerning Eye. She neither wanted Courage to undertake, nor Conduct to carry on the most difficult things, provided their End was glorious and honourable. Her Actions were free and easy, and at the same time noble and majestick; her Air at once inspir'd Love, and commanded Respect. She took the Portuguese Air with so much ease, that it seem'd natural to her. She made it her chief Study to deserve the Love and Esteem of her Husband; nor could the Austerity of her Life, a solid Devotion, and a perfect Complaisance to all his Actions, fail of doing it. She neglected all those Pleasures, which Persons of her Age and Quality usually relish; and the greatest part of her time was employ'd in Studies, which might adorn her Mind, and improve her Understanding.

The Duke thought himself compleatly happy in the possession of so accomplish'd a Lady; his Love could scarce be parallel'd, and his Confidence in her was entire: He never undertook any thing without her Advice, nor would he engage himself any farther in a matter of such consequence, without first consulting with her. He therefore shew'd her the Scheme of the Revolution; the Names of the Conspirators, and acquainted her with what had pass'd as well in the[Pg 35] Assembly held at Lisbon, as in the Conference he had had with them at Almada, and the Warmth which every one had shown upon this occasion. He told her, That the Expedition of Catalonia had so incens'd the Nobility, that they were all resolv'd to revolt, rather than to leave their native Country; he dreaded, that if he should refuse to lead them on, they would forsake him, and chuse themselves another Leader. Yet he confess'd, that the Greatness of the Danger made him dread the Event; that whilst he view'd the Throne at a distance, the flattering Idea of Royalty was most agreeable to his Mind, but that now having a nearer Prospect of it, and of the intervening Obstacles, he was startled; nor could he calmly behold those Dangers into which he must inevitably plunge himself and his whole Family, in case of a Discovery: That the People, on whom they must chiefly depend for the Success, were inconstant, and disheartned by the least Difficulty: That the Number of Nobility and Gentry which he had on his side, was not sufficient, unless supported by the Grandees of the Kingdom; who doubtless, jealous of his Fortune, would oppose it, as not being able to submit to the Government of one, whom they had all along look'd upon as their Equal. That these Considerations, as well as the little Dependance he could make on foreign Assistance, overrul'd his Ambition, and made him forget the hopes of reigning. But the Dutchess, whose Soul was truly great, and Ambition her ruling Passion, immediately declar'd herself[Pg 36] in favour of the Conspiracy. She ask'd the Duke, "Whether in case the Portuguese, accepting his Denial, should resolve to make themselves a Republick, he would side with them, or with the King of Spain?" "With his Countrymen undoubtedly, he reply'd; for whose Liberty he would willingly venture his Life." "And why can you not do for your own sake, answer'd she, what you would do as a Member of the Commonwealth? The Throne belongs to you, and should you perish in attempting to recover it, your Fate would be glorious, and rather to be envy'd than pity'd." After this she urg'd "his undoubted Right to the Crown; that Portugal was reduc'd to such a miserable State by the Castilians, that it was inconsistent with the Honour of a Person of his Quality to be an idle Looker-on; that his Children would reproach, and their Posterity curse his Memory, for neglecting so fair an Opportunity of restoring them what they ought in justice to have had." Then she represented the difference between a Sovereign and a Subject, and the pleasure of ruling, instead of obeying in a servile manner. She made him sensible, that it would be no such difficult matter to re-possess himself of the Crown; that tho he could not hope for foreign Assistance, yet were the Portuguese of themselves able to drive the Spaniards out of their Country, especially at such a favourable Juncture as this. In short, so great was her persuasive Art, that she prevailed upon the Duke to accept the Offer made him, but[Pg 37] at the same time confess'd his Prudence, in letting the Number of the Conspirators encrease before he join'd with them; nor would she advise him to appear openly in it, till the Plot was ripe.

Mean while the Court of Spain grew very jealous or him. Those extraordinary Marks of Joy, which the Lisbonites had shewn at his coming thither, had very much alarm'd d'Olivarez. It was also whisper'd about, that there were nightly Meetings and secret Assemblies held at Lisbon: So impossible it is, that a Business of such a consequence should be wholly conceal'd.

Octob. 20.

1640.Upon this several Councils were held at Madrid, in which it was resolv'd, that the only way to prevent the Portuguese from revolting, was by taking from them their Leader, in favour of whom it was suppos'd they intended to revolt. Wherefore d'Olivarez immediately dispatch'd a Courier to the Duke of Braganza, to acquaint him, that the King desir'd to be inform'd, by his own mouth, of the Strength of every Fort and Citadel, the Condition of the Sea-Ports, and what Garisons were plac'd in each of them: to this he added, that his Friends at Court were overjoy'd at the thoughts of seeing him so soon, and that every one of them were preparing to receive him with the Respect due to his Quality and Deserts.

This News thunder-struck the unhappy Prince; he was well assur'd, that since so many Pretences were made use of to get him into Spain, his Destruction was resolv'd on, and nothing less than his Life could satisfy[Pg 38] them. They had left off Caresses and Invitations, and had now sent positive Orders, which either must be obey'd, or probably open Force would be made use of. He concluded, that he was betray'd. Such is the Fear of those, whose Thoughts are taken up with great Designs, and who always imagine that the inquisitive World is prying into their Actions, and observing all their Steps. Thus did the Duke, whose Conduct had been always greater than his Courage, dread that he had plung'd himself into inevitable Destruction.

But to gain time enough to give the Conspirators notice of his Danger, by the Advice of the Dutchess, he sent a Gentleman, whose Capacity and Fidelity he was before assur'd of, to the Court of Madrid, to assure the Spanish Minister, that he would suddenly wait on the King; but had at the same time given him private Orders to find out all the Pretences imaginable for the delaying his Journey, hoping in the mean time to bring the Conspiracy to Ripeness, and thereby to shelter himself from the impending Storm.

As soon as this Gentleman arriv'd at Madrid, he assur'd the King and the Duke d'Olivarez, that his Master follow'd him. To make his Story the more plausible, he took a large House, which he furnish'd very sumptuously, then hir'd a considerable Number of Servants, to whom he before-hand gave Liveries. In short, he spar'd no Cost to persuade the Spaniards that his Master would be in a very little time at Court, and that he intended[Pg 39] to appear with an Equipage suitable to his Birth.

Some days after he pretended to have receiv'd Advice that his Master was fallen sick. When this Pretence was grown stale, he presented a Memorial to d'Olivarez, in which he desir'd that his Master's Precedence in the Court might be adjusted. He did not in the least question but that this would gain a considerable time, hoping that the Grandees, by maintaining their Rights, would oppose his Claims. But these Delays beginning to be suspected, the first Minister had the thing soon decided, and always in favour of the Duke of Braganza; so earnestly did he desire to see him once out of Portugal, and to have him safe at Madrid.

The Conspirators no sooner heard of the Orders which the Duke had receiv'd, but fearing that he might obey them, deputed Mendoza to know what he intended to do, and to engage him firmly, if possible, to their Party. This Gentleman was chosen preferably to any other, because he was Governor of a Town near Villa-viciosa; so that he could hide the real Intent of his Journey from the Spaniards, under the specious Pretence of Business. He did not dare to go directly to the Prince's House, but took an opportunity of meeting him in a Forest one morning as he was hunting; they retir'd together into the thickest part of the Wood, where Mendoza shew'd him what Danger he expos'd himself to, by going to a place where all were his Enemies: That by this inconsiderate Action the Hopes of the Nobility,[Pg 40] as well as of the People, were utterly destroy'd: That a sufficient Number of Gentlemen, who were as able to serve him, as they were willing to do it, or to sacrifice their Lives for his sake, only waited for his Consent to declare themselves in his favour: That now was the very Crisis of his Fate, and that he must this instant resolve to be Cæsar or nothing: That the Business would admit of no longer Delay, lest the Secret being divulg'd, their Designs should prove abortive. The Duke, convinc'd of the Truth of what was said to him, told him that he was of his mind, and that he might assure his Friends, that as soon as their Plot should be ripe, he would put himself at the head of them.

This Conference ended, Mendoza immediately return'd home, for fear of being suspected, and wrote to some of the Conspirators that he had been hunting; "We had almost, continued he, lost our Game in the Pursuit, but at last the Day prov'd a Day of good Sport." Some few Days after Mendoza return'd to Lisbon, and acquainted Pinto that his Master wanted him, who set out as soon as they had together drawn out a shorter Scheme to proceed upon. Coming to Villa-viciosa, the first thing he acquainted the Duke with, was the Difference which had lately happen'd at the Court of Lisbon, the Vice-Queen loudly complaining of the haughty Pride and Insolence of Vasconcellos; nor could she any longer bear that all Business should be transacted by him, whilst she enjoy'd an empty Title, without any the least Authority.[Pg 41] What made her Complaints the juster, was, that she was really a deferring Princess, and capable of discharging the Trust which was committed to her Secretary. But it was the Greatness of her Genius, and her other extraordinary Deserts, which made the Court of Spain unwilling to let her have a greater share in the Government. Pinto observ'd, that this Difference could never have happen'd in a better time, seeing that the Ministers of Spain being taken up with this Business, would not be at leisure to pry into his Actions, or to observe the Steps he should take.

The Duke of Braganza, since Mendoza's Departure, was fallen into his wonted Irresolution, and the nearer the Business came to a Crisis, the more he dreaded the Event: Pinto made use of all his Rhetorick to excite his Master's Courage, and to draw him into his former Resolution. Nay, to his Persuasions he added Threatnings; he told him, in spite of himself, the Conspirators would proclaim him King, and what Dangers must he run then, when the Crown should be fix'd upon his Head, at a time when, only for want of necessary Preparation, he was not capable of preserving it. The Dutchess join'd with this faithful Servant, and convinc'd the Duke of the Baseness of preferring Life to Honour: he, charm'd with her Courage, yet asham'd to see it greater than his own, yielded to their Persuasions.

Mean while, the Gentleman whom he had sent to Madrid, wrote daily to let him know, that he could no longer defer his Journey on[Pg 42] any pretence whatsoever, and that Olivarez refus'd to hear the Excuses which he would have made. The Duke, to gain a little longer time, order'd the Gentleman to acquaint the Spanish Minister, that he had long since been at Madrid, had he had Money enough to defray the Expence of his Journey, and to appear at Court in a manner suitable to his Quality: That as soon as he could receive a sufficient Sum, he would immediately set out.

This Business dispatch'd, he consulted with the Dutchess and Pinto about the properest Means of executing their Design: several were propos'd, but at last this was agreed upon, That the Plot must break out at Lisbon, whose Example might have a good effect upon the other Towns and Cities of the Kingdom: That the same Day wherein he was proclaim'd King in the Metropolis, he should be also proclaim'd in every Place which was under his Dependance; nay, in every Borough and Village, of which any of the Conspirators were the leading Men, they should raise the People, so that one half of the Kingdom being up, the other of course would fall into their Measures, and the few remaining Spaniards would not know on which side to turn their Arms. His own Regiment he should quarter in Elvas, whose Governour was wholly in his Interest. That as for the manner of their making themselves Masters of Lisbon, Time and Opportunity would be their best Counsellors; however, the Duke's Opinion was, that they should seize the Palace in the first place, so that by securing the Vice-Queen,[Pg 43] and the Spaniards of Note, they would be like so many Hostages in their hands, for the Behaviour of the Governour and Garison of the Citadel, who otherwise might very much annoy 'em when they were Masters of the Town. After this, the Duke having assur'd Pinto, that notwithstanding any Change of Fortune, he should still have the same place in his Affection; he sent him to Lisbon with two Letters of Trust, one for Almeida, the other for Mendoza; wherein he conjur'd 'em to continue faithful to their Promises, and resolutely and courageously to finish what they had begun.

As soon as he arriv'd at Lisbon, he deliver'd his Letters to Almeida and Mendoza, who instantly sent for Lemos and Coreo, whom Pinto had long since engag'd in the Interest of his Master. These were two rich Citizens, who had gone thro all the Offices of the City, and had the People of it very much at their command; as they still carry'd on their Trade, there were a vast Number of poor People daily employ'd by 'em, and whose Hatred to the Spaniards they had still taken care to encrease, by insinuating that there were new Taxes to be laid upon several things at the beginning of the next Year. When they observ'd any one of a fiery Temper, they would take care to discharge him, on pretence that the Castilians had utterly ruin'd their Trade, and that they were no longer able to employ them; but their Aim was to reduce them to Poverty and Want, insomuch that Necessity should oblige them to revolt: but still would they extend their[Pg 44] Charity towards them, that they might always have them at their service. Besides this, they had engag'd some of the ablest Merchants and Tradesmen in every part of Lisbon, and promis'd, that if the Conspirators would give 'em warning over night of the Hour they intended to rise, punctually at that time they would have half the City up in Arms.

Pinto being thus sure of the Citizens, turn'd his Thoughts to the other Conspirators: he advis'd them to be ready for the Execution of their Plot upon the first notice given them; that mean while he would have them pretend they had some private Quarrel, and engage their Friends to assist them, for many, he observ'd, were not fit to be entrusted with so important a Secret, and others could not in cold Blood behold the Dangers they must go thro, and yet both be very serviceable when Matters were ripe, and only their Swords wanted.

Dec. 1.

1640.Finding every body firm in their Resolutions, and impatient to revenge themselves upon the Spaniards, he conferr'd with Almeida, Mendoza, Almada, and Mello, who fix'd upon Saturday, the first of December, for the great, the important Day: Notice was immediately given to the Duke of Braganza, that he might cause himself to be proclaim'd King the same day in the Province of Alentejo, most part of which belong'd to him. After which they agreed upon meeting once more before the time.

On the Twenty-fifth of November, according to their Agreement, they met at[Pg 45] Braganza-House, where mustering their Forces, they found that they could depend upon about One Hundred and Fifty Gentlemen, (most of them Heads of Families) with their Servants and Tenants, and about Two Hundred substantial Citizens, who could bring with them a considerable Number of inferior Workmen.

Vasconcellos's Death was unanimously resolv'd on, as a just Victim, and which would be grateful to the People. Some urg'd, that the Archbishop of Braga deserv'd the same Fate, especially considering the Strength of his Genius, and the Greatness of his Courage; for it was not to be suppos'd that he would be an idle Looker-on, but would probably be more dangerous than the Secretary himself could be, by raising all the Spaniards who were in Lisbon, with their Creatures; and that whilst they were busy in making themselves Masters of the Palace, he, at the head of his People, might fling himself into the Citadel, or come to the assistance of the Vice-Queen, to whose Service he was entirely devoted; and that at such a time as this, Pity was unseasonable, and Mercy dangerous.

These Considerations made the greatest part of the Assembly consent to the Prelate's Death; and he had shar'd Vasconcellos's Fate, had not[D] Don Miguel d'Almeida interpos'd. He represented to the Conspirators, that the Death of a Man of the Prelate's Character[Pg 46] and Station, would make them odious to the People; that it would infallibly draw the Hatred of the Clergy, and of the Inquisition in particular, (a People who at this Juncture were to be dreaded) upon the Duke of Braganza, to whom they would not only give the Names of Tyrant and Usurper, but whom they would also excommunicate; that the Prince himself would be sorely griev'd to have the Day stain'd with so cruel an Action; that he himself would engage to watch him so closely on that Day, that he should not have an Opportunity of doing any thing which might be prejudicial to the common Cause. In short, he urg'd so many things in his behalf, that the Prelate's Life was granted, the Assembly not being able to deny any thing to so worthy an Advocate.

Nothing now remain'd but to regulate the Order of the March and Attack, which was agreed upon in this manner: They should divide into four Companies, which should enter the Palace by four different Ways; so that all the Avenues to it being stopt, the Spaniards might have no Communication with, or be able to assist one another: That Don Miguel d'Almeida, with his, should fall on the German Guard, at the Entrance of the Palace: That Mello Lord Ranger, his Brother, and Don Estevan d'Acugna, should attack the Guard, which was always set at a Place call'd the Fort: That the Lord-Chamberlain Emanuel Saa, Teillo de Menezes, and Pinto, should enter Vasconcellos's Apartment, whom they must immediately dispatch: That Don Antonio d'Almada, Mendoza, Don Carlos Norogna,[Pg 47] and Antonio Salsaigni, should seize the Vice-Queen, and the Spaniards which were with her, to serve for Hostages, in case of need. Mean while, some of the Gentlemen, with a few of the most reputable Citizens, should proclaim Don John, Duke of Braganza, King of Portugal throughout the City; and that the People being rais'd by their Acclamations, they should make use of them to assist, wherever they found any Opposition. After this they resolv'd to meet on the first of December in the morning, some at Almeida's, some at Almada's, and the rest at Mendoza's House, where every Man should be furnish'd with necessary Arms.

While these things were transacting at Lisbon, and that the Duke's Friends were using all their Endeavours for his Re-establishment, he receiv'd an Express from Olivarez, (who grew very jealous of his Conduct) with positive Orders to come immediately to Madrid; and that he might have nothing to colour his Delay, he remitted him a Bill upon the Royal Treasury for Ten Thousand Ducats.

The Commands laid upon him were so plain and positive, that the Duke could not put off his Journey without justly encreasing his Suspicion. He plainly foresaw, that if he did not obey those Orders, the Court of Madrid would take some such Measures as might prove fatal to him, and wholly destroy their Projection; he would not therefore refuse to obey, but made part of his Houshold immediately set out, and take the Madrid Road. In the presence of the Courier he gave several Orders relating to the Conduct[Pg 48] of those he left his Deputy-Governours, and in all respects behav'd himself like a Man who was going a long Journey. He dispatch'd a Gentleman to the Vice-Queen, to give her notice of his Departure, and wrote to Olivarez, that he would be at Madrid in eight Days time at farthest; and that he might engage the Courier to report all these things, he made him a considerable Present, under pretence of rewarding him for his expeditious Haste, in bringing him Letters from the King, and his first Ministers. At the same time he let the Conspirators know what new Orders he had receiv'd from Court, that they might see the Danger of deferring the Execution of their Design; but they were scarce in a Capacity of assisting him, an Accident having happen'd, which had almost broken all their Measures.

There was at Lisbon a Nobleman, who on all Occasions had shewn an immortal Hatred to the Spanish Government; he never call'd them any thing but Tyrants and Usurpers, and would openly rail at their unjust Proceedings, but nothing anger'd him more than the Expedition of Catalonia: d'Almada having taken care to fall often into his Company, thought there was not a truer-hearted Portuguese in the whole Kingdom, and that no one would more strenuously labour for their Liberty. But oh Heaven! how great was his Surprize! when having taken him aside, and discover'd the whole Conspiracy to him, this base, this cowardly Wretch, whose whole Courage was plac'd in his Tongue, refus'd to have any hand in the Business, or to engage[Pg 49] himself with the Conspirators, pretending that their Plot had no solid Foundation: Bold and adventrous where no Danger was, but fearful and daunted as soon as it appear'd. "Have you, said he to Almada, Forces enough to undertake so great a thing? Where is your Army to oppose the Troops of Spain, who upon the first News of the Revolt will enter the Kingdom? What Grandees have you at your head? Can they furnish you with Money sufficient to defray the Expence of a Civil War? I fear, continued he, that instead of revenging yourselves on the Spaniards, and freeing Portugal from Slavery, you will utterly ruin it, by giving the Spaniards a specious Pretence for doing what they have been so long endeavouring at."