The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Quiver, 1/1900, by Anonymous

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Quiver, 1/1900

Author: Anonymous

Release Date: September 20, 2013 [EBook #43768]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE QUIVER, 1/1900 ***

Produced by Delphine Lettau, Julia Neufeld and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The Quiver 1/1900

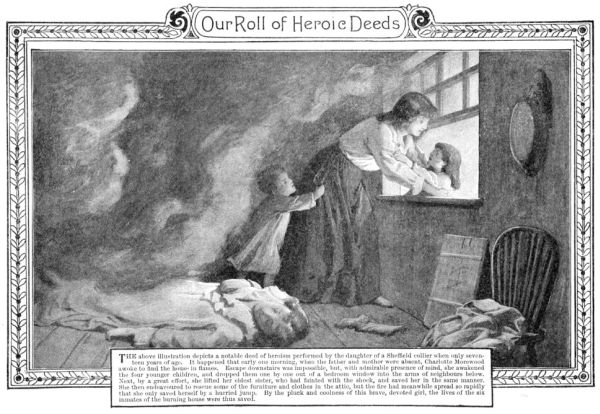

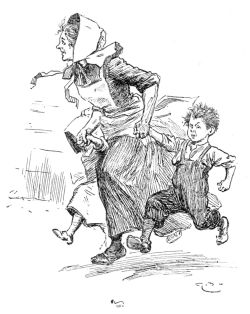

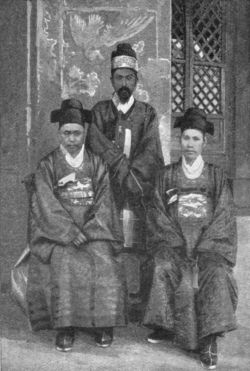

Our Roll of Heroic Deeds

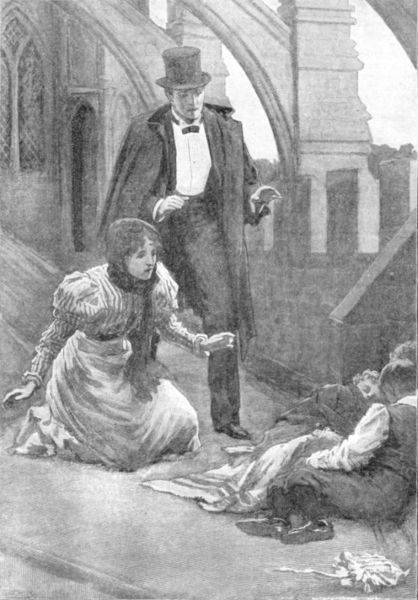

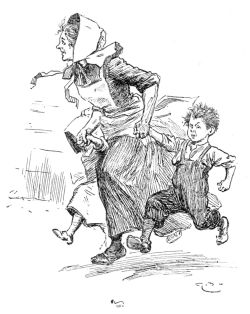

The above illustration depicts a notable deed of heroism performed by the daughter of a Sheffield collier when only seventeen

years of age. It happened that early one morning, when the father and mother were absent, Charlotte Morewood

awoke to find the house in flames. Escape downstairs was impossible, but, with admirable presence of mind, she awakened

the four younger children, and dropped them one by one out of a bedroom window into the arms of neighbours below.

Next, by a great effort, she lifted her eldest sister, who had fainted with the shock, and saved her in the same manner.

She then endeavoured to rescue some of the furniture and clothes in the attic, but the fire had meanwhile spread so rapidly

that she only saved herself by a hurried jump. By the pluck and coolness of this brave, devoted girl, the lives of the six

inmates of the burning house were thus saved.

FACING DEATH FOR CHRIST.

BASED ON AN INTERVIEW WITH THE REV. C. H. GOODMAN.

By Our Special Commissioner.

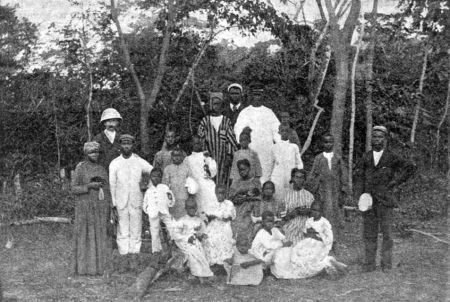

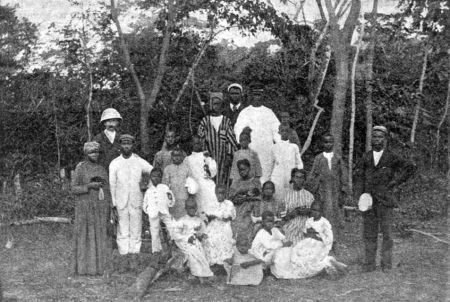

MR. GOODMAN WITH TEACHERS AND CHILDREN OF DAY SCHOOL, TIKONKO.

(Photo: The Rev. W. Vivian, F.R.G.S.)

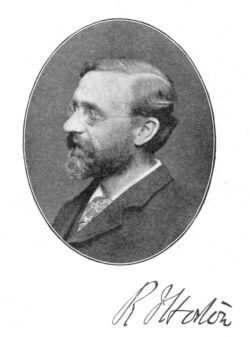

A terrible

adventure

befell the

Rev. C. H. Goodman,

missionary

in the Mendi

country, West

Africa, in the

summer of 1898.

It is really surprising

that he

is alive to tell

the tale, and, indeed,

the marks

of great suffering

were still

visible on his

face when, a few months afterwards, he

kindly told me the story.

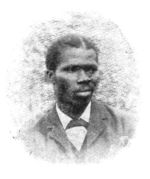

THE REV. C. H. GOODMAN.

(Photo: Mr. Stephens, Harrogate.)

The peril came on him with startling

suddenness. No bolt from the blue

could dash from the heavens more unexpectedly.

He was stationed at Tikonko,

about two hundred miles inland from

Freetown, Sierra Leone, and had been

in charge of the United Methodist Free

Church Mission there for about six

years. Suddenly, one morning, he heard

by chance that his life and the lives of

his Mission-workers had been demanded

by a neighbouring tribe.

"Is it really true," he asked his friends,

the Tikonko Mendis, "that the Bompeh

people wish me to be killed?"

"Yes, it is true."

"And you can give me no protection?"

"We fear not any."

"Then I must go back to the coast—to

the English?"

"Yes."

"Can you give me carriers to accompany

me and my helpers, and to take

food for the journey?"

"Yes, we promise that."

But Mr. Goodman could not get the

promise fulfilled—whether from insincerity[292]

or inability on the part of the Mendis

to keep it he could not discover.

What was to be done? He was the

only white man there: some coloured

people, chiefly from Free Town, and

associated with the Mission, were with

him; but the tribes all round were in

a state of terrible unrest and were ripe

for war, while, indeed, hostilities had

actually commenced in some districts.

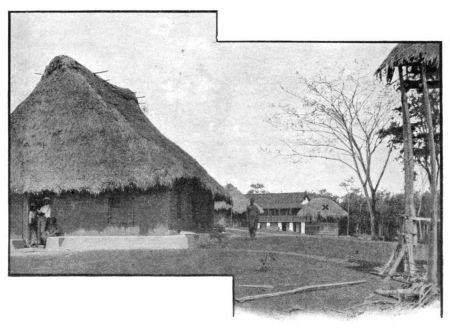

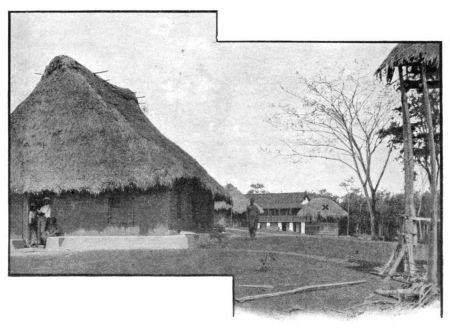

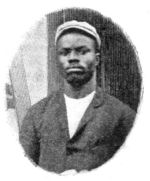

MR. ROBERTS' RESIDENCE.

(Mr. Goodman's house is to be seen in the distance.)

(Photo: The Rev. W. Vivian. F.R.G.S.)

SITE OF MURDER OF MR. ROBERTS, MR. PRATT, AND OTHERS.

(The mark X indicates the well into which their bodies were thrown.)

Mr. Goodman had hoped that the

Tikonkos would have been strong enough

to keep out of the war, but he was

disappointed; and it was now clear to

him that he could not rely upon their protection,

or upon any assistance to reach

the coast. The children and several of

the workers had left the Mission and

had taken refuge in Tikonko town,

which consists of a collection of mud-huts

surrounded by a fence, while he remained

quietly at the Mission premises

and watched.

On Monday, May 2nd, he saw many

strange men loitering about the farm

in a suspicious manner. It was evident

a crisis was impending, and he steeled

himself to prepare for the worst.

Suddenly, in the afternoon, he heard a

great noise. Rushing out, he found

that a lad, named Johnson, who was

carrying a box belonging to some of the

Mission people, was surrounded by

strange men, who were seizing the box

and ill-treating the boy.

Johnson and his wife hurried to the

rescue, but they were set upon by the

"war-boys" and beaten; their clothes

were torn off their backs, and Mr.

Johnson received such a frightful gash

across the face that his nose was nearly

severed from his body and fell off next

day.

Seizing his gun and calling to others,

Mr. Goodman hurried out of the house,

and with a yell the "war-boys" rushed

to the Mission. Mr. Goodman's little

party were hopelessly outnumbered; and

Mr. Campbell, the native school teacher

and Mr. Goodman, seeing that discretion[293]

was the better part of valour, turned

to the bush and escaped in different

directions.

Mr. Goodman did not proceed very

far. Hurrying along, he was soon able

to hide in the dense bush, his object

being to work his way to the town

and enter by the Bompeh road. If

he could reach the town, he thought

the nominal chief, Sandy, might secretly

prove his friend.

Gradually, therefore, he made his

way to the road, and then hurried to

the gate, but it was shut in his face.

THEO. ROBERTS.

(Industrial Trainer.)

THE REV. J. C. JOHNSON.

(Mission Worker.)

T. T. CAMPBELL

(School Teacher.)

ISHMAEL PRATT.

(Carpenter.)

FOUR OF THE MARTYRS.

(From Photographs by the Rev. W. Vivian, F.R.G.S.)

Back, then, to the friendly shelter

of the bush he turned, and now even

the elements seemed against him, for

a terrible tornado burst, and in a

minute he was drenched to the skin.

Alone, wet, weary, and foodless, with

savage enemies around him seeking

to kill him, his position might well

have appalled the stoutest heart. But

an Englishman, whether missionary

or soldier, must never know when he

is beaten; and so at night he made

his way again to the town, and entered

it through a hole in the fence and

hurried up to the king's compound.

Now the old chief of Tikonko had

died shortly before, and the "cry for

the dead"—that is, the time of mourning—was

not yet over, consequently

the new chief or king—whom the missionary

called Sandy—had not been fully

invested with his new powers.

THE MISSION HOUSE BEFORE ITS DESTRUCTION.

(From a Drawing by Mrs. Vivian.)

"Oh, you have escaped," he cried, when

Mr. Goodman came to him. "I am glad

indeed. Yes, I will help you, but it is

not safe for you to remain in the town.[294]

The 'war-boys' are eager to kill you.

Where will you go? Ah! you shall appear

as one of my wives."

Thus the palaver was short but decisive.

Disguised as a woman—an expedient

forced on him by urgent necessity—the

missionary was conveyed that night out

of the town to a hut in the bush belonging

to Sandy. Silently through the darksome

night the little party crept along, and the

missionary was left there alone. He

was supposed to be one of the chief's

wives, who was ill. In the morning the

imaginary wife sought once more the

friendly protection of the dense bush, and

at night he returned again to the hut.

Stealthily, one of his friendly boys

brought him now and again a little food.

The lad had secured one of the Mission

boxes and procured from it a tin of cocoa,

and this cocoa he brought to the missionary,

with rice, and occasionally a little fish and

meat.

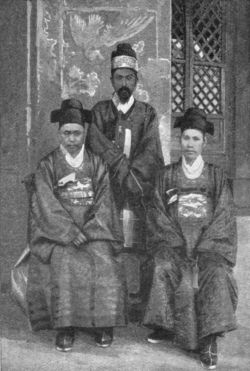

MR. GOODMAN AND HIS MENDI "BOYS."

(Photo: The Rev. W. Vivian, F.R.G.S.)

Hiding thus, while the yells of the

"war-boys" sounded far and near, the

missionary lived through those terrible

days. Tuesday came and went, also

the Wednesday and the Thursday. But

Friday morning heralded a change. A

message was brought to him that Sandy

desired to see him, and to this day Mr.

Goodman does not know whether the

message was treacherous or not. But,

trusting to its honesty, he left the hut

to visit the chief, and then, before he

had gone far, he suddenly found himself

surrounded by the yelling Bompeh "war-boys."

They caught him and shouted round him,

but did not then hurt him. Resistance

was useless, and with war-whoops and

yells of triumph they led him forward

as though to Tikonko. But when near

the fence they altered their cry: "To

Bompeh" they shouted, and to Bompeh

he was turned.

For three and a half weary hours the

missionary marched on in the blazing

sun, and without his white helmet. He

was fully surrounded by the yelling

savages, and the leader of the party

marched beside him with drawn sword.

The shouts and excitement of his captors

gradually calmed down as they walked

along; but, presently, as they neared

Bompeh town, his clothes were pulled

off his back, and clad only in pants and

vest, and without even shoes or stockings,

he crept along the burning path with

naked and bleeding feet.

[295]

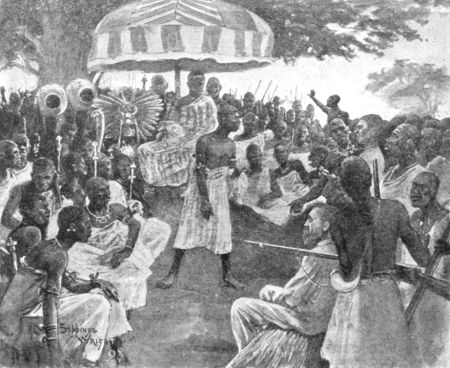

But at length the weary march was

over. Bompeh town was reached, and

then the war-horns were blown, and amid

much excitement Mr. Goodman was taken

to an open space before the king's hut,

where also the people assembled.

The trial was to be held at once; the

white man's fate was to be decided.

The chief, whose name was Gruburu,

sat on a rude kind of chair in the

middle of the people, his prime minister

near, and men and women and "war-boys"

grouped all round, chiefly according to

families. Mr. Goodman, tired with his

long journey, sat himself down on a log.

First, one of his captors spoke. The

man came out from the group, and as

he talked he walked up and down in the

open space before the king. An account

was being given of the missionary's

capture. "And," said Mr. Goodman,

"while this was going on, I prayed that

God would bring about a division in their

counsels."

When the man had finished, up rose an

old man, and by his gestures and the

anxiety he displayed, Mr. Goodman saw

with pleasure that he was pleading for him.

This gleam of friendliness—the first

that day, and met with in the stronghold

of his enemies—fell like genial warmth

upon his spirits and encouraged him to

hope.

Then a woman arose. She was a relative

of the king; and, advancing before him,

she bent before him and took his foot

in her hand as a sign of submission. "Do

not let this man die," she said. "My

son at Tikonko has sent me a message

pleading for his life. 'Do not let the

white man die,' says my son; 'he is a

good man.'"

Indeed, many messages had come to

the king in the missionary's favour.

"When we were sick," said the messages,

"he has mended us; he has done us good;

we like the way he has walked"—i.e.

they liked his manner of life.

It was the old story—conduct and

character had impressed the natives[296]

after all, and they were not wholly ungrateful.

But, see! The king is about to give

his judgment. The final decision is to

be made. Is it to be death or life?

(From a Water-Colour Drawing by Mrs. Vivian.)

THE DEVIL HOUSE AT TIKONKO.

(Where the town fetish or devil is consulted and propitiated.)

The king said: "This white man is

our friend. He has come to do us good,

and to give our picken (children) sense.

He has nothing to do with the Government.

He shall not die in my town."

Bravo, King of Bompeh! Thou hast

more common-sense and right feeling beneath

thy sable skin than some people

would have supposed.

"I was surprised," said Mr. Goodman

modestly, "to find how the influence of

the Mission had spread."

At once his clothes were returned to

him—all save his waistcoat, which was

given to the leader of his captors; he

was sheltered in a hut and allowed a

measure of freedom—more freedom, indeed,

than some of the natives who

were prisoners. But, alas! he had

escaped one great danger only to fall

into another. The hardships he had

undergone, and the malaria from which

he had suffered, induced severe illness.

Dysentery and black-water fever seized

him; they shook him in their fell grasp

until, from their power and poor food,

he became so weak that he could

scarcely stand.

His bed was a sort of raised platform

of beaten mud, about six inches

above the floor, with a mat upon it.

Sometimes he slept in his clothes. But

he became so sore from lying so long

on such a hard resting-place that

wounds were formed which troubled

him for long afterwards. Such requisites

as soap and towel were wholly wanting.

The prospect, indeed, became very

dark, and it seemed as though he had

only escaped the savages to fall a

victim to fever.

At first a boy waited on him, then

an English-speaking Mendi; but unfortunately

the king wanted this man,

and his place was taken by another.

The news of Mr. Goodman's illness

and imprisonment travelled abroad. It

came to Tikonko, and his Mission boy

Boyma sent him some quinine, which

proved very beneficial. Then one day,

though he knew it not, a friendly

chief looked in upon him as he lay

there so ill, and sent word to the

English that one of their countrymen

was a captive up there at Bompeh

town, and Colonel Cunninghame promptly

sent a demand that he should be given[297]

up alive. A great force, said the

Colonel, was coming, with plenty of

guns, to rescue him. Curiously enough,

a native declared that he had dreamed

the same thing; he had seen in his

dream a great English army with

"plenty guns" coming for the captive

Englishman. Let him, therefore, be sent

to his countrymen.

But another cause was working in

his favour. While Mr. Goodman had

been ill a battle had been fought, and

the Mendis had been disastrously beaten

by those terrible English with their

"plenty guns." The "war-boys" were

sick of the war. "Send the white man

down," they also said to the king, "to

plead that the fighting may cease."

So it was decided that he should be

sent. He was given boys to assist him

in his journey, and by their help he

made his way, though he could scarcely

walk, down to the English camp. He

arrived there on June 26th, eight weeks

from that fateful day when he had

seen the strange men loitering so suspiciously

about his Mission farm.

Alas! he found that the Mission

premises had been totally destroyed,

and, worse still, that Mr. Campbell had

been killed. Mr. Johnson, after being

kept a prisoner, was also slain, as were

some other members of the Mission,

who were Sierra Leone men.

It was therefore with a chastened

joy, and gratitude for his own escape,

that Mr. Goodman slowly made his way

to the coast. He remained at the

camp but a short time, and was then

sent on to Bonthe, Sherbro', where

he recovered a measure of strength

under the care of Commandant Alldridge.

Finally, he reached Freetown on July 21st,

and presently took ship for England.

When he returned home some of his

friends scarcely knew him. His beard

was marked with grey, his cheeks were

hollow, and his bodily weakness very

great. He looked like an old man. He

has recovered wonderfully since then,

and appears more like his natural age;

but when I saw him he was still far

from well. He suffered from the effects

of malaria even yet, and from the evil

results of the poison in his system.

Four times in his nine years of missionary

life has he suffered from the

fell "black-water" scourge.

But since his return he has been

manfully doing his duty in speaking

to many audiences of his mission work;

and, if the Committee should so decide,

he is fully prepared to return to Africa

and reinstate the Methodist Free Churches

Mission in the heart of Mendiland.

SAMPLES OF WRITING BY TIKONKO SCHOOL CHILDREN.

(Arranged by Mrs. Vivian.)

GREAT ANNIVERSARIES

IN FEBRUARY.

By the Rev. A. R. Buckland, M.A., Morning Preacher at the Foundling Hospital.

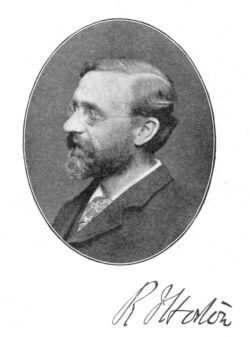

THE MARQUIS OF

SALISBURY.

(Photo: J. Phillips, Belfast.)

In this democratic

age the

birthday of Sir

Edward Coke

(February 1st, 1551-2)

can hardly be passed

over. We remember

him, not so much as

the rival of Bacon

and the prosecutor

of Raleigh, as for

his share in drawing

up the Petition

of Rights. Of his

works, one part of

his "Institutes of the

Laws of England,"

long known as

"Coke upon Littleton,"

has a place amongst the few classical

law books which are familiar by name to

the general public. Coke married for his

second wife a daughter of Lord Burghley

and grand-daughter of the great Cecil, who,

in this same month, was raised to the peerage

by Elizabeth on the suppression of the

northern rebellion. His descendant, the

present Marquis of Salisbury, belongs also to

this month, for

he was born on

February 3rd,

1830. This is

not the place in

which to discuss

a living statesman:

let us pass

to other names.

SIR ROBERT PEEL

(After the Portrait by sir Thomas

Lawrence, P.R.A.)

"Bob, you

dog, if you're

not Prime Minister,

I'll disinherit

you."

That, we are

told, was the

way in which

the father of Sir

Robert Peel

stimulated the

political

ambitions of his son. He became Prime Minister,

and is not likely soon to be forgotten.

His Corn Importation Bill is one of the

pieces of legislation which mark an epoch.

In London, too, he will be remembered for

his creation of the present police system.

Possibly there are many now who, hearing a

police constable called a "peeler," forget that

the name carries us back to the remodelling

of the London police by Mr. Peel in the

year 1829.

BISHOP HOOPER'S MONUMENT.

(Photo: Cassell and Co., Ltd.)

The same month may speak to us of

a statesman who helped to bring the

nation through a crisis of another kind.

On the last day of February, 1856, Lord

Canning disembarked at Calcutta, and within

five minutes after touching land proceeded to

take the customary oaths as Governor-General

of India. It fell upon him to deal with so

appalling a crisis as the Indian Mutiny; he

met it, as one of his biographers reminds us,[299]

in a way that "places him high on the list of

those great officers of State whose services

to their country

entitle them to

the esteem and

gratitude of every

loyal Englishman."

February is not

a great month in

ecclesiastical anniversaries.

But it was on February

9th, 1555,

that John

Hooper, Bishop

of Gloucester,

was burnt just

outside his cathedral,

where a

monument to his

memory now

stands. It was

in this month that Robert Leighton, sometime

Archbishop of Glasgow, died in London

in the year 1684. His commentary on the

Epistles of St.

Peter is still

numbered

amongst standard

homiletical

and expository

works.

BISHOP PATTESON.

(From the Portrait in the

British Museum.)

February has

some pathetic

associations

with the foreign

missionary work

of the English

Church. It was

on February

24th, 1861, that

J. C. Patteson

was consecrated

at Auckland

first Bishop for

Melanesia. The

story of his

martyrdom is one of the most moving incidents

in the history of modern missions.

His successor, J. R. Selwyn, was consecrated

in the same month in 1877.

On February 8th, 1890, there died at

Usambiro, at the south end of the Victoria

Nyanza, Alexander Mackay, the simple

layman whose work and early death did

so much to rivet attention, not only on

the Uganda Mission, but also on missionary

enterprise in general. No modern example

seems to have been more fruitful; but he

saw nothing of the wonderful development of

Uganda. The pioneer often does not live to

look on the results of his own enterprise.

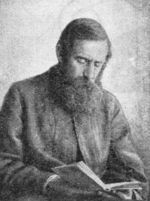

ALEXANDER MACKAY.

(The Pioneer Missionary of

Uganda.)

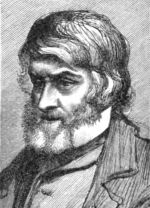

THOMAS CARLYLE.

(From a Pencil Drawing by

George Howard, Esq., M.P.)

There are some who tell us that people

do not read Dickens now. More is the pity!

Yet the flat stone over the grave of Dickens

in Westminster Abbey so often has a flower

upon it, while others of no less famous

men are bare, that the man must still be

remembered as well as his books. He was

born in this month

in the year 1812,

and died in June,

1870. Much of his

character might

be summed up in

the benediction he

put into the mouth

of Tiny Tim, "God

bless us every one."

In the same month

of February, in the

year 1881, there

died an author

and philosopher of

another type—Thomas

Carlyle,

one of the most

striking figures in

English literature,

and one of those

whose reputation was world-wide. "When

the devil's advocate has said his worst

against Carlyle, he leaves a figure still of

unblemished integrity, purity, loftiness of

purpose, and inflexible resolution to do the

right, as of a man living consciously under

his Maker's eye, and with his thoughts fixed

on the account which he would have to

render of his talents."

On February 23rd, 1807, Wilberforce's Bill

for the abolition

of the foreign

slave trade was

carried by a

majority of 283

to 16. Sir

Samuel Romilly

contrasted the

feelings of

Napoleon with

that of the man

who would that

night "lay his

head upon his

pillow and remember

that

the slave trade

was no more."

There was still,

however, much

to do; but Wilberforce

lived

to hear the news that the nation was willing

to pay twenty millions for the abolition of

slavery.

WILLIAM WILBERFORCE.

(After the Portrait by Joseph

Slater.)

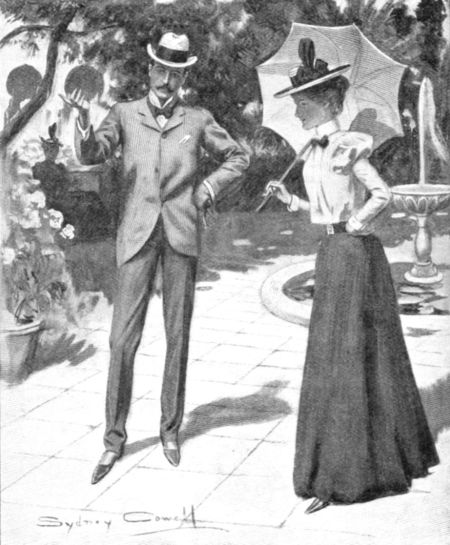

THE MINOR CANON'S DAUGHTER

THE STORY OF A CATHEDRAL TOWN.

By E. S. Curry, Author of "One of the Greatest," "Closely Veiled," Etc.

CHAPTER X.

THE SEARCH.

I t was Mr. Warde who, before

the police arrived, organised

and dispatched search

parties. The visitors and

servants from the Deanery,

with his own and the Palace

household, were scattered

through the immediate neighbourhood,

in less than half

an hour from the first summons.

Marjorie was with her mother. Mr. Pelham—after

a distracted visit to his own house,

hoping against hope that he might still find

the toddling child safe and rosy, sleeping in

her cot—had brought servants back with

him, whom he put under Mr. Warde's instructions.

For Mr. Warde knew every

inch of ground about, every possible danger

into which the little feet might have

strayed.

In the precincts of the cathedral, in the gardens

throughout the neighbourhood, in every

nook and secluded place, lights were soon

flashing and voices calling.

All that anybody knew was little enough.

Soon after eight—the hour at which Mr.

Bethune and Marjorie had gone to the Deanery—nurse

had gone to the garden to call

the children in. She found it empty, and,

pursuing her search into the cave, found

reason to be alarmed. But she did not then

alarm Mrs. Bethune. Returning to the house,

which was strangely still, she had looked

into the drawing-room.

"They have taken Barbara home," Mrs.

Bethune explained. "They will soon be back,

nurse. But it is getting late for the little

ones."

She looked so quiet and calm on her sofa,

resting, with the sense of her husband's love

folding her round, that the nurse forbore to

disturb her with her own sudden forebodings.

But she put on her bonnet, and ran up to The

Ridges, to satisfy herself against her fears.

No Barbara was there; neither she nor the

boys had been seen since the afternoon.

Barbara's nurse—forgetting for a time her

airs—accompanied her to the Canons' Court.

Together they again searched the garden;

the cathedral yard, where the darkness was

settling down over the numerous graves and

tombs; the shady Canons' Walk—calling

anxiously the names of their respective

charges. No signs were to be found of the

children. Then nurse, without troubling her

mistress, went to the Deanery, and asked for

Mr. Bethune; and from him, when he

reached his wife's side, had come the summons

to Mr. Pelham and Marjorie.

A thorough examination of the cave, at

nurse's suggestion, revealed the passage and

its exit into the Palace grounds; resulting

in Mr. Warde's systematic search throughout

the parks and neighbourhood.

Marjorie recollected Sandy's visit to her

room; and the discovery of the abstraction

of the blanket from her bed seemed to prove

that some larger scheme than merely running

away must have been in the boys' heads.

Then a new fear was started. A visit to

the little station at the bottom of the Green

had seemed for a time to furnish a clue. The

station-master reported that within the last

week the two boys had been inquiring the

price of tickets to Baskerton for a party of[301]

five. He had been struck with the answer to

his question—"All under twelve." But the

children had not travelled by the only train

that evening. The Dean, who had made this

inquiry, thereupon went home, and ordered

his carriage, and had himself driven over to

Baskerton. It was five miles away, famous

for its picturesque scenery and fishing, and

was the scene of all the picnic parties about.

Across the parks and by-lanes, filled with

roses and honeysuckle, it was only about three

miles off. David and Sandy, he knew, were

well acquainted with its delights; they had

often been included in his own parties there.

The route of the little brook for several

miles was explored by a party of men from

the Palace and The Ridges. The boys were

known to frequent it, and a day or two before

Sandy had been seen up to his waist in the

water, trying to entice a

lively water-rat.

It was wonderful how many

people helped in the search.

To all, the boys were well

known, and, now that trouble

had come upon them, well

beloved. Their fearlessness

and bonhomie were remembered,

and their mischief

only with indulgent excuses.

And Mr. Pelham was taken

to all hearts that sorrowful

night, for the sake of the

pretty baby who was lost.

No one was more energetic

and suggestive than Mrs.

Lytchett, no one kinder, no

one more tearful. It was she

who headed a search party

through the cathedral, recalling

to mind how Marjorie

had once got herself locked

up there nearly all night

through a fit of obstinacy.

But no children were discovered.

"If only the Bishop were

here—he would know what

to do," she sighed frequently,

as news kept coming in that

nothing had been found of

the missing ones. They

seemed to have vanished as

completely as if the earth

had opened and swallowed

them up. No one had seen

them—nothing had been

heard of them after Sandy's

visit to his sister's room.

"But what could he want

the blanket for?"

Mr. Warde, after two or

three fruitless journeys, had

again come back to the Court for news,

hoping that somebody else might have been

more fortunate. It was just on the edge of

dawn, in that stillness when the first faint

twitter of the birds is just beginning.

As he came down the broad pavement to

the Court gate, the eastern sky was growing

clear above the chimney stacks of the Deanery.

Lights were still shining in the windows round,

and, as he neared the gate, Marjorie came

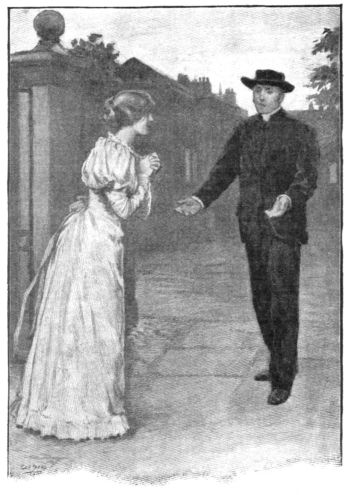

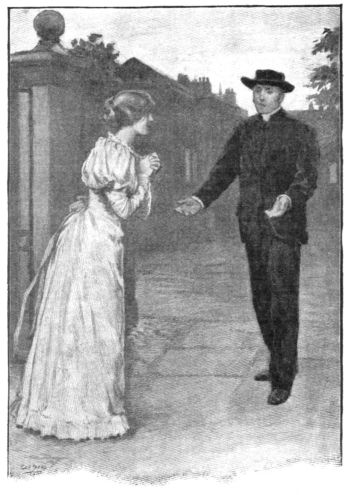

forward quickly.

The sight of her wan face was a shock to

him; she was still in the pretty evening dress,

above which, in the twilight of the dawn, her

neck and throat shone white. She had the air

of some broken lily—desolate, woeful.

Mr. Warde's heart went out to her with a

great compassion. His eyes grew dim as her

wistful glance met his.

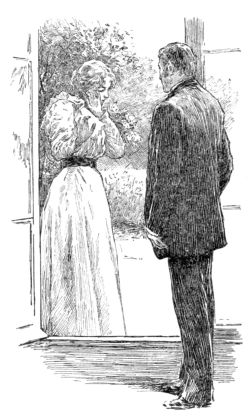

The sight of her wan face was a shock to him.

[302]

"No, dear, I can hear nothing," he said

softly, putting his arm round her. Marjorie

rested against him, letting her tired young

limbs collapse against his strength. Inspired

by some instinct she did not understand, she

had left her mother's sofa, where Mr. Pelham

was now sitting, waiting for the return of a

messenger. They two, it seemed to Marjorie,

with a mutual sorrow could understand each

other. She felt somehow restless, uneasy,

unworthy, as she coldly responded to Mr.

Pelham's sympathy and care. At his suggestion

she had come away to prepare some tea

for her mother, and in passing through the

hall had been lured to the open door by the

sound of Mr. Warde's footsteps on the flagstones.

The quick, firm tread encouraged hope.

She could rest on him. The very sight of his

kind, familiar face seemed to renew her strength

and courage.

"See! on that little tower on the chapel."

After a minute's silence, during which his

hand had caressed the soft waves of her hair,

he asked, "What could Sandy want the blanket

for? I have been trying to think."

"So have we—mother and I. Poor mother!"

Marjorie sighed.

"Is she alone?" he asked.

"No. Mr. Pelham is with her; he understands,

he is tender and careful; and she is

full of hope now—she comforts him. Father

has gone to the river."

Marjorie gave a little shudder.

"You are cold," Mr. Warde said briskly.

"Let me advise you, dear. Go and change

your dress; put on something warm. By that

time I shall have got some food and shall

bring it in. I expect you have no servants

left."

"No. They are all—somewhere."

She allowed herself to be led back to

the house, and as he stood watching

her ascend the stairs, the man's heart

gave a bound of rejoicing. She had

come to him willingly, of her own

accord. What though it were sorrow that

had brought her? She was his now for

ever, of her own free will. He stood looking

after her, with face upraised, a thanksgiving

in his heart. And thus for the last time he

looked on Marjorie, rejoicing. Never again

without pain was he to hear the soft swish of

her dress, the soft fall of her foot. But in those

few seconds he lived through an æon of joy.

He could not guess the force of the feeling

which had driven her from Mr. Pelham's side.

The same sorrow that had sent her to Mr.

Warde had also taught her that she must

shun the man who could now be nothing to

her. Marjorie's was a very simple nature.

When she realised a fact, she did not play with

it. Matter-of-fact duty was a real power with

her. So she had responded to the strong

training which the calm approval or disapproval

shining in her father's quiet eyes

had sufficiently imposed.

As the different search parties came back,

all with the same "no news," Mr. Warde had

a table of provisions brought out into the Court.

He was too busy caring for the needs of the

many weary volunteers to go again into Mr.

Bethune's house; but nurse had by this time

returned, and was tearfully waiting on her

mistress.

"Nothing could have happened to them all,"

the Dean said briskly, "or we must have found

some trace. It is the most mysterious thing

I ever knew in my life. They are all together

in some safe place, I feel convinced."

"My mistress thinks now that they are

kept," nurse, overhearing, said; "she is sure

the boys would understand that she would be

anxious, and they are always careful about

Miss Barbie. But if only we could know!"

and nurse departed sobbing.

The dawn had broadened into morning, the

tips of the cathedral spires were red in the[303]

sunlight, and many of the unavailing searchers

were at last going slowly to their homes.

Nothing more could be done than had been

done. Mr. Warde's servants were clearing

away the débris of the meal; whilst he himself

was again hurrying along the flagged path

to the cathedral, with the intention of again

thoroughly searching its many nooks and

crannies in the daylight. He feared he knew

not what, recollecting Sandy's adventurous

spirit.

Mr. Bethune was sitting beside his wife, her

hand in his, as once before that night, looking

out upon the still garden. Marjorie, seeing

them thus, noting the far-away look in her

father's eyes (as though visions were being

vouchsafed to the weary man, unseen by other

eyes), noting, too, that his calmness was bringing

a look of peace and trust to the wan face

of her mother—turned involuntarily to the

other bereaved and, as she remembered, so

desperately lonely man.

"Come into the garden," she said, her eyes

full of pity. "Now that it is light we have a

better chance; we may find something."

He followed her across the dewy lawn, as

she led the way quickly to the untidy corner

so eloquent of the little workers. Spades and

baskets lay scattered about; a cap of Sandy's

hung on a currant-bush, where it had been put

to dry after the washing in the bath; a large

fragment of bread and butter, dropped in the

hasty departure, lay in the path. The tears

at last welled into Marjorie's eyes, as she

saw Mr. Pelham stoop and pick up a little

shoe.

"It is my baby's," he said softly. "God keep

her!"

They paused together on the garden path,

and Marjorie's eyes turned to the rose-tinged

pinnacles of the beautiful cathedral. To all

the dwellers in its precincts it was almost like

a living presence, dominating all their lives

and thoughts.

The length of the choir, terminating in the

big central tower, was before them, whilst in

the distance rose the twin spires. The morning

mist was fleeing before the sun, now lighting

each finial. Shadows still lay under the

flying buttresses, and along the lower plane

of the south aisle roof and chapel.

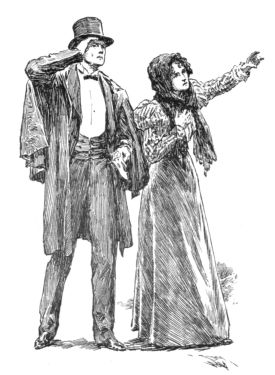

Mr. Pelham, after a moment's look at the

girl's rapt face, turned also to gaze at the scene

on which her eyes were resting.

Suddenly Marjorie gave a little cry, instantly

suppressed.

"What is that?" she said rapidly. "See!

on that little tower on the chapel?"

"I see," he answered, "something fluttering,

you mean—something blue."

Both pairs of eyes were concentrated in a

fixed and painful gaze.

"It is a ribbon," Marjorie said hoarsely.

"Barbie was wearing——" She paused, turning

her dilated eyes to her companion's face.

"My baby's sash—it is tied there," he said

quickly; "it is a signal."

He turned to her, and for a second their

encountering eyes were eloquent. Under the

shock of sudden hope, the joy, the emotion,

the agitation of the moment, the man's self-control

vanished. His eyes spoke their message—hers

replied—both of them taken unawares.

"Hush!" said Marjorie, putting up her

hands as if answering speech. "I know the

way," she faltered. "Father has keys; wait,

don't tell them yet, till we are sure. It is the

chapel roof, where they were mending. Sandy

knew."

She turned swiftly, the man following with

eager strides.

CHAPTER XI.

JUVENILE ADVENTURERS.

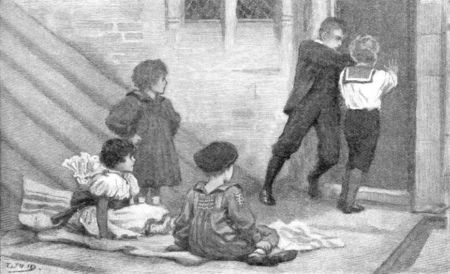

A big yew-tree hid the corner of the wall, where the adventurers, on their

enterprise, dropped down into the

cathedral yard. Numerous square

tombstones and old monuments made splendid

hiding-places. There was only one little bit

of open space to cross, where the evening

sunshine cast long shadows, and where for

a few moments the strange little truant procession

looked a procession of giants.

David and Sandy each held a hand of

Barbara, she having declined to be carried.

Ross and Orme followed solemnly. If anybody

had met them, the boys would have

turned down the path to their home, and

their presence there would have seemed quite

natural. But no one passed—no one was in

sight. David had chosen the time for his

move well. The Court households were busy

preparing for dinner. And though windows

commanded the cathedral yard, from none,

as it turned out, was the start of the little

party into the world observed. Once across

the grass, they were soon hidden by the many

projections and buttresses and corners of

the walls.

In the angle of the south aisle and its

chapel was the tiny room whence the spiral

staircase started, in the thickness of the wall,

up to the clerestory of the choir. It also

led through a narrow door lower down, on

to the roof of the south aisle. Sandy knew

all the keys of the cathedral, and the place

in Mr. Galton's house where each hung. The

door of the little room was, however, open;

Mr. Galton therefore was somewhere about,

though he often lingered on his last look

round. They must be quick.

In a few minutes the excited children were[304]

mounting the spiral staircase. David went

first, helping Barbara's unaccustomed feet;

Sandy came last, having closed the little door

of communication at the foot of the stairs.

They were embarked on their "climb up the

mountain." Issuing through the narrow door

which came first in sight, the delighted

children found themselves in the wide gutter

at the base of the roof. Guarded by its low

parapet, it was as safe as their own garden,

provided they did not attempt to climb.

David gave strict orders that they were to

keep under the "shelter of the forts," and on

no account to show their faces to the enemy.

Up here, they were in another world—a

delightful, wide, spacious world, whence they

could look down on the earth they had left.

The Palace grounds lay below them; beyond

were the parks, intersected by their hedges,

like the sections of a map. From the flat

chapel roof they could see their own garden

and Mr. Warde's, with the Deanery trees

beyond.

"Ross, and Orme, and Barbie, remember

you're our family now, and you must do

what you are bid," was David's solemn reminder

to them of the altered condition of

things.

Up and down the children ran, with a

pitter-patter of clamouring feet on the leads.

Barbara was a little unhappy because she could

not make as much noise as the boys, owing

to the make of her shoes, and to her misfortune

in having lost one in transit. Sandy

set this right.

"Stop the march!" he ordered. "You'll

give notice to the enemy, you duffers"—this

to the wide-eyed boys—"where we

are." So they stopped. Ross then proceeded

to clamber on hands and knees up the incline

of the roof, and, turning, to slide down

on his other side. This amusement lasted all

three some time. When their clothes looked

pretty well spoilt, the fun palled. Then

came supper, the crowning act of the evening's

proceedings. After this, they intended

to return to ordinary life and the earth

they had left; abandoning their fortress till

another opportunity arrived. They intended

to be at home before they would be much

missed.

But all this had taken longer than they

thought, and when the "family" was called

to its repast the little boys refused to be

hurried. With much self-denial, this meal

had been saved. They meant to enjoy it. By

the time they were satisfied, the darkness and

cold were beginning to be appreciably perceived.

Then Sandy hugged himself for his pioneering

knowledge.

"No settlers goes wivout blankets," he announced.

"Knew we should want it."

"Hurry up," David urged, beginning to be

a little alarmed at the aspect of things in

their aërial world. "We've got to get Barbie

home. It's time to go."

Ten minutes later the boy turned a white

face to the expectant babes behind him. He

and Sandy had pushed with all their might

at the little iron door, which had so easily

admitted them to the roof. It was fast and

firm—locked up securely for the night—and

they were prisoners. Probably they would

not be released until the workmen arrived

in the morning.

"I wouldn't mind, if we could let mother

know, not to be frightened," the boy said,

"and Barbie's father. Think, Sandy; couldn't

we let 'em know?"

Sandy desisted from fruitless bangings on

the door, propped his elbows on the parapet,

and put his head between his hands in

the most approved attitude of thinking.

Possibly, this attitude was useful for another

purpose than thinking. Sandy was only

seven, but he had a fervent belief in his

mother's fragility, and in the power of himself

and his brothers to keep her laughing

presence on her sofa or to banish her elsewhere.

He had heard things said which

made him realise that a very little thing

might transfer her to a narrower couch—in

a sunny, railed-off corner just under the

cathedral walls. Already a little white stone

marked the resting-place of "Archibald, aged

one year." Sandy sometimes pitied Archibald

for being all by himself there. He had

one day suggested to his mother that "P'r'aps

one of us ought to go and mind him—as he

was so little." For answer, the mother had

gathered the bright head on to her breast,

fervently breathing, "No, Sandy, mother

can't let one go, not the very littlest bit of

any of you. God is minding little Archie

better than we can."

So up there in the air, within sight of the

familiar garden—within sound almost of the

mother who as yet was not concerned about

him—her little son may be excused if, in

process of his thinking, he blinked away a

tear. The responsibility was so great. This

had been his scheme more than David's. And

there was Barbie's father, too. But he wasted

no sentiment on him.

"My finks is all in a mess," he said at last,

lifting his face. "On'y we must signal. It's

like a desert island up here. P'r'aps we might

frow down something."

The gathering darkness, alas! hid the fluttering

signal which, after some protestations

from Barbara, they tied to a carved projection.

It was the longest thing they had about them.

How tiny it looked up there, they did not

realise.

[305]

The little feet were growing weary, the

"family" by this time were showing signs of

restive discontent.

"Ain't we got no beds in this home?"

asked Ross, his hands in his pockets, his legs

wide apart, surveying the leads, of whose

hardness he had made ample trial.

"Not yet," said Sandy cheerily. Whatever

he felt himself, he was not going to let the

babes be unhappy, if he could help it. "On'y

pioneers to-night. Beds have to be made."

"Nur' did maked Ross's bed—see'd her—mornin',"

announced Ross in a dissatisfied tone;

and he brought his brows together, and signified

generally that he was disgusted.

"No barf?" inquired Orme, planting himself

by his elder brother in a similar revolutionary

attitude.

"Bar?" echoed Barbara, unwilling to be

kept out of whatever anarchy might be going.

"Barbedie's bar?" she inquired of Sandy; and

it said much for Sandy's ability in translating

languages that he quite understood what she

was demanding.

David turned out his pockets, in the hope

of finding enough string to let down a basket,

or a letter describing their distressed condition.

But the utmost length they could attain, when

every pocket had been ransacked, and all their

ties, and hat ribbons, and pocket-handkerchiefs

tied together, was about midway down the long

windows. No hope that way, even if the darkness

of the summer night had not by this time

settled down upon the land. David gave it up

at last.

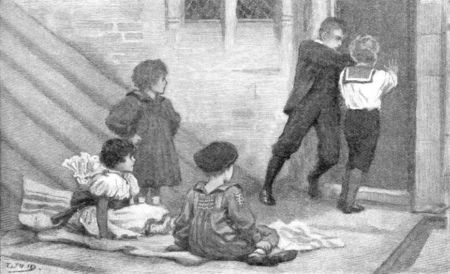

David and Sandy pushed with all their might.

"Somebody'll p'r'aps remember us," he said

with a catch in his voice. "Mother——"; and

then, for the sake of his manhood, he stopped

short. No one remembered having ever seen

a tear from David.

"We'd best put the fam'ly to bed," suggested

Sandy at this period.

"They'll be awful cold," responded David.

"Not in the blanket, an' us sittin' close round

outside to keep out the cold. Hens sit on

their little ones, so do cats—curl round 'em,

that is—and there's our jackets," said Sandy

lightly.

But first there were remonstrances from the

babies to combat, when it was explained to

them what they were expected to do.

"Orme kicks an' frows off all the clothes,"

objected Ross.

"So do Ross," eagerly excused Orme. But

the novelty of Barbara as a bed-fellow was

some consolation.

"Barbedie no go bed—in f'ock," remarked

Barbara indignantly.

Sandy plumped down upon the leads, and

took her on his insufficient knees.

When she was quite settled there, with her

arm round his neck to keep herself from

slipping, Sandy explained matters.

"It's 'stead of your nightie-gown, Barbie,"

with an entreaty in his tone, in itself a sufficient

betrayal of weakness to the baby's feminine[306]

intelligence. "We forgot to bring your nightie-gown."

"Fesh it," she ordered, looking up at David,

who stood by.

"Can't, Barbie—very sorry," David said

apologetically.

"Fesh Barbedie's nightie-gown," she said

majestically to the two revolutionaries.

But not all the boys' chivalric devotion,

unstinted through that troublous night, could

produce the desired garment. At last, arrayed

in David's coat as a substitute, over her own

dainty garments, little Barbedie Pelham fell to

repose.

By this time the two little boys, huddled

together like kittens or young-puppies on the

outspread blanket, had fallen fast asleep.

Barbara was snuggled in beside them, and the

blanket carefully wrapped round the three.

Sandy and David, with their backs against the

parapet—the latter with Barbara's head upon

his knees, whilst Sandy's performed the same

office of pillow for his little brothers—prepared

to win through the hours of darkness as

patiently as they might. No word of reproof

or bitterness had been said by either boy.

Each bore his share manfully of the difficulty,

for which both were perhaps equally responsible.

Down below, the lanterns flashed in and out

of the ruins, and across the Palace grounds.

Voices called, which, if the boys heard at all,

seemed to them only the distant sounds of the

day, to which they were accustomed. Their

own frantic shouts some time ago, even Sandy's

whistle, had been unheard and unheeded.

When the midnight chimes rang out softly

over their heads, Sandy, rousing, said sleepily,

"We forgot somefing, Dave. I've been

dreamin' 'bout it."

"What?" David asked. He had not yet

slept, and his mind had been busy, thinking,

wondering, sorrowing, chiefly about his

mother. In difficulties, hers was the personality

which always presented itself to her

children.

"We've forgot all our prayers."

"Say them now," suggested David after a

pause.

"It'll wake 'em!"

"Not if we don't move."

"Will it be proper prayers sittin' here?"

"Old Mrs. Jones always sits in church," suggested

David.

"I b'lieve her legs won't bend."

"Mother can't kneel down," David said in

a low voice.

"More she can." Sandy was hopeful again

at this thought. "There's two apiece," he

went on thoughtfully, "and one over. You say

yours an' Ross's—I'll say mine an' Orme's.

How 'bout Barbie's? We couldn't say half

each, could we?" doubtfully.

"No; we will both say Barbie's prayers

for her," decided David.

The low voices stopped. For a space there

was silence. Then Sandy spoke—

"Have you nearly done, Dave? I've got

as far's Barbie's."

There was no response, and Sandy, respecting

the silence which he took for the hush

of devotion, held his peace, and essayed for

the third time his evening prayer.

In a few moments, whilst below was desolation

and the anguish of bereavement—up

above, under the stars, all the children slept.

CHAPTER XII.

FOUND!

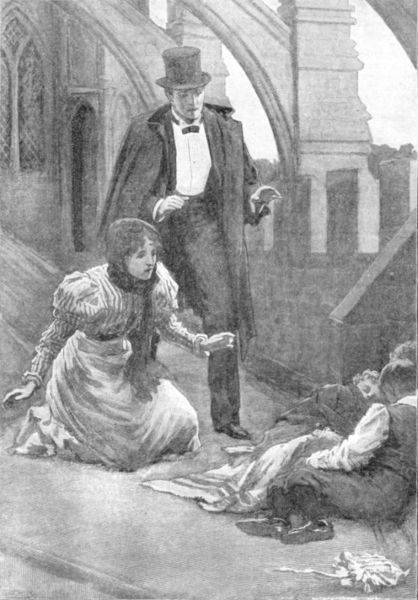

Meeting no one, Marjorie and Mr.

Pelham hastily ascended the spiral

stairs.

Issuing on to the leads, Marjorie

glanced hastily round. Together they hurried,

till, under the little turret, they stood beside

the, as yet, unawakened group. It looked very

pathetic in the morning greyness, the little

huddled-up party, which the sun had not yet

reached.

The man's frame trembled as he stooped—doubting,

fearing, his keen eyes noting the

care which had been bestowed upon his

little child. Not much of her was visible—only

a rosy cheek, under the tangle of hair

which lay across David's knee. The boy's

body had sunk slightly as the muscles relaxed

in sleep; and he and Sandy were

now propped together. Both of them were

jacketless: Sandy's little body was covered

only by his vest.

David's hand lay protectingly across Barbara,

over whom his jacket lay outspread.

She was warm and rosy; so were the two

babies curled up under the little coat—a

scanty covering—of which Sandy had divested

himself.

Marjorie sank down beside Sandy. He

looked white and wan, and there was a look

of disturbance and unrest on his sleeping

face. His head rested uncomfortably against

David's shoulder. Solicitously, she gathered

his unprotected little body into her warm

arms; and at her movement he opened

startled blue eyes upon her.

"Is it mornin'?" he asked; then quickly,

"Is the fam'ly safe?"

"How could you, Sandy?" Marjorie asked,

tenderly kissing the impertinent little nose

turned up to her. And that was all the reproach

Sandy ever heard.

"THE LITTLE HUDDLED-UP PARTY."

"Didn't mean to, Margie," eagerly. "The

door got locked 'fore we got down. How

[308]

did you guess we were here?" he went on,

the fascination of the "game," now that he

again felt safe and irresponsible, filling his

imagination. "Was it the signal?"

He listened much gratified, as Marjorie

described how the fluttering sash had caught

her sight.

The children woke one by one, Barbara

climbing into her father's arms to be divested

of her strange night-clothes. She returned

the coat to its owner, with a gracious

"Barbedie's done."

Sandy and David listened amazed to the

warmth of Mr. Pelham's thanks.

"You have been good to my baby. I

shall never forget it, never. You are two

little men."

With hurrying, trembling fingers, Marjorie

tidied up the children—some impulse making

her wish her mother's first sight of them to

be wholly without alarm. Barbara refused

to leave her father's arms, so her rescued

sash was tied on under his eloquent eyes.

Now that they had once delivered their

message, they were masterful and compelling.

Marjorie's fell before them; but something in

the quiver of her lip, and the wanness of

her face in the sunlight, under his closer

scrutiny, made him hasten to speak. He

caught her fingers, and they lay for a

moment pressed close against his breast.

"Mine, Marjorie! Mine now," he said.

"Dearest, do not shrink," he whispered, turning

hurriedly to see what was producing the

startled change in the kindling face before

him. Mr. Warde stood in the doorway surveying

the little scene.

With just a glance at the two, who for

the moment had forgotten everyone but

themselves, he stooped and picked up Orme—a

disconsolate, woe-begone baby, whose

ideas would need much readjusting after

this eventful night.

The others followed, pitter-patter down the

stairs, and along the gravelled path. But it

was Marjorie who entered first through the

open door into her mother's presence.

Mr. Bethune still sat beside his wife's

couch. He put up a hand to hush the intruder,

but Marjorie saw beyond him the

wide, questioning eyes and the wave of

colour rushing into her mother's face. She

did not know that she herself—radiant,

sparkling, with a look upon her face only

to be seen on a maiden's face in presence of

her beloved—was sufficient herald of good

news. It scarcely needed her words.

"All quite safe, mother," even if Sandy's

rush past her restraining hand had not told

the tale.

The children entered like a conquering

army. Mr. Warde slid Orme, murmuring

satisfaction, down on to the sofa beside his

mother, and watched with an unaccountable

pang at his heart as she gathered them all

into her arms. The parents accepted David's

rapid "Didn't mean to, father," and his explanation

of the mishap which they had

never counted on—too glad to see them safe,

too accustomed to their enterprise, too certain

that what they said was true, to give the

scolding they perhaps deserved.

As the news of their safety spread, sympathisers

flocked in. Like a young turkey-cock

lifting up its crest, Sandy stood a captive

at Mrs. Lytchett's knee, his jacket held tightly

in her firm grasp.

"I hope your father's going to whip you,"

she said severely.

"Ain't," said Sandy.

"Then he ought. Do you know you've

nearly killed your mother?"

Sandy's glance crossed the room, his conscience

giving a repentant twinge.

His mother's laughing, merry eyes met his,

and repentance fled.

"Let me go, please," giving his jacket a tug.

"I want to go to my mother." Sandy always

said "My mother" when he wished to be

impressive.

Mrs. Lytchett watched him insinuate his

small body to his mother's side, where he stood

defiant, only the mother guessing all that the

clinging clasp of his fingers round her arm

was meant to say.

Marjorie came down to say that the little

ones were safe in bed; and David and Sandy

walked off beside her with uplifted heads.

With the house still, and the children of

which it had been bereaved once more within

its walls, with the need for exertion and

control giving place to a languor which would

not permit sleep, Marjorie felt a load like lead

descend upon her. In spite of visions that

came to her wakeful senses, of ardent eyes and

a tender tone, although her fingers tingled still

with the warm clasp of those stronger ones,

she was very unhappy. On her bed, alone with

rushing thoughts, staring with wakeful eyes on

to the green bravery outside her window, she

thought over all that had happened, and knew

that she had played a sorry part. An engaged

girl—she had let another man make love to her.

Marjorie shrank as she realised her action.

"What have I done? It came to me

upon the roof! Oh! why didn't I find out

before? What can I tell Mr. Warde? How

can I tell him that I never cared for him a

bit? Is it I—can it be I, who have behaved

so badly? But I must tell him, straight

away. Not a minute longer than I can help

will I be so double-faced."

At her usual hour she dressed and went

downstairs. The empty breakfast-room added

strength to her resolve. Pausing but for a[309]

moment on the doorstep, to catch at her slipping

courage, she ran down the flagged path of the

Court, and knocked at Mr. Warde's door.

Mr. Warde, like herself, had been wakeful.

Marjorie's face on the roof had been a startling

revelation. And yet he had to confess to

himself that in his inmost heart he had gauged

rightly her love. Even in the dawn, whilst he

had rejoiced at its expression, a cold hand had

seemed to pluck it away. And now—he had

seen her kindling face—he had seen the

mounting flush, he had seen the love-light in

her dark eyes, in that glance when he had

surprised the lovers. It was a very different

girl who had borne his caresses, when for a

few moments she had leant her tired body

against his strength.

He realised it all. She loved Antony

Pelham; she only bore with him.

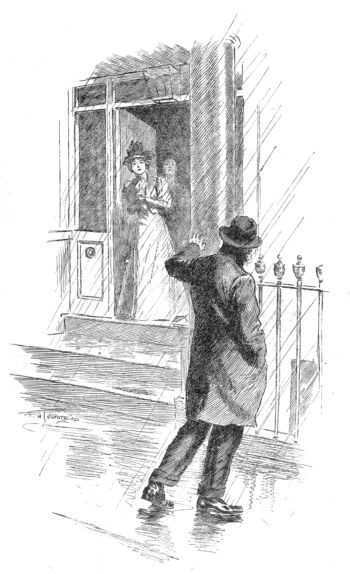

Entering Mr. Warde's house, the door at the

end of the hall leading into the garden stood

open before her. Many a time in her childish life,

Marjorie had sought her friend by way of the

study window. Some impulse now made her

seek that mode of approach. It was a French

window, not quite open to the ground. She

had to mount two steps, and step over a low

framework, which in former days her small

feet had found a sufficient barrier.

The window was wide open. Marjorie tapped

upon the pane. Mr. Warde was sitting at his

bureau, and she could not see his face.

"May I come in?"

As the loved voice fell upon his ear, the

man rose, and pushed the letter he was writing

aside.

"Like old days, Marjorie," he smiled, coming

forward to meet her, but his face looked pale

and drawn.

Something in hers, something to him admirable

in the courage which had prompted

her visit—for he knew why she had come—some

desire to save her pain made him say:

"I was writing to you, Marjorie."

"Yes?" Her troubled eyes sought some

comfort from his.

"But now you have come—it was good of you

to come, Marjorie—I did not like to disturb

you, or I would have saved you. Sit there in

the old place—your chair has never been

moved."

But instead, Marjorie moved restlessly to the

window, and looked out upon the trim luxuriance

of the rose-filled garden. Her courage

was oozing fast in face of his kindness and

the old associations.

"I came to tell you," she said slowly, "that

what I said the other day was wrong. I have

found out—that I cannot——"

"I know, Marjorie. No need to say it," he

said softly.

"I have behaved very badly," she went on.

"I let you think I cared for you. I did not

know—then. I never did care. I never can—I

know now." Unconsciously her tone took a

note of triumph, which made her hearer wince.

He forced himself to reply:

"It was a mistake, dear. I realised that it

was only a chance—that you were but a child

whom I have loved very dearly. That is it,

Marjorie. That is how it is between us."

She lifted her foot over the threshold of the

window, and the straying rose-branches fell

about her. She looked very slight and young,

as she stood there for a moment, the sun

burnishing the bright tendrils of her hair

into a halo round her face. The man's soul

went out in a sigh of longing as he saw the

beauty of the picture—saw her standing as he

had dreamt she would stand, his own loved

possession, in her home.

"I think you will be happy," he forced himself

to say; "I think Mr. Pelham——"

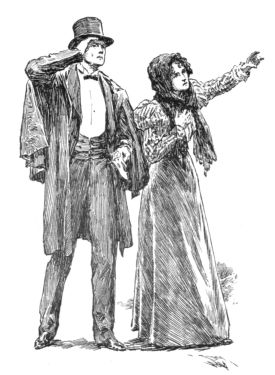

She put up her hands to ward off his speech.

She put up her hands to ward off his speech,

and her face grew scarlet.

[310]

"Good-bye," she said softly.

There was a rustle of soft drapery, a hasty

footfall, a blank. The window was vacant.

The man stared at it, still for a moment

possessed with the vision of her presence. Then

he turned, and looked painfully round the

luxurious room.

All was there that man could want—every

expression of a cultivated taste. As he looked, his

loneliness—the loneliness that would never now

be satisfied—fell in desolation round him.

The adventurers were gathered on the lawn

on a rug and cushions Marjorie had found for

them. After a long sleep, as school was out of

the question for that day, they had spent some

hours in shovelling the earth back into their

hole.

"Never knew such a funny fing in all my

life!" Sandy had exclaimed during this process.

"It all came out, and on'y 'bout half will go in.

How do you splain that, Dave?"

"Don't want to explain," said David, jumping

in and stamping vigorously. "It's got to

go, whether it will or no."

"It's like a grave," Sandy said, observing

him. "On'y there's nothing buried. You'll

get buried in a minute, Orme, if you don't

look out."

"Me s'ant."

"You will. There!" as a clatter of earth

fell over and around the busy baby. "Didn't

I tell you so?"

Orme looked round, his chubby moon-face a

surprised interrogation. Then as fast as he

could trot, he went off to his mother. To

her he imparted the information that the

"'ky had fell, an' it was a dirty 'ky."

It was after they had tired themselves

with digging that the four had sought Marjorie

and a fairy story. In the middle of

this, when the prince and the heroine were

engaged in a customary understanding, Marjorie

suddenly broke off in her narrative

and relapsed into thought.

Marjorie suddenly broke off in her narrative.

"Seems, Margie, as if you felt dreffle 'bout

something," said David.

Marjorie did not reply. Her thoughts had

ascended the hill, and there was a dreamy,

unseeing look in her eyes.

Almost every day Ross and Orme go and

stamp upon the mound of earth in the

corner of the garden, the monument of the

boys' enterprise. Ross does it out of hatred,

and Orme in the hope of bringing down

the "ky."

But to Marjorie that mound tells a tale of

love, found and won—and mistakes buried,

happily before it was too late. Sometimes

her young brothers wonder at some unlooked-for

expression of affection, and look at her reproachfully,

resenting the sudden kiss. Sandy

one day said to her—

"Why did you kiss Orme—sudden—like

that? He ain't gooder than usual—an' he's

dirty."

"Yes, I like him dirty. He reminded

me——"

She stopped at the sound of a step.

"'Minded you? Your cheeks get redder an'

redder the nearer Mr. Pelham comes. 'Minded

you—what?"

"Of that dreadful night," she whispered.

But it was no "dreadful" reminiscence that

shone in the welcome of her uplifted eye.

THE END.

THE POWER OF A GREAT PURPOSE

"None of these things move me."—Acts xx. 24.

A Sermon Preached before the Queen by the Very Rev. the Dean of Windsor

The "things" of which

St. Paul spoke were

very definite things

indeed. They were

the things which

befell him as he

continued to fulfill

his ministry and to

proclaim the Gospel

in Jerusalem and

elsewhere. It is true

he says that he did not know the

things that would befall him when he

reached Jerusalem. He meant that he

could not exactly describe beforehand all

that would happen to him. But his

experience of the past could have left

him in no doubt as to the sort of experience

that awaited him in the future.

Bonds and imprisonment, persecution in

its many different forms, opposition to

the great message which he had to

deliver, contempt and ridicule, hardship

and toil, pain and the risk of death—these

were the things with which, his

experience had been filled since he became

an apostle of Christ. They were

the things which, as he well knew, he

should have to encounter whithersoever

he might go. They were the things

which he had clearly before his mind

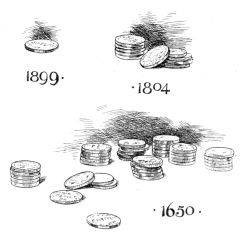

when he declared "None of these things

move me."

As he speaks the words, we are at

once placed in the presence of that life

which is one of the great treasures of

the Church of Christ—that life, the

record of which has animated tens of

thousands of the soldiers of Christ, and

has encouraged myriads of sufferers in

their times of need, and has, over and

over again, made men heroes and

martyrs. Delicate health, unceasing toil,

bodily suffering, constant privations, long

journeys by sea and land, long imprisonments,

cruel scourgings, vexations and

disappointments, and the ever-present

danger of death—such were the experiences

of that life. We, as we read the

record, wonder at the steadfastness and endurance

which made such a life possible.

And while we admire the set purpose

and the unflinching courage of the

man, we pity him for the things which

made up the experiences of his life.

But he does not for a moment pity

himself. On the contrary, he says of it

all, "None of these things move me."

What did St. Paul really mean by

saying that the sufferings of his life did

not move him?

Is he speaking the language of mere

bravado? Have we before us a man

who is merely giving utterance to great

swelling words? Is this some proud

and foolish boaster who does not mean

what he says? Men of this sort are not

by any means uncommon. We have not

to go far to come across those who, to

judge by their fine words and their

swaggering boastfulness, are brave and

good, and superior to others, but who

are, in reality, cowardly and mean and

contemptible. Such men are to be met

with in all departments of human life—in

the family circle, in society, in

politics, in the church. But no one

that ever lived on this earth has been

farther from the character of an empty

boaster than the Apostle Paul. There

were two reasons why it was impossible

that he could ever have been a mere

boaster. One reason is that he was

absolutely true to his very heart's core.

The other reason is that all his thoughts

of himself were thoughts of the very

deepest humility. The man who could

feel himself to be the "chief of sinners,"

and whose whole life was manifestly

sincere and true, was quite incapable of

a windy boast. It is plain that mere

bravado could have had nothing whatever

to do with the words "None of

these things move me."

Then, are his words those of a Stoic?

Are we listening to the language of

one whose philosophy has taught him

that human virtue could have no more

conspicuous triumph than to be able to

suppress every emotion of the soul, and

to petrify into a marble death that

warm, living thing which God has given

to every man, and which we call his

"heart"? There were those in St.[312]

Paul's days who were philosophers after

this sort. They were the men who

succeeded in killing all feeling. They

practised their philosophy so well, and

were so obedient to its principles, that

they were never conscious of a real

transport of joy, and refused to acknowledge

any pangs of sorrow. They turned

themselves from men into marble statues.

A Stoic could move about the world

with a cold, contemptuous smile upon

his lips; and as he passed through

scenes of joy and happiness, as he

listened to the happy laughter of an

innocent maiden, or watched the bounding

joyousness of a young man in the

heyday of his youth, as he looked upon

the agonies of bodily suffering, or witnessed

the bitter tears of some bereaved

one, or stood in the presence of the

terrible realities of death, he could say—and

say it with truth—"None of these

things move me."

Is it with this stoical indifference

that St. Paul speaks? We might as

well imagine that the sun could become

cold and dark, as that the warm, tender

heart of the apostle could become

stoical. A very cursory glance at that

life, so full of love and tenderness, is

enough to tell us that there could

have been nothing of the Stoic about

the apostle. A single moment's recollection

will bring to our memories words

that he spoke or wrote, which could

only have come from a nature that was

sensitive, tender, and emotional. St.

Paul was one who loved strongly and

felt deeply. He was easily lifted up

with joy, and cut to the quick by pain

and suffering. His love and sympathy

flowed out to all around him. He

welcomed the love and sympathy of

others. The warm heart that was in

him spoke to and influenced the hearts

of others; for, as Goethe says,

"You never can make heart throb with heart

Unless your own heart first has struck the tone."

Assuredly he was far from being anything

approaching to a Stoic. On the

contrary, he was a man who daily grew

more and more into the likeness of

Him Who suffered, and felt, and loved

more than any other man, Who, in his

wonderful tenderness and boundless sympathy,

is the Great Model for us to copy.

When, therefore, St. Paul said, "None

of these things move me," he could

not possibly have said it out of the

cold, passionless heart of a Stoic.

What, then, did he really mean by

what he said? He himself has made

plain to us what he meant. He says

that he must finish his course with

joy, and the ministry, which he has

received of the Lord Jesus, to testify

the gospel of the grace of God. Nothing

must interfere with the fulfilment of

his ministry. That ministry was his

life's work, to which he had been

specially called. There could be no

possibility of mistake about it. From

the time of his conversion no shadow

of a misgiving or doubt concerning it

had ever for a moment crossed his

mind. He was absolutely certain that

he was commissioned by God to testify

the gospel of His grace. His mission

was to go whithersoever the providence

of God might lead him—over land or

sea, in sunshine or in storm—in order

that he might proclaim the great

message of the love of God. The thought

of that mission so entirely possessed

him, so penetrated his whole being,

that nothing in the world could turn

him aside from it, even for a moment.

And the steadfast purpose of his heart

to fulfil his ministry at all costs is

breathed out in his words, "None of

these things move me." He meant that

nothing, however vexatious or disappointing

or painful, could hold him

back from his great work. The Holy

Ghost had witnessed to him that bonds

and imprisonment awaited him. It made

no difference. Nothing could move him.

He had received his charge to preach

the gospel, and preach it he must.

We cannot but admire this courageous

steadfastness of purpose, this unswerving

faithfulness. But behind it all, and inspiring

it all, there was the clear, bright,

living faith—the open eye of his soul—which

looked full on the great reality

of the love of God. His faith was absolutely

convinced of the love of God to

him and to all mankind. The great

certainty lighted up an answering love

in his heart towards God and towards all

men; and therefore, come what might,

he must preach Christ. No doubt steadfastness

and courage lie in the words,

"None of these things move me." Yet

even more are they the words of faith.

He who speaks them is one who knows

in Whom he has believed.

[313]

Why is it that we are not able to do

greater things for God? Why do we so

easily lose heart? Why does our energy

so quickly flag? Why are our sacrifices

so poor and small? Why does our

courage so soon ebb away? Why do we

so cry out when we are hurt? Why is

our endurance so short-lived? Surely

the reason is plain. If we had the

strong faith of St. Paul, instead of a

faith that is so often feeble and halting

and irresolute, we should be better able

to pass through the varied experiences

of human life and say, "None of these

things move me. Nothing can move me

from my trust in God and from the

work which He has given me to do."

But there is a further meaning in the

apostle's words. They express the living

faith which inspired the steadfastness of

purpose with which he clung to his life's

work. Yet they express more than this.

As he speaks there is a scene before his

eyes which, no doubt, he had often

witnessed. He sees the runners in a race

striving together for victory. He sees

the one who, when the race is run,

receives the prize. He sees the joy of

victory that beams in his eyes as the

chaplet is placed on his brow.

It is a picture of himself. He is

running in a race. He is still in the

midst of the course. And he expects to

finish his course with the joy of victory.

That is the hope set before him, and

from that hope nothing could move him.

It is out of the assuredness of that hope,