The Life of

Ludwig van Beethoven

By Alexander Wheelock Thayer

Edited, revised and amended from the original English manuscript and the German editions of Hermann Deiters and Hugo Riemann, concluded, and all the documents newly translated

By

Henry Edward Krehbiel

Volume II

Published by

The Beethoven Association

New York

SECOND PRINTING

Copyright, 1921.

By Henry Edward Krehbiel

From the press of G. Schirmer, Inc., New York

Printed in the U. S. A.

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I. The Year 1803—Cherubini’s Operas in Vienna and Rivalry between Schikaneder and the Imperial Theatres—Beethoven’s Engagement at the Theater-an-der-Wien—“Christus am Ölberg” again—Bridgetower and the “Kreutzer” Sonata—Career of the Violinist—Negotiations with Thomson for the Scottish Songs—New Friends—Willibrord Mähler’s Portrait of Beethoven—Compositions of the Year—A Pianoforte from Erard | 1 |

| Chapter II. The Year 1804—Schikaneder Sells His Theatre and is then Dismissed from the Management—Beethoven’s Contract Ended and Renewed by Baron Braun—The “Sinfonia Eroica”—Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia—Quarrel between Beethoven and von Breuning—The “Waldstein” Sonata—Sonnleithner, Treitschke and Gaveaux—Paër and His Opera “Leonora”—“Fidelio” Begun—Beethoven’s Growing Popularity—Publications of the Year | 22 |

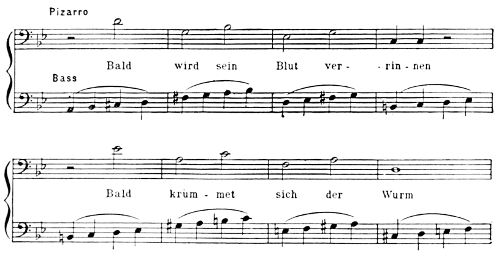

| Chapter III. The Year 1805—Schuppanzigh’s First Quartet Concerts—First Public Performance of the “Eroica”—Pleyel—The Opera “Leonore,” or “Fidelio”; Jahn’s Study of the Sketchbook—The Singers and the Production—Vienna Abandoned by the Aristocracy as French Advance—Röckel’s Story of the Revision of the Opera—Compositions and Publications of the Year | 41 |

| [vi]Chapter IV. The Year 1806—Repetitions of “Fidelio”: A Revision of the Book by von Breuning—Changes in the Opera—The “Leonore” Overtures—A Second Failure—Beethoven Withdraws the Opera from the Theatre—Marriage of Karl Kaspar van Beethoven—A Journey to Silesia—Beethoven Leaves Prince Lichnowsky’s Country-seat in Anger—George Thomson and His Scottish Songs—Compositions and Publications of the Year—The “Appassionata” Sonata and Rasoumowsky Quartets—Reception of the Quartets in Russia and England—The Concerto for Violin | 57 |

| Chapter V. Beethoven’s Friends and Patrons in the First Lustrum of the Nineteenth Century—Archduke Rudolph, an Imperial Pupil—Count Andreas Rasoumowsky—Countess Erdödy—Baroness Ertmann—Marie Bigot—Therese Malfatti—Nanette Streicher—Doctor Zizius—Anecdotes | 78 |

| Chapter VI. Princes and Counts as Theatrical Directors: Beethoven Appeals for an Appointment—Vain Expectations—Subscription Concerts at Prince Lobkowitz’s—The Symphony in B-flat—Overture to “Coriolan”—Contract with Clementi—Errors in the Dates of Important Letters—The Mass in C—A Falling-out with Hummel—The “Leonore” Overtures again—Performances of Beethoven’s Works at the “Liebhaber” Concerts—The Year 1807 | 98 |

| Chapter VII. The Year 1808—Johann van Beethoven Collects a Debt and Buys an Apothecary Shop in Linz—Wilhelm Rust—Plans for New Operas—Sketches for “Macbeth”—Imitative Music and the “Pastoral” Symphony—Count Oppersdorff and the Fourth Symphony—A Call to Cassel—Organization of Rasoumowsky’s Quartet—Appreciation of Beethoven in Vienna: Disagreement with Orchestral Musicians—Mishaps at the Performance of the Choral Fantasia | 114 |

| Chapter VIII. Jerome Bonaparte’s Invitation—A New Plan to Keep Beethoven in Vienna—The Annuity Contract—Ries’s Disappointment—Farewell to Archduke Rudolph in a Sonata—The Siege and Capitulation of Vienna—Seyfried’s “Studies”—Reissig’s Songs—An Abandoned Concert—Commission for Music to “Egmont”—Increased Cost of Living in Vienna—Dilatory Debtors—Products of 1809 | 135 |

| [vii]Chapter IX. The Years 1807-09: a Retrospect—Beethoven’s Intellectual Development and Attainments: Growth after Emancipation from Domestic Cares—His Natural Disposition—Eager in Self-Instruction—Interest in Oriental Studies—His Religious Beliefs—Attitude towards the Church | 163 |

| Chapter X. The Year 1810—Disappointing Decrease in Productivity—The Music for “Egmont”—Money from Clementi, and a Marriage Project—A New Infatuation Prompts Attention to Dress—Therese Malfatti—Beethoven’s Relations with Bettina von Arnim—Her Correspondence with Goethe—A Question of Authenticity Discussed—Beethoven’s Letter to Bettina—An Active Year with the Publishers | 170 |

| Chapter XI. The Year 1811—Bettina von Arnim—The Letters between Beethoven and Goethe—The Great Trio in B-flat—Music for a New Theatre in Pesth: “The Ruins of Athens” and “King Stephen”—Compositions and Publications of the Year | 196 |

| Chapter XII. The Year 1812—Reduction of Income from the Annuity—The Austrian “Finanzpatent”—Legal Obligation of the Signers to the Agreement—First Performance of the Pianoforte Concerto in E-flat—A Second Visit to Teplitz—Beethoven and Goethe—Amalie Sebald—Beethoven in Linz—He Drives His Brother Johann into a Detested Marriage—Rode and the Sonata Op. 96—Spohr—The Seventh and Eighth Symphonies—Mälzel and His Metronome—A Canon and the Allegretto of the Eighth Symphony | 211 |

| Chapter XIII. The Year 1813—Beethoven’s Journal—Illness of Karl Kaspar van Beethoven—He Requests the Appointment of His Brother as Guardian of His Son—Death of Prince Kinsky—Obligations under the Annuity Agreement—Beethoven’s Earnings—Mälzel and “Wellington’s Victory”—Battle Pieces and Their Popularity—Postponement of the Projected Visit to London—The Seventh Symphony—Spohr on Beethoven’s Conducting—Concerts, Compositions and Publications of the Year | 239 |

| [viii]Chapter XIV. The Year 1814—Success of “Wellington’s Victory”—Umlauf Rescues a Performance—Revival and Revision of “Fidelio”—Changes Made in the Opera—Success Attained—The Eighth Symphony—Beethoven Plays in the Great Trio in B-flat—Anton Schindler Appears on the Scene—The Quarrel with Mälzel—Legal Controversy and Compromise—Moscheles and the Pianoforte Score of “Fidelio”—The Vienna Congress—Tribute from a Scottish Poet—Weissenbach—Tomaschek—Meyerbeer—Rasoumowsky’s Palace Destroyed by Fire | 261 |

| Chapter XV. The Year 1815—New Opera Projects Considered—“Romulus and Remus”—Settlements with the Heirs of Prince Kinsky—Unjust Aspersions on the Conduct of Kinsky and Lobkowitz—“The Mount of Olives” in England—Negotiations with English Publishers—Diabelli—Charles Neate—Death of Karl Kaspar van Beethoven—His Wishes with regard to the Guardianship of His Son—Growth of Beethoven’s Intimacy with Schindler—Compositions and Publications of the Year | 304 |

| Chapter XVI. The Year 1816—A Commission from the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde—Guardianship of Nephew Karl—Giannatasio del Rio—Beethoven’s Music in London—The Philharmonic Society—Three Overtures Composed, Bought and Discarded—Birchall and Neate—The Erdödys—Fanny Giannatasio—“An die ferne Geliebte”—Major-General Kyd—Accusations against Neate—Letters to Sir George Smart—Anselm Hüttenbrenner—The Year’s Productions | 329 |

| Chapter XVII. The Year 1817—Beethoven and the Public Journals of Vienna—Fanny Giannatasio’s Journal—Extracts from Beethoven’s “Tagebuch”—The London Philharmonic Society again—Propositions Submitted by Ries—Nephew Karl and His Mother—Beethoven’s Pedagogical Suggestions to Czerny—Cipriani Potter—Marschner—Marie Pachler-Koschak—Another Mysterious Passion—Beethoven and Mälzel’s Metronome—An Unproductive Year | 358 |

| Chapter XVIII. The Year 1818—Gift of a Pianoforte from John Broadwood—The Composer Takes Personal Charge of His Nephew—His Unfitness as Foster-father and Guardian—Abandonment of His Projected Visit to London—The Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde’s Oratorio—The Nephew and a Mother’s Legal Struggle for Possession of Her Son—The Case Reviewed—The Predicate “van” and Beethoven’s Nobility—Archduke Rudolph Becomes Archbishop of Olmütz—Work on the Mass in D, Ninth Symphony and Grand Trio in B-flat | 390 |

The Year 1803—Cherubini’s Operas in Vienna—Beethoven’s Engagement at the Theater-an-der-Wien—“Christus am Ölberg” again—Bridgetower and the “Kreutzer” Sonata—-Negotiations with Thomson—New Friends—Mähler’s Portrait of Beethoven.

Kotzebue, after a year of activity in Vienna as Alxinger’s successor in the direction, under the banker Baron von Braun, of the Court Theatre, then a year of exile in Siberia (1800), whence he was recalled by that semi-maniac Paul, who was moved thereto by the delight which the little drama “Der Leibkutscher Peters III.” had given him—then a short time in Jena, where his antagonism to Goethe broke out into an open quarrel, established himself in Berlin. There he began, with Garlieb Merkel (1802), the publication of a polemical literary journal called the “Freymüthige,” Goethe, the Schlegels and their party being the objects of their polemics. Spazier’s “Zeitung für die Elegante Welt” (Leipsic) was its leading opponent, until the establishment of a new literary journal at Jena.

At the beginning of 1803, Kotzebue was again in Vienna on his way to Italy. Some citations from the “Freymüthige” of this time have an especial value, as coming, beyond a doubt, from his pen. His position in society, his knowledge from experience of theatrical affairs in Vienna, his personal acquaintance with Beethoven and the other persons mentioned, all combine to enable him to speak with authority. An article in No. 58 (April 12) on the “Amusements of the Viennese after Carnival,” gives a peep into the salon-life of the capital, and introduces to us divers matters of so much interest, as to excuse the want of novelty in certain parts.

... Amateur concerts at which unconstrained pleasure prevails are frequent. The beginning is usually made with a quartet by Haydn or Mozart; then follows, let us say, an air by Salieri or Paër, then a pianoforte piece with or without another instrument obbligato, and the[2] concert closes as a rule with a chorus or something of the kind from a favorite opera. The most excellent pianoforte pieces that won admiration during the last carnival were a new quintet[1] by Beethoven, clever, serious, full of deep significance and character, but occasionally a little too glaring, here and there Odensprünge in the manner of this master; then a quartet by Anton Eberl, dedicated to the Empress, lighter in character, full of fine yet profound invention, originality, fire and strength, brilliant and imposing. Of all the musical compositions which have appeared of late these are certainly two of the best. Beethoven has for a short time past been engaged, at a considerable salary, by the Theater-an-der-Wien, and will soon produce at that playhouse an oratorio of his composition entitled “Christus am Ölberg.” Amongst the artists on the violin the most notable are Clement, Schuppanzigh (who gives the concerts in the Augarten in the summer) and Luigi Tomasini. Clement (Director of the orchestra an-der-Wien) is an admirable concert player; Schuppanzigh performs quartets very agreeably. Good dilettanti are Eppinger, Molitor and others. Great artists on the pianoforte are Beethofen [sic], Hummel, Madame Auernhammer and others. The famous Abbé Vogler is also here at present, and plays fugues in particular with great precision, although his rather heavy touch betrays the organist. Among the amateurs Baroness Ertmann plays with amazing precision, clearness and delicacy, and Fräulein Kurzbeck touches the keys with high intelligence and deep feeling. Mesdames von Frank and Natorp, formerly Gerardi and Sessi, are excellent singers.

A few words may be added to this picture from other sources. Salieri’s duties being now confined to the sacred music of the Imperial Chapel, Süssmayr being far gone in the consumption of which he died on Sept. 16 (of this year—1803), Conti retaining but the name of orchestral director (he too died the next year), Liechtenstein and Weigl were now the conductors of the Imperial Opera; Henneberg and Seyfried held the same position under Schikaneder, as in the old house, so now in the new.

Schuppanzigh’s summer concerts in the Augarten, and Salieri’s Widows and Orphans concerts at Christmas and in Holy Week, were still the only regular public ones. Vogler had come from Prague in December, and Paër, who had removed to Dresden at Easter, 1802, was again in Vienna to produce his cantata “Das Heilige Grab,” at the Widows and Orphans Concert. It was a period of dearth at Vienna in operatic composition. At the Court Theatre Liechtenstein had failed disastrously; Weigl had not been able to follow up the success of his “Corsär,” and several years more elapsed before he obtained a permanent name in musical annals by his “Schweizerfamilie.” Salieri’s style had become too familiar to all Vienna[3] longer to possess the charms of freshness and novelty. In the Theater-an-der-Wien, Teyber, Henneberg, Seyfried and others composed to order and executed their work satisfactorily enough—indeed, sometimes with decided, though fleeting, success. But no new work, for some time past, composed to the order of either of these theatres, had possessed such qualities as to secure a brilliant and prolonged existence. From another source, however, a new, fresh and powerful musical sensation had been experienced during the past year at both: and in this wise:

Schikaneder produced, on the 23rd of March, a new opera which had been very favorably received at Paris, called “Lodoiska,” the music composed “by a certain Cherubini.” The applause gained by this opera induced the Court Theatre to send for the score of another opera by the same composer, and prepare it for production on the 14th of August, under the title “Die Tage der Gefahr.” Schikaneder, with his usual shrewdness, meantime was secretly rehearsing the same work, of which Seyfried in the beginning of July had made the then long journey to Munich to obtain a copy, and on the 13th—one day in advance of the rival stage—the musical public was surprised and amused to see “announced on the bill-board of the Wiener Theater the new opera ‘Graf Armand, oder Die zwei unvergessliche Tage.’” In the adaptation and performance of the work, each house had its points of superiority and of inferiority; on the whole, there was little to choose between them; the result in both was splendid. The rivalry between the two stages became very spirited. The Court Theatre selected from the new composer’s other works the “Medea,” and brought it out November 6. Schikaneder followed, December 18, with “Der Bernardsberg” (“Elise”), “sadly mutilated.” Twenty years later Beethoven attested the ineffaceable impression which Cherubini’s music had made upon him. While the music of the new master was thus attracting and delighting crowded audiences at both theatres, the wealthy and enterprising Baron Braun went to Paris and entered into negotiations with Cherubini, which resulted in his engagement to compose one or more operas for the Vienna stage. Besides this “a large number of new theatrical representations from Paris” were expected (in August, 1802) upon the Court stage. “Baron Braun, who is expected to return from Paris, is bringing the most excellent ballets and operas with him, all of which will be performed here most carefully according to the taste of the French.” Thus the “Allg. Mus. Zeitung.”

These facts bring us to the most valuable and interesting notice contained in the article from the “Freymüthige”—the earliest record of Beethoven’s engagement as composer for the Theater-an-der-Wien.

Zitterbarth, the merchant with whose money the new edifice had been built and put in successful operation, “who had no knowledge of theatrical matters outside of the spoken drama,” left the stage direction entirely in the hands of Schikaneder. In the department of opera that director had a most valuable assistant in Sebastian Meier—the second husband of Mozart’s sister-in-law, Mme. Hofer, the original Queen of Night—a man described by Castelli as a moderately gifted bass singer, but a very good actor, and of the noblest and most refined taste in vocal music, opera as well as oratorio; to whom the praise is due of having induced Schikaneder to bring out so many of the finest new French works, those of Cherubini included. It is probable, therefore, that, just now, when Baron von Braun was reported to have secured Cherubini for his theatre, and it became necessary to discover some new means of keeping up a successful competition, Meier’s advice may have had no small weight with Schikaneder. Defeat was certain unless the operas, attractive mainly from their scenery and grotesque humor, founded upon the “Thousand and One Nights” and their thousand and one imitations, and set to trivial and commonplace tunes, should give place to others of a higher order, quickened by music more serious, dignified and significant.

Whether Abbé Georg Joseph Vogler was really a great and profound musician, as C. M. von Weber, Gänsbacher and Meyerbeer held him to be, or a charlatan, was a matter much disputed in those days, as the same question in relation to certain living composers is in ours. Whatever the truth was, by his polemical writings, his extraordinary self-laudation, his high tone at the courts whither he had been called, his monster concerts, and his almost unperformable works, he had made himself an object of profound curiosity, to say the least. Moreover, his music for the drama “Hermann von Staufen, oder das Vehmgericht,” performed October 3, 1801, at the Theater-an-der-Wien (if the same as in “Hermann von Unna,” as it doubtless was), was well fitted to awaken confidence in his talents. His appearance in Vienna just now was, therefore, a piece of good fortune for Schikaneder, who immediately engaged him for his theatre.

Whether Beethoven had talents for operatic composition, no one could yet know; but his works had already spread to[5] Paris, London, Edinburgh, and had gained him the fame of being the greatest living instrumental composer—Father Haydn of course excepted—and this much might be accepted as certain: viz., that his name alone, like Vogler’s, would secure the theatre from pecuniary loss in the production of one work; and, perhaps—who could foretell?—he might develop powers in this new field which would raise him to the level of even Cherubini! He was personally known to Schikaneder, having played in the old theatre, and his “Prometheus” music was a success at the Court Theatre. So he, too, was engaged. The correspondent of the “Zeitung für die Elegante Welt” positively states, under date of June 29th: “Beethoven is composing an opera by Schikaneder.” There is nothing very improbable in this, though circumstances intervened which prevented the execution of such a project. Still the fact remains, that Schikaneder—that strange compound of wit and absurdity; of poetic instinct and grotesque humor; of shrewd and profitable enterprise and lavish prodigality; who lived like a prince and died like a pauper—has connected his name honorably with both Mozart and Beethoven.

These plain and obvious facts have been so misrepresented as to make it appear that this engagement of Beethoven was a grand stroke of policy conceived and executed by Baron von Braun, who, at the Theater-an-der-Wien (“newly built and to be opened in 1804”), had suddenly become aware of a genius and talent, to which, notwithstanding the “Prometheus” music, at the Imperial Opera, he had been oblivious during the preceding ten years! The date of the transaction is a sufficient confutation of this; as also of the notion that the success of the “Christus am Ölberg” led to his engagement. On the contrary, it was his engagement that enabled Beethoven to obtain the use of the Theater-an-der-Wien to produce that work in a concert to which we now come.

The “Wiener Zeitung” of Saturday, March 26 and Wednesday, March 30, 1803, contained the following

Notice

On the 5th (not the 4th) of April, Herr Ludwig van Beethoven will produce a new oratorio set to music by him, “Christus am Ölberg,” in the R. I. privil. Theater-an-der-Wien. The other pieces also to be performed will be announced on the large bill-board.

Beethoven must have felt no small confidence in the power of his name to awaken the curiosity and interest of the musical public, for he doubled the prices of the first chairs, tripled those[6] of the reserved and demanded 12 ducats (instead of 4 florins) for each box. But it was his first public appearance as a dramatic vocal composer, and on his posters he had several days before announced with much pomp that all the works would be of his composition. The result, however, answered his expectations, “for the concert yielded him 1800 florins.”

The works actually performed were the first and second Symphonies, the Pianoforte Concerto in C minor and “Christus am Ölberg”; some others, according to Ries, were intended, but, owing to the length of the concert, which began at the early hour of six, were omitted in the performance. As no copy of the printed programme has been discovered, there is no means of deciding what these pieces were; but the “Adelaide,” the Scena et Aria “Ah, perfido!” and the trio “Tremate, empj, tremate,” suggest themselves, as vocal pieces well fitted to break the monotony of such a mass of orchestral music. It seems strange—knowing as we do Beethoven’s vast talent for improvisation—that no extempore performance is reported.

“The symphonies and concertos,” says Seyfried, “which Beethoven produced for the first time (1803 and 1808) for his benefit at the Theater-an-der-Wien, the oratorio, and the opera, I rehearsed according to his instructions with the singers, conducted all the orchestral rehearsals and personally conducted the performance.”[2]

The final general rehearsal was held in the theatre on the day of performance, Tuesday, April 5. On that morning, as was often the case when Beethoven needed assistance in his labors, young Ries was called to him early—about 5 o’clock. “I found him in bed,” says Ries, “writing on separate sheets of paper. To my question what it was he answered, ‘Trombones.’ At the concert the trombone parts were played from these sheets. Had the copyist forgotten to copy these parts? Were they an afterthought? I was too young at the time to observe the artistic interest of the incident; but probably the trombones were an afterthought, as Beethoven might as easily have had the uncopied parts as the copied.” The correspondent of the “Zeitung für die Elegante Welt” renders a probable solution of Ries’s doubt easy. He found the music to the “Christus” to be “on the whole good, and there are a few admirable passages, an air of the Seraph with trombone accompaniment in particular being of admirable effect.” Beethoven had probably found the aria “Erzittre, Erde” to fail of its intended effect,[7] and added the trombone on the morning of the final rehearsal, to be retained or not as should prove advisable upon trial.[3] Ries continues:

The rehearsal began at 8 o’clock in the morning. It was a terrible rehearsal, and at half after 2 everybody was exhausted and more or less dissatisfied. Prince Karl Lichnowsky, who attended the rehearsal from the beginning, had sent for bread and butter, cold meat and wine in large baskets. He pleasantly asked all to help themselves and this was done with both hands, the result being that good nature was restored again. Then the Prince requested that the oratorio be rehearsed once more from the beginning, so that it might go well in the evening and Beethoven’s first work in this genre be worthily presented. And so the rehearsal began again.

Seyfried in the article above quoted gives a reminiscence of this concert:

At the performance of the Concerto he asked me to turn the pages for him; but—heaven help me!—that was easier said than done. I saw almost nothing but empty leaves; at the most on one page or the other a few Egyptian hieroglyphs wholly unintelligible to me scribbled down to serve as clues for him; for he played nearly all of the solo part from memory, since, as was so often the case, he had not had time to put it all on paper.[4] He gave me a secret glance whenever he was at the end of one of the invisible passages and my scarcely concealable anxiety not to miss the decisive moment amused him greatly and he laughed heartily at the jovial supper which we ate afterwards.

The impression made on reading the few contemporary notices of this concert is that the new works produced were, on the whole, coldly received. The short report (by Kotzebue?) in the “Freymüthige” said:

Even our doughty Beethofen, whose oratorio “Christus am Ölberg” was performed for the first time at surburban Theater-an-der-Wien, was not altogether fortunate, and despite the efforts of his many admirers was unable to achieve really marked approbation. True, the two symphonies and single passages in the oratorio were voted very beautiful, but the work in its entirety was too long, too artificial in structure and lacking expressiveness, especially in the vocal parts. The text, by F. X. Huber, seemed to have been as superficially written as the music. But the concert brought 1800 florins to Beethofen and he, as well as Abbé Vogler, has been engaged for the theatre. He is to write one opera, Vogler three; for this they are to receive 10 per cent. of the receipts at the first ten performances, besides free lodgings.

The writer in the “Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung” alone speaks of the “Christus” as having been received with “extraordinary approval.” Three months afterwards another correspondent flatly contradicts this: “In the interest of truth,” he writes, “I am obliged to contradict a report in the ‘Musikalische Zeitung’; Beethoven’s cantata did not please.” To this Schindler remarks: “Even the composer agreed with this to this extent—that in later years he unhesitatingly declared that it had been a mistake to treat the part of Christ in the modern vocal style. The abandonment of the work after the first performance, as well as its tardy appearance in print (about 1810), permit us to conclude that the author was not particularly satisfied with the manner in which he had solved the problem, and that he probably made material changes in the music.” The “Wiener Zeitung” of July 30, 1803, gives all the comment necessary on the “abandonment” and probable changes in the work, by announcing that “the favorable reception” of the oratorio had induced the Society of Amateur Concerts to resolve to repeat it on August 4. Moreover, Sebastian Meier’s concert of March 27, 1804, opened with the second Symphony of Beethoven and closed with “Christus am Ölberg,” being its fourth performance in one year.[5]

A few days after this public appearance we have a sight of Beethoven again in private life. Dr. Joh. Th. Helm, the famous physician and professor in Prague, then a young man just of the composer’s age (he was born December 11, 1770), accompanied Count Prichnowsky on a visit to Vienna. On the morning of the 16th of April these two gentlemen met Beethoven in the street, who, knowing the Count, invited them to Schuppanzigh’s, “where some of his pianoforte sonatas which Kleinhals had transcribed as string quartets were to be rehearsed. We met,” writes Held, in his manuscript autobiography (the citations were communicated to this work by Dr. Edmund Schebek of Prague)

a number of the best musicians gathered together, such as the violinists Krumbholz, Möser (of Berlin), the mulatto Bridgethauer, who in London had been in the service of the then Prince of Wales, also a Herr Schreiber and the 12 years’ old[6] Kraft who played second. Even then Beethoven’s muse transported me to higher regions, and the desire of all of these artists to have our musical director Wenzel[9] Praupner in Vienna confirmed me in my opinion of the excellence of his conducting. Since then I have often met Beethoven at concerts. His piquant conceits modified the gloominess, I might say the lugubriousness, of his countenance. His criticisms were very keen, as I learned most clearly at concerts of the harpist Nadermann of Saxony and Mara, who was already getting along in years.

The “Bridgethauer,” mentioned by Held—whose incorrect writing of the name conveys to the German its correct pronunciation—was the “American ship captain who associated much with Beethoven” mentioned by Schindler and his copyists.

George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower—a bright mulatto then 24 years old, son of an African father and German or Polish mother, an applauded public violinist in London at the age of ten years, and long in the service, as musician, of the Prince of Wales, afterwards George IV—was never in America and knew as much probably of a ship and the science of navigation as ordinary shipmasters do of the violin and the mysteries of musical counterpoint. In 1802 he obtained leave of absence to visit his mother in Dresden and to use the waters of Teplitz and Carlsbad, which leave was prolonged that he might spend a few months in Vienna. His playing in public and private at Dresden had secured him such favorable letters of introduction as gained him a most brilliant reception in the highest musical circles of the Austrian capital, where he arrived a few days before Held met him at Schuppanzigh’s. Beethoven, to whom he was introduced by Prince Lichnowsky, readily gave him aid in a public concert. The date of the concert has not been determined precisely; it was probably on May 24th. It has an interest on account of Beethoven’s connection with it; for the day of the concert was the date of the completion and performance of the “Kreutzer” Sonata.

The famous Sonata in A minor, Op. 47, with concertante violin, dedicated to Rudolph Kreutzer in Paris [says Ries on page 82 of the “Notizen”], was originally composed by Beethoven for Bridgetower, an English artist. Here things did not go much better (Ries is referring to the tardiness of the composition of the horn sonata which Beethoven wrote for Punto), although a large part of the first Allegro was ready at an early date. Bridgetower pressed him greatly because the date of his concert had been set and he wanted to study his part. One morning Beethoven summoned me at half after 4 o’clock and said: “Copy the violin part of the first Allegro quickly.” (His ordinary copyist was otherwise engaged.) The pianoforte part was noted down only here and there in parts. Bridgetower had to play the marvellously beautiful theme and variations in F from Beethoven’s manuscript at the concert in the Augarten at 8 o’clock in the morning because there was no time to copy it. The final Allegro, however, was beau[10]tifully written, since it originally belonged to the Sonata in A major (Op. 30), which is dedicated to Czar Alexander. In its place Beethoven, thinking it too brilliant for the A major Sonata, put the variations which now form the finale.[7]

Bridgetower was thoughtful enough to leave in his copy of the Sonata a note upon that first performance of it, as follows:

Relative to Beethoven’s Op. 47.

When I accompanied him in this Sonata-Concertante at Wien, at the repetition of the first part of the Presto, I imitated the flight, at the 18th bar, of the pianoforte of this movement thus:

He jumped up, embraced me, saying: “Noch einmal, mein lieber Bursch!” (“Once again, my dear boy!”) Then he held the open pedal during this flight, the chord of C as at the ninth bar.

Beethoven’s expression in the Andante was so chaste, which always characterized the performance of all his slow movements, that it was unanimously hailed to be repeated twice.

George Polgreen Bridgetower.

Bridgetower was mentioned in a letter from Beethoven to Baron von Wetzlar, in this language, under date May 18:

Although we have never addressed each other I do not hesitate to recommend to you the bearer, Mr. Brishdower, a very capable virtuoso who has a complete command of his instrument.

Besides his concertos he plays quartets admirably. I greatly wish that you make him known to others. He has commended himself favorably to Lobkowitz and Fries and all other eminent lovers (of music).

I think it would be not at all a bad idea if you were to take him for an evening to Therese Schönfeld, where I know many friends assemble and at your house. I know that you will thank me for having made you acquainted with him.

Bridgetower, when advanced in years, talking with Mr. Thirlwall about Beethoven, told him that at the time the Sonata, Op. 47, was composed, he and the composer were constant companions, and that the first copy bore a dedication to him; but before he departed from Vienna they had a quarrel about a girl, and Beethoven then dedicated the work to Rudolph Kreutzer.[8]

When Beethoven removed from the house “am Peter” to the theatre building, he took his brother Karl (Kaspar) to live[13] with him,[9] as twenty years later he gave a room to his factotum Schindler. This change of lodgings took place, according to Seyfried, before the concert of April 5—which is confirmed by the brother’s new address being contained in the “Staats-Schematismus” for 1803—that annual publication being usually ready for distribution in April.[10] At the beginning of the warm season Beethoven, as was his annual custom, appears to have passed some weeks in Baden to refresh himself and revive his energies after the irregular, exciting and fatiguing city life of the winter, before retiring to the summer lodgings, whose position he describes in a note to Ries (“Notizen,” p. 128) as “in Oberdöbling No. 4, the street to the left where you go down the mountain to Heiligenstadt.”

The Herrengasse is still “die Strasse links” at the extremity of the village, as it was then; but the multiplication of houses and the change in their numbers render it uncertain which in those days bore the number 4. At all events it had, in 1803, gardens, vineyards or green fields both in front and rear. True, it was half an hour’s walk farther than from Heiligenstadt to the scenes in which he had composed the second Symphony, the preceding summer; but, to compensate for this, it was so much nearer the city—was in the more immediate vicinity of that arm of the Danube called the “Canal”—and almost under its windows was the gorge of the Krottenbach, which separates Döbling from Heiligenstadt, and which, as it extends inland from the river, spreads into a fine vale, then very solitary and still very beautiful. This was the house, this the summer, and these the scenes, in which the composer wrought out the[14] conceptions that during the past five years had been assuming form and consistency in his mind, to which Bernadotte may have given the original impulse, and which we know as the “Heroic Symphony.”[11]

Let us turn to Stephan von Breuning and a new friend or two. Archduke Karl, by a commission dated January 9, 1801, had been made Chief of the “Staats- und Konferenzial-Departement für das Kriegs- und Marine-Wesen,” and retained the position still, notwithstanding his assumption of the functions of Hoch- und Deutsch-Meister. He undertook to introduce a wide-reaching reform at the War Department, which demanded an increase in the number of Secretaries and scriveners. Stephan von Breuning is the second in the list of five appointed in 1804, Ignatz von Gleichenstein the fifth. It is believed, that the Archduke had discovered the fine business talents, the zeal in the discharge of duty and the perfect trustworthiness of Breuning at the Teutonic House, and that at his special invitation the young man this year exchanged the service of the Order for that of the State. There is abundant evidence, that the young Rhinelanders then in Vienna were bound to each other by more than the usual ties: most of them were fugitives from French tyranny, and liable to conscription if found in the places of their birth, though this was not the case with Breuning. There was, in addition to the ordinary feeling of nationality, a common sense of exile to unite them. Between Breuning and Gleichenstein therefore—two amiable and talented young men thus thrown into daily intercourse—an immediate and warm friendship would naturally spring up; and an introduction of the latter to Breuning’s friend Beethoven would inevitably follow, in case they had not known each other in the old Bonn days.

Another young Rhinelander, to whom Beethoven became much attached, and who returned the kindness with warm affection for him personally and a boundless admiration for his genius, became known to the composer also just at this time. Willibrord Joseph Mähler, a native of Coblentz—who died in 1860, at the age of 82 years, as pensioned Court Secretary—was a man of remarkably varied artistic talents, by which, however, since he cultivated them only as a dilettante and without[15] confining himself to any one art, he achieved no great distinction. He wrote respectable poetry and set it to correct and not unpleasing music; sang well enough to be recorded in Boeckh’s “Merkwürdigkeiten der Haupt- und Residenz-Stadt Wien” (1823) as “amateur singer,” and painted sufficiently well to be named, on another page of Boeckh, “amateur portrait painter.” He painted that portrait of the composer, about 1804-5, which is still in possession of the Beethoven family, and a second 1814-15—(Mr. Mähler could not recall the precise date)—once owned by Prof. Karajan. Several of the portraits now in possession of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna are from his pencil; but two or three of the very best specimens of his skill have been sold to a gentleman in Boston, U.S.A.[12]

Soon after Beethoven returned from his summer lodgings to his apartment in the theatre building, Mähler, who had then recently arrived in Vienna, was taken by Breuning thither to be introduced. They found him busily at work finishing the “Heroic Symphony.” After some conversation, at the desire of Mähler to hear him play, Beethoven, instead of beginning an extempore performance, gave his visitors the finale of the new Symphony; but at its close, without a pause, he continued in free fantasia for two hours, “during all which time,” said Mr. Mähler to the present writer, “there was not a measure which was faulty, or which did not sound original.” He added, that one circumstance attracted his particular notice; viz.: “that Beethoven played with his hands so very still; wonderful as his execution was, there was no tossing of them to and fro, up and down; they seemed to glide right and left over the keys, the fingers alone doing the work.” To Mr. Mähler, as to most others who have recorded their impressions of Beethoven’s improvisations, they were the non plus ultra of the art.

There was, however, be it noted in passing, a class of good musicians, small in number and exceptional in taste, who, precisely at this time, had discovered a rival to Beethoven, in this his own special field. Thus Gänsbacher writes, as cited by Frölich in his “Biographie Voglers”:

Sonnleithner gave a musical soirée in honor of Vogler and invited Beethoven among others. Vogler improvised at the pianoforte on a theme given to him by Beethoven, 4½ measures long, first an Adagio and then fugued. Vogler then gave Beethoven a theme of three measures (the scale of C major, alla breve). Beethoven’s excellent pianoforte playing, combined with an abundance of the most beautiful[16] thoughts, surprised me beyond measure, but could not stir up the enthusiasm in me which had been inspired by Vogler’s learned playing, which was beyond parallel in respect of its harmonic and contrapuntal treatment.

An undated note of Beethoven, to Mähler, which belongs to a somewhat later period—since its date is not ascertainable nor of much importance—may be inserted here, as an introduction to Mr. Mähler’s remarks upon the portrait to which it refers:

I beg of you to return my portrait to me as soon as you have made sufficient use of it—if you need it longer I beg of you at least to make haste—I have promised the portrait to a lady, a stranger who saw it here, that she may hang it in her room during her stay of several weeks. Who can withstand such charming importunities, as a matter of course a portion of the lovely favors which I shall thus garner will also fall to you.

To the question what picture is here referred to, Mr. Mähler replied in substance: “It was a portrait, which I painted soon after coming to Vienna, in which Beethoven is represented, at nearly full length, sitting; the left hand rests upon a lyre, the right is extended, as if, in a moment of musical enthusiasm, he was beating time; in the background is a temple of Apollo. Oh! If I could but know what became of the picture!”

“What!” was the answer, to the great satisfaction of the old gentleman, “the picture is hanging at this moment in the home of Madame van Beethoven, widow, in the Josephstadt, and I have a copy of it.”[13]

The extended right hand—though, like the rest of the picture, not very artistically executed—was evidently painted with care. It is rather broad for the length, is muscular and nervous, as the hand of a great pianist necessarily grows through much practice; but, on the whole, is neatly formed and well proportioned. Anatomically, it corresponds so perfectly with all the authentic descriptions of Beethoven’s person, that this alone proves it to have been copied from nature and not drawn after the painter’s fancy. Whoever saw a long, delicate hand with fingers exquisitely tapering, like Mendelssohn’s, joined to the short stout muscular figure of a Beethoven or a Schubert?

A few of Beethoven’s letters belonging to this period must be introduced here. The first, dated September 22, 1803, addressed to Hoffmeister, is as follows:

Herewith I declare all the works concerning which you have written to me to be your property; the list of them will be copied again and sent to you signed by me as your confessed property. I also agree to the price, 50 ducats. Does this satisfy you?

Perhaps I may be able to send you instead of the variations for violin and violoncello a set of variations for four hands on a song of mine with which you will also have to print the poem by Goethe, as I wrote these variations in an album as a souvenir and consider them better than the others; are you content?

The transcriptions are not by me, but I revised them and improved them in part, therefore do not come along with an announcement that I had arranged them, because if you do you will lie, and, I haven’t either time or patience for such work. Are you agreed?

Now farewell, I can wish you only large success, and I would willingly give you everything as a gift if it were possible for me thus to get through the world, but—consider, everything about me has an official appointment and knows what he has to live on, but, good God, where at the Imperial Court is there a place for a parvum talentum com ego?

In this year began the correspondence with Thomson. George Thomson, a Scotch gentleman (born March 4, 1757, at Limekilns, Dunfermline, died at Leith, February 18, 1851), distinguished himself by tastes and acquirements which led to his appointment, when still a young man, as “Secretary to the Board of Trustees for the Encouragement of Arts and Manufactures in Scotland”—a Board established at the time of the Union of the Kingdoms, 1707 (not the Crowns, 1603), of England and Scotland—an office from which he retired upon a full pension after a service of fifty years. He was, especially, a promoter of all good music and an earnest reviver of ancient Scotch melody. As one means of improving the public taste and at the same time of giving currency to Scotch national airs, he had published sonatas with such melodies for themes, composed for him by Pleyel in Paris, and Koželuch in Vienna—-two instrumental composers enjoying then a European reputation now difficult to appreciate. The fame of the new composer at Vienna having now reached Edinburgh, Thomson applied to him for works of a like character. Only the signature of the reply seems to be in Beethoven’s hand:

A Monsieur

George Thomson, Nr. 28 York Place

Edinburgh. North Britain

Vienna le 5. 8bre 1803.

Monsieur!

J’ai reçu avec bien de plaisir votre lettre du 20 Juillet. Entrant volontiers dans vos propositions je dois vous declarer que je suis prêt de composer pour vous six sonates telles que vous les desirez y intro[18]duisant même les airs ecossais d’une manière laquelle la nation Ecossaise trouvera la plus favorable et le plus d’accord avec le genie de ses chansons. Quant au honoraire je crois que trois cent ducats pour six sonates ne sera pas trop, vu qu’en Allemagne on me donne autant pour pareil nombre de sonates même sans accompagnement.

Je vous previens en même tems que vous devez accelerer votre declaration, par ce qu’on me propose tant d’engagements qu’après quelque tems je ne saurois peutêtre aussitôt satisfaire à vos demandes.—Je vous prie de me pardonner, que cette reponse est si retardée ce qui n’a été causée que par mon sejour à la campagne et plusieurs occupations tres pressantes.—Aimant de preference les airs eccossais je me plairai particulierement dans la composition de vos sonates, et j’ose avancer que si nos interêts s’accorderront sur le honoraire, vous serez parfaitement contenté.

Agréez les assurances de mon estime distingué.

Louis van Beethoven.

Mr. Thomson’s endorsement of this letter is this:

50 D. 1803. Louis van Beethoven, Vienna, demands 300 ducats for composing six Sonatas for me. Replied 8th Nov. that I would give no more than 150, taking 3 of the Sonatas when ready and the other 3 in six months after; giving him leave to publish in Germany on his own account, the day after publication in London.

The sonatas were never composed. Not long afterwards, on October 22, Beethoven, enraged at efforts to reprint his works, issued the following characteristic fulmination in large type, filling an entire page of the journal:

Warning.

Herr Carl Zulehner, a reprinter at Mayence, has announced an edition of all my works for pianoforte and string instruments. I hold it to be my duty hereby publicly to inform all friends of music that I have not the slightest part in this edition. I should not have offered to make a collection of my works, a proceeding which I hold to be premature at the best, without first consulting with the publishers and caring for the correctness which is wanting in some of the individual publications. Moreover, I wish to call attention to the fact that the illicit edition in question can never be complete, inasmuch as some new works will soon appear in Paris, which Herr Zulehner, as a French subject, will not be permitted to reprint. I shall soon make full announcement of a collection of my works to be made under my supervision and after a severe revision.[14]

Alexander Macco, the painter, after executing a portrait of the Queen of Prussia, in 1801, which caused much discussion in the public press but secured to him a pension of 100 thalers, went from Berlin to Dresden, Prague, and, in the summer of 1802, to Vienna. Here he became a great admirer of Beethoven, both as man and artist, and claimed and enjoyed so much of his society as the state of his mind and body would allow him to grant to any stranger. Macco remained but a few months here and then returned to Prague, whence he wrote the next year offering to Beethoven for composition an oratorio text by Prof. A. G. Meissner—a name just then well known in musical circles because of the publication of the first volume of the biography of Kapellmeister Naumann. If Meissner had not removed from Prague to Fulda in 1805, and if Europe had remained at peace, perhaps Beethoven might, two or three years later, have availed himself of the offer; just now he felt bound to decline it, which he did in a letter dated November 2, 1803. In it he said:

I am sorry, too, that I could not be oftener with you in Vienna, but there are periods in human life which have to be overcome and often they are not looked upon from the right point of view, it appears that as a great artist you are not wholly unfamiliar with such, and so—I have not, as I observe, lost your good will, of which fact I am glad because I esteem you highly and wish that I might have such an artist in my profession to associate with. Meissner’s proposal is very welcome, nothing could be more desirable than to receive such a poem from him, who is so highly honored as a writer and who understands musical poetry better than any other German author, but at present it is impossible for me to write this oratorio because I am just beginning my opera which, together with the performance, may occupy me till Easter—if Meissner is not in a hurry to publish his poem I should be glad if he were to leave the composition of it to me, and if the poem is not completed I wish he would not hurry it, since before or after Easter I would come to Prague and let him hear some of my compositions, which would make him more familiar with my manner of writing, and either—inspire him further—or perhaps, make him stop altogether, etc.

Was, then, the correspondent of the “Zeitung für die Elegante Welt” right? Had Beethoven really received one of Schikaneder’s heroic texts? This much is certain: that in the words “because I am just beginning my opera,” no reference is made to the “Leonore” (“Fidelio”). They may only express his expectation of beginning such a work immediately; or they may refer to one already begun, of which a fragment has been preserved. In Rubric II of the sale catalogue of Beethoven’s manuscripts and music, No. 67, is a “vocal piece with orchestra,[20] complete, but not entirely orchestrated.” It is an operatic trio[15]; the dramatis personæ are Porus, Volivia, Sartagones; the handwriting is that of this part of the composer’s life; and the music is the basis of the subsequent grand duet in “Fidelio,” “O namenlose Freude.” The temptation is strong to believe that Schikaneder had given Beethoven another “Alexander,” the scenes laid in India—a supplement to that with which his new theatre had been opened two years before. However this was, circumstances occurred, which prevented its completion, or indeed the composition by Beethoven of any text prepared by Schikaneder.

The compositions which may safely be dated 1803, are few in comparison with those of 1802. The works published in the course of the year were the two Pianoforte Sonatas, Op. 31, Nos. 1 and 2 (in Nägeli’s “Répertoire des Clavecinistes”); the three Violin Sonatas, Op. 30 (Industrie-Comptoir); the two sets of Variations, Op. 34 and 35 (Breitkopf and Härtel); the seven Bagatelles, Op. 33 (Industrie-Comptoir); the Romanza in G for Violin, Op. 40 (Hoffmeister and Kühnel); the arrangement for Pianoforte and Flute (or Violin) Op. 41 of the Serenade (Op. 25), which was not made by Beethoven but examined by him and “corrected in parts” (Hoffmeister and Kühnel); the two Preludes for Pianoforte, Op. 39 (Hoffmeister and Kühnel); two songs, “La Partenza” and “Ich liebe dich” (Traeg); a song, “Das Glück der Freundschaft,” Op. 88 (Löschenkerl in Vienna and Simrock in Bonn), of which Nottebohm found a sketch amongst the sketches for the “Eroica” Symphony in the book used in 1803 and which, therefore, though it may have been an early work, was probably rewritten in 1803; and the six Sacred Songs by Gellert, dedicated to Count Browne (Artaria). The two great works of the year were the “Kreutzer” Sonata for Violin and the “Sinfonia Eroica.” The title of the former, “Sonata per il Pianoforte ed un Violino obligato in uno stilo (stile) molto concertante quasi come d’un Concerto,” is found on the inner side of the last sheet of the sketchbook of 1803 described by Nottebohm. Beethoven wrote the word “brillante” after “stilo” but scratched it out. It is obvious that he wished to emphasize the difference between this Sonata and its predecessors. Simrock’s tardiness in publishing the Sonata annoyed Beethoven. He became impatient and wrote to the publisher as follows, under date of October 4, 1804:

Dear, best Herr Simrock, I have been waiting with longing for the Sonata which I gave you—but in vain—please write me what the condition of affairs is concerning it—whether or not you accepted it from me merely as food for moths—or do you wish to obtain a special Imperial privilegium in connection with it?—well it seems to me that might have been accomplished long ago.—Where in hiding is this slow devil—who is to drive out the sonata—you are generally the quick devil, are known as Faust once was as being in league with the imp of darkness and for this reason you are loved by your comrades; but again—where in hiding is your devil—or what kind of a devil is it that sits on my sonata and with whom you have a misunderstanding?—Hurry, then, and tell me when I shall see the sonata given to the light of day—when you have told me the date I will at once send a little note to Kreutzer, which you will please be kind enough to enclose when you send a copy (as you in any event will send your copies to Paris or even, perhaps, have them printed there)—this Kreutzer is a dear, good fellow who during his stay here[16] gave me much pleasure. I prefer his unassuming manner and unaffectedness to all the Extérieur or intérieur of all the virtuosi—as the sonata is written for a thoroughly capable violinist, the dedication to him is all the more appropriate—although we correspond with each other (i. e., a letter from me once a year)—I hope he will not have learned anything about it....

As a proof of the growing appreciation of Beethoven in foreign lands it may be remarked here that in the summer of 1803 he received an Erard pianoforte as a gift from the celebrated Parisian maker. The instrument belongs to the museum at Linz and used to bear an inscription, on the authority of Beethoven’s brother Johann, that it was given to the composer by the city of Paris in 1804. The archives of the Erard firm show, however, that on the 18th of Thermidor, in the XIth year of the Republic (1803), Sébastien Erard made a present of “un piano forme clavecin” to Ludwig van Beethoven in Vienna.

The Year 1804—The “Sinfonia Eroica”—Beethoven and Breuning—The “Waldstein” Sonata—Sonnleithner, Treitschke and Gaveaux—“Fidelio” Begun—Beethoven’s Popularity.

During the winter 1803-04 negotiations were in progress the result of which put an end for the present to Beethoven’s operatic aspirations. Let Treitschke, a personal actor in the scenes, explain:[17]

On February 24, 1801, the first performance of “Die Zauberflöte” took place in the Royal Imperial Court Theatre beside the Kärnthnerthor. Orchestra and chorus as well as the representatives of Sarastro (Weinmüller), the Queen of Night (Mme. Rosenbaum), Pamina (Demoiselle Saal) and the Moor (Lippert) were much better than before. It remained throughout the year the only admired German opera. The loss of large receipts and the circumstance that many readings were changed, the dialogue shortened and the name of the author omitted from all mention, angered S. (Schikaneder) greatly. He did not hesitate to give free vent to his gall, and to parody some of the vulnerable passages in the performance. Thus the change of costume accompanying the metamorphosis of the old woman into Papagena seldom succeeded. Schikaneder, when he repeated the opera at his theatre, sent a couple of tailors on to the stage who slowly accomplished the disrobing, etc. These incidents would be trifles had they not been followed by such significant consequences; for from that time dated the hatred and jealousy which existed between the German operas of the two theatres, which alternately persecuted every novelty and ended in Baron von Braun, then manager of the Court Theatre, purchasing the Theater-an-der-Wien in 1804, by which act everything came under the staff of a single shepherd but never became a single flock.

Zitterbarth had, some months before, purchased of Schikaneder all his rights in the property, paying him 100,000 florins for the privilegium alone; and, therefore, being absolute master, “had permitted a dicker down to the sum of 1,060,000 florins Vienna standard.... The contract was signed on February[23] 11th and on the 16th the Theater-an-der-Wien under the new arrangement was opened with Méhul’s opera ‘Ariodante.’”[18]

Zitterbarth had retained Schikaneder as director; but now Baron Braun dismissed him, and the Secretary of the Court Theatres, Joseph von Sonnleithner, for the present acted in that capacity.

The sale of the theatre made void the contracts with Vogler and Beethoven, except as to the first of Vogler’s three operas, “Samori” (text by Huber), which being ready was put in rehearsal and produced May 7th.

It was no time for Baron Braun, with three theatres on his hands, to make new contracts with composers, until the reins were fairly in his grasp, and the affairs of the new purchase brought into order and in condition to work smoothly; nor was there any necessity of haste; the repertory was so well supplied, that the list of new pieces for the year reached the number of forty-three, of which eighteen were operas or Singspiele. So Beethoven, who had already occupied the free lodgings in the theatre building for the year which his contract with Zitterbarth and Schikaneder granted him, was compelled to move. Stephan von Breuning even then lived in the house in which in 1827 he died. It was the large pile of building belonging to the Esterhazy estates, known as “das rothe Haus,” which stood at a right angle to the Schwarzspanier house and church, and fronted upon the open space where now stands the new Votiv-Kirche. Here also Beethoven now took apartments.[19]

It is worth noting, that this was the year—October, 1803 to October, 1804—of C. M. von Weber’s first visit to Vienna, and of his studies under Vogler. He was then but eighteen years old and “the delicate little man” made no very favorable impression upon Beethoven. But at a later period, when Weber’s noble dramatic talent became developed and known, no former prejudice prevented the great symphonist’s due appreciation and hearty acknowledgment of it.

Among the noted strangers who came to Vienna this spring was Clementi.

“He sent word to Beethoven that he would like to see him.” “Clementi will wait a long time before Beethoven goes to him,” was the reply. Thus Czerny.

When he came (says Ries) Beethoven wanted to go to him at once, but his brother put it into his head that Clementi ought to[24] make the first visit. Though much older Clementi would probably have done so had not gossip begun to concern itself with the matter. Thus it came about that Clementi was in Vienna a long time without knowing Beethoven except by sight. Often we dined at the same table in the Swan, Clementi with his pupil Klengel and Beethoven with me; all knew each other but no one spoke to the other, or confined himself to a greeting. The two pupils had to imitate their masters, because they feared they would otherwise lose their lessons. This would surely have been the case with me because there was no possibility of a middle-way with Beethoven. (“Notizen,” p. 101.)

Early in the Spring a fair copy of the “Sinfonia Eroica” had been made to be forwarded to Paris through the French embassy, as Moritz Lichnowsky informed Schindler.

In this symphony (says Ries) Beethoven had Buonaparte in his mind, but as he was when he was First Consul. Beethoven esteemed him greatly at the time and likened him to the greatest Roman consuls. I as well as several of his more intimate friends saw a copy of the score lying upon his table, with the word “Buonaparte” at the extreme top of the title-page and at the extreme bottom “Luigi van Beethoven,” but not another word. Whether, and with what the space between was to be filled out, I do not know. I was the first to bring him the intelligence that Buonaparte had proclaimed himself emperor, whereupon he flew into a rage and cried out: “Is then he, too, nothing more than an ordinary human being? Now he, too, will trample on all the rights of man and indulge only his ambition. He will exalt himself above all others, become a tyrant!” Beethoven went to the table, took hold of the title-page by the top, tore it in two and threw it on the floor. The first page was rewritten and only then did the symphony receive the title: “Sinfonia eroica.”

There can be no mistake in this; for Count Moritz Lichnowsky, who happened to be with Beethoven when Ries brought the offensive news, described the scene to Schindler years before the publication of the “Notizen,”

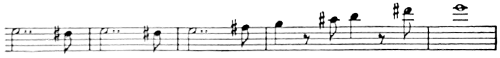

The Acts of the French Tribunate and Senate, which elevated the First Consul to the dignity of Emperor, are dated May 3, 4, and 17. Napoleon’s assumption of the crown occurred on the 18th and the solemn proclamation was issued on the 20th. Even in those days, news of so important an event would not have required ten days to reach Vienna. At the very latest, then, a fair copy of the “Sinfonia Eroica,” was complete early in May, 1804. That it was a copy, the two credible witnesses, Ries and Lichnowsky, attest. Beethoven’s own score—purchased at the sale in 1827, for 3 fl. 10 kr., Vienna standard (less than 3½ francs), by the Vienna composer Hr. Joseph Dessauer—could not have been the one referred to above. It is,[25] from beginning to end, disfigured by erasures and corrections, and the title-page could never have answered to Ries’ description. It is this:

A note to the funeral march, is evidently a direction to the copyist, as are the remarks on the title-page:

N. B. The notes in the bass which have stems upwards are for the violoncellos, those downward for the bass-viol.

One of the two words erased from the title was “Bonaparte”; and just under his own name Beethoven wrote with a lead pencil in large letters, nearly obliterated but still legible, “Composed on Bonaparte.”

It is confidently submitted, therefore, that all the traditions derived from Czerny, Dr. Bertolini and whomsoever, that the opening Allegro is a description of a naval battle, and that the Marcia funebre was written in commemoration of Nelson or Gen. Abercrombie,[20] are mistakes, and that Schindler is correct; and again, that the date “804 im August,” is not that of the composition of the Symphony. It is written with a different ink, darker than the rest of the title, and may have been inserted long afterwards, Beethoven’s memory playing him false. The two “violin adagios with orchestral accompaniment” offered by Kaspar van Beethoven to André in November, 1802,[26] cannot well be anything but the two Romances, yet that in G, Op. 40, bears the date 1803. Perhaps Kaspar wrote before it was complete. But what can be said to this? It is perfectly well known that Op. 124 was performed on October 3, 1822; yet the copy sent to Stumpff in London bore this title: “Overture by Ludwig van Beethoven, composed for the opening of the Josephstadt Theatre, towards the end of September, 1823, and performed for the first time on October 3, 1824, Op. 124.” That the “804 im August” may be an error, is at all events possible, if not established as such. “Afterwards,” continues Ries, “Prince Lobkowitz bought this composition for several years’ [?] use, and it was performed several times in his palace.”

There is “an anecdote told by a person who enjoyed Beethoven’s society,”[21] in Schmidt’s “Wiener Musik-Zeitung” (1843, p. 28), according to which, as may readily be believed, this work, then so difficult, new, original, strange in its effects and of such unusual length, did not please. Some time after this humiliating failure Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia paid a visit to the same cavalier (Lobkowitz) in his countryseat.... To give him a surprise, the new and, of course, to him utterly unknown symphony, was played to the Prince, who “listened to it with tense attention which grew with every movement.” At the close he proved his admiration by requesting the favor of an immediate repetition; and, after an hour’s pause, as his stay was too limited to admit of another concert, a second. “The impression made by the music was general and its lofty contents were now recognized.”

To those who have had occasion to study the character of Louis Ferdinand as a man and a musician, and who know that at the precise time here indicated he was really upon a journey that took him near certain estates of Prince Lobkowitz, there is nothing improbable in the anecdote. If it be true, and the occurrence really took place at Raudnitz or some other “countryseat” of the Prince’s, the rehearsals and first performances of the Symphony at Vienna had occurred, weeks, perhaps months, before “804 im August.” However this be, Ries was present at the first rehearsal and incurred the danger of receiving a box on the ear from his master.

In the first Allegro occurs a wicked whim (böse Laune) of Beethoven’s for the horn; in the second part, several measures before the[27] theme recurs in its entirety, Beethoven has the horn suggest it at a place where the two violins are still holding a second chord. To one unfamiliar with the score this must always sound as if the horn player had made a miscount and entered at the wrong place. At the first rehearsal of the symphony, which was horrible, but at which the horn player made his entry correctly, I stood beside Beethoven, and, thinking that a blunder had been made I said: “Can’t the damned hornist count?—it sounds infamously false!” I think I came pretty close to receiving a box on the ear. Beethoven did not forgive the slip for a long time. (P. 79, “Notizen.”)

It was bad economy for two young, single men, each to have and pay for a complete suite of apartments in the same house, especially for two who were connected by so many ties of friendship as Breuning and Beethoven. Either lodging contained ample room for both; and Beethoven therefore very soon gave up his and moved into the other. Breuning had his own housekeeper and cook and they also usually dined together at home. This arrangement had hardly been effected when Beethoven was seized with a severe sickness, which when conquered still left him the victim of an obstinate intermittent fever.

Every language has its proverbs to the effect that he who serves not himself is ill served. So Beethoven discovered, when it was too late, that due notice had not been given to the agent of Esterhazy, and that he was bound for the rent of the apartments previously occupied. The question, who was in fault, came up one day at dinner in the beginning of July, and ended in a sudden quarrel in which Beethoven became so angry as to leave the table and the house and retire to Baden with the determination to sacrifice the rent here and pay for another lodging, rather than remain under the same roof with Breuning. “Breuning,” says Ries, “a hot-head like Beethoven, grew so enraged at Beethoven’s conduct because the incident occurred in the presence of his brother.” It is clear, however, that he soon became cool and instantly did his best to prevent the momentary breach from becoming permanent, by writing—as may be gathered from Beethoven’s allusions to it—a manly, sensible and friendly invitation to forgive and forget. But Beethoven, worn with illness, his nerves unstrung, made restless, unhappy, petulant by his increasing deafness, was for a time obstinate. His wrath must run its course. It found vent in the following letters to Ries, and then the paroxysm soon passed.

The first of the letters was written in the beginning of 1804,

Dear Ries: Since Breuning did not scruple by his conduct to present my character to you and the landlord as that of a miserable,[28] beggarly, contemptible fellow I single you out first to give my answer to Breuning by word of mouth. Only to the one and first point of his letter which I answer only in order to vindicate my character in your eyes. Say to him, then, that it never occurred to me to reproach him because of the tardiness of the notice, and that, if Breuning was really to blame for it, my desire to live amicably with all the world is much too precious and dear to me that I should give pain to one of my friends for a few hundreds and more. You know yourself that altogether jocularly I accused you of being to blame that the notice did not arrive on time. I am sure that you will remember this; I had forgotten all about the matter. Now my brother began at the table and said that he believed it was Breuning’s fault; I denied it at once and said that you were to blame. It appears to me that was plain enough to show that I did not hold him to blame. Thereupon Breuning jumped up like a madman and said he would call up the landlord. This conduct in the presence of all the persons with whom I associate made me lose my self-control; I also jumped up, upset my chair, went away and did not return. This behavior induced Breuning to put me in such a light before you and the house-steward, and to write me a letter also which I have answered only with silence. I have nothing more to say to Breuning. His mode of thought and action in regard to me proves that there never ought to have been a friendly relationship between him and me and such certainly will not exist in the future. I have told you all this because your statements degraded all my habits of thinking and acting. I know that if you had known the facts you would certainly not have made them, and this satisfies me.

Now I beg of you, dear Ries! immediately on receipt of this letter go to my brother, the apothecary, and tell him that I shall leave Baden in a few days and that he must engage the lodgings in Döbling immediately you have informed him. I was near to coming to-day; I am tired of being here, it revolts me. Urge him for heaven’s sake to rent the lodgings at once because I want to get into them immediately. Tell it to him and do not show him any part of what is written on the other page; I want to show him from all possible points of view that I am not so small-minded as he and wrote to him only after this (Breuning’s) letter, although my resolution to end our friendship is and will remain firm.

Your friend

Beethoven.

Not long thereafter there followed a second letter, which Ries gives as follows:

Baden, July 14, 1804.

If you, dear Ries, are able to find better quarters I shall be glad. I want them on a large quiet square or on the ramparts.... I will take care to be at the rehearsal on Wednesday. It is not pleasant to me that it is at Schuppanzigh’s. He ought to be grateful if my humiliations make him thinner. Farewell, dear Ries! We are having bad weather here and I am not safe from people; I must flee in order to be alone.

From a third letter, dated “Baden, July 24, 1804,” Ries prints the following excerpt:

... No doubt you were surprised at the Breuning affair; believe me, dear (friend), my eruption was only the outburst consequent on many unpleasant encounters between us before. I have the talent in many cases to conceal my sensitiveness and repress it; but if I am irritated at a time when I am more susceptible than usual to anger, I burst out more violently than anybody else. Breuning certainly has excellent qualities, but he thinks he is free from all faults and his greatest ones are those which he thinks he sees in others. He has a spirit of pettiness which I have despised since childhood. My judgment almost predicted the course which affairs would take with Breuning, since our modes of thinking, acting and feeling are so different, but I thought these difficulties might also be overcome;—experience has refuted me. And now, no more friendship! I have found only two friends in the world with whom I have never had a misunderstanding, but what men! One is dead, the other still lives. Although we have not heard from each other in nearly six years I know that I occupy the first place in his heart as he does in mine. The foundation of friendship demands the greatest similarity between the hearts and souls of men. I ask no more than that you read the letter which I wrote to Breuning and his letter to me. No, he shall never again hold the place in my heart which once he occupied. He who can think a friend capable of such base thoughts and be guilty of such base conduct towards him is not worth my friendship.

The reader knows too well the character of Breuning to be prejudiced against him by all these harsh expressions written by Beethoven in a fit of choler of which he heartily repented and “brought forth fruits meet for repentance.” But, as Ries says, “these letters together with their consequences are too beautiful a testimony to Beethoven’s character to be omitted here,” the more so as they introduce, by the allusions in them, certain matters of more or less interest from the “Notizen” of Ries. Thus Ries writes:

One evening I came to Baden to continue my lessons. There I found a handsome young woman sitting on the sofa with him. Thinking that I might be intruding I wanted to go at once, but Beethoven detained me and said: “Play for the time being.” He and the lady remained seated behind me. I had already played for a long time when Beethoven suddenly called out: “Ries, play some love music”; a little later, “Something melancholy!” then, “Something passionate!” etc.

From what I heard I could come to the conclusion that in some manner he must have offended the lady and was trying to make amends by an exhibition of good humor. At last he jumped up and shouted: “Why, all those things are by me!” I had played nothing but movements from his works, connecting them with short transition-phrases, which seemed to please him. The lady soon went away and to my great amazement Beethoven did not know who she was. I learned[30] that she had come in shortly before me in order to make Beethoven’s acquaintance. We followed her in order to discover her lodgings and later her station. We saw her from a distance (it was moonlight),[22] but suddenly she disappeared. Chatting on all manner of topics we walked for an hour and a half in the beautiful valley adjoining. On going, however, Beethoven said: “I must find out who she is and you must help me.” A long time afterward I met her in Vienna and discovered that she was the mistress of a foreign prince. I reported the intelligence to Beethoven, but never heard anything more about her either from him or anybody else.

The rehearsal at Schuppanzigh’s on “Wednesday” (18th) mentioned in the letter of July 14th, was for the benefit of Ries, who was to play in the first of the second series of the regular Augarten Thursday concerts which took place the next day (19th) or, perhaps, the 26th. Ries says on page 113 of the “Notizen”:

Beethoven had given me his beautiful Concerto in C minor (Op. 37) in manuscript so that I might make my first public appearance as his pupil with it; and I am the only one who ever appeared as such while Beethoven was alive.... Beethoven himself conducted, but he only turned the pages and never, perhaps, was a concerto more beautifully accompanied. We had two large rehearsals. I had asked Beethoven to write a cadenza for me, but he refused and told me to write one myself and he would correct it. Beethoven was satisfied with my composition and made few changes; but there was an extremely brilliant and very difficult passage in it, which, though he liked it, seemed to him too venturesome, wherefore he told me to write another in its place. A week before the concert he wanted to hear the cadenza again. I played it and floundered in the passage; he again, this time a little ill-naturedly, told me to change it. I did so, but the new passage did not satisfy me; I therefore studied the other, and zealously, but was not quite sure of it. When the cadenza was reached in the public concert Beethoven quietly sat down. I could not persuade myself to choose the easier one. When I boldly began the more difficult one, Beethoven violently jerked his chair; but the cadenza went through all right and Beethoven was so delighted that he shouted “Bravo!” loudly. This electrified the entire audience and at once gave me a standing among the artists. Afterward, while expressing his satisfaction he added: “But all the same you are willful! If you had made a slip in the passage I would never have given you another lesson.”

A little farther on in his book Ries writes (p. 115):

The pianoforte part of the C minor Concerto was never completely written out in the score; Beethoven wrote it down on separate sheets of paper expressly for me.

This confirms Seyfried, as quoted on a preceding page.

“Not on my life would I have believed that I could be so lazy as I am here. If it is followed by an outburst of industry,[31] something worth while may be accomplished,” Beethoven wrote at the end of his letter of July 24. He was right. His brother Johann secured for him the lodging at Döbling where he passed the rest of the summer, and where the two Sonatas Op. 53 and 54, certainly “something worth while,” were composed. In one of the long walks, previously described by Ries,

in which we went so far astray that we did not get back to Döbling, where Beethoven lived, until nearly 8 o’clock, he had been all the time humming and sometimes howling, always up and down, without singing any definite notes. In answer to my question what it was he said: “A theme for the last movement of the sonata has occurred to me.” When we entered the room he ran to the pianoforte without taking off his hat. I took a seat in a corner and he soon forgot all about me. Now he stormed for at least an hour with the beautiful finale of the sonata. Finally he got up, was surprised still to see me and said: “I cannot give you a lesson to-day, I must do some more work.”

The Sonata in question was that in F minor, Op. 57. Ries had in the meantime fulfilled Beethoven’s wish for a new lodging on the ramparts, by engaging for him one on the Mölkerbastei three or four houses only from Prince Lichnowsky in the Pasqualati house—“from the fourth storey of which there was a beautiful view,” namely, over the broad Glacis, the northwestern suburb of the city and the mountains in the distance. “He moved out of this several times,” says Ries, “but always returned to it, so that, as I afterwards heard, Baron Pasqualati was good-natured enough to say: ‘The lodging will not be rented; Beethoven will come back.’” To what extent Ries was correctly informed in this we will not now conjecture. The lessons of Förster’s little boy had been interrupted so long as his teacher dwelt in the distant theatre buildings; they were now renewed, the first being particularly impressed upon his memory by a severe reproof from Beethoven for ascending the four lofty flights of stairs too rapidly, and entering out of breath: “Youngster, you will ruin your lungs if you are not more careful,” said he in substance.