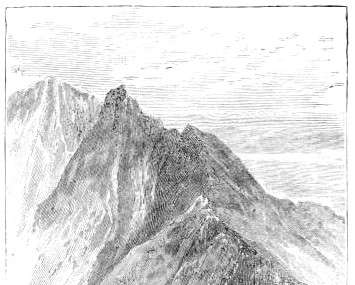

GARFIELD PEAK.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Crest of the Continent

A Summer's Ramble in the Rocky Mountains and Beyond

Author: Ernest Ingersoll

Release Date: June 24, 2013 [eBook #43020]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CREST OF THE CONTINENT***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/crestofcontinent00inge |

The original pagination has been retained in the right margin. The sequence is sometimes disrupted as full page illustrations have been moved to convenient paragraph breaks.

There are two footnotes, which are moved to the end of the text, and linked for easy reference in the text.

Detailed comments on any corrections that were made may be found in a Transcriber’s Note at the end of this text.

A RECORD OF

A SUMMER’S RAMBLE IN THE ROCKY

MOUNTAINS AND BEYOND.

By ERNEST INGERSOLL.

TWENTY NINTH EDITION.

CHICAGO:

R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS, PUBLISHERS.

1887.

COPYRIGHT,

BY S. K. HOOPER,

1885.

R. R. Donnelley & Sons, The Lakeside Press, Chicago.

TO

THE PEOPLE OF COLORADO,

SAGACIOUS IN PERCEIVING, DILIGENT IN DEVELOPING,

AND WISE IN ENJOYING

THE

RESOURCES AND ATTRACTIONS OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS,

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

WITH

THE HOMAGE OF

THE AUTHOR.

Probably nothing in this artificial world is more deceptive than absolute candor. Hence, though the ensuing text may lack nothing in straightforwardness of assertion, and seem impossible to misunderstand, it may be worth while to say distinctly, here at the start, that it is all true. We actually did make such an excursion, in such cars, and with such equipments, as I have described; and we would like to do it again.

It was wild and rough in many respects. Re-arranging the trip, luxuries might be added, and certain inconveniences avoided; but I doubt whether, in so doing, we should greatly increase the pleasure or the profit.

“No man should desire a soft life,” wrote King Ælfred the Great. Roughing it, within reasonable grounds, is the marrow of this sort of recreation. What a pungent and wholesome savor to the healthy taste there is in the very phrase! The zest with which one goes about an expedition of any kind in the Rocky Mountains is phenomenal in itself; I despair of making it credited or comprehended by inexperienced lowlanders. We are told that the joys of Paradise will not only actually be greater than earthly pleasures, but that they will be further magnified by our increased spiritual sensitiveness to the “good times” of heaven. Well, in the same way, the senses are so quickened by the clear, vivifying climate of the western uplands in summer, that an experience is tenfold more pleasurable there than it could become in the Mississippi valley. I elsewhere have had something to say about this exhilaration of body and soul in the high Rockies, which you will perhaps pardon me for repeating briefly, for it was written honestly, long ago, and outside of the present connection.

“At sunrise breakfast is over, the mules and everybody else have been good-natured and you feel the glory of mere existence as you vault into the saddle and break into a gallop. Not that this or that particular day is so different from other pleasant mornings, but all that we call the weather is constituted in the most perfect proportions. The air is ‘nimble and sweet,’ and you ride gayly across meadows, through sunny woods of pine and aspen, and between granite knolls that are piled up in the most noble and romantic proportions....

“Sometimes it seems, when camp is reached, that one hardly has strength to make another move; but after dinner one finds himself able and willing to do a great deal....

“One’s sleep in the crisp air, after the fatigues of the day, is sound and serene.... You awake at daylight a little chilly, re-adjust your blankets, and want again to sleep. The sun may pour forth from the ‘golden window of the east’ and flood the world with limpid light; the stars may pale and the jet of the midnight sky be diluted to that pale and perfect morning-blue into which you gaze to unmeasured depths; the air may become a pervading Champagne, dry and delicate, every draught of which tingles the lungs and spurs the blood along the veins with joyous speed; the landscape may woo the eyes with airy undulations of prairie or snow-pointed pinnacles lifted sharply against the azure—yet sleep chains you. That very quality of the atmosphere which contributes to all this beauty and makes it so delicious to be awake, makes it equally blessed to slumber. Lying there in the open air, breathing the pure elixir of the untainted mountains, you come to think even the confinement of a flapping tent oppressive, and the ventilation of a sheltering spruce-bough bad.”

That was written out of a sincere enthusiasm, which made as naught a whole season’s hardship and work, before there was hardly a wagon-road, much less a railway, beyond the front range.

This exordium, my friendly reader, is all to show to you: That we went to the Rockies and beyond them, as we say we did; that we knew what we were after, and found the apples of these Hesperides not dust and ashes but veritable golden fruit; and, finally, that you may be persuaded to test for yourself this natural and lasting enjoyment.

The grand and alluring mountains are still there,—everlasting hills, unchangeable refuges from weariness, anxiety and strife! The railway grows wider and permits a longer and even more varied journey than was ours. Cars can be fitted up as we fitted ours or in a way as much better as you like. Year by year the facilities for wayside comforts and short branch-excursions are multiplied, with the increase of population and culture.

If you are unable, or do not choose, to undertake all this preparation, I still urge upon you the pleasure and utility of going to the Rocky Mountains, travelling into their mighty heart in comfortable and luxurious public conveyances. Nowhere will a holiday count for more in rest, and in food for subsequent thought and recollection.

| I—At the Base of the Rockies. | |

| First Impressions of the Mountains. A Problem, and its Solution. Denver—Descriptive and Historical. The Resources which Assure its Future. Some General Information concerning the Mining, Stock Raising and Agricultural Interests of Colorado. | 13 |

| II—Along the Foothills. | |

| The Expedition Moves. Its Personnel. The Romantic Attractions of the Divide. Light on Monument Park. Colorado Springs, a City of Homes, of Morality and Culture. Its Pleasant Environs: Glen Eyrie, Blair Athol, Austin’s Glen, the Cheyenne Cañons | 26 |

| III—A Mountain Spa. | |

| Manitou, and the Mineral Springs. The Ascent of Pike’s Peak; bronchos and blue noses. Ute Pass, and Rainbow Falls. The Garden of the Gods. Manitou Park. Williams’ Cañon, and the Cave of the Winds. An Indian Legend. | 36 |

| IV—Pueblo and its Furnaces. | |

| The Largest Smelter in the World. The Colorado Coal and Iron Company. Pueblo’s Claims as a Trade Center, and its Tributary Railway System. A Chapter of Facts and Figures in support of the New Pittsburgh. | 51 |

| V—Over the Sangre de Cristo. | |

| Up and down Veta Mountain, with some Extracts from a letter. Veta Pass, and the Muleshoe Curve. Spanish Peaks. Beautiful Scenery, and Famous Railroading. A general outline of the Rocky Mountain Ranges. | 60 |

| VI—San Luis Park. | |

| A Fertile and Well-watered Valley. The Method of Irrigation. Sierra Blanca. A Digression to describe the Home on Wheels. Alamosa, Antonito and Conejos. Cattle, Sheep and Agriculture in the largest Mountain Park. | 71 |

| VII—The Invasion of New Mexico. | |

| Barranca, among the Sunflowers. An Excursion to Ojo Caliente, and Description of the Hot Springs. Pre-historic Relics—a Rich Field for the Archæologist. Señor vs. Burro. An Ancient Church, with its Sacred Images. | 81 |

| VIII—El Mexicano y Puebloano. | |

| Comanche Cañon and Embudo. The Penitentes. The Rio Grande Valley; Alcalde, Chamita and Espanola. New Mexican Life, Homes and Industries. The Indian Pueblos, and their Strange History. Architecture, Pottery, and Threshing. | 92 |

| IX—Santa Fe and the Sacred Valley. | |

| Santa Fe, the Oldest City in the United States. Fact and Tradition. San Fernandez de Taos—the Home of Kit Carson. Pueblo de Taos Birthplace of Montezuma, and Typical and Well-Preserved. The Festival of St. Geronimo. Exit Amos. | 106 |

| X—Toltec Gorge. | |

| Heading for the San Juan Country. From Mesa to Mountain Top. The Curl of the Whiplash. Above the silvery Los Pinos. Phantom Curve. A Startling Peep from Toltec Tunnel. Eva Cliff. “In Memoriam.” | 115 |

| XI—Along the Southern Border. | |

| The Piños-Chama Summit. Trout and Game. The Groves of Chama. Mexican Rural Life at Tierra Amarilla. The Iron Trail. Rio San Juan and its Tributaries. Pagosa Springs. Apache Visitors. The Southern Utes. Durango. | 120 |

| XII—The Queen of the Cañons. | |

| Geology of the Sierra San Juan. The Attractions of Trimble Springs. Beauty and Fertility of the Animas Valley. The Cañon of the River of Lost Souls. Engineering under difficulties. The Needles, and Garfield Peak. | 129 |

| XIII—Silver San Juan. | |

| Geological Resume. Scraps of History. Snow-shoes and Avalanches. The Mining Camps of Animas Forks, Mineral Point, Eureka and Howardville. Early Days in Baker’s Park. Poughkeepsie, Picayune and Cunningham Gulches. The Hanging. | 136 |

| XIV—Beyond the Ranges. | |

| Ophir, Rico, and the La Plata Mountains. Everything triangular. Mixed Mineralogy, Real bits of Beauty. “When I sell my Mine.” An Unbiased Opinion. Placer vs. Fissure Vein Mining. | 149 |

| XV—The Antiquities of the Rio San Juan. | |

| Rugged Trails. Searching for Antiquities. The Discovery. Habitations of a Lost Race. Prehistoric Architecture, “Temple or Refrigerator.” “Ruins, Ancient beyond all Knowing.” Guesses and Traditions. Some Appropriate Verses. | 156 |

| XVI—On the Upper Rio Grande. | |

| Good-bye and Welcome. Del Norte and the Gold Summit. Among the River Ranches. Wagon Wheel Springs. Healing Power of the Waters. The Gap and its History. A Day’s Trout Fishing. | 166 |

| XVII—El Moro and Cañon City. | |

| A Great Natural Fortress. Down in a Coal Mine. The Coke Ovens. Huerfano Park and its Coal. Cañon City Historically. Coal Measures. Resources of the Foothills. | 177 |

| XVIII—In the Wet Mountain Valley. | |

| Grape Creek Cañon. The Dome of the Temple. Wet Mountain Valley. The Legend of Rosita. Hardscrabble District. Silver Cliff and its Strange Mine. The Foothills of the Sierra Mojada. Geological Theories. | 185 |

| XIX—The Royal Gorge. | |

| The Grand Cañon of the Arkansas. Its Culminating Chasm the Royal Gorge. Beetling Cliffs and Narrow Waters. Running the Gauntlet. Wonders of Plutonic Force. A Story of the Cañon. | 193 |

| XX—The Arkansas Valley. | |

| Entering Brown’s Cañon. The Iron Mines of Calumet. Salida. Farming on the Arkansas. Buena Vista. Granate and its Gold Placers,—Twin Lakes. Malta and its Charcoal Burners. A Burned-out Gulch. | 201 |

| XXI—Camp of the Carbonates. | |

| California Gulch. How Boughtown was Built. Some Lively Scenes. Discovery of Carbonates. The Rush of 1878. The Founding of Leadville. A Happy Grave Digger. Practice and Theory of Mining. Reducing the Ores. | 209 |

| XXII—Across the Tennessee and Fremont’s Pass. | |

| Hay Meadows on the Upper Arkansas. Climbing Tennessee Pass. Mount of the Holy Cross. Red Cliff. Ore in Battle Mountain. Through Eagle River Cañon. The Artist’s Elysium. Two Miles in the Air. On the Blue. | 222 |

| XXIII—From Poncho Springs to Villa Grove. | |

| In Hot Water. A Pretty Village and Fine Outlook. Pluto’s Reservoirs. The Madame’s Letter. Poncho Pass. The Sangre de Cristo Again. Villa Grove. Silver and Iron. | 225 |

| XXIV—Through Marshall Pass. | |

| The Unknown Gunnison. A Wonder of Progress. Climbing the Mountains in a Parlor Car. Four Hours of Scenic Delight. Culmination of Man’s Skill. On the Crest of the Continent. The Mysterious Descent. | 243 |

| XXV—Gunnison and Crested Butte. | |

| Tomichi Valley. Gunnison from Oregon to St. Louis. Captain Gunnison’s Discoveries. A Discussion with Chief Ouray. A Beautiful Landscape. Crested Butte. Anthracite in the Rockies. | 250 |

| XXVI—A Trip to Lake City. | |

| Lake City. A Picture from Nature. A Hard Pillow. The Mining Interests. Alpine Grandeur of the Scenery. The Home of the Bear and the Elk. Game, Game, Game. 262 | |

| XXVII—Impressions of the Black Cañon. | |

| The Observation Car. Gunnison River. Trout Fishing Again. The Rock Cleft in Twain. A Beautiful Cataract. A Mighty Needle. The Cañon Black yet Sunny. Impressions of the Cañon. Majestic Forms and Splendid Colors. | 266 |

| XXVIII—The Uncompahgre Valley. | |

| Cline’s Ranch. Montrose. The Madame and Chum Respectfully Decline. The Trip to Ouray. The Military Post. Chief Ouray’s Widow. The Road on the Bluff. Hot Springs. Brilliant Stars. | 273 |

| XXIX—Ouray and Red Mountain. | |

| A Pretty Mountain Town. Trials of the Prospectors. A Tradition. From Silverton to Ouray by Wagon. Enchanting Gorges and Alluring Peaks. The Yankee Girl. A Cave of Carbonates. Vermillion Cliffs. Dallas Station. | 278 |

| XXX—Montrose and Delta. | |

| Playing Billiards. Caught in the Act. A Well-Watered District. Coal and Cattle. A Fruit Garden. A Big Irrigating Ditch. The Snowy Elk Mountains. A Substantial Track. A Long Bridge. | 290 |

| XXXI—The Grand River Valley. | |

| An Honest Circular. Grand Junction. Staking Out Ranches. The Recipe for Good Soil. Watering the Valley. Value of Water. Some Big Corn in the Far West. A Land of Plenty. Going West. | 296 |

| XXXII—The Colorado Cañons. | |

| A Memorable Night-Journey. Skirting the Uncompahgre Plateau. Origin of the Sierra La Sal. Crossing the Green River. Wonders of Erosive Work. An Indian Tradition. The Marvelous Cañons of the Colorado. | 303 |

| XXXIII—Crossing the Wasatch. | |

| The Tall Cliffs of Price River and Castle Cañon. Castle Gate. The Summit of the Wasatch. “Indians!” San Pete and Sevier Valleys. “Like Iser Rolling Rapidly.” Through the Cañon of the Spanish Fork. Mount Nebo. | 312 |

| XXXIV—By Utah Lakes. | |

| Rural Scenes Beside Lake Utah. Spanish Fork, Springville, Provo and Nephi. Relics of Indian Wars. Pretty Fruit Sellers. First Sight of Deseret and the Great Salt Lake. Ogden and Its History. | 317 |

| XXXV—Salt Lake City. | |

| Sunday in Salt Lake City. The Tabernacle and the Temple. Early Days in Utah. Shady Trees and Sparkling Brooks. Social Peculiarities of the City. Mining and Mercantile Prosperity. Religious Sects. Schools and Seminaries. | 324 |

| XXXVI—Salt Lake and the Wasatch. | |

| The Ride to Salt Lake. A Salt Water Bath. Keep Your Mouth Shut. The Shore of the Lake. An Exciting Chase. A Trip to Alta. Stone for the Temple. An Exhilarating Ride. | 335 |

| XXXVII—Au Revoir. | |

| At Last. On Jordan’s Banks. Chum’s Grandfather. Let Every Injun Carry his Own Skillet. The Parting Toast. Good-Night. | 342 |

| PAGE | |

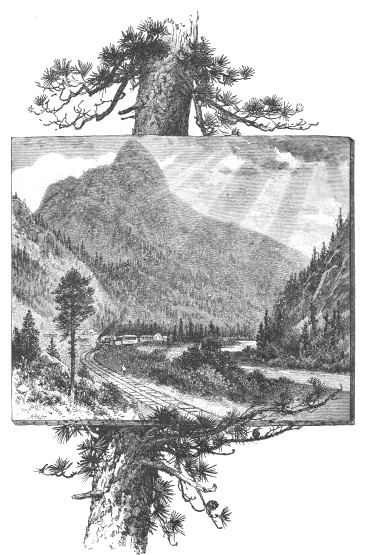

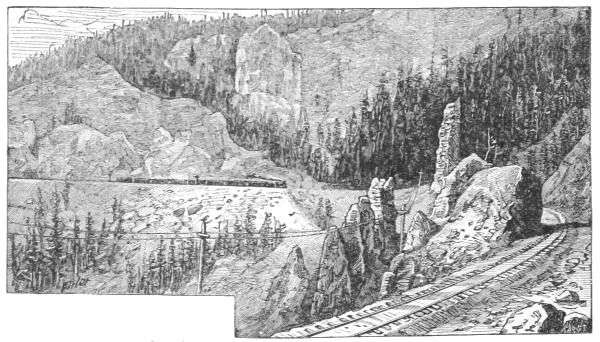

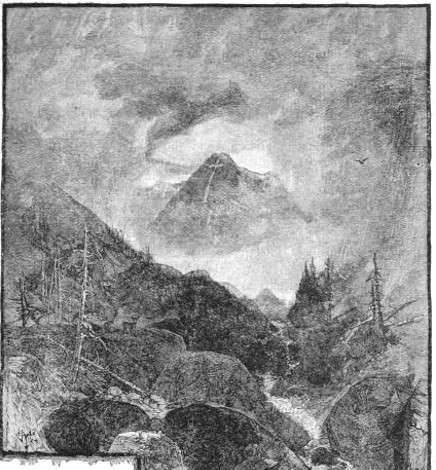

| Garfield Peak | Frontispiece. |

| Denver | 17 |

| Depot at Palmer Lake | 20 |

| Phœbe’s Arch | 21 |

| Monument Park | 24 |

| In Queen’s Cañon | 28 |

| Cheyenne Falls | 31 |

| In North Cheyenne Cañon | 34 |

| A Glimpse of Manitou and Pike’s Peak | 37 |

| The Mineral Springs | 40 |

| Pike’s Peak Trail | 45 |

| Rainbow Falls | 49 |

| Garden of the Gods | 53 |

| Entrance to Cave of the Winds | 57 |

| Alabaster Hall | 62 |

| Veta Pass | 67 |

| Crest of Veta Mountain | 69 |

| Spanish Peaks from Veta Pass | 75 |

| Sangre de Cristo Summits | 78 |

| Sierra Blanca | 83 |

| Ojo Caliente | 86 |

| Embudo, Rio Grande Valley | 89 |

| New Mexican Life | 94 |

| A Patriarch | 98 |

| Maid and Matron | 99 |

| Old Church of San Juan | 102 |

| Pueblo de Taos | 107 |

| Phantom Curve | 112 |

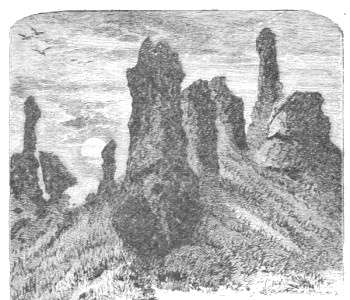

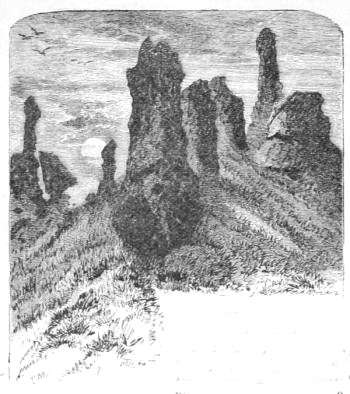

| Phantom Rocks | 118 |

| In Memoriam | 119 |

| Toltec Gorge | 125 |

| Eva Cliff | 130 |

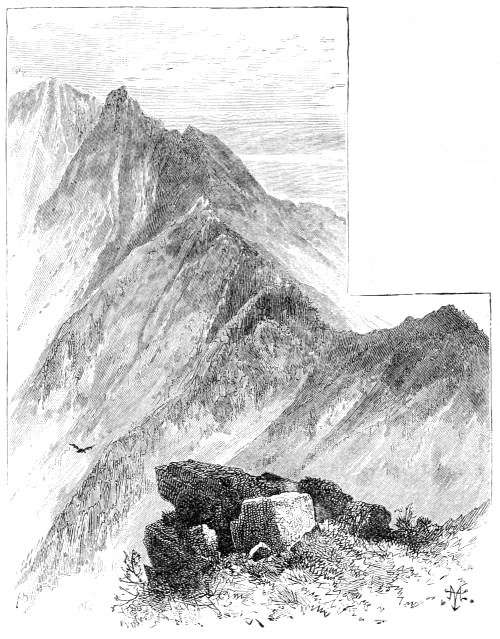

| Garfield Memorial | 131 |

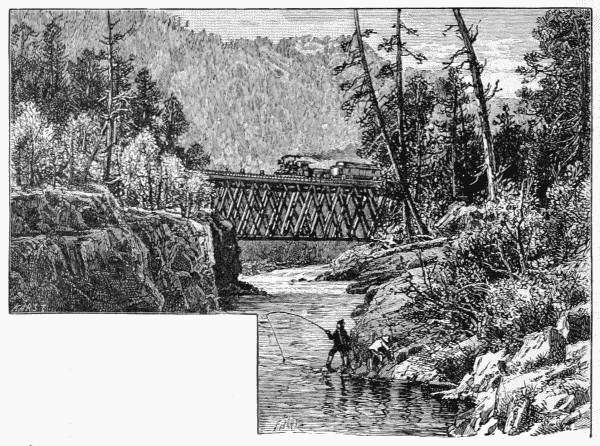

| Near the Piños-Chama Summit | 136 |

| Chiefs of the Southern Utes | 141 |

| Cañon of the Rio de Las Animas | 146 |

| On the River of Lost Souls | 152 |

| Animas Cañon and the Needles | 157 |

| Silverton and Sultan Mountain | 162 |

| Cliff Dwellings | 168 |

| Wagon Wheel Gap | 173 |

| Up the Rio Grande | 178 |

| Grape Creek Cañon | 181 |

| Grand Cañon of the Arkansas | 186 |

| The Royal Gorge | 191 |

| Brown’s Cañon | 194 |

| Twin Lakes | 199 |

| The Old Route to Leadville | 202 |

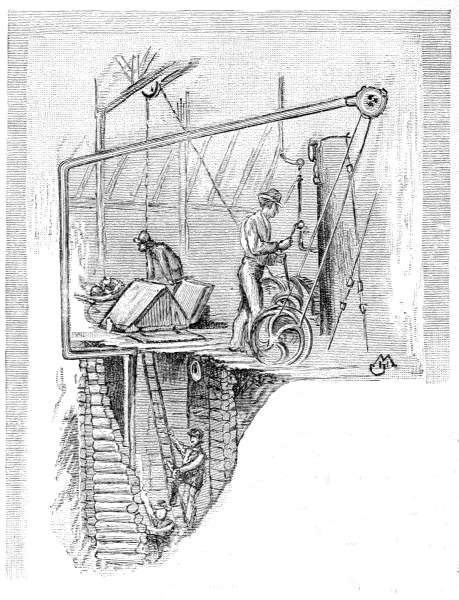

| The Shaft House | 204 |

| Bottom of the Shaft | 205 |

| Athwart an Incline | 206 |

| The Jig Drill | 207 |

| Fremont Pass | 211 |

| Cascades of the Blue | 214 |

| Mount of the Holy Cross | 219 |

| Marshall Pass—Eastern Slope | 223 |

| Marshall Pass—Western Slope | 227 |

| Crested Butte Mountain and Lake | 230 |

| Ruby Falls | 232 |

| Approach to the Black Cañon | 235 |

| Black Cañon of the Gunnison | 241 |

| Currecanti Needle, Black Cañon | 247 |

| A Ute Council Fire | 251 |

| Ouray | 255 |

| Gate of Lodore | 261 |

| Winnie’s Grotto | 264 |

| Echo Rock | 267 |

| Gunnison’s Butte | 271 |

| Buttes of the Cross | 274 |

| Marble Cañon | 279 |

| Grand Cañon of the Colorado | 283 |

| Grand Cañon, from To-ro-Wasp | 287 |

| Exploring the Walls | 292 |

| Castle Gate | 297 |

| In Spanish Fork Cañon | 300 |

| Tramway in Little Cottonwood Cañon | 305 |

| Salt Lake City | 311 |

| Mormon Temple, Tabernacle and Assembly Hall | 325 |

| Great Salt Lake | 331 |

Old Woodcock says that if Providence had not made him a justice of the peace, he’d have been a vagabond himself. No such kind interference prevailed in my case. I was a vagabond from my cradle. I never could be sent to school alone like other children—they always had to see me there safe, and fetch me back again. The rambling bump monopolized my whole head. I am sure my godfather must have been the Wandering Jew or a king’s messenger. Here I am again, en route, and sorely puzzled to know whither.—The Loiterings of Arthur O’Leary.

“‘There are the Rocky Mountains!’ I strained my eyes in the direction of his finger, but for a minute could see nothing. Presently sight became adjusted to a new focus, and out against a bright sky dawned slowly the undefined shimmering trace of something a little bluer. Still it seemed nothing tangible. It might have passed for a vapor effect of the horizon, had not the driver called it otherwise. Another minute and it took slightly more certain shape. It cannot be described by any Eastern analogy; no other far mountain view that I ever saw is at all like it. If you have seen those sea-side albums which ladies fill with algæ during their summer holiday, and in those albums have been startled, on turning over a page suddenly, to see an exquisite marine ghost appear, almost evanescent in its faint azure, but still a literal existence, which had been called up from the deeps, and laid to rest with infinite delicacy and difficulty,—then you will form some conception of the first view of the Rocky Mountains. It is impossible to imagine them built of earth, rock, anything terrestrial; to fancy them cloven by horrible chasms, or shaggy with giant woods. They are made out of the air and the sunshine which show them. Nature has dipped her pencil in the faintest solution of ultramarine, and drawn it once across the Western sky with a hand tender as Love’s. Then when sight becomes still better adjusted, you find the most delicate division taking place in this pale blot of beauty, near its upper edge. It is rimmed with a mere thread of opaline and crystalline light. For a moment it sways before you and is confused. But your eagerness grows steadier, you see plainer and know that you are looking on the everlasting snow, the ice that never melts. As the entire fact in all its meaning possesses you completely, you feel a sensation which is as new to your life as it is impossible of repetition. I confess (I should be ashamed not to) that my first view of the Rocky Mountains had no way of expressing itself save in tears. To see what they looked, and to know what they were, was like a sudden revelation of the truth that the spiritual is the only real and substantial; that the eternal things of the universe are they which, afar off, seem dim and faint.”

There are the Rocky Mountains! Ludlow saw them after days of rough riding in a dusty stage-coach. Our plains journey had been a matter of a few hours only, and in the luxurious ease of a Pullman sleeping car; but our hearts, too, were stirred, and we eagerly watched them rise higher and higher, and perfect their ranks, as we threaded the bluffs into Pueblo. Then there they were again, all the way up to Denver; and when we arose in the morning and glanced out of the hotel window, the first objects our glad eyes rested on were the snow-tipped peaks filling the horizon.

Thither Madame ma femme and I proposed to ourselves to go for an early autumn ramble, gathering such friends and accomplices as presented themselves. But how? That required some study. There were no end of ways. We were given advice enough to make a substantial appendix to the present volume, though I suspect that it would be as useless to print it for you as it was to talk it to us. We could walk. We could tramp, with burros to carry our luggage, and with or without other burros to carry ourselves. We could form an alliance, offensive and defensive, with a number of pack mules. We could hire an ambulance sort of wagon, with bedroom and kitchen and all the other attachments. We could go by railway to certain points, and there diverge. Or, as one sober youth suggested, we needn’t go at all. But it remained for us to solve the problem after all. As generally happens in this life of ours, the fellow who gets on owes it to his own momentum, for the most part. It came upon us quite by inspiration. We jumped to the conclusion; which, as the Madame truly observed, is not altogether wrong if only you look before you leap. That is a good specimen of feminine logic in general, and the Madame’s in particular.

But what was the inspiration—the conclusion—the decision? You are all impatience to know it, of course. It was this:

Charter a train!

Recovering our senses after this startling generalization, particulars came in order. Spreading out the crisp and squarely-folded map of Colorado, we began to study it with novel interest, and very quickly discovered that if our brilliant inspiration was really to be executed, we must confine ourselves to the narrow-gauge lines. Tracing these with one prong of a hair pin, it was apparent that they ran almost everywhere in the mountainous parts of the State, and where they did not go now they were projected for speedy completion. Closer inspection, as to the names of the lines, discovered that nearly all of this wide-branching system bore the mystical letters D. & R. G., which evidently enough (after you had learned it) stood for—

“Why, Denver and Ryo Grand, of course,” exclaims the Madame, contemptuous of any one who didn’t know that.

“Not by a long shot!” I reply triumphantly, “Denver and Reeo Grandy is the name of the railway—Mexican words.”

“Oh, indeed!” is what I hear; a very lofty nose, naturally a trifle uppish, is what I see.

Deciding that our best plan is to take counsel with the officers of the Denver and Rio Grande railway, we go immediately to interview Mr. Hooper, the General Passenger Agent, among whose many duties is that of receiving, counseling, and arranging itineraries for all sorts of pilgrims. An hour’s discussion perfected our arrangements, and set the workmen at the shops busy in preparing the cars for our migratory residence.

The realization that our scheme, which up to this point had seemed akin to a wild dream, was now rapidly growing into a promising reality, did not diminish our enthusiasm. Indeed we experienced an exhilaration which was quite phenomenal. Was it the very light wine we partook at luncheon? Perish the suspicion! Possibly it was the popularly asserted effect of the rarefied atmosphere. But kinder to our self-esteem than either of these was the thought that our approaching journey had something to do with our elevation, and we accepted it as an explanation.

But we had yet a few days to spare, and we could employ them profitably in looking over this Denver, the marvelous city of the plains. We studied it first from Capitol Hill, as our artist has done, though his picture, so excellently reproduced, can convey but the shadow of the substance. Then we nearly encompassed the town, going southward on Broadway until we had passed Cherry Creek, and détouring across Platte River to the westward and northward, on the high plateau which stretches away to the foothills. The city lies at an altitude of 5,197 feet, near the western border of the plains, and within twelve miles of the mountains,—the Colorado or front range of which may be seen for an extent of over two hundred miles. In the north, Long’s Peak rears its majestic proportions against the azure sky. Westward, Mounts Rosalie and Evans rise grandly above the other summits of the snowy range, and Gray’s and James’ Peaks peer from among their gigantic brethren; while historic Pike’s Peak, the mighty landmark that guided the gold-hunters of ’59, plainly shows its white crest eighty miles to the south. The great plains stretch out for hundreds of miles to the north, east and south. Near the smelting works at Argo, we retrace our way and re-enter the city.

It is the metropolis of the Rocky Mountains, and a stroll through these scores of solid blocks of salesrooms and factories exhibits at once the fact that it is as the commercial center of the mountainous interior that Denver thrives, and congratulates herself upon the promise of a continually prosperous future. She long ago safely passed that crisis which has proved fatal to so many incipient Western cities. Every year proves anew the wisdom and foresight of her founders; and I think her assertion that she is to be the largest city between Chicago and San Francisco is likely to be realized. Most of her leading business men came here at the beginning, but their energies were hampered when every article had to be hauled six hundred miles across the plains by teams. It frequently used to happen that merchants would sell their goods completely out, put up their shutters and go a-fishing for weeks, before the new semi-yearly supplies arrived. Everybody therefore looked forward, with good reason, to railway communication as the beginning of a new era of prosperity, and watched with keen interest the approach of the Union Pacific lines from Omaha and Kansas City. These were completed, by the northern routes, in 1869 and 1870; and a few months later the enterprising Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe sent its tracks and trains through to the mountains, and then came the Burlington route, a most welcome acquisition, adding another link to the transcontinental chain, which now binds the East to the West, the Atlantic to the Pacific coast. At Pueblo, the Denver and Rio Grande, meeting the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe, was already prepared to make this new route available to Denver and much of Colorado, and adopting a liberal policy, at once exerted an immense influence upon the speedy development and prosperity of the State.

Thus, in a year or two, the young city found itself removed from total isolation to a central position on various railways, east and west, and to its mill came the varied grist of a circle hundreds of miles in radius. Now blossomed the booming season of business which sagacious eyes had foreseen. The town had less than four thousand inhabitants in 1870. A year from that time her population was nearly fifteen thousand, and her tax-valuation had increased from three to ten millions of dollars. It was a time of happy investment, of incessant building and improvement, and of grand speculation. Mines flourished, crops were abundant, cattle and sheep grazed in a hundred valleys hitherto tenanted by antelope alone, and everybody had plenty of money. Then came a shadow of storm in the East, and the sound of the thunder-clap of 1873 was heard in Denver, if the bolt of the panic was not felt. The banks suddenly became cautious in loans; speculators declined to buy, and sold at a sacrifice. Merchants found that trade was dull, and ranchmen got less for their products. It was a “set-back” to Denver, and two years of stagnation followed. But she only dug the more money out of the ground to fill her depleted pockets, and survived the “hard times” with far less sacrifice of fortune and pride than did most of the Eastern cities. None of her banks went under, nor even certifieda check, and most of her business houses weathered the storm. The unhealthy reign of speculation was effectually checked, and business was placed upon a compact and solid foundation. Then came 1875 and 1876, which were “grasshopper years,” when no crops of consequence were raised throughout the State, and a large amount of money was sent East to pay for flour and grain. This was a particularly hard blow, but the bountiful harvest of 1877 compensated, and the export of beeves and sheep, with their wool, hides and tallow, was the largest ever made up to that time.

The issue of this successful year with miner, farmer and stock-ranger, yielding them more than $15,000,000, a large proportion of which was an addition to the intrinsic wealth of the world, had an almost magical effect upon the city. Commerce revived, a buoyant feeling prevailed among all classes, and merchants enjoyed a remunerative trade. Money was “easy,” rents advanced, and the real estate business assumed a healthier tone. Generous patronage of the productive industries throughout the whole State was made visible in the quickened trade of the city, which rendered the year an important one in the history of Denver’s progress. So, out of the barrenness of the cactus-plain, and through this turbulent history, has arisen a cultivated and beautiful city of 75,000 people, which is truly a metropolis. Her streets are broad, straight, and everywhere well shaded with lines of cottonwoods and maples, abundant in foliage and of graceful shape. On each side of every street flows a constant stream of water, often as clear and cool as a mountain brook. The source is a dozen miles southward, whence the water is conducted in an open channel. There are said to be over 260 miles of these irrigating ditches or gutters, and 250,000 shade-trees.

For many blocks in the southern and western quarter of the town,—from Fourteenth to Thirtieth streets, and from Arapahoe to Broadway and the new suburbs beyond—you will see only elegant and comfortable houses. Homes succeed one another in endlessly varying styles of architecture, and vie in attractiveness, each surrounded by lawns and gardens abounding in flowers. All look new and ornate, while some of the dwellings of wealthy citizens are palatial in size and furnishing, and with porches well occupied during the long, cool twilight characteristic of the summer evening in this climate, giving a very attractive air of opulence and ease. Even the stranger may share in the general enjoyment, for never was there a city with so many and such pleasant hotels, the largest of which, the Windsor and the St. James, are worthy of Broadway or Chestnut street.

The power which has wrought all this change in a short score of years, truly making the desert to bloom, is water; or, more correctly, that is the great instrument used, for the power is the will and pride of the intelligent men and women who form the leading portion of the citizens. Water is pumped from the Platte, by the Holly system, and forced over the city with such power that in case of fire no steam-engine is necessary to send a strong stream through the hose. The keeping of a turf and garden, after it is once begun, is merely a matter of watering. The garden is kept moist mainly by flooding from the irrigating ditch in the street or alley, but the turf of the lawn and the shrubbery owe their greenness to almost incessant sprinkling by the hand-hose. Fountains are placed in nearly every yard. After dinner (for Denver dines at five o’clock as a rule), the father of the house lights his cigar and turns hose-man for an hour, while he chats with friends; or the small boys bribe each other to let them lay the dust in the street, to the imminent peril of passers-by; and young ladies escape the too engrossing attention of complimentary admirers by busily sprinkling heliotrope and mignonette, hinting at a possible different use of the weapon if admiration becomes too ardent. The swish and gurgle and sparkle of water are always present, and always must be; for so Denver defies the desert and dissipates the dreaded dust.

Their climate is one of the things Denverites boast of. That the air is pure and invigorating is to be expected at a point right out on a plateau a mile above sea-level, with a range of snow burdened mountains within sight. From the beginning to the end of warm weather it rarely rains, except occasional thunder and hail storms in July and August. September witnesses a few storms, succeeded by cool, charming weather, when the haze and smoke is filtered from the bracing air, and the landscape robes itself in its most enchanting hues. The coldest weather occurs after New Year’s Day, and lasts sometimes until April. Then come the May storms and floods, followed by a charming summer. The barometer holds itself pretty steady throughout the year. There is a vast quantity of electricity in the air, and the displays of lightning are magnificent and occasionally destructive. Sunshine is very abundant. One can by no means judge from the brightest day in New York of the wonderful glow sunlight has here. During 1884 there were 205 clear days, 126 fair, and 34 cloudy, the sun being totally obscured on only 18 days; and yet this record is more unfavorable than the average for a number of years. Summer heat often reaches a hundred in the shade at midday; but with sunset comes coolness, and the nights allow refreshing sleep. In winter the mercury sometimes sinks twenty degrees below zero; but one does not feel this severity as much as he would a far less degree of cold in the damp, raw climate of the coast. Snow is frequent, but rarely plentiful enough for sleighing.

Denver is built not only with the capital of her own citizens, but constructed of materials close at hand. Very substantial bricks, kilned in the suburbs, are the favorite material. Then there is a pinkish trachyte, almost as light as pumice, and ringing under a blow with a metallic clink, that is largely employed in trimmings. Sandstone, marble and limestone are abundant enough for all needs. Coarse lumber is supplied by the high pine forests, but all the hard wood and fine lumber is brought from the East. The fuel of the city was formerly wholly lignite coal, which comes from the foothills; but the extension of the railway to Cañon City, El Moro and the Gunnison, have made the harder and less sulphurous coals accessible and cheap.

And while she has been looking well after the material attractions, Denver has kept pace with the progress of the times in modern advantages. She is very proud of her school-buildings, constructed and managed upon the most improved plans; of her fine churches, of her State and county offices, her seminaries of higher learning, and of her natural history and historical association. Her Grand Opera House is the most elegant on the continent, her business blocks are extensive and costly, and the Union Depot ranks with the best of similar structures. Gas was introduced several years ago, and the system, which now includes nearly all sections of the city, is being constantly improved and extended. The Brush electric light has been in very general use for nearly three years, and the Edison incandescent lamps are now being employed. The telephone is found in hundreds of business places and residences, the exchange at the close of last year numbering 709 subscribers. The water supply is distributed through forty miles of mains, the consumption averaging three million gallons per day, exclusive of the contributions of the irrigating ditches and the numerous artesian wells. The steam heating works evaporate one hundred thousand gallons of water daily, delivering the product through three miles of mains and nearly two miles of service pipes; this being the only company out of twenty seven of its nature in the country which has proved a financial success. Street car lines traverse the thoroughfares in all directions, and transport over two million passengers annually. Two district messenger companies are generously patronized. The regular police force consists of some forty-five patrolmen and detectives, aside from the Chief and his assistants; and a distinct organization is the Merchant’s Police, numbering twenty men. A paid Fire Department is maintained, at an annual expense of $56,000, and the alarm system embraces twenty-six miles of wire and fifty signal boxes. There are published six daily newspapers, one being in German, and a score of weeklies. All are well conducted and prosperous.

A branch of the United States Mint is located here, but is used for assays only, and not for coinage. An appropriation has been made by Congress for a handsome building, the site has been selected, and work is now being pushed forward. The post-office is a source of considerable revenue to the Government. There are six National and two State banks, with a paid in capital of $870,000, and showing a surplus of $754,000 at the close of 1883. The deposits for the year amounted to $8,396,200, and the loans and discounts approximated $4,500,000. The shops of the Denver and Rio Grande railway are doubtless the most extensive in the West, employing over 800 men, and turning out during the year 2 express, 8 mail, 4 combination, 522 box, 303 stock, 25 refrigerator, 197 flat, and 300 coal cars, together with 8 cabooses. In addition they have produced 350 frogs, 200 switch stands, and all the iron work for the bridges on 350 miles of new road, The year’s shipments of the Boston and Colorado Smelting Company aggregate, in silver, gold, and copper, $3,907,000; and in the same time the Grant smelter has treated, in silver, lead and gold, $6,348,868. Finally, from the statistics at hand it appears that the volume of Denver’s trade for the year referred to, apart from the industries above mentioned, and real estate transactions, has exceeded the snug sum of $58,856,998. In the meantime the taxable valuation of property in Arapahoe county has increased $6,600,000.

These facts establish, beyond the slightest doubt, the truth that Denver stands upon a firm financial basis. This the casual stranger can hardly fail to surmise when he glances at her magnificent buildings, and statistics will confirm the surmise.

Denver society is cosmopolitan. Famous and brilliant persons are constantly appearing from all quarters of the globe. Five hundred people a day, it is said, enter Colorado, and nine-tenths of this multitude pass through Denver. Nowadays, “the tour” of the United States is incomplete if this mountain city is omitted. Thus the registers of her hotels bear many foreign autographs of world-wide reputation. Surprise is often expressed by the critical among these visitors (why, I do not understand) at the totally unexpected degree of intelligence, appreciation of the more refined methods of thought and handiwork, and the knowledge of science, that greet them here. Matters of art and music, particularly, find friends and cultivation among the educated and generous families who have built up society; and there are schools and associations devoted to sustaining the interest in them, just as there are reading circles and literary clubs. And, withal, there is the most charming freedom of acquaintance and intercourse—the polish and good-breeding of rank, delivered from all chill and exclusiveness or regard for “who was your grandfather.” Yet this winsome good-fellowship by no means descends to vulgarity, or permits itself to be abused. After all, it is only New York and New England and Ohio, transplanted and considerably enlivened.

Returning to our consideration of Denver’s resources, it will readily be seen that she stands as the supply-depot and money-receiver of three great branches of industry and wealth, namely, mining, stock-raising and agriculture.

The first of these is the most important. Many of the richest proprietors live and spend their profits here. Then, too, the machinery which the mining and the reduction of the ores require, and the tools, clothing and provisions of the men, mainly come from here. Long ago ex-Governor Gilpin, worthily one of the most famous of Colorado’s representative men, and an enthusiast upon the subject of her virtues and loveliness, prophesied the immense wealth which would continue to be delved from the crevices of her rocky frame, and was called a visionary for his pains; but his prophesies have aggregated more in the fulfillment than they promised in the foretelling, and his “visions” have netted him a most satisfactory fortune. About 75,000 lodes have been discovered in Colorado, and numberless placers. Only a small proportion of these, of course, were worked remuneratively, but the cash yield of the twenty years since the discovery of the precious metals, has averaged over $7,000,000 a year, and has increased from $200,000 in 1869 to over $26,376,562 in 1883. Not half of this is gold, yet it is only since 1870 that silver has been mined at all in Colorado. These statistics show the total yield of the State in gold and silver thus far to exceed $154,000,000, not to mention tellurium, copper, iron, lead and coal. Surely this alone is sufficient employment of capital and production of original wealth—genuine making of money—to ensure the permanent support of the city.

The second great source of revenue to Denver, is the cattle and sheep of the State. The wonderful worthless-looking buffalo grass, growing in little tufts so scattered that the dust shows itself everywhere between, and turning sere and shriveled before the spring rains are fairly over, has proved one of Colorado’s most prolific avenues of wealth. The herds now reported in the State count up 1,461,945 head, and the annual shipments amount to 100,000, at an average of $20 apiece, giving $2,000,000 as the yearly yield. Add the receipts for the sales of hides and tallow, and the home consumption, amounting to about $60,000, and you have a figure not far from $3,500,000 to represent the total annual income from this branch of productive industry. The whole value of the cattle investments in the State is estimated by good judges at $14,000,000, nearly one-fourth of which is the property of citizens of Denver. Yet this sum, great as it is for a pioneer region, represents only two-thirds of Colorado’s live stock. Last year about 1,500,000 sheep were sheared, and more capital is being invested in them. Perhaps the total value of sheep ranches is not less than $5,000,000, the annual income from which approaches $1,300,000.

The third large item of prosperity is agriculture, although it advances in the face of much opposition. In 1883 the production of the chief crops was as follows: hay, 266,500 tons; wheat, 1,750,840 bushels; oats, 1,186,534 bushels; corn, 598,975 bushels; barley, 265,180 bushels; rye, 78,030 bushels, and potatoes, 851,000 bushels. Add to this vegetables and small fruits, and the yield of the soil in Colorado is brought to over $9,000,000 in value. Farmers are learning better and better how to produce the very best results by means of scientific irrigation, and the tillage is annually wider.

Nor is this the whole story. Denver is rapidly growing into a manufacturing center. Here are rolling mills, iron foundries, smelters, machine shops, woolen mills, shoe factories, glass works, carriage and harness factories, breweries, and so on through a long list. The flouring mills are very valuable, representing an investment of $350,000, and handling half the wheat crop of Colorado. I have dwelt upon these somewhat prosy statements in order to point out fully what rich resources Denver has behind her, and how it happens that she finds herself, at twenty-three years of age, amazingly strong commercially. Not only a large proportion of the money which gives existence to these enterprises (nearly every householder in the city has a financial interest in one or several mines, stock-ranges or farms), but, as I have intimated, the current supplies that sustain them, are procured in Denver, and a very large percentage of their profits finds its way directly to this focus.

Denver thus becomes to all Colorado what Paris is to France. Through all the enormous area, from Wyoming far into New Mexico, and westward to Utah, she has had no formidable rival until South Pueblo rose to contest the trade of all the southern half of this commercial territory. That she advances with the rapidly thickening population of the State and its increasing needs, is apparent to every one who has noted the gigantic strides with which Denver has grown, and the ease with which she wears her imperial honors. Every extension of the railways, every good crop, every new mineral district developed, every increase of stock-ranges, directly and instantly affects the great central mart. This sound business basis being present, the opportunity to pleasantly dispose of the money made is, of course, not long in presenting itself. It thus happens that Denver shows, in a wonderful measure, the amenities of intellectual culture that make life so attractive in the old-established centers of civilization, where selected society, thoughtful study, and the riches of art, have ripened to maturity through long time and under gracious traditions. There is an abundance here, therefore, to please the eye and touch the heart as well as fill the pockets, and year by year the city is becoming more and more a desirable place in which to dwell as well as to do business.

—Stanley H. Ray.

While we were codifying our impressions of Denver, the workmen at the shops had been busy. We were busy, too, in other than literary ways, and badgered our new acquaintances at the railway offices at all sorts of times and with every manner of want. The butcher and baker were harassed, and jolly old Salomon, the grocer, came in for his share of the nuisance. But it didn’t last long, for one afternoon, just three days from the birth of the happy thought, we were in our special train and rushing away to the South.

Not till then did this haphazard crowd—for we had enlisted three gentlemen into our company—inquire seriously whither we were going. What did it matter? We were wild with joy because of going at all. Had we not bed and provender with us? Why could we not go on always? have it said of us when living, Going, going, and written over us when dead—Gone!

I have mentioned three companions besides the Madame. At least two of the gentlemen you would recognize at once, were I to give you their names. The Artist is famed on both sides of the Atlantic for the masterly productions of his brush. He is a wide traveler and an enthusiast over mountain scenery. The Photographer is likewise a genius, and literally a compendium of scientific knowledge and exploration. Connected for many years with the Geological Surveys of this region, his practical experience renders him an especially valuable coadjutor. The Musician is young in years, with the scroll of fame before him. But he comes of good stock, and faith is strong. And there is still another, our Amos, of sable hue, who has our fortunes, to a large extent, in his keeping, for does he not preside over our commissary? We shall know him better by and by.

Our train consisted of three cars; and when we had passed the great works at Burnham, we resolved ourselves into an investigating committee and started on a tour of inspection. We found our quarters exceedingly well-arranged and comfortable, although in some confusion from the hasty manner in which our loose supplies had been tumbled in. So the committee postponed its report.

“How smoothly we bowl along!” remarked the Musician.

“And in what superb condition are the roadbed and track,” added the Photographer.

Yet so gentle and noiseless was the motion that it required the testimony of the speed-indicator to convince us that we were making thirty-five miles per hour. We had passed the huge Exposition building at our left, flitted by the picturesque village of Littleton, with its neat stone depot and white flouring-mills, and were approaching Acequia (which you must pronounce A-sáy-ke-a) along a shelving embankment overlooking the Platte. Away to the west and across the valley, we could discern a yellow band, which the Photographer explained was the new canal under construction by an English company, and which was intended to convey the water of the Platte, from a point far up its cañon, to Denver. The canal or ditch here emerges from the mountains and bears away to the southward for some distance, until it nears Plum Creek, crossing which, by means of an aqueduct, it turns sharply to the northward, and apparently climbs the higher table-lands in the direction of Denver. As observed from the car window the anomaly seems indisputable, the deception of course being attributable to the ascending grade of the railway. This is one of several cases in the State which will be pointed out, by old-timers to new-comers, as veritable instances where water runs up hill.

The valleys of Plum Creek and its branches are of good width, and hollowed out of the modern deposits so as to form beautiful and fertile lands, while on each side a terrace extends down from the mountains, like a lawn. Following up the main valley we reach Castle Rock, with its immense hay ranches and fortress-butte, and beyond is Larkspur, named after one of the most striking of the plains birds. Thence the run is through a section of billowy plains or depressed foot-hills, up a steady ninety-feet grade to the Divide, in whose vicinity we encounter a succession of high buttes and mesas, the lower portions being composed of sandstone, while the tops are of igneous rock or lava. These constantly suggest artificial forms of towers, castles and fortifications, in some places rising nearly a thousand feet above the railway. Not infrequently the cliffs are so regularly disposed that it is hard to believe them merely natural formations. The entire scenery of this great ridge, and extending far out into the plains, is of an unique and interesting character. Near the summit there are remarkable evidences of its having been the coast-line of an ancient sea. The streams which rise on the northern slope of this watershed find their way into the Platte, while those on the southern declivity flow into the Arkansas. The Divide has a good covering of pines, often arranged by nature with park-like symmetry, and forming a charming contrast with the bare but beautifully colored cliffs. This region has been a chief source of Denver’s lumber supply, and the timber tract is estimated to contain about 70,000 acres.

On the Divide is a beautiful sheet of water, known as Palmer Lake from which is derived a large quantity of the purest ice. Here a novel and attractive depot has been erected by the railway company, and extensive improvements, including a dancing pavilion and summer hotel, cottages and boat-houses, have been made. In the hottest seasons the temperature is always cool and invigorating, and no spot within accessible distance is so well adapted for an economical and delightful resort for Denverites. On the southern face of the hill the rock-formations break out into still more marked resemblances to ruined castles, showing moats, arches and turrets. It follows that our Artist was enraptured with the romantic features of the place, and the Photographer insisted on taking out his camera and getting at work. One of his results, Phebe’s Arch, is contributed to the pictorial fund of this volume. The descent from the Divide is rapid, and our attention is absorbed by the swiftly changing panorama. Close by are the mountains—their snowy pyramids holding entranced your eyes from far, far out on the plains. “In variety and harmony of form,” said Bayard Taylor of them: “in effect against the dark blue sky, in breadth and grandeur, I know of no external picture of the Alps which can be placed beside it. If you could take away the valley of the Rhone, and unite the Alps of Savoy with the Bernese Oberland, you might obtain a tolerable idea of this view of the Rocky Mountains.” Pike’s Peak is constantly in sight, and every curve in the steel road presents it in a different aspect.

Presently we find ourselves on the bank of Monument Creek, pass the station of the same name, and soon encounter a series of small basins, and side valleys, green-carpeted and with gently sloping and wooded sides.

“Observe those odd rocks!” suddenly exclaims the Madame. “Notice how, all along the bluff, stand rows of little images, like the carved figure-friezes of the Parthenon; and how those great isolated rocks have been left like the discarded and broken furniture of Gog and Magog.”

“Yes,” I say, “but the tone of your imagery is low. Long, long ago a higher sentiment called them ‘monuments,’ and this whole illy-defined region of grotesquely-cut sandstones, Monument Park.”

And then we all fall into a discussion of the process of formation of these quaint obelisks, which is interrupted by the Artist.

“Here is some pertinent testimony in Ludlow’s admirable book, the ‘Heart of the Continent,’ which by your leave I will read to you. Ready?”

“Fire away!” we reply, and do the same with our cigars, making a treaty of amity in the blaze of a mutual match.

“‘I ascended one of the most practicable hills among the number crowned by sculpturesque formations. The hill was a mere mass of sand and débris from decayed rocks, about a hundred feet high, conical, and bearing on its summit an irregular group of pillars. After a protracted examination, I found the formation to consist of a peculiar friable conglomerate, which has no precise parallel in any of our Eastern strata. Some of the pillars were nearly cylindrical, others were long cones; and a number were spindle-shaped, or like a buoy set on end. With hardly an exception, they were surmounted by capitals of remarkable projection beyond their base. These I found slightly different in composition from the shafts. The conglomerate of the latter was an irregular mixture of fragments from all the hypogene rocks of the range, including quartzose pebbles, pure crystals of silex, various crystalline sandstones, gneiss, solitary horn-blende and feldspar, nodular iron stones, rude agates and gun-flint; the whole loosely cemented in a matrix composed of clay, lime (most likely from the decomposition of gypsum), and red oxide of iron. The disk which formed the largely projecting capital seemed to represent the original diameter of the pillar, and apparently retained its proportions in virtue of a much closer texture and larger per cent. of iron in its composition. These were often so apparent that the pillars had a contour of the most rugged description, and a tinge of pale cream yellow, while the capitals were of a brick-dust color, with excess of red oxide, and nearly as uniform in their granulation as fine millstone-grit. The shape of these formations seemed, therefore, to turn on the comparative resistance to atmospheric influences possessed by their various parts. Many other indications ... led me to narrow down all the hypothetical agencies which might have produced them, to a single one,—air, in its chemical or mechanical operations, and usually in both.... One characteristic of the Rocky Mountains is its system of vast indentations, cutting through from the top to the bottom of the range. Some of these take the form of funnels, others are deep, tortuous galleries known as passes or cañons; but all have their openings toward the plains. The descending masses of air fall into these funnels or sinuous canals, as they slide down, concentrating themselves and acquiring a vertical motion. When they issue from the mouth of the gorge at the base of the range, they are gigantic augers, with a revolution faster than man’s cunningest machinery, and a cutting-edge of silex, obtained from the first sand heap caught up by their fury. Thus armed with their own resistless motion and an incisive thread of the hardest mineral next to the diamond, they sweep on over the plains to excavate, pull down, or carve in new forms, whatever friable formation lies in their way.’”

By this time Colorado Springs was at hand, and as we had decided, like all other sensible people who come to Colorado, to sojourn awhile there and at Manitou, our cars were side-tracked. And while Amos betook himself to the preparation of our evening meal, we admired the gorgeous sunset, and disposed our effects for the first night out.

Henry Ward Beecher once said that while the new birth was necessary to a true Christian life, it was very important that one be born well the first time. Colorado Springs was born well. It was organized on the colony plan, and the first stake was driven in July, 1871. Intelligent and far-seeing men were leaders of the enterprise, and in no way was their sagacity more apparent than in the insertion, in every deed of transfer, of a clause prohibiting, upon pain of forfeiture, the sale or manufacture of alcoholic beverages on the premises conveyed. This temperance clause was introduced by General W. J. Palmer, the president of the colony, who during his services as engineer of railway extensions, had observed the destruction which the unrestrained traffic in intoxicants worked to life and property. It was not sentiment, but a sound business precaution, as the result has proved. Of course this provision has been contested, but it has been legally sustained, and has given the town the best moral tone of any in Colorado. The location was also wisely chosen, broad and regular streets were carefully laid out, a system of irrigation established, thousands of trees planted, and reservations for parks set aside. Some of the avenues running north and south might with propriety be designated boulevards, being 140 feet in width, with double roadways separated by parallel rows of trees. Other trees shade the walks at either side, and at their roots flow rapid streamlets of clearest water. The drives are smooth and hard, and the soil never becomes muddy, the moisture penetrating rapidly through the light gravelly loam. The gentle inclination southward renders drainage a very simple matter.

Seen from the railway, the town appears to be located upon a considerable elevation. In fact it stands upon a plateau in the midst of a valley. The thirty-five miles of streets and avenues are closely lined with substantial business blocks, pretentious residences, or tasty cottages. The pink and white stone of the Manitou quarries is largely used; and pent-roofs, ornamental gables, red chimneys, and the whole category of renaissance peculiarities, have representation in the architecture. The dwellers in these abodes are principally of the cultured and refined classes. Invalids from the intellectual centers of the East find health and congenial society here, while numbers of opulent mine owners and stockmen make the Springs their winter home.

The public buildings are all creditable; the Deaf-Mute Institute, Colorado College, the churches and schools being specially noteworthy. The Opera House is a veritable bijou, handsome and convenient in all its appointments, and with a single exception not surpassed west of the Missouri. The new hotel, The Antlers, erected at a cost of over $125,000, is of stone, and is without doubt the most artistic and elegant structure of its kind in the State. It occupies a sightly position at the edge of the plateau, and from its balconies and verandas a marvelous and most inspiring view is presented. The foothills lie along the west, about five miles distant, the massive outlines of Cheyenne Mountain a little to the left, and the huge red towers that mark the gateway to the Garden of the Gods lifting their crests over the Mesa at the right, while above them all is reared the snow-crowned summit of Pike’s Peak. To the north, is seen in the foreground the gray shoulders of the buttes, and in the distance the dark pine-covered elevation of the Divide. Easterly the land rises gently in a gray, grass-clad plain, until it cuts the blue horizon with a level line; while southward the mountains trend away, purple in the distance.

Colorado Springs lies under the shadow of Pike’s Peak; and in the short autumn days the sun drops out of sight behind the mountain with startling suddenness at four o’clock. Then come the cool shadows, when fires have to be replenished, and doors and windows closed. From ten o’clock until the sun hides behind the hills, the blue skies, the soft breezes, the grateful warmth, suggest that month in which, if ever, come perfect days. The June roses are absent but the days are as rare as a day in June. The average temperature here is sixty degrees, and there are about three hundred days of sunshine in the year.

Within a radius of ten miles about the Springs are to be found more “interesting, varied and famous scenic attractions than in any similar compass the country over,” we are told by the guide, and we are quite ready to believe when they are recounted. A drive of three miles across the Mesa, with its magnificent mountain view, brings you to Glen Eyrie, the secluded home of General Palmer, originator of the Denver and Rio Grande railway. “At the entrance you pass a little lodge—a sonnet in architecture, if one may so express it—the small but perfect rendering of a harmonious thought; you cross and recross a rushing, tumbling mountain brook over a dozen different bridges, some rustic, some of masonry, but each a gem in design and fitness; then at last, after the mind is properly tuned, as it were, to perfect accord, the full symphony bursts upon you. In the shadow of the eternal rock, with the wonderful background of mountains, surrounded by all that art can lend nature, is this delicious anachronism of a Queen Anne house, in sage-green and deep dull red, with arched balconies under pointed gables, and carved projections over mullioned windows, and trellised porches, with stained glass loopholes and an avalanche of roofs.” A little distance from the house strange forms of red sandstone lift their heads far above the foliage, like a file of genii marching down on solemn mission from their abodes in mountain caves, while on the ledges of the gray bluffs opposite the eagles have built their nests. Farther up the Glen, and yet a part of it, is Queen’s Cañon, a most rugged gorge, in which the wildness of nature has been for the most part unopposed. The same turbulent brook comes dashing down, in a series of cascades and rapids, from the Devil’s Punch-Bowl, near the head of the Cañon. Rustic bridges cross it near the foot, one of which is made the subject of an engraving; but soon the pathway breaks into a mere trail, which leads over boulders and fallen tree-trunks, or clings to precipitous cliffs which tower high overhead.

One mile north of Glen Eyrie is Blair Athol, with its exquisitely tinted pink sandstone pillars; while about the same distance to the south is the Garden of the Gods, which it seems, however, more proper to classify with Manitou’s environs. Five miles northeasterly from the Springs are Austin’s Bluffs, and a few miles west of these, Monument Park. Nearer by, and due west, are the Red and Bear Creek Cañons. An excellent way of reaching Pike’s Peak is by the Cheyenne Mountain toll road, which terminates in a good trail passing the Seven Lakes. The Cheyenne Cañons, at the northern base of the mountain of the same name, are greatly frequented, and justly rank high in the category. They are two in number.

South Cheyenne Cañon is full of surprises. “The vulgar linear measure of its length is out of harmony with the winding path over rocks, between straight pines, and across the rushing waters of the brook that boils down the whole rocky cut. The stream, tossing over its rough bed and dropping into sandy pools, drives one from side to side of the narrow passage-way for foothold. Eleven times one crosses it, by stepping from one rolling and uncertain stone to another, by balancing across the lurching trunk of a felled tree, or by dams of driftwood; and, finally, skirting a huge boulder that juts out into the water, and jumping from rock to rock, the head of the Cañon is reached. The narrow gorge ends in a round well of granite, down one side of which leaps, slides, foams and rushes a series of waterfalls. Seven falls in line drop the water from the melted snow above into this cup. Looking from below, one sees (as in our illustration) only three, that, starting down the last almost perpendicular wall and striking ledges in the rock, and oblique crevices, send their jet shooting in a curved spray to the pool. In this deep hollow only the noonday sun ever shines, and a narrow bank of snow lies against one side in the shadow of the cliff. Going up the Cañon, with the roar of the waters ahead and the wild path before one, the loftiness and savage wildness of the walls catch only a dizzying glance, but coming out, their sides seem to touch the heavens and to be measureless. The eye can hardly take in the vast height, and with the afternoon sun touching only the extreme tops, one realizes in what a crevice and fissure of the rocks the Cañon winds. Across the widest place between the walls a girl could throw a stone, and from that it narrows even more. The cool, dim light down at the base contrasts strangely with the red blaze that reflects from the top of the high walls; and emerging from one group of pine trees, a turn in the Cañon confronts one with a whole wall of sandstone burning in the intense sunlight. A comparison between this and the Via Mala and the other wild gorges of the Alps is impossible, but had legend and history and poetry followed it for centuries, South Cheyenne Cañon would have its great features acknowledged. Let a ruined tower stand at its entrance, whence robber knights had swooped down upon travelers and picked out the teeth of wealthy Hebrews; let a nation fight for its liberty through its chasm; and then let my Lord Byron turn loose the flood of his imagery upon it. After all, its wildness and untouched solitude are most impressive; and without history, save of the seasons, or sound, save of the wind, the water and the eagles, centuries have kept it for the small world that knows it now.” So discourses a very charming lady writer.

North Cheyenne Cañon is scarcely less interesting, though less widely known. Its beauty is of a milder type, the walls advancing and retreating, and anon breaking into gaily-colored pinnacles on which the sunlight plays in strange freaks of light and shade. The little brook winds like a silver band beside the path, encircling the boulders which it cannot leap, and all the while singing softly to the rhythm of swaying vines. The birds chirp in unison as they skip from rock to rock, and in the harmony and essence of the scene all are subdued—save the Artist, whose deft pencil cannot weary in so much loveliness. When words fail, it is fortunate he is at hand to rescue writer and reader alike.

It was during our stay at Colorado Springs we made acquaintance with the burro. It is the nightingale of Colorado; its range of voice is limited, consisting indeed of only two notes; but the amount of eloquence, the superb quality, the deep resonance and flexible sinuosity which can be thrown by this natural musician into such a small compass are tremendous. As they lope down the street, the larboard ear in air, while the starboard droops limply, the long tapir-like nose quivering with the mighty volume of sound which is pouring through it, the sloping Chinese eyes looking at you sideways with the lack-lustre expression of their race, and an artistic kick thrown in occasionally to produce the tremolo that adds the last touch of grace to the ringing voice, you are overwhelmed.

We betook ourselves to the train one evening, after our by no means thorough exploration of the neighborhood, and began our preparations for a few days’ absence at Manitou. It was only five miles away, and we had decided not to take our cars up. Retiring early, we fell asleep to dream of new pleasures, for which our appetites were already whetted.

—Petrarch.

As well omit the Lions of St. Mark from a visit to Venice, as to pass by Manitou in a tour of Colorado. Manitou, the sacred health-fountains of Indian tradition, the shrine of disabled mountaineers, the “Saratoga” of the Rockies.

Leaving Colorado Springs, a branch of the railway swings gracefully around the low hills in which the Mesa terminates, and points for the gap in the mountains directly to the west. Nearly three miles from the junction we pass the driving park, and immediately after run up to Colorado City, the first capital of the Territory, and now a quiet little hamlet, whose chief industry is the production of much beer. Recalling the temperance proclivities of the Springs, it is unfortunately not strange that a drive to Colorado City in the long summer evenings should prove so attractive to the ardent youth of untamed blood. Then the road passes into the clusters of cottonwoods and willows which fringe the brook, crossing, recrossing, and dashing through patches of sunlight, whence the huge colored pinnacles in the Garden of the Gods are descried over the broken hills at the right. It is a striking ride, and curiously the location of the railway has not been allowed to mar its native beauty. Describing the contour of a projecting foothill, we obtain our first glimpse of Manitou, with its great hotels, its cut-stone cottages, and its picturesque station. Just across the way, and in the lowest depression of the narrow vale, is a charming villa, embowered in shrubbery, with quaint gables and porches, and phenomenal lawns and flower-beds. It is the home of Dr. W. A. Bell, for years vice-president of the Denver and Rio Grande railway.

The village itself is grouped in careless ease along the steep and bushy slopes of the valley, straggling about and abounding in miniature chalets, precisely as a mountain village ought to do. The Fontaine-qui-Bouille, full of the sprightliness of its youth in Ute Pass, and its escapade at Rainbow Falls, comes dashing and splashing, and singing its happy song:

Down close to this frolicsome, icy-cold stream, are built the larger hotels, the Beebee and Manitou, surrounded by groves of cottonwood, aspen, wild cherry and box elder. They are cheery, clean, homelike, and handsomely furnished. The broad piazzas afford the finest views of Pike’s Peak, Cameron’s Cone, and their confreres. Here gather the “beauty and chivalry” of many climes, and in the long, soft evenings, devoid of dew or moisture, the cozy nooks offer the seclusion for—we had nearly said, flirtation—or cool refuge from the heated dancing-hall. Rustic bridges cross the brook, leading into a labyrinth of shade and on up to the crags behind. At the rear of the hotels, Lover’s Lane, a most romantic ramble, starts out in a half-mile maze through arbors, and flowering shrubs, and over little precipices, for the springs. Beside the path, and in out of-the-way spots among the bushes, are alluring seats, only large enough for two, where you may sit, while at your feet the selfsame brooklet murmurs:

Further up stream, a little way, are the homes of the citizens, and more hotels and boarding places—the Cliff House, Barker’s, and a dozen others. Here, too, on the banks of the creek, boiling up in basins of their own secretion, and hidden under rustic kiosks of a later date, are the springs themselves. They are six in number, varying in temperature from 43° to 56° F., and are strongly charged with carbonic acid. “Coming up the valley,” writes an authority, “the first is the Shoshone, bubbling up under a wooden canopy, close beside the main road of the village, and often called the Sulphur Spring, from the yellow deposit left around it. A few yards further on, and in a ledge of rock overhanging the right bank of the Fontaine, is the Navajo (shown in the foreground of our picture), containing carbonates of soda, lime and magnesia, and still more strongly charged with carbonic acid, having a refreshing taste similar to seltzer water. From this rocky basin, pipes conduct the water to the bath-house, which is situated on the stream a little below. Crossing by a pretty rustic bridge, we come to the Manitou, close to an ornamental summer-house; its taste and properties nearly resemble the Navajo. Recrossing the stream and walking a quarter of a mile up the Ute Pass road, following the right bank of the Fontaine, we find, close to its brink, the Ute Soda. This resembles the Manitou and Navajo, but is chemically less powerful, though much enjoyed for a refreshing draught. Retracing one’s steps to within two hundred yards of the Manitou Spring, we cross a bridge leading over a stream which joins the Fontaine at almost a right angle from the southwest; following up the right bank of this mountain brook, which is called Ruxton’s Creek, we enter the most beautiful of the tributary valleys of Manitou. Traversing the winding road among rocks and trees for nearly half a mile, we reach a pavilion close to the right bank of the creek, in which we find the Iron Ute, the water being highly effervescent, of the temperature of 44° 3´ F., and very agreeable in spite of its marked chalybeate taste. Continuing up the left bank of the stream for a few hundred yards, we reach the last of the springs that have been analyzed—the Little Chief; this is less agreeable in taste, being less effervescent and more strongly impregnated with sulphate of soda than any of the other springs, and containing nearly as much iron as the Iron Ute.

“These springs have from time immemorial enjoyed a reputation as healing waters among the Indians, who, when driven from the glen by the inroads of civilization, left behind them wigwams to which they used to bring their sick; believing, as they did, that the Good Spirit breathed into the waters the breath of life, they bathed and drank of them, thinking thereby to find a cure for every ill; yet it has been found that they thought most highly of their virtues when their bones and joints were racked with pain, their skins covered with unsightly blotches, or their warriors weakened by wounds or mountain sickness. During the seasons that the use of these waters has been under observation, it has been noticed that rheumatism, certain skin diseases, and cases of debility have been much benefited, so far confirming the experience of the past. The Manitou and Navajo have also been highly praised for their relief of old kidney and liver troubles, and the Iron Ute for chronic alcoholism and uterine derangements. Many of the phthisical patients who come to this dry, bracing air in increasing numbers are also said to have drunk of the waters with evident advantage.

“Professor Loew (chemist to the Wheeler expedition), speaking of the Manitou Springs as a group, says, very justly, they resemble those of Ems, and excel those of Spa—two of the most celebrated in Europe.

“On looking at the analyses of the Manitou group it will be seen that they all contain carbonic acid and carbonate of soda, yet they vary in some of their other constituents. We will, therefore, divide them into three groups of carbonated soda waters: 1. The carbonated soda waters proper, comprising the Navajo, Manitou and Ute Soda, in which the soda and carbonic acid have the chief action. 2. The purging carbonated soda waters, comprising the Little Chief and Shoshone, where the action of the soda and carbonic acid is markedly modified by the sulphates of soda and potash. 3. The ferruginous carbonated soda waters where the action of the carbonic acid and soda is modified by the carbonate of iron, comprising the Iron Ute and the Little Chief, which latter belongs to this group as well as to the preceding one.”

Such are the medicinal fountains that not only have proved themselves blessings to thousands of invalids, sick of pharmacy, but cause the summer days here to be haunted by pleasure seekers, who make the health of some afflicted friend, or weariness from overwork in them selves, excuse for coming; or boldly assert themselves here purely for pleasure. Time was when this entrance to a score of glens was a rendezvous for game and primitively wild. Even a dozen years ago it would answer to this description, and now one need not go far in winter to find successful shooting. “In summer time,” to quote the Earl of Dunraven, “beautiful but dangerous creatures roam the park. The tracks of tiny little shoes are more frequent than the less interesting, but harmless footprints of mountain sheep. You are more likely to catch a glimpse of the hem of a white petticoat in the distance than of the glancing form of a deer. The marks of carriage wheels are more plentiful than elk signs, and you are not now so liable to be scared by the human-like track of a gigantic bear as by the appalling impress of a number eleven boot.”

Do not imagine, however, that all the boot-tracks mark “the appalling impress of a number eleven.” The Madame tells me they dress as well at Manitou as at Saratoga; to me this seems a doubtful kind of compliment, but she intended it to cover the perfection of summer toilets. At Manitou, indeed, you do all you think it proper to do in the Green Mountains, or at White Sulphur, or any other upland resort, but in far more delightfully unconventional ways, and the enjoyment is proportionately increased.