Project Gutenberg's Introducing the American Spirit, by Edward A. Steiner This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Introducing the American Spirit Author: Edward A. Steiner Release Date: January 22, 2013 [EBook #41898] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK INTRODUCING THE AMERICAN SPIRIT *** Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

INTRODUCING THE

AMERICAN SPIRIT

| By EDWARD A. STEINER | |

| The Confession of a Hyphenated American | |

| 12mo, boards | net 50c. |

| Introducing the American Spirit | |

| What it Means to a Citizen and How it Appears to an Alien. 12mo, cloth | net $1.00 |

| From Alien to Citizen | |

| The Story of My Life in America. Illustrated, 8vo, cloth | net $1.50 |

| The Broken Wall | |

| Stories of the Mingling Folk. Illustrated, 12mo, cloth | net $1.00 |

| Against the Current | |

| Simple Chapters from a Complex Life. 12mo, cloth | net $1.25 |

| The Immigrant Tide—Its Ebb and Flow | |

| Illustrated, 8vo, cloth | net $1.50 |

| On the Trail of The Immigrant | |

| Illustrated, 12mo, cloth | net $1.50 |

| The Mediator | |

| A Tale of the Old World and the New. Illustrated, 12mo, cloth | net $1.25 |

| Tolstoy, the Man and His Message | |

| A Biographical Interpretation. Revised and enlarged. Illustrated, 12mo, cloth | net $1.50 |

| The Parable of the Cherries | |

| Illustrated, 12mo, boards | net 50c. |

| The Cup of Elijah | |

| Idyll Envelope Series. Decorated | net 25c. |

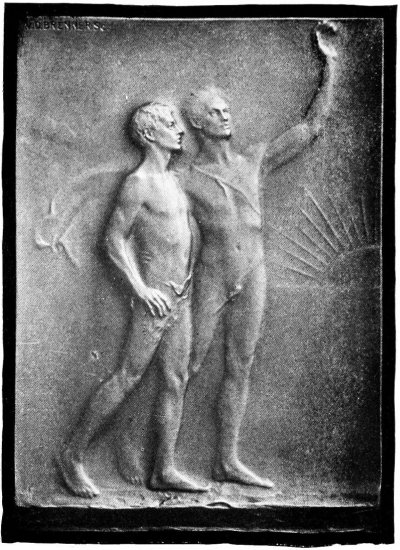

Courtesy of The Survey

V. D. Brenner

THE AMERICAN SPIRIT

By

Edward A. Steiner

Author of “From Alien to Citizen,” “The

Immigrant Tide,” etc.

New York Chicago Toronto

Fleming H. Revell Company

London and Edinburgh

Copyright, 1910, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue

Chicago: 80 Wabash Avenue

Toronto: 25 Richmond Street, W.

London: 21 Paternoster Square

Edinburgh: 100 Princes Street

To

Professor Richard Hochdoerfer, Ph. D.

erudite scholar and most lovable

friend, this book is dedicated

“Das ist ganz Americanish.” Whenever a German says this, he means that it is something which is practical, lavish, daringly reckless or lawless.

It means a short cut to achievement, a disregard of convention, an absence of those qualities which have given to the older nations of the world that fine, distinguishing flavor which is a fruit of the spirit.

Many attempts have been made to enlighten the Old World upon that point; but in spite of exchange-professorships and some notable, interpretative books upon the subject, we are still only the “Land of the Dollar.”

We are not loved as a nation, largely because we are not understood, and we are not understood because we do not understand ourselves, and we do not understand ourselves because we have not studied ourselves in the light of the spirit of other nations.

Coming to this country a product of Germanic civilization, knowing intimately the Slavic, Semitic, and Latin spirit, the writer was compelled to compare and to choose. Yet he would never have dared write upon this subject; not only because it was a difficult task, but because he had been so completely weaned from the Old World spirit that he had lost the proper perspective. Moreover, of formal books upon this subject there was no dearth.

During the last ten years, however, he has had the advantage of being the cicerone of distinguished Europeans who came to study various phases of our institutional life, and they brought the opportunity of fresh comparisons and also of new view-points in this realm of the national spirit.

These unconventional studies, most of which received their inspiration through the visit of the Herr Director and his charming wife, are here offered as an Introduction to the American Spirit, not only to the Herr Director and the Frau Directorin, but to those Americans who do not realize that a nation, as well as man, “cannot live by bread alone;” that its most precious asset, its greatest element of strength, is its Spirit, and that the elements out of which the Spirit is made, are so rare, so delicate, that when once wasted they cannot readily be replaced.

As the sin against the Holy Spirit is the one sin for which the Gospel holds out no forgiveness for the individual, so there seems to be no hope for the nation which transgresses against this most vital element of its higher life.

Inasmuch also as the Spirit is something which guides and cannot be guided, these informal introductions appear in no geographic or historic sequence, but are necessarily left to the leading of the spirit, of which “no man knoweth whence it cometh or whither it goeth.”

E. A. S.

Grinnell, Iowa.

| I. | The Herr Director Meets The American Spirit | 15 |

| II. | Our National Creed | 35 |

| III. | The Spirit Out-of-Doors | 58 |

| IV. | The Spirit at Lake Mohonk | 74 |

| V. | Lobster and Mince Pie | 92 |

| VI. | The Herr Director and The “Missoury” Spirit | 112 |

| VII. | The Herr Director and the College Spirit | 129 |

| VIII. | The Russian Soul and the American Spirit | 147 |

| IX. | Chicago | 166 |

| X. | Where the Spirit is Young | 184 |

| XI. | The American Spirit Among The Mormons | 199 |

| XII. | The California Confession Of Faith | 216 |

| XIII. | The Grinnell Spirit | 237 |

| XIV. | The Commencement and The End | 249 |

| XV. | The Challenge of the American Spirit | 262 |

THE Herr Director and I were sitting over our coffee in the Café Bauer, Unter den Linden. In the midst of my account of some of the men of America and the idealistic movements in which they are interested, he rudely interrupted with: “You may tell that to some one who has never been in the United States; but not to me who have travelled through the length and breadth of it three times.” He said it in an ungenerous, impatient way, although his last visit was thirty years ago and his journeys across this continent necessarily hurried. I dared not say much more, for I am apt to lose my temper when any one anywhere, criticizes my adopted country or questions my glowing accounts of it.

But I did say: “When you come over the next time, let me be your guide.”

“Why should I want to go over again?” he replied. “It’s a noisy, dirty, hopelessly materialistic country. You have sky-scrapers, but no beauty; money, but no ideals; garishness, but no comfort. You have despatch, but no courtesy; you are ingenious, but not thorough; you have fine clothes, but no style; churches, but no religion; universities, but no learning. No, I have been there three times. That’s enough. I know all about it. Fertig!” And with that he dismissed me without giving me a chance to relieve my feelings, of which there were many; although he took advantage of a minute that was left and told me that I was an Unausstehlicher Americaner whose judgment had been warped by my great love for my adopted country.

Evidently the Herr Director reversed his decision not to come to this country; for the following spring I received a cablegram to meet him on the arrival of his ship at the Hamburg-American dock, which of course I promptly did. The Herr Director and the Frau Directorin stepped onto the soil of the United States with a predisposition to be martyrs, to endure the sufferings entailed by travel with as little grace as possible, and to suppress to the utmost all pleasurable emotion.

On the other hand, I was determined to show off my United States from its best side, to woo and win the Herr Director’s and the Frau Directorin’s approval. In my laudable endeavor I seemed to be supported by that divine providence which watches over the whole world in general, but over the United States in particular. The weather was perfect, the sky festooned in fleecy clouds, the air charged by a divine energy; and when the sun shines upon the harbor of New York—well, even the most taciturn European cannot resist it.

The Herr Director and the Frau Directorin greeted all the good Lord’s endeavor and mine, with an air of condescension as something due their station. From force of habit they worried and fussed about their baggage, although there was nothing to worry or fuss about, for it was safe on its way to the hotel. They were shot under the river and the busy streets of Manhattan and whirled up to the twenty-first story of their thirty-two-storied hotel without having taken more than a dozen steps to reach it.

The Herr Director and the Frau Directorin refused to be impressed by the rooms assigned them, in which not a single comfort or luxury was missing, and complained because they were not as big as barns and the ceilings not as high as a cathedral. The Frau Directorin eyed the bath-room almost in silence; but she did wonder why they put out a whole month’s supply of towels at once, instead of doing it in the provident European way of one towel every other day.

The Herr Director and the Frau Directorin, like all Europeans who can afford to travel, are exceedingly æsthetic, and at the same time fond of good food, and their first approving smile was won at the breakfast table, when they were each face to face with half a grapefruit of vast circumference, reposing upon a bed of crushed ice. Their smiles broadened when they had introduced their palates to an American breakfast food, a crispy bit of nut-flavored air bubble, floating upon thick, rich cream; and, although they had made up their minds that American coffee was vile and they must not taste it, they could not resist its aroma, and drank it with a relish.

When the Herr Director said: “Der Kaffee ist gut,” I knew that my prayers were being answered, and that the good Lord still loves the United States of America.

Most of us have shown off something—a baby, school-children, a schoolhouse, a town, an automobile, a cemetery. You know that feeling of pride which thrills you, that fear lest pride have a fall if it or they fail to “show up.” But have you ever tried to show off a country—a country which you love with a lover’s passion; a country whose virtues are so many, whose defects are so obvious; a country whose glory you have gloried in before the whole world, but whose halo has so many rust spots that you wish you might have had a chance to use Sapolio on it ere you let it shine before your visitors? A country of one hundred million inhabitants, of whom every fourth person smells of the steerage, when you wish that they all smelled of the Mayflower; a country where more people are ready to die for its freedom than anywhere, and more people ought to be in the penitentiary for abusing that freedom; a country of vast distances, bound together by huge railways and controlled by unsavory politicians; a country with more homely virtues, more virtuous homes, than anywhere else, yet where the divorce courts never cease their grinding and alimonies have no end?

Ah! to show off such a country, and to have to begin to do it in New York, beats showing off babies, school-children, automobiles, and cemeteries.

The Herr Director was sure he would hate our sky-scrapers; he had seen them from the ship, and the assaulted sky-line looked to him like the huge mouth of an old woman with its isolated, protruding teeth. Frankly, I myself am not interested in sky-scrapers; I prefer the elm trees which shade the streets of the quiet town where I live. I thank God daily for the men who had faith enough to plant trees upon those wind-swept prairies. They were mighty spirits who came to the edges of civilization and drove the wilderness farther and farther back by drawing furrows, sowing wheat, and planting trees—those men whom heat and a relentless desert could not separate from that other ocean with its Golden Gate to the sunset and the oldest world. Determining to have and to hold it till time is no more, they proceeded to unite the two oceans in holy wedlock. A task which involved another nation in hopeless scandal and bankruptcy, they completed with as little ceremony as that which prevails at a wedding before a justice of the peace. Those were the men who went among savages, yet did not become like them; who for homes dug holes in the ground among rattlesnakes, prairie-dogs, and moles, and made of such homes the beginnings of towns and cities.

If I admire the sky-scrapers it is because they are an attempt on the part of this same type of people to do pioneering among the clouds. Public lands being exhausted, they proceed to annex the sky and people it, now that the frontier is no more.

What the Herr Director and the Frau Directorin would say to the sky-scraper meant to me, not whether they would say it is beautiful or ugly, but whether they would discover in it the Spirit of America, the daring spirit of the pioneers who built Towers of Babel, though reversing the process; for they began with a confusion of tongues which outbabeled Babel, and finished on a day of Pentecost when men said: “We do hear them all speaking our own tongue, the mighty works of God.”

We moved along Broadway, pressing through the crowds, the Herr Director puffing and panting, the Frau Directorin doing likewise. The Flatiron Building with its accentuated leanness lured them on until we came to the open space of Madison Square and they were face to face with the Metropolitan tower.

The Herr Director said: “Gott im Himmel!” The Frau Directorin said: “Um Gottes Himmels Willen!” And then they gazed their fill in silence.

I have never “done” Europe with a guide, nor have I ever had an American city introduced to me through a megaphone, so I scarcely knew what to say.

I did not know the exact height of that tower, nor how many tons of steel support it, nor the size of the clock dial which tells the time of day up there “among the dizzy flocks of sky-scrapers”; but I did know that the tower represented some big, daring thing, an expression of the spirit which could not be defined nor easily interpreted to another.

After his first outburst the Herr Director continued to say nothing—he was stunned; so was the Frau Directorin. We walked on, looking up, higher and higher still, until our eyes met another tower, the Woolworth Building—a shrewd Yankee five-and-ten-cent enterprise, flowering into purest Gothic.

The cathedrals of Europe are wonderful, undoubtedly. Master minds drew the plans and master hands built them, slowly, by an age-long process. They turned religious ideals into stone lace and lilies, hideous gargoyles and brave flying buttresses, aisles and naves and rose windows. Yes, they are quite wonderful. But to turn spools of thread, granite-ware, and dust-cloths into this glory of steel and stone is, to me, more marvellous still. The spirit of the pioneer cleaving the sky has become beautiful as it has ascended.

We are worrying a great deal about our lack of sensitiveness to beauty and form; we chide ourselves as being crude and unresponsive to art; we rush madly into the study of æsthetics and buy Old Masters at the price of a king’s ransom; yet we are not truly fostering America’s art sense. It ought not to come in the Old World’s way—by glorifying dogmas and creeds, by petrifying religion into buttresses and incasing our dead in tombs of beryl and onyx. It ought not to come with its mixture of paganism and religion, its armless Venus and its headless Victory. It should come first as it is coming—with the making of homes good to live in, factories planned to work in, stores fit to do business in, and schools built to teach in. It is coming—yes, it is coming.

But when our strong boys shall make filagree silver ornaments, carve pretty things on bits of ivory, or exhaust their energy in painting a lock of hair—when that time comes, we shall be an old people ready for our ornamented tombs.

Next I took the Herr Director and the Frau Directorin through a portal flanked by pillars worthy to crown any Athenian hill; I led them into a Parthenon in which Athena herself might have joyed to be worshipped, and we heard the echoing and reëchoing of a chant which lacked nothing but incense and organ notes to make one think one’s self in an Old World cathedral. The chant was not a Miserere, but a call to entrust one’s self to the depths of the earth—to descend into tubes of steel, beneath the river, and then travel to the fair cities of the living, throbbing, thriving West. It was a railway terminal without choking smoke, blinding dust, or deafening noise; also without that hideous mechanical ugliness which Ruskin so hated. This was merely a place from which one started to reach Oshkosh or Kokomo, Keokuk, Kalamazoo, or Kankakee. Yet more beautiful portals never swung to mortals in their fairest dreams of journeying to the abodes of bliss. The Spirit of America, at last crowned by beauty.

We reached our hotel fairly exhausted by our morning’s walk; but, after being properly refreshed, the Herr Director ventured to criticize.

“Yes, you are a wonderfully resourceful people, keen and energetic, but chaotic. You take an Italian campanile and elongate it fifty times; or a Gothic church, and attenuate it; or a Romanesque cathedral, and support it by Ionic pillars; or a cigar box, and enlarge it a million times. You put all these things side by side, and no one asks: Will they harmonize, or will they clash?

“Each man builds as he pleases, although he may blot out the other man’s work and waste colossal energy merely to express himself. The result is confusion. You can feel that unrest, that discord, in the air. My nerves fairly ache! No, we shall not go out this afternoon. We must rest our nerves.”

The Herr Director always spoke for his wife as well as for himself, thus expressing the collective spirit of the Old World. They both retired for a long rest, while I was left wondering how to introduce New York to them in the evening.

At five o’clock in the afternoon they emerged from their apartments, their wearied Old World nerves rested, and, after being stimulated by a cup of coffee, were ready for further adventures.

Broadway at that hour of the afternoon is bewildering. The shoppers have almost deserted it, and it is crowded by the clerks who served them, the cashiers who received their money, the girls who trimmed their hats, the men who cut their garments, the bookkeepers and the floor-walkers.

Whole towns seem to pour out of the department stores and lofts; the makers and menders of garments flee from the heart of the city, from this pulsing machine which has been going at a dangerous speed. They go from it eagerly, with a brave show of courage, as if the ten hours’ labor had not broken their spirits or wearied their energy. To count the ants of a busy hill would be easier than even to estimate the numbers of that throng.

They climb the steps of the elevated railway trains, and crowd them, and cram the cars until they fairly bulge.

They lay siege to the surface cars, which merely crawl through the busy streets, so heavy are they and so closely does one car follow the other.

They descend into the depths of the earth, and breathe the humid, human air of those noisy catacombs. They walk by companies, regiments, and great armies, dodging automobiles which infest the streets with their speed and their stenches.

They accomplish it all with so little friction to each other’s spirit, with such a silent good nature, with such a sense of self-reliance, and with so little official machinery to control them, that even the Herr Director said:

“This is wonderful!” although he declared that he would suffocate in that throng, and the Frau Directorin cried out every few minutes, “Um Gottes Himmels Willen!”

There was an absence of politeness, but we saw little rudeness; there were accidents, but the crowd did not lose its head; there were discomforts, but little display of ill nature; each for himself, and yet no clashing. The American crowd is more wonderful than the American sky-scrapers.

At the Royal Opera in Vienna, the approach to the ticket office is guarded by steel inclosures in which every prospective buyer is separated from the other, and one has to zigzag between these pens until he reaches the official’s window. Crowding is rendered impossible, but, to make the obviously impossible more actually impossible, there is the usual number of uniformed guards.

Watch the American crowd—this group of unlike, self-centered individuals; in a moment it is organized, it obeys itself—or rather, it obeys its spirit, the American spirit of self-direction, with its genius for organization.

To me, the American crowd is so wonderful because it shows this other side of its spirit. It is heterogeneous, like the architecture of its buildings, perhaps even more so—if that be possible.

Here are Jews from Russia’s crowded Pale, where they had to slink along with shuffling gait and dared go so far and no farther—so fast and no faster.

There are the Slavic peasants, who on their native soil, prodded by the goad, moved ox-like along an endless furrow, drawing the plow of autocracy.

Next is the Italian, volatile and yet static with his age-long burdens, with his fiery nature cramped into his diminutive frame.

Here is the Negro, the child-man, the shackles of whose slavery are scarcely broken.

The Asiatic, too, comes with hardly courage enough to lift his softly treading feet; while leading them all is this strident, giant child of the Anglo-Saxon race whose wind-swept cradle was rocked by freedom, and who with dominant will has spanned the oceans and crossed the mountains.

Of these myriads whom he leads, some will be a drag upon progress, and detain the strong or perhaps retard the race; yet they are trying to keep up, and by their efforts, by delving in the deep, by feeding with their brute strength our huge enginery, may make the flowering of the American spirit easier.

Yes, the Anglo-Saxon is leading them; but will he continue to lead, now that he no longer travels in the prairie schooner, but in the automobile—now that he wields the golf club and tennis racket, rather than the spade and plow on the prairie?

Will he now lead them from the breakers of Newport as well as once he led them from Plymouth Rock?

Will he lead them from the exclusive club as once he led them into the inclusive home?

These were the doubts which filled my mind, but which I did not share with my guests as I guided them; for we were to spend the evening together, and one needs all one’s faith in New York at night.

We spent the early evening hours travelling around the world. We went to Arabia, where dusky children from the desert play in the gutters of Bleecker Street; to Greece, where Spartan and Athenian youth dream of the golden days of Pericles; to China, with its joss-house, its faint odors of sandalwood, and its stronger odors wafted from the Bowery. We visited Russia, and saw its ghetto-dwellers more numerous than Abraham ever thought his progeny would become; we spent some time in Hungary, with its Gulyas and Czardas. We went to Bohemia, with its Narodni Dom; to Italy, south and north, with its strings of garlic, its festoons of sausages, its hurdy-gurdy, and its rich harvest of children. We had glimpses of France, of its table d’hôte and painted women; travelled through darkest Africa, touched upon India, and then were back again upon Broadway.

As in the sky above us the architectures of the world strive to blend and fuse, making a mighty new impress; so below, these colonies to the right and colonies to the left, like the huge limbs of some ill-shapen monster, try to blend into America.

What is it all to be when blended?

Of course we went to the theater. We saw a German problem play made over to please the American taste. The Herr Director knew the play almost by heart, and he nearly jumped upon the stage in righteous indignation when in the last act, where the author drops all his characters into a bottomless pit and everything ends in confusion, the play ended in the conventional “God-bless-you-my-children,” “happy-ever-after” manner.

We walked the streets of New York until past midnight, and finally looked down upon it from the roof of our hostelry. We could see the moon creeping out and shedding its mellow glow over the gayly lighted city. The noises were almost musical up there—like sustained organ notes—and we talked about the play with its happy ending.

“You are right,” I said; “that happy ending is foolish and childish. Things do not always end happily; but this thing, this experiment in making a nation out of torn fragments, this founding of cities in a day out of second and third hand material, this experiment in man-making and nation-building must end well; for, if it doesn’t, God’s great experiment has failed. Shall I say, God’s last experiment has failed? You see we mustn’t fail—it must end well.”

The streets were all but silent. From the great clock on the Metropolitan tower hanging in mid-air, came the flashes that marked the morning hour. Thick mists floated in from the sea and filled the narrow, chasm-like streets with weird, fantastic shapes.

The Herr Director said good-night. The Frau Directorin did likewise. They said it very solemnly, as behooves those who have looked deep into the heart of a great mystery who have felt the touch of a mighty spirit striving, struggling, agonizing to shape a new nation out of the world’s refuse.

THE Herr Director and the Frau Directorin wished to go to church on Sunday, and after eating a piously late breakfast I spread before them New York City’s religious bill of fare, bewildering in its variety and puzzling in its terminology.

I gave them a choice between four varieties of Catholics: Roman, Greek, Old and Apostolic; more than twice that number of Lutherans, separated one from the other by degrees of orthodoxy and nearness to or farness from their historic confessions.

There were Methodists who were free and those who were Episcopalian, Episcopalians who were not Methodists but were reformed, and those who made no such pretensions; all these invited us to worship with them.

Many varieties of Baptists announced their sermons and services, offering a choice between those who were free and those who were just Baptists, and between those who were Baptists on the Seventh Day and those who did not specify the day on which they were Baptists.

We also had a chance to discriminate between Dutch Reformed, German Reformed or Presbyterian Reformed, and United Presbyterians divided from other Presbyterians (presumably unreformed) for reasons known to the Fathers who died long since.

If we had been radically inclined we might have browsed among Unitarians, Ethical Culturists, and could even have worshipped among those who make a religion out of not having any.

The most interesting column to the Herr Director was that which contained our exotic cults, those we have imported and those which prove that we have not neglected our home industry.

It was disconcerting to me, who was trying to introduce our national spirit, to realize how varied its religious expression is, and the Herr Director got no little amusement out of the story I told him of the student in one of our colleges who, it is said, came to the librarian and asked for a book on “Wild Religions I have Met.” When the librarian suggested it might be Seton Thompson’s book on Wild Animals, he said it was not in the department of Zoölogy, but in Philosophy in which the assignment for the reading was given. The book was then quickly found. It was Prof. William James’ “The Varieties of Religious Experience.”

When we succeeded in rescuing the Frau Directorin out of the maze of Sunday Supplements in which she was entangled, we started in pursuit of a proper place of worship, in anything but a worshipful mood. I was bent upon showing that which is vastly more difficult to interpret than sky-scrapers, the Herr Director was doubtful that we had any religious spirit at all, and the Frau Directorin mourned the fact that she had to leave behind her so much paper which might have served such good purposes if she had it at home.

Fifth Avenue recovers something of its departed exclusiveness on Sunday morning; for although the cheaper stores are crowding upon those which never descend to bargain counters, this is not true of the churches. They still are in good repute, and await the stated hour of service on Sunday morning without excitement, having advertised nothing, offering no ecclesiastical bargains; content to live as the birds of the air, whom the “Heavenly Father feedeth.” The street was almost deserted; here and there a taxicab darted on its way to or from the railway station; the hour of the limousines had not yet come, and the people who strolled along were evidently, like ourselves, unfashionable sojourners seeking a tabernacle in Gotham’s wilderness.

Sauntering along the street was less interesting than usual, for not only were there no crowds, the shop-windows were all artistically curtained and there was nothing to see. The Frau Directorin did not like it at all, “for what good is it to walk along the shopping streets if you can’t look into the shops?”

“You see, my dear,” the Herr Director remarked, “that is to help you obey one of the ten commandments which womankind is especially prone to break, ‘Thou shalt not covet.’ Incidentally it proves that we are in a country in which you are allowed to do as you please every day and do nothing on Sunday.”

“No,” I replied, “it merely proves that we are trying to save one day a week from the contamination of our materialistic existence.”

“It merely proves,” he echoed, “that you have inherited from your Anglo-Saxon ancestors the worst thing they could leave you: their hypocrisy. I stepped behind a curtained bar this morning and found it running at full blast. You evidently do your drinking in private on Sunday and your praying in public. You know we in Germany do the opposite.”

“No, you do your praying and drinking both in public, and both seem to be a part of your religion,” I answered. “Very likely you are right. There is about us this taint of hypocrisy; but that only shows that we are a deeply religious people, conscious of the fact that our ideals are upon a higher plane than our performance. We are not as eager as you are to proclaim our frailties from the housetop.

“The average American wants you to believe him to be a pretty decent fellow till you find him out to be different; while you Germans make a virtue of a certain kind of brutal frankness, which is worse than hypocrisy, since you try to make it an excuse for all sorts of private and national sins. The real criminal is never a hypocrite.”

I do not know what would have happened to me if at that moment we had not reached St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The full, rich organ notes seemed to soothe the Herr Director’s ruffled spirit, and our discussion ended as we entered the welcoming portal.

In a church which in all places and all ages remains the same, there was nothing for my guests to see or hear to which they were not accustomed. There was the priest, alone with the great mystery which he was enacting, and by his side the diminutive ministrants. The crowd which filled every available space in that huge interior was silent and reverent. Now the tinkling of a bell, like a command from Heaven, bade all kneel, and now the same bell bade them rise. The incense, the stately chant, and then the hushed, expectant throng going forward to partake from the priest’s hand of the means of grace, which he alone could offer in the name of the one Holy Catholic Church—all this could not fail to impress us.

Into the august and solemn atmosphere there came from a near-by church the chimed notes of a hymn-tune such as the people once sang defiantly when they proclaimed their religious freedom. It was a spiritual war tune which soldiers could sing, and strangely enough it seemed to fit into this atmosphere as if it were the one thing which the service needed. It recalled the self-assertion of the people before their God, their man God, who was born in a stable, who worshipped as He worked, and worked as He worshipped, hurling His anathemas at those who blocked the gates of the kingdom to them who would enter, yet did not enter themselves.

Evidently the Herr Director felt as I felt; for he whispered to me, “The Reformation.” When I nodded my approval, he said: “But see how unmoved she is, this rock-founded church. It will take something more than hymn-tunes to disturb her.”

We left the Cathedral while the hungry multitude was being fed with the Sacrament of our Lord, and our spirits, too, had been fed, although we were not of that fold.

While the Roman Catholics were finishing their worship, the Protestants were making ready to begin. The first bells had chimed appealingly, not commandingly, and a thin stream of worshippers appeared on the Avenue, growing thinner as it divided, entering one or the other of those edifices where men were to worship according to the dictates of their conscience, their taste, or their social position.

Many strangers, like ourselves, were looking critically at the church bulletins as yesterday we had looked into the show windows, and it was the Frau Directorin who said she felt as if she were going shopping for religion.

The Herr Director said that he had no objection to our inventing or importing as many religions as we pleased; but he did object to our exporting any, for we were making the task of regulating and controlling them very difficult. Moreover he did not see how we could develop any kind of common, national ideals with such a confusion of religions. “You have, or pretend to have, a democratic government, and your strongest church is monarchic to the core.”

I had to admit that religiously we are a very chaotic people, and that we are daily adding to that chaos; yet these facts might prove what I had been trying to make clear to him: That this is fundamentally a religious country, and that as a whole we are the most religious people in the world. I supported this statement by quoting a good German authority, the late Prof. Karl Lamprecht, who thinks we have a great future as a people, because we are “capable of religious improvement.”

“Improvement!” The Herr Director sniffed derisively. “Wherever I look I see improvements: churches turned into theaters, theaters into churches, and residences which are still perfectly good turned into sky-scrapers. Chaos is not an improvement upon order. Nothing is finished, nothing complete, not even your religion.”

Just then we were compelled to pass along a wooden walk from which we looked into a canyon blasted out of the rock, upon which still stood the foundation of the house which was being turned into a sky-scraper.

“You see, that is the way we improve; we go deeper each time,” I remarked.

“But in religion,” the Herr Director retorted, “you do not go deeper, you go higher, and that is no improvement.”

For the second time the chimes were pealing, and we entered a sanctuary of friendly yet dignified English Gothic. An usher, who looked very American and well fed and out of place, guided us to a pew in the more than half empty church, from which nothing was missing in the way of ecclesiastical furnishings. One thing it lacked and that no architect can build and no money can buy—Spirit.

The organ was played by a master, the processional was splendidly staged, the rector looked prosperously pious, prayers were read and confessions uttered without any disquieting, spiritual agony, and the anthems were correctly sung by the picturesque boys’ choir. The curate preached a sermon on manliness; a sermon so thin and emasculated that even the Frau Directorin, whose English is limited, could understand it, and said she would like to come again “for the good English.”

I left the church deeply disappointed, and to the Herr Director’s taunts about “improvements” I did not reply, realizing more than ever how difficult and dangerous is this task of introducing the Spirit, especially when one goes to church in the spirit of pride, rather than in the spirit of meekness.

No clergyman can spoil the whole of Sunday, for there is always the dinner, and having found a table d’hôte in harmony with the Herr Director’s national and religious ideals, we continued our discussion somewhat fitfully, if, at times, rather vehemently.

One of the things the Herr Director missed in the church where we tried to worship was reverence. He missed it everywhere and thought it due to the fact that we do not teach religion in the public schools.

This was rather amusing to me, for just prior to that statement he had told me of one of his nephews who, upon approaching his final examinations, said: “If it were not for this accursed religion I could get through without trouble;” and I called his attention to the fact that although I had no difficulty with my “exams” in religion, invariably having an “Ausgezeichnet” which is equivalent to an A, I was always “Schlecht” in conduct.

I had found religious instruction a very irreligious procedure, for the man who taught it was irreligious enough to whip me so that I could not lie upon my back for a week, the cause being that I would not say yes to his credo. Moreover I told the Herr Director I thought all religious instruction irreligious which did not teach the child its whole duty to society, but taught religion from only the narrowing racial or sectarian standpoint.

Religion, I pointed out to him, can after all not be taught; it has to be caught. It is a contagion which comes from a spiritual personality, and our public schools are not religious or irreligious because certain subjects are found or not found in their curricula, but because the teachers have this spiritual personality or lack it. I am convinced that this ethical quality predominates in our public schools, not only because so many of our teachers are women, but because we are fundamentally a religious people.

At this point I became conscious that the attention of the Herr Director and the Frau Directorin had flagged; for their response to my homily was an eloquent tribute to the tenderness of the breast of a Long Island duck, which they had been enjoying while I talked. As they were consequently in a lenient mood towards the whole world and therefore the United States, I renewed my laudable and difficult effort, and, as is often best, through the medium of a story.

At the time the elective system was introduced into Harvard University, attendance upon chapel was made voluntary. “I understand,” said a severe critic of this procedure, “that you have made God elective in your college.”

“No,” replied the astute president, “I understand that God has made Himself elective everywhere.”

The point of my story was lost upon both my guests. When I paused, the Frau Directorin asked me how it was possible to serve so lavish a bill of fare for so little money, and the Herr Director asked the waiter why they called this a Long Island duck when the portions were so short. Thus the conviction was forced upon me that our environment was not conducive to the discussion of the American Spirit and that I must await a more auspicious occasion.

Late in the afternoon that occasion came; not on Fifth Avenue but on one of those streets where churches are fewest and humanity thickest; where Sunday brings liberation from toil, where cleanliness and godliness have an equally difficult task in coming or abiding; where nations and races must mingle and cannot easily blend, where the America which is to be is in the making, and where the Spirit must manifest itself if we are to be a nation with common ideals.

I like to take my friends to the East Side of New York City. I glory in its self-respect, its brave struggle against poverty and disease, its bright children filling all the available space and asserting their childhood by playing in the busy street, defying its noisy traffic. They make of each hurdy-gurdy the center of a great festival, dancing as the elves are said to dance, because it is their nature to.

I like to point out the faces of Patriarchs, Prophets and Madonnas—faces seamed by care and sorrow, yet lighted by a divine radiance and as unconscious of it as were those upon whom it shone in such fullness on that great East Side of the Universe which we now call the Holy Land.

I like to have my friends meet my East Side friends, the young working girls, who dress in good taste, help support a family, and maintain an unstained character in spite of small wages and the temptations of a great city. I like them to meet the growing boys who are hungry for the best the city holds, and who dream the dream of making the East Side in particular, and New York in general, a better place in which to live.

I am never ashamed to take my friends into the tenement houses, except as I am ashamed that they exist at all, with their stenches and the dearly bought space with twenty-four hours of darkness and no free access of air. Of the people who live within I am never ashamed, for they are the brave ones, to whom labor is prayer, and living a sacrifice. I like best to show off the East Side of New York on Sunday, for here it is most welcomed with its respite from labor, its chance at clean clothes, its opportunity to visit and be again something more than a machine.

On Fifth Avenue the Sabbath is made for the few, on the East Side it is made for the many; on Fifth Avenue God seems hard to find, on the East Side He comes down upon the street. They are indeed worse than infidels who do not feel His Spirit brooding over the crowd, and His guardian angels watching over those children—else how could they survive? Best of all I know where those Angels live, and it is there I took the Herr Director and the Frau Directorin; I was sure they would never leave the place doubting that we are a religious people. Evidently the children also knew where their Angels live for the place was in a state of siege. It is not strange that they knew, for their ancestors had walked and talked with angels, and they were not yet old enough to have lost the faith of their fathers. Troops of children there were; mere children carrying children, and where there was an only child, which is rare on the East Side, it was brought by a grandfather and grandmother, children themselves now, and old enough to again believe in angels.

There were flowers in the room and they were for the children; bowers of roses, red roses, wafting their incense and driving out the mouldy, tenement house air which clung to the little ones. There was music, and they sang—sang as I know God wanted them to sing—gay, happy songs, which seem to be denied the children who sing in the churches.

How I wished that the picturesque little choir boys on Fifth Avenue, who sang sixteenth century music and Augustinian theology, might have had a chance to sing as those East Side children sang—full throated, lustily, joyously; songs which made them shiver from very joy, and which made the Frau Directorin weep copiously.

How I wished that the priest who chanted Psalms in Latin, and the other priest who intoned them in English as dead as Latin, could have been there and have heard those children recite the same Psalms, in East Side English. Yes, I have often wished that David himself might hear them; I am sure he would be proud that he had a share in writing them, even as the priests might be ashamed that they had never known just what precious reading they are.

No one preached to the children although they heard the good tidings, and no one told them to be good although they were given a chance to know how good God is, when men give Him a chance.

There was a sacrament, a holy one; roses were given the children, and the Angels who gave them shed their blood, for the roses had thorns. The next week the children were to be taken where the roses grew, and they would see that

But they would not have to see the garden to know that God is.

We broke bread with the Angels and looked into their joyously weary faces, and then we talked about the very thing I wanted my guests to know, namely: That underneath all our religious or rather credal chaos, we have a national creed if not a national religion.

The Herr Director suggested that the fundamental doctrine of our creed is “in gold we trust,” and then he began a dissertation upon our national materialism.

Perhaps so, I conceded; but I doubted that we are more materialistic than the people of the older world, in fact I was inclined to believe that we are less so; which of course the Herr Director stoutly denied, and I as stoutly affirmed. In justice to myself I must say that when my country’s honor is not at stake I am less dogmatic.

“Perhaps we are equally materialistic,” I continued, “but we are certainly more generous. We make money faster than the people of the Old World, but we also give it away faster, and I believe that there is no country in which there is such a contempt for the merely rich man.”

“I suppose the second article in your national creed,” the Herr Director interrupted, “is that you are the biggest country and the best people under the Sun.

“If I were suggesting a motto for a new coinage I would put on one side of it ‘In Gold We Trust,’ and on the other ‘The Biggest and The Best.’”

Ignoring this somewhat merited slur I said: “The first and only doctrine of our national creed which we have as yet formulated is that we have a great national destiny.”

At that the Herr Director jumped excitedly from his seat, and said somewhat sneeringly, “Oh, you mean you have a place under the Sun. All nations have such a creed, but when we Germans try to realize it, you call us a menace to civilization.”

It was a tense moment in my relationship to my guests, but I ventured to say: “We have a better reason for the faith which is in us than most other nations, for we are trying to realize it without killing off other people. In fact we are trying to realize it at a greater hazard than that of being conquered by an alien enemy. We are keeping open these doors which have swung both ways freely, for nearly three hundred years, and your Old World weary ones have been coming; bringing their traditions, their ideals, their worn out faiths and their heaped up wrath. We did not forbid them; they have come to our towns, our schools, our homes, they are here for better for worse, and we cannot divorce them, or drive them away.

“Yes,” I continued, much to the discomfiture of the Herr Director, “we have a meaning to the Old World, a larger meaning than you think. We have a place under the Sun, not to satisfy national ambitions; but to keep alive faith in humanity.”

The Angels around the table were disquieted by our vehemence, the Frau Directorin urged that it was growing late, and we left that center of quiet which we had so disturbed, to return to our hotel. We entered a street car crowded beyond its capacity by burly Irishmen the worse for liquor, good-natured Slavs none the better for it, aggressive looking Russian Jews and sleek Chinamen. There were mothers with their crying babies, and thoughtless boys and girls chewing gum most viciously. After the Herr Director and the Frau Directorin had been jostled unmercifully, we left the uncomfortable car, and when we were again breathing unpolluted air the Herr Director asked quizzically:

“Do you still believe in humanity?”

Boldly and bravely I answered: “Yes, I believe,” and lifting my face to the stars I whispered: “Lord, help my unbelief.”

MUCH to my regret the Herr Director did not sleep well that second night in the United States. His nerves had suffered from those first thronging impressions, he looked pale and was decidedly irritable; “for how could a man sleep or be expected to sleep in this business canyon, loud from the thunder of the elevated, and bright from the flashing of illuminated signs?” Together they had the effect of an electric storm upon him.

When he did fall asleep he dreamed that the Metropolitan Tower, the Woolworth Building and St. Patrick’s Cathedral were dancing Tango upon his chest.

This nightmare may have been due to the fact that just before retiring we witnessed an exhibition of this modern madness, which seemed to be indulged in everywhere except in the churches and possibly the barber shops. Partly also, perhaps, because the Herr Director insisted upon eating lobster shortly before midnight, in spite of the fact that I warned him against that indulgence. It was one of those generous, United States lobsters, and not the diminutive shell-fish with which cultured Europeans merely tickle their palates.

The Herr Director had repeatedly pointed out our bad habit of leaving a great deal of food on our plates, and to impress upon me his better manners, he had eaten the entire lobster.

I had not slept well that night either, in spite of the fact that I had eaten sparingly. I think it was the Herr Director himself who had “got on my nerves,” and I was finding this task of “showing off” my beloved United States difficult and exacting.

That morning we were to leave New York and I would introduce my guests to the great American out-of-doors, and the prospect added to my already uncomfortable frame of mind.

If only we might start from that marvellous Central Station in the heart of the city; but in order to reach our destination, which was Lake Mohonk, we had to cross the West Side where it is irredeemably tawdry and ugly, and take one of the ferry-boats to Weehawken. This somewhat inconvenient procedure made the Herr Director doubly critical.

The Fates were against us, for it was a hot, humid day, the car was crowded, and the start from Weehawken anything but auspicious.

In Europe the Herr Director travels second class when he travels officially (the first, as is well known, being reserved for Americans and fools), and third when he travels incognito, for he is a thrifty soul. Nevertheless, he did not like our cars, they were “obtrusively decorated,” and privacy was impossible. Why should he have to look at a hundred or more human heads variously “frisired”?

I suggested that we take seats in front, which we succeeded in doing, and then he found that if he wished to take off his collar, he would have to do it with two hundred or more human eyes fastened upon him, when the hundred people possessing them had no business to see what he was doing.

I have already confessed how sensitive I am to criticism of anything American, no matter how just the criticism may be. So sensitive am I, that had he reflected upon the good looks of my wife, he could scarcely have hurt me more than when he reflected upon the beauty and arrangement of an American railway car.

And yet I have often wondered why our American genius seems to have exhausted itself when it evolved the present type of car, having done nothing to it except adding or taking away some of its “gingerbread.” Nevertheless I lost my patience and told him that if he liked to travel cooped in with seven other passengers, four of whom he must face and two of whom might at any moment poke their elbows into his ribs; if he preferred to breathe air polluted by seven other people, and have a fresh supply of ozone only at periods and in quantities regulated by law, I did not admire his taste. As far as I was concerned I preferred to travel in this big room on wheels, rather than in a jail-like box to which the conductor alone had the key. Anyway this represented American democracy with its unpartitioned space; but if he really wanted it, I could get him a stateroom in the Pullman, and he could ride in isolated splendor and be aristocratically stuffy and uncomfortable.

When the Frau Directorin in typical German phraseology complained about the draft: “Um Gottes Willen ein Zug!” I decided to save the day, and we retreated to the Pullman stateroom.

There they rested themselves back and looked tolerably happy while I, silently but fervently, prayed that this particular train would not disgrace itself by “committing” an accident.

The big, American out-of-doors, even where it is old and its waste spaces are cultivated and hedged about, has something which is characteristically American. Of course nature knows no political boundary; the grass is green everywhere, the sky is blue, cattle and sheep, like man, have a long and honorable ancestry. Yet there is a difference which may not be due to what nature is, but to man’s attitude towards her and his treatment of her.

I have noticed this in passing through Europe; how unerringly one knows where Germanic boundaries end and those of the Slav begin. German fields and forests are trim and orderly; Slavic territory so ill kept and ill used that when one has a glimpse of a village even from the swift moving train, the difference is obvious.

Sometimes I am inclined to believe that this attitude of man affects his environment as much as we know the environment affects him. I wonder just how much of the American out-of-doors, with its generous but not gentle aspect, its subdued but untamed spirit, is due to those valiant men who came from across the sea, and in so doing restored a bit of their long-lost courage, and made masters of men who so long had been serfs and knaves.

I had hoped that the sudden burst of the Hudson upon my guests’ vision would thrill them; but if they were thrilled, they were careful to conceal it. When I suggested the likeness of the Hudson to the Rhine, the Herr Director took it as a personal affront and said you might as well compare St. Patrick’s Cathedral and that of Cologne. They are both churches and Gothic; the Hudson and the Rhine are two rivers, and both are big.

Nevertheless I insisted that there is an evident resemblance which would be complete if the Hudson had a ruined castle here and there, or a picturesquely cramped village huddling against the hillside.

“Yes, and beside castles and picturesque villages,” the Herr Director replied tartly, “you need a thousand years of culture and the same traditions which make the shores of the Rhine sacred to us; you also need generations of patiently plodding peasants who have made a sacrament of their toil. One glance at your rotting boats lying along the shore, at the untilled, gaping spaces and glaring, inartistic sign-boards which disfigure it, is sufficient to distinguish the two rivers or perhaps even the two countries.”

Having thus forcefully delivered himself, he scornfully pointed out the waste places and the unkempt-looking fields, asking me whether I still dared compare anything in this out-of-doors with the fine economy and splendid supervision of the natural resources of his own country.

Shamefacedly I acknowledged my country’s guilt, and the guilt which was evident on the majestic shores of the Hudson. We are wasteful, extravagant and reckless—great defects in our national spirit, and most in evidence in our treatment of nature’s beauty and wealth. We shall have to remedy that, in fact we are just beginning to do it; if not from any sense of guilt, from the same sheer necessity which makes the nations of the Old World careful of their national wealth.

“The Conservation of our National Resources” is a fine phrase; it represents not only an economic, but a spiritual gain—this feeling of responsibility for the next generation. It is a new and most valuable asset of our national spirit; yet I must confess that I fear the coming of a day when we, too, shall have to practice the sordid little economies of the Old World and think with anxiety about the to-morrow.

It has always seemed to me that here the miracle of the loaves and fishes might be performed indefinitely, and that there always would be left over the baskets full of fragments. Somehow, in common with the rest of mankind, I have associated generous plenty with the American spirit, and I trust we shall never have just our dole and no more.

I recall walking one evening with the Herr Director and the Frau Directorin through the well-regulated, officially trimmed and “Streng Verboten” forest which encircles his native city. My children were with us—young, vigorous, American savages, who have a superabundance of the American spirit although they have not a drop of American blood in their veins. We passed a small mound of freshly mown hay and they promptly jumped into it, tossing a few handfuls as an offering to their aboriginal deity, the wind. If they had dashed into the plateglass window of a jeweler’s shop or had desecrated the most holy shrine, they could not have caused greater consternation.

“Um Gottes Himmels Willen die Polizei!” cried the Herr Director and the Frau Directorin echoed: “Die Polizei!”

Although this happened about ten years ago, my children have not forgotten their fright.

I suppose we still lack this virtue of economy, and yet I hope we may not lose that certain largeness of nature and that generosity of spirit which have characterized us.

I love the generous spaces, the unfenced lawns, which make of the whole village one common park; the grass and clover free to the touch of our children’s feet, the fragrant flowers wasting their bloom, and berries and cherries enough for the wild things of the woods. May the future not bring more high walls and narrow lanes, big game preserves for the rich, and scant patches of soil for the poor; castles for capital and tenements for labor. And may we never see written over every blade of grass: “Streng Verboten.”

I realized that the Herr Director spoke truly when he said that what we lack over here is a healthy class spirit, which the German farmer has. A sort of pride in his calling which makes him care for the soil and nourish it with a lover’s passion. To him robbing the soil is as great a crime as it would be to rob his children. It is not only the Emperor who regards himself as a partner with God, and sometimes the senior partner; the commonest, poorest peasant is apt to say as he drenches his field with the accumulated compost: “Ich und Gott.”

Speaking of the farmer, the Herr Director admitted that in Germany as elsewhere there is a trend to the city; but the tide is held back by the pride of the German farmer, who glories in having his traditions, his folksongs, and, above all, this sense of partnership with God.

We scarcely have such a thing as a farmer class; we have merely merchandizers in dirt who sell not only the products of the soil, but unhesitatingly the soil itself.

The land which we see from the car window, which the pioneers won from this boundless space, these houses and sheltering groves, the homesteads in which a great race was cradled, are all for sale, now that the soil is robbed of its fertility and the robbers have moved on to repeat the process elsewhere. We are doing something, he admitted, to stem the tide to the cities; we are introducing agricultural training into our public schools and are making the raising of corn and wheat a science, but not as yet a sacrament.

We stayed over night in one of the half-asleep towns on the shores of the river, a town whose history is written upon the headstones in the cemetery, in the center of which the stately meeting-house stands. We met the descendants of those who sleep there, whose pride lies in the fact that their forefathers were the pioneers who fought the Indians, the fevers and each other. Their houses are full of old furniture shipped from England and Holland, and we ate their food and drank their tea from costly silver and exquisite china which they have inherited.

We looked upon the portraits of their ancestors and were told of their virtues and their fame; we saw fine memorials to the past in churches and town halls and rode in their automobiles, to see the farms bequeathed to them. One thing, alas! they have not and never will have—descendants.

On one of the farms we saw a swarthy Italian with a bright red rose behind his ear. His wife and children were working with him in the field, and they were doing this strange thing as they pulled weeds from the onion beds—they were singing. The Herr Director said significantly, “These are the heirs to all this,” and I think he was a true prophet.

It is a wonderful thing to invent agricultural machinery and to discover new methods by which two blades of grass can be made to grow where but one grew; yet if only some one could tune our dull American ears, so that our farmers might catch the melody of the singing land and sing with it; if our boys and girls would love wild roses well enough to wear them—if, and that is a very big if—some one could teach us Americans to be proud of having descendants, we might add a new note to the great American out-of-doors, and keep it American.

That night we sat upon a wide verandah, overlooking a valley through which the Hudson rolled majestically; we saw populous cities, picturesque villages and bounteous farms; we looked into the heart of the out-of-doors and I was proud of it and of its free people, who ought to be a grateful people. There was deep silence everywhere; no sound except that of the birds, and they did not sing jubilantly as birds ought to sing in so blessed a place and on so glorious an evening. No one sang except the same Italian who was coming home with his wife and numerous progeny. He still wore the rose behind his ear, although it had faded. Those who sat with us had every luxury and more money than they knew how to spend; but they could not sing, for they were old, children there were none, and if there had been, they would not have been singing—they would have had a victrola.

After the Italian had eaten his frugal but pungent fare he came to the big verandah to get his orders for the next day, and the Herr Director spoke Italian to him and he replied in that language which in itself is almost a song. His mistress asked him to bring his wife and children to sing for us. His wife did not come but the children came. They would not sing an Italian song, it is true—that was just for themselves, in the fields where only God heard. They sang some sentimental thing they had heard in the “movies”—chewing gum the while. I asked them to sing something their teacher taught them but they knew nothing except “My Country ’tis of Thee” and the “Star Spangled Banner,” both of which they sang joylessly and not understandingly. How and why should they understand when the Americans did not?

It was a day full of dismal failure in my attempt to impress upon my guests the American spirit, and the failure of it was “rubbed” in by the Herr Director, who, as he bade me good-night, quoted as a parting shot this bit of German verse:

The rub was in his inference that we have no song because we have no noble spirit.

MANY years ago the Herr Director and I were tramping through the Hartz Mountains in northern Germany. He had not yet achieved portliness and fame; while to me, America was still the land of Indians and buffaloes, and I had never dreamed of going there. We were climbing the Brocken, and that which thrilled me more than its granite steeps and deeply mysterious pines was, the hundreds of school-boys and girls we met, singing as they climbed, and who, when they rested, listened to their teachers who stimulated their imagination and their patriotism by telling them the stories which had woven themselves around those mountains.

The Catskills are not unlike the Hartz, and I remarked upon it as the Herr Director and I were climbing the Walkill Range. Our destination was Lake Mohonk, the scene of the Conference for International Arbitration, organized and supported by that noble Quaker, Albert K. Smiley; and now after his death continued by his able and generous brother Daniel Smiley, and his gracious wife.

The Frau Directorin, with hundreds of other guests, had been met at the railroad station by carriages, this being one of the few places left upon earth where the automobile is excluded.

The Herr Director was not climbing as easily as he climbed thirty years ago, and neither was I, although I made a brave show and led the way, frequently leaving him in the rear, much to his disgust.

“Yes,” he said, mopping his brow and looking about critically, “this is somewhat like the Hartz,” and my heart gave a joyous leap at his admission; “but several things are missing: Good company, merry songs and, above all, places of refreshment.”

Of course I could offer him no better company than I was, as there are not many people in America who climb when they can ride for nothing; and the only refreshment available was clear water from a shaded spring. As we drank he recalled laughingly how, when we stopped at one of those nature’s fountains in the Hartz, a man who had watched us, came running out of his house and warned us that we might catch cold in our stomachs, at the same time politely offering to guide us to a place where we would get something not so dangerously cold, and with tempting foam at the top.

I have long ago been weaned from the German custom of mixing refreshments and scenery; but one does miss the boys and girls, the merry, happy throngs, their sentimental songs and their fervent, poetic patriotism. Involuntarily my mind reverted to a scene the Herr Director and I witnessed after we had finally reached the summit of our mountain in the Hartz. It was nearly evening, and we could look far and wide above the forest into the happy and beautiful country. On the very topmost peak stood a corpulent German, surrounded by his genial group. He was reciting with fervor and genuine passion, in the broadest Berlinese dialect, one of their treasured poems which begins with these lines:

If this should happen over here, of which there is no danger, he would be laughed at, if noticed at all; over there he was treated like a high priest who called the faithful to prayer.

As a people we lack not only poetic imagination, we lack also this identification of our country with the best in nature. Our youth may be to blame for that, or perhaps we have so much of nature and so much which is beautiful that we have not been able to encompass it. Yet there must be something very important lacking in such Americans as the one whom I met very recently. He had just returned from a “Seeing America First” tour, and had seen everything from Niagara to the Big Tree groves of California. When I asked him what he thought of it all he said, coolly, “Oh! it’s a big country.” Naturally I did not tell this nor the following to the Herr Director.

A few years ago I went with a group of Americans to see one of the famous ice caves in the Alps. The accommodating guides had lighted candles in the labyrinth and the sight was enchanting. One of my party, a dry-goods dealer, said with genuine enthusiasm: “My! I wish I could get such a shade of silk in New York.” The other said: “Too bad; so much perfectly good ice going to waste.” He belonged to the much maligned tribe of ice-men. The rest of the men said nothing, although one of them did remark when we reached our hotel: “This only shows how slow they are over here. In the good old United States we would light that show with electricity.” He belongs to the tribe whose name is legion.

The Herr Director, as my readers have found, was very chary of his praise, in fact thus far I had not heard a good word from him for my United States; but that evening as we looked from the Mountain House down upon the dark, deep lake, the rock gardens and the quaint bowers on every promontory, granite walls broken and scattered, and the rich valley between us and the Catskills, he did say: “This is the most beautiful spot I have ever seen!”

Of course his generous mood was partially gendered by the unequalled hospitality of our host and hostess and by the sight of his fellow guests, who represented not only the entire United States, but the United States at its best. Moreover, he and his wife had received a more than cordial welcome because they were representative foreigners and spoke English with a “cute accent.”

I almost felt a slight touch of jealousy upon that point although I am not of a jealous nature. But I have noticed this: to the degree that my English has improved, to that degree I have become less interesting to my American friends, so that I have sometimes been tempted to wish that I too might speak English with a “cute accent.”

The happy day was almost spoiled for me by the discovery that our trunks had not arrived. The Herr Director worked himself into a frenzy and the Frau Directorin had dire forebodings of having to spend the three days in the same shirt-waist. Telegrams were sent in all directions, while the Herr Director called our much boasted of baggage system hard names; my “best laid schemes” seemed about to “gang agley” when much to my relief the trunks arrived, and I felt once more assured of the divine favor in my most strenuous efforts to “boost” my United States.

The Herr Director had come to this country to take part in the Mohonk Conference, and being a prudent man, he submitted his address to me. It was written with Teutonic thoroughness and as void of places of refreshment as the Sahara Desert or the Walkill Range we had climbed.

I suggested a thorough revision, the cutting out of many statistics and resting his case, not upon pure business, but upon the higher plane of pure justice. He insisted upon retaining his statistics and also his appeal to the selfish and materialistic side of his audience; for he knew “something about Americans” and still doubted their idealism.

The next morning after breakfast we attended prayers, which is a part of the daily program of this hostelry, and presided over by the host, who usually reads the Scriptures, announces a hymn and then leads in prayer. It is as impressive as it is simple and dignified, and the Herr Director and his wife did their first singing in America when they joined in a hymn whose tune is an old German folk-song.

The program which followed the prayer service was dominated by specialists in International Law and they were dry and concise enough to suit even the Herr Director; while the dreamers and agitators, whom he expected to hear, were almost altogether unrepresented. In fact they have grown less in this assembly each year, largely because it is thought that the whole subject has reached the point when it is a practical question to be discussed by men of affairs. No one knew better than the Herr Director how inevitable was the next great war and how far we were from the practical Court of International Arbitration.

The epilogue to that great world drama had been spoken in the Balkan, and spoken with vehemence, passion and fierce cruelty, and he knew its bearing upon the whole tense situation in Europe. Yet I am sure that even he did not know how many nations would be involved, nor how costly and deadly would be the conflict. He did foreshadow in his own condemnation of England and of England’s foreign policy the element of hate between the two related nations, which was to play so important a part in the present war.

The afternoon is playtime at Lake Mohonk, and most generous are the provisions for recreation; but the Herr Director did not ride or drive, nor play golf or tennis. He stayed in his room rewriting his paper, having sensed something of the Spirit of Lake Mohonk.

It is a very dignified room in which the problem of International Arbitration is discussed, and although it never loses its hospitable, home-like air, one always has the feeling of being before a high tribunal, where anything but the most serious mood seems out of place; although a jest sometimes relieves the discussion.

An audience of about four hundred people gathered that evening, men and women in varied walks of life, coming from all the states in the Union and from many foreign countries.

There were captains of industry and of infantry, admirals of fleets and presidents of colleges, statesmen and politicians, ministers, lawyers and journalists. Their views ranged from those who believe that war is an unavoidable event in human history, and that a little blood letting now and then is necessary for the best of men, to those who teach that war is a curse and that a certain warrior who compared it to the worst place which human imagination can conceive, might be sued for libelling his Satanic Majesty who presides over that place or state. On the whole, they represented the men of action and men without illusions although with high ideals. The Herr Director’s paper, minus its statistics, and keenly critical rather than laudatory, was received with applause, and he stepped from the platform in the best humor in which I had seen him since he reached the United States.

The real joy of the Lake Mohonk Conference, and of all conferences, is the human touch, and after the long evening session the Herr Director became the center of an interesting group of men who, while smoking their cigars, lost some of their American reserve and became sufficiently animated to hear and tell stories; so it was long past midnight when the informal session ended.

Frequently the Herr Director asked questions about things which he could not understand, and it was at such times that I sought to enlighten him, or have him enlightened by others; for he had become sceptical as to my own ability to inform him regarding anything American.

He could not understand, for instance, that all this lavish entertainment was free, and suggested that it must be a sort of gigantic American advertising scheme, carefully concealed. When he was told that to secure a room during the season one must apply long in advance, and most likely have fair credentials before being accepted as a guest, he merely shook his head and murmured something about these “inexplicable Americans.”

He also did not see how an hotel could flourish in any civilized country without permitting the accepted social diversions, such as card playing, dancing, and drinking something stronger than the mild beverages served at the soda fountain.

He wanted to know how it was that three or four hundred Americans would take three days of their time to discuss a theme which had little or nothing to do with profits. All the Americans he had known about were void of ideals, and had no time for anything but business or poker. In fact he was astonished not to see poker chips littering the sidewalks.

I told him that while it is true that the average American business man is always in a hurry, and gives little time to wholesome recreation, it is also true that in no country with which I am familiar do men of business give their time so generously to the consideration of the common welfare as here. They do this, not having the incentive constantly held out to the European business man, namely: Recognition by the state and the reward which sovereigns may bestow, in much coveted titles and decorations. The average well-inclined American business man is incredibly patient, sitting through tedious meetings, listening to reports of various philanthropies, and earns a martyr’s crown attending those interminably long banquets with their assault upon his digestion and their appeal to his sympathies.

At Lake Mohonk the Herr Director met business men employing thousands of clerks to whom they grant vacations and holidays without legal compulsion, and for whom they have inaugurated welfare plans of far-reaching importance. It was certainly a revelation to him that the number of Americans who are something more than animated money bags is growing larger every day.

The still more difficult thing to explain to him was the frank and open discussions of national policies and the evident international view-point of those who took part in them. In all the discussions the most striking note was: “The United States wants not territory, not unfair advantage over other nations nor aggrandizement at the expense of lesser peoples, nor war, certainly not for conquest.”

The Herr Director intimated that in the exalted mood induced by being members of this conference, we could afford to be generous; but that at a time of national excitement we are no better than other people, taking what we can get and asking no questions.

“Uncle Sam was not wholly disinterested in Cuba, was he? and as far as Mexico is concerned, who fermented the trouble there but this same Uncle Sam, that you might have an excuse to swallow as much of Mexico as you wanted?”

Instantly my mind travelled to the time of the Spanish-American war, when I was in Europe, and the Herr Director was editing an influential German newspaper. He wrote an editorial, accusing the United States of beginning the war with Spain for the sole purpose of annexing the “Pearl of the Antilles,” and when I disputed his theory we nearly severed our “diplomatic relations.”

I now again vigorously pressed my point, to the great amusement of my friends and the chagrin of the Herr Director, who could not easily refute my statements; for while I acknowledged being an “Unausstehlicher Americaner,” I happen to know the Old World policies as well as he does.

I mentioned Austria-Hungary, and its taking over of Bosnia and Herzegovina, without so much as “by your leave”—and Germany which, to salve its hurt, sent a fleet of warships to China and helped the German eagle bury its beak in the Yellow Dragon’s tail. I mentioned France in Algeria, and England everywhere—“and Uncle Sam in the Philippines,” he interrupted.

I took full advantage of that interruption to remind him that Uncle Sam is the only power which ever paid for anything gained by that right which in Europe seems to be the only right;—the right of might.

It was a difficult task which I had undertaken, to convince the Herr Director that the American Spirit is different from that of the Old World, and in spite of me he insisted that we are not a bit better than other people, but only so situated that we can afford to be generous. I assured him that I preferred to boast of our fair dealing with lesser peoples than of our victorious battles, and that I am never so loyally and enthusiastically American as when I think of our being just, rather than mighty.