CHRISTMAS EVE.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Leaves for a Christmas Bough, by Unknown

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Leaves for a Christmas Bough

Love, Truth, and Hope

Author: Unknown

Release Date: January 18, 2013 [EBook #41865]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LEAVES FOR A CHRISTMAS BOUGH ***

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Brian Wilcox and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

CHRISTMAS EVE.

Love, Truth, and Hope.

Recollections of the many pleasant hours passed with a certain juvenile circle, not fifty miles from Boston, and associations connected with this joyous season, have induced the feeble effort of collecting a few stray leaves for its amusement. Hoping that their many defects, arising from a hasty preparation amid various cares and occupations, may be kindly pardoned, they are presented as a trifling Gift for the Holidays.

To that group, bound together by a mutual sympathy in each other's joys[6] and fleeting sorrows, it may not be uninteresting to recall the days of "Auld Lang Syne." The scene will be a chequered one, for amid the frolic and sunshine, some tears will have been shed; while with hours of hard and thoughtful study, the bitterness of failure will sometimes appear.

But the bright and beautiful so far prevail over the rest, that such only need be recalled; and while enjoying those sweet remembrances, let us be merry and glad together. With truth and goodness as our constant aim, let us strive to make daily progress in the school of life, and though we may be separated on Earth, we may hope for a blissful reunion in Heaven.

| Preface, | 5 |

| A Letter from Santa Claus, | 9 |

| Rigolette, | 14 |

| A Story for Minna, | 19 |

| A Story for Nellie and Molly, | 21 |

| The School-Teacher's Song, | 24 |

| Letter from the West, | 26 |

| A Sketch for the Members of the "Sunbeam Society," | 31 |

| Scraps about Dogs, | 34 |

| A Letter from a little Girl to a Sick Schoolmate, | 39 |

| Who is my Neighbour? | 46 |

| A Few Rhymes for Dan, | 51 |

| A Story for Little Emma, | 53 |

| A Story told under the Great Elm Tree, | 55 |

| A Letter, | 60 |

| A Conversation on Fairs, | 65 |

| A True Sketch for the Two Sisters, | 68 |

| Scraps from a Journal, picked up in a gale of Wind, | 71 |

| An Incident, | 76 |

| A Story for Willie, | 78 |

| A Letter, | 81 |

| A Parody on the Mower's Song, | 87 |

| A Few Rhymes for "Charlie Boy," | 89 |

| A Story for Lizzie, | 91 |

| The German Musicians, | 94 |

| Letter from a Little Girl to an Absent Schoolmate, | 102 |

| An Account of a Sea-Shore Visit, | 107 |

| A Tribute to the Memory of a Sunday-School Scholar, | 113 |

| A Simple Story for Georgy, | 118 |

| A Story for Sweet Little Fanny, | 121 |

| Sketches from a Fireside Journal, | 124 |

| Unda, or the Fountain Fairy, | 128 |

My dear Children:

As I have always been in the habit of meeting with you on this Anniversary, and as I cannot expect to see you all together this year, for the sake of old times I am going to write you a letter. Perhaps you are not aware that I have been a silent spectator of your daily occupations, but so it is.

I generally take a nap from one year to another, so after our glorious celebration at the "Bee-Hive," I packed myself away in the stove-pipe for that purpose; but the hum of merry voices kept me awake, and thus I lay and listened to what was going on. The fairies, in whom you perhaps all believe, have also been quite numerous in your vicinity, and from my relationship to them, I have often heard of your excursions over hill and dale, and the many gay times you have enjoyed together.

I travel over many regions at this season of the year, and in order to accomplish all I wish, in my endeavors to please the young folks, I shall begin my preparations a little earlier than usual, so you need not wonder if I visit some of you a little before Christmas and New Year, with one of my gifts. This will consist of a few of the simplest little sketches, letters, and reminiscenses of the various occurrences in which you have participated, and I hope the contents of this "Christmas Bough" will give you as much satisfaction as those of by-gone seasons, when the festive pine-tree erected to my honor has been loaded with gay and glittering gifts.

I trust you will all enjoy the holiday, and with glad and grateful hearts fully appreciate the many privileges you enjoy, as the children of kind parents, and the objects of interest to affectionate friends. Of course you will be most forcibly reminded of the Giver of all these blessings, and you will love to listen about the "gentle child Jesus," in honor of whose birth the day is celebrated.

By looking back upon the past year, you can see what steps you have taken in self-improvement, what you have learned, what left unlearned; and the retrospect will help you to form new plans for the future, which now rises bright and beautifully before you. One little girl will have the satisfaction of having almost conquered a peevish temper, which made her very disagreeable; another will have acquired habits of neatness and order, so necessary to comfort and enjoyment.

This scholar will have an increase of memory, and thus avoid the repetition of that troublesome phrase, "Oh, I forgot;" and that one will become more thoughtful, and will not consider the excuse, "I didn't think," sufficient to cover her frequent blunders. A nice, hearty little fellow that I know will have learned to read fluently, and to love his books for the sake of all the good and pleasant things he can find in them; while another rogue will be kind and gentle to his sisters, and give up the naughty habit of teasing his companions. The proud child will learn her true value, and not think herself better than her mates, on account of her pretty face, fine clothes, or handsome residence; while best of all these changes, the cowardly and deceitful will be ever brave and truthful, finding that honesty is the greatest safeguard, and truthfulness a shield from many temptations.

All foolish quarrels will be forgotten, and the spirit of love and good will pervade all their actions, as the children resolve to aid their kind parents in family cares, the brother and sister mutually assisting each other, and with cheerful, bright faces make a perpetual sunshine at home. In this delightful progress, the claims of those who have always served you as devoted domestics, will not be forgotten; and by your thoughtfulness, you can thus atone for many an unkind word or heedless exaction on your part.

As children of benevolent parents, you will help to bestow gifts upon the poor and needy, and nothing, I know from watching you all, will be more pleasant than this part of the Christmas rejoicings. I shall want to hear from you in answer to this lengthy epistle, for I know you are all used to writing; and be assured I shall ever feel a sincere and hearty interest in your welfare, and whatever may be your position in life, memory will carry me back to the happy days spent in the pretty village of D. And now, as I draw on my seven-leagued boots for other scenes, I will wish you all a "Merry Christmas," and a "Happy New Year."

"Santa Claus."

A little girl, thinking it was very difficult to write compositions, once went to her teacher, and said, "Will you please tell me how to begin? for I do not know what to say first." "How would you begin, if you were to relate the subject to me?" "Oh! it would be very easy to talk it all, but to write it properly is very hard." "Well, my dear, just suppose yourself talking to me, and for once forget the difficulties of a composition, and I have no doubt you will succeed." Pointing to an engraving of Rigolette, she continued, "Go and write a description of that picture, and if you will patiently persevere till it is carefully finished, I will tell you a story about your favorite.

"There is a young girl sitting by a window, looking at her Canary birds. She seems to be very busy with her work, but she stops sewing for a moment, to listen to the singing of the birds. Her face is very beautiful; her hair is dark and neatly parted on her forehead. Her eyes are brown, perhaps black; her nose straight, her cheeks rosy, and her mouth sweet and smiling. She has a handkerchief tied round her head, and she wears a dark, nice-fitting dress. The furniture in the room is a large old-fashioned table, a high-back chair, and on the window-seat is a pot of pretty flowers. The green blind is drawn up, and in the distance, the top of a church is seen, so I suppose the room is very high. The birds' cage is covered with chick-weed and flowers, and I guess they are very happy and contented. Her hands are white and handsome, but her thimble is blue, and different from any I ever saw, and I should think she was hemming a handkerchief."

As a reward for her ready acquiescence, the following little sketch was written: "Rigolette was a young French girl, in Paris, and earned her livelihood by following the trade of a seamstress. She had been left an orphan at a very early age, but from her joyous, happy temperament, she had acquired her name, which signifies 'The Warbler.' For the people who adopted her, she performed the duties of a faithful daughter, and was ever cheerful, active, and industrious. She was placed in the midst of poor and even wicked people, but her native love of the good and beautiful saved her from contamination.

"As a young girl of twenty, when deprived of her early protectors, she lived by herself, with her two Canaries, 'Ramonette and Papa Crétu,' for her companions; and solaced by their songs, with the native buoyancy of youth and health, she passed a busy, contented life. Though possessing very limited means, she was most charitable, supporting a poor family for a whole winter, and often cheering the sick and lonely. She was proverbial, in all the neighborhood, for her neatness, taste, industry, good humor, and active benevolence. She thus became the friend, the assistant, the confident, and adviser, whenever it was in her power to aid others, and like a sunbeam she gladdened many a dark and gloomy apartment.

"Still, she was used to suffering, and sorrow visited her young heart when her cousin was unjustly thrown into prison. Nobly did she devote herself to him, when deserted by all others, and many were the efforts she made to gain his release.

"Meanwhile she made the acquaintance of a German prince, who, in order to become acquainted with his subjects, travelled through his dominions in disguise. Through his efforts the cousin was released, and made the proprietor of a fine farm. By daily intercourse the good prince became intimately acquainted with the excellent French girl, and fully appreciated her many estimable qualities. By her means the prince's daughter, who had long been lost, was joyfully restored to his affection, and to her proper rank in society.

"Soon after Rigolette was married, and the prince made her a handsome present on her wedding day. A beautiful rose-wood box, containing many tasteful articles of apparel, and various ornaments to adorn her country home, was sent to her with this inscription: "To Industry, Prudence, and Goodness." Her gratitude for all these favors was unbounded, and many kind, affectionate letters passed between them, keeping up a continued interest through life. The example of one such good and cheerful being is a blessing to all around, imparting the purest pleasure, and teaching a valuable lesson to those who come within its genial influence."

There was once a little mouse, that was kept in a nice little trap, and carefully tended by many good children. It was a great pet, and grew fat and plump every day. It was so tame that it would sit up just like a squirrel, and eat its little dinner without the least fear of those around.

Sometimes it would wash its face like a kitten, and then, after a race round the room, creep back to its wire cage and take a long nap. It had a soft, warm bed of cotton and wool, which it would pull to pieces before it went to sleep, to the great amusement of all the boys and girls, who daily watched its capers.

No mouse ever had a pleasanter time, or greater dainties at its command. It had plenty of cheese and sugar, and though it had no companions, it seemed to play as much as it liked, and to be very happy. On the table near it stood a globe full of gold fishes sailing in the water, and over its head were two yellow Canary birds. What they thought of each other, I can't say; but it was a strange sight to see the beast, birds, and fishes thus brought together.

No cat ever disturbed little mousey's retreat, but alas, one cold winter night, it froze to death! From its fate, if you ever are allowed to keep pet animals, remember to take good care of them, for they are helpless creatures, and dependent upon you for constant watchfulness.

Hanging high above the school-room door, there was a little brown leaf, which flew round and round in airy circles, and at last, attracting the notice of certain inquisitive "little folks," was called "the little bird." Upon being swept down from its winter's perch, the following little scrap was found rolled up in its folds.

"To day has been dull and rainy, but I was in an atmosphere full of sunshine, for nice little boys and sweet little girls were near me on one side of the room, and on the other, busy young misses and maidens. The "wee little ones" said a nice lesson from Peabody's Primer, which is a very pretty book, and I could see they were improving very much.

"Then the second class, composed of youngsters about six or seven years old, recited from the Spelling Book, the Geography, the Mental Arithmetic, and then read from a book all about animals, birds, and fishes. They all answered briskly, stood up very straight, turned out their toes, and looked so smiling you would have thought they were playing a very pleasant game.

"Once in a while they could not answer the questions correctly, and then down went a little boy or girl a place lower in the class; but in spite of that they all kept good natured, and were thus saved from getting into more trouble.

"One darling little girl, who had sometimes been tempted to pout and spoil her face by crying, made a great effort to keep calm when she lost the head of the row, and succeeded. 'I didn't cry, did I?' said she, 'and I am determined I never will again.'

"Then the teacher kissed her beaming face, and the sweet child felt as happy as her teacher, at the consciousness of her great victory, and all her little companions were very glad with her, for they loved each other dearly."

Come away girls, to labor,

Brightly glows the young day;

Come away, every young neighbor,

To the school-room away.

The clear echo ringing,

Is heard on the lawn,

While the school-girl is singing

Her joys in the morn.

In the bright glancing school-room,

From tree and from stream,

O'er each rose-tinted cheek-bloom,

How plays the Sun's beam.

Come away, &c.

Come, each happy young maiden,

Your lesson prepare,

With heads freely laden

With Learning's sweet fare.

Come away, &c

Then the blithe ones come bounding,

Aroused by the call,

And their voices resounding

Good lessons from all.

Come away, &c.

Hark! the scholars now wending,

The street-side along,

Are cheerily blending

Their shouts and their song.

Come away, &c.

River-Side, St. Charles.

My dear Coz:

Here I am settled down at the far West, on a pretty little farm, and enjoying every earthly blessing. I am surrounded by a family of merry children, who frolic round from morn till night, enjoying every moment of the bright sunshine, and never tired of admiring the beauties all around them. Perhaps a description of my pets may amuse you, so with a mother's natural pride, I will draw a picture of their various traits.

My oldest son is a tall, black-eyed boy, and a most gentlemanly little fellow of his age, assisting his father on the farm, and often lending his aid to me in the school-room, when, amid the cares of teaching, I need a monitor. Young as he is, the native energy of his mind makes the smaller ones bend to his will, and they are very fond of him, in spite of his exactions.

Charlie, the second, is very precocious, and astonishes us all, by the readiness with which he acquires every thing, and I look forward to the time when he will be as great a student as his father.

Annie is a fair-haired, gentle lassie, with deep, earnest blue eyes, a most delicate complexion, which, from her great sensitiveness, is the perfect index of her feelings. She is very conscientious, and has never once deceived me. She is fond of her needle, and will be a most efficient help in the cares of the household, as she is ever most happy when quietly seated at my side.

Ada, her sister, is a perfect contrast, with large, black eyes, and a face glowing with health and happiness. She is not at all pretty, but her constant good humor and lively sympathy impart an animated and pleasant expression, as agreeable to us as beauty. With her brothers she is a great favorite, ready for any plan of theirs, and though she is often in mischief, her merry laugh procures a speedy pardon. As I look out of the window, I see the group coming in from the woods, loaded with flowers and mosses, and Ada mounted on the white poney, looking like a gipsey queen surrounded by her subjects.

The two youngest, Arthur and Mabel, are the darlings of all, and are the objects of general pride and attention, particularly the former, who is beginning to show quite a taste for mechanics.

In looking at my children, I am often reminded of our own childish days, when together we roamed in the pleasant village of D., free as birds and careless of aught beside the present. Do you remember those good old times, when, with our teacher, we took such pleasant walks, hunting for wild flowers to press in our herbaliums, and the frolics we had going after berries or nuts?

Then our summer picnics, at Powder Rock, Pine Grove, Vine Rock, Cow Island, Harrison Grove, Table Mount, Job's Island, the Farm, and other favorite spots too numerous to mention. In winter, too, can we ever forget the "Quilting Bee," followed in the evening by the "Candy Scrape"; our famous French class nights, when we performed "Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme;" and last but not least the representation of the "Knapsack?"

With these scenes of pleasure, comes the memory of more serious hours, passed in improving study, and instructive courses of reading. The Examinations, at which we quaked with fear, in the presence of the Committee and the assembled parents. But they generally ended with unalloyed pleasure, as we received our premiums for any progress in our lessons, or any steady effort to acquire good habits. Our attempts at Composition, the subject of so many sighs and groans, and the great stumbling block in our path of learning. I have yet several relics of our mimic Post Office, which helped us more than any thing else in conquering the difficulties of writing.

When my children have been very good, I entertain them with a perusal of my various notes and letters, and nothing pleases them better than selections from my old Journal. I keep up with them the same routine we had at school, making a pleasant walk, or a little gathering of the neighbor's children, the result of a fortnight's earnest attention to books and work, and seldom do I have to banish any of the happy circle. But if laziness, selfishness, or wilful naughtiness of any kind is manifested, the offender is debarred from the anticipated enjoyment.

And now, dear Coz, I shall expect an answer to my lengthy epistle, with a full account of Henry, Emma, Molley, and Dan, of whom my little ones often draw imaginary pictures, believing them to be possessed of every perfection.

Ever Yours, with kisses from all here, I remain,

Mary Cribbens.

In a certain town situated on the banks of the winding Charles, and in the neighborhood of a village church, there is an humble school-house, shaded by magnificent elm trees, the pride of the place. In the interior stand two rows of green desks, flanked by sober-looking chairs, and occupied by scholars of all ages from five to fifteen. In the centre is a venerable stove, which for many years has been the presiding genius of the place, and has retained its stand in the midst of various revolutions. In winter it imparts its generous warmth to roast chestnuts and apples, and in summer it serves as a graceful pedestal for flowers, while its long funnel, raised over the heads of those below, seems like a protecting arm.

On its walls hang various maps, drawings, and pictures, one in particular, the object of their admiration and regard; each having some pleasant association, and all combining to add a pleasant aspect to the room. At the upper end of the apartment, which is used as a dressing-room, library, and play-house, &c., &c., are two great tablets, with the following inscriptions:

"There's not a leaf within the bower

There's not a bird upon the tree,

There's not a dew drop on the flower,

But bears the impress, Lord of Thee!

God, thou art good! Each perfumed flower,

The smiling fields, the dark green wood,

The insect fluttering for an hour;

All things proclaim that God is good."

Near the said stove is a table covered with books and work, scattered round in most elegant confusion, while in the centre stands a beautiful white vase, filled with the sweetest flowers. Near by are "the little ones," making their first attempts at writing and drawing upon the slate, or perhaps sewing upon their many-colored patchwork. In the larger circle may be seen the older sisters and companions industriously plying their needles and pencils, while listening to the reading of some interesting book.

In this circle are various specimens of happy childhood; some being plump and rosy, others pale and thin, some tall and some short, some with black eyes and others with blue or grey, but the countenances of all lit up by the earnest expression of eager interest. With the sunshine playing round their young heads, clustering together, there cannot be a more fascinating picture, or one more worthy of an artist's hand; for what is a more beautiful sight than a group of bright-faced, busy-fingered children?

In the depth of winter, all the dogs in a certain inland town were supposed to be seized with madness. Numbers fell victims to the mania for murdering them, and the noble hound, the fierce mastiff, the graceful spaniel, the sagacious Newfoundland, were, with the common cur, alike liable to death. Fierce-eyed men roamed through the streets, thirsting for blood, and waited to destroy their prey by open assault, or with the treacherous snare of poisoned meat.

The snow lay cold and bright upon all the ground, glittering icicles gemmed all the trees, and no sounds were heard besides the ringing of the merry sleigh-bells, making music through the frosty streets. All is still at the Bee-Hive, when suddenly a boisterous knock is heard at the door, and upon opening it, the well known features of a dog-killer appear.

"Whose dog is this?" he asks in a loud voice. "I really don't know," is the timid reply, "but I believe he belongs to one of the scholars." "Well, he has been sleeping all the morning on the snow, and he looks very queer, so I guess he's mad, and I must kill him." Immediately the mistress of the dog sprang to the door, and with beseeching tones, exclaimed, "Oh, don't kill him, for it is my dog! Poor Rover! He shall not be killed!" The man still brandishes his club, the symptoms of the dog are pronounced those of genuine Hydrophobia, but after a spirited consultation, the dog's life is spared, and he goes home with his happy mistress.

Not long after, he was missing, and it is supposed that being in daily fear of his life, and understanding the fate that awaited him, he travelled off to parts unknown, thereby proving his superior sagacity.

Long may his young defender retain the warm heart and compassionate feelings displayed on that occasion; for a love of the noble animals that serve us is one sign of a kindly, generous soul, and in a woman is most estimable.

Talking of dogs, it may not be amiss to mention one or two other specimens of the canine race that have distinguished themselves in times of yore. Tiger will not be forgotten by those who enjoyed the famous coasting matches, when, after the swift ride down the steep hills of "Auld lang syne," he so readily offered his vigorous services, and after floundering through the snow, brought back the sled to its owner again.

Bruno, too, the companion of many pleasant walks, the attendant on many a boat-ride, swimming half the distance, the ready assistant at any race, and the guardian of his young friends, will not be unremembered.

But first of all in fame, and last in the hearts of those who knew him, will the memory of dear "Old Nep" be cherished. Of him a volume might be written in praise of his youthful grace and beauty, and his superior intelligence, as he increased in years. Sharpened by his intercourse with man he could understand the language addressed to him, and even when spoken of he shewed by signs that he comprehended the remarks made in his presence.

He could carry messages, go on errands with a basket in his mouth, carry bundles, play ball, leap, jump, and slide with the greatest agility. Besides these and many other accomplishments, he could draw a little carriage, harnessed like a horse, and obey all the commands of his young master with untiring patience.

For faithfulness as a watch dog, and for devotion to the interests of the family, by every member of which he was dearly loved, few dogs can compare with him. For a well spent life, and for acting well the part assigned him, he might be cited as an example even to the human race, some of whom might blush at the superior excellence of the dog.

New Year's Day.

My dear Annie:

As I have a holiday to-day, and can not get up to see you, I am going to write you a letter. We are all very sorry that you are not well enough to be in school yet, but are hoping every day to see you again. I will write you something about our Christmas celebration, as it was the pleasantest we have ever had yet, I think.

We were very busy for a good while before making things to put on the tree, and there was a great deal of whispering every day with our teacher, who helped us all, and had to keep a great many secrets. Then we practised our prettiest songs from the School-Singer, and recited our different pieces of poetry, and besides all that we reviewed a good many lessons. When the day itself came, we were almost crazy with delight, and with the many things we had to do. Some of us left invitations for the parents and all the old scholars to come, some helped make the curtains, which altered the school-room so you would not have known it. Some of us helped make evergreen trimming to dress the walls, while the boys went after two beautiful pine trees, to put at the end of the room, and some of us fixed the candles in tin stands which we called our silver chandeliers. The young ladies were busy trimming the church close by, so we could run in there for a minute, to look at the beautiful great Cross behind the pulpit, and the wreaths and festoons, for the people were going to celebrate Christmas eve.

Then in the afternoon we brought all our presents to put on the trees, and they looked beautifully, and there were so many things we had to have a table besides. Then we made a platform of the benches, and fixed the chairs all round the room for the company; the boys put up a curtain for us in front of the trees, and after every thing was ready, we arranged ourselves as we were to sit in the evening. Soon after tea we all went to the school-room early, and I brought a rake and some hay, for I was to be one of the seasons.

There was an address by one of the young gentlemen, and then we all sang a Christmas song, but I felt so frightened, I could'nt sing very loud. Then the curtains dropped, and we were arranged as the four seasons. When it was raised, the two Marys represented Spring; I was Summer, with a broad-brimmed hat on, and a rake in my hand, and little Emma sat by my side, holding flowers. I said the mower's song, and then we all sang another piece. Next came N., dressed as Autumn, with a beautiful wreath of dried grasses on her head, a sickle in her hand, and close by her side, dear little Lena knelt with a basket of grapes and apples. Then Ellen appeared as "Winter," dressed in a red tunic trimmed with white fur, a muff in her hands, and a fur cap on her head, and she looked very pretty. "Jack Frost" was at her feet kneeling on a sled, with skates on his shoulders; he said a long piece of poetry about "Christmas Eve," and every now and then he rattled some sleigh-bells.

After the "Four Seasons," two of the smallest children stood up a minute as "Day and Night"; one of them, with rosy cheeks, blue eyes, and light hair, had a white veil thrown over her head, and the other, with coal black eyes, and dark hair, had on a black veil, and I think it was the prettiest thing we had. Dear Abby was the "New Year" of 1849, holding a large silver cross in her hand, and she said her piece beautifully. Then Agnes came out as the "Old Year," dressed as an old woman with a high-crowned cap; she said her piece very perfectly, and she made every body laugh, she did her part so well.

Last of all, Santa Claus appeared, all dressed in furs, and holding a bag of presents, and then we all sang together our last song, a great deal better than the others.

A gentleman then helped give out the presents, but there was such a crowd, it was hard work to get them. Just then one of the trees caught fire; and somebody rushing to put it out, tipped over one of the trees, making a great crash, but no harm was done. It took almost an hour to give the presents, and after that we all went home with our arms full of pretty things. The next day we came to the school-room to look over our gifts, and put the room to rights; then we had some cake and peanuts, instead of the night before; for you know that is always our usual treat, and then we all went to church together.

I hear you had a great many presents, and we hope you liked those the scholars sent you. It has been very cold since Christmas, so we have not had any sleigh-rides, but we have been on the ice almost every afternoon, and we have fine times sliding and skating. The great girls go by moonlight, and have been up to Wigwam Pond, which is just like a silver floor.

Do you remember those times when we used to slide on your pond near the old mill, and how we cried if we fell down or our fingers were cold? The little brook all frozen up and filled with crystals, we thought was like a Fairy's palace, it was so glittering and had so many colors.

Every day, at noon, when the snow is soft, we make snow forts, and we have made a great snow man, which is our giant, and at night he gets real hard. Then we play "English and Americans," like our history lessons, but the Americans always beat, because the most girls take that side. We all send love to you, and many kisses, and hope you will soon get well, for we are getting on very fast with our lessons.

A Happy New Year to you.

Yours ever,

"Lizzie."

"Mother," said a little girl to Mrs. Franklin, as they were seated one day at their sewing, "will you be so kind as to tell me the real meaning of the word neighbour? Our teacher in the Sunday School gave us the text, 'Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself,' for our subject of thought during the week, and she wants us to tell her who our neighbours are. Now I suppose all who live in the same street are really neighbours, though I am sure I know very few of them."

"Your idea, my dear Emily, is correct as far as it goes; but we are not only required to feel an interest in the dwellers in the same street, but also in all those with whom we come in contact, whether rich or poor, high or low, young or old, provided we can be of service to them."

"Well then, mother, if all my schoolmates are my neighbours, Sarah Howe, Julia Boyd, and even Kitty Gray come in the number; and I am sure I cannot love them as well as I do you, or sister Elizabeth, or dear Father."

"That, my dear, is not strictly required; but a certain degree of kindly interest, enough to treat them well whenever you meet, or in other words, as you should like to be treated yourself." "This is quite a new idea to me, but I do not think I could love Kitty Gray; for she is always cross and selfish, and all the girls have determined to have nothing to do with her."

"I hardly think this determination is a Christian one, though I acknowledge it is very difficult to bear with such disagreeable qualities. But did you never think, that by being kind and gentle among yourselves to poor Kitty Gray, you might make her amiable and pleasing? Remember, 'a soft answer turneth away wrath,' and certainly, a continued series of kindness will produce a much more beneficial effect than coldness and studied neglect."

"I suppose you are right, Mother, but then I can't be different from the other girls, for they will laugh at me, and say I have left their friendship for such girls as Kitty Gray."

"This need not be, my dear girl, if you act with a right spirit; and I do not see why you cannot be Kitty's friend, without leaving your old companions. Besides, if they are really good girls, better than Kitty herself, they will not only admire your conduct, but imitate it immediately. But the clock is striking eight, and when you return tell me of your success."

She reached the school, greeted all the scholars, and none more kindly than Kitty Gray, who was sitting by herself as usual, the image of discontent and unhappiness. The latter was not a little surprised, at this unusual mark of attention, and repaid Emily's kindness by a bright glance of pleasure, which seemed to say, "I will not forget this."

The girls also noticed the change in Emily's conduct, and asked her the reason of it. She replied, that she was going to try the effect of kindness upon poor Kitty, and begged them to join in the benevolent project. As she was a general favorite, they readily acceded to her plan, and when the hour for recess came, many a schoolmate proffered the poor girl some act of kindness, that probably had never noticed her before. She was invited to join in all the games, had bountiful presents of luncheon, and several offers of help, if she found her lessons difficult.

Poor Kitty was quite softened by these unexpected tokens of regard, and when Emily explained the reasons of her former coldness, she resolved to correct her bad traits of character, and to be altogether a different girl.

Emily went home with a smiling face and happy heart, and told her mother the adventures of the morning, being more than rewarded by the approving smile of Mrs. Franklin, who gave her permission to invite Kitty, with a few other girls, to spend the afternoon.

They had a merry time together, and their affectionate and obliging manners to each other, showed very plainly that the law of love was in all their hearts. And ever after did Emily act up to the spirit of these divine words, "Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself." May all Sunday School scholars endeavor to do the same, and they will have the joy of a good conscience and their heavenly Father's love.

Cousin Kate.

There was a little puppy once,

With silken hair and bright black face,

Who, that he might not be a dunce,

Was sent to school to learn apace.

A pint of milk and crust of bread,

Was every day his usual food;

And for his rest a basket bed,

Was made up warm, and nice, and good.

He gambolled, frisked, and frolicked round,

So full of fun the livelong day,

That often did the room resound

With laughter at his tricks and play.

And when he had learned all he could,

To keep him safe from every harm,

They took him from all those he loved,

And now he's living on a farm.

Now large he's grown, and now he's seen,

With fringing tail and drooping ears;

With piercing eye and scent so keen,

"Hunter's" a dog above his peers.

And now for game the field he scours,

Following the huntsman with his gun;

But I know he thinks those school-day hours,

His greatest glee, his grandest fun.

In the shade of a leafy Butter-nut tree, a rosy cheeked little girl sat looking up at the blue sky, with many curious thoughts running through her head. A friend came and sat down beside her, and to make the time pass pleasantly, told the following little story:

Once upon a time, a cluster of boys and girls gathered under this tree, for the sake of enjoying the beauty around them, whilst they studied and worked in the warm sunshine.

Just in the midst, a visitor approached, and to their great delight Peter Parley stood before them. They could scarcely believe their eyes, for they imagined him an old man, but right glad were they to listen to his pleasant talk.

He told them of many things he had seen in foreign lands, of his love for good children, and of his pleasure in serving such a happy, busy group. He also reminded them of the great Fisher Ames, who had lived on that very spot, and was the friend of the immortal Washington.

He particularly impressed upon the minds of the boys, the importance of forming correct habits in early life; and said if they had the right spirit, they too might become great and good men.

Just before he left, he showed them a new book which he had been preparing for their improvement, and which he hoped they would read for his sake. They all promised they would; and before he said good-by he shook hands with each one, they all begging him to come and see them again.

After that memorable visit, many were the pleasant readings from the "Cabinet Library," and often was Peter Parley remembered by the inhabitants of the "Bird's Nest."

Well, patience young folks; don't all besiege me at once, and I will tell you about my own school-days. As the day is so warm and bright, I will make the scene at the South, among the thick pine woods of Georgia.

I can distinctly recollect the singular features of the spot where I was sent to school, but it will be impossible to bring it to your mind's eye. There were about half a dozen log houses, and an Academy standing in the midst, like the Court-House there in the square; and being a neat wooden house of two stories, we thought it very grand.

The little church was about a mile off, all by itself in the woods; but why it was placed at such a distance, we never could tell, unless it was to give people a pleasant walk on Sunday morning.

The preacher was the school-master of the place, and, as I remember, was a very pleasant man, besides being a most excellent teacher. I remember the day I was first ushered into the school-room, filled with strange faces, when the master, patting me upon the head, said, "Here is a little stranger, and I hope you will do all you can to keep her from being home-sick."

The kind admonition had its effect, and before the day was past, their warm hospitality made me feel as if among brothers and sisters.

Many were the pleasures of my sojourn in Springfield, and among them, the excursions after wild flowers and birds were not the least frequent.

Once I caught a great Gopher, or Land Turtle, sleeping under a tree, and brought him home in triumph. This creature has a tawny-colored shell on his back, and underneath is a yellow one, ending in a square shaped protuberance like a spade, and with this he digs his burrow or den. In these sand holes I often played, turning them into a baby house, with the pine cones for my numerous family of dolls.

Sometimes the master went off with us, to show us the process of making pitch and tar, the dusky figures of the blacks tending the operation looking like so many imps. We often came across the huge coach-whip snake, so named from its resemblance to a whip-lash, and the hoop-snake, only found, I believe, in those regions, and of which the negroes are very much afraid. The flocks of wild pigeons which break the trees by their weight, were objects of unceasing delight, and for weeks we were feasted upon their delicate meat.

But my flower garden was my greatest pride, surrounded with a little crooked fence, looking just like a row of herring-bone stitch, and the soil as black as ink. I can now see the bright blue spider-wort, the sweet-williams, the pinks, the ladies'-delight, and the clustering roses, making the homely log cabin most beautiful in my sight.

The house, of one story, was built of logs, and with a chimney outside. The chinks between the logs were filled up with clay, which in case of the heavy rains so prevalent there, was not the least protection against the storm; so we were frequently liable to an inundation.

The Crackers, a most ignorant and degraded class of poor people, used to pass through the woods on their way to market, where they carried things to sell. Their language is very uncouth, and their complexion very sallow, the effects of chills and fevers, and as some say from eating the yellow clay off the chimneys. Their bonnets were made of white cloth, and the tops of their wagons were of the same pattern, and are something like the covering of a butcher's cart here, but much lower and smaller. My old nurse, a free black woman, took good care of me, feeding me with sweet potatoes, rice, and hominy, and, as a great treat, with ground-nuts, which she parched to perfection. When I was sick, she hung a charm around my neck, firmly believing it performed the cure.

The scholars were a merry, lively set, and in the winter evenings had a "Speaking Club," which I was allowed to attend, as a reward for conquering the mysteries of Long Division, and the spelling of such words as "Phthysic," "Catsup," &c. To me the rough blanket curtain concealed the most glorious scenes, and as I saw the performance of "Rolla and Pizarro," and listened to the musical cadences of Scott, or "The death of Absalom," by Willis, I felt wrapt in an Elysium.

But now, girls, recess is over, and I will stop my description, or I shall run the risk of seeming egotistical.

The Oaks.

My dear Daughter:

I was very glad to hear from you, and I hope you continue as well as when you left home; for, of course, I consider your health of the greatest importance. To preserve this, I am excessively anxious to have you walk regularly every day, as often as twice, if possible. Be sure and keep up the habit of cold bathing, and do not forget your usual attention to your nails, teeth, and hair, for though I am not near to remind you of this care, you are now old enough to take it upon yourself. Remember the gold pencil your father has offered, if you cure yourself of the disagreeable habit of biting your nails; so make the effort, at least for his sake.

Try hard to have all your lessons well prepared out of school, so that there will be time to look them over; and then if any difficulty occurs, it may be solved by the Teacher before recitation. While reciting, pay strict attention to all the explanations and illustrations given, for these are often of more value than the mere text, and by your interest you will make light the labor of instruction.

Be punctual in your hours of attendance, for then no time will be lost, and a valuable habit will be formed, of great use in after life.

Of course your social disposition will lead you to get acquainted with the other girls; but do be particular in your choice of companions, and always ask yourself, if they are such as your parents would approve, or will tend to improve you.

Do not in any case repeat the sayings of one scholar to another, for nothing is more hateful than a habit of tattling, or a greater cause of mischief and unhappiness. Do not fancy it is the sign of a frank disposition, to report the harsh sayings made by one girl to another, but on the contrary, try to create peace and love among all your mates.

Above all, be pleasant and affectionate in your bearing to your Teachers, for nothing will more quickly endear you to them, or so fully repay them for all their labors for your improvement.

Do not forget my advice about romping with boys, a common habit with school-girls of your age; it is very foolish, and liable to be carried to excess, as you yourself know, in the late troubles at the Academy here. Be always truthful, and learn to bear a laugh at your expense, when you know you are in the right; for ridicule is far lighter to bear than the reproaches of conscience. You are so sensitive by nature, that I shall particularly caution you in this respect, as I know your tears are apt to overflow, even at trifling occurrences. These directions I hope will not seem too tedious to you, as my motive for sending them, is to make your duties lighter, and the time spent away from home more profitable.

All these regulations are not incompatible with plenty of recreation, and when you play, do it in earnest; give full vent to your over-flowing spirits, and take plenty of exercise with your hoop and ball. It is a pleasant sight to see a young girl enjoying her games, and the one who works and studies the hardest, will play with the greatest zest.

I particularly depend upon your keeping a journal, and anticipate great pleasure in reading it; for any thing interesting to you, no matter how trifling, will be interesting to me. Write to me often, freely and unreservedly, and if you will just imagine you are talking to me, you will have no difficulty in keeping up quite a correspondence with me. If I am ambitious for you in any one point, it is that you should be a fluent writer, and should excel in Composition.

When you return home, if I see that you have improved your time, and appreciate the advantages of attending Mr. C.'s school, I will do all I can to make the vacation pass pleasantly. Besides a certain amount of reading and sewing, you are to enjoy yourself, riding, walking, and visiting as you fancy, for I mean to have the time a season of recreation.

How do you like taking dancing lessons, and are you holding yourself more erect than formerly? As to your request about music lessons, I think you had better give up that plan for the present, for you have as much as you ought to do, and in a few years, you will have more time to practise thoroughly. When you leave school, you shall have the best instruction on the piano and in singing.

Good night, my dear child. With love and remembrances from every member

of the family,

I remain,

Your Affectionate Mother.

Georgia. "Well, Sarah, I've come to invite you to attend our Fair this afternoon. Susy and I have been busy getting every thing ready, and we want you to come very much. The price of admission is six pins."

Sarah. "Well, that isn't much I'm sure, and I will ask my mother. I am afraid she will not let me go, for I have not finished my work, and I know she disapproves of Fairs."

Georgia. "Oh, this is only a make believe Fair, and so it can't do any harm. Besides, all we can earn we are going to give to the ladies, for the improvement of the Burying-Ground, and that is a good object."

The mother just entering, Sarah asks her permission to attend the proposed Fair.

Mother. "Where is to be, my dear?"

Georgia. "At the hotel; and when it is over, we are to have a dance in the Hall."

Sarah. "Oh, mother, say, can I go?"

Mother. "I am afraid I must deny your request, for I dislike to have you engage in such excitements at your age, and more than all, I do not wish to have you at such public places so late in the evening, as will be the case. Wait till you are eighteen, and then there will be plenty of time for such gayeties, if you fancy them; but now, I want you to be contented with a child's pleasures."

Sarah. "Oh, mother, I want to go so much; for Ellen, and Fanny, and Lizzie, and Kitty are all going, and their mothers are willing."

Mother. "They are the best judges of their own actions, but I do not feel willing to have you there, and if you bear the disappointment patiently, you may invite your young friends to tea next Saturday afternoon."

Sarah. "Oh, thank you, mother; and I can give the twenty-five cents I get for making this shirt, to the 'Ladies' Society' for improving the Burying-Ground."

Mother. "Well, you may, my dear. Good-by, Georgia."

On a beautiful farm in Worcester County, where nature seems to have lavished all her charms, and where man is a vigorous rival in his efforts to adorn the land, there sparkles a beautiful pond. On the borders of that pond there is a pretty white house, in which the following little occurrence took place.

Late in the evening a poor woman arrived, bearing in her arms a sick baby, and leading by the hand a little tired girl. The woman was kindly cared for, and a place of rest provided for the night, while food was given to herself and children.

Upon asking her destination, she said she had just arrived from Ireland in search of her sister, who was the mother of the little children. The letter containing the directions had been lost, so there was no clue to the parents, and she was left sad and lonely.

The little baby grew worse during the night, and in the morning, before any physician could arrive, breathed its last in the arms of its nurse. The poor woman seemed distracted with her grief, and constantly mourned, "Oh! would that its mother could see her own handsome boy!" The little girl watched everything that was going on with a quiet smile, and thinking her little brother was asleep, kept saying, "Why don't he wake? Poor brother, he is very sick."

Seeing her aunt weep as the beautiful child was about to be laid in its last resting-place, she said, "Don't cry, he'll soon be well again; I'll give him some of my cake, and then I know he'll be better."

'Twas a touching scene to see such heart-rending grief in the woman, and the happy unconsciousness of the little girl. The poor creature could not be comforted, as she thought of her sister's loss and her own responsibility; but in her moments of calmness she was engaged in earnest prayer.

As a last act of devotion, she placed a little cross, made of two pine sticks, upon the breast of the infant, and then, as if feeling some consolation from this act of her faith, she quietly resigned the body for burial.

Emma and Lina.

Monday. Began the duties of the day by reciting the texts of the day before, the commandments, and then reading in the Testament. We were all very busy, and tried to have a good beginning for the week, so our lessons were well said, and no one was kept in. We sewed all the afternoon, and listened to the reading of "Kings and Queens," by Abbot, and we like it very much.

Tuesday. The day was bright and beautiful, and after our lessons were over, we all went to a printing office to see the process of setting types, and printing newspapers, and we had a present of some types for ourselves. In the afternoon, we had a drawing lesson, and some of us have begun landscapes.

After school we all visited the jail, to see some little children there, and we wondered what they had done to be put in such a place. We did not want to see the convicts, but we took a peep into the little stone cells, and heard some one singing.

Wednesday. We sang a whole hour, as some visitors come into the school, and then recited our lessons as usual. In the afternoon, several old scholars and the Sunday School class, were invited to hear a new story, called "A Trap to catch a Sunbeam," and we enjoyed it very much. Before they left we played games on the green, and then sat down to crack nuts and talk. In the evening all the family went to a lecture, but I staid at home to study.

Thursday. It stormed hard, so we said all our lessons early to have a little longer recess. We danced cotillons and learned how to waltz, as one of the girls was so kind as to show us, and we think she is a grand teacher. We brought our dinners and all staid at noon, when we had a fine time playing "Still Palm," "Keeping House," and acting Charades.

Friday. We were all as busy as bees, and the teacher was very happy because we were good. At recess we all picked up the yellow leaves, and pinned them on our shoulders, as a badge of our belonging to the "Sunbeam Society;" and the first one who was not good natured, was to forfeit membership.

In the afternoon we read as usual, and then counted up the pieces of work finished off during the week, and there was quite a variety of useful and tasteful articles. Susy had a pair of Polish boots; Jenny several yards of edging; Lizzy a tidy; Sarah a bead purse; Julia a sack; Lily a bag; Annie a pair of slippers and scarf; Angelina a quilt; Abby a book mark; Mary a sampler; Emeline a pair of pantalets; Isabella a dress; besides handkerchiefs, towels, and knit dishcloths, from the little ones.

After school we visited the paper factory, and saw a great many curious operations; cutting pasteboard, coloring and polishing paper, enamelling cards, and then most wonderful of all, the making of marbled paper.

Saturday. We all said poetry, and made preparations for the coming Examination; then, after the marks were counted, we changed our desks for the next fortnight, and the gold cross was given to the best scholar.

In the afternoon we went to see some Indians make baskets in their tent, and came away each with a specimen of their work. We then went to the church steps, heard an address on the subject, and were requested to read all we could find about the Indians, and at some future day to make them a subject for composition.

Sunday. I attended Sunday School, and heard a very interesting address from the Superintendent on the duty of being good, and several pretty anecdotes were told to illustrate the subject. The minister joined in the exercises, and some hymns were sung preparatory to an approaching Sunday School celebration on Fast-day. We are all very much pleased at the prospect, for we anticipated hearing some excellent speakers.

Our lesson was as usual from "the Parables," and the scholars wrote an

abstract from the "Pearl of great price." I went to church in the

morning, and heard a very fine sermon on the duty of a contented and

grateful disposition.

Susy A.

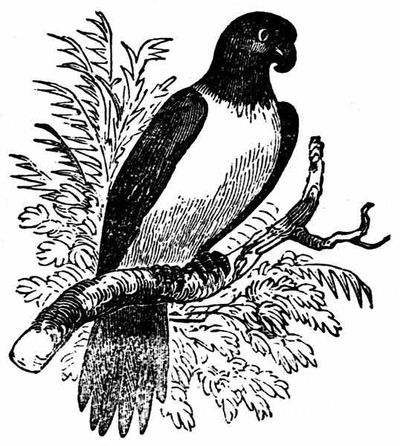

On a warm summer's day, as a class of little folks were reading from their Natural History, in flew a lovely "bluebird," of which they were at that moment reading a description.

Struck by the coincidence, they were allowed to examine his brilliant plumage, his bright eyes and little beak, all of which he bore very quietly, and then was set at liberty.

His flight was watched, and soon after he was seen to visit a grape-jar placed in a neighbouring garden, and they recognized him as one of the pets of a good lady who had often watched them from her window, whilst patiently lingering in her last sickness. All her kindness came back to their minds, and many were the pleasant things said about her goodness, and their sorrow for her loss. They remembered her care of the two blue birds, and of all the dumb creatures under her ever watchful eye; her interest for the lone and friendless, and her unwearied attendance at the sick and dying bed.

More than all they thought of the pleasant hours they had passed under her roof, and of her gentleness and affectionate manner towards them. For her sake they resolved to be good children; and all that knew her must try to grow up as kind and benevolent to all around them, as was this excellent and most disinterested woman.

Once upon a time, when leaves were falling and cold winds began to blow, a birthday was to be celebrated. It was too late for pleasant summer walks, and too early for winter sports, so what could be devised for this important occasion. At last it came into the head of somebody, to have a tea-party, and the idea was so acceptable, that it was declared a unanimous vote.

The one useful boy offered to do errands, and bring all the necessary articles; while the girls were to provide the feast and to array all tastefully within the school-room. Many were the expedients, strange the metamorphoses occasioned by the fete, and great was the fun thereof to all concerned.

An ironing board placed upon two barrels, was converted into a beautiful extension table, and was gracefully draped with a large white cloth. The well-worn black-board became an elegant buffet, and instead of long rows of figures, held pails of crystal water and jugs of sweet, fresh milk. A solar lamp of diminutive size graced the centre of the table, which groaned under the weight of cake, dough-nuts, bread and butter, and a variety of other articles too numerous to mention.

One of the youngest was lady hostess, and presided at the head of the table, aided in her duties by several nimble waiting maids. Distinguished guests were invited, and partook of the ample refreshments.

After a proper attention to the feast, the table was nicely cleared, the dishes washed and wiped, and every thing put into the neatest order by the young house-keepers. Then a merry set of dances followed to the pleasant music of the piano, and after those, songs and choruses pealed forth from the harmonious throng.

Last of all, Charades and Tableaux added brilliancy to the festival. Among the words chosen for representation, were "Capital," "Caprice," "Childhood," and "Washington," and the actors excelled themselves.

All had a delightful time, and after one last song, sung with warmly grasped hands, and hearts full of affection, they departed to their various homes. Who will forget that birthday tea-party, on Thanksgiving Eve?

The Village of Trees.

My dear Mother:

I was very glad indeed to get your letter last week. I will try to do all you wish, though I have already been silly enough to have one or two crying spells. But I think I shall soon cure myself, for I have such pleasant times, I have more cause for laughing than tears, and I mean to keep up the good habit.

I have to study very hard, for the teacher is very particular; and the scholars are so bright, that I must work to keep up with them. Out of school we have grand times together, and this Spring we have formed a Club, which we call the "Sunrise Society;" and we get up very early and all go off to walk by six o'clock.

We have been in every direction, and I only wish you knew the delightful walks there are here. One of the pleasantest is to the "Falls," near the factories, through a narrow winding path, by the side of a beautiful pond, the waters of which flow over a dam. As we look underneath the bridge, the water rushes down with great rapidity and force, and the noise is very loud. There is a beautiful grove close by, with rocks scattered along the side of the stream, which runs quietly on after its foaming, whirling jump over the dam, and it is a very romantic spot. There are many other pleasant places, called "Rose Cottage;" "Lover's Lane;" "Sandy Valley;" "Powder House Rock;" "Spider's Village;" "Tyot Woods;" "Harrison Grove;" "West Retreat;" and "Purgatory;" and when you come, I will show them all to you.

After school for the day is over, we often walk again; so you see I shall have plenty of exercise. Yesterday, as there was no school, we all went to the Court-House, to hear some speeches by two distinguished lawyers, in a very interesting case, and the room was crowded. We went early and carried our work, but we soon had to put it away for want of elbow room. We learned something about the manner of trying a case before a jury. There was one speaker who was very much interested in what he was saying, and the ladies all seemed to like him the best; so I hoped he would gain the case, and I believe he did.

Last week the weather was very warm and pleasant, so we rolled hoop at recess and had fine fun. In the afternoon we sew and draw; and lately we have been making garments for a poor woman and her family in another part of the town.

After making up a large bundle, we all went to see her. She seemed very much obliged to us, and dressed up her children to show us how nicely the clothes fitted. We have very interesting lessons in History about the Queens of England; and besides that we have been reading about Marie Antoinette, who suffered so dreadfully in the French Revolution.

The little scholars have been reading some of "Mary Howitt's tales;" "The Cousins in Ohio;" and the "Life of Robert Swain," which is very interesting. We are all very busy with Arithmetic, and as each one gets through any difficult section, we receive a pictured card as a sort of certificate. The little ones have been learning the Multiplication Table, and one of them had a cunning little slate given to her, for reciting perfectly at the fortnight's review.

Last Saturday we all went into town with our teacher, to see "Bayne's Panorama of a Voyage to Europe," and we had to write a description of it for our composition. We had a very pleasant time and it was very beautiful; though I can remember but little about the scenes, they came so fast one after another. We all liked the storm at sea, the icebergs, and the views on the river Rhine very much; but we think Banvard's Panorama of the Mississippi was the best. As we had been writing a description of the Telegraph, we stopped at a place where it was made, examined all the different parts, and had them explained to us; and some of these days we are to see a message sent to New York.

You ask me to tell you everything, so I will end my letter, by relating an event which took place in our school-room. As we were all sitting round the fire, studying our lessons, down tumbled the stove-pipe with a tremendous noise, scattering soot in every direction. Fortunately no one was hurt; but we were all very much frightened. We had a longer play time than usual, while a man was repairing the damage.

P.S. I forgot to tell you that I went to see a little play performed, called "Old Poz." We had a fine time, for all the characters were well dressed and the parts were well acted. We did not have much scenery, but that was no matter, we had such a grand curtain. After the play we had a young "Indian Girl," in complete costume, and "The three Sisters of Scio," which puzzled the audience very much indeed. I went to bed later than usual, but I had all my lessons perfect the next day; so I do not think it did me any harm. But if you do not like such things, I will not go again.

With a kiss, I remain

Your Affectionate Daughter,

Polly Prippets

When early morning's ruddy light

Bids man to labor go,

We haste, with faces fresh and bright,

Our early walk to go.

Chorus.

And then at school we next appear,

To pass the hours away,

And all is lively, sprightly here,

Like merry, merry May.

Chorus.

The scholars come in gladsome train,

And skip along the way,

Rejoiced to con their books again,

As flies the happy day.

Chorus.

With jokes, and jests, and lively din,

We eat our recess cheer;

While in the healthful game we join,

With nought to make us fear.

Chorus.

When evening's shades begin to fall,

In study's busy hum,

We willing list to learning's call,

And think of days to come.

Chorus.

We'll fill our heads with ample store,

Our hearts with love are stirred;

And thus, before youth's days are o'er,

For age our armor gird.

Chorus.

And when life's harvest all is done,

We'll give our souls the wing,

And happy spirits all as one,

Make Heaven with music ring.

Chorus.

CHORUS.

We scholars—dal de ral dey,

We'll study and then we will play;

Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, play!

Hey-day! yes play—hey-day;

We'll study and then we will play

There was a brown squirrel on a tree

Hopping about so merrily;

And spying below some children near,

Said, "I wonder what they're doing here?"

Busy they brought both stones and sticks,

And ovens and fires they tried to fix,

Grand parlors too, sprang up beside,

Their greatest work, their greatest pride!

And there were Emma, and Willy, and Molly,

All so bright, and merry, and jolly;

With Charley too, and roguish Dan,

Named for the great New Hampshire man.

Says Bunny, "I'll try if I can see

Anything there, will do for me;"

So slyly he peeped from his high seat,

As they were munching their luncheon treat.

Says Molly to Willy and rosy Ju,

"Here's a piece of cake for both of you;"

And in the sunshine they cosily sat,

Eating and talking childish chat.

But pretty soon their play was o'er,

And each went in at the school-room door;

Then down came Bunny and ate their crumbs,

And then sat coolly wiping his thumbs.

A little sparrow who had been very carefully, reared by her mother, was one day permitted to go off by herself to see a little of the great world. Delighted with her freedom, she hopped from bough to bough, and finally alighted near a school-house.

Kindly voices met her ears, and friendly faces soon came out to watch her motions. Without fear of molestation, she picked up the bread and cake scattered round, and eyed the children with her bright black eyes.

Soon after she came again, bringing a little mate; and together they chirped their thanks, and for a long time were regular and welcome visitors.

One morning, feeling less timid than usual, one of them hopped into the school-room, watching everything with a keen interest; but thinking he might intrude, he flew away, very much pleased with the song the children sung to him. It is so pretty, we will sing it now for those who did not hear it on that occasion.

"With your singing,

Pleasure bringing,

Come sweet lovely bird again;

Winter sighing

Off is hieing,

Joy again with you shall reign.

Fruits and berries,

Plums and cherries,

Now shall be your welcome meat;

Come to cheer us,

Do not fear us,

Glad indeed your songs we'll greet.

None shall harm you,

None alarm you,

Sacred be your dear retreat;

Love shall guard you,

Love reward you,

For your music pure and sweet.

Oh how hateful,

How ungrateful,

He who would disturb your rest!

No dear treasure,

Wake your measure,

Softly may you cheer my breast."

On a dark, rainy day, two weary-looking street minstrels took shelter from the storm, under the projecting roof of a horse shed. Not far from the place stood a small but pretty school-house, in which might be seen a group of bright-faced and busy children; some conning their lessons, some reciting with earnest attention, and others rejoicing with childhood's happy freedom from care, at a temporary release from some expected recitation.

The teacher, during the intervals of occupation, spied out the poor wanderers, and feeling a desire to help them, she concluded to invite them into the school-room, after receiving a promise from the sympathizing circle, that the interruption should not interfere in the least with their studies. Accordingly, the foreigners, who had begun to find their covering insufficient against the drenching rain, very gladly accepted the invitation, and modestly took their places at the farther end of the apartment.

Many bright and inquisitive eyes were turned upon them; but remembering their promise, the children again turned their prompt attention to their various exercises, and while the strangers were busily engaged with some books and a slate, they soon accomplished their required duties.

As a reward for their attention, they were allowed at recess to listen to several gay tunes upon the organ, accompanied by the tambourine, and very soon their lively feet joined in a merry dance. After this irrepressible ebullition of their glee, they each played a tune themselves, and when fully satisfied, voluntarily presented the tired ones with donations from their luncheon baskets, and with flowers that decked the room.

With these the boy made a wreath for his sister's head, but the girl adorned the little image of the virgin placed upon the organ; and then after a few entreaties, they both sang some German songs. In return the scholars sang their prettiest pieces from the "School Singer," and at any familiar melody, the faces of the listeners beamed with pleasure and delight. Before the group was dismissed for home, the boy asked for a pen and paper; and during the time he was left alone, he wrote the following history of himself and his pretty sister for the teacher and her scholars.

"My name is Hendrik Glaubenstein, and I am fourteen years old. My sister Gertruyd, who is as good as an angel, is just sixteen. We have left our poor old father and mother in Germany, and have come to this happy country to make money.

I went to school every winter, and in summer I staid at home on account of work; but after it was done, my sister and I studied together, sometimes in the fields, sometimes in our little cabin. My sister earned all she could by spinning yarn and knitting stockings, which I took once a fortnight to the nearest town to sell. In the mean time I earned all I could, by driving the sheep of a rich neighbor of ours to pasture.

But somehow or other, we did not get along, as well as we wanted to; and we always found it difficult to get the rent ready for our landlord, who was cruel and bad tempered. What to do we did not know, so I had at last to give up my winter's schooling, to do errands for a little money.

Finally I bought me an organ, and with that I continued to pick up something at the Fairs; and I often had a kind word from the ladies and gentlemen, who would listen to me and give me silver pieces. At home my sister always sang with me when I practised, and we could make different parts to our music. I begged her to go with me sometimes, for I knew we could get more money if she would help me with her voice. But she said she could not leave our poor old mother, so I wandered round alone.

In one of my journeys, I met a lad who said he was going to America, and he told me if I would go too, I should make money fast, and we should come home rich men. I told my sister all about this, and she thought it would be a good plan, but that I should not go alone, for I was too young.

After waiting a little while, we got our sister Liesle and her husband Klaus, to come and live with mother, and then we made ready to leave as fast possible. As soon as we could get enough money to pay our passage, with many tears we bade good-bye to all at home; and then with prayers to the good God, we travelled on foot through France, till we reached the sea-shore. Here, we were stowed away in the great hold of the ship, with many other poor companions; and sometimes we were sick, and sometimes we were hungry, for we did not bring enough victuals to last us all our voyage. But Gertruyd was so pleasant to the others, helping the women to take care of their babies, and often singing her pretty songs, that every one gave us something, and we managed to get along.

When we reached New York we were in great trouble, for we knew nobody, and had no home to go to; but the good God took care of us, and made a kind lady notice us standing alone on the Battery. We told her our wants, and after giving us a supper and a nice bed for the night, she sent us to some poor Germans, where we staid till we had learned a little of the American language.

We did very well for a while, singing together, while my sister played upon the tambourine; but soon there were so many other organ players in the streets, that we thought we would go to some other towns near by. We went all through New York, and now we are going to travel over your pleasant State, and if we do well we can go home in two years. Then I shall buy a farm, and a cow for our dear old mother and father, and then we can all live together as happy as princes. Gertruyd can marry our friend Cornelius, for though he is poor, she has always liked him.

Many good people have offered us both nice places; but I like my organ too well to give it up, and my sister will not leave me for never so fine a home, because she promised mother to take care of me always. We live on as little as possible, and dress in very poor clothes so as to save all we can; for we say, no one will care how we look, if we are only tidy and honest, and make trouble for nobody.

The Virgin Mother, to whom we have erected a shrine in our organ, smiles upon us, and will keep us from all harm, so we need fear nothing. We are both well contented with little; and as long as we do not lose our voices, we can make several dollars a day, and so we are happy. Good-bye to you, and the kind-hearted children who have been so pleasant to us, and that God will bless you all, is the prayer of Hendrik and his sister Gertruyd."

Sunny Side.

My dear Lily:

As you were so kind as to remember me at Christmas, I will write you a letter about our other yearly festival, the "May-day Coronation." Of course, you remember many of our pleasant gatherings, at different rural spots, on that occasion. But I do not think we ever had a pleasanter time than this year at May Mount; for so we christened the place where we had our party.

Early in the morning, we voted for the Queen, and after every one had written their choice on the big slate, we found that Annie was unanimously elected. We were all delighted, as she had been so long separated from us, and then she chose her maids of honor and two pages. We selected some pretty songs, and all rehearsed the pieces of poetry we intended for our Queen; then we were very busy finishing off moss baskets, and making bouquets and wreaths for the procession.

We had two beautiful banners, all trimmed round with evergreen; one had on it, "All Hail, thou lovely May;" and the other, "Sweet Spring has come." We also twined a tall May-pole with evergreen and put on the top a great wreath of daffies. For a throne we had an armchair, and on each side two large bouquets of flowers. These were sent us from Boston, besides three beautiful wreaths for the Queen and her maids of honor. The wild flowers were so plentiful, that we had very pretty wreaths for all the subjects too, which we cannot say every year.

At two o'clock we all started, each one carrying baskets of refreshments for the table, which was to be laid in pic-nic style. We had a great deal of fun walking over to the place, for the wind blew quite strong, and we had as much as we could do to get all our things safely to Riverdale. After we arrived in the little wood, we chose a green mound for the throne, and spread carpets round for fear of dampness; and then, while the young ladies made the arrangements for the celebration, we scampered off for wild flowers.

The boys were just as full of fun as they could be, and one of them caught a little snake and chased us; but we did not mind any thing, we felt so happy ourselves. One of the girls tore her dress, and another fell out of the swing, which one of the gentlemen kindly put up for us; but we determined to laugh at everything.

Soon the parents and company all assembled, and then we went through our usual ceremonies. Our Queen looked sweetly, and the wreaths were very becoming to all the girls. Each one said a piece of poetry to her majesty, and then kissing her hand, said, "Long live the Queen of May." We had a bishop, who put on the crowns and made a nice little address; and then the pages introduced all the ladies and gentlemen to the Queen, who sat smiling and blushing at her honors.

Then we all stood in a circle and sang our May song round the May-pole, but the wind scattered our voices, and they did not sound so well as in school. After that, we played games and went to the top of Prospect Rock, from which we could see the river, the woods and all the village, which looked very pretty with its three churches, and nice white houses.

After we had rambled round till we were tired, we took some refreshment at the table, which was loaded with good things and looked very pretty. Then we repeated several of our songs, by particular request; and we did a great deal better than at first. Just before sunset we packed up all the things and prepared to go home. Some of us rode, packed eight or nine, close in a wagon, and the rest of us walked home.

We stopped a moment at the old apple-tree, where the first May-party was gathered, and some of the oldest girls gave an account of the "Prince of Wales," who was present on the occasion.

We had a grand time, and I hope we may have just such another every year. I pressed my wreath as a memento of the occasion, and have put it away to show you, when you come to make me a visit. With love to all your sisters, I remain your affectionate schoolmate,

Agnes.

Two little girls, rejoicing in the names of Mary and Maimée, were one summer recommended to visit the sea-shore, to regain the health and strength which they had lost by too steady an application to study. After being duly prepared, one by the "Good Aunt," whom every body knew and loved for her many acts of disinterestedness; the other by a most excellent mother, they both started off with friend "Maimiotti" for a snug little nook at Lynn.