This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Lancashire

Brief Historical and Descriptive Notes

Author: Leo H. (Leo Hartley) Grindon

Release Date: August 26, 2012 [eBook #40584]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LANCASHIRE***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/cu31924028040032 |

LANCASHIRE

HISTORICAL & DESCRIPTIVE NOTES

BY

LEO H. GRINDON

Lancashire

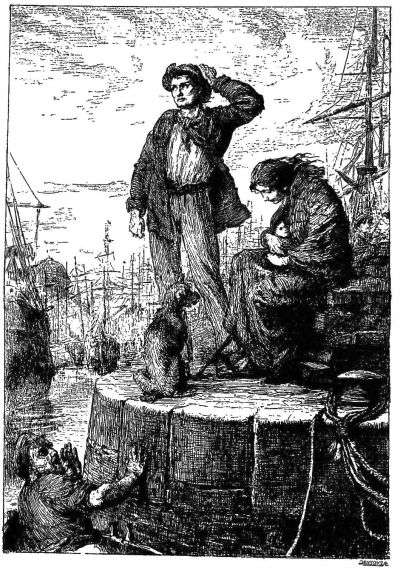

EMIGRANTS AT LIVERPOOL

BRIEF HISTORICAL AND

DESCRIPTIVE NOTES

WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS

London

SEELEY AND CO., LIMITED

Essex Street, Strand

1892

The following Chapters were written for the Portfolio of 1881, in which they appeared month by month. Only a limited space being allowed for them, though liberally enlarged whenever practicable, not one of the many subjects demanding notice could be dealt with at length. While reprinting, a few additional particulars have been introduced; but even with these, in many cases where there should be pages there is only a paragraph. Lancashire is not a county to be disposed of so briefly. The present work makes no pretension to be more than an index to the principal facts of interest which pertain to it, the details, in almost every instance, still awaiting the treatment they so well deserve. If I have succeeded in marking out the foundations for a superstructure to be raised some day by an abler hand, I shall be content. It is for every man to begin something, to the best of his power, that may be useful to his fellow-creatures, though it may not be permitted to him to enjoy the greater pleasure of completing it.

Some of the commendations passed upon Lancashire may seem to come of the partiality of a man for his own county. It may be well for me to say that, although a resident in Manchester for forty years, my native place is Bristol.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Leading Characteristics of the County | 1 |

| II. | Liverpool | 26 |

| III. | The Cotton District and the Manufacture Of Cotton | 66 |

| IV. | Manchester | 99 |

| V. | Miscellaneous Industrial Occupations | 134 |

| VI. | Peculiarities of Character, Dialect, and Pastimes | 170 |

| VII. | The Inland Scenery south of Lancaster | 194 |

| VIII. | The Seashore and the Lake District | 227 |

| IX. | The Ancient Castles and Monastic Buildings | 252 |

| X. | The Old Churches and the Old Halls | 282 |

| XI. | The Old Halls (continued) | 303 |

| XII. | The Natural History and the Fossils | 334 |

| PAGE | ||

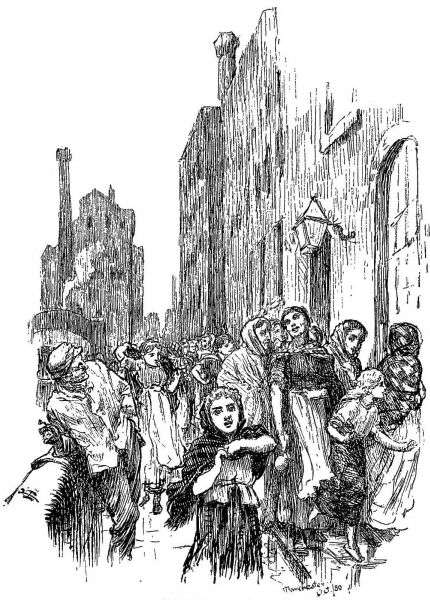

| Emigrants at Liverpool | By G. P. Jacomb Hood | Frontispiece |

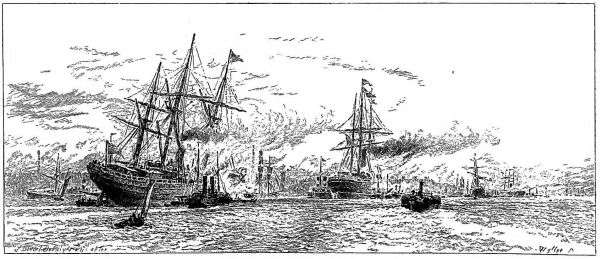

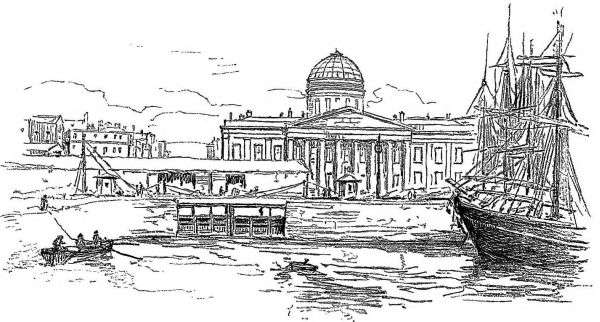

| Shipping on the Mersey | By A. Brunet-Debaines | 27 |

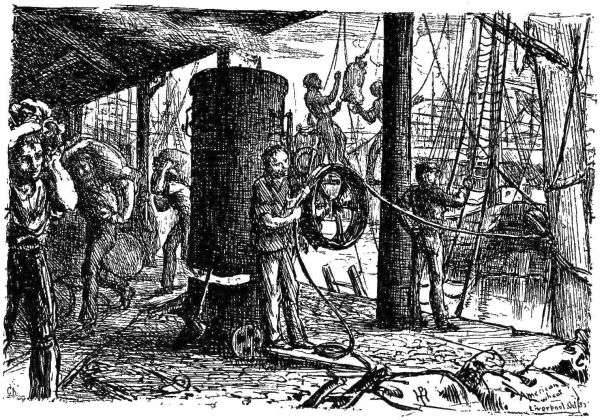

| American Wheat at Liverpool | 31 | |

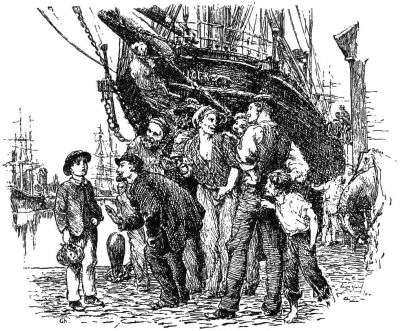

| Ran away to Sea | 35 | |

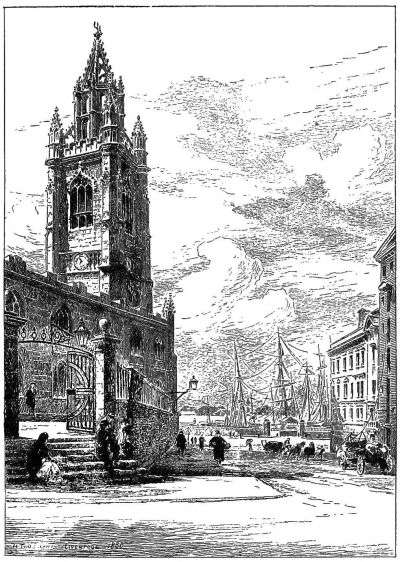

| St. Nicholas Church, Liverpool | By H. Toussaint | 43 |

| The Custom-house, Liverpool | 51 | |

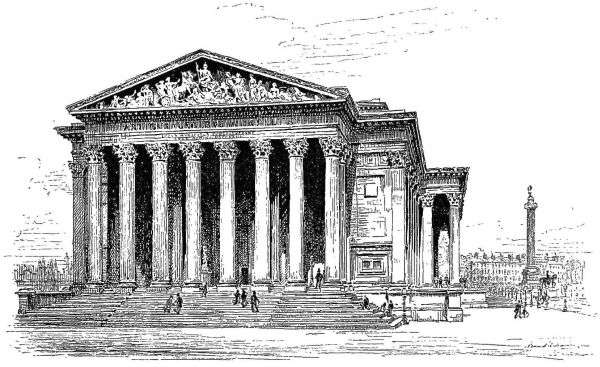

| St. George's Hall, Liverpool | 57 | |

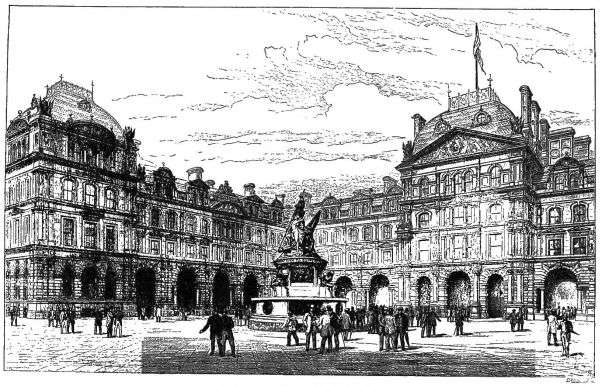

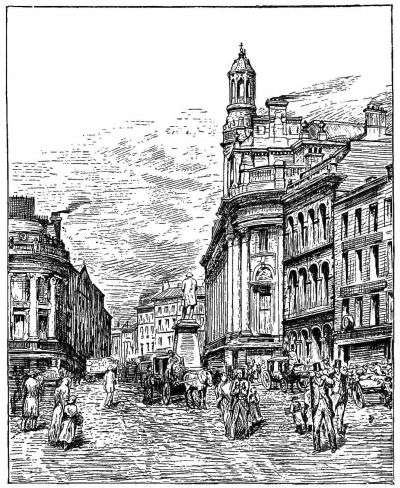

| The Exchange, Liverpool | By R. Kent Thomas | 61 |

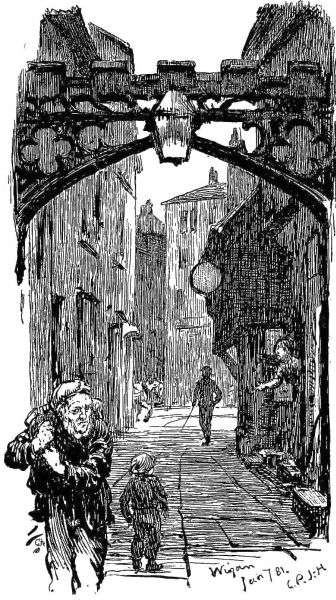

| Wigan | 71 | |

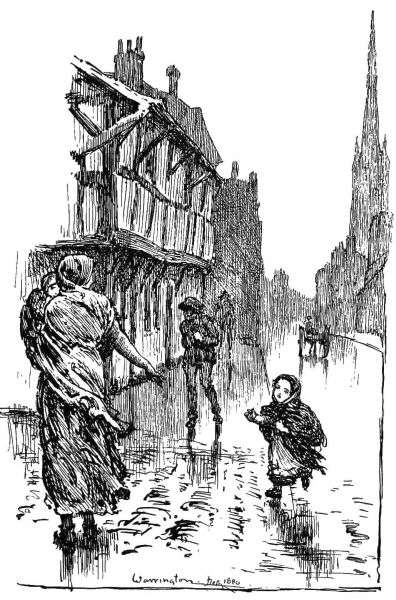

| Warrington | 75 | |

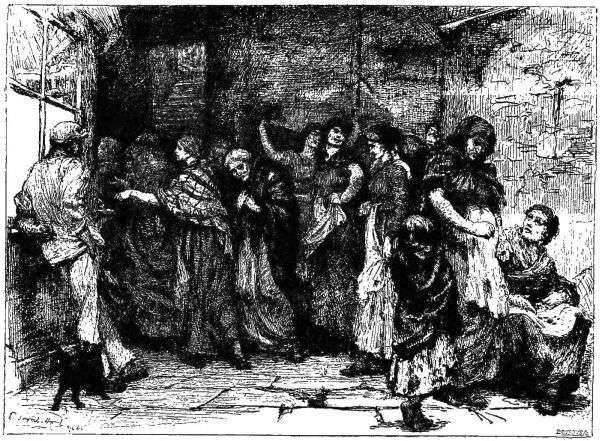

| The Dinner Hour | 85 | |

| Pay-Day in a Cotton Mill | By G. P. Jacomb Hood | 89 |

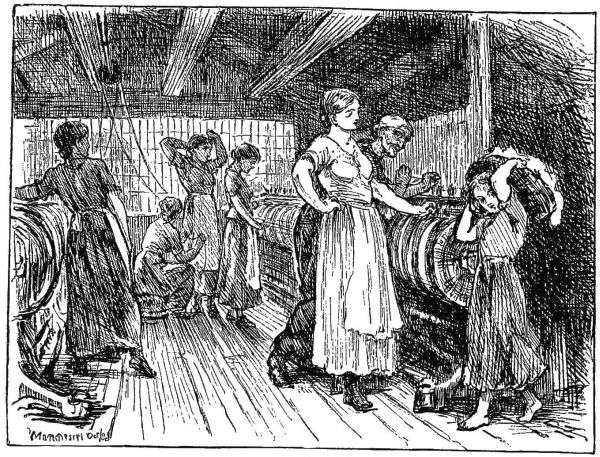

| In a Cotton Factory | 95 | |

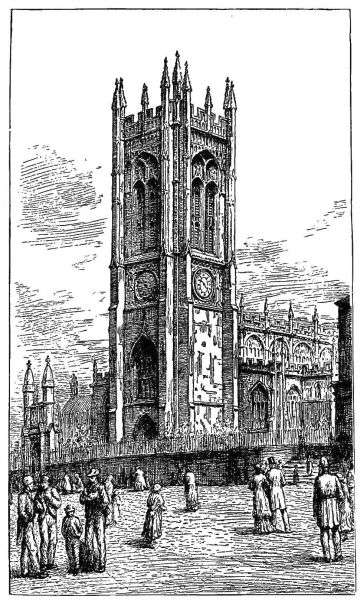

| Manchester Cathedral | 107 | |

| St. Anne's Square, Manchester | 112 | |

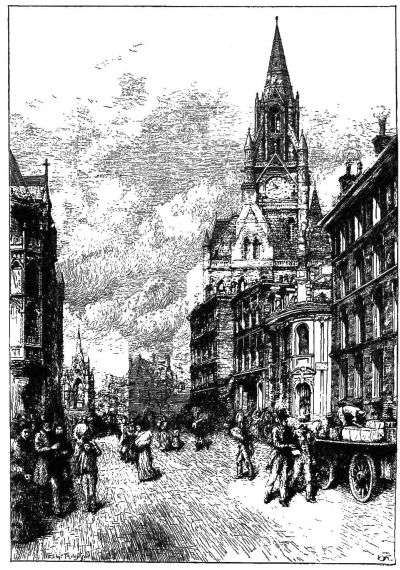

| Town Hall, Manchester | By T. Riley | 117 |

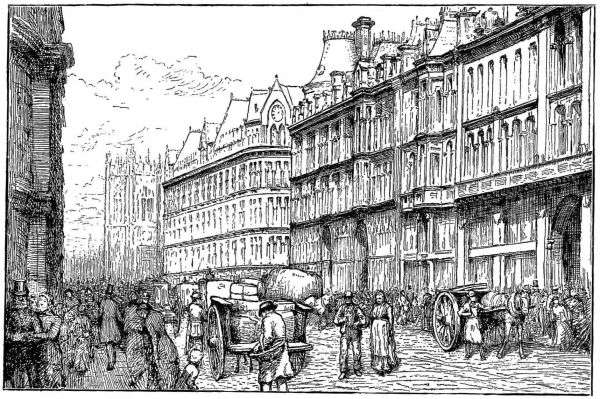

| Deansgate, Manchester | 123 | |

| In the Wire Works | 148 | |

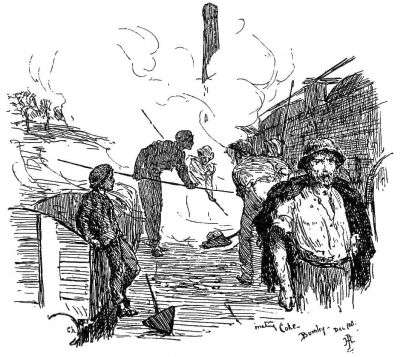

| Making Coke | 151 | |

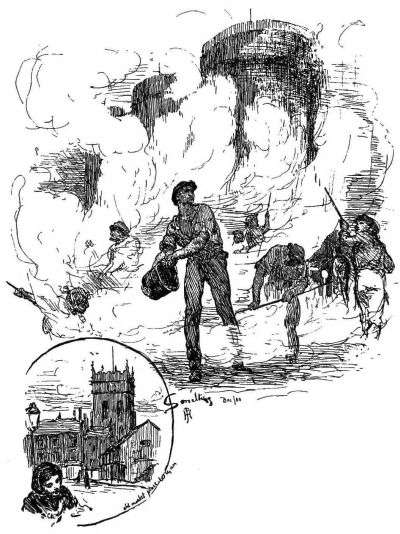

| Smelting | 154 | |

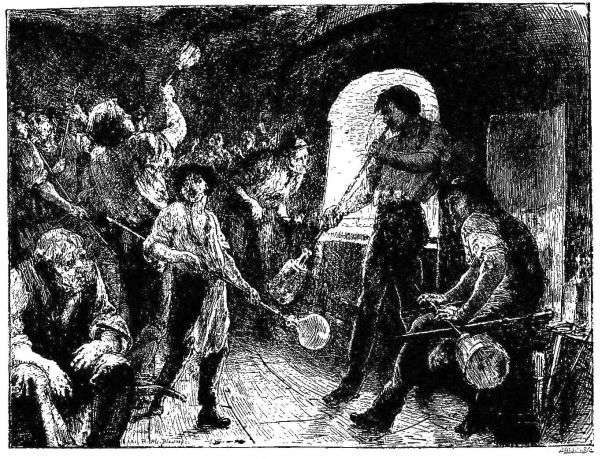

| Glass-Blowing | By G. P. Jacomb Hood | 157 |

| On the Bridgewater Canal | By G. P. Jacomb Hood | 161 |

| On the Bridgewater Canal | 165 | |

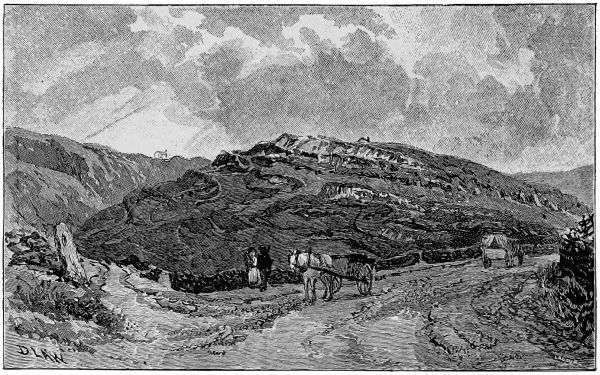

| Blackstone Edge | 195 | |

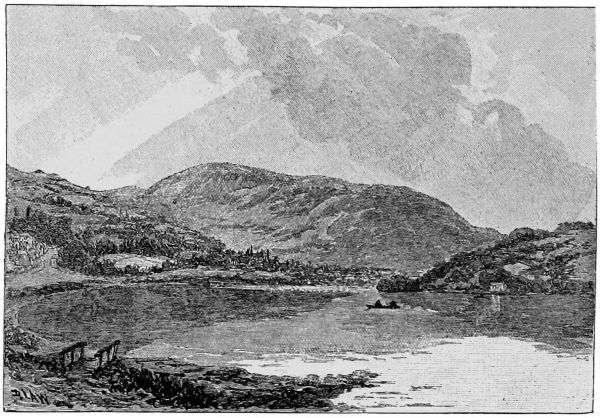

| The Lake at Littleborough | 199 | |

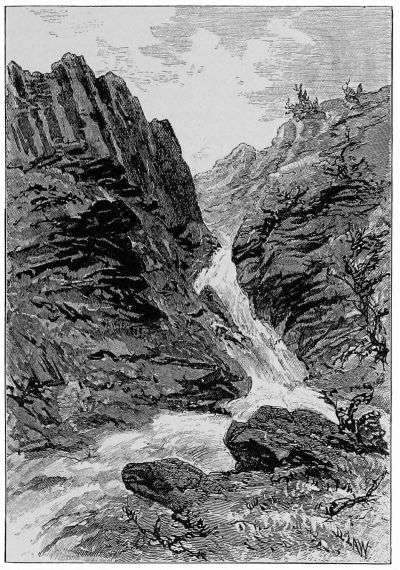

| Waterfall in Cliviger | 203 | |

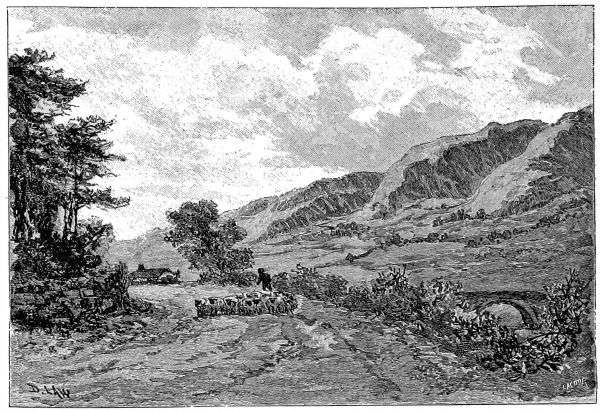

| In the Burnley Valley | 211 | |

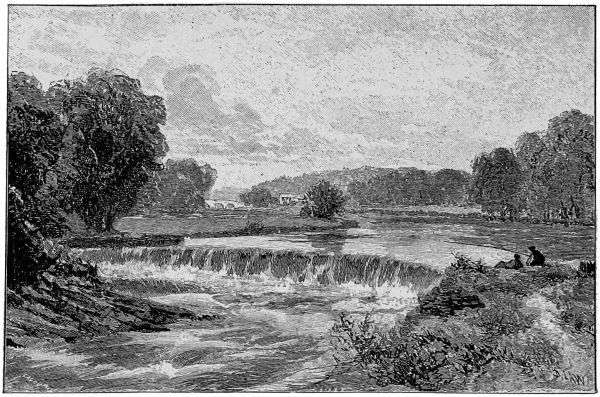

| The Ribble at Clitheroe | 219 | |

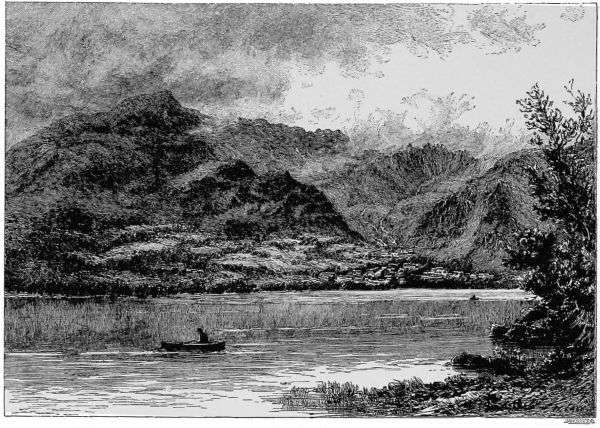

| Coniston | By David Law | 241 |

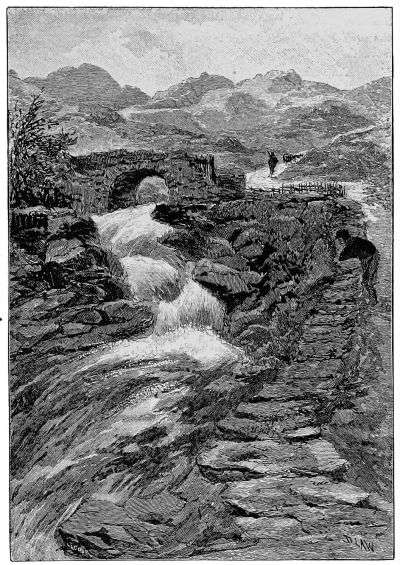

| Near the Copper Mines, Coniston | 247 | |

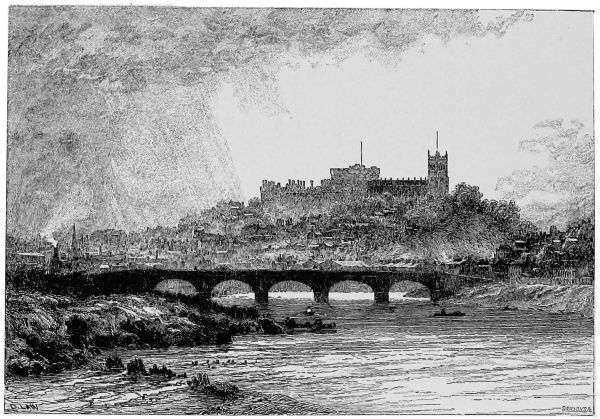

| Lancaster | By David Law | 259 |

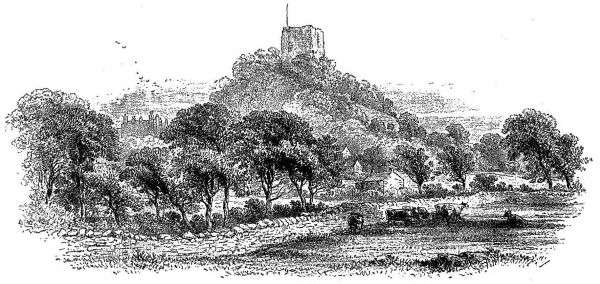

| Clitheroe Castle | 263 | |

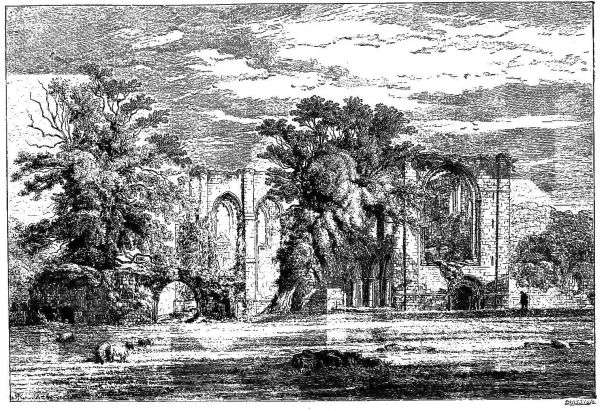

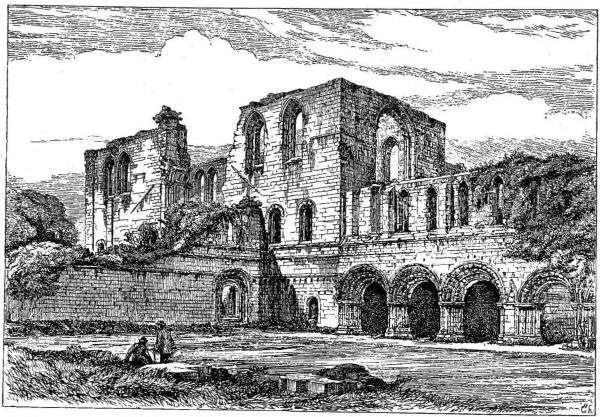

| Furness Abbey | 271 | |

| Furness Abbey | By R. Kent Thomas | 275 |

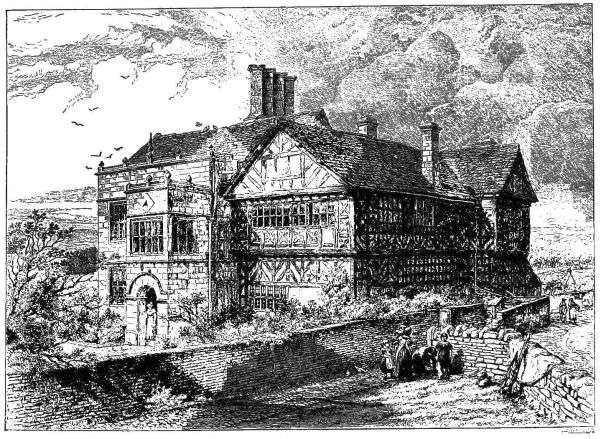

| Darcy Lever, near Bolton | 305 | |

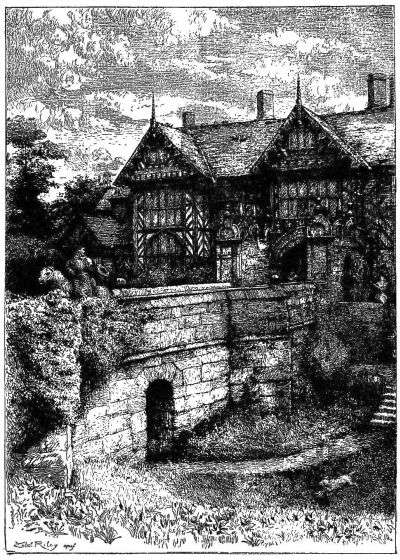

| Speke Hall | By T. Riley | 309 |

| Hale Hall | 311 | |

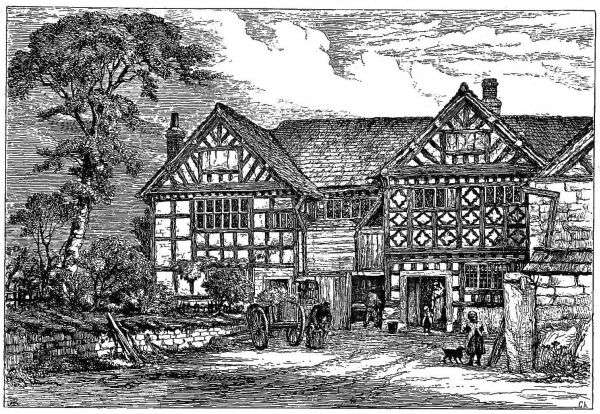

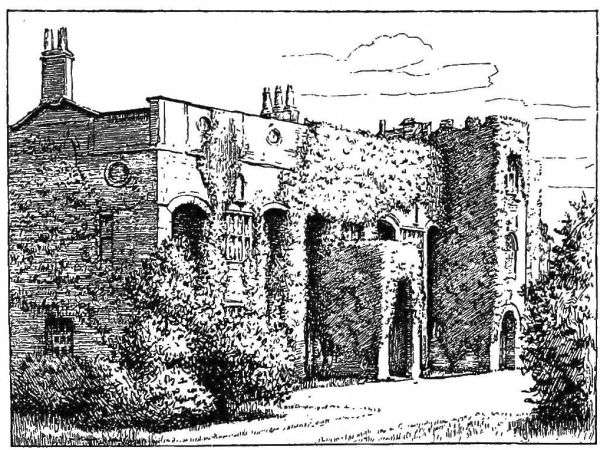

| Hall in the Wood | By R. Kent Thomas | 315 |

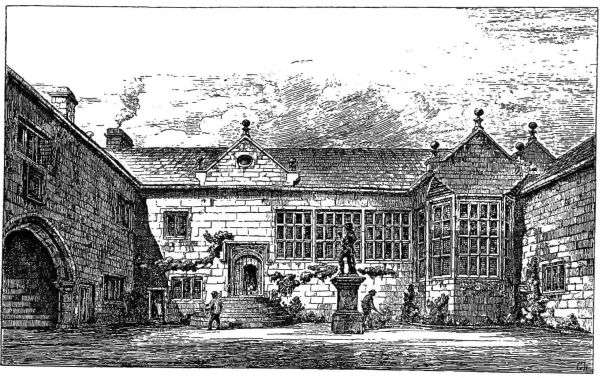

| Hoghton Tower | 325 | |

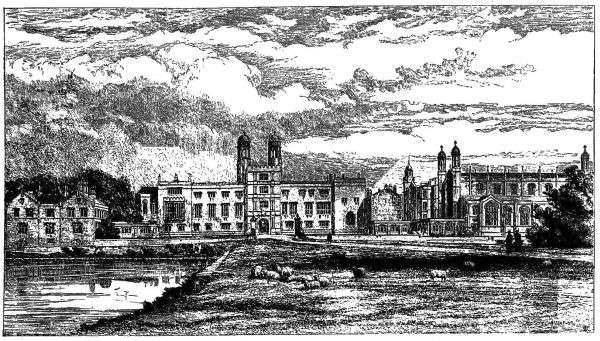

| Stonyhurst | By R. Kent Thomas | 329 |

Directly connected with the whole world, through the medium of its shipping and manufactures, Lancashire is commercially to Great Britain what the Forum was to ancient Rome—the centre from which roads led towards every principal province of the empire. Being nearer to the Atlantic, Liverpool commands a larger portion of our commerce with North America even than London: it is from the Mersey that the great westward steamers chiefly sail. The biographies of the distinguished men who had their birthplace in Lancashire, and lived there always, many of them living still, would fill a volume. A second would hardly suffice to tell of those who, though not natives, have identified themselves at various periods with Lancashire[Pg 2] movements and occupations. No county has drawn into its population a larger number of individuals of the powerful classes, some taking up their permanent abode in it, others coming for temporary purposes. In cultivated circles in the large towns the veritable Lancashire men are always fewer in number than those born elsewhere, or whose fathers did not belong to Lancashire. No trifling item is it in the county annals that the immortal author of the Advancement of Learning represented, as member of Parliament, for four years (1588-1592) the town which in 1809 gave birth to William Ewart Gladstone, and which, during the boyhood of the latter, sent Canning to the House of Commons.[1] In days to come England will point to Lancashire as the cradle also of the Stanleys, one generation after another, of Sir Robert Peel, John Bright, and Richard Cobden. The value to the country of the several men, the soundness of their legislative policy, the consistency of their lines of reasoning, is at this moment not the question. They are types of the vigorous constructive genius which has made England great and free, and so far they are types of the [Pg 3]aboriginal Lancashire temper. Lancashire has been the birthplace also of a larger number of mechanical inventions, invaluable to the human race; and the scene of a larger number of the applications of science to great purposes, than any other fragment of the earth's surface of equal dimensions. It is in Lancashire that we find the principal portion of the early history of steam and steam-engines, the first railway of pretension to magnitude forming a part of it. The same county had already led the way in regard to the English Canal system—that mighty network of inland navigation of which the Manchester Ship Canal, now in process of construction, will, when complete, be the member wonderful above all others. No trivial undertaking can that be considered; no distrust can there be of one in regard to its promise for the future, which has the support of no fewer than 38,000 shareholders. Here, too, in Lancashire, we have the most interesting part of the early history of the use of gas for lighting purposes. In Lancashire, again, were laid the foundations of the whole of the stupendous industry represented in the cotton-manufacture, with calico-printing, and the allied arts of pattern design. The literary work of Lancashire has been abreast of the county industry and scientific life. Mr. Sutton's List [Pg 4] of Lancashire Authors, published in 1876, since which time many others have come to the front, contains the names of nearly 1250, three-fourths of whom, he tells us, were born within the frontiers—men widely various, of necessity, in wit and aim, more various still in fertility, some never going beyond a pamphlet or an "article,"—useful, nevertheless, in their generation, and deserving a place in the honourable catalogue. Historians, antiquaries, poets, novelists, biographers, financiers, find a place in it, with scholars, critics, naturalists, divines. Every one acquainted with books knows that William Roscoe wrote in Liverpool. Bailey's Festus, one of the most remarkable poems of the age, was originally published in Manchester. The standard work upon British Bryology was produced in Warrington, and, like the life of Lorenzo de Medici, by a solicitor—the late William Wilson. Nowhere in the provinces have there been more conspicuous examples of exact and delicate philosophical and mathematical experiment and observation than such as in Manchester enabled Dalton to determine the profoundest law in chemistry; and Horrox, the young curate of Hoole, long before, to be the first of mankind to watch a transit of Venus, providing thereby for astronomers the means[Pg 5] towards new departures of the highest moment. During the Franco-Prussian war, when communication with the interior of Paris was manageable only by the employment of carrier-pigeons and the use of micro-photography, it was again a Lancashire man who had to be thanked for the art of concentrating a page of newspaper to the size of a postage-stamp. Possibly there were two or three contemporaneous inventors, but the first to make micro-photography—after the spectroscope, the most exquisite combination of chemical and optical science yet introduced to the world—public and practical, was the late Mr. J. B. Dancer, of Manchester.

Generous and substantial designs for promoting the education of the people, and their enjoyment,—habits also of thrift and of self-culture, are characteristic of Lancashire. Some have had their origin upon the middle social platform; others have sprung from the civilised among the rich.[2] The Co-operative system, with its varied capacities for rendering good service to the provident and careful, had its beginning in Rochdale. The first place to copy Dr. Birkbeck's Mechanics' Institution was Manchester, in which town the first provincial [Pg 6]School of Medicine was founded, and which to-day holds the headquarters of the Victoria University. Manchester, again, was the first town in England to take advantage of the Free Libraries Act of 1850, opening on September 2d, 1852, with Liverpool in its immediate wake. The Chetham Free Library (Manchester) had already existed for 200 years, conferring benefits upon the community which it would be difficult to over-estimate. Other Lancashire towns—Darwen, Oldham, Southport, and Preston, for example, have latterly possessed themselves of capital libraries, so that, including the fine old collection at Warrington, the number of books now within reach of Lancashire readers, pro rata for the population, certainly has no parallel out of London. An excellent feature in the management of several of these libraries consists in the effort made to attain completeness in special departments. Rochdale aims at a complete collection of books relating to wool; Wigan desires to possess all that has been written about engineering; the Manchester library contains nearly eight hundred volumes having reference to cotton. In the last-named will also be found the nucleus of a collection which promises to be the finest in the country, of books illustrative of English dialects. The Manchester libraries[Pg 7] collectively, or Free and Subscription taken together, are specially rich in botanical and horticultural works—many of them magnificently illustrated and running to several volumes—the sum of the titles amounting to considerably over a thousand. Liverpool, too, is well provided with books of this description, counting among them that splendid Lancashire work, Roscoe's Monandrian Plants, the drawings for which were chiefly made in the Liverpool Botanic Garden—the fourth founded in England, or first after Chelsea, Oxford, and Cambridge, and specially interesting in having been set on foot, in 1800, by Roscoe himself.

The legitimate and healthful recreation of the multitude is in Lancashire, with the thoughtful, as constant an object as their intellectual succour. The public parks in the suburbs of many of the principal Lancashire towns, with their playgrounds and gymnasia, are unexcelled. Manchester has no fewer than five, including the recent noble gift of the "Whitworth." Salford has good reason to be proud of its "Peel Park." Blackburn, Preston, Oldham, Lancaster, Wigan, Southport, and Heywood have also done their best.

In Lancashire have always been witnessed the most vigorous and persistent struggles made in this country for civil and political liberty[Pg 8] and the amendment of unjust laws. Sometimes, unhappily, they have seemed to indicate disaffection; and enthusiasts, well-meaning but extremely unwise—so commonly the case with their class—have never failed to obtain plenty of support, often prejudicial to the very cause they sought to uphold. But the ways of the people, considered as a community, deducting the intemperate and the zealots, have always been patriotic, and there has never been lack of determination to uphold the throne. The modern Volunteer movement, as the late Sir James Picton once reminded us, may be fairly said to have originated in Liverpool; the First Lancashire Rifles, which claims to be the oldest Volunteer company, having been organised there in 1859. In any case the promptitude of the act showed the vitality of that fine old Lancashire disposition to defend the right, which at the commencement of the Civil Wars rendered the county so conspicuous for its loyalty. It was in Lancashire that the first blood was shed on behalf of Charles the First, and that the last effort, before Worcester, was made in favour of his son—this in the celebrated battle of Wigan Lane. It was the same loyalty which, in 1644, sustained Charlotte de la Tremouille, Countess of Derby, in the famous three months' defence of Lathom House, when besieged by[Pg 9] Fairfax. Charlotte, a lady of French extraction, might quite excusably be supposed to have had less care for the king than an Englishwoman. But she was now the wife of a Lancashire man, and that was enough for her heart; she attuned herself to the Earl's own devotedness, became practically a Lancashire woman, and took equal shares with him in his unflinching fervour. The faithfulness to great trusts which always marks the noble wife, however humble her social position, however exalted her rank and title, with concurrent temptations to wrongdoing, doubtless lay at the foundation of Charlotte's personal heroism. But it was her pasturing, so to speak, in Lancashire, which brought it up to fruition. Of course, she owed much to the fidelity of her Lancashire garrison. Without it, her own brave spirit would not have sufficed. Lancashire men have always made good soldiers. Several were knighted "when the fight was done" at Poitiers and Agincourt. The Middleton archers distinguished themselves at Flodden. The gallant 47th—the "Lancashire Lads"—were at the Alma, and at Inkerman formed part of the "thin red line." There is equally good promise for the future, should occasion arise. At the great Windsor Review of the Volunteers in July 1881, when 50,000 were[Pg 10] brought together, it was unanimously allowed by the military critics that, without the slightest disrespect to the many other fine regiments upon the ground, the most distinguished for steadiness, physique, and discipline, as well as the numerically strongest, was the 1st Manchester. So striking was the spectacle that the Queen inquired specially for the name of the corps which reflected so much honour upon its county. In the return published in the General Orders of the Army, February 1882, it is stated that the 2d Battalion of the South Lancashire had then attained the proud distinction of being its "best signalling corps." The efforts made in Lancashire to obtain changes for the better in the statute-book had remarkable illustration in the establishment of the Anti-Corn-Law League, the original idea of which was of much earlier date than is commonly supposed, having occupied men's minds, both in Manchester and Liverpool, as far back as the year 1825. The celebrated cry six years later for Reform in the representation was not heard more loudly even in Birmingham than in the metropolis of the cotton trade.

The pioneers of every kind of religious movement have, like the leaders in civil and political reform, always found Lancashire responsive; and, as with practical scientific[Pg 11] inventions, it is to this county that the most interesting part of the early history of non-conforming bodies very generally pertains. George Fox, the founder of the "Society of Friends," commenced his earnest work in the neighbourhood of Ulverston. "Denominations" of every kind have also in this county maintained themselves vigorously, and there are none which do not here still exist in their strength. The "Established Church," as elsewhere, holds the foremost place, and pursues, as always, the even tenour of its way. During the forty-three years that Manchester has been the centre of a diocese, there have been built within the bishopric (including certain rebuildings on a larger scale) not fewer than 300 new churches. The late tireless Bishop Fraser "confirmed" young people at the rate of 11,000 every year. The strength of the Wesleyans is declared by their contributions to the great Thanksgiving Fund, which amounted, on 15th November 1880, to nearly a quarter of the entire sum then subscribed, viz. to about £65,000 out of the £293,000. They possess a college at Didsbury; not far from which, at Withington, the Congregationalists likewise have one of their own. The long standing and the power of the Presbyterians is illustrated in their owning the oldest place of worship in[Pg 12] Manchester next to the "Cathedral,"—the "chapel" in Cross Street,—a building which dates from the early part of the sixteenth century. The sympathy of Lancashire with the Church of Rome has been noted from time immemorial;—perhaps it would be more accurately said that there has been a stauncher allegiance here than in many other places to hereditary creed. The Catholic diocese of Salford (in which Manchester and several of the neighbouring towns are included) claimed in 1879 a seventh of the entire population.[3] Stonyhurst, near Clitheroe, is the seat of the chief provincial Jesuit college. Lastly, it is an interesting concurrent fact, that of the seventy Societies or congregations in England which profess the faith called the "New Jerusalem," Lancashire contains no fewer than twenty-four.

The historical associations offered in many parts of Lancashire are by no means inferior to those of other counties. One of the most interesting of the old Roman roads crosses Blackstone Edge. Names of places near the south-west coast tell of the Scandinavian Vikings. In 1323 Robert Bruce and his army of Scots ravaged the northern districts and nearly destroyed Preston. The neighbourhood of that town witnessed the Stuart enter[Pg 13]prise of 1715, and of Prince Charles Edward's march through the county in 1745 many memorials still exist.

The ruins of two of the most renowned of the old English abbeys are also here—Whalley, with its long record of benevolence, and Furness, scarcely surpassed in manifold interest even by Fountains. One of the very few remaining examples of an ancient castle belongs to the famous old town from which John o' Gaunt received his title.[4] Parish churches of remote foundation, with sculptures and lettered monuments, supply the antiquary with pleasing variety. Old halls are numerous; and connected with these, with the abbeys, and other relics of the past, we find innumerable entertaining legends and traditions, often rendered so much the more attractive through preserving, in part, the county speech of the olden time, to be dealt with by and by.

In the sports, manners, and customs which still linger where not superseded by modern ones, there is yet further curious material for observation, and the same may be said of the recreations of the staid and reflecting among the operative classes. It is in Lancashire that [Pg 14]"science in humble life" has always had its most numerous and remarkable illustrations. Natural history, in particular, forms one of the established pastimes in the cotton districts and among the men who are connected with the daylight work of the collieries. Many of the working-men botanists are banded into societies or clubs, which often possess libraries, and were founded before any living can remember. Music, especially choral and part-singing, has been cultivated in Lancashire with a devotion equalled only perhaps in Yorkshire, and certainly nowhere excelled. Both the air and the words of the most popular Christmas hymn in use among Protestants, "Christians, awake!" were composed within the sound, or nearly so, of the Manchester old church bells. The verses were written by Dr. Byrom, of stenographic fame;[5] the music, which compares well with the "Adeste Fideles" itself,—the song of Christmas with other communions,—was the production of John Wainwright. On a lower level we find the far-famed Lancashire Hand-bell Ringers. The facilities provided in Lancashire for self-culture have already been spoken of. That private education and school discipline are effective may be assumed, perhaps, from the circumstance that in October 1880 [Pg 15]the girl who at the Oxford Local Examinations stood highest in all England belonged to Liverpool.

Not without significance either is it that the coveted distinction of "Senior Wrangler" was won by a Lancashire man on five occasions within the twenty years ending February 1881. Three of the victors went up from Liverpool, one from Manchester, and one from the Wigan grammar-school. Lancashire may well be proud of such a list as this; feeling added pleasure in knowing that the gold medal, with prize of ten guineas, offered by the Council of Trinity College, London, for the best essay on "Middle-class Education, its Influence on Commercial Pursuits," was won in 1880 by a Lancashire lady—Miss Agnes Amy Bulley, of the Manchester College for Women.

The list of artists, chiefly painters, identified with the county appears from Mr. Nodal's researches to be not far short of a hundred, the earliest having been Hamlet Winstanley, of Warrington, where he died in 1756. Many of his productions, family portraits and views in the neighbourhood, are contained in the Knowsley collection. Two of these Lancashire artists—Joseph Farrington, R.A., and William Green—were among the first to disclose the beauties of the Lake District, by means of[Pg 16] lithography or engraved views prepared from their drawings. Farrington's twenty views appeared in 1789. Green's series of sixty was issued from Ambleside in 1814. A very curious circumstance connected with art in its way, is that Focardi's well-known droll statuette, "The Dirty Boy," was produced in Lancashire! Focardi happened to be in Preston looking for employment. Waiting one morning for breakfast, and going downstairs to ascertain the cause of the delay, through a half-open door he descried the identical old woman and the identical dirty boy! Here at last was a subject for his chisel. He got £500 for the marble, and the purchasers acknowledge that it was the most profitable investment they ever made.

The scenery presented in many portions of the county vies with the choicest to be found anywhere south of the Tweed. The artist turns with reluctance from the banks of the Lune and the Duddon. The largest and loveliest of the English lakes, supreme Windermere, belongs essentially to Lancashire: peaceful Coniston and lucid Esthwaite are entirely within the borders, and close by rise some of the loftiest of the English mountains. The top of "Coniston Old Man"—alt maen, or "the high rock"—is 2577 feet[Pg 17] above the sea. The part which contains the lakes and mountains is detached, and properly belongs to the Lake District, emphatically so called, being reached from the south only by passing over the lowermost portion of Westmoreland, though accessible by a perilous way, when the tide is out, across the Morecambe sands. Still it is Lancashire, a circumstance often surprising to those who, very naturally, associate the idea of the "Lakes" with the homes of Southey and Wordsworth, with Ambleside, and Helvellyn, and Lodore.

The geological character of this outlying piece being altogether different from that of the county in general, Lancashire presents a variety of surface entirely its own. At one extremity we have the cold, soft clay so useful to brickmakers; on reaching the Lakes we find the slate rocks of the very earliest ages. Much of the eastern edge of the county is skirted by the broad bare hills which constitute the central vertebræ of the "backbone of England," the imposing "Pennine range," which extends from Derbyshire to the Cheviots, and conceals the three longest of the English railway tunnels, one of which both begins and ends in Lancashire. The rock composing them is millstone-grit, with its customary gray and weather-beaten crags and ferny ravines. Plenty of tell-tale[Pg 18] gullies declare the vehemence of the winter storms that beat above, and in many of these the rush of water never ceases. Those who seek solitude, the romantic, and the picturesque, know these hills well; in parts, where there is moorland, the sportsman resorts to them for grouse.

In various places the rise of the ground is very considerable, far greater than would be anticipated when first sallying forth from Manchester, though on clear days, looking northwards, when a view can be obtained, there is pleasant intimation of distant hills. Rivington Pike, not far from Bolton, is 1545 feet above the sea-level. Pendle, near Clitheroe, where the rock changes to limestone, is 1803. The millstone-grit reappears intermittently as far as Lancaster, but afterwards limestone becomes predominant, continuing nearly to the slate rocks. It is to the limestone that Grange, one of the prettiest places in this part of the country, owes much of its scenic charm as well as salubrity. Not only does it give the bold and ivied tors which usually indicate calcareous rock. Suiting many kinds of ornamental trees, especially those which retain their foliage throughout the year, we owe to it in no slight measure the innumerable shining evergreens which at Grange, even[Pg 19] in mid-winter, constantly tempt one to exclaim with Virgil, when caressing his beloved Italy, "Hic ver assiduum!"

The southernmost part of the county has for its surface-rock chiefly the upper new red sandstone, a formation not favourable to fine hill-scenery, though the long ridges for which it is distinguished, at all events in Lancashire and Cheshire, often give a decided character to the landscape. The highest point in the extreme south-west, or near Liverpool, occupied by Everton church, has an elevation of no more than 250 feet, or less than a tenth of that of "Coniston Old Man." Ashurst, between Wigan and Ormskirk, and Billinge, between Wigan and St. Helens, make amends, the beacon upon the latter being 633 feet above the sea. The prospects from the two last named are very fine. They are interesting to the topographer as having been first resorted to as fit spots for beacons and signal-fires when the Spanish Armada was expected, watchers upon the airy heights of Rivington, Pendle, and Brown Wardle, standing ready to transmit the news farther inland. It is interesting to recall to mind that the news of the sailing of the Armada in the memorable July of 1588 was brought to England by one of the old Liverpool mariners, the captain of a little[Pg 20] vessel that traded with the Mediterranean and the coast of Africa.

Very different is the western margin of this changeful county, the whole extent from the Mersey to Duddon Bridge being washed by the Irish Sea. But, although maritime, it has none of the prime factors of seaside scenery,—broken rocks and cliffs,—not, at least, until after passing Morecambe Bay. From Liverpool onwards there is only level sand, and, to the casual visitor, apparently never anything besides; for the tide, which is swift to go out, recedes very far, and seldom seems anxious to come in. Blackpool is exceptional. Here the roll of the water is often glorious, and the dimples in calm weather are such as would have satisfied old Æschylus. On the whole, however, the coast must be pronounced monotonous, and the country that borders on it uninteresting. But whatever may be wanting in the way of rocks and cliffs, the need is fully compensated by the exceeding beauty in parts of the sandhills, especially near Birkdale and St. Anne's, where for miles they have the semblance of a miniature mountain range. Intervening there are broad, green, peaty plateaux, which, becoming saturated after rain, allow of the growth of countless wild-flowers. Orchises of several sorts, the pearly grass of[Pg 21] Parnassus, the pyrola that imitates the lily of the valley—all come to these wild sandhills to rejoice in the breath of the ocean, which, like that of the heavens, here "smells wooingly." Looking seawards, though it is seldom that we have tossing surge, there is further compensation very generally in the beauty of sunset—the old-fashioned but inestimable privilege of the western coast of our island—part of the "daily bread" of those who thank God consistently for His infinite bounty to man's soul as well as body, and which no people in the world command more perfectly than the inhabitants of the coast of Lancashire. Seated on those quiet sandhills, on a calm September evening, one may often contemplate on the trembling water a path of crimson light more beautiful than one of velvet laid down for the feet of a queen.

At the northern extremity of the county, as near Ulverstone, there are rocky and turf-clad promontories; but even at Humphrey Head, owing to the flatness of the adjacent sands, there is seldom any considerable amount of surf.

The most remarkable feature of the sea-margin of Lancashire consists in the number of its estuaries. The largest of these form the outlets of the Ribble and the Wyre, at the mouth of the last of which is the comparatively[Pg 22] new port of Fleetwood. The estuary of the Mersey (the southern shore of which belongs to Cheshire) is peculiarly interesting, on account of the seemingly recent origin of most of the lower portion. Ptolemy, the Roman geographer, writing about a.d. 130, though he speaks of the Dee and the Ribble, makes no mention of the Mersey, which, had the river existed in its present form and width, he could hardly have overlooked.[6] No mention is made of it either in the Antonine Itinerary; and as stumps of old oaks of considerable magnitude, which had evidently grown in situ, were not very long ago distinguishable on the northern margin when the tide was out, near where the Liverpool people used to bathe, the conclusion is quite legitimate that the level of the bed of the estuary must in the Celtic times, at the part where the ferry steamers go, have been much higher, and the stream proportionately narrow, perhaps a mere brook, with salt-marshes right and left. "Liverpool" was originally the name, simply and purely, of the estuary, indicating, in its derivation, not a town, or a village, but simply water. How far [Pg 23]upwards the brook, with its swamp or morass, extended, it is not possible to tell, though probably there was always a sheet of water near the present Runcorn. Depression of the shore, with plenty of old tree-stumps, certifying an extinct forest, is plainly observable a few miles distant on the Cheshire coast, just below New Brighton.

In several parts of Lancashire, especially in the extreme south-east, the surface is occupied by wet and dreary wastes, composed of peat, and locally called "mosses." That they have been formed since the commencement of the Christian era there can be little doubt, abundance of remains of the branches of trees being found near the clay floor upon which the peat has gradually arisen. The most noted of these desolate flats is that one called Chat, or St. Chad's Moss, the scene of the special difficulty in the construction of the original Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Nothing can exceed the dismalness of the mosses during nine or ten months of the year. Absolutely level, stretching for several miles, treeless, and with a covering only of brown and wiry scrub, Nature seems expiring in them. June kindly brings a change. Everything has its festival some time. For a short period they are strewed with the summer snow of the cotton-sedge,—the[Pg 24] "cana" of Ossian, "Her bosom was whiter than the down of cana"; and again, in September, they are amethyst-tinted for two or three weeks with the bloom of the heather. During the last quarter of a century the extent of these mosses has been much reduced, by draining and cultivation at the margins, and in course of time they will probably disappear.

Forests were once a feature of a good part of Lancashire. Long subsequently to the time of the Conquest, much of the county was still covered with trees. The celebrated "Carta de Foresta," or "Forest Charter," under which the clearing of the ground of England for farming purposes first became general and continuous, was granted only in the reign of Henry III., a.d. 1224, or contemporaneously with the uprise of Salisbury Cathedral, a date thus rendered easy of remembrance.

Here and there the trees were allowed to remain; and among these reserved portions of the original Lancashire "wild wood" it is interesting to find West Derby, the "western home of wild animals," thus named because so valuable as a hunting-ground.[7] No forest, in the current sense of the word, has survived in [Pg 25]Lancashire to the present day. Even single trees of patriarchal age are almost unknown. Agriculture, when commenced, proceeded vigorously, chiefly, however, in regard to meadow and pasture; cornfields have never been either numerous or extensive, except in the district beyond Preston called the Fylde—an immense breadth of alluvial drift, grateful in almost all parts for good farming.

The situation of this great city is in some respects one of the most enviable in the country. Stretching along the upper bank of an unrivalled estuary, 1200 yards across where narrowest, and the river current of which flows westwards, it is near enough to the sea to be called a maritime town, yet sufficiently far inland never to suffer any of the discomforts of the open coast. Upon the opposite side of the water the ground rises gently. Birkenhead, the energetic new Liverpool of the last fifty years, covers the nearer slopes; in the distance there are towers and spires, with glimpses of trees, and even of windmills that tell of wheat not far away.

Liverpool itself is pleasantly undulated. Walking through the busy

streets there is constant sense of rise and fall. An ascent that can

be called toilsome is never met with; [Pg 27]

[Pg 28]

[Pg 29]nor, except concurrently with

the docks, and in some of the remoter parts of the town, is there any

long continuity of flatness.

SHIPPING ON THE MERSEY

Compared with the other two principal English seaports, London and Bristol, the superiority of position is incontestable. A town situated upon the edge of an estuary must needs have quite exceptional advantages. London is indebted for its wealth and grandeur more to its having been the metropolis for a thousand years than to the service directly rendered by the Thames; and as for Bristol, the wonder is that with a stream like the Avon it should still count with the trio, and retain its ancient title of Queen of the West. Away from the water-side, Liverpool loses. There are no green downs and "shadowy woods" reached in half-an-hour from the inmost of the city, such as give character to Clifton; nor, upon the whole, can the scenery of the neighbourhood be said to present any but the very mildest and simplest features. Only in the district which includes Mossley, Allerton, Toxteth, and Otterspool, is there any approach to the picturesque. Hereabouts we find meadows and rural lanes; and a few miles up the stream, the Cheshire hills begin to show plainly. Yet not far from the Prince's Park there is a little ravine that aforetime, when[Pg 30] farther away from the borough boundaries, and when the name was given, would seem to have been another Kelvin Grove,—

Fairyland, tram-cars, and the hard facts of a great city, present few points of contact—Liverpool contrives to unite them in "Exchange to Dingle, 3d. inside." Among the dainty little poems left us by Roscoe, who was quick to recognise natural beauty, there is one upon the disappearance of the brooklet which, descending from springs now dried up, once babbled down this pretty dell with its tribute to the river.

To the stranger approaching Liverpool by railway, these inviting bits

of the adjacent country are, unfortunately, not visible. But let him

not murmur. When, after passing through the town, he steps upon the

Landing-stage and looks out upon the heaving water, with its countless

craft, endless in variety, and representing every nation that

possesses ships, he is compensated. The whole world does not present

anything in its way more abounding with life. A third of a mile in

length, broad enough for [Pg 31]

[Pg 32]

[Pg 33]the parade of troops, imperceptibly

adjusting itself to every condition of the tide, the Liverpool

Landing-stage, regarded simply as a work of constructive art, is a

wonderful sight. It is the scene of the daily movement of many

thousands of human beings, some departing, others just arrived; and,

above all there is the many-hued outlook right and left.

AMERICAN WHEAT AT LIVERPOOL

Thoroughly to appreciate the nobleness, the capacities, and the use made of this magnificent river, a couple of little voyages should be undertaken: one towards the entrance, where the tall white shaft of the lighthouse comes in view; the other, ascending the stream as far as Rock Ferry. By this means the extent of the docks and the magnitude of the neighbouring warehouses may in some degree be estimated. Up the river and down, from the middle portion of the Landing-stage, without reckoning Birkenhead, the line of sea-wall measures more than six miles. The water area of the docks approaches 270 acres; the length of surrounding quay-margin is nearly twenty miles. The double voyage gives opportunity also for observation of the many majestic vessels which are either moving or at anchor in mid-channel. Merchantmen predominate, but in addition there are almost invariably two or three of the superb steamers[Pg 34] which have their proper home upon the Atlantic, and in a few hours will be away. The great Companies whose names are so familiar—the Cunard, the Allan, the White Star, the Inman, and five or six others—despatch between them no fewer than ten of these splendid vessels every week, and fortnightly two extra, the same number arriving at similar intervals. Columbus's largest ship was about ninety tons; the steamers spoken of are mostly from 2000 to 5000 tons; a few are of 8000 or 9000 tons. Besides these, there are the South Americans, the steamers to the East and West Indies, China, Japan, and the West Coast of Africa, the weight varying from 1500 to 4000 tons, more than fifty of these mighty vessels going out every month, and as many coming in. The total number of ships and steamers actually in the docks, Birkenhead included, on the 6th of December 1880 was 438.

A fairly fine day, a sunshiny one if possible, should be selected for these little voyages, not merely because of its pleasantness, but in order to observe the astonishing distance to which the river-life extends. Like every other town in our island, Liverpool knows full well what is meant by fog and rain. "Some days must be dark and dreary." At times it is scarcely[Pg 35] possible for the ferry-boats to find their way across, and not a sound is to be heard except to convey warning or alarm. But the gloomy hours, fortunately, do not come often. The local meteorologists acknowledge an excellent average of cheerful weather,—the prevailing kind along the whole extent of the lower Lancashire coast, the hills being too distant to arrest the passage of the clouds,—and the man who misses his boat two or three times running must indeed be unlucky. Happily,[Pg 36] these uncertainties and vexations of the bygones, actual and possible, have now been neutralised, say since 20th January 1886, by the construction of the Cheshire Lines tunnel under the river.

RAN AWAY TO SEA

Nothing, on a fine day, can be more exhilarating than three or four hours upon the Mersey. Liverpool, go where we may, is, in the better parts, a place emphatically of exhilarations. The activity of the river-life is prefigured in the jauntiness of the movement in the streets; the display in the shop-windows, at all events where one has to make way for the current of well-dressed ladies which at noon adds in no slight measure to the various gaiety of the scene, is a constant stimulus to the fancy—felt so much the more if one's railway ticket for the day has been purchased in homely Stockport, or dull Bury, or unadorned Middleton, or even in thronged Manchester. Still it is upon the water that the impression is most animating. High up the river, generally near the Rock Ferry pier, a guardship is stationed—usually an ironclad. Beyond this we come upon four old men-of-war used as training-ships. The Conway, a naval school for young officers, accommodates 150, including many of good birth, who pay £50 a-year apiece. The Indefatigable gives gratuitous teaching to the[Pg 37] sons of sailors, orphans, and other homeless boys. The Akbar and the Clarence are Reformatory schools, the first for misbehaving Protestant lads, the other for Catholics. The good work done by these Reformatories is immense. During the three years 1876 to 1878, the number passed out of the two vessels was 1890, and of these no fewer than 1420 had been converted into capital young seamen.[8]

Who will write us a book upon the immeasurable minor privileges of life, the things we are apt to pass by and take no note of, because "common"? Sailing upon this glorious river, how beautiful overhead the gleam, against the azure, of the sea-gulls! Liverpool is just near enough to the saltwater for them to come as daily visitants, just far enough for them to be never so many as to spoil the sweet charm of the unexpected: for the moment they make one forget even the ships. Man's most precious and enduring possessions are the loveliness and the significance of nature. Were all things valued as they deserve, perhaps these cheery sea-birds would have their due.

The Liverpool docks are more remarkable than those even of London. Some of the [Pg 38]famed receptacles fed from the Thames are more capacious, and the number of vessels they contain when full is proportionately greater than is possible in the largest of the Liverpool. But in London there are not so many, nor is there so great a variety of cargo seen upon the quays, nor is the quantity of certain imports so vast. In the single month of October 1880 Liverpool imported from North America of apples alone no fewer than 167,400 barrels. Most of the docks are devoted to particular classes of ships or steamers, or to special branches of trade. The King's Dock is the chief scene of the reception of tobacco, the quantity of which brought into Liverpool is second only to the London import; while the Brunswick is chiefly devoted to the ships bringing timber. The magnificent Langton and Alexandra Docks, opened in September 1881, are reserved for the ocean steamers, which previously had to lie at anchor in the channel, considerably to the disadvantage of all concerned, but which now enjoy all the privileges of the smallest craft. At intervals along the quays there are huge cranes for lifting; and very interesting is it to note the care taken that their strength, though herculean, shall not be overtaxed, every crane being marked according to its power,[Pg 39] "Not to lift more than two tons," or whatever other weight it is adapted to. Like old Bristol, Liverpool holds her docks in her arms. In London, as an entertaining German traveller told his countrymen some fifty years ago, a merchant, when he wants to despatch an order to his ship in the docks, "must often send his clerk down by the railroad; in Liverpool he may almost make himself heard in the docks out of his counting-house."[9] This comes mainly of the town and the docks having grown up together.

The "dockmen" are well worth notice. None of the loading and unloading of the ships is done by the sailors. As soon as the vessel is safely "berthed," the consignees contract with an intermediate operator called a stevedore,[10] who engages as many men as he requires, paying them 4s. 6d. per day, and for half-days and quarter-days in proportion. Nowhere do we see a better illustration than is supplied in Liverpool of the primitive Judean market-places, "Why stand ye here all the day idle?" "Because no man hath hired us." Work enough for all there never is: a circumstance not surprising when we consider that [Pg 40]the total number of day-labourers in Liverpool is estimated at 30,000. The non-employed, who are believed to be always about one-half, or 15,000, congregate near the water; a favourite place of assembly appears to be the pavement adjoining the Baths. The dockmen correspond to the male adults among the operatives in the cotton-mill districts, with the great distinction that they are employed and paid by time, and that they are not helped by the girls and women of their families, who in the factories are quite as useful and important as the rougher sex. They correspond also to the "pitmen" of collieries, and to journeymen labourers in general. Most of them are Irish—as many, it is said, as nine-tenths of the 30,000—and as usual with that race of people, they have their homes near together. These are chiefly in the district including Scotland Road, where a very different scene awaits the tourist. Faction-fights are the established recreation; the men engage in the streets, the women hurl missiles from the roofs of the houses. Liverpool has a profoundly mournful as well as a brilliant side: Canon Kingsley once said that the handsomest set of men he had ever beheld at one view was the group assembled within the quadrangle of the Liverpool Exchange: the Income-tax assessment[Pg 41] of Liverpool amounts to nearly sixteen millions sterling: the people claim to be "Evangelical" beyond compare; and that they have intellectual power none will dispute:—behind the scenes the fact remains that nowhere in our island is there deeper destitution and profounder spiritual darkness.[11] When the famished and ignorant have to be dealt with, it is better to begin with supply of good food than with aëriform benedictions. Lady Hope (née Miss Elizabeth R. Cotton) has shown that among the genuine levers of civilisation there are none more substantial than good warm coffee and cocoa. Liverpool, fully understanding this, is giving to the philanthropic all over England a lesson which, if discreetly taken up, cannot fail to tell immensely on the morals, as well as the physical needs, of the poor and destitute. All along the line of the docks there are "cocoa-shops," some of them upon wheels, metallic tickets, called "cocoa-pennies," giving access.

Liverpool is a town of comparatively modern date, being far younger

than Warrington, Preston, Lancaster, and many another which

commercially it has superseded. The name does not occur in Domesday

Book, com[Pg 42]piled a.d. 1086, nor till the time of King John does even

the river seem to have been much used. English commerce during the era

of the Crusades did not extend beyond continental Europe, the

communications with which were confined to London, Bristol, and a few

inconsiderable places on the southern coasts. Passengers to Ireland

went chiefly by way of the Dee, and upon the Mersey there were only a

few fishing-boats. At the commencement of the thirteenth century came

a change. The advantages of the Mersey as a harbour were perceived,

and the fishing village upon the northern shore asked for a charter,

which in 1207 was granted. Liverpool, as a borough, is thus now in its

685th year. That this great and opulent city should virtually have

begun life just at the period indicated is a circumstance of no mean

interest, since the reign of John, up till the time of the barons'

gathering at Runnymede, was utterly bare of historical incident, and

the condition of the country in general was poor and depressed.

Cœur de Lion, the popular idol, though scarcely ever seen at home,

was dead. John, the basest monarch who ever sat upon the throne of

England, had himself extinguished every spark of loyal sentiment by

his cruel murder of Prince Arthur. Art was nearly [Pg 43]

[Pg 44]

[Pg 45]passive, and

literature, except in the person of Layamon, had no existence. Such

was the age, overcast and silent, in which the foundations of

Liverpool were laid: contemplating the times, and all that has come of

the event, one cannot but think of acorn-planting in winter, and

recall the image in Faust,—

ST. NICHOLAS CHURCH, LIVERPOOL

The growth of the new borough was for a long period very slow. In 1272, the year of the accession of Edward I., Liverpool consisted of only 168 houses, occupied (computing on the usual basis) by about 840 people; and even a century later, when Edward III. appealed to the nation to support him in his attack upon France, though Bristol supplied twenty-four vessels and 800 men, Liverpool could furnish no more than one solitary barque with a crew of six. It was shortly after this date that the original church of "Our Lady and St. Nicholas" was erected. Were the building, as it existed for upwards of 400 years, still intact, or nearly so, Liverpool would possess no memorial of the past more attractive. But in the first place, in 1774, the body was taken down and rebuilt. Then, in 1815, the same was done with the tower, the architect[Pg 46] wisely superseding the primitive spire with the beautiful lantern by which St. Nicholas's is now recognised even from the opposite side of the water. Of the original ecclesiastical establishment all that remains is the graveyard, once embellished with trees, and in particular with a "great Thorne," in summer white and fragrant, which the tasteless and ruthless old rector of the time was formally and most justly impeached for destroying "without leave or license." Wilful and needless slaying of ornamental trees, such as no money can buy or replace, and which have taken perhaps a century or more to grow, is always an act of ingratitude, if not of the nature of a crime, and never less excusable than when committed on consecrated ground. The dedication to St. Nicholas shows that the old Liverpool townsfolk were superstitious, if not pious. It is St. Nicholas who on the strength of the legend is found in Dibdin as "the sweet little cherub"—

Up to 1699 the building in question was only the "chappell of Leverpoole," the parish in which the town lay being Walton.

In 1533, or shortly afterwards, temp. Henry VIII., John Leland visited Liverpool, which[Pg 47] he describes as being "a pavid Towne," with a castle, and a "Stone Howse," the residence of the "Erle of Derbe." He adds, that there was a small custom-house, at which the dues were paid upon linen-yarn brought from Dublin and Belfast for transmission to Manchester[12]. A fortunate circumstance it has always been for Ireland that she possesses so near and ready a customer for her various produce as wealthy Liverpool. Fifty years later, Camden describes the town as "neat and populous"—the former epithet needing translation; and by the time of Cromwell the amount of shipping had nearly doubled: the Mersey, it hardly needs saying, is the natural westward channel for the commerce of the whole of the active district which has Manchester for its centre, and the value of this was now fast becoming apparent. By the end of the sixteenth century south-east Lancashire was becoming distinguished for its productive power. A large and constantly increasing supply of manufactures adapted for export implied imports. The interests of Manchester and Liverpool soon declared themselves alike. Of no two places in the world can it be said with more truth, that they have "lived and loved together, through many changing years"; though it [Pg 48]may be a question whether they have always "wept each other's tears." In addition to the impulse given to shippers by extended manufacturing, the captains who sailed upon the Irish Sea found in the Mersey their securest haven, the more so since the Dee was now silting up—a misfortune for once so favoured Chester which at last threw it commercially quite into the shade. The Lune was also destined to lose in favour: an event not without a certain kind of pathos, since cotton was imported into Lancaster long before it was brought to Liverpool. Conditions of all kinds being so happy, prosperity was assured. Liverpool had now only to be thankful, industrious, honest, and prudent.

Singular to say, in the year 1635 Liverpool was not thought worthy of a place in the map of England. In Selden's Mare Clausum, seu de Dominio Maris there is a map in which Preston, Wigan, Manchester, and Chester, are all set down, but, although the Mersey lies in readiness, there is no Liverpool!

The period of the Restoration was particularly eventful. The Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of 1666 led to a large migration of Londoners into Lancashire, and especially to Liverpool, trade with the North American "Plantations," and with the sugar-producing[Pg 49] islands of the Caribbean Sea, being now rapidly progressive. Contemporaneously there was a flocking thither of younger sons of country squires, who, anticipating the Duke of Argyll of to-day, saw that commerce is the best of tutors. From these descended some of the most eminent of the old Liverpool families. The increasing demand for sugar in England led, unfortunately, to sad self-contamination. Following the example of Bristol, Liverpool gave itself to the slave-trade, and for ninety-seven years, 1709 to 1806, the whole tone and tendency of the local sentiment were debased by it. The Roscoes, the Rathbones, and others among the high-minded, did their best to arouse their brother merchants to the iniquity of the traffic, and to counteract the moral damage to the community; but mischief of such a character sinks deep, and the lapse of generations is required to efface it entirely. Mr. W. W. Briggs considers that the shadow is still perceptible.[13] Politely called the "West India trade," no doubt legitimate commerce was bound up with the shocking misdeed, but the kernel was the same. It began with barter of the manufactures of Manchester, Sheffield, and Birmingham, for the negroes demanded, first, by the sugar-planters, and afterwards, in Vir[Pg 50]ginia, for the tobacco-farms. Infamous fraud could not but follow; and a certain callousness, attributable in part to ignorance of the methods employed, was engendered even in those who had no interest in the results. When George III. was but newly crowned, slaves of both sexes were at times openly sold by advertisement in Liverpool! Money was made fast by the trade in human beings, and many men accumulated great fortunes, memorials of which it would not be hard to find. All this, we may be thankful, is now done with for ever. To recall the story is painful but unavoidable, since no sketch of the history of Liverpool can be complete without reference to it. There is no need, however, to dwell further upon it. Escape always from the thought of crime as soon as possible. Every one, at all events, must acknowledge that, notwithstanding the outcry by the interested that the total ruin of Liverpool, with downfall of Church and State, would ensue upon abolition, the town has done better without the slave-trade.

The period of most astonishing expansion has been that which, as in

Manchester, may be termed the strictly modern one. The best of the

public buildings have been erected within the memory of living men.

Most of the docks [Pg 51]

[Pg 52]

[Pg 53]have been constructed since 1812. The first

steamboat upon the Mersey turned its paddles in 1815. The first steam

voyage to New York commemorates 1838. In Liverpool, it should not be

forgotten, originated directly afterwards the great scheme which gave

rise to the "Peninsular and Oriental," upon which followed in turn the

Suez Railway, and then the Suez Canal. The current era has also

witnessed an immense influx into Liverpool of well-informed American,

Canadian, and continental merchants, Germans particularly. These have

brought (and every year sees new arrivals) the habits of thought, the

special views, and the fruits of the widely diverse social and

political training peculiar to the respective nationalities.

THE CUSTOM-HOUSE, LIVERPOOL

A very considerable number of the native English Liverpool merchants have resided, sometimes for a lengthened period, in foreign countries. Maintaining correspondence with those countries, having connections one with another all over the world, they are kept alive to everything that has relation to commerce. They can tell us about the harvests in all parts of the world, the value of gold and silver, and the operation of legal enactments. Residence abroad supplies new and more liberal ideas, and enables men to judge more accurately.[Pg 54] The result is that, although Liverpool, like other places, contains its full quota of the incurably ignorant and prejudiced, the spirit and the method of the mercantile community are in the aggregate thoughtful, inviting, and enjoyable. The occupations of the better class of merchants, and their constant consociation with one another, require and develop not only business powers, but the courtesies which distinguish gentlemen. A stamp is given quite different from that which comes of life spent habitually among "hands";[14] the impression upon the mind of the visitor is that, whatever may be the case elsewhere, in Liverpool ability and good manners are in partnership. And this not only in commercial transactions: the characteristics observable in office hours reappear in the privacy of home.

The description of business transacted in Liverpool is almost peculiar to the place. After the shipbuilders and the manufacturers of shipping adjuncts, chain-cables, etc., there are few men in the superior mercantile class who produce anything. Liverpool is a city of agents. Its function is not to make, but to transfer. Nearly every bale or box of mer[Pg 55]chandise that enters the town is purely en route. Hence it comes that Liverpool gathers up coin even when times are "bad." Whether the owner of the merchandise eventually loses or gains, Liverpool has to be paid the expenses of the passing through. Much of the raw material that comes from abroad changes hands several times before the final despatch, though not by any means through the ordinary old-fashioned processes of mere buying and selling. In the daily reports of the cotton-market a certain quantity is always distinguished as bought "upon speculation." The adventurous do not wait for the actual arrival of the particular article they devote their attention to. Like the Covent Garden wholesale fruitmen, who risk purchase of the produce of the Kentish cherry-orchards while the trees are only in bloom, the Liverpool cotton brokers deal in what they call "futures."

Another curious feature is the problematical character of every man's

day. The owner of a cotton-mill or an iron-foundry proceeds, like a

train upon the rails, according to a definite and preconcerted plan. A

Liverpool foreign merchant, when leaving home in the morning, is

seldom able to forecast what will happen before night. Telegrams from

distant countries are prone to bring news that changes the whole[Pg 56]

complexion of affairs. The limitless foreign connections tend also to

render his sympathies cosmopolitan rather than such as pertain to

old-fashioned citizens pure and simple. Once a day at least his

thoughts and desires are in some far-away part of the globe. Broadly

speaking, the merchants, like their ships in the river, are only at

anchor in Liverpool. The owner of a "works" must remain with his

bricks and mortar; the Liverpool merchant, if he pleases, can weigh

and depart. Though the day is marked by conjecture, it is natural to

hope for good. Hence much of the sprightliness of the Liverpool

character—the perennial uncertainty underlying the equally

well-marked disposition to "eat, drink, and be merry, for to-morrow we

die," or, at all events, may die. This in turn seems to account for

the high percentage of shops of the glittering class and that deal in

luxuries. Making their money in the way they do, the Liverpool people

care less to hoard it than to indulge in the spending. How open-handed

they can be when called upon is declared by the sums raised for the

Bishopric and the University College. In proportion, they have more

money than other people, the inhabitants of London alone excepted. The

income-tax assessment has already been mentioned as nearly sixteen

[Pg 57]

[Pg 58]

[Pg 59]millions. The actual sum for the year ending 5th April 1876 was

£15,943,000, against Manchester, £13,907,000, Birmingham, £6,473,884,

London, £50,808,000. The superiority in comparison with Manchester may

come partly, perhaps, of certain firms in the last-named place

returning from the country towns or villages where their "works" are

situated. Liverpool is self-contained, Manchester is diffused.

ST. GEORGE'S HALL, LIVERPOOL

Liverpool may well be proud of her public buildings. Opinions differ

in regard to the large block which includes the Custom-house, commonly

called "Revenue Buildings"; but none dispute the claim of the

sumptuous edifice known as St. George's Hall to represent the

architecture of ancient Greece in the most successful degree yet

attained in England. The eastern façade is more than 400 feet in

length; at the southern extremity there is an octostyle Corinthian

portico, the tympanum filled with ornament. Strange, considering the

local wealth and the local claim of a character for thoroughness and

taste, that this magnificent structure should be allowed to remain

unfinished, still wanting, as it does, the sculptures which formed an

integral part of Mr. Elmes' carefully considered whole. Closely

adjacent are the Free Library and the new[Pg 60] Art Gallery, and, in Dale

Street, the Public Offices, the Townhall, and the Exchange, which is

arcaded. Among other meritorious buildings, either classical or in the

Italian palazzo style, we find the Philharmonic Hall and the Adelphi

Hotel. The Free Library is one of the best-frequented places in

Liverpool. The number of readers exceeded in 1880, in proportion to

the population, that of every other large town in England where a Free

Library exists. In Leeds, during the year ending at Michaelmas, the

number was 648,589; in Birmingham, 658,000; in Manchester, 958,000; in

Liverpool, 1,163,795. In the Reference Department the excess was

similar, the issues therefrom having been in Liverpool one-half; in

Leeds and Birmingham, two-fifths; in Manchester, one-fifth. The

Liverpool people seem apt to take advantage of their opportunities of

every kind. When the Naturalists' Field Club starts for the country,

the number is three or four times greater in proportion to the whole

number of members than in other places where, with similar objects,

clubs have been founded. Many, of course, join in the trips for the

sake of the social enjoyment; whether as much work is accomplished

when out is undecided. They are warm supporters also of literary and

scientific institutions, [Pg 61]

[Pg 62]

[Pg 63]the number of which, as well as of

societies devoted to music and the fine arts, is in Liverpool

exceptionally high. At the last "Associated Soirée," the Presidents of

no fewer than fifteen were present. Educational, charitable, and

curative institutions exist in equal plenty. It was Liverpool that in

1791 led the way in the foundation of Asylums for the Blind. The

finest ecclesiastical establishment belongs to the Catholics, who in

Liverpool, as in Lancashire generally, have stood firm to the faith of

their fathers ever since 1558, and were never so powerful a body as at

present. The new Art Gallery seems to introduce an agreeable prophecy.

Liverpool has for more than 140 years striven unsuccessfully to give

effect to the honourable project of 1769, when it sought to tread in

the steps of the Royal Academy, founded a few months previously. There

are now fair indications of rejuvenescence, and, if we mistake not,

there is a quickening appreciation of the intrinsically pure and

worthy, coupled with indifference to the qualities which catch and

content the vulgar—mere bigness and showiness. Slender as the

appreciation may be, still how much more precious than the bestowal of

patronage, in ostentation of pocket, beginning there and ending there,

which all true and noble art disdains.

THE EXCHANGE, LIVERPOOL

Liverpool must not be quitted without a parting word upon a feature certainly by no means peculiar to the town, but which to the observant is profoundly interesting and suggestive. This consists in the through movement of the emigrants, and the arrangements made for their departure. Our views and vignettes give some idea of what may be seen upon the river and on board the ships. But it is impossible to render in full the interesting spectacle presented by the strangers who come in the first instance from northern Europe. These arrive, by way of Hull, chiefly from Sweden and Denmark, and, to a small extent, from Russia and Germany—German emigrants to America usually going from their own ports, and by way of the English Channel. Truly astonishing are the piles of luggage on view at the railway stations during the few hours or days which elapse before they go on board. While waiting, they saunter about the streets in parties of six or eight, full of wonder and curiosity, but still impressing every one with their honest countenances and inoffensive manners and behaviour. There are very few children among these foreigners, most of whom appear to be in the prime of life, an aged parent now and then accompanying[Pg 65] son or daughter. In 1880 there left Liverpool as emigrants the prodigious number of 183,502. Analysis gave—English, 74,969; Scotch, 1811; Irish, 27,986; foreigners, 74,115.

First in the long list of Lancashire manufacturing towns, by reason of its magnitude and wealth, comes Manchester. By and by we shall speak of this great city in particular. For the present the name must be taken in the broader sense, equally its own, which carries with it the idea of an immense district. Lancashire, eastwards from Warrington, upwards as far as Preston, is dotted over with little Manchesters, and these in turn often possess satellites. The idea of Manchester as a place of cotton factories covers also a portion of Cheshire, and extends even into Derbyshire and Yorkshire—Stockport, Hyde, Stalybridge, Dukinfield, Saddleworth, Glossop, essentially belong to it. To all these towns and villages Manchester stands in the relation of a Royal Exchange. It is the reservoir, at the same[Pg 67] time, into which they pour their various produce. Manchester acquired this distinguished position partly by accident, mainly through its very easy access to Liverpool. At one time it had powerful rivals in Blackburn and Bolton. Blackburn lost its chance through the frantic hostility of the lower orders towards machinery, inconsiderate men of property giving them countenance—excusably only under the law that mental delusions, like bodily ailments, are impartial in choice of victims. Bolton, on the other hand, though sensible, was too near to compete permanently, neither had it similar access to Liverpool. The old salerooms in Bolton, with their galleries and piazzas, now all gone, were ninety years ago a striking and singular feature of that busy hive of spinning and weaving bees.

Most of these little Manchesters are places of comparatively new growth. A century ago nearly all were insignificant villages or hamlets. Even the names of the greater portion were scarcely known beyond the boundaries of their respective parishes. How unimportant they were in earlier times is declared by the vast area of many of the latter, the parishes in Lancashire, as everywhere else, having been marked out according to the ability of the population to maintain a church and pastor.[Pg 68] It is not in manufacturing Lancashire as in the old-fashioned rural counties,—Kent, Sussex, Hampshire, and appled Somerset,—where on every side one is allured by some beautiful memorial of the lang syne. "Sweet Auburn, loveliest village of the plain" is not here. Everything, where Cotton reigns, presents the newness of aspect of an Australian colony. The archæological scraps—such few as there may be—are usually submerged, even in the older towns, in the "full sea" of recent building. Even in the graveyards, the places of all others which in their tombstones and inscriptions unite past and present so tenderly, the imagination has usually to turn away unfed. In place of yew-trees old as York Minster, if there be anything in the way of green monument, it is a soiled and disconsolate shrub from the nearest nursery garden.

The situation of these towns is often pleasing enough: sometimes it is picturesque, and even romantic. Having begun in simple homesteads, pitched where comfort and safety seemed best assured, they are often found upon gentle eminences, the crests of which, as at Oldham, they now overlap; others, like Stalybridge, lie in deep hollows, or, like Blackburn, have gradually spread from the margin of a stream. Not a few of these primitive sites[Pg 69] have the ancient character pleasingly commemorated in their names, as Haslingden, the "place of hazel-nuts." The eastern border of the county being characterised by lofty and rocky hills, the localities of the towns and villages are there often really favoured in regard to scenery. This also gives great interest to the approaches, as when, after leaving Todmorden, we move through the sinuous gorge that, bordered by Cliviger, "mother of rocks," leads on to Burnley. The higher grounds are bleak and sterile, but the warmth and fertility of the valleys make amends. In any case, there is never any lack of the beauty which comes of the impregnation of wild nature with the outcome of human intelligence. Manchester itself occupies part of a broad level, usually clay-floored, and with peat-mosses touching the frontiers. In the bygones nothing was sooner found than standing water: the world probably never contained a town that only thirty to a hundred years ago possessed so many ponds, many of them still in easy recollection, to say nothing of as many more within the compass of an afternoon's walk.

Rising under the influence of a builder so unambitious as the genius

of factories and operatives' cottages, no wonder that a very[Pg 70] few

years ago the Lancashire cotton towns seemed to vie with one another

which should best deserve the character of cold, hard, dreary, and

utterly unprepossessing. The streets, excepting the principal artery

(originally the road through the primitive village, as in the case of

Newton Lane, Manchester), not being susceptible of material change,

mostly remain as they were—narrow, irregular, and close-built.

Happily, of late there has been improvement. Praiseworthy aspirations

in regard to public buildings are not uncommon, and even in the

meanest towns are at times undeniably successful. In the principal

centres—Manchester, Bolton, Rochdale, and another or two—the old

meagreness and unsightliness are daily becoming less marked, and a

good deal that is really magnificent is in progress as well as

completed. Unfortunately, the efforts of the architect fall only too

soon under the relentless influence of the factory and the foundry.

Manchester is in this respect an illustration of the whole group; the

noblest and most elegant buildings sooner or later get smoke-begrimed.

Sombre as the Lancashire towns become under that influence, if there

be collieries in the neighbourhood, as in the case of well-named

"coaly Wigan," the dismal hue is intensified, and in dull and rainy

weather grows [Pg 71]

[Pg 72]

[Pg 73]still worse. On sunshiny days one is reminded of a

sullen countenance constrained to smile against the will.

WIGAN

A "Lancashire scene" has been said to resolve into "bare hills and chimneys"; and as regards the cotton districts the description is, upon the whole, not inaccurate. Chimneys predominate innumerably in the landscape, a dark pennon usually undulating from every summit—perhaps not pretty pictorially, but in any case a gladsome sight, since it means work, wages, food, for those below, and a fire upon the hearth at home. Though the sculptor may look with dismay upon his ornaments in marble once white as a lily, now under its visitation gray as November, never mind—the smoke denotes human happiness and content for thousands: when her chimneys are smokeless, operative Lancashire is hungry and sad.

In the towns most of the chimneys belong to the factories—buildings of remarkable appearance. The very large ones are many storeys high, their broad and lofty fronts presenting tier upon tier of monotonous square windows. Decoration seems to be studiously avoided, though there is often plenty of scope for inexpensive architectural effects that, to say the least, would be welcome. Seen by day, they seem deserted; after dark, when the innumerable[Pg 74] windows are lighted up, the spectacle changes and becomes unique. Were it desired to illuminate in honour of a prince, to render a factory more brilliant from the interior would be scarcely possible. Like all other great masses of masonry, the very large ones, though somewhat suggestive of prisons, if not grand, are impressive. In semi-rural localities, where less tarnished by smoke, especially when tolerably new, and not obscured by the contact of inferior buildings, they are certainly very fine objects. The material, it is scarcely needful to say, is red brick.

All the towns belonging to the Manchester family-circle present more or less decidedly the features mentioned. They differ from one another not in style, or habits, or physiognomy; the difference is simply that one makes calico, another muslins, and that they cover a less or greater extent of ground. The social, moral, and intellectual qualities of the various places form quite another subject of consideration. For the present it must wait; except with the remark that a Lancashire manufacturing town, however humble, is seldom without a lyceum, or some similar institution; and if wealthy, is prone to emulate cities. Witness the beautiful Art Exhibition held not long ago at Darwen!

WARRINGTON

The industrial history of the important Lancashire cotton towns, although their modern development covers less than ninety years, dates from the beginning of the fourteenth century. As early as a.d. 1311, temp. Edward II., friezes were manufactured at Colne, but, as elsewhere in the country, they would seem to have been coarse and of little value. "The English at that time," says quaint old Fuller, "knew no more what to do with their wool than the sheep that weare it, as to any artificial curious drapery." The great bulk of the native produce of wool was transmitted to Flanders and the Rhenish provinces, where it was woven, England repurchasing the cloth. Edward III., allowing himself to be guided by the far-reaching sagacity of his wise queen, Philippa, resolved that the manufacture should be kept at home. Parties of the Flemish weavers were easily induced to come over, the more so because wretchedly treated in their own country. Manchester, Bolton, Rochdale, and Warrington, were tenanted almost immediately, and a new character was at once given to the textile productions both of the district and the island in general. Furness Abbey was then in its glory; its fertile pastures supplied the wants of these industrious people: they seem, however, not to have cared to push[Pg 78] their establishments so far, keeping in the south and east of the county, over which they gradually spread, carrying, wherever they went, the "merry music of the loom." The same period witnessed the original use of coal—again, it is believed, through the advice of Philippa; the two great sources of Lancashire prosperity being thus in their rise contemporaneous. The numerous little rivers and waterfalls of East Lancashire contributed to the success of the new adventurers. Fulling-mills and dye-works were erected upon the margins: the particular spots are now only conjectural; mementoes of these ancient works are nevertheless preserved in the springing up occasionally, to the present day, on the lower Lancashire river-banks, of plants botanically alien to the neighbourhood. These are specially the fullers' teasel, Dipsacus fullonum, and the dyers' weed, Reseda luteola, both of which were regularly used, the refuse, with seeds, cast into the stream being carried many miles down and deposited where the plants now renew themselves. The retention of their vitality by seeds properly ripened, when buried too deep for the operation of the atmosphere, sunshine, and moisture, all at once, is well known to naturalists, as well as their germination when brought near enough to the surface of the[Pg 79] ground. This ancient woollen manufacture endured for quite 300 years. Cotton then became a competitor, and gradually superseded it; Rochdale and a few other places alone vindicating the old traditions.