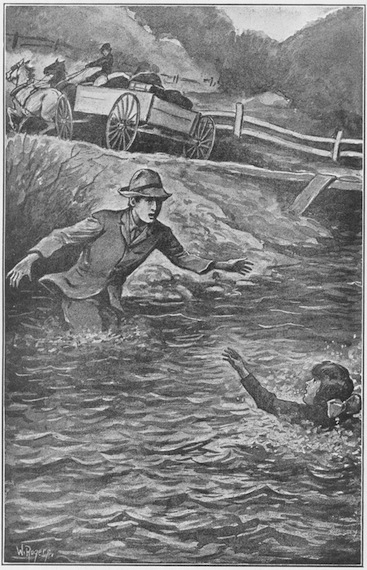

LUCAS TORE DOWN THE BANK AND WADED

RIGHT INTO THE STREAM. Frontispiece (Page 61.)

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Girls of Hillcrest Farm

The Secret of the Rocks

Author: Amy Bell Marlowe

Release Date: May 16, 2010 [eBook #32401]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GIRLS OF HILLCREST FARM***

THE GIRLS OF

HILLCREST FARM

OR

THE SECRET OF THE ROCKS

BY

AMY BELL MARLOWE

AUTHOR OF

THE OLDEST OF FOUR, A LITTLE MISS NOBODY,

THE GIRL FROM SUNSET RANCH, ETC.

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1914, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

The Girls of Hillcrest Farm

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Everything at Once! | 1 |

| II. | Aunt Jane Proposes | 10 |

| III. | The Doctor Disposes | 24 |

| IV. | The Pilgrimage | 37 |

| V. | Lucas Pritchett | 51 |

| VI. | Neighbors | 61 |

| VII. | Hillcrest | 73 |

| VIII. | The Whisper in the Dark | 85 |

| IX. | Morning at Hillcrest | 96 |

| X. | The Venture | 109 |

| XI. | At the Schoolhouse | 126 |

| XII. | The Green-Eyed Monster | 134 |

| XIII. | Lyddy Doesn’t Want It | 144 |

| XIV. | The Colesworths | 161 |

| XV. | Another Boarder | 171 |

| XVI. | The Ball Keeps Rolling | 184 |

| XVII. | The Runaway Grandmother | 192 |

| XVIII. | The Queer Boarder | 199 |

| XIX. | Widow Harrison’s Troubles | 208 |

| XX. | The Temperance Club Again | 216 |

| XXI. | Caught | 224 |

| XXII. | The Hidden Treasure | 236 |

| XXIII. | The Vendue | 248 |

| XXIV. | Professor Spink’s Bottles | 258 |

| XXV. | In the Old Doctor’s Office | 269 |

| XXVI. | A Blow-up | 276 |

| XXVII. | They Lose a Boarder | 283 |

| XXVIII. | The Secret Revealed | 289 |

| XXIX. | An Automobile Race | 298 |

| XXX. | The Hillcrest Company, Limited | 303 |

Whenever she heard the siren of the ladder-truck, as it swung out of its station on the neighboring street, Lydia Bray ran to the single window of the flat that looked out on Trimble Avenue.

They were four flights up. There were twenty-three other families in this “double-decker.” A fire in the house was the oldest Bray girl’s nightmare by night and haunting spectre by day.

Lydia just couldn’t get used to these quarters, and they had been here now three months. The old, quiet home on the edge of town had been so different. To it she had returned from college so short a time ago to see her mother die and find their affairs in a state of chaos.

2For her father was one of those men who leave everything to the capable management of their wives. Euphemia, or “’Phemie,” was only a schoolgirl, then, in her junior year at high school; “Lyddy” was a sophomore at Littleburg when her mother died, and she had never gone back.

She couldn’t. There were two very good reasons why her own and even ’Phemie’s education had to cease abruptly. Their mother’s income, derived from their grandmother’s estate, ceased with her death. They could not live, let alone pursue education “on the heights,” upon Mr. Bray’s wages as overseer in one of the rooms of the hat factory.

“Mother’s hundred dollars a month was just the difference between poverty and comfort,” Lyddy had decided, when she took the strings of the household into her own hands.

“I haven’t that hundred dollars a month; father makes but fifteen dollars weekly; you will have to go to work at something, ’Phemie, and so will I.”

And no longer could they pay twenty-five dollars a month house rent. Lyddy had first placed her sister with a millinery firm at six dollars weekly, and had then found this modest tenement about half-way between her father’s factory and 3 ’Phemie’s millinery shop, so that it would be equally handy for both workers.

As for herself, Lyddy wished to obtain some employment that would occupy only a part of her day, and in this she had been unsuccessful as yet. She religiously bought a paper every morning, and went through the “help wanted” columns, answering every one that looked promising. She had tried many kinds of “work at home for ladies,” and canvassing, and the like. The latter did not pay for shoe-leather, and the “work at home” people were mostly swindlers. Lyddy was no needle-woman, so she could not make anything as a seamstress.

She had promised her mother to keep the family together and make a home for her father. Mr. Bray was not well. For almost two years now the doctor had been warning him to get out of the factory and into some other business. The felt-dust was hurting him.

He had come in but the minute before and had at once gone to lie down, exhausted by his climb up the four flights of stairs. ’Phemie had not yet returned from work, for it was nearing Easter, despite the rawness of the days, and the millinery shop was busy until late. They always waited supper for ’Phemie.

Now, when Lyddy ran to the window at the 4 raucous shriek of the ladder-truck siren, she hoped she would see her sister turning the corner into the avenue, where the electric arc-light threw a great circle of radiance upon the wet walk.

But although there was the usual crowd at the corner, and all seemed to be in a hurry to-night, Lyddy saw nothing of either her sister or the ladder-truck. She went back to the kitchen, satisfied that the fire apparatus had not swung into their street, so the tenement must be safe for the time being.

She finished laying the table for supper. Once she looked up. There was that man at the window again!

That is, he would be a man some day, Lyddy told herself. But she believed, big as he was, he was just a hobbledehoy-boy. He was a boy who, if one looked at him, just had to smile. And he was always working in a white apron and brown straw cuff-shields at that window which was a little above the level of Lyddy’s kitchen window.

Lyddy Bray abominated flirting and such silly practises. And although the boy at the window was really good to look upon–cleanly shaven, rosy-cheeked, with good eyes set wide apart, and a firm, broad chin–Lyddy did not like to see him every time she raised her eyes from her own kitchen tasks.

5Often, even on dark days, she drew the shade down so that she should have more privacy. For sometimes the young man looked idly out of the window and Lyddy believed that, had she given him any encouragement, he would have opened his own window and spoken to her.

The place in which he worked was a tall loft building; she believed he was employed in some sort of chemical laboratory. There were retorts, and strange glass and copper instruments in partial view upon his bench.

Now, having lighted the gas, Lyddy stepped to the window to pull down the shade closely and shut the young man out. He was staring with strange eagerness at her–or, at least, in her direction.

“Master Impudence!” murmured Lyddy.

He flung up his window just as she reached for the shade. But she saw then that he was looking above her story.

“It’s those Smith girls, I declare,” thought Lyddy. “Aren’t they bold creatures? And–really–I thought he was too nice a boy―”

That was the girl of it! She was shocked at the thought of having any clandestine acquaintance with the young man opposite; yet it cheapened him dreadfully in Lyddy’s eyes to see him fall prey to the designing girls in the flat above. 6 The Smith girls had flaunted their cheap finery in the faces of Lyddy and ’Phemie Bray ever since the latter had come here to live.

She did not pull the shade down for a moment. That boy certainly was acting in a most outrageous manner!

His body was thrust half-way out of the window as he knelt on his bench among the retorts. She saw several of the delicate glass instruments overturned by his vigorous motions. She saw his lips open and he seemed to be shouting something to those in the window above.

“How rude of him,” thought the disappointed Lyddy. He had looked to be such a nice young man.

Again she would have pulled down the shade, but the boy’s actions stayed her hand.

He leaped back from the window and disappeared–for just a moment. Then he staggered into view, thrust a long and wide plank through his open window, and, bearing down upon it, shoved hard and fast, thrusting the novel bridge up to the sill of the window above Lyddy’s own.

“What under the sun does that fellow mean to do?” gasped the girl, half tempted to raise her own window so as to look up the narrow shaft between the two buildings.

7“He never would attempt to cross over to their flat,” thought Lyddy. “That would be quite too–ri–dic–u–lous―”

The youth was adjusting the plank. At first he could not steady it upon the sill above Lyddy’s kitchen window. And how dangerous it would be if he attempted to “walk the plank.”

And then there was a roaring sound above, a glare of light, a crash of glass and a billow of black smoke suddenly–but only for a moment–filled the space between the two buildings!

The girl almost fell to the floor. She had always been afraid of fire, and it had been ever in her mind since they moved into this big tenement house. And now it had come without her knowing it!

While she thought the young man to be trying to enter into a flirtation with the girls in the flat above, the house was afire! No wonder so many people had seemed running at the corner when she looked out of the front window. The ladder-truck had swung around into the avenue without her seeing it. Doubtless the street in front of the tenement was choked with fire-fighting apparatus.

“Oh, dear me!” gasped Lyddy, reeling for the moment.

8Then she dashed for the bedroom where her father lay. Smoke was sifting in from the hall through the cracks about the ill-hung door.

“Father! Father!” she gasped.

He lay on the bed, as still as though sleeping. But the noise above should have aroused him by this time, had her own shrill cry not done so.

Yet he did not move.

Lyddy leaped to the bedside, seizing her father’s shoulder with desperate clutch. She shook his frail body, and the head wagged from side to side on the pillow in so horrible a way–so lifeless and helpless–that she was smitten with terror.

Was he dead? He had never been like this before, she was positive.

She tore open his waistcoat and shirt and placed her hand upon his heart. It was beating–but, oh, how feebly!

And then she heard the flat door opened with a key–’Phemie’s key. Her sister cried:

“Dear me, Lyddy! the hall is full of smoke. It isn’t your stove that’s smoking so, I hope? And here’s Aunt Jane Hammond come to see us. I met her on the street, and these four flights of stairs have almost killed her―Why! what’s happened, Lyddy?” the younger girl broke off 9 to ask, as her sister’s pale face appeared at the bedroom door.

“Everything–everything’s happened at once, I guess,” replied Lyddy, faintly. “Father’s sick–we’ve got company–and the house is afire!”

Aunt Jane Hammond stalked into the meagerly furnished parlor, and looked around. It was the first time she had been to see the Bray girls since their “come down” in the world.

She was a tall, gaunt woman–their mother’s half-sister, and much older than Mrs. Bray would have been had she lived. Aunt Jane, indeed, had been married herself when her father, Dr. “Polly” Phelps, had married his second wife.

“I must–say I–expected to–see some–angels sit–ting a–round–when I got up here,” panted Aunt Jane, grimly, and dropping into the most comfortable chair. “Couldn’t you have got a mite nearer heaven, if you’d tried, Lyddy Bray?”

“Ye-es,” gasped Lyddy. “There’s another story on top of this; but it’s afire just now.”

“What?” shrieked Aunt Jane.

“Do you really mean it, Lyddy?” cried her sister. “And that’s what the smoke means?”

“Well,” declared their aunt, “them firemen 11 will have to carry me out, then. I couldn’t walk downstairs again right now, for no money!”

’Phemie ran to the hall door. But when she opened it a great blast of choking smoke drove in.

“Oh, oh!” she cried. “We can’t escape by the stairway. What’ll we do? What shall we do?”

“There’s the fire-escape,” said Lyddy, trembling so that she could scarcely stand.

“What?” cried Aunt Jane again. “Me go down one o’ them dinky little ladders–and me with a hole as big as a half-dollar in the back of my stockin’? I never knowed it till I got started from home; the seam just gave.”

“I’d look nice going down that ladder. I guess not, says Con!” and she shook her head so vigorously that all the little jet trimmings upon her bonnet danced and sparkled in the gaslight just as her beadlike, black eyes snapped and danced.

“We–we’re in danger, Lyddy!” cried ’Phemie, tremulously.

“Oh, the boy!” exclaimed Lyddy, and flew to the kitchen, just in time to see the Smith family sliding down the plank into the laboratory–the two girls ahead, then Mother Smith, then Johnny Smith, and then the father. And all 12 while the boy next door held the plank firmly in place against the window-sill of the burning flat.

Lyddy threw up the window and screamed something to him as the last Smith passed him and disappeared. She couldn’t have told what she said, for the very life of her; but the young man across the shaft knew what she meant.

He drew back the plank a little way, swung his weight upon the far end of it, and then let it drop until it was just above the level of her sill.

“Grab it and pull, Miss!” he called across the intervening space.

Lyddy obeyed. There was great confusion in the hall now, and overhead the fire roared loudly. The firemen were evidently pressing up the congested stairway with a line or two of hose, and driving the frightened people back into their tenements. If the fire was confined to the upper floor of the double-decker there would be really little danger to those below.

But Lyddy was too frightened to realize this last fact. She planted the end of the plank upon her own sill and saw that it was secure. But it sloped upward more than a trifle. How would they ever be able to creep up that inclined plane–and four flights from the bottom of the shaft?

But to her consternation, the young fellow 13 across the way deliberately stepped out upon the plank, sat down, and slid swiftly across to her. Lyddy sprang back with a cry, and he came in at the window and stood before her.

“I don’t believe you’re in any danger, Miss,” he said. “The firemen are on the roof, and probably up through the halls, too. The fire has burned a vent through the roof and―Yes! hear the water?”

She could plainly hear the swish of the streams from the hosepipes. Then the water thundered on the floor above their heads. Almost at once small streams began to pour through the ceiling.

“Oh, oh!” cried Lyddy. “Right on the supper table!”

A stream fell hissing on the stove. The big boy drew her swiftly out of the room into her father’s bedroom.

“That ceiling will come down,” he said, hastily. “I’m sorry–but if you’re insured you’ll be all right.”

Lyddy at that moment remembered that she had never taken out insurance on the poor sticks of furniture left from the wreck of their larger home. Yet, if everything was spoiled―

“What’s the matter with him?” asked the young fellow, looking at the bed where Mr. Bray lay. He had wonderfully sharp eyes, it seemed.

14“I don’t know–I don’t know,” moaned Lyddy. “Do you think it is the smoke? He has been ill a long time–almost too sick to work―”

“Your father?”

“Yes, sir,” said the girl.

“I’ll get an ambulance, if you say so–and a doctor. Are you afraid to stay here now? Are you all alone but for him?”

“My sister–and my aunt,” gasped Lyddy. “They’re in the front room.”

“Keep ’em there,” said the young man. “Maybe they won’t pour so much water into those front rooms. Look out for the ceilings. You might be hurt if they came down.”

He found the key and unlocked and opened the door from the bedroom to the hall. The smoke cloud was much thinner. But a torrent of water was pouring down the stairs, and the shouting and stamping of the firemen above were louder.

Two black, serpent-like lines of hose encumbered the stairs.

“Take care of yourself,” called the young man. “I’ll be back in a jiffy with the doctor,” and, bareheaded, and in shirt-sleeves as he was, he dashed down the dark and smoky stairway.

Lyddy bent over her father again; he was 15 breathing more peacefully, it seemed. But when she spoke to him he did not answer.

’Phemie ran in, crying. “What is the matter with father?” she demanded, as she noted his strange silence. Then, without waiting for an answer, she snapped:

“And Aunt Jane’s got her head out of the window scolding at the firemen in the street because they do not come up and carry her downstairs again.”

“Oh, the fire’s nearly out, I guess,” groaned Lyddy.

Then the girls clutched each other and were stricken speechless as a great crash sounded from the kitchen. As the young man from the laboratory had prophesied, the ceiling had fallen.

“And I had the nicest biscuits for supper I ever made,” moaned Lyddy. “They were just as fluffy―”

“Oh, bother your biscuits!” snapped ’Phemie. “Have you had the doctor for father?”

“I–I’ve sent for one,” replied Lyddy, faintly, suddenly conscience-stricken by the fact that she had accepted the assistance of the young stranger, to whom she had never been introduced! “Oh, dear! I hope he comes soon.”

“How long has he been this way, Lyd? Why didn’t you send for me?” demanded the younger 16 sister, clasping her hands and leaning over the unconscious man.

“Why, he came home from work just as usual. I–I didn’t notice that he was worse,” replied the older girl, breathlessly. “He said he’d lie down―”

“You should have called the doctor then.”

“Why, dear, I tell you he seemed just the same. He almost always lies down when he comes home now. You know that.”

“Forgive me, Lyddy!” exclaimed ’Phemie, contritely. “Of course you are just as careful of father as you can be. But–but it’s so awful to see him lie like this.”

“He fainted without my knowing a thing about it,” moaned Lyddy.

“Oh! if it’s only just a faint―”

“He couldn’t even have heard the noise upstairs over the fire.”

Just then a stream of water descended through the cracked bedroom ceiling, first upon the back of ’Phemie’s neck, and then upon the drugget which covered the floor.

“Suppose this ceiling falls, too?” wailed Lyddy, wringing her hands.

“I hope not! And we’ll have to pay the doctor when he comes, Lyd. Have you got money enough in your purse?”

“I’ll not have any more after this week,” broke out ’Phemie, suddenly. “They told me to-day the rush for Easter would be over Saturday night and they would have to let me go till next season. Isn’t that mean?”

Lydia Bray had sat down upon the edge of their father’s bed.

“I guess everything has happened at once,” she sighed. “I don’t see what we shall do, ’Phemie.”

There came a scream from Aunt Jane. She charged into the bedroom wildly, the back of her dress all wet and her bonnet dangling over one ear.

“Why, your parlor ceiling is just spouting water, girls!” she cried.

Then she turned to look closely at the man on the bed. “John Bray looks awful bad, Lyddy. What does the doctor say?”

Before her niece could reply there came a thundering knock at the hall door.

“The doctor!” cried ’Phemie.

Lyddy feared it was the young stranger returning, and she could only gasp. What should she say to him if he came in? How introduce him to Aunt Jane?

But the latter lady took affairs into her own 18 hands at this juncture and went to the door. She unlocked and threw it open. Several helmets and glistening rubber coats appeared vaguely in the hall.

“Getting wet down here some; aren’t you?” asked one of the firemen. “We’ll spread some tarpaulins over your stuff. Fire’s out–about.”

“And the water’s in,” returned Aunt Jane, tartly. “Nice time to come and try to save a body’s furniture―”

“Get it out of the adjusters. They’ll be around,” said the fireman, with a grin.

“How much insurance have you, Lyddy?” demanded the aunt, when the firemen, after covering the already wet and bedraggled furniture, had clumped out in their heavy boots.

“Not a penny, Aunt Jane!” cried her niece, wildly. “I never thought of it!”

“Ha! you’re not so much like your mother, then, as I thought. She would never have overlooked such a detail.”

“I know it! I know it!” moaned Lyddy.

“Now, you stop that, Aunt Jane!” exclaimed the bolder ’Phemie. “Don’t you hound Lyd. She’s done fine–of course she has! But anybody might forget a thing like insurance.”

“Humph!” grunted the old lady. Then she began again:

19“And what’s the matter with John?”

“It’s the shop, Aunt,” replied Lyddy. “He cannot stand the work any longer. I wish he might never go back to that place again.”

“And how are you going to live? What’s ’Phemie getting a week?”

“Nothing–after this week,” returned the younger girl, shortly. “I sha’n’t have any work, and I’ve only been earning six dollars.”

“Humph!” observed Aunt Jane for a second time.

There came a light tap on the door. They could hear it, for the confusion and shouting in the house had abated. The fire scare was over; but the floor above was gutted, and a good deal of damage by water had been done on this floor.

It was a physician, bag in hand. ’Phemie let him in. Lyddy explained how her father had come home and lain down and she had found him, when the fire scare began, unconscious on the bed–just as he lay now.

A few questions explained to the physician the condition of Mr. Bray, and his own observation revealed the condition of the tenement.

“He will be better off at the hospital. You are about wrecked here, I see. That young man who called me said he would ring up the City Hospital.”

20The girls were greatly troubled; but Aunt Jane was practical.

“Of course, that’s the best place for him,” she said. “Why! this flat isn’t fit for a well person to stay in, let alone a sick man, until it is cleared up. I shall take you girls out with me to my boarding house for the night. Then–we’ll see.”

The physician brought Mr. Bray to his senses; but the poor man knew nothing about the fire, and was too weak to object when they told him he was to be removed to the hospital for a time.

The ambulance came and the young interne and the driver brought in the stretcher, covered Mr. Bray with a gray blanket, and took him away. The interne told the girls they could see their father in the morning and he, too, said it was mainly exhaustion that had brought about the sudden attack.

Aunt Jane had been stalking about the sloppy flat–from the ruined kitchen to the front window.

“Shut and lock that kitchen window, and lock the doors, and we’ll go out and find a lodging,” she said, briefly. “You girls can bring a bag for the night. Mine’s at the station hard by; I’m glad I didn’t bring it up here.”

It was when Lyddy shut and locked the kitchen window that she remembered the young man 21 again. The plank had been removed, the laboratory window was closed, and the place unlighted.

“I guess he has some of the instincts of a gentleman, after all,” she told herself. “He didn’t come back to bother me after doing what he could to help.”

Two hours later the Bray girls were seated in their aunt’s comfortable room at a boarding house on a much better block than the one on which the tenement stood. Aunt Jane had ordered up tea and toast, and was sipping the one and nibbling the other contentedly before a grate fire.

“This is what I call comfort,” declared the old lady, who still kept her bonnet on–nor would she remove it save to change it for a nightcap when she went to bed.

“This is what I call comfort. A pleasant room in a house where I have no responsibilities, and enough noise outside to assure me that I am in a live town. My goodness me! when Hammond came along and wanted to marry me, and I knew I could leave Hillcrest and never have to go back―Well, I just about jumped down that man’s throat I was so eager to say ‘Yes!’ Marry him? I’d ha’ married a Choctaw Injun, if he’d promised to take me to the city.”

“Why, Aunt Jane!” exclaimed Lyddy. 22 “Hillcrest Farm is a beautiful place. Mother took us there once to see it. Don’t you remember, ’Phemie? She loved it, too.”

“And I wish she’d had it as a gift from the old doctor,” grumbled Aunt Jane. “But it wasn’t to be. It’s never been anything but a nuisance to me, if I was born there.”

“Why, the view from the porch is the loveliest I ever saw,” said Lyddy.

“And all that romantic pile of rocks at the back of the farm!” exclaimed ’Phemie.

“Ha! what’s a view?” demanded the old lady, in her brusk way. “Just dirt and water. And that’s what they say we’re made of. I like to study human bein’s, I do; so I’d ruther have my view in town.”

“But it’s so pretty―”

“Fudge!” snapped Aunt Jane. “I’ve seen the time, when I was a growin’ gal, and the old doctor was off to see patients, that I’ve stood on that same porch at Hillcrest and just cried for the sight of somethin’ movin’ on the face of Natur’ besides a cow.

“View, indeed!” she pursued, hotly. “If I’ve got to look at views, I want plenty of ‘life’ in ’em; and I want the human figgers to be right up close in the foreground, too!”

’Phemie laughed. “And I think it would be 23 just blessed to get out of this noisy, dirty city, and live in a place like Hillcrest. Wouldn’t you like it, Lyd?”

“I’d love it!” declared her sister.

“Well, I declare!” exclaimed Aunt Jane, sitting bolt upright, and looking actually startled. “Ain’t that a way out, mebbe?”

“What do you mean, Aunt Jane?” asked Lydia, quickly.

“You know how I’m fixed, girls. Hammond left me just money enough so’t I can live as I like to live–and no more. The farm’s never been aught but an expense to me. Cyrus Pritchett is supposed to farm a part of it on shares; but my share of the crops never pays more’n the taxes and the repairs to the roofs of the old buildings.

“It’d be a shelter to ye. The furniture stands jest as it did in the old doctor’s day. Ye could move right in–and I expect it would mean a lease of life to your father.

“A second-hand man wouldn’t give ye ten dollars for your stuff in that flat. It’s ruined. Ye couldn’t live comfortable there any more. But if ye wanter go to Hillcrest I’m sure ye air more than welcome to the use of the place, and perhaps ye might git a bigger share of the crops out of Cyrus if ye was there, than I’ve been able to git.

“What d’you say, girls–what d’you say?”

The Bray girls scarcely slept a wink that night. Not alone were they excited by the incidents of the evening, and the sudden illness of their father; but the possibilities arising out of Aunt Jane Hammond’s suggestion fired the imagination of both Lyddy and ’Phemie.

These sisters were eminently practical girls, and they came of practical stock–as note the old-fashioned names which their unromantic parents had put upon them in their helpless infancy.

Yet there is a dignity to “Lydia” and a beauty to “Euphemia” which the thoughtless may not at once appreciate.

Practical as they were, the thought of going to the old farmhouse to live–if their father could be moved to it at once–added a zest to their present situation which almost made their misfortune seem a blessing.

Their furniture was spoiled, as Aunt Jane had said. And father was sick–a self-evident fact. This sudden ill turn which Mr. Bray had suffered 25 worried both of his daughters more than any other trouble–indeed, more than all the others in combination.

Their home was ruined–but, somehow, they would manage to find a shelter. ’Phemie would have no more work in her present position after this week, and Lyddy had secured no work at all; but fortune must smile upon their efforts and bring them work in time.

These obstacles seemed small indeed beside the awful thought of their father’s illness. How very, very weak and ill he had looked when he was carried out of the flat on that stretcher! The girls clung together in their bed in the lodging house, and whispered about it, far into the night.

“Suppose he never comes out of that hospital?” suggested ’Phemie, in a trembling voice.

“Oh, ’Phemie! don’t!” begged her sister. “He can’t be so ill as all that. It’s just a breakdown, as that doctor said. He has overworked. He–he mustn’t ever go back to that hat shop again.”

“I know,” breathed ’Phemie; “but what will he do?”

“It isn’t up to him to do anything–it’s up to us,” declared Lyddy, with some measure of her confidence returning. “Why, look at us! Two 26 big, healthy girls, with four capable hands and the average amount of brains.

“I know, as city workers, we are arrant failures,” she continued, in a whisper, for their room was right next to Aunt Jane’s, and the partition was thin.

“Do you suppose we could do better in the country?” asked ’Phemie, slowly.

“And if I am not mistaken the house is full of old, fine furniture,” observed Lyddy.

“Well!” sighed the younger sister, “we’d be sheltered, anyway. But how about eating? Lyddy! I have such an appetite.”

“She says we can have her share of the crops if we will pay the taxes and make the necessary repairs.”

“Crops! what do you suppose is growing in those fields at this time of the year?”

“Nothing much. But if we could get out there early we might have a garden and see to it that Mr. Pritchett planted a proper crop. And we could have chickens–I’d love that,” said Lyddy.

“Oh, goodness, gracious me! Wouldn’t we all love it–father, too? But how can we even get out there, much more live till vegetables and chickens are ripe, on nothing a week?”

“That–is–what–I–don’t–see–yet,” admitted Lyddy, slowly.

27“It’s very kind of Aunt Jane,” complained ’Phemie. “But it’s just like opening the door of Heaven to a person who has no wings! We can’t even reach Hillcrest.”

“You and I could,” said her sister, vigorously.

“How, please?”

“We could walk.”

“Why, Lyd! It’s fifty miles if it’s a step!”

“It’s nearer seventy. Takes two hours on the train to the nearest station; and then you ride up the mountain a long, long way. But we could walk it.”

“And be tramps–regular tramps,” cried ’Phemie.

“Well, I’d rather be a tramp than a pauper,” declared the older sister, vigorously.

“But poor father!”

“That’s just it,” agreed Lydia. “Of course, we can do nothing of the kind. We cannot leave him while he is sick, nor can we take him out there to Hillcrest if he gets on his feet again―”

“Oh, Lyddy! don’t talk that way. He is going to be all right after a few days’ rest.”

“I do not think he will ever be well if he goes back to work in that hat factory. If we could only get him to Hillcrest.”

“And there we’d all starve to death in a hurry,” 28 grumbled ’Phemie, punching the hard, little boarding-house pillow. “Oh, dear! what’s the use of talking? There is no way out!”

“There’s always a way out–if we think hard enough,” returned her sister.

“Wish you’d promulgate one,” sniffed ’Phemie.

“I am going to think–and you do the same.”

“I’m going to―”

“Snore!” finished ’Phemie. That ended the discussion for the time being. But Lydia lay awake and racked her tired brain for hours.

The pale light of the raw March morning streaked the window-pane when Lydia was awakened by her sister hurrying into her clothes for the day’s work at the millinery store. There would be but two days more for her there.

And then?

It was a serious problem. Lydia had perhaps ten dollars in her reserve fund. Father might not be paid for his full week if he did not go back to the shop. His firm was not generous, despite the fact that Mr. Bray had worked so long for them. A man past forty, who is frequently sick a day or two at a time, soon wears out the patience of employers, especially when there is young blood in the firm.

’Phemie would get her week’s pay Saturday night. Altogether, Lyddy might find thirty dollars 29 in her hand with which to face the future for all three of them!

What could she get for their soaked furniture? These thoughts were with her while she was dressing.

’Phemie had hurried away after making her sister promise to telephone as to her father’s condition the minute they allowed Lyddy to see him at the hospital. Aunt Jane was a luxurious lie-abed, and had ordered tea and toast for nine o’clock. Her oldest niece put on her shabby hat and coat and went out to the nearest lunch-room, where coffee and rolls were her breakfast.

Then she walked down to Trimble Avenue and approached the huge, double-decker where they had lived. Salvage men were already carrying away the charred fragments of the furniture from the top floor. Lyddy hoped that, unlike herself, the Smiths and the others up there had been insured against fire.

She plodded wearily up the four flights and unlocked one of the flat doors and entered. Two of the salvage men followed her in and removed the tarpaulins–which had been worse than useless.

“No harm done but a little water, Miss,” said one of them, consolingly. “But you talk up to the adjuster and he’ll make it all right.”

30They all thought, of course, that the Brays’ furniture was insured. Lyddy closed the door and looked over the wrecked flat.

The parlor furniture coverings were all stained, and the carpet’s colors had “run” fearfully. Many of their little keepsakes and “gim-cracks” had been broken when the tarpaulins were spread.

The bedrooms were in better shape, although the bedding was somewhat wet. But the kitchen was ruined.

“Of course,” thought Lyddy, “there wasn’t much to ruin. Everything was cheap enough. But what a mess to clean up!”

She looked out of the window across the air-shaft. There was the boy!

He nodded and beckoned to her. He had his own window open. Lydia considered that she had no business to talk with this young man; yet he had played the “friend in need” the evening before.

“How’s your father?” he called, the moment she opened her window.

“I do not know yet. They told me not to come to the hospital until nine-thirty.”

“I guess you’re in a mess over there–eh?” he said, with his most boyish smile.

But Lyddy was not for idle converse. She 31 nodded, thanked him for his kindness the evening before, and firmly shut the window. She thought she knew how to keep that young man in his place.

But she hadn’t the heart to do anything toward tidying up the flat now. And how she wished she might not have to do it!

“If we could only take our clothing and the bedding and little things, and walk out,” she murmured, standing in the middle of the little parlor.

To try to “pick up the pieces” here was going to be dreadfully hard.

“I wish some fairy would come along and transport us all to Hillcrest Farm in the twinkling of an eye,” said Lyddy to herself. “I–I’d rather starve out there than live as we have for the past three months here.”

She went to the door of the flat just as somebody tapped gently on the panel. A poorly dressed Jewish man stood hesitating on the threshold.

“I’m sorry,” said Lyddy, hastily; “but we had trouble here last night–a fire. I can’t cook anything, and really haven’t a thing to give―”

Her mother had boasted that she had never turned away a beggar hungry from her door, and the oldest Bray girl always tried to feed the deserving. The man shook his head eagerly.

32“You ain’t de idee got, lady,” he said. “I know dere vas a fire. I foller de fires, lady.”

“You follow the fires?” returned Lyddy, in wonder.

“Yes, lady. Don’dt you vant to sell de house-holdt furnishings? I pay de highest mar-r-ket brice for ’em. Yes, lady–I pay cash.”

“Why–why―”

“You vas nodt insured–yes?”

“No,” admitted Lyddy.

“Den I bay you cash for de goots undt you go undt puy new–ain’dt idt?”

But Lyddy wasn’t thinking of buying new furniture–not at all. She opened the door wider.

“Come in and look,” she invited. “What will you pay?”

“Clodings, too?” he asked, shrewdly.

“No, no! We will keep the clothing, bedding and kitchenware, and the like. Just the furniture.”

The man went through the flat quickly, but his bright, beady eyes missed nothing. Finally he said:

“I gif you fifteen tollar, lady.”

“Oh, no! that is too little,” gasped Lyddy.

She had begun to figure mentally what it would cost to replace even the poor little things they had. And yet, if she could get any fair price 33 for the goods she was almost tempted to sell out.

“Lady! believe me, I make a goot offer,” declared the man. “But I must make it a profit–no?”

“I couldn’t sell for so little.”

“How much you vant, den?” he asked shrewdly.

“Oh! a great deal more than that. Ten dollars more, at least.”

“Twenty-fife tollars!” he cried, wringing his hands. “Belief me, lady, I shouldt be shtuck!”

His use of English would have amused Lyddy at another time; but the girl’s mind was set upon something more important. If she only could get enough money together to carry them all to Hillcrest Farm–and to keep them going for a while!

“Fifteen dollars would not do me much good, I am afraid,” the girl said.

“Oh, lady! you could buy a whole new house-furnishings mit so much money down–undt pay for de rest on de installment.”

“No,” replied Lyddy, firmly. “I want to get away from here altogether. I want to get out into the country. My father is sick; we had to send him to the hospital last night.”

The second-hand man shook his head. “You 34 vas a kindt-hearted lady,” he said, with less of his professional whine. “I gif you twenty.”

And above that sum Lyddy could not move him. But she would not decide then and there. She felt that she must see her father, and consult with ’Phemie, and possibly talk to Aunt Jane, too.

“You come here to-morrow morning and I’ll tell you,” she said, finally.

She locked the flat again and followed the man down the long flights to the street. It was not far to the hospital and Lyddy did not arrive there much before the visitors’ hour.

The house physician called her into his office before she went up to the ward in which her father had been placed. Already she was assured that he was comfortable, so the keenness of her anxiety was allayed.

“What are your circumstances, Miss Bray?” demanded the medical head of the hospital, bluntly. “I mean your financial circumstances?”

“We–we are poor, sir. And we were burned out last night, and have no insurance. I do not know what we really shall do–yet.”

“You are the house-mother–eh?” he demanded.

“I am the oldest. There are only Euphemia and me, beside poor papa―”

35“Well, it’s regarding your father I must speak. He’s in a bad way. We can do him little good here, save that he will rest and have nourishing food. But if he goes back to work again―”

“I know it’s bad for him!” cried Lyddy, with clasped hands. “But what can we do? He will crawl out to the shop as long as they will let him come―”

“He’ll not crawl out for a couple of weeks–I’ll see to that,” said the doctor, grimly. “He’ll stay here. But beyond that time I cannot promise. Our public wards are very crowded, and of course, you have no relatives, nor friends, able to furnish a private room―”

“Oh, no, sir!” gasped Lyddy.

“Nor is that the best for him. He ought to be out of the city altogether–country air and food–mountain air especially―”

“Hillcrest!” exclaimed Lyddy, aloud.

“What’s that?” the doctor snapped at her, quickly.

She told him about the farm–where it was, and all.

“That’s a good place for him,” replied the physician, coolly. “It’s three or four hundred feet higher above sea-level than the city. It will do him more good to live in that air than a ton 36 of medicine. And he can go in two weeks, or so. Good-morning, Miss Bray,” and the busy doctor hurried away to his multitude of duties, having disposed of Mr. Bray’s case on the instant.

Lydia Bray was shocked indeed when they allowed her in the ward to see her father. A nurse had drawn a screen about the bed, and nodded to her encouragingly.

The pallor of Mr. Bray’s countenance, as he lay there with his eyes closed, unaware of her presence, frightened the girl. She had never seen him utterly helpless before. He had managed to get around every day, even if sometimes he could not go to work.

But now the forces of his system seemed to have suddenly given out. He had overtaxed Nature, and she was paying him for it.

“Lyddy!” he whispered, when finally his heavy-lidded eyes opened and he saw her standing beside the cot.

The girl made a brave effort to look and speak cheerfully; and Mr. Bray’s comprehension was so dulled that she carried the matter off very successfully while she remained.

She spoke cheerfully; she chatted about their last night’s experiences; she even laughed over 38 some of Aunt Jane’s sayings–Aunt Jane was always a source of much amusement to Mr. Bray.

But the nurse had warned her to be brief, and soon she was beckoned away. She knew he was in good hands at the hospital, and that they would do all that they could for him. But what the house physician had told her was uppermost in her mind as she left the institution.

How were they to get to Hillcrest–and live after arriving there?

“If that man paid me twenty dollars for our furniture, I might have fifty dollars in hand,” she thought. “It will cost us something like two dollars each for our fares. And then there would be the freight and baggage, and transportation for ourselves up to Hillcrest from the station.

“And how would it do to bring father to an old, unheated house–and so early in the spring? I guess the doctor didn’t think about that.

“And how will we live until it is time for us to go–until father is well enough to be moved? All our little capital will be eaten up!”

Lyddy’s practical sense then came to her aid. Saturday night ’Phemie would get through at the millinery shop. They must not remain dependent upon Aunt Jane longer than over Sunday.

“The thing to do,” she decided, “is for ’Phemie and me to start for Hillcrest immediately–on 39 Monday morning at the latest. If one of us has to come back for father when he can be moved, all right. The cost will not be so great. Meanwhile we can be getting the old house into shape to receive him.”

She found Aunt Jane sitting before her fire, with a tray of tea and toast beside her, and her bonnet already set jauntily a-top of her head, the strings flowing.

“You found that flat in a mess, I’ll be bound!” observed Aunt Jane.

Lydia admitted it. She also told her what the second-hand man had offered.

“Twenty dollars?” cried Aunt Jane. “Take it, quick, before he has a change of heart!”

But when Lyddy told her of what the doctor at the hospital had said about Mr. Bray, and how they really seemed forced into taking up with the offer of Hillcrest, the old lady looked and spoke more seriously.

“You’re just as welcome to the use of the old house, and all you can make out of the farm-crop, as you can be. I stick to what I told you last night. But I dunno whether you can really be comfortable there.”

“We’ll find out; we’ll try it,” returned Lyddy, bravely. “Nothing like trying, Aunt Jane.”

“Humph! there’s a good many things better 40 than trying, sometimes. You’ve got to have sense in your trying. If it was me, I wouldn’t go to Hillcrest for any money you could name!

“But then,” she added, “I’m old and you are young. I wish I could sell the old place for a decent sum; but an abandoned farm on the top of a mountain, with the railroad station six miles away, ain’t the kind of property that sells easy in the real estate market, lemme tell you!

“Besides, there ain’t much of the two hundred acres that’s tillable. Them romantic-looking rocks that ’Phemie was exclaimin’ over last night, are jest a nuisance. Humph! the old doctor used to say there was money going to waste up there in them rocks, though. I remember hearing him talk about it once or twice; but jest what he meant I never knew.”

“Mineral deposits?” asked Lyddy, hopefully.

“Not wuth anything. Time an’ agin there’s been college professors and such, tappin’ the rocks all over the farm for ‘specimens.’ But there ain’t nothing in the line of precious min’rals in that heap of rocks at the back of Hillcrest Farm–believe me!

“Dr. Polly useter say, however, that there was curative waters there. He used ’em some in his practise towards the last. But he died suddent, you know, and nobody ever knew where he got 41 the water–’nless ’twas Jud Spink. And Jud had run away with a medicine show years before father died.

“Well!” sighed Aunt Jane. “If you can find any way of makin’ a livin’ out of Hillcrest Farm, you’re welcome to it. And–just as that hospital doctor says–it may do your father good to live there for a spell. But me–it always give me the fantods, it was that lonesome.”

It seemed, as Aunt Jane said, “a way opened.” Yet Lyddy Bray could not see very far ahead. As she told ’Phemie that night, they could get to the farm, bag and baggage; but how they would exist after their arrival was a question not so easy to answer.

Lyddy had gone to one of the big grocers and bought and paid for an order of staple groceries and canned goods which would be delivered at the railroad station nearest to Hillcrest on Monday morning. Thus all their possessions could be carted up to the farm at once.

She had spent the afternoon at the flat collecting the clothing, bedding, and other articles they proposed taking with them. These goods she had taken out by an expressman and shipped by freight before six o’clock.

In the morning she met the second-hand man at the ruined flat and he paid her the twenty dollars 42 as promised. And Lyddy was glad to shake the dust of the Trimble Avenue double-decker from her feet.

As she turned away from the door she heard a quick step behind her and an eager voice exclaimed:

“I say! I say! You’re not moving; are you?”

Lydia was exceedingly disturbed. She knew that boy in the laboratory window had been watching closely what was going on in the flat. And now he had dared follow her. She turned upon him a face of pronounced disapproval.

“I–I beg your pardon,” he stammered. “But I hope your father’s better? Nothing’s happened to–to him?”

“We are going to take him away from the city–thank you,” replied Lyddy, impersonally.

She noted with satisfaction that he had run out without his cap, and in his work-apron. He could not follow her far in such a rig through the public streets, that was sure.

“I–I’m awful sorry to have you go,” he said, stammeringly. “But I hope it will be beneficial to your father. I–I― You see, my own father is none too well and we have often talked of his living out of town somewhere–not so far but that I could run out for the week-end, you know.”

43Lyddy merely nodded. She would not encourage him by a single word.

“Well–I wish you all kinds of luck!” exclaimed the young fellow, finally, holding out his hand.

“Thank you,” returned the very proper Lyddy, and failed to see his proffered hand, turning promptly and walking away, not even vouchsafing him a backward look when she turned the corner, although she knew very well that he was still standing, watching her.

“He may be a very nice young man,” thought Lyddy; “but, then―”

Sunday the two girls spent a long hour with their father. They found him prepared for the move in prospect for the family–indeed, he was cheerful about it. The house physician had evidently taken time to speak to the invalid about the change he advised.

“Perhaps by fall I shall be my own self again, and we can come back to town and all go to work. We’ll worry along somehow in the country for one season, I am sure,” said Mr. Bray.

But that was what troubled Lyddy more than anything else. They were all so vague as to what they should do at Hillcrest–how they would be able to live there!

Father said something about when he used to 44 have a garden in their backyard, and how nice the fresh vegetables were; and how mother had once kept hens. But Lyddy could not see yet how they were to have either a garden or poultry.

They were all three enthusiastic–to each other. And the father was sure that in a fortnight he would be well enough to travel alone to Hillcrest; they must not worry about him. Aunt Jane was to remain in town all that time, and she promised to report frequently to the girls regarding their father’s condition.

“I certainly wish I could help you gals out with money,” said the old lady that evening. “You’re the only nieces I’ve got, and I feel as kindly towards you as towards anybody in this wide world.

“Maybe we can get a chance to sell the farm. If we can, I’ll help you then with a good, round sum. Now, then! you fix up the old place and make it look less like the Wrath o’ Fate had struck it and maybe some foolish rich man will come along and want to buy it. If you find a customer, I’ll pay you a right fat commission, girls.”

But this was “all in the offing;” the Bray girls were concerned mostly with their immediate adventures.

45To set forth on this pilgrimage to Hillcrest Farm–and alone–was an event fraught with many possibilities. Both Lyddy and ’Phemie possessed their share of imagination, despite their practical characters; and despite the older girl’s having gone to college for two years, she, or ’Phemie, knew little about the world at large.

So they looked forward to Monday morning as the Great Adventure.

It was a moist, sweet morning, even in the city, when they betook themselves early to the railway station, leaving Aunt Jane luxuriously sipping tea and nibbling toast in bed–this time with her nightcap on.

March had come in like a lion; but its lamblike qualities were now manifest and it really did seem as though the breath of spring permeated the atmosphere–even down here in the smoky, dirty city. The thought of growing things inspired ’Phemie to stop at a seed store near the station and squander a few pennies in sweet-peas.

“I know mother used to put them in just as soon as she could dig at all in the ground,” she told her sister.

“I don’t believe they’ll be a very profitable crop,” observed Lyddy.

“My goodness me!” exclaimed ’Phemie, 46 “let’s retain a little sentiment, Lyd! We can’t eat ’em–no; but they’re sweet and restful to look at. I’m going to have moon-flowers and morning-glories, too,” and she recklessly expended more pennies for those seeds.

Their train was waiting when they reached the station and the sisters boarded it in some excitement. ’Phemie’s gaiety increased the nearer they approached to Bridleburg, which was their goal. She was a plump, rosy girl, with broad, thick plaits of light-brown hair (“molasses-color” she called it in contempt) which she had begun to “do up” only upon going to work. She had a quick blue eye, a laughing mouth, rather wide, but fine; a nose that an enemy–had laughing, good-natured Euphemia Bray owned one–might have called “slightly snubbed,” and her figure was just coming into womanhood.

Lydia’s appearance was entirely different. They did not look much like sisters, to state the truth.

The older girl was tall, straight as a dart, with a dignity of carriage beyond her years, dark hair that waved very prettily and required little dressing, and a clear, colorless complexion. Her eyes were very dark gray, her nose high and well chiseled, like Aunt Jane’s. She was more of a 47 Phelps. Aunt Jane declared Lyddy resembled Dr. Apollo, or “Polly,” Phelps more than had either of his own children.

The train passed through a dun and sodden country. The late thaw and the rains had swept the snow from these lowlands; the unfilled fields were brown and bare.

Here and there, however, rye and wheat sprouted green and promising, and in the distance a hedge of water-maples along the river bank seemed standing in a purple mist, for their young leaves were already pushing into the light.

“There will be pussy-willows,” exclaimed ’Phemie, “and hepaticas in the woods. Think of that, Lyddy Bray!”

“And the house will be as damp as the tomb–and not a stick of wood cut–and no stoves,” returned the older girl.

“Oh, dear, me! you’re such an old grump!” ejaculated ’Phemie. “Why try to cross bridges before you come to them?”

“Lucky for you, Miss, that I do think ahead,” retorted Lyddy with some sharpness.

There was a grade before the train climbed into Bridleburg. Back of the straggling old town the mountain ridge sloped up, a green and brown wall, breaking the wind from the north and west, thus partially sheltering the town. 48 There was what farmers call “early land” about Bridleburg, and some trucking was carried on.

But the town itself was much behind the times–being one of those old-fashioned New England settlements left uncontaminated by the mill interests and not yet awakened by the summer visitor, so rife now in most of the quiet villages of the six Pilgrim States.

The rambling wooden structure with its long, unroofed platform, which served Bridleburg as a station, showed plainly what the railroad company thought of the town. Many villages of less population along the line boasted modern station buildings, grass plots, and hedges. All that surrounded Bridleburg’s barrack-like depôt was a plaza of bare, rolled cinders.

On this were drawn up the two ’buses from the rival hotels–the “New Brick Hotel,” built just after the Civil War, and the Eagle House. Their respective drivers called languidly for customers as the passengers disembarked from the train.

Most of these were traveling men, or townspeople. It was only mid-forenoon and Lyddy did not wish to spend either time or money at the local hostelries, so she shook her head firmly at the ’bus drivers.

“We want to get settled by night at Hillcrest–if 49 we can,” she told ’Phemie. “Let’s see if your baggage and freight are here, first of all.”

She waited until the station agent was at leisure and learned that all their goods–a small, one-horse load–had arrived.

“You two girls goin’ up to the old Polly Phelps house?” ejaculated the agent, who was a “native son” and knew all about the “old doctor,” as Dr. Apollo Phelps had been known throughout two counties and on both sides of the mountain ridge.

“Why, it ain’t fit for a stray cat to live in, I don’t believe–that house ain’t,” he added. “More’n twenty year since the old doctor died, and it’s been shut up ever since.

“What! you his grandchildren? Sho! Mis’ Bray–I remember. She was the old doctor’s daughter by his secon’ wife. Ya-as.

“Well, if I was you, I’d go to Pritchett’s house to stop first. Can’t be that the old house is fit to live in, an’ Pritchett is your nighest neighbor.”

“Thank you,” Lyddy said, quietly. “And can you tell me whom we could get to transport our goods–and ourselves–to the top of the ridge?”

“Huh? Why! I seen Pritchett’s long-laiged boy in town jest now–Lucas Pritchett. He ain’t got away yet,” responded the station agent.

50“I ventur’ to say you’ll find him up Market Street a piece–at Birch’s store, or the post-office. This train brung in the mail.

“If he’s goin’ up light he oughter be willin’ to help you out cheap. It’s a six-mile tug, you know; you wouldn’t wanter walk it.”

He pointed up the mountainside. Far, far toward the summit of the ridge, nestling in a background of brown and green, was a splash of vivid white.

“That’s Pritchett’s,” vouchsafed the station agent. “If Dr. Polly Phelps’ house had a coat of whitewash you could see it, too–jest to the right and above Pritchett’s. Highest house on the ridge, it is, and a mighty purty site, to my notion.”

The Bray girls walked up the village street, which opened directly out of the square. It might have been a quarter of a mile in length, the red brick courthouse facing them at the far end, flanked by the two hotels. When “court sat” Bridleburg was a livelier town than at present.

On either hand were alternately rows of one, or two-story “blocks” of stores and offices, or roomy old homesteads set in the midst of their own wide, terraced lawns.

There were a few pleasant-looking people on the walks and most of these turned again to look curiously after the Bray girls. Strangers–save in court week–were a novelty in Bridleburg, that was sure.

Market Street was wide and maple-shaded. Here and there before the stores were “hitching racks”–long wooden bars with iron rings set every few feet–to which a few horses, or teams, were hitched. Many of the vehicles were buckboards, much appreciated in the hill country; but there were farm wagons, as well. It was for 52 one of these latter the Bray girls were in search. The station agent had described Lucas Pritchett’s rig.

“There it is,” gasped the quick-eyed ’Phemie, “Oh, Lyd! do look at those ponies. They’re as ragged-looking as an old cowhide trunk.”

“And that wagon,” sighed Lyddy. “Shall we ride in it? We’ll be a sight going through the village.”

“We’d better wait and see if he’ll take us,” remarked ’Phemie. “But I should worry about what people here think of us!”

As she spoke a lanky fellow, with a lean and sallow face, lounged out of the post-office and across the walk to the heads of the disreputable-looking ponies. He wore a long snuff-colored overcoat that might have been in the family for two or three generations, and his overalls were stuck into the tops of leg-boots.

“That’s Lucas–sure,” whispered ’Phemie.

But she hung back, just the same, and let her sister do the talking. And the first effect of Lyddy’s speech upon Lucas Pritchett was most disconcerting.

“Good morning!” Lyddy said, smiling upon the lanky young farmer. “You are Mr. Lucas Pritchett, I presume?”

He made no audible reply, although his lips 53 moved and they saw his very prominent Adam’s apple rise and fall convulsively. A wave of red suddenly washed up over his face like a big breaker rolling up a sea-beach; and each individual freckle at once took on a vividness of aspect that was fairly startling to the beholder.

“You are Mr. Pritchett?” repeated Lyddy, hearing a sudden half-strangled giggle from ’Phemie, who was behind her.

“Ya-as–I be,” finally acknowledged the bashful Lucas, that Adam’s apple going up and down again like the slide on a trombone.

“You are going home without much of a load; aren’t you, Mr. Pritchett?” pursued Lyddy, with a glance into the empty wagon-body.

“Ya-as–I be,” repeated Lucas, with another gulp, trying to look at both girls at once and succeeding only in looking cross-eyed.

“We are going to be your nearest neighbors, Mr. Pritchett,” said Lyddy, briskly. “Our aunt, Mrs. Hammond, has loaned us Hillcrest to live in and we have our baggage and some other things at the railway station to be carted up to the house. Will you take it–and us? And how much will you charge?”

Lucas just gasped–’Phemie declared afterward, “like a dying fish.” This was altogether too much for Lucas to grasp at once; but he had followed 54 Lyddy up to a certain point. He held forth a broad, grimed, calloused palm, and faintly exclaimed:

“You’re Mis’ Hammon’s nieces? Do tell! Maw’ll be pleased to see ye–an’ so’ll Sairy.”

He shook hands solemnly with Lyddy and then with ’Phemie, who flashed him but a single glance from her laughing eyes. The “Italian sunset effect,” as ’Phemie dubbed Lucas’s blushes, began to fade out of his countenance.

“Can you take us home with you?” asked Lyddy, impatient to settle the matter.

“I surely can,” exclaimed Lucas. “You hop right in.”

“No. We want to know what you will charge first–for us and the things at the depôt?”

“Not a big load; air they?” queried Lucas, doubtfully. “You know the hill’s some steep.”

Lyddy enumerated the packages, Lucas checking them off with nods.

“I see,” he said. “We kin take ’em all. You hop in―”

But ’Phemie was pulling the skirt of her sister’s jacket and Lyddy said:

“No. We have some errands to do. We’ll meet you up the street. That is your way home?” and she indicated the far end of Market Street.

“And what will you charge us?”

“Not more’n a dollar, Miss,” he said, grinning. “I wouldn’t ax ye nothin’; but this is dad’s team and when I git a job like this he allus expects his halvings.”

“All right, Mr. Pritchett. We’ll pay you a dollar,” agreed Lyddy, in her sedate way. “And we’ll meet you up the street.”

Lucas unhitched the ponies and stepped into the wagon. When he turned them and gave them their heads the ragged little beasts showed that they were a good deal like the proverbial singed cat–far better than they looked.

“I thought you didn’t care what people thought of you here?” observed Lyddy to her sister, as the wagon went rattling down the street. “Yet it seems you don’t wish to ride through Bridleburg in Mr. Pritchett’s wagon.”

“My goodness!” gasped ’Phemie, breathless from giggling. “I don’t mind the wagon. But he’s a freak, Lyd!”

“Sh!”

“Did you ever see such a face? And those freckles!” went on the girl, heedless of her sister’s admonishing voice.

“Somebody may hear you,” urged Lyddy.

“What if?”

56“And repeat what you say to him.”

“And that should worry me!” returned ’Phemie, gaily. “Oh, dear, Lyd! don’t be a grump. This is all a great, big joke–the people and all. And Lucas is certainly the capsheaf. Did you ever in your life before even imagine such a freak?”

But Lyddy would not join in her hilarity.

“These country people may seem peculiar to us, who come fresh from the city,” she said, with some gravity. “But I wonder if we don’t appear quite as ‘queer’ and ‘green’ to them as they do to us?”

“We couldn’t,” gasped ’Phemie. “Hurry on, Lyd. Don’t let him overtake us before we get to the edge of town.”

They passed the courthouse and waited for Lucas and the farm wagon on the outskirts of the village–where the more detached houses gave place to open fields. No plow had been put into these lower fields as yet; still, the coming spring had breathed upon the landscape and already the banks by the wayside were turning green.

’Phemie became enthusiastic at once and before Lucas hove in view, evidently anxiously looking for them, the younger girl had gathered a great bunch of early flowers.

“They’re mighty purty,” commented the young 57 farmer, as the girls climbed over the wheel with their muddy boots and all.

’Phemie, giggling, took her seat on the other side of him. She had given one look at the awkwardly arranged load on the wagon-body and at once became helpless with suppressed laughter. If the girls she had worked with in the millinery store for the last few months could see them and their “lares and penates” perched upon this farm wagon, with this son of Jehu for a driver!

“I reckon you expect to stay a spell?” said Lucas, with a significant glance from the conglomerate load to Lyddy.

“Yes–we hope to,” replied the oldest Bray girl. “Do you think the house is in very bad shape inside?”

“I dunno. We never go in it, Miss,” responded Lucas, shaking his head. “Mis’ Hammon’ never left us the key–not to upstairs. Dad’s stored cider and vinegar in the cellar under the east ell for sev’ral years. It’s a better cellar’n we’ve got.

“An’ I dunno what dad’ll say,” he added, “to your goin’ up there to live.”

“What’s he got to do with it?” asked ’Phemie, quickly.

“Why, we work the farm on shares an’ we was calc’latin’ to do so this year.”

58“Our living in the house doesn’t interfere with that arrangement,” said Lyddy, quietly. “Aunt Jane told us all about that. I have a letter from her for your father.”

“Aw–well,” commented Lucas, slowly.

The ponies had begun to mount the rise in earnest now. They tugged eagerly at the load, and trotted on the level stretches as though tireless. Lyddy commented upon this, and Lucas flushed with delight at her praise.

“They’re hill-bred, they be,” he said, proudly. “Tackle ’em to a buggy, or a light cart, an’ up hill or down hill means the same to ’em. They won’t break their trot.

“When it comes plowin’ time we clip ’em, an’ then they don’t look so bad in harness,” confided the young fellow. “If–if you like, I’ll take you drivin’ over the hills some day–when the roads git settled.”

“Thank you,” responded Lyddy, non-committally.

But ’Phemie giggled “How nice!” and watched the red flow into the young fellow’s face with wicked appreciation.

The roads certainly had not “settled” after the winter frosts, if this one they were now climbing was a proper sample. ’Phemie and Lyddy held on with both hands to the smooth board which 59 served for a seat to the springless wagon–and they were being bumped about in a most exciting way.

’Phemie began to wonder if Lucas was not quite as much amused by their unfamiliarity with this method of transportation as she was by his bashfulness and awkward manners. Lyddy fairly wailed, at last:

“Wha–what a dread–dreadful ro-o-o-ad!” and she seized Lucas suddenly by the arm nearest to her and frankly held on, while the forward wheel on her side bounced into the air.

“Oh, this ain’t bad for a mountain road,” the young farmer declared, calmly.

“Oh, oh!” squealed ’Phemie, the wheel on her side suddenly sinking into a deep rut, so that she slid to the extreme end of the board.

“Better ketch holt on me, Miss,” advised Lucas, crooking the arm nearest ’Phemie. “You city folks ain’t useter this kind of travelin’, I can see.”

But ’Phemie refused, unwilling to be “beholden” to him, and the very next moment the ponies clattered over a culvert, through which the brown flood of a mountain stream spurted in such volume that the pool below the road was both deep and angry-looking.

There was a washout gullied in the road here. 60 Down went the wheel on ’Phemie’s side, and with the lurch the young girl lost her insecure hold upon the plank.

With a screech she toppled over, plunging sideways from the wagon-seat, and as the hard-bitted ponies swept on ’Phemie dived into the foam-streaked pool!

Lucas Pritchett was not as slow as he seemed.

In one motion he drew in the plunging ponies to a dead stop, thrust the lines into Lyddy’s hands, and vaulted over the wheel of the farm wagon.

“Hold ’em!” he commanded, pulling off the long, snuff-colored overcoat. Flinging it behind him he tore down the bank and, in his high boots, waded right into the stream.

Poor ’Phemie was beyond her depth, although she rose “right side up” when she came to the surface. And when Lucas seized her she had sense enough not to struggle much.

“Oh, oh, oh!” she moaned. “The wa–water is s-so cold!”

“I bet ye it is!” agreed the young fellow, and gathering her right up into his arms, saturated as her clothing was, he bore her to the bank and clambered to where Lyddy was doing all she could to hold the restive ponies.

“Whoa, Spot and Daybright!” commanded 62 the young farmer, soothing the ponies much quicker than he could his human burden. “Now, Miss, you’re all right―”

“All r-r-right!” gasped ’Phemie, her teeth chattering like castanets. “I–I’m anything but right!”

“Oh, ’Phemie! you might have been drowned,” cried her anxious sister.

“And now I’m likely to be frozen stiff right here in this road. Mrs. Lot wasn’t a circumstance to me. She only turned to salt, while I am be-be-coming a pillar of ice!”

But Lucas had set her firmly on her feet, and now he snatched up the old overcoat which had so much amused ’Phemie, and wrapped it about her, covering her from neck to heel.

“In you go–sit ’twixt your sister and me this time,” panted the young man. “We’ll hustle home an’ maw’ll git you ’twixt blankets in a hurry.”

“She’ll get her death!” moaned Lyddy, holding the coat close about the wet girl.

“Look out! We’ll travel some now,” exclaimed Lucas, leaping in, and having seized the reins, he shook them over the backs of the ponies and shouted to them.

The remainder of that ride up the mountain was merely a nightmare for the girls. Lucas allowed 63 the ponies to lose no time, despite the load they drew. But haste was imperative.

A ducking in an icy mountain brook at this time of the year might easily be fraught with serious consequences. Although it was drawing toward noon and the sun was now shining, there was no great amount of warmth in the air. Lucas must have felt the keen wind himself, for he was wet, too; but he neither shivered nor complained.

Luckily they were well up the mountainside when the accident occurred. The ponies flew around a bend where a grove of trees had shut off the view, and there lay the Pritchett house and outbuildings, fresh in their coat of whitewash.

“Maw and Sairy’ll see to ye now,” cried Lucas, as he neatly clipped the gatepost with one hub and brought the lathered ponies to an abrupt stop in the yard beside the porch.

“Hi, Maw!” he added, as a very stout woman appeared in the doorway–quite filling the opening, in fact. “Hi, Maw! Here’s Mis’ Hammon’s nieces–an’ one of ’em’s been in Pounder’s Brook!”

“For the land’s sake!” gasped the farmer’s wife, pulling a pair of steel-bowed spectacles down from her brows that she might peer through them at the Bray girls. “Ain’t it a mite airly for sech didoes as them?”

64“Why, Maw!” sputtered Lucas, growing red again. “She didn’t go for to do it–no, ma’am!”

“Wa-al! I didn’t know. City folks is funny. But come in–do! Mis’ Hammon’s nieces, d’ye say? Then you must be John Horrocks Bray’s gals–ain’t ye?”

“We are,” said Lyddy, who had quickly climbed out over the wheel and now eased down the clumsy bundle which was her sister. “Can you stand, ’Phemie?”

“Ye-es,” chattered her sister.

“I hope you can take us in for a little while, Mrs. Pritchett,” went on the older girl. “We are going up to Hillcrest to live.”

“Take ye in? Sure! An’ ’twon’t be the first city folks we’ve harbored,” declared the lady, chuckling comfortably. “They’re beginnin’ to come as thick as spatters in summer to Bridleburg, an’ some of ’em git clear up this way― For the land’s sake! that gal’s as wet as sop.”

“It–it was wet water I tumbled into,” stuttered ’Phemie.

Mrs. Pritchett ushered them into the big, warm kitchen, where the table was already set for dinner. A young woman–not so very young, either–as lank and lean as Lucas himself, was busy 65 at the stove. She turned to stare at the visitors with near-sighted eyes.

“This is my darter, Sairy,” said “Maw” Pritchett. “She taught school two terms to Pounder’s school; but it was bad for her eyes. I tell her to git specs; but she ’lows she’s too young for sech things.”

“The oculists advise glasses nowadays for very young persons,” observed Lyddy politely, as Sairy Pritchett bobbed her head at them in greeting.

“So I tell her,” declared the farmer’s wife. “But she won’t listen to reason. Ye know how young gals air!”

This assumption of Sairy’s extreme youth, and that Lyddy would understand her foibles because she was so much older, amused the latter immensely. Sairy was about thirty-five.

Meanwhile Mrs. Pritchett bustled about with remarkable spryness to make ’Phemie comfortable. There was a warm bedroom right off the kitchen–for this was an old-fashioned New England farmhouse–and in this the younger Bray girl took off her wet clothing. Lyddy brought in their bag and ’Phemie managed to make herself dry and tidy–all but her great plaits of hair–in a very short time.

She would not listen to Mrs. Pritchett’s advice that she go to bed. But she swallowed a bowl 66 of hot tea and then declared herself “as good as new.”

The Bray girls had now to tell Mrs. Pritchett and her daughter their reason for coming to Hillcrest, and what they hoped to do there.

“For the land’s sake!” gasped the farmer’s wife. “I dunno what Cyrus’ll say to this.”

It struck Lyddy that they all seemed to be somewhat in fear of what Mr. Pritchett might say. He seemed to be a good deal of a “bogie” in the family.

“We shall not interfere with Mr. Pritchett’s original arrangement with Aunt Jane,” exclaimed Lyddy, patiently.

“Well, ye’ll hafter talk to Cyrus when he comes in to dinner,” said the farmer’s wife. “I dunno how he’ll take it.”

“We should worry about how he ‘takes it,’” commented ’Phemie in Lyddy’s ear. “I guess we’ve got the keys to Hillcrest and Aunt Jane’s permission to live in the house and make what we can off the place. What more is there to it?”

But the older Bray girl caught a glimpse of Cyrus Pritchett as he came up the path from the stables, and she saw that he was nothing at all like his rotund and jolly wife–not in outward appearance, at least.

The Pritchett children got their extreme height 67 from Cyrus–and their leanness. He was a grizzled man, whose head stooped forward because he was so tall, and who looked fiercely on the world from under penthouse brows.

Every feature of his countenance was grim and forbidding. His cheeks were gray, with a stubble of grizzled beard upon them. When he came in and was introduced to the visitors he merely grunted an acknowledgment of their names and immediately dropped into his seat at the head of the table.

As the others came flocking about the board, Cyrus Pritchett opened his lips just once, and not until the grace had been uttered did the visitors understand that it was meant for a reverence before meat.

“For wha’ we’re ’bout to r’ceive make us tru’ grat’ful–pass the butter, Sairy,” and the old man helped himself generously and began at once to stow the provender away without regard to the need or comfort of the others about his board.

But Maw Pritchett and her son and daughter seemed to be used to the old man’s way, and they helped each other and the Bray girls with no niggard hand. Nor did the shuttle of conversation lag.

“Why, I ain’t been in the old doctor’s house since he died,” said Mrs. Pritchett, reflectively. 68 “Mis’ Hammon’, she’s been up here two or three times, an’ she allus goes up an’ looks things over; but I’m too fat for walkin’ up to Hillcrest–I be,” concluded the lady, with a chuckle.

She seemed as jolly and full of fun as her husband was morose. Cyrus Pritchett only glowered on the Bray girls when he looked at them at all.

But Lyddy and ’Phemie joined in the conversation with the rest of the family. ’Phemie, although she had made so much fun of Lucas at first, now made amends by declaring him to be a hero–and sticking to it!

“I’d never have got out of that pool if it hadn’t been for Lucas,” she repeated; “unless I could have drunk up the water and walked ashore that way! And o-o-oh! wasn’t it cold!”

“Hope you’re not going to feel the effects of it later,” said her sister, still anxious.

“I’m all right,” assured the confident ’Phemie.

“I dunno as it’ll be fit for you gals to stay in the old house to-night,” urged Mrs. Pritchett. “You’ll hafter have some wood cut.”

“I’ll do that when I take their stuff up to Hillcrest,” said Lucas, eagerly, but flushing again as though stricken with a sudden fever.

“There are no stoves in the house, I suppose?” Lyddy asked, wistfully.

69“Bless ye! Dr. Polly wouldn’t never have a stove in his house, saving a cook-stove in the kitchen, an’ of course, that’s ate up with rust afore this,” exclaimed the farmer’s wife. “He said open fireplaces assured every room its proper ventilation. He didn’t believe in these new-fangled ways of shuttin’ up chimbleys. My! but he was powerful sot on fresh air an’ sunshine.

“Onct,” pursued Mrs. Pritchett, “he was called to see Mis’ Fibbetts–she that was a widder and lived on ’tother side of the ridge, on the road to Adams. She had a mis’ry of some kind, and was abed with all the winders of her room tight closed.

“‘Open them winders,’ says Dr. Polly to the neighbor what was a-nussin’ of Mis’ Fibbetts.

“Next time he come the winders was down again. Dr. Polly warn’t no gentle man, an’ he swore hard, he did. He flung up the winders himself, an’ stamped out o’ the room.

“It was right keen weather,” chuckled Mrs. Pritchett, her double chins shaking with enjoyment, “and Mis’ Fibbetts was scart to death of a leetle air. Minute Dr. Polly was out o’ sight she made the neighbor woman shet the winders ag’in.

“But when Dr. Polly turned up the ridge road he craned out’n the buggy an’ he seen the winders 70 shet. He jerked his old boss aroun’, drove back to the house, stalked into the sick woman’s room, cane in hand, and smashed every pane of glass in them winders, one after another.

“‘Now I reckon ye’ll git air enough to cure ye ’fore ye git them mended,’ says he, and marched him out again. An’ sure ’nough old Mis’ Fibbetts got well an’ lived ten year after. But she never had a good word for Dr. Polly Phelps, jest the same,” chuckled the narrator.

“Well, we’ll make out somehow about fires,” said Lyddy, cheerfully, “if Lucas can cut us enough wood to keep them going.”

“I sure can,” declared the ever-ready youth, and just here Cyrus Pritchett, having eaten his fill, broke in upon the conversation in a tone that quite startled Lyddy and ’Phemie Bray.

“I wanter know what ye mean to do up there on the old Polly Phelps place?” he asked, pushing back his chair, having set down his coffee-cup noisily, and wiped his cuff across his lips. “I gotta oral contract with Jane Hammon’ to work that farm. It’s been in force year arter year for more’n ten good year. An’ that contract ain’t to be busted so easy.”

“Now, Father!” admonished Mrs. Pritchett; but the old man glared at her and she at once subsided.

71Cyrus Pritchett certainly was a masterful man in his own household. Lucas dropped his gaze to his plate and his face flamed again. But Sairy turned actually pale.