The Project Gutenberg EBook of Side-stepping with Shorty, by Sewell Ford This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Side-stepping with Shorty Author: Sewell Ford Illustrator: Francis Vaux Wilson Release Date: March 15, 2010 [EBook #31659] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIDE-STEPPING WITH SHORTY *** Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | SHORTY AND THE PLUTE |

| II. | ROUNDING UP MAGGIE |

| III. | UP AGAINST BENTLEY |

| IV. | THE TORTONIS' STAR ACT |

| V. | PUTTING PINCKNEY ON THE JOB |

| VI. | THE SOARING OF THE SAGAWAS |

| VII. | RINKEY AND THE PHONY LAMP |

| VIII. | PINCKNEY AND THE TWINS |

| IX. | A LINE ON PEACOCK ALLEY |

| X. | SHORTY AND THE STRAY |

| XI. | WHEN ROSSITER CUT LOOSE |

| XII. | TWO ROUNDS WITH SYLVIE |

| XIII. | GIVING BOMBAZOULA THE HOOK |

| XIV. | A HUNCH FOR LANGDON |

| XV. | SHORTY'S GO WITH ART |

| XVI. | WHY WILBUR DUCKED |

| XVII. | WHEN SWIFTY WAS GOING SOME |

| XVIII. | PLAYING WILBUR TO SHOW |

| XIX. | AT HOME WITH THE DILLONS |

| XX. | THE CASE OF RUSTY QUINN |

Notice any gold dust on my back? No? Well it's a wonder there ain't, for I've been up against the money bags so close I expect you can find eagle prints all over me.

That's what it is to build up a rep. Looks like all the fat wads in New York was gettin' to know about Shorty McCabe, and how I'm a sure cure for everything that ails 'em. You see, I no sooner take hold of one down and outer, sweat the high livin' out of him, and fix him up like new with a private course of rough house exercises, than he passes the word along to another; and so it goes.

This last was the limit, though. One day I'm called to the 'phone by some mealy mouth that wants to know if this is the Physical Culture Studio.

"Sure as ever," says I.

"Well," says he, "I'm secretary to Mr. Fletcher Dawes."

"That's nice," says I. "How's Fletch?"

"Mr. Dawes," says he, "will see the professah at fawh o'clock this awfternoon."

"Is that a guess," says I, "or has he been havin' his fortune told?"

"Who is this?" says the gent at the other end of the wire, real sharp and sassy.

"Only me," says I.

"Well, who are you?" says he.

"I'm the witness for the defence," says I. "I'm Professor McCabe, P. C. D., and a lot more that I don't use on week days."

"Oh!" says he, simmerin' down a bit. "This is Professor McCabe himself, is it? Well, Mr. Fletcher Dawes requiahs youah services. You are to repawt at his apartments at fawh o'clock this awfternoon—fawh o'clock, understand?"

"Oh, yes," says I. "That's as plain as a dropped egg on a plate of hash. But say, Buddy; you tell Mr. Dawes that next time he wants me just to pull the string. If that don't work, he can whistle; and when he gets tired of whistlin', and I ain't there, he'll know I ain't comin'. Got them directions? Well, think hard, and maybe you'll figure it out later. Ta, ta, Mister Secretary." With that I hangs up the receiver and winks at Swifty Joe.

"Swifty," says I, "they'll be usin' us for rubber stamps if we don't look out."

"Who was the guy?" says he.

"Some pinhead up to Fletcher Dawes's," says I.

"Hully chee!" says Swifty.

Funny, ain't it, how most everyone'll prick up their ears at that name? And it don't mean so much money as John D.'s or Morgan's does, either. But what them two and Harriman don't own is divided up among Fletcher Dawes and a few others. Maybe it's because Dawes is such a free spender that he's better advertised. Anyway, when you say Fletcher Dawes you think of a red-faced gent with a fistful of thousand-dollar bills offerin' to buy the White House for a stable.

But say, he might have twice as much, and I wouldn't hop any quicker. I'm only livin' once, and it may be long or short, but while it lasts I don't intend to do the lackey act for anyone.

Course, I thinks the jolt I gave that secretary chap closes the incident. But around three o'clock that same day, though, I looks down from the front window and sees a heavy party in a fur lined overcoat bein' helped out of a shiny benzine wagon by a pie faced valet, and before I'd done guessin' where they was headed for they shows up in the office door.

"My name is Dawes. Fletcher Dawes," says the gent in the overcoat.

"I could have guessed that," says I. "You look somethin' like the pictures they print of you in the Sunday papers."

"I'm sorry to hear it," says he.

But say, he's less of a prize hog than you'd think, come to get near—forty-eight around the waist, I should say, and about a number sixteen collar. You wouldn't pick him out by his face as the kind of a man that you'd like to have holdin' a mortgage on the old homestead, though, nor one you'd like to sit opposite to in a poker game—eyes about a quarter of an inch apart, lima bean ears buttoned down close, and a mouth like a crack in the pavement.

He goes right at tellin' what he wants and when he wants it, sayin' he's a little out of condition and thinks a few weeks of my trainin' was just what he needed. Also he throws out that I might come up to the Brasstonia and begin next day.

"Yes?" says I. "I heard somethin' like that over the 'phone."

"From Corson, eh?" says he. "He's an ass! Never mind him. You'll be up to-morrow?"

"Say," says I, "where'd you get the idea I went out by the day?"

"Why," says he, "it seems to me I heard something about——"

"Maybe they was personal friends of mine," says I. "That's different. Anybody else comes here to see me."

"Ah!" says he, suckin' in his breath through his teeth and levelin' them blued steel eyes of his at me. "I suppose you have your price?"

"No," says I; "but I'll make one, just special for you. It'll be ten dollars a minute."

Say, what's the use? We saves up till we gets a little wad of twenties about as thick as a roll of absorbent cotton, and with what we got in the bank and some that's lent out, we feel as rich as platter gravy. Then we bumps up against a really truly plute, and gets a squint at his dinner check, and we feels like panhandlers workin' a side street. Honest, with my little ten dollars a minute gallery play, I thought I was goin' to have him stunned.

"That's satisfactory," says he. "To-morrow, at four."

That's all. I'm still standin' there with my mouth open when he's bein' tucked in among the tiger skins. And I'm bought up by the hour, like a bloomin' he massage artist! Feel? I felt like I'd fit loose in a gas pipe.

But Swifty, who's had his ear stretched out and his eyes bugged all the time, begins to do the walk around and look me over as if I was a new wax figger in a museum.

"Ten plunks a minute!" says he. "Hully chee!"

"Ah, forget it!" says I. "D'ye suppose I want to be reminded that I've broke into the bath rubber class? G'wan! Next time you see me prob'ly I'll be wearin' a leather collar and a tag. Get the mitts on, you South Brooklyn bridge rusher, and let me show you how I can hit before I lose my nerve altogether!"

Swifty says he ain't been used so rough since the time he took the count from Cans; but it was a relief to my feelin's; and when he come to reckon up that I'd handed him two hundred dollars' worth of punches without chargin' him a red, he says he'd be proud to have me do it every day.

If it hadn't been that I'd chucked the bluff myself, I'd scratched the Dawes proposition. But I ain't no hand to welch; so up I goes next afternoon, with my gym. suit in a bag, and gets my first inside view of the Brasstonia, where the plute hangs out. And say, if you think these down town twenty-five-a-day joints is swell, you ought to get some Pittsburg friend to smuggle you into one of these up town apartment hotels that's run exclusively for trust presidents. Why, they don't have any front doors at all. You're expected to come and go in your bubble, but the rules lets you use a cab between certain hours.

I tries to walk in, and was held up by a three hundred pound special cop in grey and gold, and made to prove that I didn't belong in the baggage elevator or the ash hoist. Then I'm shown in over the Turkish rugs to a solid gold passenger lift, set in a velvet arm chair, and shot up to the umpteenth floor.

I was lookin' to find Mr. Dawes located in three or four rooms and bath, but from what I could judge of the size of his ranch he must pay by acreage instead of the square foot, for he has a whole wing to himself. And as for hired help, they was standin' around in clusters, all got up in baby blue and silver, with mugs as intelligent as so many frozen codfish. Say, it would give me chillblains on the soul to have to live with that gang lookin' on!

I'm shunted from one to the other, until I gets to Dawes, and he leads the way into a big room with rubber mats, punchin' bags, and all the fixin's you could think of.

"Will this do?" says he.

"It'll pass," says I. "And if you'll chase out that bunch of employment bureau left-overs, we'll get down to business."

"But," says he, "I thought you might need some of my men to——"

"I don't," says I, "and while you're mixin' it with me you won't, either."

At that he shoos 'em all out and shuts the door. I opens the window so's to get in some air that ain't been strained and currycombed and scented with violets, and then we starts to throw the shot bag around. I find Fletcher is short winded and soft. He's got a bad liver and a worse heart, for five or six years' trainin' on wealthy water and pâté de foie gras hasn't done him any good. Inside of ten minutes he knows just how punky he is himself, and he's ready to follow any directions I lay down.

As I'm leavin', a nice, slick haired young feller calls me over and hands me an old rose tinted check. It was for five hundred and twenty.

"Fifty-two minutes, professor," says he.

"Oh, let that pyramid," says I, tossin' it back.

Honest, I never shied so at money before, but somehow takin' that went against the grain. Maybe it was the way it was shoved at me.

I'd kind of got interested in the job of puttin' Dawes on his feet, though, and Thursday I goes up for another session. Just as I steps off the elevator at his floor I hears a scuffle, and out comes a couple of the baby blue bunch, shoving along an old party with her bonnet tilted over one ear. I gets a view of her face, though, and I sees she's a nice, decent lookin' old girl, that don't seem to be either tanked or batty, but just kind of scared. A Willie boy in a frock coat was followin' along behind, and as they gets to me he steps up, grabs her by the arm, and snaps out:

"Now you leave quietly, or I'll hand you over to the police! Understand?"

That scares her worse than ever, and she rolls her eyes up to me in that pleadin' way a dog has when he's been hurt.

"Hear that?" says one of the baby blues, shakin' her up.

My fingers went into bunches as sudden as if I'd touched a live wire, but I keeps my arms down. "Ah, say!" says I. "I don't see any call for the station-house drag out just yet. Loosen up there a bit, will you?"

"Mind your business!" says one of 'em, givin' me the glary eye.

"Thanks," says I. "I was waitin' for an invite," and I reaches out and gets a shut-off grip on their necks. It didn't take 'em long to loosen up after that.

"Here, here!" says the Willie that I'd spotted for Corson. "Oh, it's you is it, professor?"

"Yes, it's me," says I, still holdin' the pair at arms' length. "What's the row?"

"Why," says Corson, "this old woman——"

"Lady," says I.

"Aw—er—yes," says he. "She insists on fawcing her way in to see Mr. Dawes."

"Well," says I, "she ain't got no bag of dynamite, or anything like that, has she?"

"I just wanted a word with Fletcher," says she, buttin' in—"just a word or two."

"Friend of yours?" says I.

"Why— Well, we have known each other for forty years," says she.

"That ought to pass you in," says I,

"But she refuses to give her name," says Corson.

"I am Mrs. Maria Dawes," says she, holdin' her chin up and lookin' him straight between the eyes.

"You're not on the list," says Corson.

"List be blowed!" says I. "Say, you peanut head, can't you see this is some relation? You ought to have sense enough to get a report from the boss, before you carry out this quick bounce business. Perhaps you're puttin' your foot in it, son."

Then Corson weakens, and the old lady throws me a look that was as good as a vote of thanks. And say, when she'd straightened her lid and pulled herself together, she was as ladylike an old party as you'd want to meet. There wa'n't much style about her, but she was dressed expensive enough—furs, and silks, and sparks in her ears. Looked like one of the sort that had been up against a long run of hard luck and had come through without gettin' sour.

While we was arguin', in drifts Mr. Dawes himself. I gets a glimpse of his face when he first spots the old girl, and if ever I see a mouth shut like a safe door, and a jaw stiffen as if it had turned to concrete, his did.

"What does this mean, Maria?" he says between his teeth.

"I couldn't help it, Fletcher," says she. "I wanted to see you about little Bertie."

"Huh!" grunts Fletcher. "Well, step in this way. McCabe, you can come along too."

I wa'n't stuck on the way it was said, and didn't hanker for mixin' up with any such reunions; but it didn't look like Maria had any too many friends handy, so I trots along. When we're shut in, with the draperies pulled, Mr. Dawes plants his feet solid, shoves his hands down into his pockets, and looks Maria over careful.

"Then you have lost the address of my attorneys?" says he, real frosty.

That don't chill Maria at all. She acted like she was used to it. "No," says she; "but I'm tired of talking to lawyers. I couldn't tell them about Bertie, and how lonesome I've been without him these last two years. Can't I have him, Fletcher?"

About then I begins to get a glimmer of what it was all about, and by the time she'd gone on for four or five minutes I had the whole story. Maria was the ex-Mrs. Fletcher Dawes. Little Bertie was a grandson; and grandma wanted Bertie to come and live with her in the big Long Island place that Fletcher had handed her when he swapped her off for one of the sextet, and settled up after the decree was granted.

Hearin' that brought the whole thing back, for the papers printed pages about the Daweses; rakin' up everything, from the time Fletcher run a grocery store and lodgin' house out to Butte, and Maria helped him sell flour and canned goods, besides makin' beds, and jugglin' pans, and takin' in washin' on the side; to the day Fletcher euchred a prospector out of the mine that gave him his start.

"You were satisfied with the terms of the settlement, when it was made," says Mr. Dawes.

"I know," says she; "but I didn't think how badly I should miss Bertie. That is an awful big house over there, and I am getting to be an old woman now, Fletcher."

"Yes, you are," says he, his mouth corners liftin' a little. "But Bertie's in school, where he ought to be and where he is going to stay. Anything more?"

I looks at Maria. Her upper lip was wabblin' some, but that's all. "No, Fletcher," says she. "I shall go now."

She was just about startin', when there's music on the other side of the draperies. It sounds like Corson was havin' his troubles with another female. Only this one had a voice like a brass cornet, and she was usin' it too.

"Why can't I go in there?" says she. "I'd like to know why! Eh, what's that? A woman in there?"

And in she comes. She was a pippin, all right. As she yanks back the curtain and rushes in she looks about as friendly as a spotted leopard that's been stirred up with an elephant hook; but when she sizes up the comp'ny that's present she cools off and lets go a laugh that gives us an iv'ry display worth seein'.

"Oh!" says she. "Fletchy, who's the old one?"

Say, I expect Dawes has run into some mighty worryin' scenes before now, havin' been indicted once or twice and so on, but I'll bet he never bucked up against the equal of this before. He opens his mouth a couple of times, but there don't seem to be any language on tap. The missus was ready, though.

"Maria Dawes is my name, my dear," says she.

"Maria!" says the other one, lookin' some staggered. "Why—why, then you—you're Number One!"

Maria nods her head.

Then Fletcher gets his tongue out of tangle. "Maria," says he, "this is my wife, Maizie."

"Yes?" says Maria, as gentle as a summer night. "I thought this must be Maizie. You're very young and pretty, aren't you? I suppose you go about a lot? But you must be careful of Fletcher. He always was foolish about staying up too late, and eating things that hurt him. I used to have to warn him against black coffee and welsh rabbits. He will eat them, and then he has one of his bad spells. Fletcher is fifty-six now, you know, and——"

"Maria!" says Mr. Dawes, his face the colour of a boiled beet, "that's enough of this foolishness! Here, Corson! Show this lady out!"

"Yes, I was just going, Fletcher," says she.

"Good-bye, Maria!" sings out Maizie, and then lets out another of her soprano ha-ha's, holdin' her sides like she was tickled to death. Maybe it was funny to her; it wa'n't to Fletcher.

"Come, McCabe," says he; "we'll get to work."

Say, I can hold in about so long, and then I've got to blow off or else bust a cylinder head. I'd had about enough of this "Come, McCabe" business, too. "Say, Fletchy," says I, "don't be in any grand rush. I ain't so anxious to take you on as you seem to think."

"What's that?" he spits out.

"You keep your ears open long enough and you'll hear it all," says I; for I was gettin' hotter an' hotter under the necktie. "I just want to say that I've worked up a grouch against this job durin' the last few minutes. I guess I'll chuck it up."

That seemed to go in deep. Mr. Dawes, he brings his eyes together until nothin' but the wrinkle keeps 'em apart, and he gets the hectic flush on his cheek bones. "I don't understand," says he.

"This is where I quit," says I. "That's all."

"But," says he, "you must have some reason."

"Sure," says I; "two of 'em. One's just gone out. That's the other," and I jerks my thumb at Maizie.

She'd been rollin' her eyes from me to Dawes, and from Dawes back to me. "What does this fellow mean by that?" says Maizie. "Fletcher, why don't you have him thrown out?"

"Yes, Fletcher," says I, "why don't you? I'd love to be thrown out just now!"

Someway, Fletcher wasn't anxious, although he had lots of bouncers standin' idle within call. He just stands there and looks at his toes, while Maizie tongue lashes first me and then him. When she gets through I picks up my hat.

"So long, Fletchy," says I. "What work I put in on you the other day I'm goin' to make you a present of. If I was you, I'd cash that check and buy somethin' that would please Maizie."

"D'jer annex another five or six hundred up to the Brasstonia this afternoon?" asks Swifty, when I gets back.

"Nix," says I. "All I done was to organise a wife convention and get myself disliked. That ten-a-minute deal is off. But say, Swifty, just remember I've dodged makin' the bath rubber class, and I'm satisfied at that."

Say, who was tellin' you? Ah, g'wan! Them sea shore press agents is full of fried eels. Disguises; nothin'! Them folks I has with me was the real things. The Rev. Doc. Akehead? Not much. That was my little old Bishop. And it wa'n't any slummin' party at all. It was just a little errand of mercy that got switched.

It was this way: The Bishop, he shows up at the Studio for his reg'lar medicine ball work, that I'm givin' him so's he can keep his equator from gettin' the best of his latitude. That's all on the quiet, though. It's somethin' I ain't puttin' on the bulletin board, or includin' in my list of references, understand?

Well, we has had our half-hour session and the Bishop has just made a break for the cold shower and the dressin' room, while I'm preparin' to shed my workin' clothes for the afternoon; when in pops Swifty Joe, closin' the gym. door behind him real soft and mysterious.

"Shorty," says he in that hoarse whisper he gets on when he's excited, "she's—she's come!"

"Who's come?" says I.

"S-s-sh!" says he, wavin' his hands. "It's the old girl; and she's got a gun!"

"Ah, say!" says I. "Come out of the trance. What old girl? And what about the gun?"

Maybe you've never seen Swifty when he's real stirred up? He wears a corrugated brow, and his lower jaw hangs loose, leavin' the Mammoth Cave wide open, and his eyes bug out like shoe buttons. His thoughts come faster than he can separate himself from the words; so it's hard gettin' at just what he means to say. But, as near as I can come to it, there's a wide female party waitin' out in the front office for me, with blood in her eye and a self cockin' section of the unwritten law in her fist.

Course, I knows right off there must be some mistake, or else it's a case of dope, and I says so. But Swifty is plumb sure she knew who she was askin' for when she calls for me, and begs me not to go out. He's for ringin' up the police.

"Ring up nobody!" says I. "S'pose I want this thing gettin' into the papers? If a Lady Bughouse has strayed in here, we got to shoo her out as quiet as possible. She can't shoot if we rush her. Come on!"

I will say for Swifty Joe that, while he ain't got any too much sense, there's no ochre streak in him. When I pulls open the gym. door and gives the word, we went through neck and neck.

"Look out!" he yells, and I sees him makin' a grab at the arm of a broad beamed old party, all done up nicely in grey silk and white lace.

And say, it's lucky I got a good mem'ry for profiles; for if I hadn't seen right away it was Purdy Bligh's Aunt Isabella, and that the gun was nothin' but her silver hearin' tube, we might have been tryin' to explain it to her yet. As it is, I'm just near enough to make a swipe for Swifty's right hand with my left, and I jerks his paw back just as she turns around from lookin' out of the window and gets her lamps on us. Say, we must have looked like a pair of batty ones, standin' there holdin' hands and starin' at her! But it seems that folks as deaf as she is ain't easy surprised. All she does is feel around her for her gold eye glasses with one hand, and fit the silver hearin' machine to her off ear with the other. It's one of these pepper box affairs, and I didn't much wonder that Swifty took it for a gun.

"Are you Professor McCabe?" says she.

"Sure!" I hollers; and Swifty, not lookin' for such strenuous conversation, goes up in the air about two feet.

"I beg pardon," says the old girl; "but will you kindly speak into the audiphone."

So I steps up closer, forgettin' that I still has the clutch on Swifty, and drags him along.

"Ahr, chee!" says Swifty. "This ain't no brother act, is it?"

With that I lets him go, and me and Aunt Isabella gets down to business. I was lookin' for some tale about Purdy—tell you about him some day—but it looks like this was a new deal; for she opens up by askin' if I knew a party by the name of Dennis Whaley.

"Do I?" says I. "I've known Dennis ever since I can remember knowin' anybody. He's runnin' my place out to Primrose Park now."

"I thought so," says Aunt Isabella. "Then perhaps you know a niece of his, Margaret Whaley?"

I didn't; but I'd heard of her. She's Terence Whaley's girl, that come over from Skibbereen four or five years back, after near starvin' to death one wet season when the potato crop was so bad. Well, it seems Maggie has worked a couple of years for Aunt Isabella as kitchen girl. Then she's got ambitious, quit service, and got a flatwork job in a hand laundry—eight per, fourteen hours a day, Saturday sixteen.

I didn't tumble why all this was worth chinnin' about until Aunt Isabella reminds me that she's president and board of directors of the Lady Pot Wrestlers' Improvement Society. She's one of the kind that spends her time tryin' to organise study classes for hired girls who have different plans for spendin' their Thursday afternoons off.

Seems that Aunt Isabella has been keepin' special tabs on Maggie, callin' at the laundry to give her good advice, and leavin' her books to read,—which I got a tintype of her readin', not,—and otherwise doin' the upliftin' act accordin' to rule. But along in the early summer Maggie had quit the laundry without consultin' the old girl about it. Aunt Isabella kept on the trail, though, run down her last boardin' place, and begun writin' her what she called helpful letters. She kept this up until she was handed the ungrateful jolt. The last letter come back to her with a few remarks scribbled across the face, indicatin' that readin' such stuff gave Maggie a pain in the small of her back. But the worst of it all was, accordin' to Aunt Isabella, that Maggie was in Coney Island.

"Think of it!" says she. "That poor, innocent girl, living in that dreadfully wicked place! Isn't it terrible?"

"Oh, I don't know," says I. "It all depends."

"Hey?" says the old girl. "What say?"

Ever try to carry on a debate through a silver salt shaker? It's the limit. Thinkin' it would be a lot easier to agree with her, I shouts out, "Sure thing!" and nods my head. She nods back and rolls her eyes.

"She must be rescued at once!" says Aunt Isabella. "Her uncle ought to be notified. Can't you send for him?"

As it happens, Dennis had come down that mornin' to see an old friend of his that was due to croak; so I figures it out that the best way would be to get him and the old lady together and let 'em have it out. I chases Swifty down to West 11th-st. to bring Dennis back in a hurry, and invites Aunt Isabella to make herself comfortable until he comes.

She's too excited to sit down, though. She goes pacin' around the front office, now and then lookin' me over suspicious,—me bein' still in my gym. suit,—and then sizin' up the sportin' pictures on the wall. My art exhibit is mostly made up of signed photos of Jeff and Fitz and Nelson in their ring costumes, and it was easy to see she's some jarred.

"I hope this is a perfectly respectable place, young man," says she.

"It ain't often pulled by the cops," says I.

Instead of calmin' her down, that seems to stir her up worse'n ever. "I should hope not!" says she. "How long must I wait here?"

"No longer'n you feel like waitin', ma'am," says I.

And just then the gym. door opens, and in walks the Bishop, that I'd clean forgot all about.

"Why, Bishop!" squeals Aunt Isabella. "You here!"

Say, it didn't need any second sight to see that the Bishop would have rather met 'most anybody else at that particular minute; but he hands her the neat return. "It appears that I am," says he. "And you?"

Well, it was up to her to do the explainin'. She gives him the whole history of Maggie Whaley, windin' up with how she's been last heard from at Coney Island.

"Isn't it dreadful, Bishop?" says she. "And can't you do something to help rescue her?"

Now I was lookin' for the Bishop to say somethin' soothin'; but hanged if he don't chime in and admit that it's a sad case and he'll do what he can to help. About then Swifty shows up with Dennis, and Aunt Isabella lays it before him. Now, accordin' to his own account, Dennis and Terence always had it in for each other at home, and he never took much stock in Maggie, either. But after he'd listened to Aunt Isabella for a few minutes, hearin' her talk about his duty to the girl, and how she ought to be yanked off the toboggan of sin, he takes it as serious as any of 'em.

"Wurrah, wurrah!" says he, "but this do be a black day for the Whaleys! It's the McGuigan blood comin' out in her. What's to be done, mum?"

Aunt Isabella has a program all mapped out. Her idea is to get up a rescue expedition on the spot, and start for Coney. She says Dennis ought to go; for he's Maggie's uncle and has got some authority; and she wants the Bishop, to do any prayin' over her that may be needed.

"As for me," says she, "I shall do my best to persuade her to leave her wicked companions."

Well, they was all agreed, and ready to start, when it comes out that not one of the three has ever been to the island in their lives, and don't know how to get there. At that I sees the Bishop lookin' expectant at me.

"Shorty," says he, "I presume you are somewhat familiar with this—er—wicked resort?"

"Not the one you're talkin' about," says I. "I've been goin' to Coney every year since I was old enough to toddle; and I'll admit there has been seasons when some parts of it was kind of tough; but as a general proposition it never looked wicked to me."

That kind of puzzles the Bishop. He says he's always understood that the island was sort of a vent hole for the big sulphur works. Aunt Isabella is dead sure of it too, and hints that maybe I ain't much of a judge. Anyway, she thinks I'd be a good guide for a place of that kind, and prods the Bishop on to urge me to go.

"Well," says I, "just for a flier, I will."

So, as soon as I've changed my clothes, we starts for the iron steamboats, and plants ourselves on the upper deck. And say, we was a sporty lookin' bunch—I don't guess! There was the Bishop, in his little flat hat and white choker,—you couldn't mistake what he was,—and Aunt Isabella, with her grey hair and her grey and white costume, lookin' about as giddy as a marble angel on a tombstone. Then there's Dennis, who has put on the black whip cord Prince Albert he always wears when he's visitin' sick friends or attendin' funerals. The only festive lookin' point about him was the russet coloured throat hedge he wears in place of a necktie.

Honest, I felt sorry for them suds slingers that travels around the deck singin' out, "Who wants the waiter?" Every time one would come our way he'd get as far as "Who wants——" and then he'd switch off with an "Ah, chee!" and go away disgusted.

All the way down, the old girl has her eye out for wickedness. The sight of Adolph, the grocery clerk, dippin' his beak into a mug of froth, moves her to sit up and give him the stony glare; while a glimpse of a young couple snugglin' up against each other along the rail almost gives her a spasm.

"Such brazen depravity!" says she to the Bishop.

By the time we lands at the iron pier she has knocked Coney so much that I has worked up a first class grouch.

"Come on!" says I. "Let's have Maggie's address and get through with this rescue business before all you good folks is soggy with sin."

Then it turns out she ain't got any address at all. The most she knows is that Maggie's somewhere on the island.

"Well," I shouts into the tube, "Coney's something of a place, you see! What's your idea of findin' her?"

"We must search," says Aunt Isabella, prompt and decided.

"Mean to throw out a regular drag net?" says I.

She does. Well, say, if you've ever been to Coney on a good day, when there was from fifty to a hundred thousand folks circulatin' about, you've got some notion of what a proposition of that kind means. Course, I wa'n't goin to tackle the job with any hope of gettin' away with it; but right there I'm struck with a pleasin' thought.

"Do I gather that I'm to be the Commander Peary of this expedition?" says I.

It was a unanimous vote that I was.

"Well," says I, "you know you can't carry it through on hot air. It takes coin to get past the gates in this place."

Aunt Isabella says she's prepared to stand all the expense. And what do you suppose she passes out? A green five!

"Ah, say, this ain't any Sunday school excursion," says I. "Why, that wouldn't last us a block. Guess you'll have to dig deeper or call it off."

She was game, though. She brings up a couple of tens next dip, the Bishop adds two more, and I heaves in one on my own hook.

"Now understand," says I, "if I'm headin' this procession there mustn't be any hangin' back or arguin' about the course. Coney's no place for a quitter, and there's some queer corners in it; but we're lookin' for a particular party, so we can't skip any. Follow close, don't ask me fool questions, and everybody keep their eye skinned for Maggie. Is that clear?"

They said it was.

"Then we're off in a bunch. This way!" says I.

Say, it was almost too good to be true. I hadn't more'n got 'em inside of Dreamland before they has their mouths open and their eyes popped, and they was so rattled they didn't know whether they was goin' up or comin' down. The Bishop grabs me by the elbow, Aunt Isabella gets a desperate grip on his coat tails, and Dennis hooks two fingers into the back of her belt. When we lines up like that we has the fat woman takin' her first camel ride pushed behind the screen. The barkers out in front of the dime attractions takes one look at us and loses their voices for a whole minute—and it takes a good deal to choke up one of them human cyclones. I gives 'em back the merry grin and blazes ahead.

First thing I sees that looks good is the wiggle-waggle brass staircase, where half of the steps goes up as the other comes down.

"Now, altogether!" says I, feedin' the coupons to the ticket man, and I runs 'em up against the liver restorer at top speed. Say that exhibition must have done the rubbernecks good! First we was all jolted up in a heap, then we was strung out like a yard of frankfurters; but I kept 'em at it until we gets to the top. Aunt Isabella has lost her breath and her bonnet has slid over one ear, the Bishop is red in the face, and Dennis is puffin' like a freight engine.

"No Maggie here," says I. "We'll try somewhere else."

No. 2 on the event card was the water chutes, and while we was slidin' up on the escalator they has a chance to catch their wind. They didn't get any more'n they needed though; for just as Aunt Isabella has started to ask the platform man if he'd seen anything of Maggie Whaley, a boat comes up on the cogs, and I yells for 'em to jump in quick. The next thing they knew we was scootin' down that slide at the rate of a hundred miles an hour, with three of us holdin' onto our hats, and one lettin' out forty squeals to the minute.

"O-o-o o-o-o!" says Aunt Isabella, as we hits the water and does the bounding bounce.

"That's right," says I; "let 'em know you're here. It's the style."

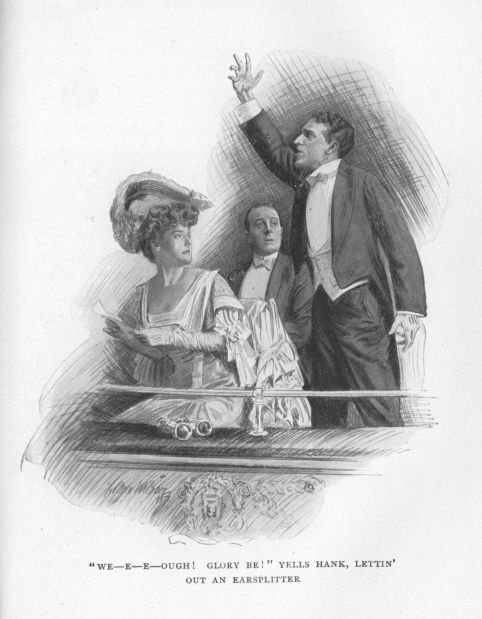

Before they've recovered from the chute ride I've hustled 'em over to one of them scenic railroads, where you're yanked up feet first a hundred feet or so, and then shot down through painted canvas mountains for about a mile. Say, it was a hummer, too! I don't know what there is about travellin' fast; but it always warms up my blood, and about the third trip I feels like sendin' out yelps of joy.

Course, I didn't expect it would have any such effect on the Bishop; but as we went slammin' around a sharp corner I gets a look at his face. And would you believe it, he's wearin' a reg'lar breakfast food grin! Next plunge we take I hears a whoop from the back seat, and I knows that Dennis has caught it, too.

I was afraid maybe the old girl has fainted; but when we brings up at the bottom and I has a chance to turn around, I finds her still grippin' the car seat, her feet planted firm, and a kind of wild, reckless look in her eyes.

"We did that last lap a little rapid," says I. "Maybe we ought to cover the ground again, just to be sure we didn't miss Maggie. How about repeatin' eh?"

"I—I wouldn't mind," says she.

"Good!" says I. "Percy, send her off for another spiel."

And we encores the performance, with Dennis givin' the Donnybrook call, and the smile on the Bishop's face growin' wider and wider. Fun? I've done them same stunts with a gang of real sporting men, and, never had the half of it.

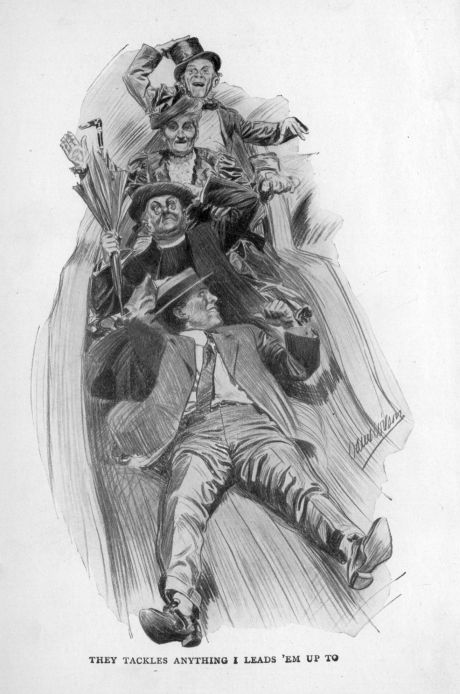

After that my crowd was ready for anything. They forgets all about the original proposition, and tackles anything I leads them up to, from bumpin' the bumps to ridin' down in the tubs on the tickler. When we'd got through with Dreamland and the Steeplechase, we wanders down the Bowery and hits up some hot dog and green corn rations.

By the time I gets ready to lead them across Surf-ave. to Luna Park it was dark, and about a million incandescents had been turned on. Well, you know the kind of picture they gets their first peep at. Course, it's nothin' but white stucco and gold leaf and electric light, with the blue sky beyond. But say, first glimpse you get, don't it knock your eye out?

"Whist!" says Dennis, gawpin' up at the front like lie meant to swallow it. "Is ut the Blessed Gates we're comin' to?"

"Magnificent!" says the Bishop.

And just then Aunt Isabella gives a gasp and sings out, "Maggie!"

Well, as Dennis says afterwards, in tellin' Mother Whaley about it, "Glory be, would yez think ut? I hears her spake thot name, and up I looks, and as I'm a breathin' man, there sits Maggie Whaley in a solid goold chariot all stuck with jools, her hair puffed out like a crown, and the very neck of her blazin' with pearls and di'monds. Maggie Whaley, mind ye, the own daughter of Terence, that's me brother; and her the boss of a place as big as the houses of parli'ment and finer than Windsor castle on the King's birthday!"

It was Maggie all right. She was sittin' in a chariot too—you've seen them fancy ticket booths they has down to Luna. And she has had her hair done up by an upholsterer, and put through a crimpin' machine. That and the Brazilian near-gem necklace she wears does give her a kind of a rich and fancy look, providin' you don't get too close.

She wasn't exactly bossin' the show. She was sellin' combination tickets, that let you in on so many rackets for a dollar. She'd chucked the laundry job for this, and she was lookin' like she was glad she'd made the shift. But here was four of us who'd come to rescue her and lead her back to the ironin' board.

Aunt Isabella makes the first break. She tells Maggie who she is and why she's come. "Margaret," says she, "I do hope you will consent to leave this wicked life. Please say you will, Margaret!"

"Ah, turn it off!" says Maggie. "Me back to the sweat box at eight per when I'm gettin' fourteen for this? Not on your ping pongs! Fade, Aunty, fade!"

Then the Bishop is pushed up to take his turn. He says he is glad to meet Maggie, and hopes she likes her new job. Maggie says she does. She lets out, too, that she's engaged to the gentleman what does a refined acrobatic specialty in the third attraction on the left, and that when they close in the fall he's goin' to coach her up so's they can do a double turn in the continuous houses next winter at from sixty to seventy-five per, each. So if she ever irons another shirt, it'll be just to show that she ain't proud.

And that's where the rescue expedition goes out of business with a low, hollow plunk. Among the three of 'em not one has a word left to say.

"Well, folks," says I, "what are we here for? Shall we finish the evenin' like we begun? We're only alive once, you know, and this is the only Coney there is. How about it?"

Did we? Inside of two minutes Maggie has sold us four entrance tickets, and we're headed for the biggest and wooziest thriller to be found in the lot.

"Shorty," says the Bishop, as we settles ourselves for a ride home on the last boat, "I trust I have done nothing unseemly this evening."

"What! You?" says I. "Why, Bishop, you're a reg'lar ripe old sport; and any time you feel like cuttin' loose again, with Aunt Isabella or without, just send in a call for me."

Say, where's Palopinto, anyway? Well neither did I. It's somewhere around Dallas, but that don't help me any. Texas, eh? You sure don't mean it! Why, I thought there wa'n't nothin' but one night stands down there. But this Palopinto ain't in that class at all. Not much! It's a real torrid proposition. No, I ain't been there; but I've been up against Bentley, who has.

He wa'n't mine, to begin with. I got him second hand. You see, he come along just as I was havin' a slack spell. Mr. Gordon—yes, Pyramid Gordon—he calls up on the 'phone and says he's in a hole. Seems he's got a nephew that's comin' on from somewhere out West to take a look at New York, and needs some one to keep him from fallin' off Brooklyn Bridge.

"How's he travellin'," says I; "tagged, in care of the conductor?"

"Oh, no," says Mr. Gordon. "He's about twenty-two, and able to take care of himself anywhere except in a city like this." Then he wants to know how I'm fixed for time.

"I got all there is on the clock," says I.

"And would you be willing to try keeping Bentley out of mischief until I get back?" says he.

"Sure as ever," says I. "I don't s'pose he's any holy terror; is he?"

Pyramid said he wa'n't quite so bad as that. He told me that Bentley'd been brought up on a big cattle ranch out there, and that now he was boss.

"He's been making a lot of money recently, too," says Mr. Gordon, "and he insists on a visit East. Probably he will want to let New York know that he has arrived, but you hold him down."

"Oh, I'll keep him from liftin' the lid, all right," says I.

"That's the idea, Shorty," says he. "I'll write a note telling him all about you, and giving him a few suggestions."

I had a synopsis of Bentley's time card, so as soon's he'd had a chance to open up his trunk and wash off some of the car dust I was waitin' at the desk in the Waldorf.

Now of course, bein' warned ahead, and hearin' about this cattle ranch business, I was lookin' for a husky boy in a six inch soft-brim and leather pants. I'd calculated on havin' to persuade him to take off his spurs and leave his guns with the clerk.

But what steps out of the elevator and answers to the name of Bentley is a Willie boy that might have blown in from Asbury Park or Far Rockaway. He was draped in a black and white checked suit that you could broil a steak on, with the trousers turned up so's to show the openwork silk socks, and the coat creased up the sides like it was made over a cracker box. His shirt was a MacGregor plaid, and the band around his Panama was a hand width Roman stripe.

"Gee!" thinks I, "if that's the way cow boys dress nowadays, no wonder there's scandals in the beef business!"

But if you could forget his clothes long enough to size up what was in 'em, you could see that Bentley was a mild enough looker. There's lots of bank messengers and brokers' clerks just like him comin' over from Brooklyn and Jersey every mornin'. He was about five feet eight, and skimpy built, and he had one of these recedin' faces that looked like it was tryin' to get away from his nose.

But then, it ain't always the handsome boys that behaves the best, and the more I got acquainted with Bentley, the better I thought of him. He said he was mighty glad I showed up instead of Mr. Gordon.

"Uncle Henry makes me weary," says he. "I've just been reading a letter from him, four pages, and most of it was telling me what not to do. And this the first time I was ever in New York since I've been old enough to remember!"

"You'd kind of planned to see things, eh?" says I.

"Why, yes," says Bentley. "There isn't much excitement out on the ranch, you know. Of course, we ride into Palopinto once or twice a month, and sometimes take a run up to Dallas; but that's not like getting to New York."

"No," says I. "I guess you're able to tell the difference between this burg and them places you mention, without lookin' twice. What is Dallas, a water tank stop?"

"It's a little bigger'n that," says he, kind of smilin'.

But he was a nice, quiet actin' youth; didn't talk loud, nor go through any tough motions. I see right off that I'd been handed the wrong set of specifications, and I didn't lose any time framin' him up accordin' to new lines. I knew his kind like a book. You could turn him loose in New York for a week, and the most desperate thing he'd find to do would be smokin' cigarettes on the back seat of a rubberneck waggon. And yet he'd come all the way from the jumpin' off place to have a little innocent fun.

"Uncle Henry wrote me," says he, "that while I'm here I'd better take in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and visit St. Patrick's Cathedral and Grant's Tomb. But say, I'd like something a little livelier than that, you know."

He was so mild about it that I works up enough sympathy to last an S. P. C. A. president a year. I could see just what he was achin' for. It wa'n't a sight of oil paintin's or churches. He wanted to be able to go back among the flannel shirts and tell the boys tales that would make their eyes stick out. He was ambitious to go on a regular cut up, but didn't know how, and wouldn't have had the nerve to tackle it alone if he had known.

Now, I ain't ever done any red light pilotin', and didn't have any notion of beginnin' then, especially with a youngster as nice and green as Bentley; but right there and then I did make up my mind that I'd steer him up against somethin' more excitin' than a front view of Grace Church at noon. It was comin' to him.

"See here, Bentley," says I, "I've passed my word to kind of look after you, and keep you from rippin' things up the back here in little old New York; but seein' as this is your first whack at it, if you'll promise to stop when I say 'Whoa!' and not let on about it afterwards to your Uncle Henry, I'll just show you a few things that they don't have out West," and I winks real mysterious.

"Oh, will you?" says Bentley. "By ginger! I'm your man!"

So we starts out lookin' for the menagerie. It was all I could do, though, to keep my eyes off'm that trousseau of his.

"They don't build clothes like them in Palopinto, do they?" says I.

"Oh, no," says Bentley. "I stopped off in Chicago and got this outfit. I told them I didn't care what it cost, but I wanted the latest."

"I guess you got it," says I. "That's what I'd call a night edition, base ball extra. You mustn't mind folks giraffin' at you. They always do that to strangers."

Bentley didn't mind. Fact is, there wa'n't much that did seem to faze him a whole lot. He'd never rode in the subway before, of course, but he went to readin' the soaps ads just as natural as if he lived in Harlem. I expect that was what egged me on to try and get a rise out of him. You see, when they come in from the rutabaga fields and the wheat orchards, we want 'em to open their mouths and gawp. If they do, we give 'em the laugh; but if they don't, we feel like they was throwin' down the place. So I lays out to astonish Bentley.

First I steers him across Mulberry Bend and into a Pell-st. chop suey joint that wouldn't be runnin' at all if it wa'n't for the Sagadahoc and Elmira folks the two dollar tourin' cars bring down. With all the Chinks gabblin' around outside, though, and the funny, letterin' on the bill of fare, I thought that would stun him some. He just looked around casual, though, and laid into his suey and rice like it was a plate of ham-and, not even askin' if he couldn't buy a pair of chopsticks as a souvenir.

"There's a bunch of desperate characters," says I, pointin' to a table where a gang of Park Row compositors was blowin' themselves to a platter of chow-ghi-sumen.

"Yes?" says he.

"There's Chuck Connors, and Mock Duck, and Bill the Brute, and One Eyed Mike!" I whispers.

"I'm glad I saw them," says Bentley.

"We'll take a sneak before the murderin' begins," say I. "Maybe you'll read about how many was killed, in the mornin' papers."

"I'll look for it," says he.

Say, it was discouragin'. We takes the L up to 23rd and goes across and up the east side of Madison Square.

"There," says I, pointin' out the Manhattan Club, that's about as lively as the Subtreasury on a Sunday, "that's Canfield's place. We'd go in and see 'em buck the tiger, only I got a tip that Bingham's goin' to pull it to-night. That youngster in the straw hat just goin' in is Reggie."

"Well, well!" says Bentley.

Oh, I sure did show Bentley a lot of sights that evenin', includin' a wild tour through the Tenderloin—in a Broadway car. We winds up at a roof garden, and, just to give Bentley an extra shiver, I asks the waiter if we wa'n't sittin' somewhere near the table that Harry and Evelyn had the night he was overcome by emotional insanity.

"You're at the very one, sir," he says. Considerin' we was ten blocks away, he was a knowin' waiter.

"This identical table; hear that, Bentley?" says I.

"You don't say!" says he.

"Let's have a bracer," says I. "Ever drink a soda cocktail, Bentley?"

He said he hadn't.

"Then bring us two, real stiff ones," says I. You know how they're made—a dash of bitters, a spoonful of bicarbonate, and a bottle of club soda, all stirred up in a tall glass, almost as intoxicatin' as buttermilk.

"Don't make your head dizzy, does it?" says I.

"A little," says Bentley; "but then, I'm not used to mixed drinks. We take root beer generally, when we're out on a tear."

"You cow boys must be a fierce lot when you're loose," says I.

Bentley grinned, kind of reminiscent. "We do raise the Old Harry once in awhile," says he. "The last time we went up to Dallas I drank three different kinds of soda water, and we guyed a tamale peddler so that a policeman had to speak to us."

Say! what do you think of that? Wouldn't that freeze your blood?

Once I got him started, Bentley told me a lot about life on the ranch; how they had to milk and curry down four thousand steers every night; and about their playin' checkers at the Y. M. C. A. branch evenin's, and throwin' spit balls at each other durin' mornin' prayers. I'd always thought these stage cow boys was all a pipe dream, but I never got next to the real thing before.

It was mighty interestin', the way he told it, too. They get prizes for bein' polite to each other durin' work hours, and medals for speakin' gentle to the cows. Bentley said he had four of them medals, but he hadn't worn 'em East for fear folks would think he was proud. That gave me a line on where he got his quiet ways from. It was the trainin' he got on the ranch. He said it was grand, too, when a crowd of the boys came ridin' home from town, sometimes as late as eleven o'clock at night, to hear 'em singin' "Onward, Christian Soldier" and tunes like that.

"I expect you do have a few real tough citizens out that way, though," says I.

"Yes," said he, speakin' sad and regretful, "once in awhile. There was one came up from Las Vegas last Spring, a low fellow that they called Santa Fe Bill. He tried to start a penny ante game, but we discouraged him."

"Run him off the reservation, eh?" says I.

"No," says Bentley, "we made him give up his ticket to our annual Sunday school picnic. He was never the same after that."

Well, say, I had it on the card to blow Bentley to a Welsh rabbit after the show, at some place where he could get a squint at a bunch of our night bloomin' summer girls, but I changed the program. I took him away durin' intermission, in time to dodge the new dancer that Broadway was tryin' hard to be shocked by, and after we'd had a plate of ice cream in one of them celluloid papered all-nights, I led Bentley back to the hotel and tipped a bell hop a quarter to tuck him in bed.

Somehow, I didn't feel just right about the way I'd been stringin' Bentley. I hadn't started out to do it, either; but he took things in so easy, and was so willin' to stand for anything, that I couldn't keep from it. And it did seem a shame that he must go back without any tall yarns to spring. Honest, I was so twisted up in my mind, thinkin' about Bentley, that I couldn't go to sleep, so I sat out on the front steps of the boardin' house for a couple of hours, chewin' it all over. I was just thinkin' of telephonin' to the hotel chaplain to call on Bentley in the mornin', when me friend Barney, the rounds, comes along.

"Say, Shorty," says he, "didn't I see you driftin' around town earlier in the evenin' with a young sport in mornin' glory clothes?"

"He was no sport," says I. "That was Bentley. He's a Y. M. C. A. lad in disguise."

"It's a grand disguise," says Barney. "Your quiet friend is sure livin' up to them clothes."

"You're kiddin'," says I. "It would take a live one to do credit to that harness. When I left Bentley at half-past ten he was in the elevator on his way up to bed."

"I don't want to meet any that's more alive than your Bentley," says he. "There must have been a hole in the roof. Anyway, he shows up on my beat about eleven, picks out a swell café, butts into a party of soubrettes, flashes a thousand dollar bill, and begins to buy wine for everyone in sight. Inside of half an hour he has one of his new made lady friends doin' a high kickin' act on the table, and when the manager interferes Bentley licks two waiters to a standstill and does up the house detective with a chair. Why, I has to get two of my men to help me gather him in. You can find him restin' around to the station house now."

"Barney," says I, "you must be gettin' colour blind. That can't be Bentley."

"You go around and take a look at him," says he.

Well, just to satisfy Barney, I did. And say, it was Bentley, all right! He was some mussed, but calm and contented.

"Bentley," says I, reprovin' like, "you're a bird, you are! How did it happen? Did some one drug you?"

"Guess that ice cream must have gone to my head," says he, grinnin'.

"Come off!" says I. "I've had a report on you, and from what you've got aboard you ought to be as full as a goat."

He wa'n't, though. He was as sober as me, and that after absorbin' a quart or so of French foam.

"If I can fix it so's to get you out on bail," says I, "will you quit this red paint business and be good?"

"G'wan!" says he. "I'd rather stay here than go around with you any more. You put me asleep, you do, and I can get all the sleep I want without a guide. Chase yourself!"

I was some sore on Bentley by that time; but I went to court the next mornin', when he paid his fine and was turned adrift. I starts in with some good advice, but Bentley shuts me off quick.

"Cut it out!" says he. "New York may seem like a hot place to Rubes like you; but you can take it from me that, for a pure joy producer, Palopinto has got it burned to a blister. Why, there's more doing on some of our back streets than you can show up on the whole length of Broadway. No more for me! I'm goin' back where I can spend my money and have my fun without bein' stopped and asked to settle before I've hardly got started."

He was dead in earnest, too. He'd got on a train headed West before I comes out of my dream. Then I begins to see a light. It was a good deal of a shock to me when it did come, but I has to own up that Bentley was a ringer. All that talk about mornin' prayers and Sunday school picnics was just dope, and while I was so busy dealin' out josh, to him, he was handin' me the lemon.

My mouth was still puckered and my teeth on edge, when Mr. Gordon gets me on the 'phone and wants to know how about Bentley.

"He's come and gone," says I.

"So soon?" says he. "I hope New York wasn't too much for him."

"Not at all," says I; "he was too much for New York. But while you was givin' him instructions, why didn't you tell him to make a noise like a hornet? It might have saved me from bein' stung."

Texas, eh? Well, say, next time I sees a map of that State I'm goin' to hunt up Palopinto and draw a ring around it with purple ink.

What I was after was a souse in the Sound; but say, I never know just what's goin' to happen to me when I gets to roamin' around Westchester County!

I'd started out from Primrose Park to hoof it over to a little beach a ways down shore, when along comes Dominick with his blue dump cart. Now, Dominick's a friend of mine, and for a foreigner he's the most entertainin' cuss I ever met. I like talkin' with him. He can make the English language sound more like a lullaby than most of your high priced opera singers; and as for bein' cheerful, why, he's got a pair of eyes like sunny days.

Course, he wears rings in his ears, and likely a seven inch knife down the back of his neck. He ain't perfumed with violets either, when you get right close to; but the ash collectin' business don't call for peau d'Espagne, does it?

"Hallo!" says Dominick. "You lika ride?"

Well, I can't say I'm stuck on bein' bounced around in an ash chariot; but I knew Dominick meant well, so in I gets. We'd been joltin' along for about four blocks, swappin' pigeon toed conversation, when there shows up on the road behind us the fanciest rig I've seen outside of a circus. In front, hitched up tandem, was a couple of black and white patchwork ponies that looked like they'd broke out of a sportin' print. Say, with their shiny hoofs and yeller harness, it almost made your eyes ache to look at 'em. But the buggy was part of the picture, too. It was the dizziest ever—just a couple of upholstered settees, balanced back to back on a pair of rubber tired wheels, with the whole shootin' match, cushions and all, a blazin' turkey red.

On the nigh side was a coachman, with his bandy legs cased in white pants and yeller topped boots; and on the other—well, say! you talk about your polka dot symphonies! Them spots was as big as quarters, and those in the parasol matched the ones in her dress.

I'd been gawpin' at the outfit a couple of minutes before I could see anything but the dots, and then all of a sudden I tumbles that it's Sadie. She finds me about the same time, and jabs her sun shade into the small of the driver's back, to make him pull up. I tells Dominick to haul in, too, but his old skate is on his hind legs, with his ears pointed front, wakin' up for the first time in five years, so I has to drop out over the tail board.

"Well, what do you think of the rig?" says Sadie.

"I guess me and Dominick's old crow bait has about the same thoughts along that line," says I. "Can you blame us?"

"It is rather giddy, isn't it?" says she.

"'Most gave me the blind staggers," says I. "You ought to distribute smoked glasses along the route of procession. Did you buy it some dark night, or was it made to order after somethin' you saw in a dream?"

"The idea!" says Sadie. "This jaunting car is one I had sent over from Paris, to help my ponies get a blue ribbon at the Hill'n'dale horse show. And that's what it did, too."

"Blue ribbon!" says I. "The judges must have been colour blind."

"Oh, I don't know," says Sadie, stickin' her tongue out at me. "After that I've a good notion to make you walk."

"I don't know as I'd have nerve enough to ride in that, anyway," says I. "Is it a funeral you're goin' to?"

"Next thing to it," says she. "But come on, Shorty; get aboard and I'll tell you all about it."

So I steps up alongside the spotted silk, and the driver lets the ponies loose. Say, it was like ridin' sideways in a roller coaster.

Sadie said she was awful glad to see me just then. She had a job on hand that she hated to do, and she needed some one to stand in her corner and cheer her up while she tackled it. Seems she'd got rash a few days before and made a promise to lug the Duke and Duchess of Kildee over to call on the Wigghorns. Sadie'd been actin' as sort of advance agent for Their Dukelets durin' their splurge over here, and Mrs. Wigghorn had mesmerised her into makin' a date for a call. This was the day.

It would have gone through all right if some one hadn't put the Duke wise to what he was up against. Maybe you know about the Wigghorns? Course, they've got the goods, for about a dozen years ago old Wigghorn choked a car patent out of some poor inventor, and his bank account's been pyramidin' so fast ever since that now he's in the eight figure class; but when it comes to bein' in the monkey dinner crowd, they ain't even counted as near-silks.

"Why," says Sadie, "I've heard that they have their champagne standing in rows on the sideboard, and that they serve charlotte russe for breakfast!"

"That's an awful thing to repeat," says I.

"Oh, well," says she, "Mrs. Wigghorn's a good natured soul, and I do think the Duke might have stood her for an afternoon. He wouldn't though, and now I've got to go there and call it off, just as she's got herself into her diamond stomacher, probably, to receive them."

"You couldn't ring in a couple of subs?" says I. For a minute Sadie's blue eyes lights up like I'd passed her a plate of peach ice cream. "If I only could!" says she. Then she shakes her head. "No," she says, "I should hate to lie. And, anyway, there's no one within reach who could play their parts."

"That bein' the case," says I, "it looks like you'd have to go ahead and break the sad news. What do you want me to do—hold a bucket for the tears?"

Sadie said all she expected of me was to help her forget it afterwards; so we rolls along towards Wigghorn Arms. We'd got within a mile of there when we meets a Greek peddler with a bunch of toy balloons on his shoulder, and in less'n no time at all them crazy-quilt ponies was tryin' to do back somersaults and other fool stunts. In the mix up one of 'em rips a shoe almost off, and Mr. Coachman says he'll have to chase back to a blacksmith shop and have it glued on.

"Oh, bother!" says Sadie. "Well, hurry up about it. We'll walk along as far as Apawattuck Inn and wait there."

It wa'n't much of a walk. The Apawattuck's a place where they deal out imitation shore dinners to trolley excursionists, and fusel oil high balls to the bubble trade. The name sounds well enough, but that ain't satisfyin' when you're real hungry. We were only killin' time, though, so it didn't matter. We strolled up just as fearless as though their clam chowders was fit to eat.

And that's what fetched us up against the Tortonis. They was well placed, at a corner veranda table where no one could miss seein' 'em; and, as they'd just finished a plate of chicken salad and a pint of genuine San José claret, they was lookin' real comfortable and elegant.

Say, to see the droop eyed way they sized us up as we makes our entry, you'd think they was so tired doin' that sort of thing that life was hardly worth while. You'd never guess they'd been livin' in a hall bed room on crackers and bologna ever since the season closed, and that this was their first real feed of the summer, on the strength of just havin' been booked for fifty performances. He was wearin' one of them torrid suits you see in Max Blumstein's show window, with a rainbow band on his straw pancake, and one of these flannel collar shirts that you button under the chin with a brass safety pin. She was sportin' a Peter Pan peekaboo that would have made Comstock gasp. And neither of 'em had seen a pay day for the last two months.

But it was done good, though. They had the tray jugglers standin' around respectful, and the other guests wonderin' how two such real House of Mirthers should happen to stray in where the best dishes on the card wa'n't more'n sixty cents a double portion.

Course, I ain't never been real chummy with Tortoni—his boardin' house name's Skinny Welch, you know—but I've seen him knockin' around the Rialto off'n on for years; so, as I goes by to the next table, I lifts my lid and says, "Hello, Skin. How goes it?" Say, wa'n't that friendly enough? But what kind of a come back do I get? He just humps his eyebrows, as much as to say, "How bold some of these common folks is gettin' to be!" and then turns the other way. Sadie and I look at each other and swap grins.

"What happened?" says she.

"I had a fifteen cent lump of Hygeia passed to me," says I. "And with the ice trust still on top, I calls it extravagant."

"Who are the personages?" says she.

"Well, the last reports I had of 'em," says I, "they were the Tortonis, waitin' to do a parlour sketch on the bargain day matinée circuit; but from the looks now I guesses they're travellin' incog—for the afternoon, anyway."

"How lovely!" says Sadie.

Our seltzer lemonades come along just then, so there was business with the straws. I'd just fished out the last piece of pineapple when Jeems shows up on the drive with the spotted ponies and that side saddle cart. I gave Sadie the nudge to look at the Tortonis. They had their eyes glued to that outfit, like a couple of Hester-st. kids lookin' at a hoky poky waggon.

And it wa'n't no common "Oh, I wish I could swipe that" look, either. It was a heap deeper'n that. The whole get up, from the red wheels to the silver rosettes, must have hit 'em hard, for they held their breath most a minute, and never moved. The girl was the first to break away. She turns her face out towards the Sound and sighs. Say, it must be tough to have ambitions like that, and never get nearer to 'em than now and then a ten block hansom ride.

About then Jeems catches Sadie's eye, and salutes with the whip.

"Did you get it fixed?" says she.

He says it's all done like new.

Signor Tortoni hadn't been losin' a look nor a word, and the minute he ties us up to them speckled ponies he maps out a change of act. Before I could call the waiter and get my change, Tortoni was right on the ground.

"I beg pardon," says he, "but isn't this my old friend, Professor McCabe?"

"You've sure got a comin' memory, Skinny," says I.

"Why!" says he, gettin' a grip on my paw, "how stupid of me! Really, professor, you've grown so distinguished looking that I didn't place you at all. Why, this is a great pleasure, a very great pleasure, indeed!"

"Ye-e-es?" says I.

But say, I couldn't rub it in. He was so dead anxious to connect himself with that red cart before the crowd that I just let him spiel away. Inside of two minutes the honours had been done all around, and Sadie was bein' as nice to the girl as she knew how. And Sadie knows, though! She'd heard that sigh, Sadie had; and it didn't jar me a bit when she gives them the invite to take a little drive down the road with us.

Well, it was worth the money, just to watch Skinny judgin' up the house out of the corner of his eye. I'll bet there wa'n't one in the audience that he didn't know just how much of it they was takin' in; and by the easy way he leaned across the seat back and chinned to Sadie, as we got started, you'd thought he'd been brought up in one of them carts. The madam wa'n't any in the rear, either. She was just as much to home as if she'd been usin' up a green transfer across 34th. If the style was new to her, or the motion gave her a tingly feelin' down her back, she never mentioned it.

They did lose their breath a few, though, when we struck Wigghorn Arms. It's a whackin' big place, all fenced in with fancy iron work and curlicue gates fourteen feet high.

"I've just got to run in a minute and say a word to Mrs. Wigghorn," says Sadie. "I hope you don't mind waiting?"

Oh no, they didn't. They said so in chorus, and as we looped the loop through the shrubbery and began to get glimpses of window awnings and tiled roof, I could tell by the way they acted that they'd just as soon wait inside as not.

Mrs. Wigghorn wasn't takin' any chances on havin' Their Dukelets drive up, leave their cards, and skidoo. She was right out front holdin' down a big porch rocker, with her eyes peeled up the drive. And she was costumed for the part. I don't know just what it was she had on, but I've seen plush parlour suits covered with stuff like that. She's a sizable old girl anyway, but in that rig, and with her store hair puffed out, she loomed up like a bale of hay in a door.

"Why, how do you do!" she squeals, makin' a swoop at Sadie as soon as the wheels stopped turnin'. "And you did bring them along, didn't you? Now don't say a word until I get Peter—he's just gone in to brush the cigar ashes off his vest. We want to be presented to the Duke and Duchess together, you know. Peter! Pe-ter!" she shouts, and in through the front door she waddles, yellin' for the old man.

And say, just by the look Sadie gave me I knew what was runnin' through her head.

"Shorty," says she, "I've a mind to do it."

"Flag it," says. "You ain't got time."

But there was no stoppin' her. "Listen," says she to the Tortonis. "Can't you play Duke and Duchess of Kildee for an hour or so?"

"What are the lines?" says Skinny.

"You've got to improvise as you go along," says she. "Can you do it?"

"It's a pipe for me," says he. "Flossy, do you come in on it?"

Did she? Why, Flossy was diggin' up her English accent while he was askin' the question, and by the time Mrs. Wigghorn got back, draggin' Peter by the lapel of his dress coat, the Tortonis was fairly oozin' aristocracy. It was "Chawmed, don'tcher know!" and "My word!" right along from the drop of the hat.

I didn't follow 'em inside, and was just as glad I didn't have to. Sittin' out there, expectin' to hear the lid blow off, made me nervous enough. I wasn't afraid either of 'em would go shy on front; but when I remembered Flossy's pencilled eyebrows, and Skinny's flannel collar, I says to myself, "That'll queer 'em as soon as they get in a good light and there's time for the details to soak in." And I didn't know what kind of trouble the Wigghorns might stir up for Sadie, when they found out how bad they'd been toasted.

It was half an hour before Sadie showed up again, and she was lookin' merry.

"What have they done with 'em," says I—"dropped 'em down the well?"

Sadie snickered as she climbed in and told Jeems to whip up the team. "Mr. and Mrs. Wigghorn," says she, "have persuaded the Duke and Duchess to spend the week's end at Wigghorn Arms."

"Gee!" says I. "Can they run the bluff that long?"

"It's running itself," says Sadie. "The Wigghorns are so overcome with the honour that they hardly know whether they're afoot or horseback; and as for your friends, they're more British than the real articles ever thought of being. I stayed until they'd looked through the suite of rooms they're to occupy, and when I left they were being towed out to the garage to pick out a touring car that suited them. They seemed already to be bored to death, too."

"Good!" say I. "Now maybe you'll take me over to the beach and let me get in a quarter's worth of swim."

"Can't you put it off, Shorty?" says she. "I want you to take the next train into town and do an errand for me. Go to the landlady at this number, East 15th-st., and tell her to send Mr. Tortoni's trunk by express."

Well, I did it. It took a ten to make the landlady loosen up on the wardrobe, too; but considerin' the solid joy I've had, thinkin' about Skinny and Flossy eatin' charlotte russe for breakfast, and all that, I guess I'm gettin' a lot for my money. It ain't every day you have a chance to elevate a vaudeville team to the peerage.

Well, say, this is where we mark up one on Pinckney. And it's time too, for he's done the grin act at me so often he was comin' to think I was gettin' into the Slivers class. You know about Pinckney. He's the bubble on top of the glass, the snapper on the whip lash, the sunny spot at the club. He's about as serious as a kitten playin' with a string, and the cares on his mind weigh 'most as heavy as an extra rooster feather on a spring bonnet.

That's what comes of havin' a self raisin' income, a small list of relatives, and a moderate thirst. If anything bobs up that needs to be worried over—like whether he's got vests enough to last through a little trip to London and back, or whether he's doubled up on his dates—why, he just tells his man about it, and then forgets. For a trouble dodger he's got the little birds in the trees carryin' weight. Pinckney's liable to show up at the Studio here every day for a week, and then again I won't get a glimpse of him for a month. It's always safe to expect him when you see him, and it's a waste of time wonderin' what he'll be up to next. But one of the things I likes most about Pinckney is that he ain't livin' yesterday or to-morrow. It's always this A. M. with him, and the rest of the calendar takes care of itself.

So I wa'n't any surprised, as I was doin' a few laps on the avenue awhile back, to hear him give me the hail.

"Oh, I say, Shorty!" says he, wavin' his stick.

"Got anything on?"

"Nothin' but my clothes," says I.

"Good!" says he. "Come with me, then."

"Sure you know where you're goin'?" says I.

Oh, yes, he was—almost. It was some pier or other he was headed for, and he has the number wrote down on a card—if he could find the card. By luck he digs it up out of his cigarette case, where his man has put it on purpose, and then he proceeds to whistle up a cab. Say, if it wa'n't for them cabbies, I reckon Pinckney would take root somewhere.

"Meetin' some one, or seein' 'em off?" says I, as we climbs in.

"Hanged if I know yet," says Pinckney.

"Maybe it's you that's goin'?" says I.

"Oh, no," says he. "That is, I hadn't planned to, you know. And come to think of it, I believe I am to meet—er—Jack and Jill."

"Names sound kind of familiar," says I. "What's the breed?"

"What would be your guess?" says he.

"A pair of spotted ponies," says I.

"By Jove!" says he, "I hadn't thought of ponies."

"Say," says I, sizin' him up to see if he was handin' me a josh, "you don't mean to give out that you're lookin' for a brace of something to come in on the steamer, and don't know whether they'll be tame or wild, long haired or short, crated or live stock?"

"Live stock!" says he, beamin'. "That's exactly the word I have been trying to think of. That's what I shall ask for. Thanks, awfully, Shorty, for the hint."

"You're welcome," says I. "It looks like you need all the help along that line you can get. Do you remember if this pair was somethin' you sent for, or is it a birthday surprise?"

With that he unloads as much of the tale as he's accumulated up to date. Seems he'd just got a cablegram from some firm in London that signs themselves Tootle, Tupper & Tootle, sayin' that Jack and Jill would be on the Lucania, as per letter.

"And then you lost the letter?" says I.

No, he hadn't lost it, not that he knew of. He supposes that it's with the rest of last week's mail, that he hasn't looked over yet. The trouble was he'd been out of town, and hadn't been back more'n a day or so—and he could read letters when there wa'n't anything else to do. That's Pinckney, from the ground up.

"Why not go back and get the letter now?" says I. "Then you'll know all about Jack and Jill."

"Oh, bother!" says he. "That would spoil all the fun. Let's see what they're like first, and read about them afterwards."

"If it suits you," says I, "it's all the same to me. Only you won't know whether to send for a hostler or an animal trainer."

"Perhaps I'd better engage both," says Pinckney. If they'd been handy, he would have, too; but they wa'n't, so down we sails to the pier, where the folks was comin' ashore.

First thing Pinckney spies after we has rushed the gangplank is a gent with a healthy growth of underbrush on his face and a lot of gold on his sleeves. By the way they got together, I see that they was old friends.

"I hear you have something on board consigned to me, Captain?" says Pinckney. "Something in the way of live stock, eh?" and he pokes Cap in the ribs with his cane.

"Right you are," says Cappie, chucklin' through his whiskers. "And the liveliest kind of live stock we ever carried, sir."

Pinckney gives me the nudge, as much as to say he'd struck it first crack, and then he remarks, "Ah! And where are they now?"

"Why," says the Cap, "they were cruising around the promenade deck a minute ago; but, Lor' bless you, sir! there's no telling where they are now—up on the bridge, or down in the boiler room. They're a pair of colts, those two."

"Colts!" says Pinckney, gaspin'. "You mean ponies, don't you?"

"Well, well, ponies or colts, it's all one. They're lively enough for either, and—Heigho! Here they come, the rascals!"

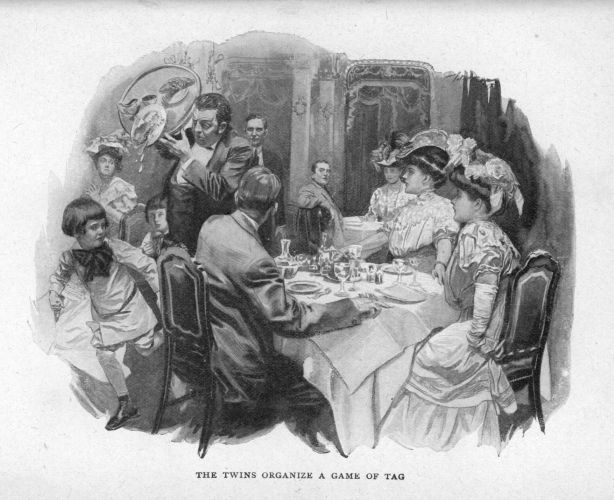

There's whoop and a scamper, and along the deck rushes a couple of six- or seven-year old youngsters, that makes a dive for the Cap'n, catches him around either leg, and almost upsets him. They was twins, and it didn't need the kilt suits just alike and the hair boxed just the same to show it, either. They couldn't have been better matched if they'd been a pair of socks, and the faces of 'em was all grins and mischief. Say, anyone with a heart in him couldn't help takin' to kids like that, providin' they didn't take to him first.

"Here you are, sir," says the Cap'n,—"here's your Jack and Jill, and I wish you luck with them. It'll be a good month before I can get back discipline aboard; but I'm glad I had the bringing of 'em over. Here you are, you holy terrors,—here's the Uncle Pinckney you've been howling for!"

At that they let loose of the Cap, gives a war-whoop in chorus, and lands on Pinckney with a reg'lar flyin' tackle, both talkin' to once. Well say, he didn't know whether to holler for help or laugh. He just stands there and looks foolish, while one of 'em shins up and gets an overhand holt on his lilac necktie.

About then I notices some one bearin' down on us from the other side of the deck. She was one of these tall, straight, deep chested, wide eyed girls, built like the Goddess of Liberty, and with cheeks like a bunch of sweet peas. Say, she was all right, she was; and if it hadn't been for the Paris clothes she was wearin' home I could have made a guess whether she come from Denver, or Dallas, or St. Paul. Anyway, we don't raise many of that kind in New York. She has her eyes on the youngsters.

"Good-bye, Jack and Jill," says she, wavin' her hand at 'em.

But nobody gets past them kids as easy as that. They yells "Miss Gertrude!" at her like she was a mile off, and points to Pinckney, and inside of a minute they has towed 'em together, pushed 'em up against the rail, and is makin' 'em acquainted at the rate of a mile a minute.