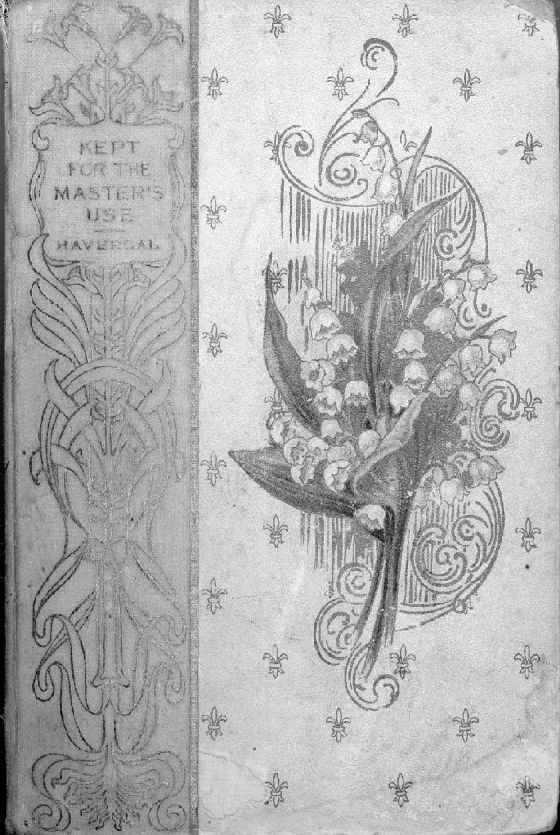

Project Gutenberg's Kept for the Master's Use, by Frances Ridley Havergal

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Kept for the Master's Use

Author: Frances Ridley Havergal

Release Date: March 15, 2010 [EBook #31647]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK KEPT FOR THE MASTER'S USE ***

Produced by Bryan Ness, Stephen Hutcheson and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Kept for

the Master’s

Use

By

Frances Ridley

Havergal

Philadelphia

Henry Altemus Company

Copyrighted 1895, by Henry Altemus.

HENRY ALTEMUS, MANUFACTURER,

PHILADELPHIA.

[3]

CONTENTS.

- I. Our Lives kept for Jesus, 9

- II. Our Moments kept for Jesus, 26

- III. Our Hands kept for Jesus, 34

- IV. Our Feet kept for Jesus, 46

- V. Our Voices kept for Jesus, 51

- VI. Our Lips kept for Jesus, 66

- VII. Our Silver and Gold kept for Jesus, 79

- VIII. Our Intellects kept for Jesus, 91

- IX. Our Wills kept for Jesus, 96

- X. Our Hearts kept for Jesus, 104

- XI. Our Love kept for Jesus, 109

- XII. Our Selves kept for Jesus, 115

- XIII. Christ for us, 122

[5]

PREFATORY NOTE.

My beloved sister Frances finished revising the

proofs of this book shortly before her death on

Whit Tuesday, June 3, 1879, but its publication

was to be deferred till the Autumn.

In appreciation of the deep and general sympathy

flowing in to her relatives, they wish that its

publication should not be withheld. Knowing her

intense desire that Christ should be magnified,

whether by her life or in her death, may it be to

His glory that in these pages she, being dead,

‘Yet speaketh!’

MARIA V. G. HAVERGAL.

Oakhampton, Worchestershire.

[7]

KEPT

FOR

The Master’s Use.

[8]

Take my life, and let it be

Consecrated, Lord, to Thee.

Take my moments and my days;

Let them flow in ceaseless praise.

Take my hands, and let them move

At the impulse of Thy love.

Take my feet, and let them be

Swift and ‘beautiful’ for Thee.

Take my voice, and let me sing

Always, only, for my King.

Take my lips and let them be

Filled with messages from Thee.

Take my silver and my gold;

Not a mite would I withhold.

Take my intellect, and use

Every power as Thou shalt choose.

Take my will and make it Thine;

It shall be no longer mine.

Take my heart; it is Thine own;

It shall be Thy royal throne.

Take my love; my Lord, I pour

At Thy feet its treasure-store.

Take myself, and I will be

Ever, only, ALL for Thee.

[9]

CHAPTER I.

Our Lives kept for Jesus.

‘Keep my life, that it may be

Consecrated, Lord, to Thee.’

Many a heart has echoed the little song:

‘Take my life, and let it be

Consecrated, Lord, to Thee!’

And yet those echoes have not been, in every case

and at all times, so clear, and full, and firm, so

continuously glad as we would wish, and perhaps

expected. Some of us have said:

‘I launch me forth upon a sea

Of boundless love and tenderness;’

and after a little we have found, or fancied, that

there is a hidden leak in our barque, and though we

are doubtless still afloat, yet we are not sailing with

the same free, exultant confidence as at first. What

is it that has dulled and weakened the echo of our

consecration song? what is the little leak that hinders

the swift and buoyant course of our consecrated

life? Holy Father, let Thy loving spirit

[10]

guide the hand that writes, and strengthen the heart

of every one who reads what shall be written, for

Jesus’ sake.

While many a sorrowfully varied answer to these

questions may, and probably will, arise from touched

and sensitive consciences, each being shown by

God’s faithful Spirit the special sin, the special

yielding to temptation which has hindered and

spoiled the blessed life which they sought to enter

and enjoy, it seems to me that one or other of two

things has lain at the outset of the failure and disappointment.

First, it may have arisen from want of the simplest

belief in the simplest fact, as well as want of

trust in one of the simplest and plainest words our

gracious Master ever uttered! The unbelieved fact

being simply that He hears us; the untrusted word

being one of those plain, broad foundation-stones

on which we rested our whole weight, it may be

many years ago, and which we had no idea we ever

doubted, or were in any danger of doubting now,—‘Him

that cometh to Me I will in no wise cast

out.’

‘Take my life!’ We have said it or sung it before

the Lord, it may be many times; but if it were

only once whispered in His ear with full purpose of

heart, should we not believe that He heard it?

And if we know that He heard it, should we not

believe that He has answered it, and fulfilled this,

our heart’s desire? For with Him hearing means

heeding. Then why should we doubt that He did

verily take our lives when we offered them—our

[11]

bodies when we presented them? Have we not

been wronging His faithfulness all this time by

practically, even if unconsciously, doubting whether

the prayer ever really reached Him? And if so, is it

any wonder that we have not realized all the power

and joy of full consecration? By some means or other

He has to teach us to trust implicitly at every step

of the way. And so, if we did not really trust in

this matter, He has had to let us find out our want

of trust by withholding the sensible part of the

blessing, and thus stirring us up to find out why it

is withheld.

An offered gift must be either accepted or refused.

Can He have refused it when He has said,

‘Him that cometh to Me I will in no wise cast out’?

If not, then it must have been accepted. It is just

the same process as when we came to Him first of

all, with the intolerable burden of our sins. There

was no help for it but to come with them to Him,

and take His word for it that He would not and did

not cast us out. And so coming, so believing, we

found rest to our souls; we found that His word

was true, and that His taking away our sins was

a reality.

Some give their lives to Him then and there, and

go forth to live thenceforth not at all unto themselves,

but unto Him who died for them. This is

as it should be, for conversion and consecration

ought to be simultaneous. But practically it is not

very often so, except with those in whom the bringing

out of darkness into marvellous light has been

sudden and dazzling, and full of deepest contrasts.

More frequently the work resembles the case of the

[12]

Hebrew servant described in Exodus xxi., who,

after six years’ experience of a good master’s service,

dedicates himself voluntarily, unreservedly,

and irrevocably to it, saying, ‘I love my master; I

will not go out free;’ the master then accepting and

sealing him to a life-long service, free in law, yet

bound in love. This seems to be a figure of later

consecration founded on experience and love.

And yet, as at our first coming, it is less than

nothing, worse than nothing that we have to bring;

for our lives, even our redeemed and pardoned lives,

are not only weak and worthless, but defiled and

sinful. But thanks be to God for the Altar that

sanctifieth the gift, even our Lord Jesus Christ

Himself! By Him we draw nigh unto God; to

Him, as one with the Father, we offer our living

sacrifice; in Him, as the Beloved of the Father, we

know it is accepted. So, dear friends, when once

He has wrought in us the desire to be altogether

His own, and put into our hearts the prayer, ‘Take

my life,’ let us go on our way rejoicing, believing

that He has taken our lives, our hands, our feet, our

voices, our intellects, our wills, our whole selves, to

be ever, only, all for Him. Let us consider that a

blessedly settled thing; not because of anything we

have felt, or said, or done, but because we know

that He heareth us, and because we know that He

is true to His word.

But suppose our hearts do not condemn us in

this matter, our disappointment may arise from another

cause. It may be that we have not received,

because we have not asked a fuller and further

[13]

blessing. Suppose that we did believe, thankfully

and surely, that the Lord heard our prayer, and that

He did indeed answer and accept us, and set us apart

for Himself; and yet we find that our consecration

was not merely miserably incomplete, but that we

have drifted back again almost to where we were

before. Or suppose things are not quite so bad as

that, still we have not quite all we expected; and

even if we think we can truly say, ‘O God, my heart

is fixed,’ we find that, to our daily sorrow, somehow

or other the details of our conduct do not

seem to be fixed, something or other is perpetually

slipping through, till we get perplexed and distressed.

Then we are tempted to wonder whether

after all there was not some mistake about it, and

the Lord did not really take us at our word, although

we took Him at His word. And then the

struggle with one doubt, and entanglement, and

temptation only seems to land us in another. What

is to be done then?

First, I think, very humbly and utterly honestly

to search and try our ways before our God, or

rather, as we shall soon realize our helplessness to

make such a search, ask Him to do it for us, praying

for His promised Spirit to show us unmistakably

if there is any secret thing with us that is hindering

both the inflow and outflow of His grace to

us and through us. Do not let us shrink from

some unexpected flash into a dark corner; do not

let us wince at the sudden touching of a hidden

plague-spot. The Lord always does His own work

thoroughly if we will only let Him do it; if we put

our case into His hands, He will search and probe

[14]

fully and firmly, though very tenderly. Very painfully,

it may be, but only that He may do the very

thing we want,—cleanse us and heal us thoroughly,

so that we may set off to walk in real newness of

life. But if we do not put it unreservedly into His

hands, it will be no use thinking or talking about

our lives being consecrated to Him. The heart that

is not entrusted to Him for searching, will not be

undertaken by Him for cleansing; the life that

fears to come to the light lest any deed should be

reproved, can never know the blessedness and the

privileges of walking in the light.

But what then? When He has graciously again

put a new song in our mouth, and we are singing,

‘Ransomed, healed, restored, forgiven,

Who like me His praise should sing?’

and again with fresh earnestness we are saying,

‘Take my life, and let it be

Consecrated, Lord, to Thee!’

are we only to look forward to the same disappointing

experience over again? are we always to stand

at the threshold? Consecration is not so much a

step as a course; not so much an act, as a position

to which a course of action inseparably belongs.

In so far as it is a course and a position, there must

naturally be a definite entrance upon it, and a time,

it may be a moment, when that entrance is made.

That is when we say, ‘Take’; but we do not want

to go on taking a first step over and over again.

[15]

What we want now is to be maintained in that position,

and to fulfil that course. So let us go on to

another prayer. Having already said, ‘Take my

life, for I cannot give it to Thee,’ let us now say,

with deepened conviction, that without Christ we

really can do nothing,—‘Keep my life, for I cannot

keep it for Thee.’

Let us ask this with the same simple trust to

which, in so many other things, He has so liberally

and graciously responded. For this is the confidence

that we have in Him, that if we ask anything

according to His will, He heareth us; and if

we know that He hears us, whatsoever we ask, we

know that we have the petitions that we desired of

Him. There can be no doubt that this petition is

according to His will, because it is based upon

many a promise. May I give it to you just as it

floats through my own mind again and again, knowing

whom I have believed, and being persuaded that

He is able to keep that which I have committed unto

Him?

Keep my life, that it may be

Consecrated, Lord, to Thee.

Keep my moments and my days;

Let them flow in ceaseless praise.

Keep my hands, that they may move

At the impulse of Thy love.

Keep my feet, that they may be

Swift and ‘beautiful’ for Thee.

Keep my voice, that I may sing

Always, only, for my King.

[16]

Keep my lips, that they may be

Filled with messages from Thee.

Keep my silver and my gold;

Not a mite would I withhold.

Keep my intellect, and use

Every power as Thou shalt choose.

Keep my will, oh, keep it Thine!

For it is no longer mine.

Keep my heart; it is Thine own;

It is now Thy royal throne.

Keep my love; my Lord, I pour

At Thy feet its treasure-store.

Keep myself, that I may be

Ever, only, ALL for Thee.

Yes! He who is able and willing to take unto

Himself, is no less able and willing to keep for

Himself. Our willing offering has been made by

His enabling grace, and this our King has ‘seen

with joy.’ And now we pray, ‘Keep this for ever

in the imagination of the thoughts of the heart of

Thy people’ (1 Chron. xxix. 17, 18).

This blessed ‘taking,’ once for all, which we

may quietly believe as an accomplished fact, followed

by the continual ‘keeping,’ for which He

will be continually inquired of by us, seems analogous

to the great washing by which we have part

in Christ, and the repeated washing of the feet for

which we need to be continually coming to Him.

For with the deepest and sweetest consciousness

[17]

that He has indeed taken our lives to be His very

own, the need of His active and actual keeping of

them in every detail and at every moment is most

fully realized. But then we have the promise of

our faithful God, ‘I the Lord do keep it, I will

keep it night and day.’ The only question is, will

we trust this promise, or will we not? If we do, we

shall find it come true. If not, of course it will

not be realized. For unclaimed promises are like

uncashed cheques; they will keep us from bankruptcy,

but not from want. But if not, why not?

What right have we to pick out one of His faithful

sayings, and say we don’t expect Him to fulfil

that? What defence can we bring, what excuse can

we invent, for so doing?

If you appeal to experience against His faithfulness

to His word, I will appeal to experience too,

and ask you, did you ever really trust Jesus to fulfil

any word of His to you, and find your trust

deceived? As to the past experience of the details

of your life not being kept for Jesus, look a little

more closely at it, and you will find that though you

may have asked, you did not trust. Whatever you

did really trust Him to keep, He has kept, and the

unkept things were never really entrusted. Scrutinize

this past experience as you will, and it will

only bear witness against your unfaithfulness, never

against His absolute faithfulness.

Yet this witness must not be unheeded. We

must not forget the things that are behind till they

are confessed and forgiven. Let us now bring all

this unsatisfactory past experience, and, most of all,

the want of trust which has been the poison-spring

[18]

of its course, to the precious blood of Christ, which

cleanseth us, even us, from all sin, even this sin.

Perhaps we never saw that we were not trusting

Jesus as He deserves to be trusted; if so, let us

wonderingly hate ourselves the more that we could

be so trustless to such a Saviour, and so sinfully

dark and stupid that we did not even see it. And

oh, let us wonderingly love Him the more that He

has been so patient and gentle with us, upbraiding

not, though in our slow-hearted foolishness we have

been grieving Him by this subtle unbelief, and

then, by His grace, may we enter upon a new era

of experience, our lives kept for Him more fully

than ever before, because we trust Him more simply

and unreservedly to keep them!

Here we must face a question, and perhaps a difficulty.

Does it not almost seem as if we were at

this point led to trusting to our trust, making everything

hinge upon it, and thereby only removing a

subtle dependence upon ourselves one step farther

back, disguising instead of renouncing it? If

Christ’s keeping depends upon our trusting, and

our continuing to trust depends upon ourselves, we

are in no better or safer position than before, and

shall only be landed in a fresh series of disappointments.

The old story, something for the sinner to

do, crops up again here, only with the ground

shifted from ‘works’ to trust. Said a friend to me,

‘I see now! I did trust Jesus to do everything

else for me, but I thought that this trusting was

something that I had got to do.’ And so, of

course, what she ‘had got to do’ had been a

[19]

perpetual effort and frequent failure. We can no

more trust and keep on trusting than we can do

anything else of ourselves. Even in this it must

be ‘Jesus only’; we are not to look to Him only to

be the Author and Finisher of our faith, but we are

to look to Him for all the intermediate fulfilment

of the work of faith (2 Thess. i. 11); we must ask

Him to go on fulfilling it in us, committing even

this to His power.

For we both may and must

Commit our very faith to Him,

Entrust to him our trust.

What a long time it takes us to come down to the

conviction, and still more to the realization of the

fact that without Him we can do nothing, but that

He must work all our works in us! This is the

work of God, that ye believe in Him whom He has

sent. And no less must it be the work of God that

we go on believing, and that we go on trusting.

Then, dear friends, who are longing to trust Him

with unbroken and unwavering trust, cease the

effort and drop the burden, and now entrust your

trust to Him! He is just as well able to keep that

as any other part of the complex lives which we

want Him to take and keep for Himself. And oh,

do not pass on content with the thought, ‘Yes,

that is a good idea; perhaps I should find that a

great help!’ But, ‘Now, then, do it.’ It is no

help to the sailor to see a flash of light across a

dark sea, if he does not instantly steer accordingly.

Consecration is not a religiously selfish thing. If

it sinks into that, it ceases to be consecration. We

[20]

want our lives kept, not that we may feel happy,

and be saved the distress consequent on wandering,

and get the power with God and man, and all the

other privileges linked with it. We shall have all

this, because the lower is included in the higher;

but our true aim, if the love of Christ constraineth

us, will be far beyond this. Not for ‘me’ at all but

‘for Jesus’; not for my safety, but for His glory;

not for my comfort, but for His joy; not that I may

find rest, but that He may see the travail of His soul,

and be satisfied! Yes, for Him I want to be kept.

Kept for His sake; kept for His use; kept to be His

witness; kept for His joy! Kept for Him, that in

me He may show forth some tiny sparkle of His

light and beauty; kept to do His will and His work in

His own way; kept, it may be, to suffer for His sake;

kept for Him, that He may do just what seemeth

Him good with me; kept, so that no other lord

shall have any more dominion over me, but that

Jesus shall have all there is to have;—little enough,

indeed, but not divided or diminished by any other

claim. Is not this, O you who love the Lord—is

not this worth living for, worth asking for, worth

trusting for?

This is consecration, and I cannot tell you the

blessedness of it. It is not the least use arguing

with one who has had but a taste of its blessedness,

and saying to him, ‘How can these things be?’ It

is not the least use starting all sorts of difficulties

and theoretical suppositions about it with such a

one, any more than it was when the Jews argued

with the man who said, ‘One thing I know, that

whereas I was blind, now I see.’ The Lord Jesus

[21]

does take the life that is offered to Him, and He

does keep the life for Himself that is entrusted to

Him; but until the life is offered we cannot know

the taking, and until the life is entrusted we cannot

know or understand the keeping. All we can do is

to say, ‘O taste and see!’ and bear witness to the

reality of Jesus Christ, and set to our seal that we

have found Him true to His every word, and that

we have proved Him able even to do exceeding

abundantly above all we asked or thought. Why

should we hesitate to bear this testimony? We

have done nothing at all; we have, in all our

efforts, only proved to ourselves, and perhaps to

others, that we had no power either to give or keep

our lives. Why should we not, then, glorify His

grace by acknowledging that we have found Him so

wonderfully and tenderly gracious and faithful in

both taking and keeping as we never supposed or

imagined? I shall never forget the smile and emphasis

with which a poor working man bore this

witness to his Lord. I said to him, ‘Well, H., we

have a good Master, have we not?’ ‘Ah,’ said he,

‘a deal better than ever I thought!’ That summed

up his experience, and so it will sum up the experience

of every one who will but yield their lives

wholly to the same good Master.

I cannot close this chapter without a word with

those, especially my younger friends, who, although

they have named the name of Christ, are saying,

‘Yes, this is all very well for some people, or for

older people, but I am not ready for it; I can’t say

I see my way to this sort of thing.’ I am going to

[22]

take the lowest ground for a minute, and appeal to

your ‘past experience.’ Are you satisfied with

your experience of the other ‘sort of thing’? Your

pleasant pursuits, your harmless recreations, your

nice occupations, even your improving ones, what

fruit are you having from them? Your social intercourse,

your daily talks and walks, your investments

of all the time that remains to you over and above

the absolute duties God may have given you, what

fruit that shall remain have you from all this? Day

after day passes on, and year after year, and what

shall the harvest be? What is even the present return?

Are you getting any real and lasting satisfaction

out of it all? Are you not finding that

things lose their flavour, and that you are spending

your strength day after day for nought? that you

are no more satisfied than you were a year ago—rather

less so, if anything? Does not a sense of

hollowness and weariness come over you as you go

on in the same round, perpetually getting through

things only to begin again? It cannot be otherwise.

Over even the freshest and purest earthly

fountains the Hand that never makes a mistake has

written, ‘He that drinketh of this water shall thirst

again.’ Look into your own heart and you will

find a copy of that inscription already traced,

‘Shall thirst again.’ And the characters are being

deepened with every attempt to quench the inevitable

thirst and weariness in life, which can only be

satisfied and rested in full consecration to God.

For ‘Thou hast made us for Thyself, and the heart

never resteth till it findeth rest in Thee.’ To-day

I tell you of a brighter and happier life, whose inscription

[23]

is, ‘Shall never thirst,’—a life that is no

dull round-and-round in a circle of unsatisfactorinesses,

but a life that has found its true and entirely

satisfactory centre, and set itself towards a

shining and entirely satisfactory goal, whose brightness

is cast over every step of the way. Will you

not seek it?

Do not shrink, and suspect, and hang back from

what it may involve, with selfish and unconfiding

and ungenerous half-heartedness. Take the word

of any who have willingly offered themselves unto

the Lord, that the life of consecration is ‘a deal

better than they thought!’ Choose this day whom

you will serve with real, thorough-going, whole-hearted

service, and He will receive you; and you

will find, as we have found, that He is such a good

Master that you are satisfied with His goodness,

and that you will never want to go out free. Nay,

rather take His own word for it; see what He says:

‘If they obey and serve Him, they shall spend their

days in prosperity, and their years in pleasures.’

You cannot possibly understand that till you are

really in His service! For He does not give, nor

even show, His wages before you enter it. And He

says, ‘My servants shall sing for joy of heart.’ But

you cannot try over that song to see what it is like,

you cannot even read one bar of it, till your nominal

or even promised service is exchanged for real

and undivided consecration. But when He can

call you ‘My servant,’ then you will find yourself

singing for joy of heart, because He says you shall.

‘And who, then, is willing to consecrate his service

this day unto the Lord?’

[24]

‘Do not startle at the term, or think, because

you do not understand all it may include, you are

therefore not qualified for it. I dare say it comprehends

a great deal more than either you or I

understand, but we can both enter into the spirit of

it, and the detail will unfold itself as long as our

probation shall last. Christ demands a hearty consecration

in will, and He will teach us what that

involves in act.’

This explains the paradox that ‘full consecration’

may be in one sense the act of a moment, and in

another the work of a lifetime. It must be complete

to be real, and yet if real, it is always incomplete;

a point of rest, and yet a perpetual progression.

Suppose you make over a piece of ground to

another person. You give it up, then and there,

entirely to that other; it is no longer in your own

possession; you no longer dig and sow, plant and

reap, at your discretion or for your own profit. His

occupation of it is total; no other has any right to

an inch of it; it is his affair thenceforth what crops

to arrange for and how to make the most of it. But

his practical occupation of it may not appear all at

once. There may be waste land which he will take

into full cultivation only by degrees, space wasted

for want of draining or by over fencing, and odd

corners lost for want of enclosing; fields yielding

smaller returns than they might because of hedgerows

too wide and shady, and trees too many and

spreading, and strips of good soil trampled into

uselessness for want of defined pathways.

Just so is it with our lives. The transaction of,

[25]

so to speak, making them over to God is definite

and complete. But then begins the practical development

of consecration. And here He leads on

‘softly, according as the children be able to endure.’

I do not suppose any one sees anything like

all that it involves at the outset. We have not

a notion what an amount of waste of power there

has been in our lives; we never measured out the

odd corners and the undrained bits, and it never

occurred to us what good fruit might be grown in

our straggling hedgerows, nor how the shade of our

trees has been keeping the sun from the scanty

crops. And so, season by season, we shall be sometimes

not a little startled, yet always very glad, as

we find that bit by bit the Master shows how much

more may be made of our ground, how much more

He is able to make of it than we did; and we shall

be willing to work under Him and do exactly what

He points out, even if it comes to cutting down a

shady tree, or clearing out a ditch full of pretty

weeds and wild-flowers.

As the seasons pass on, it will seem as if there

was always more and more to be done; the very

fact that He is constantly showing us something

more to be done in it, proving that it is really His

ground. Only let Him have the ground, no matter

how poor or overgrown the soil may be, and then

‘He will make her wilderness like Eden, and her

desert like the garden of the Lord.’ Yes, even our

‘desert’! And then we shall sing, ‘My

beloved has gone down into His garden, to the

beds of spices, to feed in the gardens and to

gather lilies.’

[26]

Made for Thyself, O God!

Made for Thy love, Thy service, Thy delight;

Made to show forth Thy wisdom, grace, and might;

Made for Thy praise, whom veiled archangels laud:

Oh, strange and glorious thought, that we may be

A joy to Thee!

Yet the heart turns away

From this grand destiny of bliss, and deems

’Twas made for its poor self, for passing dreams,

Chasing illusions melting day by day,

Till for ourselves we read on this world’s best,

‘This is not rest!’

CHAPTER II.

Our Moments kept for Jesus.

‘Keep my moments and my days;

Let them flow in ceaseless praise.’

It may be a little help to writer and reader if we

consider some of the practical details of the life

which we desire to have ‘kept for Jesus’ in the

order of the little hymn at the beginning of this

book, with the one word ‘take’ changed to ‘keep.’

So we will take a couplet for each chapter.

The first point that naturally comes up is that

which is almost synonymous with life—our time.

And this brings us at once face to face with one of

our past difficulties, and its probable cause.

[27]

When we take a wide sweep, we are so apt to

be vague. When we are aiming at generalities

we do not hit the practicalities. We forget that

faithfulness to principle is only proved by faithfulness

in detail. Has not this vagueness had

something to do with the constant ineffectiveness

of our feeble desire that our time should be devoted

to God?

In things spiritual, the greater does not always

include the less, but, paradoxically, the less more

often includes the greater. So in this case, time is

entrusted to us to be traded with for our Lord. But

we cannot grasp it as a whole. We instinctively

break it up ere we can deal with it for any purpose.

So when a new year comes round, we commit it with

special earnestness to the Lord. But as we do so,

are we not conscious of a feeling that even a year is

too much for us to deal with? And does not this

feeling, that we are dealing with a larger thing than

we can grasp, take away from the sense of reality?

Thus we are brought to a more manageable measure;

and as the Sunday mornings or the Monday mornings

come round, we thankfully commit the opening

week to Him, and the sense of help and rest is renewed

and strengthened. But not even the six or

seven days are close enough to our hand; even

to-morrow exceeds our tiny grasp, and even to-morrow’s

grace is therefore not given to us. So we

find the need of considering our lives as a matter of

day by day, and that any more general committal and

consecration of our time does not meet the case so

truly. Here we have found much comfort and help,

and if results have not been entirely satisfactory,

[28]

they have, at least, been more so than before we

reached this point of subdivision.

But if we have found help and blessing by going

a certain distance in one direction, is it not probable

we shall find more if we go farther in the same?

And so, if we may commit the days to our Lord,

why not the hours, and why not the moments? And

may we not expect a fresh and special blessing in

so doing?

We do not realize the importance of moments.

Only let us consider those two sayings of God about

them, ‘In a moment shall they die,’ and, ‘We shall

all be changed in a moment,’ and we shall think

less lightly of them. Eternal issues may hang upon

any one of them, but it has come and gone before

we can even think about it. Nothing seems less

within the possibility of our own keeping, yet

nothing is more inclusive of all other keeping.

Therefore let us ask Him to keep them for us.

Are they not the tiny joints in the harness through

which the darts of temptation pierce us? Only give

us time, we think, and we should not be overcome.

Only give us time, and we could pray and resist,

and the devil would flee from us! But he comes

all in a moment; and in a moment—an unguarded,

unkept one—we utter the hasty or exaggerated word,

or think the un-Christ-like thought, or feel the un-Christ-like

impatience or resentment.

But even if we have gone so far as to say, ‘Take

my moments,’ have we gone the step farther, and

really let Him take them—really entrusted them to

Him? It is no good saying ‘take,’ when we do not

let go. How can another keep that which we are keeping

[29]

hold of? So let us, with full trust in His power,

first commit these slippery moments to Him,—put

them right into His hand,—and then we may trustfully

and happily say, ‘Lord, keep them for me!

Keep every one of the quick series as it arises. I

cannot keep them for Thee; do Thou keep them

for Thyself!’

But the sanctified and Christ-loving heart cannot

be satisfied with only negative keeping. We do not

want only to be kept from displeasing Him, but to

be kept always pleasing Him. Every ‘kept from’

should have its corresponding and still more blessed

‘kept for.’ We do not want our moments to be

simply kept from Satan’s use, but kept for His use;

we want them to be not only kept from sin, but kept

for His praise.

Do you ask, ‘But what use can he make of mere

moments?’ I will not stay to prove or illustrate

the obvious truth that, as are the moments so will

be the hours and the days which they build. You

understand that well enough. I will answer your

question as it stands.

Look back through the history of the Church

in all ages, and mark how often a great work and

mighty influence grew out of a mere moment in the

life of one of God’s servants; a mere moment, but

overshadowed and filled with the fruitful power of

the Spirit of God. The moment may have been

spent in uttering five words, but they have fed five

thousand, or even five hundred thousand. Or it

may have been lit by the flash of a thought that

has shone into hearts and homes throughout the

[30]

land, and kindled torches that have been borne

into earth’s darkest corners. The rapid speaker

or the lonely thinker little guessed what use

his Lord was making of that single moment. There

was no room in it for even a thought of that. If

that moment had not been, though perhaps unconsciously,

‘kept for Jesus,’ but had been otherwise

occupied, what a harvest to His praise would have

been missed!

The same thing is going on every day. It is

generally a moment—either an opening or a culminating

one—that really does the work. It is not

so often a whole sermon as a single short sentence

in it that wings God’s arrow to a heart. It is seldom

a whole conversation that is the means of

bringing about the desired result, but some sudden

turn of thought or word, which comes with the

electric touch of God’s power. Sometimes it is

less than that; only a look (and what is more momentary?)

has been used by Him for the pulling

down of strongholds. Again, in our own quiet

waiting upon God, as moment after moment glides

past in the silence at His feet, the eye resting upon

a page of His Word, or only looking up to Him

through the darkness, have we not found that He

can so irradiate one passing moment with His light

that its rays never die away, but shine on and on

through days and years? Are not such moments

proved to have been kept for Him? And if some,

why not all?

This view of moments seems to make it clearer

that it is impossible to serve two masters, for it is

evident that the service of a moment cannot be

[31]

divided. If it is occupied in the service of self, or

any other master, it is not at the Lord’s disposal;

He cannot make use of what is already occupied.

Oh, how much we have missed by not placing

them at his disposal! What might He not have

done with the moments freighted with self or

loaded with emptiness, which we have carelessly

let drift by! Oh, what might have been if they

had all been kept for Jesus! How He might

have filled them with His light and life, enriching

our own lives that have been impoverished by the

waste, and using them in far-spreading blessing

and power!

While we have been undervaluing these fractions

of eternity, what has our gracious God been doing

in them? How strangely touching are the words,

‘What is man, that Thou shouldest set Thine heart

upon him, and that Thou shouldest visit him every

morning, and try him every moment?’ Terribly

solemn and awful would be the thought that He

has been trying us every moment, were it not for

the yearning gentleness and love of the Father

revealed in that wonderful expression of wonder,

‘What is man, that Thou shouldest set Thine heart

upon him?’ Think of that ceaseless setting of

His heart upon us, careless and forgetful children

as we have been! And then think of those other

words, none the less literally true because given

under a figure: ‘I, the Lord, do keep it; I will

water it every moment.’

We see something of God’s infinite greatness

and wisdom when we try to fix our dazzled gaze

[32]

on infinite space. But when we turn to the marvels

of the microscope, we gain a clearer view and

more definite grasp of these attributes by gazing on

the perfection of His infinitesimal handiworks.

Just so, while we cannot realize the infinite love

which fills eternity, and the infinite vistas of the

great future are ‘dark with excess of light’ even to

the strongest telescopes of faith, we see that love

magnified in the microscope of the moments,

brought very close to us, and revealing its unspeakable

perfection of detail to our wondering sight.

But we do not see this as long as the moments

are kept in our own hands. We are like little

children closing our fingers over diamonds. How

can they receive and reflect the rays of light, analyzing

them into all the splendour of their prismatic

beauty, while they are kept shut up tight in

the dirty little hands? Give them up; let our

Father hold them for us, and throw His own great

light upon them, and then we shall see them full

of fair colours of His manifold loving-kindnesses;

and let Him always keep them for us, and then we

shall always see His light and His love reflected in

them.

And then, surely, they shall be filled with praise.

Not that we are to be always singing hymns, and

using the expressions of other people’s praise, any

more than the saints in glory are always literally

singing a new song. But praise will be the tone,

the colour, the atmosphere in which they flow;

none of them away from it or out of it.

Is it a little too much for them all to ‘flow in

ceaseless praise’? Well, where will you stop?

[33]

What proportion of your moments do you think

enough for Jesus? How many for the spirit of

praise, and how many for the spirit of heaviness?

Be explicit about it, and come to an understanding.

If He is not to have all, then how much? Calculate,

balance, and apportion. You will not be able

to do this in heaven—you know it will be all praise

there; but you are free to halve your service of

praise here, or to make the proportion what you

will.

Yet,—He made you for His glory.

Yet,—He chose you that you should be to the

praise of His glory.

Yet,—He loves you every moment, waters you

every moment, watches you unslumberingly, cares

for you unceasingly.

Yet,—He died for you!

Dear friends, one can hardly write it without

tears. Shall you or I remember all this love, and

hesitate to give all our moments up to Him? Let

us entrust Him with them, and ask Him to keep

them all, every single one, for His own beloved

self, and fill them all with His praise, and let them

all be to His praise!

[34]

Chapter III.

Our Hands Kept for Jesus.

‘Keep my hands, that they may move

At the impulse of Thy love.’

When the Lord has said to us, ‘Is thine heart

right, as My heart is with thy heart?’ the

next word seems to be, ‘If it be, give Me thine

hand.’

What a call to confidence, and love, and free,

loyal, happy service is this! and how different will

the result of its acceptance be from the old lamentation:

‘We labour and have no rest; we have

given the hand to the Egyptians and to the Assyrians.’

In the service of these ‘other lords,’ under

whatever shape they have presented themselves, we

shall have known something of the meaning of having

‘both the hands full with travail and vexation

of spirit.’ How many a thing have we ‘taken in

hand,’ as we say, which we expected to find an

agreeable task, an interest in life, a something

towards filling up that unconfessed ‘aching void’

which is often most real when least acknowledged;

and after a while we have found it change under our

hands into irksome travail, involving perpetual vexation

[35]

of spirit! The thing may have been of the earth

and for the world, and then no wonder it failed to satisfy

even the instinct of work, which comes natural

to many of us. Or it may have been right enough

in itself, something for the good of others so far as

we understood their good, and unselfish in all but

unravelled motive, and yet we found it full of

tangled vexations, because the hands that held it

were not simply consecrated to God. Well, if so,

let us bring these soiled and tangle-making hands to

the Lord, ‘Let us lift up our heart with our hands’

to Him, asking Him to clear and cleanse them.

If He says, ‘What is that in thine hand?’ let us

examine honestly whether it is something which He

can use for His glory or not. If not, do not let us

hesitate an instant about dropping it. It may be

something we do not like to part with; but the

Lord is able to give thee much more than this, and

the first glimpse of the excellency of the knowledge

of Christ Jesus your Lord will enable us to count

those things loss which were gain to us.

But if it is something which He can use, He will

make us do ever so much more with it than before.

Moses little thought what the Lord was going to

make him do with that ‘rod in his hand’! The

first thing he had to do with it was to ‘cast it on

the ground,’ and see it pass through a startling

change. After this he was commanded to take it

up again, hard and terrifying as it was to do so.

But when it became again a rod in his hand, it was

no longer what it was before, the simple rod of a

wandering desert shepherd. Henceforth it was

‘the rod of God in his hand’ (Ex. iv. 20), wherewith

[36]

he should do signs, and by which God Himself

would do ‘marvellous things’ (Ps. lxxviii. 12).

If we look at any Old Testament text about consecration,

we shall see that the marginal reading of

the word is, ‘fill the hand’ (e. g.

Ex. xxviii. 41;

1 Chron. xxix. 5). Now, if our hands are full of

‘other things,’ they cannot be filled with ‘the

things that are Jesus Christ’s’; there must be emptying

before there can be any true filling. So if we

are sorrowfully seeing that our hands have not been

kept for Jesus, let us humbly begin at the beginning,

and ask Him to empty them thoroughly, that

He may fill them completely.

For they must be emptied. Either we come to

our Lord willingly about it, letting Him unclasp

their hold, and gladly dropping the glittering

weights they have been carrying, or, in very love,

He will have to force them open, and wrench from

the reluctant grasp the ‘earthly things’ which are

so occupying them that He cannot have His rightful

use of them. There is only one other alternative,

a terrible one,—to be let alone till the day

comes when not a gentle Master, but the relentless

king of terrors shall empty the trembling hands as

our feet follow him out of the busy world into the

dark valley, for ‘it is certain we can carry nothing

out.’

Yet the emptying and the filling are not all that

has to be considered. Before the hands of the

priests could be filled with the emblems of consecration,

they had to be laid upon the emblem of

[37]

atonement (Lev. viii. 14, etc.). That came first.

‘Aaron and his sons laid their hands upon the head

of the bullock for the sin-offering.’ So the transference

of guilt to our Substitute, typified by that

act, must precede the dedication of ourselves to

God.

‘My faith would lay her hand

On that dear head of Thine,

While like a penitent I stand,

And there confess my sin.’

The blood of that Holy Substitute was shed ‘to

make reconciliation upon the altar.’ Without that

reconciliation we cannot offer and present ourselves

to God; but this being made, Christ Himself

presents us. And you, that were sometime

alienated, and enemies in your mind by wicked

works, yet now hath He reconciled in the body of

His flesh through death, to present you holy and

unblamable and unreprovable in His sight.

Then Moses ‘brought the ram for the burnt-offering;

and Aaron and his sons laid their hands

upon the head of the ram, and Moses burnt the

whole ram upon the altar; it was a burnt-offering

for a sweet savour, and an offering made by fire unto

the Lord.’ Thus Christ’s offering was indeed a

whole one, body, soul, and spirit, each and all suffering

even unto death. These atoning sufferings,

accepted by God for us, are, by our own free act,

accepted by us as the ground of our acceptance.

Then, reconciled and accepted, we are ready for

consecration; for then ‘he brought the other ram;

the ram of consecration; and Aaron and his sons

[38]

laid their hands upon the head of the ram.’ Here

we see Christ, ‘who is consecrated for evermore.’

We enter by faith into union with Him who said,

‘For their sakes I sanctify Myself, that they also

might be sanctified through the truth.’

After all this, their hands were filled with ‘consecrations

for a sweet savour,’ so, after laying the

hand of our faith upon Christ, suffering and dying

for us, we are to lay that very same hand of faith,

and in the very same way, upon Him as consecrated

for us, to be the source and life and power of our

consecration. And then our hands shall be filled

with ‘consecrations,’ filled with Christ, and filled

with all that is a sweet savour to God in Him.

‘And who then is willing to fill his hand this

day unto the Lord?’ Do you want an added

motive? Listen again: ‘Fill your hands to-day

to the Lord, that He may bestow upon you a blessing

this day.’ Not a long time hence, not even to-morrow,

but ‘this day.’ Do you not want a blessing?

Is not your answer to your Father’s ‘What

wilt thou?’ the same as Achsah’s, ‘Give me a blessing!’

Here is His promise of just what you so

want; will you not gladly fulfil His condition? A

blessing shall immediately follow. He does not

specify what it shall be; He waits to reveal it. You

will find it such a blessing as you had not supposed

could be for you—a blessing that shall verily make

you rich, with no sorrow added—a blessing this

day.

All that has been said about consecration applies

to our literal members. Stay a minute, and look

[39]

at your hand, the hand that holds this little book as

you read it. See how wonderfully it is made; how

perfectly fitted for what it has to do; how ingeniously

connected with the brain, so as to yield that

instantaneous and instinctive obedience without

which its beautiful mechanism would be very little

good to us! Your hand, do you say? Whether it

is soft and fair with an easy life, or rough and strong

with a working one, or white and weak with illness,

it is the Lord Jesus Christ’s. It is not your own

at all; it belongs to Him. He made it, for without

Him was not anything made that was made, not

even your hand. And He has the added right of

purchase—He has bought it that it might be one of

His own instruments. We know this very well, but

have we realized it? Have we really let Him have

the use of these hands of ours? and have we ever

simply and sincerely asked Him to keep them for

His own use?

Does this mean that we are always to be doing

some definitely ‘religious’ work, as it is called?

No, but that all that we do is to be always definitely

done for Him. There is a great difference. If the

hands are indeed moving ‘at the impulse of His

love,’ the simplest little duties and acts are transfigured

into holy service to the Lord.

‘A servant with this clause

Makes drudgery divine;

Who sweeps a room as for Thy laws,

Makes that and the action fine.’

George Herbert.

A Christian school-girl loves Jesus; she wants to

please Him all day long, and so she practices her

[40]

scales carefully and conscientiously. It is at the

impulse of His love that her fingers move so steadily

through the otherwise tiresome exercises. Some

day her Master will find a use for her music; but

meanwhile it may be just as really done unto Him

as if it were Mr. Sankey at his organ, swaying the

hearts of thousands. The hand of a Christian lad

traces his Latin verses, or his figures, or his copying.

He is doing his best, because a banner has

been given him that it may be displayed, not so

much by talk as by continuance in well-doing.

And so, for Jesus’ sake, his hand moves accurately

and perseveringly.

A busy wife, or daughter, or servant has a number

of little manual duties to perform. If these are

done slowly and leisurely, they may be got through,

but there will not be time left for some little service

to the poor, or some little kindness to a suffering or

troubled neighbour, or for a little quiet time alone

with God and His word. And so the hands move

quickly, impelled by the loving desire for service or

communion, kept in busy motion for Jesus’ sake.

Or it may be that the special aim is to give no occasion

of reproach to some who are watching, but

so to adorn the doctrine that those may be won by

the life who will not be won by the word. Then

the hands will have their share to do; they will

move carefully, neatly, perhaps even elegantly,

making every thing around as nice as possible, letting

their intelligent touch be seen in the details of

the home, and even of the dress, doing or arranging

all the little things decently and in order for Jesus’

sake. And so on with every duty in every position.

[41]

It may seem an odd idea, but a simple glance at

one’s hand, with the recollection, ‘This hand is

not mine; it has been given to Jesus, and it must

be kept for Jesus,’ may sometimes turn the scale in

a doubtful matter, and be a safeguard from certain

temptations. With that thought fresh in your mind

as you look at your hand, can you let it take up

things which, to say the very least, are not ‘for

Jesus’? things which evidently cannot be used, as

they most certainly are not used, either for Him or

by Him? Cards, for instance! Can you deliberately

hold in it books of a kind which you know

perfectly well, by sadly repeated experience, lead

you farther from instead of nearer to Him? books

which must and do fill your mind with those ‘other

things’ which, entering in, choke the word? books

which you would not care to read at all, if your

heart were burning within you at the coming of

His feet to bless you? Next time any temptation

of this sort approaches, just look at your hand!

It was of a literal hand that our Lord Jesus spoke

when He said, ‘Behold, the hand of him that betrayeth

Me is with Me on the table;’ and, ‘He

that dippeth his hand with Me in the dish, the

same shall betray Me.’ A hand so near to Jesus,

with Him on the table, touching His own hand in

the dish at that hour of sweetest, and closest, and

most solemn intercourse, and yet betraying Him!

That same hand taking the thirty pieces of silver!

What a tremendous lesson of the need of keeping

for our hands! Oh that every hand that is with

Him at His sacramental table, and that takes the

memorial bread, may be kept from any faithless

[42]

and loveless motion! And again, it was by literal

‘wicked hands’ that our Lord Jesus was crucified

and slain. Does not the thought that human

hands have been so treacherous and cruel to our

beloved Lord make us wish the more fervently

that our hands may be totally faithful and devoted

to Him?

Danger and temptation to let the hands move at

other impulses is every bit as great to those who

have nothing else to do but to render direct service,

and who think they are doing nothing else. Take

one practical instance—our letter-writing. Have

we not been tempted (and fallen before the temptation),

according to our various dispositions, to let

the hand that holds the pen move at the impulse to

write an unkind thought of another; or to say a

clever and sarcastic thing, or a slightly coloured

and exaggerated thing, which will make our point

more telling; or to let out a grumble or a suspicion;

or to let the pen run away with us into flippant

and trifling words, unworthy of our high and

holy calling? Have we not drifted away from the

golden reminder, ‘Should he reason with unprofitable

talk, and with speeches wherewith he can do

no good?’ Why has this been, perhaps again and

again? Is it not for want of putting our hands

into our dear Master’s hand, and asking and trusting

Him to keep them? He could have kept; He

would have kept!

Whatever our work or our special temptations

may be, the principle remains the same, only let us

apply it for ourselves.

[43]

Perhaps one hardly needs to say that the kept

hands will be very gentle hands. Quick, angry

motions of the heart will sometimes force themselves

into expression by the hand, though the

tongue may be restrained. The very way in which

we close a door or lay down a book may be a victory

or a defeat, a witness to Christ’s keeping or a

witness that we are not truly being kept. How can

we expect that God will use this member as an instrument

of righteousness unto Him, if we yield it

thus as an instrument of unrighteousness unto sin?

Therefore let us see to it, that it is at once yielded

to Him whose right it is; and let our sorrow that

it should have been even for an instant desecrated

to Satan’s use, lead us to entrust it henceforth to

our Lord, to be kept by the power of God through

faith ‘for the Master’s use.’

For when the gentleness of Christ dwells in us,

He can use the merest touch of a finger. Have we

not heard of one gentle touch on a wayward shoulder

being the turning-point of a life? I have known

a case in which the Master made use of less than

that—only the quiver of a little finger being made

the means of touching a wayward heart.

What must the touch of the Master’s own hand

have been! One imagines it very gentle, though

so full of power. Can He not communicate both

the power and the gentleness? When He touched

the hand of Peter’s wife’s mother, she arose and

ministered unto them. Do you not think the hand

which Jesus had just touched must have ministered

very excellently? As we ask Him to ‘touch our lips

with living fire,’ so that they may speak effectively

[44]

for Him, may we not ask Him to touch our hands,

that they may minister effectively, and excel in all

that they find to do for Him? Then our hands

shall be made strong by the hands of the Mighty

God of Jacob.

It is very pleasant to feel that if our hands are indeed

our Lord’s, we may ask Him to guide them,

and strengthen them, and teach them. I do not

mean figuratively, but quite literally. In everything

they do for Him (and that should be everything

we ever undertake) we want to do it well—better

and better. ‘Seek that ye may excel.’ We

are too apt to think that He has given us certain

natural gifts, but has nothing practically to do with

the improvement of them, and leaves us to ourselves

for that. Why not ask him to make these

hands of ours more handy for His service, more

skilful in what is indicated as the ‘next thynge’ they

are to do? The ‘kept’ hands need not be clumsy

hands. If the Lord taught David’s hands to war and

his fingers to fight, will He not teach our hands, and

fingers too, to do what He would have them do?

The Spirit of God must have taught Bezaleel’s

hands as well as his head, for he was filled with it

not only that he might devise cunning works, but

also in cutting of stones and carving of timber. And

when all the women that were wise-hearted did spin

with their hands, the hands must have been made

skilful as well as the hearts made wise to prepare

the beautiful garments and curtains.

There is a very remarkable instance of the hand

of the Lord, which I suppose signifies in that case

[45]

the power of His Spirit, being upon the hand of a

man. In 1 Chron. xxviii. 19, we read: ‘All this,

said David, the Lord made me understand in writing

by His hand upon me, even all the works of

this pattern.’ This cannot well mean that the Lord

gave David a miraculously written scroll, because,

a few verses before, it says that he had it all by the

Spirit. So what else can it mean but that as David

wrote, the hand of the Lord was upon his hand,

impelling him to trace, letter by letter, the right

words of description for all the details of the temple

that Solomon should build, with its courts and

chambers, its treasuries and vessels? Have we not

sometimes sat down to write, feeling perplexed and

ignorant, and wishing some one were there to tell

us what to say? At such a moment, whether it

were a mere note for post, or a sheet for press, it is

a great comfort to recollect this mighty laying of a

Divine hand upon a human one, and ask for the

same help from the same Lord. It is sure to be

given!

And now, dear friend, what about your own

hands? Are they consecrated to the Lord who

loves you? And if they are, are you trusting Him

to keep them, and enjoying all that is involved in

that keeping? Do let this be settled with your

Master before you go on to the next chapter.

After all, this question will hinge on another, Do

you love Him? If you really do, there can surely

be neither hesitation about yielding them to Him,

nor about entrusting them to Him to be kept. Does

He love you? That is the truer way of putting it;

[46]

for it is not our love to Christ, but the love of

Christ to us which constraineth us. And this is

the impulse of the motion and the mode of the

keeping. The steam-engine does not move when

the fire is not kindled, nor when it is gone out; no

matter how complete the machinery and abundant

the fuel, cold coals will neither set it going nor

keep it working. Let us ask Him so to shed

abroad His love in our hearts by the Holy Ghost

which is given unto us, that it may be the perpetual

and only impulse of every action of our daily life.

Chapter IV.

Our Feet kept for Jesus.

‘Keep my feet, that they may be

Swift and beautiful for Thee.’

The figurative keeping of the feet of His saints,

with the promise that when they run they

shall not stumble, is a most beautiful and helpful

subject. But it is quite distinct from the literal

keeping for Jesus of our literal feet.

There is a certain homeliness about the idea which

helps to make it very real. These very feet of ours

are purchased for Christ’s service by the precious

drops which fell from His own torn and pierced feet

upon the cross. They are to be His errand-runners.

[47]

How can we let the world, the flesh, and the

devil have the use of what has been purchased with

such payment?

Shall ‘the world’ have the use of them? Shall

they carry us where the world is paramount, and

the Master cannot be even named, because the mention

of His Name would be so obviously out of

place? I know the apparent difficulties of a subject

which will at once occur in connection with this,

but they all vanish when our bright banner is loyally

unfurled, with its motto, ‘All for Jesus!’ Do

you honestly want your very feet to be ‘kept for

Jesus’? Let these simple words, ‘Kept for Jesus,’

ring out next time the dancing difficulty or any

other difficulty of the same kind comes up, and I

know what the result will be!

Shall ‘the flesh’ have the use of them? Shall they

carry us hither and thither merely because we like

to go, merely because it pleases ourselves to take

this walk or pay this visit? And after all, what a

failure it is! If people only would believe it, self-pleasing

is always a failure in the end. Our good

Master gives us a reality and fulness of pleasure in

pleasing Him which we never get out of pleasing

ourselves.

Shall ‘the devil’ have the use of them? Oh no,

of course not! We start back at this, as a highly

unnecessary question. Yet if Jesus has not, Satan

has. For as all are serving either the Prince of

Life or the prince of this world, and as no man can

serve two masters, it follows that if we are not serving

the one, we are serving the other. And Satan

is only too glad to disguise this service under the

[48]

less startling form of the world, or the still less

startling one of self. All that is not ‘kept for

Jesus,’ is left for self or the world, and therefore

for Satan.

There is no fear but that our Lord will have

many uses for what is kept by Him for Himself.

‘How beautiful are the feet of them that bring glad

tidings of good things!’ That is the best use of

all; and I expect the angels think those feet beautiful,

even if they are cased in muddy boots or

goloshes.

Once the question was asked, ‘Wherefore wilt

thou run, my son, seeing that thou hast no tidings

ready?’ So if we want to have these beautiful feet,

we must have the tidings ready which they are to

bear. Let us ask Him to keep our hearts so freshly

full of His good news of salvation, that our mouths

may speak out of their abundance. ‘If the clouds

be full of rain, they empty themselves upon the

earth.’ The ‘two olive branches empty the golden

oil out of themselves.’ May we be so filled with

the Spirit that we may thus have much to pour out

for others!

Besides the great privilege of carrying water from

the wells of salvation, there are plenty of cups of

cold water to be carried in all directions; not to

the poor only,—ministries of love are often as much

needed by a rich friend. But the feet must be kept

for these; they will be too tired for them if they

are tired out for self-pleasing. In such services we

are treading in the blessed steps of His most holy

life, who ‘went about doing good.’

[49]

Then there is literal errand-going,—just to fetch

something that is needed for the household, or

something that a tired relative wants, whether asked

or unasked. Such things should come first instead

of last, because these are clearly indicated

as our Lord’s will for us to do, by the position

in which He has placed us; while what seems

more direct service, may be after all not so directly

apportioned by Him. ‘I have to go and buy

some soap,’ said one with a little sigh. The sigh

was waste of breath, for her feet were going to

do her Lord’s will for that next half-hour much

more truly than if they had carried her to her

well-worked district, and left the soap to take its

chance.

A member of the Young Women’s Christian

Association wrote a few words on this subject,

which, I think, will be welcome to many more than

she expected them to reach:—

‘May it not be a comfort to those of us who feel

we have not the mental or spiritual power that

others have, to notice that the living sacrifice mentioned

in Rom. xii. 1 is our “bodies”? Of course,

that includes the mental power, but does it not

also include the loving, sympathizing glance, the

kind, encouraging word, the ready errand for

another, the work of our hands, opportunities for

all of which come oftener in the day than for the

mental power we are often tempted to envy? May

we be enabled to offer willingly that which we have.

For if there be first a willing mind, it is accepted

according to that a man hath, and not according to

that he hath not.’

[50]

If our feet are to be kept at His disposal, our

eyes must be ever toward the Lord for guidance.

We must look to Him for our orders where to go.

Then He will be sure to give them. ‘The steps

of a good man are ordered by the Lord.’ Very

often we find that they have been so very literally

ordered for us that we are quite astonished,—just as

if He had not promised!

Do not smile at a very homely thought! If our

feet are not our own, ought we not to take care of

them for Him whose they are? Is it quite right to

be reckless about ‘getting wet feet,’ which might

be guarded against either by forethought or afterthought,

when there is, at least, a risk of hindering

our service thereby? Does it please the Master

when even in our zeal for His work we annoy

anxious friends by carelessness in little things of

this kind?

May every step of our feet be more and more

like those of our beloved Master. Let us continually

consider Him in this, and go where He would

have gone, on the errands which He would have

done, ‘following hard’ after Him. And let us

look on to the time when our feet shall stand in the

gates of the heavenly Jerusalem, when holy feet

shall tread the streets of the holy city; no longer

pacing any lonely path, for He hath said, ‘They

shall walk with Me in white.’

‘And He hath said, “How beautiful the feet!”

The “feet” so weary, travel-stained, and worn—

The “feet” that humbly, patiently have borne

The toilsome way, the pressure, and the heat.

[51]

‘The “feet,” not hasting on with wingèd might,

Nor strong to trample down the opposing foe;

So lowly, and so human, they must go

By painful steps to scale the mountain height.

‘Not unto all the tuneful lips are given,

The ready tongue, the words so strong and sweet;

Yet all may turn, with humble, willing “feet,”

And bear to darkened souls the light from heaven.

‘And fall they while the goal far distant lies,

With scarce a word yet spoken for their Lord—

His sweet approval He doth yet accord;

Their “feet” are beauteous in the Master’s eyes.

‘With weary human “feet” He, day by day,

Once trod this earth to work His acts of love;

And every step is chronicled above

His servants take to follow in His way.’

Sarah Geraldina Stock.

Chapter V.

Our Voices kept for Jesus.

‘Keep my voice, and let me sing

Always, only, for my King.’

I have wondered a little at being told by an experienced

worker, that in many cases the voice

seems the last and hardest thing to yield entirely to

the King; and that many who think and say they

[52]

have consecrated all to the Lord and His service,

‘revolt’ when it comes to be a question of whether

they shall sing ‘always, only,’ for their King. They

do not mind singing a few general sacred songs,

but they do not see their way to really singing

always and only unto and for Him. They want to

bargain and balance a little. They question and

argue about what proportion they may keep for

self-pleasing and company-pleasing, and how much

they must ‘give up’; and who will and who won’t

like it; and what they ‘really must sing,’ and what

they ‘really must not sing’ at certain times and

places; and what ‘won’t do,’ and what they ‘can’t

very well help,’ and so on. And so when the question,

‘How much owest thou unto my Lord?’ is

applied to this particularly pleasant gift, it is not

met with the loyal, free-hearted, happy response,

‘All! yes, all for Jesus!’

I know there are special temptations around this

matter. Vain and selfish ones—whispering how

much better a certain song suits your voice, and

how much more likely to be admired. Faithless

ones—suggesting doubts whether you can make the

holy song ‘go.’ Specious ones—asking whether

you ought not to please your neighbours, and

hushing up the rest of the precept, ‘Let every

one of you please his neighbour for his good to

edification’ (Rom. xv. 2). Cowardly

ones—telling you that it is just a little too much to expect

of you, and that you are not called upon to wave

your banner in people’s very faces, and provoke

surprise and remark, as this might do. And so

the banner is kept furled, the witness for Jesus is

[53]

not borne, and you sing for others and not for

your King.

The words had passed your lips, ‘Take my

voice!’ And yet you will not let Him have it;

you will not let Him have that which costs you

something, just because it costs you something!

And yet He lent you that pleasant voice that you

might use it for Him. And yet He, in the sureness

of His perpetual presence, was beside you all the

while, and heard every note as you sang the songs

which were, as your inmost heart knew, not for

Him.

Where is your faith? Where is the consecration

you have talked about? The voice has not been

kept for Him, because it has not been truly and unreservedly

given to Him. Will you not now say,

‘Take my voice, for I had not given it to Thee;

keep my voice, for I cannot keep it for Thee’?

And He will keep it! You cannot tell, till you

have tried, how surely all the temptations flee when

it is no longer your battle but the Lord’s; nor how

completely and curiously all the difficulties vanish,

when you simply and trustfully go forward in the

path of full consecration in this matter. You will

find that the keeping is most wonderfully real. Do

not expect to lay down rules and provide for every

sort of contingency. If you could, you would miss

the sweetness of the continual guidance in the

‘kept’ course. Have only one rule about it—just

to look up to your Master about every single song

you are asked or feel inclined to sing. If you are

‘willing and obedient,’ you will always meet His

guiding eye. He will always keep the voice that is

[54]

wholly at His disposal. Soon you will have such

experience of His immediate guidance that you will

be utterly satisfied with it, and only sorrowfully

wonder you did not sooner thus simply lean on it.

I have just received a letter from one who has

laid her special gift at the feet of the Giver, yielding

her voice to Him with hearty desire that it

might be kept for His use. She writes: ‘I had

two lessons on singing while in Germany from our

Master. One was very sweet. A young girl wrote

to me, that when she had heard me sing, “O come,

every one that thirsteth,” she went away and prayed

that she might come, and she did come, too. Is

not He good? The other was: I had been tempted

to join the Gesang Verein in N——. I prayed to

be shown whether I was right in so doing or not.

I did not see my way clear, so I went. The singing

was all secular. The very first night I went I

caught a bad cold on my chest, which prevented me

from singing again at all till Christmas. Those

were better than any lessons from a singing master!’

Does not this illustrate both the keeping from and

the keeping for? In the latter case I believe she

honestly wished to know her Lord’s will,—whether

the training and practice were needed for His better

service with her music, and that, therefore, she

might take them for His sake; or whether the concomitants

and influence would be such as to hinder

the close communion with Him which she had

found so precious, and that, therefore, she was to

trust Him to give her ‘much more than this.’ And

so, at once, He showed her unmistakeably what He

would have her not do, and gave her the sweet

[55]

consciousness that He Himself was teaching her

and taking her at her word. I know what her passionate

love for music is, and how very real and