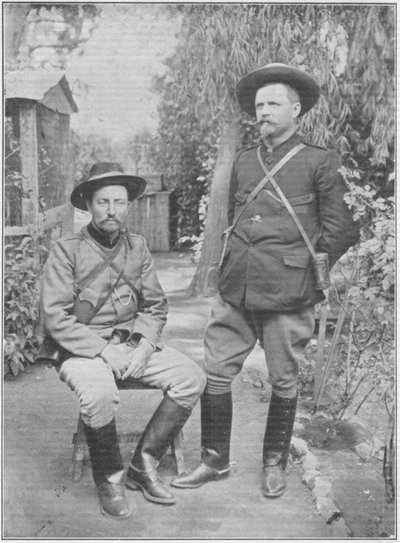

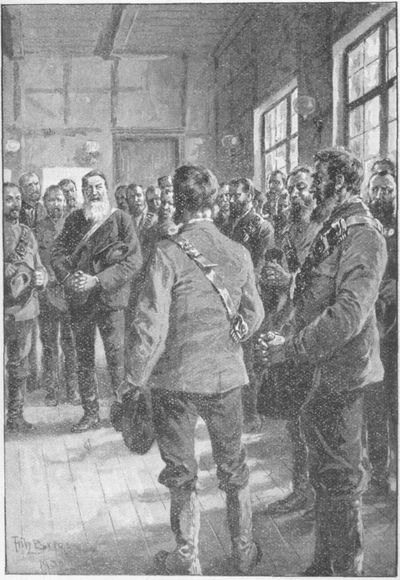

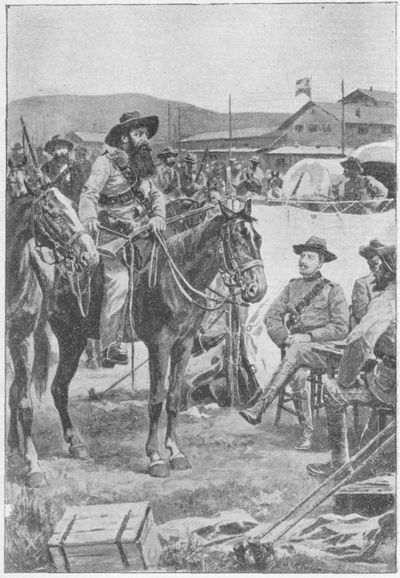

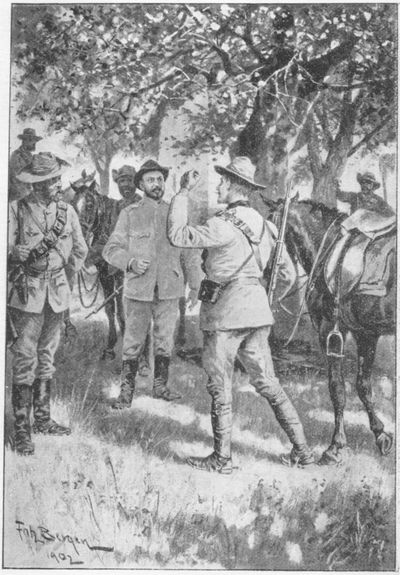

General Ben Viljoen and his Secretary (Mr. J. Visser).

Project Gutenberg's My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, by Ben Viljoen This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War Author: Ben Viljoen Illustrator: P. Van Breda Release Date: April 11, 2008 [EBook #25049] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ANGLO-BOER WAR *** Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Christine P. Travers and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.

Page 453: The sentence "which [missing word] consider it as still improper to disclose." has been changed to "which I consider as still improper to disclose."

General Ben Viljoen and his Secretary (Mr. J. Visser).

BY

(ASSISTANT COMMANDANT-GENERAL OF THE TRANSVAAL BURGHER FORCES AND MEMBER FOR JOHANNESBURG IN THE TRANSVAAL VOLKSRAAD)

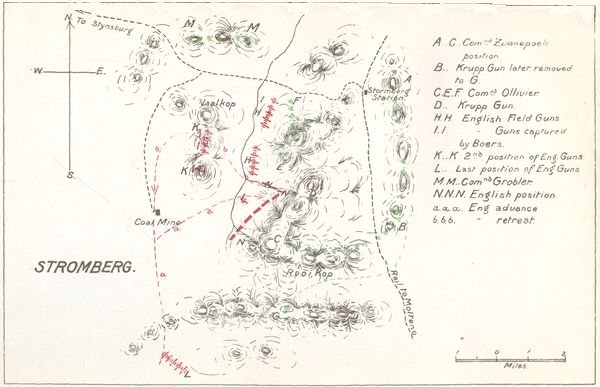

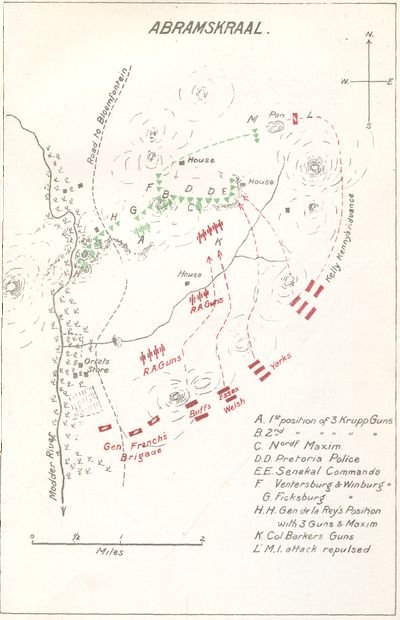

Maps from Drawings by P. Van Breda

LONDON:

HOOD, DOUGLAS, & HOWARD,

11, CLIFFORD'S INN, E.C.

1902.

General Ben Viljoen, while engaged on this work, requested me to write a short introduction to it. This request I gladly comply with.

General Viljoen was a prisoner-of-war at Broadbottom Camp, St. Helena, where, after two years' service in South Africa, I was stationed with my regiment. It was at the General's further request that I conveyed this work to Europe for publication.

The qualities which particularly endeared this brave and justly-famous Boer officer to us were his straightforwardness and unostentatious manner, his truthfulness, and (p. 006) the utter absence of affectation that distinguishes him. I am certain that he has written his simple narrative with candour and impartiality, and I feel equally certain, from what I know of him, that this most popular of our late opponents has reviewed the exciting episodes of the War with an honesty, an intelligence, and a humour which many previous publications on the War have lacked.

During his stay at St. Helena I became deeply attached to General Viljoen; and in conclusion I trust that this work, which entailed many hours of labour, will yield him a handsome recompense.

THEODORE BRINCKMAN, C.B.

Colonel Commanding,

3rd, The Buffs (East Kent Regt.)

Tarbert,

Loch Fyne,

Scotland.

September, 1902

Page

PREFACE BY COL. THEODORE BRINCKMAN, C.B. 5

THE AUTHOR TO THE READER 9

CHAPTER

APPENDIX 523

In offering my readers my reminiscences of the late War, I feel that it is necessary to ask their indulgence and to plead extenuating circumstances for many obvious shortcomings.

It should be pointed out that the preparation of this work was attended with many difficulties and disabilities, of which the following were only a few:—

(1) This is my first attempt at writing a book, and as a simple Afrikander I lay no claim to any literary ability.

(2) When captured by the British forces I was deprived of all my notes, and have been compelled to consult and depend largely upon my memory for my facts and data. I would wish to (p. 010) add, however, that the notes and minutiæ they took from me referred only to events and incidents covering six months of the War. Twice before my capture, various diaries I had compiled fell into British hands; and on a third occasion, when our camp at Dalmanutha was burned out by a "grass-fire," other notes were destroyed.

(3) I wrote this book while a prisoner-of-war, fettered, as it were, by the strong chains with which a British "parole" is circumscribed. I was, so to say, bound hand and foot, and always made to feel sensibly the humiliating position to which we, as prisoners-of-war on this island, were reduced. Our unhappy lot was rendered unnecessarily unpleasant by the insulting treatment offered us by Colonel Price, who appeared to me an excellent prototype of Napoleon's custodian, Sir Hudson Lowe. One has only to read Lord Rosebery's work, "The Last Phase of Napoleon," to realise the insults and (p. 011) indignities Sir Hudson Lowe heaped upon a gallant enemy.

We Boers experienced similar treatment from our custodian, Colonel Price, who appeared to be possessed with the very demon of distrust and who conjured up about us the same fantastic and mythical plans of escape as Sir Hudson Lowe attributed to Napoleon. It is to his absurd suspicions about our safe custody that I trace the bitterly offensive regulations enforced on us.

While engaged upon this work, Colonel Price could have pounced down upon me at any moment, and, having discovered the manuscript, would certainly have promptly pronounced the writing of it in conflict with the terms of my "parole."

I have striven as far as possible to refrain from criticism, except when compelled to do so, and to give a coherent story, so that the reader may easily follow the episodes I have sketched. I have also endeavoured to be impartial, or, at least, so impartial as an erring human being can be who has just (p. 012) quitted the bloody battlefields of a bitter struggle.

But the sword is still wet, and the wound is not yet healed.

I would assure my readers that it has not been without hesitation that I launch this work upon the world. There have been many amateur and professional writers who have preceded me in overloading the reading public with what purport to be "true histories" of the War. But having been approached by friends to add my little effort to the ponderous tomes of War literature, I have written down that which I saw with my own eyes, and that which I personally experienced. If seeing is believing, the reader may lend credence to my recital of every incident I have herein recounted.

During the last stages of the struggle, when we were isolated from the outside world, we read in newspapers and other printed matter captured from the British so many romantic and fabulous stories about ourselves, that we were sometimes in doubt whether people in Europe and elsewhere would really (p. 013) believe that we were ordinary human beings and not legendary monsters. On these occasions I read circumstantial reports of my death, and once a long, and by no means flattering, obituary (extending over several columns of a newspaper) in which I was compared to Garibaldi, "Jack the Ripper," and Aguinaldo. On another occasion I learned from British newspapers of my capture, conviction, and execution in the Cape Colony for wearing the insignia of the Red Cross. I read that I had been brought before a military court at De Aar and sentenced to be shot, and what was worse, the sentence was duly confirmed and carried out. A very lurid picture was drawn of the execution. Bound to a chair, and placed near my open grave, I had met my doom with "rare stoicism and fortitude." "At last," concluded my amiable biographer, "this scoundrel, robber, and guerilla leader, Viljoen, has been safely removed, and will trouble the British Army no longer." I also learned with mingled feelings of amazement and pride that, being imprisoned at Mafeking at the commencement of hostilities, (p. 014) General Baden-Powell had kindly exchanged me for Lady Sarah Wilson.

To be honest, none of the above-mentioned reports were strictly accurate. I can assure the reader that I was never killed in action or executed at De Aar, I was never in Mafeking or any other prison in my life (save here at St. Helena), nor was I in the Cape Colony during the War. I never masqueraded with a Red Cross, and I was never exchanged for Lady Sarah Wilson. Her ladyship's friends would have found me a very poor exchange.

It is also quite inaccurate and unfair to describe me as a "thief" and "a scoundrel". It was, indeed, not an heroic thing to do, seeing that the chivalrous gentlemen of the South African Press who employed the epithets were safely beyond my view and reach, and I had no chance of correcting their quite erroneous impressions. I could neither refute nor defend myself against their infamous libels, and for the rest, my friend "Mr. Atkins" kept us all exceedingly busy.

That which is left of Ben Viljoen after the (p. 015) several "coups de grace" in the field and the tragic execution at De Aar, still "pans" out at a fairly robust young person—quite an ordinary young fellow, indeed, thirty-four years of age, of middle height and build. Somewhere in the Marais Quartier of Paris—where the French Huguenots came from—there was an ancestral Viljoen from whom I am descended. In the War just concluded I played no great part of my own seeking. I met many compatriots who were better soldiers than myself; but on occasions I was happily of some small service to my Cause and to my people.

The chapters I append are, like myself, simple in form. If I have become notorious it is not my fault; it is the fault of the newspaper paragraphist, the snap-shooter, and the autograph fiend; and in these pages I have endeavoured, as far as possible, to leave the stage to more prominent actors, merely offering myself as guide to the many battlefields on which we have waged our unhappy struggle.

I shall not disappoint the reader by promising (p. 016) him sensational or thrilling episodes. He will find none such in these pages; he will find only a naked and unembellished story.

BEN J. VILJOEN.

(Assistant Commandant-General

of the Republican Forces.)

St. Helena,

June, 1902[Back to Table of Contents]

THE WAR CLOUDS GATHER.

In 1895 the political clouds gathered thickly and grew threatening. They were unmistakable in their portent. War was meant, and we heard the martial thunder rumbling over our heads.

The storm broke in the shape of an invasion from Rhodesia on our Western frontiers, a raid planned by soldiers of a friendly power.

However one may endeavour to argue the chief cause of the South African war to other issues, it remains an irrebuttable fact that the Jameson Raid was primarily responsible for (p. 018) the hostilities which eventually took place between Great Britain and the Boer Republics.

Mr. Rhodes, the sponsor and deus ex machinâ of the Raid, could not agree with Mr. Paul Kruger, and had failed in his efforts to establish friendly relations with him. Mr. Kruger, quite as stubborn and ambitious as Mr. Rhodes, placed no faith in the latter's amiable proposals, and the result was that fierce hatred was engendered between the two Gideons, a racial rancour spreading to fanatical lengths.

Dr. Jameson's stupid raid is now a matter of history; but from that fateful New Year's Day of 1896 we Boers date the terrible trials and sufferings to which our poor country has been exposed. To that mischievous incident, indeed, we directly trace the struggle now terminated.

This invasion, which was synchronous with an armed rebellion at Johannesburg, was followed by the arrest and imprisonment of the so-called gold magnates of the Witwatersrand. Whether these exceedingly wealthy but extremely degenerate sons of Albion and (p. 019) Germania deserved the death sentence pronounced upon their leaders at Pretoria for high treason it is not for me to judge.

I do recall, however, what an appeal for mercy there went up, how piteously the Transvaal Government was petitioned and supplicated, and finally moved "to forgive and forget." The same faction who now press so obdurately for "no mercy" upon the Colonial Afrikanders who joined us, then supplicated all the Boer gods for forgiveness.

Meantime the Republic was plagued by the rinderpest scourge, which wrought untold havoc throughout the country. This scourge was preceded by the dynamite disaster at Vrededorp (near Johannesburg) and the railway disaster at Glencoe in Natal. It was succeeded by a smallpox epidemic, which, in spite of medical efforts, grew from sporadic to epidemic and visited all classes of the Rand, exacting victims wherever it travelled. During the same period difficulties occurred in Swaziland necessitating the despatch of a strong commando to the disaffected district and the maintenance of a garrison at Bremersdorp. (p. 020) The following year hostilities were commenced against the Magato tribe in the north of the Republic.

After an expensive expedition, lasting six months, the rebellion was quelled. There was little doubt that the administration of unfaithful native commissioners was in part responsible for the difficulties, but there is less doubt that external influences also contributed to the rebellion. This is not the time, however, to tear open old wounds.

Mr. Rhodes has disappeared from the stage for ever; he died as he had lived. His relentless enemy Mr. Kruger, who was pulling the strings at the other end, is still alive. Perhaps the old man may be spared to see the end of the bloody drama; it was undoubtedly he and Mr. Rhodes who played the leading parts in the prologue.

Which of these two "Big Men" took the greatest share in bringing about the Disaster which has drenched South Africa with blood and draped it in mourning, it would be improper for me at this period to suggest. Mr. Rhodes has been summoned before a (p. 021) Higher Tribunal; Mr. Kruger has still to come up for judgment before the people whose fate, and very existence as a nation, are, at the time of writing, wavering in the balance.

We have been at one another's throats, and for this we have to thank our "statesmen." It is to be hoped that our leaders of the future will attach more value to human lives, and that Boer and Briton will be enabled to live amicably side by side.

A calm and statesmanlike government by men free from ambition and racial rancour, by men of unblemished reputation, will be the only means of pacifying South Africa and keeping South Africa pacified.[Back to Table of Contents]

AND THE WAR STORM BREAKS.

It was during a desultory discussion of an ordinary sessions of the Second Volksraad, in which I represented Johannesburg, that one day in September, 1899—to be precise, the afternoon of the 28th—the messenger of the House came to me with a note, and whispered, "A message from General Joubert, Sir; it is urgent, and the General says it requires your immediate attention."

I broke the seal of the envelope with some trepidation. I guessed its contents, and a few of my colleagues in the Chamber hung over me almost speechless with excitement, whispering curiously, "Jong, is dit fout?"—"Is this correct. Is it war?"

Everybody knew, of course, that we were in for a supreme crisis, that the relations between Great Britain and our Republic were strained (p. 023) to the bursting point, that bitter diplomatic notes had been exchanged between the governments of the two countries for months past, and that a collision, an armed collision, was sooner or later inevitable.

Being "Fighting-Commandant" of the Witwatersrand goldfields, and, therefore, an officer of the Transvaal army, my movements on that day excited great interest among my colleagues in the Chamber. After reading General Joubert's note I said, as calmly as possible: "Yes, the die is cast; I am leaving for the Natal frontier. Good-bye. I must now quit the house. Who knows, perhaps for ever!"

General Joubert's mandate was couched as follows:—

"You are hereby ordered to proceed with the Johannesburg commando to Volksrust to-morrow, Friday evening, at 8 o'clock. Your field cornets have already received instructions to commandeer the required number of burghers and the necessary horses, waggons, and equipment. Instructions have also been given for the necessary railway conveyances to be held ready. Further instructions will reach you."

Previous to my departure next morning (p. 024) I made a hurried call at Commandant-General Joubert's offices. The ante-chamber leading to the Generalissimo's "sanctum-sanctorum" was crowded with brilliantly-uniformed officers of our State Artillery, and it was only by dint of using my elbows very vigorously that I gained admission to my chief-in-command.

The old General seemed to feel keenly the gravity of the situation. He looked careworn and troubled: "Good-morning, Commandant," he said; "aren't you away yet?"

I explained that I was on my way to the railway station, but I thought before I left I'd like to see him about one or two things.

"Well, go on, what is it?" General Joubert enquired, petulantly.

"I want to know, General Joubert," I said, "whether England has declared war against us, or whether we are taking the lead. And another thing, what sort of general have I to report myself to at Volksrust?"

The old warrior, without looking up or immediately answering me, drew various cryptic and hieroglyphic pothooks and figures (p. 025) on the paper before him. Then he suddenly lifted his eyes and pierced me with a look, at which I quailed and trembled.

He said very slowly: "Look here; there is as yet no declaration of war, and hostilities have not yet commenced. You and my other officers should understand that very clearly, because possibly the differences between ourselves and Great Britain may still be settled. We are only going to occupy our frontiers because England's attitude is extremely provocative, and if England see that we are fully prepared and that we do not fear her threats, she will perhaps be wise in time and reconsider the situation. We also want to place ourselves in a position to prevent and quell a repetition of the Jameson Raid with more force than we exerted in 1896."

An hour afterwards I was on board a train travelling to Johannesburg in the company of General Piet Cronje and his faithful wife. General Cronje told me that he was proceeding to the western districts of the Republic to take up the command of the Potchefstroom and Lichtenburg burghers. His instructions, (p. 026) he said, were to protect the Western frontier.

I left General Cronje at Johannesburg on the 29th September, 1899, and never saw him again until I met him at St. Helena nearly two and a half years afterwards, on the 25th March, 1902. When I last saw him we greeted each other as free men, as free and independent legislators and officers of a free Republic. We fought for our rights to live as a nation.

Now I meet the veteran Cronje a broken old man, captive like myself, far away from our homes and our country.

Then and Now!

Then we went abroad free and freedom-loving men, burning with patriotism. Our wives and our women-folk watched us go; full of sorrow and anxiety, but satisfied that we were going abroad in our country's cause.

And Now!

Two promising and prosperous Republics wrecked, their fair homesteads destroyed, their people in mourning, and thousands of innocent (p. 027) women and children the victims of a cruel war.

There is scarcely an Afrikander family without an unhealable wound. Everywhere the traces of the bloody struggle; and, alas, most poignant and distressing fact of all, burghers who fought side by side with us in the earlier stages of the struggle are now to be found in the ranks of the enemy.

These wretched men, ignoring their solemn duty, left their companions in the lurch without sense of shame or respect for the braves who fell fighting for their land and people.

Oh, day of judgment! The Afrikander nation will yet avenge your treachery.[Back to Table of Contents]

THE INVASION OF NATAL.

After taking leave of my friend Cronje at Johannesburg Station, my first duty was to visit my various field cornets. About four o'clock that afternoon I found my commando was as nearly ready as could be expected. When I say ready, I mean ready on paper only, as later experience showed. My three field cornets were required to equip 900 mounted men with waggons and provisions, and of course they had carte blanche to commandeer. Only fully enfranchised burghers of the South African Republic were liable to be commandeered, and in Johannesburg town there was an extraordinary conglomeration of cosmopolitans amenable to this gentle process of enlistment.

It would take up too much time to adequately describe the excitement of Johannesburg on this memorable day. Thousands (p. 029) of Uitlanders were flying from their homes, contenting themselves, in their hurry to get away, to stand in Kaffir or coal trucks and to expose themselves cheerfully to the fierce sun, and other elements. The streets were palpitating with burghers ready to proceed to the frontier that night, and with refugees speeding to the stations. Everybody was in a state of intense feeling. One was half-hearted, another cheerful, and a third thirsting for blood, while many of my men were under the influence of alcohol.

When it was known that I had arrived in the town my room in the North Western Hotel was besieged. I was approached by all sorts of people pleading exemption from commando duty. One Boer said he knew that his solemn duty was to fight for his country and his freedom, but he would rather decline. Another declared that he could not desert his family; while yet another came forward with a story that of his four horses, three had been commandeered, and that these horses were his only means of subsistence. A fourth complained that his waggons and (p. 030) mules had been clandestinely (although officially) removed. Many malingerers suddenly discovered acute symptoms of heart disease and brought easily-obtained doctor's certificates, assuring me that tragic consequences would attend their exposure in the field. Ladies came to me pleading exemption for their husbands, sisters for brothers, mothers for sons, all offering plausible reasons why their loved ones should be exempted from commando duty. It was very difficult to deal with all these clamorous visitors. I was much in the position of King Solomon, though lacking his wisdom. But I would venture to say that his ancient majesty himself would have been perplexed had he been in my place. It is necessary that the reader should know that the main part of the population was composed of all nationalities and lacked every element of Boer discipline.

On the evening of the 29th of September, I left with the Johannesburg commando in two trains. Two-thirds of my men had no personal acquaintance with me, and at the (p. 031) departure there was some difficulty because of this. One burgher came into my private compartment uninvited. He evidently forgot his proper place, and when I suggested to him that the compartment was private and reserved for officers, he told me to go to the devil, and I was compelled to remove him somewhat precipitately from the carriage. This same man was afterwards one of my most trustworthy scouts.

The following afternoon we reached Standerton, where I received telegraphic instructions from General Joubert to join my commando to that of Captain Schiel, who was in charge of the German Corps, and to place myself under the supreme command of Jan Kock, a member of the Executive Council, who had been appointed a general by the Government.

We soon discovered that quite one-third of the horses we had taken with us were untrained for the serious business of fighting, and also that many of the new burghers of foreign nationality had not the slightest idea how to ride. Our first parade, or (p. 032) "Wapenschouwing" gave food for much hilarity. Here one saw horses waltzing and jumping, while over there a rider was biting the sand, and towards evening the doctors had several patients. It may be stated that although not perfectly equipped in the matter of ambulances, we had three physicians with us, Doctors Visser, Marais, and Shaw. Our spiritual welfare was being looked after by the Reverends Nel and Martins, but not for long, as both these gentlemen quickly found that commando life was unpleasant and left us spiritually to ourselves, even as the European Powers left us politically. But I venture to state that no member of my commando really felt acutely the loss of the theological gentlemen who primarily accompanied us.

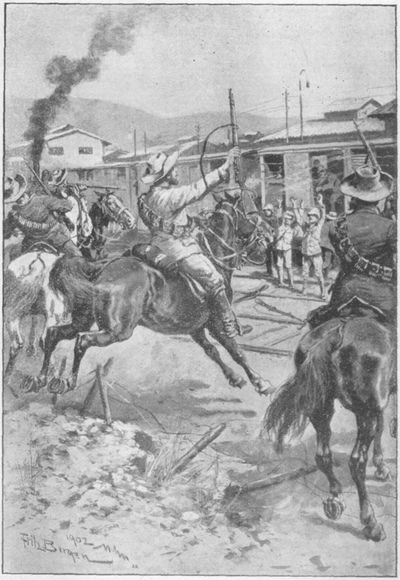

The Capture of the Train at Elandslaagte.

On the following day General Kock and a large staff arrived at the laager, and, together with the German Corps, we trekked to Paardakop and Klip River, in the Orange Free State, where we were to occupy Botha's Pass. My convoy comprised about a hundred carts, mostly drawn by mules, and it was amusing (p. 033) to see the variety of provisions my worthy field-cornets had gathered together. There were three full waggons of lime-juice and other unnecessary articles which I caused to be unloaded at the first halting-place to make room for more serviceable provisions. It should be mentioned that of my three field-cornets only one, the late Piet Joubert of Jeppestown, actually accompanied my commando. The others sent substitutes, perhaps because they did not like to expose themselves to the change of air. We rested some days at the Klip River, in the Orange Free State, and from thence I was sent with a small escort of burghers by our General to Harrismith to meet a number of Free State officers. After travelling two days I came upon Chief Free State Commandant Prinsloo, who afterwards deserted, and other officers. The object of my mission was to organise communications with these officers. On the 11th of October, having returned to my commando, we received a report that our Government had despatched the Ultimatum to England, and that the time specified for (p. 034) the reply to that document had elapsed. Hostilities had begun.

We received orders to invade Natal, and crossed the frontier that very evening. I, with a patrol of 50 men, had not crossed the frontier very far when one of my scouts rode up with the report that a large British force was in sight on the other side of the River Ingogo. I said to myself at the time: "If this be true the British have rushed up fairly quickly, and the fat will be in the fire very soon."

We then broke into scattered formation and carefully proceeded into Natal. After much reconnoitring and concealment, however, we soon discovered that the "large English force" was only a herd of cattle belonging to friendly Boers, and that the camp consisted of two tents occupied by some Englishmen and Kaffirs who were mending a defective bridge. We also came across a cart drawn by four bullocks belonging to a Natal farmer, and I believe this was the first plunder we captured in Natal. The Englishman, who said he knew nothing about any war, received a pass to (p. 035) proceed with his servants to the English lines, and he left with the admonition to in future read the newspapers and learn when war was imminent. Next day our entire commando was well into Natal. The continuous rain and cold of the Drakenbergen rendered our first experience of veldt life, if not unbearable, very discouraging. We numbered a fairly large commando, as Commandant J. Lombard, commanding the Hollander corps, had also joined us. Close by Newcastle we encountered a large number of commandos, and a general council of war was held under the presidency of Commandant General Joubert. It was here decided that Generals Lukas Meyer and Dijl Erasmus should take Dundee, which an English garrison held, while our commandos under General Kock were instructed to occupy the Biggarburg Pass. Preceded by scouts we wound our way in that direction, leaving all our unnecessary baggage in the shape of provisions and ammunition waggons at Newcastle.

One of my acting field-cornets and the field-cornets of the German commando, prompted by goodness knows what, pressed (p. 036) forward south, actually reaching the railway station at Elandslaagte. A goods train was just steaming into the station, and it was captured by these foolhardy young Moltkes. I was much dissatisfied with this action, and sent a messenger ordering them to retire after having destroyed the railway. On the same night I received instructions from General Kock to proceed with two hundred men and a cannon to Elandslaagte, and I also learned that Captain Schiel and his German Corps had left in the same direction.

Imagine, we had gone further than had actually been decided at the council of war, and we pressed forward still further without any attempt being made to keep in touch with the other commandos on our left and right. Seeing the inexpediency of this move, I went to the General in command and expressed my objections to it. But General Kock was firmly decided on the point, and said, "Go along, my boy." We reached Elandslaagte at midnight; it was raining very heavily. After scrambling for positions in (p. 037) the darkness, although I had already sufficiently seen that the lie of the land suggested no strategic operations, we retired to rest. Two days later occurred the fateful battle.[Back to Table of Contents]

DEFEATED AT ELANDSLAAGTE.

In the grey dawn of the 21st of October a number of scouts I had despatched overnight in the direction of Ladysmith returned with the tidings that "the khakis were coming." "Where are they, and how many are there of them?" I asked. "Commandant," the chief scout replied, "I don't know much about these things, but I should think that the English number quite a thousand mounted men, and they have guns, and they have already passed Modderspruit." To us amateur soldiers this report was by no means reassuring, and I confess I hoped fervently that the English might stay away for some little time longer.

It was at sunrise that the first shot I heard in this war was fired. Presently the men we dreaded were visible on the ridges of hills south of the little red railway station at (p. 039) Elandslaagte. Some of my men hailed the coming fight with delight; others, more experienced in the art of war, turned deadly pale. That is how the Boers felt in their first battle. The awkward way in which many of my men sought cover, demonstrated at once how inexperienced in warfare we youngsters were. We started with our guns and tried a little experimental shooting. The second and third shots appeared to be effective; at any rate, as far as we could judge, they seemed to disturb the equanimity of the advancing troops. I saw an ammunition cart deprived of its team and generally smashed.

The British guns appeared to be of very small calibre indeed. Certainly they failed to reach us, and all the harm they did was to send a shell through a Boer ambulance within the range of fire. This shot was, I afterwards ascertained, purely accidental. When the British found that we too, strange to say, had guns, and, what is more, knew how to use them, they retired towards Ladysmith. But this was merely a ruse; they had gone back to fetch more. Still, though it was a ruse, we (p. 040) were cleverly deceived by it, and while we were off-saddling and preparing the mid-day meal they were arranging a new and more formidable attack. From the Modderspruit siding they were pouring troops brought down by rail, and although we had a splendid chance of shelling the newcomers from the high kopje we occupied, General Kock, who was in supreme command of our corps, for some reason which has never been explained, refused to permit us to fire upon them. I went to General Kock and pleaded with him, but he was adamant. This was a bitter disappointment to me, but I consoled myself with the thought that the General was much older than myself, and had been fighting since he was a baby. I therefore presumed he knew better. Possibly if we younger commanders had had more authority in the earlier stages of the war, and had had less to deal with arrogant and stupid old men, we should have reached Durban and Cape Town.

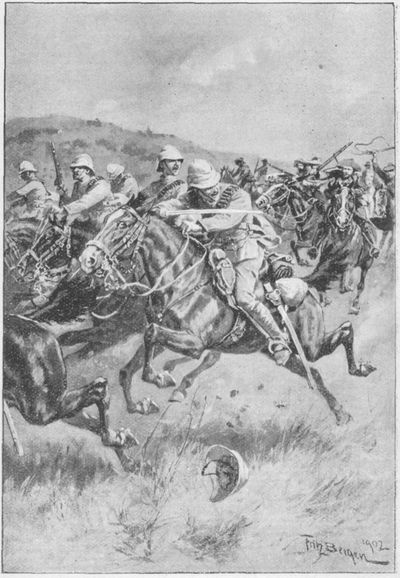

I must here again confess that none of my men displayed any of the martial determination with which they had so buoyantly proceeded (p. 041) from Johannesburg. To put it bluntly, some of them were "footing" it and the English cavalry, taking advantage of this, were rapidly outflanking them. The British tactics were plain enough. General French had placed his infantry in the centre with three field batteries (fifteen pounders), while his cavalry, with Maxims, encompassed our right and left. He was forming a crescent, with the obvious purpose of turning our position with his right and left wing. When charging at the close of the attack the cavalry, which consisted mainly of lancers, were on both our flanks, and completely prevented our retreat. It was not easy to estimate the number of our assailant's forces. Judging roughly, I calculated they numbered between 5,000 and 6,000, while we were 800 all told, and our artillery consisted merely of two Nordenfeldt guns with shell, and no grape shot.

The British certainly meant business that day. It was the baptismal fire of the Imperial Light Horse, a corps principally composed of Johannesburgers, who were politically and racially our bitter enemies. And what was (p. 042) more unfortunate, our guns were so much exposed that they were soon silenced. For a long time we did our best to keep our opponents at bay, but they came in crushing numbers, and speedily dead and maimed burghers covered the veldt. Then the Gordon Highlanders and the other infantry detachments commenced to storm our positions. We got them well within the range of our rifle fire, and made our presence felt; but they kept pushing on with splendid determination and indomitable pluck, though their ranks were being decimated before our very eyes.

This was the first, as it was the last time in the War that I heard a British band playing to cheer attacking "Tommies." I believe it used to be a British war custom to rouse martial instincts with lively music, but something must have gone wrong with the works in this War, there must have occurred a rift in the lute, for ever after this first battle of Elandslaagte the British abandoned flags, banners, and bands and other quite unnecessary furniture.

About half an hour before sunset, the enemy had come up close to our positions and on all (p. 043) sides a terrible battle raged. To keep them back was now completely out of the question. They had forced their way between a kloof, and while rushing up with my men towards them, my rifle was smashed by a bullet. A wounded burgher handed me his and I joined Field-Cornet Peter Joubert who, with seven other burghers, was defending the kloof. We poured a heavy fire into the British, but they were not to be shaken off. Again and again they rushed up in irresistible strength, gallantly encouraged by their brave officers. Poor Field-Cornet Joubert perished at this point.

When the sun had set and the awful scene was enveloped in darkness there was a dreadful spectacle of maimed Germans, Hollanders, Frenchmen, Irishmen, Americans, and Boers lying on the veldt. The groans of the wounded were heartrending; the dead could no longer speak. Another charge, and the British, encouraged by their success, had taken our last position, guns and all. My only resource now was to flee, and the battle of Elandslaagte was a thing of the past.[Back to Table of Contents]

PURSUED BY THE LANCERS.

Another last look at the bloody scene. It was very hard to have to beat an ignominious retreat, but it was harder still to have to go without being able to attend to one's wounded comrades, who were piteously crying aloud for help. To have to leave them in the hands of the enemy was exceedingly distressing to me. But there was no other course open, and fleeing, I hoped I might "live to fight another day." I got away, accompanied by Fourie and my Kaffir servant. "Let us go," I said, "perhaps we shall be able to fall in with some more burghers round here and have another shot at them." Behind us the British lancers were shouting "Stop, stop, halt you —— Boers!" They fired briskly at us, but our little ponies responded gamely to the spur and, aided by the darkness, we rode on safely. Still the (p. 045) lancers did not abandon the chase, and followed us for a long distance. From time to time we could hear the pitiful cries and entreaties of burghers who were being "finished off," but we could see nothing. My man and I had fleet horses in good condition, those of the pursuing lancers were big and clumsy.

My adjutant, Piet Fourie, however, was not so fortunate as myself. He was overtaken and made a prisoner. Revolvers were being promiscuously fired at us, and at times the distance between us and our pursuers grew smaller. We could plainly hear them shouting "Stop, or I'll shoot you," or "Halt, you damned Boer, or I'll run my lance through your blessed body."

We really had no time to take much notice of these pretty compliments. It was a race for life and freedom. Looking round furtively once more I could distinguish my pursuers; I could see their long assegais; I could hear the snorting of their unwieldy horses, the clattering of their swords. These unpleasant combinations were enough to strike terror into the heart of any ordinary man.

(p. 046) Everything now depended upon the fleetness and staying power of my sturdy little Boer pony, Blesman. He remained my faithful friend long after he had got me out of this scrape; he was shot, poor little chap, the day when they made me a prisoner. Poor Blesman, to you I owe my life! Blesman was plainly in league against all that was British; from the first he displayed Anglophobia of a most acute character. He has served me in good stead, and now lies buried, faithful little heart, in a Lydenburg ditch.

In my retreat Sunday River had to be crossed. It was deep, but deep or not, we had to get through it. We were going at such a pace that we nearly tumbled down the banks. The precipice must have been very steep; all I remember is finding myself in the water with Blesman by my side. The poor chap had got stuck with his four legs in the drift sand. I managed to liberate him, and after a lot of scrambling and struggling and wading through the four foot stream, I got to the other side. On the opposite bank the British were still firing. (p. 047) I therefore decided to lie low in the water, hoping to delude them into thinking I was killed or drowned. My stratagem was successful. I heard one of my pursuers say, "We've finished him," and with a few more pyrotechnic farewells they retraced their steps towards Ladysmith.

On the other side, however, more horsemen came in pursuit. Unquestionably the British, fired by their splendid success, were following up their victory with great vigour, and again I was compelled to hide in the long grass into which my native servant, with Ethiopian instinct, had already crept. While I was travelling along on foot my man had rescued my horse from the muddy banks of the river.

When all was said and done I had escaped with a good wetting. Now for Newcastle. I had still my rifle, revolver, and cartridges left to me; my field-glass I had lost, probably in the river. Water there was plenty, but food I had none. The track to Newcastle to a stranger, such as I was in that part of the country, was difficult (p. 048) to discover. To add to my perplexities I did not know what had happened at Dundee, where I had been told a strong British garrison was in occupation. Therefore, in straying in that direction I ran the risk of being captured.

Finally, however, I came upon a kaffir kraal. I was curtly hailed in the kaffir language, and upon my asking my swarthy friends to show me the road, half a dozen natives, armed with assegais, appeared on the scene. I clasped my revolver, as their attitude seemed suspicious. After they had inspected me closely, one of the elders of the community said: "You is one of dem Boers vat runs avay? We look on and you got dum dum to-day. Now we hold you, we take you English magistrate near Ladysmith." But I know my kaffir, and I sized up this black Englishman instantly. "The fact is," I said, "I'm trekking with a commando of 500 men, and we are doing a bit of scouting round your kraal. If you will show me the way to the Biggersbergen I will give you 5s. on account." My amiable and dusky friend insisted on (p. 049) 7s. 6d., but after I had intimated that if he did not accept 5s. I should certainly burn his entire outfit, slaughter all his women and kill all his cattle, he acquiesced. A young Zulu was deputed as my guide, but I had to use my fists and make pretty play with my revolver, and generally hint at a sudden death, or he would have left me in the lurch. He muttered to himself for some time, and suddenly terminated his soliloquy by turning on his heels and disappearing in the darkness.

The light of a lantern presently showed a railway station, which I rightly guessed to be Waschbank. Here two Englishmen, probably railway officials, came up to me, accompanied by my treacherous guide. The latter had obviously been good enough to warn the officials at the station of my approach, but luckily they were unarmed. One of them said, "You've lost your way, it appears," to which I replied, "Oh, no, indeed; I'm on the right track I think." "But," he persisted, "you won't find any of your people here now; you've been cut to pieces at Elandslaagte and Lukas Meyer's and Erasmus's forces round (p. 050) Dundee have been crushed. You had better come along with me to Ladysmith. I promise you decent treatment." I took care not to get in between them, and, remaining at a little distance, said, revolver in hand, "Thanks very much, it's awfully good of you. I have no business to transact in Ladysmith for the moment and will now continue my journey. Good-night." "No, no, no, wait a minute," returned the man who had spoken first, "you know you can't pass here." "We shall see about that," I said. They rushed upon me, but ere they could overpower me I had levelled my revolver. The first speaker tried to disarm me, but I shook him off and shot him. He fell, and as far I know, or could see, was not fatally wounded. The other man, thinking discretion the better part of valour, disappeared in the darkness, and my unfaithful guide had edged away as soon as he saw the glint of my gun.

My adventures on that terrible night were, however, not to end with this mild diversion. About an hour after daybreak, I came upon a barn upon which the legend "Post Office (p. 051) Savings Bank" was inscribed. A big Newfoundland dog lay on the threshold, and although he wagged his tail in a not unfriendly manner, he did not seem disposed to take any special notice of me. There was a passage between the barn and some stables at the back and I went down to prospect the latter. What luck if there had been a horse for me there! Of course I should only have wanted to borrow it, but there was a big iron padlock on the door, though inside the stables I heard the movements of an animal. A horse meant to me just then considerably more than three kingdoms to King Richard. For the first time in my life I did some delicate burglary and housebreaking to boot. But the English declare that all is fair in love and war, and they ought to know.

I discovered an iron bar, which enabled me to wrench off the lock from the stable door, and, having got so far with my burglarious performance, I entered cautiously, and I may say nervously. Creeping up to the manger I fumbled about till I caught hold of a strap to which the animal was tied, cut the strap (p. 052) through and led the horse away. I was wondering why it went so slowly and that I had almost to drag the poor creature along. Once outside I found to my utter disgust that my spoil was a venerable and decrepit donkey. Disappointed and disheartened, I abandoned my booty, leaving that ancient mule brooding meditatively outside the stable door and clearly wondering why he had been selected for a midnight excursion. But there was no time to explain or apologise, and as the mule clearly could not carry me as fast as my own legs, I left him to his meditations.

At dawn, when the first rays of the sun lit up the Biggersbergen in all their grotesque beauty, I realised for the first time where I was, and found that I was considerably more than 12 miles from Elandslaagte, the fateful scene of yesterday. Tired out, half-starved and as disconsolate as the donkey in the stable, I sat myself on an anthill. For 24 hours I had been foodless, and was now quite exhausted. I fell into a reverie; all the past day's adventures passed graphically before my eyes as in a kaleidoscope; all the horrors and (p. 053) carnage of the battle, the misery of my maimed comrades, who only yesterday had answered the battle-cry full of vigour and youth, the pathos of the dead who, cut down in the prime of their life and buoyant health, lay yonder on the veldt, far away from wives and daughters and friends for ever more.

While in a brown study on this anthill, 30 men on horseback suddenly dashed up towards me from the direction of Elandslaagte. I threw myself flat on my face, seeking the anthill as cover, prepared to sell my life dearly should they prove to be Englishmen. As soon as they observed me they halted, and sent one of their number up to me. Evidently they knew not whether I was friend or foe, for they reconnoitred my prostrate form behind the anthill with great circumspection and caution; but I speedily recognised comrades-in-arms. I think the long tail which is peculiar to the Basuto pony enabled me to identify them as such, and one friend, who was their outpost, brought me a reserve horse, and what was even better, had extracted from his saddle-bag a tin of welcome bully beef to (p. 054) stay my gnawing hunger. But they brought sad tidings, these good friends. Slain on the battlefield lay Assistant-Commandant J. C. Bodenstein and Major Hall, of the Johannesburg Town Council, two of my bravest officers, whose loss I still regret.

We rode on slowly, and all along the road we fell in with groups of burghers. There was no question that our ranks were demoralised and heartsick. Commandant-General Joubert had made Dannhauser Station his headquarters and thither we wended our way. But though we approached our general with hearts weighed down with sorrow, so strange and complex a character is the Boers', that by the time we reached him we had gathered together 120 stragglers, and had recovered our spirits and our courage. I enjoyed a most refreshing rest on an unoccupied farm and sent a messenger to Joubert asking him for an appointment for the following morning to hand in my report of the ill-fated battle. The messenger, however, brought back a verbal answer that the General was exceedingly angry and had sent no reply. (p. 055) On retiring that night I found my left leg injured in several places by splinters of shell and stone. My garments had to be soaked in water to remove them, but after I had carefully cleaned my wounds they very soon healed.

The next morning I waited on the Commandant-General. He received me very coldly, and before I could venture a word said reproachfully: "Why didn't you obey orders and stop this side of the Biggarsbergen, as the Council of War decided you should do?" He followed up the reproach with a series of questions: "Where's your general?" "How many men have you lost?" "How many English have you killed?" I said deferentially: "Well, General, you know I am not to be bullied like this. You know you placed me in a subordinate position under the command of General Kock, and now you lay all the blame for yesterday's disaster on my shoulders. However, I am sorry to say General Kock is wounded and in British hands. I don't know how many men we have lost; I suppose about 30 or 40 killed and approximately (p. 056) 100 wounded. The British must have lost considerably more, but I am not making any estimate."

The grey-bearded generalissimo cooled a little and spoke more kindly, although he gave me to understand he did not think much of the Johannesburg commando. I replied that they had been fighting very pluckily, and that by retiring they hoped to retrieve their fortunes some other day. "H'm," returned the General, "some of your burghers have made so masterly a retreat that they have already got to Newcastle, and I have just wired Field-Cornet Pienaar, who is in charge, that I should suggest to him to wait a little there, as I propose sending him some railway carriages to enable him to retreat still further. As for those Germans and Hollanders with you, they may go to Johannesburg; I won't have them here any more."

"General," I protested, "this is not quite fair. These people have volunteered to fight for, and with us; we cannot blame them in this matter. It is most unfortunate that Elandslaagte should have been lost, but as (p. 057) far as I can see there was no help for it." The old General appeared lost in thought; he seemed to take but little notice of what I said. Finally he looked up and fixed his small glittering eyes upon me as if he wished to read my most inmost thoughts.

"Yes," he said, "I know all about that. At Dundee things have gone just as badly. Lukas Meyer made a feeble attack, and Erasmus left him in the lurch. The two were to charge simultaneously, but Erasmus failed him at a critical moment, which means a loss of 130 men killed and wounded, and Lukas Meyer in retreat across the Buffalo River. And now Elandslaagte on the top of all! All this owing to the disobedience and negligence of my chief officers."

The old man spoke in this strain for some time, until I grew tired and left. But just as I was on the point of proceeding from his tent, he said: "Look here, Commandant, reorganise your commando as quickly as you can, and report to me as soon as you are ready." He also gave me permission to incorporate in the reorganised commando (p. 058) various Hollander and German stragglers who were loafing round about, although he seemed to entertain an irradicable prejudice against the Dutch and German corps.

The Commandant of the Hollander corps, Volksraad Member Lombard, came out of the battle unscathed; his captain, Mr. B. J. Verselewel de Witt Hamer, had been made a prisoner; the Commandant of the German corps, Captain A. Schiel, fell wounded into British hands, while among the officers who were killed in action I should mention Dr. H. J. Coster, the bravest Hollander the Transvaal ever saw, the most brilliant member of the Pretoria Bar, who laid down his life because in a stupid moment Kruger had taunted him and his compatriots with cowardice.[Back to Table of Contents]

RISKING JOUBERT'S ANGER.

After the above unpleasant but fairly successful interview with our Commander-in-Chief, I left the men I had gathered round me in charge of a field-cornet, and proceeded by train to Newcastle to collect the scattered remnants of my burghers, and to obtain mules and waggons for my convoy. For, as I have previously stated, it was at Newcastle we had left all our commissariat-waggons and draught cattle under a strong escort. On arrival I summoned the burghers together, and addressing them in a few words, pointed out that we should, so soon as possible, resume the march, in order to reach the fighting line without delay, and there retrieve the pride and honour of our commando.

"Our beloved country," I said, "as well as our dead, wounded and missing comrades, (p. 060) require us not to lose courage at this first reverse, but to continue the righteous struggle even against overwhelming odds," and so on, in this strain.

I honestly cannot understand why we should have been charged with cowardice at the battle of Elandslaagte, although many of us seemed to apprehend that this would be the case. We had made a good fight of it, but overwhelmed by an organised force of disciplined men, eight or ten times our number, we had been vanquished, and the British were the first to admit that we had manfully and honourably defended our positions. To put a wrong construction on our defeat was a libel on all who had bravely fought the fight, and I resented it. There are such things as the fortunes of war, and as only one side can win, it cannot always be the same. However, I soon discovered that a small number of our burghers did not seem inclined to join in the prolongation of the struggle. To have forced them to rejoin us would have served no purpose, so I thought the best policy would be to send them home on furlough (p. 061) until they had recovered their spirits and their courage. No doubt the scorn and derision to which they would be subjected by their wives and sisters would soon induce them to take up arms again and to fulfil the duties their country required. I therefore requested those who had neither the courage nor the inclination to return to the front to fall out, and about thirty men fell back, bowing their heads in shame. They were jeered at and chaffed by their fellows, the majority of whom had elected to proceed. But the shock of Elandslaagte had been too much for the weaker brethren, who seemed deaf to every argument, and only wanted to go home. I gave each of these a pass to proceed by rail to Johannesburg, which read as follows:—

"Permit..................................... to go to Johannesburg on account of cowardice, at Government's expense."

They put the permit in their pockets without suspecting its contents, and departed with their kit to the station to catch the first available train.

(p. 062) The reader will now have formed an idea of the disastrous moral effect of this defeat, and the subsequent difficulty of getting a commando up to its original fighting strength. But in spite of this I am proud to say that by far the greater number of the Johannesburgers were gathered round me and prepared to march to meet the enemy once more.

My trap and all its contents had been captured by the enemy at Elandslaagte, and I found it necessary to obtain new outfits, &c., at Newcastle. This was no easy matter, as some of the storekeepers had moved the greater part of their goods to a safer place, while some commandos had appropriated most of the remainder. What was left had been commandeered by Mr. J. Moodie, a favourite of General Joubert, who was posing there as Resident Justice of the Peace; and he did not feel inclined to let any of these goods out of his possession. By alternately buying and looting, or in other words stealing, I managed to get an outfit by the next morning, and at break of day we left for Dannhauser (p. 063) Station, arriving there the same evening without further noteworthy incident.

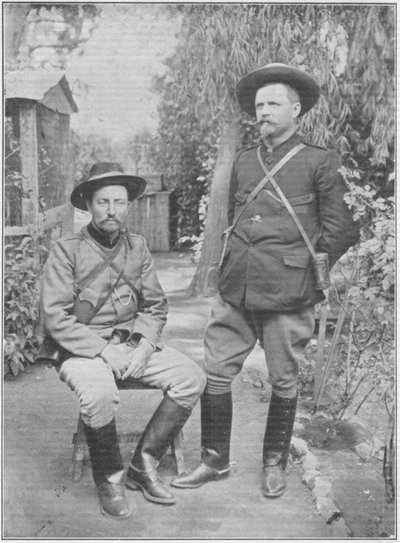

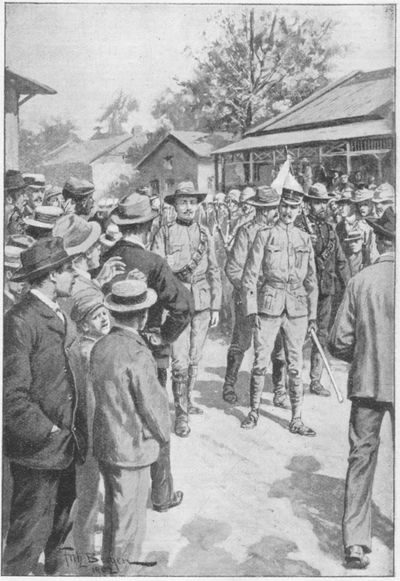

Next day, when the Johannesburg corps turned out, we numbered 485 mounted men, all fully equipped. On arrival at Glencoe Station I received a telegram from General Joubert informing me that he had defeated the enemy at Nicholson's Nek near Ladysmith that day (October 30, 1899) taking 1,300 prisoners, who would arrive at Glencoe the following morning. He desired me to conduct them to Pretoria under a strong escort. What a flattering order! To conduct prisoners-of-war, taken by other burghers! Were we then fit for nothing but police duty?

However, orders have to be obeyed, so I sent one of my officers with 40 men to take the prisoners to Pretoria, and reported to the Commandant-General by telegram that his order had been executed, also asking for instructions as to where I was to proceed with my commando. The reply I received was as follows:—

"Pitch your camp near Dundee, and maintain law and order in the Province, also aid (p. 064) the Justice of the Peace in forwarding captured goods, ammunition, provisions, etc., to Pretoria, and see that you are not attacked a second time."

This was more than flesh and blood could bear; more than a "white man" could stand. It was not less than a personal insult, which I deeply resented. Evidently my chief had resolved to keep us in the background; he would not trust our commando in the fighting line. In short, he would not keep his word and give us another chance to recoup our losses.

I had, however, made up my mind, and ordered the commando to march to Ladysmith. If the General would not have me at the front I should cease to be an officer. And, although I had no friends of influence who could help me I resolved to take the bull by the horns, and leave the rest to fate.

On the 1st November, 1899, we reached the main army near Ladysmith, and I went at once to tell General Joubert in person that my men wanted to fight, and not to play policemen in the rear of the army. Having given the order to dismount I proceeded (p. 065) to Joubert's tent, walked in with as much boldness as I could muster, and saluted the General, who was fortunately alone. I at once opened my case, telling him how unfair it was to keep us in the rear, and that the burghers were loudly protesting against such treatment. This plea was generally used throughout the campaign when an officer required something to be granted him. At first the old General was very wrathful. He said I had disobeyed his orders and that he had a mind to have me shot for breach of discipline. However, after much storming in his fine bass voice, he grew calmer, and in stentorian tones ordered me for the time being to join General Schalk Burger, who was operating near Lombard's Kop in the siege of Ladysmith.

That same evening I arrived there with my commando and reported myself to Lieut-General Burger. One of his adjutants, Mr. Joachim Fourie, who distinguished himself afterwards on repeated occasions and was killed in action near his house in the Carolina district, showed me a place to laager in. (p. 066) We pitched our tents on the same spot where a few days before Generals White and French had been defeated, and there awaited developments.

At this place the British, during the battle of Nicholson's Nek, had hidden a large quantity of rifle and gun ammunition in a hole in the ground, covering it up with grass, which gave it the appearance of a heap of rubbish. One of the burghers who feared this would be injurious to the health of our men in camp, set the grass on fire, and this soon penetrated to the ammunition. A tremendous explosion occurred, and it seemed as if there were a real battle in progress. From all sides burghers dashed up on horseback to learn where the fighting was taking place. General Joubert sent an adjutant to enquire whether the Johannesburgers were now killing each other for a change, and why I could not keep my men under better control. I asked this gentleman to be kind enough to see for himself what was taking place, and to tell the Commandant-General that I could manage well enough to keep my men in order, but (p. 067) could not be aware of the exact spot where the enemy had chosen to hide their ammunition.

Meanwhile, it became daily more evident to me how greatly Joubert depreciated my commando, and that we would have to behave very well and fight very bravely to regain his favour. Other commandos also seemed to have no better opinion, and spoke of us as the laager which had to run at Elandslaagte, forgetting how even General Meyer's huge commando had been obliged to retreat in the greatest confusion at Dundee. If all the details of this Dundee engagement were published it would be discovered that it was a Boer disaster only second to that of Elandslaagte.

We were now, however, at any rate at the front. I sent out my outposts and fixed my positions, which were very far from good; but I decided to make no complaints. We had resolved to do our very best to vindicate our honour, and to prove that our accusers had no reason to call us either cowards or good-for-nothings.[Back to Table of Contents]

THE BOER GENERAL'S SUPERSTITIONS.

A few days after we had arrived before Ladysmith we joined an expedition to reconnoitre the British entrenchments, and my commando was ordered near some forts on the north-westerly side of the town. Both small and large artillery were being fired from each side. We approached within 800 paces of a fort; it was broad daylight and the enemy could therefore see us distinctly, knew the exact range, and received us with a perfect hailstorm of fire. Our only chance was to seek cover behind kopjes and in ditches, for on any Boer showing his head the bullets whistled round his ears. Here two of my burghers were severely wounded, and we had some considerable trouble to get them through the firing line to our ambulance. At last, (p. 069) late in the afternoon, came the order to retire, and we retired after having achieved nothing.

I fail to this day to see the use of this reconnoitring, but at Ladysmith everything was equally mysterious and perplexing. It was perhaps that my knowledge of military matters was too limited to understand the subtle manœuvres of those days. But I have made up my mind not to criticise our leader's military strategy, though I must say at this juncture that the whole siege of Ladysmith and the manner in which the besieged garrison was ineffectually pounded at with our big guns for several months, seem to me an unfathomable mystery, which, owing to Joubert's untimely death, will never be explained satisfactorily. But I venture to describe Joubert's policy outside Ladysmith as stupid and primitive, and in another chapter I shall again refer to it.

After another fortnight or so, we were ordered away to guard another position to the south-west of Ladysmith, as the Free State commando under Commandant Nel, and, unless I am mistaken, under Field-Cornet (p. 070) Christian de Wet (afterwards the world-famous chief Commander of the Orange Free State, and of whom all Afrikanders are justly proud), had to go to Cape Colony.

Here I was under the command of Dijl Erasmus, who was then General and a favourite of General Joubert. We had plenty of work given us. Trenches had to be dug and forts had to be constructed and remodelled. At this time an expedition ventured to Estcourt, under General Louis Botha, who replaced General L. Meyer, sent home on sick leave. My commando joined the expedition under Field-Cornet J. Kock, who afterwards caused me a lot of trouble.

I can say but little of this expedition to Estcourt, save that the Commander-in-Chief accompanied it. But for his being with us, I am convinced that General Botha would have pushed on at least as far as Pietermaritzburg, for the English were at that time quite unable to stop our progress. But after we got to Estcourt, practically unopposed, Joubert, though our burghers had been victorious in battle after battle, ordered us to retreat. The (p. 071) only explanation General Joubert ever vouchsafed about the recall of this expedition was that in a heavy thunderstorm which had been raging for two nights near Estcourt, two Boers had been struck by lightning, which, according to his doctrine, was an infallible sign from the Almighty that the commandos were to proceed no further. It seems incredible that in these enlightened days we should find such a man in command of an army; it is, nevertheless, a fact that the loss of two burghers induced our Commandant-General to recall victorious commandos who were carrying all before them. The English at Pietermaritzburg, and even at Durban, were trembling lest we should push forward to the coast, knowing full well that in no wise could they have arrested our progress. And what an improvement in our position this would have meant! As it was, our retirement encouraged the British to push forward their fighting line so far as Chieveley Station, near the Tugela river, and the commandos had to take up a position in the "randjes," on the westerly banks of the Tugela.[Back to Table of Contents]

THE "GREAT POWERS" TO INTERVENE.

During the retreat of our army to the frontier of the Transvaal Republic nothing of importance occurred. Here again confusion reigned supreme, and none of the commandos were over-anxious to form rearguards. Our Hollander Railway Company made a point of placing a respectful distance between her rolling-stock and the enemy, and, anxious to lose as few carriages as possible, raised innumerable difficulties when asked to transport our men, provisions and ammunition. Our generals had meantime proceeded to Laing's Nek by rail to seek new positions, and there was no one to maintain order and discipline.

About 150 Natal Afrikanders who had joined our commandos when these under (p. 073) the late General Joubert occupied the districts about Newcastle and Ladysmith, now found themselves in an awkward position. They elected to come with us, accompanied by their families and live stock, and they offered a most heartrending spectacle. Long rows of carts and wagons wended their way wearily along the road to Laing's Nek. Women in tears, with their children and infants in arms, cast reproachful glances at us as being the cause of their misery. Others occupied themselves more usefully in driving their cattle. Altogether it was a scene the like of which I hope never to see again.

The Natal kaffirs now had an opportunity of displaying their hatred towards the Boers. As soon as we had left a farm and its male inhabitants had gone, they swooped down on the place and wrought havoc and ruin, plundering and looting to their utmost carrying capacity. Some even assaulted women and children, and the most awful atrocities were committed. I attach more blame to the whites who encouraged these plundering bands, especially some of the Imperial troops (p. 074) and Natal men in military service. Not understanding the bestial nature of the kaffirs, they used them to help carry out their work of destruction, and although they gave them no actual orders to molest the people, they took no proper steps of preventing this.

When our commando passed through Newcastle, we found the place almost entirely deserted, excepting for a few British subjects who had taken an oath of neutrality to the Boers.

I regret to have to state that during our retreat a number of irresponsible persons set fire to the Government buildings in that town. It is said that an Italian officer burned a public hall on no reasonable pretext; certainly he never received orders to that effect. As may be expected of an invading army, some of our burgher patrols and other isolated bodies of troops looted and destroyed a number of houses which had been temporarily deserted. But with the exception of these few cases, I can state that no outrages were committed by us in Natal, and no property was needlessly destroyed.

(p. 075) On our arrival at Laing's Nek a Council of War was immediately held to decide our future plans.

We now found ourselves once more on the old battlefields of 1880 and 1881, where Boer and Briton had met 20 years before to decide by trial of arms who should be master of the S. A. Republic. Traces of that desperate struggle were still plainly visible, and the historic height of Majuba stood there, an isolated sentinel, recalling to us the battle in which the unfortunate Colley lost both the day and his life.

I was told off to take up a position in the Nek where the wagon-road runs to the east across the railway-tunnel, and here we made preparations for digging trenches and placing our guns. Soon after we had completed our entrenchments we once more saw the enemy. They were lying at Schuinshoogte on the Ingogo, and had sent a mounted corps with two guns to the Nek. Although we had no idea of the enemy's strength, we were fully prepared to meet the attack; the Pretoria, Lydenburg and other laagers were posted to (p. 076) the left on the summit of Majuba Hill, and other commandos held good positions on the east. But the enemy evidently thought that we had fled all the way back to Pretoria, and not expecting to find the Nek occupied, advanced quite unconcerned. We fired a few volleys at them, which caused them to halt in considerable surprise, and, replying with a little artillery fire, they quickly returned to Schuinshoogte. We had, however, to be on our guard both day and night. It was bitterly cold at the time and a strong easterly wind was blowing.

Next day something occurred which afforded a change to the monotony of our situation, namely, the arrival from Pretoria of Mr. John Lombaard, member of the First Volksraad for Bethel. He asked permission to address us and informed us that we need only hold out another fortnight, for news from Europe had reached them to the effect that the Great Powers had decided to put an end to the War. This communication emanating from such a semi-official source was believed by a certain number of our men, but I think (p. 077) it did very little to brighten up the spirits of the majority, or arouse them from the lethargy into which they seemed to have fallen. A fortnight passed, and a month, without us hearing anything further of this expected intervention, and I have never been able to discover on whose authority and by whose orders Mr. Lombaard made to us that remarkable communication.

Meantime, General Buller did not seem at all anxious to attack us, perhaps fearing a repetition of the "accidents" on the Tugela; or possibly he thought that our position was too strong. For some reason, therefore, Laing's Nek was never attacked, and Buller afterwards, having made a huge "detour," broke through Botha's Pass. Meanwhile, Lord Roberts and his forces were marching without opposition through the Orange Free State, and I was ordered to proceed to Vereeniging with my commando. We left Laing's Nek on the 19th of May, and proceeded to the Free State frontier by rail.[Back to Table of Contents]

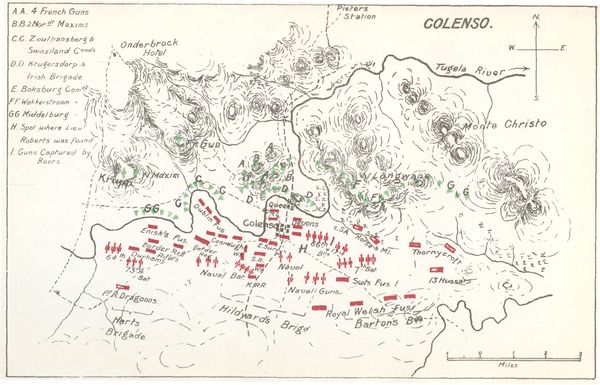

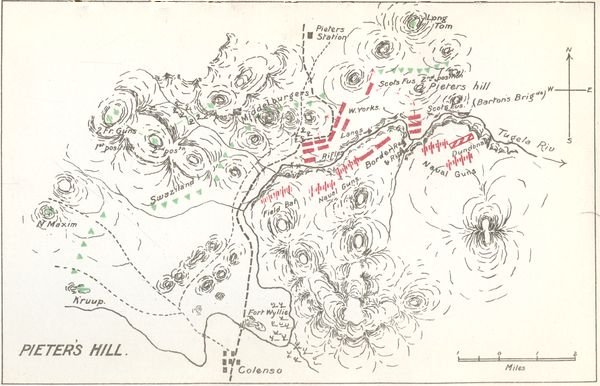

COLENSO AND SPION KOP FIGHTS.

Eight days after my commando had been stationed in my new position under General Erasmus, I received instructions to march to Potgietersdrift, on the Upper Tugela, near Spion Kop, and there to put myself at Andries Cronje's disposal. This gentleman was then a general in the Orange Free State Army, and although a very venerable looking person, was not very successful as a commander. Up to the 14th of December, 1899, no noteworthy incident took place, and nothing was done but a little desultory scouting along the Tugela, and the digging of trenches.

At last came the welcome order summoning us to action; and we were bidden to march on Colenso Heights with 200 men to fill up the ranks, as a fight was imminent. (p. 079) We left under General Cronje and arrived the next morning at daybreak, and a few hours after began the battle now known to the world as the Battle of Colenso (15th December, 1899).

I afterwards heard that the commandos under General Cronje were to cross the river and attack the enemy's left flank. This did not happen, as the greatest confusion prevailed owing to the various contradictory orders given by the generals. For instance, I myself received four contradictory orders from four generals within the space of ten minutes. I, however, took the initiative in moving my men up to the river to attempt the capture of a battery of guns on the enemy's left flank which had been left unprotected, as was the case with the ten guns which fell into our hands later in the day. I had approached within 1,400 paces of the enemy, and my burghers were following close behind me when an adjutant from General Botha (accompanied by a gentleman named C. Fourie, who was then also parading as a general) galloped up (p. 080) to us and ordered us at once to join the Ermelo commando, which was said to be too weak to resist the attacks of the enemy. We hurried thither as quickly as we could round the rear of the fighting line, where we were obliged to off-saddle and walk up to the position of the Ermelo burghers. This was no easy task; the battle was now in full swing, and the enemy's shells were bursting in dozens around us, and in the burning sun we had to run some miles.

When we arrived at our destination Mr. Fourie (the pseudo general) and his adjutant could nowhere be found. As to the Ermelo burghers, they said they were quite comfortable, and had asked for no assistance.

Not a single shell had reached them, for a clump of aloe trees stood a hundred yards away, which the English presumably had taken for Boers, judging by the terrific bombardment these trees were being subjected to.

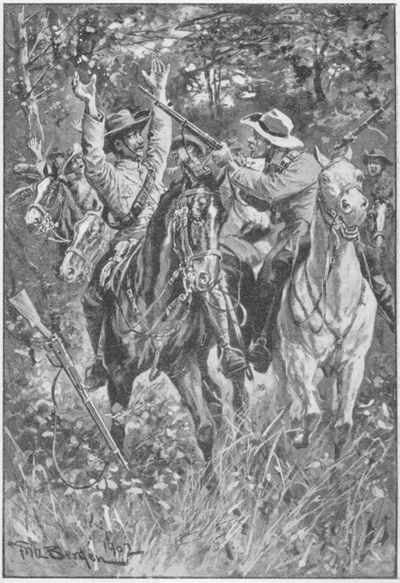

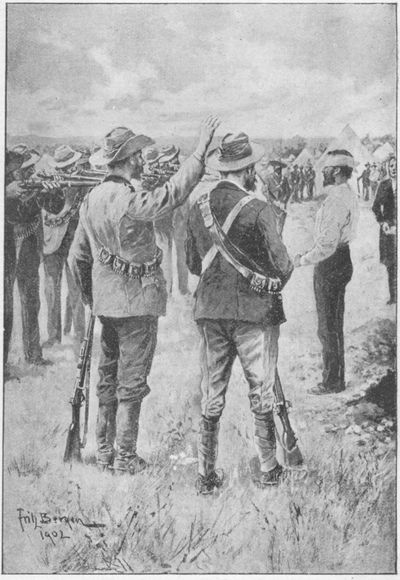

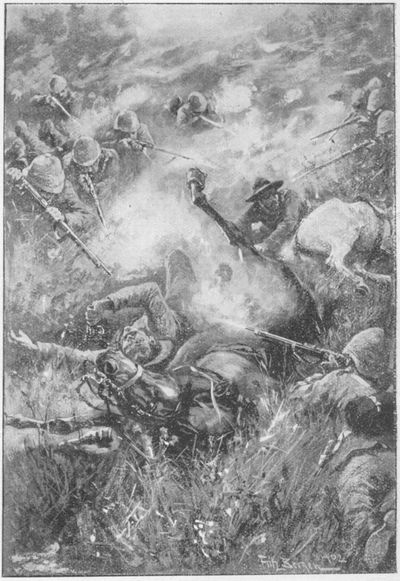

Along the Tugela—Coming suddenly upon an English Outpost.

By this time the attack was repulsed, and General Buller was in full retreat to Chieveley, though our commando had been unable to take an active part in the fighting, at which (p. 081) we were greatly disappointed. It is much to be regretted that the retreat of the enemy was not followed up at once. Had this been done, the campaign in Natal would have taken an entirely different aspect, and very probably would have been attended by a more favourable conclusion. I consider myself far from a prophet, but this I know; and if we had then and on subsequent occasions followed up our successes, the result of the Campaign would have been far more satisfactory to us.

After I had assisted in bringing away through the river the guns we had taken, and seen to other matters which required my immediate attention, I was ordered to remain with the Ermelo commando at Colenso, near Toomdrift, and to await there further instructions.

A few weeks of inactivity followed, the English sending us each day a few samples of their shells from their 4·7 Naval guns. Unfortunately, our guns were of much smaller calibre, and we could send them no suitable reply. As a rule we would lie in the trenches, and a burgher would be on the look-out. So (p. 082) soon as he saw the flash of an English gun, he would cry out; "There's a shell," and we then sought cover, so that the enemy seldom succeeded in harming us.

One day one of these big shells fell amongst a group of fourteen burghers who were at dinner. The shell struck a sharp rock, which it splintered into fragments, and was emitting its yellow lyddite; but, fortunately, the fuse refused to burn, and the shell did not explode, so we had a narrow escape that day from a small catastrophe.

My laager had been at Potgietersdrift all this time, and for the time being we were deprived of our tents. We were not sorry, therefore, when we were ordered to leave Colenso and to return to our camp.

A few days after we were told off to take up a position at the junction of the Little and the Big Tugela, between Spion Kop and Colenso. Here we celebrated our first Christmas in the field; our friends at Johannesburg had sent us a quantity of presents by means of a friend, Attorney Raaff, comprising cakes, cigars, cigarettes, tobacco and other luxuries. Along (p. 083) this part of the Tugela we found a fair quantity of vegetables, and poultry, and as their respective owners had fled we were unable to pay for what we had. We were obliged, therefore, to "borrow" all these things for the banquet befitting to the occasion.

But General Buller had not quite finished with us yet. He marched on Spion Kop, but with the exception of a feint attack nothing of importance happened then. One day I went across the river with a patrol to discover what the enemy was doing, when we suddenly came across nine English spies, who fled as soon as they saw us. We galloped after them, trying to cut them off from the main body, which was at a little distance away from us, and would no doubt have overtaken them, but, riding at a breakneck speed over a mountain ridge, we found ourselves suddenly confronted with a strong English mounted corps, apparently engaged in drilling. We were only 500 paces away from them, and we jumped off our horses, and opened fire. But there were only a dozen of us, and the enemy soon began sending us a few shells, and prepared to (p. 084) attack us with their whole force. About a hundred mounted men, with horses in the best of condition, set off to pursue us.

We were obliged to ride back by the same path we had come by, which was fortunate for us, as we knew the way and could ride through crevices and dongas without any hesitation. In this way we soon gave our pursuers the slip.

Buller's forces seemed at first to have the intention of forcing their way through near Potgietersdrift, and they took possession of all the "randts" on their side of the river, causing us to strengthen the position on our side. We thus had to shift our commando again to Potgietersdrift, where we soon had the enemy's Naval guns playing on our positions. This continued day and night for a whole week.

It seemed as if General Buller were determined to annihilate all the Boers with his lyddite shells, so as to enable the soldiers to walk at their leisure to the release of Ladysmith. Certainly we suffered considerably from lyddite fumes.

(p. 085) The British next made a feint attack near Potgietersdrift, advancing with a great clamour till they had come within 2,000 paces of us, where they occupied various "randts" and kopjes, always under cover of their artillery. Once they came a little too close to our positions, and we suddenly opened fire on them. The result was that their ambulance waggons were seen to become very busy driving backwards and forwards.

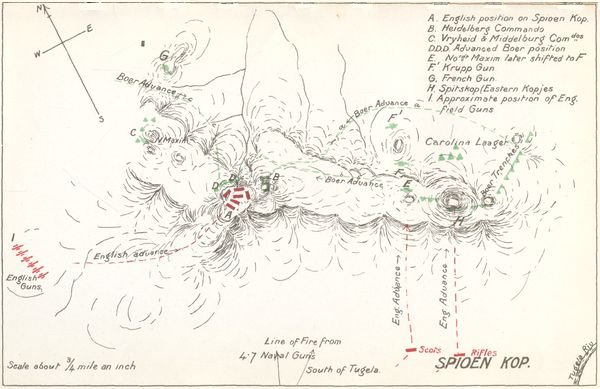

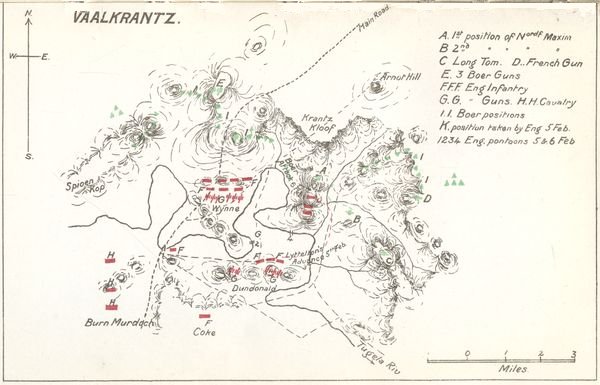

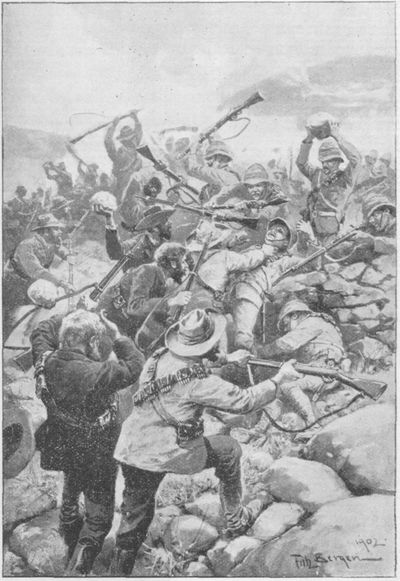

This "feint," however, was only made in order to divert our attention, while Buller was concentrating his troops and guns on Spion Kop. The ruse succeeded to a large extent, and on the 21st January the memorable battle of Spion Kop (near the Upper Tugela) began.

General Warren, who, I believe, was in command here, had ordered another "feint" attack from the extreme right wing. General Cronje and the Free Staters had taken up a position at Spion Kop, assisted by the commandos of General Erasmus and Schalk Burger.

The fight lasted the whole of that day and (p. 086) the next, and became more and more fierce. Luckily General Botha appeared on the scene in time, and re-arranged matters so well and with so much energy that the enemy found itself well employed, and was kept in check at all points.

I had been ordered to defend the position at Potgietersdrift, but the fighting round Spion Kop became so serious that I was obliged to send up a field cornet with his men as a reinforcement, which was soon followed by a second contingent, making altogether 200 Johannesburgers in the fight, of whom nine were killed and 18 wounded. The enemy had reached the top of the "kop" on the evening of the second day of the fight, not, however, without having sustained considerable losses. At this juncture one of our generals felt so disheartened that he sent away his carts, and himself left the battlefield.

But General Botha kept his ground like a man, surrounded by the faithful little band who had already borne the brunt of this important battle. And one can imagine our delight when next morning we found that (p. 087) the English had retreated, leaving that immense battlefield, strewn with hundreds of dead and wounded, in our hands.

"What made them leave so suddenly last night," was the question we asked each other then, and which remains unanswered to this day.