The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Story of My Life, by Egerton Ryerson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Story of My Life

Being Reminiscences of Sixty Years' Public Service in Canada

Author: Egerton Ryerson

Editor: J. George Hodgins

Release Date: February 12, 2008 [EBook #24586]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STORY OF MY LIFE ***

Produced by Stacy Brown, Jason Isbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

BY THE LATE

(Being Reminiscences of Sixty Years' Public Service in Canada.)

PREPARED UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF HIS LITERARY TRUSTEES:

THE REV. S.S. NELLES, D.D., LL.D., THE REV. JOHN POTTS. D.D., AND J. GEORGE HODGINS, ESQ., LL.D.

EDITED BY

J. GEORGE HODGINS, Esq., LL.D.

WITH PORTRAIT AND ENGRAVINGS.

TORONTO:

WILLIAM BRIGGS, 78 and 80 KING STREET EAST.

1884.

Entered, according to the Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year one thousand eight hundred and eighty-three, by Mary Ryerson and Charles Egerton Ryerson, in the Office of the Minister of Agriculture, Ottawa.

| Preface | ix |

| Estimate of Rev. Dr. Ryerson's Character and Labours | 17 |

| CHAPTER I.—1803-1825. | |

| Sketch of Early Life | 23 |

| CHAPTER II.—1824-1825. | |

| Extracts from Dr. Ryerson's Diary of 1824 and 1825 | 32 |

| CHAPTER III.—1825-1826. | |

| First Year of Ministry and First Controversy | 47 |

| CHAPTER IV.—1826-1827. | |

| Missionary to the River Credit Indians | 58 |

| CHAPTER V.—1826-1827. | |

| Diary of Labours among Indians | 64 |

| CHAPTER VI.—1827-1828. | |

| Labours and Trials.—Civil Rights Controversy | 80 |

| CHAPTER VII.—1828-1829. | |

| Ryanite Schism.—M. E. Church of Canada organized | 87 |

| CHAPTER VIII.—1829-1832. | |

| Establishment of the Christian Guardian.—Church Claims resisted | 93 |

| CHAPTER IX.—1831-1832. | |

| Methodist Affairs in Upper Canada.—Proposed Union with the British Conference | 107 |

| CHAPTER X.—1833. | |

| Union between the British and Canadian Conferences | 114 |

| CHAPTER XI.—1833-1834. | |

| "Impressions of England" and their effects | 121 |

| CHAPTER XII.—1834. | |

| Events following the Union.—Division and Strife | 141 |

| CHAPTER XIII.—1834-1835. | |

| Second Retirement from the Guardian Editorship | 144 |

| CHAPTER XIV.—1835-1836. | |

| Second Mission to England.—Upper Canada Academy | 152 |

| CHAPTER XV.—1835-1836. | |

| The "Grievance" Report; Its Object and Failure | 155 |

| CHAPTER XVI.—1836-1837. | |

| Dr. Ryerson's Diary of his Second Mission to England | 158 |

| CHAPTER XVII.—1836. | |

| Publication of the Hume and Roebuck Letters | 167 |

| CHAPTER XVIII.—1836-1837. | |

| Important Events transpiring in England | 170 |

| CHAPTER XIX.—1837-1839. | |

| Return to Canada.—The Chapel Property Cases | 172 |

| CHAPTER XX.—1837. | |

| The Coming Crisis.—Rebellion of 1837 | 175 |

| CHAPTER XXI.—1837-1838. | |

| Sir F. B. Head and the Upper Canada Academy | 179 |

| CHAPTER XXII.—1838. | |

| Victims of the Rebellion.—State of the Country | 182 |

| CHAPTER XXIII.—1795-1861. | |

| Sketch of Mr. William Lyon Mackenzie | 185 |

| CHAPTER XXIV.—1838. | |

| Defence of the Hon. Marshall Spring Bidwell | 188 |

| CHAPTER XXV.—1838. | |

| Return to the Editorship of the Guardian | 199 |

| CHAPTER XXVI.—1838-1840. | |

| Enemies and Friends Within and Without | 205 |

| CHAPTER XXVII.—1778-1867. | |

| The Honourable and Right Reverend Bishop Strachan | 213 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII.—1791-1836. | |

| The Clergy Reserves and Rectories Questions | 218 |

| CHAPTER XXIX.—1838. | |

| The Clergy Reserve Controversy Renewed | 225 |

| CHAPTER XXX.—1838-1839. | |

| The Ruling Party and the Reserves.—"Divide et Impera." | 236 |

| CHAPTER XXXI.—1839. | |

| Strategy in the Clergy Reserve Controversy | 245 |

| CHAPTER XXXII.—1839. | |

| Sir G. Arthur's Partizanship.—State of the Province | 250 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII.—1838-1840. | |

| The New Era.—Lord Durham and Lord Sydenham | 257 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV.—1840. | |

| Proposal to leave Canada.—Dr. Ryerson's Visit to England | 269 |

| CHAPTER XXXV.—1840-1841. | |

| Last Pastoral Charge.—Lord Sydenham's Death | 282 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI.—1841. | |

| Dr. Ryerson's Attitude toward the Church of England | 291 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII.—1841-1842. | |

| Victoria College.—Hon. W. H. Draper.—Sir Charles Bagot | 301 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII.—1843. | |

| Episode in the case of Hon. Marshall S. Bidwell | 308 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX.—1844. | |

| Events preceding the Defence of Lord Metcalfe | 312 |

| CHAPTER XL.—1844. | |

| Preliminary Correspondence on the Metcalfe Crisis | 319 |

| CHAPTER XLI.—1844. | |

| Sir Charles Metcalfe Defended against his Councillors | 328 |

| CHAPTER XLII.—1844-1845. | |

| After the Contest.—Reaction and Reconstruction | 337 |

| CHAPTER XLIII.—1841-1844. | |

| Dr. Ryerson appointed Superintendent of Education | 342 |

| CHAPTER XLIV.—1844-1846. | |

| Dr. Ryerson's First Educational Tour in Europe | 352 |

| CHAPTER XLV.—1844-1857. | |

| Episode in Dr. Ryerson's European Travels.—Pope Pius IX | 365 |

| CHAPTER XLVI.—1844-1876. | |

| Ontario School System.—Retirement of Dr. Ryerson | 368 |

| CHAPTER XLVII.—1845-1846. | |

| Illness and Final Retirement of Lord Metcalfe | 375 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII.—1843-1844. | |

| Clergy Reserve Question Re-Opened.—Disappointments | 378 |

| CHAPTER XLIX.—1846-1848. | |

| Re-Union of the British and Canadian Conferences | 383 |

| CHAPTER L.—1846-1853. | |

| Miscellaneous Events and Incidents of 1846-1853 | 410 |

| CHAPTER LI.—1849. | |

| The Bible in the Ontario Public Schools | 423 |

| CHAPTER LII.—1850-1853. | |

| The Clergy Reserve Question Transferred to Canada | 433 |

| CHAPTER LIII.—1851. | |

| Personal Episode in the Clergy Reserve Question | 454 |

| CHAPTER LIV.—1854-1855. | |

| Resignation on the Class-Meeting Question.—Discussion | 470 |

| CHAPTER LV.—1855. | |

| Dr. Ryerson resumes his Position in the Conference | 491 |

| CHAPTER LVI.—1855-1856. | |

| Personal Episode in the Class-Meeting Discussion | 499 |

| CHAPTER LVII.—1855-1856. | |

| Dr. Ryerson's Third Educational Tour in Europe | 514 |

| CHAPTER LVIII.—1859-1862. | |

| Denominational Colleges and the University Controversy | 518 |

| CHAPTER LIX.—1861-1866. | |

| Personal Incidents.—Dr. Ryerson's Visits to Norfolk County | 534 |

| CHAPTER LX.—1867. | |

| Last Educational Visit to Europe.—Rev. Dr. Punshon | 539 |

| CHAPTER LXI.—1867. | |

| Dr. Ryerson's Address on the New Dominion of Canada | 547 |

| CHAPTER LXII.—1868-1869. | |

| Correspondence with Hon. Geo. Brown—Dr. Punshon | 554 |

| CHAPTER LXIII.—1870-1875. | |

| Miscellaneous Closing Events and Correspondence | 559 |

| CHAPTER LXIV.—1875-1876. | |

| Correspondence with Rev. J. Ryerson, Dr. Punshon, etc. | 573 |

| CHAPTER LXV.—1877-1882. | |

| Closing Years of Dr. Ryerson's Life Labours | 585 |

| CHAPTER LXVI.—1882. | |

| The Funeral Ceremonies | 593 |

| Tributes to Dr. Ryerson's Memory and Estimates of his Character and Work | 598 |

| Portrait of Rev. Dr. Ryerson | Frontispiece |

| Indian Village at River Credit, in 1837 | 59 |

| John Jones' House at the Credit, where Dr. Ryerson Resided | 65 |

| Old Credit Mission, 1837 | 73 |

| Old Adelaide Street Methodist Church | 283 |

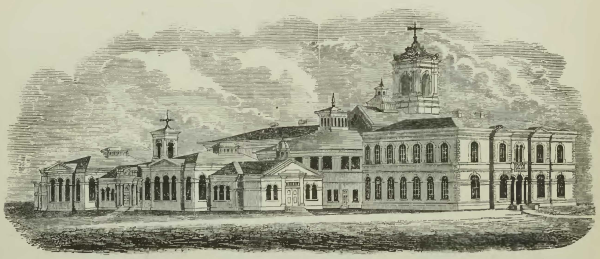

| Victoria College, Cobourg | 302 |

| Ontario Educational Department and Normal School | 421, 422 |

| Educational Exhibit at Philadelphia | 584, 585 |

| Metropolitan Church | 564 |

| Dr. Ryerson's Residence in Toronto | 587 |

Twelve months ago, I began to collect the necessary material for the completion of "The Story of My Life," which my venerated and beloved friend, Dr. Ryerson, had only left in partial outline. These materials, in the shape of letters, papers, and documents, were fortunately most abundant. The difficulty that I experienced was to select from such a miscellaneous collection a sufficient quantity of suitable matter, which I could afterwards arrange and group into appropriate chapters. This was not easily done, so as to form a connected record of the life and labours of a singularly gifted man, whose name was intimately connected with every public question which was discussed, and every prominent event which took place in Upper Canada from 1825 to 1875-78.

Public men of the present day looked upon Dr. Ryerson practically as one of their own contemporaries—noted for his zeal and energy in the successful management of a great Public Department, and as the founder of a system of Popular Education which, in his hands, became the pride and glory of Canadians, and was to those beyond the Dominion, an ideal system—the leading features of which they would gladly see incorporated in their own. In this estimate of Dr. Ryerson's labours they were quite correct. And in their appreciation of the statesmanlike qualities of mind, which devised and developed such a system in the midst of difficulties which would have appalled less resolute hearts, they were equally correct.

But, after all, how immeasurably does this partial view of his character and labours fall short of a true estimate of that character and of those labours![Pg x]

As a matter of fact, Dr. Ryerson's great struggle for the civil and religious freedom which we now enjoy, was almost over when he assumed the position of Chief Director of our Educational System. No one can read the record of his labours from 1825 to 1845, as detailed in the following pages, without being impressed with the fact that, had he done no more for his native country than that which is therein recorded, he would have accomplished a great work, and have earned the gratitude of his fellow-countrymen.

It was my good fortune to enjoy Dr. Ryerson's warm, personal friendship since 1841. It has also been my distinguished privilege to be associated with him in the accomplishment of his great educational work since 1844. I have been able, therefore, to turn my own personal knowledge of most of the events outlined in this volume to account in its preparation. In regard to what transpired before 1841, I have frequently heard many narratives in varied forms from Dr. Ryerson's lips.

My own intimate relations with Dr. Ryerson, and the character of our close personal friendship are sufficiently indicated in his private letters to me, published in various parts of the book, but especially in Chapter liii. And yet they fail to convey the depth and sincerity of his personal attachment, and the feeling of entire trust and confidence which existed between us.

I am glad to say that I was not alone in this respect. Dr. Ryerson had the faculty, so rare in official life, of attaching his assistants and subordinates of every grade to himself personally. He always had a pleasant word for them, and made them feel that their interests were safe in his hands. They therefore respected and trusted him fully, and he never failed to acknowledge their fidelity and devotion in the public service.

I had, for some time before he ceased to be the Head of the Education Department, looked forward with pain and anxiety to that inevitable event. Pain, that he and I were at length to be separated in the carrying forward of the great work of our lives, in which it had been my pride and pleasure to be his principal assistant. Anxiety at what, from my knowledge of him, I feared would be the effect of release from the work on fully accomplishing which he had so earnestly set his heart. Nor were my fears groundless. To a man of his application and[Pg xi] ardent temperament, the feeling that his work was done sensibly affected him. He lost a good deal of his elasticity, and during the last few years of his life, very perceptibly failed.

The day on which he took official leave of the Department was indeed a memorable one. As he bade farewell to each of his assistants in the office, he and they were deeply moved. He could not, however, bring himself to utter a word to me at our official parting, but as soon as he reached home he wrote to me the following tender and loving note:—

171 Victoria Street, Toronto,

Monday Evening, February 21st, 1876.

My Dear Hodgins,—I felt too deeply to-day when parting with you in the Office to be able to say a word. I was quite overcome with the thought of severing our official connection, which has existed between us for thirty-two years, during the whole of which time, without interruption, we have laboured as one mind and heart in two bodies, and I believe with a single eye to promote the best interests of our country, irrespective of religious sect or political party—to devise, develop, and mature a system of instruction which embraces and provides for every child in the land a good education; good teachers to teach; good inspectors to oversee the Schools; good maps, globes, and text-books; good books to read; and every provision whereby Municipal Councils and Trustees can provide suitable accommodation, teachers, and facilities for imparting education and knowledge to the rising generation of the land.

While I devoted the year 1845 to visiting educating countries and investigating their system of instruction, in order to devise one for our country, you devoted the same time in Dublin in mastering, under the special auspices of the Board of Education there, the several different branches of their Education Office, in administering the system of National Education in Ireland, so that in the details of our Education Office here, as well as in our general school system, we have been enabled to build up the most extensive establishment in the country, leaving nothing, as far as I know, to be devised in the completeness of its arrangements, and in the good character and efficiency of its officers. Whatever credit or satisfaction may attach to the accomplishment[Pg xii] of this work, I feel that you are entitled to share equally with myself. Could I have believed that I might have been of any service to you, or to others with whom I have laboured so cordially, or that I could have advanced the school system, I would not have voluntarily retired from office. But all circumstances considered, and entering within a few days upon my 74th year, I have felt that this was the time for me to commit to other hands the reins of the government of the public school system, and labour during the last hours of my day and life, in a more retired sphere.

But my heart is, and ever will be, with you in its sympathies and prayers, and neither you nor yours will more truly rejoice in your success and happiness, than

Your old life-long Friend

And Fellow-labourer,

E. Ryerson.

Dr. Ryerson was confessedly a man of great intellectual resources. Those who read what he has written on the question—perilous to any writer in the early days of the history of this Province—of equal civil and religious rights for the people of Upper Canada, will be impressed with the fact that he had thoroughly mastered the great principles of civil and religious liberty, and expounded them not only with courage, but with clearness and force. His papers on the clergy reserve question, and the rights of the Canadian Parliament in the matter, were statesmanlike and exhaustive.

His exposition of a proposed system of education for his native country was both philosophical and eminently practical. As a Christian Minister, he was possessed of rare gifts, both in the pulpit and on the platform; while his warm sympathies and his deep religious experience, made him not only a "son of consolation," but a beloved and welcome visitor in the homes of the sorrowing and the afflicted. Among his brethren he exercised great personal influence; and in the counsels of the Conference he occupied a trusted and foremost place.

Thus we see that Dr. Ryerson's character was a many-sided one; while his talents were remarkably versatile. He was an[Pg xiii] able writer on public affairs; a noted Wesleyan Minister, and a successful and skilful leader among his brethren. But his fame in the future will mainly rest upon the fact that he was a distinguished Canadian Educationist, and the Founder of a great system of Public Education for Upper Canada. What makes this widely conceded excellence in his case the more marked, was the fact that the soil on which he had to labour was unprepared, and the social condition of the country was unpropitious. English ideas of schools for the poor, supported by subscriptions and voluntary offerings, prevailed in Upper Canada; free schools were unknown; the very principle on which they rest—that is, that the rateable property of the country is responsible for the education of the youth of the land—was denounced as communistic, and an invasion of the rights of property; while "compulsory education"—the proper and necessary complement of free schools—was equally denounced as the essence of "Prussian despotism," and an impertinent and unjustifiable interference with "the rights of British subjects."

It was a reasonable boast at the time that only systems of popular education, based upon the principle of free schools, were possible in the republican American States, where the wide diffusion of education was regarded as a prime necessity for the stability and success of republican institutions, and, therefore, was fostered with unceasing care. It was the theme on which the popular orator loved to dilate to a people on whose sympathies with the subject he could always confidently reckon. The practical mind of Dr. Ryerson, however, at once saw that the American idea of free schools was the true one. He moreover perceived that by giving his countrymen facilities for freely discussing the question among the ratepayers once a year, they would educate themselves into the idea, without any interference from the State. These facilities were provided in 1850; and for twenty-one years the question of free-schools versus rate-bill schools (lees, &c.) was discussed every January in from 3,000 to 5,000 school sections, until free schools became voluntarily the rule, and rate-bill schools the exception. In 1871, by common consent, the free school principle was incorporated into our school system by the Legislature, and has ever since been the universal practice. In the adoption of this principle, and in the[Pg xiv] successful administration of the Education Department, Dr. Ryerson at length demonstrated that a popular (or, as it had been held in the United States, the democratic) system of public schools was admirably adapted to our monarchical institutions. In point of fact, leading American educationists have often pointed out that the Canadian system of public education was more efficient in all of its details and more practically successful in its results, than was the ordinary American school system in any one of the States of the Union. Thus it is that the fame of Dr. Ryerson as a successful founder of our educational system, rests upon a solid basis. What has been done by him will not be undone; and the ground gone over by him will not require to be traversed again. In the "Story of My Life," not much has been said upon the subject with which Dr. Ryerson's name has been most associated. It was distinctively the period of his public life, and its record will be found in the official literature of his Department. The personal reminiscences left by him are scanty, and of themselves would present an utterly inadequate picture of his educational work. Such a history may one day be written as would do it justice, but I feel that in such a work as the present it is better not to attempt a task, the proper performance of which would make demands upon the space and time at my disposal that could not be easily met.

There was one rôle in which Dr. Ryerson pre-eminently excelled—that of a controversialist. There was nothing spasmodic in his method of controversy, although there might be in the times and occasions of his indulging in it. He was a well-read man and an accurate thinker. His habit, when he meditated a descent upon a foe, was to thoroughly master the subject in dispute; to collect and arrange his materials, and then calmly and deliberately study the whole subject—especially the weak points in his adversary's case, and the strong points of his own. His habits of study in early life contributed to his after success in this matter. He was an indefatigable student; and so thoroughly did he in early life ground himself in English subjects—grammar, logic, rhetoric—and the classics, and that, too, under the most adverse circumstances, that, in his subsequent active career as a writer and controversialist, he evinced a power and readiness with his tongue and pen, that often astonished[Pg xv] those who were unacquainted with the laborious thoroughness of his previous mental preparation.

It was marvellous with what wonderful effect he used the material at hand. Like a skilful general defending a position—and his study was always to act on the defensive—he masked his batteries, and was careful not to exhaust his ammunition in the first encounter. He never offered battle without having a sufficient force in reserve to overwhelm his opponent. He never exposed a weak point, nor espoused a worthless cause. He always fought for great principles, which to him were sacred, and he defended them to the utmost of his ability, when they were attacked. In such cases, Dr. Ryerson was careful not to rush into print until he had fully mastered the subject in dispute. This statement may be questioned, and apparent examples to the contrary adduced; but the writer knows better, for he knows the facts. In most cases Dr. Ryerson scented the battle from afar. Many a skirmish was improvised, and many a battle was privately fought out before the Chief advanced to repel an attack, or to fire the first shot in defence of his position.

A word as to the character of this work. It may be objected that I have dealt largely with subjects of no practical interest now—with dead issues, and with controversies for great principles, which, although important, acrimonious, and spirited at the time, have long since lost their interest. Let such critics reflect that the "Story" of such a "Life" as that of Dr. Ryerson cannot be told without a statement of the toils and difficulties which he encountered, and the triumphs which he achieved? For this reason I have written as I have done, recounting them as briefly as the subjects would permit.

In the preparation of this work I am indebted to the co-operation of my co-trustees the Rev. Dr. Potts and Rev. Dr. Nelles, whose long and intimate acquaintance with Dr. Ryerson (quite apart from their acknowledged ability) rendered their counsels of great value.

And now my filial task is done,—imperfectly, very imperfectly I admit. While engaged in the latter part of the work a deep[Pg xvi] dark shadow fell—suddenly fell—upon my peaceful, happy home. This great sorrow has almost paralyzed my energies, and has rendered it very difficult for me to concentrate my thoughts on the loving task which twelve months ago I had so cheerfully begun. Under these circumstances, I can but crave the indulgence of the readers of these memorial pages of my revered and honoured Friend, the Rev. Dr. Ryerson—the foremost Canadian of his time.

Toronto, 17th May, 1883.

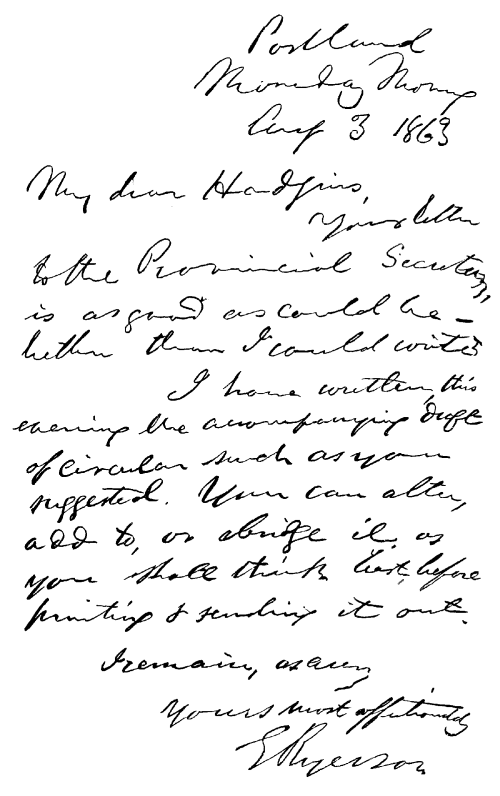

On the accompanying page, I give a fac-simile of the well-known hand-writing of Dr. Ryerson, one of the many notes which I received from him.

[This is the same note, transcribed:]

Portland

Monday Morning

Aug 3 1863

My dear Hodgins,

Your letter to the Provincial Secretary is as good as could be—better than I could write.

I have written this evening the accompanying draft of circular such as you suggested. You can alter, add to, or abridge it as you shall think best, before printing & sending it out.

I remain, as ever,

Yours most affectionately

E Ryerson

By the Rev. William Ormiston, D.D., LL.D.

New York, Oct. 6th, 1882.

My Dear Dr. Hodgins,—It affords me the sincerest pleasure, tinged with sadness, to record, at your request, the strong feelings of devoted personal affection which I long cherished for our mutual father and friend, Rev. Dr. Ryerson; and the high estimate, which, during an intimacy of nearly forty years, I had been led to form of his lofty intellectual endowments, his great moral worth, and his pervading spiritual power. He was very dear to me while he lived, and now his memory is to me a precious, peculiar treasure.

In the autumn of 1843, I went to Victoria College, doubting much whether I was prepared to matriculate as a freshman. Though my attainments in some of the subjects prescribed for examination were far in advance of the requirements, in other subjects, I knew I was sadly deficient. On the evening of my arrival, while my mind was burdened with the importance of the step I had taken, and by no means free from anxiety about the issue, Dr. Ryerson, at that time Principal of the College, visited me in my room. I shall never forget that interview. He took me by the hand; and few men could express as much by a mere hand-shake as he. It was a welcome, an encouragement, an inspiration, and an earnest of future fellowship and friendship. It lessened the timid awe I naturally felt towards one in such an elevated position,—I had never before seen a Principal of a College,—it dissipated all boyish awkwardness, and awakened filial confidence. He spoke of Scotland, my native land, and of her noble sons, distinguished in every branch of philosophy and literature; specially of the number, the diligence, the frugality, self-denial, and success of her college students. In this way, he soon led me to tell him of my parentage, past life and efforts, present hopes and aspirations. His manner was so gracious and paternal—his sympathy so quick and genuine—his counsel so ready and cheering—his assurances so grateful and inspiriting, that not only was my heart his from that hour, but my future career seemed brighter and more certain than it had ever appeared before.[Pg 18]

Many times in after years, have I been instructed, and guided, and delighted with his conversation, always replete with interest and information; but that first interview I can never forget: it is as fresh and clear to me to-day as it was on the morning after it took place. It has exerted a profound, enduring, moulding influence on my whole life. For what, under God, I am, and have been enabled to achieve, I owe more to that noble, unselfish, kind-hearted man than to any one else.

Dr. Ryerson was, at that time, in the prime of a magnificent manhood. His well-developed, finely-proportioned, firmly-knit frame; his broad, lofty brow; his keen, penetrating eye, and his genial, benignant face, all proclaimed him every inch a man. His mental powers vigorous and well-disciplined, his attainments in literature varied and extensive, his experience extended and diversified, his fame as a preacher of great pathos and power widely-spread, his claims as a doughty, dauntless champion of the rights of the people to civil and religious liberty generally acknowledged, his powers of expression marvellous in readiness, richness, and beauty, his manners affable and winning, his presence magnetic and impressive,—he stood in the eye of the youthful, ardent, aspiring student, a tower of strength, a centre of healthy, helpful influences—a man to be admired and honoured, loved and feared, imitated and followed. And I may add that frequent intercourse for nearly forty years, and close official relations for more than ten, only deepened and confirmed the impressions first made. A more familiar acquaintance with his domestic, social, and religious life, a more thorough knowledge of his mind and heart, constantly increased my appreciation of his worth, my esteem for his character, and my affection for his person.

Not a few misunderstood, undervalued, or misrepresented his public conduct, but it will be found that those who knew him best, loved him most, and that many who were constrained to differ from him, in his management of public affairs, did full justice to the purity and generosity of his motives, to the nobility, loftiness, and ultimate success of his aims, and to the disinterestedness and value of his varied and manifold labours for the country, and for the Church of Christ.

As a teacher, he was earnest and efficient, eloquent and inspiring, but he expected and exacted rather too much work from the average student. His own ready and affluent mind sympathized keenly with the apt, bright scholar, to whom his praise was warmly given, but he scarcely made sufficient allowance for the dullness or lack of previous preparation which failed to keep pace with him in his long and rapid strides; hence his censures were occasionally severe. His methods of[Pg 19] examination furnished the very best kind of mental discipline, fitted alike to cultivate the memory and to strengthen the judgment. All the students revered him, but the best of the class appreciated him most. His counsels were faithful and judicious; his admonitions paternal and discriminating; his rebukes seldom administered, but scathingly severe. No student ever left his presence, without resolving to do better, to aim higher, and to win his approval.

His acceptance of the office of Chief Superintendent of Education, while offering to him the sphere of his life's work, and giving to the country the very service it needed—the man for the place—was a severe trial to the still struggling College, and a bitter disappointment to some young, ambitious hearts.

Into this new arena he entered with a resolute determination to succeed, and he spared no pains, effort, or sacrifice to fit himself thoroughly for the onerous duties of the office to which he had been appointed. Of its nature, importance, and far-reaching results, he had a distinct, vivid perception, and clearly realized and fully felt the responsibilities it imposed. He steadfastly prosecuted his work with a firm, inflexible will, unrelaxing tenacity of purpose, an amazing fertility of expedient, an exhaustless amount of information, a most wonderful skill in adaptation, a matchless ability in unfolding and vindicating his plans, a rare adroitness in meeting and removing difficulties—great moderation in success, and indomitable perseverance under discouragement, calm patience when misapprehended, unflinching courage when opposed,—until he achieved the consummation of his wishes, the establishment of a system of public education second to none in its efficiency and adaptation to the condition and circumstances of the people. The system is a noble monument to the singleness of purpose, the unwavering devotion, the tireless energy, the eminent ability, and the administrative powers of Dr. Ryerson, and it will render his name a familiar word for many generations in Canadian schools and homes; and place him high in the list of the great men of other lands, distinguished in the same field of labour. His entire administration of the Department of Public Instruction was patient and prudent, vigorous and vigilant, sagacious and successful.

He repeatedly visited Europe, not for mere recreation or personal advantage, but for the advancement of the interests of religion and education in the Province. During these tours, there were opened to him the most extended fields of observation and enquiry, from which he gathered ample stores of information which he speedily rendered available for the perfecting, as far as practicable, the entire system of Public Instruction.[Pg 20]

A prominent figure in Canadian history for three score years, actively and ceaselessly engaged in almost every department of patriotic and philanthropic, Christian and literary, enterprise, Dr. Ryerson was a strong tower in support or defence of every good cause, and no such cause failed to secure the powerful aid of his advocacy by voice and pen. His was truly a catholic and charitable spirit. Nothing human was alien to him. A friend of all good men, he enjoyed the confidence and esteem of all, even of those whose opinions or policy on public questions he felt constrained to refute or oppose. He commanded the respect, and secured the friendship of men of every rank, and creed, and party. None could better appreciate his ability and magnanimity than those who encountered him as an opponent, or were compelled to acknowledge him as victor. His convictions were strong, his principles firm, his purposes resolute, and he could, and did maintain them, with chivalrous daring, against any and every assault.

In the heat of controversy, while repelling unworthy insinuations, his indignation was sometimes roused, and his language not unfrequently was fervid, and forcible, and scathingly severe, but seldom, if ever, personally rancorous or bitter. When violently or vilely assailed his sensitive nature keenly felt the wound, but though he earned many a scar, he bore no malice.

His intellectual powers, of a high order, admirably balanced, and invigorated by long and severe discipline, found their expression in word and work, by pulpit, press, and platform, in the achievements of self-denying, indefatigable industry, and in wise and lofty statesmanship.

His moral nature was elevated and pure. He was generous, sympathetic, benevolent, faithful, trusting, and trustworthy. He rejoiced sincerely in the weal, and deeply felt the woes of others, and his ready hand obeyed the dictates of his loving, liberal heart.

His religious life was marked by humility, consistency, and cheerfulness. The simplicity of his faith in advanced life was childlike, and sublime. His trust in God never faltered, and, at the end of his course, his hopes of eternal life, through Jesus Christ our Lord, were radiant and triumphant.

Dr. Ryerson was truly a great man, endowed with grand qualities of mind and heart, which he consecrated to high and holy aims; and though, in early life, and in his public career, beset with many difficulties, he heroically achieved for himself, among his own people, a most enviable renown. His work and his worth universally appreciated, his influence widely acknowledged, his services highly valued, his name a household word[Pg 21] throughout the Dominion, and his memory a legacy and an inspiration to future generations.

And while Canada owes more to him than any other of her sons, his fame is not confined to the land of his birth, which he loved so well, and served so faithfully, but in Britain and in the United States of America his name is well known, and is classed with their own deserving worthies.

Whatever judgment may be formed of some parts of his eventful and distinguished career as a public man, there can be but one opinion as to the eminent and valuable services he has rendered to his country, as a laborious, celebrated pioneer preacher, an able ecclesiastical leader, a valiant and veteran advocate of civil and religious liberty—as the founder and administrator of a system of public education second to that of no other land—as the President and life-long patron of Victoria University, whose oldest living alumnus will hold his memory dear to life's close, when severed friends will be reunited; and whose successive classes will revere as the first President and firm friend of their Alma Mater, as the promoter of popular education, the ally of all teachers, and an example to all young men.

I lay this simple wreath on the memorial of one, whom I found able and helpful as a teacher in my youth—wise and prudent as an adviser in after life—generous and considerate as a superior officer—tender and true as a friend. He loved me, and was beloved by me. He doubtless had his faults, but I cannot recall them; and very few, I venture to think, will ever seek to mention them. The green turf which rests on his grave covers them. His memory will live as one of the purest, kindest, best of men. A patriot, a scholar, a Christian—the servant of God, the friend of man.

Yours, very faithfully, in bonds of truest friendship,

W. Ormiston.

To J. George Hodgins, Esq., LL.D., Toronto

1803-1825.

Sketch of Early Life.

I have several times been importuned to furnish a sketch of my life for books of biography of public men, published both in Canada and the United States; but I have uniformly declined, assigning as a reason a wish to have nothing of the kind published during my lifetime. Finding, however, that some circumstances connected with my early history have been misapprehended and misrepresented by adversaries, and that my friends are anxious that I should furnish some information on the subject, and being now in the seventieth year of my age, I sit down in this my Long Point Island Cottage, retired from the busy world, to give some account of my early life, on this blessed Sabbath day, indebted to the God of the Sabbath for all that I am,—morally, intellectually, and as a public man, as well as for all my hopes of a future life.

I was born on the 24th of March, 1803, in the Township of Charlotteville, near the Village of Vittoria, in the then London District, now the County of Norfolk. My Father had been an officer in the British Army during the American Revolution, being a volunteer in the Prince of Wales' Regiment of New Jersey, of which place he was a native. His forefathers were from Holland, and his more remote ancestors were from Denmark.

At the close of the American Revolutionary War, he, with many others of the same class, went to New Brunswick, where he married my Mother, whose maiden name was Stickney, a descendant of one of the early Massachusetts Puritan settlers.[Pg 24]

Near the close of the last century my Father, with his family, followed an elder brother to Canada,[1] where he drew some 2,500 acres of land from the Government, for his services in the army, besides his pension. My Father settled on 600 acres of land lying about half-way between the present Village of Vittoria and Port Ryerse, where my uncle Samuel settled, and where he built the first mill in the County of Norfolk.

On the organization of the London District in 1800, for legal purposes, my uncle was the Lieutenant of the County, issuing commissions in his own name to militia officers; he was also Chairman of the Quarter Sessions. My Father was appointed High Sheriff in 1800, but held the office only six years, when he resigned it in behalf of the late Colonel John Bostwick (then a surveyor), who subsequently married my eldest sister, and who owned what is now Port Stanley, and was at one time a Member of Parliament for the County of Middlesex.

My Father devoted himself exclusively to agriculture, and I learned to do all kinds of farm-work. The district grammar-school was then kept within half-a-mile of my Father's residence, by Mr. James Mitchell (afterwards Judge Mitchell), an excellent classical scholar; he came from Scotland with the late Rt. Rev. Dr. Strachan, first Bishop of Toronto. Mr. Mitchell married my youngest sister. He treated me with much kindness. When I recited to him my lessons in English grammar he often said that he had never studied the English grammar himself, that he wrote and spoke English by the Latin grammar. At the age of fourteen I had the opportunity of attending a course of instruction in the English language given by two professors, the one an Englishman, and the other an American, who taught nothing but English grammar. They professed in one course of instruction, by lectures, to enable a diligent pupil to parse any sentence in the English language. I was sent to attend these lectures, the only boarding abroad for school instruction I ever enjoyed. My previous knowledge of the letter of the grammar was of great service to me, and gave me an advantage over other pupils, so that before the end of the course I was generally called up to give visitors an illustration of the success of the system, which was certainly the most effective I have ever since witnessed, having charts, etc., to illustrate the agreement and government of words.

This whole course of instruction by two able men, who did[Pg 25] nothing but teach grammar from one week's end to another had to me all the attraction of a charm and a new discovery. It gratified both curiosity and ambition, and I pursued it with absorbing interest, until I had gone through Murray's two volumes of "Expositions and Exercises," Lord Kames' "Elements of Criticism," and Blair's "Lectures on Rhetoric," of which I still have the notes which I then made. The same professors obtained sufficient encouragement to give a second course of instruction and lectures at Vittoria, and one of them becoming ill, the other solicited my Father to allow me to assist him, as it would be useful to me, while it would enable him to fulfil his engagements. Thus, before I was sixteen, I was inducted as a teacher, by lecturing on my native language. This course of instruction, and exercises in English, have proved of the greatest advantage to me, not less in enabling me to study foreign languages than in using my own.

But that to which I am principally indebted for any studious habits, mental energy, or even capacity or decision of character, is religious instruction, poured into my mind in my childhood by a Mother's counsels, and infused into my heart by a Mother's prayers and tears. When very small, under six years of age, having done something naughty, my Mother took me into her bedroom, told me how bad and wicked what I had done was, and what pain it caused her, kneeled down, clasped me to her bosom, and prayed for me. Her tears, falling upon my head, seemed to penetrate to my very heart. This was my first religious impression, and was never effaced. Though thoughtless, and full of playful mischief, I never afterwards knowingly grieved my Mother, or gave her other than respectful and kind words.

At the close of the American War, in 1815, when I was twelve years of age, my three elder brothers, George, William, and John, became deeply religious, and I imbibed the same spirit. My consciousness of guilt and sinfulness was humbling, oppressive, and distressing; and my experience of relief, after lengthened fastings, watchings, and prayers, was clear, refreshing, and joyous. In the end I simply trusted in Christ, and looked to Him for a present salvation; and, as I looked up in my bed, the light appeared to my mind, and, as I thought, to my bodily eye also, in the form of One, white-robed, who approached the bedside with a smile, and with more of the expression of the countenance of Titian's Christ than of any person whom I have ever seen. I turned, rose to my knees, bowed my head, and covered my face, rejoiced with trembling, saying to a brother who was lying beside me, that the Saviour was now near us. The change within was more marked than[Pg 26] anything without and, perhaps, the inward change may have suggested what appeared an outward manifestation. I henceforth had new views, new feelings, new joys, and new strength. I truly delighted in the law of the Lord, after the inward man, and—

From that time I became a diligent student, and new quickness and strength seemed to be imparted to my understanding and memory. While working on the farm I did more than ordinary day's work, that it might show how industrious, instead of lazy, as some said, religion made a person. I studied between three and six o'clock in the morning, carried a book in my pocket during the day to improve odd moments by reading or learning, and then reviewed my studies of the day aloud while walking out in the evening.

To the Methodist way of religion my Father was, at that time, extremely opposed, and refused me every facility for acquiring knowledge while I continued to go amongst them. I did not, however, formally join them, in order to avoid his extreme displeasure. A kind friend offered to give me any book that I would commit to memory, and submit to his examination of the same. In this way I obtained my first Latin grammar, "Watts on the Mind," and "Watts' Logic."

My eldest brother, George, after the war, went to Union College, U.S., where he finished his collegiate studies. He was a fellow-student with the late Dr. Wayland, and afterwards succeeded my brother-in-law as Master of the London District Grammar School. His counsels, examinations, and ever kind assistance were a great encouragement and of immense service to me; and though he and I have since differed in religious opinions, no other than most affectionate brotherly feeling has ever existed between us to this day.[2]

When I had attained the age of eighteen, the Methodist minister in charge of the circuit which embraced our neighbourhood, thought it not compatible with the rules of the Church to allow, as had been done for several years, the privileges of a member without my becoming one. I then gave in my name for membership. Information of this was soon communicated to my Father, who, in the course of a few days, said to me: "Egerton, I understand you have joined the Methodists; you must either leave them or leave my house." He said no more, and I well knew that the decree was final; but I had formed[Pg 27] my decision in view of all possible consequences, and I had the aid of a Mother's prayers, and a Mother's tenderness, and a conscious Divine strength according to my need. The next day I left home and became usher in the London District Grammar School, applying myself to my new work with much diligence and earnestness, so that I soon succeeded in gaining the good-will of parents and pupils, and they were quite satisfied with my services,—leaving the head master to his favourite pursuits of gardening and building!

During two years I was thus teacher and student, advancing considerably in classical studies. I took great delight in "Locke on the Human Understanding," Paley's "Moral and Political Philosophy," and "Blackstone's Commentaries," especially the sections of the latter on the Prerogatives of the Crown, the Rights of the Subject, and the Province of Parliament.

As my Father complained that the Methodists had robbed him of his son, and of the fruits of that son's labours, I wished to remove that ground of complaint as far as possible by hiring an English farm-labourer, then just arrived in Canada, in my place, and paid him out of the proceeds of my own labour for two years. But although the farmer was the best hired man my Father had ever had, the result of his farm-productions during these two years did not equal those of the two years that I had been the chief labourer on the farm, and my Father came to me one day uttering the single sentence, "Egerton, you must come home," and then walked away. My first promptings would have led me to say, "Father, you have expelled me from your house for being a Methodist; I am so still. I have employed a man for you in my place for two years, during which time I have been a student and a teacher, and unaccustomed to work on a farm, I cannot now resume it." But I had left home for the honour of religion, and I thought the honour of religion would be promoted by my returning home, and showing still that the religion so much spoken against would enable me to leave the school for the plough and the harvest-field, as it had enabled me to leave home without knowing at the moment whether I should be a teacher or a farm-labourer.

I relinquished my engagement as teacher within a few days, engaging again on the farm with such determination and purpose that I ploughed every acre of ground for the season, cradled every stalk of wheat, rye, and oats, and mowed every spear of grass, pitched the whole, first on a waggon, and then from the waggon on the hay-mow or stack. While the neighbours were astonished at the possibility of one man doing so much work, I neither felt fatigue nor depression,[Pg 28] for "the joy of the Lord was my strength," both of body and mind, and I made nearly, if not quite, as much progress in my studies as I had done while teaching school. My Father then became changed in regard both to myself and the religion I professed, desiring me to remain at home; but, having been enabled to maintain a good conscience in the sight of God, and a good report before men, in regard to my filial duty during my minority, I felt that my life's work lay in another direction. I had refused, indeed, the advice of senior Methodist ministers to enter into the ministerial work, feeling myself as yet unqualified for it, and still doubting whether I should ever engage in it, or in another profession.

I felt a strong desire to pursue further my classical studies, and determined, with the kind counsel and aid of my eldest brother, to proceed to Hamilton, and place myself for a year under the tuition of a man of high reputation both as a scholar and a teacher, the late John Law, Esq., then head master of the Gore District Grammar School. I applied myself with such ardour, and prepared such an amount of work in both Latin and Greek, that Mr. Law said it was impossible for him to give the time and hear me read all that I had prepared, and that he would, therefore, examine me on the translation and construction of the more difficult passages, remarking more than once that it was impossible for any human mind to sustain long the strain that I was imposing upon mine. In the course of some six months his apprehensions were realized, as I was seized with a brain fever, and on partially recovering took cold, which resulted in inflammation of the lungs by which I was so reduced that my physician, the late Dr. James Graham, of Norfolk, pronounced my case hopeless, and my death was hourly expected.

In that extremity, while I felt even a desire to depart and be with Christ, I was oppressed with the consciousness that I should have yielded to the counsels of the chief ministers of my Church, as I could have made nearly as much progress in my classical studies, and at the same time been doing some good to the souls of men, instead of refusing to speak in public as I had done. I then and there vowed that if I should be restored to life and health, I would not follow my own counsels, but would yield to the openings and calls which might be made in the Church by its chief ministers. That very moment the cloud was removed; the light of the glory of God shone into my mind and heart with a splendour and power that I had never before experienced. My Mother, entering the room a few moments after, exclaimed: "Egerton, your countenance is changed, you are getting better!" My[Pg 29] bodily recovery was rapid; but the recovery of my mind from the shock which it had experienced was slower, and for some weeks I could not even read, much less study. While thus recovering, I exercised myself as I best could in writing down my meditations.

My Father so earnestly solicited me to return, that he offered me a deed of his farm if I would do so and live with him; but I declined acceding to his request under any circumstances, expressing my conviction that even could I do so, I thought it unwise and wrong for any parent to place himself in a position of dependence upon any of his children for support, so long as he could avoid doing so. One day, entering my room and seeing a manuscript lying on the bed, he asked me what I had been writing, and wished me to read it. I had written a meditation on part of the last verse of the 73rd Psalm: "it is good for me to draw near to God." When I read to him what I had written my Father rose with a sigh, remarking: "Egerton, I don't think you will ever return home again," and he never afterwards mooted the subject, except in a general way.

On recovering, I returned to Hamilton and resumed my studies; shortly after which I went on a Saturday to a quarterly meeting, held about twelve miles from Hamilton, at "The Fifty," a neighborhood two or three miles west of Grimsby, where I expected to meet my brother William, who was one of the ministers on the circuit, which was then called the Niagara Circuit—embracing the whole Niagara Peninsula, from five miles east of Hamilton, and across to the west of Fort Erie. But my brother did not attend, and I learned that he had been laid aside from his ministerial work by bleeding of the lungs. Between love-feast and preaching on Sunday morning, the presiding elder, the Rev. Thomas Madden, the late Hugh Willson, and the late Smith Griffin (grandfather of the Rev. W. S. Griffin), circuit stewards, called me aside and asked if I had any engagements that would prevent me from coming on the circuit to supply the place of my brother William, who might be unable to resume his work for, perhaps, a year or more.

I felt that the vows of God were upon me, and I was for some moments speechless from emotion. On recovering, I said I had no engagements beyond my own plans and purposes; but I was yet weak in body from severe illness, and I had no means for anything else than pursuing my studies, for which aid had been provided.

One of the stewards replied that he would give me a horse, and the other that he would provide me with a saddle and bridle. I then felt that I had no choice but to fulfill the vow[Pg 30] which I had made, on what was supposed to my deathbed. I returned to Hamilton, settled with my instructor and for my lodgings, and made my first attempt at preaching at or near Beamsville, on Easter Sunday, 1825, in the morning, from the 5th verse of the 126th Psalm: "They that sow in tears shall reap in joy;" and in the afternoon at "The Fifty," on "The Resurrection of Christ."—Acts ii. 24.

Toronto, Nov. 11th, 1880.

Such was the sketch of my life which I wrote on Sabbath in my Long Point Island Cottage, on the 24th of March, 1873, the 70th anniversary of my birthday. I know not that I can add anything to the foregoing story of my early life that would be worth writing or reading.

[In his cottage at Long Point, on his seventy-fifth birthday, Dr. Ryerson wrote the following paper, which Dr. Potts read on the occasion of his funeral discourse. It will be read with profoundest interest, as one of the noblest of those Christian experiences which are the rich heritage of the Church.—J. G. H.]

Long Point Island Cottage, March 24th, 1878.

I am this day seventy-five years of age, and this day fifty-three years ago, after resisting many solicitations to enter the ministry, and after long and painful struggles, I decided to devote my life and all to the ministry of the Methodist Church.

The predominant feeling of my heart is that of gratitude and humiliation; gratitude for God's unbounded mercy, patience, and compassion, in the bestowment of almost uninterrupted health, and innumerable personal, domestic, and social blessings for more than fifty years of a public life of great labour and many dangers; and humiliation under a deep-felt consciousness of personal unfaithfulness, of many defects, errors, and neglects in public duties. Many tell me that I have been useful to the Church and the country; but my own consciousness tells me that I have learned little, experienced little, done little in comparison of what I might and ought to have known and done. By the grace of God I am spared; by His grace I am what I am; all my trust for salvation is in the efficacy of Jesus' atoning blood. I know whom I have trusted, and "am persuaded that He is able to keep that which I have committed unto Him against that day." I have no melancholy feelings or fears. The joy of the Lord is my strength. I feel that I am now on the bright side of seventy-five. As the evening twilight of my[Pg 31] earthly life advances, my spiritual sun shines with increased splendour. This has been my experience for the last year. With an increased sense of my own sinfulness, unworthiness, and helplessness, I have an increased sense of the blessedness of pardon, the indwelling of the Comforter, and the communion of saints.

Here, on bended knees, I give myself, and all I have and am, afresh to Him whom I have endeavoured to serve, but very imperfectly, for more than threescore years. All helpless, myself, I most humbly and devoutly pray that Divine strength may be perfected in my weakness, and that my last days on earth may be my best days—best days of implicit faith and unreserved consecration, best days of simple scriptural ministrations and public usefulness, best days of change from glory to glory, and of becoming meet for the inheritance of the saints in light, until my Lord shall dismiss me from the service of warfare and the weariness of toil to the glories of victory and the repose of rest.

E. Ryerson.

[1] My father's eldest brother Samuel was known as Samuel Ryerse, in consequence of the manner in which his name was spelled in his Army Commission which he held; but the original family name was Ryerson.

[2] This brother of Dr. Ryerson's passed quietly away on the 19th of December, 1882, aged 92. Dr. Ryerson died on the 19th of February of the same year, aged 79. Their father, Col. Ryerson, died at the age of 94.—J. G. H.

1824-1825.

Extracts from my diary of 1824 and 1825.

The foregoing sketch of my early life may be properly followed by extracts from my diary; pourtraying my mental and spiritual exercises and labours during a few months before and after I commenced the work of an itinerant Methodist Preacher.

The extracts are as follow, and are very brief in comparison to the entire diary, which extends over eight years from 1824, to 1832, after which time I ceased to write a daily diary, and wrote in a journal the principal occurrences and doings in which I was concerned.[3]

Hamilton, August 12th, 1824.—I arrived here the day after I left home. Mr. John Law (with whom I am to study) received me with all the affection and kindness of a sincere and disinterested friend. Even, without expecting it, he told me that his library was at my service; that he did not wish me to join any class, but to read by myself, that he might pay every attention, and give me every assistance in his power. Indeed he answered my highest expectation. I am stopping with Mr. John Aikman. He is one of the most respectable men in this vicinity. I shall be altogether retired. At the Court of Assize, the Chief-Justice and the Attorney-General will stop here, which will make a very agreeable change for a few days. To pursue my studies with indefatigable industry, and ardent zeal, will be my set purpose, so that I may never have to mourn the loss of my precious time.

Aug. 16th.—This day I commenced my studies by reading Latin and Greek with Mr. Law. I began the duties of the day in imploring the assistance of God; for without Him I cannot do anything. God has been pleased to open my understanding, to enlighten my mind, and to show me the necessity and blessedness of an unreserved and habitual devotion to his heavenly will. I have heard Bishop Hedding preach, also Rev. Nathan Bangs. I am resolved to improve my time more diligently, and to give myself wholly to God. Oh, may his long-suffering mercy bear with me, his wisdom guide, his power support and defend me, and may his mercy bring me off triumphant in the dying day!

Aug. 17th.—I have been reading Virgil's Georgics. I find them very difficult,[Pg 33] and have only read seventy lines. In my spiritual concerns I have been greatly blessed; and felt more anxiously concerned for my soul's salvation, have prayed more than usual, and experienced a firmer confidence in the blessed promises of the Gospel. I have enjoyed sweet intercourse with my Saviour, my soul resting on his divine word, with a prayerful acquiescence in his dispensations. But alas! what evil have I done, how much time have I lost, how many idle words have I spoken; how should these considerations lead me to watch my thoughts, to husband my time with judgment, and govern my tongue as with a bridle! Oh, Lord bless me and prosper me in all my ways and labours, and keep me to thyself!

Aug. 18th.—The Lord has abundantly blessed me this day both in my spiritual and classical pursuits. I have been able to pursue my studies with facility, and have felt his Holy Spirit graciously enlightening my mind, showing me the necessity of separating myself from the world, and being given up entirely to his service.

Aug. 19th.—I have this day proved that, with every temptation, the Lord makes a way for my escape. I have enjoyed much peace. Oh, Lord, help me to improve my precious time, so as to overcome the assaults and escape the snares of the adversary!

Aug. 20th.—In all the vicissitudes of life, how clearly is the mysterious providence and superintending care of Jehovah manifested! how strikingly can I observe the divine interposition of my heavenly Father, and how sensibly do I realize his benevolence, kindness, and mercy in the whole moral and blessed economy of his equitable and infinitely wise government! On no object do I cast my eyes without observing an affecting instance of a benevolent and overruling power; and, while in mental contemplations my mind is absorbed, my admiration rises still higher to the exalted purposes and designs of Almighty God. I behold in the soul noble faculties, superior powers of imagination, and capacious desires, unfilled by anything terrestrial, and wishes unsatisfied by the widest grasp of human ambition. What is this but immortality? Oh, that my soul may feed on food immortal!

Another week is gone, eternally gone! What account can I give to my Almighty Judge for my conduct and opportunities? Has my improvement kept pace with the panting steeds of unretarded time? Must I give an account of every idle word, thought, and deed? Oh, merciful God! if the most righteous, devoted, and holy scarcely are saved, where stall I appear? How do my vain thoughts, and unprofitable conversation, swell heaven's register? Where is my watchfulness! Where are my humility, purity, and hatred of sin? Where is my zeal? Alas! alas! they are things unpractised, unfelt, almost unknown to me. How little do I share in the toils, the labours, or the sorrows of the righteous, and consequently how little do I participate in their confidence, their joys, their heavenly prospects? Oh, may these awful considerations drive me closer to God, and incite to a more diligent improvement of my precious time, so that I may bear the mark of a real follower of Christ!

Aug. 22nd.—Sabbath.—When I arose this morning I endeavoured to dedicate myself afresh to God in prayer, with a full determination to improve the day to his glory, and to spend it in his service. Accordingly, I spent the morning in prayer, reading, and meditation; but when I came to mingle with the worldly-minded, my devotions and meditations were dampened and distracted, my thoughts unprofitable and vain. I attended a Methodist Class-meeting where I felt myself forcibly convinced of my shortcomings. Sure I am that unless I am more vigilant, zealous, and watchful, I shall never reach the Paradise of God. I must be willing to bear reproach for Christ's sake, confess him before men, or I never can be owned by him in the presence of his Father, and the holy angels.[Pg 34]

Merciful God! forbid that I should barter away my heavenly inheritance for a transient gleam of momentary joy, and the empty round of worldly pleasure:

Aug. 23rd.—I have been abundantly prospered in my studies to-day; and have been enabled to maintain an outward conformity in my conduct. But alas! how blind to my own interest, to deprive myself of the highest blessings and exalted honours the Almighty has to bestow. Oh, Lord! help me henceforth to be wise unto salvation. May I be sober and watch unto prayer! Amen.

Aug. 24th.—Through the mercy of God I have been enabled in a good degree to overcome my besetments, and have this day maintained more consistency in conversation and conduct. Still I feel too much deterred by the fear of man, and thirst too ardently for the honours of the world. Merciful God! give me more grace, wisdom, and strength, that I may triumphantly overcome and escape to heaven at last!

I shall finish the first book of the Georgics to-day, which is the seventh day since I commenced them. I expect to finish them in four weeks from this time. My mind improves, and I feel much encouraged. My labour is uniform and constant, from the dawn of day till near eleven at night. I have not a moment to play on the flute.

Aug. 25th.—There is nothing like implicit trust in the Almighty for assistance, protection, and assurance! His past dispensations and dealings with me leave not the least suspicion of his inviolable veracity, and his efficacious promises cheer the sadness, calm the fears of every soul that practically reposes in and seeks after him. The truth of this, blessed be God, I have in some measure experienced to-day. Help me, O Lord, with increasing grace to attain still more sublime enjoyments and triumphant prospects!

Aug. 26th.—I feel a growing indifference to worldly pleasures, and increasing love to God, to holiness, and heaven. Entire confidence in a superintending Providence heals the wounded heart of even the disconsolate widow, and gives the oil of joy for sorrow, and the garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness.

Aug. 27th.—This day I attended a funeral; those connected with it were very ignorant; how strikingly this showed to me the advantages of a good education. God forbid that I should idle away my golden moments. Help me to choose the better part, and honour God in all things!

Aug. 28th.—The labours of another week are ended; during it I have enjoyed much of the presence of God; surely the religion of Christ dazzles all the magnificence of human glory; were I only to regard the happiness of this life, I would embrace its doctrines, practice its laws, and exert my influence for its extension.

Aug. 29th.—Sabbath.—The blessings of the Lord have abundantly surrounded me this day, and my heart has been enlarged.

Aug. 30th.—In observing my actions and words this day, I find I have done many things that are culpable; and yet, blessed be God, his goodness to me is profuse. Help me to watch and pray that I enter not into temptation.

Aug. 31st.—How many youths around me do I see trifling away the greatest part of their time, and profaning their Maker's name? My soul magnifies His name that I have decided to be on the Lord's side; how many evils have I escaped; how many blessings obtained; what praise enjoyed, through the influence of this religion. To God be all the glory![Pg 35]

September 1st.—In no subject can we employ our thoughts more profitably than on the atonement of Christ, and justification through his merits. With wonder we gaze on the love of Deity; with profound awe we behold a God descending from heaven to earth. Unbounded love! Unmeasured grace! And while in deep silence his death wraps all nature; while his yielding breath rends the temple and shakes earth's deep foundations; may my redeemed soul in silent rapture tune her grateful song aloft; and fired by this blood-bought theme, may I mend my pace towards my heavenly inheritance!

I generally close up the labours of the day by writing a short essay or theme on some religious subject. In doing this I have two objects in view: the improvement of my mind and heart. And what could be more appropriate than to close the day by reflection upon God, and heaven, and time, and eternity? No private employment, except that of prayer, have I found more pleasing and profitable than this. Youth is the seed-time of the life that now is, as well as of that which is to come. Youthful piety is the germ of true honour, lawful prosperity, and everlasting blessedness. One day of humble, devotional piety in youth will add more to our happiness at the last end of life than a year of repentance and humiliation in old age. I have no intention of entering the ministry, and yet I prefer religious topics. To-day I have chosen the atonement of our Lord, and have written a few thoughts on it.

Sept. 2nd.—Implicit trust in a superintending Providence is a constant source of comfort and support to me.

Sept. 3rd.—God has blessed me to-day in my studies. I have also felt the efficacy of Divine aid. Help me still, most merciful God!

Sept. 4th.—In the course of the past week I have experienced various feelings, especially with respect to the dealings of Divine Providence with me; but in all I have had this consolation, that whatever happens, "the will of the Lord be done." It is my duty to perform and obey.

Sept. 5th.—This morning I attended church and heard a sermon on Ezekiel xviii. 27. When we consider the importance of repentance, its connection with our eternal happiness, surely every feeling heart, and ministers especially, should exhibit with burning zeal the conditions of salvation, the slavery of vice, the heinousness of sin, the vanity of human glory, and the uncertainty of life.

Sept. 6th.—When I laid aside my studies to commit my evening thoughts to paper, my mind wandered on various subjects, until much time was lost; the best antidote against this is, not to put off to the next moment what can be done in this. We should be firm and decided in all our pursuits, and whatever our minds "find to do, do it with all our might."

Sept. 7th.—The mutual dependence of men cements society, and their social intercourse communicates pleasure. If we are called to endure the pains and inconveniences of poverty, possessing this we forget all; and in the pleasant walks of wealth, it adds to every elegance a charm. Friendship associated with religion, elevates all the ties of Christian love and mutual pleasure.

Sept. 8th.—I have found myself too much mingled with the common crowd, and like others, too indifferent to the subject of all others the chief.

Sept. 9th.—We "cannot serve God and Mammon." May I be firm in my attachment to the Saviour, remembering that "godliness has the promise of the life that now is, and of that which is to come."

Sept. 12th.—I heard a practical sermon on making our "calling and election sure," which closed with these words, "He that calleth upon the name of the Lord shall be saved." I felt condemned on account of my negligence, and resolved, by God's help, to gain victory over my tendency to inconsistencies of life and conduct.[Pg 36]

Sept. 14th.—I observe men embarked on the stream of time, and carried forward with irresistible force to that universal port which shall receive the whole human family. Amongst this passing crowd, how few are there who reflect upon the design and end of their voyage; surfeited with pleasure, involved in life's busy concerns, the future, with its awful realities, is forgotten and time, not eternity, is placed in the foreground.

Sept, 15th.—In a letter to my brother George, to-day, I said:—It would be superfluous for me to tell you that the letter I received from you gave me unspeakable pleasure. Your fears with respect to my injuring my health are groundless, for I must confess I don't possess half that application and burning zeal in these all-important pursuits that I ought to have. For who can estimate the value of a liberal education? Who can sufficiently prize that in which all the powers of the human mind can expand to their utmost and astonishing extent? What industry can outstretch the worth of that knowledge, by which we can travel back to the remotest ages, and live the lives of all antiquity? Nay, who can set bounds to the value of those attainments, by which we can, as it were, fly from world to world, and gaze on all the glories of creation; by which we can glide down the stream of time, and penetrate the unorganized regions of uncreated futurity? My heart burns while I write. Although literature presents the highest objects of ambition to the most refined mind, yet I consider health, in comparison with other temporal enjoyments, the most bountiful, and highest gift of heaven.

I have read three books of the Georgics, and three odes of Horace, but this last week I have read scarcely any, as I have had a great deal of company, and there has been no school. But I commence again to-day with all my might. The Attorney-General stops at Mr. Aikman's during Court. I find him very agreeable. He conversed with me more than an hour last night, in the most sociable, open manner possible.

Sept. 16th.—There is nothing of greater importance than to commence early to form our characters and regulate our conduct. Observation daily proves that man's condition in this world is generally the result of his own conduct. When we come to maturity, we perceive there is a right and a wrong in the actions of men; many who possess the same hereditary advantages, are not equally prosperous in life; some by virtuous conduct rise to respectability, honour, and happiness; while others by mean and vicious actions, forfeit the advantages of their birth, and sink into ignominy and disgrace. How necessary that in early life useful habits should be formed, and turbulent passions restrained, so that when manhood and old age come, the mind be not enervated by the follies and vices of youth, but, supported and strengthened by the Divine Being, be enabled to say, "O God, thou hast taught me from my youth, and now when I am old and grey-headed, O God, thou wilt not forsake me!"

Sept. 21st.—I have just parted with an old and faithful friend, who has left for another kingdom. How often has he kindly reproved me, and how oft have we gone to the house of God together! We may never meet again on earth, but what a mercy to have a good hope of meeting in the better land!

Sept. 23rd.—When I reflect on the millions of the human family who know nothing of Christ, my soul feels intensely for their deliverance. What a vast uncultivated field in my own country for ministers to employ their whole time and talents in exalting a crucified Saviour. Has God designed this sacred task for me? If it be Thy will, may all obstacles be removed, my heart be sanctified and my hands made pure.

Sept. 26th.—I have been much oppressed with a man-fearing spirit, but what have I to fear if God be for me? Oh, Lord, enable me to become a bold witness for Jesus Christ!

Sept. 28th.—In all the various walks of life, I find obstructions and[Pg 37] labours, surrounded with foes, powerful as well as subtle; although I have all the promises of the Gospel to comfort and support me, yet find exertion on my own part absolutely necessary. When heaven proclaims victory, it is only that which succeeds labour. I consider it a divine requisition that my whole course of conduct, both in political and social life, should be governed by the infallible precepts of revelation; hypocrisy is inexcusable, even in the most trifling circumstances.

Sept. 29th.—I find difficulties to overcome in my literary pursuits, I had never anticipated; and it is only by the most indefatigable labour I can succeed. I am much oppressed by the labours of this day. I need Divine aid in this as well as in spiritual pursuits.

Sept. 30th.—I have been enabled to study with considerable facility. Prayer I find the most profitable employment, practice the best instructor, and thanksgiving the sweetest recreation. May this be my experience every day!

October, 2nd.—I am another week nearer my eternal destiny! Am I nearer heaven, and better prepared for death than at its commencement? Do I view sin with greater abhorence? Are my views of the Deity more enlarged? Is it my meat and drink to do his holy will? Oh, my God, how much otherwise!

From the 3rd to the 9th Oct.—During this period the afflicting hand of God has been upon me; thank God, when distressed with bodily pain, I have felt a firm assurance of Divine favour, so that all fear of death has been taken away. My soul is too unholy to meet a holy God, and mingle with the society of the blest. Oh, God, save me from the deceitfulness of my own heart!

Oct. 10th, Sabbath.—I am rapidly recovering health and strength. The Lord is my refuge and comfort. Surrounded by temptations, the applause of men is often too fascinating, and my treacherous heart dresses things in false colours. But, bless God, in his goodness and mercy he recalls my wandering steps, and invites me to dwell in safety under the shadow of his wing.

Oct. 11th.—No graces are of more importance than patience and perseverance. They give consistency and dignity to character. We may possess the most sparkling talents and the most interesting qualities, but without these graces, the former lose their lustre, and the latter their charms. In religion their influence is more important, as they form the character, by enabling us to surmount difficulties and remove obstacles. I am far from thinking them constitutional virtues, with a little additional cultivation, but I consider them the gift of heaven, less common than is generally imagined, though sometimes faintly counterfeited. They differ from natural or moral excellence in this being the proper and consistent exercise of those virtues.

Oct. 12th.—It is two weeks to-day since I first wrote home. A week ago I received a kind letter from my brother George, but was too ill with fever to read it, or to write in reply until to-day. I said: "I feel truly thankful to you for the tender concern and warm interest which you express in your letter. Tell my dear Mother that I share with her her afflictions, and that I am daily more forcibly convinced that every earthly comfort and advantage is transient and unsatisfactory, that this is not our home, but that our highest happiness amidst these fluctuating scenes, is to insure the favour and protection of him who alone can raise us above afflictions and calamities."