The Project Gutenberg EBook of Blue Bonnet in Boston, by

Caroline E. Jacobs and Lela H. Richards

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Blue Bonnet in Boston

or, Boarding-School Days at Miss North's

Author: Caroline E. Jacobs

Lela H. Richards

Illustrator: John Goss

Release Date: December 19, 2007 [EBook #23916]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BLUE BONNET IN BOSTON ***

Produced by Mark C. Orton, Linda McKeown, Jacqueline Jeremy

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

The Blue Bonnet Series

BLUE BONNET

IN BOSTON

Or, Boarding-school Days at Miss North's

BY

CAROLINE E. JACOBS

AND

LELA H. RICHARDS

A SEQUEL TO

A TEXAS BLUE BONNET

AND

BLUE BONNET'S RANCH PARTY

Illustrated by

JOHN GOSS

THE PAGE COMPANY

BOSTON: PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1914

By the Page Company

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London

All rights reserved

Made in U. S. A.

PRINTED BY C. H. SIMONDS COMPANY

BOSTON, MASS., U. S. A.

| chapter | page | |

| I. | The Wail of the We Are Sevens | 1 |

| II. | A Week-End | 20 |

| III. | In Boston | 40 |

| IV. | A Surprise | 54 |

| V. | Boarding-School | 74 |

| VI. | New Friends | 98 |

| VII. | In Trouble | 117 |

| VIII. | Penance | 134 |

| IX. | Woodford | 153 |

| X. | Under a Cloud | 172 |

| XI. | The Cloud Lifts | 191 |

| XII. | Initiated | 208 |

| XIII. | Sunday | 227 |

| XIV. | Settlement Work | 239 |

| XV. | A Harvard Tea | 255 |

| XVI. | Anticipations | 274 |

| XVII. | The Gathering of the Clans | 294 |

| XVIII. | Kitty's Cotillion | 313 |

| XIX. | A Surprise Party | 333 |

| XX. | The Junior Spread | 344 |

| XXI. | The Lambs' Frolic | 359 |

| XXII. | Commencement | 377 |

| page | ||

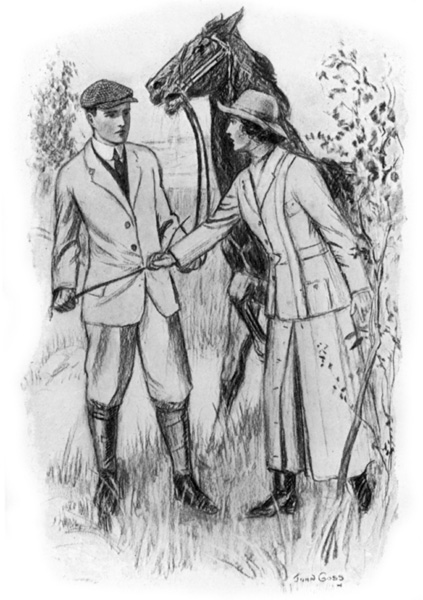

| "She wrenched the whip from Alec's hand" (See page 308) | Frontispiece | |

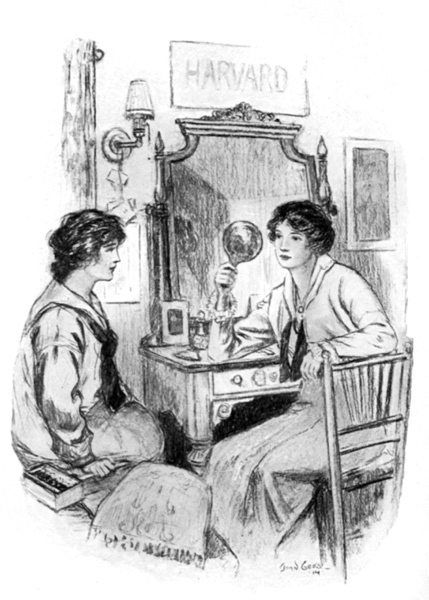

| "Blue Bonnet took the mirror and looked at herself from all angles" | 140 | |

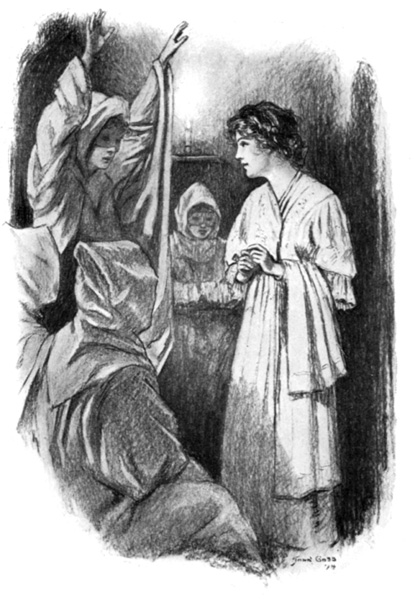

| "The ghost in the centre of the group rose" | 216 | |

| "Gabriel looked up in disdain" | 245 | |

| "She was holding on to Uncle Cliff's coat lapels" | 288 | |

| "She was Oonah, The bewitching little Irish maiden" | 357 | |

Blue Bonnet raised the blind of the car window, which had been drawn all the afternoon to shut out the blazing sun, and took a view of the flying landscape. Then she consulted the tiny watch at her wrist and sat up with a start.

"Grandmother!" she said excitedly, "we'll soon be in Woodford; that is, in just an hour. We're on time, you know. Hadn't we better be getting our things together?"

Mrs. Clyde straightened up from the pillows, which Blue Bonnet had arranged comfortably for her afternoon nap, and peered out at the rolling hills and green meadow-lands.

"I think we have plenty of time, Blue Bonnet," she said, smiling into the girl's eager face. "But perhaps we would better freshen up a bit. You are sure we are on time?"

"Yes, I asked the conductor when I went back to see Solomon at the last station. Four-twenty [2]sharp, at Woodford, he told Solomon, and Solomon licked his hand with joy. Poor doggie! I don't believe he appreciates the value of travel, even if he has seen Texas and New York and Boston. He loathes the baggage-car, though I must say the men all along the way have been perfectly splendid to him. But then, any one would fall in love with Solomon, he's such a dear."

Mrs. Clyde recalled the five dollar bill she had witnessed Mr. Ashe pass to the baggage-man at the beginning of the journey, and the money she had given by his instruction along the way, and wondered how much Solomon's real worth had contributed to his care.

"I'm so glad we're arriving in the afternoon," Blue Bonnet said, as she gathered up magazines and various other articles that littered the section. "There's something so flat about getting anywhere in the morning—nothing to do but sit round waiting for trunks that have been delayed, and wander about the house. I wonder if Aunt Lucinda told the girls we were coming?"

Mrs. Clyde fancied not. A quiet home-coming after so strenuous a summer was much to be desired.

Blue Bonnet and the We Are Sevens had parted company in New York several weeks before, the girls going on to Woodford in care of the General, in order not to miss the first week of school.

[3]The stay in New York had been particularly gratifying to Blue Bonnet, for there had been ample time while waiting for Aunt Lucinda to arrive from her summer's outing in Europe, to do some of the things left undone on her last visit. A day at the Metropolitan Museum proved a delight; the shops fascinating—especially Tiffany's, where Blue Bonnet spent hours over shining trays, mysterious designs in monograms, and antique gold settings, leaving an order that quite amazed Grandmother Clyde, until she learned that the purchase was for Uncle Cliff.

Then there had been a delightful week with the Boston relatives, Aunt Lucinda going straight to Woodford to open the house and make things comfortable for her mother's arrival.

Cousin Tracy, as on that other memorable visit, had proved an ideal host. To be sure, a motor car had been substituted for the sightseeing bus so dear to Blue Bonnet's heart, but she found it, on the whole, quite as enjoyable, and confided to Cousin Tracy as they sped through the crooked little streets or walked through the beloved Common, that she liked Boston ever so much better than New York, it seemed so nice and countrified. There was a second visit to Bunker Hill and the Library, to which Blue Bonnet brought fresh enthusiasm, more stories of Cousin Tracy's coins and medals, and so the days passed all too swiftly.

[4]"Well, at last!" Blue Bonnet exclaimed, as the train began to slacken speed and the familiar "Next stop Woodford" echoed through the car. "Here we are, Grandmother, home again!" She was at the door before the car came to a standstill.

"Doesn't look as exciting as it did when Uncle Cliff and I arrived in the Wanderer, does it?" Blue Bonnet's eyes swept the almost deserted station.

Miss Clyde stood at the end of the long platform, her eyes turned expectantly toward the rear Pullman, with Denham, the coachman, at a respectful distance.

Blue Bonnet sprang from the car steps, greeted Aunt Lucinda affectionately, shook hands with Denham and rushed for the baggage-car to release Solomon.

"He's perfectly wild to see you, Aunt Lucinda," she called back, as she ran toward the car—a compliment which Solomon himself verified a moment later with joyful leaps and yelps and much wagging of tail.

"My, but it seems nice to get home," Blue Bonnet said as she sank back cosily in the carriage and heaved a sigh of content. The sigh shamed her a little. It seemed, somehow, disloyal to Uncle Cliff and Texas. She sat up straight and turned her head away from the houses with their trim [5]orderly dooryards and well-kept hedges, and, for a moment, fixed her mind with passionate loyalty on the lonely wind-swept stretches of her native state; the battered and weatherbeaten ranch-house, Benita—But only for a moment. The green rolling hills, the giant arching elms, Grandmother's stately house just coming into view, proved too alluring, and salving her conscience with the thought that it was her own dear mother's country she had at last learned to love, gave herself up to the full enjoyment of her surroundings.

Katie and faithful Delia were awaiting the arrival of the family on the veranda, their joy at the reunion showing in every line of their happy faces. Blue Bonnet shook hands with them cordially, deposited a load of magazines and wraps in Delia's willing arms and ran in to the house.

In the sitting-room tea was ready to be served. Blue Bonnet curled up in one of the deep armchairs and eyed the table appreciatively. How good it looked—the thin slices of bread and butter, the fresh marmalade, the wonderful Clyde cookies. She leaned back and smiled contentedly.

"Come, Blue Bonnet," Miss Clyde said, entering the room followed by Delia with a brass kettle of steaming water, "make yourself tidy quickly. Tea is all ready."

"All right, Aunt Lucinda, I sha'n't be a minute, I'm quite famished," and to prove the fact Blue [6]Bonnet helped herself to a handful of cookies on her way out of the room.

Aunt Lucinda cast an inquiring glance in her mother's direction.

"I fear you will find Blue Bonnet a bit spoiled, Lucinda," Mrs. Clyde said with some hesitancy. "But we must not be too severe with her. The girls have led a wild, carefree existence all summer. I have done my best to look after them carefully, but I found seven rather a handful."

Something in Mrs. Clyde's tone made her daughter turn and look at her closely. Was it imagination, or did she seem unusually fatigued? Miss Clyde had often wondered during the summer if the responsibility of so many girls had not been too much of a tax on her mother's strength and patience, but her letters had been so cheerful, so uncomplaining, that she had tried to put the thought out of her mind, attributing it to overanxiety.

Blue Bonnet's entrance prevented further questioning.

"I think, if you don't mind, Grandmother, I'll run over and see the General a minute. I promised Alec to look after him," Blue Bonnet said, putting down her tea-cup.

"That would be very nice, Blue Bonnet," Mrs. Clyde answered with a nod and a smile. "The General is going to miss Alec very much this winter."

[7]As Blue Bonnet passed her Grandmother she stooped and putting her arm round her shoulder gave her a gentle hug. Mrs. Clyde reached up and patted the girl's face tenderly. Whatever had been her care, love had lightened the burden, there could be no doubt of that.

"You can't think what a trump she's been, Aunt Lucinda," Blue Bonnet said, straightening the bow at her grandmother's neck. "A regular brick! Why, she's had all the girls at her feet this blessed summer."

"It would have been more to the point if I had had them in hand," her grandmother replied; making haste to add, as she met Blue Bonnet's puzzled eyes, "not but that they were good girls, very good girls indeed."

Blue Bonnet whistled to Solomon and went out of the front door, banging it carelessly. Miss Clyde looked annoyed.

"I am afraid we are going to have to begin all over again with Blue Bonnet," she said with some concern. "She seems so hoydenish. I noticed it immediately."

"It is a good deal the exuberance of youth, Lucinda. Surplus energy has to be worked off somehow. We must be patient with her."

"I have been thinking," Miss Clyde replied, "that it would be wise not to enter Blue Bonnet in the Boston school immediately. If we could [8]keep her with us until after the holidays we could perhaps interest her in some home duties—the girls will all be in school, and we could have her more to ourselves, and, perhaps, smooth down some of these rough corners."

Mrs. Clyde looked wistful.

"I shall miss the dear child so," she said. "I wish we might keep her with us a bit longer. Boarding-school will be the beginning of a long break, I fear."

"It is because of the association that I particularly wish her to enter Miss North's school. She will meet refined girls from some of our old New England families, and the influence cannot fail to be helpful. I hope she will not be tempted to tell them that her grandmother is a brick," Miss Clyde added as an afterthought, but her smile was indulgent rather than critical.

"Girls are much the same the world over," her mother answered with the wisdom of experience. "Blue Bonnet is very like her mother. She was a great romp, but she passed the hoydenish period in safety, so will Blue Bonnet; never fear."

"She must be taught order and system; and a little domestic science under Katie might not come amiss, since she will some day be at the head of a household," Miss Clyde went on, and her mother signified approval. "Then there is mending and [9]darning. On the whole, I think the next three months might be made very profitable to Blue Bonnet right here at home. I am not at all sure but that too much emphasis is given to the cultural side of education, and too little to the domestic these days. A girl to be well educated should be well rounded."

After dinner, when the fire in the grate had been lighted—for the autumn evenings were beginning to bring chill to the air—and the family gathered for an hour's chat before bed, Miss Clyde broached the subject to Blue Bonnet.

"How would you like to continue your vacation for three months longer, Blue Bonnet, to stay on here with Grandmother and me until after the holidays?"

"And have no studies at all?" Blue Bonnet interrupted, her eyes widening with surprise. "What a lark!"

"Well, there would be duties," Miss Clyde admitted. "One could not be altogether idle and keep happy."

"We should like you to be our dear home girl for a while longer, Blue Bonnet," Mrs. Clyde said gently. "It is going to be very hard to give you up."

"But I shall be at home for the week-ends."

"We hope so, dear, if it does not interfere too much with your studies. Sometimes there is dis[10]traction in change of scene and habit. When you enter Miss North's school, you will be under her supervision, not ours—subject to her approval."

A little pucker wrinkled Blue Bonnet's brow.

"Shall I? Oh, dear, I do so hate being supervised. I mean by strangers, Grandmother. Will she be terribly strict, and—interfering?"

"Not any more than will be for your interest and welfare."

"Well, I reckon it will be all right. I want to do what you think best for me."

Mrs. Clyde could not withheld the triumphant look that she turned toward her daughter. It said plainer than words, "you see how amenable she is, how sweet her nature."

"And I could see a lot of the girls, even if they are in school. Perhaps the Club could meet oftener."

Miss Clyde was silent. Discretion and diplomacy often availed where hard and fast rules failed with Blue Bonnet. She could be led, easily—never driven.

Miss Clyde's silence puzzled Blue Bonnet more than the unexpected news that she was to remain in Woodford another three months had done. She was unusually keen and alert, intuitive to a degree, and while Aunt Lucinda's manner was all that could be desired, she felt that she had been a dis[11]appointment in some way. She rose a little wearily and going to the piano ran her fingers over the keys.

"Let us have a little music, dear, before we retire. It will seem good to hear you play again," Mrs. Clyde said.

Blue Bonnet drifted into one air after another listlessly, as if her thoughts were miles away from the keyboard over which her hands wandered so prettily. The familiar melodies floated plaintively through the still room. She played half through an old favorite, then rose suddenly. When she turned to her grandmother for her usual goodnight kiss her eyes were a little dim with tears. She struggled to hide them, and, excusing herself on the pretext of unpacking her trunks, started for the stairs.

Miss Clyde had risen from her chair as Blue Bonnet rose from the piano. She waited until Blue Bonnet had said good night to her grandmother, then she put her arm affectionately over the girl's shoulder and patted her reassuringly.

"I hope our little girl is not going to be homesick," she said. "There will be much to do in the next three months—much that is pleasant. Some day soon you and I will run up to Boston and have a look at Miss North's school and find out something about its requirements. We shall have a good deal of shopping to do, too. Suitable [12]frocks play as important a part at boarding-school as elsewhere."

Miss Clyde smiled one of her rare sweet smiles, and Blue Bonnet felt as if a weight had been lifted from her heart.

"Aunt Lucinda is a good deal of a dear," she said to herself, as she perched on the window-seat in her bedroom and looked out into the moonlight. "She wants me to be happy. I suppose she doesn't always understand me, any more than I do her. I reckon we'll have to sort of take each other on faith." And lightly humming a little tune she jumped up from the window-seat and plunged madly into the unpacking.

"As long as this is Saturday, would you mind, Grandmother, if I had the girls in this afternoon?" Blue Bonnet inquired at the breakfast-table next morning. And Mrs. Clyde replied:

"Not at all, dear. They will be so busy in school during the week. I will see what Katie has planned for to-day, and, if she can manage it, you might ask them to lunch."

A visit to the kitchen resulted favorably.

"Oh, you're such a duck, Grandmother," Blue Bonnet assured her. "I'll 'phone them right up," an operation which consumed the better part of an hour, since there was so much to relate after a separation of several weeks.

"I'll just run down to the barn and give Chula [13]a lump of sugar and feed Solomon the first thing," Blue Bonnet said as she turned from the telephone.

"Have you made your room tidy?" Miss Clyde inquired, coming out in to the hall at that moment.

"Oh, dear, history repeats itself, doesn't it, Aunt Lucinda?" Blue Bonnet's good-natured laugh was contagious. Miss Clyde smiled in spite of herself.

"I haven't made my bed yet, Aunt Lucinda, if that's what you mean. I hate making it up warm—it's not sanitary, is it? You've said so yourself, often."

Miss Clyde's smile deepened. Blue Bonnet's sudden conversion to the laws of hygiene was too amusing.

"I fancy two hours of this autumn air will have restored its freshness," she said. "Have you finished your unpacking?"

Blue Bonnet recalled the piles of fluffy whiteness that covered chairs and window-seat, and, turning, went up-stairs quickly.

It took some time to get the room in proper order. It might, not have taken so long if the view from the south window had not been so pleasant. Out in the garden the dahlias and coreopsis nodded and beckoned coaxingly, the soft wind stirred the leaves in the apple-trees, and Solomon frisked and rolled with glee in the sunshine.

At last it was finished, at least the furniture had been relieved of its burdens, and the bed made in [14]the most approved fashion. Blue Bonnet was free to join Solomon, and to gather a great bunch of the golden-hued coreopsis to adorn the lunch table. She was thinking of a little plan, as she cut the long stems and arranged the flowers with taste and precision; a little plan she had barely time to execute before Kitty Clark's familiar, "Ooh-hoo, Ooh-hoo!" echoed from somewhere in the vicinity of the front gate.

"I suppose I'm loads too early, but I could hardly wait to see you, Blue Bonnet," was her cheery greeting. "We've all been pining away for you. New York must have been fascinating to have kept you so long."

Blue Bonnet admitted that it was. She even opened her lips to tell of some of its enchantments, but Kitty went on irrelevantly:

"You've missed a heap at school. I suppose you can catch up, but you'll have to dig in, I can tell you. The Czar"—Kitty's name for Mr. Hunt—"isn't bestowing any more favors than usual."

Blue Bonnet's first impulse was to tell Kitty that she would not be back in school with the We Are Sevens this year, but she thought better of it and waited.

Kitty rambled on.

"Latin's a perfect fright and—oh, Blue Bonnet, what, do you think? Miss Rankin's engaged! Yes, she is, honest, truly. She's got a ring, a [15]beauty! She wore it turned in the first two weeks, but now she's picked up courage and turned it round so everybody can see it. She's going to quit after Christmas. They're going to live in Boston. He's a lawyer—Sarah Blake's father knows him, and says he's right nice."

Kitty's patronizing air nettled Blue Bonnet as much as it amused her.

"Why shouldn't he be nice?" she inquired a bit sharply. "Miss Rankin's nice herself."

The remark went over Kitty's head, and the appearance of Sarah Blake down the roadway put a stop to the gossip.

It was the gayest kind of a little party that made the rafters in Mrs. Clyde's dining-room ring with laughter an hour later. Blue Bonnet had insisted upon Grandmother and Aunt Lucinda lunching with them, so Mrs. Clyde sat at one end of the broad board and Miss Clyde at the other.

Blue Bonnet's coreopsis had been rearranged, and put in a charming brown basket. From beneath the basket, and quite concealed from sight, were seven little boxes attached to yellow ribbons which ran to each of the We Are Sevens' plates.

Blue Bonnet could scarcely wait for the dessert to be cleared away before she told the girls to pull the ribbons.

When the boxes came in view there was a scream of delight.

[16]Nimble-fingered Kitty was the first to open hers, and the rest were not long following suit, revealing to the enraptured gaze quaint and oddly designed gold rings, the monogram of the We Are Sevens forming a seal.

There was a rush for Blue Bonnet's side of the table, where that young person was deluged with caresses and many expressions of gratitude.

"It's Uncle Cliff—he did it," Blue Bonnet managed to say when she could extricate herself. "That is, he suggested it—gave me the money—and I had them made at Tiffany's."

There was a chorus of praise for Uncle Cliff, which must have made his ears ring to the point of deafness, even in far-off Texas.

Amanda made a suggestion.

"Let's go up-stairs in the clubroom and organize a Sorority. W. A. S. looks kind of Greeky in a monogram. We can have rings instead of pins for our insignia."

The idea met with instant favor. There was another rush for the stairs, and a few moments later the Club members were comfortably settled in their quarters with Amanda in the Chair.

Amanda was not quite clear as to the manner of procedure, but she gracefully waved a tack hammer found on the window-sill, in lieu of a gavel, and demanded order.

When quiet at last descended upon the disturbed [17]and noisy assemblage, Blue Bonnet asked if she might have the floor. She looked appealingly at the Chair.

Debby rose to a point of order.

"We've got to elect officers," she said. "Amanda hasn't been elected. I move that Blue Bonnet Ashe be our chairman."

This Was the very opportunity Blue Bonnet wanted for her announcement. She made Debby a profound bow, pushing Amanda out of the way unceremoniously.

"I thank you all for this very great honor," she began, clearing her throat in the most professional manner. She had once attended a woman's club with Miss Clyde in Boston. "But owing to my absence from the city the coming winter I—"

There was a roar of protest from the Club members, en masse.

"I shall be leaving you about the first of January—"

This announcement prevented the further order of business. Cries of "What for? Where to? For how long?" assailed Blue Bonnet.

She made her plans and prospects clear to them.

At first the girls seemed stunned. Joy turned to lamentation. There arose a chorus of wails, plaintive and doleful. They kept it up for some time—in concert—with Sarah Blake looking on in awed [18]silence, forlorn and tearful, as if a real tragedy had descended upon her.

Blue Bonnet took the tack hammer from Amanda's apathetic hand and rapped for order.

"I neglected to state," she said, "that I shall be at home for the week-ends—at least I hope to be. I see no reason why the Club can't go on. I'm sure Grandmother would love to let you have this room when I'm not here. Let's go on with the business. I nominate Sarah Blake for president. It takes brains and dignity to be the president of a Sorority. Sarah has both."

"Well, I like that!" Kitty exclaimed with some feeling. "I suppose the rest of us have neither."

"Now, don't get stuffy, Kitty. You know I'm never personal. I meant no reflection on anybody."

"We can't organize a Sorority, anyhow," Kitty objected. "They only have them in colleges and high schools."

"I guess we can have one of our own if we want to," Amanda broke in. "We can originate one, can't we? Everything has to have a beginning, doesn't it?"

"Oh, I suppose you can call it what you like," Kitty said with a toss of her head.

There was some discussion, but Sarah finally received the majority vote and went in with flying colors.

That evening, from her accustomed seat on the [19]hearth rug before a glowing fire, Blue Bonnet told her grandmother of the afternoon's experiences.

"The girls seem sorry to have me go away this winter," she said. "And, oh, Grandmother, you should have heard them wail when I told them."

She leaned her head against her grandmother's knee and a little smile wrinkled the corners of her mouth.

"I hate to leave them, too," she said. "They're such fun."

Mrs. Clyde smoothed the girl's hair gently as she answered:

"I want you to be happy, dear, but it can't all be fun. Aunt Lucinda has a plan for you, which I think we will begin with Monday. You are entering your seventeenth year, now, Blue Bonnet, and there are duties and responsibilities which you can no longer evade."

Blue Bonnet sighed unconsciously.

"I suppose there are, Grandmother," she said, "but—couldn't we just put them off until—well—until Monday?"

Blue Bonnet came down to breakfast Monday morning a trifle uncertain as to whether the day was to be pleasant or profitable to her. She had a very clear conviction that it could not be both. In her experience profitable things were stupid—invariably!

It was raining—a condition of weather Miss Clyde hailed with delight.

"Just the very day to go through the linen closet," she said to Blue Bonnet as they rose from the table. "I think we will begin there this morning."

Blue Bonnet looked out at the lowering clouds and followed her aunt meekly. She, too, was glad that it was raining; otherwise she should have longed to be galloping over the country roads on Chula.

Mrs. Clyde's linen closet was a joy to behold; a room of itself, light and airy, with the smoothest of cedar shelves and deep cavernous drawers for blankets and down comforts.

Blue Bonnet had been in the room occasionally, when she had been sent for sheets for an unex[21]pected guest. She had brought away the refreshing odor of sweet lavender in her nostrils, and a vision of the neatly piled linen before her eyes.

To-day she watched her aunt as she opened drawers, took the white covers from blankets and comforts, inspected sheets and patch-work quilts with an eye to necessary darning.

What a dreadful waste of time to have cut up all those little patches and have sewn them together, Blue Bonnet thought, as her aunt folded a quilt and returned it to its particular place on the shelf. She felt sure that Aunt Lucinda could have bought much prettier quilts with less bother.

"It seems almost like a sanctuary, here," she said at last, leaning against the window and watching the proceedings with interest. "It's so beautifully clean, and I adore that lavender smell. Where does it come from?"

Miss Clyde reached under a sheet and brought forth a small bag made of white tarlatan filled with dried flowers and leaves.

Blue Bonnet buried her nose in it.

"Oh, I love it," she said. "I must get some and send it to Benita. Benita is very particular about our beds. She says my mother was."

"She could not have been a Clyde and escaped that, my dear. It is a passion with all of us—linen and fine china."

Blue Bonnet nodded brightly.

[22]"When I have a home I shall have a linen closet just like this," she said, glancing about admiringly.

"Then you cannot begin too soon to learn how to take care of it. Few things require closer supervision than a linen closet, in any home. You must learn to mend; not ordinary mending, but fine darning."

Miss Clyde cast her eye over a pile of sheets. She opened one and handed it to Blue Bonnet, directing her attention to a rent which had been skillfully repaired in one corner.

Blue Bonnet noted the stitches of gossamer fineness with absorbed interest. Then she folded the sheet carefully and handed it back with a sigh.

"I never could do it, Aunt Lucinda. Never, in a thousand years. I know I couldn't. I hate sewing."

"Then I fear you could never have a linen closet like this, Blue Bonnet. Mending represents but a small part of the detail and system necessary to good housekeeping."

"But, maybe, perhaps I could hire some one. Couldn't I, don't you think?"

"You certainly could not instruct servants if you did not know how to work, yourself. That would be quite impossible. Could your teachers have imparted their knowledge to you if they, themselves, had not been students?"

[23]The argument seemed plausible. Blue Bonnet's sigh deepened.

"I shall employ a trained housekeeper," she said, as if that settled the question.

"Then you will miss the joy that comes through laboring with your own hands—the joy of accomplishment, Blue Bonnet. I hope you will change your mind."

Miss Clyde took a careful survey of a shelf where sheets were piled, and from it she filled her mending basket.

"Delia has overlooked these in my absence," she said, almost apologetically. "Linen should always be mended carefully before it is put away."

She straightened the window blinds to a correct line, closed all drawers carefully, and ushering Blue Bonnet into the hall, locked the door behind them.

In the sitting-room the rain beat furiously at the window-panes, a cold east wind rattled the casements, but a glowing fire in the grate offset the gloom.

Miss Clyde drew a chair up to the fire and took a piece from the basket.

"Bring up a small chair, Blue Bonnet. One without arms will be best." Blue Bonnet drew the chair up slowly.

Miss Clyde found her thimble and selected a proper needle.

"Go up and get your work-basket, Blue Bonnet."

[24]When Blue Bonnet came down with her basket her aunt was holding a sheet up to the light.

"It is growing thin in places," she said, laying it on Blue Bonnet's knee, "but a few stitches will preserve it for some time yet."

The next hour was one not soon to be forgotten by Blue Bonnet. Threads knotted at the most impossible places; stitches were too long, sometimes too short. Her hands grew hot and sticky. At the end of an hour her cheeks were flushed and her head ached.

Miss Clyde took the work from the tired and clumsy fingers and smoothed the hair back from the warm brow.

"I think you have done very well for the first time, Blue Bonnet. Next time it will come easier. You would better rest now, and perhaps Grandmother will read to us until lunch time."

"Yes," Mrs. Clyde said, "I will indeed. What shall it be, Blue Bonnet?"

Blue Bonnet thought a minute, then she clapped her hands softly.

"I know, Grandmother. Thoreau! I read something of his this summer on the ranch, and I liked it."

Mrs. Clyde went into the library, coming back presently with Robert Louis Stevenson's "Men and Books."

"Perhaps you would like to know something of [25]Thoreau's life, Blue Bonnet. Mr. Stevenson gives a fair glimpse of him. At least he does not spare his eccentricities. We view him from all quarters."

The lunch bell rang long before Blue Bonnet thought it time.

"Mark the place, Grandmother," she said, as they went into the dining-room. "I want to hear it all. I don't think I should have liked Thoreau personally, but there certainly is a nice streak in him—the way he loved animals and nature—isn't there?"

About four o'clock in the afternoon the clouds began to break, and Blue Bonnet in stout shoes and raincoat started off with Solomon for a run.

Her grandmother and aunt watched her as she turned her steps in the direction of the schoolhouse.

"Blue Bonnet is a gregarious soul," Miss Clyde said, turning away from the window. "She loves companionship. She likes to move in flocks."

"Most girls do, Lucinda. I often wondered how her mother ever endured the loneliness of a Texas ranch, with her disposition. She seemed to find room in her heart for all the world. But it is not a bad trait," Mrs. Clyde added. "It is a part of the impulsive temperament."

The next few days passed much as Monday had, except that the duties, not to become too irksome, were varied. There was a morning in the kitchen, when Blue Bonnet was instructed into the mys[26]teries of breadmaking and the preparing of vegetables.

It was on this particular morning that Mrs. Clyde, going to the kitchen door to speak with Katie, found Blue Bonnet, apron covered, standing before the immaculate white sink, her hands encased in rubber gloves, with a potato, which she was endeavoring to peel, poised on the extreme end of a fork.

For the first time in nearly twenty years of service, Katie permitted herself the familiarity of a wink in her mistress's direction, and Mrs. Clyde slipped away noiselessly, wearing a very broad smile.

But, if the mornings were tiresome, the afternoons more than compensated. There were long rides on Chula; afternoons when Blue Bonnet came in looking as rosy as one of the late peonies in her grandmother's garden.

"Grandmother!" she would call, dashing up the side drive and halting Chula at the door. "Grandmother, come and look at us!"

Mrs. Clyde would hasten to the door to find Blue Bonnet decked from hat brim to stirrups with trailing vines in gorgeous hues, goldenrod and chrysanthemums tied in huge bunches to her saddle.

Nor was Chula neglected. Often she sported a flaming wreath—her mane bunches of flowers.

"Take all the flowers in," Blue Bonnet would [27]call to Delia. "This week will see the very last of them. The man at the Dalton farm says there is sure to be frost most any night."

When the mail came on Saturday morning there was a pleasant diversion. Miss Clyde sorted the letters and handed a pamphlet to Blue Bonnet. It proved to be a catalogue of Miss North's school, and interested Blue Bonnet greatly. She seated herself in her favorite chair in the sitting-room and turned the pages eagerly.

"Oh, Aunt Lucinda, it's quite expensive, isn't it? A thousand two hundred dollars a year; and that doesn't include—let's see—'use of piano, seat in church, laundry, doctor's bills, music lessons, fencing and riding'—but then I wouldn't have to have all the extras. I could cut out the fencing and riding, of course, and the seat in church—"

"Elizabeth!"

Blue Bonnet turned quickly. It was the first time she had heard her baptismal name in months.

"I beg your pardon, Aunt Lucinda. I didn't think. Please excuse me."

"Certainly, Blue Bonnet. But remember that it is very bad taste to be irreverent."

Blue Bonnet brought the catalogue over to Miss Clyde, and together they looked through it.

"It seems just the place for you, Blue Bonnet," Miss Clyde said. "The location on Commonwealth Avenue is ideal. It is within walking distance of [28]most of the places where you will want to go. This is a great advantage."

Blue Bonnet curled herself up comfortably in the deep chair and looked out through the window dreamily. Slowly a smile wreathed her lips.

"Aunt Lucinda," she said after a moment, "do you know what I'd just love to do? I've been thinking of how much more I have than most girls, and I wish I could pass some of the good things along. Now, there's Carita Judson. Wouldn't she just adore a year in Boston? Why couldn't I ask her to go with me to Miss North's? There's that great big room I'm to have with a bath, and all those advantages—" Blue Bonnet paused.

Miss Clyde was silent for a moment. Blue Bonnet's impulses bewildered her sometimes, they were so stupendous.

Blue Bonnet was insistent.

"There's all that money coming to me that my father left," she went on, "and Uncle Cliff says that some day there will be more—from him. What ever am I going to do with it? Carita Judson has an awfully poor sort of a time, Aunt Lucinda, awfully poor. She mothers all those small children in the family—"

"I daresay for that very reason she could not well be spared."

Miss Clyde was more than half in sympathy with Blue Bonnet's idea; she knew through her mother [29]of Carita's fine father, of the girl's sweetness and refinement in spite of her restricted means and surroundings, but she did not wish to encourage Blue Bonnet in what seemed an impossibility.

Blue Bonnet jumped up from her chair.

"I'm going to write to Uncle Cliff about it this very minute," she said, moving toward the door. "I know he'll think it is a perfectly splendid idea."

"Would it not be better to wait until we have visited the school?" her aunt inquired tactfully. "There might not be room for Carita. The number of pupils is limited, you know. Suppose you wait until Uncle Cliff comes at Christmas. You could consult him then. It would be very unwise to get Carita's hopes up and then disappoint her."

Blue Bonnet had not thought of this.

"But I shall ask him the minute he comes," she assured her aunt as she left the room, taking the catalogue with her. "Just the very minute! I know what he'll say, too, Aunt Lucinda. He'll say that happiness is the best interest one can get out of an investment. I've heard him, no end of times!"

The week ended delightfully for Blue Bonnet.

"It's a sort of reward of merit for working so hard all these mornings," she said, as her grandmother granted permission to follow out a plan of Amanda Parker's.

[30]Amanda's aunt had the second time invited the We Are Sevens for a week-end at the farm.

The girls were to take the street car as far as it would carry them—to be met at that point by a hay wagon.

Blue Bonnet was in high glee. A natural lover of the country, visions of a glorious time rose before her eyes.

She appeared at the corner drug store, where the girls were to take the interurban, a few minutes late. Aunt Lucinda had so many instructions at the last moment that she had been delayed.

The girls were all gathered, looking anxiously down the street. When Blue Bonnet appeared in the snowiest of white sweaters and tam-o'-shanter, as jaunty and blooming as if she were out for an afternoon walk, they immediately protested.

"For ever more, why didn't you wear your old clothes, Blue Bonnet?" Kitty Clark inquired. "That sweater will be pot black before you go a mile, and you'll be as freckled as a turkey egg without some shade for your face."

"The sweater will wash, thank you, that's why I wore it, and I'm not the freckly kind."

The shot was unintentional, but Kitty colored to the roots of her red gold hair.

"You are fortunate," she said. "I am."

"That's the penalty you pay for having such a [31]peach of a complexion," Blue Bonnet retorted, and the breach was healed.

At the end of the car line the hay-rack was waiting. The girls climbed on.

"Wait," Blue Bonnet shouted, jumping off quickly, "I almost forgot I want a picture of you."

While she adjusted the camera, the girls struck fantastic poses, Debby perching herself airily on the end gate of the wagon.

There was a warning cry from the girls, which the staid and sober farm horses misinterpreted. Off they started at a mad gallop, leaving the bewildered Debby a crumpled heap in the roadway.

She was on her feet before Blue Bonnet reached her, laughing and crying in a breath.

"How stupid," she panted. "I might have known that gate would fly open. I guess I'm not hurt any."

Blue Bonnet felt Debby's arms and limbs and made her stretch herself. Then they fell in each other's arms and laughed until they were weak and hysterical.

"It's a good thing the roads are a bit soft," Blue Bonnet assured her, when she could get her breath. "You're something of a sight with all that mud on you, but it broke your fall."

"Praise be!" Debby murmured, struggling to remove some of the dirt that insisted upon clinging [32]to her skirts. "I'll take mud to a broken limb, any day."

The rest of the journey was made in safety. Once the wagon halted for Sarah Blake to change her seat. Sitting just over the wheel was not altogether desirable. Sarah's stomach rebelled. The whiteness of her lips spoke louder than words. Blue Bonnet changed places with her cheerfully, keeping strangely silent after the first half mile.

"What makes Blue Bonnet so still?" Kitty inquired, surprised.

"Take this seat and find out, Little Miss Why," Blue Bonnet retorted with an effort. "Maybe you haven't as much regard for your tongue as I have. I want to keep mine whole."

The low, rambling farmhouse surrounded by green hills and ancient oaks, with cattle grazing peacefully on the gentle slopes, and the farm dog yelping frantically at the big gates, gave Blue Bonnet the worst pang of homesickness she had felt since she left the ranch.

Wreaths of blue smoke curled upward lazily from the kitchen chimney, and from the dooryard came the most tantalizing odors of chicken frying, coffee boiling, and fresh doughnuts.

Blue Bonnet jumped from the wagon and filled her lungs with the delicious fragrance.

"Girls," she cried, "just smell! It's chicken and coffee and—"

[33]"Doughnuts," Amanda finished with rapture. "Wait until you taste them! Aunt Priscilla is a wonder at cooking. She has the best things you ever ate in your life."

Aunt Priscilla appeared in the doorway at that moment, a wholesome sweet-faced woman of middle age, and took the girls in to the spare bedroom to lay off their things and wash before supper.

Blue Bonnet took off her cap and sweater and laid them lightly on the high feather bed with its wonderful patch-work quilt—the "rising sun" pattern running riot through it.

"It's so clean I hate to muss it up with my things," she said, casting about for a chair.

"I speak for this bed," Kitty said, depositing her things carelessly. "I slept in it the last time we came. It's as good as a toboggan. You keep going down and down and—"

"We're going to draw for it," Amanda announced from the wash-stand where she was wrestling with Debby's mud. "It will hold four; the other three girls will have to go in the next room."

"Why couldn't we bring the other bed in here—I mean the springs and mattress?" Debby suggested. "Do you think your aunt would care, Amanda?"

Amanda volunteered to ask.

Blue Bonnet took her turn at the wash basin and then wandered into the parlor. She looked about [34]wonderingly. Family portraits done in crayon adorned the walls. A queer little piano, short half an octave, occupied one corner of the room, a marble-topped table, the other. A plush photograph album, a Bible and a copy of Pilgrim's Progress lay on the table. The carpet was green, bold with red roses; roses so vivid in coloring that they seemed to vie with the scarlet geraniums that filled the south window to overflowing.

But over it all a spirit of peace and contentment rested—a homey atmosphere, unmistakable and refreshing. Blue Bonnet gazed through the one unobstructed window of the little room wistfully. Twilight was closing in. Somewhere out in the field a cow bell tinkled, and a boy's voice called to the cattle. How familiar it all was.

Amanda's voice broke the stillness.

"Why, Blue Bonnet Ashe," she said, coming in the room followed by her aunt with a lamp, "what are you doing in here all alone? You look as if you had seen a ghost. Come right out in the kitchen. Aunt Priscilla has supper all on the table."

And such a supper as it was!

The chicken, and there seemed an endless amount, was piled high on an old blue platter that Blue Bonnet fancied her grandmother would have paid almost any price for. Fluffy potatoes, flakey biscuits, golden cream and butter, preserves in variety—[35]everything from a farmhouse larder that could tempt the appetite and gratify the taste.

"I feel as if I never could eat another mouthful as long as I live," Blue Bonnet declared as she rose from the table.

"That's just the way I used to feel last summer on the ranch after one of old Gertrudis' meals," Kitty said.

Amanda's aunt suggested a run down the lane.

Down the lane they ran, laughing and calling; old Shep, stirred from his usual calm, barking and bounding at their heels.

It was too dark for a walk, so the girls soon retraced their steps, settling themselves in the parlor for a visit with the family before going to bed.

"Do any of you play?" inquired Amanda's aunt, looking toward the odd little piano.

"Blue Bonnet does," Kitty announced promptly. "Come, 'little Tommy Tucker must sing for his supper.'"

Blue Bonnet went over to the piano. Kitty's remark served as a reminder. She was glad to repay Amanda's aunt for some of her kindness.

The piano was sadly out of tune, but it is doubtful if Amanda's relatives would have enjoyed a symphony concert as much as Blue Bonnet's simple ballads—the familiar little airs which she gave unsparingly.

After she had quite exhausted her stock, there [36]were clamors for repetition, until Blue Bonnet felt that she had wiped out the debt of the entire "We Are Sevens."

Amanda's aunt was found to be quite reasonable about transferring the bed from the back room. Amanda and the small son of the household undertook its removal, Kitty giving orders.

"Anybody would think you were going to sleep in it, Kitty, you're so particular," Amanda objected. "Get busy and help some."

"I spoke for the big bed," Kitty reminded.

"Yes, and it was selfish of you. We're going to draw for the big bed. I told you that before."

There was a shout of laughter a minute later when Kitty pulled the short slip for the bed on the floor.

Sarah Blake offered to change with her, but the others objected.

"You're an obliging dear, Sarah," Kitty said appreciatively, "but I will stay where I'm put. I don't want to take your place."

Later in the night Sarah wished that she had. She wondered as she shrank to the edge of the bed and tried to make herself as small as possible, if three persons to a bed on the floor, wouldn't have been preferable to the rail which fell to her lot.

It was long past midnight when the last joke was told, the last giggle suppressed. The fun might [37]have gone on indefinitely if, from somewhere in the house, Amanda's uncle's boot hadn't fallen ominously, and Amanda's aunt cleared her throat audibly.

Morning found them up with the larks. There was a stroll down the shady lane before breakfast, and afterward, when the dishes were cleared away and the bedrooms restored to proper order, Amanda's uncle insisted upon piling them all in the big farm wagon and taking them to church.

"It seems to me that it is so much easier to be good—that is, to be religious, in the country," Blue Bonnet said as they neared the meeting-house, and the bell in the small tower rang out slowly. "There's something comes over you when you hear the bell calling, and see the people gathering—"

Kitty quoted.

Blue Bonnet nodded.

"I reckon so—that's as near as you can come to it. There are feelings there aren't any words for, you know, Kitty—kind of indescribable."

The sight of seven pretty, attractive girls—city girls—in one pew, occasioned some comment in church; otherwise there was scarcely a ripple to disturb the calm that rested upon the congregation.

"Unless some one will kindly volunteer to play [38]the organ to-day," the minister said, rising in the pulpit, "we shall have to sing without music. Our organist is sick."

Blue Bonnet glanced about her. No one seemed inclined to offer services. There was a silence of several seconds. The minister waited. Then Amanda's aunt leaned over and whispered something in Blue Bonnet's ear.

Blue Bonnet rose instantly and went to the organ.

She was a little nervous. She knew that organs differed somewhat from pianos, and she wasn't familiar with them, but it never occurred to her to hesitate when she seemed to be needed. She found the hymn and started out bravely. Sometimes the music weakened a little when Blue Bonnet, absorbed in the notes, forgot to use the pedals, but, on the whole, it was not bad, and the minister's hearty handshake and radiant smile after the service more than compensated for any embarrassment she had suffered.

"It has been perfectly glorious," Blue Bonnet declared to Amanda's aunt as they parted with her at daybreak Monday morning. "We've just loved every minute of our visit here, and would you mind—all of you—I want the whole family—standing out there by the big gate while I get a picture of you? I couldn't possibly forget you after the perfectly lovely time you've given us, but I'd like [39]the picture to show to Grandmother and Aunt Lucinda."

"Oh, Blue Bonnet," Kitty complained, "haven't you enough pictures yet? You've been taking them for a year—and more!"

Blue Bonnet quite ignored the remark as she proceeded to line up Amanda's aunt and her family. She got several snaps, and as she put away her kodak she promised to remember the group with pictures—a promise fulfilled, much to the delight of the farm people, later.

"I think," Miss Clyde said to her mother one morning late in November, as she put the last article in her suitcase and snapped it shut, "that Blue Bonnet and I will go to a hotel this time. We shall be out shopping all day and making arrangements for Blue Bonnet at school, so that there will be little time for visiting. If you should need me for anything you might wire the Copley Plaza."

"Are you not afraid Honora and Augusta will feel hurt?" Mrs. Clyde remonstrated. "They enjoy Blue Bonnet so much, it seems a pity not to let them see all they can of her."

"They will have plenty of visits with her later on, Mother. I feel sure they will understand. If you keep well, and everything is all right here, we might extend our visit over Sunday. In that case we should go to them, of course."

Blue Bonnet embraced her grandmother affectionately.

"Don't get lonesome, that's a duck," she exclaimed, bestowing an extra kiss.

"Blue Bonnet, please address your grandmother [41]less familiarly. Those expressions you have acquired are not respectful. I cannot tolerate them any longer," Miss Clyde spoke a trifle sharply.

Blue Bonnet looked surprised.

"I didn't mean it for disrespect, Aunt Lucinda. I only meant it for love; but I won't do it again if it annoys you."

"It does annoy me very much, dear. Stop and think of the word you used just now. A duck! In what possible way could your grandmother resemble a duck?"

"I didn't say she resembled one, Aunt Lucinda. I said—"

But any shade of distinction was too much for Miss Clyde's patience.

"We will not argue the question, Blue Bonnet. Please eliminate the word from your vocabulary. It is inelegant as well as inexpressive."

Blue Bonnet looked a little rebellious as she waved to her grandmother and followed Miss Clyde to the carriage. She wished Aunt Lucinda would grant her a little leeway in her mode of expression—it was so troublesome to always pick and choose words. Besides, she had her own opinion as to the expressiveness of slang. Grandmother was a duck, a perfect—

"Take good care of yourself, dearie," the gentle voice was at that moment calling, "and if you stay over Sunday, send Grandmother a postal."

[42]Blue Bonnet promised, Denham touched the whip to the horses, and she and Aunt Lucinda were off.

The first visit of the afternoon was to the school. Miss Clyde telephoned Miss North for an appointment, which was made for five o'clock. Miss North also hoped, the maid said, that it would be convenient for Miss Clyde and her niece to dine with her at six, and see something of the school and the girls.

Blue Bonnet was delighted. She had been formally entered in the school some weeks before, her tuition paid, her room engaged for the first of January. This had been necessary on account of limited accommodations.

Miss North was awaiting her guests in her living-room at the head of the first flight of stairs. She took Blue Bonnet's hand cordially, and held it for a moment in a friendly grasp.

"And this is the new member of our family," she said with a pleasant smile, as she brought forth chairs.

Blue Bonnet looked about while her aunt and Miss North chatted.

The room pleased her, it was in such exquisite taste. Soft rugs carpeted the polished floor; beautiful pictures graced the walls; old mahogany lent its air of elegance, and books abounded everywhere.

Miss North pressed a button on her desk after a moment and a neat maid entered.

[43]"Ask Mrs. Goodwin to come here, Martha, please."

Mrs. Goodwin must have been in waiting, for she made her appearance quickly; a motherly looking woman with an alert, cheerful countenance.

"Our house-mother, Mrs. Goodwin, Miss Clyde—Miss Ashe. Miss Clyde would like to see the room we have reserved for her niece, Mrs. Goodwin."

Mrs. Goodwin led the way up a second flight of stairs.

"I am sorry, Miss Clyde, that we could not give Miss Ashe a room alone as you desired, but entering so late it is quite impossible. I am sure she will enjoy her room-mate however, a Miss Cross from Bangor, Maine. We think it a wise plan to put an Eastern and a Western girl together when possible—the influence is wholesome to both."

She rapped softly on a door at the front of the building.

"May we come in, Miss Joy?" she said to the girl who opened the door slowly, book in hand.

"Certainly," she answered, far from cordially, and, acknowledging the introductions, went over to the window where she resumed her reading.

The room was large and airy—a corner room with four windows. Mrs. Goodwin threw up the blinds of the south windows.

"The view is beautiful from here," she said.

[44]She crossed the room and opened a door, disclosing a small hall.

"The bathroom and closets are here."

Between the large west windows were two single beds, and in a corner a grate with an open fire gave a homey touch. There was a desk in the room too. Blue Bonnet supposed it was to be used jointly. She looked about; there was plenty of room for another. She would ask Aunt Lucinda to buy one for her; and a bookcase to hold some of her favorite volumes.

Blue Bonnet was exceedingly quiet during the rest of the tour through the building, and at dinner. When she was alone with her aunt in the street she burst forth:

"I just can't do it, Aunt Lucinda. I never in this world can room with that girl and be happy. Joy Cross! Who ever heard of such a name? It's plain to be seen which she'll be. A cross, all right!"

Miss Clyde looked at Blue Bonnet in amazement.

"Anybody would know to look at her she couldn't be a joy! Did you notice how she shook hands, Aunt Lucinda?"

"That will do, Blue Bonnet. It is very unjust to criticize people you don't know. Appearances are often deceiving. Miss Cross may prove a delightful companion—"

[45]"Oh, no, Aunt Lucinda. She couldn't—not with that nose. It's the long thin kind—the kind that pokes into everything. And her eyes! Did you notice her eyes? They're that awfully light kind of blue—they look so cold and unfeeling; and she was so—so—un-cordial when Mrs. Goodwin said I was to room with her. She wasn't even polite. She didn't say she was glad, or that would be nice or—she didn't say anything—"

"There wasn't time to say much," Miss Clyde answered.

"Grandmother says there is always time for courtesy," Blue Bonnet flashed, and Miss Clyde knew that her niece had the best of the argument.

"Nothing can be done at present, Blue Bonnet. You heard Mrs. Goodwin say that all the rooms are taken. Perhaps some change can be made later—but now—"

"Now, I shall just have to take up my cross and bear it, of course; but I sha'n't cling to it a minute longer than I have to, you may be sure of that."

Despite the seeming irreverence, Miss Clyde smiled. Blue Bonnet's tempestuous little outbursts were often entertaining if they were reprehensible. They sometimes reminded Miss Clyde of a Fourth of July sky-rocket. They glowed in brilliancy and ended in—nothing! Likely enough Blue Bonnet [46]would finish the term quite adoring her room-mate. She ventured to suggest this.

Blue Bonnet scorned the idea. She was sure that she should just hate her!

Blue Bonnet was up early the next morning, ready for the shopping expedition which promised to be of more than ordinary interest. Aunt Lucinda seemed inclined to be almost extravagant, Blue Bonnet thought, as together they made out the shopping list and pored over the advertisements in the papers.

"Let's begin at Hollander's, Aunt Lucinda," Blue Bonnet said. "I love Hollander's. We could get the Peter Thompsons there, and my evening dresses and slippers and things."

The "evening dresses" amused Miss Clyde.

"I am afraid you did not read the school catalogue very carefully, Blue Bonnet. It especially requested simplicity of dress."

"I know it did, Aunt Lucinda, but you saw how sweetly the girls were gowned at dinner. Perhaps the dresses were simple, but they looked expensive and—dressy," she added for want of a better word. "That pretty dark girl that sat next me had on the darlingest pink organdy with a Dutch neck. Oh, it was so dear. I wonder where she got it?"

She had not long to wonder. The Boston shops seemed to have anticipated the needs of girls all over the country. Blue Bonnet stood entranced [47]before cases of the daintiest frocks that could be imagined.

"Oh, Aunt Lucinda," she exclaimed, holding up two that attracted her, "I can't make up my mind which of these is the prettier. I adore this blue crepe with these sweet buttons, but the white organdy is such a love with that white fixing—and, oh, will you look at that yellow chiffon! I suppose I couldn't have chiffon, could I? It looks too partified."

Miss Clyde thought not.

"But you might try on the white, and the blue gown," she said.

They fitted admirably with a few alterations, and to Blue Bonnet's great joy Miss Clyde took both—and yet another; a sheer white linen lawn with a pink silk slip, which called forth all the adjectives Blue Bonnet could muster.

Then came an exciting moment when slippers and hose were selected; dainty but serviceable underwear, and the little accessories that count for so much in a girl's wardrobe.

"I feel exactly as if I were getting a trousseau," Blue Bonnet said, as they started for a tailor's, where she was to be measured for suits. "And, Aunt Lucinda, there's just one more thing I want—two things! A desk and some books. You saw that desk in the room I am to have. Well, the cross—I mean Miss Cross—had her things in [48]it. I saw them. I don't want to share it with her. We'd be forever getting mixed up and fussing. I'd like to avoid that."

Miss Clyde remembered the check Mr. Ashe had sent—the half of which had not yet been spent, and the instructions that everything was to be provided for Blue Bonnet's happiness and comfort. Had she a right to refuse? She, too, wanted Blue Bonnet to be happy and comfortable, but her New England training from youth up made the lavish spending of money almost an impossibility. She greatly feared that the increased allowance Mr. Ashe had insisted upon giving Blue Bonnet for her private use at boarding-school, would inculcate habits of extravagance.

After they left the tailor's a desk was soon found, suitable in every particular—mahogany, of course, since the other furniture in the room was.

Coming out of the furniture store Miss Clyde and Blue Bonnet passed a floral shop. Blue Bonnet gave a little cry of surprise.

"Look, Aunt Lucinda, there's Cousin Tracy!"

She slipped up to him quietly, putting her arm through his. He turned in a dazed sort of fashion.

"Well, well," he said. "Where did you come from?"

"Woodford."

"When, pray?"

"Yesterday."

[49]Mr. Winthrop seemed surprised, and Miss Clyde made haste to explain.

"Look here," he said, putting his hands on Blue Bonnet's shoulders and turning her toward the florist's window.

A miniature football game was being shown in gorgeous crimson and gold settings. The field was outlined in flowers and the little men in caps and sweaters were most fascinating.

Blue Bonnet gave his arm a squeeze.

"It's the Harvard-Yale game, isn't it,—to-morrow? I'm crazy about it. Oh, I do hope Harvard wins! My father was a Harvard man. So are you, I remember."

"Want to see it?" Cousin Tracy asked, as if seeing a Harvard-Yale game were the simplest thing possible.

Blue Bonnet fairly jumped for joy.

"Could I? Could we get tickets?"

Cousin Tracy nodded and touched his breast pocket significantly.

"I have two. Right by the cheering section."

She crossed her hands in an ecstatic little fashion that expressed the greatest excitement and joy.

"You wouldn't mind, would you, Aunt Lucinda? Why, the We Are Sevens wouldn't get over it in a week. It seems too good to be true."

Before Miss Clyde and Blue Bonnet parted with Mr. Winthrop all arrangements had been completed, [50]and Blue Bonnet walked away as if she were treading on air.

That night the following letter found its way into the Boston mail:

"Copley Plaza Hotel, Boston, Mass.,

"November 28th, 19—.

"Dearest Uncle Cliff:—

"Aunt Lucinda and I came up here yesterday to buy my clothes for school, and also to see what kind of a room I was to have when I come up for good the first of January.

"Aunt Lucinda has been awfully nice about everything, letting me get most of the things I wanted. I have some loves of dresses, which I won't take time now to describe, as you will be in Woodford so soon for Christmas and will see them. They will be fresh, too, for Aunt Lucinda says I can't wear any of them until I am at Miss North's. Aunt Lucinda bought me a perfect treasure of a desk—mahogany, with the cunningest shelves underneath for books. She bought me some new books, too—some that I've wanted for a long time. There's 'The Life of Helen Keller;' grandmother has one, and I simply adore it; and Thoreau's 'Week on the Merrimac,' and one or two of Stevenson's—Robert Louis, you know—and a new 'Little Colonel,' my old one is worn to shreds. Oh, yes, and a beautiful new dictionary; [51]it looks too full of information for anything, and there's a perfectly dear atlas with it besides. We got a copy of Helen Hunt's 'Ramona,' too. We don't know yet if Miss North will allow me to have any love stories; but, if she won't, Aunt Lucinda will keep it for me. I wouldn't part with it for anything. We had such fun getting the books; only Aunt Lucinda kept fussing about modern bookstores, and wishing that I might have seen the 'Old Corner Book Store,' where she used to come when she was a girl. She says she used to spend whole days there browsing around—she really said that—and poking under the counters and behind things for what she wanted. Just fancy! I think a nice polite clerk that comes up to you with a pleasant smile and says, 'What can I do for you, Madam?' is much nicer, don't you?

"I've saved the worst of my news for the last. I hope it won't make you unhappy, for there will be some way out of it, I reckon. It's this: I hate the room-mate I've got to have. She's perfectly horrid—you wouldn't like her a bit, Uncle Cliff; and the way she shakes hands—well, it makes you feel as if you were going to have to support her until she got through with the ordeal—so limp, and lack-a-daisy. She's tall and thin, with straw-colored hair and white eyelashes and cold blue eyes, and she's from Bangor, Maine. I tried to talk with her for a minute while Aunt Lucinda and the house-[52]mother were making arrangements about me, but all I could gather was that she was a Senior, and from the State of Maine. Why do you suppose these Easterners always say from the State of something? Seems so much easier to just say Maine.

"There was another girl that I sat next to at dinner (we stayed to dinner) who was real nice and so pretty. Her name is Annabel Jackson, and she's from Tennessee. She had on such sweet clothes. I didn't talk to her much, for I couldn't get the other one off my mind—Joy Cross, from the State of Maine. Such a name! Joy! If it could only have been Patience or Hope or Faith—even Dolores, but I suppose it couldn't.

"Uncle Cliff, I've been wishing so that Carita Judson could go to school here at Miss North's with me. She has such a hard time with all those babies to tend. I told Aunt Lucinda that I wished I could send her out of some of my money, but she said to wait until you got here and then talk it over. I don't know whether she could get a room now or not, the school is so full this year—that's why I have to have the cross. You could be thinking it over, couldn't you, Uncle Cliff, and let me know as soon as you come?

"I reckon I've about got to the end of my news now, except that Cousin Tracy is going to take me to the Harvard-Yale game to-morrow. I'm so wild over it that I know I sha'n't sleep a wink to-night. [53]I will write Alec about it when I get back to Woodford and tell him to give the letter to you and Uncle Joe to read.

"Give my love to all the folks on the ranch. How's Benita? Did she like the lavender bags I sent for the sheets? I hope she uses them as I told her. I rather thought she might hang them around her neck or give them to Juanita. I know if the We Are Sevens were here they would send heaps of love. Aunt Lucinda sends her best regards. I am counting the days now until Christmas. I check off every day on the calendar until I see you.

"P. S. Please tell Alec that Aunt Lucinda has promised to look after the General and Solomon when I'm gone. I am going to miss Chula awfully, but there is a riding-school where Miss North lets the girls get horses and ride with a teacher.

"P. S. Miss North seems very nice, but you never can tell how people are going to be until you live with them, I hope for the best. B. B."

"Well, to begin at the very beginning," Blue Bonnet said, looking into the eager faces of the We Are Sevens, "we took an automobile from Cousin Tracy's house, where we were staying over the week-end. Of course we could have taken the Cambridge subway, but Cousin Tracy said we were to have all the frills; and, anyway, the subway is so jammed on the day of the game that it takes forever to get anywhere—especially home, after everything is over. Why, Cousin Tracy says—"

"Yes, we know all about that," Kitty said, "get on to the game."

"Well, we took the automobile and went straight to the Stadium. You never saw so many automobiles in all your life. They would reach from here to—"

"Oh, Blue Bonnet, we don't care a rap about the automobiles," Kitty declared impatiently. "What did you do when you got to the Stadium?"

"We took our seats. You see, we got to the Stadium about one o'clock, and as the game didn't begin until two, we had a perfectly lovely time [55]watching the people gather. Cousin Tracy said there were about forty thousand. The cheering section was just a solid mass of college men, with a band at the bottom, and the most elastic lot of cheer leaders in white sweaters you ever saw. This is the way they do it."

Blue Bonnet dug her elbows into her knees, supported her face in her hands and yelled:

"'Har´-vard! Har´-vard! Har´-vard!'

"And Yale would yell out like the snapping of a whip:

"'Yale! Yale! Yale!'

"But the most exciting moment was when the Yale men came trotting out on the field in white blankets and blue legs."

"In blue legs!" exclaimed Sarah Blake in surprise.

"Well, that was the impression. A few minutes later the Harvard team came trotting on. They had black sweaters and red legs. They peeled off the black sweaters though, showing crimson underneath. Then the game began. I can see them yet."

Blue Bonnet closed her eyes and her lips curled in a smile.

"Then what? Go on!" said Debby.

"Then they played. And how they played, Kitty! And when it was over and Harvard had won. Did you hear me?—Harvard won—twenty to nothing, and for the first time in years, [56]it was as if—well, as if pandemonium were let loose."

The high tension of the We Are Sevens relaxed for a brief second.

"And then," Blue Bonnet went on, "then, the funniest thing happened. The students jumped down from their seats and performed a serpentine dance the entire length of the field. When they got to the goal posts they threw their derbies over. It was too funny to see the black hats flying thick and fast." Blue Bonnet laughed merrily.

"A man passed us afterward with the most pathetic-looking thing on his head; it hardly resembled a hat, it was so crushed and battered; but he was explaining to a friend that it would do to get him home. He looked so silly; but he didn't seem to care a speck. Why, they all lost their heads completely. Even Cousin Tracy—you know how terribly dignified he is—got so excited that he began singing

"at the top of his voice. Everybody went perfectly crazy."

"Then what happened?"

"Much, Amanda. We went up on top of the Stadium. It has a promenade all round it, on top; the view is beautiful—the Charles River, and Cambridge across it, and thousands and thousands [57]of automobiles, and the crowd moving in a solid mass—the people still cheering and laughing—oh, it was great! I felt as if I wanted to stay on forever!"

"It must have been heavenly," Kitty murmured. "Did the girls look pretty?"

"Pretty? Well, they certainly did. I was just going to tell you about that. The Yale girls all wore big bunches of violets—a Yale emblem. The Harvard girls wore dark red chrysanthemums. I had some, and a pennant, which I waved madly. There were more pretty gowns than you ever saw at one time in all your life. Great splashes of color all through the crowd; and the furs—that reminds me: all of a sudden I realized that my fur was gone. The white fox that Uncle Cliff gave me last Christmas. You can imagine the sinking sensation of my heart."

"Oh, dear, you lost it?" Sarah murmured.

"Yes, but I found it. It had slipped off my back and dropped behind the seat. You can believe I held on to it mighty tight after that."

Blue Bonnet sighed deeply as she recalled the averted tragedy.

"Did you go home then?"

"Go home? Well, I should say not. People never go home until they have to, after a big game like that; they're too excited—they have to work it off gradually. Cousin Tracy and I went to din[58]ner where there were loads of Harvard people dining. After dinner we went to a light opera, and there—"

Again Blue Bonnet went off into peals of laughter.

"—a man came out and had the audacity to sing:

"Imagine! Why, the Harvard men didn't let him finish the first line before they had him off the stage—"

"Mobbed him?" Sarah gasped.

"Call it what you like. I don't think they injured him, for he came back and sang Harvard songs—nothing else; sang like an angel, too."

"Oh, but you were in luck, Blue Bonnet," Kitty sighed. "I could die happy if I'd had your chance."

"It does make you feel that way, Kitty. I can see myself telling my grandchildren about that game. It's almost like an inheritance, something you can pass along. I've cut out all the notices from the papers and kept the literature they passed around. Now, I think I've told you every blessed thing. Would you all like to come up-stairs and see my new clothes?"

There was an immediate rush for Blue Bonnet's room.

Miss Clyde wondered an hour later, when she [59]rapped at the door and glanced in, if the place would ever again take on its natural shape and order. Bureau drawers yawned; furniture was pulled about; the window-seat held a mass of underwear, shoes and dresses; but the faces of the We Are Sevens reflected pride and approval.

"Aunt Lucinda," Blue Bonnet called, "Sarah says she will come over Saturday and help sew the markers on my clothes. Isn't that lovely?"

"It is very kind of Sarah, I am sure."

"And, Aunt Lucinda, don't you think it would be nice to have a little tea, or luncheon or something, and let all the girls help?"

"It would be nice to have the girls, Blue Bonnet, but—"

Miss Clyde hesitated. She had seen samples of the We Are Sevens' sewing, and visions of Blue Bonnet's underwear after it had braved the first wash, rose before her eyes.

"But what?"

"Marking clothes is rather a particular piece of work, you know."

Blue Bonnet glanced about quickly to see if this reflection had given offence. None was visible. A relieved expression was rather more in evidence.

"I think I could help, perhaps, Miss Clyde," Sarah said, determined not to have her one accomplishment thrust aside so lightly.

"I am sure you could, Sarah, and thank you very [60]much; your work is always beautiful. Perhaps you would do some of the handkerchiefs."

The next two weeks seemed to take wings—they flew along so fast. The grey days had come; bleak, raw days when clouds hung over the hills, threatening snow and ice.

"Only five days now until Uncle Cliff comes," Blue Bonnet said one morning, pausing in her sewing—she was making bureau scarfs for her room at school, taking the greatest pride and interest in them.

"Five days! I can hardly wait. Grandmother, did you ever think what Uncle Cliff's been to me? Why, he's been father, mother, brother, sister! Many's the time on the ranch when I'd get lonesome he'd play tag with me, or marbles, or cut paper dolls and make me swings—anything to make me happy. Seems like I'm only just beginning to understand how much I owe him; always before I've just kind of taken everything for granted. Sometimes I can hardly wait until I'm grown up to make a nice home for him—to take care of him, and do the things—the little things men like to have done for them."

Miss Clyde turned and scrutinized Blue Bonnet's face closely.

What was this child saying? This woman-child, who only yesterday was romping through the house, indulging in childish dreams—childish sports.

[61]"I'm beginning to feel grown up, sometimes, Grandmother. Going on seventeen is a pretty good age, isn't it? It won't be long now until I'm twenty-one, and then I suppose I'll have to take up responsibilities—learn how to run the ranch."

She sighed heavily.

"I fancy Uncle Cliff will stand back of you for some time yet, dear."

Blue Bonnet nodded confidently.

"Yes, and there's Alec. Pretty soon he'll know how to manage everything on the ranch, too. Uncle Cliff's getting awfully fond of him. Maybe when Alec is through school he'll make him manager of the whole place. Wouldn't that be fine? I think Alec will always be better out in the open. He can't stand city life, it's too cramped for him."

"It certainly would be fine for Alec."

"Yes, and for Uncle Cliff, too. He gets mighty tired of the grind—that's what he calls it sometimes. Why, his little trips East are about the only pleasure he has; and yet—I don't believe you could drive him off the Blue Bonnet Ranch. He loves everything about it, from the smallest yearling to each blade of grass. He says my father did too, and his father. It's a kind of a family trait."

She laughed softly.

"And you have inherited the feeling?" Grandmother asked.

[62]"Oh, I love it," the girl answered. "Of course I love it—but I'm not crazy to winter and summer on it."

Mrs. Clyde seemed satisfied. It would be easier to transplant Uncle Cliff sometime in the future, she thought, than to sacrifice Blue Bonnet to the Texas wilderness. The bond between herself and the child was riveting so close that the thought of a possible separation often appalled her. Yet she did not wish to be selfish; Blue Bonnet's allegiance was to her uncle—there could be no doubt of that.

"By the way, Grandmother, did I tell you that the General has a new picture of Alec? It's just fine. I'll run over and get it."

She was back in the shortest possible time, excited and breathless.

"There he is," she said, thrusting the picture in her grandmother's hands. "Did you ever see anybody change so in your life? That shows what Texas air will do for people. Why, he's fat, positively fat, for him, isn't he?"

"He certainly seems to have grown stouter," Mrs. Clyde admitted.

"And those corduroys—don't they look good—and the sombrero?"

Blue Bonnet's face glowed.

"I don't think you like it," she said, after a moment, taking the picture in her own hands and regarding it jealously.

[63]"Why, yes, I do, dear. Only it seems a bit strange to see Alec in that garb. It is cowboy style, is it not?"

"Yes, but it's cowboy dress, and cowboy life, and cowboy freedom that has given Alec health. He'd never have got it here in Woodford in a thousand years."

"That is true, Blue Bonnet. You are right. What did the General think of the picture?"

"He loves it! I reckon it looked better to him than a West Point uniform with nothing inside of it."

Mrs. Clyde smiled.

"I think the General got over that dream long ago, Blue Bonnet. He is perfectly delighted with Alec's recovery."

Blue Bonnet put the picture on the mantel-shelf, and, folding her work neatly, went to the window and looked out. She stood a moment lost in thought.

"I think I'll go for a gallop, Grandmother," she said, turning suddenly. "I've just time before dinner. I won't have many more chances."

"The clouds look heavy, dear."

"I know; that's why I want to go. I love the damp air in my face. It's so refreshing."

But out among the hills where the clouds lay the thickest and the wind blew the sharpest, the world seemed a little dreary to Blue Bonnet.

[64]"You poor little things," she said to the sparrows hopping from fence to tree forlornly. "The prospect of a New England winter is not as alluring as it might be, is it? Why don't you try Texas? It's warm down there—and sunshiny—and—

"What's the matter with me?" she said, pulling herself up in the saddle. Then she laughed.