The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Castaways, by Harry Collingwood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Castaways

Author: Harry Collingwood

Illustrator: T.C. Dugdale

Release Date: November 15, 2007 [EBook #23491]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CASTAWAYS ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Harry Collingwood

"The Castaways"

Chapter One.

Miss Onslow.

It was on a wet, dreary, dismal afternoon, toward the end of October 18—, that I found myself en route for Gravesend, to join the clipper ship City of Cawnpore, in the capacity of cuddy passenger, bound for Calcutta.

The wind was blowing strong from the south-east, and came sweeping along, charged with frequent heavy rain squalls that dashed fiercely against the carriage windows, while the atmosphere was a mere dingy, brownish grey expanse of shapeless vapour, so all-pervading that it shut out not only the entire firmament but also a very considerable portion of the landscape.

There had been a time, not so very long ago—while I was hunting slavers on the West Coast, grilling under a scorching African sun day after day and month after month, with pitiless monotony—when the mere recollection of such weather as this had made me long for a taste of it as a priceless luxury; but now, after some five months’ experience of the execrable British climate, I folded my cloak more closely about me, as I gazed through the carriage windows at the rain-blurred landscape, and blessed the physician who was sending me southward in search of warmth and sunshine and the strong salt breeze once more.

For it was in pursuit of renewed health and strength that I was about to undertake the voyage; a spell of over two years of hard, uninterrupted service upon the Coast—during which a more than average allowance of wounds and fever had fallen to my share—had compelled me to invalid home; and now, with my wounds healed, the fever banished from my system, and in possession of a snug little, recently-acquired competence that rendered it unnecessary for me to follow the sea as a profession, I—Charles Conyers, R.N., aged twenty-seven—was, by the fiat of my medical adviser, about to seek, on the broad ocean, that life-giving tonic which is unobtainable elsewhere, and which was all that I now needed to entirely reinvigorate my constitution and complete my restoration to perfect health.

Upon my arrival at Gravesend I was glad to find that the rain had ceased, for the moment, although the sky still looked full of it. I therefore lost no time in making my way down to the river, where I forthwith engaged a waterman to convey me, and the few light articles I had brought with me, off to the ship.

The City of Cawnpore was a brand-new iron ship, of some twelve hundred tons register, modelled like a frigate, full-rigged, and as handsome a craft in every respect as I had ever seen. I had seen her before, of course, in the Docks, when I had gone down to inspect her and choose my cabin; but she was then less than half loaded; her decks were dirty and lumbered up with bales and cases of cargo; her jib-booms were rigged in, and her topgallant-masts down on deck; and altogether she was looking her worst; while now, lying well out toward the middle of the stream as she was, she looked a perfect picture, as she lay with her bows pointing down-stream, straining lightly at her cable upon the last of the flood-tide, loaded down just sufficiently, as it seemed, to put her into perfect sailing trim, her black hull with its painted ports showing up in strong contrast to the peasoup-coloured flood upon which she rode, her lofty masts stayed to a hair, and all accurately parallel, gleaming like ruddy gold against the dingy murk of the wild-looking sky. Her yards were all squared with the nicest precision, and the new cream-white canvas snugly furled upon them and the booms; the red ensign streamed from the gaff-end; and the burgee, or house flag—a red star in a white diamond upon a blue field—cut with a swallow tail in the present instance to indicate that her skipper was the commodore of the fleet—fluttered at the main-royal-masthead.

“She’s a pretty ship, sir; a very pretty ship; as handsome a vessel as I’ve ever see’d a lyin’ off this here town,” remarked the waterman who was pulling me off to her, noting perhaps the admiration in my gaze. “And she’s a good staunch ship, too; well built, well found, and well manned—the owners of them ‘red star’ liners won’t have nothin’ less than the very best of everything in their ships and aboard of ’em—and I hopes your honour’ll have a very pleasant voyage, I’m sure. You ought to, for there’s some uncommon nice people goin’ out in her; I took three of ’em off myself in this here very same boat ’bout a hour ago. And one of ’em—ah, she is a beauty, she is, and no mistake! handsome as a hangel; and such eyes—why, sir, they’re that bright and they sparkles to that extent that you won’t want no stars not so long as she’s on deck.”

“Indeed,” answered I, with languid interest, yet glad nevertheless to learn that there was to be at least one individual of agreeable personality on board. Then, as we drew up toward the accommodation ladder, I continued: “Back your starboard oar; pull port; way enough! Lay in your oars and look out for the line that they are about to heave to you!”

“Ay, ay, sir,” answered the fellow, as he proceeded with slow deliberation but a great show of alacrity to obey my injunctions. “Dash my buttons,” he continued, “if I didn’t think as you’d seen a ship afore to-day, and knowed the stem from the starn of her. Says I to myself, when I seen the way that you took hold of them yoke-lines, and the knowin’ cock of your heye as you runned it over this here vessel’s hull and spars and her riggin’—‘this here gent as I’ve a got hold of is a sailor, he is, and as sich he’ll know what a hard life of it we pore watermen has; and I shouldn’t wonder but what—knowin’ the hardness of the life—he’ll’—thank’ee, sir; I wishes you a wery pleasant voyage, with all my ’eart, sir. Take hold, steward; these is all the things the gent has brought along of ’im.”

I was received at the gangway by a fine sailorly-looking man, some thirty-five years of age, and of about middle height, sturdily built, and with a frank, alert, pleasant expression of face, who introduced himself to me as the chief mate—Murgatroyd by name—following up his self-introduction with the information that Captain Dacre had not yet come down from town, but might be expected on board in time for dinner.

It was just beginning to rain rather sharply again, or I should have been disposed to remain on deck for a while and improve my acquaintance with this genial-looking sailor; as it was, I merely paused beside him long enough to note that the deck between the foremast and the mainmast seemed to be crowded with rough, round-backed, awkward-looking men, having the appearance of navvies or something of that kind; also that the main hatch was partially closed by a grating through an aperture in which, at the after port angle of the hatchway, other men of a like sort were passing up and down by means of a ladder. The mate caught my inquiring glance as it wandered over the rough-looking crowd, and replied to it by remarking:

“Miners, and such-like—a hundred and twenty of ’em—going out to develop a new mine somewhere up among the Himalayas, so I’m told. Rather a tough lot, by the look of ’em, Mr Conyers; but I’ll take care that they don’t annoy the cuddy passengers; and they’ll soon shake down when once we’re at sea.”

“No doubt,” I replied. “Poor fellows! they appear to be indifferent enough to the idea of leaving their native land; but how many of them, I wonder, will live to return to it. Steward,” I continued, as I turned away to follow the man who was carrying my hand baggage below for me, “is there anyone in the same cabin with me?”

“No, sir; you’ve got it all to yourself, sir,” was the reply. “There was a young gent,” he continued—“one of a family of six as was goin’ out with us—who was to have been put in along with you, sir; but the father have been took suddenly ill, so they’re none of ’em going. Consequence is that we’ve only got thirty cuddy passengers aboard, instead of thirty-six, which is our full complement. Your trunks is under the bottom berth, sir, and I’ve unstrapped ’em. Anything more I can do for you, sir?”

I replied in the negative, thanking the man for his attention; and then, as he closed the cabin-door behind him, I seated myself upon a sofa and looked round at the snug and roomy apartment which, if all went well, I was to occupy during the voyage of the ship to India and back.

The room was some ten feet long, by eight feet wide, and seven feet high to the underside of the beams. It was set athwartships, instead of fore and aft as was at that period more frequently the fashion; and it was furnished with two bunks, or beds, one over the other, built against the bulkhead that divided the cabin from that next it. The lower bunk was “made up” with bed, bedding, and pillows complete, ready for occupation; but the upper bunk, not being required, had been denuded of its bedding, leaving only the open framework of the bottom, which was folded back and secured against the bulkhead, out of the way, thus leaving plenty of air space above me when I should be turned in. At the foot of the bunks there was a nice deep, double chest of drawers, surmounted by an ornamental rack-work arrangement containing a brace of water-bottles, with tumblers to match, together with vacant spaces for the reception of such matters as brushes and combs, razor-cases, and other odds and ends. Then there was a wash-stand, with a toilet-glass above it, and a cupboard beneath the basin containing two large metal ewers of fresh water; and alongside the wash-stand hung a couple of large, soft towels. There was a fine big bull’s eye in the deck overhead, and a circular port in the ship’s side, big enough for me to have crept through with some effort, had I so wished, the copper frame of which was glazed with plate glass a full inch thick. Beneath this port was the short sofa, upholstered in black horsehair, upon which I sat; and, screwed to the ship’s side in such a position as to be well out of the way, yet capable of pretty completely illuminating the cabin, was a handsome little silver-plated lamp, already lighted, hung in gimbals and surmounted by a frosted glass globe very prettily chased with a pattern of flowers and leaves and birds. The bulkheads were painted a dainty cream colour, with gilt mouldings; a heavy curtain of rich material screened the door; and the deck of the cabin was covered with a thick, handsome carpet. “What a contrast,” thought I, “to my miserable, stuffy little dog-hole of a cabin aboard the old Hebe!” And I sat there so long, meditating upon the times that were gone, and the scenes of the past, that I lost all consciousness of my surroundings, and was only awakened from my brown study—or was it a quiet little nap?—by the loud clanging of the first dinner bell. Thus admonished, I went to work with a will to get into my dress clothes—for those were the days when such garments were de rigueur aboard all liners of any pretensions—and was quite ready to make my way to the saloon when the second and final summons to dinner pealed forth.

The cuddy, or main saloon of the ship, was on deck, under the full poop, while the sleeping accommodation was below; consequently by the time that I had reached the vestibule upon which the cuddy doors opened, I found myself in the midst of quite a little crowd of more or less well-dressed people who were jostling each other in a gentle, well-bred sort of way in their eagerness to get into the saloon. They were mostly silent, as is the way of the English among strangers, but a few, here and there, who seemed to have already made each other’s acquaintance, passed the usual inane remarks about the absurdly inconvenient arrangements generally of the ship. Some half a dozen stewards were showing the passengers to their places at table, as they passed in through the doorways; and upon my entrance I was at once pounced upon by one of the aforesaid stewards, who, in semi-confidential tones, remarked:

“This way, if you please, sir. It’s Cap’n Dacre’s orders that you was to be seated close alongside of him.”

As I followed the man down the length of the roomy, handsome apartment, I could scarcely realise that it was the same that I had seen when the ship lay loading in the dock. Then, the deck (or floor, as a landsman would call it) was carpetless, the tables, chairs, sofas, lamps, and walls of the cabin were draped in brown holland, to protect them from the all-penetrating dust and dirt that is always flying about, more or less, during the handling of cargo, and the room was lighted only by the skylights; now, I found myself in a scene as brilliant, after its own fashion, as that afforded by the dining-room of a first-class hotel. The saloon was of the full width of the ship, and some forty feet long by about eight feet high; the sides and the ceiling were panelled, and painted in cream, light blue, and gold; and it was furnished with three tables—one on either side of the cabin, running fore-and-aft, with a good wide gangway between, and one athwartships and abaft the other two, with seats on the after side of it only, so that no one was called upon to turn his or her back upon those sitting at the other two tables. The tables were gleaming with snow-white napery, crystal, and silver; and were further adorned with handsome flowering plants in painted china bowls, placed at frequent intervals; the deck was covered with a carpet in which one’s feet sank ankle deep; the sofas were upholstered in stamped purple velvet; and the whole scene was illuminated by the soft yet brilliant light of three clusters of three lamps each suspended over the centres of the several tables. Abaft the aftermost table I caught a glimpse of a piano, open, with some sheets of music upon it, as though someone had already been trying the tone of the instrument.

Conducted by the steward, I presently found myself installed in a chair, between two ladies, one of whom was seated alongside the skipper, on his right. This lady was young—apparently about twenty-one or twenty-two years of age, above medium height—if one could form a correct judgment of her stature as she sat at the table—a rich and brilliant brunette, crowned with a wealth of most beautiful and luxuriant golden-chestnut hair, and altogether the most perfectly lovely creature that I had ever beheld. I felt certain, the moment my eyes rested upon her, that she must certainly be the subject of my friend the waterman’s enthusiastic eulogies. The other lady—she who occupied the seat on my right—was stout, elderly, grey-haired, and very richly attired in brocade and lace, with a profusion of jewellery about her. She was also loud-voiced, for as I passed behind her toward my seat she shouted to the elderly, military-looking man on her right:

“Now, Pat, don’t ye attempt to argue wid me; I shall be ill to-morrow, no matther what I ait, or don’t ait; so I shall take a good dinner and injoy mesilf while I can!”

Captain Dacre—a very fine-looking, handsome, whitehaired man, attired in a fairly close imitation of a naval captain’s uniform, and looking a thorough sailor all over—was already seated; but upon seeing me he rose, stretched out his hand, and remarked:

“Lieutenant Conyers, I presume? Welcome, sir, aboard the City of Cawnpore; and I hope that when next you see Gravesend you will have fully recovered the health and strength you are going to sea to look for. It is not often, Mr Conyers, that I have a brother sailor upon my passenger list, so when I am so fortunate I make the most of him by providing him—as in your case—with a berth at the table as nearly alongside me as possible. Allow me to make you known to your neighbours. Miss Onslow, permit me to introduce Lieutenant Conyers of our Royal Navy. Lady O’Brien—General Sir Patrick O’Brien—Lieutenant Conyers.”

Miss Onslow—the beauty on my left—acknowledged the introduction with a very queenly and distant bow; Lady O’Brien looked me keenly in the eyes for an instant, and then shook hands with me very heartily; and the general murmured something about being glad to make my acquaintance, and forthwith addressed himself with avidity to the plate of soup which one of the stewards placed before him.

Presently, having finished his soup, the general leaned forward and stared hard at me for a moment. Then he remarked:

“Excuse me, Conyers—it is no use being formal, when we are about to be cooped up together on board ship for the next two months, is it?—are you the man that got so shockingly hacked about at the capture of that piratical slaver, the—the—hang it all, I’ve forgotten her name now?”

“If you refer to the Preciosa, I must plead guilty to the soft impeachment,” answered I.

“Ah!” he exclaimed, “hang me if I didn’t think so when I heard your name, and saw that scar across your forehead. Wonderfully plucky thing to do, sir; as plucky a thing, I think, as I ever heard of! I must get you to tell me all about it, some time or another—here, steward, hang it all, man, this sherry is corked! Bring me another bottle!”

I am rather a shy man, and this sudden identification of me in connection with an affair that I had already grown heartily tired of hearing referred to, and that I fondly hoped would now be speedily forgotten by my friends, was distinctly disconcerting; I therefore seized upon the opportunity afforded me by the mishap to the general’s sherry to divert the conversation into another channel, by turning to my lovely left-hand neighbour with the inquiry:

“Is this your first experience of shipboard, Miss Onslow?”

“This will be my third voyage to India, Mr Conyers,” she answered, with an air of surprise at my temerity in addressing her, and such proud, stately dignity and lofty condescension that I caught myself thinking:

“Hillo, Charley, my lad, what sort of craft is this you are exchanging salutes with? You will have to take care what you are about with her, my fine fellow, or you will be finding that some of her guns are shotted!”

But I was not to be deterred from making an effort to render myself agreeable, simply because the manner of the young lady was almost chillingly distant, so I returned:

“Indeed! then you are quite a seasoned traveller. And how does the sea use you? Does it treat you kindly?”

“If you mean Am I ill at sea? I am glad to say that I am not!” she replied. “I love the sea; but I hate voyaging upon it.”

“That sounds somewhat paradoxical, does it not?” I ventured to insinuate.

“Possibly it does,” she admitted. “What I mean is that, while I never enjoy such perfect health anywhere as I do when at sea, and while I passionately admire the ever-changing beauty and poetry of the ocean and sky in their varying moods, I find it distinctly irksome and unpleasant to be pent up for months within the narrow confines of a ship, with no possibility of escape from my surroundings however unpleasant they may be. There is no privacy, and no change on board a ship; one is compelled to meet the same people day after day, and to be brought into more or less intimate contact with them, whether one wishes it or not.”

“That is undoubtedly true,” I acknowledged, “so far, at least, as meeting the same people day after day is concerned. But surely one need not necessarily be brought into intimate contact with them, unless so minded; it is not difficult to make the average person understand that anything approaching to intimacy is unwelcome.”

“Is it not?” she retorted drily. “Then I am afraid that my experience has been more unfortunate than yours. I have more than once been obliged to be actually rude to people before. I could succeed in convincing them that I would prefer not to be on intimate terms with them.”

And therewith Miss Onslow ever so slightly turned herself away from me, and addressed herself to the contents of her plate with a manner that seemed indicative of a desire to terminate the conversation.

I thought that I already began to understand this very charming and interesting young lady. I had not the remotest idea who or what she was, beyond the bare fact that her name was Onslow, but her style and her manners—despite her singular hauteur—stamped her unmistakably as one accustomed to move in a high plane of society; that she was inordinately proud and intensely exclusive was clear, but I had an idea that this fault—if such it could be considered—was due rather to training than to any innate imperfection of character; and I could conceive that—the barrier of her exclusiveness once passed—she might prove to be winsome and fascinating beyond the power of words to express. But I had a suspicion that the man who should be bold enough to attempt the passage of that barrier would have to face many a rebuff, as well as the very strong probability of ultimate ignominious, irretrievable defeat; and as I was then—and still am, for that matter—a rather sensitive individual, I quickly determined that I at least would not dare such a fate. Moreover, I seemed to find in the drift of what she had said—and more particularly in her manner of saying it—a hint that possibly I might be one of those with whom she would prefer not to be on terms of intimacy.

“Well,” thought I, “if that is her wish, it shall certainly be gratified; she is a surpassingly beautiful creature, but I can admire and enjoy the contemplation of her beauty, as I would that of some rare and exquisite picture, without obtruding myself offensively upon her attention; and although she has all the appearance of being clever, refined, and possessed of a brilliant intellect, those qualities will have no irresistible attraction for me if she intends to hide them behind a cold, haughty, repellant manner.” And therewith I dismissed her from my mind, and addressed myself to the skipper, “This new ship of yours is a magnificent craft, Captain,” said I. “I fell incontinently in love with her as the waterman was pulling me off alongside. She is far and away the most handsome ship I have ever set eyes on.”

“Ay,” answered Dacre heartily, his whole face kindling with enthusiasm, “she is a beauty, and no mistake. You have some fine, handsome frigates in the service, Mr Conyers, but I doubt whether the best of them will compare with the City of Cawnpore for beauty, speed, or seagoing qualities. My word, sir, but it would have done you good to have seen her before she was put into the water. Shapely? shapely is not the word for it, she is absolutely beautiful! She is to other craft what,”—here his eye rested upon Miss Onslow’s unconscious face for an instant—“a perfectly lovely woman is to a fat old dowdy. There is only one fault I have to find with her, and that is only a fault in my eyes; there are many who regard it as a positive and important merit.”

“And pray what may that be?” I inquired. And, as I asked the question, several of the passengers who had overheard the skipper’s remark craned forward over the table in eager anticipation of his reply.

“Why, sir,” answered Dacre, “she is built of iron instead of good, sound, wholesome heart of oak; that’s the fault I find with her. I have never been shipmates with iron before, and I confess I don’t like it. Of course,” he continued—judging, perhaps, from some of the passengers’ looks that he had said something a trifle indiscreet—“it is only prejudice on my part; I can’t explain my objection to iron; everybody who ought to know anything about the matter declares that iron is immensely strong compared with wood, and I sincerely believe them; still, there the feeling is, and I expect it will take me a month or two to get over it. You see, I have been brought up and have spent upwards of forty years of my life in wooden ships, and I suppose I am growing a trifle too old to readily take up newfangled notions.”

“Ah, Captain, I have met with men of your sort before,” remarked the general; “you are by no means the first person with a prejudice. But you’ll get over it, my dear fellow; you’ll get over it. And when you have done so you’ll acknowledge that there’s nothing like iron for shipbuilding. Apropos of seafaring matters, what sort of a voyage do you think we shall have?”

The skipper shrugged his shoulders.

“Who can tell?” he answered. “Everything depends upon the weather; and what is more fickle than that?—outside the limits of the trade-winds and the monsoons, I mean, of course. If we are unlucky enough to meet with a long spell of calms on the Line—well, that means a long passage. But give me as much wind as I can show all plain sail to, and no farther for’ard than abeam, and I’ll undertake to land you all at Calcutta within sixty days from to-day.”

We were still discussing the probability of the skipper being able to fulfil his promise, when a howling squall swept through the taut rigging and between the masts of the ship, causing the whole fabric to vibrate with a barely perceptible tremor, while the swish and patter of heavy rain resounded upon the glass of the skylights.

“Whew!” ejaculated the general, “what a lively prospect for to-night! What are we to do after dinner to amuse ourselves; and where are we men to go for our smoke?”

“I think,” said I, “we shall find a very comfortable place for a smoke under the overhang of the poop. The tide is ebbing strong by this time, so the ship will be riding more or less stern-on to the wind, and we shall find a very satisfactory lee and shelter at the spot that I have named.”

“Ay,” assented the skipper. “And when you have finished smoking, what can you wish for better than this fine saloon, in which to play cards, or read, or even to organise an impromptu concert? There is a capital piano abaft there; and I am sure that among so distinguished a company there must be plenty of good musicians.”

And so indeed it proved; for when, having finished our smoke, the general and some half a dozen more of us returned to the cuddy, we found that several of the younger ladies of the party had already produced their music, and were doing their best to make the evening pass pleasantly for themselves and others. Miss Onslow was one of the exceptions; she had not produced any music, nor, apparently, did she intend to take anything more than a passive part in the entertainment; indeed it is going almost too far to say even so much as that, for it appeared doubtful whether she even condescended so far as to regard herself as one of the audience; she had provided herself with a book, and had curled herself up comfortably in the corner most distant from the piano, and was reading with an air of absorption and interest so pronounced as really to be almost offensive to the performers. In almost anyone else the manifestation of so profound an indifference to the efforts of others to please would have been regarded as an indication of ill-breeding; but in her case—well, she was so regally and entrancingly lovely that somehow one felt as though her beauty justified everything, and that it was an act of condescension and a favour that she graced the cuddy with her presence at all. And indeed I was very much disposed to think that this was her own view of the matter. Be that as it may, we all spent an exceedingly pleasant evening; and when I turned into my bunk that night I felt very well satisfied with the prospects of the voyage before me.

Chapter Two.

At sea—a wreck in sight.

I was awakened at six o’clock the next morning by the men chorussing at the windlass, and the quick clank of the pawls that showed how thoroughly Jack was putting his heart into his work, and how quickly he was walking the ship up to her anchor. I scrambled out of my bunk, and took a peep through the port in the ship’s side, to see what the weather was like; it was scarcely daylight yet; the glass of the port was blurred with the quick splashing of rain, and the sky was simply a blot of scurrying, dirty grey vapour. I made a quick mental reference to the condition of the tide, deducting therefrom the direction of the ship’s head, and thus arrived at the fact that the wind still hung in the same quarter as yesterday, or about south-east; after which I turned in again, the weather being altogether too dismal to tempt me out on deck at so early an hour. As I did so there was a loud cry or command, the chorussing at the windlass abruptly ceased, and in the silence that temporarily ensued I caught the muffled sound of the steam blowing-off from the tug’s waste-pipe, mingled with the faint sound of hailing from somewhere ahead, answered in the stentorian tones of Mr Murgatroyd’s voice. Then the windlass was manned once more, and the pawls clanked slowly, sullenly, irregularly, for a time, growing slower and slower still until there ensued a long pause, during which I heard the mate encouraging the crew to a special effort by shouting: “Heave, boys! heave and raise the dead! break him out! another pawl! heave!” and so on; then there occurred a sudden wrenching jerk, followed by a shout of triumph from the crew, the windlass pawls resumed their clanking at a rapid rate for a few minutes longer when they finally ceased, and I knew that our anchor was a-trip and that we had started on our long journey.

Everybody appeared at breakfast that morning, naturally; there was nothing to prevent them, for we were still in the river, in smooth water, and the ship glided along so steadily that some of us were actually ignorant of the fact of our being under way until made aware of it by certain remarks passed at the breakfast-table. After breakfast, the weather being as “dirty” as ever, I donned my mackintosh and a pair of sea boots with which I had provided myself in anticipation of such occasions as this, and went on deck to look round and smoke a pipe. A few other men followed my example, among others the general, who presently joined me in my perambulation of the poop; and I soon found that, despite a certain peremptoriness and dictatorial assertiveness of manner, which I attributed to his profession, and his position in it, he was a very fine fellow, and a most agreeable companion, with an apparently inexhaustible fund of anecdote and reminiscence. Incidentally I learned from him that Miss Onslow was the daughter of Sir Philip Onslow, an Indian judge and a friend of Sir Patrick O’Brien, and that she was proceeding to Calcutta under the chaperonage of Lady Kathleen, the general’s wife. While we were still chatting together, the young lady herself came on deck, well wrapped up in a long tweed cloak that reached to her ankles, and the general, with an apology to me for his desertion, stepped forward and gallantly offered his arm, which she accepted. And she remained on deck the whole of the morning, with the wind blustering about her and the rain dashing in her face every time that she faced it in her passage from the wheel grating to the break of the poop, to the great benefit of her complexion. She was the only lady who ventured on deck that day—for the weather was so thick that there was nothing to see, beyond an occasional buoy marking out the position of a sandbank, a grimy Geordie, loaded down to her covering-board, driving along up the river under a brace of patched and sooty topsails, or an inward-bound south-spainer in tow of a tug; but this fact of her being the only representative of her sex on deck appeared to disconcert Miss Onslow not at all; she was as absolutely self-possessed as though she and the general had been in sole possession of the deck, as indeed they were, so far as she was concerned, for she calmly and utterly ignored the presence of the rest of us, excepting the skipper, with whom and with the general she conversed with much vivacity. By the arrival of tiffin-time we had drawn far enough down the river to be just meeting the first of the sea knocked up by the strong breeze, and I noticed that already a few of the seats at table that had been occupied at breakfast-time were vacant—among them that of Lady O’Brien—but my left-hand neighbour exhibited a thoroughly healthy appetite—due in part, probably, to her long promenade on deck in the wind and the rain. She was still as stately and distant in manner as ever, however, when I attempted to enter into conversation with her, and I met with such scant encouragement that ere the meal was half over I desisted, leaving to the skipper the task of further entertaining her.

By six o’clock that night we were abreast of the buoy which marks Longnose Ledge, when the pilot shifted his helm for the Elbow, and we began to feel in earnest the influence of the short, choppy sea, into which the City of Cawnpore was soon plunging her sharp stem to the height of the hawse pipes, to the rapidly-increasing discomfort of many of the passengers. By seven o’clock—which was the dinner-hour—we were well round the Elbow, and heading to pass inside the Goodwin and through the Downs, with most of our fore-and-aft canvas set; and now we had not only a pitching but also a rolling motion to contend with; and although the latter was as yet comparatively slight, it was still sufficient to induce a further number of our cuddy party to seek the seclusion of their cabins, with the result that when we sat down to dinner we did not muster quite a dozen, all told. But among those present was my left-hand neighbour, Miss Onslow, faultlessly attired, and to all appearance as completely at her ease as though she were dining ashore. The general made a gallant effort to occupy his accustomed seat, but the soup proved too much for him, and he was compelled to retreat, muttering something apologetic and not very intelligible about his liver. We remained in tow until the tug had dragged us down abreast the South Foreland, where she left us, taking the pilot with her; and half an hour later we were heading down Channel under all plain sail to our topgallant-sails.

When I went on deck to get my after-dinner smoke the prospect was as dreary and dismal as it could well be. It was dark as a wolf’s mouth; for the moon was well advanced in her last quarter—which is as good as saying that there was no moon at all—and the thickness overhead not only obliterated the stars but also rendered it impossible for any of their light to reach us; one consequence of which was that when standing at the break of the poop it taxed one’s eyesight to the utmost to see as far as the bows of the ship; the wind was freshening, with frequent rain squalls that, combined with the intense darkness, circumscribed the visible horizon to a radius of about half a cable’s length on either hand; and through this all but opaque blackness the ship was thrashing along at a speed of fully ten knots, with a continuous crying and storming of wind aloft through the rigging and in the hollows of the straining canvas, and a deep hissing and sobbing sound of water along the bends, to which was added the rhythmical thunderous roaring of the bow wave, and a frequent grape-shot pattering of spray on the fore deck as the fabric plunged with irresistible momentum into the hollows of the short, snappy Channel seas. It was black and blusterous, and everything was dripping wet; I was heartily thankful, therefore, that it was my privilege to go below and turn in just when I pleased, instead of having to stand a watch and strain my eyeballs to bursting point in the endeavour to avoid running foul of some of the numerous craft that were knocking about in the Channel on that blind and dismal night.

When my berth steward brought me my coffee next morning he informed me, in reply to my inquiries, that the weather had improved somewhat during the night, and that, in his opinion, the temperature on deck was mild enough for me to take a salt-water bath in the ship’s head, if I pleased. I accordingly jumped out of my bunk and, hastily donning my bathing togs, made my way on deck. I was no sooner on my feet, however, than I became aware that the ship was particularly lively. She was on the port tack, and was heeling over considerably, so much so indeed that, when she rolled to leeward, to keep my footing without holding on to something was pretty nearly as much as I could well manage. Then there was a continuous vibrant thrill pervading the entire fabric, suggestive of the idea that her blood was roused and that she was quivering with eager excitement, which, to the initiated, is an unfailing sign that the ship is travelling fast through the water. Upon reaching the deck I found the watch engaged in the task of washing decks and polishing the brasswork, while Mr Murgatroyd, as officer of the watch, paced to and fro athwart the fore end of the poop, pausing every time he reached the weather side of the deck to fling a quick, keen glance to windward, and another aloft at the bending topmasts and straining rigging.

For Mr Murgatroyd was “carrying on” and driving the ship quite as much as was consistent with prudence; the wind, it is true, had moderated slightly from its boisterous character of the previous day, and was now steady; but it was still blowing strong, and had hauled round a point or two until it was square abeam; yet, although the lower yards were braced well forward, the ship was under all three royals, and fore and main-topgallant and topmast studding-sails, with a lower studding-sail upon the foremast! She was lying down to it like a racing yacht, with the foam seething and hissing and brimming to her rail at every lee roll, and the lee scuppers all afloat, while she swept along with the eager, headlong, impetuous speed of a sentient creature flying for its life. The wailing and crying of the wind aloft—especially when the ship rolled to windward—was loud enough and weird enough to fill the heart of a novice with dismay, but to the ear of the seaman it sang a song of wild, hilarious sea music, fittingly accompanied by the deep, intermittent thunder of the bow wave as it leapt and roared, glassy smooth, in a curling snow-crowned breaker from the sharp, shearing stem at every wild plunge of it into the heart of an on-rushing wave. I ran up the poop ladder, and stood to windward, a fathom back from the break of the poop, where I could obtain the best possible view of the ship; and I thought I had never before beheld so magnificent and perfect a picture as she presented of triumphant, domineering strength and power, and of reckless, breathless, yet untiring speed.

“Morning, Mr Conyers,” shouted Murgatroyd, halting alongside me as I stood gazing at the pallid blue sky across which great masses of cloud were rapidly sweeping—to be outpaced by the low-flying shreds and tatters of steamy scud—the opaque, muddy green waste of foaming, leaping waters, and the flying ship swaying her broad spaces of damp-darkened canvas, her tapering and buckling spars, and her tautly-strained rigging in long arcs athwart the scurrying clouds as she leapt and plunged and sheared her irresistible way onward in the midst of a wild chaos and dizzying swirl and hurry of foaming spume: “what think you of this for a grand morning, eh, sir? Is this breeze good enough for you? And what’s your opinion of the City of Cawnpore, now, sir?”

“It is a magnificent morning for sailing, Mr Murgatroyd,” I replied; “a magnificent morning—that would be none the worse for an occasional glint of sunshine, which, however, may come by and by; and, as for the ship, she is a wonder, a perfect flyer—why, she must be reeling off her thirteen knots at the least.”

“You’ve hit it, sir, pretty closely; she was going thirteen and a half when we hove the log at four bells, and she hasn’t eased up anything since,” was the reply.

“Ah,” said I, “that is grand sailing—with the wind where it is. But you are driving her rather hard, aren’t you? stretching the kinks out of your new rigging, eh?”

“Well, perhaps we are,” admitted the mate, with a short laugh, as he glanced at the slender upper spars, that were whipping about like fishing-rods. “But you know, Mr Conyers, we’re obliged to do it; there is so much opposition nowadays, and people are in such a deuce of a hurry always to get to the place that they are bound to, that the line owning the fastest ships gets the most patronage; and there’s the whole thing in a nutshell.”

“Just so; and it is all well enough, in its way—if you don’t happen to get dismasted. But I find the morning air rather nipping, so I will get my bath and go below again. Will you kindly allow one of your men to play upon me with the head-pump, Mr Murgatroyd?”

“Certainly, Mr Conyers, with pleasure, sir,” answered the mate. “Bosun, just tell off a man to pump for Mr Conyers, will ye!”

The ship was by this time so lively that I was not at all surprised to meet but a meagre muster at the breakfast-table. Yet, of the few present, Miss Onslow was one, and the soaring and plunging and the wild lee rolls of the ship appeared to affect her no more than if she were sitting at home in her own breakfast-room. She was silent, as usual, but her rich colour, and the evident relish with which she partook of the food placed before her, bore witness to the fact that her silence was due to inclination alone. About an hour after breakfast the young lady made her appearance upon the poop, well wrapped up, and began to pace to and fro with an assured footing and an easy, graceful poise of her body to the movements of the deck beneath her that was, to my mind at least, the very poetry of motion. The skipper and I happened to be walking together, at the moment of her appearance, and of course we both with one accord sprang forward and, cap in hand, proffered the support of our arms. She accepted that of the skipper with a graciousness of manner that was to be paralleled only by the frigid dignity with which she declined mine.

The breeze held strong all that day, and for the five days following, gradually hauling round, however, and heading us, until, with our yards braced hard in against the lee rigging, and the three royals and mizzen topgallant-sail stowed, we went thrashing away to the westward against a heavy head-sea that kept our decks streaming as far aft as the mainmast, instead of bowling away across the Bay under studding-sails, as we had hoped. Then we fell in with light weather for nearly a week, that enabled all hands in the cuddy to find their sea legs and a good hearty appetite once more, the ship slowly traversing her way to the southward, meanwhile; and finally we got a westerly wind that, beginning gently enough to permit of our showing skysails to it, ended in a regular North Atlantic gale that compelled us to heave-to for forty-two hours before it blew itself out.

The gale was at its height, blowing with almost hurricane fury, with a terrific sea running, about twenty hours after its development, and we in the cuddy were, with about half a dozen exceptions, seated at breakfast when, above the howling of the wind, I faintly caught the notes of a hail that seemed to proceed from somewhere aloft.

“Where away?” sharply responded the voice of the chief mate from the poop overhead.

I heard the reply given, but the noises of the ship, the shriek of the gale through the rigging, and the resounding shock of a sea that smote us upon the weather bow at the moment, prevented my catching the words; I had no difficulty, however, in gathering, from Mr Murgatroyd’s inquiry, that something had drifted within our sphere of vision, probably another vessel, hove-to like ourselves. A minute or two later, however, Mr Fletcher, the third mate, presented himself at the cuddy door and said, addressing himself to the skipper:

“Mr Murgatroyd’s respects, sir; and there’s a partially dismasted barque, that appears to be in a sinking condition, and with a signal of distress flying, about eight miles away, broad on the lee bow. And Mr Murgatroyd would be glad to know, sir, if it’s your wish that we should edge down towards her?”

“Yes, certainly,” answered Captain Dacre. “Request Mr Murgatroyd to do what is necessary; and say that I will be on deck myself, shortly.”

The intelligence that a real, genuine wreck was in sight, with the probability that her crew were in a situation of extreme peril, sent quite a thrill of excitement pulsating through the cuddy; with the result that breakfast was more or less hurriedly despatched; and within a few minutes the skipper, Miss Onslow, and myself were all that remained seated at the table, the rest having hurried on deck to catch the earliest possible glimpse of so novel a sight as Mr Murgatroyd’s message promised them.

As for Dacre and myself, we were far too thoroughly seasoned hands to hurry—the ship was hastening to the assistance of the stranger, and nothing more could be done for the present; and it was perfectly evident that Miss Onslow had no intention of descending to so undignified an act as that of joining in the general rush on deck. But that she was not unsympathetic was evidenced by the earnestness with which she turned to the skipper and inquired:

“Do you think, Captain, that there are any people on that wreck?”

“Any people?” reiterated the skipper. “Why, yes, my dear young lady, I’m very much afraid that there are.”

“You are afraid!” returned Miss Onslow. “Why do you use that word? If there are any people there, you will rescue them, will you not?”

“Of course—if we can!” answered the skipper. “But that is just the point: can we rescue them? Mr Murgatroyd’s message stated that the wreck appears to be in a sinking condition. Now, if that surmise of the mate’s turns out to be correct, the question is: Will she remain afloat until the gale moderates and the sea goes down sufficiently to admit of boats being lowered? If not, it may turn out to be a very bad job for the poor souls; eh, Mr Conyers?”

“It may indeed,” I answered, “for it is certain that no boat of ours could live for five minutes in the sea that is now running. And if that barometer,”—pointing to a very fine instrument that hung, facing us, in the skylight—“is to be believed, the gale is not going to break just yet.”

“Oh dear, but that is dreadful!” the girl exclaimed, clasping her hands tightly together in her agitation—and one could see, by the whitening of her lips and the horror expressed in her widely-opened eyes, that her emotion was not simulated; it was thoroughly real and genuine. “I never thought of that! Do I understand you to mean, then, Captain, that even when we reach the wreck it may be impossible to help those on board?”

“Yes,” answered Dacre; “you may understand that, Miss Onslow. Of course we shall stand by them until the gale breaks; and if, when we get alongside, we find that their condition is very critical, some special effort to rescue them will have to be made. But, while doing all that may be possible, I must take care not to unduly risk my own ship, and the lives which have been intrusted to my charge; and, keeping that point in view, it may prove impossible to do anything to help them.”

“And you think there is no hope that the gale will soon abate?” she demanded.

“I see no prospect of it, as yet,” answered the skipper. “The barometer is the surest guide a sailor has, in respect of the weather; and, as Mr Conyers just now remarked, ours affords not a particle of hope.”

“Oh, how cruel—how relentlessly cruel—the wind and the sea are!” exclaimed this girl whose pride I had hitherto deemed superior to any other emotion. “I hope—oh, Captain, I most fervently hope that you will be able to save those poor creatures, who must now be suffering all the protracted horrors of a lingering death!”

“You may trust me, my dear young lady,” answered the skipper heartily. “Whatever it may prove possible to do, I will do for them. If they are to be drowned it shall be through no lack of effort on my part to save them. And now, if you will excuse me, I will leave Mr Conyers to entertain you, while I go on deck and see how things look.”

The girl instantly froze again. “I will not inflict myself upon Mr Conyers—who is doubtless dying for his after-breakfast smoke,” she answered, with a complete return of all her former hauteur of manner. “I have finished breakfast, and shall join Lady O’Brien on deck.”

And therewith she rose from her seat and, despite the wild movements of the ship, made her way with perfect steadiness and an assured footing toward the ladder or stairs that led downward to the sleeping-rooms, on her way to her cabin.

“A queer girl, by George!” exclaimed Dacre, as she disappeared. “She seems quite determined to keep everybody at a properly respectful distance—especially you. Have you offended her?”

“Certainly not—so far as I am aware,” I answered. “It is pride, skipper; nothing but pride. She simply deems herself of far too fine a clay to associate with ordinary human pots and pans. Well, she may be as distant as she pleases, so far as I am concerned; for, thank God, I am not in love with her, despite her surpassing beauty!”

And forthwith I seized my cap, and followed the captain up the companion ladder to the poop.

Upon my arrival on deck I found that we were under way once more, Mr Murgatroyd having set the fore-topmast staysail and swung the head yards; and now, with the mate in the weather mizen rigging to con the ship through the terrific sea that was running, we were “jilling” along down toward the wreck, which, from the height of the poop, now showed on the horizon line whenever we both happened to top a surge at the same moment. The entire cuddy party were by this time assembled on the poop, and every eye was intently fixed upon the small, misty image that at irregular intervals reared itself sharply upon the jagged and undulating line of the horizon, and I believe that every telescope and opera-glass in the ship was brought to bear upon it. After studying her carefully through my own powerful instrument for about ten minutes I made her out to be a small barque, of about five hundred tons register, with her foremast gone at a height of about twenty feet from the deck, her main-topmast gone just above the level of the lower-mast-head, and her mizenmast intact. I noticed that she appeared to be floating very deep in the water, and that most of the seas that met her seemed to be sweeping her fore and aft; and I believed I could detect the presence of a small group of people huddled up together abaft the skylight upon her short poop. An ensign of some sort was stopped half-way up the mizen rigging, as a signal of distress; and after a while I made it out to be the tricolour.

“Johnny Crapaud—a Frenchman!” I exclaimed to the skipper, who was standing near me, working away at her with the ship’s telescope.

“A Frenchman, eh!” responded the skipper. “Can you make out the colours of that ensign from here? If so, that must be an uncommonly good glass of yours, Mr Conyers.”

“Take it, and test it for yourself,” I answered, handing him the instrument.

He took it, and applied it to his eye, the other end of the tube swaying wildly to the rolling and plunging of the ship.

“Ay,” he said presently, handing the glass back to me, “French she is, and no mistake! Now that is rather a nuisance, for I am ashamed to say that I don’t know French nearly well enough to communicate with her. How the dickens are we to understand one another when it comes to making arrangements?”

“Well, if you can find no better way, I shall be very pleased to act as interpreter for you,” I said. “My knowledge of the French language is quite sufficient for that.”

“Thank you, Mr Conyers; I am infinitely obliged to you. I will thankfully avail myself of all the assistance you can give me,” answered the skipper.

The sea being rather in our favour than otherwise, we drove down toward the wreck at a fairly rapid pace, despite the extremely short sail that we were under; and as we approached her the first thing we made out with any distinctness was that the barque was lying head to wind, evidently held in that position by the wreck of the foremast, which, with all attached, was under the bows, still connected with the hull by the standing and running rigging. This was so far satisfactory, in that it acted as a sort of floating anchor, to which the unfortunate craft rode, and which prevented her falling off into the trough of the sea. It would also, probably, to some extent facilitate any efforts that we might be able to make to get alongside her to take her people off.

To get alongside! Ay; but how was it to be done in that wild sea? The aspect of the ocean had been awe-inspiring enough before this forlorn and dying barque had drifted within our ken; but now that she was there to serve as a scale by which to measure the height of the surges, and to bring home to us a realising sense of their tremendous and irresistible power by showing how fearfully and savagely they flung and battered about the poor maimed fabric, it became absolutely terrifying, as was to be seen by the blanched faces and quailing, cowering figures of the crowd on the poop who, stood watching the craft in her death throes. Hitherto the violence of the sea had been productive in them of nothing worse than a condition of more or less discomfort; but now that they had before their eyes an exemplification of what old ocean could do with man and man’s handiwork, if it once succeeded in getting the upper hand, they were badly frightened; frightened for themselves, and still more frightened for the poor wretches yonder who had been conquered in their battle with the elements, and were now being done to death by their triumphant foe. And it was no reproach to them that they were so; for the sight upon which they were gazing, and which was now momentarily growing plainer to the view, was well calculated to excite a feeling of awe and terror in the heart of the bravest there, having in mind the fact that we were looking upon a drama that might at any moment become a tragedy involving the destruction of nearly or quite a dozen fellow beings. Even I, seasoned hand as I was, found myself moved to a feeling of horrible anxiety as I watched the wreck through my telescope.

For the feeling was growing upon me that we were going to be too late, and that we were doomed to see that little crouching, huddling knot of humanity perish miserably, without the power to help them. We were by this time about a mile distant from the wreck; and another seven or eight minutes would carry us alongside. But what might not happen in those few minutes? Why, the barque might founder at any moment, and carry all hands down with her. For we could by this time see that the hull was submerged to the channels; and so deadly languid and sluggish were her movements that almost every sea made a clean sweep over her, fore and aft, rendering her main deck untenable, and her poop but a meagre and precarious place of refuge.

And even if she continued to float until we reached her, and for some time afterward, how were her unfortunate people to be transferred from her deck to our own? One had only to note the wild rush of the surges, their height, and the fierceness with which they broke as they swept down upon our own ship, and the headlong reeling and plunging of her as she met their assault, to realise the absolute impossibility of lowering a boat from her without involving the frail craft and her crew in instant destruction; and how otherwise were those poor, half-drowned wretches to be got at and saved. Something might perhaps be done by means of a hawser, if its end could by any means be put on board the sinking craft; but here again the difficulties were such as to render the plan to all appearance impracticable. Yet it seemed to offer the only imaginable solution of the problem; for presently, as we continued to roll and stagger down toward the doomed barque, Captain Dacre turned to me and said:

“There is only one way to do this job, Mr Conyers; and that is for the Frenchmen to float the end of a heaving-line down to us, by which we may be able to send them a hawser with a bosun’s chair and hauling lines attached. If it is not troubling you too much, perhaps you will kindly hail them and explain my intentions, presently. I shall shave athwart her stern, as closely as I dare, with my main-topsail aback, so that you may have plenty of time to tell them what, our plans are, and what we want them to do.”

“Very well,” said I; “I will undertake the hailing part of the business with pleasure. Have you a speaking-trumpet?”

“Of course,” answered the skipper. “Here, boy,”—to one of the apprentices who happened to be standing near—“jump below and fetch the speaking-trumpet for Mr Conyers. You will find it slung from one of the deck beams in my cabin.”

Dacre then took charge of the ship in person, conning her from the weather mizen rigging, and sending Murgatroyd for’ard with instructions to clear away the towing-hawser, and to fit it with a traveller, bosun’s chair, and hauling-lines, blocks, etcetera, all ready for sending the end aboard the barque when communication should have been established with her. And at the same time, the boy having brought the speaking-trumpet on deck, and handed it to me, I stationed myself in the mizen rigging, alongside the skipper, for convenience of communication between him and myself.

Chapter Three.

We rescue the crew of a French barque.

We were now drawing close down upon the barque, steering a course that, if persisted in, would have resulted in our striking her fair amidships on her starboard broadside, but which, by attention to the helm at the proper moment, with a due allowance for our own heavy lee drift, was intended to take us close enough to the sinking craft to enable us to speak her. Presently, at a word from the skipper, the third mate—who was acting as the captain’s aide—sang out for some men to lay aft and back the main-topsail; and at the same moment the helm was eased gently up, with the result that our bows fell off just sufficiently to clear the barque’s starboard quarter.

I shall never forget the sight that the unfortunate craft presented at that moment. Her foremast and jib-boom were under the bows, with all attached, and were hanging, a tangled mass of raffle, by the shrouds and stays, leaving about twenty feet of naked, jagged, and splintered stump of the lower-mast standing above the deck; and her main-topmast was also gone; but the wreckage of this had been cut away and had gone adrift, leaving only the heel in the cap, and the ragged ends of the topmast shrouds streaming from the rim of the top. She had been a very smart-looking little vessel in her time, painted black with false ports, and under her bowsprit she sported a handsomely-carved half-length figure of a crowned woman, elaborately painted and gilded. She carried a short topgallant forecastle forward, and a full poop aft, reaching to within about twenty-five feet from the mainmast; and between these two structures the bulwarks had been completely swept away, leaving only a jagged stump of a stanchion here and there protruding above the covering-board. She was sunk so low in the water that her channels were buried; and the water that was in her, making its way slowly and with difficulty through the interstices of her cargo, had at this time collected forward, and was pinning her head down to such an extent that her bows were unable to lift to the ’scend of the sea, with the result that every sea broke, hissing white, over her topgallant forecastle, and swept right aft to the poop, against the front of which it dashed itself, as against the vertical face of a rock, throwing blinding and drenching clouds of spray over the little group of cowering people who crouched as closely as they could huddle behind the meagre and inadequate shelter of the skylight.

I counted fourteen of these poor souls, and in the midst of them, occupying the most sheltered spot on the whole deck, I noticed what at first looked like a bundle of tarpaulin, but as we swept up on the barque’s starboard quarter I saw one of the men gently pull a corner of the tarpaulin aside with one hand, while he pointed at the City of Cawnpore with the other, and, to my amazement, the head and face of a woman—a young woman—looked out at us with an expression of mingled hope and despair that was dreadful to see.

“Good God, there’s a woman among them!” exclaimed Dacre. “We must save her—we must save them all, if we can; but it looks as if we shall not be given much time to do it in. I suppose they want to be taken off? They’ll never be mad enough to wish to stick to that wreck, eh? Hail them, Mr Conyers; you know what to say!”

“Barque ahoy!” I hailed, in French, as, with main-topsail aback, we surged and wallowed slowly athwart the stern of the stranger, “do you wish to be taken off?”

At the first sound of my voice, the man who had pointed us out to the woman rose stiffly to his feet and staggered aft to the taffrail, with his hand to his ear.

“But yes,” he shouted back, in the same language; “our ship is sinking, and—”

“All right,” I interrupted—for time was precious—“we will endeavour to get the end of a hawser aboard you. Have you any light heaving-line that you can veer down to us by means of a float? If so, get it ready, and we will try to pick it up on our return. We are now about to stand on and take room to wear, when we will come back and endeavour to establish a connection between the two craft. Have the line ready and veered well away to leeward at once.”

“But, monsieur,” replied the man, wringing his hands, “we have no line—no anything—you see all that we have,”—indicating the bare poop with a frantic gesture.

“You have a lot of small stuff among the gear upon your mizenmast,” I retorted; but although I pointed to the mast in question, and the man glanced aloft as I did so, I very much doubted whether he comprehended my meaning, for our lee drift was so rapid that we were by this time almost beyond hailing distance.

“Fill the main-topsail,” shouted the skipper. “What have you arranged?” he demanded, turning to me.

I told him. He stamped on the rail with impatience. “It is clear that it will not do to trust overmuch to them for help; we shall have to do everything ourselves. Mr Murgatroyd!” he shouted.

The mate came aft.

“Is that hawser nearly ready?” demanded the skipper.

“All but, sir,” answered the mate. “Another five minutes will do it.”

“Then,” said the skipper, “your next job, sir, will be to muster all the light line you can lay your hands upon, and range it along the larboard rail—which will be our weather rail, presently, when we have got the ship round—and station half a dozen men, or more, all along the weather rail, each with a coil, and let them stand by to heave as we cross the barque’s stern. My object is to get a line aboard her as quickly as possible, by means of which we may send the hawser to them. For they appear to be a pretty helpless lot aboard there, and, if they are to be saved, there is very little time to lose.”

“Ay, ay, sir,” responded Murgatroyd; and away he went to perform this additional duty.

Captain Dacre now showed the stuff of which he was made, handling his ship with the most consummate skill and judgment, wearing her round upon the port tack the moment that he could do so with the certainty of again fetching the barque, and ranging up under her stern as closely as he dared approach. Eight of the strongest and most skilful seamen in the ship were ranged along the weather rail, and as we drew up on the barque’s starboard quarter—with our main-topsail once more thrown aback—man after man hurled his coil of light, pliant line with all his strength, in the endeavour to get the end of it aboard the barque. But such was the strength of the gale that line after line fell short—checked as effectually in its career as though it had been dashed against a solid wall—and although, after his first failure, each man hauled in his line and, re-coiling it with the utmost rapidity, attempted another cast, all were unsuccessful, and we had the mortification of feeling that at least twenty minutes of priceless time had been expended to no purpose. And what made it all the worse was that during that twenty minutes absolutely nothing had been done by the Frenchmen toward the preparation of a line to veer down to us. Within three minutes of the moment when the first line had been hove we were once more out of hailing distance, and the main yards were again being swung.

“We will have another try,” said the skipper; “but if we fail again it will be all up with them—if, indeed, it is not already too late. That barque cannot possibly live another half-hour!”

There seemed to be no room to regard this otherwise than as a plain, literal statement of an incontrovertible fact; we were all agreed that the unfortunate craft had settled perceptibly in the water since we had first sighted her; and at the same rate another half-hour would suffice to annihilate the very small margin of buoyancy that appeared to be still remaining to her, even if she escaped being earlier sunk out of hand by some more than usually heavy sea. But this seemed to have been temporarily lost sight of by the little crowd of onlookers that clustered closely round us on the poop, in the absorbing interest attendant upon our endeavours to get a line on board the barque, and was only recalled to them—and that, too, in a very abrupt and startling manner—by the significance of the skipper’s last remark. The imminence and deadly nature of the Frenchmen’s peril was brought home to them anew; and now they seemed to realise, for the first time, the possibility that they might be called upon to witness at close quarters the appalling spectacle not only of a foundering ship but also of the drowning of all her people. Instantly quite a little hubbub arose among the excited passengers, General O’Brien and some half a dozen other men among them pressing about poor Dacre with suggestions and proposals of the most impossible character. And in the midst of it all I heard Miss Onslow’s clear, rich voice exclaiming bitterly:

“Cruel! cruel! To think that we are so near, and yet it seems impossible to bridge the few remaining yards of space that intervene between those poor creatures and the safety that we enjoy! Surely it can be done, if only anyone were clever enough to think of the way!”

“Now, ladies and gentlemen,” remonstrated the skipper, “please don’t consider me rude if I say that none of you know what you are talking about. There are only two ways of getting a line aboard that wreck; one way is, to carry it, and the other, to heave it. The former is impossible, with the sea that is now running; and the latter we have already tried once, unsuccessfully, and are now about to try again. If any of you can think of any other practicable way, I shall be glad to listen to you; but, if not, please leave me alone, and let me give my whole mind to the job!”

Meanwhile I had been watching the run of the sea, at first idly, and with no other feeling than that of wonder that any vessel in the water-logged condition of the barque could continue to live in it, for it was as high and as steep a sea as I had ever beheld, and it broke incessantly over the barque with a fury that rendered her continued existence above water a constantly-recurring marvel. Heavy as it was, however, it was not so bad as the surf that everlastingly beat upon the sandy shores of the West Coast; and as I realised this fact I also remembered that upon more than one occasion it had been necessary for me to swim through that surf to save my life! “Surely,” thought I, “the man who has fought his way through the triple line of a West African surf ought to be able to swim twenty or thirty fathoms in this sea!” The idea seemed to come to me as an inspiration; and, undeterred by the thought that the individual who should essay the feat of swimming from the one ship to the other would be seriously hampered by being compelled to drag a lengthening trail of light rope behind him, I turned to the skipper and said:

“Captain Dacre, there appears to be but one sure way of getting a line aboard that wreck, and that is for someone to swim with it—Stop a moment—I know that you are about to pronounce the feat impossible; but I believe I can do it, and, at all events, I am perfectly willing to make the attempt. Give me something light—such as a pair of signal halliards—to drag after me, and let a good hand have the paying of it out, so that I may neither be checked by having it paid out too slowly, nor hampered on the other hand by having to drag a heavy bight after me; and I think I shall be able to manage it. And if I succeed, bend the end of a heaving-line on to the other directly you see that I have got hold, and we will soon get the hawser aboard and the end made fast somewhere.”

The skipper looked at me fixedly for several seconds, as though mentally measuring my ability to execute the task I had offered to undertake. Then he answered:

“Upon my word, Mr Conyers, I scarcely know what to say to your extraordinarily plucky proposal. If you had been a landsman I should not have entertained the idea for a moment; and, even as it is, I am by no means sure that I should be justified in permitting you to make the attempt. But you are a sailor of considerable experience; you fully understand all the difficulty and the danger of the service you have offered to undertake; and I suppose you have some hope of being successful, or you would not have volunteered. And upon my word I am beginning to think, with you, that the course you suggest is the only one likely to be of any service to those poor souls yonder—so I suppose—I must say—Yes, and God be with you!”

The little crowd round about us, who had been listening with breathless interest, cheered and clapped their hands at this pronouncement of the skipper’s—the cheer being taken up by the crowd of miners gathered in the waist—and General O’Brien, who was standing at my elbow, seized my hand and shook it enthusiastically as he exclaimed:

“God bless you, Conyers; God bless you, my boy; every man and woman among us will pray for your safety and success!”

“Thanks, General,” answered I. “The knowledge that I have the sympathy and good wishes of you all will add strength to my arm and courage to my heart; but the issue is in God’s hands, and if it be His will, I shall succeed.” Then, turning to the skipper, I said:

“I propose that you shall take the ship up as close as possible to the wreck, precisely as you did at first; and I will dive from the flying-jib-boom-end—which will approach the wreck more closely than our hull; and it will be for you to watch and so manoeuvre the ship—either by easing up the fore-topmast staysail sheet, or in any other way that you may think best—that she shall be kept fair abreast of and dead to leeward of the wreck until we can get the end of the hawser aboard and made fast. After that I think we may trust to the difference in the rate of the drift of the two craft to keep the hawser taut.”

“Yes, yes,” answered the skipper; “you may trust to me to do my part, Mr Conyers. If you can only manage to get the end of the hawser aboard and fast to the wreck, I will attend to the other part of the job. And now, you had better go and get ready for your swim; for I am about to wear ship.”

I hurried away to my cabin and shifted into ordinary bathing attire; and while thus engaged I became aware that Dacre was wearing ship and getting her round upon the starboard tack once more. By the time that my preparations were completed and I had made my way out on the main deck, the ship was round, and heading up for the wreck again. As I appeared, threading my way forward among the great burly miners who were clustering thick in the waist, they raised a cheer, and the cuddy party again clapped their hands, some of them shouting an encouraging word or two after me.

On the forecastle I encountered Murgatroyd, the chief mate, who held a coil of small thin line in his hand.

“Here you are, Mr Conyers,” he exclaimed, as I joined him. “This coil is the main signal halliards, which I have unrove for the purpose—they are better than new, for they have been stretched and have had the kinks taken out of them. And if they are not enough, here are the fore halliards, all ready for bending on at a second’s notice. I shall pay out for you, so you may depend upon having the line properly tended. Now, how will you have the end? will you have it round your waist, or—?”

“No,” said I. “Give it me as a standing bowline, which I can pass over my shoulder and under my arm. So; that will do. Is the hawser fitted, and all ready for paying out?”

“Yes,” answered the mate, “everything is quite ready. I’ve left about five fathoms of bare end for bending on; and I think you can’t do much better than take a turn with it round the mizenmast, under the spider-band.”

“That is exactly what I thought of doing,” said I. “In fact it is about the only suitable place.”

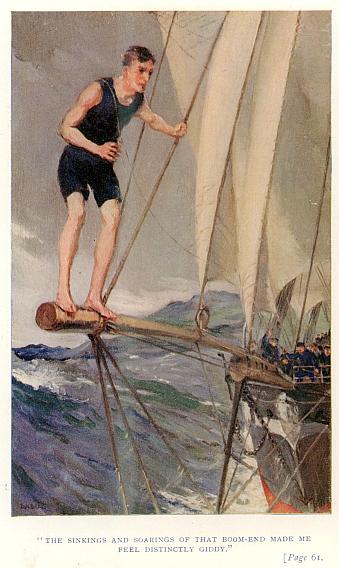

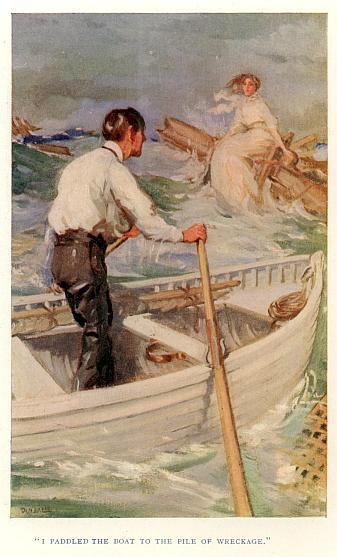

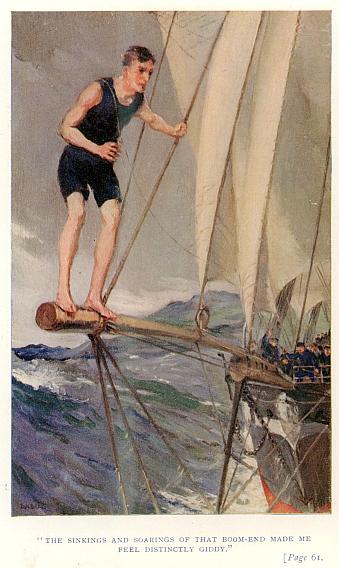

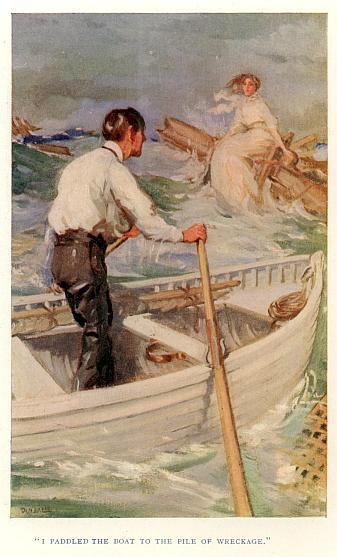

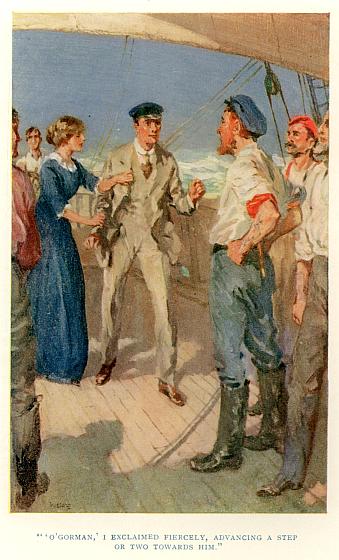

I stood talking with Murgatroyd until we were once more almost within hail of the barque, when, with the bowline at the end of the line over my left shoulder and under my right arm, I laid out to the flying-jib-boom-end, upon which I took my stand, steadying myself by grasping the royal stay in my left hand. The motion away out there, at the far extremity of that long spar, was tremendous; so much so, indeed, that seasoned as I was to the wild and erratic movements of a ship in heavy weather, the sinkings and soarings and flourishings of that boom-end, as the vessel plunged and staggered down toward the wreck, made me feel distinctly giddy. The wait was not a very long one, however, and in less than five minutes I found myself abreast the barque’s starboard quarter, and within a hundred feet of it. I was now as close to the wreck as Captain Dacre dared put me; so, as the ship met a heavy sea and flung me high aloft above the white water that seethed and swirled about the stern of the sinking craft, I let go my hold upon the stay and, poising myself for an instant upon the up-hove extremity of the boom, raised my hands above my head as I bent my body toward the water, and took off for a deep dive, my conviction being that I should do far better by swimming under water than on the surface. As I rushed downward I heard Dacre shout: “There he goes! God be with him!” and then I struck the water, head downward, almost perpendicularly, and the only sound I heard was the hissing of the water in my ears as the blue-green light about me grew gradually more and more dim. With my body slightly curved, and my back a trifle hollowed, I knew that even while plunging downward I was also rushing toward the barque, and presently I struck out strongly, arms and legs, as I caught sight, through the water, of a huge dark body, at no great distance, that I knew to be the swaying hull for which I was making. At length, gasping for breath, I rose to the surface, and found that I was within twenty feet of the barque’s stern, with the whole of her crew upon their feet, anxiously watching me, while a man stood at her taffrail, holding a coil of rope in his hand. The instant he saw me he shouted: “Look out, monsieur; I am about to heave!”

“All right; heave!” I shouted in return, gasping in the midst of the wild popple that leaped about the labouring craft; and the next instant a flake of the uncoiling end of the line hit me sharply across the face. I seized it tightly, and sang out:

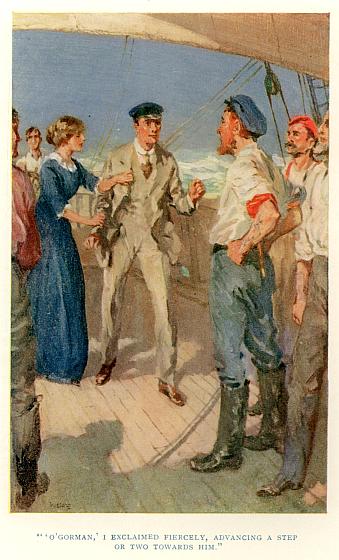

“Haul me to the starboard mizen chains!” The man flung up his hand in reply and, holding on to the rope, started at a run along the deck, dragging me after him. It was a good job that I had thought of taking a turn round one arm, or in his eagerness he would have dragged the rope out of my grasp; as it was, the strain he brought to bear, added to that of the long length of line trailing behind me, almost tore my arms out of their sockets. Moreover, I was half suffocated by the deluge of water that came crashing down upon me like a cataract off the deck of the wreck every time that she rolled toward me. Luckily, this condition of affairs was of but brief duration; and presently I found myself in the wake of the mizen chains, and in imminent danger of being struck and driven under by the overhanging channel piece; I watched my opportunity, however, and, as the barque rolled toward me I seized the lanyards of one of the shrouds, got a footing, somehow, and dragged myself in over the rail. I felt terribly exhausted by the brief but fierce buffeting I had received alongside; but time was precious—the City of Cawnpore was still square athwart the stern of the wreck, but driving away to leeward at a terrible rate, and I knew that unless we were very smart we should still fail to get the hawser from her—so I flung up one arm as a signal to Murgatroyd to pay out and, crying out to the Frenchmen to come and help me, began to haul upon the line I had brought aboard with me. By dint of exhortation so earnest that it almost amounted to bullying I succeeded in awaking the Frenchmen to a sense of the urgency of the case, and persuaded them to put some liveliness into their movements, by which means we quickly hauled in the whole of the signal halliards, to the other end of which a light heaving-line was bent. This also we dragged away upon for dear life, and presently I had the satisfaction of seeing the end of the City of Cawnpore’s towing-hawser being lighted out over her bows. This was a heavy piece of cordage for us to handle, but we dragged away at it breathlessly, and at length, when I had almost begun to despair of getting it aboard in time, we hauled the end in over the taffrail and, all hands of us seizing it, led it to the mizenmast, round the foot of which I had the satisfaction of passing a couple of turns and securing it. So far, so good; the most difficult part of my task was now accomplished; for I knew that Murgatroyd would attend to the work at his end of the hawser, and do everything that was necessary; so I turned to the Frenchman who had assisted me aboard, and said:

“Are you the master of this barque, monsieur?”

“At your service, monsieur,” he answered, bowing with all the grace of a dancing-master.

“Very good,” said I. “You have a lady on board, I think?”

“But yes, monsieur: my wife!” and he flourished his arm toward the bundle of tarpaulin that still remained huddled up under the shelter of the skylight.