Village of Atuona, showing peak of Temetiu

The author's house is the small white speck in the center

Village of Atuona, showing peak of Temetiu

The author's house is the small white speck in the center

There is in the nature of every man, I firmly believe, a longing to see and know the strange places of the world. Life imprisons us all in its coil of circumstance, and the dreams of romance that color boyhood are forgotten, but they do not die. They stir at the sight of a white-sailed ship beating out to the wide sea; the smell of tarred rope on a blackened wharf, or the touch of the cool little breeze that rises when the stars come out will waken them again. Somewhere over the rim of the world lies romance, and every heart yearns to go and find it.

It is not given to every man to start on the quest of the rainbow's end. Such fantastic pursuit is not for him who is bound by ties of home and duty and fortune-to-make. He has other adventure at his own door, sterner fights to wage, and, perhaps, higher rewards to gain. Still, the ledgers close sometimes on a sigh, and by the cosiest fireside one will see in the coals pictures that have nothing to do with wedding rings or balances at the bank.

It is for those who stay at home yet dream of foreign places that I have written this book, a record of one happy year spent among the simple, friendly cannibals of Atuona valley, on the island of Hiva-oa in the Marquesas. In its pages there is little of profound research, nothing, I fear, to startle the anthropologist or to revise encyclopedias; such expectation was far from my thoughts when I sailed from Papeite on the Morning Star. I went to see what I should see, and to learn whatever should be taught me by the days as they came. What I saw and what I learned the reader will see and learn, and no more.

Days, like people, give more when they are approached in not too stern a spirit. So I traveled lightly, without the heavy baggage of the ponderous-minded scholar, and the reader who embarks with me on the “long cruise” need bring with him only an open mind and a love for the strange and picturesque. He will come back, I hope, as I did, with some glimpses into the primitive customs of the long-forgotten ancestors of the white race, a deeper wonder at the mysteries of the world, and a memory of sun-steeped days on white beaches, of palms and orchids and the childlike savage peoples who live in the bread-fruit groves of “Bloody Hiva-oa.”

The author desires to express here his thanks to Rose Wilder Lane, to whose editorial assistance the publication of this book is very largely due.

Farewell to Papeite beach; at sea in the Morning Star; Darwin's theory of the continent that sank beneath the waters of the South Seas

The trade-room of the Morning Star; Lying Bill Pincher; M. L'Hermier des Plantes, future governor of the Marquesas; story of McHenry and the little native boy, His Dog

Thirty-seven days at sea; life of the sea-birds; strange phosphorescence; first sight of Fatu-hiva; history of the islands; chant of the Raiateans

Anchorage of Taha-Uka; Exploding Eggs, and his engagement as valet; inauguration of the new governor; dance on the palace lawn

First night in Atuona valley; sensational arrival of the Golden Bed; Titihuti's tattooed legs

Visit of Chief Seventh Man Who is So Angry He Wallows in the Mire; journey to Vait-hua on Tahuata island; fight with the devil-fish; story of a cannibal feast and the two who escaped

Idyllic valley of Vait-hua; the beauty of Vanquished Often; bathing on the beach; an unexpected proposal of marriage

Communal life; sport in the waves; fight of the sharks and the mother whale; a day in the mountains; death of Le Capitaine Halley; return to Atuona

The Marquesans at ten o'clock mass; a remarkable conversation about religions and Joan of Arc in which Great Fern gives his idea of the devil

The marriage of Malicious Gossip; matrimonial customs of the simple natives; the domestic difficulties of Haabuani

Filling the popoi pits in the season of the breadfruit; legend of the mei; the secret festival in a hidden valley

A walk in the jungle; the old woman in the breadfruit tree; a night in a native hut on the mountain

The household of Lam Kai Oo; copra making; marvels of the cocoanut-groves; the sagacity of pigs; and a crab that knows the laws of gravitation

Visit of Le Moine; the story of Paul Gauguin; his house, and a search for his grave beneath the white cross of Calvary

Death of Aumia; funeral chant and burial customs; causes for the death of a race

A savage dance, a drama of the sea, of danger and feasting; the rape of the lettuce

A walk to the Forbidden Place; Hot Tears, the hunchback; the story of Behold the Servant of the Priest, told by Malicious Gossip in the cave of Enamoa

A search for rubber-trees on the plateau of Ahoa; a fight with the wild white dogs; story of an ancient migration, told by the wild cattle hunters in the Cave of the Spine of the Chinaman

A feast to the men of Motopu; the making of kava, and its drinking; the story of the Girl Who Lost Her Strength

A journey to Taaoa; Kahuiti, the cannibal chief, and his story of an old war caused by an unfaithful woman

The crime of Huahine for love of Weaver of Mats; story of Tahia's white man who was eaten; the disaster that befell Honi, the white man who used his harpoon against his friends

The memorable game for the matches in the cocoanut-grove of Lam Kai Oo

Mademoiselle N——

A journey to Nuka-hiva; story of the celebration of the fête of Joan of Arc, and the miracles of the white horse and the girl

America's claim to the Marquesas; adventures of Captain Porter in 1812; war between Haapa and Tai-o-hae, and the conquest of Typee valley

A visit to Typee; story of the old man who returned too late

Journey on the Roberta; the winged cockroaches; arrival at a Swiss paradise in the valley of Oomoa

Labor in the South Seas; some random thoughts on the “survival of the fittest”

The white man who danced in Oomoa valley; a wild-boar hunt in the hills; the feast of the triumphant hunters and a dance in honor of Grelet

A visit to Hanavave; Père Olivier at home; the story of the last battle between Hanahouua and Oi, told by the sole survivor; the making of tapa cloth, and the ancient garments of the Marquesans

Fishing in Hanavave; a deep-sea battle with a shark; Red Chicken shows how to tie ropes to sharks' tails; night-fishing for dolphins, and the monster sword-fish that overturned the canoe; the native doctor dresses Red Chicken's wounds and discourses on medicine

A journey over the roof of the world to Oomoa; an encounter with a wild woman of the hills

Return in a canoe to Atuona; Tetuahunahuna relates the story of the girl who rode the white horse in the celebration of the fête of Joan of Arc in Tai-o-hae; Proof that sharks hate women; steering by the stars to Atuona beach

Sea sports; curious sea-foods found at low tide; the peculiarities of sea-centipedes and how to cook and eat them

Court day in Atuona; the case of Daughter of the Pigeon and the sewing-machine; the story of the perfidy of Drink of Beer and the death of Earth Worm who tried to kill the governor

The madman Great Moth of the Night; story of the famine and the one family that ate pig

A visit to the hermit of Taha-Uka valley; the vengeance that made the Scallamera lepers; and the hatred of Mohuto

Last days in Atuona; My Darling Hope's letter from her son

The chants of departure; night falls on the Land of the War Fleet

Village of Atuona, showing peak of Temetiu

Where the belles of Tahiti lived in the shade to whiten their complexions

Lieutenant L'Hermier des Plantes, Governor of the Marquesas Islands

The ironbound coast of the Marquesas

Schooner Fetia Taiao in the Bay of Traitors

The public dance in the garden

Antoinette, a Marquesan dancing girl

Nothing to do but rest all day

A native spearing fish from a rock

A volunteer cocoanut grove, with trees of all ages

Splitting cocoanut husks in copra making process

Cutting the meat from cocoanuts to make copra

The haka, the Marquesan national dance

The old cannibal of Taipi Valley

Enacting a human sacrifice of the Marquesans

Interior of Island of Fatu-hiva, where the author walked over the mountains

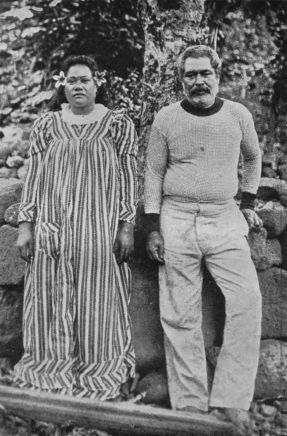

Kivi, the kava drinker with the hetairae of the valley

The Pekia, or Place of Sacrifice, at Atuona

Marquesan cannibals, wearing dress of human hair

Tepu, a Marquesan girl of the hills, and her sister

A tattooed Marquesan with carved canoe paddle

A chieftess in tapa garments with tapa parasol

Père Simeon Delmas' church at Tai-o-hae

Gathering the feis in the mountains

Starting from Hanavave for Oomoa

Where river and bay meet at Oomoa, Island of Fatu-hiva

Removing the pig cooked in the umu, or native oven

The Koina Kai, or feast in Oomoa

Putting the canoe in the water

Pascual, the giant Paumotan pilot and his friends

Spearing fish in Marquesas Islands

The gates of the Valley of Hanavave

A fisherman's house of bamboo and cocoanut leaves

Tahaiupehe, Daughter of the Pigeon, of Taaoa

Author's Note. Foreign words in a book are like rocks in a path. There are two ways of meeting the difficulty; the reader may leap over them, or use them as stepping stones. I have written this book so that they may easily be leaped over by the hasty, but he will lose much enjoyment by doing so; I would urge him to pronounce them as he goes. Marquesan words have a flavor all their own; much of the simple poetry of the islands is in them. The rules for pronouncing them are simple; consonants have the sounds usual in English, vowels have the Latin value, that is, a is ah, e is ay, i is ee, o is oh, and u is oo. Every letter is pronounced, and there are no accents. The Marquesans had no written language, and their spoken tongue was reproduced as simply as possible by the missionaries.

Farewell to Papeite beach; at sea in the Morning Star; Darwin's theory of the continent that sank beneath the waters of the South Seas.

By the white coral wall of Papeite beach the schooner Fetia Taiao (Morning Star) lay ready to put to sea. Beneath the skyward-sweeping green heights of Tahiti the narrow shore was a mass of colored gowns, dark faces, slender waving arms. All Papeite, flower-crowned and weeping, was gathered beside the blue lagoon.

Lamentation and wailing followed the brown sailors as they came over the side and slowly began to cast the moorings that held the Morning Star. Few are the ships that sail many seasons among the Dangerous Islands. They lay their bones on rock or reef or sink in the deep, and the lovers, sons and husbands of the women who weep on the beach return no more to the huts in the cocoanut groves. So, at each sailing on the “long course” the anguish is keen.

“Ia ora na i te Atua! Farewell and God keep you!” the women cried as they stood beside the half-buried cannon that serve to make fast the ships by the coral bank. From the deck of the nearby Hinano came the music of an accordeon and a chorus of familiar words:

It was the Himene Tatou Arearea. Kelly, the wandering I.W.W., self-acclaimed delegate of the mythical Union of Beach-combers and Stowaways, was at the valves of the accordeon, and about him squatted a ring of joyous natives. “Wela ka hao! Hot stuff!” they shouted.

Suddenly Caroline of the Marquesas and Mamoe of Moorea, most beautiful dancers of the quays, flung themselves into the upaupahura, the singing dance of love. Kelly began “Tome! Tome!” a Hawaiian hula. Men unloading cargo on the many schooners dropped their burdens and began to dance. Rude squareheads of the fo'c'sles beat time with pannikins. Clerks in the traders' stores and even Marechel, the barber, were swept from counters and chairs by the sensuous melody, and bareheaded in the white sun they danced beneath the crowded balconies of the Cercle Bougainville, the club by the lagoon. The harbor of Papeite knew ten minutes of unrestrained merriment, tears forgotten, while from the warehouse of the navy to the Poodle Stew café the hula reigned.

Under the gorgeous flamboyant trees that paved their shade with red-gold blossoms a group of white men sang:

The anchor was up, the lines let go, and suddenly from the sea came a wind with rain.

The girls from the Cocoanut House, a flutter of brilliant scarlet and pink gowns, fled for shelter, tossing blossoms of the sweet tiati Tahiti toward their sailor lovers as they ran. Marao, the haughty queen, drove rapidly away in her old chaise, the Princess Boots leaning out to wave a slender hand. Prince Hinoi, the fat spendthrift who might have been a king, leaned from the balcony of the club, glass in hand, and shouted, “Aroha i te revaraa!” across the deserted beach.

So we left Papeite, the gay Tahitian capital, while a slashing downpour drowned the gay flamboyant blossoms, our masts and rigging creaking in the gale, and sea breaking white on the coral reef.

Like the weeping women, who doubtless had already dried their tears, the sky began to smile before we reached the treacherous pass in the outer reef. Beyond Moto Utu, the tiny islet in the harbor that had been harem and fort in kingly days, we saw the surf foaming on the coral, and soon were through the narrow channel.

We had lifted no canvas in the lagoon, using only our engine to escape the coral traps. Past the ever-present danger, with the wind now half a gale and the rain falling again in sheets—the intermittent deluge of the season—the Morning Star, under reefed foresail, mainsail and staysail, pointed her delicate nose toward the Dangerous Islands and hit hard the open sea.

She rode the endlessly-tossing waves like a sea-gull, carrying her head with a care-free air and dipping to the waves in jaunty fashion. Her lines were very fine, tapering and beautiful, even to the eye of a land-lubber.

A hundred and six feet from stem to stern, twenty-three feet of beam and ten feet of depth, she was loaded to water's edge with cargo for the islands to which we were bound. Lumber lay in the narrow lanes between cabin-house and rails; even the lifeboats were piled with cargo. Those who reckon dangers do not laugh much in these seas. There was barely room to move about on the deck of the Morning Star; merely a few steps were possible abaft the wheel amid the play of main-sheet boom and traveler. Here, while my three fellow-passengers went below, I stood gazing at the rain-whipped illimitable waters ahead.

Where is the boy who has not dreamed of the cannibal isles, those strange, fantastic places over the rim of the world, where naked brown men move like shadows through unimagined jungles, and horrid feasts are celebrated to the “boom, boom, boom!” of the twelve-foot drums?

Years bring knowledge, paid for with the dreams of youth. The wide, vague world becomes familiar, becomes even common-place. London, Paris, Venice, many-colored Cairo, the desecrated crypts of the pyramids, the crumbling villages of Palestine, no longer glimmer before me in the iridescent glamor of fancy, for I have seen them. But something of the boyish thrill that filled me when I pored over the pages of Melville long ago returned while I stood on the deck of the Morning Star, plunging through the surging Pacific in the driving tropic rain.

Many leagues before us lay Les Isles Dangereux, the Low Archipelago, first stopping-point on our journey to the far cannibal islands yet another thousand miles away across the empty seas. Before we saw the green banners of Tahiti's cocoanut palms again we would travel not only forward over leagues of tossing water but backward across centuries of time. For in those islands isolated from the world for eons there remains a living fragment of the childhood of our Caucasian race.

Darwin's theory is that these islands are the tops of a submerged continent, or land bridge, which stretches its crippled body along the floor of the Pacific for thousands of leagues. A lost land, whose epic awaits the singer; a mystery perhaps forever to be unsolved. There are great monuments, graven objects, hieroglyphics, customs and languages, island peoples with suggestive legends—all, perhaps, remnants of a migration from Asia or Africa a hundred thousand years ago.

Over this land bridge, mayhap, ventured the Caucasian people, the dominant blood in Polynesia to-day, and when the continent fell from the sight of sun and stars save in those spots now the mountainous islands like Tahiti and the Marquesas, the survivors were isolated for untold centuries.

Here in these islands the brothers of our long-forgotten ancestors have lived and bred since the Stone Age, cut off from the main stream of mankind's development. Here they have kept the childhood customs of our white race, savage and wild, amid their primitive and savage life. Here, three centuries ago, they were discovered by the peoples of the great world, and, rudely encountering a civilization they did not build, they are dying here. With their passing vanishes the last living link with our own pre-historic past. And I was to see it, before it disappears forever.

The trade-room of the Morning Star; Lying Bill Pincher; M. L'Hermier des Plantes, future governor of the Marquesas; story of McHenry and the little native boy, His Dog.

“Come 'ave a drink!” Captain Pincher called from the cabin, and leaving the spray-swept deck where the rain drummed on the canvas awning I went down the four steps into the narrow cabin-house.

The cabin, about twenty feet long, had a tiny semi-private room for Captain Pincher, and four berths ranged about a table. Here, grouped around a demijohn of rum, I found Captain Pincher with my three fellow-passengers; McHenry and Gedge, the traders, and M. L'Hermier des Plantes, a young officer of the French colonial army, bound to the Marquesas to be their governor.

The captain was telling the story of the wreck in which he had lost his former ship. He had tied up to a reef for a game of cards with a like-minded skipper, who berthed beside him. The wind changed while they slept. Captain Pincher awoke to find his schooner breaking her backs on the coral rocks.

“Oo can say wot the blooming wind will do?” he said, thumping the table with his glass. “There was Willy's schooner tied up next to me, and 'e got a slant and slid away, while my boat busts 'er sides open on the reef, The 'ole blooming atoll was 'eaped with the blooming cargo. Willy 'ad luck; I 'ad 'ell. It's all an 'azard.”

He had not found his aitches since he left Liverpool, thirty years earlier, nor dropped his silly expletives. A gray-haired, red-faced, laughing man, stockily built, mild mannered, he proved, as the afternoon wore on, to be a man from whom Münchausen might have gained a story or two.

“They call me Lying Bill,” he said to me. “You can't believe wot I say.”

“He's straight as a mango tree, Bill Pincher is,” McHenry asserted loudly. “He's a terrible liar about stories, but he's the best seaman that comes to T'yti, and square as a biscuit tin. You know how, when that schooner was stole that he was mate on, and the rotten thief run away with her and a woman, Bill he went after 'em, and brought the schooner back from Chile. Bill, he's whatever he says he is, all right—but he can sail a schooner, buy copra and shell cheap, sell goods to the bloody natives, and bring back the money to the owners. That's what I call an honest man.”

Lying Bill received these hearty words with something less than his usual good-humor. There was no friendliness in his eye as he looked at McHenry, whose empty glass remained empty until he himself refilled it. Bullet-headed, beady-eyed, a chunk of rank flesh shaped by a hundred sordid adventures, McHenry clutched at equality with these men, and it eluded him. Lying Bill, making no reply to his enthusiastic commendation, retired to his bunk with a paper-covered novel, and to cover the rebuff McHenry turned to talk of trade with Gedge, who spoke little.

The traderoom of the Morning Star, opening from the cabin, was to me the door to romance. When I was a boy there was more flavor in traderooms than in war. To have seen one would have been as a glimpse of the Holy Grail to a sworn knight. Those traderooms of my youthful imagination smelt of rum and gun-powder, and beside them were racks of rifles to repel the dusky figures coming over the bulwarks.

The traderoom of the Morning Star was odorous, too. It had no window, and when one opened the door all was obscure at first, while smells of rank Tahiti tobacco, cheap cotton prints, a broken bottle of perfume and scented soaps struggled for supremacy. Gradually the eye discovered shelves and bins and goods heaped from floor to ceiling; pins and anchors, harpoons and pens, crackers and jewelry, cloth, shoes, medicine and tomahawks, socks and writing paper.

Trade business, McHenry's monologue explained, is not what it was. When these petty merchants dared not trust themselves ashore their guns guarded against too eager customers. But now almost every inhabited island has its little store, and the trader has to pursue his buyers, who die so fast that he must move from island to island in search of population.

“Booze is boss,” said McHenry. “I have two thousand pounds in bank in Australia, all made by selling liquor to the natives. It's against French law to sell or trade or give 'em a drop, but we all do it. If you don't have it, you can't get cargo. In the diving season it's the only damn thing that'll pass. The divers'll dig up from five to fifteen dollars a bottle for it, depending on the French being on the job or not. Ain't that so, Gedge?”

“C'est vrai,” Gedge assented. He spoke in French, ostensibly for the benefit of M. L'Hermier des Plantes. That young governor of the Marquesas was not given to saying much, his chief interest in life appearing to be an ample black whisker, to which he devoted incessant tender care. After a few words of broken English he had turned a negligent attention to the pages of a Marquesan dictionary, in preparation for his future labors among the natives. Gedge, however, continued to talk in the language of courts.

It was obvious that McHenry's twenty-five years in French possessions had not taught him the white man's language. He demanded brusquely, “What are you oui-oui-ing for?” and occasionally interjected a few words of bastard French in an attempt to be jovial. To this Gedge paid little attention.

Gedge was chief of the commercial part of the expedition, and his manner proclaimed it. Thin-lipped, cunning-eyed, but strong and self-reliant, he was absorbed in the chances of trade. He had been twenty years in the Marquesas islands. A shrewd man among kanakas, unscrupulous by his own account, he had prospered. Now, after selling his business, he was paying a last visit to his long-time home to settle accounts.

“'Is old woman is a barefoot girl among the cannibals,” Lying Bill said to me later. “'E 'as given a 'ole army of ostriches to fortune, 'e 'as.”

One of Captain Pincher's own sons was assistant to the engineer, Ducat, and helped in the cargo work. The lad lived forward with the crew, so that we saw nothing of him socially, and his father never spoke to him save to give an order or a reprimand. Native mothers mourn often the lack of fatherly affection in their white mates. Illegitimate children are held cheap by the whites.

For two days at sea after leaving Papeite we did not see the sun. This was the rainy and hot season, a time of calms and hurricanes, of sudden squalls and maddening quietudes, when all signs fail and the sailor must stand by for the whims of the wind if he would save himself and his ship. For hours we raced along at seven or eight knots, with a strong breeze on the quarter and the seas ruffling about our prow. For still longer hours we pushed through a windless calm by motor power. Showers fell incessantly.

We lived in pajamas, barefooted, unshaven and unwashed. Fresh water was limited, as it would be impossible to replenish our casks for many weeks. McHenry said it was not difficult to accustom one's self to lack of water, both externally and internally.

There was a demijohn of strong Tahitian rum always on tap in the cabin. Here we sat to eat and remained to drink and read and smoke. There was Bordeaux wine at luncheon and dinner, Martinique and Tahitian rum and absinthe between meals. The ship's bell was struck by the steersman every half hour, and McHenry made it the knell of an ounce.

Captain Pincher took a jorum every hour or two and retired to his berth and novels, leaving the navigation of the Morning Star to the under-officers. Ducat, the third officer, a Breton, joined us at meals. He was a decent, clever fellow in his late twenties, ambitious and clear-headed, but youthfully impressed by McHenry's self-proclaimed wickedness.

One night after dinner he and McHenry were bantering each other after a few drinks of rum. McHenry said, “Say, how's your kanaka woman?”

Ducat's fingers tightened on his glass. Then, speaking English and very precisely, he asked, “Do you mean my wife?”

“I mean your old woman. What's this wife business?”

“She is my wife, and we have two children.”

McHenry grinned. “I know all that. Didn't I know her before you? She was mine first.”

Ducat got up. We all got up. The air became tense, and in the silence there seemed no motion of ship or wave. I said to myself, “This is murder.”

Ducat, very pale, an inscrutable look on his face, his black eyes narrowed, said quietly, “Monsieur, do you mean that?”

“Why, sure I do? Why shouldn't I mean it? It's true.”

None of us moved, but it was as if each of us stepped back, leaving the two men facing each other. In this circle no one would interfere. It was not our affair. Our detachment isolated the two—McHenry quite drunk, in full command of his senses but with no controlling intelligence; Ducat not at all drunk, studying the situation, considering in his rage and humiliation what would best revenge him on this man.

Ducat spoke, “McHenry, come out of this cabin with me.”

“What for?”

“Come with me.”

“Oh, all right, all right,” McHenry said.

We stepped back as they passed us. They went up the steps to the deck. Ducat paused at the break of the poop and stood there, speaking to McHenry. We could not hear his words. The schooner tossed idly, a faint creaking of the rigging came down to us in the cabin. The same question was in every eye. Then Ducat turned on his heel, and McHenry was left alone.

Our question was destined to remain unanswered. Whatever Ducat had said, it was something that hushed McHenry forever. He never mentioned the subject again, nor did any of us. But McHenry's attitude had subtly changed. Ducat's words had destroyed that last secret refuge of the soul in which every man keeps the vestiges of self-justification and self-respect.

McHenry sought me out that night while I sat on the cabin-house gazing at the great stars of the Southern Cross, and began to talk.

“Now take me,” he said, “I'm not so bad. I'm as good as most people. As a matter of fact, I ain't done anything more in my life than anybody'd've done, if they had the chance. Look at me—I had a singlet an' a pair of dungarees when I landed on the beach in T'yti, an' look at me now! I ain't done so bad!”

He must have felt the unconvincing ring of his tone, lacking the full and complacent self-assurance usual to it, for as if groping for something to make good the lack he sought backward through his memories and unfolded bit by bit the tale of his experiences. Scotch born of drunken parents, he had been reared in the slums of American cities and the forecastles of American ships. A waif, newsboy, loafer, gang-fighter and water-front pirate, he had come into the South Seas twenty-five years earlier, shanghaied when drunk in San Francisco. He looked back proudly on a quarter of a century of trading, thieving, selling contraband rum and opium, pearl-buying and gambling.

But this pride on which he had so long depended failed him now. Successful fights that he had waged, profitable crimes committed, grew pale upon his tongue. Listening in the darkness while the engine drove us through a black sea and the canvas awning flapped overhead, I felt the baffled groping behind his words.

“So I don't take nothing from no man!” he boasted, and fell into uneasy silence. “The folks in these islands know me, all right!” he asserted, and again was dumb.

“Now there was a kid, a little Penryn boy,” he said suddenly. “When I was a trader on Penryn he was there, and he used to come around my store. That kid liked me. Why, that kid, he was crazy about me! It's a fact, he was crazy about me, that kid was.”

His voice was fumbling back toward its old assurance, but there was wonder in it, as though he was incredulous of this foothold he had stumbled upon. He repeated, “That kid was crazy about me!

“He used to hang around, and help me with the canned goods, and he'd go fishing with me, and shooting. He was a regular—what do you call 'em? These dogs that go after things for you? He'd go under the water and bring in the big fish for me. And he liked to do it. You never saw anything like the way that kid was.

“I used to let him come into the store and hang around, you know. Not that I cared anything for the kid myself; I ain't that kind. But I'd just give him some tinned biscuits now and then, the way you'd do. He didn't have no father or mother. His father had been eaten by a shark, and his mother was dead. The kid didn't have any name because his mother had died so young he hadn't got any name, and his father hadn't called him anything but boy. He give himself a name to me, and that was ‘Your Dog.’

“He called himself my dog, you see. But his name for it was Your Dog, and that was because he fetched and carried for me, like as if he was one. He was that kind of kid. Not that I paid much attention to him.

“You know there's a leper settlement on Penryn, off across the lagoon. I ain't afraid of leprosy y'understand, because I've dealt with 'em for years, ate with 'em an' slept with 'em, an' all that, like everybody down here. But all the same I don't want to have 'em right around me all the time. So one day the doctor come to look over the natives, and he come an' told me the little kid, My Dog, was a leper.

“Now I wasn't attached to the kid. I ain't attached to nobody. I ain't that kind of a man. But the kid was sort of used to me, and I was used to havin' him around. He used to come in through the window. He'd just come in, nights, and sit there an' never say a word. When I was goin' to bed he'd say, ‘McHenry, Your Dog is goin' now, but can't Your Dog sleep here?’ Well, I used to let him sleep on the floor, no harm in that. But if he was a leper he'd got to go to the settlement, so I told him so.

“He made such a fuss, cryin' around—By God, I had to boot him out of the place. I said: ‘Get out. I don't want you snivelin' around me.’ So he went.

“It's a rotten, God-forsaken place, I guess. I don't know. The government takes care of 'em. It ain't my affair. I guess for a leper colony it ain't so bad.

“Anyway, I was goin' to sell out an' leave Penryn. The diving season was over. One night I had the door locked an' was goin' over my accounts to see if I couldn't collect some more dough from the natives. I heard a noise, and By God! there comin' through the window was My Dog. He come up to me, and I said: ‘Stand away, there!’ I ain't afraid of leprosy, but there's no use takin' chances. You never know.

“Well sir, that kid threw himself down on the floor, and he said, ‘McHenry, I knowed you was goin' away and I had to come to see you.’ That's what he said in his Kanaka lingo.

“He was cryin', and he looked pretty bad. He said he couldn't stand the settlement. He said, ‘I don't never see you there. Can't I live here an' be Your Dog again?’

“I said, ‘You got to go to the settlement.’ I wasn't goin' to get into trouble on account of no Kanaka kid.

“Now, that kid had swum about five miles in the night, with sharks all around him—the very place where his father had gone into a shark. That kid thought a lot of me. Well, I made him go back. ‘If you don't go, the doctor will come, an' then you got to go,’ I said. ‘You better get out. I'm goin' away, anyhow,’ I said. I was figuring on my accounts, an' I didn't want to be bothered with no fool kid.

“Well, he hung around awhile, makin' a fuss, till I opened the door an' told him to git. Then he went quiet enough. He went right down the beach into the water an' swum away, back to the settlement. Now look here, that kid liked me. He knowed me well, too—he was around my store pretty near all the time I was in Penryn. He was a fool kid. My Dog, that was the name he give himself. An' while I was in T'yti, here, I get a letter from the trader that took over my store, and he sent me a letter from that kid. It was wrote in Kanaka. He couldn't write much, but a little. Here, I'll show you the letter. You'll see what that kid thought of me.”

In the light from the open cabin window I read the letter, painfully written on cheap, blue-lined paper.

“Greetings to you, McHenry, in Tahiti, from Your Dog. It is hard to live without you. It is long since I have seen you. It is hard. I go to join my father. I give myself to the mako. To you, McHenry, from Your Dog, greetings and farewell.”

Across the bottom of the letter was written in English: “The kid disappeared from the leper settlement. They think he drowned himself.”

Thirty-seven days at sea; life of the sea-birds; strange phosphorescence; first sight of Fatu-hiva; history of the islands; chant of the Raiateans.

Thirty-seven days at sea brought us to the eve of our landing in Hiva-oa in the Marquesas. Thirty-seven monotonous days, varied only by rain-squalls and sun, by calm or threatening seas, by the changing sky. Rarely a passing schooner lifted its sail above the far circle of the horizon. It was as though we journeyed through space to another world.

Yet all around us there was life—life in a thousand varying forms, filling the sea and the air. On calm mornings the swelling waves were splashed by myriads of leaping fish, the sky was the playground of innumerable birds, soaring, diving, following their accustomed ways through their own strange world oblivious of the human creatures imprisoned on a bit of wood below them. Surrounded by a universe filled with pulsing, sentient life clothed in such multitudinous forms, man learns humility. He shrinks to a speck on an illimitable ocean.

I spent long afternoons lying on the cabin-house, watching the frigates, the tropics, gulls, boobys, and other sea-birds that sported through the sky in great numbers. The frigate-birds were called by the sailors the man-of-war bird, and also the sea-hawk. They are marvelous flyers, owing to the size of the pectoral muscles, which compared with those of other birds are extraordinarily large. They cannot rest on the water, but must sustain their flights from land to land, yet here they were in mid-ocean.

My eyes would follow one higher and higher till he became a mere dot in the blue, though but a few minutes earlier he had risen from his pursuit of fish in the water. He spread his wings fully and did not move them as he climbed from air-level to air-level, but his long forked tail expanded and closed continuously.

Sighting a school of flying-fish, which had been driven to frantic leaps from the sea by pursuing bonito, he begins to descend. First his coming down is like that of an aeroplane, in spirals, but a thousand feet from his prey he volplanes; he falls like a rocket, and seizing a fish in the air, he wings his way again to the clouds.

If he cannot find flying-fish, he stops gannets and terns in mid-air and makes them disgorge their catch, which he seizes as it falls. Refusal to give up the food is punished by blows on the head, but the gannets and terns so fear the frigate that they seldom have the courage to disobey. I think a better name for the frigate would be pirate, for he is a veritable pirate of the air. Yet no law restrains him.

I observed that the male frigate has a red pouch under the throat which he puffs up with air when he flies far. It must have some other purpose, for the female lacks it, and she needs wind-power more than the male. It is she who seeks the food when, having laid her one egg on the sand, she goes abroad, leaving her husband to keep the egg warm.

The tropic-bird, often called the boatswain, or phaëton, also climbs to great heights, and is seldom found out of these latitudes. He is a beautiful bird, white, or rose-colored with long carmine tail-feathers. In the sun these roseate birds are brilliant objects as they fly jerkily against the bright blue sky, or skim over the sea, rising and falling in their search for fish. I have seen them many times with the frigates, with whom they are great friends. It would appear that there is a bond between them; I have never seen the frigate rob his beautiful companion.

In such idle observations and the vague wonders that arose from them, the days passed. An interminable game of cards progressed in the cabin, in which I occasionally took a hand. Gedge and Lying Bill exchanged reminiscences. McHenry drank steadily. The future governor of the Marquesas added a galon to his sleeves, marking his advance to a first lieutenancy in the French colonial army. He was a very soft, sleek man, a little worn already, his black hair a trifle thin, but he was plump, his skin white as milk, and his jetty beard and mustache elaborately cared for. He was much before the mirror, combing and brushing and plucking. Compared to us unkempt wretches, he was as a dandy to a tramp.

The ice, which was packed in boxes of sawdust on deck, afforded one cold drink in which to toast the gallant future governor, and that was the last of it. At night the Tahitian sailors helped themselves, and we bade farewell to ice until once more we saw Papeite.

It was no refreshment to reflect that had we dredging apparatus long enough we could procure from the sea-bottom buckets of ooze that would have cooled our drinks almost to the freezing point. Scientists have done this. Lying Bill was loth to believe the story and the explanation, that an icy stream flows from the Antarctic through a deep valley in the sea-depths.

“It's contrar-iry to nature,” he affirmed. “The depper you go the 'otter it is. In mines the 'eat is worse the farther down. And 'ow about 'ell?”

I slept on the deck. It was sickeningly hot below. The squalls had passed, and as we neared Hiva-oa the sea became glassy smooth, but the leagues-long, lazy roll of it rocked the schooner like a cradle.

The night before the islands were to come into view the sea was lit by phosphorescence so magnificently that even my shipmates, absorbed in écarté below, called to one another to view it. The engine took us along at about six knots, and every gentle wave that broke was a lamp of loveliness. The wake of the Morning Star was a milky path lit with trembling fragments of brilliancy, and below the surface, beside the rudder, was a strip of green light from which a billion sparks of fire shot to the air. Far behind, until the horizon closed upon the ocean, our wake was curiously remindful of the boulevard of a great city seen through a mist, the lights fading in the dim distance, but sparkling still.

I went forward and stood by the cathead. The blue water stirred by the bow was wonderfully bright, a mass of coruscating phosphorescence that lighted the prow like a lamp. It was as if lightning played beneath the waves, so luminous, so scintillating the water and its reflection upon the ship.

The living organisms of the sea were en fete that night, as though to celebrate my coming to the islands of which I had so long dreamed. I smiled at the fancy, well knowing that the minute pyrocistis, having come to the surface during the calm that followed the storms, were showing in that glorious fire the panic caused among them by the cataclysm of our passing. But the individual is ever an egoist. It seems to man that the universe is a circle about him and his affairs. It may as well seem the same to the pyrocistis.

Far about the ship the waves twinkled in green fire, disturbed even by the ruffling breeze. I drew up a bucketful of the water. In the darkness of the cabin it gave no light until I passed my hand through it. That was like opening a door into a room flooded by electricity; the table, the edges of the bunks, the uninterested faces of my shipmates, leaped from the shadows. Marvels do not seem marvelous to men to live among them.

I lay long awake on deck, watching the eerily lighted sea and the great stars that hung low in the sky, and to my fancy it seemed that the air had changed, that some breath from the isles before us had softened the salty tang of the sea-breeze.

Land loomed at daybreak, dark, gloomy, and inhospitable. Rain fell drearily as we passed Fatu-hiva, the first of the Marquesas Islands sighted from the south. We had climbed from Tahiti, seventeen degrees south of the equator, to between eleven and ten degrees south, and we had made a westward of ten degrees. The Marquesas Islands lay before us, dull spots of dark rock upon the gray water.

They are not large, any of these islands; sixty or seventy miles is the greatest circumference. Some of the eleven are quite small, and have no people now. On the map of the world they are the tiniest pin-pricks. Few dwellers in Europe or America know anything about them. Most travelers have never heard of them. No liners touch them; no wire or wireless connects them with the world. No tourists visit them. Their people perish. Their trade languishes. In Tahiti, whence they draw almost all their sustenance, where their laws are made, and to which they look at the capital of the world, only a few men, who traded here, could tell me anything about the Marquesas. These men had only the vague, exaggerated ideas of the sailor, who goes ashore once or twice a year and knows nothing of the native life.

Seven hundred and fifty miles as the frigate flies separates these islands from Tahiti, but no distance can measure the difference between the happiness of Tahiti, the sparkling, brilliant loveliness of that flower-decked island, and the stern, forbidding aspect of the Marquesas lifting from the sea as we neared them. Gone were the laughing vales, the pale-green hills, the luring, feminine guise of nature, the soft-lapping waves upon a peaceful, shining shore. The spirit that rides the thunder had claimed these bleak and desolate islands for his own.

While the schooner made her way cautiously past the grim and rocky headlands of Fatu-hiva I was overwhelmed with a feeling of solemnity, of sadness; such a feeling as I have known to sweep over an army the night before a battle, when letters are written to loved ones and comrades entrusted with messages.

That gaunt, dark shore itself recalls that the history of the Marquesas is written in blood, a black spot on the white race. It is a history of evil wrought by civilization, of curses heaped on a strange, simple people by men who sought to exploit them or to mold them to another pattern, who destroyed their customs and their happiness and left them to die, apathetic, wretched, hardly knowing their own miserable plight.

The French have had their flag over the Marquesas since 1842. In 1521 Magellan must have passed between the Marquesas and Paumotas, but he does not mention them. Seventy-three years later a Spanish flotilla sent from Callao by Don Garcia Hurtado de Mendoza, viceroy of Peru, found this island of Fatu-hiva, and its commander, Mendaña, named the group for the viceroy's lady, Las Islas Marquesas de Mendoza.

One hundred and eighty years passed, and Captain Cook again discovered the islands, and a Frenchman, Etienne Marchand, discovered the northern group. The fires of liberty were blazing high in his home land, and Marchand named his group the Isles of the Revolution, in celebration of the victories of the French people. A year earlier an American, Ingraham, had sighted this same group and given it the name of his own beloved hero, Washington.

Had not Captain Porter failed to establish American rule in 1813 in the island of Nuka-hiva, which he called Madison, the Marquesas might have been American. Porter's name, like that of Mendaña, is linked with deeds of cruelty. The Spaniard was without pity; the American may plead that his killings were reprisals or measures of safety for himself. Murder of Polynesians was little thought of. Schooners trained their guns on islands for pleasure or practice, and destroyed villages with all their inhabitants.

“To put the fear of God in the nigger's hearts,” were the words of many a sanguinary captain and crew. They did not, of course, mean that literally. They meant the fear of themselves, and of all whites. They used the name of God in vain, for after a century and more of such intermittent effort the Polynesians have small fear or faith for the God of Christians, despite continuous labors of missionaries. God seems to have forgotten them.

The French made the islands their political possessions with little difficulty. The Marquesans had no king or single chief. There were many tribes and clans, and it was easy to persuade or compel petty chiefs to sign declarations and treaties. But it was not easy to kill the independence of the people, and France virtually abandoned and retook the islands several times, her rule fluctuating with political conditions at home.

There were wars, horrible, bloody scenes, when the clansmen slew the whites and ate them, and the bones of many a gallant French officer and sea-captain have moldered where they were heaped after the orgy following victory. But, as always, the white slew his hundreds to the natives' one, and in time he drove the devil of liberty and defense of native land from the heart of the Marquesan.

Before the French achieved this, however, the white had sowed a crop of deadly evils among the Marquesans that cut them down faster than war, and left them desolate, dying, passing to extinction.

As I looked from the deck of the Morning Star I was struck by the fittingness of the scene. Fatu-hiva had been left behind and Hiva-oa, our destination, was before us, bleak and threatening. To my eyes it appeared as it had been in the eyes of the gentler Polynesians of old time, the abode of demons and of a race of terrible warriors. Hence descended the Marquesans, Vikings of the Pacific, in giant canoes, and sprang upon the fighting men of the Tahitians, the Raiateans and the Paumotans, slaughtering their hundreds and carrying away scores to feast upon in the High Places.

This was the ancient chant of the Raiateans, sung in the old days before the whites came, when they thought of the deeds that were done by the more-than-human men who lived on these desolate islands.

Anchorage of Taha-Uka; Exploding Eggs, and his engagement as valet; inauguration of the new governor; dance on the palace lawn.

As we approached Hiva-oa the giant height of Temetiu slowly lifted four thousand feet above the sea, swathed in blackest clouds. Below, purple-black valleys came one by one into view, murky caverns of dank vegetation. Towering precipices, seamed and riven, rose above the vast welter of the gray sea.

Slowly we crept into the wide Bay of Traitors and felt our way into the anchorage of Taha-Uka, a long and narrow passage between frowning cliffs, spray-dashed walls of granite lashed fiercely by the sea. All along the bluffs were cocoanut-palms, magnificent, waving their green fronds in the breeze. Darker green, the mountains towered above them, and far on the higher slopes we saw wild goats leaping from crag to crag and wild horses running in the upper valleys.

A score or more of white ribbons depended from the lofty heights, and through the binoculars I saw them to be waterfalls. They were like silver cords swaying in the wind, and when brought nearer by the glasses, I saw that some of them were heavy torrents while others, gauzy as wisps of chiffon, hardly veiled the black walls behind them.

The whole island dripped. The air was saturated, the decks were wet, and along the shelves of basalt that jutted from the cliffs a hundred blow-holes spouted and roared. In ages of endeavor the ocean had made chambers in the rock and cut passages to the top, through which, at every surge of the pounding waves, the water rushed and rose high in the air.

Iron-bound, the mariner calls this coast, and the word makes one see the powerful, severe mold of it. Molten rock fused in subterranean fires and cast above the sea cooled into these ominous ridges, and stern unyielding walls.

There upon the deck I determined not to leave until I had lived for a time amid these wild scenes. My intention had been to voyage with the Morning Star, returning with her to Tahiti, but a mysterious voice called to me from the dusky valleys. I could not leave without penetrating into those abrupt and melancholy depths of forest, without endeavoring, though ever so feebly, to stir the cold brew of legend and tale fast disappearing in stupor and forgetfulness.

Lying Bill protested volubly; he liked company and would regret my contribution to the expense account. Gedge joined him in serious opposition to the plan, urging that I would not be able to find a place to live, that there was no hotel, club, lodging, or food for a stranger. But I was determined to stay, though I must sleep under a breadfruit-tree. As I was a mere roamer, with no calendar or even a watch, I had but to fetch my few belongings ashore and be a Marquesan. These belongings I gathered together, and finding me obdurate, Lying Bill reluctantly agreed to set them on the beach.

On either side of Taha-Uka inlet are landing-places, one in front of a store, the other leading only to the forest. These are stairways cut in the basaltic wall of the cliffs, and against them the waves pound continuously. The beach of Taha-Uka was a mile from where we lay and not available for traffic, but around a shoulder of the bluffs was hidden the tiny bay of Atuona, where goods could be landed.

While we discussed this, around those jutting rocks shot a small out-rigger canoe, frail and hardly large enough to hold the body of a slender Marquesan boy who paddled it. About his middle he wore a red and yellow pareu, and his naked body was like a small and perfect statue as he handled his tiny craft. When he came over the side I saw that he was about thirteen years old and very handsome, tawny in complexion, with regular features and an engaging smile.

His name, he said, was Nakohu, which means Exploding Eggs. This last touch was all that was needed; without further ado I at once engaged him as valet for the period of my stay in the Marquesas. His duties would be to help in conveying my luggage ashore, to aid me in the mysteries of cooking breadfruit and such other edibles as I might discover, and to converse with me in Marquesan. In return, he was to profit by the honor of being attached to my person, by an option on such small articles as I might leave behind on my departure, and by the munificent salary of about five cents a day. His gratitude and delight knew no bounds.

Hardly had the arrangement been made, when a whaleboat rowed by Marquesans followed in the wake of the canoe, and a tall, rangy Frenchman climbed aboard the Morning Star. He was Monsieur André Bauda, agent special, commissaire, postmaster; a beau sabreur, veteran of many campaigns in Africa, dressed in khaki, medals on his chest, full of gay words and fierce words, drinking his rum neat, and the pink of courtesy. He had come to examine the ship's papers, and to receive the new governor.

A look of blank amazement appeared upon the round face of M. L'Hermier des Plantes when it was conveyed to him that this solitary whaleboat had brought a solitary white to welcome him to his seat of government. He had been assiduously preparing for his reception for many hours and was immaculately dressed in white duck, his legs in high, brightly-polished boots, his two stripes in velvet on his sleeve, and his military cap shining. He knew no more about the Marquesas than I, having come directly via Tahiti from France, and he was plainly dumfounded and dismayed. Was all that tender care of his whiskers to be wasted on scenery?

However, after a drink or two he resignedly took his belongings, and dropping into the wet and dirty boat with Bauda, he lifted an umbrella over his gaudy cap and disappeared in the rain.

“'E's got a bloomin' nice place to live in,” remarked Lying Bill. “Now, if 'e 'd a-been 'ere when I come 'e 'd a-seen something! I come 'ere thirty-five years ago when I was a young kid. I come with a skipper and I was the only crew. Me and him, and I was eighteen, and the boat was the Victor. I lived 'ere and about for ten years. Them was the days for a little excitement. There was a chief, Mohuho, who'd a-killed me if I 'adn't been tapu'd by Vaekehu, the queen, wot took a liking to me, me being a kid, and white. I've seen Mohuho shoot three natives from cocoanut-trees just to try a new gun. 'E was a bad 'un, 'e was. There was something doing every day, them days. God, wot it is to be young!”

A little later Lying Bill, Ducat, and I, with my new valet's canoe in the wake of our boat, rounded the cliffs that had shut off our view of Atuona Valley. It lay before us, a long and narrow stretch of sand behind a foaming and heavy surf; beyond, a few scattered wooden buildings among palm and banian-trees, and above, the ribbed gaunt mountains shutting in a deep and gloomy ravine. It was a lonely, beautiful place, ominous, melancholy, yet majestic.

“Bloody Hiva-oa,” this island was called. Long after the French had subdued by terror the other isles of the group, Hiva-oa remained obdurate, separate, and untamed. It was the last stronghold of brutishness, of cruel chiefs and fierce feuds, of primitive and terrible customs. And of “the man-eating isle of Hiva-oa” Atuona Valley was the capital.

We landed on the beach dry-shod, through the skill of the boat-steerer and the strength of the Tahitian sailors, who carried us through the surf and set my luggage among the thick green vines that met the tide. We were dressed to call upon the governor, whose inauguration was to take place that afternoon, and leaving my belongings in care of the faithful Exploding Eggs, we set off up the valley.

The rough road, seven or eight feet wide, was raised on rocks above the jungle and was bordered by giant banana plants and cocoanuts. At this season all was a swamp below us, the orchard palms standing many feet deep in water and mud, but their long green fronds and the darker tangle of wild growth on the steep mountain-sides were beautiful.

The government house was set half a mile farther on in the narrowing ravine, and on the way we passed a desolate dwelling, squalid, set in the marsh, its battered verandas and open doors disclosing a wretched mingling of native bareness with poverty-stricken European fittings. On the tottering veranda sat a ragged Frenchman, bearded and shaggy-haired, and beside him three girls as blonde as German Mädchens. Their white delicate faces and blue eyes, in such surroundings, struck one like a blow. The eldest was a girl of eighteen years, melancholy, though pretty, wearing like the others a dirty gown and no shoes or stockings. The man was in soiled overalls, and reeling drunk.

“That is Baufré,” said Ducat. “He is always drunk. He married the daughter of an Irish trader, a former officer in the British Indian Light Cavalry. Baufré was a sous-officier in the French forces here. There is no native blood in those girls. What will become of them, I wonder?”

A few hundred yards further on was the palace. It was a wooden house of four or five rooms, with an ample veranda, surrounded by an acre of ground fenced in. The sward was the brilliantly green, luxuriant wild growth that in these islands covers every foot of earth surface. Cocoanuts and mango-trees rose from this volunteer lawn, and under them a dozen rosebushes, thick with excessively fragrant bloom. Pineapples grew against the palings, and a bed of lettuce flourished in the rear beside a tiny pharmacy, a kitchen, and a shelter for servants.

On the spontaneous verdure before the veranda three score Marquesans stood or squatted, the men in shirts and overalls and the women in tunics. Their skins, not brown nor red nor yellow, but tawny like that of the white man deeply tanned by the sun, reminded me again that these people may trace back their ancestry to the Caucasian cradle. The hair of the women was adorned with gay flowers or the leaves of the false coffee bush. Their single garments of gorgeous colors clung to their straight, rounded bodies, their dark eyes were soft and full of light as the eyes of deer, and their features, clean-cut and severe, were of classic lines.

The men, tall and massive, seemed awkwardly constricted in ill-fitting, blue cotton overalls such as American laborers wear over street-clothes. Their huge bodies seemed about to break through the flimsy bindings, and the carriage of their striking heads made the garments ridiculous. Most of them had fairly regular features on a large scale, their mouths wide, and their lips full and sensual. They wore no hats or ornaments, though it has ever been the custom of all Polynesians to put flowers and wreaths upon their heads.

Men and women were waiting with a kind of apathetic resignation; melancholy and unresisting despair seemed the only spirit left to them.

On the veranda with the governor and Bauda were several whites, one a French woman to whom we were presented. Madame Bapp, fat and red-faced, in a tight silk gown over corsets, was twice the size of her husband, a dapper, small man with huge mustaches, a paper collar to his ears, and a fiery, red-velvet cravat.

On a table were bottles of absinthe and champagne, and several demijohns of red wine stood on the floor. All our company attacked the table freight and drank the warm champagne.

A seamy-visaged Frenchman, Pierre Guillitoue, the village butcher—a philosopher and anarchist, he told me—rapped with a bottle on the veranda railing. The governor, in every inch of gold lace possible, made a gallant figure as he rose and faced the people. His whiskers were aglow with dressing. The ceremony began with an address by a native, Haabunai.

Intrepreted by Guillitoue, Haabunai said that the Marquesans were glad to have a new governor, a wise man who would cure their ills, a just ruler, and a friend; then speaking directly to his own people, he praised extravagantly the newcomer, so that Guillitoue choked in his translation, and ceased, and mixed himself a glass of absinthe and water.

The governor replied briefly in French. He said that he had come in their interest; that he would not cheat them or betray them; that he would make them well if they were sick. The French flag was their flag; the French people loved them. The Marquesans listened without interest, as if he spoke of some one in Tibet who wanted to sell a green elephant.

In the South Seas a meeting out-of-doors means a dance. The Polynesians have ever made this universal human expression of the rhythmic principle of motion the chief evidence of emotion, and particularly of elation. Civilization has all but stifled it in many islands. Christianity has made it a sin. It dies hard, for it is the basic outlet of strong natural feeling, and the great group entertainment of these peoples.

The speeches done, the governor suggested that the national spirit be interpreted to him in pantomine.

“They must be enlivened with alcohol or they will not move,” said Guillitoue.

“Mon dieu!” he replied. “It is the ‘Folies Bergère’ over again! Give them wine!”

Bauda ordered Flag, the native gendarme, and Song of the Nightingale, a prisoner, to carry a demijohn of Bordeaux wine to the garden. With two glasses they circulated the claret until each Marquesan had a pint or so. Song of the Nightingale was a middle-aged savage, with a wicked, leering face, and whiskers from his ears to the corners of his mouth, surely a strange product of the Marquesan race, none of whose men will permit any hair to grow on lip or cheek. While Song circulated the wine M. Bauda enlightened me as to the crime that had made him prisoner. He was serving eighteen months for selling cocoanut brandy.

When the cask was emptied the people began the dance. Three rows were formed, one of women between two of men, in Indian file facing the veranda. Haabunai and Song of the Nightingale brought forth the drums. These were about four feet high, barbaric instruments of skin stretched over hollow logs, and the “Boom-Boom” that came from them when they were struck by the hands of the two strong men was thrilling and strange.

The dance was formal, slow, and melancholy. Haabunai gave the order of it, shouting at the top of his voice. The women, with blue and scarlet Chinese shawls of silk tied about their hips, moved stiffly, without interest or spontaneous spirit, as though constrained and indifferent. Though the dances were licentious, they conveyed no meaning and expressed no emotion. The men gestured by rote, appealing mutely to the spectators, so that one might fancy them orators whose voices failed to reach one. There was no laughter, not even a smile.

“Give them another demijohn!” said the governor.

The juice of the grape dissolved melancholy. When the last of it had flowed the dance was resumed. The women began a spirited danse du ventre. Their eyes now sparkled, their bodies were lithe and graceful. McHenry rushed on to the lawn and taking his place among them copied their motions in antics that set them roaring with the hearty roars of the conquered at the asininity of the conquerors. They tried to continue the dance, but could not for merriment.

One of the dancers advanced toward the veranda and in a ceremonious way kissed the governor upon the lips. That young executive was much surprised, but returned the salute and squeezed her tiny waist. All the company laughed at this, except Madame Bapp, who glared angrily and exclaimed, “Coquine!” which means hussy.

The Marquesans have no kisses in their native love-making, but smell one or rub noses, as do the Eskimo. Whites, however, have taught kisses in all their variety.

The governor had the girl drink a glass of champagne. She was perhaps sixteen years old, a charming girl, smiling, simple, and lovely. Her skin, like that of all Marquesans, was olive, not brown like the Hawaiians' or yellow like the Chinese, but like that of whites grown dark in the sun. She had black, streaming hair, sloe eyes, and an arch expression. Her manner was artlessly ingratiating, and her sweetness of disposition was not marked by hauteur. When I noticed that her arm was tattoed, she slipped off her dress and sat naked to the waist to show all her adornment.

There was an inscription of three lines stretching from her shoulder to her wrist, the letters nearly an inch in length, crowded together in careless inartistry. The legend was as follows:

“TAHIAKEANA TEIKIMOEATIPANIE PAHAKA AVII ANIPOENUIMATILAILI TETUATONOEINUHAPALIILII”

These were the names given her at birth, and tattooed in her childhood. She was called, she said, Tahiakeana, Weaver of Mats.

Seeing her success among us and noting the champagne, her companions began to thrust forward on to the veranda to share her luck. This angered the governor, who thought his dignity assailed. At Bauda's order, the gendarme and Song of the Nightingale dismissed the visitors, put McHenry to sleep under a tree, and escorted the new executive and me to Bauda's home on the beach.

There in his board shanty, six by ten feet, we ate our first dinner in the islands, while the wind surged through swishing palm-leaves outside, and nuts fell now and then upon the iron roof with the resounding crash of bombs. It was a plain, but plentiful, meal of canned foods, served by the tawny gendarme and the wicked Song, whose term of punishment for distributing brandy seemed curiously suited to his crime.

At midnight I accompanied a happy governor to his palace, which had one spare bedroom, sketchily furnished. During the night the slats of my bed gave way with a dreadful din, and I woke to find the governor in pajamas of rose-colored silk, with pistol in hand, shedding electric rays upon me from a battery lamp. There was anxiety in his manner as he said:

“You never can tell. A chief's son tried to kill my predecessor. I do not know these Marquesans. We are few whites here. And, mon dieu! the guardian of the palace is himself a native!”

Marquesans in Sunday clothes

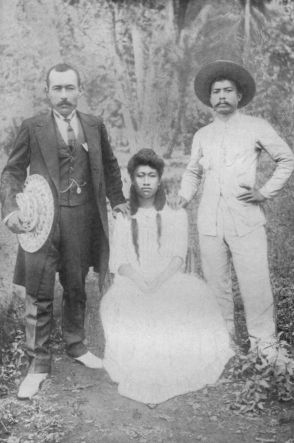

The daughter of Titihuti, chieftess of Hiva-Oa. On the left her husband,

Pierre Pradorat, on the right, his brother

First night in Atuona valley; sensational arrival of the Golden Bed; Titi-huti's tattooed legs.

It was necessary to find at once a residence for my contemplated stay in Atuona, for the schooner sailed on the morrow, and my brief glimpse of the Marquesans had whetted my desire to live among them. I would not accept the courteous invitation of the governor to stay at the palace, for officialdom never knows its surroundings, and grandeur makes for no confidence from the lowly.

Lam Kai Oo, an aged Chinaman whom I encountered at the trader's store, came eagerly to my rescue with an offered lease of his deserted store and bakeshop. From Canton he had been brought in his youth by the labor bosses of western America to help build the transcontinental railway, and later another agency had set him down in Taha-Uka to grow cotton for John Hart. He saw the destruction of that plantation, escaped the plague of opium, and with his scant savings made himself a petty merchant in Atuona. Now he was old and had retired up the valley to the home he had long established there beside his copra furnace and his shrine of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

He led me to the abandoned shack, a long room, tumbledown, moist, festooned with cobwebs, the counters and benches black with reminiscences of twenty thousand tradings and Chinese meals. The windows were but half a dozen bars, and the heavy vapors of a cruel past hung about the sombre walls. Though opium had long been contraband, its acrid odor permeated the worn furnishings. Here with some misgivings I prepared to spend my second night in Hiva-oa.

I left the palace late, and found the shack by its location next the river on the main road. Midnight had come, no creature stirred as I opened the door. The few stars in the black velvet pall of the sky seemed to ray out positive darkness, and the spirit of Po, the Marquesan god of evil, breathed from the unseen, shuddering forest. I tried to damn my mood, but found no profanity utterable. Rain began to fall, and I pushed into the den.

A glimpse of the dismal interior did not cheer me. I locked the door with the great iron key, spread my mat, and blew out the lantern. Soon from out the huge brick oven where for decades Lam Kai Oo had baked his bread there stole scratching, whispering forms that slid along the slippery floor and leaped about the seats where many long since dead had sat. I lay quiet with a will to sleep, but the hair stirred on my scalp.

The darkness was incredible, burdensome, like a weight. The sound of the wind and the rain in the breadfruit forest and the low roar of the torrent became only part of the silence in which those invisible presences crept and rustled. Try as I would I could recall no good deed of mine to shine for me in that shrouded confine. The Celtic vision of my forefathers, that strange mixture of the terrors of Druid and soggarth, danced on the creaking floor, and witch-lights gleamed on ceiling and timbers. I thought to dissolve it all with a match, but whether all awake or partly asleep, I had no strength to reach it.

Then something clammily touched my face, and with a bound I had the lantern going. No living thing moved in the circle of its rays. My flesh crawled on my bones, and sitting upright on my mat I chanted aloud from the Bible in French with Tahitian parallels. The glow of a pipe and the solace of tobacco aided the rhythm of the prophets in dispelling the ghosts of the gloom, but never shipwrecked mariner greeted the dawn with greater joy than I.

In its pale light I peered through the barred windows—the windows of the Chinese the world over—and saw four men who had set down a coffin to rest themselves and smoke a cigarette. They sat on the rude box covered with a black cloth and passed the pandanus-wrapped tobacco about. Naked, except for loin-cloths, their tawny skins gleaming wet in the gray light, rings of tattooing about their eyes, they made a strange picture against the jungle growth.

They were without fire for they had got into a deep place crossing the stream and had wet their matches. I handed a box through the bars, and by reckless use of the few words of Marquesan I recalled, and bits of French they knew, helped out by scraps of Spanish one had gained from the Chilean murderer who milked the cows for the German trader, I learned that the corpse was that of a woman of sixty years, whose agonies had been soothed by the ritual of the Catholic church. The bearers were taking her to Calvary cemetery on the hill.

Their cigarettes smoked, they rose and took up the long poles on which the coffin was swung. Moving with the tread of panthers, firm, noiseless, and graceful, they disappeared into the forest and I was left alone with the morning sun and the glistening leaves of the rain-wet breadfruit-trees.

On the beach an hour later I met Gedge, who asked me with a quizzical eye how I had enjoyed my first night among the Kanakas. I replied that I had seldom passed such a night, spoke glowingly of the forest and the stream, and said that I was still determined to remain behind when the schooner sailed.

“Well, if you will stay,” said he, and the trader's look came into his eye, “I've got just the thing you want. You don't want to lie on a mat where the thousand-legs can get you—and if they get you, you die. You want to live right. Now listen to me; I got the best brass bed ever a king slept on. Double thickness, heavy brass bed, looks like solid gold. Springs that would hold the schooner, double-thick mattress, sheets and pillows all embroidered like it belonged to a duchess. Fellow was going to be married that I brought it for, but now he's lying up there in Calvary in a bed they dug for him. I'll let you have it cheap—three hundred francs. It's worth double. What do you say?”

A brass bed, a golden bed in the cannibal islands!

“It's a go,” I said.

On the deck of the Morning Star I beheld the packing-cases brought up from the hold, and my new purchase with all its parts and appurtenances loaded in a ship's boat, with the iron box that held my gold. So I arrived in Atuona for the second time, high astride the sewed-up mattress on top of the metal parts, and so deftly did the Tahitians handle the oars that, though we rode the surf right up to the creeping jungle flowers that met the tide on Atuona beach, I was not wet except by spray.

Our arrival was watched by a score of Marquesan chiefs who had been summoned by Bauda for the purpose, as he told me, of being urged to thrash the tax-tree more vigorously. The meeting adjourned instantly, and they hastened down from the frame building that housed the government offices. Their curiosity could not be restrained. A score of eager hands stripped the coverings from the brass bed, and exposed the glittering head and foot pieces in the brilliant sunlight. Exclamations of amazement and delight greeted the marvel. This was another wonder from the white men's isles, indicative of wealth and royal taste.

From all sides other natives came hastening. My brass bed and I were the center of a gesticulating circle, dark eyes rolled with excitement and naked shoulder jostled shoulder. Three chiefs, tattooed and haughty, personally erected the bed, and when I disclosed the purpose of the mattress, placed it in position. Every woman present now pushed forward and begged the favor of being allowed to bounce upon it. It became a diversion attended with high honor. Controversies meantime raged about the bed. Many voices estimated the number of mats that would be necessary to equal the thickness of the mattress, but none found a comparison worthy of its softness and elasticity.

In the midst of this mêlée one woman, whose eyes and facial contour betrayed Chinese blood, but who was very comely and neat, pushed forward and pointing to the glittering center of attraction repeated over and over.

“Kisskisskissa? Kisskisskissa?”

For awhile I was disposed to credit her with a sudden affection for me, but soon resolved her query into the French “Qu'est-ce que c'est que ca? What is that?”

She was Apporo, wife of Puhei, Great Fern, she said, and she owned a house in which her father, a Chinaman, had recently died. This house she earnestly desired to give me in exchange for the golden bed, and we struck a bargain. I was to live in the house of Apporo and, on departing, to leave her the bed. Great Fern, her husband, was called to seal the compact. He was a giant in stature, dark skinned, with a serene countenance and crisp hair. They agreed to clean the house thoroughly and to give me possession at once.

They were really mad to have the bed, in all its shiny golden beauty, and once the arrangement was made they could hardly give over examining it, crawling beneath it, smoothing the mattress and fingering the springs. They shook it, poked it, patted it, and finally Apporo, filled with feminine pride, arrogated to herself the sole privilege of bouncing upon it.

Lam Kai Oo wailed his loss of a tenant.

“You savee thlat house belong lep',” he argued earnestly. “My sto'e littee dirty, but I fixum. You go thlat lep' house, bimeby flinger dlop, toe dlop, nose he go.” He grimaced frightfully, and indicated in pantomime the ravages of leprosy upon the human form.

His appeal was in vain. The Golden Bed, upraised on the shoulders of four stalwart chiefs, began its triumphal progress up the valley road. Behind it officiously walked Exploding Eggs, puffed up with importance, regarded on all sides with respect as Tueni Oki Kiki, Keeper of the Golden Bed, but jostled for position by Apporo, envied of women. Behind them up the rough road hastened the rest of the village, eager to see the installation of the marvel in its new quarters, and I followed the barbaric procession leisurely.

My new residence was a mile from the beach, and off the main thoroughfare, though this mattered little. The roads built decades ago by the French are so ruined and neglected that not a thousand feet of them remain in all the islands. No wheel supports a vehicle, not even a wheelbarrow. Trails thread the valleys and climb the hills, and traffic is by horse and human.

My Golden Bed, lurching precariously in the narrow path, led me through tangled jungle growth to the first sight of my new home, a small house painted bright blue and roofed with corrugated iron. Set in the midst of the forest, it was raised from the ground on a paepae, a great platform made of basalt stones, black, smooth and big, the very flesh of the Marquesas Islands. Every house built by a native since their time began has been set on a paepae, and mine had been erected in days beyond the memory of any living man. It was fifty feet broad and as long, raised eight feet from the earth, which was reached by worn steps.

Above the small blue-walled house the rocky peak of Temetiu rose steeply, four thousand feet into the air, its lower reaches clothed in jungle-vines, and trees, its summit dark green under a clear sky, but black when the sun was hidden. Most of the hours of the day it was but a dim shadow above a belt of white clouds, but up to its mysterious heights a broken ridge climbed sheer from the valley, and upon it browsed the wild boar and the crag-loving goat.

Beside the house the river brawled through a greenwood of bread-fruit-, cocoanut-, vi-apple-, mango- and lime-trees. The tropical heat distilled from their leaves a drowsy woodland odor which filled the two small whitewashed rooms, and the shadows of the trees, falling through the wide unglassed windows, made a sun-flecked pattern on the black stone floor. This was the House of Lepers, now rechristened the House of the Golden Bed, which was to be my home through the unknown days before me.

The next day I watched the Morning Star lift her sails and move slowly out of the Bay of Traitors into the open sea, with less regret than I have ever felt in that moment of wistfulness which attends the departure of a sailing-ship. Exploding Eggs, at my side, read correctly my returning eyes. “Kaoha!” he said, with a wide smile of welcome, and with him and Vai, my next-door neighbor, I returned gladly to my paepae.

Vai, or in English, Water, was a youth of twenty years, a dandy; on ordinary occasions naked, except for the pareu about his loins, but on Sundays or when courting rejoicing in the gayest of Europeanized clothes. He lived near me in a small house on the river-bank with his mother and sister. All were of a long line of chiefs, and all marvelously large and handsome.

The mother, Titihuti, would have been beloved of the ancient artists who might have drawn her for an Amazon. I have never seen another woman of such superb carriage. Her hair was blood-red, her brow lofty, and an indescribable air of majesty and pride spoke eloquently of her descent from fathers and mothers of power. She had wonderful legs, statuesque in mold, and tattooed from ankles to thigh in most amazing patterns. To a Marquesan of her generation the tattooed legs of a shapely woman were the highest reach of art.